User login

Young Faculty Hot Topics: How to find mentors

As someone less than 1 year into practice, I believe mentorship is one of the most critical essentials as a trainee and a junior attending. I have been privileged to have excellent mentors throughout my training and now, in my first job. A lot of this is luck, but I also have always put mentorship at the top of my list when looking for fellowships and jobs. In fact, part of the reason I took the job I currently have is because the contract clearly stated who my clinical and academic mentors would be. This showed the department’s dedication to grooming junior staff appropriately. Below is my take on how to find mentors.

Have multiple mentors

It’s good to have multiple mentors, each of whom can provide a different kind of mentorship. For junior faculty, key areas of mentorship include:

- Building clinical volume.

- Establishing your reputation as a safe and competent clinician/surgeon.

- Designing your academic/research career.

- Planning your overall career.

- Solving any political/administrative issues.

Currently, my division chief is my clinical/general mentor, from whom I seek clinical advice, political advice should I find myself in a tough situation as a junior attending, and personal advice, as well. We meet monthly to go over various things including clinical/research projects and any clinical issues. I have an academic mentor, who is a basic scientist; we review research ideas together. He reads over and critiques my grants, and he picks apart my presentations. I also have a very senior mentor, a retired thoracic surgeon, whom I seek when I have a challenging case; it is crucial to identify a senior surgeon who has an abundance of experience so you can pick his or her brain – a true resource. This is in addition to the mentors I have from my training, with whom I am still in contact. I think it is important to have mentors outside of your current work for certain situations.

Mentors do not have to be in your discipline

It’s useful to have mentors from different fields. As I stated above, my academic mentor is a basic scientist. I am a thoracic surgeon, but I consider my general surgery residency chair, who is an accomplished surgical oncologist, and my residency program director, a general surgeon, to be two of my important mentors. I think it’s a good idea to have someone outside of your discipline as your mentor, even someone in a nonsurgical discipline, as long as she or he provides what you need, such as general career decisions and research mentorship. Having people from different disciplines adds more perspective and depth. For women, female mentors may provide input on career decisions at different life stages.

Do your homework about your would-be mentors

When deciding among different jobs, I did as much homework as possible in researching my would-be clinical mentors, who in most cases are also your senior partners. This included speaking with other junior faculty members within the division, people who had worked with the person in the past, and current mentors who may know them. In my mind, I found the most valuable resources to be people who had worked in the past with potential new mentors or senior partners. They can provide unbiased, sometimes negative, opinions that others might be less willing to provide. In fact, I probably spent more time trying to understand to the negative comments, since this provided valuable information, too.

I always asked questions specific to the mentorship. Were they around to help you in the OR when needed, or was it more of a verbal “I’ll be around”? Were they good about giving the juniors clinical volume and sharing OR time? Did you feel like you grew under his or her mentorship?

In conclusion, my advice about mentorship is to have multiple mentors, each for different purposes. For those looking for fellowships and jobs, learning all you can about your would-be mentors goes a long way toward ensuring an ideal position.

Dr. Suzuki is a general thoracic surgeon at Boston Medical Center.

As someone less than 1 year into practice, I believe mentorship is one of the most critical essentials as a trainee and a junior attending. I have been privileged to have excellent mentors throughout my training and now, in my first job. A lot of this is luck, but I also have always put mentorship at the top of my list when looking for fellowships and jobs. In fact, part of the reason I took the job I currently have is because the contract clearly stated who my clinical and academic mentors would be. This showed the department’s dedication to grooming junior staff appropriately. Below is my take on how to find mentors.

Have multiple mentors

It’s good to have multiple mentors, each of whom can provide a different kind of mentorship. For junior faculty, key areas of mentorship include:

- Building clinical volume.

- Establishing your reputation as a safe and competent clinician/surgeon.

- Designing your academic/research career.

- Planning your overall career.

- Solving any political/administrative issues.

Currently, my division chief is my clinical/general mentor, from whom I seek clinical advice, political advice should I find myself in a tough situation as a junior attending, and personal advice, as well. We meet monthly to go over various things including clinical/research projects and any clinical issues. I have an academic mentor, who is a basic scientist; we review research ideas together. He reads over and critiques my grants, and he picks apart my presentations. I also have a very senior mentor, a retired thoracic surgeon, whom I seek when I have a challenging case; it is crucial to identify a senior surgeon who has an abundance of experience so you can pick his or her brain – a true resource. This is in addition to the mentors I have from my training, with whom I am still in contact. I think it is important to have mentors outside of your current work for certain situations.

Mentors do not have to be in your discipline

It’s useful to have mentors from different fields. As I stated above, my academic mentor is a basic scientist. I am a thoracic surgeon, but I consider my general surgery residency chair, who is an accomplished surgical oncologist, and my residency program director, a general surgeon, to be two of my important mentors. I think it’s a good idea to have someone outside of your discipline as your mentor, even someone in a nonsurgical discipline, as long as she or he provides what you need, such as general career decisions and research mentorship. Having people from different disciplines adds more perspective and depth. For women, female mentors may provide input on career decisions at different life stages.

Do your homework about your would-be mentors

When deciding among different jobs, I did as much homework as possible in researching my would-be clinical mentors, who in most cases are also your senior partners. This included speaking with other junior faculty members within the division, people who had worked with the person in the past, and current mentors who may know them. In my mind, I found the most valuable resources to be people who had worked in the past with potential new mentors or senior partners. They can provide unbiased, sometimes negative, opinions that others might be less willing to provide. In fact, I probably spent more time trying to understand to the negative comments, since this provided valuable information, too.

I always asked questions specific to the mentorship. Were they around to help you in the OR when needed, or was it more of a verbal “I’ll be around”? Were they good about giving the juniors clinical volume and sharing OR time? Did you feel like you grew under his or her mentorship?

In conclusion, my advice about mentorship is to have multiple mentors, each for different purposes. For those looking for fellowships and jobs, learning all you can about your would-be mentors goes a long way toward ensuring an ideal position.

Dr. Suzuki is a general thoracic surgeon at Boston Medical Center.

As someone less than 1 year into practice, I believe mentorship is one of the most critical essentials as a trainee and a junior attending. I have been privileged to have excellent mentors throughout my training and now, in my first job. A lot of this is luck, but I also have always put mentorship at the top of my list when looking for fellowships and jobs. In fact, part of the reason I took the job I currently have is because the contract clearly stated who my clinical and academic mentors would be. This showed the department’s dedication to grooming junior staff appropriately. Below is my take on how to find mentors.

Have multiple mentors

It’s good to have multiple mentors, each of whom can provide a different kind of mentorship. For junior faculty, key areas of mentorship include:

- Building clinical volume.

- Establishing your reputation as a safe and competent clinician/surgeon.

- Designing your academic/research career.

- Planning your overall career.

- Solving any political/administrative issues.

Currently, my division chief is my clinical/general mentor, from whom I seek clinical advice, political advice should I find myself in a tough situation as a junior attending, and personal advice, as well. We meet monthly to go over various things including clinical/research projects and any clinical issues. I have an academic mentor, who is a basic scientist; we review research ideas together. He reads over and critiques my grants, and he picks apart my presentations. I also have a very senior mentor, a retired thoracic surgeon, whom I seek when I have a challenging case; it is crucial to identify a senior surgeon who has an abundance of experience so you can pick his or her brain – a true resource. This is in addition to the mentors I have from my training, with whom I am still in contact. I think it is important to have mentors outside of your current work for certain situations.

Mentors do not have to be in your discipline

It’s useful to have mentors from different fields. As I stated above, my academic mentor is a basic scientist. I am a thoracic surgeon, but I consider my general surgery residency chair, who is an accomplished surgical oncologist, and my residency program director, a general surgeon, to be two of my important mentors. I think it’s a good idea to have someone outside of your discipline as your mentor, even someone in a nonsurgical discipline, as long as she or he provides what you need, such as general career decisions and research mentorship. Having people from different disciplines adds more perspective and depth. For women, female mentors may provide input on career decisions at different life stages.

Do your homework about your would-be mentors

When deciding among different jobs, I did as much homework as possible in researching my would-be clinical mentors, who in most cases are also your senior partners. This included speaking with other junior faculty members within the division, people who had worked with the person in the past, and current mentors who may know them. In my mind, I found the most valuable resources to be people who had worked in the past with potential new mentors or senior partners. They can provide unbiased, sometimes negative, opinions that others might be less willing to provide. In fact, I probably spent more time trying to understand to the negative comments, since this provided valuable information, too.

I always asked questions specific to the mentorship. Were they around to help you in the OR when needed, or was it more of a verbal “I’ll be around”? Were they good about giving the juniors clinical volume and sharing OR time? Did you feel like you grew under his or her mentorship?

In conclusion, my advice about mentorship is to have multiple mentors, each for different purposes. For those looking for fellowships and jobs, learning all you can about your would-be mentors goes a long way toward ensuring an ideal position.

Dr. Suzuki is a general thoracic surgeon at Boston Medical Center.

Young Faculty Hot Topics: Saying “yes” or saying “no”

The vast majority of us did not end up where we are today by saying “no” to opportunities throughout medical school, surgical training and now early in our clinical practice. In fact, many of us likely said “yes” to just about everything that came our way, and this was reasonable as the number of opportunities was manageable. As you move along your career as a cardiothoracic surgeon, the opportunities increase, especially if you consistently turn in a high performance.

A discussion of what to say “yes” or “no” to would be remiss without considering your individual career goals and time management. You’ve heard it before and here it is again: Write down your 5- and 10-year career plan. If you do not know where you are heading, you cannot plot the course. Then, based on those long-term career goals, drill down to your annual goals. Begin by identifying deadlines on the academic calendar each year and then work backward to determine what needs to be done in the months prior to those deadlines. Once you have a clear idea of what needs to be done on a month-by-month basis, on the Sunday of each week, create a list of daily goals. This method turns your long-term career goals into doable-size pieces of a larger puzzle that will keep you on trajectory.

Once you have charted your course using the above methods or some variation of them, you will have a clear idea of what opportunities are aligned with your long-term career plan. For example, if your goals are to build your clinical practice and become a program director, you may prioritize attending a course to introduce a new surgical technique into your practice and becoming the clerkship director for medical students instead of serving on hospital committees. Solicit advice from mentors and colleagues regarding certain opportunities if you are unsure whether these will help you achieve your career goals. Furthermore, identify senior cardiothoracic surgeons who have achieved the goals you are aiming for and ask them how they arrived at their position.

Oftentimes, it’s not about saying “yes” or “no,” but rather seeking out opportunities. Saying “yes” to opportunities that are pertinent to your career goals is critical, but there are other factors to consider when deciding whether to accept an opportunity. A major factor is the ratio of benefit to time commitment; clearly, the greater the benefit and the lower the time commitment, the better. However, there may be some opportunities that are beneficial and require a fair amount of time. Only you can decide whether the time necessary to commit to an opportunity is worth the benefit. Another factor to consider is what academic milestones are necessary for promotion at your institution; this may also vary by academic track within an institution. Be familiar with these requirements, and factor them into your goals as they are the foundation upon which you climb the academic ladder within your department.

Lastly, consider all the potential advantages of certain opportunities. For example, every year the STS solicits self-nominations for committees: Are there any committees that pertain to your career goals that will allow you to network with other cardiothoracic surgeons who may then become a mentor, sponsor, or collaborator?

I’m going to state the obvious: Only you know how you are spending every minute of every hour of each day. Why do I mention this? If you have said “yes” to too many things and are stretched too thin, you are at risk of underperforming and may begin to feel underappreciated; nobody else may realize how many hours you are working, but they will notice if your performance is subpar. Not only that, but you may be at risk of burnout. Unlike residency training, where we sprinted every day (and sometimes all night) and the light at the end of the tunnel was within view, we are now in an endurance race and need to pace ourselves for long, successful, and fulfilling careers. Ideally, we deliver what we promise, but if that balance is tipped, err on the side of underpromising and overdelivering. That scenario is much better than overpromising and underdelivering since the latter not only leads to a performance that might be less than your best but also could decrease your future opportunities.

When offered an opportunity, do not say “yes” immediately; collect some intel regarding the time commitment, determine whether it is aligned with your career goals and, if need be, discuss it with mentors and trusted colleagues before you say “yes.” Once you decide to say “yes,” jump in and hit the ground running! The beginning of your career is an exciting time with some flexibility in terms of choosing your own career adventures. Always be realistic about your goals and time to ensure a long, rewarding career.

Dr. Brown is a general thoracic surgeon at UC Davis Medical Center, Calif.

The vast majority of us did not end up where we are today by saying “no” to opportunities throughout medical school, surgical training and now early in our clinical practice. In fact, many of us likely said “yes” to just about everything that came our way, and this was reasonable as the number of opportunities was manageable. As you move along your career as a cardiothoracic surgeon, the opportunities increase, especially if you consistently turn in a high performance.

A discussion of what to say “yes” or “no” to would be remiss without considering your individual career goals and time management. You’ve heard it before and here it is again: Write down your 5- and 10-year career plan. If you do not know where you are heading, you cannot plot the course. Then, based on those long-term career goals, drill down to your annual goals. Begin by identifying deadlines on the academic calendar each year and then work backward to determine what needs to be done in the months prior to those deadlines. Once you have a clear idea of what needs to be done on a month-by-month basis, on the Sunday of each week, create a list of daily goals. This method turns your long-term career goals into doable-size pieces of a larger puzzle that will keep you on trajectory.

Once you have charted your course using the above methods or some variation of them, you will have a clear idea of what opportunities are aligned with your long-term career plan. For example, if your goals are to build your clinical practice and become a program director, you may prioritize attending a course to introduce a new surgical technique into your practice and becoming the clerkship director for medical students instead of serving on hospital committees. Solicit advice from mentors and colleagues regarding certain opportunities if you are unsure whether these will help you achieve your career goals. Furthermore, identify senior cardiothoracic surgeons who have achieved the goals you are aiming for and ask them how they arrived at their position.

Oftentimes, it’s not about saying “yes” or “no,” but rather seeking out opportunities. Saying “yes” to opportunities that are pertinent to your career goals is critical, but there are other factors to consider when deciding whether to accept an opportunity. A major factor is the ratio of benefit to time commitment; clearly, the greater the benefit and the lower the time commitment, the better. However, there may be some opportunities that are beneficial and require a fair amount of time. Only you can decide whether the time necessary to commit to an opportunity is worth the benefit. Another factor to consider is what academic milestones are necessary for promotion at your institution; this may also vary by academic track within an institution. Be familiar with these requirements, and factor them into your goals as they are the foundation upon which you climb the academic ladder within your department.

Lastly, consider all the potential advantages of certain opportunities. For example, every year the STS solicits self-nominations for committees: Are there any committees that pertain to your career goals that will allow you to network with other cardiothoracic surgeons who may then become a mentor, sponsor, or collaborator?

I’m going to state the obvious: Only you know how you are spending every minute of every hour of each day. Why do I mention this? If you have said “yes” to too many things and are stretched too thin, you are at risk of underperforming and may begin to feel underappreciated; nobody else may realize how many hours you are working, but they will notice if your performance is subpar. Not only that, but you may be at risk of burnout. Unlike residency training, where we sprinted every day (and sometimes all night) and the light at the end of the tunnel was within view, we are now in an endurance race and need to pace ourselves for long, successful, and fulfilling careers. Ideally, we deliver what we promise, but if that balance is tipped, err on the side of underpromising and overdelivering. That scenario is much better than overpromising and underdelivering since the latter not only leads to a performance that might be less than your best but also could decrease your future opportunities.

When offered an opportunity, do not say “yes” immediately; collect some intel regarding the time commitment, determine whether it is aligned with your career goals and, if need be, discuss it with mentors and trusted colleagues before you say “yes.” Once you decide to say “yes,” jump in and hit the ground running! The beginning of your career is an exciting time with some flexibility in terms of choosing your own career adventures. Always be realistic about your goals and time to ensure a long, rewarding career.

Dr. Brown is a general thoracic surgeon at UC Davis Medical Center, Calif.

The vast majority of us did not end up where we are today by saying “no” to opportunities throughout medical school, surgical training and now early in our clinical practice. In fact, many of us likely said “yes” to just about everything that came our way, and this was reasonable as the number of opportunities was manageable. As you move along your career as a cardiothoracic surgeon, the opportunities increase, especially if you consistently turn in a high performance.

A discussion of what to say “yes” or “no” to would be remiss without considering your individual career goals and time management. You’ve heard it before and here it is again: Write down your 5- and 10-year career plan. If you do not know where you are heading, you cannot plot the course. Then, based on those long-term career goals, drill down to your annual goals. Begin by identifying deadlines on the academic calendar each year and then work backward to determine what needs to be done in the months prior to those deadlines. Once you have a clear idea of what needs to be done on a month-by-month basis, on the Sunday of each week, create a list of daily goals. This method turns your long-term career goals into doable-size pieces of a larger puzzle that will keep you on trajectory.

Once you have charted your course using the above methods or some variation of them, you will have a clear idea of what opportunities are aligned with your long-term career plan. For example, if your goals are to build your clinical practice and become a program director, you may prioritize attending a course to introduce a new surgical technique into your practice and becoming the clerkship director for medical students instead of serving on hospital committees. Solicit advice from mentors and colleagues regarding certain opportunities if you are unsure whether these will help you achieve your career goals. Furthermore, identify senior cardiothoracic surgeons who have achieved the goals you are aiming for and ask them how they arrived at their position.

Oftentimes, it’s not about saying “yes” or “no,” but rather seeking out opportunities. Saying “yes” to opportunities that are pertinent to your career goals is critical, but there are other factors to consider when deciding whether to accept an opportunity. A major factor is the ratio of benefit to time commitment; clearly, the greater the benefit and the lower the time commitment, the better. However, there may be some opportunities that are beneficial and require a fair amount of time. Only you can decide whether the time necessary to commit to an opportunity is worth the benefit. Another factor to consider is what academic milestones are necessary for promotion at your institution; this may also vary by academic track within an institution. Be familiar with these requirements, and factor them into your goals as they are the foundation upon which you climb the academic ladder within your department.

Lastly, consider all the potential advantages of certain opportunities. For example, every year the STS solicits self-nominations for committees: Are there any committees that pertain to your career goals that will allow you to network with other cardiothoracic surgeons who may then become a mentor, sponsor, or collaborator?

I’m going to state the obvious: Only you know how you are spending every minute of every hour of each day. Why do I mention this? If you have said “yes” to too many things and are stretched too thin, you are at risk of underperforming and may begin to feel underappreciated; nobody else may realize how many hours you are working, but they will notice if your performance is subpar. Not only that, but you may be at risk of burnout. Unlike residency training, where we sprinted every day (and sometimes all night) and the light at the end of the tunnel was within view, we are now in an endurance race and need to pace ourselves for long, successful, and fulfilling careers. Ideally, we deliver what we promise, but if that balance is tipped, err on the side of underpromising and overdelivering. That scenario is much better than overpromising and underdelivering since the latter not only leads to a performance that might be less than your best but also could decrease your future opportunities.

When offered an opportunity, do not say “yes” immediately; collect some intel regarding the time commitment, determine whether it is aligned with your career goals and, if need be, discuss it with mentors and trusted colleagues before you say “yes.” Once you decide to say “yes,” jump in and hit the ground running! The beginning of your career is an exciting time with some flexibility in terms of choosing your own career adventures. Always be realistic about your goals and time to ensure a long, rewarding career.

Dr. Brown is a general thoracic surgeon at UC Davis Medical Center, Calif.

Learn More about Medicare Reimbursement, Reporting Requirements

The Society for Vascular Surgery will hold two Q&A town-hall webinars Sept. 12 and 19 on Medicare reimbursement and how it will affect members’ practices.

The webinars will feature an open Q&A forum to provide information to those still struggling with how they will obtain the required data for Medicare reimbursement. Participants need to submit their questions in advance at the end of the linked short survey, to eliminate duplicate questions and assure complete answers can be prepared for presentation.

The first webinar will be at 1 p.m. Eastern Time, Tuesday, Sept. 12, and the second will be at 7 p.m. Eastern Time Tuesday, Sept. 19. Register here and complete the survey here.

The Society for Vascular Surgery will hold two Q&A town-hall webinars Sept. 12 and 19 on Medicare reimbursement and how it will affect members’ practices.

The webinars will feature an open Q&A forum to provide information to those still struggling with how they will obtain the required data for Medicare reimbursement. Participants need to submit their questions in advance at the end of the linked short survey, to eliminate duplicate questions and assure complete answers can be prepared for presentation.

The first webinar will be at 1 p.m. Eastern Time, Tuesday, Sept. 12, and the second will be at 7 p.m. Eastern Time Tuesday, Sept. 19. Register here and complete the survey here.

The Society for Vascular Surgery will hold two Q&A town-hall webinars Sept. 12 and 19 on Medicare reimbursement and how it will affect members’ practices.

The webinars will feature an open Q&A forum to provide information to those still struggling with how they will obtain the required data for Medicare reimbursement. Participants need to submit their questions in advance at the end of the linked short survey, to eliminate duplicate questions and assure complete answers can be prepared for presentation.

The first webinar will be at 1 p.m. Eastern Time, Tuesday, Sept. 12, and the second will be at 7 p.m. Eastern Time Tuesday, Sept. 19. Register here and complete the survey here.

Sleep Strategies

The definition of mild obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) has varied over the years depending upon several factors, but based upon all definitions, it is highly prevalent. Depending upon presence of symptoms and gender, the prevalence may be as high 28% in men and 26% in women. (Young et al. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230).

Typically, a combination of symptoms and frequency of respiratory events is required to make the diagnosis. Based upon the International Classification of Sleep Disorders-3rd edition (ICSD-3), the threshold apnea hypopnea index (AHI) for diagnosis depends upon the presence or absence of symptoms. If an individual has no symptoms, an AHI of 15 events per hour or more is required to make a diagnosis of OSA. However, there are several concerns about whether or not an individual may be “symptomatic.” This is most relevant when driving privileges may be at risk, such as with a commercial drivers’ licensing.

The presence of other comorbid disease can be used as criteria, including hypertension, mood disorder, cognitive dysfunction, coronary artery disease, stroke, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. If no signs, symptoms, or comorbid diseases are present, then an AHI greater than 15 events per hour or more is required to make the diagnosis of OSA (Chowdrui et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:e37).

There is still debate regarding the association of mild OSA and cardiovascular disease and whether treatment may prevent or reduce cardiovascular outcomes. The four main clinical outcomes typically reported are hypertension, cardiovascular events, cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, and arrhythmias.

A large clinical cohort of patients referred for sleep studies showed no association of mild OSA with different composite outcomes. Kendzerska and colleagues evaluated a composite outcome (myocardial infarction, stroke, CHF, revascularization procedures, or death from any cause) during a median follow-up of 68 months. No association of mild OSA with the composite cardiovascular endpoint was identified compared with those without OSA (Kendzerska et al. PLoS Med. 2014;11[2]:e1001599). Only one population-based study (MrOS Sleep Study) looked at the association between mild OSA and nocturnal arrhythmias in elderly men. The study did not find an increased risk for atrial fibrillation or complex ventricular ectopy in patients with mild OSA vs no OSA (Mehra et al. Arch Intern Med. 2009; 169:1147).

Several cohort studies have reported mild OSA is not associated with increased cardiovascular mortality. In the 18-year follow-up of the Wisconsin Cohort Study, it was found that mild OSA was not associated with cardiovascular mortality (HR, 1.8; 95% CI, 0.7–4.9). All-cause mortality was also not significantly increased in the mild OSA group compared with the no-OSA group in the Wisconsin cohort after 8 years of follow-up (adjusted HR, 1.6; 95% CI, 0.8–2.8). In summary, compared with subjects without OSA, available evidence from population-based longitudinal studies indicates that mild OSA is not associated with increased cardiovascular or all-cause mortality.

Does treatment of mild OSA vs no treatment change cardiovascular or mortality outcomes? This is still debated with no definitive answer. There have been several studies that have examined different therapies for OSA to reduce cardiovascular events. Typical events include coronary artery disease, hypertension, heart failure, stroke, arrhythmias, and cardiovascular disease-related mortality. However, most studies have examined cohorts with moderate to severe OSA with limited evaluation in the mild OSA category.

An observational study evaluated the effects of CPAP specifically in patients with mild OSA. There was no significant difference in the risk of developing hypertension among those patients ineligible for CPAP therapy, active on therapy, or those who declined therapy (Marin et al. JAMA. 2012; 307:2169). In contrast, a retrospective longitudinal cohort with normal blood pressure at baseline (mild OSA without preexisting cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or hyperlipidemia) did show decrease in mean arterial blood pressure of 2 mm Hg in the treatment group (Jaimchariyatam et al. Sleep Med. 2010;11:837). The MOSAIC trial was a multicenter randomized trial that evaluated the effects of CPAP on cardiac function in minimally symptomatic patients with OSA. The use of CPAP reduced the oxygen desaturation index (ODI) and Epworth Sleepiness Scale values. However, 6 months of therapy did not change functional or structural parameters measured by echocardiogram or cardiac magnetic resonance scanning in patients with mild to moderate OSA (Craig et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11[9]:967). A single retrospective study reported the effects of CPAP in patients with mild OSA and all-cause mortality. The study compared treatment with patients using CPAP more than 4 hours vs a combined group of nonadherent and those who refused therapy (Hudgel et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8:9). There was no significant difference in all-cause mortality in the two groups. However, this study did not analyze the impact of therapy on cardiovascular-specific mortality.

To date, there have been no studies that have evaluated the impact of treatment of mild OSA on cardiovascular events, arrhythmias, or stroke. In addition, there have been no randomized studies assessing treatment of mild OSA on fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events. There is inadequate evidence regarding the effect of mild OSA on elevated blood pressure, neurologic cognition, quality of life, and cardiovascular consequences. Future research is needed to investigate the impact of mild OSA on these outcomes.

In summary, mild OSA is a very prevalent disease but the association with hypertension remains unclear and the literature to date suggests no association with other cardiovascular outcomes. In addition, no clear prevention of cardiovascular outcomes with treatment has been proven in the setting of mild OSA.

Dr. Duthuluru is Assistant Professor, Dr. Nazir is Assistant Professor, and Dr. Stevens is Associate Professor at the University of Kansas Medical Center.

The definition of mild obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) has varied over the years depending upon several factors, but based upon all definitions, it is highly prevalent. Depending upon presence of symptoms and gender, the prevalence may be as high 28% in men and 26% in women. (Young et al. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230).

Typically, a combination of symptoms and frequency of respiratory events is required to make the diagnosis. Based upon the International Classification of Sleep Disorders-3rd edition (ICSD-3), the threshold apnea hypopnea index (AHI) for diagnosis depends upon the presence or absence of symptoms. If an individual has no symptoms, an AHI of 15 events per hour or more is required to make a diagnosis of OSA. However, there are several concerns about whether or not an individual may be “symptomatic.” This is most relevant when driving privileges may be at risk, such as with a commercial drivers’ licensing.

The presence of other comorbid disease can be used as criteria, including hypertension, mood disorder, cognitive dysfunction, coronary artery disease, stroke, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. If no signs, symptoms, or comorbid diseases are present, then an AHI greater than 15 events per hour or more is required to make the diagnosis of OSA (Chowdrui et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:e37).

There is still debate regarding the association of mild OSA and cardiovascular disease and whether treatment may prevent or reduce cardiovascular outcomes. The four main clinical outcomes typically reported are hypertension, cardiovascular events, cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, and arrhythmias.

A large clinical cohort of patients referred for sleep studies showed no association of mild OSA with different composite outcomes. Kendzerska and colleagues evaluated a composite outcome (myocardial infarction, stroke, CHF, revascularization procedures, or death from any cause) during a median follow-up of 68 months. No association of mild OSA with the composite cardiovascular endpoint was identified compared with those without OSA (Kendzerska et al. PLoS Med. 2014;11[2]:e1001599). Only one population-based study (MrOS Sleep Study) looked at the association between mild OSA and nocturnal arrhythmias in elderly men. The study did not find an increased risk for atrial fibrillation or complex ventricular ectopy in patients with mild OSA vs no OSA (Mehra et al. Arch Intern Med. 2009; 169:1147).

Several cohort studies have reported mild OSA is not associated with increased cardiovascular mortality. In the 18-year follow-up of the Wisconsin Cohort Study, it was found that mild OSA was not associated with cardiovascular mortality (HR, 1.8; 95% CI, 0.7–4.9). All-cause mortality was also not significantly increased in the mild OSA group compared with the no-OSA group in the Wisconsin cohort after 8 years of follow-up (adjusted HR, 1.6; 95% CI, 0.8–2.8). In summary, compared with subjects without OSA, available evidence from population-based longitudinal studies indicates that mild OSA is not associated with increased cardiovascular or all-cause mortality.

Does treatment of mild OSA vs no treatment change cardiovascular or mortality outcomes? This is still debated with no definitive answer. There have been several studies that have examined different therapies for OSA to reduce cardiovascular events. Typical events include coronary artery disease, hypertension, heart failure, stroke, arrhythmias, and cardiovascular disease-related mortality. However, most studies have examined cohorts with moderate to severe OSA with limited evaluation in the mild OSA category.

An observational study evaluated the effects of CPAP specifically in patients with mild OSA. There was no significant difference in the risk of developing hypertension among those patients ineligible for CPAP therapy, active on therapy, or those who declined therapy (Marin et al. JAMA. 2012; 307:2169). In contrast, a retrospective longitudinal cohort with normal blood pressure at baseline (mild OSA without preexisting cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or hyperlipidemia) did show decrease in mean arterial blood pressure of 2 mm Hg in the treatment group (Jaimchariyatam et al. Sleep Med. 2010;11:837). The MOSAIC trial was a multicenter randomized trial that evaluated the effects of CPAP on cardiac function in minimally symptomatic patients with OSA. The use of CPAP reduced the oxygen desaturation index (ODI) and Epworth Sleepiness Scale values. However, 6 months of therapy did not change functional or structural parameters measured by echocardiogram or cardiac magnetic resonance scanning in patients with mild to moderate OSA (Craig et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11[9]:967). A single retrospective study reported the effects of CPAP in patients with mild OSA and all-cause mortality. The study compared treatment with patients using CPAP more than 4 hours vs a combined group of nonadherent and those who refused therapy (Hudgel et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8:9). There was no significant difference in all-cause mortality in the two groups. However, this study did not analyze the impact of therapy on cardiovascular-specific mortality.

To date, there have been no studies that have evaluated the impact of treatment of mild OSA on cardiovascular events, arrhythmias, or stroke. In addition, there have been no randomized studies assessing treatment of mild OSA on fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events. There is inadequate evidence regarding the effect of mild OSA on elevated blood pressure, neurologic cognition, quality of life, and cardiovascular consequences. Future research is needed to investigate the impact of mild OSA on these outcomes.

In summary, mild OSA is a very prevalent disease but the association with hypertension remains unclear and the literature to date suggests no association with other cardiovascular outcomes. In addition, no clear prevention of cardiovascular outcomes with treatment has been proven in the setting of mild OSA.

Dr. Duthuluru is Assistant Professor, Dr. Nazir is Assistant Professor, and Dr. Stevens is Associate Professor at the University of Kansas Medical Center.

The definition of mild obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) has varied over the years depending upon several factors, but based upon all definitions, it is highly prevalent. Depending upon presence of symptoms and gender, the prevalence may be as high 28% in men and 26% in women. (Young et al. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230).

Typically, a combination of symptoms and frequency of respiratory events is required to make the diagnosis. Based upon the International Classification of Sleep Disorders-3rd edition (ICSD-3), the threshold apnea hypopnea index (AHI) for diagnosis depends upon the presence or absence of symptoms. If an individual has no symptoms, an AHI of 15 events per hour or more is required to make a diagnosis of OSA. However, there are several concerns about whether or not an individual may be “symptomatic.” This is most relevant when driving privileges may be at risk, such as with a commercial drivers’ licensing.

The presence of other comorbid disease can be used as criteria, including hypertension, mood disorder, cognitive dysfunction, coronary artery disease, stroke, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. If no signs, symptoms, or comorbid diseases are present, then an AHI greater than 15 events per hour or more is required to make the diagnosis of OSA (Chowdrui et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:e37).

There is still debate regarding the association of mild OSA and cardiovascular disease and whether treatment may prevent or reduce cardiovascular outcomes. The four main clinical outcomes typically reported are hypertension, cardiovascular events, cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, and arrhythmias.

A large clinical cohort of patients referred for sleep studies showed no association of mild OSA with different composite outcomes. Kendzerska and colleagues evaluated a composite outcome (myocardial infarction, stroke, CHF, revascularization procedures, or death from any cause) during a median follow-up of 68 months. No association of mild OSA with the composite cardiovascular endpoint was identified compared with those without OSA (Kendzerska et al. PLoS Med. 2014;11[2]:e1001599). Only one population-based study (MrOS Sleep Study) looked at the association between mild OSA and nocturnal arrhythmias in elderly men. The study did not find an increased risk for atrial fibrillation or complex ventricular ectopy in patients with mild OSA vs no OSA (Mehra et al. Arch Intern Med. 2009; 169:1147).

Several cohort studies have reported mild OSA is not associated with increased cardiovascular mortality. In the 18-year follow-up of the Wisconsin Cohort Study, it was found that mild OSA was not associated with cardiovascular mortality (HR, 1.8; 95% CI, 0.7–4.9). All-cause mortality was also not significantly increased in the mild OSA group compared with the no-OSA group in the Wisconsin cohort after 8 years of follow-up (adjusted HR, 1.6; 95% CI, 0.8–2.8). In summary, compared with subjects without OSA, available evidence from population-based longitudinal studies indicates that mild OSA is not associated with increased cardiovascular or all-cause mortality.

Does treatment of mild OSA vs no treatment change cardiovascular or mortality outcomes? This is still debated with no definitive answer. There have been several studies that have examined different therapies for OSA to reduce cardiovascular events. Typical events include coronary artery disease, hypertension, heart failure, stroke, arrhythmias, and cardiovascular disease-related mortality. However, most studies have examined cohorts with moderate to severe OSA with limited evaluation in the mild OSA category.

An observational study evaluated the effects of CPAP specifically in patients with mild OSA. There was no significant difference in the risk of developing hypertension among those patients ineligible for CPAP therapy, active on therapy, or those who declined therapy (Marin et al. JAMA. 2012; 307:2169). In contrast, a retrospective longitudinal cohort with normal blood pressure at baseline (mild OSA without preexisting cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or hyperlipidemia) did show decrease in mean arterial blood pressure of 2 mm Hg in the treatment group (Jaimchariyatam et al. Sleep Med. 2010;11:837). The MOSAIC trial was a multicenter randomized trial that evaluated the effects of CPAP on cardiac function in minimally symptomatic patients with OSA. The use of CPAP reduced the oxygen desaturation index (ODI) and Epworth Sleepiness Scale values. However, 6 months of therapy did not change functional or structural parameters measured by echocardiogram or cardiac magnetic resonance scanning in patients with mild to moderate OSA (Craig et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11[9]:967). A single retrospective study reported the effects of CPAP in patients with mild OSA and all-cause mortality. The study compared treatment with patients using CPAP more than 4 hours vs a combined group of nonadherent and those who refused therapy (Hudgel et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8:9). There was no significant difference in all-cause mortality in the two groups. However, this study did not analyze the impact of therapy on cardiovascular-specific mortality.

To date, there have been no studies that have evaluated the impact of treatment of mild OSA on cardiovascular events, arrhythmias, or stroke. In addition, there have been no randomized studies assessing treatment of mild OSA on fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events. There is inadequate evidence regarding the effect of mild OSA on elevated blood pressure, neurologic cognition, quality of life, and cardiovascular consequences. Future research is needed to investigate the impact of mild OSA on these outcomes.

In summary, mild OSA is a very prevalent disease but the association with hypertension remains unclear and the literature to date suggests no association with other cardiovascular outcomes. In addition, no clear prevention of cardiovascular outcomes with treatment has been proven in the setting of mild OSA.

Dr. Duthuluru is Assistant Professor, Dr. Nazir is Assistant Professor, and Dr. Stevens is Associate Professor at the University of Kansas Medical Center.

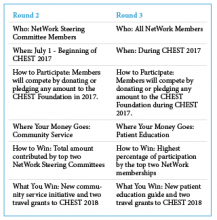

CHEST Foundation NetWorks Challenge

The CHEST Foundation is proud to announce the winners of the first round of the 2017 NetWorks Challenge! Our first place winner, Home-Based Mechanical Ventilation and Neuromuscular Disease NetWork, and our second place finisher, Women’s Health NetWork, both receive session time at CHEST 2017 on a topic of their choice and two travel grants to help their NetWork members attend CHEST 2017.

The Women’s Health NetWork was directly behind our first place finishers with more than 90% participation. Their session, “Care of the Critically Ill Pregnant Woman: Balancing Two Patients and Two Lives” will be on Monday, October 30, 1:30

Don’t forget, there is still time to win Round 2 and Round 3 of the NetWorks Challenge.

Learn more about the challenge at chestfoundation.org/networkschallenge.

The CHEST Foundation is proud to announce the winners of the first round of the 2017 NetWorks Challenge! Our first place winner, Home-Based Mechanical Ventilation and Neuromuscular Disease NetWork, and our second place finisher, Women’s Health NetWork, both receive session time at CHEST 2017 on a topic of their choice and two travel grants to help their NetWork members attend CHEST 2017.

The Women’s Health NetWork was directly behind our first place finishers with more than 90% participation. Their session, “Care of the Critically Ill Pregnant Woman: Balancing Two Patients and Two Lives” will be on Monday, October 30, 1:30

Don’t forget, there is still time to win Round 2 and Round 3 of the NetWorks Challenge.

Learn more about the challenge at chestfoundation.org/networkschallenge.

The CHEST Foundation is proud to announce the winners of the first round of the 2017 NetWorks Challenge! Our first place winner, Home-Based Mechanical Ventilation and Neuromuscular Disease NetWork, and our second place finisher, Women’s Health NetWork, both receive session time at CHEST 2017 on a topic of their choice and two travel grants to help their NetWork members attend CHEST 2017.

The Women’s Health NetWork was directly behind our first place finishers with more than 90% participation. Their session, “Care of the Critically Ill Pregnant Woman: Balancing Two Patients and Two Lives” will be on Monday, October 30, 1:30

Don’t forget, there is still time to win Round 2 and Round 3 of the NetWorks Challenge.

Learn more about the challenge at chestfoundation.org/networkschallenge.

NetWorks

Gender Disparities in Occupational Health

Over the past few decades, the presence of women in the workforce has changed significantly. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Population Survey, in 2015, 46.8% of the workforce included women compared with 28.6% in 1948. Along with this change, there has been an increased focus on gender disparities in occupational health.

Gender differences in occupational asthma were also seen in snow crab processing plant workers. Women were significantly more likely to have occupational asthma than men. However, they found that overall, women had a greater cumulative exposure to crab allergens, which may be a major contributor to this disparity (Howse et al. Environ Res. 2006;101[2]:163).

Although several occupational health studies are beginning to highlight gender disparities, a major confounding factor is that of occupational segregation, meaning the under-representation of one gender in some jobs and over-representation in others. Differences in jobs and tasks even within the same job title between men and women are often major contributors to gender disparities [WHO Dept of Gender, Women and Health, 2006]. Also, several studies suggest that more women should be included in toxicology and occupational cancer studies, since currently, they have included mostly men (Sorrentino et al. Ann Ist Super Sanità. 2016;52[2]:190). Perhaps future studies can improve the overall understanding of these important contributing factors to gender disparities in occupational health.

Krystal Cleven, MD

Fellow-in-Training Member

Does Beta-agonist Therapy With Albuterol Cause Lactic Acidosis?

Cohen and associates (Clin Sci Mol Med. 1977;53:405) suggested that lactic acidosis can occur in at least two different physiologic clinical presentations. Type A occurs when oxygen delivery to the tissues is compromised. Dodda and Spiro (Respir Care. 2012;57[12]:2115) indicated that type A lactic acidosis was due to hypoxemia, as seen in inadequate tissue oxygenation during an exacerbation of asthma. In severe asthma, pulsus paradoxus and air trapping (causing intrinsic positive end-expiratory pressure, or PEEP) served to decrease tissue oxygenation by decreasing cardiac output and venous return, leading to type A lactic acidosis. Bates and associates (Pediatrics. 2014;133[4]:e1087) considered the role of intrapulmonary arteriovenous anastomoses (IPAVs) when a status asthmaticus patient improved after cessation of beta-agonist therapy. Type B lactic acidosis occurs when lactate production was increased or lactate removal was decreased even when oxygen was delivered to tissue. Amaducci (http://www.emresident.org/gasping-air-albuterol-induced-lactic-acidosis/) explained how high dosages of albuterol, beyond 1 mg/kg, created an increased adrenergic state that, with reduced tissue perfusion, increased glycolysis and pyruvate production, resulting in measurable hyperlactatemia. The authors (Br J Med Pract. 2011;4[2]:a420) noted that lactic acidosis also occurs in acute severe asthma due to inadequate oxygen delivery to the respiratory muscles to meet an elevated oxygen demand or due to fatiguing respiratory muscles. Ganaie and Hughes reported a case of lactic acidosis caused by treatment with salbutamol. Salbutamol is the most commonly used short-acting beta-agonist. Stimulation of beta-adrenergic receptors leads to a variety of metabolic effects, including increase in glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis, and lipolysis, thus contributing to lactic acidosis. All authors agreed that the mechanism of albuterol-caused lactic acidosis was poorly understood.

Douglas E. Masini, EdD, FCCP

Steering Committee Member

Withdrawal of OSA Screening Regulation for Commercial Motor Vehicle Operators

Compared with the general US population, the prevalence of sleep apnea (SA) is higher among commercial motor vehicle (CMV) drivers (Berger et al. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54[8]:1017). Additionally, the risk of motor vehicle accidents is higher among individuals with SA compared with those without SA (Tregear et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5[6]:573), and treatment of SA is associated with a reduction in this risk (Mahssa et al. Sleep. 2015;38[3]341).

However, after reviewing the public input and data, the FRA and FMCSA recently announced that there was “not enough information available to support moving forward with a rulemaking action,” and, therefore, they are no longer pursuing the regulation that would require SA screening for truck drivers and train engineers (Federal Register August 2017;49 CFR 391,240,242). See CHEST’s press release at www.chestnet.org/News/Press-Releases/2017/08/American-College-of-Chest-Physicians-Responds-to-DOT-Withdrawal-of-Sleep-Apnea-Screening. The FMCSA endorses existing resources,such as the North American Fatigue Management Program (NAFMP) (www.nafmp.org), which is a web-based program designed to reduce driver fatigue and includes information on SA screening and treatment. The medical examiners, however, will have the ultimate responsibility to screen, diagnose, and treat SA based on their medical knowledge and clinical experience.

Vaishnavi Kundel, MD

NetWork Member

Steering Committee Member

Corrections to previous NetWork articles

July 2017

Clinical Research

Mohsin Ijaz’s name was misspelled.

August 2017

Transplant

The name under Shruti Gadre’s photograph is wrong. It says Dr. Ahya instead of Dr. Gadre.

The authorship of the article at the end of the article is incorrect. It says Vivek Ahya, instead of Shruti Gadre and Marie Budev.

Gender Disparities in Occupational Health

Over the past few decades, the presence of women in the workforce has changed significantly. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Population Survey, in 2015, 46.8% of the workforce included women compared with 28.6% in 1948. Along with this change, there has been an increased focus on gender disparities in occupational health.

Gender differences in occupational asthma were also seen in snow crab processing plant workers. Women were significantly more likely to have occupational asthma than men. However, they found that overall, women had a greater cumulative exposure to crab allergens, which may be a major contributor to this disparity (Howse et al. Environ Res. 2006;101[2]:163).

Although several occupational health studies are beginning to highlight gender disparities, a major confounding factor is that of occupational segregation, meaning the under-representation of one gender in some jobs and over-representation in others. Differences in jobs and tasks even within the same job title between men and women are often major contributors to gender disparities [WHO Dept of Gender, Women and Health, 2006]. Also, several studies suggest that more women should be included in toxicology and occupational cancer studies, since currently, they have included mostly men (Sorrentino et al. Ann Ist Super Sanità. 2016;52[2]:190). Perhaps future studies can improve the overall understanding of these important contributing factors to gender disparities in occupational health.

Krystal Cleven, MD

Fellow-in-Training Member

Does Beta-agonist Therapy With Albuterol Cause Lactic Acidosis?

Cohen and associates (Clin Sci Mol Med. 1977;53:405) suggested that lactic acidosis can occur in at least two different physiologic clinical presentations. Type A occurs when oxygen delivery to the tissues is compromised. Dodda and Spiro (Respir Care. 2012;57[12]:2115) indicated that type A lactic acidosis was due to hypoxemia, as seen in inadequate tissue oxygenation during an exacerbation of asthma. In severe asthma, pulsus paradoxus and air trapping (causing intrinsic positive end-expiratory pressure, or PEEP) served to decrease tissue oxygenation by decreasing cardiac output and venous return, leading to type A lactic acidosis. Bates and associates (Pediatrics. 2014;133[4]:e1087) considered the role of intrapulmonary arteriovenous anastomoses (IPAVs) when a status asthmaticus patient improved after cessation of beta-agonist therapy. Type B lactic acidosis occurs when lactate production was increased or lactate removal was decreased even when oxygen was delivered to tissue. Amaducci (http://www.emresident.org/gasping-air-albuterol-induced-lactic-acidosis/) explained how high dosages of albuterol, beyond 1 mg/kg, created an increased adrenergic state that, with reduced tissue perfusion, increased glycolysis and pyruvate production, resulting in measurable hyperlactatemia. The authors (Br J Med Pract. 2011;4[2]:a420) noted that lactic acidosis also occurs in acute severe asthma due to inadequate oxygen delivery to the respiratory muscles to meet an elevated oxygen demand or due to fatiguing respiratory muscles. Ganaie and Hughes reported a case of lactic acidosis caused by treatment with salbutamol. Salbutamol is the most commonly used short-acting beta-agonist. Stimulation of beta-adrenergic receptors leads to a variety of metabolic effects, including increase in glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis, and lipolysis, thus contributing to lactic acidosis. All authors agreed that the mechanism of albuterol-caused lactic acidosis was poorly understood.

Douglas E. Masini, EdD, FCCP

Steering Committee Member

Withdrawal of OSA Screening Regulation for Commercial Motor Vehicle Operators

Compared with the general US population, the prevalence of sleep apnea (SA) is higher among commercial motor vehicle (CMV) drivers (Berger et al. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54[8]:1017). Additionally, the risk of motor vehicle accidents is higher among individuals with SA compared with those without SA (Tregear et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5[6]:573), and treatment of SA is associated with a reduction in this risk (Mahssa et al. Sleep. 2015;38[3]341).

However, after reviewing the public input and data, the FRA and FMCSA recently announced that there was “not enough information available to support moving forward with a rulemaking action,” and, therefore, they are no longer pursuing the regulation that would require SA screening for truck drivers and train engineers (Federal Register August 2017;49 CFR 391,240,242). See CHEST’s press release at www.chestnet.org/News/Press-Releases/2017/08/American-College-of-Chest-Physicians-Responds-to-DOT-Withdrawal-of-Sleep-Apnea-Screening. The FMCSA endorses existing resources,such as the North American Fatigue Management Program (NAFMP) (www.nafmp.org), which is a web-based program designed to reduce driver fatigue and includes information on SA screening and treatment. The medical examiners, however, will have the ultimate responsibility to screen, diagnose, and treat SA based on their medical knowledge and clinical experience.

Vaishnavi Kundel, MD

NetWork Member

Steering Committee Member

Corrections to previous NetWork articles

July 2017

Clinical Research

Mohsin Ijaz’s name was misspelled.

August 2017

Transplant

The name under Shruti Gadre’s photograph is wrong. It says Dr. Ahya instead of Dr. Gadre.

The authorship of the article at the end of the article is incorrect. It says Vivek Ahya, instead of Shruti Gadre and Marie Budev.

Gender Disparities in Occupational Health

Over the past few decades, the presence of women in the workforce has changed significantly. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Population Survey, in 2015, 46.8% of the workforce included women compared with 28.6% in 1948. Along with this change, there has been an increased focus on gender disparities in occupational health.

Gender differences in occupational asthma were also seen in snow crab processing plant workers. Women were significantly more likely to have occupational asthma than men. However, they found that overall, women had a greater cumulative exposure to crab allergens, which may be a major contributor to this disparity (Howse et al. Environ Res. 2006;101[2]:163).

Although several occupational health studies are beginning to highlight gender disparities, a major confounding factor is that of occupational segregation, meaning the under-representation of one gender in some jobs and over-representation in others. Differences in jobs and tasks even within the same job title between men and women are often major contributors to gender disparities [WHO Dept of Gender, Women and Health, 2006]. Also, several studies suggest that more women should be included in toxicology and occupational cancer studies, since currently, they have included mostly men (Sorrentino et al. Ann Ist Super Sanità. 2016;52[2]:190). Perhaps future studies can improve the overall understanding of these important contributing factors to gender disparities in occupational health.

Krystal Cleven, MD

Fellow-in-Training Member

Does Beta-agonist Therapy With Albuterol Cause Lactic Acidosis?

Cohen and associates (Clin Sci Mol Med. 1977;53:405) suggested that lactic acidosis can occur in at least two different physiologic clinical presentations. Type A occurs when oxygen delivery to the tissues is compromised. Dodda and Spiro (Respir Care. 2012;57[12]:2115) indicated that type A lactic acidosis was due to hypoxemia, as seen in inadequate tissue oxygenation during an exacerbation of asthma. In severe asthma, pulsus paradoxus and air trapping (causing intrinsic positive end-expiratory pressure, or PEEP) served to decrease tissue oxygenation by decreasing cardiac output and venous return, leading to type A lactic acidosis. Bates and associates (Pediatrics. 2014;133[4]:e1087) considered the role of intrapulmonary arteriovenous anastomoses (IPAVs) when a status asthmaticus patient improved after cessation of beta-agonist therapy. Type B lactic acidosis occurs when lactate production was increased or lactate removal was decreased even when oxygen was delivered to tissue. Amaducci (http://www.emresident.org/gasping-air-albuterol-induced-lactic-acidosis/) explained how high dosages of albuterol, beyond 1 mg/kg, created an increased adrenergic state that, with reduced tissue perfusion, increased glycolysis and pyruvate production, resulting in measurable hyperlactatemia. The authors (Br J Med Pract. 2011;4[2]:a420) noted that lactic acidosis also occurs in acute severe asthma due to inadequate oxygen delivery to the respiratory muscles to meet an elevated oxygen demand or due to fatiguing respiratory muscles. Ganaie and Hughes reported a case of lactic acidosis caused by treatment with salbutamol. Salbutamol is the most commonly used short-acting beta-agonist. Stimulation of beta-adrenergic receptors leads to a variety of metabolic effects, including increase in glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis, and lipolysis, thus contributing to lactic acidosis. All authors agreed that the mechanism of albuterol-caused lactic acidosis was poorly understood.

Douglas E. Masini, EdD, FCCP

Steering Committee Member

Withdrawal of OSA Screening Regulation for Commercial Motor Vehicle Operators

Compared with the general US population, the prevalence of sleep apnea (SA) is higher among commercial motor vehicle (CMV) drivers (Berger et al. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54[8]:1017). Additionally, the risk of motor vehicle accidents is higher among individuals with SA compared with those without SA (Tregear et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5[6]:573), and treatment of SA is associated with a reduction in this risk (Mahssa et al. Sleep. 2015;38[3]341).

However, after reviewing the public input and data, the FRA and FMCSA recently announced that there was “not enough information available to support moving forward with a rulemaking action,” and, therefore, they are no longer pursuing the regulation that would require SA screening for truck drivers and train engineers (Federal Register August 2017;49 CFR 391,240,242). See CHEST’s press release at www.chestnet.org/News/Press-Releases/2017/08/American-College-of-Chest-Physicians-Responds-to-DOT-Withdrawal-of-Sleep-Apnea-Screening. The FMCSA endorses existing resources,such as the North American Fatigue Management Program (NAFMP) (www.nafmp.org), which is a web-based program designed to reduce driver fatigue and includes information on SA screening and treatment. The medical examiners, however, will have the ultimate responsibility to screen, diagnose, and treat SA based on their medical knowledge and clinical experience.

Vaishnavi Kundel, MD

NetWork Member

Steering Committee Member

Corrections to previous NetWork articles

July 2017

Clinical Research

Mohsin Ijaz’s name was misspelled.

August 2017

Transplant

The name under Shruti Gadre’s photograph is wrong. It says Dr. Ahya instead of Dr. Gadre.

The authorship of the article at the end of the article is incorrect. It says Vivek Ahya, instead of Shruti Gadre and Marie Budev.

This month in CHEST : Editor’s picks

Giants in Chest Medicine

Jack Hirsh, MD, FCCP.

By Dr. S. Z. Goldhaber.

Original Research

IVIg for Treatment of Severe Refractory Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia.

By Dr. A. Padmanabhan et al.

The Impact of Statin Drug Use on All-Cause Mortality in Patients With COPD:

A Population-Based Cohort Study.

By Dr. A. J. Raymakers et al.

Pathologic Findings and Prognosis in a Large Prospective Cohort of Chronic Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis.

By Dr. P. Wang et al.

Evidence-based Medicine

Etiologies of Chronic Cough in Pediatric Cohorts: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report.

By Dr. A. B. Chang et al, on behalf of the CHEST Expert Cough Panel.

Giants in Chest Medicine

Jack Hirsh, MD, FCCP.

By Dr. S. Z. Goldhaber.

Original Research

IVIg for Treatment of Severe Refractory Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia.

By Dr. A. Padmanabhan et al.

The Impact of Statin Drug Use on All-Cause Mortality in Patients With COPD:

A Population-Based Cohort Study.

By Dr. A. J. Raymakers et al.

Pathologic Findings and Prognosis in a Large Prospective Cohort of Chronic Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis.

By Dr. P. Wang et al.

Evidence-based Medicine

Etiologies of Chronic Cough in Pediatric Cohorts: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report.

By Dr. A. B. Chang et al, on behalf of the CHEST Expert Cough Panel.

Giants in Chest Medicine

Jack Hirsh, MD, FCCP.

By Dr. S. Z. Goldhaber.

Original Research

IVIg for Treatment of Severe Refractory Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia.

By Dr. A. Padmanabhan et al.

The Impact of Statin Drug Use on All-Cause Mortality in Patients With COPD:

A Population-Based Cohort Study.

By Dr. A. J. Raymakers et al.

Pathologic Findings and Prognosis in a Large Prospective Cohort of Chronic Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis.

By Dr. P. Wang et al.

Evidence-based Medicine

Etiologies of Chronic Cough in Pediatric Cohorts: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report.

By Dr. A. B. Chang et al, on behalf of the CHEST Expert Cough Panel.

CHEST 2017 Keynote Speaker

John O’Leary is a father of four, business owner, speaker, writer, and former hospital chaplain—a fortunate guy. But he attributes the best of everything he has to an unfortunate event that happened back in 1987.

At the age of 9, O’Leary was involved in a house fire that left burns on 100% of his body, 87% of which were third degree. Doctors gave O’Leary less than a 1% chance to live, odds that were overwhelming—but not entirely impossible to beat.

Despite what the health-care professionals told his mother, when O’Leary asked her if he was going to die, she responded by asking her son if he wanted to die or if he wanted to live: a question that O’Leary says must have taken lot more courage for a mother to ask than it did for a 9-year-old to answer.

Although he was taken aback, the answer seemed obvious to O’Leary. Of course he wanted to live. And live he did, but only after 5 months in the hospital and the amputation of all of his fingers.

After he returned to school 18 months later with his classmates welcoming him back with a parade, O’Leary didn’t see the necessity in sharing his story. “I always knew my story, I just never truly embraced it.”

O’Leary’s father told him that he wanted to thank the community members who truly helped their family through the tough times and that he planned to do so by writing a book. With the help of O’Leary’s mother, 100 copies of Overwhelming Odds were originally printed and given to members of the community. Today, over 70,000 copies of their book have been sold.

When some Girl Scouts approached O’Leary and asked him to share his story with their troop and their parents, his life changed. O’Leary says that he now tries to say yes to each person/organization that asks him to share. As a result, he has said yes over 1,500 times and has even made a life of it.

“We confuse being out of bed with being awake, being at work with being fully engaged, or being with a patient with being actively present for and with that patient,” O’Leary says of accidental living. “That’s not really awake; that’s not alive. It’s more of sleepwalking through life.”

O’Leary believes that too often we give away the freedom of life to things that are out of our control and that he feels it is his job to remind his listeners that there are a lot of things in our control on which we should be fully living. “We want people to realize they have the ability to be actively present in every engagement and every decision, every thought, and every word, and ultimately, every result in their lives.”

CHEST Annual Meeting 2017 is one of the events that O’Leary has recently said “yes” to, and he is very excited about it. “As things continue to change…we can forget why we got into what we got into,” O’Leary says. “I am excited to remind everyone at CHEST about the profoundly beautiful nature of their work and how it has the ability to affect both the staff and patients.”

Members of O’Leary’s medical team, as well as other hospital staff members, were crucial to his survival and improved health. One of his doctors was not only a respected physician and surgeon but also a powerful leader who was capable of reminding every member of the hospital of their purpose and necessity to a patient’s life, something that O’Leary hopes can be common in every health-care team.

“When you have the chance to influence men and women who serve patients and teams and impact lives and do it generationally—I think we forget that it is a generational ripple effect; my kids are where and who they are today because doctors, nurses, practitioners, and janitors showed up 30 years ago.”

John O’Leary is a father of four, business owner, speaker, writer, and former hospital chaplain—a fortunate guy. But he attributes the best of everything he has to an unfortunate event that happened back in 1987.

At the age of 9, O’Leary was involved in a house fire that left burns on 100% of his body, 87% of which were third degree. Doctors gave O’Leary less than a 1% chance to live, odds that were overwhelming—but not entirely impossible to beat.

Despite what the health-care professionals told his mother, when O’Leary asked her if he was going to die, she responded by asking her son if he wanted to die or if he wanted to live: a question that O’Leary says must have taken lot more courage for a mother to ask than it did for a 9-year-old to answer.

Although he was taken aback, the answer seemed obvious to O’Leary. Of course he wanted to live. And live he did, but only after 5 months in the hospital and the amputation of all of his fingers.

After he returned to school 18 months later with his classmates welcoming him back with a parade, O’Leary didn’t see the necessity in sharing his story. “I always knew my story, I just never truly embraced it.”

O’Leary’s father told him that he wanted to thank the community members who truly helped their family through the tough times and that he planned to do so by writing a book. With the help of O’Leary’s mother, 100 copies of Overwhelming Odds were originally printed and given to members of the community. Today, over 70,000 copies of their book have been sold.

When some Girl Scouts approached O’Leary and asked him to share his story with their troop and their parents, his life changed. O’Leary says that he now tries to say yes to each person/organization that asks him to share. As a result, he has said yes over 1,500 times and has even made a life of it.

“We confuse being out of bed with being awake, being at work with being fully engaged, or being with a patient with being actively present for and with that patient,” O’Leary says of accidental living. “That’s not really awake; that’s not alive. It’s more of sleepwalking through life.”

O’Leary believes that too often we give away the freedom of life to things that are out of our control and that he feels it is his job to remind his listeners that there are a lot of things in our control on which we should be fully living. “We want people to realize they have the ability to be actively present in every engagement and every decision, every thought, and every word, and ultimately, every result in their lives.”

CHEST Annual Meeting 2017 is one of the events that O’Leary has recently said “yes” to, and he is very excited about it. “As things continue to change…we can forget why we got into what we got into,” O’Leary says. “I am excited to remind everyone at CHEST about the profoundly beautiful nature of their work and how it has the ability to affect both the staff and patients.”

Members of O’Leary’s medical team, as well as other hospital staff members, were crucial to his survival and improved health. One of his doctors was not only a respected physician and surgeon but also a powerful leader who was capable of reminding every member of the hospital of their purpose and necessity to a patient’s life, something that O’Leary hopes can be common in every health-care team.

“When you have the chance to influence men and women who serve patients and teams and impact lives and do it generationally—I think we forget that it is a generational ripple effect; my kids are where and who they are today because doctors, nurses, practitioners, and janitors showed up 30 years ago.”

John O’Leary is a father of four, business owner, speaker, writer, and former hospital chaplain—a fortunate guy. But he attributes the best of everything he has to an unfortunate event that happened back in 1987.

At the age of 9, O’Leary was involved in a house fire that left burns on 100% of his body, 87% of which were third degree. Doctors gave O’Leary less than a 1% chance to live, odds that were overwhelming—but not entirely impossible to beat.

Despite what the health-care professionals told his mother, when O’Leary asked her if he was going to die, she responded by asking her son if he wanted to die or if he wanted to live: a question that O’Leary says must have taken lot more courage for a mother to ask than it did for a 9-year-old to answer.

Although he was taken aback, the answer seemed obvious to O’Leary. Of course he wanted to live. And live he did, but only after 5 months in the hospital and the amputation of all of his fingers.

After he returned to school 18 months later with his classmates welcoming him back with a parade, O’Leary didn’t see the necessity in sharing his story. “I always knew my story, I just never truly embraced it.”

O’Leary’s father told him that he wanted to thank the community members who truly helped their family through the tough times and that he planned to do so by writing a book. With the help of O’Leary’s mother, 100 copies of Overwhelming Odds were originally printed and given to members of the community. Today, over 70,000 copies of their book have been sold.

When some Girl Scouts approached O’Leary and asked him to share his story with their troop and their parents, his life changed. O’Leary says that he now tries to say yes to each person/organization that asks him to share. As a result, he has said yes over 1,500 times and has even made a life of it.

“We confuse being out of bed with being awake, being at work with being fully engaged, or being with a patient with being actively present for and with that patient,” O’Leary says of accidental living. “That’s not really awake; that’s not alive. It’s more of sleepwalking through life.”

O’Leary believes that too often we give away the freedom of life to things that are out of our control and that he feels it is his job to remind his listeners that there are a lot of things in our control on which we should be fully living. “We want people to realize they have the ability to be actively present in every engagement and every decision, every thought, and every word, and ultimately, every result in their lives.”