User login

For MD-IQ only

Advanced and Metastatic Prostate Cancer Treatment and Management

Prostate Cancer – Presentation and Diagnosis

Healthy lifestyle may offset genetic risk in prostate cancer

In men at the highest risk of dying from prostate cancer, having the highest healthy lifestyle scores cut the risk of fatal disease in half, said study author Anna Plym, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard School of Public Health, both in Boston. She presented these findings at the American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting 2021: Week 1 (Abstract 822).

Dr. Plym noted that about 58% of the variability in prostate cancer risk is accounted for by genetic factors, with common single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) accounting for a substantial proportion of prostate cancer susceptibility.

A recent study showed that a polygenic risk score (PRS) derived by combining information from 269 SNPs was “highly predictive” of prostate cancer, Dr. Plym said. There was a 10-fold gradient in disease risk between the lowest and highest genetic risk deciles, and the pattern was consistent across ethnic groups.

In addition, Dr. Plym noted, previous studies have suggested that a healthy lifestyle reduces lethal prostate cancer risk.

What has remained unclear is whether the risk for both developing prostate cancer and experiencing progression to lethal disease can be offset by adherence to a healthy lifestyle.

To investigate, Dr. Plym and colleagues used the 269-SNP PRS to quantify the genetic risk of prostate cancer in 10,443 men enrolled in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. The men were divided into quartiles according to genetic risk.

The investigators also classified the men using a validated lifestyle score. For this score, one point was given for each of the following: not currently smoking or having quit 10 or more years ago, body mass index under 30 kg/m2, high vigorous physical activity, high intake of tomatoes and fatty fish, and low intake of processed meat. Patients with 1-2 points were considered the least healthy, those with 3 points were moderately healthy, and those with 4-6 points were the most healthy.

The outcomes assessed were overall prostate cancer and lethal prostate cancer (i.e., metastatic disease or prostate cancer–specific death).

No overall benefit of healthy lifestyle

At a median follow-up of 18 years, 2,111 cases of prostate cancer were observed. And at a median follow-up of 22 years, 238 lethal prostate cancer events occurred.

Men in the highest genetic risk quartile were five times more likely to develop prostate cancer (hazard ratio, 5.39; 95% confidence interval, 4.59-6.34) and three times more likely to develop lethal prostate cancer (HR, 3.43; 95% CI, 2.29-5.14), when compared with men in the lowest genetic risk quartile.

Adherence to a healthy lifestyle did not decrease the risk of prostate cancer overall (HR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.84-1.22), nor did it affect men in the lower genetic risk quartiles.

However, healthy lifestyle did appear to affect men in the highest genetic risk quartile. Men with the highest healthy lifestyle scores had roughly half the risk of lethal prostate cancer, compared to men with the lowest lifestyle scores (3% vs. 6%).

A counterbalance to genetic risk

Dr. Plym observed that the rate of lethal disease in men with the best lifestyle scores matched the rate for the study population as a whole (3%), suggesting that healthy lifestyle may counterbalance high genetic risk.

She added that previous research has confirmed physical activity as a protective factor, but more study is needed to shed light on the relative benefit of the healthy lifestyle components.

In addition, further research is necessary to explain why the benefit was limited to lethal prostate cancer risk in men with the highest genetic risk.

Dr. Plym speculated that the genetic variants contributing to a high PRS may also be the variants that have the strongest interaction with lifestyle factors. For men with a genetic predisposition to prostate cancer, she added, these findings underscore the potential value of surveillance.

“Our findings add to current evidence suggesting that men with a high genetic risk may benefit from a targeted prostate cancer screening program, aiming at detecting a potentially lethal prostate cancer while it is still curable,” she said.

Charles Swanton, MBPhD, of the Francis Crick Institute and UCL Cancer Institute in London, raised the possibility that competing risk issues could be at play.

If a healthy lifestyle leads to longer life, he asked, does that make it more likely that patients will live long enough to die from their prostate cancer because they are not dying from cardiovascular disease, complications of diabetes, etc.? In that case, is the healthy lifestyle really affecting prostate cancer at all?

Dr. Plym responded that, among those in the highest genetic risk group with an unhealthy lifestyle, the increased risk for prostate cancer exceeded the risk for other illnesses.

This study was funded by the DiNovi Family Foundation, the National Cancer Institute, the William Casey Foundation, the Swedish Society for Medical Research, and the Prostate Cancer Foundation. Dr. Plym declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Swanton disclosed relationships with numerous companies, including Pfizer, Novartis, and GlaxoSmithKline.

In men at the highest risk of dying from prostate cancer, having the highest healthy lifestyle scores cut the risk of fatal disease in half, said study author Anna Plym, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard School of Public Health, both in Boston. She presented these findings at the American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting 2021: Week 1 (Abstract 822).

Dr. Plym noted that about 58% of the variability in prostate cancer risk is accounted for by genetic factors, with common single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) accounting for a substantial proportion of prostate cancer susceptibility.

A recent study showed that a polygenic risk score (PRS) derived by combining information from 269 SNPs was “highly predictive” of prostate cancer, Dr. Plym said. There was a 10-fold gradient in disease risk between the lowest and highest genetic risk deciles, and the pattern was consistent across ethnic groups.

In addition, Dr. Plym noted, previous studies have suggested that a healthy lifestyle reduces lethal prostate cancer risk.

What has remained unclear is whether the risk for both developing prostate cancer and experiencing progression to lethal disease can be offset by adherence to a healthy lifestyle.

To investigate, Dr. Plym and colleagues used the 269-SNP PRS to quantify the genetic risk of prostate cancer in 10,443 men enrolled in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. The men were divided into quartiles according to genetic risk.

The investigators also classified the men using a validated lifestyle score. For this score, one point was given for each of the following: not currently smoking or having quit 10 or more years ago, body mass index under 30 kg/m2, high vigorous physical activity, high intake of tomatoes and fatty fish, and low intake of processed meat. Patients with 1-2 points were considered the least healthy, those with 3 points were moderately healthy, and those with 4-6 points were the most healthy.

The outcomes assessed were overall prostate cancer and lethal prostate cancer (i.e., metastatic disease or prostate cancer–specific death).

No overall benefit of healthy lifestyle

At a median follow-up of 18 years, 2,111 cases of prostate cancer were observed. And at a median follow-up of 22 years, 238 lethal prostate cancer events occurred.

Men in the highest genetic risk quartile were five times more likely to develop prostate cancer (hazard ratio, 5.39; 95% confidence interval, 4.59-6.34) and three times more likely to develop lethal prostate cancer (HR, 3.43; 95% CI, 2.29-5.14), when compared with men in the lowest genetic risk quartile.

Adherence to a healthy lifestyle did not decrease the risk of prostate cancer overall (HR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.84-1.22), nor did it affect men in the lower genetic risk quartiles.

However, healthy lifestyle did appear to affect men in the highest genetic risk quartile. Men with the highest healthy lifestyle scores had roughly half the risk of lethal prostate cancer, compared to men with the lowest lifestyle scores (3% vs. 6%).

A counterbalance to genetic risk

Dr. Plym observed that the rate of lethal disease in men with the best lifestyle scores matched the rate for the study population as a whole (3%), suggesting that healthy lifestyle may counterbalance high genetic risk.

She added that previous research has confirmed physical activity as a protective factor, but more study is needed to shed light on the relative benefit of the healthy lifestyle components.

In addition, further research is necessary to explain why the benefit was limited to lethal prostate cancer risk in men with the highest genetic risk.

Dr. Plym speculated that the genetic variants contributing to a high PRS may also be the variants that have the strongest interaction with lifestyle factors. For men with a genetic predisposition to prostate cancer, she added, these findings underscore the potential value of surveillance.

“Our findings add to current evidence suggesting that men with a high genetic risk may benefit from a targeted prostate cancer screening program, aiming at detecting a potentially lethal prostate cancer while it is still curable,” she said.

Charles Swanton, MBPhD, of the Francis Crick Institute and UCL Cancer Institute in London, raised the possibility that competing risk issues could be at play.

If a healthy lifestyle leads to longer life, he asked, does that make it more likely that patients will live long enough to die from their prostate cancer because they are not dying from cardiovascular disease, complications of diabetes, etc.? In that case, is the healthy lifestyle really affecting prostate cancer at all?

Dr. Plym responded that, among those in the highest genetic risk group with an unhealthy lifestyle, the increased risk for prostate cancer exceeded the risk for other illnesses.

This study was funded by the DiNovi Family Foundation, the National Cancer Institute, the William Casey Foundation, the Swedish Society for Medical Research, and the Prostate Cancer Foundation. Dr. Plym declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Swanton disclosed relationships with numerous companies, including Pfizer, Novartis, and GlaxoSmithKline.

In men at the highest risk of dying from prostate cancer, having the highest healthy lifestyle scores cut the risk of fatal disease in half, said study author Anna Plym, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard School of Public Health, both in Boston. She presented these findings at the American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting 2021: Week 1 (Abstract 822).

Dr. Plym noted that about 58% of the variability in prostate cancer risk is accounted for by genetic factors, with common single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) accounting for a substantial proportion of prostate cancer susceptibility.

A recent study showed that a polygenic risk score (PRS) derived by combining information from 269 SNPs was “highly predictive” of prostate cancer, Dr. Plym said. There was a 10-fold gradient in disease risk between the lowest and highest genetic risk deciles, and the pattern was consistent across ethnic groups.

In addition, Dr. Plym noted, previous studies have suggested that a healthy lifestyle reduces lethal prostate cancer risk.

What has remained unclear is whether the risk for both developing prostate cancer and experiencing progression to lethal disease can be offset by adherence to a healthy lifestyle.

To investigate, Dr. Plym and colleagues used the 269-SNP PRS to quantify the genetic risk of prostate cancer in 10,443 men enrolled in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. The men were divided into quartiles according to genetic risk.

The investigators also classified the men using a validated lifestyle score. For this score, one point was given for each of the following: not currently smoking or having quit 10 or more years ago, body mass index under 30 kg/m2, high vigorous physical activity, high intake of tomatoes and fatty fish, and low intake of processed meat. Patients with 1-2 points were considered the least healthy, those with 3 points were moderately healthy, and those with 4-6 points were the most healthy.

The outcomes assessed were overall prostate cancer and lethal prostate cancer (i.e., metastatic disease or prostate cancer–specific death).

No overall benefit of healthy lifestyle

At a median follow-up of 18 years, 2,111 cases of prostate cancer were observed. And at a median follow-up of 22 years, 238 lethal prostate cancer events occurred.

Men in the highest genetic risk quartile were five times more likely to develop prostate cancer (hazard ratio, 5.39; 95% confidence interval, 4.59-6.34) and three times more likely to develop lethal prostate cancer (HR, 3.43; 95% CI, 2.29-5.14), when compared with men in the lowest genetic risk quartile.

Adherence to a healthy lifestyle did not decrease the risk of prostate cancer overall (HR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.84-1.22), nor did it affect men in the lower genetic risk quartiles.

However, healthy lifestyle did appear to affect men in the highest genetic risk quartile. Men with the highest healthy lifestyle scores had roughly half the risk of lethal prostate cancer, compared to men with the lowest lifestyle scores (3% vs. 6%).

A counterbalance to genetic risk

Dr. Plym observed that the rate of lethal disease in men with the best lifestyle scores matched the rate for the study population as a whole (3%), suggesting that healthy lifestyle may counterbalance high genetic risk.

She added that previous research has confirmed physical activity as a protective factor, but more study is needed to shed light on the relative benefit of the healthy lifestyle components.

In addition, further research is necessary to explain why the benefit was limited to lethal prostate cancer risk in men with the highest genetic risk.

Dr. Plym speculated that the genetic variants contributing to a high PRS may also be the variants that have the strongest interaction with lifestyle factors. For men with a genetic predisposition to prostate cancer, she added, these findings underscore the potential value of surveillance.

“Our findings add to current evidence suggesting that men with a high genetic risk may benefit from a targeted prostate cancer screening program, aiming at detecting a potentially lethal prostate cancer while it is still curable,” she said.

Charles Swanton, MBPhD, of the Francis Crick Institute and UCL Cancer Institute in London, raised the possibility that competing risk issues could be at play.

If a healthy lifestyle leads to longer life, he asked, does that make it more likely that patients will live long enough to die from their prostate cancer because they are not dying from cardiovascular disease, complications of diabetes, etc.? In that case, is the healthy lifestyle really affecting prostate cancer at all?

Dr. Plym responded that, among those in the highest genetic risk group with an unhealthy lifestyle, the increased risk for prostate cancer exceeded the risk for other illnesses.

This study was funded by the DiNovi Family Foundation, the National Cancer Institute, the William Casey Foundation, the Swedish Society for Medical Research, and the Prostate Cancer Foundation. Dr. Plym declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Swanton disclosed relationships with numerous companies, including Pfizer, Novartis, and GlaxoSmithKline.

FROM AACR 2021

CCR score can guide treatment decisions after radiation in prostate cancer

The score can identify patients in whom the risk of metastasis after dose-escalated radiation is so small that adding ADT no longer makes clinical sense, according to investigator Jonathan Tward, MD, PhD, of the Genitourinary Cancer Center at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

His group’s study, which included 741 patients, showed that, below a CCR score of 2.112, the 10-year risk of metastasis was 4.2% with radiation therapy (RT) alone and 3.9% with the addition of ADT.

“Whether you have RT alone, RT plus any duration of ADT, insufficient duration ADT, or sufficient ADT duration by guideline standard, the risk of metastasis never exceeds 5% at 10 years” even in high- and very-high-risk men, Dr. Tward said.

He and his team found that half the men in their study with unfavorable intermediate-risk disease, 20% with high-risk disease, and 5% with very-high-risk disease scored below the CCR threshold.

This implies that, for many men, ADT after radiation “adds unnecessary morbidity for an extremely small absolute risk reduction in metastasis-free survival,” Dr. Tward said at the 2021 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium, where he presented the findings (Abstract 195).

Value of CCR

The CCR score tells you if the relative metastasis risk reduction with ADT after radiation – about 50% based on clinical trials – translates to an absolute risk reduction that would matter, Dr. Tward said in an interview.

“Each patient has in their own mind what that risk reduction is that works for them,” he added.

For some patients, a 1%-2% drop in absolute risk is worth it, he said, but most patients wouldn’t be willing to endure the side effects of hormone therapy if the absolute benefit is less than 5%.

The CCR score is a validated prognosticator of metastasis and death in localized prostate cancer. It’s an amalgam of traditional clinical risk factors from the Cancer of the Prostate Risk Assessment (CAPRA) score and the cell-cycle progression (CCP) score, which measures expression of cell-cycle proliferation genes for a sense of how quickly tumor cells are dividing.

The CCP test is available commercially as Prolaris. It is used mostly to make the call between active surveillance and treatment, Dr. Tward explained, “but I had a hunch this off-the-shelf test would be very good at” helping with ADT decisions after radiation.

‘Uncomfortable’ findings, barriers to acceptance

“People are going to be very uncomfortable with these findings because it’s been ingrained in our heads for the past 20-30 years that you must use hormone therapy with high-risk prostate cancer, and you should use hormone therapy with intermediate risk,” Dr. Tward said.

“It took me a while to believe my own data, but we have used this test for several years to help men decide if they would like to have hormone therapy after radiation. Patients clearly benefit from this information,” he said.

The 2.112 cut point for CCR was determined from a prior study that was presented at GUCS 2020 (Abstract 346) and recently accepted for publication.

In the validation study Dr. Tward presented at GUCS 2021, 70% of patients had intermediate-risk disease, and 30% had high- or very-high-risk disease according to National Comprehensive Cancer Network criteria.

All 741 patients received RT equivalent to at least 75.6 Gy at 1.8 Gy per fraction, with 84% getting or exceeding 79.2 Gy. About half the men (53%) had ADT after RT.

Genetic testing was done on stored biopsy samples years after the men were treated. Half of them were below the CCR threshold of 2.112. For those above it, the 10-year risk of metastasis was 25.3%.

CCR outperformed CCP alone, CAPRA alone, and NCCN risk groupings for predicting metastasis risk after RT.

Though this validation study was “successful,” additional research is needed, according to study discussant Richard Valicenti, MD, of the University of California, Davis.

“Widespread acceptance for routine use faces challenges since no biomarker has been prospectively tested or shown to improve long-term outcome,” Dr. Valicenti said. “Clearly, the CCR score may provide highly precise, personalized estimates and justifies testing in tiered and appropriately powered noninferiority studies according to NCCN risk groups. We eagerly await the completion and reporting of such trials so that we have a more personalized approach to treating men with prostate cancer.”

The current study was funded by Myriad Genetics, the company that developed the Prolaris test. Dr. Tward disclosed relationships with Myriad Genetics, Bayer, Blue Earth Diagnostics, Janssen Scientific Affairs, and Merck. Dr. Valicenti has no disclosures.

The score can identify patients in whom the risk of metastasis after dose-escalated radiation is so small that adding ADT no longer makes clinical sense, according to investigator Jonathan Tward, MD, PhD, of the Genitourinary Cancer Center at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

His group’s study, which included 741 patients, showed that, below a CCR score of 2.112, the 10-year risk of metastasis was 4.2% with radiation therapy (RT) alone and 3.9% with the addition of ADT.

“Whether you have RT alone, RT plus any duration of ADT, insufficient duration ADT, or sufficient ADT duration by guideline standard, the risk of metastasis never exceeds 5% at 10 years” even in high- and very-high-risk men, Dr. Tward said.

He and his team found that half the men in their study with unfavorable intermediate-risk disease, 20% with high-risk disease, and 5% with very-high-risk disease scored below the CCR threshold.

This implies that, for many men, ADT after radiation “adds unnecessary morbidity for an extremely small absolute risk reduction in metastasis-free survival,” Dr. Tward said at the 2021 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium, where he presented the findings (Abstract 195).

Value of CCR

The CCR score tells you if the relative metastasis risk reduction with ADT after radiation – about 50% based on clinical trials – translates to an absolute risk reduction that would matter, Dr. Tward said in an interview.

“Each patient has in their own mind what that risk reduction is that works for them,” he added.

For some patients, a 1%-2% drop in absolute risk is worth it, he said, but most patients wouldn’t be willing to endure the side effects of hormone therapy if the absolute benefit is less than 5%.

The CCR score is a validated prognosticator of metastasis and death in localized prostate cancer. It’s an amalgam of traditional clinical risk factors from the Cancer of the Prostate Risk Assessment (CAPRA) score and the cell-cycle progression (CCP) score, which measures expression of cell-cycle proliferation genes for a sense of how quickly tumor cells are dividing.

The CCP test is available commercially as Prolaris. It is used mostly to make the call between active surveillance and treatment, Dr. Tward explained, “but I had a hunch this off-the-shelf test would be very good at” helping with ADT decisions after radiation.

‘Uncomfortable’ findings, barriers to acceptance

“People are going to be very uncomfortable with these findings because it’s been ingrained in our heads for the past 20-30 years that you must use hormone therapy with high-risk prostate cancer, and you should use hormone therapy with intermediate risk,” Dr. Tward said.

“It took me a while to believe my own data, but we have used this test for several years to help men decide if they would like to have hormone therapy after radiation. Patients clearly benefit from this information,” he said.

The 2.112 cut point for CCR was determined from a prior study that was presented at GUCS 2020 (Abstract 346) and recently accepted for publication.

In the validation study Dr. Tward presented at GUCS 2021, 70% of patients had intermediate-risk disease, and 30% had high- or very-high-risk disease according to National Comprehensive Cancer Network criteria.

All 741 patients received RT equivalent to at least 75.6 Gy at 1.8 Gy per fraction, with 84% getting or exceeding 79.2 Gy. About half the men (53%) had ADT after RT.

Genetic testing was done on stored biopsy samples years after the men were treated. Half of them were below the CCR threshold of 2.112. For those above it, the 10-year risk of metastasis was 25.3%.

CCR outperformed CCP alone, CAPRA alone, and NCCN risk groupings for predicting metastasis risk after RT.

Though this validation study was “successful,” additional research is needed, according to study discussant Richard Valicenti, MD, of the University of California, Davis.

“Widespread acceptance for routine use faces challenges since no biomarker has been prospectively tested or shown to improve long-term outcome,” Dr. Valicenti said. “Clearly, the CCR score may provide highly precise, personalized estimates and justifies testing in tiered and appropriately powered noninferiority studies according to NCCN risk groups. We eagerly await the completion and reporting of such trials so that we have a more personalized approach to treating men with prostate cancer.”

The current study was funded by Myriad Genetics, the company that developed the Prolaris test. Dr. Tward disclosed relationships with Myriad Genetics, Bayer, Blue Earth Diagnostics, Janssen Scientific Affairs, and Merck. Dr. Valicenti has no disclosures.

The score can identify patients in whom the risk of metastasis after dose-escalated radiation is so small that adding ADT no longer makes clinical sense, according to investigator Jonathan Tward, MD, PhD, of the Genitourinary Cancer Center at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

His group’s study, which included 741 patients, showed that, below a CCR score of 2.112, the 10-year risk of metastasis was 4.2% with radiation therapy (RT) alone and 3.9% with the addition of ADT.

“Whether you have RT alone, RT plus any duration of ADT, insufficient duration ADT, or sufficient ADT duration by guideline standard, the risk of metastasis never exceeds 5% at 10 years” even in high- and very-high-risk men, Dr. Tward said.

He and his team found that half the men in their study with unfavorable intermediate-risk disease, 20% with high-risk disease, and 5% with very-high-risk disease scored below the CCR threshold.

This implies that, for many men, ADT after radiation “adds unnecessary morbidity for an extremely small absolute risk reduction in metastasis-free survival,” Dr. Tward said at the 2021 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium, where he presented the findings (Abstract 195).

Value of CCR

The CCR score tells you if the relative metastasis risk reduction with ADT after radiation – about 50% based on clinical trials – translates to an absolute risk reduction that would matter, Dr. Tward said in an interview.

“Each patient has in their own mind what that risk reduction is that works for them,” he added.

For some patients, a 1%-2% drop in absolute risk is worth it, he said, but most patients wouldn’t be willing to endure the side effects of hormone therapy if the absolute benefit is less than 5%.

The CCR score is a validated prognosticator of metastasis and death in localized prostate cancer. It’s an amalgam of traditional clinical risk factors from the Cancer of the Prostate Risk Assessment (CAPRA) score and the cell-cycle progression (CCP) score, which measures expression of cell-cycle proliferation genes for a sense of how quickly tumor cells are dividing.

The CCP test is available commercially as Prolaris. It is used mostly to make the call between active surveillance and treatment, Dr. Tward explained, “but I had a hunch this off-the-shelf test would be very good at” helping with ADT decisions after radiation.

‘Uncomfortable’ findings, barriers to acceptance

“People are going to be very uncomfortable with these findings because it’s been ingrained in our heads for the past 20-30 years that you must use hormone therapy with high-risk prostate cancer, and you should use hormone therapy with intermediate risk,” Dr. Tward said.

“It took me a while to believe my own data, but we have used this test for several years to help men decide if they would like to have hormone therapy after radiation. Patients clearly benefit from this information,” he said.

The 2.112 cut point for CCR was determined from a prior study that was presented at GUCS 2020 (Abstract 346) and recently accepted for publication.

In the validation study Dr. Tward presented at GUCS 2021, 70% of patients had intermediate-risk disease, and 30% had high- or very-high-risk disease according to National Comprehensive Cancer Network criteria.

All 741 patients received RT equivalent to at least 75.6 Gy at 1.8 Gy per fraction, with 84% getting or exceeding 79.2 Gy. About half the men (53%) had ADT after RT.

Genetic testing was done on stored biopsy samples years after the men were treated. Half of them were below the CCR threshold of 2.112. For those above it, the 10-year risk of metastasis was 25.3%.

CCR outperformed CCP alone, CAPRA alone, and NCCN risk groupings for predicting metastasis risk after RT.

Though this validation study was “successful,” additional research is needed, according to study discussant Richard Valicenti, MD, of the University of California, Davis.

“Widespread acceptance for routine use faces challenges since no biomarker has been prospectively tested or shown to improve long-term outcome,” Dr. Valicenti said. “Clearly, the CCR score may provide highly precise, personalized estimates and justifies testing in tiered and appropriately powered noninferiority studies according to NCCN risk groups. We eagerly await the completion and reporting of such trials so that we have a more personalized approach to treating men with prostate cancer.”

The current study was funded by Myriad Genetics, the company that developed the Prolaris test. Dr. Tward disclosed relationships with Myriad Genetics, Bayer, Blue Earth Diagnostics, Janssen Scientific Affairs, and Merck. Dr. Valicenti has no disclosures.

FROM GUCS 2021

Declines in PSA screening may account for rise in metastatic prostate cancers

Between 2008 and 2016, the mean incidence of prostate cancers that were metastatic at diagnosis increased from 6.4 to 9.0 per 100,000 men. During the same period, the mean percentage of men undergoing PSA screening decreased from 61.8% to 50.5%, Vidit Sharma, MD, reported in a poster session at the 2021 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium (Abstract 228).

A random-effects linear regression model demonstrated that longitudinal reductions across states in PSA screening were indeed associated with increased age-adjusted incidence of metastatic prostate cancer, said Dr. Sharma, the lead author of the study and a health services fellow in urologic oncology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

The regression coefficient per 100,000 men was 14.9, confirming that states with greater declines in screening had greater increases in prostate cancers that were metastatic at diagnosis, he added, noting that, “overall, variation in PSA screening explained 27% of the longitudinal variation in metastatic disease at diagnosis.”

Dr. Sharma and colleagues had reviewed North American Association of Central Cancer Registries data from 2002 to 2016 for each state and extracted survey-weighted PSA screening estimates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. The researchers noted wide variations in screening across states, but they said across-the-board declines were evident beginning in 2010, marking a “worrisome consequence that needs attention.”

Robert Dreicer, MD, deputy director of the University of Virginia Cancer Center, Charlottesville, agreed, noting in a press statement that the findings suggest reduced PSA screening may come at the cost of more men presenting with metastatic disease.

“Patients should discuss the risks and benefits associated with PSA screening with their doctor to identify the best approach for them,” Dr. Dreicer said.

PSA screening has been shown to reduce prostate cancer metastasis and mortality, but screening has also been linked to overdiagnosis and overtreatment of prostate cancer. As a result, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) “found insufficient evidence to recommend PSA screening in 2008 and later recommended against PSA screening in 2012,” Dr. Sharma said.

Several studies subsequently showed a rise in metastatic prostate cancer diagnosis, but the role of PSA screening reductions in those findings was unclear. In 2018, the USPSTF updated its recommendations, stating that men aged 55-69 years should make “an individual decision about whether to be screened after a conversation with their clinician about the potential benefits and harms.”

The task force recommended against PSA screening in men older than 70 years.

The current study “strengthens the epidemiological evidence that reductions in PSA screening may be responsible for at least some of the increase in metastatic prostate cancer diagnoses,” Dr. Sharma said. He added that he and his coauthors support shared decision-making policies to optimize PSA screening approaches to reduce the incidence of metastatic prostate cancer, such as those recommended in the 2018 USPSTF update.

Dr. Sharma disclosed research funding from the Veterans Affairs Health Services Research & Development Fellowship. He and his colleagues had no other disclosures.

Between 2008 and 2016, the mean incidence of prostate cancers that were metastatic at diagnosis increased from 6.4 to 9.0 per 100,000 men. During the same period, the mean percentage of men undergoing PSA screening decreased from 61.8% to 50.5%, Vidit Sharma, MD, reported in a poster session at the 2021 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium (Abstract 228).

A random-effects linear regression model demonstrated that longitudinal reductions across states in PSA screening were indeed associated with increased age-adjusted incidence of metastatic prostate cancer, said Dr. Sharma, the lead author of the study and a health services fellow in urologic oncology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

The regression coefficient per 100,000 men was 14.9, confirming that states with greater declines in screening had greater increases in prostate cancers that were metastatic at diagnosis, he added, noting that, “overall, variation in PSA screening explained 27% of the longitudinal variation in metastatic disease at diagnosis.”

Dr. Sharma and colleagues had reviewed North American Association of Central Cancer Registries data from 2002 to 2016 for each state and extracted survey-weighted PSA screening estimates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. The researchers noted wide variations in screening across states, but they said across-the-board declines were evident beginning in 2010, marking a “worrisome consequence that needs attention.”

Robert Dreicer, MD, deputy director of the University of Virginia Cancer Center, Charlottesville, agreed, noting in a press statement that the findings suggest reduced PSA screening may come at the cost of more men presenting with metastatic disease.

“Patients should discuss the risks and benefits associated with PSA screening with their doctor to identify the best approach for them,” Dr. Dreicer said.

PSA screening has been shown to reduce prostate cancer metastasis and mortality, but screening has also been linked to overdiagnosis and overtreatment of prostate cancer. As a result, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) “found insufficient evidence to recommend PSA screening in 2008 and later recommended against PSA screening in 2012,” Dr. Sharma said.

Several studies subsequently showed a rise in metastatic prostate cancer diagnosis, but the role of PSA screening reductions in those findings was unclear. In 2018, the USPSTF updated its recommendations, stating that men aged 55-69 years should make “an individual decision about whether to be screened after a conversation with their clinician about the potential benefits and harms.”

The task force recommended against PSA screening in men older than 70 years.

The current study “strengthens the epidemiological evidence that reductions in PSA screening may be responsible for at least some of the increase in metastatic prostate cancer diagnoses,” Dr. Sharma said. He added that he and his coauthors support shared decision-making policies to optimize PSA screening approaches to reduce the incidence of metastatic prostate cancer, such as those recommended in the 2018 USPSTF update.

Dr. Sharma disclosed research funding from the Veterans Affairs Health Services Research & Development Fellowship. He and his colleagues had no other disclosures.

Between 2008 and 2016, the mean incidence of prostate cancers that were metastatic at diagnosis increased from 6.4 to 9.0 per 100,000 men. During the same period, the mean percentage of men undergoing PSA screening decreased from 61.8% to 50.5%, Vidit Sharma, MD, reported in a poster session at the 2021 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium (Abstract 228).

A random-effects linear regression model demonstrated that longitudinal reductions across states in PSA screening were indeed associated with increased age-adjusted incidence of metastatic prostate cancer, said Dr. Sharma, the lead author of the study and a health services fellow in urologic oncology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

The regression coefficient per 100,000 men was 14.9, confirming that states with greater declines in screening had greater increases in prostate cancers that were metastatic at diagnosis, he added, noting that, “overall, variation in PSA screening explained 27% of the longitudinal variation in metastatic disease at diagnosis.”

Dr. Sharma and colleagues had reviewed North American Association of Central Cancer Registries data from 2002 to 2016 for each state and extracted survey-weighted PSA screening estimates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. The researchers noted wide variations in screening across states, but they said across-the-board declines were evident beginning in 2010, marking a “worrisome consequence that needs attention.”

Robert Dreicer, MD, deputy director of the University of Virginia Cancer Center, Charlottesville, agreed, noting in a press statement that the findings suggest reduced PSA screening may come at the cost of more men presenting with metastatic disease.

“Patients should discuss the risks and benefits associated with PSA screening with their doctor to identify the best approach for them,” Dr. Dreicer said.

PSA screening has been shown to reduce prostate cancer metastasis and mortality, but screening has also been linked to overdiagnosis and overtreatment of prostate cancer. As a result, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) “found insufficient evidence to recommend PSA screening in 2008 and later recommended against PSA screening in 2012,” Dr. Sharma said.

Several studies subsequently showed a rise in metastatic prostate cancer diagnosis, but the role of PSA screening reductions in those findings was unclear. In 2018, the USPSTF updated its recommendations, stating that men aged 55-69 years should make “an individual decision about whether to be screened after a conversation with their clinician about the potential benefits and harms.”

The task force recommended against PSA screening in men older than 70 years.

The current study “strengthens the epidemiological evidence that reductions in PSA screening may be responsible for at least some of the increase in metastatic prostate cancer diagnoses,” Dr. Sharma said. He added that he and his coauthors support shared decision-making policies to optimize PSA screening approaches to reduce the incidence of metastatic prostate cancer, such as those recommended in the 2018 USPSTF update.

Dr. Sharma disclosed research funding from the Veterans Affairs Health Services Research & Development Fellowship. He and his colleagues had no other disclosures.

FROM GUCS 2021

Liquid Biopsies in a Veteran Patient Population With Advanced Prostate and Lung Non-Small Cell Carcinomas: A New Paradigm and Unique Challenge in Personalized Medicine

The advent of liquid biopsies targeting genetic mutations in solid tumors is a major milestone in the field of precision oncology.1 Conventional methods of obtaining tissue for molecular studies are limited by sample size and often do not represent the entire bulk of the tumor.2 This newer minimally invasive, revolutionary technique analyzes circulating cell-free DNA carrying tumor-specific alterations (circulating tumor DNA [ctDNA]) in peripheral blood and detects signature genomic alterations.1 Tp53 mutations have been reported in 25 to 40% of prostatic cancers and > 50% of non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLC), being more common in late-stage and hormone refractory prostate cancers.3,4 Tp53 mutation has been found to be associated with poor prognosis and increased germline mutations.5

The veteran patient population has distinct demographic characteristics that make veterans more vulnerable to genetic mutations and malignancies, including risk of exposure to Agent Orange, smoking, substance abuse, and asbestos. This area is understudied and extremely sparse in the literature for frequency of genetic mutations, risk factors in solid malignancies occurring in the veteran patient population, and the clinical impact of these risk factors. We herein present a quality assurance study for the utility of liquid biopsies regarding the frequency of DNA damage repair (DDR) gene, Tp53, and androgen receptor (AR) mutations. The clinical impact in advanced lung and prostate cancers in the veteran patient population and frequency are the quality assurance observations that are the study endpoints.

Methods

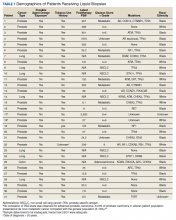

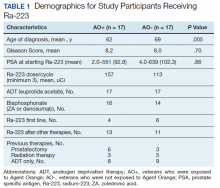

We reviewed for quality assurance documentation from the Foundation Medicine (www.foundationmedicine.com) cancer biomarker tests on liquid biopsies performed at the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz Veteran Affairs Medical Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania from May 2019 to April 15, 2020. All biopsies were performed on cancers with biochemical, imaging or tissue evidence of advanced tumor progression. The testing was performed on advanced solid malignancies, including NSCLC, prostate adenocarcinoma, and metastatic colon cancer. Statistical data for adequacy; cases with notable mutations; frequency; and type of mutations of AR, DDR, and Tp53 were noted. General and specific risk factors associated with the veteran patient population were studied and matched with the type of mutations (Table 1).

Results

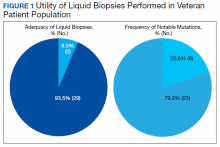

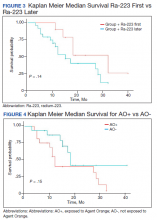

Thirty-one liquid biopsies were performed over this period—23 for prostate cancer, 7 for patients with lung cancer patients, and 1 for a patient with colon cancer. Of 31 cases, sensitivity/adequacy of liquid biopsy for genetic mutation was detected in 29 (93.5%) cases (Figure 1). Two inadequate biopsies (both from patients with prostate cancer) were excluded from the study, leaving 29 liquid biopsies with adequate ctDNA for analysis that were considered for further statistical purpose—21 prostate, 7 lung, and 1 colon cancer.

Multiple (common and different) genetic mutations were identified; however, our study subcategorized the mutations into the those that were related to prostate cancer, lung cancer, and some common mutations that occur in both cancers. Only the significant ones will be discussed in this review and equivocal result for AR is excluded from this study. Of the 21 prostate cancers, 4 (19.0%) had directed the targeted therapy to driver mutation (AR being most common in prostate cancer), while KRAS mutation, which was more common in lung cancer, was detected in 2/7 (28.6%) lung cancers. Mutations common to both cancer types were DDR gene mutations, which is a broad name for numerous genes including CDK12, ATM, and CHEK2.

Of all cases irrespective of the cancer type, 23/29 (79.3%) showed notable mutations. DDR gene mutations were found in 6 of 21 (28.5%) patients with prostate cancer and 8 of 23 (34.7%) patients with advanced prostate and lung cancers, indicating poor outcome and possible resistance to the current therapy. Of 23 patients showing mutations irrespective of the cancer type, 15 (65.2%) harbored Tp53 mutations, which is much more frequent in veteran patient population when compared with the literature. Fifteen of the 31 (48.4%) total patients were Vietnam War-era veterans who were potentially exposed to Agent Orange and 20 (64.5%) patients who were not Vietnam War-era veterans had a history that included smoking (Figure 2).

Discussion

The veteran patient population is a unique cohort due to its distinct demographic characteristics with a high volume of cancer cases diagnosed each year. According to data from VA Central Cancer Registry (VACCR), the most frequently diagnosed cancers are prostate (29%) and lung (18%).6

Liquid biopsy is a novel, promising technology that uses ctDNA and circulating tumor cells in peripheral blood for detecting genetic alterations through next generation sequencing.7-9 The advent of this minimally invasive, revolutionary technology has been a breakthrough in the field of precision oncology for prognosis, to monitor treatment response or resistance to therapy and further personalize cancer therapy.9,10

Comprehensive genomic profiling by liquid biopsy has many advantages over the molecular studies performed on tissue biopsy. Due to the tumor heterogeneity, tissue samples may not represent the full profile of the tumor genomics of cancer, while liquid biopsy has full presentation of the disease.11,12 Many times, tissue biopsy may be limited by a sample size that precludes full genetic profiling in addition to higher total cost, potential technical issues during processing, and possible side effects of the biopsy procedure.7,13 Additionally, as the tumor progresses, new driver mutations other than the ones previously detected on the primary tissue may emerge, which can confer resistance to the existing therapy.7,13

Advanced prostatic and lung carcinomas with biochemical, distant organ, or bony progression harbor unique signature genetic mutations indicating poor prognosis, lack of response or resistance to the existing therapy, and high risk of relapse.14,15 Some of the unique characteristics of the veteran patient population include a more aged patient population multiple comorbidities, higher frequency of > 1 type of cancer, advanced cancer stage at presentation, and specific risks factors such as exposure to Agent Orange in veterans who served during the Vietnam War era.16,17 We studied the utility of liquid biopsy in cancer care, including type and incidence of genomic alterations associated with advanced prostate and lung cancers, in this unique patient population.

The amount of cell-free DNA (cfDNA), also known as ctDNA varies widely in cancer patients. Some of the factors associated with low concentration of cfDNA are disease stage, intervening therapy, proliferation rates, and tumor vascularization.18,19 In the peripheral blood, of the total cfDNA, fractions of cfDNA varies from 0.01 to 90%.18,19 All samples containing ≥ 20 ng cfDNA (20 - 100 ng) were subjected to the hybrid capture-based NGS FoundationACT assay.20 In our study, 2 specimens did not meet the minimum criteria of adequacy (20 ng cfDNA); however, the overall adequacy rate for the detection of mutation, irrespective of the cancer type was 29 of 31 (93.5%) with only 2 inadequate samples. This rate is higher than the rate reported in the literature, which is about 70%.20

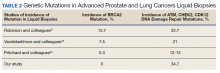

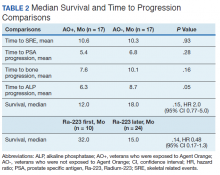

Significant differences were encountered in the incidence of DNA damage repair genes including Tp53 mutations when compared with those in the general patient population (Table 2). According to recent National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, all prostate cancers should be screened for DDR gene mutations as these genes are common in aggressive prostate cancers and strongly associated with poor outcomes and shortened survival. Due to relatively high frequency of DDR gene mutations in advanced prostatic cancers, liquid biopsy in patients with these advanced stage prostate cancers may be a useful tool in clinical decision making and exploring targeted therapy.20

Mutations in BRCA2, ATM, CDK12, and CHEK2 (DDR gene family) are common. Incidence of ATM and CDK12 mutations in the literature is 3 to 6% of cases.21 Of 21 liquid biopsies of advanced prostate cancer patients, we found combined DDR gene mutation of ATM, CHEK2, and CDK12 genes in 6 (28.5%) cases, which is substantially higher than the 3 to 6% rate reported in the literature.21-24 Of the 23 patients who had notable mutations in our liquid biopsies, including both advanced prostate and lung cancer cases, 8 (34.7%) also showed mutation of the genes of DDR family. Our study did not show BRCA2 mutation, which is otherwise common in the literature.

We also evaluated the frequency of the most commonly occurring genetic mutations, Tp53 in advanced solid malignancies, especially advanced prostate and NSCLC. Previous studies have reported Tp53 mutation in association with risk factors (carcinogens) of cancer and have been a surrogate marker of poor survival or lack of response of therapy.25 Knowledge of Tp53 mutation is crucial for closer disease monitoring, preparing the patient for rapid progression, and encouraging the physician to prepare future lines of therapy.25-27 Although Tp53 mutation varies with histologic type and tissue of origin, Beltran and colleagues reported it in 30 to 40% of tumors, while Robles and colleagues reported about 40 to 42% incidence.25,27

Our study showed notable mutations in 23 of 29 adequate cases. Further, our study showed a high frequency of mutated Tp53 in 65.2% of combined advanced prostate and NSCLC cases. We then correlated cases of Vietnam War-era veterans with risk potential of Agent Orange exposure and Tp53 mutation. We found 7 of 15 Vietnam War-era veterans were positive for Tp53 mutations irrespective of the cancer type. The high incidence of Tp53 mutations in advanced prostate and lung carcinomas in the veteran patient population makes this tumor marker an aspiration not only as a surrogate of aggressive disease and tumor progression, but also as a key marker for targeted therapy in advanced prostate and lung cancers with loss of Tp53 function (Figure 3).

Mutations and amplifications in the AR gene are fundamental to progression of prostate cancer associated with advanced, hormone-refractory prostate cancer with the potential for targeted therapy with AR inhibitors. In our study, AR amplification was detected in 4 of 21 (19%) advanced prostate cancer cases, which is significantly lower than the 30 to 50% previously reported in the literature.28-32 Neither AR amplification or mutation was noted in advanced NSCLC in our study as previously reported in literature by Brennan and colleagues and Wang and colleagues.33-35 This is significant as it provides a pathway for future studies to focus on additional driver mutations for targeted therapies in advanced prostate carcinoma. To date, AR gene mutation does not play a role for personalized therapy in advanced NSCLC. Perhaps, a large cohort study with longitudinal analysis is needed for absolutely ruling out the possibility of personalized medicine in advanced lung cancer using this biomarker.

Conclusions

Liquid biopsy successfully provides precision-based oncology and information for decision making in this unique population of veterans. Difference in frequency of the genetic mutations in this cohort can provide future insight into disease progression, lack of response, and mechanism of resistance to the implemented therapy. Future studies focused on this veteran patient population are needed for developing targeted therapies and patient tailored oncologic therapy. ctDNA has a high potential for monitoring clinically relevant cancer-related genetic and epigenetic modifications for discovering more detailed information on the tumor characterization. Although larger cohort trial with longitudinal analyses are needed, high prevalence of DDR gene and Tp53 mutation in our study instills promising hope for therapeutic interventions in this unique cohort.

The minimally invasive liquid biopsy shows a great promise as both diagnostic and prognostic tool in the personalized clinical management of advanced prostate, and NSCLC in the veteran patient population with unique demographic characteristics. De novo metastatic prostate cancer is more common in veterans when compared with the general population, and therefore veterans may benefit by liquid biopsy. Differences in the frequency of genetic mutations (DDR, TP53, AR) in this cohort provides valuable information for disease progression, lack of response, mechanism of resistance to the implemented therapy and clinical decision making. Precision oncology can be further tailored for this cohort by focusing on DNA repair genes and Tp53 mutations for future targeted therapy.

1

9

16. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Review the Health Effects in Vietnam Veterans of Exposure to Herbicides (Fourth Biennial Update). Veterans and Agent Orange: Update 2002. National Academies Press (US); 2003.

17. Eibner C, Krull H, Brown KM, et al. Current and projected characteristics and unique health care needs of the patient population served by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Rand Health Q. 2016;5(4):13. Published 2016 May 9.

18. Saarenheimo J, Eigeliene N, Andersen H, Tiirola M, Jekunen A. The value of liquid biopsies for guiding therapy decisions in non-small cell lung cancer. Front Oncol. 2019;9:129. Published 2019 Mar 5.doi:10.3389/fonc.2019.00129

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31. Antonarakis ES, Lu C, Luber B, et al. Clinical significance of androgen receptor splice variant-7 mRNA detection in circulating tumor cells of men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with first- and second-line abiraterone and enzalutamide. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(19):2149-2156. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.70.1961

32

33. Jung A, Kirchner T. Liquid biopsy in tumor genetic diagnosis. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115(10):169-174. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2018.0169

34. Brennan S, Wang AR, Beyer H, et al. Androgen receptor as a potential target in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2017;77(Suppl13): abstract nr 4121. doi:10.1158/1538-7445.AM2017-4121

35. Wang AR, Beyer H, Brennan S, et al. Androgen receptor drives differential gene expression in KRAS-mediated non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2018;78(Suppl 13): abstract nr 3946. doi:10.1158/1538-7445.AM2018-3946

The advent of liquid biopsies targeting genetic mutations in solid tumors is a major milestone in the field of precision oncology.1 Conventional methods of obtaining tissue for molecular studies are limited by sample size and often do not represent the entire bulk of the tumor.2 This newer minimally invasive, revolutionary technique analyzes circulating cell-free DNA carrying tumor-specific alterations (circulating tumor DNA [ctDNA]) in peripheral blood and detects signature genomic alterations.1 Tp53 mutations have been reported in 25 to 40% of prostatic cancers and > 50% of non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLC), being more common in late-stage and hormone refractory prostate cancers.3,4 Tp53 mutation has been found to be associated with poor prognosis and increased germline mutations.5

The veteran patient population has distinct demographic characteristics that make veterans more vulnerable to genetic mutations and malignancies, including risk of exposure to Agent Orange, smoking, substance abuse, and asbestos. This area is understudied and extremely sparse in the literature for frequency of genetic mutations, risk factors in solid malignancies occurring in the veteran patient population, and the clinical impact of these risk factors. We herein present a quality assurance study for the utility of liquid biopsies regarding the frequency of DNA damage repair (DDR) gene, Tp53, and androgen receptor (AR) mutations. The clinical impact in advanced lung and prostate cancers in the veteran patient population and frequency are the quality assurance observations that are the study endpoints.

Methods

We reviewed for quality assurance documentation from the Foundation Medicine (www.foundationmedicine.com) cancer biomarker tests on liquid biopsies performed at the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz Veteran Affairs Medical Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania from May 2019 to April 15, 2020. All biopsies were performed on cancers with biochemical, imaging or tissue evidence of advanced tumor progression. The testing was performed on advanced solid malignancies, including NSCLC, prostate adenocarcinoma, and metastatic colon cancer. Statistical data for adequacy; cases with notable mutations; frequency; and type of mutations of AR, DDR, and Tp53 were noted. General and specific risk factors associated with the veteran patient population were studied and matched with the type of mutations (Table 1).

Results

Thirty-one liquid biopsies were performed over this period—23 for prostate cancer, 7 for patients with lung cancer patients, and 1 for a patient with colon cancer. Of 31 cases, sensitivity/adequacy of liquid biopsy for genetic mutation was detected in 29 (93.5%) cases (Figure 1). Two inadequate biopsies (both from patients with prostate cancer) were excluded from the study, leaving 29 liquid biopsies with adequate ctDNA for analysis that were considered for further statistical purpose—21 prostate, 7 lung, and 1 colon cancer.

Multiple (common and different) genetic mutations were identified; however, our study subcategorized the mutations into the those that were related to prostate cancer, lung cancer, and some common mutations that occur in both cancers. Only the significant ones will be discussed in this review and equivocal result for AR is excluded from this study. Of the 21 prostate cancers, 4 (19.0%) had directed the targeted therapy to driver mutation (AR being most common in prostate cancer), while KRAS mutation, which was more common in lung cancer, was detected in 2/7 (28.6%) lung cancers. Mutations common to both cancer types were DDR gene mutations, which is a broad name for numerous genes including CDK12, ATM, and CHEK2.

Of all cases irrespective of the cancer type, 23/29 (79.3%) showed notable mutations. DDR gene mutations were found in 6 of 21 (28.5%) patients with prostate cancer and 8 of 23 (34.7%) patients with advanced prostate and lung cancers, indicating poor outcome and possible resistance to the current therapy. Of 23 patients showing mutations irrespective of the cancer type, 15 (65.2%) harbored Tp53 mutations, which is much more frequent in veteran patient population when compared with the literature. Fifteen of the 31 (48.4%) total patients were Vietnam War-era veterans who were potentially exposed to Agent Orange and 20 (64.5%) patients who were not Vietnam War-era veterans had a history that included smoking (Figure 2).

Discussion

The veteran patient population is a unique cohort due to its distinct demographic characteristics with a high volume of cancer cases diagnosed each year. According to data from VA Central Cancer Registry (VACCR), the most frequently diagnosed cancers are prostate (29%) and lung (18%).6

Liquid biopsy is a novel, promising technology that uses ctDNA and circulating tumor cells in peripheral blood for detecting genetic alterations through next generation sequencing.7-9 The advent of this minimally invasive, revolutionary technology has been a breakthrough in the field of precision oncology for prognosis, to monitor treatment response or resistance to therapy and further personalize cancer therapy.9,10

Comprehensive genomic profiling by liquid biopsy has many advantages over the molecular studies performed on tissue biopsy. Due to the tumor heterogeneity, tissue samples may not represent the full profile of the tumor genomics of cancer, while liquid biopsy has full presentation of the disease.11,12 Many times, tissue biopsy may be limited by a sample size that precludes full genetic profiling in addition to higher total cost, potential technical issues during processing, and possible side effects of the biopsy procedure.7,13 Additionally, as the tumor progresses, new driver mutations other than the ones previously detected on the primary tissue may emerge, which can confer resistance to the existing therapy.7,13

Advanced prostatic and lung carcinomas with biochemical, distant organ, or bony progression harbor unique signature genetic mutations indicating poor prognosis, lack of response or resistance to the existing therapy, and high risk of relapse.14,15 Some of the unique characteristics of the veteran patient population include a more aged patient population multiple comorbidities, higher frequency of > 1 type of cancer, advanced cancer stage at presentation, and specific risks factors such as exposure to Agent Orange in veterans who served during the Vietnam War era.16,17 We studied the utility of liquid biopsy in cancer care, including type and incidence of genomic alterations associated with advanced prostate and lung cancers, in this unique patient population.

The amount of cell-free DNA (cfDNA), also known as ctDNA varies widely in cancer patients. Some of the factors associated with low concentration of cfDNA are disease stage, intervening therapy, proliferation rates, and tumor vascularization.18,19 In the peripheral blood, of the total cfDNA, fractions of cfDNA varies from 0.01 to 90%.18,19 All samples containing ≥ 20 ng cfDNA (20 - 100 ng) were subjected to the hybrid capture-based NGS FoundationACT assay.20 In our study, 2 specimens did not meet the minimum criteria of adequacy (20 ng cfDNA); however, the overall adequacy rate for the detection of mutation, irrespective of the cancer type was 29 of 31 (93.5%) with only 2 inadequate samples. This rate is higher than the rate reported in the literature, which is about 70%.20

Significant differences were encountered in the incidence of DNA damage repair genes including Tp53 mutations when compared with those in the general patient population (Table 2). According to recent National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, all prostate cancers should be screened for DDR gene mutations as these genes are common in aggressive prostate cancers and strongly associated with poor outcomes and shortened survival. Due to relatively high frequency of DDR gene mutations in advanced prostatic cancers, liquid biopsy in patients with these advanced stage prostate cancers may be a useful tool in clinical decision making and exploring targeted therapy.20

Mutations in BRCA2, ATM, CDK12, and CHEK2 (DDR gene family) are common. Incidence of ATM and CDK12 mutations in the literature is 3 to 6% of cases.21 Of 21 liquid biopsies of advanced prostate cancer patients, we found combined DDR gene mutation of ATM, CHEK2, and CDK12 genes in 6 (28.5%) cases, which is substantially higher than the 3 to 6% rate reported in the literature.21-24 Of the 23 patients who had notable mutations in our liquid biopsies, including both advanced prostate and lung cancer cases, 8 (34.7%) also showed mutation of the genes of DDR family. Our study did not show BRCA2 mutation, which is otherwise common in the literature.

We also evaluated the frequency of the most commonly occurring genetic mutations, Tp53 in advanced solid malignancies, especially advanced prostate and NSCLC. Previous studies have reported Tp53 mutation in association with risk factors (carcinogens) of cancer and have been a surrogate marker of poor survival or lack of response of therapy.25 Knowledge of Tp53 mutation is crucial for closer disease monitoring, preparing the patient for rapid progression, and encouraging the physician to prepare future lines of therapy.25-27 Although Tp53 mutation varies with histologic type and tissue of origin, Beltran and colleagues reported it in 30 to 40% of tumors, while Robles and colleagues reported about 40 to 42% incidence.25,27

Our study showed notable mutations in 23 of 29 adequate cases. Further, our study showed a high frequency of mutated Tp53 in 65.2% of combined advanced prostate and NSCLC cases. We then correlated cases of Vietnam War-era veterans with risk potential of Agent Orange exposure and Tp53 mutation. We found 7 of 15 Vietnam War-era veterans were positive for Tp53 mutations irrespective of the cancer type. The high incidence of Tp53 mutations in advanced prostate and lung carcinomas in the veteran patient population makes this tumor marker an aspiration not only as a surrogate of aggressive disease and tumor progression, but also as a key marker for targeted therapy in advanced prostate and lung cancers with loss of Tp53 function (Figure 3).

Mutations and amplifications in the AR gene are fundamental to progression of prostate cancer associated with advanced, hormone-refractory prostate cancer with the potential for targeted therapy with AR inhibitors. In our study, AR amplification was detected in 4 of 21 (19%) advanced prostate cancer cases, which is significantly lower than the 30 to 50% previously reported in the literature.28-32 Neither AR amplification or mutation was noted in advanced NSCLC in our study as previously reported in literature by Brennan and colleagues and Wang and colleagues.33-35 This is significant as it provides a pathway for future studies to focus on additional driver mutations for targeted therapies in advanced prostate carcinoma. To date, AR gene mutation does not play a role for personalized therapy in advanced NSCLC. Perhaps, a large cohort study with longitudinal analysis is needed for absolutely ruling out the possibility of personalized medicine in advanced lung cancer using this biomarker.

Conclusions

Liquid biopsy successfully provides precision-based oncology and information for decision making in this unique population of veterans. Difference in frequency of the genetic mutations in this cohort can provide future insight into disease progression, lack of response, and mechanism of resistance to the implemented therapy. Future studies focused on this veteran patient population are needed for developing targeted therapies and patient tailored oncologic therapy. ctDNA has a high potential for monitoring clinically relevant cancer-related genetic and epigenetic modifications for discovering more detailed information on the tumor characterization. Although larger cohort trial with longitudinal analyses are needed, high prevalence of DDR gene and Tp53 mutation in our study instills promising hope for therapeutic interventions in this unique cohort.

The minimally invasive liquid biopsy shows a great promise as both diagnostic and prognostic tool in the personalized clinical management of advanced prostate, and NSCLC in the veteran patient population with unique demographic characteristics. De novo metastatic prostate cancer is more common in veterans when compared with the general population, and therefore veterans may benefit by liquid biopsy. Differences in the frequency of genetic mutations (DDR, TP53, AR) in this cohort provides valuable information for disease progression, lack of response, mechanism of resistance to the implemented therapy and clinical decision making. Precision oncology can be further tailored for this cohort by focusing on DNA repair genes and Tp53 mutations for future targeted therapy.

The advent of liquid biopsies targeting genetic mutations in solid tumors is a major milestone in the field of precision oncology.1 Conventional methods of obtaining tissue for molecular studies are limited by sample size and often do not represent the entire bulk of the tumor.2 This newer minimally invasive, revolutionary technique analyzes circulating cell-free DNA carrying tumor-specific alterations (circulating tumor DNA [ctDNA]) in peripheral blood and detects signature genomic alterations.1 Tp53 mutations have been reported in 25 to 40% of prostatic cancers and > 50% of non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLC), being more common in late-stage and hormone refractory prostate cancers.3,4 Tp53 mutation has been found to be associated with poor prognosis and increased germline mutations.5

The veteran patient population has distinct demographic characteristics that make veterans more vulnerable to genetic mutations and malignancies, including risk of exposure to Agent Orange, smoking, substance abuse, and asbestos. This area is understudied and extremely sparse in the literature for frequency of genetic mutations, risk factors in solid malignancies occurring in the veteran patient population, and the clinical impact of these risk factors. We herein present a quality assurance study for the utility of liquid biopsies regarding the frequency of DNA damage repair (DDR) gene, Tp53, and androgen receptor (AR) mutations. The clinical impact in advanced lung and prostate cancers in the veteran patient population and frequency are the quality assurance observations that are the study endpoints.

Methods

We reviewed for quality assurance documentation from the Foundation Medicine (www.foundationmedicine.com) cancer biomarker tests on liquid biopsies performed at the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz Veteran Affairs Medical Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania from May 2019 to April 15, 2020. All biopsies were performed on cancers with biochemical, imaging or tissue evidence of advanced tumor progression. The testing was performed on advanced solid malignancies, including NSCLC, prostate adenocarcinoma, and metastatic colon cancer. Statistical data for adequacy; cases with notable mutations; frequency; and type of mutations of AR, DDR, and Tp53 were noted. General and specific risk factors associated with the veteran patient population were studied and matched with the type of mutations (Table 1).

Results

Thirty-one liquid biopsies were performed over this period—23 for prostate cancer, 7 for patients with lung cancer patients, and 1 for a patient with colon cancer. Of 31 cases, sensitivity/adequacy of liquid biopsy for genetic mutation was detected in 29 (93.5%) cases (Figure 1). Two inadequate biopsies (both from patients with prostate cancer) were excluded from the study, leaving 29 liquid biopsies with adequate ctDNA for analysis that were considered for further statistical purpose—21 prostate, 7 lung, and 1 colon cancer.

Multiple (common and different) genetic mutations were identified; however, our study subcategorized the mutations into the those that were related to prostate cancer, lung cancer, and some common mutations that occur in both cancers. Only the significant ones will be discussed in this review and equivocal result for AR is excluded from this study. Of the 21 prostate cancers, 4 (19.0%) had directed the targeted therapy to driver mutation (AR being most common in prostate cancer), while KRAS mutation, which was more common in lung cancer, was detected in 2/7 (28.6%) lung cancers. Mutations common to both cancer types were DDR gene mutations, which is a broad name for numerous genes including CDK12, ATM, and CHEK2.

Of all cases irrespective of the cancer type, 23/29 (79.3%) showed notable mutations. DDR gene mutations were found in 6 of 21 (28.5%) patients with prostate cancer and 8 of 23 (34.7%) patients with advanced prostate and lung cancers, indicating poor outcome and possible resistance to the current therapy. Of 23 patients showing mutations irrespective of the cancer type, 15 (65.2%) harbored Tp53 mutations, which is much more frequent in veteran patient population when compared with the literature. Fifteen of the 31 (48.4%) total patients were Vietnam War-era veterans who were potentially exposed to Agent Orange and 20 (64.5%) patients who were not Vietnam War-era veterans had a history that included smoking (Figure 2).

Discussion

The veteran patient population is a unique cohort due to its distinct demographic characteristics with a high volume of cancer cases diagnosed each year. According to data from VA Central Cancer Registry (VACCR), the most frequently diagnosed cancers are prostate (29%) and lung (18%).6

Liquid biopsy is a novel, promising technology that uses ctDNA and circulating tumor cells in peripheral blood for detecting genetic alterations through next generation sequencing.7-9 The advent of this minimally invasive, revolutionary technology has been a breakthrough in the field of precision oncology for prognosis, to monitor treatment response or resistance to therapy and further personalize cancer therapy.9,10

Comprehensive genomic profiling by liquid biopsy has many advantages over the molecular studies performed on tissue biopsy. Due to the tumor heterogeneity, tissue samples may not represent the full profile of the tumor genomics of cancer, while liquid biopsy has full presentation of the disease.11,12 Many times, tissue biopsy may be limited by a sample size that precludes full genetic profiling in addition to higher total cost, potential technical issues during processing, and possible side effects of the biopsy procedure.7,13 Additionally, as the tumor progresses, new driver mutations other than the ones previously detected on the primary tissue may emerge, which can confer resistance to the existing therapy.7,13

Advanced prostatic and lung carcinomas with biochemical, distant organ, or bony progression harbor unique signature genetic mutations indicating poor prognosis, lack of response or resistance to the existing therapy, and high risk of relapse.14,15 Some of the unique characteristics of the veteran patient population include a more aged patient population multiple comorbidities, higher frequency of > 1 type of cancer, advanced cancer stage at presentation, and specific risks factors such as exposure to Agent Orange in veterans who served during the Vietnam War era.16,17 We studied the utility of liquid biopsy in cancer care, including type and incidence of genomic alterations associated with advanced prostate and lung cancers, in this unique patient population.

The amount of cell-free DNA (cfDNA), also known as ctDNA varies widely in cancer patients. Some of the factors associated with low concentration of cfDNA are disease stage, intervening therapy, proliferation rates, and tumor vascularization.18,19 In the peripheral blood, of the total cfDNA, fractions of cfDNA varies from 0.01 to 90%.18,19 All samples containing ≥ 20 ng cfDNA (20 - 100 ng) were subjected to the hybrid capture-based NGS FoundationACT assay.20 In our study, 2 specimens did not meet the minimum criteria of adequacy (20 ng cfDNA); however, the overall adequacy rate for the detection of mutation, irrespective of the cancer type was 29 of 31 (93.5%) with only 2 inadequate samples. This rate is higher than the rate reported in the literature, which is about 70%.20

Significant differences were encountered in the incidence of DNA damage repair genes including Tp53 mutations when compared with those in the general patient population (Table 2). According to recent National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, all prostate cancers should be screened for DDR gene mutations as these genes are common in aggressive prostate cancers and strongly associated with poor outcomes and shortened survival. Due to relatively high frequency of DDR gene mutations in advanced prostatic cancers, liquid biopsy in patients with these advanced stage prostate cancers may be a useful tool in clinical decision making and exploring targeted therapy.20

Mutations in BRCA2, ATM, CDK12, and CHEK2 (DDR gene family) are common. Incidence of ATM and CDK12 mutations in the literature is 3 to 6% of cases.21 Of 21 liquid biopsies of advanced prostate cancer patients, we found combined DDR gene mutation of ATM, CHEK2, and CDK12 genes in 6 (28.5%) cases, which is substantially higher than the 3 to 6% rate reported in the literature.21-24 Of the 23 patients who had notable mutations in our liquid biopsies, including both advanced prostate and lung cancer cases, 8 (34.7%) also showed mutation of the genes of DDR family. Our study did not show BRCA2 mutation, which is otherwise common in the literature.

We also evaluated the frequency of the most commonly occurring genetic mutations, Tp53 in advanced solid malignancies, especially advanced prostate and NSCLC. Previous studies have reported Tp53 mutation in association with risk factors (carcinogens) of cancer and have been a surrogate marker of poor survival or lack of response of therapy.25 Knowledge of Tp53 mutation is crucial for closer disease monitoring, preparing the patient for rapid progression, and encouraging the physician to prepare future lines of therapy.25-27 Although Tp53 mutation varies with histologic type and tissue of origin, Beltran and colleagues reported it in 30 to 40% of tumors, while Robles and colleagues reported about 40 to 42% incidence.25,27

Our study showed notable mutations in 23 of 29 adequate cases. Further, our study showed a high frequency of mutated Tp53 in 65.2% of combined advanced prostate and NSCLC cases. We then correlated cases of Vietnam War-era veterans with risk potential of Agent Orange exposure and Tp53 mutation. We found 7 of 15 Vietnam War-era veterans were positive for Tp53 mutations irrespective of the cancer type. The high incidence of Tp53 mutations in advanced prostate and lung carcinomas in the veteran patient population makes this tumor marker an aspiration not only as a surrogate of aggressive disease and tumor progression, but also as a key marker for targeted therapy in advanced prostate and lung cancers with loss of Tp53 function (Figure 3).