User login

Woman with transplanted uterus gives birth to boy

It’s the first time that a baby has been born to a woman with a transplanted uterus outside of a clinical trial. Officials from University of Alabama–Birmingham Hospital, where the 2-year process took place, said in a statement on July 24 that the birth sets its uterus transplant program on track to perhaps become covered under insurance plans.

The process of uterus transplant, in vitro fertilization, and pregnancy involves 50 medical providers and is open to women who have uterine factor infertility (UFI). The condition may affect up to 5% of reproductive-age women worldwide. Women with UFI cannot carry a pregnancy to term because they were either born without a uterus, had it removed via hysterectomy, or have a uterus that does not function properly.

The woman, whom the hospital identified as Mallory, moved with her family to the Birmingham area to enter the transplant program, which is one of four programs operating in the United States. Mallory learned when she was 17 years old that she was born without a uterus because of Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome. Her first child, a daughter, was born after her sister carried the pregnancy as a surrogate.

Mallory received her uterus from a deceased donor. Her son was born in May.

“As with other types of organ transplants, the woman must take immunosuppressive medications to prevent the body from rejecting the transplanted uterus,” the transplant program’s website states. “After the baby is born and if the woman does not want more children, the transplanted uterus is removed with a hysterectomy procedure, and the woman no longer needs to take antirejection medications.”

“There are all different ways to grow your family if you have uterine factor infertility, but this [uterus transplantation] is what I feel like I knew that I was supposed to do,” Mallory said in a statement. “I mean, just hearing the cry at first was just, you know, mind blowing.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

It’s the first time that a baby has been born to a woman with a transplanted uterus outside of a clinical trial. Officials from University of Alabama–Birmingham Hospital, where the 2-year process took place, said in a statement on July 24 that the birth sets its uterus transplant program on track to perhaps become covered under insurance plans.

The process of uterus transplant, in vitro fertilization, and pregnancy involves 50 medical providers and is open to women who have uterine factor infertility (UFI). The condition may affect up to 5% of reproductive-age women worldwide. Women with UFI cannot carry a pregnancy to term because they were either born without a uterus, had it removed via hysterectomy, or have a uterus that does not function properly.

The woman, whom the hospital identified as Mallory, moved with her family to the Birmingham area to enter the transplant program, which is one of four programs operating in the United States. Mallory learned when she was 17 years old that she was born without a uterus because of Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome. Her first child, a daughter, was born after her sister carried the pregnancy as a surrogate.

Mallory received her uterus from a deceased donor. Her son was born in May.

“As with other types of organ transplants, the woman must take immunosuppressive medications to prevent the body from rejecting the transplanted uterus,” the transplant program’s website states. “After the baby is born and if the woman does not want more children, the transplanted uterus is removed with a hysterectomy procedure, and the woman no longer needs to take antirejection medications.”

“There are all different ways to grow your family if you have uterine factor infertility, but this [uterus transplantation] is what I feel like I knew that I was supposed to do,” Mallory said in a statement. “I mean, just hearing the cry at first was just, you know, mind blowing.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

It’s the first time that a baby has been born to a woman with a transplanted uterus outside of a clinical trial. Officials from University of Alabama–Birmingham Hospital, where the 2-year process took place, said in a statement on July 24 that the birth sets its uterus transplant program on track to perhaps become covered under insurance plans.

The process of uterus transplant, in vitro fertilization, and pregnancy involves 50 medical providers and is open to women who have uterine factor infertility (UFI). The condition may affect up to 5% of reproductive-age women worldwide. Women with UFI cannot carry a pregnancy to term because they were either born without a uterus, had it removed via hysterectomy, or have a uterus that does not function properly.

The woman, whom the hospital identified as Mallory, moved with her family to the Birmingham area to enter the transplant program, which is one of four programs operating in the United States. Mallory learned when she was 17 years old that she was born without a uterus because of Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome. Her first child, a daughter, was born after her sister carried the pregnancy as a surrogate.

Mallory received her uterus from a deceased donor. Her son was born in May.

“As with other types of organ transplants, the woman must take immunosuppressive medications to prevent the body from rejecting the transplanted uterus,” the transplant program’s website states. “After the baby is born and if the woman does not want more children, the transplanted uterus is removed with a hysterectomy procedure, and the woman no longer needs to take antirejection medications.”

“There are all different ways to grow your family if you have uterine factor infertility, but this [uterus transplantation] is what I feel like I knew that I was supposed to do,” Mallory said in a statement. “I mean, just hearing the cry at first was just, you know, mind blowing.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Pregnancy risks elevated in women with chronic pancreatitis

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- A retrospective analysis of hospital discharge records from the National Inpatient Sample database between 2009 and 2019 was conducted.

- The sample included 3,094 pregnancies with chronic pancreatitis and roughly 40.8 million pregnancies without this condition.

- The study focused on primary maternal outcomes and primary perinatal outcomes in pregnancies affected by chronic pancreatitis after accounting for relevant covariates.

TAKEAWAY:

- Chronic pancreatitis pregnancies had elevated rates of gestational diabetes (adjusted odds ratio, 1.63), gestational hypertensive complications (aOR, 2.48), preterm labor (aOR, 3.10), and small size for gestational age (aOR, 2.40).

- Women with chronic pancreatitis and a history of renal failure were more prone to gestational hypertensive complications (aOR, 20.09).

- Women with alcohol-induced chronic pancreatitis had a 17-fold higher risk for fetal death (aOR, 17.15).

- Pregnancies with chronic pancreatitis were associated with longer hospital stays and higher hospital costs.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our study provides novel insights into the impact of chronic pancreatitis on maternal and fetal health. The implications of our findings are critical for health care professionals, particularly those involved in preconception counseling. Pregnant women with chronic pancreatitis should be under the care of a multidisciplinary team of health care providers,” the authors advise.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Chengu Niu, MD, with Rochester General Hospital, Rochester, N.Y. It was published online July 18 in Digestive and Liver Disease. The study had no specific funding.

LIMITATIONS:

The authors note potential inaccuracies because of coding in the National Inpatient Sample database, a lack of detailed information regarding medication use, and a lack of follow-up clinical information. The findings are specific to the United States and may not be applicable to other countries.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors have no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- A retrospective analysis of hospital discharge records from the National Inpatient Sample database between 2009 and 2019 was conducted.

- The sample included 3,094 pregnancies with chronic pancreatitis and roughly 40.8 million pregnancies without this condition.

- The study focused on primary maternal outcomes and primary perinatal outcomes in pregnancies affected by chronic pancreatitis after accounting for relevant covariates.

TAKEAWAY:

- Chronic pancreatitis pregnancies had elevated rates of gestational diabetes (adjusted odds ratio, 1.63), gestational hypertensive complications (aOR, 2.48), preterm labor (aOR, 3.10), and small size for gestational age (aOR, 2.40).

- Women with chronic pancreatitis and a history of renal failure were more prone to gestational hypertensive complications (aOR, 20.09).

- Women with alcohol-induced chronic pancreatitis had a 17-fold higher risk for fetal death (aOR, 17.15).

- Pregnancies with chronic pancreatitis were associated with longer hospital stays and higher hospital costs.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our study provides novel insights into the impact of chronic pancreatitis on maternal and fetal health. The implications of our findings are critical for health care professionals, particularly those involved in preconception counseling. Pregnant women with chronic pancreatitis should be under the care of a multidisciplinary team of health care providers,” the authors advise.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Chengu Niu, MD, with Rochester General Hospital, Rochester, N.Y. It was published online July 18 in Digestive and Liver Disease. The study had no specific funding.

LIMITATIONS:

The authors note potential inaccuracies because of coding in the National Inpatient Sample database, a lack of detailed information regarding medication use, and a lack of follow-up clinical information. The findings are specific to the United States and may not be applicable to other countries.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors have no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- A retrospective analysis of hospital discharge records from the National Inpatient Sample database between 2009 and 2019 was conducted.

- The sample included 3,094 pregnancies with chronic pancreatitis and roughly 40.8 million pregnancies without this condition.

- The study focused on primary maternal outcomes and primary perinatal outcomes in pregnancies affected by chronic pancreatitis after accounting for relevant covariates.

TAKEAWAY:

- Chronic pancreatitis pregnancies had elevated rates of gestational diabetes (adjusted odds ratio, 1.63), gestational hypertensive complications (aOR, 2.48), preterm labor (aOR, 3.10), and small size for gestational age (aOR, 2.40).

- Women with chronic pancreatitis and a history of renal failure were more prone to gestational hypertensive complications (aOR, 20.09).

- Women with alcohol-induced chronic pancreatitis had a 17-fold higher risk for fetal death (aOR, 17.15).

- Pregnancies with chronic pancreatitis were associated with longer hospital stays and higher hospital costs.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our study provides novel insights into the impact of chronic pancreatitis on maternal and fetal health. The implications of our findings are critical for health care professionals, particularly those involved in preconception counseling. Pregnant women with chronic pancreatitis should be under the care of a multidisciplinary team of health care providers,” the authors advise.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Chengu Niu, MD, with Rochester General Hospital, Rochester, N.Y. It was published online July 18 in Digestive and Liver Disease. The study had no specific funding.

LIMITATIONS:

The authors note potential inaccuracies because of coding in the National Inpatient Sample database, a lack of detailed information regarding medication use, and a lack of follow-up clinical information. The findings are specific to the United States and may not be applicable to other countries.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors have no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Cancer Patients: Who’s at Risk for Venous Thromboembolism?

Patients with cancer are at a high risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE)—in fact, it’s one of the leading causes of death in patients who receive systemic therapy for cancer. But as cancer treatment has evolved, have the incidence and risk of VTE changed too?

Researchers from Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System in Massachusetts conducted a study with 434,203 veterans to evaluate the pattern of VTE incidence over 16 years, focusing on the types of cancer, treatment, race and ethnicity, and other factors related to cancer-associated thrombosis (CAT).

In contrast with other large population studies, this study found the overall incidence of CAT remained largely stable over time. At 12 months, the incidence was 4.5%, with yearly trends ranging between 4.2% and 4.7%. “As expected,” the researchers say, the subset of patients receiving systemic therapy had a higher incidence of VTE at 12 months (7.7%) than did the overall cohort. The pattern was “particularly pronounced” in gynecologic, testicular, and kidney cancers, where the incidence of VTE was 2 to 3 times higher in the treated cohort compared with the overall cohort.

Cancer type and diagnosis were the most statistically and clinically significant associations with CAT, with up to a 6-fold difference between cancer subtypes. The patients at the highest risk of VTE were those with pancreatic cancer and acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

Most studies have focused only on patients with solid tumors, but these researchers observed novel patterns among patients with hematologic neoplasms. Specifically, a higher incidence of VTE among patients with aggressive vs indolent leukemias and lymphomas. This trend, the researchers say, may be associated in part with catheter-related events.

Furthermore, the type of system treatment was associated with the risk of VTE, the researchers say, although to a lesser extent. Chemotherapy- and immunotherapy-based regimens had the highest risk of VTE, relative to no treatment. Targeted and endocrine therapy also carried a higher risk compared with no treatment but to a lesser degree.

The researchers found significant heterogeneity by race and ethnicity across cancer types. Non-Hispanic Black patients had about 20% higher risk of VTE compared with non-Hispanic White patients. Asian and Pacific Islander patients had about 20% lower risk compared with non-Hispanic White patients.

Male sex was also associated with VTE. However, “interestingly,” the researchers note, neighborhood-level socioeconomic factors and patients’ comorbidities were not associated with CAT but were associated with mortality.

Their results suggest that patient- and treatment-specific factors play a critical role in assessing the risk of CAT, and “ongoing efforts to identify these patterns are of utmost importance for risk stratification and prognostic assessment.”

Patients with cancer are at a high risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE)—in fact, it’s one of the leading causes of death in patients who receive systemic therapy for cancer. But as cancer treatment has evolved, have the incidence and risk of VTE changed too?

Researchers from Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System in Massachusetts conducted a study with 434,203 veterans to evaluate the pattern of VTE incidence over 16 years, focusing on the types of cancer, treatment, race and ethnicity, and other factors related to cancer-associated thrombosis (CAT).

In contrast with other large population studies, this study found the overall incidence of CAT remained largely stable over time. At 12 months, the incidence was 4.5%, with yearly trends ranging between 4.2% and 4.7%. “As expected,” the researchers say, the subset of patients receiving systemic therapy had a higher incidence of VTE at 12 months (7.7%) than did the overall cohort. The pattern was “particularly pronounced” in gynecologic, testicular, and kidney cancers, where the incidence of VTE was 2 to 3 times higher in the treated cohort compared with the overall cohort.

Cancer type and diagnosis were the most statistically and clinically significant associations with CAT, with up to a 6-fold difference between cancer subtypes. The patients at the highest risk of VTE were those with pancreatic cancer and acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

Most studies have focused only on patients with solid tumors, but these researchers observed novel patterns among patients with hematologic neoplasms. Specifically, a higher incidence of VTE among patients with aggressive vs indolent leukemias and lymphomas. This trend, the researchers say, may be associated in part with catheter-related events.

Furthermore, the type of system treatment was associated with the risk of VTE, the researchers say, although to a lesser extent. Chemotherapy- and immunotherapy-based regimens had the highest risk of VTE, relative to no treatment. Targeted and endocrine therapy also carried a higher risk compared with no treatment but to a lesser degree.

The researchers found significant heterogeneity by race and ethnicity across cancer types. Non-Hispanic Black patients had about 20% higher risk of VTE compared with non-Hispanic White patients. Asian and Pacific Islander patients had about 20% lower risk compared with non-Hispanic White patients.

Male sex was also associated with VTE. However, “interestingly,” the researchers note, neighborhood-level socioeconomic factors and patients’ comorbidities were not associated with CAT but were associated with mortality.

Their results suggest that patient- and treatment-specific factors play a critical role in assessing the risk of CAT, and “ongoing efforts to identify these patterns are of utmost importance for risk stratification and prognostic assessment.”

Patients with cancer are at a high risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE)—in fact, it’s one of the leading causes of death in patients who receive systemic therapy for cancer. But as cancer treatment has evolved, have the incidence and risk of VTE changed too?

Researchers from Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System in Massachusetts conducted a study with 434,203 veterans to evaluate the pattern of VTE incidence over 16 years, focusing on the types of cancer, treatment, race and ethnicity, and other factors related to cancer-associated thrombosis (CAT).

In contrast with other large population studies, this study found the overall incidence of CAT remained largely stable over time. At 12 months, the incidence was 4.5%, with yearly trends ranging between 4.2% and 4.7%. “As expected,” the researchers say, the subset of patients receiving systemic therapy had a higher incidence of VTE at 12 months (7.7%) than did the overall cohort. The pattern was “particularly pronounced” in gynecologic, testicular, and kidney cancers, where the incidence of VTE was 2 to 3 times higher in the treated cohort compared with the overall cohort.

Cancer type and diagnosis were the most statistically and clinically significant associations with CAT, with up to a 6-fold difference between cancer subtypes. The patients at the highest risk of VTE were those with pancreatic cancer and acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

Most studies have focused only on patients with solid tumors, but these researchers observed novel patterns among patients with hematologic neoplasms. Specifically, a higher incidence of VTE among patients with aggressive vs indolent leukemias and lymphomas. This trend, the researchers say, may be associated in part with catheter-related events.

Furthermore, the type of system treatment was associated with the risk of VTE, the researchers say, although to a lesser extent. Chemotherapy- and immunotherapy-based regimens had the highest risk of VTE, relative to no treatment. Targeted and endocrine therapy also carried a higher risk compared with no treatment but to a lesser degree.

The researchers found significant heterogeneity by race and ethnicity across cancer types. Non-Hispanic Black patients had about 20% higher risk of VTE compared with non-Hispanic White patients. Asian and Pacific Islander patients had about 20% lower risk compared with non-Hispanic White patients.

Male sex was also associated with VTE. However, “interestingly,” the researchers note, neighborhood-level socioeconomic factors and patients’ comorbidities were not associated with CAT but were associated with mortality.

Their results suggest that patient- and treatment-specific factors play a critical role in assessing the risk of CAT, and “ongoing efforts to identify these patterns are of utmost importance for risk stratification and prognostic assessment.”

Regional Meeting Focuses on Women’s Cancer Survivorship

As the number of female veterans continues to grow, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is adjusting by focusing more on breast/gynecological cancer and referring fewer cases to outside clinicians.

The VA’s effort reflects the reality that female veterans from the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq are approaching the ages—50s, 60s, and 70s—when cancer diagnoses become more common, said Sarah Colonna, MD, national medical director of breast oncology for VA's Breast and Gynecologic Oncology System of Excellence and an oncologist at the Huntsman Cancer Institute and Wahlen VA Medical Center in Salt Lake City, Utah. “This is preparation for the change that we know is coming.”

In response, the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO) is devoting a regional meeting in Tampa, Florida (July 29, 2023) to improving survivorship for patients with women’s cancers. “This meeting is designed to educate both cancer experts and primary care providers on the care of women who have already gone through breast and gynecological cancer treatment,” Colonna explained.

Adherence Challenges

Colonna will speak in a session about the importance of adherence to endocrine therapy. “When we prescribe endocrine therapy for breast cancer, we usually ask women to stay on it for 5 to 10 years, and sometimes that’s hard for them,” she said. “I’ll talk about tips and tricks to help women stay on endocrine therapy for the long haul because we know that is linked to better survival.”

Between two-thirds and three-quarters of women with breast cancer are advised to stay on endocrine drugs, she said, but the medications can be difficult to tolerate due to adverse effects such as hot flashes and sleep disturbances.

In addition, patients are often anxious about the medications. “Women are very leery of anything that changes or makes their hormones different,” Colonna noted. “They feel like it’s messing with something that is natural for them.”

Colonna urges colleagues to focus on their “soft skills,” the ability to absorb and validate the worries of patients. Instead of dismissing them, she said, focus on messages that acknowledge concerns but are also firm: “That’s real, that sucks. But we’ve got to do it.”

It’s also helpful to guide patients away from thinking that taking a pill every day means they’re sick. “I try to flip that paradigm: ‘You’re taking this pill every day because you have power over this thing that happened to you.’”

Education is also key, she said, so that patients “understand very clearly why this medication is important for them: It increases the chance of surviving breast cancer or it increases the chances that the cancer will never come back in your arm or in your breast. Then, whether they make a decision to take it or not, at least they’re making the choice with knowledge.”

As for adverse effects, Colonna said medications such as antidepressants and painkillers can relieve hot flashes, which can disturb sleep.

Identifying the best strategy to address adverse effects “requires keeping in frequent contact with the patient during the first 6 months of endocrine therapy, which are really critical,” she said. “Once they’ve been on it for a year, they can see the light at the end of the tunnel and hang in there even if they have adverse effects.”

Some guidelines suggest that no doctor visits are needed until the 6-month mark, but Colonna prefers to check in at the 4- to 6-week mark, even if it’s just via a phone call. Otherwise, “often they’ll stop taking the pill, and then you won’t know about it until you see them at 6 six months.” At that point, she said, a critical period for treatment has passed.

The Role of Nurse Navigators

In another session at the Tampa regional meeting, AVAHO president-elect Cindy Bowman, MSN, RN, OCN, will moderate a session about the role of nurse navigators in VA cancer care. She is the coordinator of the Cancer Care Navigation Program at the C. W. Bill Young VA Medical Center in Bay Pines, Florida.

“Veterans become survivors the day they’re diagnosed with cancer,” she said. Within the VA, cancer-care navigator teams developed over the past decade aim to help patients find their way forward through survivorship, she said, and nurses are crucial to the effort.

As Sharp and Scheid reported in a 2018 Journal Oncology Navigation Survivorship article, “research demonstrates that navigation can improve access to the cancer care system by addressing barriers, as well as facilitating quality care. The benefits of patient navigation for improving cancer patient outcomes is considerable.” McKenney and colleagues found that “patient navigation has been demonstrated to increase access to screening, shorten time to diagnostic resolution, and improve cancer outcomes, particularly in health disparity populations, such as women of color, rural populations, and poor women.”

According to Bowman, “it has become standard practice to have nurse navigators be there each step of the way from a high suspicion of cancer to diagnosis and through the clinical workup into active treatment and survivorship.” Within the VA, she said, “the focus right now is to look at standardizing care that all VAs will be able to offer holistic, comprehensive cancer-care navigation teams.”

At the regional meeting, Bowman’s session will include updates from nurse navigators about helping patients through breast/gynecological cancer, abnormal mammograms, and survivorship.

Nurse navigators are typically the second medical professionals who talk to cancer patients after their physicians, Bowman said. The unique knowledge of oncology nurse navigators gives them invaluable insight into treatment plans and cancer drug regimens, she said.

“They’re able to sit down and discuss the actual cancer drug regimen with patients—what each of those drugs do, how they’re administered, the short-term and long-term side effects,” she said. “They have the knowledge about all aspects of cancer care that can really only come from somebody who’s specialty trained.”

Other sessions at the AVAHO regional meeting will highlight breast cancer and lymphedema, breast cancer and bone health; diet, exercise and cancer; sexual health for breast/gynecological cancer survivors; and imaging surveillance after diagnosis.

As the number of female veterans continues to grow, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is adjusting by focusing more on breast/gynecological cancer and referring fewer cases to outside clinicians.

The VA’s effort reflects the reality that female veterans from the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq are approaching the ages—50s, 60s, and 70s—when cancer diagnoses become more common, said Sarah Colonna, MD, national medical director of breast oncology for VA's Breast and Gynecologic Oncology System of Excellence and an oncologist at the Huntsman Cancer Institute and Wahlen VA Medical Center in Salt Lake City, Utah. “This is preparation for the change that we know is coming.”

In response, the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO) is devoting a regional meeting in Tampa, Florida (July 29, 2023) to improving survivorship for patients with women’s cancers. “This meeting is designed to educate both cancer experts and primary care providers on the care of women who have already gone through breast and gynecological cancer treatment,” Colonna explained.

Adherence Challenges

Colonna will speak in a session about the importance of adherence to endocrine therapy. “When we prescribe endocrine therapy for breast cancer, we usually ask women to stay on it for 5 to 10 years, and sometimes that’s hard for them,” she said. “I’ll talk about tips and tricks to help women stay on endocrine therapy for the long haul because we know that is linked to better survival.”

Between two-thirds and three-quarters of women with breast cancer are advised to stay on endocrine drugs, she said, but the medications can be difficult to tolerate due to adverse effects such as hot flashes and sleep disturbances.

In addition, patients are often anxious about the medications. “Women are very leery of anything that changes or makes their hormones different,” Colonna noted. “They feel like it’s messing with something that is natural for them.”

Colonna urges colleagues to focus on their “soft skills,” the ability to absorb and validate the worries of patients. Instead of dismissing them, she said, focus on messages that acknowledge concerns but are also firm: “That’s real, that sucks. But we’ve got to do it.”

It’s also helpful to guide patients away from thinking that taking a pill every day means they’re sick. “I try to flip that paradigm: ‘You’re taking this pill every day because you have power over this thing that happened to you.’”

Education is also key, she said, so that patients “understand very clearly why this medication is important for them: It increases the chance of surviving breast cancer or it increases the chances that the cancer will never come back in your arm or in your breast. Then, whether they make a decision to take it or not, at least they’re making the choice with knowledge.”

As for adverse effects, Colonna said medications such as antidepressants and painkillers can relieve hot flashes, which can disturb sleep.

Identifying the best strategy to address adverse effects “requires keeping in frequent contact with the patient during the first 6 months of endocrine therapy, which are really critical,” she said. “Once they’ve been on it for a year, they can see the light at the end of the tunnel and hang in there even if they have adverse effects.”

Some guidelines suggest that no doctor visits are needed until the 6-month mark, but Colonna prefers to check in at the 4- to 6-week mark, even if it’s just via a phone call. Otherwise, “often they’ll stop taking the pill, and then you won’t know about it until you see them at 6 six months.” At that point, she said, a critical period for treatment has passed.

The Role of Nurse Navigators

In another session at the Tampa regional meeting, AVAHO president-elect Cindy Bowman, MSN, RN, OCN, will moderate a session about the role of nurse navigators in VA cancer care. She is the coordinator of the Cancer Care Navigation Program at the C. W. Bill Young VA Medical Center in Bay Pines, Florida.

“Veterans become survivors the day they’re diagnosed with cancer,” she said. Within the VA, cancer-care navigator teams developed over the past decade aim to help patients find their way forward through survivorship, she said, and nurses are crucial to the effort.

As Sharp and Scheid reported in a 2018 Journal Oncology Navigation Survivorship article, “research demonstrates that navigation can improve access to the cancer care system by addressing barriers, as well as facilitating quality care. The benefits of patient navigation for improving cancer patient outcomes is considerable.” McKenney and colleagues found that “patient navigation has been demonstrated to increase access to screening, shorten time to diagnostic resolution, and improve cancer outcomes, particularly in health disparity populations, such as women of color, rural populations, and poor women.”

According to Bowman, “it has become standard practice to have nurse navigators be there each step of the way from a high suspicion of cancer to diagnosis and through the clinical workup into active treatment and survivorship.” Within the VA, she said, “the focus right now is to look at standardizing care that all VAs will be able to offer holistic, comprehensive cancer-care navigation teams.”

At the regional meeting, Bowman’s session will include updates from nurse navigators about helping patients through breast/gynecological cancer, abnormal mammograms, and survivorship.

Nurse navigators are typically the second medical professionals who talk to cancer patients after their physicians, Bowman said. The unique knowledge of oncology nurse navigators gives them invaluable insight into treatment plans and cancer drug regimens, she said.

“They’re able to sit down and discuss the actual cancer drug regimen with patients—what each of those drugs do, how they’re administered, the short-term and long-term side effects,” she said. “They have the knowledge about all aspects of cancer care that can really only come from somebody who’s specialty trained.”

Other sessions at the AVAHO regional meeting will highlight breast cancer and lymphedema, breast cancer and bone health; diet, exercise and cancer; sexual health for breast/gynecological cancer survivors; and imaging surveillance after diagnosis.

As the number of female veterans continues to grow, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is adjusting by focusing more on breast/gynecological cancer and referring fewer cases to outside clinicians.

The VA’s effort reflects the reality that female veterans from the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq are approaching the ages—50s, 60s, and 70s—when cancer diagnoses become more common, said Sarah Colonna, MD, national medical director of breast oncology for VA's Breast and Gynecologic Oncology System of Excellence and an oncologist at the Huntsman Cancer Institute and Wahlen VA Medical Center in Salt Lake City, Utah. “This is preparation for the change that we know is coming.”

In response, the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO) is devoting a regional meeting in Tampa, Florida (July 29, 2023) to improving survivorship for patients with women’s cancers. “This meeting is designed to educate both cancer experts and primary care providers on the care of women who have already gone through breast and gynecological cancer treatment,” Colonna explained.

Adherence Challenges

Colonna will speak in a session about the importance of adherence to endocrine therapy. “When we prescribe endocrine therapy for breast cancer, we usually ask women to stay on it for 5 to 10 years, and sometimes that’s hard for them,” she said. “I’ll talk about tips and tricks to help women stay on endocrine therapy for the long haul because we know that is linked to better survival.”

Between two-thirds and three-quarters of women with breast cancer are advised to stay on endocrine drugs, she said, but the medications can be difficult to tolerate due to adverse effects such as hot flashes and sleep disturbances.

In addition, patients are often anxious about the medications. “Women are very leery of anything that changes or makes their hormones different,” Colonna noted. “They feel like it’s messing with something that is natural for them.”

Colonna urges colleagues to focus on their “soft skills,” the ability to absorb and validate the worries of patients. Instead of dismissing them, she said, focus on messages that acknowledge concerns but are also firm: “That’s real, that sucks. But we’ve got to do it.”

It’s also helpful to guide patients away from thinking that taking a pill every day means they’re sick. “I try to flip that paradigm: ‘You’re taking this pill every day because you have power over this thing that happened to you.’”

Education is also key, she said, so that patients “understand very clearly why this medication is important for them: It increases the chance of surviving breast cancer or it increases the chances that the cancer will never come back in your arm or in your breast. Then, whether they make a decision to take it or not, at least they’re making the choice with knowledge.”

As for adverse effects, Colonna said medications such as antidepressants and painkillers can relieve hot flashes, which can disturb sleep.

Identifying the best strategy to address adverse effects “requires keeping in frequent contact with the patient during the first 6 months of endocrine therapy, which are really critical,” she said. “Once they’ve been on it for a year, they can see the light at the end of the tunnel and hang in there even if they have adverse effects.”

Some guidelines suggest that no doctor visits are needed until the 6-month mark, but Colonna prefers to check in at the 4- to 6-week mark, even if it’s just via a phone call. Otherwise, “often they’ll stop taking the pill, and then you won’t know about it until you see them at 6 six months.” At that point, she said, a critical period for treatment has passed.

The Role of Nurse Navigators

In another session at the Tampa regional meeting, AVAHO president-elect Cindy Bowman, MSN, RN, OCN, will moderate a session about the role of nurse navigators in VA cancer care. She is the coordinator of the Cancer Care Navigation Program at the C. W. Bill Young VA Medical Center in Bay Pines, Florida.

“Veterans become survivors the day they’re diagnosed with cancer,” she said. Within the VA, cancer-care navigator teams developed over the past decade aim to help patients find their way forward through survivorship, she said, and nurses are crucial to the effort.

As Sharp and Scheid reported in a 2018 Journal Oncology Navigation Survivorship article, “research demonstrates that navigation can improve access to the cancer care system by addressing barriers, as well as facilitating quality care. The benefits of patient navigation for improving cancer patient outcomes is considerable.” McKenney and colleagues found that “patient navigation has been demonstrated to increase access to screening, shorten time to diagnostic resolution, and improve cancer outcomes, particularly in health disparity populations, such as women of color, rural populations, and poor women.”

According to Bowman, “it has become standard practice to have nurse navigators be there each step of the way from a high suspicion of cancer to diagnosis and through the clinical workup into active treatment and survivorship.” Within the VA, she said, “the focus right now is to look at standardizing care that all VAs will be able to offer holistic, comprehensive cancer-care navigation teams.”

At the regional meeting, Bowman’s session will include updates from nurse navigators about helping patients through breast/gynecological cancer, abnormal mammograms, and survivorship.

Nurse navigators are typically the second medical professionals who talk to cancer patients after their physicians, Bowman said. The unique knowledge of oncology nurse navigators gives them invaluable insight into treatment plans and cancer drug regimens, she said.

“They’re able to sit down and discuss the actual cancer drug regimen with patients—what each of those drugs do, how they’re administered, the short-term and long-term side effects,” she said. “They have the knowledge about all aspects of cancer care that can really only come from somebody who’s specialty trained.”

Other sessions at the AVAHO regional meeting will highlight breast cancer and lymphedema, breast cancer and bone health; diet, exercise and cancer; sexual health for breast/gynecological cancer survivors; and imaging surveillance after diagnosis.

Number of cervical cancer screenings linked to higher preterm birth risk

For each additional recommended screening before childbirth, there was a direct increase in absolute PTD risk of 0.073 (95% confidence interval, 0.026-0.120), according to a study led by Rebecca A. Bromley-Dulfano, MS, an MD candidate at Stanford (Calif.) University and a PhD candidate in health policy at Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

There was no significant change in very preterm delivery (VPTD) risk, but mothers with hypertension or diabetes were at higher PTD risk.

Women in this younger age group are more prone to PTD. According to the study’s estimate, an additional 73 PTDs per 100,000 women could be expected for every 1 additional recommended screening before childbirth. For the year 2018, that translated to an estimated 1,348 PTDs that could have been averted, with reduced screening requirements (3% relative reduction).

“If you screen someone for cervical cancer and find a cervical lesion, the possible next steps can include a biopsy and an excisional procedure to remove the lesion,” Ms. Bromley-Dulfano explained, “and these procedures which remove a small (mostly diseased) part of the cervix have been shown to slightly increase the risk of PTD. Particularly in young individuals with a cervix who are known to have high rates of lesion regression and who have more potential childbearing years ahead of them, it is important to weigh the oncological benefits with the adverse birth outcome risks.”

Young women are more likely to have false-positive results on Papanicolaou tests and lesion regression within 2 years but may undergo unnecessary treatment, the authors noted.

Cervical excision procedures have previously been associated in clinical trials with an increase in PTB risk.

In their 2017 decision model in a fictive cohort, for example, Kamphuis and colleagues found the most intensive screening program was associated with an increase in maternal life years of 9%, a decrease in cervical cancer incidence of 67%, and a decrease in cervical cancer deaths of 75%. But those gains came at the cost of 250% more preterm births, compared with the least intensive program.

“These results can be used in future simulation models integrating oncological trade-offs to help ascertain optimal screening strategies,” the researchers wrote.

While the optimal screening strategy must trade off the oncologic benefits of cancer detection against the neonatal harms of overtreatment, the ideal age of cervical cancer screening onset and frequency remain uncertain, the authors noted. Recent American Cancer Society guidelines recommending less frequent screening for some diverge from those of other societies.

“The first and foremost priority is for gynecologists to continue to have individualized conversations with patients about all of the benefits and risks of procedures that patients undergo and to understand the benefits and risks influencing screening guidelines,” Ms. Bromley-Dulfano said.

Cross-sectional study

The study used data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics to analyze associations between cervical cancer screening guidelines and birth outcomes women who had a singleton nulliparous birth from 19916 to 2018. Gestational age and maternal characteristics were drawn from birth certificates.

The mean age of the 11,333,151 multiracial cohort of women was 20.9 years, and 6.8% had hypertension or diabetes. The mean number of guideline-recommended screenings by time of childbirth was 2.4. Overall, PTD and very PTD occurred in 1,140,490 individuals (10.1%) and 333,040 (2.9%) of births, respectively.

Those with hypertension or diabetes had a somewhat higher PTD risk: 0.26% (95% CI, 0.11-0.4) versus 0.06% (95% CI, 0.01-0.10; Wald test, P < .001).

Offering an outsider’s perspective on the analysis, ob.gyn. Fidel A. Valea, MD, director of gynecologic oncology at the Northwell Health Cancer Institute in New Hyde Park, N.Y., urged caution in drawing conclusions from large population analyses such as this.

“This study had over 11 million data points. Often these large numbers will show statistical differences that are not clinically significant,” he said in an interview. He noted that while small studies have shown a possible impact of frequent Pap tests on cervical function, “this is not 100% proven. Research from Texas showed that screening made a difference only in cases of dysplasia.”

Dr. Valea also noted that screening guidelines have already changed over the lengthy time span of the study and do reflect the concerns of the study authors.

“We know that the HPV virus is cleared more readily by young women than older women and so we have made adjustments and test them less frequently and we test them less early.” He added that conservative options are recommended even in the case of dysplasia.

In defense of the Pap smear test, he added: “It has virtually wiped out cervical cancer in the U.S., bringing it from No. 1 to No. 13.” While broadening HPV vaccination programs may impact guidelines in the future, “vaccination is still in its infancy. We have to wait until women have lived long to enough to see an impact.”

As to why this age group is more vulnerable to PTD, Dr. Valea said, “It’s likely multifactorial, with lifestyle and other factors involved.” Although based on U.S. data, the authors said their results may be useful for other public health entities, particularly in countries where cervical cancer is considerably more prevalent.

This work received no specific funding. The authors and Dr. Valea disclosed no competing interests.

For each additional recommended screening before childbirth, there was a direct increase in absolute PTD risk of 0.073 (95% confidence interval, 0.026-0.120), according to a study led by Rebecca A. Bromley-Dulfano, MS, an MD candidate at Stanford (Calif.) University and a PhD candidate in health policy at Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

There was no significant change in very preterm delivery (VPTD) risk, but mothers with hypertension or diabetes were at higher PTD risk.

Women in this younger age group are more prone to PTD. According to the study’s estimate, an additional 73 PTDs per 100,000 women could be expected for every 1 additional recommended screening before childbirth. For the year 2018, that translated to an estimated 1,348 PTDs that could have been averted, with reduced screening requirements (3% relative reduction).

“If you screen someone for cervical cancer and find a cervical lesion, the possible next steps can include a biopsy and an excisional procedure to remove the lesion,” Ms. Bromley-Dulfano explained, “and these procedures which remove a small (mostly diseased) part of the cervix have been shown to slightly increase the risk of PTD. Particularly in young individuals with a cervix who are known to have high rates of lesion regression and who have more potential childbearing years ahead of them, it is important to weigh the oncological benefits with the adverse birth outcome risks.”

Young women are more likely to have false-positive results on Papanicolaou tests and lesion regression within 2 years but may undergo unnecessary treatment, the authors noted.

Cervical excision procedures have previously been associated in clinical trials with an increase in PTB risk.

In their 2017 decision model in a fictive cohort, for example, Kamphuis and colleagues found the most intensive screening program was associated with an increase in maternal life years of 9%, a decrease in cervical cancer incidence of 67%, and a decrease in cervical cancer deaths of 75%. But those gains came at the cost of 250% more preterm births, compared with the least intensive program.

“These results can be used in future simulation models integrating oncological trade-offs to help ascertain optimal screening strategies,” the researchers wrote.

While the optimal screening strategy must trade off the oncologic benefits of cancer detection against the neonatal harms of overtreatment, the ideal age of cervical cancer screening onset and frequency remain uncertain, the authors noted. Recent American Cancer Society guidelines recommending less frequent screening for some diverge from those of other societies.

“The first and foremost priority is for gynecologists to continue to have individualized conversations with patients about all of the benefits and risks of procedures that patients undergo and to understand the benefits and risks influencing screening guidelines,” Ms. Bromley-Dulfano said.

Cross-sectional study

The study used data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics to analyze associations between cervical cancer screening guidelines and birth outcomes women who had a singleton nulliparous birth from 19916 to 2018. Gestational age and maternal characteristics were drawn from birth certificates.

The mean age of the 11,333,151 multiracial cohort of women was 20.9 years, and 6.8% had hypertension or diabetes. The mean number of guideline-recommended screenings by time of childbirth was 2.4. Overall, PTD and very PTD occurred in 1,140,490 individuals (10.1%) and 333,040 (2.9%) of births, respectively.

Those with hypertension or diabetes had a somewhat higher PTD risk: 0.26% (95% CI, 0.11-0.4) versus 0.06% (95% CI, 0.01-0.10; Wald test, P < .001).

Offering an outsider’s perspective on the analysis, ob.gyn. Fidel A. Valea, MD, director of gynecologic oncology at the Northwell Health Cancer Institute in New Hyde Park, N.Y., urged caution in drawing conclusions from large population analyses such as this.

“This study had over 11 million data points. Often these large numbers will show statistical differences that are not clinically significant,” he said in an interview. He noted that while small studies have shown a possible impact of frequent Pap tests on cervical function, “this is not 100% proven. Research from Texas showed that screening made a difference only in cases of dysplasia.”

Dr. Valea also noted that screening guidelines have already changed over the lengthy time span of the study and do reflect the concerns of the study authors.

“We know that the HPV virus is cleared more readily by young women than older women and so we have made adjustments and test them less frequently and we test them less early.” He added that conservative options are recommended even in the case of dysplasia.

In defense of the Pap smear test, he added: “It has virtually wiped out cervical cancer in the U.S., bringing it from No. 1 to No. 13.” While broadening HPV vaccination programs may impact guidelines in the future, “vaccination is still in its infancy. We have to wait until women have lived long to enough to see an impact.”

As to why this age group is more vulnerable to PTD, Dr. Valea said, “It’s likely multifactorial, with lifestyle and other factors involved.” Although based on U.S. data, the authors said their results may be useful for other public health entities, particularly in countries where cervical cancer is considerably more prevalent.

This work received no specific funding. The authors and Dr. Valea disclosed no competing interests.

For each additional recommended screening before childbirth, there was a direct increase in absolute PTD risk of 0.073 (95% confidence interval, 0.026-0.120), according to a study led by Rebecca A. Bromley-Dulfano, MS, an MD candidate at Stanford (Calif.) University and a PhD candidate in health policy at Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

There was no significant change in very preterm delivery (VPTD) risk, but mothers with hypertension or diabetes were at higher PTD risk.

Women in this younger age group are more prone to PTD. According to the study’s estimate, an additional 73 PTDs per 100,000 women could be expected for every 1 additional recommended screening before childbirth. For the year 2018, that translated to an estimated 1,348 PTDs that could have been averted, with reduced screening requirements (3% relative reduction).

“If you screen someone for cervical cancer and find a cervical lesion, the possible next steps can include a biopsy and an excisional procedure to remove the lesion,” Ms. Bromley-Dulfano explained, “and these procedures which remove a small (mostly diseased) part of the cervix have been shown to slightly increase the risk of PTD. Particularly in young individuals with a cervix who are known to have high rates of lesion regression and who have more potential childbearing years ahead of them, it is important to weigh the oncological benefits with the adverse birth outcome risks.”

Young women are more likely to have false-positive results on Papanicolaou tests and lesion regression within 2 years but may undergo unnecessary treatment, the authors noted.

Cervical excision procedures have previously been associated in clinical trials with an increase in PTB risk.

In their 2017 decision model in a fictive cohort, for example, Kamphuis and colleagues found the most intensive screening program was associated with an increase in maternal life years of 9%, a decrease in cervical cancer incidence of 67%, and a decrease in cervical cancer deaths of 75%. But those gains came at the cost of 250% more preterm births, compared with the least intensive program.

“These results can be used in future simulation models integrating oncological trade-offs to help ascertain optimal screening strategies,” the researchers wrote.

While the optimal screening strategy must trade off the oncologic benefits of cancer detection against the neonatal harms of overtreatment, the ideal age of cervical cancer screening onset and frequency remain uncertain, the authors noted. Recent American Cancer Society guidelines recommending less frequent screening for some diverge from those of other societies.

“The first and foremost priority is for gynecologists to continue to have individualized conversations with patients about all of the benefits and risks of procedures that patients undergo and to understand the benefits and risks influencing screening guidelines,” Ms. Bromley-Dulfano said.

Cross-sectional study

The study used data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics to analyze associations between cervical cancer screening guidelines and birth outcomes women who had a singleton nulliparous birth from 19916 to 2018. Gestational age and maternal characteristics were drawn from birth certificates.

The mean age of the 11,333,151 multiracial cohort of women was 20.9 years, and 6.8% had hypertension or diabetes. The mean number of guideline-recommended screenings by time of childbirth was 2.4. Overall, PTD and very PTD occurred in 1,140,490 individuals (10.1%) and 333,040 (2.9%) of births, respectively.

Those with hypertension or diabetes had a somewhat higher PTD risk: 0.26% (95% CI, 0.11-0.4) versus 0.06% (95% CI, 0.01-0.10; Wald test, P < .001).

Offering an outsider’s perspective on the analysis, ob.gyn. Fidel A. Valea, MD, director of gynecologic oncology at the Northwell Health Cancer Institute in New Hyde Park, N.Y., urged caution in drawing conclusions from large population analyses such as this.

“This study had over 11 million data points. Often these large numbers will show statistical differences that are not clinically significant,” he said in an interview. He noted that while small studies have shown a possible impact of frequent Pap tests on cervical function, “this is not 100% proven. Research from Texas showed that screening made a difference only in cases of dysplasia.”

Dr. Valea also noted that screening guidelines have already changed over the lengthy time span of the study and do reflect the concerns of the study authors.

“We know that the HPV virus is cleared more readily by young women than older women and so we have made adjustments and test them less frequently and we test them less early.” He added that conservative options are recommended even in the case of dysplasia.

In defense of the Pap smear test, he added: “It has virtually wiped out cervical cancer in the U.S., bringing it from No. 1 to No. 13.” While broadening HPV vaccination programs may impact guidelines in the future, “vaccination is still in its infancy. We have to wait until women have lived long to enough to see an impact.”

As to why this age group is more vulnerable to PTD, Dr. Valea said, “It’s likely multifactorial, with lifestyle and other factors involved.” Although based on U.S. data, the authors said their results may be useful for other public health entities, particularly in countries where cervical cancer is considerably more prevalent.

This work received no specific funding. The authors and Dr. Valea disclosed no competing interests.

FROM JAMA HEALTH FORUM

An STI upsurge requires a nimble approach to care

Except for a drop in the number of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) early in the COVID-19 pandemic (March and April 2020), the incidence of STIs has been rising throughout this century.1 In 2018, 1 in 5 people in the United States had an STI; 26 million new cases were reported that year, resulting in direct costs of $16 billion—85% of which was for the care of HIV infection.2 Also that year, infection with Chlamydia trachomatis (chlamydia), Trichomonas vaginalis (trichomoniasis), herpesvirus type 2 (genital herpes), and/or human papillomavirus (condylomata acuminata) constituted 97.6% of all prevalent and 93.1% of all incident STIs.3 Almost half (45.5%) of new cases of STIs occur in people between the ages of 15 and 24 years.3

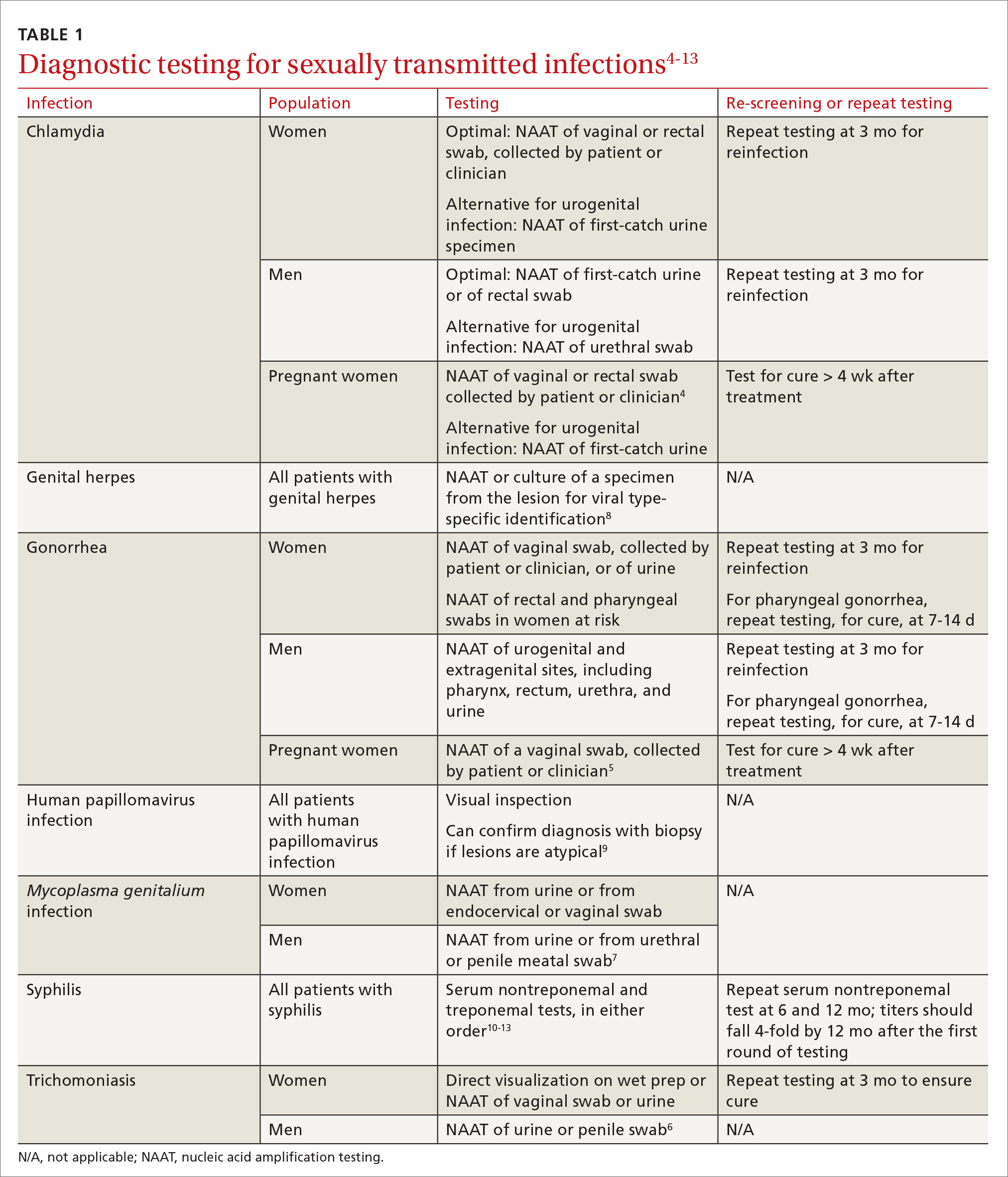

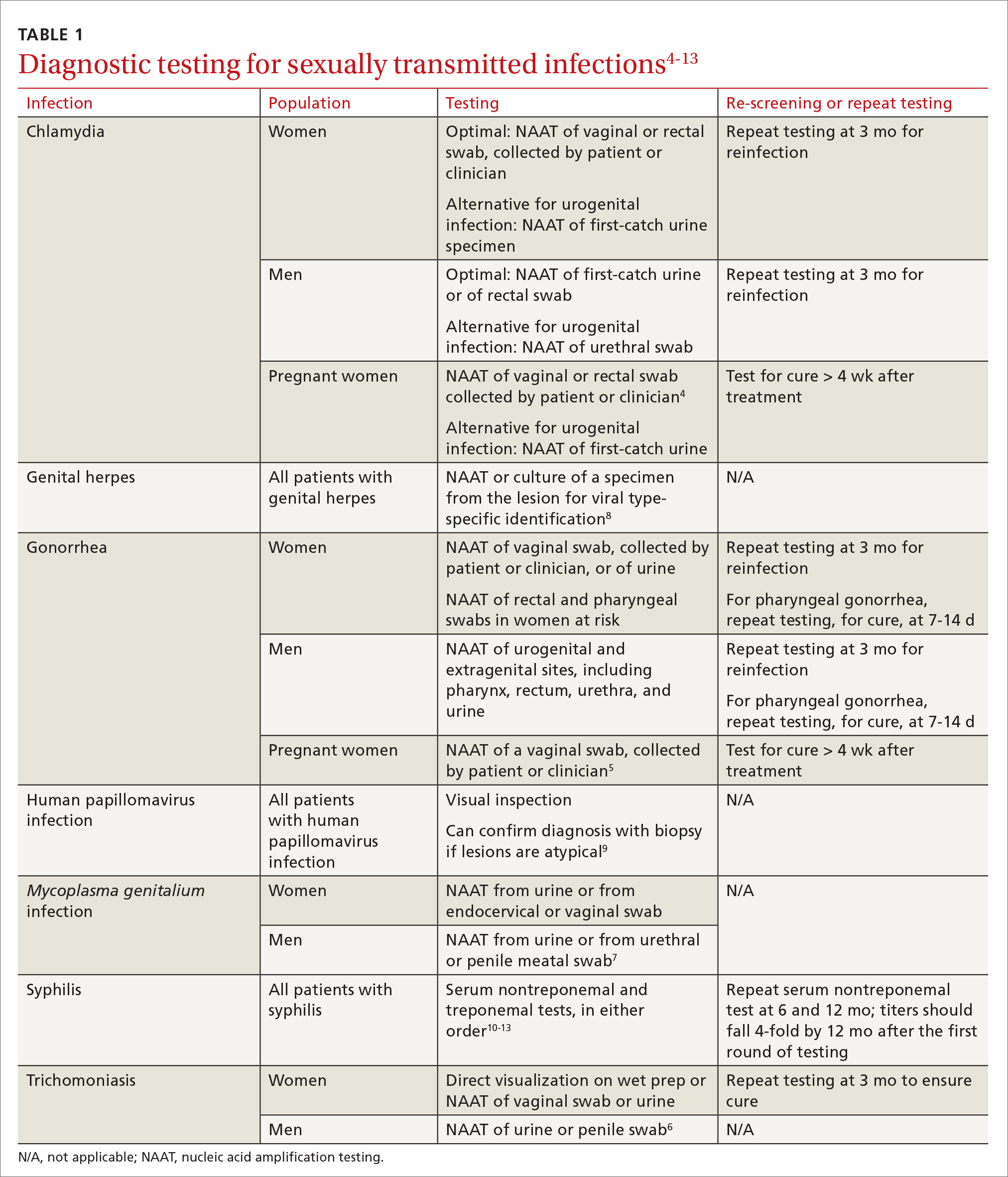

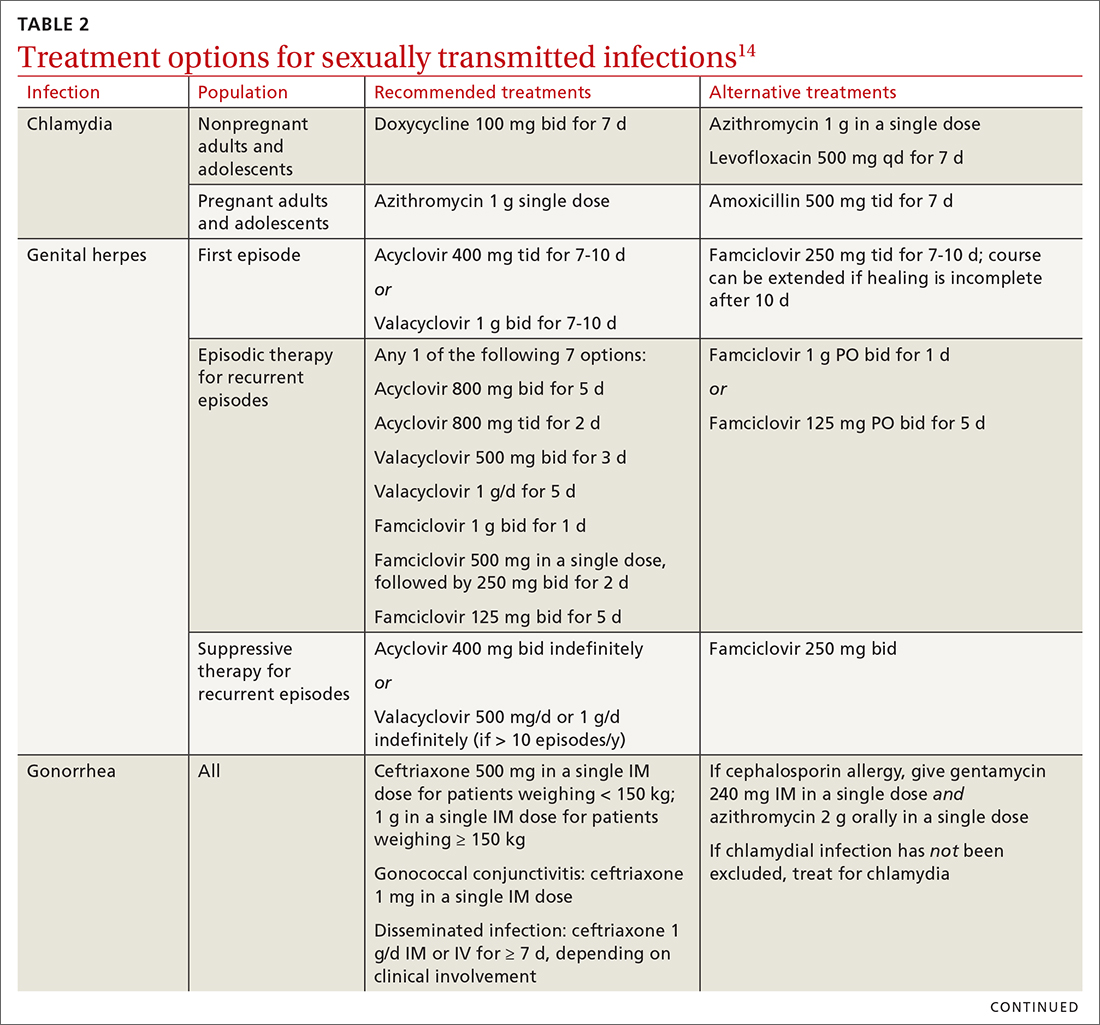

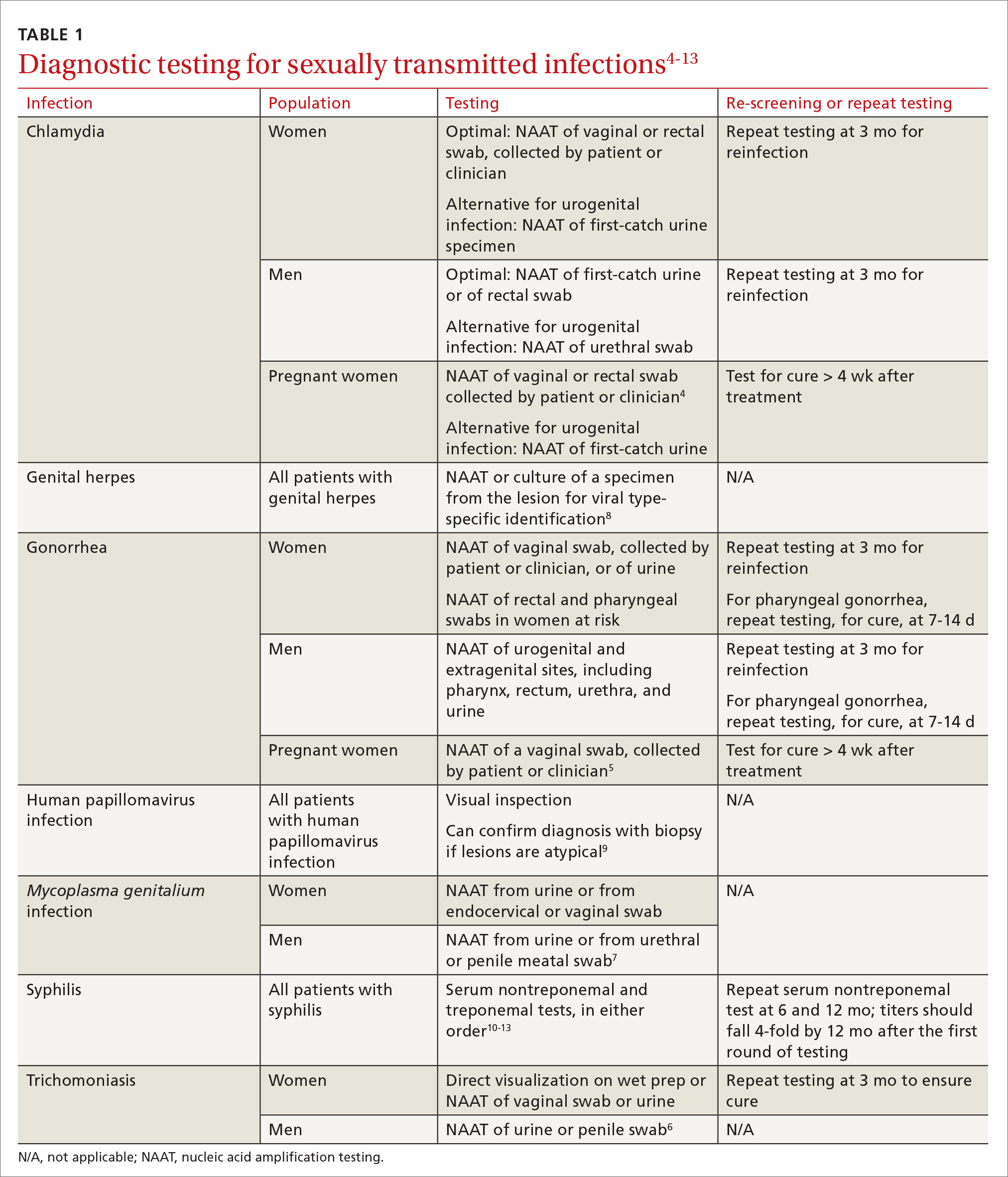

Three factors—changing social patterns, including the increase of social networking; the ability of antiviral therapy to decrease the spread of HIV, leading to a reduction in condom use; and increasing antibiotic resistance—have converged to force changes in screening and treatment recommendations. In this article, we summarize updated guidance for primary care clinicians from several sources—including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP)—on diagnosing STIs (TABLE 14-13) and providing guideline-based treatment (Table 214). Because of the breadth and complexity of HIV disease, it is not addressed here.

Chlamydia

Infection with Chlamydia trachomatis—the most commonly reported bacterial STI in the United States—primarily causes cervicitis in women and proctitis in men, and can cause urethritis and pharyngitis in men and women. Prevalence is highest in sexually active people younger than 24 years.15

Because most infected people are asymptomatic and show no signs of illness on physical exam, screening is recommended for all sexually active women younger than 25 years and all men who have sex with men (MSM).4 No studies have established proper screening intervals; a reasonable approach, therefore, is to repeat screening for patients who have a sexual history that confers a new or persistent risk for infection since their last negative result.

Depending on the location of the infection, symptoms of chlamydia can include vaginal or penile irritation or discharge, dysuria, pelvic or rectal pain, and sore throat. Breakthrough bleeding in a patient who is taking an oral contraceptive should raise suspicion for chlamydia.

Untreated chlamydia can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), tubo-ovarian abscess, tubal factor infertility, ectopic pregnancy, and chronic pelvic pain. Infection can be transmitted vertically (mother to baby) antenatally, which can cause ophthalmia neonatorum and pneumonia in these newborns.

Diagnosis. The diagnosis of chlamydia is made using nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT). Specimens can be collected by the clinician or the patient (self collected) using a vaginal, rectal, or oropharyngeal swab, or a combination of these, and can be obtained from urine or liquid-based cytology material.16

Continue to: Treatment

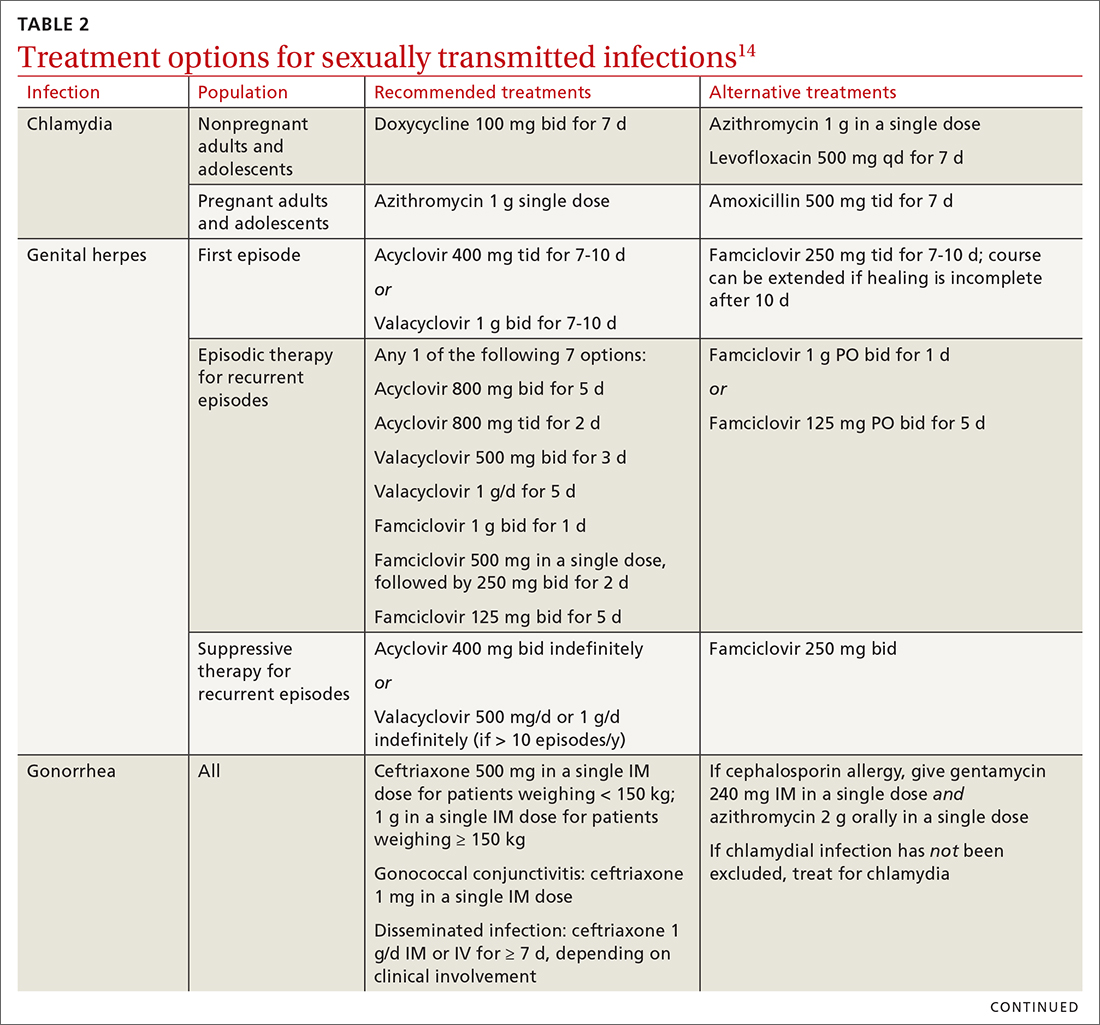

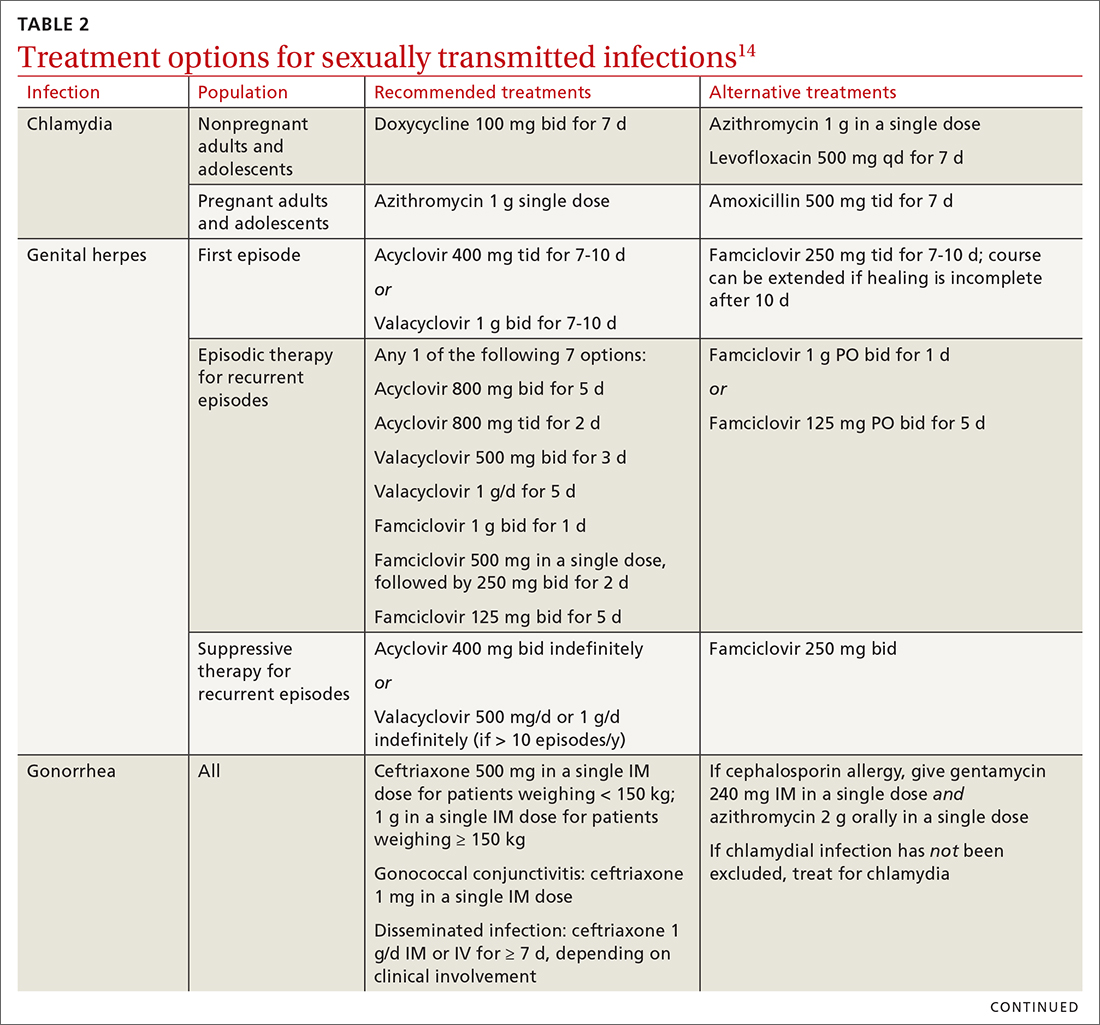

Treatment. Recommendations for treating chlamydia were updated by the CDC in its 2021 treatment guidelines (Table 214). Doxycycline 100 mg bid for 7 days is the preferred regimen; alternative regiments are (1) azithromycin 1 g in a single dose and (2) levofloxacin 500 mg daily for 7 days.4 A meta-analysis17 and a Cochrane review18 showed that the rate of treatment failure was higher among men when they were treated with azithromycin instead of doxycycline; furthermore, a randomized controlled trial demonstrated that doxycycline is more effective than azithromycin (cure rate, 100%, compared to 74%) at treating rectal chlamydia in MSM.19

Azithromycin is efficacious for urogenital infection in women; however, there is concern that the 33% to 83% of women who have concomitant rectal infection (despite reporting no receptive anorectal sexual activity) would be insufficiently treated. Outside pregnancy, the CDC does not recommend a test of cure but does recommend follow-up testing for reinfection in 3 months. Patients should abstain from sexual activity until 7 days after all sexual partners have been treated.

Expedited partner therapy (EPT) is the practice of treating sexual partners of patients with known chlamydia (and patients with gonococcal infection). Unless prohibited by law in your state, offer EPT to patients with chlamydia if they cannot ensure that their sexual partners from the past 60 days will seek timely treatment.a

Evidence to support EPT comes from 3 US clinical trials, whose subjects comprised heterosexual men and women with chlamydia or gonorrhea.21-23 The role of EPT for MSM is unclear; data are limited. Shared decision-making is recommended to determine whether EPT should be provided, to ensure that co-infection with other bacterial STIs (eg, syphilis) or HIV is not missed.24-26

a Visit www.cdc.gov/std/ept to read updated information about laws and regulations regarding EPT in your state.20

Gonorrhea

Gonorrhea is the second most-reported bacterial communicable disease.5 Infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae causes urethral discharge in men, leading them to seek treatment; infected women, however, are often asymptomatic. Infected men and women might not recognize symptoms until they have transmitted the disease. Women have a slower natural clearance of gonococcal infection, which might explain their higher prevalence.27 Delayed recognition of symptoms can result in complications, including PID.5

Diagnosis. Specimens for NAAT can be obtained from urine, endocervical, vaginal, rectal, pharyngeal, and male urethral specimens. Reported sexual behaviors and exposures of women and transgender or gender-diverse people should be taken into consideration to determine whether rectal or pharyngeal testing, or both, should be performed.28 MSM should be screened annually at sites of contact, including the urethra, rectum, and pharynx.28 All patients with urogenital or rectal gonorrhea should be asked about oral sexual exposure; if reported, pharyngeal testing should be performed.5

NAAT of urine is at least as sensitive as testing of an endocervical specimen; the same specimen can be used to test for chlamydia and gonorrhea. Patient-collected specimens are a reasonable alternative to clinician-collected swab specimens.29

Continue to: Treatment

Treatment is complicated by the ability of gonorrhea to develop resistance. Intramuscular ceftriaxone 500 mg in a single dose cures 98% to 99% of infections in the United States; however, monitoring local resistance patterns in the community is an important component of treatment.28 (See Table 214 for an alternative regimen for cephalosporin-allergic patients and for treating gonococcal conjunctivitis and disseminated infection.)

In 2007, the CDC identified widespread quinolone-resistant gonococcal strains; therefore, fluoroquinolones no longer are recommended for treating gonorrhea.30 Cefixime has demonstrated only limited success in treating pharyngeal gonorrhea and does not attain a bactericidal level as high as ceftriaxone does; cefixime therefore is recommended only if ceftriaxone is unavailable.28 The national Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project is finding emerging evidence of the reduced susceptibility of N gonorrhoeae to azithromycin—making dual therapy for gonococcal infection no longer a recommendation.28

Patients should abstain from sex until 7 days after all sex partners have been treated for gonorrhea. As with chlamydia, the CDC does not recommend a test of cure for uncomplicated urogenital or rectal gonorrhea unless the patient is pregnant, but does recommend testing for reinfection 3 months after treatment.14 For patients with pharyngeal gonorrhea, a test of cure is recommended 7 to 14 days after initial treatment, due to challenges in treatment and because this site of infection is a potential source of antibiotic resistance.28

Trichomoniasis

T vaginalis, the most common nonviral STI worldwide,31 can manifest as a yellow-green vaginal discharge with or without vaginal discomfort, dysuria, epididymitis, and prostatitis; most cases, however, are asymptomatic. On examination, the cervix might be erythematous with punctate lesions (known as strawberry cervix).

Unlike most STIs, trichomoniasis is as common in women older than 24 years as it is in younger women. Infection is associated with a lower educational level, lower socioeconomic status, and having ≥ 2 sexual partners in the past year.32 Prevalence is approximately 10 times as high in Black women as it is in White women.

T vaginalis infection is associated with an increase in the risk for preterm birth, premature rupture of membranes, cervical cancer, and HIV infection. With a lack of high-quality clinical trials on the efficacy of screening, women with HIV are the only group for whom routine screening is recommended.6

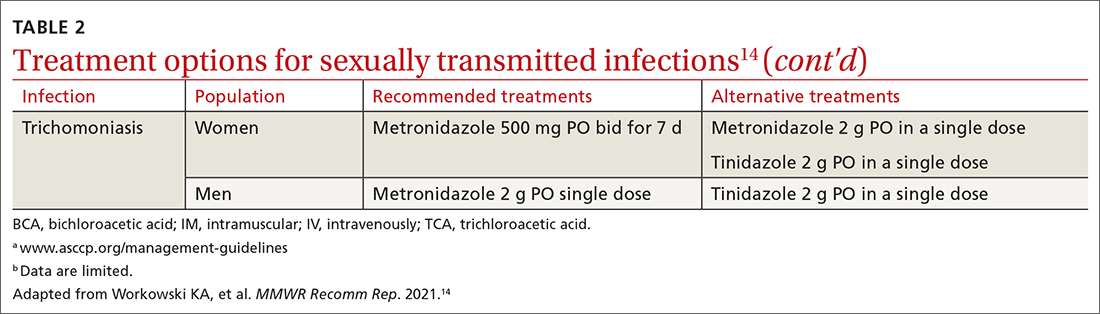

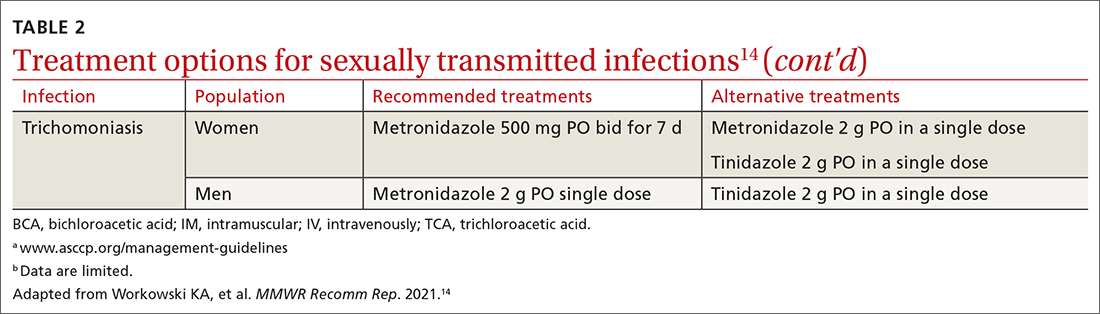

Diagnosis. NAAT for trichomoniasis is now available in conjunction with gonorrhea and chlamydia testing of specimens on vaginal or urethral swabs and of urine specimens and liquid Pap smears.

Continue to: Treatment

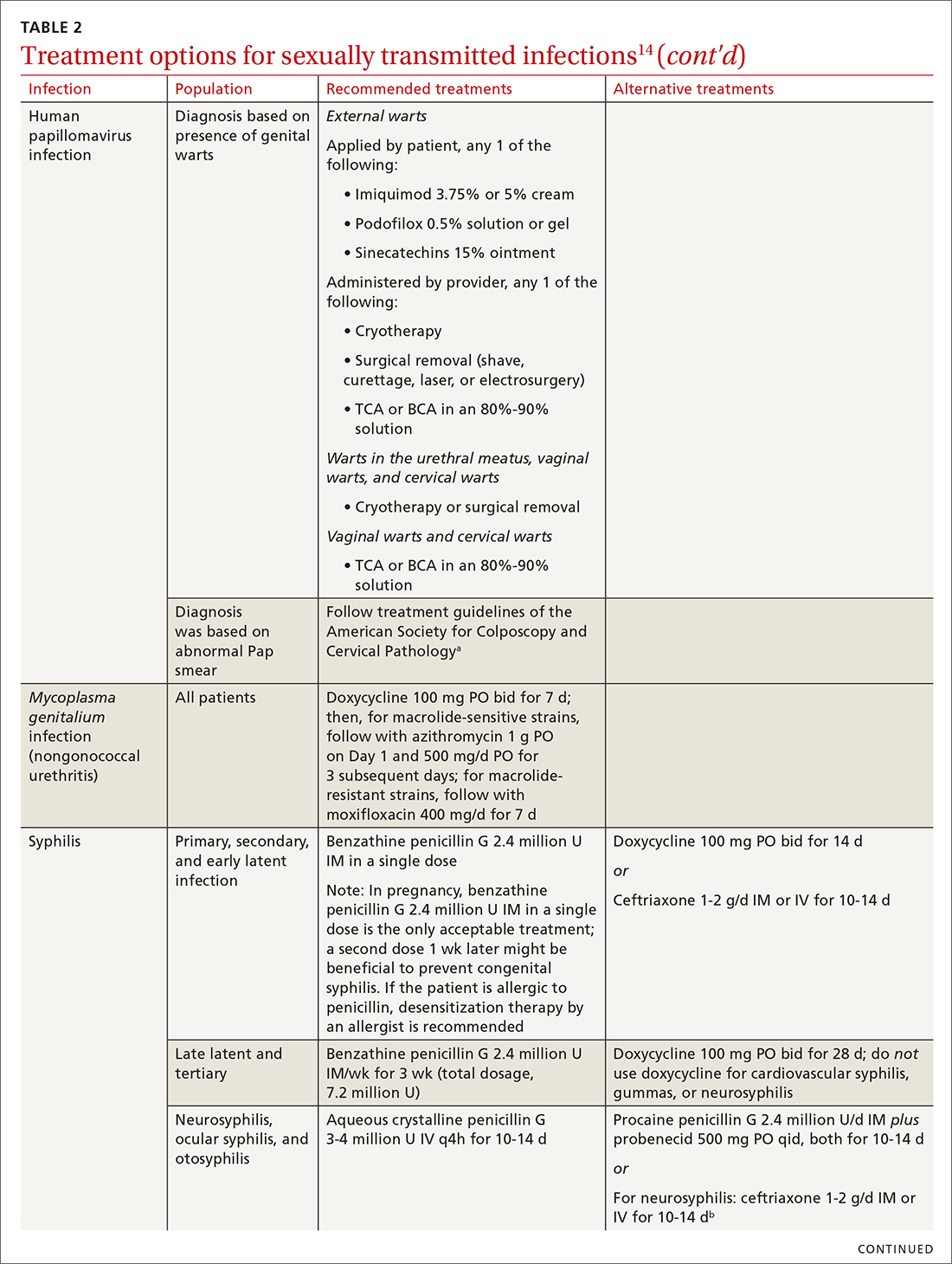

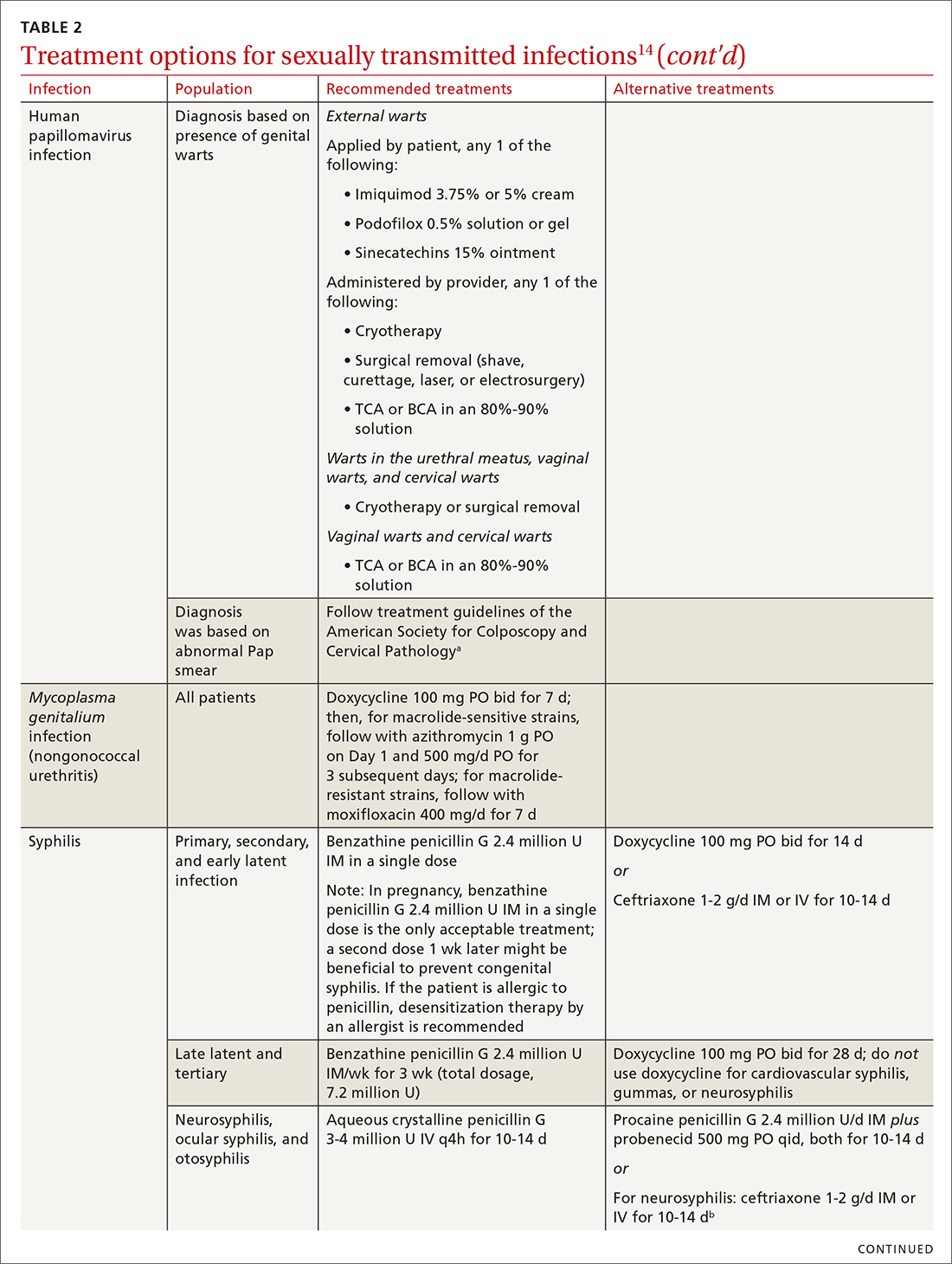

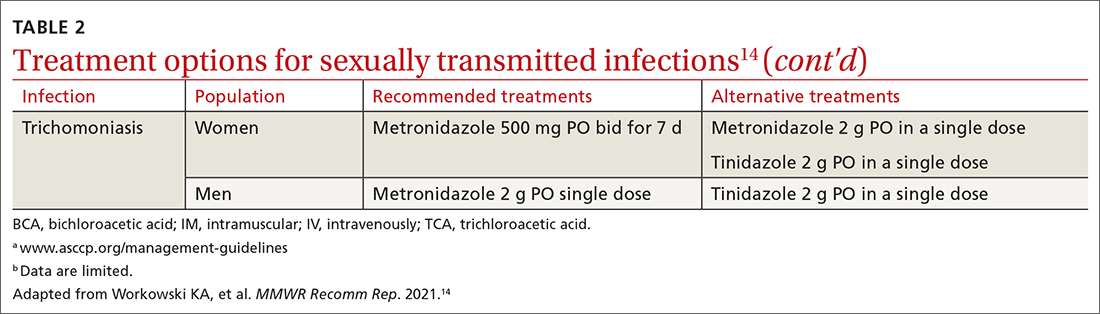

Treatment. Because of greater efficacy, the treatment recommendation for women has changed from a single 2-g dose of oral metronidazole to 500 mg twice daily for 7 days. The 2-g single oral dose is still recommended for men7 (Table 214 lists alternative regimens).

Mycoplasma genitalium

Infection with M genitalium is common and often asymptomatic. The disease causes approximately 20% of all cases of nongonococcal and nonchlamydial urethritis in men and about 40% of persistent or recurrent infections. M genitalium is present in approximately 20% of women with cervicitis and has been associated with PID, preterm delivery, spontaneous abortion, and infertility.

There are limited and conflicting data regarding outcomes in infected patients other than those with persistent or recurrent infection; furthermore, resistance to azithromycin is increasing rapidly, resulting in an increase in treatment failures. Screening therefore is not recommended, and testing is recommended only in men with nongonococcal urethritis.33,34

Diagnosis. NAAT can be performed on urine or on a urethral, penile meatal, endocervical, or vaginal swab; men with recurrent urethritis or women with recurrent cervicitis should be tested. NAAT also can be considered in women with PID. Testing the specimen for the microorganism’s resistance to macrolide antibiotics is recommended (if such testing is available).

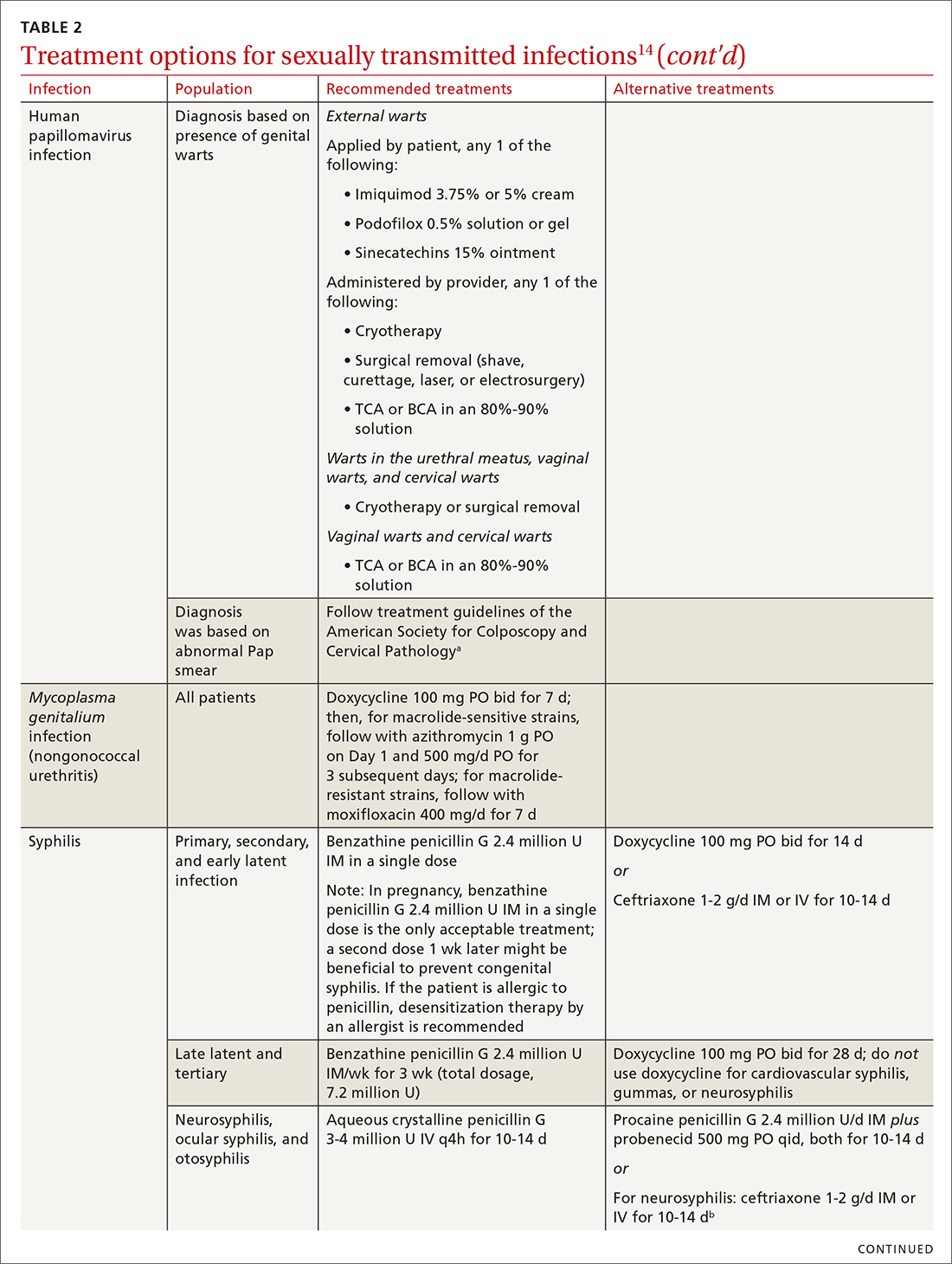

Treatment is initiated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 7 days. If the organism is macrolide sensitive, follow with azithromycin 1 g orally on Day 1, then 500 mg/d for 3 more days. If the organism is macrolide resistant or testing is unavailable, follow doxycycline with oral moxifloxacin 400 mg/d for 7 days.33

Genital herpes (mostly herpesvirus type 2)

Genital herpes, characterized by painful, recurrent outbreaks of genital and anal lesions,35 is a lifelong infection that increases in prevalence with age.8 Because many infected people have disease that is undiagnosed or mild or have unrecognizable symptoms during viral shedding, most genital herpes infections are transmitted by people who are unaware that they are contagious.36 Herpesvirus type 2 (HSV-2) causes most cases of genital herpes, although an increasing percentage of cases are attributed to HSV type 1 (HSV-1) through receptive oral sex from a person who has an oral HSV-1 lesion.

Importantly, HSV-2–infected people are 2 to 3 times more likely to become infected with HIV than people who are not HSV-2 infected.37 This is because CD4+ T cells concentrate at the site of HSV lesions and express a higher level of cell-surface receptors that HIV uses to enter cells. HIV replicates 3 to 5 times more quickly in HSV-infected tissue.38

Continue to: HSV can become disseminated...

HSV can become disseminated, particularly in immunosuppressed people, and can manifest as encephalitis, hepatitis, and pneumonitis. Beyond its significant burden on health, HSV carries significant psychosocial consequences.9

Diagnosis. Clinical diagnosis can be challenging if classic lesions are absent at evaluation. If genital lesions are present, HSV can be identified by NAAT or culture of a specimen of those lesions. False-negative antibody results might be more frequent in early stages of infection; repeating antibody testing 12 weeks after presumed time of acquisition might therefore be indicated, based on clinical judgment. HSV-2 antibody positivity implies anogenital infection because almost all HSV-2 infections are sexually acquired.

HSV-1 antibody positivity alone is more difficult to interpret because this finding does not distinguish between oral and genital lesions, and most HSV-1 seropositivity is acquired during childhood.36 HSV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of blood should not be performed to diagnose genital herpes infection, except in settings in which there is concern about disseminated infection.

Treatment. Management should address the acute episode and the chronic nature of genital herpes. Antivirals will not eradicate latent

- attenuate current infection

- prevent recurrence

- improve quality of life

- suppress the virus to prevent transmission to sexual partners.

All patients experiencing an initial episode of genital herpes should be treated, regardless of symptoms, due to the potential for prolonged or severe symptoms during recurrent episodes.9 Three drugs—acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir—are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat genital herpes and appear equally effective (TABLE 214).

Antiviral therapy for recurrent genital HSV infection can be administered either as suppressive therapy to reduce the frequency of recurrences or episodically to shorten the duration of lesions:

- Suppressive therapy reduces the frequency of recurrence by 70% to 80% among patients with frequent outbreaks. Long-term safety and efficacy are well established.

- Episodic therapy is most effective if started within 1 day after onset of lesions or during the prodrome.36

There is no specific recommendation for when to choose suppressive over episodic therapy; most patients prefer suppressive therapy because it improves quality of life. Use shared clinical decision-making to determine the best option for an individual patient.

Continue to: Human papillomavirus

Human papillomavirus

Condylomata acuminata (genital warts) are caused by human papillomavirus (HPV), most commonly types 6 and 11, which manifest as soft papules or plaques on the external genitalia, perineum, perianal skin, and groin. The warts are usually asymptomatic but can be painful or pruritic, depending on size and location.

Diagnosis is made by visual inspection and can be confirmed by biopsy if lesions are atypical. Lesions can resolve spontaneously, remain unchanged, or grow in size or number.

Treatment. The aim of treatment is relief of symptoms and removal of warts. Treatment does not eradicate HPV infection. Multiple treatments are available that can be applied by the patient as a cream, gel, or ointment or administered by the provider, including cryotherapy, surgical removal, and solutions. The decision on how to treat should be based on the number, size, and

HPV-associated cancers and precancers. This is a broad (and separate) topic. HPV types 16 and 18 cause most cases of cervical, penile, vulvar, vaginal, anal, and oropharyngeal cancer and precancer.39 The USPSTF, the American Cancer Society, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists all have recommendations for cervical cancer screening in the United States.40 Refer to guidelines of the ASCCP for recommendations on abnormal screening tests.41

Prevention of genital warts. The 9-valent HPV vaccine available in the United States is safe and effective and helps protect against viral types 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58. Types 6 and 11 are the principal causes of genital warts. Types 16 and 18 cause 66% of cervical cancer. The vaccination series can be started at age 9 years and is recommended for everyone through age 26 years. Only 2 doses are needed if the first dose is given prior to age 15 years; given after that age, a 3-dose series is utilized. Refer to CDC vaccine guidelines42 for details on the exact timing of vaccination.

Vaccination for women ages 27 to 45 years is not universally recommended because most people have been exposed to HPV by that age. However, the vaccine can still be administered, depending on clinical circumstances and the risk for new infection.42

Syphilis

Caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum, syphilis manifests across a spectrum—from congenital to tertiary. The inability of medical science to develop a method for culturing the spirochete has confounded diagnosis and treatment.

Continue to: Since reaching a historic...

Since reaching a historic nadir of incidence in 2000 (5979 cases in the United States), there has been an increasingly rapid rise in that number: to 130,000 in 2020. More than 50% of cases are in MSM; however, the number of cases in heterosexual women is rapidly increasing.43

Routine screening for syphilis should be performed in any person who is at risk: all pregnant women in the first trimester (and in the third trimester and at delivery if they are at risk or live in a community where prevalence is high) and annually in sexually active MSM or anyone with HIV infection.10

Diagnosis. Examination by dark-field microscopy, testing by PCR, and direct fluorescent antibody assay for T pallidum from lesion tissue or exudate provide definitive diagnosis for early and congenital syphilis, but are often unavailable.

Presumptive diagnosis requires 2 serologic tests:

- Nontreponemal tests (the VDRL and rapid plasma reagin tests) identify anticardiolipin antibodies released during syphilis infection, although results also can be elevated in autoimmune disease or after certain immunizations, including the COVID-19 vaccine.

- Treponemal tests (the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorbed assay, T pallidum particulate agglutination assay, enzyme immunoassay, and chemiluminescence immunoassay) are specific antibody tests.

Historically, reactive nontreponemal tests, which are less expensive and easier to perform, were followed by a treponemal test to confirm the presumptive diagnosis. This method continues to be reasonable when screening patients in a low-prevalence population.11 The reverse sequence screening algorithm (ie, begin with a treponemal test) is now frequently used. With this method, a positive treponemal test must be confirmed with a nontreponemal test. If the treponemal test is positive and the nontreponemal test is negative, another treponemal test must be positive to confirm the diagnosis. This algorithm is useful in high-risk populations because it provides earlier detection of recently acquired syphilis and enhanced detection of late latent syphilis.12,13,44 The CDC has not stated a diagnostic preference.

Once the diagnosis is made, a complete history (including a sexual history and a history of syphilis testing and treatment) and a physical exam are necessary to confirm stage of disease.45

Special circumstances. Neurosyphilis, ocular syphilis, and otosyphilis refer to the site of infection and can occur at any stage of disease. The nervous system usually is infected within hours of initial infection, but symptoms might take weeks or years to develop—or might never manifest. Any time a patient develops neurologic, ophthalmologic, or audiologic symptoms, careful neurologic and ophthalmologic evaluation should be performed and the patient should be tested for HIV.

Continue to: Lumbar puncture is warranted...

Lumbar puncture is warranted for evaluation of cerebrospinal fluid if neurologic symptoms are present but is not necessary for isolated ocular syphilis or otosyphilis without neurologic findings. Treatment should not be delayed for test results if ocular syphilis is suspected because permanent blindness can develop. Any patient at high risk for an STI who presents with neurologic or ophthalmologic symptoms should be tested for syphilis and HIV.45

Pregnant women who have a diagnosis of syphilis should be treated with penicillin immediately because treatment ≥ 30 days prior to delivery is likely to prevent most cases of congenital syphilis. However, a course of penicillin might not prevent stillbirth or congenital syphilis in a gravely infected fetus, evidenced by fetal syphilis on a sonogram at the time of treatment. Additional doses of penicillin in pregnant women with early syphilis might be indicated if there is evidence of fetal syphilis on ultrasonography. All women who deliver a stillborn infant (≥ 20 weeks’ gestation) should be tested for syphilis at delivery.46

All patients in whom primary or secondary syphilis has been diagnosed should be tested for HIV at the time of diagnosis and treatment; if the result is negative, they should be offered preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP; discussed shortly). If the incidence of HIV in your community is high, repeat testing for HIV in 3 months. Clinical and serologic evaluation should be performed 6 and 12 months after treatment.47