User login

Official Newspaper of the American College of Surgeons

ACS NSQIP to mark 10th anniversary in New York

The 2014 American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP®) Conference at the New York, NY, Hilton Midtown, July 26-29, will mark ACS NSQIP’s 10th anniversary.

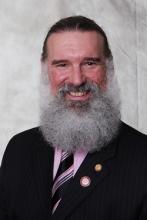

Keynote speakers will include Andrew L. Warshaw, MD, FACS, FRCSEd(Hon), ACS President-Elect, W. Gerald Austen Distinguished Professor of Surgery, Harvard Medical School, and surgeon-in-chief and chairman emeritus, department of surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who will speak on Surgery: Where Are We Going?; and Linda K. Groah, MSN, RN, CNOR, chief executive officer and executive director of the Association of Perioperative Registered Nurse, who will address the question, Accountability and Quality Care: Are They a Match?

The ACS NSQIP Conference this year again will focus on lessons in achieving health care quality and ways to continually develop leadership.

Highlights in the General Session will include Reducing Surgical Site Infection (SSI): A Surgical Imperative; Creating Value: Understanding the Quality/Cost Equation; and Regulatory Update: The Alphabet Soup of Programs and Reporting—Basic Understanding of How ACS NSQIP and ACS Can Help You and Your Hospital. Preconference workshops will take place Saturday, July 26.

For more information, refer to the ACS NSQIP Conference brochure at http://www.acsnsqipconference.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/ACS-NSQIP-National-Conference-Brochure_FINAL-5-15.pdf.

The 2014 American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP®) Conference at the New York, NY, Hilton Midtown, July 26-29, will mark ACS NSQIP’s 10th anniversary.

Keynote speakers will include Andrew L. Warshaw, MD, FACS, FRCSEd(Hon), ACS President-Elect, W. Gerald Austen Distinguished Professor of Surgery, Harvard Medical School, and surgeon-in-chief and chairman emeritus, department of surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who will speak on Surgery: Where Are We Going?; and Linda K. Groah, MSN, RN, CNOR, chief executive officer and executive director of the Association of Perioperative Registered Nurse, who will address the question, Accountability and Quality Care: Are They a Match?

The ACS NSQIP Conference this year again will focus on lessons in achieving health care quality and ways to continually develop leadership.

Highlights in the General Session will include Reducing Surgical Site Infection (SSI): A Surgical Imperative; Creating Value: Understanding the Quality/Cost Equation; and Regulatory Update: The Alphabet Soup of Programs and Reporting—Basic Understanding of How ACS NSQIP and ACS Can Help You and Your Hospital. Preconference workshops will take place Saturday, July 26.

For more information, refer to the ACS NSQIP Conference brochure at http://www.acsnsqipconference.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/ACS-NSQIP-National-Conference-Brochure_FINAL-5-15.pdf.

The 2014 American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP®) Conference at the New York, NY, Hilton Midtown, July 26-29, will mark ACS NSQIP’s 10th anniversary.

Keynote speakers will include Andrew L. Warshaw, MD, FACS, FRCSEd(Hon), ACS President-Elect, W. Gerald Austen Distinguished Professor of Surgery, Harvard Medical School, and surgeon-in-chief and chairman emeritus, department of surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who will speak on Surgery: Where Are We Going?; and Linda K. Groah, MSN, RN, CNOR, chief executive officer and executive director of the Association of Perioperative Registered Nurse, who will address the question, Accountability and Quality Care: Are They a Match?

The ACS NSQIP Conference this year again will focus on lessons in achieving health care quality and ways to continually develop leadership.

Highlights in the General Session will include Reducing Surgical Site Infection (SSI): A Surgical Imperative; Creating Value: Understanding the Quality/Cost Equation; and Regulatory Update: The Alphabet Soup of Programs and Reporting—Basic Understanding of How ACS NSQIP and ACS Can Help You and Your Hospital. Preconference workshops will take place Saturday, July 26.

For more information, refer to the ACS NSQIP Conference brochure at http://www.acsnsqipconference.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/ACS-NSQIP-National-Conference-Brochure_FINAL-5-15.pdf.

Medicare’s 2015 outpatient proposal continues focus on bundled pay

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ proposed rule on outpatient department and ambulatory surgery center payment for 2015 expands the agency’s focus on bundling pay for device-related procedures, largely in cardiology, neurology, oncology, and gynecology.

The Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) rule also continues the same payment rate for outpatient drug delivery such as chemotherapy. That payment rate has been a source of disappointment for oncologists. The American Society of Clinical Oncology has said in the past that, with the additional impact of budget sequestration, the actual payment for delivering chemotherapy drugs falls by 28%.

The agency is proposing again in 2015 to continue paying average sales price plus 6% for non–pass through drugs and biologicals that are administered under Part B of Medicare.

Proposed on July 3, the rule will be published on July 14. It covers payment for 4,000 hospitals, including general acute care hospitals, inpatient rehabilitation facilities, inpatient psychiatric facilities, long-term acute care hospitals, children’s hospitals, and cancer hospitals. It also applies to 5,300 ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs) that participate in Medicare.

Overall, the government is proposing to increase payments to outpatient departments by 2%. The CMS expects to pay out some $57 billion for outpatient services in 2015. Payments to ASCs will increase just over 1% to $4 billion in 2015.

The agency is proposing to expand its Comprehensive Ambulatory Payment Classification (APC) policy, which was first discussed in its 2014 rule. The idea is to give a single Medicare payment and require a single beneficiary copayment for the entire hospital stay for a group of 28 procedures, including pacemaker insertion, implantation of neurostimulators, and stereotactic radiosurgery. It also would cover implantable cardioverter defibrillators.

The single, bundled payments would begin in 2015.

The proposed rule also contains several adjustments to both the Hospital Outpatient Quality Reporting Program and the ASC Quality Reporting Program. On the hospital side, the CMS is proposing to remove three quality measures, stating that performance has been uniformly high among reporting facilities. Those measures are aspirin at arrival (cardiac care), timing of prophylaxis antibiotics, and prophylactic antibiotic selection for surgical patients. The agency is proposing to add a claims-based measure – facility 7-day risk-standardized hospital visit rate after outpatient colonoscopy – for 2017 and beyond.

For ASCs, the agency is proposing to continue its effort to align measures with the hospital program. In 2015, ASCs will be required to report on the 7-day risk-standardized visit rate after outpatient colonoscopy measure.

The CMS is accepting comments on the proposed rule until Sept. 2, 2014. A final rule will be issued by Nov. 1.

On Twitter @aliciaault

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ proposed rule on outpatient department and ambulatory surgery center payment for 2015 expands the agency’s focus on bundling pay for device-related procedures, largely in cardiology, neurology, oncology, and gynecology.

The Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) rule also continues the same payment rate for outpatient drug delivery such as chemotherapy. That payment rate has been a source of disappointment for oncologists. The American Society of Clinical Oncology has said in the past that, with the additional impact of budget sequestration, the actual payment for delivering chemotherapy drugs falls by 28%.

The agency is proposing again in 2015 to continue paying average sales price plus 6% for non–pass through drugs and biologicals that are administered under Part B of Medicare.

Proposed on July 3, the rule will be published on July 14. It covers payment for 4,000 hospitals, including general acute care hospitals, inpatient rehabilitation facilities, inpatient psychiatric facilities, long-term acute care hospitals, children’s hospitals, and cancer hospitals. It also applies to 5,300 ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs) that participate in Medicare.

Overall, the government is proposing to increase payments to outpatient departments by 2%. The CMS expects to pay out some $57 billion for outpatient services in 2015. Payments to ASCs will increase just over 1% to $4 billion in 2015.

The agency is proposing to expand its Comprehensive Ambulatory Payment Classification (APC) policy, which was first discussed in its 2014 rule. The idea is to give a single Medicare payment and require a single beneficiary copayment for the entire hospital stay for a group of 28 procedures, including pacemaker insertion, implantation of neurostimulators, and stereotactic radiosurgery. It also would cover implantable cardioverter defibrillators.

The single, bundled payments would begin in 2015.

The proposed rule also contains several adjustments to both the Hospital Outpatient Quality Reporting Program and the ASC Quality Reporting Program. On the hospital side, the CMS is proposing to remove three quality measures, stating that performance has been uniformly high among reporting facilities. Those measures are aspirin at arrival (cardiac care), timing of prophylaxis antibiotics, and prophylactic antibiotic selection for surgical patients. The agency is proposing to add a claims-based measure – facility 7-day risk-standardized hospital visit rate after outpatient colonoscopy – for 2017 and beyond.

For ASCs, the agency is proposing to continue its effort to align measures with the hospital program. In 2015, ASCs will be required to report on the 7-day risk-standardized visit rate after outpatient colonoscopy measure.

The CMS is accepting comments on the proposed rule until Sept. 2, 2014. A final rule will be issued by Nov. 1.

On Twitter @aliciaault

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ proposed rule on outpatient department and ambulatory surgery center payment for 2015 expands the agency’s focus on bundling pay for device-related procedures, largely in cardiology, neurology, oncology, and gynecology.

The Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) rule also continues the same payment rate for outpatient drug delivery such as chemotherapy. That payment rate has been a source of disappointment for oncologists. The American Society of Clinical Oncology has said in the past that, with the additional impact of budget sequestration, the actual payment for delivering chemotherapy drugs falls by 28%.

The agency is proposing again in 2015 to continue paying average sales price plus 6% for non–pass through drugs and biologicals that are administered under Part B of Medicare.

Proposed on July 3, the rule will be published on July 14. It covers payment for 4,000 hospitals, including general acute care hospitals, inpatient rehabilitation facilities, inpatient psychiatric facilities, long-term acute care hospitals, children’s hospitals, and cancer hospitals. It also applies to 5,300 ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs) that participate in Medicare.

Overall, the government is proposing to increase payments to outpatient departments by 2%. The CMS expects to pay out some $57 billion for outpatient services in 2015. Payments to ASCs will increase just over 1% to $4 billion in 2015.

The agency is proposing to expand its Comprehensive Ambulatory Payment Classification (APC) policy, which was first discussed in its 2014 rule. The idea is to give a single Medicare payment and require a single beneficiary copayment for the entire hospital stay for a group of 28 procedures, including pacemaker insertion, implantation of neurostimulators, and stereotactic radiosurgery. It also would cover implantable cardioverter defibrillators.

The single, bundled payments would begin in 2015.

The proposed rule also contains several adjustments to both the Hospital Outpatient Quality Reporting Program and the ASC Quality Reporting Program. On the hospital side, the CMS is proposing to remove three quality measures, stating that performance has been uniformly high among reporting facilities. Those measures are aspirin at arrival (cardiac care), timing of prophylaxis antibiotics, and prophylactic antibiotic selection for surgical patients. The agency is proposing to add a claims-based measure – facility 7-day risk-standardized hospital visit rate after outpatient colonoscopy – for 2017 and beyond.

For ASCs, the agency is proposing to continue its effort to align measures with the hospital program. In 2015, ASCs will be required to report on the 7-day risk-standardized visit rate after outpatient colonoscopy measure.

The CMS is accepting comments on the proposed rule until Sept. 2, 2014. A final rule will be issued by Nov. 1.

On Twitter @aliciaault

Initial cholecystectomy bests standard approach for suspected common duct stone

For patients at intermediate risk for having a common duct stone, initial cholecystectomy resulted in a shorter hospital stay, fewer invasive procedures, and no increase in morbidity, compared with the standard approach of doing a common duct exploration via endoscopic ultrasound followed by (if indicated) endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and cholecystectomy, according to a report published online July 8 in JAMA.

At present there are no specific guidelines as to the initial treatment approach for patients who present to the emergency department with suspected choledocholithiasis and who are at intermediate risk for retaining a common duct stone. In contrast, guidelines recommend initial laparoscopic cholecystectomy for patients at low risk for a retained common duct stone and preoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) followed by cholecystectomy for those at high risk, said Dr. Pouya Iranmanesh of the divisions of digestive surgery and transplant surgery, Geneva University Hospital, and his associates.

They performed a single-center randomized clinical trial comparing these two approaches in 100 intermediate-risk patients who presented to the emergency department during a 2-year period with sudden abdominal pain in the right upper quadrant and/or epigastric region, which was associated with elevated liver enzymes and the presence of a gallstone on ultrasound. Patients were included in the study whether they had associated acute cholecystitis or not and were randomly assigned to undergo either initial emergency laparoscopic cholecystectomy with intraoperative cholangiogram (50 patients) or initial common duct ultrasound exploration followed by (if indicated) ERCP and cholecystectomy (50 control subjects).

The median length of hospital stay was significantly shorter for the initial-cholecystectomy group (5 days) than for the control group (8 days), and the total number of procedures (endoscopic ultrasounds, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatographies, and ERCPs) also was significantly smaller (25 vs. 71). In particular, the number of endoscopic ultrasounds was only 10 in the initial-cholecystectomy group, compared with 54 in the control group. All 50 patients in the control group (100%) underwent at least one common duct investigation exclusive of the intraoperative cholangiogram, compared with only 20 patients (40%) in the initial-cholecystectomy group, the investigators reported (JAMA 2014 July 8 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.7587]).

The two study groups had similar rates of conversion to laparotomy, similar operation times, a similar number of failed intraoperative cholangiograms, and similar results on quality of life measures at 1 month and 6 months after hospital discharge. The rates of complications (8% vs 14%) and of severe complications (4% vs 8%) were approximately twice as high in the control group as in the initial-cholecystectomy group.

Since 30 (60%) of the patients in the initial-cholecystectomy group never needed any common duct investigation, it follows that many intermediate-risk patients in real-world practice are undergoing unnecessary common duct procedures. A policy of performing a cholecystectomy first ensures that only patients who retain common duct stones will undergo such invasive procedures, Dr. Iranmanesh and his associates said.

Dr. Iranmanesh and his associates reported no relevant financial disclosures.

For patients at intermediate risk for having a common duct stone, initial cholecystectomy resulted in a shorter hospital stay, fewer invasive procedures, and no increase in morbidity, compared with the standard approach of doing a common duct exploration via endoscopic ultrasound followed by (if indicated) endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and cholecystectomy, according to a report published online July 8 in JAMA.

At present there are no specific guidelines as to the initial treatment approach for patients who present to the emergency department with suspected choledocholithiasis and who are at intermediate risk for retaining a common duct stone. In contrast, guidelines recommend initial laparoscopic cholecystectomy for patients at low risk for a retained common duct stone and preoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) followed by cholecystectomy for those at high risk, said Dr. Pouya Iranmanesh of the divisions of digestive surgery and transplant surgery, Geneva University Hospital, and his associates.

They performed a single-center randomized clinical trial comparing these two approaches in 100 intermediate-risk patients who presented to the emergency department during a 2-year period with sudden abdominal pain in the right upper quadrant and/or epigastric region, which was associated with elevated liver enzymes and the presence of a gallstone on ultrasound. Patients were included in the study whether they had associated acute cholecystitis or not and were randomly assigned to undergo either initial emergency laparoscopic cholecystectomy with intraoperative cholangiogram (50 patients) or initial common duct ultrasound exploration followed by (if indicated) ERCP and cholecystectomy (50 control subjects).

The median length of hospital stay was significantly shorter for the initial-cholecystectomy group (5 days) than for the control group (8 days), and the total number of procedures (endoscopic ultrasounds, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatographies, and ERCPs) also was significantly smaller (25 vs. 71). In particular, the number of endoscopic ultrasounds was only 10 in the initial-cholecystectomy group, compared with 54 in the control group. All 50 patients in the control group (100%) underwent at least one common duct investigation exclusive of the intraoperative cholangiogram, compared with only 20 patients (40%) in the initial-cholecystectomy group, the investigators reported (JAMA 2014 July 8 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.7587]).

The two study groups had similar rates of conversion to laparotomy, similar operation times, a similar number of failed intraoperative cholangiograms, and similar results on quality of life measures at 1 month and 6 months after hospital discharge. The rates of complications (8% vs 14%) and of severe complications (4% vs 8%) were approximately twice as high in the control group as in the initial-cholecystectomy group.

Since 30 (60%) of the patients in the initial-cholecystectomy group never needed any common duct investigation, it follows that many intermediate-risk patients in real-world practice are undergoing unnecessary common duct procedures. A policy of performing a cholecystectomy first ensures that only patients who retain common duct stones will undergo such invasive procedures, Dr. Iranmanesh and his associates said.

Dr. Iranmanesh and his associates reported no relevant financial disclosures.

For patients at intermediate risk for having a common duct stone, initial cholecystectomy resulted in a shorter hospital stay, fewer invasive procedures, and no increase in morbidity, compared with the standard approach of doing a common duct exploration via endoscopic ultrasound followed by (if indicated) endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and cholecystectomy, according to a report published online July 8 in JAMA.

At present there are no specific guidelines as to the initial treatment approach for patients who present to the emergency department with suspected choledocholithiasis and who are at intermediate risk for retaining a common duct stone. In contrast, guidelines recommend initial laparoscopic cholecystectomy for patients at low risk for a retained common duct stone and preoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) followed by cholecystectomy for those at high risk, said Dr. Pouya Iranmanesh of the divisions of digestive surgery and transplant surgery, Geneva University Hospital, and his associates.

They performed a single-center randomized clinical trial comparing these two approaches in 100 intermediate-risk patients who presented to the emergency department during a 2-year period with sudden abdominal pain in the right upper quadrant and/or epigastric region, which was associated with elevated liver enzymes and the presence of a gallstone on ultrasound. Patients were included in the study whether they had associated acute cholecystitis or not and were randomly assigned to undergo either initial emergency laparoscopic cholecystectomy with intraoperative cholangiogram (50 patients) or initial common duct ultrasound exploration followed by (if indicated) ERCP and cholecystectomy (50 control subjects).

The median length of hospital stay was significantly shorter for the initial-cholecystectomy group (5 days) than for the control group (8 days), and the total number of procedures (endoscopic ultrasounds, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatographies, and ERCPs) also was significantly smaller (25 vs. 71). In particular, the number of endoscopic ultrasounds was only 10 in the initial-cholecystectomy group, compared with 54 in the control group. All 50 patients in the control group (100%) underwent at least one common duct investigation exclusive of the intraoperative cholangiogram, compared with only 20 patients (40%) in the initial-cholecystectomy group, the investigators reported (JAMA 2014 July 8 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.7587]).

The two study groups had similar rates of conversion to laparotomy, similar operation times, a similar number of failed intraoperative cholangiograms, and similar results on quality of life measures at 1 month and 6 months after hospital discharge. The rates of complications (8% vs 14%) and of severe complications (4% vs 8%) were approximately twice as high in the control group as in the initial-cholecystectomy group.

Since 30 (60%) of the patients in the initial-cholecystectomy group never needed any common duct investigation, it follows that many intermediate-risk patients in real-world practice are undergoing unnecessary common duct procedures. A policy of performing a cholecystectomy first ensures that only patients who retain common duct stones will undergo such invasive procedures, Dr. Iranmanesh and his associates said.

Dr. Iranmanesh and his associates reported no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Initial cholecystectomy for patients at intermediate risk for common duct stone results in shorter hospital stays and fewer invasive procedures.

Major finding: The median length of hospital stay was significantly shorter for the initial-cholecystectomy group (5 days) than for the control group (8 days), and the total number of procedures (endoscopic ultrasounds, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatographies, and ERCPs) also was significantly smaller (25 vs. 71).

Data source: A single-center randomized clinical trial comparing 50 patients who had initial cholecystectomy with 50 who had common duct exploration followed by ERCP and cholecystectomy; follow-up was done at 1 and 6 months.

Disclosures: Dr. Iranmanesh and his associates reported no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

Initial cholecystectomy bests standard approach for suspected common duct stone

For patients at intermediate risk for having a common duct stone, initial cholecystectomy resulted in a shorter hospital stay, fewer invasive procedures, and no increase in morbidity, compared with the standard approach of doing a common duct exploration via endoscopic ultrasound followed by (if indicated) endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and cholecystectomy, according to a report published online July 8 in JAMA.

At present there are no specific guidelines as to the initial treatment approach for patients who present to the emergency department with suspected choledocholithiasis and who are at intermediate risk for retaining a common duct stone. In contrast, guidelines recommend initial laparoscopic cholecystectomy for patients at low risk for a retained common duct stone and preoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) followed by cholecystectomy for those at high risk, said Dr. Pouya Iranmanesh of the divisions of digestive surgery and transplant surgery, Geneva University Hospital, and his associates.

They performed a single-center randomized clinical trial comparing these two approaches in 100 intermediate-risk patients who presented to the emergency department during a 2-year period with sudden abdominal pain in the right upper quadrant and/or epigastric region, which was associated with elevated liver enzymes and the presence of a gallstone on ultrasound. Patients were included in the study whether they had associated acute cholecystitis or not and were randomly assigned to undergo either initial emergency laparoscopic cholecystectomy with intraoperative cholangiogram (50 patients) or initial common duct ultrasound exploration followed by (if indicated) ERCP and cholecystectomy (50 control subjects).

The median length of hospital stay was significantly shorter for the initial-cholecystectomy group (5 days) than for the control group (8 days), and the total number of procedures (endoscopic ultrasounds, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatographies, and ERCPs) also was significantly smaller (25 vs. 71). In particular, the number of endoscopic ultrasounds was only 10 in the initial-cholecystectomy group, compared with 54 in the control group. All 50 patients in the control group (100%) underwent at least one common duct investigation exclusive of the intraoperative cholangiogram, compared with only 20 patients (40%) in the initial-cholecystectomy group, the investigators reported (JAMA 2014 July 8 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.7587]).

The two study groups had similar rates of conversion to laparotomy, similar operation times, a similar number of failed intraoperative cholangiograms, and similar results on quality of life measures at 1 month and 6 months after hospital discharge. The rates of complications (8% vs 14%) and of severe complications (4% vs 8%) were approximately twice as high in the control group as in the initial-cholecystectomy group.

Since 30 (60%) of the patients in the initial-cholecystectomy group never needed any common duct investigation, it follows that many intermediate-risk patients in real-world practice are undergoing unnecessary common duct procedures. A policy of performing a cholecystectomy first ensures that only patients who retain common duct stones will undergo such invasive procedures, Dr. Iranmanesh and his associates said.

Dr. Iranmanesh and his associates reported no relevant financial disclosures.

For patients at intermediate risk for having a common duct stone, initial cholecystectomy resulted in a shorter hospital stay, fewer invasive procedures, and no increase in morbidity, compared with the standard approach of doing a common duct exploration via endoscopic ultrasound followed by (if indicated) endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and cholecystectomy, according to a report published online July 8 in JAMA.

At present there are no specific guidelines as to the initial treatment approach for patients who present to the emergency department with suspected choledocholithiasis and who are at intermediate risk for retaining a common duct stone. In contrast, guidelines recommend initial laparoscopic cholecystectomy for patients at low risk for a retained common duct stone and preoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) followed by cholecystectomy for those at high risk, said Dr. Pouya Iranmanesh of the divisions of digestive surgery and transplant surgery, Geneva University Hospital, and his associates.

They performed a single-center randomized clinical trial comparing these two approaches in 100 intermediate-risk patients who presented to the emergency department during a 2-year period with sudden abdominal pain in the right upper quadrant and/or epigastric region, which was associated with elevated liver enzymes and the presence of a gallstone on ultrasound. Patients were included in the study whether they had associated acute cholecystitis or not and were randomly assigned to undergo either initial emergency laparoscopic cholecystectomy with intraoperative cholangiogram (50 patients) or initial common duct ultrasound exploration followed by (if indicated) ERCP and cholecystectomy (50 control subjects).

The median length of hospital stay was significantly shorter for the initial-cholecystectomy group (5 days) than for the control group (8 days), and the total number of procedures (endoscopic ultrasounds, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatographies, and ERCPs) also was significantly smaller (25 vs. 71). In particular, the number of endoscopic ultrasounds was only 10 in the initial-cholecystectomy group, compared with 54 in the control group. All 50 patients in the control group (100%) underwent at least one common duct investigation exclusive of the intraoperative cholangiogram, compared with only 20 patients (40%) in the initial-cholecystectomy group, the investigators reported (JAMA 2014 July 8 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.7587]).

The two study groups had similar rates of conversion to laparotomy, similar operation times, a similar number of failed intraoperative cholangiograms, and similar results on quality of life measures at 1 month and 6 months after hospital discharge. The rates of complications (8% vs 14%) and of severe complications (4% vs 8%) were approximately twice as high in the control group as in the initial-cholecystectomy group.

Since 30 (60%) of the patients in the initial-cholecystectomy group never needed any common duct investigation, it follows that many intermediate-risk patients in real-world practice are undergoing unnecessary common duct procedures. A policy of performing a cholecystectomy first ensures that only patients who retain common duct stones will undergo such invasive procedures, Dr. Iranmanesh and his associates said.

Dr. Iranmanesh and his associates reported no relevant financial disclosures.

For patients at intermediate risk for having a common duct stone, initial cholecystectomy resulted in a shorter hospital stay, fewer invasive procedures, and no increase in morbidity, compared with the standard approach of doing a common duct exploration via endoscopic ultrasound followed by (if indicated) endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and cholecystectomy, according to a report published online July 8 in JAMA.

At present there are no specific guidelines as to the initial treatment approach for patients who present to the emergency department with suspected choledocholithiasis and who are at intermediate risk for retaining a common duct stone. In contrast, guidelines recommend initial laparoscopic cholecystectomy for patients at low risk for a retained common duct stone and preoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) followed by cholecystectomy for those at high risk, said Dr. Pouya Iranmanesh of the divisions of digestive surgery and transplant surgery, Geneva University Hospital, and his associates.

They performed a single-center randomized clinical trial comparing these two approaches in 100 intermediate-risk patients who presented to the emergency department during a 2-year period with sudden abdominal pain in the right upper quadrant and/or epigastric region, which was associated with elevated liver enzymes and the presence of a gallstone on ultrasound. Patients were included in the study whether they had associated acute cholecystitis or not and were randomly assigned to undergo either initial emergency laparoscopic cholecystectomy with intraoperative cholangiogram (50 patients) or initial common duct ultrasound exploration followed by (if indicated) ERCP and cholecystectomy (50 control subjects).

The median length of hospital stay was significantly shorter for the initial-cholecystectomy group (5 days) than for the control group (8 days), and the total number of procedures (endoscopic ultrasounds, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatographies, and ERCPs) also was significantly smaller (25 vs. 71). In particular, the number of endoscopic ultrasounds was only 10 in the initial-cholecystectomy group, compared with 54 in the control group. All 50 patients in the control group (100%) underwent at least one common duct investigation exclusive of the intraoperative cholangiogram, compared with only 20 patients (40%) in the initial-cholecystectomy group, the investigators reported (JAMA 2014 July 8 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.7587]).

The two study groups had similar rates of conversion to laparotomy, similar operation times, a similar number of failed intraoperative cholangiograms, and similar results on quality of life measures at 1 month and 6 months after hospital discharge. The rates of complications (8% vs 14%) and of severe complications (4% vs 8%) were approximately twice as high in the control group as in the initial-cholecystectomy group.

Since 30 (60%) of the patients in the initial-cholecystectomy group never needed any common duct investigation, it follows that many intermediate-risk patients in real-world practice are undergoing unnecessary common duct procedures. A policy of performing a cholecystectomy first ensures that only patients who retain common duct stones will undergo such invasive procedures, Dr. Iranmanesh and his associates said.

Dr. Iranmanesh and his associates reported no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Initial cholecystectomy for patients at intermediate risk for common duct stone results in shorter hospital stays and fewer invasive procedures.

Major finding: The median length of hospital stay was significantly shorter for the initial-cholecystectomy group (5 days) than for the control group (8 days), and the total number of procedures (endoscopic ultrasounds, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatographies, and ERCPs) also was significantly smaller (25 vs. 71).

Data source: A single-center randomized clinical trial comparing 50 patients who had initial cholecystectomy with 50 who had common duct exploration followed by ERCP and cholecystectomy; follow-up was done at 1 and 6 months.

Disclosures: Dr. Iranmanesh and his associates reported no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

Accountable care organizations may fuel new litigation theories

The aim of accountable care organizations is to improve health care quality, enhance care coordination, and reduce unnecessary costs. But the new health care delivery models are raising questions about possible hidden legal dangers for participating physicians.

"We’re talking about unchartered territory," said Christopher E. DiGiacinto, a medical liability defense attorney and partner in a New York law firm that focuses on the defense of professional liability claims including those brought against health care professionals and others. "There’s been a lot of uncertainty about how [ACOs] will affect the landscape of litigation. It could go any number of ways."

Mr. DiGiacinto cowrote an article in the 2013 summer issue of Risk Management Quarterly, the journal of the Association for Healthcare Risk Management of New York, detailing malpractice risks doctors may face within ACOs (RMQ Summer 2013). The liability dangers stem primarily from federal guidelines that outline how ACOs should operate and how doctors can enhance their practices.

For example, the Affordance Care Act requires that ACOs share medical information across multiple health care environments to improve knowledge among providers and to eliminate duplication of treatment across the care continuum. But such enhanced record maintenance could expose physicians to increased liability, Mr. DiGiacinto said. A plaintiff’s attorney could claim a doctor’s failure to access a patient’s prior medical records led to a subsequent poor medical outcome.

"There’s going to be a lot more data in this model, which is great for patients and allowing physicians to track patients," he said. "The downside for physicians is, where in the past, they might only be responsible for their own record and knowledge of the patient from their own perspective, now, they’re being responsible for knowing the [patient’s] history from other doctors. There’s going to be a wealth of information that could be used against them."

ACOs also create the potential for a heightened duty of informed consent for physicians, said Julian D. "Bo" Bobbitt Jr., senior partner and head of a health law group at a law firm in Raleigh, N.C. Federal guidelines call for ACOs to promote patient engagement during individualized treatment by involving patients and their families in making medical decisions.

"Under Medicare ACO regulations, there has to be a patient care plan and there has to be significant commitment to patient and family engagement and joint decision making," Mr. Bobbitt said. "What happens if you did a care plan, but you didn’t follow it? You were supposed to engage the family, but you didn’t?"

In such an instance, it’s possible a family member could sue, claiming he or she was not involved enough in the medical decision–making process, said Mr. Bobbitt.

Physicians who help create ACOs or hold administrative positions within the organizations may also be more at risk for being sued, say liability experts, whether or not they were directly involved in patient care.

In the past, entities such as HMOs were rarely sued for the actions of participants because such corporate structures are not generally responsible for the rendering of care, Mr. DiGiacinto said. However, federal guidelines recommend that medical professionals be involved in the corporate structure of ACOs, and that the organizations be accountable for the care they provide. This framework could fuel vicarious liability or corporate negligence claims in which the ACO itself is said to be liable for care provided to patients, according to the Accountable Care Legal Guide and RMQ article. In addition, physician leaders could potentially be sued for alleged negligent credentialing of other health professionals in the ACO, said legal experts.

But some, such as Christi J. Braun, believe suggested ACO litigation dangers are being overblown. Clinically integrated networks are designed to improve quality across all care providers, said Ms. Braun, a Washington-based health care antitrust attorney and cochair of the American Health Lawyers Association’s Accountable Care Organization Task Force.

"Even if you may not be following the protocols all the time, just the fact that you’re looking at best practices and trying to apply best practices makes it more likely that you’re going to provide better care on a more consistent basis," she said. "That actually reduces liability."

At the same time, physicians should not be so focused on following federal guidelines that they allow metrics and benchmarks to override quality medical judgment, said Brandy A. Boone, an Alabama-based senior risk management consultant for a national medical liability insurer.

"I think the biggest risk associated with ACOs or any other arrangement where physicians are incentivized to keep costs down by the prospect of making more money is the allegation that necessary tests or treatments were not offered or recommended because of the effect on reimbursement," Ms. Boone said. "We always caution our insured physicians that treatment recommendations should never be based on the patient’s ability to pay. While the majority of physicians would never actually let reimbursement sway their clinical decisions, avoiding that perception is also very important."

Only time will tell how ACO guidelines will affect malpractice cases. Often, it takes years for case law and legal precedents to develop around new issues and more clearly define boundaries, Mr. Bobbitt said.

In the meantime, litigation experts recommend that physicians joining ACOs protect themselves from lawsuits by thoroughly documenting patient interactions and clinical decision making. Mr. Bobbitt suggests also that physicians participating in ACOs become involved in developing best practice guidelines and ensuring those guidelines are clinically valid. Having a strong voice will empower physicians and assure ACO guidelines act as a lawsuit shield, rather than a sword.

"It can be a legal minefield, but it is navigable," Mr. Bobbitt said. "As an attorney and health care adviser, I try to convey that yes, there are legal issues – novel legal issues – but at the same time, this is such a positive improvement to health care, it is navigable if done right."

The aim of accountable care organizations is to improve health care quality, enhance care coordination, and reduce unnecessary costs. But the new health care delivery models are raising questions about possible hidden legal dangers for participating physicians.

"We’re talking about unchartered territory," said Christopher E. DiGiacinto, a medical liability defense attorney and partner in a New York law firm that focuses on the defense of professional liability claims including those brought against health care professionals and others. "There’s been a lot of uncertainty about how [ACOs] will affect the landscape of litigation. It could go any number of ways."

Mr. DiGiacinto cowrote an article in the 2013 summer issue of Risk Management Quarterly, the journal of the Association for Healthcare Risk Management of New York, detailing malpractice risks doctors may face within ACOs (RMQ Summer 2013). The liability dangers stem primarily from federal guidelines that outline how ACOs should operate and how doctors can enhance their practices.

For example, the Affordance Care Act requires that ACOs share medical information across multiple health care environments to improve knowledge among providers and to eliminate duplication of treatment across the care continuum. But such enhanced record maintenance could expose physicians to increased liability, Mr. DiGiacinto said. A plaintiff’s attorney could claim a doctor’s failure to access a patient’s prior medical records led to a subsequent poor medical outcome.

"There’s going to be a lot more data in this model, which is great for patients and allowing physicians to track patients," he said. "The downside for physicians is, where in the past, they might only be responsible for their own record and knowledge of the patient from their own perspective, now, they’re being responsible for knowing the [patient’s] history from other doctors. There’s going to be a wealth of information that could be used against them."

ACOs also create the potential for a heightened duty of informed consent for physicians, said Julian D. "Bo" Bobbitt Jr., senior partner and head of a health law group at a law firm in Raleigh, N.C. Federal guidelines call for ACOs to promote patient engagement during individualized treatment by involving patients and their families in making medical decisions.

"Under Medicare ACO regulations, there has to be a patient care plan and there has to be significant commitment to patient and family engagement and joint decision making," Mr. Bobbitt said. "What happens if you did a care plan, but you didn’t follow it? You were supposed to engage the family, but you didn’t?"

In such an instance, it’s possible a family member could sue, claiming he or she was not involved enough in the medical decision–making process, said Mr. Bobbitt.

Physicians who help create ACOs or hold administrative positions within the organizations may also be more at risk for being sued, say liability experts, whether or not they were directly involved in patient care.

In the past, entities such as HMOs were rarely sued for the actions of participants because such corporate structures are not generally responsible for the rendering of care, Mr. DiGiacinto said. However, federal guidelines recommend that medical professionals be involved in the corporate structure of ACOs, and that the organizations be accountable for the care they provide. This framework could fuel vicarious liability or corporate negligence claims in which the ACO itself is said to be liable for care provided to patients, according to the Accountable Care Legal Guide and RMQ article. In addition, physician leaders could potentially be sued for alleged negligent credentialing of other health professionals in the ACO, said legal experts.

But some, such as Christi J. Braun, believe suggested ACO litigation dangers are being overblown. Clinically integrated networks are designed to improve quality across all care providers, said Ms. Braun, a Washington-based health care antitrust attorney and cochair of the American Health Lawyers Association’s Accountable Care Organization Task Force.

"Even if you may not be following the protocols all the time, just the fact that you’re looking at best practices and trying to apply best practices makes it more likely that you’re going to provide better care on a more consistent basis," she said. "That actually reduces liability."

At the same time, physicians should not be so focused on following federal guidelines that they allow metrics and benchmarks to override quality medical judgment, said Brandy A. Boone, an Alabama-based senior risk management consultant for a national medical liability insurer.

"I think the biggest risk associated with ACOs or any other arrangement where physicians are incentivized to keep costs down by the prospect of making more money is the allegation that necessary tests or treatments were not offered or recommended because of the effect on reimbursement," Ms. Boone said. "We always caution our insured physicians that treatment recommendations should never be based on the patient’s ability to pay. While the majority of physicians would never actually let reimbursement sway their clinical decisions, avoiding that perception is also very important."

Only time will tell how ACO guidelines will affect malpractice cases. Often, it takes years for case law and legal precedents to develop around new issues and more clearly define boundaries, Mr. Bobbitt said.

In the meantime, litigation experts recommend that physicians joining ACOs protect themselves from lawsuits by thoroughly documenting patient interactions and clinical decision making. Mr. Bobbitt suggests also that physicians participating in ACOs become involved in developing best practice guidelines and ensuring those guidelines are clinically valid. Having a strong voice will empower physicians and assure ACO guidelines act as a lawsuit shield, rather than a sword.

"It can be a legal minefield, but it is navigable," Mr. Bobbitt said. "As an attorney and health care adviser, I try to convey that yes, there are legal issues – novel legal issues – but at the same time, this is such a positive improvement to health care, it is navigable if done right."

The aim of accountable care organizations is to improve health care quality, enhance care coordination, and reduce unnecessary costs. But the new health care delivery models are raising questions about possible hidden legal dangers for participating physicians.

"We’re talking about unchartered territory," said Christopher E. DiGiacinto, a medical liability defense attorney and partner in a New York law firm that focuses on the defense of professional liability claims including those brought against health care professionals and others. "There’s been a lot of uncertainty about how [ACOs] will affect the landscape of litigation. It could go any number of ways."

Mr. DiGiacinto cowrote an article in the 2013 summer issue of Risk Management Quarterly, the journal of the Association for Healthcare Risk Management of New York, detailing malpractice risks doctors may face within ACOs (RMQ Summer 2013). The liability dangers stem primarily from federal guidelines that outline how ACOs should operate and how doctors can enhance their practices.

For example, the Affordance Care Act requires that ACOs share medical information across multiple health care environments to improve knowledge among providers and to eliminate duplication of treatment across the care continuum. But such enhanced record maintenance could expose physicians to increased liability, Mr. DiGiacinto said. A plaintiff’s attorney could claim a doctor’s failure to access a patient’s prior medical records led to a subsequent poor medical outcome.

"There’s going to be a lot more data in this model, which is great for patients and allowing physicians to track patients," he said. "The downside for physicians is, where in the past, they might only be responsible for their own record and knowledge of the patient from their own perspective, now, they’re being responsible for knowing the [patient’s] history from other doctors. There’s going to be a wealth of information that could be used against them."

ACOs also create the potential for a heightened duty of informed consent for physicians, said Julian D. "Bo" Bobbitt Jr., senior partner and head of a health law group at a law firm in Raleigh, N.C. Federal guidelines call for ACOs to promote patient engagement during individualized treatment by involving patients and their families in making medical decisions.

"Under Medicare ACO regulations, there has to be a patient care plan and there has to be significant commitment to patient and family engagement and joint decision making," Mr. Bobbitt said. "What happens if you did a care plan, but you didn’t follow it? You were supposed to engage the family, but you didn’t?"

In such an instance, it’s possible a family member could sue, claiming he or she was not involved enough in the medical decision–making process, said Mr. Bobbitt.

Physicians who help create ACOs or hold administrative positions within the organizations may also be more at risk for being sued, say liability experts, whether or not they were directly involved in patient care.

In the past, entities such as HMOs were rarely sued for the actions of participants because such corporate structures are not generally responsible for the rendering of care, Mr. DiGiacinto said. However, federal guidelines recommend that medical professionals be involved in the corporate structure of ACOs, and that the organizations be accountable for the care they provide. This framework could fuel vicarious liability or corporate negligence claims in which the ACO itself is said to be liable for care provided to patients, according to the Accountable Care Legal Guide and RMQ article. In addition, physician leaders could potentially be sued for alleged negligent credentialing of other health professionals in the ACO, said legal experts.

But some, such as Christi J. Braun, believe suggested ACO litigation dangers are being overblown. Clinically integrated networks are designed to improve quality across all care providers, said Ms. Braun, a Washington-based health care antitrust attorney and cochair of the American Health Lawyers Association’s Accountable Care Organization Task Force.

"Even if you may not be following the protocols all the time, just the fact that you’re looking at best practices and trying to apply best practices makes it more likely that you’re going to provide better care on a more consistent basis," she said. "That actually reduces liability."

At the same time, physicians should not be so focused on following federal guidelines that they allow metrics and benchmarks to override quality medical judgment, said Brandy A. Boone, an Alabama-based senior risk management consultant for a national medical liability insurer.

"I think the biggest risk associated with ACOs or any other arrangement where physicians are incentivized to keep costs down by the prospect of making more money is the allegation that necessary tests or treatments were not offered or recommended because of the effect on reimbursement," Ms. Boone said. "We always caution our insured physicians that treatment recommendations should never be based on the patient’s ability to pay. While the majority of physicians would never actually let reimbursement sway their clinical decisions, avoiding that perception is also very important."

Only time will tell how ACO guidelines will affect malpractice cases. Often, it takes years for case law and legal precedents to develop around new issues and more clearly define boundaries, Mr. Bobbitt said.

In the meantime, litigation experts recommend that physicians joining ACOs protect themselves from lawsuits by thoroughly documenting patient interactions and clinical decision making. Mr. Bobbitt suggests also that physicians participating in ACOs become involved in developing best practice guidelines and ensuring those guidelines are clinically valid. Having a strong voice will empower physicians and assure ACO guidelines act as a lawsuit shield, rather than a sword.

"It can be a legal minefield, but it is navigable," Mr. Bobbitt said. "As an attorney and health care adviser, I try to convey that yes, there are legal issues – novel legal issues – but at the same time, this is such a positive improvement to health care, it is navigable if done right."

Accountable care organizations may fuel new litigation theories

The aim of accountable care organizations is to improve health care quality, enhance care coordination, and reduce unnecessary costs. But the new health care delivery models are raising questions about possible hidden legal dangers for participating physicians.

"We’re talking about unchartered territory," said Christopher E. DiGiacinto, a medical liability defense attorney and partner in a New York law firm that focuses on the defense of professional liability claims including those brought against health care professionals and others. "There’s been a lot of uncertainty about how [ACOs] will affect the landscape of litigation. It could go any number of ways."

Mr. DiGiacinto cowrote an article in the 2013 summer issue of Risk Management Quarterly, the journal of the Association for Healthcare Risk Management of New York, detailing malpractice risks doctors may face within ACOs (RMQ Summer 2013). The liability dangers stem primarily from federal guidelines that outline how ACOs should operate and how doctors can enhance their practices.

For example, the Affordance Care Act requires that ACOs share medical information across multiple health care environments to improve knowledge among providers and to eliminate duplication of treatment across the care continuum. But such enhanced record maintenance could expose physicians to increased liability, Mr. DiGiacinto said. A plaintiff’s attorney could claim a doctor’s failure to access a patient’s prior medical records led to a subsequent poor medical outcome.

"There’s going to be a lot more data in this model, which is great for patients and allowing physicians to track patients," he said. "The downside for physicians is, where in the past, they might only be responsible for their own record and knowledge of the patient from their own perspective, now, they’re being responsible for knowing the [patient’s] history from other doctors. There’s going to be a wealth of information that could be used against them."

ACOs also create the potential for a heightened duty of informed consent for physicians, said Julian D. "Bo" Bobbitt Jr., senior partner and head of a health law group at a law firm in Raleigh, N.C. Federal guidelines call for ACOs to promote patient engagement during individualized treatment by involving patients and their families in making medical decisions.

"Under Medicare ACO regulations, there has to be a patient care plan and there has to be significant commitment to patient and family engagement and joint decision making," Mr. Bobbitt said. "What happens if you did a care plan, but you didn’t follow it? You were supposed to engage the family, but you didn’t?"

In such an instance, it’s possible a family member could sue, claiming he or she was not involved enough in the medical decision–making process, said Mr. Bobbitt.

Physicians who help create ACOs or hold administrative positions within the organizations may also be more at risk for being sued, say liability experts, whether or not they were directly involved in patient care.

In the past, entities such as HMOs were rarely sued for the actions of participants because such corporate structures are not generally responsible for the rendering of care, Mr. DiGiacinto said. However, federal guidelines recommend that medical professionals be involved in the corporate structure of ACOs, and that the organizations be accountable for the care they provide. This framework could fuel vicarious liability or corporate negligence claims in which the ACO itself is said to be liable for care provided to patients, according to the Accountable Care Legal Guide and RMQ article. In addition, physician leaders could potentially be sued for alleged negligent credentialing of other health professionals in the ACO, said legal experts.

But some, such as Christi J. Braun, believe suggested ACO litigation dangers are being overblown. Clinically integrated networks are designed to improve quality across all care providers, said Ms. Braun, a Washington-based health care antitrust attorney and cochair of the American Health Lawyers Association’s Accountable Care Organization Task Force.

"Even if you may not be following the protocols all the time, just the fact that you’re looking at best practices and trying to apply best practices makes it more likely that you’re going to provide better care on a more consistent basis," she said. "That actually reduces liability."

At the same time, physicians should not be so focused on following federal guidelines that they allow metrics and benchmarks to override quality medical judgment, said Brandy A. Boone, an Alabama-based senior risk management consultant for a national medical liability insurer.

"I think the biggest risk associated with ACOs or any other arrangement where physicians are incentivized to keep costs down by the prospect of making more money is the allegation that necessary tests or treatments were not offered or recommended because of the effect on reimbursement," Ms. Boone said. "We always caution our insured physicians that treatment recommendations should never be based on the patient’s ability to pay. While the majority of physicians would never actually let reimbursement sway their clinical decisions, avoiding that perception is also very important."

Only time will tell how ACO guidelines will affect malpractice cases. Often, it takes years for case law and legal precedents to develop around new issues and more clearly define boundaries, Mr. Bobbitt said.

In the meantime, litigation experts recommend that physicians joining ACOs protect themselves from lawsuits by thoroughly documenting patient interactions and clinical decision making. Mr. Bobbitt suggests also that physicians participating in ACOs become involved in developing best practice guidelines and ensuring those guidelines are clinically valid. Having a strong voice will empower physicians and assure ACO guidelines act as a lawsuit shield, rather than a sword.

"It can be a legal minefield, but it is navigable," Mr. Bobbitt said. "As an attorney and health care adviser, I try to convey that yes, there are legal issues – novel legal issues – but at the same time, this is such a positive improvement to health care, it is navigable if done right."

The aim of accountable care organizations is to improve health care quality, enhance care coordination, and reduce unnecessary costs. But the new health care delivery models are raising questions about possible hidden legal dangers for participating physicians.

"We’re talking about unchartered territory," said Christopher E. DiGiacinto, a medical liability defense attorney and partner in a New York law firm that focuses on the defense of professional liability claims including those brought against health care professionals and others. "There’s been a lot of uncertainty about how [ACOs] will affect the landscape of litigation. It could go any number of ways."

Mr. DiGiacinto cowrote an article in the 2013 summer issue of Risk Management Quarterly, the journal of the Association for Healthcare Risk Management of New York, detailing malpractice risks doctors may face within ACOs (RMQ Summer 2013). The liability dangers stem primarily from federal guidelines that outline how ACOs should operate and how doctors can enhance their practices.

For example, the Affordance Care Act requires that ACOs share medical information across multiple health care environments to improve knowledge among providers and to eliminate duplication of treatment across the care continuum. But such enhanced record maintenance could expose physicians to increased liability, Mr. DiGiacinto said. A plaintiff’s attorney could claim a doctor’s failure to access a patient’s prior medical records led to a subsequent poor medical outcome.

"There’s going to be a lot more data in this model, which is great for patients and allowing physicians to track patients," he said. "The downside for physicians is, where in the past, they might only be responsible for their own record and knowledge of the patient from their own perspective, now, they’re being responsible for knowing the [patient’s] history from other doctors. There’s going to be a wealth of information that could be used against them."

ACOs also create the potential for a heightened duty of informed consent for physicians, said Julian D. "Bo" Bobbitt Jr., senior partner and head of a health law group at a law firm in Raleigh, N.C. Federal guidelines call for ACOs to promote patient engagement during individualized treatment by involving patients and their families in making medical decisions.

"Under Medicare ACO regulations, there has to be a patient care plan and there has to be significant commitment to patient and family engagement and joint decision making," Mr. Bobbitt said. "What happens if you did a care plan, but you didn’t follow it? You were supposed to engage the family, but you didn’t?"

In such an instance, it’s possible a family member could sue, claiming he or she was not involved enough in the medical decision–making process, said Mr. Bobbitt.

Physicians who help create ACOs or hold administrative positions within the organizations may also be more at risk for being sued, say liability experts, whether or not they were directly involved in patient care.

In the past, entities such as HMOs were rarely sued for the actions of participants because such corporate structures are not generally responsible for the rendering of care, Mr. DiGiacinto said. However, federal guidelines recommend that medical professionals be involved in the corporate structure of ACOs, and that the organizations be accountable for the care they provide. This framework could fuel vicarious liability or corporate negligence claims in which the ACO itself is said to be liable for care provided to patients, according to the Accountable Care Legal Guide and RMQ article. In addition, physician leaders could potentially be sued for alleged negligent credentialing of other health professionals in the ACO, said legal experts.

But some, such as Christi J. Braun, believe suggested ACO litigation dangers are being overblown. Clinically integrated networks are designed to improve quality across all care providers, said Ms. Braun, a Washington-based health care antitrust attorney and cochair of the American Health Lawyers Association’s Accountable Care Organization Task Force.

"Even if you may not be following the protocols all the time, just the fact that you’re looking at best practices and trying to apply best practices makes it more likely that you’re going to provide better care on a more consistent basis," she said. "That actually reduces liability."

At the same time, physicians should not be so focused on following federal guidelines that they allow metrics and benchmarks to override quality medical judgment, said Brandy A. Boone, an Alabama-based senior risk management consultant for a national medical liability insurer.

"I think the biggest risk associated with ACOs or any other arrangement where physicians are incentivized to keep costs down by the prospect of making more money is the allegation that necessary tests or treatments were not offered or recommended because of the effect on reimbursement," Ms. Boone said. "We always caution our insured physicians that treatment recommendations should never be based on the patient’s ability to pay. While the majority of physicians would never actually let reimbursement sway their clinical decisions, avoiding that perception is also very important."

Only time will tell how ACO guidelines will affect malpractice cases. Often, it takes years for case law and legal precedents to develop around new issues and more clearly define boundaries, Mr. Bobbitt said.

In the meantime, litigation experts recommend that physicians joining ACOs protect themselves from lawsuits by thoroughly documenting patient interactions and clinical decision making. Mr. Bobbitt suggests also that physicians participating in ACOs become involved in developing best practice guidelines and ensuring those guidelines are clinically valid. Having a strong voice will empower physicians and assure ACO guidelines act as a lawsuit shield, rather than a sword.

"It can be a legal minefield, but it is navigable," Mr. Bobbitt said. "As an attorney and health care adviser, I try to convey that yes, there are legal issues – novel legal issues – but at the same time, this is such a positive improvement to health care, it is navigable if done right."

The aim of accountable care organizations is to improve health care quality, enhance care coordination, and reduce unnecessary costs. But the new health care delivery models are raising questions about possible hidden legal dangers for participating physicians.

"We’re talking about unchartered territory," said Christopher E. DiGiacinto, a medical liability defense attorney and partner in a New York law firm that focuses on the defense of professional liability claims including those brought against health care professionals and others. "There’s been a lot of uncertainty about how [ACOs] will affect the landscape of litigation. It could go any number of ways."

Mr. DiGiacinto cowrote an article in the 2013 summer issue of Risk Management Quarterly, the journal of the Association for Healthcare Risk Management of New York, detailing malpractice risks doctors may face within ACOs (RMQ Summer 2013). The liability dangers stem primarily from federal guidelines that outline how ACOs should operate and how doctors can enhance their practices.

For example, the Affordance Care Act requires that ACOs share medical information across multiple health care environments to improve knowledge among providers and to eliminate duplication of treatment across the care continuum. But such enhanced record maintenance could expose physicians to increased liability, Mr. DiGiacinto said. A plaintiff’s attorney could claim a doctor’s failure to access a patient’s prior medical records led to a subsequent poor medical outcome.

"There’s going to be a lot more data in this model, which is great for patients and allowing physicians to track patients," he said. "The downside for physicians is, where in the past, they might only be responsible for their own record and knowledge of the patient from their own perspective, now, they’re being responsible for knowing the [patient’s] history from other doctors. There’s going to be a wealth of information that could be used against them."

ACOs also create the potential for a heightened duty of informed consent for physicians, said Julian D. "Bo" Bobbitt Jr., senior partner and head of a health law group at a law firm in Raleigh, N.C. Federal guidelines call for ACOs to promote patient engagement during individualized treatment by involving patients and their families in making medical decisions.

"Under Medicare ACO regulations, there has to be a patient care plan and there has to be significant commitment to patient and family engagement and joint decision making," Mr. Bobbitt said. "What happens if you did a care plan, but you didn’t follow it? You were supposed to engage the family, but you didn’t?"

In such an instance, it’s possible a family member could sue, claiming he or she was not involved enough in the medical decision–making process, said Mr. Bobbitt.

Physicians who help create ACOs or hold administrative positions within the organizations may also be more at risk for being sued, say liability experts, whether or not they were directly involved in patient care.

In the past, entities such as HMOs were rarely sued for the actions of participants because such corporate structures are not generally responsible for the rendering of care, Mr. DiGiacinto said. However, federal guidelines recommend that medical professionals be involved in the corporate structure of ACOs, and that the organizations be accountable for the care they provide. This framework could fuel vicarious liability or corporate negligence claims in which the ACO itself is said to be liable for care provided to patients, according to the Accountable Care Legal Guide and RMQ article. In addition, physician leaders could potentially be sued for alleged negligent credentialing of other health professionals in the ACO, said legal experts.

But some, such as Christi J. Braun, believe suggested ACO litigation dangers are being overblown. Clinically integrated networks are designed to improve quality across all care providers, said Ms. Braun, a Washington-based health care antitrust attorney and cochair of the American Health Lawyers Association’s Accountable Care Organization Task Force.

"Even if you may not be following the protocols all the time, just the fact that you’re looking at best practices and trying to apply best practices makes it more likely that you’re going to provide better care on a more consistent basis," she said. "That actually reduces liability."

At the same time, physicians should not be so focused on following federal guidelines that they allow metrics and benchmarks to override quality medical judgment, said Brandy A. Boone, an Alabama-based senior risk management consultant for a national medical liability insurer.

"I think the biggest risk associated with ACOs or any other arrangement where physicians are incentivized to keep costs down by the prospect of making more money is the allegation that necessary tests or treatments were not offered or recommended because of the effect on reimbursement," Ms. Boone said. "We always caution our insured physicians that treatment recommendations should never be based on the patient’s ability to pay. While the majority of physicians would never actually let reimbursement sway their clinical decisions, avoiding that perception is also very important."

Only time will tell how ACO guidelines will affect malpractice cases. Often, it takes years for case law and legal precedents to develop around new issues and more clearly define boundaries, Mr. Bobbitt said.

In the meantime, litigation experts recommend that physicians joining ACOs protect themselves from lawsuits by thoroughly documenting patient interactions and clinical decision making. Mr. Bobbitt suggests also that physicians participating in ACOs become involved in developing best practice guidelines and ensuring those guidelines are clinically valid. Having a strong voice will empower physicians and assure ACO guidelines act as a lawsuit shield, rather than a sword.

"It can be a legal minefield, but it is navigable," Mr. Bobbitt said. "As an attorney and health care adviser, I try to convey that yes, there are legal issues – novel legal issues – but at the same time, this is such a positive improvement to health care, it is navigable if done right."

Fee schedule: Medicare gives details on care coordination pay, SGR cut

Starting Jan. 1, 2015, Medicare will pay physicians about $42 for certain care management services outside of the face-to-face office visit, according to a new government proposal.

The proposed rule for the 2015 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule, released on July 3, offers details on how officials at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) plan to roll out the new chronic care management services payments that begin in 2015. The proposal also expands telehealth services offered by Medicare and makes changes to the Open Payments program.

CMS proposes to pay $41.92 for a new G-code for chronic care management services provided to patients with two or more chronic conditions that are expected to last at least a year. The code could be billed only once a month for each patient.

To bill for the code, physicians would have to offer some type of 24/7 access, continuity of care, care management for chronic conditions including medication reconciliation, creation of a patient-centered care plan, management of care transitions including visits to the hospital and emergency department, and coordination with community-based services.

In the 2015 Physician Fee Schedule, CMS is also proposing to require that physicians use certified electronic health record technology.

The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), members of which would benefit from the coding change, applauded CMS for proposing the care management code. But the AAFP said the benefit of the code would be overshadowed were Congress to allow the scheduled cut to the Medicare Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) formula to go into effect on April 1, 2015.

The fee schedule proposal reiterates that physicians will face a 20.9% across-the-board fee cut next year if Congress does not repeal or postpone the SGR.

"The AAFP welcomes the new code but we also look to a day when policies designed to strengthen primary medical care are not undermined by drastic cuts to the underlying foundation on which all payment is based," Dr. Reid Blackwelder, AAFP president, said in a statement.

The proposed fee schedule also seeks to add annual wellness visits, psychoanalysis, psychotherapy, and prolonged evaluation and management services to the list of telehealth services that can be furnished to Medicare beneficiaries under the telehealth benefit.

Medicare also proposes to redefine screening colonoscopy to include anesthesia. With this proposed change, Medicare beneficiaries would not have to pay coinsurance on the anesthesia portion of the procedure when it is provided separately by an anesthesiologist.

CMS is also planning to make changes to the Open Payments program, which requires drug and device manufacturers to report on the payments and transfers of value made to physicians and teaching hospitals.

Agency officials want to completely exclude reporting on continuing medical education payments made by industry. Under the current framework, CMS excluded most CME reporting, if the event met the accreditation or certification requirements of five organizations. However, the proposal would broaden that provision to include any CME event in which the industry provides funding but is not involved in selecting or paying speakers. If finalized, the changes would take effect in 2015.

On Twitter @MaryEllenNY

Starting Jan. 1, 2015, Medicare will pay physicians about $42 for certain care management services outside of the face-to-face office visit, according to a new government proposal.

The proposed rule for the 2015 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule, released on July 3, offers details on how officials at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) plan to roll out the new chronic care management services payments that begin in 2015. The proposal also expands telehealth services offered by Medicare and makes changes to the Open Payments program.

CMS proposes to pay $41.92 for a new G-code for chronic care management services provided to patients with two or more chronic conditions that are expected to last at least a year. The code could be billed only once a month for each patient.

To bill for the code, physicians would have to offer some type of 24/7 access, continuity of care, care management for chronic conditions including medication reconciliation, creation of a patient-centered care plan, management of care transitions including visits to the hospital and emergency department, and coordination with community-based services.

In the 2015 Physician Fee Schedule, CMS is also proposing to require that physicians use certified electronic health record technology.

The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), members of which would benefit from the coding change, applauded CMS for proposing the care management code. But the AAFP said the benefit of the code would be overshadowed were Congress to allow the scheduled cut to the Medicare Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) formula to go into effect on April 1, 2015.

The fee schedule proposal reiterates that physicians will face a 20.9% across-the-board fee cut next year if Congress does not repeal or postpone the SGR.