User login

Official Newspaper of the American College of Surgeons

Even mild preop sepsis boosts postop thrombosis risk

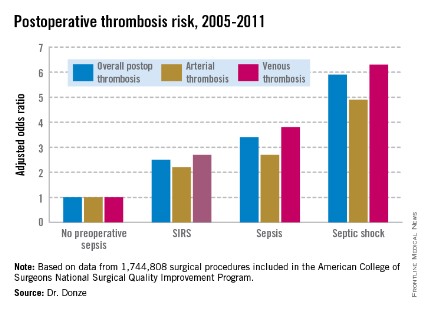

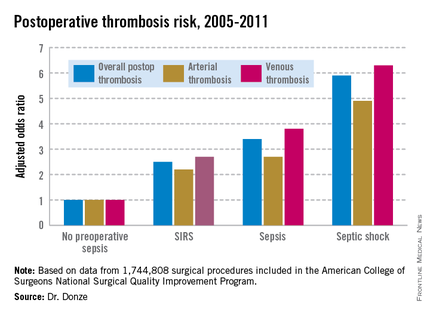

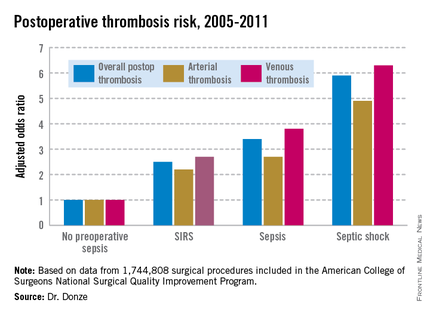

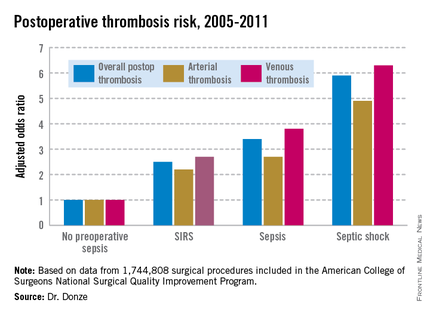

WASHINGTON – Preoperative sepsis proved to be an important independent risk factor for both arterial and venous thrombosis during or after surgery in an analysis of nearly 1.75 million U.S. surgical procedures.

The take-home message here is that the risk-benefit assessment of surgical procedures should take into account the presence of sepsis. And if the surgery can’t be delayed, prophylaxis against arterial as well as venous thrombosis should be employed, Dr. Jacques Donze said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Another key finding in this study was that the risk of postoperative thrombosis varied according to the severity of preoperative sepsis. Even the early form of sepsis known as systemic inflammatory response syndrome, or SIRS, was associated with a 2.5-fold increased risk.

"Include even early signs of sepsis as a risk factor," urged Dr. Donze of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

Also, preoperative sepsis was a risk factor for postoperative thrombosis in connection with outpatient elective surgery as well as inpatient operations, he added.

Dr. Donze presented an analysis of 1,744,808 surgical procedures performed during 2005-2011 at 314 U.S. hospitals participating in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. This large, prospective, observational registry is known for its high-quality data.

Within 48 hours prior to surgery, 7.8% of patients – totaling more than 136,000 – had SIRS, sepsis, or septic shock. Their postoperative thrombosis rate was 4.2%, compared with a 1.2% rate in patients without sepsis. In a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for potential confounding factors, the postoperative thrombosis risk climbed with increasing severity of preoperative sepsis.

SIRS was defined on the basis of temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, WBC count, and/or the presence of anion gap acidosis. "Sepsis" was defined as SIRS plus infection. And septic shock required the presence of sepsis plus documented organ dysfunction, such as hypotension.

The importance of recognizing this newly spotlighted sepsis/postoperative thrombosis connection is that most of the other known risk factors for thrombosis in surgical patients, including age, cancer, renal failure, and immobilization, are nonmodifiable, Dr. Donze observed.

Among the factors known to contribute to thrombosis are a hypercoagulable state, a proinflammatory state, hypoxemia, hypotension, and endothelial dysfunction. "All of these factors can be triggered by sepsis," Dr. Donze noted.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study.

WASHINGTON – Preoperative sepsis proved to be an important independent risk factor for both arterial and venous thrombosis during or after surgery in an analysis of nearly 1.75 million U.S. surgical procedures.

The take-home message here is that the risk-benefit assessment of surgical procedures should take into account the presence of sepsis. And if the surgery can’t be delayed, prophylaxis against arterial as well as venous thrombosis should be employed, Dr. Jacques Donze said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Another key finding in this study was that the risk of postoperative thrombosis varied according to the severity of preoperative sepsis. Even the early form of sepsis known as systemic inflammatory response syndrome, or SIRS, was associated with a 2.5-fold increased risk.

"Include even early signs of sepsis as a risk factor," urged Dr. Donze of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

Also, preoperative sepsis was a risk factor for postoperative thrombosis in connection with outpatient elective surgery as well as inpatient operations, he added.

Dr. Donze presented an analysis of 1,744,808 surgical procedures performed during 2005-2011 at 314 U.S. hospitals participating in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. This large, prospective, observational registry is known for its high-quality data.

Within 48 hours prior to surgery, 7.8% of patients – totaling more than 136,000 – had SIRS, sepsis, or septic shock. Their postoperative thrombosis rate was 4.2%, compared with a 1.2% rate in patients without sepsis. In a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for potential confounding factors, the postoperative thrombosis risk climbed with increasing severity of preoperative sepsis.

SIRS was defined on the basis of temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, WBC count, and/or the presence of anion gap acidosis. "Sepsis" was defined as SIRS plus infection. And septic shock required the presence of sepsis plus documented organ dysfunction, such as hypotension.

The importance of recognizing this newly spotlighted sepsis/postoperative thrombosis connection is that most of the other known risk factors for thrombosis in surgical patients, including age, cancer, renal failure, and immobilization, are nonmodifiable, Dr. Donze observed.

Among the factors known to contribute to thrombosis are a hypercoagulable state, a proinflammatory state, hypoxemia, hypotension, and endothelial dysfunction. "All of these factors can be triggered by sepsis," Dr. Donze noted.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study.

WASHINGTON – Preoperative sepsis proved to be an important independent risk factor for both arterial and venous thrombosis during or after surgery in an analysis of nearly 1.75 million U.S. surgical procedures.

The take-home message here is that the risk-benefit assessment of surgical procedures should take into account the presence of sepsis. And if the surgery can’t be delayed, prophylaxis against arterial as well as venous thrombosis should be employed, Dr. Jacques Donze said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Another key finding in this study was that the risk of postoperative thrombosis varied according to the severity of preoperative sepsis. Even the early form of sepsis known as systemic inflammatory response syndrome, or SIRS, was associated with a 2.5-fold increased risk.

"Include even early signs of sepsis as a risk factor," urged Dr. Donze of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

Also, preoperative sepsis was a risk factor for postoperative thrombosis in connection with outpatient elective surgery as well as inpatient operations, he added.

Dr. Donze presented an analysis of 1,744,808 surgical procedures performed during 2005-2011 at 314 U.S. hospitals participating in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. This large, prospective, observational registry is known for its high-quality data.

Within 48 hours prior to surgery, 7.8% of patients – totaling more than 136,000 – had SIRS, sepsis, or septic shock. Their postoperative thrombosis rate was 4.2%, compared with a 1.2% rate in patients without sepsis. In a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for potential confounding factors, the postoperative thrombosis risk climbed with increasing severity of preoperative sepsis.

SIRS was defined on the basis of temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, WBC count, and/or the presence of anion gap acidosis. "Sepsis" was defined as SIRS plus infection. And septic shock required the presence of sepsis plus documented organ dysfunction, such as hypotension.

The importance of recognizing this newly spotlighted sepsis/postoperative thrombosis connection is that most of the other known risk factors for thrombosis in surgical patients, including age, cancer, renal failure, and immobilization, are nonmodifiable, Dr. Donze observed.

Among the factors known to contribute to thrombosis are a hypercoagulable state, a proinflammatory state, hypoxemia, hypotension, and endothelial dysfunction. "All of these factors can be triggered by sepsis," Dr. Donze noted.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study.

AT ACC 14

Major finding: Preoperative sepsis is a strong independent risk factor for postoperative arterial and venous thrombosis; the more severe the sepsis, the greater the thrombosis risk.

Data source: This was an analysis of nearly 1.75 million surgical procedures at 314 U.S. hospitals detailed in the American College of Surgeons National Quality Improvement Program registry.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Antitrust issues in health care (Part I)

This article introduces United States antitrust laws and discusses their application in health care. Part 2 will summarize major court decisions covering that subject.

Question: Antitrust laws:

A. Are based in part on the physician-patient trust relationship.

B. Prohibit anticompetitive behavior.

C. Regulate business activities but not professional services.

D. A, B, and C are correct.

E. B and C are correct.

Answer: B. Economic interests are best served in a freely competitive marketplace. Trade restraints such as price fixing and monopolization tend to promote inefficiency and increase profit for the perpetrators, at the expense of consumer welfare.

Accordingly, Congress enacted the Sherman Antitrust Act way back in 1890 to promote competition and outlaw unreasonable restraint of trade. Additional laws prohibit mergers that substantially lessen competition, price discrimination, and unfair trade practices. Collectively, these are known as the antitrust laws, the term reflecting their initial purpose to prevent commercial traders from forming anticompetitive groups or "trusts."

The Department of Justice (DOJ), the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), and their state counterparts enforce these laws, which have nothing whatsoever to do with the doctor-patient trust relationship.

Section I of the Sherman Act, the paramount antitrust statute, declares that "Every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, is declared to be illegal." Section II stipulates, "Every person who shall monopolize, or attempt to monopolize, or combine or conspire with any other person or persons, to monopolize any part of the trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, shall be deemed guilty of a felony."

Other important laws are Sections 4 and 7 of the Clayton Antitrust Act and Section 5(a)(1) of the Federal Trade Commission Act, which outlaws "unfair methods of competition in or affecting commerce ... " Additionally, all states have their own antitrust statutes, which in some cases may be more restrictive than the federal laws are.

These laws initially targeted anticompetitive business practices. In 1975, the U.S. Supreme Court declared that there was to be no "learned profession" exemption, although special considerations may apply.1 However, activities of state government officials and employees are exempt from antitrust scrutiny under the so-called "state action doctrine," which confers immunity if an exemption is clearly articulated and affirmatively expressed as state policy, and there is active state supervision of the conduct in question.

Antitrust issues are ubiquitous in health care, and fall into seven major categories: 1) price fixing; 2) boycotts; 3) market division; 4) monopolization; 5) joint ventures; 6) exclusive contracts, and 7) peer review.

1. Price fixing. An agreement to fix prices is the most egregious example of anticompetitive conduct, so much so that the courts will use a per se analysis, i.e., without need to consider other factors, to arrive at its decision. Price fixing does not require any party to show market dominance or power, and its presence can be inferred from circumstances and agreements, which can be either oral or written.

For example, physician fee schedules or guidelines by a medical association would constitute price fixing. Even an agreement to fix maximum prices, as opposed to minimum prices, has been ruled illegal. At a practical level, physicians should avoid sharing pricing information with anyone, especially with colleagues, unless strict FTC "safety zone" criteria are satisfied.

2. Boycotts. Group boycotts are usually per se illegal, but in the health care industry, a rule of reason analysis is frequently used. Courts will look at the circumstances and purpose of the boycott, its pro- and anti-competitive effects, and whether there are other less restrictive ways to achieve the purported goal.

Affiliating physicians face this risk when forming alliances, as boycott questions may arise when a doctor is inappropriately excluded, which deprives him/her from earning a living in the relevant market.

A related controversial issue is the unionization of doctors. Unionization protects labor rights, especially those of medical residents, and offers greater parity in collective bargaining. On the other hand, the danger is in tying a physician’s obligations to the interests of other workers who may not share the same ethical commitment to patients.2

Strikes by doctors are likely to interfere with patient care, raise serious ethical questions, and may also be in violation of antitrust laws although boycotts for sociopolitical and noncommercial reasons are not specifically prohibited.

3. Market division. Agreements to restrict competition by dividing or allocating territories or patients are illegal per se under the Sherman Act.

4. Monopolization. Section 2 of the Sherman Act prohibits monopolization and attempts to monopolize. Examples are predatory pricing, long-term exclusive contracts, and refusal to deal. Mergers and acquisitions may substantially lessen competition with the tendency to create a monopoly, and they are subject to Section 7 of the Clayton Act. Proof of monopolization requires an inquiry into the relevant product and geographic markets (usually greater than 50%-60% market share), and regularly requires an economist’s expertise at trial.

As a general proposition, restraint of trade and monopolistic charges are difficult to prove. Monopoly through "the exercise of skill, foresight, and industry" does not constitute monopolizing conduct.

5. Joint ventures. The two main ways physicians form network joint ventures are: 1) join together in an entity with shared financial risks and clinical integration, and 2) join a looser network without integration to simply facilitate the flow of information for contracting purposes between physicians and other payers, the so-called messenger method.

Many health delivery systems involve joint venture agreements among practitioners or groups of health professionals and health care institutions, e.g., physician hospital organizations (PHOs), independent practice associations (IPAs), and preferred physician organization (PPOs). Physicians and physician practice groups may become targets if their attempted efforts at joint ventures are deemed to be a pretext for price fixing or otherwise anticompetitive.

The DOJ and FTC have promulgated guidelines regarding joint venture structures and will perform a review of the proposal upon request.3

However, under Obamacare, which promotes the efficient integration of health services through competition such as accountable care organizations, these guidelines are likely to be revised in the near future.

6. Exclusive contracts. Many hospitals have exclusive contracts with health professionals such as radiologists, anesthesiologists, and pathologists. Patients using the facility may be forced to use the services of these providers ("tying arrangement"). If the hospital does not possess requisite market power, or force the acceptance of the service, such agreements may pass antitrust scrutiny.

7. Peer review. The Health Care Quality Improvement Act (42 U.S.C. §§ 1101 et seq.) immunizes physicians and others performing peer review activities from federal antitrust claims so long as peer review was carried out: 1) in reasonable belief that the action was in furtherance of quality health care; 2) after reasonable effort to obtain the facts; 3) after an adequate notice and hearing procedure; 4) in reasonable belief that the action was warranted; and 5) any adverse outcome was reported to the National Practitioners’ Data Bank.

A doctor who is judged wanting in peer review occasionally asserts a discriminatory or anticompetitive intent, and may file a retaliatory lawsuit. One caveat: Peer review deliberations are always held in strict confidence. Disparaging a doctor under review in an unrelated forum constitutes a violation of the peer review process, which risks nullification of discovery protection and antitrust immunity.

Antitrust problems are highly fact dependent and analytically complex, and therefore require counsel with special expertise and experience. Issues are surprisingly prevalent and may be counterintuitive, affecting not only parties in joint ventures and mergers, but also the solo office or hospital practitioner. Matters of medical staffing, joint purchasing, information exchange, managed care negotiation, peer review and price agreements are some examples.

Penalties are severe, and may cover more than simple cease and desist orders. Some behavior constitutes criminality punishable by prison terms, though this is rare in the health care arena.

More often, the guilty parties face heavy monetary fines from both governmental officials as well as private litigants who can join in the lawsuit and stand to benefit from awards of treble damages and attorneys’ fees.

References:

1. Goldfarb v. Virginia State Bar 421 U.S. 773, 1975.

2. Code of Medical Ethics, AMA, 9.025, 2012-2013 edition.

3. Statements of Antitrust Enforcement Policy in Health Care. Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission (1996).

Dr. Tan is professor emeritus of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical or legal advice. Some of the articles in this series are adapted from the author’s 2006 book, "Medical Malpractice: Understanding the Law, Managing the Risk," and his 2012 Halsbury treatise, "Medical Negligence and Professional Misconduct." For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

This article introduces United States antitrust laws and discusses their application in health care. Part 2 will summarize major court decisions covering that subject.

Question: Antitrust laws:

A. Are based in part on the physician-patient trust relationship.

B. Prohibit anticompetitive behavior.

C. Regulate business activities but not professional services.

D. A, B, and C are correct.

E. B and C are correct.

Answer: B. Economic interests are best served in a freely competitive marketplace. Trade restraints such as price fixing and monopolization tend to promote inefficiency and increase profit for the perpetrators, at the expense of consumer welfare.

Accordingly, Congress enacted the Sherman Antitrust Act way back in 1890 to promote competition and outlaw unreasonable restraint of trade. Additional laws prohibit mergers that substantially lessen competition, price discrimination, and unfair trade practices. Collectively, these are known as the antitrust laws, the term reflecting their initial purpose to prevent commercial traders from forming anticompetitive groups or "trusts."

The Department of Justice (DOJ), the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), and their state counterparts enforce these laws, which have nothing whatsoever to do with the doctor-patient trust relationship.

Section I of the Sherman Act, the paramount antitrust statute, declares that "Every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, is declared to be illegal." Section II stipulates, "Every person who shall monopolize, or attempt to monopolize, or combine or conspire with any other person or persons, to monopolize any part of the trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, shall be deemed guilty of a felony."

Other important laws are Sections 4 and 7 of the Clayton Antitrust Act and Section 5(a)(1) of the Federal Trade Commission Act, which outlaws "unfair methods of competition in or affecting commerce ... " Additionally, all states have their own antitrust statutes, which in some cases may be more restrictive than the federal laws are.

These laws initially targeted anticompetitive business practices. In 1975, the U.S. Supreme Court declared that there was to be no "learned profession" exemption, although special considerations may apply.1 However, activities of state government officials and employees are exempt from antitrust scrutiny under the so-called "state action doctrine," which confers immunity if an exemption is clearly articulated and affirmatively expressed as state policy, and there is active state supervision of the conduct in question.

Antitrust issues are ubiquitous in health care, and fall into seven major categories: 1) price fixing; 2) boycotts; 3) market division; 4) monopolization; 5) joint ventures; 6) exclusive contracts, and 7) peer review.

1. Price fixing. An agreement to fix prices is the most egregious example of anticompetitive conduct, so much so that the courts will use a per se analysis, i.e., without need to consider other factors, to arrive at its decision. Price fixing does not require any party to show market dominance or power, and its presence can be inferred from circumstances and agreements, which can be either oral or written.

For example, physician fee schedules or guidelines by a medical association would constitute price fixing. Even an agreement to fix maximum prices, as opposed to minimum prices, has been ruled illegal. At a practical level, physicians should avoid sharing pricing information with anyone, especially with colleagues, unless strict FTC "safety zone" criteria are satisfied.

2. Boycotts. Group boycotts are usually per se illegal, but in the health care industry, a rule of reason analysis is frequently used. Courts will look at the circumstances and purpose of the boycott, its pro- and anti-competitive effects, and whether there are other less restrictive ways to achieve the purported goal.

Affiliating physicians face this risk when forming alliances, as boycott questions may arise when a doctor is inappropriately excluded, which deprives him/her from earning a living in the relevant market.

A related controversial issue is the unionization of doctors. Unionization protects labor rights, especially those of medical residents, and offers greater parity in collective bargaining. On the other hand, the danger is in tying a physician’s obligations to the interests of other workers who may not share the same ethical commitment to patients.2

Strikes by doctors are likely to interfere with patient care, raise serious ethical questions, and may also be in violation of antitrust laws although boycotts for sociopolitical and noncommercial reasons are not specifically prohibited.

3. Market division. Agreements to restrict competition by dividing or allocating territories or patients are illegal per se under the Sherman Act.

4. Monopolization. Section 2 of the Sherman Act prohibits monopolization and attempts to monopolize. Examples are predatory pricing, long-term exclusive contracts, and refusal to deal. Mergers and acquisitions may substantially lessen competition with the tendency to create a monopoly, and they are subject to Section 7 of the Clayton Act. Proof of monopolization requires an inquiry into the relevant product and geographic markets (usually greater than 50%-60% market share), and regularly requires an economist’s expertise at trial.

As a general proposition, restraint of trade and monopolistic charges are difficult to prove. Monopoly through "the exercise of skill, foresight, and industry" does not constitute monopolizing conduct.

5. Joint ventures. The two main ways physicians form network joint ventures are: 1) join together in an entity with shared financial risks and clinical integration, and 2) join a looser network without integration to simply facilitate the flow of information for contracting purposes between physicians and other payers, the so-called messenger method.

Many health delivery systems involve joint venture agreements among practitioners or groups of health professionals and health care institutions, e.g., physician hospital organizations (PHOs), independent practice associations (IPAs), and preferred physician organization (PPOs). Physicians and physician practice groups may become targets if their attempted efforts at joint ventures are deemed to be a pretext for price fixing or otherwise anticompetitive.

The DOJ and FTC have promulgated guidelines regarding joint venture structures and will perform a review of the proposal upon request.3

However, under Obamacare, which promotes the efficient integration of health services through competition such as accountable care organizations, these guidelines are likely to be revised in the near future.

6. Exclusive contracts. Many hospitals have exclusive contracts with health professionals such as radiologists, anesthesiologists, and pathologists. Patients using the facility may be forced to use the services of these providers ("tying arrangement"). If the hospital does not possess requisite market power, or force the acceptance of the service, such agreements may pass antitrust scrutiny.

7. Peer review. The Health Care Quality Improvement Act (42 U.S.C. §§ 1101 et seq.) immunizes physicians and others performing peer review activities from federal antitrust claims so long as peer review was carried out: 1) in reasonable belief that the action was in furtherance of quality health care; 2) after reasonable effort to obtain the facts; 3) after an adequate notice and hearing procedure; 4) in reasonable belief that the action was warranted; and 5) any adverse outcome was reported to the National Practitioners’ Data Bank.

A doctor who is judged wanting in peer review occasionally asserts a discriminatory or anticompetitive intent, and may file a retaliatory lawsuit. One caveat: Peer review deliberations are always held in strict confidence. Disparaging a doctor under review in an unrelated forum constitutes a violation of the peer review process, which risks nullification of discovery protection and antitrust immunity.

Antitrust problems are highly fact dependent and analytically complex, and therefore require counsel with special expertise and experience. Issues are surprisingly prevalent and may be counterintuitive, affecting not only parties in joint ventures and mergers, but also the solo office or hospital practitioner. Matters of medical staffing, joint purchasing, information exchange, managed care negotiation, peer review and price agreements are some examples.

Penalties are severe, and may cover more than simple cease and desist orders. Some behavior constitutes criminality punishable by prison terms, though this is rare in the health care arena.

More often, the guilty parties face heavy monetary fines from both governmental officials as well as private litigants who can join in the lawsuit and stand to benefit from awards of treble damages and attorneys’ fees.

References:

1. Goldfarb v. Virginia State Bar 421 U.S. 773, 1975.

2. Code of Medical Ethics, AMA, 9.025, 2012-2013 edition.

3. Statements of Antitrust Enforcement Policy in Health Care. Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission (1996).

Dr. Tan is professor emeritus of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical or legal advice. Some of the articles in this series are adapted from the author’s 2006 book, "Medical Malpractice: Understanding the Law, Managing the Risk," and his 2012 Halsbury treatise, "Medical Negligence and Professional Misconduct." For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

This article introduces United States antitrust laws and discusses their application in health care. Part 2 will summarize major court decisions covering that subject.

Question: Antitrust laws:

A. Are based in part on the physician-patient trust relationship.

B. Prohibit anticompetitive behavior.

C. Regulate business activities but not professional services.

D. A, B, and C are correct.

E. B and C are correct.

Answer: B. Economic interests are best served in a freely competitive marketplace. Trade restraints such as price fixing and monopolization tend to promote inefficiency and increase profit for the perpetrators, at the expense of consumer welfare.

Accordingly, Congress enacted the Sherman Antitrust Act way back in 1890 to promote competition and outlaw unreasonable restraint of trade. Additional laws prohibit mergers that substantially lessen competition, price discrimination, and unfair trade practices. Collectively, these are known as the antitrust laws, the term reflecting their initial purpose to prevent commercial traders from forming anticompetitive groups or "trusts."

The Department of Justice (DOJ), the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), and their state counterparts enforce these laws, which have nothing whatsoever to do with the doctor-patient trust relationship.

Section I of the Sherman Act, the paramount antitrust statute, declares that "Every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, is declared to be illegal." Section II stipulates, "Every person who shall monopolize, or attempt to monopolize, or combine or conspire with any other person or persons, to monopolize any part of the trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, shall be deemed guilty of a felony."

Other important laws are Sections 4 and 7 of the Clayton Antitrust Act and Section 5(a)(1) of the Federal Trade Commission Act, which outlaws "unfair methods of competition in or affecting commerce ... " Additionally, all states have their own antitrust statutes, which in some cases may be more restrictive than the federal laws are.

These laws initially targeted anticompetitive business practices. In 1975, the U.S. Supreme Court declared that there was to be no "learned profession" exemption, although special considerations may apply.1 However, activities of state government officials and employees are exempt from antitrust scrutiny under the so-called "state action doctrine," which confers immunity if an exemption is clearly articulated and affirmatively expressed as state policy, and there is active state supervision of the conduct in question.

Antitrust issues are ubiquitous in health care, and fall into seven major categories: 1) price fixing; 2) boycotts; 3) market division; 4) monopolization; 5) joint ventures; 6) exclusive contracts, and 7) peer review.

1. Price fixing. An agreement to fix prices is the most egregious example of anticompetitive conduct, so much so that the courts will use a per se analysis, i.e., without need to consider other factors, to arrive at its decision. Price fixing does not require any party to show market dominance or power, and its presence can be inferred from circumstances and agreements, which can be either oral or written.

For example, physician fee schedules or guidelines by a medical association would constitute price fixing. Even an agreement to fix maximum prices, as opposed to minimum prices, has been ruled illegal. At a practical level, physicians should avoid sharing pricing information with anyone, especially with colleagues, unless strict FTC "safety zone" criteria are satisfied.

2. Boycotts. Group boycotts are usually per se illegal, but in the health care industry, a rule of reason analysis is frequently used. Courts will look at the circumstances and purpose of the boycott, its pro- and anti-competitive effects, and whether there are other less restrictive ways to achieve the purported goal.

Affiliating physicians face this risk when forming alliances, as boycott questions may arise when a doctor is inappropriately excluded, which deprives him/her from earning a living in the relevant market.

A related controversial issue is the unionization of doctors. Unionization protects labor rights, especially those of medical residents, and offers greater parity in collective bargaining. On the other hand, the danger is in tying a physician’s obligations to the interests of other workers who may not share the same ethical commitment to patients.2

Strikes by doctors are likely to interfere with patient care, raise serious ethical questions, and may also be in violation of antitrust laws although boycotts for sociopolitical and noncommercial reasons are not specifically prohibited.

3. Market division. Agreements to restrict competition by dividing or allocating territories or patients are illegal per se under the Sherman Act.

4. Monopolization. Section 2 of the Sherman Act prohibits monopolization and attempts to monopolize. Examples are predatory pricing, long-term exclusive contracts, and refusal to deal. Mergers and acquisitions may substantially lessen competition with the tendency to create a monopoly, and they are subject to Section 7 of the Clayton Act. Proof of monopolization requires an inquiry into the relevant product and geographic markets (usually greater than 50%-60% market share), and regularly requires an economist’s expertise at trial.

As a general proposition, restraint of trade and monopolistic charges are difficult to prove. Monopoly through "the exercise of skill, foresight, and industry" does not constitute monopolizing conduct.

5. Joint ventures. The two main ways physicians form network joint ventures are: 1) join together in an entity with shared financial risks and clinical integration, and 2) join a looser network without integration to simply facilitate the flow of information for contracting purposes between physicians and other payers, the so-called messenger method.

Many health delivery systems involve joint venture agreements among practitioners or groups of health professionals and health care institutions, e.g., physician hospital organizations (PHOs), independent practice associations (IPAs), and preferred physician organization (PPOs). Physicians and physician practice groups may become targets if their attempted efforts at joint ventures are deemed to be a pretext for price fixing or otherwise anticompetitive.

The DOJ and FTC have promulgated guidelines regarding joint venture structures and will perform a review of the proposal upon request.3

However, under Obamacare, which promotes the efficient integration of health services through competition such as accountable care organizations, these guidelines are likely to be revised in the near future.

6. Exclusive contracts. Many hospitals have exclusive contracts with health professionals such as radiologists, anesthesiologists, and pathologists. Patients using the facility may be forced to use the services of these providers ("tying arrangement"). If the hospital does not possess requisite market power, or force the acceptance of the service, such agreements may pass antitrust scrutiny.

7. Peer review. The Health Care Quality Improvement Act (42 U.S.C. §§ 1101 et seq.) immunizes physicians and others performing peer review activities from federal antitrust claims so long as peer review was carried out: 1) in reasonable belief that the action was in furtherance of quality health care; 2) after reasonable effort to obtain the facts; 3) after an adequate notice and hearing procedure; 4) in reasonable belief that the action was warranted; and 5) any adverse outcome was reported to the National Practitioners’ Data Bank.

A doctor who is judged wanting in peer review occasionally asserts a discriminatory or anticompetitive intent, and may file a retaliatory lawsuit. One caveat: Peer review deliberations are always held in strict confidence. Disparaging a doctor under review in an unrelated forum constitutes a violation of the peer review process, which risks nullification of discovery protection and antitrust immunity.

Antitrust problems are highly fact dependent and analytically complex, and therefore require counsel with special expertise and experience. Issues are surprisingly prevalent and may be counterintuitive, affecting not only parties in joint ventures and mergers, but also the solo office or hospital practitioner. Matters of medical staffing, joint purchasing, information exchange, managed care negotiation, peer review and price agreements are some examples.

Penalties are severe, and may cover more than simple cease and desist orders. Some behavior constitutes criminality punishable by prison terms, though this is rare in the health care arena.

More often, the guilty parties face heavy monetary fines from both governmental officials as well as private litigants who can join in the lawsuit and stand to benefit from awards of treble damages and attorneys’ fees.

References:

1. Goldfarb v. Virginia State Bar 421 U.S. 773, 1975.

2. Code of Medical Ethics, AMA, 9.025, 2012-2013 edition.

3. Statements of Antitrust Enforcement Policy in Health Care. Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission (1996).

Dr. Tan is professor emeritus of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical or legal advice. Some of the articles in this series are adapted from the author’s 2006 book, "Medical Malpractice: Understanding the Law, Managing the Risk," and his 2012 Halsbury treatise, "Medical Negligence and Professional Misconduct." For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

High-dose steroids tame post-EVAR inflammation

BOSTON – Preoperative high-dose methylprednisolone dramatically reduced inflammation and enhanced recovery after endovascular aortic repair without increased morbidity in a prospective, double-blinded randomized study.

The primary outcome of modified systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) developed in 92% on placebo and 27% given methylprednisolone (relative risk, 0.29; P less than .001).

The effect was particularly striking in patients with three or more SIRS criteria, with an overall number needed to treat of 1.5, Dr. Henrik Kehlet said at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

Tempering the postoperative inflammatory response with methylprednisolone also significantly trimmed hospital stays from 3 to 2 days (P less than .001) and morphine requirements from 10 mg to 0 mg (P less than .001).

Medical morbidity was reduced in the methylprednisolone group, but not significantly (23% vs. 36%; P = .1), as was surgical morbidity (20% vs. 21%; P = 1.0).

Importantly, there was no sign of an increase in diagnosed (23% vs. 17%) or treated (1% vs. 3%) endoleaks on computed tomography scan among 146 patients evaluable at 3 months’ follow-up, said Dr. Kehlet, professor of perioperative therapy and head of the surgical pathophysiology section at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen University, and the oft-described "father" of rapid recovery.

About 40%-60% of patients undergoing endovascular aortic repair (EVAR) will develop postoperative SIRS. Although there is limited surgical injury with the minimally invasive procedure, there is still a stress response because the prosthesis releases proinflammatory mediators from the thrombus in the aortic aneurysm, he explained.

Invited discussant Dr. Basil Pruitt of the division of trauma at the University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, observed that the findings take on added import in light of a 7,500-patient study presented at the recent American College of Cardiology meeting showing that methylprednisolone conferred no significant benefit and was associated with a 15% increased risk of postoperative heart attack plus death when given during cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. He also questioned whether the glucocorticosteroid lowered the metabolic rate, as this would impair wound healing, or induced hypoglycemia or glucose intolerance.

"Do those findings and the concerns noted above simply define patient groups in whom methylprednisolone should not be infused preoperatively or, alternatively, do they define a threshold of physiologic or operative insult beyond which the effect of methylprednisolone is outweighed by the magnitude of injury and the associated systemic inflammatory response syndrome?" he asked.

Dr. Kehlet responded that he was unable to determine why that particular abstract found increased morbidity, but noted that the same authors previously published a systematic review (Eur. Heart J. 2008;29:2592-600) supporting reduced morbidity with steroid use in cardiopulmonary bypass.

He added, "The effect may depend on the type of injury, as you mention; cardiopulmonary bypass [is] a very special injury with many mediators of the stress response, compared to other surgical operations. We need more studies. And, finally, if you want to find out about the real outcomes, you must integrate the pharmacologic intervention with an optimized, fast-track setup."

Dr. Kehlet said they did not measure metabolic rate, but that no clinical problem was observed in the limited number of diabetics (n = 22) in their study. This finding is also supported by a huge, multicenter Dutch trial, in which intraoperative high-dose dexamethasone was associated with higher postoperative glucose levels in cardiopulmonary bypass patients, but had no effect on diabetes in subgroup analyses or on the primary endpoint of major morbidity at 30 days (JAMA 2012;308:1761-7).

For Dr. Kehlet's single-center, double-blinded study, 153 patients undergoing EVAR for abdominal aortic aneurysm were randomly assigned to receive a preoperative single dose of placebo or what was described as a single "old-fashioned sepsis dose of methylprednisolone" at 30 mg/kg. The two groups were similar at baseline with respect to age, comorbidities, aneurysm size, thrombus volume, EVAR procedures, and blood loss.

A modified version of SIRS was assessed during the first 4 days after surgery and defined by two or more of the following criteria: fever of more than 38° C (100.4° F) or less than 36° C (96.8° F), heart rate of more than 90 beats per minute, respiratory rate of more than 20 breaths per minute or arterial carbon dioxide tension of less than 4.3 kPa (32.25 mm Hg), and a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of more than 75 mg/L. The traditional fourth SIRS criterion of leukocytosis was replaced with CRP level because glucocorticoids always lead to leukocytosis, Dr. Kehlet noted.

Among 150 evaluable patients, high-dose methylprednisolone almost completely eliminated the proinflammatory activities of interleukin (IL)-6 (186 pg/mL vs. 20 mg/dL; P less than .001), IL-8, and CRP.

Among other inflammatory parameters, methylprednisolone reduced soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 levels, but did not modify the d-dimer response, metalloproteinase-9, or myeloperoxidase, he said.

By 3 months, mortality was similar at 3% in the methylprednisolone group and 1% in the placebo group (P less than .5).

"What we don’t know is what the optimal dose-response relationship is because we used a very high dose and, of course, this was only 150 patients, so the safety issues cannot be answered based on this study, but the results are promising for future large-scale studies in this interesting operation," Dr. Kehlet concluded.

Dr. Kehlet and his coauthors reported no financial disclosures.

The complete manuscript of this study and its presentation at the American Surgical Association’s 134th annual meeting, April 2014, in Boston, is anticipated to be published in the Annals of Surgery, pending editorial review.

BOSTON – Preoperative high-dose methylprednisolone dramatically reduced inflammation and enhanced recovery after endovascular aortic repair without increased morbidity in a prospective, double-blinded randomized study.

The primary outcome of modified systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) developed in 92% on placebo and 27% given methylprednisolone (relative risk, 0.29; P less than .001).

The effect was particularly striking in patients with three or more SIRS criteria, with an overall number needed to treat of 1.5, Dr. Henrik Kehlet said at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

Tempering the postoperative inflammatory response with methylprednisolone also significantly trimmed hospital stays from 3 to 2 days (P less than .001) and morphine requirements from 10 mg to 0 mg (P less than .001).

Medical morbidity was reduced in the methylprednisolone group, but not significantly (23% vs. 36%; P = .1), as was surgical morbidity (20% vs. 21%; P = 1.0).

Importantly, there was no sign of an increase in diagnosed (23% vs. 17%) or treated (1% vs. 3%) endoleaks on computed tomography scan among 146 patients evaluable at 3 months’ follow-up, said Dr. Kehlet, professor of perioperative therapy and head of the surgical pathophysiology section at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen University, and the oft-described "father" of rapid recovery.

About 40%-60% of patients undergoing endovascular aortic repair (EVAR) will develop postoperative SIRS. Although there is limited surgical injury with the minimally invasive procedure, there is still a stress response because the prosthesis releases proinflammatory mediators from the thrombus in the aortic aneurysm, he explained.

Invited discussant Dr. Basil Pruitt of the division of trauma at the University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, observed that the findings take on added import in light of a 7,500-patient study presented at the recent American College of Cardiology meeting showing that methylprednisolone conferred no significant benefit and was associated with a 15% increased risk of postoperative heart attack plus death when given during cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. He also questioned whether the glucocorticosteroid lowered the metabolic rate, as this would impair wound healing, or induced hypoglycemia or glucose intolerance.

"Do those findings and the concerns noted above simply define patient groups in whom methylprednisolone should not be infused preoperatively or, alternatively, do they define a threshold of physiologic or operative insult beyond which the effect of methylprednisolone is outweighed by the magnitude of injury and the associated systemic inflammatory response syndrome?" he asked.

Dr. Kehlet responded that he was unable to determine why that particular abstract found increased morbidity, but noted that the same authors previously published a systematic review (Eur. Heart J. 2008;29:2592-600) supporting reduced morbidity with steroid use in cardiopulmonary bypass.

He added, "The effect may depend on the type of injury, as you mention; cardiopulmonary bypass [is] a very special injury with many mediators of the stress response, compared to other surgical operations. We need more studies. And, finally, if you want to find out about the real outcomes, you must integrate the pharmacologic intervention with an optimized, fast-track setup."

Dr. Kehlet said they did not measure metabolic rate, but that no clinical problem was observed in the limited number of diabetics (n = 22) in their study. This finding is also supported by a huge, multicenter Dutch trial, in which intraoperative high-dose dexamethasone was associated with higher postoperative glucose levels in cardiopulmonary bypass patients, but had no effect on diabetes in subgroup analyses or on the primary endpoint of major morbidity at 30 days (JAMA 2012;308:1761-7).

For Dr. Kehlet's single-center, double-blinded study, 153 patients undergoing EVAR for abdominal aortic aneurysm were randomly assigned to receive a preoperative single dose of placebo or what was described as a single "old-fashioned sepsis dose of methylprednisolone" at 30 mg/kg. The two groups were similar at baseline with respect to age, comorbidities, aneurysm size, thrombus volume, EVAR procedures, and blood loss.

A modified version of SIRS was assessed during the first 4 days after surgery and defined by two or more of the following criteria: fever of more than 38° C (100.4° F) or less than 36° C (96.8° F), heart rate of more than 90 beats per minute, respiratory rate of more than 20 breaths per minute or arterial carbon dioxide tension of less than 4.3 kPa (32.25 mm Hg), and a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of more than 75 mg/L. The traditional fourth SIRS criterion of leukocytosis was replaced with CRP level because glucocorticoids always lead to leukocytosis, Dr. Kehlet noted.

Among 150 evaluable patients, high-dose methylprednisolone almost completely eliminated the proinflammatory activities of interleukin (IL)-6 (186 pg/mL vs. 20 mg/dL; P less than .001), IL-8, and CRP.

Among other inflammatory parameters, methylprednisolone reduced soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 levels, but did not modify the d-dimer response, metalloproteinase-9, or myeloperoxidase, he said.

By 3 months, mortality was similar at 3% in the methylprednisolone group and 1% in the placebo group (P less than .5).

"What we don’t know is what the optimal dose-response relationship is because we used a very high dose and, of course, this was only 150 patients, so the safety issues cannot be answered based on this study, but the results are promising for future large-scale studies in this interesting operation," Dr. Kehlet concluded.

Dr. Kehlet and his coauthors reported no financial disclosures.

The complete manuscript of this study and its presentation at the American Surgical Association’s 134th annual meeting, April 2014, in Boston, is anticipated to be published in the Annals of Surgery, pending editorial review.

BOSTON – Preoperative high-dose methylprednisolone dramatically reduced inflammation and enhanced recovery after endovascular aortic repair without increased morbidity in a prospective, double-blinded randomized study.

The primary outcome of modified systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) developed in 92% on placebo and 27% given methylprednisolone (relative risk, 0.29; P less than .001).

The effect was particularly striking in patients with three or more SIRS criteria, with an overall number needed to treat of 1.5, Dr. Henrik Kehlet said at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

Tempering the postoperative inflammatory response with methylprednisolone also significantly trimmed hospital stays from 3 to 2 days (P less than .001) and morphine requirements from 10 mg to 0 mg (P less than .001).

Medical morbidity was reduced in the methylprednisolone group, but not significantly (23% vs. 36%; P = .1), as was surgical morbidity (20% vs. 21%; P = 1.0).

Importantly, there was no sign of an increase in diagnosed (23% vs. 17%) or treated (1% vs. 3%) endoleaks on computed tomography scan among 146 patients evaluable at 3 months’ follow-up, said Dr. Kehlet, professor of perioperative therapy and head of the surgical pathophysiology section at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen University, and the oft-described "father" of rapid recovery.

About 40%-60% of patients undergoing endovascular aortic repair (EVAR) will develop postoperative SIRS. Although there is limited surgical injury with the minimally invasive procedure, there is still a stress response because the prosthesis releases proinflammatory mediators from the thrombus in the aortic aneurysm, he explained.

Invited discussant Dr. Basil Pruitt of the division of trauma at the University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, observed that the findings take on added import in light of a 7,500-patient study presented at the recent American College of Cardiology meeting showing that methylprednisolone conferred no significant benefit and was associated with a 15% increased risk of postoperative heart attack plus death when given during cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. He also questioned whether the glucocorticosteroid lowered the metabolic rate, as this would impair wound healing, or induced hypoglycemia or glucose intolerance.

"Do those findings and the concerns noted above simply define patient groups in whom methylprednisolone should not be infused preoperatively or, alternatively, do they define a threshold of physiologic or operative insult beyond which the effect of methylprednisolone is outweighed by the magnitude of injury and the associated systemic inflammatory response syndrome?" he asked.

Dr. Kehlet responded that he was unable to determine why that particular abstract found increased morbidity, but noted that the same authors previously published a systematic review (Eur. Heart J. 2008;29:2592-600) supporting reduced morbidity with steroid use in cardiopulmonary bypass.

He added, "The effect may depend on the type of injury, as you mention; cardiopulmonary bypass [is] a very special injury with many mediators of the stress response, compared to other surgical operations. We need more studies. And, finally, if you want to find out about the real outcomes, you must integrate the pharmacologic intervention with an optimized, fast-track setup."

Dr. Kehlet said they did not measure metabolic rate, but that no clinical problem was observed in the limited number of diabetics (n = 22) in their study. This finding is also supported by a huge, multicenter Dutch trial, in which intraoperative high-dose dexamethasone was associated with higher postoperative glucose levels in cardiopulmonary bypass patients, but had no effect on diabetes in subgroup analyses or on the primary endpoint of major morbidity at 30 days (JAMA 2012;308:1761-7).

For Dr. Kehlet's single-center, double-blinded study, 153 patients undergoing EVAR for abdominal aortic aneurysm were randomly assigned to receive a preoperative single dose of placebo or what was described as a single "old-fashioned sepsis dose of methylprednisolone" at 30 mg/kg. The two groups were similar at baseline with respect to age, comorbidities, aneurysm size, thrombus volume, EVAR procedures, and blood loss.

A modified version of SIRS was assessed during the first 4 days after surgery and defined by two or more of the following criteria: fever of more than 38° C (100.4° F) or less than 36° C (96.8° F), heart rate of more than 90 beats per minute, respiratory rate of more than 20 breaths per minute or arterial carbon dioxide tension of less than 4.3 kPa (32.25 mm Hg), and a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of more than 75 mg/L. The traditional fourth SIRS criterion of leukocytosis was replaced with CRP level because glucocorticoids always lead to leukocytosis, Dr. Kehlet noted.

Among 150 evaluable patients, high-dose methylprednisolone almost completely eliminated the proinflammatory activities of interleukin (IL)-6 (186 pg/mL vs. 20 mg/dL; P less than .001), IL-8, and CRP.

Among other inflammatory parameters, methylprednisolone reduced soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 levels, but did not modify the d-dimer response, metalloproteinase-9, or myeloperoxidase, he said.

By 3 months, mortality was similar at 3% in the methylprednisolone group and 1% in the placebo group (P less than .5).

"What we don’t know is what the optimal dose-response relationship is because we used a very high dose and, of course, this was only 150 patients, so the safety issues cannot be answered based on this study, but the results are promising for future large-scale studies in this interesting operation," Dr. Kehlet concluded.

Dr. Kehlet and his coauthors reported no financial disclosures.

The complete manuscript of this study and its presentation at the American Surgical Association’s 134th annual meeting, April 2014, in Boston, is anticipated to be published in the Annals of Surgery, pending editorial review.

AT ASA 2014

Major finding: Systemic inflammatory response syndrome developed in 92% on placebo and 27% given methylprednisolone (relative risk, 0.29; P less than .001).

Data source: A single-center, randomized double-blinded study in 153 patients undergoing EVAR for abdominal aortic aneurysm.

Disclosures: Dr. Kehlet and his coauthors reported no financial disclosures.

Affordable Care Act sign-ups hit 8 million

In the Affordable Care Act’s first open enrollment period, 8 million Americans signed up for private health insurance through the state and federal health marketplaces.

President Obama announced the latest figures on April 17, more than 2 weeks after the close of the first open enrollment period. Though March 31 was the deadline for signing up, individuals who had started the process by the deadline were given until April 15 to complete the process. During that time, nearly 1 million additional people signed up for health plans.

More young people have signed up for coverage as well. President Obama reported that in the federally run marketplaces, 35% of the sign-ups were from individuals under age 35, including children. About 28% of sign-ups were from young adults aged 18-34 years. That’s similar to the percentage of young adults who signed up for insurance in Massachusetts during the first year of its health reform effort, according to the White House.

"The Affordable Care Act is working," President Obama said during a White House press conference.

He once again called on the ACA’s opponents to stop trying to repeal it.

Rep. Fred Upton (R- Mich.), chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, said the law has disrupted health care for millions of Americans, limited access to physicians, and caused insurance premiums to skyrocket.

"The administration still has not answered basic questions about enrollment and why it will not support fairness for all," Rep. Upton said in a statement.

On Twitter @maryellenny

In the Affordable Care Act’s first open enrollment period, 8 million Americans signed up for private health insurance through the state and federal health marketplaces.

President Obama announced the latest figures on April 17, more than 2 weeks after the close of the first open enrollment period. Though March 31 was the deadline for signing up, individuals who had started the process by the deadline were given until April 15 to complete the process. During that time, nearly 1 million additional people signed up for health plans.

More young people have signed up for coverage as well. President Obama reported that in the federally run marketplaces, 35% of the sign-ups were from individuals under age 35, including children. About 28% of sign-ups were from young adults aged 18-34 years. That’s similar to the percentage of young adults who signed up for insurance in Massachusetts during the first year of its health reform effort, according to the White House.

"The Affordable Care Act is working," President Obama said during a White House press conference.

He once again called on the ACA’s opponents to stop trying to repeal it.

Rep. Fred Upton (R- Mich.), chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, said the law has disrupted health care for millions of Americans, limited access to physicians, and caused insurance premiums to skyrocket.

"The administration still has not answered basic questions about enrollment and why it will not support fairness for all," Rep. Upton said in a statement.

On Twitter @maryellenny

In the Affordable Care Act’s first open enrollment period, 8 million Americans signed up for private health insurance through the state and federal health marketplaces.

President Obama announced the latest figures on April 17, more than 2 weeks after the close of the first open enrollment period. Though March 31 was the deadline for signing up, individuals who had started the process by the deadline were given until April 15 to complete the process. During that time, nearly 1 million additional people signed up for health plans.

More young people have signed up for coverage as well. President Obama reported that in the federally run marketplaces, 35% of the sign-ups were from individuals under age 35, including children. About 28% of sign-ups were from young adults aged 18-34 years. That’s similar to the percentage of young adults who signed up for insurance in Massachusetts during the first year of its health reform effort, according to the White House.

"The Affordable Care Act is working," President Obama said during a White House press conference.

He once again called on the ACA’s opponents to stop trying to repeal it.

Rep. Fred Upton (R- Mich.), chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, said the law has disrupted health care for millions of Americans, limited access to physicians, and caused insurance premiums to skyrocket.

"The administration still has not answered basic questions about enrollment and why it will not support fairness for all," Rep. Upton said in a statement.

On Twitter @maryellenny

Data derail dogma of elective diverticulitis surgery

BOSTON – The risks of readmission and emergency surgery are low for patients with acute diverticulitis initially managed nonoperatively, a population-based, competing risk analysis found.

At a median of 3.9 years (range, 1.7-6.4 years) after discharge among 14,124 patients, only 8% required urgent readmission. Of these, 22% went on to urgent surgery and 20%, to elective surgery after additional episodes.

Among the remaining 12,981 patients with no urgent readmissions, 9% went on to elective surgery, 13% died of other causes, and 78% had no events in follow-up, Dr. Debbie Li said at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

The 5-year cumulative incidence was 9% for readmission, 1.9% for emergency surgery, and 14.1% for all-cause mortality.

"Elective colectomy may not be warranted for the majority of patients in the absence of chronic symptoms or multiple frequent recurrences," she said.

Elective colectomy has traditionally been recommended for patients at high risk for future recurrence and emergency surgery based on the indications of age less than 50 years, complicated disease including perforation and abscess, and two or more episodes of uncomplicated disease. Evidence is building, however, to challenge these indications, and guidelines are evolving, said Dr. Li, a general surgery resident at the University of Toronto.

The current study used administrative data to identify all patients in Ontario, Canada, treated nonoperatively at first hospitalization for diverticulitis from 2002 to 2012. Time-to-event and competing-risk regression analyses were performed, with data adjusted for such potential confounders as sex, medical comorbidity, neighborhood income quintile, rural residency, and calendar year of index admission.

Data are limited on the natural history of diverticulitis, and the few population-based studies that have been conducted have not accounted for competing risks such as elective colectomy or death, Dr. Li said.

The patients’ median age was 59 years, 79% had uncomplicated index disease, 18% had complicated disease (abscess, fistula, and perforation) with no abscess drain, and 3% had complicated disease with an abscess drain.

Young patients had more readmissions than those 50 years and older (10.5% vs. 8.4%; P less than .001), but not more emergency surgery (1.8% vs. 2.0%; P = .52), she said.

For patients older than 50 years, the risk of death by other causes was 10 times the risk of an emergency surgery for diverticulitis (19.5% vs. 2%).

Patients with complicated rather than uncomplicated index disease had more readmissions (12% vs. 8.2%; P less than .001) and urgent surgery (4.3% vs. 1.4%; P less than .001).

In adjusted analyses, young age was associated with more readmissions (hazard ratio, 1.24), but not subsequent emergency surgery (HR, 0.83). Complicated disease (HR, 3.15) and multiple recurrences (HR, 2.41) predicted an increased risk for emergency surgery.

"Young age, complicated disease, and multiple recurrences do infer increased relative risk, but the vast majority (85%) of such patients remain recurrence free," Dr. Li said.

Invited discussant Dr. David Schoetz, professor of surgery, Tufts University, Boston, said, "While it’s reassuring that even complicated diverticulitis can be safely managed without subsequent operation, there still must be a subgroup who should be offered early surgery."

With disease severity more common in younger patients and overall mortality less than 1%, perhaps aggressive surgery would be justified in those younger than 50 years, he suggested.

Dr. Li responded that an administrative database is unable to capture clinical nuances such as which patients had ongoing symptoms, chronic persistent disease, or reduced quality of life, and that a prospective trial would be needed to identify which subgroup of patients will need aggressive surgery.

Older patients, those with more complicated disease, and those with greater medical comorbidities are more likely to undergo urgent surgery, according to ongoing analyses of roughly 4,000 patients, treated during the same time period, but excluded from the current analysis because they underwent surgery at index admission. Previously published work also suggests that patients with a higher body mass index have poorer outcomes.

A recent systematic review of diverticulitis surgery (JAMA Surg. 2014;149:292-303) reported that complicated recurrence after an episode of uncomplicated diverticulitis is rare, occurring in less than 5% of cases. The authors called for existing guidelines to be updated and said that decisions to proceed with elective surgery should be based instead on patient-reported frequency and severity of symptoms.

The complete manuscript of this study and its presentation at the American Surgical Association’s 134th annual meeting, April 2014, in Boston, is anticipated to be published in the Annals of Surgery, pending editorial review.

Dr. Li and her coauthors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

urgent surgery, elective surgery, Dr. Debbie Li, American Surgical Association, colectomy, abscess, fistula, perforation, abscess drain, Young patients,

BOSTON – The risks of readmission and emergency surgery are low for patients with acute diverticulitis initially managed nonoperatively, a population-based, competing risk analysis found.

At a median of 3.9 years (range, 1.7-6.4 years) after discharge among 14,124 patients, only 8% required urgent readmission. Of these, 22% went on to urgent surgery and 20%, to elective surgery after additional episodes.

Among the remaining 12,981 patients with no urgent readmissions, 9% went on to elective surgery, 13% died of other causes, and 78% had no events in follow-up, Dr. Debbie Li said at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

The 5-year cumulative incidence was 9% for readmission, 1.9% for emergency surgery, and 14.1% for all-cause mortality.

"Elective colectomy may not be warranted for the majority of patients in the absence of chronic symptoms or multiple frequent recurrences," she said.

Elective colectomy has traditionally been recommended for patients at high risk for future recurrence and emergency surgery based on the indications of age less than 50 years, complicated disease including perforation and abscess, and two or more episodes of uncomplicated disease. Evidence is building, however, to challenge these indications, and guidelines are evolving, said Dr. Li, a general surgery resident at the University of Toronto.

The current study used administrative data to identify all patients in Ontario, Canada, treated nonoperatively at first hospitalization for diverticulitis from 2002 to 2012. Time-to-event and competing-risk regression analyses were performed, with data adjusted for such potential confounders as sex, medical comorbidity, neighborhood income quintile, rural residency, and calendar year of index admission.

Data are limited on the natural history of diverticulitis, and the few population-based studies that have been conducted have not accounted for competing risks such as elective colectomy or death, Dr. Li said.

The patients’ median age was 59 years, 79% had uncomplicated index disease, 18% had complicated disease (abscess, fistula, and perforation) with no abscess drain, and 3% had complicated disease with an abscess drain.

Young patients had more readmissions than those 50 years and older (10.5% vs. 8.4%; P less than .001), but not more emergency surgery (1.8% vs. 2.0%; P = .52), she said.

For patients older than 50 years, the risk of death by other causes was 10 times the risk of an emergency surgery for diverticulitis (19.5% vs. 2%).

Patients with complicated rather than uncomplicated index disease had more readmissions (12% vs. 8.2%; P less than .001) and urgent surgery (4.3% vs. 1.4%; P less than .001).

In adjusted analyses, young age was associated with more readmissions (hazard ratio, 1.24), but not subsequent emergency surgery (HR, 0.83). Complicated disease (HR, 3.15) and multiple recurrences (HR, 2.41) predicted an increased risk for emergency surgery.

"Young age, complicated disease, and multiple recurrences do infer increased relative risk, but the vast majority (85%) of such patients remain recurrence free," Dr. Li said.

Invited discussant Dr. David Schoetz, professor of surgery, Tufts University, Boston, said, "While it’s reassuring that even complicated diverticulitis can be safely managed without subsequent operation, there still must be a subgroup who should be offered early surgery."

With disease severity more common in younger patients and overall mortality less than 1%, perhaps aggressive surgery would be justified in those younger than 50 years, he suggested.

Dr. Li responded that an administrative database is unable to capture clinical nuances such as which patients had ongoing symptoms, chronic persistent disease, or reduced quality of life, and that a prospective trial would be needed to identify which subgroup of patients will need aggressive surgery.

Older patients, those with more complicated disease, and those with greater medical comorbidities are more likely to undergo urgent surgery, according to ongoing analyses of roughly 4,000 patients, treated during the same time period, but excluded from the current analysis because they underwent surgery at index admission. Previously published work also suggests that patients with a higher body mass index have poorer outcomes.

A recent systematic review of diverticulitis surgery (JAMA Surg. 2014;149:292-303) reported that complicated recurrence after an episode of uncomplicated diverticulitis is rare, occurring in less than 5% of cases. The authors called for existing guidelines to be updated and said that decisions to proceed with elective surgery should be based instead on patient-reported frequency and severity of symptoms.

The complete manuscript of this study and its presentation at the American Surgical Association’s 134th annual meeting, April 2014, in Boston, is anticipated to be published in the Annals of Surgery, pending editorial review.

Dr. Li and her coauthors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

BOSTON – The risks of readmission and emergency surgery are low for patients with acute diverticulitis initially managed nonoperatively, a population-based, competing risk analysis found.

At a median of 3.9 years (range, 1.7-6.4 years) after discharge among 14,124 patients, only 8% required urgent readmission. Of these, 22% went on to urgent surgery and 20%, to elective surgery after additional episodes.

Among the remaining 12,981 patients with no urgent readmissions, 9% went on to elective surgery, 13% died of other causes, and 78% had no events in follow-up, Dr. Debbie Li said at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

The 5-year cumulative incidence was 9% for readmission, 1.9% for emergency surgery, and 14.1% for all-cause mortality.

"Elective colectomy may not be warranted for the majority of patients in the absence of chronic symptoms or multiple frequent recurrences," she said.

Elective colectomy has traditionally been recommended for patients at high risk for future recurrence and emergency surgery based on the indications of age less than 50 years, complicated disease including perforation and abscess, and two or more episodes of uncomplicated disease. Evidence is building, however, to challenge these indications, and guidelines are evolving, said Dr. Li, a general surgery resident at the University of Toronto.

The current study used administrative data to identify all patients in Ontario, Canada, treated nonoperatively at first hospitalization for diverticulitis from 2002 to 2012. Time-to-event and competing-risk regression analyses were performed, with data adjusted for such potential confounders as sex, medical comorbidity, neighborhood income quintile, rural residency, and calendar year of index admission.

Data are limited on the natural history of diverticulitis, and the few population-based studies that have been conducted have not accounted for competing risks such as elective colectomy or death, Dr. Li said.

The patients’ median age was 59 years, 79% had uncomplicated index disease, 18% had complicated disease (abscess, fistula, and perforation) with no abscess drain, and 3% had complicated disease with an abscess drain.

Young patients had more readmissions than those 50 years and older (10.5% vs. 8.4%; P less than .001), but not more emergency surgery (1.8% vs. 2.0%; P = .52), she said.

For patients older than 50 years, the risk of death by other causes was 10 times the risk of an emergency surgery for diverticulitis (19.5% vs. 2%).

Patients with complicated rather than uncomplicated index disease had more readmissions (12% vs. 8.2%; P less than .001) and urgent surgery (4.3% vs. 1.4%; P less than .001).

In adjusted analyses, young age was associated with more readmissions (hazard ratio, 1.24), but not subsequent emergency surgery (HR, 0.83). Complicated disease (HR, 3.15) and multiple recurrences (HR, 2.41) predicted an increased risk for emergency surgery.

"Young age, complicated disease, and multiple recurrences do infer increased relative risk, but the vast majority (85%) of such patients remain recurrence free," Dr. Li said.

Invited discussant Dr. David Schoetz, professor of surgery, Tufts University, Boston, said, "While it’s reassuring that even complicated diverticulitis can be safely managed without subsequent operation, there still must be a subgroup who should be offered early surgery."

With disease severity more common in younger patients and overall mortality less than 1%, perhaps aggressive surgery would be justified in those younger than 50 years, he suggested.

Dr. Li responded that an administrative database is unable to capture clinical nuances such as which patients had ongoing symptoms, chronic persistent disease, or reduced quality of life, and that a prospective trial would be needed to identify which subgroup of patients will need aggressive surgery.

Older patients, those with more complicated disease, and those with greater medical comorbidities are more likely to undergo urgent surgery, according to ongoing analyses of roughly 4,000 patients, treated during the same time period, but excluded from the current analysis because they underwent surgery at index admission. Previously published work also suggests that patients with a higher body mass index have poorer outcomes.

A recent systematic review of diverticulitis surgery (JAMA Surg. 2014;149:292-303) reported that complicated recurrence after an episode of uncomplicated diverticulitis is rare, occurring in less than 5% of cases. The authors called for existing guidelines to be updated and said that decisions to proceed with elective surgery should be based instead on patient-reported frequency and severity of symptoms.

The complete manuscript of this study and its presentation at the American Surgical Association’s 134th annual meeting, April 2014, in Boston, is anticipated to be published in the Annals of Surgery, pending editorial review.

Dr. Li and her coauthors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

urgent surgery, elective surgery, Dr. Debbie Li, American Surgical Association, colectomy, abscess, fistula, perforation, abscess drain, Young patients,

urgent surgery, elective surgery, Dr. Debbie Li, American Surgical Association, colectomy, abscess, fistula, perforation, abscess drain, Young patients,

AT ASA 2014

Key clinical point: As recurrence is very rare, conservative nonoperative treatment should be considered first.

Major finding: The 5-year cumulative incidence was 9% for readmission, 1.9% for emergency surgery, and 14.1% for all-cause mortality.

Data source: A population-based, competing risk analysis of 14,124 patients with initial nonoperative management of diverticulitis.

Disclosures: Dr. Li and her coauthors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Some providers quicker to tube feed end-of-life elderly

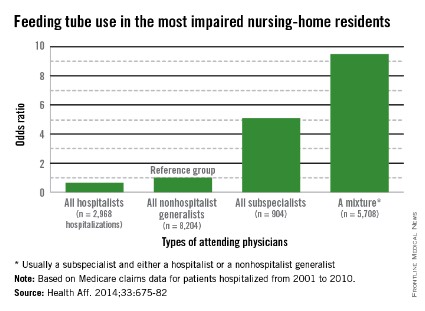

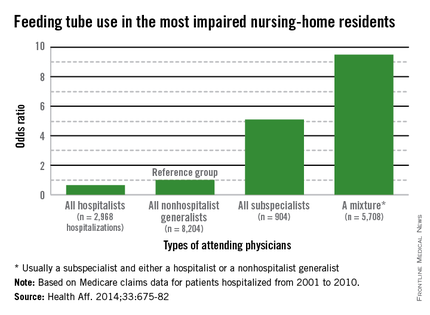

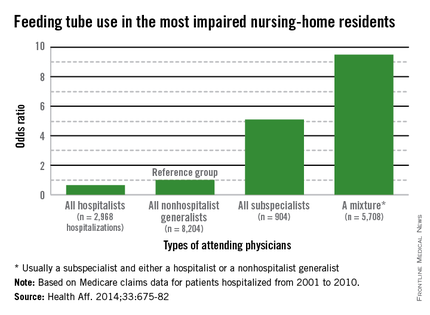

Hospitalists who care for dementia patients near the end of life are much less likely to introduce a feeding tube than other physicians who follow such patients.

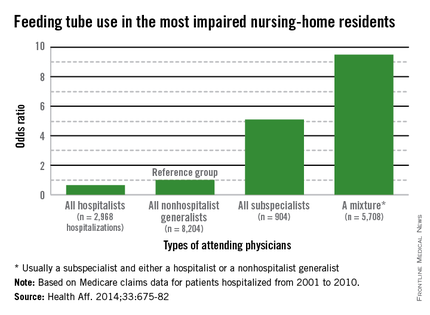

Compared with nonhospital generalists, hospitalists were 22% less likely to tube-feed hospitalized nursing home residents – and even less likely to tube-feed patients who were the most severely impaired (35%). In contrast, subspecialists were five times more likely to insert a tube. When a mixed group of physicians was on the case, rates were even higher, with a 9-fold increase overall and a 9.5-fold increase for severely demented patients.

The findings clearly illustrate that nonhospitalists could benefit from some education about the most appropriate interventions when patients near the end of life enter a hospital, Dr. Joan Teno and her associates reported in the April issue of Health Affairs (Health Aff. April 2014;33:675-82).