User login

Official Newspaper of the American College of Surgeons

Real-world CAS results in Medicare patients not up to trial standards

The presence of competing risks and overall lower levels of provider proficiency appeared to limit the benefits of carotid artery stenting in Medicare beneficiaries, according to the results of a large retrospective cohort study of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services CAS database (2005-2009).

Periprocedural mortality was more than twice the rate in this patient population than in those earlier patients those involved in the pivotal CREST and SAPPHIRE clinical trials, according to a report published online Jan. 12 in JAMA Neurology [doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.3638].

“The higher risk of periprocedural complications and the burden of competing risks owing to age and comorbidity burden must be carefully considered when deciding between carotid stenosis treatments for Medicare beneficiaries,” according to Jessica J. Jalbert, Ph.D., of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and her colleagues.

Over 22,000 patients were assessed in the study. The mean patient age was just over 76 years, 60.5% were men, and 94% were white. Approximately half were symptomatic, 91.2% were at high surgical risk, and 97.4% had carotid stenosis of at least 70%.

Almost 80% of the patients undergoing carotid artery stenting (CAS) met the SAPPHIRE trial indications and about half met at least one of the SAPPHIRE criteria for high surgical risk.

In the mean follow-up of approximately 2 years, mortality risks exceeded one-third for patients who were 80 years of age or older (41.5% mortality risk), symptomatic (37.3% risk), at high surgical risk with symptomatic carotid stenosis of at least 50% (37.3% risk), or admitted nonelectively (36.2% risk). In addition, among asymptomatic patients, mortality after the periprocedural period exceeded one-third for patients at least 80 years old.

Of particular concern, few of these Medicare beneficiaries undergoing CAS as per the National Coverage Determinations were treated by providers with proficiency levels similar to those required in the clinical trials. This is a potential problem because lower annual volume and early operator experience are associated with increased periprocedural mortality, the authors wrote.

CAS was performed primarily by male physicians (98.4%), specializing in cardiology (52.9%), practicing within a group (79.4%), and residing in the South (42.5%). The mean number of past-year CAS procedures performed was only 13.9 for physicians and 29.8 for hospitals. This translated to more than 80% of the physicians not meeting the minimum CAS volume requirements and/or minimum complication rates of the SAPPHIRE trial, and more than 90% not meeting the requirements of the CREST trial.

“Our results may support concerns about the limited generalizability of [randomized clinical trial] findings,” the researchers stated.

“Real-world observational studies comparing CAS, carotid endarterectomy, and medical management are needed to determine the performance of carotid stenosis treatment options for Medicare beneficiaries,” Dr. Jalbert and her colleagues concluded.

The authors reported no relevant disclosures. The study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

The presence of competing risks and overall lower levels of provider proficiency appeared to limit the benefits of carotid artery stenting in Medicare beneficiaries, according to the results of a large retrospective cohort study of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services CAS database (2005-2009).

Periprocedural mortality was more than twice the rate in this patient population than in those earlier patients those involved in the pivotal CREST and SAPPHIRE clinical trials, according to a report published online Jan. 12 in JAMA Neurology [doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.3638].

“The higher risk of periprocedural complications and the burden of competing risks owing to age and comorbidity burden must be carefully considered when deciding between carotid stenosis treatments for Medicare beneficiaries,” according to Jessica J. Jalbert, Ph.D., of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and her colleagues.

Over 22,000 patients were assessed in the study. The mean patient age was just over 76 years, 60.5% were men, and 94% were white. Approximately half were symptomatic, 91.2% were at high surgical risk, and 97.4% had carotid stenosis of at least 70%.

Almost 80% of the patients undergoing carotid artery stenting (CAS) met the SAPPHIRE trial indications and about half met at least one of the SAPPHIRE criteria for high surgical risk.

In the mean follow-up of approximately 2 years, mortality risks exceeded one-third for patients who were 80 years of age or older (41.5% mortality risk), symptomatic (37.3% risk), at high surgical risk with symptomatic carotid stenosis of at least 50% (37.3% risk), or admitted nonelectively (36.2% risk). In addition, among asymptomatic patients, mortality after the periprocedural period exceeded one-third for patients at least 80 years old.

Of particular concern, few of these Medicare beneficiaries undergoing CAS as per the National Coverage Determinations were treated by providers with proficiency levels similar to those required in the clinical trials. This is a potential problem because lower annual volume and early operator experience are associated with increased periprocedural mortality, the authors wrote.

CAS was performed primarily by male physicians (98.4%), specializing in cardiology (52.9%), practicing within a group (79.4%), and residing in the South (42.5%). The mean number of past-year CAS procedures performed was only 13.9 for physicians and 29.8 for hospitals. This translated to more than 80% of the physicians not meeting the minimum CAS volume requirements and/or minimum complication rates of the SAPPHIRE trial, and more than 90% not meeting the requirements of the CREST trial.

“Our results may support concerns about the limited generalizability of [randomized clinical trial] findings,” the researchers stated.

“Real-world observational studies comparing CAS, carotid endarterectomy, and medical management are needed to determine the performance of carotid stenosis treatment options for Medicare beneficiaries,” Dr. Jalbert and her colleagues concluded.

The authors reported no relevant disclosures. The study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

The presence of competing risks and overall lower levels of provider proficiency appeared to limit the benefits of carotid artery stenting in Medicare beneficiaries, according to the results of a large retrospective cohort study of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services CAS database (2005-2009).

Periprocedural mortality was more than twice the rate in this patient population than in those earlier patients those involved in the pivotal CREST and SAPPHIRE clinical trials, according to a report published online Jan. 12 in JAMA Neurology [doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.3638].

“The higher risk of periprocedural complications and the burden of competing risks owing to age and comorbidity burden must be carefully considered when deciding between carotid stenosis treatments for Medicare beneficiaries,” according to Jessica J. Jalbert, Ph.D., of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, and her colleagues.

Over 22,000 patients were assessed in the study. The mean patient age was just over 76 years, 60.5% were men, and 94% were white. Approximately half were symptomatic, 91.2% were at high surgical risk, and 97.4% had carotid stenosis of at least 70%.

Almost 80% of the patients undergoing carotid artery stenting (CAS) met the SAPPHIRE trial indications and about half met at least one of the SAPPHIRE criteria for high surgical risk.

In the mean follow-up of approximately 2 years, mortality risks exceeded one-third for patients who were 80 years of age or older (41.5% mortality risk), symptomatic (37.3% risk), at high surgical risk with symptomatic carotid stenosis of at least 50% (37.3% risk), or admitted nonelectively (36.2% risk). In addition, among asymptomatic patients, mortality after the periprocedural period exceeded one-third for patients at least 80 years old.

Of particular concern, few of these Medicare beneficiaries undergoing CAS as per the National Coverage Determinations were treated by providers with proficiency levels similar to those required in the clinical trials. This is a potential problem because lower annual volume and early operator experience are associated with increased periprocedural mortality, the authors wrote.

CAS was performed primarily by male physicians (98.4%), specializing in cardiology (52.9%), practicing within a group (79.4%), and residing in the South (42.5%). The mean number of past-year CAS procedures performed was only 13.9 for physicians and 29.8 for hospitals. This translated to more than 80% of the physicians not meeting the minimum CAS volume requirements and/or minimum complication rates of the SAPPHIRE trial, and more than 90% not meeting the requirements of the CREST trial.

“Our results may support concerns about the limited generalizability of [randomized clinical trial] findings,” the researchers stated.

“Real-world observational studies comparing CAS, carotid endarterectomy, and medical management are needed to determine the performance of carotid stenosis treatment options for Medicare beneficiaries,” Dr. Jalbert and her colleagues concluded.

The authors reported no relevant disclosures. The study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

Key clinical point: Mortality risks exceeded one-third for patients who were 80 years of age or older, symptomatic, at high surgical risk with symptomatic carotid stenosis of at least 50%, or admitted nonelectively.

Major finding: More than 80% of the physicians performing CAS in the real world did not meet the minimum CAS volume requirements and/or minimum complication rates of the SAPPPHIRE trial.

Data source: Data were obtained from a large retrospective cohort study of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services CAS database (2005-2009).

Disclosures: The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

FDA approves first internal tissue adhesive for use in abdominoplasty

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a urethane-based surgical adhesive for use during abdominoplasty, the first synthetic tissue adhesive approved for internal use, the FDA announced on Feb. 4.

The approved indication for the adhesive, called TissuGlu, is for “the approximation of tissue layers where subcutaneous dead space exists between the tissue planes in abdominoplasty.” The use of this product “will help some abdominoplasty patients get back to their daily routine after surgery more quickly than if surgical drains had been inserted,” Dr. William Maisel, deputy director for science at the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the statement announcing the approval.

To apply TissuGlu, the surgeon uses a hand-held applicator to apply drops of the adhesive to the tissue surface, then positions the abdominoplasty flap in place. “Water in the patient’s tissue starts a chemical reaction that bonds the flaps together. The surgeon then proceeds with standard closure of the skin using sutures,” according to the statement, which adds that use of an internal adhesive to connect the tissue flaps “may reduce or eliminate the need for postoperative surgical draining of fluid between the abdominoplasty tissue flaps.”

The data reviewed by the FDA included a study of 130 patients who were undergoing an elective abdominoplasty; surgical drains were used in half of the patients and half received TissuGlu only. Among those who received TissuGlu only, 73% required no postoperative interventions to drain fluid that had accumulated between the abdominoplasty tissue flaps, but those who needed interventions “were more likely to require another operation to insert surgical drains,” the statement said.

Patients treated with TissuGlu who did not require a surgical drain were “generally able to return to most daily activities such as showering, climbing stairs, and resuming their usual routines sooner than those who had surgical drains,” but the levels of surgery-related pain or discomfort reported by the patients were not different between the two groups.

Cohera Medical is the manufacturer of TissuGlu, which has been on the market in the European Union since 2011, according to the company.

TissuGlu was reviewed at a meeting of the FDA’s general and plastic surgery devices advisory panel in August 2014.

Information on the approval, as well as patient and physician labeling, is available on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a urethane-based surgical adhesive for use during abdominoplasty, the first synthetic tissue adhesive approved for internal use, the FDA announced on Feb. 4.

The approved indication for the adhesive, called TissuGlu, is for “the approximation of tissue layers where subcutaneous dead space exists between the tissue planes in abdominoplasty.” The use of this product “will help some abdominoplasty patients get back to their daily routine after surgery more quickly than if surgical drains had been inserted,” Dr. William Maisel, deputy director for science at the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the statement announcing the approval.

To apply TissuGlu, the surgeon uses a hand-held applicator to apply drops of the adhesive to the tissue surface, then positions the abdominoplasty flap in place. “Water in the patient’s tissue starts a chemical reaction that bonds the flaps together. The surgeon then proceeds with standard closure of the skin using sutures,” according to the statement, which adds that use of an internal adhesive to connect the tissue flaps “may reduce or eliminate the need for postoperative surgical draining of fluid between the abdominoplasty tissue flaps.”

The data reviewed by the FDA included a study of 130 patients who were undergoing an elective abdominoplasty; surgical drains were used in half of the patients and half received TissuGlu only. Among those who received TissuGlu only, 73% required no postoperative interventions to drain fluid that had accumulated between the abdominoplasty tissue flaps, but those who needed interventions “were more likely to require another operation to insert surgical drains,” the statement said.

Patients treated with TissuGlu who did not require a surgical drain were “generally able to return to most daily activities such as showering, climbing stairs, and resuming their usual routines sooner than those who had surgical drains,” but the levels of surgery-related pain or discomfort reported by the patients were not different between the two groups.

Cohera Medical is the manufacturer of TissuGlu, which has been on the market in the European Union since 2011, according to the company.

TissuGlu was reviewed at a meeting of the FDA’s general and plastic surgery devices advisory panel in August 2014.

Information on the approval, as well as patient and physician labeling, is available on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a urethane-based surgical adhesive for use during abdominoplasty, the first synthetic tissue adhesive approved for internal use, the FDA announced on Feb. 4.

The approved indication for the adhesive, called TissuGlu, is for “the approximation of tissue layers where subcutaneous dead space exists between the tissue planes in abdominoplasty.” The use of this product “will help some abdominoplasty patients get back to their daily routine after surgery more quickly than if surgical drains had been inserted,” Dr. William Maisel, deputy director for science at the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the statement announcing the approval.

To apply TissuGlu, the surgeon uses a hand-held applicator to apply drops of the adhesive to the tissue surface, then positions the abdominoplasty flap in place. “Water in the patient’s tissue starts a chemical reaction that bonds the flaps together. The surgeon then proceeds with standard closure of the skin using sutures,” according to the statement, which adds that use of an internal adhesive to connect the tissue flaps “may reduce or eliminate the need for postoperative surgical draining of fluid between the abdominoplasty tissue flaps.”

The data reviewed by the FDA included a study of 130 patients who were undergoing an elective abdominoplasty; surgical drains were used in half of the patients and half received TissuGlu only. Among those who received TissuGlu only, 73% required no postoperative interventions to drain fluid that had accumulated between the abdominoplasty tissue flaps, but those who needed interventions “were more likely to require another operation to insert surgical drains,” the statement said.

Patients treated with TissuGlu who did not require a surgical drain were “generally able to return to most daily activities such as showering, climbing stairs, and resuming their usual routines sooner than those who had surgical drains,” but the levels of surgery-related pain or discomfort reported by the patients were not different between the two groups.

Cohera Medical is the manufacturer of TissuGlu, which has been on the market in the European Union since 2011, according to the company.

TissuGlu was reviewed at a meeting of the FDA’s general and plastic surgery devices advisory panel in August 2014.

Information on the approval, as well as patient and physician labeling, is available on the FDA website.

Republican-controlled House votes to repeal ACA

Once again, the Republican-controlled House voted to repeal the Affordable Care Act.

But for the first time, this bill – H.R. 596 – could get a vote in the Republican-controlled Senate, something that did not happen for the 56 bills to repeal or dismantle the health reform law while Democrats controlled that chamber.

H.R. 596 passed the House on Feb. 3 by a 239-186 vote, with three Republicans voting against repeal and no Democrats voting for it. The bill calls for the repeal of the ACA and directs the Congressional committees with jurisdiction over health care to draft replacement legislation.

President Obama has vowed repeatedly to veto any legislation that repeals the health care reform law.

Debate preceding the vote focused on the usual arguments, with Republicans asserting the ACA has increased health insurance costs and premiums while serving as a job killer.

During debate on the House floor, Rep. Gary Palmer (R-Ala.) argued that 4 years after passage of the law, 41 million people are still without health insurance, and that premiums “have skyrocketed,” with some seeing increases as high as 78%. He added that there are “millions of people out of full-time work and millions more forced into part-time jobs.”

Democrats praised the growth in covered lives, as well as the slowdown in growth of Medicare costs in calling on members to vote against the bill.

Rep. Lois Capps (D-Calif.) noted that a repeal vote “will actually take health insurance away from millions of Americans,” adding that the ACA “is not perfect and there are clear areas where we could work together to build on and improve this law, but today’s repeal vote would turn back time, reverting back to a system everyone agreed was broken.”

Democrats also complained that the bill did not go through regular order through the committee hearing and markup process, but rather went straight to the floor for a vote with no amendments allowed to be introduced during the debate.

Once again, the Republican-controlled House voted to repeal the Affordable Care Act.

But for the first time, this bill – H.R. 596 – could get a vote in the Republican-controlled Senate, something that did not happen for the 56 bills to repeal or dismantle the health reform law while Democrats controlled that chamber.

H.R. 596 passed the House on Feb. 3 by a 239-186 vote, with three Republicans voting against repeal and no Democrats voting for it. The bill calls for the repeal of the ACA and directs the Congressional committees with jurisdiction over health care to draft replacement legislation.

President Obama has vowed repeatedly to veto any legislation that repeals the health care reform law.

Debate preceding the vote focused on the usual arguments, with Republicans asserting the ACA has increased health insurance costs and premiums while serving as a job killer.

During debate on the House floor, Rep. Gary Palmer (R-Ala.) argued that 4 years after passage of the law, 41 million people are still without health insurance, and that premiums “have skyrocketed,” with some seeing increases as high as 78%. He added that there are “millions of people out of full-time work and millions more forced into part-time jobs.”

Democrats praised the growth in covered lives, as well as the slowdown in growth of Medicare costs in calling on members to vote against the bill.

Rep. Lois Capps (D-Calif.) noted that a repeal vote “will actually take health insurance away from millions of Americans,” adding that the ACA “is not perfect and there are clear areas where we could work together to build on and improve this law, but today’s repeal vote would turn back time, reverting back to a system everyone agreed was broken.”

Democrats also complained that the bill did not go through regular order through the committee hearing and markup process, but rather went straight to the floor for a vote with no amendments allowed to be introduced during the debate.

Once again, the Republican-controlled House voted to repeal the Affordable Care Act.

But for the first time, this bill – H.R. 596 – could get a vote in the Republican-controlled Senate, something that did not happen for the 56 bills to repeal or dismantle the health reform law while Democrats controlled that chamber.

H.R. 596 passed the House on Feb. 3 by a 239-186 vote, with three Republicans voting against repeal and no Democrats voting for it. The bill calls for the repeal of the ACA and directs the Congressional committees with jurisdiction over health care to draft replacement legislation.

President Obama has vowed repeatedly to veto any legislation that repeals the health care reform law.

Debate preceding the vote focused on the usual arguments, with Republicans asserting the ACA has increased health insurance costs and premiums while serving as a job killer.

During debate on the House floor, Rep. Gary Palmer (R-Ala.) argued that 4 years after passage of the law, 41 million people are still without health insurance, and that premiums “have skyrocketed,” with some seeing increases as high as 78%. He added that there are “millions of people out of full-time work and millions more forced into part-time jobs.”

Democrats praised the growth in covered lives, as well as the slowdown in growth of Medicare costs in calling on members to vote against the bill.

Rep. Lois Capps (D-Calif.) noted that a repeal vote “will actually take health insurance away from millions of Americans,” adding that the ACA “is not perfect and there are clear areas where we could work together to build on and improve this law, but today’s repeal vote would turn back time, reverting back to a system everyone agreed was broken.”

Democrats also complained that the bill did not go through regular order through the committee hearing and markup process, but rather went straight to the floor for a vote with no amendments allowed to be introduced during the debate.

VIDEO: Postsurgical readmissions present pay-for-performance challenges

The causes of most hospital readmissions after surgery may complicate the use of performance-based reimbursement to reduce such returns.

“The reasons why patients come back after surgery are due to expected complications,” not the worsening of existing medical conditions, noted Dr. Karl Y. Bilimoria of Northwestern University, Chicago, and lead author of a new study on what drives 30-day hospital readmissions after surgery (JAMA 2015;313:483-95).

In a video interview, Dr. Bilimoria discussed the challenges that the timing and causes of postsurgical readmissions present for prevention programs and for pay-for-performance initiatives.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The causes of most hospital readmissions after surgery may complicate the use of performance-based reimbursement to reduce such returns.

“The reasons why patients come back after surgery are due to expected complications,” not the worsening of existing medical conditions, noted Dr. Karl Y. Bilimoria of Northwestern University, Chicago, and lead author of a new study on what drives 30-day hospital readmissions after surgery (JAMA 2015;313:483-95).

In a video interview, Dr. Bilimoria discussed the challenges that the timing and causes of postsurgical readmissions present for prevention programs and for pay-for-performance initiatives.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The causes of most hospital readmissions after surgery may complicate the use of performance-based reimbursement to reduce such returns.

“The reasons why patients come back after surgery are due to expected complications,” not the worsening of existing medical conditions, noted Dr. Karl Y. Bilimoria of Northwestern University, Chicago, and lead author of a new study on what drives 30-day hospital readmissions after surgery (JAMA 2015;313:483-95).

In a video interview, Dr. Bilimoria discussed the challenges that the timing and causes of postsurgical readmissions present for prevention programs and for pay-for-performance initiatives.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Study: Surgical readmissions tied to new discharge complications, not prior conditions

Surgical site infection and ileus were the most frequent reason for hospital readmission within 30 days, according to an analysis of data from the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program.

The findings, published online in the Feb. 3 JAMA, suggest that policies that penalize hospitals for readmissions may be ineffective and potentially counterproductive.

Dr. Karl Y. Bilimoria of Northwestern University, Chicago, and his colleagues examined patient data from 346 hospitals participating in the American College of Surgeon’s National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) between January 2012 and December 2012. Readmission rates and reasons were assessed for all surgical procedures and for six representative operations: bariatric surgery, colectomy or proctectomy, hysterectomy, total hip or knee arthroplasty, ventral hernia repair, and lower extremity vascular bypass (JAMA 2015;313;483-95 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.18614]).

Of the 498, 875 patient sample, the overall readmission rate was 5.7%. For individual procedures, the readmission rate ranged from 3.8% for hysterectomy to 14.9% for lower extremity vascular bypass.

The most common reason for readmission was surgical site infection (SSI; 19.5%), ranging from 11.4% after bariatric surgery to 36.4% after lower extremity vascular bypass. Ileus was the most common reason for readmission after bariatric surgery (24.5%) and the second most common reason overall (10.3%). Other common causes for readmission included dehydration or nutritional deficiency, bleeding or anemia, venous thromboembolism, and prosthesis or graft issues (after arthroplasty and lower extremity vascular bypass procedures). Only 2% of patients were readmitted for the same complication they had experienced during their index hospitalization. Just 3% of patients readmitted for SSIs had experienced an SSI during their index hospitalization.

The results show readmissions after surgery may not be an appropriate measure for pay-for-performance and cost-containment programs, such as the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Service’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, Dr. Bilimoria said. Performance targets without accepted courses of intervention might be more prone to unintended or ineffective behaviors and consequences, he noted.

“Surgical readmissions mostly reflect postdischarge complications, and readmission rates may be difficult to reduce until effective strategies are put forth to reduce common complications such as SSI,” he said. “Efforts should focus on reducing complication rates overall than simply those that occur after discharge, and this will subsequently reduce readmission rates as well.”

On Twitter @legal_med

These findings provide an unprecedented opportunity to apply these lessons and make substantial reductions in surgical complications, Dr. Lucian L. Leape said in an editorial accompanying the study.

Changing systems is hard work and requires serious commitment. Changing hospital systems is especially difficult because of long-standing traditions and entrenched practices. Successful change requires leadership by those with the will, the determination, and the perseverance to overcome obstacles and motivate colleagues. It requires commitment, which comes from a sense of urgency and a sense of possibility.

One way to develop a sense of urgency is to translate rates into numbers – i.e., actual patients. For example, in this study, surgical site infections accounted for 19.5% of the unplanned readmissions. Even though this only represents 1% of the 498,875 ACS NSQIP patients undergoing surgery in 2012, that 1% equals 5,565 patients. Reducing that number by half would reduce pain and suffering for more than 2,700 patients. If similar success were achieved nationwide, the total would be many times that.

Dr. Lucian L. Leape is with the department of health policy and management at Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, and made these comments in an accompanying editorial (doi:10.1001/jama.2014.18666). He reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

These findings provide an unprecedented opportunity to apply these lessons and make substantial reductions in surgical complications, Dr. Lucian L. Leape said in an editorial accompanying the study.

Changing systems is hard work and requires serious commitment. Changing hospital systems is especially difficult because of long-standing traditions and entrenched practices. Successful change requires leadership by those with the will, the determination, and the perseverance to overcome obstacles and motivate colleagues. It requires commitment, which comes from a sense of urgency and a sense of possibility.

One way to develop a sense of urgency is to translate rates into numbers – i.e., actual patients. For example, in this study, surgical site infections accounted for 19.5% of the unplanned readmissions. Even though this only represents 1% of the 498,875 ACS NSQIP patients undergoing surgery in 2012, that 1% equals 5,565 patients. Reducing that number by half would reduce pain and suffering for more than 2,700 patients. If similar success were achieved nationwide, the total would be many times that.

Dr. Lucian L. Leape is with the department of health policy and management at Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, and made these comments in an accompanying editorial (doi:10.1001/jama.2014.18666). He reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

These findings provide an unprecedented opportunity to apply these lessons and make substantial reductions in surgical complications, Dr. Lucian L. Leape said in an editorial accompanying the study.

Changing systems is hard work and requires serious commitment. Changing hospital systems is especially difficult because of long-standing traditions and entrenched practices. Successful change requires leadership by those with the will, the determination, and the perseverance to overcome obstacles and motivate colleagues. It requires commitment, which comes from a sense of urgency and a sense of possibility.

One way to develop a sense of urgency is to translate rates into numbers – i.e., actual patients. For example, in this study, surgical site infections accounted for 19.5% of the unplanned readmissions. Even though this only represents 1% of the 498,875 ACS NSQIP patients undergoing surgery in 2012, that 1% equals 5,565 patients. Reducing that number by half would reduce pain and suffering for more than 2,700 patients. If similar success were achieved nationwide, the total would be many times that.

Dr. Lucian L. Leape is with the department of health policy and management at Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, and made these comments in an accompanying editorial (doi:10.1001/jama.2014.18666). He reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Surgical site infection and ileus were the most frequent reason for hospital readmission within 30 days, according to an analysis of data from the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program.

The findings, published online in the Feb. 3 JAMA, suggest that policies that penalize hospitals for readmissions may be ineffective and potentially counterproductive.

Dr. Karl Y. Bilimoria of Northwestern University, Chicago, and his colleagues examined patient data from 346 hospitals participating in the American College of Surgeon’s National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) between January 2012 and December 2012. Readmission rates and reasons were assessed for all surgical procedures and for six representative operations: bariatric surgery, colectomy or proctectomy, hysterectomy, total hip or knee arthroplasty, ventral hernia repair, and lower extremity vascular bypass (JAMA 2015;313;483-95 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.18614]).

Of the 498, 875 patient sample, the overall readmission rate was 5.7%. For individual procedures, the readmission rate ranged from 3.8% for hysterectomy to 14.9% for lower extremity vascular bypass.

The most common reason for readmission was surgical site infection (SSI; 19.5%), ranging from 11.4% after bariatric surgery to 36.4% after lower extremity vascular bypass. Ileus was the most common reason for readmission after bariatric surgery (24.5%) and the second most common reason overall (10.3%). Other common causes for readmission included dehydration or nutritional deficiency, bleeding or anemia, venous thromboembolism, and prosthesis or graft issues (after arthroplasty and lower extremity vascular bypass procedures). Only 2% of patients were readmitted for the same complication they had experienced during their index hospitalization. Just 3% of patients readmitted for SSIs had experienced an SSI during their index hospitalization.

The results show readmissions after surgery may not be an appropriate measure for pay-for-performance and cost-containment programs, such as the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Service’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, Dr. Bilimoria said. Performance targets without accepted courses of intervention might be more prone to unintended or ineffective behaviors and consequences, he noted.

“Surgical readmissions mostly reflect postdischarge complications, and readmission rates may be difficult to reduce until effective strategies are put forth to reduce common complications such as SSI,” he said. “Efforts should focus on reducing complication rates overall than simply those that occur after discharge, and this will subsequently reduce readmission rates as well.”

On Twitter @legal_med

Surgical site infection and ileus were the most frequent reason for hospital readmission within 30 days, according to an analysis of data from the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program.

The findings, published online in the Feb. 3 JAMA, suggest that policies that penalize hospitals for readmissions may be ineffective and potentially counterproductive.

Dr. Karl Y. Bilimoria of Northwestern University, Chicago, and his colleagues examined patient data from 346 hospitals participating in the American College of Surgeon’s National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) between January 2012 and December 2012. Readmission rates and reasons were assessed for all surgical procedures and for six representative operations: bariatric surgery, colectomy or proctectomy, hysterectomy, total hip or knee arthroplasty, ventral hernia repair, and lower extremity vascular bypass (JAMA 2015;313;483-95 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.18614]).

Of the 498, 875 patient sample, the overall readmission rate was 5.7%. For individual procedures, the readmission rate ranged from 3.8% for hysterectomy to 14.9% for lower extremity vascular bypass.

The most common reason for readmission was surgical site infection (SSI; 19.5%), ranging from 11.4% after bariatric surgery to 36.4% after lower extremity vascular bypass. Ileus was the most common reason for readmission after bariatric surgery (24.5%) and the second most common reason overall (10.3%). Other common causes for readmission included dehydration or nutritional deficiency, bleeding or anemia, venous thromboembolism, and prosthesis or graft issues (after arthroplasty and lower extremity vascular bypass procedures). Only 2% of patients were readmitted for the same complication they had experienced during their index hospitalization. Just 3% of patients readmitted for SSIs had experienced an SSI during their index hospitalization.

The results show readmissions after surgery may not be an appropriate measure for pay-for-performance and cost-containment programs, such as the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Service’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, Dr. Bilimoria said. Performance targets without accepted courses of intervention might be more prone to unintended or ineffective behaviors and consequences, he noted.

“Surgical readmissions mostly reflect postdischarge complications, and readmission rates may be difficult to reduce until effective strategies are put forth to reduce common complications such as SSI,” he said. “Efforts should focus on reducing complication rates overall than simply those that occur after discharge, and this will subsequently reduce readmission rates as well.”

On Twitter @legal_med

Key clinical point: The majority of 30-day readmissions after surgery are associated with new postdischarge complications and not the worsening of medical conditions patients had when initially hospitalized.

Major finding: Of 498,875 patients, the overall unplanned readmission rate was 5.7%. Only 2% of patients were readmitted for the same complication they had experienced during their index hospitalization. The most common reason for readmission was surgical site infections (19.5%).

Data source: A study of 346 hospitals participating in the American College of Surgeon’s National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) between January and December 2012.

Disclosures: The investigators reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

The private-academic surgeon salary gap: Would you pick academia if you stood to lose $1.3 million?

LAKE BUENA VISTA, FLA. – Academic surgeons earn an average of 10% or $1.3 million less in gross income across their lifetime than surgeons in private practice, an analysis shows.

Some surgical specialties fare better than others, with academic neurosurgeons having the largest reduction in gross income at $4.2 million (-24.2%), while academic pediatric surgeons earn $238,376 more (1.53%) than their private practice counterparts. They were the only ones to do so.

Several academic surgical specialties did not make the 10% average including trauma surgeons whose lifetime earnings were down 12% or $2.4 million, vascular surgeons at 13.8% or $1.7 million, and surgical oncologists at 12.2% or $1.3 million.

“The concern that we have is that the academic surgeons are where the education of the future lies,” lead study author Dr. Joseph Martin Lopez said at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST).

Every year a new class of surgeons is faced with the question of academic practice or private practice, but they are also struggling with increasing student loan debt and longer training as more surgical residents elect to enter fellowship rather than general practice. This growing financial liability coupled with declining physician reimbursement could rapidly shift physician practices and thus threaten the fiscal viability of certain surgical fields or academic surgical careers.

“The more financially irresponsible you make it to become an academic surgeon, the more we put at risk our current mode of training,” Dr. Lopez of Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, N.C., said.

To account for additional factors outside gross income, the investigators ran the numbers using a second analysis, a net present value calculation, however, and came up with roughly the same salary gap to contend with.

Net present value (NPV) calculations are commonly used in business to calculate the profitability of an investment and also have been used in the medical field to gauge return on investment for various careers. The NPV calculation accounts for positive and negative cash flows over the entire length of a career, using in this case, a 5% discount rate and adjusting for inflation, Dr. Lopez explained.

Both the lifetime gross income and 5% NPV calculation used data from the Medical Group Management Association’s 2012 physician salary report, the 2012 Association of American Medical Colleges physician salary report, and the AAMC database for residency and fellow salary.

The NPV assumed a career length of 37-39 years, based on a retirement age of 65 years for all specialties. Positive cash flows included annual salary less federal income tax. Negative cash flows included the average principal for student loans, according to the AAMC, and interest at 5%, the average for the three largest student loan lenders in 2014, he said. Student loan repayment was calculated for a fixed-rate loan to be paid over 25 years beginning after residency or any required fellowship.

The average reduction in 5% NPV across surgical specialties for an academic surgeon versus a privately employed surgeon was 12.8% or $246,499, Dr. Lopez said.

Once again, academic neurosurgeons had the largest reduction in 5% NPV at 25.5% or a loss of $619,681, followed closely by trauma surgeons (23% or $381,179) and surgical oncologists (16.3% or $256,373). Academic pediatric surgeons had the smallest reduction in 5% NPV at 4.2% or $88,827.

During a discussion of the provocative poster, attendees questioned whether it was fair to say that private surgeons make more money without acknowledging the risk they face, compared with surgeons employed in an academic setting.

Dr. Lopez countered that increasingly, even private surgeons are no longer truly private surgeons.

“More and more surgical groups are being bought up by hospitals, and even the private surgical groups are being bought up by hospitals, which does stabilize your income to some extent,” he said. “We all still have RVU goals to meet and RVU incentives that make it so you can get paid a little more, but it’s something that’s a consideration. It is a risk-reward to be a private surgeon. Depending on how your contract is structured or how your group decides to pay the partners, it may be that if you don’t take very much call or take that many cases, you’ll end up on the short end of the stick.”

Dr. Ben L. Zarzaur, a general surgeon at Indiana University in Indianapolis who comoderated the poster discussion, pointed out that market pressures unaccounted for in the model can dramatically influence a surgeon’s salary over a lifetime.

Dr. Lopez agreed, citing how the increasing number of stent placements by cardiologists, for example, has impacted the bottom line of cardiothoracic surgeons. The NPV calculation was specifically used, however, because it gets at market forces such as inflation and return on investment, not addressed by gross income figures alone.

Finally, Dr. Zarzaur turned and asked the relatively young crowd what they would do if offered $600,000 a year, but had to work 110 hours a week or could get $250,000 and work only 40 hours a week. Most responded that they’d choose the former to repay their student loans and then switch to the lower-paying position. Responders made much of job satisfaction, work-life balance, and the ability of surgeons in academic practice to take time away from clinical work to conduct research, their ready access to continuing medical education, and their ability to educate the next generation of surgeons.

“Any time we see this academic-private disparity, you have to think about these secondary gains,” Dr. Zarzaur said. “This is really interesting work. It gets into why we choose what we do, why we’d take $600,000, work 110 hours a week, and get our rear ends kicked. The flip side is, if I saw this, why would you ever go into academics? But people still choose to do it. I’m in academics so there’s a bias, but we choose to do it anyway up to a point. I don’t know where that point is, but up to a point we do.”

LAKE BUENA VISTA, FLA. – Academic surgeons earn an average of 10% or $1.3 million less in gross income across their lifetime than surgeons in private practice, an analysis shows.

Some surgical specialties fare better than others, with academic neurosurgeons having the largest reduction in gross income at $4.2 million (-24.2%), while academic pediatric surgeons earn $238,376 more (1.53%) than their private practice counterparts. They were the only ones to do so.

Several academic surgical specialties did not make the 10% average including trauma surgeons whose lifetime earnings were down 12% or $2.4 million, vascular surgeons at 13.8% or $1.7 million, and surgical oncologists at 12.2% or $1.3 million.

“The concern that we have is that the academic surgeons are where the education of the future lies,” lead study author Dr. Joseph Martin Lopez said at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST).

Every year a new class of surgeons is faced with the question of academic practice or private practice, but they are also struggling with increasing student loan debt and longer training as more surgical residents elect to enter fellowship rather than general practice. This growing financial liability coupled with declining physician reimbursement could rapidly shift physician practices and thus threaten the fiscal viability of certain surgical fields or academic surgical careers.

“The more financially irresponsible you make it to become an academic surgeon, the more we put at risk our current mode of training,” Dr. Lopez of Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, N.C., said.

To account for additional factors outside gross income, the investigators ran the numbers using a second analysis, a net present value calculation, however, and came up with roughly the same salary gap to contend with.

Net present value (NPV) calculations are commonly used in business to calculate the profitability of an investment and also have been used in the medical field to gauge return on investment for various careers. The NPV calculation accounts for positive and negative cash flows over the entire length of a career, using in this case, a 5% discount rate and adjusting for inflation, Dr. Lopez explained.

Both the lifetime gross income and 5% NPV calculation used data from the Medical Group Management Association’s 2012 physician salary report, the 2012 Association of American Medical Colleges physician salary report, and the AAMC database for residency and fellow salary.

The NPV assumed a career length of 37-39 years, based on a retirement age of 65 years for all specialties. Positive cash flows included annual salary less federal income tax. Negative cash flows included the average principal for student loans, according to the AAMC, and interest at 5%, the average for the three largest student loan lenders in 2014, he said. Student loan repayment was calculated for a fixed-rate loan to be paid over 25 years beginning after residency or any required fellowship.

The average reduction in 5% NPV across surgical specialties for an academic surgeon versus a privately employed surgeon was 12.8% or $246,499, Dr. Lopez said.

Once again, academic neurosurgeons had the largest reduction in 5% NPV at 25.5% or a loss of $619,681, followed closely by trauma surgeons (23% or $381,179) and surgical oncologists (16.3% or $256,373). Academic pediatric surgeons had the smallest reduction in 5% NPV at 4.2% or $88,827.

During a discussion of the provocative poster, attendees questioned whether it was fair to say that private surgeons make more money without acknowledging the risk they face, compared with surgeons employed in an academic setting.

Dr. Lopez countered that increasingly, even private surgeons are no longer truly private surgeons.

“More and more surgical groups are being bought up by hospitals, and even the private surgical groups are being bought up by hospitals, which does stabilize your income to some extent,” he said. “We all still have RVU goals to meet and RVU incentives that make it so you can get paid a little more, but it’s something that’s a consideration. It is a risk-reward to be a private surgeon. Depending on how your contract is structured or how your group decides to pay the partners, it may be that if you don’t take very much call or take that many cases, you’ll end up on the short end of the stick.”

Dr. Ben L. Zarzaur, a general surgeon at Indiana University in Indianapolis who comoderated the poster discussion, pointed out that market pressures unaccounted for in the model can dramatically influence a surgeon’s salary over a lifetime.

Dr. Lopez agreed, citing how the increasing number of stent placements by cardiologists, for example, has impacted the bottom line of cardiothoracic surgeons. The NPV calculation was specifically used, however, because it gets at market forces such as inflation and return on investment, not addressed by gross income figures alone.

Finally, Dr. Zarzaur turned and asked the relatively young crowd what they would do if offered $600,000 a year, but had to work 110 hours a week or could get $250,000 and work only 40 hours a week. Most responded that they’d choose the former to repay their student loans and then switch to the lower-paying position. Responders made much of job satisfaction, work-life balance, and the ability of surgeons in academic practice to take time away from clinical work to conduct research, their ready access to continuing medical education, and their ability to educate the next generation of surgeons.

“Any time we see this academic-private disparity, you have to think about these secondary gains,” Dr. Zarzaur said. “This is really interesting work. It gets into why we choose what we do, why we’d take $600,000, work 110 hours a week, and get our rear ends kicked. The flip side is, if I saw this, why would you ever go into academics? But people still choose to do it. I’m in academics so there’s a bias, but we choose to do it anyway up to a point. I don’t know where that point is, but up to a point we do.”

LAKE BUENA VISTA, FLA. – Academic surgeons earn an average of 10% or $1.3 million less in gross income across their lifetime than surgeons in private practice, an analysis shows.

Some surgical specialties fare better than others, with academic neurosurgeons having the largest reduction in gross income at $4.2 million (-24.2%), while academic pediatric surgeons earn $238,376 more (1.53%) than their private practice counterparts. They were the only ones to do so.

Several academic surgical specialties did not make the 10% average including trauma surgeons whose lifetime earnings were down 12% or $2.4 million, vascular surgeons at 13.8% or $1.7 million, and surgical oncologists at 12.2% or $1.3 million.

“The concern that we have is that the academic surgeons are where the education of the future lies,” lead study author Dr. Joseph Martin Lopez said at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST).

Every year a new class of surgeons is faced with the question of academic practice or private practice, but they are also struggling with increasing student loan debt and longer training as more surgical residents elect to enter fellowship rather than general practice. This growing financial liability coupled with declining physician reimbursement could rapidly shift physician practices and thus threaten the fiscal viability of certain surgical fields or academic surgical careers.

“The more financially irresponsible you make it to become an academic surgeon, the more we put at risk our current mode of training,” Dr. Lopez of Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, N.C., said.

To account for additional factors outside gross income, the investigators ran the numbers using a second analysis, a net present value calculation, however, and came up with roughly the same salary gap to contend with.

Net present value (NPV) calculations are commonly used in business to calculate the profitability of an investment and also have been used in the medical field to gauge return on investment for various careers. The NPV calculation accounts for positive and negative cash flows over the entire length of a career, using in this case, a 5% discount rate and adjusting for inflation, Dr. Lopez explained.

Both the lifetime gross income and 5% NPV calculation used data from the Medical Group Management Association’s 2012 physician salary report, the 2012 Association of American Medical Colleges physician salary report, and the AAMC database for residency and fellow salary.

The NPV assumed a career length of 37-39 years, based on a retirement age of 65 years for all specialties. Positive cash flows included annual salary less federal income tax. Negative cash flows included the average principal for student loans, according to the AAMC, and interest at 5%, the average for the three largest student loan lenders in 2014, he said. Student loan repayment was calculated for a fixed-rate loan to be paid over 25 years beginning after residency or any required fellowship.

The average reduction in 5% NPV across surgical specialties for an academic surgeon versus a privately employed surgeon was 12.8% or $246,499, Dr. Lopez said.

Once again, academic neurosurgeons had the largest reduction in 5% NPV at 25.5% or a loss of $619,681, followed closely by trauma surgeons (23% or $381,179) and surgical oncologists (16.3% or $256,373). Academic pediatric surgeons had the smallest reduction in 5% NPV at 4.2% or $88,827.

During a discussion of the provocative poster, attendees questioned whether it was fair to say that private surgeons make more money without acknowledging the risk they face, compared with surgeons employed in an academic setting.

Dr. Lopez countered that increasingly, even private surgeons are no longer truly private surgeons.

“More and more surgical groups are being bought up by hospitals, and even the private surgical groups are being bought up by hospitals, which does stabilize your income to some extent,” he said. “We all still have RVU goals to meet and RVU incentives that make it so you can get paid a little more, but it’s something that’s a consideration. It is a risk-reward to be a private surgeon. Depending on how your contract is structured or how your group decides to pay the partners, it may be that if you don’t take very much call or take that many cases, you’ll end up on the short end of the stick.”

Dr. Ben L. Zarzaur, a general surgeon at Indiana University in Indianapolis who comoderated the poster discussion, pointed out that market pressures unaccounted for in the model can dramatically influence a surgeon’s salary over a lifetime.

Dr. Lopez agreed, citing how the increasing number of stent placements by cardiologists, for example, has impacted the bottom line of cardiothoracic surgeons. The NPV calculation was specifically used, however, because it gets at market forces such as inflation and return on investment, not addressed by gross income figures alone.

Finally, Dr. Zarzaur turned and asked the relatively young crowd what they would do if offered $600,000 a year, but had to work 110 hours a week or could get $250,000 and work only 40 hours a week. Most responded that they’d choose the former to repay their student loans and then switch to the lower-paying position. Responders made much of job satisfaction, work-life balance, and the ability of surgeons in academic practice to take time away from clinical work to conduct research, their ready access to continuing medical education, and their ability to educate the next generation of surgeons.

“Any time we see this academic-private disparity, you have to think about these secondary gains,” Dr. Zarzaur said. “This is really interesting work. It gets into why we choose what we do, why we’d take $600,000, work 110 hours a week, and get our rear ends kicked. The flip side is, if I saw this, why would you ever go into academics? But people still choose to do it. I’m in academics so there’s a bias, but we choose to do it anyway up to a point. I don’t know where that point is, but up to a point we do.”

AT THE EAST SCIENTIFIC ASSEMBLY

Key clinical point: Whether calculated as gross lifetime income or 5% net present value, a salary disparity exists between academic and private practice surgeons.

Major finding: Academic surgeons earn an average of 10% or $1.3 million less in gross lifetime income than surgeons in private practice.

Data source: Salary analysis and net present value calculation.

Disclosures: Dr. Lopez and his coauthors reported having no financial disclosures. Dr. Zarzaur disclosed honorarium from and serving as an advisor for Merck.

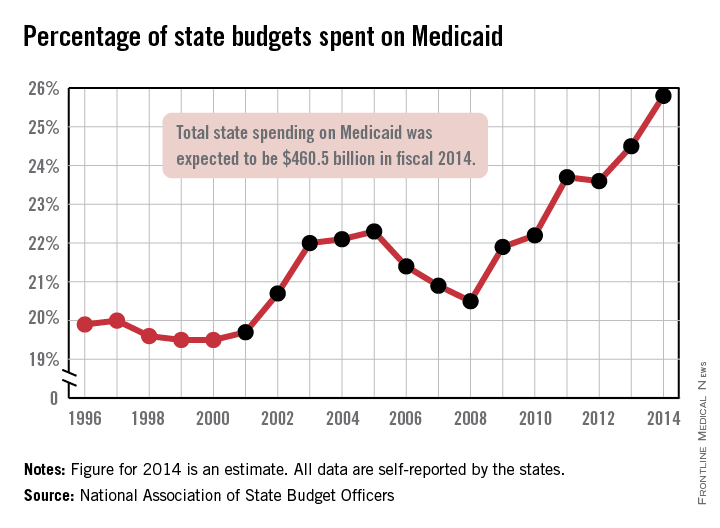

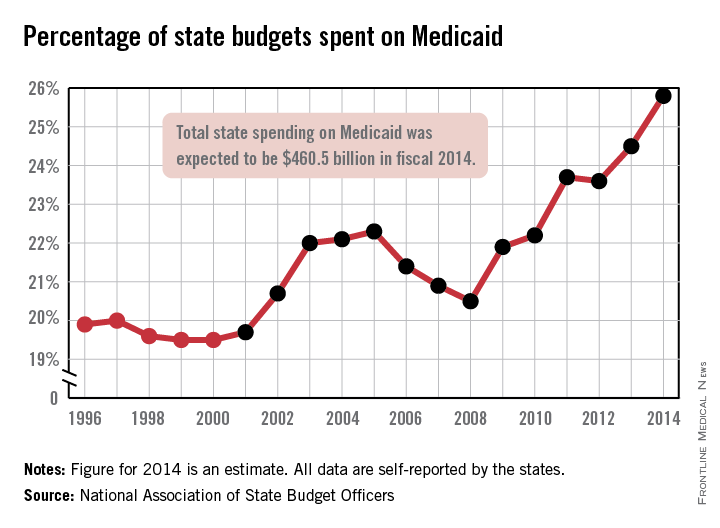

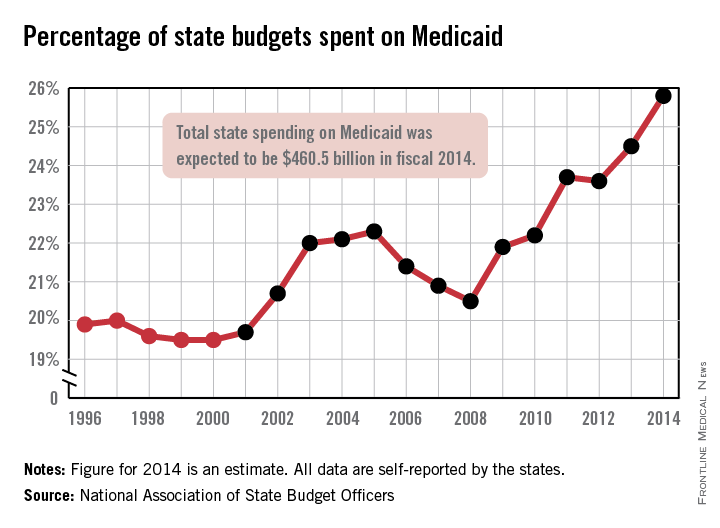

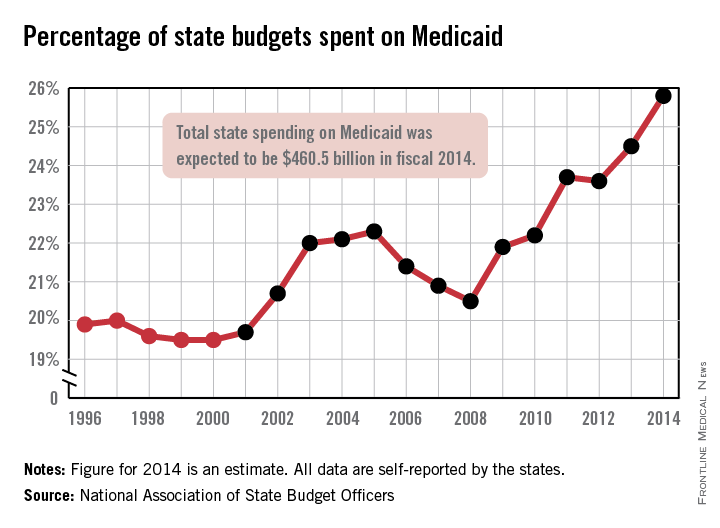

Medicaid’s share of state budgets was nearly 26% in 2014

States spent more than a quarter of their budgets on Medicaid for the first time in 2014, with the total share estimated at 25.8% by the National Association of State Budget Officers.

That 25.8% represents expenditures of $460.5 billion, excluding administration costs – an increase of 11.3% over 2013. Medicaid was the single largest component of total state spending last year, NASBO noted in its annual State Expenditure Report, and has been every year since 2009.

State funding for Medicaid increased by 2.7% in 2014, while the federal share of funding went up by an estimated 17.8%, compared with 2013. Medicaid enrollment was projected to increase by 8.3% across all states in 2014 after going up 1.5% in 2013; it is expected to increase by 13.2% in fiscal 2015, NASBO said.

“Implementation of the Affordable Care Act has greatly increased the number of individuals served in the Medicaid program in 2014 and thereafter,” the report noted, adding that the ACA’s Medicaid eligibility expansion option is expected to “add approximately 18.3 million individuals by 2021.”

States spent more than a quarter of their budgets on Medicaid for the first time in 2014, with the total share estimated at 25.8% by the National Association of State Budget Officers.

That 25.8% represents expenditures of $460.5 billion, excluding administration costs – an increase of 11.3% over 2013. Medicaid was the single largest component of total state spending last year, NASBO noted in its annual State Expenditure Report, and has been every year since 2009.

State funding for Medicaid increased by 2.7% in 2014, while the federal share of funding went up by an estimated 17.8%, compared with 2013. Medicaid enrollment was projected to increase by 8.3% across all states in 2014 after going up 1.5% in 2013; it is expected to increase by 13.2% in fiscal 2015, NASBO said.

“Implementation of the Affordable Care Act has greatly increased the number of individuals served in the Medicaid program in 2014 and thereafter,” the report noted, adding that the ACA’s Medicaid eligibility expansion option is expected to “add approximately 18.3 million individuals by 2021.”

States spent more than a quarter of their budgets on Medicaid for the first time in 2014, with the total share estimated at 25.8% by the National Association of State Budget Officers.

That 25.8% represents expenditures of $460.5 billion, excluding administration costs – an increase of 11.3% over 2013. Medicaid was the single largest component of total state spending last year, NASBO noted in its annual State Expenditure Report, and has been every year since 2009.

State funding for Medicaid increased by 2.7% in 2014, while the federal share of funding went up by an estimated 17.8%, compared with 2013. Medicaid enrollment was projected to increase by 8.3% across all states in 2014 after going up 1.5% in 2013; it is expected to increase by 13.2% in fiscal 2015, NASBO said.

“Implementation of the Affordable Care Act has greatly increased the number of individuals served in the Medicaid program in 2014 and thereafter,” the report noted, adding that the ACA’s Medicaid eligibility expansion option is expected to “add approximately 18.3 million individuals by 2021.”

Hospital participation in surgical quality program results in minimal improvements

Hospitals participating in a monitoring and feedback program for surgical quality showed no more improvement in patient mortality, serious complications, reoperation, or readmission than hospitals not participating in the program, according to two separate reports published online Feb. 3 in JAMA.

Both research groups concluded that feedback on outcomes alone may not be sufficient to improve surgical outcomes.

The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) is an extensive clinical registry that provides participating hospitals with detailed descriptions of outcomes such as mortality, length of stay, and complications, allowing them to benchmark their performance relative to other participating hospitals and focus their efforts to improve care on the areas in which they perform poorly. The information is not reported publicly. Proponents contend that this targeting has already improved surgical outcomes as reported in several single-center studies, but others argue that any improvements noted so far might have occurred over time anyway.

The best way to examine the question would be to compare outcomes between participating and nonparticipating hospitals, according to the two groups of investigators who did just that in these studies. However, the American College of Surgeons took issue with both study designs and released a statement taking exception to their approach to measuring surgical complications.

In the first study, researchers analyzed 30-day outcomes during a 10-year period at 263 hospitals participating in the ACS NSQIP and 526 nonparticipating propensity-matched hospitals across the United States. They focused on patients aged 65-99 years undergoing 11 high-risk general or vascular surgical procedures that are most in need of quality improvement: esophagectomy, pancreatic resection, colon resection, gastrectomy, liver resection, ventral hernia repair, cholecystectomy, appendectomy, abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, lower-extremity bypass, and carotid endarterectomy, said Dr. Nicholas H. Osborne of the Center for Healthcare Outcomes and Policy, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and a vascular surgeon at the university and his associates.

They found “slight trends toward improved outcomes” in NSQIP hospitals over time, but control hospitals showed the same trends. For example, 30-day mortality declined from 4.6% to 4.2% in participating hospitals during the study period, and similarly declined from 4.9% to 4.6% in nonparticipating hospitals. However, further analysis showed no statistically significant reductions after enrollment in the NSQIP in 30-day mortality, serious complications, reoperations, or readmissions, Dr. Osborne and his associates said (JAMA 2015 Feb. 3 [doi:10.1001/jama.2015.25]).

The underlying reasons for a lack of improvement among participating hospitals aren’t yet known, but it is possible that hospitals never implemented quality improvement efforts after being informed of their shortcomings, or that they implemented ineffective remedies. “Clinical quality improvement is challenging for hospitals. Changing physician practice requires complex, sustained, multifaceted interventions, and most hospitals may not have the expertise or resources to launch effective quality improvement interventions,” Dr. Osborne and his associates added.

In the second study, researchers analyzed surgical outcomes over a 4-year period among 113 academic hospitals in a health care system database; 39% of these hospitals participated in the NSQIP, receiving feedback on their performance, and the remaining 61% did not. This study evaluated 345,357 hospitalizations for 16 elective general and vascular surgeries, including many of the procedures covered in Dr. Osborne’s study plus mastectomy, thyroid procedures, open or laparoscopic colectomy, prostatectomy, and bariatric procedures, said Dr. David A. Etzioni, a surgeon at Mayo Clinic Arizona, Phoenix, and of the Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery, and his associates.

This study also showed a slight decrease over time in postoperative complications, serious complications, and mortality at both NSQIP and non-NSQIP hospitals. “After accounting for patient risk, procedure type, underlying hospital performance, and temporal trends, the [statistical] model demonstrated no significant differences over time between NSQIP and non-NSQIP hospitals in terms of likelihood of complications, serious complications, or mortality,” Dr. Etzioni and his associates said (JAMA 2015 Feb. 3 [doi:10.1001/jama.2015.90]).

Their findings indicate that quality reports do not necessarily translate into evidence-based strategies for quality improvement and “suggest that a surgical outcomes reporting system does not provide a clear mechanism for quality improvement,” they noted.

In response to these reports, the American College of Surgeons released a statement emphasizing that claims data such as those used by both Osborne et al. and Etzioni et al. “are inaccurate and inappropriate for measuring surgical complications.” Furthermore, Dr. Clifford Ko, ACS director of the division of research and optimal patient care, called it “irresponsible to use data that are known to be an inaccurate measure of quality to determine the effectiveness of a quality improvement program.”

In addition, real-world experience shows that hospitals tend to focus on specific complications one at a time (such as surgical site infections) rather than amalgamating all complications. Hospitals also tend to address performance by separate specialties (such as urology) rather than on particular procedures (such as prostatectomy), according to the ACS statement.

Dr. Osborne’s study was supported in part by the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Osborne reported having no financial disclosures; one of his associates reported ties to Arbor Metrix. Dr. Etzioni’s study did not list any sources of financial support. Dr. Etzioni and his associates reported having no financial disclosures.

Observational studies using large databases rarely get better than these two reports, which used sophisticated risk adjustments and achieved unusually rigorous matching of controls. But the studies by Osborne et al. and Etzioni et al. are not the final word on whether NSQIP can help improve the quality of surgical care.

The most likely explanation for the lack of improvement after feedback on surgical performance is that this information is necessary but not sufficient to effect change. The skills for improving processes and cultures do not yet pervade U.S. hospitals, to say the least. Proponents of NSQIP must link its information more energetically to the processes of learning, skill building, and change within participating hospitals.

David M. Berwick, M.D., is president emeritus and senior fellow at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, Cambridge, Mass. He reported no relevant financial conflicts of interest. Dr. Berwick made these remarks in an editorial accompanying the two reports (JAMA 2015;313:469-70).

Observational studies using large databases rarely get better than these two reports, which used sophisticated risk adjustments and achieved unusually rigorous matching of controls. But the studies by Osborne et al. and Etzioni et al. are not the final word on whether NSQIP can help improve the quality of surgical care.

The most likely explanation for the lack of improvement after feedback on surgical performance is that this information is necessary but not sufficient to effect change. The skills for improving processes and cultures do not yet pervade U.S. hospitals, to say the least. Proponents of NSQIP must link its information more energetically to the processes of learning, skill building, and change within participating hospitals.

David M. Berwick, M.D., is president emeritus and senior fellow at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, Cambridge, Mass. He reported no relevant financial conflicts of interest. Dr. Berwick made these remarks in an editorial accompanying the two reports (JAMA 2015;313:469-70).

Observational studies using large databases rarely get better than these two reports, which used sophisticated risk adjustments and achieved unusually rigorous matching of controls. But the studies by Osborne et al. and Etzioni et al. are not the final word on whether NSQIP can help improve the quality of surgical care.

The most likely explanation for the lack of improvement after feedback on surgical performance is that this information is necessary but not sufficient to effect change. The skills for improving processes and cultures do not yet pervade U.S. hospitals, to say the least. Proponents of NSQIP must link its information more energetically to the processes of learning, skill building, and change within participating hospitals.

David M. Berwick, M.D., is president emeritus and senior fellow at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, Cambridge, Mass. He reported no relevant financial conflicts of interest. Dr. Berwick made these remarks in an editorial accompanying the two reports (JAMA 2015;313:469-70).

Hospitals participating in a monitoring and feedback program for surgical quality showed no more improvement in patient mortality, serious complications, reoperation, or readmission than hospitals not participating in the program, according to two separate reports published online Feb. 3 in JAMA.

Both research groups concluded that feedback on outcomes alone may not be sufficient to improve surgical outcomes.

The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) is an extensive clinical registry that provides participating hospitals with detailed descriptions of outcomes such as mortality, length of stay, and complications, allowing them to benchmark their performance relative to other participating hospitals and focus their efforts to improve care on the areas in which they perform poorly. The information is not reported publicly. Proponents contend that this targeting has already improved surgical outcomes as reported in several single-center studies, but others argue that any improvements noted so far might have occurred over time anyway.

The best way to examine the question would be to compare outcomes between participating and nonparticipating hospitals, according to the two groups of investigators who did just that in these studies. However, the American College of Surgeons took issue with both study designs and released a statement taking exception to their approach to measuring surgical complications.

In the first study, researchers analyzed 30-day outcomes during a 10-year period at 263 hospitals participating in the ACS NSQIP and 526 nonparticipating propensity-matched hospitals across the United States. They focused on patients aged 65-99 years undergoing 11 high-risk general or vascular surgical procedures that are most in need of quality improvement: esophagectomy, pancreatic resection, colon resection, gastrectomy, liver resection, ventral hernia repair, cholecystectomy, appendectomy, abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, lower-extremity bypass, and carotid endarterectomy, said Dr. Nicholas H. Osborne of the Center for Healthcare Outcomes and Policy, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and a vascular surgeon at the university and his associates.

They found “slight trends toward improved outcomes” in NSQIP hospitals over time, but control hospitals showed the same trends. For example, 30-day mortality declined from 4.6% to 4.2% in participating hospitals during the study period, and similarly declined from 4.9% to 4.6% in nonparticipating hospitals. However, further analysis showed no statistically significant reductions after enrollment in the NSQIP in 30-day mortality, serious complications, reoperations, or readmissions, Dr. Osborne and his associates said (JAMA 2015 Feb. 3 [doi:10.1001/jama.2015.25]).

The underlying reasons for a lack of improvement among participating hospitals aren’t yet known, but it is possible that hospitals never implemented quality improvement efforts after being informed of their shortcomings, or that they implemented ineffective remedies. “Clinical quality improvement is challenging for hospitals. Changing physician practice requires complex, sustained, multifaceted interventions, and most hospitals may not have the expertise or resources to launch effective quality improvement interventions,” Dr. Osborne and his associates added.

In the second study, researchers analyzed surgical outcomes over a 4-year period among 113 academic hospitals in a health care system database; 39% of these hospitals participated in the NSQIP, receiving feedback on their performance, and the remaining 61% did not. This study evaluated 345,357 hospitalizations for 16 elective general and vascular surgeries, including many of the procedures covered in Dr. Osborne’s study plus mastectomy, thyroid procedures, open or laparoscopic colectomy, prostatectomy, and bariatric procedures, said Dr. David A. Etzioni, a surgeon at Mayo Clinic Arizona, Phoenix, and of the Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery, and his associates.

This study also showed a slight decrease over time in postoperative complications, serious complications, and mortality at both NSQIP and non-NSQIP hospitals. “After accounting for patient risk, procedure type, underlying hospital performance, and temporal trends, the [statistical] model demonstrated no significant differences over time between NSQIP and non-NSQIP hospitals in terms of likelihood of complications, serious complications, or mortality,” Dr. Etzioni and his associates said (JAMA 2015 Feb. 3 [doi:10.1001/jama.2015.90]).

Their findings indicate that quality reports do not necessarily translate into evidence-based strategies for quality improvement and “suggest that a surgical outcomes reporting system does not provide a clear mechanism for quality improvement,” they noted.

In response to these reports, the American College of Surgeons released a statement emphasizing that claims data such as those used by both Osborne et al. and Etzioni et al. “are inaccurate and inappropriate for measuring surgical complications.” Furthermore, Dr. Clifford Ko, ACS director of the division of research and optimal patient care, called it “irresponsible to use data that are known to be an inaccurate measure of quality to determine the effectiveness of a quality improvement program.”

In addition, real-world experience shows that hospitals tend to focus on specific complications one at a time (such as surgical site infections) rather than amalgamating all complications. Hospitals also tend to address performance by separate specialties (such as urology) rather than on particular procedures (such as prostatectomy), according to the ACS statement.

Dr. Osborne’s study was supported in part by the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Osborne reported having no financial disclosures; one of his associates reported ties to Arbor Metrix. Dr. Etzioni’s study did not list any sources of financial support. Dr. Etzioni and his associates reported having no financial disclosures.

Hospitals participating in a monitoring and feedback program for surgical quality showed no more improvement in patient mortality, serious complications, reoperation, or readmission than hospitals not participating in the program, according to two separate reports published online Feb. 3 in JAMA.

Both research groups concluded that feedback on outcomes alone may not be sufficient to improve surgical outcomes.

The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP) is an extensive clinical registry that provides participating hospitals with detailed descriptions of outcomes such as mortality, length of stay, and complications, allowing them to benchmark their performance relative to other participating hospitals and focus their efforts to improve care on the areas in which they perform poorly. The information is not reported publicly. Proponents contend that this targeting has already improved surgical outcomes as reported in several single-center studies, but others argue that any improvements noted so far might have occurred over time anyway.

The best way to examine the question would be to compare outcomes between participating and nonparticipating hospitals, according to the two groups of investigators who did just that in these studies. However, the American College of Surgeons took issue with both study designs and released a statement taking exception to their approach to measuring surgical complications.