User login

Surgical Treatment of Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer in Older Adult Veterans

Skin cancer is the most diagnosed cancer in the United States. Nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSC), which include basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, are usually cured with removal.1 The incidence of NMSC increases with age and is commonly found in nursing homes and geriatric units. These cancers are not usually metastatic or fatal but can cause local destruction and disfigurement if neglected.2 The current standard of care is to treat diagnosed NMSC; however, the dermatology and geriatric care literature have questioned the logic of treating asymptomatic skin cancers that will not affect a patient’s life expectancy.2-4

Forty-seven percent of the current living veteran population is aged ≥ 65 years.5 Older adult patients are frequently referred to the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) surgical service for the treatment of NMSC. The veteran population includes a higher percentage of individuals at an elevated risk of skin cancers (older, White, and male) compared with the general population.6 World War II veterans deployed in regions closer to the equator have been found to have an elevated risk of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin carcinomas.7 A retrospective study of Vietnam veterans exposed to Agent Orange (2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzodioxin) found a significantly higher risk of invasive NMSC in Fitzpatrick skin types I-IV compared with an age-matched subset of the general population.8 Younger veterans who were deployed in Afghanistan and Iraq for Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom worked at more equatorial latitudes than the rest of the US population and may be at increased risk of NMSC. Inadequate sunscreen access, immediate safety concerns, outdoor recreational activities, harsh weather, and insufficient emphasis on sun protection have created a multifactorial challenge for the military population. Riemenschneider and colleagues recommended targeted screening for at-risk veteran patients and prioritizing annual skin cancer screenings during medical mission physical examinations for active military.7

The plastic surgery service regularly receives consults from dermatology, general surgery, and primary care to remove skin cancers on the face, scalp, hands, and forearms. Skin cancer treatment can create serious hardships for older adult patients and their families with multiple appointments for the consult, procedure, and follow-up. Patients are often told to hold their anticoagulant medications when the surgery will be performed on a highly vascular region, such as the scalp or face. This can create wide swings in their laboratory test values and result in life-threatening complications from either bleeding or clotting. The appropriateness of offering surgery to patients with serious comorbidities and a limited life expectancy has been questioned.2-4 The purpose of this study was to measure the morbidity and unrelated 5-year mortality for patients with skin cancer referred to the plastic surgery service to help patients and families make a more informed treatment decision, particularly when the patients are aged > 80 years and have significant life-threatening comorbidities.

Methods

The University of Florida and Malcom Randall VA Medical Center Institutional review board in Gainesville, approved a retrospective review of all consults completed by the plastic surgery service for the treatment of NMSC performed from July 1, 2011 to June 30, 2015. Data collected included age and common life-limiting comorbidities at the time of referral. Morbidities were found on the electronic health record, including coronary artery disease (CAD), congestive heart failure (CHF), cerebral vascular disease (CVD), peripheral vascular disease, dementia, chronic kidney disease (CKD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), tobacco use, diabetes mellitus (DM), liver disease, alcohol use, and obstructive sleep apnea.

Treatment, complications, and 5-year mortality were recorded. A χ2 analysis with P value < .05 was used to determine statistical significance between individual risk factors and 5-year mortality. The relative risk of 5-year mortality was calculated by combining advanced age (aged > 80 years) with the individual comorbidities.

Results

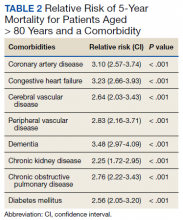

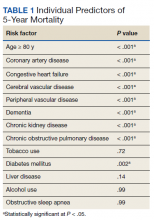

Over 4 years, 800 consults for NMSC were completed by the plastic surgery service. Treatment decisions included 210 excisions (with or without reconstruction) in the operating room, 402 excisions (with or without reconstruction) under local anesthesia in clinic, 55 Mohs surgical dermatology referrals, 21 other service or hospital referrals, and 112 patient who were observed, declined intervention, or died prior to intervention. Five-year mortality was 28.6%. No patients died of NMSC. The median age at consult submission for patients deceased 5 years later was 78 years. Complication rate was 5% and included wound infection, dehiscence, bleeding, or graft loss. Two patients, both deceased within 5 years, had unplanned admissions due to bleeding from either a skin graft donor site or recipient bleeding. Aged ≥ 80 years, CAD, CHF, CVD, peripheral vascular disease, dementia, CKD, COPD, and DM were all found individually to be statistically significant predictors of 5-year mortality (Table 1). Combining aged ≥ 80 years plus CAD, CHF, or dementia all increased the 5-year mortality by a relative risk of > 3 (Table 2).

Discussion

The standard of care is to treat NMSC. Most NMSCs are treated surgically without consideration of patient age or life expectancy.2,4,9,10 A prospective cohort study involving a university-based private practice and a VA medical center in San Francisco found a 22.6% overall 5-year mortality and a 43.3% mortality in the group defined as limited life expectancy (LLE) based on age (≥ 85 years) and medical comorbidities. None died due to the NMSC. Leading cause of death was cardiac, cerebrovascular, and respiratory disease, lung and prostate cancer, and Alzheimer disease. The authors suggested the LLE group may be exposed to wound complications without benefiting from the treatment.4

Another study of 440 patients receiving excision for biopsy-proven facial NMSC at the Roudebush VA Medical Center in Indianapolis, Indiana, found no residual carcinoma in 35.3% of excisions, and in patients aged > 90 years, more than half of the excisions had no residual carcinoma. More than half of the patients aged > 90 years died within 1 year, not as a result of the NMSC. The authors argued for watchful waiting in select patients to maximize comfort and outcomes.10

NMSCs are often asymptomatic and not immediately life threatening. Although NMSCs tend to have a favorable prognosis, studies have found that NMSC may be a marker for other poor health outcomes. A significant increased risk for all-cause mortality was found for patients with a history of SCC, which may be attributed to immune status.11 The aging veteran population has more complex health care needs to be considered when developing surgical treatment plans. These medical problems may limit their life expectancy much sooner than the skin cancer will become symptomatic. We found that individuals aged ≥ 80 years who had CAD, CHF, or dementia had a relative risk of 3 or higher for 5-year mortality. The leading cause of death in the United States in years 2011 to 2015 was heart disease. Alzheimer disease was the sixth leading cause of death in those same years.12-14

Skin cancer excisions do not typically require general anesthesia, deep sedation, or large fluid shifts; however, studies have found that when frail patients undergo low-risk procedures, they tend to have a higher mortality rate than their healthier counterparts.15 Frailty is a concept that identifies patients who are at increased risk of dying in 6 to 60 months due to a decline in their physical reserve. Frail patients have increased rates of perioperative mortality and complications. Various tools have been used to assess the components of physical performance, speed, mobility, nutrition status, mental health, and cognition.16 Frailty screening has been initiated in several VA hospitals, including our own in Gainesville, Florida, with the goal of decreasing postoperative morbidity and mortality in older adult patients.17 The patients are given a 1-page screening assessment that asks about their living situation, medical conditions, nutrition status, cognition, and activities of daily living. The results can trigger the clinician to rethink the surgical plan and mobilize more resources to optimize the patient’s health. This study period precedes the initiative at our institution.

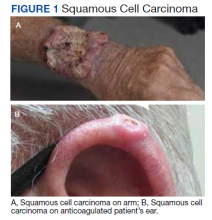

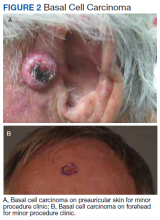

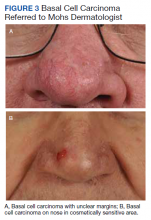

The plastic surgery service’s routine practice is to excise skin cancers in the operating room if sedation or general anesthesia will be needed (Figure 1A), for optimal control of bleeding (Figure 1B) in a patient who cannot safely stop blood thinners, or for excision of a highly vascularized area such as the scalp. Surgery is offered in an office-based setting if the area can be closed primarily, left open to close secondarily, or closed with a small skin graft under local anesthesia only (Figure 2). We prefer treating frail patients in the minor procedure clinic, when possible, to avoid the risks of sedation and the additional preoperative visits and transportation requirements. NMSC with unclear margins (Figure 3A) or in cosmetically sensitive areas where tissue needs to be preserved (Figure 3B) are referred to the Mohs dermatologist. The skin cancers in this study were most frequently found on the face, scalp, hands, and forearms based on referral patterns.

Other treatment options for NMSC include curettage and electrodessication, cryotherapy, and radiation; however, ours is a surgical service and patients are typically referred to us by primary care or dermatology when those are not reasonable or desirable options.18 Published complication rates of patients having skin cancer surgery without age restriction have a rate of 3% to 6%, which is consistent with our study of 5%.19-21 Two bleeding complications that needed to be admitted did not require more than a bedside procedure and neither required transfusions. One patient had been instructed to continue taking coumadin during the perioperative office-based procedure due to a recent carotid stent placement in the setting of a rapidly growing basal cell on an easily accessible location.

The most noted comorbidity in patients with wound complications was found to be DM; however, this was not found to be a statistically significant risk factor for wound complications (P = .10). We do not have a set rule for advising for or against NMSC surgery. We do counsel frail patients and their families that not all cancer is immediately life threatening and will work with them to do whatever makes the most sense to achieve their goals, occasionally accepting positive margins in order to debulk a symptomatic growth. The objective of this paper is to contribute to the discussion of performing invasive procedures on older adult veterans with life-limiting comorbidities. Patients and their families will have different thresholds for what they feel needs intervention, especially if other medical problems are consuming much of their time. We also have the community care referral option for patients whose treatment decisions are being dictated by travel hardships.

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this study is that the data were obtained from a closed system. Patients tend to stay long-term within the VA and their health record is accessible throughout the country as long as they are seen at a VA facility. Complications, therefore, return to the treating service or primary care, who would route the patient back to the surgeon.

One limitation of the study is that this is a retrospective review from 2011. The authors are limited to data that are recorded in the patient record. Multiple health care professionals saw the patients and notes lack consistency in detail. Size of the lesions were not consistently recorded and did not get logged into our database for that reason.

Conclusions

Treatment of NMSC in older adult patients has a low morbidity but needs to be balanced against a patient and family’s goals when the patient presents with life-limiting comorbidities. An elevated 5-year mortality in patients aged > 80 years with serious unrelated medical conditions is intuitive, but this study may help put treatment plans into perspective for families and health care professionals who want to provide an indicated service while maximizing patient quality of life.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System, Gainesville, Florida.

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2021. Accessed May 26, 2022. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2021/cancer-facts-and-figures-2021.pdf

2. Albert A, Knoll MA, Conti JA, Zbar RIS. Non-melanoma skin cancers in the older patient. Curr Oncol Rep. 2019;21(9):79. Published 2019 Jul 29. doi:10.1007/s11912-019-0828-9

3. Linos E, Chren MM, Stijacic Cenzer I, Covinsky KE. Skin cancer in U.S. elderly adults: does life expectancy play a role in treatment decisions? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(8):1610-1615. doi:10.1111/jgs.14202

4. Linos E, Parvataneni R, Stuart SE, Boscardin WJ, Landefeld CS, Chren MM. Treatment of nonfatal conditions at the end of life: nonmelanoma skin cancer. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(11):1006-1012. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.639

5. O’Malley KA, Vinson L, Kaiser AP, Sager Z, Hinrichs K. Mental health and aging veterans: how the Veterans Health Administration meets the needs of aging veterans. Public Policy Aging Rep. 2020;30(1):19-23. doi:10.1093/ppar/prz027

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Profile of veterans: 2017. Accessed May 26, 2022. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/SpecialReports/Profile_of_Veterans_2017.pdf 7. Riemenschneider K, Liu J, Powers JG. Skin cancer in the military: a systematic review of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer incidence, prevention, and screening among active duty and veteran personnel. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(6):1185-1192. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.062

8. Clemens MW, Kochuba AL, Carter ME, Han K, Liu J, Evans K. Association between Agent Orange exposure and nonmelanotic invasive skin cancer: a pilot study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133(2):432-437. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000436859.40151.cf

9. Cameron MC, Lee E, Hibler BP, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: epidemiology; pathophysiology; clinical and histological subtypes; and disease associations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(2):303-317. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.03.060

10. Chauhan R, Munger BN, Chu MW, et al. Age at diagnosis as a relative contraindication for intervention in facial nonmelanoma skin cancer. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(4):390-392. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2017.5073

11. Barton V, Armeson K, Hampras S, et al. Nonmelanoma skin cancer and risk of all-cause and cancer-related mortality: a systematic review. Arch Dermatol Res. 2017;309(4):243-251. doi:10.1007/s00403-017-1724-5

12. Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2013. NCHS Data Brief 178. Accessed May 26, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db178.htm

13. Xu JQ, Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2012. NCHS Data Brief 168. Accessed May 26, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db168.htm

14. Xu JQ, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2015. NCHS Data Brief 267. Accessed May 26, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db267.htm

15. Varley PR , Borrebach JD, Arya S, et al. Clinical utility of the risk analysis index as a prospective frailty screening tool within a multi-practice, multi-hospital integrated healthcare system. Ann Surg. 2021;274(6):e1230-e1237. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003808

16. Hall DE, Arya S , Schmid KK, et al. Development and initial validation of the risk analysis index for measuring frailty in surgical populations. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(2):175-182. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2016.4202

17. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research & Development. Improving healthcare for aging veterans. Updated August 30, 2017. Accessed May 26, 2022. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/news/feature/aging0917.cfm

18. Leus AJG, Frie M, Haisma MS, et al. Treatment of keratinocyte carcinoma in elderly patients – a review of the current literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(9):1932-1943. doi:10.1111/jdv.16268

19. Amici JM, Rogues AM, Lasheras A, et al. A prospective study of the incidence of complications associated with dermatological surgery. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153(5):967-971. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06861.x

20. Arguello-Guerra L, Vargas-Chandomid E, Díaz-González JM, Méndez-Flores S, Ruelas-Villavicencio A, Domínguez-Cherit J. Incidence of complications in dermatological surgery of melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer in patients with multiple comorbidity and/or antiplatelet-anticoagulants. Five-year experience in our hospital. Cir Cir. 2019;86(1):15-23. doi:10.24875/CIRUE.M18000003

21. Keith DJ, de Berker DA, Bray AP, Cheung ST, Brain A, Mohd Mustapa MF. British Association of Dermatologists’ national audit on nonmelanoma skin cancer excision, 2014. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42(1):46-53. doi:10.1111/ced.12990

Skin cancer is the most diagnosed cancer in the United States. Nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSC), which include basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, are usually cured with removal.1 The incidence of NMSC increases with age and is commonly found in nursing homes and geriatric units. These cancers are not usually metastatic or fatal but can cause local destruction and disfigurement if neglected.2 The current standard of care is to treat diagnosed NMSC; however, the dermatology and geriatric care literature have questioned the logic of treating asymptomatic skin cancers that will not affect a patient’s life expectancy.2-4

Forty-seven percent of the current living veteran population is aged ≥ 65 years.5 Older adult patients are frequently referred to the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) surgical service for the treatment of NMSC. The veteran population includes a higher percentage of individuals at an elevated risk of skin cancers (older, White, and male) compared with the general population.6 World War II veterans deployed in regions closer to the equator have been found to have an elevated risk of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin carcinomas.7 A retrospective study of Vietnam veterans exposed to Agent Orange (2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzodioxin) found a significantly higher risk of invasive NMSC in Fitzpatrick skin types I-IV compared with an age-matched subset of the general population.8 Younger veterans who were deployed in Afghanistan and Iraq for Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom worked at more equatorial latitudes than the rest of the US population and may be at increased risk of NMSC. Inadequate sunscreen access, immediate safety concerns, outdoor recreational activities, harsh weather, and insufficient emphasis on sun protection have created a multifactorial challenge for the military population. Riemenschneider and colleagues recommended targeted screening for at-risk veteran patients and prioritizing annual skin cancer screenings during medical mission physical examinations for active military.7

The plastic surgery service regularly receives consults from dermatology, general surgery, and primary care to remove skin cancers on the face, scalp, hands, and forearms. Skin cancer treatment can create serious hardships for older adult patients and their families with multiple appointments for the consult, procedure, and follow-up. Patients are often told to hold their anticoagulant medications when the surgery will be performed on a highly vascular region, such as the scalp or face. This can create wide swings in their laboratory test values and result in life-threatening complications from either bleeding or clotting. The appropriateness of offering surgery to patients with serious comorbidities and a limited life expectancy has been questioned.2-4 The purpose of this study was to measure the morbidity and unrelated 5-year mortality for patients with skin cancer referred to the plastic surgery service to help patients and families make a more informed treatment decision, particularly when the patients are aged > 80 years and have significant life-threatening comorbidities.

Methods

The University of Florida and Malcom Randall VA Medical Center Institutional review board in Gainesville, approved a retrospective review of all consults completed by the plastic surgery service for the treatment of NMSC performed from July 1, 2011 to June 30, 2015. Data collected included age and common life-limiting comorbidities at the time of referral. Morbidities were found on the electronic health record, including coronary artery disease (CAD), congestive heart failure (CHF), cerebral vascular disease (CVD), peripheral vascular disease, dementia, chronic kidney disease (CKD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), tobacco use, diabetes mellitus (DM), liver disease, alcohol use, and obstructive sleep apnea.

Treatment, complications, and 5-year mortality were recorded. A χ2 analysis with P value < .05 was used to determine statistical significance between individual risk factors and 5-year mortality. The relative risk of 5-year mortality was calculated by combining advanced age (aged > 80 years) with the individual comorbidities.

Results

Over 4 years, 800 consults for NMSC were completed by the plastic surgery service. Treatment decisions included 210 excisions (with or without reconstruction) in the operating room, 402 excisions (with or without reconstruction) under local anesthesia in clinic, 55 Mohs surgical dermatology referrals, 21 other service or hospital referrals, and 112 patient who were observed, declined intervention, or died prior to intervention. Five-year mortality was 28.6%. No patients died of NMSC. The median age at consult submission for patients deceased 5 years later was 78 years. Complication rate was 5% and included wound infection, dehiscence, bleeding, or graft loss. Two patients, both deceased within 5 years, had unplanned admissions due to bleeding from either a skin graft donor site or recipient bleeding. Aged ≥ 80 years, CAD, CHF, CVD, peripheral vascular disease, dementia, CKD, COPD, and DM were all found individually to be statistically significant predictors of 5-year mortality (Table 1). Combining aged ≥ 80 years plus CAD, CHF, or dementia all increased the 5-year mortality by a relative risk of > 3 (Table 2).

Discussion

The standard of care is to treat NMSC. Most NMSCs are treated surgically without consideration of patient age or life expectancy.2,4,9,10 A prospective cohort study involving a university-based private practice and a VA medical center in San Francisco found a 22.6% overall 5-year mortality and a 43.3% mortality in the group defined as limited life expectancy (LLE) based on age (≥ 85 years) and medical comorbidities. None died due to the NMSC. Leading cause of death was cardiac, cerebrovascular, and respiratory disease, lung and prostate cancer, and Alzheimer disease. The authors suggested the LLE group may be exposed to wound complications without benefiting from the treatment.4

Another study of 440 patients receiving excision for biopsy-proven facial NMSC at the Roudebush VA Medical Center in Indianapolis, Indiana, found no residual carcinoma in 35.3% of excisions, and in patients aged > 90 years, more than half of the excisions had no residual carcinoma. More than half of the patients aged > 90 years died within 1 year, not as a result of the NMSC. The authors argued for watchful waiting in select patients to maximize comfort and outcomes.10

NMSCs are often asymptomatic and not immediately life threatening. Although NMSCs tend to have a favorable prognosis, studies have found that NMSC may be a marker for other poor health outcomes. A significant increased risk for all-cause mortality was found for patients with a history of SCC, which may be attributed to immune status.11 The aging veteran population has more complex health care needs to be considered when developing surgical treatment plans. These medical problems may limit their life expectancy much sooner than the skin cancer will become symptomatic. We found that individuals aged ≥ 80 years who had CAD, CHF, or dementia had a relative risk of 3 or higher for 5-year mortality. The leading cause of death in the United States in years 2011 to 2015 was heart disease. Alzheimer disease was the sixth leading cause of death in those same years.12-14

Skin cancer excisions do not typically require general anesthesia, deep sedation, or large fluid shifts; however, studies have found that when frail patients undergo low-risk procedures, they tend to have a higher mortality rate than their healthier counterparts.15 Frailty is a concept that identifies patients who are at increased risk of dying in 6 to 60 months due to a decline in their physical reserve. Frail patients have increased rates of perioperative mortality and complications. Various tools have been used to assess the components of physical performance, speed, mobility, nutrition status, mental health, and cognition.16 Frailty screening has been initiated in several VA hospitals, including our own in Gainesville, Florida, with the goal of decreasing postoperative morbidity and mortality in older adult patients.17 The patients are given a 1-page screening assessment that asks about their living situation, medical conditions, nutrition status, cognition, and activities of daily living. The results can trigger the clinician to rethink the surgical plan and mobilize more resources to optimize the patient’s health. This study period precedes the initiative at our institution.

The plastic surgery service’s routine practice is to excise skin cancers in the operating room if sedation or general anesthesia will be needed (Figure 1A), for optimal control of bleeding (Figure 1B) in a patient who cannot safely stop blood thinners, or for excision of a highly vascularized area such as the scalp. Surgery is offered in an office-based setting if the area can be closed primarily, left open to close secondarily, or closed with a small skin graft under local anesthesia only (Figure 2). We prefer treating frail patients in the minor procedure clinic, when possible, to avoid the risks of sedation and the additional preoperative visits and transportation requirements. NMSC with unclear margins (Figure 3A) or in cosmetically sensitive areas where tissue needs to be preserved (Figure 3B) are referred to the Mohs dermatologist. The skin cancers in this study were most frequently found on the face, scalp, hands, and forearms based on referral patterns.

Other treatment options for NMSC include curettage and electrodessication, cryotherapy, and radiation; however, ours is a surgical service and patients are typically referred to us by primary care or dermatology when those are not reasonable or desirable options.18 Published complication rates of patients having skin cancer surgery without age restriction have a rate of 3% to 6%, which is consistent with our study of 5%.19-21 Two bleeding complications that needed to be admitted did not require more than a bedside procedure and neither required transfusions. One patient had been instructed to continue taking coumadin during the perioperative office-based procedure due to a recent carotid stent placement in the setting of a rapidly growing basal cell on an easily accessible location.

The most noted comorbidity in patients with wound complications was found to be DM; however, this was not found to be a statistically significant risk factor for wound complications (P = .10). We do not have a set rule for advising for or against NMSC surgery. We do counsel frail patients and their families that not all cancer is immediately life threatening and will work with them to do whatever makes the most sense to achieve their goals, occasionally accepting positive margins in order to debulk a symptomatic growth. The objective of this paper is to contribute to the discussion of performing invasive procedures on older adult veterans with life-limiting comorbidities. Patients and their families will have different thresholds for what they feel needs intervention, especially if other medical problems are consuming much of their time. We also have the community care referral option for patients whose treatment decisions are being dictated by travel hardships.

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this study is that the data were obtained from a closed system. Patients tend to stay long-term within the VA and their health record is accessible throughout the country as long as they are seen at a VA facility. Complications, therefore, return to the treating service or primary care, who would route the patient back to the surgeon.

One limitation of the study is that this is a retrospective review from 2011. The authors are limited to data that are recorded in the patient record. Multiple health care professionals saw the patients and notes lack consistency in detail. Size of the lesions were not consistently recorded and did not get logged into our database for that reason.

Conclusions

Treatment of NMSC in older adult patients has a low morbidity but needs to be balanced against a patient and family’s goals when the patient presents with life-limiting comorbidities. An elevated 5-year mortality in patients aged > 80 years with serious unrelated medical conditions is intuitive, but this study may help put treatment plans into perspective for families and health care professionals who want to provide an indicated service while maximizing patient quality of life.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System, Gainesville, Florida.

Skin cancer is the most diagnosed cancer in the United States. Nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSC), which include basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, are usually cured with removal.1 The incidence of NMSC increases with age and is commonly found in nursing homes and geriatric units. These cancers are not usually metastatic or fatal but can cause local destruction and disfigurement if neglected.2 The current standard of care is to treat diagnosed NMSC; however, the dermatology and geriatric care literature have questioned the logic of treating asymptomatic skin cancers that will not affect a patient’s life expectancy.2-4

Forty-seven percent of the current living veteran population is aged ≥ 65 years.5 Older adult patients are frequently referred to the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) surgical service for the treatment of NMSC. The veteran population includes a higher percentage of individuals at an elevated risk of skin cancers (older, White, and male) compared with the general population.6 World War II veterans deployed in regions closer to the equator have been found to have an elevated risk of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin carcinomas.7 A retrospective study of Vietnam veterans exposed to Agent Orange (2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzodioxin) found a significantly higher risk of invasive NMSC in Fitzpatrick skin types I-IV compared with an age-matched subset of the general population.8 Younger veterans who were deployed in Afghanistan and Iraq for Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom worked at more equatorial latitudes than the rest of the US population and may be at increased risk of NMSC. Inadequate sunscreen access, immediate safety concerns, outdoor recreational activities, harsh weather, and insufficient emphasis on sun protection have created a multifactorial challenge for the military population. Riemenschneider and colleagues recommended targeted screening for at-risk veteran patients and prioritizing annual skin cancer screenings during medical mission physical examinations for active military.7

The plastic surgery service regularly receives consults from dermatology, general surgery, and primary care to remove skin cancers on the face, scalp, hands, and forearms. Skin cancer treatment can create serious hardships for older adult patients and their families with multiple appointments for the consult, procedure, and follow-up. Patients are often told to hold their anticoagulant medications when the surgery will be performed on a highly vascular region, such as the scalp or face. This can create wide swings in their laboratory test values and result in life-threatening complications from either bleeding or clotting. The appropriateness of offering surgery to patients with serious comorbidities and a limited life expectancy has been questioned.2-4 The purpose of this study was to measure the morbidity and unrelated 5-year mortality for patients with skin cancer referred to the plastic surgery service to help patients and families make a more informed treatment decision, particularly when the patients are aged > 80 years and have significant life-threatening comorbidities.

Methods

The University of Florida and Malcom Randall VA Medical Center Institutional review board in Gainesville, approved a retrospective review of all consults completed by the plastic surgery service for the treatment of NMSC performed from July 1, 2011 to June 30, 2015. Data collected included age and common life-limiting comorbidities at the time of referral. Morbidities were found on the electronic health record, including coronary artery disease (CAD), congestive heart failure (CHF), cerebral vascular disease (CVD), peripheral vascular disease, dementia, chronic kidney disease (CKD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), tobacco use, diabetes mellitus (DM), liver disease, alcohol use, and obstructive sleep apnea.

Treatment, complications, and 5-year mortality were recorded. A χ2 analysis with P value < .05 was used to determine statistical significance between individual risk factors and 5-year mortality. The relative risk of 5-year mortality was calculated by combining advanced age (aged > 80 years) with the individual comorbidities.

Results

Over 4 years, 800 consults for NMSC were completed by the plastic surgery service. Treatment decisions included 210 excisions (with or without reconstruction) in the operating room, 402 excisions (with or without reconstruction) under local anesthesia in clinic, 55 Mohs surgical dermatology referrals, 21 other service or hospital referrals, and 112 patient who were observed, declined intervention, or died prior to intervention. Five-year mortality was 28.6%. No patients died of NMSC. The median age at consult submission for patients deceased 5 years later was 78 years. Complication rate was 5% and included wound infection, dehiscence, bleeding, or graft loss. Two patients, both deceased within 5 years, had unplanned admissions due to bleeding from either a skin graft donor site or recipient bleeding. Aged ≥ 80 years, CAD, CHF, CVD, peripheral vascular disease, dementia, CKD, COPD, and DM were all found individually to be statistically significant predictors of 5-year mortality (Table 1). Combining aged ≥ 80 years plus CAD, CHF, or dementia all increased the 5-year mortality by a relative risk of > 3 (Table 2).

Discussion

The standard of care is to treat NMSC. Most NMSCs are treated surgically without consideration of patient age or life expectancy.2,4,9,10 A prospective cohort study involving a university-based private practice and a VA medical center in San Francisco found a 22.6% overall 5-year mortality and a 43.3% mortality in the group defined as limited life expectancy (LLE) based on age (≥ 85 years) and medical comorbidities. None died due to the NMSC. Leading cause of death was cardiac, cerebrovascular, and respiratory disease, lung and prostate cancer, and Alzheimer disease. The authors suggested the LLE group may be exposed to wound complications without benefiting from the treatment.4

Another study of 440 patients receiving excision for biopsy-proven facial NMSC at the Roudebush VA Medical Center in Indianapolis, Indiana, found no residual carcinoma in 35.3% of excisions, and in patients aged > 90 years, more than half of the excisions had no residual carcinoma. More than half of the patients aged > 90 years died within 1 year, not as a result of the NMSC. The authors argued for watchful waiting in select patients to maximize comfort and outcomes.10

NMSCs are often asymptomatic and not immediately life threatening. Although NMSCs tend to have a favorable prognosis, studies have found that NMSC may be a marker for other poor health outcomes. A significant increased risk for all-cause mortality was found for patients with a history of SCC, which may be attributed to immune status.11 The aging veteran population has more complex health care needs to be considered when developing surgical treatment plans. These medical problems may limit their life expectancy much sooner than the skin cancer will become symptomatic. We found that individuals aged ≥ 80 years who had CAD, CHF, or dementia had a relative risk of 3 or higher for 5-year mortality. The leading cause of death in the United States in years 2011 to 2015 was heart disease. Alzheimer disease was the sixth leading cause of death in those same years.12-14

Skin cancer excisions do not typically require general anesthesia, deep sedation, or large fluid shifts; however, studies have found that when frail patients undergo low-risk procedures, they tend to have a higher mortality rate than their healthier counterparts.15 Frailty is a concept that identifies patients who are at increased risk of dying in 6 to 60 months due to a decline in their physical reserve. Frail patients have increased rates of perioperative mortality and complications. Various tools have been used to assess the components of physical performance, speed, mobility, nutrition status, mental health, and cognition.16 Frailty screening has been initiated in several VA hospitals, including our own in Gainesville, Florida, with the goal of decreasing postoperative morbidity and mortality in older adult patients.17 The patients are given a 1-page screening assessment that asks about their living situation, medical conditions, nutrition status, cognition, and activities of daily living. The results can trigger the clinician to rethink the surgical plan and mobilize more resources to optimize the patient’s health. This study period precedes the initiative at our institution.

The plastic surgery service’s routine practice is to excise skin cancers in the operating room if sedation or general anesthesia will be needed (Figure 1A), for optimal control of bleeding (Figure 1B) in a patient who cannot safely stop blood thinners, or for excision of a highly vascularized area such as the scalp. Surgery is offered in an office-based setting if the area can be closed primarily, left open to close secondarily, or closed with a small skin graft under local anesthesia only (Figure 2). We prefer treating frail patients in the minor procedure clinic, when possible, to avoid the risks of sedation and the additional preoperative visits and transportation requirements. NMSC with unclear margins (Figure 3A) or in cosmetically sensitive areas where tissue needs to be preserved (Figure 3B) are referred to the Mohs dermatologist. The skin cancers in this study were most frequently found on the face, scalp, hands, and forearms based on referral patterns.

Other treatment options for NMSC include curettage and electrodessication, cryotherapy, and radiation; however, ours is a surgical service and patients are typically referred to us by primary care or dermatology when those are not reasonable or desirable options.18 Published complication rates of patients having skin cancer surgery without age restriction have a rate of 3% to 6%, which is consistent with our study of 5%.19-21 Two bleeding complications that needed to be admitted did not require more than a bedside procedure and neither required transfusions. One patient had been instructed to continue taking coumadin during the perioperative office-based procedure due to a recent carotid stent placement in the setting of a rapidly growing basal cell on an easily accessible location.

The most noted comorbidity in patients with wound complications was found to be DM; however, this was not found to be a statistically significant risk factor for wound complications (P = .10). We do not have a set rule for advising for or against NMSC surgery. We do counsel frail patients and their families that not all cancer is immediately life threatening and will work with them to do whatever makes the most sense to achieve their goals, occasionally accepting positive margins in order to debulk a symptomatic growth. The objective of this paper is to contribute to the discussion of performing invasive procedures on older adult veterans with life-limiting comorbidities. Patients and their families will have different thresholds for what they feel needs intervention, especially if other medical problems are consuming much of their time. We also have the community care referral option for patients whose treatment decisions are being dictated by travel hardships.

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this study is that the data were obtained from a closed system. Patients tend to stay long-term within the VA and their health record is accessible throughout the country as long as they are seen at a VA facility. Complications, therefore, return to the treating service or primary care, who would route the patient back to the surgeon.

One limitation of the study is that this is a retrospective review from 2011. The authors are limited to data that are recorded in the patient record. Multiple health care professionals saw the patients and notes lack consistency in detail. Size of the lesions were not consistently recorded and did not get logged into our database for that reason.

Conclusions

Treatment of NMSC in older adult patients has a low morbidity but needs to be balanced against a patient and family’s goals when the patient presents with life-limiting comorbidities. An elevated 5-year mortality in patients aged > 80 years with serious unrelated medical conditions is intuitive, but this study may help put treatment plans into perspective for families and health care professionals who want to provide an indicated service while maximizing patient quality of life.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System, Gainesville, Florida.

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2021. Accessed May 26, 2022. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2021/cancer-facts-and-figures-2021.pdf

2. Albert A, Knoll MA, Conti JA, Zbar RIS. Non-melanoma skin cancers in the older patient. Curr Oncol Rep. 2019;21(9):79. Published 2019 Jul 29. doi:10.1007/s11912-019-0828-9

3. Linos E, Chren MM, Stijacic Cenzer I, Covinsky KE. Skin cancer in U.S. elderly adults: does life expectancy play a role in treatment decisions? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(8):1610-1615. doi:10.1111/jgs.14202

4. Linos E, Parvataneni R, Stuart SE, Boscardin WJ, Landefeld CS, Chren MM. Treatment of nonfatal conditions at the end of life: nonmelanoma skin cancer. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(11):1006-1012. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.639

5. O’Malley KA, Vinson L, Kaiser AP, Sager Z, Hinrichs K. Mental health and aging veterans: how the Veterans Health Administration meets the needs of aging veterans. Public Policy Aging Rep. 2020;30(1):19-23. doi:10.1093/ppar/prz027

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Profile of veterans: 2017. Accessed May 26, 2022. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/SpecialReports/Profile_of_Veterans_2017.pdf 7. Riemenschneider K, Liu J, Powers JG. Skin cancer in the military: a systematic review of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer incidence, prevention, and screening among active duty and veteran personnel. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(6):1185-1192. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.062

8. Clemens MW, Kochuba AL, Carter ME, Han K, Liu J, Evans K. Association between Agent Orange exposure and nonmelanotic invasive skin cancer: a pilot study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133(2):432-437. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000436859.40151.cf

9. Cameron MC, Lee E, Hibler BP, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: epidemiology; pathophysiology; clinical and histological subtypes; and disease associations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(2):303-317. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.03.060

10. Chauhan R, Munger BN, Chu MW, et al. Age at diagnosis as a relative contraindication for intervention in facial nonmelanoma skin cancer. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(4):390-392. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2017.5073

11. Barton V, Armeson K, Hampras S, et al. Nonmelanoma skin cancer and risk of all-cause and cancer-related mortality: a systematic review. Arch Dermatol Res. 2017;309(4):243-251. doi:10.1007/s00403-017-1724-5

12. Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2013. NCHS Data Brief 178. Accessed May 26, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db178.htm

13. Xu JQ, Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2012. NCHS Data Brief 168. Accessed May 26, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db168.htm

14. Xu JQ, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2015. NCHS Data Brief 267. Accessed May 26, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db267.htm

15. Varley PR , Borrebach JD, Arya S, et al. Clinical utility of the risk analysis index as a prospective frailty screening tool within a multi-practice, multi-hospital integrated healthcare system. Ann Surg. 2021;274(6):e1230-e1237. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003808

16. Hall DE, Arya S , Schmid KK, et al. Development and initial validation of the risk analysis index for measuring frailty in surgical populations. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(2):175-182. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2016.4202

17. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research & Development. Improving healthcare for aging veterans. Updated August 30, 2017. Accessed May 26, 2022. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/news/feature/aging0917.cfm

18. Leus AJG, Frie M, Haisma MS, et al. Treatment of keratinocyte carcinoma in elderly patients – a review of the current literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(9):1932-1943. doi:10.1111/jdv.16268

19. Amici JM, Rogues AM, Lasheras A, et al. A prospective study of the incidence of complications associated with dermatological surgery. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153(5):967-971. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06861.x

20. Arguello-Guerra L, Vargas-Chandomid E, Díaz-González JM, Méndez-Flores S, Ruelas-Villavicencio A, Domínguez-Cherit J. Incidence of complications in dermatological surgery of melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer in patients with multiple comorbidity and/or antiplatelet-anticoagulants. Five-year experience in our hospital. Cir Cir. 2019;86(1):15-23. doi:10.24875/CIRUE.M18000003

21. Keith DJ, de Berker DA, Bray AP, Cheung ST, Brain A, Mohd Mustapa MF. British Association of Dermatologists’ national audit on nonmelanoma skin cancer excision, 2014. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42(1):46-53. doi:10.1111/ced.12990

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2021. Accessed May 26, 2022. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2021/cancer-facts-and-figures-2021.pdf

2. Albert A, Knoll MA, Conti JA, Zbar RIS. Non-melanoma skin cancers in the older patient. Curr Oncol Rep. 2019;21(9):79. Published 2019 Jul 29. doi:10.1007/s11912-019-0828-9

3. Linos E, Chren MM, Stijacic Cenzer I, Covinsky KE. Skin cancer in U.S. elderly adults: does life expectancy play a role in treatment decisions? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(8):1610-1615. doi:10.1111/jgs.14202

4. Linos E, Parvataneni R, Stuart SE, Boscardin WJ, Landefeld CS, Chren MM. Treatment of nonfatal conditions at the end of life: nonmelanoma skin cancer. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(11):1006-1012. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.639

5. O’Malley KA, Vinson L, Kaiser AP, Sager Z, Hinrichs K. Mental health and aging veterans: how the Veterans Health Administration meets the needs of aging veterans. Public Policy Aging Rep. 2020;30(1):19-23. doi:10.1093/ppar/prz027

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Profile of veterans: 2017. Accessed May 26, 2022. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/SpecialReports/Profile_of_Veterans_2017.pdf 7. Riemenschneider K, Liu J, Powers JG. Skin cancer in the military: a systematic review of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer incidence, prevention, and screening among active duty and veteran personnel. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(6):1185-1192. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.062

8. Clemens MW, Kochuba AL, Carter ME, Han K, Liu J, Evans K. Association between Agent Orange exposure and nonmelanotic invasive skin cancer: a pilot study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133(2):432-437. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000436859.40151.cf

9. Cameron MC, Lee E, Hibler BP, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: epidemiology; pathophysiology; clinical and histological subtypes; and disease associations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(2):303-317. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.03.060

10. Chauhan R, Munger BN, Chu MW, et al. Age at diagnosis as a relative contraindication for intervention in facial nonmelanoma skin cancer. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(4):390-392. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2017.5073

11. Barton V, Armeson K, Hampras S, et al. Nonmelanoma skin cancer and risk of all-cause and cancer-related mortality: a systematic review. Arch Dermatol Res. 2017;309(4):243-251. doi:10.1007/s00403-017-1724-5

12. Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2013. NCHS Data Brief 178. Accessed May 26, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db178.htm

13. Xu JQ, Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2012. NCHS Data Brief 168. Accessed May 26, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db168.htm

14. Xu JQ, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2015. NCHS Data Brief 267. Accessed May 26, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db267.htm

15. Varley PR , Borrebach JD, Arya S, et al. Clinical utility of the risk analysis index as a prospective frailty screening tool within a multi-practice, multi-hospital integrated healthcare system. Ann Surg. 2021;274(6):e1230-e1237. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003808

16. Hall DE, Arya S , Schmid KK, et al. Development and initial validation of the risk analysis index for measuring frailty in surgical populations. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(2):175-182. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2016.4202

17. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research & Development. Improving healthcare for aging veterans. Updated August 30, 2017. Accessed May 26, 2022. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/news/feature/aging0917.cfm

18. Leus AJG, Frie M, Haisma MS, et al. Treatment of keratinocyte carcinoma in elderly patients – a review of the current literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(9):1932-1943. doi:10.1111/jdv.16268

19. Amici JM, Rogues AM, Lasheras A, et al. A prospective study of the incidence of complications associated with dermatological surgery. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153(5):967-971. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06861.x

20. Arguello-Guerra L, Vargas-Chandomid E, Díaz-González JM, Méndez-Flores S, Ruelas-Villavicencio A, Domínguez-Cherit J. Incidence of complications in dermatological surgery of melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer in patients with multiple comorbidity and/or antiplatelet-anticoagulants. Five-year experience in our hospital. Cir Cir. 2019;86(1):15-23. doi:10.24875/CIRUE.M18000003

21. Keith DJ, de Berker DA, Bray AP, Cheung ST, Brain A, Mohd Mustapa MF. British Association of Dermatologists’ national audit on nonmelanoma skin cancer excision, 2014. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42(1):46-53. doi:10.1111/ced.12990

SARS-CoV-2: A Novel Precipitant of Ischemic Priapism

Priapism is a disorder that occurs when the penis maintains a prolonged erection in the absence of appropriate stimulation. The disorder is typically divided into subgroups based on arterial flow: low flow (ischemic) and high flow (nonischemic). Ischemic priapism is the most common form and results from venous congestion due to obstructed outflow and inability of cavernous smooth muscle to contract, resulting in compartment syndrome, tissue hypoxia, hypercapnia, and acidosis.1 Conditions that result in hypercoagulable states and hyperviscosity are associated with ischemic priapism. COVID-19 is well known to cause an acute respiratory illness and systemic inflammatory response and has been increasingly associated with coagulopathy. Studies have shown that 20% to 55% of patients admitted to the hospital for COVID-19 show objective laboratory evidence of a hypercoagulable state.2

To date, there are 6 reported cases of priapism occurring in the setting of COVID-19 with all cases demonstrating the ischemic subtype. The onset of priapism from the beginning of infectious symptoms ranged from 2 days to more than a month. Five of the cases occurred in patients with critical COVID-19 and 1 in the setting of mild disease.3-8 Two critically ill patients did not receive treatment for their ischemic priapism as they were transitioned to expectant management and/or comfort measures.Most were treated with cavernosal blood aspiration and intracavernosal injections of phenylephrine or ethylephrine. Some patients were managed with prophylactic doses of anticoagulation after the identification of priapism; others were transitioned to therapeutic doses. Two patients were followed postdischarge; one patient reported normal nighttime erections with sexual desire 2 weeks postdischarge, and another patient, who underwent a bilateral T-shunt procedure after unsuccessful phenylephrine injections, reported complete erectile dysfunction at 3 months postdischarge.4,7 There was a potentially confounding variable in 2 cases in which propofol infusions were used for sedation management in the setting of mechanical ventilation.6,8 Propofol has been linked to priapism through its blockade of sympathetic activation resulting in persistent relaxation of cavernosal smooth muscle.9 We present a unique case of COVID-19–associated ischemic priapism as our patient had moderate rather than critical COVID-19.

Case Presentation

A 67-year-old male patient presented to the emergency department for a painful erection of 34-hour duration. The patient had been exposed to COVID-19 roughly 2 months prior. Since the exposure, he had experienced headache, nonproductive cough, sore throat, and decreased appetite with weight loss. His medical history included hypertension, thoracic aortic aneurysm, B-cell type chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), and obstructive sleep apnea. Daily outpatient medications included atenolol 100 mg, hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg, and omeprazole 20 mg. The patient stopped tobacco use about 30 years previously. He reported no alcohol consumption or illicit drug use and had no previous episodes of prolonged erection.

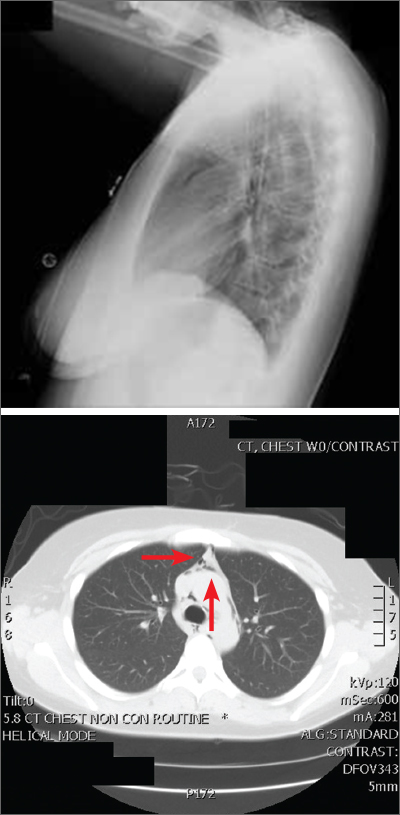

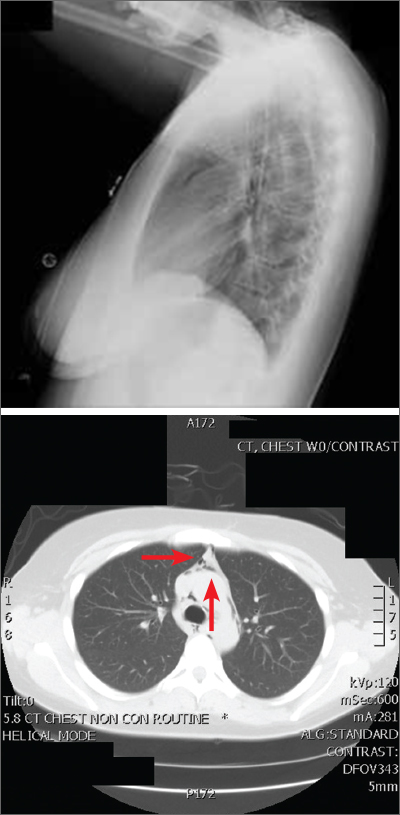

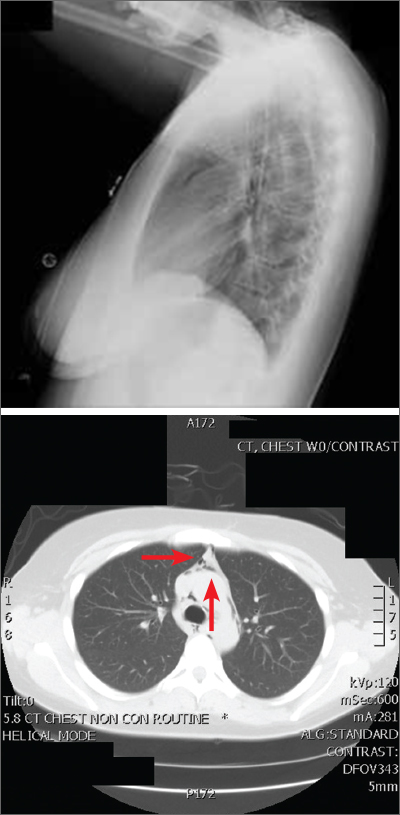

The patient was afebrile, hemodynamically stable, and had an oxygen saturation of 92% on room air. Physical examination revealed clear breath sounds and an erect circumcised penis without any lesions, discoloration, or skin necrosis. Laboratory data were remarkable for the following values: 125,660 cells/μL white blood cells (WBCs), 13.82 × 103/ μL neutrophils, 110.58 × 103/μL lymphocytes, 1.26 × 103/μL monocytes, no blasts, 9.4 gm/dL hemoglobin, 100.3 fl mean corpuscular volume, 417,000 cells/μL platelets, 23,671 ng/mL D-dimer, 29.6 seconds activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), 16.3 seconds prothrombin time, 743 mg/dL fibrinogen, 474 U/L lactate dehydrogenase, and 202.1 mg/dL haptoglobin. A nasopharyngeal reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction test resulted positive for the SARS-CoV-2 virus, and subsequent chest X-ray revealed bilateral, hazy opacities predominantly in a peripheral distribution. Computed tomography (CT) angiogram of the chest did not reveal pulmonary emboli, pneumothorax, effusions, or lobar consolidation. However, it displayed bilateral ground-glass opacities with interstitial consolidation worst in the upper lobes. Corporal aspiration and blood gas analysis revealed a pH of 7.05, P

Differential Diagnosis

The first consideration in the differential diagnosis of priapism is to differentiate between ischemic and nonischemic. Based on the abnormal blood gas results above, this case clearly falls within the ischemic spectrum. Ischemic priapism secondary to CLL-induced hyperleukocytosis was considered. It has been noted that up to 20% of priapism cases in adults are related to hematologic disorders.10 While it is not uncommon to see hyperleukocytosis (total WBC count > 100 × 109/L) in CLL, leukostasis is rare with most reports demonstrating WBC counts > 1000 × 109/L.11 Hematology, vascular surgery, and urology services were consulted and agreed that ischemic priapism was due to microthrombi or pelvic vein thrombosis secondary to COVID-19–associated coagulopathy (CAC) was the most likely etiology.

Treatment

After corporal aspiration, intracorporal phenylephrine was administered. Diluted phenylephrine (100 ug/mL) was injected every 5 to 10 minutes while intermittently aspirating and irrigating multiple sites along the lateral length of the penile shaft. This initial procedure reduced the erection from 100% to 30% rigidity, with repeat blood gas analysis revealing minimal improvement. CT of the abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast revealed no evidence of pelvic thrombi. A second round of phenylephrine injections were administered, resulting in detumescence. The patient was treated with 2 to 3 L/min of oxygen supplementation via nasal cannula, a 5-day course of remdesivir and low-intensity heparin drip. Following the initial low-intensity heparin drip, the patient transitioned to therapeutic enoxaparin and subsequently was discharged on apixaban for a 3-month course. Since discharge, the patient followed up with hematology. He tolerated and completed the anticoagulation regimen without any recurrences of priapism or residual deficits.

Discussion

Recent studies have overwhelmingly analyzed the incidence and presentation of thrombotic complications in critically ill patients with COVID-19. CAC has been postulated to result from endotheliopathy along with immune cell activation and propagation of coagulation. While COVID-19 has been noted to create lung injury through binding angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptors expressed on alveolar pneumocytes, it increasingly has been found to affect endothelial cells throughout the body. Recent postmortem analyses have demonstrated direct viral infection of endothelial cells with consequent diffuse endothelial inflammation, as evidenced by viral inclusions, sequestered immune cells, and endothelial apoptosis.12,13 Manifestations of this endotheliopathy have been delineated through various studies.

An early retrospective study in Wuhan, China, illustrated that 36% of the first 99 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 demonstrated an elevated D-dimer, 6% an elevated aPTT, and 5% an elevated prothrombin time.14 Another retrospective study conducted in Wuhan found a 25% incidence of venous thromboembolic complications in critically ill patients with severe COVID-19.15 In the Netherlands, a study reported the incidence of arterial and venous thrombotic complications to be 31% in 184 critically ill patients with COVID-19, with 81% of these cases involving pulmonary emboli.16

To our knowledge, our patient is the seventh reported case of ischemic priapism occurring in the setting of a COVID-19 infection, and the first to have occurred in its moderate form. Ischemic priapism is often a consequence of penile venous outflow obstruction and resultant stasis of hypoxic blood.7 The prothrombotic state induced by CAC has been proposed to cause the obstruction of small emissary veins in the subtunical space and in turn lead to venous stasis, which propagates the formation of ischemic priapism.8 Furthermore, 4 of the previously reported cases shared laboratory data on their patients, and all demonstrated elevated D-dimer and fibrinogen levels, which strengthens this hypothesis.3,5,7,8 CLL presents a potential confounding variable in this case; however, as we have reviewed earlier, the risk of leukostasis at WBC counts < 1000 × 109/L is very low.11 It is also probable that the patient had some level of immune dysregulation secondary to CLL, leading to his prolonged course and slow clearance of the virus.

Conclusions

Although only a handful of CAC cases leading to ischemic priapism have been reported, the true incidence may be much higher. While our case highlights the importance of considering COVID-19 infection in the differential diagnosis of ischemic priapism, more research is needed to understand incidence and definitively establish a causative relationship.

1. Pryor J, Akkus E, Alter G, et al. Priapism. J Sex Med. 2004;1(1):116-120. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2004.10117.x

2. Lee SG, Fralick M, Sholzberg M. Coagulopathy associated with COVID-19. CMAJ. 2020;192(21):E583. doi:10.1503/cmaj.200685

3. Lam G, McCarthy R, Haider R. A peculiar case of priapism: the hypercoagulable state in patients with severe COVID-19 infection. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2020;7(8):001779. doi:10.12890/2020_001779

4. Addar A, Al Fraidi O, Nazer A, Althonayan N, Ghazwani Y. Priapism for 10 days in a patient with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia: a case report. J Surg Case Rep. 2021;2021(4):rjab020. doi:10.1093/jscr/rjab020

5. Lamamri M, Chebbi A, Mamane J, et al. Priapism in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Am J Emerg Med. 2021;39:251.e5-251.e7. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2020.06.027

6. Silverman ML, VanDerVeer SJ, Donnelly TJ. Priapism in COVID-19: a thromboembolic complication. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;45:686.e5-686.e6. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2020.12.072

7. Giuliano AFM, Vulpi M, Passerini F, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection as a determining factor to the precipitation of ischemic priapism in a young patient with asymptomatic COVID-19. Case Rep Urol. 2021;2021:9936891. doi:10.1155/2021/9936891

8. Carreno BD, Perez CP, Vasquez D, Oyola JA, Suarez O, Bedoya C. Veno-occlusive priapism in COVID-19 disease. Urol Int. 2021;105(9-10):916-919. doi:10.1159/000514421

9. Senthilkumaran S, Shah S, Ganapathysubramanian, Balamurgan N, Thirumalaikolundusubramanian P. Propofol and priapism. Indian J Pharmacol. 2010;42(4):238-239. doi:10.4103/0253-7613.68430

10. Qu M, Lu X, Wang L, Liu Z, Sun Y, Gao X. Priapism secondary to chronic myeloid leukemia treated by a surgical cavernosa-corpus spongiosum shunt: case report. Asian J Urol. 2019;6(4):373-376. doi:10.1016/j.ajur.2018.12.004

11. Singh N, Singh Lubana S, Dabrowski L, Sidhu G. Leukostasis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Am J Case Rep. 2020;21:e924798. doi:10.12659/AJCR.924798

12. Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P, et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10234):1417-1418. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5

13. Connors JM, Levy JH. COVID-19 and its implications for thrombosis and anticoagulation. Blood. 2020;135(23):2033-2040. doi:10.1182/blood.2020006000

14. Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507-513. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7

15. Cui S, Chen S, Li X, Liu S, Wang F. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(6):1421-1424. doi:10.1111/jth.14830

16. Klok FA, Kruip M, van der Meer NJM, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145-147. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013

Priapism is a disorder that occurs when the penis maintains a prolonged erection in the absence of appropriate stimulation. The disorder is typically divided into subgroups based on arterial flow: low flow (ischemic) and high flow (nonischemic). Ischemic priapism is the most common form and results from venous congestion due to obstructed outflow and inability of cavernous smooth muscle to contract, resulting in compartment syndrome, tissue hypoxia, hypercapnia, and acidosis.1 Conditions that result in hypercoagulable states and hyperviscosity are associated with ischemic priapism. COVID-19 is well known to cause an acute respiratory illness and systemic inflammatory response and has been increasingly associated with coagulopathy. Studies have shown that 20% to 55% of patients admitted to the hospital for COVID-19 show objective laboratory evidence of a hypercoagulable state.2

To date, there are 6 reported cases of priapism occurring in the setting of COVID-19 with all cases demonstrating the ischemic subtype. The onset of priapism from the beginning of infectious symptoms ranged from 2 days to more than a month. Five of the cases occurred in patients with critical COVID-19 and 1 in the setting of mild disease.3-8 Two critically ill patients did not receive treatment for their ischemic priapism as they were transitioned to expectant management and/or comfort measures.Most were treated with cavernosal blood aspiration and intracavernosal injections of phenylephrine or ethylephrine. Some patients were managed with prophylactic doses of anticoagulation after the identification of priapism; others were transitioned to therapeutic doses. Two patients were followed postdischarge; one patient reported normal nighttime erections with sexual desire 2 weeks postdischarge, and another patient, who underwent a bilateral T-shunt procedure after unsuccessful phenylephrine injections, reported complete erectile dysfunction at 3 months postdischarge.4,7 There was a potentially confounding variable in 2 cases in which propofol infusions were used for sedation management in the setting of mechanical ventilation.6,8 Propofol has been linked to priapism through its blockade of sympathetic activation resulting in persistent relaxation of cavernosal smooth muscle.9 We present a unique case of COVID-19–associated ischemic priapism as our patient had moderate rather than critical COVID-19.

Case Presentation

A 67-year-old male patient presented to the emergency department for a painful erection of 34-hour duration. The patient had been exposed to COVID-19 roughly 2 months prior. Since the exposure, he had experienced headache, nonproductive cough, sore throat, and decreased appetite with weight loss. His medical history included hypertension, thoracic aortic aneurysm, B-cell type chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), and obstructive sleep apnea. Daily outpatient medications included atenolol 100 mg, hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg, and omeprazole 20 mg. The patient stopped tobacco use about 30 years previously. He reported no alcohol consumption or illicit drug use and had no previous episodes of prolonged erection.

The patient was afebrile, hemodynamically stable, and had an oxygen saturation of 92% on room air. Physical examination revealed clear breath sounds and an erect circumcised penis without any lesions, discoloration, or skin necrosis. Laboratory data were remarkable for the following values: 125,660 cells/μL white blood cells (WBCs), 13.82 × 103/ μL neutrophils, 110.58 × 103/μL lymphocytes, 1.26 × 103/μL monocytes, no blasts, 9.4 gm/dL hemoglobin, 100.3 fl mean corpuscular volume, 417,000 cells/μL platelets, 23,671 ng/mL D-dimer, 29.6 seconds activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), 16.3 seconds prothrombin time, 743 mg/dL fibrinogen, 474 U/L lactate dehydrogenase, and 202.1 mg/dL haptoglobin. A nasopharyngeal reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction test resulted positive for the SARS-CoV-2 virus, and subsequent chest X-ray revealed bilateral, hazy opacities predominantly in a peripheral distribution. Computed tomography (CT) angiogram of the chest did not reveal pulmonary emboli, pneumothorax, effusions, or lobar consolidation. However, it displayed bilateral ground-glass opacities with interstitial consolidation worst in the upper lobes. Corporal aspiration and blood gas analysis revealed a pH of 7.05, P

Differential Diagnosis

The first consideration in the differential diagnosis of priapism is to differentiate between ischemic and nonischemic. Based on the abnormal blood gas results above, this case clearly falls within the ischemic spectrum. Ischemic priapism secondary to CLL-induced hyperleukocytosis was considered. It has been noted that up to 20% of priapism cases in adults are related to hematologic disorders.10 While it is not uncommon to see hyperleukocytosis (total WBC count > 100 × 109/L) in CLL, leukostasis is rare with most reports demonstrating WBC counts > 1000 × 109/L.11 Hematology, vascular surgery, and urology services were consulted and agreed that ischemic priapism was due to microthrombi or pelvic vein thrombosis secondary to COVID-19–associated coagulopathy (CAC) was the most likely etiology.

Treatment

After corporal aspiration, intracorporal phenylephrine was administered. Diluted phenylephrine (100 ug/mL) was injected every 5 to 10 minutes while intermittently aspirating and irrigating multiple sites along the lateral length of the penile shaft. This initial procedure reduced the erection from 100% to 30% rigidity, with repeat blood gas analysis revealing minimal improvement. CT of the abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast revealed no evidence of pelvic thrombi. A second round of phenylephrine injections were administered, resulting in detumescence. The patient was treated with 2 to 3 L/min of oxygen supplementation via nasal cannula, a 5-day course of remdesivir and low-intensity heparin drip. Following the initial low-intensity heparin drip, the patient transitioned to therapeutic enoxaparin and subsequently was discharged on apixaban for a 3-month course. Since discharge, the patient followed up with hematology. He tolerated and completed the anticoagulation regimen without any recurrences of priapism or residual deficits.

Discussion

Recent studies have overwhelmingly analyzed the incidence and presentation of thrombotic complications in critically ill patients with COVID-19. CAC has been postulated to result from endotheliopathy along with immune cell activation and propagation of coagulation. While COVID-19 has been noted to create lung injury through binding angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptors expressed on alveolar pneumocytes, it increasingly has been found to affect endothelial cells throughout the body. Recent postmortem analyses have demonstrated direct viral infection of endothelial cells with consequent diffuse endothelial inflammation, as evidenced by viral inclusions, sequestered immune cells, and endothelial apoptosis.12,13 Manifestations of this endotheliopathy have been delineated through various studies.

An early retrospective study in Wuhan, China, illustrated that 36% of the first 99 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 demonstrated an elevated D-dimer, 6% an elevated aPTT, and 5% an elevated prothrombin time.14 Another retrospective study conducted in Wuhan found a 25% incidence of venous thromboembolic complications in critically ill patients with severe COVID-19.15 In the Netherlands, a study reported the incidence of arterial and venous thrombotic complications to be 31% in 184 critically ill patients with COVID-19, with 81% of these cases involving pulmonary emboli.16

To our knowledge, our patient is the seventh reported case of ischemic priapism occurring in the setting of a COVID-19 infection, and the first to have occurred in its moderate form. Ischemic priapism is often a consequence of penile venous outflow obstruction and resultant stasis of hypoxic blood.7 The prothrombotic state induced by CAC has been proposed to cause the obstruction of small emissary veins in the subtunical space and in turn lead to venous stasis, which propagates the formation of ischemic priapism.8 Furthermore, 4 of the previously reported cases shared laboratory data on their patients, and all demonstrated elevated D-dimer and fibrinogen levels, which strengthens this hypothesis.3,5,7,8 CLL presents a potential confounding variable in this case; however, as we have reviewed earlier, the risk of leukostasis at WBC counts < 1000 × 109/L is very low.11 It is also probable that the patient had some level of immune dysregulation secondary to CLL, leading to his prolonged course and slow clearance of the virus.

Conclusions

Although only a handful of CAC cases leading to ischemic priapism have been reported, the true incidence may be much higher. While our case highlights the importance of considering COVID-19 infection in the differential diagnosis of ischemic priapism, more research is needed to understand incidence and definitively establish a causative relationship.

Priapism is a disorder that occurs when the penis maintains a prolonged erection in the absence of appropriate stimulation. The disorder is typically divided into subgroups based on arterial flow: low flow (ischemic) and high flow (nonischemic). Ischemic priapism is the most common form and results from venous congestion due to obstructed outflow and inability of cavernous smooth muscle to contract, resulting in compartment syndrome, tissue hypoxia, hypercapnia, and acidosis.1 Conditions that result in hypercoagulable states and hyperviscosity are associated with ischemic priapism. COVID-19 is well known to cause an acute respiratory illness and systemic inflammatory response and has been increasingly associated with coagulopathy. Studies have shown that 20% to 55% of patients admitted to the hospital for COVID-19 show objective laboratory evidence of a hypercoagulable state.2

To date, there are 6 reported cases of priapism occurring in the setting of COVID-19 with all cases demonstrating the ischemic subtype. The onset of priapism from the beginning of infectious symptoms ranged from 2 days to more than a month. Five of the cases occurred in patients with critical COVID-19 and 1 in the setting of mild disease.3-8 Two critically ill patients did not receive treatment for their ischemic priapism as they were transitioned to expectant management and/or comfort measures.Most were treated with cavernosal blood aspiration and intracavernosal injections of phenylephrine or ethylephrine. Some patients were managed with prophylactic doses of anticoagulation after the identification of priapism; others were transitioned to therapeutic doses. Two patients were followed postdischarge; one patient reported normal nighttime erections with sexual desire 2 weeks postdischarge, and another patient, who underwent a bilateral T-shunt procedure after unsuccessful phenylephrine injections, reported complete erectile dysfunction at 3 months postdischarge.4,7 There was a potentially confounding variable in 2 cases in which propofol infusions were used for sedation management in the setting of mechanical ventilation.6,8 Propofol has been linked to priapism through its blockade of sympathetic activation resulting in persistent relaxation of cavernosal smooth muscle.9 We present a unique case of COVID-19–associated ischemic priapism as our patient had moderate rather than critical COVID-19.

Case Presentation

A 67-year-old male patient presented to the emergency department for a painful erection of 34-hour duration. The patient had been exposed to COVID-19 roughly 2 months prior. Since the exposure, he had experienced headache, nonproductive cough, sore throat, and decreased appetite with weight loss. His medical history included hypertension, thoracic aortic aneurysm, B-cell type chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), and obstructive sleep apnea. Daily outpatient medications included atenolol 100 mg, hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg, and omeprazole 20 mg. The patient stopped tobacco use about 30 years previously. He reported no alcohol consumption or illicit drug use and had no previous episodes of prolonged erection.

The patient was afebrile, hemodynamically stable, and had an oxygen saturation of 92% on room air. Physical examination revealed clear breath sounds and an erect circumcised penis without any lesions, discoloration, or skin necrosis. Laboratory data were remarkable for the following values: 125,660 cells/μL white blood cells (WBCs), 13.82 × 103/ μL neutrophils, 110.58 × 103/μL lymphocytes, 1.26 × 103/μL monocytes, no blasts, 9.4 gm/dL hemoglobin, 100.3 fl mean corpuscular volume, 417,000 cells/μL platelets, 23,671 ng/mL D-dimer, 29.6 seconds activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), 16.3 seconds prothrombin time, 743 mg/dL fibrinogen, 474 U/L lactate dehydrogenase, and 202.1 mg/dL haptoglobin. A nasopharyngeal reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction test resulted positive for the SARS-CoV-2 virus, and subsequent chest X-ray revealed bilateral, hazy opacities predominantly in a peripheral distribution. Computed tomography (CT) angiogram of the chest did not reveal pulmonary emboli, pneumothorax, effusions, or lobar consolidation. However, it displayed bilateral ground-glass opacities with interstitial consolidation worst in the upper lobes. Corporal aspiration and blood gas analysis revealed a pH of 7.05, P

Differential Diagnosis

The first consideration in the differential diagnosis of priapism is to differentiate between ischemic and nonischemic. Based on the abnormal blood gas results above, this case clearly falls within the ischemic spectrum. Ischemic priapism secondary to CLL-induced hyperleukocytosis was considered. It has been noted that up to 20% of priapism cases in adults are related to hematologic disorders.10 While it is not uncommon to see hyperleukocytosis (total WBC count > 100 × 109/L) in CLL, leukostasis is rare with most reports demonstrating WBC counts > 1000 × 109/L.11 Hematology, vascular surgery, and urology services were consulted and agreed that ischemic priapism was due to microthrombi or pelvic vein thrombosis secondary to COVID-19–associated coagulopathy (CAC) was the most likely etiology.

Treatment