User login

Pathway appears key to fighting adenovirus

Using an animal model they developed, researchers have identified a pathway that inhibits replication of the adenovirus.

The team generated a new strain of Syrian hamster, a model in which human adenovirus replicates and causes illness similar to that observed in humans.

Experiments with this model suggested the Type I interferon pathway plays a key role in inhibiting adenovirus replication.

“[L]ike many other viruses, adenovirus can replicate at will when a patient’s immune system is suppressed,” said William Wold, PhD, of Saint Louis University in Missouri.

“Adenovirus can become very dangerous, such as for a child who is undergoing a bone marrow transplant to treat leukemia.”

Previously, Dr Wold led a research team that identified the Syrian hamster as an appropriate animal model to study adenovirus because species C human adenoviruses replicate in these animals.

For the current study, which was published in PLOS Pathogens, Dr Wold and his colleagues conducted experiments with a new Syrian hamster strain. In these animals, the STAT2 gene was functionally knocked out by site-specific gene targeting.

The researchers found that STAT2-knockout hamsters were extremely sensitive to infection with type 5 human adenovirus (Ad5).

The team infected both STAT2-knockout hamsters and wild-type controls with Ad5. Knockout hamsters had 100 to 1000 times the viral load of controls.

The knockout hamsters also had pathology characteristic of advanced adenovirus infection—yellow, mottled livers and enlarged gall bladders—whereas controls did not.

The adaptive immune response to Ad5 remained intact in the STAT2-knockout hamsters, as surviving animals were able to clear the virus.

However, the Type 1 interferon response was hampered in these animals. Knocking out STAT2 disrupted the Type 1 interferon pathway by interrupting the cascade of cell signaling.

The researchers said their findings suggest the disrupted Type I interferon pathway contributed to the increased Ad5 replication in the STAT2-knockout hamsters.

“Besides providing an insight into adenovirus infection in humans, our results are also interesting from the perspective of the animal model,” Dr Wold said. “The STAT2-knockout Syrian hamster may also be an important animal model for studying other viral infections, including Ebola, hanta, and dengue viruses.”

The model was created by Zhongde Wang, PhD, and his colleagues at Utah State University in Logan, Utah. Dr Wang’s lab is the first to develop gene-targeting technologies in the Syrian hamster.

“The success we achieved in conducting gene-targeting in the Syrian hamster has provided the opportunity to create models for many of the human diseases for which there are either no existent animal models or severe limitations in the available animal models,” Dr Wang said. ![]()

Using an animal model they developed, researchers have identified a pathway that inhibits replication of the adenovirus.

The team generated a new strain of Syrian hamster, a model in which human adenovirus replicates and causes illness similar to that observed in humans.

Experiments with this model suggested the Type I interferon pathway plays a key role in inhibiting adenovirus replication.

“[L]ike many other viruses, adenovirus can replicate at will when a patient’s immune system is suppressed,” said William Wold, PhD, of Saint Louis University in Missouri.

“Adenovirus can become very dangerous, such as for a child who is undergoing a bone marrow transplant to treat leukemia.”

Previously, Dr Wold led a research team that identified the Syrian hamster as an appropriate animal model to study adenovirus because species C human adenoviruses replicate in these animals.

For the current study, which was published in PLOS Pathogens, Dr Wold and his colleagues conducted experiments with a new Syrian hamster strain. In these animals, the STAT2 gene was functionally knocked out by site-specific gene targeting.

The researchers found that STAT2-knockout hamsters were extremely sensitive to infection with type 5 human adenovirus (Ad5).

The team infected both STAT2-knockout hamsters and wild-type controls with Ad5. Knockout hamsters had 100 to 1000 times the viral load of controls.

The knockout hamsters also had pathology characteristic of advanced adenovirus infection—yellow, mottled livers and enlarged gall bladders—whereas controls did not.

The adaptive immune response to Ad5 remained intact in the STAT2-knockout hamsters, as surviving animals were able to clear the virus.

However, the Type 1 interferon response was hampered in these animals. Knocking out STAT2 disrupted the Type 1 interferon pathway by interrupting the cascade of cell signaling.

The researchers said their findings suggest the disrupted Type I interferon pathway contributed to the increased Ad5 replication in the STAT2-knockout hamsters.

“Besides providing an insight into adenovirus infection in humans, our results are also interesting from the perspective of the animal model,” Dr Wold said. “The STAT2-knockout Syrian hamster may also be an important animal model for studying other viral infections, including Ebola, hanta, and dengue viruses.”

The model was created by Zhongde Wang, PhD, and his colleagues at Utah State University in Logan, Utah. Dr Wang’s lab is the first to develop gene-targeting technologies in the Syrian hamster.

“The success we achieved in conducting gene-targeting in the Syrian hamster has provided the opportunity to create models for many of the human diseases for which there are either no existent animal models or severe limitations in the available animal models,” Dr Wang said. ![]()

Using an animal model they developed, researchers have identified a pathway that inhibits replication of the adenovirus.

The team generated a new strain of Syrian hamster, a model in which human adenovirus replicates and causes illness similar to that observed in humans.

Experiments with this model suggested the Type I interferon pathway plays a key role in inhibiting adenovirus replication.

“[L]ike many other viruses, adenovirus can replicate at will when a patient’s immune system is suppressed,” said William Wold, PhD, of Saint Louis University in Missouri.

“Adenovirus can become very dangerous, such as for a child who is undergoing a bone marrow transplant to treat leukemia.”

Previously, Dr Wold led a research team that identified the Syrian hamster as an appropriate animal model to study adenovirus because species C human adenoviruses replicate in these animals.

For the current study, which was published in PLOS Pathogens, Dr Wold and his colleagues conducted experiments with a new Syrian hamster strain. In these animals, the STAT2 gene was functionally knocked out by site-specific gene targeting.

The researchers found that STAT2-knockout hamsters were extremely sensitive to infection with type 5 human adenovirus (Ad5).

The team infected both STAT2-knockout hamsters and wild-type controls with Ad5. Knockout hamsters had 100 to 1000 times the viral load of controls.

The knockout hamsters also had pathology characteristic of advanced adenovirus infection—yellow, mottled livers and enlarged gall bladders—whereas controls did not.

The adaptive immune response to Ad5 remained intact in the STAT2-knockout hamsters, as surviving animals were able to clear the virus.

However, the Type 1 interferon response was hampered in these animals. Knocking out STAT2 disrupted the Type 1 interferon pathway by interrupting the cascade of cell signaling.

The researchers said their findings suggest the disrupted Type I interferon pathway contributed to the increased Ad5 replication in the STAT2-knockout hamsters.

“Besides providing an insight into adenovirus infection in humans, our results are also interesting from the perspective of the animal model,” Dr Wold said. “The STAT2-knockout Syrian hamster may also be an important animal model for studying other viral infections, including Ebola, hanta, and dengue viruses.”

The model was created by Zhongde Wang, PhD, and his colleagues at Utah State University in Logan, Utah. Dr Wang’s lab is the first to develop gene-targeting technologies in the Syrian hamster.

“The success we achieved in conducting gene-targeting in the Syrian hamster has provided the opportunity to create models for many of the human diseases for which there are either no existent animal models or severe limitations in the available animal models,” Dr Wang said. ![]()

To match bone marrow donors and recipients, ask about grandma

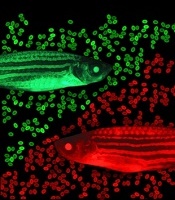

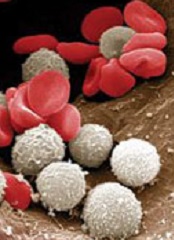

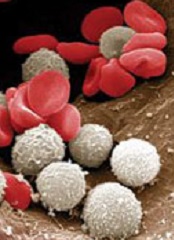

Photo by Chad McNeeley

Asking bone marrow donors about their grandparents’ ancestry may help match donors to the appropriate recipients, according to research published in PLOS ONE.

Investigators found that when donors were self-reporting their race/ethnicity and included information on their grandparents’ ancestry, their responses often matched their genetics better than when they simply selected from standard race/ethnicity categories.

The investigators said these results show that more research is needed to refine methods for collecting and interpreting information on race/ethnicity for medical purposes.

“In medicine, we’ve been under the assumption that it’s just a matter of presenting people with the right check boxes,” said Jill Hollenbach, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco. “It turns out that it’s much more complex than that.”

She and her colleagues noted that identifying a 10/10 human leukocyte antigen (HLA) match in the National Marrow Donor Program’s Be The Match Registry can be difficult because most of the donors submitted samples at a time when genotyping was much less advanced than it is today.

To find likely matches to pursue, the registry uses bioinformatics to weed out the donors unlikely to have matching HLA genes. Although HLA genes are highly variable, certain variations are found at higher frequencies in some regions of the world than others.

A patient with geographic ancestry in East Asia, for example, is more likely to have the same HLA variation as someone with origins in East Asia, rather than someone with European ancestry.

To obtain such information, most medical facilities use the patients’ race/ethnicity self-identification as a proxy. This can be challenging for people who trace their ancestry to multiple origins.

“The United States census uses a “check all that apply” technique, which is OK, but we want to try to get a little more refined to improve our matching efficiency,” said study author Martin Maiers, director of Bioinformatics Research at the Be The Match Registry.

To assess the extent to which different means of self-identification correspond to genetic ancestry, the investigators recruited 1752 potential donors from the Be The Match Registry.

The team sent participants a questionnaire with multiple measures of self-identification, including race/ethnicity and geographic ancestry, and asked participants to assign geographic ancestry to their grandparents. Participants also submitted cheek swabs as DNA samples.

By analyzing the cheek swabs, the investigators genotyped 93 ancestry informative markers to identify the participants’ genetic ancestry. This revealed a strong correlation between the ancestry markers and HLA genes.

Unfortunately, no measure of self-identification showed complete correspondence with a donor’s genetic ancestry. However, information about the geographic origins of the donors’ grandparents corresponded most closely with genetics, particularly for participants with ancestry from multiple continents.

“The conventional wisdom of the last decade or two has been that race is a social construct,” Dr Hollenbach said. “That’s true, but race is also part of the language of self-identification in [the US]. Let’s understand how these different forms of self-identification and genetic ancestry intersect to improve transplant matching for people of all ancestral backgrounds.” ![]()

Photo by Chad McNeeley

Asking bone marrow donors about their grandparents’ ancestry may help match donors to the appropriate recipients, according to research published in PLOS ONE.

Investigators found that when donors were self-reporting their race/ethnicity and included information on their grandparents’ ancestry, their responses often matched their genetics better than when they simply selected from standard race/ethnicity categories.

The investigators said these results show that more research is needed to refine methods for collecting and interpreting information on race/ethnicity for medical purposes.

“In medicine, we’ve been under the assumption that it’s just a matter of presenting people with the right check boxes,” said Jill Hollenbach, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco. “It turns out that it’s much more complex than that.”

She and her colleagues noted that identifying a 10/10 human leukocyte antigen (HLA) match in the National Marrow Donor Program’s Be The Match Registry can be difficult because most of the donors submitted samples at a time when genotyping was much less advanced than it is today.

To find likely matches to pursue, the registry uses bioinformatics to weed out the donors unlikely to have matching HLA genes. Although HLA genes are highly variable, certain variations are found at higher frequencies in some regions of the world than others.

A patient with geographic ancestry in East Asia, for example, is more likely to have the same HLA variation as someone with origins in East Asia, rather than someone with European ancestry.

To obtain such information, most medical facilities use the patients’ race/ethnicity self-identification as a proxy. This can be challenging for people who trace their ancestry to multiple origins.

“The United States census uses a “check all that apply” technique, which is OK, but we want to try to get a little more refined to improve our matching efficiency,” said study author Martin Maiers, director of Bioinformatics Research at the Be The Match Registry.

To assess the extent to which different means of self-identification correspond to genetic ancestry, the investigators recruited 1752 potential donors from the Be The Match Registry.

The team sent participants a questionnaire with multiple measures of self-identification, including race/ethnicity and geographic ancestry, and asked participants to assign geographic ancestry to their grandparents. Participants also submitted cheek swabs as DNA samples.

By analyzing the cheek swabs, the investigators genotyped 93 ancestry informative markers to identify the participants’ genetic ancestry. This revealed a strong correlation between the ancestry markers and HLA genes.

Unfortunately, no measure of self-identification showed complete correspondence with a donor’s genetic ancestry. However, information about the geographic origins of the donors’ grandparents corresponded most closely with genetics, particularly for participants with ancestry from multiple continents.

“The conventional wisdom of the last decade or two has been that race is a social construct,” Dr Hollenbach said. “That’s true, but race is also part of the language of self-identification in [the US]. Let’s understand how these different forms of self-identification and genetic ancestry intersect to improve transplant matching for people of all ancestral backgrounds.” ![]()

Photo by Chad McNeeley

Asking bone marrow donors about their grandparents’ ancestry may help match donors to the appropriate recipients, according to research published in PLOS ONE.

Investigators found that when donors were self-reporting their race/ethnicity and included information on their grandparents’ ancestry, their responses often matched their genetics better than when they simply selected from standard race/ethnicity categories.

The investigators said these results show that more research is needed to refine methods for collecting and interpreting information on race/ethnicity for medical purposes.

“In medicine, we’ve been under the assumption that it’s just a matter of presenting people with the right check boxes,” said Jill Hollenbach, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco. “It turns out that it’s much more complex than that.”

She and her colleagues noted that identifying a 10/10 human leukocyte antigen (HLA) match in the National Marrow Donor Program’s Be The Match Registry can be difficult because most of the donors submitted samples at a time when genotyping was much less advanced than it is today.

To find likely matches to pursue, the registry uses bioinformatics to weed out the donors unlikely to have matching HLA genes. Although HLA genes are highly variable, certain variations are found at higher frequencies in some regions of the world than others.

A patient with geographic ancestry in East Asia, for example, is more likely to have the same HLA variation as someone with origins in East Asia, rather than someone with European ancestry.

To obtain such information, most medical facilities use the patients’ race/ethnicity self-identification as a proxy. This can be challenging for people who trace their ancestry to multiple origins.

“The United States census uses a “check all that apply” technique, which is OK, but we want to try to get a little more refined to improve our matching efficiency,” said study author Martin Maiers, director of Bioinformatics Research at the Be The Match Registry.

To assess the extent to which different means of self-identification correspond to genetic ancestry, the investigators recruited 1752 potential donors from the Be The Match Registry.

The team sent participants a questionnaire with multiple measures of self-identification, including race/ethnicity and geographic ancestry, and asked participants to assign geographic ancestry to their grandparents. Participants also submitted cheek swabs as DNA samples.

By analyzing the cheek swabs, the investigators genotyped 93 ancestry informative markers to identify the participants’ genetic ancestry. This revealed a strong correlation between the ancestry markers and HLA genes.

Unfortunately, no measure of self-identification showed complete correspondence with a donor’s genetic ancestry. However, information about the geographic origins of the donors’ grandparents corresponded most closely with genetics, particularly for participants with ancestry from multiple continents.

“The conventional wisdom of the last decade or two has been that race is a social construct,” Dr Hollenbach said. “That’s true, but race is also part of the language of self-identification in [the US]. Let’s understand how these different forms of self-identification and genetic ancestry intersect to improve transplant matching for people of all ancestral backgrounds.” ![]()

T-cell finding may have broad implications

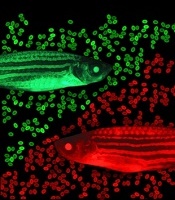

resolution microscope

Image courtesy of UNSW

Early exposure to inflammatory cytokines can “paralyze” CD4 T cells, according to research published in Immunity.

The study suggests this mechanism may act as a firewall, shutting down the immune response before it gets out of hand.

According to researchers, this discovery could lead to more effective immunotherapies for cancer and reduce the need for immunosuppressants in transplant patients, among other applications.

“There’s a 3-signal process to activate T cells, of which each component is essential for proper activation,” said study author Gail Sckisel, PhD, of the University of California, Davis in Sacramento.

“But no one had really looked at what happens if they are delivered out of sequence. If the third signal—cytokines—is given prematurely, it basically paralyzes CD4 T cells.”

To be activated, T cells must first recognize an antigen, receive appropriate costimulatory signals, and then encounter inflammatory cytokines to expand the immune response. Until now, no one realized that sending the third signal early—as is done with some immunotherapies—could actually hamper overall immunity.

“These stimulatory immunotherapies are designed to activate the immune system,” Dr Sckisel explained. “But considering how T cells respond, that approach could damage a patient’s ability to fight off pathogens. While immunotherapies might fight cancer, they may also open the door to opportunistic infections.”

She and her colleagues demonstrated this principle in mice. After they received systemic immunotherapy, the animals had trouble mounting a primary T-cell response.

The researchers confirmed this finding in samples from patients receiving high-dose interleukin 2 to treat metastatic melanoma.

“We need to be very careful because immunotherapy could be generating both short-term gain and long-term loss,” said study author William Murphy, PhD, also of the University of California, Davis.

“The patients who were receiving immunotherapy were totally shut down, which shows how profoundly we were suppressing the immune system.”

In addition to illuminating how T cells respond to cancer immunotherapy, the study also provides insights into autoimmune disorders. The researchers believe this CD4 paralysis mechanism could play a role in preventing autoimmunity, a hypothesis they supported by testing immunotherapy in a multiple sclerosis model.

By shutting down CD4 T cells, immune stimulation prevented an autoimmune response. This provides the opportunity to paralyze the immune system to prevent autoimmunity or modulate it to accept transplanted cells or entire organs.

“Transplant patients go on immunosuppressants for the rest of their lives, but if we could safely induce paralysis just prior to surgery, it’s possible that patients could develop tolerance,” Dr Sckisel said.

CD4 paralysis may also be co-opted by pathogens, such as HIV, which could use this chronic inflammation response to disable the immune system.

“This really highlights the importance of CD4 T cells,” Dr Murphy said. “The fact that they’re regulated and suppressed means they are definitely the orchestrators we need to take into account. It also shows how smart HIV is. The virus has been telling us CD4 T cells are critical because that’s what it attacks.”

The team’s next step is to continue this research in older mice. Age can bring a measurable loss in immune function, and inflammation may play a role in that process.

“For elderly people who have flu or pneumonia, their immune systems are activated, but maybe they can’t fight anything else,” Dr Murphy said. “This could change how we treat people who are very sick. If we can block pathways that suppress the immune response, we may be able to better fight infection.” ![]()

resolution microscope

Image courtesy of UNSW

Early exposure to inflammatory cytokines can “paralyze” CD4 T cells, according to research published in Immunity.

The study suggests this mechanism may act as a firewall, shutting down the immune response before it gets out of hand.

According to researchers, this discovery could lead to more effective immunotherapies for cancer and reduce the need for immunosuppressants in transplant patients, among other applications.

“There’s a 3-signal process to activate T cells, of which each component is essential for proper activation,” said study author Gail Sckisel, PhD, of the University of California, Davis in Sacramento.

“But no one had really looked at what happens if they are delivered out of sequence. If the third signal—cytokines—is given prematurely, it basically paralyzes CD4 T cells.”

To be activated, T cells must first recognize an antigen, receive appropriate costimulatory signals, and then encounter inflammatory cytokines to expand the immune response. Until now, no one realized that sending the third signal early—as is done with some immunotherapies—could actually hamper overall immunity.

“These stimulatory immunotherapies are designed to activate the immune system,” Dr Sckisel explained. “But considering how T cells respond, that approach could damage a patient’s ability to fight off pathogens. While immunotherapies might fight cancer, they may also open the door to opportunistic infections.”

She and her colleagues demonstrated this principle in mice. After they received systemic immunotherapy, the animals had trouble mounting a primary T-cell response.

The researchers confirmed this finding in samples from patients receiving high-dose interleukin 2 to treat metastatic melanoma.

“We need to be very careful because immunotherapy could be generating both short-term gain and long-term loss,” said study author William Murphy, PhD, also of the University of California, Davis.

“The patients who were receiving immunotherapy were totally shut down, which shows how profoundly we were suppressing the immune system.”

In addition to illuminating how T cells respond to cancer immunotherapy, the study also provides insights into autoimmune disorders. The researchers believe this CD4 paralysis mechanism could play a role in preventing autoimmunity, a hypothesis they supported by testing immunotherapy in a multiple sclerosis model.

By shutting down CD4 T cells, immune stimulation prevented an autoimmune response. This provides the opportunity to paralyze the immune system to prevent autoimmunity or modulate it to accept transplanted cells or entire organs.

“Transplant patients go on immunosuppressants for the rest of their lives, but if we could safely induce paralysis just prior to surgery, it’s possible that patients could develop tolerance,” Dr Sckisel said.

CD4 paralysis may also be co-opted by pathogens, such as HIV, which could use this chronic inflammation response to disable the immune system.

“This really highlights the importance of CD4 T cells,” Dr Murphy said. “The fact that they’re regulated and suppressed means they are definitely the orchestrators we need to take into account. It also shows how smart HIV is. The virus has been telling us CD4 T cells are critical because that’s what it attacks.”

The team’s next step is to continue this research in older mice. Age can bring a measurable loss in immune function, and inflammation may play a role in that process.

“For elderly people who have flu or pneumonia, their immune systems are activated, but maybe they can’t fight anything else,” Dr Murphy said. “This could change how we treat people who are very sick. If we can block pathways that suppress the immune response, we may be able to better fight infection.” ![]()

resolution microscope

Image courtesy of UNSW

Early exposure to inflammatory cytokines can “paralyze” CD4 T cells, according to research published in Immunity.

The study suggests this mechanism may act as a firewall, shutting down the immune response before it gets out of hand.

According to researchers, this discovery could lead to more effective immunotherapies for cancer and reduce the need for immunosuppressants in transplant patients, among other applications.

“There’s a 3-signal process to activate T cells, of which each component is essential for proper activation,” said study author Gail Sckisel, PhD, of the University of California, Davis in Sacramento.

“But no one had really looked at what happens if they are delivered out of sequence. If the third signal—cytokines—is given prematurely, it basically paralyzes CD4 T cells.”

To be activated, T cells must first recognize an antigen, receive appropriate costimulatory signals, and then encounter inflammatory cytokines to expand the immune response. Until now, no one realized that sending the third signal early—as is done with some immunotherapies—could actually hamper overall immunity.

“These stimulatory immunotherapies are designed to activate the immune system,” Dr Sckisel explained. “But considering how T cells respond, that approach could damage a patient’s ability to fight off pathogens. While immunotherapies might fight cancer, they may also open the door to opportunistic infections.”

She and her colleagues demonstrated this principle in mice. After they received systemic immunotherapy, the animals had trouble mounting a primary T-cell response.

The researchers confirmed this finding in samples from patients receiving high-dose interleukin 2 to treat metastatic melanoma.

“We need to be very careful because immunotherapy could be generating both short-term gain and long-term loss,” said study author William Murphy, PhD, also of the University of California, Davis.

“The patients who were receiving immunotherapy were totally shut down, which shows how profoundly we were suppressing the immune system.”

In addition to illuminating how T cells respond to cancer immunotherapy, the study also provides insights into autoimmune disorders. The researchers believe this CD4 paralysis mechanism could play a role in preventing autoimmunity, a hypothesis they supported by testing immunotherapy in a multiple sclerosis model.

By shutting down CD4 T cells, immune stimulation prevented an autoimmune response. This provides the opportunity to paralyze the immune system to prevent autoimmunity or modulate it to accept transplanted cells or entire organs.

“Transplant patients go on immunosuppressants for the rest of their lives, but if we could safely induce paralysis just prior to surgery, it’s possible that patients could develop tolerance,” Dr Sckisel said.

CD4 paralysis may also be co-opted by pathogens, such as HIV, which could use this chronic inflammation response to disable the immune system.

“This really highlights the importance of CD4 T cells,” Dr Murphy said. “The fact that they’re regulated and suppressed means they are definitely the orchestrators we need to take into account. It also shows how smart HIV is. The virus has been telling us CD4 T cells are critical because that’s what it attacks.”

The team’s next step is to continue this research in older mice. Age can bring a measurable loss in immune function, and inflammation may play a role in that process.

“For elderly people who have flu or pneumonia, their immune systems are activated, but maybe they can’t fight anything else,” Dr Murphy said. “This could change how we treat people who are very sick. If we can block pathways that suppress the immune response, we may be able to better fight infection.” ![]()

FDA approves brentuximab vedotin as consolidation

Photo from Business Wire

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris) for use as consolidation treatment after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (auto-HSCT) in patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) at high risk of relapse or progression.

The drug is the first FDA-approved consolidation option available to these patients.

The approval was based on results of the phase 3 AETHERA trial.

Results from this trial also served to convert a prior accelerated approval of brentuximab vedotin to regular approval. The drug is now fully approved for the treatment of classical HL patients who have failed auto-HSCT and those who have failed at least 2 prior multi-agent chemotherapy regimens and are not candidates for auto-HSCT.

Brentuximab vedotin is also FDA-approved to treat patients with systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma who have failed at least 1 prior multi-agent chemotherapy regimen. The drug has accelerated approval for this indication based on overall response rate. Continued approval for this indication may be contingent upon verification and description of clinical benefit in confirmatory trials.

AETHERA trial

The trial was designed to compare brentuximab vedotin to placebo, both administered for up to 16 cycles (approximately 1 year) every 3 weeks following auto-HSCT. Results from the trial were published in The Lancet in March and presented at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting.

The study enrolled 329 HL patients at risk of relapse or progression, including 165 on the brentuximab vedotin arm and 164 on the placebo arm.

Patients were eligible for enrollment in the AETHERA trial if they had a history of primary refractory HL, relapsed within a year of receiving frontline chemotherapy, and/or had disease outside of the lymph nodes at the time of pre-auto-HSCT relapse.

Brentuximab vedotin conferred a significant increase in progression-free survival over placebo, with a hazard ratio of 0.57 (P=0.001). The median progression-free survival was 43 months for patients who received brentuximab vedotin and 24 months for patients who received placebo.

The most common adverse events (≥20%), of any grade and regardless of causality, in the brentuximab vedotin arm were neutropenia (78%), peripheral sensory neuropathy (56%), thrombocytopenia (41%), anemia (27%), upper respiratory tract infection (26%), fatigue (24%), peripheral motor neuropathy (23%), nausea (22%), cough (21%), and diarrhea (20%).

The most common adverse events (≥20%), of any grade and regardless of causality, in the placebo arm were neutropenia (34%), upper respiratory tract infection (23%), and thrombocytopenia (20%).

In all, 67% of patients on the brentuximab vedotin arm experienced peripheral neuropathy. Of those patients, 85% had resolution (59%) or partial improvement (26%) in symptoms at the time of their last evaluation, with a median time to improvement of 23 weeks (range, 0.1-138). ![]()

Photo from Business Wire

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris) for use as consolidation treatment after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (auto-HSCT) in patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) at high risk of relapse or progression.

The drug is the first FDA-approved consolidation option available to these patients.

The approval was based on results of the phase 3 AETHERA trial.

Results from this trial also served to convert a prior accelerated approval of brentuximab vedotin to regular approval. The drug is now fully approved for the treatment of classical HL patients who have failed auto-HSCT and those who have failed at least 2 prior multi-agent chemotherapy regimens and are not candidates for auto-HSCT.

Brentuximab vedotin is also FDA-approved to treat patients with systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma who have failed at least 1 prior multi-agent chemotherapy regimen. The drug has accelerated approval for this indication based on overall response rate. Continued approval for this indication may be contingent upon verification and description of clinical benefit in confirmatory trials.

AETHERA trial

The trial was designed to compare brentuximab vedotin to placebo, both administered for up to 16 cycles (approximately 1 year) every 3 weeks following auto-HSCT. Results from the trial were published in The Lancet in March and presented at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting.

The study enrolled 329 HL patients at risk of relapse or progression, including 165 on the brentuximab vedotin arm and 164 on the placebo arm.

Patients were eligible for enrollment in the AETHERA trial if they had a history of primary refractory HL, relapsed within a year of receiving frontline chemotherapy, and/or had disease outside of the lymph nodes at the time of pre-auto-HSCT relapse.

Brentuximab vedotin conferred a significant increase in progression-free survival over placebo, with a hazard ratio of 0.57 (P=0.001). The median progression-free survival was 43 months for patients who received brentuximab vedotin and 24 months for patients who received placebo.

The most common adverse events (≥20%), of any grade and regardless of causality, in the brentuximab vedotin arm were neutropenia (78%), peripheral sensory neuropathy (56%), thrombocytopenia (41%), anemia (27%), upper respiratory tract infection (26%), fatigue (24%), peripheral motor neuropathy (23%), nausea (22%), cough (21%), and diarrhea (20%).

The most common adverse events (≥20%), of any grade and regardless of causality, in the placebo arm were neutropenia (34%), upper respiratory tract infection (23%), and thrombocytopenia (20%).

In all, 67% of patients on the brentuximab vedotin arm experienced peripheral neuropathy. Of those patients, 85% had resolution (59%) or partial improvement (26%) in symptoms at the time of their last evaluation, with a median time to improvement of 23 weeks (range, 0.1-138). ![]()

Photo from Business Wire

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris) for use as consolidation treatment after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (auto-HSCT) in patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) at high risk of relapse or progression.

The drug is the first FDA-approved consolidation option available to these patients.

The approval was based on results of the phase 3 AETHERA trial.

Results from this trial also served to convert a prior accelerated approval of brentuximab vedotin to regular approval. The drug is now fully approved for the treatment of classical HL patients who have failed auto-HSCT and those who have failed at least 2 prior multi-agent chemotherapy regimens and are not candidates for auto-HSCT.

Brentuximab vedotin is also FDA-approved to treat patients with systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma who have failed at least 1 prior multi-agent chemotherapy regimen. The drug has accelerated approval for this indication based on overall response rate. Continued approval for this indication may be contingent upon verification and description of clinical benefit in confirmatory trials.

AETHERA trial

The trial was designed to compare brentuximab vedotin to placebo, both administered for up to 16 cycles (approximately 1 year) every 3 weeks following auto-HSCT. Results from the trial were published in The Lancet in March and presented at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting.

The study enrolled 329 HL patients at risk of relapse or progression, including 165 on the brentuximab vedotin arm and 164 on the placebo arm.

Patients were eligible for enrollment in the AETHERA trial if they had a history of primary refractory HL, relapsed within a year of receiving frontline chemotherapy, and/or had disease outside of the lymph nodes at the time of pre-auto-HSCT relapse.

Brentuximab vedotin conferred a significant increase in progression-free survival over placebo, with a hazard ratio of 0.57 (P=0.001). The median progression-free survival was 43 months for patients who received brentuximab vedotin and 24 months for patients who received placebo.

The most common adverse events (≥20%), of any grade and regardless of causality, in the brentuximab vedotin arm were neutropenia (78%), peripheral sensory neuropathy (56%), thrombocytopenia (41%), anemia (27%), upper respiratory tract infection (26%), fatigue (24%), peripheral motor neuropathy (23%), nausea (22%), cough (21%), and diarrhea (20%).

The most common adverse events (≥20%), of any grade and regardless of causality, in the placebo arm were neutropenia (34%), upper respiratory tract infection (23%), and thrombocytopenia (20%).

In all, 67% of patients on the brentuximab vedotin arm experienced peripheral neuropathy. Of those patients, 85% had resolution (59%) or partial improvement (26%) in symptoms at the time of their last evaluation, with a median time to improvement of 23 weeks (range, 0.1-138). ![]()

Improved HSCT outcomes due to conditioning or chemo?

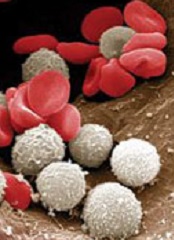

Photo courtesy of NHS

Investigators have reported favorable results of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) in a small study of patients with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML).

The team said the positive outcomes may be a result of conditioning with busulfan and melphalan (BuMel) or the conventional-dose chemotherapy some patients received before HSCT.

Regardless, all 7 patients studied are in remission at more than 1 year of follow-up.

“The lack of transplant-related mortality in the group of children we studied . . . suggests that BuMel may represent a successful HSCT high-dose chemotherapy regimen,” said study author Hisham Abdel-Azim, MD, of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles in California.

“It is also possible that administering conventional-dose chemotherapy before HSCT to patients with more progressive disease may have contributed to the improved outcomes.”

Dr Abdel-Azim and his colleagues described this research in a letter to Blood.

Conventional chemo and transplant

The investigators retrospectively analyzed 7 JMML patients with a median age of 2.6 years at HSCT.

Five patients received conventional-dose chemotherapy before transplant. All of these patients received mercaptopurine. One received hydroxyurea as well, and another patient received fludarabine, cytarabine, and cis-retinoic acid.

As for transplant, 2 patients received a 10/10 HLA-matched related bone marrow graft, 1 received a 9/10 HLA-matched related bone marrow graft, 1 received a 9/10 HLA-matched unrelated bone marrow graft, and 3 patients received cord blood grafts.

The median total nucleated cell count was 4.2 × 108 cells/kg, and the median CD34 cell dose was 3.3 × 106 cells/kg.

Conditioning and GVHD prophylaxis

All 7 patients received backbone conditioning with BuMel: Bu at 1 mg/kg dose every 6 hours intravenously on days −8 to −5 (with therapeutic drug monitoring to achieve overall concentration steady state [CSS] of 800-1000 ng/mL) and Mel at 45 mg/m2 per day intravenously on days −4 to −2.

The median Bu CSS and area under the curve were 884 µg/L (range, 560-1096) and 1293 µmol/L-minute (range, 819-1601), respectively.

The patient with a 9/10 HLA-matched related graft received BuMel and fludarabine at 35 mg/m2 per day intravenously on days −7 to −4.

The patient with the 9/10 HLA-matched unrelated graft received BuMel and alemtuzumab at 12 mg/m2 intravenously on day −10 and 20 mg/m2 on day −9, with methylprednisolone at 2 mg/kg per day in divided doses during the alemtuzumab infusion.

The patients who received cord blood grafts received BuMel and rabbit antithymocyte globulin at 2.5 mg/kg per day intravenously on days −4 to −1. They also received methylprednisolone at 2 mg/kg per day in divided doses during antithymocyte globulin infusion, then tapered over 6 weeks.

All patients received tacrolimus as graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis. Patients who received bone marrow grafts also received methotrexate at 5 mg/m2 on days 3, 6, and 11.

Outcomes

The median time to neutrophil engraftment (≥500/mm3) was 20 days, and the median time to platelet engraftment (≥20 000/mm3) was 36 days.

Six patients (85.7%) achieved predominant (>95%) donor hematopoietic stem cell engraftment.

One patient who received a cord blood graft had autologous recovery at day 54. She went on to receive a related haploidentical HSCT on day 105. One hundred days later, she is in remission, with predominant donor chimerism.

The patient who received the 9/10 HLA-matched related graft developed grade 4 acute GVHD, followed by severe chronic GVHD that required bowel resection.

This patient and one of the patients who received a 10/10 HLA-matched related graft developed severe sinusoidal obstructive syndrome, which resolved with supportive care.

At a median follow-up of 25.3 months (range, 6-99.3), all 7 patients are in remission.

The investigators said their target Bu CSS may have contributed to the improved outcomes they observed, or pre-HSCT chemotherapy may have been a contributing factor. A prospective clinical trial could provide answers. ![]()

Photo courtesy of NHS

Investigators have reported favorable results of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) in a small study of patients with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML).

The team said the positive outcomes may be a result of conditioning with busulfan and melphalan (BuMel) or the conventional-dose chemotherapy some patients received before HSCT.

Regardless, all 7 patients studied are in remission at more than 1 year of follow-up.

“The lack of transplant-related mortality in the group of children we studied . . . suggests that BuMel may represent a successful HSCT high-dose chemotherapy regimen,” said study author Hisham Abdel-Azim, MD, of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles in California.

“It is also possible that administering conventional-dose chemotherapy before HSCT to patients with more progressive disease may have contributed to the improved outcomes.”

Dr Abdel-Azim and his colleagues described this research in a letter to Blood.

Conventional chemo and transplant

The investigators retrospectively analyzed 7 JMML patients with a median age of 2.6 years at HSCT.

Five patients received conventional-dose chemotherapy before transplant. All of these patients received mercaptopurine. One received hydroxyurea as well, and another patient received fludarabine, cytarabine, and cis-retinoic acid.

As for transplant, 2 patients received a 10/10 HLA-matched related bone marrow graft, 1 received a 9/10 HLA-matched related bone marrow graft, 1 received a 9/10 HLA-matched unrelated bone marrow graft, and 3 patients received cord blood grafts.

The median total nucleated cell count was 4.2 × 108 cells/kg, and the median CD34 cell dose was 3.3 × 106 cells/kg.

Conditioning and GVHD prophylaxis

All 7 patients received backbone conditioning with BuMel: Bu at 1 mg/kg dose every 6 hours intravenously on days −8 to −5 (with therapeutic drug monitoring to achieve overall concentration steady state [CSS] of 800-1000 ng/mL) and Mel at 45 mg/m2 per day intravenously on days −4 to −2.

The median Bu CSS and area under the curve were 884 µg/L (range, 560-1096) and 1293 µmol/L-minute (range, 819-1601), respectively.

The patient with a 9/10 HLA-matched related graft received BuMel and fludarabine at 35 mg/m2 per day intravenously on days −7 to −4.

The patient with the 9/10 HLA-matched unrelated graft received BuMel and alemtuzumab at 12 mg/m2 intravenously on day −10 and 20 mg/m2 on day −9, with methylprednisolone at 2 mg/kg per day in divided doses during the alemtuzumab infusion.

The patients who received cord blood grafts received BuMel and rabbit antithymocyte globulin at 2.5 mg/kg per day intravenously on days −4 to −1. They also received methylprednisolone at 2 mg/kg per day in divided doses during antithymocyte globulin infusion, then tapered over 6 weeks.

All patients received tacrolimus as graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis. Patients who received bone marrow grafts also received methotrexate at 5 mg/m2 on days 3, 6, and 11.

Outcomes

The median time to neutrophil engraftment (≥500/mm3) was 20 days, and the median time to platelet engraftment (≥20 000/mm3) was 36 days.

Six patients (85.7%) achieved predominant (>95%) donor hematopoietic stem cell engraftment.

One patient who received a cord blood graft had autologous recovery at day 54. She went on to receive a related haploidentical HSCT on day 105. One hundred days later, she is in remission, with predominant donor chimerism.

The patient who received the 9/10 HLA-matched related graft developed grade 4 acute GVHD, followed by severe chronic GVHD that required bowel resection.

This patient and one of the patients who received a 10/10 HLA-matched related graft developed severe sinusoidal obstructive syndrome, which resolved with supportive care.

At a median follow-up of 25.3 months (range, 6-99.3), all 7 patients are in remission.

The investigators said their target Bu CSS may have contributed to the improved outcomes they observed, or pre-HSCT chemotherapy may have been a contributing factor. A prospective clinical trial could provide answers. ![]()

Photo courtesy of NHS

Investigators have reported favorable results of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) in a small study of patients with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML).

The team said the positive outcomes may be a result of conditioning with busulfan and melphalan (BuMel) or the conventional-dose chemotherapy some patients received before HSCT.

Regardless, all 7 patients studied are in remission at more than 1 year of follow-up.

“The lack of transplant-related mortality in the group of children we studied . . . suggests that BuMel may represent a successful HSCT high-dose chemotherapy regimen,” said study author Hisham Abdel-Azim, MD, of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles in California.

“It is also possible that administering conventional-dose chemotherapy before HSCT to patients with more progressive disease may have contributed to the improved outcomes.”

Dr Abdel-Azim and his colleagues described this research in a letter to Blood.

Conventional chemo and transplant

The investigators retrospectively analyzed 7 JMML patients with a median age of 2.6 years at HSCT.

Five patients received conventional-dose chemotherapy before transplant. All of these patients received mercaptopurine. One received hydroxyurea as well, and another patient received fludarabine, cytarabine, and cis-retinoic acid.

As for transplant, 2 patients received a 10/10 HLA-matched related bone marrow graft, 1 received a 9/10 HLA-matched related bone marrow graft, 1 received a 9/10 HLA-matched unrelated bone marrow graft, and 3 patients received cord blood grafts.

The median total nucleated cell count was 4.2 × 108 cells/kg, and the median CD34 cell dose was 3.3 × 106 cells/kg.

Conditioning and GVHD prophylaxis

All 7 patients received backbone conditioning with BuMel: Bu at 1 mg/kg dose every 6 hours intravenously on days −8 to −5 (with therapeutic drug monitoring to achieve overall concentration steady state [CSS] of 800-1000 ng/mL) and Mel at 45 mg/m2 per day intravenously on days −4 to −2.

The median Bu CSS and area under the curve were 884 µg/L (range, 560-1096) and 1293 µmol/L-minute (range, 819-1601), respectively.

The patient with a 9/10 HLA-matched related graft received BuMel and fludarabine at 35 mg/m2 per day intravenously on days −7 to −4.

The patient with the 9/10 HLA-matched unrelated graft received BuMel and alemtuzumab at 12 mg/m2 intravenously on day −10 and 20 mg/m2 on day −9, with methylprednisolone at 2 mg/kg per day in divided doses during the alemtuzumab infusion.

The patients who received cord blood grafts received BuMel and rabbit antithymocyte globulin at 2.5 mg/kg per day intravenously on days −4 to −1. They also received methylprednisolone at 2 mg/kg per day in divided doses during antithymocyte globulin infusion, then tapered over 6 weeks.

All patients received tacrolimus as graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis. Patients who received bone marrow grafts also received methotrexate at 5 mg/m2 on days 3, 6, and 11.

Outcomes

The median time to neutrophil engraftment (≥500/mm3) was 20 days, and the median time to platelet engraftment (≥20 000/mm3) was 36 days.

Six patients (85.7%) achieved predominant (>95%) donor hematopoietic stem cell engraftment.

One patient who received a cord blood graft had autologous recovery at day 54. She went on to receive a related haploidentical HSCT on day 105. One hundred days later, she is in remission, with predominant donor chimerism.

The patient who received the 9/10 HLA-matched related graft developed grade 4 acute GVHD, followed by severe chronic GVHD that required bowel resection.

This patient and one of the patients who received a 10/10 HLA-matched related graft developed severe sinusoidal obstructive syndrome, which resolved with supportive care.

At a median follow-up of 25.3 months (range, 6-99.3), all 7 patients are in remission.

The investigators said their target Bu CSS may have contributed to the improved outcomes they observed, or pre-HSCT chemotherapy may have been a contributing factor. A prospective clinical trial could provide answers. ![]()

Lipids aid engraftment of HSPCs

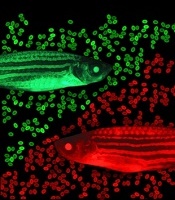

zebrafish used in the study

Image by Jonathan Henninger

and Vera Binder

Using zebrafish drug-screening models, researchers have identified a family of lipids that aid the engraftment of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs).

The lipids, known as epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs), boosted HSPC engraftment in zebrafish and mice.

The researchers therefore believe EETs could help make human HSPC transplants, particularly umbilical cord blood transplants, more efficient and effective.

“Ninety percent of cord blood units can’t be used because they’re too small,” said Leonard Zon, MD, of Boston Children’s Hospital in Massachusetts.

“If you add these chemicals, you might be able to use more units. Being able to get engraftment allows you to pick a smaller cord blood sample that might be a better match.”

Dr Zon and his colleagues described their work with EETs in Nature.

EETs appear to work by stimulating cell migration. They were among the top hits in a screen of 500 known compounds the researchers conducted.

In the past, such screens have led Dr Zon’s team to compounds that boost HSPC numbers, such as prostaglandin. But the new drug screen was designed to assess HSPCs’ transplantability and engraftment.

The screen was done in a lab-created strain of zebrafish called Casper. Because Casper is translucent, Dr Zon and his colleagues could visually compare the engraftment of transplanted HSPCs chemically tagged to glow green or red.

The researchers first used tagging to color the fishes’ marrow either red or green, then removed HSPCs for transplantation. The green cells were incubated with various chemicals, while the red cells were left untreated.

The team then injected a mixture of green and red HSPCs into other groups of zebrafish (10 fish per test chemical). And they visually tracked the cells’ activity, measuring the green-to-red ratio.

“The expectation was that if a chemical didn’t increase engraftment, all the fish would be equal parts red and green,” Dr Zon said. “But if it was effective, green marrow would predominate.”

That was the case for green marrow incubated with EETs, a finding that held up over thousands of transplants.

“In a mouse system, this experiment would cost $3 million,” Dr Zon noted. “In fish, it cost about $150,000.”

In a smaller-scale set of mouse experiments, the team confirmed EETs’ efficacy in promoting homing and engraftment of HSPCs.

EETs are chemical cousins of prostaglandin. Both are made from arachidonic acid, and both are made during inflammation. But EETs work in a different way, by activating the PI3K pathway. EETs also enhanced PI3K activity in human blood vessel cells in vitro.

After more studies in human cells to determine exactly how EETs work, Dr Zon hopes to begin clinical trials of EETs within the next 2 years, likely in the setting of cord blood transplant. The lab is also investigating its other top hits from the zebrafish screen.

“Every new pathway that we find has the chance of making stem cell engraftment and migration even better,” Dr Zon said. “I think we’ll end up being able to manipulate this process.” ![]()

zebrafish used in the study

Image by Jonathan Henninger

and Vera Binder

Using zebrafish drug-screening models, researchers have identified a family of lipids that aid the engraftment of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs).

The lipids, known as epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs), boosted HSPC engraftment in zebrafish and mice.

The researchers therefore believe EETs could help make human HSPC transplants, particularly umbilical cord blood transplants, more efficient and effective.

“Ninety percent of cord blood units can’t be used because they’re too small,” said Leonard Zon, MD, of Boston Children’s Hospital in Massachusetts.

“If you add these chemicals, you might be able to use more units. Being able to get engraftment allows you to pick a smaller cord blood sample that might be a better match.”

Dr Zon and his colleagues described their work with EETs in Nature.

EETs appear to work by stimulating cell migration. They were among the top hits in a screen of 500 known compounds the researchers conducted.

In the past, such screens have led Dr Zon’s team to compounds that boost HSPC numbers, such as prostaglandin. But the new drug screen was designed to assess HSPCs’ transplantability and engraftment.

The screen was done in a lab-created strain of zebrafish called Casper. Because Casper is translucent, Dr Zon and his colleagues could visually compare the engraftment of transplanted HSPCs chemically tagged to glow green or red.

The researchers first used tagging to color the fishes’ marrow either red or green, then removed HSPCs for transplantation. The green cells were incubated with various chemicals, while the red cells were left untreated.

The team then injected a mixture of green and red HSPCs into other groups of zebrafish (10 fish per test chemical). And they visually tracked the cells’ activity, measuring the green-to-red ratio.

“The expectation was that if a chemical didn’t increase engraftment, all the fish would be equal parts red and green,” Dr Zon said. “But if it was effective, green marrow would predominate.”

That was the case for green marrow incubated with EETs, a finding that held up over thousands of transplants.

“In a mouse system, this experiment would cost $3 million,” Dr Zon noted. “In fish, it cost about $150,000.”

In a smaller-scale set of mouse experiments, the team confirmed EETs’ efficacy in promoting homing and engraftment of HSPCs.

EETs are chemical cousins of prostaglandin. Both are made from arachidonic acid, and both are made during inflammation. But EETs work in a different way, by activating the PI3K pathway. EETs also enhanced PI3K activity in human blood vessel cells in vitro.

After more studies in human cells to determine exactly how EETs work, Dr Zon hopes to begin clinical trials of EETs within the next 2 years, likely in the setting of cord blood transplant. The lab is also investigating its other top hits from the zebrafish screen.

“Every new pathway that we find has the chance of making stem cell engraftment and migration even better,” Dr Zon said. “I think we’ll end up being able to manipulate this process.” ![]()

zebrafish used in the study

Image by Jonathan Henninger

and Vera Binder

Using zebrafish drug-screening models, researchers have identified a family of lipids that aid the engraftment of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs).

The lipids, known as epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs), boosted HSPC engraftment in zebrafish and mice.

The researchers therefore believe EETs could help make human HSPC transplants, particularly umbilical cord blood transplants, more efficient and effective.

“Ninety percent of cord blood units can’t be used because they’re too small,” said Leonard Zon, MD, of Boston Children’s Hospital in Massachusetts.

“If you add these chemicals, you might be able to use more units. Being able to get engraftment allows you to pick a smaller cord blood sample that might be a better match.”

Dr Zon and his colleagues described their work with EETs in Nature.

EETs appear to work by stimulating cell migration. They were among the top hits in a screen of 500 known compounds the researchers conducted.

In the past, such screens have led Dr Zon’s team to compounds that boost HSPC numbers, such as prostaglandin. But the new drug screen was designed to assess HSPCs’ transplantability and engraftment.

The screen was done in a lab-created strain of zebrafish called Casper. Because Casper is translucent, Dr Zon and his colleagues could visually compare the engraftment of transplanted HSPCs chemically tagged to glow green or red.

The researchers first used tagging to color the fishes’ marrow either red or green, then removed HSPCs for transplantation. The green cells were incubated with various chemicals, while the red cells were left untreated.

The team then injected a mixture of green and red HSPCs into other groups of zebrafish (10 fish per test chemical). And they visually tracked the cells’ activity, measuring the green-to-red ratio.

“The expectation was that if a chemical didn’t increase engraftment, all the fish would be equal parts red and green,” Dr Zon said. “But if it was effective, green marrow would predominate.”

That was the case for green marrow incubated with EETs, a finding that held up over thousands of transplants.

“In a mouse system, this experiment would cost $3 million,” Dr Zon noted. “In fish, it cost about $150,000.”

In a smaller-scale set of mouse experiments, the team confirmed EETs’ efficacy in promoting homing and engraftment of HSPCs.

EETs are chemical cousins of prostaglandin. Both are made from arachidonic acid, and both are made during inflammation. But EETs work in a different way, by activating the PI3K pathway. EETs also enhanced PI3K activity in human blood vessel cells in vitro.

After more studies in human cells to determine exactly how EETs work, Dr Zon hopes to begin clinical trials of EETs within the next 2 years, likely in the setting of cord blood transplant. The lab is also investigating its other top hits from the zebrafish screen.

“Every new pathway that we find has the chance of making stem cell engraftment and migration even better,” Dr Zon said. “I think we’ll end up being able to manipulate this process.” ![]()

Modified T cells may improve auto-SCT outcomes in MM

Photo from Penn Medicine

Infusions of modified autologous T cells may improve responses in multiple myeloma (MM) patients undergoing autologous stem cell transplant (auto-SCT), according to research published in Nature Medicine.

Researchers said patients who received the T cells—which were engineered to express an affinity-enhanced T-cell receptor (TCR)—after auto-SCT had a better response rate than is expected for MM patients undergoing auto-SCT. At day 100, the overall response rate was 90%.

The researchers also said the T cells were safe. There were no treatment-related deaths, and all 7 serious adverse events were resolved.

“This study shows us that these TCR-specific T cells are safe and feasible . . . , but it also revealed encouraging antitumor activity and showed impressive, durable T-cell persistence,” said study author Carl June, MD, of the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

The research was a collaboration between the University of Maryland School of Medicine, the Perelman School of Medicine, and Adaptimmune, a clinical stage biopharmaceutical company that owns the core TCR technology and funded the study.

The study included 20 evaluable patients with advanced MM. They received an average of 2.4 billion autologous T cells 2 days after undergoing auto-SCT.

The T cells were engineered to express an affinity-enhanced TCR recognizing a naturally processed peptide shared by the cancer-testis antigens NY-ESO-1 and LAGE-1. Up to 60% of advanced myelomas have been reported to express NY-ESO-1 and/or LAGE-1, which is correlated with tumor proliferation and poorer outcomes.

Response and survival

“The majority of patients who participated in this trial had a meaningful degree of clinical benefit,” said study author Aaron P. Rapoport, MD, of the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore.

“Even patients who later relapsed after achieving a complete response to treatment or didn’t have a complete response had periods of disease control that I believe they would not have otherwise experienced. Some patients are still in remission after nearly 3 years.”

Treatment responses were as follows:

| Outcome | Prior

to infusion |

Day

42 |

Day

100 |

Day

180 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete

response (CR) |

1 | 2 | ||

| Stringent

CR |

1 | 2 | 2 | |

| Near

CR |

1 | 6 | 11 | 8 |

| Very

good partial response |

2 | 7 | 2 | 2 |

| Partial

response |

6 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Stable

disease |

6 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Progressive

disease |

5 | 1 | 3 |

A subset of patients received lenalidomide maintenance after day 100, and 1 patient had died by the 180-day mark, as a result of disease progression.

The researchers noted that relapse was associated with a loss of the engineered T cells, which suggests methods for sustaining long-term persistence of the cells could improve outcomes.

At a median follow up of 21.1 months, 75% of patients were still alive, 50% were progression-free, and 25% had died after disease progression.

At a median follow up of 30.1 months, the median progression-free survival was 19.1 months, and the median overall survival was 32.1 months.

Adverse events

There were no treatment-related deaths, and all 7 serious adverse events were resolved. The serious events included grade 3 gastrointestinal graft-vs-host disease (GVHD), grade 3 hypoxia, grade 3 dehydration, grade 4 neutropenia, grade 4 hyponatremia, grade 4 hypotension, and grade 4 pancytopenia.

There were 17 adverse events that were considered probably related to treatment. These were gastrointestinal GVHD (3 grade 3), skin GVHD (2 grade 2), fatigue (1 grade 1), fever (2 grade 1-2), rash (3 grade 1-3), diarrhea (2 grade 1-2), sinus tachycardia (1 grade 1), injection site reaction/extravasation changes (1 grade 1), weakness (1 grade 1), and hypotension (1 grade 3).

“This study suggests that treatment with engineered T cells is not only safe but of potential clinical benefit to patients with certain types of aggressive multiple myeloma,” Dr Rapoport said. “Our findings provide a strong foundation for further research in the field of cellular immunotherapy for myeloma to help achieve even better results for our patients.” ![]()

Photo from Penn Medicine

Infusions of modified autologous T cells may improve responses in multiple myeloma (MM) patients undergoing autologous stem cell transplant (auto-SCT), according to research published in Nature Medicine.

Researchers said patients who received the T cells—which were engineered to express an affinity-enhanced T-cell receptor (TCR)—after auto-SCT had a better response rate than is expected for MM patients undergoing auto-SCT. At day 100, the overall response rate was 90%.

The researchers also said the T cells were safe. There were no treatment-related deaths, and all 7 serious adverse events were resolved.

“This study shows us that these TCR-specific T cells are safe and feasible . . . , but it also revealed encouraging antitumor activity and showed impressive, durable T-cell persistence,” said study author Carl June, MD, of the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

The research was a collaboration between the University of Maryland School of Medicine, the Perelman School of Medicine, and Adaptimmune, a clinical stage biopharmaceutical company that owns the core TCR technology and funded the study.

The study included 20 evaluable patients with advanced MM. They received an average of 2.4 billion autologous T cells 2 days after undergoing auto-SCT.

The T cells were engineered to express an affinity-enhanced TCR recognizing a naturally processed peptide shared by the cancer-testis antigens NY-ESO-1 and LAGE-1. Up to 60% of advanced myelomas have been reported to express NY-ESO-1 and/or LAGE-1, which is correlated with tumor proliferation and poorer outcomes.

Response and survival

“The majority of patients who participated in this trial had a meaningful degree of clinical benefit,” said study author Aaron P. Rapoport, MD, of the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore.

“Even patients who later relapsed after achieving a complete response to treatment or didn’t have a complete response had periods of disease control that I believe they would not have otherwise experienced. Some patients are still in remission after nearly 3 years.”

Treatment responses were as follows:

| Outcome | Prior

to infusion |

Day

42 |

Day

100 |

Day

180 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete

response (CR) |

1 | 2 | ||

| Stringent

CR |

1 | 2 | 2 | |

| Near

CR |

1 | 6 | 11 | 8 |

| Very

good partial response |

2 | 7 | 2 | 2 |

| Partial

response |

6 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Stable

disease |

6 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Progressive

disease |

5 | 1 | 3 |

A subset of patients received lenalidomide maintenance after day 100, and 1 patient had died by the 180-day mark, as a result of disease progression.

The researchers noted that relapse was associated with a loss of the engineered T cells, which suggests methods for sustaining long-term persistence of the cells could improve outcomes.

At a median follow up of 21.1 months, 75% of patients were still alive, 50% were progression-free, and 25% had died after disease progression.

At a median follow up of 30.1 months, the median progression-free survival was 19.1 months, and the median overall survival was 32.1 months.

Adverse events

There were no treatment-related deaths, and all 7 serious adverse events were resolved. The serious events included grade 3 gastrointestinal graft-vs-host disease (GVHD), grade 3 hypoxia, grade 3 dehydration, grade 4 neutropenia, grade 4 hyponatremia, grade 4 hypotension, and grade 4 pancytopenia.

There were 17 adverse events that were considered probably related to treatment. These were gastrointestinal GVHD (3 grade 3), skin GVHD (2 grade 2), fatigue (1 grade 1), fever (2 grade 1-2), rash (3 grade 1-3), diarrhea (2 grade 1-2), sinus tachycardia (1 grade 1), injection site reaction/extravasation changes (1 grade 1), weakness (1 grade 1), and hypotension (1 grade 3).

“This study suggests that treatment with engineered T cells is not only safe but of potential clinical benefit to patients with certain types of aggressive multiple myeloma,” Dr Rapoport said. “Our findings provide a strong foundation for further research in the field of cellular immunotherapy for myeloma to help achieve even better results for our patients.” ![]()

Photo from Penn Medicine

Infusions of modified autologous T cells may improve responses in multiple myeloma (MM) patients undergoing autologous stem cell transplant (auto-SCT), according to research published in Nature Medicine.

Researchers said patients who received the T cells—which were engineered to express an affinity-enhanced T-cell receptor (TCR)—after auto-SCT had a better response rate than is expected for MM patients undergoing auto-SCT. At day 100, the overall response rate was 90%.

The researchers also said the T cells were safe. There were no treatment-related deaths, and all 7 serious adverse events were resolved.

“This study shows us that these TCR-specific T cells are safe and feasible . . . , but it also revealed encouraging antitumor activity and showed impressive, durable T-cell persistence,” said study author Carl June, MD, of the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

The research was a collaboration between the University of Maryland School of Medicine, the Perelman School of Medicine, and Adaptimmune, a clinical stage biopharmaceutical company that owns the core TCR technology and funded the study.

The study included 20 evaluable patients with advanced MM. They received an average of 2.4 billion autologous T cells 2 days after undergoing auto-SCT.

The T cells were engineered to express an affinity-enhanced TCR recognizing a naturally processed peptide shared by the cancer-testis antigens NY-ESO-1 and LAGE-1. Up to 60% of advanced myelomas have been reported to express NY-ESO-1 and/or LAGE-1, which is correlated with tumor proliferation and poorer outcomes.

Response and survival

“The majority of patients who participated in this trial had a meaningful degree of clinical benefit,” said study author Aaron P. Rapoport, MD, of the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore.

“Even patients who later relapsed after achieving a complete response to treatment or didn’t have a complete response had periods of disease control that I believe they would not have otherwise experienced. Some patients are still in remission after nearly 3 years.”

Treatment responses were as follows:

| Outcome | Prior

to infusion |

Day

42 |

Day

100 |

Day

180 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete

response (CR) |

1 | 2 | ||

| Stringent

CR |

1 | 2 | 2 | |

| Near

CR |

1 | 6 | 11 | 8 |

| Very

good partial response |

2 | 7 | 2 | 2 |

| Partial

response |

6 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Stable

disease |

6 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Progressive

disease |

5 | 1 | 3 |

A subset of patients received lenalidomide maintenance after day 100, and 1 patient had died by the 180-day mark, as a result of disease progression.

The researchers noted that relapse was associated with a loss of the engineered T cells, which suggests methods for sustaining long-term persistence of the cells could improve outcomes.

At a median follow up of 21.1 months, 75% of patients were still alive, 50% were progression-free, and 25% had died after disease progression.

At a median follow up of 30.1 months, the median progression-free survival was 19.1 months, and the median overall survival was 32.1 months.

Adverse events

There were no treatment-related deaths, and all 7 serious adverse events were resolved. The serious events included grade 3 gastrointestinal graft-vs-host disease (GVHD), grade 3 hypoxia, grade 3 dehydration, grade 4 neutropenia, grade 4 hyponatremia, grade 4 hypotension, and grade 4 pancytopenia.

There were 17 adverse events that were considered probably related to treatment. These were gastrointestinal GVHD (3 grade 3), skin GVHD (2 grade 2), fatigue (1 grade 1), fever (2 grade 1-2), rash (3 grade 1-3), diarrhea (2 grade 1-2), sinus tachycardia (1 grade 1), injection site reaction/extravasation changes (1 grade 1), weakness (1 grade 1), and hypotension (1 grade 3).

“This study suggests that treatment with engineered T cells is not only safe but of potential clinical benefit to patients with certain types of aggressive multiple myeloma,” Dr Rapoport said. “Our findings provide a strong foundation for further research in the field of cellular immunotherapy for myeloma to help achieve even better results for our patients.”

ASCO updates guideline on CSFs

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has updated its clinical practice guideline on hematopoietic colony-stimulating factors (CSFs).

The guideline includes recommendations on the use of CSFs in the context of lymphoma, solid tumor malignancies, pediatric leukemia, and hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

There are no recommendations pertaining to adults with acute myeloid leukemia or myelodysplastic syndromes.

ASCO’s previous guideline on CSFs was issued in 2006. For the update, an ASCO expert panel conducted a formal systematic review of relevant articles from the medical literature published from October 2005 through September 2014.

Key recommendations from the resulting guideline are as follows.

Pegfilgrastim, filgrastim, tbo-filgrastim, and filgrastim-sndz (and other biosimilars, as they become available) can be used for the prevention of treatment-related febrile neutropenia.

For patients with lymphomas or solid tumors, primary prophylaxis with a CSF should be given during all cycles of chemotherapy in patients who have an approximately 20% or higher risk for febrile neutropenia on the basis of patient-, disease-, and treatment-related factors.

However, clinicians should also consider using chemotherapy regimens that do not require CSF administration but are as effective as regimens that do require a CSF.

Patients with lymphomas or solid tumors should receive secondary febrile neutropenia prophylaxis with a CSF if they experienced a neutropenic complication from a previous cycle of chemotherapy (for which they did not receive primary prophylaxis) when a reduced dose or treatment delay may compromise disease-free survival, overall survival, or treatment outcome.

However, the guideline also says that, in many clinical situations, dose reductions or delays may be a reasonable alternative.

CSFs should not be routinely used for patients with neutropenia who are afebrile or as adjunctive treatment with antibiotic therapy for patients with fever and neutropenia.

Dose-dense regimens with CSF support should only be used within an appropriately designed clinical trial or if use of the regimen is supported by convincing efficacy data. The guideline says that, for non-Hodgkin lymphoma, data on the value of dose-dense regimens with CSF support are limited and conflicting.

In the context of transplant, CSFs may be used alone, after chemotherapy, or in combination with plerixafor to mobilize peripheral blood stem cells. To reduce the duration of severe neutropenia, CSFs should be administered after autologous stem cell transplant and may be administered after allogeneic stem cell transplant.

CSFs should be avoided in patients receiving concomitant chemotherapy and radiation, particularly involving the mediastinum. CSFs may be considered in patients receiving radiation alone if the clinician expects prolonged treatment delays due to neutropenia.

Patients who are exposed to lethal doses of total-body radiotherapy, but not doses high enough to lead to certain death resulting from injury to other organs, should promptly receive CSFs or pegylated granulocyte CSFs.

Clinicians should consider prophylactic CSF for patients with diffuse aggressive lymphoma who are 65 or older and are receiving curative chemotherapy (R-CHOP), particularly if they have comorbidities.