User login

Gods and Monsters

For the first time in history, four generations of physicians work side by side in the U.S. health care system. An expanding population, longer life expectancies, and later retirement ages all contribute to this phenomenon. Each of these generations has made significant contributions to modern surgery and how we practice it. For better and for worse.

Traditionalists, or the Greatest Generation, were true surgical pioneers. DeBakey, Cooley, Fogarty, their names now adorn everything from instruments to medical centers. They truly founded the modern system of surgery. Born between 1900 and 1945, Traditionalists were forged in the crucibles of the Great War and the Great Depression. Their core values were hard work, discipline, and sacrifice. A large number were combat veterans who valued conformity and adherence to the rules. Traditionalists set up our current hierarchical departments of surgery. Mirroring their values, they employed a military chain of command approach. Many traditionalists rose to positions of absolute power, and some were corrupted by this power. Gods became monsters. Abuse, both verbal and physical, came to be commonplace and accepted in the surgical work environment.

Born between 1946 and 1964, Baby Boomers were raised in the aftermath of a war none of them saw. More optimistic and idealistic than the Traditionalists, the Boomers valued success. Their goals became more individualistic. Chasing money, titles, and recognition, Boomers wanted to build a stellar career. Fifty-hour work weeks became 70, 80, or 90. Ambition led to wealth, dramatic successes, and remarkable careers. Their choices also led to divorce, drug abuse, and suicide. While burnout has become a modern concern, its roots are clearly tied to this era. Now serving as our deans and department chairs, the Boomers also made several notable contributions. Specific to our field, Boomers oversaw the development of vascular surgery as an independent specialty and the expansion of fellowship training programs. Coming of age in the 1960s, Boomers also led the integration of our field with the acceptance of both minorities and women.

When I first heard the term “Generation X” I thought “Dumb name, won’t last.” Not my best prediction. Born between 1965 and 1980, Generation X grew up during the home computer revolution. Quick to adopt new technologies, Gen Xers were far more adaptive to change than previous generations. Labeled as having short attention spans, most Gen Xers were task/goal oriented. While these attributes helped drive the endovascular revolution, they also may be the reason we have approximately 983 FDA-approved devices to treat SFA disease. Generation X entered surgical training eager to please the more senior Traditionalists and Boomers. This wouldn’t last. Children of divorce and latch-key kids, Generation Xers are eclectic, resourceful, and self-reliant. Most of all they value freedom. Watching their predecessors work themselves and others to near death, Generation X revolted. Uncapped duty hours, limitless call, and pyramidal residencies were all institutions in the 1980s, and they all fell. Generation X were portrayed as nihilistic slackers, but their true motivation was often distrust of institutions. Watching the Boomers descend into burnout, Xers tried to achieve a more reasonable work-life balance. Though they successfully fought for lessening the abuses of surgical training, few Gen Xers actually reaped the benefits. I vividly recall watching slack-jawed as an intern scrubbed out of a case to go home because he was post call. A Martian landing in the OR and offering to assist with the anastomosis would have brought no less amazement.

With their careers spanning the endovascular revolution, Generation X has seen perhaps the greatest era of transformation in our profession. Our competition is no longer general or cardiac surgery, but rather interventional radiology and interventional cardiology. Gen X is also the first generation to earn less than its predecessors. Throw in their obscene tuition payments and one can see how Gen Xers fell well short of the financial heights of the Traditionalists and Boomers. The Gen Xers are the masters of the work hard/play hard ethos. You will see them at VEITH entertaining their European colleagues at 3 a.m. and then running the 6 a.m. breakfast sessions. While the Boomers often seemed old by 40, Xers appear desperate to salvage their lost youth.

Born between 1981 and 2006, Millennials are already the most populous generation. Their chief attributes are confidence, sociability, and a realistic outlook. Knowing they can’t please everyone, they rarely try. They want work to be meaningful in and of itself. They also value teamwork over individual approaches. Millennials are civic minded and have a strong sense of volunteerism. Their parents often tried to shelter them from the evils of the world, and they were the first generation of children with schedules. Because of their upbringing, Millennials are far more likely to seek guidance than the independent-minded Gen Xers. Raised to believe their voice mattered, they are now often reviled for it. It is with some degree of awe that I watch our Millennial students brazenly march into the dean’s and chancellor’s office to discuss their “careers.” As a medical student I first saw my dean at graduation, and I certainly didn’t even know what a chancellor was. Generation X is often baffled by the self-interest Millennials exude. But we shouldn’t be, we have seen it before. Raised by Baby Boomers (The Me Generation), Millennials inherited their self-driven outlook. This is also the reason Boomers and Millennials struggle to work together. They are too alike. Boomers see Millennials as “snowflakes” who are scared of work and selfie obsessed. Millennials bristle at the authoritarian nature of Boomers.

For vascular surgery to advance as a field, we need to recruit, train, and mentor this new generation. If only there was some guide: “The Proper Care and Feeding of Millennials." As senior attendings, program directors, and section chiefs, Generation X must now serve as a bridge between two larger forces, the Boomers and their offspring, the Millennials. Of course, whatever generation you are from is the best, but we must confront our biases. It is easy to seek out the same personalities to be your trainees and partners. Don’t. This pool will shrink every year. Millennials are more self-aware of their capabilities and therefore of their limitations. We may become flustered by their need for hand-holding, but what if it is appropriate? Was all of the autonomy you were granted during training truly good for the patients? Graduated responsibility and roles that push their limits help Millennials grow. I know they don’t value punctuality or dress codes, but they are better team players and openly motivated by learning. I formed our integrated vascular residency with two positions per year specifically to foster the team building Millennials crave. Yes, this is the generation that got 8th-place trophies so you must constantly award progress. Fortunately, now that surgery is unencumbered by such things as massive salaries and status, Millennials enter our workforce with purer intentions.

We may want to make Millennials match our values, traits, and behaviors, but each generation has departed radically from the ethos of their predecessors. Let’s see what the kids can do.

Dr. Sheahan is a professor of surgery and Program Director, Vascular Surgery Residency and Fellowship Programs, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, School of Medicine, New Orleans. He is also the Deputy Medical Editor of Vascular Specialist.

For the first time in history, four generations of physicians work side by side in the U.S. health care system. An expanding population, longer life expectancies, and later retirement ages all contribute to this phenomenon. Each of these generations has made significant contributions to modern surgery and how we practice it. For better and for worse.

Traditionalists, or the Greatest Generation, were true surgical pioneers. DeBakey, Cooley, Fogarty, their names now adorn everything from instruments to medical centers. They truly founded the modern system of surgery. Born between 1900 and 1945, Traditionalists were forged in the crucibles of the Great War and the Great Depression. Their core values were hard work, discipline, and sacrifice. A large number were combat veterans who valued conformity and adherence to the rules. Traditionalists set up our current hierarchical departments of surgery. Mirroring their values, they employed a military chain of command approach. Many traditionalists rose to positions of absolute power, and some were corrupted by this power. Gods became monsters. Abuse, both verbal and physical, came to be commonplace and accepted in the surgical work environment.

Born between 1946 and 1964, Baby Boomers were raised in the aftermath of a war none of them saw. More optimistic and idealistic than the Traditionalists, the Boomers valued success. Their goals became more individualistic. Chasing money, titles, and recognition, Boomers wanted to build a stellar career. Fifty-hour work weeks became 70, 80, or 90. Ambition led to wealth, dramatic successes, and remarkable careers. Their choices also led to divorce, drug abuse, and suicide. While burnout has become a modern concern, its roots are clearly tied to this era. Now serving as our deans and department chairs, the Boomers also made several notable contributions. Specific to our field, Boomers oversaw the development of vascular surgery as an independent specialty and the expansion of fellowship training programs. Coming of age in the 1960s, Boomers also led the integration of our field with the acceptance of both minorities and women.

When I first heard the term “Generation X” I thought “Dumb name, won’t last.” Not my best prediction. Born between 1965 and 1980, Generation X grew up during the home computer revolution. Quick to adopt new technologies, Gen Xers were far more adaptive to change than previous generations. Labeled as having short attention spans, most Gen Xers were task/goal oriented. While these attributes helped drive the endovascular revolution, they also may be the reason we have approximately 983 FDA-approved devices to treat SFA disease. Generation X entered surgical training eager to please the more senior Traditionalists and Boomers. This wouldn’t last. Children of divorce and latch-key kids, Generation Xers are eclectic, resourceful, and self-reliant. Most of all they value freedom. Watching their predecessors work themselves and others to near death, Generation X revolted. Uncapped duty hours, limitless call, and pyramidal residencies were all institutions in the 1980s, and they all fell. Generation X were portrayed as nihilistic slackers, but their true motivation was often distrust of institutions. Watching the Boomers descend into burnout, Xers tried to achieve a more reasonable work-life balance. Though they successfully fought for lessening the abuses of surgical training, few Gen Xers actually reaped the benefits. I vividly recall watching slack-jawed as an intern scrubbed out of a case to go home because he was post call. A Martian landing in the OR and offering to assist with the anastomosis would have brought no less amazement.

With their careers spanning the endovascular revolution, Generation X has seen perhaps the greatest era of transformation in our profession. Our competition is no longer general or cardiac surgery, but rather interventional radiology and interventional cardiology. Gen X is also the first generation to earn less than its predecessors. Throw in their obscene tuition payments and one can see how Gen Xers fell well short of the financial heights of the Traditionalists and Boomers. The Gen Xers are the masters of the work hard/play hard ethos. You will see them at VEITH entertaining their European colleagues at 3 a.m. and then running the 6 a.m. breakfast sessions. While the Boomers often seemed old by 40, Xers appear desperate to salvage their lost youth.

Born between 1981 and 2006, Millennials are already the most populous generation. Their chief attributes are confidence, sociability, and a realistic outlook. Knowing they can’t please everyone, they rarely try. They want work to be meaningful in and of itself. They also value teamwork over individual approaches. Millennials are civic minded and have a strong sense of volunteerism. Their parents often tried to shelter them from the evils of the world, and they were the first generation of children with schedules. Because of their upbringing, Millennials are far more likely to seek guidance than the independent-minded Gen Xers. Raised to believe their voice mattered, they are now often reviled for it. It is with some degree of awe that I watch our Millennial students brazenly march into the dean’s and chancellor’s office to discuss their “careers.” As a medical student I first saw my dean at graduation, and I certainly didn’t even know what a chancellor was. Generation X is often baffled by the self-interest Millennials exude. But we shouldn’t be, we have seen it before. Raised by Baby Boomers (The Me Generation), Millennials inherited their self-driven outlook. This is also the reason Boomers and Millennials struggle to work together. They are too alike. Boomers see Millennials as “snowflakes” who are scared of work and selfie obsessed. Millennials bristle at the authoritarian nature of Boomers.

For vascular surgery to advance as a field, we need to recruit, train, and mentor this new generation. If only there was some guide: “The Proper Care and Feeding of Millennials." As senior attendings, program directors, and section chiefs, Generation X must now serve as a bridge between two larger forces, the Boomers and their offspring, the Millennials. Of course, whatever generation you are from is the best, but we must confront our biases. It is easy to seek out the same personalities to be your trainees and partners. Don’t. This pool will shrink every year. Millennials are more self-aware of their capabilities and therefore of their limitations. We may become flustered by their need for hand-holding, but what if it is appropriate? Was all of the autonomy you were granted during training truly good for the patients? Graduated responsibility and roles that push their limits help Millennials grow. I know they don’t value punctuality or dress codes, but they are better team players and openly motivated by learning. I formed our integrated vascular residency with two positions per year specifically to foster the team building Millennials crave. Yes, this is the generation that got 8th-place trophies so you must constantly award progress. Fortunately, now that surgery is unencumbered by such things as massive salaries and status, Millennials enter our workforce with purer intentions.

We may want to make Millennials match our values, traits, and behaviors, but each generation has departed radically from the ethos of their predecessors. Let’s see what the kids can do.

Dr. Sheahan is a professor of surgery and Program Director, Vascular Surgery Residency and Fellowship Programs, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, School of Medicine, New Orleans. He is also the Deputy Medical Editor of Vascular Specialist.

For the first time in history, four generations of physicians work side by side in the U.S. health care system. An expanding population, longer life expectancies, and later retirement ages all contribute to this phenomenon. Each of these generations has made significant contributions to modern surgery and how we practice it. For better and for worse.

Traditionalists, or the Greatest Generation, were true surgical pioneers. DeBakey, Cooley, Fogarty, their names now adorn everything from instruments to medical centers. They truly founded the modern system of surgery. Born between 1900 and 1945, Traditionalists were forged in the crucibles of the Great War and the Great Depression. Their core values were hard work, discipline, and sacrifice. A large number were combat veterans who valued conformity and adherence to the rules. Traditionalists set up our current hierarchical departments of surgery. Mirroring their values, they employed a military chain of command approach. Many traditionalists rose to positions of absolute power, and some were corrupted by this power. Gods became monsters. Abuse, both verbal and physical, came to be commonplace and accepted in the surgical work environment.

Born between 1946 and 1964, Baby Boomers were raised in the aftermath of a war none of them saw. More optimistic and idealistic than the Traditionalists, the Boomers valued success. Their goals became more individualistic. Chasing money, titles, and recognition, Boomers wanted to build a stellar career. Fifty-hour work weeks became 70, 80, or 90. Ambition led to wealth, dramatic successes, and remarkable careers. Their choices also led to divorce, drug abuse, and suicide. While burnout has become a modern concern, its roots are clearly tied to this era. Now serving as our deans and department chairs, the Boomers also made several notable contributions. Specific to our field, Boomers oversaw the development of vascular surgery as an independent specialty and the expansion of fellowship training programs. Coming of age in the 1960s, Boomers also led the integration of our field with the acceptance of both minorities and women.

When I first heard the term “Generation X” I thought “Dumb name, won’t last.” Not my best prediction. Born between 1965 and 1980, Generation X grew up during the home computer revolution. Quick to adopt new technologies, Gen Xers were far more adaptive to change than previous generations. Labeled as having short attention spans, most Gen Xers were task/goal oriented. While these attributes helped drive the endovascular revolution, they also may be the reason we have approximately 983 FDA-approved devices to treat SFA disease. Generation X entered surgical training eager to please the more senior Traditionalists and Boomers. This wouldn’t last. Children of divorce and latch-key kids, Generation Xers are eclectic, resourceful, and self-reliant. Most of all they value freedom. Watching their predecessors work themselves and others to near death, Generation X revolted. Uncapped duty hours, limitless call, and pyramidal residencies were all institutions in the 1980s, and they all fell. Generation X were portrayed as nihilistic slackers, but their true motivation was often distrust of institutions. Watching the Boomers descend into burnout, Xers tried to achieve a more reasonable work-life balance. Though they successfully fought for lessening the abuses of surgical training, few Gen Xers actually reaped the benefits. I vividly recall watching slack-jawed as an intern scrubbed out of a case to go home because he was post call. A Martian landing in the OR and offering to assist with the anastomosis would have brought no less amazement.

With their careers spanning the endovascular revolution, Generation X has seen perhaps the greatest era of transformation in our profession. Our competition is no longer general or cardiac surgery, but rather interventional radiology and interventional cardiology. Gen X is also the first generation to earn less than its predecessors. Throw in their obscene tuition payments and one can see how Gen Xers fell well short of the financial heights of the Traditionalists and Boomers. The Gen Xers are the masters of the work hard/play hard ethos. You will see them at VEITH entertaining their European colleagues at 3 a.m. and then running the 6 a.m. breakfast sessions. While the Boomers often seemed old by 40, Xers appear desperate to salvage their lost youth.

Born between 1981 and 2006, Millennials are already the most populous generation. Their chief attributes are confidence, sociability, and a realistic outlook. Knowing they can’t please everyone, they rarely try. They want work to be meaningful in and of itself. They also value teamwork over individual approaches. Millennials are civic minded and have a strong sense of volunteerism. Their parents often tried to shelter them from the evils of the world, and they were the first generation of children with schedules. Because of their upbringing, Millennials are far more likely to seek guidance than the independent-minded Gen Xers. Raised to believe their voice mattered, they are now often reviled for it. It is with some degree of awe that I watch our Millennial students brazenly march into the dean’s and chancellor’s office to discuss their “careers.” As a medical student I first saw my dean at graduation, and I certainly didn’t even know what a chancellor was. Generation X is often baffled by the self-interest Millennials exude. But we shouldn’t be, we have seen it before. Raised by Baby Boomers (The Me Generation), Millennials inherited their self-driven outlook. This is also the reason Boomers and Millennials struggle to work together. They are too alike. Boomers see Millennials as “snowflakes” who are scared of work and selfie obsessed. Millennials bristle at the authoritarian nature of Boomers.

For vascular surgery to advance as a field, we need to recruit, train, and mentor this new generation. If only there was some guide: “The Proper Care and Feeding of Millennials." As senior attendings, program directors, and section chiefs, Generation X must now serve as a bridge between two larger forces, the Boomers and their offspring, the Millennials. Of course, whatever generation you are from is the best, but we must confront our biases. It is easy to seek out the same personalities to be your trainees and partners. Don’t. This pool will shrink every year. Millennials are more self-aware of their capabilities and therefore of their limitations. We may become flustered by their need for hand-holding, but what if it is appropriate? Was all of the autonomy you were granted during training truly good for the patients? Graduated responsibility and roles that push their limits help Millennials grow. I know they don’t value punctuality or dress codes, but they are better team players and openly motivated by learning. I formed our integrated vascular residency with two positions per year specifically to foster the team building Millennials crave. Yes, this is the generation that got 8th-place trophies so you must constantly award progress. Fortunately, now that surgery is unencumbered by such things as massive salaries and status, Millennials enter our workforce with purer intentions.

We may want to make Millennials match our values, traits, and behaviors, but each generation has departed radically from the ethos of their predecessors. Let’s see what the kids can do.

Dr. Sheahan is a professor of surgery and Program Director, Vascular Surgery Residency and Fellowship Programs, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, School of Medicine, New Orleans. He is also the Deputy Medical Editor of Vascular Specialist.

JVS, JVS-VL Editors Seek Members' Help for Reviews, Meta-analyses

The staffs of the Journal of Vascular Surgery and Journal of Vascular Surgery: Venous & Lymphatic Disorders are interested in creating a list of SVS members who have interest, expertise and resources to perform high-quality systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

If interested, please submit your name, institution and topics consistent with your area of expertise. Members may reach out directly via email to Dr. Cynthia Shortell, assistant editor of reviews for JVS-VL, and Dr. Ron Fairman, assistant editor of reviews for JVS.

The staffs of the Journal of Vascular Surgery and Journal of Vascular Surgery: Venous & Lymphatic Disorders are interested in creating a list of SVS members who have interest, expertise and resources to perform high-quality systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

If interested, please submit your name, institution and topics consistent with your area of expertise. Members may reach out directly via email to Dr. Cynthia Shortell, assistant editor of reviews for JVS-VL, and Dr. Ron Fairman, assistant editor of reviews for JVS.

The staffs of the Journal of Vascular Surgery and Journal of Vascular Surgery: Venous & Lymphatic Disorders are interested in creating a list of SVS members who have interest, expertise and resources to perform high-quality systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

If interested, please submit your name, institution and topics consistent with your area of expertise. Members may reach out directly via email to Dr. Cynthia Shortell, assistant editor of reviews for JVS-VL, and Dr. Ron Fairman, assistant editor of reviews for JVS.

PAD Resources for SVS Members

September is Peripheral Artery Disease Awareness Month. To help SVS members educate patients and to spread awareness about vascular surgeons, we have prepared several things you can share.

1. An infographic for patients and their families. We urge you to print it and post around the office or your institution.

2. A quick resource web page for patients, offering patients a PAD video playlist and links to articles and information on PAD.

3. The latest PAD research information for physicians, along with clinical practice guideline links. If you have contacts among primary care physicians or other referrers, please feel free to send them this link.

4. Two press releases on PAD, to share with your communications people, public relations departments and/or patients

• Don't Fall for These 6 Internet Myths About Statins

• Often misdiagnosed, PAD can be mild or deadly

September is Peripheral Artery Disease Awareness Month. To help SVS members educate patients and to spread awareness about vascular surgeons, we have prepared several things you can share.

1. An infographic for patients and their families. We urge you to print it and post around the office or your institution.

2. A quick resource web page for patients, offering patients a PAD video playlist and links to articles and information on PAD.

3. The latest PAD research information for physicians, along with clinical practice guideline links. If you have contacts among primary care physicians or other referrers, please feel free to send them this link.

4. Two press releases on PAD, to share with your communications people, public relations departments and/or patients

• Don't Fall for These 6 Internet Myths About Statins

• Often misdiagnosed, PAD can be mild or deadly

September is Peripheral Artery Disease Awareness Month. To help SVS members educate patients and to spread awareness about vascular surgeons, we have prepared several things you can share.

1. An infographic for patients and their families. We urge you to print it and post around the office or your institution.

2. A quick resource web page for patients, offering patients a PAD video playlist and links to articles and information on PAD.

3. The latest PAD research information for physicians, along with clinical practice guideline links. If you have contacts among primary care physicians or other referrers, please feel free to send them this link.

4. Two press releases on PAD, to share with your communications people, public relations departments and/or patients

• Don't Fall for These 6 Internet Myths About Statins

• Often misdiagnosed, PAD can be mild or deadly

Comments sought on VTE Guidelines

The American Society of Hematology (ASH) is seeking feedback from SVS members by Oct. 2 on its draft recommendations for ASH guidelines on VTE in the context of pregnancy and Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia.

The guidelines have been posted for comment. Members can review the comment page here and download the draft recommendations. The page includes a link to the online survey where members can provide their comments.

The American Society of Hematology (ASH) is seeking feedback from SVS members by Oct. 2 on its draft recommendations for ASH guidelines on VTE in the context of pregnancy and Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia.

The guidelines have been posted for comment. Members can review the comment page here and download the draft recommendations. The page includes a link to the online survey where members can provide their comments.

The American Society of Hematology (ASH) is seeking feedback from SVS members by Oct. 2 on its draft recommendations for ASH guidelines on VTE in the context of pregnancy and Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia.

The guidelines have been posted for comment. Members can review the comment page here and download the draft recommendations. The page includes a link to the online survey where members can provide their comments.

How is MACRA Data Gathering Going? Final 2017 90-day Reporting Period Begins Oct. 2

Payment adjustments for Medicare reimbursement come in 2019 -- but the adjustments are based on data being collected now, in 2017. If you have not begun collecting data as yet, you MUST begin no later than Oct. 2, 2017!

You will be required to send in your performance data no later than March 31, 2018. If your practice is participating in a CMS-approved Alternative Payment Model (APM), MIPS participation is not required. For 2017 there is currently no APM specific to vascular surgery. The SVS has formed a Task Force to develop a vascular APM.

The first payment adjustments based on performance go into effect on Jan. 1, 2019. Those members who do not participate in 2017 will receive a 4 percent penalty from Medicare.

SVS has held four webinars recently helping members learn what they need to know for the changes. View the materials here.

Payment adjustments for Medicare reimbursement come in 2019 -- but the adjustments are based on data being collected now, in 2017. If you have not begun collecting data as yet, you MUST begin no later than Oct. 2, 2017!

You will be required to send in your performance data no later than March 31, 2018. If your practice is participating in a CMS-approved Alternative Payment Model (APM), MIPS participation is not required. For 2017 there is currently no APM specific to vascular surgery. The SVS has formed a Task Force to develop a vascular APM.

The first payment adjustments based on performance go into effect on Jan. 1, 2019. Those members who do not participate in 2017 will receive a 4 percent penalty from Medicare.

SVS has held four webinars recently helping members learn what they need to know for the changes. View the materials here.

Payment adjustments for Medicare reimbursement come in 2019 -- but the adjustments are based on data being collected now, in 2017. If you have not begun collecting data as yet, you MUST begin no later than Oct. 2, 2017!

You will be required to send in your performance data no later than March 31, 2018. If your practice is participating in a CMS-approved Alternative Payment Model (APM), MIPS participation is not required. For 2017 there is currently no APM specific to vascular surgery. The SVS has formed a Task Force to develop a vascular APM.

The first payment adjustments based on performance go into effect on Jan. 1, 2019. Those members who do not participate in 2017 will receive a 4 percent penalty from Medicare.

SVS has held four webinars recently helping members learn what they need to know for the changes. View the materials here.

AGA members meet with Rep. Gene Green at Baylor College

In-district meetings with congressional representatives provide a great opportunity for AGA members to establish working relationships with legislators, and help make the voices of our profession and our patients heard.

Members of the Baylor College of Medicine gastroenterology division – Avi Ketwaroo, MD; Richa Shukla, MD; Yamini Natarajan, MD; and Jordan Shapiro, MD – had the opportunity to meet with U.S. Rep. Gene Green, a Democrat from Texas’ 29th Congressional District, as part of AGA’s efforts to link constituents with local representatives. The group discussed the importance of supporting increases in NIH funding to maintain similar levels based on biomedical research inflation, the importance of screening colonoscopy, and improving access to care by opposing the repeal of the Affordable Care Act.

Watch an AGA webinar, available in the AGA Community resource library for AGA members only (community.gastro.org) to learn more about how to set up congressional meetings in your district or contact Navneet Buttar, AGA government and political affairs manager, at [email protected] or 240-482-3221.

[email protected]

In-district meetings with congressional representatives provide a great opportunity for AGA members to establish working relationships with legislators, and help make the voices of our profession and our patients heard.

Members of the Baylor College of Medicine gastroenterology division – Avi Ketwaroo, MD; Richa Shukla, MD; Yamini Natarajan, MD; and Jordan Shapiro, MD – had the opportunity to meet with U.S. Rep. Gene Green, a Democrat from Texas’ 29th Congressional District, as part of AGA’s efforts to link constituents with local representatives. The group discussed the importance of supporting increases in NIH funding to maintain similar levels based on biomedical research inflation, the importance of screening colonoscopy, and improving access to care by opposing the repeal of the Affordable Care Act.

Watch an AGA webinar, available in the AGA Community resource library for AGA members only (community.gastro.org) to learn more about how to set up congressional meetings in your district or contact Navneet Buttar, AGA government and political affairs manager, at [email protected] or 240-482-3221.

[email protected]

In-district meetings with congressional representatives provide a great opportunity for AGA members to establish working relationships with legislators, and help make the voices of our profession and our patients heard.

Members of the Baylor College of Medicine gastroenterology division – Avi Ketwaroo, MD; Richa Shukla, MD; Yamini Natarajan, MD; and Jordan Shapiro, MD – had the opportunity to meet with U.S. Rep. Gene Green, a Democrat from Texas’ 29th Congressional District, as part of AGA’s efforts to link constituents with local representatives. The group discussed the importance of supporting increases in NIH funding to maintain similar levels based on biomedical research inflation, the importance of screening colonoscopy, and improving access to care by opposing the repeal of the Affordable Care Act.

Watch an AGA webinar, available in the AGA Community resource library for AGA members only (community.gastro.org) to learn more about how to set up congressional meetings in your district or contact Navneet Buttar, AGA government and political affairs manager, at [email protected] or 240-482-3221.

[email protected]

AGA comments on Quality Payment proposed rule

AGA provided comments on a proposed rule describing potential changes to the Quality Payment Program (QPP) established under the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) for the 2018 performance year. AGA thanks the many members who also submitted comments to CMS to tell the agency how proposed changes will impact you.

For year two, CMS proposed many policies that increase flexibility and incentives under the QPP. However, many proposals target solo practitioners, small practices, and other eligible clinicians with special circumstances. While we support these proposals, AGA’s comments to CMS also ask for changes that are needed to make the QPP work for all gastroenterologists, such as reducing the number of points needed to avoid a payment penalty.

CMS will finalize changes to the QPP during the fall of 2017. Final changes will take effect with the performance period that begins on Jan. 1, 2018. Performance during 2018 will impact payment for services in 2020. AGA members will be notified as soon as the rule is made available by CMS.

Still unsure how to participate in year one?

Make sure your practice is prepared for the 2017 performance year. If you are eligible to participate in 2017, but choose not to, your rates will decrease by 4% in 2019. AGA’s MACRA resource center provides customized advice based on your practice situation to get you on track. It’s not too late to start, but if you wait until Oct. 2, 2017, the deadline to start submitting claims, it will be. Get started now, http://www.gastro.org/macra.

AGA provided comments on a proposed rule describing potential changes to the Quality Payment Program (QPP) established under the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) for the 2018 performance year. AGA thanks the many members who also submitted comments to CMS to tell the agency how proposed changes will impact you.

For year two, CMS proposed many policies that increase flexibility and incentives under the QPP. However, many proposals target solo practitioners, small practices, and other eligible clinicians with special circumstances. While we support these proposals, AGA’s comments to CMS also ask for changes that are needed to make the QPP work for all gastroenterologists, such as reducing the number of points needed to avoid a payment penalty.

CMS will finalize changes to the QPP during the fall of 2017. Final changes will take effect with the performance period that begins on Jan. 1, 2018. Performance during 2018 will impact payment for services in 2020. AGA members will be notified as soon as the rule is made available by CMS.

Still unsure how to participate in year one?

Make sure your practice is prepared for the 2017 performance year. If you are eligible to participate in 2017, but choose not to, your rates will decrease by 4% in 2019. AGA’s MACRA resource center provides customized advice based on your practice situation to get you on track. It’s not too late to start, but if you wait until Oct. 2, 2017, the deadline to start submitting claims, it will be. Get started now, http://www.gastro.org/macra.

AGA provided comments on a proposed rule describing potential changes to the Quality Payment Program (QPP) established under the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) for the 2018 performance year. AGA thanks the many members who also submitted comments to CMS to tell the agency how proposed changes will impact you.

For year two, CMS proposed many policies that increase flexibility and incentives under the QPP. However, many proposals target solo practitioners, small practices, and other eligible clinicians with special circumstances. While we support these proposals, AGA’s comments to CMS also ask for changes that are needed to make the QPP work for all gastroenterologists, such as reducing the number of points needed to avoid a payment penalty.

CMS will finalize changes to the QPP during the fall of 2017. Final changes will take effect with the performance period that begins on Jan. 1, 2018. Performance during 2018 will impact payment for services in 2020. AGA members will be notified as soon as the rule is made available by CMS.

Still unsure how to participate in year one?

Make sure your practice is prepared for the 2017 performance year. If you are eligible to participate in 2017, but choose not to, your rates will decrease by 4% in 2019. AGA’s MACRA resource center provides customized advice based on your practice situation to get you on track. It’s not too late to start, but if you wait until Oct. 2, 2017, the deadline to start submitting claims, it will be. Get started now, http://www.gastro.org/macra.

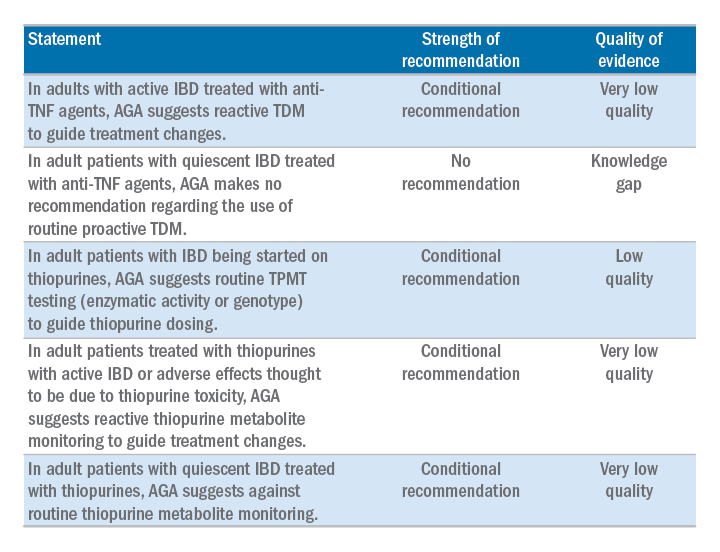

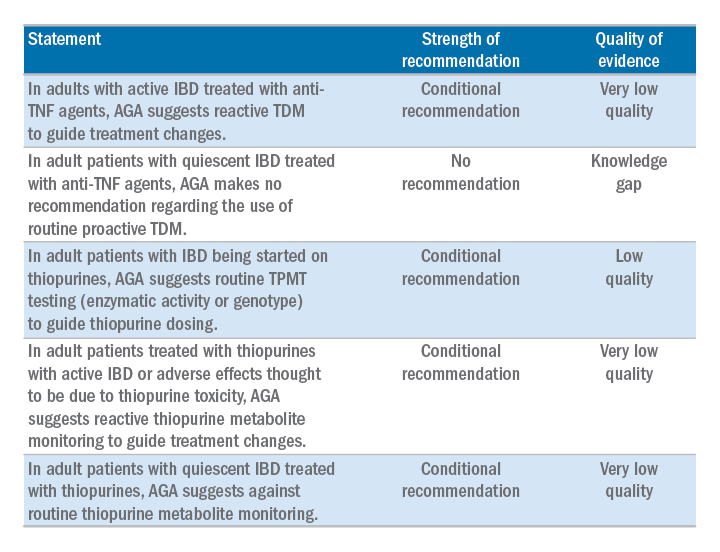

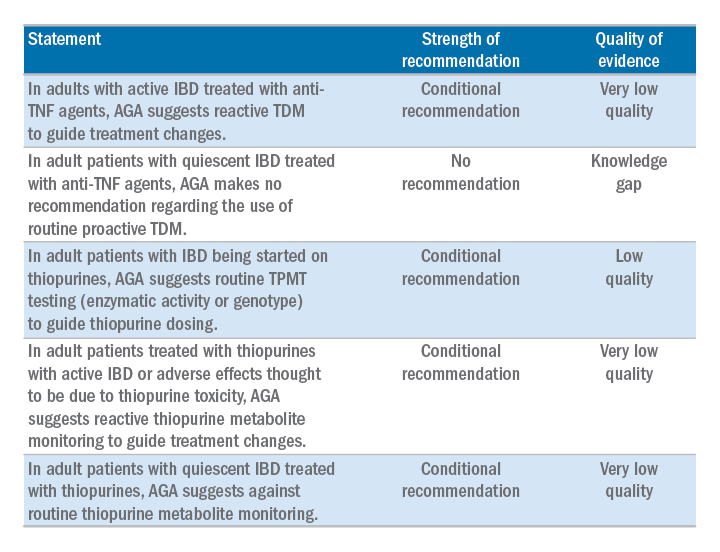

AGA releases new clinical guideline on therapeutic drug monitoring in IBD

AGA has issued a new clinical guideline on the role of therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) in the management of IBD, published in the September 2017 issue of Gastroenterology. The guideline focuses on the application of TDM for biologic therapy, specifically anti–tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF) agents and thiopurines, and addresses questions about the risks and benefits of reactive TDM, routine proactive TDM, or no TDM in guiding treatment changes. AGA’s recommendations include:

The guideline is accompanied by a technical review, Clinical Decision Support Tool, and patient companion, which provides key points and important information directly to patients about this approach, written at an appropriate reading level. Access the patient companion in the Patient Info Center, www.gastro.org/IBD.

AGA has issued a new clinical guideline on the role of therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) in the management of IBD, published in the September 2017 issue of Gastroenterology. The guideline focuses on the application of TDM for biologic therapy, specifically anti–tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF) agents and thiopurines, and addresses questions about the risks and benefits of reactive TDM, routine proactive TDM, or no TDM in guiding treatment changes. AGA’s recommendations include:

The guideline is accompanied by a technical review, Clinical Decision Support Tool, and patient companion, which provides key points and important information directly to patients about this approach, written at an appropriate reading level. Access the patient companion in the Patient Info Center, www.gastro.org/IBD.

AGA has issued a new clinical guideline on the role of therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) in the management of IBD, published in the September 2017 issue of Gastroenterology. The guideline focuses on the application of TDM for biologic therapy, specifically anti–tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF) agents and thiopurines, and addresses questions about the risks and benefits of reactive TDM, routine proactive TDM, or no TDM in guiding treatment changes. AGA’s recommendations include:

The guideline is accompanied by a technical review, Clinical Decision Support Tool, and patient companion, which provides key points and important information directly to patients about this approach, written at an appropriate reading level. Access the patient companion in the Patient Info Center, www.gastro.org/IBD.

Make a difference – support AGA’s Research Awards program

Many breakthroughs have been achieved through gastroenterological and hepatological research over the past century, forming the basis of the modern medical practice. As the charitable arm of the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), the AGA Research Foundation contributes to this tradition of discovery by providing a key source of funding at a critical juncture in a young researcher’s career.

“The Research Scholar Award will have a pivotal effect on my future career,” said Michael Dougan, MD, PhD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, 2017 Research Scholar Award recipient. “This award enables me to establish my own research infrastructure, and lay the experimental foundations for my future work as a clinician‐scientist striving to understand the complex interplay between the immune system, metabolism, and cancer.”

By joining others in donating to the AGA Research Foundation, you will help to foster a new pipeline of scientists – the next generation of leaders in GI.

Make a tax-deductible donation and help us keep the best and brightest investigators working in gastroenterology and hepatology. Donate at www.gastro.org/dontateonline or by mail to 4930 Del Ray Avenue, Bethesda, MD 20814.

Many breakthroughs have been achieved through gastroenterological and hepatological research over the past century, forming the basis of the modern medical practice. As the charitable arm of the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), the AGA Research Foundation contributes to this tradition of discovery by providing a key source of funding at a critical juncture in a young researcher’s career.

“The Research Scholar Award will have a pivotal effect on my future career,” said Michael Dougan, MD, PhD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, 2017 Research Scholar Award recipient. “This award enables me to establish my own research infrastructure, and lay the experimental foundations for my future work as a clinician‐scientist striving to understand the complex interplay between the immune system, metabolism, and cancer.”

By joining others in donating to the AGA Research Foundation, you will help to foster a new pipeline of scientists – the next generation of leaders in GI.

Make a tax-deductible donation and help us keep the best and brightest investigators working in gastroenterology and hepatology. Donate at www.gastro.org/dontateonline or by mail to 4930 Del Ray Avenue, Bethesda, MD 20814.

Many breakthroughs have been achieved through gastroenterological and hepatological research over the past century, forming the basis of the modern medical practice. As the charitable arm of the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), the AGA Research Foundation contributes to this tradition of discovery by providing a key source of funding at a critical juncture in a young researcher’s career.

“The Research Scholar Award will have a pivotal effect on my future career,” said Michael Dougan, MD, PhD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, 2017 Research Scholar Award recipient. “This award enables me to establish my own research infrastructure, and lay the experimental foundations for my future work as a clinician‐scientist striving to understand the complex interplay between the immune system, metabolism, and cancer.”

By joining others in donating to the AGA Research Foundation, you will help to foster a new pipeline of scientists – the next generation of leaders in GI.

Make a tax-deductible donation and help us keep the best and brightest investigators working in gastroenterology and hepatology. Donate at www.gastro.org/dontateonline or by mail to 4930 Del Ray Avenue, Bethesda, MD 20814.

CMS releases some good news for ASCs

CMS released the Medicare Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) final rule, which affects hospital payments and includes provisions for ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs) and physician payments.

Thanks to the AGA members who submitted comments to the proposed rule, CMS withdrew plans to publicly post facility accreditation reviews and correction plans. Below is a summary of AGA’s position and where CMS landed on each issue.

1. Public display of final accreditation surveys and plans of correction.

Summary of AGA position – AGA urged CMS to withdraw its proposal making ASC accreditation surveys open to the public. To support shared transparency objectives, AGA recommended that if CMS were to finalize its proposal, the agency should first develop standards and a framework that considers both violation severity and scope.

CMS final rule – After consideration of the public comments received, CMS will not make ASC accreditation surveys open to the public. CMS was concerned that the suggestion to have accrediting organizations post their survey reports would appear as if it was attempting to circumvent current law, which prohibits CMS from disclosing survey reports or compelling the accrediting organizations to disclose the reports themselves.

2. EHR Incentive Program certification requirements for payment year 2018.

Summary of AGA position – AGA supported increased flexibility for 2018 and urged CMS to allow use of EHR technology certified to the 2014 software edition OR the 2015 software edition for the 2018 EHR Incentive Program.

CMS final rule – CMS will allow health care providers to use either 2014 or 2015 CEHRT or a combination of 2014 and 2015 CEHRT for the 2018 EHR Incentive Program.

3. Exception for ASC-based physicians under the EHR Incentive Program for payment years 2017 and 2018.

Summary of AGA position – AGA encouraged CMS to define ASC-based as a physician or other eligible professional who provides more than 50% of Medicare billed services in an ASC. AGA was concerned that implementing a higher threshold would leave certain physicians exposed to payment penalties, because the meaningful use requirement is set at 50% or more.

CMS final rule – Unfortunately, CMS set the definition of “ASC-based” as those who provide 75% of all services in an ASC, based on previous statutory definitions.

Policy changes are effective on Oct. 1, 2017, and changes to the 2017 and 2018 EHR Incentive Program apply immediately to the 2015 and 2016 reporting period, and provide relief that will impact 2017 and 2018 payments.

CMS released the Medicare Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) final rule, which affects hospital payments and includes provisions for ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs) and physician payments.

Thanks to the AGA members who submitted comments to the proposed rule, CMS withdrew plans to publicly post facility accreditation reviews and correction plans. Below is a summary of AGA’s position and where CMS landed on each issue.

1. Public display of final accreditation surveys and plans of correction.

Summary of AGA position – AGA urged CMS to withdraw its proposal making ASC accreditation surveys open to the public. To support shared transparency objectives, AGA recommended that if CMS were to finalize its proposal, the agency should first develop standards and a framework that considers both violation severity and scope.

CMS final rule – After consideration of the public comments received, CMS will not make ASC accreditation surveys open to the public. CMS was concerned that the suggestion to have accrediting organizations post their survey reports would appear as if it was attempting to circumvent current law, which prohibits CMS from disclosing survey reports or compelling the accrediting organizations to disclose the reports themselves.

2. EHR Incentive Program certification requirements for payment year 2018.

Summary of AGA position – AGA supported increased flexibility for 2018 and urged CMS to allow use of EHR technology certified to the 2014 software edition OR the 2015 software edition for the 2018 EHR Incentive Program.

CMS final rule – CMS will allow health care providers to use either 2014 or 2015 CEHRT or a combination of 2014 and 2015 CEHRT for the 2018 EHR Incentive Program.

3. Exception for ASC-based physicians under the EHR Incentive Program for payment years 2017 and 2018.

Summary of AGA position – AGA encouraged CMS to define ASC-based as a physician or other eligible professional who provides more than 50% of Medicare billed services in an ASC. AGA was concerned that implementing a higher threshold would leave certain physicians exposed to payment penalties, because the meaningful use requirement is set at 50% or more.

CMS final rule – Unfortunately, CMS set the definition of “ASC-based” as those who provide 75% of all services in an ASC, based on previous statutory definitions.

Policy changes are effective on Oct. 1, 2017, and changes to the 2017 and 2018 EHR Incentive Program apply immediately to the 2015 and 2016 reporting period, and provide relief that will impact 2017 and 2018 payments.

CMS released the Medicare Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) final rule, which affects hospital payments and includes provisions for ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs) and physician payments.

Thanks to the AGA members who submitted comments to the proposed rule, CMS withdrew plans to publicly post facility accreditation reviews and correction plans. Below is a summary of AGA’s position and where CMS landed on each issue.

1. Public display of final accreditation surveys and plans of correction.

Summary of AGA position – AGA urged CMS to withdraw its proposal making ASC accreditation surveys open to the public. To support shared transparency objectives, AGA recommended that if CMS were to finalize its proposal, the agency should first develop standards and a framework that considers both violation severity and scope.

CMS final rule – After consideration of the public comments received, CMS will not make ASC accreditation surveys open to the public. CMS was concerned that the suggestion to have accrediting organizations post their survey reports would appear as if it was attempting to circumvent current law, which prohibits CMS from disclosing survey reports or compelling the accrediting organizations to disclose the reports themselves.

2. EHR Incentive Program certification requirements for payment year 2018.

Summary of AGA position – AGA supported increased flexibility for 2018 and urged CMS to allow use of EHR technology certified to the 2014 software edition OR the 2015 software edition for the 2018 EHR Incentive Program.

CMS final rule – CMS will allow health care providers to use either 2014 or 2015 CEHRT or a combination of 2014 and 2015 CEHRT for the 2018 EHR Incentive Program.

3. Exception for ASC-based physicians under the EHR Incentive Program for payment years 2017 and 2018.

Summary of AGA position – AGA encouraged CMS to define ASC-based as a physician or other eligible professional who provides more than 50% of Medicare billed services in an ASC. AGA was concerned that implementing a higher threshold would leave certain physicians exposed to payment penalties, because the meaningful use requirement is set at 50% or more.

CMS final rule – Unfortunately, CMS set the definition of “ASC-based” as those who provide 75% of all services in an ASC, based on previous statutory definitions.

Policy changes are effective on Oct. 1, 2017, and changes to the 2017 and 2018 EHR Incentive Program apply immediately to the 2015 and 2016 reporting period, and provide relief that will impact 2017 and 2018 payments.