User login

Therapeutic Highlights From ACTRIMS 2023

The latest research on disease-modifying therapies presented at the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ACTRIMS) 2023 annual meeting is reported by Dr Jennifer Graves from the University of California, San Diego.

Dr Graves first discusses a small study exploring the effects of an intermittent calorie restriction (ICR) diet on adipokine levels, metabolic and immune/inflammatory biomarkers, and MRI measurements. Researchers found that short-term ICR can improve metabolic and immunologic profiles in patients with MS.

Next, Dr Graves discusses a trial that successively measured changes in proteins in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients treated with tolebrutinib and ocrelizumab as evidence of therapeutic efficacy. This study provides early evidence of the impact of these medications directly in the central nervous system.

She then details a study evaluating autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (aHSCT) as an MS treatment. The study found that aHSCT has a durable effect for up to 5-10 years compared to our current available regimens.

Finally, Dr Graves highlights the National MS Society Barancik Prize winner Dr Ruth Ann Marrie. Dr Marrie is a pioneer for her research in comorbidities and their effect on MS treatment decisions, especially in choosing disease-modifying therapies.

--

Jennifer S.O. Graves, MD, PhD, Associate Professor, Director Neuroimmunology Research, Department of Neurosciences, University of California, San Diego

Jennifer S.O. Graves, MD, PhD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) on an advisory board for: TG Therapeutics; Bayer

Received research grant from: Sanofi; EMD Serono; Biogen; ATARA; Octave

The latest research on disease-modifying therapies presented at the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ACTRIMS) 2023 annual meeting is reported by Dr Jennifer Graves from the University of California, San Diego.

Dr Graves first discusses a small study exploring the effects of an intermittent calorie restriction (ICR) diet on adipokine levels, metabolic and immune/inflammatory biomarkers, and MRI measurements. Researchers found that short-term ICR can improve metabolic and immunologic profiles in patients with MS.

Next, Dr Graves discusses a trial that successively measured changes in proteins in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients treated with tolebrutinib and ocrelizumab as evidence of therapeutic efficacy. This study provides early evidence of the impact of these medications directly in the central nervous system.

She then details a study evaluating autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (aHSCT) as an MS treatment. The study found that aHSCT has a durable effect for up to 5-10 years compared to our current available regimens.

Finally, Dr Graves highlights the National MS Society Barancik Prize winner Dr Ruth Ann Marrie. Dr Marrie is a pioneer for her research in comorbidities and their effect on MS treatment decisions, especially in choosing disease-modifying therapies.

--

Jennifer S.O. Graves, MD, PhD, Associate Professor, Director Neuroimmunology Research, Department of Neurosciences, University of California, San Diego

Jennifer S.O. Graves, MD, PhD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) on an advisory board for: TG Therapeutics; Bayer

Received research grant from: Sanofi; EMD Serono; Biogen; ATARA; Octave

The latest research on disease-modifying therapies presented at the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ACTRIMS) 2023 annual meeting is reported by Dr Jennifer Graves from the University of California, San Diego.

Dr Graves first discusses a small study exploring the effects of an intermittent calorie restriction (ICR) diet on adipokine levels, metabolic and immune/inflammatory biomarkers, and MRI measurements. Researchers found that short-term ICR can improve metabolic and immunologic profiles in patients with MS.

Next, Dr Graves discusses a trial that successively measured changes in proteins in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients treated with tolebrutinib and ocrelizumab as evidence of therapeutic efficacy. This study provides early evidence of the impact of these medications directly in the central nervous system.

She then details a study evaluating autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (aHSCT) as an MS treatment. The study found that aHSCT has a durable effect for up to 5-10 years compared to our current available regimens.

Finally, Dr Graves highlights the National MS Society Barancik Prize winner Dr Ruth Ann Marrie. Dr Marrie is a pioneer for her research in comorbidities and their effect on MS treatment decisions, especially in choosing disease-modifying therapies.

--

Jennifer S.O. Graves, MD, PhD, Associate Professor, Director Neuroimmunology Research, Department of Neurosciences, University of California, San Diego

Jennifer S.O. Graves, MD, PhD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) on an advisory board for: TG Therapeutics; Bayer

Received research grant from: Sanofi; EMD Serono; Biogen; ATARA; Octave

Reports of dysuria and nocturia

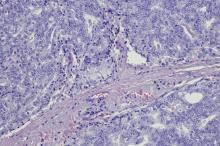

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of small cell carcinoma of the prostate (SCCP).

SCCP is a rare and aggressive cancer that comprises 1%–5% of all prostate cancers (if mixed cases with adenocarcinoma are included). Similar to small cell carcinoma of the lung or other small cell primaries, SCCP is characterized by a primary tumor of the prostate gland that expresses small cell morphology and high-grade features, including minimal cytoplasm, nuclear molding, fine chromatin pattern, extensive tumor necrosis and apoptosis, variable tumor giant cells, and a high mitotic rate. Patients often have disproportionally low PSA levels despite having large metastatic burden and visceral disease. Pathologic diagnosis is made on the basis of prostate biopsy using characteristics of small cell tumors and immunohistochemical staining for neuroendocrine markers, such as CD56, chromogranin A, synaptophysin, and neuron-specific enolase.

SCCP arises de novo in approximately 50% of cases; it also occurs in patients with previous or concomitant prostate adenocarcinoma. Patients are often symptomatic at diagnosis because of the extent of the tumor. The aggressive nature and high proliferation rate associated with SCCP result in an increased risk for lytic or blastic bone, visceral, and brain metastases. In addition, paraneoplastic syndromes (eg, the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion, Cushing syndrome, and hypercalcemia) frequently occur as a result of the release of peptides.

SCCP metastasizes early in its course and is associated with a poor prognosis. It has a median survival of < 1 year. Fluorodeoxyglucose PET-CT are useful for staging and monitoring treatment response; in addition, given the disease's predilection for brain metastases, MRI of the brain should be considered.

The optimal treatment for patients with metastatic SCCP has not yet been determined. Localized SCCP is treated aggressively, typically with a multimodality approach involving chemotherapy with concurrent or consolidative radiotherapy.

According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), platinum-based combination chemotherapy (cisplatin-etoposide, carboplatin-etoposide, docetaxel-carboplatin, cabazitaxel-carboplatin) is the first-line approach for patients with metastatic disease.

Physicians are also advised to consult the NCCN guidelines for small cell lung cancer because the behavior of SCCP is similar to that of small cell carcinoma of the lung. Immunotherapy with pembrolizumab may be used for platinum-resistant extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma. However, sipuleucel-T is not recommended for patients with SCCP.

Chad R. Tracy, MD, Professor; Director, Minimally Invasive Surgery, Department of Urology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa

Chad R. Tracy, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant for: CVICO Medical Solutions.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of small cell carcinoma of the prostate (SCCP).

SCCP is a rare and aggressive cancer that comprises 1%–5% of all prostate cancers (if mixed cases with adenocarcinoma are included). Similar to small cell carcinoma of the lung or other small cell primaries, SCCP is characterized by a primary tumor of the prostate gland that expresses small cell morphology and high-grade features, including minimal cytoplasm, nuclear molding, fine chromatin pattern, extensive tumor necrosis and apoptosis, variable tumor giant cells, and a high mitotic rate. Patients often have disproportionally low PSA levels despite having large metastatic burden and visceral disease. Pathologic diagnosis is made on the basis of prostate biopsy using characteristics of small cell tumors and immunohistochemical staining for neuroendocrine markers, such as CD56, chromogranin A, synaptophysin, and neuron-specific enolase.

SCCP arises de novo in approximately 50% of cases; it also occurs in patients with previous or concomitant prostate adenocarcinoma. Patients are often symptomatic at diagnosis because of the extent of the tumor. The aggressive nature and high proliferation rate associated with SCCP result in an increased risk for lytic or blastic bone, visceral, and brain metastases. In addition, paraneoplastic syndromes (eg, the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion, Cushing syndrome, and hypercalcemia) frequently occur as a result of the release of peptides.

SCCP metastasizes early in its course and is associated with a poor prognosis. It has a median survival of < 1 year. Fluorodeoxyglucose PET-CT are useful for staging and monitoring treatment response; in addition, given the disease's predilection for brain metastases, MRI of the brain should be considered.

The optimal treatment for patients with metastatic SCCP has not yet been determined. Localized SCCP is treated aggressively, typically with a multimodality approach involving chemotherapy with concurrent or consolidative radiotherapy.

According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), platinum-based combination chemotherapy (cisplatin-etoposide, carboplatin-etoposide, docetaxel-carboplatin, cabazitaxel-carboplatin) is the first-line approach for patients with metastatic disease.

Physicians are also advised to consult the NCCN guidelines for small cell lung cancer because the behavior of SCCP is similar to that of small cell carcinoma of the lung. Immunotherapy with pembrolizumab may be used for platinum-resistant extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma. However, sipuleucel-T is not recommended for patients with SCCP.

Chad R. Tracy, MD, Professor; Director, Minimally Invasive Surgery, Department of Urology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa

Chad R. Tracy, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant for: CVICO Medical Solutions.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of small cell carcinoma of the prostate (SCCP).

SCCP is a rare and aggressive cancer that comprises 1%–5% of all prostate cancers (if mixed cases with adenocarcinoma are included). Similar to small cell carcinoma of the lung or other small cell primaries, SCCP is characterized by a primary tumor of the prostate gland that expresses small cell morphology and high-grade features, including minimal cytoplasm, nuclear molding, fine chromatin pattern, extensive tumor necrosis and apoptosis, variable tumor giant cells, and a high mitotic rate. Patients often have disproportionally low PSA levels despite having large metastatic burden and visceral disease. Pathologic diagnosis is made on the basis of prostate biopsy using characteristics of small cell tumors and immunohistochemical staining for neuroendocrine markers, such as CD56, chromogranin A, synaptophysin, and neuron-specific enolase.

SCCP arises de novo in approximately 50% of cases; it also occurs in patients with previous or concomitant prostate adenocarcinoma. Patients are often symptomatic at diagnosis because of the extent of the tumor. The aggressive nature and high proliferation rate associated with SCCP result in an increased risk for lytic or blastic bone, visceral, and brain metastases. In addition, paraneoplastic syndromes (eg, the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion, Cushing syndrome, and hypercalcemia) frequently occur as a result of the release of peptides.

SCCP metastasizes early in its course and is associated with a poor prognosis. It has a median survival of < 1 year. Fluorodeoxyglucose PET-CT are useful for staging and monitoring treatment response; in addition, given the disease's predilection for brain metastases, MRI of the brain should be considered.

The optimal treatment for patients with metastatic SCCP has not yet been determined. Localized SCCP is treated aggressively, typically with a multimodality approach involving chemotherapy with concurrent or consolidative radiotherapy.

According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), platinum-based combination chemotherapy (cisplatin-etoposide, carboplatin-etoposide, docetaxel-carboplatin, cabazitaxel-carboplatin) is the first-line approach for patients with metastatic disease.

Physicians are also advised to consult the NCCN guidelines for small cell lung cancer because the behavior of SCCP is similar to that of small cell carcinoma of the lung. Immunotherapy with pembrolizumab may be used for platinum-resistant extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma. However, sipuleucel-T is not recommended for patients with SCCP.

Chad R. Tracy, MD, Professor; Director, Minimally Invasive Surgery, Department of Urology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa

Chad R. Tracy, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant for: CVICO Medical Solutions.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 69-year-old nonsmoking African American man presents with reports of dysuria, nocturia, and unintentional weight loss. He reveals no other lower urinary tract symptoms, pelvic pain, night sweats, back pain, or excessive fatigue. Digital rectal exam reveals an enlarged prostate with a firm, irregular nodule at the right side of the gland. Laboratory tests reveal a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level of 2.22 ng/mL; a comprehensive metabolic panel and CBC are within normal limits. The patient is 6 ft 1 in and weighs 187 lb.

A transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy is performed. Histologic examination reveals immunoreactivity for the neuroendocrine markers synaptophysin, chromogranin A, and expression of transcription factor 1. A proliferation of small cells (> 4 lymphocytes in diameter) is noted, with scant cytoplasm, poorly defined borders, finely granular salt-and-pepper chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, and a high mitotic count. Evidence of perineural invasion is noted.

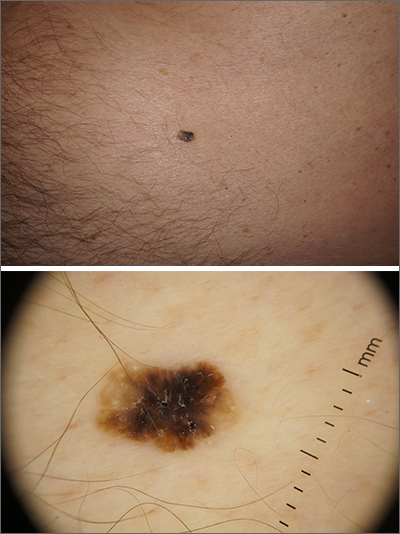

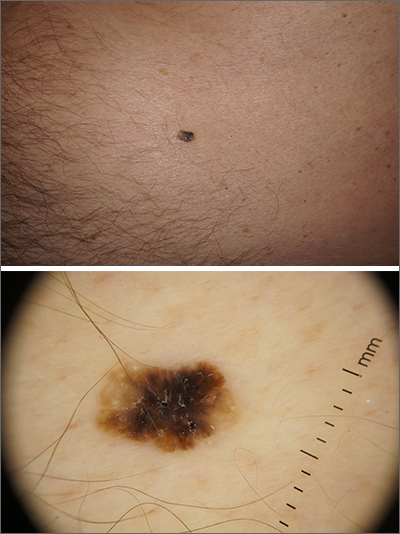

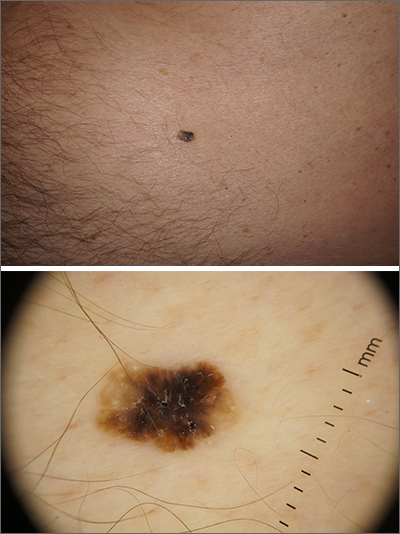

Solitary abdominal papule

Dermoscopy revealed an 8-mm scaly brown-black papule that lacked melanocytic features (pigment network, globules, streaks, or homogeneous blue or brown color) but had milia-like cysts and so-called “fat fingers” (short, straight to curved radial projections1). These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis (SK).

SKs go by many names and are often confused with nevi. Some patients might know them by such names as “age spots” or “liver spots.” Patients often have many SKs on their body; the back and skin folds are common locations. Patients may be unhappy about the way they look and may describe occasional discomfort when the SKs rub against clothes and inflammation that occurs spontaneously or with trauma.

Classic SKs have a well-demarcated border and waxy, stuck-on appearance. There are times when it is difficult to distinguish between an SK and a melanocytic lesion. Thus, a biopsy may be necessary. In addition, SKs are so common that collision lesions may occur. (Collision lesions result when 2 histologically distinct neoplasms occur adjacent to each other and cause an unusual clinical appearance with features of each lesion.) The atypical clinical features in a collision lesion may prompt a biopsy to exclude malignancy.

Dermoscopic features of SKs include well-demarcated borders, milia-like cysts (white circular inclusions), comedo-like openings (brown/black circular inclusions), fissures and ridges, hairpin vessels, and fat fingers.

Cryotherapy is a quick and efficient treatment when a patient would like the lesions removed. Curettage or light electrodessication may be less likely to cause post-inflammatory hypopigmentation in patients with darker skin types. These various destructive therapies are often considered cosmetic and are unlikely to be covered by insurance unless there is documentation of significant inflammation or discomfort. In this case, the lesion was not treated.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Wang S, Rabinovitz H, Oliviero M, et al. Solar lentigines, seborrheic keratoses, and lichen planus-like keratoses. In: Marghoob A, Malvehy J, Braun, R, eds. Atlas of Dermoscopy. 2nd ed. Informa Healthcare; 2012: 58-69.

Dermoscopy revealed an 8-mm scaly brown-black papule that lacked melanocytic features (pigment network, globules, streaks, or homogeneous blue or brown color) but had milia-like cysts and so-called “fat fingers” (short, straight to curved radial projections1). These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis (SK).

SKs go by many names and are often confused with nevi. Some patients might know them by such names as “age spots” or “liver spots.” Patients often have many SKs on their body; the back and skin folds are common locations. Patients may be unhappy about the way they look and may describe occasional discomfort when the SKs rub against clothes and inflammation that occurs spontaneously or with trauma.

Classic SKs have a well-demarcated border and waxy, stuck-on appearance. There are times when it is difficult to distinguish between an SK and a melanocytic lesion. Thus, a biopsy may be necessary. In addition, SKs are so common that collision lesions may occur. (Collision lesions result when 2 histologically distinct neoplasms occur adjacent to each other and cause an unusual clinical appearance with features of each lesion.) The atypical clinical features in a collision lesion may prompt a biopsy to exclude malignancy.

Dermoscopic features of SKs include well-demarcated borders, milia-like cysts (white circular inclusions), comedo-like openings (brown/black circular inclusions), fissures and ridges, hairpin vessels, and fat fingers.

Cryotherapy is a quick and efficient treatment when a patient would like the lesions removed. Curettage or light electrodessication may be less likely to cause post-inflammatory hypopigmentation in patients with darker skin types. These various destructive therapies are often considered cosmetic and are unlikely to be covered by insurance unless there is documentation of significant inflammation or discomfort. In this case, the lesion was not treated.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Dermoscopy revealed an 8-mm scaly brown-black papule that lacked melanocytic features (pigment network, globules, streaks, or homogeneous blue or brown color) but had milia-like cysts and so-called “fat fingers” (short, straight to curved radial projections1). These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis (SK).

SKs go by many names and are often confused with nevi. Some patients might know them by such names as “age spots” or “liver spots.” Patients often have many SKs on their body; the back and skin folds are common locations. Patients may be unhappy about the way they look and may describe occasional discomfort when the SKs rub against clothes and inflammation that occurs spontaneously or with trauma.

Classic SKs have a well-demarcated border and waxy, stuck-on appearance. There are times when it is difficult to distinguish between an SK and a melanocytic lesion. Thus, a biopsy may be necessary. In addition, SKs are so common that collision lesions may occur. (Collision lesions result when 2 histologically distinct neoplasms occur adjacent to each other and cause an unusual clinical appearance with features of each lesion.) The atypical clinical features in a collision lesion may prompt a biopsy to exclude malignancy.

Dermoscopic features of SKs include well-demarcated borders, milia-like cysts (white circular inclusions), comedo-like openings (brown/black circular inclusions), fissures and ridges, hairpin vessels, and fat fingers.

Cryotherapy is a quick and efficient treatment when a patient would like the lesions removed. Curettage or light electrodessication may be less likely to cause post-inflammatory hypopigmentation in patients with darker skin types. These various destructive therapies are often considered cosmetic and are unlikely to be covered by insurance unless there is documentation of significant inflammation or discomfort. In this case, the lesion was not treated.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Wang S, Rabinovitz H, Oliviero M, et al. Solar lentigines, seborrheic keratoses, and lichen planus-like keratoses. In: Marghoob A, Malvehy J, Braun, R, eds. Atlas of Dermoscopy. 2nd ed. Informa Healthcare; 2012: 58-69.

1. Wang S, Rabinovitz H, Oliviero M, et al. Solar lentigines, seborrheic keratoses, and lichen planus-like keratoses. In: Marghoob A, Malvehy J, Braun, R, eds. Atlas of Dermoscopy. 2nd ed. Informa Healthcare; 2012: 58-69.

Widespread Erosions in Intertriginous Areas

The Diagnosis: Darier Disease

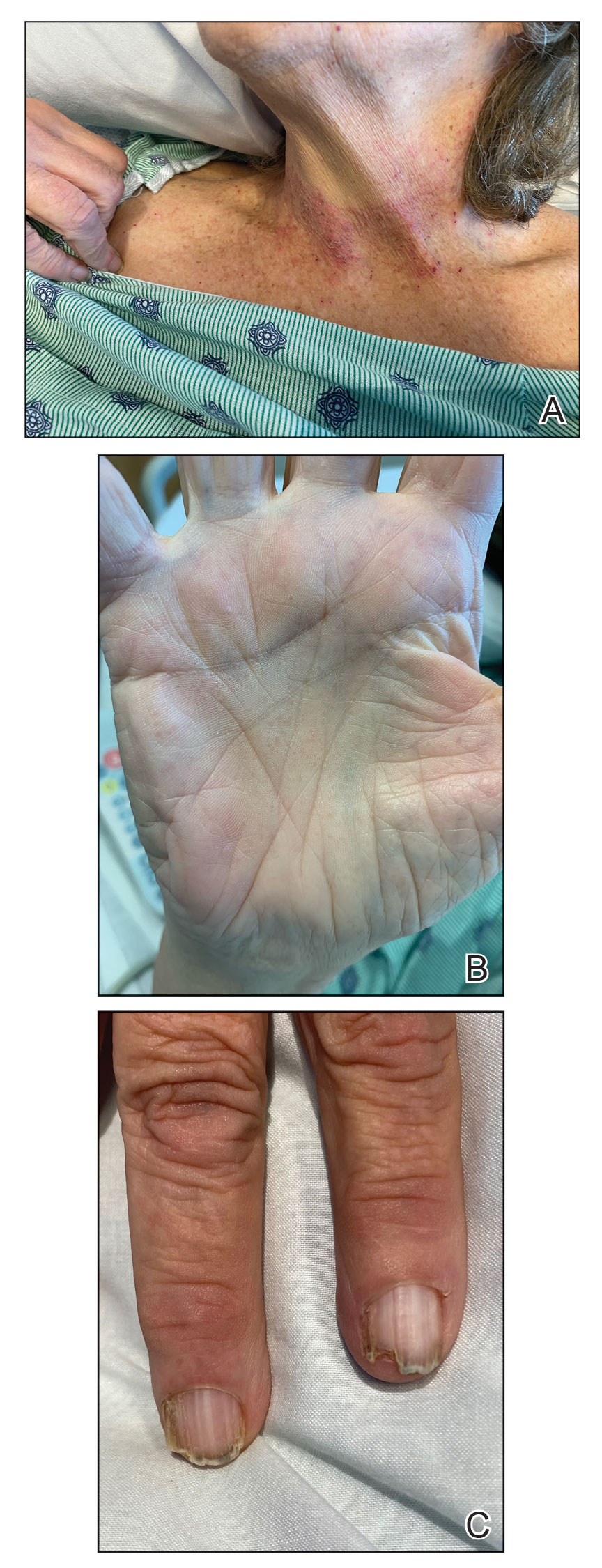

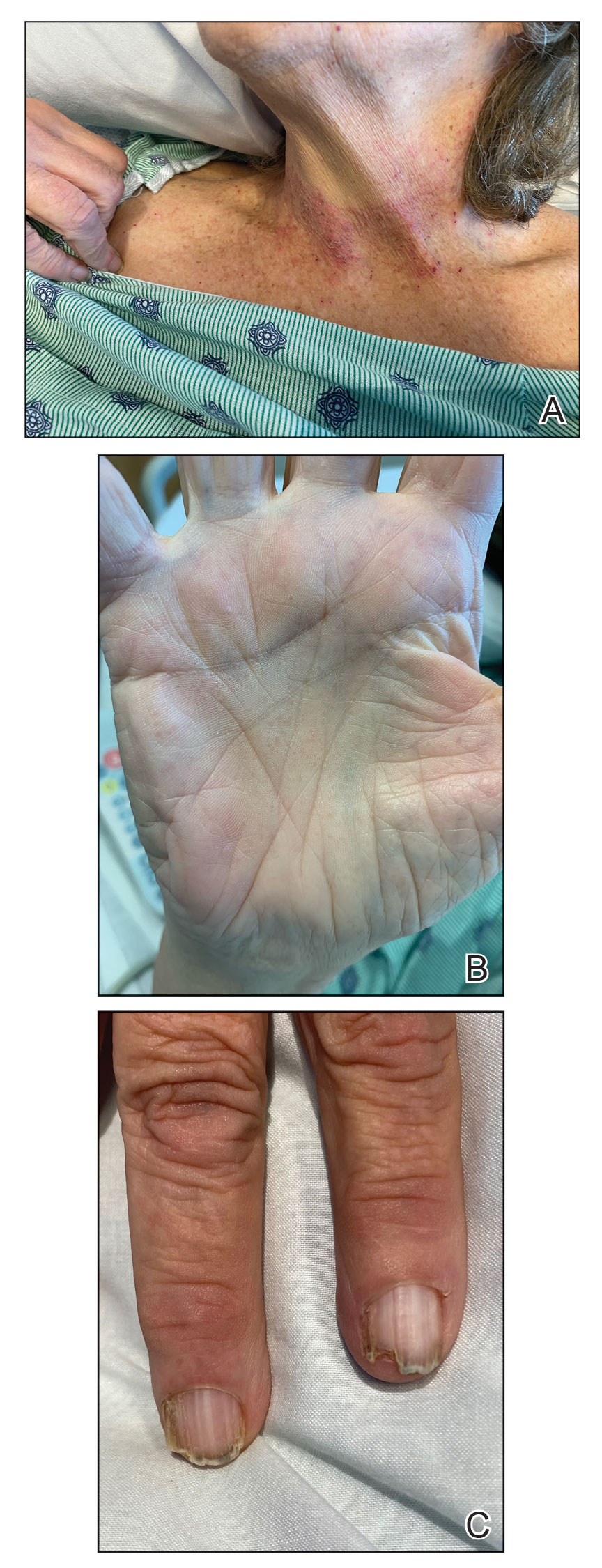

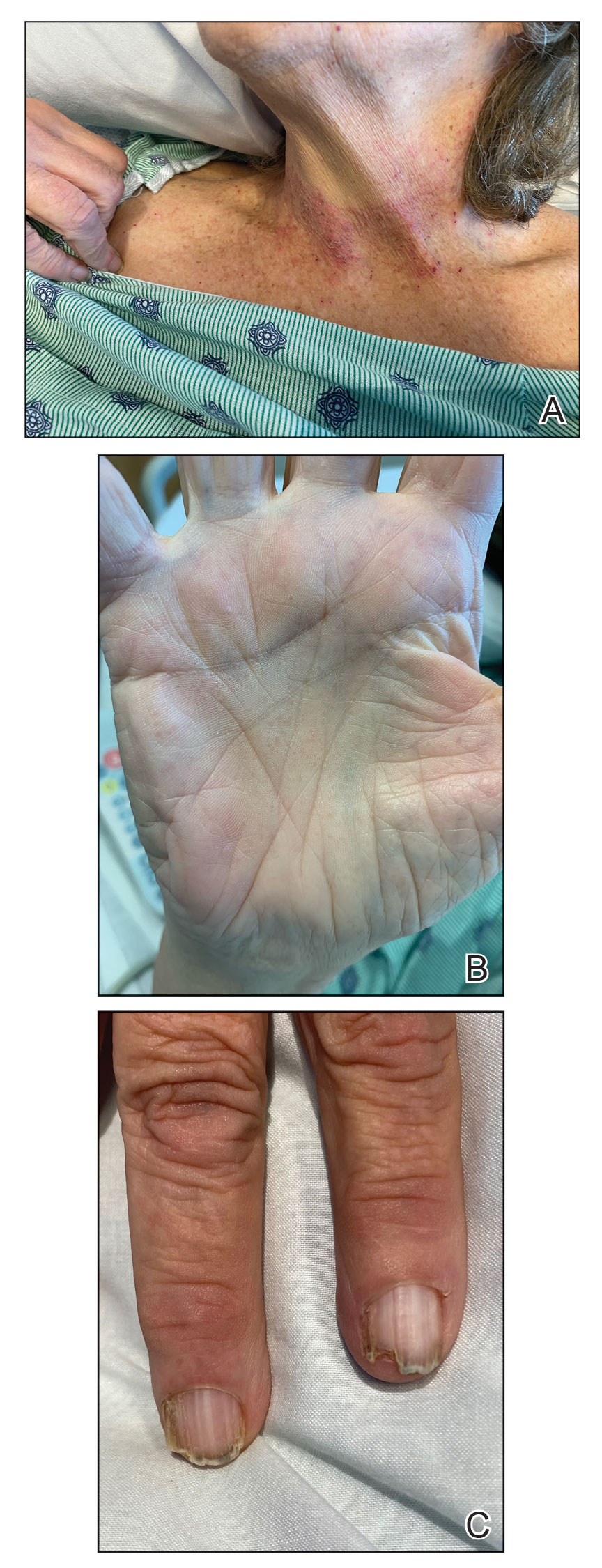

A clinical diagnosis of Darier disease was made from the skin findings of pruritic, malodorous, keratotic papules in a seborrheic distribution and pathognomonic nail dystrophy, along with a family history that demonstrated autosomal-dominant inheritance. The ulcerations were suspected to be caused by a superimposed herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection in the form of eczema herpeticum. The clinical diagnosis was later confirmed via punch biopsy. Pathology results demonstrated focal acantholytic dyskeratosis, which was consistent with Darier disease given the focal nature and lack of acanthosis. The patient’s father and sister also were confirmed to have Darier disease by an outside dermatologist.

Darier disease is a rare keratinizing autosomaldominant genodermatosis that occurs due to a mutation in the ATP2A2 gene, which encodes a sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase pump that decreases cell adhesion between keratinocytes, leading to epidermal acantholysis and dyskeratosis and ultimately a disrupted skin barrier.1,2 Darier disease often presents in childhood and adolescence with papules in a seborrheic distribution on the central chest and back (Figure, A); the intertriginous folds also may be involved. Darier disease can manifest with palmoplantar pits (Figure, B), a cobblestonelike texture of the oral mucosa, acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf, and nail findings with alternating red and white longitudinal streaks in the nail bed resembling a candy cane along with characteristic V nicking deformities of the nails themselves (Figure, C). Chronic flares may occur throughout one’s lifetime, with patients experiencing more symptoms in the summer months due to heat, sweat, and UV light exposure, as well as infections that irritate the skin and worsen dyskeratosis. Studies have revealed an association between Darier disease and neuropsychiatric conditions, including major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder.3,4

The skin barrier is compromised in patients with Darier disease, thereby making secondary infection more likely to occur. Polymerase chain reaction swabs of our patient’s purulent ulcerations were positive for HSV type 1, further strengthening a diagnosis of secondary eczema herpeticum, which occurs when patients have widespread HSV superinfecting pre-existing skin conditions such as atopic dermatitis, Darier disease, and Hailey-Hailey disease.5-7 The lesions are characterized by a monomorphic eruption of umbilicated vesicles on an erythematous base. Lesions can progress to punched-out ulcers and erosions with hemorrhagic crusts that coalesce, forming scalloped borders, similar to our patient’s presentation.8

Hailey-Hailey disease, a genodermatosis that alters calcium signaling with an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern, was unlikely in our patient due to the presence of nail abnormalities and palmar pits that are characteristic of Darier disease. From a purely histopathologic standpoint, Grover disease was considered with skin biopsy demonstrating acantholytic dyskeratosis but was not compatible with the clinical context. Furthermore, trials of antibiotics with group A Streptococcus and Staphylococcus aureus coverage failed in our patient, and she lacked systemic symptoms that would be supportive of a cellulitis diagnosis. The punched-out lesions suggested that an isolated exacerbation of atopic dermatitis was not sufficient to explain all of the clinical findings.

Eczema herpeticum must be considered in the differential diagnosis for patients with underlying Darier disease and widespread ulcerations. Our patient had more recent punched-out ulcerations in the intertriginous regions, with other areas showing later stages of confluent ulcers with scalloped borders. Delayed diagnosis and treatment of eczema herpeticum combined with severe Darier disease can lead to increased risk for hospitalization and rarely fatality.8,9

Our patient was started on intravenous acyclovir until the lesions crusted and then was transitioned to a suppressive dose of oral valacyclovir given the widespread distribution. The Darier disease itself was managed with topical steroids and a zinc oxide barrier, serving as protectants to pathogens through microscopic breaks in the skin. Our patient also had a mild case of candidal intertrigo that was exacerbated by obesity and managed with topical ketoconazole. Gabapentin, hydromorphone, and acetaminophen were used for pain. She was discharged 10 days after admission with substantial improvement of both the HSV lesions and the irritation from her Darier disease. At follow-up visits 20 days later and again 6 months after discharge, she had been feeling well without any HSV flares.

The eczema herpeticum likely arose from our patient’s chronic skin barrier impairment attributed to Darier disease, leading to the cutaneous inoculation of HSV. Our patient and her family members had never been evaluated by a dermatologist until late in life during this hospitalization. Medication compliance with a suppressive dose of oral valacyclovir and topical steroids is vital to prevent flares of both eczema herpeticum and Darier disease, respectively. This case highlights the importance of dermatology consultation for complex cutaneous findings, as delayed diagnosis and treatment can lead to increased morbidity and mortality.

- Cooper SM, Burge SM. Darier’s disease: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:97-105. doi:10.2165/00128071-200304020-00003

- Dhitavat J, Cobbold C, Leslie N, et al. Impaired trafficking of the desmoplakins in cultured Darier’s disease keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:1349-1355. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12557.x

- Nakamura T, Kazuno AA, Nakajima K, et al. Loss of function mutations in ATP2A2 and psychoses: a case report and literature survey. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;70:342-350. doi:10.1111/pcn.12395

- Gordon-Smith K, Jones LA, Burge SM, et al. The neuropsychiatric phenotype in Darier disease. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:515-522. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09834.x

- Hemani SA, Edmond MB, Jaggi P, et al. Frequency and clinical features associated with eczema herpeticum in hospitalized children with presumed atopic dermatitis skin infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39:263-266. doi:10.1097/INF.0000000000002542

- Tayabali K, Pothiwalla H, Lowitt M. Eczema herpeticum in Darier’s disease: a topical storm. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2019;9:347-350. doi:10.1080/20009666.2019.1650590

- Lee GH, Kim YM, Lee SY, et al. A case of eczema herpeticum with Hailey-Hailey disease. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:311-314. doi:10.5021/ad.2009.21.3.311

- Nikkels AF, Beauthier F, Quatresooz P, et al. Fatal herpes simplex virus infection in Darier disease under corticotherapy. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:293-297.

- Vogt KA, Lohse CM, El-Azhary RA, et al. Kaposi varicelliform eruption in patients with Darier disease: a 20-year retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:481-484. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.12.001

The Diagnosis: Darier Disease

A clinical diagnosis of Darier disease was made from the skin findings of pruritic, malodorous, keratotic papules in a seborrheic distribution and pathognomonic nail dystrophy, along with a family history that demonstrated autosomal-dominant inheritance. The ulcerations were suspected to be caused by a superimposed herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection in the form of eczema herpeticum. The clinical diagnosis was later confirmed via punch biopsy. Pathology results demonstrated focal acantholytic dyskeratosis, which was consistent with Darier disease given the focal nature and lack of acanthosis. The patient’s father and sister also were confirmed to have Darier disease by an outside dermatologist.

Darier disease is a rare keratinizing autosomaldominant genodermatosis that occurs due to a mutation in the ATP2A2 gene, which encodes a sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase pump that decreases cell adhesion between keratinocytes, leading to epidermal acantholysis and dyskeratosis and ultimately a disrupted skin barrier.1,2 Darier disease often presents in childhood and adolescence with papules in a seborrheic distribution on the central chest and back (Figure, A); the intertriginous folds also may be involved. Darier disease can manifest with palmoplantar pits (Figure, B), a cobblestonelike texture of the oral mucosa, acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf, and nail findings with alternating red and white longitudinal streaks in the nail bed resembling a candy cane along with characteristic V nicking deformities of the nails themselves (Figure, C). Chronic flares may occur throughout one’s lifetime, with patients experiencing more symptoms in the summer months due to heat, sweat, and UV light exposure, as well as infections that irritate the skin and worsen dyskeratosis. Studies have revealed an association between Darier disease and neuropsychiatric conditions, including major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder.3,4

The skin barrier is compromised in patients with Darier disease, thereby making secondary infection more likely to occur. Polymerase chain reaction swabs of our patient’s purulent ulcerations were positive for HSV type 1, further strengthening a diagnosis of secondary eczema herpeticum, which occurs when patients have widespread HSV superinfecting pre-existing skin conditions such as atopic dermatitis, Darier disease, and Hailey-Hailey disease.5-7 The lesions are characterized by a monomorphic eruption of umbilicated vesicles on an erythematous base. Lesions can progress to punched-out ulcers and erosions with hemorrhagic crusts that coalesce, forming scalloped borders, similar to our patient’s presentation.8

Hailey-Hailey disease, a genodermatosis that alters calcium signaling with an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern, was unlikely in our patient due to the presence of nail abnormalities and palmar pits that are characteristic of Darier disease. From a purely histopathologic standpoint, Grover disease was considered with skin biopsy demonstrating acantholytic dyskeratosis but was not compatible with the clinical context. Furthermore, trials of antibiotics with group A Streptococcus and Staphylococcus aureus coverage failed in our patient, and she lacked systemic symptoms that would be supportive of a cellulitis diagnosis. The punched-out lesions suggested that an isolated exacerbation of atopic dermatitis was not sufficient to explain all of the clinical findings.

Eczema herpeticum must be considered in the differential diagnosis for patients with underlying Darier disease and widespread ulcerations. Our patient had more recent punched-out ulcerations in the intertriginous regions, with other areas showing later stages of confluent ulcers with scalloped borders. Delayed diagnosis and treatment of eczema herpeticum combined with severe Darier disease can lead to increased risk for hospitalization and rarely fatality.8,9

Our patient was started on intravenous acyclovir until the lesions crusted and then was transitioned to a suppressive dose of oral valacyclovir given the widespread distribution. The Darier disease itself was managed with topical steroids and a zinc oxide barrier, serving as protectants to pathogens through microscopic breaks in the skin. Our patient also had a mild case of candidal intertrigo that was exacerbated by obesity and managed with topical ketoconazole. Gabapentin, hydromorphone, and acetaminophen were used for pain. She was discharged 10 days after admission with substantial improvement of both the HSV lesions and the irritation from her Darier disease. At follow-up visits 20 days later and again 6 months after discharge, she had been feeling well without any HSV flares.

The eczema herpeticum likely arose from our patient’s chronic skin barrier impairment attributed to Darier disease, leading to the cutaneous inoculation of HSV. Our patient and her family members had never been evaluated by a dermatologist until late in life during this hospitalization. Medication compliance with a suppressive dose of oral valacyclovir and topical steroids is vital to prevent flares of both eczema herpeticum and Darier disease, respectively. This case highlights the importance of dermatology consultation for complex cutaneous findings, as delayed diagnosis and treatment can lead to increased morbidity and mortality.

The Diagnosis: Darier Disease

A clinical diagnosis of Darier disease was made from the skin findings of pruritic, malodorous, keratotic papules in a seborrheic distribution and pathognomonic nail dystrophy, along with a family history that demonstrated autosomal-dominant inheritance. The ulcerations were suspected to be caused by a superimposed herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection in the form of eczema herpeticum. The clinical diagnosis was later confirmed via punch biopsy. Pathology results demonstrated focal acantholytic dyskeratosis, which was consistent with Darier disease given the focal nature and lack of acanthosis. The patient’s father and sister also were confirmed to have Darier disease by an outside dermatologist.

Darier disease is a rare keratinizing autosomaldominant genodermatosis that occurs due to a mutation in the ATP2A2 gene, which encodes a sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase pump that decreases cell adhesion between keratinocytes, leading to epidermal acantholysis and dyskeratosis and ultimately a disrupted skin barrier.1,2 Darier disease often presents in childhood and adolescence with papules in a seborrheic distribution on the central chest and back (Figure, A); the intertriginous folds also may be involved. Darier disease can manifest with palmoplantar pits (Figure, B), a cobblestonelike texture of the oral mucosa, acrokeratosis verruciformis of Hopf, and nail findings with alternating red and white longitudinal streaks in the nail bed resembling a candy cane along with characteristic V nicking deformities of the nails themselves (Figure, C). Chronic flares may occur throughout one’s lifetime, with patients experiencing more symptoms in the summer months due to heat, sweat, and UV light exposure, as well as infections that irritate the skin and worsen dyskeratosis. Studies have revealed an association between Darier disease and neuropsychiatric conditions, including major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder.3,4

The skin barrier is compromised in patients with Darier disease, thereby making secondary infection more likely to occur. Polymerase chain reaction swabs of our patient’s purulent ulcerations were positive for HSV type 1, further strengthening a diagnosis of secondary eczema herpeticum, which occurs when patients have widespread HSV superinfecting pre-existing skin conditions such as atopic dermatitis, Darier disease, and Hailey-Hailey disease.5-7 The lesions are characterized by a monomorphic eruption of umbilicated vesicles on an erythematous base. Lesions can progress to punched-out ulcers and erosions with hemorrhagic crusts that coalesce, forming scalloped borders, similar to our patient’s presentation.8

Hailey-Hailey disease, a genodermatosis that alters calcium signaling with an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern, was unlikely in our patient due to the presence of nail abnormalities and palmar pits that are characteristic of Darier disease. From a purely histopathologic standpoint, Grover disease was considered with skin biopsy demonstrating acantholytic dyskeratosis but was not compatible with the clinical context. Furthermore, trials of antibiotics with group A Streptococcus and Staphylococcus aureus coverage failed in our patient, and she lacked systemic symptoms that would be supportive of a cellulitis diagnosis. The punched-out lesions suggested that an isolated exacerbation of atopic dermatitis was not sufficient to explain all of the clinical findings.

Eczema herpeticum must be considered in the differential diagnosis for patients with underlying Darier disease and widespread ulcerations. Our patient had more recent punched-out ulcerations in the intertriginous regions, with other areas showing later stages of confluent ulcers with scalloped borders. Delayed diagnosis and treatment of eczema herpeticum combined with severe Darier disease can lead to increased risk for hospitalization and rarely fatality.8,9

Our patient was started on intravenous acyclovir until the lesions crusted and then was transitioned to a suppressive dose of oral valacyclovir given the widespread distribution. The Darier disease itself was managed with topical steroids and a zinc oxide barrier, serving as protectants to pathogens through microscopic breaks in the skin. Our patient also had a mild case of candidal intertrigo that was exacerbated by obesity and managed with topical ketoconazole. Gabapentin, hydromorphone, and acetaminophen were used for pain. She was discharged 10 days after admission with substantial improvement of both the HSV lesions and the irritation from her Darier disease. At follow-up visits 20 days later and again 6 months after discharge, she had been feeling well without any HSV flares.

The eczema herpeticum likely arose from our patient’s chronic skin barrier impairment attributed to Darier disease, leading to the cutaneous inoculation of HSV. Our patient and her family members had never been evaluated by a dermatologist until late in life during this hospitalization. Medication compliance with a suppressive dose of oral valacyclovir and topical steroids is vital to prevent flares of both eczema herpeticum and Darier disease, respectively. This case highlights the importance of dermatology consultation for complex cutaneous findings, as delayed diagnosis and treatment can lead to increased morbidity and mortality.

- Cooper SM, Burge SM. Darier’s disease: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:97-105. doi:10.2165/00128071-200304020-00003

- Dhitavat J, Cobbold C, Leslie N, et al. Impaired trafficking of the desmoplakins in cultured Darier’s disease keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:1349-1355. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12557.x

- Nakamura T, Kazuno AA, Nakajima K, et al. Loss of function mutations in ATP2A2 and psychoses: a case report and literature survey. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;70:342-350. doi:10.1111/pcn.12395

- Gordon-Smith K, Jones LA, Burge SM, et al. The neuropsychiatric phenotype in Darier disease. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:515-522. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09834.x

- Hemani SA, Edmond MB, Jaggi P, et al. Frequency and clinical features associated with eczema herpeticum in hospitalized children with presumed atopic dermatitis skin infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39:263-266. doi:10.1097/INF.0000000000002542

- Tayabali K, Pothiwalla H, Lowitt M. Eczema herpeticum in Darier’s disease: a topical storm. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2019;9:347-350. doi:10.1080/20009666.2019.1650590

- Lee GH, Kim YM, Lee SY, et al. A case of eczema herpeticum with Hailey-Hailey disease. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:311-314. doi:10.5021/ad.2009.21.3.311

- Nikkels AF, Beauthier F, Quatresooz P, et al. Fatal herpes simplex virus infection in Darier disease under corticotherapy. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:293-297.

- Vogt KA, Lohse CM, El-Azhary RA, et al. Kaposi varicelliform eruption in patients with Darier disease: a 20-year retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:481-484. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.12.001

- Cooper SM, Burge SM. Darier’s disease: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:97-105. doi:10.2165/00128071-200304020-00003

- Dhitavat J, Cobbold C, Leslie N, et al. Impaired trafficking of the desmoplakins in cultured Darier’s disease keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:1349-1355. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12557.x

- Nakamura T, Kazuno AA, Nakajima K, et al. Loss of function mutations in ATP2A2 and psychoses: a case report and literature survey. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;70:342-350. doi:10.1111/pcn.12395

- Gordon-Smith K, Jones LA, Burge SM, et al. The neuropsychiatric phenotype in Darier disease. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:515-522. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09834.x

- Hemani SA, Edmond MB, Jaggi P, et al. Frequency and clinical features associated with eczema herpeticum in hospitalized children with presumed atopic dermatitis skin infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39:263-266. doi:10.1097/INF.0000000000002542

- Tayabali K, Pothiwalla H, Lowitt M. Eczema herpeticum in Darier’s disease: a topical storm. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2019;9:347-350. doi:10.1080/20009666.2019.1650590

- Lee GH, Kim YM, Lee SY, et al. A case of eczema herpeticum with Hailey-Hailey disease. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:311-314. doi:10.5021/ad.2009.21.3.311

- Nikkels AF, Beauthier F, Quatresooz P, et al. Fatal herpes simplex virus infection in Darier disease under corticotherapy. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:293-297.

- Vogt KA, Lohse CM, El-Azhary RA, et al. Kaposi varicelliform eruption in patients with Darier disease: a 20-year retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:481-484. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.12.001

A 72-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with painful, erythematic, pruritic, and purulent lesions in intertriginous regions including the inframammary, infra-abdominal, and inguinal folds with a burning sensation of 1 week’s duration. Her medical history was notable for obesity and major depressive disorder. She was empirically treated for cellulitis, but there was no improvement with cefazolin or clindamycin. Dermatology was consulted. Physical examination revealed gray-brown, slightly umbilicated papules in the inframammary region that were malodorous upon lifting the folds. Grouped, punched-out ulcerations with scalloped borders were superimposed onto these papules. Further examination revealed a macerated erythematous plaque in the infra-abdominal and inguinal regions with punched-out ulcers. Hemecrusted papules were observed in seborrheic areas including the anterior neck, hairline, and trunk. Few subtle keratotic pits were localized on the palms. She reported similar flares in the past but never saw a dermatologist and noted that her father and sister had similar papules in a seborrheic distribution. Nail abnormalities included red and white alternating subungual streaks with irregular texture including V nicking of the distal nails.

Depression and emotional lability

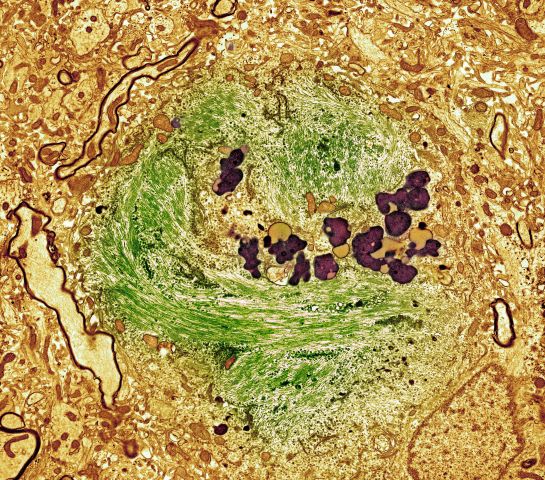

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of Alzheimer's disease (AD), which probably was preceded by chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

AD is the most prevalent cause of cognitive impairment and dementia worldwide. Presently, approximately 50 million individuals are affected by AD; by 2050, the number of affected individuals globally is expected to reach 152 million. AD has a prolonged and progressive disease course that begins with neuropathologic changes in the brain years before onset of clinical manifestations. These changes include the accumulation of beta-amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and neuroinflammation. Neuroimaging studies have shown that beta-amyloid plaques begin to deposit in the brain ≥ 10 years before the start of cognitive decline. Patients with AD normally present with slowly progressive memory loss; as the disease progresses, other areas of cognition are affected. Patients may experience language disorders (eg, anomic aphasia or anomia) and impairment in visuospatial skills and executive functions. Slowly progressive behavioral changes may also occur.

CTE is a neurodegenerative disorder that is believed to be the long-term consequence of repetitive head trauma. Its incidence is highest among athletes of high-impact sports, such as boxing or American football, and victims of domestic violence. Clinically, CTE can be indistinguishable from AD. Although neuropathologic differences exist, they can be confirmed only on postmortem examination. Patients with CTE may present with behavioral symptoms, such as aggression, depression, emotional lability, apathy, and suicidal feelings, as well as motor symptoms, including tremor, ataxia, incoordination, and dysarthria. Cognitive symptoms, including attention and concentration deficits and memory impairment, also occur. CTE is also associated with the development of dementia and may predispose patients to early-onset AD.

Curative therapies do not exist for AD; thus, management centers on symptomatic treatment for neuropsychiatric or cognitive symptoms. Cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist are the standard medical therapies used in patients with AD. For patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia, several newly approved antiamyloid therapies are also available. These include aducanumab, a first-in-class amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2021, and lecanemab, another amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2023. Presently, both aducanumab and lecanemab are recommended only for the treatment of patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia, the population in which their safety and efficacy were demonstrated in clinical trials.

Psychotropic agents may be used to treat symptoms, such as depression, agitation, aggression, hallucinations, delusions, and sleep disorders, which can be problematic. Behavioral interventions may also be used, normally in combination with pharmacologic interventions (eg, anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders and specific manifestations). Regular physical activity and exercise may help to delay disease progression and are recommended as an adjunct to the medical management of AD.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of Alzheimer's disease (AD), which probably was preceded by chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

AD is the most prevalent cause of cognitive impairment and dementia worldwide. Presently, approximately 50 million individuals are affected by AD; by 2050, the number of affected individuals globally is expected to reach 152 million. AD has a prolonged and progressive disease course that begins with neuropathologic changes in the brain years before onset of clinical manifestations. These changes include the accumulation of beta-amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and neuroinflammation. Neuroimaging studies have shown that beta-amyloid plaques begin to deposit in the brain ≥ 10 years before the start of cognitive decline. Patients with AD normally present with slowly progressive memory loss; as the disease progresses, other areas of cognition are affected. Patients may experience language disorders (eg, anomic aphasia or anomia) and impairment in visuospatial skills and executive functions. Slowly progressive behavioral changes may also occur.

CTE is a neurodegenerative disorder that is believed to be the long-term consequence of repetitive head trauma. Its incidence is highest among athletes of high-impact sports, such as boxing or American football, and victims of domestic violence. Clinically, CTE can be indistinguishable from AD. Although neuropathologic differences exist, they can be confirmed only on postmortem examination. Patients with CTE may present with behavioral symptoms, such as aggression, depression, emotional lability, apathy, and suicidal feelings, as well as motor symptoms, including tremor, ataxia, incoordination, and dysarthria. Cognitive symptoms, including attention and concentration deficits and memory impairment, also occur. CTE is also associated with the development of dementia and may predispose patients to early-onset AD.

Curative therapies do not exist for AD; thus, management centers on symptomatic treatment for neuropsychiatric or cognitive symptoms. Cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist are the standard medical therapies used in patients with AD. For patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia, several newly approved antiamyloid therapies are also available. These include aducanumab, a first-in-class amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2021, and lecanemab, another amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2023. Presently, both aducanumab and lecanemab are recommended only for the treatment of patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia, the population in which their safety and efficacy were demonstrated in clinical trials.

Psychotropic agents may be used to treat symptoms, such as depression, agitation, aggression, hallucinations, delusions, and sleep disorders, which can be problematic. Behavioral interventions may also be used, normally in combination with pharmacologic interventions (eg, anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders and specific manifestations). Regular physical activity and exercise may help to delay disease progression and are recommended as an adjunct to the medical management of AD.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of Alzheimer's disease (AD), which probably was preceded by chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

AD is the most prevalent cause of cognitive impairment and dementia worldwide. Presently, approximately 50 million individuals are affected by AD; by 2050, the number of affected individuals globally is expected to reach 152 million. AD has a prolonged and progressive disease course that begins with neuropathologic changes in the brain years before onset of clinical manifestations. These changes include the accumulation of beta-amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and neuroinflammation. Neuroimaging studies have shown that beta-amyloid plaques begin to deposit in the brain ≥ 10 years before the start of cognitive decline. Patients with AD normally present with slowly progressive memory loss; as the disease progresses, other areas of cognition are affected. Patients may experience language disorders (eg, anomic aphasia or anomia) and impairment in visuospatial skills and executive functions. Slowly progressive behavioral changes may also occur.

CTE is a neurodegenerative disorder that is believed to be the long-term consequence of repetitive head trauma. Its incidence is highest among athletes of high-impact sports, such as boxing or American football, and victims of domestic violence. Clinically, CTE can be indistinguishable from AD. Although neuropathologic differences exist, they can be confirmed only on postmortem examination. Patients with CTE may present with behavioral symptoms, such as aggression, depression, emotional lability, apathy, and suicidal feelings, as well as motor symptoms, including tremor, ataxia, incoordination, and dysarthria. Cognitive symptoms, including attention and concentration deficits and memory impairment, also occur. CTE is also associated with the development of dementia and may predispose patients to early-onset AD.

Curative therapies do not exist for AD; thus, management centers on symptomatic treatment for neuropsychiatric or cognitive symptoms. Cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist are the standard medical therapies used in patients with AD. For patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia, several newly approved antiamyloid therapies are also available. These include aducanumab, a first-in-class amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2021, and lecanemab, another amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2023. Presently, both aducanumab and lecanemab are recommended only for the treatment of patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia, the population in which their safety and efficacy were demonstrated in clinical trials.

Psychotropic agents may be used to treat symptoms, such as depression, agitation, aggression, hallucinations, delusions, and sleep disorders, which can be problematic. Behavioral interventions may also be used, normally in combination with pharmacologic interventions (eg, anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders and specific manifestations). Regular physical activity and exercise may help to delay disease progression and are recommended as an adjunct to the medical management of AD.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 51-year-old man presents with complaints of progressively worsening cognitive impairments, particularly in executive functioning and episodic memory, as well as depression, apathy, and emotional lability. The patient is accompanied by his wife, who states that he often becomes irritable and "flies off the handle" without provocation. The patient's depressive symptoms began approximately 18 months ago, shortly after his mother's death from heart failure. Both he and his wife initially attributed his symptoms to the grieving process; however, in the past 6 months, his depression and mood swings have become increasingly frequent and intense. In addition, he was recently mandated to go on administrative leave from his job as an IT manager because of poor performance and angry outbursts in the workplace. The patient believes that his forgetfulness and difficulty regulating his emotions are the result of the depression he is experiencing. His goal today is to "get on some medication" to help him better manage his emotions and return to work. Although his wife is supportive of her husband, she is concerned about her husband's rapidly progressing deficits in short-term memory and is uncertain that they are related to his emotional symptoms.

The patient's medical history is notable for nine concussions sustained during his time as a high school and college football player; only one resulted in loss of consciousness. He does not currently take any medications. There is no history of tobacco use, illicit drug use, or excessive alcohol consumption. There is no family history of dementia. His current height and weight are 6 ft 3 in and 223 lb, and his BMI is 27.9.

No abnormalities are noted on physical exam; the patient's blood pressure, pulse oximetry, and heart rate are within normal ranges. Laboratory tests are all within normal ranges, including thyroid-stimulating hormone and vitamin B12 levels. The patient scores 24 on the Mini-Mental State Examination, which is a set of 11 questions that doctors and other healthcare professionals commonly use to check for cognitive impairment. His clinician orders a brain MRI, which reveals a tau-positive neurofibrillary tangle in the neocortex.

Progressive back pain

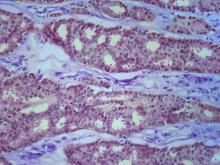

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of advanced/metastatic breast cancer.

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed life-threatening cancer and the second-leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women worldwide. In the United States, an estimated 287,850 new cases of invasive breast cancer were diagnosed in 2022 and 43,250 women died of the disease. Globally, approximately 2.3 million new diagnoses and 685,000 breast cancer–related deaths were reported in 2020.

Tumor size, nodal spread, and distant metastases (TNM) at the time of diagnosis are key prognostic factors. Immunohistochemistry tumor markers (ie, estrogen receptor [ER], progesterone receptor [PR], and HER2), as well as grade and Ki-67 expression, have also been shown to be independent predictors of breast cancer death and are used together with TNM to guide treatment decisions.

Despite advances in breast cancer diagnosis and treatment, metastatic recurrence remains a significant problem. Although the incidence of distance relapse is declining and survival times for patients with recurrent disease are improving, 20%-30% of patients with early breast cancer still die of metastatic disease. Metastatic breast cancer recurrence can arise months to decades after initial diagnosis and treatment.

According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, biopsy is a critical component of the workup for patients with recurrent or stage IV disease. This is because biopsy ensures accurate determination of metastatic/recurrent disease and tumor histology and enables biomarker determination and selection of appropriate treatment. Soft-tissue tumor biopsy is preferred over bone sites unless a portion of the biopsy can be protected from harsh decalcification solution to preserve more accurate evaluation of biomarkers. Determination of HR status (ER and PR) and HER2 status should be repeated in all cases when diagnostic tissue is obtained because ER and PR assays may be falsely negative or falsely positive, and there may be discordance between the primary and metastatic tumors. According to the NCCN panel, re-testing the receptor status of recurrent disease should be performed, particularly when it was previously unknown, originally negative, or not overexpressed.

Additionally, the staging evaluation of patients who present with recurrent or stage IV breast cancer should include history and physical exam; a complete blood cell count, liver function tests, chest diagnostic CT, bone scan, and radiography of any long or weight-bearing bones that are painful or appear abnormal on bone scan; diagnostic CT of the abdomen (with or without diagnostic CT of the pelvis) or MRI of the abdomen; and biopsy documentation of first recurrence whenever possible. The use of sodium fluoride PET or PET/CT for evaluating patients with recurrent disease is generally discouraged.

Presently, metastatic breast cancer remains incurable. However, in recent years, the treatment landscape for metastatic breast cancer has significantly advanced in all breast cancer subtypes, leading to improvements in progression-free survival and even overall survival in some cases. For example, newer, targeted approaches directly address mutation drivers and allow precise delivery of chemotherapeutic agents. Detailed guidance on the treatment of breast cancer can be found here and in the full NCCN guidelines.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, Assistant Member, Department of Breast Oncology, Moffitt Cancer Center, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of advanced/metastatic breast cancer.

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed life-threatening cancer and the second-leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women worldwide. In the United States, an estimated 287,850 new cases of invasive breast cancer were diagnosed in 2022 and 43,250 women died of the disease. Globally, approximately 2.3 million new diagnoses and 685,000 breast cancer–related deaths were reported in 2020.

Tumor size, nodal spread, and distant metastases (TNM) at the time of diagnosis are key prognostic factors. Immunohistochemistry tumor markers (ie, estrogen receptor [ER], progesterone receptor [PR], and HER2), as well as grade and Ki-67 expression, have also been shown to be independent predictors of breast cancer death and are used together with TNM to guide treatment decisions.

Despite advances in breast cancer diagnosis and treatment, metastatic recurrence remains a significant problem. Although the incidence of distance relapse is declining and survival times for patients with recurrent disease are improving, 20%-30% of patients with early breast cancer still die of metastatic disease. Metastatic breast cancer recurrence can arise months to decades after initial diagnosis and treatment.

According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, biopsy is a critical component of the workup for patients with recurrent or stage IV disease. This is because biopsy ensures accurate determination of metastatic/recurrent disease and tumor histology and enables biomarker determination and selection of appropriate treatment. Soft-tissue tumor biopsy is preferred over bone sites unless a portion of the biopsy can be protected from harsh decalcification solution to preserve more accurate evaluation of biomarkers. Determination of HR status (ER and PR) and HER2 status should be repeated in all cases when diagnostic tissue is obtained because ER and PR assays may be falsely negative or falsely positive, and there may be discordance between the primary and metastatic tumors. According to the NCCN panel, re-testing the receptor status of recurrent disease should be performed, particularly when it was previously unknown, originally negative, or not overexpressed.

Additionally, the staging evaluation of patients who present with recurrent or stage IV breast cancer should include history and physical exam; a complete blood cell count, liver function tests, chest diagnostic CT, bone scan, and radiography of any long or weight-bearing bones that are painful or appear abnormal on bone scan; diagnostic CT of the abdomen (with or without diagnostic CT of the pelvis) or MRI of the abdomen; and biopsy documentation of first recurrence whenever possible. The use of sodium fluoride PET or PET/CT for evaluating patients with recurrent disease is generally discouraged.

Presently, metastatic breast cancer remains incurable. However, in recent years, the treatment landscape for metastatic breast cancer has significantly advanced in all breast cancer subtypes, leading to improvements in progression-free survival and even overall survival in some cases. For example, newer, targeted approaches directly address mutation drivers and allow precise delivery of chemotherapeutic agents. Detailed guidance on the treatment of breast cancer can be found here and in the full NCCN guidelines.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, Assistant Member, Department of Breast Oncology, Moffitt Cancer Center, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of advanced/metastatic breast cancer.

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed life-threatening cancer and the second-leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women worldwide. In the United States, an estimated 287,850 new cases of invasive breast cancer were diagnosed in 2022 and 43,250 women died of the disease. Globally, approximately 2.3 million new diagnoses and 685,000 breast cancer–related deaths were reported in 2020.

Tumor size, nodal spread, and distant metastases (TNM) at the time of diagnosis are key prognostic factors. Immunohistochemistry tumor markers (ie, estrogen receptor [ER], progesterone receptor [PR], and HER2), as well as grade and Ki-67 expression, have also been shown to be independent predictors of breast cancer death and are used together with TNM to guide treatment decisions.

Despite advances in breast cancer diagnosis and treatment, metastatic recurrence remains a significant problem. Although the incidence of distance relapse is declining and survival times for patients with recurrent disease are improving, 20%-30% of patients with early breast cancer still die of metastatic disease. Metastatic breast cancer recurrence can arise months to decades after initial diagnosis and treatment.

According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, biopsy is a critical component of the workup for patients with recurrent or stage IV disease. This is because biopsy ensures accurate determination of metastatic/recurrent disease and tumor histology and enables biomarker determination and selection of appropriate treatment. Soft-tissue tumor biopsy is preferred over bone sites unless a portion of the biopsy can be protected from harsh decalcification solution to preserve more accurate evaluation of biomarkers. Determination of HR status (ER and PR) and HER2 status should be repeated in all cases when diagnostic tissue is obtained because ER and PR assays may be falsely negative or falsely positive, and there may be discordance between the primary and metastatic tumors. According to the NCCN panel, re-testing the receptor status of recurrent disease should be performed, particularly when it was previously unknown, originally negative, or not overexpressed.

Additionally, the staging evaluation of patients who present with recurrent or stage IV breast cancer should include history and physical exam; a complete blood cell count, liver function tests, chest diagnostic CT, bone scan, and radiography of any long or weight-bearing bones that are painful or appear abnormal on bone scan; diagnostic CT of the abdomen (with or without diagnostic CT of the pelvis) or MRI of the abdomen; and biopsy documentation of first recurrence whenever possible. The use of sodium fluoride PET or PET/CT for evaluating patients with recurrent disease is generally discouraged.

Presently, metastatic breast cancer remains incurable. However, in recent years, the treatment landscape for metastatic breast cancer has significantly advanced in all breast cancer subtypes, leading to improvements in progression-free survival and even overall survival in some cases. For example, newer, targeted approaches directly address mutation drivers and allow precise delivery of chemotherapeutic agents. Detailed guidance on the treatment of breast cancer can be found here and in the full NCCN guidelines.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, Assistant Member, Department of Breast Oncology, Moffitt Cancer Center, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 62-year-old nonsmoking woman presents with progressive moderate to severe back pain. The patient has a history of endometriosis and node-positive invasive ductal breast cancer, which was diagnosed 15 years ago. The tumor was hormone receptor (HR)–positive and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)–negative. After a lumpectomy, she received adjuvant chemotherapy, followed by radiation therapy and 5 years of adjuvant oral endocrine therapy. Physical examination reveals several large palpable nodes in the right axillary region; no abnormalities are noted in either breast or the left axillary region.

The patient is 5 ft 7 in and weighs 152 lb (BMI, 23.8). At her last visit, 3 years earlier, she weighed 176 lb. She states her weight loss has been unintentional and began about 6 months ago. The patient denies any respiratory or abdominal symptoms; she does report increasing fatigue, which she attributes to her back pain. Complete blood cell count values are within normal range, except for an elevated alkaline phosphatase level (215 IU/L).

A subsequent axillary lymph node ultrasound reveals several irregular hypoechoic masses in the right axilla of various sizes, the largest being 2.4 cm. PET, CT, and a bone scan were also performed and revealed multiple suspicious lesions in the spine and several pulmonary nodules.

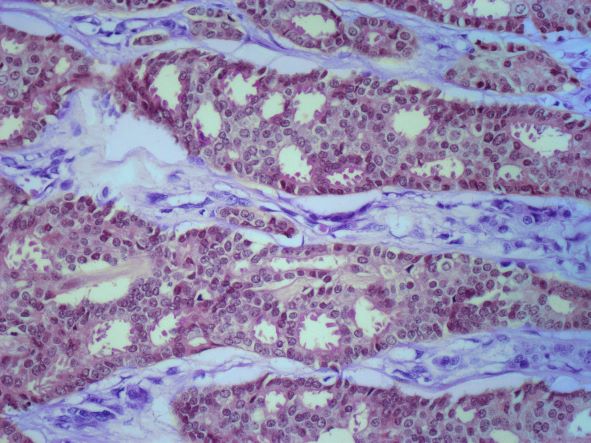

Cyclosporine-Induced Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome: An Adverse Effect in a Patient With Atopic Dermatitis

To the Editor:

Cyclosporine is an immunomodulatory medication that impacts T-lymphocyte function through calcineurin inhibition and suppression of IL-2 expression. Oral cyclosporine at low doses (1–3 mg/kg/d) is one of the more common systemic treatment options for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. At these doses it has been shown to have therapeutic benefit in several skin conditions, including chronic spontaneous urticaria,1 psoriasis,2 and atopic dermatitis.3 When used at higher doses for conditions such as glomerulonephritis or transplantation, adverse effects may be notable, and close monitoring of drug metabolism as well as end-organ function is required. In contrast, severe adverse effects are uncommon with the lower doses of cyclosporine used for cutaneous conditions, and monitoring serum drug levels is not routinely practiced.4

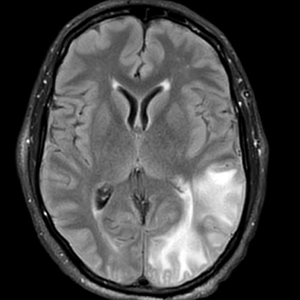

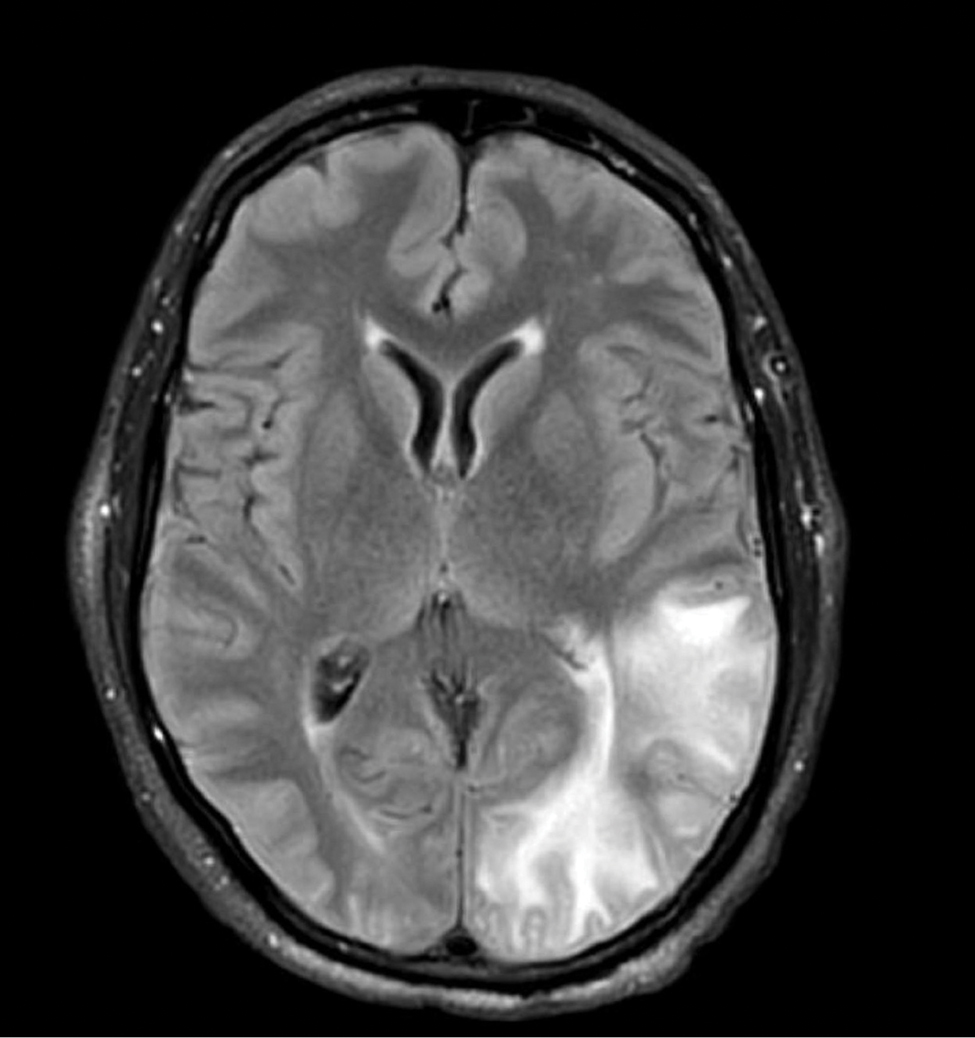

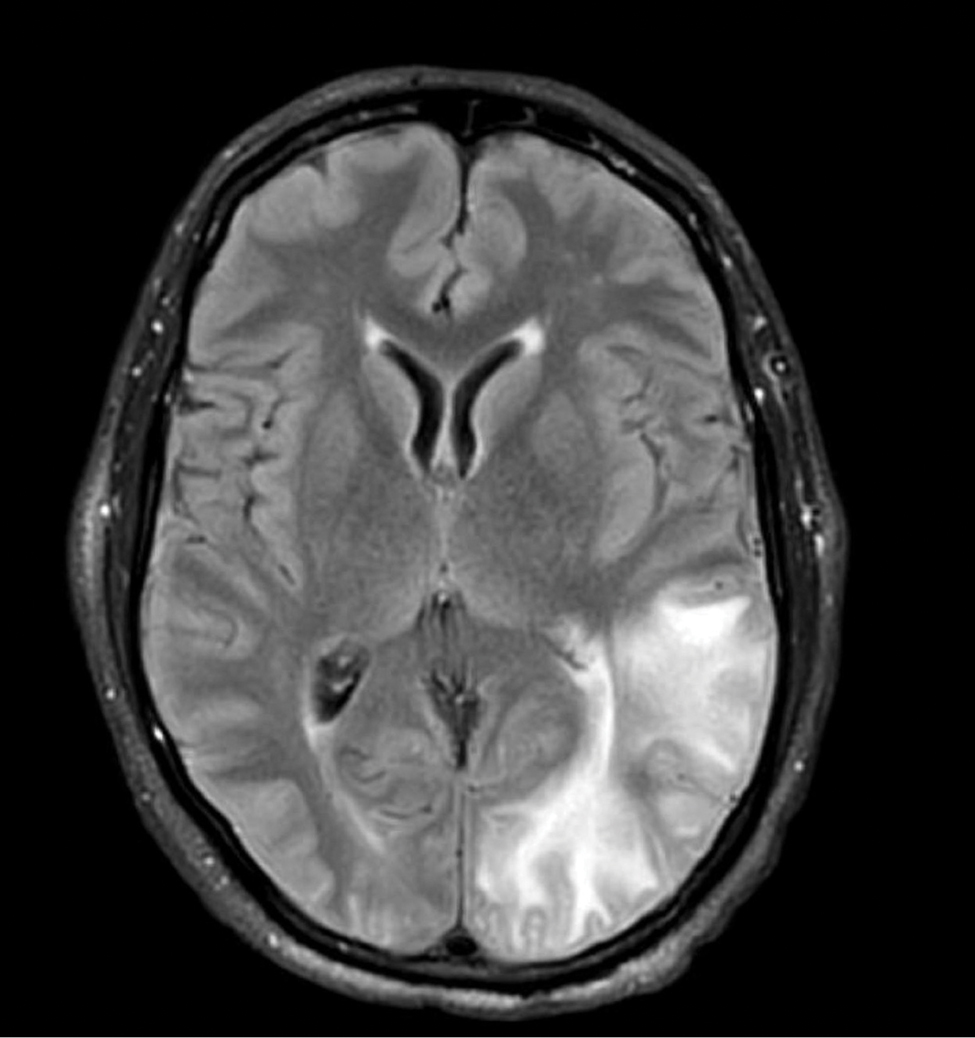

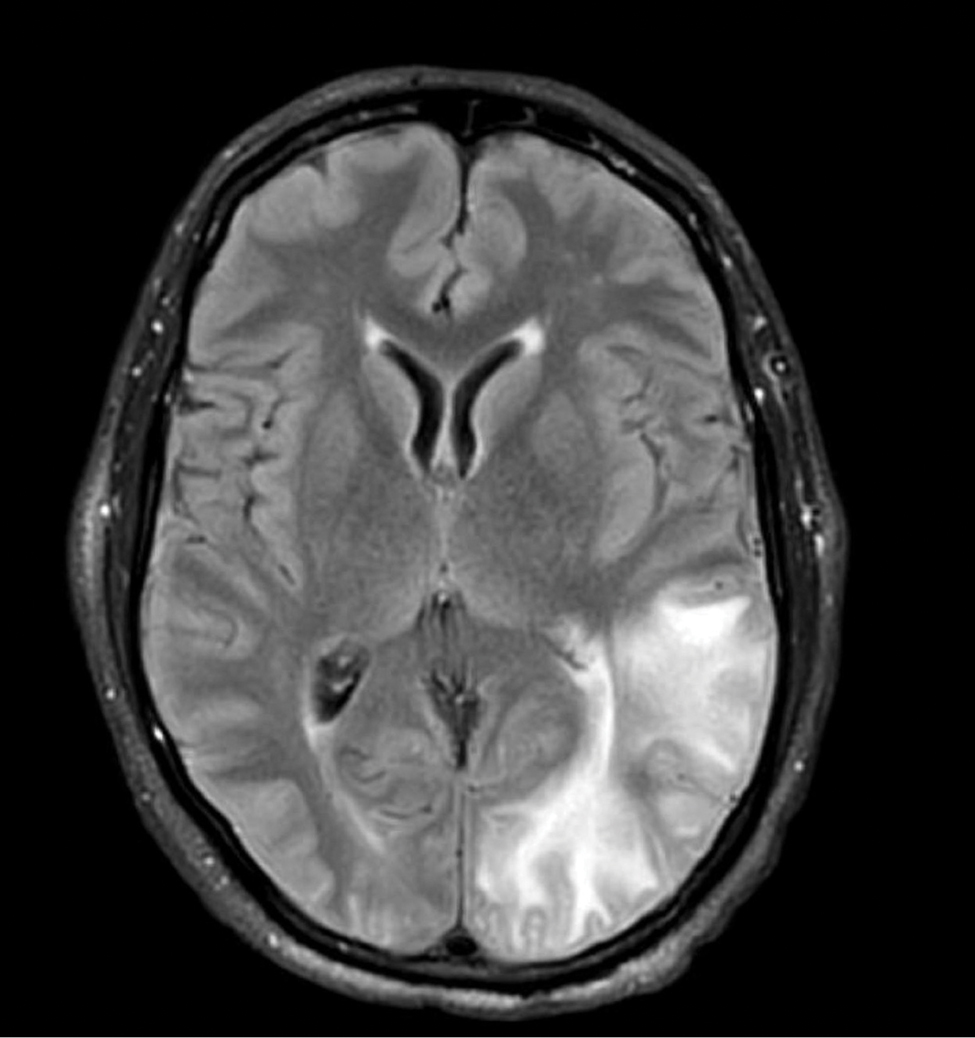

A 58-year-old man was referred to clinic with severe atopic dermatitis refractory to maximal topical therapy prescribed by an outside physician. He was started on cyclosporine as an anticipated bridge to dupilumab biologic therapy. He had no history of hypertension, renal disease, or hepatic insufficiency prior to starting therapy. He demonstrated notable clinical improvement at a cyclosporine dosage of 300 mg/d (equating to 3.7 mg/kg/d). Three months after initiation of therapy, the patient presented to a local emergency department with new-onset seizurelike activity, confusion, and agitation. He was normotensive with clinical concern for status epilepticus. An initial laboratory assessment included a complete blood cell count, serum electrolyte panel, and urine toxicology screen, which were unremarkable. Computed tomography of the head showed confluent white-matter hypodensities in the left parietal-temporal-occipital lobes. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed innumerable peripherally distributed foci of microhemorrhage and vasogenic edema within the left parietal-temporal-occipital lobes (Figure).

He was intubated and sedated with admission to the medical intensive care unit, where a random cyclosporine level drawn approximately 9 hours after the prior dose was noted to be 263 ng/mL. Although target therapeutic levels for cyclosporine vary based on indication, toxic supratherapeutic levels generally are considered to be greater than 400 ng/mL.5 He had no evidence of acute kidney injury, uremia, or hypertension throughout hospitalization. An electroencephalogram showed left parieto-occipital periodic epileptiform discharges with generalized slowing. Cyclosporine was discontinued, and he was started on levetiracetam. His clinical and neuroimaging findings improved over the course of the 1-week hospitalization without any further intervention. Four weeks after hospitalization, he had full neurologic, electroencephalogram, and imaging recovery. Based on the presenting symptoms, transient neuroimaging findings, and full recovery with discontinuation of cyclosporine, the patient was diagnosed with cyclosporine-induced posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES).

The diagnosis of PRES requires evidence of acute neurologic symptoms and radiographic findings of cortical/subcortical white-matter changes on computed tomography or MRI consistent with edema. The pathophysiology is not fully understood but appears to be related to vasogenic edema, primarily impacting the posterior aspect of the brain. There have been many reported offending agents, and symptoms typically resolve following cessation of these medications. Cases of cyclosporine-induced PRES have been reported, but most occurred at higher doses within weeks of medication initiation. Two cases of cyclosporine-induced PRES treated with cutaneous dosing have been reported; neither patient was taking it for atopic dermatitis.6

Cyclosporine-induced PRES remains a pathophysiologic conundrum. However, there is evidence to support direct endothelial damage causing cellular apoptosis in the brain of mouse models that is medication specific and not necessarily related to the dosages used.7 Our case highlights a rare but important adverse event associated with even low-dose cyclosporine use that should be considered in patients currently taking cyclosporine who present with acute neurologic changes.

- Kulthanan K, Chaweekulrat P, Komoltri C, et al. Cyclosporine for chronic spontaneous urticaria: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:586-599. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.07.017

- Armstrong AW, Read C. Pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and treatment of psoriasis: a review. JAMA. 2020;323:1945-1960. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.4006

- Seger EW, Wechter T, Strowd L, et al. Relative efficacy of systemic treatments for atopic dermatitis [published online October 6, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:411-416.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.053

- Blake SC, Murrell DF. Monitoring trough levels in cyclosporine for atopic dermatitis: a systematic review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:843-853. doi:10.1111/pde.13999

- Tapia C, Nessel TA, Zito PM. Cyclosporine. StatPearls Publishing: 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482450/

- Cosottini M, Lazzarotti G, Ceravolo R, et al. Cyclosporine‐related posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) in non‐transplant patient: a case report and literature review. Eur J Neurol. 2003;10:461-462. doi:10.1046/j.1468-1331.2003.00608_1.x

- Kochi S, Takanaga H, Matsuo H, et al. Induction of apoptosis in mouse brain capillary endothelial cells by cyclosporin A and tacrolimus. Life Sci. 2000;66:2255-2260. doi:10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00554-3

To the Editor:

Cyclosporine is an immunomodulatory medication that impacts T-lymphocyte function through calcineurin inhibition and suppression of IL-2 expression. Oral cyclosporine at low doses (1–3 mg/kg/d) is one of the more common systemic treatment options for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. At these doses it has been shown to have therapeutic benefit in several skin conditions, including chronic spontaneous urticaria,1 psoriasis,2 and atopic dermatitis.3 When used at higher doses for conditions such as glomerulonephritis or transplantation, adverse effects may be notable, and close monitoring of drug metabolism as well as end-organ function is required. In contrast, severe adverse effects are uncommon with the lower doses of cyclosporine used for cutaneous conditions, and monitoring serum drug levels is not routinely practiced.4

A 58-year-old man was referred to clinic with severe atopic dermatitis refractory to maximal topical therapy prescribed by an outside physician. He was started on cyclosporine as an anticipated bridge to dupilumab biologic therapy. He had no history of hypertension, renal disease, or hepatic insufficiency prior to starting therapy. He demonstrated notable clinical improvement at a cyclosporine dosage of 300 mg/d (equating to 3.7 mg/kg/d). Three months after initiation of therapy, the patient presented to a local emergency department with new-onset seizurelike activity, confusion, and agitation. He was normotensive with clinical concern for status epilepticus. An initial laboratory assessment included a complete blood cell count, serum electrolyte panel, and urine toxicology screen, which were unremarkable. Computed tomography of the head showed confluent white-matter hypodensities in the left parietal-temporal-occipital lobes. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed innumerable peripherally distributed foci of microhemorrhage and vasogenic edema within the left parietal-temporal-occipital lobes (Figure).