User login

Hospitalists who care for dementia patients near the end of life are much less likely to introduce a feeding tube than other physicians who follow such patients.

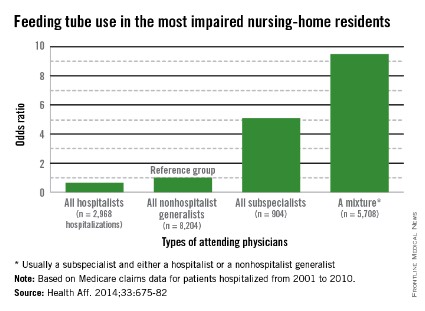

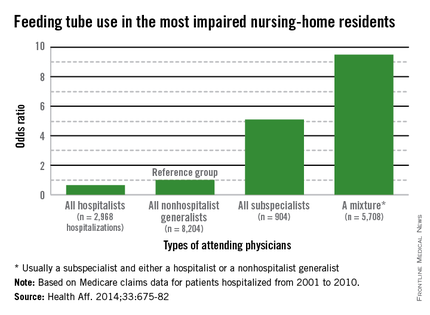

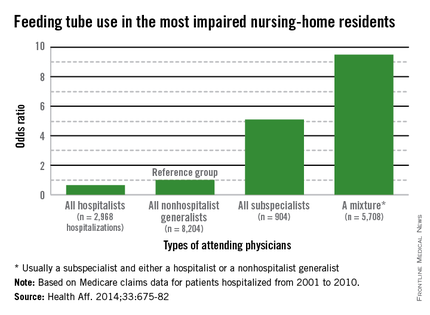

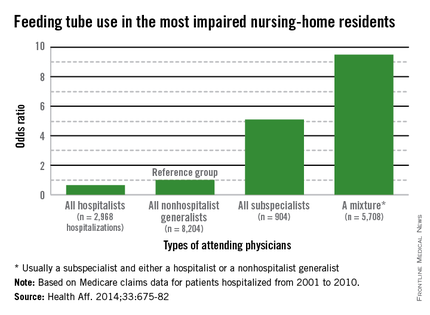

Compared with nonhospital generalists, hospitalists were 22% less likely to tube-feed hospitalized nursing home residents – and even less likely to tube-feed patients who were the most severely impaired (35%). In contrast, subspecialists were five times more likely to insert a tube. When a mixed group of physicians was on the case, rates were even higher, with a 9-fold increase overall and a 9.5-fold increase for severely demented patients.

The findings clearly illustrate that nonhospitalists could benefit from some education about the most appropriate interventions when patients near the end of life enter a hospital, Dr. Joan Teno and her associates reported in the April issue of Health Affairs (Health Aff. April 2014;33:675-82).

"It may be that subspecialists do not have adequate knowledge about the risks and benefits of using feeding tubes in people with advanced dementia," said Dr. Teno of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and her coauthors. "Hospitals should educate physicians about the lack of efficacy of PEG [percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy] feeding tubes, compared with hand feeding, in prolonging survival and preventing aspiration pneumonias and pressure ulcers in people with advanced dementia. In addition, hospitals should examine how they staff the role of attending physician and ensure coordination of care when patient hand-offs are made between different types of attending physicians."

Such education would bring all physicians up to speed with position statements against tube feeding for this group of patients. The issue sits atop the Choosing Wisely lists of both the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine and the American Geriatrics Society. The American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine states that "feeding tubes do not result in improved survival, prevention of aspiration pneumonia, or improved healing of pressure ulcers. Feeding tube use in such patients has actually been associated with pressure ulcer development, use of physical and pharmacological restraints, and patient distress about the tube itself."

Internal medicine physician Eric G. Tangalos of the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., works closely with hospitalists. He agrees with the concept that tube feeding can impose even more distress on both these patients and their families. "As a medical profession and a society, we have yet to accept some of the futility of our actions and continue to ignore the burdens tube feedings place on patients, families, and the health care system once a hospitalization has come to its conclusion," he said in an interview.

Dr. Teno and her team looked at the rate of feeding tube insertion in fee-for-service Medicare patients with advanced dementia who were within 90 days of death and hospitalized with a diagnosis of urinary tract infection, sepsis, pneumonia, or dehydration. The study examined decisions made by four groups of physicians who cared for these patients: hospitalists, nonhospitalist generalists (geriatricians, general practitioners, internists, and family physicians), subspecialists, and mixed groups that included a subspecialist and either a hospitalist or nonhospitalist generalist.

The cohort comprised 53,492 patients hospitalized from 2001 to 2010. The patients’ mean age was 85 years. About 60% had a do not resuscitate order, and 10% had an order against tube feeding.

The rate of hospitalists as attending physicians increased from 11% in 2001 to 28% in 2010. The portion of patients seen by a mixture of attending physicians increased from 29% in 2001 to 38% in 2010.

The rates of tube feeding were lowest when a hospitalist or nonhospitalist generalist was the attending physician (1.6% and 2.2%, respectively). Subspecialists had significantly higher rates (11%). The highest rate occurred when there were mixed groups of physicians involved in the patient’s care (15.6%).

Using the nonhospitalist generalists as a reference group, the researchers found that hospitalists were 22% less likely to insert a tube overall and 35% less likely to do so when the patient had very severe cognitive and physical impairment.

Conversely, subspecialists were five times more likely to commence tube feeding for all patients and for very severely impaired patients. The mixed groups were the most likely to begin tube feeding – almost 9 times more likely overall and 9.5 times more likely for the most severely impaired patients.

"Our finding that subspecialists had a higher rate of insertions of PEG feeding tubes might reflect their lack of experience in providing care for people with advanced dementia," the authors wrote.

The mixed-physician group could be seen as a proxy for discontinuity of care among the attending physicians, they noted. Prior studies have found that such discontinuity was associated with longer hospital stays.

"There may be a lack of care coordination during patient hand offs between attending physicians that begins a cascade of events, ending with the insertion of a PEG feeding tube."

Dr. Diane E. Meier, professor of geriatrics and palliative medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and director of the Center to Advance Palliative Care, agreed that group care without a leader creates confusion. "One of the hallmarks of modern medicine in the U.S. is fragmentation. It is typical for a person with dementia to have a different specialist for every organ system, a problem compounded in the hospital when a completely new group of specialists is brought into the care team. The problem with this abundance of doctors is that no one is really in charge of the whole patient and what makes the most sense for the patient as a person. Organ- and specialty-specific decision making leads to bad practices – including trying to ‘solve’ a feeding difficulty as if it is an isolated problem when the real issue is progressive brain failure – a terminal illness that cannot be fixed with a feeding tube."

The study not only questions the feeding tube issue, but also the wisdom of repeatedly hospitalizing elderly patients with severe dementia who could be in the last phase of life – especially for conditions that are expected complications of severe dementia. The authors suggested that there may be financial motives to admit fee-for-service patients.

"The fee-for-service system provides incentives to hospitalize nursing home residents with severe dementia because such hospitalizations qualify the patients for skilled nursing home services. Bundling of payments and institutional special needs plans that reverse these financial incentives may reduce health care expenditures and improve the quality of care for nursing home residents with advanced dementia by avoiding burdensome transitions between facilities and the stress of relocation."

The National Institute on Aging funded the study. Dr. Teno made no financial declarations.

Hospitalists who care for dementia patients near the end of life are much less likely to introduce a feeding tube than other physicians who follow such patients.

Compared with nonhospital generalists, hospitalists were 22% less likely to tube-feed hospitalized nursing home residents – and even less likely to tube-feed patients who were the most severely impaired (35%). In contrast, subspecialists were five times more likely to insert a tube. When a mixed group of physicians was on the case, rates were even higher, with a 9-fold increase overall and a 9.5-fold increase for severely demented patients.

The findings clearly illustrate that nonhospitalists could benefit from some education about the most appropriate interventions when patients near the end of life enter a hospital, Dr. Joan Teno and her associates reported in the April issue of Health Affairs (Health Aff. April 2014;33:675-82).

"It may be that subspecialists do not have adequate knowledge about the risks and benefits of using feeding tubes in people with advanced dementia," said Dr. Teno of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and her coauthors. "Hospitals should educate physicians about the lack of efficacy of PEG [percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy] feeding tubes, compared with hand feeding, in prolonging survival and preventing aspiration pneumonias and pressure ulcers in people with advanced dementia. In addition, hospitals should examine how they staff the role of attending physician and ensure coordination of care when patient hand-offs are made between different types of attending physicians."

Such education would bring all physicians up to speed with position statements against tube feeding for this group of patients. The issue sits atop the Choosing Wisely lists of both the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine and the American Geriatrics Society. The American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine states that "feeding tubes do not result in improved survival, prevention of aspiration pneumonia, or improved healing of pressure ulcers. Feeding tube use in such patients has actually been associated with pressure ulcer development, use of physical and pharmacological restraints, and patient distress about the tube itself."

Internal medicine physician Eric G. Tangalos of the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., works closely with hospitalists. He agrees with the concept that tube feeding can impose even more distress on both these patients and their families. "As a medical profession and a society, we have yet to accept some of the futility of our actions and continue to ignore the burdens tube feedings place on patients, families, and the health care system once a hospitalization has come to its conclusion," he said in an interview.

Dr. Teno and her team looked at the rate of feeding tube insertion in fee-for-service Medicare patients with advanced dementia who were within 90 days of death and hospitalized with a diagnosis of urinary tract infection, sepsis, pneumonia, or dehydration. The study examined decisions made by four groups of physicians who cared for these patients: hospitalists, nonhospitalist generalists (geriatricians, general practitioners, internists, and family physicians), subspecialists, and mixed groups that included a subspecialist and either a hospitalist or nonhospitalist generalist.

The cohort comprised 53,492 patients hospitalized from 2001 to 2010. The patients’ mean age was 85 years. About 60% had a do not resuscitate order, and 10% had an order against tube feeding.

The rate of hospitalists as attending physicians increased from 11% in 2001 to 28% in 2010. The portion of patients seen by a mixture of attending physicians increased from 29% in 2001 to 38% in 2010.

The rates of tube feeding were lowest when a hospitalist or nonhospitalist generalist was the attending physician (1.6% and 2.2%, respectively). Subspecialists had significantly higher rates (11%). The highest rate occurred when there were mixed groups of physicians involved in the patient’s care (15.6%).

Using the nonhospitalist generalists as a reference group, the researchers found that hospitalists were 22% less likely to insert a tube overall and 35% less likely to do so when the patient had very severe cognitive and physical impairment.

Conversely, subspecialists were five times more likely to commence tube feeding for all patients and for very severely impaired patients. The mixed groups were the most likely to begin tube feeding – almost 9 times more likely overall and 9.5 times more likely for the most severely impaired patients.

"Our finding that subspecialists had a higher rate of insertions of PEG feeding tubes might reflect their lack of experience in providing care for people with advanced dementia," the authors wrote.

The mixed-physician group could be seen as a proxy for discontinuity of care among the attending physicians, they noted. Prior studies have found that such discontinuity was associated with longer hospital stays.

"There may be a lack of care coordination during patient hand offs between attending physicians that begins a cascade of events, ending with the insertion of a PEG feeding tube."

Dr. Diane E. Meier, professor of geriatrics and palliative medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and director of the Center to Advance Palliative Care, agreed that group care without a leader creates confusion. "One of the hallmarks of modern medicine in the U.S. is fragmentation. It is typical for a person with dementia to have a different specialist for every organ system, a problem compounded in the hospital when a completely new group of specialists is brought into the care team. The problem with this abundance of doctors is that no one is really in charge of the whole patient and what makes the most sense for the patient as a person. Organ- and specialty-specific decision making leads to bad practices – including trying to ‘solve’ a feeding difficulty as if it is an isolated problem when the real issue is progressive brain failure – a terminal illness that cannot be fixed with a feeding tube."

The study not only questions the feeding tube issue, but also the wisdom of repeatedly hospitalizing elderly patients with severe dementia who could be in the last phase of life – especially for conditions that are expected complications of severe dementia. The authors suggested that there may be financial motives to admit fee-for-service patients.

"The fee-for-service system provides incentives to hospitalize nursing home residents with severe dementia because such hospitalizations qualify the patients for skilled nursing home services. Bundling of payments and institutional special needs plans that reverse these financial incentives may reduce health care expenditures and improve the quality of care for nursing home residents with advanced dementia by avoiding burdensome transitions between facilities and the stress of relocation."

The National Institute on Aging funded the study. Dr. Teno made no financial declarations.

Hospitalists who care for dementia patients near the end of life are much less likely to introduce a feeding tube than other physicians who follow such patients.

Compared with nonhospital generalists, hospitalists were 22% less likely to tube-feed hospitalized nursing home residents – and even less likely to tube-feed patients who were the most severely impaired (35%). In contrast, subspecialists were five times more likely to insert a tube. When a mixed group of physicians was on the case, rates were even higher, with a 9-fold increase overall and a 9.5-fold increase for severely demented patients.

The findings clearly illustrate that nonhospitalists could benefit from some education about the most appropriate interventions when patients near the end of life enter a hospital, Dr. Joan Teno and her associates reported in the April issue of Health Affairs (Health Aff. April 2014;33:675-82).

"It may be that subspecialists do not have adequate knowledge about the risks and benefits of using feeding tubes in people with advanced dementia," said Dr. Teno of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and her coauthors. "Hospitals should educate physicians about the lack of efficacy of PEG [percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy] feeding tubes, compared with hand feeding, in prolonging survival and preventing aspiration pneumonias and pressure ulcers in people with advanced dementia. In addition, hospitals should examine how they staff the role of attending physician and ensure coordination of care when patient hand-offs are made between different types of attending physicians."

Such education would bring all physicians up to speed with position statements against tube feeding for this group of patients. The issue sits atop the Choosing Wisely lists of both the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine and the American Geriatrics Society. The American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine states that "feeding tubes do not result in improved survival, prevention of aspiration pneumonia, or improved healing of pressure ulcers. Feeding tube use in such patients has actually been associated with pressure ulcer development, use of physical and pharmacological restraints, and patient distress about the tube itself."

Internal medicine physician Eric G. Tangalos of the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., works closely with hospitalists. He agrees with the concept that tube feeding can impose even more distress on both these patients and their families. "As a medical profession and a society, we have yet to accept some of the futility of our actions and continue to ignore the burdens tube feedings place on patients, families, and the health care system once a hospitalization has come to its conclusion," he said in an interview.

Dr. Teno and her team looked at the rate of feeding tube insertion in fee-for-service Medicare patients with advanced dementia who were within 90 days of death and hospitalized with a diagnosis of urinary tract infection, sepsis, pneumonia, or dehydration. The study examined decisions made by four groups of physicians who cared for these patients: hospitalists, nonhospitalist generalists (geriatricians, general practitioners, internists, and family physicians), subspecialists, and mixed groups that included a subspecialist and either a hospitalist or nonhospitalist generalist.

The cohort comprised 53,492 patients hospitalized from 2001 to 2010. The patients’ mean age was 85 years. About 60% had a do not resuscitate order, and 10% had an order against tube feeding.

The rate of hospitalists as attending physicians increased from 11% in 2001 to 28% in 2010. The portion of patients seen by a mixture of attending physicians increased from 29% in 2001 to 38% in 2010.

The rates of tube feeding were lowest when a hospitalist or nonhospitalist generalist was the attending physician (1.6% and 2.2%, respectively). Subspecialists had significantly higher rates (11%). The highest rate occurred when there were mixed groups of physicians involved in the patient’s care (15.6%).

Using the nonhospitalist generalists as a reference group, the researchers found that hospitalists were 22% less likely to insert a tube overall and 35% less likely to do so when the patient had very severe cognitive and physical impairment.

Conversely, subspecialists were five times more likely to commence tube feeding for all patients and for very severely impaired patients. The mixed groups were the most likely to begin tube feeding – almost 9 times more likely overall and 9.5 times more likely for the most severely impaired patients.

"Our finding that subspecialists had a higher rate of insertions of PEG feeding tubes might reflect their lack of experience in providing care for people with advanced dementia," the authors wrote.

The mixed-physician group could be seen as a proxy for discontinuity of care among the attending physicians, they noted. Prior studies have found that such discontinuity was associated with longer hospital stays.

"There may be a lack of care coordination during patient hand offs between attending physicians that begins a cascade of events, ending with the insertion of a PEG feeding tube."

Dr. Diane E. Meier, professor of geriatrics and palliative medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and director of the Center to Advance Palliative Care, agreed that group care without a leader creates confusion. "One of the hallmarks of modern medicine in the U.S. is fragmentation. It is typical for a person with dementia to have a different specialist for every organ system, a problem compounded in the hospital when a completely new group of specialists is brought into the care team. The problem with this abundance of doctors is that no one is really in charge of the whole patient and what makes the most sense for the patient as a person. Organ- and specialty-specific decision making leads to bad practices – including trying to ‘solve’ a feeding difficulty as if it is an isolated problem when the real issue is progressive brain failure – a terminal illness that cannot be fixed with a feeding tube."

The study not only questions the feeding tube issue, but also the wisdom of repeatedly hospitalizing elderly patients with severe dementia who could be in the last phase of life – especially for conditions that are expected complications of severe dementia. The authors suggested that there may be financial motives to admit fee-for-service patients.

"The fee-for-service system provides incentives to hospitalize nursing home residents with severe dementia because such hospitalizations qualify the patients for skilled nursing home services. Bundling of payments and institutional special needs plans that reverse these financial incentives may reduce health care expenditures and improve the quality of care for nursing home residents with advanced dementia by avoiding burdensome transitions between facilities and the stress of relocation."

The National Institute on Aging funded the study. Dr. Teno made no financial declarations.

FROM HEALTH AFFAIRS

Major finding: Primary care doctors and subspecialists were up to 9 times more likely to initiate tube feeding in hospitalized patients with severe dementia.

Data source: Data are from a review of more than 53,000 Medicare fee-for-service nursing home patients.

Disclosures: The National Institute on Aging sponsored the study. Dr. Teno had no financial disclosures.