User login

Aortic stenosis: Who should undergo surgery, transcatheter valve replacement?

For some patients with aortic stenosis, the choice of management is simple; for others it is less so. Patients who have severe, symptomatic stenosis and who have low surgical risk should undergo aortic valve replacement. But if the stenosis is severe but asymptomatic, or if the patient is at higher surgical risk, or if there seems to be a mismatch in the hemodynamic variables, the situation is more complicated.

Fortunately, we have evidence and guidelines to go on. In this paper we review the indications for surgical and transcatheter aortic valve replacement, focusing on the areas of less certainty.

AN INDOLENT DISEASE, UNTIL IT ISN’T

Aortic stenosis is the most common valvular disease and the third most prevalent form of cardiovascular disease in the Western world, after hypertension and coronary artery disease. It is largely a disease of the elderly; its prevalence increases with age, and it is present in 2% to 7% of patients over age 65.1,2

At first, its course is indolent, as it progresses slowly over years to decades. However, this is followed by rapid clinical deterioration and a high death rate after symptoms develop.

SURGICAL AORTIC VALVE REPLACEMENT FOR SEVERE SYMPTOMATIC STENOSIS

Classic symptoms of aortic stenosis include angina, heart failure, and syncope. Once symptoms appear, patients with severe aortic stenosis should be promptly referred for surgical aortic valve replacement, as survival is poor unless outflow obstruction is relieved (Figure 1). The onset of symptoms confers a poor prognosis: patients die within an average of 5 years after the onset of angina, 3 years after the onset of syncope, and 2 years after the onset of heart failure symptoms. The overall mortality rate is 75% at 3 years without surgery.3,4 Furthermore, 8% to 34% of patients with symptoms die suddenly.

Advances in prosthetic-valve design, cardiopulmonary bypass, surgical technique, and anesthesia have steadily improved the outcomes of aortic valve surgery. An analysis of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) database in 2006 showed that during the previous decade the death rate during isolated aortic valve replacement decreased from 3.4% to 2.6%. For patients under age 70 at the time of surgery, the rate of death was 1.3%, and in those ages 80 to 85, the 30-day mortality rate was less than 5%.5

Patients who survive surgery enjoy a near-normal life expectancy: 99% survive at least 5 years, 85% at least 10 years, and 82% at least 15 years.6,7 Nearly all have improvement in their ejection fraction and heart failure symptoms, and those who had more advanced symptoms before surgery enjoy the most benefit afterward.8,9

Recommendation. Surgical valve replacement for symptomatic severe aortic stenosis receives a class I recommendation, level of evidence B, in the current guidelines from the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA).10,11 (See Table 1 for an explanation of the classes of recommendations and levels of evidence.)

TWO RISK-ASSESSMENT SCORES

There are two widely used scores for assessing the risk of aortic valve replacement: the European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation (EuroSCORE) and the STS score. Each has limitations.

The EuroSCORE was developed to predict the risk of dying in the hospital after adult cardiac surgery. It has been shown to predict the short-term and the long-term risk of death after heart valve surgery.12 Unfortunately, it overestimates the dangers of isolated aortic valve replacement in the patients at highest risk.13,14

The STS score, a logistic model, reflects more closely the operative and 30-day mortality rates for the patients at highest risk undergoing surgical aortic valve replacement.15,16 It was used to assess patients for surgical or transcatheter aortic valve replacement in the Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves (PARTNER) trial.17

These risk scores, though not perfect, are helpful as part of an overall estimation of risk that includes functional status, cardiac function, and comorbidities.

OTHER INDICATIONS FOR SURGICAL AORTIC VALVE REPLACEMENT

For patients with severe but asymptomatic aortic stenosis, surgical referral is standard practice in several circumstances.

Asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis with a low ejection fraction

Early studies found significant differences in survival beginning as early as 3 years after valve replacement between those whose preoperative ejection fraction was greater than 50% and those with a lower ejection fraction.4 Delaying surgery in these patients may lead to irreversible left ventricular dysfunction and worse survival.

Recommendation. The AHA and the ACC recommend surgical aortic valve replacement for patients who have no symptoms and whose left ventricular ejection fraction is less than 50% (class I indication, level of evidence C).10,11

Asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis in patients undergoing other cardiac surgery

Recommendation. Even if it is causing no symptoms, a severely stenotic aortic valve ought to be replaced if the ejection fraction is greater than 50% and the patient is undergoing another type of heart surgery, such as coronary artery bypass grafting, aortic surgery, or surgery on other heart valves (class I indication, level of evidence B).10,11

Asymptomatic moderate aortic stenosis in patients undergoing other cardiac surgery

When patients with a mildly or moderately stenotic aortic valve undergo other types of cardiac surgery, the decision to replace the valve is more difficult. Clinicians have to consider the increase in risk caused by adding aortic valve replacement to the planned surgery compared with the future likelihood of aortic stenosis progressing to a severe symptomatic state and eventually requiring a second cardiac surgery.

We have no evidence from a large prospective randomized controlled trial regarding prophylactic valve replacement at the time of coronary bypass surgery. However, a review of outcomes from the STS database between 1995 and 2000 found that patients under age 70 with a peak aortic gradient greater than “about 28 mm Hg” (correlating with a moderate degree of stenosis) benefited from prophylactic valve replacement at the time of coronary artery bypass surgery.18

These conclusions were supported by a subsequent retrospective analysis that found a significant survival advantage at 8 years in favor of prophylactic valve replacement at the time of bypass surgery for those with moderate (but not mild) aortic stenosis.19

Recommendation. The AHA and ACC give a class IIb endorsement, level of evidence B, for aortic valve replacement in patients with asymptomatic moderate aortic stenosis undergoing coronary bypass, valve, or aortic surgery.10,11

SEVERE ASYMPTOMATIC STENOSIS: WHICH TESTS HELP IN DECIDING?

A patient without symptoms presents a greater challenge than one with symptoms.

If surgery is deferred, the prognosis is usually excellent in such patients. Pellikka et al20 found that patients with severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis who did not undergo surgery had a rate of sudden cardiac death of about 1% per year of follow-up. However, physicians worry about missing the rapid development of symptoms of aortic stenosis in patients who previously had none. Pallikka et al also found that, at 5 years, only 20% of patients had not undergone aortic valve replacement or had not died of cardiovascular causes.20

Many researchers advocate surgical aortic valve replacement for severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis. However, the operative risk is 3% overall and has to be weighed against the 1%-per-year risk of death in patients who do not undergo surgery. Therefore, we need a way to identify a subgroup of patients without symptoms who are at higher risk.

Exercise stress testing

Some patients might subconsciously adapt to aortic stenosis by reducing their physical activity. In these “asymptomatic” patients, exercise stress testing can uncover symptoms in around 40%.21

In a group of people with severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis, a positive treadmill test (defined as an abnormal blood pressure response, ST segment changes, symptoms such as limiting dyspnea, chest discomfort, or dizziness on a modified Bruce protocol, or complex ventricular arrhythmias) strongly predicted the onset of symptoms or the need for surgery. At 24 months, only 19% of those who had had a positive exercise test result remained alive, symptom-free, and without valve replacement, compared with 85% of those who had had a negative test result.22

Subsequent study found that symptoms with exercise were the strongest predictor of the onset of symptoms of aortic stenosis, especially among patients under age 70, in whom the symptoms of fatigue and breathlessness are more specific than in the elderly.23

Recommendation. Exercise testing is recommended in patients with severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis (class IIa indication, level of evidence B) as a means of identifying those who are likely to develop symptoms or who might benefit from surgery. Surgery for those who have an abnormal exercise stress response receives a class IIb, level of evidence C recommendation from the ACC/AHA and a class IC from the European Society of Cardiology.24,25

Exercise stress echocardiography to measure change in transvalvular gradient

Emerging data suggest that exercise stress echocardiography may provide incremental prognostic information in patients with severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis. In fact, two studies showed that an exercise-induced increase in the transvalvular gradient of more than 20 mm Hg26 or 18 mm Hg27 predicts future cardiac events. This increase reflects fixed valve stenosis with limited valve compliance.

Other echocardiographic variables

Additional data have shown that severe aortic stenosis (valve area < 0.6 cm2), aortic velocity greater than 4.0 m/s, and severe calcification confer a higher risk of developing symptoms.28,29

Recommendation. The ACC and AHA say that surgical aortic valve replacement may be considered in patients without symptoms who have a high likelihood of rapid progression of aortic stenosis (ie, who are older or have severe calcification or coronary artery disease) or if surgery might be delayed at the time of symptom onset (class IIb, level of evidence C).

Aortic valve replacement can also be considered for extremely severe aortic stenosis (valve area < 0.6 cm2), mean gradient > 60 mm Hg, and velocity > 5.0 m/s if the operative mortality rate is 1.0% or less (class IIb, level of evidence C).

Brain natriuretic peptide levels

Measuring the brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) level may help if symptoms are unclear; higher levels suggest cardiac decompensation.28

One study showed that BNP levels are higher in patients with symptomatic aortic stenosis than in those with asymptomatic severe disease, and correlate with symptom severity.30 In addition, in two other studies, higher BNP and N-terminal BNP levels were shown to predict disease progression, symptom onset, and poorer event-free survival.31,32

In severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis, natriuretic peptides may provide important prognostic information beyond clinical and echocardiographic evaluation. Furthermore, in a recent study, Monin et al33 proposed a risk score that integrates peak aortic jet velocity, BNP level, and sex (women being at higher risk) in predicting who would benefit from early surgery in patients with severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis.33

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

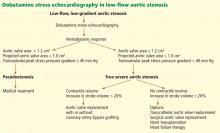

Low-output, low-gradient aortic stenosis: True severe stenosis vs pseudostenosis

Patients with a low ejection fraction (< 50%) and a high mean transvalvular gradient (> 30 or 40 mm Hg) pose no therapeutic dilemma. They have true afterload mismatch and improve markedly with surgery.34 However, patients with an even lower ejection fraction (< 35% or 40%) and a low mean transvalvular gradient (< 30 or 40 mm Hg) pose more of a problem.

It is hard to tell if these patients have true severe aortic stenosis or pseudostenosis due to primary myocardial dysfunction. In pseudostenosis, the aortic valves are moderately diseased, and leaflet opening is reduced by a failing ventricle. When cardiac output is low, the formulae used to calculate the aortic valve area become less accurate, so that patients with cardiomyopathy who have only mild or moderate aortic stenosis may appear to have severe stenosis.

Patients with pseudostenosis have a high risk of dying during surgical aortic valve replacement, approaching 50%, and benefit more from evidence-based heart failure management.35,36 In patients with true stenosis, ventricular dysfunction is mainly a result of severe stenosis and should improve after aortic valve replacement.

Dobutamine stress echocardiography can be used in patients with low-flow, low-gradient aortic stenosis to distinguish true severe stenosis from pseudostenosis. Dobutamine, an inotropic drug, increases the stroke volume so that patients with true severe aortic stenosis increase their transvalvular gradient and velocity with no or minimal change in the valve area. Conversely, in patients with pseudostenosis, the increase in stroke volume will open the aortic valve further and cause no or minimal increase in transvalvular gradient and velocity, but will increase the calculated valve area, confirming that aortic stenosis only is mild to moderate.37

Patients with low-flow, low-gradient aortic stenosis are at higher risk during surgical aortic valve replacement. Many studies have reported a 30-day mortality rate between 9% and 18%, although risks vary considerably within this population.38,39

Contractile reserve. Dobutamine stress echocardiography has also been used to identify patients with severe aortic stenosis who can increase their ejection fraction and stroke volume (Figure 2).40,41 These patients are said to have “contractile reserve” and do better with surgery than those who lack adequate contractile reserve. Contractile reserve is defined as an increase of more than 20% in stroke volume during low-dose dobutamine infusion.42,43 In one small nonrandomized study, patients with contractile reserve had a 5% mortality rate at 30 days, compared with 32% in patients with no contractile reserve.44,45

In fact, patients with no contractile reserve have a high operative mortality rate during aortic valve replacement, but those who survive the operation have improvements in symptoms, functional class, and ejection fraction similar to those in patients who do have contractile reserve.46

On the other hand, if patients with no contractile reserve are treated conservatively, they have a much worse prognosis than those managed surgically.47 While it is true that patients without contractile reserve did not have a statistically significant difference in mortality rates with aortic valve replacement (P = .07) in a study by Monin et al,44 the difference was staggering between the group who underwent aortic valve replacement and the group who received medical treatment alone (hazard ratio = 0.47, 95% confidence interval 0.31–1.05, P = .07). The difference in the mortality rates may not have reached statistical significance because of the study’s small sample size.

A few years later, the same group published a similar paper with a larger study sample, focusing on patients with no contractile reserve. Using 42 propensity-matched patients, they found a statistically significantly higher 5-year survival rate in patients with no contractile reserve who underwent aortic valve replacement than in similar patients who received medical management (65% ± 11% vs 11 ± 7%, P = .019).47

Hence, surgery may be a better option than medical treatment for this select high-risk group despite the higher operative mortality risk. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation may also offer an interesting alternative to surgical aortic valve replacement in this particular subset of patients.48

Low-gradient ‘severe’ aortic stenosis with preserved ejection fraction or ‘paradoxically low-flow aortic stenosis’

Low-gradient “severe” aortic stenosis with a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction is a recently recognized clinical entity in patients with severe aortic stenosis who present with a lower-than-expected transvalvular gradient on the basis of generally accepted values.49 (A patient with severe aortic stenosis and preserved ejection fraction is expected to generate a mean transaortic gradient greater than 40 mm Hg.24) This situation remains incompletely understood but has been shown in retrospective studies to foretell a poor prognosis.50–52

This subgroup of patients has pronounced left ventricular concentric remodeling with a small left ventricular cavity, impaired left ventricular filling, and reduced systolic longitudinal myocardial shortening.44

Herrmann et al53 provided more insight into the pathophysiology by showing that patients with this condition exhibit more pronounced myocardial fibrosis on myocardial biopsy and more pronounced late subendocardial enhancement on magnetic resonance imaging. These patients also displayed a significant decrease in mitral ring displacement and systolic strain. These abnormalities result in a low stroke volume despite a preserved ejection fraction and consequently a lower transvalvular gradient (< 40 mm Hg).

This disease pattern, in which the low gradient is interpreted as mild to moderate aortic stenosis, may lead to underestimation of stenosis severity and, thus, to inappropriate delay of aortic valve replacement.

However, other conditions can cause this hemodynamic situation with a lower-than-expected gradient. It can arise from a small left ventricle that correlates with a small body size, yielding a lower-than-normal stroke volume, measurement errors in determining stroke volume and valve area by Doppler echocardiography, systemic hypertension (which can influence estimation of the gradient by Doppler echocardiography), and inconsistency in the definition of severe aortic stenosis in the current guidelines relating to cutoffs of valve area in relation to those of jet velocity and gradient.54

This subgroup of patients seems to be at a more advanced stage and has a poorer prognosis if treated medically rather than surgically. When symptomatic, low-gradient severe aortic stenosis should be treated surgically, with one study showing excellent outcomes with aortic valve replacement.50

However, a recent study by Jander et al55 showed that patients with low-gradient severe aortic stenosis and normal ejection fraction have outcomes similar to those in patients with moderate aortic stenosis, suggesting a strategy of medical therapy and close monitoring.55 Of note, the subset of patients reported in this substudy of the Simvastatin and Ezetimibe in Aortic Stenosis (SEAS) trial did not really fit the pattern of low-gradient severe aortic stenosis described by Hachicha et al50 and other groups.51,56 These patients had aortic valve areas in the severe range but mean transaortic gradients in the moderate range, and in light of the other echocardiographic findings in these patients, the area-gradient discordances were predominantly due to small body surface area and measurement errors. These patients indeed had near-normal left ventricular size, no left ventricular hypertrophy, and no evidence of concentric remodeling.

Finally, the findings of the study by Jander et al55 are discordant with those of another substudy of the SEAS trial,57 which reported that paradoxical low-flow aortic stenosis occurred in about 7% of the cohort (compared with 52% in the study by Jander et al55) and was associated with more pronounced concentric remodeling and more severe impairment of myocardial function.

Whether intervention in patients with low-gradient severe aortic stenosis and valve area less than 1.0 cm2 improves outcomes remains to be confirmed and reproduced in future prospective studies.

Elderly patients

The risks of cardiac surgery increase with age. Older patients may be more deconditioned and have more comorbidities than younger patients, placing them at greater risk of a poor outcome.

Several retrospective studies of valve replacement in octogenarians have found that operative mortality rates range from 5.7% to 9% during isolated aortic valve replacement.58–60 Note that, using the STS score, the operative mortality risk increases only from 1.2% in a 70-year-old man with no comorbidities to 1.8% in an 80-year-old man undergoing aortic valve replacement plus coronary artery bypass grafting.61

As in younger patients, valve replacement results in a significant survival benefit and symptomatic improvement. Yet up to 30% of patients with severe aortic stenosis are not referred for surgery because surgery is believed to be too risky.62 The conditions most frequently cited by physicians when declining to refer patients for surgery include a low ejection fraction, advanced age, and advanced comorbidities. None of these is an absolute contraindication to surgery.

A recent retrospective study of 443 elderly patients (mean age 79.5) showed that those with left ventricular concentric remodeling, lower stroke volume, elevated left ventricular filling pressures, and mildly elevated pulmonary artery pressures have a very bad prognosis, with a mortality rate of 50.5% at 3.3 ± 2.7 years.63

Despite the higher operative mortality risk, these patients face a dismal prognosis when treated medically and should be referred to a cardiologist or cardiothoracic surgeon for an assessment of their operative risk and, potentially, for referral for catheter-based valve replacement.

Acutely ill patients

In critically ill patients with aortic stenosis and cardiogenic shock, the use of intravenous sodium nitroprusside increases cardiac output and decreases pulmonary artery wedge pressure, allowing patients to transition to surgery or vasodilator therapy. The mechanism seems to be an increase in myocardial contractility rather than a decrease in peripheral resistance. The reduction in filling pressure and concurrent increase in coronary blood flow relieves ischemia and subsequently enhances contractility.64

TRANSCATHETER AORTIC VALVE REPLACEMENT

Until recently, patients with severe aortic stenosis who were deemed to be at high surgical risk were referred for balloon valvuloplasty as a palliative option. The procedure consists of balloon inflation across the aortic valve to relieve the stenosis.

Most patients have improved symptoms and a decrease in pressure gradient immediately after the procedure, but the results are not durable, with a high restenosis rate within 6 to 12 months and no decrease in the mortality rate.65 (There is some evidence that serial balloon dilation improves survival.66)

The procedure has several limitations, including a risk of embolic stroke, myocardial infarction, and, sometimes, perforation of the left ventricle. It is only used in people who do not wish to have surgery or as a bridge to surgical aortic valve replacement in hemodynamically unstable patients.

Advances in transcatheter technologies have made nonsurgical valve replacement a reality that is increasingly available to a broader population of patients. The first percutaneous valve replacement in a human was performed in 2002.67 Since then, multiple registries from centers around the world, especially in Europe, have shown that it can be performed in high-risk patients with outcomes very comparable to those of surgical aortic valve replacement as predicted by the STS score and EuroSCORE.68,69 Procedural success rates have increased from around 80% in the initial experience to over 95% in the most current series.70

Results from randomized trials

The long-awaited PARTNER A and B trials have been published.

The PARTNER B trial17 randomized patients with severe aortic stenosis who were not considered by the STS score to be suitable candidates for surgery to standard therapy (which included balloon valvoplasty in 84%) or transcatheter aortic valve replacement. There was a dramatic 20% absolute improvement in survival at 1 year with transcatheter replacement, with the survival curve continuing to diverge at 1 year. The rate of death from any cause was 30.7% with transcatheter aortic valve replacement vs 50.7% with standard therapy (hazard ratio with transcatheter replacement 0.55; P < .001).

The major concerns about transcatheter aortic valve replacement borne out in the study are procedural complications, namely stroke and vascular events. At 30 days, transcatheter replacement, as compared with standard therapy, was associated with a higher incidence of major stroke (5.0% vs 1.1%, P = .06) and major vascular complications (16.2% vs 1.1%, P < .001).17

On the other hand, the PARTNER A trial randomized high-risk patients deemed operable by the STS score to either transcatheter or surgical aortic valve replacement. The rate of death at 1 year from any cause was similar in both groups (24.2% vs 26.8%; P = .44), but again at the expense of higher rates of vascular complications (11.0% vs 3.2%, P < .001 at 30 days) and stroke (5.1% vs 2.4%; P = .07 at 1 year) in the transcatheter group. However, the surgical group had higher rates of major bleeding (19.5% vs 9.3%; P < .001) and new-onset atrial fibrillation (16.0% vs 8.6%, P = .06).71

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement has modernized the way we treat aortic stenosis and without a shred of doubt will become the standard of therapy for severe symptomatic aortic stenosis in patients who are not candidates for surgery. For the high-risk operable patient, the benefit of avoiding a sternotomy should be weighed against the higher risk of stroke and vascular complications with the transcatheter procedure. The availability of smaller delivery systems, better expertise, and better vascular access selection should decrease the rate of complications in the future.

- Stewart BF, Siscovick D, Lind BK, et al. Clinical factors associated with calcific aortic valve disease. Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997; 29:630–634.

- Iung B, Baron G, Butchart EG, et al. A prospective survey of patients with valvular heart disease in Europe: The Euro Heart Survey on Valvular Heart Disease. Eur Heart J 2003; 24:1231–1243.

- Ross J, Braunwald E. Aortic stenosis. Circulation 1968; 38(suppl 1):61–67.

- Schwarz F, Baumann P, Manthey J, et al. The effect of aortic valve replacement on survival. Circulation 1982; 66:1105–1110.

- Brown JM, O’Brien SM, Wu C, Sikora JA, Griffith BP, Gammie JS. Isolated aortic valve replacement in North America comprising 108,687 patients in 10 years: changes in risks, valve types, and outcomes in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009; 137:82–90.

- Kvidal P, Bergström R, Malm T, Ståhle E. Long-term follow-up of morbidity and mortality after aortic valve replacement with a mechanical valve prosthesis. Eur Heart J 2000; 21:1099–1111.

- Ståhle E, Kvidal P, Nyström SO, Bergström R. Long-term relative survival after primary heart valve replacement. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1997; 11:81–91.

- Sharma UC, Barenbrug P, Pokharel S, Dassen WR, Pinto YM, Maessen JG. Systematic review of the outcome of aortic valve replacement in patients with aortic stenosis. Ann Thorac Surg 2004; 78:90–95.

- Vaquette B, Corbineau H, Laurent M, et al. Valve replacement in patients with critical aortic stenosis and depressed left ventricular function: predictors of operative risk, left ventricular function recovery, and long term outcome. Heart 2005; 91:1324–1329.

- American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions; Society of Thoracic Surgeons, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Kanu C, et al. ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (writing committee to revise the 1998 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease): developed in collaboration with the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists: endorsed by the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation 2006; 114:e84–e231.

- Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K, et al; 2006 Writing Committee Members; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force. 2008 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 1998 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease): endorsed by the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation 2008; 118:e523–e661.

- Nashef SA, Roques F, Hammill BG, et al; EuroSCORE Project Group. Validation of European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation (EuroSCORE) in North American cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2002; 22:101–105.

- Grossi EA, Schwartz CF, Yu PJ, et al. High-risk aortic valve replacement: are the outcomes as bad as predicted? Ann Thorac Surg 2008; 85:102–106.

- Kalavrouziotis D, Li D, Buth KJ, Légaré JF. The European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation (EuroSCORE) is not appropriate for withholding surgery in high-risk patients with aortic stenosis: a retrospective cohort study. J Cardiothorac Surg 2009; 4:32.

- Dewey TM, Brown D, Ryan WH, Herbert MA, Prince SL, Mack MJ. Reliability of risk algorithms in predicting early and late operative outcomes in high-risk patients undergoing aortic valve replacement. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2008; 135:180–187.

- Wendt D, Osswald BR, Kayser K, et al. Society of Thoracic Surgeons score is superior to the EuroSCORE determining mortality in high risk patients undergoing isolated aortic valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg 2009; 88:468–474.

- Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, et al; PARTNER Trial Investigators. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:1597–1607.

- Smith WT, Ferguson TB, Ryan T, Landolfo CK, Peterson ED. Should coronary artery bypass graft surgery patients with mild or moderate aortic stenosis undergo concomitant aortic valve replacement? A decision analysis approach to the surgical dilemma. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004; 44:1241–1247.

- Pereira JJ, Balaban K, Lauer MS, Lytle B, Thomas JD, Garcia MJ. Aortic valve replacement in patients with mild or moderate aortic stenosis and coronary bypass surgery. Am J Med 2005; 118:735–742.

- Pellikka PA, Sarano ME, Nishimura RA, et al. Outcome of 622 adults with asymptomatic, hemodynamically significant aortic stenosis during prolonged follow-up. Circulation 2005; 111:3290–3295.

- Ennezat PV, Maréchaux S, Iung B, Chauvel C, LeJemtel TH, Pibarot P. Exercise testing and exercise stress echocardiography in asymptomatic aortic valve stenosis. Heart 2009; 95:877–884.

- Amato MC, Moffa PJ, Werner KE, Ramires JA. Treatment decision in asymptomatic aortic valve stenosis: role of exercise testing. Heart 2001; 86:381–386.

- Das P, Rimington H, Chambers J. Exercise testing to stratify risk in aortic stenosis. Eur Heart J 2005; 26:1309–1313.

- American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to revise the 1998 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease); Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K, et al. ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (writing Committee to Revise the 1998 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease) developed in collaboration with the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists endorsed by the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 48:e1–e148.

- Vahanian A, Baumgartner H, Bax J, et al; Task Force on the Management of Valvular Hearth Disease of the European Society of Cardiology; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease: The Task Force on the Management of Valvular Heart Disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2007; 28:230–268.

- Maréchaux S, Hachicha Z, Bellouin A, et al. Usefulness of exercise-stress echocardiography for risk stratification of true asymptomatic patients with aortic valve stenosis. Eur Heart J 2010; 31:1390–1397.

- Lancellotti P, Lebois F, Simon M, Tombeux C, Chauvel C, Pierard LA. Prognostic importance of quantitative exercise Doppler echocardiography in asymptomatic valvular aortic stenosis. Circulation 2005; 112(suppl 9):I377–1382.

- Otto CM. Valvular aortic stenosis: disease severity and timing of intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 47:2141–2151.

- Rosenhek R, Binder T, Porenta G, et al. Predictors of outcome in severe, asymptomatic aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med 2000; 343:611–617.

- Lim P, Monin JL, Monchi M, et al. Predictors of outcome in patients with severe aortic stenosis and normal left ventricular function: role of B-type natriuretic peptide. Eur Heart J 2004; 25:2048–2053.

- Gerber IL, Legget ME, West TM, Richards AM, Stewart RA. Usefulness of serial measurement of N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide plasma levels in asymptomatic patients with aortic stenosis to predict symptomatic deterioration. Am J Cardiol 2005; 95:898–901.

- Bergler-Klein J, Klaar U, Heger M, et al. Natriuretic peptides predict symptom-free survival and postoperative outcome in severe aortic stenosis. Circulation 2004; 109:2302–2308.

- Monin JL, Lancellotti P, Monchi M, et al. Risk score for predicting outcome in patients with asymptomatic aortic stenosis. Circulation 2009; 120:69–75.

- Carabello BA, Green LH, Grossman W, Cohn LH, Koster JK, Collins JJ. Hemodynamic determinants of prognosis of aortic valve replacement in critical aortic stenosis and advanced congestive heart failure. Circulation 1980; 62:42–48.

- Connolly HM, Oh JK, Schaff HV, et al. Severe aortic stenosis with low transvalvular gradient and severe left ventricular dysfunction: result of aortic valve replacement in 52 patients. Circulation 2000; 101:1940–1946.

- Brogan WC, Grayburn PA, Lange RA, Hillis LD. Prognosis after valve replacement in patients with severe aortic stenosis and a low transvalvular pressure gradient. J Am Coll Cardiol 1993; 21:1657–1660.

- Burwash IG. Low-flow, low-gradient aortic stenosis: from evaluation to treatment. Curr Opin Cardiol 2007; 22:84–91.

- Connolly HM, Oh JK, Orszulak TA, et al. Aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis with severe left ventricular dysfunction. Prognostic indicators. Circulation 1997; 95:2395–2400.

- Pai RG, Varadarajan P, Razzouk A. Survival benefit of aortic valve replacement in patients with severe aortic stenosis with low ejection fraction and low gradient with normal ejection fraction. Ann Thorac Surg 2008; 86:1781–1789.

- Blais C, Burwash IG, Mundigler G, et al. Projected valve area at normal flow rate improves the assessment of stenosis severity in patients with low-flow, low-gradient aortic stenosis: the multicenter TOPAS (Truly or Pseudo-Severe Aortic Stenosis) study. Circulation 2006; 113:711–721.

- Clavel MA, Burwash IG, Mundigler G, et al. Validation of conventional and simplified methods to calculate projected valve area at normal flow rate in patients with low flow, low gradient aortic stenosis: the multicenter TOPAS (True or Pseudo Severe Aortic Stenosis) study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2010; 23:380–386.

- Monin JL, Monchi M, Gest V, Duval-Moulin AM, Dubois-Rande JL, Gueret P. Aortic stenosis with severe left ventricular dysfunction and low transvalvular pressure gradients: risk stratification by low-dose dobutamine echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001; 37:2101–2107.

- Nishimura RA, Grantham JA, Connolly HM, Schaff HV, Higano ST, Holmes DR. Low-output, low-gradient aortic stenosis in patients with depressed left ventricular systolic function: the clinical utility of the dobutamine challenge in the catheterization laboratory. Circulation 2002; 106:809–813.

- Monin JL, Quéré JP, Monchi M, et al. Low-gradient aortic stenosis: operative risk stratification and predictors for long-term outcome: a multicenter study using dobutamine stress hemodynamics. Circulation 2003; 108:319–324.

- Monin JL, Guéret P. Calcified aortic stenosis with left ventricular dysfunction and low transvalvular gradients. Must one reject surgery in certain cases?. (In French.) Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss 2003; 96:864–870.

- Quere JP, Monin JL, Levy F, et al. Influence of preoperative left ventricular contractile reserve on postoperative ejection fraction in low-gradient aortic stenosis. Circulation 2006; 113:1738–1744.

- Tribouilloy C, Lévy F, Rusinaru D, et al. Outcome after aortic valve replacement for low-flow/low-gradient aortic stenosis without contractile reserve on dobutamine stress echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 53:1865–1873.

- Clavel MA, Webb JG, Rodés-Cabau J, et al. Comparison between transcatheter and surgical prosthetic valve implantation in patients with severe aortic stenosis and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. Circulation 2010; 122:1928–1936.

- Dumesnil JG, Pibarot P, Carabello B. Paradoxical low flow and/or low gradient severe aortic stenosis despite preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: implications for diagnosis and treatment. Eur Heart J 2010; 31:281–289.

- Hachicha Z, Dumesnil JG, Bogaty P, Pibarot P. Paradoxical low-flow, low-gradient severe aortic stenosis despite preserved ejection fraction is associated with higher afterload and reduced survival. Circulation 2007; 115:2856–2864.

- Barasch E, Fan D, Chukwu EO, et al. Severe isolated aortic stenosis with normal left ventricular systolic function and low transvalvular gradients: pathophysiologic and prognostic insights. J Heart Valve Dis 2008; 17:81–88.

- Dumesnil JG, Pibarot P, Carabello B. Paradoxical low flow and/or low gradient severe aortic stenosis despite preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: implications for diagnosis and treatment. Eur Heart J 2010; 31:281–289.

- Herrmann S, Störk S, Niemann M, et al. Low-gradient aortic valve stenosis myocardial fibrosis and its influence on function and outcome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58:402–412.

- Minners J, Allgeier M, Gohlke-Baerwolf C, Kienzle RP, Neumann FJ, Jander N. Inconsistent grading of aortic valve stenosis by current guidelines: haemodynamic studies in patients with apparently normal left ventricular function. Heart 2010; 96:1463–1468.

- Jander N, Minners J, Holme I, et al. Outcome of patients with low-gradient “severe” aortic stenosis and preserved ejection fraction. Circulation 2011; 123:887–895.

- Lancellotti P, Donal E, Magne J, et al. Impact of global left ventricular afterload on left ventricular function in asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis: a two-dimensional speckle-tracking study. Eur J Echocardiogr 2010; 11:537–543.

- Cramariuc D, Cioffi G, Rieck AE, et al. Low-flow aortic stenosis in asymptomatic patients: valvular-arterial impedance and systolic function from the SEAS Substudy. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2009; 2:390–399.

- Craver JM, Puskas JD, Weintraub WW, et al. 601 octogenarians undergoing cardiac surgery: outcome and comparison with younger age groups. Ann Thorac Surg 1999; 67:1104–1110.

- Alexander KP, Anstrom KJ, Muhlbaier LH, et al. Outcomes of cardiac surgery in patients > or = 80 years: results from the National Cardiovascular Network. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 35:731–738.

- Collart F, Feier H, Kerbaul F, et al. Valvular surgery in octogenarians: operative risks factors, evaluation of Euroscore and long term results. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2005; 27:276–280.

- Kurtz CE, Otto CM. Aortic stenosis: clinical aspects of diagnosis and management, with 10 illustrative case reports from a 25-year experience. Medicine (Baltimore) 2010; 89:349–379.

- Iung B, Cachier A, Baron G, et al. Decision-making in elderly patients with severe aortic stenosis: why are so many denied surgery? Eur Heart J 2005; 26:2714–2720.

- Kahn J, Petillo F, Rhee PDY, et al. Echocardiographic predictors of mortality in patients with severe isolated aortic stenosis and normal left ventricular ejection fraction who do not undergo aortic valve replacement. American Society of Echocardiography 2011 Scientific Sessions; June 13, 2011; Montreal, QC. http://www.abstractsonline.com/Plan/ViewAbstract.aspx?sKey=845e6287-66e1-4df5-8aef-8f5da16ef94a&cKey=5e5438dd-20df-48bfbee7-5f867fce66e6&mKey=%7bAE58A7EE-7140-41D6-9C7ED375E33DDABD%7d. Accessed May 27, 2012.

- Popovic ZB, Khot UN, Novaro GM, et al. Effects of sodium nitroprusside in aortic stenosis associated with severe heart failure: pressure-volume loop analysis using a numerical model. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2005; 288:H416–H423.

- Otto CM, Mickel MC, Kennedy JW, et al. Three-year outcome after balloon aortic valvuloplasty. Insights into prognosis of valvular aortic stenosis. Circulation 1994; 89:642–650.

- Letac B, Cribier A, Eltchaninoff H, Koning R, Derumeaux G. Evaluation of restenosis after balloon dilatation in adult aortic stenosis by repeat catheterization. Am Heart J 1991; 122:55–60.

- Cribier A, Eltchaninoff H, Bash A, et al. Percutaneous transcatheter implantation of an aortic valve prosthesis for calcific aortic stenosis: first human case description. Circulation 2002; 106:3006–3008.

- Grube E, Schuler G, Buellesfeld L, et al. Percutaneous aortic valve replacement for severe aortic stenosis in high-risk patients using the second- and current third-generation self-expanding CoreValve prosthesis: device success and 30-day clinical outcome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 50:69–76.

- Webb JG, Altwegg L, Masson JB, Al Bugami S, Al Ali A, Boone RA. A new transcatheter aortic valve and percutaneous valve delivery system. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 53:1855–1858.

- Clavel MA, Webb JG, Pibarot P, et al. Comparison of the hemodynamic performance of percutaneous and surgical bioprostheses for the treatment of severe aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 53:1883–1891.

- Smith CR, Leon MB, Mack MJ, et al; PARTNER Trial Investigators. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic-valve replacement in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2011; 364:2187–2198.

For some patients with aortic stenosis, the choice of management is simple; for others it is less so. Patients who have severe, symptomatic stenosis and who have low surgical risk should undergo aortic valve replacement. But if the stenosis is severe but asymptomatic, or if the patient is at higher surgical risk, or if there seems to be a mismatch in the hemodynamic variables, the situation is more complicated.

Fortunately, we have evidence and guidelines to go on. In this paper we review the indications for surgical and transcatheter aortic valve replacement, focusing on the areas of less certainty.

AN INDOLENT DISEASE, UNTIL IT ISN’T

Aortic stenosis is the most common valvular disease and the third most prevalent form of cardiovascular disease in the Western world, after hypertension and coronary artery disease. It is largely a disease of the elderly; its prevalence increases with age, and it is present in 2% to 7% of patients over age 65.1,2

At first, its course is indolent, as it progresses slowly over years to decades. However, this is followed by rapid clinical deterioration and a high death rate after symptoms develop.

SURGICAL AORTIC VALVE REPLACEMENT FOR SEVERE SYMPTOMATIC STENOSIS

Classic symptoms of aortic stenosis include angina, heart failure, and syncope. Once symptoms appear, patients with severe aortic stenosis should be promptly referred for surgical aortic valve replacement, as survival is poor unless outflow obstruction is relieved (Figure 1). The onset of symptoms confers a poor prognosis: patients die within an average of 5 years after the onset of angina, 3 years after the onset of syncope, and 2 years after the onset of heart failure symptoms. The overall mortality rate is 75% at 3 years without surgery.3,4 Furthermore, 8% to 34% of patients with symptoms die suddenly.

Advances in prosthetic-valve design, cardiopulmonary bypass, surgical technique, and anesthesia have steadily improved the outcomes of aortic valve surgery. An analysis of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) database in 2006 showed that during the previous decade the death rate during isolated aortic valve replacement decreased from 3.4% to 2.6%. For patients under age 70 at the time of surgery, the rate of death was 1.3%, and in those ages 80 to 85, the 30-day mortality rate was less than 5%.5

Patients who survive surgery enjoy a near-normal life expectancy: 99% survive at least 5 years, 85% at least 10 years, and 82% at least 15 years.6,7 Nearly all have improvement in their ejection fraction and heart failure symptoms, and those who had more advanced symptoms before surgery enjoy the most benefit afterward.8,9

Recommendation. Surgical valve replacement for symptomatic severe aortic stenosis receives a class I recommendation, level of evidence B, in the current guidelines from the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA).10,11 (See Table 1 for an explanation of the classes of recommendations and levels of evidence.)

TWO RISK-ASSESSMENT SCORES

There are two widely used scores for assessing the risk of aortic valve replacement: the European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation (EuroSCORE) and the STS score. Each has limitations.

The EuroSCORE was developed to predict the risk of dying in the hospital after adult cardiac surgery. It has been shown to predict the short-term and the long-term risk of death after heart valve surgery.12 Unfortunately, it overestimates the dangers of isolated aortic valve replacement in the patients at highest risk.13,14

The STS score, a logistic model, reflects more closely the operative and 30-day mortality rates for the patients at highest risk undergoing surgical aortic valve replacement.15,16 It was used to assess patients for surgical or transcatheter aortic valve replacement in the Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves (PARTNER) trial.17

These risk scores, though not perfect, are helpful as part of an overall estimation of risk that includes functional status, cardiac function, and comorbidities.

OTHER INDICATIONS FOR SURGICAL AORTIC VALVE REPLACEMENT

For patients with severe but asymptomatic aortic stenosis, surgical referral is standard practice in several circumstances.

Asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis with a low ejection fraction

Early studies found significant differences in survival beginning as early as 3 years after valve replacement between those whose preoperative ejection fraction was greater than 50% and those with a lower ejection fraction.4 Delaying surgery in these patients may lead to irreversible left ventricular dysfunction and worse survival.

Recommendation. The AHA and the ACC recommend surgical aortic valve replacement for patients who have no symptoms and whose left ventricular ejection fraction is less than 50% (class I indication, level of evidence C).10,11

Asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis in patients undergoing other cardiac surgery

Recommendation. Even if it is causing no symptoms, a severely stenotic aortic valve ought to be replaced if the ejection fraction is greater than 50% and the patient is undergoing another type of heart surgery, such as coronary artery bypass grafting, aortic surgery, or surgery on other heart valves (class I indication, level of evidence B).10,11

Asymptomatic moderate aortic stenosis in patients undergoing other cardiac surgery

When patients with a mildly or moderately stenotic aortic valve undergo other types of cardiac surgery, the decision to replace the valve is more difficult. Clinicians have to consider the increase in risk caused by adding aortic valve replacement to the planned surgery compared with the future likelihood of aortic stenosis progressing to a severe symptomatic state and eventually requiring a second cardiac surgery.

We have no evidence from a large prospective randomized controlled trial regarding prophylactic valve replacement at the time of coronary bypass surgery. However, a review of outcomes from the STS database between 1995 and 2000 found that patients under age 70 with a peak aortic gradient greater than “about 28 mm Hg” (correlating with a moderate degree of stenosis) benefited from prophylactic valve replacement at the time of coronary artery bypass surgery.18

These conclusions were supported by a subsequent retrospective analysis that found a significant survival advantage at 8 years in favor of prophylactic valve replacement at the time of bypass surgery for those with moderate (but not mild) aortic stenosis.19

Recommendation. The AHA and ACC give a class IIb endorsement, level of evidence B, for aortic valve replacement in patients with asymptomatic moderate aortic stenosis undergoing coronary bypass, valve, or aortic surgery.10,11

SEVERE ASYMPTOMATIC STENOSIS: WHICH TESTS HELP IN DECIDING?

A patient without symptoms presents a greater challenge than one with symptoms.

If surgery is deferred, the prognosis is usually excellent in such patients. Pellikka et al20 found that patients with severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis who did not undergo surgery had a rate of sudden cardiac death of about 1% per year of follow-up. However, physicians worry about missing the rapid development of symptoms of aortic stenosis in patients who previously had none. Pallikka et al also found that, at 5 years, only 20% of patients had not undergone aortic valve replacement or had not died of cardiovascular causes.20

Many researchers advocate surgical aortic valve replacement for severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis. However, the operative risk is 3% overall and has to be weighed against the 1%-per-year risk of death in patients who do not undergo surgery. Therefore, we need a way to identify a subgroup of patients without symptoms who are at higher risk.

Exercise stress testing

Some patients might subconsciously adapt to aortic stenosis by reducing their physical activity. In these “asymptomatic” patients, exercise stress testing can uncover symptoms in around 40%.21

In a group of people with severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis, a positive treadmill test (defined as an abnormal blood pressure response, ST segment changes, symptoms such as limiting dyspnea, chest discomfort, or dizziness on a modified Bruce protocol, or complex ventricular arrhythmias) strongly predicted the onset of symptoms or the need for surgery. At 24 months, only 19% of those who had had a positive exercise test result remained alive, symptom-free, and without valve replacement, compared with 85% of those who had had a negative test result.22

Subsequent study found that symptoms with exercise were the strongest predictor of the onset of symptoms of aortic stenosis, especially among patients under age 70, in whom the symptoms of fatigue and breathlessness are more specific than in the elderly.23

Recommendation. Exercise testing is recommended in patients with severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis (class IIa indication, level of evidence B) as a means of identifying those who are likely to develop symptoms or who might benefit from surgery. Surgery for those who have an abnormal exercise stress response receives a class IIb, level of evidence C recommendation from the ACC/AHA and a class IC from the European Society of Cardiology.24,25

Exercise stress echocardiography to measure change in transvalvular gradient

Emerging data suggest that exercise stress echocardiography may provide incremental prognostic information in patients with severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis. In fact, two studies showed that an exercise-induced increase in the transvalvular gradient of more than 20 mm Hg26 or 18 mm Hg27 predicts future cardiac events. This increase reflects fixed valve stenosis with limited valve compliance.

Other echocardiographic variables

Additional data have shown that severe aortic stenosis (valve area < 0.6 cm2), aortic velocity greater than 4.0 m/s, and severe calcification confer a higher risk of developing symptoms.28,29

Recommendation. The ACC and AHA say that surgical aortic valve replacement may be considered in patients without symptoms who have a high likelihood of rapid progression of aortic stenosis (ie, who are older or have severe calcification or coronary artery disease) or if surgery might be delayed at the time of symptom onset (class IIb, level of evidence C).

Aortic valve replacement can also be considered for extremely severe aortic stenosis (valve area < 0.6 cm2), mean gradient > 60 mm Hg, and velocity > 5.0 m/s if the operative mortality rate is 1.0% or less (class IIb, level of evidence C).

Brain natriuretic peptide levels

Measuring the brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) level may help if symptoms are unclear; higher levels suggest cardiac decompensation.28

One study showed that BNP levels are higher in patients with symptomatic aortic stenosis than in those with asymptomatic severe disease, and correlate with symptom severity.30 In addition, in two other studies, higher BNP and N-terminal BNP levels were shown to predict disease progression, symptom onset, and poorer event-free survival.31,32

In severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis, natriuretic peptides may provide important prognostic information beyond clinical and echocardiographic evaluation. Furthermore, in a recent study, Monin et al33 proposed a risk score that integrates peak aortic jet velocity, BNP level, and sex (women being at higher risk) in predicting who would benefit from early surgery in patients with severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis.33

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Low-output, low-gradient aortic stenosis: True severe stenosis vs pseudostenosis

Patients with a low ejection fraction (< 50%) and a high mean transvalvular gradient (> 30 or 40 mm Hg) pose no therapeutic dilemma. They have true afterload mismatch and improve markedly with surgery.34 However, patients with an even lower ejection fraction (< 35% or 40%) and a low mean transvalvular gradient (< 30 or 40 mm Hg) pose more of a problem.

It is hard to tell if these patients have true severe aortic stenosis or pseudostenosis due to primary myocardial dysfunction. In pseudostenosis, the aortic valves are moderately diseased, and leaflet opening is reduced by a failing ventricle. When cardiac output is low, the formulae used to calculate the aortic valve area become less accurate, so that patients with cardiomyopathy who have only mild or moderate aortic stenosis may appear to have severe stenosis.

Patients with pseudostenosis have a high risk of dying during surgical aortic valve replacement, approaching 50%, and benefit more from evidence-based heart failure management.35,36 In patients with true stenosis, ventricular dysfunction is mainly a result of severe stenosis and should improve after aortic valve replacement.

Dobutamine stress echocardiography can be used in patients with low-flow, low-gradient aortic stenosis to distinguish true severe stenosis from pseudostenosis. Dobutamine, an inotropic drug, increases the stroke volume so that patients with true severe aortic stenosis increase their transvalvular gradient and velocity with no or minimal change in the valve area. Conversely, in patients with pseudostenosis, the increase in stroke volume will open the aortic valve further and cause no or minimal increase in transvalvular gradient and velocity, but will increase the calculated valve area, confirming that aortic stenosis only is mild to moderate.37

Patients with low-flow, low-gradient aortic stenosis are at higher risk during surgical aortic valve replacement. Many studies have reported a 30-day mortality rate between 9% and 18%, although risks vary considerably within this population.38,39

Contractile reserve. Dobutamine stress echocardiography has also been used to identify patients with severe aortic stenosis who can increase their ejection fraction and stroke volume (Figure 2).40,41 These patients are said to have “contractile reserve” and do better with surgery than those who lack adequate contractile reserve. Contractile reserve is defined as an increase of more than 20% in stroke volume during low-dose dobutamine infusion.42,43 In one small nonrandomized study, patients with contractile reserve had a 5% mortality rate at 30 days, compared with 32% in patients with no contractile reserve.44,45

In fact, patients with no contractile reserve have a high operative mortality rate during aortic valve replacement, but those who survive the operation have improvements in symptoms, functional class, and ejection fraction similar to those in patients who do have contractile reserve.46

On the other hand, if patients with no contractile reserve are treated conservatively, they have a much worse prognosis than those managed surgically.47 While it is true that patients without contractile reserve did not have a statistically significant difference in mortality rates with aortic valve replacement (P = .07) in a study by Monin et al,44 the difference was staggering between the group who underwent aortic valve replacement and the group who received medical treatment alone (hazard ratio = 0.47, 95% confidence interval 0.31–1.05, P = .07). The difference in the mortality rates may not have reached statistical significance because of the study’s small sample size.

A few years later, the same group published a similar paper with a larger study sample, focusing on patients with no contractile reserve. Using 42 propensity-matched patients, they found a statistically significantly higher 5-year survival rate in patients with no contractile reserve who underwent aortic valve replacement than in similar patients who received medical management (65% ± 11% vs 11 ± 7%, P = .019).47

Hence, surgery may be a better option than medical treatment for this select high-risk group despite the higher operative mortality risk. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation may also offer an interesting alternative to surgical aortic valve replacement in this particular subset of patients.48

Low-gradient ‘severe’ aortic stenosis with preserved ejection fraction or ‘paradoxically low-flow aortic stenosis’

Low-gradient “severe” aortic stenosis with a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction is a recently recognized clinical entity in patients with severe aortic stenosis who present with a lower-than-expected transvalvular gradient on the basis of generally accepted values.49 (A patient with severe aortic stenosis and preserved ejection fraction is expected to generate a mean transaortic gradient greater than 40 mm Hg.24) This situation remains incompletely understood but has been shown in retrospective studies to foretell a poor prognosis.50–52

This subgroup of patients has pronounced left ventricular concentric remodeling with a small left ventricular cavity, impaired left ventricular filling, and reduced systolic longitudinal myocardial shortening.44

Herrmann et al53 provided more insight into the pathophysiology by showing that patients with this condition exhibit more pronounced myocardial fibrosis on myocardial biopsy and more pronounced late subendocardial enhancement on magnetic resonance imaging. These patients also displayed a significant decrease in mitral ring displacement and systolic strain. These abnormalities result in a low stroke volume despite a preserved ejection fraction and consequently a lower transvalvular gradient (< 40 mm Hg).

This disease pattern, in which the low gradient is interpreted as mild to moderate aortic stenosis, may lead to underestimation of stenosis severity and, thus, to inappropriate delay of aortic valve replacement.

However, other conditions can cause this hemodynamic situation with a lower-than-expected gradient. It can arise from a small left ventricle that correlates with a small body size, yielding a lower-than-normal stroke volume, measurement errors in determining stroke volume and valve area by Doppler echocardiography, systemic hypertension (which can influence estimation of the gradient by Doppler echocardiography), and inconsistency in the definition of severe aortic stenosis in the current guidelines relating to cutoffs of valve area in relation to those of jet velocity and gradient.54

This subgroup of patients seems to be at a more advanced stage and has a poorer prognosis if treated medically rather than surgically. When symptomatic, low-gradient severe aortic stenosis should be treated surgically, with one study showing excellent outcomes with aortic valve replacement.50

However, a recent study by Jander et al55 showed that patients with low-gradient severe aortic stenosis and normal ejection fraction have outcomes similar to those in patients with moderate aortic stenosis, suggesting a strategy of medical therapy and close monitoring.55 Of note, the subset of patients reported in this substudy of the Simvastatin and Ezetimibe in Aortic Stenosis (SEAS) trial did not really fit the pattern of low-gradient severe aortic stenosis described by Hachicha et al50 and other groups.51,56 These patients had aortic valve areas in the severe range but mean transaortic gradients in the moderate range, and in light of the other echocardiographic findings in these patients, the area-gradient discordances were predominantly due to small body surface area and measurement errors. These patients indeed had near-normal left ventricular size, no left ventricular hypertrophy, and no evidence of concentric remodeling.

Finally, the findings of the study by Jander et al55 are discordant with those of another substudy of the SEAS trial,57 which reported that paradoxical low-flow aortic stenosis occurred in about 7% of the cohort (compared with 52% in the study by Jander et al55) and was associated with more pronounced concentric remodeling and more severe impairment of myocardial function.

Whether intervention in patients with low-gradient severe aortic stenosis and valve area less than 1.0 cm2 improves outcomes remains to be confirmed and reproduced in future prospective studies.

Elderly patients

The risks of cardiac surgery increase with age. Older patients may be more deconditioned and have more comorbidities than younger patients, placing them at greater risk of a poor outcome.

Several retrospective studies of valve replacement in octogenarians have found that operative mortality rates range from 5.7% to 9% during isolated aortic valve replacement.58–60 Note that, using the STS score, the operative mortality risk increases only from 1.2% in a 70-year-old man with no comorbidities to 1.8% in an 80-year-old man undergoing aortic valve replacement plus coronary artery bypass grafting.61

As in younger patients, valve replacement results in a significant survival benefit and symptomatic improvement. Yet up to 30% of patients with severe aortic stenosis are not referred for surgery because surgery is believed to be too risky.62 The conditions most frequently cited by physicians when declining to refer patients for surgery include a low ejection fraction, advanced age, and advanced comorbidities. None of these is an absolute contraindication to surgery.

A recent retrospective study of 443 elderly patients (mean age 79.5) showed that those with left ventricular concentric remodeling, lower stroke volume, elevated left ventricular filling pressures, and mildly elevated pulmonary artery pressures have a very bad prognosis, with a mortality rate of 50.5% at 3.3 ± 2.7 years.63

Despite the higher operative mortality risk, these patients face a dismal prognosis when treated medically and should be referred to a cardiologist or cardiothoracic surgeon for an assessment of their operative risk and, potentially, for referral for catheter-based valve replacement.

Acutely ill patients

In critically ill patients with aortic stenosis and cardiogenic shock, the use of intravenous sodium nitroprusside increases cardiac output and decreases pulmonary artery wedge pressure, allowing patients to transition to surgery or vasodilator therapy. The mechanism seems to be an increase in myocardial contractility rather than a decrease in peripheral resistance. The reduction in filling pressure and concurrent increase in coronary blood flow relieves ischemia and subsequently enhances contractility.64

TRANSCATHETER AORTIC VALVE REPLACEMENT

Until recently, patients with severe aortic stenosis who were deemed to be at high surgical risk were referred for balloon valvuloplasty as a palliative option. The procedure consists of balloon inflation across the aortic valve to relieve the stenosis.

Most patients have improved symptoms and a decrease in pressure gradient immediately after the procedure, but the results are not durable, with a high restenosis rate within 6 to 12 months and no decrease in the mortality rate.65 (There is some evidence that serial balloon dilation improves survival.66)

The procedure has several limitations, including a risk of embolic stroke, myocardial infarction, and, sometimes, perforation of the left ventricle. It is only used in people who do not wish to have surgery or as a bridge to surgical aortic valve replacement in hemodynamically unstable patients.

Advances in transcatheter technologies have made nonsurgical valve replacement a reality that is increasingly available to a broader population of patients. The first percutaneous valve replacement in a human was performed in 2002.67 Since then, multiple registries from centers around the world, especially in Europe, have shown that it can be performed in high-risk patients with outcomes very comparable to those of surgical aortic valve replacement as predicted by the STS score and EuroSCORE.68,69 Procedural success rates have increased from around 80% in the initial experience to over 95% in the most current series.70

Results from randomized trials

The long-awaited PARTNER A and B trials have been published.

The PARTNER B trial17 randomized patients with severe aortic stenosis who were not considered by the STS score to be suitable candidates for surgery to standard therapy (which included balloon valvoplasty in 84%) or transcatheter aortic valve replacement. There was a dramatic 20% absolute improvement in survival at 1 year with transcatheter replacement, with the survival curve continuing to diverge at 1 year. The rate of death from any cause was 30.7% with transcatheter aortic valve replacement vs 50.7% with standard therapy (hazard ratio with transcatheter replacement 0.55; P < .001).

The major concerns about transcatheter aortic valve replacement borne out in the study are procedural complications, namely stroke and vascular events. At 30 days, transcatheter replacement, as compared with standard therapy, was associated with a higher incidence of major stroke (5.0% vs 1.1%, P = .06) and major vascular complications (16.2% vs 1.1%, P < .001).17

On the other hand, the PARTNER A trial randomized high-risk patients deemed operable by the STS score to either transcatheter or surgical aortic valve replacement. The rate of death at 1 year from any cause was similar in both groups (24.2% vs 26.8%; P = .44), but again at the expense of higher rates of vascular complications (11.0% vs 3.2%, P < .001 at 30 days) and stroke (5.1% vs 2.4%; P = .07 at 1 year) in the transcatheter group. However, the surgical group had higher rates of major bleeding (19.5% vs 9.3%; P < .001) and new-onset atrial fibrillation (16.0% vs 8.6%, P = .06).71

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement has modernized the way we treat aortic stenosis and without a shred of doubt will become the standard of therapy for severe symptomatic aortic stenosis in patients who are not candidates for surgery. For the high-risk operable patient, the benefit of avoiding a sternotomy should be weighed against the higher risk of stroke and vascular complications with the transcatheter procedure. The availability of smaller delivery systems, better expertise, and better vascular access selection should decrease the rate of complications in the future.

For some patients with aortic stenosis, the choice of management is simple; for others it is less so. Patients who have severe, symptomatic stenosis and who have low surgical risk should undergo aortic valve replacement. But if the stenosis is severe but asymptomatic, or if the patient is at higher surgical risk, or if there seems to be a mismatch in the hemodynamic variables, the situation is more complicated.

Fortunately, we have evidence and guidelines to go on. In this paper we review the indications for surgical and transcatheter aortic valve replacement, focusing on the areas of less certainty.

AN INDOLENT DISEASE, UNTIL IT ISN’T

Aortic stenosis is the most common valvular disease and the third most prevalent form of cardiovascular disease in the Western world, after hypertension and coronary artery disease. It is largely a disease of the elderly; its prevalence increases with age, and it is present in 2% to 7% of patients over age 65.1,2

At first, its course is indolent, as it progresses slowly over years to decades. However, this is followed by rapid clinical deterioration and a high death rate after symptoms develop.

SURGICAL AORTIC VALVE REPLACEMENT FOR SEVERE SYMPTOMATIC STENOSIS

Classic symptoms of aortic stenosis include angina, heart failure, and syncope. Once symptoms appear, patients with severe aortic stenosis should be promptly referred for surgical aortic valve replacement, as survival is poor unless outflow obstruction is relieved (Figure 1). The onset of symptoms confers a poor prognosis: patients die within an average of 5 years after the onset of angina, 3 years after the onset of syncope, and 2 years after the onset of heart failure symptoms. The overall mortality rate is 75% at 3 years without surgery.3,4 Furthermore, 8% to 34% of patients with symptoms die suddenly.

Advances in prosthetic-valve design, cardiopulmonary bypass, surgical technique, and anesthesia have steadily improved the outcomes of aortic valve surgery. An analysis of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) database in 2006 showed that during the previous decade the death rate during isolated aortic valve replacement decreased from 3.4% to 2.6%. For patients under age 70 at the time of surgery, the rate of death was 1.3%, and in those ages 80 to 85, the 30-day mortality rate was less than 5%.5

Patients who survive surgery enjoy a near-normal life expectancy: 99% survive at least 5 years, 85% at least 10 years, and 82% at least 15 years.6,7 Nearly all have improvement in their ejection fraction and heart failure symptoms, and those who had more advanced symptoms before surgery enjoy the most benefit afterward.8,9

Recommendation. Surgical valve replacement for symptomatic severe aortic stenosis receives a class I recommendation, level of evidence B, in the current guidelines from the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA).10,11 (See Table 1 for an explanation of the classes of recommendations and levels of evidence.)

TWO RISK-ASSESSMENT SCORES

There are two widely used scores for assessing the risk of aortic valve replacement: the European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation (EuroSCORE) and the STS score. Each has limitations.

The EuroSCORE was developed to predict the risk of dying in the hospital after adult cardiac surgery. It has been shown to predict the short-term and the long-term risk of death after heart valve surgery.12 Unfortunately, it overestimates the dangers of isolated aortic valve replacement in the patients at highest risk.13,14

The STS score, a logistic model, reflects more closely the operative and 30-day mortality rates for the patients at highest risk undergoing surgical aortic valve replacement.15,16 It was used to assess patients for surgical or transcatheter aortic valve replacement in the Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves (PARTNER) trial.17

These risk scores, though not perfect, are helpful as part of an overall estimation of risk that includes functional status, cardiac function, and comorbidities.

OTHER INDICATIONS FOR SURGICAL AORTIC VALVE REPLACEMENT

For patients with severe but asymptomatic aortic stenosis, surgical referral is standard practice in several circumstances.

Asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis with a low ejection fraction

Early studies found significant differences in survival beginning as early as 3 years after valve replacement between those whose preoperative ejection fraction was greater than 50% and those with a lower ejection fraction.4 Delaying surgery in these patients may lead to irreversible left ventricular dysfunction and worse survival.

Recommendation. The AHA and the ACC recommend surgical aortic valve replacement for patients who have no symptoms and whose left ventricular ejection fraction is less than 50% (class I indication, level of evidence C).10,11

Asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis in patients undergoing other cardiac surgery

Recommendation. Even if it is causing no symptoms, a severely stenotic aortic valve ought to be replaced if the ejection fraction is greater than 50% and the patient is undergoing another type of heart surgery, such as coronary artery bypass grafting, aortic surgery, or surgery on other heart valves (class I indication, level of evidence B).10,11

Asymptomatic moderate aortic stenosis in patients undergoing other cardiac surgery

When patients with a mildly or moderately stenotic aortic valve undergo other types of cardiac surgery, the decision to replace the valve is more difficult. Clinicians have to consider the increase in risk caused by adding aortic valve replacement to the planned surgery compared with the future likelihood of aortic stenosis progressing to a severe symptomatic state and eventually requiring a second cardiac surgery.

We have no evidence from a large prospective randomized controlled trial regarding prophylactic valve replacement at the time of coronary bypass surgery. However, a review of outcomes from the STS database between 1995 and 2000 found that patients under age 70 with a peak aortic gradient greater than “about 28 mm Hg” (correlating with a moderate degree of stenosis) benefited from prophylactic valve replacement at the time of coronary artery bypass surgery.18

These conclusions were supported by a subsequent retrospective analysis that found a significant survival advantage at 8 years in favor of prophylactic valve replacement at the time of bypass surgery for those with moderate (but not mild) aortic stenosis.19

Recommendation. The AHA and ACC give a class IIb endorsement, level of evidence B, for aortic valve replacement in patients with asymptomatic moderate aortic stenosis undergoing coronary bypass, valve, or aortic surgery.10,11

SEVERE ASYMPTOMATIC STENOSIS: WHICH TESTS HELP IN DECIDING?

A patient without symptoms presents a greater challenge than one with symptoms.

If surgery is deferred, the prognosis is usually excellent in such patients. Pellikka et al20 found that patients with severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis who did not undergo surgery had a rate of sudden cardiac death of about 1% per year of follow-up. However, physicians worry about missing the rapid development of symptoms of aortic stenosis in patients who previously had none. Pallikka et al also found that, at 5 years, only 20% of patients had not undergone aortic valve replacement or had not died of cardiovascular causes.20

Many researchers advocate surgical aortic valve replacement for severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis. However, the operative risk is 3% overall and has to be weighed against the 1%-per-year risk of death in patients who do not undergo surgery. Therefore, we need a way to identify a subgroup of patients without symptoms who are at higher risk.

Exercise stress testing

Some patients might subconsciously adapt to aortic stenosis by reducing their physical activity. In these “asymptomatic” patients, exercise stress testing can uncover symptoms in around 40%.21

In a group of people with severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis, a positive treadmill test (defined as an abnormal blood pressure response, ST segment changes, symptoms such as limiting dyspnea, chest discomfort, or dizziness on a modified Bruce protocol, or complex ventricular arrhythmias) strongly predicted the onset of symptoms or the need for surgery. At 24 months, only 19% of those who had had a positive exercise test result remained alive, symptom-free, and without valve replacement, compared with 85% of those who had had a negative test result.22

Subsequent study found that symptoms with exercise were the strongest predictor of the onset of symptoms of aortic stenosis, especially among patients under age 70, in whom the symptoms of fatigue and breathlessness are more specific than in the elderly.23

Recommendation. Exercise testing is recommended in patients with severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis (class IIa indication, level of evidence B) as a means of identifying those who are likely to develop symptoms or who might benefit from surgery. Surgery for those who have an abnormal exercise stress response receives a class IIb, level of evidence C recommendation from the ACC/AHA and a class IC from the European Society of Cardiology.24,25

Exercise stress echocardiography to measure change in transvalvular gradient

Emerging data suggest that exercise stress echocardiography may provide incremental prognostic information in patients with severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis. In fact, two studies showed that an exercise-induced increase in the transvalvular gradient of more than 20 mm Hg26 or 18 mm Hg27 predicts future cardiac events. This increase reflects fixed valve stenosis with limited valve compliance.

Other echocardiographic variables