User login

Open-capsule PPIs linked to faster ulcer healing after Roux-en-Y

The use of proton pump inhibitors in opened instead of closed capsules was associated with a nearly fourfold shorter median healing time among patients who developed marginal ulcers after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, in a single-center retrospective cohort study.

In contrast, the specific class of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) did not affect healing times, wrote Allison R. Schulman, MD, and her associates at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. The report is in the April issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.10.015). “Given these results and the high prevalence of marginal ulceration in this patient population, further study in a randomized controlled setting is warranted, and use of open-capsule PPIs should be considered as a low-risk, low-cost alternative,” they added.

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is one of the most common types of gastric bypass surgeries in the world, and up to 16% of patients develop postsurgical ulcers at the gastrojejunal anastomosis, the investigators noted. Acidity is a prime suspect in these “marginal ulcerations” because bypassing the acid-buffering duodenum exposes the jejunum to acid from the stomach, they added. High-dose PPIs are the main treatment, but there is no consensus on the formulation or dose of therapy. Because Roux-en-Y creates a small gastric pouch and hastens small-bowel transit, closed capsules designed to break down in the stomach “even may make their way to the colon before breakdown occurs,” they wrote.

They reviewed medical charts from patients who developed marginal ulcerations after undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass at their hospital from 2000 through 2015. A total of 115 patients received open-capsule PPIs and 49 received intact capsules. All were followed until their ulcers healed.

For the open-capsule group, median time to healing was 91 days, compared with 342 days for the closed-capsule group (P less than .001). Importantly, capsule type was the only independent predictor of healing time (hazard ratio, 6.0; 95% confidence interval, 3.7 to 9.8; P less than .001) in a Cox regression model that included other known correlates of ulcer healing, including age, smoking status, the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, Helicobacter pylori infection, the length of the gastric pouch, and the presence of fistulae or foreign bodies such as sutures or staples.

The use of sucralfate also did not affect time to ulcer healing, reflecting “many previous studies showing a lack of definitive benefit to this medication,” the researchers said. The findings have “tremendous implications” for health care utilization, they added. Indeed, patients who received open-capsule PPIs needed significantly fewer endoscopic procedures (median, 1.2 versus 1.8; P = .02) and used fewer health care resources overall ($7,206 versus $11,009; P = .05) compared with those prescribed intact PPI capsules.

This study was limited to patients who developed ulcer symptoms and underwent repeated surveillance endoscopies after surgery, the researchers noted. Selection bias is always a concern with retrospective studies, but insurers always covered both types of therapy and the choice of capsule type was entirely up to providers, all of whom consistently prescribed either open- or closed-capsule PPI therapy, they added.

The investigators did not acknowledge external funding sources. Dr. Schulman and four coinvestigators reported having no competing interests. One coinvestigator disclosed ties to Olympus, Boston Scientific, and Covidien.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are frequently employed to treat marginal ulcers after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB). In a retrospective study, Schulman et al. compared intact vs. “open” PPI capsules.

They state that “this may be overcome by use of a soluble form of PPI,” but don’t state what is meant by “soluble PPI” or how the open-capsule PPI was delivered. Among the PPIs they reported using to compare intact vs. open capsules was Protonix [pantoprazole] which is not produced as a capsule, and soluble Prevacid [lansoprazole], which is an orally disintegrating tablet that should provide characteristics similar to an “open capsule.”

PPI capsules provide PPI in enteric-coated granules, which are designed to protect the PPI from acid degradation in the stomach of individuals with intact gastrointestinal tracts and allow more of the PPI dose to reach the small intestine where it is absorbed. If capsules really fail to release their enteric-coated granules until very distally in RYGB patients, bypassing this step to allow earlier release of PPI makes intuitive sense; formulations such as suspensions and rapidly disintegrating tablets that deliver enteric-coated granules without capsules are currently available.

However, if this is an issue, administering a suspension of uncoated PPI with bicarbonate potentially might be the most attractive option, given more rapid absorption than PPI delivered as enteric-coated granules.

Loren Laine, MD, AGAF, professor of medicine, digestive diseases, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has no conflicts of interest.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are frequently employed to treat marginal ulcers after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB). In a retrospective study, Schulman et al. compared intact vs. “open” PPI capsules.

They state that “this may be overcome by use of a soluble form of PPI,” but don’t state what is meant by “soluble PPI” or how the open-capsule PPI was delivered. Among the PPIs they reported using to compare intact vs. open capsules was Protonix [pantoprazole] which is not produced as a capsule, and soluble Prevacid [lansoprazole], which is an orally disintegrating tablet that should provide characteristics similar to an “open capsule.”

PPI capsules provide PPI in enteric-coated granules, which are designed to protect the PPI from acid degradation in the stomach of individuals with intact gastrointestinal tracts and allow more of the PPI dose to reach the small intestine where it is absorbed. If capsules really fail to release their enteric-coated granules until very distally in RYGB patients, bypassing this step to allow earlier release of PPI makes intuitive sense; formulations such as suspensions and rapidly disintegrating tablets that deliver enteric-coated granules without capsules are currently available.

However, if this is an issue, administering a suspension of uncoated PPI with bicarbonate potentially might be the most attractive option, given more rapid absorption than PPI delivered as enteric-coated granules.

Loren Laine, MD, AGAF, professor of medicine, digestive diseases, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has no conflicts of interest.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are frequently employed to treat marginal ulcers after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB). In a retrospective study, Schulman et al. compared intact vs. “open” PPI capsules.

They state that “this may be overcome by use of a soluble form of PPI,” but don’t state what is meant by “soluble PPI” or how the open-capsule PPI was delivered. Among the PPIs they reported using to compare intact vs. open capsules was Protonix [pantoprazole] which is not produced as a capsule, and soluble Prevacid [lansoprazole], which is an orally disintegrating tablet that should provide characteristics similar to an “open capsule.”

PPI capsules provide PPI in enteric-coated granules, which are designed to protect the PPI from acid degradation in the stomach of individuals with intact gastrointestinal tracts and allow more of the PPI dose to reach the small intestine where it is absorbed. If capsules really fail to release their enteric-coated granules until very distally in RYGB patients, bypassing this step to allow earlier release of PPI makes intuitive sense; formulations such as suspensions and rapidly disintegrating tablets that deliver enteric-coated granules without capsules are currently available.

However, if this is an issue, administering a suspension of uncoated PPI with bicarbonate potentially might be the most attractive option, given more rapid absorption than PPI delivered as enteric-coated granules.

Loren Laine, MD, AGAF, professor of medicine, digestive diseases, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has no conflicts of interest.

The use of proton pump inhibitors in opened instead of closed capsules was associated with a nearly fourfold shorter median healing time among patients who developed marginal ulcers after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, in a single-center retrospective cohort study.

In contrast, the specific class of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) did not affect healing times, wrote Allison R. Schulman, MD, and her associates at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. The report is in the April issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.10.015). “Given these results and the high prevalence of marginal ulceration in this patient population, further study in a randomized controlled setting is warranted, and use of open-capsule PPIs should be considered as a low-risk, low-cost alternative,” they added.

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is one of the most common types of gastric bypass surgeries in the world, and up to 16% of patients develop postsurgical ulcers at the gastrojejunal anastomosis, the investigators noted. Acidity is a prime suspect in these “marginal ulcerations” because bypassing the acid-buffering duodenum exposes the jejunum to acid from the stomach, they added. High-dose PPIs are the main treatment, but there is no consensus on the formulation or dose of therapy. Because Roux-en-Y creates a small gastric pouch and hastens small-bowel transit, closed capsules designed to break down in the stomach “even may make their way to the colon before breakdown occurs,” they wrote.

They reviewed medical charts from patients who developed marginal ulcerations after undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass at their hospital from 2000 through 2015. A total of 115 patients received open-capsule PPIs and 49 received intact capsules. All were followed until their ulcers healed.

For the open-capsule group, median time to healing was 91 days, compared with 342 days for the closed-capsule group (P less than .001). Importantly, capsule type was the only independent predictor of healing time (hazard ratio, 6.0; 95% confidence interval, 3.7 to 9.8; P less than .001) in a Cox regression model that included other known correlates of ulcer healing, including age, smoking status, the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, Helicobacter pylori infection, the length of the gastric pouch, and the presence of fistulae or foreign bodies such as sutures or staples.

The use of sucralfate also did not affect time to ulcer healing, reflecting “many previous studies showing a lack of definitive benefit to this medication,” the researchers said. The findings have “tremendous implications” for health care utilization, they added. Indeed, patients who received open-capsule PPIs needed significantly fewer endoscopic procedures (median, 1.2 versus 1.8; P = .02) and used fewer health care resources overall ($7,206 versus $11,009; P = .05) compared with those prescribed intact PPI capsules.

This study was limited to patients who developed ulcer symptoms and underwent repeated surveillance endoscopies after surgery, the researchers noted. Selection bias is always a concern with retrospective studies, but insurers always covered both types of therapy and the choice of capsule type was entirely up to providers, all of whom consistently prescribed either open- or closed-capsule PPI therapy, they added.

The investigators did not acknowledge external funding sources. Dr. Schulman and four coinvestigators reported having no competing interests. One coinvestigator disclosed ties to Olympus, Boston Scientific, and Covidien.

The use of proton pump inhibitors in opened instead of closed capsules was associated with a nearly fourfold shorter median healing time among patients who developed marginal ulcers after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, in a single-center retrospective cohort study.

In contrast, the specific class of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) did not affect healing times, wrote Allison R. Schulman, MD, and her associates at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. The report is in the April issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.10.015). “Given these results and the high prevalence of marginal ulceration in this patient population, further study in a randomized controlled setting is warranted, and use of open-capsule PPIs should be considered as a low-risk, low-cost alternative,” they added.

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is one of the most common types of gastric bypass surgeries in the world, and up to 16% of patients develop postsurgical ulcers at the gastrojejunal anastomosis, the investigators noted. Acidity is a prime suspect in these “marginal ulcerations” because bypassing the acid-buffering duodenum exposes the jejunum to acid from the stomach, they added. High-dose PPIs are the main treatment, but there is no consensus on the formulation or dose of therapy. Because Roux-en-Y creates a small gastric pouch and hastens small-bowel transit, closed capsules designed to break down in the stomach “even may make their way to the colon before breakdown occurs,” they wrote.

They reviewed medical charts from patients who developed marginal ulcerations after undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass at their hospital from 2000 through 2015. A total of 115 patients received open-capsule PPIs and 49 received intact capsules. All were followed until their ulcers healed.

For the open-capsule group, median time to healing was 91 days, compared with 342 days for the closed-capsule group (P less than .001). Importantly, capsule type was the only independent predictor of healing time (hazard ratio, 6.0; 95% confidence interval, 3.7 to 9.8; P less than .001) in a Cox regression model that included other known correlates of ulcer healing, including age, smoking status, the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, Helicobacter pylori infection, the length of the gastric pouch, and the presence of fistulae or foreign bodies such as sutures or staples.

The use of sucralfate also did not affect time to ulcer healing, reflecting “many previous studies showing a lack of definitive benefit to this medication,” the researchers said. The findings have “tremendous implications” for health care utilization, they added. Indeed, patients who received open-capsule PPIs needed significantly fewer endoscopic procedures (median, 1.2 versus 1.8; P = .02) and used fewer health care resources overall ($7,206 versus $11,009; P = .05) compared with those prescribed intact PPI capsules.

This study was limited to patients who developed ulcer symptoms and underwent repeated surveillance endoscopies after surgery, the researchers noted. Selection bias is always a concern with retrospective studies, but insurers always covered both types of therapy and the choice of capsule type was entirely up to providers, all of whom consistently prescribed either open- or closed-capsule PPI therapy, they added.

The investigators did not acknowledge external funding sources. Dr. Schulman and four coinvestigators reported having no competing interests. One coinvestigator disclosed ties to Olympus, Boston Scientific, and Covidien.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: The use of proton pump inhibitors in opened instead of closed capsules was associated with a nearly fourfold shorter median healing time among patients who developed ulcers at the gastrojejunal anastomosis after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

Major finding: The median time to ulcer healing was 91.0 versus 342.0 days for the open- and closed-capsule groups, respectively (P less than .001).

Data source: A single-center retrospective study of 162 patients.

Disclosures: The investigators did not acknowledge external funding sources. Dr. Schulman and four coinvestigators reported having no competing interests. One coinvestigator disclosed ties to Olympus, Boston Scientific, and Covidien.

AGA Clinical Practice Update: Using FLIP to assess upper GI tract still murky territory

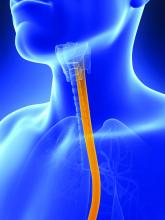

New clinical practice advice has been issued for use of the functional lumen imaging probe (FLIP) to assess disorders of the upper gastrointestinal tract, with the main takeaway being the device’s potency in diagnosing achalasia.

“Although the strongest data appear to be focused on the management of achalasia, emerging evidence supports the clinical relevance of FLIP in the assessment of disease severity and as an outcome measure in [eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE)] intervention trials,” wrote the authors of the update, led by John E. Pandolfino, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago. The report is in the March issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.

10.022).

In terms of evaluating the LES, however, FLIP can be used during laparoscopic Heller myotomy or peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) as a way of monitoring the LES. Using FLIP this way can help clinicians and surgeons personalize the procedure to each patient, even while it’s ongoing. FLIP also can be used with dilation balloons, with the balloon diameter allowing dilation measurement without the need to also use fluoroscopy.

For treating gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), the evidence found in existing literature points with less certainty toward use of FLIP.

“The role of FLIP for physiologic evaluation and management in GERD remains appealing; however, the level of evidence is low and currently FLIP should not be used in routine GERD management,” the authors explained. “Future outcome studies are needed to substantiate the utility of FLIP in GERD and to develop metrics that predict severity and treatment response after antireflux procedures.”

FLIP can be used in managing eosinophilic esophagitis, but is recommended only in certain scenarios. According to the authors, FLIP can be used to measure esophageal narrowing and the overall esophageal body. FLIP also can be used to measure esophageal distensibility, and, in the case of at least one study reviewed by the authors, allows “significantly greater accuracy and precision in estimating the effects of remodeling” in certain patients.

Dr. Pandolfino and his colleagues warned that “current recommendations are limited by the low level of evidence and lack of generalized availability of the analysis paradigms.” They noted the need for “further outcome studies that validate the distensibility plateau threshold and further refinements in software analyses to make this methodology more generalizable.”

Overall, the authors concluded, more study still needs to be done to ascertain exactly what FLIP is capable of and when it can be used to greatest effect. In addition to evaluating its benefit in patients with GERD, research should focus on how to make data obtained via FLIP easier to interpret and put to use.

“More work is needed [that] focuses on optimizing data analysis, standardizing protocols, and defining outcome metrics prior to the widespread adoption [of FLIP] into general clinical practice,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Pandolfino disclosed relationships with Medtronic and Sandhill Scientific. Other coauthors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

*This story updated on 3/9/2017.

New clinical practice advice has been issued for use of the functional lumen imaging probe (FLIP) to assess disorders of the upper gastrointestinal tract, with the main takeaway being the device’s potency in diagnosing achalasia.

“Although the strongest data appear to be focused on the management of achalasia, emerging evidence supports the clinical relevance of FLIP in the assessment of disease severity and as an outcome measure in [eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE)] intervention trials,” wrote the authors of the update, led by John E. Pandolfino, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago. The report is in the March issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.

10.022).

In terms of evaluating the LES, however, FLIP can be used during laparoscopic Heller myotomy or peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) as a way of monitoring the LES. Using FLIP this way can help clinicians and surgeons personalize the procedure to each patient, even while it’s ongoing. FLIP also can be used with dilation balloons, with the balloon diameter allowing dilation measurement without the need to also use fluoroscopy.

For treating gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), the evidence found in existing literature points with less certainty toward use of FLIP.

“The role of FLIP for physiologic evaluation and management in GERD remains appealing; however, the level of evidence is low and currently FLIP should not be used in routine GERD management,” the authors explained. “Future outcome studies are needed to substantiate the utility of FLIP in GERD and to develop metrics that predict severity and treatment response after antireflux procedures.”

FLIP can be used in managing eosinophilic esophagitis, but is recommended only in certain scenarios. According to the authors, FLIP can be used to measure esophageal narrowing and the overall esophageal body. FLIP also can be used to measure esophageal distensibility, and, in the case of at least one study reviewed by the authors, allows “significantly greater accuracy and precision in estimating the effects of remodeling” in certain patients.

Dr. Pandolfino and his colleagues warned that “current recommendations are limited by the low level of evidence and lack of generalized availability of the analysis paradigms.” They noted the need for “further outcome studies that validate the distensibility plateau threshold and further refinements in software analyses to make this methodology more generalizable.”

Overall, the authors concluded, more study still needs to be done to ascertain exactly what FLIP is capable of and when it can be used to greatest effect. In addition to evaluating its benefit in patients with GERD, research should focus on how to make data obtained via FLIP easier to interpret and put to use.

“More work is needed [that] focuses on optimizing data analysis, standardizing protocols, and defining outcome metrics prior to the widespread adoption [of FLIP] into general clinical practice,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Pandolfino disclosed relationships with Medtronic and Sandhill Scientific. Other coauthors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

*This story updated on 3/9/2017.

New clinical practice advice has been issued for use of the functional lumen imaging probe (FLIP) to assess disorders of the upper gastrointestinal tract, with the main takeaway being the device’s potency in diagnosing achalasia.

“Although the strongest data appear to be focused on the management of achalasia, emerging evidence supports the clinical relevance of FLIP in the assessment of disease severity and as an outcome measure in [eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE)] intervention trials,” wrote the authors of the update, led by John E. Pandolfino, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago. The report is in the March issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.

10.022).

In terms of evaluating the LES, however, FLIP can be used during laparoscopic Heller myotomy or peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) as a way of monitoring the LES. Using FLIP this way can help clinicians and surgeons personalize the procedure to each patient, even while it’s ongoing. FLIP also can be used with dilation balloons, with the balloon diameter allowing dilation measurement without the need to also use fluoroscopy.

For treating gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), the evidence found in existing literature points with less certainty toward use of FLIP.

“The role of FLIP for physiologic evaluation and management in GERD remains appealing; however, the level of evidence is low and currently FLIP should not be used in routine GERD management,” the authors explained. “Future outcome studies are needed to substantiate the utility of FLIP in GERD and to develop metrics that predict severity and treatment response after antireflux procedures.”

FLIP can be used in managing eosinophilic esophagitis, but is recommended only in certain scenarios. According to the authors, FLIP can be used to measure esophageal narrowing and the overall esophageal body. FLIP also can be used to measure esophageal distensibility, and, in the case of at least one study reviewed by the authors, allows “significantly greater accuracy and precision in estimating the effects of remodeling” in certain patients.

Dr. Pandolfino and his colleagues warned that “current recommendations are limited by the low level of evidence and lack of generalized availability of the analysis paradigms.” They noted the need for “further outcome studies that validate the distensibility plateau threshold and further refinements in software analyses to make this methodology more generalizable.”

Overall, the authors concluded, more study still needs to be done to ascertain exactly what FLIP is capable of and when it can be used to greatest effect. In addition to evaluating its benefit in patients with GERD, research should focus on how to make data obtained via FLIP easier to interpret and put to use.

“More work is needed [that] focuses on optimizing data analysis, standardizing protocols, and defining outcome metrics prior to the widespread adoption [of FLIP] into general clinical practice,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Pandolfino disclosed relationships with Medtronic and Sandhill Scientific. Other coauthors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

*This story updated on 3/9/2017.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

AGA Clinical Practice Update: PPIs should be prescribed sparingly, carefully

Updated best practice statements regarding the use of proton pump inhibitors first detail what types of patients should be using short and long-term PPIs.

“When PPIs are appropriately prescribed, their benefits are likely to outweigh their risks [but] when PPIs are inappropriately prescribed, modest risks become important because there is no potential benefit,” wrote the authors of the updated guidance, published in the March issue of Gastroenterology.

“There is currently insufficient evidence to recommend specific strategies for mitigating PPI adverse effects,” noted Daniel E. Freedberg, MD, of Columbia University, New York, and his colleagues.

PPIs should be used on a short-term basis for individuals with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or conditions such as erosive esophagitis. These patients can also use PPIs for maintenance and occasional symptom management, but those with uncomplicated GERD should be weaned off PPIs if they respond favorably to them.

If a patient is unable to be weaned off PPIs, then ambulatory esophageal pH and impedance monitoring should be done, as this will allow clinicians to determine if the patient has a functional syndrome or GERD. Lifelong PPI treatment should not be considered until this step is taken, according to the new best practice statements.

“Short-term PPIs are highly effective for uncomplicated GERD [but] because patients who cannot reduce PPIs face lifelong therapy, we would consider testing for an acid-related disorder in this situation,” the authors explained. “However, there is no high-quality evidence on which to base this recommendation.”

Patients who have symptomatic GERD or Barrett’s esophagus, either symptomatic or asymptomatic, should be on long-term PPI treatment. Patients who are at a higher risk for NSAID-induced ulcer bleeding should be taking PPIs if they continue to take NSAIDs.

When recommending long-term PPI treatment for a patient, the patient need not use probiotics on a regular basis; there appears to be no need to routinely check the patient’s bone mineral density, serum creatinine, magnesium, or vitamin B12 level on a regular basis. In addition, they need not consume more than the Recommended Dietary Allowance of calcium, magnesium, or vitamin B12.

Finally, the authors state that “specific PPI formulations should not be selected based on potential risks.” This is because no evidence has been found indicating that PPI formulations can be ranked in any way based on risk.

These recommendations come from the AGA’s Clinical Practice Updates Committee, which pored through studies published through July 2016 in the PubMed, EMbase, and Cochrane library databases. Expert opinions and quality assessments on each study contributed to forming these best practice statements.

“In sum, the best current strategies for mitigating the potential risks of long-term PPIs are to avoid prescribing them when they are not indicated and to reduce them to their minimum dose when they are indicated,” Dr. Freedberg and his colleagues concluded.

The researchers did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

Updated best practice statements regarding the use of proton pump inhibitors first detail what types of patients should be using short and long-term PPIs.

“When PPIs are appropriately prescribed, their benefits are likely to outweigh their risks [but] when PPIs are inappropriately prescribed, modest risks become important because there is no potential benefit,” wrote the authors of the updated guidance, published in the March issue of Gastroenterology.

“There is currently insufficient evidence to recommend specific strategies for mitigating PPI adverse effects,” noted Daniel E. Freedberg, MD, of Columbia University, New York, and his colleagues.

PPIs should be used on a short-term basis for individuals with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or conditions such as erosive esophagitis. These patients can also use PPIs for maintenance and occasional symptom management, but those with uncomplicated GERD should be weaned off PPIs if they respond favorably to them.

If a patient is unable to be weaned off PPIs, then ambulatory esophageal pH and impedance monitoring should be done, as this will allow clinicians to determine if the patient has a functional syndrome or GERD. Lifelong PPI treatment should not be considered until this step is taken, according to the new best practice statements.

“Short-term PPIs are highly effective for uncomplicated GERD [but] because patients who cannot reduce PPIs face lifelong therapy, we would consider testing for an acid-related disorder in this situation,” the authors explained. “However, there is no high-quality evidence on which to base this recommendation.”

Patients who have symptomatic GERD or Barrett’s esophagus, either symptomatic or asymptomatic, should be on long-term PPI treatment. Patients who are at a higher risk for NSAID-induced ulcer bleeding should be taking PPIs if they continue to take NSAIDs.

When recommending long-term PPI treatment for a patient, the patient need not use probiotics on a regular basis; there appears to be no need to routinely check the patient’s bone mineral density, serum creatinine, magnesium, or vitamin B12 level on a regular basis. In addition, they need not consume more than the Recommended Dietary Allowance of calcium, magnesium, or vitamin B12.

Finally, the authors state that “specific PPI formulations should not be selected based on potential risks.” This is because no evidence has been found indicating that PPI formulations can be ranked in any way based on risk.

These recommendations come from the AGA’s Clinical Practice Updates Committee, which pored through studies published through July 2016 in the PubMed, EMbase, and Cochrane library databases. Expert opinions and quality assessments on each study contributed to forming these best practice statements.

“In sum, the best current strategies for mitigating the potential risks of long-term PPIs are to avoid prescribing them when they are not indicated and to reduce them to their minimum dose when they are indicated,” Dr. Freedberg and his colleagues concluded.

The researchers did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

Updated best practice statements regarding the use of proton pump inhibitors first detail what types of patients should be using short and long-term PPIs.

“When PPIs are appropriately prescribed, their benefits are likely to outweigh their risks [but] when PPIs are inappropriately prescribed, modest risks become important because there is no potential benefit,” wrote the authors of the updated guidance, published in the March issue of Gastroenterology.

“There is currently insufficient evidence to recommend specific strategies for mitigating PPI adverse effects,” noted Daniel E. Freedberg, MD, of Columbia University, New York, and his colleagues.

PPIs should be used on a short-term basis for individuals with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or conditions such as erosive esophagitis. These patients can also use PPIs for maintenance and occasional symptom management, but those with uncomplicated GERD should be weaned off PPIs if they respond favorably to them.

If a patient is unable to be weaned off PPIs, then ambulatory esophageal pH and impedance monitoring should be done, as this will allow clinicians to determine if the patient has a functional syndrome or GERD. Lifelong PPI treatment should not be considered until this step is taken, according to the new best practice statements.

“Short-term PPIs are highly effective for uncomplicated GERD [but] because patients who cannot reduce PPIs face lifelong therapy, we would consider testing for an acid-related disorder in this situation,” the authors explained. “However, there is no high-quality evidence on which to base this recommendation.”

Patients who have symptomatic GERD or Barrett’s esophagus, either symptomatic or asymptomatic, should be on long-term PPI treatment. Patients who are at a higher risk for NSAID-induced ulcer bleeding should be taking PPIs if they continue to take NSAIDs.

When recommending long-term PPI treatment for a patient, the patient need not use probiotics on a regular basis; there appears to be no need to routinely check the patient’s bone mineral density, serum creatinine, magnesium, or vitamin B12 level on a regular basis. In addition, they need not consume more than the Recommended Dietary Allowance of calcium, magnesium, or vitamin B12.

Finally, the authors state that “specific PPI formulations should not be selected based on potential risks.” This is because no evidence has been found indicating that PPI formulations can be ranked in any way based on risk.

These recommendations come from the AGA’s Clinical Practice Updates Committee, which pored through studies published through July 2016 in the PubMed, EMbase, and Cochrane library databases. Expert opinions and quality assessments on each study contributed to forming these best practice statements.

“In sum, the best current strategies for mitigating the potential risks of long-term PPIs are to avoid prescribing them when they are not indicated and to reduce them to their minimum dose when they are indicated,” Dr. Freedberg and his colleagues concluded.

The researchers did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Report of potential interaction between PPIs, clopidogrel

The January 2009 issue of GI & Hepatology News (GIHN) featured an article on the potential drug interaction between proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and clopidogrel.

In the study of interest, researchers retrospectively reviewed 16,000 patients prescribed clopidogrel after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and found that those patients also on a PPI were 1.5 times as likely to suffer from a myocardial infarction, stroke, or be hospitalized for angina as those not on a PPI. A second study mentioned in the GIHN article, a post hoc analysis of the CREDO trial, found a higher rate of ischemic events in patients on a PPI, but this increase was seen whether the patient was on clopidogrel or not. The conflicting data presented a management challenge for cardiologists and gastroenterologists alike.

Multiple subsequent studies, including a large randomized trial, COGENT (N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1909-17), comparing omeprazole with placebo in patients on clopidogrel, found no significant interaction. A consensus document published in December 2010 acknowledged the potential risks from pharmacodynamic studies but suggested that the clinical data were unclear.

This story speaks to the power of research to change practice, the importance of effectively communicating research findings to the public, and the fact that the practice of medicine is often an exercise in balancing conflicting data on behalf of our patients.

Ziad Gellad, MD, MPH, is associate professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C.; a faculty member at the Duke Clinical Research Institute; and an Associate Editor of GI & Hepatology News.

The January 2009 issue of GI & Hepatology News (GIHN) featured an article on the potential drug interaction between proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and clopidogrel.

In the study of interest, researchers retrospectively reviewed 16,000 patients prescribed clopidogrel after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and found that those patients also on a PPI were 1.5 times as likely to suffer from a myocardial infarction, stroke, or be hospitalized for angina as those not on a PPI. A second study mentioned in the GIHN article, a post hoc analysis of the CREDO trial, found a higher rate of ischemic events in patients on a PPI, but this increase was seen whether the patient was on clopidogrel or not. The conflicting data presented a management challenge for cardiologists and gastroenterologists alike.

Multiple subsequent studies, including a large randomized trial, COGENT (N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1909-17), comparing omeprazole with placebo in patients on clopidogrel, found no significant interaction. A consensus document published in December 2010 acknowledged the potential risks from pharmacodynamic studies but suggested that the clinical data were unclear.

This story speaks to the power of research to change practice, the importance of effectively communicating research findings to the public, and the fact that the practice of medicine is often an exercise in balancing conflicting data on behalf of our patients.

Ziad Gellad, MD, MPH, is associate professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C.; a faculty member at the Duke Clinical Research Institute; and an Associate Editor of GI & Hepatology News.

The January 2009 issue of GI & Hepatology News (GIHN) featured an article on the potential drug interaction between proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and clopidogrel.

In the study of interest, researchers retrospectively reviewed 16,000 patients prescribed clopidogrel after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and found that those patients also on a PPI were 1.5 times as likely to suffer from a myocardial infarction, stroke, or be hospitalized for angina as those not on a PPI. A second study mentioned in the GIHN article, a post hoc analysis of the CREDO trial, found a higher rate of ischemic events in patients on a PPI, but this increase was seen whether the patient was on clopidogrel or not. The conflicting data presented a management challenge for cardiologists and gastroenterologists alike.

Multiple subsequent studies, including a large randomized trial, COGENT (N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1909-17), comparing omeprazole with placebo in patients on clopidogrel, found no significant interaction. A consensus document published in December 2010 acknowledged the potential risks from pharmacodynamic studies but suggested that the clinical data were unclear.

This story speaks to the power of research to change practice, the importance of effectively communicating research findings to the public, and the fact that the practice of medicine is often an exercise in balancing conflicting data on behalf of our patients.

Ziad Gellad, MD, MPH, is associate professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C.; a faculty member at the Duke Clinical Research Institute; and an Associate Editor of GI & Hepatology News.

BOS beat placebo for eosinophilic esophagitis

Budesonide oral suspension (BOS) was safe and significantly outperformed placebo on validated measures of eosinophilic esophagitis, according to a first-in-kind, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, phase II trial presented in the March issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.11.021).

The novel topical corticosteroid formulation yielded a significant histologic response and was associated with 3 fewer days of dysphagia over 2 weeks compared with placebo, reported Evan S. Dellon, MD, MPH, of University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and his associates. “There were no unexpected safety signals, and compliance with medication was high, suggesting that this formulation can be reliably used,” they wrote. Their findings earned BOS (SHP621) an FDA Breakthrough Therapy Designation in June 2016. Although corticosteroids are first-line therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis, symptom response in other studies has been mixed, and the Food and Drug Administration had approved neither fluticasone nor budesonide for this disease, the researchers noted. They formulated BOS to adhere better to the esophageal mucosa in order to enhance esophageal delivery while decreasing unwanted pulmonary deposition.

For the study, they randomly assigned 93 patients aged 11-40 years with eosinophilic esophagitis to receive either placebo or 2 mg BOS twice daily. By week 12, Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire scores had fallen by 14.3 points with BOS group and by 7.5 points with placebo (P = .001). Endoscopic severity scores dropped by 3.8 points with BOS and rose by 0.4 points with placebo (P less than .0001). Rates of histologic response were 39% and 3%, respectively (P less than .0001). Nonresponders averaged 10 kg more body weight than responders, and had been diagnosed about 21 months earlier (average disease duration, 46 months and 25 months, respectively).

Rates of reported adverse effects were similar with BOS (47%) and placebo (50%). Individual rates of nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory infections, and oropharyngeal pain also were comparable between groups, but one patient stopped BOS after developing dyspnea, nausea, and vomiting that were considered treatment related. Esophageal candidiasis developed in two BOS recipients – a rate similar rate to that in a prior study of BOS (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Jan 13. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.05.02), and a lower percentage than in other studies of topical steroids for eosinophilic esophagitis, according to the researchers. Morning cortisol levels were similar between groups, and there were no adverse laboratory effects, they added.

Patients in this trial had severe symptoms and histology and were highly compliant with treatment. They filled out at least 70% of their symptom diary, had at least 15 eosinophils per high-power frame from at least two esophageal levels on screening endoscopy, and reported at least 4 days of dysphagia during the second half of a 4-week, blinded placebo run-in period. Researchers should consider using these strict inclusion criteria in future trials of eosinophilic esophagitis, especially because previous studies have failed to show a treatment benefit for topical steroid therapy, the investigators noted.

Meritage Pharma, which is now a part of the Shire group, makes budesonide oral suspension and sponsored the study. Dr. Dellon disclosed ties to Meritage, Receptos, Regeneron, Aptalis, Banner Life Sciences, Novartis, and Roche. All five coinvestigators disclosed ties to industry, including Meritage, Shire, Receptos, Regeneron, and Biogen Idec.

Budesonide oral suspension (BOS) was safe and significantly outperformed placebo on validated measures of eosinophilic esophagitis, according to a first-in-kind, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, phase II trial presented in the March issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.11.021).

The novel topical corticosteroid formulation yielded a significant histologic response and was associated with 3 fewer days of dysphagia over 2 weeks compared with placebo, reported Evan S. Dellon, MD, MPH, of University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and his associates. “There were no unexpected safety signals, and compliance with medication was high, suggesting that this formulation can be reliably used,” they wrote. Their findings earned BOS (SHP621) an FDA Breakthrough Therapy Designation in June 2016. Although corticosteroids are first-line therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis, symptom response in other studies has been mixed, and the Food and Drug Administration had approved neither fluticasone nor budesonide for this disease, the researchers noted. They formulated BOS to adhere better to the esophageal mucosa in order to enhance esophageal delivery while decreasing unwanted pulmonary deposition.

For the study, they randomly assigned 93 patients aged 11-40 years with eosinophilic esophagitis to receive either placebo or 2 mg BOS twice daily. By week 12, Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire scores had fallen by 14.3 points with BOS group and by 7.5 points with placebo (P = .001). Endoscopic severity scores dropped by 3.8 points with BOS and rose by 0.4 points with placebo (P less than .0001). Rates of histologic response were 39% and 3%, respectively (P less than .0001). Nonresponders averaged 10 kg more body weight than responders, and had been diagnosed about 21 months earlier (average disease duration, 46 months and 25 months, respectively).

Rates of reported adverse effects were similar with BOS (47%) and placebo (50%). Individual rates of nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory infections, and oropharyngeal pain also were comparable between groups, but one patient stopped BOS after developing dyspnea, nausea, and vomiting that were considered treatment related. Esophageal candidiasis developed in two BOS recipients – a rate similar rate to that in a prior study of BOS (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Jan 13. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.05.02), and a lower percentage than in other studies of topical steroids for eosinophilic esophagitis, according to the researchers. Morning cortisol levels were similar between groups, and there were no adverse laboratory effects, they added.

Patients in this trial had severe symptoms and histology and were highly compliant with treatment. They filled out at least 70% of their symptom diary, had at least 15 eosinophils per high-power frame from at least two esophageal levels on screening endoscopy, and reported at least 4 days of dysphagia during the second half of a 4-week, blinded placebo run-in period. Researchers should consider using these strict inclusion criteria in future trials of eosinophilic esophagitis, especially because previous studies have failed to show a treatment benefit for topical steroid therapy, the investigators noted.

Meritage Pharma, which is now a part of the Shire group, makes budesonide oral suspension and sponsored the study. Dr. Dellon disclosed ties to Meritage, Receptos, Regeneron, Aptalis, Banner Life Sciences, Novartis, and Roche. All five coinvestigators disclosed ties to industry, including Meritage, Shire, Receptos, Regeneron, and Biogen Idec.

Budesonide oral suspension (BOS) was safe and significantly outperformed placebo on validated measures of eosinophilic esophagitis, according to a first-in-kind, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, phase II trial presented in the March issue of Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.11.021).

The novel topical corticosteroid formulation yielded a significant histologic response and was associated with 3 fewer days of dysphagia over 2 weeks compared with placebo, reported Evan S. Dellon, MD, MPH, of University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and his associates. “There were no unexpected safety signals, and compliance with medication was high, suggesting that this formulation can be reliably used,” they wrote. Their findings earned BOS (SHP621) an FDA Breakthrough Therapy Designation in June 2016. Although corticosteroids are first-line therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis, symptom response in other studies has been mixed, and the Food and Drug Administration had approved neither fluticasone nor budesonide for this disease, the researchers noted. They formulated BOS to adhere better to the esophageal mucosa in order to enhance esophageal delivery while decreasing unwanted pulmonary deposition.

For the study, they randomly assigned 93 patients aged 11-40 years with eosinophilic esophagitis to receive either placebo or 2 mg BOS twice daily. By week 12, Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire scores had fallen by 14.3 points with BOS group and by 7.5 points with placebo (P = .001). Endoscopic severity scores dropped by 3.8 points with BOS and rose by 0.4 points with placebo (P less than .0001). Rates of histologic response were 39% and 3%, respectively (P less than .0001). Nonresponders averaged 10 kg more body weight than responders, and had been diagnosed about 21 months earlier (average disease duration, 46 months and 25 months, respectively).

Rates of reported adverse effects were similar with BOS (47%) and placebo (50%). Individual rates of nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory infections, and oropharyngeal pain also were comparable between groups, but one patient stopped BOS after developing dyspnea, nausea, and vomiting that were considered treatment related. Esophageal candidiasis developed in two BOS recipients – a rate similar rate to that in a prior study of BOS (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Jan 13. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.05.02), and a lower percentage than in other studies of topical steroids for eosinophilic esophagitis, according to the researchers. Morning cortisol levels were similar between groups, and there were no adverse laboratory effects, they added.

Patients in this trial had severe symptoms and histology and were highly compliant with treatment. They filled out at least 70% of their symptom diary, had at least 15 eosinophils per high-power frame from at least two esophageal levels on screening endoscopy, and reported at least 4 days of dysphagia during the second half of a 4-week, blinded placebo run-in period. Researchers should consider using these strict inclusion criteria in future trials of eosinophilic esophagitis, especially because previous studies have failed to show a treatment benefit for topical steroid therapy, the investigators noted.

Meritage Pharma, which is now a part of the Shire group, makes budesonide oral suspension and sponsored the study. Dr. Dellon disclosed ties to Meritage, Receptos, Regeneron, Aptalis, Banner Life Sciences, Novartis, and Roche. All five coinvestigators disclosed ties to industry, including Meritage, Shire, Receptos, Regeneron, and Biogen Idec.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: Budesonide oral suspension (BOS) (2 mg twice daily) was safe and significantly outperformed placebo on validated measures of eosinophilic esophagitis.

Major finding: Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire scores decreased by 14.3 points with BOS and by 7.5 points with placebo (P = .001). Endoscopic severity scores decreased by 3.8 points and rose by 0.4 points, respectively (P less than .0001).

Data source: A 12-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, phase II trial of 93 adolescents and adults with eosinophilic esophagitis.

Disclosures: Meritage Pharma, which is now a part of the Shire group, makes budesonide oral suspension and sponsored the study. Dr. Dellon disclosed ties to Meritage, Receptos, Regeneron, Aptalis, Banner Life Sciences, Novartis, and Roche. All five coinvestigators disclosed ties to industry, including Meritage, Shire, Receptos, Regeneron, and Biogen Idec.

VIDEO: No difference between PPI and H2RA for low-dose aspirin gastroprotection

Among patients on low-dose aspirin at risk for recurrent GI bleeding, there were slightly fewer GI bleeds or ulcers when patients were on the proton pump inhibitor rabeprazole (Aciphex) instead of the histamine2-receptor antagonist famotidine (Pepcid), but the difference was not statistically significant according to a study reported in the January issue of Gastroenterology.

SOURCE: American Gastroenterological Association

In a 270-subject, double-blind, randomized trial in Hong Kong and Japan led by Francis Chan, MD, of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, investigators found, “Among high-risk aspirin users, the incidence of recurrent bleeding is comparable with either use of PPI [proton pump inhibitor] or H2RA [H2-receptor antagonist].” However, “since a small difference in efficacy cannot be excluded, PPI probably remains the preferred treatment for long-term protection against upper GI bleeding in high-risk aspirin users” (Gastroenterology. 2016 Sep 15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.09.006).

Even so, “our findings suggest that famotidine may be a reasonable alternative option for aspirin users who disfavor long-term PPI therapy,” they said.

Because of concerns about the long-term safety of PPIs, including the association between PPIs and increased risk of serious cardiovascular events in patients on clopidogrel (Plavix), clinicians have been looking for alternatives. The findings reassure that H2RAs are a reasonable choice; many clinicians have already turned to them.

All 270 subjects had previously had endoscopically confirmed ulcer bleeding while on low-dose aspirin (325 mg or less per day). “Considering clinicians will be most concerned with the adequacy of gastroprotective treatment effect in aspirin users with the highest risk, we exclusively enrolled patients with endoscopy-proven upper GI bleeding,” Dr. Chan and his colleagues said.

After the ulcers healed, the subjects resumed aspirin (80 mg) daily and were randomized to either famotidine 40 mg once daily (n = 132) or rabeprazole 20 mg daily (n = 138) for up to 12 months. Helicobacter pylori was eradicated prior to randomization in patients who tested positive. Subjects were evaluated every 2 months, with repeat endoscopy for symptoms of upper GI bleeding or significant drops in hemoglobin, as well as at the end of the study.

During the 12-month study period, upper GI bleeding recurred in one patient receiving rabeprazole (0.7%) and four receiving famotidine (3.1%; P = .16). The composite endpoint of recurrent bleeding or endoscopic ulcers at month 12 was reached by nine patients in the rabeprazole group (7.9%) and 13 receiving famotidine (12.4%; P = .26).

“Our findings indicate that both treatments are comparable in preventing recurrent upper GI bleeding in high-risk aspirin users, although a small difference in efficacy cannot be excluded,” the investigators said.

Over two-thirds of the subjects were men, and the mean age was 73 years. About a quarter in the PPI group and almost 40% in the H2RA group had H. pylori cleared before randomization.

The Research Grant Council of Hong Kong funded the work. Dr. Chan has served as a consultant to Pfizer, Eisai, Takeda, and Otsuka, and has received research grants from Pfizer and lecture fees from Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and Takeda. Several other authors reported similar industry disclosures.

Aspirin is widely used for primary and secondary prophylaxis of cardiovascular disease. Dr. Chan and colleagues present a randomized, controlled trial comparing rabeprazole 20 mg once a day to famotidine 40 mg once a day in preventing recurrent GI hemorrhage and endoscopic ulcers in low-dose (less than 325 mg) aspirin users. The authors conclude that no statistical difference was found between the two agents. The study contrasts with another study from Hong Kong, which found that proton pump inhibitors were more effective.

The authors are to be complimented on this important addition to the literature but the reader should not conclude that H2-receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors are equivalent in preventing recurrent bleeding from aspirin-induced ulcers.

Nimish Vakil, MD, AGAF, is clinical professor of medicine at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He has consulted for Ironwood and AstraZeneca.

Aspirin is widely used for primary and secondary prophylaxis of cardiovascular disease. Dr. Chan and colleagues present a randomized, controlled trial comparing rabeprazole 20 mg once a day to famotidine 40 mg once a day in preventing recurrent GI hemorrhage and endoscopic ulcers in low-dose (less than 325 mg) aspirin users. The authors conclude that no statistical difference was found between the two agents. The study contrasts with another study from Hong Kong, which found that proton pump inhibitors were more effective.

The authors are to be complimented on this important addition to the literature but the reader should not conclude that H2-receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors are equivalent in preventing recurrent bleeding from aspirin-induced ulcers.

Nimish Vakil, MD, AGAF, is clinical professor of medicine at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He has consulted for Ironwood and AstraZeneca.

Aspirin is widely used for primary and secondary prophylaxis of cardiovascular disease. Dr. Chan and colleagues present a randomized, controlled trial comparing rabeprazole 20 mg once a day to famotidine 40 mg once a day in preventing recurrent GI hemorrhage and endoscopic ulcers in low-dose (less than 325 mg) aspirin users. The authors conclude that no statistical difference was found between the two agents. The study contrasts with another study from Hong Kong, which found that proton pump inhibitors were more effective.

The authors are to be complimented on this important addition to the literature but the reader should not conclude that H2-receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors are equivalent in preventing recurrent bleeding from aspirin-induced ulcers.

Nimish Vakil, MD, AGAF, is clinical professor of medicine at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He has consulted for Ironwood and AstraZeneca.

Among patients on low-dose aspirin at risk for recurrent GI bleeding, there were slightly fewer GI bleeds or ulcers when patients were on the proton pump inhibitor rabeprazole (Aciphex) instead of the histamine2-receptor antagonist famotidine (Pepcid), but the difference was not statistically significant according to a study reported in the January issue of Gastroenterology.

SOURCE: American Gastroenterological Association

In a 270-subject, double-blind, randomized trial in Hong Kong and Japan led by Francis Chan, MD, of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, investigators found, “Among high-risk aspirin users, the incidence of recurrent bleeding is comparable with either use of PPI [proton pump inhibitor] or H2RA [H2-receptor antagonist].” However, “since a small difference in efficacy cannot be excluded, PPI probably remains the preferred treatment for long-term protection against upper GI bleeding in high-risk aspirin users” (Gastroenterology. 2016 Sep 15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.09.006).

Even so, “our findings suggest that famotidine may be a reasonable alternative option for aspirin users who disfavor long-term PPI therapy,” they said.

Because of concerns about the long-term safety of PPIs, including the association between PPIs and increased risk of serious cardiovascular events in patients on clopidogrel (Plavix), clinicians have been looking for alternatives. The findings reassure that H2RAs are a reasonable choice; many clinicians have already turned to them.

All 270 subjects had previously had endoscopically confirmed ulcer bleeding while on low-dose aspirin (325 mg or less per day). “Considering clinicians will be most concerned with the adequacy of gastroprotective treatment effect in aspirin users with the highest risk, we exclusively enrolled patients with endoscopy-proven upper GI bleeding,” Dr. Chan and his colleagues said.

After the ulcers healed, the subjects resumed aspirin (80 mg) daily and were randomized to either famotidine 40 mg once daily (n = 132) or rabeprazole 20 mg daily (n = 138) for up to 12 months. Helicobacter pylori was eradicated prior to randomization in patients who tested positive. Subjects were evaluated every 2 months, with repeat endoscopy for symptoms of upper GI bleeding or significant drops in hemoglobin, as well as at the end of the study.

During the 12-month study period, upper GI bleeding recurred in one patient receiving rabeprazole (0.7%) and four receiving famotidine (3.1%; P = .16). The composite endpoint of recurrent bleeding or endoscopic ulcers at month 12 was reached by nine patients in the rabeprazole group (7.9%) and 13 receiving famotidine (12.4%; P = .26).

“Our findings indicate that both treatments are comparable in preventing recurrent upper GI bleeding in high-risk aspirin users, although a small difference in efficacy cannot be excluded,” the investigators said.

Over two-thirds of the subjects were men, and the mean age was 73 years. About a quarter in the PPI group and almost 40% in the H2RA group had H. pylori cleared before randomization.

The Research Grant Council of Hong Kong funded the work. Dr. Chan has served as a consultant to Pfizer, Eisai, Takeda, and Otsuka, and has received research grants from Pfizer and lecture fees from Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and Takeda. Several other authors reported similar industry disclosures.

Among patients on low-dose aspirin at risk for recurrent GI bleeding, there were slightly fewer GI bleeds or ulcers when patients were on the proton pump inhibitor rabeprazole (Aciphex) instead of the histamine2-receptor antagonist famotidine (Pepcid), but the difference was not statistically significant according to a study reported in the January issue of Gastroenterology.

SOURCE: American Gastroenterological Association

In a 270-subject, double-blind, randomized trial in Hong Kong and Japan led by Francis Chan, MD, of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, investigators found, “Among high-risk aspirin users, the incidence of recurrent bleeding is comparable with either use of PPI [proton pump inhibitor] or H2RA [H2-receptor antagonist].” However, “since a small difference in efficacy cannot be excluded, PPI probably remains the preferred treatment for long-term protection against upper GI bleeding in high-risk aspirin users” (Gastroenterology. 2016 Sep 15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.09.006).

Even so, “our findings suggest that famotidine may be a reasonable alternative option for aspirin users who disfavor long-term PPI therapy,” they said.

Because of concerns about the long-term safety of PPIs, including the association between PPIs and increased risk of serious cardiovascular events in patients on clopidogrel (Plavix), clinicians have been looking for alternatives. The findings reassure that H2RAs are a reasonable choice; many clinicians have already turned to them.

All 270 subjects had previously had endoscopically confirmed ulcer bleeding while on low-dose aspirin (325 mg or less per day). “Considering clinicians will be most concerned with the adequacy of gastroprotective treatment effect in aspirin users with the highest risk, we exclusively enrolled patients with endoscopy-proven upper GI bleeding,” Dr. Chan and his colleagues said.

After the ulcers healed, the subjects resumed aspirin (80 mg) daily and were randomized to either famotidine 40 mg once daily (n = 132) or rabeprazole 20 mg daily (n = 138) for up to 12 months. Helicobacter pylori was eradicated prior to randomization in patients who tested positive. Subjects were evaluated every 2 months, with repeat endoscopy for symptoms of upper GI bleeding or significant drops in hemoglobin, as well as at the end of the study.

During the 12-month study period, upper GI bleeding recurred in one patient receiving rabeprazole (0.7%) and four receiving famotidine (3.1%; P = .16). The composite endpoint of recurrent bleeding or endoscopic ulcers at month 12 was reached by nine patients in the rabeprazole group (7.9%) and 13 receiving famotidine (12.4%; P = .26).

“Our findings indicate that both treatments are comparable in preventing recurrent upper GI bleeding in high-risk aspirin users, although a small difference in efficacy cannot be excluded,” the investigators said.

Over two-thirds of the subjects were men, and the mean age was 73 years. About a quarter in the PPI group and almost 40% in the H2RA group had H. pylori cleared before randomization.

The Research Grant Council of Hong Kong funded the work. Dr. Chan has served as a consultant to Pfizer, Eisai, Takeda, and Otsuka, and has received research grants from Pfizer and lecture fees from Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and Takeda. Several other authors reported similar industry disclosures.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: During the 12-month study period, upper GI bleeding recurred in one patient receiving rabeprazole (0.7%) and four receiving famotidine (3.1%; P = .16). The composite endpoint of recurrent bleeding or endoscopic ulcers at month 12 was reached by nine patients in the rabeprazole group (7.9%) and 13 receiving famotidine (12.4%; P = .26).

Data source: A 270-subject, double-blind, randomized trial in Hong Kong and Japan.

Disclosures: The Research Grant Council of Hong Kong funded the work. The lead investigator has served as a consultant to Pfizer, Eisai, Takeda, and Otsuka, and has received research grants from Pfizer and lecture fees from Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and Takeda. Several other authors reported similar industry disclosures.

Increased death rate with platelets for aspirin/clopidogrel GI bleed

Patients with normal platelet counts who have a GI bleed while on antiplatelets were almost six times more likely to die in the hospital if they had a platelet transfusion in a retrospective cohort study from the Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

Ten of the 14 deaths in the 204 transfused patients – versus none of the 3 deaths in the 204 nontransfused patients - were due to bleeding, so it’s possible that the mortality difference was simply because patients with worse bleeding were more likely to get transfused. “On the other hand, the adjusted [odds ratios] for mortality (4.5-6.8 with different sensitivity analyses) [were] large, increasing the likelihood of a cause-and-effect relationship,” said investigators led by gastroenterologist Liam Zakko, MD, now at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Jul 25. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.07.017).

Current guidelines suggest platelet transfusions are an option for antiplatelet patients with serious GI bleeds, but the Yale team found that they did not reduce rebleeding. “The observation of increased mortality without documentation of clinical benefit suggests a very cautious approach to the use of platelet transfusion. ... We do not support the use of platelet transfusions in patients with GI [bleeds] who are taking antiplatelet agents,” the investigators wrote.

Subjects in the two groups were matched for sex, age, and GI bleed location, and all had platelet counts above 100 × 109/L. Almost everyone was on aspirin for cardiovascular protection, and 30% were on also on clopidogrel.

Just over half in both groups had upper GI bleeds, and about 40% in each group had colonic bleeds. Transfused patients had more-severe bleeding, with overall lower blood pressure and lower hemoglobin; a larger proportion was admitted to the ICU.

On univariate analyses, platelet patients had more cardiovascular events (23% vs. 13%) while in the hospital. They were also more likely to stay in the hospital for more than 4 days (47% vs. 33%) and more likely to die while there (7% vs. 1%). On multivariable analysis, only the greater risk for death during admission remained statistically significant (odds ratio, 5.57; 95% confidence interval, 1.52-27.1). The adjusted odds ratio for recurrent bleeding was not significant.

Four patients in the platelet group died from cardiovascular causes. One patient in the control group had a fatal cardiovascular event.

Although counterintuitive, the authors said that it’s possible that platelet transfusions might actually increase the risk of severe and fatal GI bleeding. “Mechanisms by which platelet transfusion would increase mortality or [GI bleeding]–related mortality are not clear,” but “platelet transfusions are reported to be proinflammatory and alter recipient immunity,” they said.

At least for now, “the most prudent way to manage patients on antiplatelet agents with [GI bleeding] is to follow current evidence-based recommendations,” including early endoscopy, endoscopic hemostatic therapy for high-risk lesions, and intensive proton pump inhibitor therapy in patients with ulcers and high-risk endoscopic features.

“Although not based on high-quality evidence, we believe that hemostatic techniques that do not cause significant tissue damage (e.g., clips rather than thermal devices or sclerosants) should be used in patients on antiplatelet agents, especially if patients are expected to remain on these agents in the future,” they said.

The mean age in the study was 74 years, and about two-thirds of the subjects were men.

The authors had no disclosures.

The management of patients with gastrointestinal bleeding on antithrombotic drugs is a major challenge for gastroenterologists. Unfortunately, the use of aspirin alone has been shown to increase the risk of GI bleed twofold, and the addition of a thienopyridine additionally increases the risk of bleeding twofold. Furthermore, there is no available agent to reverse antiplatelet affects of these drugs, which irreversibly block platelet function for the life of the platelet (8-10 days). Current recommendations for the management of severe GI bleeding in patients receiving antithrombotic therapy include platelet transfusion, including those with a normal platelet count. However, this comes with a price as reversal of platelet function may increase the rate of cardiovascular events.

Zakko et al. performed a retrospective case-control study evaluating the role of platelet transfusion in patients presenting with GI bleeding. Patients were matched by age, sex, and the location of the GI bleed. Most patients included in the study were on low-dose aspirin and almost a third of the patients were taking both aspirin and a thienopyridine. Patients receiving platelet transfusions appeared to have more severe GI bleeding compared with matched controls, as patients receiving transfusion were more likely to have been hypotensive, tachycardic, have a low hemoglobin level, and require treatment in the intensive care unit (72% vs. 28%, P less than .0001). Patients receiving platelet transfusions were also more likely than matched controls to have recurrent GI bleeding as well as major cardiovascular adverse events, including myocardial infarction and inpatient death. After adjusting for patient characteristics, patients receiving platelet transfusions were more likely to have an increased risk of death (adjusted OR, 5.57; 95% CI, 1.52-27.1). The authors conclude that “the use of platelet transfusions in patients with GI bleeding who are taking antiplatelet agents without thrombocytopenia did not reduce rebleeding but was associated with higher mortality.”

Currently, there is no convincing evidence to support platelet transfusion in patients with bleeding on aspirin and/or a thienopyridine. Because the majority of the deaths were due to GI bleeding and not cardiovascular events, the observed increase in adverse events in patients receiving platelet transfusions likely reflects more severe GI bleeding in patients receiving platelet transfusions than in controls. We should avoid platelet transfusions and focus our management on achieving adequate resuscitation, use of proton pump inhibitors for patients with high-risk ulcers, and early endoscopy with endoscopic therapy for high-risk lesions.

John R. Saltzman, MD, AGAF, is director of endoscopy, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston. He has no conflicts of interest.

The management of patients with gastrointestinal bleeding on antithrombotic drugs is a major challenge for gastroenterologists. Unfortunately, the use of aspirin alone has been shown to increase the risk of GI bleed twofold, and the addition of a thienopyridine additionally increases the risk of bleeding twofold. Furthermore, there is no available agent to reverse antiplatelet affects of these drugs, which irreversibly block platelet function for the life of the platelet (8-10 days). Current recommendations for the management of severe GI bleeding in patients receiving antithrombotic therapy include platelet transfusion, including those with a normal platelet count. However, this comes with a price as reversal of platelet function may increase the rate of cardiovascular events.

Zakko et al. performed a retrospective case-control study evaluating the role of platelet transfusion in patients presenting with GI bleeding. Patients were matched by age, sex, and the location of the GI bleed. Most patients included in the study were on low-dose aspirin and almost a third of the patients were taking both aspirin and a thienopyridine. Patients receiving platelet transfusions appeared to have more severe GI bleeding compared with matched controls, as patients receiving transfusion were more likely to have been hypotensive, tachycardic, have a low hemoglobin level, and require treatment in the intensive care unit (72% vs. 28%, P less than .0001). Patients receiving platelet transfusions were also more likely than matched controls to have recurrent GI bleeding as well as major cardiovascular adverse events, including myocardial infarction and inpatient death. After adjusting for patient characteristics, patients receiving platelet transfusions were more likely to have an increased risk of death (adjusted OR, 5.57; 95% CI, 1.52-27.1). The authors conclude that “the use of platelet transfusions in patients with GI bleeding who are taking antiplatelet agents without thrombocytopenia did not reduce rebleeding but was associated with higher mortality.”

Currently, there is no convincing evidence to support platelet transfusion in patients with bleeding on aspirin and/or a thienopyridine. Because the majority of the deaths were due to GI bleeding and not cardiovascular events, the observed increase in adverse events in patients receiving platelet transfusions likely reflects more severe GI bleeding in patients receiving platelet transfusions than in controls. We should avoid platelet transfusions and focus our management on achieving adequate resuscitation, use of proton pump inhibitors for patients with high-risk ulcers, and early endoscopy with endoscopic therapy for high-risk lesions.

John R. Saltzman, MD, AGAF, is director of endoscopy, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston. He has no conflicts of interest.

The management of patients with gastrointestinal bleeding on antithrombotic drugs is a major challenge for gastroenterologists. Unfortunately, the use of aspirin alone has been shown to increase the risk of GI bleed twofold, and the addition of a thienopyridine additionally increases the risk of bleeding twofold. Furthermore, there is no available agent to reverse antiplatelet affects of these drugs, which irreversibly block platelet function for the life of the platelet (8-10 days). Current recommendations for the management of severe GI bleeding in patients receiving antithrombotic therapy include platelet transfusion, including those with a normal platelet count. However, this comes with a price as reversal of platelet function may increase the rate of cardiovascular events.

Zakko et al. performed a retrospective case-control study evaluating the role of platelet transfusion in patients presenting with GI bleeding. Patients were matched by age, sex, and the location of the GI bleed. Most patients included in the study were on low-dose aspirin and almost a third of the patients were taking both aspirin and a thienopyridine. Patients receiving platelet transfusions appeared to have more severe GI bleeding compared with matched controls, as patients receiving transfusion were more likely to have been hypotensive, tachycardic, have a low hemoglobin level, and require treatment in the intensive care unit (72% vs. 28%, P less than .0001). Patients receiving platelet transfusions were also more likely than matched controls to have recurrent GI bleeding as well as major cardiovascular adverse events, including myocardial infarction and inpatient death. After adjusting for patient characteristics, patients receiving platelet transfusions were more likely to have an increased risk of death (adjusted OR, 5.57; 95% CI, 1.52-27.1). The authors conclude that “the use of platelet transfusions in patients with GI bleeding who are taking antiplatelet agents without thrombocytopenia did not reduce rebleeding but was associated with higher mortality.”

Currently, there is no convincing evidence to support platelet transfusion in patients with bleeding on aspirin and/or a thienopyridine. Because the majority of the deaths were due to GI bleeding and not cardiovascular events, the observed increase in adverse events in patients receiving platelet transfusions likely reflects more severe GI bleeding in patients receiving platelet transfusions than in controls. We should avoid platelet transfusions and focus our management on achieving adequate resuscitation, use of proton pump inhibitors for patients with high-risk ulcers, and early endoscopy with endoscopic therapy for high-risk lesions.

John R. Saltzman, MD, AGAF, is director of endoscopy, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston. He has no conflicts of interest.

Patients with normal platelet counts who have a GI bleed while on antiplatelets were almost six times more likely to die in the hospital if they had a platelet transfusion in a retrospective cohort study from the Yale University in New Haven, Conn.