User login

Official Newspaper of the American College of Surgeons

Medicare pay values procedures over cognitive services

Medicare pays three to five times more per hour for two common procedures than it does for evaluation and management services, according to a new study, and that imbalance may help push physicians away from primary care careers.

Dr. Christine A. Sinsky, an internist in Dubuque, Iowa, and Dr. David C. Dugdale, of the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, decided to delve into the disparities between pay for primary care and procedures, hypothesizing that the gap is helping tilt the health system toward an emphasis on procedural over cognitive care.

Their findings were published online Aug. 12 in JAMA Internal Medicine (doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9257).

After reviewing their data, the authors squarely blame the American Medical Association’s Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC) and Medicare for creating incentives that reward procedures over complex management of chronic illness.

The study authors compared hourly revenue for a physician performing cognitive services (CPT code 99214) to the hourly revenue generated by a physician performing either screening colonoscopy (G code 0121) or cataract extraction (CPT code 66984). They chose these codes because they are among Medicare’s most billed codes. The 99214 code ranks second, cataract extraction is fourth, and colonoscopy is 36th.

The authors focused on the work-specific relative value unit (wRVU), saying that it most accurately reflected the amount of time physicians put into a visit or procedure.

They found that doctors billing the evaluation and management (E&M) code of 99214 received hourly revenue of $87. Screening colonoscopy, on the other hand, generated hourly revenue of $320, and cataract extraction generated $423 per hour.

These wages did not correspond to time spent on services, or intensity, said Dr. Sinsky and Dr. Dugdale.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) requires physicians to spend 25 minutes face-to-face with the patient to be reimbursed for the 99214 code. There are no such requirements for procedural codes. Using reports in the literature, the authors estimated that a colonoscopy takes 13.5 minutes, and a cataract extraction takes 14 minutes.

However, the AMA’s RUC used vastly different times when it set the wRVU for both cognitive services and procedures, the authors said. According to their research, the RUC estimates that 99214 requires 40 minutes, a colonoscopy 75 minutes, and a cataract extraction 84 minutes. That results in hourly revenue of $77, $100, and $121, respectively – much less of a gap than what Dr. Sinsky and Dr. Dugdale found.

The researchers offered two explanations for the discrepancy between the RUC’s calculations and their own determinations.

First, primary care physicians are vastly underrepresented on the RUC, making up 16% of the voting members despite making up half of the U.S. physician population. The relative imbalance of primary care representation has been a source of ire for family physicians and internists.

Second, "the RUC method uses self-reported times for services in which the purpose of the survey (to establish payment rates) is known to the respondents who stand to benefit by inflated estimates," the study authors noted.

Dr. Sinsky and Dr. Dugdale said that their estimates may be conservative, because physicians who bill for cognitive services generally do a lot of work between appointments that is not reimbursed. Even if they can’t exactly quantify the gap, it is there, they said.

"Our model demonstrates that an ophthalmologist will receive more revenue from Medicare for four cataract extractions, typically requiring 1-2 hours of time, than a PCP [primary care physician] will receive for an entire day of delivering complex care for chronic illness to Medicare patients," they wrote.

Overall, the reimbursement gap is "a major contributor to the decline in the number of physicians choosing primary care careers," the researchers noted. And it likely also helps fuel the ongoing growth in "expensive procedural care," they added.

That "is worthy of further evaluation," concluded Dr. Sinsky and Dr. Dugdale.

Dr. Sinsky and Dr. Dugdale reported no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @aliciaault

Medicare pays three to five times more per hour for two common procedures than it does for evaluation and management services, according to a new study, and that imbalance may help push physicians away from primary care careers.

Dr. Christine A. Sinsky, an internist in Dubuque, Iowa, and Dr. David C. Dugdale, of the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, decided to delve into the disparities between pay for primary care and procedures, hypothesizing that the gap is helping tilt the health system toward an emphasis on procedural over cognitive care.

Their findings were published online Aug. 12 in JAMA Internal Medicine (doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9257).

After reviewing their data, the authors squarely blame the American Medical Association’s Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC) and Medicare for creating incentives that reward procedures over complex management of chronic illness.

The study authors compared hourly revenue for a physician performing cognitive services (CPT code 99214) to the hourly revenue generated by a physician performing either screening colonoscopy (G code 0121) or cataract extraction (CPT code 66984). They chose these codes because they are among Medicare’s most billed codes. The 99214 code ranks second, cataract extraction is fourth, and colonoscopy is 36th.

The authors focused on the work-specific relative value unit (wRVU), saying that it most accurately reflected the amount of time physicians put into a visit or procedure.

They found that doctors billing the evaluation and management (E&M) code of 99214 received hourly revenue of $87. Screening colonoscopy, on the other hand, generated hourly revenue of $320, and cataract extraction generated $423 per hour.

These wages did not correspond to time spent on services, or intensity, said Dr. Sinsky and Dr. Dugdale.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) requires physicians to spend 25 minutes face-to-face with the patient to be reimbursed for the 99214 code. There are no such requirements for procedural codes. Using reports in the literature, the authors estimated that a colonoscopy takes 13.5 minutes, and a cataract extraction takes 14 minutes.

However, the AMA’s RUC used vastly different times when it set the wRVU for both cognitive services and procedures, the authors said. According to their research, the RUC estimates that 99214 requires 40 minutes, a colonoscopy 75 minutes, and a cataract extraction 84 minutes. That results in hourly revenue of $77, $100, and $121, respectively – much less of a gap than what Dr. Sinsky and Dr. Dugdale found.

The researchers offered two explanations for the discrepancy between the RUC’s calculations and their own determinations.

First, primary care physicians are vastly underrepresented on the RUC, making up 16% of the voting members despite making up half of the U.S. physician population. The relative imbalance of primary care representation has been a source of ire for family physicians and internists.

Second, "the RUC method uses self-reported times for services in which the purpose of the survey (to establish payment rates) is known to the respondents who stand to benefit by inflated estimates," the study authors noted.

Dr. Sinsky and Dr. Dugdale said that their estimates may be conservative, because physicians who bill for cognitive services generally do a lot of work between appointments that is not reimbursed. Even if they can’t exactly quantify the gap, it is there, they said.

"Our model demonstrates that an ophthalmologist will receive more revenue from Medicare for four cataract extractions, typically requiring 1-2 hours of time, than a PCP [primary care physician] will receive for an entire day of delivering complex care for chronic illness to Medicare patients," they wrote.

Overall, the reimbursement gap is "a major contributor to the decline in the number of physicians choosing primary care careers," the researchers noted. And it likely also helps fuel the ongoing growth in "expensive procedural care," they added.

That "is worthy of further evaluation," concluded Dr. Sinsky and Dr. Dugdale.

Dr. Sinsky and Dr. Dugdale reported no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @aliciaault

Medicare pays three to five times more per hour for two common procedures than it does for evaluation and management services, according to a new study, and that imbalance may help push physicians away from primary care careers.

Dr. Christine A. Sinsky, an internist in Dubuque, Iowa, and Dr. David C. Dugdale, of the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, decided to delve into the disparities between pay for primary care and procedures, hypothesizing that the gap is helping tilt the health system toward an emphasis on procedural over cognitive care.

Their findings were published online Aug. 12 in JAMA Internal Medicine (doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9257).

After reviewing their data, the authors squarely blame the American Medical Association’s Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC) and Medicare for creating incentives that reward procedures over complex management of chronic illness.

The study authors compared hourly revenue for a physician performing cognitive services (CPT code 99214) to the hourly revenue generated by a physician performing either screening colonoscopy (G code 0121) or cataract extraction (CPT code 66984). They chose these codes because they are among Medicare’s most billed codes. The 99214 code ranks second, cataract extraction is fourth, and colonoscopy is 36th.

The authors focused on the work-specific relative value unit (wRVU), saying that it most accurately reflected the amount of time physicians put into a visit or procedure.

They found that doctors billing the evaluation and management (E&M) code of 99214 received hourly revenue of $87. Screening colonoscopy, on the other hand, generated hourly revenue of $320, and cataract extraction generated $423 per hour.

These wages did not correspond to time spent on services, or intensity, said Dr. Sinsky and Dr. Dugdale.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) requires physicians to spend 25 minutes face-to-face with the patient to be reimbursed for the 99214 code. There are no such requirements for procedural codes. Using reports in the literature, the authors estimated that a colonoscopy takes 13.5 minutes, and a cataract extraction takes 14 minutes.

However, the AMA’s RUC used vastly different times when it set the wRVU for both cognitive services and procedures, the authors said. According to their research, the RUC estimates that 99214 requires 40 minutes, a colonoscopy 75 minutes, and a cataract extraction 84 minutes. That results in hourly revenue of $77, $100, and $121, respectively – much less of a gap than what Dr. Sinsky and Dr. Dugdale found.

The researchers offered two explanations for the discrepancy between the RUC’s calculations and their own determinations.

First, primary care physicians are vastly underrepresented on the RUC, making up 16% of the voting members despite making up half of the U.S. physician population. The relative imbalance of primary care representation has been a source of ire for family physicians and internists.

Second, "the RUC method uses self-reported times for services in which the purpose of the survey (to establish payment rates) is known to the respondents who stand to benefit by inflated estimates," the study authors noted.

Dr. Sinsky and Dr. Dugdale said that their estimates may be conservative, because physicians who bill for cognitive services generally do a lot of work between appointments that is not reimbursed. Even if they can’t exactly quantify the gap, it is there, they said.

"Our model demonstrates that an ophthalmologist will receive more revenue from Medicare for four cataract extractions, typically requiring 1-2 hours of time, than a PCP [primary care physician] will receive for an entire day of delivering complex care for chronic illness to Medicare patients," they wrote.

Overall, the reimbursement gap is "a major contributor to the decline in the number of physicians choosing primary care careers," the researchers noted. And it likely also helps fuel the ongoing growth in "expensive procedural care," they added.

That "is worthy of further evaluation," concluded Dr. Sinsky and Dr. Dugdale.

Dr. Sinsky and Dr. Dugdale reported no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @aliciaault

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Major finding: Two common specialty procedures can generate more revenue in 1-2 hours than a primary care physician receives for an entire day’s work.

Data source: An observational study that used work relative value units to compare pay for an evaluation and management code, screening colonoscopy, and cataract extraction.

Disclosures: Dr. Sinsky and Dr. Dugdale reported no conflicts of interest.

Collaborative quality improvement projects work, expert maintains

SAN DIEGO – In the opinion of Dr. Wayne J. English, it doesn’t take much for collaborative quality improvement projects to demonstrate a return on investment.

At the national conference of the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP), he discussed his experience as a member of the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative (MBSC), a clinical outcomes registry and quality improvement program funded by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan (BCBS) "Hospitals across the state are collecting, sharing, and analyzing data, then designing and implementing changes to improve patient care, and it’s working," said Dr. English, medical director of bariatric surgery at the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute at Marquette (Mich.) General Hospital.

In 1997, a group of five hospitals in Michigan joined with Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation and Blue Care Network to collaborate on the study of variation in angiography procedures and treatment. Recommendations from the group’s analysis "contributed to dramatic decreases in coronary emergency bypass surgeries and other complications," Dr. English said. "The initiative also saved an estimated $102 million in statewide health costs over 3 years." Since then, 11 more initiatives have [been] launched to address many of the most common and costly areas of surgical and medical care in Michigan. These included cardiac imaging, vascular intervention, cardiothoracic surgery, trauma, general surgery, breast cancer, surgical outcomes, hospital medicine, knee/hip replacement, radiation oncology, and bariatric surgery.

Speaking in the context of his experience with the MBSC, Dr. English said that much of the success comes from the three-part approach to each initiative. First, funding from BCBS "enables hospitals to work in collaborative environment," he said. "BCBS provides resources for data collection and analysis along with administrative oversight."

Second, a separate coordinating center serves as a data warehouse, conducts data audits, performs data analyses, and generates comparative performance reports.

Third, participating hospitals "work together by sharing data and best practices to improve patient care throughout the state of Michigan," he said.

The MBSC collects data on perioperative care and outcomes, late outcomes, structure and process of care, technical quality, subjective aspects of quality, and cost. "There are site visits that occur on a regular basis," he said. "There are usually two surgeons and two nurses that go along on a site visit. We share ideas during those visits; these are collegial events."

The primary focus is the registry data. "We look at variation in practice and determine best evidence. We meet three times a year to analyze risk- and reliability-adjusted data, develop quality improvement projects and, ultimately, best practices," Dr. English said. Currently, the collaborative comprises 39 sites, 76 surgeons, and data on more than 40,000 patients. Approximately 6,500 patients are added into the database each year.

Notable outcomes from MBSC projects to date, he said, include a 24% decrease in complication rates from 2007 to 2009, a 35% decrease in readmission rates decreased from 2007 to 2009, and a 35% decreased in ED visits from 2007 to 2010. "The decline in ED visits alone resulted in overall savings for BCBS of Michigan of $4.7 million and an overall savings for statewide plans of $14.6 million," Dr. English said.

One of the first initiatives launched by the MBSC involved a quality improvement effort to reduce the rate of pulmonary embolism, which accounts for almost half of all deaths after bariatric surgery. Standard approaches to prophylaxis include early ambulation, compression stockings/devices, and anticoagulation.

"When we surveyed surgeons in the state of Michigan, we found that there was tremendous variation in how medical chemoprophylaxis was implemented," Dr. English noted. "Many surgeons were using low-molecular-weight heparin and/or unfractionated heparin to varying degrees preoperatively, postoperatively and post discharge, while some used none at all. So the collaborative data determined statistically significant patient risk factors and developed a VTE risk calculator to stratify the baseline risk for VTE. Once surgeons started participating and utilizing risk-stratified treatment guidelines, we started to see a downward trend on the rates of thromboembolic events."

A parallel initiative evaluated the impact of placing inferior vena cava (IVC) filters during bariatric surgery. The value of IVC filters as a prophylaxis in bariatric surgery patients "is unclear, but their use has been growing rapidly since the availability of removable filters," Dr. English said. "According to data from the collaborative, there was wide variability in utilization from never to almost 40% of patients receiving IVC filters."

After analyzing outcomes data from the MBSC, it was discovered that complication rates were significantly higher in patients who had IVC filters placed during bariatric surgery, compared with those who did not. "In fact, over half of deaths and permanent disability were directly attributable to the filter itself," he said. "Once provided with the initial data feedback, many surgeons started decreasing the use of IVC filters during bariatric surgery. Now, fewer than 2% use them."

MBSC data also showed that costs were about $13,000 less per case to perform gastric bypass procedures without the use of IVC filters. "As a result of this one quality improvement project, an estimated $1.3 million was saved over the course of 1 year while all Michigan payers saved an estimated $2.6 million over the course of 1 year," Dr. English said. "That savings is more than enough to cover the cost of operating MBSC each year."

Dr. English disclosed that he serves as a consultant for ReShape Medical.

SAN DIEGO – In the opinion of Dr. Wayne J. English, it doesn’t take much for collaborative quality improvement projects to demonstrate a return on investment.

At the national conference of the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP), he discussed his experience as a member of the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative (MBSC), a clinical outcomes registry and quality improvement program funded by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan (BCBS) "Hospitals across the state are collecting, sharing, and analyzing data, then designing and implementing changes to improve patient care, and it’s working," said Dr. English, medical director of bariatric surgery at the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute at Marquette (Mich.) General Hospital.

In 1997, a group of five hospitals in Michigan joined with Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation and Blue Care Network to collaborate on the study of variation in angiography procedures and treatment. Recommendations from the group’s analysis "contributed to dramatic decreases in coronary emergency bypass surgeries and other complications," Dr. English said. "The initiative also saved an estimated $102 million in statewide health costs over 3 years." Since then, 11 more initiatives have [been] launched to address many of the most common and costly areas of surgical and medical care in Michigan. These included cardiac imaging, vascular intervention, cardiothoracic surgery, trauma, general surgery, breast cancer, surgical outcomes, hospital medicine, knee/hip replacement, radiation oncology, and bariatric surgery.

Speaking in the context of his experience with the MBSC, Dr. English said that much of the success comes from the three-part approach to each initiative. First, funding from BCBS "enables hospitals to work in collaborative environment," he said. "BCBS provides resources for data collection and analysis along with administrative oversight."

Second, a separate coordinating center serves as a data warehouse, conducts data audits, performs data analyses, and generates comparative performance reports.

Third, participating hospitals "work together by sharing data and best practices to improve patient care throughout the state of Michigan," he said.

The MBSC collects data on perioperative care and outcomes, late outcomes, structure and process of care, technical quality, subjective aspects of quality, and cost. "There are site visits that occur on a regular basis," he said. "There are usually two surgeons and two nurses that go along on a site visit. We share ideas during those visits; these are collegial events."

The primary focus is the registry data. "We look at variation in practice and determine best evidence. We meet three times a year to analyze risk- and reliability-adjusted data, develop quality improvement projects and, ultimately, best practices," Dr. English said. Currently, the collaborative comprises 39 sites, 76 surgeons, and data on more than 40,000 patients. Approximately 6,500 patients are added into the database each year.

Notable outcomes from MBSC projects to date, he said, include a 24% decrease in complication rates from 2007 to 2009, a 35% decrease in readmission rates decreased from 2007 to 2009, and a 35% decreased in ED visits from 2007 to 2010. "The decline in ED visits alone resulted in overall savings for BCBS of Michigan of $4.7 million and an overall savings for statewide plans of $14.6 million," Dr. English said.

One of the first initiatives launched by the MBSC involved a quality improvement effort to reduce the rate of pulmonary embolism, which accounts for almost half of all deaths after bariatric surgery. Standard approaches to prophylaxis include early ambulation, compression stockings/devices, and anticoagulation.

"When we surveyed surgeons in the state of Michigan, we found that there was tremendous variation in how medical chemoprophylaxis was implemented," Dr. English noted. "Many surgeons were using low-molecular-weight heparin and/or unfractionated heparin to varying degrees preoperatively, postoperatively and post discharge, while some used none at all. So the collaborative data determined statistically significant patient risk factors and developed a VTE risk calculator to stratify the baseline risk for VTE. Once surgeons started participating and utilizing risk-stratified treatment guidelines, we started to see a downward trend on the rates of thromboembolic events."

A parallel initiative evaluated the impact of placing inferior vena cava (IVC) filters during bariatric surgery. The value of IVC filters as a prophylaxis in bariatric surgery patients "is unclear, but their use has been growing rapidly since the availability of removable filters," Dr. English said. "According to data from the collaborative, there was wide variability in utilization from never to almost 40% of patients receiving IVC filters."

After analyzing outcomes data from the MBSC, it was discovered that complication rates were significantly higher in patients who had IVC filters placed during bariatric surgery, compared with those who did not. "In fact, over half of deaths and permanent disability were directly attributable to the filter itself," he said. "Once provided with the initial data feedback, many surgeons started decreasing the use of IVC filters during bariatric surgery. Now, fewer than 2% use them."

MBSC data also showed that costs were about $13,000 less per case to perform gastric bypass procedures without the use of IVC filters. "As a result of this one quality improvement project, an estimated $1.3 million was saved over the course of 1 year while all Michigan payers saved an estimated $2.6 million over the course of 1 year," Dr. English said. "That savings is more than enough to cover the cost of operating MBSC each year."

Dr. English disclosed that he serves as a consultant for ReShape Medical.

SAN DIEGO – In the opinion of Dr. Wayne J. English, it doesn’t take much for collaborative quality improvement projects to demonstrate a return on investment.

At the national conference of the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP), he discussed his experience as a member of the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative (MBSC), a clinical outcomes registry and quality improvement program funded by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan (BCBS) "Hospitals across the state are collecting, sharing, and analyzing data, then designing and implementing changes to improve patient care, and it’s working," said Dr. English, medical director of bariatric surgery at the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute at Marquette (Mich.) General Hospital.

In 1997, a group of five hospitals in Michigan joined with Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation and Blue Care Network to collaborate on the study of variation in angiography procedures and treatment. Recommendations from the group’s analysis "contributed to dramatic decreases in coronary emergency bypass surgeries and other complications," Dr. English said. "The initiative also saved an estimated $102 million in statewide health costs over 3 years." Since then, 11 more initiatives have [been] launched to address many of the most common and costly areas of surgical and medical care in Michigan. These included cardiac imaging, vascular intervention, cardiothoracic surgery, trauma, general surgery, breast cancer, surgical outcomes, hospital medicine, knee/hip replacement, radiation oncology, and bariatric surgery.

Speaking in the context of his experience with the MBSC, Dr. English said that much of the success comes from the three-part approach to each initiative. First, funding from BCBS "enables hospitals to work in collaborative environment," he said. "BCBS provides resources for data collection and analysis along with administrative oversight."

Second, a separate coordinating center serves as a data warehouse, conducts data audits, performs data analyses, and generates comparative performance reports.

Third, participating hospitals "work together by sharing data and best practices to improve patient care throughout the state of Michigan," he said.

The MBSC collects data on perioperative care and outcomes, late outcomes, structure and process of care, technical quality, subjective aspects of quality, and cost. "There are site visits that occur on a regular basis," he said. "There are usually two surgeons and two nurses that go along on a site visit. We share ideas during those visits; these are collegial events."

The primary focus is the registry data. "We look at variation in practice and determine best evidence. We meet three times a year to analyze risk- and reliability-adjusted data, develop quality improvement projects and, ultimately, best practices," Dr. English said. Currently, the collaborative comprises 39 sites, 76 surgeons, and data on more than 40,000 patients. Approximately 6,500 patients are added into the database each year.

Notable outcomes from MBSC projects to date, he said, include a 24% decrease in complication rates from 2007 to 2009, a 35% decrease in readmission rates decreased from 2007 to 2009, and a 35% decreased in ED visits from 2007 to 2010. "The decline in ED visits alone resulted in overall savings for BCBS of Michigan of $4.7 million and an overall savings for statewide plans of $14.6 million," Dr. English said.

One of the first initiatives launched by the MBSC involved a quality improvement effort to reduce the rate of pulmonary embolism, which accounts for almost half of all deaths after bariatric surgery. Standard approaches to prophylaxis include early ambulation, compression stockings/devices, and anticoagulation.

"When we surveyed surgeons in the state of Michigan, we found that there was tremendous variation in how medical chemoprophylaxis was implemented," Dr. English noted. "Many surgeons were using low-molecular-weight heparin and/or unfractionated heparin to varying degrees preoperatively, postoperatively and post discharge, while some used none at all. So the collaborative data determined statistically significant patient risk factors and developed a VTE risk calculator to stratify the baseline risk for VTE. Once surgeons started participating and utilizing risk-stratified treatment guidelines, we started to see a downward trend on the rates of thromboembolic events."

A parallel initiative evaluated the impact of placing inferior vena cava (IVC) filters during bariatric surgery. The value of IVC filters as a prophylaxis in bariatric surgery patients "is unclear, but their use has been growing rapidly since the availability of removable filters," Dr. English said. "According to data from the collaborative, there was wide variability in utilization from never to almost 40% of patients receiving IVC filters."

After analyzing outcomes data from the MBSC, it was discovered that complication rates were significantly higher in patients who had IVC filters placed during bariatric surgery, compared with those who did not. "In fact, over half of deaths and permanent disability were directly attributable to the filter itself," he said. "Once provided with the initial data feedback, many surgeons started decreasing the use of IVC filters during bariatric surgery. Now, fewer than 2% use them."

MBSC data also showed that costs were about $13,000 less per case to perform gastric bypass procedures without the use of IVC filters. "As a result of this one quality improvement project, an estimated $1.3 million was saved over the course of 1 year while all Michigan payers saved an estimated $2.6 million over the course of 1 year," Dr. English said. "That savings is more than enough to cover the cost of operating MBSC each year."

Dr. English disclosed that he serves as a consultant for ReShape Medical.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT THE ACS NSQIP NATIONAL CONFERENCE

HIV postexposure prophylaxis guidelines revised

Revised federal guidelines for managing health care workers who are exposed to HIV recommend using at least three drugs for prophylaxis in all cases instead of assessing a person’s risk to decide on the number of drugs, among other updates to the guidelines.

Changes in the recommended drugs in preferred postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) regimens should make them easier to tolerate than earlier regimens and may increase the proportion of health care workers who are able to complete the 28-day treatment, Dr. David T. Kuhar and his associates said in the new document from the U.S. Public Health Service.

Another change is that follow-up HIV testing in health care workers on PEP can be shortened to 4 months instead of 6 months if a newer fourth-generation combination HIV p24 antigen/HIV antibody test is used, the guidelines state. The document, which updates 2005 guidelines, was published online in the journal Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology (2013 Aug. 7 [doi: 10.1086/672271]).

The updates are based on expert opinion in a working group comprised of representatives from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the National Institutes of Health, the Food and Drug Administration, and the Health Resources and Services Administration, in consultation with a panel of experts, wrote Dr. Kuhar of the CDC and his associates.

The principles of PEP remain the same: Occupational exposures to HIV in health care workers should be considered urgent medical concerns, and should be reported and managed promptly under your institution’s procedures. Determine the HIV status of the patient whose blood or other bodily fluids potentially exposed the health care worker to HIV, if possible, to guide the need for PEP. Start PEP as soon as possible (within hours) after the exposure if PEP is indicated. Expert consultation is recommended, but PEP initiation should not be delayed while waiting for a consult. Close follow-up should start within 72 hours of HIV exposure and include counseling, baseline and follow-up HIV testing, and monitoring for drug toxicity, according to the guidelines.

Clinicians can consult experts locally or can call the National Clinicians’ Post-Exposure Prophylaxis Hotline (PEPline) at 888-448-4911.

The PEPline received approximately 10,000 calls in 2012 from clinicians about potential occupational exposures to HIV, said Dr. Ronald Goldschmidt of the department of family and community medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. He is director of the university’s National HIV/AIDS Clinicians’ Consultation Center, which includes the PEPline. Dr. Goldschmidt was a member of the panel of experts that consulted on the guidelines update.

Several new antiretroviral agents have been approved since the last update to the guidelines in 2005, and more information has become available about the use and side effects of the PEP medications. Clinicians had struggled with the 2005 version’s recommendations to assess the level of risk of HIV transmission in individual exposure incidents, creating problems in deciding whether to use two or three or more drugs in PEP regiments.

The new guidelines’ preferred HIV PEP regimen is oral raltegravir (Isentress) 400 mg twice daily and once-daily Truvada (a fixed-dose combination tablet containing 300 mg of tenofovir and 200 mg of emtricitabine). "Preparation of this PEP regimen in single-dose ‘starter packets,’ which are kept on hand at sites expected to manage occupational exposures to HIV, may facilitate timely initiation of PEP," the guidelines state.

Dr. Goldschmidt cautioned that Truvada should not be used before checking for preexisting renal problems. If there’s a history of renal problems, consult an HIV expert or consider a different regimen, he said.

An appendix to the document lists recommended and contraindicated alternatives.

Although there are no new definitive data showing greater efficacy with three-drug regimens for PEP compared with two-drug regimens for occupational HIV exposures, the new recommendation to use at least three drugs rests on studies showing greater reduction of viral burden in HIV-infected patients on three antiretroviral drugs instead of two, concerns about drug resistance in source patients of occupational exposures, and better safety and tolerability with some of the newer medications. The guidelines add a caveat that two-drug PEP regimens might be considered in consultation with an expert if antiretrovirals aren’t easily available or because of adherence or toxicity issues.

None of the antiretroviral agents have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use as PEP.

The previous complicated recommendations to assess a health care worker’s level of risk after a potential exposure to HIV were enshrined in a 2001 version of the guidelines, Dr. Goldschmidt said. The 2005 revision updated the recommended drugs but didn’t simplify the risk assessment. The current update makes decision-making less confusing by recommending at least a three-drug regimen for all occupational PEP cases and using better-tolerated drugs.

"With the simplification at this point, they’re throwing away those old tables that required clinicians to assess risk" and decreased the likelihood that PEP would be administered appropriately and completed, he said.

Separate guidelines have been published previously for management of nonoccupational HIV exposure (sexual, pediatric, or perinatal exposures).

Dr. Kuhar reported having no financial disclosures. Some of his coauthors reported financial associations with Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, and other companies. Dr. Goldschmidt reported having no financial disclosures.

Exposed health care workers and those managing their exposures will now have more PEP options to consider. This offers the benefit of being able to individualize therapy to the individual; however, for providers with less experience in managing HIV exposures, having these options may be more confusing or intimidating. For that reason, expert resources like the HIV PEPline (888-448-4911) will be increasingly important.

These regimens will be more expensive. There aren’t any data to suggest that these three-drug regimens will be more effective in PEP. Here’s why the guideline authors said they made the change:

|

|

"The recommendation for consistent use of three-drug HIV PEP regimens reflects (1) studies demonstrating superior effectiveness of three drugs in reducing viral burden in HIV-infected persons compared with two agents; (2) concerns about source patient drug resistance to agents commonly used for PEP; (3) the safety and tolerability of new HIV drugs, and (4) the potential for improved PEP regimen adherence due to newer medications that are likely to have fewer side effects. Clinicians facing challenges such as antiretroviral medication availability, potential adherence and toxicity issues, and others associated with a three-drug PEP regimen might still consider a two-drug PEP regimen in consultation with an expert."

Any time you use more drugs, there is an opportunity for side effects. While the medications recommended here are generally safe and well tolerated, careful monitoring for side effects will be important for individuals receiving PEP.

In addition their improved tolerability, I think the other rationale for recommending these exact regimens is based on these regimens being less likely to have resistance.

Dr. C. Bradley Hare is medical director of the HIV/AIDS Clinic at San Francisco General Hospital. He has been a consultant or speaker for the following companies that make HIV medications: Gilead, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Merck, and AbbVie Pharmaceuticals.

Exposed health care workers and those managing their exposures will now have more PEP options to consider. This offers the benefit of being able to individualize therapy to the individual; however, for providers with less experience in managing HIV exposures, having these options may be more confusing or intimidating. For that reason, expert resources like the HIV PEPline (888-448-4911) will be increasingly important.

These regimens will be more expensive. There aren’t any data to suggest that these three-drug regimens will be more effective in PEP. Here’s why the guideline authors said they made the change:

|

|

"The recommendation for consistent use of three-drug HIV PEP regimens reflects (1) studies demonstrating superior effectiveness of three drugs in reducing viral burden in HIV-infected persons compared with two agents; (2) concerns about source patient drug resistance to agents commonly used for PEP; (3) the safety and tolerability of new HIV drugs, and (4) the potential for improved PEP regimen adherence due to newer medications that are likely to have fewer side effects. Clinicians facing challenges such as antiretroviral medication availability, potential adherence and toxicity issues, and others associated with a three-drug PEP regimen might still consider a two-drug PEP regimen in consultation with an expert."

Any time you use more drugs, there is an opportunity for side effects. While the medications recommended here are generally safe and well tolerated, careful monitoring for side effects will be important for individuals receiving PEP.

In addition their improved tolerability, I think the other rationale for recommending these exact regimens is based on these regimens being less likely to have resistance.

Dr. C. Bradley Hare is medical director of the HIV/AIDS Clinic at San Francisco General Hospital. He has been a consultant or speaker for the following companies that make HIV medications: Gilead, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Merck, and AbbVie Pharmaceuticals.

Exposed health care workers and those managing their exposures will now have more PEP options to consider. This offers the benefit of being able to individualize therapy to the individual; however, for providers with less experience in managing HIV exposures, having these options may be more confusing or intimidating. For that reason, expert resources like the HIV PEPline (888-448-4911) will be increasingly important.

These regimens will be more expensive. There aren’t any data to suggest that these three-drug regimens will be more effective in PEP. Here’s why the guideline authors said they made the change:

|

|

"The recommendation for consistent use of three-drug HIV PEP regimens reflects (1) studies demonstrating superior effectiveness of three drugs in reducing viral burden in HIV-infected persons compared with two agents; (2) concerns about source patient drug resistance to agents commonly used for PEP; (3) the safety and tolerability of new HIV drugs, and (4) the potential for improved PEP regimen adherence due to newer medications that are likely to have fewer side effects. Clinicians facing challenges such as antiretroviral medication availability, potential adherence and toxicity issues, and others associated with a three-drug PEP regimen might still consider a two-drug PEP regimen in consultation with an expert."

Any time you use more drugs, there is an opportunity for side effects. While the medications recommended here are generally safe and well tolerated, careful monitoring for side effects will be important for individuals receiving PEP.

In addition their improved tolerability, I think the other rationale for recommending these exact regimens is based on these regimens being less likely to have resistance.

Dr. C. Bradley Hare is medical director of the HIV/AIDS Clinic at San Francisco General Hospital. He has been a consultant or speaker for the following companies that make HIV medications: Gilead, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Merck, and AbbVie Pharmaceuticals.

Revised federal guidelines for managing health care workers who are exposed to HIV recommend using at least three drugs for prophylaxis in all cases instead of assessing a person’s risk to decide on the number of drugs, among other updates to the guidelines.

Changes in the recommended drugs in preferred postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) regimens should make them easier to tolerate than earlier regimens and may increase the proportion of health care workers who are able to complete the 28-day treatment, Dr. David T. Kuhar and his associates said in the new document from the U.S. Public Health Service.

Another change is that follow-up HIV testing in health care workers on PEP can be shortened to 4 months instead of 6 months if a newer fourth-generation combination HIV p24 antigen/HIV antibody test is used, the guidelines state. The document, which updates 2005 guidelines, was published online in the journal Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology (2013 Aug. 7 [doi: 10.1086/672271]).

The updates are based on expert opinion in a working group comprised of representatives from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the National Institutes of Health, the Food and Drug Administration, and the Health Resources and Services Administration, in consultation with a panel of experts, wrote Dr. Kuhar of the CDC and his associates.

The principles of PEP remain the same: Occupational exposures to HIV in health care workers should be considered urgent medical concerns, and should be reported and managed promptly under your institution’s procedures. Determine the HIV status of the patient whose blood or other bodily fluids potentially exposed the health care worker to HIV, if possible, to guide the need for PEP. Start PEP as soon as possible (within hours) after the exposure if PEP is indicated. Expert consultation is recommended, but PEP initiation should not be delayed while waiting for a consult. Close follow-up should start within 72 hours of HIV exposure and include counseling, baseline and follow-up HIV testing, and monitoring for drug toxicity, according to the guidelines.

Clinicians can consult experts locally or can call the National Clinicians’ Post-Exposure Prophylaxis Hotline (PEPline) at 888-448-4911.

The PEPline received approximately 10,000 calls in 2012 from clinicians about potential occupational exposures to HIV, said Dr. Ronald Goldschmidt of the department of family and community medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. He is director of the university’s National HIV/AIDS Clinicians’ Consultation Center, which includes the PEPline. Dr. Goldschmidt was a member of the panel of experts that consulted on the guidelines update.

Several new antiretroviral agents have been approved since the last update to the guidelines in 2005, and more information has become available about the use and side effects of the PEP medications. Clinicians had struggled with the 2005 version’s recommendations to assess the level of risk of HIV transmission in individual exposure incidents, creating problems in deciding whether to use two or three or more drugs in PEP regiments.

The new guidelines’ preferred HIV PEP regimen is oral raltegravir (Isentress) 400 mg twice daily and once-daily Truvada (a fixed-dose combination tablet containing 300 mg of tenofovir and 200 mg of emtricitabine). "Preparation of this PEP regimen in single-dose ‘starter packets,’ which are kept on hand at sites expected to manage occupational exposures to HIV, may facilitate timely initiation of PEP," the guidelines state.

Dr. Goldschmidt cautioned that Truvada should not be used before checking for preexisting renal problems. If there’s a history of renal problems, consult an HIV expert or consider a different regimen, he said.

An appendix to the document lists recommended and contraindicated alternatives.

Although there are no new definitive data showing greater efficacy with three-drug regimens for PEP compared with two-drug regimens for occupational HIV exposures, the new recommendation to use at least three drugs rests on studies showing greater reduction of viral burden in HIV-infected patients on three antiretroviral drugs instead of two, concerns about drug resistance in source patients of occupational exposures, and better safety and tolerability with some of the newer medications. The guidelines add a caveat that two-drug PEP regimens might be considered in consultation with an expert if antiretrovirals aren’t easily available or because of adherence or toxicity issues.

None of the antiretroviral agents have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use as PEP.

The previous complicated recommendations to assess a health care worker’s level of risk after a potential exposure to HIV were enshrined in a 2001 version of the guidelines, Dr. Goldschmidt said. The 2005 revision updated the recommended drugs but didn’t simplify the risk assessment. The current update makes decision-making less confusing by recommending at least a three-drug regimen for all occupational PEP cases and using better-tolerated drugs.

"With the simplification at this point, they’re throwing away those old tables that required clinicians to assess risk" and decreased the likelihood that PEP would be administered appropriately and completed, he said.

Separate guidelines have been published previously for management of nonoccupational HIV exposure (sexual, pediatric, or perinatal exposures).

Dr. Kuhar reported having no financial disclosures. Some of his coauthors reported financial associations with Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, and other companies. Dr. Goldschmidt reported having no financial disclosures.

Revised federal guidelines for managing health care workers who are exposed to HIV recommend using at least three drugs for prophylaxis in all cases instead of assessing a person’s risk to decide on the number of drugs, among other updates to the guidelines.

Changes in the recommended drugs in preferred postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) regimens should make them easier to tolerate than earlier regimens and may increase the proportion of health care workers who are able to complete the 28-day treatment, Dr. David T. Kuhar and his associates said in the new document from the U.S. Public Health Service.

Another change is that follow-up HIV testing in health care workers on PEP can be shortened to 4 months instead of 6 months if a newer fourth-generation combination HIV p24 antigen/HIV antibody test is used, the guidelines state. The document, which updates 2005 guidelines, was published online in the journal Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology (2013 Aug. 7 [doi: 10.1086/672271]).

The updates are based on expert opinion in a working group comprised of representatives from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the National Institutes of Health, the Food and Drug Administration, and the Health Resources and Services Administration, in consultation with a panel of experts, wrote Dr. Kuhar of the CDC and his associates.

The principles of PEP remain the same: Occupational exposures to HIV in health care workers should be considered urgent medical concerns, and should be reported and managed promptly under your institution’s procedures. Determine the HIV status of the patient whose blood or other bodily fluids potentially exposed the health care worker to HIV, if possible, to guide the need for PEP. Start PEP as soon as possible (within hours) after the exposure if PEP is indicated. Expert consultation is recommended, but PEP initiation should not be delayed while waiting for a consult. Close follow-up should start within 72 hours of HIV exposure and include counseling, baseline and follow-up HIV testing, and monitoring for drug toxicity, according to the guidelines.

Clinicians can consult experts locally or can call the National Clinicians’ Post-Exposure Prophylaxis Hotline (PEPline) at 888-448-4911.

The PEPline received approximately 10,000 calls in 2012 from clinicians about potential occupational exposures to HIV, said Dr. Ronald Goldschmidt of the department of family and community medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. He is director of the university’s National HIV/AIDS Clinicians’ Consultation Center, which includes the PEPline. Dr. Goldschmidt was a member of the panel of experts that consulted on the guidelines update.

Several new antiretroviral agents have been approved since the last update to the guidelines in 2005, and more information has become available about the use and side effects of the PEP medications. Clinicians had struggled with the 2005 version’s recommendations to assess the level of risk of HIV transmission in individual exposure incidents, creating problems in deciding whether to use two or three or more drugs in PEP regiments.

The new guidelines’ preferred HIV PEP regimen is oral raltegravir (Isentress) 400 mg twice daily and once-daily Truvada (a fixed-dose combination tablet containing 300 mg of tenofovir and 200 mg of emtricitabine). "Preparation of this PEP regimen in single-dose ‘starter packets,’ which are kept on hand at sites expected to manage occupational exposures to HIV, may facilitate timely initiation of PEP," the guidelines state.

Dr. Goldschmidt cautioned that Truvada should not be used before checking for preexisting renal problems. If there’s a history of renal problems, consult an HIV expert or consider a different regimen, he said.

An appendix to the document lists recommended and contraindicated alternatives.

Although there are no new definitive data showing greater efficacy with three-drug regimens for PEP compared with two-drug regimens for occupational HIV exposures, the new recommendation to use at least three drugs rests on studies showing greater reduction of viral burden in HIV-infected patients on three antiretroviral drugs instead of two, concerns about drug resistance in source patients of occupational exposures, and better safety and tolerability with some of the newer medications. The guidelines add a caveat that two-drug PEP regimens might be considered in consultation with an expert if antiretrovirals aren’t easily available or because of adherence or toxicity issues.

None of the antiretroviral agents have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use as PEP.

The previous complicated recommendations to assess a health care worker’s level of risk after a potential exposure to HIV were enshrined in a 2001 version of the guidelines, Dr. Goldschmidt said. The 2005 revision updated the recommended drugs but didn’t simplify the risk assessment. The current update makes decision-making less confusing by recommending at least a three-drug regimen for all occupational PEP cases and using better-tolerated drugs.

"With the simplification at this point, they’re throwing away those old tables that required clinicians to assess risk" and decreased the likelihood that PEP would be administered appropriately and completed, he said.

Separate guidelines have been published previously for management of nonoccupational HIV exposure (sexual, pediatric, or perinatal exposures).

Dr. Kuhar reported having no financial disclosures. Some of his coauthors reported financial associations with Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, and other companies. Dr. Goldschmidt reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM INFECTION CONTROL AND HOSPITAL EPIDEMIOLOGY

Major finding: All PEP regimens for health care workers should include at least three drugs from a new list of easier-to-tolerate regimens, and follow-up HIV testing can be shortened to 4 months if a newer fourth-generation combination HIV p24 antigen/HIV antibody test is used.

Data source: Updated guidelines by the U.S. Public Health Service, based on expert opinion.

Disclosures: Dr. Kuhar reported having no financial disclosures. Some of his coauthors reported financial associations with Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, and other companies. Dr. Goldschmidt reported having no financial disclosures.

New biomarker predicts treatment-resistant GVHD

Elevated plasma levels of the biomarker ST2, measured 2 weeks after allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation, predicted which patients who develop graft-vs.-host disease are unlikely to respond to treatment and are thus at high risk of death within 6 months, according to a report published online Aug. 8 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Approximately half of allogeneic stem-cell transplant recipients develop acute GVHD, and those who don’t respond to high-dose systemic glucocorticoids within 1 month are at high risk of dying within 6 months without relapse of the primary disease for which the transplant was performed. At present, it is difficult to predict which patients will not respond to glucocorticoids.

Adding a patient’s ST2 (suppression of tumorigenicity 2) level to the clinical grade and the target-organ stage of GVHD significantly improves risk prediction, particularly in the important subgroup of patients who have lower-GI GVHD, said Dr. Mark T. Vander Lugt of the department of pediatrics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his associates.

"The improved risk stratification of patients with GVHD with the use of ST2 may permit early evaluation of additional therapies, before the development of resistant disease," they wrote (N. Engl. J. Med. 2013 Aug. 8;369:529-39 [doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1213299]).

This early identification may also "permit more stringent monitoring and preemptive interventions."

ST2, a recently discovered member of the interleukin-1 receptor family, is expressed on hematopoietic cells that play a role in diseases mediated by type-2 helper T cells and is also secreted by endothelial cells, epithelial cells, and fibroblasts in response to inflammatory stimuli.

Dr. Vander Lugt and his colleagues assessed numerous candidate plasma biomarkers to determine which, if any, showed the strongest association with nonresponse to GVHD therapy and could thus be used as risk predictors.

They began by testing plasma samples collected 16 days after transplantation from 10 patients who went on to have a complete response to GVHD therapy and 10 who went on to have progressive GVHD. They identified and quantified 571 proteins in these samples, and found that 197 of them were overexpressed by a factor of at least 1.5 in the patients with progressive GVHD. Twelve of these proteins, in addition to ST2, could be measured using commercially available antibodies suitable for ELISA.

ST2 was the single most accurate biomarker at discriminating between plasma samples from patients who responded to GVHD therapy and plasma samples from patients who did not. The six other best biomarkers were then assessed as a panel and compared against ST2 in samples taken from 381 patients at the onset of GVHD.

The ST2 level was found to be superior to the six-biomarker panel in predicting which patients with GVHD would not respond to glucocorticoids within a month of initiating the treatment, which is an accepted surrogate 6-month mortality. It also was the best predictive biomarker when tested further in three independent cohorts totaling 673 patients, the investigators said.

Patients with high ST2 levels were 2.3 times more likely than those with low ST2 levels to develop treatment-resistant GVHD, and 3.7 times as likely to die within 6 months.

Moreover, "when measured as early as day 14 after transplantation, ST2 concentration was a better predictor of the risk of death than were the other known risk factors, including the age of the recipient, conditioning intensity, donor source, and HLA [human leukocyte antigens] match," Dr. Vander Lugt and his associates wrote.

"We believe that our results may affect the assessment of GVHD risk before the development of GVHD and at the onset of the clinical signs of GVHD; however, a generalizable definition of high risk has yet to be developed and will require larger studies," they added.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The University of Michigan has licensed a pending patent application for the biomarker test to ViraCor and any revenue will be shared with the inventors at the University of Michigan and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle.

Elevated plasma levels of the biomarker ST2, measured 2 weeks after allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation, predicted which patients who develop graft-vs.-host disease are unlikely to respond to treatment and are thus at high risk of death within 6 months, according to a report published online Aug. 8 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Approximately half of allogeneic stem-cell transplant recipients develop acute GVHD, and those who don’t respond to high-dose systemic glucocorticoids within 1 month are at high risk of dying within 6 months without relapse of the primary disease for which the transplant was performed. At present, it is difficult to predict which patients will not respond to glucocorticoids.

Adding a patient’s ST2 (suppression of tumorigenicity 2) level to the clinical grade and the target-organ stage of GVHD significantly improves risk prediction, particularly in the important subgroup of patients who have lower-GI GVHD, said Dr. Mark T. Vander Lugt of the department of pediatrics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his associates.

"The improved risk stratification of patients with GVHD with the use of ST2 may permit early evaluation of additional therapies, before the development of resistant disease," they wrote (N. Engl. J. Med. 2013 Aug. 8;369:529-39 [doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1213299]).

This early identification may also "permit more stringent monitoring and preemptive interventions."

ST2, a recently discovered member of the interleukin-1 receptor family, is expressed on hematopoietic cells that play a role in diseases mediated by type-2 helper T cells and is also secreted by endothelial cells, epithelial cells, and fibroblasts in response to inflammatory stimuli.

Dr. Vander Lugt and his colleagues assessed numerous candidate plasma biomarkers to determine which, if any, showed the strongest association with nonresponse to GVHD therapy and could thus be used as risk predictors.

They began by testing plasma samples collected 16 days after transplantation from 10 patients who went on to have a complete response to GVHD therapy and 10 who went on to have progressive GVHD. They identified and quantified 571 proteins in these samples, and found that 197 of them were overexpressed by a factor of at least 1.5 in the patients with progressive GVHD. Twelve of these proteins, in addition to ST2, could be measured using commercially available antibodies suitable for ELISA.

ST2 was the single most accurate biomarker at discriminating between plasma samples from patients who responded to GVHD therapy and plasma samples from patients who did not. The six other best biomarkers were then assessed as a panel and compared against ST2 in samples taken from 381 patients at the onset of GVHD.

The ST2 level was found to be superior to the six-biomarker panel in predicting which patients with GVHD would not respond to glucocorticoids within a month of initiating the treatment, which is an accepted surrogate 6-month mortality. It also was the best predictive biomarker when tested further in three independent cohorts totaling 673 patients, the investigators said.

Patients with high ST2 levels were 2.3 times more likely than those with low ST2 levels to develop treatment-resistant GVHD, and 3.7 times as likely to die within 6 months.

Moreover, "when measured as early as day 14 after transplantation, ST2 concentration was a better predictor of the risk of death than were the other known risk factors, including the age of the recipient, conditioning intensity, donor source, and HLA [human leukocyte antigens] match," Dr. Vander Lugt and his associates wrote.

"We believe that our results may affect the assessment of GVHD risk before the development of GVHD and at the onset of the clinical signs of GVHD; however, a generalizable definition of high risk has yet to be developed and will require larger studies," they added.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The University of Michigan has licensed a pending patent application for the biomarker test to ViraCor and any revenue will be shared with the inventors at the University of Michigan and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle.

Elevated plasma levels of the biomarker ST2, measured 2 weeks after allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation, predicted which patients who develop graft-vs.-host disease are unlikely to respond to treatment and are thus at high risk of death within 6 months, according to a report published online Aug. 8 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Approximately half of allogeneic stem-cell transplant recipients develop acute GVHD, and those who don’t respond to high-dose systemic glucocorticoids within 1 month are at high risk of dying within 6 months without relapse of the primary disease for which the transplant was performed. At present, it is difficult to predict which patients will not respond to glucocorticoids.

Adding a patient’s ST2 (suppression of tumorigenicity 2) level to the clinical grade and the target-organ stage of GVHD significantly improves risk prediction, particularly in the important subgroup of patients who have lower-GI GVHD, said Dr. Mark T. Vander Lugt of the department of pediatrics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his associates.

"The improved risk stratification of patients with GVHD with the use of ST2 may permit early evaluation of additional therapies, before the development of resistant disease," they wrote (N. Engl. J. Med. 2013 Aug. 8;369:529-39 [doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1213299]).

This early identification may also "permit more stringent monitoring and preemptive interventions."

ST2, a recently discovered member of the interleukin-1 receptor family, is expressed on hematopoietic cells that play a role in diseases mediated by type-2 helper T cells and is also secreted by endothelial cells, epithelial cells, and fibroblasts in response to inflammatory stimuli.

Dr. Vander Lugt and his colleagues assessed numerous candidate plasma biomarkers to determine which, if any, showed the strongest association with nonresponse to GVHD therapy and could thus be used as risk predictors.

They began by testing plasma samples collected 16 days after transplantation from 10 patients who went on to have a complete response to GVHD therapy and 10 who went on to have progressive GVHD. They identified and quantified 571 proteins in these samples, and found that 197 of them were overexpressed by a factor of at least 1.5 in the patients with progressive GVHD. Twelve of these proteins, in addition to ST2, could be measured using commercially available antibodies suitable for ELISA.

ST2 was the single most accurate biomarker at discriminating between plasma samples from patients who responded to GVHD therapy and plasma samples from patients who did not. The six other best biomarkers were then assessed as a panel and compared against ST2 in samples taken from 381 patients at the onset of GVHD.

The ST2 level was found to be superior to the six-biomarker panel in predicting which patients with GVHD would not respond to glucocorticoids within a month of initiating the treatment, which is an accepted surrogate 6-month mortality. It also was the best predictive biomarker when tested further in three independent cohorts totaling 673 patients, the investigators said.

Patients with high ST2 levels were 2.3 times more likely than those with low ST2 levels to develop treatment-resistant GVHD, and 3.7 times as likely to die within 6 months.

Moreover, "when measured as early as day 14 after transplantation, ST2 concentration was a better predictor of the risk of death than were the other known risk factors, including the age of the recipient, conditioning intensity, donor source, and HLA [human leukocyte antigens] match," Dr. Vander Lugt and his associates wrote.

"We believe that our results may affect the assessment of GVHD risk before the development of GVHD and at the onset of the clinical signs of GVHD; however, a generalizable definition of high risk has yet to be developed and will require larger studies," they added.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The University of Michigan has licensed a pending patent application for the biomarker test to ViraCor and any revenue will be shared with the inventors at the University of Michigan and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Major finding: Patients with high ST2 levels were 2.3 times more likely than those with low ST2 levels to develop treatment-resistant GVHD, and 3.7 times as likely to die within 6 months of transplantation

Data source: A series of laboratory studies comparing ST2 against numerous other candidate proteins as a biomarker for nonresponse to GVHD therapy.

Disclosures: The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The University of Michigan has licensed a pending patent application for the biomarker test to ViraCor and any revenue will be shared with the inventors at the University of Michigan and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle.

Health IT coordinator moving on

Upset about the federal government’s meaningful use standards? Don’t take your complaints to Dr. Farzad Mostashari. He’s stepping down from his post as national coordinator for health information technology sometime this fall.

His departure comes as physicians and hospitals are moving toward adoption of Stage 2 of meaningful use, part of the Medicare Electronic Health Record (EHR) incentive program. Dr. Mostashari also has been called to Capitol Hill in recent weeks to field questions from lawmakers on why it is taking so long to make EHR systems talk to one another.

In an e-mail to agency staff on Aug. 6, Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius praised Dr. Mostashari for his work in linking the meaningful use of EHRs to population health goals and laying a "strong foundation" for increasing the interoperability of health records.

Dr. Mostashari, who became national coordinator in 2011, will stay on in his current post for a little while as HHS officials search for a replacement. As for his plans after leaving HHS, Dr. Mostashari said that he’s not sure.

"It is difficult for me to announce that I am leaving," he wrote in an e-mail to staff at the Office of the National Coordinator of Health Information Technology. "I don’t know what I will be doing after I leave public service, but be assured that I will be by your side as we continue to battle for healthcare transformation, cheering you on."

–By Mary Ellen Schneider

On Twitter @MaryEllenNY

Upset about the federal government’s meaningful use standards? Don’t take your complaints to Dr. Farzad Mostashari. He’s stepping down from his post as national coordinator for health information technology sometime this fall.

His departure comes as physicians and hospitals are moving toward adoption of Stage 2 of meaningful use, part of the Medicare Electronic Health Record (EHR) incentive program. Dr. Mostashari also has been called to Capitol Hill in recent weeks to field questions from lawmakers on why it is taking so long to make EHR systems talk to one another.

In an e-mail to agency staff on Aug. 6, Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius praised Dr. Mostashari for his work in linking the meaningful use of EHRs to population health goals and laying a "strong foundation" for increasing the interoperability of health records.

Dr. Mostashari, who became national coordinator in 2011, will stay on in his current post for a little while as HHS officials search for a replacement. As for his plans after leaving HHS, Dr. Mostashari said that he’s not sure.

"It is difficult for me to announce that I am leaving," he wrote in an e-mail to staff at the Office of the National Coordinator of Health Information Technology. "I don’t know what I will be doing after I leave public service, but be assured that I will be by your side as we continue to battle for healthcare transformation, cheering you on."

–By Mary Ellen Schneider

On Twitter @MaryEllenNY

Upset about the federal government’s meaningful use standards? Don’t take your complaints to Dr. Farzad Mostashari. He’s stepping down from his post as national coordinator for health information technology sometime this fall.

His departure comes as physicians and hospitals are moving toward adoption of Stage 2 of meaningful use, part of the Medicare Electronic Health Record (EHR) incentive program. Dr. Mostashari also has been called to Capitol Hill in recent weeks to field questions from lawmakers on why it is taking so long to make EHR systems talk to one another.

In an e-mail to agency staff on Aug. 6, Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius praised Dr. Mostashari for his work in linking the meaningful use of EHRs to population health goals and laying a "strong foundation" for increasing the interoperability of health records.

Dr. Mostashari, who became national coordinator in 2011, will stay on in his current post for a little while as HHS officials search for a replacement. As for his plans after leaving HHS, Dr. Mostashari said that he’s not sure.

"It is difficult for me to announce that I am leaving," he wrote in an e-mail to staff at the Office of the National Coordinator of Health Information Technology. "I don’t know what I will be doing after I leave public service, but be assured that I will be by your side as we continue to battle for healthcare transformation, cheering you on."

–By Mary Ellen Schneider

On Twitter @MaryEllenNY

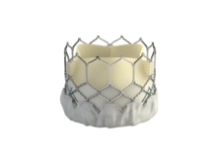

Edwards to start U.S. trial of SAPIEN 3

The Food and Drug Administration has given Edwards Lifesciences the green light to start a clinical trial on the SAPIEN 3 transcatheter aortic heart valve, which is a more advanced and improved version of the currently available SAPIEN valve.

"This is very exciting news," said Dr. Augusto Pichard, director of cardiac intervention and structural heart disease at MedStar Heart Institute in Washington, D.C. "One of the major concerns we have is vascular access. The current FDA-approved [SAPIEN] valve is large and sometimes doesn’t fit, or produces serious vascular complications," Dr. Pichard said in an interview. "The new valve has much smaller delivery size, making it very likely that many more patients would benefit from the procedure."

SAPIEN 3 also has a fabric cuff to reduce paravalvular leak, which is one of the major determinants of the procedure's long-term outcomes.

Under FDA’s conditional Investigational Device Exemption (IDE), Edwards will enroll up to 500 high-risk or inoperable patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis. The valve can be placed through transfemoral, transapical, or transaortic approach, and patients will be followed up for 1 year.

In the United States, the SAPIEN valve has been the first and only approved transcatheter aortic valve for transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), and several clinical trials by Medtronic are underway. But the valve technology has been moving forward elsewhere.

"The U.S. has lagged behind the rest of the world in access to new TAVR technology," Dr. John Carroll, a member of the STS/ACC TVT Registry Steering Committee and director of interventional cardiology and professor of medicine at the University of Colorado Hospital, Aurora, said in an interview. "This IDE being launched potentially allows us to start the process, bringing better and safer technologies to our patients."

Although the indications for SAPIEN 3 are the same as the currently used SAPIEN valve, experts say that the smaller SAPIEN 3 would benefit more patients.

"It’s been frustrating not to be able to treat many patients," said Dr. Carroll. "In TVT registry, we’ve gathered data on the initial U.S. experiences, with over 7,000 patients, and we certainly see a need for technology improvement, both smaller deliver systems and trying to eliminate paravalvular leak."

Edwards noted that the SAPIEN 3 valve is still an investigational device and is not commercially available in any country, but results from initial trials have been promising.

Dr. Pichard and Dr. Carroll said that they have observed the SAPIEN 3 placement on several occasions – overseas or via live case transmissions. They said the procedure for SAPIEN 3 is similar to the SAPIEN valve, and it appears to be easier.

Both cardiologists have been involved in Edwards’ PARTNER trials and said that they expected the patient enrollment to be rapid. They were not sure if Edwards will include their hospitals in the trial. After 1-year follow-up of the patients, the company will give the data to the FDA for a final decision.

The IDE is one of the key hurdles to initiating a clinical trial, which can potentially lead to FDA approval and commercial release. The process, if all goes as expected, could take at least 2 years.

Dr. Carroll said that he had no disclosures other than being involved in the PARTNER trial. Dr. Pichard has received honoraria from Edwards Lifesciences as a proctor for percutaneous aortic valves.

On Twitter @NaseemSMiller

The Food and Drug Administration has given Edwards Lifesciences the green light to start a clinical trial on the SAPIEN 3 transcatheter aortic heart valve, which is a more advanced and improved version of the currently available SAPIEN valve.

"This is very exciting news," said Dr. Augusto Pichard, director of cardiac intervention and structural heart disease at MedStar Heart Institute in Washington, D.C. "One of the major concerns we have is vascular access. The current FDA-approved [SAPIEN] valve is large and sometimes doesn’t fit, or produces serious vascular complications," Dr. Pichard said in an interview. "The new valve has much smaller delivery size, making it very likely that many more patients would benefit from the procedure."

SAPIEN 3 also has a fabric cuff to reduce paravalvular leak, which is one of the major determinants of the procedure's long-term outcomes.

Under FDA’s conditional Investigational Device Exemption (IDE), Edwards will enroll up to 500 high-risk or inoperable patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis. The valve can be placed through transfemoral, transapical, or transaortic approach, and patients will be followed up for 1 year.

In the United States, the SAPIEN valve has been the first and only approved transcatheter aortic valve for transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), and several clinical trials by Medtronic are underway. But the valve technology has been moving forward elsewhere.

"The U.S. has lagged behind the rest of the world in access to new TAVR technology," Dr. John Carroll, a member of the STS/ACC TVT Registry Steering Committee and director of interventional cardiology and professor of medicine at the University of Colorado Hospital, Aurora, said in an interview. "This IDE being launched potentially allows us to start the process, bringing better and safer technologies to our patients."