User login

Measles Resurgence: A Dermatologist’s Guide

Measles Resurgence: A Dermatologist’s Guide

Measles, also known as rubeola, is a highly contagious paramyxovirus that has neared elimination in the United States since 2000 due to widespread adoption of the measles vaccine; however, measles recently has made a comeback, with outbreaks reported in more than 60 countries. In the United States, vaccine hesitancy coupled with decreasing vaccination rates, international travel to endemic areas, and decreased funding and resources for monitoring and immunization programs likely led to a re-emergence of measles cases.1,2 The resurgence of measles is troubling given its infectiousness and potential severity in at-risk populations. Since measles has a basic reproduction number of 12 to 18 (ie, 1 infected individual will on average infect 12 to 18 others3), it has the capacity to spread quickly. This is why, prior to the development of the measles vaccine in the 1960s, it was responsible for millions of deaths across the globe.

Prior to the introduction of the measles vaccine, both physicians and the public generally were aware of the signs and symptoms of measles due to its prevalence; however, since there have been so few cases in recent decades, images and descriptions of patients presenting with measles can be found only in textbooks, and many physicians are ill-prepared to diagnose the disease.4 In response to the recent surge in measles cases, dermatologists—who often are among the first medical professionals to encounter febrile patients with rashes—must be prepared to bridge this divide. Herein, we review the clinical signs, diagnostic approach, operational precautions, and public health responsibilities that dermatologists must relearn amid the current measles outbreak.

Background

Measles is primarily transmitted via respiratory droplets and may remain airborne for up to 2 hours.5 It also can be transmitted through direct contact with secretions such as mucus. Indirect transmission via fomites, while certainly plausible, is thought to be the least effective mechanism of transmission.6 Following exposure, the incubation period ranges from 7 to 21 days, during which the virus replicates asymptomatically before causing clinical disease.7 Herd immunity for measles requires 93% immunity in the population; public health agencies typically target greater than 95% immunity.8 Humans are the only reservoir for the measles virus, making eradication possible.

The road to eradication began with the introduction of the measles vaccine in 1963 and subsequent development of the combined measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine in 1971. As MMR is a live vaccine, 2 doses confer approximately 97% protection.9 The first dose is given at 12 to 15 months of age, and the second dose is given at 4 to 6 years of age. Immunity is considered lifelong, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization do not recommend routine measles boosters for individuals who have completed the primary 2-dose series.10,11

Widespread vaccination led to a dramatic reduction in incidence, with many countries eliminating measles infections.7 The United States declared measles eliminated in 2000, with confirmed cases between 2000 and 2020 ranging from 37 to 1282.12 Vaccination progress stalled in the late 1990s due to vaccine hesitancy resulting from (subsequently debunked) reports of an association between the MMR vaccine and autism.13 Despite efforts to correct this misinformation, many patients continue to espouse these concerns.

Recognizing Measles: Clinical Presentation

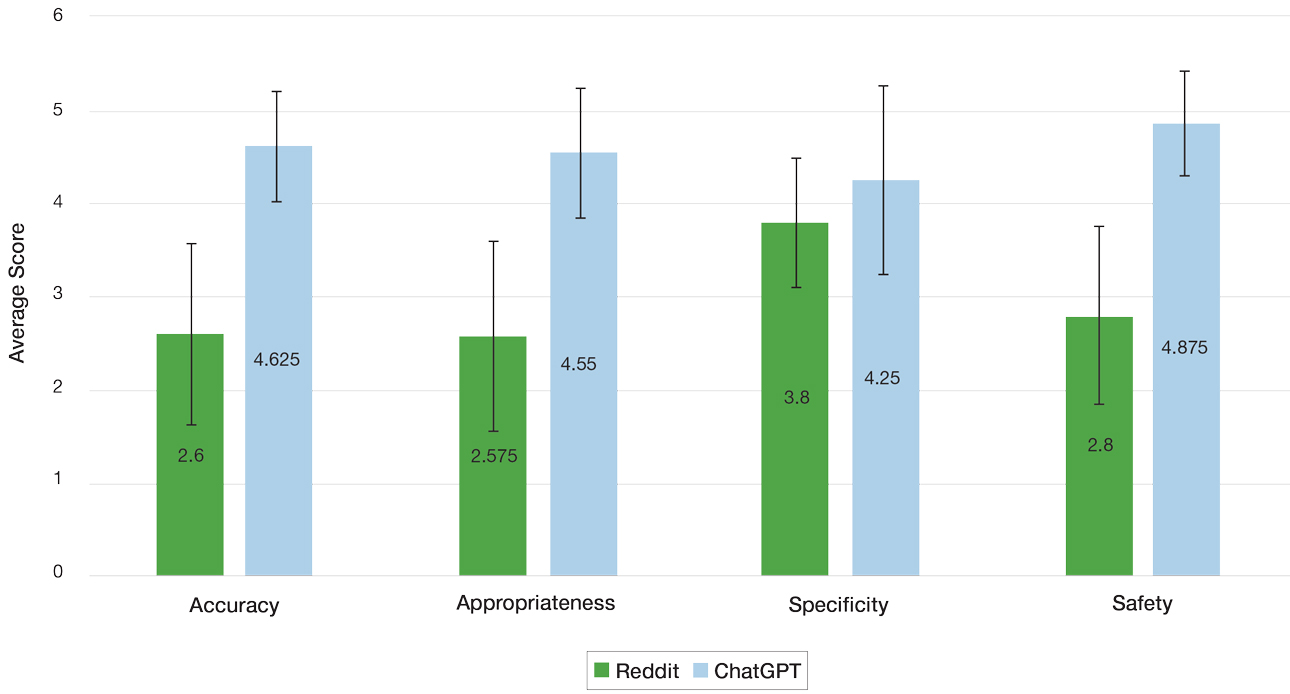

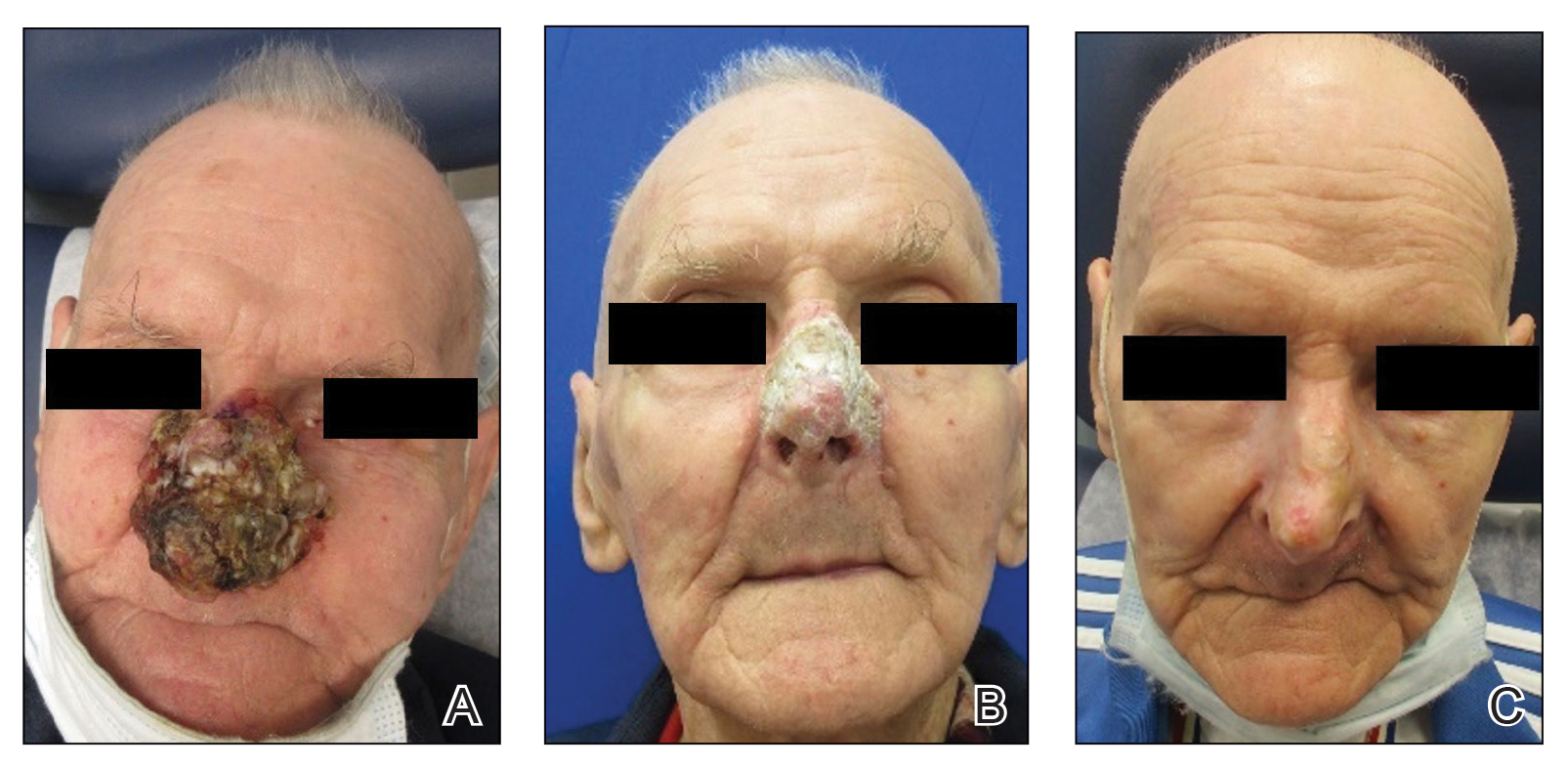

Measles, which most often manifests in childhood but also can occur in adults, follows a distinctive clinical course. The prodromal phase is characterized by high fever, cough, coryza (nasal congestion), and conjunctivitis— conjunctivitis—the 3 “Cs” that serve as early warning signs of the disease. Patients may develop small white macules on the buccal mucosa known as Koplik spots (phonetically the fourth “C”), which appear just before the rash. Three to 5 days after the onset of systemic symptoms, patients will develop a classic morbilliform exanthem. In some cases, the exanthem manifests on the head and neck (Figure 1)—first behind the ears and along the hairline, then spreading caudally to the trunk and extremities. The lesions may become confluent, with patients presenting with diffuse erythema. The exanthem fades over several days to weeks, often accompanied by superficial desquamation.14

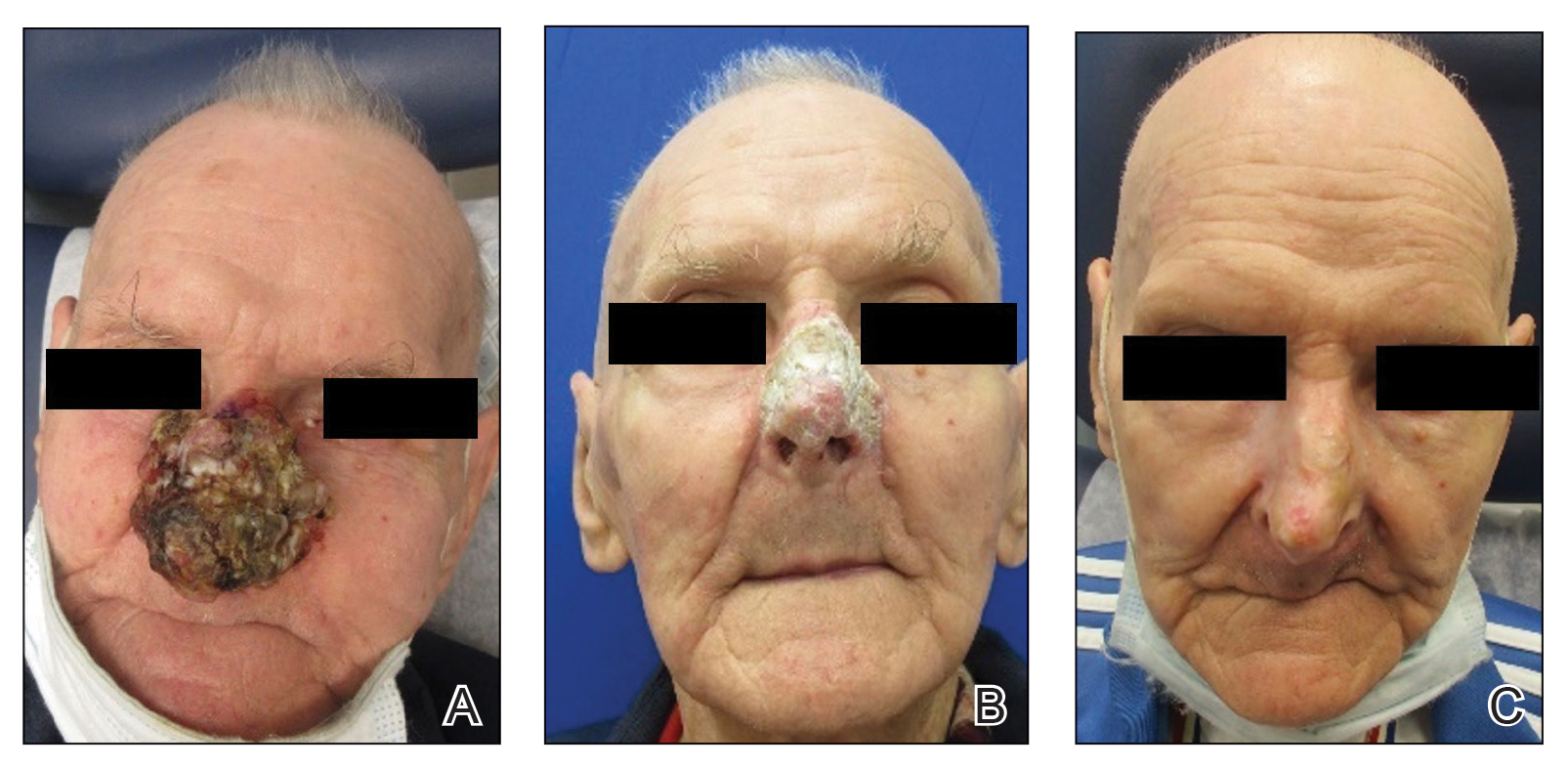

Given the nonspecificity of the early symptoms of measles, a high index of suspicion is needed for patients presenting with a febrile illness and a morbilliform eruption (Figure 2). Consideration of MMR vaccination status, exposure history, and local outbreak patterns can help guide risk stratification and the need for testing. Immunocompromised individuals, including those receiving immunosuppressive therapies for dermatologic conditions, may present atypically, lacking the prototypical exanthem or displaying milder signs and further complicating the diagnosis.15 The differential diagnosis for measles includes a drug reaction or other viral exanthem, and a detailed history may help elucidate the culprit.

Evaluation and Diagnosis

Definitive diagnosis of measles relies on both molecular and serologic testing. Nasopharyngeal swabs for measles polymerase chain reaction testing are obtained using synthetic (noncotton) swabs placed in a viral transport medium. Serum samples also should be collected for measles IgM and IgG antibody testing. Importantly, measles is a reportable illness, and testing may be coordinated with local departments of health.

Determining a patient’s immune status may be important for certain populations. Patients with documented 2-dose MMR vaccination, positive measles IgG serology, or a prior confirmed measles infection are considered immune. While a positive measles IgG indicates immunity, a negative result in an exposed patient should prompt consideration of postexposure prophylaxis with intravenous immunoglobulin.

Many patients, specifically those presenting to dermatology, are taking immunomodulatory or immunosuppressive medications—a contraindication for vaccination with the live MMR vaccine. At the time of publication, there was a single reported case of a patient taking a tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor for rheumatoid arthritis who had acquired measles.16 While the benefits of titer assessment in patients who are starting or continuing immunomodulatory therapy are not known and currently it is not recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, dermatologists might consider checking MMR titers and vaccinating (or referring for vaccination) nonimmune patients.17

Infection Control

Early identification of a suspected measles case is paramount. Patients in whom measles is a possibility should be isolated as quickly as possible, and the patient and accompanying caregivers should be masked. Clinical staff should don appropriate personal protective equipment, including an N95 mask. Coordination with the local department of health must occur as soon as measles is suspected.

If testing is an option in the outpatient setting, a nasopharyngeal viral swab and serologic titers can be obtained. If testing is not available on site, patients should be sent to appropriate care facilities; prenotification is critical to prevent nosocomial outbreaks. Patients should be encouraged to isolate and avoid public spaces and/or public transport for 4 days following development of an exanthem.18 Offices should develop clinical protocols for suspected measles cases with training for clinical and office staff.

Final Thoughts

As measles outbreaks become more prevalent, it is incumbent upon physicians to remind ourselves of the signs and symptoms of this largely eliminated disease so that we may pursue early detection and intervention strategies. The primary cutaneous manifestations of measles make dermatologists critical to early recognition and containment efforts. Dermatologists should prepare for the arrival of patients with measles by maintaining vigilance for the classic signs of the disease, implementing stringent isolation protocols, verifying patient immunity when appropriate, and partnering closely with public health authorities.

More broadly, efforts to contain and re-establish a paradigm for eliminating measles outbreaks must be pursued. Encouraging vaccination and developing programs to help combat misinformation surrounding vaccines are critical to this effort. In an era of vaccine hesitancy, measles is a multidisciplinary public health emergency. Dermatologists must remain ready.

- Bedford H, Elliman D. Measles rates are rising again. BMJ. 2024;384.

- Harris E. Measles outbreaks grow amid declining vaccination rates. JAMA. 2023;330:2242.

- Guerra FM, Bolotin S, Lim G, et al. The basic reproduction number (R0) of measles: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:E420-E428.

- Swartz MK. Measles: public and professional education. J Pediatr Health Care. 2019;33:367-368.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for measles in healthcare settings. Accessed April 27, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/infection-control/hcp/measles/

- Moss WJ, Griffin DE, Feinstone WH. Measles. In: Vaccines for Biodefense and Emerging and Neglected Diseases. Elsevier; 2009: 551-565.

- Moss WJ. Measles. Lancet. 2017;390:2490-2502.

- Maintain the vaccination coverage level of 2 doses of the MMR vaccine for children in kindergarten— IID04. Healthy People 2030 website. Accessed May 6, 2025. https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/vaccination/maintain-vaccination-coverage-level-2-doses-mmr-vaccine-children-kindergarten-iid-04

- Franconeri L, Antona D, Cauchemez S, et al. Two-dose measles vaccine effectiveness remains high over time: a French observational study, 2017–2019. Vaccine. 2023;41:5797-5804.

- World Health Organization. Measles. Accessed May 8, 2025. https:// www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/measles

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles vaccine recommendations. Accessed May 8, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/hcp/vaccine-considerations/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles cases and outbreaks. Accessed May 6, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/cases-outbreaks.html

- Dyer C. Lancet retracts Wakefield’s MMR paper. BMJ. 2010;340.

- Alves Graber EM, Andrade FJ, Bost W, et al. An update and review of measles for emergency physicians. J Emerg Med. 2020;58:610-615.

- Kaplan LJ, Daum RS, Smaron M, et al. Severe measles in immunocompromised patients. JAMA. 1992;267:1237-1241.

- Takahashi E, Kurosaka D, Yoshida K, et al. Onset of modified measles after etanercept treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. Japanese J Clin Immunol. 2010;33:37-41.

- Worth A, Waldman RA, Dieckhaus K, et al. Art of prevention: our approach to the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine in adult patients vaccinated against measles before 1968 on biologic therapy for the treatment of psoriasis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;6:94.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical overview of measles (rubeola). Accessed May 8, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/hcp/clinical-overview/index.html

Measles, also known as rubeola, is a highly contagious paramyxovirus that has neared elimination in the United States since 2000 due to widespread adoption of the measles vaccine; however, measles recently has made a comeback, with outbreaks reported in more than 60 countries. In the United States, vaccine hesitancy coupled with decreasing vaccination rates, international travel to endemic areas, and decreased funding and resources for monitoring and immunization programs likely led to a re-emergence of measles cases.1,2 The resurgence of measles is troubling given its infectiousness and potential severity in at-risk populations. Since measles has a basic reproduction number of 12 to 18 (ie, 1 infected individual will on average infect 12 to 18 others3), it has the capacity to spread quickly. This is why, prior to the development of the measles vaccine in the 1960s, it was responsible for millions of deaths across the globe.

Prior to the introduction of the measles vaccine, both physicians and the public generally were aware of the signs and symptoms of measles due to its prevalence; however, since there have been so few cases in recent decades, images and descriptions of patients presenting with measles can be found only in textbooks, and many physicians are ill-prepared to diagnose the disease.4 In response to the recent surge in measles cases, dermatologists—who often are among the first medical professionals to encounter febrile patients with rashes—must be prepared to bridge this divide. Herein, we review the clinical signs, diagnostic approach, operational precautions, and public health responsibilities that dermatologists must relearn amid the current measles outbreak.

Background

Measles is primarily transmitted via respiratory droplets and may remain airborne for up to 2 hours.5 It also can be transmitted through direct contact with secretions such as mucus. Indirect transmission via fomites, while certainly plausible, is thought to be the least effective mechanism of transmission.6 Following exposure, the incubation period ranges from 7 to 21 days, during which the virus replicates asymptomatically before causing clinical disease.7 Herd immunity for measles requires 93% immunity in the population; public health agencies typically target greater than 95% immunity.8 Humans are the only reservoir for the measles virus, making eradication possible.

The road to eradication began with the introduction of the measles vaccine in 1963 and subsequent development of the combined measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine in 1971. As MMR is a live vaccine, 2 doses confer approximately 97% protection.9 The first dose is given at 12 to 15 months of age, and the second dose is given at 4 to 6 years of age. Immunity is considered lifelong, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization do not recommend routine measles boosters for individuals who have completed the primary 2-dose series.10,11

Widespread vaccination led to a dramatic reduction in incidence, with many countries eliminating measles infections.7 The United States declared measles eliminated in 2000, with confirmed cases between 2000 and 2020 ranging from 37 to 1282.12 Vaccination progress stalled in the late 1990s due to vaccine hesitancy resulting from (subsequently debunked) reports of an association between the MMR vaccine and autism.13 Despite efforts to correct this misinformation, many patients continue to espouse these concerns.

Recognizing Measles: Clinical Presentation

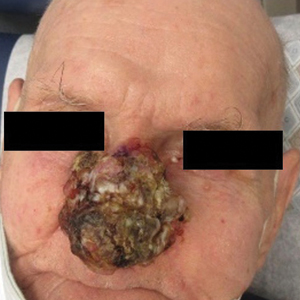

Measles, which most often manifests in childhood but also can occur in adults, follows a distinctive clinical course. The prodromal phase is characterized by high fever, cough, coryza (nasal congestion), and conjunctivitis— conjunctivitis—the 3 “Cs” that serve as early warning signs of the disease. Patients may develop small white macules on the buccal mucosa known as Koplik spots (phonetically the fourth “C”), which appear just before the rash. Three to 5 days after the onset of systemic symptoms, patients will develop a classic morbilliform exanthem. In some cases, the exanthem manifests on the head and neck (Figure 1)—first behind the ears and along the hairline, then spreading caudally to the trunk and extremities. The lesions may become confluent, with patients presenting with diffuse erythema. The exanthem fades over several days to weeks, often accompanied by superficial desquamation.14

Given the nonspecificity of the early symptoms of measles, a high index of suspicion is needed for patients presenting with a febrile illness and a morbilliform eruption (Figure 2). Consideration of MMR vaccination status, exposure history, and local outbreak patterns can help guide risk stratification and the need for testing. Immunocompromised individuals, including those receiving immunosuppressive therapies for dermatologic conditions, may present atypically, lacking the prototypical exanthem or displaying milder signs and further complicating the diagnosis.15 The differential diagnosis for measles includes a drug reaction or other viral exanthem, and a detailed history may help elucidate the culprit.

Evaluation and Diagnosis

Definitive diagnosis of measles relies on both molecular and serologic testing. Nasopharyngeal swabs for measles polymerase chain reaction testing are obtained using synthetic (noncotton) swabs placed in a viral transport medium. Serum samples also should be collected for measles IgM and IgG antibody testing. Importantly, measles is a reportable illness, and testing may be coordinated with local departments of health.

Determining a patient’s immune status may be important for certain populations. Patients with documented 2-dose MMR vaccination, positive measles IgG serology, or a prior confirmed measles infection are considered immune. While a positive measles IgG indicates immunity, a negative result in an exposed patient should prompt consideration of postexposure prophylaxis with intravenous immunoglobulin.

Many patients, specifically those presenting to dermatology, are taking immunomodulatory or immunosuppressive medications—a contraindication for vaccination with the live MMR vaccine. At the time of publication, there was a single reported case of a patient taking a tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor for rheumatoid arthritis who had acquired measles.16 While the benefits of titer assessment in patients who are starting or continuing immunomodulatory therapy are not known and currently it is not recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, dermatologists might consider checking MMR titers and vaccinating (or referring for vaccination) nonimmune patients.17

Infection Control

Early identification of a suspected measles case is paramount. Patients in whom measles is a possibility should be isolated as quickly as possible, and the patient and accompanying caregivers should be masked. Clinical staff should don appropriate personal protective equipment, including an N95 mask. Coordination with the local department of health must occur as soon as measles is suspected.

If testing is an option in the outpatient setting, a nasopharyngeal viral swab and serologic titers can be obtained. If testing is not available on site, patients should be sent to appropriate care facilities; prenotification is critical to prevent nosocomial outbreaks. Patients should be encouraged to isolate and avoid public spaces and/or public transport for 4 days following development of an exanthem.18 Offices should develop clinical protocols for suspected measles cases with training for clinical and office staff.

Final Thoughts

As measles outbreaks become more prevalent, it is incumbent upon physicians to remind ourselves of the signs and symptoms of this largely eliminated disease so that we may pursue early detection and intervention strategies. The primary cutaneous manifestations of measles make dermatologists critical to early recognition and containment efforts. Dermatologists should prepare for the arrival of patients with measles by maintaining vigilance for the classic signs of the disease, implementing stringent isolation protocols, verifying patient immunity when appropriate, and partnering closely with public health authorities.

More broadly, efforts to contain and re-establish a paradigm for eliminating measles outbreaks must be pursued. Encouraging vaccination and developing programs to help combat misinformation surrounding vaccines are critical to this effort. In an era of vaccine hesitancy, measles is a multidisciplinary public health emergency. Dermatologists must remain ready.

Measles, also known as rubeola, is a highly contagious paramyxovirus that has neared elimination in the United States since 2000 due to widespread adoption of the measles vaccine; however, measles recently has made a comeback, with outbreaks reported in more than 60 countries. In the United States, vaccine hesitancy coupled with decreasing vaccination rates, international travel to endemic areas, and decreased funding and resources for monitoring and immunization programs likely led to a re-emergence of measles cases.1,2 The resurgence of measles is troubling given its infectiousness and potential severity in at-risk populations. Since measles has a basic reproduction number of 12 to 18 (ie, 1 infected individual will on average infect 12 to 18 others3), it has the capacity to spread quickly. This is why, prior to the development of the measles vaccine in the 1960s, it was responsible for millions of deaths across the globe.

Prior to the introduction of the measles vaccine, both physicians and the public generally were aware of the signs and symptoms of measles due to its prevalence; however, since there have been so few cases in recent decades, images and descriptions of patients presenting with measles can be found only in textbooks, and many physicians are ill-prepared to diagnose the disease.4 In response to the recent surge in measles cases, dermatologists—who often are among the first medical professionals to encounter febrile patients with rashes—must be prepared to bridge this divide. Herein, we review the clinical signs, diagnostic approach, operational precautions, and public health responsibilities that dermatologists must relearn amid the current measles outbreak.

Background

Measles is primarily transmitted via respiratory droplets and may remain airborne for up to 2 hours.5 It also can be transmitted through direct contact with secretions such as mucus. Indirect transmission via fomites, while certainly plausible, is thought to be the least effective mechanism of transmission.6 Following exposure, the incubation period ranges from 7 to 21 days, during which the virus replicates asymptomatically before causing clinical disease.7 Herd immunity for measles requires 93% immunity in the population; public health agencies typically target greater than 95% immunity.8 Humans are the only reservoir for the measles virus, making eradication possible.

The road to eradication began with the introduction of the measles vaccine in 1963 and subsequent development of the combined measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine in 1971. As MMR is a live vaccine, 2 doses confer approximately 97% protection.9 The first dose is given at 12 to 15 months of age, and the second dose is given at 4 to 6 years of age. Immunity is considered lifelong, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization do not recommend routine measles boosters for individuals who have completed the primary 2-dose series.10,11

Widespread vaccination led to a dramatic reduction in incidence, with many countries eliminating measles infections.7 The United States declared measles eliminated in 2000, with confirmed cases between 2000 and 2020 ranging from 37 to 1282.12 Vaccination progress stalled in the late 1990s due to vaccine hesitancy resulting from (subsequently debunked) reports of an association between the MMR vaccine and autism.13 Despite efforts to correct this misinformation, many patients continue to espouse these concerns.

Recognizing Measles: Clinical Presentation

Measles, which most often manifests in childhood but also can occur in adults, follows a distinctive clinical course. The prodromal phase is characterized by high fever, cough, coryza (nasal congestion), and conjunctivitis— conjunctivitis—the 3 “Cs” that serve as early warning signs of the disease. Patients may develop small white macules on the buccal mucosa known as Koplik spots (phonetically the fourth “C”), which appear just before the rash. Three to 5 days after the onset of systemic symptoms, patients will develop a classic morbilliform exanthem. In some cases, the exanthem manifests on the head and neck (Figure 1)—first behind the ears and along the hairline, then spreading caudally to the trunk and extremities. The lesions may become confluent, with patients presenting with diffuse erythema. The exanthem fades over several days to weeks, often accompanied by superficial desquamation.14

Given the nonspecificity of the early symptoms of measles, a high index of suspicion is needed for patients presenting with a febrile illness and a morbilliform eruption (Figure 2). Consideration of MMR vaccination status, exposure history, and local outbreak patterns can help guide risk stratification and the need for testing. Immunocompromised individuals, including those receiving immunosuppressive therapies for dermatologic conditions, may present atypically, lacking the prototypical exanthem or displaying milder signs and further complicating the diagnosis.15 The differential diagnosis for measles includes a drug reaction or other viral exanthem, and a detailed history may help elucidate the culprit.

Evaluation and Diagnosis

Definitive diagnosis of measles relies on both molecular and serologic testing. Nasopharyngeal swabs for measles polymerase chain reaction testing are obtained using synthetic (noncotton) swabs placed in a viral transport medium. Serum samples also should be collected for measles IgM and IgG antibody testing. Importantly, measles is a reportable illness, and testing may be coordinated with local departments of health.

Determining a patient’s immune status may be important for certain populations. Patients with documented 2-dose MMR vaccination, positive measles IgG serology, or a prior confirmed measles infection are considered immune. While a positive measles IgG indicates immunity, a negative result in an exposed patient should prompt consideration of postexposure prophylaxis with intravenous immunoglobulin.

Many patients, specifically those presenting to dermatology, are taking immunomodulatory or immunosuppressive medications—a contraindication for vaccination with the live MMR vaccine. At the time of publication, there was a single reported case of a patient taking a tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor for rheumatoid arthritis who had acquired measles.16 While the benefits of titer assessment in patients who are starting or continuing immunomodulatory therapy are not known and currently it is not recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, dermatologists might consider checking MMR titers and vaccinating (or referring for vaccination) nonimmune patients.17

Infection Control

Early identification of a suspected measles case is paramount. Patients in whom measles is a possibility should be isolated as quickly as possible, and the patient and accompanying caregivers should be masked. Clinical staff should don appropriate personal protective equipment, including an N95 mask. Coordination with the local department of health must occur as soon as measles is suspected.

If testing is an option in the outpatient setting, a nasopharyngeal viral swab and serologic titers can be obtained. If testing is not available on site, patients should be sent to appropriate care facilities; prenotification is critical to prevent nosocomial outbreaks. Patients should be encouraged to isolate and avoid public spaces and/or public transport for 4 days following development of an exanthem.18 Offices should develop clinical protocols for suspected measles cases with training for clinical and office staff.

Final Thoughts

As measles outbreaks become more prevalent, it is incumbent upon physicians to remind ourselves of the signs and symptoms of this largely eliminated disease so that we may pursue early detection and intervention strategies. The primary cutaneous manifestations of measles make dermatologists critical to early recognition and containment efforts. Dermatologists should prepare for the arrival of patients with measles by maintaining vigilance for the classic signs of the disease, implementing stringent isolation protocols, verifying patient immunity when appropriate, and partnering closely with public health authorities.

More broadly, efforts to contain and re-establish a paradigm for eliminating measles outbreaks must be pursued. Encouraging vaccination and developing programs to help combat misinformation surrounding vaccines are critical to this effort. In an era of vaccine hesitancy, measles is a multidisciplinary public health emergency. Dermatologists must remain ready.

- Bedford H, Elliman D. Measles rates are rising again. BMJ. 2024;384.

- Harris E. Measles outbreaks grow amid declining vaccination rates. JAMA. 2023;330:2242.

- Guerra FM, Bolotin S, Lim G, et al. The basic reproduction number (R0) of measles: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:E420-E428.

- Swartz MK. Measles: public and professional education. J Pediatr Health Care. 2019;33:367-368.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for measles in healthcare settings. Accessed April 27, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/infection-control/hcp/measles/

- Moss WJ, Griffin DE, Feinstone WH. Measles. In: Vaccines for Biodefense and Emerging and Neglected Diseases. Elsevier; 2009: 551-565.

- Moss WJ. Measles. Lancet. 2017;390:2490-2502.

- Maintain the vaccination coverage level of 2 doses of the MMR vaccine for children in kindergarten— IID04. Healthy People 2030 website. Accessed May 6, 2025. https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/vaccination/maintain-vaccination-coverage-level-2-doses-mmr-vaccine-children-kindergarten-iid-04

- Franconeri L, Antona D, Cauchemez S, et al. Two-dose measles vaccine effectiveness remains high over time: a French observational study, 2017–2019. Vaccine. 2023;41:5797-5804.

- World Health Organization. Measles. Accessed May 8, 2025. https:// www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/measles

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles vaccine recommendations. Accessed May 8, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/hcp/vaccine-considerations/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles cases and outbreaks. Accessed May 6, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/cases-outbreaks.html

- Dyer C. Lancet retracts Wakefield’s MMR paper. BMJ. 2010;340.

- Alves Graber EM, Andrade FJ, Bost W, et al. An update and review of measles for emergency physicians. J Emerg Med. 2020;58:610-615.

- Kaplan LJ, Daum RS, Smaron M, et al. Severe measles in immunocompromised patients. JAMA. 1992;267:1237-1241.

- Takahashi E, Kurosaka D, Yoshida K, et al. Onset of modified measles after etanercept treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. Japanese J Clin Immunol. 2010;33:37-41.

- Worth A, Waldman RA, Dieckhaus K, et al. Art of prevention: our approach to the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine in adult patients vaccinated against measles before 1968 on biologic therapy for the treatment of psoriasis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;6:94.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical overview of measles (rubeola). Accessed May 8, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/hcp/clinical-overview/index.html

- Bedford H, Elliman D. Measles rates are rising again. BMJ. 2024;384.

- Harris E. Measles outbreaks grow amid declining vaccination rates. JAMA. 2023;330:2242.

- Guerra FM, Bolotin S, Lim G, et al. The basic reproduction number (R0) of measles: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:E420-E428.

- Swartz MK. Measles: public and professional education. J Pediatr Health Care. 2019;33:367-368.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for measles in healthcare settings. Accessed April 27, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/infection-control/hcp/measles/

- Moss WJ, Griffin DE, Feinstone WH. Measles. In: Vaccines for Biodefense and Emerging and Neglected Diseases. Elsevier; 2009: 551-565.

- Moss WJ. Measles. Lancet. 2017;390:2490-2502.

- Maintain the vaccination coverage level of 2 doses of the MMR vaccine for children in kindergarten— IID04. Healthy People 2030 website. Accessed May 6, 2025. https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/vaccination/maintain-vaccination-coverage-level-2-doses-mmr-vaccine-children-kindergarten-iid-04

- Franconeri L, Antona D, Cauchemez S, et al. Two-dose measles vaccine effectiveness remains high over time: a French observational study, 2017–2019. Vaccine. 2023;41:5797-5804.

- World Health Organization. Measles. Accessed May 8, 2025. https:// www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/measles

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles vaccine recommendations. Accessed May 8, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/hcp/vaccine-considerations/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles cases and outbreaks. Accessed May 6, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/cases-outbreaks.html

- Dyer C. Lancet retracts Wakefield’s MMR paper. BMJ. 2010;340.

- Alves Graber EM, Andrade FJ, Bost W, et al. An update and review of measles for emergency physicians. J Emerg Med. 2020;58:610-615.

- Kaplan LJ, Daum RS, Smaron M, et al. Severe measles in immunocompromised patients. JAMA. 1992;267:1237-1241.

- Takahashi E, Kurosaka D, Yoshida K, et al. Onset of modified measles after etanercept treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. Japanese J Clin Immunol. 2010;33:37-41.

- Worth A, Waldman RA, Dieckhaus K, et al. Art of prevention: our approach to the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine in adult patients vaccinated against measles before 1968 on biologic therapy for the treatment of psoriasis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;6:94.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical overview of measles (rubeola). Accessed May 8, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/hcp/clinical-overview/index.html

Measles Resurgence: A Dermatologist’s Guide

Measles Resurgence: A Dermatologist’s Guide

Immune Responses and Health Disparities Warrant Scabies Vaccine Development

Immune Responses and Health Disparities Warrant Scabies Vaccine Development

The scabies mite, originally known as Acarus scabiei,1 now is considered an arthropod of the class Arachnida, order Astigmata, and family Sarcoptidae.2 Scabies mites are able to adhere to the surface of human skin.3 The mites burrow and lay eggs in the top layer of the epidermis; most patients have 10 to 15 mites.3 The patient’s immune system incites an allergic reaction to the mite protein and feces in the skin, causing itching and rash.4

Scabies is common in indigenous populations and in low-income areas of developing countries.5 It is most prevalent in Africa, South America, Australia, and Southeast Asia, in part due to poverty, poor nutritional status, homelessness, and inadequate hygiene.2 In 2009, the World Health Organization declared scabies a neglected skin disease2; however, in 2010, 1.5 million disability adjusted life-years were attributed to scabies,6 and it is estimated that 200 million people worldwide have scabies at any given time. Children and elderly individuals in resource-poor communities are the most at risk. In fact, 5% to 50% of children in low-income areas have scabies.4

The purpose of this article is to provide background on scabies and its effect on the human immune system. We also discuss manipulation of the immune response for the purposes of creating a potential scabies vaccine.

Life Cycle and Transmission

The life cycle of Sarcoptes scabiei consists of 4 stages. The first is the egg. As female scabies mites burrow under the skin, they lay 2 to 3 ovular eggs per day.3 The second stage is the larva. When the egg hatches, the larva has 3 pairs of legs and travels to the surface of the skin where it burrows into the stratum corneum, creating short, nearly invisible burrows called molting pouches. After 3 to 4 days, the larva molts into a nymph, which is the third stage. The nymph has 4 pairs of legs and will continue to grow before molting into an adult, which is the fourth stage. Both the larva and nymph may be found in hair follicles or molting pouches. The fourth stage is the adult, which is round and saclike and does not have eyes. Adult females are 0.30 mm to 0.45 mm long and 0.25 mm to 0.35 mm wide, which is half the size of adult males.3 On warm skin, the female mite can crawl at a rate of 2.5 cm per minute.7

Scabies mites mate via an active male penetrating the molting pouch of a female. This only occurs once but leaves the female fertile for the rest of her life. Once a female is pregnant, she leaves her molting pouch and travels along the surface of the skin looking for a place to make her permanent burrow.3 The most common sites for scabies burrows are the axillae, umbilicus, interdigital spaces, beltline, buttocks, flexor surfaces of the wrists, female nipples, and male penile shaft.5 Once she finds an acceptable location, the female scabies mite will create a serpentine burrow and lay her eggs. Once she burrows, she will stay there and continue to lay eggs for the rest of her life, lengthening the burrow as needed.3 Female mites lay their eggs in the superficial epidermis, and the eggs take approximately 2 to 3 weeks to hatch. Female mites die 30 to 60 days later.2

Scabies infestations typically spread via the transfer of pregnant adult females during skin-to-skin contact, but they also can spread via fomites.3 During all stages of their life cycle, scabies mites can secrete enzymes that allow them to penetrate the intact epidermis in less than 30 minutes; in fact, an otherwise healthy patient with scabies must have 15 to 20 minutes of close skin-to-skin contact with an infected individual for the disease to be transmitted.7 Because scabies mites can survive for more than 3 days outside the human body, it is thought that fomites also may be involved in transmission. Scabies mites also have been collected from clothing, bedding, and furniture, which further supports the idea that fomites are involved in disease transmission.7

Clinical Manifestation of Scabies

Scabies symptoms include severe pruritus as well as linear burrows and vesicles in the interdigital spaces on the hands, wrists, arms and legs, and lower abdomen. Infants and young children also can develop a rash on the palms, soles, ankles, and scalp. Men can develop inflammatory scabies nodules on the penis and scrotum, while women can develop these nodules on the nipple.4 Type I and type IV hypersensitivity reactions contribute to the rash and itching associated with scabies infestation via host allergic and inflammatory reactions to the mites and their byproducts. Patients with scabies typically are infested with fewer than 15 mites,6 but just a few can cause substantial pruritus and scratching, leading to hyperkeratosis.8

Additionally, when patients with scabies scratch the skin, they become vulnerable to bacterial infections.4 Scabies lesions can be coinfected with group A streptococci and Staphylococcus aureus,8 potentially leading to abscesses and septicemia. These secondary infections also can cause renal and cardiac complications; in fact, in tropical areas, scabies infections are considered a risk factor for kidney disease and rheumatic heart disease.4

The 2 main forms of scabies infestations are ordinary and crusted. The most common form is ordinary scabies, which typically manifests with fewer than 15 mites per patient; crusted scabies (CS) is the more rare and extreme form.6 Cases of CS present with thousands to millions of mites per patient, leading to more widespread and severe symptoms.4 Because of the large increase in the number of mites, CS is more contagious than ordinary scabies.6

Patients with CS typically present with hyperkeratotic skin disease, as evidenced by thick scaly crusts with large numbers of mites, which can lead to permanent skin disfiguration. Patients with CS also can develop deep fissuring of the crusts, within which other microbes can gain entry to the body and lead to secondary infection and possibly sepsis and death. Also, because of the increased number of mites as well as the crusted skin, patients with CS are contagious for longer. As it is more difficult to eradicate, reinfestation is common with CS.6

Patients with compromised immune systems are predisposed to CS. Specifically, patients with HIV or human T-lymphotropic virus 1 or those undergoing organ transplantation are thought to be the most at risk for CS.6 Crusted scabies also has been identified in large numbers in patients with Down syndrome and in Aboriginal Australians; however, the reasoning for this is poorly understood.6

Immune Response

The inflammatory reaction associated with scabies infestations occurs 4 to 6 weeks after initial exposure. It is hypothesized that scabies can alter parts of the host immune system, which contributes to the delayed onset of symptoms. Scabies mites also produce inactivated protease paralogues and serpins, which help to protect the mites from the host immune system by inhibiting the complement system.6

The complement system is part of the innate immune response and is the first line of defense against pathogens. Specifically with scabies infestations, C3 and C4 complement components have been found in skin lesions.6 C3a and C4a fragments cause local inflammation, while C3a and C5a activate mast cells to release histamine and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α, further amplifying the inflammatory response; however, CS lesions show low C3 and C4, which can indicate immunodeficiency in patients with CS. It also can be due to the sheer number of mites in a CS infection causing the host immune system to be overloaded.6

Innate effector immune cells also are an important part of the innate immune response to scabies; for example, eosinophilia is seen in scabies infections. Specifically, in CS, eosinophils help modulate and sustain the T-helper (Th) 2 inflammatory response. One cytokine secreted by Th2 cells is IL-5, which is closely associated with the attraction, maturation, and survival of eosinophils.6 Eosinophils also can influence the Th1 inflammatory response in that they produce IL-12, interferon (IFN) γ, and several Toll-like receptors. Furthermore, eosinophilic expression of IL-2 can lead to expansion of regulatory T cells, while eosinophilic expression of IL-10 and transforming growth factor (TGF) Β also can suppress local inflammation by influencing regulatory T cells.6

Additionally, mast cells and basophils are important in the IgE-mediated allergic reaction as well as the host immune response to parasites. When activated, basophils and mast cells produce TNF-α, IL-6, Il-4, IL-5, and IL-13, which contribute to the Th2 inflammatory response; however, the role of mast cells and basophils in scabies infections still is poorly understood.6

Macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells (DCs) contribute to phagocytosis, antigen presentation, and differentiation of T cells, which also contribute to the inflammatory and allergic reactions associated with parasitic infections.6 Macrophages have been found in low numbers in scabies infestation, possibly due to immune-modulating molecules secreted by scabies mites. Early in an infestation, the mites secrete immune-modulating molecules, which inhibit macrophage migration to the site of inflammation, allowing the mites to grow.6 Neutrophils and DCs also are involved in the host immune response to scabies. Neutrophils are the predominant inflammatory cell infiltrate in scabies lesions. The scabies protein SMSB4 inhibits neutrophil opsonization and phagocytosis, thus suppressing bacterial killing.6 Some of the first antigen-presenting cells encountered by the antigen are DCs. They are involved in preparing the antigens for presentation to effector T cells, which leads to T-cell differentiation and activation.6

Cytokines are another important factor in the innate immune response. The host immune response to ordinary scabies is Th1-cell mediated, during which CD4+ and CD8+ T cells secrete IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2.6 Therefore, IFN- γ and TNF-α are elevated in the serum of patients with ordinary scabies. Conversely, the host immune response to CS is Th2-cell mediated. T-helper 2 cells are needed in IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reactions, and they secrete IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13. In the serum of patients with CS, IL-l4, IL-5, and IL-13 are elevated while IFN-γ is decreased.6 Additionally, IL-6, TGF-Β, IL-23, IL-1Β, or IL-18 can induce Th17 cells to generate and secrete IL-17, which enhances the inflammatory response by inducing further expression of TNF-α, IL-1Β, IL-6, keratinocytes, and fibroblasts. T-helper 17 and IL-17 also are involved in psoriasis and atopic dermatitis, as well as Leishmania major and Schistosoma japonicum.6

Regulatory T cells Tregs secrete TGF-Β and IL-10, which suppress pathologic inflammation, and IL-10 is substantially reduced in patients with CS compared to those with ordinary scabies and uninfected control patients. Additionally, IL-10 can inhibit the synthesis of TNF-γ and IFN-α. Reduced IL-10 expression can lead to proliferation of IL-17 secretion, resulting in a regulatory T cell/Th17 dysfunctional immune response.6

Immunoglobulins are antibodies that are involved in the host’s adaptive immune response. The first antibody to appear in response to an antigen is IgM, and IgM bound to scabies antigens is present in 74%6 of patients with ordinary scabies. Because IgM is the first antibody to appear in response to a scabies infection, detection of serum IgM may allow for earlier detection of scabies; however, IgM has a high cross-reactivity between scabies mites and dust mites, which can hinder scabies diagnosis via IgM detection.6

Both patients with ordinary scabies and CS also show an increased circulatory IgG concentration compared to control groups; patients with CS have higher concentrations. Increased IgG also can be in part due to concurrent bacterial infections.6 When IgG or IgM antibodies bind to a pathogen, they activate the complement cascade, which further enhances the activity of these antibodies.9

Additionally, IgA is important in mucosal immune function. In both patients with ordinary scabies and CS, there is increased IgA binding to recombinant scabies mite antigens.6 Sarcoptes scabiei proteases that are localized in the mite’s gut and scybala suggest their involvement in mite digestion and burrowing. The increased secretion of these proteases into the host skin may contribute to the increased IgA,9 and these increased IgA levels have been shown to be positively correlated with severity of scabies infection.6

Also essential in allergic and parasitic inflammation, IgE is observed at higher levels in secondary infections of scabies compared to primary infections.6 Additionally, T-cell infiltrates are implicated in adaptive immune response to scabies. CD4+ T cells are the most prevalent T cells in ordinary scabies skin lesions; however, CD4+ T cells are minimal and CD8+ T cells are elevated in CS skin lesions. The increased CD8+ T cells may cause apoptosis of keratinocytes, leading to epidermal hyperproliferation. The apoptotic keratinocytes can secrete cytokines, which can lead to tissue damage.6 These T cells also may be involved in the failure of the skin’s immune system to mount an effective response to the parasite infestation, leading to uncontrolled parasitic growth. Because patients with AIDS who are infected with scabies mites often develop CS, it is also thought that CD4+ T cells are essential in the immune response to scabies.6

Diagnosis and Current Treatment Options

Current diagnosis of scabies is based on mites, eggs, and fecal matter from the host’s skin. Dermoscopy and fluorescent dermoscopy can be helpful in identifying the mites, eggs, and feces on the patient’s skin. Scabies treatment sometimes may be based solely on symptoms without any positive tests.8

Acaricides are the current method of treatment for scabies infestations.5 Acaricides can be expensive and toxic to the environment and food sources,10 and some agents have been associated with neurotoxicity5 in children or the development of certain cancers.11 Although topical acaricides are the standard form of treatment, oral ivermectin also can be used. Ivermectin is not associated with selective fetal toxicity, but there are limited safety data in pregnant women and in children weighing less than 15 kg (33 lb). Additionally, because symptoms typically are not present during an early infection, treating everyone in the household and those who had close contact with the patient can help prevent reinfection.4

Although these drugs have been shown to be effective at treating scabies, scabies mites are becoming increasingly resistant to acaricides.5 There are 4 main proposed mechanisms for why this occurs.12 The first is through voltage-gated sodium channels, which are involved in the normal functioning of neurons and myocytes. Permethrin, a type of acaricide, binds to voltage-gated sodium channels when it is in an open or active state and prevents it from closing. This creates repetitive neuron firing and hyperactivity, which ultimately kills the scabies mite. Some mites have mutated to close this channel, which reduces the binding potential of permethrin. Glutathione S-transferase is another mechanism of resistance. It catalyzes a bond that tags drugs for elimination. Increased activity or expressivity of glutathione S-transferase by scabies mites can lead to drug resistance.12 Adenosine triphosphate– binding cassette (ABC) transporters also may contribute to this resistance. The ABC transporters use adenosine triphosphate to facilitate the import or export of molecules. Scabies mites express a protein called the multidrug-resistant protein, which is an ABC transporter that is associated with drug resistance and is present in scabies mites.12 Lastly, ligand-gated chloride channels have been implicated in scabies resistance to acaricides. Ligand-gated chloride channels also are important in normal functioning of neurons and myocytes. Some antiparasitic drugs act on these channels, leading to a continuous influx of chloride, but some scabies mites have mutated this pathway.12

Pesticides and the Risk for Cancer

Pesticides commonly are used to treat scabies; however, a link between pesticide exposure and leukemia and lymphoma has been seen through epidemiologic studies, and there also is increasing biological evidence to suggest this.11 For example, the pesticide permethrin, which works by paralyzing the nervous system of insects,13 has been associated with an increased risk for leukemia and lymphoma in humans. Permethrin is a pyrethroid and, compared to control patients, children with leukemia had higher levels of pyrethroid metabolites in their blood.14 Numerical and structural chromosomal aberrations that give rise to gene fusions are the most common abnormalities seen in leukemia, and permethrin has been shown to induce DNA breaks, chromosome aberrations, and sister chromatid exchanges.14 Permethrin also has been associated with an increased risk for multiple myeloma.13

Furthermore, in utero exposure to pesticides has been associated with an increased risk for childhood leukemia.15 Pesticide exposure shortly before conception, during pregnancy, and after birth is associated with an increased risk for acute lymphocytic leukemia.16 In fact, the children of mothers who were exposed to pesticides 3 months before conception have been found to be at least twice as likely to be diagnosed with acute lymphocytic leukemia within the first year of life compared with children whose mothers were not exposed to pesticides.17 It is hypothesized that permethrin can cross the placenta and alter the hematopoietic precursor cells in the fetus, resulting in leukemogenesis.18 Pyrethroid metabolites also have been detected in umbilical cord blood samples and breast milk.15

In contrast to the research demonstrating a link between permethrin and cancer, other studies have found no association between permethrin19 and leukemia20; non-Hodgkin lymphoma19; or cancers of the colon, rectum, pancreas, lungs, skin, female breast, prostate, and urinary bladder.20 Because of conflicting research on the link between permethrin and cancer, more research is needed.,20

Importance of a Scabies Vaccine

Because scabies mites are developing increasing treatment resistance, more radical approaches such as vaccines are becoming important. While a scabies vaccine is still aspirational, animals that have been infected for a second time with scabies demonstrate a milder response to the second infection compared to the first infection, which could mean there is a potential for disease prevention through a vaccine.21 While educating patients and physicians, reporting cases of infection, and improving drug supply and access can help decrease scabies infestations, these are costly and difficult to implement. Scabies already is most prevalent in low-income areas, so costly interventions are even less feasible. An effective, one-dose vaccine would cost less than these efforts and therefore could be implemented more easily.9

In older adults, scabies more often manifests atypically and is more likely to progress to CS. Aged care centers are prone to institutional outbreaks, even in developed countries, so a vaccine also would greatly help this population. Additionally, the number of children attending day care centers, which also are prone to scabies outbreaks, is increasing. When a child contracts scabies, all close contacts need to be treated, so a preventive vaccine can be useful.9

One potential candidate for a scabies vaccine is total mite extract. Studies show that rabbits immunized with a total mite extract induce antibodies to more antigens than rabbits naturally infested with scabies mites; however, the mites cannot be cultured in vitro, which makes obtaining a large amount of their total extract difficult. Therefore, recombinant vaccines also have been proposed, as they are more easily available.22 One recombinant vaccine candidate is recombinant S scabiei serpin (rSs-serpin). Immunization with rSs-serpin has strong immunogenicity and produced immune protection in rabbits.22

Two other recombinant vaccine candidates are the rSs chitinaselike protein (CLP) 12 and the rSsCLP5. Chitinaselike proteins are very similar to chitinases; however, they are unable to degrade chitin. They are involved in immune reactions to infections, and CLPs from scabies mites have been shown to induce the host immune response.22 For example, in a particular rabbit study, rSsCLP5 demonstrated high immunoreactivity and immunogenicity. In fact, after exposure to S scabiei, 74.3% of rabbits who were vaccinated with rSsCLP5 had no detectable lesions.5 Also, after immunization with rSsCLP5 and rSsCLP12, there were increased levels of specific IgG and IgE antibodies produced and decreased numbers of infesting mites.22 Weight loss also is associated with severe scabies infection. Rabbits vaccinated with rSsCLP5 and exposed to the parasite gained weight, indicating protection via rSsCLP5. Even rabbits who did develop symptoms of scabies after immunization with rSsCLP5 and exposure to S scabiei showed less serious manifestations.5

A combination vaccine cocktail of rSs-serpin, rSsCLP12, and rSsCLP5 also has been proposed by Shen et al.22 Four test groups and a control group (n=12 per group) were included in a vaccine trial. Between 83.33% and 91.67% of rabbits vaccinated with this mixed recombinant cocktail vaccine had no detectable skin lesions from scabies. After immunization with the cocktail vaccine, the specific serum IgG and IgE antibodies also increased. For both IgG and IgE, increased levels were first detected at 1 week postimmunization and peaked at 2 weeks postimmunization.22 A multiepitope vaccine derived from these 3 recombinant proteins also was explored by Shen et al22; fewer rabbits vaccinated with it had no detectable scabies skin lesions compared to those treated with the vaccine cocktail. Although the multiepitope vaccine yielded less immume protection, it was associated with a slower disease course and milder symptoms compared with no vaccination.22

Two more proposed scabies recombinant vaccine candidates are derived from the antigens Ssag1 and Ssag2; however, rabbits vaccinated with Ssag1 or Ssag2 showed no immune protection or mite burden reduction.22 The lack of protection could be due to denaturation or degradation of the protective antigens. It also can be due to the low abundance of these antigens, meaning they may not be vital for the mite’s survival—survival—a potential avenue for future research. The antigens also could have lost their native structure and immunogenic properties during the purification and production process. Therefore, more research is needed to investigate how to purify these vaccines to keep the peptides more structurally similar to their native makeups.10 More research also is needed to better understand the antigen or antigens and their mechanisms that elicit a protective immune response.9

Final Thoughts

Scabies causes severe pruritus in mild cases but also can lead to severe disfigurement, sepsis, and even death. Scabies infestations are seen disproportionately more often in low-income and resource-poor communities, and the current treatment options are less accessible to these populations. Scabies infestations induce a complex immune response that involves multiple aspects of both the innate and adaptive immune systems and can be targeted to create a scabies vaccine. Development of a scabies vaccine is crucial considering the growing resistance to current standard treatments. Acaricides potentially are associated with an increased risk for malignancy, which further amplifies the need for a scabies vaccine. There currently are multiple promising scabies vaccine candidates; however, more research is needed to better understand the host’s immune response to scabies as well as how to more accurately and efficiently produce the vaccine. The development of a safe, effective, economical vaccine that can be mass distributed would be beneficial in the treatment of scabies, especially in resource-poor communities.

- Arlian LG, Morgan MS. A review of Sarcoptes scabiei: past, present and future. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:297. doi:10.1186/s13071-017-2234-1

- Murray RL, Crane JS. Scabies. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Updated July 31, 2023.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC—scabies—biology. November 2, 2010. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/scabies/index.html

- World Health Organization. Scabies. May 31, 2023. Accessed May 8, 2025. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/scabies

- Shen N, Zhang H, Ren Y, et al. A chitinase-like protein from Sarcoptes scabiei as a candidate anti-mite vaccine that contributes to immune protection in rabbits. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:599. doi:10.1186/s13071- 018-3184-y

- Bhat SA, Mounsey KE, Liu X, et al. Host immune responses to the itch mite, Sarcoptes scabiei, in humans. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:385. doi:10.1186/s13071-017-2320-4

- Hicks MI, Elston DM. Scabies. Dermatolog Ther. 2009;22:279-292. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8019.2009.01243.x

- Morgan MS, Arlian LG, Rider SD, et al. A proteomic analysis of Sarcoptes scabiei (acari: Sarcoptidae). J Med Entomol. 2016;53:553-561. doi:10.1093/jme/tjv247

- Liu X, Walton S, Mounsey K. Vaccine against scabies: necessity and possibility. Parasitology. 2014;141:725-732. doi:10.1017 /s0031182013002047

- Casais R, Granda V, Balseiro A, et al. Vaccination of rabbits with immunodominant antigens from Sarcoptes scabiei induced high levels of humoral responses and pro-inflammatory cytokines but confers limited protection. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:435. doi:10.1186 /s13071-016-1717-9?

- Navarrete-Meneses MP, Pedraza-Meléndez AI, Salas-Labadía C, et al. Low concentrations of permethrin and malathion induce numerical and structural abnormalities in KMT2A and IGH genes in vitro. J Appl Toxicol. 2018;38:1262-1270. doi:10.1002/jat.3638

- Khalil S, Abbas O, Kibbi AG, et al. Scabies in the age of increasing drug resistance. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:E0005920. doi:10.1371 /journal.pntd.0005920

- Rusiecki JA, Patel R, Koutros S, et al. Cancer incidence among pesticide applicators exposed to permethrin in the Agricultural Health Study. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117:581-586. doi:10.1289 /ehp.11318

- Navarrete-Meneses MP, Salas-Labadía C, Sanabrais-Jiménez M, et al. Exposure to the insecticides permethrin and malathion induces leukemia and lymphoma-associated gene aberrations in vitro. Toxicol In Vitro. 2017;44:17-26. doi:10.1016/j.tiv.2017.06.013

- Navarrete-Meneses MDP, Pérez-Vera P. Pyrethroid pesticide exposure and hematological cancer: epidemiological, biological and molecular evidence. Rev Environ Health. 2019;34:197-210. doi:10.1515 /reveh-2018-0070

- Madrigal JM, Jones RR, Gunier RB, et al. Residential exposure to carbamate, organophosphate, and pyrethroid insecticides in house dust and risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Environ Res. 2021;201:111501. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2021.111501

- Ferreira JD, Couto AC, Pombo-de-Oliveira MS, et al. In utero pesticide exposure and leukemia in Brazilian children <2 years of age. Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121:269-275. doi:10.1289/ehp.1103942

- Borkhardt A, Wilda M, Fuchs U, et al. Congenital leukaemia after heavy abuse of permethrin during pregnancy. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2003;88:F436-F437. doi:10.1136/fn.88.5.f436

- De Roos AJ, Schinasi LH, Miligi L, et al. Occupational insecticide exposure and risk of non]Hodgkin lymphoma: a pooled case]control study from the InterLymph consortium. Int J Cancer. 2021;149:1768-1786. doi:10.1002/ijc.33740

- Boffett, P, Desai V. Exposure to permethrin and cancer risk: a systematic review. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2018;48:433-442. doi:10.1080/1040 8444.2018.1439449

- Adji A, Rumokoy LJM, Salaki CL. Scabies vaccine as a new breakthrough for the challenge of acaricides resistance. Adv Biolog Sci Res. 2020;8:208-213. doi:10.2991/absr.k.200513.036

- Shen N, Wei W, Chen Y, et al. Vaccination with a cocktail vaccine elicits significant protection against Sarcoptes scabiei in rabbits, whereas the multi-epitope vaccine offers limited protection. Exp Parasitol. 2023;245:108442. doi:10.1016/j.exppara.2022.108442

The scabies mite, originally known as Acarus scabiei,1 now is considered an arthropod of the class Arachnida, order Astigmata, and family Sarcoptidae.2 Scabies mites are able to adhere to the surface of human skin.3 The mites burrow and lay eggs in the top layer of the epidermis; most patients have 10 to 15 mites.3 The patient’s immune system incites an allergic reaction to the mite protein and feces in the skin, causing itching and rash.4

Scabies is common in indigenous populations and in low-income areas of developing countries.5 It is most prevalent in Africa, South America, Australia, and Southeast Asia, in part due to poverty, poor nutritional status, homelessness, and inadequate hygiene.2 In 2009, the World Health Organization declared scabies a neglected skin disease2; however, in 2010, 1.5 million disability adjusted life-years were attributed to scabies,6 and it is estimated that 200 million people worldwide have scabies at any given time. Children and elderly individuals in resource-poor communities are the most at risk. In fact, 5% to 50% of children in low-income areas have scabies.4

The purpose of this article is to provide background on scabies and its effect on the human immune system. We also discuss manipulation of the immune response for the purposes of creating a potential scabies vaccine.

Life Cycle and Transmission

The life cycle of Sarcoptes scabiei consists of 4 stages. The first is the egg. As female scabies mites burrow under the skin, they lay 2 to 3 ovular eggs per day.3 The second stage is the larva. When the egg hatches, the larva has 3 pairs of legs and travels to the surface of the skin where it burrows into the stratum corneum, creating short, nearly invisible burrows called molting pouches. After 3 to 4 days, the larva molts into a nymph, which is the third stage. The nymph has 4 pairs of legs and will continue to grow before molting into an adult, which is the fourth stage. Both the larva and nymph may be found in hair follicles or molting pouches. The fourth stage is the adult, which is round and saclike and does not have eyes. Adult females are 0.30 mm to 0.45 mm long and 0.25 mm to 0.35 mm wide, which is half the size of adult males.3 On warm skin, the female mite can crawl at a rate of 2.5 cm per minute.7

Scabies mites mate via an active male penetrating the molting pouch of a female. This only occurs once but leaves the female fertile for the rest of her life. Once a female is pregnant, she leaves her molting pouch and travels along the surface of the skin looking for a place to make her permanent burrow.3 The most common sites for scabies burrows are the axillae, umbilicus, interdigital spaces, beltline, buttocks, flexor surfaces of the wrists, female nipples, and male penile shaft.5 Once she finds an acceptable location, the female scabies mite will create a serpentine burrow and lay her eggs. Once she burrows, she will stay there and continue to lay eggs for the rest of her life, lengthening the burrow as needed.3 Female mites lay their eggs in the superficial epidermis, and the eggs take approximately 2 to 3 weeks to hatch. Female mites die 30 to 60 days later.2

Scabies infestations typically spread via the transfer of pregnant adult females during skin-to-skin contact, but they also can spread via fomites.3 During all stages of their life cycle, scabies mites can secrete enzymes that allow them to penetrate the intact epidermis in less than 30 minutes; in fact, an otherwise healthy patient with scabies must have 15 to 20 minutes of close skin-to-skin contact with an infected individual for the disease to be transmitted.7 Because scabies mites can survive for more than 3 days outside the human body, it is thought that fomites also may be involved in transmission. Scabies mites also have been collected from clothing, bedding, and furniture, which further supports the idea that fomites are involved in disease transmission.7

Clinical Manifestation of Scabies

Scabies symptoms include severe pruritus as well as linear burrows and vesicles in the interdigital spaces on the hands, wrists, arms and legs, and lower abdomen. Infants and young children also can develop a rash on the palms, soles, ankles, and scalp. Men can develop inflammatory scabies nodules on the penis and scrotum, while women can develop these nodules on the nipple.4 Type I and type IV hypersensitivity reactions contribute to the rash and itching associated with scabies infestation via host allergic and inflammatory reactions to the mites and their byproducts. Patients with scabies typically are infested with fewer than 15 mites,6 but just a few can cause substantial pruritus and scratching, leading to hyperkeratosis.8

Additionally, when patients with scabies scratch the skin, they become vulnerable to bacterial infections.4 Scabies lesions can be coinfected with group A streptococci and Staphylococcus aureus,8 potentially leading to abscesses and septicemia. These secondary infections also can cause renal and cardiac complications; in fact, in tropical areas, scabies infections are considered a risk factor for kidney disease and rheumatic heart disease.4

The 2 main forms of scabies infestations are ordinary and crusted. The most common form is ordinary scabies, which typically manifests with fewer than 15 mites per patient; crusted scabies (CS) is the more rare and extreme form.6 Cases of CS present with thousands to millions of mites per patient, leading to more widespread and severe symptoms.4 Because of the large increase in the number of mites, CS is more contagious than ordinary scabies.6

Patients with CS typically present with hyperkeratotic skin disease, as evidenced by thick scaly crusts with large numbers of mites, which can lead to permanent skin disfiguration. Patients with CS also can develop deep fissuring of the crusts, within which other microbes can gain entry to the body and lead to secondary infection and possibly sepsis and death. Also, because of the increased number of mites as well as the crusted skin, patients with CS are contagious for longer. As it is more difficult to eradicate, reinfestation is common with CS.6

Patients with compromised immune systems are predisposed to CS. Specifically, patients with HIV or human T-lymphotropic virus 1 or those undergoing organ transplantation are thought to be the most at risk for CS.6 Crusted scabies also has been identified in large numbers in patients with Down syndrome and in Aboriginal Australians; however, the reasoning for this is poorly understood.6

Immune Response

The inflammatory reaction associated with scabies infestations occurs 4 to 6 weeks after initial exposure. It is hypothesized that scabies can alter parts of the host immune system, which contributes to the delayed onset of symptoms. Scabies mites also produce inactivated protease paralogues and serpins, which help to protect the mites from the host immune system by inhibiting the complement system.6

The complement system is part of the innate immune response and is the first line of defense against pathogens. Specifically with scabies infestations, C3 and C4 complement components have been found in skin lesions.6 C3a and C4a fragments cause local inflammation, while C3a and C5a activate mast cells to release histamine and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α, further amplifying the inflammatory response; however, CS lesions show low C3 and C4, which can indicate immunodeficiency in patients with CS. It also can be due to the sheer number of mites in a CS infection causing the host immune system to be overloaded.6

Innate effector immune cells also are an important part of the innate immune response to scabies; for example, eosinophilia is seen in scabies infections. Specifically, in CS, eosinophils help modulate and sustain the T-helper (Th) 2 inflammatory response. One cytokine secreted by Th2 cells is IL-5, which is closely associated with the attraction, maturation, and survival of eosinophils.6 Eosinophils also can influence the Th1 inflammatory response in that they produce IL-12, interferon (IFN) γ, and several Toll-like receptors. Furthermore, eosinophilic expression of IL-2 can lead to expansion of regulatory T cells, while eosinophilic expression of IL-10 and transforming growth factor (TGF) Β also can suppress local inflammation by influencing regulatory T cells.6

Additionally, mast cells and basophils are important in the IgE-mediated allergic reaction as well as the host immune response to parasites. When activated, basophils and mast cells produce TNF-α, IL-6, Il-4, IL-5, and IL-13, which contribute to the Th2 inflammatory response; however, the role of mast cells and basophils in scabies infections still is poorly understood.6

Macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells (DCs) contribute to phagocytosis, antigen presentation, and differentiation of T cells, which also contribute to the inflammatory and allergic reactions associated with parasitic infections.6 Macrophages have been found in low numbers in scabies infestation, possibly due to immune-modulating molecules secreted by scabies mites. Early in an infestation, the mites secrete immune-modulating molecules, which inhibit macrophage migration to the site of inflammation, allowing the mites to grow.6 Neutrophils and DCs also are involved in the host immune response to scabies. Neutrophils are the predominant inflammatory cell infiltrate in scabies lesions. The scabies protein SMSB4 inhibits neutrophil opsonization and phagocytosis, thus suppressing bacterial killing.6 Some of the first antigen-presenting cells encountered by the antigen are DCs. They are involved in preparing the antigens for presentation to effector T cells, which leads to T-cell differentiation and activation.6

Cytokines are another important factor in the innate immune response. The host immune response to ordinary scabies is Th1-cell mediated, during which CD4+ and CD8+ T cells secrete IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2.6 Therefore, IFN- γ and TNF-α are elevated in the serum of patients with ordinary scabies. Conversely, the host immune response to CS is Th2-cell mediated. T-helper 2 cells are needed in IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reactions, and they secrete IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13. In the serum of patients with CS, IL-l4, IL-5, and IL-13 are elevated while IFN-γ is decreased.6 Additionally, IL-6, TGF-Β, IL-23, IL-1Β, or IL-18 can induce Th17 cells to generate and secrete IL-17, which enhances the inflammatory response by inducing further expression of TNF-α, IL-1Β, IL-6, keratinocytes, and fibroblasts. T-helper 17 and IL-17 also are involved in psoriasis and atopic dermatitis, as well as Leishmania major and Schistosoma japonicum.6

Regulatory T cells Tregs secrete TGF-Β and IL-10, which suppress pathologic inflammation, and IL-10 is substantially reduced in patients with CS compared to those with ordinary scabies and uninfected control patients. Additionally, IL-10 can inhibit the synthesis of TNF-γ and IFN-α. Reduced IL-10 expression can lead to proliferation of IL-17 secretion, resulting in a regulatory T cell/Th17 dysfunctional immune response.6

Immunoglobulins are antibodies that are involved in the host’s adaptive immune response. The first antibody to appear in response to an antigen is IgM, and IgM bound to scabies antigens is present in 74%6 of patients with ordinary scabies. Because IgM is the first antibody to appear in response to a scabies infection, detection of serum IgM may allow for earlier detection of scabies; however, IgM has a high cross-reactivity between scabies mites and dust mites, which can hinder scabies diagnosis via IgM detection.6

Both patients with ordinary scabies and CS also show an increased circulatory IgG concentration compared to control groups; patients with CS have higher concentrations. Increased IgG also can be in part due to concurrent bacterial infections.6 When IgG or IgM antibodies bind to a pathogen, they activate the complement cascade, which further enhances the activity of these antibodies.9

Additionally, IgA is important in mucosal immune function. In both patients with ordinary scabies and CS, there is increased IgA binding to recombinant scabies mite antigens.6 Sarcoptes scabiei proteases that are localized in the mite’s gut and scybala suggest their involvement in mite digestion and burrowing. The increased secretion of these proteases into the host skin may contribute to the increased IgA,9 and these increased IgA levels have been shown to be positively correlated with severity of scabies infection.6

Also essential in allergic and parasitic inflammation, IgE is observed at higher levels in secondary infections of scabies compared to primary infections.6 Additionally, T-cell infiltrates are implicated in adaptive immune response to scabies. CD4+ T cells are the most prevalent T cells in ordinary scabies skin lesions; however, CD4+ T cells are minimal and CD8+ T cells are elevated in CS skin lesions. The increased CD8+ T cells may cause apoptosis of keratinocytes, leading to epidermal hyperproliferation. The apoptotic keratinocytes can secrete cytokines, which can lead to tissue damage.6 These T cells also may be involved in the failure of the skin’s immune system to mount an effective response to the parasite infestation, leading to uncontrolled parasitic growth. Because patients with AIDS who are infected with scabies mites often develop CS, it is also thought that CD4+ T cells are essential in the immune response to scabies.6

Diagnosis and Current Treatment Options

Current diagnosis of scabies is based on mites, eggs, and fecal matter from the host’s skin. Dermoscopy and fluorescent dermoscopy can be helpful in identifying the mites, eggs, and feces on the patient’s skin. Scabies treatment sometimes may be based solely on symptoms without any positive tests.8

Acaricides are the current method of treatment for scabies infestations.5 Acaricides can be expensive and toxic to the environment and food sources,10 and some agents have been associated with neurotoxicity5 in children or the development of certain cancers.11 Although topical acaricides are the standard form of treatment, oral ivermectin also can be used. Ivermectin is not associated with selective fetal toxicity, but there are limited safety data in pregnant women and in children weighing less than 15 kg (33 lb). Additionally, because symptoms typically are not present during an early infection, treating everyone in the household and those who had close contact with the patient can help prevent reinfection.4

Although these drugs have been shown to be effective at treating scabies, scabies mites are becoming increasingly resistant to acaricides.5 There are 4 main proposed mechanisms for why this occurs.12 The first is through voltage-gated sodium channels, which are involved in the normal functioning of neurons and myocytes. Permethrin, a type of acaricide, binds to voltage-gated sodium channels when it is in an open or active state and prevents it from closing. This creates repetitive neuron firing and hyperactivity, which ultimately kills the scabies mite. Some mites have mutated to close this channel, which reduces the binding potential of permethrin. Glutathione S-transferase is another mechanism of resistance. It catalyzes a bond that tags drugs for elimination. Increased activity or expressivity of glutathione S-transferase by scabies mites can lead to drug resistance.12 Adenosine triphosphate– binding cassette (ABC) transporters also may contribute to this resistance. The ABC transporters use adenosine triphosphate to facilitate the import or export of molecules. Scabies mites express a protein called the multidrug-resistant protein, which is an ABC transporter that is associated with drug resistance and is present in scabies mites.12 Lastly, ligand-gated chloride channels have been implicated in scabies resistance to acaricides. Ligand-gated chloride channels also are important in normal functioning of neurons and myocytes. Some antiparasitic drugs act on these channels, leading to a continuous influx of chloride, but some scabies mites have mutated this pathway.12

Pesticides and the Risk for Cancer