User login

Annular Erythematous Plaques on the Back

The Diagnosis: Granuloma Annulare

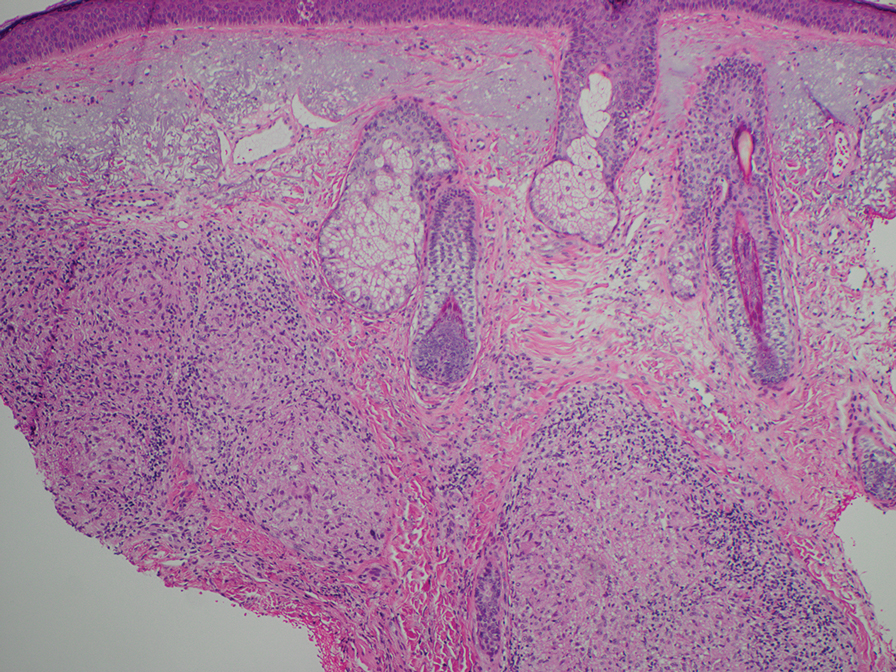

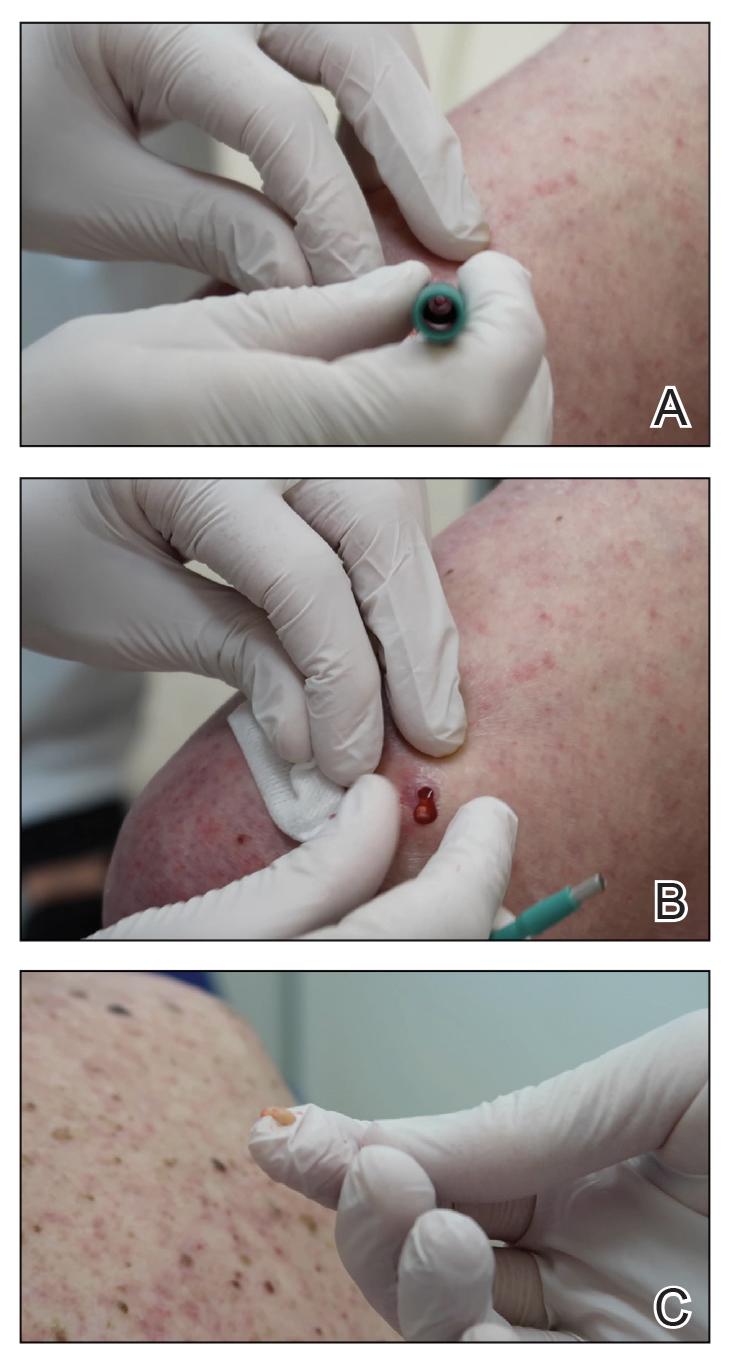

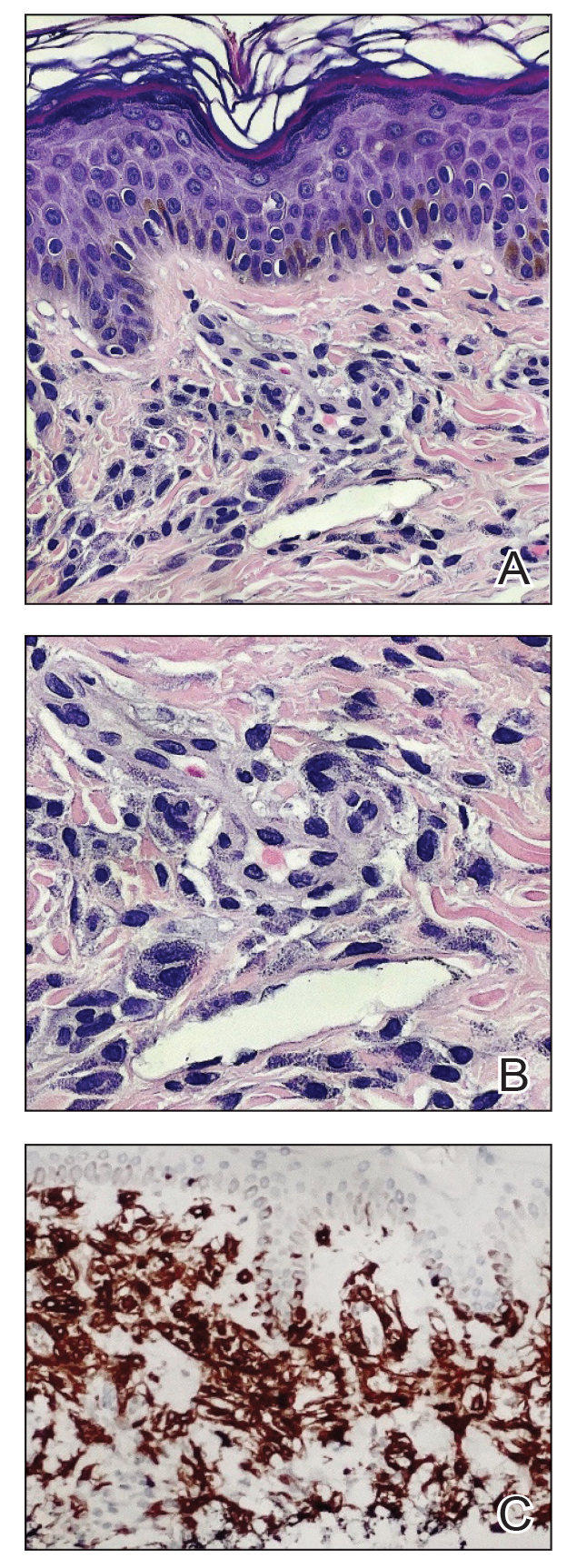

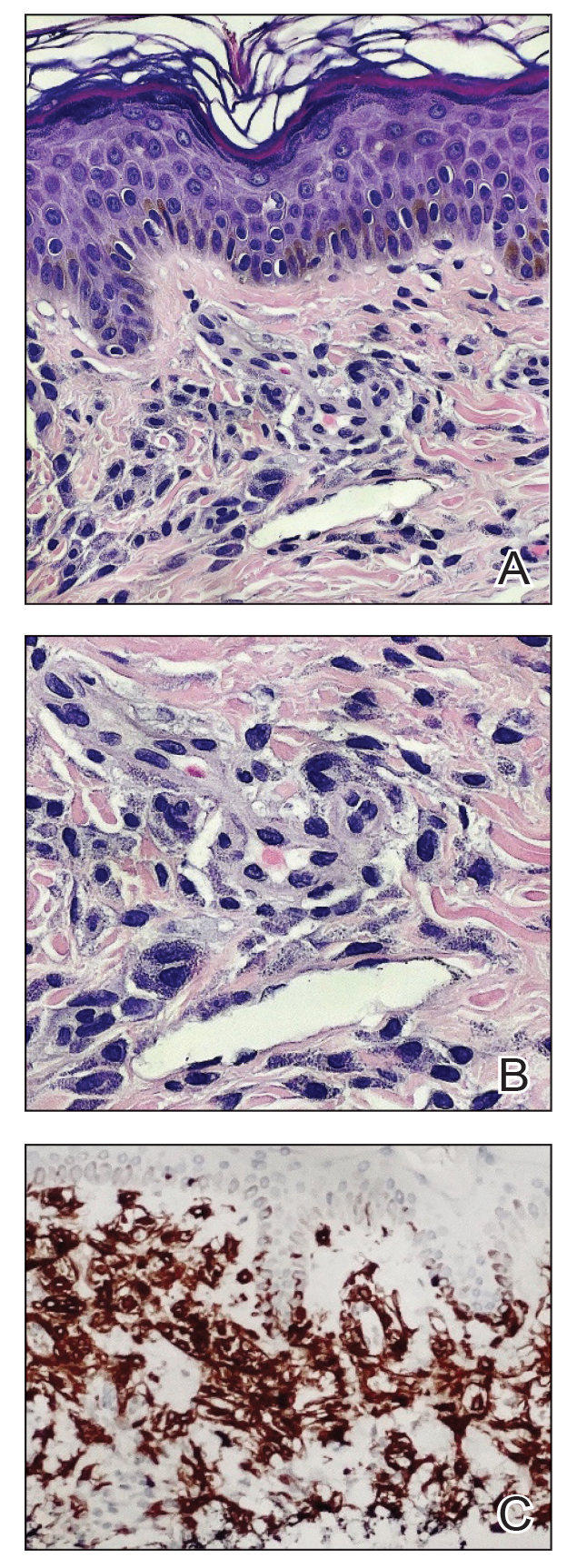

The biopsies revealed palisading granulomatous dermatitis consistent with granuloma annulare (GA). This diagnosis was supported by the clinical presentation and histopathologic findings. Although the pathogenesis of GA is unclear, it is a benign, self-limiting condition. Primarily affected sites include the trunk and forearms. Generalized GA (or GA with ≥10 lesions) may warrant workup for malignancy, as it may represent a paraneoplastic process.1 Histopathology reveals granulomas comprising a dermal lymphohistiocytic infiltrate as well as central mucin and nuclear debris. There are a few histologic subtypes of GA, including palisading and interstitial, which refer to the distribution of the histiocytic infiltrate.2,3 This case—with palisading histiocytes lining the collection of necrobiosis and mucin (bottom quiz image)—features palisading GA. Notably, GA exhibits central rather than diffuse mucin.4

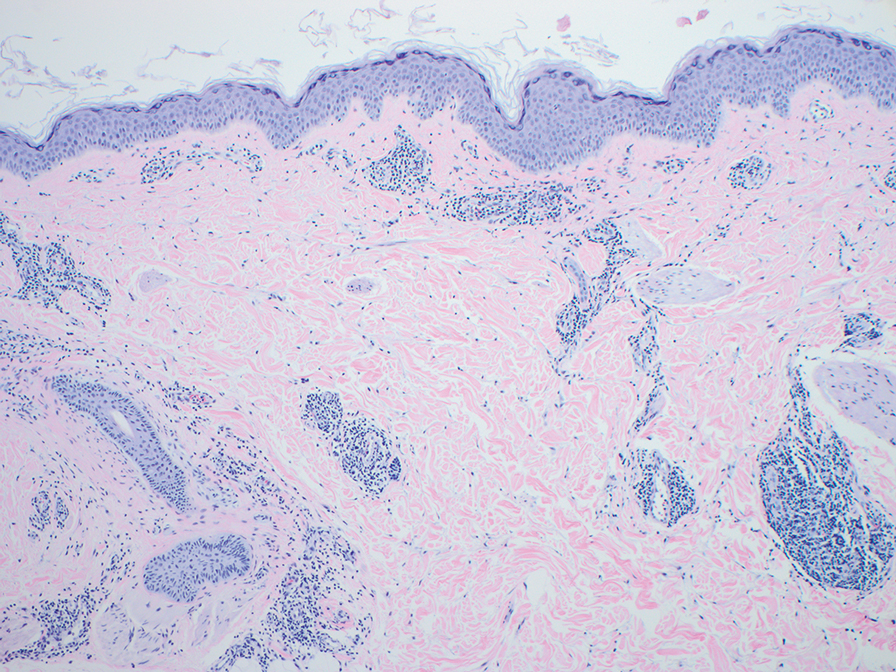

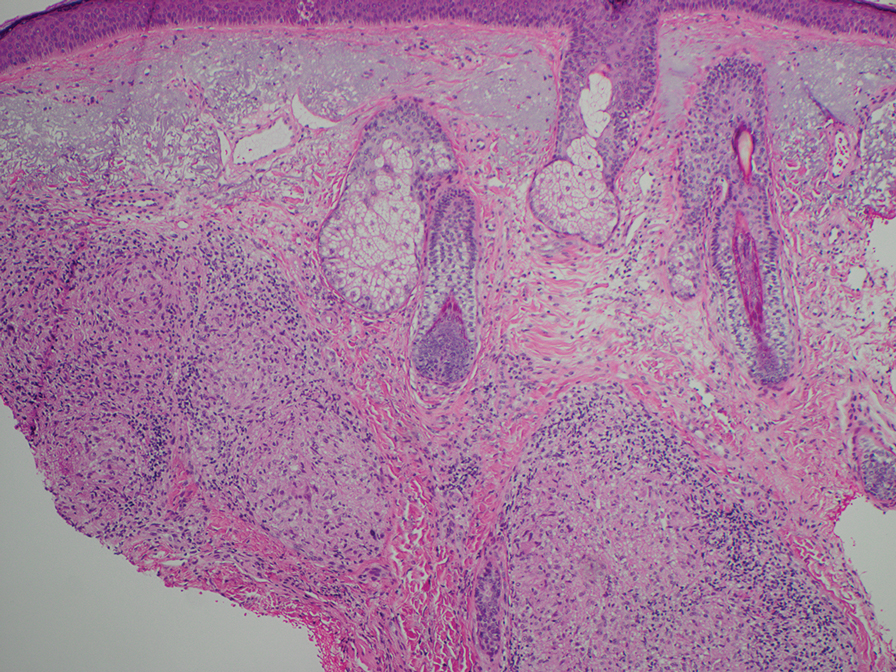

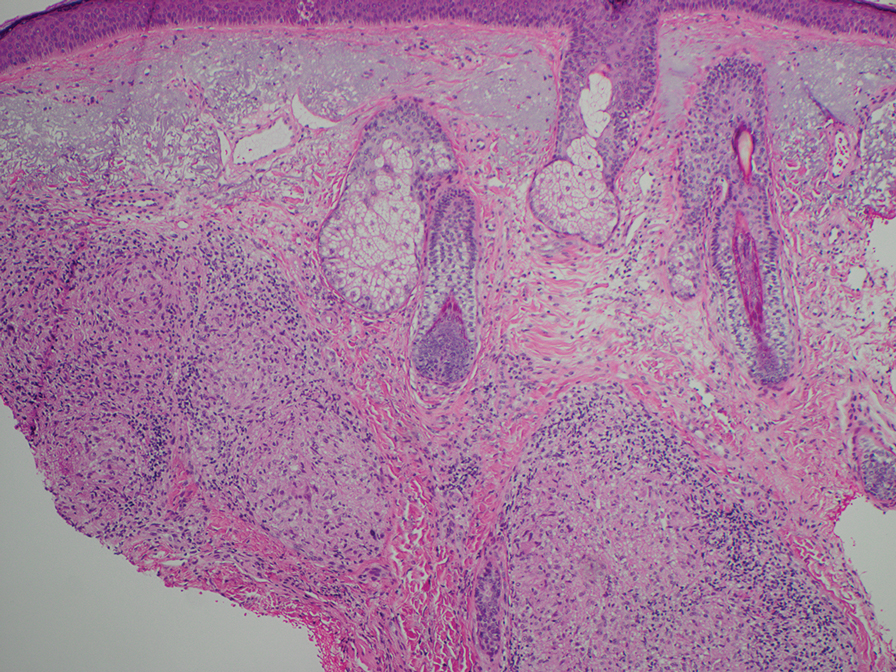

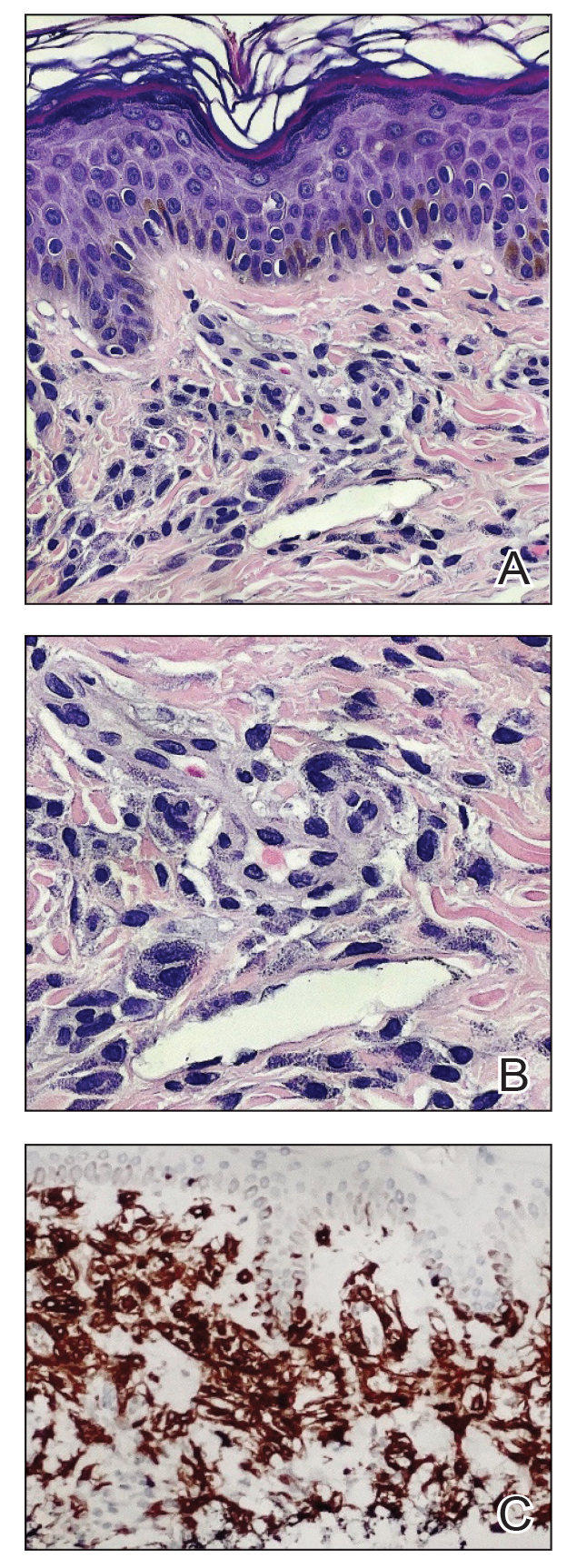

Erythema gyratum repens is a paraneoplastic arcuate erythema that manifests as erythematous figurate, gyrate, or annular plaques exhibiting a trailing scale. Clinically, erythema gyratum repens spreads rapidly—as quickly as 1 cm/d—and can be extensive (as in this case). Histopathology ruled out this diagnosis in our patient. Nonspecific findings of acanthosis, parakeratosis, and superficial spongiosis can be found in erythema gyratum repens. A superficial and deep perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate may be seen in figurate erythemas (Figure 1).5 Unlike GA, this infiltrate does not form granulomas, is more superficial, and does not contain mucin.

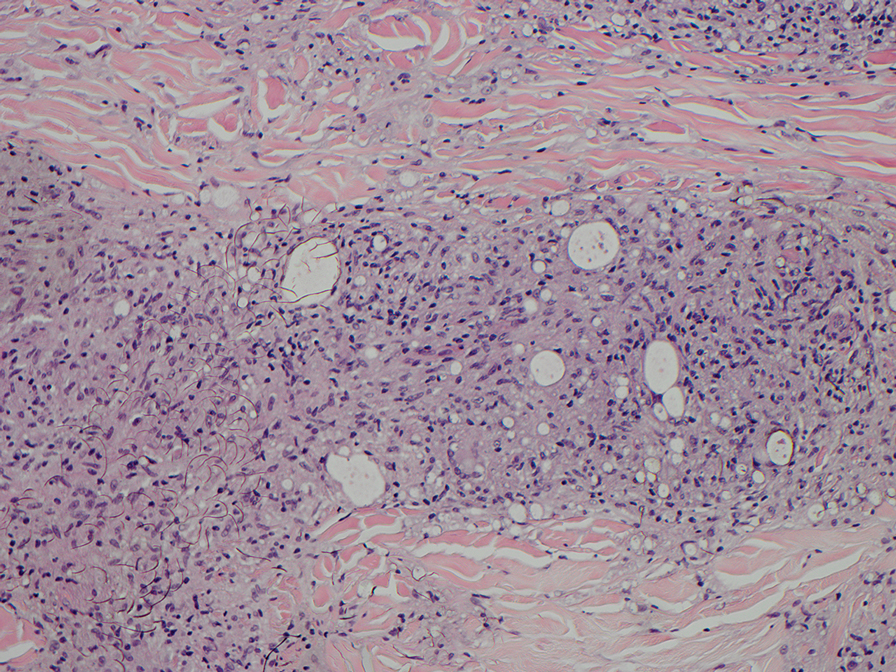

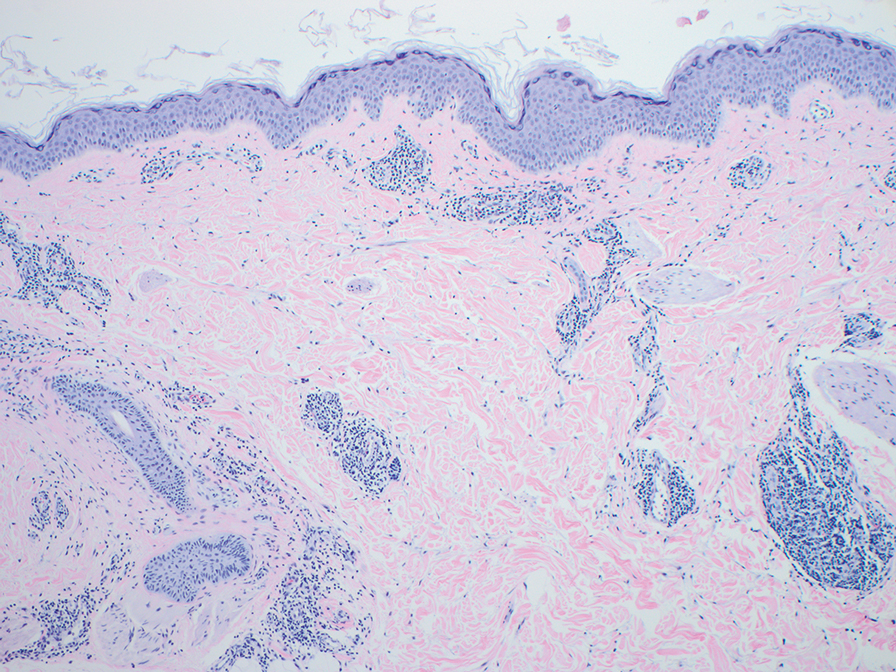

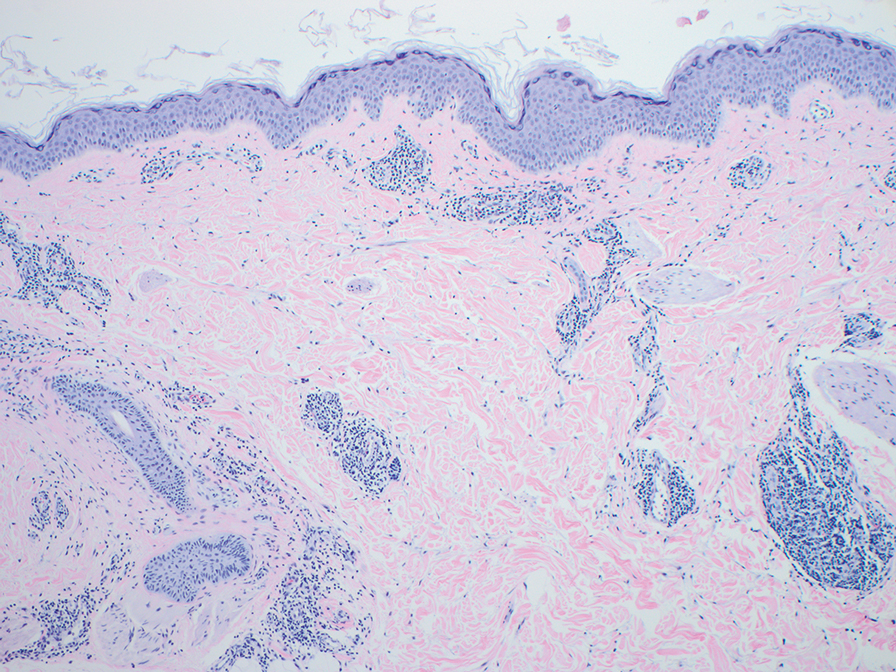

Histopathology also can help establish the diagnosis of leprosy and its specific subtype, as leprosy exists on a spectrum from tuberculoid to lepromatous, with a great deal of overlap in between.6 Lepromatous leprosy has many cutaneous clinical presentations but typically manifests as erythematous papules or nodules. It is multibacillary, and these mycobacteria form clumps known as globi that can be seen on Fite stain.7 In lepromatous leprosy, there is a characteristic dense lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (Figure 2) above which a Grenz zone can be seen.4,8 There are no well-formed granulomas in lepromatous leprosy, unlike in tuberculoid leprosy, which is paucibacillary and creates a granulomatous response surrounding nerves and adnexal structures.6

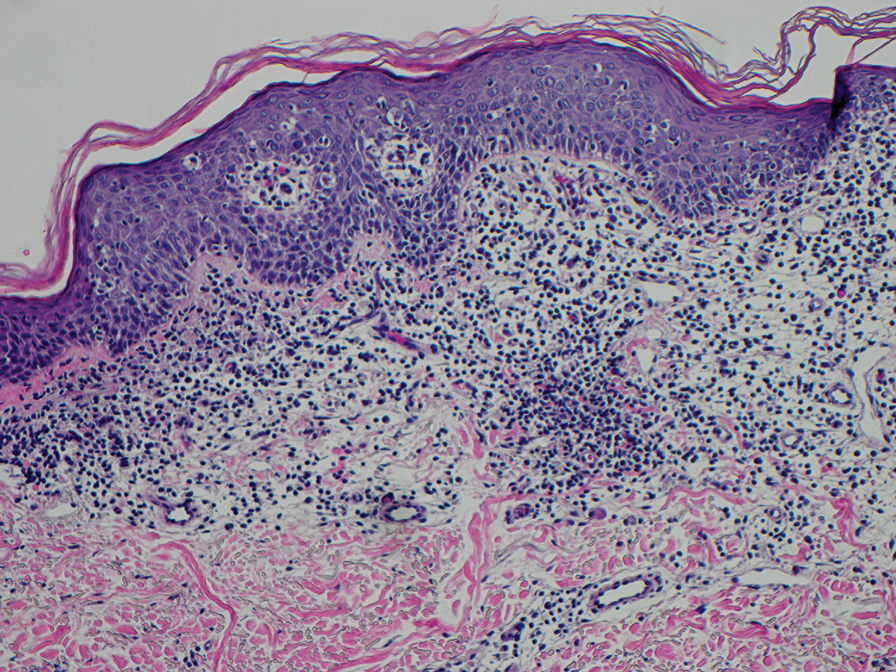

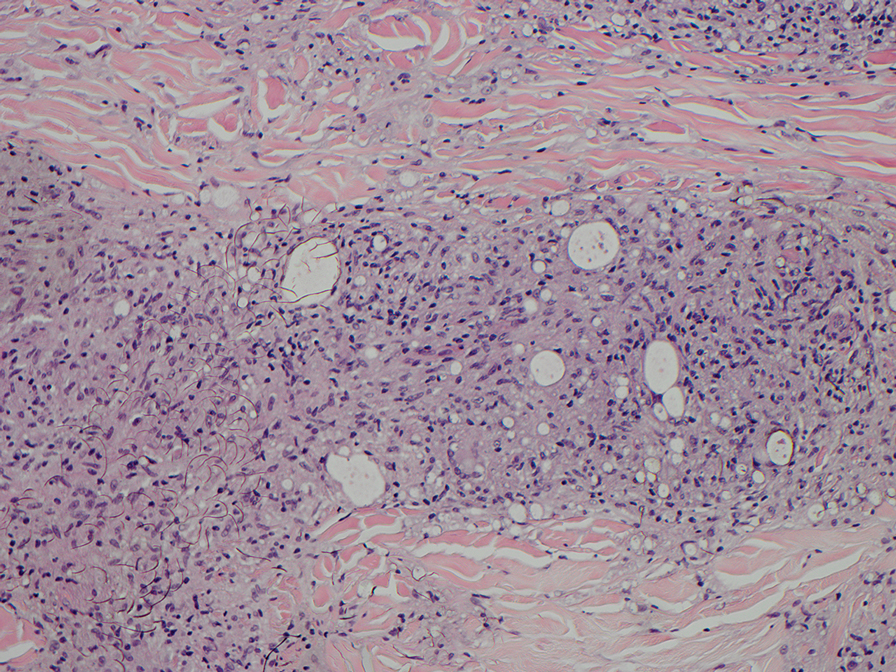

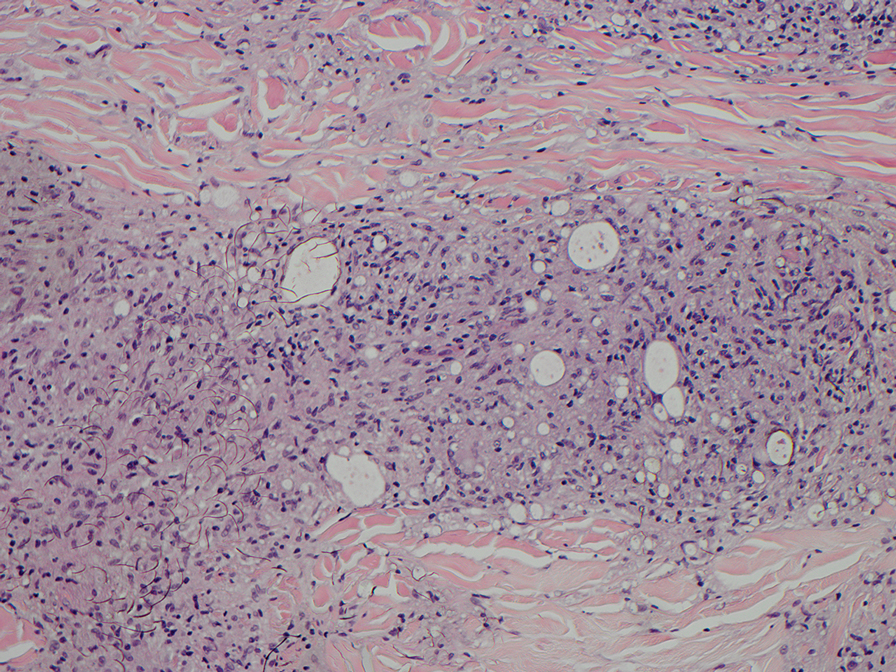

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common cutaneous lymphoma. There are patch, plaque, and tumor stages of MF, each of which exhibits various histopathologic findings.9 In early patch-stage MF, lymphocytes have perinuclear clearing, and the degree of lymphocytic infiltrate is out of proportion to the spongiosis present. Epidermotropism and Pautrier microabscesses often are present in the epidermis (Figure 3). In the plaque stage, there is a denser lymphoid infiltrate in a lichenoid pattern with epidermotropism and Pautrier microabscesses. The tumor stage shows a dense dermal lymphoid infiltrate with more atypia and typically a lack of epidermotropism. Rarely, MF can exhibit a granulomatous variant in which epithelioid histiocytes collect to form granulomas along with atypical lymphocytes.10

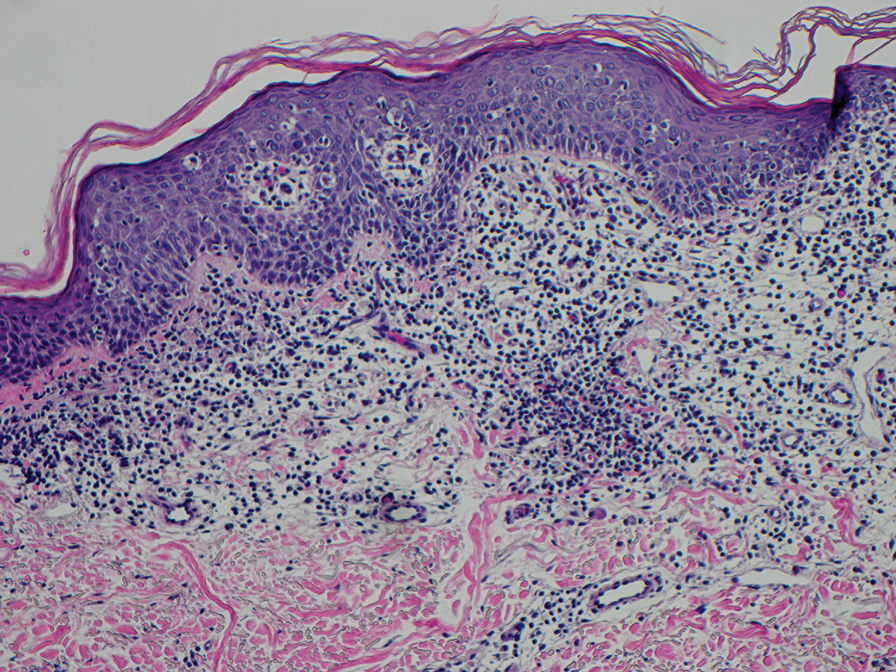

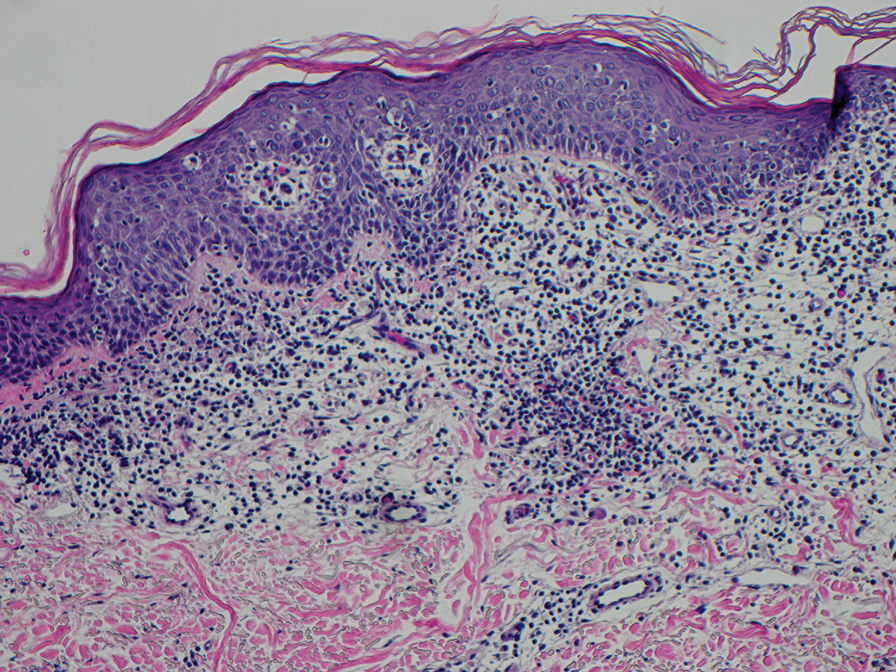

The diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis requires clinicopathologic corroboration. Histopathology demonstrates epithelioid histiocytes forming noncaseating granulomas with little to no lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 4). There typically is no necrosis or necrobiosis as there is in GA. The diagnosis of sarcoidosis can be challenging histopathologically, and stains should be used to rule out infectious processes.4 Asteroid bodies— star-shaped eosinophilic inclusions within giant cells—may be present but are nonspecific for sarcoidosis.11 Schaumann bodies—inclusions of calcifications within giant cells—also may be present and can aid in diagnosis.12

- Kovich O, Burgin S. Generalized granuloma annulare [published online December 30, 2005]. Dermatol Online J. 2005;11:23.

- Al Ameer MA, Al-Natour SH, Alsahaf HAA, et al. Eruptive granuloma annulare in an elderly man with diabetes [published online January 14, 2022]. Cureus. 2022;14:E21242. doi:10.7759/cureus.21242

- Howard A, White CR Jr. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia JL, et al, eds. Dermatology. Mosby; 2003:1455.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko CJ, et al. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Gore M, Winters ME. Erythema gyratum repens: a rare paraneoplastic rash. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12:556-558. doi:10.5811/westjem.2010.11.2090

- Maymone MBC, Laughter M, Venkatesh S, et al. Leprosy: clinical aspects and diagnostic techniques. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1-14. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.080

- Pedley JC, Harman DJ, Waudby H, et al. Leprosy in peripheral nerves: histopathological findings in 119 untreated patients in Nepal. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1980;43:198-204. doi:10.1136/jnnp.43.3.198

- Booth AV, Kovich OI. Lepromatous leprosy [published online January 27, 2007]. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:9.

- Robson A. The pathology of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Oncology (Williston Park). 2007;21(2 suppl 1):9-12.

- Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the Cutaneous Lymphoma Histopathology Task Force Group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2008.46

- Azar HA, Lunardelli C. Collagen nature of asteroid bodies of giant cells in sarcoidosis. Am J Pathol. 1969;57:81-92.

- Sreeja C, Priyadarshini A, Premika, et al. Sarcoidosis—a review article. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2022;26:242-253. doi:10.4103 /jomfp.jomfp_373_21

The Diagnosis: Granuloma Annulare

The biopsies revealed palisading granulomatous dermatitis consistent with granuloma annulare (GA). This diagnosis was supported by the clinical presentation and histopathologic findings. Although the pathogenesis of GA is unclear, it is a benign, self-limiting condition. Primarily affected sites include the trunk and forearms. Generalized GA (or GA with ≥10 lesions) may warrant workup for malignancy, as it may represent a paraneoplastic process.1 Histopathology reveals granulomas comprising a dermal lymphohistiocytic infiltrate as well as central mucin and nuclear debris. There are a few histologic subtypes of GA, including palisading and interstitial, which refer to the distribution of the histiocytic infiltrate.2,3 This case—with palisading histiocytes lining the collection of necrobiosis and mucin (bottom quiz image)—features palisading GA. Notably, GA exhibits central rather than diffuse mucin.4

Erythema gyratum repens is a paraneoplastic arcuate erythema that manifests as erythematous figurate, gyrate, or annular plaques exhibiting a trailing scale. Clinically, erythema gyratum repens spreads rapidly—as quickly as 1 cm/d—and can be extensive (as in this case). Histopathology ruled out this diagnosis in our patient. Nonspecific findings of acanthosis, parakeratosis, and superficial spongiosis can be found in erythema gyratum repens. A superficial and deep perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate may be seen in figurate erythemas (Figure 1).5 Unlike GA, this infiltrate does not form granulomas, is more superficial, and does not contain mucin.

Histopathology also can help establish the diagnosis of leprosy and its specific subtype, as leprosy exists on a spectrum from tuberculoid to lepromatous, with a great deal of overlap in between.6 Lepromatous leprosy has many cutaneous clinical presentations but typically manifests as erythematous papules or nodules. It is multibacillary, and these mycobacteria form clumps known as globi that can be seen on Fite stain.7 In lepromatous leprosy, there is a characteristic dense lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (Figure 2) above which a Grenz zone can be seen.4,8 There are no well-formed granulomas in lepromatous leprosy, unlike in tuberculoid leprosy, which is paucibacillary and creates a granulomatous response surrounding nerves and adnexal structures.6

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common cutaneous lymphoma. There are patch, plaque, and tumor stages of MF, each of which exhibits various histopathologic findings.9 In early patch-stage MF, lymphocytes have perinuclear clearing, and the degree of lymphocytic infiltrate is out of proportion to the spongiosis present. Epidermotropism and Pautrier microabscesses often are present in the epidermis (Figure 3). In the plaque stage, there is a denser lymphoid infiltrate in a lichenoid pattern with epidermotropism and Pautrier microabscesses. The tumor stage shows a dense dermal lymphoid infiltrate with more atypia and typically a lack of epidermotropism. Rarely, MF can exhibit a granulomatous variant in which epithelioid histiocytes collect to form granulomas along with atypical lymphocytes.10

The diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis requires clinicopathologic corroboration. Histopathology demonstrates epithelioid histiocytes forming noncaseating granulomas with little to no lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 4). There typically is no necrosis or necrobiosis as there is in GA. The diagnosis of sarcoidosis can be challenging histopathologically, and stains should be used to rule out infectious processes.4 Asteroid bodies— star-shaped eosinophilic inclusions within giant cells—may be present but are nonspecific for sarcoidosis.11 Schaumann bodies—inclusions of calcifications within giant cells—also may be present and can aid in diagnosis.12

The Diagnosis: Granuloma Annulare

The biopsies revealed palisading granulomatous dermatitis consistent with granuloma annulare (GA). This diagnosis was supported by the clinical presentation and histopathologic findings. Although the pathogenesis of GA is unclear, it is a benign, self-limiting condition. Primarily affected sites include the trunk and forearms. Generalized GA (or GA with ≥10 lesions) may warrant workup for malignancy, as it may represent a paraneoplastic process.1 Histopathology reveals granulomas comprising a dermal lymphohistiocytic infiltrate as well as central mucin and nuclear debris. There are a few histologic subtypes of GA, including palisading and interstitial, which refer to the distribution of the histiocytic infiltrate.2,3 This case—with palisading histiocytes lining the collection of necrobiosis and mucin (bottom quiz image)—features palisading GA. Notably, GA exhibits central rather than diffuse mucin.4

Erythema gyratum repens is a paraneoplastic arcuate erythema that manifests as erythematous figurate, gyrate, or annular plaques exhibiting a trailing scale. Clinically, erythema gyratum repens spreads rapidly—as quickly as 1 cm/d—and can be extensive (as in this case). Histopathology ruled out this diagnosis in our patient. Nonspecific findings of acanthosis, parakeratosis, and superficial spongiosis can be found in erythema gyratum repens. A superficial and deep perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate may be seen in figurate erythemas (Figure 1).5 Unlike GA, this infiltrate does not form granulomas, is more superficial, and does not contain mucin.

Histopathology also can help establish the diagnosis of leprosy and its specific subtype, as leprosy exists on a spectrum from tuberculoid to lepromatous, with a great deal of overlap in between.6 Lepromatous leprosy has many cutaneous clinical presentations but typically manifests as erythematous papules or nodules. It is multibacillary, and these mycobacteria form clumps known as globi that can be seen on Fite stain.7 In lepromatous leprosy, there is a characteristic dense lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (Figure 2) above which a Grenz zone can be seen.4,8 There are no well-formed granulomas in lepromatous leprosy, unlike in tuberculoid leprosy, which is paucibacillary and creates a granulomatous response surrounding nerves and adnexal structures.6

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common cutaneous lymphoma. There are patch, plaque, and tumor stages of MF, each of which exhibits various histopathologic findings.9 In early patch-stage MF, lymphocytes have perinuclear clearing, and the degree of lymphocytic infiltrate is out of proportion to the spongiosis present. Epidermotropism and Pautrier microabscesses often are present in the epidermis (Figure 3). In the plaque stage, there is a denser lymphoid infiltrate in a lichenoid pattern with epidermotropism and Pautrier microabscesses. The tumor stage shows a dense dermal lymphoid infiltrate with more atypia and typically a lack of epidermotropism. Rarely, MF can exhibit a granulomatous variant in which epithelioid histiocytes collect to form granulomas along with atypical lymphocytes.10

The diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis requires clinicopathologic corroboration. Histopathology demonstrates epithelioid histiocytes forming noncaseating granulomas with little to no lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 4). There typically is no necrosis or necrobiosis as there is in GA. The diagnosis of sarcoidosis can be challenging histopathologically, and stains should be used to rule out infectious processes.4 Asteroid bodies— star-shaped eosinophilic inclusions within giant cells—may be present but are nonspecific for sarcoidosis.11 Schaumann bodies—inclusions of calcifications within giant cells—also may be present and can aid in diagnosis.12

- Kovich O, Burgin S. Generalized granuloma annulare [published online December 30, 2005]. Dermatol Online J. 2005;11:23.

- Al Ameer MA, Al-Natour SH, Alsahaf HAA, et al. Eruptive granuloma annulare in an elderly man with diabetes [published online January 14, 2022]. Cureus. 2022;14:E21242. doi:10.7759/cureus.21242

- Howard A, White CR Jr. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia JL, et al, eds. Dermatology. Mosby; 2003:1455.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko CJ, et al. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Gore M, Winters ME. Erythema gyratum repens: a rare paraneoplastic rash. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12:556-558. doi:10.5811/westjem.2010.11.2090

- Maymone MBC, Laughter M, Venkatesh S, et al. Leprosy: clinical aspects and diagnostic techniques. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1-14. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.080

- Pedley JC, Harman DJ, Waudby H, et al. Leprosy in peripheral nerves: histopathological findings in 119 untreated patients in Nepal. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1980;43:198-204. doi:10.1136/jnnp.43.3.198

- Booth AV, Kovich OI. Lepromatous leprosy [published online January 27, 2007]. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:9.

- Robson A. The pathology of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Oncology (Williston Park). 2007;21(2 suppl 1):9-12.

- Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the Cutaneous Lymphoma Histopathology Task Force Group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2008.46

- Azar HA, Lunardelli C. Collagen nature of asteroid bodies of giant cells in sarcoidosis. Am J Pathol. 1969;57:81-92.

- Sreeja C, Priyadarshini A, Premika, et al. Sarcoidosis—a review article. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2022;26:242-253. doi:10.4103 /jomfp.jomfp_373_21

- Kovich O, Burgin S. Generalized granuloma annulare [published online December 30, 2005]. Dermatol Online J. 2005;11:23.

- Al Ameer MA, Al-Natour SH, Alsahaf HAA, et al. Eruptive granuloma annulare in an elderly man with diabetes [published online January 14, 2022]. Cureus. 2022;14:E21242. doi:10.7759/cureus.21242

- Howard A, White CR Jr. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia JL, et al, eds. Dermatology. Mosby; 2003:1455.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko CJ, et al. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Gore M, Winters ME. Erythema gyratum repens: a rare paraneoplastic rash. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12:556-558. doi:10.5811/westjem.2010.11.2090

- Maymone MBC, Laughter M, Venkatesh S, et al. Leprosy: clinical aspects and diagnostic techniques. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1-14. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.080

- Pedley JC, Harman DJ, Waudby H, et al. Leprosy in peripheral nerves: histopathological findings in 119 untreated patients in Nepal. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1980;43:198-204. doi:10.1136/jnnp.43.3.198

- Booth AV, Kovich OI. Lepromatous leprosy [published online January 27, 2007]. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:9.

- Robson A. The pathology of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Oncology (Williston Park). 2007;21(2 suppl 1):9-12.

- Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the Cutaneous Lymphoma Histopathology Task Force Group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2008.46

- Azar HA, Lunardelli C. Collagen nature of asteroid bodies of giant cells in sarcoidosis. Am J Pathol. 1969;57:81-92.

- Sreeja C, Priyadarshini A, Premika, et al. Sarcoidosis—a review article. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2022;26:242-253. doi:10.4103 /jomfp.jomfp_373_21

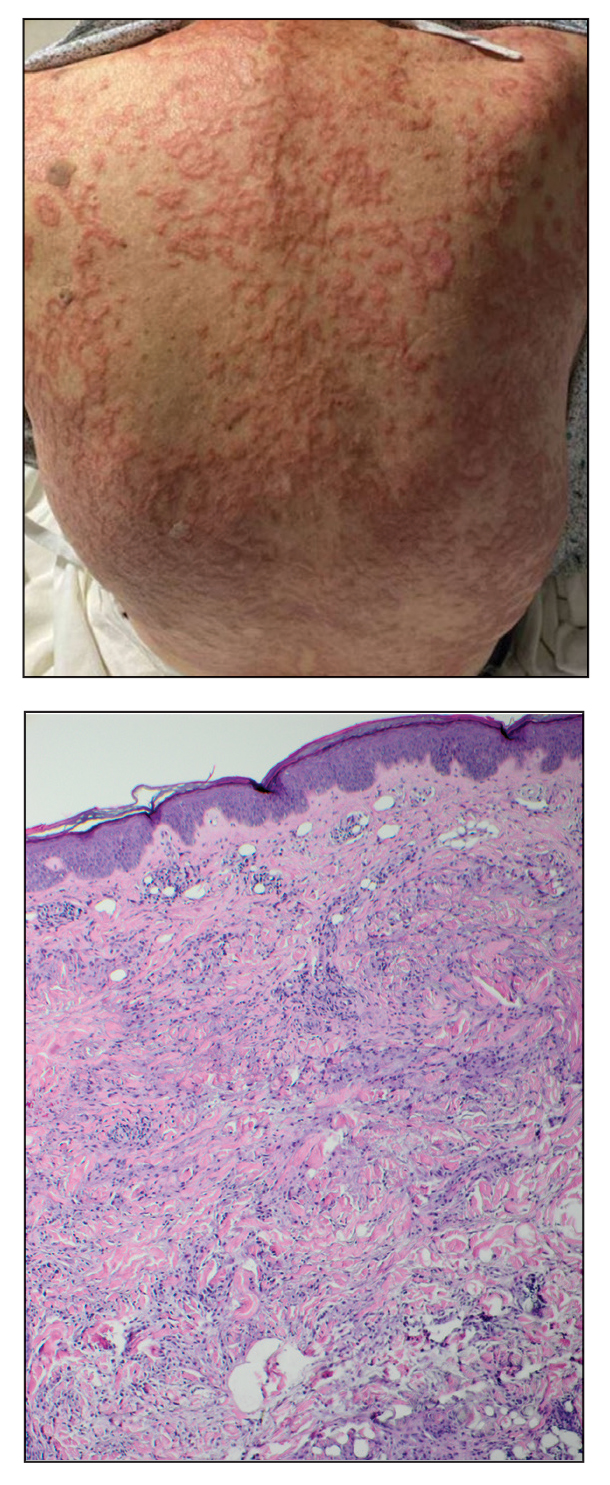

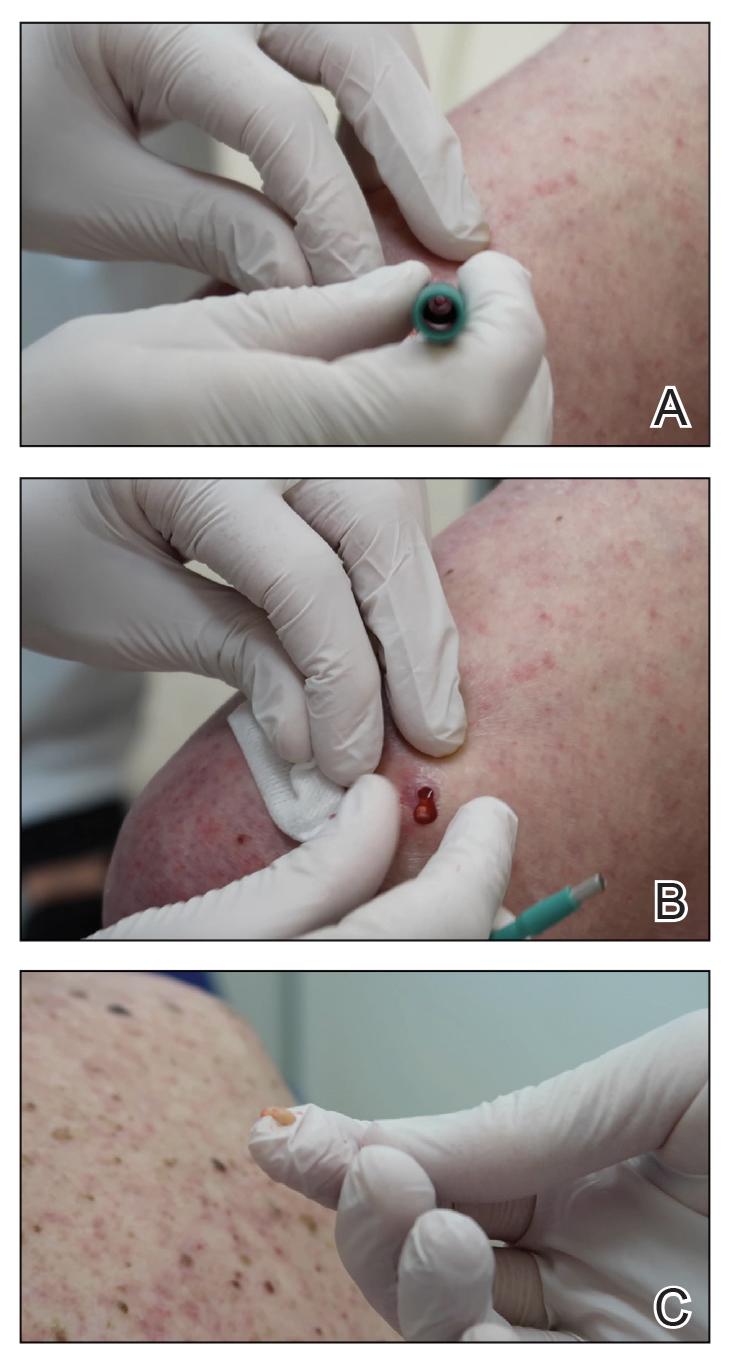

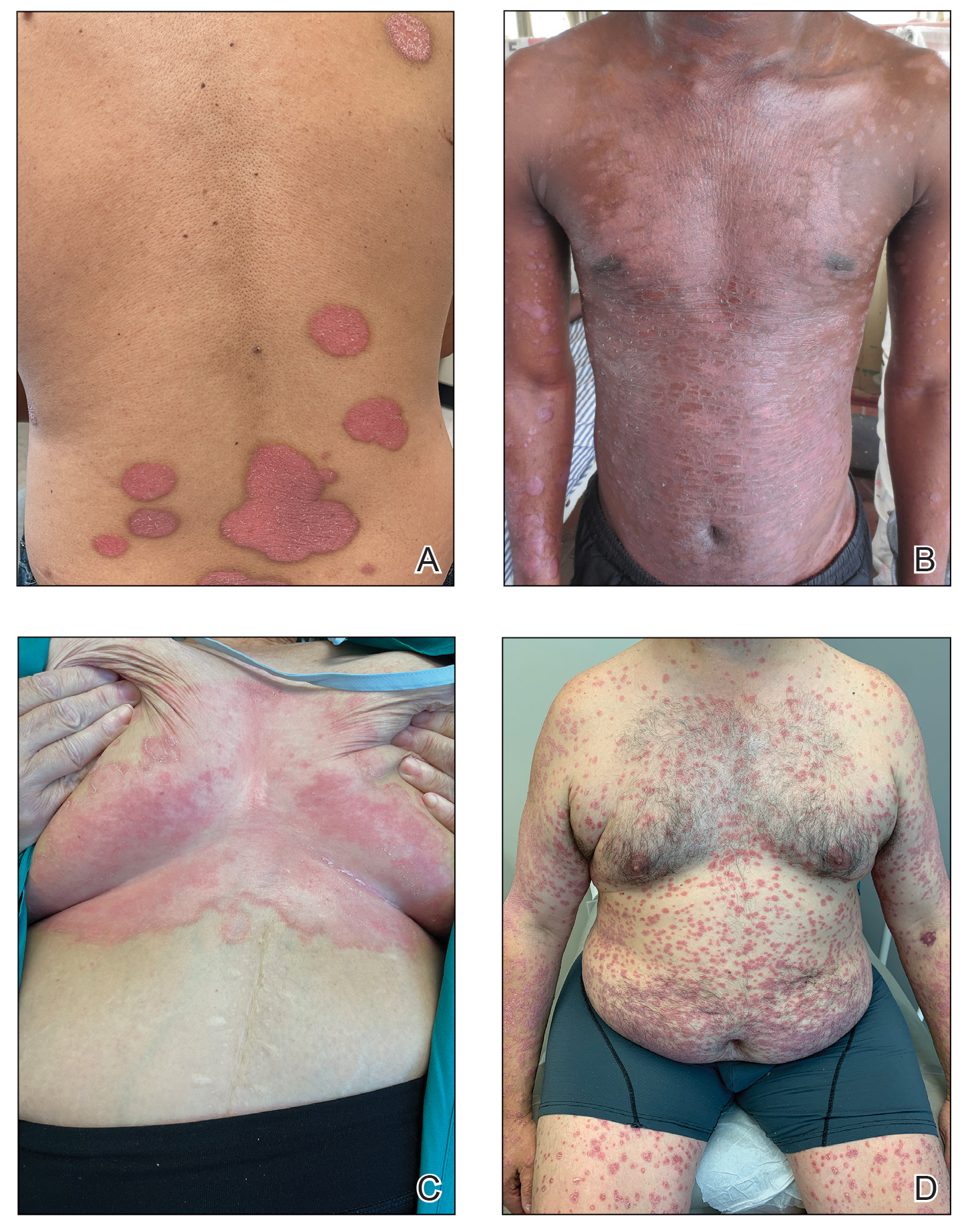

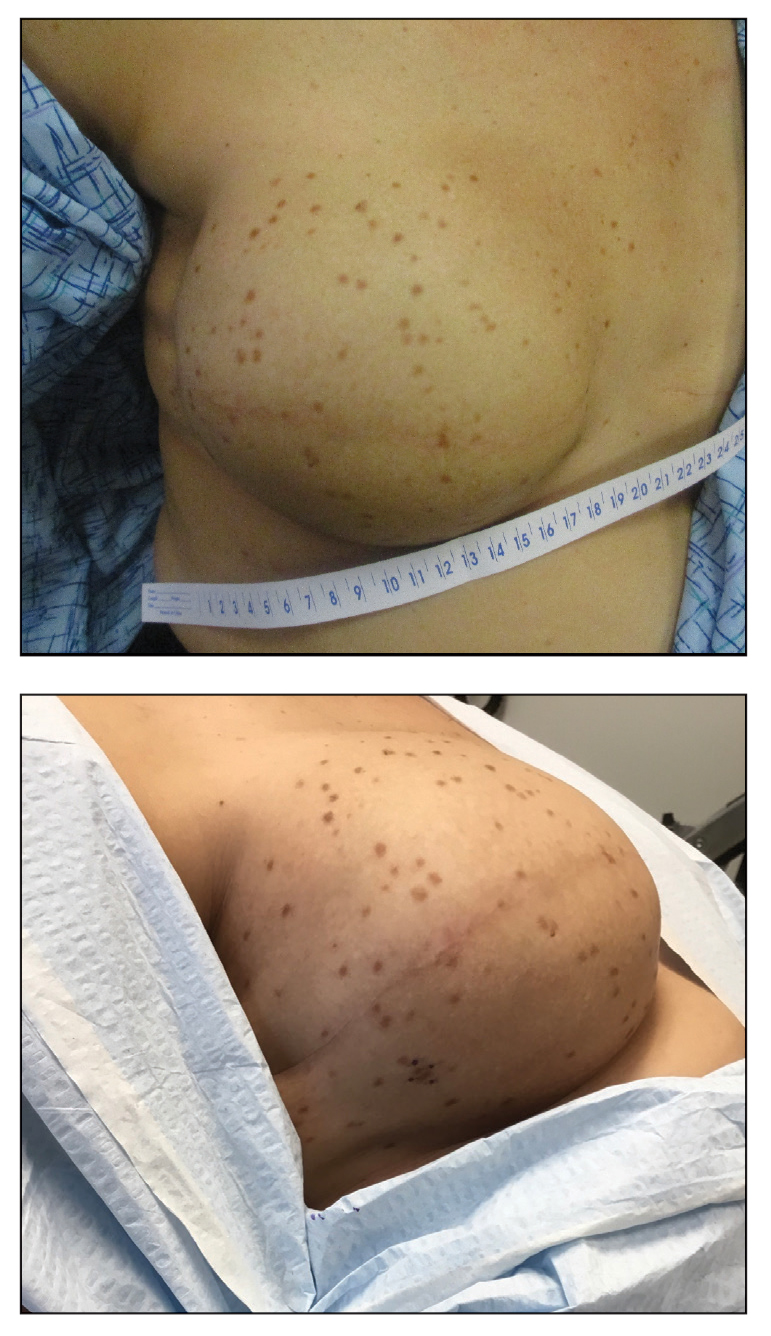

An 84-year-old man presented to the clinic for evaluation of a pruritic rash on the back of 6 months’ duration that spread to the neck and chest over the past 2 months and then to the abdomen and thighs more recently. His primary care provider prescribed a 1-week course of oral steroids and steroid cream. The oral medication did not help, but the cream alleviated the pruritus. He had a medical history of coronary artery disease, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus. He also had a rash on the forearms that had waxed and waned for many years but was not associated with pruritus. He had not sought medical care for the rash and had never treated it. Physical examination revealed pink to violaceous annular plaques with central clearing and raised borders that coalesced into larger plaques on the trunk (top). Dusky, scaly, pink plaques were present on the dorsal forearms. Three punch biopsies—2 from the upper back (bottom) and 1 from the left forearm—all demonstrated consistent findings.

The Potential Benefits of Dietary Changes in Psoriasis Patients

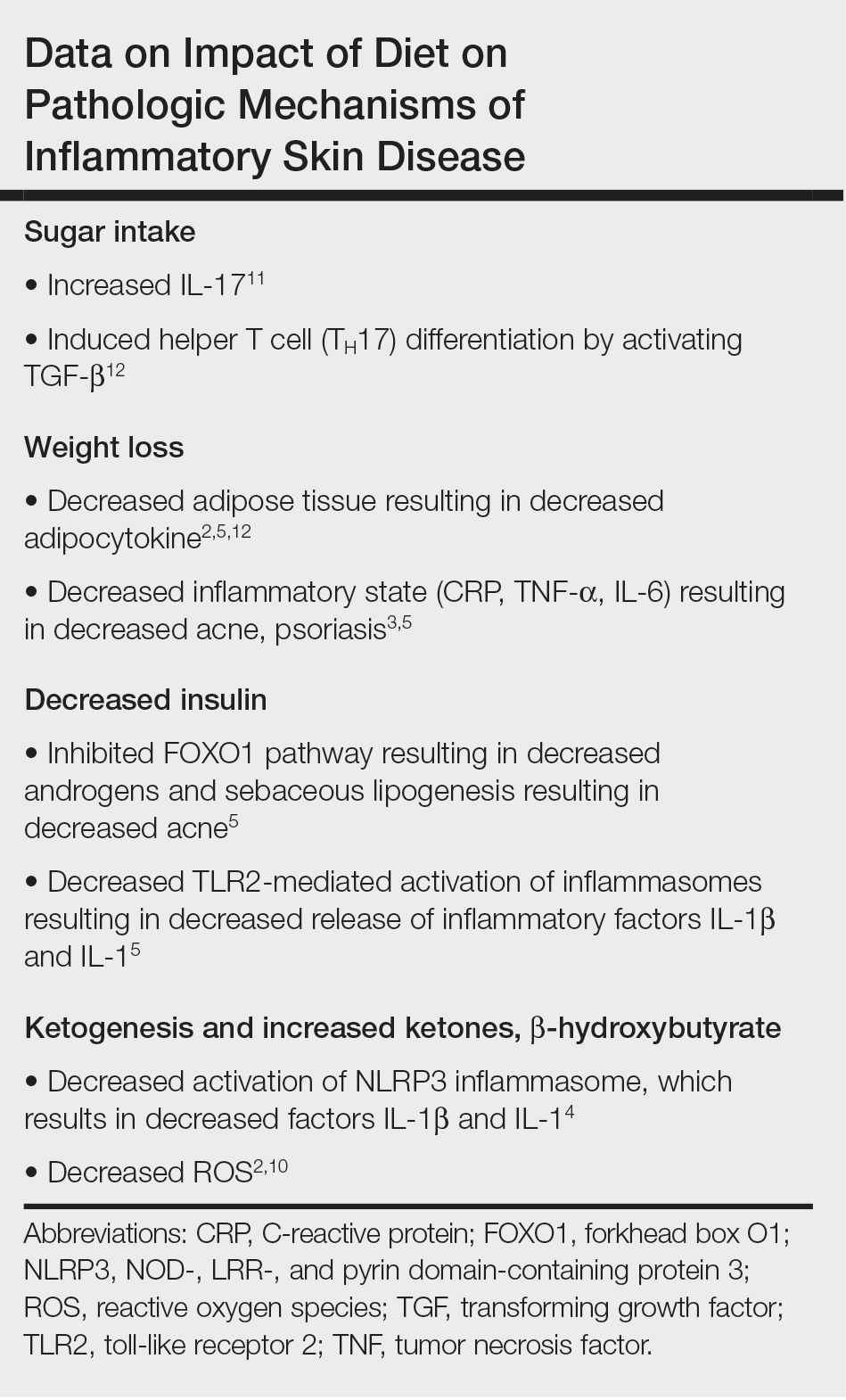

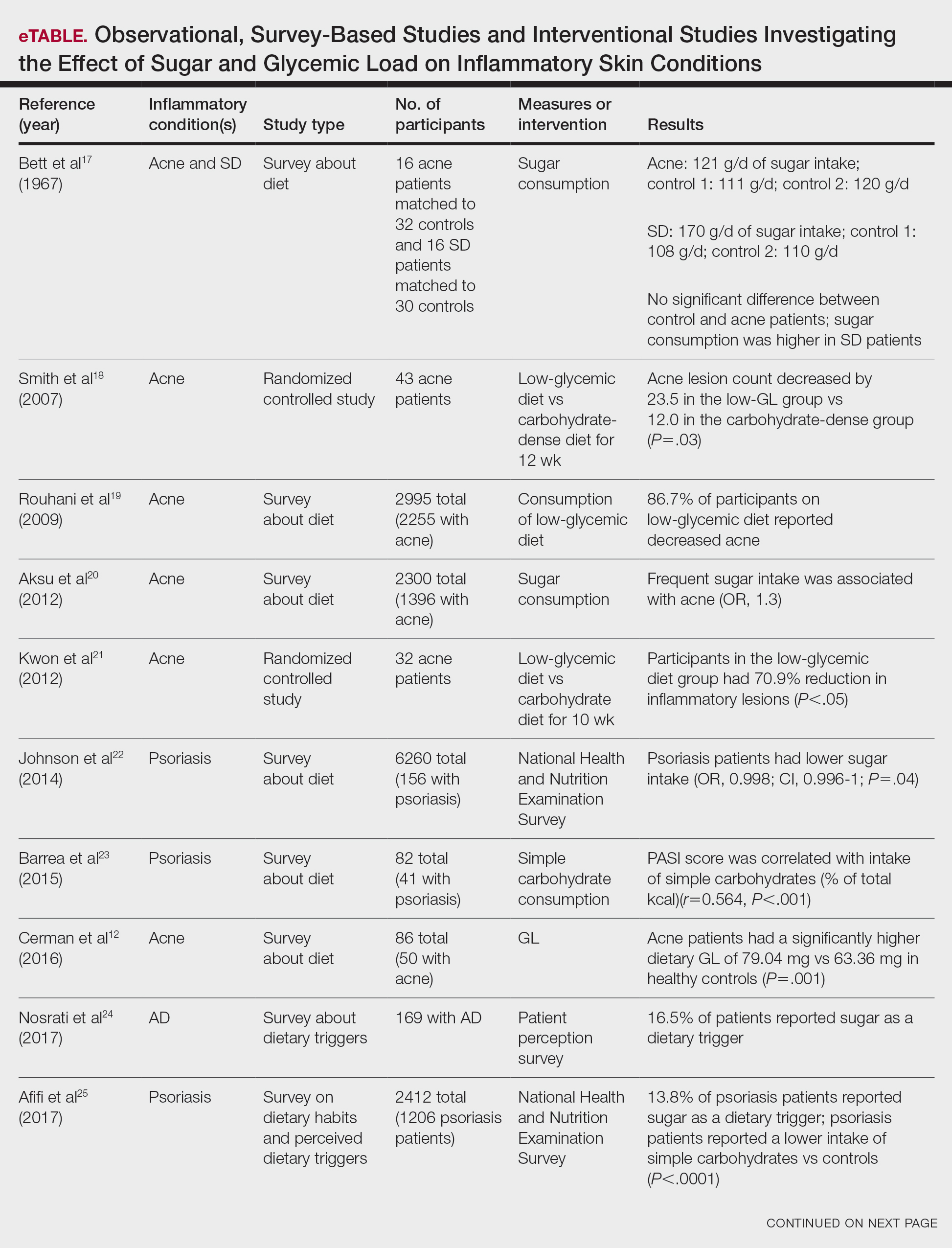

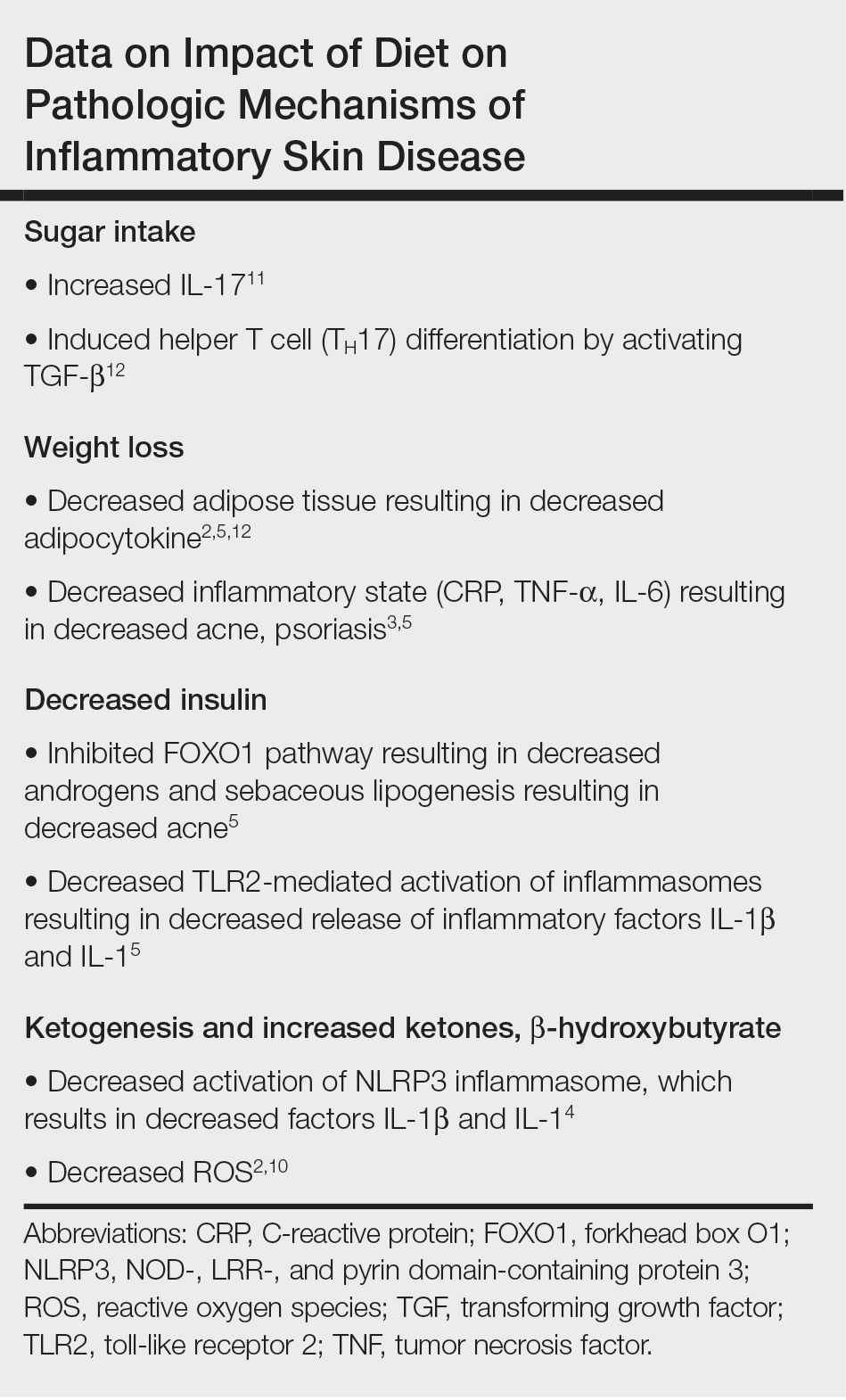

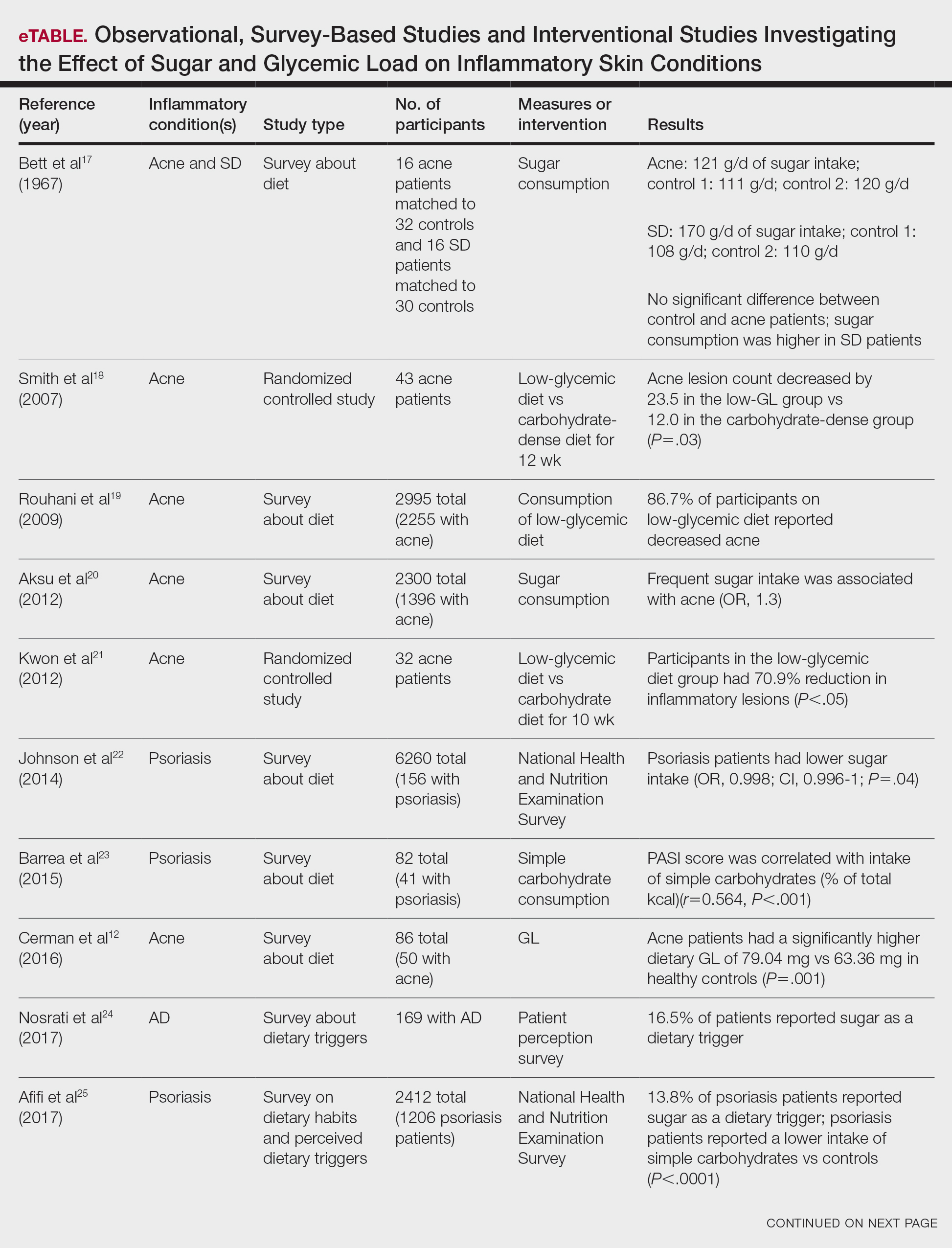

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease for which several lifestyle factors—smoking, alcohol use, and psychological stress—are associated with higher incidence and more severe disease.1-3 Diet also has been implicated as a factor that can affect psoriasis,4 and many patients have shown interest in possible dietary interventions to help their disease.5

In 2018, the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) presented dietary recommendations for patients based on results from a systematic review. From the available literature, only dietary weight reduction with hypocaloric diets in overweight or obese patients could be strongly recommended, and it has been proven that obesity is associated with worse psoriasis severity.6 Other more recent studies have shown that dietary modifications such as intermittent fasting and the ketogenic diet also led to weight loss and improved psoriasis severity in overweight patients; however, it is difficult to discern if the improvement was due to weight loss alone or if the dietary patterns themselves played a role.7,8 The paucity of well-designed studies evaluating the effects of other dietary changes has prevented further guidelines from being written. We propose that dietary patterns such as the Mediterranean diet (MeD) and vegan/vegetarian diets—even without strong data showing benefits in skin disease—may help to decrease systemic inflammation, improve gut dysbiosis, and help decrease the risk for cardiometabolic comorbidities that are associated with psoriasis.

Mediterranean Diet

The MeD is based on the dietary tendencies of inhabitants from the regions surrounding the Mediterranean Sea and is centered around nutrient-rich foods such as vegetables, olive oil, and legumes while limiting meat and dairy.9 The NPF recommended considering a trial of the MeD based on low-quality evidence.6 Observational studies have indicated that psoriasis patients are less likely to adhere to the MeD, but those who do have less severe disease.8 However, a search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms Mediterranean diet and psoriasis yielded no prospective interventional studies. Given the association of the MeD with less severe disease, it is important to understand which specific foods in the MeD could be beneficial. Intake of omega-3 fatty acids, such as those found in fatty fish, are important for modulation of systemic inflammation.7 High intake of polyphenols—found in fruits and vegetables, extra-virgin olive oil, and wine—also have been implicated in improving inflammatory diseases due to potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Individually, fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and sea fish have been associated with lowering C-reactive protein levels, which also is indicative of the benefits of these foods on systemic inflammation.7

Vegan/Vegetarian Diets

Although fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains are a substantial component of the MeD, there are limited data on vegetarian or purely vegan plant-based diets. An observational study from the NPF found that only 48.4% (15/31) of patients on the MeD vs 69.0% (20/29) on a vegan diet reported a favorable skin response.5 Two case reports also have shown beneficial results of a strict vegan diet for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, where whole-food plant-based diets also improved joint symptoms.10-12 As with any diet, those who pursue a plant-based diet should strive to consume a variety of foods to avoid nutrient deficiencies. A recent systematic meta-analysis of 141 studies evaluated nutrient status of vegan and vegetarian diets compared to pescovegetarians and those who consume meat. All dietary patterns showed varying degrees of low levels of different nutrients.13 Of note, the researchers found that vitamin B12, vitamin D, iron, zinc, iodine, calcium, and docosahexaenoic acid were lower in plant-based diets. In contrast, folate; vitamins B1, B6, C, and E; polyunsaturated fatty acids; α-linolenic acid; and magnesium intake were higher. Those who consumed meat were at risk for inadequate intake of fiber, polyunsaturated fatty acids, α-linolenic acid, folate, vitamin E, calcium, magnesium, and vitamin D, though vitamin D intake was higher than in vegans/vegetarians.13 The results of this meta-analysis indicated the importance of educating patients on what constitutes a well-rounded, micronutrient-rich diet or appropriate supplementation for any diet.

Effects on Gut Microbiome

Any changes in diet can lead to alterations in the gut microbiome, which may impact skin disease, as evidence indicates a bidirectional relationship between gut and skin health.10 A metagenomic analysis of the gut microbiota in patients with untreated plaque psoriasis revealed a signature dysbiosis for which the researchers developed a psoriasis microbiota index, suggesting the gut microbiota may play a role in psoriasis pathophysiology.14 Research shows that both the MeD and vegan/vegetarian diets, which are relatively rich in fiber and omega-3 fatty acids and low in saturated fat and animal protein compared to many diets, cause increases in dietary fiber–metabolizing bacteria that produce short-chain fatty acids. These short-chain fatty acids improve gut epithelial integrity and alleviate both gut and systemic inflammation.10

The changes to the gut microbiome induced by a high-fat diet also are concerning. In contrast to the MeD or vegan/vegetarian diets, consumption of a high-fat diet induces alterations in the composition of the gut microbiota that in turn increase the release of proinflammatory cytokines and promote higher intestinal permeability.10 Similarly, high sugar consumption promotes increased intestinal permeability and shifts the gut microbiota to organisms that can rapidly utilize simple carbohydrates at the expense of other beneficial organisms, reducing bacterial diversity.15 The Western diet, which is notable for both high fat and high sugar content, is sometimes referred to as a proinflammatory diet and has been shown to worsen psoriasiformlike lesions in mice.16 Importantly, most research indicates that high fat and high sugar consumption appear to be more prevalent in psoriasis patients,8 but the type of fat consumed in the diet matters. The Western diet includes abundant saturated fat found in meat, dairy products, palm and coconut oils, and processed foods, as well as omega-6 fatty acids that are found in meat, poultry, and eggs. Saturated fat has been shown to promote helper T cell (TH17) accumulation in the skin, and omega-6 fatty acids serve as precursors to various inflammatory lipid mediators.4 This distinction of sources of fat between the Western diet and MeD is important in understanding the diets’ different effects on psoriasis and overall health. As previously discussed, the high intake of omega-3 acids in the MeD is one of the ways it may exert its anti-inflammatory benefits.7

Next Steps in Advising Psoriasis Patients

A major limitation of the data for MeD and vegan/vegetarian diets is limited randomized controlled trials evaluating the impact of these diets on psoriasis. Thus, dietary recommendations for psoriasis are not as strong as for other diseases for which more conclusive data exist.8 Although the data on diet and psoriasis are not definitive, perhaps dermatologists should shift the question from “Does this diet definitely improve psoriasis?” to “Does this diet definitely improve my patient’s health as a whole and maybe also their psoriasis?” For instance, the MeD has been shown to reduce the risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease as well as to slow cognitive decline.17 Vegan/vegetarian diets focusing on whole vs processed foods have been shown to be highly effective in combatting obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease including severe atherosclerosis, and hypertension.18 Psoriasis patients are at increased risk for many of the ailments that the MeD and plant-based diets protect against, making these diets potentially even more impactful than for someone without psoriasis.19 Dietary recommendations should still be made in conjunction with continuing traditional therapies for psoriasis and in consultation with the patient’s primary care physician and/or dietitian; however, rather than waiting for more randomized controlled trials before making health-promoting recommendations, what would be the downside of starting now? At worst, the dietary change decreases their risk for several metabolic conditions, and at best they may even see an improvement in their psoriasis.

- Naldi L, Chatenoud L, Linder D, et al. Cigarette smoking, body mass index, and stressful life events as risk factors for psoriasis: results from an Italian case–control study. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:61-67. doi:10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23681.x

- Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Dhillon JS, et al. Psoriasis and smoking: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:304-314. doi:10.1111/bjd.12670

- Zhu K, Zhu C, Fan Y. Alcohol consumption and psoriatic risk: a meta‐analysis of case–control studies. J Dermatol. 2012;39:770-773. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2012.01577.x

- Kanda N, Hoashi T, Saeki H. Nutrition and psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:5405. doi:10.3390/ijms21155405

- Afifi L, Danesh MJ, Lee KM, et al. Dietary behaviors in psoriasis: patient-reported outcomes from a U.S. national survey. Dermatol Ther. 2017;7:227-242. doi:10.1007/s13555-017-0183-4

- Ford AR, Siegel M, Bagel J, et al. Dietary recommendations for adults with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis from the medical board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:934. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.1412

- Duchnik E, Kruk J, Tuchowska A, et al. The impact of diet and physical activity on psoriasis: a narrative review of the current evidence. Nutrients. 2023;15:840. doi:10.3390/nu15040840

- Chung M, Bartholomew E, Yeroushalmi S, et al. Dietary intervention and supplements in the management of psoriasis: current perspectives. Psoriasis Targets Ther. 2022;12:151-176. doi:10.2147/PTT.S328581

- Mazza E, Ferro Y, Pujia R, et al. Mediterranean diet in healthy aging. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25:1076-1083. doi:10.1007/s12603-021-1675-6

- Flores-Balderas X, Peña-Peña M, Rada KM, et al. Beneficial effects of plant-based diets on skin health and inflammatory skin diseases. Nutrients. 2023;15:2842. doi:10.3390/nu15132842

- Bonjour M, Gabriel S, Valencia A, et al. Challenging case in clinical practice: prolonged water-only fasting followed by an exclusively whole-plant-food diet in the management of severe plaque psoriasis. Integr Complement Ther. 2022;28:85-87. doi:10.1089/ict.2022.29010.mbo

- Lewandowska M, Dunbar K, Kassam S. Managing psoriatic arthritis with a whole food plant-based diet: a case study. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2021;15:402-406. doi:10.1177/1559827621993435

- Neufingerl N, Eilander A. Nutrient intake and status in adults consuming plant-based diets compared to meat-eaters: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2021;14:29. doi:10.3390/nu14010029

- Dei-Cas I, Giliberto F, Luce L, et al. Metagenomic analysis of gut microbiota in non-treated plaque psoriasis patients stratified by disease severity: development of a new psoriasis-microbiome index. Sci Rep. 2020;10:12754. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-69537-3

- Satokari R. High intake of sugar and the balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory gut bacteria. Nutrients. 2020;12:1348. doi:10.3390/nu12051348

- Shi Z, Wu X, Santos Rocha C, et al. Short-term Western diet intake promotes IL-23–mediated skin and joint inflammation accompanied by changes to the gut microbiota in mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2021;141:1780-1791. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2020.11.032

- Romagnolo DF, Selmin OI. Mediterranean diet and prevention of chronic diseases. Nutr Today. 2017;52:208-222. doi:10.1097/NT.0000000000000228

- Tuso PJ, Ismail MH, Ha BP, et al. Nutritional update for physicians: plant-based diets. Perm J. 2013;17:61-66. doi:10.7812/TPP/12-085

- Parisi R, Symmons DPM, Griffiths CEM, et al. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:377-385. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.339

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease for which several lifestyle factors—smoking, alcohol use, and psychological stress—are associated with higher incidence and more severe disease.1-3 Diet also has been implicated as a factor that can affect psoriasis,4 and many patients have shown interest in possible dietary interventions to help their disease.5

In 2018, the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) presented dietary recommendations for patients based on results from a systematic review. From the available literature, only dietary weight reduction with hypocaloric diets in overweight or obese patients could be strongly recommended, and it has been proven that obesity is associated with worse psoriasis severity.6 Other more recent studies have shown that dietary modifications such as intermittent fasting and the ketogenic diet also led to weight loss and improved psoriasis severity in overweight patients; however, it is difficult to discern if the improvement was due to weight loss alone or if the dietary patterns themselves played a role.7,8 The paucity of well-designed studies evaluating the effects of other dietary changes has prevented further guidelines from being written. We propose that dietary patterns such as the Mediterranean diet (MeD) and vegan/vegetarian diets—even without strong data showing benefits in skin disease—may help to decrease systemic inflammation, improve gut dysbiosis, and help decrease the risk for cardiometabolic comorbidities that are associated with psoriasis.

Mediterranean Diet

The MeD is based on the dietary tendencies of inhabitants from the regions surrounding the Mediterranean Sea and is centered around nutrient-rich foods such as vegetables, olive oil, and legumes while limiting meat and dairy.9 The NPF recommended considering a trial of the MeD based on low-quality evidence.6 Observational studies have indicated that psoriasis patients are less likely to adhere to the MeD, but those who do have less severe disease.8 However, a search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms Mediterranean diet and psoriasis yielded no prospective interventional studies. Given the association of the MeD with less severe disease, it is important to understand which specific foods in the MeD could be beneficial. Intake of omega-3 fatty acids, such as those found in fatty fish, are important for modulation of systemic inflammation.7 High intake of polyphenols—found in fruits and vegetables, extra-virgin olive oil, and wine—also have been implicated in improving inflammatory diseases due to potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Individually, fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and sea fish have been associated with lowering C-reactive protein levels, which also is indicative of the benefits of these foods on systemic inflammation.7

Vegan/Vegetarian Diets

Although fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains are a substantial component of the MeD, there are limited data on vegetarian or purely vegan plant-based diets. An observational study from the NPF found that only 48.4% (15/31) of patients on the MeD vs 69.0% (20/29) on a vegan diet reported a favorable skin response.5 Two case reports also have shown beneficial results of a strict vegan diet for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, where whole-food plant-based diets also improved joint symptoms.10-12 As with any diet, those who pursue a plant-based diet should strive to consume a variety of foods to avoid nutrient deficiencies. A recent systematic meta-analysis of 141 studies evaluated nutrient status of vegan and vegetarian diets compared to pescovegetarians and those who consume meat. All dietary patterns showed varying degrees of low levels of different nutrients.13 Of note, the researchers found that vitamin B12, vitamin D, iron, zinc, iodine, calcium, and docosahexaenoic acid were lower in plant-based diets. In contrast, folate; vitamins B1, B6, C, and E; polyunsaturated fatty acids; α-linolenic acid; and magnesium intake were higher. Those who consumed meat were at risk for inadequate intake of fiber, polyunsaturated fatty acids, α-linolenic acid, folate, vitamin E, calcium, magnesium, and vitamin D, though vitamin D intake was higher than in vegans/vegetarians.13 The results of this meta-analysis indicated the importance of educating patients on what constitutes a well-rounded, micronutrient-rich diet or appropriate supplementation for any diet.

Effects on Gut Microbiome

Any changes in diet can lead to alterations in the gut microbiome, which may impact skin disease, as evidence indicates a bidirectional relationship between gut and skin health.10 A metagenomic analysis of the gut microbiota in patients with untreated plaque psoriasis revealed a signature dysbiosis for which the researchers developed a psoriasis microbiota index, suggesting the gut microbiota may play a role in psoriasis pathophysiology.14 Research shows that both the MeD and vegan/vegetarian diets, which are relatively rich in fiber and omega-3 fatty acids and low in saturated fat and animal protein compared to many diets, cause increases in dietary fiber–metabolizing bacteria that produce short-chain fatty acids. These short-chain fatty acids improve gut epithelial integrity and alleviate both gut and systemic inflammation.10

The changes to the gut microbiome induced by a high-fat diet also are concerning. In contrast to the MeD or vegan/vegetarian diets, consumption of a high-fat diet induces alterations in the composition of the gut microbiota that in turn increase the release of proinflammatory cytokines and promote higher intestinal permeability.10 Similarly, high sugar consumption promotes increased intestinal permeability and shifts the gut microbiota to organisms that can rapidly utilize simple carbohydrates at the expense of other beneficial organisms, reducing bacterial diversity.15 The Western diet, which is notable for both high fat and high sugar content, is sometimes referred to as a proinflammatory diet and has been shown to worsen psoriasiformlike lesions in mice.16 Importantly, most research indicates that high fat and high sugar consumption appear to be more prevalent in psoriasis patients,8 but the type of fat consumed in the diet matters. The Western diet includes abundant saturated fat found in meat, dairy products, palm and coconut oils, and processed foods, as well as omega-6 fatty acids that are found in meat, poultry, and eggs. Saturated fat has been shown to promote helper T cell (TH17) accumulation in the skin, and omega-6 fatty acids serve as precursors to various inflammatory lipid mediators.4 This distinction of sources of fat between the Western diet and MeD is important in understanding the diets’ different effects on psoriasis and overall health. As previously discussed, the high intake of omega-3 acids in the MeD is one of the ways it may exert its anti-inflammatory benefits.7

Next Steps in Advising Psoriasis Patients

A major limitation of the data for MeD and vegan/vegetarian diets is limited randomized controlled trials evaluating the impact of these diets on psoriasis. Thus, dietary recommendations for psoriasis are not as strong as for other diseases for which more conclusive data exist.8 Although the data on diet and psoriasis are not definitive, perhaps dermatologists should shift the question from “Does this diet definitely improve psoriasis?” to “Does this diet definitely improve my patient’s health as a whole and maybe also their psoriasis?” For instance, the MeD has been shown to reduce the risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease as well as to slow cognitive decline.17 Vegan/vegetarian diets focusing on whole vs processed foods have been shown to be highly effective in combatting obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease including severe atherosclerosis, and hypertension.18 Psoriasis patients are at increased risk for many of the ailments that the MeD and plant-based diets protect against, making these diets potentially even more impactful than for someone without psoriasis.19 Dietary recommendations should still be made in conjunction with continuing traditional therapies for psoriasis and in consultation with the patient’s primary care physician and/or dietitian; however, rather than waiting for more randomized controlled trials before making health-promoting recommendations, what would be the downside of starting now? At worst, the dietary change decreases their risk for several metabolic conditions, and at best they may even see an improvement in their psoriasis.

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease for which several lifestyle factors—smoking, alcohol use, and psychological stress—are associated with higher incidence and more severe disease.1-3 Diet also has been implicated as a factor that can affect psoriasis,4 and many patients have shown interest in possible dietary interventions to help their disease.5

In 2018, the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) presented dietary recommendations for patients based on results from a systematic review. From the available literature, only dietary weight reduction with hypocaloric diets in overweight or obese patients could be strongly recommended, and it has been proven that obesity is associated with worse psoriasis severity.6 Other more recent studies have shown that dietary modifications such as intermittent fasting and the ketogenic diet also led to weight loss and improved psoriasis severity in overweight patients; however, it is difficult to discern if the improvement was due to weight loss alone or if the dietary patterns themselves played a role.7,8 The paucity of well-designed studies evaluating the effects of other dietary changes has prevented further guidelines from being written. We propose that dietary patterns such as the Mediterranean diet (MeD) and vegan/vegetarian diets—even without strong data showing benefits in skin disease—may help to decrease systemic inflammation, improve gut dysbiosis, and help decrease the risk for cardiometabolic comorbidities that are associated with psoriasis.

Mediterranean Diet

The MeD is based on the dietary tendencies of inhabitants from the regions surrounding the Mediterranean Sea and is centered around nutrient-rich foods such as vegetables, olive oil, and legumes while limiting meat and dairy.9 The NPF recommended considering a trial of the MeD based on low-quality evidence.6 Observational studies have indicated that psoriasis patients are less likely to adhere to the MeD, but those who do have less severe disease.8 However, a search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms Mediterranean diet and psoriasis yielded no prospective interventional studies. Given the association of the MeD with less severe disease, it is important to understand which specific foods in the MeD could be beneficial. Intake of omega-3 fatty acids, such as those found in fatty fish, are important for modulation of systemic inflammation.7 High intake of polyphenols—found in fruits and vegetables, extra-virgin olive oil, and wine—also have been implicated in improving inflammatory diseases due to potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Individually, fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and sea fish have been associated with lowering C-reactive protein levels, which also is indicative of the benefits of these foods on systemic inflammation.7

Vegan/Vegetarian Diets

Although fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains are a substantial component of the MeD, there are limited data on vegetarian or purely vegan plant-based diets. An observational study from the NPF found that only 48.4% (15/31) of patients on the MeD vs 69.0% (20/29) on a vegan diet reported a favorable skin response.5 Two case reports also have shown beneficial results of a strict vegan diet for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, where whole-food plant-based diets also improved joint symptoms.10-12 As with any diet, those who pursue a plant-based diet should strive to consume a variety of foods to avoid nutrient deficiencies. A recent systematic meta-analysis of 141 studies evaluated nutrient status of vegan and vegetarian diets compared to pescovegetarians and those who consume meat. All dietary patterns showed varying degrees of low levels of different nutrients.13 Of note, the researchers found that vitamin B12, vitamin D, iron, zinc, iodine, calcium, and docosahexaenoic acid were lower in plant-based diets. In contrast, folate; vitamins B1, B6, C, and E; polyunsaturated fatty acids; α-linolenic acid; and magnesium intake were higher. Those who consumed meat were at risk for inadequate intake of fiber, polyunsaturated fatty acids, α-linolenic acid, folate, vitamin E, calcium, magnesium, and vitamin D, though vitamin D intake was higher than in vegans/vegetarians.13 The results of this meta-analysis indicated the importance of educating patients on what constitutes a well-rounded, micronutrient-rich diet or appropriate supplementation for any diet.

Effects on Gut Microbiome

Any changes in diet can lead to alterations in the gut microbiome, which may impact skin disease, as evidence indicates a bidirectional relationship between gut and skin health.10 A metagenomic analysis of the gut microbiota in patients with untreated plaque psoriasis revealed a signature dysbiosis for which the researchers developed a psoriasis microbiota index, suggesting the gut microbiota may play a role in psoriasis pathophysiology.14 Research shows that both the MeD and vegan/vegetarian diets, which are relatively rich in fiber and omega-3 fatty acids and low in saturated fat and animal protein compared to many diets, cause increases in dietary fiber–metabolizing bacteria that produce short-chain fatty acids. These short-chain fatty acids improve gut epithelial integrity and alleviate both gut and systemic inflammation.10

The changes to the gut microbiome induced by a high-fat diet also are concerning. In contrast to the MeD or vegan/vegetarian diets, consumption of a high-fat diet induces alterations in the composition of the gut microbiota that in turn increase the release of proinflammatory cytokines and promote higher intestinal permeability.10 Similarly, high sugar consumption promotes increased intestinal permeability and shifts the gut microbiota to organisms that can rapidly utilize simple carbohydrates at the expense of other beneficial organisms, reducing bacterial diversity.15 The Western diet, which is notable for both high fat and high sugar content, is sometimes referred to as a proinflammatory diet and has been shown to worsen psoriasiformlike lesions in mice.16 Importantly, most research indicates that high fat and high sugar consumption appear to be more prevalent in psoriasis patients,8 but the type of fat consumed in the diet matters. The Western diet includes abundant saturated fat found in meat, dairy products, palm and coconut oils, and processed foods, as well as omega-6 fatty acids that are found in meat, poultry, and eggs. Saturated fat has been shown to promote helper T cell (TH17) accumulation in the skin, and omega-6 fatty acids serve as precursors to various inflammatory lipid mediators.4 This distinction of sources of fat between the Western diet and MeD is important in understanding the diets’ different effects on psoriasis and overall health. As previously discussed, the high intake of omega-3 acids in the MeD is one of the ways it may exert its anti-inflammatory benefits.7

Next Steps in Advising Psoriasis Patients

A major limitation of the data for MeD and vegan/vegetarian diets is limited randomized controlled trials evaluating the impact of these diets on psoriasis. Thus, dietary recommendations for psoriasis are not as strong as for other diseases for which more conclusive data exist.8 Although the data on diet and psoriasis are not definitive, perhaps dermatologists should shift the question from “Does this diet definitely improve psoriasis?” to “Does this diet definitely improve my patient’s health as a whole and maybe also their psoriasis?” For instance, the MeD has been shown to reduce the risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease as well as to slow cognitive decline.17 Vegan/vegetarian diets focusing on whole vs processed foods have been shown to be highly effective in combatting obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease including severe atherosclerosis, and hypertension.18 Psoriasis patients are at increased risk for many of the ailments that the MeD and plant-based diets protect against, making these diets potentially even more impactful than for someone without psoriasis.19 Dietary recommendations should still be made in conjunction with continuing traditional therapies for psoriasis and in consultation with the patient’s primary care physician and/or dietitian; however, rather than waiting for more randomized controlled trials before making health-promoting recommendations, what would be the downside of starting now? At worst, the dietary change decreases their risk for several metabolic conditions, and at best they may even see an improvement in their psoriasis.

- Naldi L, Chatenoud L, Linder D, et al. Cigarette smoking, body mass index, and stressful life events as risk factors for psoriasis: results from an Italian case–control study. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:61-67. doi:10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23681.x

- Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Dhillon JS, et al. Psoriasis and smoking: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:304-314. doi:10.1111/bjd.12670

- Zhu K, Zhu C, Fan Y. Alcohol consumption and psoriatic risk: a meta‐analysis of case–control studies. J Dermatol. 2012;39:770-773. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2012.01577.x

- Kanda N, Hoashi T, Saeki H. Nutrition and psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:5405. doi:10.3390/ijms21155405

- Afifi L, Danesh MJ, Lee KM, et al. Dietary behaviors in psoriasis: patient-reported outcomes from a U.S. national survey. Dermatol Ther. 2017;7:227-242. doi:10.1007/s13555-017-0183-4

- Ford AR, Siegel M, Bagel J, et al. Dietary recommendations for adults with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis from the medical board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:934. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.1412

- Duchnik E, Kruk J, Tuchowska A, et al. The impact of diet and physical activity on psoriasis: a narrative review of the current evidence. Nutrients. 2023;15:840. doi:10.3390/nu15040840

- Chung M, Bartholomew E, Yeroushalmi S, et al. Dietary intervention and supplements in the management of psoriasis: current perspectives. Psoriasis Targets Ther. 2022;12:151-176. doi:10.2147/PTT.S328581

- Mazza E, Ferro Y, Pujia R, et al. Mediterranean diet in healthy aging. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25:1076-1083. doi:10.1007/s12603-021-1675-6

- Flores-Balderas X, Peña-Peña M, Rada KM, et al. Beneficial effects of plant-based diets on skin health and inflammatory skin diseases. Nutrients. 2023;15:2842. doi:10.3390/nu15132842

- Bonjour M, Gabriel S, Valencia A, et al. Challenging case in clinical practice: prolonged water-only fasting followed by an exclusively whole-plant-food diet in the management of severe plaque psoriasis. Integr Complement Ther. 2022;28:85-87. doi:10.1089/ict.2022.29010.mbo

- Lewandowska M, Dunbar K, Kassam S. Managing psoriatic arthritis with a whole food plant-based diet: a case study. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2021;15:402-406. doi:10.1177/1559827621993435

- Neufingerl N, Eilander A. Nutrient intake and status in adults consuming plant-based diets compared to meat-eaters: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2021;14:29. doi:10.3390/nu14010029

- Dei-Cas I, Giliberto F, Luce L, et al. Metagenomic analysis of gut microbiota in non-treated plaque psoriasis patients stratified by disease severity: development of a new psoriasis-microbiome index. Sci Rep. 2020;10:12754. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-69537-3

- Satokari R. High intake of sugar and the balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory gut bacteria. Nutrients. 2020;12:1348. doi:10.3390/nu12051348

- Shi Z, Wu X, Santos Rocha C, et al. Short-term Western diet intake promotes IL-23–mediated skin and joint inflammation accompanied by changes to the gut microbiota in mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2021;141:1780-1791. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2020.11.032

- Romagnolo DF, Selmin OI. Mediterranean diet and prevention of chronic diseases. Nutr Today. 2017;52:208-222. doi:10.1097/NT.0000000000000228

- Tuso PJ, Ismail MH, Ha BP, et al. Nutritional update for physicians: plant-based diets. Perm J. 2013;17:61-66. doi:10.7812/TPP/12-085

- Parisi R, Symmons DPM, Griffiths CEM, et al. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:377-385. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.339

- Naldi L, Chatenoud L, Linder D, et al. Cigarette smoking, body mass index, and stressful life events as risk factors for psoriasis: results from an Italian case–control study. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:61-67. doi:10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23681.x

- Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Dhillon JS, et al. Psoriasis and smoking: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:304-314. doi:10.1111/bjd.12670

- Zhu K, Zhu C, Fan Y. Alcohol consumption and psoriatic risk: a meta‐analysis of case–control studies. J Dermatol. 2012;39:770-773. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2012.01577.x

- Kanda N, Hoashi T, Saeki H. Nutrition and psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:5405. doi:10.3390/ijms21155405

- Afifi L, Danesh MJ, Lee KM, et al. Dietary behaviors in psoriasis: patient-reported outcomes from a U.S. national survey. Dermatol Ther. 2017;7:227-242. doi:10.1007/s13555-017-0183-4

- Ford AR, Siegel M, Bagel J, et al. Dietary recommendations for adults with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis from the medical board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:934. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.1412

- Duchnik E, Kruk J, Tuchowska A, et al. The impact of diet and physical activity on psoriasis: a narrative review of the current evidence. Nutrients. 2023;15:840. doi:10.3390/nu15040840

- Chung M, Bartholomew E, Yeroushalmi S, et al. Dietary intervention and supplements in the management of psoriasis: current perspectives. Psoriasis Targets Ther. 2022;12:151-176. doi:10.2147/PTT.S328581

- Mazza E, Ferro Y, Pujia R, et al. Mediterranean diet in healthy aging. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25:1076-1083. doi:10.1007/s12603-021-1675-6

- Flores-Balderas X, Peña-Peña M, Rada KM, et al. Beneficial effects of plant-based diets on skin health and inflammatory skin diseases. Nutrients. 2023;15:2842. doi:10.3390/nu15132842

- Bonjour M, Gabriel S, Valencia A, et al. Challenging case in clinical practice: prolonged water-only fasting followed by an exclusively whole-plant-food diet in the management of severe plaque psoriasis. Integr Complement Ther. 2022;28:85-87. doi:10.1089/ict.2022.29010.mbo

- Lewandowska M, Dunbar K, Kassam S. Managing psoriatic arthritis with a whole food plant-based diet: a case study. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2021;15:402-406. doi:10.1177/1559827621993435

- Neufingerl N, Eilander A. Nutrient intake and status in adults consuming plant-based diets compared to meat-eaters: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2021;14:29. doi:10.3390/nu14010029

- Dei-Cas I, Giliberto F, Luce L, et al. Metagenomic analysis of gut microbiota in non-treated plaque psoriasis patients stratified by disease severity: development of a new psoriasis-microbiome index. Sci Rep. 2020;10:12754. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-69537-3

- Satokari R. High intake of sugar and the balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory gut bacteria. Nutrients. 2020;12:1348. doi:10.3390/nu12051348

- Shi Z, Wu X, Santos Rocha C, et al. Short-term Western diet intake promotes IL-23–mediated skin and joint inflammation accompanied by changes to the gut microbiota in mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2021;141:1780-1791. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2020.11.032

- Romagnolo DF, Selmin OI. Mediterranean diet and prevention of chronic diseases. Nutr Today. 2017;52:208-222. doi:10.1097/NT.0000000000000228

- Tuso PJ, Ismail MH, Ha BP, et al. Nutritional update for physicians: plant-based diets. Perm J. 2013;17:61-66. doi:10.7812/TPP/12-085

- Parisi R, Symmons DPM, Griffiths CEM, et al. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:377-385. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.339

Practice Points

- Psoriasis is affected by lifestyle factors such as diet, which is an area of interest for many patients.

- Low-calorie diets are strongly recommended for overweight/obese patients with psoriasis to improve their disease.

- Changes in dietary patterns, such as adopting a Mediterranean diet or a plant-based diet, also have shown promise.

The Potential for Artificial Intelligence Tools in Residency Recruitment

According to Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) statistics, there were more than 1400 dermatology applicants in 2022, with an average of almost 560 applications received per program.1,2 With the goal to expand the diversity of board-certified dermatologists, there is increasing emphasis on the holistic review of applications, forgoing filtering by discrete metrics such as AOA (American Osteopathic Association) membership and US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) scores.3 According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, holistic review focuses on an individual applicant’s experience and unique attributes in addition to their academic achievements.4 Recent strategies to enhance the residency recruitment process have included the introduction of standardized letters of recommendation, preference signaling, and supplemental applications.5,6

Because it has become increasingly important to include applicant factors and achievements that extend beyond academics, the number of data points that are required for holistic review has expanded. If each application required 20 minutes to review, this would result in 166 total hours for complete holistic review of 500 applications. Tools that can facilitate holistic review of candidates and select applicants whose interests and career goals align with individual residency programs have the potential to optimize review. Artificial intelligence (AI) may aid in this process. This column highlights some of the published research on novel AI strategies that have the potential to impact dermatology residency recruitment.

Machine Learning to Screen Applicants

Artificial intelligence involves a machine-based system that can make decisions, predictions, and recommendations when provided a given set of human-defined objectives.7 Autonomous systems, machine learning (ML), and generative AI are examples of AI models.8 Machine learning has been explored to shorten and streamline the application review process and decrease bias. Because ML is a model in which the computer learns patterns based on large amounts of input data,9 it is possible that models could be developed and used in future cycles. Some studies found that applicants were discovered who traditionally would not have made it to the next stage of consideration based primarily on academic metrics.10,11 Burk-Rafel et al10 developed and validated an ML-based decision support tool for residency program directors to use for interview invitation decisions. The tool utilized 61 variables from ERAS data from more than 8000 applications in 3 prior application cycles at a single internal medicine residency program. An interview invitation was designated as the target outcome. Ultimately, the model would output a probability score for an interview invitation. The authors were able to tune the model to a 91% sensitivity and 85% specificity; for a pool of 2000 applicants and an invite rate of 15%, 1475 applicants would be screened out with a negative predictive value of 98% with maintenance of performance, even with removal of USMLE Step 1 examination scores. Their ML model was prospectively validated during an ongoing resident selection cycle, and when compared with human review, the AI model found an additional 20 applicants to invite for interviews. They concluded that this tool could potentially augment the human review process and reveal applicants who may have otherwise been overlooked.10

Rees and Ryder11 utilized another ML screening approach with the target outcome of ranked and matriculated compared with ranked applicants based on ERAS data using 72 unique variables for more than 5000 applicants. Their model was able to identify ranked candidates from the overall applicant pool with high accuracy; identification of ranked applicants that matriculated at the program was more modest but better than random probability.11Both the Burk-Rafel et al10 and Rees and Ryder11 models excluded some unstructured data components of the residency application, such as personal statements, medical student performance evaluation letters, transcripts, and letters of reference, that some may consider strongly in the holistic review process. Drum et al12 explored the value of extraction of this type of data. They created a program to extract “snippets” of text that pertained to values of successful residents for their internal medicine–pediatrics residency program that they previously validated via a modified Delphi method, which then were annotated by expert reviewers. Natural language processing was used to train an ML algorithm (MLA) to classify snippets into 11 value categories. Four values had more than 66% agreement with human annotation: academic strength; leadership; communication; and justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion. Although this MLA has not reached high enough levels of agreement for all the predetermined success values, the authors hope to generate a model that could produce a quantitative score to use as an initial screening tool to select applicants for interview.12 This type of analysis also could be incorporated into other MLAs for further refinement of the mentoring and application process.

Knapke et al13 evaluated the use of a natural language modeling platform to look for semantic patterns in medical school applications that could predict which students would be more likely to pursue family medicine residency, thus beginning the recruitment process even before residency application. This strategy could be particularly valuable for specialties for which there may be greater need in the workforce.

AI for Administrative Purposes

Artificial intelligence also has been used for nonapplication aspects of the residency recruitment process, such as interview scheduling. In the absence of coordinated interview release dates (as was implemented in dermatology starting in the 2020-2021 application cycle), a deluge of responses to schedule an interview comes flooding in as soon as invitations for interviewees are sent out, which can produce anxiety both for applicants and residency program staff as the schedule is sorted out and can create delays at both ends. Stephens et al14 utilized a computerized scheduling program for pediatric surgery fellowship applicants. It was used in 2016 to schedule 26 interviews, and it was found to reduce the average time to schedule an interview from 14.4 hours to 1.7 hours. It also reduced the number of email exchanges needed to finalize scheduling.14

Another aspect of residency recruitment that is amenable to AI is information gathering. Many would-be applicants turn to the internet and social media to learn about residency programs—their unique qualities, assets, and potential alignment of career goals.15 This exchange often is unidirectional, as the applicant clicks through the website searching for information. Yi et al16 explored the use of a chatbot, which mimics human conversation and exchange, on their institution’s pain fellowship website. Fellowship applicants could create specific prompts, such as “Show me faculty that trained at <applicant’s home program>,” and the chatbot would reply with the answer. The researchers sent a survey to all 258 applicants to the pain fellowship program that was completed by 48 applicants. Of these respondents, more than 70% (35/48) utilized the chatbot, and 84% (40/48) stated that they had found the information that was requested. The respondents overall found the chatbot to be a useful and positive experience.16

Specific Tools to Consider

There are some tools that are publicly available for programs and applicants to use that rely on AI.

In collaboration with ERAS and the Association of American Medical Colleges, Cortex powered by Thalamus (SJ MedConnect Inc)(https://thalamusgme.com/cortex-application-screening/) offers technology-assisted holistic review of residency and fellowship applications by utilizing natural language processing and optical character recognition to aggregate data from ERAS.

Tools also are being leveraged by applicants to help them find residency programs that fit their criteria, prepare for interviews, and complete portions of the application. Match A Resident (https://www.matcharesident.com/) is a resource for the international medical graduate community. As part of the service, the “Learn More with MARai” feature uses AI to generate information on residency programs to increase applicants’ confidence going into the interview process.17 Big Interview Medical (https://www.biginterviewmedical.com/ai-feedback), a paid interview preparation system developed by interview experts, utilizes AI to provide feedback to residents practicing for the interview process by measuring the amount of natural eye contact, language used, and pace of speech. A “Power Word” score is provided that incorporates aspects such as using filler words (“umm,” “uhh”). A Pace of Speech Tool provides rate of speaking feedback presuming that there is an ideal pace to decrease the impression that the applicant is nervous. Johnstone et al18 used ChatGPT (https://chat.openai.com/auth/login) to generate 2 personal statements for anesthesia residency applicants. Based on survey responses from 31 program directors, 22 rated the statements as good or excellent.18

Ethnical Concerns and Limitations of AI

The potential use of AI tools by residency applicants inevitably brings forth consideration of biases, ethics, and current limitations. These tools are highly dependent on the quality and quantity of data used for training and validation. Information considered valuable in the holistic review of applications includes unstructured data such as personal statements and letters of recommendation, and incorporating this information can be challenging in ML models, in contrast to discrete structured data such as grades, test scores, and awards. In addition, MLAs depend on large quantities of data to optimize performance.19 Depending on the size of the applicant pool and the amount of data available, this can present a limitation for smaller programs in developing ML tools for residency recruitment. Studies evaluating the use of AI in the residency application process often are from single institutions, and therefore generalizability is uncertain. The risk for latent bias—whereby a historical or pre-existing stereotype gets perpetuated through the system—must be considered, with the development of tools to detect and address this if found. Choosing which data to use to train the model can be tricky as well as choosing the outcome of interest. For these interventions to become more resilient, programs need to self-examine what defines their criteria for a successful match to their program to incorporate this data into their ML studies. The previously described models in this overview focused on outcomes such as whether an applicant was invited to interview, whether the applicant was ranked, and whether the applicant matriculated to their program.10,11 For supervised ML models that rely on outcomes to develop a prediction, continued research as to what outcomes represent resident success (eg, passing board certification examinations, correlation with clinical performance) would be important. There also is the possibility of applicants restructuring their applications to align with goals of an AI-assisted search and using AI to generate part or all of their application. The use of ChatGPT and other AI tools in the preparation of personal statements and curriculum vitae may provide benefits such as improved efficiency and grammar support.20 However, as use becomes more widespread, there is the potential increased similarity of personal statements and likely varied opinions on the use of such tools as writing aids.21,22 Continued efforts to develop guidance on generative AI use cases is ongoing; an example is the launch of VALID AI (https://validai.health/), a collaboration among health systems, health plans, and AI research organizations and nonprofits.23

Final Thoughts

Artificial intelligence tools may be a promising resource for residency and fellowship programs seeking to find meaningful ways to select applicants who are good matches for their training environment. Prioritizing the holistic review of applications has been promoted as a method to evaluate the applicant beyond their test scores and grades. The use of MLAs may streamline this review process, aid in scheduling interviews, and help discover trends in successful matriculants.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. ERAS® Statistics. Accessed January 16, 2024. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/data/eras-statistics-data

- National Resident Matching Program, Data Release and ResearchCommittee: Results of the 2022 NRMP Program Director Survey. Accessed January 18, 2024. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/PD-Survey-Report-2022_FINALrev.pdf

- Isaq NA, Bowers S, Chen ST. Taking a “step” toward diversity in dermatology: de-emphasizing USMLE Step 1 scores in residency applications. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:209-210. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.02.008

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Holistic review in medical school admissions. Accessed January 16, 2024. https://students-residents.aamc.org/choosing-medical-career/holistic-review-medical-school-admissions

- Association of American Medical Colleges. The MyERAS® application and program signaling for 2023-24. Accessed January 16, 2024. https://students-residents.aamc.org/applying-residencies-eras/myeras-application-and-program-signaling-2023-24

- Tavarez MM, Baghdassarian A, Bailey J, et al. A call to action for standardizing letters of recommendation. J Grad Med Educ. 2022;14:642-646. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-22-00131.1

- US Department of State. Artificial intelligence (AI). Accessed January 16, 2024. https://www.state.gov/artificial-intelligence/

- Stanford University Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence. Artificial intelligence definitions. Accessed January 16, 2024.https://hai.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/2023-03/AI-Key-Terms-Glossary-Definition.pdf

- Rajkomar A, Dean J, Kohane I. Machine learning in medicine. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1347-1358. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1814259

- Burk-Rafel J, Reinstein I, Feng J, et al. Development and validation of a machine learning-based decision support tool for residency applicant screening and review. Acad Med. 2021;96(11S):S54-S61. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004317

- Rees CA, Ryder HF. Machine learning for the prediction of ranked applicants and matriculants to an internal medicine residency program. Teach Learn Med. 2023;35:277-286. doi:10.1080/10401334.2022.2059664

- Drum B, Shi J, Peterson B, et al. Using natural language processing and machine learning to identify internal medicine-pediatrics residency values in applications. Acad Med. 2023;98:1278-1282. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000005352

- Knapke JM, Mount HR, McCabe E, et al. Early identification of family physicians using qualitative admissions data. Fam Med. 2023;55:245-252. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2023.596964

- Stephens CQ, Hamilton NA, Thompson AE, et al. Use of computerized interview scheduling program for pediatric surgery match applicants. J Pediatr Surg. 2017;52:1056-1059. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.03.033

- Nickles MA, Kulkarni V, Varghese JA, et al. Dermatology residency programs’ websites in the virtual era: a cross-sectional analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:447-448. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.09.064

- Yi PK, Ray ND, Segall N. A novel use of an artificially intelligent Chatbot and a live, synchronous virtual question-and answer session for fellowship recruitment. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23:152. doi:10.1186/s12909-022-03872-z

- Introducing “Learn More with MARai”—the key to understanding your target residency programs. Match A Resident website. Published September 23, 2023. Accessed January 16, 2024. https://blog.matcharesident.com/ai-powered-residency-insights/

- Johnstone RE, Neely G, Sizemore DC. Artificial intelligence softwarecan generate residency application personal statements that program directors find acceptable and difficult to distinguish from applicant compositions. J Clin Anesth. 2023;89:111185. doi:10.1016/j.jclinane.2023.111185

- Khalid N, Qayyum A, Bilal M, et al. Privacy-preserving artificial intelligence in healthcare: techniques and applications. Comput Biol Med. 2023;158:106848. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.106848

- Birt J. How to optimize your resume for AI scanners (with tips). Indeed website. Updated December 30, 2022. Accessed January 16, 2024. https://www.indeed.com/career-advice/resumes-cover-letters/resume-ai

- Patel V, Deleonibus A, Wells MW, et al. Distinguishing authentic voices in the age of ChatGPT: comparing AI-generated and applicant-written personal statements for plastic surgery residency application. Ann Plast Surg. 2023;91:324-325. doi:10.1097/SAP.0000000000003653

- Woodfin MW. The personal statement in the age of artificial intelligence. Acad Med. 2023;98:869. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000005266

- Diaz N. UC Davis Health to lead new gen AI collaborative. Beckers Healthcare website. Published October 10, 2023. AccessedJanuary 16, 2024. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/digital-health/uc-davis-health-to-lead-new-gen-ai-collaborative.html

According to Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) statistics, there were more than 1400 dermatology applicants in 2022, with an average of almost 560 applications received per program.1,2 With the goal to expand the diversity of board-certified dermatologists, there is increasing emphasis on the holistic review of applications, forgoing filtering by discrete metrics such as AOA (American Osteopathic Association) membership and US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) scores.3 According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, holistic review focuses on an individual applicant’s experience and unique attributes in addition to their academic achievements.4 Recent strategies to enhance the residency recruitment process have included the introduction of standardized letters of recommendation, preference signaling, and supplemental applications.5,6

Because it has become increasingly important to include applicant factors and achievements that extend beyond academics, the number of data points that are required for holistic review has expanded. If each application required 20 minutes to review, this would result in 166 total hours for complete holistic review of 500 applications. Tools that can facilitate holistic review of candidates and select applicants whose interests and career goals align with individual residency programs have the potential to optimize review. Artificial intelligence (AI) may aid in this process. This column highlights some of the published research on novel AI strategies that have the potential to impact dermatology residency recruitment.

Machine Learning to Screen Applicants

Artificial intelligence involves a machine-based system that can make decisions, predictions, and recommendations when provided a given set of human-defined objectives.7 Autonomous systems, machine learning (ML), and generative AI are examples of AI models.8 Machine learning has been explored to shorten and streamline the application review process and decrease bias. Because ML is a model in which the computer learns patterns based on large amounts of input data,9 it is possible that models could be developed and used in future cycles. Some studies found that applicants were discovered who traditionally would not have made it to the next stage of consideration based primarily on academic metrics.10,11 Burk-Rafel et al10 developed and validated an ML-based decision support tool for residency program directors to use for interview invitation decisions. The tool utilized 61 variables from ERAS data from more than 8000 applications in 3 prior application cycles at a single internal medicine residency program. An interview invitation was designated as the target outcome. Ultimately, the model would output a probability score for an interview invitation. The authors were able to tune the model to a 91% sensitivity and 85% specificity; for a pool of 2000 applicants and an invite rate of 15%, 1475 applicants would be screened out with a negative predictive value of 98% with maintenance of performance, even with removal of USMLE Step 1 examination scores. Their ML model was prospectively validated during an ongoing resident selection cycle, and when compared with human review, the AI model found an additional 20 applicants to invite for interviews. They concluded that this tool could potentially augment the human review process and reveal applicants who may have otherwise been overlooked.10

Rees and Ryder11 utilized another ML screening approach with the target outcome of ranked and matriculated compared with ranked applicants based on ERAS data using 72 unique variables for more than 5000 applicants. Their model was able to identify ranked candidates from the overall applicant pool with high accuracy; identification of ranked applicants that matriculated at the program was more modest but better than random probability.11Both the Burk-Rafel et al10 and Rees and Ryder11 models excluded some unstructured data components of the residency application, such as personal statements, medical student performance evaluation letters, transcripts, and letters of reference, that some may consider strongly in the holistic review process. Drum et al12 explored the value of extraction of this type of data. They created a program to extract “snippets” of text that pertained to values of successful residents for their internal medicine–pediatrics residency program that they previously validated via a modified Delphi method, which then were annotated by expert reviewers. Natural language processing was used to train an ML algorithm (MLA) to classify snippets into 11 value categories. Four values had more than 66% agreement with human annotation: academic strength; leadership; communication; and justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion. Although this MLA has not reached high enough levels of agreement for all the predetermined success values, the authors hope to generate a model that could produce a quantitative score to use as an initial screening tool to select applicants for interview.12 This type of analysis also could be incorporated into other MLAs for further refinement of the mentoring and application process.

Knapke et al13 evaluated the use of a natural language modeling platform to look for semantic patterns in medical school applications that could predict which students would be more likely to pursue family medicine residency, thus beginning the recruitment process even before residency application. This strategy could be particularly valuable for specialties for which there may be greater need in the workforce.

AI for Administrative Purposes