User login

Readmission to non-index hospital following acute stroke linked to worse outcomes

ATLANTA – Following an acute stroke, optimizing stroke secondary prevention measures, medical complications, and transitions of care is essential to reducing 30-day readmissions and improving patient outcomes, a large analysis of national data showed.

“Care that is fragmented with readmissions to other hospitals results not only in more expensive care and longer length of stay but also increased mortality for our acute stroke patients,” lead study author Laura K. Stein, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

In 2017, a study of the Nationwide Readmissions Database demonstrated that 12.1% of patients with acute ischemic stroke were readmitted within 30 days (Stroke 2017;48:1386-8). It cited that 89.6% were unplanned and 12.9% were preventable. “However, this study did not examine whether patients were admitted to the discharging hospital or a different hospital,” said Dr. Stein, a neurologist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. “Furthermore, it did not include metrics such as cost, length of stay, and mortality with 30-day readmissions. Hospitals are increasingly held accountable and penalized for metrics such as length of stay and 30-day readmissions.”

In 2010, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services introduced the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program in an attempt to decrease readmissions following hospitalizations for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia. “In 2012, CMS started reducing Medicare payments for hospitals with excess readmissions,” said Dr. Stein, who is a fellowship-trained stroke specialist. “While readmission to the same hospital has great implications for hospital systems, any readmission has great implications for patients.”

In what is believed to be the first study of its kind, Dr. Stein and her colleagues drew from the 2013 Nationwide Readmissions Database to examine in-hospital outcomes associated with 30-day readmission to a different hospital for acute ischemic stroke. They used ICD-9 codes to identify index stroke admissions and all-cause readmissions. Outcomes of interest were length of stay, total charges, and in-hospital mortality during the 30-day readmission. The main predictor was readmission to another hospital, compared with readmission to the same hospital as the index acute stroke admission. The researchers used linear regression for the outcomes of length of stay and charges, and logistic regression for in-hospital mortality. They adjusted for several variables during the index admission, including age, sex, vascular risk factors, hospital bed size, teaching hospital status, insurance status, discharge destination, National Center for Health Statistics urban-rural location classification, length of stay, and total charges.

Of 24,545 acute stroke patients readmitted within 30 days, 7,274 (30%) were readmitted to a different hospital. The top three reasons for readmission were acute cerebrovascular disease, septicemia, and renal failure. In fully adjusted models, readmission to a different hospital was associated with an increased length of stay of 0.97 days (P less than .0001) and a mean of $7,677.28 greater total charges, compared with readmission to the same hospital (P less than .0001). The fully adjusted odds ratio for in-hospital mortality during readmission was 1.17 for readmission to another hospital vs. readmission to the same hospital (P = .0079).

“While it is conceivable that cost and length of stay could be higher with readmission to a different hospital because of a need for additional testing with a lack of familiarity with the patient, it is concerning that mortality is higher,” Dr. Stein said. “These findings emphasize the importance of optimizing secondary stroke prevention and medical complications following acute stroke before discharge. Additionally, they emphasize the importance of good transitions of care from the inpatient to outpatient setting (whether that’s to a rehabilitation facility, skilled nursing facility, or home) and accessibility of the discharging stroke team after discharge.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including its reliance of administrative data, which could include misclassification of diagnoses and comorbidities based on ICD-9 codes. “However, we have chosen ICD-9 codes for stroke that have been previously validated in the literature,” Dr. Stein said. “For instance, the validated codes for stroke as the primary discharge diagnosis have a sensitivity of 74%, specificity of 95%, and positive predictive value of 88%. Second, we do not know stroke subtype or severity of stroke. Third, we do not know what the transitions of care plan were when the patients left the hospital following index acute ischemic stroke admission and why these patients ended up being readmitted to a different hospital rather than the one that treated them for their acute stroke.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Stein L et al. Ann Neurol. 2018;84[S22]:S149. Abstract M127.

ATLANTA – Following an acute stroke, optimizing stroke secondary prevention measures, medical complications, and transitions of care is essential to reducing 30-day readmissions and improving patient outcomes, a large analysis of national data showed.

“Care that is fragmented with readmissions to other hospitals results not only in more expensive care and longer length of stay but also increased mortality for our acute stroke patients,” lead study author Laura K. Stein, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

In 2017, a study of the Nationwide Readmissions Database demonstrated that 12.1% of patients with acute ischemic stroke were readmitted within 30 days (Stroke 2017;48:1386-8). It cited that 89.6% were unplanned and 12.9% were preventable. “However, this study did not examine whether patients were admitted to the discharging hospital or a different hospital,” said Dr. Stein, a neurologist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. “Furthermore, it did not include metrics such as cost, length of stay, and mortality with 30-day readmissions. Hospitals are increasingly held accountable and penalized for metrics such as length of stay and 30-day readmissions.”

In 2010, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services introduced the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program in an attempt to decrease readmissions following hospitalizations for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia. “In 2012, CMS started reducing Medicare payments for hospitals with excess readmissions,” said Dr. Stein, who is a fellowship-trained stroke specialist. “While readmission to the same hospital has great implications for hospital systems, any readmission has great implications for patients.”

In what is believed to be the first study of its kind, Dr. Stein and her colleagues drew from the 2013 Nationwide Readmissions Database to examine in-hospital outcomes associated with 30-day readmission to a different hospital for acute ischemic stroke. They used ICD-9 codes to identify index stroke admissions and all-cause readmissions. Outcomes of interest were length of stay, total charges, and in-hospital mortality during the 30-day readmission. The main predictor was readmission to another hospital, compared with readmission to the same hospital as the index acute stroke admission. The researchers used linear regression for the outcomes of length of stay and charges, and logistic regression for in-hospital mortality. They adjusted for several variables during the index admission, including age, sex, vascular risk factors, hospital bed size, teaching hospital status, insurance status, discharge destination, National Center for Health Statistics urban-rural location classification, length of stay, and total charges.

Of 24,545 acute stroke patients readmitted within 30 days, 7,274 (30%) were readmitted to a different hospital. The top three reasons for readmission were acute cerebrovascular disease, septicemia, and renal failure. In fully adjusted models, readmission to a different hospital was associated with an increased length of stay of 0.97 days (P less than .0001) and a mean of $7,677.28 greater total charges, compared with readmission to the same hospital (P less than .0001). The fully adjusted odds ratio for in-hospital mortality during readmission was 1.17 for readmission to another hospital vs. readmission to the same hospital (P = .0079).

“While it is conceivable that cost and length of stay could be higher with readmission to a different hospital because of a need for additional testing with a lack of familiarity with the patient, it is concerning that mortality is higher,” Dr. Stein said. “These findings emphasize the importance of optimizing secondary stroke prevention and medical complications following acute stroke before discharge. Additionally, they emphasize the importance of good transitions of care from the inpatient to outpatient setting (whether that’s to a rehabilitation facility, skilled nursing facility, or home) and accessibility of the discharging stroke team after discharge.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including its reliance of administrative data, which could include misclassification of diagnoses and comorbidities based on ICD-9 codes. “However, we have chosen ICD-9 codes for stroke that have been previously validated in the literature,” Dr. Stein said. “For instance, the validated codes for stroke as the primary discharge diagnosis have a sensitivity of 74%, specificity of 95%, and positive predictive value of 88%. Second, we do not know stroke subtype or severity of stroke. Third, we do not know what the transitions of care plan were when the patients left the hospital following index acute ischemic stroke admission and why these patients ended up being readmitted to a different hospital rather than the one that treated them for their acute stroke.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Stein L et al. Ann Neurol. 2018;84[S22]:S149. Abstract M127.

ATLANTA – Following an acute stroke, optimizing stroke secondary prevention measures, medical complications, and transitions of care is essential to reducing 30-day readmissions and improving patient outcomes, a large analysis of national data showed.

“Care that is fragmented with readmissions to other hospitals results not only in more expensive care and longer length of stay but also increased mortality for our acute stroke patients,” lead study author Laura K. Stein, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

In 2017, a study of the Nationwide Readmissions Database demonstrated that 12.1% of patients with acute ischemic stroke were readmitted within 30 days (Stroke 2017;48:1386-8). It cited that 89.6% were unplanned and 12.9% were preventable. “However, this study did not examine whether patients were admitted to the discharging hospital or a different hospital,” said Dr. Stein, a neurologist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. “Furthermore, it did not include metrics such as cost, length of stay, and mortality with 30-day readmissions. Hospitals are increasingly held accountable and penalized for metrics such as length of stay and 30-day readmissions.”

In 2010, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services introduced the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program in an attempt to decrease readmissions following hospitalizations for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia. “In 2012, CMS started reducing Medicare payments for hospitals with excess readmissions,” said Dr. Stein, who is a fellowship-trained stroke specialist. “While readmission to the same hospital has great implications for hospital systems, any readmission has great implications for patients.”

In what is believed to be the first study of its kind, Dr. Stein and her colleagues drew from the 2013 Nationwide Readmissions Database to examine in-hospital outcomes associated with 30-day readmission to a different hospital for acute ischemic stroke. They used ICD-9 codes to identify index stroke admissions and all-cause readmissions. Outcomes of interest were length of stay, total charges, and in-hospital mortality during the 30-day readmission. The main predictor was readmission to another hospital, compared with readmission to the same hospital as the index acute stroke admission. The researchers used linear regression for the outcomes of length of stay and charges, and logistic regression for in-hospital mortality. They adjusted for several variables during the index admission, including age, sex, vascular risk factors, hospital bed size, teaching hospital status, insurance status, discharge destination, National Center for Health Statistics urban-rural location classification, length of stay, and total charges.

Of 24,545 acute stroke patients readmitted within 30 days, 7,274 (30%) were readmitted to a different hospital. The top three reasons for readmission were acute cerebrovascular disease, septicemia, and renal failure. In fully adjusted models, readmission to a different hospital was associated with an increased length of stay of 0.97 days (P less than .0001) and a mean of $7,677.28 greater total charges, compared with readmission to the same hospital (P less than .0001). The fully adjusted odds ratio for in-hospital mortality during readmission was 1.17 for readmission to another hospital vs. readmission to the same hospital (P = .0079).

“While it is conceivable that cost and length of stay could be higher with readmission to a different hospital because of a need for additional testing with a lack of familiarity with the patient, it is concerning that mortality is higher,” Dr. Stein said. “These findings emphasize the importance of optimizing secondary stroke prevention and medical complications following acute stroke before discharge. Additionally, they emphasize the importance of good transitions of care from the inpatient to outpatient setting (whether that’s to a rehabilitation facility, skilled nursing facility, or home) and accessibility of the discharging stroke team after discharge.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including its reliance of administrative data, which could include misclassification of diagnoses and comorbidities based on ICD-9 codes. “However, we have chosen ICD-9 codes for stroke that have been previously validated in the literature,” Dr. Stein said. “For instance, the validated codes for stroke as the primary discharge diagnosis have a sensitivity of 74%, specificity of 95%, and positive predictive value of 88%. Second, we do not know stroke subtype or severity of stroke. Third, we do not know what the transitions of care plan were when the patients left the hospital following index acute ischemic stroke admission and why these patients ended up being readmitted to a different hospital rather than the one that treated them for their acute stroke.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Stein L et al. Ann Neurol. 2018;84[S22]:S149. Abstract M127.

REPORTING FROM ANA 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The adjusted odds ratio for in-hospital mortality during readmission was 1.17 for readmission to another hospital vs. readmission to the same hospital (P = .0079).

Study details: A review of 24,545 acute stroke patients 2013 from the Nationwide Readmissions Database.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Source: Stein L et al. Ann Neurol. 2018;84[S22]:S149. Abstract M127.

Prior TIA proves less risky than stroke in AF patients

MONTREAL – Stroke and transient ischemic attack, usually joined at the hip as related histories that each flag a similar need for anticoagulation may in fact not be nearly as equivalent as conventional wisdom says.

Analysis of 2-year follow-up data from the GARFIELD-AF registry of more than 52,000 patients with newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation (AF) showed that, while patients with a history of stroke had significantly elevated rates of both all-cause mortality and stroke, those with just a history of a transient ischemic attack (TIA) had mortality and stroke rates virtually identical to AF patients with no history of a cerebrovascular event.

“A history of TIA only is not a reliable predictor of an increased risk for events,” Werner Hacke, MD, said at the World Stroke Congress. “A history of TIA should be removed from scores estimating the risk for stroke and systemic embolism in AF patients,” said Dr. Hacke, professor and chairman of the department of neurology at the University of Heidelberg (Germany).

“The weak predictive power of a history of TIA is probably caused by the relatively low reliability of establishing the diagnosis of TIA,” especially when the diagnosis is made by someone who’s not a neurologist. “It’s a very fuzzy diagnosis,” even for a neurologist, and it consistently confounds other clinicians, he said in an interview. “I’d be really careful of deciding to anticoagulate a patient [with AF] based on a history of TIA.” In the GARFIELD-AF registry, “I’m convinced that most people with a history of TIA actually never had a TIA.”

Dr. Hacke has been unable to find a good explanation of why, years ago, TIAs began to get routinely lumped with stroke. “I asked all the old AF guys when did TIA start coming in and why, and none of them could remember,” he said. “At first, they talked about a history of ‘cerebrovascular events,’ but then that became stroke and TIA, and it was as if it was one word,” always said in the same breath. Both the CHADS2 score (JAMA. 2001 Jun 13;285[22]:2864-70) and the CHA2DS2-VASc score (Chest. 2010 Feb;137[2]:263-72) make a history of stroke or TIA, as well as thromboembolism, coequal risk factors that count for 2 points when calculating the thrombotic risk score for a patient with AF.

To test whether this really made sense, Dr. Hacke and his associates decided to look at the separate consequences of a history of stroke only, compared with a history of a TIA only. They used data collected in GARFIELD-AF (Global Anticoagulant Registry in the Field), a multinational registry with 51,670 patients newly diagnosed with AF, followed for 2 years, and with complete information on their stroke and TIA history. This included 5,617 patients with a history of at least one diagnosed cerebrovascular event, including 3,362 diagnosed with stroke only, 1,788 diagnosed with TIA only, and the remaining patients diagnosed with both types of events.

When compared with AF patients without a history of any type of cerebrovascular event, those with a history of a stroke only had a statistically significant 29% increased rate of all-cause death and a 2.3-fold higher rate of stroke after adjustment for baseline demographic and clinical differences. In contrast, the patients with a history of TIA only had mortality and stroke rates during follow-up that did not differ significantly from the comparator group.

Source: Hacke W et al. World Stroke Congress, Abstract.

MONTREAL – Stroke and transient ischemic attack, usually joined at the hip as related histories that each flag a similar need for anticoagulation may in fact not be nearly as equivalent as conventional wisdom says.

Analysis of 2-year follow-up data from the GARFIELD-AF registry of more than 52,000 patients with newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation (AF) showed that, while patients with a history of stroke had significantly elevated rates of both all-cause mortality and stroke, those with just a history of a transient ischemic attack (TIA) had mortality and stroke rates virtually identical to AF patients with no history of a cerebrovascular event.

“A history of TIA only is not a reliable predictor of an increased risk for events,” Werner Hacke, MD, said at the World Stroke Congress. “A history of TIA should be removed from scores estimating the risk for stroke and systemic embolism in AF patients,” said Dr. Hacke, professor and chairman of the department of neurology at the University of Heidelberg (Germany).

“The weak predictive power of a history of TIA is probably caused by the relatively low reliability of establishing the diagnosis of TIA,” especially when the diagnosis is made by someone who’s not a neurologist. “It’s a very fuzzy diagnosis,” even for a neurologist, and it consistently confounds other clinicians, he said in an interview. “I’d be really careful of deciding to anticoagulate a patient [with AF] based on a history of TIA.” In the GARFIELD-AF registry, “I’m convinced that most people with a history of TIA actually never had a TIA.”

Dr. Hacke has been unable to find a good explanation of why, years ago, TIAs began to get routinely lumped with stroke. “I asked all the old AF guys when did TIA start coming in and why, and none of them could remember,” he said. “At first, they talked about a history of ‘cerebrovascular events,’ but then that became stroke and TIA, and it was as if it was one word,” always said in the same breath. Both the CHADS2 score (JAMA. 2001 Jun 13;285[22]:2864-70) and the CHA2DS2-VASc score (Chest. 2010 Feb;137[2]:263-72) make a history of stroke or TIA, as well as thromboembolism, coequal risk factors that count for 2 points when calculating the thrombotic risk score for a patient with AF.

To test whether this really made sense, Dr. Hacke and his associates decided to look at the separate consequences of a history of stroke only, compared with a history of a TIA only. They used data collected in GARFIELD-AF (Global Anticoagulant Registry in the Field), a multinational registry with 51,670 patients newly diagnosed with AF, followed for 2 years, and with complete information on their stroke and TIA history. This included 5,617 patients with a history of at least one diagnosed cerebrovascular event, including 3,362 diagnosed with stroke only, 1,788 diagnosed with TIA only, and the remaining patients diagnosed with both types of events.

When compared with AF patients without a history of any type of cerebrovascular event, those with a history of a stroke only had a statistically significant 29% increased rate of all-cause death and a 2.3-fold higher rate of stroke after adjustment for baseline demographic and clinical differences. In contrast, the patients with a history of TIA only had mortality and stroke rates during follow-up that did not differ significantly from the comparator group.

Source: Hacke W et al. World Stroke Congress, Abstract.

MONTREAL – Stroke and transient ischemic attack, usually joined at the hip as related histories that each flag a similar need for anticoagulation may in fact not be nearly as equivalent as conventional wisdom says.

Analysis of 2-year follow-up data from the GARFIELD-AF registry of more than 52,000 patients with newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation (AF) showed that, while patients with a history of stroke had significantly elevated rates of both all-cause mortality and stroke, those with just a history of a transient ischemic attack (TIA) had mortality and stroke rates virtually identical to AF patients with no history of a cerebrovascular event.

“A history of TIA only is not a reliable predictor of an increased risk for events,” Werner Hacke, MD, said at the World Stroke Congress. “A history of TIA should be removed from scores estimating the risk for stroke and systemic embolism in AF patients,” said Dr. Hacke, professor and chairman of the department of neurology at the University of Heidelberg (Germany).

“The weak predictive power of a history of TIA is probably caused by the relatively low reliability of establishing the diagnosis of TIA,” especially when the diagnosis is made by someone who’s not a neurologist. “It’s a very fuzzy diagnosis,” even for a neurologist, and it consistently confounds other clinicians, he said in an interview. “I’d be really careful of deciding to anticoagulate a patient [with AF] based on a history of TIA.” In the GARFIELD-AF registry, “I’m convinced that most people with a history of TIA actually never had a TIA.”

Dr. Hacke has been unable to find a good explanation of why, years ago, TIAs began to get routinely lumped with stroke. “I asked all the old AF guys when did TIA start coming in and why, and none of them could remember,” he said. “At first, they talked about a history of ‘cerebrovascular events,’ but then that became stroke and TIA, and it was as if it was one word,” always said in the same breath. Both the CHADS2 score (JAMA. 2001 Jun 13;285[22]:2864-70) and the CHA2DS2-VASc score (Chest. 2010 Feb;137[2]:263-72) make a history of stroke or TIA, as well as thromboembolism, coequal risk factors that count for 2 points when calculating the thrombotic risk score for a patient with AF.

To test whether this really made sense, Dr. Hacke and his associates decided to look at the separate consequences of a history of stroke only, compared with a history of a TIA only. They used data collected in GARFIELD-AF (Global Anticoagulant Registry in the Field), a multinational registry with 51,670 patients newly diagnosed with AF, followed for 2 years, and with complete information on their stroke and TIA history. This included 5,617 patients with a history of at least one diagnosed cerebrovascular event, including 3,362 diagnosed with stroke only, 1,788 diagnosed with TIA only, and the remaining patients diagnosed with both types of events.

When compared with AF patients without a history of any type of cerebrovascular event, those with a history of a stroke only had a statistically significant 29% increased rate of all-cause death and a 2.3-fold higher rate of stroke after adjustment for baseline demographic and clinical differences. In contrast, the patients with a history of TIA only had mortality and stroke rates during follow-up that did not differ significantly from the comparator group.

Source: Hacke W et al. World Stroke Congress, Abstract.

REPORTING FROM THE WORLD STROKE CONGRESS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The adjusted rate of stroke in patients with a TIA history was not significantly different from patients with no history.

Study details: GARFIELD-AF, a multinational registry of 52,014 patients newly diagnosed with atrial fibrillation.

Disclosures: GARFIELD-AF is funded by Bayer. Dr. Hacke has been an adviser to Boehringer Ingelheim and Cerenovus and he has received research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim.

Source: Hacke W et al. World Stroke Congress, Abstract.

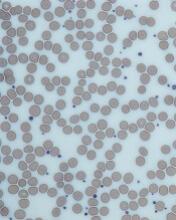

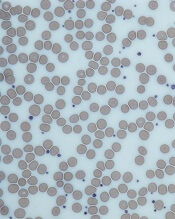

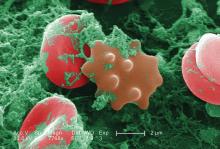

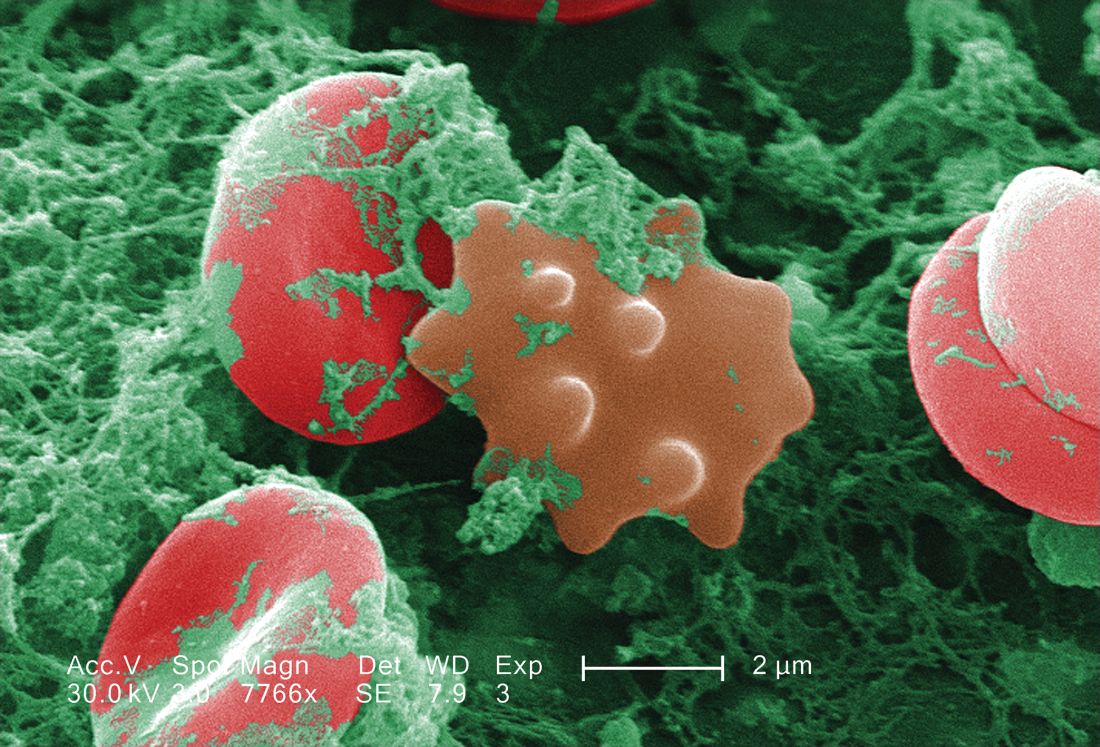

Inhibitor receives orphan designation for ITP

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation to PRN1008 for the treatment of patients with immune thrombocytopenia (ITP).

PRN1008 is an oral, reversible, covalent Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor being developed by Principia Biopharma, Inc.

Principia is conducting a phase 1/2 trial (NCT03395210) to evaluate the safety and efficacy of PRN1008 in patients with ITP.

Results of preclinical research with PRN1008 in ITP were presented at the 2017 ASH Annual Meeting.

There, researchers reported that PRN1008 significantly reduced platelet loss in a mouse model of ITP.

The team found the BTK inhibitor could diminish platelet loss in two ways:

- By reducing platelet destruction via inhibition of autoantibody/FcγR signaling in splenic macrophages

- By reducing autoantibody generation through inhibition of B-cell activation and maturation.

The researchers also assessed the effects of PRN1008 and ibrutinib on platelet function in samples from healthy volunteers and ITP patients.

Samples were treated with one of the two BTK inhibitors, and platelet aggregation was induced by platelet agonists.

Unlike ibrutinib, PRN1008 did not impact platelet aggregation in healthy volunteer or ITP patient samples.

About orphan designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the United States.

The designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation to PRN1008 for the treatment of patients with immune thrombocytopenia (ITP).

PRN1008 is an oral, reversible, covalent Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor being developed by Principia Biopharma, Inc.

Principia is conducting a phase 1/2 trial (NCT03395210) to evaluate the safety and efficacy of PRN1008 in patients with ITP.

Results of preclinical research with PRN1008 in ITP were presented at the 2017 ASH Annual Meeting.

There, researchers reported that PRN1008 significantly reduced platelet loss in a mouse model of ITP.

The team found the BTK inhibitor could diminish platelet loss in two ways:

- By reducing platelet destruction via inhibition of autoantibody/FcγR signaling in splenic macrophages

- By reducing autoantibody generation through inhibition of B-cell activation and maturation.

The researchers also assessed the effects of PRN1008 and ibrutinib on platelet function in samples from healthy volunteers and ITP patients.

Samples were treated with one of the two BTK inhibitors, and platelet aggregation was induced by platelet agonists.

Unlike ibrutinib, PRN1008 did not impact platelet aggregation in healthy volunteer or ITP patient samples.

About orphan designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the United States.

The designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation to PRN1008 for the treatment of patients with immune thrombocytopenia (ITP).

PRN1008 is an oral, reversible, covalent Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor being developed by Principia Biopharma, Inc.

Principia is conducting a phase 1/2 trial (NCT03395210) to evaluate the safety and efficacy of PRN1008 in patients with ITP.

Results of preclinical research with PRN1008 in ITP were presented at the 2017 ASH Annual Meeting.

There, researchers reported that PRN1008 significantly reduced platelet loss in a mouse model of ITP.

The team found the BTK inhibitor could diminish platelet loss in two ways:

- By reducing platelet destruction via inhibition of autoantibody/FcγR signaling in splenic macrophages

- By reducing autoantibody generation through inhibition of B-cell activation and maturation.

The researchers also assessed the effects of PRN1008 and ibrutinib on platelet function in samples from healthy volunteers and ITP patients.

Samples were treated with one of the two BTK inhibitors, and platelet aggregation was induced by platelet agonists.

Unlike ibrutinib, PRN1008 did not impact platelet aggregation in healthy volunteer or ITP patient samples.

About orphan designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the United States.

The designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved.

CHMP recommends change for eptacog alfa

The European Medicine’s Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended a change to the terms of the marketing authorization for the recombinant factor VIIa product eptacog alfa (NovoSeven).

The recommendation is to expand the approved use of eptacog alfa in patients with Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia.

Eptacog alfa is already approved by the European Commission (EC) for use in patients with Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia with antibodies to glycoprotein IIb/IIIa and/or human leukocyte antigen who have past or present refractoriness to platelet transfusions.

Now, the CHMP has recommended expanding the use of eptacog alfa to include situations in which patients are not refractory to platelet transfusions but platelets are not readily available.

The CHMP’s recommendations are reviewed by the EC, which has the authority to approve medicines for use in the European Union, Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein. The EC usually makes a decision within 67 days of CHMP recommendations.

If the EC follows the CHMP’s recommendation for eptacog alfa, the product will be approved for the treatment of bleeding episodes and for the prevention of bleeding in those undergoing surgery or invasive procedures in the following patient groups:

- Patients with congenital hemophilia with inhibitors to coagulation factors VIII or IX > 5 Bethesda units

- Patients with congenital hemophilia who are expected to have a high anamnestic response to factor VIII or factor IX administration

- Patients with acquired hemophilia

- Patients with congenital FVII deficiency

- Patients with Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia with antibodies to glycoprotein IIb/IIIa and/or human leukocyte antigen and past or present refractoriness to platelet transfusions, or where platelets are not readily available.

The European Medicine’s Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended a change to the terms of the marketing authorization for the recombinant factor VIIa product eptacog alfa (NovoSeven).

The recommendation is to expand the approved use of eptacog alfa in patients with Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia.

Eptacog alfa is already approved by the European Commission (EC) for use in patients with Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia with antibodies to glycoprotein IIb/IIIa and/or human leukocyte antigen who have past or present refractoriness to platelet transfusions.

Now, the CHMP has recommended expanding the use of eptacog alfa to include situations in which patients are not refractory to platelet transfusions but platelets are not readily available.

The CHMP’s recommendations are reviewed by the EC, which has the authority to approve medicines for use in the European Union, Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein. The EC usually makes a decision within 67 days of CHMP recommendations.

If the EC follows the CHMP’s recommendation for eptacog alfa, the product will be approved for the treatment of bleeding episodes and for the prevention of bleeding in those undergoing surgery or invasive procedures in the following patient groups:

- Patients with congenital hemophilia with inhibitors to coagulation factors VIII or IX > 5 Bethesda units

- Patients with congenital hemophilia who are expected to have a high anamnestic response to factor VIII or factor IX administration

- Patients with acquired hemophilia

- Patients with congenital FVII deficiency

- Patients with Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia with antibodies to glycoprotein IIb/IIIa and/or human leukocyte antigen and past or present refractoriness to platelet transfusions, or where platelets are not readily available.

The European Medicine’s Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended a change to the terms of the marketing authorization for the recombinant factor VIIa product eptacog alfa (NovoSeven).

The recommendation is to expand the approved use of eptacog alfa in patients with Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia.

Eptacog alfa is already approved by the European Commission (EC) for use in patients with Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia with antibodies to glycoprotein IIb/IIIa and/or human leukocyte antigen who have past or present refractoriness to platelet transfusions.

Now, the CHMP has recommended expanding the use of eptacog alfa to include situations in which patients are not refractory to platelet transfusions but platelets are not readily available.

The CHMP’s recommendations are reviewed by the EC, which has the authority to approve medicines for use in the European Union, Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein. The EC usually makes a decision within 67 days of CHMP recommendations.

If the EC follows the CHMP’s recommendation for eptacog alfa, the product will be approved for the treatment of bleeding episodes and for the prevention of bleeding in those undergoing surgery or invasive procedures in the following patient groups:

- Patients with congenital hemophilia with inhibitors to coagulation factors VIII or IX > 5 Bethesda units

- Patients with congenital hemophilia who are expected to have a high anamnestic response to factor VIII or factor IX administration

- Patients with acquired hemophilia

- Patients with congenital FVII deficiency

- Patients with Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia with antibodies to glycoprotein IIb/IIIa and/or human leukocyte antigen and past or present refractoriness to platelet transfusions, or where platelets are not readily available.

DAPT’s benefit after stroke or TIA clusters in first 21 days

MONTREAL – The optimal length for dual antiplatelet therapy in patients who have just had a mild stroke or transient ischemic attack is 21 days, a duration of combined treatment that maximized protection against major ischemic events while minimizing the extra risk for a major hemorrhage, according to a prespecified analysis of data from the POINT trial.

The POINT (Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke) trial randomized 4,881 patients with a very recent mild stroke or transient ischemic attack and without atrial fibrillation to treatment with either clopidogrel plus aspirin or aspirin alone for 90 days. Compared with aspirin alone, dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) cut the incidence of a major ischemic event by a relative 25% but also more than doubled the rate of major hemorrhage (New Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 19;377[3]:215-25).

The new, prespecified analysis looked at outcomes on a week-by-week basis over the course of 90 days of treatment, and showed that during the first 21 days the rate of major ischemic events was 5.6% among patients on aspirin only and 3.6% among those on DAPT, a statistically significant 35% relative cut in these adverse outcomes by using DAPT, Jordan J. Elm, PhD, reported at the World Stroke Congress. During the subsequent 69 days on treatment, the incidence of major ischemic events was roughly 1% in both arms of the study, showing that after 3 weeks the incremental benefit from DAPT disappeared, said Dr. Elm, a biostatistician at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston.

In contrast, the doubled rate of major hemorrhages (mostly reversible gastrointestinal bleeds) with DAPT, compared with aspirin alone, occurred at a relatively uniform rate throughout the 90 days of treatment, meaning that limiting DAPT to just 21 days could prevent many of the excess hemorrhages.

“These results suggest that limiting clopidogrel plus aspirin use to 21 days may maximize benefit and reduce risk,” Dr. Elm said, especially in light of the findings confirming the efficacy of 21 days of DAPT following a minor stroke or TIA that had been reported several years ago in the CHANCE (Clopidogrel in High-Risk Patients with Acute Nondisabling Cerebrovascular Events) trial (New Engl J Med. 2013 Jul 4;369[1]:11-9).

Although the new finding from the POINT results came in a secondary analysis, it’s statistically legitimate and should be taken into account when writing treatment guidelines, she said, emphasizing that “this is a very important analysis that is not just hypothesis generating.”

Another finding from the new analysis was that a large number of major ischemic events, and hence a large number of the events prevented by DAPT, occurred in the first 2 days following the index event, a finding made possible because the POINT investigators enrolled patients and started treatment within 12 hours of the qualifying events.

“It’s better to start treatment early,” Dr. Elm noted, but she also highlighted that major ischemic events continued to accumulate during days 3-21, suggesting that patients could still benefit from DAPT even if treatment did not start until 24 or 48 hours after their index event.

POINT received no commercial funding aside from study drugs supplied by Sanofi. Dr. Elm reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Elm JJ et al. World Stroke Congress, Late-breaking session.

The new model using data from the POINT trial confirms what had been previously shown in the CHANCE trial – that 21 days is a sensible cutoff for dual antiplatelet treatment for patients immediately following a mild stroke or transient ischemic attack. Treatment with dual antiplatelet therapy for 21 days provides the same added benefit as 90 days of treatment but with less excess bleeding. The new findings confirm that the CHANCE results were not specific to a Chinese population.

For the time being, clopidogrel is the evidence-based antiplatelet drug to pair with aspirin for this indication. Clopidogrel has the advantages of being generic, cheap, available, and familiar. It’s possible that another P2Y12 inhibitor, such as ticagrelor (Brilinta), might work even better, but that needs to be proven to justify the added expense of a brand-name antiplatelet drug.

Mike Sharma, MD , is a stroke neurologist at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont. He has been an advisor to Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer. He made these comments in an interview.

The new model using data from the POINT trial confirms what had been previously shown in the CHANCE trial – that 21 days is a sensible cutoff for dual antiplatelet treatment for patients immediately following a mild stroke or transient ischemic attack. Treatment with dual antiplatelet therapy for 21 days provides the same added benefit as 90 days of treatment but with less excess bleeding. The new findings confirm that the CHANCE results were not specific to a Chinese population.

For the time being, clopidogrel is the evidence-based antiplatelet drug to pair with aspirin for this indication. Clopidogrel has the advantages of being generic, cheap, available, and familiar. It’s possible that another P2Y12 inhibitor, such as ticagrelor (Brilinta), might work even better, but that needs to be proven to justify the added expense of a brand-name antiplatelet drug.

Mike Sharma, MD , is a stroke neurologist at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont. He has been an advisor to Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer. He made these comments in an interview.

The new model using data from the POINT trial confirms what had been previously shown in the CHANCE trial – that 21 days is a sensible cutoff for dual antiplatelet treatment for patients immediately following a mild stroke or transient ischemic attack. Treatment with dual antiplatelet therapy for 21 days provides the same added benefit as 90 days of treatment but with less excess bleeding. The new findings confirm that the CHANCE results were not specific to a Chinese population.

For the time being, clopidogrel is the evidence-based antiplatelet drug to pair with aspirin for this indication. Clopidogrel has the advantages of being generic, cheap, available, and familiar. It’s possible that another P2Y12 inhibitor, such as ticagrelor (Brilinta), might work even better, but that needs to be proven to justify the added expense of a brand-name antiplatelet drug.

Mike Sharma, MD , is a stroke neurologist at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont. He has been an advisor to Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer. He made these comments in an interview.

MONTREAL – The optimal length for dual antiplatelet therapy in patients who have just had a mild stroke or transient ischemic attack is 21 days, a duration of combined treatment that maximized protection against major ischemic events while minimizing the extra risk for a major hemorrhage, according to a prespecified analysis of data from the POINT trial.

The POINT (Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke) trial randomized 4,881 patients with a very recent mild stroke or transient ischemic attack and without atrial fibrillation to treatment with either clopidogrel plus aspirin or aspirin alone for 90 days. Compared with aspirin alone, dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) cut the incidence of a major ischemic event by a relative 25% but also more than doubled the rate of major hemorrhage (New Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 19;377[3]:215-25).

The new, prespecified analysis looked at outcomes on a week-by-week basis over the course of 90 days of treatment, and showed that during the first 21 days the rate of major ischemic events was 5.6% among patients on aspirin only and 3.6% among those on DAPT, a statistically significant 35% relative cut in these adverse outcomes by using DAPT, Jordan J. Elm, PhD, reported at the World Stroke Congress. During the subsequent 69 days on treatment, the incidence of major ischemic events was roughly 1% in both arms of the study, showing that after 3 weeks the incremental benefit from DAPT disappeared, said Dr. Elm, a biostatistician at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston.

In contrast, the doubled rate of major hemorrhages (mostly reversible gastrointestinal bleeds) with DAPT, compared with aspirin alone, occurred at a relatively uniform rate throughout the 90 days of treatment, meaning that limiting DAPT to just 21 days could prevent many of the excess hemorrhages.

“These results suggest that limiting clopidogrel plus aspirin use to 21 days may maximize benefit and reduce risk,” Dr. Elm said, especially in light of the findings confirming the efficacy of 21 days of DAPT following a minor stroke or TIA that had been reported several years ago in the CHANCE (Clopidogrel in High-Risk Patients with Acute Nondisabling Cerebrovascular Events) trial (New Engl J Med. 2013 Jul 4;369[1]:11-9).

Although the new finding from the POINT results came in a secondary analysis, it’s statistically legitimate and should be taken into account when writing treatment guidelines, she said, emphasizing that “this is a very important analysis that is not just hypothesis generating.”

Another finding from the new analysis was that a large number of major ischemic events, and hence a large number of the events prevented by DAPT, occurred in the first 2 days following the index event, a finding made possible because the POINT investigators enrolled patients and started treatment within 12 hours of the qualifying events.

“It’s better to start treatment early,” Dr. Elm noted, but she also highlighted that major ischemic events continued to accumulate during days 3-21, suggesting that patients could still benefit from DAPT even if treatment did not start until 24 or 48 hours after their index event.

POINT received no commercial funding aside from study drugs supplied by Sanofi. Dr. Elm reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Elm JJ et al. World Stroke Congress, Late-breaking session.

MONTREAL – The optimal length for dual antiplatelet therapy in patients who have just had a mild stroke or transient ischemic attack is 21 days, a duration of combined treatment that maximized protection against major ischemic events while minimizing the extra risk for a major hemorrhage, according to a prespecified analysis of data from the POINT trial.

The POINT (Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke) trial randomized 4,881 patients with a very recent mild stroke or transient ischemic attack and without atrial fibrillation to treatment with either clopidogrel plus aspirin or aspirin alone for 90 days. Compared with aspirin alone, dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) cut the incidence of a major ischemic event by a relative 25% but also more than doubled the rate of major hemorrhage (New Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 19;377[3]:215-25).

The new, prespecified analysis looked at outcomes on a week-by-week basis over the course of 90 days of treatment, and showed that during the first 21 days the rate of major ischemic events was 5.6% among patients on aspirin only and 3.6% among those on DAPT, a statistically significant 35% relative cut in these adverse outcomes by using DAPT, Jordan J. Elm, PhD, reported at the World Stroke Congress. During the subsequent 69 days on treatment, the incidence of major ischemic events was roughly 1% in both arms of the study, showing that after 3 weeks the incremental benefit from DAPT disappeared, said Dr. Elm, a biostatistician at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston.

In contrast, the doubled rate of major hemorrhages (mostly reversible gastrointestinal bleeds) with DAPT, compared with aspirin alone, occurred at a relatively uniform rate throughout the 90 days of treatment, meaning that limiting DAPT to just 21 days could prevent many of the excess hemorrhages.

“These results suggest that limiting clopidogrel plus aspirin use to 21 days may maximize benefit and reduce risk,” Dr. Elm said, especially in light of the findings confirming the efficacy of 21 days of DAPT following a minor stroke or TIA that had been reported several years ago in the CHANCE (Clopidogrel in High-Risk Patients with Acute Nondisabling Cerebrovascular Events) trial (New Engl J Med. 2013 Jul 4;369[1]:11-9).

Although the new finding from the POINT results came in a secondary analysis, it’s statistically legitimate and should be taken into account when writing treatment guidelines, she said, emphasizing that “this is a very important analysis that is not just hypothesis generating.”

Another finding from the new analysis was that a large number of major ischemic events, and hence a large number of the events prevented by DAPT, occurred in the first 2 days following the index event, a finding made possible because the POINT investigators enrolled patients and started treatment within 12 hours of the qualifying events.

“It’s better to start treatment early,” Dr. Elm noted, but she also highlighted that major ischemic events continued to accumulate during days 3-21, suggesting that patients could still benefit from DAPT even if treatment did not start until 24 or 48 hours after their index event.

POINT received no commercial funding aside from study drugs supplied by Sanofi. Dr. Elm reported no disclosures.

SOURCE: Elm JJ et al. World Stroke Congress, Late-breaking session.

REPORTING FROM THE WORLD STROKE CONGRESS

Key clinical point: All of DAPT’s extra benefit over aspirin alone in recent stroke or transient ischemic attack patients happened during the first 21 days.

Major finding: During the first 21 days, DAPT cut major ischemic events by 35%, compared with aspirin only.

Study details: A prespecified, secondary analysis from POINT, a multicenter, randomized trial with 4,881 patients.

Disclosures: POINT received no commercial funding aside from study drugs supplied by Sanofi. Dr. Elm had no disclosures.

Source: Elm JJ et al. World Stroke Congress, Late-breaking session.

CTPA overused in veterans with suspected PE

SAN ANTONIO—The recommended approach to evaluating suspected pulmonary embolism (PE) is “greatly underutilized” in the Veterans Health Administration system, according to a speaker at CHEST 2018.

A survey showed that, contrary to guideline recommendations, most Veterans Affairs sites did not require incorporation of a clinical decision rule (CDR) and D-dimer prior to the ordering of computed tomographic pulmonary angiography (CTPA) for suspected PE.

Therefore, CTPA was overused.

Nancy Hsu, MD, a pulmonologist in Los Angeles, California, discussed this finding at the meeting.

She noted that CTPA has become the imaging modality of choice for evaluating suspected PE, but it is overused and potentially avoidable in one-third of cases.

“In the 10 years following the advent of CTPA use, there was a 14-fold increase in usage, but there was no change in mortality,” Dr. Hsu said. “This is consistent with overdiagnosis.”

Indiscriminate use of CTPA results in unnecessary and avoidable radiation exposure, contrast-related reactions, and treatment-related bleeding, Dr. Hsu noted.

She and a colleague discovered CTPA overuse in the Veterans Health Administration system by conducting a survey of stakeholders at 18 Veterans Integrated Service Networks and 143 medical centers.

A total of 120 fully completed questionnaires were analyzed. Most respondents (63%) were chief physicians, and 80% had 11 or more years of experience.

Most respondents (85%) said CDR with or without D-dimer was not required before ordering CTPA. Less than 7% of respondents said they required both CDR and D-dimer before CTPA.

The biggest barrier to optimal practice may be the fear of having a patient who “falls through the cracks” based on false-negative CDR and D-dimer data, according to Dr. Hsu.

On the other hand, judicious use of CTPA likely avoids negative sequelae related to radiation, contrast exposure, and treatment-related bleeding, she said.

Dr. Hsu and her colleague, Guy Soo Hoo, MD, said they had no relationships relevant to this research.

SAN ANTONIO—The recommended approach to evaluating suspected pulmonary embolism (PE) is “greatly underutilized” in the Veterans Health Administration system, according to a speaker at CHEST 2018.

A survey showed that, contrary to guideline recommendations, most Veterans Affairs sites did not require incorporation of a clinical decision rule (CDR) and D-dimer prior to the ordering of computed tomographic pulmonary angiography (CTPA) for suspected PE.

Therefore, CTPA was overused.

Nancy Hsu, MD, a pulmonologist in Los Angeles, California, discussed this finding at the meeting.

She noted that CTPA has become the imaging modality of choice for evaluating suspected PE, but it is overused and potentially avoidable in one-third of cases.

“In the 10 years following the advent of CTPA use, there was a 14-fold increase in usage, but there was no change in mortality,” Dr. Hsu said. “This is consistent with overdiagnosis.”

Indiscriminate use of CTPA results in unnecessary and avoidable radiation exposure, contrast-related reactions, and treatment-related bleeding, Dr. Hsu noted.

She and a colleague discovered CTPA overuse in the Veterans Health Administration system by conducting a survey of stakeholders at 18 Veterans Integrated Service Networks and 143 medical centers.

A total of 120 fully completed questionnaires were analyzed. Most respondents (63%) were chief physicians, and 80% had 11 or more years of experience.

Most respondents (85%) said CDR with or without D-dimer was not required before ordering CTPA. Less than 7% of respondents said they required both CDR and D-dimer before CTPA.

The biggest barrier to optimal practice may be the fear of having a patient who “falls through the cracks” based on false-negative CDR and D-dimer data, according to Dr. Hsu.

On the other hand, judicious use of CTPA likely avoids negative sequelae related to radiation, contrast exposure, and treatment-related bleeding, she said.

Dr. Hsu and her colleague, Guy Soo Hoo, MD, said they had no relationships relevant to this research.

SAN ANTONIO—The recommended approach to evaluating suspected pulmonary embolism (PE) is “greatly underutilized” in the Veterans Health Administration system, according to a speaker at CHEST 2018.

A survey showed that, contrary to guideline recommendations, most Veterans Affairs sites did not require incorporation of a clinical decision rule (CDR) and D-dimer prior to the ordering of computed tomographic pulmonary angiography (CTPA) for suspected PE.

Therefore, CTPA was overused.

Nancy Hsu, MD, a pulmonologist in Los Angeles, California, discussed this finding at the meeting.

She noted that CTPA has become the imaging modality of choice for evaluating suspected PE, but it is overused and potentially avoidable in one-third of cases.

“In the 10 years following the advent of CTPA use, there was a 14-fold increase in usage, but there was no change in mortality,” Dr. Hsu said. “This is consistent with overdiagnosis.”

Indiscriminate use of CTPA results in unnecessary and avoidable radiation exposure, contrast-related reactions, and treatment-related bleeding, Dr. Hsu noted.

She and a colleague discovered CTPA overuse in the Veterans Health Administration system by conducting a survey of stakeholders at 18 Veterans Integrated Service Networks and 143 medical centers.

A total of 120 fully completed questionnaires were analyzed. Most respondents (63%) were chief physicians, and 80% had 11 or more years of experience.

Most respondents (85%) said CDR with or without D-dimer was not required before ordering CTPA. Less than 7% of respondents said they required both CDR and D-dimer before CTPA.

The biggest barrier to optimal practice may be the fear of having a patient who “falls through the cracks” based on false-negative CDR and D-dimer data, according to Dr. Hsu.

On the other hand, judicious use of CTPA likely avoids negative sequelae related to radiation, contrast exposure, and treatment-related bleeding, she said.

Dr. Hsu and her colleague, Guy Soo Hoo, MD, said they had no relationships relevant to this research.

Obese PE patients have lower risk of death

SAN ANTONIO—Patients with pulmonary embolism (PE) have a lower mortality risk if they are obese, according to a retrospective analysis of nearly 2 million PE discharges.

The obese patients had a lower mortality risk despite receiving more thrombolytics and mechanical intubation, said study investigator Zubair Khan, MD, of the University of Toledo Medical Center in Ohio.

“Surprisingly, the mortality of PE was significantly less in obese patients,” Dr. Khan said. “When we initiated the study, we did not expect this result.”

Dr. Khan discussed this result in a presentation at CHEST 2018.

Dr. Khan noted that the association between obesity and lower mortality, sometimes called the “obesity paradox,” has been observed in studies of other chronic health conditions, including stable heart failure, coronary artery disease, unstable angina, myocardial infarction, and also in some PE studies.

His team’s study, conducted using the National Inpatient Sample database, included adults with a primary discharge diagnosis of PE between 2002 and 2014. The researchers included 1,959,018 PE discharges, of which 312,770 (16%) had an underlying obesity diagnosis.

Obese PE patients had more risk factors and more severe disease but an overall mortality of 2.2%, compared with 3.7% in PE patients without obesity (P<0.001), Dr. Khan reported.

Hypertension was significantly more prevalent in the obese PE patients (65% vs. 50.5%; P<0.001), as was chronic lung disease and chronic liver disease.

Obese patients more often received thrombolytics (3.6% vs. 1.9%; P<0.001) and mechanical ventilation (5.8% vs. 4%; P<0.001), and they more frequently had cardiogenic shock (0.65% vs. 0.45%; P<0.001).

The obese PE patients were more often female, black, and younger than 65 years of age.

Notably, the prevalence of obesity in PE patients more than doubled over the course of the study period, from 10.2% in 2002 to 22.6% in 2014.

The lower mortality in obese patients might be explained by increased levels of endocannabinoids, which have shown protective effects in rat and mouse studies, Dr. Khan said.

“I think it’s a rich area for more and further research, especially in basic science,” he added.

Dr. Khan and his coauthors said they had no relationships relevant to the study.

SAN ANTONIO—Patients with pulmonary embolism (PE) have a lower mortality risk if they are obese, according to a retrospective analysis of nearly 2 million PE discharges.

The obese patients had a lower mortality risk despite receiving more thrombolytics and mechanical intubation, said study investigator Zubair Khan, MD, of the University of Toledo Medical Center in Ohio.

“Surprisingly, the mortality of PE was significantly less in obese patients,” Dr. Khan said. “When we initiated the study, we did not expect this result.”

Dr. Khan discussed this result in a presentation at CHEST 2018.

Dr. Khan noted that the association between obesity and lower mortality, sometimes called the “obesity paradox,” has been observed in studies of other chronic health conditions, including stable heart failure, coronary artery disease, unstable angina, myocardial infarction, and also in some PE studies.

His team’s study, conducted using the National Inpatient Sample database, included adults with a primary discharge diagnosis of PE between 2002 and 2014. The researchers included 1,959,018 PE discharges, of which 312,770 (16%) had an underlying obesity diagnosis.

Obese PE patients had more risk factors and more severe disease but an overall mortality of 2.2%, compared with 3.7% in PE patients without obesity (P<0.001), Dr. Khan reported.

Hypertension was significantly more prevalent in the obese PE patients (65% vs. 50.5%; P<0.001), as was chronic lung disease and chronic liver disease.

Obese patients more often received thrombolytics (3.6% vs. 1.9%; P<0.001) and mechanical ventilation (5.8% vs. 4%; P<0.001), and they more frequently had cardiogenic shock (0.65% vs. 0.45%; P<0.001).

The obese PE patients were more often female, black, and younger than 65 years of age.

Notably, the prevalence of obesity in PE patients more than doubled over the course of the study period, from 10.2% in 2002 to 22.6% in 2014.

The lower mortality in obese patients might be explained by increased levels of endocannabinoids, which have shown protective effects in rat and mouse studies, Dr. Khan said.

“I think it’s a rich area for more and further research, especially in basic science,” he added.

Dr. Khan and his coauthors said they had no relationships relevant to the study.

SAN ANTONIO—Patients with pulmonary embolism (PE) have a lower mortality risk if they are obese, according to a retrospective analysis of nearly 2 million PE discharges.

The obese patients had a lower mortality risk despite receiving more thrombolytics and mechanical intubation, said study investigator Zubair Khan, MD, of the University of Toledo Medical Center in Ohio.

“Surprisingly, the mortality of PE was significantly less in obese patients,” Dr. Khan said. “When we initiated the study, we did not expect this result.”

Dr. Khan discussed this result in a presentation at CHEST 2018.

Dr. Khan noted that the association between obesity and lower mortality, sometimes called the “obesity paradox,” has been observed in studies of other chronic health conditions, including stable heart failure, coronary artery disease, unstable angina, myocardial infarction, and also in some PE studies.

His team’s study, conducted using the National Inpatient Sample database, included adults with a primary discharge diagnosis of PE between 2002 and 2014. The researchers included 1,959,018 PE discharges, of which 312,770 (16%) had an underlying obesity diagnosis.

Obese PE patients had more risk factors and more severe disease but an overall mortality of 2.2%, compared with 3.7% in PE patients without obesity (P<0.001), Dr. Khan reported.

Hypertension was significantly more prevalent in the obese PE patients (65% vs. 50.5%; P<0.001), as was chronic lung disease and chronic liver disease.

Obese patients more often received thrombolytics (3.6% vs. 1.9%; P<0.001) and mechanical ventilation (5.8% vs. 4%; P<0.001), and they more frequently had cardiogenic shock (0.65% vs. 0.45%; P<0.001).

The obese PE patients were more often female, black, and younger than 65 years of age.

Notably, the prevalence of obesity in PE patients more than doubled over the course of the study period, from 10.2% in 2002 to 22.6% in 2014.

The lower mortality in obese patients might be explained by increased levels of endocannabinoids, which have shown protective effects in rat and mouse studies, Dr. Khan said.

“I think it’s a rich area for more and further research, especially in basic science,” he added.

Dr. Khan and his coauthors said they had no relationships relevant to the study.

Be proactive with prophylaxis to tame VTE

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is the No. 1 cause of preventable deaths in hospitals, and 60% of all VTE cases occur during or following hospitalization, according to Jeffrey I. Weitz, MD, of McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont.

, he said in a webinar to promote World Thrombosis Day.

“To prevent VTE, people need to be aware of the problem,” he said. Hospitalization for any reason increases the risk of VTE, but thromboprophylaxis may be underused in medical patients, compared with surgical patients, because most surgical patients are automatically considered at risk.

Prevention of VTE involves understanding the risk factors, Dr. Weitz said. He pointed to a triad of conditions that promote clotting: slow blood flow, injury to the vessel wall, and increased clotability of the blood.

In a study of VTE risk factors, recent surgery with hospitalization and trauma topped the list, but hospitalization without recent surgery was associated with a nearly 8-fold increase in risk (Arch Intern Med. 2000;160[6]:809-15).

Evidence supports the value of anticoagulant prophylaxis, Dr. Weitz said. In a 2007 meta-analysis, use of anticoagulants reduced the risk of VTE by approximately 60% (Ann Intern Med. 2007 Feb 20;146[4]:278-88), and a 2011 update showed a reduction in risk of approximately 30% (Ann Intern Med. 2011 Nov 1;155[9]:602-15).

While risk assessment remains a challenge, several models can help, said Dr. Weitz.

Current guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians suggest a shift toward individualized assessment of VTE risk, and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services mandates VTE risk assessment, Dr. Weitz said.

He offered seven steps to improve prophylaxis in the hospital:

1. Obtain commitment from hospital leadership, including formation of a committee.

2. Have a written hospital policy on thromboprophylaxis.

3. Keep the policy simple and standard in terms of who gets prophylaxis and when.

4. Use order sets, computer order entry, and decision support.

5. Make the prophylaxis decision mandatory.

6. Involve of all the members of the care team and patients.

7. Use audits to measure improvement.

Several risk assessment models for VTE in hospitalized medical patients have been studied, including the Padua and IMPROVE models, Dr. Weitz said. For any model, factoring in the D-dimer can provide more information. “If D-dimer is increased more than twice the upper limit of normal, it is a risk factor for VTE,” he said.

Another consideration in thromboprophylaxis involves extending the duration of prophylaxis beyond the hospital stay, which is becoming a larger issue because of the pressure to move patients out of the hospital as quickly as possible, Dr. Weitz said. However, trials of extended thromboprophylaxis have yielded mixed results. Extended doses of medications, including rivaroxaban, enoxaparin, apixaban, and betrixaban can reduce the risk of VTE, but can also increase the risk of major bleeding.

“I think at this point we are not yet there at identifying patients who should have thromboprophylaxis beyond the hospital stay,” Dr. Weitz said.

But VTE risk should be assessed in all hospitalized patients, and “appropriate thromboprophylaxis is essential for reducing the burden of hospital-associated VTE,” he said.

Dr. Weitz encouraged clinicians to explore more resources for managing VTE risk at worldthrombosisday.org.

Dr. Weitz reported relationships with companies including Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi-Sankyo, Pfizer, Portola, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, and Servier. He also reported research support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, and the Canadian Fund for Innovation.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is the No. 1 cause of preventable deaths in hospitals, and 60% of all VTE cases occur during or following hospitalization, according to Jeffrey I. Weitz, MD, of McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont.

, he said in a webinar to promote World Thrombosis Day.

“To prevent VTE, people need to be aware of the problem,” he said. Hospitalization for any reason increases the risk of VTE, but thromboprophylaxis may be underused in medical patients, compared with surgical patients, because most surgical patients are automatically considered at risk.

Prevention of VTE involves understanding the risk factors, Dr. Weitz said. He pointed to a triad of conditions that promote clotting: slow blood flow, injury to the vessel wall, and increased clotability of the blood.

In a study of VTE risk factors, recent surgery with hospitalization and trauma topped the list, but hospitalization without recent surgery was associated with a nearly 8-fold increase in risk (Arch Intern Med. 2000;160[6]:809-15).

Evidence supports the value of anticoagulant prophylaxis, Dr. Weitz said. In a 2007 meta-analysis, use of anticoagulants reduced the risk of VTE by approximately 60% (Ann Intern Med. 2007 Feb 20;146[4]:278-88), and a 2011 update showed a reduction in risk of approximately 30% (Ann Intern Med. 2011 Nov 1;155[9]:602-15).

While risk assessment remains a challenge, several models can help, said Dr. Weitz.

Current guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians suggest a shift toward individualized assessment of VTE risk, and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services mandates VTE risk assessment, Dr. Weitz said.

He offered seven steps to improve prophylaxis in the hospital:

1. Obtain commitment from hospital leadership, including formation of a committee.

2. Have a written hospital policy on thromboprophylaxis.

3. Keep the policy simple and standard in terms of who gets prophylaxis and when.

4. Use order sets, computer order entry, and decision support.

5. Make the prophylaxis decision mandatory.

6. Involve of all the members of the care team and patients.

7. Use audits to measure improvement.

Several risk assessment models for VTE in hospitalized medical patients have been studied, including the Padua and IMPROVE models, Dr. Weitz said. For any model, factoring in the D-dimer can provide more information. “If D-dimer is increased more than twice the upper limit of normal, it is a risk factor for VTE,” he said.

Another consideration in thromboprophylaxis involves extending the duration of prophylaxis beyond the hospital stay, which is becoming a larger issue because of the pressure to move patients out of the hospital as quickly as possible, Dr. Weitz said. However, trials of extended thromboprophylaxis have yielded mixed results. Extended doses of medications, including rivaroxaban, enoxaparin, apixaban, and betrixaban can reduce the risk of VTE, but can also increase the risk of major bleeding.

“I think at this point we are not yet there at identifying patients who should have thromboprophylaxis beyond the hospital stay,” Dr. Weitz said.

But VTE risk should be assessed in all hospitalized patients, and “appropriate thromboprophylaxis is essential for reducing the burden of hospital-associated VTE,” he said.

Dr. Weitz encouraged clinicians to explore more resources for managing VTE risk at worldthrombosisday.org.

Dr. Weitz reported relationships with companies including Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi-Sankyo, Pfizer, Portola, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, and Servier. He also reported research support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, and the Canadian Fund for Innovation.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is the No. 1 cause of preventable deaths in hospitals, and 60% of all VTE cases occur during or following hospitalization, according to Jeffrey I. Weitz, MD, of McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont.

, he said in a webinar to promote World Thrombosis Day.

“To prevent VTE, people need to be aware of the problem,” he said. Hospitalization for any reason increases the risk of VTE, but thromboprophylaxis may be underused in medical patients, compared with surgical patients, because most surgical patients are automatically considered at risk.

Prevention of VTE involves understanding the risk factors, Dr. Weitz said. He pointed to a triad of conditions that promote clotting: slow blood flow, injury to the vessel wall, and increased clotability of the blood.

In a study of VTE risk factors, recent surgery with hospitalization and trauma topped the list, but hospitalization without recent surgery was associated with a nearly 8-fold increase in risk (Arch Intern Med. 2000;160[6]:809-15).

Evidence supports the value of anticoagulant prophylaxis, Dr. Weitz said. In a 2007 meta-analysis, use of anticoagulants reduced the risk of VTE by approximately 60% (Ann Intern Med. 2007 Feb 20;146[4]:278-88), and a 2011 update showed a reduction in risk of approximately 30% (Ann Intern Med. 2011 Nov 1;155[9]:602-15).

While risk assessment remains a challenge, several models can help, said Dr. Weitz.

Current guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians suggest a shift toward individualized assessment of VTE risk, and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services mandates VTE risk assessment, Dr. Weitz said.

He offered seven steps to improve prophylaxis in the hospital:

1. Obtain commitment from hospital leadership, including formation of a committee.

2. Have a written hospital policy on thromboprophylaxis.

3. Keep the policy simple and standard in terms of who gets prophylaxis and when.

4. Use order sets, computer order entry, and decision support.

5. Make the prophylaxis decision mandatory.

6. Involve of all the members of the care team and patients.

7. Use audits to measure improvement.

Several risk assessment models for VTE in hospitalized medical patients have been studied, including the Padua and IMPROVE models, Dr. Weitz said. For any model, factoring in the D-dimer can provide more information. “If D-dimer is increased more than twice the upper limit of normal, it is a risk factor for VTE,” he said.

Another consideration in thromboprophylaxis involves extending the duration of prophylaxis beyond the hospital stay, which is becoming a larger issue because of the pressure to move patients out of the hospital as quickly as possible, Dr. Weitz said. However, trials of extended thromboprophylaxis have yielded mixed results. Extended doses of medications, including rivaroxaban, enoxaparin, apixaban, and betrixaban can reduce the risk of VTE, but can also increase the risk of major bleeding.

“I think at this point we are not yet there at identifying patients who should have thromboprophylaxis beyond the hospital stay,” Dr. Weitz said.

But VTE risk should be assessed in all hospitalized patients, and “appropriate thromboprophylaxis is essential for reducing the burden of hospital-associated VTE,” he said.

Dr. Weitz encouraged clinicians to explore more resources for managing VTE risk at worldthrombosisday.org.

Dr. Weitz reported relationships with companies including Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi-Sankyo, Pfizer, Portola, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, and Servier. He also reported research support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, and the Canadian Fund for Innovation.

FROM WORLD THROMBOSIS DAY 2018 WEBINAR

Rivaroxaban gains indication for prevention of major cardiovascular events in CAD/PAD

when taken with aspirin, Janssen Pharmaceuticals announced on October 11.

The Food and Drug Administration’s approval was based on a review of the 27,000-patient COMPASS trial, which showed last year that a low dosage of rivaroxaban (Xarelto) plus aspirin reduced the combined rate of cardiovascular disease events by 24% in patients with coronary artery disease and by 28% in participants with peripheral artery disease, compared with aspirin alone. (N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 5;377[14]:1319-30)

The flip side to the reduction in COMPASS’s combined primary endpoint was a 51% increase in major bleeding. However, that bump did not translate to increases in fatal bleeds, intracerebral bleeds, or bleeding in other critical organs.

COMPASS (Cardiovascular Outcomes for People Using Anticoagulation Strategies) studied two dosages of rivaroxaban, 2.5 mg and 5 mg twice daily, and it was the lower dosage that did the trick. Until this approval, that formulation wasn’t available; Janssen announced the coming of the 2.5-mg pill in its release.

The new prescribing information states specifically that Xarelto 2.5 mg is indicated, in combination with aspirin, to reduce the risk of major cardiovascular events, cardiovascular death, MI, and stroke in patients with chronic coronary artery disease or peripheral artery disease.

This is the sixth indication for rivaroxaban, a factor Xa inhibitor that was first approved in 2011. It is also the first indication for cardiovascular prevention for any factor Xa inhibitor. Others on the U.S. market are apixaban (Eliquis), edoxaban (Savaysa), and betrixaban (Bevyxxa).

COMPASS was presented at the 2017 annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. At that time, Eugene Braunwald, MD, of Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, commented that the trial produced “unambiguous results that should change guidelines and the management of stable coronary artery disease.” He added that the results are “an important step for thrombocardiology.”

when taken with aspirin, Janssen Pharmaceuticals announced on October 11.