User login

Naltrexone: a Novel Approach to Pruritus in Polycythemia Vera

P ruritus is a characteristic and often debilitating clinical manifestation reported by about 50% of patients with polycythemia vera (PV). The exact pathophysiology of PV-associated pruritus is poorly understood. The itch sensation may arise from a central phenomenon without skin itch receptor involvement, as is seen in opioid-induced pruritus, or peripherally via unmyelinated C fibers. Various interventions have been used with mixed results for symptom management in this patient population.1

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as paroxetine and fluoxetine, have historically demonstrated some efficacy in treating PV-associated pruritus.2 Alongside SSRIs, phlebotomy, antihistamines, phototherapy, interferon a, and myelosuppressive medications also comprise the various current treatment options. In addition to lacking efficacy, antihistamines can cause somnolence, constipation, and xerostomia.3,4 Phlebotomy and cytoreductive therapy are often effective in controlling erythrocytosis but fail to alleviate the disabling pruritus.1,5,6 More recently, suboptimal symptom alleviation has prompted the discovery of agents that target the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and Janus kinase 2 (Jak2) pathways.1

Naltrexone is an opioid antagonist shown to suppress pruritus in various dermatologic pathologies involving histamine-independent pathways.3,7,8 A systematic search strategy identified 34 studies on PV-associated pruritus, its pathophysiology and interventions, and naltrexone as a therapeutic agent. Only 1 study in the literature has described the use of naltrexone for uremic and cholestatic pruritus.9 We describe the successful use of naltrexone monotherapy for the treatment of pruritus in a patient with PV.

Case Presentation

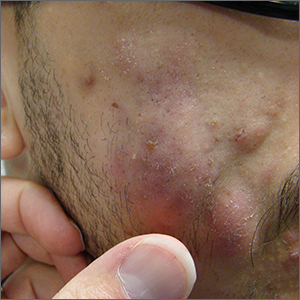

A 40-year-old man with Jak2-positive PV treated with ruxolitinib presented to the outpatient Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center Supportive Care Clinic in Houston, Texas, for severe refractory pruritus. Wheals manifested in pruritic regions of the patient’s skin without gross excoriations or erythema. Pruritus reportedly began diffusely across the posterior torso. Through the rapid progression of an episode lasting 30 to 45 minutes, the lesions and pruritus would spread to the anterior torso, extend to the upper extremities bilaterally, and finally descend to the lower extremities bilaterally. A persistent sensation of heat or warmth on the patient’s skin was present, and periodically, this would culminate in a burning sensation comparable to “lying flat on one’s back directly on a hornet’s nest…[followed by] a million stings” that was inconsistent with erythromelalgia given the absence of erythema. The intensity of the pruritic episodes was subjectively also described as “enough to make [him] want to jump off the roof of a building…[causing] moments of deep, deep frustration…[and] the worst of all the symptoms one may encounter because of [PV].”

Pruritus was exacerbated by sweating, heat, contact with any liquids on the skin, and sunburns, which doubled the intensity. The patient reported minimal, temporary relief with cannabidiol and cold fabric or air on his skin. His current regimen and nonpharmacologic efforts provided no relief and included oatmeal baths, cornstarch after showers, and patting instead of rubbing the skin with topical products. Trials with nonprescription diphenhydramine, loratadine, and calamine and zinc were not successful. He had not pursued phototherapy due to time limitations and travel constraints. He had a history of phlebotomies and hydroxyurea use, which he preferred to avoid and discontinued 1 year before presentation.

Despite improving hematocrit (< 45% goal) and platelet counts with ruxolitinib, the patient reported worsening pruritus that significantly impaired quality of life. His sleep and social and physical activities were hindered, preventing him from working. The patient’s active medications also included low-dose aspirin, sertraline, hydroxyzine, triamcinolone acetonide, and pregabalin for sciatica. Given persistent symptoms despite multimodal therapy and lifestyle modifications, the patient was started on naltrexone 25 mg daily, which provided immediate relief of symptoms. He continues to have adequate symptom control 2 years after naltrexone initiation.

Literature Review

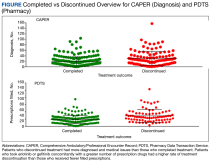

A systematic search strategy was developed with the assistance of a medical librarian in Medline Ovid, using both Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms and synonymous keywords. The strategy was then translated to Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane to extract publications investigating PV, pruritus, and/or naltrexone therapy. All searches were conducted on July 18, 2022, and the results of the literature review were as follows: 2 results from Medline Ovid; 34 results from Embase (2 were duplicates of Medline Ovid results); 3 results from Web of Science (all of which were duplicates of Medline Ovid or Embase results); and 0 results from Cochrane (Figure).

Discussion

Although pruritus is a common and often excruciating manifestation of PV, its pathophysiology remains unclear. Some patients with decreasing or newly normal hematocrit and hemoglobin levels have paradoxically experienced an intensification of their pruritus, which introduces erythropoietin signaling pathways as a potential mechanism of the symptom.8 However, iron replacement therapy for patients with exacerbated pruritus after phlebotomies has not demonstrated consistent relief of pruritus.8 Normalization of platelet levels also has not been historically associated with improvement of pruritus.8,9 It has been hypothesized that cells harboring Jak2 mutations at any stage of the hematopoietic pathway mature and accumulate to cause pruritus in PV.9 This theory has been foundational in the development of drugs with activity against cells expressing Jak2 mutations and interventions targeting histamine-releasing mast cells.9-11

The effective use of naltrexone in our patient suggests that histamine may not be the most effective or sole therapeutic target against pruritus in PV. Naltrexone targets opioid receptors in all layers of the epidermis, affecting cell adhesion and keratinocyte production, and exhibits anti-inflammatory effects through interactions with nonopioid receptors, including Toll-like receptor 4.12 The efficacy of oral naltrexone has been documented in patients with pruritus associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors, psoriasis, eczema, lichen simplex chronicus, prurigo nodularis, cholestasis, uremia, and multiple rheumatologic diseases.3,4,7-9,12-14 Opioid pathways also may be involved in peripheral and/or central processing of pruritus associated with PV.

Importantly, patients who are potential candidates for naltrexone therapy should be notified and advised of the risk of drug interactions with opioids, which could lead to symptoms of opioid withdrawal. Other common adverse effects of naltrexone include hepatotoxicity (especially in patients with a history of significant alcohol consumption), abdominal pain, nausea, arthralgias, myalgias, insomnia, headaches, fatigue, and anxiety.12 Therefore, it is integral to screen patients for opioid dependence and determine their baseline liver function. Patients should be monitored following naltrexone initiation to determine whether the drug is an appropriate and effective intervention against PV-associated pruritus.

CONCLUSIONS

This case study demonstrates that naltrexone may be a safe, effective, nonsedating, and cost-efficient oral alternative for refractory PV-associated pruritus. Future directions involve consideration of case series or randomized clinical trials investigating the efficacy of naltrexone in treating PV-associated pruritus. Further research is also warranted to better understand the pathophysiology of this symptom of PV to enhance and potentially expand medical management for patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Amy Sisson (The Texas Medical Center Library) for her guidance and support in the literature review methodology.

1. Saini KS, Patnaik MM, Tefferi A. Polycythemia vera-associated pruritus and its management. Eur J Clin Invest. 2010;40(9):828-834. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2362.2010.02334.x

2. Tefferi A, Fonseca R. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are effective in the treatment of polycythemia vera-associated pruritus. Blood. 2002;99(7):2627. doi:10.1182/blood.v99.7.2627

3. Lee J, Shin JU, Noh S, Park CO, Lee KH. Clinical efficacy and safety of naltrexone combination therapy in older patients with severe pruritus. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28(2):159-163. doi:10.5021/ad.2016.28.2.159

4. Phan NQ, Bernhard JD, Luger TA, Stander S. Antipruritic treatment with systemic mu-opioid receptor antagonists: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63(4):680-688. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.08.052

5. Metze D, Reimann S, Beissert S, Luger T. Efficacy and safety of naltrexone, an oral opiate receptor antagonist, in the treatment of pruritus in internal and dermatological diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(4):533-539.

6. Malekzad F, Arbabi M, Mohtasham N, et al. Efficacy of oral naltrexone on pruritus in atopic eczema: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(8):948-950. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03129.x

7. Terg R, Coronel E, Sorda J, Munoz AE, Findor J. Efficacy and safety of oral naltrexone treatment for pruritus of cholestasis, a crossover, double blind, placebo-controlled study. J Hepatol. 2002;37(6):717-722. doi:10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00318-5

8. Lelonek E, Matusiak L, Wrobel T, Szepietowski JC. Aquagenic pruritus in polycythemia vera: clinical characteristics. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98(5):496-500. doi:10.2340/00015555-2906

9. Siegel FP, Tauscher J, Petrides PE. Aquagenic pruritus in polycythemia vera: characteristics and influence on quality of life in 441 patients. Am J Hematol. 2013;88(8):665-669. doi:10.1002/ajh.23474

10. Al-Mashdali AF, Kashgary WR, Yassin MA. Ruxolitinib (a JAK2 inhibitor) as an emerging therapy for refractory pruritis in a patient with low-risk polycythemia vera: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(44):e27722. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000027722

11. Benevolo G, Vassallo F, Urbino I, Giai V. Polycythemia vera (PV): update on emerging treatment options. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2021;17:209-221. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S213020

12. Lee B, Elston DM. The uses of naltrexone in dermatologic conditions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(6):1746-1752. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.031

13. de Carvalho JF, Skare T. Low-dose naltrexone in rheumatological diseases. Mediterr J Rheumatol. 2023;34(1):1-6. doi:10.31138/mjr.34.1.1

14. Singh R, Patel P, Thakker M, Sharma P, Barnes M, Montana S. Naloxone and maintenance naltrexone as novel and effective therapies for immunotherapy-induced pruritus: a case report and brief literature review. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15(6):347-348. doi:10.1200/JOP.18.00797

P ruritus is a characteristic and often debilitating clinical manifestation reported by about 50% of patients with polycythemia vera (PV). The exact pathophysiology of PV-associated pruritus is poorly understood. The itch sensation may arise from a central phenomenon without skin itch receptor involvement, as is seen in opioid-induced pruritus, or peripherally via unmyelinated C fibers. Various interventions have been used with mixed results for symptom management in this patient population.1

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as paroxetine and fluoxetine, have historically demonstrated some efficacy in treating PV-associated pruritus.2 Alongside SSRIs, phlebotomy, antihistamines, phototherapy, interferon a, and myelosuppressive medications also comprise the various current treatment options. In addition to lacking efficacy, antihistamines can cause somnolence, constipation, and xerostomia.3,4 Phlebotomy and cytoreductive therapy are often effective in controlling erythrocytosis but fail to alleviate the disabling pruritus.1,5,6 More recently, suboptimal symptom alleviation has prompted the discovery of agents that target the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and Janus kinase 2 (Jak2) pathways.1

Naltrexone is an opioid antagonist shown to suppress pruritus in various dermatologic pathologies involving histamine-independent pathways.3,7,8 A systematic search strategy identified 34 studies on PV-associated pruritus, its pathophysiology and interventions, and naltrexone as a therapeutic agent. Only 1 study in the literature has described the use of naltrexone for uremic and cholestatic pruritus.9 We describe the successful use of naltrexone monotherapy for the treatment of pruritus in a patient with PV.

Case Presentation

A 40-year-old man with Jak2-positive PV treated with ruxolitinib presented to the outpatient Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center Supportive Care Clinic in Houston, Texas, for severe refractory pruritus. Wheals manifested in pruritic regions of the patient’s skin without gross excoriations or erythema. Pruritus reportedly began diffusely across the posterior torso. Through the rapid progression of an episode lasting 30 to 45 minutes, the lesions and pruritus would spread to the anterior torso, extend to the upper extremities bilaterally, and finally descend to the lower extremities bilaterally. A persistent sensation of heat or warmth on the patient’s skin was present, and periodically, this would culminate in a burning sensation comparable to “lying flat on one’s back directly on a hornet’s nest…[followed by] a million stings” that was inconsistent with erythromelalgia given the absence of erythema. The intensity of the pruritic episodes was subjectively also described as “enough to make [him] want to jump off the roof of a building…[causing] moments of deep, deep frustration…[and] the worst of all the symptoms one may encounter because of [PV].”

Pruritus was exacerbated by sweating, heat, contact with any liquids on the skin, and sunburns, which doubled the intensity. The patient reported minimal, temporary relief with cannabidiol and cold fabric or air on his skin. His current regimen and nonpharmacologic efforts provided no relief and included oatmeal baths, cornstarch after showers, and patting instead of rubbing the skin with topical products. Trials with nonprescription diphenhydramine, loratadine, and calamine and zinc were not successful. He had not pursued phototherapy due to time limitations and travel constraints. He had a history of phlebotomies and hydroxyurea use, which he preferred to avoid and discontinued 1 year before presentation.

Despite improving hematocrit (< 45% goal) and platelet counts with ruxolitinib, the patient reported worsening pruritus that significantly impaired quality of life. His sleep and social and physical activities were hindered, preventing him from working. The patient’s active medications also included low-dose aspirin, sertraline, hydroxyzine, triamcinolone acetonide, and pregabalin for sciatica. Given persistent symptoms despite multimodal therapy and lifestyle modifications, the patient was started on naltrexone 25 mg daily, which provided immediate relief of symptoms. He continues to have adequate symptom control 2 years after naltrexone initiation.

Literature Review

A systematic search strategy was developed with the assistance of a medical librarian in Medline Ovid, using both Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms and synonymous keywords. The strategy was then translated to Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane to extract publications investigating PV, pruritus, and/or naltrexone therapy. All searches were conducted on July 18, 2022, and the results of the literature review were as follows: 2 results from Medline Ovid; 34 results from Embase (2 were duplicates of Medline Ovid results); 3 results from Web of Science (all of which were duplicates of Medline Ovid or Embase results); and 0 results from Cochrane (Figure).

Discussion

Although pruritus is a common and often excruciating manifestation of PV, its pathophysiology remains unclear. Some patients with decreasing or newly normal hematocrit and hemoglobin levels have paradoxically experienced an intensification of their pruritus, which introduces erythropoietin signaling pathways as a potential mechanism of the symptom.8 However, iron replacement therapy for patients with exacerbated pruritus after phlebotomies has not demonstrated consistent relief of pruritus.8 Normalization of platelet levels also has not been historically associated with improvement of pruritus.8,9 It has been hypothesized that cells harboring Jak2 mutations at any stage of the hematopoietic pathway mature and accumulate to cause pruritus in PV.9 This theory has been foundational in the development of drugs with activity against cells expressing Jak2 mutations and interventions targeting histamine-releasing mast cells.9-11

The effective use of naltrexone in our patient suggests that histamine may not be the most effective or sole therapeutic target against pruritus in PV. Naltrexone targets opioid receptors in all layers of the epidermis, affecting cell adhesion and keratinocyte production, and exhibits anti-inflammatory effects through interactions with nonopioid receptors, including Toll-like receptor 4.12 The efficacy of oral naltrexone has been documented in patients with pruritus associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors, psoriasis, eczema, lichen simplex chronicus, prurigo nodularis, cholestasis, uremia, and multiple rheumatologic diseases.3,4,7-9,12-14 Opioid pathways also may be involved in peripheral and/or central processing of pruritus associated with PV.

Importantly, patients who are potential candidates for naltrexone therapy should be notified and advised of the risk of drug interactions with opioids, which could lead to symptoms of opioid withdrawal. Other common adverse effects of naltrexone include hepatotoxicity (especially in patients with a history of significant alcohol consumption), abdominal pain, nausea, arthralgias, myalgias, insomnia, headaches, fatigue, and anxiety.12 Therefore, it is integral to screen patients for opioid dependence and determine their baseline liver function. Patients should be monitored following naltrexone initiation to determine whether the drug is an appropriate and effective intervention against PV-associated pruritus.

CONCLUSIONS

This case study demonstrates that naltrexone may be a safe, effective, nonsedating, and cost-efficient oral alternative for refractory PV-associated pruritus. Future directions involve consideration of case series or randomized clinical trials investigating the efficacy of naltrexone in treating PV-associated pruritus. Further research is also warranted to better understand the pathophysiology of this symptom of PV to enhance and potentially expand medical management for patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Amy Sisson (The Texas Medical Center Library) for her guidance and support in the literature review methodology.

P ruritus is a characteristic and often debilitating clinical manifestation reported by about 50% of patients with polycythemia vera (PV). The exact pathophysiology of PV-associated pruritus is poorly understood. The itch sensation may arise from a central phenomenon without skin itch receptor involvement, as is seen in opioid-induced pruritus, or peripherally via unmyelinated C fibers. Various interventions have been used with mixed results for symptom management in this patient population.1

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as paroxetine and fluoxetine, have historically demonstrated some efficacy in treating PV-associated pruritus.2 Alongside SSRIs, phlebotomy, antihistamines, phototherapy, interferon a, and myelosuppressive medications also comprise the various current treatment options. In addition to lacking efficacy, antihistamines can cause somnolence, constipation, and xerostomia.3,4 Phlebotomy and cytoreductive therapy are often effective in controlling erythrocytosis but fail to alleviate the disabling pruritus.1,5,6 More recently, suboptimal symptom alleviation has prompted the discovery of agents that target the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and Janus kinase 2 (Jak2) pathways.1

Naltrexone is an opioid antagonist shown to suppress pruritus in various dermatologic pathologies involving histamine-independent pathways.3,7,8 A systematic search strategy identified 34 studies on PV-associated pruritus, its pathophysiology and interventions, and naltrexone as a therapeutic agent. Only 1 study in the literature has described the use of naltrexone for uremic and cholestatic pruritus.9 We describe the successful use of naltrexone monotherapy for the treatment of pruritus in a patient with PV.

Case Presentation

A 40-year-old man with Jak2-positive PV treated with ruxolitinib presented to the outpatient Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center Supportive Care Clinic in Houston, Texas, for severe refractory pruritus. Wheals manifested in pruritic regions of the patient’s skin without gross excoriations or erythema. Pruritus reportedly began diffusely across the posterior torso. Through the rapid progression of an episode lasting 30 to 45 minutes, the lesions and pruritus would spread to the anterior torso, extend to the upper extremities bilaterally, and finally descend to the lower extremities bilaterally. A persistent sensation of heat or warmth on the patient’s skin was present, and periodically, this would culminate in a burning sensation comparable to “lying flat on one’s back directly on a hornet’s nest…[followed by] a million stings” that was inconsistent with erythromelalgia given the absence of erythema. The intensity of the pruritic episodes was subjectively also described as “enough to make [him] want to jump off the roof of a building…[causing] moments of deep, deep frustration…[and] the worst of all the symptoms one may encounter because of [PV].”

Pruritus was exacerbated by sweating, heat, contact with any liquids on the skin, and sunburns, which doubled the intensity. The patient reported minimal, temporary relief with cannabidiol and cold fabric or air on his skin. His current regimen and nonpharmacologic efforts provided no relief and included oatmeal baths, cornstarch after showers, and patting instead of rubbing the skin with topical products. Trials with nonprescription diphenhydramine, loratadine, and calamine and zinc were not successful. He had not pursued phototherapy due to time limitations and travel constraints. He had a history of phlebotomies and hydroxyurea use, which he preferred to avoid and discontinued 1 year before presentation.

Despite improving hematocrit (< 45% goal) and platelet counts with ruxolitinib, the patient reported worsening pruritus that significantly impaired quality of life. His sleep and social and physical activities were hindered, preventing him from working. The patient’s active medications also included low-dose aspirin, sertraline, hydroxyzine, triamcinolone acetonide, and pregabalin for sciatica. Given persistent symptoms despite multimodal therapy and lifestyle modifications, the patient was started on naltrexone 25 mg daily, which provided immediate relief of symptoms. He continues to have adequate symptom control 2 years after naltrexone initiation.

Literature Review

A systematic search strategy was developed with the assistance of a medical librarian in Medline Ovid, using both Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms and synonymous keywords. The strategy was then translated to Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane to extract publications investigating PV, pruritus, and/or naltrexone therapy. All searches were conducted on July 18, 2022, and the results of the literature review were as follows: 2 results from Medline Ovid; 34 results from Embase (2 were duplicates of Medline Ovid results); 3 results from Web of Science (all of which were duplicates of Medline Ovid or Embase results); and 0 results from Cochrane (Figure).

Discussion

Although pruritus is a common and often excruciating manifestation of PV, its pathophysiology remains unclear. Some patients with decreasing or newly normal hematocrit and hemoglobin levels have paradoxically experienced an intensification of their pruritus, which introduces erythropoietin signaling pathways as a potential mechanism of the symptom.8 However, iron replacement therapy for patients with exacerbated pruritus after phlebotomies has not demonstrated consistent relief of pruritus.8 Normalization of platelet levels also has not been historically associated with improvement of pruritus.8,9 It has been hypothesized that cells harboring Jak2 mutations at any stage of the hematopoietic pathway mature and accumulate to cause pruritus in PV.9 This theory has been foundational in the development of drugs with activity against cells expressing Jak2 mutations and interventions targeting histamine-releasing mast cells.9-11

The effective use of naltrexone in our patient suggests that histamine may not be the most effective or sole therapeutic target against pruritus in PV. Naltrexone targets opioid receptors in all layers of the epidermis, affecting cell adhesion and keratinocyte production, and exhibits anti-inflammatory effects through interactions with nonopioid receptors, including Toll-like receptor 4.12 The efficacy of oral naltrexone has been documented in patients with pruritus associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors, psoriasis, eczema, lichen simplex chronicus, prurigo nodularis, cholestasis, uremia, and multiple rheumatologic diseases.3,4,7-9,12-14 Opioid pathways also may be involved in peripheral and/or central processing of pruritus associated with PV.

Importantly, patients who are potential candidates for naltrexone therapy should be notified and advised of the risk of drug interactions with opioids, which could lead to symptoms of opioid withdrawal. Other common adverse effects of naltrexone include hepatotoxicity (especially in patients with a history of significant alcohol consumption), abdominal pain, nausea, arthralgias, myalgias, insomnia, headaches, fatigue, and anxiety.12 Therefore, it is integral to screen patients for opioid dependence and determine their baseline liver function. Patients should be monitored following naltrexone initiation to determine whether the drug is an appropriate and effective intervention against PV-associated pruritus.

CONCLUSIONS

This case study demonstrates that naltrexone may be a safe, effective, nonsedating, and cost-efficient oral alternative for refractory PV-associated pruritus. Future directions involve consideration of case series or randomized clinical trials investigating the efficacy of naltrexone in treating PV-associated pruritus. Further research is also warranted to better understand the pathophysiology of this symptom of PV to enhance and potentially expand medical management for patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Amy Sisson (The Texas Medical Center Library) for her guidance and support in the literature review methodology.

1. Saini KS, Patnaik MM, Tefferi A. Polycythemia vera-associated pruritus and its management. Eur J Clin Invest. 2010;40(9):828-834. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2362.2010.02334.x

2. Tefferi A, Fonseca R. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are effective in the treatment of polycythemia vera-associated pruritus. Blood. 2002;99(7):2627. doi:10.1182/blood.v99.7.2627

3. Lee J, Shin JU, Noh S, Park CO, Lee KH. Clinical efficacy and safety of naltrexone combination therapy in older patients with severe pruritus. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28(2):159-163. doi:10.5021/ad.2016.28.2.159

4. Phan NQ, Bernhard JD, Luger TA, Stander S. Antipruritic treatment with systemic mu-opioid receptor antagonists: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63(4):680-688. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.08.052

5. Metze D, Reimann S, Beissert S, Luger T. Efficacy and safety of naltrexone, an oral opiate receptor antagonist, in the treatment of pruritus in internal and dermatological diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(4):533-539.

6. Malekzad F, Arbabi M, Mohtasham N, et al. Efficacy of oral naltrexone on pruritus in atopic eczema: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(8):948-950. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03129.x

7. Terg R, Coronel E, Sorda J, Munoz AE, Findor J. Efficacy and safety of oral naltrexone treatment for pruritus of cholestasis, a crossover, double blind, placebo-controlled study. J Hepatol. 2002;37(6):717-722. doi:10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00318-5

8. Lelonek E, Matusiak L, Wrobel T, Szepietowski JC. Aquagenic pruritus in polycythemia vera: clinical characteristics. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98(5):496-500. doi:10.2340/00015555-2906

9. Siegel FP, Tauscher J, Petrides PE. Aquagenic pruritus in polycythemia vera: characteristics and influence on quality of life in 441 patients. Am J Hematol. 2013;88(8):665-669. doi:10.1002/ajh.23474

10. Al-Mashdali AF, Kashgary WR, Yassin MA. Ruxolitinib (a JAK2 inhibitor) as an emerging therapy for refractory pruritis in a patient with low-risk polycythemia vera: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(44):e27722. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000027722

11. Benevolo G, Vassallo F, Urbino I, Giai V. Polycythemia vera (PV): update on emerging treatment options. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2021;17:209-221. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S213020

12. Lee B, Elston DM. The uses of naltrexone in dermatologic conditions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(6):1746-1752. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.031

13. de Carvalho JF, Skare T. Low-dose naltrexone in rheumatological diseases. Mediterr J Rheumatol. 2023;34(1):1-6. doi:10.31138/mjr.34.1.1

14. Singh R, Patel P, Thakker M, Sharma P, Barnes M, Montana S. Naloxone and maintenance naltrexone as novel and effective therapies for immunotherapy-induced pruritus: a case report and brief literature review. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15(6):347-348. doi:10.1200/JOP.18.00797

1. Saini KS, Patnaik MM, Tefferi A. Polycythemia vera-associated pruritus and its management. Eur J Clin Invest. 2010;40(9):828-834. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2362.2010.02334.x

2. Tefferi A, Fonseca R. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are effective in the treatment of polycythemia vera-associated pruritus. Blood. 2002;99(7):2627. doi:10.1182/blood.v99.7.2627

3. Lee J, Shin JU, Noh S, Park CO, Lee KH. Clinical efficacy and safety of naltrexone combination therapy in older patients with severe pruritus. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28(2):159-163. doi:10.5021/ad.2016.28.2.159

4. Phan NQ, Bernhard JD, Luger TA, Stander S. Antipruritic treatment with systemic mu-opioid receptor antagonists: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63(4):680-688. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.08.052

5. Metze D, Reimann S, Beissert S, Luger T. Efficacy and safety of naltrexone, an oral opiate receptor antagonist, in the treatment of pruritus in internal and dermatological diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(4):533-539.

6. Malekzad F, Arbabi M, Mohtasham N, et al. Efficacy of oral naltrexone on pruritus in atopic eczema: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(8):948-950. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03129.x

7. Terg R, Coronel E, Sorda J, Munoz AE, Findor J. Efficacy and safety of oral naltrexone treatment for pruritus of cholestasis, a crossover, double blind, placebo-controlled study. J Hepatol. 2002;37(6):717-722. doi:10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00318-5

8. Lelonek E, Matusiak L, Wrobel T, Szepietowski JC. Aquagenic pruritus in polycythemia vera: clinical characteristics. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98(5):496-500. doi:10.2340/00015555-2906

9. Siegel FP, Tauscher J, Petrides PE. Aquagenic pruritus in polycythemia vera: characteristics and influence on quality of life in 441 patients. Am J Hematol. 2013;88(8):665-669. doi:10.1002/ajh.23474

10. Al-Mashdali AF, Kashgary WR, Yassin MA. Ruxolitinib (a JAK2 inhibitor) as an emerging therapy for refractory pruritis in a patient with low-risk polycythemia vera: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(44):e27722. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000027722

11. Benevolo G, Vassallo F, Urbino I, Giai V. Polycythemia vera (PV): update on emerging treatment options. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2021;17:209-221. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S213020

12. Lee B, Elston DM. The uses of naltrexone in dermatologic conditions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(6):1746-1752. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.031

13. de Carvalho JF, Skare T. Low-dose naltrexone in rheumatological diseases. Mediterr J Rheumatol. 2023;34(1):1-6. doi:10.31138/mjr.34.1.1

14. Singh R, Patel P, Thakker M, Sharma P, Barnes M, Montana S. Naloxone and maintenance naltrexone as novel and effective therapies for immunotherapy-induced pruritus: a case report and brief literature review. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15(6):347-348. doi:10.1200/JOP.18.00797

A Case Series of Rare Immune-Mediated Adverse Reactions at the New Mexico Veterans Affairs Medical Center

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), often broadly referred to as immunotherapy, are being prescribed at increasing rates due to their effectiveness in treating a growing number of advanced solid tumors and hematologic malignancies.1 It has been well established that T-cell signaling mechanisms designed to combat foreign pathogens have been involved in the mitigation of tumor proliferation.2 This protective process can be supported or restricted by infection, medication, or mutations.

ICIs support T-cell–mediated destruction of tumor cells by inhibiting the mechanisms designed to limit autoimmunity, specifically the programmed cell death protein 1/programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) pathways. The results have been impressive, leading to an expansive number of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approvals across a diverse set of malignancies. Consequently, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded for such work in 2018.3

BACKGROUND

While altering these pathways has been shown to hinder tumor growth, the lesser restrictions on the immune system can drive unwanted autoimmune inflammation to host tissue. These toxicities are collectively known as immune-mediated adverse reactions (IMARs). Clinically and histologically, IMARs frequently manifest similarly to other autoimmune conditions and may affect any organ, including skin, liver, lungs, heart, intestine (small and large), kidneys, eyes, endocrine glands, and neurologic tissue.4,5 According to recent studies, as many as 20% to 30% of patients receiving a single ICI will experience at least 1 clinically significant IMAR, and about 13% are classified as severe; however, < 10% of patients will have their ICIs discontinued due to these reactions.6

Though infrequent, a thorough understanding of the severity of IMARs to ICIs is critical for the diagnosis and management of these organ-threatening and potentially life-threatening toxicities. With the growing use of these agents and more FDA approvals for dual checkpoint blockage (concurrent use of CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors), the absolute number of IMARs is expected to rise, thereby leading to more exposure of such events to both oncology and nononcology clinicians. Prior literature has clearly described the treatments and outcomes for many common severe toxicities; however, information regarding presentations and outcomes for rare IMARs is lacking.7

A few fascinating cases of rare toxicities have been observed at the New Mexico Veterans Affairs Medical Center (NMVAMC) in Albuquerque despite its relatively small size compared with other US Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers. As such, herein, the diagnostic evaluation, treatments, and outcomes of rare IMARs are reported for each case, and the related literature is reviewed.

Patient Selection

Patients who were required to discontinue or postpone treatment with any ICI blocking the CTLA-4 (ipilimumab), PD-1 (pembrolizumab, nivolumab, cemiplimab), or PD-L1 (atezolizumab, avelumab, durvalumab) pathways between 2015 to 2021 due to toxicity at the NMVAMC were eligible for inclusion. The electronic health record was reviewed for each eligible case, and the patient demographics, disease characteristics, toxicities, and outcomes were documented for each patient. For the 57 patients who received ICIs within the chosen period, 11 required a treatment break or discontinuation. Of these, 3 cases were selected for reporting due to the rare IMARs observed. This study was approved by the NMVAMC Institutional Review Board.

Case 1: Myocarditis

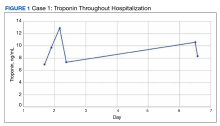

An 84-year-old man receiving a chemoimmunotherapy regimen consisting of carboplatin, pemetrexed, and pembrolizumab for recurrent, stage IV lung adenocarcinoma developed grade 4 cardiomyopathy, as defined by the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v5.0, during his treatment.8 He was treated for 2 cycles before he began experiencing an increase in liver enzymes.

The patient’s presentation was concerning for myocarditis, and he was quickly admitted to NMVAMC. Cardiac catheterization did not reveal any signs of coronary occlusive disease. Prednisone 1 mg/kg was administered immediately; however, given continued chest pain and volume overload, he was quickly transitioned to solumedrol 1000 mg IV daily. After the initiation of his treatment, the patient’s transaminitis began to resolve, and troponin levels began to decrease; however, his symptoms continued to worsen, and his troponin rose again. By the fourth day of hospitalization, the patient was treated with infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor shown to reverse ICI-induced autoimmune inflammation, with only mild improvement of his symptoms. The patient’s condition continued to deteriorate, his troponin levels remained elevated, and his family decided to withhold additional treatment. The patient died shortly thereafter.

Discussion

Cardiotoxicity resulting from ICI therapy is far less common than the other potential severe toxicities associated with ICIs. Nevertheless, many cases of ICI-induced cardiac inflammation have been reported, and it has been widely established that patients treated with ICIs are generally at higher risk for acute coronary syndrome.9-11 Acute cardiotoxicity secondary to autoimmune destruction of cardiac tissue includes myocarditis, pericarditis, and vasculitis, which may manifest with symptoms of heart failure and/or arrhythmia. Grading of ICI-induced cardiomyopathy has been defined by both CTCAE and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), with grade 4 representing moderate to severe clinical decompensation requiring IV medications in the setting of life-threatening conditions.

Review articles have described the treatment options for severe cases.7,12 As detailed in prior reports, once ICI-induced cardiomyopathy is suspected, urgent admission and immediate evaluation to rule out acute coronary syndrome should be undertaken. Given the potential for deterioration despite the occasional insidious onset, aggressive cardiac monitoring, and close follow-up to measure response to interventions should be undertaken.

Case 2: Uveitis

A 70-year-old man who received pembrolizumab as a bladder-sparing approach for his superficial bladder cancer refractory to intravesical treatments developed uveitis. Approximately 3 months following the initiation of treatment, the patient reported bilateral itchy eyes, erythema, and tearing. He had a known history of allergic conjunctivitis that predated the ICI therapy, and consequently, it was unclear whether his symptoms were reflective of a more concerning issue. The patient’s symptoms continued to wax and wane for a few months, prompting a referral to ophthalmology colleagues at NMVAMC.

Ophthalmology evaluation identified uveitic glaucoma in the setting of his underlying chronic glaucoma. Pembrolizumab was discontinued, and the patient was counseled on choosing either cystectomy or locoregional therapies if further tumors arose. However, within a few weeks of administering topical steroid drops, his symptoms markedly improved, and he wished to be restarted on pembrolizumab. His uveitis remained in remission, and he has been treated with pembrolizumab for more than 1 year since this episode. He has had no clear findings of superficial bladder cancer recurrence while receiving ICI therapy.

Discussion

Uveitis is a known complication of pembrolizumab, and it has been shown to occur in 1% of patients with this treatment.13,14 It should be noted that most of the studies of this IMAR occurred in patients with metastatic melanoma; therefore the rate of this condition in other patients is less understood. Overall, ocular IMARs secondary to anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 therapies are rare.

The most common IMAR is surface ocular disease, consisting of dry eye disease (DED), conjunctivitis, uveitis, and keratitis. Of these, the most common ocular surface disease is DED, which occurred in 1% to 4% of patients treated with ICI therapy; most of these reactions are mild and self-limiting.15 Atezolizumab has the highest association with ocular inflammation and ipilimumab has the highest association with uveitis, with reported odds ratios of 18.89 and 10.54, respectively.16 Treatment of ICI-induced uveitis generally includes topical steroids and treatment discontinuation or break.17 Oral or IV steroids, infliximab, and procedural involvement may be considered in refractory cases or those initially presenting with marked vision loss. Close communication with ophthalmology colleagues to monitor visual acuity and ocular pressure multiple times weekly during the acute phase is required for treatment titration.

Case 3: Organizing Pneumonia

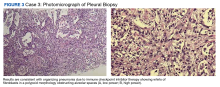

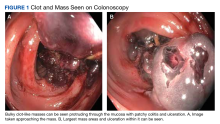

A man aged 63 years was diagnosed with malignant mesothelioma after incidentally noting a pleural effusion and thickening on routine low-dose computed tomography surveillance of pulmonary nodules. A biopsy was performed and was consistent with mesothelioma, and the patient was started on nivolumab (PD-1 inhibitor) and ipilimumab (CTLA-4 inhibitor). The patient was initiated on dual ICIs, and after 6 months of therapy, he had a promising complete response. However, after 9 months of therapy, he developed a new left upper lobe (LUL) pleural-based lesion (Figure 2A).

A biopsy was performed, and the histopathologic appearance was consistent with organizing pneumonia (OP) (Figure 3).

Discussion

ICIs can uncommonly drive pneumonitis, with the frequency adjusted based on the number of ICIs prescribed and the primary cancer involved. Across all cancers, up to 5% of patients treated with single-agent ICI therapy may experience pneumonitis, though often the findings may simply be radiographic without symptoms. Moreover, up to 10% of patients undergoing treatment for pulmonary cancer or those with dual ICI treatment regimens experience radiographic and/or clinical pneumonitis.18 The clinical manifestations include a broad spectrum of respiratory symptoms. Given the convoluting concerns of cancer progression and infection, a biopsy is often obtained. Histopathologic findings of pneumonitis may include diffuse alveolar damage and/or interstitial lung disease, with OP being a rare variant of ILD.

Among pulmonologists, OP is felt to have polymorphous imaging findings, and biopsy is required to confirm histology; however, histopathology cannot define etiology, and consequently, OP is somewhat of an umbrella diagnosis. The condition can be cryptogenic (idiopathic) or secondary to a multitude of conditions (infection, drug toxicity, or systemic disease). It is classically described as polypoid aggregations of fibroblasts that obstruct the alveolar spaces.19 This histopathologic pattern was demonstrated in our patient’s lung biopsy. Given a prior case description of ICIs, mesothelioma, OP development, and the unremarkable infectious workup, we felt that the patient’s OP was driven by his dual ICI therapy, thereby leading to the ultimate discontinuation of his ICIs and initiation of steroids.20 Thankfully, the patient had already obtained a complete response to his ICIs, and hopefully, he can attain a durable remission with the addition of maintenance chemotherapy.

CONCLUSIONS

ICIs have revolutionized the treatment of a myriad of solid tumors and hematologic malignancies, and their use internationally is expected to increase. With the alteration in immunology pathways, clinicians in all fields will need to be familiarized with IMARs secondary to these agents, including rare subtypes. In addition, the variability in presentations relative to the patients’ treatment course was significant (between 2-9 months), and this highlights that these IMARs can occur at any time point and clinicians should be ever vigilant to spot symptoms in their patients.

It was unexpected for the 3 aforementioned rare toxicities to arise at NMVAMC among only 57 treated patients, and we speculate that these findings may have been observed for 1 of 3 reasons. First, caring for 3 patients with this collection of rare toxicities may have been due to chance. Second, though there is sparse literature studying the topic, the regional environment, including sunlight exposure and air quality, may play a role in the development of one or all of these rare toxicities. Third, rates of these toxicities may be underreported in the literature or attributed to other conditions rather than due to ICIs at other sites, and the uncommon nature of these IMARs may be overstated. Investigations evaluating rates of toxicities, including those traditionally uncommonly seen, based on regional location should be conducted before any further conclusions are drawn.

1. Bagchi S, Yuan R, Engleman EG. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of cancer: clinical impact and mechanisms of response and resistance. Published online 2020. doi:10.1146/annurev-pathol-042020

2. Chen DS, Mellman I. Oncology meets immunology: The cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity. 2013;39(1):1-10. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.012

3. Smyth MJ, Teng MWL. 2018 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine. Clin Transl Immunology. 2018;7(10). doi:10.1002/cti2.1041

4. Baxi S, Yang A, Gennarelli RL, et al. Immune-related adverse events for anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 drugs: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Online). 2018;360. doi:10.1136/bmj.k793

5. Ellithi M, Elnair R, Chang GV, Abdallah MA. Toxicities of immune checkpoint inhibitors: itis-ending adverse reactions and more. Cureus. Published online February 10, 2020. doi:10.7759/cureus.6935

6. Berti A, Bortolotti R, Dipasquale M, et al. Meta-analysis of immune-related adverse events in phase 3 clinical trials assessing immune checkpoint inhibitors for lung cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021;162. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2021.103351

7. Davies M, Duffield EA. Safety of checkpoint inhibitors for cancer treatment: strategies for patient monitoring and management of immune-mediated adverse events. Immunotargets Ther. 2017;Volume 6:51-71. doi:10.2147/itt.s141577

8. US Department of Health and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events V5.0. Accessed July 17, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5584920/

9. Johnson DB, Balko JM, Compton ML, et al. Fulminant myocarditis with combination immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(18):1749-1755. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1609214

10. Mahmood SS, Fradley MG, Cohen J V., et al. Myocarditis in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(16):1755-1764. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.037

11. Wang DY, Salem JE, Cohen JV, et al. Fatal toxic effects associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(12):1721-1728. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.3923

12. Brahmer JR, Lacchetti C, Schneider BJ, et al; National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Onc. 2018;36(17):1714-1768. doi:10.1200/JCO

13. Ribas A, Hamid O, Daud A, et al. Association of pembrolizumab with tumor response and survival among patients with advanced melanoma. JAMA. 2016;315:1600-1609. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.4059

14. Dalvin LA, Shields CL, Orloff M, Sato T, Shields JA. Checkpoint inhibitor immune therapy: systemic indications and ophthalmic side effects. Retina. 2018;38(6):1063-1078. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000002181

15. Park RB, Jain S, Han H, Park J. Ocular surface disease associated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Ocular Surface. 2021;20:115-129. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2021.02.004

16. Fang T, Maberley DA, Etminan M. Ocular adverse events with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Curr Ophthalmol. 2019;31(3):319-322. doi:10.1016/j.joco.2019.05.002

17. Whist E, Symes RJ, Chang JH, et al. Uveitis caused by treatment for malignant melanoma: a case series. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2021;15(6):718-723. doi:10.1097/ICB.0000000000000876

18. Naidoo J, Wang X, Woo KM, et al. Pneumonitis in patients treated with anti-programmed death-1/programmed death ligand 1 therapy. J Clin Onc. 2017;35(7):709-717. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.68.2005

19. Yoshikawa A, Bychkov A, Sathirareuangchai S. Other nonneoplastic conditions, acute lung injury, organizing pneumonia. Accessed July 17, 2023. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/lungnontumorboop.html

20. Kuint R, Lotem M, Neuman T, et al. Organizing pneumonia following treatment with pembrolizumab for metastatic malignant melanoma–a case report. Respir Med Case Rep. 2017;20:95-97. doi:10.1016/j.rmcr.2017.01.003

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), often broadly referred to as immunotherapy, are being prescribed at increasing rates due to their effectiveness in treating a growing number of advanced solid tumors and hematologic malignancies.1 It has been well established that T-cell signaling mechanisms designed to combat foreign pathogens have been involved in the mitigation of tumor proliferation.2 This protective process can be supported or restricted by infection, medication, or mutations.

ICIs support T-cell–mediated destruction of tumor cells by inhibiting the mechanisms designed to limit autoimmunity, specifically the programmed cell death protein 1/programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) pathways. The results have been impressive, leading to an expansive number of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approvals across a diverse set of malignancies. Consequently, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded for such work in 2018.3

BACKGROUND

While altering these pathways has been shown to hinder tumor growth, the lesser restrictions on the immune system can drive unwanted autoimmune inflammation to host tissue. These toxicities are collectively known as immune-mediated adverse reactions (IMARs). Clinically and histologically, IMARs frequently manifest similarly to other autoimmune conditions and may affect any organ, including skin, liver, lungs, heart, intestine (small and large), kidneys, eyes, endocrine glands, and neurologic tissue.4,5 According to recent studies, as many as 20% to 30% of patients receiving a single ICI will experience at least 1 clinically significant IMAR, and about 13% are classified as severe; however, < 10% of patients will have their ICIs discontinued due to these reactions.6

Though infrequent, a thorough understanding of the severity of IMARs to ICIs is critical for the diagnosis and management of these organ-threatening and potentially life-threatening toxicities. With the growing use of these agents and more FDA approvals for dual checkpoint blockage (concurrent use of CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors), the absolute number of IMARs is expected to rise, thereby leading to more exposure of such events to both oncology and nononcology clinicians. Prior literature has clearly described the treatments and outcomes for many common severe toxicities; however, information regarding presentations and outcomes for rare IMARs is lacking.7

A few fascinating cases of rare toxicities have been observed at the New Mexico Veterans Affairs Medical Center (NMVAMC) in Albuquerque despite its relatively small size compared with other US Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers. As such, herein, the diagnostic evaluation, treatments, and outcomes of rare IMARs are reported for each case, and the related literature is reviewed.

Patient Selection

Patients who were required to discontinue or postpone treatment with any ICI blocking the CTLA-4 (ipilimumab), PD-1 (pembrolizumab, nivolumab, cemiplimab), or PD-L1 (atezolizumab, avelumab, durvalumab) pathways between 2015 to 2021 due to toxicity at the NMVAMC were eligible for inclusion. The electronic health record was reviewed for each eligible case, and the patient demographics, disease characteristics, toxicities, and outcomes were documented for each patient. For the 57 patients who received ICIs within the chosen period, 11 required a treatment break or discontinuation. Of these, 3 cases were selected for reporting due to the rare IMARs observed. This study was approved by the NMVAMC Institutional Review Board.

Case 1: Myocarditis

An 84-year-old man receiving a chemoimmunotherapy regimen consisting of carboplatin, pemetrexed, and pembrolizumab for recurrent, stage IV lung adenocarcinoma developed grade 4 cardiomyopathy, as defined by the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v5.0, during his treatment.8 He was treated for 2 cycles before he began experiencing an increase in liver enzymes.

The patient’s presentation was concerning for myocarditis, and he was quickly admitted to NMVAMC. Cardiac catheterization did not reveal any signs of coronary occlusive disease. Prednisone 1 mg/kg was administered immediately; however, given continued chest pain and volume overload, he was quickly transitioned to solumedrol 1000 mg IV daily. After the initiation of his treatment, the patient’s transaminitis began to resolve, and troponin levels began to decrease; however, his symptoms continued to worsen, and his troponin rose again. By the fourth day of hospitalization, the patient was treated with infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor shown to reverse ICI-induced autoimmune inflammation, with only mild improvement of his symptoms. The patient’s condition continued to deteriorate, his troponin levels remained elevated, and his family decided to withhold additional treatment. The patient died shortly thereafter.

Discussion

Cardiotoxicity resulting from ICI therapy is far less common than the other potential severe toxicities associated with ICIs. Nevertheless, many cases of ICI-induced cardiac inflammation have been reported, and it has been widely established that patients treated with ICIs are generally at higher risk for acute coronary syndrome.9-11 Acute cardiotoxicity secondary to autoimmune destruction of cardiac tissue includes myocarditis, pericarditis, and vasculitis, which may manifest with symptoms of heart failure and/or arrhythmia. Grading of ICI-induced cardiomyopathy has been defined by both CTCAE and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), with grade 4 representing moderate to severe clinical decompensation requiring IV medications in the setting of life-threatening conditions.

Review articles have described the treatment options for severe cases.7,12 As detailed in prior reports, once ICI-induced cardiomyopathy is suspected, urgent admission and immediate evaluation to rule out acute coronary syndrome should be undertaken. Given the potential for deterioration despite the occasional insidious onset, aggressive cardiac monitoring, and close follow-up to measure response to interventions should be undertaken.

Case 2: Uveitis

A 70-year-old man who received pembrolizumab as a bladder-sparing approach for his superficial bladder cancer refractory to intravesical treatments developed uveitis. Approximately 3 months following the initiation of treatment, the patient reported bilateral itchy eyes, erythema, and tearing. He had a known history of allergic conjunctivitis that predated the ICI therapy, and consequently, it was unclear whether his symptoms were reflective of a more concerning issue. The patient’s symptoms continued to wax and wane for a few months, prompting a referral to ophthalmology colleagues at NMVAMC.

Ophthalmology evaluation identified uveitic glaucoma in the setting of his underlying chronic glaucoma. Pembrolizumab was discontinued, and the patient was counseled on choosing either cystectomy or locoregional therapies if further tumors arose. However, within a few weeks of administering topical steroid drops, his symptoms markedly improved, and he wished to be restarted on pembrolizumab. His uveitis remained in remission, and he has been treated with pembrolizumab for more than 1 year since this episode. He has had no clear findings of superficial bladder cancer recurrence while receiving ICI therapy.

Discussion

Uveitis is a known complication of pembrolizumab, and it has been shown to occur in 1% of patients with this treatment.13,14 It should be noted that most of the studies of this IMAR occurred in patients with metastatic melanoma; therefore the rate of this condition in other patients is less understood. Overall, ocular IMARs secondary to anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 therapies are rare.

The most common IMAR is surface ocular disease, consisting of dry eye disease (DED), conjunctivitis, uveitis, and keratitis. Of these, the most common ocular surface disease is DED, which occurred in 1% to 4% of patients treated with ICI therapy; most of these reactions are mild and self-limiting.15 Atezolizumab has the highest association with ocular inflammation and ipilimumab has the highest association with uveitis, with reported odds ratios of 18.89 and 10.54, respectively.16 Treatment of ICI-induced uveitis generally includes topical steroids and treatment discontinuation or break.17 Oral or IV steroids, infliximab, and procedural involvement may be considered in refractory cases or those initially presenting with marked vision loss. Close communication with ophthalmology colleagues to monitor visual acuity and ocular pressure multiple times weekly during the acute phase is required for treatment titration.

Case 3: Organizing Pneumonia

A man aged 63 years was diagnosed with malignant mesothelioma after incidentally noting a pleural effusion and thickening on routine low-dose computed tomography surveillance of pulmonary nodules. A biopsy was performed and was consistent with mesothelioma, and the patient was started on nivolumab (PD-1 inhibitor) and ipilimumab (CTLA-4 inhibitor). The patient was initiated on dual ICIs, and after 6 months of therapy, he had a promising complete response. However, after 9 months of therapy, he developed a new left upper lobe (LUL) pleural-based lesion (Figure 2A).

A biopsy was performed, and the histopathologic appearance was consistent with organizing pneumonia (OP) (Figure 3).

Discussion

ICIs can uncommonly drive pneumonitis, with the frequency adjusted based on the number of ICIs prescribed and the primary cancer involved. Across all cancers, up to 5% of patients treated with single-agent ICI therapy may experience pneumonitis, though often the findings may simply be radiographic without symptoms. Moreover, up to 10% of patients undergoing treatment for pulmonary cancer or those with dual ICI treatment regimens experience radiographic and/or clinical pneumonitis.18 The clinical manifestations include a broad spectrum of respiratory symptoms. Given the convoluting concerns of cancer progression and infection, a biopsy is often obtained. Histopathologic findings of pneumonitis may include diffuse alveolar damage and/or interstitial lung disease, with OP being a rare variant of ILD.

Among pulmonologists, OP is felt to have polymorphous imaging findings, and biopsy is required to confirm histology; however, histopathology cannot define etiology, and consequently, OP is somewhat of an umbrella diagnosis. The condition can be cryptogenic (idiopathic) or secondary to a multitude of conditions (infection, drug toxicity, or systemic disease). It is classically described as polypoid aggregations of fibroblasts that obstruct the alveolar spaces.19 This histopathologic pattern was demonstrated in our patient’s lung biopsy. Given a prior case description of ICIs, mesothelioma, OP development, and the unremarkable infectious workup, we felt that the patient’s OP was driven by his dual ICI therapy, thereby leading to the ultimate discontinuation of his ICIs and initiation of steroids.20 Thankfully, the patient had already obtained a complete response to his ICIs, and hopefully, he can attain a durable remission with the addition of maintenance chemotherapy.

CONCLUSIONS

ICIs have revolutionized the treatment of a myriad of solid tumors and hematologic malignancies, and their use internationally is expected to increase. With the alteration in immunology pathways, clinicians in all fields will need to be familiarized with IMARs secondary to these agents, including rare subtypes. In addition, the variability in presentations relative to the patients’ treatment course was significant (between 2-9 months), and this highlights that these IMARs can occur at any time point and clinicians should be ever vigilant to spot symptoms in their patients.

It was unexpected for the 3 aforementioned rare toxicities to arise at NMVAMC among only 57 treated patients, and we speculate that these findings may have been observed for 1 of 3 reasons. First, caring for 3 patients with this collection of rare toxicities may have been due to chance. Second, though there is sparse literature studying the topic, the regional environment, including sunlight exposure and air quality, may play a role in the development of one or all of these rare toxicities. Third, rates of these toxicities may be underreported in the literature or attributed to other conditions rather than due to ICIs at other sites, and the uncommon nature of these IMARs may be overstated. Investigations evaluating rates of toxicities, including those traditionally uncommonly seen, based on regional location should be conducted before any further conclusions are drawn.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), often broadly referred to as immunotherapy, are being prescribed at increasing rates due to their effectiveness in treating a growing number of advanced solid tumors and hematologic malignancies.1 It has been well established that T-cell signaling mechanisms designed to combat foreign pathogens have been involved in the mitigation of tumor proliferation.2 This protective process can be supported or restricted by infection, medication, or mutations.

ICIs support T-cell–mediated destruction of tumor cells by inhibiting the mechanisms designed to limit autoimmunity, specifically the programmed cell death protein 1/programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) pathways. The results have been impressive, leading to an expansive number of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approvals across a diverse set of malignancies. Consequently, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded for such work in 2018.3

BACKGROUND

While altering these pathways has been shown to hinder tumor growth, the lesser restrictions on the immune system can drive unwanted autoimmune inflammation to host tissue. These toxicities are collectively known as immune-mediated adverse reactions (IMARs). Clinically and histologically, IMARs frequently manifest similarly to other autoimmune conditions and may affect any organ, including skin, liver, lungs, heart, intestine (small and large), kidneys, eyes, endocrine glands, and neurologic tissue.4,5 According to recent studies, as many as 20% to 30% of patients receiving a single ICI will experience at least 1 clinically significant IMAR, and about 13% are classified as severe; however, < 10% of patients will have their ICIs discontinued due to these reactions.6

Though infrequent, a thorough understanding of the severity of IMARs to ICIs is critical for the diagnosis and management of these organ-threatening and potentially life-threatening toxicities. With the growing use of these agents and more FDA approvals for dual checkpoint blockage (concurrent use of CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors), the absolute number of IMARs is expected to rise, thereby leading to more exposure of such events to both oncology and nononcology clinicians. Prior literature has clearly described the treatments and outcomes for many common severe toxicities; however, information regarding presentations and outcomes for rare IMARs is lacking.7

A few fascinating cases of rare toxicities have been observed at the New Mexico Veterans Affairs Medical Center (NMVAMC) in Albuquerque despite its relatively small size compared with other US Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers. As such, herein, the diagnostic evaluation, treatments, and outcomes of rare IMARs are reported for each case, and the related literature is reviewed.

Patient Selection

Patients who were required to discontinue or postpone treatment with any ICI blocking the CTLA-4 (ipilimumab), PD-1 (pembrolizumab, nivolumab, cemiplimab), or PD-L1 (atezolizumab, avelumab, durvalumab) pathways between 2015 to 2021 due to toxicity at the NMVAMC were eligible for inclusion. The electronic health record was reviewed for each eligible case, and the patient demographics, disease characteristics, toxicities, and outcomes were documented for each patient. For the 57 patients who received ICIs within the chosen period, 11 required a treatment break or discontinuation. Of these, 3 cases were selected for reporting due to the rare IMARs observed. This study was approved by the NMVAMC Institutional Review Board.

Case 1: Myocarditis

An 84-year-old man receiving a chemoimmunotherapy regimen consisting of carboplatin, pemetrexed, and pembrolizumab for recurrent, stage IV lung adenocarcinoma developed grade 4 cardiomyopathy, as defined by the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v5.0, during his treatment.8 He was treated for 2 cycles before he began experiencing an increase in liver enzymes.

The patient’s presentation was concerning for myocarditis, and he was quickly admitted to NMVAMC. Cardiac catheterization did not reveal any signs of coronary occlusive disease. Prednisone 1 mg/kg was administered immediately; however, given continued chest pain and volume overload, he was quickly transitioned to solumedrol 1000 mg IV daily. After the initiation of his treatment, the patient’s transaminitis began to resolve, and troponin levels began to decrease; however, his symptoms continued to worsen, and his troponin rose again. By the fourth day of hospitalization, the patient was treated with infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor shown to reverse ICI-induced autoimmune inflammation, with only mild improvement of his symptoms. The patient’s condition continued to deteriorate, his troponin levels remained elevated, and his family decided to withhold additional treatment. The patient died shortly thereafter.

Discussion

Cardiotoxicity resulting from ICI therapy is far less common than the other potential severe toxicities associated with ICIs. Nevertheless, many cases of ICI-induced cardiac inflammation have been reported, and it has been widely established that patients treated with ICIs are generally at higher risk for acute coronary syndrome.9-11 Acute cardiotoxicity secondary to autoimmune destruction of cardiac tissue includes myocarditis, pericarditis, and vasculitis, which may manifest with symptoms of heart failure and/or arrhythmia. Grading of ICI-induced cardiomyopathy has been defined by both CTCAE and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), with grade 4 representing moderate to severe clinical decompensation requiring IV medications in the setting of life-threatening conditions.

Review articles have described the treatment options for severe cases.7,12 As detailed in prior reports, once ICI-induced cardiomyopathy is suspected, urgent admission and immediate evaluation to rule out acute coronary syndrome should be undertaken. Given the potential for deterioration despite the occasional insidious onset, aggressive cardiac monitoring, and close follow-up to measure response to interventions should be undertaken.

Case 2: Uveitis

A 70-year-old man who received pembrolizumab as a bladder-sparing approach for his superficial bladder cancer refractory to intravesical treatments developed uveitis. Approximately 3 months following the initiation of treatment, the patient reported bilateral itchy eyes, erythema, and tearing. He had a known history of allergic conjunctivitis that predated the ICI therapy, and consequently, it was unclear whether his symptoms were reflective of a more concerning issue. The patient’s symptoms continued to wax and wane for a few months, prompting a referral to ophthalmology colleagues at NMVAMC.

Ophthalmology evaluation identified uveitic glaucoma in the setting of his underlying chronic glaucoma. Pembrolizumab was discontinued, and the patient was counseled on choosing either cystectomy or locoregional therapies if further tumors arose. However, within a few weeks of administering topical steroid drops, his symptoms markedly improved, and he wished to be restarted on pembrolizumab. His uveitis remained in remission, and he has been treated with pembrolizumab for more than 1 year since this episode. He has had no clear findings of superficial bladder cancer recurrence while receiving ICI therapy.

Discussion

Uveitis is a known complication of pembrolizumab, and it has been shown to occur in 1% of patients with this treatment.13,14 It should be noted that most of the studies of this IMAR occurred in patients with metastatic melanoma; therefore the rate of this condition in other patients is less understood. Overall, ocular IMARs secondary to anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 therapies are rare.

The most common IMAR is surface ocular disease, consisting of dry eye disease (DED), conjunctivitis, uveitis, and keratitis. Of these, the most common ocular surface disease is DED, which occurred in 1% to 4% of patients treated with ICI therapy; most of these reactions are mild and self-limiting.15 Atezolizumab has the highest association with ocular inflammation and ipilimumab has the highest association with uveitis, with reported odds ratios of 18.89 and 10.54, respectively.16 Treatment of ICI-induced uveitis generally includes topical steroids and treatment discontinuation or break.17 Oral or IV steroids, infliximab, and procedural involvement may be considered in refractory cases or those initially presenting with marked vision loss. Close communication with ophthalmology colleagues to monitor visual acuity and ocular pressure multiple times weekly during the acute phase is required for treatment titration.

Case 3: Organizing Pneumonia

A man aged 63 years was diagnosed with malignant mesothelioma after incidentally noting a pleural effusion and thickening on routine low-dose computed tomography surveillance of pulmonary nodules. A biopsy was performed and was consistent with mesothelioma, and the patient was started on nivolumab (PD-1 inhibitor) and ipilimumab (CTLA-4 inhibitor). The patient was initiated on dual ICIs, and after 6 months of therapy, he had a promising complete response. However, after 9 months of therapy, he developed a new left upper lobe (LUL) pleural-based lesion (Figure 2A).

A biopsy was performed, and the histopathologic appearance was consistent with organizing pneumonia (OP) (Figure 3).

Discussion

ICIs can uncommonly drive pneumonitis, with the frequency adjusted based on the number of ICIs prescribed and the primary cancer involved. Across all cancers, up to 5% of patients treated with single-agent ICI therapy may experience pneumonitis, though often the findings may simply be radiographic without symptoms. Moreover, up to 10% of patients undergoing treatment for pulmonary cancer or those with dual ICI treatment regimens experience radiographic and/or clinical pneumonitis.18 The clinical manifestations include a broad spectrum of respiratory symptoms. Given the convoluting concerns of cancer progression and infection, a biopsy is often obtained. Histopathologic findings of pneumonitis may include diffuse alveolar damage and/or interstitial lung disease, with OP being a rare variant of ILD.

Among pulmonologists, OP is felt to have polymorphous imaging findings, and biopsy is required to confirm histology; however, histopathology cannot define etiology, and consequently, OP is somewhat of an umbrella diagnosis. The condition can be cryptogenic (idiopathic) or secondary to a multitude of conditions (infection, drug toxicity, or systemic disease). It is classically described as polypoid aggregations of fibroblasts that obstruct the alveolar spaces.19 This histopathologic pattern was demonstrated in our patient’s lung biopsy. Given a prior case description of ICIs, mesothelioma, OP development, and the unremarkable infectious workup, we felt that the patient’s OP was driven by his dual ICI therapy, thereby leading to the ultimate discontinuation of his ICIs and initiation of steroids.20 Thankfully, the patient had already obtained a complete response to his ICIs, and hopefully, he can attain a durable remission with the addition of maintenance chemotherapy.

CONCLUSIONS

ICIs have revolutionized the treatment of a myriad of solid tumors and hematologic malignancies, and their use internationally is expected to increase. With the alteration in immunology pathways, clinicians in all fields will need to be familiarized with IMARs secondary to these agents, including rare subtypes. In addition, the variability in presentations relative to the patients’ treatment course was significant (between 2-9 months), and this highlights that these IMARs can occur at any time point and clinicians should be ever vigilant to spot symptoms in their patients.

It was unexpected for the 3 aforementioned rare toxicities to arise at NMVAMC among only 57 treated patients, and we speculate that these findings may have been observed for 1 of 3 reasons. First, caring for 3 patients with this collection of rare toxicities may have been due to chance. Second, though there is sparse literature studying the topic, the regional environment, including sunlight exposure and air quality, may play a role in the development of one or all of these rare toxicities. Third, rates of these toxicities may be underreported in the literature or attributed to other conditions rather than due to ICIs at other sites, and the uncommon nature of these IMARs may be overstated. Investigations evaluating rates of toxicities, including those traditionally uncommonly seen, based on regional location should be conducted before any further conclusions are drawn.

1. Bagchi S, Yuan R, Engleman EG. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of cancer: clinical impact and mechanisms of response and resistance. Published online 2020. doi:10.1146/annurev-pathol-042020

2. Chen DS, Mellman I. Oncology meets immunology: The cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity. 2013;39(1):1-10. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.012

3. Smyth MJ, Teng MWL. 2018 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine. Clin Transl Immunology. 2018;7(10). doi:10.1002/cti2.1041

4. Baxi S, Yang A, Gennarelli RL, et al. Immune-related adverse events for anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 drugs: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Online). 2018;360. doi:10.1136/bmj.k793

5. Ellithi M, Elnair R, Chang GV, Abdallah MA. Toxicities of immune checkpoint inhibitors: itis-ending adverse reactions and more. Cureus. Published online February 10, 2020. doi:10.7759/cureus.6935

6. Berti A, Bortolotti R, Dipasquale M, et al. Meta-analysis of immune-related adverse events in phase 3 clinical trials assessing immune checkpoint inhibitors for lung cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021;162. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2021.103351

7. Davies M, Duffield EA. Safety of checkpoint inhibitors for cancer treatment: strategies for patient monitoring and management of immune-mediated adverse events. Immunotargets Ther. 2017;Volume 6:51-71. doi:10.2147/itt.s141577

8. US Department of Health and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events V5.0. Accessed July 17, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5584920/

9. Johnson DB, Balko JM, Compton ML, et al. Fulminant myocarditis with combination immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(18):1749-1755. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1609214

10. Mahmood SS, Fradley MG, Cohen J V., et al. Myocarditis in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(16):1755-1764. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.037

11. Wang DY, Salem JE, Cohen JV, et al. Fatal toxic effects associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(12):1721-1728. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.3923

12. Brahmer JR, Lacchetti C, Schneider BJ, et al; National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Onc. 2018;36(17):1714-1768. doi:10.1200/JCO

13. Ribas A, Hamid O, Daud A, et al. Association of pembrolizumab with tumor response and survival among patients with advanced melanoma. JAMA. 2016;315:1600-1609. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.4059

14. Dalvin LA, Shields CL, Orloff M, Sato T, Shields JA. Checkpoint inhibitor immune therapy: systemic indications and ophthalmic side effects. Retina. 2018;38(6):1063-1078. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000002181

15. Park RB, Jain S, Han H, Park J. Ocular surface disease associated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Ocular Surface. 2021;20:115-129. doi:10.1016/j.jtos.2021.02.004

16. Fang T, Maberley DA, Etminan M. Ocular adverse events with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Curr Ophthalmol. 2019;31(3):319-322. doi:10.1016/j.joco.2019.05.002

17. Whist E, Symes RJ, Chang JH, et al. Uveitis caused by treatment for malignant melanoma: a case series. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2021;15(6):718-723. doi:10.1097/ICB.0000000000000876

18. Naidoo J, Wang X, Woo KM, et al. Pneumonitis in patients treated with anti-programmed death-1/programmed death ligand 1 therapy. J Clin Onc. 2017;35(7):709-717. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.68.2005