User login

Studies shed new light on HSPC mobilization

in the bone marrow

Two new studies have revealed elements that are key to hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell (HSPC) mobilization.

In one study, investigators discovered that elevated levels of the peptide hormone angiotensin II increases HSPC mobilization in the context of vasculopathy and sickle cell disease (SCD).

In the other study, researchers found that p62, an autophagy regulator and signal organizer, is required to maintain HSPC retention in the bone marrow.

Jose Cancelas, MD, PhD, of the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine in Ohio, is the corresponding author on both studies.

In the first paper, published in Nature Communications, Dr Cancelas and his colleagues noted that patients with vasculopathies have an increase in circulating HSPCs.

“This phenomenon may represent a stress response contributing to vascular damage repair,” he said. “So the question becomes, how can we learn from these patients?”

Using mouse models of vasculopathy and vasculopathy-associated SCD, Dr Cancelas and his colleagues showed that acute and chronic elevated levels of angiotensin II resulted in an increased pool of HSPCs.

And when the researchers administered anti-angiotensin therapy, the pool of HSPCs decreased in mice and humans with SCD.

“These results indicate a new role for angiotensin in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell trafficking under pathological conditions and define the hematopoietic consequences of anti-angiotensin therapy in vascular disease and sickle cell disease,” Dr Cancelas said.

“Every year, millions of patients receive anti-angiotensin therapies due to the harmful effects associated with chronic hyperangiotensinemia in cardiac, renal, or liver failure. Our study shows that this anti-angiotensin therapy modulates the levels of circulating stem cells and progenitors.”

In the second paper, published in Cell Reports, Dr Cancelas and his colleagues examined the role that p62 plays in HSPC mobilization.

The investigators found that, when p62 is lost in osteoblasts, mice develop a condition similar to osteoporosis in humans.

The osteoblasts cannot degrade inflammatory signals coming from macrophages. And as a consequence, the deficient osteoblasts secrete inflammatory signals that impair the retention of HSPCs in the bone marrow and allow their escape to the circulation.

Specifically, the team found that macrophages activate osteoblastic NF-kB, which results in osteopenia and HSPC egress. And p62 negatively regulates osteoblastic NF-kB activation.

Dr Cancelas noted that patients with inflammatory diseases often have osteopenia. So this research may provide insight into that phenomenon and help explain why patients with chronic inflammatory diseases have higher levels of circulating HSPCs. ![]()

in the bone marrow

Two new studies have revealed elements that are key to hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell (HSPC) mobilization.

In one study, investigators discovered that elevated levels of the peptide hormone angiotensin II increases HSPC mobilization in the context of vasculopathy and sickle cell disease (SCD).

In the other study, researchers found that p62, an autophagy regulator and signal organizer, is required to maintain HSPC retention in the bone marrow.

Jose Cancelas, MD, PhD, of the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine in Ohio, is the corresponding author on both studies.

In the first paper, published in Nature Communications, Dr Cancelas and his colleagues noted that patients with vasculopathies have an increase in circulating HSPCs.

“This phenomenon may represent a stress response contributing to vascular damage repair,” he said. “So the question becomes, how can we learn from these patients?”

Using mouse models of vasculopathy and vasculopathy-associated SCD, Dr Cancelas and his colleagues showed that acute and chronic elevated levels of angiotensin II resulted in an increased pool of HSPCs.

And when the researchers administered anti-angiotensin therapy, the pool of HSPCs decreased in mice and humans with SCD.

“These results indicate a new role for angiotensin in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell trafficking under pathological conditions and define the hematopoietic consequences of anti-angiotensin therapy in vascular disease and sickle cell disease,” Dr Cancelas said.

“Every year, millions of patients receive anti-angiotensin therapies due to the harmful effects associated with chronic hyperangiotensinemia in cardiac, renal, or liver failure. Our study shows that this anti-angiotensin therapy modulates the levels of circulating stem cells and progenitors.”

In the second paper, published in Cell Reports, Dr Cancelas and his colleagues examined the role that p62 plays in HSPC mobilization.

The investigators found that, when p62 is lost in osteoblasts, mice develop a condition similar to osteoporosis in humans.

The osteoblasts cannot degrade inflammatory signals coming from macrophages. And as a consequence, the deficient osteoblasts secrete inflammatory signals that impair the retention of HSPCs in the bone marrow and allow their escape to the circulation.

Specifically, the team found that macrophages activate osteoblastic NF-kB, which results in osteopenia and HSPC egress. And p62 negatively regulates osteoblastic NF-kB activation.

Dr Cancelas noted that patients with inflammatory diseases often have osteopenia. So this research may provide insight into that phenomenon and help explain why patients with chronic inflammatory diseases have higher levels of circulating HSPCs. ![]()

in the bone marrow

Two new studies have revealed elements that are key to hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell (HSPC) mobilization.

In one study, investigators discovered that elevated levels of the peptide hormone angiotensin II increases HSPC mobilization in the context of vasculopathy and sickle cell disease (SCD).

In the other study, researchers found that p62, an autophagy regulator and signal organizer, is required to maintain HSPC retention in the bone marrow.

Jose Cancelas, MD, PhD, of the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine in Ohio, is the corresponding author on both studies.

In the first paper, published in Nature Communications, Dr Cancelas and his colleagues noted that patients with vasculopathies have an increase in circulating HSPCs.

“This phenomenon may represent a stress response contributing to vascular damage repair,” he said. “So the question becomes, how can we learn from these patients?”

Using mouse models of vasculopathy and vasculopathy-associated SCD, Dr Cancelas and his colleagues showed that acute and chronic elevated levels of angiotensin II resulted in an increased pool of HSPCs.

And when the researchers administered anti-angiotensin therapy, the pool of HSPCs decreased in mice and humans with SCD.

“These results indicate a new role for angiotensin in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell trafficking under pathological conditions and define the hematopoietic consequences of anti-angiotensin therapy in vascular disease and sickle cell disease,” Dr Cancelas said.

“Every year, millions of patients receive anti-angiotensin therapies due to the harmful effects associated with chronic hyperangiotensinemia in cardiac, renal, or liver failure. Our study shows that this anti-angiotensin therapy modulates the levels of circulating stem cells and progenitors.”

In the second paper, published in Cell Reports, Dr Cancelas and his colleagues examined the role that p62 plays in HSPC mobilization.

The investigators found that, when p62 is lost in osteoblasts, mice develop a condition similar to osteoporosis in humans.

The osteoblasts cannot degrade inflammatory signals coming from macrophages. And as a consequence, the deficient osteoblasts secrete inflammatory signals that impair the retention of HSPCs in the bone marrow and allow their escape to the circulation.

Specifically, the team found that macrophages activate osteoblastic NF-kB, which results in osteopenia and HSPC egress. And p62 negatively regulates osteoblastic NF-kB activation.

Dr Cancelas noted that patients with inflammatory diseases often have osteopenia. So this research may provide insight into that phenomenon and help explain why patients with chronic inflammatory diseases have higher levels of circulating HSPCs. ![]()

Label changes report new side effects for hematology drugs

Credit: CDC

Several hematology drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have recently undergone label changes to reflect newly reported adverse events.

Changes have been made to the labels for the JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib (Jakafi), the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody obinutuzumab (Gazyva), the factor Xa inhibitor rivaroxaban (Xarelto), and the hematopoietic stem cell mobilizer plerixafor (Mozobil).

Plerixafor

Plerixafor is FDA-approved for use in combination with granulocyte-colony stimulating factor to mobilize hematopoietic stem cells to the peripheral blood for collection and subsequent autologous transplantation in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma and multiple myeloma.

The product’s label was changed to include a new entry under the “Adverse Reactions” heading. Postmarketing experience suggested the drug may cause abnormal dreams and nightmares.

Rivaroxaban

Rivaroxaban is a factor Xa inhibitor that’s FDA-approved to reduce the risk of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, for the treatment of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), to reduce the risk of recurrent DVT and PE, and to prevent DVT, which may lead to PE, in patients undergoing knee or hip replacement surgery.

Postmarketing experience has led to two changes to the “Adverse Reactions” section of rivaroxaban’s label. Thrombocytopenia has been added as an adverse reaction, and the term “cytolytic hepatitis” has been replaced with “hepatitis (including hepatocellular injury).”

Obinutuzumab

Obinutuzumab is a CD20-directed cytolytic antibody that is FDA-approved in combination with chlorambucil to treat patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

The “Warnings and Precautions” section of obinutuzumab’s label has been changed to reflect that fatal infections have been reported in patients who received the drug.

The label has also been changed to coincide with changes in trial data. The label now states that obinutuzumab caused grade 3 or 4 neutropenia in 33% of patients and grade 3 or 4 thrombocytopenia in 10% of patients.

Ruxolitinib

Ruxolitinib is a JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor that’s FDA-approved to treat patients with polycythemia vera (PV) who cannot tolerate or don’t respond to hydroxyurea, as well as patients with intermediate or high-risk myelofibrosis.

Ruxolitinib’s label now includes a warning that symptoms of myeloproliferative neoplasms may return about a week after discontinuing treatment. The label also advises healthcare professionals to discourage patients form interrupting or discontinuing ruxolitinib without consulting their physician.

In addition, a warning about the risk of non-melanoma skin cancer associated with ruxolitinib, as well as advice for informing patients of this risk, have been added to ruxolitinib’s label.

The label has undergone significant changes in sections 6.1, “Clinical Trials Experience in Myelofibrosis” and 6.2 “Clinical Trial Experience in Polycythemia Vera.” It now includes additional information on the risk of thrombocytopenia, anemia, and neutropenia.

Under the “Special Populations” heading, recommendations were added to reduce the drug’s dose in patients with PV and moderate or severe renal impairment, as well as PV patients with hepatic impairment. ![]()

Credit: CDC

Several hematology drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have recently undergone label changes to reflect newly reported adverse events.

Changes have been made to the labels for the JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib (Jakafi), the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody obinutuzumab (Gazyva), the factor Xa inhibitor rivaroxaban (Xarelto), and the hematopoietic stem cell mobilizer plerixafor (Mozobil).

Plerixafor

Plerixafor is FDA-approved for use in combination with granulocyte-colony stimulating factor to mobilize hematopoietic stem cells to the peripheral blood for collection and subsequent autologous transplantation in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma and multiple myeloma.

The product’s label was changed to include a new entry under the “Adverse Reactions” heading. Postmarketing experience suggested the drug may cause abnormal dreams and nightmares.

Rivaroxaban

Rivaroxaban is a factor Xa inhibitor that’s FDA-approved to reduce the risk of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, for the treatment of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), to reduce the risk of recurrent DVT and PE, and to prevent DVT, which may lead to PE, in patients undergoing knee or hip replacement surgery.

Postmarketing experience has led to two changes to the “Adverse Reactions” section of rivaroxaban’s label. Thrombocytopenia has been added as an adverse reaction, and the term “cytolytic hepatitis” has been replaced with “hepatitis (including hepatocellular injury).”

Obinutuzumab

Obinutuzumab is a CD20-directed cytolytic antibody that is FDA-approved in combination with chlorambucil to treat patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

The “Warnings and Precautions” section of obinutuzumab’s label has been changed to reflect that fatal infections have been reported in patients who received the drug.

The label has also been changed to coincide with changes in trial data. The label now states that obinutuzumab caused grade 3 or 4 neutropenia in 33% of patients and grade 3 or 4 thrombocytopenia in 10% of patients.

Ruxolitinib

Ruxolitinib is a JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor that’s FDA-approved to treat patients with polycythemia vera (PV) who cannot tolerate or don’t respond to hydroxyurea, as well as patients with intermediate or high-risk myelofibrosis.

Ruxolitinib’s label now includes a warning that symptoms of myeloproliferative neoplasms may return about a week after discontinuing treatment. The label also advises healthcare professionals to discourage patients form interrupting or discontinuing ruxolitinib without consulting their physician.

In addition, a warning about the risk of non-melanoma skin cancer associated with ruxolitinib, as well as advice for informing patients of this risk, have been added to ruxolitinib’s label.

The label has undergone significant changes in sections 6.1, “Clinical Trials Experience in Myelofibrosis” and 6.2 “Clinical Trial Experience in Polycythemia Vera.” It now includes additional information on the risk of thrombocytopenia, anemia, and neutropenia.

Under the “Special Populations” heading, recommendations were added to reduce the drug’s dose in patients with PV and moderate or severe renal impairment, as well as PV patients with hepatic impairment. ![]()

Credit: CDC

Several hematology drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have recently undergone label changes to reflect newly reported adverse events.

Changes have been made to the labels for the JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib (Jakafi), the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody obinutuzumab (Gazyva), the factor Xa inhibitor rivaroxaban (Xarelto), and the hematopoietic stem cell mobilizer plerixafor (Mozobil).

Plerixafor

Plerixafor is FDA-approved for use in combination with granulocyte-colony stimulating factor to mobilize hematopoietic stem cells to the peripheral blood for collection and subsequent autologous transplantation in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma and multiple myeloma.

The product’s label was changed to include a new entry under the “Adverse Reactions” heading. Postmarketing experience suggested the drug may cause abnormal dreams and nightmares.

Rivaroxaban

Rivaroxaban is a factor Xa inhibitor that’s FDA-approved to reduce the risk of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, for the treatment of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), to reduce the risk of recurrent DVT and PE, and to prevent DVT, which may lead to PE, in patients undergoing knee or hip replacement surgery.

Postmarketing experience has led to two changes to the “Adverse Reactions” section of rivaroxaban’s label. Thrombocytopenia has been added as an adverse reaction, and the term “cytolytic hepatitis” has been replaced with “hepatitis (including hepatocellular injury).”

Obinutuzumab

Obinutuzumab is a CD20-directed cytolytic antibody that is FDA-approved in combination with chlorambucil to treat patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

The “Warnings and Precautions” section of obinutuzumab’s label has been changed to reflect that fatal infections have been reported in patients who received the drug.

The label has also been changed to coincide with changes in trial data. The label now states that obinutuzumab caused grade 3 or 4 neutropenia in 33% of patients and grade 3 or 4 thrombocytopenia in 10% of patients.

Ruxolitinib

Ruxolitinib is a JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor that’s FDA-approved to treat patients with polycythemia vera (PV) who cannot tolerate or don’t respond to hydroxyurea, as well as patients with intermediate or high-risk myelofibrosis.

Ruxolitinib’s label now includes a warning that symptoms of myeloproliferative neoplasms may return about a week after discontinuing treatment. The label also advises healthcare professionals to discourage patients form interrupting or discontinuing ruxolitinib without consulting their physician.

In addition, a warning about the risk of non-melanoma skin cancer associated with ruxolitinib, as well as advice for informing patients of this risk, have been added to ruxolitinib’s label.

The label has undergone significant changes in sections 6.1, “Clinical Trials Experience in Myelofibrosis” and 6.2 “Clinical Trial Experience in Polycythemia Vera.” It now includes additional information on the risk of thrombocytopenia, anemia, and neutropenia.

Under the “Special Populations” heading, recommendations were added to reduce the drug’s dose in patients with PV and moderate or severe renal impairment, as well as PV patients with hepatic impairment. ![]()

Imaging reveals how HSPCs interact with niche

(green) in a zebrafish

Boston Children’s Hospital

Using a zebrafish model and enhanced imaging, a group of researchers discovered how hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) interact with their niche.

Subsequent imaging in mice showed that HSPCs behaved the same way in mammals, which suggests similar results might be observed in humans.

In fact, the researchers are already using the results of this study to inform research on hematopoietic stem cell transplants.

“The same process occurs during a bone marrow transplant as occurs in the body naturally,” said senior study investigator Leonard Zon, MD, of Boston Children’s Hospital in Massachusetts.

“Our direct visualization gives us a series of steps to target, and, in theory, we can look for drugs that affect every step of that process.”

He and his colleagues described this research in a paper published in Cell, as well as in two animations on YouTube, one that’s general and one more technical.

“Stem cell and bone marrow transplants are still very much a black box,” said study author Owen Tamplin, PhD, also of Boston Children’s Hospital.

“Cells are introduced into a patient, and, later on, we can measure recovery of their blood system, but what happens in between can’t be seen. Now, we have a system where we can actually watch that middle step.”

The researchers already knew that HSPCs bud off from cells in the aorta, then circulate in the body until they find a niche where they’re prepped for creating blood.

With the current study, the team observed how this niche forms, using time-lapse imaging of naturally transparent zebrafish embryos and a genetic modification that tagged the HSPCs green.

On arrival in its niche (in the tail in zebrafish), the newborn HSPC attaches itself to the blood vessel wall. There, chemical signals prompt it to squeeze itself through the wall and into a space just outside the blood vessel. Other cells begin to interact with the HSPC, and nearby endothelial cells wrap themselves around it.

“We think that is the beginning of making a stem cell happy in its niche, like a mother cuddling a baby,” Dr Zon said.

As the HSPC is being “cuddled,” it’s brought into contact with a nearby stromal cell that helps keep it attached.

The “cuddling” was reconstructed from confocal and electron microscopy images of the zebrafish taken during this stage. Through a series of image slices, the researchers were able to reassemble the whole 3D structure—HSPC, cuddling endothelial cells, and stromal cells.

“Nobody’s ever visualized live how a stem cell interacts with its niche,” Dr Zon said. “This is the first time we get a very high-resolution view of the process.”

Next, the cuddled HSPC begins dividing. One daughter cell leaves the niche, while the other stays. Eventually, all the HSPCs leave and begin colonizing their future site of blood production. (In zebrafish, this is in the kidney, which is similar to mammalian bone marrow.)

Additional imaging in mice revealed evidence that HSPCs go through much the same process in mammals, which makes it likely in humans too.

These detailed observations are already informing the Zon lab’s attempt to improve stem cell transplants. By conducting a chemical screen in large numbers of zebrafish embryos, the researchers found that the compound lycorine promotes interaction between the HSPC and its niche, leading to greater numbers of HSPCs in the adult fish. ![]()

(green) in a zebrafish

Boston Children’s Hospital

Using a zebrafish model and enhanced imaging, a group of researchers discovered how hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) interact with their niche.

Subsequent imaging in mice showed that HSPCs behaved the same way in mammals, which suggests similar results might be observed in humans.

In fact, the researchers are already using the results of this study to inform research on hematopoietic stem cell transplants.

“The same process occurs during a bone marrow transplant as occurs in the body naturally,” said senior study investigator Leonard Zon, MD, of Boston Children’s Hospital in Massachusetts.

“Our direct visualization gives us a series of steps to target, and, in theory, we can look for drugs that affect every step of that process.”

He and his colleagues described this research in a paper published in Cell, as well as in two animations on YouTube, one that’s general and one more technical.

“Stem cell and bone marrow transplants are still very much a black box,” said study author Owen Tamplin, PhD, also of Boston Children’s Hospital.

“Cells are introduced into a patient, and, later on, we can measure recovery of their blood system, but what happens in between can’t be seen. Now, we have a system where we can actually watch that middle step.”

The researchers already knew that HSPCs bud off from cells in the aorta, then circulate in the body until they find a niche where they’re prepped for creating blood.

With the current study, the team observed how this niche forms, using time-lapse imaging of naturally transparent zebrafish embryos and a genetic modification that tagged the HSPCs green.

On arrival in its niche (in the tail in zebrafish), the newborn HSPC attaches itself to the blood vessel wall. There, chemical signals prompt it to squeeze itself through the wall and into a space just outside the blood vessel. Other cells begin to interact with the HSPC, and nearby endothelial cells wrap themselves around it.

“We think that is the beginning of making a stem cell happy in its niche, like a mother cuddling a baby,” Dr Zon said.

As the HSPC is being “cuddled,” it’s brought into contact with a nearby stromal cell that helps keep it attached.

The “cuddling” was reconstructed from confocal and electron microscopy images of the zebrafish taken during this stage. Through a series of image slices, the researchers were able to reassemble the whole 3D structure—HSPC, cuddling endothelial cells, and stromal cells.

“Nobody’s ever visualized live how a stem cell interacts with its niche,” Dr Zon said. “This is the first time we get a very high-resolution view of the process.”

Next, the cuddled HSPC begins dividing. One daughter cell leaves the niche, while the other stays. Eventually, all the HSPCs leave and begin colonizing their future site of blood production. (In zebrafish, this is in the kidney, which is similar to mammalian bone marrow.)

Additional imaging in mice revealed evidence that HSPCs go through much the same process in mammals, which makes it likely in humans too.

These detailed observations are already informing the Zon lab’s attempt to improve stem cell transplants. By conducting a chemical screen in large numbers of zebrafish embryos, the researchers found that the compound lycorine promotes interaction between the HSPC and its niche, leading to greater numbers of HSPCs in the adult fish. ![]()

(green) in a zebrafish

Boston Children’s Hospital

Using a zebrafish model and enhanced imaging, a group of researchers discovered how hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) interact with their niche.

Subsequent imaging in mice showed that HSPCs behaved the same way in mammals, which suggests similar results might be observed in humans.

In fact, the researchers are already using the results of this study to inform research on hematopoietic stem cell transplants.

“The same process occurs during a bone marrow transplant as occurs in the body naturally,” said senior study investigator Leonard Zon, MD, of Boston Children’s Hospital in Massachusetts.

“Our direct visualization gives us a series of steps to target, and, in theory, we can look for drugs that affect every step of that process.”

He and his colleagues described this research in a paper published in Cell, as well as in two animations on YouTube, one that’s general and one more technical.

“Stem cell and bone marrow transplants are still very much a black box,” said study author Owen Tamplin, PhD, also of Boston Children’s Hospital.

“Cells are introduced into a patient, and, later on, we can measure recovery of their blood system, but what happens in between can’t be seen. Now, we have a system where we can actually watch that middle step.”

The researchers already knew that HSPCs bud off from cells in the aorta, then circulate in the body until they find a niche where they’re prepped for creating blood.

With the current study, the team observed how this niche forms, using time-lapse imaging of naturally transparent zebrafish embryos and a genetic modification that tagged the HSPCs green.

On arrival in its niche (in the tail in zebrafish), the newborn HSPC attaches itself to the blood vessel wall. There, chemical signals prompt it to squeeze itself through the wall and into a space just outside the blood vessel. Other cells begin to interact with the HSPC, and nearby endothelial cells wrap themselves around it.

“We think that is the beginning of making a stem cell happy in its niche, like a mother cuddling a baby,” Dr Zon said.

As the HSPC is being “cuddled,” it’s brought into contact with a nearby stromal cell that helps keep it attached.

The “cuddling” was reconstructed from confocal and electron microscopy images of the zebrafish taken during this stage. Through a series of image slices, the researchers were able to reassemble the whole 3D structure—HSPC, cuddling endothelial cells, and stromal cells.

“Nobody’s ever visualized live how a stem cell interacts with its niche,” Dr Zon said. “This is the first time we get a very high-resolution view of the process.”

Next, the cuddled HSPC begins dividing. One daughter cell leaves the niche, while the other stays. Eventually, all the HSPCs leave and begin colonizing their future site of blood production. (In zebrafish, this is in the kidney, which is similar to mammalian bone marrow.)

Additional imaging in mice revealed evidence that HSPCs go through much the same process in mammals, which makes it likely in humans too.

These detailed observations are already informing the Zon lab’s attempt to improve stem cell transplants. By conducting a chemical screen in large numbers of zebrafish embryos, the researchers found that the compound lycorine promotes interaction between the HSPC and its niche, leading to greater numbers of HSPCs in the adult fish. ![]()

‘Mother of bone marrow transplantation’ dies

husband, E. Donnall Thomas,

at a 2005 reunion of transplant

patients in Seattle

Photo by Jim Linna

Dorothy “Dottie” Thomas, the wife and research partner of 1990 Nobel laureate E. Donnall “Don” Thomas, MD, passed away on January 9 at the age of 92.

Don, pioneer of the bone marrow transplant (BMT), preceded Dottie in passing away himself on October 20, 2012, also at the age of 92.

The Thomases formed the core of a team that proved BMT could cure leukemias and other hematologic malignancies, work that spanned several decades.

Dottie may have gotten the name “the mother of bone marrow transplantation,” from the late George Santos, MD, a BMT expert at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland, and a colleague.

“If Dr Thomas is the father of bone marrow transplantation, then Dottie Thomas is the mother,” he once said.

“Dottie’s life had a profound impact, not just on those who knew her personally, but also countless patients,” said Gary Gilliland, MD, PhD, president and director of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, who became friends with the Thomases when he and Don served on the advisory board of the José Carreras Leukemia Foundation.

“She and Don were amazing together in both what they accomplished and the way they cared for each other. They were so sweet together. Now, their legacy continues through the many whose lives have been saved by bone marrow transplant and those who will be saved in the future. Dottie truly helped change the future of medicine. All of us at Fred Hutch are part of her legacy.”

A romantic partnership becomes a professional one

A snowball to the face during a rare Texas snowfall in 1940 precipitated a partnership in love and work between Don and Dottie that spanned 70 years.

“I was a senior at the University of Texas when she was a freshman,” Don told The Seattle Times in a 1999 interview. “I was waiting tables at the girls dormitory, which is how I got my food.”

“It snowed in Texas, which is very unusual. And I came out of the dormitory after we’d finished serving breakfast, and there was about 6 inches of snow. This girl whacked me in the face with a snowball. She still claims she was throwing it at another fellow and hit me by mistake. One thing led to another, and we seemed to hit it off.”

The couple married in December 1942. Dottie was a journalism major in college when, in March 1943, Don was admitted to Harvard University Medical School under a US Army program. Dottie got a job as a secretary with the Navy while Don attended medical school.

“Dottie and I talked it over, and we decided that if we were going to spend time together, which it turned out we liked to do, that she probably ought to change her profession,” Don told The Seattle Times. “She’d taken a lot of science in her time in school, much more than most journalists. She liked science.”

So Dottie left her Navy job and enrolled in the medical technology training program at New England Deaconess Hospital.

“Because Dottie was a hematology technician, we used to look at smears and bone marrow together when we were students,” Don said.

She worked as a medical technician for some doctors in Boston until Don had his own laboratory. Then, she began to work with him. She worked part-time when their children were small, but, otherwise, she was in the lab full-time with her husband.

“Dottie was there at Don’s side through every part of developing marrow transplantation as a science,” said Fred Appelbaum, MD, executive vice president and deputy director of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

“Besides raising 3 children together, Dottie was Don’s partner in every aspect of his professional life, from working in the laboratory to editing manuscripts and administering his research program.”

Dottie’s journalism training was a big asset to the team, according to Don.

“In the laboratory days, my friends pointed out that Dottie, who had the library experience, would go to the library and look up all the background information for a study that we were going to do, and then she would go into the laboratory and do the work and get the data, and then, with her writing skills, she’d write the paper and complete the bibliography,” Don recalled. “All I would do is sign the letter to the editor.”

The couple moved to Seattle in 1963. Don joined the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in 1975, the year its doors opened in Seattle’s First Hill neighborhood. For the next 15 years, Dottie served as the chief administrator for the Clinical Research Division. Don stepped down from the clinical leadership position in 1990 and retired from the center in 2002.

The Thomases are survived by 2 sons and a daughter, 8 grandchildren, and 2 great-grandchildren.

The family requests that people who wish to honor Dottie do so by contributing to Dottie’s Bridge, an endowment to assist young researchers. ![]()

husband, E. Donnall Thomas,

at a 2005 reunion of transplant

patients in Seattle

Photo by Jim Linna

Dorothy “Dottie” Thomas, the wife and research partner of 1990 Nobel laureate E. Donnall “Don” Thomas, MD, passed away on January 9 at the age of 92.

Don, pioneer of the bone marrow transplant (BMT), preceded Dottie in passing away himself on October 20, 2012, also at the age of 92.

The Thomases formed the core of a team that proved BMT could cure leukemias and other hematologic malignancies, work that spanned several decades.

Dottie may have gotten the name “the mother of bone marrow transplantation,” from the late George Santos, MD, a BMT expert at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland, and a colleague.

“If Dr Thomas is the father of bone marrow transplantation, then Dottie Thomas is the mother,” he once said.

“Dottie’s life had a profound impact, not just on those who knew her personally, but also countless patients,” said Gary Gilliland, MD, PhD, president and director of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, who became friends with the Thomases when he and Don served on the advisory board of the José Carreras Leukemia Foundation.

“She and Don were amazing together in both what they accomplished and the way they cared for each other. They were so sweet together. Now, their legacy continues through the many whose lives have been saved by bone marrow transplant and those who will be saved in the future. Dottie truly helped change the future of medicine. All of us at Fred Hutch are part of her legacy.”

A romantic partnership becomes a professional one

A snowball to the face during a rare Texas snowfall in 1940 precipitated a partnership in love and work between Don and Dottie that spanned 70 years.

“I was a senior at the University of Texas when she was a freshman,” Don told The Seattle Times in a 1999 interview. “I was waiting tables at the girls dormitory, which is how I got my food.”

“It snowed in Texas, which is very unusual. And I came out of the dormitory after we’d finished serving breakfast, and there was about 6 inches of snow. This girl whacked me in the face with a snowball. She still claims she was throwing it at another fellow and hit me by mistake. One thing led to another, and we seemed to hit it off.”

The couple married in December 1942. Dottie was a journalism major in college when, in March 1943, Don was admitted to Harvard University Medical School under a US Army program. Dottie got a job as a secretary with the Navy while Don attended medical school.

“Dottie and I talked it over, and we decided that if we were going to spend time together, which it turned out we liked to do, that she probably ought to change her profession,” Don told The Seattle Times. “She’d taken a lot of science in her time in school, much more than most journalists. She liked science.”

So Dottie left her Navy job and enrolled in the medical technology training program at New England Deaconess Hospital.

“Because Dottie was a hematology technician, we used to look at smears and bone marrow together when we were students,” Don said.

She worked as a medical technician for some doctors in Boston until Don had his own laboratory. Then, she began to work with him. She worked part-time when their children were small, but, otherwise, she was in the lab full-time with her husband.

“Dottie was there at Don’s side through every part of developing marrow transplantation as a science,” said Fred Appelbaum, MD, executive vice president and deputy director of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

“Besides raising 3 children together, Dottie was Don’s partner in every aspect of his professional life, from working in the laboratory to editing manuscripts and administering his research program.”

Dottie’s journalism training was a big asset to the team, according to Don.

“In the laboratory days, my friends pointed out that Dottie, who had the library experience, would go to the library and look up all the background information for a study that we were going to do, and then she would go into the laboratory and do the work and get the data, and then, with her writing skills, she’d write the paper and complete the bibliography,” Don recalled. “All I would do is sign the letter to the editor.”

The couple moved to Seattle in 1963. Don joined the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in 1975, the year its doors opened in Seattle’s First Hill neighborhood. For the next 15 years, Dottie served as the chief administrator for the Clinical Research Division. Don stepped down from the clinical leadership position in 1990 and retired from the center in 2002.

The Thomases are survived by 2 sons and a daughter, 8 grandchildren, and 2 great-grandchildren.

The family requests that people who wish to honor Dottie do so by contributing to Dottie’s Bridge, an endowment to assist young researchers. ![]()

husband, E. Donnall Thomas,

at a 2005 reunion of transplant

patients in Seattle

Photo by Jim Linna

Dorothy “Dottie” Thomas, the wife and research partner of 1990 Nobel laureate E. Donnall “Don” Thomas, MD, passed away on January 9 at the age of 92.

Don, pioneer of the bone marrow transplant (BMT), preceded Dottie in passing away himself on October 20, 2012, also at the age of 92.

The Thomases formed the core of a team that proved BMT could cure leukemias and other hematologic malignancies, work that spanned several decades.

Dottie may have gotten the name “the mother of bone marrow transplantation,” from the late George Santos, MD, a BMT expert at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland, and a colleague.

“If Dr Thomas is the father of bone marrow transplantation, then Dottie Thomas is the mother,” he once said.

“Dottie’s life had a profound impact, not just on those who knew her personally, but also countless patients,” said Gary Gilliland, MD, PhD, president and director of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, who became friends with the Thomases when he and Don served on the advisory board of the José Carreras Leukemia Foundation.

“She and Don were amazing together in both what they accomplished and the way they cared for each other. They were so sweet together. Now, their legacy continues through the many whose lives have been saved by bone marrow transplant and those who will be saved in the future. Dottie truly helped change the future of medicine. All of us at Fred Hutch are part of her legacy.”

A romantic partnership becomes a professional one

A snowball to the face during a rare Texas snowfall in 1940 precipitated a partnership in love and work between Don and Dottie that spanned 70 years.

“I was a senior at the University of Texas when she was a freshman,” Don told The Seattle Times in a 1999 interview. “I was waiting tables at the girls dormitory, which is how I got my food.”

“It snowed in Texas, which is very unusual. And I came out of the dormitory after we’d finished serving breakfast, and there was about 6 inches of snow. This girl whacked me in the face with a snowball. She still claims she was throwing it at another fellow and hit me by mistake. One thing led to another, and we seemed to hit it off.”

The couple married in December 1942. Dottie was a journalism major in college when, in March 1943, Don was admitted to Harvard University Medical School under a US Army program. Dottie got a job as a secretary with the Navy while Don attended medical school.

“Dottie and I talked it over, and we decided that if we were going to spend time together, which it turned out we liked to do, that she probably ought to change her profession,” Don told The Seattle Times. “She’d taken a lot of science in her time in school, much more than most journalists. She liked science.”

So Dottie left her Navy job and enrolled in the medical technology training program at New England Deaconess Hospital.

“Because Dottie was a hematology technician, we used to look at smears and bone marrow together when we were students,” Don said.

She worked as a medical technician for some doctors in Boston until Don had his own laboratory. Then, she began to work with him. She worked part-time when their children were small, but, otherwise, she was in the lab full-time with her husband.

“Dottie was there at Don’s side through every part of developing marrow transplantation as a science,” said Fred Appelbaum, MD, executive vice president and deputy director of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

“Besides raising 3 children together, Dottie was Don’s partner in every aspect of his professional life, from working in the laboratory to editing manuscripts and administering his research program.”

Dottie’s journalism training was a big asset to the team, according to Don.

“In the laboratory days, my friends pointed out that Dottie, who had the library experience, would go to the library and look up all the background information for a study that we were going to do, and then she would go into the laboratory and do the work and get the data, and then, with her writing skills, she’d write the paper and complete the bibliography,” Don recalled. “All I would do is sign the letter to the editor.”

The couple moved to Seattle in 1963. Don joined the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in 1975, the year its doors opened in Seattle’s First Hill neighborhood. For the next 15 years, Dottie served as the chief administrator for the Clinical Research Division. Don stepped down from the clinical leadership position in 1990 and retired from the center in 2002.

The Thomases are survived by 2 sons and a daughter, 8 grandchildren, and 2 great-grandchildren.

The family requests that people who wish to honor Dottie do so by contributing to Dottie’s Bridge, an endowment to assist young researchers. ![]()

Cord blood product gets orphan designation

Credit: NHS

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan designation to a cord blood product called NiCord for the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

NiCord consists of cells from a single cord blood unit cultured in nicotinamide—a vitamin B derivative—and cytokines that are typically used for expansion—thrombopoietin, interleukin 6, FLT3 ligand, and stem cell factor.

The FDA’s orphan drug designation for NiCord coincides with the positive opinion of the European Medicines Agency’s (EMA’s) Committee for Orphan Medicinal Products regarding NiCord as a treatment for AML. Gamida Cell, the company developing NiCord, intends to file for orphan drug status with the EMA for other indications as well.

“Receipt of orphan drug status for NiCord in the US and Europe advances Gamida Cell’s commercialization plans a major step further, as both afford significant advantages,” said Yael Margolin, President and CEO of Gamida Cell.

Orphan drug designation provides various regulatory and economic benefits, including 7 years of market exclusivity upon product approval in the US and 10 years in the European Union.

Trials of NiCord

NiCord is currently being tested in a phase 1/2 study as an investigational therapeutic treatment for hematologic malignancies. In this study, NiCord is being used as the sole stem cell source.

In a previous study, presented at the 11th Annual International Cord Blood Symposium, researchers transplanted a NiCord unit and an unmanipulated cord blood unit in patients with ALL, AML, MDS, HL, or non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

A majority of patients in this small, phase 1/2 study achieved early platelet and neutrophil engraftment. And, in some patients, that engraftment persisted for 2 years.

Eight of the 11 patients enrolled achieved engraftment with the NiCord unit, and 2 engrafted with the unmanipulated cord blood unit. One patient had primary graft failure.

There were no adverse events attributable to the NiCord unit, but 4 patients developed grade 1-2 acute GVHD, and 1 patient developed limited chronic GVHD.

For more information on NiCord, visit the Gamida Cell website. ![]()

Credit: NHS

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan designation to a cord blood product called NiCord for the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

NiCord consists of cells from a single cord blood unit cultured in nicotinamide—a vitamin B derivative—and cytokines that are typically used for expansion—thrombopoietin, interleukin 6, FLT3 ligand, and stem cell factor.

The FDA’s orphan drug designation for NiCord coincides with the positive opinion of the European Medicines Agency’s (EMA’s) Committee for Orphan Medicinal Products regarding NiCord as a treatment for AML. Gamida Cell, the company developing NiCord, intends to file for orphan drug status with the EMA for other indications as well.

“Receipt of orphan drug status for NiCord in the US and Europe advances Gamida Cell’s commercialization plans a major step further, as both afford significant advantages,” said Yael Margolin, President and CEO of Gamida Cell.

Orphan drug designation provides various regulatory and economic benefits, including 7 years of market exclusivity upon product approval in the US and 10 years in the European Union.

Trials of NiCord

NiCord is currently being tested in a phase 1/2 study as an investigational therapeutic treatment for hematologic malignancies. In this study, NiCord is being used as the sole stem cell source.

In a previous study, presented at the 11th Annual International Cord Blood Symposium, researchers transplanted a NiCord unit and an unmanipulated cord blood unit in patients with ALL, AML, MDS, HL, or non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

A majority of patients in this small, phase 1/2 study achieved early platelet and neutrophil engraftment. And, in some patients, that engraftment persisted for 2 years.

Eight of the 11 patients enrolled achieved engraftment with the NiCord unit, and 2 engrafted with the unmanipulated cord blood unit. One patient had primary graft failure.

There were no adverse events attributable to the NiCord unit, but 4 patients developed grade 1-2 acute GVHD, and 1 patient developed limited chronic GVHD.

For more information on NiCord, visit the Gamida Cell website. ![]()

Credit: NHS

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan designation to a cord blood product called NiCord for the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

NiCord consists of cells from a single cord blood unit cultured in nicotinamide—a vitamin B derivative—and cytokines that are typically used for expansion—thrombopoietin, interleukin 6, FLT3 ligand, and stem cell factor.

The FDA’s orphan drug designation for NiCord coincides with the positive opinion of the European Medicines Agency’s (EMA’s) Committee for Orphan Medicinal Products regarding NiCord as a treatment for AML. Gamida Cell, the company developing NiCord, intends to file for orphan drug status with the EMA for other indications as well.

“Receipt of orphan drug status for NiCord in the US and Europe advances Gamida Cell’s commercialization plans a major step further, as both afford significant advantages,” said Yael Margolin, President and CEO of Gamida Cell.

Orphan drug designation provides various regulatory and economic benefits, including 7 years of market exclusivity upon product approval in the US and 10 years in the European Union.

Trials of NiCord

NiCord is currently being tested in a phase 1/2 study as an investigational therapeutic treatment for hematologic malignancies. In this study, NiCord is being used as the sole stem cell source.

In a previous study, presented at the 11th Annual International Cord Blood Symposium, researchers transplanted a NiCord unit and an unmanipulated cord blood unit in patients with ALL, AML, MDS, HL, or non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

A majority of patients in this small, phase 1/2 study achieved early platelet and neutrophil engraftment. And, in some patients, that engraftment persisted for 2 years.

Eight of the 11 patients enrolled achieved engraftment with the NiCord unit, and 2 engrafted with the unmanipulated cord blood unit. One patient had primary graft failure.

There were no adverse events attributable to the NiCord unit, but 4 patients developed grade 1-2 acute GVHD, and 1 patient developed limited chronic GVHD.

For more information on NiCord, visit the Gamida Cell website. ![]()

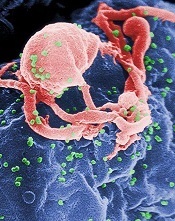

HIV doesn’t hinder lymphoma patients’ response to ASCT

a cultured lymphocyte

Credit: CDC

SAN FRANCISCO—Patients with HIV-related lymphoma (HRL) should not be excluded from clinical trials of autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) due to their HIV status, new research suggests.

Investigators found no significant difference in rates of treatment failure, disease progression, or survival between transplant-treated historical controls who had lymphoma but not HIV and patients with HRL who received the modified BEAM regimen followed by ASCT on a phase 2 trial.

This suggests patients with chemotherapy-sensitive, relapsed/refractory HRL can be treated successfully with the modified BEAM regimen, said study investigator Joseph Alvarnas, MD, of City of Hope National Medical Center in Duarte, California.

“Patients with treatment-responsive HIV infection and HIV-related lymphoma should be considered candidates for autologous transplant if they meet standard transplant criteria,” he added. “And we would argue that exclusion from clinical trials on the basis of HIV infection alone is no longer justified.”

Dr Alvarnas presented this viewpoint and the research to support it at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting as abstract 674.

The trial enrolled 43 patients with treatable HIV-1 infection, adequate organ function, and aggressive lymphoma. Three patients were excluded because they could not undergo transplant due to lymphoma progression.

Of the 40 remaining patients, 5 were female, and their median age was 46.9 years (range, 22.5-62.2). They had diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (n=16), plasmablastic lymphoma (n=2), Burkitt/Burkitt-like lymphoma (n=7), and Hodgkin lymphoma (n=15).

The pre-ASCT HIV viral load was undetectable in 31 patients. In the patients with detectable HIV, the median viral load pre-ASCT was 84 copies/μL (range, 50-17,455). The median CD4 count was 250.5/µL (range, 39-797).

Before transplant, 30 patients (75%) were in complete remission, 8 (20%) were in partial remission, and 2 (5%) had relapsed/progressive disease.

The patients underwent ASCT after conditioning with the modified BEAM regimen—carmustine at 300 mg/m2 (day -6), etoposide at 100 mg/m2 twice daily (days -5 to -2), cytarabine at 100 mg/m2 (days -5 to -2), and melphalan at 140 mg/m2 (day -1).

Combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) was held during the preparative regimen and resumed after the resolution of gastrointestinal toxicity. The investigators switched efavirenz to an alternative agent 2 or more weeks prior to the planned interruption of cART, as the drug has a long half-life. And AZT was prohibited due to its myelosuppressive effects.

Treatment results

The median follow-up was 24 months. At 100 days post-transplant, the investigators assessed 39 patients for response. One patient was not evaluable due to early death.

Thirty-six of the patients (92.3%) were in complete remission, 1 (2.6%) was in partial remission, and 2 (5.1%) had relapsed or progressive disease.

Fifteen patients reported grade 3 or higher toxicities within a year of transplant. Of the 13 unexpected grade 3-5 adverse events (reported in 9 patients), 5 were infection/sepsis, 1 was acute appendicitis, 1 was acute coronary syndrome, 2 were deep vein thromboses, 2 were gastrointestinal toxicities, and 2 were metabolic abnormalities.

Seventeen patients reported at least 1 infectious episode, 42 events in total, 9 of which were severe. Fourteen patients required readmission to the hospital after transplant.

Within a year of transplant, 5 patients had died—3 from recurrent/persistent disease, 1 due to a fungal infection, and 1 from cardiac arrest. Two additional patients died after the 1-year mark—1 of recurrent/persistent disease and 1 of heart failure.

At 12 months, the rate of overall survival was 86.6%, progression-free survival was 82.3%, progression was 12.5%, and non-relapse mortality was 5.2%.

“In order to place this within context, we had the opportunity to compare our patient experience with 151 matched controls [without HIV] from CIBMTR,” Dr Alvarnas said. “Ninety-three percent of these patients were actually transplanted within 2 years so that they were the time-concordant group, and they were matched for performance score, disease, and disease stage.”

The investigators found no significant difference between their patient group and the HIV-free controls with regard to overall mortality (P=0.56), treatment failure (P=0.10), progression (P=0.06), and treatment-related mortality (P=0.97).

Likewise, there was no significant difference in overall survival between the HRL patients and controls—86.6% and 87.7%, respectively (P=0.56). And the same was true of progression-free survival—82.3% and 69.5%, respectively (P=0.10). ![]()

a cultured lymphocyte

Credit: CDC

SAN FRANCISCO—Patients with HIV-related lymphoma (HRL) should not be excluded from clinical trials of autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) due to their HIV status, new research suggests.

Investigators found no significant difference in rates of treatment failure, disease progression, or survival between transplant-treated historical controls who had lymphoma but not HIV and patients with HRL who received the modified BEAM regimen followed by ASCT on a phase 2 trial.

This suggests patients with chemotherapy-sensitive, relapsed/refractory HRL can be treated successfully with the modified BEAM regimen, said study investigator Joseph Alvarnas, MD, of City of Hope National Medical Center in Duarte, California.

“Patients with treatment-responsive HIV infection and HIV-related lymphoma should be considered candidates for autologous transplant if they meet standard transplant criteria,” he added. “And we would argue that exclusion from clinical trials on the basis of HIV infection alone is no longer justified.”

Dr Alvarnas presented this viewpoint and the research to support it at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting as abstract 674.

The trial enrolled 43 patients with treatable HIV-1 infection, adequate organ function, and aggressive lymphoma. Three patients were excluded because they could not undergo transplant due to lymphoma progression.

Of the 40 remaining patients, 5 were female, and their median age was 46.9 years (range, 22.5-62.2). They had diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (n=16), plasmablastic lymphoma (n=2), Burkitt/Burkitt-like lymphoma (n=7), and Hodgkin lymphoma (n=15).

The pre-ASCT HIV viral load was undetectable in 31 patients. In the patients with detectable HIV, the median viral load pre-ASCT was 84 copies/μL (range, 50-17,455). The median CD4 count was 250.5/µL (range, 39-797).

Before transplant, 30 patients (75%) were in complete remission, 8 (20%) were in partial remission, and 2 (5%) had relapsed/progressive disease.

The patients underwent ASCT after conditioning with the modified BEAM regimen—carmustine at 300 mg/m2 (day -6), etoposide at 100 mg/m2 twice daily (days -5 to -2), cytarabine at 100 mg/m2 (days -5 to -2), and melphalan at 140 mg/m2 (day -1).

Combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) was held during the preparative regimen and resumed after the resolution of gastrointestinal toxicity. The investigators switched efavirenz to an alternative agent 2 or more weeks prior to the planned interruption of cART, as the drug has a long half-life. And AZT was prohibited due to its myelosuppressive effects.

Treatment results

The median follow-up was 24 months. At 100 days post-transplant, the investigators assessed 39 patients for response. One patient was not evaluable due to early death.

Thirty-six of the patients (92.3%) were in complete remission, 1 (2.6%) was in partial remission, and 2 (5.1%) had relapsed or progressive disease.

Fifteen patients reported grade 3 or higher toxicities within a year of transplant. Of the 13 unexpected grade 3-5 adverse events (reported in 9 patients), 5 were infection/sepsis, 1 was acute appendicitis, 1 was acute coronary syndrome, 2 were deep vein thromboses, 2 were gastrointestinal toxicities, and 2 were metabolic abnormalities.

Seventeen patients reported at least 1 infectious episode, 42 events in total, 9 of which were severe. Fourteen patients required readmission to the hospital after transplant.

Within a year of transplant, 5 patients had died—3 from recurrent/persistent disease, 1 due to a fungal infection, and 1 from cardiac arrest. Two additional patients died after the 1-year mark—1 of recurrent/persistent disease and 1 of heart failure.

At 12 months, the rate of overall survival was 86.6%, progression-free survival was 82.3%, progression was 12.5%, and non-relapse mortality was 5.2%.

“In order to place this within context, we had the opportunity to compare our patient experience with 151 matched controls [without HIV] from CIBMTR,” Dr Alvarnas said. “Ninety-three percent of these patients were actually transplanted within 2 years so that they were the time-concordant group, and they were matched for performance score, disease, and disease stage.”

The investigators found no significant difference between their patient group and the HIV-free controls with regard to overall mortality (P=0.56), treatment failure (P=0.10), progression (P=0.06), and treatment-related mortality (P=0.97).

Likewise, there was no significant difference in overall survival between the HRL patients and controls—86.6% and 87.7%, respectively (P=0.56). And the same was true of progression-free survival—82.3% and 69.5%, respectively (P=0.10). ![]()

a cultured lymphocyte

Credit: CDC

SAN FRANCISCO—Patients with HIV-related lymphoma (HRL) should not be excluded from clinical trials of autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) due to their HIV status, new research suggests.

Investigators found no significant difference in rates of treatment failure, disease progression, or survival between transplant-treated historical controls who had lymphoma but not HIV and patients with HRL who received the modified BEAM regimen followed by ASCT on a phase 2 trial.

This suggests patients with chemotherapy-sensitive, relapsed/refractory HRL can be treated successfully with the modified BEAM regimen, said study investigator Joseph Alvarnas, MD, of City of Hope National Medical Center in Duarte, California.

“Patients with treatment-responsive HIV infection and HIV-related lymphoma should be considered candidates for autologous transplant if they meet standard transplant criteria,” he added. “And we would argue that exclusion from clinical trials on the basis of HIV infection alone is no longer justified.”

Dr Alvarnas presented this viewpoint and the research to support it at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting as abstract 674.

The trial enrolled 43 patients with treatable HIV-1 infection, adequate organ function, and aggressive lymphoma. Three patients were excluded because they could not undergo transplant due to lymphoma progression.

Of the 40 remaining patients, 5 were female, and their median age was 46.9 years (range, 22.5-62.2). They had diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (n=16), plasmablastic lymphoma (n=2), Burkitt/Burkitt-like lymphoma (n=7), and Hodgkin lymphoma (n=15).

The pre-ASCT HIV viral load was undetectable in 31 patients. In the patients with detectable HIV, the median viral load pre-ASCT was 84 copies/μL (range, 50-17,455). The median CD4 count was 250.5/µL (range, 39-797).

Before transplant, 30 patients (75%) were in complete remission, 8 (20%) were in partial remission, and 2 (5%) had relapsed/progressive disease.

The patients underwent ASCT after conditioning with the modified BEAM regimen—carmustine at 300 mg/m2 (day -6), etoposide at 100 mg/m2 twice daily (days -5 to -2), cytarabine at 100 mg/m2 (days -5 to -2), and melphalan at 140 mg/m2 (day -1).

Combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) was held during the preparative regimen and resumed after the resolution of gastrointestinal toxicity. The investigators switched efavirenz to an alternative agent 2 or more weeks prior to the planned interruption of cART, as the drug has a long half-life. And AZT was prohibited due to its myelosuppressive effects.

Treatment results

The median follow-up was 24 months. At 100 days post-transplant, the investigators assessed 39 patients for response. One patient was not evaluable due to early death.

Thirty-six of the patients (92.3%) were in complete remission, 1 (2.6%) was in partial remission, and 2 (5.1%) had relapsed or progressive disease.

Fifteen patients reported grade 3 or higher toxicities within a year of transplant. Of the 13 unexpected grade 3-5 adverse events (reported in 9 patients), 5 were infection/sepsis, 1 was acute appendicitis, 1 was acute coronary syndrome, 2 were deep vein thromboses, 2 were gastrointestinal toxicities, and 2 were metabolic abnormalities.

Seventeen patients reported at least 1 infectious episode, 42 events in total, 9 of which were severe. Fourteen patients required readmission to the hospital after transplant.

Within a year of transplant, 5 patients had died—3 from recurrent/persistent disease, 1 due to a fungal infection, and 1 from cardiac arrest. Two additional patients died after the 1-year mark—1 of recurrent/persistent disease and 1 of heart failure.

At 12 months, the rate of overall survival was 86.6%, progression-free survival was 82.3%, progression was 12.5%, and non-relapse mortality was 5.2%.

“In order to place this within context, we had the opportunity to compare our patient experience with 151 matched controls [without HIV] from CIBMTR,” Dr Alvarnas said. “Ninety-three percent of these patients were actually transplanted within 2 years so that they were the time-concordant group, and they were matched for performance score, disease, and disease stage.”

The investigators found no significant difference between their patient group and the HIV-free controls with regard to overall mortality (P=0.56), treatment failure (P=0.10), progression (P=0.06), and treatment-related mortality (P=0.97).

Likewise, there was no significant difference in overall survival between the HRL patients and controls—86.6% and 87.7%, respectively (P=0.56). And the same was true of progression-free survival—82.3% and 69.5%, respectively (P=0.10). ![]()

Test predicts response to GVHD treatment

A newly developed algorithm could enable risk-adapted therapy for graft-vs-host disease (GVHD), researchers have reported in Lancet Haematology.

The problem with treating GVHD, the team said, is that the severity of symptoms at disease onset does not accurately define risk.

Patients with low-risk GVHD are often overtreated and experience significant side effects, while patients with high-risk GVHD can be undertreated and see their GVHD progress.

“Our goal is to provide the right treatment for each patient,” said study author James L. M. Ferrara, MD, DSc, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

“We hope to identify those patients at higher risk and design an aggressive intervention while tailoring a less-aggressive approach for those with low-risk.”

With that goal in mind, Dr Ferrara and his colleagues developed and tested a scoring system for GVHD. They collected plasma from 492 patients newly diagnosed with varying grades of GVHD and randomly assigned them to training (n=328) and test (n=164) sets.

The team used the concentrations of 3 validated biomarkers—TNFR1, ST2, and Reg3α—to create an algorithm that calculated the probability of non-relapse mortality (NRM) 6 months after GVHD onset for patients in the training set.

The researchers ranked the probabilities and identified thresholds that created 3 NRM scores. They then tested the algorithm in the test set of patients and a validation cohort of 300 additional patients who were enrolled on trials of GVHD treatment.

Results showed the algorithm works. The cumulative incidence of 6-month NRM significantly increased as the Ann Arbor GVHD score increased, and the response to primary GVHD treatment within 28 days decreased as the GVHD score increased.

In the validation set, the incidence of NRM was 8% for score 1, 27% for score 2, and 46% for score 3 (P<0.0001). Treatment response measured 86% for score 1, 67% for score 2, and 46% for score 3 (P<0.0001).

“This new scoring system will help identify patient who may not respond to standard treatments and may require an experimental and more aggressive approach,” Dr Ferrara said. “And it will also help guide treatment for patients with lower-risk GVHD who may be overtreated. This will allow us to personalize treatment at the onset of the disease. Future algorithms will prove increasingly useful to develop precision medicine for all [stem cell transplant] patients.”

To capitalize on this discovery, Dr Ferrara created the Mount Sinai Acute GVHD International Consortium (MAGIC), which consists of a group of 10 stem cell transplant centers in the US and Europe that will collaborate to use this new scoring system to test new treatments for acute GVHD.

Dr Ferrara and his colleagues have also written a protocol to treat high-risk GVHD that has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. ![]()

A newly developed algorithm could enable risk-adapted therapy for graft-vs-host disease (GVHD), researchers have reported in Lancet Haematology.

The problem with treating GVHD, the team said, is that the severity of symptoms at disease onset does not accurately define risk.

Patients with low-risk GVHD are often overtreated and experience significant side effects, while patients with high-risk GVHD can be undertreated and see their GVHD progress.

“Our goal is to provide the right treatment for each patient,” said study author James L. M. Ferrara, MD, DSc, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

“We hope to identify those patients at higher risk and design an aggressive intervention while tailoring a less-aggressive approach for those with low-risk.”

With that goal in mind, Dr Ferrara and his colleagues developed and tested a scoring system for GVHD. They collected plasma from 492 patients newly diagnosed with varying grades of GVHD and randomly assigned them to training (n=328) and test (n=164) sets.

The team used the concentrations of 3 validated biomarkers—TNFR1, ST2, and Reg3α—to create an algorithm that calculated the probability of non-relapse mortality (NRM) 6 months after GVHD onset for patients in the training set.

The researchers ranked the probabilities and identified thresholds that created 3 NRM scores. They then tested the algorithm in the test set of patients and a validation cohort of 300 additional patients who were enrolled on trials of GVHD treatment.

Results showed the algorithm works. The cumulative incidence of 6-month NRM significantly increased as the Ann Arbor GVHD score increased, and the response to primary GVHD treatment within 28 days decreased as the GVHD score increased.

In the validation set, the incidence of NRM was 8% for score 1, 27% for score 2, and 46% for score 3 (P<0.0001). Treatment response measured 86% for score 1, 67% for score 2, and 46% for score 3 (P<0.0001).

“This new scoring system will help identify patient who may not respond to standard treatments and may require an experimental and more aggressive approach,” Dr Ferrara said. “And it will also help guide treatment for patients with lower-risk GVHD who may be overtreated. This will allow us to personalize treatment at the onset of the disease. Future algorithms will prove increasingly useful to develop precision medicine for all [stem cell transplant] patients.”

To capitalize on this discovery, Dr Ferrara created the Mount Sinai Acute GVHD International Consortium (MAGIC), which consists of a group of 10 stem cell transplant centers in the US and Europe that will collaborate to use this new scoring system to test new treatments for acute GVHD.

Dr Ferrara and his colleagues have also written a protocol to treat high-risk GVHD that has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. ![]()

A newly developed algorithm could enable risk-adapted therapy for graft-vs-host disease (GVHD), researchers have reported in Lancet Haematology.

The problem with treating GVHD, the team said, is that the severity of symptoms at disease onset does not accurately define risk.

Patients with low-risk GVHD are often overtreated and experience significant side effects, while patients with high-risk GVHD can be undertreated and see their GVHD progress.

“Our goal is to provide the right treatment for each patient,” said study author James L. M. Ferrara, MD, DSc, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

“We hope to identify those patients at higher risk and design an aggressive intervention while tailoring a less-aggressive approach for those with low-risk.”

With that goal in mind, Dr Ferrara and his colleagues developed and tested a scoring system for GVHD. They collected plasma from 492 patients newly diagnosed with varying grades of GVHD and randomly assigned them to training (n=328) and test (n=164) sets.

The team used the concentrations of 3 validated biomarkers—TNFR1, ST2, and Reg3α—to create an algorithm that calculated the probability of non-relapse mortality (NRM) 6 months after GVHD onset for patients in the training set.

The researchers ranked the probabilities and identified thresholds that created 3 NRM scores. They then tested the algorithm in the test set of patients and a validation cohort of 300 additional patients who were enrolled on trials of GVHD treatment.

Results showed the algorithm works. The cumulative incidence of 6-month NRM significantly increased as the Ann Arbor GVHD score increased, and the response to primary GVHD treatment within 28 days decreased as the GVHD score increased.

In the validation set, the incidence of NRM was 8% for score 1, 27% for score 2, and 46% for score 3 (P<0.0001). Treatment response measured 86% for score 1, 67% for score 2, and 46% for score 3 (P<0.0001).

“This new scoring system will help identify patient who may not respond to standard treatments and may require an experimental and more aggressive approach,” Dr Ferrara said. “And it will also help guide treatment for patients with lower-risk GVHD who may be overtreated. This will allow us to personalize treatment at the onset of the disease. Future algorithms will prove increasingly useful to develop precision medicine for all [stem cell transplant] patients.”

To capitalize on this discovery, Dr Ferrara created the Mount Sinai Acute GVHD International Consortium (MAGIC), which consists of a group of 10 stem cell transplant centers in the US and Europe that will collaborate to use this new scoring system to test new treatments for acute GVHD.

Dr Ferrara and his colleagues have also written a protocol to treat high-risk GVHD that has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

Approach can cure even high-risk FL, study suggests

SAN FRANCISCO—Follicular lymphoma (FL) patients who receive high-dose therapy with autologous stem cell transplant (HDT/ASCT) after they’ve responded to chemotherapy can achieve long-term cancer-free survival, new research suggests.

The study showed that many patients transplanted in complete remission (CR) did not relapse and could be considered cured.

Patients transplanted in their first CR fared the best, as median progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) times were not reached.

But even patients transplanted in their second/third CR or in their first partial remission (PR) survived a median of 15 years or more, although their PFS times were shorter, at about 14 years and 3 years, respectively.

Carlos Grande García, MD, of Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre in Madrid, Spain, presented these results at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 675.)*

“In follicular lymphoma patients, intensification with high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell support offers an advantage in terms of progression-free survival in comparison with conventional chemo,” he said. “But, so far, no randomized studies have yet shown any overall survival advantage.”

“Follicular lymphoma has a long natural course, and most patients have received different salvage therapies. Probably, this is why the available phase 3 studies have had insufficient time to confirm the impact on OS.”

To investigate the impact of HDT/ASCT on OS, Dr Grande García and his colleagues conducted a retrospective study of 655 FL patients who received HDT/ASCT from 1989 to 2007. Patients with histological transformation, those undergoing a second transplant, and those with a follow-up of less than 7 years were excluded.

Patient characteristics

The median follow-up was 12 years from HDT/ASCT and 14.4 years from diagnosis. At diagnosis, the median patient age was 47, 49.6% of patients were male, and 90% had stage III/IV disease.

According to FLIPI, 33% of patients were good risk, 36% were intermediate risk, and 31% were poor risk. According to FLIPI-2, the percentages were 22%, 38%, and 40%, respectively. Thirty percent of patients had received rituximab prior to HDT/ASCT.

Thirty-one percent of patients (n=203) were in their first CR at the time of transplant, 43% of whom required more than one line of therapy to reach first CR.

Thirty-one percent of patients (n=202) were in second or third CR, 21.5% (n=149) were in first PR, 12.5% (n=81) were in sensitive relapse (defined as a response other than CR or first PR), and 5% (n=29) had overt disease (which included untreated relapsed disease, first refractory disease, and second refractory disease).

Patients received a variety of conditioning regimens, including total-body irradiation plus cyclophosphamide, BEAM (carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan), BEAC (carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and cyclophosphamide), and other regimens. They received stem cells from peripheral blood (81%), bone marrow (14%), or both sources (5%).

There were 4 graft failures and 17 early toxic deaths. Thirty-one percent of patients experienced grade 3/4 hematologic toxicities.

PFS and OS

In all patients, the median PFS was 9.25 years, and the median OS was 19.5 years.

When the researchers looked at outcomes according to patients’ status at transplant, they found the median OS and PFS were not reached among patients in first CR. At a median follow-up of 12.75 years, the OS rate was 72%, and the PFS rate was 68%.

“Beginning at 10 years from transplantation, only 6 patients have died,” Dr Grande García noted, “one from disease progression, 3 from second malignancy, [and] 2 from unrelated causes.”

For patients in second or third CR, the median OS was not reached, and the median PFS was 13.9 years. For those in first PR, the median OS was 15 years, and the median PFS was 2.6 years.

For patients with sensitive disease, the median OS was 5.1 years, and the median PFS was 2 years. For those with overt disease, the median OS was 4.4 years, and the median PFS was 0.5 years.

In multivariate analysis, the following characteristics were significant predictors of OS: being older than 47 years of age (hazard ratio [HR]=1.74, P=0.0001), female sex (HR=0.58, P=0.00004), status at HDT/ASCT (HR=2.06, P<10-5), and receipt of rituximab prior to HDT/ASCT (HR=0.61, P=0.004).

Significant predictors of PFS included age (HR=1.34, P=0.01), sex (HR=0.64, P<10-5), status at HDT/ASCT (HR=2.15, P<10-5), and rituximab use (HR=0.67, P=0.003).

For patients transplanted in first CR, only sex was a significant predictor of PFS (HR=0.48, P=0.008) and OS (HR=0.43, P=0.007).