User login

Too close for comfort: When the psychiatrist is stalked

Dr. A has been treating Ms. W, a graduate student, for depression. Ms. W made subtle comments expressing her interest in pursuing a romantic relationship with her psychiatrist. Dr. A gently redirected her, and she seemed to respond appropriately. However, over the past 2 weeks, Dr. A has seen Ms. W at a local park and at the grocery store. Today, Dr. A is startled to see Ms. W at her weekly yoga class. Dr. A plans to ask her supervisor for advice.

Dr. M is a child psychiatrist who spoke at his local school board meeting in support of masking requirements for students during COVID-19. During the discussion, Dr. M shared that, as a psychiatrist, he does not believe it is especially distressing for students to wear masks, and that doing so is a necessary public health measure. On leaving, other parents shouted, “We know who you are and where you live!” The next day, his integrated clinic started receiving threatening and harassing messages, including threats to kill him or his staff if they take part in vaccinating children against COVID-19.

Because of their work, mental health professionals—like other health care professionals—face an elevated risk of being harassed or stalked. Stalking often includes online harassment and may escalate to serious physical violence. Stalking is criminal behavior by a patient and should not be constructed as a “failure to manage transference.” This article explores basic strategies to reduce the risk of harassment and stalking, describes how to recognize early behaviors, and outlines basic steps health care professionals and their employers can take to respond to stalking and harassing behaviors.

Although this article is intended for psychiatrists, it is important to note that all health professionals have significant risk for experiencing stalking or harassment. This is due in part, but not exclusively, to our clinical work. Estimates of how many health professionals experience stalking vary substantially depending upon the study, and differences in methodologies limit easy comparison or extrapolation. More thorough reviews have reported ranges from 2% to 70% among physicians; psychiatrists and other mental health professionals appear to be at greater risk than those in other specialties and the general population.1-3 Physicians who are active on social media may also be at elevated risk.4 Unexpected communications from patients and their family members—especially those with threatening, harassing, or sexualized tones, or involving contact outside of a work setting—can be distressing. These behaviors represent potential harbingers of more dangerous behavior, including physical assault, sexual assault, or homicide. Despite their elevated risk, many psychiatrists are unaware of how to prevent or respond to stalking or harassment.

Recognizing harassment and stalking

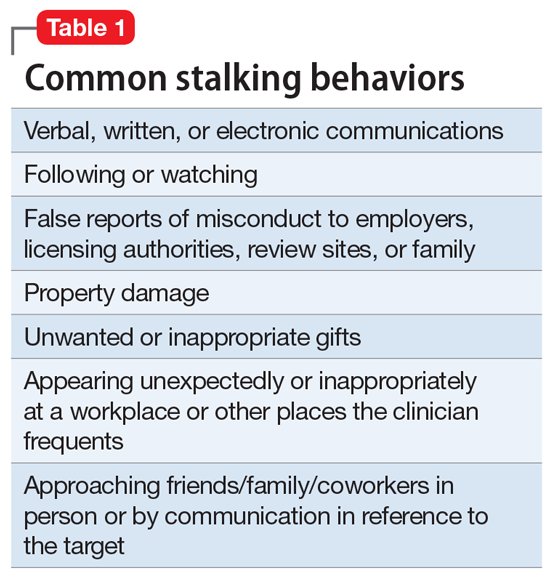

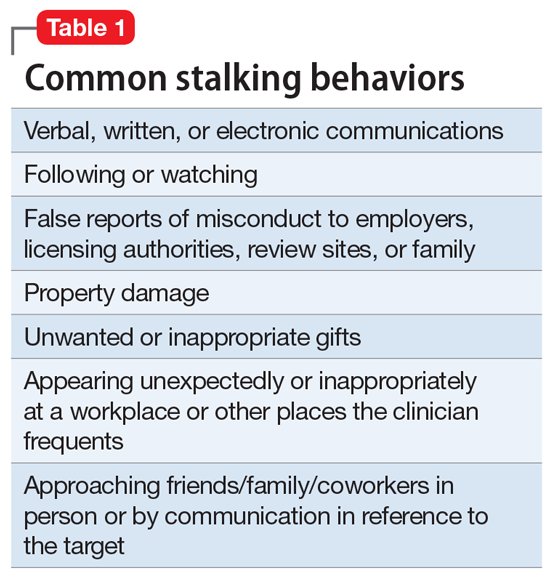

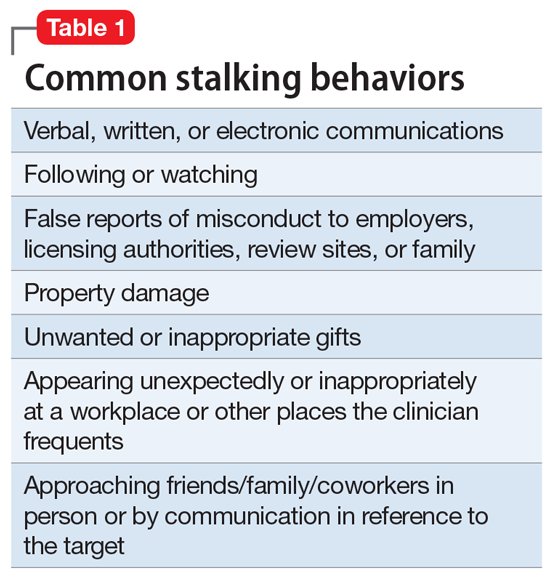

Repeated and unwanted contact or communication, regardless of intent, may constitute stalking. Legal definitions vary by jurisdiction and may not align with subjective experiences or understanding of what constitutes stalking.5 At its essence, stalking is repeated harassing behaviors likely to provoke fear in the targeted person. FOUR is a helpful mnemonic when conceptualizing the attributes of stalking: Fixated, Obsessive, Unwanted, and Repetitive.6Table 1 lists examples of common stalking behaviors. Stalking and harassing behavior may be from a known source (eg, a patient, coworker, or paramour), a masked source (ie, someone known to the target but who conceals or obscures their identity), or from otherwise unknown persons. Behaviors that persist after the person engaging in the behaviors has clearly been informed that they are unwanted or inappropriate are especially concerning. Stalking may escalate to include physical or sexual assault and, in some cases, homicide.

Stalking duration can vary substantially, as can the factors that lead to the cessation of the behavior. Indicators of increased risk for physical violence include unwanted physical presence/following of the target (“approach behaviors”), having a prior violent intimate relationship, property destruction, explicit threats, and having a prior intimate relationship with the target.7

Stalking contact or communication may be unwanted because of the content (eg, sexualized or threatening tone), location (eg, at a professional’s home), or means (eg, through social media). Stalking behaviors are not appropriate in any relationship, including a clinical relationship. They should not be treated as a “failure to manage transference” or in other victim-blaming ways.

There are multiple typologies for stalking behavior. Common motivations for stalking health professionals include resentment or grievance, misjudgment of social boundaries, and delusional fixation, including erotomania.8 Associated psychopathologies vary significantly and, while some may be more amenable to psychiatric treatment than others, psychiatrists should not feel compelled to treat patients who repeatedly violate boundaries, regardless of intent or comorbidity.

Patients are not the exclusive perpetrators of stalking; a recent study found that 4% of physicians surveyed reported current or recent stalking by a current or former intimate partner.9 When a person who is a victim of intimate partner violence is also stalked as part of the abuse, homicide risk increases.10 Workplace homicides of health care professionals are most likely to be committed by a current or former partner or other personal acquaintance, not by a patient.11 Workplace harassment and stalking of health care professionals is especially concerning because this behavior can escalate and endanger coworkers or clients.

Continue to: Risk awareness: Recognize your exposure...

Risk awareness: Recognize your exposure

About 80% of stalking involves some form of technology—often telephone calls but also online or other “cyber” elements.12 One recent survey found the rate of online harassment, including threats of physical and sexual violence, was >20% among physicians who were active on social media.4 Health professionals may be at greater risk of having patients find their personal information simply because patients routinely search online for information about new clinicians. Personal information about a clinician may be readily visible among professional information in search results, or a curious patient may simply scroll further down in the results. For a potential stalker, clicking on a search result linking to a personal social media page may be far easier than finding a home address and going in person—but the action may be just as distressing or risky for the clinician.13 Additionally, items visible in a clinician’s office—or visible in the background of those providing telehealth services from their home—may inadvertently reveal personal information about the clinician, their home, or their family.

Psychiatrists are often in a special position in relation to patients and times of crises. They may be involved in involuntary commitment—or declining an admission when a patient or family wishes it. They may be present at the time of the revelation of a serious diagnosis, abuse, injury, or death. They may be a mandated reporter of child or elder abuse.2 Additionally, physicians may be engaged in discourse on politically charged public health topics.14 These factors may increase their risk of being stalked.

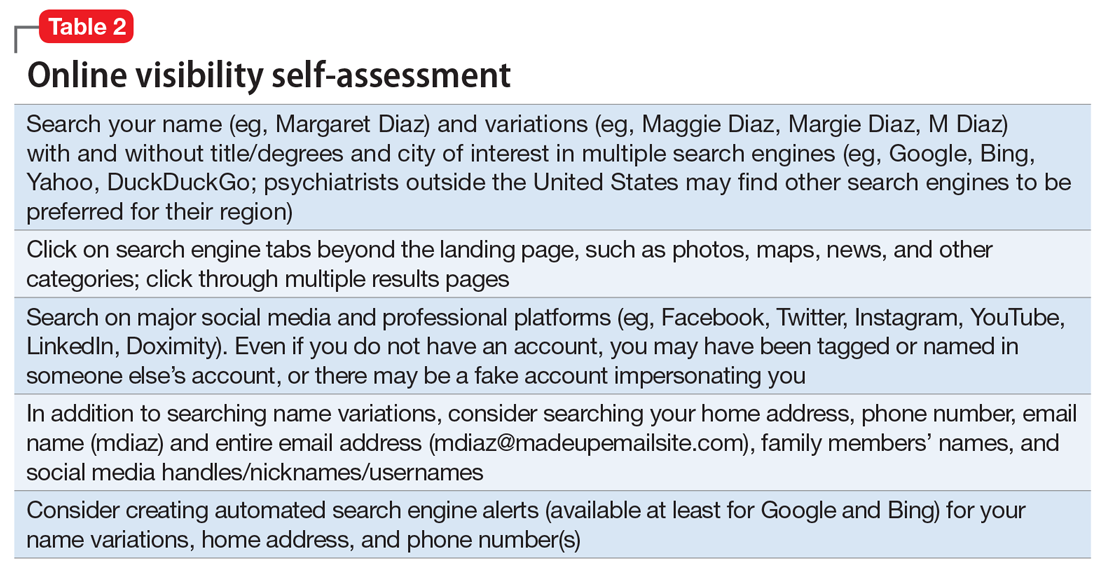

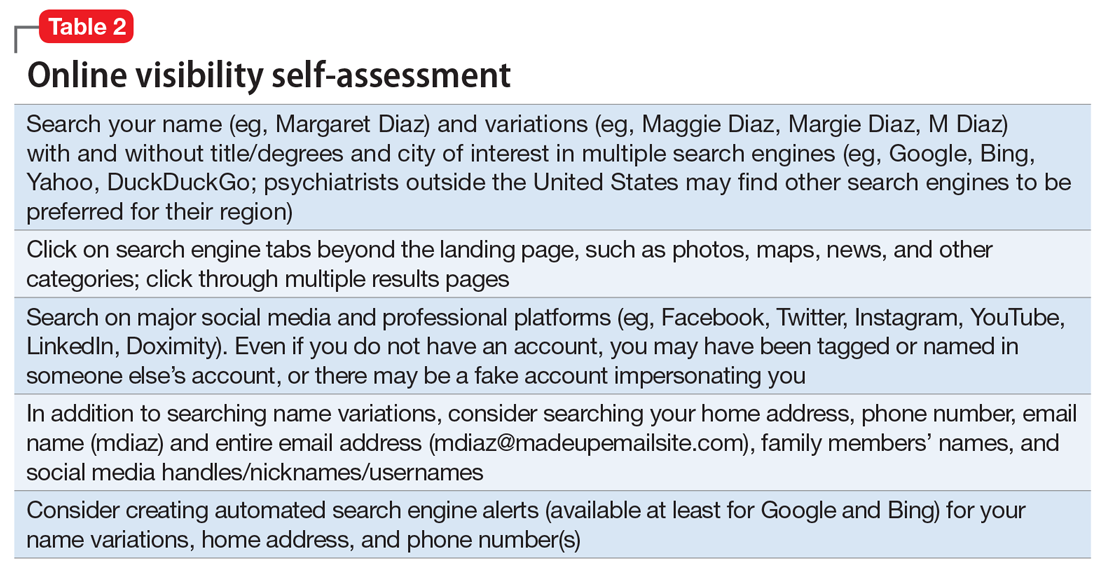

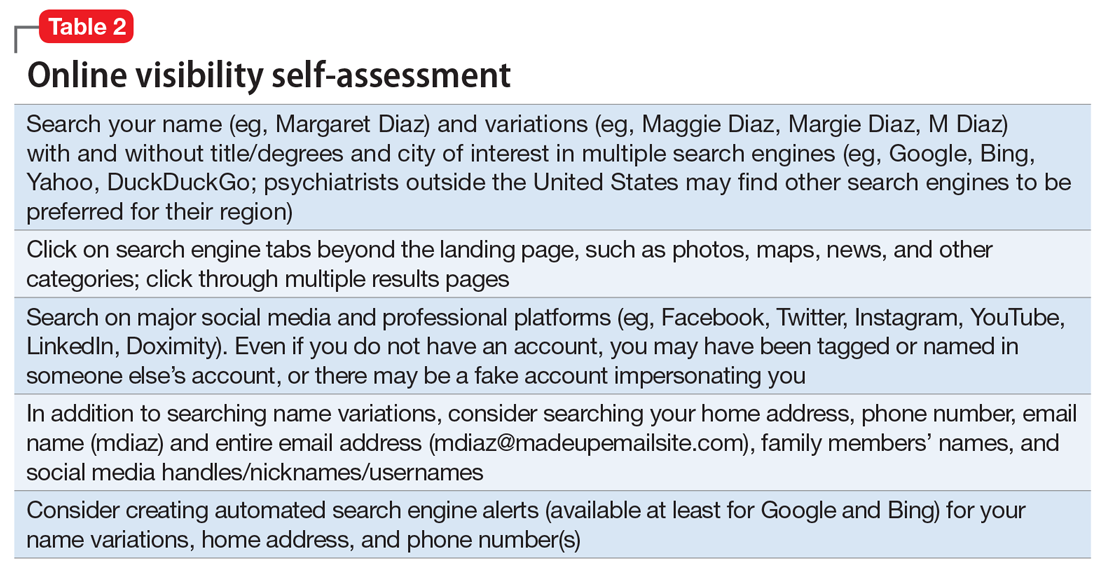

Conducting an online visibility self-assessment can be a useful way to learn what information others can find. Table 2 outlines the steps for completing this exercise. Searching multiple iterations of your current and former names (with and without degrees, titles, and cities) will yield differing results in various search engines. After establishing a baseline of what information is available online, it can be helpful to periodically repeat this exercise, and to set up automated alerts for your name, number(s), email(s), and address(es).

Basic mitigation strategies

In the modern era, being invisible online is impractical and likely impossible—especially for a health care professional. Instead, it may be prudent to limit your public visibility to professional portals (eg, LinkedIn or Doximity) and maximize privacy settings on other platforms. Another basic strategy is to avoid providing personal contact information (your home address, phone number, or personal email) for professional purposes, such as licensing and credentialing, conference submissions, or journal publications. Be aware that driving a visually distinct vehicle—one with vanity plates or distinct bumper stickers, or an exotic sportscar—can make it easier to be recognized and located. A personally recorded voicemail greeting (vs one recorded by, for example, an office manager) may be inappropriately reinforcing for some stalkers.

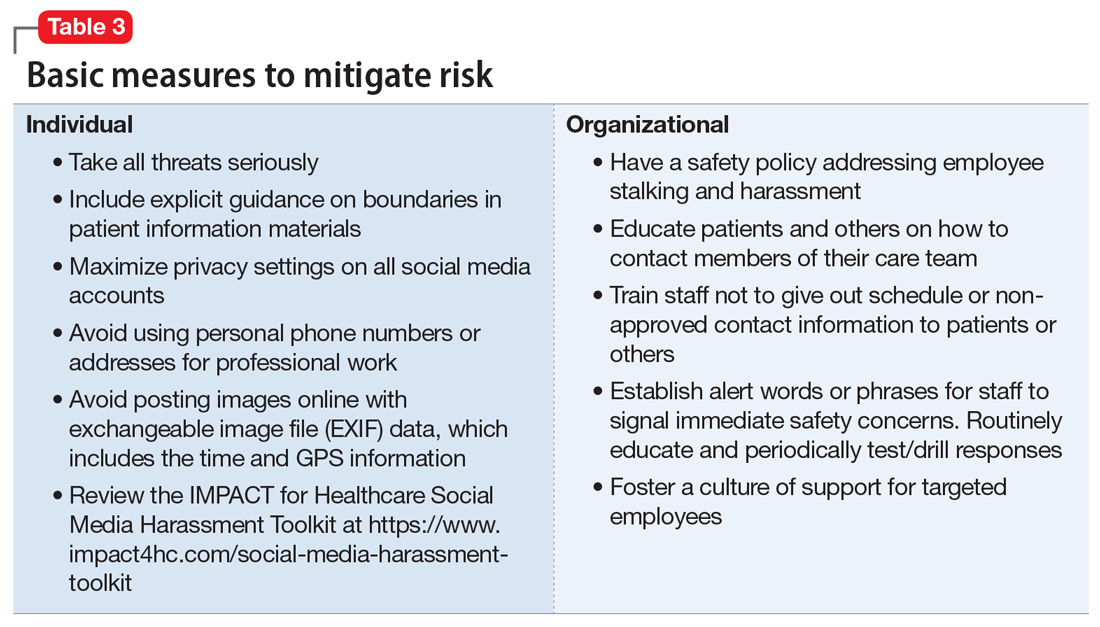

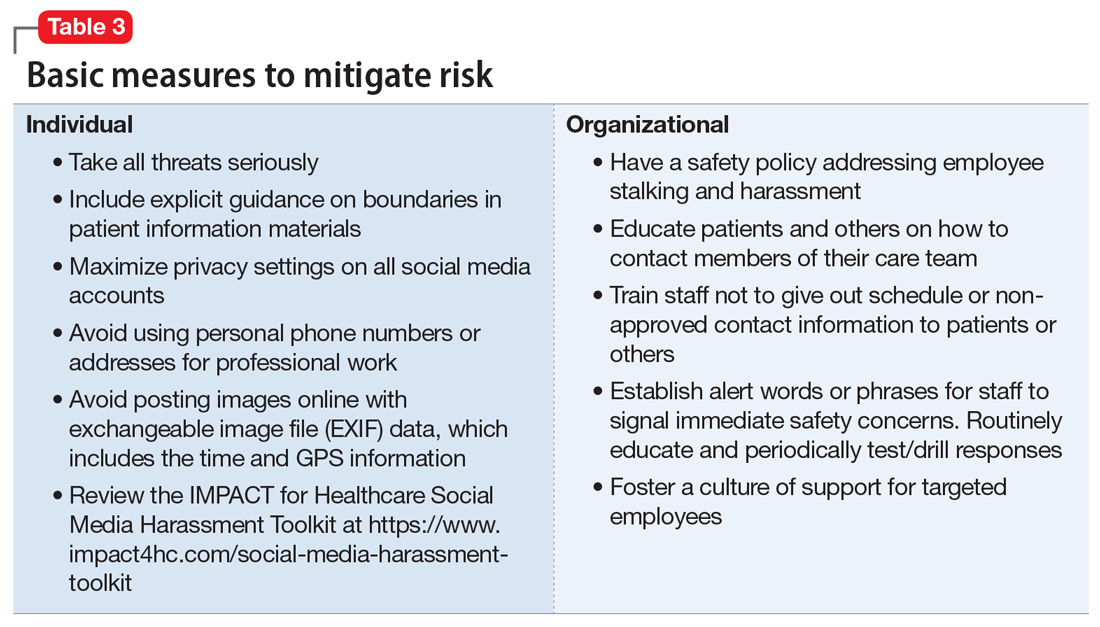

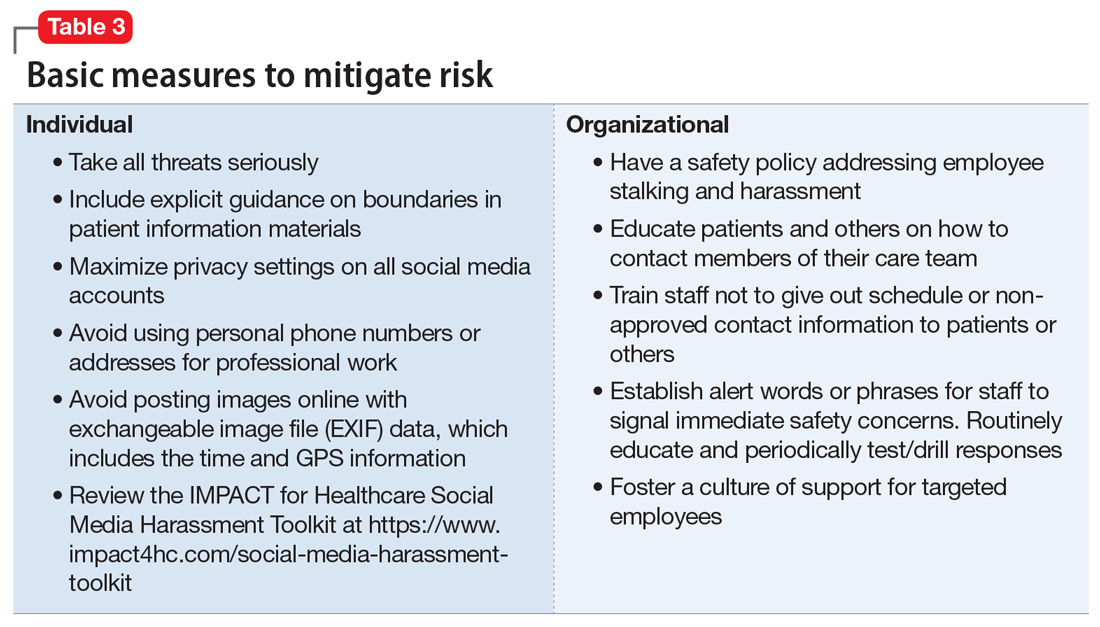

Workplaces should have an established safety policy that addresses stalking and harassment of employees. Similarly, patients and others should receive clear education on how to contact different staff, including physicians, with consideration of how and when to use electronic health information portals, office numbers, and emails. Workplaces should not disclose staff schedules. For example, a receptionist should say “I’ll have Dr. Diaz return your call when she can” instead of “Dr. Diaz is not in until tomorrow.” Avoid unnecessary location/name signals (eg, a parking spot labeled “Dr. Diaz”). Consider creating alert words or phrases for staff to use to signal they are concerned about their immediate safety—and provide education and training, including drills, to test emergency responses when the words/phrases are used. Leaders and managers should nurture a workplace culture where people are comfortable seeking support if they feel they may be the target of harassment or stalking. Many larger health care organizations have threat management programs, which can play a critical role in preventing, investigating, and responding to stalking of employees. Increasingly, threat management teams are being identified as a best practice in health care settings.15Table 3 summarizes measures to mitigate risk.

What to do when harassment or stalking occurs

Consulting with subject matter experts is essential. Approach behaviors, stalking patterns, and immediate circumstances vary highly, and so too must responses. A socially inept approach outside of the work setting by a patient may be effectively responded to with a firm explanation of why the behavior was inappropriate and a reiteration of limits. More persistent or serious threats may require taking actions for immediate safety, calling law enforcement or security (who may have the expertise to assist appropriately), or even run/hide/fight measures. Others to notify early on include human resources, supervisors, front desk staff, and coworkers. Although no single measure is always indicated and no single measure will always be effective, consultation with a specialist is always advisable.

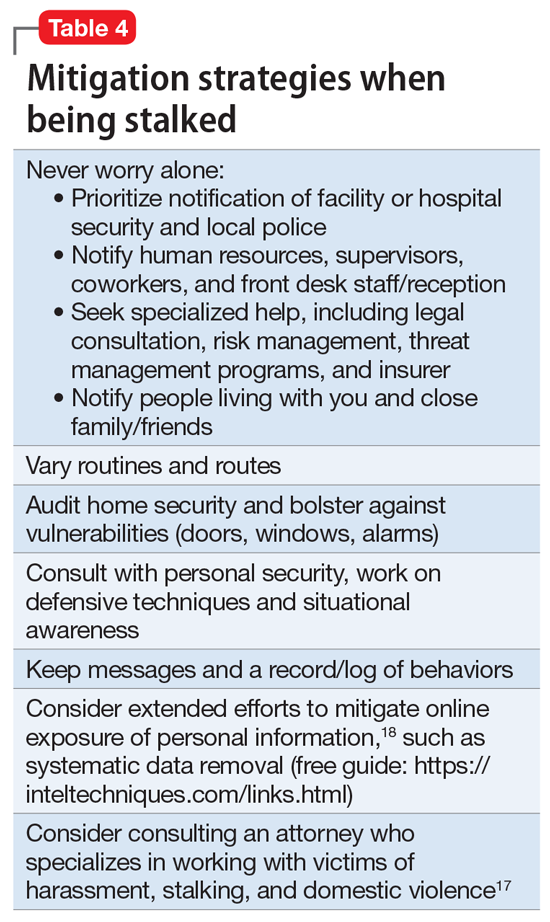

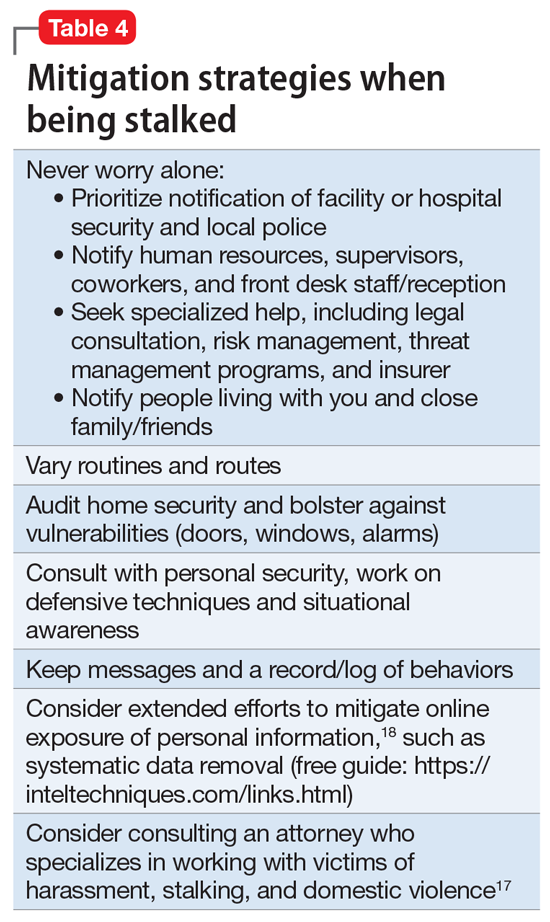

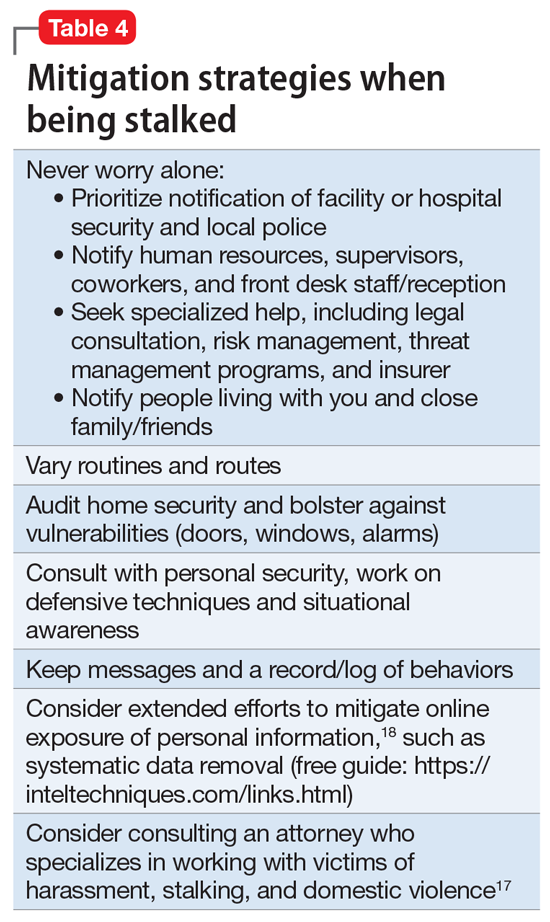

Attempting to assess your own risk may be subject to bias and error, even for an experienced forensic psychiatrist. Risk assessment in stalking and harassment cases is complex, nuanced, and beyond the scope of this article; engagement with specialized threat programs or subject matter experts is advisable.15,16 If your medical center or area has police or security officers, engage them early. Risk management, insurers, and legal can also be helpful to consult. Attorneys specializing in harassment, stalking, and domestic violence may be helpful in extreme situations.17Table 417,18 highlights steps to take.

While effective interventions to stop or redirect stalking behavior may vary, some initial considerations include changing established routines (eg, your parking location or daily/weekly patterns such as gym, class, etc.) and letting family and others you live with know what is occurring. Consider implementing and bolstering personal, work, and home security; honing situational awareness skills; and learning advanced situational awareness and self-defense techniques.

Continue to: Clinical documentation and termination of care...

Clinical documentation and termination of care

Repeated and unwanted contact behaviors by a patient may be considered grounds for termination of care by the targeted clinician. Termination may occur through a direct conversation, followed by a mailed letter explaining that the patient’s inappropriate behaviors are the basis for termination. The letter should outline steps for establishing care with another psychiatrist and signing a release to facilitate transfer of records to the next psychiatrist. Ensure that the patient has access to a reasonable supply of medications or refills according to jurisdictional standards for transfer or termination of care.19 While these are common legal standards for termination of care in the United States, clinicians would be well served by appropriate consultation to verify the most appropriate standards for their location.

Documentation of a patient’s behavior should be factual and clear. Under the 21st Century Cures Act, patients often have access to their own electronic records.20 Therefore, clinicians should avoid documenting personal security measures or other information that is not clinically relevant. Communications with legal or risk management should not be documented unless otherwise advised, because such communications may be privileged and may not be clinically relevant.

In some circumstances, continuing to treat a patient who has stalked a member of the current treatment team may be appropriate or necessary. For example, a patient may respond appropriately to redirection after an initial approach behavior and continue to make clinical progress, or may be in a forensic specialty setting with appropriate operational support to continue with treatment.

Ethical dilemmas may arise in underserved areas where there are limited options for psychiatric care and in communicating the reasons for termination to a new clinician. Consultation may help to address these issues. However, as noted before, clinicians should be permitted to discontinue and transfer treatment and should not be compelled to continue to treat a patient who has threatened or harassed them.

Organizational and employer considerations

Victims of stalking have reported that they appreciated explicit support from their supervisor, regular meetings, and measures to reduce potential stalking or violence in the workplace; unsurprisingly, victim blaming and leaving the employee to address the situation on their own were labeled experienced as negative.2 Employers may consider implementing physical security, access controls and panic alarms, and enhancing coworkers’ situational awareness.21 Explicit policies about and attention to reducing workplace violence, including stalking, are always beneficial—and in some settings such policies may be a regulatory requirement.22 Large health care organizations may benefit from developing specialized threat management programs to assist with the evaluation and mitigation of stalking and other workplace violence risks.15,23

Self-care considerations

The impact of stalking can include psychological distress, disruption of work and personal relationships, and false allegations of impropriety. Stalking can make targets feel isolated, violated, and fearful, which makes it challenging to reach out to others for support and safety. It takes time to regain a sense of safety and to find a “new normal,” particularly while experiencing and responding to stalking behavior. Notifying close personal contacts such as family and coworkers about what is occurring (without sharing protected health information) can be helpful for recovery and important for the clinician’s safety. Reaching out for organizational and legal supports is also prudent. It is also important to allow time for, and patience with, a targeted individual’s normal responses, such as decreased work performance, sleep/appetite changes, and hypervigilance, without pathologizing these common stress reactions. Further review of appropriate resources by impacted clinicians is advisable.24-26

1. Nelsen AJ, Johnson RS, Ostermeyer B, et al. The prevalence of physicians who have been stalked: a systematic review. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2015;43(2):177-182.

2. Jutasi C, McEwan TE. Stalking of professionals: a scoping review. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management. 2021;8(3):94-124.

3. Pathé MT, Meloy JR. Commentary: Stalking by patients—psychiatrists’ tales of anger, lust and ignorance. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2013;41(2):200-205.

4. Pendergrast TR, Jain S, Trueger NS, et al. Prevalence of personal attacks and sexual harassment of physicians on social media. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(4):550-552.

5. Owens JG. Why definitions matter: stalking victimization in the United States. J Interpers Violence. 2016;31(12):2196-2226.

6. College of Policing. Stalking or harassment. May 2019. Accessed March 8, 2020. https://library.college.police.uk/docs/college-of-policing/Stalking_or_harassment_guidance_200519.pdf

7. McEwan TE, Daffern M, MacKenzie RD, et al. Risk factors for stalking violence, persistence, and recurrence. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology. 2017;28(1):3856.

8. Pathé MT, Mullen PE, Purcell R. Patients who stalk doctors: their motives and management. Med J Australia. 2002;176(7):335-338.

9. Reibling ET, Distelberg B, Guptill M, et al. Intimate partner violence experienced by physicians. J Prim Care Community Health. 2020;11:2150132720965077.

10. Matias A, Gonçalves M, Soeiro C, et al. Intimate partner homicide: a meta-analysis of risk factors. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2019;50:101358.

11. US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Fact sheet. Workplace violence in healthcare, 2018. April 2020. Accessed November 24, 2021. https://www.bls.gov/iif/oshwc/cfoi/workplace-violence-healthcare-2018.htm

12. Truman JL, Morgan RE. Stalking victimization, 2016. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Report No.: NCJ 253526. April 2021. Accessed November 24, 2021. https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/stalking-victimization-2016

13. Reyns BW, Henson B, Fisher BS. Being pursued online: applying cyberlifestyle–routine activities theory to cyberstalking victimization. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2011;38(11):1149-1169.

14. Stea JN. When promoting knowledge makes you a target. Scientific American Blog Network. March 16, 2020. Accessed November 24, 2021. https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/when-promoting-knowledge-makes-you-a-target/

15. Henkel SJ. Threat assessment strategies to mitigate violence in healthcare. IAHSS Foundation. IAHSS-F RS-19-02. November 2019. Accessed November 24, 2021. https://iahssf.org/assets/IAHSS-Foundation-Threat-Assessment-Strategies-to-Mitigate-Violence-in-Healthcare.pdf

16. McEwan TE. Stalking threat and risk assessment. In: Reid Meloy J, Hoffman J (eds). International Handbook of Threat Assessment. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press; 2021:210-234.

17. Goldberg C. Nobody’s Victim: Fighting Psychos, Stalkers, Pervs, and Trolls. Plume; 2019.

18. Bazzell M. Extreme Privacy: What It Takes to Disappear. 2nd ed. Independently published; 2020.

19. Simon RI, Shuman DW. The doctor-patient relationship. Focus. 2007;5(4):423-431.

20. Department of Health and Human Services. 21st Century Cures Act: Interoperability, Information Blocking, and the ONC Health IT Certification Program Final Rule (To be codified at 45 CFR 170 and 171). Federal Register. 2020;85(85):25642-25961.

21. Sheridan L, North AC, Scott AJ. Stalking in the workplace. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management. 2019;6(2):61-75.

22. The Joint Commission. Workplace Violence Prevention Standards. R3 Report: Requirement, Rationale, Reference. Issue 30. June 18, 2021. Accessed November 24, 2021. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/standards/r3-reports/wpvp-r3-30_revised_06302021.pdf

23. Terry LP. Threat assessment teams. J Healthc Prot Manage. 2015;31(2):23-35.

24. Pathé M. Surviving Stalking. Cambridge University Press; 2002.

25. Noffsinger S. What stalking victims need to restore their mental and somatic health. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(6):43-47.

26. Mullen P, Whyte S, McIvor R; Psychiatrists’ Support Service, Royal College of Psychiatry. PSS Information Guide: Stalking. Report No. 11. 2017. Accessed November 24, 2021. https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/members/supporting-you/pss/pss-guide-11-stalking.pdf?sfvrsn=2f1c7253_2

Dr. A has been treating Ms. W, a graduate student, for depression. Ms. W made subtle comments expressing her interest in pursuing a romantic relationship with her psychiatrist. Dr. A gently redirected her, and she seemed to respond appropriately. However, over the past 2 weeks, Dr. A has seen Ms. W at a local park and at the grocery store. Today, Dr. A is startled to see Ms. W at her weekly yoga class. Dr. A plans to ask her supervisor for advice.

Dr. M is a child psychiatrist who spoke at his local school board meeting in support of masking requirements for students during COVID-19. During the discussion, Dr. M shared that, as a psychiatrist, he does not believe it is especially distressing for students to wear masks, and that doing so is a necessary public health measure. On leaving, other parents shouted, “We know who you are and where you live!” The next day, his integrated clinic started receiving threatening and harassing messages, including threats to kill him or his staff if they take part in vaccinating children against COVID-19.

Because of their work, mental health professionals—like other health care professionals—face an elevated risk of being harassed or stalked. Stalking often includes online harassment and may escalate to serious physical violence. Stalking is criminal behavior by a patient and should not be constructed as a “failure to manage transference.” This article explores basic strategies to reduce the risk of harassment and stalking, describes how to recognize early behaviors, and outlines basic steps health care professionals and their employers can take to respond to stalking and harassing behaviors.

Although this article is intended for psychiatrists, it is important to note that all health professionals have significant risk for experiencing stalking or harassment. This is due in part, but not exclusively, to our clinical work. Estimates of how many health professionals experience stalking vary substantially depending upon the study, and differences in methodologies limit easy comparison or extrapolation. More thorough reviews have reported ranges from 2% to 70% among physicians; psychiatrists and other mental health professionals appear to be at greater risk than those in other specialties and the general population.1-3 Physicians who are active on social media may also be at elevated risk.4 Unexpected communications from patients and their family members—especially those with threatening, harassing, or sexualized tones, or involving contact outside of a work setting—can be distressing. These behaviors represent potential harbingers of more dangerous behavior, including physical assault, sexual assault, or homicide. Despite their elevated risk, many psychiatrists are unaware of how to prevent or respond to stalking or harassment.

Recognizing harassment and stalking

Repeated and unwanted contact or communication, regardless of intent, may constitute stalking. Legal definitions vary by jurisdiction and may not align with subjective experiences or understanding of what constitutes stalking.5 At its essence, stalking is repeated harassing behaviors likely to provoke fear in the targeted person. FOUR is a helpful mnemonic when conceptualizing the attributes of stalking: Fixated, Obsessive, Unwanted, and Repetitive.6Table 1 lists examples of common stalking behaviors. Stalking and harassing behavior may be from a known source (eg, a patient, coworker, or paramour), a masked source (ie, someone known to the target but who conceals or obscures their identity), or from otherwise unknown persons. Behaviors that persist after the person engaging in the behaviors has clearly been informed that they are unwanted or inappropriate are especially concerning. Stalking may escalate to include physical or sexual assault and, in some cases, homicide.

Stalking duration can vary substantially, as can the factors that lead to the cessation of the behavior. Indicators of increased risk for physical violence include unwanted physical presence/following of the target (“approach behaviors”), having a prior violent intimate relationship, property destruction, explicit threats, and having a prior intimate relationship with the target.7

Stalking contact or communication may be unwanted because of the content (eg, sexualized or threatening tone), location (eg, at a professional’s home), or means (eg, through social media). Stalking behaviors are not appropriate in any relationship, including a clinical relationship. They should not be treated as a “failure to manage transference” or in other victim-blaming ways.

There are multiple typologies for stalking behavior. Common motivations for stalking health professionals include resentment or grievance, misjudgment of social boundaries, and delusional fixation, including erotomania.8 Associated psychopathologies vary significantly and, while some may be more amenable to psychiatric treatment than others, psychiatrists should not feel compelled to treat patients who repeatedly violate boundaries, regardless of intent or comorbidity.

Patients are not the exclusive perpetrators of stalking; a recent study found that 4% of physicians surveyed reported current or recent stalking by a current or former intimate partner.9 When a person who is a victim of intimate partner violence is also stalked as part of the abuse, homicide risk increases.10 Workplace homicides of health care professionals are most likely to be committed by a current or former partner or other personal acquaintance, not by a patient.11 Workplace harassment and stalking of health care professionals is especially concerning because this behavior can escalate and endanger coworkers or clients.

Continue to: Risk awareness: Recognize your exposure...

Risk awareness: Recognize your exposure

About 80% of stalking involves some form of technology—often telephone calls but also online or other “cyber” elements.12 One recent survey found the rate of online harassment, including threats of physical and sexual violence, was >20% among physicians who were active on social media.4 Health professionals may be at greater risk of having patients find their personal information simply because patients routinely search online for information about new clinicians. Personal information about a clinician may be readily visible among professional information in search results, or a curious patient may simply scroll further down in the results. For a potential stalker, clicking on a search result linking to a personal social media page may be far easier than finding a home address and going in person—but the action may be just as distressing or risky for the clinician.13 Additionally, items visible in a clinician’s office—or visible in the background of those providing telehealth services from their home—may inadvertently reveal personal information about the clinician, their home, or their family.

Psychiatrists are often in a special position in relation to patients and times of crises. They may be involved in involuntary commitment—or declining an admission when a patient or family wishes it. They may be present at the time of the revelation of a serious diagnosis, abuse, injury, or death. They may be a mandated reporter of child or elder abuse.2 Additionally, physicians may be engaged in discourse on politically charged public health topics.14 These factors may increase their risk of being stalked.

Conducting an online visibility self-assessment can be a useful way to learn what information others can find. Table 2 outlines the steps for completing this exercise. Searching multiple iterations of your current and former names (with and without degrees, titles, and cities) will yield differing results in various search engines. After establishing a baseline of what information is available online, it can be helpful to periodically repeat this exercise, and to set up automated alerts for your name, number(s), email(s), and address(es).

Basic mitigation strategies

In the modern era, being invisible online is impractical and likely impossible—especially for a health care professional. Instead, it may be prudent to limit your public visibility to professional portals (eg, LinkedIn or Doximity) and maximize privacy settings on other platforms. Another basic strategy is to avoid providing personal contact information (your home address, phone number, or personal email) for professional purposes, such as licensing and credentialing, conference submissions, or journal publications. Be aware that driving a visually distinct vehicle—one with vanity plates or distinct bumper stickers, or an exotic sportscar—can make it easier to be recognized and located. A personally recorded voicemail greeting (vs one recorded by, for example, an office manager) may be inappropriately reinforcing for some stalkers.

Workplaces should have an established safety policy that addresses stalking and harassment of employees. Similarly, patients and others should receive clear education on how to contact different staff, including physicians, with consideration of how and when to use electronic health information portals, office numbers, and emails. Workplaces should not disclose staff schedules. For example, a receptionist should say “I’ll have Dr. Diaz return your call when she can” instead of “Dr. Diaz is not in until tomorrow.” Avoid unnecessary location/name signals (eg, a parking spot labeled “Dr. Diaz”). Consider creating alert words or phrases for staff to use to signal they are concerned about their immediate safety—and provide education and training, including drills, to test emergency responses when the words/phrases are used. Leaders and managers should nurture a workplace culture where people are comfortable seeking support if they feel they may be the target of harassment or stalking. Many larger health care organizations have threat management programs, which can play a critical role in preventing, investigating, and responding to stalking of employees. Increasingly, threat management teams are being identified as a best practice in health care settings.15Table 3 summarizes measures to mitigate risk.

What to do when harassment or stalking occurs

Consulting with subject matter experts is essential. Approach behaviors, stalking patterns, and immediate circumstances vary highly, and so too must responses. A socially inept approach outside of the work setting by a patient may be effectively responded to with a firm explanation of why the behavior was inappropriate and a reiteration of limits. More persistent or serious threats may require taking actions for immediate safety, calling law enforcement or security (who may have the expertise to assist appropriately), or even run/hide/fight measures. Others to notify early on include human resources, supervisors, front desk staff, and coworkers. Although no single measure is always indicated and no single measure will always be effective, consultation with a specialist is always advisable.

Attempting to assess your own risk may be subject to bias and error, even for an experienced forensic psychiatrist. Risk assessment in stalking and harassment cases is complex, nuanced, and beyond the scope of this article; engagement with specialized threat programs or subject matter experts is advisable.15,16 If your medical center or area has police or security officers, engage them early. Risk management, insurers, and legal can also be helpful to consult. Attorneys specializing in harassment, stalking, and domestic violence may be helpful in extreme situations.17Table 417,18 highlights steps to take.

While effective interventions to stop or redirect stalking behavior may vary, some initial considerations include changing established routines (eg, your parking location or daily/weekly patterns such as gym, class, etc.) and letting family and others you live with know what is occurring. Consider implementing and bolstering personal, work, and home security; honing situational awareness skills; and learning advanced situational awareness and self-defense techniques.

Continue to: Clinical documentation and termination of care...

Clinical documentation and termination of care

Repeated and unwanted contact behaviors by a patient may be considered grounds for termination of care by the targeted clinician. Termination may occur through a direct conversation, followed by a mailed letter explaining that the patient’s inappropriate behaviors are the basis for termination. The letter should outline steps for establishing care with another psychiatrist and signing a release to facilitate transfer of records to the next psychiatrist. Ensure that the patient has access to a reasonable supply of medications or refills according to jurisdictional standards for transfer or termination of care.19 While these are common legal standards for termination of care in the United States, clinicians would be well served by appropriate consultation to verify the most appropriate standards for their location.

Documentation of a patient’s behavior should be factual and clear. Under the 21st Century Cures Act, patients often have access to their own electronic records.20 Therefore, clinicians should avoid documenting personal security measures or other information that is not clinically relevant. Communications with legal or risk management should not be documented unless otherwise advised, because such communications may be privileged and may not be clinically relevant.

In some circumstances, continuing to treat a patient who has stalked a member of the current treatment team may be appropriate or necessary. For example, a patient may respond appropriately to redirection after an initial approach behavior and continue to make clinical progress, or may be in a forensic specialty setting with appropriate operational support to continue with treatment.

Ethical dilemmas may arise in underserved areas where there are limited options for psychiatric care and in communicating the reasons for termination to a new clinician. Consultation may help to address these issues. However, as noted before, clinicians should be permitted to discontinue and transfer treatment and should not be compelled to continue to treat a patient who has threatened or harassed them.

Organizational and employer considerations

Victims of stalking have reported that they appreciated explicit support from their supervisor, regular meetings, and measures to reduce potential stalking or violence in the workplace; unsurprisingly, victim blaming and leaving the employee to address the situation on their own were labeled experienced as negative.2 Employers may consider implementing physical security, access controls and panic alarms, and enhancing coworkers’ situational awareness.21 Explicit policies about and attention to reducing workplace violence, including stalking, are always beneficial—and in some settings such policies may be a regulatory requirement.22 Large health care organizations may benefit from developing specialized threat management programs to assist with the evaluation and mitigation of stalking and other workplace violence risks.15,23

Self-care considerations

The impact of stalking can include psychological distress, disruption of work and personal relationships, and false allegations of impropriety. Stalking can make targets feel isolated, violated, and fearful, which makes it challenging to reach out to others for support and safety. It takes time to regain a sense of safety and to find a “new normal,” particularly while experiencing and responding to stalking behavior. Notifying close personal contacts such as family and coworkers about what is occurring (without sharing protected health information) can be helpful for recovery and important for the clinician’s safety. Reaching out for organizational and legal supports is also prudent. It is also important to allow time for, and patience with, a targeted individual’s normal responses, such as decreased work performance, sleep/appetite changes, and hypervigilance, without pathologizing these common stress reactions. Further review of appropriate resources by impacted clinicians is advisable.24-26

Dr. A has been treating Ms. W, a graduate student, for depression. Ms. W made subtle comments expressing her interest in pursuing a romantic relationship with her psychiatrist. Dr. A gently redirected her, and she seemed to respond appropriately. However, over the past 2 weeks, Dr. A has seen Ms. W at a local park and at the grocery store. Today, Dr. A is startled to see Ms. W at her weekly yoga class. Dr. A plans to ask her supervisor for advice.

Dr. M is a child psychiatrist who spoke at his local school board meeting in support of masking requirements for students during COVID-19. During the discussion, Dr. M shared that, as a psychiatrist, he does not believe it is especially distressing for students to wear masks, and that doing so is a necessary public health measure. On leaving, other parents shouted, “We know who you are and where you live!” The next day, his integrated clinic started receiving threatening and harassing messages, including threats to kill him or his staff if they take part in vaccinating children against COVID-19.

Because of their work, mental health professionals—like other health care professionals—face an elevated risk of being harassed or stalked. Stalking often includes online harassment and may escalate to serious physical violence. Stalking is criminal behavior by a patient and should not be constructed as a “failure to manage transference.” This article explores basic strategies to reduce the risk of harassment and stalking, describes how to recognize early behaviors, and outlines basic steps health care professionals and their employers can take to respond to stalking and harassing behaviors.

Although this article is intended for psychiatrists, it is important to note that all health professionals have significant risk for experiencing stalking or harassment. This is due in part, but not exclusively, to our clinical work. Estimates of how many health professionals experience stalking vary substantially depending upon the study, and differences in methodologies limit easy comparison or extrapolation. More thorough reviews have reported ranges from 2% to 70% among physicians; psychiatrists and other mental health professionals appear to be at greater risk than those in other specialties and the general population.1-3 Physicians who are active on social media may also be at elevated risk.4 Unexpected communications from patients and their family members—especially those with threatening, harassing, or sexualized tones, or involving contact outside of a work setting—can be distressing. These behaviors represent potential harbingers of more dangerous behavior, including physical assault, sexual assault, or homicide. Despite their elevated risk, many psychiatrists are unaware of how to prevent or respond to stalking or harassment.

Recognizing harassment and stalking

Repeated and unwanted contact or communication, regardless of intent, may constitute stalking. Legal definitions vary by jurisdiction and may not align with subjective experiences or understanding of what constitutes stalking.5 At its essence, stalking is repeated harassing behaviors likely to provoke fear in the targeted person. FOUR is a helpful mnemonic when conceptualizing the attributes of stalking: Fixated, Obsessive, Unwanted, and Repetitive.6Table 1 lists examples of common stalking behaviors. Stalking and harassing behavior may be from a known source (eg, a patient, coworker, or paramour), a masked source (ie, someone known to the target but who conceals or obscures their identity), or from otherwise unknown persons. Behaviors that persist after the person engaging in the behaviors has clearly been informed that they are unwanted or inappropriate are especially concerning. Stalking may escalate to include physical or sexual assault and, in some cases, homicide.

Stalking duration can vary substantially, as can the factors that lead to the cessation of the behavior. Indicators of increased risk for physical violence include unwanted physical presence/following of the target (“approach behaviors”), having a prior violent intimate relationship, property destruction, explicit threats, and having a prior intimate relationship with the target.7

Stalking contact or communication may be unwanted because of the content (eg, sexualized or threatening tone), location (eg, at a professional’s home), or means (eg, through social media). Stalking behaviors are not appropriate in any relationship, including a clinical relationship. They should not be treated as a “failure to manage transference” or in other victim-blaming ways.

There are multiple typologies for stalking behavior. Common motivations for stalking health professionals include resentment or grievance, misjudgment of social boundaries, and delusional fixation, including erotomania.8 Associated psychopathologies vary significantly and, while some may be more amenable to psychiatric treatment than others, psychiatrists should not feel compelled to treat patients who repeatedly violate boundaries, regardless of intent or comorbidity.

Patients are not the exclusive perpetrators of stalking; a recent study found that 4% of physicians surveyed reported current or recent stalking by a current or former intimate partner.9 When a person who is a victim of intimate partner violence is also stalked as part of the abuse, homicide risk increases.10 Workplace homicides of health care professionals are most likely to be committed by a current or former partner or other personal acquaintance, not by a patient.11 Workplace harassment and stalking of health care professionals is especially concerning because this behavior can escalate and endanger coworkers or clients.

Continue to: Risk awareness: Recognize your exposure...

Risk awareness: Recognize your exposure

About 80% of stalking involves some form of technology—often telephone calls but also online or other “cyber” elements.12 One recent survey found the rate of online harassment, including threats of physical and sexual violence, was >20% among physicians who were active on social media.4 Health professionals may be at greater risk of having patients find their personal information simply because patients routinely search online for information about new clinicians. Personal information about a clinician may be readily visible among professional information in search results, or a curious patient may simply scroll further down in the results. For a potential stalker, clicking on a search result linking to a personal social media page may be far easier than finding a home address and going in person—but the action may be just as distressing or risky for the clinician.13 Additionally, items visible in a clinician’s office—or visible in the background of those providing telehealth services from their home—may inadvertently reveal personal information about the clinician, their home, or their family.

Psychiatrists are often in a special position in relation to patients and times of crises. They may be involved in involuntary commitment—or declining an admission when a patient or family wishes it. They may be present at the time of the revelation of a serious diagnosis, abuse, injury, or death. They may be a mandated reporter of child or elder abuse.2 Additionally, physicians may be engaged in discourse on politically charged public health topics.14 These factors may increase their risk of being stalked.

Conducting an online visibility self-assessment can be a useful way to learn what information others can find. Table 2 outlines the steps for completing this exercise. Searching multiple iterations of your current and former names (with and without degrees, titles, and cities) will yield differing results in various search engines. After establishing a baseline of what information is available online, it can be helpful to periodically repeat this exercise, and to set up automated alerts for your name, number(s), email(s), and address(es).

Basic mitigation strategies

In the modern era, being invisible online is impractical and likely impossible—especially for a health care professional. Instead, it may be prudent to limit your public visibility to professional portals (eg, LinkedIn or Doximity) and maximize privacy settings on other platforms. Another basic strategy is to avoid providing personal contact information (your home address, phone number, or personal email) for professional purposes, such as licensing and credentialing, conference submissions, or journal publications. Be aware that driving a visually distinct vehicle—one with vanity plates or distinct bumper stickers, or an exotic sportscar—can make it easier to be recognized and located. A personally recorded voicemail greeting (vs one recorded by, for example, an office manager) may be inappropriately reinforcing for some stalkers.

Workplaces should have an established safety policy that addresses stalking and harassment of employees. Similarly, patients and others should receive clear education on how to contact different staff, including physicians, with consideration of how and when to use electronic health information portals, office numbers, and emails. Workplaces should not disclose staff schedules. For example, a receptionist should say “I’ll have Dr. Diaz return your call when she can” instead of “Dr. Diaz is not in until tomorrow.” Avoid unnecessary location/name signals (eg, a parking spot labeled “Dr. Diaz”). Consider creating alert words or phrases for staff to use to signal they are concerned about their immediate safety—and provide education and training, including drills, to test emergency responses when the words/phrases are used. Leaders and managers should nurture a workplace culture where people are comfortable seeking support if they feel they may be the target of harassment or stalking. Many larger health care organizations have threat management programs, which can play a critical role in preventing, investigating, and responding to stalking of employees. Increasingly, threat management teams are being identified as a best practice in health care settings.15Table 3 summarizes measures to mitigate risk.

What to do when harassment or stalking occurs

Consulting with subject matter experts is essential. Approach behaviors, stalking patterns, and immediate circumstances vary highly, and so too must responses. A socially inept approach outside of the work setting by a patient may be effectively responded to with a firm explanation of why the behavior was inappropriate and a reiteration of limits. More persistent or serious threats may require taking actions for immediate safety, calling law enforcement or security (who may have the expertise to assist appropriately), or even run/hide/fight measures. Others to notify early on include human resources, supervisors, front desk staff, and coworkers. Although no single measure is always indicated and no single measure will always be effective, consultation with a specialist is always advisable.

Attempting to assess your own risk may be subject to bias and error, even for an experienced forensic psychiatrist. Risk assessment in stalking and harassment cases is complex, nuanced, and beyond the scope of this article; engagement with specialized threat programs or subject matter experts is advisable.15,16 If your medical center or area has police or security officers, engage them early. Risk management, insurers, and legal can also be helpful to consult. Attorneys specializing in harassment, stalking, and domestic violence may be helpful in extreme situations.17Table 417,18 highlights steps to take.

While effective interventions to stop or redirect stalking behavior may vary, some initial considerations include changing established routines (eg, your parking location or daily/weekly patterns such as gym, class, etc.) and letting family and others you live with know what is occurring. Consider implementing and bolstering personal, work, and home security; honing situational awareness skills; and learning advanced situational awareness and self-defense techniques.

Continue to: Clinical documentation and termination of care...

Clinical documentation and termination of care

Repeated and unwanted contact behaviors by a patient may be considered grounds for termination of care by the targeted clinician. Termination may occur through a direct conversation, followed by a mailed letter explaining that the patient’s inappropriate behaviors are the basis for termination. The letter should outline steps for establishing care with another psychiatrist and signing a release to facilitate transfer of records to the next psychiatrist. Ensure that the patient has access to a reasonable supply of medications or refills according to jurisdictional standards for transfer or termination of care.19 While these are common legal standards for termination of care in the United States, clinicians would be well served by appropriate consultation to verify the most appropriate standards for their location.

Documentation of a patient’s behavior should be factual and clear. Under the 21st Century Cures Act, patients often have access to their own electronic records.20 Therefore, clinicians should avoid documenting personal security measures or other information that is not clinically relevant. Communications with legal or risk management should not be documented unless otherwise advised, because such communications may be privileged and may not be clinically relevant.

In some circumstances, continuing to treat a patient who has stalked a member of the current treatment team may be appropriate or necessary. For example, a patient may respond appropriately to redirection after an initial approach behavior and continue to make clinical progress, or may be in a forensic specialty setting with appropriate operational support to continue with treatment.

Ethical dilemmas may arise in underserved areas where there are limited options for psychiatric care and in communicating the reasons for termination to a new clinician. Consultation may help to address these issues. However, as noted before, clinicians should be permitted to discontinue and transfer treatment and should not be compelled to continue to treat a patient who has threatened or harassed them.

Organizational and employer considerations

Victims of stalking have reported that they appreciated explicit support from their supervisor, regular meetings, and measures to reduce potential stalking or violence in the workplace; unsurprisingly, victim blaming and leaving the employee to address the situation on their own were labeled experienced as negative.2 Employers may consider implementing physical security, access controls and panic alarms, and enhancing coworkers’ situational awareness.21 Explicit policies about and attention to reducing workplace violence, including stalking, are always beneficial—and in some settings such policies may be a regulatory requirement.22 Large health care organizations may benefit from developing specialized threat management programs to assist with the evaluation and mitigation of stalking and other workplace violence risks.15,23

Self-care considerations

The impact of stalking can include psychological distress, disruption of work and personal relationships, and false allegations of impropriety. Stalking can make targets feel isolated, violated, and fearful, which makes it challenging to reach out to others for support and safety. It takes time to regain a sense of safety and to find a “new normal,” particularly while experiencing and responding to stalking behavior. Notifying close personal contacts such as family and coworkers about what is occurring (without sharing protected health information) can be helpful for recovery and important for the clinician’s safety. Reaching out for organizational and legal supports is also prudent. It is also important to allow time for, and patience with, a targeted individual’s normal responses, such as decreased work performance, sleep/appetite changes, and hypervigilance, without pathologizing these common stress reactions. Further review of appropriate resources by impacted clinicians is advisable.24-26

1. Nelsen AJ, Johnson RS, Ostermeyer B, et al. The prevalence of physicians who have been stalked: a systematic review. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2015;43(2):177-182.

2. Jutasi C, McEwan TE. Stalking of professionals: a scoping review. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management. 2021;8(3):94-124.

3. Pathé MT, Meloy JR. Commentary: Stalking by patients—psychiatrists’ tales of anger, lust and ignorance. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2013;41(2):200-205.

4. Pendergrast TR, Jain S, Trueger NS, et al. Prevalence of personal attacks and sexual harassment of physicians on social media. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(4):550-552.

5. Owens JG. Why definitions matter: stalking victimization in the United States. J Interpers Violence. 2016;31(12):2196-2226.

6. College of Policing. Stalking or harassment. May 2019. Accessed March 8, 2020. https://library.college.police.uk/docs/college-of-policing/Stalking_or_harassment_guidance_200519.pdf

7. McEwan TE, Daffern M, MacKenzie RD, et al. Risk factors for stalking violence, persistence, and recurrence. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology. 2017;28(1):3856.

8. Pathé MT, Mullen PE, Purcell R. Patients who stalk doctors: their motives and management. Med J Australia. 2002;176(7):335-338.

9. Reibling ET, Distelberg B, Guptill M, et al. Intimate partner violence experienced by physicians. J Prim Care Community Health. 2020;11:2150132720965077.

10. Matias A, Gonçalves M, Soeiro C, et al. Intimate partner homicide: a meta-analysis of risk factors. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2019;50:101358.

11. US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Fact sheet. Workplace violence in healthcare, 2018. April 2020. Accessed November 24, 2021. https://www.bls.gov/iif/oshwc/cfoi/workplace-violence-healthcare-2018.htm

12. Truman JL, Morgan RE. Stalking victimization, 2016. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Report No.: NCJ 253526. April 2021. Accessed November 24, 2021. https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/stalking-victimization-2016

13. Reyns BW, Henson B, Fisher BS. Being pursued online: applying cyberlifestyle–routine activities theory to cyberstalking victimization. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2011;38(11):1149-1169.

14. Stea JN. When promoting knowledge makes you a target. Scientific American Blog Network. March 16, 2020. Accessed November 24, 2021. https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/when-promoting-knowledge-makes-you-a-target/

15. Henkel SJ. Threat assessment strategies to mitigate violence in healthcare. IAHSS Foundation. IAHSS-F RS-19-02. November 2019. Accessed November 24, 2021. https://iahssf.org/assets/IAHSS-Foundation-Threat-Assessment-Strategies-to-Mitigate-Violence-in-Healthcare.pdf

16. McEwan TE. Stalking threat and risk assessment. In: Reid Meloy J, Hoffman J (eds). International Handbook of Threat Assessment. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press; 2021:210-234.

17. Goldberg C. Nobody’s Victim: Fighting Psychos, Stalkers, Pervs, and Trolls. Plume; 2019.

18. Bazzell M. Extreme Privacy: What It Takes to Disappear. 2nd ed. Independently published; 2020.

19. Simon RI, Shuman DW. The doctor-patient relationship. Focus. 2007;5(4):423-431.

20. Department of Health and Human Services. 21st Century Cures Act: Interoperability, Information Blocking, and the ONC Health IT Certification Program Final Rule (To be codified at 45 CFR 170 and 171). Federal Register. 2020;85(85):25642-25961.

21. Sheridan L, North AC, Scott AJ. Stalking in the workplace. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management. 2019;6(2):61-75.

22. The Joint Commission. Workplace Violence Prevention Standards. R3 Report: Requirement, Rationale, Reference. Issue 30. June 18, 2021. Accessed November 24, 2021. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/standards/r3-reports/wpvp-r3-30_revised_06302021.pdf

23. Terry LP. Threat assessment teams. J Healthc Prot Manage. 2015;31(2):23-35.

24. Pathé M. Surviving Stalking. Cambridge University Press; 2002.

25. Noffsinger S. What stalking victims need to restore their mental and somatic health. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(6):43-47.

26. Mullen P, Whyte S, McIvor R; Psychiatrists’ Support Service, Royal College of Psychiatry. PSS Information Guide: Stalking. Report No. 11. 2017. Accessed November 24, 2021. https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/members/supporting-you/pss/pss-guide-11-stalking.pdf?sfvrsn=2f1c7253_2

1. Nelsen AJ, Johnson RS, Ostermeyer B, et al. The prevalence of physicians who have been stalked: a systematic review. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2015;43(2):177-182.

2. Jutasi C, McEwan TE. Stalking of professionals: a scoping review. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management. 2021;8(3):94-124.

3. Pathé MT, Meloy JR. Commentary: Stalking by patients—psychiatrists’ tales of anger, lust and ignorance. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2013;41(2):200-205.

4. Pendergrast TR, Jain S, Trueger NS, et al. Prevalence of personal attacks and sexual harassment of physicians on social media. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(4):550-552.

5. Owens JG. Why definitions matter: stalking victimization in the United States. J Interpers Violence. 2016;31(12):2196-2226.

6. College of Policing. Stalking or harassment. May 2019. Accessed March 8, 2020. https://library.college.police.uk/docs/college-of-policing/Stalking_or_harassment_guidance_200519.pdf

7. McEwan TE, Daffern M, MacKenzie RD, et al. Risk factors for stalking violence, persistence, and recurrence. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology. 2017;28(1):3856.

8. Pathé MT, Mullen PE, Purcell R. Patients who stalk doctors: their motives and management. Med J Australia. 2002;176(7):335-338.

9. Reibling ET, Distelberg B, Guptill M, et al. Intimate partner violence experienced by physicians. J Prim Care Community Health. 2020;11:2150132720965077.

10. Matias A, Gonçalves M, Soeiro C, et al. Intimate partner homicide: a meta-analysis of risk factors. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2019;50:101358.

11. US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Fact sheet. Workplace violence in healthcare, 2018. April 2020. Accessed November 24, 2021. https://www.bls.gov/iif/oshwc/cfoi/workplace-violence-healthcare-2018.htm

12. Truman JL, Morgan RE. Stalking victimization, 2016. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Report No.: NCJ 253526. April 2021. Accessed November 24, 2021. https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/stalking-victimization-2016

13. Reyns BW, Henson B, Fisher BS. Being pursued online: applying cyberlifestyle–routine activities theory to cyberstalking victimization. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2011;38(11):1149-1169.

14. Stea JN. When promoting knowledge makes you a target. Scientific American Blog Network. March 16, 2020. Accessed November 24, 2021. https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/when-promoting-knowledge-makes-you-a-target/

15. Henkel SJ. Threat assessment strategies to mitigate violence in healthcare. IAHSS Foundation. IAHSS-F RS-19-02. November 2019. Accessed November 24, 2021. https://iahssf.org/assets/IAHSS-Foundation-Threat-Assessment-Strategies-to-Mitigate-Violence-in-Healthcare.pdf

16. McEwan TE. Stalking threat and risk assessment. In: Reid Meloy J, Hoffman J (eds). International Handbook of Threat Assessment. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press; 2021:210-234.

17. Goldberg C. Nobody’s Victim: Fighting Psychos, Stalkers, Pervs, and Trolls. Plume; 2019.

18. Bazzell M. Extreme Privacy: What It Takes to Disappear. 2nd ed. Independently published; 2020.

19. Simon RI, Shuman DW. The doctor-patient relationship. Focus. 2007;5(4):423-431.

20. Department of Health and Human Services. 21st Century Cures Act: Interoperability, Information Blocking, and the ONC Health IT Certification Program Final Rule (To be codified at 45 CFR 170 and 171). Federal Register. 2020;85(85):25642-25961.

21. Sheridan L, North AC, Scott AJ. Stalking in the workplace. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management. 2019;6(2):61-75.

22. The Joint Commission. Workplace Violence Prevention Standards. R3 Report: Requirement, Rationale, Reference. Issue 30. June 18, 2021. Accessed November 24, 2021. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/standards/r3-reports/wpvp-r3-30_revised_06302021.pdf

23. Terry LP. Threat assessment teams. J Healthc Prot Manage. 2015;31(2):23-35.

24. Pathé M. Surviving Stalking. Cambridge University Press; 2002.

25. Noffsinger S. What stalking victims need to restore their mental and somatic health. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(6):43-47.

26. Mullen P, Whyte S, McIvor R; Psychiatrists’ Support Service, Royal College of Psychiatry. PSS Information Guide: Stalking. Report No. 11. 2017. Accessed November 24, 2021. https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/members/supporting-you/pss/pss-guide-11-stalking.pdf?sfvrsn=2f1c7253_2

Olanzapine-samidorphan combination for schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder

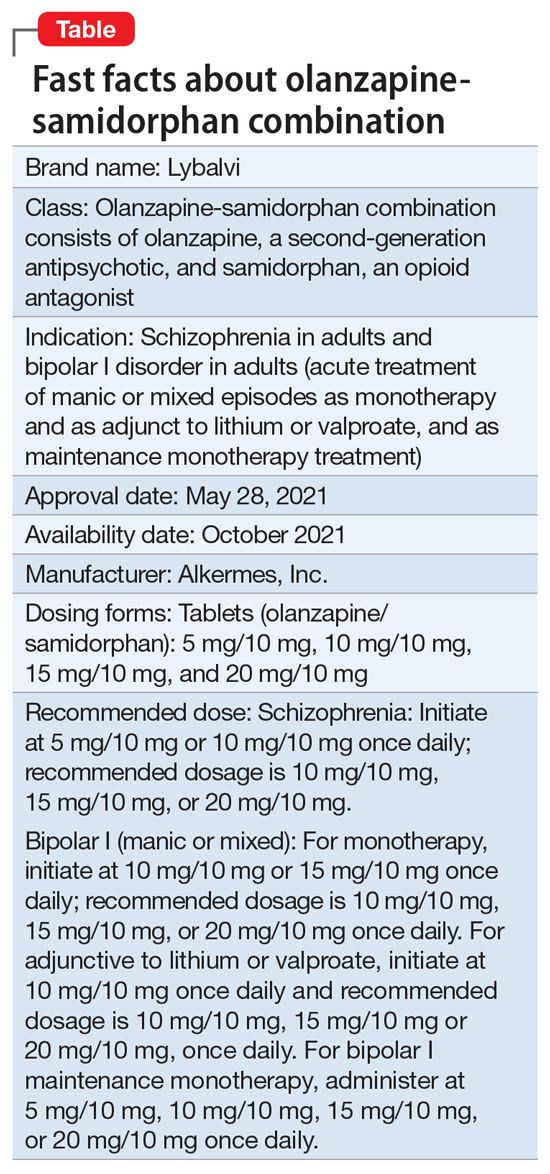

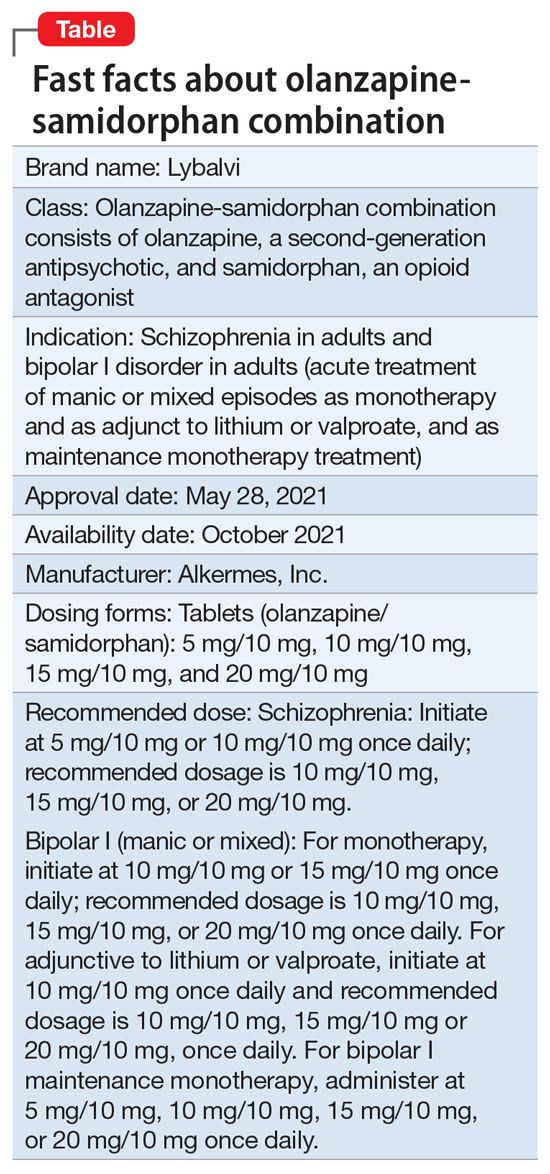

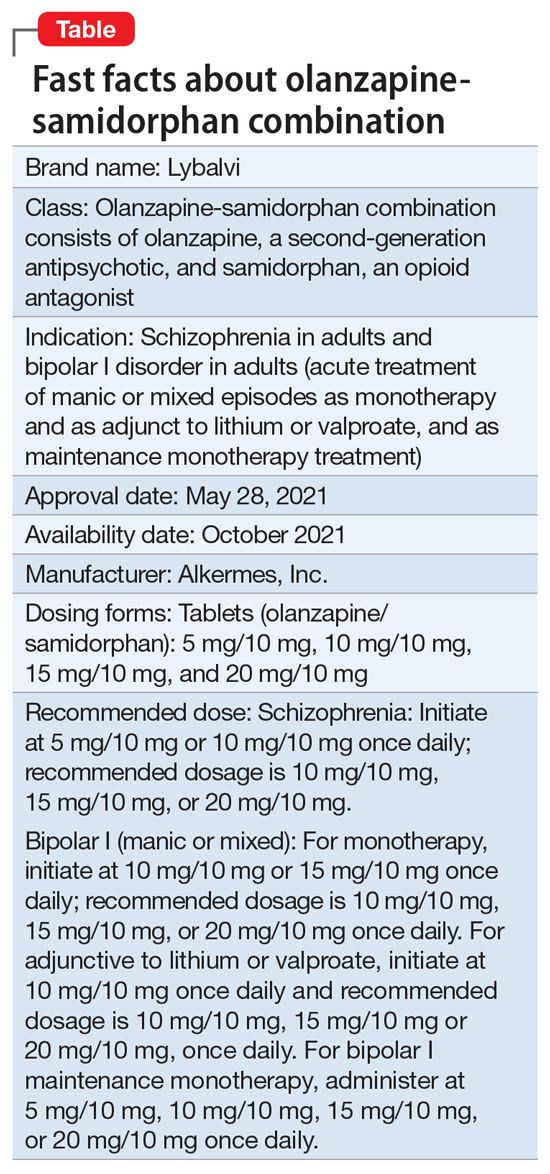

Approved by the FDA on May 28, 2021, olanzapine-samidorphan combination (OSC) (Lybalvi, manufactured and distributed by Alkermes, Inc. Waltham, MA USA) is intended to help mitigate some of the weight gain that can be anticipated with the use of olanzapine alone (Table).1-3 Olanzapine (Zyprexa, originally manufactured and distributed by Eli Lilly and Company/Lilly USA, LLC, Indianapolis, IN USA) is a second-generation antipsychotic that has been available for a quarter century.4 Although highly efficacious,5,6 olanzapine has been associated with weight gain, at times substantial, as well as disturbances in glucose and lipid metabolism.7 The addition of samidorphan, an opioid antagonist, to olanzapine in a single tablet may act to decrease the amount of long-term weight gain that can be expected for some patients taking olanzapine alone, consequently minimizing the anticipated increase in waist circumference (a proxy for the measurement of burden imposed by metabolically active adipose tissue). Approval of OSC for the treatment of schizophrenia was based on 2 pivotal randomized controlled trials and their extension studies.8-11 Approval of OSC for bipolar I disorder (acute treatment of manic/mixed episodes as a monotherapy or adjunctive to lithium or valproate, and as a monotherapy maintenance treatment) was based on legacy studies conducted with olanzapine, after establishing that samidorphan does not alter the pharmacokinetics of olanzapine, including in combination with lithium or valproate.3,12,13 OSC should be distinguished from a different combination product, olanzapine-fluoxetine combination (Symbyax, originally manufactured and distributed by Eli Lilly and Company/Lilly USA, LLC, Indianapolis, IN USA), approved for acute depressive episodes associated with bipolar I disorder and for treatment-resistant depression.14

OSC offers the potential to consider olanzapine earlier in the treatment of schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder, especially among practitioners who might otherwise be hesitant to prescribe this agent because of concerns over the risk of excessive weight gain.

OSC is available in 4 dosage strengths containing 5 mg, 10 mg, 15 mg, or 20 mg of olanzapine; all tablets contain 10 mg of samidorphan.2 The recommended starting dose for OSC mirrors the language contained in the legacy olanzapine product label.4 For schizophrenia, the recommended initial dose (olanzapine/samidorphan) is 5 mg/10 mg or 10 mg/10 mg once daily. For bipolar I manic or mixed episodes, the recommended starting dose for monotherapy is 10 mg/10 mg or 15 mg/10 mg, and for use with lithium or valproate, 10 mg/10 mg. For all indications, the recommended target dose can be 10 mg/10 mg, 15 mg/10 mg, or 20 mg/10 mg, with 5 mg/10 mg as an additional potential dose for maintenance monotherapy of bipolar I disorder. The maximum dose is 20 mg/10 mg once daily. Because the amount of samidorphan in each tablet is fixed at 10 mg, combining tablets of OSC, or cutting OSC tablets in half, is not advisable.

Continue to: How it works...

How it works

Product labeling notes that olanzapine is an atypical antipsychotic, that its efficacy in schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder could be mediated through a combination of dopamine and serotonin type 2 (5HT2) antagonism, and that the mechanism of action of samidorphan could be mediated through opioid receptor antagonism.2

The pharmacodynamic profile of olanzapine is complex.2 It binds with high affinity to the following receptors: serotonin 5HT2A/2C, 5HT6 (Ki = 4, 11, and 5 nM, respectively), dopamine D1-4 (Ki = 11-31 nM), histamine H1 (Ki = 7 nM), and adrenergic alpha-1 receptors (Ki = 19 nM). Olanzapine is an antagonist with moderate affinity binding for serotonin 5HT3 (Ki = 57 nM) and muscarinic M1-5 (Ki = 73, 96, 132, 32, and 48 nM, respectively). Olanzapine binds with low affinity to gamma aminobutyric acid type A (GABA-A), benzodiazepine, and beta-adrenergic receptors (Ki >10 µM). Olanzapine’s muscarinic receptor affinity can explain why olanzapine can be associated with constipation, dry mouth, and tachycardia, all adverse reactions possibly related to cholinergic antagonism. Thus, OSC should be used with caution in patients with a current diagnosis or prior history of urinary retention, clinically significant prostatic hypertrophy, constipation, or a history of paralytic ileus or related conditions; a potential drug-drug interaction can be anticipated with concomitant use of anticholinergic medications.2 Other pharmacodynamic drug-drug interactions that can occur with the olanzapine component of OSC include the possibility that diazepam, alcohol, or other CNS-acting drugs may potentiate orthostatic hypotension, and there may be a need to reduce the dosage of concomitantly prescribed antihypertensive drugs in patients being treated for hypertension. Moreover, OSC is not recommended in patients receiving levodopa and dopamine agonists.

Samidorphan binds to the mu-, kappa-, and delta-opioid receptors (Ki = .052, .23, and 2.7 nM, respectively).2 Samidorphan is an antagonist at the mu-opioid receptors with partial agonist activity at kappa- and delta-opioid receptors. A major human metabolite of samidorphan (N-dealkylated) binds to the mu-, kappa-, and delta-opioid receptors (Ki = .26, 23, and 56 nM, respectively), and functions as a mu-opioid receptor agonist. The N-oxide major human metabolite binds to mu-, kappa-, and delta-opioid receptors (Ki = 8, 110, and 280 nM, respectively) and functions as a mu-opioid receptor antagonist. This profile differs from that of other opioid antagonists such as naltrexone.15,16

OSC is not a scheduled drug subject to the Controlled Substances Act. Because samidorphan functions as an opioid antagonist, OSC is contraindicated in patients using opioids or undergoing acute opioid withdrawal.2

Regarding cardiac electrophysiology, OSC was not observed to prolong the electrocardiogram QTc interval to any clinically relevant extent when tested at doses up to 30 mg/30 mg (1.5 times and 3 times the maximum recommended daily dosage of olanzapine and samidorphan, respectively).17

Clinical pharmacokinetics

The pharmacokinetics of both olanzapine and samidorphan are linear over the clinical dose range and there is no pharmacokinetic interaction between olanzapine and samidorphan after oral administration of OSC.2 Coadministration of OSC with lithium or valproate does not have a clinically significant effect on systemic exposure of lithium or valproate.13 OSC steady-state concentrations of olanzapine and samidorphan are reached within 7 days, with accumulation at steady state being 2-fold for olanzapine and 1.3-fold for samidorphan (at 5 days). Elimination half-life for olanzapine is 35 to 52 hours, and for samidorphan, 7 to 11 hours. Olanzapine is metabolized primarily via UGT1A4 and CYP1A2, whereas samidorphan is primarily metabolized by CYP3A4. Consequently, concomitant use of OSC with strong CYP3A4 inducers is not recommended. The recommendation regarding CYP1A2 modulators and OSC are similar to those for olanzapine2,4: consider reducing the dosage of the olanzapine component in OSC when used concomitantly with strong CYP1A2 inhibitors, and consider increasing the dosage of the olanzapine component in OSC when used concomitantly with CYP1A2 inducers. Because cigarette smoke contains polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons that act as CYP1A2 inducers,18 olanzapine clearance is much higher in smokers than in nonsmokers.2 This translates to potentially clinically relevant differences when optimizing the dose. In a study of patients with schizophrenia, olanzapine concentrations were lower in self-reported smokers (16.5, 34.2, and 60.9 ng/mL) than in self-reported nonsmokers (25.6, 43.4, and 113.2 ng/mL) for dosages of 10, 20, and 40 mg/d, respectively.19 In contrast, samidorphan pharmacokinetics are not affected by smoking status.2

No dose adjustment of OSC is needed in patients with hepatic or renal impairment; however, OSC is not recommended for patients with end-stage renal disease because this has not been specifically studied.2

Continue to: Efficacy...

Efficacy

The efficacy of OSC in the treatment of schizophrenia in adults is supported, in part, by the extensive legacy of studies of orally administered olanzapine.2 For OSC specifically, acute efficacy was primarily demonstrated in a randomized, double-blind, phase 3, 4-week study establishing superiority vs placebo in acutely exacerbated patients with schizophrenia.8 Mitigation of weight gain was assessed separately in a randomized, double-blind, phase 3, 24-week study comparing OSC with olanzapine in non-acute outpatients with schizophrenia.10 Both of these 2 trials were accompanied by 52-week open-label extension studies.9,11

The 4-week study evaluated the antipsychotic efficacy of OSC in 401 patients experiencing an acute exacerbation or relapse of schizophrenia who required inpatient treatment.8 Patients were required to have a Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score ≥80, with a score ≥4 on at least 3 of selected positive symptoms, and a Clinical Global Impression-Severity (CGI-S) score ≥4 at baseline and screening. Patients were required to be inpatients for the first 2 weeks of the study, and were encouraged to remain as inpatients for all 4 weeks. Patients were randomized to receive OSC, olanzapine, or placebo. Dosing was once-daily and flexible based on clinical response and tolerability for the first 2 weeks of the study, and fixed thereafter. Patients assigned to OSC could receive 10 mg/10 mg or 20 mg/10 mg, and patients randomized to olanzapine could receive 10 mg or 20 mg. The study compared OSC with placebo, with olanzapine serving as an active control. Treatment with OSC resulted in significant improvements in symptoms compared with placebo at Week 4, as measured by changes in PANSS total scores from baseline. Improvement in PANSS scores with OSC relative to placebo was similar to that observed with olanzapine. The antipsychotic efficacy of OSC relative to placebo was also supported by improvements in CGI-S scores. Thus, the inclusion of samidorphan in OSC did not negatively impact the antipsychotic efficacy of olanzapine.

In the 24-week study, 561 patients were randomized to OSC or olanzapine.10 There was no placebo control. Patients were treated with doses of OSC 10 mg/10 mg or 20 mg/10 mg, or with doses of olanzapine 10 mg or 20 mg. Dosing was flexible for the first 4 weeks of the study and fixed thereafter. Eligible patients were age 18 to 55 years (younger than the 4-week study, where the maximum age was 70 years), with a body mass index of 18 to 30 kg/m2 (lower than the upper limit of 40 kg/m2 used in the 4-week study). In contrast to the acutely exacerbated patients in the 4-week study, patients were required to have a PANSS total score of 50 to 90, CGI-S score ≤4, and symptoms suitable for outpatient treatment. The co-primary endpoints were percent change from baseline in body weight and proportion of patients who gained ≥10% body weight at Week 24. Treatment with OSC or olanzapine resulted in similar improvements in PANSS total and CGI-S scores, but treatment with OSC was associated with statistically significantly less weight gain than treatment with olanzapine, and with a smaller proportion of patients who gained ≥10% body weight. The least squares mean percent weight change from baseline to the end of treatment was 4.2% with OSC vs 6.6% with olanzapine. Although patients treated with OSC or olanzapine had similar weight gain for the first 4 weeks of treatment, OSC weight gain stabilized after approximately the 6th week, whereas patients who received olanzapine continued to gain weight throughout the remainder of the treatment period. The risk of gaining ≥10% body weight from baseline was reduced by 50% with OSC compared with olanzapine. Moreover, the odds of gaining ≥7% body weight from baseline at Week 24 were also reduced by 50% for OSC compared with olanzapine. OSC was also associated with smaller increases in waist circumference compared with olanzapine, which was observable as early as Week 1. The risk of experiencing a 5-cm increase in waist circumference was 50% lower for patients treated with OSC vs olanzapine, a relevant threshold in assessing risk of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease.20 However, changes in metabolic laboratory parameters in patients treated with OSC or olanzapine were generally small and were similar between groups. In addition, there were little differences between the 2 treatment groups in metabolic parameter changes considered to be of potential clinical significance, based on commonly used thresholds.

Patients on stable, chronic olanzapine therapy were not specifically studied, so the weight effect of switching from olanzapine to OSC is unknown.For bipolar I manic or mixed episodes, the use of OSC as monotherapy or in combination with lithium or valproate, as well as for maintenance monotherapy, was approved based on legacy clinical trials with olanzapine, as described in product labeling,2,4 as well as pharmacokinetic data evidencing that OSC did not have a clinically significant effect on the pharmacokinetics of lithium or valproate.13 A study is in progress to evaluate the effect of OSC compared with olanzapine on body weight in young adults with schizophrenia, schizophreniform, or bipolar I disorder who are early in their illness (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03187769).

Overall tolerability and safety

The systemic safety and tolerability profile for OSC would be expected to be similar to that for olanzapine, unless there are adverse events that are specifically related to the samidorphan component. In the 4-week acute study described above,8 adverse events that occurred at least twice the rate of placebo with OSC included increased weight (18.7%, 14.3%, 3.0%, for OSC, olanzapine, and placebo, respectively), somnolence (9.0%, 9.8%, 2.2%), dry mouth (7.5%, 5.3%, 0.7%), and headache (6.0%, 5.3%, 3.0%). In the 24-week study,10 which did not have a placebo control, the most commonly reported adverse events (≥10% of patients) were increased weight (24.8% vs 36.2% for OSC vs olanzapine), somnolence (21.2% vs 18.1%), dry mouth (12.8% vs 8.0%), and increased appetite (10.9% vs 12.3%). In both studies, rates of discontinuation due to adverse events were low and similar between groups (in the 4-week study, 1.5% for OSC, 2.3% for olanzapine, and 5.2% for placebo; in the 24-week study, 12.0% for OSC and 9.8% for olanzapine).

In the 2 open-label, phase 3, 52-week extension studies,9,11 long-term tolerability was evidenced by low rates discontinuation due to adverse events (≤6%). Neither extension study reported any clinically meaningful changes over time in hematology, biochemistry, vital signs, or electrocardiogram parameters.3 In addition to durability of antipsychotic response as evidenced by sustained improvements in PANSS and CGI-S scores over time, waist circumference and weight remained stable, and the observed long-term changes in weight were consistent with weight changes observed with other second-generation antipsychotics.3 Long-term changes in metabolic laboratory parameter values were small and remained stable, and there was little change in glycosylated hemoglobin (hemoglobin A1c) values, which suggests that glycemic control was maintained with long-term OSC treatment.3 Caveats to consider are that the extension studies were open label without comparators, and they may have selected for patients who responded favorably to OSC treatment in the preceding studies.3Warnings and precautions in OSC product labeling are generally similar to those for other second-generation antipsychotics,21 other than warnings and precautions specifically related to samidorphan being an opioid antagonist, and special mention of “Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms” and “Anticholinergic (Antimuscarinic) Effects” warnings, which also are contained in the olanzapine legacy label.2,4

Summary