User login

The fourth trimester: Achieving improved postpartum care

The field of ob.gyn. has long focused significantly more attention on the prenatal period – on determining the optimal frequency of ultrasound examinations, for instance, and on screening for diabetes and other conditions – than on women’s health and well-being after delivery.

The traditional 6-week postpartum visit has too often been a quick and cursory visit, with new mothers typically navigating the preceding postpartum transitions on their own.

The need to redefine postpartum care was a central message of Haywood Brown, MD, who in 2017 served as the president of the America College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Dr. Brown established a task force whose work resulted in important guidance for taking a more comprehensive and patient-centered approach to postpartum care.1

Improved care in the “fourth trimester,” as it has come to be known, is comprehensive and includes ensuring that our patients have a solid transition to health care beyond the pregnancy. We also hope that it will help us to reduce maternal mortality, given that more than half of pregnancy-related deaths occur after delivery.

Timing and frequency of contact

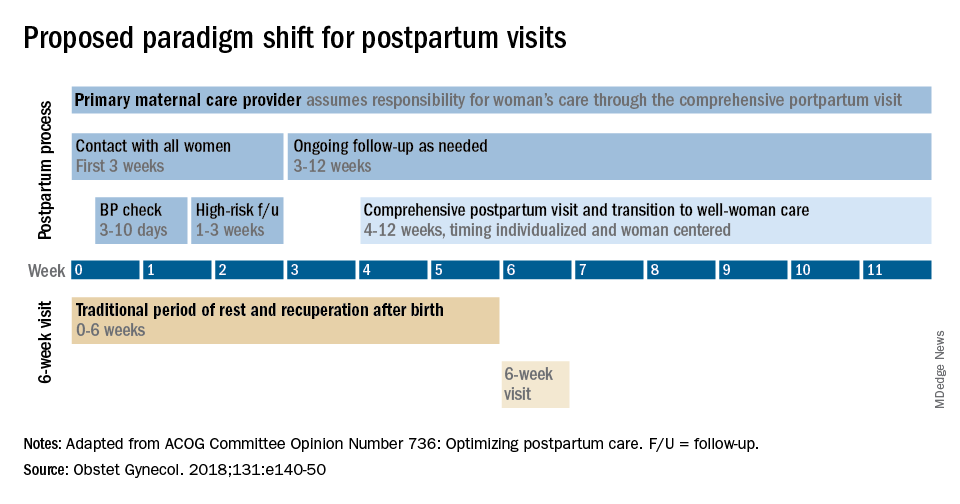

Historically, we’ve had a single 6-week postpartum visit, with little or no maternal support or patient contact before this visit unless the patient reported a complication. In the new paradigm, as described in the ACOG committee opinion on optimizing postpartum care, maternal care should be an ongoing process.1

so that any questions or concerns may be addressed and support can be provided.

This should be followed by individualized, ongoing care until a comprehensive postpartum visit covering physical, social, and psychological well-being is conducted by 12 weeks after birth – anytime between 4 and 12 weeks.

By stressing the importance of postpartum care during prenatal visits – and by talking about some of its key elements such as mental health, breastfeeding, and chronic disease management – we can let our patients know that postpartum care is not just an afterthought, but that it involves planning backed by evidence and expert opinion. Currently, as many as 40% of women do not attend a postpartum visit; early discussion, it is hoped, will increase attendance.

Certain high-risk groups should be seen or screened earlier than 3 weeks post partum. For instance, women who have hypertensive disorders of pregnancy should be evaluated no later than 7-10 days post partum, and women with severe hypertension should be seen within 72 hours, according to ACOG.

Early blood pressure checks – and follow-up as necessary – are critical for reducing the risk of postpartum stroke and other complications. I advocate uniformly checking blood pressure within several days after hospital discharge for all women who have hypertension at the end of their pregnancy.

Other high-risk conditions requiring early follow-up include diabetes and autoimmune conditions such as lupus, multiple sclerosis, and psoriasis that may flare in the postpartum period. Women with a history of postpartum depression similarly may benefit from early contact; they are at higher risk of having depression again, and there are clearly effective treatments, both medication and psychotherapy based.

In between the initial early contact (by 7-10 days post partum or by 3 weeks post partum) and the comprehensive visit between 4 and 12 weeks, the need for and timing of patient contact can be individualized. Some women will need only a brief contact and a visit at 8-10 weeks, while others will need much more. Our goal, as in all of medicine, is to provide individualized, patient-centered care.

Methods of contact

With the exception of the final comprehensive visit, postpartum care need not occur in person. Some conditions require an early office visit, but in general, as ACOG states, the usefulness of an in-person visit should be weighed against the burden of traveling to and attending that visit.

For many women, in-person visits are difficult, and we must be creative in utilizing telemedicine and phone support, text messaging, and app-based support. Having practiced during this pandemic, we are better positioned than ever before to make it relatively easy for new mothers to obtain ongoing postpartum care.

Notably, research is demonstrating that the use of technology may allow us to provide improved care and monitoring of hypertension in the postpartum period. For example, a randomized trial published in 2018 of over 200 women with a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy found that text-based surveillance with home blood pressure monitoring was more effective than usual in-person blood pressure checks in meeting clinical guidelines for postpartum monitoring.2

Women in the texting group were significantly more likely to have a single blood pressure obtained in the first 10 days post partum than women in the office group.

Postpartum care is also not a completely physician-driven endeavor. Much of what is needed to help women successfully navigate the fourth trimester can be provided by certified nurse midwives, advanced practice nurses, and other members of our maternal care teams.

Components of postpartum care

The postpartum care plan should be comprehensive, and having a checklist to guide one through initial and comprehensive visits may be helpful. The ACOG committee opinion categorizes the components of postpartum care into seven domains: mood and emotional well-being; infant care and feeding; sexuality, contraception, and birth spacing; sleep and fatigue; physical recovery from birth; chronic disease management; and health maintenance.1

The importance of screening for depression and anxiety cannot be emphasized enough. Perinatal depression is highly prevalent: It affects as many as one in seven women and can result in adverse short- and long-term effects on both the mother and child.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has offered guidance for years, most recently in 2019 with its recommendations that clinicians refer pregnant and postpartum women who are at increased risk for depression to counseling interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy.3 There is evidence that some form of treatment for women who screen positive reduces the risk of perinatal depression.

Additionally, there is emerging evidence that postpartum PTSD may be as prevalent as postpartum depression.4 As ACOG points out, trauma is “in the eye of the beholder,” and an estimated 3%-16% of women have PTSD related to a traumatic birth experience. Complications like shoulder dystocia or postpartum hemorrhage, in which delivery processes rapidly change course, can be experienced as traumatic by women even though they and their infants are healthy. The risk of posttraumatic stress should be on our radar screen.

Interpregnancy intervals similarly are not discussed enough. We do not commonly talk to patients about how pregnancy and breastfeeding are nutritionally depleting and how it takes time to replenish these stores – yet birth spacing is so important.

Compared with interpregnancy intervals of at least 18 months, intervals shorter than 6 months were associated in a meta-analysis with increased risks of preterm birth, low birth weight, and small for gestational age.5 Optimal birth spacing is one of the few low-cost interventions available for reducing pregnancy complications in the future.

Finally, that chronic disease management is a domain of postpartum care warrants emphasis. We must work to ensure that patients have a solid plan of care in place for their diabetes, hypertension, lupus, or other chronic conditions. This includes who will provide that ongoing care, as well as when medical management should be restarted.

Some women are aware of the importance of timely care – of not waiting for 12 months, for instance, to see an internist or specialist – but others are not.

Again, certain health conditions such as multiple sclerosis and RA necessitate follow-up within a couple weeks after delivery so that medications can be restarted or dose adjustments made. The need for early postpartum follow-up can be discussed during prenatal visits, along with anticipatory guidance about breastfeeding, the signs and symptoms of perinatal depression and anxiety, and other components of the fourth trimester.

Dr. Macones has no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 May;131(5):e140-50.

2. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018 Apr 27;27(11):871-7.

3. JAMA. 2019 Feb 12;321(6):580-7.

4. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014 Jul;34:389-401.JAMA. 2006 Apr 19;295(15):1809-23.

The field of ob.gyn. has long focused significantly more attention on the prenatal period – on determining the optimal frequency of ultrasound examinations, for instance, and on screening for diabetes and other conditions – than on women’s health and well-being after delivery.

The traditional 6-week postpartum visit has too often been a quick and cursory visit, with new mothers typically navigating the preceding postpartum transitions on their own.

The need to redefine postpartum care was a central message of Haywood Brown, MD, who in 2017 served as the president of the America College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Dr. Brown established a task force whose work resulted in important guidance for taking a more comprehensive and patient-centered approach to postpartum care.1

Improved care in the “fourth trimester,” as it has come to be known, is comprehensive and includes ensuring that our patients have a solid transition to health care beyond the pregnancy. We also hope that it will help us to reduce maternal mortality, given that more than half of pregnancy-related deaths occur after delivery.

Timing and frequency of contact

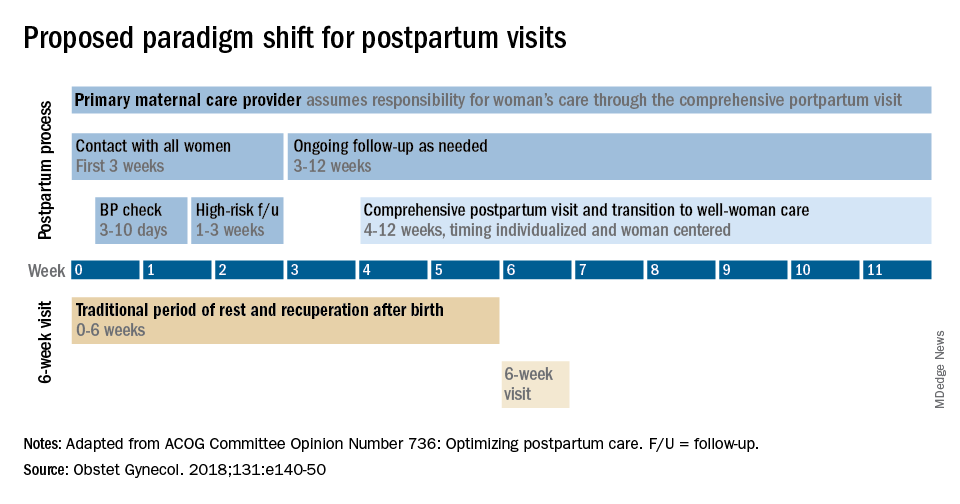

Historically, we’ve had a single 6-week postpartum visit, with little or no maternal support or patient contact before this visit unless the patient reported a complication. In the new paradigm, as described in the ACOG committee opinion on optimizing postpartum care, maternal care should be an ongoing process.1

so that any questions or concerns may be addressed and support can be provided.

This should be followed by individualized, ongoing care until a comprehensive postpartum visit covering physical, social, and psychological well-being is conducted by 12 weeks after birth – anytime between 4 and 12 weeks.

By stressing the importance of postpartum care during prenatal visits – and by talking about some of its key elements such as mental health, breastfeeding, and chronic disease management – we can let our patients know that postpartum care is not just an afterthought, but that it involves planning backed by evidence and expert opinion. Currently, as many as 40% of women do not attend a postpartum visit; early discussion, it is hoped, will increase attendance.

Certain high-risk groups should be seen or screened earlier than 3 weeks post partum. For instance, women who have hypertensive disorders of pregnancy should be evaluated no later than 7-10 days post partum, and women with severe hypertension should be seen within 72 hours, according to ACOG.

Early blood pressure checks – and follow-up as necessary – are critical for reducing the risk of postpartum stroke and other complications. I advocate uniformly checking blood pressure within several days after hospital discharge for all women who have hypertension at the end of their pregnancy.

Other high-risk conditions requiring early follow-up include diabetes and autoimmune conditions such as lupus, multiple sclerosis, and psoriasis that may flare in the postpartum period. Women with a history of postpartum depression similarly may benefit from early contact; they are at higher risk of having depression again, and there are clearly effective treatments, both medication and psychotherapy based.

In between the initial early contact (by 7-10 days post partum or by 3 weeks post partum) and the comprehensive visit between 4 and 12 weeks, the need for and timing of patient contact can be individualized. Some women will need only a brief contact and a visit at 8-10 weeks, while others will need much more. Our goal, as in all of medicine, is to provide individualized, patient-centered care.

Methods of contact

With the exception of the final comprehensive visit, postpartum care need not occur in person. Some conditions require an early office visit, but in general, as ACOG states, the usefulness of an in-person visit should be weighed against the burden of traveling to and attending that visit.

For many women, in-person visits are difficult, and we must be creative in utilizing telemedicine and phone support, text messaging, and app-based support. Having practiced during this pandemic, we are better positioned than ever before to make it relatively easy for new mothers to obtain ongoing postpartum care.

Notably, research is demonstrating that the use of technology may allow us to provide improved care and monitoring of hypertension in the postpartum period. For example, a randomized trial published in 2018 of over 200 women with a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy found that text-based surveillance with home blood pressure monitoring was more effective than usual in-person blood pressure checks in meeting clinical guidelines for postpartum monitoring.2

Women in the texting group were significantly more likely to have a single blood pressure obtained in the first 10 days post partum than women in the office group.

Postpartum care is also not a completely physician-driven endeavor. Much of what is needed to help women successfully navigate the fourth trimester can be provided by certified nurse midwives, advanced practice nurses, and other members of our maternal care teams.

Components of postpartum care

The postpartum care plan should be comprehensive, and having a checklist to guide one through initial and comprehensive visits may be helpful. The ACOG committee opinion categorizes the components of postpartum care into seven domains: mood and emotional well-being; infant care and feeding; sexuality, contraception, and birth spacing; sleep and fatigue; physical recovery from birth; chronic disease management; and health maintenance.1

The importance of screening for depression and anxiety cannot be emphasized enough. Perinatal depression is highly prevalent: It affects as many as one in seven women and can result in adverse short- and long-term effects on both the mother and child.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has offered guidance for years, most recently in 2019 with its recommendations that clinicians refer pregnant and postpartum women who are at increased risk for depression to counseling interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy.3 There is evidence that some form of treatment for women who screen positive reduces the risk of perinatal depression.

Additionally, there is emerging evidence that postpartum PTSD may be as prevalent as postpartum depression.4 As ACOG points out, trauma is “in the eye of the beholder,” and an estimated 3%-16% of women have PTSD related to a traumatic birth experience. Complications like shoulder dystocia or postpartum hemorrhage, in which delivery processes rapidly change course, can be experienced as traumatic by women even though they and their infants are healthy. The risk of posttraumatic stress should be on our radar screen.

Interpregnancy intervals similarly are not discussed enough. We do not commonly talk to patients about how pregnancy and breastfeeding are nutritionally depleting and how it takes time to replenish these stores – yet birth spacing is so important.

Compared with interpregnancy intervals of at least 18 months, intervals shorter than 6 months were associated in a meta-analysis with increased risks of preterm birth, low birth weight, and small for gestational age.5 Optimal birth spacing is one of the few low-cost interventions available for reducing pregnancy complications in the future.

Finally, that chronic disease management is a domain of postpartum care warrants emphasis. We must work to ensure that patients have a solid plan of care in place for their diabetes, hypertension, lupus, or other chronic conditions. This includes who will provide that ongoing care, as well as when medical management should be restarted.

Some women are aware of the importance of timely care – of not waiting for 12 months, for instance, to see an internist or specialist – but others are not.

Again, certain health conditions such as multiple sclerosis and RA necessitate follow-up within a couple weeks after delivery so that medications can be restarted or dose adjustments made. The need for early postpartum follow-up can be discussed during prenatal visits, along with anticipatory guidance about breastfeeding, the signs and symptoms of perinatal depression and anxiety, and other components of the fourth trimester.

Dr. Macones has no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 May;131(5):e140-50.

2. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018 Apr 27;27(11):871-7.

3. JAMA. 2019 Feb 12;321(6):580-7.

4. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014 Jul;34:389-401.JAMA. 2006 Apr 19;295(15):1809-23.

The field of ob.gyn. has long focused significantly more attention on the prenatal period – on determining the optimal frequency of ultrasound examinations, for instance, and on screening for diabetes and other conditions – than on women’s health and well-being after delivery.

The traditional 6-week postpartum visit has too often been a quick and cursory visit, with new mothers typically navigating the preceding postpartum transitions on their own.

The need to redefine postpartum care was a central message of Haywood Brown, MD, who in 2017 served as the president of the America College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Dr. Brown established a task force whose work resulted in important guidance for taking a more comprehensive and patient-centered approach to postpartum care.1

Improved care in the “fourth trimester,” as it has come to be known, is comprehensive and includes ensuring that our patients have a solid transition to health care beyond the pregnancy. We also hope that it will help us to reduce maternal mortality, given that more than half of pregnancy-related deaths occur after delivery.

Timing and frequency of contact

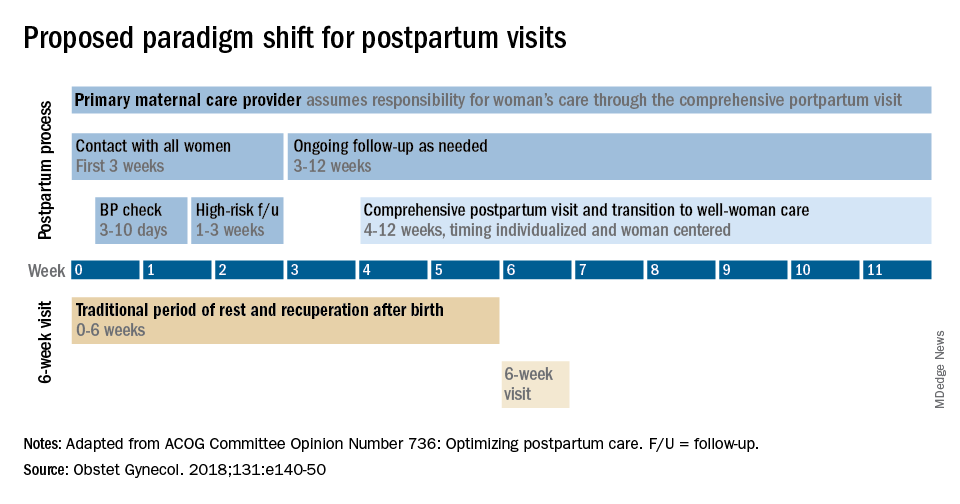

Historically, we’ve had a single 6-week postpartum visit, with little or no maternal support or patient contact before this visit unless the patient reported a complication. In the new paradigm, as described in the ACOG committee opinion on optimizing postpartum care, maternal care should be an ongoing process.1

so that any questions or concerns may be addressed and support can be provided.

This should be followed by individualized, ongoing care until a comprehensive postpartum visit covering physical, social, and psychological well-being is conducted by 12 weeks after birth – anytime between 4 and 12 weeks.

By stressing the importance of postpartum care during prenatal visits – and by talking about some of its key elements such as mental health, breastfeeding, and chronic disease management – we can let our patients know that postpartum care is not just an afterthought, but that it involves planning backed by evidence and expert opinion. Currently, as many as 40% of women do not attend a postpartum visit; early discussion, it is hoped, will increase attendance.

Certain high-risk groups should be seen or screened earlier than 3 weeks post partum. For instance, women who have hypertensive disorders of pregnancy should be evaluated no later than 7-10 days post partum, and women with severe hypertension should be seen within 72 hours, according to ACOG.

Early blood pressure checks – and follow-up as necessary – are critical for reducing the risk of postpartum stroke and other complications. I advocate uniformly checking blood pressure within several days after hospital discharge for all women who have hypertension at the end of their pregnancy.

Other high-risk conditions requiring early follow-up include diabetes and autoimmune conditions such as lupus, multiple sclerosis, and psoriasis that may flare in the postpartum period. Women with a history of postpartum depression similarly may benefit from early contact; they are at higher risk of having depression again, and there are clearly effective treatments, both medication and psychotherapy based.

In between the initial early contact (by 7-10 days post partum or by 3 weeks post partum) and the comprehensive visit between 4 and 12 weeks, the need for and timing of patient contact can be individualized. Some women will need only a brief contact and a visit at 8-10 weeks, while others will need much more. Our goal, as in all of medicine, is to provide individualized, patient-centered care.

Methods of contact

With the exception of the final comprehensive visit, postpartum care need not occur in person. Some conditions require an early office visit, but in general, as ACOG states, the usefulness of an in-person visit should be weighed against the burden of traveling to and attending that visit.

For many women, in-person visits are difficult, and we must be creative in utilizing telemedicine and phone support, text messaging, and app-based support. Having practiced during this pandemic, we are better positioned than ever before to make it relatively easy for new mothers to obtain ongoing postpartum care.

Notably, research is demonstrating that the use of technology may allow us to provide improved care and monitoring of hypertension in the postpartum period. For example, a randomized trial published in 2018 of over 200 women with a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy found that text-based surveillance with home blood pressure monitoring was more effective than usual in-person blood pressure checks in meeting clinical guidelines for postpartum monitoring.2

Women in the texting group were significantly more likely to have a single blood pressure obtained in the first 10 days post partum than women in the office group.

Postpartum care is also not a completely physician-driven endeavor. Much of what is needed to help women successfully navigate the fourth trimester can be provided by certified nurse midwives, advanced practice nurses, and other members of our maternal care teams.

Components of postpartum care

The postpartum care plan should be comprehensive, and having a checklist to guide one through initial and comprehensive visits may be helpful. The ACOG committee opinion categorizes the components of postpartum care into seven domains: mood and emotional well-being; infant care and feeding; sexuality, contraception, and birth spacing; sleep and fatigue; physical recovery from birth; chronic disease management; and health maintenance.1

The importance of screening for depression and anxiety cannot be emphasized enough. Perinatal depression is highly prevalent: It affects as many as one in seven women and can result in adverse short- and long-term effects on both the mother and child.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has offered guidance for years, most recently in 2019 with its recommendations that clinicians refer pregnant and postpartum women who are at increased risk for depression to counseling interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy.3 There is evidence that some form of treatment for women who screen positive reduces the risk of perinatal depression.

Additionally, there is emerging evidence that postpartum PTSD may be as prevalent as postpartum depression.4 As ACOG points out, trauma is “in the eye of the beholder,” and an estimated 3%-16% of women have PTSD related to a traumatic birth experience. Complications like shoulder dystocia or postpartum hemorrhage, in which delivery processes rapidly change course, can be experienced as traumatic by women even though they and their infants are healthy. The risk of posttraumatic stress should be on our radar screen.

Interpregnancy intervals similarly are not discussed enough. We do not commonly talk to patients about how pregnancy and breastfeeding are nutritionally depleting and how it takes time to replenish these stores – yet birth spacing is so important.

Compared with interpregnancy intervals of at least 18 months, intervals shorter than 6 months were associated in a meta-analysis with increased risks of preterm birth, low birth weight, and small for gestational age.5 Optimal birth spacing is one of the few low-cost interventions available for reducing pregnancy complications in the future.

Finally, that chronic disease management is a domain of postpartum care warrants emphasis. We must work to ensure that patients have a solid plan of care in place for their diabetes, hypertension, lupus, or other chronic conditions. This includes who will provide that ongoing care, as well as when medical management should be restarted.

Some women are aware of the importance of timely care – of not waiting for 12 months, for instance, to see an internist or specialist – but others are not.

Again, certain health conditions such as multiple sclerosis and RA necessitate follow-up within a couple weeks after delivery so that medications can be restarted or dose adjustments made. The need for early postpartum follow-up can be discussed during prenatal visits, along with anticipatory guidance about breastfeeding, the signs and symptoms of perinatal depression and anxiety, and other components of the fourth trimester.

Dr. Macones has no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 May;131(5):e140-50.

2. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018 Apr 27;27(11):871-7.

3. JAMA. 2019 Feb 12;321(6):580-7.

4. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014 Jul;34:389-401.JAMA. 2006 Apr 19;295(15):1809-23.

The fourth trimester

As we approach the end of this year, one of the most surreal times in human history, we will look back on the many things we taught ourselves, the many things we took for granted, the many things we were grateful for, the many things we missed, and the many things we plan to do once we can do things again. Among the many things 2020 taught us to appreciate was the very real manifestation of the old adage, “prevention is the best medicine.” To prevent transmission of SARS-CoV-2, we wore masks, we sanitized everything, we avoided crowds, we traded in-person meetings for virtual meetings, we learned how to homeschool our children, and we delayed seeing relatives and friends.

Ob.gyns. in small and large practices around the world had the tremendous challenge of balancing necessary in-person prenatal care services with keeping their patients and babies safe. Labor and delivery units had even greater demands to keep women and neonates free of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Practices quickly put into place new treatment protocols and new management strategies to maintain the health of their staff while ensuring a high quality of care.

While we have focused much of our attention on greater precautions during pregnancy and childbirth, an important component of care is the immediate postpartum period – colloquially referred to as the “fourth trimester” – which remains critical to maintaining physical and mental health and well-being.

Despite concerns regarding COVID-19 safety, we should continue monitoring our patients during these crucial first weeks after childbirth. This year of social isolation, financial strain, and incredible uncertainty has created additional stress in many women’s lives. The usual support that some women would receive from family members, friends, and other mothers in the early days post partum may not be available. The pandemic also has further highlighted inequities in access to health care for vulnerable groups. In addition, restrictions have increased the incidence of intimate partner violence as many women and children have needed to shelter with their abusers. Perhaps now more than any time previously, ob.gyns. must be attuned to their patients’ needs and be ready to provide compassionate and sensitive care.

In this final month of the year, we have invited George A. Macones, MD, professor and chair of the department of women’s health at the University of Texas, Austin, to address the importance of care in the final “trimester” of pregnancy – the first 3 months post partum.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is executive vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He is the medical editor of this column. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Contact him at [email protected].

*This version has been updated to correct an erroneous byline, photo, and bio.

As we approach the end of this year, one of the most surreal times in human history, we will look back on the many things we taught ourselves, the many things we took for granted, the many things we were grateful for, the many things we missed, and the many things we plan to do once we can do things again. Among the many things 2020 taught us to appreciate was the very real manifestation of the old adage, “prevention is the best medicine.” To prevent transmission of SARS-CoV-2, we wore masks, we sanitized everything, we avoided crowds, we traded in-person meetings for virtual meetings, we learned how to homeschool our children, and we delayed seeing relatives and friends.

Ob.gyns. in small and large practices around the world had the tremendous challenge of balancing necessary in-person prenatal care services with keeping their patients and babies safe. Labor and delivery units had even greater demands to keep women and neonates free of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Practices quickly put into place new treatment protocols and new management strategies to maintain the health of their staff while ensuring a high quality of care.

While we have focused much of our attention on greater precautions during pregnancy and childbirth, an important component of care is the immediate postpartum period – colloquially referred to as the “fourth trimester” – which remains critical to maintaining physical and mental health and well-being.

Despite concerns regarding COVID-19 safety, we should continue monitoring our patients during these crucial first weeks after childbirth. This year of social isolation, financial strain, and incredible uncertainty has created additional stress in many women’s lives. The usual support that some women would receive from family members, friends, and other mothers in the early days post partum may not be available. The pandemic also has further highlighted inequities in access to health care for vulnerable groups. In addition, restrictions have increased the incidence of intimate partner violence as many women and children have needed to shelter with their abusers. Perhaps now more than any time previously, ob.gyns. must be attuned to their patients’ needs and be ready to provide compassionate and sensitive care.

In this final month of the year, we have invited George A. Macones, MD, professor and chair of the department of women’s health at the University of Texas, Austin, to address the importance of care in the final “trimester” of pregnancy – the first 3 months post partum.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is executive vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He is the medical editor of this column. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Contact him at [email protected].

*This version has been updated to correct an erroneous byline, photo, and bio.

As we approach the end of this year, one of the most surreal times in human history, we will look back on the many things we taught ourselves, the many things we took for granted, the many things we were grateful for, the many things we missed, and the many things we plan to do once we can do things again. Among the many things 2020 taught us to appreciate was the very real manifestation of the old adage, “prevention is the best medicine.” To prevent transmission of SARS-CoV-2, we wore masks, we sanitized everything, we avoided crowds, we traded in-person meetings for virtual meetings, we learned how to homeschool our children, and we delayed seeing relatives and friends.

Ob.gyns. in small and large practices around the world had the tremendous challenge of balancing necessary in-person prenatal care services with keeping their patients and babies safe. Labor and delivery units had even greater demands to keep women and neonates free of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Practices quickly put into place new treatment protocols and new management strategies to maintain the health of their staff while ensuring a high quality of care.

While we have focused much of our attention on greater precautions during pregnancy and childbirth, an important component of care is the immediate postpartum period – colloquially referred to as the “fourth trimester” – which remains critical to maintaining physical and mental health and well-being.

Despite concerns regarding COVID-19 safety, we should continue monitoring our patients during these crucial first weeks after childbirth. This year of social isolation, financial strain, and incredible uncertainty has created additional stress in many women’s lives. The usual support that some women would receive from family members, friends, and other mothers in the early days post partum may not be available. The pandemic also has further highlighted inequities in access to health care for vulnerable groups. In addition, restrictions have increased the incidence of intimate partner violence as many women and children have needed to shelter with their abusers. Perhaps now more than any time previously, ob.gyns. must be attuned to their patients’ needs and be ready to provide compassionate and sensitive care.

In this final month of the year, we have invited George A. Macones, MD, professor and chair of the department of women’s health at the University of Texas, Austin, to address the importance of care in the final “trimester” of pregnancy – the first 3 months post partum.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is executive vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He is the medical editor of this column. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. Contact him at [email protected].

*This version has been updated to correct an erroneous byline, photo, and bio.

Scientific power will save us

COVID-19 numbers again are increasing dramatically. Community infection rates have nearly doubled, and hospitals and health care workers are stretched beyond their limits. It is difficult not to feel anger about how poorly this pandemic was managed (mismanaged) by so many officials in charge and by a large segment of our population who still refuse protective actions to limit spread. While politics and ideology continue to cost American lives, scientific firepower will emerge as our saving grace.

My editorial board and I are entering our final year at the helm of GI & Hepatology News. AGA issued a search for the next Editor in Chief (EIC), who will take over October 2021. I urge anyone interested to apply (https://gastro.org/news/prestigious-aga-publications-seek-new-editors-in-chief/). As EIC, you will choose the next editorial board and forge professional friendships that are gratifying. You will assume responsibility for the content, where you must balance your own views with those of both the AGA and our readership.

As EIC, each month I am given space for 300 words to communicate interesting ideas and opinions. The AGA gives the newspaper great editorial freedom, and I hope we have supported AGA’s mission and values when we publish its official newspaper. I always have next month’s editorial in mind, and I look for useful phrases, quotes, ideas, and opinions. If you are interested in becoming EIC, please email [email protected] for more information.

I would be remiss not to acknowledge the contribution that Lora McGlade has made to GI & Hepatology News. She has been my partner, as the Frontline Medical Communications Editor in charge of GI & Hepatology News. Next month, she will move on to assume a new role. I cannot thank her enough for helping make this newspaper work. As the months go on, I will highlight the contributions of others from the AGA, our Board, and Frontline.

Please stay safe and do not let your guard down. COVID-19 is merciless and relentless. “If you think research is expensive, try disease.” – Mary Lasker.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGA

Editor in Chief

COVID-19 numbers again are increasing dramatically. Community infection rates have nearly doubled, and hospitals and health care workers are stretched beyond their limits. It is difficult not to feel anger about how poorly this pandemic was managed (mismanaged) by so many officials in charge and by a large segment of our population who still refuse protective actions to limit spread. While politics and ideology continue to cost American lives, scientific firepower will emerge as our saving grace.

My editorial board and I are entering our final year at the helm of GI & Hepatology News. AGA issued a search for the next Editor in Chief (EIC), who will take over October 2021. I urge anyone interested to apply (https://gastro.org/news/prestigious-aga-publications-seek-new-editors-in-chief/). As EIC, you will choose the next editorial board and forge professional friendships that are gratifying. You will assume responsibility for the content, where you must balance your own views with those of both the AGA and our readership.

As EIC, each month I am given space for 300 words to communicate interesting ideas and opinions. The AGA gives the newspaper great editorial freedom, and I hope we have supported AGA’s mission and values when we publish its official newspaper. I always have next month’s editorial in mind, and I look for useful phrases, quotes, ideas, and opinions. If you are interested in becoming EIC, please email [email protected] for more information.

I would be remiss not to acknowledge the contribution that Lora McGlade has made to GI & Hepatology News. She has been my partner, as the Frontline Medical Communications Editor in charge of GI & Hepatology News. Next month, she will move on to assume a new role. I cannot thank her enough for helping make this newspaper work. As the months go on, I will highlight the contributions of others from the AGA, our Board, and Frontline.

Please stay safe and do not let your guard down. COVID-19 is merciless and relentless. “If you think research is expensive, try disease.” – Mary Lasker.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGA

Editor in Chief

COVID-19 numbers again are increasing dramatically. Community infection rates have nearly doubled, and hospitals and health care workers are stretched beyond their limits. It is difficult not to feel anger about how poorly this pandemic was managed (mismanaged) by so many officials in charge and by a large segment of our population who still refuse protective actions to limit spread. While politics and ideology continue to cost American lives, scientific firepower will emerge as our saving grace.

My editorial board and I are entering our final year at the helm of GI & Hepatology News. AGA issued a search for the next Editor in Chief (EIC), who will take over October 2021. I urge anyone interested to apply (https://gastro.org/news/prestigious-aga-publications-seek-new-editors-in-chief/). As EIC, you will choose the next editorial board and forge professional friendships that are gratifying. You will assume responsibility for the content, where you must balance your own views with those of both the AGA and our readership.

As EIC, each month I am given space for 300 words to communicate interesting ideas and opinions. The AGA gives the newspaper great editorial freedom, and I hope we have supported AGA’s mission and values when we publish its official newspaper. I always have next month’s editorial in mind, and I look for useful phrases, quotes, ideas, and opinions. If you are interested in becoming EIC, please email [email protected] for more information.

I would be remiss not to acknowledge the contribution that Lora McGlade has made to GI & Hepatology News. She has been my partner, as the Frontline Medical Communications Editor in charge of GI & Hepatology News. Next month, she will move on to assume a new role. I cannot thank her enough for helping make this newspaper work. As the months go on, I will highlight the contributions of others from the AGA, our Board, and Frontline.

Please stay safe and do not let your guard down. COVID-19 is merciless and relentless. “If you think research is expensive, try disease.” – Mary Lasker.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGA

Editor in Chief

How much longer?

SHM has changed direction as needed during the pandemic

“How much longer?” As a kid, I can remember the long holiday car ride with my parents from my home in Annapolis, Md., to Upstate New York where my grandparents lived. At the time, the ride felt like an eternity: endless miles of frozen landscape, limited food, and a brother who constantly crossed over the invisible line that was my side of the car.

We made our parents crazy asking, “how much longer?” every few minutes. This was the late 1970s, with no GPS or Google Maps to give you arrival times to the minute, traffic warnings, or reroutes when the inevitable delays occurred. We just plowed ahead, and my parents’ answer was always something vague like, “in a few hours” or “we’re about halfway through.” They did not know when we’d arrive with certainty either.

We at SHM have that same feeling about the pandemic. How much longer? No one can tell us when the COVID-19 threat will abate. The experts’ answers are understandably vague, and the tools for forecasting are non-existent. Months? That is the best we know for now.

At SHM, we believe we will make it through this journey by adapting to roadblocks, providing tools for success to our professional community, and identifying opportunities for us to connect with each other, even if that means virtually.

Like the rest of the planet, the spring of 2020 hit SHM with a shock. Hospital Medicine 2020 (HM20) in San Diego was shaping up to be the largest Annual Conference SHM ever had, the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2020 (PHM20) conference was well planned and expected to be a huge success, regional SHM chapters were meeting (and growing), and membership was thriving. I was transitioning out of my roles at Johns Hopkins and looking forward to my new role as CEO of SHM. All in all, March 2020 began with a fantastic outlook.

Wow, what a difference a few weeks made. We watched as the pandemic spread across regions of the country, concerned for the wellbeing of our patients and our hospitalists. We saw how our members were at the forefront of patient care during this crisis and understood that SHM had to adapt rapidly to meet their needs in real time.

By May, SHM had canceled HM20, Chapter activity was halted, PHM20 was on its way to being canceled, SHM committee work was put on hold, and I was spending my last few months at Hopkins as the chief medical officer at the Baltimore Convention Center Field Hospital (which we got up and running in less than a month)! Whew.

But just like my dad could pivot our 1970s Chevy station wagon around a traffic jam in a flash, so too did SHM leadership start navigating around the COVID-19 landscape. As soon as HM20 was canceled, SHM immediately began planning for a virtual offering in August. We had hoped to attract at least 100 attendees and we were thrilled to have more than 1,000! PHM20 was switched from an in-person to a virtual meeting with 634 attendees. We launched numerous COVID-19 webinars and made our clinical and educational offerings open access. Our Public Policy Committee was active around both COVID-19 and hospitalist-related topics – immigration, telehealth, wellbeing, and financial impacts, to name a few. (And I even met with the POTUS & advocated for PPE.) The Journal of Hospital Medicine worked with authors to get important publications out at record speed. And of course, The Hospitalist connected all of us to our professional leaders and experts.

By the fall of 2020, SHM had actively adjusted to the “new normal” of this pandemic: SHM staff have settled into their new “work from home” environments, SHM Chapters are connecting members in the virtual world, SHM’s 2021 Annual Conference will be all virtual – rebranded as “SHM Converge” – and the State of Hospital Medicine Report (our every-other-year source for trends in hospital medicine) now has a COVID-19 supplement, which was developed at lightning speed. Even our SHM Board of Directors is meeting virtually! All this while advancing the routine work at SHM, which never faltered. Our work on resources for quality improvement, the opioid epidemic, wellbeing, diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI), leadership, professional development, advocacy, and so much more is as active as ever.

I don’t know how much longer we have on this very long pandemic journey, so I’ll use my father’s answer of “we’re about halfway through.” We have been immersed in it for months already, with months still ahead. But regardless of the upcoming twists and turns COVID-19 forces you, our patients, and our larger society to take, SHM is ready to change direction faster than a 1970s Chevy. The SHM staff, leadership, and members will be sure that hospitalists receive the tools to navigate these unprecedented times. Our patients need our skills to get through this as safely as possible. While we may not be able to tell them “how much longer,” we can certainly be prepared for the long road ahead as we begin 2021.

Dr. Howell is CEO of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

SHM has changed direction as needed during the pandemic

SHM has changed direction as needed during the pandemic

“How much longer?” As a kid, I can remember the long holiday car ride with my parents from my home in Annapolis, Md., to Upstate New York where my grandparents lived. At the time, the ride felt like an eternity: endless miles of frozen landscape, limited food, and a brother who constantly crossed over the invisible line that was my side of the car.

We made our parents crazy asking, “how much longer?” every few minutes. This was the late 1970s, with no GPS or Google Maps to give you arrival times to the minute, traffic warnings, or reroutes when the inevitable delays occurred. We just plowed ahead, and my parents’ answer was always something vague like, “in a few hours” or “we’re about halfway through.” They did not know when we’d arrive with certainty either.

We at SHM have that same feeling about the pandemic. How much longer? No one can tell us when the COVID-19 threat will abate. The experts’ answers are understandably vague, and the tools for forecasting are non-existent. Months? That is the best we know for now.

At SHM, we believe we will make it through this journey by adapting to roadblocks, providing tools for success to our professional community, and identifying opportunities for us to connect with each other, even if that means virtually.

Like the rest of the planet, the spring of 2020 hit SHM with a shock. Hospital Medicine 2020 (HM20) in San Diego was shaping up to be the largest Annual Conference SHM ever had, the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2020 (PHM20) conference was well planned and expected to be a huge success, regional SHM chapters were meeting (and growing), and membership was thriving. I was transitioning out of my roles at Johns Hopkins and looking forward to my new role as CEO of SHM. All in all, March 2020 began with a fantastic outlook.

Wow, what a difference a few weeks made. We watched as the pandemic spread across regions of the country, concerned for the wellbeing of our patients and our hospitalists. We saw how our members were at the forefront of patient care during this crisis and understood that SHM had to adapt rapidly to meet their needs in real time.

By May, SHM had canceled HM20, Chapter activity was halted, PHM20 was on its way to being canceled, SHM committee work was put on hold, and I was spending my last few months at Hopkins as the chief medical officer at the Baltimore Convention Center Field Hospital (which we got up and running in less than a month)! Whew.

But just like my dad could pivot our 1970s Chevy station wagon around a traffic jam in a flash, so too did SHM leadership start navigating around the COVID-19 landscape. As soon as HM20 was canceled, SHM immediately began planning for a virtual offering in August. We had hoped to attract at least 100 attendees and we were thrilled to have more than 1,000! PHM20 was switched from an in-person to a virtual meeting with 634 attendees. We launched numerous COVID-19 webinars and made our clinical and educational offerings open access. Our Public Policy Committee was active around both COVID-19 and hospitalist-related topics – immigration, telehealth, wellbeing, and financial impacts, to name a few. (And I even met with the POTUS & advocated for PPE.) The Journal of Hospital Medicine worked with authors to get important publications out at record speed. And of course, The Hospitalist connected all of us to our professional leaders and experts.

By the fall of 2020, SHM had actively adjusted to the “new normal” of this pandemic: SHM staff have settled into their new “work from home” environments, SHM Chapters are connecting members in the virtual world, SHM’s 2021 Annual Conference will be all virtual – rebranded as “SHM Converge” – and the State of Hospital Medicine Report (our every-other-year source for trends in hospital medicine) now has a COVID-19 supplement, which was developed at lightning speed. Even our SHM Board of Directors is meeting virtually! All this while advancing the routine work at SHM, which never faltered. Our work on resources for quality improvement, the opioid epidemic, wellbeing, diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI), leadership, professional development, advocacy, and so much more is as active as ever.

I don’t know how much longer we have on this very long pandemic journey, so I’ll use my father’s answer of “we’re about halfway through.” We have been immersed in it for months already, with months still ahead. But regardless of the upcoming twists and turns COVID-19 forces you, our patients, and our larger society to take, SHM is ready to change direction faster than a 1970s Chevy. The SHM staff, leadership, and members will be sure that hospitalists receive the tools to navigate these unprecedented times. Our patients need our skills to get through this as safely as possible. While we may not be able to tell them “how much longer,” we can certainly be prepared for the long road ahead as we begin 2021.

Dr. Howell is CEO of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

“How much longer?” As a kid, I can remember the long holiday car ride with my parents from my home in Annapolis, Md., to Upstate New York where my grandparents lived. At the time, the ride felt like an eternity: endless miles of frozen landscape, limited food, and a brother who constantly crossed over the invisible line that was my side of the car.

We made our parents crazy asking, “how much longer?” every few minutes. This was the late 1970s, with no GPS or Google Maps to give you arrival times to the minute, traffic warnings, or reroutes when the inevitable delays occurred. We just plowed ahead, and my parents’ answer was always something vague like, “in a few hours” or “we’re about halfway through.” They did not know when we’d arrive with certainty either.

We at SHM have that same feeling about the pandemic. How much longer? No one can tell us when the COVID-19 threat will abate. The experts’ answers are understandably vague, and the tools for forecasting are non-existent. Months? That is the best we know for now.

At SHM, we believe we will make it through this journey by adapting to roadblocks, providing tools for success to our professional community, and identifying opportunities for us to connect with each other, even if that means virtually.

Like the rest of the planet, the spring of 2020 hit SHM with a shock. Hospital Medicine 2020 (HM20) in San Diego was shaping up to be the largest Annual Conference SHM ever had, the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2020 (PHM20) conference was well planned and expected to be a huge success, regional SHM chapters were meeting (and growing), and membership was thriving. I was transitioning out of my roles at Johns Hopkins and looking forward to my new role as CEO of SHM. All in all, March 2020 began with a fantastic outlook.

Wow, what a difference a few weeks made. We watched as the pandemic spread across regions of the country, concerned for the wellbeing of our patients and our hospitalists. We saw how our members were at the forefront of patient care during this crisis and understood that SHM had to adapt rapidly to meet their needs in real time.

By May, SHM had canceled HM20, Chapter activity was halted, PHM20 was on its way to being canceled, SHM committee work was put on hold, and I was spending my last few months at Hopkins as the chief medical officer at the Baltimore Convention Center Field Hospital (which we got up and running in less than a month)! Whew.

But just like my dad could pivot our 1970s Chevy station wagon around a traffic jam in a flash, so too did SHM leadership start navigating around the COVID-19 landscape. As soon as HM20 was canceled, SHM immediately began planning for a virtual offering in August. We had hoped to attract at least 100 attendees and we were thrilled to have more than 1,000! PHM20 was switched from an in-person to a virtual meeting with 634 attendees. We launched numerous COVID-19 webinars and made our clinical and educational offerings open access. Our Public Policy Committee was active around both COVID-19 and hospitalist-related topics – immigration, telehealth, wellbeing, and financial impacts, to name a few. (And I even met with the POTUS & advocated for PPE.) The Journal of Hospital Medicine worked with authors to get important publications out at record speed. And of course, The Hospitalist connected all of us to our professional leaders and experts.

By the fall of 2020, SHM had actively adjusted to the “new normal” of this pandemic: SHM staff have settled into their new “work from home” environments, SHM Chapters are connecting members in the virtual world, SHM’s 2021 Annual Conference will be all virtual – rebranded as “SHM Converge” – and the State of Hospital Medicine Report (our every-other-year source for trends in hospital medicine) now has a COVID-19 supplement, which was developed at lightning speed. Even our SHM Board of Directors is meeting virtually! All this while advancing the routine work at SHM, which never faltered. Our work on resources for quality improvement, the opioid epidemic, wellbeing, diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI), leadership, professional development, advocacy, and so much more is as active as ever.

I don’t know how much longer we have on this very long pandemic journey, so I’ll use my father’s answer of “we’re about halfway through.” We have been immersed in it for months already, with months still ahead. But regardless of the upcoming twists and turns COVID-19 forces you, our patients, and our larger society to take, SHM is ready to change direction faster than a 1970s Chevy. The SHM staff, leadership, and members will be sure that hospitalists receive the tools to navigate these unprecedented times. Our patients need our skills to get through this as safely as possible. While we may not be able to tell them “how much longer,” we can certainly be prepared for the long road ahead as we begin 2021.

Dr. Howell is CEO of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

What the Biden-Harris COVID-19 Advisory Board is missing

On Nov. 9, the Biden-Harris administration announced the members of its COVID-19 Advisory Board. Among them were many esteemed infectious disease and public health experts – encouraging, given that, for now, the COVID-19 pandemic shows no signs of slowing down. Not among them was a mental health professional.

As psychiatrists, we did not find this omission surprising, given the sidelined role our specialty too often plays among medical professionals. But we did find it disappointing. Not having a single behavioral health provider on the advisory board will prove to be a mistake that could affect millions of Americans.

Studies continue to roll in showing that patients with COVID-19 can present during and after infection with neuropsychiatric symptoms, including delirium, psychosis, and anxiety. In July, a meta-analysis published in The Lancet regarding the neuropsychological outcomes of earlier diseases caused by coronaviruses – severe acute respiratory syndrome and Middle East respiratory syndrome – suggested that, in the short term, close to one-quarter of patients experienced confusion representative of delirium. In the long term, following recovery, respondents frequently reported emotional lability, impaired concentration, and traumatic memories. Additionally, more recent research published in The Lancet suggests that rates of psychiatric disorders, dementia, and insomnia are significantly higher among survivors of COVID-19. This study echoes the findings of an article in JAMA from September that reported that, among patients who were hospitalized for COVID-19, mortality rates were higher for those who had previously been diagnosed with a psychiatric condition. And overall, the pandemic has been associated with significantly increased rates of anxiety and depression symptoms.

Although this research is preliminary,

This is especially true when you consider the following:

- It is very difficult to diagnose and treat mental health symptoms in a primary care setting that is already overburdened. Doing so results in delayed treatment and increased costs.

- In the long term, COVID-19 survivors will overburden the already underfunded mental healthcare system.

- Additional unforeseen psychological outcomes stem from the myriad traumas of events in 2020 (eg, racial unrest, children out of school, loss of jobs, the recent election).

Psychiatric disorders are notoriously difficult to diagnose and treat in the outpatient primary care setting, which is why mental health professionals will need to be a more integral part of the postpandemic treatment model and should be represented on the advisory board. Each year in the United States, there are more than 8 million doctors’ visits for depression, and more than half of these are in the primary care setting. Yet fewer than half of those patients leave with a diagnosis of depression or are treated for it.

Historically, screening for depression in the primary care setting is difficult given its broad presentation of symptoms, which include nonspecific physical complaints, such as digestive problems, headaches, insomnia, or general aches and pains. These shortcomings exist despite multiple changes in guidelines, such as regarding the use of self-screening tools and general screening for specific populations, such as postpartum women.

But screening alone has not been an effective strategy, especially when certain groups are less likely to be screened. These include older adults, Black persons, and men, all of whom are at higher risk for mortality after COVID-19. There is a failure to consistently apply standards of universal screening across all patient groups, and even if it occurs, there is a failure to establish reliable treatment and follow-up regimens. As clinicians, imagine how challenging diagnosis and treatment of more complicated psychiatric syndromes, such as somatoform disorder, will be in the primary care setting after the pandemic.

When almost two-thirds of symptoms in primary care are already “medically unexplained,” how do we expect primary care doctors to differentiate between those presenting with vague coronavirus-related “brain fog,” the run of the mill worrywart, and the 16%-34% with legitimate hypochondriasis of somatoform disorder who won’t improve without the involvement of a mental health provider?

A specialty in short supply

The mental health system we have now is inadequate for those who are currently diagnosed with mental disorders. Before the pandemic, emergency departments were boarding increasing numbers of patients with psychiatric illness because beds on inpatient units were unavailable. Individuals with insurance faced difficulty finding psychiatrists or psychotherapists who took insurance or who were availabile to accept new patients, given the growing shortage of providers in general. Community health centers continued to grapple with decreases in federal and state funding despite public political support for parity. Individuals with substance use faced few options for the outpatient, residential, or pharmacologic treatment that many needed to maintain sobriety.

Since the pandemic, we have seen rates of anxiety, depression, and suicidal thinking increase among adults and youth while many clinics have been forced to lay off employees, reduce services, or close their doors. As psychiatrists, we not only see the lack of treatment options for our patients but are forced to find creative solutions to meet their needs. How are we supposed to adapt (or feel confident) when individuals with or without previous mental illness face downstream consequences after COVID-19 when not one of our own is represented in the advisory board? How can we feel confident that downstream solutions acknowledge and address the intricacy of the behavioral health system that we, as mental health providers, know so intimately?

And what about the cumulative impact of everything else that has happened in 2020 in addition to the pandemic?! Although cataloging the various negative events that have happened this year is beyond the scope of this discussion, such lists have been compiled by the mainstream media and include the Australian brush fires, the crisis in Armenia, racial protests, economic uncertainties, and the run-up to and occurrence of the 2020 presidential election. Research is solid in its assertion that chronic stress can disturb our immune and cardiovascular systems, as well as mental health, leading to depression or anxiety. As a result of the pandemic itself, plus the events of this year, mental health providers are already warning not only of the current trauma underlying our day-to-day lives but also that of years to come.

More importantly, healthcare providers, both those represented by members of the advisory board and those who are not, are not immune to these issues. Before the pandemic, rates of suicide among doctors were already above average compared with other professions. After witnessing death repeatedly, self-isolation, the risk for infection to family, and dealing with the continued resistance to wearing masks, who knows what the eventual psychological toll our medical workforce will be?

Mental health providers have stepped up to the plate to provide care outside of traditional models to meet the needs that patients have now. One survey found that 81% of behavioral health providers began using telehealth for the first time in the past 6 months, owing to the COVID-19 pandemic. If not for the sake of the mental health of the Biden-Harris advisory board members themselves, who as doctors are likely to downplay the impact when struggling with mental health concerns in their own lives, a mental health provider deserves a seat at the table.

Plus, the outcomes speak for themselves when behavioral health providers collaborate with primary care providers to give treatment or when mental health experts are members of health crisis teams. Why wouldn’t the same be true for the Biden-Harris advisory board?

Kali Cyrus, MD, MPH, is an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral medicine at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland. She sees patients in private practice and offers consultation services in diversity strategy. Ranna Parekh, MD, MPH, is past deputy medical director and director of diversity and health equity for the American Psychiatric Association. She is currently a consultant psychiatrist at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and the chief diversity and inclusion officer at the American College of Cardiology.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

On Nov. 9, the Biden-Harris administration announced the members of its COVID-19 Advisory Board. Among them were many esteemed infectious disease and public health experts – encouraging, given that, for now, the COVID-19 pandemic shows no signs of slowing down. Not among them was a mental health professional.

As psychiatrists, we did not find this omission surprising, given the sidelined role our specialty too often plays among medical professionals. But we did find it disappointing. Not having a single behavioral health provider on the advisory board will prove to be a mistake that could affect millions of Americans.

Studies continue to roll in showing that patients with COVID-19 can present during and after infection with neuropsychiatric symptoms, including delirium, psychosis, and anxiety. In July, a meta-analysis published in The Lancet regarding the neuropsychological outcomes of earlier diseases caused by coronaviruses – severe acute respiratory syndrome and Middle East respiratory syndrome – suggested that, in the short term, close to one-quarter of patients experienced confusion representative of delirium. In the long term, following recovery, respondents frequently reported emotional lability, impaired concentration, and traumatic memories. Additionally, more recent research published in The Lancet suggests that rates of psychiatric disorders, dementia, and insomnia are significantly higher among survivors of COVID-19. This study echoes the findings of an article in JAMA from September that reported that, among patients who were hospitalized for COVID-19, mortality rates were higher for those who had previously been diagnosed with a psychiatric condition. And overall, the pandemic has been associated with significantly increased rates of anxiety and depression symptoms.

Although this research is preliminary,

This is especially true when you consider the following:

- It is very difficult to diagnose and treat mental health symptoms in a primary care setting that is already overburdened. Doing so results in delayed treatment and increased costs.

- In the long term, COVID-19 survivors will overburden the already underfunded mental healthcare system.

- Additional unforeseen psychological outcomes stem from the myriad traumas of events in 2020 (eg, racial unrest, children out of school, loss of jobs, the recent election).

Psychiatric disorders are notoriously difficult to diagnose and treat in the outpatient primary care setting, which is why mental health professionals will need to be a more integral part of the postpandemic treatment model and should be represented on the advisory board. Each year in the United States, there are more than 8 million doctors’ visits for depression, and more than half of these are in the primary care setting. Yet fewer than half of those patients leave with a diagnosis of depression or are treated for it.

Historically, screening for depression in the primary care setting is difficult given its broad presentation of symptoms, which include nonspecific physical complaints, such as digestive problems, headaches, insomnia, or general aches and pains. These shortcomings exist despite multiple changes in guidelines, such as regarding the use of self-screening tools and general screening for specific populations, such as postpartum women.

But screening alone has not been an effective strategy, especially when certain groups are less likely to be screened. These include older adults, Black persons, and men, all of whom are at higher risk for mortality after COVID-19. There is a failure to consistently apply standards of universal screening across all patient groups, and even if it occurs, there is a failure to establish reliable treatment and follow-up regimens. As clinicians, imagine how challenging diagnosis and treatment of more complicated psychiatric syndromes, such as somatoform disorder, will be in the primary care setting after the pandemic.

When almost two-thirds of symptoms in primary care are already “medically unexplained,” how do we expect primary care doctors to differentiate between those presenting with vague coronavirus-related “brain fog,” the run of the mill worrywart, and the 16%-34% with legitimate hypochondriasis of somatoform disorder who won’t improve without the involvement of a mental health provider?

A specialty in short supply

The mental health system we have now is inadequate for those who are currently diagnosed with mental disorders. Before the pandemic, emergency departments were boarding increasing numbers of patients with psychiatric illness because beds on inpatient units were unavailable. Individuals with insurance faced difficulty finding psychiatrists or psychotherapists who took insurance or who were availabile to accept new patients, given the growing shortage of providers in general. Community health centers continued to grapple with decreases in federal and state funding despite public political support for parity. Individuals with substance use faced few options for the outpatient, residential, or pharmacologic treatment that many needed to maintain sobriety.

Since the pandemic, we have seen rates of anxiety, depression, and suicidal thinking increase among adults and youth while many clinics have been forced to lay off employees, reduce services, or close their doors. As psychiatrists, we not only see the lack of treatment options for our patients but are forced to find creative solutions to meet their needs. How are we supposed to adapt (or feel confident) when individuals with or without previous mental illness face downstream consequences after COVID-19 when not one of our own is represented in the advisory board? How can we feel confident that downstream solutions acknowledge and address the intricacy of the behavioral health system that we, as mental health providers, know so intimately?

And what about the cumulative impact of everything else that has happened in 2020 in addition to the pandemic?! Although cataloging the various negative events that have happened this year is beyond the scope of this discussion, such lists have been compiled by the mainstream media and include the Australian brush fires, the crisis in Armenia, racial protests, economic uncertainties, and the run-up to and occurrence of the 2020 presidential election. Research is solid in its assertion that chronic stress can disturb our immune and cardiovascular systems, as well as mental health, leading to depression or anxiety. As a result of the pandemic itself, plus the events of this year, mental health providers are already warning not only of the current trauma underlying our day-to-day lives but also that of years to come.

More importantly, healthcare providers, both those represented by members of the advisory board and those who are not, are not immune to these issues. Before the pandemic, rates of suicide among doctors were already above average compared with other professions. After witnessing death repeatedly, self-isolation, the risk for infection to family, and dealing with the continued resistance to wearing masks, who knows what the eventual psychological toll our medical workforce will be?

Mental health providers have stepped up to the plate to provide care outside of traditional models to meet the needs that patients have now. One survey found that 81% of behavioral health providers began using telehealth for the first time in the past 6 months, owing to the COVID-19 pandemic. If not for the sake of the mental health of the Biden-Harris advisory board members themselves, who as doctors are likely to downplay the impact when struggling with mental health concerns in their own lives, a mental health provider deserves a seat at the table.

Plus, the outcomes speak for themselves when behavioral health providers collaborate with primary care providers to give treatment or when mental health experts are members of health crisis teams. Why wouldn’t the same be true for the Biden-Harris advisory board?

Kali Cyrus, MD, MPH, is an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral medicine at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland. She sees patients in private practice and offers consultation services in diversity strategy. Ranna Parekh, MD, MPH, is past deputy medical director and director of diversity and health equity for the American Psychiatric Association. She is currently a consultant psychiatrist at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and the chief diversity and inclusion officer at the American College of Cardiology.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

On Nov. 9, the Biden-Harris administration announced the members of its COVID-19 Advisory Board. Among them were many esteemed infectious disease and public health experts – encouraging, given that, for now, the COVID-19 pandemic shows no signs of slowing down. Not among them was a mental health professional.

As psychiatrists, we did not find this omission surprising, given the sidelined role our specialty too often plays among medical professionals. But we did find it disappointing. Not having a single behavioral health provider on the advisory board will prove to be a mistake that could affect millions of Americans.

Studies continue to roll in showing that patients with COVID-19 can present during and after infection with neuropsychiatric symptoms, including delirium, psychosis, and anxiety. In July, a meta-analysis published in The Lancet regarding the neuropsychological outcomes of earlier diseases caused by coronaviruses – severe acute respiratory syndrome and Middle East respiratory syndrome – suggested that, in the short term, close to one-quarter of patients experienced confusion representative of delirium. In the long term, following recovery, respondents frequently reported emotional lability, impaired concentration, and traumatic memories. Additionally, more recent research published in The Lancet suggests that rates of psychiatric disorders, dementia, and insomnia are significantly higher among survivors of COVID-19. This study echoes the findings of an article in JAMA from September that reported that, among patients who were hospitalized for COVID-19, mortality rates were higher for those who had previously been diagnosed with a psychiatric condition. And overall, the pandemic has been associated with significantly increased rates of anxiety and depression symptoms.

Although this research is preliminary,

This is especially true when you consider the following:

- It is very difficult to diagnose and treat mental health symptoms in a primary care setting that is already overburdened. Doing so results in delayed treatment and increased costs.

- In the long term, COVID-19 survivors will overburden the already underfunded mental healthcare system.

- Additional unforeseen psychological outcomes stem from the myriad traumas of events in 2020 (eg, racial unrest, children out of school, loss of jobs, the recent election).

Psychiatric disorders are notoriously difficult to diagnose and treat in the outpatient primary care setting, which is why mental health professionals will need to be a more integral part of the postpandemic treatment model and should be represented on the advisory board. Each year in the United States, there are more than 8 million doctors’ visits for depression, and more than half of these are in the primary care setting. Yet fewer than half of those patients leave with a diagnosis of depression or are treated for it.

Historically, screening for depression in the primary care setting is difficult given its broad presentation of symptoms, which include nonspecific physical complaints, such as digestive problems, headaches, insomnia, or general aches and pains. These shortcomings exist despite multiple changes in guidelines, such as regarding the use of self-screening tools and general screening for specific populations, such as postpartum women.

But screening alone has not been an effective strategy, especially when certain groups are less likely to be screened. These include older adults, Black persons, and men, all of whom are at higher risk for mortality after COVID-19. There is a failure to consistently apply standards of universal screening across all patient groups, and even if it occurs, there is a failure to establish reliable treatment and follow-up regimens. As clinicians, imagine how challenging diagnosis and treatment of more complicated psychiatric syndromes, such as somatoform disorder, will be in the primary care setting after the pandemic.

When almost two-thirds of symptoms in primary care are already “medically unexplained,” how do we expect primary care doctors to differentiate between those presenting with vague coronavirus-related “brain fog,” the run of the mill worrywart, and the 16%-34% with legitimate hypochondriasis of somatoform disorder who won’t improve without the involvement of a mental health provider?

A specialty in short supply