User login

Skin Lesions on the Face and Chest

The Diagnosis: Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm

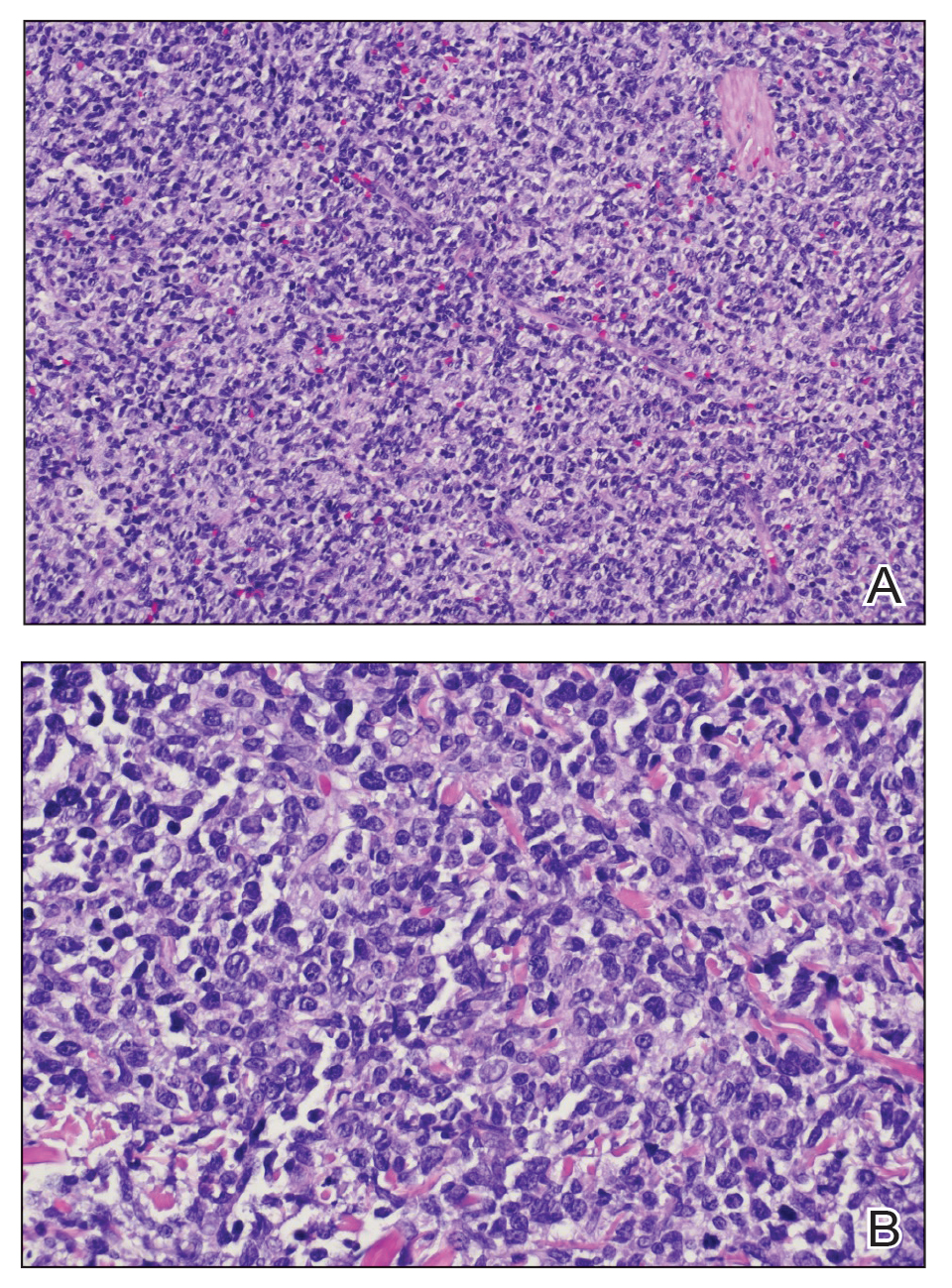

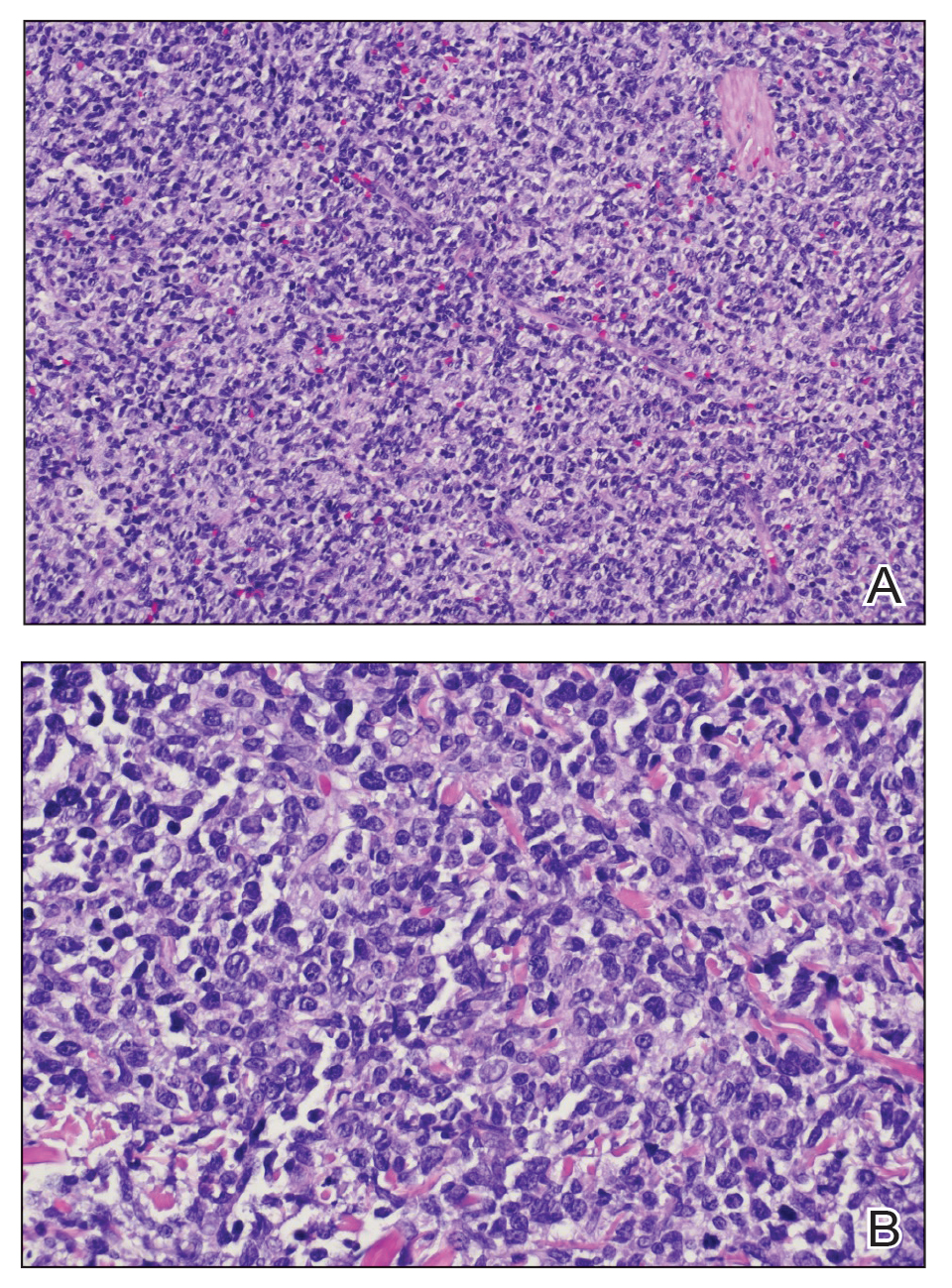

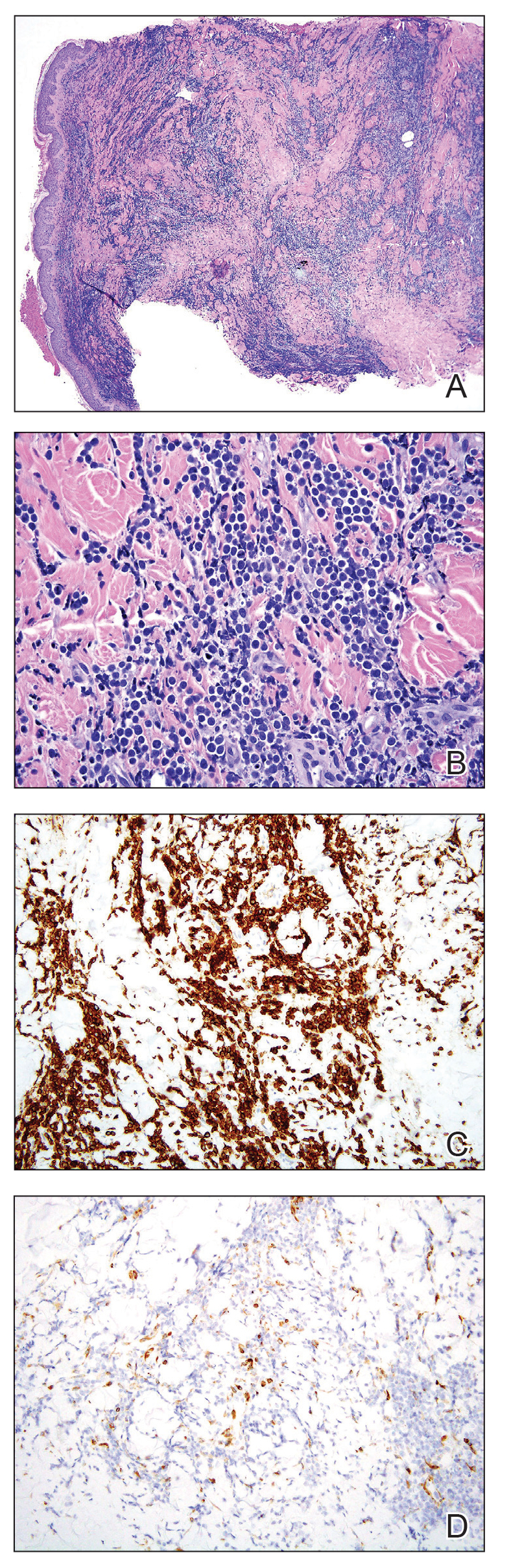

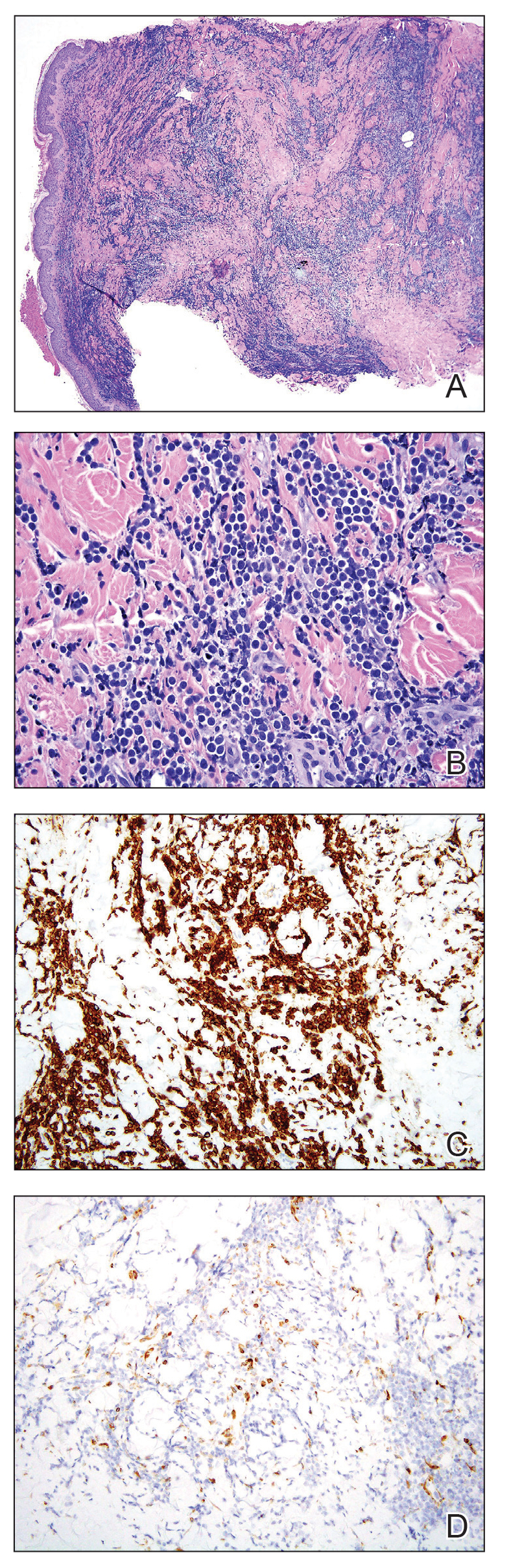

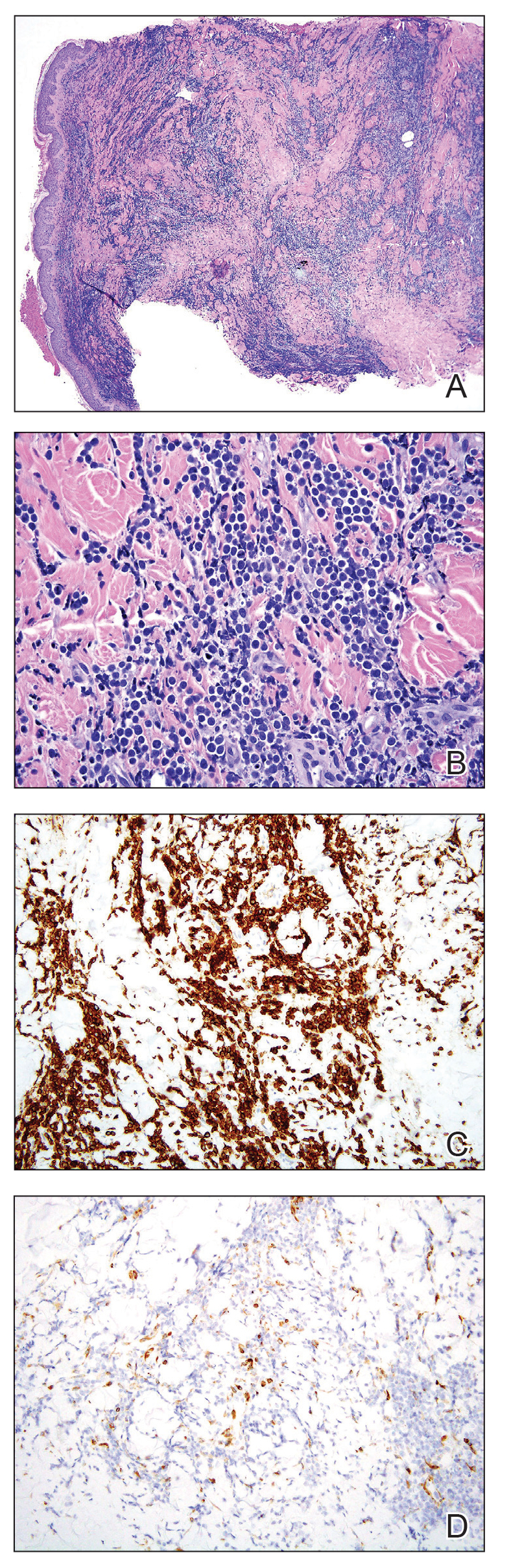

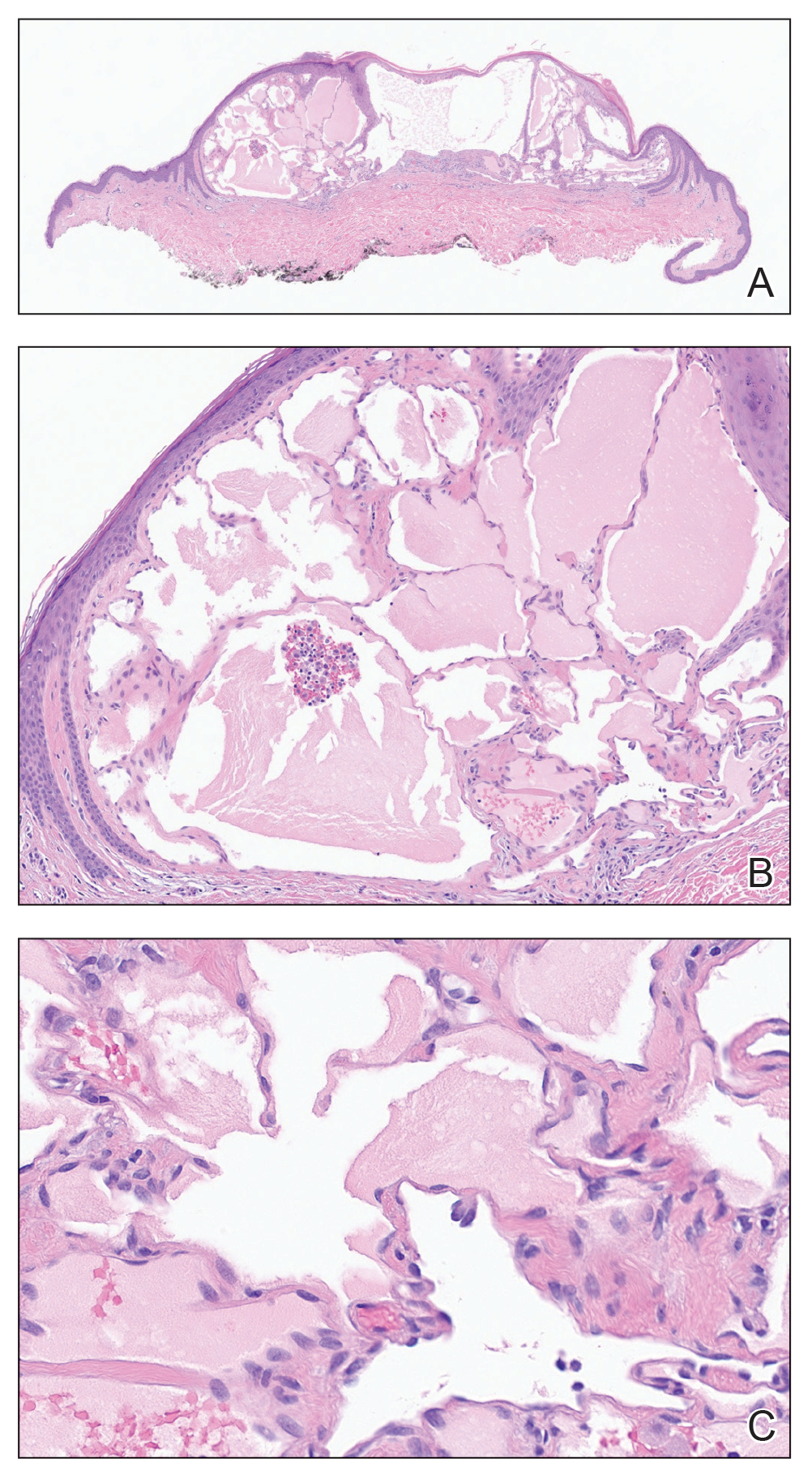

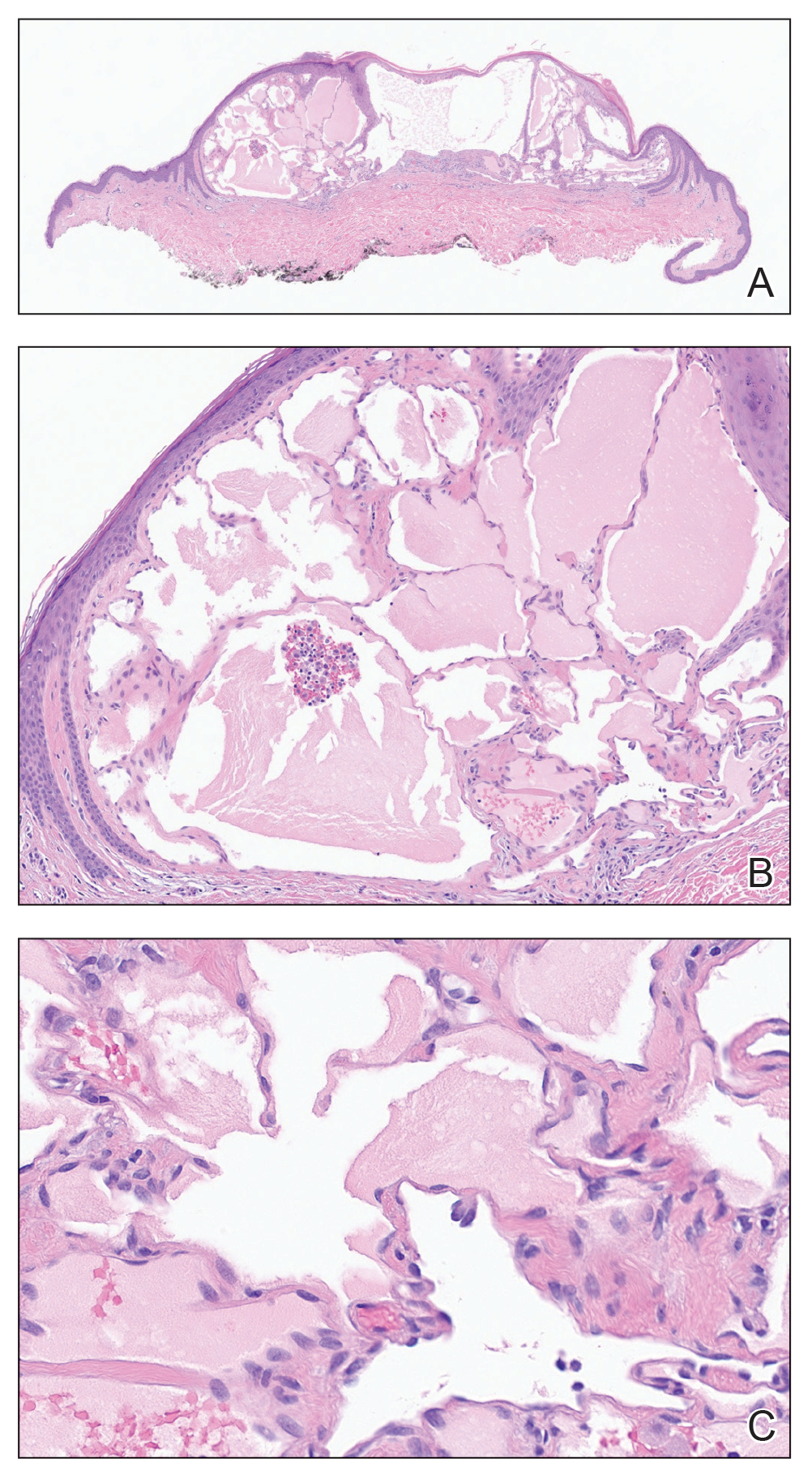

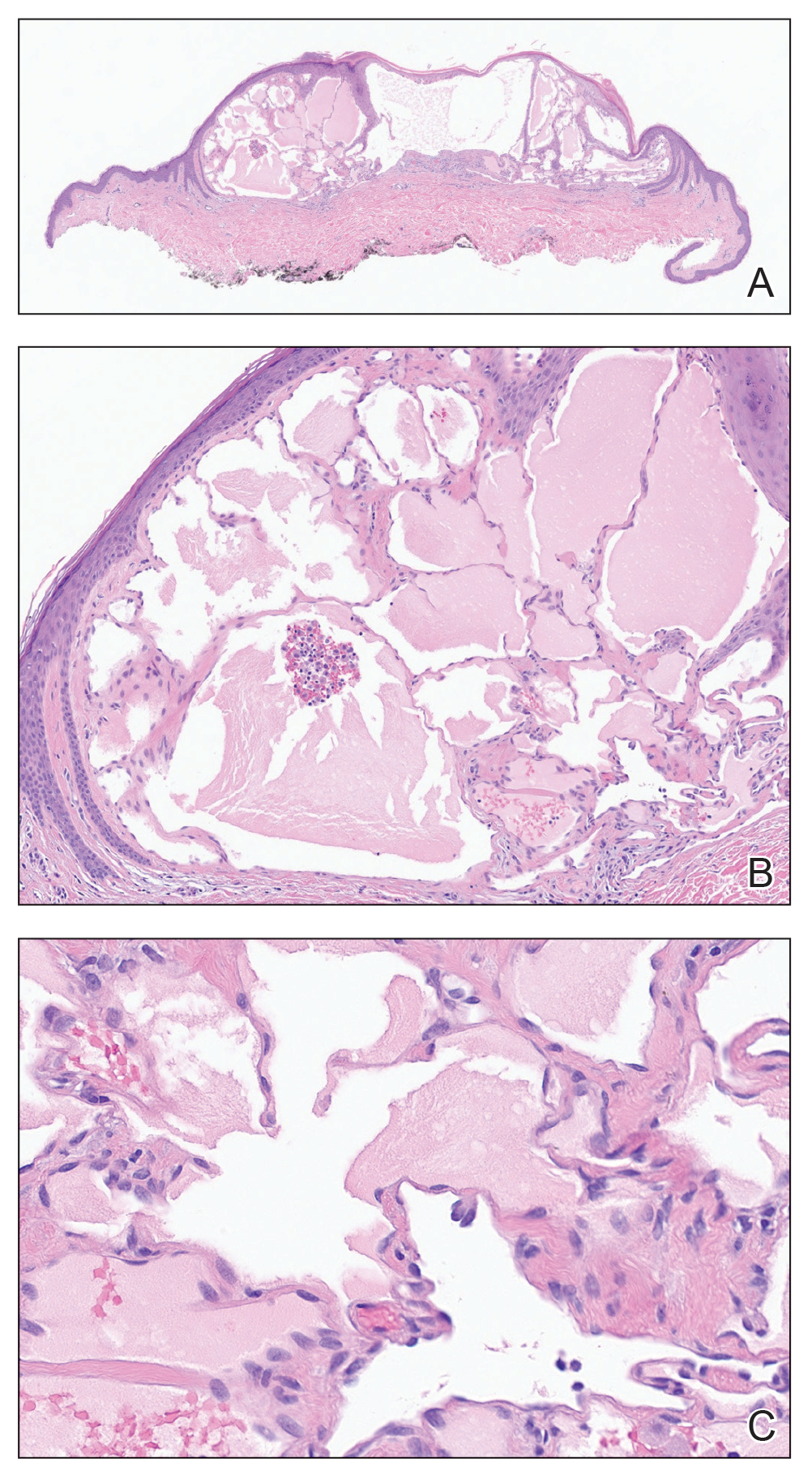

Cutaneous plasmacytoma initially was suspected because of the patient’s history of monoclonal gammopathy as well as angiosarcoma due to the purpuric vascular appearance of the lesions. However, histopathology revealed a pleomorphic cellular dermal infiltrate characterized by atypical cells with mediumlarge nuclei, fine chromatin, and small nucleoli; the cells also had little cytoplasm (Figure). The infiltrate did not involve the epidermis but extended into the subcutaneous tissue. Immunohistochemistry revealed that the cells were positive for CD45, CD43, CD4, CD7, CD56, CD123, CD33, T-cell leukemia/lymphoma protein 1, and CD68. The cells were negative for CD2, CD3, CD5, CD8, T-cell intracellular antigen 1, CD13, CD15, CD19, CD20, CD21, CD23, cyclin D1, Bcl-2, Bcl-6, CD10, PAX5, MUM1, lysozyme, myeloperoxidase, perforin, granzyme B, CD57, CD34, CD117, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase, activin receptorlike kinase 1 βF1, Epstein-Barr virus– encoded small RNA, CD30, CD163, and pancytokeratin. Thus, the clinical and histopathologic findings led to a diagnosis of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN), a rare and aggressive hematologic malignancy.

Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm affects males older than 60 years.1 It is characterized by the clonal proliferation of precursor plasmacytoid dendritic cells—otherwise known as professional type I interferonproducing cells or plasmacytoid monocytes—of myeloid origin. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells have been renamed on several occasions, reflecting uncertainties of their histogenesis. The diagnosis of BPDCN requires a biopsy showing the morphology of plasmacytoid dendritic blast cells and immunophenotypic criteria established by either immunohistochemistry or flow cytometry.2,3 Tumor cells morphologically show an immature blastic appearance, and the diagnosis rests upon the demonstration of CD4 and CD56, together with markers more restricted to plasmacytoid dendritic cells (eg, BDCA-2, CD123, T-cell leukemia/lymphoma protein 1, CD2AP, BCL11A) and negativity for lymphoid and myeloid lineage–associated antigens.1,4

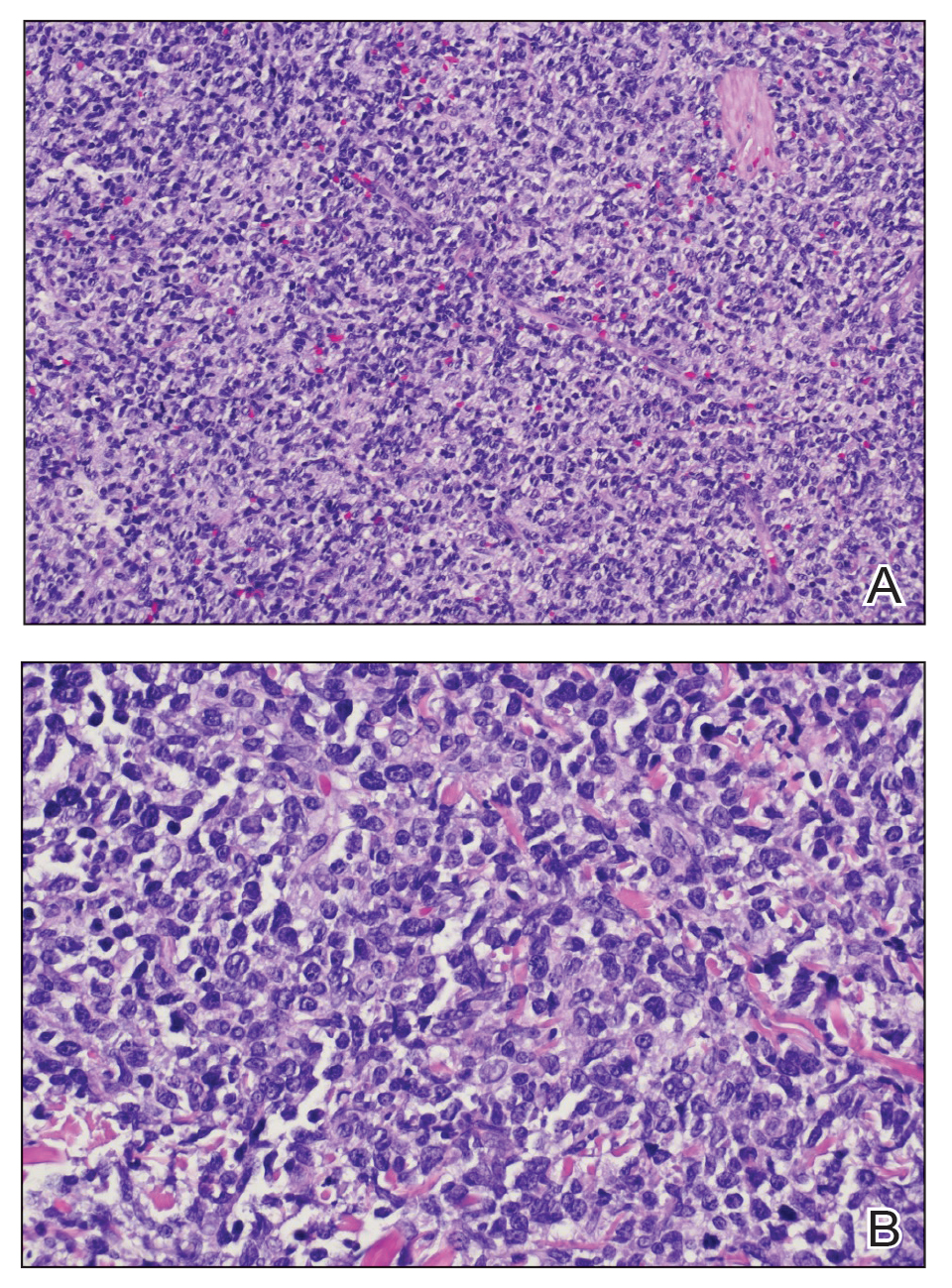

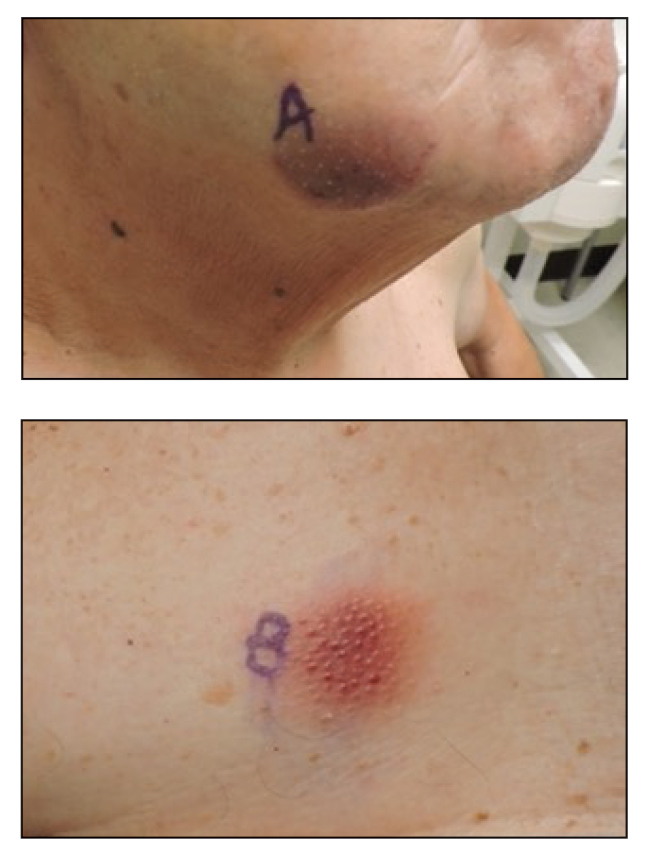

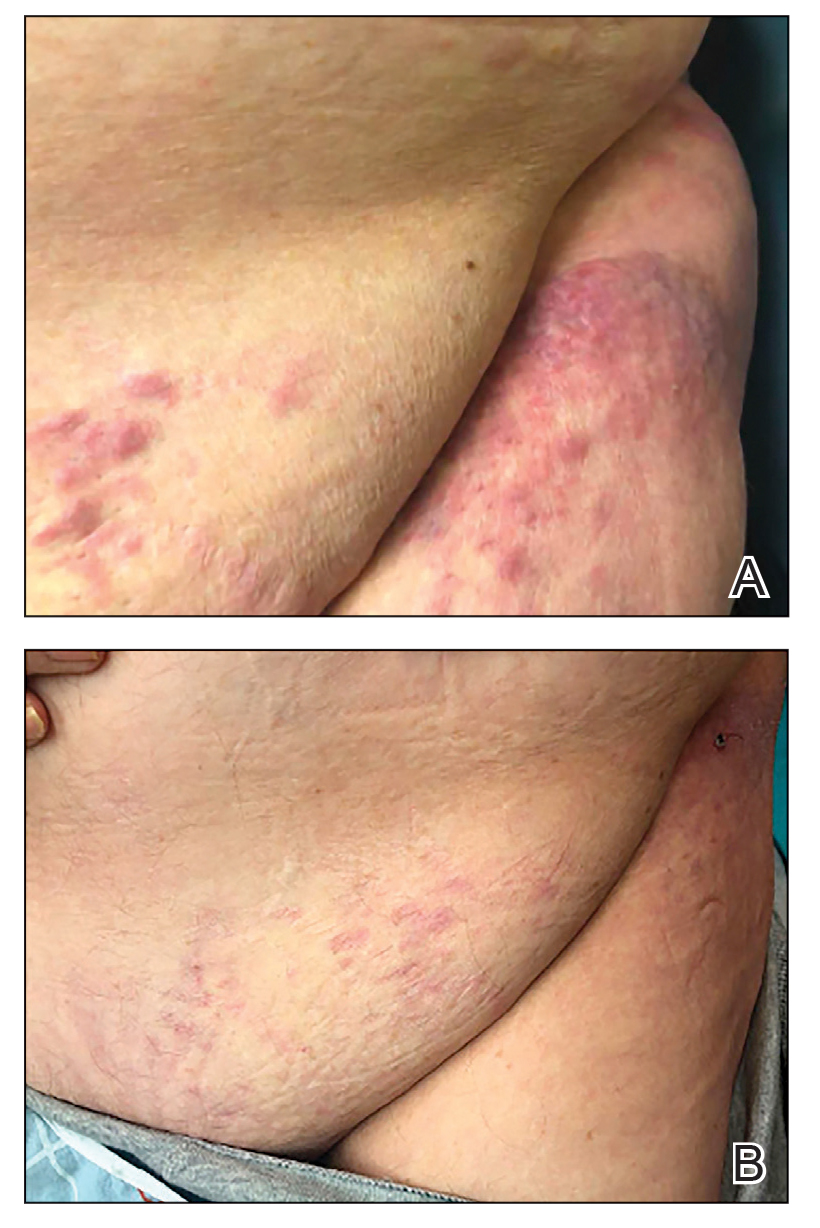

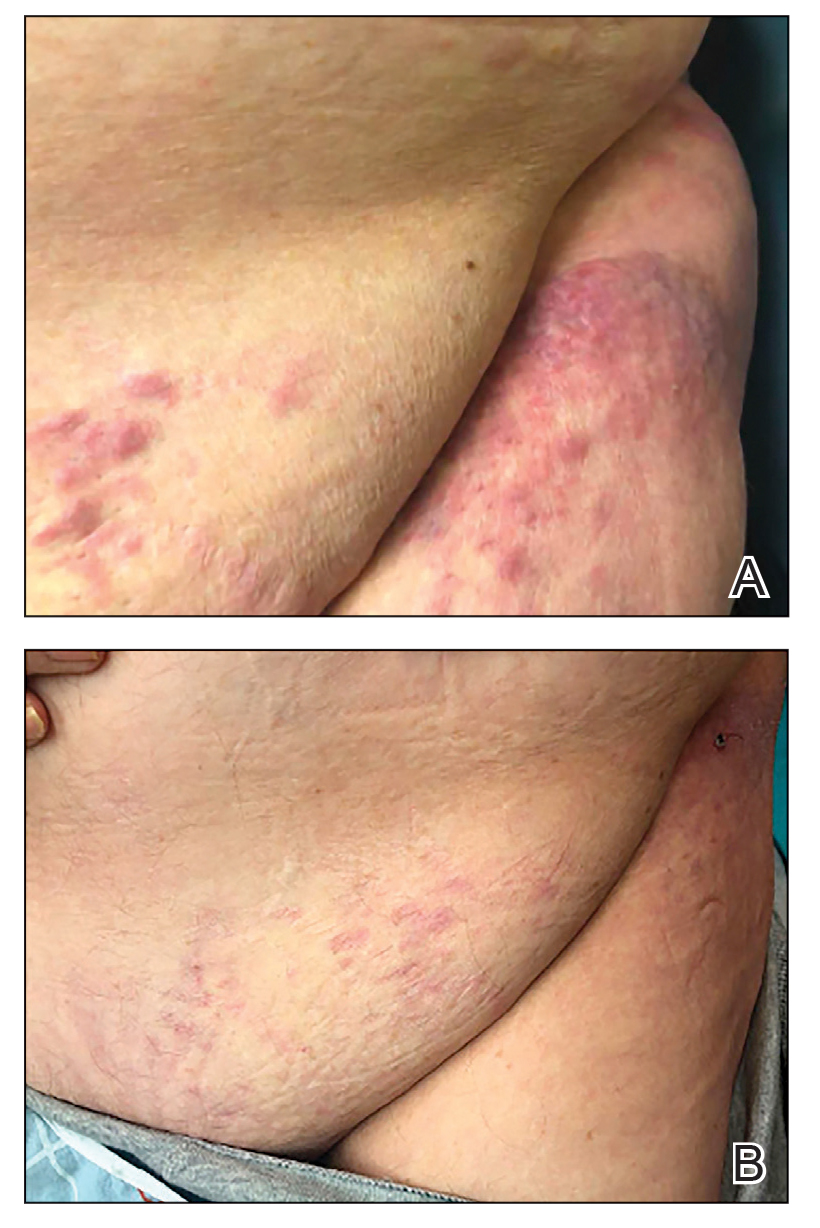

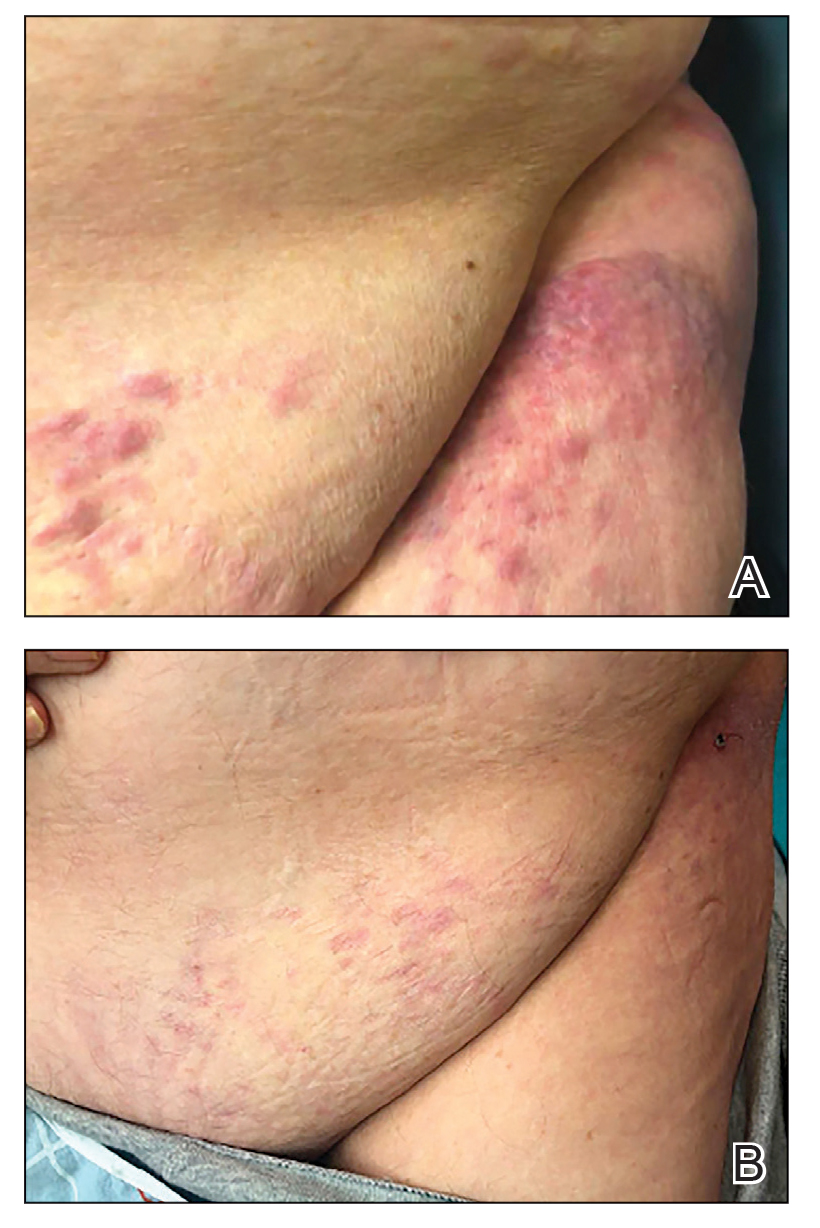

Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasms account for less than 1% of all hematopoietic neoplasms. Cutaneous lesions occur in 64% of patients with the disease and often are the reason patients seek medical care.5 Clinical findings include numerous erythematous and violaceous papules, nodules, and plaques that resemble purpura or vasculitis. Cutaneous lesions can vary in size from a few millimeters to 10 cm and vary in color. Moreover, patients often present with bruiselike patches, disseminated lesions, or mucosal lesions.1 Extracutaneous involvement includes lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and cytopenia caused by bone marrow infiltration, which may be present at diagnosis or during disease progression. Bone marrow involvement often is present with thrombocytopenia, anemia, and neutropenia. One-third of patients with BPDCN have central nervous system involvement and no disease relapse.6 Other affected sites include the liver, lungs, tonsils, soft tissues, and eyes. Patients with BPDCN may present with a history of myeloid neoplasms, such as acute/chronic myeloid leukemia, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, or myelodysplastic syndrome.4 Our case highlights the importance of skin biopsy for making the correct diagnosis, as BPDCN manifests with cutaneous lesions that are nonspecific for neoplastic or nonneoplastic etiologies.

Given the aggressive nature of BPDCN, along with its potential for acute leukemic transformation, treatment has been challenging due to both poor response rates and lack of consensus and treatment strategies. Historically, patients who have received high-dose acute leukemia–based chemotherapy followed by an allogeneic stem cell transplant during the first remission appeared to have the best outcomes.7 Conventional treatments have included surgical excision with radiation and various leukemia-based chemotherapy regimens, with hyper- CVAD (fractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone-methotrexate, and cytarabine) being the most commonly used regimen.7,8 Venetoclax, a B-cell lymphoma 2 protein inhibitor, has shown promise when used in combination with hyper-CVAD. For older patients who may not tolerate aggressive chemotherapy, hypomethylating agents are preferred for their tolerability. Although tagraxofusp, a CD123-directed cytotoxin, has been utilized, Sapienza et al9 demonstrated an association with capillary leak syndrome.

Leukemia cutis is characterized by infiltration of the skin by malignant leukocytes, often associated with a prior diagnosis of systemic leukemia or myelodysplasia. Extramedullary accumulation of leukemic cells typically is referred to as myeloid sarcoma, while leukemia cutis serves as a general term for specific skin involvement.10 In rare instances, cutaneous lesions may manifest as the initial sign of systemic disease.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas comprise a diverse group of non-Hodgkin lymphomas that manifest as malignant monoclonal T-lymphocyte infiltration in the skin. Mycosis fungoides, Sézary syndrome, and primary cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphomas are among the key subtypes. Histologically, differentiating these conditions from benign inflammatory disorders can be challenging due to subtle features such as haloed lymphocytes, epidermotropism, and Pautrier microabscesses seen in mycosis fungoides.11

Multiple myeloma involves monoclonal plasma cell proliferation, primarily affecting bone and bone marrow. Extramedullary plasmacytomas can occur outside these sites through hematogenous spread or adjacent infiltration, while metastatic plasmacytomas result from metastasis. Cutaneous plasmacytomas may arise from hematogenous dissemination or infiltration from neighboring structures.12

Extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type, manifests as aggressive mid-facial necrotizing lesions with extranodal involvement, notably in the nasal/paranasal area. These lesions can cause local destruction of cartilage, bone, and soft tissues and may progress through stages or arise de novo. Diagnostic challenges arise from the historical variety of terms used to describe extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, including midline lethal granuloma and lymphomatoid granulomatosis.13

- Cheng W, Yu TT, Tang AP, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: progress in cell origin, molecular biology, diagnostic criteria and therapeutic approaches. Curr Med Sci. 2021;41:405-419. doi:10.1007/s11596-021-2393-3

- Chang HJ, Lee MD, Yi HG, et al. A case of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm initially mimicking cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Cancer Res Treat. 2010;42:239-243. doi:10.4143/crt.2010.42.4.239

- Garnache-Ottou F, Vidal C, Biichlé S, et al. How should we diagnose and treat blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm patients? Blood Adv. 2019;3:4238-4251. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000647

- Sweet K. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm. Curr Opin Hematol. 2020;27:103-107. doi:10.1097/moh.0000000000000569

- Julia F, Petrella T, Beylot-Barry M, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: clinical features in 90 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:579-586. doi:10.1111/bjd.12412

- Molina Castro D, Perilla Suárez O, Cuervo-Sierra J, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm with central nervous system involvement: a case report. Cureus. 2022;14:e23888. doi:10.7759 /cureus.23888

- Grushchak S, Joy C, Gray A, et al. Novel treatment of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:E9452.

- Lim MS, Lemmert K, Enjeti A. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN): a rare entity. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016:bcr2015214093. doi:10.1136/bcr-2015-214093

- Sapienza MR, Pileri A, Derenzini E, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: state of the art and prospects. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11:595. doi:10.3390/cancers11050595

- Wang CX, Pusic I, Anadkat MJ. Association of leukemia cutis with survival in acute myeloid leukemia. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:826. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.0052

- Ralfkiaer U, Hagedorn PH, Bangsgaard N, et al. Diagnostic micro RNA profiling in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL). Blood. 2011;118: 5891-5900. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-06-358382

- Tsang DS, Le LW, Kukreti V. Treatment and outcomes for primary cutaneous extramedullary plasmacytoma: a case series. Curr Oncol. 2016;23:630-646. doi:10.3747/co.23.3288

- Lee J, Kim W, Park Y, et al. Nasal-type NK/T cell lymphoma: clinical features and treatment outcome. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1226-1230. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6602502

The Diagnosis: Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm

Cutaneous plasmacytoma initially was suspected because of the patient’s history of monoclonal gammopathy as well as angiosarcoma due to the purpuric vascular appearance of the lesions. However, histopathology revealed a pleomorphic cellular dermal infiltrate characterized by atypical cells with mediumlarge nuclei, fine chromatin, and small nucleoli; the cells also had little cytoplasm (Figure). The infiltrate did not involve the epidermis but extended into the subcutaneous tissue. Immunohistochemistry revealed that the cells were positive for CD45, CD43, CD4, CD7, CD56, CD123, CD33, T-cell leukemia/lymphoma protein 1, and CD68. The cells were negative for CD2, CD3, CD5, CD8, T-cell intracellular antigen 1, CD13, CD15, CD19, CD20, CD21, CD23, cyclin D1, Bcl-2, Bcl-6, CD10, PAX5, MUM1, lysozyme, myeloperoxidase, perforin, granzyme B, CD57, CD34, CD117, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase, activin receptorlike kinase 1 βF1, Epstein-Barr virus– encoded small RNA, CD30, CD163, and pancytokeratin. Thus, the clinical and histopathologic findings led to a diagnosis of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN), a rare and aggressive hematologic malignancy.

Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm affects males older than 60 years.1 It is characterized by the clonal proliferation of precursor plasmacytoid dendritic cells—otherwise known as professional type I interferonproducing cells or plasmacytoid monocytes—of myeloid origin. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells have been renamed on several occasions, reflecting uncertainties of their histogenesis. The diagnosis of BPDCN requires a biopsy showing the morphology of plasmacytoid dendritic blast cells and immunophenotypic criteria established by either immunohistochemistry or flow cytometry.2,3 Tumor cells morphologically show an immature blastic appearance, and the diagnosis rests upon the demonstration of CD4 and CD56, together with markers more restricted to plasmacytoid dendritic cells (eg, BDCA-2, CD123, T-cell leukemia/lymphoma protein 1, CD2AP, BCL11A) and negativity for lymphoid and myeloid lineage–associated antigens.1,4

Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasms account for less than 1% of all hematopoietic neoplasms. Cutaneous lesions occur in 64% of patients with the disease and often are the reason patients seek medical care.5 Clinical findings include numerous erythematous and violaceous papules, nodules, and plaques that resemble purpura or vasculitis. Cutaneous lesions can vary in size from a few millimeters to 10 cm and vary in color. Moreover, patients often present with bruiselike patches, disseminated lesions, or mucosal lesions.1 Extracutaneous involvement includes lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and cytopenia caused by bone marrow infiltration, which may be present at diagnosis or during disease progression. Bone marrow involvement often is present with thrombocytopenia, anemia, and neutropenia. One-third of patients with BPDCN have central nervous system involvement and no disease relapse.6 Other affected sites include the liver, lungs, tonsils, soft tissues, and eyes. Patients with BPDCN may present with a history of myeloid neoplasms, such as acute/chronic myeloid leukemia, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, or myelodysplastic syndrome.4 Our case highlights the importance of skin biopsy for making the correct diagnosis, as BPDCN manifests with cutaneous lesions that are nonspecific for neoplastic or nonneoplastic etiologies.

Given the aggressive nature of BPDCN, along with its potential for acute leukemic transformation, treatment has been challenging due to both poor response rates and lack of consensus and treatment strategies. Historically, patients who have received high-dose acute leukemia–based chemotherapy followed by an allogeneic stem cell transplant during the first remission appeared to have the best outcomes.7 Conventional treatments have included surgical excision with radiation and various leukemia-based chemotherapy regimens, with hyper- CVAD (fractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone-methotrexate, and cytarabine) being the most commonly used regimen.7,8 Venetoclax, a B-cell lymphoma 2 protein inhibitor, has shown promise when used in combination with hyper-CVAD. For older patients who may not tolerate aggressive chemotherapy, hypomethylating agents are preferred for their tolerability. Although tagraxofusp, a CD123-directed cytotoxin, has been utilized, Sapienza et al9 demonstrated an association with capillary leak syndrome.

Leukemia cutis is characterized by infiltration of the skin by malignant leukocytes, often associated with a prior diagnosis of systemic leukemia or myelodysplasia. Extramedullary accumulation of leukemic cells typically is referred to as myeloid sarcoma, while leukemia cutis serves as a general term for specific skin involvement.10 In rare instances, cutaneous lesions may manifest as the initial sign of systemic disease.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas comprise a diverse group of non-Hodgkin lymphomas that manifest as malignant monoclonal T-lymphocyte infiltration in the skin. Mycosis fungoides, Sézary syndrome, and primary cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphomas are among the key subtypes. Histologically, differentiating these conditions from benign inflammatory disorders can be challenging due to subtle features such as haloed lymphocytes, epidermotropism, and Pautrier microabscesses seen in mycosis fungoides.11

Multiple myeloma involves monoclonal plasma cell proliferation, primarily affecting bone and bone marrow. Extramedullary plasmacytomas can occur outside these sites through hematogenous spread or adjacent infiltration, while metastatic plasmacytomas result from metastasis. Cutaneous plasmacytomas may arise from hematogenous dissemination or infiltration from neighboring structures.12

Extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type, manifests as aggressive mid-facial necrotizing lesions with extranodal involvement, notably in the nasal/paranasal area. These lesions can cause local destruction of cartilage, bone, and soft tissues and may progress through stages or arise de novo. Diagnostic challenges arise from the historical variety of terms used to describe extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, including midline lethal granuloma and lymphomatoid granulomatosis.13

The Diagnosis: Blastic Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Neoplasm

Cutaneous plasmacytoma initially was suspected because of the patient’s history of monoclonal gammopathy as well as angiosarcoma due to the purpuric vascular appearance of the lesions. However, histopathology revealed a pleomorphic cellular dermal infiltrate characterized by atypical cells with mediumlarge nuclei, fine chromatin, and small nucleoli; the cells also had little cytoplasm (Figure). The infiltrate did not involve the epidermis but extended into the subcutaneous tissue. Immunohistochemistry revealed that the cells were positive for CD45, CD43, CD4, CD7, CD56, CD123, CD33, T-cell leukemia/lymphoma protein 1, and CD68. The cells were negative for CD2, CD3, CD5, CD8, T-cell intracellular antigen 1, CD13, CD15, CD19, CD20, CD21, CD23, cyclin D1, Bcl-2, Bcl-6, CD10, PAX5, MUM1, lysozyme, myeloperoxidase, perforin, granzyme B, CD57, CD34, CD117, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase, activin receptorlike kinase 1 βF1, Epstein-Barr virus– encoded small RNA, CD30, CD163, and pancytokeratin. Thus, the clinical and histopathologic findings led to a diagnosis of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN), a rare and aggressive hematologic malignancy.

Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm affects males older than 60 years.1 It is characterized by the clonal proliferation of precursor plasmacytoid dendritic cells—otherwise known as professional type I interferonproducing cells or plasmacytoid monocytes—of myeloid origin. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells have been renamed on several occasions, reflecting uncertainties of their histogenesis. The diagnosis of BPDCN requires a biopsy showing the morphology of plasmacytoid dendritic blast cells and immunophenotypic criteria established by either immunohistochemistry or flow cytometry.2,3 Tumor cells morphologically show an immature blastic appearance, and the diagnosis rests upon the demonstration of CD4 and CD56, together with markers more restricted to plasmacytoid dendritic cells (eg, BDCA-2, CD123, T-cell leukemia/lymphoma protein 1, CD2AP, BCL11A) and negativity for lymphoid and myeloid lineage–associated antigens.1,4

Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasms account for less than 1% of all hematopoietic neoplasms. Cutaneous lesions occur in 64% of patients with the disease and often are the reason patients seek medical care.5 Clinical findings include numerous erythematous and violaceous papules, nodules, and plaques that resemble purpura or vasculitis. Cutaneous lesions can vary in size from a few millimeters to 10 cm and vary in color. Moreover, patients often present with bruiselike patches, disseminated lesions, or mucosal lesions.1 Extracutaneous involvement includes lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and cytopenia caused by bone marrow infiltration, which may be present at diagnosis or during disease progression. Bone marrow involvement often is present with thrombocytopenia, anemia, and neutropenia. One-third of patients with BPDCN have central nervous system involvement and no disease relapse.6 Other affected sites include the liver, lungs, tonsils, soft tissues, and eyes. Patients with BPDCN may present with a history of myeloid neoplasms, such as acute/chronic myeloid leukemia, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, or myelodysplastic syndrome.4 Our case highlights the importance of skin biopsy for making the correct diagnosis, as BPDCN manifests with cutaneous lesions that are nonspecific for neoplastic or nonneoplastic etiologies.

Given the aggressive nature of BPDCN, along with its potential for acute leukemic transformation, treatment has been challenging due to both poor response rates and lack of consensus and treatment strategies. Historically, patients who have received high-dose acute leukemia–based chemotherapy followed by an allogeneic stem cell transplant during the first remission appeared to have the best outcomes.7 Conventional treatments have included surgical excision with radiation and various leukemia-based chemotherapy regimens, with hyper- CVAD (fractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone-methotrexate, and cytarabine) being the most commonly used regimen.7,8 Venetoclax, a B-cell lymphoma 2 protein inhibitor, has shown promise when used in combination with hyper-CVAD. For older patients who may not tolerate aggressive chemotherapy, hypomethylating agents are preferred for their tolerability. Although tagraxofusp, a CD123-directed cytotoxin, has been utilized, Sapienza et al9 demonstrated an association with capillary leak syndrome.

Leukemia cutis is characterized by infiltration of the skin by malignant leukocytes, often associated with a prior diagnosis of systemic leukemia or myelodysplasia. Extramedullary accumulation of leukemic cells typically is referred to as myeloid sarcoma, while leukemia cutis serves as a general term for specific skin involvement.10 In rare instances, cutaneous lesions may manifest as the initial sign of systemic disease.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas comprise a diverse group of non-Hodgkin lymphomas that manifest as malignant monoclonal T-lymphocyte infiltration in the skin. Mycosis fungoides, Sézary syndrome, and primary cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphomas are among the key subtypes. Histologically, differentiating these conditions from benign inflammatory disorders can be challenging due to subtle features such as haloed lymphocytes, epidermotropism, and Pautrier microabscesses seen in mycosis fungoides.11

Multiple myeloma involves monoclonal plasma cell proliferation, primarily affecting bone and bone marrow. Extramedullary plasmacytomas can occur outside these sites through hematogenous spread or adjacent infiltration, while metastatic plasmacytomas result from metastasis. Cutaneous plasmacytomas may arise from hematogenous dissemination or infiltration from neighboring structures.12

Extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type, manifests as aggressive mid-facial necrotizing lesions with extranodal involvement, notably in the nasal/paranasal area. These lesions can cause local destruction of cartilage, bone, and soft tissues and may progress through stages or arise de novo. Diagnostic challenges arise from the historical variety of terms used to describe extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, including midline lethal granuloma and lymphomatoid granulomatosis.13

- Cheng W, Yu TT, Tang AP, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: progress in cell origin, molecular biology, diagnostic criteria and therapeutic approaches. Curr Med Sci. 2021;41:405-419. doi:10.1007/s11596-021-2393-3

- Chang HJ, Lee MD, Yi HG, et al. A case of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm initially mimicking cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Cancer Res Treat. 2010;42:239-243. doi:10.4143/crt.2010.42.4.239

- Garnache-Ottou F, Vidal C, Biichlé S, et al. How should we diagnose and treat blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm patients? Blood Adv. 2019;3:4238-4251. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000647

- Sweet K. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm. Curr Opin Hematol. 2020;27:103-107. doi:10.1097/moh.0000000000000569

- Julia F, Petrella T, Beylot-Barry M, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: clinical features in 90 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:579-586. doi:10.1111/bjd.12412

- Molina Castro D, Perilla Suárez O, Cuervo-Sierra J, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm with central nervous system involvement: a case report. Cureus. 2022;14:e23888. doi:10.7759 /cureus.23888

- Grushchak S, Joy C, Gray A, et al. Novel treatment of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:E9452.

- Lim MS, Lemmert K, Enjeti A. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN): a rare entity. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016:bcr2015214093. doi:10.1136/bcr-2015-214093

- Sapienza MR, Pileri A, Derenzini E, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: state of the art and prospects. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11:595. doi:10.3390/cancers11050595

- Wang CX, Pusic I, Anadkat MJ. Association of leukemia cutis with survival in acute myeloid leukemia. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:826. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.0052

- Ralfkiaer U, Hagedorn PH, Bangsgaard N, et al. Diagnostic micro RNA profiling in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL). Blood. 2011;118: 5891-5900. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-06-358382

- Tsang DS, Le LW, Kukreti V. Treatment and outcomes for primary cutaneous extramedullary plasmacytoma: a case series. Curr Oncol. 2016;23:630-646. doi:10.3747/co.23.3288

- Lee J, Kim W, Park Y, et al. Nasal-type NK/T cell lymphoma: clinical features and treatment outcome. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1226-1230. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6602502

- Cheng W, Yu TT, Tang AP, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: progress in cell origin, molecular biology, diagnostic criteria and therapeutic approaches. Curr Med Sci. 2021;41:405-419. doi:10.1007/s11596-021-2393-3

- Chang HJ, Lee MD, Yi HG, et al. A case of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm initially mimicking cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Cancer Res Treat. 2010;42:239-243. doi:10.4143/crt.2010.42.4.239

- Garnache-Ottou F, Vidal C, Biichlé S, et al. How should we diagnose and treat blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm patients? Blood Adv. 2019;3:4238-4251. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000647

- Sweet K. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm. Curr Opin Hematol. 2020;27:103-107. doi:10.1097/moh.0000000000000569

- Julia F, Petrella T, Beylot-Barry M, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: clinical features in 90 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:579-586. doi:10.1111/bjd.12412

- Molina Castro D, Perilla Suárez O, Cuervo-Sierra J, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm with central nervous system involvement: a case report. Cureus. 2022;14:e23888. doi:10.7759 /cureus.23888

- Grushchak S, Joy C, Gray A, et al. Novel treatment of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:E9452.

- Lim MS, Lemmert K, Enjeti A. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN): a rare entity. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016:bcr2015214093. doi:10.1136/bcr-2015-214093

- Sapienza MR, Pileri A, Derenzini E, et al. Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm: state of the art and prospects. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11:595. doi:10.3390/cancers11050595

- Wang CX, Pusic I, Anadkat MJ. Association of leukemia cutis with survival in acute myeloid leukemia. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:826. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.0052

- Ralfkiaer U, Hagedorn PH, Bangsgaard N, et al. Diagnostic micro RNA profiling in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL). Blood. 2011;118: 5891-5900. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-06-358382

- Tsang DS, Le LW, Kukreti V. Treatment and outcomes for primary cutaneous extramedullary plasmacytoma: a case series. Curr Oncol. 2016;23:630-646. doi:10.3747/co.23.3288

- Lee J, Kim W, Park Y, et al. Nasal-type NK/T cell lymphoma: clinical features and treatment outcome. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1226-1230. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6602502

A 79-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with multiple skin lesions of 4 months’ duration. The patient had a history of monoclonal gammopathy and reported no changes in medication, travel, or trauma. He reported tenderness only when trying to comb hair over the left occipital nodule. He denied fevers, night sweats, weight loss, or poor appetite. Physical examination revealed 4 concerning skin lesions: a 3×3-cm violaceous nodule with underlying ecchymosis on the right medial jaw (top), a 3×2.5-cm violaceous nodule on the posterior occiput, a pink plaque with 1-mm vascular papules on the right mid-chest (bottom), and a 4×2.5-cm oval pink patch on the left side of the lower back. Punch biopsies were performed on the right medial jaw nodule and right mid-chest plaque.

Commentary: Choosing Treatments of AD, and Possible Connection to Learning Issues, April 2024

Not everyone with AD treated with dupilumab gets clear or almost clear in clinical trials. The study by Cork and colleagues looked to see whether those patients who did not get to clear or almost clear were still having clinically meaningful improvement. To test this, the investigators looked at patients who still had mild or worse disease and then at the proportion of those patients at week 16 who achieved a composite endpoint encompassing clinically meaningful changes in AD signs, symptoms, and quality of life: ≥50% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index or ≥4-point reduction in worst scratch/itch numerical rating scale, or ≥6-point reduction in Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index/Infants' Dermatitis Quality of Life Index. Significantly more patients, both clinically and statistically significantly more, receiving dupilumab vs placebo achieved the composite endpoint (77.7% vs 24.6%; P < .0001).

The "success rate" reported in clinical trials underestimates how often patients can be successfully treated with dupilumab. I don't need a complicated composite outcome to know this. I just use the standardized 2-point Patient Global Assessment measure. I ask patients, "How are you doing?" If they say "Great," that's success. If they say, "Not so good," that's failure. I think about 80% of patients with AD treated with dupilumab have success based on this standard.

Hand dermatitis can be quite resistant to treatment. Even making a diagnosis can be challenging, as psoriasis and dermatitis of the hands looks so similar to me (and when I used to send biopsies and ask the pathologist whether it's dermatitis or psoriasis, invariably the dermatopathologist responded "yes"). The study by Kamphuis and colleagues examined the efficacy of abrocitinib in just over 100 patients with hand eczema who were enrolled in the BioDay registry. Such registries are very helpful for assessing real-world results. The drug seemed reasonably successful, with only about 30% discontinuing treatment. About two thirds of the discontinuations were due to inefficacy and about one third to an adverse event.

I think there's real value in prescribing the treatments patients want. Studies like the one by Ameen and colleagues, using a discrete-choice methodology, allows one to determine patients' average preferences. In this study, the discrete-choice approach found that patients prefer safety over other attributes. Some years ago, my colleagues and I queried patients to get a sense of their quantitative preferences for different treatments. Our study also found that patients preferred safety over other attributes. However, when we asked them to choose among different treatment options, they didn't choose the safest one. I think they believe that they prefer safety, but I'm not sure they really do. In any case, the average preference of the entire population of people with AD isn't really all that important when we've got just one patient sitting in front of us. It's that particular patient's preference that should drive the treatment plan.

Not everyone with AD treated with dupilumab gets clear or almost clear in clinical trials. The study by Cork and colleagues looked to see whether those patients who did not get to clear or almost clear were still having clinically meaningful improvement. To test this, the investigators looked at patients who still had mild or worse disease and then at the proportion of those patients at week 16 who achieved a composite endpoint encompassing clinically meaningful changes in AD signs, symptoms, and quality of life: ≥50% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index or ≥4-point reduction in worst scratch/itch numerical rating scale, or ≥6-point reduction in Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index/Infants' Dermatitis Quality of Life Index. Significantly more patients, both clinically and statistically significantly more, receiving dupilumab vs placebo achieved the composite endpoint (77.7% vs 24.6%; P < .0001).

The "success rate" reported in clinical trials underestimates how often patients can be successfully treated with dupilumab. I don't need a complicated composite outcome to know this. I just use the standardized 2-point Patient Global Assessment measure. I ask patients, "How are you doing?" If they say "Great," that's success. If they say, "Not so good," that's failure. I think about 80% of patients with AD treated with dupilumab have success based on this standard.

Hand dermatitis can be quite resistant to treatment. Even making a diagnosis can be challenging, as psoriasis and dermatitis of the hands looks so similar to me (and when I used to send biopsies and ask the pathologist whether it's dermatitis or psoriasis, invariably the dermatopathologist responded "yes"). The study by Kamphuis and colleagues examined the efficacy of abrocitinib in just over 100 patients with hand eczema who were enrolled in the BioDay registry. Such registries are very helpful for assessing real-world results. The drug seemed reasonably successful, with only about 30% discontinuing treatment. About two thirds of the discontinuations were due to inefficacy and about one third to an adverse event.

I think there's real value in prescribing the treatments patients want. Studies like the one by Ameen and colleagues, using a discrete-choice methodology, allows one to determine patients' average preferences. In this study, the discrete-choice approach found that patients prefer safety over other attributes. Some years ago, my colleagues and I queried patients to get a sense of their quantitative preferences for different treatments. Our study also found that patients preferred safety over other attributes. However, when we asked them to choose among different treatment options, they didn't choose the safest one. I think they believe that they prefer safety, but I'm not sure they really do. In any case, the average preference of the entire population of people with AD isn't really all that important when we've got just one patient sitting in front of us. It's that particular patient's preference that should drive the treatment plan.

Not everyone with AD treated with dupilumab gets clear or almost clear in clinical trials. The study by Cork and colleagues looked to see whether those patients who did not get to clear or almost clear were still having clinically meaningful improvement. To test this, the investigators looked at patients who still had mild or worse disease and then at the proportion of those patients at week 16 who achieved a composite endpoint encompassing clinically meaningful changes in AD signs, symptoms, and quality of life: ≥50% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index or ≥4-point reduction in worst scratch/itch numerical rating scale, or ≥6-point reduction in Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index/Infants' Dermatitis Quality of Life Index. Significantly more patients, both clinically and statistically significantly more, receiving dupilumab vs placebo achieved the composite endpoint (77.7% vs 24.6%; P < .0001).

The "success rate" reported in clinical trials underestimates how often patients can be successfully treated with dupilumab. I don't need a complicated composite outcome to know this. I just use the standardized 2-point Patient Global Assessment measure. I ask patients, "How are you doing?" If they say "Great," that's success. If they say, "Not so good," that's failure. I think about 80% of patients with AD treated with dupilumab have success based on this standard.

Hand dermatitis can be quite resistant to treatment. Even making a diagnosis can be challenging, as psoriasis and dermatitis of the hands looks so similar to me (and when I used to send biopsies and ask the pathologist whether it's dermatitis or psoriasis, invariably the dermatopathologist responded "yes"). The study by Kamphuis and colleagues examined the efficacy of abrocitinib in just over 100 patients with hand eczema who were enrolled in the BioDay registry. Such registries are very helpful for assessing real-world results. The drug seemed reasonably successful, with only about 30% discontinuing treatment. About two thirds of the discontinuations were due to inefficacy and about one third to an adverse event.

I think there's real value in prescribing the treatments patients want. Studies like the one by Ameen and colleagues, using a discrete-choice methodology, allows one to determine patients' average preferences. In this study, the discrete-choice approach found that patients prefer safety over other attributes. Some years ago, my colleagues and I queried patients to get a sense of their quantitative preferences for different treatments. Our study also found that patients preferred safety over other attributes. However, when we asked them to choose among different treatment options, they didn't choose the safest one. I think they believe that they prefer safety, but I'm not sure they really do. In any case, the average preference of the entire population of people with AD isn't really all that important when we've got just one patient sitting in front of us. It's that particular patient's preference that should drive the treatment plan.

Placing New Therapies for Myasthenia Gravis in the Treatment Paradigm

Nicholas J. Silvestri, MD: Hi there. My name is Dr Nick Silvestri, and I'm at the University of Buffalo. Today, I'd like to answer a few questions that I commonly receive from colleagues about the treatment of myasthenia gravis. As you know, over the past several years, we've had many new treatments approved to treat myasthenia gravis. One of the common questions that I get is, how do these new treatments fit into my treatment paradigm?

First and foremost, I'd like to say that we've been very successful at treating myasthenia gravis for many years. The mainstay of therapy has typically been acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, corticosteroids, and nonsteroidal immunosuppressants. These medicines by and large have helped control the disease in many, but maybe not all, patients.

The good news about these treatments is they're very efficacious, and as I said, they are able to treat most patients with myasthenia gravis. But the bad news on these medications is that they can have some serious short- and long-term consequences. So as I think about the treatment paradigm right now in 2024 and treating patients with myasthenia gravis, I typically start with prednisone or corticosteroids and transition patients onto an oral immunosuppressant.

But because it takes about a year for those oral immunosuppressants to become effective, I'm typically using steroids as a bridge. The goal, really, is to have patients on an oral immunosuppressant alone at the 1-year mark or thereabouts so that we don't have patients on steroids.

When it comes to the new therapies, one of the things that I'm doing is I'm using them, if a patient does not respond to an oral immunosuppressant or in situations where patients have medical comorbidities that make me not want to use steroids or use steroids at high doses.

Specifically, FcRn antagonists are often used as next-line therapy after an oral immunosuppressant fails or if I don't feel comfortable using prednisone at the outset and possibly bringing the patient to the oral immunosuppressant. The rationale behind this is that these medications are effective. They've been shown to be effective in clinical trials. They work fairly quickly, usually within 2-4 weeks. They're convenient for patients. And they have a pretty good safety profile.

The major side effects with the FcRn antagonists tend to be an increased risk for infection, which is true for most medications used to treat myasthenia gravis. One is associated with headache. And they can be associated with joint pains and infusion issues as well. But by and large, they are well tolerated. So again, if a patient is not responding to an oral immunosuppressant or it has toxicity or side effects, or I'm leery of using prednisone, I'll typically use an FcRn antagonist.

The other main class of medications is complement inhibitors. There are three complement inhibitors approved to use in the United States. Complement inhibitors are also very effective medications. I've used them with success in a number of patients, and I think that the paradigm is shifting.

I've used complement inhibitors, as with the FcRn antagonists, in patients who aren't responding to the first line of therapy or if they have toxicity. I've also used complement inhibitors in instances where patients have not responded very robustly to FcRn antagonists, which thankfully is the minority of patients, but it's worth noting.

I view the treatment paradigm for 2024 as oral immunosuppressant first, then FcRn antagonist next, and then complement inhibitor next. But to be truthful, we don't have head-to-head comparisons right now. What works for one patient may not work for another. In myasthenia gravis, it would be great to have biomarkers that allow us to predict who would respond to what form of therapy better.

In other words, it would be great to be able to send off a test to know whether a patient would respond to an oral immunosuppressant better than perhaps to one of the newer therapies, or whether a patient would respond to an FcRn antagonist better than a complement inhibitor or vice versa. That's really one of the gold standards or holy grails in the treatment of myasthenia gravis.

Another thing that comes up in relation to the first question has to do with, what patient characteristics do I keep in mind when selecting therapies? There's a couple of things. I think that first and foremost, many of our patients with myasthenia gravis are women of childbearing age. So we want to be mindful that many pregnancies are not planned, and be careful when we're choosing therapies that might have a role or might be deleterious to fetuses.

This is particularly true with oral immunosuppressants, many of which are contraindicated in pregnancy. But medical comorbidities in general are helpful to understand. Again, using the corticosteroid example, in patients with high blood pressure, diabetes, or osteoporosis, I'm very leery about corticosteroids and may use one of the newer therapies earlier on.

Another aspect is patient preference. We have oral therapies, we have intravenous therapies, we now have subcutaneous therapies. Route of administration is very important to consider as well, not only for patient comfort — some patients may prefer intravenous routes of administration vs subcutaneous — but also for patient convenience.

Many of our patients with myasthenia gravis have very busy lives, with full-time jobs and other responsibilities, such as parenting or taking care of parents that are maybe older in age. So I think that tolerability and convenience are very important to getting patients the therapies they need and allowing patients the flexibility and convenience to be able to live their lives as well.

I hope this was helpful to you. I look forward to speaking with you again at some point in the very near future. Stay well.

Nicholas J. Silvestri, MD: Hi there. My name is Dr Nick Silvestri, and I'm at the University of Buffalo. Today, I'd like to answer a few questions that I commonly receive from colleagues about the treatment of myasthenia gravis. As you know, over the past several years, we've had many new treatments approved to treat myasthenia gravis. One of the common questions that I get is, how do these new treatments fit into my treatment paradigm?

First and foremost, I'd like to say that we've been very successful at treating myasthenia gravis for many years. The mainstay of therapy has typically been acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, corticosteroids, and nonsteroidal immunosuppressants. These medicines by and large have helped control the disease in many, but maybe not all, patients.

The good news about these treatments is they're very efficacious, and as I said, they are able to treat most patients with myasthenia gravis. But the bad news on these medications is that they can have some serious short- and long-term consequences. So as I think about the treatment paradigm right now in 2024 and treating patients with myasthenia gravis, I typically start with prednisone or corticosteroids and transition patients onto an oral immunosuppressant.

But because it takes about a year for those oral immunosuppressants to become effective, I'm typically using steroids as a bridge. The goal, really, is to have patients on an oral immunosuppressant alone at the 1-year mark or thereabouts so that we don't have patients on steroids.

When it comes to the new therapies, one of the things that I'm doing is I'm using them, if a patient does not respond to an oral immunosuppressant or in situations where patients have medical comorbidities that make me not want to use steroids or use steroids at high doses.

Specifically, FcRn antagonists are often used as next-line therapy after an oral immunosuppressant fails or if I don't feel comfortable using prednisone at the outset and possibly bringing the patient to the oral immunosuppressant. The rationale behind this is that these medications are effective. They've been shown to be effective in clinical trials. They work fairly quickly, usually within 2-4 weeks. They're convenient for patients. And they have a pretty good safety profile.

The major side effects with the FcRn antagonists tend to be an increased risk for infection, which is true for most medications used to treat myasthenia gravis. One is associated with headache. And they can be associated with joint pains and infusion issues as well. But by and large, they are well tolerated. So again, if a patient is not responding to an oral immunosuppressant or it has toxicity or side effects, or I'm leery of using prednisone, I'll typically use an FcRn antagonist.

The other main class of medications is complement inhibitors. There are three complement inhibitors approved to use in the United States. Complement inhibitors are also very effective medications. I've used them with success in a number of patients, and I think that the paradigm is shifting.

I've used complement inhibitors, as with the FcRn antagonists, in patients who aren't responding to the first line of therapy or if they have toxicity. I've also used complement inhibitors in instances where patients have not responded very robustly to FcRn antagonists, which thankfully is the minority of patients, but it's worth noting.

I view the treatment paradigm for 2024 as oral immunosuppressant first, then FcRn antagonist next, and then complement inhibitor next. But to be truthful, we don't have head-to-head comparisons right now. What works for one patient may not work for another. In myasthenia gravis, it would be great to have biomarkers that allow us to predict who would respond to what form of therapy better.

In other words, it would be great to be able to send off a test to know whether a patient would respond to an oral immunosuppressant better than perhaps to one of the newer therapies, or whether a patient would respond to an FcRn antagonist better than a complement inhibitor or vice versa. That's really one of the gold standards or holy grails in the treatment of myasthenia gravis.

Another thing that comes up in relation to the first question has to do with, what patient characteristics do I keep in mind when selecting therapies? There's a couple of things. I think that first and foremost, many of our patients with myasthenia gravis are women of childbearing age. So we want to be mindful that many pregnancies are not planned, and be careful when we're choosing therapies that might have a role or might be deleterious to fetuses.

This is particularly true with oral immunosuppressants, many of which are contraindicated in pregnancy. But medical comorbidities in general are helpful to understand. Again, using the corticosteroid example, in patients with high blood pressure, diabetes, or osteoporosis, I'm very leery about corticosteroids and may use one of the newer therapies earlier on.

Another aspect is patient preference. We have oral therapies, we have intravenous therapies, we now have subcutaneous therapies. Route of administration is very important to consider as well, not only for patient comfort — some patients may prefer intravenous routes of administration vs subcutaneous — but also for patient convenience.

Many of our patients with myasthenia gravis have very busy lives, with full-time jobs and other responsibilities, such as parenting or taking care of parents that are maybe older in age. So I think that tolerability and convenience are very important to getting patients the therapies they need and allowing patients the flexibility and convenience to be able to live their lives as well.

I hope this was helpful to you. I look forward to speaking with you again at some point in the very near future. Stay well.

Nicholas J. Silvestri, MD: Hi there. My name is Dr Nick Silvestri, and I'm at the University of Buffalo. Today, I'd like to answer a few questions that I commonly receive from colleagues about the treatment of myasthenia gravis. As you know, over the past several years, we've had many new treatments approved to treat myasthenia gravis. One of the common questions that I get is, how do these new treatments fit into my treatment paradigm?

First and foremost, I'd like to say that we've been very successful at treating myasthenia gravis for many years. The mainstay of therapy has typically been acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, corticosteroids, and nonsteroidal immunosuppressants. These medicines by and large have helped control the disease in many, but maybe not all, patients.

The good news about these treatments is they're very efficacious, and as I said, they are able to treat most patients with myasthenia gravis. But the bad news on these medications is that they can have some serious short- and long-term consequences. So as I think about the treatment paradigm right now in 2024 and treating patients with myasthenia gravis, I typically start with prednisone or corticosteroids and transition patients onto an oral immunosuppressant.

But because it takes about a year for those oral immunosuppressants to become effective, I'm typically using steroids as a bridge. The goal, really, is to have patients on an oral immunosuppressant alone at the 1-year mark or thereabouts so that we don't have patients on steroids.

When it comes to the new therapies, one of the things that I'm doing is I'm using them, if a patient does not respond to an oral immunosuppressant or in situations where patients have medical comorbidities that make me not want to use steroids or use steroids at high doses.

Specifically, FcRn antagonists are often used as next-line therapy after an oral immunosuppressant fails or if I don't feel comfortable using prednisone at the outset and possibly bringing the patient to the oral immunosuppressant. The rationale behind this is that these medications are effective. They've been shown to be effective in clinical trials. They work fairly quickly, usually within 2-4 weeks. They're convenient for patients. And they have a pretty good safety profile.

The major side effects with the FcRn antagonists tend to be an increased risk for infection, which is true for most medications used to treat myasthenia gravis. One is associated with headache. And they can be associated with joint pains and infusion issues as well. But by and large, they are well tolerated. So again, if a patient is not responding to an oral immunosuppressant or it has toxicity or side effects, or I'm leery of using prednisone, I'll typically use an FcRn antagonist.

The other main class of medications is complement inhibitors. There are three complement inhibitors approved to use in the United States. Complement inhibitors are also very effective medications. I've used them with success in a number of patients, and I think that the paradigm is shifting.

I've used complement inhibitors, as with the FcRn antagonists, in patients who aren't responding to the first line of therapy or if they have toxicity. I've also used complement inhibitors in instances where patients have not responded very robustly to FcRn antagonists, which thankfully is the minority of patients, but it's worth noting.

I view the treatment paradigm for 2024 as oral immunosuppressant first, then FcRn antagonist next, and then complement inhibitor next. But to be truthful, we don't have head-to-head comparisons right now. What works for one patient may not work for another. In myasthenia gravis, it would be great to have biomarkers that allow us to predict who would respond to what form of therapy better.

In other words, it would be great to be able to send off a test to know whether a patient would respond to an oral immunosuppressant better than perhaps to one of the newer therapies, or whether a patient would respond to an FcRn antagonist better than a complement inhibitor or vice versa. That's really one of the gold standards or holy grails in the treatment of myasthenia gravis.

Another thing that comes up in relation to the first question has to do with, what patient characteristics do I keep in mind when selecting therapies? There's a couple of things. I think that first and foremost, many of our patients with myasthenia gravis are women of childbearing age. So we want to be mindful that many pregnancies are not planned, and be careful when we're choosing therapies that might have a role or might be deleterious to fetuses.

This is particularly true with oral immunosuppressants, many of which are contraindicated in pregnancy. But medical comorbidities in general are helpful to understand. Again, using the corticosteroid example, in patients with high blood pressure, diabetes, or osteoporosis, I'm very leery about corticosteroids and may use one of the newer therapies earlier on.

Another aspect is patient preference. We have oral therapies, we have intravenous therapies, we now have subcutaneous therapies. Route of administration is very important to consider as well, not only for patient comfort — some patients may prefer intravenous routes of administration vs subcutaneous — but also for patient convenience.

Many of our patients with myasthenia gravis have very busy lives, with full-time jobs and other responsibilities, such as parenting or taking care of parents that are maybe older in age. So I think that tolerability and convenience are very important to getting patients the therapies they need and allowing patients the flexibility and convenience to be able to live their lives as well.

I hope this was helpful to you. I look forward to speaking with you again at some point in the very near future. Stay well.

Multiple Sclerosis Highlights From ACTRIMS 2024

Andrew Solomon, MD, from the University of Vermont in Burlington, highlights key findings presented at the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ACTRIMS) Forum 2024.

Dr Solomon begins by discussing a study on the potential benefits of antipyretics to manage overheating associated with exercise, a common symptom among MS patients. Results showed that MS patients who took aspirin or acetaminophen had less increase in body temperature after a maximal exercise test than those who took placebo.

He next reports on a study that examined whether a combination of two imaging biomarkers specific for MS, namely the central vein sign and the paramagnetic rim lesion, could improve diagnostic specificity. This study found that the presence of at least one of the signs contributed to improved diagnosis.

Dr Solomon then discusses a post hoc analysis of the ULTIMATE I and II trials which reconsidered how to confirm relapses of MS. The study found that follow-up MRI could distinguish relapse from pseudoexacerbations.

Finally, he reports on a study that examined the feasibility and tolerability of low-field brain MRI in MS. The equipment is smaller, portable, and more cost-effective than standard MRI and has high acceptability from patients. Although the precision of these devices needs further testing, Dr Solomon suggests that portable MRI could make MS diagnosis and monitoring available to broader populations.

--

Andrew J. Solomon, MD, Professor, Neurological Sciences, Larner College of Medicine, University of Vermont; Division Chief, Multiple Sclerosis, University Health Center, Burlington, Vermont

Andrew J. Solomon, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Received research grant from: Bristol Myers Squibb

Andrew Solomon, MD, from the University of Vermont in Burlington, highlights key findings presented at the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ACTRIMS) Forum 2024.

Dr Solomon begins by discussing a study on the potential benefits of antipyretics to manage overheating associated with exercise, a common symptom among MS patients. Results showed that MS patients who took aspirin or acetaminophen had less increase in body temperature after a maximal exercise test than those who took placebo.

He next reports on a study that examined whether a combination of two imaging biomarkers specific for MS, namely the central vein sign and the paramagnetic rim lesion, could improve diagnostic specificity. This study found that the presence of at least one of the signs contributed to improved diagnosis.

Dr Solomon then discusses a post hoc analysis of the ULTIMATE I and II trials which reconsidered how to confirm relapses of MS. The study found that follow-up MRI could distinguish relapse from pseudoexacerbations.

Finally, he reports on a study that examined the feasibility and tolerability of low-field brain MRI in MS. The equipment is smaller, portable, and more cost-effective than standard MRI and has high acceptability from patients. Although the precision of these devices needs further testing, Dr Solomon suggests that portable MRI could make MS diagnosis and monitoring available to broader populations.

--

Andrew J. Solomon, MD, Professor, Neurological Sciences, Larner College of Medicine, University of Vermont; Division Chief, Multiple Sclerosis, University Health Center, Burlington, Vermont

Andrew J. Solomon, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Received research grant from: Bristol Myers Squibb

Andrew Solomon, MD, from the University of Vermont in Burlington, highlights key findings presented at the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ACTRIMS) Forum 2024.

Dr Solomon begins by discussing a study on the potential benefits of antipyretics to manage overheating associated with exercise, a common symptom among MS patients. Results showed that MS patients who took aspirin or acetaminophen had less increase in body temperature after a maximal exercise test than those who took placebo.

He next reports on a study that examined whether a combination of two imaging biomarkers specific for MS, namely the central vein sign and the paramagnetic rim lesion, could improve diagnostic specificity. This study found that the presence of at least one of the signs contributed to improved diagnosis.

Dr Solomon then discusses a post hoc analysis of the ULTIMATE I and II trials which reconsidered how to confirm relapses of MS. The study found that follow-up MRI could distinguish relapse from pseudoexacerbations.

Finally, he reports on a study that examined the feasibility and tolerability of low-field brain MRI in MS. The equipment is smaller, portable, and more cost-effective than standard MRI and has high acceptability from patients. Although the precision of these devices needs further testing, Dr Solomon suggests that portable MRI could make MS diagnosis and monitoring available to broader populations.

--

Andrew J. Solomon, MD, Professor, Neurological Sciences, Larner College of Medicine, University of Vermont; Division Chief, Multiple Sclerosis, University Health Center, Burlington, Vermont

Andrew J. Solomon, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Received research grant from: Bristol Myers Squibb

Treating Active Psoriatic Arthritis When the First-Line Biologic Fails

Over the past two decades, the therapeutic landscape for psoriatic arthritis (PsA) has been transformed by the introduction of more than a dozen targeted therapies.

For most patients with active PsA, a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor is recommended as the first-line biologic therapy. But some patients do not achieve an adequate response to TNF inhibitors or are intolerant to these therapies.

Choosing the right treatment after failure of the first biologic requires that clinicians consider several factors. Dr Atul Deodhar, of Oregon Health & Science University, discusses guidelines from the American College of Rheumatology/National Psoriasis Foundation and the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA) for appropriate treatment strategies.

He also discusses factors critical to the optimal choice of the next therapy, such as the domains of disease activity, patient comorbidities, and whether the biologic's failure was primary or secondary.

Aside from choosing a new biologic, Dr Deodhar notes that there are other options to intensify the effect of the initial biologic. He says the clinician and patient may consider increasing the dose and frequency of the initial biologic medication or moving to a combination therapy by adding another drug, such as methotrexate.

--

Atul A. Deodhar, MD, Professor of Medicine, Division of Arthritis and Rheumatic Diseases, School of Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University; Medical Director, Rheumatology Clinics, OHSU Hospital, Portland, Oregon

Atul A. Deodhar, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant, for: Bristol Myers Squibb; Eli Lilly; Janssen; MoonLake; Novartis; Pfizer; UCB

Serve(d) as a speaker for: Eli Lilly; Novartis; Pfizer; UCB

Received research grant from: AbbVie; Bristol Myers Squibb; Celgene; Janssen; MoonLake; Novartis; Pfizer; UCB

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Bristol Myers Squibb; Eli Lilly; Janssen; Novartis; Pfizer; Samsung Bioepis; UCB

Over the past two decades, the therapeutic landscape for psoriatic arthritis (PsA) has been transformed by the introduction of more than a dozen targeted therapies.

For most patients with active PsA, a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor is recommended as the first-line biologic therapy. But some patients do not achieve an adequate response to TNF inhibitors or are intolerant to these therapies.

Choosing the right treatment after failure of the first biologic requires that clinicians consider several factors. Dr Atul Deodhar, of Oregon Health & Science University, discusses guidelines from the American College of Rheumatology/National Psoriasis Foundation and the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA) for appropriate treatment strategies.

He also discusses factors critical to the optimal choice of the next therapy, such as the domains of disease activity, patient comorbidities, and whether the biologic's failure was primary or secondary.

Aside from choosing a new biologic, Dr Deodhar notes that there are other options to intensify the effect of the initial biologic. He says the clinician and patient may consider increasing the dose and frequency of the initial biologic medication or moving to a combination therapy by adding another drug, such as methotrexate.

--

Atul A. Deodhar, MD, Professor of Medicine, Division of Arthritis and Rheumatic Diseases, School of Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University; Medical Director, Rheumatology Clinics, OHSU Hospital, Portland, Oregon

Atul A. Deodhar, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant, for: Bristol Myers Squibb; Eli Lilly; Janssen; MoonLake; Novartis; Pfizer; UCB

Serve(d) as a speaker for: Eli Lilly; Novartis; Pfizer; UCB

Received research grant from: AbbVie; Bristol Myers Squibb; Celgene; Janssen; MoonLake; Novartis; Pfizer; UCB

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Bristol Myers Squibb; Eli Lilly; Janssen; Novartis; Pfizer; Samsung Bioepis; UCB

Over the past two decades, the therapeutic landscape for psoriatic arthritis (PsA) has been transformed by the introduction of more than a dozen targeted therapies.

For most patients with active PsA, a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor is recommended as the first-line biologic therapy. But some patients do not achieve an adequate response to TNF inhibitors or are intolerant to these therapies.

Choosing the right treatment after failure of the first biologic requires that clinicians consider several factors. Dr Atul Deodhar, of Oregon Health & Science University, discusses guidelines from the American College of Rheumatology/National Psoriasis Foundation and the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA) for appropriate treatment strategies.

He also discusses factors critical to the optimal choice of the next therapy, such as the domains of disease activity, patient comorbidities, and whether the biologic's failure was primary or secondary.

Aside from choosing a new biologic, Dr Deodhar notes that there are other options to intensify the effect of the initial biologic. He says the clinician and patient may consider increasing the dose and frequency of the initial biologic medication or moving to a combination therapy by adding another drug, such as methotrexate.

--

Atul A. Deodhar, MD, Professor of Medicine, Division of Arthritis and Rheumatic Diseases, School of Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University; Medical Director, Rheumatology Clinics, OHSU Hospital, Portland, Oregon

Atul A. Deodhar, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a consultant, for: Bristol Myers Squibb; Eli Lilly; Janssen; MoonLake; Novartis; Pfizer; UCB

Serve(d) as a speaker for: Eli Lilly; Novartis; Pfizer; UCB

Received research grant from: AbbVie; Bristol Myers Squibb; Celgene; Janssen; MoonLake; Novartis; Pfizer; UCB

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Bristol Myers Squibb; Eli Lilly; Janssen; Novartis; Pfizer; Samsung Bioepis; UCB

Long-Acting Injectables in the Management of Bipolar 1 Disorder

Bipolar 1 disorder is a chronic and disabling mental health disorder that results in cognitive, functional, and social impairments associated with an increased risk for hospitalization and premature death.

Bipolar 1 disorder is characterized by manic episodes that last for at least 7 days, or manic symptoms that are so severe that they require immediate medical care. Depressive episodes also occur.

Dr Michael Thase, from the University of Pennsylvania, explains that although ongoing treatment is essential to prevent relapse and recurrence, particularly after a hospitalization, adherence can be serious problem.

Long-acting injectable (LAI) agents can act as a bridge between oral medications initiated in hospital and ongoing prevention therapies.

Dr Thase says LAIs can help improve adherence and patient quality of life, and are effective against relapses in adults with bipolar 1 disorder.

--

Michael E. Thase, MD, Professor of Psychiatry, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Michael E. Thase, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as an advisor or consultant for: Acadia, Inc; Akili, Inc; Alkermes PLC; Allergan, Inc; Axsome Therapeutics, Inc; Biohaven, Inc; Bocemtium Consulting, SL; Boehringer Ingelheim International; CatalYm GmbH; Clexio Biosciences; Gerson Lehrman Group, Inc; H Lundbeck, A/S; Jazz Pharmaceuticals; Janssen; Johnson & Johnson; Luye Pharma Group, Ltd; Merck & Company, Inc; Otsuka Pharmaceuticals Company, Ltd; Pfizer, Inc; Sage Pharmaceuticals; Seelos Therapeutics; Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Inc; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Ltd

Receive research funding from: Acadia, Inc; Allergan, Inc; AssureRx; Axsome Therapeutics, Inc; Biohaven, Inc; Intracellular, Inc; Johnson & Johnson; Otsuka Pharmaceuticals Company, Ltd; Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI); Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Ltd

Receive royalties from: American Psychiatric Foundation; Guilford Publications; Herald House; Kluwer-Wolters; W.W. Norton & Company, Inc

Bipolar 1 disorder is a chronic and disabling mental health disorder that results in cognitive, functional, and social impairments associated with an increased risk for hospitalization and premature death.

Bipolar 1 disorder is characterized by manic episodes that last for at least 7 days, or manic symptoms that are so severe that they require immediate medical care. Depressive episodes also occur.

Dr Michael Thase, from the University of Pennsylvania, explains that although ongoing treatment is essential to prevent relapse and recurrence, particularly after a hospitalization, adherence can be serious problem.

Long-acting injectable (LAI) agents can act as a bridge between oral medications initiated in hospital and ongoing prevention therapies.

Dr Thase says LAIs can help improve adherence and patient quality of life, and are effective against relapses in adults with bipolar 1 disorder.

--

Michael E. Thase, MD, Professor of Psychiatry, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Michael E. Thase, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as an advisor or consultant for: Acadia, Inc; Akili, Inc; Alkermes PLC; Allergan, Inc; Axsome Therapeutics, Inc; Biohaven, Inc; Bocemtium Consulting, SL; Boehringer Ingelheim International; CatalYm GmbH; Clexio Biosciences; Gerson Lehrman Group, Inc; H Lundbeck, A/S; Jazz Pharmaceuticals; Janssen; Johnson & Johnson; Luye Pharma Group, Ltd; Merck & Company, Inc; Otsuka Pharmaceuticals Company, Ltd; Pfizer, Inc; Sage Pharmaceuticals; Seelos Therapeutics; Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Inc; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Ltd

Receive research funding from: Acadia, Inc; Allergan, Inc; AssureRx; Axsome Therapeutics, Inc; Biohaven, Inc; Intracellular, Inc; Johnson & Johnson; Otsuka Pharmaceuticals Company, Ltd; Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI); Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Ltd

Receive royalties from: American Psychiatric Foundation; Guilford Publications; Herald House; Kluwer-Wolters; W.W. Norton & Company, Inc

Bipolar 1 disorder is a chronic and disabling mental health disorder that results in cognitive, functional, and social impairments associated with an increased risk for hospitalization and premature death.

Bipolar 1 disorder is characterized by manic episodes that last for at least 7 days, or manic symptoms that are so severe that they require immediate medical care. Depressive episodes also occur.

Dr Michael Thase, from the University of Pennsylvania, explains that although ongoing treatment is essential to prevent relapse and recurrence, particularly after a hospitalization, adherence can be serious problem.

Long-acting injectable (LAI) agents can act as a bridge between oral medications initiated in hospital and ongoing prevention therapies.

Dr Thase says LAIs can help improve adherence and patient quality of life, and are effective against relapses in adults with bipolar 1 disorder.

--

Michael E. Thase, MD, Professor of Psychiatry, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Michael E. Thase, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as an advisor or consultant for: Acadia, Inc; Akili, Inc; Alkermes PLC; Allergan, Inc; Axsome Therapeutics, Inc; Biohaven, Inc; Bocemtium Consulting, SL; Boehringer Ingelheim International; CatalYm GmbH; Clexio Biosciences; Gerson Lehrman Group, Inc; H Lundbeck, A/S; Jazz Pharmaceuticals; Janssen; Johnson & Johnson; Luye Pharma Group, Ltd; Merck & Company, Inc; Otsuka Pharmaceuticals Company, Ltd; Pfizer, Inc; Sage Pharmaceuticals; Seelos Therapeutics; Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Inc; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Ltd

Receive research funding from: Acadia, Inc; Allergan, Inc; AssureRx; Axsome Therapeutics, Inc; Biohaven, Inc; Intracellular, Inc; Johnson & Johnson; Otsuka Pharmaceuticals Company, Ltd; Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI); Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Ltd

Receive royalties from: American Psychiatric Foundation; Guilford Publications; Herald House; Kluwer-Wolters; W.W. Norton & Company, Inc

Don't Miss the Dx: A 63-Year-Old Man With Proptosis, Diplopia, and Upper-Body Weakness

Presentation

A 63-year-old man presented to his primary care provider with ptosis, diplopia, dysphagia, and fatigue/weakness of arms and shoulders after mild activity (eg, raking leaves in his yard, carrying groceries, housework). His ocular symptoms had been present for about 5 months but his arm/shoulder muscle weakness was recent.

Physical examination revealed weakness after repeated/sustained muscle contraction followed by improvement with rest or an ice-pack test (see "Diagnosis" below), and a tentative diagnosis of generalized myasthenia gravis (gMG) was made. The patient was referred to a neurologist for serologic testing, which was positive for anti-AChR MG antibody, confirming the diagnosis of gMG.

Treatment was initiated with pyridostigmine, with reevaluation and treatment escalation as necessary.

gMG is generally defined as a process beginning with localized manifestations of MG, typically ocular muscle involvement. In some patients it remains localized and is considered ocular MG, while in the remaining patients it becomes generalized, most often within 1 year of onset.

Clinical findings in patients presenting with gMG can include:

Extraocular muscle weakness (85% of patients) causing diplopia, ptosis, or both

Bulbar muscle weakness (15% of patients)

Difficulty chewing, dysphagia, hoarseness, dysarthria

Facial muscle involvement causing inability to show facial expressions, and neck muscle involvement impairing head posture (dropped-head syndrome)

Upper limbs more affected than lower

Proximal muscles involved more than distal

Myasthenic crisis, considered a medical emergency due to weakness of the diaphragm and intercostal muscles, secondary to a lower respiratory tract infection

Differential Diagnosis

Several potential diagnoses should be considered on the basis of this patient's presentation.

Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome: An autoimmune or paraneoplastic disorder producing fluctuating muscle weakness that improves with physical activity, differentiating it from MG

Cavernous sinus thrombosis: Also called cavernous sinus syndrome, can present with persistent ocular findings, photophobia, chemosis, and headache

Brainstem gliomas: Can present with dysphagia, muscle weakness, diplopia, drooping eyelids, slurred speech, and/or difficulty breathing

Multiple sclerosis: Can present with a range of typically fluctuating clinical features, including but not limited to the classic findings of paresthesias, spinal cord and cerebellar symptoms, optic neuritis, diplopia, trigeminal neuralgia, and fatigue

Botulism: Can present with ptosis, diplopia, difficulty moving the eyes, progressive weakness, and difficulty breathing caused by a toxin produced by Clostridium botulinum

Tickborne disease: Can present with headache, fatigue, myalgia, rash, and arthralgia, which can mimic the symptoms of other diseases

Polymyositis/dermatomyositis: Characteristically present with symmetrical proximal muscle weakness, typical rash (dermatomyositis only), elevated serum muscle enzymes, anti-muscle antibodies, and myopathic changes on electromyography

Graves ophthalmopathy: Also known as thyroid eye disease, can present with photophobia, eye discomfort including gritty eye sensations, lacrimation or dry eye, proptosis, diplopia, and eyelid retraction

Thyrotoxicosis: Can present with heat intolerance, palpitations, anxiety, fatigue, weight loss, and muscle weakness

Diagnosis

On the basis of this patient's clinical presentation and serology, his diagnosis is generalized AChR MG, class III.

Table. Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America Clinical Classification

Commonly performed tests and diagnostic criteria in patients with suspected MG include:

History/physical examination

AChR antibody is highly specific (80% positive in gMG, approximately 50% positive in ocular MG)

Anti-MUSK antibody (approximately 20% positive, typically in patients negative for AChR antibody)

Anti-LRP4 antibody, in patients negative for anti-AChR or anti-MUSK antibody

Detecting established pathogenic antibodies against some synaptic molecules in a patient with clinical features of MG is virtually diagnostic. The presence of AChR antibody confirmed the diagnosis in the case presented above. Although the titer of AChR autoantibodies does not correlate with disease severity, fluctuations in titers in an individual patient have been reported to correlate with the severity of muscle weakness and to predict exacerbations. Accordingly, serial testing for AChR autoantibodies can influence therapeutic decisions.

Electrodiagnostic studies (useful in patients with negative serology)

Repetitive nerve stimulation

Single-fiber electromyography

Tests to help confirm that ocular symptoms are due to MG in the absence of positive serology

Edrophonium (Tensilon) test: Can induce dramatic but only short-term recovery from symptoms (particularly ocular symptoms)

Ice-pack test: Used mainly in ocular MG, in which it can temporarily improve ptosis

Chest CT/MRI, to screen for thymoma in patients with MG

Laboratory tests to screen for other autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis (rheumatoid factor), systemic lupus erythematosus (ANA), and thyroid eye disease (anti-thyroid antibodies), which may occur concomitantly with MG

Management

The most recent recommendations for management of MG were published in 2021, updating the 2016 International Consensus Guidance for Management of Myasthenia Gravis by the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America.

MG can be managed pharmacologically and nonpharmacologically. Pharmacologic treatment includes acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, biologics, and immunosuppressive/immunomodulatory agents. Corticosteroids are used primarily in patients with clinically significant, severe muscle weakness and/or poor response to acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (pyridostigmine).

Pharmacotherapy

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors

Pyridostigmine, an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor used for symptomatic treatment and maintenance therapy, is the only agent in this class used routinely in the clinical setting of MG

Biologics

Rituximab, a chimeric CD20-directed cytolytic antibody that mediates lysis of B lymphocytes

Eculizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody that specifically binds to the complement protein C5 with high affinity, preventing formation of membrane attack protein (MAC)

Rozanolixizumab, a neonatal Fc receptor blocker that decreases circulating IgG