User login

Official Newspaper of the American College of Surgeons

Visit ACS Central during Clinical Congress

Make the most of your American College of Surgeons (ACS) Clinical Congress 2017 experience by visiting the new ACS Central area designed specifically for our members. ACS Central visitors will have opportunities to meet College staff; learn about the latest ACS programs, products, and services; purchase ACS materials; and make ACS Central a convenient gathering space during the meeting. While there, you can also update your member profile and receive a flash drive with your own professional photo to keep.

ACS Central also will house the ACS Theatre, which will feature presentations on the following new ACS programs and products during lunch hours Monday through Wednesday:

• Monday: The Surgeon Specific Registry

• Tuesday: Improving Surgical Care and Recovery (ISCR)

• Wednesday: Optimal Resources for Surgical Quality and Safety (the “red book”)

The ACS Theatre also will be used for meet-and-greets with ACS leaders. Posters outlining the schedule for the day will be located throughout ACS Central, and alerts will be sent out through the app and social media.

ACS Central will be open 9:00 am–4:30 pm Monday through Wednesday in the San Diego Convention Center, Exhibit Hall.

The following select ACS Programs also will have a presence Sunday through Thursday in the main lobby of the San Diego Convention Center and in the Registration Area:

• ACS Foundation and Fellows Leadership Society

• American College of Surgeons Professional Association-SurgeonsPAC

• Mobile Connect

• Become a Member/Member Services booth, where you can join the ACS, pay your membership dues, or get answers to questions about your membership

In addition, MyCME and Webcast Sales Booths will be located throughout the Convention Center and open the same hours as registration Monday through Thursday. To view other conference resources, go to the Clinical Congress 2017 Resources web page at facs.org/clincon2017/resources .

Make the most of your American College of Surgeons (ACS) Clinical Congress 2017 experience by visiting the new ACS Central area designed specifically for our members. ACS Central visitors will have opportunities to meet College staff; learn about the latest ACS programs, products, and services; purchase ACS materials; and make ACS Central a convenient gathering space during the meeting. While there, you can also update your member profile and receive a flash drive with your own professional photo to keep.

ACS Central also will house the ACS Theatre, which will feature presentations on the following new ACS programs and products during lunch hours Monday through Wednesday:

• Monday: The Surgeon Specific Registry

• Tuesday: Improving Surgical Care and Recovery (ISCR)

• Wednesday: Optimal Resources for Surgical Quality and Safety (the “red book”)

The ACS Theatre also will be used for meet-and-greets with ACS leaders. Posters outlining the schedule for the day will be located throughout ACS Central, and alerts will be sent out through the app and social media.

ACS Central will be open 9:00 am–4:30 pm Monday through Wednesday in the San Diego Convention Center, Exhibit Hall.

The following select ACS Programs also will have a presence Sunday through Thursday in the main lobby of the San Diego Convention Center and in the Registration Area:

• ACS Foundation and Fellows Leadership Society

• American College of Surgeons Professional Association-SurgeonsPAC

• Mobile Connect

• Become a Member/Member Services booth, where you can join the ACS, pay your membership dues, or get answers to questions about your membership

In addition, MyCME and Webcast Sales Booths will be located throughout the Convention Center and open the same hours as registration Monday through Thursday. To view other conference resources, go to the Clinical Congress 2017 Resources web page at facs.org/clincon2017/resources .

Make the most of your American College of Surgeons (ACS) Clinical Congress 2017 experience by visiting the new ACS Central area designed specifically for our members. ACS Central visitors will have opportunities to meet College staff; learn about the latest ACS programs, products, and services; purchase ACS materials; and make ACS Central a convenient gathering space during the meeting. While there, you can also update your member profile and receive a flash drive with your own professional photo to keep.

ACS Central also will house the ACS Theatre, which will feature presentations on the following new ACS programs and products during lunch hours Monday through Wednesday:

• Monday: The Surgeon Specific Registry

• Tuesday: Improving Surgical Care and Recovery (ISCR)

• Wednesday: Optimal Resources for Surgical Quality and Safety (the “red book”)

The ACS Theatre also will be used for meet-and-greets with ACS leaders. Posters outlining the schedule for the day will be located throughout ACS Central, and alerts will be sent out through the app and social media.

ACS Central will be open 9:00 am–4:30 pm Monday through Wednesday in the San Diego Convention Center, Exhibit Hall.

The following select ACS Programs also will have a presence Sunday through Thursday in the main lobby of the San Diego Convention Center and in the Registration Area:

• ACS Foundation and Fellows Leadership Society

• American College of Surgeons Professional Association-SurgeonsPAC

• Mobile Connect

• Become a Member/Member Services booth, where you can join the ACS, pay your membership dues, or get answers to questions about your membership

In addition, MyCME and Webcast Sales Booths will be located throughout the Convention Center and open the same hours as registration Monday through Thursday. To view other conference resources, go to the Clinical Congress 2017 Resources web page at facs.org/clincon2017/resources .

ACS scores victory for trauma research

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) has been working with members of the U.S. Senate Committee on Appropriations to advocate for inclusion of trauma research language in the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies (Labor-HHS) Appropriations Bill for fiscal year 2018. More specifically, the ACS is requesting that the committee report language stress the importance of trauma research and encourage the National Institutes of Health to establish a trauma research agenda to minimize death, disability, and injury by ensuring that patient-specific trauma care is based on scientifically validated findings. Committee report language is included in appropriations legislation to guide the administration and departments in their support of the committee’s priorities. The report and bill await further action in the Senate. The bill contains base discretionary funding for the agencies.

For more information about the College’s policy positions on trauma, contact Justin Rosen, ACS Congressional Lobbyist, at [email protected] or 202-672-1528.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) has been working with members of the U.S. Senate Committee on Appropriations to advocate for inclusion of trauma research language in the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies (Labor-HHS) Appropriations Bill for fiscal year 2018. More specifically, the ACS is requesting that the committee report language stress the importance of trauma research and encourage the National Institutes of Health to establish a trauma research agenda to minimize death, disability, and injury by ensuring that patient-specific trauma care is based on scientifically validated findings. Committee report language is included in appropriations legislation to guide the administration and departments in their support of the committee’s priorities. The report and bill await further action in the Senate. The bill contains base discretionary funding for the agencies.

For more information about the College’s policy positions on trauma, contact Justin Rosen, ACS Congressional Lobbyist, at [email protected] or 202-672-1528.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) has been working with members of the U.S. Senate Committee on Appropriations to advocate for inclusion of trauma research language in the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies (Labor-HHS) Appropriations Bill for fiscal year 2018. More specifically, the ACS is requesting that the committee report language stress the importance of trauma research and encourage the National Institutes of Health to establish a trauma research agenda to minimize death, disability, and injury by ensuring that patient-specific trauma care is based on scientifically validated findings. Committee report language is included in appropriations legislation to guide the administration and departments in their support of the committee’s priorities. The report and bill await further action in the Senate. The bill contains base discretionary funding for the agencies.

For more information about the College’s policy positions on trauma, contact Justin Rosen, ACS Congressional Lobbyist, at [email protected] or 202-672-1528.

The right choice? Surgery “offered” or “recommended”?

The story was not unusual for a late-night surgical consultation request by the emergency department. The patient was a 32-year-old man who had presented to the emergency room with crampy abdominal pain. He initially had felt distended, but – during the 3 hours since his presentation to the hospital – the pain and distention had resolved. A CT of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained shortly after the patient arrived in the emergency department. The study showed some dilated small bowel along with a worrisome spiral pattern of the mesentery that suggested a midgut volvulus. The finding was surprising to the surgical resident examining the patient given that the patient now had a soft and nontender abdomen on exam. The white blood cell count was not elevated, and the electrolyte levels were all normal.

When presented with this recommendation, the patient declined the recommended surgery. He stated that he felt fine and that this would be a bad time to have an operation and miss work. The patient ultimately left the hospital only to present 5 days later with peritonitis. When he was emergently explored on the second admission, he was found to have a significant amount of gangrenous small bowel that required resection.

The case was presented at the M and M (morbidity and mortality) conference the following week. When asked about the prior hospital admission, the resident reported that the patient had been “offered surgery,” and in the context of “shared decision making,” the patient had chosen to go home. This characterization of the interactions with the patient raised concern among several of the attending surgeons present. Was the patient only “offered” surgery, or was he strongly recommended to have surgery to avoid potentially risking his life? Was the patient’s refusal to have surgery despite the risks actually a case of “shared decision making”?

These questions are but a few of the many that can arise when language is used indiscriminately. Although, in the contemporary era of “patient-centered decision making,” it is common to think about every recommendation as an offer of alternative therapies, I worry that describing the interaction in this fashion is potentially misleading. Patients should not be offered potentially life-saving treatments – those treatments should be strongly recommended. Certainly, we must accept that patients can refuse even the most strongly recommended treatments, but a patient’s refusal to follow a strong recommendation for surgery should not be characterized as shared decision making. “Shared decision making” suggests that there are medically acceptable choices that the physician has offered the patient, from which the patient can make a choice based on his or her preferences and values. The case above is not shared decision making but one of respecting the patient’s autonomous choices even if we do not agree with the choices made.

There are undoubtedly situations in which there is a choice among reasonable medical options. When there is a such a choice to be made, as surgeons, we should help our patients understand the options so that they can make a decision that best fits with their values and goals. However, when the only choice is whether to have the recommended surgery or decline it, we have now moved beyond shared decision making. In that circumstance, we should strongly recommend what we believe is the better option while still respecting the autonomy of patients to decline our recommendation.

Shared decision making often is viewed as the pinnacle of ethical practice – that is, involving patients in the decisions to be made about their own health. Although I agree that we do want to educate our patients and encourage them to make what we consider safe medical decisions, when we recommend a safe choice and the patient declines it, we are no longer talking about shared decision making. In such circumstances, we are in the realm of respecting patients’ choices even when we disagree with those choices. Our responsibility as surgeons is to recommend what we think is safe but respect their choices whether we agree or not. We should do more than simply offer surgery when it is potentially life threatening not to have it.

Dr. Angelos is the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics, chief of endocrine surgery, and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

The story was not unusual for a late-night surgical consultation request by the emergency department. The patient was a 32-year-old man who had presented to the emergency room with crampy abdominal pain. He initially had felt distended, but – during the 3 hours since his presentation to the hospital – the pain and distention had resolved. A CT of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained shortly after the patient arrived in the emergency department. The study showed some dilated small bowel along with a worrisome spiral pattern of the mesentery that suggested a midgut volvulus. The finding was surprising to the surgical resident examining the patient given that the patient now had a soft and nontender abdomen on exam. The white blood cell count was not elevated, and the electrolyte levels were all normal.

When presented with this recommendation, the patient declined the recommended surgery. He stated that he felt fine and that this would be a bad time to have an operation and miss work. The patient ultimately left the hospital only to present 5 days later with peritonitis. When he was emergently explored on the second admission, he was found to have a significant amount of gangrenous small bowel that required resection.

The case was presented at the M and M (morbidity and mortality) conference the following week. When asked about the prior hospital admission, the resident reported that the patient had been “offered surgery,” and in the context of “shared decision making,” the patient had chosen to go home. This characterization of the interactions with the patient raised concern among several of the attending surgeons present. Was the patient only “offered” surgery, or was he strongly recommended to have surgery to avoid potentially risking his life? Was the patient’s refusal to have surgery despite the risks actually a case of “shared decision making”?

These questions are but a few of the many that can arise when language is used indiscriminately. Although, in the contemporary era of “patient-centered decision making,” it is common to think about every recommendation as an offer of alternative therapies, I worry that describing the interaction in this fashion is potentially misleading. Patients should not be offered potentially life-saving treatments – those treatments should be strongly recommended. Certainly, we must accept that patients can refuse even the most strongly recommended treatments, but a patient’s refusal to follow a strong recommendation for surgery should not be characterized as shared decision making. “Shared decision making” suggests that there are medically acceptable choices that the physician has offered the patient, from which the patient can make a choice based on his or her preferences and values. The case above is not shared decision making but one of respecting the patient’s autonomous choices even if we do not agree with the choices made.

There are undoubtedly situations in which there is a choice among reasonable medical options. When there is a such a choice to be made, as surgeons, we should help our patients understand the options so that they can make a decision that best fits with their values and goals. However, when the only choice is whether to have the recommended surgery or decline it, we have now moved beyond shared decision making. In that circumstance, we should strongly recommend what we believe is the better option while still respecting the autonomy of patients to decline our recommendation.

Shared decision making often is viewed as the pinnacle of ethical practice – that is, involving patients in the decisions to be made about their own health. Although I agree that we do want to educate our patients and encourage them to make what we consider safe medical decisions, when we recommend a safe choice and the patient declines it, we are no longer talking about shared decision making. In such circumstances, we are in the realm of respecting patients’ choices even when we disagree with those choices. Our responsibility as surgeons is to recommend what we think is safe but respect their choices whether we agree or not. We should do more than simply offer surgery when it is potentially life threatening not to have it.

Dr. Angelos is the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics, chief of endocrine surgery, and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

The story was not unusual for a late-night surgical consultation request by the emergency department. The patient was a 32-year-old man who had presented to the emergency room with crampy abdominal pain. He initially had felt distended, but – during the 3 hours since his presentation to the hospital – the pain and distention had resolved. A CT of the abdomen and pelvis was obtained shortly after the patient arrived in the emergency department. The study showed some dilated small bowel along with a worrisome spiral pattern of the mesentery that suggested a midgut volvulus. The finding was surprising to the surgical resident examining the patient given that the patient now had a soft and nontender abdomen on exam. The white blood cell count was not elevated, and the electrolyte levels were all normal.

When presented with this recommendation, the patient declined the recommended surgery. He stated that he felt fine and that this would be a bad time to have an operation and miss work. The patient ultimately left the hospital only to present 5 days later with peritonitis. When he was emergently explored on the second admission, he was found to have a significant amount of gangrenous small bowel that required resection.

The case was presented at the M and M (morbidity and mortality) conference the following week. When asked about the prior hospital admission, the resident reported that the patient had been “offered surgery,” and in the context of “shared decision making,” the patient had chosen to go home. This characterization of the interactions with the patient raised concern among several of the attending surgeons present. Was the patient only “offered” surgery, or was he strongly recommended to have surgery to avoid potentially risking his life? Was the patient’s refusal to have surgery despite the risks actually a case of “shared decision making”?

These questions are but a few of the many that can arise when language is used indiscriminately. Although, in the contemporary era of “patient-centered decision making,” it is common to think about every recommendation as an offer of alternative therapies, I worry that describing the interaction in this fashion is potentially misleading. Patients should not be offered potentially life-saving treatments – those treatments should be strongly recommended. Certainly, we must accept that patients can refuse even the most strongly recommended treatments, but a patient’s refusal to follow a strong recommendation for surgery should not be characterized as shared decision making. “Shared decision making” suggests that there are medically acceptable choices that the physician has offered the patient, from which the patient can make a choice based on his or her preferences and values. The case above is not shared decision making but one of respecting the patient’s autonomous choices even if we do not agree with the choices made.

There are undoubtedly situations in which there is a choice among reasonable medical options. When there is a such a choice to be made, as surgeons, we should help our patients understand the options so that they can make a decision that best fits with their values and goals. However, when the only choice is whether to have the recommended surgery or decline it, we have now moved beyond shared decision making. In that circumstance, we should strongly recommend what we believe is the better option while still respecting the autonomy of patients to decline our recommendation.

Shared decision making often is viewed as the pinnacle of ethical practice – that is, involving patients in the decisions to be made about their own health. Although I agree that we do want to educate our patients and encourage them to make what we consider safe medical decisions, when we recommend a safe choice and the patient declines it, we are no longer talking about shared decision making. In such circumstances, we are in the realm of respecting patients’ choices even when we disagree with those choices. Our responsibility as surgeons is to recommend what we think is safe but respect their choices whether we agree or not. We should do more than simply offer surgery when it is potentially life threatening not to have it.

Dr. Angelos is the Linda Kohler Anderson Professor of Surgery and Surgical Ethics, chief of endocrine surgery, and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the University of Chicago.

From the Editors: Halsted, Holmes, and penguins

Is it not ironic that in a profession that is always seeking answers – What does this patient have? Is that mass malignant? What’s the best way to make a diagnosis? – too much information has become a major problem?

Unlike William Stewart Halsted or Theodor Billroth, who blazed surgical trails in an age when much was unknown, today’s surgeons face a jungle of information obscuring the trail ahead. Every morning we wake up to another 30 or 40 unread emails. Journals multiply on our desks. The books we need to read pile up and spill over onto our desks, bookshelves, and side tables. Sometimes, it makes one long for the old days when definitive answers might not be found in the literature. These days, we know it is likely that someone has published exactly what we need at any particular moment, and yet finding it in the jungle of information can be a great challenge.

Another outcome of too much information is the accumulation in our brains of unsorted bits of medical/surgical knowledge. Some of those bits are pearls, and others are just gum wrappers that take up space. It becomes an overwhelming task of ranking, sorting, prioritizing, and discarding.

A friend of mine years of ago called his brain an iceberg on which thousands of penguins stand. The penguins just kept coming and, finally, in order to learn anything new, he had to push some penguins off the iceberg. We have a lot of penguins on our icebergs these days.

This brings to mind many doctors’ favorite fictional character, Sherlock Holmes. That denizen of 221B Baker Street was a master at data management. He always had the right information available in his head relevant for the mystery at hand. How did he do it? Recall that Dr. Watson (a surgeon, I might add) was intermittently shocked by what Holmes didn’t know, to which the tobacco- and opiate-addicted hero would reply that he purposely forgot things that did not help him solve his cases.

And so, what is the modern surgeon – who must keep in the forefront of his or her mind every best practice, algorithm, and guideline – to do in this age of too much information? Like Holmes, we need to sort what is critical from what is not and let go of those items that no longer are germane. We then need to triage the vast amount of information delivered to us yearly, weekly, monthly, daily, hourly. The stream of little notes flashing at you from your black mirror (the screen of your mobile device) needs to be controlled lest it control you.

So, might I suggest a few strategies I have used to triage the flow of information? For hourly and daily information, I tend to ignore everything except ACS NewsScope and the ACS Communities items I find most interesting. For monthly information, I tend to use ACS Surgery News (plug intended) because it is “news” – the stuff that just happened in the meeting sphere or has not yet hit print (sorry, e-publication). The Journal of the American College of Surgeons is another monthly source that is reliable.

You may see a theme here. I’ve used the American College of Surgeons as my main filter. What gets through the editors of these outlets generally is viable and useful information. That’s what I need to know for right now. Such knowledge allows me to push those penguins no longer needed off my iceberg and greet the new ones with joy. We often wonder what the benefit of membership in the College may be. For me, these filters are worth the price of admission.

Dr. Hughes is clinical professor in the department of surgery and director of medical education at the Kansas University School of Medicine, Salina Campus, and Co-Editor of ACS Surgery News.

Is it not ironic that in a profession that is always seeking answers – What does this patient have? Is that mass malignant? What’s the best way to make a diagnosis? – too much information has become a major problem?

Unlike William Stewart Halsted or Theodor Billroth, who blazed surgical trails in an age when much was unknown, today’s surgeons face a jungle of information obscuring the trail ahead. Every morning we wake up to another 30 or 40 unread emails. Journals multiply on our desks. The books we need to read pile up and spill over onto our desks, bookshelves, and side tables. Sometimes, it makes one long for the old days when definitive answers might not be found in the literature. These days, we know it is likely that someone has published exactly what we need at any particular moment, and yet finding it in the jungle of information can be a great challenge.

Another outcome of too much information is the accumulation in our brains of unsorted bits of medical/surgical knowledge. Some of those bits are pearls, and others are just gum wrappers that take up space. It becomes an overwhelming task of ranking, sorting, prioritizing, and discarding.

A friend of mine years of ago called his brain an iceberg on which thousands of penguins stand. The penguins just kept coming and, finally, in order to learn anything new, he had to push some penguins off the iceberg. We have a lot of penguins on our icebergs these days.

This brings to mind many doctors’ favorite fictional character, Sherlock Holmes. That denizen of 221B Baker Street was a master at data management. He always had the right information available in his head relevant for the mystery at hand. How did he do it? Recall that Dr. Watson (a surgeon, I might add) was intermittently shocked by what Holmes didn’t know, to which the tobacco- and opiate-addicted hero would reply that he purposely forgot things that did not help him solve his cases.

And so, what is the modern surgeon – who must keep in the forefront of his or her mind every best practice, algorithm, and guideline – to do in this age of too much information? Like Holmes, we need to sort what is critical from what is not and let go of those items that no longer are germane. We then need to triage the vast amount of information delivered to us yearly, weekly, monthly, daily, hourly. The stream of little notes flashing at you from your black mirror (the screen of your mobile device) needs to be controlled lest it control you.

So, might I suggest a few strategies I have used to triage the flow of information? For hourly and daily information, I tend to ignore everything except ACS NewsScope and the ACS Communities items I find most interesting. For monthly information, I tend to use ACS Surgery News (plug intended) because it is “news” – the stuff that just happened in the meeting sphere or has not yet hit print (sorry, e-publication). The Journal of the American College of Surgeons is another monthly source that is reliable.

You may see a theme here. I’ve used the American College of Surgeons as my main filter. What gets through the editors of these outlets generally is viable and useful information. That’s what I need to know for right now. Such knowledge allows me to push those penguins no longer needed off my iceberg and greet the new ones with joy. We often wonder what the benefit of membership in the College may be. For me, these filters are worth the price of admission.

Dr. Hughes is clinical professor in the department of surgery and director of medical education at the Kansas University School of Medicine, Salina Campus, and Co-Editor of ACS Surgery News.

Is it not ironic that in a profession that is always seeking answers – What does this patient have? Is that mass malignant? What’s the best way to make a diagnosis? – too much information has become a major problem?

Unlike William Stewart Halsted or Theodor Billroth, who blazed surgical trails in an age when much was unknown, today’s surgeons face a jungle of information obscuring the trail ahead. Every morning we wake up to another 30 or 40 unread emails. Journals multiply on our desks. The books we need to read pile up and spill over onto our desks, bookshelves, and side tables. Sometimes, it makes one long for the old days when definitive answers might not be found in the literature. These days, we know it is likely that someone has published exactly what we need at any particular moment, and yet finding it in the jungle of information can be a great challenge.

Another outcome of too much information is the accumulation in our brains of unsorted bits of medical/surgical knowledge. Some of those bits are pearls, and others are just gum wrappers that take up space. It becomes an overwhelming task of ranking, sorting, prioritizing, and discarding.

A friend of mine years of ago called his brain an iceberg on which thousands of penguins stand. The penguins just kept coming and, finally, in order to learn anything new, he had to push some penguins off the iceberg. We have a lot of penguins on our icebergs these days.

This brings to mind many doctors’ favorite fictional character, Sherlock Holmes. That denizen of 221B Baker Street was a master at data management. He always had the right information available in his head relevant for the mystery at hand. How did he do it? Recall that Dr. Watson (a surgeon, I might add) was intermittently shocked by what Holmes didn’t know, to which the tobacco- and opiate-addicted hero would reply that he purposely forgot things that did not help him solve his cases.

And so, what is the modern surgeon – who must keep in the forefront of his or her mind every best practice, algorithm, and guideline – to do in this age of too much information? Like Holmes, we need to sort what is critical from what is not and let go of those items that no longer are germane. We then need to triage the vast amount of information delivered to us yearly, weekly, monthly, daily, hourly. The stream of little notes flashing at you from your black mirror (the screen of your mobile device) needs to be controlled lest it control you.

So, might I suggest a few strategies I have used to triage the flow of information? For hourly and daily information, I tend to ignore everything except ACS NewsScope and the ACS Communities items I find most interesting. For monthly information, I tend to use ACS Surgery News (plug intended) because it is “news” – the stuff that just happened in the meeting sphere or has not yet hit print (sorry, e-publication). The Journal of the American College of Surgeons is another monthly source that is reliable.

You may see a theme here. I’ve used the American College of Surgeons as my main filter. What gets through the editors of these outlets generally is viable and useful information. That’s what I need to know for right now. Such knowledge allows me to push those penguins no longer needed off my iceberg and greet the new ones with joy. We often wonder what the benefit of membership in the College may be. For me, these filters are worth the price of admission.

Dr. Hughes is clinical professor in the department of surgery and director of medical education at the Kansas University School of Medicine, Salina Campus, and Co-Editor of ACS Surgery News.

VIDEO: Sildenafil improves cerebrovascular reactivity in chronic TBI

SAN DIEGO – The healthy brain is a master of autoregulation, continuously adjusting blood flow to meet metabolic demand.

But in traumatic brain injury, cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR) breaks down; blood vessels don’t dilate as they should to deliver nutrients and oxygen, leading to progressive neurologic decline.

Sildenafil (Viagra) – a vasodilator in injured blood vessels – might help, according to ongoing research at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Researchers there gave sildenafil to inpatients with persistent symptoms at least 6 months after traumatic brain injury and measured CVR by a novel MRI technique an hour later. “Sildenafil was able to correct the deficit in CVR in many cases. We are hopeful this could be a useful therapy,” said principal investigator Ramon Diaz-Arrastia, MD, a professor of neurology at the university.

He explained the work in an interview at annual meeting of the American Neurological Association. The next step is to see if sildenafil helps CVR in acute traumatic brain injury, and in people who have had multiple, mild brain traumas, including professional athletes.

SAN DIEGO – The healthy brain is a master of autoregulation, continuously adjusting blood flow to meet metabolic demand.

But in traumatic brain injury, cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR) breaks down; blood vessels don’t dilate as they should to deliver nutrients and oxygen, leading to progressive neurologic decline.

Sildenafil (Viagra) – a vasodilator in injured blood vessels – might help, according to ongoing research at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Researchers there gave sildenafil to inpatients with persistent symptoms at least 6 months after traumatic brain injury and measured CVR by a novel MRI technique an hour later. “Sildenafil was able to correct the deficit in CVR in many cases. We are hopeful this could be a useful therapy,” said principal investigator Ramon Diaz-Arrastia, MD, a professor of neurology at the university.

He explained the work in an interview at annual meeting of the American Neurological Association. The next step is to see if sildenafil helps CVR in acute traumatic brain injury, and in people who have had multiple, mild brain traumas, including professional athletes.

SAN DIEGO – The healthy brain is a master of autoregulation, continuously adjusting blood flow to meet metabolic demand.

But in traumatic brain injury, cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR) breaks down; blood vessels don’t dilate as they should to deliver nutrients and oxygen, leading to progressive neurologic decline.

Sildenafil (Viagra) – a vasodilator in injured blood vessels – might help, according to ongoing research at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Researchers there gave sildenafil to inpatients with persistent symptoms at least 6 months after traumatic brain injury and measured CVR by a novel MRI technique an hour later. “Sildenafil was able to correct the deficit in CVR in many cases. We are hopeful this could be a useful therapy,” said principal investigator Ramon Diaz-Arrastia, MD, a professor of neurology at the university.

He explained the work in an interview at annual meeting of the American Neurological Association. The next step is to see if sildenafil helps CVR in acute traumatic brain injury, and in people who have had multiple, mild brain traumas, including professional athletes.

AT ANA 2017

Over 40% of Americans have experience with medical errors

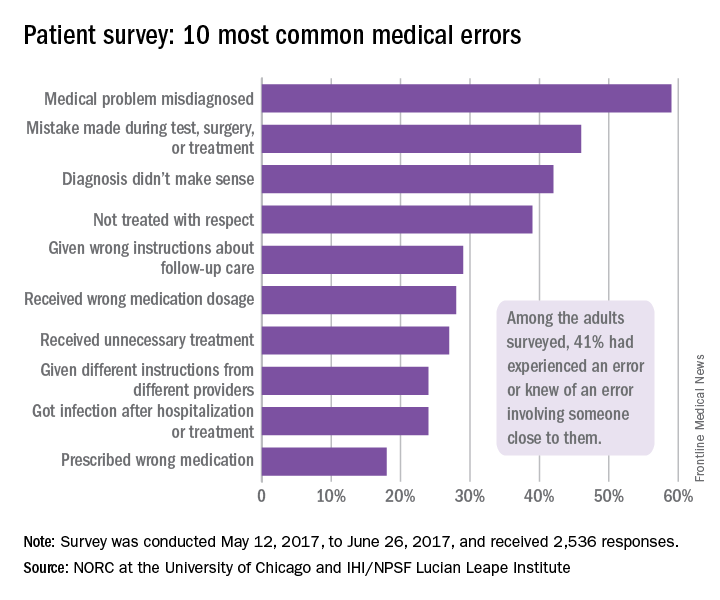

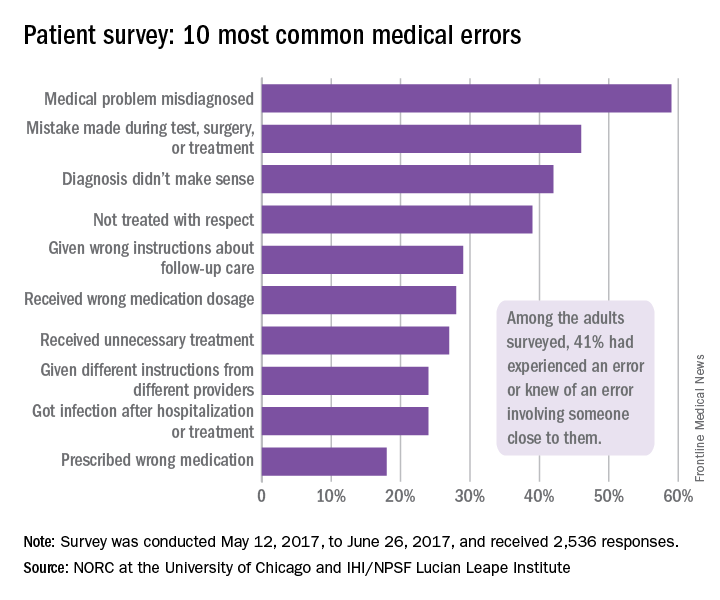

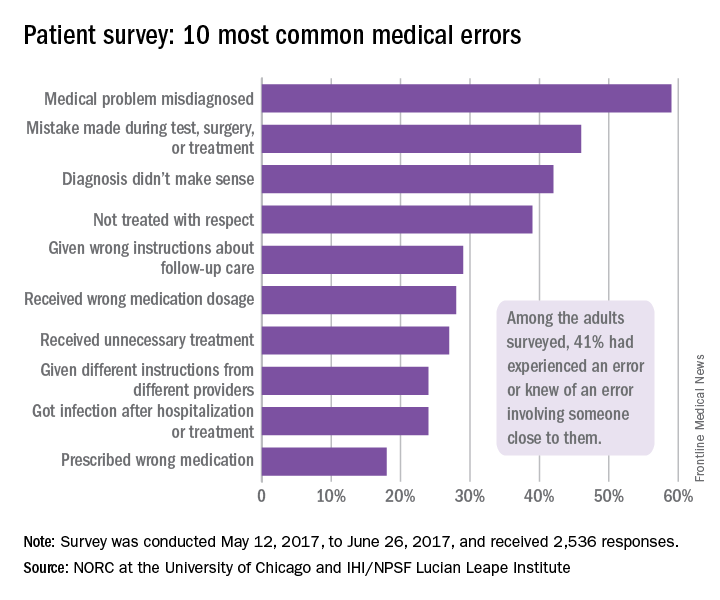

More than 40% of adults have either experienced a medical error or been involved in the care of someone who did, according to a recent national survey.

Specifically, 21% of American adults said that they have personally experienced a medical error and 31% said that they have been involved in the care of another person who experienced an error. The combined total, which includes some overlap, was 41% in the survey conducted by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI)/National Patient Safety Foundation (NPSF) and National Opinion Research Center (NORC), a nonpartisan research institution at the University of Chicago, .

Medical errors were defined for respondents as “mistakes [that] sometimes result in no harm, while other times they may result in additional or prolonged treatment, emotional distress, disability, or death,” investigators at IHI/NPSF and NORC said in their report.

A misdiagnosed medical problem was the most common type of medical error, reported by 59% of those with error experience. The next most common type of error was a mistake during a test, surgery, or treatment, which was mentioned by 46% of those with error experience, followed by a diagnosis that didn’t make sense (42%), lack of respect (39%), and incorrect instructions about follow-up care (29%), the IHI/HPSF and NORC report indicated.

Feelings of disrespect were more common among younger respondents: 46% of those aged 18-44 years said they were not treated with respect by a health care provider, compared with 34% of those aged 45 years and older. No differences in disrespect were seen with regard to socioeconomic status, health literacy, or English language proficiency. Those who spoke a language other than English at home, however, were more than twice as likely to get the wrong medication from a physician (34%) than were those who did not (15%), the report showed.

The survey, which had a sampling error of plus or minus 3.2 percentage points, was conducted between May 12, 2017, and June 26, 2017, and involved 2,536 respondents. It was conducted with support from Medtronic.

More than 40% of adults have either experienced a medical error or been involved in the care of someone who did, according to a recent national survey.

Specifically, 21% of American adults said that they have personally experienced a medical error and 31% said that they have been involved in the care of another person who experienced an error. The combined total, which includes some overlap, was 41% in the survey conducted by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI)/National Patient Safety Foundation (NPSF) and National Opinion Research Center (NORC), a nonpartisan research institution at the University of Chicago, .

Medical errors were defined for respondents as “mistakes [that] sometimes result in no harm, while other times they may result in additional or prolonged treatment, emotional distress, disability, or death,” investigators at IHI/NPSF and NORC said in their report.

A misdiagnosed medical problem was the most common type of medical error, reported by 59% of those with error experience. The next most common type of error was a mistake during a test, surgery, or treatment, which was mentioned by 46% of those with error experience, followed by a diagnosis that didn’t make sense (42%), lack of respect (39%), and incorrect instructions about follow-up care (29%), the IHI/HPSF and NORC report indicated.

Feelings of disrespect were more common among younger respondents: 46% of those aged 18-44 years said they were not treated with respect by a health care provider, compared with 34% of those aged 45 years and older. No differences in disrespect were seen with regard to socioeconomic status, health literacy, or English language proficiency. Those who spoke a language other than English at home, however, were more than twice as likely to get the wrong medication from a physician (34%) than were those who did not (15%), the report showed.

The survey, which had a sampling error of plus or minus 3.2 percentage points, was conducted between May 12, 2017, and June 26, 2017, and involved 2,536 respondents. It was conducted with support from Medtronic.

More than 40% of adults have either experienced a medical error or been involved in the care of someone who did, according to a recent national survey.

Specifically, 21% of American adults said that they have personally experienced a medical error and 31% said that they have been involved in the care of another person who experienced an error. The combined total, which includes some overlap, was 41% in the survey conducted by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI)/National Patient Safety Foundation (NPSF) and National Opinion Research Center (NORC), a nonpartisan research institution at the University of Chicago, .

Medical errors were defined for respondents as “mistakes [that] sometimes result in no harm, while other times they may result in additional or prolonged treatment, emotional distress, disability, or death,” investigators at IHI/NPSF and NORC said in their report.

A misdiagnosed medical problem was the most common type of medical error, reported by 59% of those with error experience. The next most common type of error was a mistake during a test, surgery, or treatment, which was mentioned by 46% of those with error experience, followed by a diagnosis that didn’t make sense (42%), lack of respect (39%), and incorrect instructions about follow-up care (29%), the IHI/HPSF and NORC report indicated.

Feelings of disrespect were more common among younger respondents: 46% of those aged 18-44 years said they were not treated with respect by a health care provider, compared with 34% of those aged 45 years and older. No differences in disrespect were seen with regard to socioeconomic status, health literacy, or English language proficiency. Those who spoke a language other than English at home, however, were more than twice as likely to get the wrong medication from a physician (34%) than were those who did not (15%), the report showed.

The survey, which had a sampling error of plus or minus 3.2 percentage points, was conducted between May 12, 2017, and June 26, 2017, and involved 2,536 respondents. It was conducted with support from Medtronic.

Two Senators reach deal on a health law fix

After nearly 2 months of negotiations, key senators said on Oct. 17 that they have reached a bipartisan deal on a proposal intended to stabilize the Affordable Care Act’s insurance market, which has been rocked by recent actions by President Donald Trump.

Sens. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) and Patty Murray (D-Wash.), respectively the chairman and the top Democrat of the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee, negotiated the emerging deal. The milestone agreement, they said, would guarantee payment of cost-sharing reduction subsidies that help some policyholders with low incomes afford their deductibles and other out-of-pocket costs for 2 years, 2018 and 2019.

President Trump announced on Oct. 12 that he would stop funding the subsidies, which also have been the subject of a long-running lawsuit.

Even if it fails to become law, the deal marks a singular achievement that has been almost completely missing in Congress for the past 8 years – a bipartisan compromise on how to make the nation’s health insurance system work.

“This is an agreement I am proud to support,” Sen. Murray said on the Senate floor, “because of the message it sends about how to get things done.”

The proposal – which will require 60 votes to pass the Senate and agreement from a still-dubious House of Representatives – also would restore $110 million in ACA outreach funding cut by the Trump administration. That funding would help guide eligible individuals to sign up for coverage on the health insurance exchanges during the open enrollment period that runs from Nov. 1 to Dec. 15.

In exchange for those provisions, urged by Democrats and state officials, Republicans would win some changes to make it easier for states to apply for waivers that would let them experiment with alternative ways to provide and subsidize health insurance. The deal also would allow the sale of less comprehensive catastrophic plans in the health exchanges. Currently, such plans can be sold only to those under age 30 years.

On the Senate floor, Sen. Alexander said, “This agreement avoids chaos. I don’t know a Democrat or a Republican who benefits from chaos.”

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) reserved judgment about the deal.

Both parties still have some major disagreements when it comes to health care, Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) told reporters on Oct. 17, but “I think there’s a growing consensus that in the short term we need stability in the markets. So we’ve achieved stability if this agreement becomes law.”

More than 60 senators have already participated in the meetings that led to the deal, Sen. Alexander said on the Senate floor. But the path to passage in the House is uncertain – with many conservatives vehemently opposed to anything that could be construed as helping the ACA succeed.

Rep. Mark Walker (R-N.C.), chairman of the conservative Republican Study Committee, tweeted on Oct. 17: “The GOP should focus on repealing & replacing Obamacare, not trying to save it. This bailout is unacceptable.”

Both Sen. Murray and Sen. Alexander said that they were still struggling over language to make sure that if the cost-sharing payments are resumed, insurers would not receive a windfall by keeping both those payments and the higher premiums that many states are allowing in anticipation of the payments being ended.

“We want to make sure that the cost-sharing payments go to the benefit of consumers, not the insurance companies,” Sen. Alexander said.

President Trump, who as recently as Oct. 16 called the cost-sharing subsidies “a payoff” to insurance companies, took credit for the negotiations. “If I didn’t cut the CSRs, they wouldn’t be meeting,” he said. That was not, in fact, the case. The negotiations had picked up some weeks ago after being called off earlier in September while the Senate tried for one last-ditch repeal vote.

On Oct. 13, White House Budget Director Mick Mulvaney told Politico that the president would not allow a short-term fix, calling a restoration of the cost-sharing reduction funds “corporate welfare and bailouts for the insurance companies.”

But on Oct. 17 the president hailed the deal. “We think it’s going to not only save money, but give people much better health care with a very, very much smaller premium spike,” he told reporters.

Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

After nearly 2 months of negotiations, key senators said on Oct. 17 that they have reached a bipartisan deal on a proposal intended to stabilize the Affordable Care Act’s insurance market, which has been rocked by recent actions by President Donald Trump.

Sens. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) and Patty Murray (D-Wash.), respectively the chairman and the top Democrat of the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee, negotiated the emerging deal. The milestone agreement, they said, would guarantee payment of cost-sharing reduction subsidies that help some policyholders with low incomes afford their deductibles and other out-of-pocket costs for 2 years, 2018 and 2019.

President Trump announced on Oct. 12 that he would stop funding the subsidies, which also have been the subject of a long-running lawsuit.

Even if it fails to become law, the deal marks a singular achievement that has been almost completely missing in Congress for the past 8 years – a bipartisan compromise on how to make the nation’s health insurance system work.

“This is an agreement I am proud to support,” Sen. Murray said on the Senate floor, “because of the message it sends about how to get things done.”

The proposal – which will require 60 votes to pass the Senate and agreement from a still-dubious House of Representatives – also would restore $110 million in ACA outreach funding cut by the Trump administration. That funding would help guide eligible individuals to sign up for coverage on the health insurance exchanges during the open enrollment period that runs from Nov. 1 to Dec. 15.

In exchange for those provisions, urged by Democrats and state officials, Republicans would win some changes to make it easier for states to apply for waivers that would let them experiment with alternative ways to provide and subsidize health insurance. The deal also would allow the sale of less comprehensive catastrophic plans in the health exchanges. Currently, such plans can be sold only to those under age 30 years.

On the Senate floor, Sen. Alexander said, “This agreement avoids chaos. I don’t know a Democrat or a Republican who benefits from chaos.”

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) reserved judgment about the deal.

Both parties still have some major disagreements when it comes to health care, Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) told reporters on Oct. 17, but “I think there’s a growing consensus that in the short term we need stability in the markets. So we’ve achieved stability if this agreement becomes law.”

More than 60 senators have already participated in the meetings that led to the deal, Sen. Alexander said on the Senate floor. But the path to passage in the House is uncertain – with many conservatives vehemently opposed to anything that could be construed as helping the ACA succeed.

Rep. Mark Walker (R-N.C.), chairman of the conservative Republican Study Committee, tweeted on Oct. 17: “The GOP should focus on repealing & replacing Obamacare, not trying to save it. This bailout is unacceptable.”

Both Sen. Murray and Sen. Alexander said that they were still struggling over language to make sure that if the cost-sharing payments are resumed, insurers would not receive a windfall by keeping both those payments and the higher premiums that many states are allowing in anticipation of the payments being ended.

“We want to make sure that the cost-sharing payments go to the benefit of consumers, not the insurance companies,” Sen. Alexander said.

President Trump, who as recently as Oct. 16 called the cost-sharing subsidies “a payoff” to insurance companies, took credit for the negotiations. “If I didn’t cut the CSRs, they wouldn’t be meeting,” he said. That was not, in fact, the case. The negotiations had picked up some weeks ago after being called off earlier in September while the Senate tried for one last-ditch repeal vote.

On Oct. 13, White House Budget Director Mick Mulvaney told Politico that the president would not allow a short-term fix, calling a restoration of the cost-sharing reduction funds “corporate welfare and bailouts for the insurance companies.”

But on Oct. 17 the president hailed the deal. “We think it’s going to not only save money, but give people much better health care with a very, very much smaller premium spike,” he told reporters.

Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

After nearly 2 months of negotiations, key senators said on Oct. 17 that they have reached a bipartisan deal on a proposal intended to stabilize the Affordable Care Act’s insurance market, which has been rocked by recent actions by President Donald Trump.

Sens. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) and Patty Murray (D-Wash.), respectively the chairman and the top Democrat of the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee, negotiated the emerging deal. The milestone agreement, they said, would guarantee payment of cost-sharing reduction subsidies that help some policyholders with low incomes afford their deductibles and other out-of-pocket costs for 2 years, 2018 and 2019.

President Trump announced on Oct. 12 that he would stop funding the subsidies, which also have been the subject of a long-running lawsuit.

Even if it fails to become law, the deal marks a singular achievement that has been almost completely missing in Congress for the past 8 years – a bipartisan compromise on how to make the nation’s health insurance system work.

“This is an agreement I am proud to support,” Sen. Murray said on the Senate floor, “because of the message it sends about how to get things done.”

The proposal – which will require 60 votes to pass the Senate and agreement from a still-dubious House of Representatives – also would restore $110 million in ACA outreach funding cut by the Trump administration. That funding would help guide eligible individuals to sign up for coverage on the health insurance exchanges during the open enrollment period that runs from Nov. 1 to Dec. 15.

In exchange for those provisions, urged by Democrats and state officials, Republicans would win some changes to make it easier for states to apply for waivers that would let them experiment with alternative ways to provide and subsidize health insurance. The deal also would allow the sale of less comprehensive catastrophic plans in the health exchanges. Currently, such plans can be sold only to those under age 30 years.

On the Senate floor, Sen. Alexander said, “This agreement avoids chaos. I don’t know a Democrat or a Republican who benefits from chaos.”

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) reserved judgment about the deal.

Both parties still have some major disagreements when it comes to health care, Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) told reporters on Oct. 17, but “I think there’s a growing consensus that in the short term we need stability in the markets. So we’ve achieved stability if this agreement becomes law.”

More than 60 senators have already participated in the meetings that led to the deal, Sen. Alexander said on the Senate floor. But the path to passage in the House is uncertain – with many conservatives vehemently opposed to anything that could be construed as helping the ACA succeed.

Rep. Mark Walker (R-N.C.), chairman of the conservative Republican Study Committee, tweeted on Oct. 17: “The GOP should focus on repealing & replacing Obamacare, not trying to save it. This bailout is unacceptable.”

Both Sen. Murray and Sen. Alexander said that they were still struggling over language to make sure that if the cost-sharing payments are resumed, insurers would not receive a windfall by keeping both those payments and the higher premiums that many states are allowing in anticipation of the payments being ended.

“We want to make sure that the cost-sharing payments go to the benefit of consumers, not the insurance companies,” Sen. Alexander said.

President Trump, who as recently as Oct. 16 called the cost-sharing subsidies “a payoff” to insurance companies, took credit for the negotiations. “If I didn’t cut the CSRs, they wouldn’t be meeting,” he said. That was not, in fact, the case. The negotiations had picked up some weeks ago after being called off earlier in September while the Senate tried for one last-ditch repeal vote.

On Oct. 13, White House Budget Director Mick Mulvaney told Politico that the president would not allow a short-term fix, calling a restoration of the cost-sharing reduction funds “corporate welfare and bailouts for the insurance companies.”

But on Oct. 17 the president hailed the deal. “We think it’s going to not only save money, but give people much better health care with a very, very much smaller premium spike,” he told reporters.

Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Study: Varicose vein procedures should be offered to patients 65 years and older

Older and younger patients benefited from varicose vein procedures, a finding that calls into question the use of compression therapy as the primary treatment for patients aged 65 years and older, according to the results of a prospectively maintained database study of all patients in the Vascular Quality Initiative Varicose Vein Registry–participating centers.

Procedures for varicose veins in 1,068 patients aged 65 years or older showed similar improvement in Clinical, Etiology, Anatomy, and Pathophysiology class and Venous Clinical Severity Score, compared with a group of 2,691 younger patients, according to a report published in Journal of Vascular Surgery: Venous and Lymphatic Disorders. Among patients younger than 65 years, 57.4% had an improvement, compared with 52% of patients aged 65 years or older.

However, the younger patients had more improvement in patient-reported outcomes, according to Danielle C. Sutzko, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and her colleagues (J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2017 Sep;5[5]:647-57).

One of the main limitations of the study was the fact that only 62% of procedures within the Vascular Quality Initiative Varicose Vein Registry had follow-up.

“Patients older than 65 years appear to benefit from appropriate varicose vein procedures and should not be denied interventions on their varicose veins and venous insufficiency on the basis of their age only,” the researchers concluded.

Dr. Sutzko and her colleagues reported having no conflicts of interest.

Older and younger patients benefited from varicose vein procedures, a finding that calls into question the use of compression therapy as the primary treatment for patients aged 65 years and older, according to the results of a prospectively maintained database study of all patients in the Vascular Quality Initiative Varicose Vein Registry–participating centers.

Procedures for varicose veins in 1,068 patients aged 65 years or older showed similar improvement in Clinical, Etiology, Anatomy, and Pathophysiology class and Venous Clinical Severity Score, compared with a group of 2,691 younger patients, according to a report published in Journal of Vascular Surgery: Venous and Lymphatic Disorders. Among patients younger than 65 years, 57.4% had an improvement, compared with 52% of patients aged 65 years or older.

However, the younger patients had more improvement in patient-reported outcomes, according to Danielle C. Sutzko, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and her colleagues (J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2017 Sep;5[5]:647-57).

One of the main limitations of the study was the fact that only 62% of procedures within the Vascular Quality Initiative Varicose Vein Registry had follow-up.

“Patients older than 65 years appear to benefit from appropriate varicose vein procedures and should not be denied interventions on their varicose veins and venous insufficiency on the basis of their age only,” the researchers concluded.

Dr. Sutzko and her colleagues reported having no conflicts of interest.

Older and younger patients benefited from varicose vein procedures, a finding that calls into question the use of compression therapy as the primary treatment for patients aged 65 years and older, according to the results of a prospectively maintained database study of all patients in the Vascular Quality Initiative Varicose Vein Registry–participating centers.

Procedures for varicose veins in 1,068 patients aged 65 years or older showed similar improvement in Clinical, Etiology, Anatomy, and Pathophysiology class and Venous Clinical Severity Score, compared with a group of 2,691 younger patients, according to a report published in Journal of Vascular Surgery: Venous and Lymphatic Disorders. Among patients younger than 65 years, 57.4% had an improvement, compared with 52% of patients aged 65 years or older.

However, the younger patients had more improvement in patient-reported outcomes, according to Danielle C. Sutzko, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and her colleagues (J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2017 Sep;5[5]:647-57).

One of the main limitations of the study was the fact that only 62% of procedures within the Vascular Quality Initiative Varicose Vein Registry had follow-up.

“Patients older than 65 years appear to benefit from appropriate varicose vein procedures and should not be denied interventions on their varicose veins and venous insufficiency on the basis of their age only,” the researchers concluded.

Dr. Sutzko and her colleagues reported having no conflicts of interest.

FROM JOURNAL OF VASCULAR SURGERY: VENOUS AND LYMPHATIC DISORDERS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Among patients younger than 65, 57.4% had an improvement, compared to 52% of patients aged 65 years or older.

Data source: Prospectively captured data for all patients in the Vascular Quality Initiative Varicose Vein Registry–participating centers.

Disclosures: Dr. Sutzko and her colleagues reported having no conflicts of interest.

Ideal intubation position still unknown

In critically ill adults undergoing endotracheal intubation, the ramped position does not significantly improve oxygenation compared with the sniffing position, according to results of a multicenter, randomized trial of 260 patients treated in an intensive care unit.

Moreover, “[ramped] position appeared to worsen glottic view and increase the number of attempts required for successful intubation,” wrote Matthew W. Semler, MD, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., and his coauthors (Chest. 2017 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.03.061).

The ramped and sniffing positions are the two most common patient positions used during emergent intubation, according to investigators. The sniffing position is characterized by supine torso, neck flexed forward, and head extended, while ramped position involves elevating the torso and head.

Some believe the ramped position may offer superior anatomic alignment of the upper airway; however, only a few observational studies suggest it is associated with fewer complications than the sniffing position, the authors wrote.

Accordingly, they conducted a multicenter randomized trial with a primary endpoint of lowest arterial oxygen saturation, hypothesizing that the endpoint would be higher for the ramped position: “Our primary outcome of lowest arterial oxygen saturation is an established endpoint in ICU intubation trials, and is linked to periprocedural cardiac arrest and death,” they wrote.

The investigators instead found that median lowest arterial oxygen saturation was not statistically different between groups, at 93% for the ramped position, and 92% for the sniffing position (P = 0.27), published data show.

Further results showed that the ramped position appeared to be associated with poor glottic view and more difficult intubation. The incidence of grade III (only epiglottis) or grade IV (no visible glottis structures) views were 25.4% for ramped vs. 11.5% for sniffing (P = .01), while the rate of first-attempt intubation was 76.2% for ramped vs 85.4% for sniffing (P = .02).

While the findings are compelling, the authors were forthcoming about the potential limitations of the study and differences compared with earlier investigations. Notably, they said, all prior controlled trials of patient positioning during endotracheal intubation were conducted in the operating room, rather than in the ICU.

Also, the operators’ skill levels may further explain differences in this study’s outcomes from those of similar studies, the researchers noted. Earlier studies included patients intubated by one or two senior anesthesiologists from one center, while this trial involved 30 operators across multiple centers, with the average operator having performed 60 previous intubations. “Thus, our findings may generalize to settings in which airway management is performed by trainees, but whether results would be similar among expert operators remains unknown,” the investigators noted.

The authors reported no potential conflicts of interest. One coauthor reported serving on an advisory board for Avisa Pharma.

Editorialists praised the multicenter, randomized design of this study, and its total recruitment of 260 patients. They also noted several limitations of the study that “could shed some light” on the group’s conclusions (Chest. 2017 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.06.002).

“The results diverge from [operating room] literature of the past 15 years that suggest that the ramped position is the preferred intubation position for obese patients or those with an anticipated difficult airway.” This may have been caused by shortcomings of this study’s design and differences between it and other research exploring the topic of patient positioning during endotracheal intubation, they wrote.

The study lacked a prespecified algorithm for preoxygenation and the operators had relatively low amounts of experience with intubations. Finally, the beds used in this study could contribute to the divergences between this intensive care unit experience and the operating room literature. The operating room table is narrower, firmer, and more stable, while by contrast, the ICU bed is wider and softer, they noted. This “may make initial positioning, maintenance of positioning, and accessing the patient’s head more difficult.”

Nevertheless, “[this] important study provides ideas for further study of optimal positioning in the ICU and adds valuable data to the sparse literature on the subject in the ICU setting,” they concluded.

James Aaron Scott, DO, Jens Matthias Walz, MD, FCCP, and Stephen O. Heard, MD, FCCP, are in the department of anesthesiology and perioperative medicine, UMass Memorial Medical Center, Worcester, Mass. The authors reported no conflicts of interest. These comments are based on their editorial.

Editorialists praised the multicenter, randomized design of this study, and its total recruitment of 260 patients. They also noted several limitations of the study that “could shed some light” on the group’s conclusions (Chest. 2017 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.06.002).

“The results diverge from [operating room] literature of the past 15 years that suggest that the ramped position is the preferred intubation position for obese patients or those with an anticipated difficult airway.” This may have been caused by shortcomings of this study’s design and differences between it and other research exploring the topic of patient positioning during endotracheal intubation, they wrote.

The study lacked a prespecified algorithm for preoxygenation and the operators had relatively low amounts of experience with intubations. Finally, the beds used in this study could contribute to the divergences between this intensive care unit experience and the operating room literature. The operating room table is narrower, firmer, and more stable, while by contrast, the ICU bed is wider and softer, they noted. This “may make initial positioning, maintenance of positioning, and accessing the patient’s head more difficult.”

Nevertheless, “[this] important study provides ideas for further study of optimal positioning in the ICU and adds valuable data to the sparse literature on the subject in the ICU setting,” they concluded.

James Aaron Scott, DO, Jens Matthias Walz, MD, FCCP, and Stephen O. Heard, MD, FCCP, are in the department of anesthesiology and perioperative medicine, UMass Memorial Medical Center, Worcester, Mass. The authors reported no conflicts of interest. These comments are based on their editorial.

Editorialists praised the multicenter, randomized design of this study, and its total recruitment of 260 patients. They also noted several limitations of the study that “could shed some light” on the group’s conclusions (Chest. 2017 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.06.002).

“The results diverge from [operating room] literature of the past 15 years that suggest that the ramped position is the preferred intubation position for obese patients or those with an anticipated difficult airway.” This may have been caused by shortcomings of this study’s design and differences between it and other research exploring the topic of patient positioning during endotracheal intubation, they wrote.

The study lacked a prespecified algorithm for preoxygenation and the operators had relatively low amounts of experience with intubations. Finally, the beds used in this study could contribute to the divergences between this intensive care unit experience and the operating room literature. The operating room table is narrower, firmer, and more stable, while by contrast, the ICU bed is wider and softer, they noted. This “may make initial positioning, maintenance of positioning, and accessing the patient’s head more difficult.”

Nevertheless, “[this] important study provides ideas for further study of optimal positioning in the ICU and adds valuable data to the sparse literature on the subject in the ICU setting,” they concluded.

James Aaron Scott, DO, Jens Matthias Walz, MD, FCCP, and Stephen O. Heard, MD, FCCP, are in the department of anesthesiology and perioperative medicine, UMass Memorial Medical Center, Worcester, Mass. The authors reported no conflicts of interest. These comments are based on their editorial.

In critically ill adults undergoing endotracheal intubation, the ramped position does not significantly improve oxygenation compared with the sniffing position, according to results of a multicenter, randomized trial of 260 patients treated in an intensive care unit.

Moreover, “[ramped] position appeared to worsen glottic view and increase the number of attempts required for successful intubation,” wrote Matthew W. Semler, MD, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., and his coauthors (Chest. 2017 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.03.061).

The ramped and sniffing positions are the two most common patient positions used during emergent intubation, according to investigators. The sniffing position is characterized by supine torso, neck flexed forward, and head extended, while ramped position involves elevating the torso and head.

Some believe the ramped position may offer superior anatomic alignment of the upper airway; however, only a few observational studies suggest it is associated with fewer complications than the sniffing position, the authors wrote.

Accordingly, they conducted a multicenter randomized trial with a primary endpoint of lowest arterial oxygen saturation, hypothesizing that the endpoint would be higher for the ramped position: “Our primary outcome of lowest arterial oxygen saturation is an established endpoint in ICU intubation trials, and is linked to periprocedural cardiac arrest and death,” they wrote.

The investigators instead found that median lowest arterial oxygen saturation was not statistically different between groups, at 93% for the ramped position, and 92% for the sniffing position (P = 0.27), published data show.

Further results showed that the ramped position appeared to be associated with poor glottic view and more difficult intubation. The incidence of grade III (only epiglottis) or grade IV (no visible glottis structures) views were 25.4% for ramped vs. 11.5% for sniffing (P = .01), while the rate of first-attempt intubation was 76.2% for ramped vs 85.4% for sniffing (P = .02).

While the findings are compelling, the authors were forthcoming about the potential limitations of the study and differences compared with earlier investigations. Notably, they said, all prior controlled trials of patient positioning during endotracheal intubation were conducted in the operating room, rather than in the ICU.

Also, the operators’ skill levels may further explain differences in this study’s outcomes from those of similar studies, the researchers noted. Earlier studies included patients intubated by one or two senior anesthesiologists from one center, while this trial involved 30 operators across multiple centers, with the average operator having performed 60 previous intubations. “Thus, our findings may generalize to settings in which airway management is performed by trainees, but whether results would be similar among expert operators remains unknown,” the investigators noted.

The authors reported no potential conflicts of interest. One coauthor reported serving on an advisory board for Avisa Pharma.

In critically ill adults undergoing endotracheal intubation, the ramped position does not significantly improve oxygenation compared with the sniffing position, according to results of a multicenter, randomized trial of 260 patients treated in an intensive care unit.

Moreover, “[ramped] position appeared to worsen glottic view and increase the number of attempts required for successful intubation,” wrote Matthew W. Semler, MD, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., and his coauthors (Chest. 2017 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.03.061).

The ramped and sniffing positions are the two most common patient positions used during emergent intubation, according to investigators. The sniffing position is characterized by supine torso, neck flexed forward, and head extended, while ramped position involves elevating the torso and head.

Some believe the ramped position may offer superior anatomic alignment of the upper airway; however, only a few observational studies suggest it is associated with fewer complications than the sniffing position, the authors wrote.

Accordingly, they conducted a multicenter randomized trial with a primary endpoint of lowest arterial oxygen saturation, hypothesizing that the endpoint would be higher for the ramped position: “Our primary outcome of lowest arterial oxygen saturation is an established endpoint in ICU intubation trials, and is linked to periprocedural cardiac arrest and death,” they wrote.

The investigators instead found that median lowest arterial oxygen saturation was not statistically different between groups, at 93% for the ramped position, and 92% for the sniffing position (P = 0.27), published data show.

Further results showed that the ramped position appeared to be associated with poor glottic view and more difficult intubation. The incidence of grade III (only epiglottis) or grade IV (no visible glottis structures) views were 25.4% for ramped vs. 11.5% for sniffing (P = .01), while the rate of first-attempt intubation was 76.2% for ramped vs 85.4% for sniffing (P = .02).

While the findings are compelling, the authors were forthcoming about the potential limitations of the study and differences compared with earlier investigations. Notably, they said, all prior controlled trials of patient positioning during endotracheal intubation were conducted in the operating room, rather than in the ICU.

Also, the operators’ skill levels may further explain differences in this study’s outcomes from those of similar studies, the researchers noted. Earlier studies included patients intubated by one or two senior anesthesiologists from one center, while this trial involved 30 operators across multiple centers, with the average operator having performed 60 previous intubations. “Thus, our findings may generalize to settings in which airway management is performed by trainees, but whether results would be similar among expert operators remains unknown,” the investigators noted.

The authors reported no potential conflicts of interest. One coauthor reported serving on an advisory board for Avisa Pharma.

FROM CHEST

Key clinical point: During endotracheal intubation of critically ill adults, use of the ramped position did not significantly improve oxygenation compared with the sniffing position, and it increased the number of attempts needed to achieve successful intubation.

Major finding: The median lowest arterial oxygen saturation was 93% for the ramped position and 92% for the sniffing position (P = .27).

Data source: Multicenter, randomized trial of 260 critically ill adults undergoing endotracheal intubation.

Disclosures: The authors reported no potential conflicts of interest. One coauthor reported serving on an advisory board for Avisa Pharma.

ACS Clinical Congress: Don’t miss these sessions

The ACS Clinical Congress will get underway on Saturday, Oct. 21, in San Diego. The vast array of sessions, presentations, and special events can be overwhelming. The best way to manage your time is to download the meeting app and start planning to attend must-see sessions and other events. The app lets you search by day, speaker, track, and type of session, so you can build your daily schedule and connect with colleagues. The ACS Surgery News editorial team, reporters, and videographers will be on site covering many sessions and posting stories and interviews daily on the web page.

Don’t miss these sessions

Acoustic gunshot sensor technology impacts trauma care.

Press Conference: TUESDAY, OCTOBER 24 - 10:30-11:00 a.m.

Location: Room 21 – San Diego Convention Center (Upper level)

~~~~

Lessons Learned from Las Vegas and other Major Intentional Mass Casualty Events.

Panel Session: TUESDAY, OCTOBER 24 – 8:00 – 9:30 a.m.

Location: 2, Upper Level of the San Diego Convention Center.

The ACS Surgery News editorial team offers the following picks among the hundreds of panels, sessions, and scientific forums:

•PS101: Controversies in the Management of Complicated Diverticulitis (Monday, Oct. 23, 9:45 am - 11:15 am, Hall F)

•PS104: The Gut Microbiome: Implications for Surgical Complications (Monday, Oct. 23, 9:45 am - 11:15 am, Room 20D)

•PS108: Management of Axilla in Breast Cancer (Monday, Oct. 23, 9:45 am - 11:15 am, 20A)