User login

Hospitalists Can Address Causes of Skyrocketing Health Care Costs

Alarms about our nation’s health-care costs have been sounding for well over a decade. According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), spending on U.S. health care doubled between 1999 and 2011, climbing to $2.7 trillion from $1.3 trillion, and now represents 17.9% of the United States’ GDP.1

“The medical care system is bankrupting the country,” Paul B. Ginsburg, PhD, president of the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC), based in Washington, D.C., says bluntly. A four-decade-long upward spending trend is “unsustainable,” he wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine with Chapin White, PhD, a senior health researcher at HSC.2

Recent reports suggest that rising premiums and out-of-pocket costs are rendering the price of health care untenable for the average consumer. A 2011 RAND Corp. study found that, for the average American family, the rate of increased costs for health care had outpaced growth in earnings from 1999 to 2009.3 And last year, for the first time, the cost of health care for a typical American family of four surpassed $20,000, the annual Milliman Medical Index reported.4

Should hospitalists be concerned, professionally and personally, about these trends? Absolutely, say hospitalist leaders who spoke with The Hospitalist. HM clinicians have much to contribute at both the macro level (addressing systemic causes of overutilization through quality improvement and other initiatives) and at the micro level, by understanding their personal contributions and by engaging patients and their families in shared decision-making.

But getting at and addressing the root causes of rising health-care costs, according to health-care policy analysts and veteran hospitalists, will require major shifts in thinking and processes.

Contributors to Rising Costs

It’s difficult to pinpoint the root causes of the recent surge in health-care costs. Victor Fuchs, emeritus professor of economics and health research and policy at Stanford University, points to the U.S.’ high administrative costs and complicated billing systems.5 A fragmented, nontransparent system for negotiating fees between insurers and providers also plays a role, as demonstrated in a Consumer Reports investigation into geographic variations in costs for common tests and procedures. A complete blood count might be as low as $15 or as high as $105; a colonoscopy ranges from $800 to $3,160.6

Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, SFHM, an SHM Public Policy Committee member and AMA delegate, says rising costs are a provider-specific issue. He challenges colleagues to take an honest look at their own practice patterns to assess whether they’re contributing to overuse of resources (see “A Lesson in Change,”).

“The culture of practice has developed so that this is not going to change overnight,” says Dr. Flansbaum, director of hospitalist services at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City. That’s because many physicians fail to view their own decisions as a problem. For example, says Dr. Flansbaum, “an oncologist may not identify a third round of chemotherapy as an embodiment of the problem, or a gastroenterologist might not embody the colonoscopy at Year Four instead of Year Five as the problem. We must come to grips with the usual mindset, look in the mirror, and admit, ‘Maybe we are part of the problem.’”

—Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, SFHM

Potential Solutions

Hospitalists, intensivists, and ED clinicians are tasked with finding a balance between being prudent stewards of resources and staying within a comfort zone that promotes patient safety. SHM supports the goals of the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely campaign, which aims to reduce waste by curtailing duplicative and unnecessary care (see “Better Choices, Better Care,” March 2013). Also included in the campaign (www.ChoosingWisely.org) are the American College of Physicians’ recommendations against low-value testing (e.g. obtaining imaging studies in patients with nonspecific low back pain).

“Those recommendations are not going to solve our health spending problem,” says White, “but they are part of a broader move to give permission to clinicians, based on evidence, to follow more conservative practice patterns.”

Still, counters David I. Auerbach, PhD, a health economist at RAND in Boston and author of the RAND study, “there’s another value to these tests that the cost-effectiveness equations do not always consider, which is, they can bring peace of mind. We’re trying to nudge patients down the pathway that we think is best for them without rationing care. That’s a delicate balance.”

Dr. Flansbaum says SHM’s Public Policy Committee has discussed a variety of issues related to rising costs, although the group has not directly tackled advice in the form of a white paper. He suggests some ways that hospitalists can address cost savings:

- Involve patients in shared decision-making, and discuss the evidence against unnecessary testing;

- Utilize generic medications on discharge, when available, especially if patients are uninsured or have limited drug coverage with their insurance plans;

- Use palliative care whenever appropriate; and

- Adhere to transitional-care standards.

On the macro level, HM has “always been the specialty invited to champion the important discussion relating to resource utilization, and the evidence-based medicine driving that resource utilization,” says Christopher Frost, MD, FHM, medical director of hospital medicine at the Hospital Corporation of America (HCA) in Nashville, Tenn. He points to SHM’s leadership with Project BOOST (www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost) as one example of addressing the utilization of resources in caring for older adults (see “Resources for Improving Transitions in Care,”).

What else can hospitalists do? Going forward, says Dan Fuller, president and co-founder of IN Compass Health in Alpharetta, Ga., it might be a good idea for the SHM Practice Analysis Committee, of which he’s a member, to look at its possible role in the issue.

—Dr. Frederickson

Embrace Reality

Whatever the downstream developments around the Affordable Care Act, Dr. Ginsburg is “confident” that Medicare policies will continue in a direction of reduced reimbursements. Thomas Frederickson, MD, FACP, FHM, MBA, medical director of the hospital medicine service at Alegent Health in Omaha, Neb., agrees with such an assessment. He also believes that hospitalists are in a prime position to improve care delivery at less cost. To do so, though, requires deliberate partnership-building with outpatient providers to better bridge the transitions of care.

At his institution, Dr. Frederickson says, hospitalists invite themselves to primary-care physicians’ (PCP) meetings. This facilitates rapport so that calls to PCPs at discharge not only communicate essential clinical information, but also build confidence in the hospitalists’ care of their patients. As hospitalists demonstrate value, they must intentionally put metrics in place so that administrators appreciate the need to keep the census at a certain level, Dr. Frederickson says.

“We need the time to make these calls, to sit down with families,” he says. “This adds value to our health system and to society at large.”

SHM does a good job, says Dr. Frost, of being part of the conversation as the hospital C-suite focuses more on episodes of care.

“The intensity of that discussion is getting dialed up and will be driven more by government and the payors,” he adds. The challenge going forward will be to bridge those arenas just outside the acute episode of care, where hospitalists have ownership of processes, to those where they do not have as much control. If payors apply broader definitions to the episode of care, Dr. Frost says, hospitalists might be “invited to play an increasing role, that of ‘transitionist.’”

And in that context, he says, hospitalists need to look at length of stay with a new lens.

Partnership-building will become more important as the definition of “episode of care” expands beyond the hospital stay to the post-acute setting.

“Including post-acute care in the episode of care is a core aspect of the whole” value-based purchasing approach, Dr. Ginsburg says. “Hospitals [and hospitalists] will be wise to opt for the model with the greatest potential to reduce costs, particularly costs incurred by other providers.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

References

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National health expenditures 2011 highlights. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/Downloads/highlights.pdf. Accessed May 6, 2013. costs how much? Consumer Reports website. Available at: http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/magazine/ 2012/07/that-ct-scan-costs-how-much/index.htm. Accessed Aug. 2, 2012.

- White C, Ginsburg PB. Slower growth in Medicare spending—is this the new normal? N Engl J Med. 2012;366(12):1073-1075.

- Auerbach DI, Kellermann AL. A decade of health care cost growth has wiped out real income gains for an average US family. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(9):1630-1636.

- Milliman Inc. 2012 Milliman Medical Index. Milliman Inc. website. Available at: http://publications.milliman.com/periodicals/mmi/pdfs/milliman-medical-index-2012.pdf. Accessed Aug. 1, 2012.

- Kolata G. Knotty challenges in health care costs. The New York Times website. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/06/health/policy/an-interview-with-victor-fuchs-on-health-care-costs.html. Accessed March 8, 2012.

- Consumer Reports. That CT scan costs how much? Consumer Reports website. Available at: http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/magazine/ 2012/07/that-ct-scan-costs-how-much/index.htm.

Alarms about our nation’s health-care costs have been sounding for well over a decade. According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), spending on U.S. health care doubled between 1999 and 2011, climbing to $2.7 trillion from $1.3 trillion, and now represents 17.9% of the United States’ GDP.1

“The medical care system is bankrupting the country,” Paul B. Ginsburg, PhD, president of the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC), based in Washington, D.C., says bluntly. A four-decade-long upward spending trend is “unsustainable,” he wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine with Chapin White, PhD, a senior health researcher at HSC.2

Recent reports suggest that rising premiums and out-of-pocket costs are rendering the price of health care untenable for the average consumer. A 2011 RAND Corp. study found that, for the average American family, the rate of increased costs for health care had outpaced growth in earnings from 1999 to 2009.3 And last year, for the first time, the cost of health care for a typical American family of four surpassed $20,000, the annual Milliman Medical Index reported.4

Should hospitalists be concerned, professionally and personally, about these trends? Absolutely, say hospitalist leaders who spoke with The Hospitalist. HM clinicians have much to contribute at both the macro level (addressing systemic causes of overutilization through quality improvement and other initiatives) and at the micro level, by understanding their personal contributions and by engaging patients and their families in shared decision-making.

But getting at and addressing the root causes of rising health-care costs, according to health-care policy analysts and veteran hospitalists, will require major shifts in thinking and processes.

Contributors to Rising Costs

It’s difficult to pinpoint the root causes of the recent surge in health-care costs. Victor Fuchs, emeritus professor of economics and health research and policy at Stanford University, points to the U.S.’ high administrative costs and complicated billing systems.5 A fragmented, nontransparent system for negotiating fees between insurers and providers also plays a role, as demonstrated in a Consumer Reports investigation into geographic variations in costs for common tests and procedures. A complete blood count might be as low as $15 or as high as $105; a colonoscopy ranges from $800 to $3,160.6

Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, SFHM, an SHM Public Policy Committee member and AMA delegate, says rising costs are a provider-specific issue. He challenges colleagues to take an honest look at their own practice patterns to assess whether they’re contributing to overuse of resources (see “A Lesson in Change,”).

“The culture of practice has developed so that this is not going to change overnight,” says Dr. Flansbaum, director of hospitalist services at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City. That’s because many physicians fail to view their own decisions as a problem. For example, says Dr. Flansbaum, “an oncologist may not identify a third round of chemotherapy as an embodiment of the problem, or a gastroenterologist might not embody the colonoscopy at Year Four instead of Year Five as the problem. We must come to grips with the usual mindset, look in the mirror, and admit, ‘Maybe we are part of the problem.’”

—Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, SFHM

Potential Solutions

Hospitalists, intensivists, and ED clinicians are tasked with finding a balance between being prudent stewards of resources and staying within a comfort zone that promotes patient safety. SHM supports the goals of the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely campaign, which aims to reduce waste by curtailing duplicative and unnecessary care (see “Better Choices, Better Care,” March 2013). Also included in the campaign (www.ChoosingWisely.org) are the American College of Physicians’ recommendations against low-value testing (e.g. obtaining imaging studies in patients with nonspecific low back pain).

“Those recommendations are not going to solve our health spending problem,” says White, “but they are part of a broader move to give permission to clinicians, based on evidence, to follow more conservative practice patterns.”

Still, counters David I. Auerbach, PhD, a health economist at RAND in Boston and author of the RAND study, “there’s another value to these tests that the cost-effectiveness equations do not always consider, which is, they can bring peace of mind. We’re trying to nudge patients down the pathway that we think is best for them without rationing care. That’s a delicate balance.”

Dr. Flansbaum says SHM’s Public Policy Committee has discussed a variety of issues related to rising costs, although the group has not directly tackled advice in the form of a white paper. He suggests some ways that hospitalists can address cost savings:

- Involve patients in shared decision-making, and discuss the evidence against unnecessary testing;

- Utilize generic medications on discharge, when available, especially if patients are uninsured or have limited drug coverage with their insurance plans;

- Use palliative care whenever appropriate; and

- Adhere to transitional-care standards.

On the macro level, HM has “always been the specialty invited to champion the important discussion relating to resource utilization, and the evidence-based medicine driving that resource utilization,” says Christopher Frost, MD, FHM, medical director of hospital medicine at the Hospital Corporation of America (HCA) in Nashville, Tenn. He points to SHM’s leadership with Project BOOST (www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost) as one example of addressing the utilization of resources in caring for older adults (see “Resources for Improving Transitions in Care,”).

What else can hospitalists do? Going forward, says Dan Fuller, president and co-founder of IN Compass Health in Alpharetta, Ga., it might be a good idea for the SHM Practice Analysis Committee, of which he’s a member, to look at its possible role in the issue.

—Dr. Frederickson

Embrace Reality

Whatever the downstream developments around the Affordable Care Act, Dr. Ginsburg is “confident” that Medicare policies will continue in a direction of reduced reimbursements. Thomas Frederickson, MD, FACP, FHM, MBA, medical director of the hospital medicine service at Alegent Health in Omaha, Neb., agrees with such an assessment. He also believes that hospitalists are in a prime position to improve care delivery at less cost. To do so, though, requires deliberate partnership-building with outpatient providers to better bridge the transitions of care.

At his institution, Dr. Frederickson says, hospitalists invite themselves to primary-care physicians’ (PCP) meetings. This facilitates rapport so that calls to PCPs at discharge not only communicate essential clinical information, but also build confidence in the hospitalists’ care of their patients. As hospitalists demonstrate value, they must intentionally put metrics in place so that administrators appreciate the need to keep the census at a certain level, Dr. Frederickson says.

“We need the time to make these calls, to sit down with families,” he says. “This adds value to our health system and to society at large.”

SHM does a good job, says Dr. Frost, of being part of the conversation as the hospital C-suite focuses more on episodes of care.

“The intensity of that discussion is getting dialed up and will be driven more by government and the payors,” he adds. The challenge going forward will be to bridge those arenas just outside the acute episode of care, where hospitalists have ownership of processes, to those where they do not have as much control. If payors apply broader definitions to the episode of care, Dr. Frost says, hospitalists might be “invited to play an increasing role, that of ‘transitionist.’”

And in that context, he says, hospitalists need to look at length of stay with a new lens.

Partnership-building will become more important as the definition of “episode of care” expands beyond the hospital stay to the post-acute setting.

“Including post-acute care in the episode of care is a core aspect of the whole” value-based purchasing approach, Dr. Ginsburg says. “Hospitals [and hospitalists] will be wise to opt for the model with the greatest potential to reduce costs, particularly costs incurred by other providers.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

References

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National health expenditures 2011 highlights. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/Downloads/highlights.pdf. Accessed May 6, 2013. costs how much? Consumer Reports website. Available at: http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/magazine/ 2012/07/that-ct-scan-costs-how-much/index.htm. Accessed Aug. 2, 2012.

- White C, Ginsburg PB. Slower growth in Medicare spending—is this the new normal? N Engl J Med. 2012;366(12):1073-1075.

- Auerbach DI, Kellermann AL. A decade of health care cost growth has wiped out real income gains for an average US family. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(9):1630-1636.

- Milliman Inc. 2012 Milliman Medical Index. Milliman Inc. website. Available at: http://publications.milliman.com/periodicals/mmi/pdfs/milliman-medical-index-2012.pdf. Accessed Aug. 1, 2012.

- Kolata G. Knotty challenges in health care costs. The New York Times website. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/06/health/policy/an-interview-with-victor-fuchs-on-health-care-costs.html. Accessed March 8, 2012.

- Consumer Reports. That CT scan costs how much? Consumer Reports website. Available at: http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/magazine/ 2012/07/that-ct-scan-costs-how-much/index.htm.

Alarms about our nation’s health-care costs have been sounding for well over a decade. According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), spending on U.S. health care doubled between 1999 and 2011, climbing to $2.7 trillion from $1.3 trillion, and now represents 17.9% of the United States’ GDP.1

“The medical care system is bankrupting the country,” Paul B. Ginsburg, PhD, president of the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC), based in Washington, D.C., says bluntly. A four-decade-long upward spending trend is “unsustainable,” he wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine with Chapin White, PhD, a senior health researcher at HSC.2

Recent reports suggest that rising premiums and out-of-pocket costs are rendering the price of health care untenable for the average consumer. A 2011 RAND Corp. study found that, for the average American family, the rate of increased costs for health care had outpaced growth in earnings from 1999 to 2009.3 And last year, for the first time, the cost of health care for a typical American family of four surpassed $20,000, the annual Milliman Medical Index reported.4

Should hospitalists be concerned, professionally and personally, about these trends? Absolutely, say hospitalist leaders who spoke with The Hospitalist. HM clinicians have much to contribute at both the macro level (addressing systemic causes of overutilization through quality improvement and other initiatives) and at the micro level, by understanding their personal contributions and by engaging patients and their families in shared decision-making.

But getting at and addressing the root causes of rising health-care costs, according to health-care policy analysts and veteran hospitalists, will require major shifts in thinking and processes.

Contributors to Rising Costs

It’s difficult to pinpoint the root causes of the recent surge in health-care costs. Victor Fuchs, emeritus professor of economics and health research and policy at Stanford University, points to the U.S.’ high administrative costs and complicated billing systems.5 A fragmented, nontransparent system for negotiating fees between insurers and providers also plays a role, as demonstrated in a Consumer Reports investigation into geographic variations in costs for common tests and procedures. A complete blood count might be as low as $15 or as high as $105; a colonoscopy ranges from $800 to $3,160.6

Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, SFHM, an SHM Public Policy Committee member and AMA delegate, says rising costs are a provider-specific issue. He challenges colleagues to take an honest look at their own practice patterns to assess whether they’re contributing to overuse of resources (see “A Lesson in Change,”).

“The culture of practice has developed so that this is not going to change overnight,” says Dr. Flansbaum, director of hospitalist services at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City. That’s because many physicians fail to view their own decisions as a problem. For example, says Dr. Flansbaum, “an oncologist may not identify a third round of chemotherapy as an embodiment of the problem, or a gastroenterologist might not embody the colonoscopy at Year Four instead of Year Five as the problem. We must come to grips with the usual mindset, look in the mirror, and admit, ‘Maybe we are part of the problem.’”

—Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, SFHM

Potential Solutions

Hospitalists, intensivists, and ED clinicians are tasked with finding a balance between being prudent stewards of resources and staying within a comfort zone that promotes patient safety. SHM supports the goals of the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely campaign, which aims to reduce waste by curtailing duplicative and unnecessary care (see “Better Choices, Better Care,” March 2013). Also included in the campaign (www.ChoosingWisely.org) are the American College of Physicians’ recommendations against low-value testing (e.g. obtaining imaging studies in patients with nonspecific low back pain).

“Those recommendations are not going to solve our health spending problem,” says White, “but they are part of a broader move to give permission to clinicians, based on evidence, to follow more conservative practice patterns.”

Still, counters David I. Auerbach, PhD, a health economist at RAND in Boston and author of the RAND study, “there’s another value to these tests that the cost-effectiveness equations do not always consider, which is, they can bring peace of mind. We’re trying to nudge patients down the pathway that we think is best for them without rationing care. That’s a delicate balance.”

Dr. Flansbaum says SHM’s Public Policy Committee has discussed a variety of issues related to rising costs, although the group has not directly tackled advice in the form of a white paper. He suggests some ways that hospitalists can address cost savings:

- Involve patients in shared decision-making, and discuss the evidence against unnecessary testing;

- Utilize generic medications on discharge, when available, especially if patients are uninsured or have limited drug coverage with their insurance plans;

- Use palliative care whenever appropriate; and

- Adhere to transitional-care standards.

On the macro level, HM has “always been the specialty invited to champion the important discussion relating to resource utilization, and the evidence-based medicine driving that resource utilization,” says Christopher Frost, MD, FHM, medical director of hospital medicine at the Hospital Corporation of America (HCA) in Nashville, Tenn. He points to SHM’s leadership with Project BOOST (www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost) as one example of addressing the utilization of resources in caring for older adults (see “Resources for Improving Transitions in Care,”).

What else can hospitalists do? Going forward, says Dan Fuller, president and co-founder of IN Compass Health in Alpharetta, Ga., it might be a good idea for the SHM Practice Analysis Committee, of which he’s a member, to look at its possible role in the issue.

—Dr. Frederickson

Embrace Reality

Whatever the downstream developments around the Affordable Care Act, Dr. Ginsburg is “confident” that Medicare policies will continue in a direction of reduced reimbursements. Thomas Frederickson, MD, FACP, FHM, MBA, medical director of the hospital medicine service at Alegent Health in Omaha, Neb., agrees with such an assessment. He also believes that hospitalists are in a prime position to improve care delivery at less cost. To do so, though, requires deliberate partnership-building with outpatient providers to better bridge the transitions of care.

At his institution, Dr. Frederickson says, hospitalists invite themselves to primary-care physicians’ (PCP) meetings. This facilitates rapport so that calls to PCPs at discharge not only communicate essential clinical information, but also build confidence in the hospitalists’ care of their patients. As hospitalists demonstrate value, they must intentionally put metrics in place so that administrators appreciate the need to keep the census at a certain level, Dr. Frederickson says.

“We need the time to make these calls, to sit down with families,” he says. “This adds value to our health system and to society at large.”

SHM does a good job, says Dr. Frost, of being part of the conversation as the hospital C-suite focuses more on episodes of care.

“The intensity of that discussion is getting dialed up and will be driven more by government and the payors,” he adds. The challenge going forward will be to bridge those arenas just outside the acute episode of care, where hospitalists have ownership of processes, to those where they do not have as much control. If payors apply broader definitions to the episode of care, Dr. Frost says, hospitalists might be “invited to play an increasing role, that of ‘transitionist.’”

And in that context, he says, hospitalists need to look at length of stay with a new lens.

Partnership-building will become more important as the definition of “episode of care” expands beyond the hospital stay to the post-acute setting.

“Including post-acute care in the episode of care is a core aspect of the whole” value-based purchasing approach, Dr. Ginsburg says. “Hospitals [and hospitalists] will be wise to opt for the model with the greatest potential to reduce costs, particularly costs incurred by other providers.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

References

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National health expenditures 2011 highlights. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/Downloads/highlights.pdf. Accessed May 6, 2013. costs how much? Consumer Reports website. Available at: http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/magazine/ 2012/07/that-ct-scan-costs-how-much/index.htm. Accessed Aug. 2, 2012.

- White C, Ginsburg PB. Slower growth in Medicare spending—is this the new normal? N Engl J Med. 2012;366(12):1073-1075.

- Auerbach DI, Kellermann AL. A decade of health care cost growth has wiped out real income gains for an average US family. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(9):1630-1636.

- Milliman Inc. 2012 Milliman Medical Index. Milliman Inc. website. Available at: http://publications.milliman.com/periodicals/mmi/pdfs/milliman-medical-index-2012.pdf. Accessed Aug. 1, 2012.

- Kolata G. Knotty challenges in health care costs. The New York Times website. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/06/health/policy/an-interview-with-victor-fuchs-on-health-care-costs.html. Accessed March 8, 2012.

- Consumer Reports. That CT scan costs how much? Consumer Reports website. Available at: http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/magazine/ 2012/07/that-ct-scan-costs-how-much/index.htm.

Letters: Medicare Official Says 'Physician Compare' Website Does Not Provide Performance Data on Individual Doctors

I read the article “Call for Transparency in Health-Care Performance Results to Impact Hospitalists” (January 2013, p. 47) by Shaun Frost, MD, SFHM, president of the Society of Hospital Medicine, with interest. I’d like to clarify a key point about Physician Compare. In the article, the statement that the Physician Compare website (www.medicare.gov/find-a-doctor) provides performance information on individual doctors is inaccurate.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) states that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) must have a plan in place by Jan. 1, 2013, to include quality-of-care information on the site. To meet that requirement, CMS has established a plan that initiates a phased approach to public reporting. The 2012 Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) Final Rule was the first step in that phased approach. This rule established that the first measures to be reported on the site would be group-level measures for data collected no sooner than program year 2012. A second critical step is the 2013 PFS Proposed Rule, which outlines a longer-term public reporting plan. According to this plan, we expect the first set of group-level quality measure data to be included on the site in calendar year 2014. We are targeting publishing individual-level quality measures no sooner than 2015 reflecting data collected in program year 2014, if technically feasible.

As you may be aware, Physician Compare is undergoing a redesign to significantly improve the underlying database and thus the information on Physician Compare, as well as the ease of use and functionality of the site. We’ll be unveiling the redesigned site soon. We welcome your feedback and look forward to maintaining a dialogue with you as Physician Compare continues to evolve.

Rashaan Byers, MPH, social science research analyst, Centers forMedicare & Medicaid Services, Center for Clinical Standards & Quality, Quality Measurement & Health Assessment Group

Dr. Frost responds:

I thank Mr. Byers for his clarification regarding the current content on the CMS Physician Compare website, and agree that at the present time the website does not report individual physician clinical performance data.

Physician Compare, however, does currently report if an individual physician participated in the CMS Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) by stating “this professional chose to take part in Medicare’s PQRS, and reported quality information satisfactorily for the year 2010.” For those physicians who did not participate in PQRS, their personal website pages do not make reference to the PQRS program.

As the intent of transparency is to educate consumers to make informed choices about where to seek health care, care providers should know that their participation in PQRS is currently publically reported. It is, therefore, possible that patient decisions about whom to seek care from may be influenced by this.

As acknowledged in my January 2013 column in The Hospitalist, Physician Compare currently reports very little information. We should expect this to change, however, as Medicare moves forward with developing a plan to publically report valid and reliable individual physician performance metrics. CMS’ clarification of the timeline by which we can expect to see more detailed information is thus greatly appreciated.

The take-home message for hospitalists is that public reporting of care provider performance will become increasingly comprehensive and transparent in the future. As pointed out, CMS’ present plan targets the publication of individual, physician-level quality measures as soon as 2015, which will reflect actual performance during program year 2014. The measurement period is thus less than one year away, so it behooves us all to focus ever more intently on delivering high-value healthcare.

Shaun Frost, MD, SFHM, past president, SHM

I read the article “Call for Transparency in Health-Care Performance Results to Impact Hospitalists” (January 2013, p. 47) by Shaun Frost, MD, SFHM, president of the Society of Hospital Medicine, with interest. I’d like to clarify a key point about Physician Compare. In the article, the statement that the Physician Compare website (www.medicare.gov/find-a-doctor) provides performance information on individual doctors is inaccurate.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) states that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) must have a plan in place by Jan. 1, 2013, to include quality-of-care information on the site. To meet that requirement, CMS has established a plan that initiates a phased approach to public reporting. The 2012 Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) Final Rule was the first step in that phased approach. This rule established that the first measures to be reported on the site would be group-level measures for data collected no sooner than program year 2012. A second critical step is the 2013 PFS Proposed Rule, which outlines a longer-term public reporting plan. According to this plan, we expect the first set of group-level quality measure data to be included on the site in calendar year 2014. We are targeting publishing individual-level quality measures no sooner than 2015 reflecting data collected in program year 2014, if technically feasible.

As you may be aware, Physician Compare is undergoing a redesign to significantly improve the underlying database and thus the information on Physician Compare, as well as the ease of use and functionality of the site. We’ll be unveiling the redesigned site soon. We welcome your feedback and look forward to maintaining a dialogue with you as Physician Compare continues to evolve.

Rashaan Byers, MPH, social science research analyst, Centers forMedicare & Medicaid Services, Center for Clinical Standards & Quality, Quality Measurement & Health Assessment Group

Dr. Frost responds:

I thank Mr. Byers for his clarification regarding the current content on the CMS Physician Compare website, and agree that at the present time the website does not report individual physician clinical performance data.

Physician Compare, however, does currently report if an individual physician participated in the CMS Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) by stating “this professional chose to take part in Medicare’s PQRS, and reported quality information satisfactorily for the year 2010.” For those physicians who did not participate in PQRS, their personal website pages do not make reference to the PQRS program.

As the intent of transparency is to educate consumers to make informed choices about where to seek health care, care providers should know that their participation in PQRS is currently publically reported. It is, therefore, possible that patient decisions about whom to seek care from may be influenced by this.

As acknowledged in my January 2013 column in The Hospitalist, Physician Compare currently reports very little information. We should expect this to change, however, as Medicare moves forward with developing a plan to publically report valid and reliable individual physician performance metrics. CMS’ clarification of the timeline by which we can expect to see more detailed information is thus greatly appreciated.

The take-home message for hospitalists is that public reporting of care provider performance will become increasingly comprehensive and transparent in the future. As pointed out, CMS’ present plan targets the publication of individual, physician-level quality measures as soon as 2015, which will reflect actual performance during program year 2014. The measurement period is thus less than one year away, so it behooves us all to focus ever more intently on delivering high-value healthcare.

Shaun Frost, MD, SFHM, past president, SHM

I read the article “Call for Transparency in Health-Care Performance Results to Impact Hospitalists” (January 2013, p. 47) by Shaun Frost, MD, SFHM, president of the Society of Hospital Medicine, with interest. I’d like to clarify a key point about Physician Compare. In the article, the statement that the Physician Compare website (www.medicare.gov/find-a-doctor) provides performance information on individual doctors is inaccurate.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) states that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) must have a plan in place by Jan. 1, 2013, to include quality-of-care information on the site. To meet that requirement, CMS has established a plan that initiates a phased approach to public reporting. The 2012 Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) Final Rule was the first step in that phased approach. This rule established that the first measures to be reported on the site would be group-level measures for data collected no sooner than program year 2012. A second critical step is the 2013 PFS Proposed Rule, which outlines a longer-term public reporting plan. According to this plan, we expect the first set of group-level quality measure data to be included on the site in calendar year 2014. We are targeting publishing individual-level quality measures no sooner than 2015 reflecting data collected in program year 2014, if technically feasible.

As you may be aware, Physician Compare is undergoing a redesign to significantly improve the underlying database and thus the information on Physician Compare, as well as the ease of use and functionality of the site. We’ll be unveiling the redesigned site soon. We welcome your feedback and look forward to maintaining a dialogue with you as Physician Compare continues to evolve.

Rashaan Byers, MPH, social science research analyst, Centers forMedicare & Medicaid Services, Center for Clinical Standards & Quality, Quality Measurement & Health Assessment Group

Dr. Frost responds:

I thank Mr. Byers for his clarification regarding the current content on the CMS Physician Compare website, and agree that at the present time the website does not report individual physician clinical performance data.

Physician Compare, however, does currently report if an individual physician participated in the CMS Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) by stating “this professional chose to take part in Medicare’s PQRS, and reported quality information satisfactorily for the year 2010.” For those physicians who did not participate in PQRS, their personal website pages do not make reference to the PQRS program.

As the intent of transparency is to educate consumers to make informed choices about where to seek health care, care providers should know that their participation in PQRS is currently publically reported. It is, therefore, possible that patient decisions about whom to seek care from may be influenced by this.

As acknowledged in my January 2013 column in The Hospitalist, Physician Compare currently reports very little information. We should expect this to change, however, as Medicare moves forward with developing a plan to publically report valid and reliable individual physician performance metrics. CMS’ clarification of the timeline by which we can expect to see more detailed information is thus greatly appreciated.

The take-home message for hospitalists is that public reporting of care provider performance will become increasingly comprehensive and transparent in the future. As pointed out, CMS’ present plan targets the publication of individual, physician-level quality measures as soon as 2015, which will reflect actual performance during program year 2014. The measurement period is thus less than one year away, so it behooves us all to focus ever more intently on delivering high-value healthcare.

Shaun Frost, MD, SFHM, past president, SHM

Hospitalists Poised to Advance Health Care Through Teamwork

The problems that ail the American health-care system are numerous, complex, and interrelated. In writing about how to fix our chronically dysfunctional system, Hoffman and Emanuel recently cautioned that single solutions will not be effective.1 In their estimation, “individually implemented changes are divisive rather than unifying,” and “the cure … to this complex problem … will require a multimodal approach with a focus on re-engineering the entire care delivery process.”

If single solutions are insufficient (or even counterproductive and divisive), health care’s key stakeholders must figure out how to work more effectively together. In a nutshell, effective collaboration is critical. Those who collaborate well will thrive in the future, while those who are unable to break down silos to innovatively engage their patients, colleagues, and communities will fail.

Our Tradition of Teamwork

Hospitalists understand the importance of collaboration, as teamwork has been a fundamental value of our specialty since its inception. We have a rich tradition of creating novel, collaborative working relationships with a diverse group of key stakeholders that includes primary-care providers (PCPs), nurses, subspecialists, surgeons, case managers, social workers, nursing homes, transitional-care units, home health agencies, hospice programs, and hospital administrators. We have created innovative, collaborative strategies to effectively and safely comanage patients with other physicians, navigate care transitions, and integrate the input of the many people required to manage day-to-day hospital care.

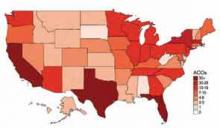

These experiences will serve us well in a future in which collaboration is essential. We should plan to share our expertise in creating effective teams by assuming leadership roles within our institutions as they implement collaborative initiatives on a larger scale through such concepts as the accountable-care organization (ACO).

We should furthermore plan to seek out new, collaborative opportunities by identifying novel agendas to champion. Two critically important, novel agendas for hospitalists to advance are:

- Enhanced physician-patient collaboration; and

- Collaboration to share and propagate new innovation among hospitalists and HM programs across the country.

True Collaboration with Patients

In my last column, I wrote about how enhancing the patient experience of care will have far-reaching, positive effects on health-care reform.2 Attending to the patient experience has been proven to enhance patient satisfaction, care quality, and care affordability. Initiatives to enhance care experience thus hold promise as global, Triple Aim (better health and better care at lower cost) effectors.

The key to improving patient experience is patient engagement, and the key to patient engagement is incorporating patient expectations into the care planning process. The question thus becomes, “How do physicians identify and appropriately act on patient expectations?” The answer is by collaborating with patients to arrive at care decisions that respect their interests. Care providers must work together with patients to create care plans that respect patient preferences, values, and goals. This will require shared decision-making characterized by collaborative discussions that help patients decide between multiple acceptable health-care choices in accordance with their expectations.

SHM is commissioning a Patient Experience Advisory Board to identify how the society can support its members to effectively collaborate with patients and their loved ones. Expect in the near future to learn more from SHM about how to truly engage your patients to enhance the value of the care you deliver.

The Commodification of Health-Care Quality and Affordability

I recently learned of a subspecialty group that had created a new clinical protocol that promised to deliver higher-quality, more affordable care to their patients. When asked if they would share this with physicians outside of their own group, they flat-out refused. What would motivate a physician group to refuse to collaborate with their community to propagate a new innovation that promises to enhance the value of health care? The answer may lie with an economic concept known as commodification.

Commodification is the process by which an item that possesses no economic interest is assigned monetary worth, and hence how economic values can replace social values that previously governed how the item was treated. Commodification describes a transformation of relationships formerly untainted by commerce into commercial relationships that are influenced by monetary interests.

As payors move away from reimbursing providers simply for performing services (volume-based purchasing) to paying them for the value they deliver (value-based purchasing), we must acknowledge that we are “commodifying” health-care quality and affordability. By doing so, the economic viability of medical practices and health-care institutions will depend on delivering value, and to the extent that this determines a competitive advantage in the marketplace, providers might be reluctant to share innovations in quality and affordability.

We must not let this happen to health care. Competing on the ability to effectively deploy and manage new innovations to enhance quality and affordability is acceptable. Competing, however, on the access to these innovations is ethically unacceptable for an industry that is indispensable to the health and well-being of its consumers.

Coke and Pepsi do not provide indispensable products to society. It is thus fine for soft-drink makers to keep their recipes top secret and fight vigorously to prevent others from gaining access to their innovations. Health-care providers, however, cannot morally defend refusing to share new products and processes that decrease costs, improve patient experience, decrease morbidity, prolong life, or otherwise enhance quality.

We must, therefore, strive to continuously collaborate with our hospitalist colleagues and HM programs across the country to propagate new innovation. When someone builds a better mouse trap, it should be shared freely so that all patients have the opportunity to benefit. We must not let the pursuit of economic competitive advantage prevent us from collaborating and sharing ideas on how to make our health-care system better.

Conclusion

Fixing health care is complicated, and employing collaboration in order to do so will be required. Hospitalists have vast experience in working effectively with others, and should leverage this experience to lead the charge on efforts to enhance physician-patient collaboration. Hospitalists should strive to continuously collaborate with their colleagues to ensure open access to new discoveries that improve health-care quality and affordability. Those interested in learning more about how to be successful collaborators might find it helpful to seek out additional resources on the subject. Collaboration, by Morten T. Hansen, is a good source on how to turn this concept into action.3

References

- Hoffman A, Emanuel E. Reengineering US health care. JAMA. 2013;309(7):661-662.

- Frost, S. A matter of perspective: deconstructing satisfaction measurements by focusing on patient goals. The Hospitalist. 2013:17(3):59.

- Hansen M. Collaboration: how leaders avoid the traps, create unity, and reap big results. Boston: Harvard Business Press; 2009.

The problems that ail the American health-care system are numerous, complex, and interrelated. In writing about how to fix our chronically dysfunctional system, Hoffman and Emanuel recently cautioned that single solutions will not be effective.1 In their estimation, “individually implemented changes are divisive rather than unifying,” and “the cure … to this complex problem … will require a multimodal approach with a focus on re-engineering the entire care delivery process.”

If single solutions are insufficient (or even counterproductive and divisive), health care’s key stakeholders must figure out how to work more effectively together. In a nutshell, effective collaboration is critical. Those who collaborate well will thrive in the future, while those who are unable to break down silos to innovatively engage their patients, colleagues, and communities will fail.

Our Tradition of Teamwork

Hospitalists understand the importance of collaboration, as teamwork has been a fundamental value of our specialty since its inception. We have a rich tradition of creating novel, collaborative working relationships with a diverse group of key stakeholders that includes primary-care providers (PCPs), nurses, subspecialists, surgeons, case managers, social workers, nursing homes, transitional-care units, home health agencies, hospice programs, and hospital administrators. We have created innovative, collaborative strategies to effectively and safely comanage patients with other physicians, navigate care transitions, and integrate the input of the many people required to manage day-to-day hospital care.

These experiences will serve us well in a future in which collaboration is essential. We should plan to share our expertise in creating effective teams by assuming leadership roles within our institutions as they implement collaborative initiatives on a larger scale through such concepts as the accountable-care organization (ACO).

We should furthermore plan to seek out new, collaborative opportunities by identifying novel agendas to champion. Two critically important, novel agendas for hospitalists to advance are:

- Enhanced physician-patient collaboration; and

- Collaboration to share and propagate new innovation among hospitalists and HM programs across the country.

True Collaboration with Patients

In my last column, I wrote about how enhancing the patient experience of care will have far-reaching, positive effects on health-care reform.2 Attending to the patient experience has been proven to enhance patient satisfaction, care quality, and care affordability. Initiatives to enhance care experience thus hold promise as global, Triple Aim (better health and better care at lower cost) effectors.

The key to improving patient experience is patient engagement, and the key to patient engagement is incorporating patient expectations into the care planning process. The question thus becomes, “How do physicians identify and appropriately act on patient expectations?” The answer is by collaborating with patients to arrive at care decisions that respect their interests. Care providers must work together with patients to create care plans that respect patient preferences, values, and goals. This will require shared decision-making characterized by collaborative discussions that help patients decide between multiple acceptable health-care choices in accordance with their expectations.

SHM is commissioning a Patient Experience Advisory Board to identify how the society can support its members to effectively collaborate with patients and their loved ones. Expect in the near future to learn more from SHM about how to truly engage your patients to enhance the value of the care you deliver.

The Commodification of Health-Care Quality and Affordability

I recently learned of a subspecialty group that had created a new clinical protocol that promised to deliver higher-quality, more affordable care to their patients. When asked if they would share this with physicians outside of their own group, they flat-out refused. What would motivate a physician group to refuse to collaborate with their community to propagate a new innovation that promises to enhance the value of health care? The answer may lie with an economic concept known as commodification.

Commodification is the process by which an item that possesses no economic interest is assigned monetary worth, and hence how economic values can replace social values that previously governed how the item was treated. Commodification describes a transformation of relationships formerly untainted by commerce into commercial relationships that are influenced by monetary interests.

As payors move away from reimbursing providers simply for performing services (volume-based purchasing) to paying them for the value they deliver (value-based purchasing), we must acknowledge that we are “commodifying” health-care quality and affordability. By doing so, the economic viability of medical practices and health-care institutions will depend on delivering value, and to the extent that this determines a competitive advantage in the marketplace, providers might be reluctant to share innovations in quality and affordability.

We must not let this happen to health care. Competing on the ability to effectively deploy and manage new innovations to enhance quality and affordability is acceptable. Competing, however, on the access to these innovations is ethically unacceptable for an industry that is indispensable to the health and well-being of its consumers.

Coke and Pepsi do not provide indispensable products to society. It is thus fine for soft-drink makers to keep their recipes top secret and fight vigorously to prevent others from gaining access to their innovations. Health-care providers, however, cannot morally defend refusing to share new products and processes that decrease costs, improve patient experience, decrease morbidity, prolong life, or otherwise enhance quality.

We must, therefore, strive to continuously collaborate with our hospitalist colleagues and HM programs across the country to propagate new innovation. When someone builds a better mouse trap, it should be shared freely so that all patients have the opportunity to benefit. We must not let the pursuit of economic competitive advantage prevent us from collaborating and sharing ideas on how to make our health-care system better.

Conclusion

Fixing health care is complicated, and employing collaboration in order to do so will be required. Hospitalists have vast experience in working effectively with others, and should leverage this experience to lead the charge on efforts to enhance physician-patient collaboration. Hospitalists should strive to continuously collaborate with their colleagues to ensure open access to new discoveries that improve health-care quality and affordability. Those interested in learning more about how to be successful collaborators might find it helpful to seek out additional resources on the subject. Collaboration, by Morten T. Hansen, is a good source on how to turn this concept into action.3

References

- Hoffman A, Emanuel E. Reengineering US health care. JAMA. 2013;309(7):661-662.

- Frost, S. A matter of perspective: deconstructing satisfaction measurements by focusing on patient goals. The Hospitalist. 2013:17(3):59.

- Hansen M. Collaboration: how leaders avoid the traps, create unity, and reap big results. Boston: Harvard Business Press; 2009.

The problems that ail the American health-care system are numerous, complex, and interrelated. In writing about how to fix our chronically dysfunctional system, Hoffman and Emanuel recently cautioned that single solutions will not be effective.1 In their estimation, “individually implemented changes are divisive rather than unifying,” and “the cure … to this complex problem … will require a multimodal approach with a focus on re-engineering the entire care delivery process.”

If single solutions are insufficient (or even counterproductive and divisive), health care’s key stakeholders must figure out how to work more effectively together. In a nutshell, effective collaboration is critical. Those who collaborate well will thrive in the future, while those who are unable to break down silos to innovatively engage their patients, colleagues, and communities will fail.

Our Tradition of Teamwork

Hospitalists understand the importance of collaboration, as teamwork has been a fundamental value of our specialty since its inception. We have a rich tradition of creating novel, collaborative working relationships with a diverse group of key stakeholders that includes primary-care providers (PCPs), nurses, subspecialists, surgeons, case managers, social workers, nursing homes, transitional-care units, home health agencies, hospice programs, and hospital administrators. We have created innovative, collaborative strategies to effectively and safely comanage patients with other physicians, navigate care transitions, and integrate the input of the many people required to manage day-to-day hospital care.

These experiences will serve us well in a future in which collaboration is essential. We should plan to share our expertise in creating effective teams by assuming leadership roles within our institutions as they implement collaborative initiatives on a larger scale through such concepts as the accountable-care organization (ACO).

We should furthermore plan to seek out new, collaborative opportunities by identifying novel agendas to champion. Two critically important, novel agendas for hospitalists to advance are:

- Enhanced physician-patient collaboration; and

- Collaboration to share and propagate new innovation among hospitalists and HM programs across the country.

True Collaboration with Patients

In my last column, I wrote about how enhancing the patient experience of care will have far-reaching, positive effects on health-care reform.2 Attending to the patient experience has been proven to enhance patient satisfaction, care quality, and care affordability. Initiatives to enhance care experience thus hold promise as global, Triple Aim (better health and better care at lower cost) effectors.

The key to improving patient experience is patient engagement, and the key to patient engagement is incorporating patient expectations into the care planning process. The question thus becomes, “How do physicians identify and appropriately act on patient expectations?” The answer is by collaborating with patients to arrive at care decisions that respect their interests. Care providers must work together with patients to create care plans that respect patient preferences, values, and goals. This will require shared decision-making characterized by collaborative discussions that help patients decide between multiple acceptable health-care choices in accordance with their expectations.

SHM is commissioning a Patient Experience Advisory Board to identify how the society can support its members to effectively collaborate with patients and their loved ones. Expect in the near future to learn more from SHM about how to truly engage your patients to enhance the value of the care you deliver.

The Commodification of Health-Care Quality and Affordability

I recently learned of a subspecialty group that had created a new clinical protocol that promised to deliver higher-quality, more affordable care to their patients. When asked if they would share this with physicians outside of their own group, they flat-out refused. What would motivate a physician group to refuse to collaborate with their community to propagate a new innovation that promises to enhance the value of health care? The answer may lie with an economic concept known as commodification.

Commodification is the process by which an item that possesses no economic interest is assigned monetary worth, and hence how economic values can replace social values that previously governed how the item was treated. Commodification describes a transformation of relationships formerly untainted by commerce into commercial relationships that are influenced by monetary interests.

As payors move away from reimbursing providers simply for performing services (volume-based purchasing) to paying them for the value they deliver (value-based purchasing), we must acknowledge that we are “commodifying” health-care quality and affordability. By doing so, the economic viability of medical practices and health-care institutions will depend on delivering value, and to the extent that this determines a competitive advantage in the marketplace, providers might be reluctant to share innovations in quality and affordability.

We must not let this happen to health care. Competing on the ability to effectively deploy and manage new innovations to enhance quality and affordability is acceptable. Competing, however, on the access to these innovations is ethically unacceptable for an industry that is indispensable to the health and well-being of its consumers.

Coke and Pepsi do not provide indispensable products to society. It is thus fine for soft-drink makers to keep their recipes top secret and fight vigorously to prevent others from gaining access to their innovations. Health-care providers, however, cannot morally defend refusing to share new products and processes that decrease costs, improve patient experience, decrease morbidity, prolong life, or otherwise enhance quality.

We must, therefore, strive to continuously collaborate with our hospitalist colleagues and HM programs across the country to propagate new innovation. When someone builds a better mouse trap, it should be shared freely so that all patients have the opportunity to benefit. We must not let the pursuit of economic competitive advantage prevent us from collaborating and sharing ideas on how to make our health-care system better.

Conclusion

Fixing health care is complicated, and employing collaboration in order to do so will be required. Hospitalists have vast experience in working effectively with others, and should leverage this experience to lead the charge on efforts to enhance physician-patient collaboration. Hospitalists should strive to continuously collaborate with their colleagues to ensure open access to new discoveries that improve health-care quality and affordability. Those interested in learning more about how to be successful collaborators might find it helpful to seek out additional resources on the subject. Collaboration, by Morten T. Hansen, is a good source on how to turn this concept into action.3

References

- Hoffman A, Emanuel E. Reengineering US health care. JAMA. 2013;309(7):661-662.

- Frost, S. A matter of perspective: deconstructing satisfaction measurements by focusing on patient goals. The Hospitalist. 2013:17(3):59.

- Hansen M. Collaboration: how leaders avoid the traps, create unity, and reap big results. Boston: Harvard Business Press; 2009.

AMA Report Offers Nine Steps to Help PCPs Prevent Readmissions

The American Medical Association recently released a report developed by a 21-member expert panel proposing a nine-step plan for primary-care-physician (PCP) practices to play an integral role in improving care transitions and preventing avoidable rehospitalizations.2 The report recommends focusing on more than just the hospital-admitting diagnosis, conducting a thorough patient health assessment, clarifying the patient’s short- and long-term goals, and coordinating care with other care settings.

With simultaneous research in JAMA concluding that the vast majority of readmissions are for reasons unrelated to the previous hospital stay, coordination between the inpatient and outpatient teams is crucial to successful transitions of care.3 Moreover, a recent survey showed that nearly 30% of PCPs say they miss alerts about patients’ test results from an electronic health record (EHR) notification system.4 According to the survey by Hardeep Singh, MD, MPH, and colleagues from the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center in Houston, the doctors received on average 63 such alerts per day. Seventy percent reported that they cannot effectively manage the alerts, and more than half said that the current EHR notification system makes it possible to miss test results.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Quinn K, Neeman N, Mourad M, Sliwka D. Communication coaching: A multifaceted intervention to improve physician-patient communication [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S108.

- Sokol PE, Wynia MK. There and Home Again, Safely: Five Responsibilities of Ambulatory Practices in High Quality Care Transitions. American Medical Association website. http://www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/patient-safety/ambulatory-practices.pdf. Accessed February 12, 2013.

- Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, et al. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA. 2013;309(4):355-363.

- JAMA Internal Medicine. Nearly one-third of physicians report missing electronic notification of test results. JAMA Internal Medicine website. Available at: http://media.jamanetwork.com/news-item/nearly-one-third-of-physicians-report-missing-electronic-notification-of-test-results/.Accessed April 8, 2013.

- Miliard M. VA enlists telehealth for disasters. Healthcare IT News website. http://www.healthcareitnews.com/news/va-enlists-telehealth-disasters. Published February 27, 2013. Accessed April 1, 2013.

The American Medical Association recently released a report developed by a 21-member expert panel proposing a nine-step plan for primary-care-physician (PCP) practices to play an integral role in improving care transitions and preventing avoidable rehospitalizations.2 The report recommends focusing on more than just the hospital-admitting diagnosis, conducting a thorough patient health assessment, clarifying the patient’s short- and long-term goals, and coordinating care with other care settings.

With simultaneous research in JAMA concluding that the vast majority of readmissions are for reasons unrelated to the previous hospital stay, coordination between the inpatient and outpatient teams is crucial to successful transitions of care.3 Moreover, a recent survey showed that nearly 30% of PCPs say they miss alerts about patients’ test results from an electronic health record (EHR) notification system.4 According to the survey by Hardeep Singh, MD, MPH, and colleagues from the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center in Houston, the doctors received on average 63 such alerts per day. Seventy percent reported that they cannot effectively manage the alerts, and more than half said that the current EHR notification system makes it possible to miss test results.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Quinn K, Neeman N, Mourad M, Sliwka D. Communication coaching: A multifaceted intervention to improve physician-patient communication [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S108.

- Sokol PE, Wynia MK. There and Home Again, Safely: Five Responsibilities of Ambulatory Practices in High Quality Care Transitions. American Medical Association website. http://www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/patient-safety/ambulatory-practices.pdf. Accessed February 12, 2013.

- Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, et al. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA. 2013;309(4):355-363.

- JAMA Internal Medicine. Nearly one-third of physicians report missing electronic notification of test results. JAMA Internal Medicine website. Available at: http://media.jamanetwork.com/news-item/nearly-one-third-of-physicians-report-missing-electronic-notification-of-test-results/.Accessed April 8, 2013.

- Miliard M. VA enlists telehealth for disasters. Healthcare IT News website. http://www.healthcareitnews.com/news/va-enlists-telehealth-disasters. Published February 27, 2013. Accessed April 1, 2013.

The American Medical Association recently released a report developed by a 21-member expert panel proposing a nine-step plan for primary-care-physician (PCP) practices to play an integral role in improving care transitions and preventing avoidable rehospitalizations.2 The report recommends focusing on more than just the hospital-admitting diagnosis, conducting a thorough patient health assessment, clarifying the patient’s short- and long-term goals, and coordinating care with other care settings.

With simultaneous research in JAMA concluding that the vast majority of readmissions are for reasons unrelated to the previous hospital stay, coordination between the inpatient and outpatient teams is crucial to successful transitions of care.3 Moreover, a recent survey showed that nearly 30% of PCPs say they miss alerts about patients’ test results from an electronic health record (EHR) notification system.4 According to the survey by Hardeep Singh, MD, MPH, and colleagues from the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center in Houston, the doctors received on average 63 such alerts per day. Seventy percent reported that they cannot effectively manage the alerts, and more than half said that the current EHR notification system makes it possible to miss test results.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Quinn K, Neeman N, Mourad M, Sliwka D. Communication coaching: A multifaceted intervention to improve physician-patient communication [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S108.

- Sokol PE, Wynia MK. There and Home Again, Safely: Five Responsibilities of Ambulatory Practices in High Quality Care Transitions. American Medical Association website. http://www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/patient-safety/ambulatory-practices.pdf. Accessed February 12, 2013.

- Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, et al. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA. 2013;309(4):355-363.

- JAMA Internal Medicine. Nearly one-third of physicians report missing electronic notification of test results. JAMA Internal Medicine website. Available at: http://media.jamanetwork.com/news-item/nearly-one-third-of-physicians-report-missing-electronic-notification-of-test-results/.Accessed April 8, 2013.

- Miliard M. VA enlists telehealth for disasters. Healthcare IT News website. http://www.healthcareitnews.com/news/va-enlists-telehealth-disasters. Published February 27, 2013. Accessed April 1, 2013.

UCSF Engages Hospitalists to Improve Patient Communication

In a poster presented at HM12, Kathryn Quinn, MPH, CPPS, FACHE, described how her quality team at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) developed a checklist to improve physician communication with patients, then taught it to the attending hospitalist faculty.1 The project began with a list of 29 best practices for patient-physician interaction, as identified in medical literature. Hospitalists then voted for the elements they felt were most important to their practice, as well as those best able to be measured, and a top-10 list was created.

Quinn, the program manager for quality and safety in the division of hospital medicine at UCSF, says the communication best practices were “chosen by the people whose practices we are trying to change.”

The quality team presented the best practices in one-hour training sessions that included small-group role plays, explains co-investigator and UCSF hospitalist Diane Sliwka, MD. The training extended to outpatient physicians, medical specialists, and chief residents. Participants also were provided a laminated pocket card listing the interventions. They also received feedback from structured observations with patients on service.

Quinn says UCSF hospitalists have improved at knocking and asking permission to enter patient rooms, introducing themselves by name and role, and encouraging questions at the end of the interaction. They have been less successful at inquiring about the patient’s concerns early in the interview and at discussing duration of treatment and next steps.

“We learned that it takes more than just talk,” Quinn says. “Just telling physicians how to improve communication doesn’t mean it’s easy to do.”

Still to be determined is the project’s impact on patient satisfaction scores, although the hospitalists reported that they found the training and feedback helpful.

References

- Quinn K, Neeman N, Mourad M, Sliwka D. Communication coaching: A multifaceted intervention to improve physician-patient communication [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S108.

- Sokol PE, Wynia MK. There and Home Again, Safely: Five Responsibilities of Ambulatory Practices in High Quality Care Transitions. American Medical Association website. http://www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/patient-safety/ambulatory-practices.pdf. Accessed February 12, 2013.

- Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, et al. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA. 2013;309(4):355-363.

- JAMA Internal Medicine. Nearly one-third of physicians report missing electronic notification of test results. JAMA Internal Medicine website. Available at: http://media.jamanetwork.com/news-item/nearly-one-third-of-physicians-report-missing-electronic-notification-of-test-results/.Accessed April 8, 2013.

- Miliard M. VA enlists telehealth for disasters. Healthcare IT News website. http://www.healthcareitnews.com/news/va-enlists-telehealth-disasters. Published February 27, 2013. Accessed April 1, 2013.

In a poster presented at HM12, Kathryn Quinn, MPH, CPPS, FACHE, described how her quality team at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) developed a checklist to improve physician communication with patients, then taught it to the attending hospitalist faculty.1 The project began with a list of 29 best practices for patient-physician interaction, as identified in medical literature. Hospitalists then voted for the elements they felt were most important to their practice, as well as those best able to be measured, and a top-10 list was created.

Quinn, the program manager for quality and safety in the division of hospital medicine at UCSF, says the communication best practices were “chosen by the people whose practices we are trying to change.”

The quality team presented the best practices in one-hour training sessions that included small-group role plays, explains co-investigator and UCSF hospitalist Diane Sliwka, MD. The training extended to outpatient physicians, medical specialists, and chief residents. Participants also were provided a laminated pocket card listing the interventions. They also received feedback from structured observations with patients on service.

Quinn says UCSF hospitalists have improved at knocking and asking permission to enter patient rooms, introducing themselves by name and role, and encouraging questions at the end of the interaction. They have been less successful at inquiring about the patient’s concerns early in the interview and at discussing duration of treatment and next steps.

“We learned that it takes more than just talk,” Quinn says. “Just telling physicians how to improve communication doesn’t mean it’s easy to do.”

Still to be determined is the project’s impact on patient satisfaction scores, although the hospitalists reported that they found the training and feedback helpful.

References

- Quinn K, Neeman N, Mourad M, Sliwka D. Communication coaching: A multifaceted intervention to improve physician-patient communication [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S108.

- Sokol PE, Wynia MK. There and Home Again, Safely: Five Responsibilities of Ambulatory Practices in High Quality Care Transitions. American Medical Association website. http://www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/patient-safety/ambulatory-practices.pdf. Accessed February 12, 2013.

- Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, et al. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA. 2013;309(4):355-363.

- JAMA Internal Medicine. Nearly one-third of physicians report missing electronic notification of test results. JAMA Internal Medicine website. Available at: http://media.jamanetwork.com/news-item/nearly-one-third-of-physicians-report-missing-electronic-notification-of-test-results/.Accessed April 8, 2013.

- Miliard M. VA enlists telehealth for disasters. Healthcare IT News website. http://www.healthcareitnews.com/news/va-enlists-telehealth-disasters. Published February 27, 2013. Accessed April 1, 2013.

In a poster presented at HM12, Kathryn Quinn, MPH, CPPS, FACHE, described how her quality team at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) developed a checklist to improve physician communication with patients, then taught it to the attending hospitalist faculty.1 The project began with a list of 29 best practices for patient-physician interaction, as identified in medical literature. Hospitalists then voted for the elements they felt were most important to their practice, as well as those best able to be measured, and a top-10 list was created.

Quinn, the program manager for quality and safety in the division of hospital medicine at UCSF, says the communication best practices were “chosen by the people whose practices we are trying to change.”