User login

Integrating Massage Therapy Into the Health Care of Female Veterans

There are approximately 2 million female veterans in the United States, representing about 10% of the veteran population.1 In 2015, 456,000 female veterans used the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care services. The VA predicts an increase in utilization over the next 20 years.2

Female veterans are more likely to have musculoskeletal disorder multimorbidity compared with male veterans and have higher rates of depressive and bipolar disorders, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).3,4 Compared with male veterans, female veterans are younger, more likely to be unmarried and to have served during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.3 Fifty-five percent of women veterans vs 41% of men veterans have a service-connected disability, and a greater percentage of women veterans have a service connection rating > 50%.5 The top service-connected disabilities for women veterans are PTSD, major depressive disorder, migraines, and lumbosacral or cervical strain.2 In addition, one-third of women veterans using VA health care report experiencing military sexual trauma (MST).6 Military service may impact the health of female veterans both physically and mentally. Providing treatments and programs to improve their health and their health care experience are current VA priorities.

The VA is changing the way health care is conceptualized and delivered by implementing a holistic model of care known as Whole Health, which seeks to empower and equip patients to take charge of their health, blending conventional medicine with self-care and complementary and integrative health (CIH) approaches, such as massage therapy, yoga, acupuncture, and meditation.7 CIH therapies can help improve physical and mental health with little to no adverse effects.8-10

As part of the Whole Health initiative at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System (VAAAHS) in Michigan, the massage program was expanded in 2017 to offer relaxation massages to female veterans attending the women’s health clinic, which provides gynecologic care. Patients visiting a gynecology clinic often experience anxiety and pain related to invasive procedures and examinations. This is especially true for female veterans who experienced MST.11

VAAAHS has 1 staff massage therapist (MT). To expand the program to the women’s health clinic, volunteer licensed MTs were recruited and trained in specific procedures by the staff MT.

Several studies have demonstrated the effect of therapeutic massage on pain and anxiety in predominantly male veteran study populations, including veterans needing postsurgical and palliative care as well as those experiencing chronic pain and knee osteoarthritis.12-16 Little is known about the effects of massage therapy on female veterans. The purpose of this pilot study was to examine the effects of massage therapy among female veterans participating in the women’s health massage program.

Methods

The setting for this pre-post intervention study was VAAAHS. Veterans were called in advance by clinic staff and scheduled for 60-minute appointments either before or after their clinic appointment, depending on availability. MTs were instructed to provide relaxation massage using Swedish massage techniques with moderate pressure, avoiding deep pressure techniques.

The volunteer MTs gave the participants a survey to provide comments and to rate baseline pain and other symptoms prior to and following the massage. The MT left the room to provide privacy while completing the survey. The staff included the symptom data in the massage note as clinical outcomes and entered them into the electronic health record. Massages were given from October 1, 2017 to June 30, 2018. Data including symptom scores, demographics, the presence of chronic pain, mental health diagnoses, patient comments, and opioid use were abstracted from the electronic health record by 2 members of the study team and entered into an Excel database. This study was approved by the VAAAHS Institutional Review Board.

Study Measures

Pain intensity, pain unpleasantness (the affective component of pain), anxiety, shortness of breath, relaxation, and inner peace were rated pre- and postmassage on a 0 to 10 scale. Shortness of breath was included due to the relationship between breathing and anxiety. Inner peace was assessed to measure the calming effects of massage therapy. Beck and colleagues found the concept of inner peace was an important outcome of massage therapy.17 The scale anchors for pain intensity were “no pain” and “severe pain”; and “not at all unpleasant” and “as unpleasant as it can be” for pain unpleasantness. For anxiety, the anchors were “no anxiety” and “as anxious as I can be.” Anchors for relaxation and inner peace were reversed so that a 0 indicated low relaxation and inner peace while a 10 indicated the highest state of relaxation and inner peace.

Chronic pain was defined as pain existing for > 3 months. A history of chronic pain was determined from a review and synthesis of primary care and specialty care recorded diagnoses, patient concerns, and service-connected disabilities. The diagnoses included lumbosacral or cervical strain, chronic low back, joint (knee, shoulder, hip, ankle), neck, or pelvic pain, fibromyalgia, headache, migraine, osteoarthritis, and myofascial pain syndrome. The presence of mental health conditions, including depression, anxiety, bipolar disorders, and PTSD, were similarly determined by a review of mental health clinical notes. Sex was determined from the gynecology note.

Statistical Analysis

Means and medians were calculated for short-term changes in symptom scores. Due to skewness in the short-term changes, significance was tested using a nonparametric sign test. Significance was adjusted using the Bonferroni correction to protect the overall type I error level at 5% from multiple testing. We also assessed for differences in symptom changes in 4 subgroups, using an unadjusted general linear model: those with (1) chronic pain vs without; (2) an anxiety diagnosis vs without; (3) depression vs without; and (4) a PTSD diagnosis vs without. Data were analyzed using SPSS 25 and SAS 9.4.

Results

Results are based on the first massage received by 96 unique individuals (Table 1). Fifty-one (53%) patients were aged 21 to 40 years, and 45 (47%) were aged ≥ 41 years. Most participants (80%) had had a previous massage. Seven (7%) participants were currently on prescription opioids; 76 (79%) participants had a history of one or more chronic pain diagnoses (eg, back pain, migraine headaches, fibromyalgia) and 78 (81%) had a history of a mental health diagnosis (eg, depression, anxiety, PTSD). Massage sessions ranged from 30 to 60 minutes; most patients received massage therapy for 50 minutes.

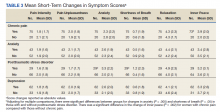

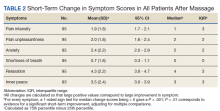

Prior to massage, mean scores were 3.9 pain intensity, 3.7 pain unpleasantness, 3.8 anxiety, 1.0 shortness of breath, 4.0 relaxation, and 4.2 inner peace. Short-term changes in symptom scores are shown in Table 2. The mean score for pain intensity decreased by 1.9 points, pain unpleasantness by 2.0 points, anxiety by 2.4 points. The greatest change occurred for relaxation, which increased by 4.3 points. All changes in symptoms were statistically significant (P < .001). For subgroup comparisons

Verbal feedback and written comments about the massage experience were all favorable: No adverse events were reported.

Discussion

Massage therapy may be a useful treatment for female veterans experiencing chronic pain, anxiety disorders, depression, or situational anxiety related to gynecologic procedures. After receiving a relaxation massage, female veterans reported decreased pain intensity, pain unpleasantness, and anxiety while reporting increased relaxation and feelings of inner peace. The effects of massage were consistent for all the symptoms or characteristics assessed, suggesting that massage may act on the body in multiple ways.

These changes parallel those seen in a palliative care population primarily composed of male veterans.14 However, the female veterans in this cohort experienced greater changes in relaxation and feelings of inner peace, which may be partly due to relief of tension related to an upcoming stressful appointment. The large mean decrease in anxiety level among female veterans with PTSD is notable as well as the larger increase in inner peace in those with chronic pain.

Many patients expressed their gratitude for the massage and interest in having access to more massage therapy. Female patients who have experienced sexual trauma or other trauma may especially benefit from massage prior to painful, invasive gynecologic procedures. Anecdotally, 2 nurse chaperones in the clinic mentioned separately to the massage program supervisor that the massages helped some very anxious women better tolerate an invasive procedure that would have been otherwise extremely difficult.

Female veterans are more likely to have musculoskeletal issues after deployment and have higher rates of anxiety, PTSD, and depression compared with those of male veterans.3,4,18,19 Determining relationships between and causes of chronic pain, depression, and PTSD is very challenging but the increased prevalence of chronic pain and comorbid mental health conditions in female veterans may be partially related to MST or other trauma experiences.20-22 Female veterans are most likely to have more than one source of chronic pain.23-25 Female patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain report more pain-related disability.26 Furthermore, greater disability in the context of depression is reported by women with pain compared with those of men.27 Most (78%) female veterans in a primary care population reported chronic pain.23 Similarly, 79% of the female veterans in this study population had chronic pain and 81% had a history of mental health disorders, including depression, anxiety, and PTSD.

Studies have shown that massage therapy improves pain in populations experiencing chronic low back, neck, and knee pain.28-32 A 2020 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality review determined there is some evidence that massage therapy is helpful for chronic low back and neck pain and fibromyalgia.33 Research also has demonstrated that massage reduces anxiety and depression in several different population types.13,34,35 Li and colleagues showed that foot massage increased oxytocin levels in healthy males.36 Although further research is needed to determine the mechanisms of massage therapy, there are important physiologic effects. Unlike most medications, massage therapy is unique in that it can impact health and well-being through multiple mechanisms; for example, by reducing pain, improving mood, providing a sense of social connection and/or improving mobility.

Patients using CIH therapies report greater awareness of the need for ongoing engagement in their own care and health behavior changes.37,38

Driscoll and colleagues reported that women veterans are interested in conservative treatment for their chronic musculoskeletal pain and are open to using CIH therapies.39 Research suggests that veterans are interested in and, in some cases, already using massage therapy.23,40-43 Access to massage therapy and other CIH therapies offers patients choice and control over the types and timing of therapy they receive, exemplified by the 80% of patients in our study who previously received a massage and sought another before a potentially stressful situation.

Access to massage therapy or other CIH therapies may reduce the need for more expensive procedures. Although research on the cost-effectiveness of massage therapy is limited, Herman and colleagues did an economic evaluation of CIH therapies in a veteran population, finding that CIH users had lower annual health care costs and lower pain in the year after CIH started. Sensitivity analyses indicated similar results for acupuncture, chiropractic care, and massage but higher costs for those with 8 or more visits.44

The prevalence of comorbid mental health conditions with MSD suggests that female veterans may benefit from multidisciplinary treatment of pain and depression.3,26 Women-centered programs would be both encouraging and validating to women.39 Massage therapy can be combined with physical therapy, yoga, tai chi, and meditation programs to improve pain, anxiety, strength, and flexibility and can be incorporated into a multimodal treatment plan. Likewise, other subpopulations of female veterans with chronic pain, mental health conditions, or cancer could be targeted with multidisciplinary programs that include massage therapy.

Limitations

This study has several limitations including lack of a control group, a self-selected population, the lack of objective biochemical measurements, and possible respondent bias to please the MTs. Eighty percent had previously experienced massage therapy and may have been biased toward the effects of massage before receiving the intervention. The first report of the effects of massage therapy in an exclusively female veteran population is a major strength of this study.

Further research including randomized controlled trials is needed, especially in populations with coexisting chronic pain and mental health disorders, as is exploring the acceptability of massage therapy for female veterans with MST. Finding viable alternatives to medications has become even more important as the nation addresses the challenge of the opioid crisis.45,46

Conclusions

Female veterans are increasingly seeking VA health care.

Acknowledgments

The authors express our gratitude to the Women Veteran Program Manager, Cheryl Allen, RN; Massage Therapists Denise McGee and Kimberly Morro; Dara Ganoczy, MPH, for help with statistical analysis; and Mark Hausman, MD, for leadership support.

1. US Department of Veteran Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Veteran population. Updated April 14, 2021. Accessed January 6, 2022. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/veteran_population.asp

2. US Department of Veteran Affairs. Women veterans report: the past, present, and future of women veterans. Published February 2017. Accessed January 6, 2022. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/specialreports/women_veterans_2015_final.pdf

3. Higgins DM, Fenton BT, Driscoll MA, et al. Gender differences in demographic and clinical correlates among veterans with musculoskeletal disorders. Womens Health Issues. 2017;27(4):463-470. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2017.01.008

4. Lehavot K, Goldberg SB, Chen JA, et al. Do trauma type, stressful life events, and social support explain women veterans’ high prevalence of PTSD?. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;53(9):943-953. doi:10.1007/s00127-018-1550-x

5. Levander XA, Overland MK. Care of women veterans. Med Clin North Am. 2015;99(3):651-662. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2015.01.013

6. US Department of Veteran Affairs. Facts and statistics about women veterans. Updated May 28. 2020. Accessed January 6, 2022. https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/womenshealth/latestinformation/facts.asp

7. Krejci LP, Carter K, Gaudet T. Whole health: the vision and implementation of personalized, proactive, patient-driven health care for veterans. Med Care. 2014;52(12)(suppl 5):S5-S8. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000226

8. Elwy AR, Taylor SL, Zhao S, et al. Participating in complementary and integrative health approaches is associated with veterans’ patient-reported outcomes over time. Med Care. 2020;58:S125-S132. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001357

9. Smeeding SJ, Bradshaw DH, Kumpfer K, Trevithick S, Stoddard GJ. Outcome evaluation of the Veterans Affairs Salt Lake City Integrative Health Clinic for chronic pain and stress-related depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16(8):823-835. doi:10.1089/acm.2009.0510

10. Hull A, Brooks Holliday S, Eickhoff C, et al. Veteran participation in the integrative health and wellness program: impact on self-reported mental and physical health outcomes. Psychol Serv. 2019;16(3):475-483. doi:10.1037/ser0000192

11. Zephyrin LC. Reproductive health management for the care of women veterans [published correction appears in Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Mar;127(3):605]. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(2):383-392. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001252

12. Piotrowski MM, Paterson C, Mitchinson A, Kim HM, Kirsh M, Hinshaw DB. Massage as adjuvant therapy in the management of acute postoperative pain: a preliminary study in men. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197(6):1037-1046. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2003.07.020

13. Mitchinson AR, Kim HM, Rosenberg JM, et al. Acute postoperative pain management using massage as an adjuvant therapy: a randomized trial. Arch Surg. 2007;142(12):1158-1167. doi:10.1001/archsurg.142.12.1158

14. Mitchinson A, Fletcher CE, Kim HM, Montagnini M, Hinshaw DB. Integrating massage therapy within the palliative care of veterans with advanced illnesses: an outcome study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2014;31(1):6-12. doi:10.1177/1049909113476568

15. Fletcher CE, Mitchinson AR, Trumble EL, Hinshaw DB, Dusek JA. Perceptions of other integrative health therapies by veterans with pain who are receiving massage. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2016;53(1):117-126. doi:10.1682/JRRD.2015.01.0015

16. Juberg M, Jerger KK, Allen KD, Dmitrieva NO, Keever T, Perlman AI. Pilot study of massage in veterans with knee osteoarthritis. J Altern Complement Med. 2015;21(6):333-338. doi:10.1089/acm.2014.0254

17. Beck I, Runeson I, Blomqvist K. To find inner peace: soft massage as an established and integrated part of palliative care. Int J Palliate Nurse. 2009;15(11):541-545. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2009.15.11.45493

18. Haskell SG, Ning Y, Krebs E, et al. Prevalence of painful musculoskeletal conditions in female and male veterans in 7 years after return from deployment in Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom. Clin J Pain. 2012;28(2):163-167. doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e318223d951

19. Maguen S, Ren L, Bosch JO, Marmar CR, Seal KH. Gender differences in mental health diagnoses among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans enrolled in veterans affairs health care. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(12):2450-2456. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.166165

20. Outcalt SD, Kroenke K, Krebs EE, et al. Chronic pain and comorbid mental health conditions: independent associations of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression with pain, disability, and quality of life. J Behav Med. 2015;38(3):535-543. doi:10.1007/s10865-015-9628-3

21. Gibson CJ, Maguen S, Xia F, Barnes DE, Peltz CB, Yaffe K. Military sexual trauma in older women veterans: prevalence and comorbidities. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(1):207-213. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05342-7

22. Tan G, Teo I, Srivastava D, et al. Improving access to care for women veterans suffering from chronic pain and depression associated with trauma. Pain Med. 2013;14(7):1010-1020. doi:10.1111/pme.12131

23. Haskell SG, Heapy A, Reid MC, Papas RK, Kerns RD. The prevalence and age-related characteristics of pain in a sample of women veterans receiving primary care. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2006;15(7):862-869. doi:10.1089/jwh.2006.15.862

24. Driscoll MA, Higgins D, Shamaskin-Garroway A, et al. Examining gender as a correlate of self-reported pain treatment use among recent service veterans with deployment-related musculoskeletal disorders. Pain Med. 2017;18(9):1767-1777. doi:10.1093/pm/pnx023

25. Weimer MB, Macey TA, Nicolaidis C, Dobscha SK, Duckart JP, Morasco BJ. Sex differences in the medical care of VA patients with chronic non-cancer pain. Pain Med. 2013;14(12):1839-1847. doi:10.1111/pme.12177

26. Stubbs D, Krebs E, Bair M, et al. Sex differences in pain and pain-related disability among primary care patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain Med. 2010;11(2):232-239. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00760.x

27. Keogh E, McCracken LM, Eccleston C. Gender moderates the association between depression and disability in chronic pain patients. Eur J Pain. 2006;10(5):413-422. doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.05.007

28. Miake-Lye IM, Mak S, Lee J, et al. Massage for pain: an evidence map. J Altern Complement Med. 2019;25(5):475-502. doi:10.1089/acm.2018.0282

29. Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Kahn J, et al. A comparison of the effects of 2 types of massage and usual care on chronic low back pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(1):1-9. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-155-1-201107050-00002

30. Sherman KJ, Cook AJ, Wellman RD, et al. Five-week outcomes from a dosing trial of therapeutic massage for chronic neck pain. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(2):112-120. doi:10.1370/afm.1602

31. Perlman AI, Sabina A, Williams AL, Njike VY, Katz DL. Massage therapy for osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(22):2533-2538. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.22.2533

32. Perlman A, Fogerite SG, Glass O, et al. Efficacy and safety of massage for osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized clinical trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(3):379-386. doi:10.1007/s11606-018-4763-5

33. Skelly AC, Chou R, Dettori JR, et al. Noninvasive Nonpharmacological Treatment for Chronic Pain: A Systematic Review Update. Comparative Effectiveness Review. No. 227. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2020. doi:10.23970/AHRQEPCCER227

34. Moyer CA, Rounds J, Hannum JW. A meta-analysis of massage therapy research. Psychol Bull. 2004;130(1):3-18. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.130.1.3

35. Field T, Hernandez-Reif M, Diego M, Schanberg S, Kuhn C. Cortisol decreases and serotonin and dopamine increase following massage therapy. Int J Neurosci. 2005;115(10):1397-1413. doi:10.1080/ 00207450590956459

36. Li Q, Becker B, Wernicke J, et al. Foot massage evokes oxytocin release and activation of orbitofrontal cortex and superior temporal sulcus. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019;101:193-203. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.11.016

37. Eaves ER, Sherman KJ, Ritenbaugh C, et al. A qualitative study of changes in expectations over time among patients with chronic low back pain seeking four CAM therapies. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2015;15:12. Published 2015 Feb 5. doi:10.1186/s12906-015-0531-9

38. Bishop FL, Lauche R, Cramer H, et al. Health behavior change and complementary medicine use: National Health Interview Survey 2012. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019;55(10):632. Published 2019 Sep 24. doi:10.3390/medicina55100632

39. Driscoll MA, Knobf MT, Higgins DM, Heapy A, Lee A, Haskell S. Patient experiences navigating chronic pain management in an integrated health care system: a qualitative investigation of women and men. Pain Med. 2018;19(suppl 1):S19-S29. doi:10.1093/pm/pny139

40. Denneson LM, Corson K, Dobscha SK. Complementary and alternative medicine use among veterans with chronic noncancer pain. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2011;48(9):1119-1128. doi:10.1682/jrrd.2010.12.0243

41. Taylor SL, Herman PM, Marshall NJ, et al. Use of complementary and integrated health: a retrospective analysis of U.S. veterans with chronic musculoskeletal pain nationally. J Altern Complement Med. 2019;25(1):32-39. doi:10.1089/acm.2018.0276

42. Evans EA, Herman PM, Washington DL, et al. Gender differences in use of complementary and integrative health by U.S. military veterans with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Womens Health Issues. 2018;28(5):379-386. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2018.07.003

43. Reinhard MJ, Nassif TH, Bloeser K, et al. CAM utilization among OEF/OIF veterans: findings from the National Health Study for a New Generation of US Veterans. Med Care. 2014;52(12)(suppl 5):S45-S49. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000229

44. Herman PM, Yuan AH, Cefalu MS, et al. The use of complementary and integrative health approaches for chronic musculoskeletal pain in younger US Veterans: An economic evaluation. PLoS One. 2019;14(6):e0217831. Published 2019 Jun 5. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0217831

45. Jonas WB, Schoomaker EB. Pain and opioids in the military: we must do better. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(8):1402-1403. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2114

46. Han B, Compton WM, Blanco C, Crane E, Lee J, Jones CM. Prescription opioid use, misuse, and use disorders in U.S. adults: 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(5):293-301. doi:10.7326/M17-0865

There are approximately 2 million female veterans in the United States, representing about 10% of the veteran population.1 In 2015, 456,000 female veterans used the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care services. The VA predicts an increase in utilization over the next 20 years.2

Female veterans are more likely to have musculoskeletal disorder multimorbidity compared with male veterans and have higher rates of depressive and bipolar disorders, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).3,4 Compared with male veterans, female veterans are younger, more likely to be unmarried and to have served during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.3 Fifty-five percent of women veterans vs 41% of men veterans have a service-connected disability, and a greater percentage of women veterans have a service connection rating > 50%.5 The top service-connected disabilities for women veterans are PTSD, major depressive disorder, migraines, and lumbosacral or cervical strain.2 In addition, one-third of women veterans using VA health care report experiencing military sexual trauma (MST).6 Military service may impact the health of female veterans both physically and mentally. Providing treatments and programs to improve their health and their health care experience are current VA priorities.

The VA is changing the way health care is conceptualized and delivered by implementing a holistic model of care known as Whole Health, which seeks to empower and equip patients to take charge of their health, blending conventional medicine with self-care and complementary and integrative health (CIH) approaches, such as massage therapy, yoga, acupuncture, and meditation.7 CIH therapies can help improve physical and mental health with little to no adverse effects.8-10

As part of the Whole Health initiative at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System (VAAAHS) in Michigan, the massage program was expanded in 2017 to offer relaxation massages to female veterans attending the women’s health clinic, which provides gynecologic care. Patients visiting a gynecology clinic often experience anxiety and pain related to invasive procedures and examinations. This is especially true for female veterans who experienced MST.11

VAAAHS has 1 staff massage therapist (MT). To expand the program to the women’s health clinic, volunteer licensed MTs were recruited and trained in specific procedures by the staff MT.

Several studies have demonstrated the effect of therapeutic massage on pain and anxiety in predominantly male veteran study populations, including veterans needing postsurgical and palliative care as well as those experiencing chronic pain and knee osteoarthritis.12-16 Little is known about the effects of massage therapy on female veterans. The purpose of this pilot study was to examine the effects of massage therapy among female veterans participating in the women’s health massage program.

Methods

The setting for this pre-post intervention study was VAAAHS. Veterans were called in advance by clinic staff and scheduled for 60-minute appointments either before or after their clinic appointment, depending on availability. MTs were instructed to provide relaxation massage using Swedish massage techniques with moderate pressure, avoiding deep pressure techniques.

The volunteer MTs gave the participants a survey to provide comments and to rate baseline pain and other symptoms prior to and following the massage. The MT left the room to provide privacy while completing the survey. The staff included the symptom data in the massage note as clinical outcomes and entered them into the electronic health record. Massages were given from October 1, 2017 to June 30, 2018. Data including symptom scores, demographics, the presence of chronic pain, mental health diagnoses, patient comments, and opioid use were abstracted from the electronic health record by 2 members of the study team and entered into an Excel database. This study was approved by the VAAAHS Institutional Review Board.

Study Measures

Pain intensity, pain unpleasantness (the affective component of pain), anxiety, shortness of breath, relaxation, and inner peace were rated pre- and postmassage on a 0 to 10 scale. Shortness of breath was included due to the relationship between breathing and anxiety. Inner peace was assessed to measure the calming effects of massage therapy. Beck and colleagues found the concept of inner peace was an important outcome of massage therapy.17 The scale anchors for pain intensity were “no pain” and “severe pain”; and “not at all unpleasant” and “as unpleasant as it can be” for pain unpleasantness. For anxiety, the anchors were “no anxiety” and “as anxious as I can be.” Anchors for relaxation and inner peace were reversed so that a 0 indicated low relaxation and inner peace while a 10 indicated the highest state of relaxation and inner peace.

Chronic pain was defined as pain existing for > 3 months. A history of chronic pain was determined from a review and synthesis of primary care and specialty care recorded diagnoses, patient concerns, and service-connected disabilities. The diagnoses included lumbosacral or cervical strain, chronic low back, joint (knee, shoulder, hip, ankle), neck, or pelvic pain, fibromyalgia, headache, migraine, osteoarthritis, and myofascial pain syndrome. The presence of mental health conditions, including depression, anxiety, bipolar disorders, and PTSD, were similarly determined by a review of mental health clinical notes. Sex was determined from the gynecology note.

Statistical Analysis

Means and medians were calculated for short-term changes in symptom scores. Due to skewness in the short-term changes, significance was tested using a nonparametric sign test. Significance was adjusted using the Bonferroni correction to protect the overall type I error level at 5% from multiple testing. We also assessed for differences in symptom changes in 4 subgroups, using an unadjusted general linear model: those with (1) chronic pain vs without; (2) an anxiety diagnosis vs without; (3) depression vs without; and (4) a PTSD diagnosis vs without. Data were analyzed using SPSS 25 and SAS 9.4.

Results

Results are based on the first massage received by 96 unique individuals (Table 1). Fifty-one (53%) patients were aged 21 to 40 years, and 45 (47%) were aged ≥ 41 years. Most participants (80%) had had a previous massage. Seven (7%) participants were currently on prescription opioids; 76 (79%) participants had a history of one or more chronic pain diagnoses (eg, back pain, migraine headaches, fibromyalgia) and 78 (81%) had a history of a mental health diagnosis (eg, depression, anxiety, PTSD). Massage sessions ranged from 30 to 60 minutes; most patients received massage therapy for 50 minutes.

Prior to massage, mean scores were 3.9 pain intensity, 3.7 pain unpleasantness, 3.8 anxiety, 1.0 shortness of breath, 4.0 relaxation, and 4.2 inner peace. Short-term changes in symptom scores are shown in Table 2. The mean score for pain intensity decreased by 1.9 points, pain unpleasantness by 2.0 points, anxiety by 2.4 points. The greatest change occurred for relaxation, which increased by 4.3 points. All changes in symptoms were statistically significant (P < .001). For subgroup comparisons

Verbal feedback and written comments about the massage experience were all favorable: No adverse events were reported.

Discussion

Massage therapy may be a useful treatment for female veterans experiencing chronic pain, anxiety disorders, depression, or situational anxiety related to gynecologic procedures. After receiving a relaxation massage, female veterans reported decreased pain intensity, pain unpleasantness, and anxiety while reporting increased relaxation and feelings of inner peace. The effects of massage were consistent for all the symptoms or characteristics assessed, suggesting that massage may act on the body in multiple ways.

These changes parallel those seen in a palliative care population primarily composed of male veterans.14 However, the female veterans in this cohort experienced greater changes in relaxation and feelings of inner peace, which may be partly due to relief of tension related to an upcoming stressful appointment. The large mean decrease in anxiety level among female veterans with PTSD is notable as well as the larger increase in inner peace in those with chronic pain.

Many patients expressed their gratitude for the massage and interest in having access to more massage therapy. Female patients who have experienced sexual trauma or other trauma may especially benefit from massage prior to painful, invasive gynecologic procedures. Anecdotally, 2 nurse chaperones in the clinic mentioned separately to the massage program supervisor that the massages helped some very anxious women better tolerate an invasive procedure that would have been otherwise extremely difficult.

Female veterans are more likely to have musculoskeletal issues after deployment and have higher rates of anxiety, PTSD, and depression compared with those of male veterans.3,4,18,19 Determining relationships between and causes of chronic pain, depression, and PTSD is very challenging but the increased prevalence of chronic pain and comorbid mental health conditions in female veterans may be partially related to MST or other trauma experiences.20-22 Female veterans are most likely to have more than one source of chronic pain.23-25 Female patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain report more pain-related disability.26 Furthermore, greater disability in the context of depression is reported by women with pain compared with those of men.27 Most (78%) female veterans in a primary care population reported chronic pain.23 Similarly, 79% of the female veterans in this study population had chronic pain and 81% had a history of mental health disorders, including depression, anxiety, and PTSD.

Studies have shown that massage therapy improves pain in populations experiencing chronic low back, neck, and knee pain.28-32 A 2020 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality review determined there is some evidence that massage therapy is helpful for chronic low back and neck pain and fibromyalgia.33 Research also has demonstrated that massage reduces anxiety and depression in several different population types.13,34,35 Li and colleagues showed that foot massage increased oxytocin levels in healthy males.36 Although further research is needed to determine the mechanisms of massage therapy, there are important physiologic effects. Unlike most medications, massage therapy is unique in that it can impact health and well-being through multiple mechanisms; for example, by reducing pain, improving mood, providing a sense of social connection and/or improving mobility.

Patients using CIH therapies report greater awareness of the need for ongoing engagement in their own care and health behavior changes.37,38

Driscoll and colleagues reported that women veterans are interested in conservative treatment for their chronic musculoskeletal pain and are open to using CIH therapies.39 Research suggests that veterans are interested in and, in some cases, already using massage therapy.23,40-43 Access to massage therapy and other CIH therapies offers patients choice and control over the types and timing of therapy they receive, exemplified by the 80% of patients in our study who previously received a massage and sought another before a potentially stressful situation.

Access to massage therapy or other CIH therapies may reduce the need for more expensive procedures. Although research on the cost-effectiveness of massage therapy is limited, Herman and colleagues did an economic evaluation of CIH therapies in a veteran population, finding that CIH users had lower annual health care costs and lower pain in the year after CIH started. Sensitivity analyses indicated similar results for acupuncture, chiropractic care, and massage but higher costs for those with 8 or more visits.44

The prevalence of comorbid mental health conditions with MSD suggests that female veterans may benefit from multidisciplinary treatment of pain and depression.3,26 Women-centered programs would be both encouraging and validating to women.39 Massage therapy can be combined with physical therapy, yoga, tai chi, and meditation programs to improve pain, anxiety, strength, and flexibility and can be incorporated into a multimodal treatment plan. Likewise, other subpopulations of female veterans with chronic pain, mental health conditions, or cancer could be targeted with multidisciplinary programs that include massage therapy.

Limitations

This study has several limitations including lack of a control group, a self-selected population, the lack of objective biochemical measurements, and possible respondent bias to please the MTs. Eighty percent had previously experienced massage therapy and may have been biased toward the effects of massage before receiving the intervention. The first report of the effects of massage therapy in an exclusively female veteran population is a major strength of this study.

Further research including randomized controlled trials is needed, especially in populations with coexisting chronic pain and mental health disorders, as is exploring the acceptability of massage therapy for female veterans with MST. Finding viable alternatives to medications has become even more important as the nation addresses the challenge of the opioid crisis.45,46

Conclusions

Female veterans are increasingly seeking VA health care.

Acknowledgments

The authors express our gratitude to the Women Veteran Program Manager, Cheryl Allen, RN; Massage Therapists Denise McGee and Kimberly Morro; Dara Ganoczy, MPH, for help with statistical analysis; and Mark Hausman, MD, for leadership support.

There are approximately 2 million female veterans in the United States, representing about 10% of the veteran population.1 In 2015, 456,000 female veterans used the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care services. The VA predicts an increase in utilization over the next 20 years.2

Female veterans are more likely to have musculoskeletal disorder multimorbidity compared with male veterans and have higher rates of depressive and bipolar disorders, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).3,4 Compared with male veterans, female veterans are younger, more likely to be unmarried and to have served during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.3 Fifty-five percent of women veterans vs 41% of men veterans have a service-connected disability, and a greater percentage of women veterans have a service connection rating > 50%.5 The top service-connected disabilities for women veterans are PTSD, major depressive disorder, migraines, and lumbosacral or cervical strain.2 In addition, one-third of women veterans using VA health care report experiencing military sexual trauma (MST).6 Military service may impact the health of female veterans both physically and mentally. Providing treatments and programs to improve their health and their health care experience are current VA priorities.

The VA is changing the way health care is conceptualized and delivered by implementing a holistic model of care known as Whole Health, which seeks to empower and equip patients to take charge of their health, blending conventional medicine with self-care and complementary and integrative health (CIH) approaches, such as massage therapy, yoga, acupuncture, and meditation.7 CIH therapies can help improve physical and mental health with little to no adverse effects.8-10

As part of the Whole Health initiative at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System (VAAAHS) in Michigan, the massage program was expanded in 2017 to offer relaxation massages to female veterans attending the women’s health clinic, which provides gynecologic care. Patients visiting a gynecology clinic often experience anxiety and pain related to invasive procedures and examinations. This is especially true for female veterans who experienced MST.11

VAAAHS has 1 staff massage therapist (MT). To expand the program to the women’s health clinic, volunteer licensed MTs were recruited and trained in specific procedures by the staff MT.

Several studies have demonstrated the effect of therapeutic massage on pain and anxiety in predominantly male veteran study populations, including veterans needing postsurgical and palliative care as well as those experiencing chronic pain and knee osteoarthritis.12-16 Little is known about the effects of massage therapy on female veterans. The purpose of this pilot study was to examine the effects of massage therapy among female veterans participating in the women’s health massage program.

Methods

The setting for this pre-post intervention study was VAAAHS. Veterans were called in advance by clinic staff and scheduled for 60-minute appointments either before or after their clinic appointment, depending on availability. MTs were instructed to provide relaxation massage using Swedish massage techniques with moderate pressure, avoiding deep pressure techniques.

The volunteer MTs gave the participants a survey to provide comments and to rate baseline pain and other symptoms prior to and following the massage. The MT left the room to provide privacy while completing the survey. The staff included the symptom data in the massage note as clinical outcomes and entered them into the electronic health record. Massages were given from October 1, 2017 to June 30, 2018. Data including symptom scores, demographics, the presence of chronic pain, mental health diagnoses, patient comments, and opioid use were abstracted from the electronic health record by 2 members of the study team and entered into an Excel database. This study was approved by the VAAAHS Institutional Review Board.

Study Measures

Pain intensity, pain unpleasantness (the affective component of pain), anxiety, shortness of breath, relaxation, and inner peace were rated pre- and postmassage on a 0 to 10 scale. Shortness of breath was included due to the relationship between breathing and anxiety. Inner peace was assessed to measure the calming effects of massage therapy. Beck and colleagues found the concept of inner peace was an important outcome of massage therapy.17 The scale anchors for pain intensity were “no pain” and “severe pain”; and “not at all unpleasant” and “as unpleasant as it can be” for pain unpleasantness. For anxiety, the anchors were “no anxiety” and “as anxious as I can be.” Anchors for relaxation and inner peace were reversed so that a 0 indicated low relaxation and inner peace while a 10 indicated the highest state of relaxation and inner peace.

Chronic pain was defined as pain existing for > 3 months. A history of chronic pain was determined from a review and synthesis of primary care and specialty care recorded diagnoses, patient concerns, and service-connected disabilities. The diagnoses included lumbosacral or cervical strain, chronic low back, joint (knee, shoulder, hip, ankle), neck, or pelvic pain, fibromyalgia, headache, migraine, osteoarthritis, and myofascial pain syndrome. The presence of mental health conditions, including depression, anxiety, bipolar disorders, and PTSD, were similarly determined by a review of mental health clinical notes. Sex was determined from the gynecology note.

Statistical Analysis

Means and medians were calculated for short-term changes in symptom scores. Due to skewness in the short-term changes, significance was tested using a nonparametric sign test. Significance was adjusted using the Bonferroni correction to protect the overall type I error level at 5% from multiple testing. We also assessed for differences in symptom changes in 4 subgroups, using an unadjusted general linear model: those with (1) chronic pain vs without; (2) an anxiety diagnosis vs without; (3) depression vs without; and (4) a PTSD diagnosis vs without. Data were analyzed using SPSS 25 and SAS 9.4.

Results

Results are based on the first massage received by 96 unique individuals (Table 1). Fifty-one (53%) patients were aged 21 to 40 years, and 45 (47%) were aged ≥ 41 years. Most participants (80%) had had a previous massage. Seven (7%) participants were currently on prescription opioids; 76 (79%) participants had a history of one or more chronic pain diagnoses (eg, back pain, migraine headaches, fibromyalgia) and 78 (81%) had a history of a mental health diagnosis (eg, depression, anxiety, PTSD). Massage sessions ranged from 30 to 60 minutes; most patients received massage therapy for 50 minutes.

Prior to massage, mean scores were 3.9 pain intensity, 3.7 pain unpleasantness, 3.8 anxiety, 1.0 shortness of breath, 4.0 relaxation, and 4.2 inner peace. Short-term changes in symptom scores are shown in Table 2. The mean score for pain intensity decreased by 1.9 points, pain unpleasantness by 2.0 points, anxiety by 2.4 points. The greatest change occurred for relaxation, which increased by 4.3 points. All changes in symptoms were statistically significant (P < .001). For subgroup comparisons

Verbal feedback and written comments about the massage experience were all favorable: No adverse events were reported.

Discussion

Massage therapy may be a useful treatment for female veterans experiencing chronic pain, anxiety disorders, depression, or situational anxiety related to gynecologic procedures. After receiving a relaxation massage, female veterans reported decreased pain intensity, pain unpleasantness, and anxiety while reporting increased relaxation and feelings of inner peace. The effects of massage were consistent for all the symptoms or characteristics assessed, suggesting that massage may act on the body in multiple ways.

These changes parallel those seen in a palliative care population primarily composed of male veterans.14 However, the female veterans in this cohort experienced greater changes in relaxation and feelings of inner peace, which may be partly due to relief of tension related to an upcoming stressful appointment. The large mean decrease in anxiety level among female veterans with PTSD is notable as well as the larger increase in inner peace in those with chronic pain.

Many patients expressed their gratitude for the massage and interest in having access to more massage therapy. Female patients who have experienced sexual trauma or other trauma may especially benefit from massage prior to painful, invasive gynecologic procedures. Anecdotally, 2 nurse chaperones in the clinic mentioned separately to the massage program supervisor that the massages helped some very anxious women better tolerate an invasive procedure that would have been otherwise extremely difficult.

Female veterans are more likely to have musculoskeletal issues after deployment and have higher rates of anxiety, PTSD, and depression compared with those of male veterans.3,4,18,19 Determining relationships between and causes of chronic pain, depression, and PTSD is very challenging but the increased prevalence of chronic pain and comorbid mental health conditions in female veterans may be partially related to MST or other trauma experiences.20-22 Female veterans are most likely to have more than one source of chronic pain.23-25 Female patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain report more pain-related disability.26 Furthermore, greater disability in the context of depression is reported by women with pain compared with those of men.27 Most (78%) female veterans in a primary care population reported chronic pain.23 Similarly, 79% of the female veterans in this study population had chronic pain and 81% had a history of mental health disorders, including depression, anxiety, and PTSD.

Studies have shown that massage therapy improves pain in populations experiencing chronic low back, neck, and knee pain.28-32 A 2020 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality review determined there is some evidence that massage therapy is helpful for chronic low back and neck pain and fibromyalgia.33 Research also has demonstrated that massage reduces anxiety and depression in several different population types.13,34,35 Li and colleagues showed that foot massage increased oxytocin levels in healthy males.36 Although further research is needed to determine the mechanisms of massage therapy, there are important physiologic effects. Unlike most medications, massage therapy is unique in that it can impact health and well-being through multiple mechanisms; for example, by reducing pain, improving mood, providing a sense of social connection and/or improving mobility.

Patients using CIH therapies report greater awareness of the need for ongoing engagement in their own care and health behavior changes.37,38

Driscoll and colleagues reported that women veterans are interested in conservative treatment for their chronic musculoskeletal pain and are open to using CIH therapies.39 Research suggests that veterans are interested in and, in some cases, already using massage therapy.23,40-43 Access to massage therapy and other CIH therapies offers patients choice and control over the types and timing of therapy they receive, exemplified by the 80% of patients in our study who previously received a massage and sought another before a potentially stressful situation.

Access to massage therapy or other CIH therapies may reduce the need for more expensive procedures. Although research on the cost-effectiveness of massage therapy is limited, Herman and colleagues did an economic evaluation of CIH therapies in a veteran population, finding that CIH users had lower annual health care costs and lower pain in the year after CIH started. Sensitivity analyses indicated similar results for acupuncture, chiropractic care, and massage but higher costs for those with 8 or more visits.44

The prevalence of comorbid mental health conditions with MSD suggests that female veterans may benefit from multidisciplinary treatment of pain and depression.3,26 Women-centered programs would be both encouraging and validating to women.39 Massage therapy can be combined with physical therapy, yoga, tai chi, and meditation programs to improve pain, anxiety, strength, and flexibility and can be incorporated into a multimodal treatment plan. Likewise, other subpopulations of female veterans with chronic pain, mental health conditions, or cancer could be targeted with multidisciplinary programs that include massage therapy.

Limitations

This study has several limitations including lack of a control group, a self-selected population, the lack of objective biochemical measurements, and possible respondent bias to please the MTs. Eighty percent had previously experienced massage therapy and may have been biased toward the effects of massage before receiving the intervention. The first report of the effects of massage therapy in an exclusively female veteran population is a major strength of this study.

Further research including randomized controlled trials is needed, especially in populations with coexisting chronic pain and mental health disorders, as is exploring the acceptability of massage therapy for female veterans with MST. Finding viable alternatives to medications has become even more important as the nation addresses the challenge of the opioid crisis.45,46

Conclusions

Female veterans are increasingly seeking VA health care.

Acknowledgments

The authors express our gratitude to the Women Veteran Program Manager, Cheryl Allen, RN; Massage Therapists Denise McGee and Kimberly Morro; Dara Ganoczy, MPH, for help with statistical analysis; and Mark Hausman, MD, for leadership support.

1. US Department of Veteran Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Veteran population. Updated April 14, 2021. Accessed January 6, 2022. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/veteran_population.asp

2. US Department of Veteran Affairs. Women veterans report: the past, present, and future of women veterans. Published February 2017. Accessed January 6, 2022. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/specialreports/women_veterans_2015_final.pdf

3. Higgins DM, Fenton BT, Driscoll MA, et al. Gender differences in demographic and clinical correlates among veterans with musculoskeletal disorders. Womens Health Issues. 2017;27(4):463-470. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2017.01.008

4. Lehavot K, Goldberg SB, Chen JA, et al. Do trauma type, stressful life events, and social support explain women veterans’ high prevalence of PTSD?. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;53(9):943-953. doi:10.1007/s00127-018-1550-x

5. Levander XA, Overland MK. Care of women veterans. Med Clin North Am. 2015;99(3):651-662. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2015.01.013

6. US Department of Veteran Affairs. Facts and statistics about women veterans. Updated May 28. 2020. Accessed January 6, 2022. https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/womenshealth/latestinformation/facts.asp

7. Krejci LP, Carter K, Gaudet T. Whole health: the vision and implementation of personalized, proactive, patient-driven health care for veterans. Med Care. 2014;52(12)(suppl 5):S5-S8. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000226

8. Elwy AR, Taylor SL, Zhao S, et al. Participating in complementary and integrative health approaches is associated with veterans’ patient-reported outcomes over time. Med Care. 2020;58:S125-S132. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001357

9. Smeeding SJ, Bradshaw DH, Kumpfer K, Trevithick S, Stoddard GJ. Outcome evaluation of the Veterans Affairs Salt Lake City Integrative Health Clinic for chronic pain and stress-related depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16(8):823-835. doi:10.1089/acm.2009.0510

10. Hull A, Brooks Holliday S, Eickhoff C, et al. Veteran participation in the integrative health and wellness program: impact on self-reported mental and physical health outcomes. Psychol Serv. 2019;16(3):475-483. doi:10.1037/ser0000192

11. Zephyrin LC. Reproductive health management for the care of women veterans [published correction appears in Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Mar;127(3):605]. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(2):383-392. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001252

12. Piotrowski MM, Paterson C, Mitchinson A, Kim HM, Kirsh M, Hinshaw DB. Massage as adjuvant therapy in the management of acute postoperative pain: a preliminary study in men. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197(6):1037-1046. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2003.07.020

13. Mitchinson AR, Kim HM, Rosenberg JM, et al. Acute postoperative pain management using massage as an adjuvant therapy: a randomized trial. Arch Surg. 2007;142(12):1158-1167. doi:10.1001/archsurg.142.12.1158

14. Mitchinson A, Fletcher CE, Kim HM, Montagnini M, Hinshaw DB. Integrating massage therapy within the palliative care of veterans with advanced illnesses: an outcome study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2014;31(1):6-12. doi:10.1177/1049909113476568

15. Fletcher CE, Mitchinson AR, Trumble EL, Hinshaw DB, Dusek JA. Perceptions of other integrative health therapies by veterans with pain who are receiving massage. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2016;53(1):117-126. doi:10.1682/JRRD.2015.01.0015

16. Juberg M, Jerger KK, Allen KD, Dmitrieva NO, Keever T, Perlman AI. Pilot study of massage in veterans with knee osteoarthritis. J Altern Complement Med. 2015;21(6):333-338. doi:10.1089/acm.2014.0254

17. Beck I, Runeson I, Blomqvist K. To find inner peace: soft massage as an established and integrated part of palliative care. Int J Palliate Nurse. 2009;15(11):541-545. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2009.15.11.45493

18. Haskell SG, Ning Y, Krebs E, et al. Prevalence of painful musculoskeletal conditions in female and male veterans in 7 years after return from deployment in Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom. Clin J Pain. 2012;28(2):163-167. doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e318223d951

19. Maguen S, Ren L, Bosch JO, Marmar CR, Seal KH. Gender differences in mental health diagnoses among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans enrolled in veterans affairs health care. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(12):2450-2456. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.166165

20. Outcalt SD, Kroenke K, Krebs EE, et al. Chronic pain and comorbid mental health conditions: independent associations of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression with pain, disability, and quality of life. J Behav Med. 2015;38(3):535-543. doi:10.1007/s10865-015-9628-3

21. Gibson CJ, Maguen S, Xia F, Barnes DE, Peltz CB, Yaffe K. Military sexual trauma in older women veterans: prevalence and comorbidities. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(1):207-213. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05342-7

22. Tan G, Teo I, Srivastava D, et al. Improving access to care for women veterans suffering from chronic pain and depression associated with trauma. Pain Med. 2013;14(7):1010-1020. doi:10.1111/pme.12131

23. Haskell SG, Heapy A, Reid MC, Papas RK, Kerns RD. The prevalence and age-related characteristics of pain in a sample of women veterans receiving primary care. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2006;15(7):862-869. doi:10.1089/jwh.2006.15.862

24. Driscoll MA, Higgins D, Shamaskin-Garroway A, et al. Examining gender as a correlate of self-reported pain treatment use among recent service veterans with deployment-related musculoskeletal disorders. Pain Med. 2017;18(9):1767-1777. doi:10.1093/pm/pnx023

25. Weimer MB, Macey TA, Nicolaidis C, Dobscha SK, Duckart JP, Morasco BJ. Sex differences in the medical care of VA patients with chronic non-cancer pain. Pain Med. 2013;14(12):1839-1847. doi:10.1111/pme.12177

26. Stubbs D, Krebs E, Bair M, et al. Sex differences in pain and pain-related disability among primary care patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain Med. 2010;11(2):232-239. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00760.x

27. Keogh E, McCracken LM, Eccleston C. Gender moderates the association between depression and disability in chronic pain patients. Eur J Pain. 2006;10(5):413-422. doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.05.007

28. Miake-Lye IM, Mak S, Lee J, et al. Massage for pain: an evidence map. J Altern Complement Med. 2019;25(5):475-502. doi:10.1089/acm.2018.0282

29. Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Kahn J, et al. A comparison of the effects of 2 types of massage and usual care on chronic low back pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(1):1-9. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-155-1-201107050-00002

30. Sherman KJ, Cook AJ, Wellman RD, et al. Five-week outcomes from a dosing trial of therapeutic massage for chronic neck pain. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(2):112-120. doi:10.1370/afm.1602

31. Perlman AI, Sabina A, Williams AL, Njike VY, Katz DL. Massage therapy for osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(22):2533-2538. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.22.2533

32. Perlman A, Fogerite SG, Glass O, et al. Efficacy and safety of massage for osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized clinical trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(3):379-386. doi:10.1007/s11606-018-4763-5

33. Skelly AC, Chou R, Dettori JR, et al. Noninvasive Nonpharmacological Treatment for Chronic Pain: A Systematic Review Update. Comparative Effectiveness Review. No. 227. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2020. doi:10.23970/AHRQEPCCER227

34. Moyer CA, Rounds J, Hannum JW. A meta-analysis of massage therapy research. Psychol Bull. 2004;130(1):3-18. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.130.1.3

35. Field T, Hernandez-Reif M, Diego M, Schanberg S, Kuhn C. Cortisol decreases and serotonin and dopamine increase following massage therapy. Int J Neurosci. 2005;115(10):1397-1413. doi:10.1080/ 00207450590956459

36. Li Q, Becker B, Wernicke J, et al. Foot massage evokes oxytocin release and activation of orbitofrontal cortex and superior temporal sulcus. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019;101:193-203. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.11.016

37. Eaves ER, Sherman KJ, Ritenbaugh C, et al. A qualitative study of changes in expectations over time among patients with chronic low back pain seeking four CAM therapies. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2015;15:12. Published 2015 Feb 5. doi:10.1186/s12906-015-0531-9

38. Bishop FL, Lauche R, Cramer H, et al. Health behavior change and complementary medicine use: National Health Interview Survey 2012. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019;55(10):632. Published 2019 Sep 24. doi:10.3390/medicina55100632

39. Driscoll MA, Knobf MT, Higgins DM, Heapy A, Lee A, Haskell S. Patient experiences navigating chronic pain management in an integrated health care system: a qualitative investigation of women and men. Pain Med. 2018;19(suppl 1):S19-S29. doi:10.1093/pm/pny139

40. Denneson LM, Corson K, Dobscha SK. Complementary and alternative medicine use among veterans with chronic noncancer pain. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2011;48(9):1119-1128. doi:10.1682/jrrd.2010.12.0243

41. Taylor SL, Herman PM, Marshall NJ, et al. Use of complementary and integrated health: a retrospective analysis of U.S. veterans with chronic musculoskeletal pain nationally. J Altern Complement Med. 2019;25(1):32-39. doi:10.1089/acm.2018.0276

42. Evans EA, Herman PM, Washington DL, et al. Gender differences in use of complementary and integrative health by U.S. military veterans with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Womens Health Issues. 2018;28(5):379-386. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2018.07.003

43. Reinhard MJ, Nassif TH, Bloeser K, et al. CAM utilization among OEF/OIF veterans: findings from the National Health Study for a New Generation of US Veterans. Med Care. 2014;52(12)(suppl 5):S45-S49. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000229

44. Herman PM, Yuan AH, Cefalu MS, et al. The use of complementary and integrative health approaches for chronic musculoskeletal pain in younger US Veterans: An economic evaluation. PLoS One. 2019;14(6):e0217831. Published 2019 Jun 5. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0217831

45. Jonas WB, Schoomaker EB. Pain and opioids in the military: we must do better. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(8):1402-1403. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2114

46. Han B, Compton WM, Blanco C, Crane E, Lee J, Jones CM. Prescription opioid use, misuse, and use disorders in U.S. adults: 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(5):293-301. doi:10.7326/M17-0865

1. US Department of Veteran Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Veteran population. Updated April 14, 2021. Accessed January 6, 2022. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/veteran_population.asp

2. US Department of Veteran Affairs. Women veterans report: the past, present, and future of women veterans. Published February 2017. Accessed January 6, 2022. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/specialreports/women_veterans_2015_final.pdf

3. Higgins DM, Fenton BT, Driscoll MA, et al. Gender differences in demographic and clinical correlates among veterans with musculoskeletal disorders. Womens Health Issues. 2017;27(4):463-470. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2017.01.008

4. Lehavot K, Goldberg SB, Chen JA, et al. Do trauma type, stressful life events, and social support explain women veterans’ high prevalence of PTSD?. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;53(9):943-953. doi:10.1007/s00127-018-1550-x

5. Levander XA, Overland MK. Care of women veterans. Med Clin North Am. 2015;99(3):651-662. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2015.01.013

6. US Department of Veteran Affairs. Facts and statistics about women veterans. Updated May 28. 2020. Accessed January 6, 2022. https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/womenshealth/latestinformation/facts.asp

7. Krejci LP, Carter K, Gaudet T. Whole health: the vision and implementation of personalized, proactive, patient-driven health care for veterans. Med Care. 2014;52(12)(suppl 5):S5-S8. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000226

8. Elwy AR, Taylor SL, Zhao S, et al. Participating in complementary and integrative health approaches is associated with veterans’ patient-reported outcomes over time. Med Care. 2020;58:S125-S132. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001357

9. Smeeding SJ, Bradshaw DH, Kumpfer K, Trevithick S, Stoddard GJ. Outcome evaluation of the Veterans Affairs Salt Lake City Integrative Health Clinic for chronic pain and stress-related depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16(8):823-835. doi:10.1089/acm.2009.0510

10. Hull A, Brooks Holliday S, Eickhoff C, et al. Veteran participation in the integrative health and wellness program: impact on self-reported mental and physical health outcomes. Psychol Serv. 2019;16(3):475-483. doi:10.1037/ser0000192

11. Zephyrin LC. Reproductive health management for the care of women veterans [published correction appears in Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Mar;127(3):605]. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(2):383-392. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001252

12. Piotrowski MM, Paterson C, Mitchinson A, Kim HM, Kirsh M, Hinshaw DB. Massage as adjuvant therapy in the management of acute postoperative pain: a preliminary study in men. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197(6):1037-1046. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2003.07.020

13. Mitchinson AR, Kim HM, Rosenberg JM, et al. Acute postoperative pain management using massage as an adjuvant therapy: a randomized trial. Arch Surg. 2007;142(12):1158-1167. doi:10.1001/archsurg.142.12.1158

14. Mitchinson A, Fletcher CE, Kim HM, Montagnini M, Hinshaw DB. Integrating massage therapy within the palliative care of veterans with advanced illnesses: an outcome study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2014;31(1):6-12. doi:10.1177/1049909113476568

15. Fletcher CE, Mitchinson AR, Trumble EL, Hinshaw DB, Dusek JA. Perceptions of other integrative health therapies by veterans with pain who are receiving massage. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2016;53(1):117-126. doi:10.1682/JRRD.2015.01.0015

16. Juberg M, Jerger KK, Allen KD, Dmitrieva NO, Keever T, Perlman AI. Pilot study of massage in veterans with knee osteoarthritis. J Altern Complement Med. 2015;21(6):333-338. doi:10.1089/acm.2014.0254

17. Beck I, Runeson I, Blomqvist K. To find inner peace: soft massage as an established and integrated part of palliative care. Int J Palliate Nurse. 2009;15(11):541-545. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2009.15.11.45493

18. Haskell SG, Ning Y, Krebs E, et al. Prevalence of painful musculoskeletal conditions in female and male veterans in 7 years after return from deployment in Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom. Clin J Pain. 2012;28(2):163-167. doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e318223d951

19. Maguen S, Ren L, Bosch JO, Marmar CR, Seal KH. Gender differences in mental health diagnoses among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans enrolled in veterans affairs health care. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(12):2450-2456. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.166165

20. Outcalt SD, Kroenke K, Krebs EE, et al. Chronic pain and comorbid mental health conditions: independent associations of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression with pain, disability, and quality of life. J Behav Med. 2015;38(3):535-543. doi:10.1007/s10865-015-9628-3

21. Gibson CJ, Maguen S, Xia F, Barnes DE, Peltz CB, Yaffe K. Military sexual trauma in older women veterans: prevalence and comorbidities. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(1):207-213. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05342-7

22. Tan G, Teo I, Srivastava D, et al. Improving access to care for women veterans suffering from chronic pain and depression associated with trauma. Pain Med. 2013;14(7):1010-1020. doi:10.1111/pme.12131

23. Haskell SG, Heapy A, Reid MC, Papas RK, Kerns RD. The prevalence and age-related characteristics of pain in a sample of women veterans receiving primary care. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2006;15(7):862-869. doi:10.1089/jwh.2006.15.862

24. Driscoll MA, Higgins D, Shamaskin-Garroway A, et al. Examining gender as a correlate of self-reported pain treatment use among recent service veterans with deployment-related musculoskeletal disorders. Pain Med. 2017;18(9):1767-1777. doi:10.1093/pm/pnx023

25. Weimer MB, Macey TA, Nicolaidis C, Dobscha SK, Duckart JP, Morasco BJ. Sex differences in the medical care of VA patients with chronic non-cancer pain. Pain Med. 2013;14(12):1839-1847. doi:10.1111/pme.12177

26. Stubbs D, Krebs E, Bair M, et al. Sex differences in pain and pain-related disability among primary care patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain Med. 2010;11(2):232-239. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00760.x

27. Keogh E, McCracken LM, Eccleston C. Gender moderates the association between depression and disability in chronic pain patients. Eur J Pain. 2006;10(5):413-422. doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.05.007

28. Miake-Lye IM, Mak S, Lee J, et al. Massage for pain: an evidence map. J Altern Complement Med. 2019;25(5):475-502. doi:10.1089/acm.2018.0282

29. Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Kahn J, et al. A comparison of the effects of 2 types of massage and usual care on chronic low back pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(1):1-9. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-155-1-201107050-00002

30. Sherman KJ, Cook AJ, Wellman RD, et al. Five-week outcomes from a dosing trial of therapeutic massage for chronic neck pain. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(2):112-120. doi:10.1370/afm.1602

31. Perlman AI, Sabina A, Williams AL, Njike VY, Katz DL. Massage therapy for osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(22):2533-2538. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.22.2533

32. Perlman A, Fogerite SG, Glass O, et al. Efficacy and safety of massage for osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized clinical trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(3):379-386. doi:10.1007/s11606-018-4763-5

33. Skelly AC, Chou R, Dettori JR, et al. Noninvasive Nonpharmacological Treatment for Chronic Pain: A Systematic Review Update. Comparative Effectiveness Review. No. 227. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2020. doi:10.23970/AHRQEPCCER227

34. Moyer CA, Rounds J, Hannum JW. A meta-analysis of massage therapy research. Psychol Bull. 2004;130(1):3-18. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.130.1.3

35. Field T, Hernandez-Reif M, Diego M, Schanberg S, Kuhn C. Cortisol decreases and serotonin and dopamine increase following massage therapy. Int J Neurosci. 2005;115(10):1397-1413. doi:10.1080/ 00207450590956459

36. Li Q, Becker B, Wernicke J, et al. Foot massage evokes oxytocin release and activation of orbitofrontal cortex and superior temporal sulcus. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019;101:193-203. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.11.016

37. Eaves ER, Sherman KJ, Ritenbaugh C, et al. A qualitative study of changes in expectations over time among patients with chronic low back pain seeking four CAM therapies. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2015;15:12. Published 2015 Feb 5. doi:10.1186/s12906-015-0531-9

38. Bishop FL, Lauche R, Cramer H, et al. Health behavior change and complementary medicine use: National Health Interview Survey 2012. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019;55(10):632. Published 2019 Sep 24. doi:10.3390/medicina55100632

39. Driscoll MA, Knobf MT, Higgins DM, Heapy A, Lee A, Haskell S. Patient experiences navigating chronic pain management in an integrated health care system: a qualitative investigation of women and men. Pain Med. 2018;19(suppl 1):S19-S29. doi:10.1093/pm/pny139

40. Denneson LM, Corson K, Dobscha SK. Complementary and alternative medicine use among veterans with chronic noncancer pain. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2011;48(9):1119-1128. doi:10.1682/jrrd.2010.12.0243

41. Taylor SL, Herman PM, Marshall NJ, et al. Use of complementary and integrated health: a retrospective analysis of U.S. veterans with chronic musculoskeletal pain nationally. J Altern Complement Med. 2019;25(1):32-39. doi:10.1089/acm.2018.0276

42. Evans EA, Herman PM, Washington DL, et al. Gender differences in use of complementary and integrative health by U.S. military veterans with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Womens Health Issues. 2018;28(5):379-386. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2018.07.003

43. Reinhard MJ, Nassif TH, Bloeser K, et al. CAM utilization among OEF/OIF veterans: findings from the National Health Study for a New Generation of US Veterans. Med Care. 2014;52(12)(suppl 5):S45-S49. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000229

44. Herman PM, Yuan AH, Cefalu MS, et al. The use of complementary and integrative health approaches for chronic musculoskeletal pain in younger US Veterans: An economic evaluation. PLoS One. 2019;14(6):e0217831. Published 2019 Jun 5. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0217831

45. Jonas WB, Schoomaker EB. Pain and opioids in the military: we must do better. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(8):1402-1403. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2114

46. Han B, Compton WM, Blanco C, Crane E, Lee J, Jones CM. Prescription opioid use, misuse, and use disorders in U.S. adults: 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(5):293-301. doi:10.7326/M17-0865

Chewing xylitol gum may modestly reduce preterm birth

In the country with one of the highest rates of preterm birth in the world, these early deliveries dropped by 24% with a simple intervention: chewing gum with xylitol during pregnancy. The decrease in preterm births was linked to improvement in oral health, according to research presented at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Although the findings, from a randomized controlled trial of women in Malawi, barely reached statistical significance, the researchers also documented a reduction in periodontitis (gum disease) that appears to correlate with the reduction in early deliveries, according to Kjersti Aagaard, MD, PhD, of Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital, both in Houston.

“For a while, we have known about the association with poor oral health and preterm birth but I am not aware of a study of this magnitude suggesting a simple and effective treatment option,” said Ilina Pluym, MD, an assistant professor in maternal fetal medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, who attended the presentation. Dr. Pluym called the new data “compelling” and said the study “adds to our possible strategies to treat a condition that causes a significant burden of disease worldwide.” The findings must be replicated, ideally in countries with lower rates of preterm birth and periodontal disease to see if the effect is similar, before broadly implementing this cheap and simple intervention.

Preterm birth is a leading cause of infant mortality and a major underlying cause of health problems in children under 5 worldwide. As many as 42% of children born preterm have a health condition related to their prematurity or do not survive childhood.

About one in five babies in Malawi are born between 26 and 37 weeks, about double the U.S. rate of 10.8% preterm births, which in this country is considered births that occur between 23 and 37 weeks’ gestation. Researchers also chose Malawi for the trial because residents there see preterm birth as a widespread problem that must be addressed, Dr. Aagaard said.

Multiple previous studies have found a link between periodontal disease and deliveries that are preterm or low birth weight, Dr. Aagaard told attendees. However, 11 randomized controlled trials that involved treating periodontal disease did not reduce preterm birth despite improving periodontitis and oral health.

Dr. Aagaard’s team decided to test the effectiveness of xylitol – a natural prebiotic found in fruits, vegetables, and bran – because harmful oral bacteria cannot metabolize the substance, and regular use of xylitol reduces the number of harmful mouth bacteria while increasing the number of good microbes in the mouth. In addition, a study in 2006 found that children up to 4 years old had fewer cavities and ear infections when their mothers chewed gum containing xylitol and other compounds. Dr. Aagaard noted that gums without xylitol do not appear to produce the same improvements in oral health.

Before beginning the trial, Dr. Aagaard’s group spent 3 years doing a “run-in” study to ensure a larger, longer-term trial in Malawi was feasible. That initial study found a reduction in tooth decay and periodontal inflammation with use of xylitol. The researchers also learned that participants preferred gum over lozenges or lollipops. Nearly all the participants (92%) chewed the gum twice daily.

Among 10,069 women who enrolled in the trial, 96% remained in it until the end. Of the initial total, 4,029 participants underwent an oral health assessment at the start of the study, and 920 had a follow-up oral health assessment.

Of the 4,349 women who chewed xylitol gum, 12.6% gave birth before 37 weeks, compared with 16.5% preterm births among the 5,321 women in the control group – a 24% reduction (P = .045). The 16.5% rate among women not chewing gum was still lower than the national rate of 19.6%, possibly related to the education the participants received, according to the researchers.

No statistically significant reduction occurred for births at less than 34 weeks, but the reduction in late preterm births – babies born between 34 and 37 weeks – was also borderline in statistical significance (P = .049). Only 9.9% of women chewing xylitol gum had a late preterm birth compared to 13.5% of women who only received health education.

The researchers estimated it would take 26 pregnant women chewing xylitol gum to prevent one preterm birth. At a cost of $24-$29 per pregnancy for the gum, preventing each preterm birth in a community would cost $623-$754.

The researchers also observed a 30% reduction in newborns weighing less than 2,500 g (5.5 pounds), with 8.9% of low-birth-weight babies born to moms chewing gum and 12.9% of low-birth-weight babies born to those not provided gum (P = .046). They attributed this reduction in low birth weight to the lower proportion of late preterm births. The groups showed no significant differences in stillbirths or newborn deaths.

The researchers did, however, find a significant reduction in periodontitis among the women who chewed xylitol gum who came for follow-up dental visits. The prevalence of periodontal disease dropped from 31% to 27% in those not chewing gum but from 31% to 21% in gum chewers (P = .04).

“This cannot be attributed to overall oral health, as dental caries composite scores did not significantly differ while periodontitis measures did,” Dr. Aagaard said.

One limitation of the trial is that it was randomized by health centers instead by individual women, although the researchers tried to account for differences that might exist between the populations going to different facilities. Nor did the researchers assess how frequently the participants chewed gum – although the fact that the gum-chewing group had better oral health suggests they appear to have done so regularly.