User login

Drospirenone vs norethindrone progestin-only pills. Is there a clear winner?

Contraception and family planning have improved the health of all people by reducing maternal mortality, improving maternal and child health through birth spacing, supporting full education attainment, and advancing workforce participation.1 Contraception is cost-effective and should be supported by all health insurers. One economic study reported that depending on the contraceptive method utilized, up to $7 of health care costs were saved for each dollar spent on contraceptive services and supplies.2

Progestin-only pills (POPs) are an important contraceptive option for people in the following situations who3:

- have a contraindication to estrogen-containing contraceptives

- are actively breastfeeding

- are less than 21 days since birth

- have a preference to avoid estrogen.

POPs are contraindicated for women who have breast cancer, abnormal uterine bleeding, or active liver disease and for women who are pregnant. A history of bariatric surgery with a malabsorption procedure (Roux-en-Y and biliopancreatic diversion) and the use of antiepileptic medications that are strong enzyme inducers are additional situations where the risk of POP may outweigh the benefit.3 Alternative progestin-only options include the subdermal etonogestrel implant, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, and levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine devices. These 3 options provide superior contraceptive efficacy to POP.

As a contraceptive, norethindrone at a dose of 0.35 mg daily has two major flaws:

- it does not reliably inhibit ovulation

- it has a short half-life.

In clinical studies, norethindrone inhibits ovulation in approximately 50% of cycles.4,5 Because norethindrone at a dose of 0.35 mg does not reliably inhibit ovulation it relies on additional mechanisms for contraceptive efficacy, including thickening of the cervical mucus to block sperm entry into the upper reproductive tract, reduced fallopian tube motility, and thinning of the endometrium.6

Norethindrone POP is formulated in packs of 28 pills containing 0.35 mg intended for daily continuous administration and no medication-free intervals. One rationale for the low dose of 0.35 mg in norethindrone POP is that it approximates the lowest dose with contraceptive efficacy for breastfeeding women, which has the benefit of minimizing exposure of the baby to the medication. Estrogen-progestin birth control pills containing norethindrone as the progestin reliably inhibit ovulation and have a minimum of 1 mg of norethindrone in each hormone pill. A POP with 1 mg of norethindrone per pill would likely have greater contraceptive efficacy. When taken daily, norethindrone acetate 5 mg (Aygestin) suppresses ovarian estrogen production, ovulation, and often causes cessation of uterine bleeding.7 The short half-life of norethindrone (7.7 hours) further exacerbates the problem of an insufficient daily dose.6 The standard guidance is that norethindrone must be taken at the same time every day, a goal that is nearly impossible to achieve. If a dose of norethindrone is taken >3 hours late, backup contraception is recommended for 48 hours.6

Drospirenone is a chemical analogue of spironolactone. Drospirenone is a progestin that suppresses LH and FSH and has anti-androgenic and partial anti-mineralocorticoid effects.8 Drospirenone POP contains 4 mg of a nonmicronized formulation that is believed to provide a pharmacologically similar area under the curve in drug metabolism studies to the 3 mg of micronized drospirenone, present in drospirenone-containing estrogen-progestin contraceptives.8 It is provided in a pack of 28 pills with 24 drospirenone pills and 4 pills without hormone. Drospirenone has a long half-life of 30 to 34 hours.8 If ≥2 drospirenone pills are missed, backup contraception is recommended for 7 days.9 The contraceptive effectiveness of drospirenone POP is thought to be similar to estrogen-progestin pills.8 Theoretically, drospirenone, acting as an anti-mineralocorticoid, can cause hyperkalemia. People with renal and adrenal insufficiency are most vulnerable to this adverse effect and should not be prescribed drospirenone. Women taking drospirenone and a medication that strongly inhibits CYP3A4, an enzyme involved in drospirenone degradation—including ketoconazole, indinavir, boceprevir, and clarithromycin—may have increased circulating levels of drospirenone and be at an increased risk of hyperkalemia. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) suggests that clinicians consider monitoring potassium concentration in women taking drospirenone who are also prescribed a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor.9 In people with normal renal and adrenal function, drospirenone-induced hyperkalemia is not commonly observed.9

Drospirenone 4 mg has been reported to not affect the natural balance of pro- and anti-coagulation factors in women.10 Drospirenone 4 mg daily has been reported to cause a modest decrease in systolic (-8 mm Hg) and diastolic (-5 mm Hg) blood pressure for women with a baseline blood pressure ≥130 mm Hg. Drospirenone 4 mg daily did not change blood pressure measurement in women with a baseline systolic blood pressure <130 mm Hg.11 For women using drospirenone POP, circulating estradiol concentration is usually >30 pg/mL, with a mean concentration of 51 pg/mL.12,13 Drospirenone POP does not result in a significant change in body weight.14 Preliminary studies suggest that drospirenone is an effective contraceptive in women with a BMI >30 kg/m2.14,15 Drospirenone enters breast milk and the relative infant dose is reported to be 1.5%.9 In general, breastfeeding is considered reasonably safe when the relative infant dose of a medication is <10%.16

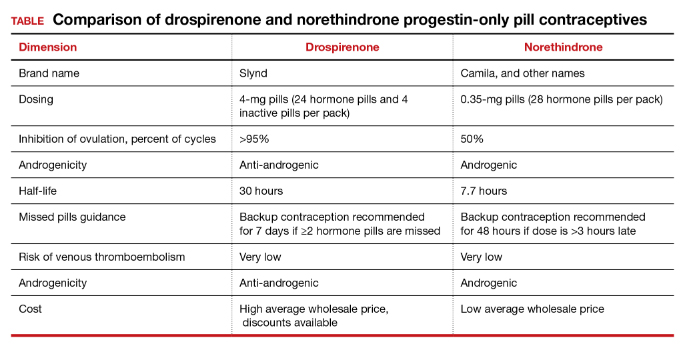

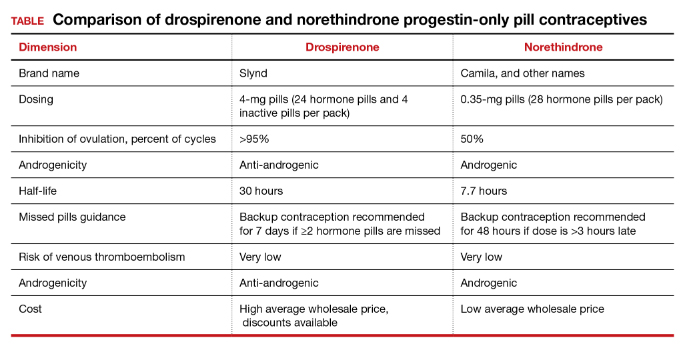

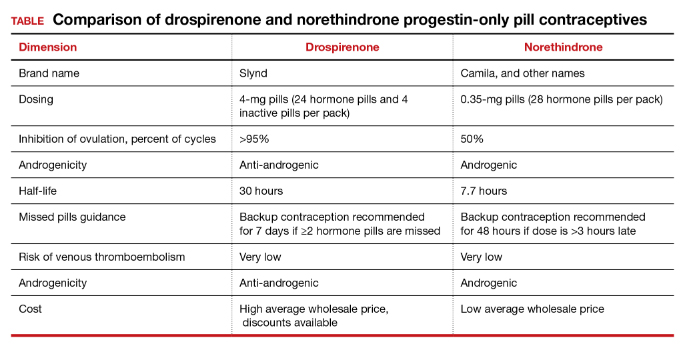

The most common adverse effect reported with both norethindrone and drospirenone POP is unscheduled uterine bleeding. With norethindrone POP about 50% of users have a relatively preserved monthly bleeding pattern and approximately 50% have bleeding between periods, spotting and/or prolonged bleeding.17,18 A similar frequency of unscheduled uterine bleeding has been reported with drospirenone POP.14,19 Unscheduled and bothersome uterine bleeding is a common reason people discontinue POP. For drospirenone POP, the FDA reports a Pearl Index of 4.9 Other studies report a Pearl Index of 0.73 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.31 to 1.43) for drospirenone POP.14 For norethindrone POP, the FDA reports that in typical use about 5% of people using the contraceptive method would become pregnant.6 The TABLE provides a comparison of the key features of the two available POP contraceptives. My assessment is that drospirenone has superior contraceptive properties over norethindrone POP. However, a head-to-head clinical trial would be necessary to determine the relative contraceptive effectiveness of drospirenone versus norethindrone POP.

Maintaining contraception access

Access to contraception without a copayment is an important component of a comprehensive and equitable insurance program.20 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) advocates that all people “should have unhindered and affordable access to all U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved contraceptives.”21 ACOG also calls for the “full implementation of the Affordable Care Act requirement that new and revised private health insurance plans cover all U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved contraceptives without cost sharing, including nonequivalent options within one method category.” The National Women’s Law Center22 provides helpful resources to ensure access to legislated contraceptive benefits, including a phone script for speaking with an insurance benefits agent23 and a toolkit for advocating for your contraceptive choice.24 We need to ensure that people have unfettered access to all FDA-approved contraceptives because access to contraception is an important component of public health. Although drospirenone is more costly than norethindrone POP, drospirenone contraception should be available to all patients seeking POP contraception. ●

- Kavanaugh ML, Andreson RM. Contraception and beyond: the health benefits of services provided at family planning centers, NY. Guttmacher Institute. 2013. www.gutmacher.org/pubs/helth-benefits.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2022.

- Foster DG, Rostovtseva DP, Brindis CD, et al. Cost savings from the provision of specific methods of contraception in a publicly funded program. Am J Pub Health. 2009;99:446-451.

- Curtis M, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-103.

- Rice CF, Killick SR, Dieben T, et al. A comparison of the inhibition of ovulation achieved by desogestrel 75 µg and levonorgestrel 30 µg daily. Human Reprod. 1999;14:982-985.

- Milsom I, Korver T. Ovulation incidence with oral contraceptives: a literature review. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2008;34:237-246.

- OrthoMicronor [package insert]. OrthoMcNeil: Raritan, New Jersey. June 2008.

- Brown JB, Fotherby K, Loraine JA. The effect of norethisterone and its acetate on ovarian and pituitary function during the menstrual cycle. J Endocrinol. 1962;25:331-341.

- Romer T, Bitzer J, Egarter C, et al. Oral progestins in hormonal contraception: importance and future perspectives of a new progestin only-pill containing 4 mg drospirenone. Geburtsch Frauenheilk. 2021;81:1021-1030.

- Slynd [package insert]. Exeltis: Florham Park, New Jersey. May 2019.

- Regidor PA, Colli E, Schindlre AE. Drospirenone as estrogen-free pill and hemostasis: coagulatory study results comparing a novel 4 mg formulation in a 24+4 cycle with desogestrel 75 µg per day. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2016;32:749-751.

- Palacios S, Colli E, Regidor PA. Efficacy and cardiovascular safety of the new estrogen-free contraceptive pill containing 4 mg drospirenone alone in a 24/4 regime. BMC Womens Health. 2020;20:218.

- Hadji P, Colli E, Regidor PA. Bone health in estrogen-free contraception. Osteoporosis Int. 2019;30:2391-2400.

- Mitchell VE, Welling LM. Not all progestins are created equally: considering unique progestins individually in psychobehavioral research. Adapt Human Behav Physiol. 2020;6:381-412.

- Palacios S, Colli E, Regidor PA. Multicenter, phase III trials on the contraceptive efficacy, tolerability and safety of a new drospirenone-only pill. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2019;98:1549-1557.

- Archer DF, Ahrendt HJ, Drouin D. Drospirenone-only oral contraceptive: results from a multicenter noncomparative trial of efficacy, safety and tolerability. Contraception. 2015;92:439-444.

- Anderson PO, Sauberan JB. Modeling drug passage into human milk. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;100:42-52. doi: 10.1002/cpt.377.

- Belsey EM. Vaginal bleeding patterns among women using one natural and eight hormonal methods of contraception. Contraception. 1988;38:181-206.

- Broome M, Fotherby K. Clinical experience with the progestin-only pill. Contraception. 1990;42:489-495.

- Apter D, Colli E, Gemzell-Danielsson K, et al. Multicenter, open-label trial to assess the safety and tolerability of drospirenone 4.0 mg over 6 cycles in female adolescents with a 7-cycle extension phase. Contraception. 2020;101:412.

- Birth control benefits. Healthcare.gov website. https://www.healthcare.gov/coverage/birth-control-benefits/. Accessed January 13, 2022.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Access to contraception. Committee Opinion No. 615. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:250-256.

- Health care and reproductive rights. National Women’s Law Center website. https://nwlc.org/issue/health-care. Accessed January 13, 2022.

- How to find out if your health plan covers birth control at no cost to you. National Women’s Law Center website. https://nwlc.org/sites/default/files/072014-insuranceflowchart_vupdated.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2022.

- Toolkit: Getting the coverage you deserve. National Women’s Law Center website. https://nwlc.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/final_nwlclogo_preventive servicestoolkit_9-25-13.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2022.

Contraception and family planning have improved the health of all people by reducing maternal mortality, improving maternal and child health through birth spacing, supporting full education attainment, and advancing workforce participation.1 Contraception is cost-effective and should be supported by all health insurers. One economic study reported that depending on the contraceptive method utilized, up to $7 of health care costs were saved for each dollar spent on contraceptive services and supplies.2

Progestin-only pills (POPs) are an important contraceptive option for people in the following situations who3:

- have a contraindication to estrogen-containing contraceptives

- are actively breastfeeding

- are less than 21 days since birth

- have a preference to avoid estrogen.

POPs are contraindicated for women who have breast cancer, abnormal uterine bleeding, or active liver disease and for women who are pregnant. A history of bariatric surgery with a malabsorption procedure (Roux-en-Y and biliopancreatic diversion) and the use of antiepileptic medications that are strong enzyme inducers are additional situations where the risk of POP may outweigh the benefit.3 Alternative progestin-only options include the subdermal etonogestrel implant, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, and levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine devices. These 3 options provide superior contraceptive efficacy to POP.

As a contraceptive, norethindrone at a dose of 0.35 mg daily has two major flaws:

- it does not reliably inhibit ovulation

- it has a short half-life.

In clinical studies, norethindrone inhibits ovulation in approximately 50% of cycles.4,5 Because norethindrone at a dose of 0.35 mg does not reliably inhibit ovulation it relies on additional mechanisms for contraceptive efficacy, including thickening of the cervical mucus to block sperm entry into the upper reproductive tract, reduced fallopian tube motility, and thinning of the endometrium.6

Norethindrone POP is formulated in packs of 28 pills containing 0.35 mg intended for daily continuous administration and no medication-free intervals. One rationale for the low dose of 0.35 mg in norethindrone POP is that it approximates the lowest dose with contraceptive efficacy for breastfeeding women, which has the benefit of minimizing exposure of the baby to the medication. Estrogen-progestin birth control pills containing norethindrone as the progestin reliably inhibit ovulation and have a minimum of 1 mg of norethindrone in each hormone pill. A POP with 1 mg of norethindrone per pill would likely have greater contraceptive efficacy. When taken daily, norethindrone acetate 5 mg (Aygestin) suppresses ovarian estrogen production, ovulation, and often causes cessation of uterine bleeding.7 The short half-life of norethindrone (7.7 hours) further exacerbates the problem of an insufficient daily dose.6 The standard guidance is that norethindrone must be taken at the same time every day, a goal that is nearly impossible to achieve. If a dose of norethindrone is taken >3 hours late, backup contraception is recommended for 48 hours.6

Drospirenone is a chemical analogue of spironolactone. Drospirenone is a progestin that suppresses LH and FSH and has anti-androgenic and partial anti-mineralocorticoid effects.8 Drospirenone POP contains 4 mg of a nonmicronized formulation that is believed to provide a pharmacologically similar area under the curve in drug metabolism studies to the 3 mg of micronized drospirenone, present in drospirenone-containing estrogen-progestin contraceptives.8 It is provided in a pack of 28 pills with 24 drospirenone pills and 4 pills without hormone. Drospirenone has a long half-life of 30 to 34 hours.8 If ≥2 drospirenone pills are missed, backup contraception is recommended for 7 days.9 The contraceptive effectiveness of drospirenone POP is thought to be similar to estrogen-progestin pills.8 Theoretically, drospirenone, acting as an anti-mineralocorticoid, can cause hyperkalemia. People with renal and adrenal insufficiency are most vulnerable to this adverse effect and should not be prescribed drospirenone. Women taking drospirenone and a medication that strongly inhibits CYP3A4, an enzyme involved in drospirenone degradation—including ketoconazole, indinavir, boceprevir, and clarithromycin—may have increased circulating levels of drospirenone and be at an increased risk of hyperkalemia. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) suggests that clinicians consider monitoring potassium concentration in women taking drospirenone who are also prescribed a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor.9 In people with normal renal and adrenal function, drospirenone-induced hyperkalemia is not commonly observed.9

Drospirenone 4 mg has been reported to not affect the natural balance of pro- and anti-coagulation factors in women.10 Drospirenone 4 mg daily has been reported to cause a modest decrease in systolic (-8 mm Hg) and diastolic (-5 mm Hg) blood pressure for women with a baseline blood pressure ≥130 mm Hg. Drospirenone 4 mg daily did not change blood pressure measurement in women with a baseline systolic blood pressure <130 mm Hg.11 For women using drospirenone POP, circulating estradiol concentration is usually >30 pg/mL, with a mean concentration of 51 pg/mL.12,13 Drospirenone POP does not result in a significant change in body weight.14 Preliminary studies suggest that drospirenone is an effective contraceptive in women with a BMI >30 kg/m2.14,15 Drospirenone enters breast milk and the relative infant dose is reported to be 1.5%.9 In general, breastfeeding is considered reasonably safe when the relative infant dose of a medication is <10%.16

The most common adverse effect reported with both norethindrone and drospirenone POP is unscheduled uterine bleeding. With norethindrone POP about 50% of users have a relatively preserved monthly bleeding pattern and approximately 50% have bleeding between periods, spotting and/or prolonged bleeding.17,18 A similar frequency of unscheduled uterine bleeding has been reported with drospirenone POP.14,19 Unscheduled and bothersome uterine bleeding is a common reason people discontinue POP. For drospirenone POP, the FDA reports a Pearl Index of 4.9 Other studies report a Pearl Index of 0.73 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.31 to 1.43) for drospirenone POP.14 For norethindrone POP, the FDA reports that in typical use about 5% of people using the contraceptive method would become pregnant.6 The TABLE provides a comparison of the key features of the two available POP contraceptives. My assessment is that drospirenone has superior contraceptive properties over norethindrone POP. However, a head-to-head clinical trial would be necessary to determine the relative contraceptive effectiveness of drospirenone versus norethindrone POP.

Maintaining contraception access

Access to contraception without a copayment is an important component of a comprehensive and equitable insurance program.20 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) advocates that all people “should have unhindered and affordable access to all U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved contraceptives.”21 ACOG also calls for the “full implementation of the Affordable Care Act requirement that new and revised private health insurance plans cover all U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved contraceptives without cost sharing, including nonequivalent options within one method category.” The National Women’s Law Center22 provides helpful resources to ensure access to legislated contraceptive benefits, including a phone script for speaking with an insurance benefits agent23 and a toolkit for advocating for your contraceptive choice.24 We need to ensure that people have unfettered access to all FDA-approved contraceptives because access to contraception is an important component of public health. Although drospirenone is more costly than norethindrone POP, drospirenone contraception should be available to all patients seeking POP contraception. ●

Contraception and family planning have improved the health of all people by reducing maternal mortality, improving maternal and child health through birth spacing, supporting full education attainment, and advancing workforce participation.1 Contraception is cost-effective and should be supported by all health insurers. One economic study reported that depending on the contraceptive method utilized, up to $7 of health care costs were saved for each dollar spent on contraceptive services and supplies.2

Progestin-only pills (POPs) are an important contraceptive option for people in the following situations who3:

- have a contraindication to estrogen-containing contraceptives

- are actively breastfeeding

- are less than 21 days since birth

- have a preference to avoid estrogen.

POPs are contraindicated for women who have breast cancer, abnormal uterine bleeding, or active liver disease and for women who are pregnant. A history of bariatric surgery with a malabsorption procedure (Roux-en-Y and biliopancreatic diversion) and the use of antiepileptic medications that are strong enzyme inducers are additional situations where the risk of POP may outweigh the benefit.3 Alternative progestin-only options include the subdermal etonogestrel implant, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, and levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine devices. These 3 options provide superior contraceptive efficacy to POP.

As a contraceptive, norethindrone at a dose of 0.35 mg daily has two major flaws:

- it does not reliably inhibit ovulation

- it has a short half-life.

In clinical studies, norethindrone inhibits ovulation in approximately 50% of cycles.4,5 Because norethindrone at a dose of 0.35 mg does not reliably inhibit ovulation it relies on additional mechanisms for contraceptive efficacy, including thickening of the cervical mucus to block sperm entry into the upper reproductive tract, reduced fallopian tube motility, and thinning of the endometrium.6

Norethindrone POP is formulated in packs of 28 pills containing 0.35 mg intended for daily continuous administration and no medication-free intervals. One rationale for the low dose of 0.35 mg in norethindrone POP is that it approximates the lowest dose with contraceptive efficacy for breastfeeding women, which has the benefit of minimizing exposure of the baby to the medication. Estrogen-progestin birth control pills containing norethindrone as the progestin reliably inhibit ovulation and have a minimum of 1 mg of norethindrone in each hormone pill. A POP with 1 mg of norethindrone per pill would likely have greater contraceptive efficacy. When taken daily, norethindrone acetate 5 mg (Aygestin) suppresses ovarian estrogen production, ovulation, and often causes cessation of uterine bleeding.7 The short half-life of norethindrone (7.7 hours) further exacerbates the problem of an insufficient daily dose.6 The standard guidance is that norethindrone must be taken at the same time every day, a goal that is nearly impossible to achieve. If a dose of norethindrone is taken >3 hours late, backup contraception is recommended for 48 hours.6

Drospirenone is a chemical analogue of spironolactone. Drospirenone is a progestin that suppresses LH and FSH and has anti-androgenic and partial anti-mineralocorticoid effects.8 Drospirenone POP contains 4 mg of a nonmicronized formulation that is believed to provide a pharmacologically similar area under the curve in drug metabolism studies to the 3 mg of micronized drospirenone, present in drospirenone-containing estrogen-progestin contraceptives.8 It is provided in a pack of 28 pills with 24 drospirenone pills and 4 pills without hormone. Drospirenone has a long half-life of 30 to 34 hours.8 If ≥2 drospirenone pills are missed, backup contraception is recommended for 7 days.9 The contraceptive effectiveness of drospirenone POP is thought to be similar to estrogen-progestin pills.8 Theoretically, drospirenone, acting as an anti-mineralocorticoid, can cause hyperkalemia. People with renal and adrenal insufficiency are most vulnerable to this adverse effect and should not be prescribed drospirenone. Women taking drospirenone and a medication that strongly inhibits CYP3A4, an enzyme involved in drospirenone degradation—including ketoconazole, indinavir, boceprevir, and clarithromycin—may have increased circulating levels of drospirenone and be at an increased risk of hyperkalemia. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) suggests that clinicians consider monitoring potassium concentration in women taking drospirenone who are also prescribed a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor.9 In people with normal renal and adrenal function, drospirenone-induced hyperkalemia is not commonly observed.9

Drospirenone 4 mg has been reported to not affect the natural balance of pro- and anti-coagulation factors in women.10 Drospirenone 4 mg daily has been reported to cause a modest decrease in systolic (-8 mm Hg) and diastolic (-5 mm Hg) blood pressure for women with a baseline blood pressure ≥130 mm Hg. Drospirenone 4 mg daily did not change blood pressure measurement in women with a baseline systolic blood pressure <130 mm Hg.11 For women using drospirenone POP, circulating estradiol concentration is usually >30 pg/mL, with a mean concentration of 51 pg/mL.12,13 Drospirenone POP does not result in a significant change in body weight.14 Preliminary studies suggest that drospirenone is an effective contraceptive in women with a BMI >30 kg/m2.14,15 Drospirenone enters breast milk and the relative infant dose is reported to be 1.5%.9 In general, breastfeeding is considered reasonably safe when the relative infant dose of a medication is <10%.16

The most common adverse effect reported with both norethindrone and drospirenone POP is unscheduled uterine bleeding. With norethindrone POP about 50% of users have a relatively preserved monthly bleeding pattern and approximately 50% have bleeding between periods, spotting and/or prolonged bleeding.17,18 A similar frequency of unscheduled uterine bleeding has been reported with drospirenone POP.14,19 Unscheduled and bothersome uterine bleeding is a common reason people discontinue POP. For drospirenone POP, the FDA reports a Pearl Index of 4.9 Other studies report a Pearl Index of 0.73 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.31 to 1.43) for drospirenone POP.14 For norethindrone POP, the FDA reports that in typical use about 5% of people using the contraceptive method would become pregnant.6 The TABLE provides a comparison of the key features of the two available POP contraceptives. My assessment is that drospirenone has superior contraceptive properties over norethindrone POP. However, a head-to-head clinical trial would be necessary to determine the relative contraceptive effectiveness of drospirenone versus norethindrone POP.

Maintaining contraception access

Access to contraception without a copayment is an important component of a comprehensive and equitable insurance program.20 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) advocates that all people “should have unhindered and affordable access to all U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved contraceptives.”21 ACOG also calls for the “full implementation of the Affordable Care Act requirement that new and revised private health insurance plans cover all U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved contraceptives without cost sharing, including nonequivalent options within one method category.” The National Women’s Law Center22 provides helpful resources to ensure access to legislated contraceptive benefits, including a phone script for speaking with an insurance benefits agent23 and a toolkit for advocating for your contraceptive choice.24 We need to ensure that people have unfettered access to all FDA-approved contraceptives because access to contraception is an important component of public health. Although drospirenone is more costly than norethindrone POP, drospirenone contraception should be available to all patients seeking POP contraception. ●

- Kavanaugh ML, Andreson RM. Contraception and beyond: the health benefits of services provided at family planning centers, NY. Guttmacher Institute. 2013. www.gutmacher.org/pubs/helth-benefits.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2022.

- Foster DG, Rostovtseva DP, Brindis CD, et al. Cost savings from the provision of specific methods of contraception in a publicly funded program. Am J Pub Health. 2009;99:446-451.

- Curtis M, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-103.

- Rice CF, Killick SR, Dieben T, et al. A comparison of the inhibition of ovulation achieved by desogestrel 75 µg and levonorgestrel 30 µg daily. Human Reprod. 1999;14:982-985.

- Milsom I, Korver T. Ovulation incidence with oral contraceptives: a literature review. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2008;34:237-246.

- OrthoMicronor [package insert]. OrthoMcNeil: Raritan, New Jersey. June 2008.

- Brown JB, Fotherby K, Loraine JA. The effect of norethisterone and its acetate on ovarian and pituitary function during the menstrual cycle. J Endocrinol. 1962;25:331-341.

- Romer T, Bitzer J, Egarter C, et al. Oral progestins in hormonal contraception: importance and future perspectives of a new progestin only-pill containing 4 mg drospirenone. Geburtsch Frauenheilk. 2021;81:1021-1030.

- Slynd [package insert]. Exeltis: Florham Park, New Jersey. May 2019.

- Regidor PA, Colli E, Schindlre AE. Drospirenone as estrogen-free pill and hemostasis: coagulatory study results comparing a novel 4 mg formulation in a 24+4 cycle with desogestrel 75 µg per day. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2016;32:749-751.

- Palacios S, Colli E, Regidor PA. Efficacy and cardiovascular safety of the new estrogen-free contraceptive pill containing 4 mg drospirenone alone in a 24/4 regime. BMC Womens Health. 2020;20:218.

- Hadji P, Colli E, Regidor PA. Bone health in estrogen-free contraception. Osteoporosis Int. 2019;30:2391-2400.

- Mitchell VE, Welling LM. Not all progestins are created equally: considering unique progestins individually in psychobehavioral research. Adapt Human Behav Physiol. 2020;6:381-412.

- Palacios S, Colli E, Regidor PA. Multicenter, phase III trials on the contraceptive efficacy, tolerability and safety of a new drospirenone-only pill. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2019;98:1549-1557.

- Archer DF, Ahrendt HJ, Drouin D. Drospirenone-only oral contraceptive: results from a multicenter noncomparative trial of efficacy, safety and tolerability. Contraception. 2015;92:439-444.

- Anderson PO, Sauberan JB. Modeling drug passage into human milk. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;100:42-52. doi: 10.1002/cpt.377.

- Belsey EM. Vaginal bleeding patterns among women using one natural and eight hormonal methods of contraception. Contraception. 1988;38:181-206.

- Broome M, Fotherby K. Clinical experience with the progestin-only pill. Contraception. 1990;42:489-495.

- Apter D, Colli E, Gemzell-Danielsson K, et al. Multicenter, open-label trial to assess the safety and tolerability of drospirenone 4.0 mg over 6 cycles in female adolescents with a 7-cycle extension phase. Contraception. 2020;101:412.

- Birth control benefits. Healthcare.gov website. https://www.healthcare.gov/coverage/birth-control-benefits/. Accessed January 13, 2022.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Access to contraception. Committee Opinion No. 615. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:250-256.

- Health care and reproductive rights. National Women’s Law Center website. https://nwlc.org/issue/health-care. Accessed January 13, 2022.

- How to find out if your health plan covers birth control at no cost to you. National Women’s Law Center website. https://nwlc.org/sites/default/files/072014-insuranceflowchart_vupdated.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2022.

- Toolkit: Getting the coverage you deserve. National Women’s Law Center website. https://nwlc.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/final_nwlclogo_preventive servicestoolkit_9-25-13.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2022.

- Kavanaugh ML, Andreson RM. Contraception and beyond: the health benefits of services provided at family planning centers, NY. Guttmacher Institute. 2013. www.gutmacher.org/pubs/helth-benefits.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2022.

- Foster DG, Rostovtseva DP, Brindis CD, et al. Cost savings from the provision of specific methods of contraception in a publicly funded program. Am J Pub Health. 2009;99:446-451.

- Curtis M, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-103.

- Rice CF, Killick SR, Dieben T, et al. A comparison of the inhibition of ovulation achieved by desogestrel 75 µg and levonorgestrel 30 µg daily. Human Reprod. 1999;14:982-985.

- Milsom I, Korver T. Ovulation incidence with oral contraceptives: a literature review. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2008;34:237-246.

- OrthoMicronor [package insert]. OrthoMcNeil: Raritan, New Jersey. June 2008.

- Brown JB, Fotherby K, Loraine JA. The effect of norethisterone and its acetate on ovarian and pituitary function during the menstrual cycle. J Endocrinol. 1962;25:331-341.

- Romer T, Bitzer J, Egarter C, et al. Oral progestins in hormonal contraception: importance and future perspectives of a new progestin only-pill containing 4 mg drospirenone. Geburtsch Frauenheilk. 2021;81:1021-1030.

- Slynd [package insert]. Exeltis: Florham Park, New Jersey. May 2019.

- Regidor PA, Colli E, Schindlre AE. Drospirenone as estrogen-free pill and hemostasis: coagulatory study results comparing a novel 4 mg formulation in a 24+4 cycle with desogestrel 75 µg per day. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2016;32:749-751.

- Palacios S, Colli E, Regidor PA. Efficacy and cardiovascular safety of the new estrogen-free contraceptive pill containing 4 mg drospirenone alone in a 24/4 regime. BMC Womens Health. 2020;20:218.

- Hadji P, Colli E, Regidor PA. Bone health in estrogen-free contraception. Osteoporosis Int. 2019;30:2391-2400.

- Mitchell VE, Welling LM. Not all progestins are created equally: considering unique progestins individually in psychobehavioral research. Adapt Human Behav Physiol. 2020;6:381-412.

- Palacios S, Colli E, Regidor PA. Multicenter, phase III trials on the contraceptive efficacy, tolerability and safety of a new drospirenone-only pill. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2019;98:1549-1557.

- Archer DF, Ahrendt HJ, Drouin D. Drospirenone-only oral contraceptive: results from a multicenter noncomparative trial of efficacy, safety and tolerability. Contraception. 2015;92:439-444.

- Anderson PO, Sauberan JB. Modeling drug passage into human milk. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;100:42-52. doi: 10.1002/cpt.377.

- Belsey EM. Vaginal bleeding patterns among women using one natural and eight hormonal methods of contraception. Contraception. 1988;38:181-206.

- Broome M, Fotherby K. Clinical experience with the progestin-only pill. Contraception. 1990;42:489-495.

- Apter D, Colli E, Gemzell-Danielsson K, et al. Multicenter, open-label trial to assess the safety and tolerability of drospirenone 4.0 mg over 6 cycles in female adolescents with a 7-cycle extension phase. Contraception. 2020;101:412.

- Birth control benefits. Healthcare.gov website. https://www.healthcare.gov/coverage/birth-control-benefits/. Accessed January 13, 2022.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Access to contraception. Committee Opinion No. 615. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:250-256.

- Health care and reproductive rights. National Women’s Law Center website. https://nwlc.org/issue/health-care. Accessed January 13, 2022.

- How to find out if your health plan covers birth control at no cost to you. National Women’s Law Center website. https://nwlc.org/sites/default/files/072014-insuranceflowchart_vupdated.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2022.

- Toolkit: Getting the coverage you deserve. National Women’s Law Center website. https://nwlc.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/final_nwlclogo_preventive servicestoolkit_9-25-13.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2022.

Early Diagnosis and Management of Tardive Dyskinesia

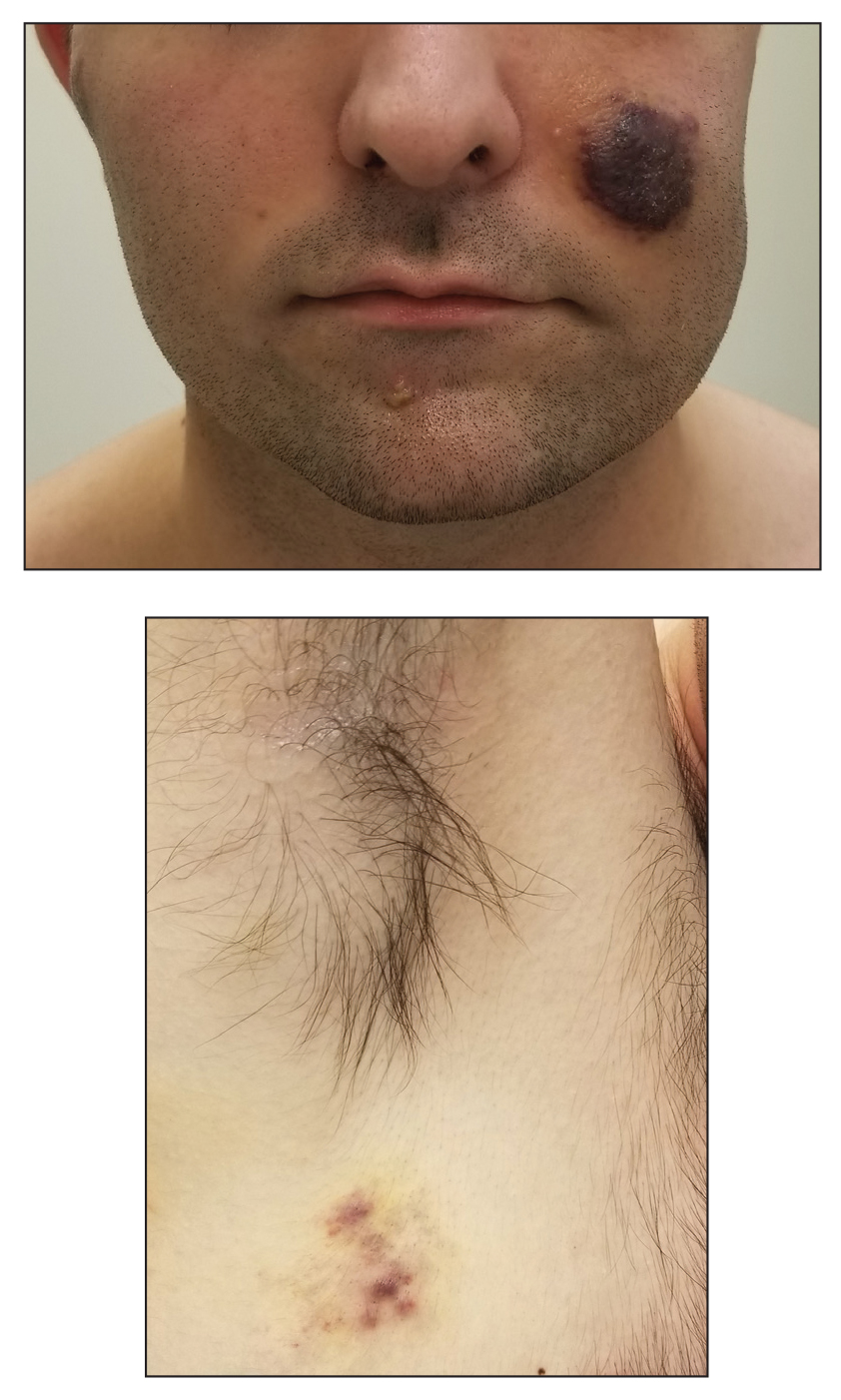

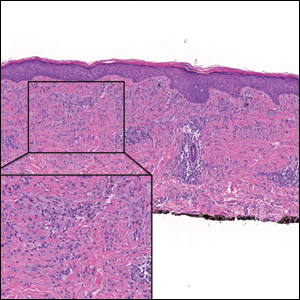

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) is a delayed movement disorder resulting from treatment with dopamine receptor–blocking medications, Dr Karen Anderson of Georgetown University School of Medicine explains. TD is most commonly associated with long-term use of antipsychotic drugs.

TD is characterized by involuntary, jerking movements of the tongue, lips, face, trunk, extremities, or the whole body. Although its characteristic movements are sometimes viewed as cosmetic, TD can interfere with patients’ quality of life and add to the stigma of mental illness.

The sooner TD is diagnosed, the more likely it is for patients to achieve remission spontaneously and without treatment. To that end, patients who are prescribed antipsychotic medication should be evaluated at baseline and regularly thereafter using the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS), which rates abnormal movements.

The optimal first step in TD management is to stop the dopamine receptor–blocking medication, but this option may not be possible in patients with chronic conditions, such as manic depression and schizophrenia. In these patients, dose reduction or switching to a newer antipsychotic may provide relief.

Two vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors are approved to treat TD and have been found to not worsen patients’ underlying psychiatric condition. Dr Anderson cautions that patients treated with a VMAT2 inhibitor will require monitoring because side effects of these agents include suicidal ideation.

--

Karen Anderson, MD, Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Neurology, Georgetown University School of Medicine; Washington, DC

Karen Anderson, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Neurocrine; Teva

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) is a delayed movement disorder resulting from treatment with dopamine receptor–blocking medications, Dr Karen Anderson of Georgetown University School of Medicine explains. TD is most commonly associated with long-term use of antipsychotic drugs.

TD is characterized by involuntary, jerking movements of the tongue, lips, face, trunk, extremities, or the whole body. Although its characteristic movements are sometimes viewed as cosmetic, TD can interfere with patients’ quality of life and add to the stigma of mental illness.

The sooner TD is diagnosed, the more likely it is for patients to achieve remission spontaneously and without treatment. To that end, patients who are prescribed antipsychotic medication should be evaluated at baseline and regularly thereafter using the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS), which rates abnormal movements.

The optimal first step in TD management is to stop the dopamine receptor–blocking medication, but this option may not be possible in patients with chronic conditions, such as manic depression and schizophrenia. In these patients, dose reduction or switching to a newer antipsychotic may provide relief.

Two vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors are approved to treat TD and have been found to not worsen patients’ underlying psychiatric condition. Dr Anderson cautions that patients treated with a VMAT2 inhibitor will require monitoring because side effects of these agents include suicidal ideation.

--

Karen Anderson, MD, Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Neurology, Georgetown University School of Medicine; Washington, DC

Karen Anderson, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Neurocrine; Teva

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) is a delayed movement disorder resulting from treatment with dopamine receptor–blocking medications, Dr Karen Anderson of Georgetown University School of Medicine explains. TD is most commonly associated with long-term use of antipsychotic drugs.

TD is characterized by involuntary, jerking movements of the tongue, lips, face, trunk, extremities, or the whole body. Although its characteristic movements are sometimes viewed as cosmetic, TD can interfere with patients’ quality of life and add to the stigma of mental illness.

The sooner TD is diagnosed, the more likely it is for patients to achieve remission spontaneously and without treatment. To that end, patients who are prescribed antipsychotic medication should be evaluated at baseline and regularly thereafter using the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS), which rates abnormal movements.

The optimal first step in TD management is to stop the dopamine receptor–blocking medication, but this option may not be possible in patients with chronic conditions, such as manic depression and schizophrenia. In these patients, dose reduction or switching to a newer antipsychotic may provide relief.

Two vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors are approved to treat TD and have been found to not worsen patients’ underlying psychiatric condition. Dr Anderson cautions that patients treated with a VMAT2 inhibitor will require monitoring because side effects of these agents include suicidal ideation.

--

Karen Anderson, MD, Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Neurology, Georgetown University School of Medicine; Washington, DC

Karen Anderson, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Neurocrine; Teva

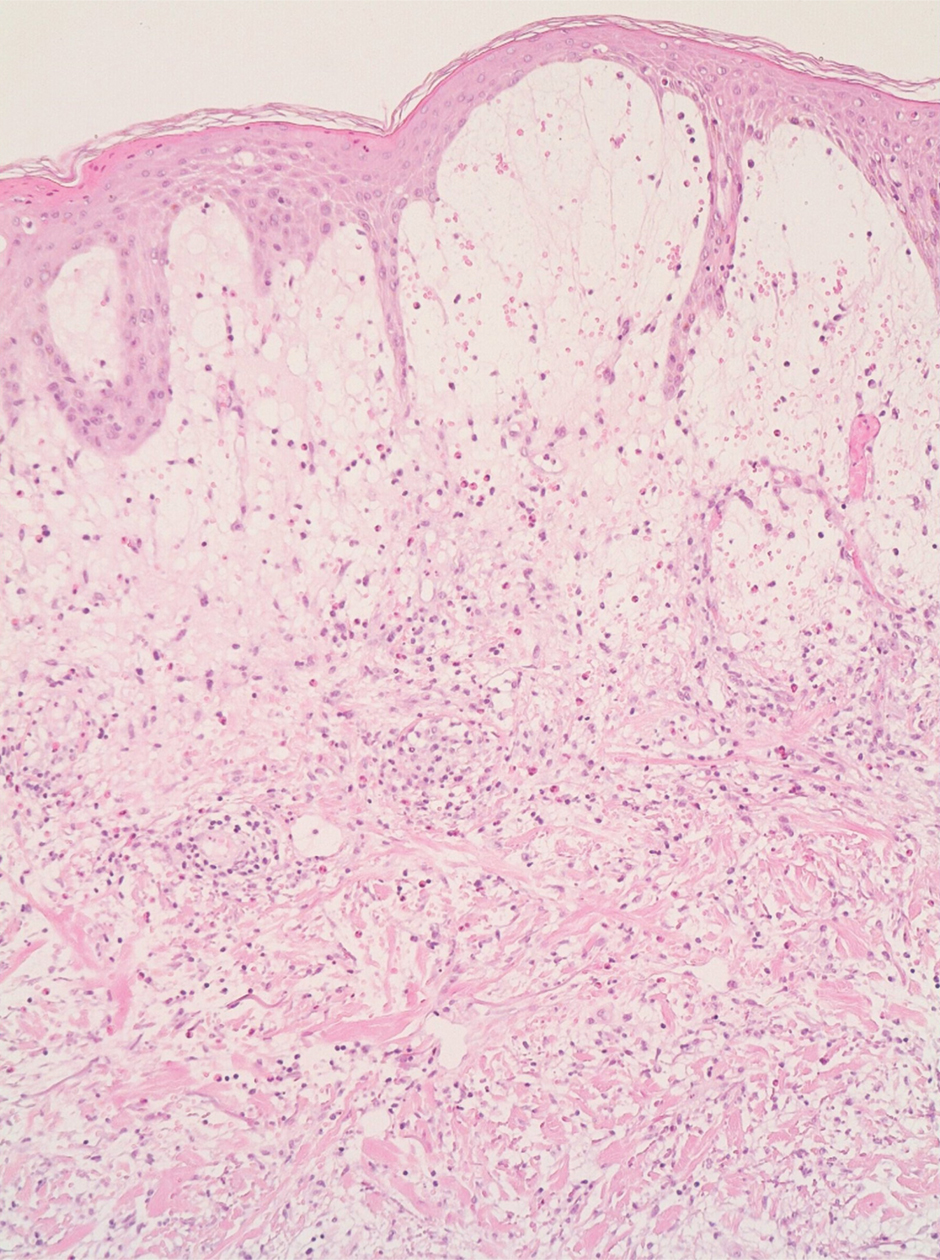

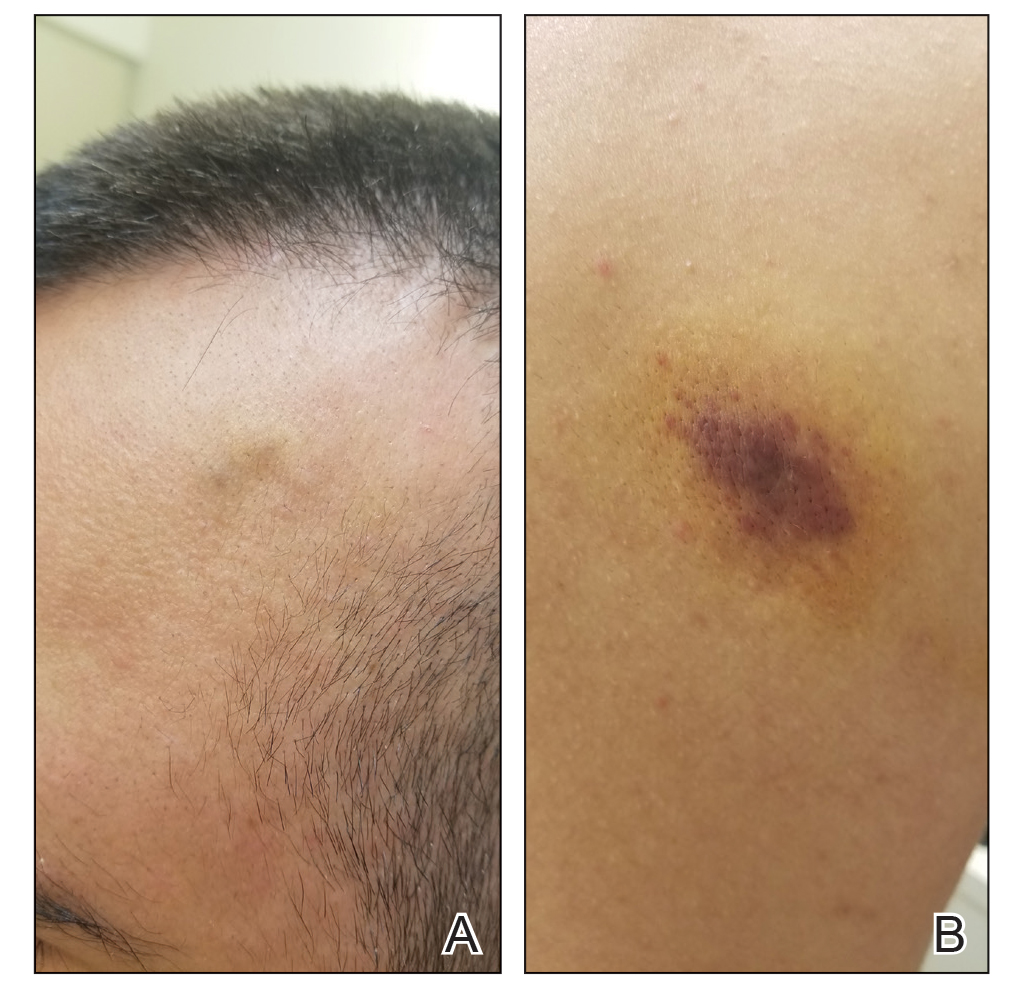

Multifactorial Effects of Endometriosis as a Chronic Systemic Disease

Can you talk about your research thus far and what your overall lab work has shown regarding endometriosis as a chronic systemic disease?

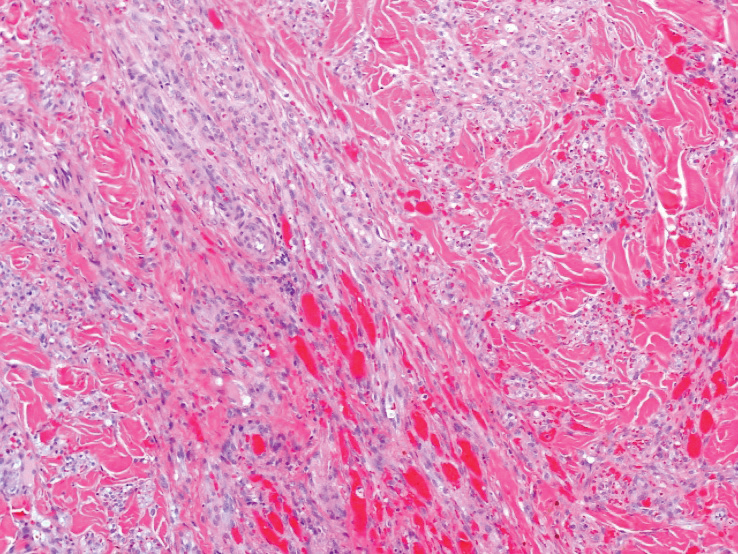

Dr. Flores: Endometriosis has traditionally been characterized by its pelvic manifestation however, it is important to understand that it is profoundly more than a pelvic disease—it is a chronic, systemic disease with multifactorial effects throughout the body.

We and other groups have found increased expression of several inflammatory cytokines in women with endometriosis. Our lab has found that compared to women without endometriosis, women with endometriosis not only have certain inflammatory cytokines elevated but also have altered expression of microRNAs. MicroRNAs are small noncoding RNAs that bind to and modulate translation of mRNA. To help determine whether these miRNAs were involved in mediating increased expression of inflammatory cytokines in women with endometriosis, we then transfected these miRNAs into a macrophage cell line, and again found altered inflammatory cytokine expression. We and others have also found a role for stem cells (from bone marrow and other sources) in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. In addition, we have found that in endometriosis, women have a low body-mass index and altered metabolism, which is related to induction of induction of hepatic (anorexigenic) gene expression and microRNA-mediated changes in adipocyte (metabolic) gene expression. Furthermore, we have found altered gene expression in regions of the brain associated with anxiety and depression and altered pain sensitization. Taken together, this work helps provide support for the systemic nature of endometriosis.

How can your findings in this space help us in diagnosing clinically and ultimately avoid diagnostic delay?

Dr. Flores: It’s about understanding that endometriosis is not just a pelvic disease and understanding that endometriosis is leading to inflammation and altered expression of miRNAs which allows endometriosis to have long-range effects. For example, women with endometriosis commonly have anxiety and depression and low BMI. As mentioned earlier, we have found that in a murine model of endometriosis, there is altered gene expression in regions of the brain associated with anxiety and depression and altered metabolism in a murine model of endometriosis. Other groups have also found changes in brain volume in these same areas in women with endometriosis, and we have seen low BMI in women with endometriosis. In fact, a common misconception was that being thin was a risk factor for endometriosis, however we have found that the endometriosis itself, is causing women alteration in genes associated with metabolism.

With respect to the endometrium, in addition to being a pelvic pain disorder, we also see that women with endometriosis have a higher likelihood of having infertility. And we think that's in part because one, just like the lesions can be resistant to progesterone, the endometrium of these women can also be resistant to progesterone. Progesterone is necessary for decidualization/implantation. We have also seen that stem cells can be recruited and ultimately incorrectly incorporated into the endometrium, which may also contribute to infertility in women with endometriosis.

If we can understand this multifactorial nature of endometriosis, I think this will help us not only shift toward diagnosing endometriosis clinically, but also avoid diagnostic delay. If we can understand that endometriosis is not just a pelvic disorder, but that It can also involve altered mood, bowel/bladder symptoms, inflammation, altered metabolism and/or cause infertility, I think that will ultimately help us to diagnosing earlier.

In addition, we can also utilize pelvic pain symptomatology to help with diagnosis as well. We can ask about cyclic pelvic pain that's been getting progressively worse over the years, not responding to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications. Also, in understanding that endometriosis can affect other organs, asking about cyclic pain/symptoms in other areas, such as cyclical bowel or bladder symptoms.

Thinking about the fact that if you do have a patient like that, you're seeing that they have altered mood symptoms, or alterations in inflammatory markers. Maybe that will help us shift from a disease that was typically only considered to be diagnosed by surgery, by switching to a clinical diagnosis for endometriosis. Doing that will hopefully help avoid diagnostic delay.

If we understand that while we typically describe endometriosis as causing cyclic pain symptoms, sometimes because of the existing diagnostic delay, ultimately women can present with chronic pelvic pain. Thus, it's also important to ask patients presenting with chronic pelvic pain what the symptoms were like beforehand (i.e., was the pain cyclic and progressively worsening over the years/before it became chronic) doing so will also help in terms of diagnosing sooner.

Lastly, circulating miRNAs have been considered promising biomarker candidates because they are stable in circulation and have highly specific expression profiles. We have found that the combination of several miRNAs reliably distinguished endometriosis patients from controls, and a prospective, blinded study showed that the combination of several miRNAs could be used to accurately identify patients with endometriosis, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.93.

Roughly 11%, or more than 6.5 million, women in the United States between the ages of 15–44 years, may have endometriosis. Is this disease more common in any particular age range or ethnicity?

Dr. Flores: We’re actually actively investigating that right now. And I think what makes it challenging, especially with respect to the age range, is now we're -- I think in part because of so much more awareness and more research is being done looking at this disease as a chronic systemic disease-- we're now starting to see/diagnose adolescents with endometriosis.

I think as we start gathering more information about these individuals, we'll be able to better say if there is a particular age range. Right now, we usually say it's in the reproductive years, however for some women it may be later if they were not diagnosed earlier. Conversely, some who are hopefully reading this, and also who conduct research on endometriosis, may be able to diagnose someone earlier that may have been missed until they were in their 30s or 40s, for example.

With respect to ethnicity, I'm the task force leader for diversity, equity, and inclusion in research and recruitment. This is something that I'm actively starting to work on, as are other groups. I don't have the answer for that yet, but as we continue to collect more data, we will have more information on this.

What are some of the existing hormonal therapies you rely upon as well as the biomarkers in predicting response to treatment, and are there any new research or treatments on the horizon?

Dr. Flores: I'll first start by telling you a bit about our existing treatment regimens, and then how I decide who would benefit from a given one. First line has always been progestin-based therapy, either in the form of a combined oral contraceptive pill or as progesterone only pills. However, up to 1/3 of women fail progestin-based therapy—this is termed progesterone resistance.

When progestin-based therapies fail, we then rely on other agents that are focused more on estrogen deprivation because, while we don't know the complete etiology of endometriosis, we do know that it is estrogen-dependent. There are two classes— gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists and GnRH antagonists. The agonist binds to the GnRH receptors, and initially can cause a flare effect due to its agonist properties, initially stimulate release of estradiol, and ultimately the GnRH receptor becomes downregulated and estradiol is decreased to the menopausal range. As a result we routinely provided add-back therapy with norethindrone to help prevent hot flashes and ensure bone protection.

Within the past three years, there has been a new oral GnRH receptor antagonist approved for treating endometriosis. The medication is available as a once a day or twice a day dosing regimen. As this is a GnRH antagonist, upon binding to the GnRH receptor, it blocks receptor activity, thus avoiding the flare affect; essentially, within 24 hours, there is a decrease in estradiol production.

As two doses are available, you can tailor how much you dial down estrogen for a given patient. The low dose lowers estradiol to a range of 40 picograms while the high (twice a day) dosing lowers your estrogen to about 6 picograms. Also, although it was not studied originally in terms of giving add-back therapy for the higher dose, given the safety (and effectiveness) of add-back therapy with GnRH agonists we are using the same norethindrone add-back therapy for women who are taking the GnRH receptor antagonist.

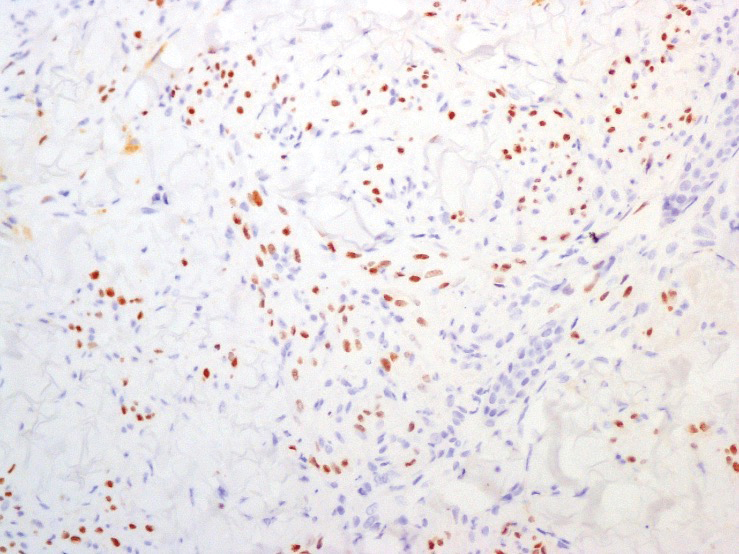

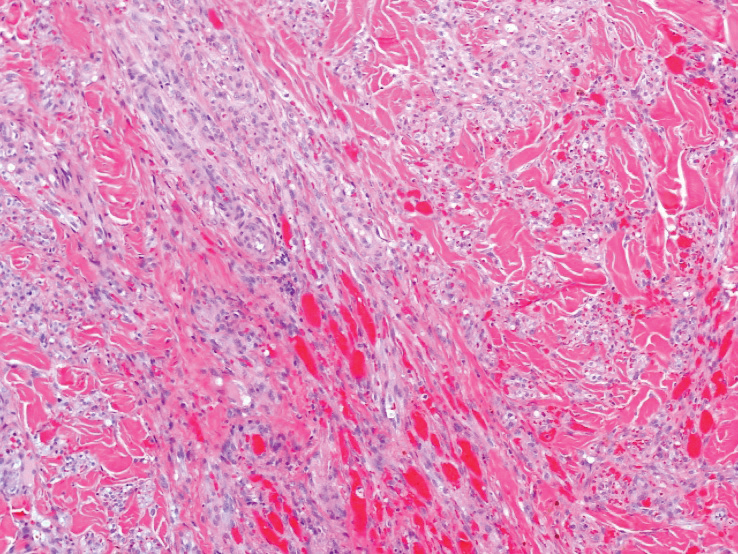

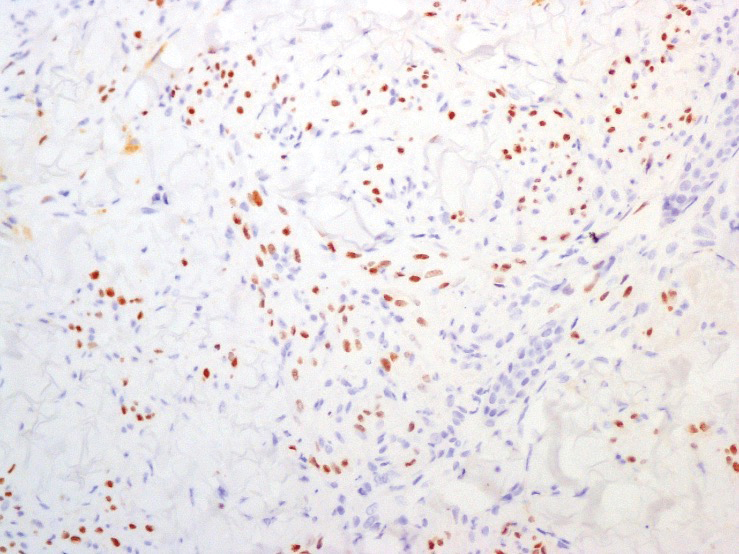

The next question is, how do we decide which medication a given patient receives? To answer that, I will tell you a bit about my precision-based medicine research. As mentioned before, while progestin-based therapy is first-line, failure rates are high, and unfortunately, we previously have not been able to identify who will or will not respond to first-line therapy. As such, I decided to assess progesterone receptor expression in endometriotic lesions from women who had undergone surgery for endometriosis, and determine whether progesterone receptor expression levels in lesions could be used to predict response to progestin-based therapy. I found that in women that had high levels of the progesterone receptor, they responded completely to progestin-based therapy-- there was a 100% response rate to progestin-based therapy. This is in sharp contrast to women who had low PR expression, where there was only a 6% response rate to progestin-based therapy.

While this is great with respect to being able to predict who will or will not respond to first line therapy, the one limitation is that would mean that women have to undergo surgery in order to determine progesterone receptor status/response to progestin-based therapy. However, given that within two to five years following surgery, up to 50% of women will have recurrence of pain symptoms, where I see my test coming into play is postoperatively. This is because many times , women who had pain, or who were failing a given agent, are placed back on that same medical therapy they were failing after surgery. Usually that was a progestin. Therefore, instead of putting them on that same therapy that they were failing, we can use my test to place them on an alternative therapy (such as a GnRH analogue) that more specifically targets estradiol production.

In terms of future directions with respect to treatment, there is a microRNA that has been found to be low in women with endometriosis—miRNALet-7b. In a murine model of endometriosis, we have found that if we supplement with Let-7, there is decreased inflammation and decreased lesion size of endometriosis. We have also found that supplementing miRNA Let-7b in human endometriotic lesions results in decreased inflammation in cell culture.

That would be future directions in terms of focusing on microRNAs and seeing how we can manipulate those to essentially block inflammation and lesion growth. Furthermore, such treatment would be non-hormonal, which would be a novel therapeutic approach.

As-Sanie S, Harris RE, Napadow V, et al. Changes in regional gray matter volume in women with chronic pelvic pain: a voxel-based morphometry study. Pain. 2012;153(5):1006-1014.

Ballard K, Lowton K, Wright J. What's the delay? A qualitative study of women's experiences of reaching a diagnosis of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(5):1296-1301

Cosar E, Mamillapalli R, Ersoy GS, Cho S, Seifer B, Taylor HS. Serum microRNAs as diagnostic markers of endometriosis: a comprehensive array-based analysis. Fertil Steril. 2016;106(2):402-409.

Flores VA, Vanhie A, Dang T, Taylor HS. Progesterone Receptor Status Predicts Response to Progestin Therapy in Endometriosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018 Dec 1;103(12):4561-4568

Goetz TG, Mamillapalli R, Taylor HS. Low Body Mass Index in Endometriosis Is Promoted by Hepatic Metabolic Gene Dysregulation in Mice. Biol Reprod. 2016;95(6):115.

Li T, et al. Endometriosis alters brain electrophysiology, gene expression and increases pain sensitization, anxiety, and depression in female mice. Biol Reprod. 2018;99(2):349-359.

Moustafa S, Burn M, Mamillapalli R, Nematian S, Flores V, Taylor HS. Accurate diagnosis of endometriosis using serum microRNAs. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223(4):557.e1-557.e11.

Nematian SE, et al. Systemic Inflammation Induced by microRNAs: Endometriosis-Derived Alterations in Circulating microRNA 125b-5p and Let-7b-5p Regulate Macrophage Cytokine Production. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(1):64-74.

Nnoaham KE, Hummelshoj L, Webster P, et al. Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: a multicenter study across ten countries. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(2):366-373.e8.

Rogers PA, D'Hooghe TM, Fazleabas A, et al. Defining future directions for endometriosis research: workshop report from the 2011 World Congress of Endometriosis In Montpellier, France. Reprod Sci. 2013;20(5):483-499.

Taylor HS, Kotlyar AM, Flores VA. Endometriosis is a chronic systemic disease: clinical challenges and novel innovations. Lancet. 2021 Feb 27

Zolbin MM, et al. Adipocyte alterations in endometriosis: reduced numbers of stem cells and microRNA induced alterations in adipocyte metabolic gene expression. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2019;17(1):36.

Can you talk about your research thus far and what your overall lab work has shown regarding endometriosis as a chronic systemic disease?

Dr. Flores: Endometriosis has traditionally been characterized by its pelvic manifestation however, it is important to understand that it is profoundly more than a pelvic disease—it is a chronic, systemic disease with multifactorial effects throughout the body.

We and other groups have found increased expression of several inflammatory cytokines in women with endometriosis. Our lab has found that compared to women without endometriosis, women with endometriosis not only have certain inflammatory cytokines elevated but also have altered expression of microRNAs. MicroRNAs are small noncoding RNAs that bind to and modulate translation of mRNA. To help determine whether these miRNAs were involved in mediating increased expression of inflammatory cytokines in women with endometriosis, we then transfected these miRNAs into a macrophage cell line, and again found altered inflammatory cytokine expression. We and others have also found a role for stem cells (from bone marrow and other sources) in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. In addition, we have found that in endometriosis, women have a low body-mass index and altered metabolism, which is related to induction of induction of hepatic (anorexigenic) gene expression and microRNA-mediated changes in adipocyte (metabolic) gene expression. Furthermore, we have found altered gene expression in regions of the brain associated with anxiety and depression and altered pain sensitization. Taken together, this work helps provide support for the systemic nature of endometriosis.

How can your findings in this space help us in diagnosing clinically and ultimately avoid diagnostic delay?

Dr. Flores: It’s about understanding that endometriosis is not just a pelvic disease and understanding that endometriosis is leading to inflammation and altered expression of miRNAs which allows endometriosis to have long-range effects. For example, women with endometriosis commonly have anxiety and depression and low BMI. As mentioned earlier, we have found that in a murine model of endometriosis, there is altered gene expression in regions of the brain associated with anxiety and depression and altered metabolism in a murine model of endometriosis. Other groups have also found changes in brain volume in these same areas in women with endometriosis, and we have seen low BMI in women with endometriosis. In fact, a common misconception was that being thin was a risk factor for endometriosis, however we have found that the endometriosis itself, is causing women alteration in genes associated with metabolism.

With respect to the endometrium, in addition to being a pelvic pain disorder, we also see that women with endometriosis have a higher likelihood of having infertility. And we think that's in part because one, just like the lesions can be resistant to progesterone, the endometrium of these women can also be resistant to progesterone. Progesterone is necessary for decidualization/implantation. We have also seen that stem cells can be recruited and ultimately incorrectly incorporated into the endometrium, which may also contribute to infertility in women with endometriosis.

If we can understand this multifactorial nature of endometriosis, I think this will help us not only shift toward diagnosing endometriosis clinically, but also avoid diagnostic delay. If we can understand that endometriosis is not just a pelvic disorder, but that It can also involve altered mood, bowel/bladder symptoms, inflammation, altered metabolism and/or cause infertility, I think that will ultimately help us to diagnosing earlier.

In addition, we can also utilize pelvic pain symptomatology to help with diagnosis as well. We can ask about cyclic pelvic pain that's been getting progressively worse over the years, not responding to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications. Also, in understanding that endometriosis can affect other organs, asking about cyclic pain/symptoms in other areas, such as cyclical bowel or bladder symptoms.

Thinking about the fact that if you do have a patient like that, you're seeing that they have altered mood symptoms, or alterations in inflammatory markers. Maybe that will help us shift from a disease that was typically only considered to be diagnosed by surgery, by switching to a clinical diagnosis for endometriosis. Doing that will hopefully help avoid diagnostic delay.

If we understand that while we typically describe endometriosis as causing cyclic pain symptoms, sometimes because of the existing diagnostic delay, ultimately women can present with chronic pelvic pain. Thus, it's also important to ask patients presenting with chronic pelvic pain what the symptoms were like beforehand (i.e., was the pain cyclic and progressively worsening over the years/before it became chronic) doing so will also help in terms of diagnosing sooner.

Lastly, circulating miRNAs have been considered promising biomarker candidates because they are stable in circulation and have highly specific expression profiles. We have found that the combination of several miRNAs reliably distinguished endometriosis patients from controls, and a prospective, blinded study showed that the combination of several miRNAs could be used to accurately identify patients with endometriosis, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.93.

Roughly 11%, or more than 6.5 million, women in the United States between the ages of 15–44 years, may have endometriosis. Is this disease more common in any particular age range or ethnicity?

Dr. Flores: We’re actually actively investigating that right now. And I think what makes it challenging, especially with respect to the age range, is now we're -- I think in part because of so much more awareness and more research is being done looking at this disease as a chronic systemic disease-- we're now starting to see/diagnose adolescents with endometriosis.

I think as we start gathering more information about these individuals, we'll be able to better say if there is a particular age range. Right now, we usually say it's in the reproductive years, however for some women it may be later if they were not diagnosed earlier. Conversely, some who are hopefully reading this, and also who conduct research on endometriosis, may be able to diagnose someone earlier that may have been missed until they were in their 30s or 40s, for example.

With respect to ethnicity, I'm the task force leader for diversity, equity, and inclusion in research and recruitment. This is something that I'm actively starting to work on, as are other groups. I don't have the answer for that yet, but as we continue to collect more data, we will have more information on this.

What are some of the existing hormonal therapies you rely upon as well as the biomarkers in predicting response to treatment, and are there any new research or treatments on the horizon?

Dr. Flores: I'll first start by telling you a bit about our existing treatment regimens, and then how I decide who would benefit from a given one. First line has always been progestin-based therapy, either in the form of a combined oral contraceptive pill or as progesterone only pills. However, up to 1/3 of women fail progestin-based therapy—this is termed progesterone resistance.

When progestin-based therapies fail, we then rely on other agents that are focused more on estrogen deprivation because, while we don't know the complete etiology of endometriosis, we do know that it is estrogen-dependent. There are two classes— gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists and GnRH antagonists. The agonist binds to the GnRH receptors, and initially can cause a flare effect due to its agonist properties, initially stimulate release of estradiol, and ultimately the GnRH receptor becomes downregulated and estradiol is decreased to the menopausal range. As a result we routinely provided add-back therapy with norethindrone to help prevent hot flashes and ensure bone protection.

Within the past three years, there has been a new oral GnRH receptor antagonist approved for treating endometriosis. The medication is available as a once a day or twice a day dosing regimen. As this is a GnRH antagonist, upon binding to the GnRH receptor, it blocks receptor activity, thus avoiding the flare affect; essentially, within 24 hours, there is a decrease in estradiol production.

As two doses are available, you can tailor how much you dial down estrogen for a given patient. The low dose lowers estradiol to a range of 40 picograms while the high (twice a day) dosing lowers your estrogen to about 6 picograms. Also, although it was not studied originally in terms of giving add-back therapy for the higher dose, given the safety (and effectiveness) of add-back therapy with GnRH agonists we are using the same norethindrone add-back therapy for women who are taking the GnRH receptor antagonist.

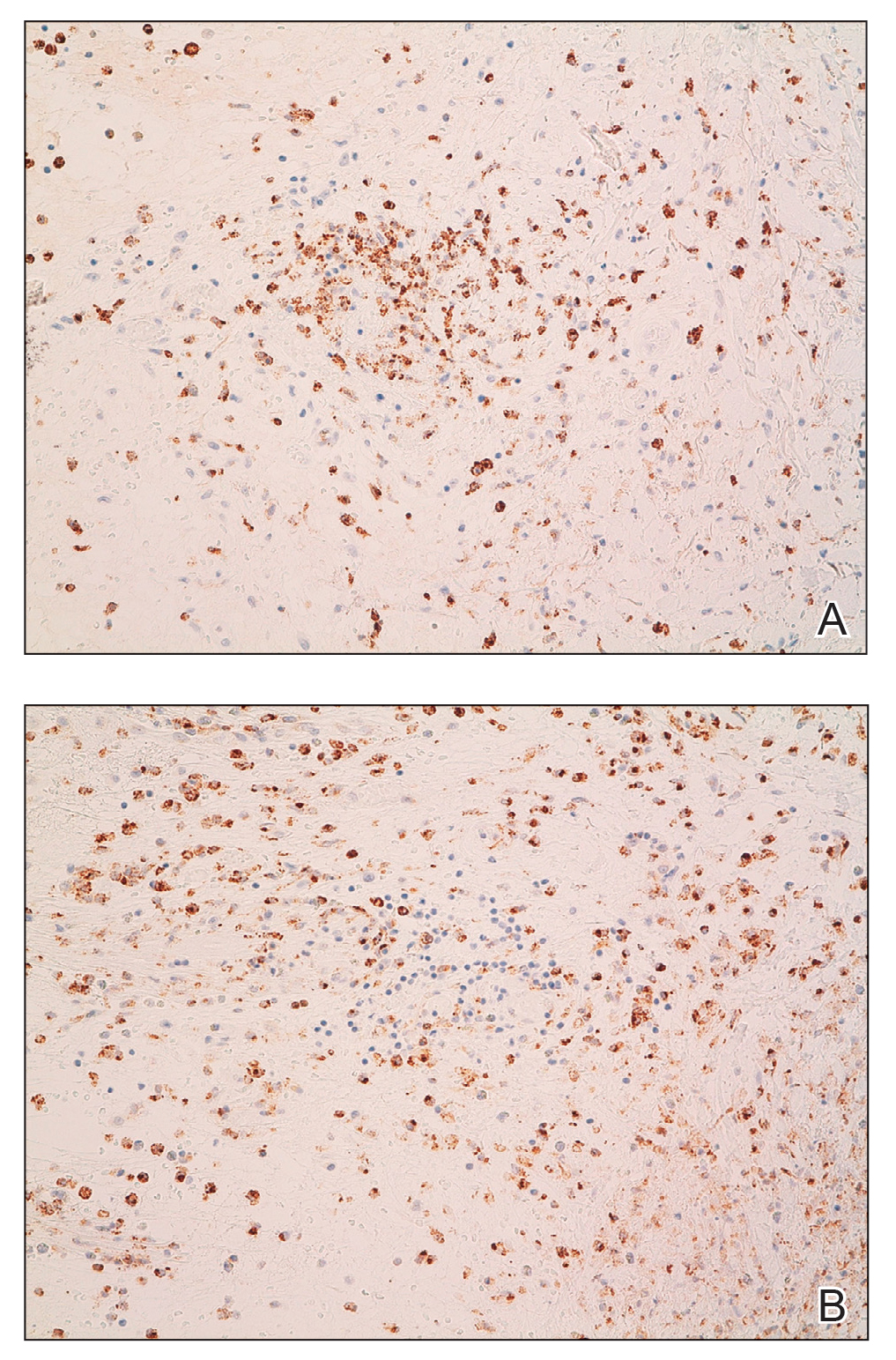

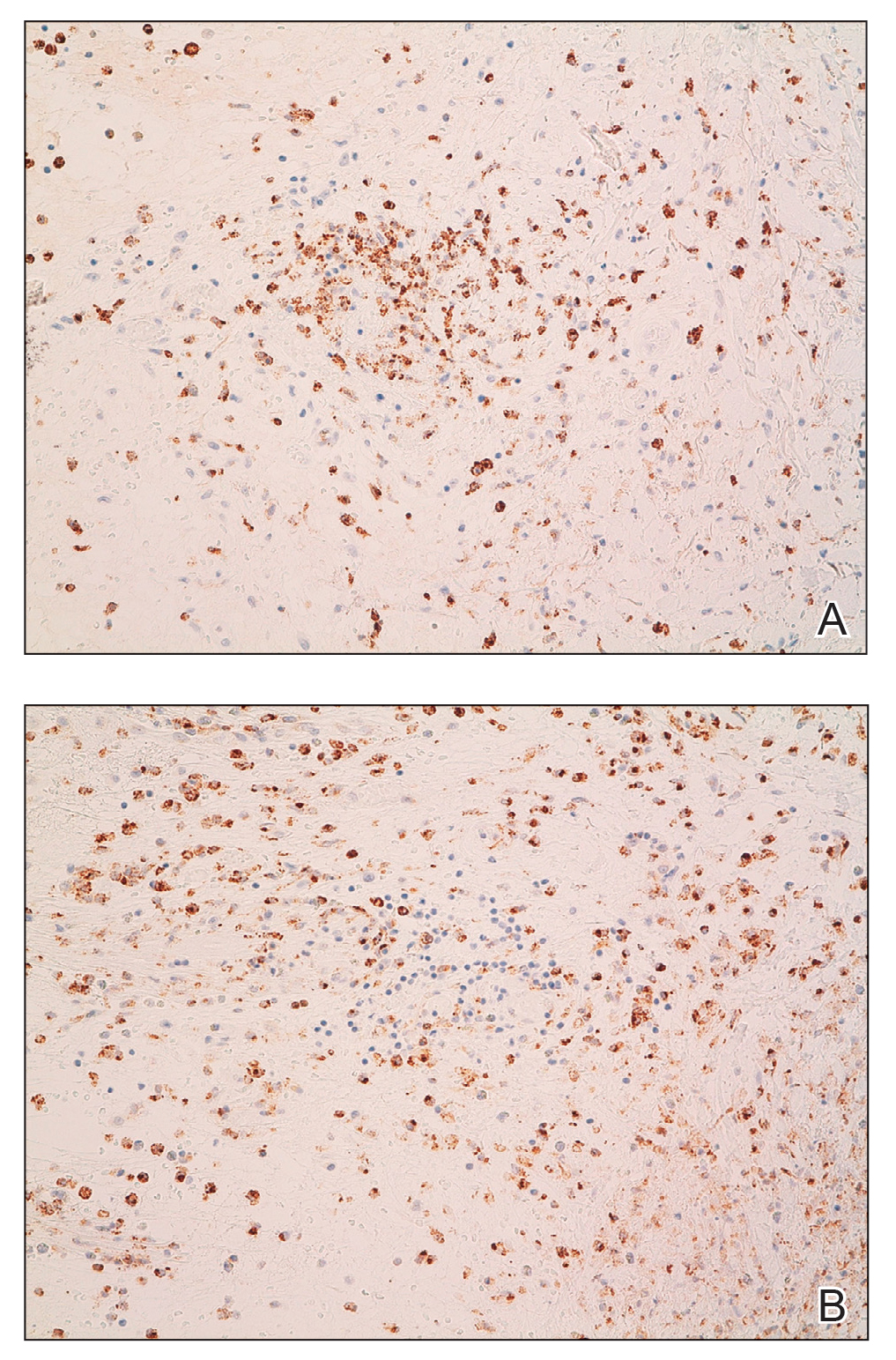

The next question is, how do we decide which medication a given patient receives? To answer that, I will tell you a bit about my precision-based medicine research. As mentioned before, while progestin-based therapy is first-line, failure rates are high, and unfortunately, we previously have not been able to identify who will or will not respond to first-line therapy. As such, I decided to assess progesterone receptor expression in endometriotic lesions from women who had undergone surgery for endometriosis, and determine whether progesterone receptor expression levels in lesions could be used to predict response to progestin-based therapy. I found that in women that had high levels of the progesterone receptor, they responded completely to progestin-based therapy-- there was a 100% response rate to progestin-based therapy. This is in sharp contrast to women who had low PR expression, where there was only a 6% response rate to progestin-based therapy.

While this is great with respect to being able to predict who will or will not respond to first line therapy, the one limitation is that would mean that women have to undergo surgery in order to determine progesterone receptor status/response to progestin-based therapy. However, given that within two to five years following surgery, up to 50% of women will have recurrence of pain symptoms, where I see my test coming into play is postoperatively. This is because many times , women who had pain, or who were failing a given agent, are placed back on that same medical therapy they were failing after surgery. Usually that was a progestin. Therefore, instead of putting them on that same therapy that they were failing, we can use my test to place them on an alternative therapy (such as a GnRH analogue) that more specifically targets estradiol production.

In terms of future directions with respect to treatment, there is a microRNA that has been found to be low in women with endometriosis—miRNALet-7b. In a murine model of endometriosis, we have found that if we supplement with Let-7, there is decreased inflammation and decreased lesion size of endometriosis. We have also found that supplementing miRNA Let-7b in human endometriotic lesions results in decreased inflammation in cell culture.

That would be future directions in terms of focusing on microRNAs and seeing how we can manipulate those to essentially block inflammation and lesion growth. Furthermore, such treatment would be non-hormonal, which would be a novel therapeutic approach.

Can you talk about your research thus far and what your overall lab work has shown regarding endometriosis as a chronic systemic disease?

Dr. Flores: Endometriosis has traditionally been characterized by its pelvic manifestation however, it is important to understand that it is profoundly more than a pelvic disease—it is a chronic, systemic disease with multifactorial effects throughout the body.

We and other groups have found increased expression of several inflammatory cytokines in women with endometriosis. Our lab has found that compared to women without endometriosis, women with endometriosis not only have certain inflammatory cytokines elevated but also have altered expression of microRNAs. MicroRNAs are small noncoding RNAs that bind to and modulate translation of mRNA. To help determine whether these miRNAs were involved in mediating increased expression of inflammatory cytokines in women with endometriosis, we then transfected these miRNAs into a macrophage cell line, and again found altered inflammatory cytokine expression. We and others have also found a role for stem cells (from bone marrow and other sources) in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. In addition, we have found that in endometriosis, women have a low body-mass index and altered metabolism, which is related to induction of induction of hepatic (anorexigenic) gene expression and microRNA-mediated changes in adipocyte (metabolic) gene expression. Furthermore, we have found altered gene expression in regions of the brain associated with anxiety and depression and altered pain sensitization. Taken together, this work helps provide support for the systemic nature of endometriosis.

How can your findings in this space help us in diagnosing clinically and ultimately avoid diagnostic delay?

Dr. Flores: It’s about understanding that endometriosis is not just a pelvic disease and understanding that endometriosis is leading to inflammation and altered expression of miRNAs which allows endometriosis to have long-range effects. For example, women with endometriosis commonly have anxiety and depression and low BMI. As mentioned earlier, we have found that in a murine model of endometriosis, there is altered gene expression in regions of the brain associated with anxiety and depression and altered metabolism in a murine model of endometriosis. Other groups have also found changes in brain volume in these same areas in women with endometriosis, and we have seen low BMI in women with endometriosis. In fact, a common misconception was that being thin was a risk factor for endometriosis, however we have found that the endometriosis itself, is causing women alteration in genes associated with metabolism.

With respect to the endometrium, in addition to being a pelvic pain disorder, we also see that women with endometriosis have a higher likelihood of having infertility. And we think that's in part because one, just like the lesions can be resistant to progesterone, the endometrium of these women can also be resistant to progesterone. Progesterone is necessary for decidualization/implantation. We have also seen that stem cells can be recruited and ultimately incorrectly incorporated into the endometrium, which may also contribute to infertility in women with endometriosis.

If we can understand this multifactorial nature of endometriosis, I think this will help us not only shift toward diagnosing endometriosis clinically, but also avoid diagnostic delay. If we can understand that endometriosis is not just a pelvic disorder, but that It can also involve altered mood, bowel/bladder symptoms, inflammation, altered metabolism and/or cause infertility, I think that will ultimately help us to diagnosing earlier.

In addition, we can also utilize pelvic pain symptomatology to help with diagnosis as well. We can ask about cyclic pelvic pain that's been getting progressively worse over the years, not responding to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications. Also, in understanding that endometriosis can affect other organs, asking about cyclic pain/symptoms in other areas, such as cyclical bowel or bladder symptoms.

Thinking about the fact that if you do have a patient like that, you're seeing that they have altered mood symptoms, or alterations in inflammatory markers. Maybe that will help us shift from a disease that was typically only considered to be diagnosed by surgery, by switching to a clinical diagnosis for endometriosis. Doing that will hopefully help avoid diagnostic delay.

If we understand that while we typically describe endometriosis as causing cyclic pain symptoms, sometimes because of the existing diagnostic delay, ultimately women can present with chronic pelvic pain. Thus, it's also important to ask patients presenting with chronic pelvic pain what the symptoms were like beforehand (i.e., was the pain cyclic and progressively worsening over the years/before it became chronic) doing so will also help in terms of diagnosing sooner.

Lastly, circulating miRNAs have been considered promising biomarker candidates because they are stable in circulation and have highly specific expression profiles. We have found that the combination of several miRNAs reliably distinguished endometriosis patients from controls, and a prospective, blinded study showed that the combination of several miRNAs could be used to accurately identify patients with endometriosis, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.93.

Roughly 11%, or more than 6.5 million, women in the United States between the ages of 15–44 years, may have endometriosis. Is this disease more common in any particular age range or ethnicity?

Dr. Flores: We’re actually actively investigating that right now. And I think what makes it challenging, especially with respect to the age range, is now we're -- I think in part because of so much more awareness and more research is being done looking at this disease as a chronic systemic disease-- we're now starting to see/diagnose adolescents with endometriosis.

I think as we start gathering more information about these individuals, we'll be able to better say if there is a particular age range. Right now, we usually say it's in the reproductive years, however for some women it may be later if they were not diagnosed earlier. Conversely, some who are hopefully reading this, and also who conduct research on endometriosis, may be able to diagnose someone earlier that may have been missed until they were in their 30s or 40s, for example.

With respect to ethnicity, I'm the task force leader for diversity, equity, and inclusion in research and recruitment. This is something that I'm actively starting to work on, as are other groups. I don't have the answer for that yet, but as we continue to collect more data, we will have more information on this.

What are some of the existing hormonal therapies you rely upon as well as the biomarkers in predicting response to treatment, and are there any new research or treatments on the horizon?

Dr. Flores: I'll first start by telling you a bit about our existing treatment regimens, and then how I decide who would benefit from a given one. First line has always been progestin-based therapy, either in the form of a combined oral contraceptive pill or as progesterone only pills. However, up to 1/3 of women fail progestin-based therapy—this is termed progesterone resistance.

When progestin-based therapies fail, we then rely on other agents that are focused more on estrogen deprivation because, while we don't know the complete etiology of endometriosis, we do know that it is estrogen-dependent. There are two classes— gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists and GnRH antagonists. The agonist binds to the GnRH receptors, and initially can cause a flare effect due to its agonist properties, initially stimulate release of estradiol, and ultimately the GnRH receptor becomes downregulated and estradiol is decreased to the menopausal range. As a result we routinely provided add-back therapy with norethindrone to help prevent hot flashes and ensure bone protection.

Within the past three years, there has been a new oral GnRH receptor antagonist approved for treating endometriosis. The medication is available as a once a day or twice a day dosing regimen. As this is a GnRH antagonist, upon binding to the GnRH receptor, it blocks receptor activity, thus avoiding the flare affect; essentially, within 24 hours, there is a decrease in estradiol production.

As two doses are available, you can tailor how much you dial down estrogen for a given patient. The low dose lowers estradiol to a range of 40 picograms while the high (twice a day) dosing lowers your estrogen to about 6 picograms. Also, although it was not studied originally in terms of giving add-back therapy for the higher dose, given the safety (and effectiveness) of add-back therapy with GnRH agonists we are using the same norethindrone add-back therapy for women who are taking the GnRH receptor antagonist.

The next question is, how do we decide which medication a given patient receives? To answer that, I will tell you a bit about my precision-based medicine research. As mentioned before, while progestin-based therapy is first-line, failure rates are high, and unfortunately, we previously have not been able to identify who will or will not respond to first-line therapy. As such, I decided to assess progesterone receptor expression in endometriotic lesions from women who had undergone surgery for endometriosis, and determine whether progesterone receptor expression levels in lesions could be used to predict response to progestin-based therapy. I found that in women that had high levels of the progesterone receptor, they responded completely to progestin-based therapy-- there was a 100% response rate to progestin-based therapy. This is in sharp contrast to women who had low PR expression, where there was only a 6% response rate to progestin-based therapy.

While this is great with respect to being able to predict who will or will not respond to first line therapy, the one limitation is that would mean that women have to undergo surgery in order to determine progesterone receptor status/response to progestin-based therapy. However, given that within two to five years following surgery, up to 50% of women will have recurrence of pain symptoms, where I see my test coming into play is postoperatively. This is because many times , women who had pain, or who were failing a given agent, are placed back on that same medical therapy they were failing after surgery. Usually that was a progestin. Therefore, instead of putting them on that same therapy that they were failing, we can use my test to place them on an alternative therapy (such as a GnRH analogue) that more specifically targets estradiol production.

In terms of future directions with respect to treatment, there is a microRNA that has been found to be low in women with endometriosis—miRNALet-7b. In a murine model of endometriosis, we have found that if we supplement with Let-7, there is decreased inflammation and decreased lesion size of endometriosis. We have also found that supplementing miRNA Let-7b in human endometriotic lesions results in decreased inflammation in cell culture.

That would be future directions in terms of focusing on microRNAs and seeing how we can manipulate those to essentially block inflammation and lesion growth. Furthermore, such treatment would be non-hormonal, which would be a novel therapeutic approach.

As-Sanie S, Harris RE, Napadow V, et al. Changes in regional gray matter volume in women with chronic pelvic pain: a voxel-based morphometry study. Pain. 2012;153(5):1006-1014.