User login

PMS: pNfL could serve as biomarker for disability progression and drug response

Key clinical point: Plasma neurofilament light chain (pNfL) could serve as an effective biomarker for identifying disability progression and monitoring treatment response in progressive multiple sclerosis (PMS).

Major finding: High vs. low pNfL levels increased the risk for 3-month confirmed disability progression (CDP) by 32% (P = .0055) and 49% (P = .0268) and 6-month CDP by 26% (P = .0417) and 48% (P = .0431) in patients with secondary PMS (SPMS) and primary PMS (PPMS), respectively. pNfL levels were lower in patients treated with siponimod or fingolimod vs. placebo.

Study details: This was a post hoc analysis of EXPAND and INFORMS studies including 1452 and 378 patients with SPMS and PPMS, respectively, who received siponimod, fingolimod, or placebo.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland. Some authors, including the lead author, reported being current or former employees of Novartis Pharma AG and some authors reported serving on advisory boards or receiving grants, speaker honoraria, lecture fees, or consulting fees from various sources, including Novartis Pharma AG.

Source: Leppert D et al. blood neurofilament light in progressive multiple sclerosis: Post hoc analysis of 2 randomized controlled trials. Neurology. 2022 (Apr 4). Doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000200258

Key clinical point: Plasma neurofilament light chain (pNfL) could serve as an effective biomarker for identifying disability progression and monitoring treatment response in progressive multiple sclerosis (PMS).

Major finding: High vs. low pNfL levels increased the risk for 3-month confirmed disability progression (CDP) by 32% (P = .0055) and 49% (P = .0268) and 6-month CDP by 26% (P = .0417) and 48% (P = .0431) in patients with secondary PMS (SPMS) and primary PMS (PPMS), respectively. pNfL levels were lower in patients treated with siponimod or fingolimod vs. placebo.

Study details: This was a post hoc analysis of EXPAND and INFORMS studies including 1452 and 378 patients with SPMS and PPMS, respectively, who received siponimod, fingolimod, or placebo.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland. Some authors, including the lead author, reported being current or former employees of Novartis Pharma AG and some authors reported serving on advisory boards or receiving grants, speaker honoraria, lecture fees, or consulting fees from various sources, including Novartis Pharma AG.

Source: Leppert D et al. blood neurofilament light in progressive multiple sclerosis: Post hoc analysis of 2 randomized controlled trials. Neurology. 2022 (Apr 4). Doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000200258

Key clinical point: Plasma neurofilament light chain (pNfL) could serve as an effective biomarker for identifying disability progression and monitoring treatment response in progressive multiple sclerosis (PMS).

Major finding: High vs. low pNfL levels increased the risk for 3-month confirmed disability progression (CDP) by 32% (P = .0055) and 49% (P = .0268) and 6-month CDP by 26% (P = .0417) and 48% (P = .0431) in patients with secondary PMS (SPMS) and primary PMS (PPMS), respectively. pNfL levels were lower in patients treated with siponimod or fingolimod vs. placebo.

Study details: This was a post hoc analysis of EXPAND and INFORMS studies including 1452 and 378 patients with SPMS and PPMS, respectively, who received siponimod, fingolimod, or placebo.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland. Some authors, including the lead author, reported being current or former employees of Novartis Pharma AG and some authors reported serving on advisory boards or receiving grants, speaker honoraria, lecture fees, or consulting fees from various sources, including Novartis Pharma AG.

Source: Leppert D et al. blood neurofilament light in progressive multiple sclerosis: Post hoc analysis of 2 randomized controlled trials. Neurology. 2022 (Apr 4). Doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000200258

MS: Fingolimod cessation safe if followed by prompt commencement of new therapy

Key clinical point: The average relapse rates and the rate of severe relapses did not increase significantly after fingolimod discontinuation in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS); however, delaying the commencement of immunotherapy increased the risk for relapse.

Major finding: The annualized relapse rate (ARR) was not significantly different during and after fingolimod cessation (mean difference −0.06; 95% CI −0.14 to 0.01), with no severe relapses reported in the year prior and after fingolimod cessation. However, delaying the recommencement of therapy from 2 to 4 months vs. beginning within 2 months (odds ratio 1.67; 95% CI 1.22-2.27) was associated with a higher risk for relapse.

Study details: Findings are from an analysis of 685 patients with relapsing MS who received fingolimod therapy for at least 12 months and were followed-up for at least 12 months after fingolimod cessation.

Disclosures: Open access funding was enabled by CAUL and its member institutions. Some authors declared receiving research support, personal compensation, speaker or consulting fees, or nonfinancial support from various sources.

Source: Malpas CB et al. Multiple sclerosis relapses following cessation of fingolimod. Clin Drug Investig. 2022;42:355-364 (Mar 18). Doi: 10.1007/s40261-022-01129-7

Key clinical point: The average relapse rates and the rate of severe relapses did not increase significantly after fingolimod discontinuation in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS); however, delaying the commencement of immunotherapy increased the risk for relapse.

Major finding: The annualized relapse rate (ARR) was not significantly different during and after fingolimod cessation (mean difference −0.06; 95% CI −0.14 to 0.01), with no severe relapses reported in the year prior and after fingolimod cessation. However, delaying the recommencement of therapy from 2 to 4 months vs. beginning within 2 months (odds ratio 1.67; 95% CI 1.22-2.27) was associated with a higher risk for relapse.

Study details: Findings are from an analysis of 685 patients with relapsing MS who received fingolimod therapy for at least 12 months and were followed-up for at least 12 months after fingolimod cessation.

Disclosures: Open access funding was enabled by CAUL and its member institutions. Some authors declared receiving research support, personal compensation, speaker or consulting fees, or nonfinancial support from various sources.

Source: Malpas CB et al. Multiple sclerosis relapses following cessation of fingolimod. Clin Drug Investig. 2022;42:355-364 (Mar 18). Doi: 10.1007/s40261-022-01129-7

Key clinical point: The average relapse rates and the rate of severe relapses did not increase significantly after fingolimod discontinuation in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS); however, delaying the commencement of immunotherapy increased the risk for relapse.

Major finding: The annualized relapse rate (ARR) was not significantly different during and after fingolimod cessation (mean difference −0.06; 95% CI −0.14 to 0.01), with no severe relapses reported in the year prior and after fingolimod cessation. However, delaying the recommencement of therapy from 2 to 4 months vs. beginning within 2 months (odds ratio 1.67; 95% CI 1.22-2.27) was associated with a higher risk for relapse.

Study details: Findings are from an analysis of 685 patients with relapsing MS who received fingolimod therapy for at least 12 months and were followed-up for at least 12 months after fingolimod cessation.

Disclosures: Open access funding was enabled by CAUL and its member institutions. Some authors declared receiving research support, personal compensation, speaker or consulting fees, or nonfinancial support from various sources.

Source: Malpas CB et al. Multiple sclerosis relapses following cessation of fingolimod. Clin Drug Investig. 2022;42:355-364 (Mar 18). Doi: 10.1007/s40261-022-01129-7

Granuloma Faciale in Woman With Levamisole-Induced Vasculitis

To the Editor:

A 53-year-old Hispanic woman presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of an expanding plaque on the right cheek of 2 months’ duration. The patient stated the plaque began as a pimple, which she picked with subsequent spread laterally across the cheek. The area was intermittently tender, but she denied tingling, burning, or pruritus of the site. She had been treated with doxycycline and amoxicillin–clavulanic acid prior to presentation without improvement. She had a history of levamisole-induced vasculitis approximately 6 months prior. A review of systems was notable for diffuse joint pain. The patient denied tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use in the preceding 3 months and denied any changes in her medications or in health within the last year.

Physical examination revealed a well-appearing, alert, and afebrile patient with a pink, well-demarcated plaque on the right cheek (Figure 1). The borders of the plaque were indurated, and the lateral aspect of the plaque was eroded secondary to digital manipulation by the patient. She had no cervical lymphadenopathy. There were no other abnormal cutaneous findings.

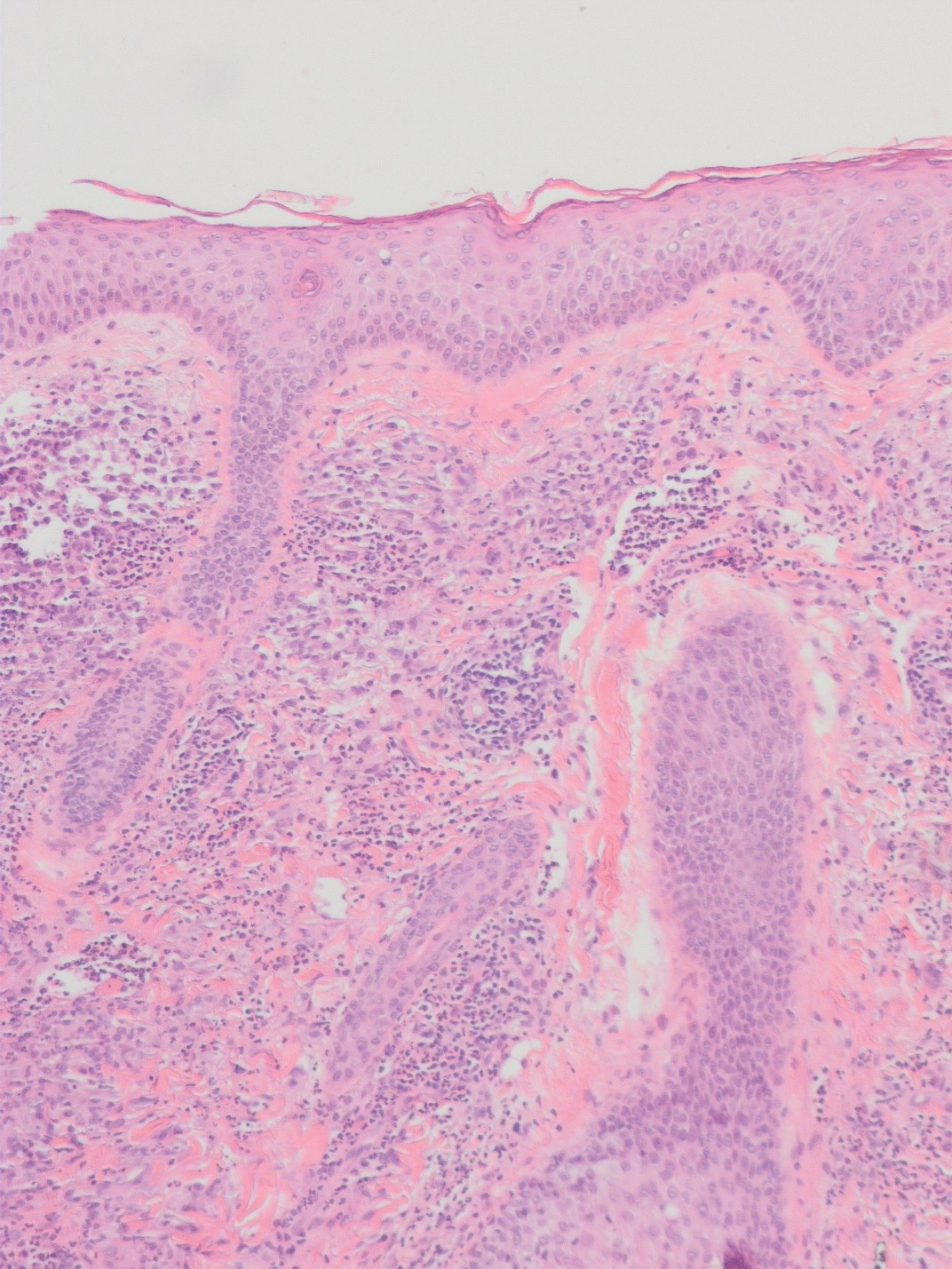

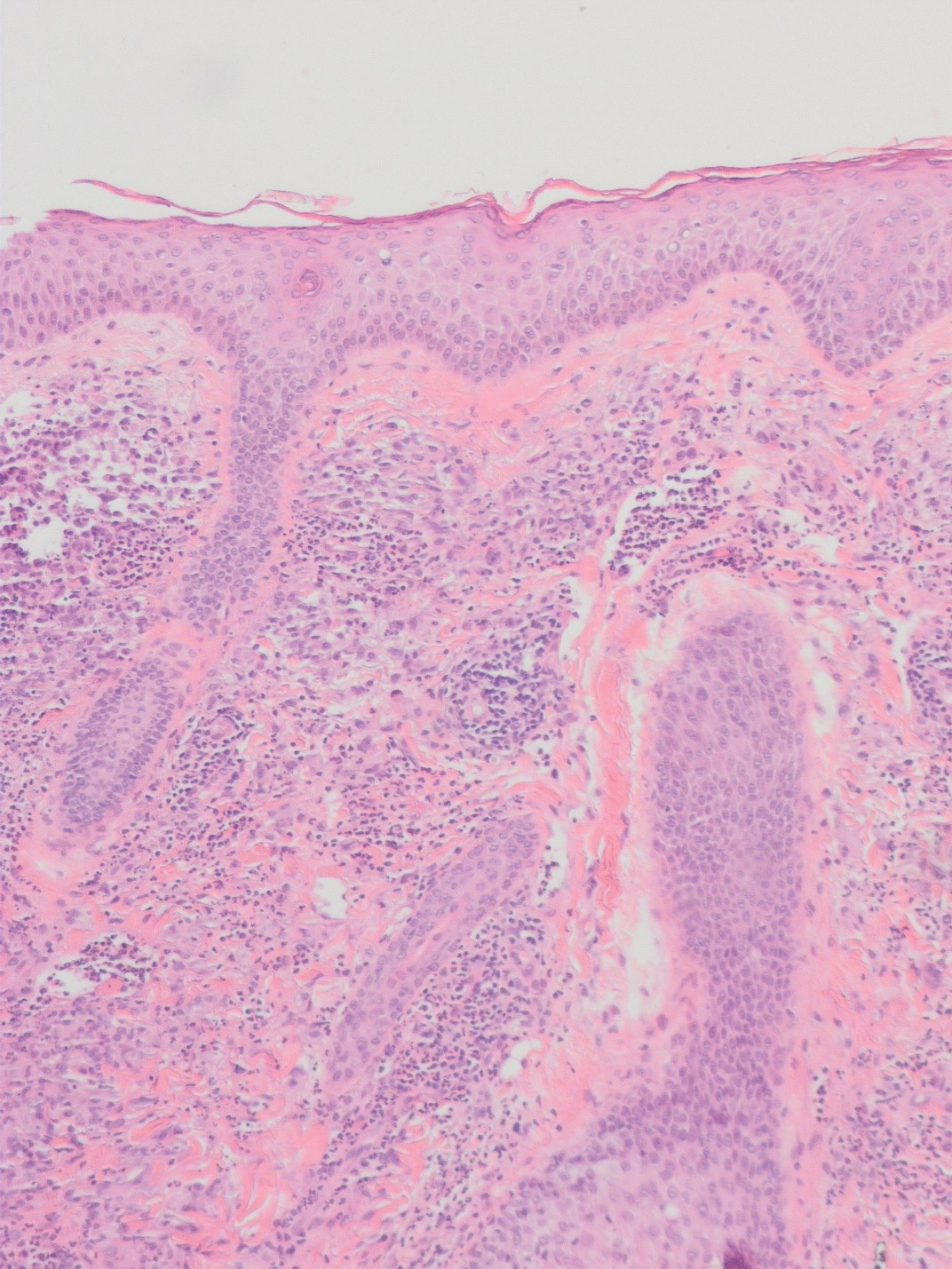

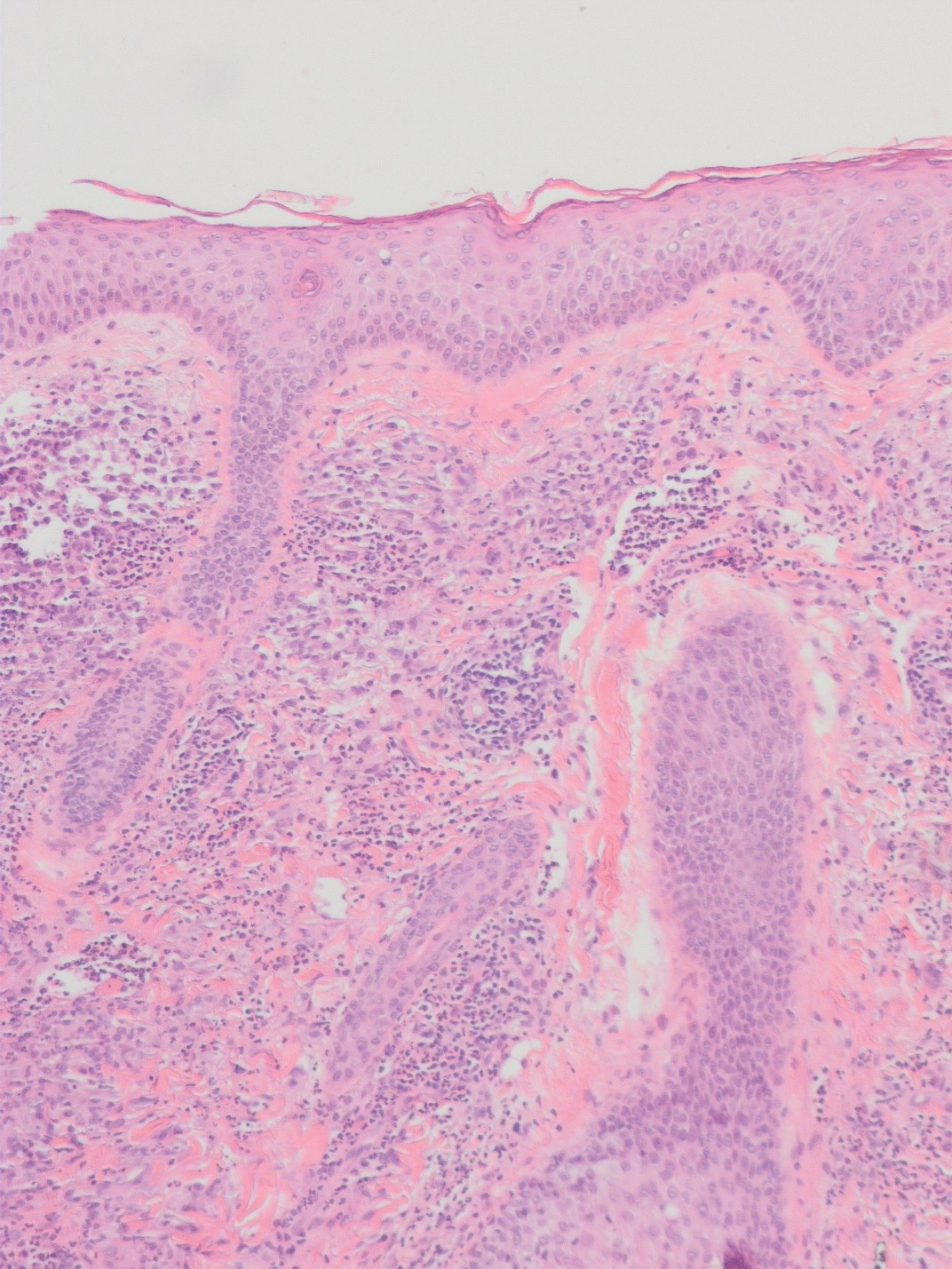

There is a broad differential diagnosis for a pink expanding plaque on the face, which requires histopathologic correlation for correct diagnosis. Three broad categories in the differential are infectious (eg, bacterial, fungal), medication related (eg, fixed drug eruption), and granulomatous (eg, granuloma faciale [GF], sarcoidosis, tumid lupus, leprosy, granulomatous rosacea). A biopsy of the lesion revealed a mixed inflammatory cell dermal infiltrate with perivascular accentuation and intense vasculitis that was consistent with GF (Figure 2). Gomori methenamine-silver, periodic acid–Schiff, Fite-Faraco, acid-fast bacilli, and Gram staining were negative for organisms. Tissue cultures were negative for bacterial, mycobacterial, and fungal etiology. The patient was started on high-potency topical steroids with a 50% improvement in the appearance of the skin lesion at 1-month follow-up.

Granuloma faciale is a rare chronic inflammatory dermatosis with a predilection for the face that is difficult to diagnose and treat. The diagnosis is based on clinical and histologic findings, and it typically presents as single or multiple, well-demarcated, red-brown nodules, papules, or plaques that range from several millimeters to centimeters in diameter.1,2 Extrafacial lesions may be seen.3 Granuloma faciale usually is asymptomatic but occasionally has associated pruritus and rarely ulceration. The prevalence and pathophysiology of GF is not well defined; however, GF more commonly is reported in middle-aged White males.1

Histologic examination of GF reveals a mixed inflammatory cellular infiltrate in the upper dermis. A grenz zone, which is a narrow area of the papillary dermis uninvolved by the underlying pathology, may be seen.1 Contrary to the name, granulomas are not found histologically. Rather, vascular changes or damage frequently are present and may indicate a small vessel vasculitis pathologic mechanism. Granuloma faciale also has been associated with follicular ostia accentuation and telangiectases.4

Many cases of GF have been misdiagnosed as sarcoidosis, lymphoma, lupus, and basal cell carcinoma.1 In addition, GF shares many clinical and histologic features with erythema elevatum diutinum (EED). However, the defining features that suggest EED over GF is that EED has a predilection for the skin overlying the joints. Histopathologically, EED displays granulomas and fibrosis with few eosinophils.5,6

The variable response of GF to treatments and lack of efficacy data have contributed to the complexity and uncertainty of managing GF. The current first-line therapies are topical tacrolimus,7 cryotherapy,8 or corticosteroid therapy.9

- Ortonne N, Wechsler J, Bagot M, et al. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathologic study of 66 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1002-1009.

- Marcoval J, Moreno A, Peyr J. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:269-273.

- Nasiri S, Rahimi H, Farnaghi A, et al. Granuloma faciale with disseminated extra facial lesions. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:5.

- Roustan G, Sánchez Yus E, Salas C, et al. Granuloma faciale with extrafacial lesions. Dermatology. 1999;198:79-82.

- LeBoit PE. Granuloma faciale: a diagnosis deserving of dignity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:440-443.

- Ziemer M, Koehler MJ, Weyers W. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a chronic leukocytoclastic vasculitis microscopically indistinguishable from granuloma faciale? J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:876-883.

- Cecchi R, Pavesi M, Bartoli L, et al. Topical tacrolimus in the treatment of granuloma faciale. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1463-1465.

- Panagiotopoulos A, Anyfantakis V, Rallis E, et al. Assessment of the efficacy of cryosurgery in the treatment of granuloma faciale. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:357-360.

- Radin DA, Mehregan DR. Granuloma faciale: distribution of the lesions and review of the literature. Cutis. 2003;72:213-219.

To the Editor:

A 53-year-old Hispanic woman presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of an expanding plaque on the right cheek of 2 months’ duration. The patient stated the plaque began as a pimple, which she picked with subsequent spread laterally across the cheek. The area was intermittently tender, but she denied tingling, burning, or pruritus of the site. She had been treated with doxycycline and amoxicillin–clavulanic acid prior to presentation without improvement. She had a history of levamisole-induced vasculitis approximately 6 months prior. A review of systems was notable for diffuse joint pain. The patient denied tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use in the preceding 3 months and denied any changes in her medications or in health within the last year.

Physical examination revealed a well-appearing, alert, and afebrile patient with a pink, well-demarcated plaque on the right cheek (Figure 1). The borders of the plaque were indurated, and the lateral aspect of the plaque was eroded secondary to digital manipulation by the patient. She had no cervical lymphadenopathy. There were no other abnormal cutaneous findings.

There is a broad differential diagnosis for a pink expanding plaque on the face, which requires histopathologic correlation for correct diagnosis. Three broad categories in the differential are infectious (eg, bacterial, fungal), medication related (eg, fixed drug eruption), and granulomatous (eg, granuloma faciale [GF], sarcoidosis, tumid lupus, leprosy, granulomatous rosacea). A biopsy of the lesion revealed a mixed inflammatory cell dermal infiltrate with perivascular accentuation and intense vasculitis that was consistent with GF (Figure 2). Gomori methenamine-silver, periodic acid–Schiff, Fite-Faraco, acid-fast bacilli, and Gram staining were negative for organisms. Tissue cultures were negative for bacterial, mycobacterial, and fungal etiology. The patient was started on high-potency topical steroids with a 50% improvement in the appearance of the skin lesion at 1-month follow-up.

Granuloma faciale is a rare chronic inflammatory dermatosis with a predilection for the face that is difficult to diagnose and treat. The diagnosis is based on clinical and histologic findings, and it typically presents as single or multiple, well-demarcated, red-brown nodules, papules, or plaques that range from several millimeters to centimeters in diameter.1,2 Extrafacial lesions may be seen.3 Granuloma faciale usually is asymptomatic but occasionally has associated pruritus and rarely ulceration. The prevalence and pathophysiology of GF is not well defined; however, GF more commonly is reported in middle-aged White males.1

Histologic examination of GF reveals a mixed inflammatory cellular infiltrate in the upper dermis. A grenz zone, which is a narrow area of the papillary dermis uninvolved by the underlying pathology, may be seen.1 Contrary to the name, granulomas are not found histologically. Rather, vascular changes or damage frequently are present and may indicate a small vessel vasculitis pathologic mechanism. Granuloma faciale also has been associated with follicular ostia accentuation and telangiectases.4

Many cases of GF have been misdiagnosed as sarcoidosis, lymphoma, lupus, and basal cell carcinoma.1 In addition, GF shares many clinical and histologic features with erythema elevatum diutinum (EED). However, the defining features that suggest EED over GF is that EED has a predilection for the skin overlying the joints. Histopathologically, EED displays granulomas and fibrosis with few eosinophils.5,6

The variable response of GF to treatments and lack of efficacy data have contributed to the complexity and uncertainty of managing GF. The current first-line therapies are topical tacrolimus,7 cryotherapy,8 or corticosteroid therapy.9

To the Editor:

A 53-year-old Hispanic woman presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of an expanding plaque on the right cheek of 2 months’ duration. The patient stated the plaque began as a pimple, which she picked with subsequent spread laterally across the cheek. The area was intermittently tender, but she denied tingling, burning, or pruritus of the site. She had been treated with doxycycline and amoxicillin–clavulanic acid prior to presentation without improvement. She had a history of levamisole-induced vasculitis approximately 6 months prior. A review of systems was notable for diffuse joint pain. The patient denied tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use in the preceding 3 months and denied any changes in her medications or in health within the last year.

Physical examination revealed a well-appearing, alert, and afebrile patient with a pink, well-demarcated plaque on the right cheek (Figure 1). The borders of the plaque were indurated, and the lateral aspect of the plaque was eroded secondary to digital manipulation by the patient. She had no cervical lymphadenopathy. There were no other abnormal cutaneous findings.

There is a broad differential diagnosis for a pink expanding plaque on the face, which requires histopathologic correlation for correct diagnosis. Three broad categories in the differential are infectious (eg, bacterial, fungal), medication related (eg, fixed drug eruption), and granulomatous (eg, granuloma faciale [GF], sarcoidosis, tumid lupus, leprosy, granulomatous rosacea). A biopsy of the lesion revealed a mixed inflammatory cell dermal infiltrate with perivascular accentuation and intense vasculitis that was consistent with GF (Figure 2). Gomori methenamine-silver, periodic acid–Schiff, Fite-Faraco, acid-fast bacilli, and Gram staining were negative for organisms. Tissue cultures were negative for bacterial, mycobacterial, and fungal etiology. The patient was started on high-potency topical steroids with a 50% improvement in the appearance of the skin lesion at 1-month follow-up.

Granuloma faciale is a rare chronic inflammatory dermatosis with a predilection for the face that is difficult to diagnose and treat. The diagnosis is based on clinical and histologic findings, and it typically presents as single or multiple, well-demarcated, red-brown nodules, papules, or plaques that range from several millimeters to centimeters in diameter.1,2 Extrafacial lesions may be seen.3 Granuloma faciale usually is asymptomatic but occasionally has associated pruritus and rarely ulceration. The prevalence and pathophysiology of GF is not well defined; however, GF more commonly is reported in middle-aged White males.1

Histologic examination of GF reveals a mixed inflammatory cellular infiltrate in the upper dermis. A grenz zone, which is a narrow area of the papillary dermis uninvolved by the underlying pathology, may be seen.1 Contrary to the name, granulomas are not found histologically. Rather, vascular changes or damage frequently are present and may indicate a small vessel vasculitis pathologic mechanism. Granuloma faciale also has been associated with follicular ostia accentuation and telangiectases.4

Many cases of GF have been misdiagnosed as sarcoidosis, lymphoma, lupus, and basal cell carcinoma.1 In addition, GF shares many clinical and histologic features with erythema elevatum diutinum (EED). However, the defining features that suggest EED over GF is that EED has a predilection for the skin overlying the joints. Histopathologically, EED displays granulomas and fibrosis with few eosinophils.5,6

The variable response of GF to treatments and lack of efficacy data have contributed to the complexity and uncertainty of managing GF. The current first-line therapies are topical tacrolimus,7 cryotherapy,8 or corticosteroid therapy.9

- Ortonne N, Wechsler J, Bagot M, et al. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathologic study of 66 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1002-1009.

- Marcoval J, Moreno A, Peyr J. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:269-273.

- Nasiri S, Rahimi H, Farnaghi A, et al. Granuloma faciale with disseminated extra facial lesions. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:5.

- Roustan G, Sánchez Yus E, Salas C, et al. Granuloma faciale with extrafacial lesions. Dermatology. 1999;198:79-82.

- LeBoit PE. Granuloma faciale: a diagnosis deserving of dignity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:440-443.

- Ziemer M, Koehler MJ, Weyers W. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a chronic leukocytoclastic vasculitis microscopically indistinguishable from granuloma faciale? J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:876-883.

- Cecchi R, Pavesi M, Bartoli L, et al. Topical tacrolimus in the treatment of granuloma faciale. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1463-1465.

- Panagiotopoulos A, Anyfantakis V, Rallis E, et al. Assessment of the efficacy of cryosurgery in the treatment of granuloma faciale. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:357-360.

- Radin DA, Mehregan DR. Granuloma faciale: distribution of the lesions and review of the literature. Cutis. 2003;72:213-219.

- Ortonne N, Wechsler J, Bagot M, et al. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathologic study of 66 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1002-1009.

- Marcoval J, Moreno A, Peyr J. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:269-273.

- Nasiri S, Rahimi H, Farnaghi A, et al. Granuloma faciale with disseminated extra facial lesions. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:5.

- Roustan G, Sánchez Yus E, Salas C, et al. Granuloma faciale with extrafacial lesions. Dermatology. 1999;198:79-82.

- LeBoit PE. Granuloma faciale: a diagnosis deserving of dignity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:440-443.

- Ziemer M, Koehler MJ, Weyers W. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a chronic leukocytoclastic vasculitis microscopically indistinguishable from granuloma faciale? J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:876-883.

- Cecchi R, Pavesi M, Bartoli L, et al. Topical tacrolimus in the treatment of granuloma faciale. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1463-1465.

- Panagiotopoulos A, Anyfantakis V, Rallis E, et al. Assessment of the efficacy of cryosurgery in the treatment of granuloma faciale. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:357-360.

- Radin DA, Mehregan DR. Granuloma faciale: distribution of the lesions and review of the literature. Cutis. 2003;72:213-219.

Practice Points

- Granuloma faciale is a benign dermal process presenting with a red-brown plaque on the face of adults that typically is not ulcerated unless physically manipulated.

- Skin biopsy often is required for correct diagnosis.

- Granuloma faciale does not resolve spontaneously and tends to be chronic.

Necrosis of the Ear Following Skin Cancer Resection

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) frequently is used in surgical removal of cancerous cutaneous lesions on cosmetically sensitive areas and anatomically challenging sites, including the ears. The vascular supply of the ear is complex and includes several watershed regions that are susceptible to injury during surgical resection or operative closure.

Case Reports

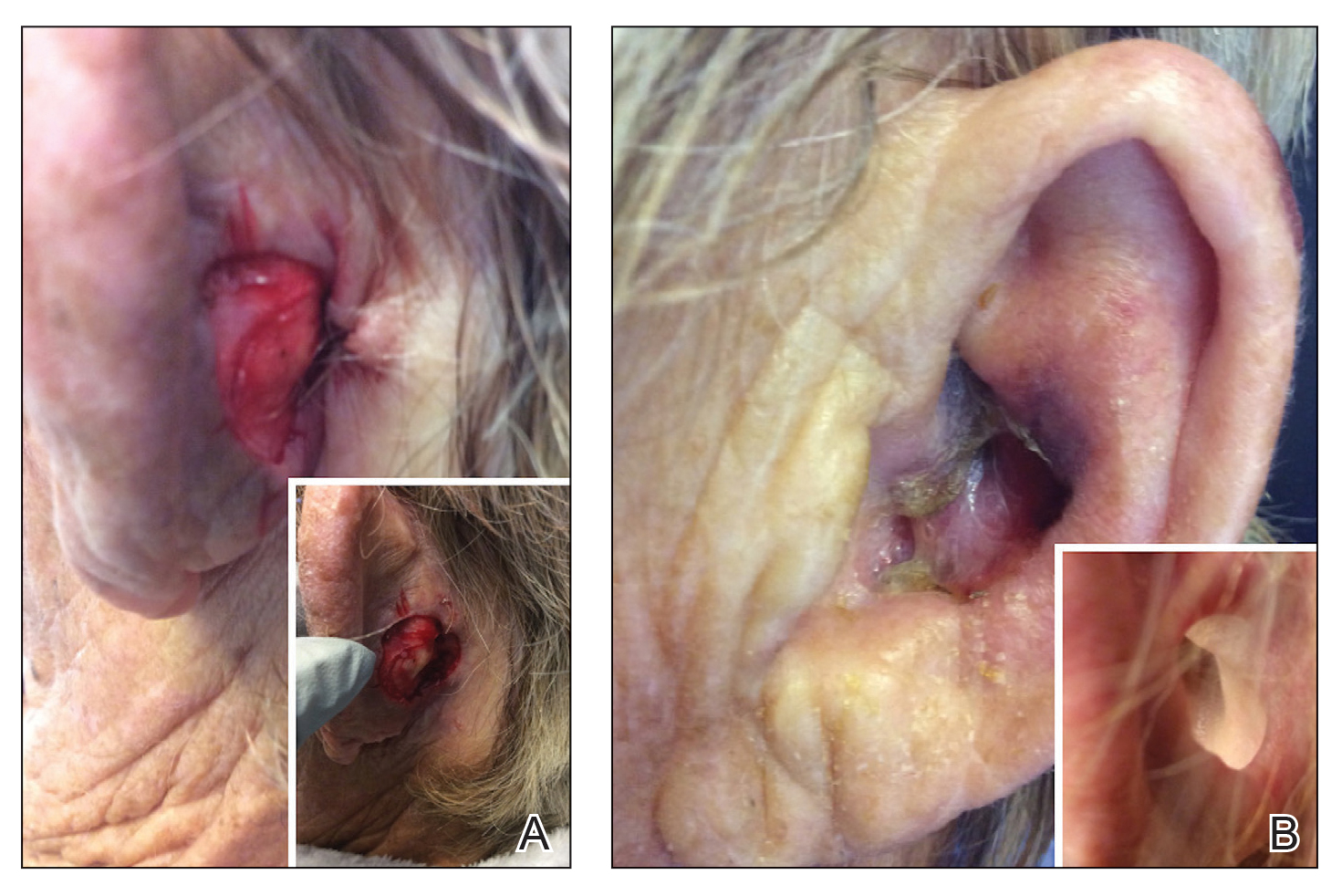

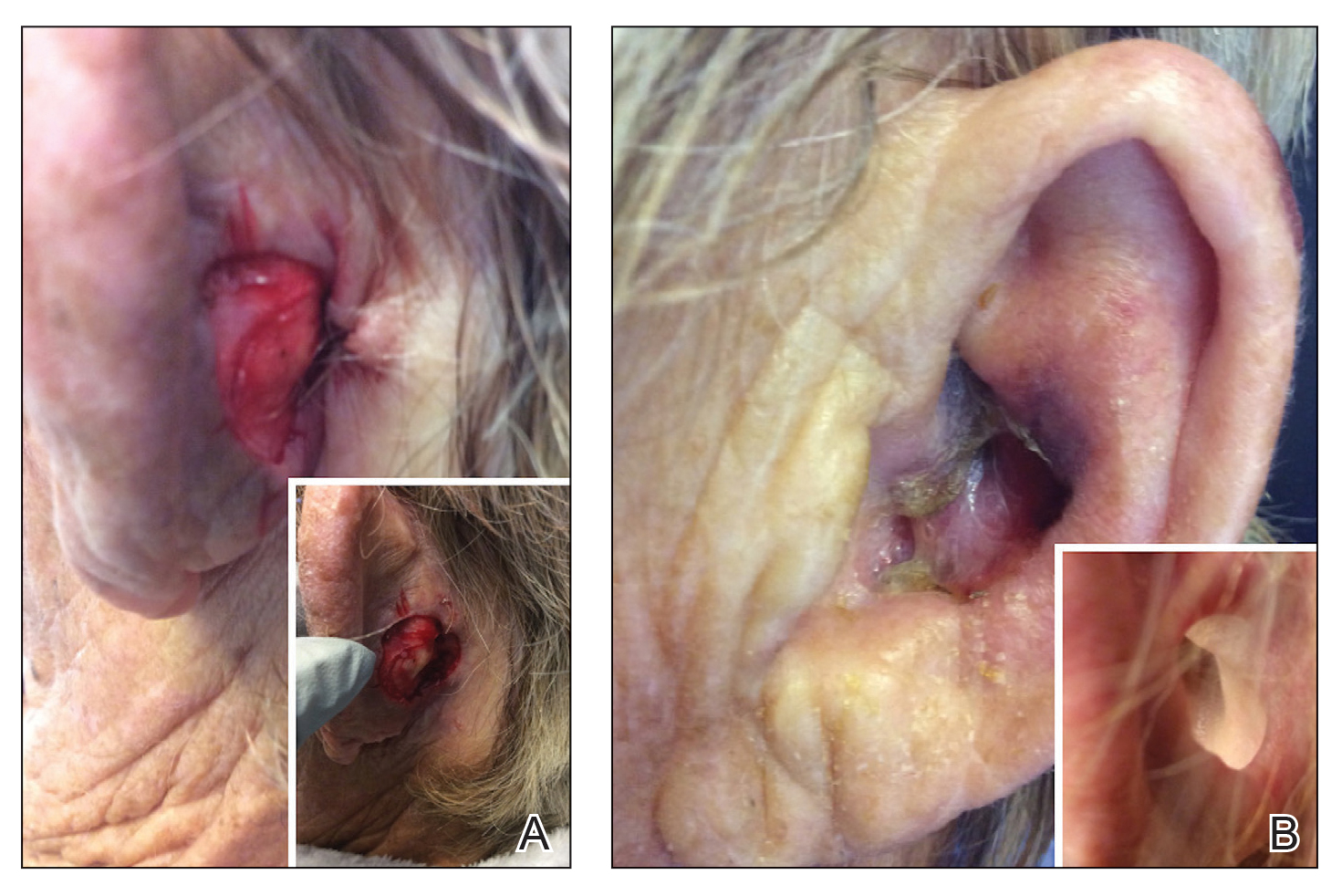

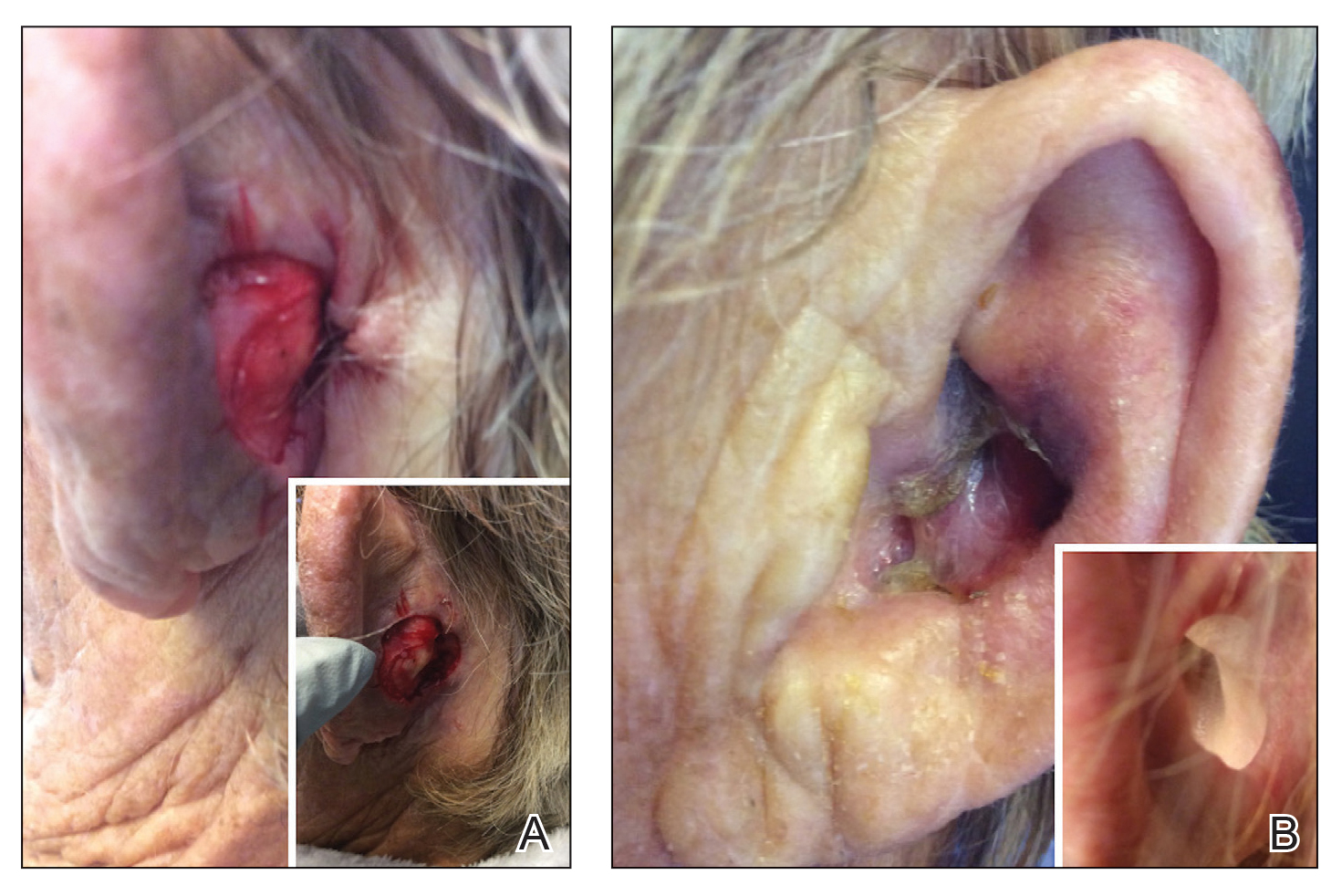

Patient 1—An 82-year-old woman with a 100-pack-year smoking history and no known history of diabetes mellitus or coronary artery disease presented with a superficial and micronodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC) of the left postauricular skin of approximately 18 months’ duration. Mohs micrographic surgery was performed for lesion removal. The BCC was noted to be deeply penetrating and by the second stage was to the depth of the deep subcutaneous tissue (Figure 1A [inset]). Frozen section histopathology revealed a micronodular and superficial BCC. A 2.1×2.0-cm postoperative defect including the posterior surface of the ear, postauricular sulcus, and postauricular scalp remained. To minimize the area left to heal via secondary intention, partial layered closure was performed by placing four 4-0 polyglactin sutures from the scalp side of the defect on the postauricular skin to the postauricular sulcus (Figure 1A).

The patient presented to the clinic on postoperative day (POD) 4, noting pain and redness since the evening of the surgery on the anterior surface of the ear, specifically the cavum concha. Physical examination revealed that the incision site appeared to be healing as expected, but the cavum concha demonstrated erosions and ecchymosis (Figure 1B). A fluid culture was collected, and the patient was started on doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 10 days. The patient returned to the clinic at POD 10 with skin sloughing and a small border of dark purple discoloration, consistent with early necrosis.

At the 1-month postsurgery follow-up visit, the wound had persistent anterior sloughing and discoloration with adherent debris suggestive of vascular compromise. At the 5-month wound check, the left conchal bowl had a 1-cm through-and-through defect of the concha cavum (Figure 1B [inset]). The favored etiology was occlusion of the posterior auricular artery during the patient’s MMS and reconstruction. Once healed, options including reconstruction, prosthesis, and no treatment were discussed with the patient. The patient decided to pursue partial closure of the defect.

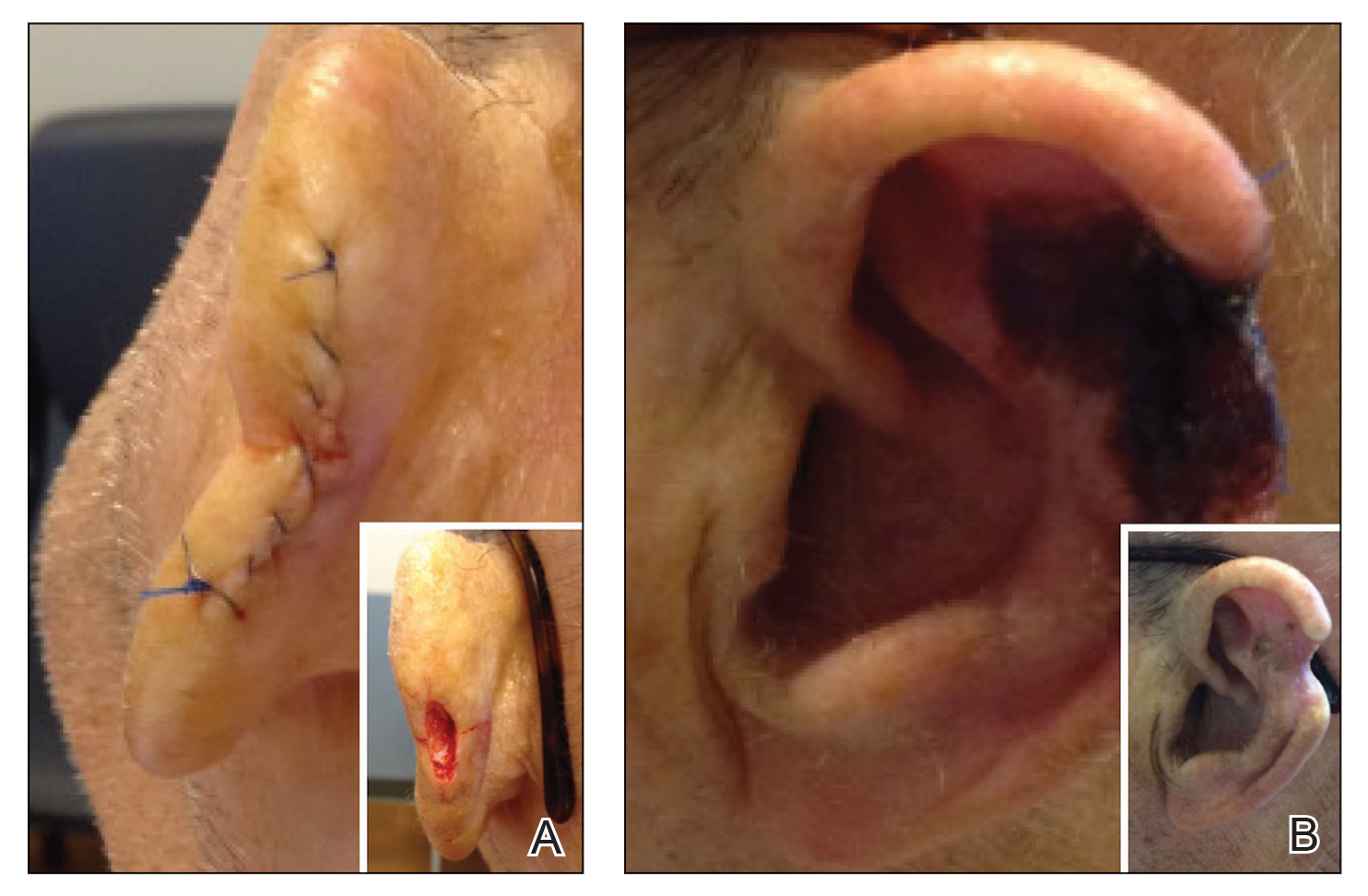

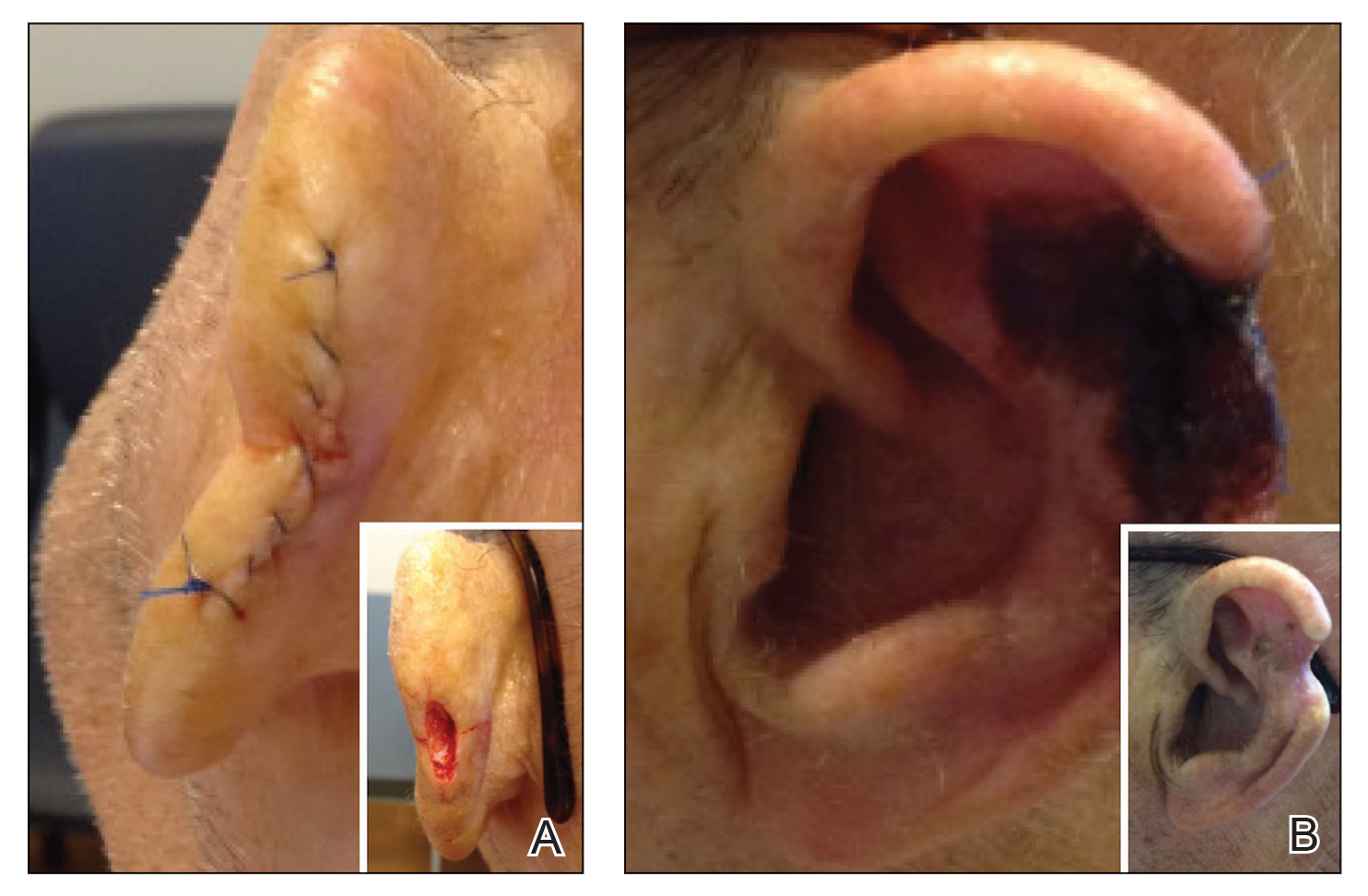

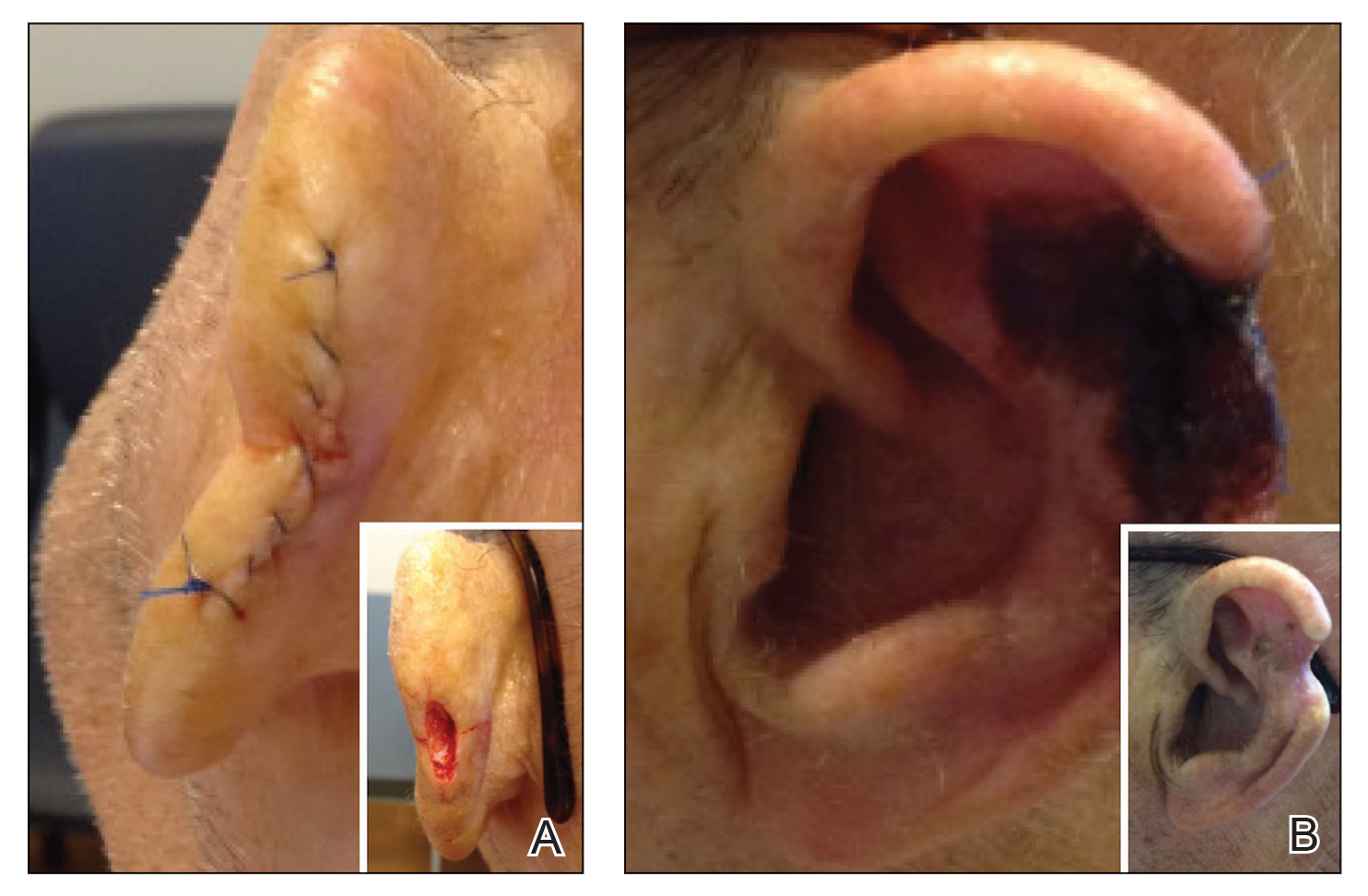

Patient 2—A 71-year-old man with coronary artery disease and no known smoking or diabetes mellitus history presented with a 0.7×0.6-cm cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma of the left helix (Figure 2A [inset]). Mohs micrographic surgery was completed, resulting in a 1.1×1.0-cm defect that extended to the perichondrium. Given the location and size, a linear closure was performed with a deep layer of 5-0 polyglactin sutures and a cutaneous layer of 6-0 polypropylene sutures. The final closure length was 2.1 cm (Figure 2A).

On POD 14, the patient presented for suture removal and reported the onset of brown discoloration of the ear on POD 3. Physical examination revealed the left ear appeared dusky around the mid helix with extension onto the antihelix (Figure 2B). Because one of the main concerns was necrosis, a thin layer of nitropaste ointment 2% was prescribed to be applied twice daily to the affected area, in addition to liberal application of petroleum jelly. On POD 21, the left mid helix demonstrated a well-defined area of necrosis on the helical rim extending to the antihelix, and conservative treatment was continued. Four weeks later, the left ear had a prominent eschar, which was debrided. On follow-up 6 weeks later, the area was well healed with an obvious notched defect of the helix and scaphoid fossa (Figure 2B [inset]). The favored etiology was occlusion of the middle helical arcade during the patient’s MMS and reconstruction. Reconstructive options were discussed with the patient; however, he declined any further reconstructive intervention.

Comment

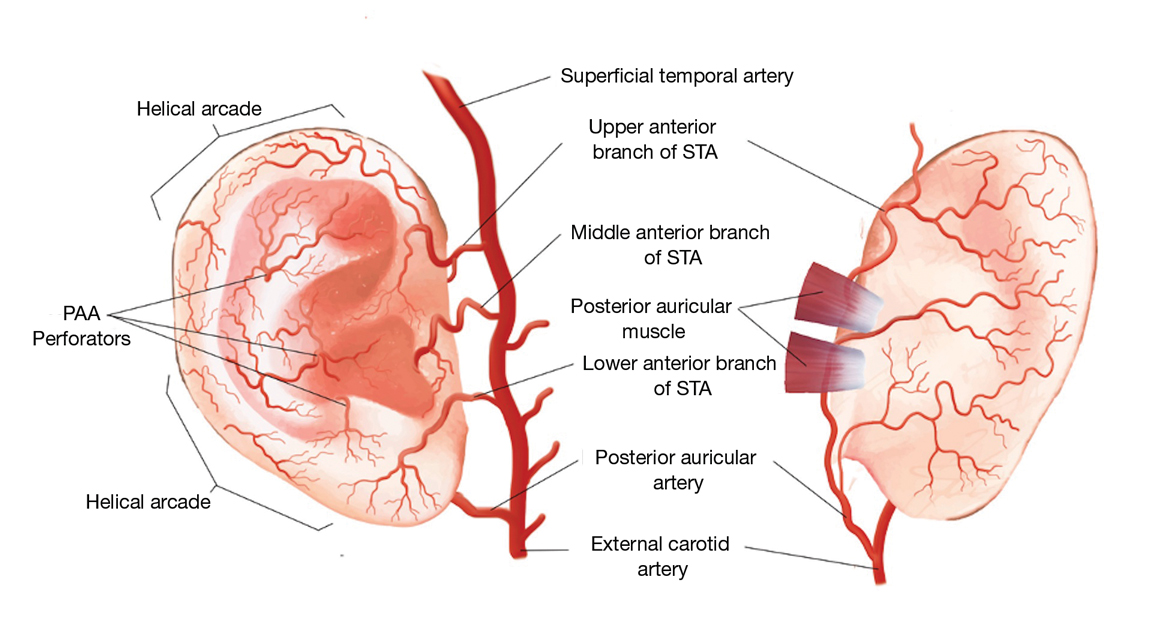

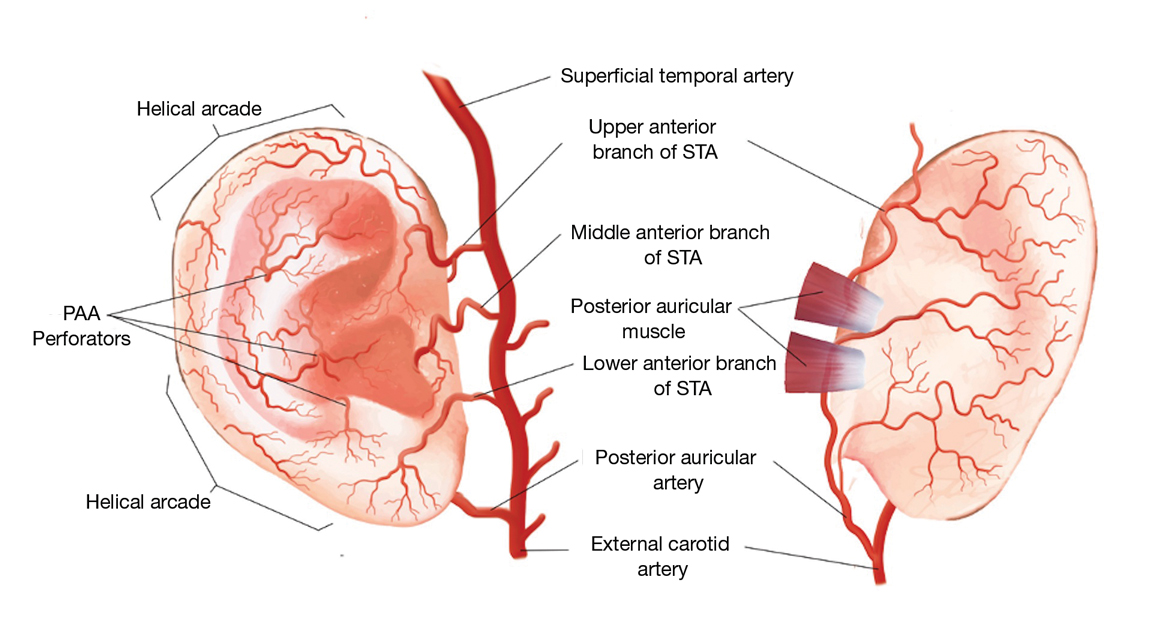

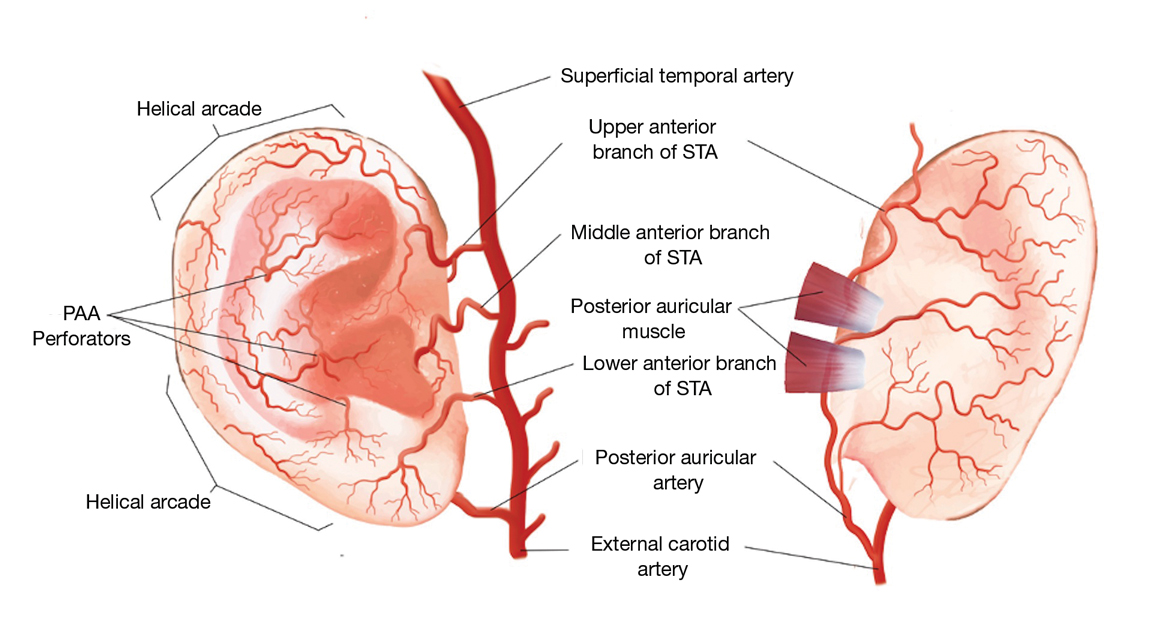

Auricular Vasculature—In our patients, the auricular vascular supply was compromised during routine MMS followed by reconstruction, resulting in tissue necrosis. Given the relative frequency of these procedures and the risk for tissue necrosis, a review of the auricular vasculature with special attention to the conchal bowl and helical rim was warranted (Figure 3).

The auricle is supplied by 2 main arterial sources arising from the external carotid artery: the superficial temporal artery (STA) supplying the anterior auricle and the posterior auricular artery (PAA) supplying the posterior auricle and the concha.1 Anastomoses between these 2 blood supplies occur through perforating arteries and vascular arcades.

As the STA courses cranially, it moves from a deep position—deep to the parotidomasseteric fascia—to the superficial temporal fascia approximately 1 cm anterior and superior to the tragus. In approximately 80% of patients, 3 perpendicular branches stem from the STA—the upper, middle, and lower anterior branches—which supply the ascending helix, tragus, and lower margin of the earlobe, respectively.2 The upper anterior branch of the STA joins other branches to form 2 dominant arcades: the first with the nonperforating branches of the PAA forming the upper third of the helical arcade, and the second with the lower anterior branch of the STA forming the middle portion of the helical arcade.3,4 In 75% of patients, the middle helical arcade was identified as a single connecting artery, whereas in the remaining 25% of patients, a robust capillary network was formed.2 In patient 2, the middle helical arcade was likely disrupted during closure, resulting in the helical necrosis seen postoperatively.

The second main blood supply of the auricle is the PAA, which enters in a more superficial position after traversing superiorly from the meatal cartilage, between the mastoid process and the posterior surface of the concha. From this point, the PAA runs in the deep subcutaneous tissue in the groove formed by the conchal cartilage and the mastoid process. Near the midpoint of the postauricular groove, it passes inferior to the postauricular muscle. The PAA has multiple radial branches that anastomose with helical branches; it also sends perforating branches (there were 2–4 branches in a recent study2) through the cartilage to the anterior surface of the concha. The 2 primary perforating arteries most commonly are located at the level of the antihelix and the antitragus.5 These arteries transverse through a vascular foramen located approximately 11 mm from the tragus in the horizontal plane and supply blood to the conchal bowl.6 In patient 1, the PAA itself, or the perforating arteries that course anteriorly through the vascular foramen, was likely disrupted, resulting in the conchal defect.

Special Considerations Before Surgery—As evidenced by these cases, special attention is needed during operative planning to account for the external ear vascular arcades. Damage to the helical arcades (patient 2) or the perforating arteries within the conchal bowl (patient 1) can lead to unintended consequences such as postoperative tissue necrosis. Tissue manipulation in these areas should be approached cautiously and with the least invasive treatment and closure options available. In doing so, blood flow and tissue integrity can be maintained, resulting in improved postoperative outcomes. Further research is warranted to identify the best intervention in cases involving these watershed regions.

- Park C, Lineaweaver WC, Rumly TO, et al. Arterial supply of the anterior ear. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;90:38-44. doi:10.1097/00006534-199207000-00005

- Zilinsky I, Erdmann D, Weissman O, et al. Reevaluation of the arterial blood supply of the auricle. J Anat. 2017;230:315-324. doi:10.1111/joa.12550

- Erdmann D, Bruno AD, Follmar KE, et al. The helical arcade: anatomic basis for survival in near-total ear avulsion. J Craniofac Surg. 2009;20:245-248. doi:10.1097/SCS.0b013e318184343a

- Zilinsky I, Cotofana S, Hammer N, et al. The arterial blood supply of the helical rim and the earlobe-based advancement flap (ELBAF): a new strategy for reconstructions of helical rim defects. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2015;68:56-62. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2014.08.062

- Henoux M, Espitalier F, Hamel A, et al. Vascular supply of the auricle: anatomical study and applications to external ear reconstruction. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:87-97. doi:10.1097/dss.0000000000000928

- Wilson C, Iwanaga J, Simonds E, et al. The conchal vascular foramen of the posterior auricular artery: application to conchal cartilage grafting. Kurume Med J. 2018;65:7-10. doi:10.2739/kurumemedj.MS651002

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) frequently is used in surgical removal of cancerous cutaneous lesions on cosmetically sensitive areas and anatomically challenging sites, including the ears. The vascular supply of the ear is complex and includes several watershed regions that are susceptible to injury during surgical resection or operative closure.

Case Reports

Patient 1—An 82-year-old woman with a 100-pack-year smoking history and no known history of diabetes mellitus or coronary artery disease presented with a superficial and micronodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC) of the left postauricular skin of approximately 18 months’ duration. Mohs micrographic surgery was performed for lesion removal. The BCC was noted to be deeply penetrating and by the second stage was to the depth of the deep subcutaneous tissue (Figure 1A [inset]). Frozen section histopathology revealed a micronodular and superficial BCC. A 2.1×2.0-cm postoperative defect including the posterior surface of the ear, postauricular sulcus, and postauricular scalp remained. To minimize the area left to heal via secondary intention, partial layered closure was performed by placing four 4-0 polyglactin sutures from the scalp side of the defect on the postauricular skin to the postauricular sulcus (Figure 1A).

The patient presented to the clinic on postoperative day (POD) 4, noting pain and redness since the evening of the surgery on the anterior surface of the ear, specifically the cavum concha. Physical examination revealed that the incision site appeared to be healing as expected, but the cavum concha demonstrated erosions and ecchymosis (Figure 1B). A fluid culture was collected, and the patient was started on doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 10 days. The patient returned to the clinic at POD 10 with skin sloughing and a small border of dark purple discoloration, consistent with early necrosis.

At the 1-month postsurgery follow-up visit, the wound had persistent anterior sloughing and discoloration with adherent debris suggestive of vascular compromise. At the 5-month wound check, the left conchal bowl had a 1-cm through-and-through defect of the concha cavum (Figure 1B [inset]). The favored etiology was occlusion of the posterior auricular artery during the patient’s MMS and reconstruction. Once healed, options including reconstruction, prosthesis, and no treatment were discussed with the patient. The patient decided to pursue partial closure of the defect.

Patient 2—A 71-year-old man with coronary artery disease and no known smoking or diabetes mellitus history presented with a 0.7×0.6-cm cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma of the left helix (Figure 2A [inset]). Mohs micrographic surgery was completed, resulting in a 1.1×1.0-cm defect that extended to the perichondrium. Given the location and size, a linear closure was performed with a deep layer of 5-0 polyglactin sutures and a cutaneous layer of 6-0 polypropylene sutures. The final closure length was 2.1 cm (Figure 2A).

On POD 14, the patient presented for suture removal and reported the onset of brown discoloration of the ear on POD 3. Physical examination revealed the left ear appeared dusky around the mid helix with extension onto the antihelix (Figure 2B). Because one of the main concerns was necrosis, a thin layer of nitropaste ointment 2% was prescribed to be applied twice daily to the affected area, in addition to liberal application of petroleum jelly. On POD 21, the left mid helix demonstrated a well-defined area of necrosis on the helical rim extending to the antihelix, and conservative treatment was continued. Four weeks later, the left ear had a prominent eschar, which was debrided. On follow-up 6 weeks later, the area was well healed with an obvious notched defect of the helix and scaphoid fossa (Figure 2B [inset]). The favored etiology was occlusion of the middle helical arcade during the patient’s MMS and reconstruction. Reconstructive options were discussed with the patient; however, he declined any further reconstructive intervention.

Comment

Auricular Vasculature—In our patients, the auricular vascular supply was compromised during routine MMS followed by reconstruction, resulting in tissue necrosis. Given the relative frequency of these procedures and the risk for tissue necrosis, a review of the auricular vasculature with special attention to the conchal bowl and helical rim was warranted (Figure 3).

The auricle is supplied by 2 main arterial sources arising from the external carotid artery: the superficial temporal artery (STA) supplying the anterior auricle and the posterior auricular artery (PAA) supplying the posterior auricle and the concha.1 Anastomoses between these 2 blood supplies occur through perforating arteries and vascular arcades.

As the STA courses cranially, it moves from a deep position—deep to the parotidomasseteric fascia—to the superficial temporal fascia approximately 1 cm anterior and superior to the tragus. In approximately 80% of patients, 3 perpendicular branches stem from the STA—the upper, middle, and lower anterior branches—which supply the ascending helix, tragus, and lower margin of the earlobe, respectively.2 The upper anterior branch of the STA joins other branches to form 2 dominant arcades: the first with the nonperforating branches of the PAA forming the upper third of the helical arcade, and the second with the lower anterior branch of the STA forming the middle portion of the helical arcade.3,4 In 75% of patients, the middle helical arcade was identified as a single connecting artery, whereas in the remaining 25% of patients, a robust capillary network was formed.2 In patient 2, the middle helical arcade was likely disrupted during closure, resulting in the helical necrosis seen postoperatively.

The second main blood supply of the auricle is the PAA, which enters in a more superficial position after traversing superiorly from the meatal cartilage, between the mastoid process and the posterior surface of the concha. From this point, the PAA runs in the deep subcutaneous tissue in the groove formed by the conchal cartilage and the mastoid process. Near the midpoint of the postauricular groove, it passes inferior to the postauricular muscle. The PAA has multiple radial branches that anastomose with helical branches; it also sends perforating branches (there were 2–4 branches in a recent study2) through the cartilage to the anterior surface of the concha. The 2 primary perforating arteries most commonly are located at the level of the antihelix and the antitragus.5 These arteries transverse through a vascular foramen located approximately 11 mm from the tragus in the horizontal plane and supply blood to the conchal bowl.6 In patient 1, the PAA itself, or the perforating arteries that course anteriorly through the vascular foramen, was likely disrupted, resulting in the conchal defect.

Special Considerations Before Surgery—As evidenced by these cases, special attention is needed during operative planning to account for the external ear vascular arcades. Damage to the helical arcades (patient 2) or the perforating arteries within the conchal bowl (patient 1) can lead to unintended consequences such as postoperative tissue necrosis. Tissue manipulation in these areas should be approached cautiously and with the least invasive treatment and closure options available. In doing so, blood flow and tissue integrity can be maintained, resulting in improved postoperative outcomes. Further research is warranted to identify the best intervention in cases involving these watershed regions.

Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) frequently is used in surgical removal of cancerous cutaneous lesions on cosmetically sensitive areas and anatomically challenging sites, including the ears. The vascular supply of the ear is complex and includes several watershed regions that are susceptible to injury during surgical resection or operative closure.

Case Reports

Patient 1—An 82-year-old woman with a 100-pack-year smoking history and no known history of diabetes mellitus or coronary artery disease presented with a superficial and micronodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC) of the left postauricular skin of approximately 18 months’ duration. Mohs micrographic surgery was performed for lesion removal. The BCC was noted to be deeply penetrating and by the second stage was to the depth of the deep subcutaneous tissue (Figure 1A [inset]). Frozen section histopathology revealed a micronodular and superficial BCC. A 2.1×2.0-cm postoperative defect including the posterior surface of the ear, postauricular sulcus, and postauricular scalp remained. To minimize the area left to heal via secondary intention, partial layered closure was performed by placing four 4-0 polyglactin sutures from the scalp side of the defect on the postauricular skin to the postauricular sulcus (Figure 1A).

The patient presented to the clinic on postoperative day (POD) 4, noting pain and redness since the evening of the surgery on the anterior surface of the ear, specifically the cavum concha. Physical examination revealed that the incision site appeared to be healing as expected, but the cavum concha demonstrated erosions and ecchymosis (Figure 1B). A fluid culture was collected, and the patient was started on doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 10 days. The patient returned to the clinic at POD 10 with skin sloughing and a small border of dark purple discoloration, consistent with early necrosis.

At the 1-month postsurgery follow-up visit, the wound had persistent anterior sloughing and discoloration with adherent debris suggestive of vascular compromise. At the 5-month wound check, the left conchal bowl had a 1-cm through-and-through defect of the concha cavum (Figure 1B [inset]). The favored etiology was occlusion of the posterior auricular artery during the patient’s MMS and reconstruction. Once healed, options including reconstruction, prosthesis, and no treatment were discussed with the patient. The patient decided to pursue partial closure of the defect.

Patient 2—A 71-year-old man with coronary artery disease and no known smoking or diabetes mellitus history presented with a 0.7×0.6-cm cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma of the left helix (Figure 2A [inset]). Mohs micrographic surgery was completed, resulting in a 1.1×1.0-cm defect that extended to the perichondrium. Given the location and size, a linear closure was performed with a deep layer of 5-0 polyglactin sutures and a cutaneous layer of 6-0 polypropylene sutures. The final closure length was 2.1 cm (Figure 2A).

On POD 14, the patient presented for suture removal and reported the onset of brown discoloration of the ear on POD 3. Physical examination revealed the left ear appeared dusky around the mid helix with extension onto the antihelix (Figure 2B). Because one of the main concerns was necrosis, a thin layer of nitropaste ointment 2% was prescribed to be applied twice daily to the affected area, in addition to liberal application of petroleum jelly. On POD 21, the left mid helix demonstrated a well-defined area of necrosis on the helical rim extending to the antihelix, and conservative treatment was continued. Four weeks later, the left ear had a prominent eschar, which was debrided. On follow-up 6 weeks later, the area was well healed with an obvious notched defect of the helix and scaphoid fossa (Figure 2B [inset]). The favored etiology was occlusion of the middle helical arcade during the patient’s MMS and reconstruction. Reconstructive options were discussed with the patient; however, he declined any further reconstructive intervention.

Comment

Auricular Vasculature—In our patients, the auricular vascular supply was compromised during routine MMS followed by reconstruction, resulting in tissue necrosis. Given the relative frequency of these procedures and the risk for tissue necrosis, a review of the auricular vasculature with special attention to the conchal bowl and helical rim was warranted (Figure 3).

The auricle is supplied by 2 main arterial sources arising from the external carotid artery: the superficial temporal artery (STA) supplying the anterior auricle and the posterior auricular artery (PAA) supplying the posterior auricle and the concha.1 Anastomoses between these 2 blood supplies occur through perforating arteries and vascular arcades.

As the STA courses cranially, it moves from a deep position—deep to the parotidomasseteric fascia—to the superficial temporal fascia approximately 1 cm anterior and superior to the tragus. In approximately 80% of patients, 3 perpendicular branches stem from the STA—the upper, middle, and lower anterior branches—which supply the ascending helix, tragus, and lower margin of the earlobe, respectively.2 The upper anterior branch of the STA joins other branches to form 2 dominant arcades: the first with the nonperforating branches of the PAA forming the upper third of the helical arcade, and the second with the lower anterior branch of the STA forming the middle portion of the helical arcade.3,4 In 75% of patients, the middle helical arcade was identified as a single connecting artery, whereas in the remaining 25% of patients, a robust capillary network was formed.2 In patient 2, the middle helical arcade was likely disrupted during closure, resulting in the helical necrosis seen postoperatively.

The second main blood supply of the auricle is the PAA, which enters in a more superficial position after traversing superiorly from the meatal cartilage, between the mastoid process and the posterior surface of the concha. From this point, the PAA runs in the deep subcutaneous tissue in the groove formed by the conchal cartilage and the mastoid process. Near the midpoint of the postauricular groove, it passes inferior to the postauricular muscle. The PAA has multiple radial branches that anastomose with helical branches; it also sends perforating branches (there were 2–4 branches in a recent study2) through the cartilage to the anterior surface of the concha. The 2 primary perforating arteries most commonly are located at the level of the antihelix and the antitragus.5 These arteries transverse through a vascular foramen located approximately 11 mm from the tragus in the horizontal plane and supply blood to the conchal bowl.6 In patient 1, the PAA itself, or the perforating arteries that course anteriorly through the vascular foramen, was likely disrupted, resulting in the conchal defect.

Special Considerations Before Surgery—As evidenced by these cases, special attention is needed during operative planning to account for the external ear vascular arcades. Damage to the helical arcades (patient 2) or the perforating arteries within the conchal bowl (patient 1) can lead to unintended consequences such as postoperative tissue necrosis. Tissue manipulation in these areas should be approached cautiously and with the least invasive treatment and closure options available. In doing so, blood flow and tissue integrity can be maintained, resulting in improved postoperative outcomes. Further research is warranted to identify the best intervention in cases involving these watershed regions.

- Park C, Lineaweaver WC, Rumly TO, et al. Arterial supply of the anterior ear. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;90:38-44. doi:10.1097/00006534-199207000-00005

- Zilinsky I, Erdmann D, Weissman O, et al. Reevaluation of the arterial blood supply of the auricle. J Anat. 2017;230:315-324. doi:10.1111/joa.12550

- Erdmann D, Bruno AD, Follmar KE, et al. The helical arcade: anatomic basis for survival in near-total ear avulsion. J Craniofac Surg. 2009;20:245-248. doi:10.1097/SCS.0b013e318184343a

- Zilinsky I, Cotofana S, Hammer N, et al. The arterial blood supply of the helical rim and the earlobe-based advancement flap (ELBAF): a new strategy for reconstructions of helical rim defects. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2015;68:56-62. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2014.08.062

- Henoux M, Espitalier F, Hamel A, et al. Vascular supply of the auricle: anatomical study and applications to external ear reconstruction. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:87-97. doi:10.1097/dss.0000000000000928

- Wilson C, Iwanaga J, Simonds E, et al. The conchal vascular foramen of the posterior auricular artery: application to conchal cartilage grafting. Kurume Med J. 2018;65:7-10. doi:10.2739/kurumemedj.MS651002

- Park C, Lineaweaver WC, Rumly TO, et al. Arterial supply of the anterior ear. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;90:38-44. doi:10.1097/00006534-199207000-00005

- Zilinsky I, Erdmann D, Weissman O, et al. Reevaluation of the arterial blood supply of the auricle. J Anat. 2017;230:315-324. doi:10.1111/joa.12550

- Erdmann D, Bruno AD, Follmar KE, et al. The helical arcade: anatomic basis for survival in near-total ear avulsion. J Craniofac Surg. 2009;20:245-248. doi:10.1097/SCS.0b013e318184343a

- Zilinsky I, Cotofana S, Hammer N, et al. The arterial blood supply of the helical rim and the earlobe-based advancement flap (ELBAF): a new strategy for reconstructions of helical rim defects. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2015;68:56-62. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2014.08.062

- Henoux M, Espitalier F, Hamel A, et al. Vascular supply of the auricle: anatomical study and applications to external ear reconstruction. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:87-97. doi:10.1097/dss.0000000000000928

- Wilson C, Iwanaga J, Simonds E, et al. The conchal vascular foramen of the posterior auricular artery: application to conchal cartilage grafting. Kurume Med J. 2018;65:7-10. doi:10.2739/kurumemedj.MS651002

Practice Points

- The auricular vasculature supply is complex and forms several anastomoses and arcades, making it susceptible to vascular compromise.

- Damage to the auricular helical arcades or perforating branches can result in postoperative tissue necrosis.

- Clinicians should pay special attention during operative planning for Mohs micrographic surgery to account for the external ear vascular arcades and, when possible, should choose the least invasive treatment and closure options available.

Gastric cancer: Robotic gastrectomy has superior outcomes in patients with obesity

Key clinical point: In patients with early-stage gastric cancer and visceral obesity, robotic gastrectomy (RG) is associated with lower incidence of postoperative complications and improved survival vs. laparoscopic gastrectomy (LG).

Major finding: In patients with high visceral fat area (VFA), RG vs. LG was associated with lower incidences of all complications (2.7% vs. 8.2%; P = .019) and intra-abdominal infectious complications (2.0% vs. 6.6%; P = .048). LG was an independent risk factor for overall (odds ratio [OR] 3.281; P = .012) and intra-abdominal infectious (OR 3.462; P = .021) complications in patients with high VFA. The overall survival in patients with high VFA was significantly higher with RG vs. LG (P = .045).

Study details: This article reports a retrospective study of 1306 patients with clinical stage I-II gastric cancer who underwent minimally invasive gastrectomy between 2012 and 2020.

Disclosures: No funding source was identified for this study. The authors received personal fees outside this work.

Source: Hikage M et al. Advantages of a robotic approach compared with laparoscopy gastrectomy for patients with high visceral fat area. Surg Endosc. 2022 (Mar 16). Doi: 10.1007/s00464-022-09178-x

Key clinical point: In patients with early-stage gastric cancer and visceral obesity, robotic gastrectomy (RG) is associated with lower incidence of postoperative complications and improved survival vs. laparoscopic gastrectomy (LG).

Major finding: In patients with high visceral fat area (VFA), RG vs. LG was associated with lower incidences of all complications (2.7% vs. 8.2%; P = .019) and intra-abdominal infectious complications (2.0% vs. 6.6%; P = .048). LG was an independent risk factor for overall (odds ratio [OR] 3.281; P = .012) and intra-abdominal infectious (OR 3.462; P = .021) complications in patients with high VFA. The overall survival in patients with high VFA was significantly higher with RG vs. LG (P = .045).

Study details: This article reports a retrospective study of 1306 patients with clinical stage I-II gastric cancer who underwent minimally invasive gastrectomy between 2012 and 2020.

Disclosures: No funding source was identified for this study. The authors received personal fees outside this work.

Source: Hikage M et al. Advantages of a robotic approach compared with laparoscopy gastrectomy for patients with high visceral fat area. Surg Endosc. 2022 (Mar 16). Doi: 10.1007/s00464-022-09178-x

Key clinical point: In patients with early-stage gastric cancer and visceral obesity, robotic gastrectomy (RG) is associated with lower incidence of postoperative complications and improved survival vs. laparoscopic gastrectomy (LG).

Major finding: In patients with high visceral fat area (VFA), RG vs. LG was associated with lower incidences of all complications (2.7% vs. 8.2%; P = .019) and intra-abdominal infectious complications (2.0% vs. 6.6%; P = .048). LG was an independent risk factor for overall (odds ratio [OR] 3.281; P = .012) and intra-abdominal infectious (OR 3.462; P = .021) complications in patients with high VFA. The overall survival in patients with high VFA was significantly higher with RG vs. LG (P = .045).

Study details: This article reports a retrospective study of 1306 patients with clinical stage I-II gastric cancer who underwent minimally invasive gastrectomy between 2012 and 2020.

Disclosures: No funding source was identified for this study. The authors received personal fees outside this work.

Source: Hikage M et al. Advantages of a robotic approach compared with laparoscopy gastrectomy for patients with high visceral fat area. Surg Endosc. 2022 (Mar 16). Doi: 10.1007/s00464-022-09178-x

Gastric cancer: LNR can help select patients for adjuvant chemotherapy

Key clinical point: Adjuvant chemotherapy (ACT) after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) and surgery significantly improved survival in patients with locally advanced gastric cancer (LAGC) with a lymph node ratio (LNR) of ≥9%.

Major finding: At 3 years, the overall survival (OS) was significantly higher in patients who received ACT (60.1% vs. 49.3%; P = .02) vs. those who did not. ACT was associated with significantly improved OS at 3 years in patients with higher (≥9%) LNR (46.6% vs. 21.7%; P < .001). ACT improved OS at 3 years in patients with an LNR of ≥9% in an external validation cohort (53.0% vs. 26.3%; P = .04).

Study details: This article reports on a multicenter retrospective cohort study including 353 patients with LAGC undergoing curative-intent gastrectomy after NACT and an external validation cohort of 109 patients.

Disclosures: No funding source was identified for this study. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Lin J-X et al. Association of adjuvant chemotherapy with overall survival among patients with locally advanced gastric cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(4):e225557 (Apr 1). Doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.5557

Key clinical point: Adjuvant chemotherapy (ACT) after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) and surgery significantly improved survival in patients with locally advanced gastric cancer (LAGC) with a lymph node ratio (LNR) of ≥9%.

Major finding: At 3 years, the overall survival (OS) was significantly higher in patients who received ACT (60.1% vs. 49.3%; P = .02) vs. those who did not. ACT was associated with significantly improved OS at 3 years in patients with higher (≥9%) LNR (46.6% vs. 21.7%; P < .001). ACT improved OS at 3 years in patients with an LNR of ≥9% in an external validation cohort (53.0% vs. 26.3%; P = .04).

Study details: This article reports on a multicenter retrospective cohort study including 353 patients with LAGC undergoing curative-intent gastrectomy after NACT and an external validation cohort of 109 patients.

Disclosures: No funding source was identified for this study. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Lin J-X et al. Association of adjuvant chemotherapy with overall survival among patients with locally advanced gastric cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(4):e225557 (Apr 1). Doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.5557

Key clinical point: Adjuvant chemotherapy (ACT) after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) and surgery significantly improved survival in patients with locally advanced gastric cancer (LAGC) with a lymph node ratio (LNR) of ≥9%.

Major finding: At 3 years, the overall survival (OS) was significantly higher in patients who received ACT (60.1% vs. 49.3%; P = .02) vs. those who did not. ACT was associated with significantly improved OS at 3 years in patients with higher (≥9%) LNR (46.6% vs. 21.7%; P < .001). ACT improved OS at 3 years in patients with an LNR of ≥9% in an external validation cohort (53.0% vs. 26.3%; P = .04).

Study details: This article reports on a multicenter retrospective cohort study including 353 patients with LAGC undergoing curative-intent gastrectomy after NACT and an external validation cohort of 109 patients.

Disclosures: No funding source was identified for this study. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Lin J-X et al. Association of adjuvant chemotherapy with overall survival among patients with locally advanced gastric cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(4):e225557 (Apr 1). Doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.5557

Salt intake is associated with higher risk for gastric cancer

Key clinical point: Salty taste preference, always using table salt, and a greater high-salt and salt-preserved foods intake are associated with a higher risk for gastric cancer.

Major finding: The risk for gastric cancer was higher with salty vs. tasteless taste preference (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.59; 95% CI 1.25-2.03), always vs. never using table salt (aOR 1.33; 95% CI 1.16-1.54), and the highest vs. lowest tertile of high-salt and salt-preserved foods intake (aOR 1.24; 95% CI 1.01-1.51). There was no significant association for the highest vs. lowest tertile of total sodium intake (aOR 1.08; 95% CI 0.82-1.43).

Study details: This study was an individual participant data meta-analysis of 25 studies including 10,283 patients with gastric cancer and 24,643 control individuals.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Portuguese Ministry of Science, Technology, and Higher Education; Instituto de Saúde Pública da Universidade do Porto; Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro; and others. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Morais S et al. Salt intake and gastric cancer: A pooled analysis within the Stomach cancer Pooling (StoP) Project. Cancer Causes Control. 2022;33:779-791 (Mar 19). Doi: 10.1007/s10552-022-01565-y

Key clinical point: Salty taste preference, always using table salt, and a greater high-salt and salt-preserved foods intake are associated with a higher risk for gastric cancer.

Major finding: The risk for gastric cancer was higher with salty vs. tasteless taste preference (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.59; 95% CI 1.25-2.03), always vs. never using table salt (aOR 1.33; 95% CI 1.16-1.54), and the highest vs. lowest tertile of high-salt and salt-preserved foods intake (aOR 1.24; 95% CI 1.01-1.51). There was no significant association for the highest vs. lowest tertile of total sodium intake (aOR 1.08; 95% CI 0.82-1.43).

Study details: This study was an individual participant data meta-analysis of 25 studies including 10,283 patients with gastric cancer and 24,643 control individuals.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Portuguese Ministry of Science, Technology, and Higher Education; Instituto de Saúde Pública da Universidade do Porto; Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro; and others. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Morais S et al. Salt intake and gastric cancer: A pooled analysis within the Stomach cancer Pooling (StoP) Project. Cancer Causes Control. 2022;33:779-791 (Mar 19). Doi: 10.1007/s10552-022-01565-y

Key clinical point: Salty taste preference, always using table salt, and a greater high-salt and salt-preserved foods intake are associated with a higher risk for gastric cancer.

Major finding: The risk for gastric cancer was higher with salty vs. tasteless taste preference (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.59; 95% CI 1.25-2.03), always vs. never using table salt (aOR 1.33; 95% CI 1.16-1.54), and the highest vs. lowest tertile of high-salt and salt-preserved foods intake (aOR 1.24; 95% CI 1.01-1.51). There was no significant association for the highest vs. lowest tertile of total sodium intake (aOR 1.08; 95% CI 0.82-1.43).

Study details: This study was an individual participant data meta-analysis of 25 studies including 10,283 patients with gastric cancer and 24,643 control individuals.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Portuguese Ministry of Science, Technology, and Higher Education; Instituto de Saúde Pública da Universidade do Porto; Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro; and others. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Morais S et al. Salt intake and gastric cancer: A pooled analysis within the Stomach cancer Pooling (StoP) Project. Cancer Causes Control. 2022;33:779-791 (Mar 19). Doi: 10.1007/s10552-022-01565-y

Cimetropium bromide use during endoscopy improves gastric neoplasm detection rate

Key clinical point: The use vs. nonuse of cimetropium bromide as premedication is associated with higher gastric neoplasm detection rate during esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) screening.

Major finding: In 41,670 matched participants, the gastric neoplasm detection rate was significantly higher in the cimetropium bromide vs. control group (0.30% vs. 0.19%; P = .02). Cimetropium bromide use vs. nonuse was associated with a significantly higher combined detection rate of dysplasia and early gastric cancer (0.27% vs. 0.17%; P = .02). Cimetropium bromide was associated with higher odds for the detection of gastric neoplasms (odds ratio 1.42; P = .03).

Study details: This article reports a propensity score-matched retrospective cohort study of 67,683 participants who received EGD screening with cimetropium bromide (41.8%) or without (control group; 58.2%).

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology, Korea; and Myongji Hospital. The authors declared no competing interests.

Source: Kim SY et al. Assessment of cimetropium bromide use for the detection of gastric neoplasms during esophagogastroduodenoscopy. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(3):e223827 (Mar 23). Doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.3827

Key clinical point: The use vs. nonuse of cimetropium bromide as premedication is associated with higher gastric neoplasm detection rate during esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) screening.

Major finding: In 41,670 matched participants, the gastric neoplasm detection rate was significantly higher in the cimetropium bromide vs. control group (0.30% vs. 0.19%; P = .02). Cimetropium bromide use vs. nonuse was associated with a significantly higher combined detection rate of dysplasia and early gastric cancer (0.27% vs. 0.17%; P = .02). Cimetropium bromide was associated with higher odds for the detection of gastric neoplasms (odds ratio 1.42; P = .03).

Study details: This article reports a propensity score-matched retrospective cohort study of 67,683 participants who received EGD screening with cimetropium bromide (41.8%) or without (control group; 58.2%).

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology, Korea; and Myongji Hospital. The authors declared no competing interests.

Source: Kim SY et al. Assessment of cimetropium bromide use for the detection of gastric neoplasms during esophagogastroduodenoscopy. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(3):e223827 (Mar 23). Doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.3827

Key clinical point: The use vs. nonuse of cimetropium bromide as premedication is associated with higher gastric neoplasm detection rate during esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) screening.

Major finding: In 41,670 matched participants, the gastric neoplasm detection rate was significantly higher in the cimetropium bromide vs. control group (0.30% vs. 0.19%; P = .02). Cimetropium bromide use vs. nonuse was associated with a significantly higher combined detection rate of dysplasia and early gastric cancer (0.27% vs. 0.17%; P = .02). Cimetropium bromide was associated with higher odds for the detection of gastric neoplasms (odds ratio 1.42; P = .03).

Study details: This article reports a propensity score-matched retrospective cohort study of 67,683 participants who received EGD screening with cimetropium bromide (41.8%) or without (control group; 58.2%).

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology, Korea; and Myongji Hospital. The authors declared no competing interests.

Source: Kim SY et al. Assessment of cimetropium bromide use for the detection of gastric neoplasms during esophagogastroduodenoscopy. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(3):e223827 (Mar 23). Doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.3827

Gastric cancer: Modified Glasgow prognostic score predicts sarcopenia

Key clinical point: Modified Glasgow prognostic score (mGPS) predicts sarcopenia and is a strong prognostic factor for overall survival in patients with advanced gastric cancer or esophagogastric junction cancer undergoing first-line treatment.

Major finding: Baseline mGPS was significantly correlated with baseline mean muscle attenuation (P < .0001). The mGPS was a strong prognostic factor for overall survival (P < .0001) and progression-free survival (P < .001).

Study details: Computed tomography was performed in 509 patients with advanced gastric or esophagogastric junction cancer from the phase 3 EXPAND trial who received first-line platinum-fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy.

Disclosures: No funding source was identified for this study. The authors received personal fees and research grants outside this work.

Source: Hacker UT et al. Modified Glasgow prognostic score (mGPS) is correlated with sarcopenia and dominates the prognostic role of baseline body composition parameters in advanced gastric and esophagogastric junction cancer patients undergoing first-line treatment from the phase III EXPAND trial. Ann Oncol. 2022 (Apr 4). Doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.03.274

Key clinical point: Modified Glasgow prognostic score (mGPS) predicts sarcopenia and is a strong prognostic factor for overall survival in patients with advanced gastric cancer or esophagogastric junction cancer undergoing first-line treatment.

Major finding: Baseline mGPS was significantly correlated with baseline mean muscle attenuation (P < .0001). The mGPS was a strong prognostic factor for overall survival (P < .0001) and progression-free survival (P < .001).

Study details: Computed tomography was performed in 509 patients with advanced gastric or esophagogastric junction cancer from the phase 3 EXPAND trial who received first-line platinum-fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy.

Disclosures: No funding source was identified for this study. The authors received personal fees and research grants outside this work.

Source: Hacker UT et al. Modified Glasgow prognostic score (mGPS) is correlated with sarcopenia and dominates the prognostic role of baseline body composition parameters in advanced gastric and esophagogastric junction cancer patients undergoing first-line treatment from the phase III EXPAND trial. Ann Oncol. 2022 (Apr 4). Doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.03.274

Key clinical point: Modified Glasgow prognostic score (mGPS) predicts sarcopenia and is a strong prognostic factor for overall survival in patients with advanced gastric cancer or esophagogastric junction cancer undergoing first-line treatment.

Major finding: Baseline mGPS was significantly correlated with baseline mean muscle attenuation (P < .0001). The mGPS was a strong prognostic factor for overall survival (P < .0001) and progression-free survival (P < .001).

Study details: Computed tomography was performed in 509 patients with advanced gastric or esophagogastric junction cancer from the phase 3 EXPAND trial who received first-line platinum-fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy.

Disclosures: No funding source was identified for this study. The authors received personal fees and research grants outside this work.

Source: Hacker UT et al. Modified Glasgow prognostic score (mGPS) is correlated with sarcopenia and dominates the prognostic role of baseline body composition parameters in advanced gastric and esophagogastric junction cancer patients undergoing first-line treatment from the phase III EXPAND trial. Ann Oncol. 2022 (Apr 4). Doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.03.274

Early gastric cancer: Undifferentiated-predominant mixed-type is more aggressive

Key clinical point: Patients with undifferentiated-predominant mixed-type (MU) early-stage gastric cancer (EGC) had a higher risk for submucosal invasion and lymph node metastasis vs. pure undifferentiated-type (PU) EGC.

Major finding: Patients with MU vs. PU EGC had a significantly higher risk for submucosal invasion (odds ratio [OR] 2.19; 95% CI 1.90-2.52) and lymph node metastasis (OR 2.28; 95% CI 1.72-3.03). There was no difference in the risk for lymphovascular invasion in patients with MU vs. PU EGC (OR 1.81; 95% CI 0.84-3.87).

Study details: This article was a meta-analysis of 12 observational studies including 5644 patients with early gastric cancer.

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by the International Science and Technology Cooperation Fund of Changzhou, China, Young Medical Talents of Jiangsu Province, Changzhou Special Fund for Introducing Foreign Talents, and others. The authors declared no competing interests.

Source: Yang P et al. Undifferentiated-predominant mixed-type early gastric cancer is more aggressive than pure undifferentiated type: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e054473 (Apr 7). Doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-054473

Key clinical point: Patients with undifferentiated-predominant mixed-type (MU) early-stage gastric cancer (EGC) had a higher risk for submucosal invasion and lymph node metastasis vs. pure undifferentiated-type (PU) EGC.

Major finding: Patients with MU vs. PU EGC had a significantly higher risk for submucosal invasion (odds ratio [OR] 2.19; 95% CI 1.90-2.52) and lymph node metastasis (OR 2.28; 95% CI 1.72-3.03). There was no difference in the risk for lymphovascular invasion in patients with MU vs. PU EGC (OR 1.81; 95% CI 0.84-3.87).

Study details: This article was a meta-analysis of 12 observational studies including 5644 patients with early gastric cancer.

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by the International Science and Technology Cooperation Fund of Changzhou, China, Young Medical Talents of Jiangsu Province, Changzhou Special Fund for Introducing Foreign Talents, and others. The authors declared no competing interests.

Source: Yang P et al. Undifferentiated-predominant mixed-type early gastric cancer is more aggressive than pure undifferentiated type: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e054473 (Apr 7). Doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-054473

Key clinical point: Patients with undifferentiated-predominant mixed-type (MU) early-stage gastric cancer (EGC) had a higher risk for submucosal invasion and lymph node metastasis vs. pure undifferentiated-type (PU) EGC.

Major finding: Patients with MU vs. PU EGC had a significantly higher risk for submucosal invasion (odds ratio [OR] 2.19; 95% CI 1.90-2.52) and lymph node metastasis (OR 2.28; 95% CI 1.72-3.03). There was no difference in the risk for lymphovascular invasion in patients with MU vs. PU EGC (OR 1.81; 95% CI 0.84-3.87).

Study details: This article was a meta-analysis of 12 observational studies including 5644 patients with early gastric cancer.

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by the International Science and Technology Cooperation Fund of Changzhou, China, Young Medical Talents of Jiangsu Province, Changzhou Special Fund for Introducing Foreign Talents, and others. The authors declared no competing interests.

Source: Yang P et al. Undifferentiated-predominant mixed-type early gastric cancer is more aggressive than pure undifferentiated type: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e054473 (Apr 7). Doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-054473