User login

Papular Rash in a New Tattoo

The Diagnosis: Allergic Contact Dermatitis

This patient’s history and physical examination were most consistent with a diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis, likely from an additive or diluent solution within the tattoo ink. Her history of a similar transient reaction following tattooing 2 weeks prior lent credence to an allergic etiology. She was treated with triamcinolone cream 0.1% as well as mupirocin ointment 2% for use as both an emollient and for precautionary antimicrobial coverage. The rash resolved within 2 days, and she reported no recurrence at a 6-month follow-up. The cosmesis of her tattoo was preserved.

Acute cellulitis may follow tattooing, but the absence of warmth, pain, or purulence on physical examination made this diagnosis less likely in this patient. Sarcoidosis or other granulomatous reactions may present as papules or nodules arising within a tattoo but would be unlikely to occur the next day. Nontuberculous mycobacterial infection likewise tends to present subacutely or chronically rather than immediately following tattoo application.

Tattooing has existed for millennia and is becoming increasingly popular.1,2 The tattooing process entails introduction of insoluble pigment compounds into the dermis to create a permanent design on the skin, which most often is accomplished via needling. As a result, tattooed skin is susceptible to both acute and chronic complications. Acute complications prominently include allergic hypersensitivity reactions and pyogenic bacterial infections. Chronic granulomatous, inflammatory, or infectious complications also can occur.

Allergic eczematous reactions to tattooing are well documented in the literature and are thought to originate from sensitization to pigment molecules themselves or alternatively to ink diluent compounds.3 Although reactions to ink diluent chemicals typically are self-resolving, allergic reactions to pigment can persist beyond the acute phase, as these insoluble compounds intentionally remain embedded in the dermis. The mechanism of action may involve haptenization of pigment molecules that then induces allergic hypersensitivity.3,4 Black pigment typically is derived from carbon black (ie, amorphous combustion byproducts such as soot). Colored inks historically consisted of inorganic heavy metal–containing salts prior to the modern introduction of synthetic azo and polycyclic dyes. These newer colored pigments appear to be less allergenic than their metallic predecessors; however, epidemiologic studies have suggested that allergic reactions still occur more commonly in colored tattoos than black tattoos.1 Overall, these reactions may occur in as many as one-third of individuals who receive tattoos.2,4

As with any process that disrupts skin integrity, tattooing carries a risk for transmitting various infectious pathogens. Microbes may originate from adjacent skin, contaminated needles, ink bottles, or nonsterile ink diluents. Although tattoo parlors and artists may undergo licensing to demonstrate adherence to hygienic standards, regulations vary between states and do not include testing of ink or ink additives to ensure sterility.4,5 Staphylococci and streptococci commonly are implicated in acute pyogenic skin infections following tattooing.5,6 Nontuberculous mycobacteria increasingly are being recognized as causative organisms for granulomatous lesions developing subacutely or even months after receiving a new tattoo.5,7 Local and systemic viral infections also may be transmitted during tattooing; cases of tattoo-transmitted viral warts, molluscum contagiosum, and hepatitis B and C viruses all have been observed.5,6,8 Herpes simplex virus transmission (colloquially termed herpes compunctorum) and HIV transmission through tattooing also are hypothesized to be possible, though there is a paucity of known cases for each.8,9

Chronic inflammatory, granulomatous, or neoplastic lesions may arise within tattooed skin months or years after tattooing. Foreign body granulomas, sarcoidosis, pseudolymphoma, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, and keratoacanthoma are some representative entities.3,5 Cases of cancerous lesions in tattooed skin have been documented, but their incidence appears similar to nontattooed skin.3 These broad categories of lesions are clinically diverse but may be difficult to definitively diagnose on examination alone; therefore, a biopsy should be strongly considered for any subacute to chronic skin lesions within a tattoo. Patients may be hesitant to disrupt the cosmesis of a tattoo but should be counseled on the attendant risks and benefits to make an informed decision regarding biopsy.

- Wenzel SM, Rittmann I, Landthaler M, et al. Adverse reactions after tattooing: review of the literature and comparison to results of a survey. Dermatology. 2013;226:138-147.

- Liszewski W, Kream E, Helland S, et al. The demographics and rates of tattoo complications, regret, and unsafe tattooing practices: a crosssectional study. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:1283-1289.

- Islam PS, Chang C, Selmi C, et al. Medical complications of tattoos: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;50:273-286.

- Serup J, Carlsen KH, Sepehri M. Tattoo complaints and complications: diagnosis and clinical spectrum. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2015;48:48-60.

- Simunovic C, Shinohara MM. Complications of decorative tattoos: recognition and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:525-536.

- Kazandjieva J, Tsankov N. Tattoos: dermatological complications. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:375-382.

- Sergeant A, Conaglen P, Laurenson IF, et al. Mycobacterium chelonae infection: a complication of tattooing. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:140-142.

- Cohen PR. Tattoo-associated viral infections: a review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2021;14:1529-1540.

- Doll DC. Tattooing in prison and HIV infection. Lancet. 1988;1:66-67.

The Diagnosis: Allergic Contact Dermatitis

This patient’s history and physical examination were most consistent with a diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis, likely from an additive or diluent solution within the tattoo ink. Her history of a similar transient reaction following tattooing 2 weeks prior lent credence to an allergic etiology. She was treated with triamcinolone cream 0.1% as well as mupirocin ointment 2% for use as both an emollient and for precautionary antimicrobial coverage. The rash resolved within 2 days, and she reported no recurrence at a 6-month follow-up. The cosmesis of her tattoo was preserved.

Acute cellulitis may follow tattooing, but the absence of warmth, pain, or purulence on physical examination made this diagnosis less likely in this patient. Sarcoidosis or other granulomatous reactions may present as papules or nodules arising within a tattoo but would be unlikely to occur the next day. Nontuberculous mycobacterial infection likewise tends to present subacutely or chronically rather than immediately following tattoo application.

Tattooing has existed for millennia and is becoming increasingly popular.1,2 The tattooing process entails introduction of insoluble pigment compounds into the dermis to create a permanent design on the skin, which most often is accomplished via needling. As a result, tattooed skin is susceptible to both acute and chronic complications. Acute complications prominently include allergic hypersensitivity reactions and pyogenic bacterial infections. Chronic granulomatous, inflammatory, or infectious complications also can occur.

Allergic eczematous reactions to tattooing are well documented in the literature and are thought to originate from sensitization to pigment molecules themselves or alternatively to ink diluent compounds.3 Although reactions to ink diluent chemicals typically are self-resolving, allergic reactions to pigment can persist beyond the acute phase, as these insoluble compounds intentionally remain embedded in the dermis. The mechanism of action may involve haptenization of pigment molecules that then induces allergic hypersensitivity.3,4 Black pigment typically is derived from carbon black (ie, amorphous combustion byproducts such as soot). Colored inks historically consisted of inorganic heavy metal–containing salts prior to the modern introduction of synthetic azo and polycyclic dyes. These newer colored pigments appear to be less allergenic than their metallic predecessors; however, epidemiologic studies have suggested that allergic reactions still occur more commonly in colored tattoos than black tattoos.1 Overall, these reactions may occur in as many as one-third of individuals who receive tattoos.2,4

As with any process that disrupts skin integrity, tattooing carries a risk for transmitting various infectious pathogens. Microbes may originate from adjacent skin, contaminated needles, ink bottles, or nonsterile ink diluents. Although tattoo parlors and artists may undergo licensing to demonstrate adherence to hygienic standards, regulations vary between states and do not include testing of ink or ink additives to ensure sterility.4,5 Staphylococci and streptococci commonly are implicated in acute pyogenic skin infections following tattooing.5,6 Nontuberculous mycobacteria increasingly are being recognized as causative organisms for granulomatous lesions developing subacutely or even months after receiving a new tattoo.5,7 Local and systemic viral infections also may be transmitted during tattooing; cases of tattoo-transmitted viral warts, molluscum contagiosum, and hepatitis B and C viruses all have been observed.5,6,8 Herpes simplex virus transmission (colloquially termed herpes compunctorum) and HIV transmission through tattooing also are hypothesized to be possible, though there is a paucity of known cases for each.8,9

Chronic inflammatory, granulomatous, or neoplastic lesions may arise within tattooed skin months or years after tattooing. Foreign body granulomas, sarcoidosis, pseudolymphoma, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, and keratoacanthoma are some representative entities.3,5 Cases of cancerous lesions in tattooed skin have been documented, but their incidence appears similar to nontattooed skin.3 These broad categories of lesions are clinically diverse but may be difficult to definitively diagnose on examination alone; therefore, a biopsy should be strongly considered for any subacute to chronic skin lesions within a tattoo. Patients may be hesitant to disrupt the cosmesis of a tattoo but should be counseled on the attendant risks and benefits to make an informed decision regarding biopsy.

The Diagnosis: Allergic Contact Dermatitis

This patient’s history and physical examination were most consistent with a diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis, likely from an additive or diluent solution within the tattoo ink. Her history of a similar transient reaction following tattooing 2 weeks prior lent credence to an allergic etiology. She was treated with triamcinolone cream 0.1% as well as mupirocin ointment 2% for use as both an emollient and for precautionary antimicrobial coverage. The rash resolved within 2 days, and she reported no recurrence at a 6-month follow-up. The cosmesis of her tattoo was preserved.

Acute cellulitis may follow tattooing, but the absence of warmth, pain, or purulence on physical examination made this diagnosis less likely in this patient. Sarcoidosis or other granulomatous reactions may present as papules or nodules arising within a tattoo but would be unlikely to occur the next day. Nontuberculous mycobacterial infection likewise tends to present subacutely or chronically rather than immediately following tattoo application.

Tattooing has existed for millennia and is becoming increasingly popular.1,2 The tattooing process entails introduction of insoluble pigment compounds into the dermis to create a permanent design on the skin, which most often is accomplished via needling. As a result, tattooed skin is susceptible to both acute and chronic complications. Acute complications prominently include allergic hypersensitivity reactions and pyogenic bacterial infections. Chronic granulomatous, inflammatory, or infectious complications also can occur.

Allergic eczematous reactions to tattooing are well documented in the literature and are thought to originate from sensitization to pigment molecules themselves or alternatively to ink diluent compounds.3 Although reactions to ink diluent chemicals typically are self-resolving, allergic reactions to pigment can persist beyond the acute phase, as these insoluble compounds intentionally remain embedded in the dermis. The mechanism of action may involve haptenization of pigment molecules that then induces allergic hypersensitivity.3,4 Black pigment typically is derived from carbon black (ie, amorphous combustion byproducts such as soot). Colored inks historically consisted of inorganic heavy metal–containing salts prior to the modern introduction of synthetic azo and polycyclic dyes. These newer colored pigments appear to be less allergenic than their metallic predecessors; however, epidemiologic studies have suggested that allergic reactions still occur more commonly in colored tattoos than black tattoos.1 Overall, these reactions may occur in as many as one-third of individuals who receive tattoos.2,4

As with any process that disrupts skin integrity, tattooing carries a risk for transmitting various infectious pathogens. Microbes may originate from adjacent skin, contaminated needles, ink bottles, or nonsterile ink diluents. Although tattoo parlors and artists may undergo licensing to demonstrate adherence to hygienic standards, regulations vary between states and do not include testing of ink or ink additives to ensure sterility.4,5 Staphylococci and streptococci commonly are implicated in acute pyogenic skin infections following tattooing.5,6 Nontuberculous mycobacteria increasingly are being recognized as causative organisms for granulomatous lesions developing subacutely or even months after receiving a new tattoo.5,7 Local and systemic viral infections also may be transmitted during tattooing; cases of tattoo-transmitted viral warts, molluscum contagiosum, and hepatitis B and C viruses all have been observed.5,6,8 Herpes simplex virus transmission (colloquially termed herpes compunctorum) and HIV transmission through tattooing also are hypothesized to be possible, though there is a paucity of known cases for each.8,9

Chronic inflammatory, granulomatous, or neoplastic lesions may arise within tattooed skin months or years after tattooing. Foreign body granulomas, sarcoidosis, pseudolymphoma, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, and keratoacanthoma are some representative entities.3,5 Cases of cancerous lesions in tattooed skin have been documented, but their incidence appears similar to nontattooed skin.3 These broad categories of lesions are clinically diverse but may be difficult to definitively diagnose on examination alone; therefore, a biopsy should be strongly considered for any subacute to chronic skin lesions within a tattoo. Patients may be hesitant to disrupt the cosmesis of a tattoo but should be counseled on the attendant risks and benefits to make an informed decision regarding biopsy.

- Wenzel SM, Rittmann I, Landthaler M, et al. Adverse reactions after tattooing: review of the literature and comparison to results of a survey. Dermatology. 2013;226:138-147.

- Liszewski W, Kream E, Helland S, et al. The demographics and rates of tattoo complications, regret, and unsafe tattooing practices: a crosssectional study. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:1283-1289.

- Islam PS, Chang C, Selmi C, et al. Medical complications of tattoos: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;50:273-286.

- Serup J, Carlsen KH, Sepehri M. Tattoo complaints and complications: diagnosis and clinical spectrum. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2015;48:48-60.

- Simunovic C, Shinohara MM. Complications of decorative tattoos: recognition and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:525-536.

- Kazandjieva J, Tsankov N. Tattoos: dermatological complications. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:375-382.

- Sergeant A, Conaglen P, Laurenson IF, et al. Mycobacterium chelonae infection: a complication of tattooing. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:140-142.

- Cohen PR. Tattoo-associated viral infections: a review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2021;14:1529-1540.

- Doll DC. Tattooing in prison and HIV infection. Lancet. 1988;1:66-67.

- Wenzel SM, Rittmann I, Landthaler M, et al. Adverse reactions after tattooing: review of the literature and comparison to results of a survey. Dermatology. 2013;226:138-147.

- Liszewski W, Kream E, Helland S, et al. The demographics and rates of tattoo complications, regret, and unsafe tattooing practices: a crosssectional study. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:1283-1289.

- Islam PS, Chang C, Selmi C, et al. Medical complications of tattoos: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;50:273-286.

- Serup J, Carlsen KH, Sepehri M. Tattoo complaints and complications: diagnosis and clinical spectrum. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2015;48:48-60.

- Simunovic C, Shinohara MM. Complications of decorative tattoos: recognition and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:525-536.

- Kazandjieva J, Tsankov N. Tattoos: dermatological complications. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:375-382.

- Sergeant A, Conaglen P, Laurenson IF, et al. Mycobacterium chelonae infection: a complication of tattooing. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:140-142.

- Cohen PR. Tattoo-associated viral infections: a review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2021;14:1529-1540.

- Doll DC. Tattooing in prison and HIV infection. Lancet. 1988;1:66-67.

A healthy 21-year-old woman presented with a pruritic papulovesicular rash on the left arm of 2 days’ duration. The day before rash onset, she received a black ink tattoo on the left arm to complete the second half of a monochromatic sleevestyle design. She previously underwent initial tattooing of the left arm by the same artist 2 weeks prior and experienced a similar but less extensive rash that self-resolved after 1 week. She had 8 older tattoos on various other body parts and denied any reactions. Physical examination showed numerous scattered papules and papulovesicles confined to areas of newly tattooed skin throughout the left arm. In the larger swaths of the tattoo, the papules coalesced into well-defined plaques. There was a discrete rim of faint erythema bordering the newly tattooed skin. No erosions, ulcerations, or purulent areas were observed, and there was no tenderness or excess warmth of the affected skin. Adjacent previously tattooed areas of the left arm were unaffected.

NSCLC- Clinical Presentation

Complaints of cough and fatigue

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) large cell carcinoma.

Lung cancer is the most common cancer worldwide and has the highest mortality rate of all cancers. It comprises two major subtypes: NSCLC and small cell lung cancer (SCLC). Histologically, NSCLC is further classified as adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma with or without neuroendocrine features. Large cell carcinoma accounts for 9% of all cases and is frequently associated with poor prognosis. Most patients with NSCLC large cell carcinoma are older than 60 years and are diagnosed with stage III or IV disease. NSCLC large cell carcinoma appears to occur more commonly in men than in women and in patients with a history of smoking. It often presents as a large mass with central necrosis.

NSCLC is often asymptomatic in its early stages. The most frequently reported signs and symptoms of lung cancer include:

• Cough

• Chest pain

• Shortness of breath

• Coughing up blood

• Wheezing

• Hoarseness

• Recurring infections, such as bronchitis and pneumonia

• Weight loss and loss of appetite

• Fatigue

Signs and symptoms of metastatic disease may include bone pain, spinal cord impingement, or neurologic problems, such as headache, weakness or numbness of limbs, dizziness, and seizures.

All patients with NSCLC require a complete staging workup to evaluate the extent of disease because stage plays a central role in treatment selection. After physical examination and a complete blood count, a chest radiograph is often the first test performed. Chest radiographs may show a pulmonary nodule, mass, or infiltrate; mediastinal widening; atelectasis; hilar enlargement; and/or pleural effusion.

Various methods are available to confirm the diagnosis, and the method chosen may be determined at least in part by lesion location. These include:

• Bronchoscopy

• Sputum cytology

• Mediastinoscopy

• Thoracentesis

• Thoracoscopy

• Transthoracic needle biopsy (CT- or fluoroscopy-guided)

According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), the diagnosis of NSCLC large cell carcinoma requires a thoroughly sampled resected tumor with immunohistochemical stains that exclude adenocarcinoma (TTF-1, napsin A) and squamous cell (p40, p63) carcinoma. Nonresected specimens or cytology specimens are insufficient for its diagnosis. NSCLC large cell carcinoma lacks the cytologic, architectural, and histochemical features of small cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, or squamous cell carcinoma and is undifferentiated.

When the NSCLC histologic subtype is determined, molecular testing should be performed as part of broad molecular profiling with the goal of identifying rare driver mutations for which effective drugs may already be available or to appropriately counsel patients regarding the availability of clinical trials. NSCLC diagnostic standards include the detection of EGFR, BRAF, and MET mutations, ERBB2 (HER2) expression, and the analysis of ALK, ROS1, RET, and NTRK translocations. In addition, analysis of programmed death-ligand 1 expression is necessary to identify patients who may benefit from the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Surgery combined with chemotherapy has been shown to improve the prognosis of patients with NSCLC large cell carcinoma. Preferred regimens in various lines of treatment and according to molecular characteristics can be found in the NCCN guidelines.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) large cell carcinoma.

Lung cancer is the most common cancer worldwide and has the highest mortality rate of all cancers. It comprises two major subtypes: NSCLC and small cell lung cancer (SCLC). Histologically, NSCLC is further classified as adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma with or without neuroendocrine features. Large cell carcinoma accounts for 9% of all cases and is frequently associated with poor prognosis. Most patients with NSCLC large cell carcinoma are older than 60 years and are diagnosed with stage III or IV disease. NSCLC large cell carcinoma appears to occur more commonly in men than in women and in patients with a history of smoking. It often presents as a large mass with central necrosis.

NSCLC is often asymptomatic in its early stages. The most frequently reported signs and symptoms of lung cancer include:

• Cough

• Chest pain

• Shortness of breath

• Coughing up blood

• Wheezing

• Hoarseness

• Recurring infections, such as bronchitis and pneumonia

• Weight loss and loss of appetite

• Fatigue

Signs and symptoms of metastatic disease may include bone pain, spinal cord impingement, or neurologic problems, such as headache, weakness or numbness of limbs, dizziness, and seizures.

All patients with NSCLC require a complete staging workup to evaluate the extent of disease because stage plays a central role in treatment selection. After physical examination and a complete blood count, a chest radiograph is often the first test performed. Chest radiographs may show a pulmonary nodule, mass, or infiltrate; mediastinal widening; atelectasis; hilar enlargement; and/or pleural effusion.

Various methods are available to confirm the diagnosis, and the method chosen may be determined at least in part by lesion location. These include:

• Bronchoscopy

• Sputum cytology

• Mediastinoscopy

• Thoracentesis

• Thoracoscopy

• Transthoracic needle biopsy (CT- or fluoroscopy-guided)

According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), the diagnosis of NSCLC large cell carcinoma requires a thoroughly sampled resected tumor with immunohistochemical stains that exclude adenocarcinoma (TTF-1, napsin A) and squamous cell (p40, p63) carcinoma. Nonresected specimens or cytology specimens are insufficient for its diagnosis. NSCLC large cell carcinoma lacks the cytologic, architectural, and histochemical features of small cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, or squamous cell carcinoma and is undifferentiated.

When the NSCLC histologic subtype is determined, molecular testing should be performed as part of broad molecular profiling with the goal of identifying rare driver mutations for which effective drugs may already be available or to appropriately counsel patients regarding the availability of clinical trials. NSCLC diagnostic standards include the detection of EGFR, BRAF, and MET mutations, ERBB2 (HER2) expression, and the analysis of ALK, ROS1, RET, and NTRK translocations. In addition, analysis of programmed death-ligand 1 expression is necessary to identify patients who may benefit from the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Surgery combined with chemotherapy has been shown to improve the prognosis of patients with NSCLC large cell carcinoma. Preferred regimens in various lines of treatment and according to molecular characteristics can be found in the NCCN guidelines.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) large cell carcinoma.

Lung cancer is the most common cancer worldwide and has the highest mortality rate of all cancers. It comprises two major subtypes: NSCLC and small cell lung cancer (SCLC). Histologically, NSCLC is further classified as adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma with or without neuroendocrine features. Large cell carcinoma accounts for 9% of all cases and is frequently associated with poor prognosis. Most patients with NSCLC large cell carcinoma are older than 60 years and are diagnosed with stage III or IV disease. NSCLC large cell carcinoma appears to occur more commonly in men than in women and in patients with a history of smoking. It often presents as a large mass with central necrosis.

NSCLC is often asymptomatic in its early stages. The most frequently reported signs and symptoms of lung cancer include:

• Cough

• Chest pain

• Shortness of breath

• Coughing up blood

• Wheezing

• Hoarseness

• Recurring infections, such as bronchitis and pneumonia

• Weight loss and loss of appetite

• Fatigue

Signs and symptoms of metastatic disease may include bone pain, spinal cord impingement, or neurologic problems, such as headache, weakness or numbness of limbs, dizziness, and seizures.

All patients with NSCLC require a complete staging workup to evaluate the extent of disease because stage plays a central role in treatment selection. After physical examination and a complete blood count, a chest radiograph is often the first test performed. Chest radiographs may show a pulmonary nodule, mass, or infiltrate; mediastinal widening; atelectasis; hilar enlargement; and/or pleural effusion.

Various methods are available to confirm the diagnosis, and the method chosen may be determined at least in part by lesion location. These include:

• Bronchoscopy

• Sputum cytology

• Mediastinoscopy

• Thoracentesis

• Thoracoscopy

• Transthoracic needle biopsy (CT- or fluoroscopy-guided)

According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), the diagnosis of NSCLC large cell carcinoma requires a thoroughly sampled resected tumor with immunohistochemical stains that exclude adenocarcinoma (TTF-1, napsin A) and squamous cell (p40, p63) carcinoma. Nonresected specimens or cytology specimens are insufficient for its diagnosis. NSCLC large cell carcinoma lacks the cytologic, architectural, and histochemical features of small cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, or squamous cell carcinoma and is undifferentiated.

When the NSCLC histologic subtype is determined, molecular testing should be performed as part of broad molecular profiling with the goal of identifying rare driver mutations for which effective drugs may already be available or to appropriately counsel patients regarding the availability of clinical trials. NSCLC diagnostic standards include the detection of EGFR, BRAF, and MET mutations, ERBB2 (HER2) expression, and the analysis of ALK, ROS1, RET, and NTRK translocations. In addition, analysis of programmed death-ligand 1 expression is necessary to identify patients who may benefit from the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Surgery combined with chemotherapy has been shown to improve the prognosis of patients with NSCLC large cell carcinoma. Preferred regimens in various lines of treatment and according to molecular characteristics can be found in the NCCN guidelines.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

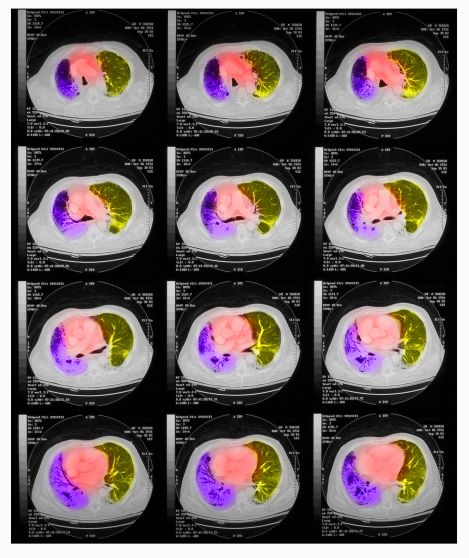

A 67-year-old White man presents to the emergency department with reports of cough, dyspnea, fatigue, hoarseness, and unintentional weight loss. The patient states that his symptoms began approximately 3 weeks earlier and have progressively worsened. In the past year, he has been treated twice for respiratory infections (bronchitis and pneumonia approximately 6 and 9 months before the current presentation, respectively). He has a 45-year history of smoking (45 pack-years). The patient's vital signs include temperature of 100.4 °F, blood pressure of 142/80 mm Hg, and pulse ox of 95%. Physical examination reveals rales in the left side of the chest and decreased breath sounds in bilateral bases of the lungs. The patient appears cachexic. He is 6 ft 2 in and weighs 163 lb.

A chest radiograph reveals a large mass in the left lung field. A subsequent CT of the chest reveals encasement of the left upper and lower lobe bronchus with extensive mediastinal lymphadenopathy and areas of necrosis. Immunohistochemical analysis of the resected tumor reveals a malignant, poorly differentiated epithelial neoplasm composed of large, atypical cells. There is no morphologic or immunohistochemical evidence of glandular, squamous, or neuroendocrine differentiation.

Fat Necrosis of the Breast Mimicking Breast Cancer in a Male Patient Following Wax Hair Removal

To the Editor:

Fat necrosis of the breast is a benign inflammatory disease of adipose tissue commonly observed after trauma in the female breast during the perimenopausal period.1 Fat necrosis of the male breast is rare, first described by Silverstone2 in 1949; the condition usually presents with unilateral, painful or asymptomatic, firm nodules, which in rare cases are observed as skin retraction and thickening, ecchymosis, erythematous plaque–like cellulitis, local depression, and/or discoloration of the breast skin.3-5

Diagnosis of fat necrosis of the male breast may need to be confirmed via biopsy in conjunction with clinical and radiologic findings because the condition can mimic breast cancer.1 We report a case of bilateral fat necrosis of the breast mimicking breast cancer following wax hair removal.

A 42-year-old man presented to our outpatient dermatology clinic for evaluation of redness, swelling, and hardness of the skin of both breasts of 3 weeks’ duration. The patient had a history of wax hair removal of the entire anterior aspect of the body. He reported an erythematous, edematous, warm plaque that developed on the breasts 2 days after waxing. The plaque did not respond to antibiotics. The swelling and induration progressed over the 2 weeks after the patient was waxed. The patient had no family history of breast cancer. He had a standing diagnosis of gynecomastia. He denied any history of fat or filler injection in the affected area.

Dermatologic examination revealed erythematous, edematous, indurated, asymptomatic plaques with a peau d’orange appearance on the bilateral pectoral and presternal region. Minimal retraction of the right areola was noted (Figure 1). The bilateral axillary lymph nodes were palpable.

Laboratory results including erythrocyte sedimentation rate (108 mm/h [reference range, 2–20 mm/h]), C-reactive protein (9.2 mg/dL [reference range, >0.5 mg/dL]), and ferritin levels (645

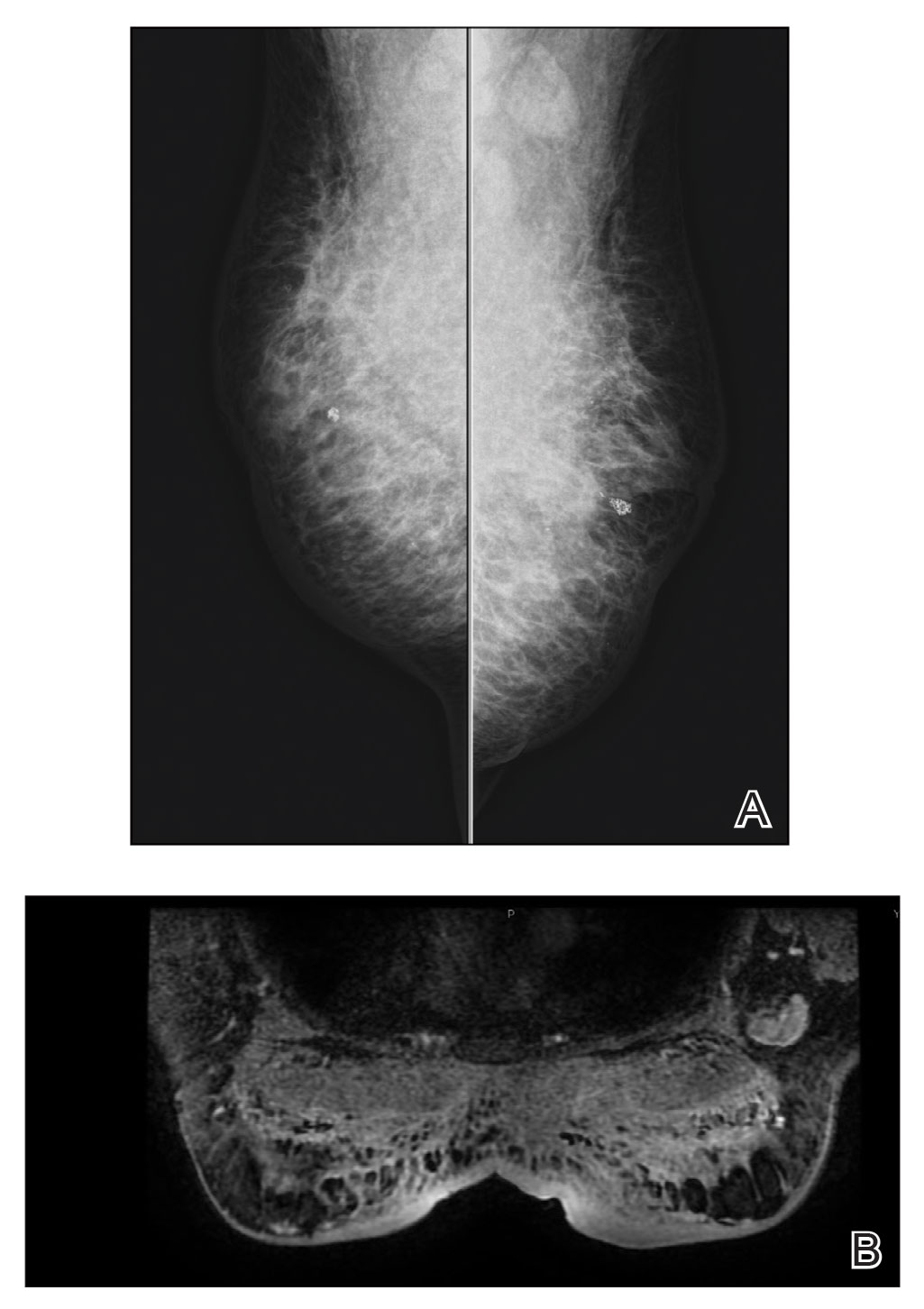

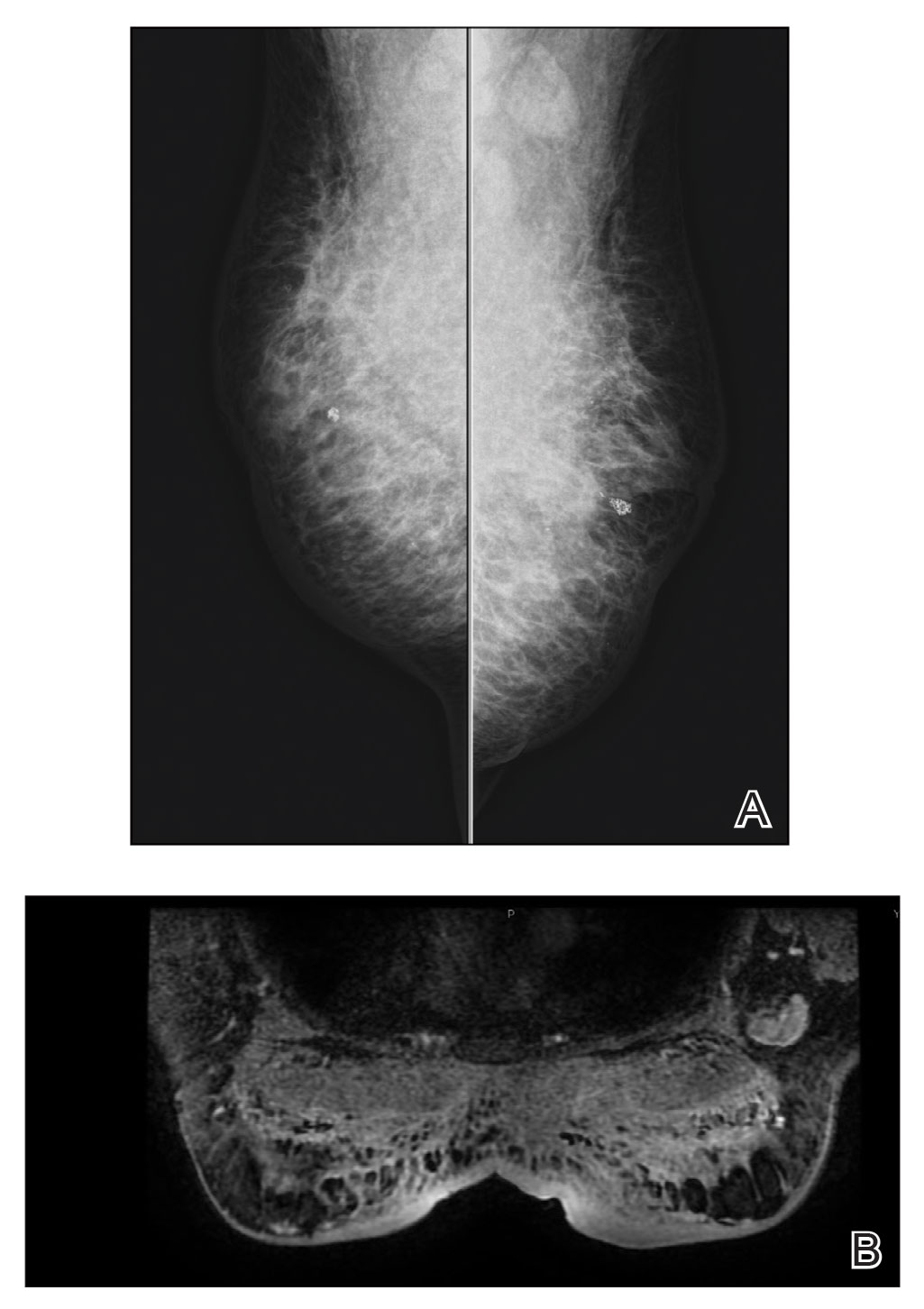

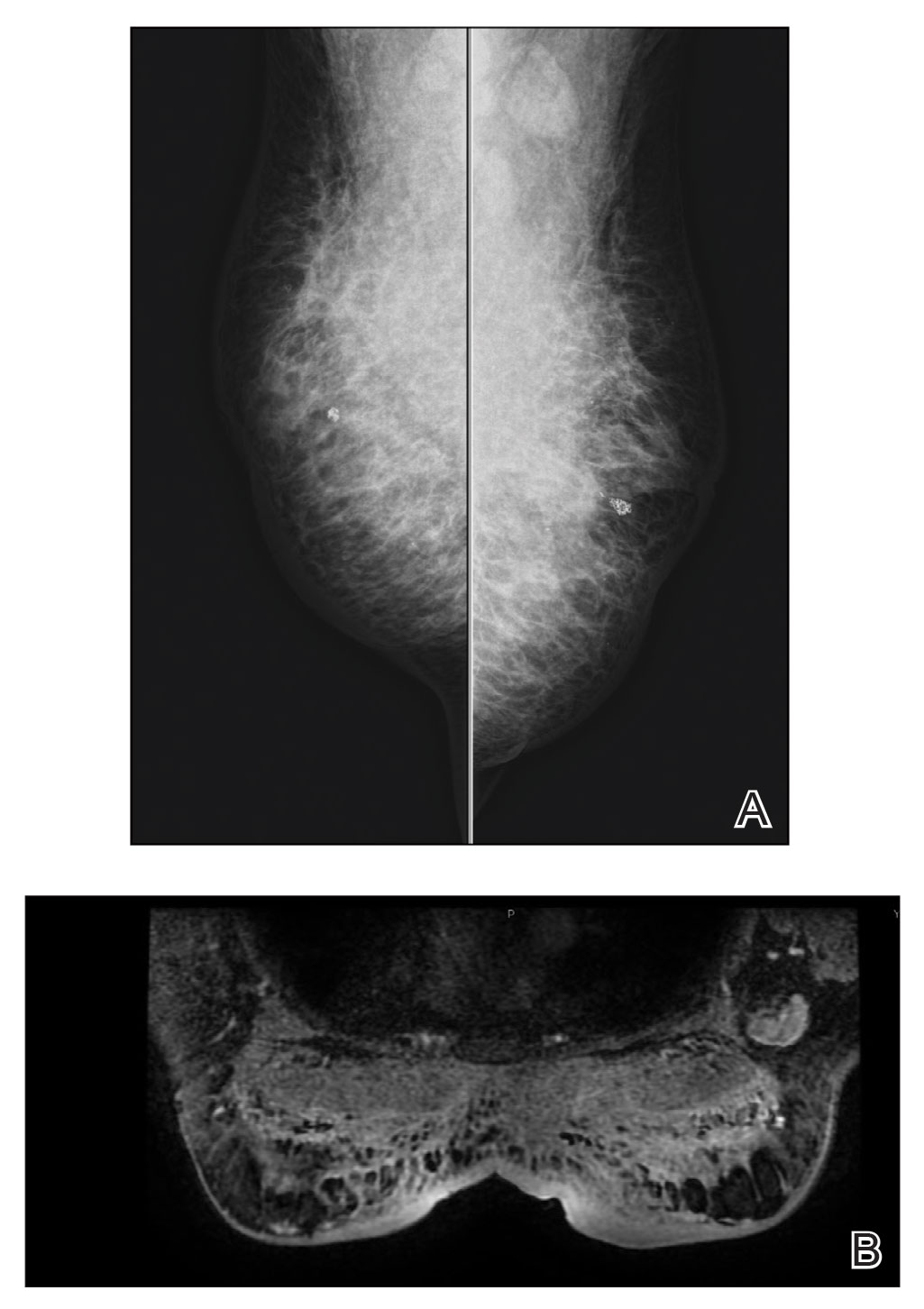

Mammography of both breasts revealed a Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) score of 4 with a suspicious abnormality (ie, diffuse edema of the breast, multiple calcifications in a nonspecific pattern, oil cysts with calcifications, and bilateral axillary lymphadenopathy with a diameter of 2.5 cm and a thick and irregular cortex)(Figure 2A). Ultrasonography of both breasts revealed an inflammatory breast. Magnetic resonance imaging showed similar findings with diffuse edema and a heterogeneous appearance. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging showed diffuse contrast enhancement in both breasts extending to the pectoral muscles and axillary regions, consistent with inflammatory changes (Figure 2B).

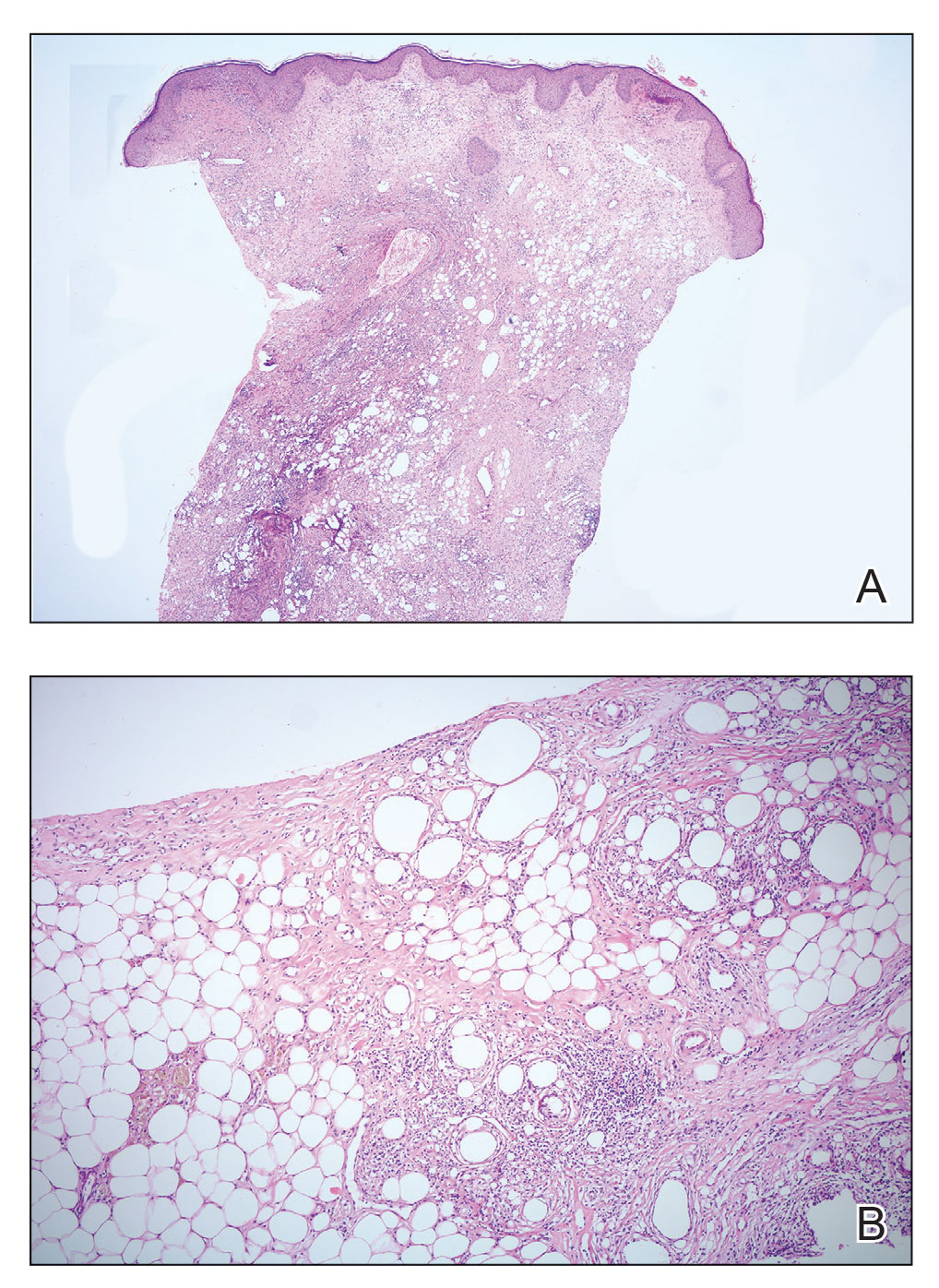

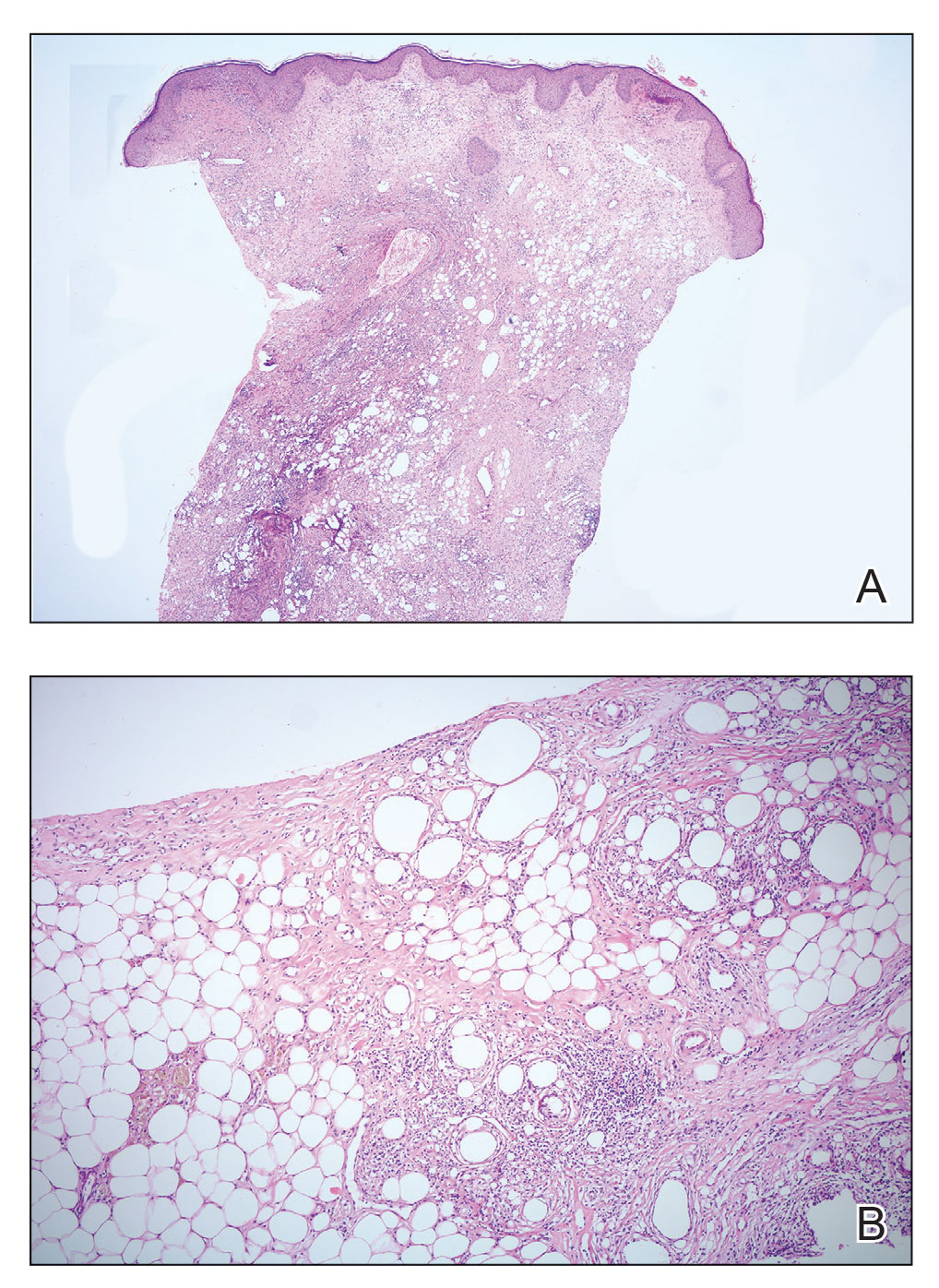

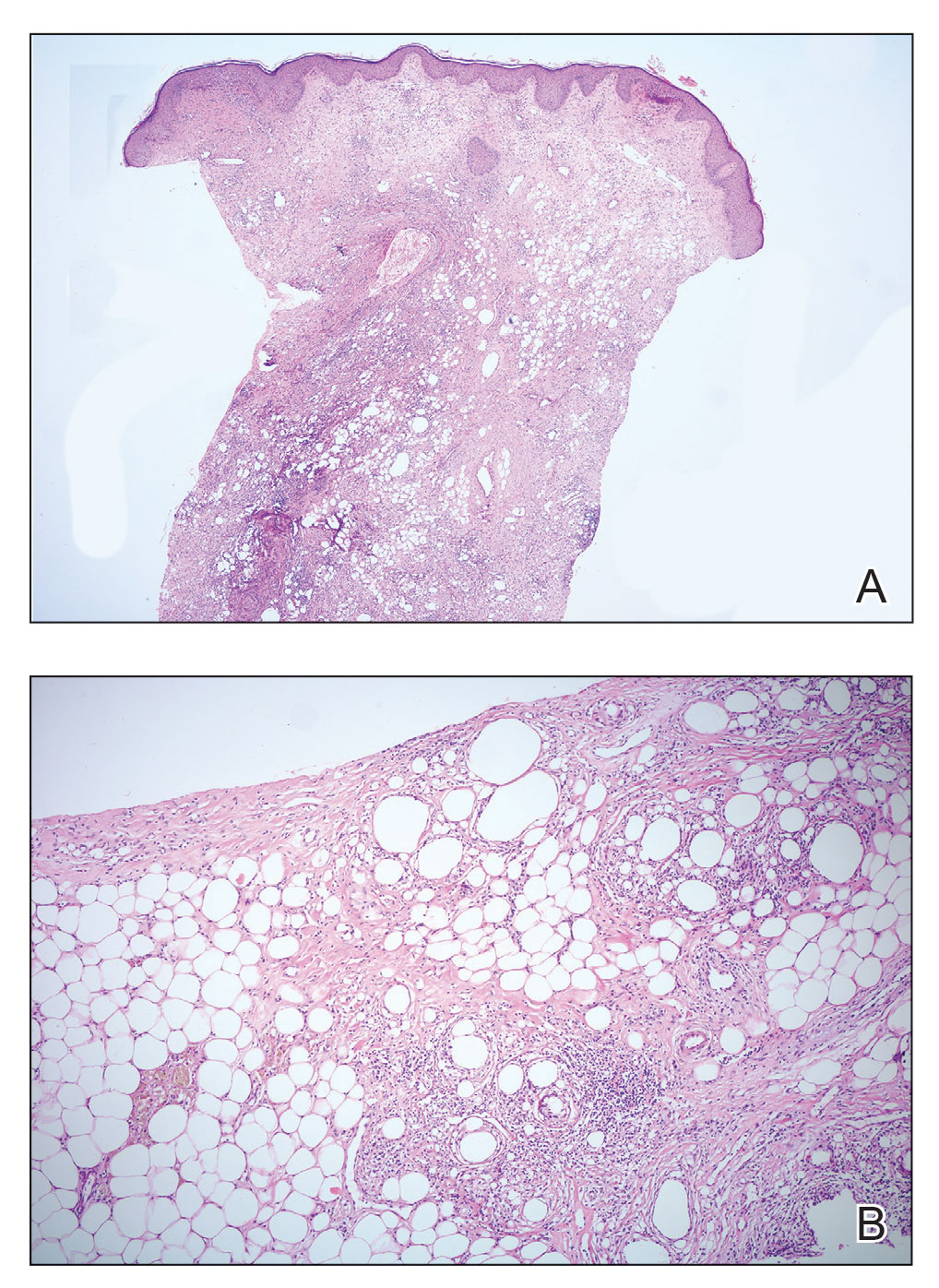

Because of difficulty differentiating inflammation and an infiltrating tumor, histopathologic examination was recommended by radiology. Results from a 5-mm punch biopsy from the right breast yielded the following differential diagnoses: cellulitis, panniculitis, inflammatory breast cancer, subcutaneous fat necrosis, and paraffinoma. Histopathologic examination of the skin revealed a normal epidermis and a dense inflammatory cell infiltrate comprising lymphocytes and monocytes in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Marked fibrosis also was noted in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Lipophagic fat necrosis accompanied by a variable inflammatory cell infiltrate consisted of histiocytes and neutrophils (Figure 3A). Pankeratin immunostaining was negative. Fat necrosis was present in a biopsy specimen obtained from the right breast; no signs of malignancy were present (Figure 3B). Fine-needle aspiration of the axillary lymph nodes was benign. Given these histopathologic findings, malignancy was excluded from the differential diagnosis. Paraffinoma also was ruled out because the patient insistently denied any history of fat or filler injection.

Based on the clinical, histopathologic, and radiologic findings, as well as the history of minor trauma due to wax hair removal, a diagnosis of fat necrosis of the breast was made. Intervention was not recommended by the plastic surgeons who subsequently evaluated the patient, because the additional trauma may aggravate the lesion. He was treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

At 6-month follow-up, there was marked reduction in the erythema and edema but no notable improvement of the induration. A potent topical steroid was added to the treatment, but only slight regression of the induration was observed.

The normal male breast is comprised of fat and a few secretory ducts.6 Gynecomastia and breast cancer are the 2 most common conditions of the male breast; fat necrosis of the male breast is rare. In a study of 236 male patients with breast disease, only 5 had fat necrosis.7

Fat necrosis of the breast can be observed with various clinical and radiological presentations. Subcutaneous nodules, skin retraction and thickening, local skin depression, and ecchymosis are the more common presentations of fat necrosis.3-5 In our case, the first symptoms of disease were similar to those seen in cellulitis. The presentation of fat necrosis–like cellulitis has been described only rarely in the medical literature. Haikin et al5 reported a case of fat necrosis of the leg in a child that presented with cellulitis followed by induration, which did not respond to antibiotics, as was the case with our patient.5

Blunt trauma, breast reduction surgery, and breast augmentation surgery can cause fat necrosis of the breast1,4; in some cases, the cause cannot be determined.8 The only pertinent history in our patient was wax hair removal. Fat necrosis was an unexpected complication, but hair removal can be considered minor trauma; however, this is not commonly reported in the literature following hair removal with wax. In a study that reviewed diseases of the male breast, the investigators observed that all male patients with fat necrosis had pseudogynecomastia (adipomastia).7 Although our patient’s entire anterior trunk was epilated, only the breast was affected. This situation might be explained by underlying gynecomastia because fat necrosis is common in areas of the body where subcutaneous fat tissue is dense.

Fat necrosis of the breast can be mistaken—both clinically and radiologically—for malignancy, such as in our case. Diagnosis of fat necrosis of the breast should be a diagnosis of exclusion; therefore, histopathologic confirmation of the lesion is imperative.9

In conclusion, fat necrosis of the male breast is rare. The condition can present as cellulitis. Hair removal with wax might be a cause of fat necrosis. Because breast cancer and fat necrosis can exhibit clinical and radiologic similarities, the diagnosis of fat necrosis should be confirmed by histopathologic analysis in conjunction with clinical and radiologic findings.

- Tan PH, Lai LM, Carrington EV, et al. Fat necrosis of the breast—a review. Breast. 2006;15:313-318. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2005.07.003

- Silverstone M. Fat necrosis of the breast with report of a case in a male. Br J Surg. 1949;37:49-52. doi:10.1002/bjs.18003714508

- Akyol M, Kayali A, Yildirim N. Traumatic fat necrosis of male breast. Clin Imaging. 2013;37:954-956. doi:10.1016/j.clinimag.2013.05.009

- Crawford EA, King JJ, Fox EJ, et al. Symptomatic fat necrosis and lipoatrophy of the posterior pelvis following trauma. Orthopedics. 2009;32:444. doi:10.3928/01477447-20090511-25

- Haikin Herzberger E, Aviner S, Cherniavsky E. Posttraumatic fat necrosis presented as cellulitis of the leg. Case Rep Pediatr. 2012;2012:672397. doi:10.1155/2012/672397

- Michels LG, Gold RH, Arndt RD. Radiography of gynecomastia and other disorders of the male breast. Radiology. 1977;122:117-122. doi:10.1148/122.1.117

- Günhan-Bilgen I, Bozkaya H, Ustün E, et al. Male breast disease: clinical, mammographic, and ultrasonographic features. Eur J Radiol. 2002;43:246-255. doi:10.1016/s0720-048x(01)00483-1

- Chala LF, de Barros N, de Camargo Moraes P, et al. Fat necrosis of the breast: mammographic, sonographic, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2004;33:106-126. doi:10.1067/j.cpradiol.2004.01.001

- Pullyblank AM, Davies JD, Basten J, et al. Fat necrosis of the female breast—Hadfield re-visited. Breast. 2001;10:388-391. doi:10.1054/brst.2000.0287

To the Editor:

Fat necrosis of the breast is a benign inflammatory disease of adipose tissue commonly observed after trauma in the female breast during the perimenopausal period.1 Fat necrosis of the male breast is rare, first described by Silverstone2 in 1949; the condition usually presents with unilateral, painful or asymptomatic, firm nodules, which in rare cases are observed as skin retraction and thickening, ecchymosis, erythematous plaque–like cellulitis, local depression, and/or discoloration of the breast skin.3-5

Diagnosis of fat necrosis of the male breast may need to be confirmed via biopsy in conjunction with clinical and radiologic findings because the condition can mimic breast cancer.1 We report a case of bilateral fat necrosis of the breast mimicking breast cancer following wax hair removal.

A 42-year-old man presented to our outpatient dermatology clinic for evaluation of redness, swelling, and hardness of the skin of both breasts of 3 weeks’ duration. The patient had a history of wax hair removal of the entire anterior aspect of the body. He reported an erythematous, edematous, warm plaque that developed on the breasts 2 days after waxing. The plaque did not respond to antibiotics. The swelling and induration progressed over the 2 weeks after the patient was waxed. The patient had no family history of breast cancer. He had a standing diagnosis of gynecomastia. He denied any history of fat or filler injection in the affected area.

Dermatologic examination revealed erythematous, edematous, indurated, asymptomatic plaques with a peau d’orange appearance on the bilateral pectoral and presternal region. Minimal retraction of the right areola was noted (Figure 1). The bilateral axillary lymph nodes were palpable.

Laboratory results including erythrocyte sedimentation rate (108 mm/h [reference range, 2–20 mm/h]), C-reactive protein (9.2 mg/dL [reference range, >0.5 mg/dL]), and ferritin levels (645

Mammography of both breasts revealed a Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) score of 4 with a suspicious abnormality (ie, diffuse edema of the breast, multiple calcifications in a nonspecific pattern, oil cysts with calcifications, and bilateral axillary lymphadenopathy with a diameter of 2.5 cm and a thick and irregular cortex)(Figure 2A). Ultrasonography of both breasts revealed an inflammatory breast. Magnetic resonance imaging showed similar findings with diffuse edema and a heterogeneous appearance. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging showed diffuse contrast enhancement in both breasts extending to the pectoral muscles and axillary regions, consistent with inflammatory changes (Figure 2B).

Because of difficulty differentiating inflammation and an infiltrating tumor, histopathologic examination was recommended by radiology. Results from a 5-mm punch biopsy from the right breast yielded the following differential diagnoses: cellulitis, panniculitis, inflammatory breast cancer, subcutaneous fat necrosis, and paraffinoma. Histopathologic examination of the skin revealed a normal epidermis and a dense inflammatory cell infiltrate comprising lymphocytes and monocytes in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Marked fibrosis also was noted in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Lipophagic fat necrosis accompanied by a variable inflammatory cell infiltrate consisted of histiocytes and neutrophils (Figure 3A). Pankeratin immunostaining was negative. Fat necrosis was present in a biopsy specimen obtained from the right breast; no signs of malignancy were present (Figure 3B). Fine-needle aspiration of the axillary lymph nodes was benign. Given these histopathologic findings, malignancy was excluded from the differential diagnosis. Paraffinoma also was ruled out because the patient insistently denied any history of fat or filler injection.

Based on the clinical, histopathologic, and radiologic findings, as well as the history of minor trauma due to wax hair removal, a diagnosis of fat necrosis of the breast was made. Intervention was not recommended by the plastic surgeons who subsequently evaluated the patient, because the additional trauma may aggravate the lesion. He was treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

At 6-month follow-up, there was marked reduction in the erythema and edema but no notable improvement of the induration. A potent topical steroid was added to the treatment, but only slight regression of the induration was observed.

The normal male breast is comprised of fat and a few secretory ducts.6 Gynecomastia and breast cancer are the 2 most common conditions of the male breast; fat necrosis of the male breast is rare. In a study of 236 male patients with breast disease, only 5 had fat necrosis.7

Fat necrosis of the breast can be observed with various clinical and radiological presentations. Subcutaneous nodules, skin retraction and thickening, local skin depression, and ecchymosis are the more common presentations of fat necrosis.3-5 In our case, the first symptoms of disease were similar to those seen in cellulitis. The presentation of fat necrosis–like cellulitis has been described only rarely in the medical literature. Haikin et al5 reported a case of fat necrosis of the leg in a child that presented with cellulitis followed by induration, which did not respond to antibiotics, as was the case with our patient.5

Blunt trauma, breast reduction surgery, and breast augmentation surgery can cause fat necrosis of the breast1,4; in some cases, the cause cannot be determined.8 The only pertinent history in our patient was wax hair removal. Fat necrosis was an unexpected complication, but hair removal can be considered minor trauma; however, this is not commonly reported in the literature following hair removal with wax. In a study that reviewed diseases of the male breast, the investigators observed that all male patients with fat necrosis had pseudogynecomastia (adipomastia).7 Although our patient’s entire anterior trunk was epilated, only the breast was affected. This situation might be explained by underlying gynecomastia because fat necrosis is common in areas of the body where subcutaneous fat tissue is dense.

Fat necrosis of the breast can be mistaken—both clinically and radiologically—for malignancy, such as in our case. Diagnosis of fat necrosis of the breast should be a diagnosis of exclusion; therefore, histopathologic confirmation of the lesion is imperative.9

In conclusion, fat necrosis of the male breast is rare. The condition can present as cellulitis. Hair removal with wax might be a cause of fat necrosis. Because breast cancer and fat necrosis can exhibit clinical and radiologic similarities, the diagnosis of fat necrosis should be confirmed by histopathologic analysis in conjunction with clinical and radiologic findings.

To the Editor:

Fat necrosis of the breast is a benign inflammatory disease of adipose tissue commonly observed after trauma in the female breast during the perimenopausal period.1 Fat necrosis of the male breast is rare, first described by Silverstone2 in 1949; the condition usually presents with unilateral, painful or asymptomatic, firm nodules, which in rare cases are observed as skin retraction and thickening, ecchymosis, erythematous plaque–like cellulitis, local depression, and/or discoloration of the breast skin.3-5

Diagnosis of fat necrosis of the male breast may need to be confirmed via biopsy in conjunction with clinical and radiologic findings because the condition can mimic breast cancer.1 We report a case of bilateral fat necrosis of the breast mimicking breast cancer following wax hair removal.

A 42-year-old man presented to our outpatient dermatology clinic for evaluation of redness, swelling, and hardness of the skin of both breasts of 3 weeks’ duration. The patient had a history of wax hair removal of the entire anterior aspect of the body. He reported an erythematous, edematous, warm plaque that developed on the breasts 2 days after waxing. The plaque did not respond to antibiotics. The swelling and induration progressed over the 2 weeks after the patient was waxed. The patient had no family history of breast cancer. He had a standing diagnosis of gynecomastia. He denied any history of fat or filler injection in the affected area.

Dermatologic examination revealed erythematous, edematous, indurated, asymptomatic plaques with a peau d’orange appearance on the bilateral pectoral and presternal region. Minimal retraction of the right areola was noted (Figure 1). The bilateral axillary lymph nodes were palpable.

Laboratory results including erythrocyte sedimentation rate (108 mm/h [reference range, 2–20 mm/h]), C-reactive protein (9.2 mg/dL [reference range, >0.5 mg/dL]), and ferritin levels (645

Mammography of both breasts revealed a Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) score of 4 with a suspicious abnormality (ie, diffuse edema of the breast, multiple calcifications in a nonspecific pattern, oil cysts with calcifications, and bilateral axillary lymphadenopathy with a diameter of 2.5 cm and a thick and irregular cortex)(Figure 2A). Ultrasonography of both breasts revealed an inflammatory breast. Magnetic resonance imaging showed similar findings with diffuse edema and a heterogeneous appearance. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging showed diffuse contrast enhancement in both breasts extending to the pectoral muscles and axillary regions, consistent with inflammatory changes (Figure 2B).

Because of difficulty differentiating inflammation and an infiltrating tumor, histopathologic examination was recommended by radiology. Results from a 5-mm punch biopsy from the right breast yielded the following differential diagnoses: cellulitis, panniculitis, inflammatory breast cancer, subcutaneous fat necrosis, and paraffinoma. Histopathologic examination of the skin revealed a normal epidermis and a dense inflammatory cell infiltrate comprising lymphocytes and monocytes in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Marked fibrosis also was noted in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Lipophagic fat necrosis accompanied by a variable inflammatory cell infiltrate consisted of histiocytes and neutrophils (Figure 3A). Pankeratin immunostaining was negative. Fat necrosis was present in a biopsy specimen obtained from the right breast; no signs of malignancy were present (Figure 3B). Fine-needle aspiration of the axillary lymph nodes was benign. Given these histopathologic findings, malignancy was excluded from the differential diagnosis. Paraffinoma also was ruled out because the patient insistently denied any history of fat or filler injection.

Based on the clinical, histopathologic, and radiologic findings, as well as the history of minor trauma due to wax hair removal, a diagnosis of fat necrosis of the breast was made. Intervention was not recommended by the plastic surgeons who subsequently evaluated the patient, because the additional trauma may aggravate the lesion. He was treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

At 6-month follow-up, there was marked reduction in the erythema and edema but no notable improvement of the induration. A potent topical steroid was added to the treatment, but only slight regression of the induration was observed.

The normal male breast is comprised of fat and a few secretory ducts.6 Gynecomastia and breast cancer are the 2 most common conditions of the male breast; fat necrosis of the male breast is rare. In a study of 236 male patients with breast disease, only 5 had fat necrosis.7

Fat necrosis of the breast can be observed with various clinical and radiological presentations. Subcutaneous nodules, skin retraction and thickening, local skin depression, and ecchymosis are the more common presentations of fat necrosis.3-5 In our case, the first symptoms of disease were similar to those seen in cellulitis. The presentation of fat necrosis–like cellulitis has been described only rarely in the medical literature. Haikin et al5 reported a case of fat necrosis of the leg in a child that presented with cellulitis followed by induration, which did not respond to antibiotics, as was the case with our patient.5

Blunt trauma, breast reduction surgery, and breast augmentation surgery can cause fat necrosis of the breast1,4; in some cases, the cause cannot be determined.8 The only pertinent history in our patient was wax hair removal. Fat necrosis was an unexpected complication, but hair removal can be considered minor trauma; however, this is not commonly reported in the literature following hair removal with wax. In a study that reviewed diseases of the male breast, the investigators observed that all male patients with fat necrosis had pseudogynecomastia (adipomastia).7 Although our patient’s entire anterior trunk was epilated, only the breast was affected. This situation might be explained by underlying gynecomastia because fat necrosis is common in areas of the body where subcutaneous fat tissue is dense.

Fat necrosis of the breast can be mistaken—both clinically and radiologically—for malignancy, such as in our case. Diagnosis of fat necrosis of the breast should be a diagnosis of exclusion; therefore, histopathologic confirmation of the lesion is imperative.9

In conclusion, fat necrosis of the male breast is rare. The condition can present as cellulitis. Hair removal with wax might be a cause of fat necrosis. Because breast cancer and fat necrosis can exhibit clinical and radiologic similarities, the diagnosis of fat necrosis should be confirmed by histopathologic analysis in conjunction with clinical and radiologic findings.

- Tan PH, Lai LM, Carrington EV, et al. Fat necrosis of the breast—a review. Breast. 2006;15:313-318. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2005.07.003

- Silverstone M. Fat necrosis of the breast with report of a case in a male. Br J Surg. 1949;37:49-52. doi:10.1002/bjs.18003714508

- Akyol M, Kayali A, Yildirim N. Traumatic fat necrosis of male breast. Clin Imaging. 2013;37:954-956. doi:10.1016/j.clinimag.2013.05.009

- Crawford EA, King JJ, Fox EJ, et al. Symptomatic fat necrosis and lipoatrophy of the posterior pelvis following trauma. Orthopedics. 2009;32:444. doi:10.3928/01477447-20090511-25

- Haikin Herzberger E, Aviner S, Cherniavsky E. Posttraumatic fat necrosis presented as cellulitis of the leg. Case Rep Pediatr. 2012;2012:672397. doi:10.1155/2012/672397

- Michels LG, Gold RH, Arndt RD. Radiography of gynecomastia and other disorders of the male breast. Radiology. 1977;122:117-122. doi:10.1148/122.1.117

- Günhan-Bilgen I, Bozkaya H, Ustün E, et al. Male breast disease: clinical, mammographic, and ultrasonographic features. Eur J Radiol. 2002;43:246-255. doi:10.1016/s0720-048x(01)00483-1

- Chala LF, de Barros N, de Camargo Moraes P, et al. Fat necrosis of the breast: mammographic, sonographic, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2004;33:106-126. doi:10.1067/j.cpradiol.2004.01.001

- Pullyblank AM, Davies JD, Basten J, et al. Fat necrosis of the female breast—Hadfield re-visited. Breast. 2001;10:388-391. doi:10.1054/brst.2000.0287

- Tan PH, Lai LM, Carrington EV, et al. Fat necrosis of the breast—a review. Breast. 2006;15:313-318. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2005.07.003

- Silverstone M. Fat necrosis of the breast with report of a case in a male. Br J Surg. 1949;37:49-52. doi:10.1002/bjs.18003714508

- Akyol M, Kayali A, Yildirim N. Traumatic fat necrosis of male breast. Clin Imaging. 2013;37:954-956. doi:10.1016/j.clinimag.2013.05.009

- Crawford EA, King JJ, Fox EJ, et al. Symptomatic fat necrosis and lipoatrophy of the posterior pelvis following trauma. Orthopedics. 2009;32:444. doi:10.3928/01477447-20090511-25

- Haikin Herzberger E, Aviner S, Cherniavsky E. Posttraumatic fat necrosis presented as cellulitis of the leg. Case Rep Pediatr. 2012;2012:672397. doi:10.1155/2012/672397

- Michels LG, Gold RH, Arndt RD. Radiography of gynecomastia and other disorders of the male breast. Radiology. 1977;122:117-122. doi:10.1148/122.1.117

- Günhan-Bilgen I, Bozkaya H, Ustün E, et al. Male breast disease: clinical, mammographic, and ultrasonographic features. Eur J Radiol. 2002;43:246-255. doi:10.1016/s0720-048x(01)00483-1

- Chala LF, de Barros N, de Camargo Moraes P, et al. Fat necrosis of the breast: mammographic, sonographic, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2004;33:106-126. doi:10.1067/j.cpradiol.2004.01.001

- Pullyblank AM, Davies JD, Basten J, et al. Fat necrosis of the female breast—Hadfield re-visited. Breast. 2001;10:388-391. doi:10.1054/brst.2000.0287

Practice Points

- Fat necrosis of the breast can be mistaken—both clinically and radiologically—for malignancy; therefore, diagnosis should be confirmed by histopathology in conjunction with clinical and radiologic findings.

- Fat necrosis of the male breast is rare, and hair removal with wax may be a rare cause of the disease.

NSCLC- The Basics

SCLC: Presentation and Diagnosis

Older woman presents with shortness of breath

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is the most aggressive lung cancer subtype, has a poor prognosis, and is highly associated with smoking. It accounts for 10%-15% of all lung cancers. Rapid tumor growth may lead to obstruction of major airways, with distal collapse leading to postobstructive pneumonitis, infection, and fever. SCLCs usually grow rapidly and metastasize to mediastinal lymph nodes relatively early in the course of the disease. At presentation, patients may have very large intrathoracic tumors, and distinguishing the primary tumor from lymph node metastases may be difficult.

CT of all common sites of metastasis should be performed to stage the disease. CT scanning of the thorax (lungs and mediastinum) and commonly involved abdominal viscera is the minimum requirement in standard staging workup of SCLC. Intravenous contrast agents should be used whenever possible. In the United States, CT scans of the chest and upper abdomen to include the liver and adrenal glands are standard. The liver is a common site of metastasis.

Most cases of SCLC will present in advanced stages, be inoperable, and have a dismal prognosis. Only about 5% of patients present at an early stage (Ia, Ib, or IIa). The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend that these patients be managed with aggressive chemoradiation therapy; in some, lobectomy associated with mediastinal lymph node dissection may be performed. The NCCN notes that advanced disease is managed primarily with chemotherapy, mainly for palliation and symptom control. Older patients, such as the current patient, who have a good performance status (ECOG 0 or 1) and intact organ function should receive standard carboplatin-based chemotherapy. However, even those who have poor prognostic factors (eg, poor performance status, medically significant concomitant conditions) may still be considered for chemotherapy if appropriate precautions are taken to avoid excessive toxicity and further decline in performance status.

Unlike non-SCLC, which has seen waves of new drug approvals from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the prognosis for SCLC has not changed substantially in the past two decades and remains poor. However, the FDA approved atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin and etoposide for first-line treatment of adult patients with extensive-stage SCLC. Further, the approval of durvalumab in combination with chemotherapy; and the approval of lurbinectedin, a novel chemotherapy agent approved for second-line treatment of SCLC, have added to the therapeutic options for patients with SCLC.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is the most aggressive lung cancer subtype, has a poor prognosis, and is highly associated with smoking. It accounts for 10%-15% of all lung cancers. Rapid tumor growth may lead to obstruction of major airways, with distal collapse leading to postobstructive pneumonitis, infection, and fever. SCLCs usually grow rapidly and metastasize to mediastinal lymph nodes relatively early in the course of the disease. At presentation, patients may have very large intrathoracic tumors, and distinguishing the primary tumor from lymph node metastases may be difficult.

CT of all common sites of metastasis should be performed to stage the disease. CT scanning of the thorax (lungs and mediastinum) and commonly involved abdominal viscera is the minimum requirement in standard staging workup of SCLC. Intravenous contrast agents should be used whenever possible. In the United States, CT scans of the chest and upper abdomen to include the liver and adrenal glands are standard. The liver is a common site of metastasis.

Most cases of SCLC will present in advanced stages, be inoperable, and have a dismal prognosis. Only about 5% of patients present at an early stage (Ia, Ib, or IIa). The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend that these patients be managed with aggressive chemoradiation therapy; in some, lobectomy associated with mediastinal lymph node dissection may be performed. The NCCN notes that advanced disease is managed primarily with chemotherapy, mainly for palliation and symptom control. Older patients, such as the current patient, who have a good performance status (ECOG 0 or 1) and intact organ function should receive standard carboplatin-based chemotherapy. However, even those who have poor prognostic factors (eg, poor performance status, medically significant concomitant conditions) may still be considered for chemotherapy if appropriate precautions are taken to avoid excessive toxicity and further decline in performance status.

Unlike non-SCLC, which has seen waves of new drug approvals from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the prognosis for SCLC has not changed substantially in the past two decades and remains poor. However, the FDA approved atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin and etoposide for first-line treatment of adult patients with extensive-stage SCLC. Further, the approval of durvalumab in combination with chemotherapy; and the approval of lurbinectedin, a novel chemotherapy agent approved for second-line treatment of SCLC, have added to the therapeutic options for patients with SCLC.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is the most aggressive lung cancer subtype, has a poor prognosis, and is highly associated with smoking. It accounts for 10%-15% of all lung cancers. Rapid tumor growth may lead to obstruction of major airways, with distal collapse leading to postobstructive pneumonitis, infection, and fever. SCLCs usually grow rapidly and metastasize to mediastinal lymph nodes relatively early in the course of the disease. At presentation, patients may have very large intrathoracic tumors, and distinguishing the primary tumor from lymph node metastases may be difficult.

CT of all common sites of metastasis should be performed to stage the disease. CT scanning of the thorax (lungs and mediastinum) and commonly involved abdominal viscera is the minimum requirement in standard staging workup of SCLC. Intravenous contrast agents should be used whenever possible. In the United States, CT scans of the chest and upper abdomen to include the liver and adrenal glands are standard. The liver is a common site of metastasis.

Most cases of SCLC will present in advanced stages, be inoperable, and have a dismal prognosis. Only about 5% of patients present at an early stage (Ia, Ib, or IIa). The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend that these patients be managed with aggressive chemoradiation therapy; in some, lobectomy associated with mediastinal lymph node dissection may be performed. The NCCN notes that advanced disease is managed primarily with chemotherapy, mainly for palliation and symptom control. Older patients, such as the current patient, who have a good performance status (ECOG 0 or 1) and intact organ function should receive standard carboplatin-based chemotherapy. However, even those who have poor prognostic factors (eg, poor performance status, medically significant concomitant conditions) may still be considered for chemotherapy if appropriate precautions are taken to avoid excessive toxicity and further decline in performance status.

Unlike non-SCLC, which has seen waves of new drug approvals from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the prognosis for SCLC has not changed substantially in the past two decades and remains poor. However, the FDA approved atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin and etoposide for first-line treatment of adult patients with extensive-stage SCLC. Further, the approval of durvalumab in combination with chemotherapy; and the approval of lurbinectedin, a novel chemotherapy agent approved for second-line treatment of SCLC, have added to the therapeutic options for patients with SCLC.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

A 72-year-old woman presents with shortness of breath, a productive cough, chest pain, some fatigue, anorexia, a recent 18-pound weight loss, and a history of hypertension. She is currently a smoker and has a 45–pack-year smoking history. On physical examination she has some dullness to percussion with some decreased breath sounds. She has a distended abdomen and complains of itchy skin. The chest x-ray shows a left hilar mass and a 5.4-cm left upper-lobe mass. A CT scan reveals a hilar mass with a mediastinal extension.

Shortness of breath and chest pain

Liver biopsy will reveal the cause of the liver dysfunction and confirm whether this patient has small cell lung cancer (SCLC), as suspected, and whether it has spread to the liver. This will affect chemotherapy options.

Most cases of SCLC will present in advanced stages, be inoperable, and have a dismal prognosis. Only about 5% of patients present at an early stage (Ia, Ib, or IIa). The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend that patients with advanced disease be managed with aggressive chemoradiation therapy and immunotherapy.

SCLC is the most aggressive lung cancer subtype. It is almost always associated with smoking. It accounts for 10%-15% of all lung cancers. Rapid tumor growth may lead to obstruction of major airways, with distal collapse leading to postobstructive pneumonitis, infection, and fever. About 70% of patients show metastatic spread at presentation, and the liver is one of the most common sites of metastasis.

Unlike non-SCLC, for which the prognosis has improved in part because of several new drug approvals from the US Food and Drug Administration, the prognosis for SCLC has not changed substantially in the past two decades and remains poor. However, with immunotherapy, the outlook may be improving. The NCCN recommends atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin and etoposide for first-line treatment of adult patients with extensive-stage SCLC. Furthermore, the approval of durvalumab in combination with chemotherapy and the approval of lurbinectedin, a novel chemotherapy agent approved for second-line treatment of SCLC, have added to the therapeutic options for patients with advanced SCLC.

Maurie Markman, MD, President, Department of Medical Oncology, Cancer Treatment Centers of America.

Maurie Markman, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Merck

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: AstraZeneca; Novis; Glaxo Smith Kline

Received research grants from: AstraZeneca; Novis; GSK; Merck

Liver biopsy will reveal the cause of the liver dysfunction and confirm whether this patient has small cell lung cancer (SCLC), as suspected, and whether it has spread to the liver. This will affect chemotherapy options.

Most cases of SCLC will present in advanced stages, be inoperable, and have a dismal prognosis. Only about 5% of patients present at an early stage (Ia, Ib, or IIa). The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend that patients with advanced disease be managed with aggressive chemoradiation therapy and immunotherapy.

SCLC is the most aggressive lung cancer subtype. It is almost always associated with smoking. It accounts for 10%-15% of all lung cancers. Rapid tumor growth may lead to obstruction of major airways, with distal collapse leading to postobstructive pneumonitis, infection, and fever. About 70% of patients show metastatic spread at presentation, and the liver is one of the most common sites of metastasis.

Unlike non-SCLC, for which the prognosis has improved in part because of several new drug approvals from the US Food and Drug Administration, the prognosis for SCLC has not changed substantially in the past two decades and remains poor. However, with immunotherapy, the outlook may be improving. The NCCN recommends atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin and etoposide for first-line treatment of adult patients with extensive-stage SCLC. Furthermore, the approval of durvalumab in combination with chemotherapy and the approval of lurbinectedin, a novel chemotherapy agent approved for second-line treatment of SCLC, have added to the therapeutic options for patients with advanced SCLC.

Maurie Markman, MD, President, Department of Medical Oncology, Cancer Treatment Centers of America.

Maurie Markman, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Merck

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: AstraZeneca; Novis; Glaxo Smith Kline

Received research grants from: AstraZeneca; Novis; GSK; Merck

Liver biopsy will reveal the cause of the liver dysfunction and confirm whether this patient has small cell lung cancer (SCLC), as suspected, and whether it has spread to the liver. This will affect chemotherapy options.

Most cases of SCLC will present in advanced stages, be inoperable, and have a dismal prognosis. Only about 5% of patients present at an early stage (Ia, Ib, or IIa). The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend that patients with advanced disease be managed with aggressive chemoradiation therapy and immunotherapy.

SCLC is the most aggressive lung cancer subtype. It is almost always associated with smoking. It accounts for 10%-15% of all lung cancers. Rapid tumor growth may lead to obstruction of major airways, with distal collapse leading to postobstructive pneumonitis, infection, and fever. About 70% of patients show metastatic spread at presentation, and the liver is one of the most common sites of metastasis.

Unlike non-SCLC, for which the prognosis has improved in part because of several new drug approvals from the US Food and Drug Administration, the prognosis for SCLC has not changed substantially in the past two decades and remains poor. However, with immunotherapy, the outlook may be improving. The NCCN recommends atezolizumab in combination with carboplatin and etoposide for first-line treatment of adult patients with extensive-stage SCLC. Furthermore, the approval of durvalumab in combination with chemotherapy and the approval of lurbinectedin, a novel chemotherapy agent approved for second-line treatment of SCLC, have added to the therapeutic options for patients with advanced SCLC.

Maurie Markman, MD, President, Department of Medical Oncology, Cancer Treatment Centers of America.

Maurie Markman, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Merck

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: AstraZeneca; Novis; Glaxo Smith Kline

Received research grants from: AstraZeneca; Novis; GSK; Merck

A 64-year-old man presents with shortness of breath, a productive cough, chest pain, some fatigue, anorexia, a recent 15-lb weight loss, jaundice, and a history of type 2 diabetes. He is a college professor and has a 35–pack-year smoking history; he quit 3 years ago.

On physical examination, he has dullness to percussion and decreased breath sounds. His laboratory data reveal elevated serum liver enzyme levels. Chest radiography shows a left hilar mass and a 5.6-cm left upper lobe mass. CT reveals a hilar mass with a bilateral mediastinal extension and pneumonia. PET shows activity in the left upper lobe mass, with supraclavicular nodal areas and liver lesions. MRI shows that there are no metastases to the brain.

SCLC: The Basics

A love letter to Black birthing people from Black birth workers, midwives, and physicians

A few years ago, my partner emailed me about a consult.

“Dr. Carter, I had the pleasure of seeing Mrs. Smith today for a preconception consult for chronic hypertension. As a high-risk Black woman, she wants to know what we’re going to do to make sure that she doesn’t die in pregnancy or childbirth. I told her that you’re better equipped to answer this question.”

I was early in my career, and the only thing I could assume that equipped me to answer this question over my partners was my identity as a Black woman living in America.

Mrs. Smith was copied on the message and replied with a long list of follow-up questions and a request for an in-person meeting with me. I was conflicted. As a friend, daughter, and mother, I understood her fear and wanted to be there for her. As a newly appointed assistant professor on the tenure track with 20% clinical time, my clinical responsibilities easily exceeded 50% (in part, because I failed to set boundaries). I spent countless hours of uncompensated time serving on diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives and mentoring and volunteering for multiple community organizations; I was acutely aware that I would be measured against colleagues who rise through the ranks, unencumbered by these social, moral, and ethical responsibilities, collectively known as the “Black tax.”1

I knew from prior experiences and the tone of Mrs. Smith’s email that it would be a tough, long meeting that would set a precedent of concierge level care that only promised to intensify once she became pregnant. I agonized over my reply. How could I balance providing compassionate care for this patient with my young research program, which I hoped to nurture so that it would one day grow to have population-level impact?

It took me 2 days to finally reply to the message with a kind, but firm, email stating that I would be happy to see her for a follow-up preconception visit. It was my attempt to balance accessibility with boundaries. She did not reply.

Did I fail her?

The fact that I still think of Mrs. Smith may indicate that I did the wrong thing. In fact, writing the first draft of this letter was a therapeutic experience, and I addressed it to Mrs. Smith. As I shared the experience and letter with friends in the field, however, everyone had similar stories. The letter continued to pass between colleagues, who each made it infinitely better. This collective process created the beautiful love letter to Black birthing people that we share here.

We call upon all of our obstetric clinician colleagues to educate themselves to be equally, ethically, and equitably equipped to care for and serve historically marginalized women and birthing people. We hope that this letter will aid in the journey, and we encourage you to share it with patients to open conversations that are too often left closed.

Continue to: Our love letter to Black women and birthing people...

Our love letter to Black women and birthing people

We see you, we hear you, we know you are scared, and we are you. In recent years, the press has amplified gross inequities in maternal care and outcomes that we, as Black birth workers, midwives, and physicians, already knew to be true. We grieve, along with you regarding the recently reported pregnancy-related deaths of Mrs. Kira Johnson,2 Dr. Shalon Irving,3 Dr. Chaniece Wallace,4 and so many other names we do not know because their stories did not receive national attention, but we know that they represented the best of us, and they are gone too soon. As Black birth workers, midwives, physicians, and more, we have a front-row seat to the United States’ serious obstetric racism, manifested in biased clinical interactions, unjust hospital policies, and an inequitable health care system that leads to disparities in maternal morbidity and mortality for Black women.

Unfortunately, this is not anything new, and the legacy dates back to slavery and the disregard for Black people in this country. What has changed is our increased awareness of these health injustices. This collective consciousness of the risk that is carried with our pregnancies casts a shadow of fear over a period that should be full of the joy and promise of new life. We fear that our personhood will be disregarded, our pain will be ignored, and our voices silenced by a medical system that has sought to dominate our bodies and experiment on them without our permission.5 While this history is reprehensible, and our collective risk as Black people is disproportionately high, our purpose in writing this letter is to help Black birthing people recapture the joy and celebration that should be theirs in pregnancy and in the journey to parenthood.