User login

Gut Reaction

At 480-bed Emory University Hospital Midtown in Atlanta, the physicians and staff seemingly are doing all the right things to foil one of hospital’s archenemies: Clostridium difficile. The bacteria, better known as C. diff, is responsible for a sharp rise in hospital-acquired infections over the past decade, rivaling even MRSA.

In 2010, Emory Midtown launched a campaign to boost awareness of the importance of hand washing before and after treating patients infected with C. diff and those likely to be infected. They also began using the polymerase-chain-reaction-based assay to detect the bacteria, a test with much higher sensitivity that helps to more efficiently identify those infected so control measures can be more prompt and targeted. They use a hypochlorite mixture to clean the rooms of those infected, which is considered a must. And a committee monitors the use of antibiotics to prevent overuse—often the scapegoat for the rise of the hard-to-kill bacteria.

Still, at Emory, the rate of C. diff is about the same as the national average, says hospitalist Ketino Kobaidze, MD, assistant professor at the Emory University School of Medicine and a member of the antimicrobial stewardship and infectious disease control committees at Midtown. While Dr. Kobaidze says her institution is doing a good job of trying to keep C. diff under control, she thinks hospitalists can do more.

“My feeling is that we are not as involved as we’re supposed to be,” she says. “I think we need to be a little bit more proactive, be involved in committees and research activities across the hospital.”

—Kevin Kavanagh, MD, founder, Health Watch USA

You Are Not Alone

The experience at Emory Midtown is far from unusual—healthcare facilities, and hospitalists, across the country have seen healthcare-related C. diff cases more than double since 2001 to between 400,000 and 500,000 a year, says Carolyn Gould, MD, a medical epidemiologist in the division of healthcare quality promotion at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta.

Hospitalists, whether they realize it or not, are intimately involved in how well the C. diff outbreak is controlled. Infectious-disease (ID) specialists say hospitalists are perfectly situated to make an impact in efforts to help curb the outbreak.

“Hospitalists are critical to this effort,” Dr. Gould says. “They’re in the hospital day in and day out, and they’re constantly interacting with the patients, staff, and administration. They’re often the first on the scene to see a patient who might have suddenly developed diarrhea; they’re the first to react. I think they’re in a prime position to play a leadership role to prevent C. diff infections.”

They’re also situated well to work with infection-control experts on antimicrobial stewardship programs, she says.

“I look at hospitalists just like I would have looked at internists managing their own patients 15 years ago,” says Stuart Cohen, MD, an ID expert with the University of California at Davis and a fellow with the Infectious Diseases Society of America who was lead author of the latest published IDSA guidelines on C. diff treatment. “And so they’re the first-line people.”

continued below...

A Tough Bug

Believed to be aided largely by the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics that knock out the colon’s natural flora, C. diff in the hospital—as well as nursing homes and acute-care facilities—has raged for much of the past decade. Its rise is tied to the emergence of a new hypervirulent strain known as BI/NAP1/027, or NAP1 for short. The strain is highly resistant to fluoroquinolones, such as ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin, which are used often in healthcare settings.

“A fluoroquinolone will wipe out a lot of your normal flora in your gut,” Dr. Gould says. “But it won’t wipe out C. diff, in particular this hypervirulent strain. And so this strain can flourish in the presence of fluoroquinolones.” The strain produces up to 15 to 20 times more toxins than other C. diff strains, according to some data, she adds.

Vancomycin (Vanconin) and metronidazole (Flagyl) are the most common antibiotics used to treat patients infected with C. diff. Mortality rates are higher among the elderly, largely because of their weaker immune system, Dr. Gould says. Studies have generally shown mortality rates of 10% or a bit lower.1

More recent studies have shown that the number of hospital-related C. diff cases might have begun to level off in 2008 and 2009. Dr. Gould says she thinks the leveling off is for real, but there is debate over what the immediate future holds.

“There’s a lot of work and initiatives, especially state-based initiatives, that are being done in hospitals. And there’s reason to believe they’re effective,” she says, adding it’s harder to get a good picture of the problem in long-term care facilities and in the community.

Dr. Cohen with the IDSA says it’s too soon to say whether the problem is hitting a plateau. “CDC data are always a couple of years behind,” he says. “Until you see another data point, you can’t tell whether that’s just a transient flattening and whether it’s going to keep going up or not.”

Kevin Kavanagh, MD, founder of the patient advocacy group Health Watch USA and a retired otolaryngologist in Kentucky who has taken a keen interest in the C. diff problem, says he doesn’t think the end of the tunnel is within view yet.

“I think C. diff is going to get worse before it gets better,” Dr. Kavanagh says. “And that’s not necessarily because the healthcare profession isn’t doing due diligence. This is a tough organism.—it can be tough to treat and can be very tough to kill.”

The Best Defense?

Because C. diff lives within protective spores, sound hand hygiene practices and room-cleaning practices are essential for keeping infections to a minimum. Alcohol-based hand sanitizers, effective against other organisms including MRSA, do not kill C. diff. The bacteria must be mechanically removed through hand washing.

And even hand washing might not be totally effective at getting rid of the spores, which means it’s important for healthcare workers to gown and glove in high-risk rooms.

Sodium hypochlorite solutions, or bleach mixtures, have to be used to clean rooms occupied by patients with C. diff, and the prevailing thought is to clean the rooms of patients suspected of having C. diff, even if those cases might not be confirmed.

Equally important to cleaning and hand washing is systemwide emphasis on antibiotic stewardship. A 2011 study at the State University of New York Buffalo found that the risk of a C. diff infection rose with the number of antibiotics taken.2

—Carolyn Gould, MD, medical epidemiologist, division of healthcare quality promotion, Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta

While a broad-spectrum antibiotic might be necessary at first, once the results of cultures are received, the treatment should be finely tailored to kill only the problem bacteria so that the body’s natural defenses aren’t broken down, Dr. Gould explains.

“If someone is very sick and you’re not sure what is going on, it’s very reasonable to treat them empirically with broad-spectrum antibiotics,” she says. “The important thing is that you send the appropriate cultures before so that you know what you’re treating and you can optimize those antibiotics with daily assessments.”

It’s clear why an overreliance on broad-spectrum drugs prevails in U.S. health settings, Dr. Cohen acknowledges. Recent literature suggests treating critically ill patients with wide-ranging antimicrobials as the mortality rate can be twice as high with narrower options. “I think people have gotten very quick to give broad-spectrum therapy,” he says.

continued below...

National Response, Localized Attention

Dr. Kavanagh of Health Watch USA says that more information about C. diff is needed, particularly publicly available numbers of infections at hospitals. Some states require those figures to be reported, but most don’t. And there is no current federal mandate on reporting of C. diff cases, although acute-care hospitals will be required to report C. diff infection rates starting in 2013.

“We really have scant data,” he says. “There is not a lot of reporting if you look at the nation on a whole. And I think that underscores one of the reasons why you need to have data for action. You need to have reporting of these organisms to the National Healthcare Safety Network so that the CDC can monitor and can make plans and can do effective interventions.

“You want to know where the areas of highest infection are,” he adds. “You want to know what interventions work and don’t work. If you don’t have a national coordinated reporting system, it really makes it difficult to address the problem. C. diff is going to be much harder to control than MRSA or other bacteria because it changes into a hard-to-kill dormant spore stage and then re-occurs at some point.”

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has proposed adding C. diff infections to the list of hospital-acquired conditions that will not be reimbursable. It is widely hoped that such a measure will go a long way toward stamping out the problem.

Dr. Kobaidze of Emory notes that C. diff is a dynamic problem, always adapting and posing new challenges. And hospitalists should be more involved in answering these questions through research. One recent question, she points out, is whether proton pump inhibitor use is related to the rise of C. diff.

Ultimately, though, controlling C. diff in hospitals might come down to what is done day to day inside the hospital. And hospitalists can play a big role.

Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSCR, SFHM, a hospitalist and medical director of quality at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston, says that a full-time pharmacist on the hospital’s antimicrobial stewardship committee is always reviewing antibiotic prescriptions and is prepared to flag cases in which a broad-spectrum is used when one with a more narrow scope might be more appropriate.

The hospital has done its best, as part of its “renovation cycle,” to standardize the layouts of rooms “so that the second you open the door you know exactly where the alcohol gel is and where the soap and the sink is going to be.” The idea is to make compliance as “mindless” as possible. Such efforts can be hampered by structural limitations though, she says.

HM group leaders, she suggests, can play an important part simply by being good role models—gowning and gloving without complaint before entering high-risk rooms and reinforcing the message that such efforts have real effects on patient safety.

But she also acknowledges that “it always sounds easy....There has to be some level of redundancy built into the hospital system. This is more of a system thing than the individual hospitalist.”

One level of redundancy at MUSC that has been particularly effective, she says, are “secret shoppers” who keep an eye out for medical teams that might not be washing their hands as they go in and out of high-risk rooms. Each unit is responsible for their hand hygiene numbers—which include both self-reported figures and those obtained by the secret onlookers—and those numbers are made available to the hospital.

Those units with the best numbers are sometimes given a reward, such as a pizza party, but it’s colleagues’ knowledge of the numbers that matters most, she says.

“That, in and of itself, is a powerful motivator,” Dr. Scheurer says. “We bring it to all of our quality operations meetings, all the administrators, the CEO, the CMO. It’s very motivating for every unit. They don’t want to be the trailing unit.”

Tom Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Miami.

References

- Orenstein R, Aronhalt KC, McManus JE Jr., Fedraw LA. A targeted strategy to wipe out Clostridium difficile. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32(11):1137-1139.

- Stevens V, Dumyati G, Fine LS, Fisher SG, van Wijngaarden E. Cumulative antibiotic exposures over time and the risk of Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(1):42-48.

At 480-bed Emory University Hospital Midtown in Atlanta, the physicians and staff seemingly are doing all the right things to foil one of hospital’s archenemies: Clostridium difficile. The bacteria, better known as C. diff, is responsible for a sharp rise in hospital-acquired infections over the past decade, rivaling even MRSA.

In 2010, Emory Midtown launched a campaign to boost awareness of the importance of hand washing before and after treating patients infected with C. diff and those likely to be infected. They also began using the polymerase-chain-reaction-based assay to detect the bacteria, a test with much higher sensitivity that helps to more efficiently identify those infected so control measures can be more prompt and targeted. They use a hypochlorite mixture to clean the rooms of those infected, which is considered a must. And a committee monitors the use of antibiotics to prevent overuse—often the scapegoat for the rise of the hard-to-kill bacteria.

Still, at Emory, the rate of C. diff is about the same as the national average, says hospitalist Ketino Kobaidze, MD, assistant professor at the Emory University School of Medicine and a member of the antimicrobial stewardship and infectious disease control committees at Midtown. While Dr. Kobaidze says her institution is doing a good job of trying to keep C. diff under control, she thinks hospitalists can do more.

“My feeling is that we are not as involved as we’re supposed to be,” she says. “I think we need to be a little bit more proactive, be involved in committees and research activities across the hospital.”

—Kevin Kavanagh, MD, founder, Health Watch USA

You Are Not Alone

The experience at Emory Midtown is far from unusual—healthcare facilities, and hospitalists, across the country have seen healthcare-related C. diff cases more than double since 2001 to between 400,000 and 500,000 a year, says Carolyn Gould, MD, a medical epidemiologist in the division of healthcare quality promotion at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta.

Hospitalists, whether they realize it or not, are intimately involved in how well the C. diff outbreak is controlled. Infectious-disease (ID) specialists say hospitalists are perfectly situated to make an impact in efforts to help curb the outbreak.

“Hospitalists are critical to this effort,” Dr. Gould says. “They’re in the hospital day in and day out, and they’re constantly interacting with the patients, staff, and administration. They’re often the first on the scene to see a patient who might have suddenly developed diarrhea; they’re the first to react. I think they’re in a prime position to play a leadership role to prevent C. diff infections.”

They’re also situated well to work with infection-control experts on antimicrobial stewardship programs, she says.

“I look at hospitalists just like I would have looked at internists managing their own patients 15 years ago,” says Stuart Cohen, MD, an ID expert with the University of California at Davis and a fellow with the Infectious Diseases Society of America who was lead author of the latest published IDSA guidelines on C. diff treatment. “And so they’re the first-line people.”

continued below...

A Tough Bug

Believed to be aided largely by the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics that knock out the colon’s natural flora, C. diff in the hospital—as well as nursing homes and acute-care facilities—has raged for much of the past decade. Its rise is tied to the emergence of a new hypervirulent strain known as BI/NAP1/027, or NAP1 for short. The strain is highly resistant to fluoroquinolones, such as ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin, which are used often in healthcare settings.

“A fluoroquinolone will wipe out a lot of your normal flora in your gut,” Dr. Gould says. “But it won’t wipe out C. diff, in particular this hypervirulent strain. And so this strain can flourish in the presence of fluoroquinolones.” The strain produces up to 15 to 20 times more toxins than other C. diff strains, according to some data, she adds.

Vancomycin (Vanconin) and metronidazole (Flagyl) are the most common antibiotics used to treat patients infected with C. diff. Mortality rates are higher among the elderly, largely because of their weaker immune system, Dr. Gould says. Studies have generally shown mortality rates of 10% or a bit lower.1

More recent studies have shown that the number of hospital-related C. diff cases might have begun to level off in 2008 and 2009. Dr. Gould says she thinks the leveling off is for real, but there is debate over what the immediate future holds.

“There’s a lot of work and initiatives, especially state-based initiatives, that are being done in hospitals. And there’s reason to believe they’re effective,” she says, adding it’s harder to get a good picture of the problem in long-term care facilities and in the community.

Dr. Cohen with the IDSA says it’s too soon to say whether the problem is hitting a plateau. “CDC data are always a couple of years behind,” he says. “Until you see another data point, you can’t tell whether that’s just a transient flattening and whether it’s going to keep going up or not.”

Kevin Kavanagh, MD, founder of the patient advocacy group Health Watch USA and a retired otolaryngologist in Kentucky who has taken a keen interest in the C. diff problem, says he doesn’t think the end of the tunnel is within view yet.

“I think C. diff is going to get worse before it gets better,” Dr. Kavanagh says. “And that’s not necessarily because the healthcare profession isn’t doing due diligence. This is a tough organism.—it can be tough to treat and can be very tough to kill.”

The Best Defense?

Because C. diff lives within protective spores, sound hand hygiene practices and room-cleaning practices are essential for keeping infections to a minimum. Alcohol-based hand sanitizers, effective against other organisms including MRSA, do not kill C. diff. The bacteria must be mechanically removed through hand washing.

And even hand washing might not be totally effective at getting rid of the spores, which means it’s important for healthcare workers to gown and glove in high-risk rooms.

Sodium hypochlorite solutions, or bleach mixtures, have to be used to clean rooms occupied by patients with C. diff, and the prevailing thought is to clean the rooms of patients suspected of having C. diff, even if those cases might not be confirmed.

Equally important to cleaning and hand washing is systemwide emphasis on antibiotic stewardship. A 2011 study at the State University of New York Buffalo found that the risk of a C. diff infection rose with the number of antibiotics taken.2

—Carolyn Gould, MD, medical epidemiologist, division of healthcare quality promotion, Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta

While a broad-spectrum antibiotic might be necessary at first, once the results of cultures are received, the treatment should be finely tailored to kill only the problem bacteria so that the body’s natural defenses aren’t broken down, Dr. Gould explains.

“If someone is very sick and you’re not sure what is going on, it’s very reasonable to treat them empirically with broad-spectrum antibiotics,” she says. “The important thing is that you send the appropriate cultures before so that you know what you’re treating and you can optimize those antibiotics with daily assessments.”

It’s clear why an overreliance on broad-spectrum drugs prevails in U.S. health settings, Dr. Cohen acknowledges. Recent literature suggests treating critically ill patients with wide-ranging antimicrobials as the mortality rate can be twice as high with narrower options. “I think people have gotten very quick to give broad-spectrum therapy,” he says.

continued below...

National Response, Localized Attention

Dr. Kavanagh of Health Watch USA says that more information about C. diff is needed, particularly publicly available numbers of infections at hospitals. Some states require those figures to be reported, but most don’t. And there is no current federal mandate on reporting of C. diff cases, although acute-care hospitals will be required to report C. diff infection rates starting in 2013.

“We really have scant data,” he says. “There is not a lot of reporting if you look at the nation on a whole. And I think that underscores one of the reasons why you need to have data for action. You need to have reporting of these organisms to the National Healthcare Safety Network so that the CDC can monitor and can make plans and can do effective interventions.

“You want to know where the areas of highest infection are,” he adds. “You want to know what interventions work and don’t work. If you don’t have a national coordinated reporting system, it really makes it difficult to address the problem. C. diff is going to be much harder to control than MRSA or other bacteria because it changes into a hard-to-kill dormant spore stage and then re-occurs at some point.”

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has proposed adding C. diff infections to the list of hospital-acquired conditions that will not be reimbursable. It is widely hoped that such a measure will go a long way toward stamping out the problem.

Dr. Kobaidze of Emory notes that C. diff is a dynamic problem, always adapting and posing new challenges. And hospitalists should be more involved in answering these questions through research. One recent question, she points out, is whether proton pump inhibitor use is related to the rise of C. diff.

Ultimately, though, controlling C. diff in hospitals might come down to what is done day to day inside the hospital. And hospitalists can play a big role.

Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSCR, SFHM, a hospitalist and medical director of quality at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston, says that a full-time pharmacist on the hospital’s antimicrobial stewardship committee is always reviewing antibiotic prescriptions and is prepared to flag cases in which a broad-spectrum is used when one with a more narrow scope might be more appropriate.

The hospital has done its best, as part of its “renovation cycle,” to standardize the layouts of rooms “so that the second you open the door you know exactly where the alcohol gel is and where the soap and the sink is going to be.” The idea is to make compliance as “mindless” as possible. Such efforts can be hampered by structural limitations though, she says.

HM group leaders, she suggests, can play an important part simply by being good role models—gowning and gloving without complaint before entering high-risk rooms and reinforcing the message that such efforts have real effects on patient safety.

But she also acknowledges that “it always sounds easy....There has to be some level of redundancy built into the hospital system. This is more of a system thing than the individual hospitalist.”

One level of redundancy at MUSC that has been particularly effective, she says, are “secret shoppers” who keep an eye out for medical teams that might not be washing their hands as they go in and out of high-risk rooms. Each unit is responsible for their hand hygiene numbers—which include both self-reported figures and those obtained by the secret onlookers—and those numbers are made available to the hospital.

Those units with the best numbers are sometimes given a reward, such as a pizza party, but it’s colleagues’ knowledge of the numbers that matters most, she says.

“That, in and of itself, is a powerful motivator,” Dr. Scheurer says. “We bring it to all of our quality operations meetings, all the administrators, the CEO, the CMO. It’s very motivating for every unit. They don’t want to be the trailing unit.”

Tom Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Miami.

References

- Orenstein R, Aronhalt KC, McManus JE Jr., Fedraw LA. A targeted strategy to wipe out Clostridium difficile. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32(11):1137-1139.

- Stevens V, Dumyati G, Fine LS, Fisher SG, van Wijngaarden E. Cumulative antibiotic exposures over time and the risk of Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(1):42-48.

At 480-bed Emory University Hospital Midtown in Atlanta, the physicians and staff seemingly are doing all the right things to foil one of hospital’s archenemies: Clostridium difficile. The bacteria, better known as C. diff, is responsible for a sharp rise in hospital-acquired infections over the past decade, rivaling even MRSA.

In 2010, Emory Midtown launched a campaign to boost awareness of the importance of hand washing before and after treating patients infected with C. diff and those likely to be infected. They also began using the polymerase-chain-reaction-based assay to detect the bacteria, a test with much higher sensitivity that helps to more efficiently identify those infected so control measures can be more prompt and targeted. They use a hypochlorite mixture to clean the rooms of those infected, which is considered a must. And a committee monitors the use of antibiotics to prevent overuse—often the scapegoat for the rise of the hard-to-kill bacteria.

Still, at Emory, the rate of C. diff is about the same as the national average, says hospitalist Ketino Kobaidze, MD, assistant professor at the Emory University School of Medicine and a member of the antimicrobial stewardship and infectious disease control committees at Midtown. While Dr. Kobaidze says her institution is doing a good job of trying to keep C. diff under control, she thinks hospitalists can do more.

“My feeling is that we are not as involved as we’re supposed to be,” she says. “I think we need to be a little bit more proactive, be involved in committees and research activities across the hospital.”

—Kevin Kavanagh, MD, founder, Health Watch USA

You Are Not Alone

The experience at Emory Midtown is far from unusual—healthcare facilities, and hospitalists, across the country have seen healthcare-related C. diff cases more than double since 2001 to between 400,000 and 500,000 a year, says Carolyn Gould, MD, a medical epidemiologist in the division of healthcare quality promotion at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta.

Hospitalists, whether they realize it or not, are intimately involved in how well the C. diff outbreak is controlled. Infectious-disease (ID) specialists say hospitalists are perfectly situated to make an impact in efforts to help curb the outbreak.

“Hospitalists are critical to this effort,” Dr. Gould says. “They’re in the hospital day in and day out, and they’re constantly interacting with the patients, staff, and administration. They’re often the first on the scene to see a patient who might have suddenly developed diarrhea; they’re the first to react. I think they’re in a prime position to play a leadership role to prevent C. diff infections.”

They’re also situated well to work with infection-control experts on antimicrobial stewardship programs, she says.

“I look at hospitalists just like I would have looked at internists managing their own patients 15 years ago,” says Stuart Cohen, MD, an ID expert with the University of California at Davis and a fellow with the Infectious Diseases Society of America who was lead author of the latest published IDSA guidelines on C. diff treatment. “And so they’re the first-line people.”

continued below...

A Tough Bug

Believed to be aided largely by the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics that knock out the colon’s natural flora, C. diff in the hospital—as well as nursing homes and acute-care facilities—has raged for much of the past decade. Its rise is tied to the emergence of a new hypervirulent strain known as BI/NAP1/027, or NAP1 for short. The strain is highly resistant to fluoroquinolones, such as ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin, which are used often in healthcare settings.

“A fluoroquinolone will wipe out a lot of your normal flora in your gut,” Dr. Gould says. “But it won’t wipe out C. diff, in particular this hypervirulent strain. And so this strain can flourish in the presence of fluoroquinolones.” The strain produces up to 15 to 20 times more toxins than other C. diff strains, according to some data, she adds.

Vancomycin (Vanconin) and metronidazole (Flagyl) are the most common antibiotics used to treat patients infected with C. diff. Mortality rates are higher among the elderly, largely because of their weaker immune system, Dr. Gould says. Studies have generally shown mortality rates of 10% or a bit lower.1

More recent studies have shown that the number of hospital-related C. diff cases might have begun to level off in 2008 and 2009. Dr. Gould says she thinks the leveling off is for real, but there is debate over what the immediate future holds.

“There’s a lot of work and initiatives, especially state-based initiatives, that are being done in hospitals. And there’s reason to believe they’re effective,” she says, adding it’s harder to get a good picture of the problem in long-term care facilities and in the community.

Dr. Cohen with the IDSA says it’s too soon to say whether the problem is hitting a plateau. “CDC data are always a couple of years behind,” he says. “Until you see another data point, you can’t tell whether that’s just a transient flattening and whether it’s going to keep going up or not.”

Kevin Kavanagh, MD, founder of the patient advocacy group Health Watch USA and a retired otolaryngologist in Kentucky who has taken a keen interest in the C. diff problem, says he doesn’t think the end of the tunnel is within view yet.

“I think C. diff is going to get worse before it gets better,” Dr. Kavanagh says. “And that’s not necessarily because the healthcare profession isn’t doing due diligence. This is a tough organism.—it can be tough to treat and can be very tough to kill.”

The Best Defense?

Because C. diff lives within protective spores, sound hand hygiene practices and room-cleaning practices are essential for keeping infections to a minimum. Alcohol-based hand sanitizers, effective against other organisms including MRSA, do not kill C. diff. The bacteria must be mechanically removed through hand washing.

And even hand washing might not be totally effective at getting rid of the spores, which means it’s important for healthcare workers to gown and glove in high-risk rooms.

Sodium hypochlorite solutions, or bleach mixtures, have to be used to clean rooms occupied by patients with C. diff, and the prevailing thought is to clean the rooms of patients suspected of having C. diff, even if those cases might not be confirmed.

Equally important to cleaning and hand washing is systemwide emphasis on antibiotic stewardship. A 2011 study at the State University of New York Buffalo found that the risk of a C. diff infection rose with the number of antibiotics taken.2

—Carolyn Gould, MD, medical epidemiologist, division of healthcare quality promotion, Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta

While a broad-spectrum antibiotic might be necessary at first, once the results of cultures are received, the treatment should be finely tailored to kill only the problem bacteria so that the body’s natural defenses aren’t broken down, Dr. Gould explains.

“If someone is very sick and you’re not sure what is going on, it’s very reasonable to treat them empirically with broad-spectrum antibiotics,” she says. “The important thing is that you send the appropriate cultures before so that you know what you’re treating and you can optimize those antibiotics with daily assessments.”

It’s clear why an overreliance on broad-spectrum drugs prevails in U.S. health settings, Dr. Cohen acknowledges. Recent literature suggests treating critically ill patients with wide-ranging antimicrobials as the mortality rate can be twice as high with narrower options. “I think people have gotten very quick to give broad-spectrum therapy,” he says.

continued below...

National Response, Localized Attention

Dr. Kavanagh of Health Watch USA says that more information about C. diff is needed, particularly publicly available numbers of infections at hospitals. Some states require those figures to be reported, but most don’t. And there is no current federal mandate on reporting of C. diff cases, although acute-care hospitals will be required to report C. diff infection rates starting in 2013.

“We really have scant data,” he says. “There is not a lot of reporting if you look at the nation on a whole. And I think that underscores one of the reasons why you need to have data for action. You need to have reporting of these organisms to the National Healthcare Safety Network so that the CDC can monitor and can make plans and can do effective interventions.

“You want to know where the areas of highest infection are,” he adds. “You want to know what interventions work and don’t work. If you don’t have a national coordinated reporting system, it really makes it difficult to address the problem. C. diff is going to be much harder to control than MRSA or other bacteria because it changes into a hard-to-kill dormant spore stage and then re-occurs at some point.”

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has proposed adding C. diff infections to the list of hospital-acquired conditions that will not be reimbursable. It is widely hoped that such a measure will go a long way toward stamping out the problem.

Dr. Kobaidze of Emory notes that C. diff is a dynamic problem, always adapting and posing new challenges. And hospitalists should be more involved in answering these questions through research. One recent question, she points out, is whether proton pump inhibitor use is related to the rise of C. diff.

Ultimately, though, controlling C. diff in hospitals might come down to what is done day to day inside the hospital. And hospitalists can play a big role.

Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSCR, SFHM, a hospitalist and medical director of quality at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston, says that a full-time pharmacist on the hospital’s antimicrobial stewardship committee is always reviewing antibiotic prescriptions and is prepared to flag cases in which a broad-spectrum is used when one with a more narrow scope might be more appropriate.

The hospital has done its best, as part of its “renovation cycle,” to standardize the layouts of rooms “so that the second you open the door you know exactly where the alcohol gel is and where the soap and the sink is going to be.” The idea is to make compliance as “mindless” as possible. Such efforts can be hampered by structural limitations though, she says.

HM group leaders, she suggests, can play an important part simply by being good role models—gowning and gloving without complaint before entering high-risk rooms and reinforcing the message that such efforts have real effects on patient safety.

But she also acknowledges that “it always sounds easy....There has to be some level of redundancy built into the hospital system. This is more of a system thing than the individual hospitalist.”

One level of redundancy at MUSC that has been particularly effective, she says, are “secret shoppers” who keep an eye out for medical teams that might not be washing their hands as they go in and out of high-risk rooms. Each unit is responsible for their hand hygiene numbers—which include both self-reported figures and those obtained by the secret onlookers—and those numbers are made available to the hospital.

Those units with the best numbers are sometimes given a reward, such as a pizza party, but it’s colleagues’ knowledge of the numbers that matters most, she says.

“That, in and of itself, is a powerful motivator,” Dr. Scheurer says. “We bring it to all of our quality operations meetings, all the administrators, the CEO, the CMO. It’s very motivating for every unit. They don’t want to be the trailing unit.”

Tom Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Miami.

References

- Orenstein R, Aronhalt KC, McManus JE Jr., Fedraw LA. A targeted strategy to wipe out Clostridium difficile. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32(11):1137-1139.

- Stevens V, Dumyati G, Fine LS, Fisher SG, van Wijngaarden E. Cumulative antibiotic exposures over time and the risk of Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(1):42-48.

Is a Post-Discharge Clinic in Your Hospital's Future?

The hospitalist concept was established on the foundation of timely, informative handoffs to primary-care physicians (PCPs) once a patient’s hospital stay is complete. With sicker patients and shorter hospital stays, pending test results, and complex post-discharge medication regimens to sort out, this handoff is crucial to successful discharges. But what if a discharged patient can’t get in to see the PCP, or has no established PCP?

Recent research on hospital readmissions by the Dartmouth Atlas Project found that only 42% of hospitalized Medicare patients had any contact with a primary-care clinician within 14 days of discharge.1 For patients with ongoing medical needs, such missed connections are a major contributor to hospital readmissions, and thus a target for hospitals and HM groups wanting to control their readmission rates before Medicare imposes reimbursement penalties starting in October 2012 (see “Value-Based Purchasing Raises the Stakes,” May 2011, p. 1).

One proposed solution is the post-discharge clinic, typically located on or near a hospital’s campus and staffed by hospitalists, PCPs, or advanced-practice nurses. The patient can be seen once or a few times in the post-discharge clinic to make sure that health education started in the hospital is understood and followed, and that prescriptions ordered in the hospital are being taken on schedule.

—Lauren Doctoroff, MD, hospitalist, director, post-discharge clinic, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston

Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, FHM, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, describes hospitalist-led post-discharge clinics as “Band-Aids for an inadequate primary-care system.” What would be better, he says, is focusing on the underlying problem and working to improve post-discharge access to primary care. Dr. Williams acknowledges, however, that sometimes a patch is needed to stanch the blood flow—e.g., to better manage care transitions—while waiting on healthcare reform and medical homes to improve care coordination throughout the system.

Working in a post-discharge clinic might seem like “a stretch for many hospitalists, especially those who chose this field because they didn’t want to do outpatient medicine,” says Lauren Doctoroff, MD, a hospitalist who directs a post-discharge clinic at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in Boston. “But there are times when it may be appropriate for hospital-based doctors to extend their responsibility out of the hospital.”

Dr. Doctoroff also says that working in such a clinic can be practice-changing for hospitalists. “All of a sudden, you have a different view of your hospitalized patients, and you start to ask different questions while they’re in the hospital than you ever did before,” she explains.

What is a Post-Discharge Clinic?

The post-discharge clinic, also known as a transitional-care clinic or after-care clinic, is intended to bridge medical coverage between the hospital and primary care. The clinic at BIDMC is for patients affiliated with its Health Care Associates faculty practice “discharged from either our hospital or another hospital, who need care that their PCP or specialist, because of scheduling conflicts, cannot provide within the needed time frame,” Dr. Doctoroff says.

Four hospitalists from BIDMC’s large HM group were selected to staff the clinic. The hospitalists work in one-month rotations (a total of three months on service per year), and are relieved of other responsibilities during their month in clinic. They provide five half-day clinic sessions per week, with a 40-minute-per-patient visit schedule. Thirty minutes are allotted for patients referred from the hospital’s ED who did not get admitted to the hospital but need clinical follow-up.

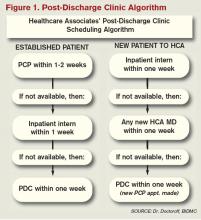

The clinic is based in a BIDMC-affiliated primary-care practice, “which allows us to use its administrative structure and logistical support,” Dr. Doctoroff explains. “A hospital-based administrative service helps set up outpatient visits prior to discharge using computerized physician order entry and a scheduling algorhythm.” (See Figure 1) Patients who can be seen by their PCP in a timely fashion are referred to the PCP office; if not, they are scheduled in the post-discharge clinic. “That helps preserve the PCP relationship, which I think is paramount,” she says.

The first two years were spent getting the clinic established, but in the near future, BIDMC will start measuring such outcomes as access to care and quality. “But not necessarily readmission rates,” Dr. Doctoroff adds. “I know many people think of post-discharge clinics in the context of preventing readmissions, although we don’t have the data yet to fully support that. In fact, some readmissions may result from seeing a doctor. If you get a closer look at some patients after discharge and they are doing badly, they are more likely to be readmitted than if they had just stayed home.” In such cases, readmission could actually be a better outcome for the patient, she notes.

Dr. Doctoroff describes a typical user of her post-discharge clinic as a non-English-speaking patient who was discharged from the hospital with severe back pain from a herniated disk. “He came back to see me 10 days later, still barely able to walk. He hadn’t been able to fill any of the prescriptions from his hospital stay. Within two hours after I saw him, we got his meds filled and outpatient services set up,” she says. “We take care of many patients like him in the hospital with acute pain issues, whom we discharge as soon as they can walk, and later we see them limping into outpatient clinics. It makes me think differently now about how I plan their discharges.”

—Shay Martinez, MD, hospitalist, medical director, Harborview Medical Center, Seattle

Who else needs these clinics? Dr. Doctoroff suggests two ways of looking at the question.

“Even for a simple patient admitted to the hospital, that can represent a significant change in the medical picture—a sort of sentinel event. In the discharge clinic, we give them an opportunity to review the hospitalization and answer their questions,” she says. “A lot of information presented to patients in the hospital is not well heard, and the initial visit may be their first time to really talk about what happened.” For other patients with conditions such as congestive heart failure (CHF), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), or poorly controlled diabetes, treatment guidelines might dictate a pattern for post-discharge follow-up—for example, medical visits in seven or 10 days.

In Seattle, Harborview Medical Center established its After Care Clinic, staffed by hospitalists and nurse practitioners, to provide transitional care for patients discharged from inpatient wards or the ED in need of follow-up, says medical director and hospitalist Shay Martinez, MD. A second priority is to see any CHF patient within 48 hours of discharge.

“We try to limit patients to a maximum of three visits in our clinic,” she says. “At that point, we help them get established in a medical home, either here in one of our primary-care clinics, or in one of the many excellent community clinics in the area.

“This model works well with our patient population. We actually try to do primary care on the inpatient side as well. Our hospitalists are specialized in that approach, given our patient population. We see a lot of immigrants, non-English speakers, people with low health literacy, and the homeless, many of whom lack primary care,” Dr. Martinez says. “We do medication reconciliation, reassessments, and follow-ups with lab tests. We also try to assess who is more likely to be a no-show, and who needs more help with scheduling follow-up appointments.”

Clinical coverage of post-discharge clinics varies by setting, staffing, and scope. If demand is low, hospitalists or ED physicians can be called off the floor to see patients who return to the clinic, or they could staff the clinic after their hospitalist shift ends. Post-discharge clinic staff whose schedules are light can flex into providing primary-care visits in the clinic. Post-discharge can also could be provided in conjunction with—or as an alternative to—physician house calls to patients’ homes. Some post-discharge clinics work with medical call centers or telephonic case managers; some even use telemedicine.

It also could be a growth opportunity for hospitalist practices. “It is an exciting potential role for hospitalists interested in doing a little outpatient care,” Dr. Martinez says. “This is also a good way to be a safety net for your safety-net hospital.”

continued below...

Partner with Community

Tallahassee (Fla.) Memorial Hospital (TMH) in February launched a transitional-care clinic in collaboration with faculty from Florida State University, community-based health providers, and the local Capital Health Plan. Hospitalists don’t staff the clinic, but the HM group is its major source of referrals, says Dean Watson, MD, chief medical officer at TMH. Patients can be followed for up to eight weeks, during which time they get comprehensive assessments, medication review and optimization, and referral by the clinic social worker to a PCP and to available community services.

“Three years ago, we came up with the idea for a patient population we know is at high risk for readmission. Why don’t we partner with organizations in the community, form a clinic, teach students and residents, and learn together?” Dr. Watson says. “In addition to the usual patients, TMH targets those who have been readmitted to the hospital three times or more in the past year.”

The clinic, open five days a week, is staffed by a physician, nurse practitioner, telephonic nurse, and social worker, and also has a geriatric assessment clinic.

“We set up a system to identify patients through our electronic health record, and when they come to the clinic, we focus on their social environment and other non-medical issues that might cause readmissions,” he says. The clinic has a pharmacy and funds to support medications for patients without insurance. “In our first six months, we reduced emergency room visits and readmissions for these patients by 68 percent.”

One key partner, Capital Health Plan, bought and refurbished a building, and made it available for the clinic at no cost. Capital’s motivation, says Tom Glennon, a senior vice president for the plan, is its commitment to the community and to community service.

“We’re a nonprofit HMO. We’re focused on what we can do to serve the community, and we’re looking at this as a way for the hospital to have fewer costly, unreimbursed bouncebacks,” Glennon says. “That’s a win-win for all of us.”

Most of the patients who use the clinic are not members of Capital Health Plan, Glennon adds. “If we see CHP members turning up at the transitions clinic, then we have a problem—a breakdown in our case management,” he explains. “Our goal is to have our members taken care of by primary-care providers.”

Hard Data? Not So Fast

How many post-discharge clinics are in operation today is not known. Fundamental financial data, too, are limited, but some say it is unlikely a post-discharge clinic will cover operating expenses from billing revenues alone.

Thus, such clinics will require funding from the hospital, HM group, health system, or health plans, based on the benefits the clinic provides to discharged patients and the impact on 30-day readmissions (for more about the logistical challenges post-discharge clinics present, see “What Do PCPs Think?”).

Some also suggest that many of the post-discharge clinics now in operation are too new to have demonstrated financial impact or return on investment. “We have not yet been asked to show our financial viability,” Dr. Doctoroff says. “I think the clinic leadership thinks we are fulfilling other goals for now, such as creating easier access for their patients after discharge.”

Amy Boutwell, MD, MPP, a hospitalist at Newton Wellesley Hospital in Massachusetts and founder of Collaborative Healthcare Strategies, is among the post-discharge skeptics. She agrees with Dr. Williams that the post-discharge concept is more of a temporary fix to the long-term issues in primary care. “I think the idea is getting more play than actual activity out there right now,” she says. “We need to find opportunities to manage transitions within our scope today and tomorrow while strategically looking at where we want to be in five years [as hospitals and health systems].”

Dr. Boutwell says she’s experienced the frustration of trying to make follow-up appointments with physicians who don’t have any open slots for hospitalized patients awaiting discharge. “We think of follow up as physician-led, but there are alternatives and physician extenders,” she says. “It is well-documented that our healthcare system underuses home health care and other services that might be helpful. We forget how many other opportunities there are in our communities to get another clinician to touch the patient.”

Hospitalists, as key players in the healthcare system, can speak out in support of strengthening primary-care networks and building more collaborative relationships with PCPs, according to Dr. Williams. “If you’re going to set up an outpatient clinic, ideally, have it staffed by PCPs who can funnel the patients into primary-care networks. If that’s not feasible, then hospitalists should proceed with caution, since this approach begins to take them out of their scope of practice,” he says.

With 13 years of experience in urban hospital settings, Dr. Williams is familiar with the dangers unassigned patients present at discharge. “But I don’t know that we’ve yet optimized the hospital discharge process at any hospital in the United States,” he says.

That said, Dr. Williams knows his hospital in downtown Chicago is now working to establish a post-discharge clinic. It will be staffed by PCPs and will target patients who don’t have a PCP, are on Medicaid, or lack insurance.

“Where it starts to make me uncomfortable,” Dr. Williams says, “is what happens when you follow patients out into the outpatient setting?

It’s hard to do just one visit and draw the line. Yes, you may prevent a readmission, but the patient is still left with chronic illness and the need for primary care.”

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer based in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Goodman, DC, Fisher ES, Chang C. After Hospitalization: A Dartmouth Atlas Report on Post-Acute Care for Medicare Beneficiaries. Dartmouth Atlas website. Available at: www.dartmouthatlas.org/downloads/reports/Post_discharge_events_092811.pdf. Accessed Nov. 3, 2011.

- Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, Leung A, Williams MV. Interventions to reduce 3-day rehospitalization: A systematic review. Ann Int Med. 2011;155(8): 520-528.

- Misky GJ, Wald HL, Coleman EA. Post-hospitalization transitions: Examining the effects of timing of primary care provider follow-up. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(7):392-397.

- Shu CC, Hsu NC, Lin YF, et al. Integrated post-discharge transitional care in Taiwan. BMC Medicine website. Available at: www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/9/96. Accessed Nov. 1, 2011.

The hospitalist concept was established on the foundation of timely, informative handoffs to primary-care physicians (PCPs) once a patient’s hospital stay is complete. With sicker patients and shorter hospital stays, pending test results, and complex post-discharge medication regimens to sort out, this handoff is crucial to successful discharges. But what if a discharged patient can’t get in to see the PCP, or has no established PCP?

Recent research on hospital readmissions by the Dartmouth Atlas Project found that only 42% of hospitalized Medicare patients had any contact with a primary-care clinician within 14 days of discharge.1 For patients with ongoing medical needs, such missed connections are a major contributor to hospital readmissions, and thus a target for hospitals and HM groups wanting to control their readmission rates before Medicare imposes reimbursement penalties starting in October 2012 (see “Value-Based Purchasing Raises the Stakes,” May 2011, p. 1).

One proposed solution is the post-discharge clinic, typically located on or near a hospital’s campus and staffed by hospitalists, PCPs, or advanced-practice nurses. The patient can be seen once or a few times in the post-discharge clinic to make sure that health education started in the hospital is understood and followed, and that prescriptions ordered in the hospital are being taken on schedule.

—Lauren Doctoroff, MD, hospitalist, director, post-discharge clinic, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston

Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, FHM, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, describes hospitalist-led post-discharge clinics as “Band-Aids for an inadequate primary-care system.” What would be better, he says, is focusing on the underlying problem and working to improve post-discharge access to primary care. Dr. Williams acknowledges, however, that sometimes a patch is needed to stanch the blood flow—e.g., to better manage care transitions—while waiting on healthcare reform and medical homes to improve care coordination throughout the system.

Working in a post-discharge clinic might seem like “a stretch for many hospitalists, especially those who chose this field because they didn’t want to do outpatient medicine,” says Lauren Doctoroff, MD, a hospitalist who directs a post-discharge clinic at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in Boston. “But there are times when it may be appropriate for hospital-based doctors to extend their responsibility out of the hospital.”

Dr. Doctoroff also says that working in such a clinic can be practice-changing for hospitalists. “All of a sudden, you have a different view of your hospitalized patients, and you start to ask different questions while they’re in the hospital than you ever did before,” she explains.

What is a Post-Discharge Clinic?

The post-discharge clinic, also known as a transitional-care clinic or after-care clinic, is intended to bridge medical coverage between the hospital and primary care. The clinic at BIDMC is for patients affiliated with its Health Care Associates faculty practice “discharged from either our hospital or another hospital, who need care that their PCP or specialist, because of scheduling conflicts, cannot provide within the needed time frame,” Dr. Doctoroff says.

Four hospitalists from BIDMC’s large HM group were selected to staff the clinic. The hospitalists work in one-month rotations (a total of three months on service per year), and are relieved of other responsibilities during their month in clinic. They provide five half-day clinic sessions per week, with a 40-minute-per-patient visit schedule. Thirty minutes are allotted for patients referred from the hospital’s ED who did not get admitted to the hospital but need clinical follow-up.

The clinic is based in a BIDMC-affiliated primary-care practice, “which allows us to use its administrative structure and logistical support,” Dr. Doctoroff explains. “A hospital-based administrative service helps set up outpatient visits prior to discharge using computerized physician order entry and a scheduling algorhythm.” (See Figure 1) Patients who can be seen by their PCP in a timely fashion are referred to the PCP office; if not, they are scheduled in the post-discharge clinic. “That helps preserve the PCP relationship, which I think is paramount,” she says.

The first two years were spent getting the clinic established, but in the near future, BIDMC will start measuring such outcomes as access to care and quality. “But not necessarily readmission rates,” Dr. Doctoroff adds. “I know many people think of post-discharge clinics in the context of preventing readmissions, although we don’t have the data yet to fully support that. In fact, some readmissions may result from seeing a doctor. If you get a closer look at some patients after discharge and they are doing badly, they are more likely to be readmitted than if they had just stayed home.” In such cases, readmission could actually be a better outcome for the patient, she notes.

Dr. Doctoroff describes a typical user of her post-discharge clinic as a non-English-speaking patient who was discharged from the hospital with severe back pain from a herniated disk. “He came back to see me 10 days later, still barely able to walk. He hadn’t been able to fill any of the prescriptions from his hospital stay. Within two hours after I saw him, we got his meds filled and outpatient services set up,” she says. “We take care of many patients like him in the hospital with acute pain issues, whom we discharge as soon as they can walk, and later we see them limping into outpatient clinics. It makes me think differently now about how I plan their discharges.”

—Shay Martinez, MD, hospitalist, medical director, Harborview Medical Center, Seattle

Who else needs these clinics? Dr. Doctoroff suggests two ways of looking at the question.

“Even for a simple patient admitted to the hospital, that can represent a significant change in the medical picture—a sort of sentinel event. In the discharge clinic, we give them an opportunity to review the hospitalization and answer their questions,” she says. “A lot of information presented to patients in the hospital is not well heard, and the initial visit may be their first time to really talk about what happened.” For other patients with conditions such as congestive heart failure (CHF), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), or poorly controlled diabetes, treatment guidelines might dictate a pattern for post-discharge follow-up—for example, medical visits in seven or 10 days.

In Seattle, Harborview Medical Center established its After Care Clinic, staffed by hospitalists and nurse practitioners, to provide transitional care for patients discharged from inpatient wards or the ED in need of follow-up, says medical director and hospitalist Shay Martinez, MD. A second priority is to see any CHF patient within 48 hours of discharge.

“We try to limit patients to a maximum of three visits in our clinic,” she says. “At that point, we help them get established in a medical home, either here in one of our primary-care clinics, or in one of the many excellent community clinics in the area.

“This model works well with our patient population. We actually try to do primary care on the inpatient side as well. Our hospitalists are specialized in that approach, given our patient population. We see a lot of immigrants, non-English speakers, people with low health literacy, and the homeless, many of whom lack primary care,” Dr. Martinez says. “We do medication reconciliation, reassessments, and follow-ups with lab tests. We also try to assess who is more likely to be a no-show, and who needs more help with scheduling follow-up appointments.”

Clinical coverage of post-discharge clinics varies by setting, staffing, and scope. If demand is low, hospitalists or ED physicians can be called off the floor to see patients who return to the clinic, or they could staff the clinic after their hospitalist shift ends. Post-discharge clinic staff whose schedules are light can flex into providing primary-care visits in the clinic. Post-discharge can also could be provided in conjunction with—or as an alternative to—physician house calls to patients’ homes. Some post-discharge clinics work with medical call centers or telephonic case managers; some even use telemedicine.

It also could be a growth opportunity for hospitalist practices. “It is an exciting potential role for hospitalists interested in doing a little outpatient care,” Dr. Martinez says. “This is also a good way to be a safety net for your safety-net hospital.”

continued below...

Partner with Community

Tallahassee (Fla.) Memorial Hospital (TMH) in February launched a transitional-care clinic in collaboration with faculty from Florida State University, community-based health providers, and the local Capital Health Plan. Hospitalists don’t staff the clinic, but the HM group is its major source of referrals, says Dean Watson, MD, chief medical officer at TMH. Patients can be followed for up to eight weeks, during which time they get comprehensive assessments, medication review and optimization, and referral by the clinic social worker to a PCP and to available community services.

“Three years ago, we came up with the idea for a patient population we know is at high risk for readmission. Why don’t we partner with organizations in the community, form a clinic, teach students and residents, and learn together?” Dr. Watson says. “In addition to the usual patients, TMH targets those who have been readmitted to the hospital three times or more in the past year.”

The clinic, open five days a week, is staffed by a physician, nurse practitioner, telephonic nurse, and social worker, and also has a geriatric assessment clinic.

“We set up a system to identify patients through our electronic health record, and when they come to the clinic, we focus on their social environment and other non-medical issues that might cause readmissions,” he says. The clinic has a pharmacy and funds to support medications for patients without insurance. “In our first six months, we reduced emergency room visits and readmissions for these patients by 68 percent.”

One key partner, Capital Health Plan, bought and refurbished a building, and made it available for the clinic at no cost. Capital’s motivation, says Tom Glennon, a senior vice president for the plan, is its commitment to the community and to community service.

“We’re a nonprofit HMO. We’re focused on what we can do to serve the community, and we’re looking at this as a way for the hospital to have fewer costly, unreimbursed bouncebacks,” Glennon says. “That’s a win-win for all of us.”

Most of the patients who use the clinic are not members of Capital Health Plan, Glennon adds. “If we see CHP members turning up at the transitions clinic, then we have a problem—a breakdown in our case management,” he explains. “Our goal is to have our members taken care of by primary-care providers.”

Hard Data? Not So Fast

How many post-discharge clinics are in operation today is not known. Fundamental financial data, too, are limited, but some say it is unlikely a post-discharge clinic will cover operating expenses from billing revenues alone.

Thus, such clinics will require funding from the hospital, HM group, health system, or health plans, based on the benefits the clinic provides to discharged patients and the impact on 30-day readmissions (for more about the logistical challenges post-discharge clinics present, see “What Do PCPs Think?”).

Some also suggest that many of the post-discharge clinics now in operation are too new to have demonstrated financial impact or return on investment. “We have not yet been asked to show our financial viability,” Dr. Doctoroff says. “I think the clinic leadership thinks we are fulfilling other goals for now, such as creating easier access for their patients after discharge.”

Amy Boutwell, MD, MPP, a hospitalist at Newton Wellesley Hospital in Massachusetts and founder of Collaborative Healthcare Strategies, is among the post-discharge skeptics. She agrees with Dr. Williams that the post-discharge concept is more of a temporary fix to the long-term issues in primary care. “I think the idea is getting more play than actual activity out there right now,” she says. “We need to find opportunities to manage transitions within our scope today and tomorrow while strategically looking at where we want to be in five years [as hospitals and health systems].”

Dr. Boutwell says she’s experienced the frustration of trying to make follow-up appointments with physicians who don’t have any open slots for hospitalized patients awaiting discharge. “We think of follow up as physician-led, but there are alternatives and physician extenders,” she says. “It is well-documented that our healthcare system underuses home health care and other services that might be helpful. We forget how many other opportunities there are in our communities to get another clinician to touch the patient.”

Hospitalists, as key players in the healthcare system, can speak out in support of strengthening primary-care networks and building more collaborative relationships with PCPs, according to Dr. Williams. “If you’re going to set up an outpatient clinic, ideally, have it staffed by PCPs who can funnel the patients into primary-care networks. If that’s not feasible, then hospitalists should proceed with caution, since this approach begins to take them out of their scope of practice,” he says.

With 13 years of experience in urban hospital settings, Dr. Williams is familiar with the dangers unassigned patients present at discharge. “But I don’t know that we’ve yet optimized the hospital discharge process at any hospital in the United States,” he says.

That said, Dr. Williams knows his hospital in downtown Chicago is now working to establish a post-discharge clinic. It will be staffed by PCPs and will target patients who don’t have a PCP, are on Medicaid, or lack insurance.

“Where it starts to make me uncomfortable,” Dr. Williams says, “is what happens when you follow patients out into the outpatient setting?

It’s hard to do just one visit and draw the line. Yes, you may prevent a readmission, but the patient is still left with chronic illness and the need for primary care.”

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer based in Oakland, Calif.

References

- Goodman, DC, Fisher ES, Chang C. After Hospitalization: A Dartmouth Atlas Report on Post-Acute Care for Medicare Beneficiaries. Dartmouth Atlas website. Available at: www.dartmouthatlas.org/downloads/reports/Post_discharge_events_092811.pdf. Accessed Nov. 3, 2011.

- Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, Leung A, Williams MV. Interventions to reduce 3-day rehospitalization: A systematic review. Ann Int Med. 2011;155(8): 520-528.

- Misky GJ, Wald HL, Coleman EA. Post-hospitalization transitions: Examining the effects of timing of primary care provider follow-up. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(7):392-397.

- Shu CC, Hsu NC, Lin YF, et al. Integrated post-discharge transitional care in Taiwan. BMC Medicine website. Available at: www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/9/96. Accessed Nov. 1, 2011.

The hospitalist concept was established on the foundation of timely, informative handoffs to primary-care physicians (PCPs) once a patient’s hospital stay is complete. With sicker patients and shorter hospital stays, pending test results, and complex post-discharge medication regimens to sort out, this handoff is crucial to successful discharges. But what if a discharged patient can’t get in to see the PCP, or has no established PCP?

Recent research on hospital readmissions by the Dartmouth Atlas Project found that only 42% of hospitalized Medicare patients had any contact with a primary-care clinician within 14 days of discharge.1 For patients with ongoing medical needs, such missed connections are a major contributor to hospital readmissions, and thus a target for hospitals and HM groups wanting to control their readmission rates before Medicare imposes reimbursement penalties starting in October 2012 (see “Value-Based Purchasing Raises the Stakes,” May 2011, p. 1).

One proposed solution is the post-discharge clinic, typically located on or near a hospital’s campus and staffed by hospitalists, PCPs, or advanced-practice nurses. The patient can be seen once or a few times in the post-discharge clinic to make sure that health education started in the hospital is understood and followed, and that prescriptions ordered in the hospital are being taken on schedule.

—Lauren Doctoroff, MD, hospitalist, director, post-discharge clinic, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston

Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP, FHM, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, describes hospitalist-led post-discharge clinics as “Band-Aids for an inadequate primary-care system.” What would be better, he says, is focusing on the underlying problem and working to improve post-discharge access to primary care. Dr. Williams acknowledges, however, that sometimes a patch is needed to stanch the blood flow—e.g., to better manage care transitions—while waiting on healthcare reform and medical homes to improve care coordination throughout the system.

Working in a post-discharge clinic might seem like “a stretch for many hospitalists, especially those who chose this field because they didn’t want to do outpatient medicine,” says Lauren Doctoroff, MD, a hospitalist who directs a post-discharge clinic at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in Boston. “But there are times when it may be appropriate for hospital-based doctors to extend their responsibility out of the hospital.”

Dr. Doctoroff also says that working in such a clinic can be practice-changing for hospitalists. “All of a sudden, you have a different view of your hospitalized patients, and you start to ask different questions while they’re in the hospital than you ever did before,” she explains.

What is a Post-Discharge Clinic?

The post-discharge clinic, also known as a transitional-care clinic or after-care clinic, is intended to bridge medical coverage between the hospital and primary care. The clinic at BIDMC is for patients affiliated with its Health Care Associates faculty practice “discharged from either our hospital or another hospital, who need care that their PCP or specialist, because of scheduling conflicts, cannot provide within the needed time frame,” Dr. Doctoroff says.

Four hospitalists from BIDMC’s large HM group were selected to staff the clinic. The hospitalists work in one-month rotations (a total of three months on service per year), and are relieved of other responsibilities during their month in clinic. They provide five half-day clinic sessions per week, with a 40-minute-per-patient visit schedule. Thirty minutes are allotted for patients referred from the hospital’s ED who did not get admitted to the hospital but need clinical follow-up.

The clinic is based in a BIDMC-affiliated primary-care practice, “which allows us to use its administrative structure and logistical support,” Dr. Doctoroff explains. “A hospital-based administrative service helps set up outpatient visits prior to discharge using computerized physician order entry and a scheduling algorhythm.” (See Figure 1) Patients who can be seen by their PCP in a timely fashion are referred to the PCP office; if not, they are scheduled in the post-discharge clinic. “That helps preserve the PCP relationship, which I think is paramount,” she says.

The first two years were spent getting the clinic established, but in the near future, BIDMC will start measuring such outcomes as access to care and quality. “But not necessarily readmission rates,” Dr. Doctoroff adds. “I know many people think of post-discharge clinics in the context of preventing readmissions, although we don’t have the data yet to fully support that. In fact, some readmissions may result from seeing a doctor. If you get a closer look at some patients after discharge and they are doing badly, they are more likely to be readmitted than if they had just stayed home.” In such cases, readmission could actually be a better outcome for the patient, she notes.

Dr. Doctoroff describes a typical user of her post-discharge clinic as a non-English-speaking patient who was discharged from the hospital with severe back pain from a herniated disk. “He came back to see me 10 days later, still barely able to walk. He hadn’t been able to fill any of the prescriptions from his hospital stay. Within two hours after I saw him, we got his meds filled and outpatient services set up,” she says. “We take care of many patients like him in the hospital with acute pain issues, whom we discharge as soon as they can walk, and later we see them limping into outpatient clinics. It makes me think differently now about how I plan their discharges.”

—Shay Martinez, MD, hospitalist, medical director, Harborview Medical Center, Seattle

Who else needs these clinics? Dr. Doctoroff suggests two ways of looking at the question.

“Even for a simple patient admitted to the hospital, that can represent a significant change in the medical picture—a sort of sentinel event. In the discharge clinic, we give them an opportunity to review the hospitalization and answer their questions,” she says. “A lot of information presented to patients in the hospital is not well heard, and the initial visit may be their first time to really talk about what happened.” For other patients with conditions such as congestive heart failure (CHF), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), or poorly controlled diabetes, treatment guidelines might dictate a pattern for post-discharge follow-up—for example, medical visits in seven or 10 days.

In Seattle, Harborview Medical Center established its After Care Clinic, staffed by hospitalists and nurse practitioners, to provide transitional care for patients discharged from inpatient wards or the ED in need of follow-up, says medical director and hospitalist Shay Martinez, MD. A second priority is to see any CHF patient within 48 hours of discharge.

“We try to limit patients to a maximum of three visits in our clinic,” she says. “At that point, we help them get established in a medical home, either here in one of our primary-care clinics, or in one of the many excellent community clinics in the area.

“This model works well with our patient population. We actually try to do primary care on the inpatient side as well. Our hospitalists are specialized in that approach, given our patient population. We see a lot of immigrants, non-English speakers, people with low health literacy, and the homeless, many of whom lack primary care,” Dr. Martinez says. “We do medication reconciliation, reassessments, and follow-ups with lab tests. We also try to assess who is more likely to be a no-show, and who needs more help with scheduling follow-up appointments.”

Clinical coverage of post-discharge clinics varies by setting, staffing, and scope. If demand is low, hospitalists or ED physicians can be called off the floor to see patients who return to the clinic, or they could staff the clinic after their hospitalist shift ends. Post-discharge clinic staff whose schedules are light can flex into providing primary-care visits in the clinic. Post-discharge can also could be provided in conjunction with—or as an alternative to—physician house calls to patients’ homes. Some post-discharge clinics work with medical call centers or telephonic case managers; some even use telemedicine.

It also could be a growth opportunity for hospitalist practices. “It is an exciting potential role for hospitalists interested in doing a little outpatient care,” Dr. Martinez says. “This is also a good way to be a safety net for your safety-net hospital.”

continued below...

Partner with Community

Tallahassee (Fla.) Memorial Hospital (TMH) in February launched a transitional-care clinic in collaboration with faculty from Florida State University, community-based health providers, and the local Capital Health Plan. Hospitalists don’t staff the clinic, but the HM group is its major source of referrals, says Dean Watson, MD, chief medical officer at TMH. Patients can be followed for up to eight weeks, during which time they get comprehensive assessments, medication review and optimization, and referral by the clinic social worker to a PCP and to available community services.

“Three years ago, we came up with the idea for a patient population we know is at high risk for readmission. Why don’t we partner with organizations in the community, form a clinic, teach students and residents, and learn together?” Dr. Watson says. “In addition to the usual patients, TMH targets those who have been readmitted to the hospital three times or more in the past year.”

The clinic, open five days a week, is staffed by a physician, nurse practitioner, telephonic nurse, and social worker, and also has a geriatric assessment clinic.

“We set up a system to identify patients through our electronic health record, and when they come to the clinic, we focus on their social environment and other non-medical issues that might cause readmissions,” he says. The clinic has a pharmacy and funds to support medications for patients without insurance. “In our first six months, we reduced emergency room visits and readmissions for these patients by 68 percent.”

One key partner, Capital Health Plan, bought and refurbished a building, and made it available for the clinic at no cost. Capital’s motivation, says Tom Glennon, a senior vice president for the plan, is its commitment to the community and to community service.

“We’re a nonprofit HMO. We’re focused on what we can do to serve the community, and we’re looking at this as a way for the hospital to have fewer costly, unreimbursed bouncebacks,” Glennon says. “That’s a win-win for all of us.”

Most of the patients who use the clinic are not members of Capital Health Plan, Glennon adds. “If we see CHP members turning up at the transitions clinic, then we have a problem—a breakdown in our case management,” he explains. “Our goal is to have our members taken care of by primary-care providers.”

Hard Data? Not So Fast

How many post-discharge clinics are in operation today is not known. Fundamental financial data, too, are limited, but some say it is unlikely a post-discharge clinic will cover operating expenses from billing revenues alone.