User login

The costs of surviving cancer

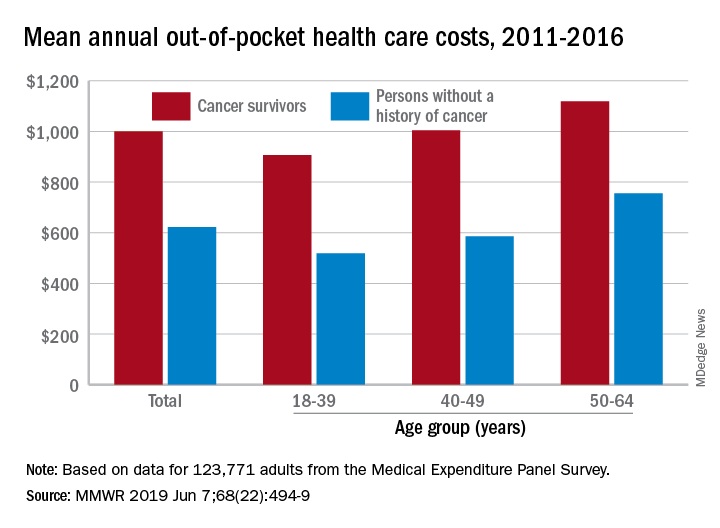

Cancer survivors have significantly higher out-of-pocket medical costs than those with no history of cancer, and a quarter of those survivors have some type of material hardship related to their diagnosis, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Along with those material financial hardships – the need to borrow money, go into debt, or declare bankruptcy – more than 34% of cancer survivors aged 18-64 years experienced psychological financial hardship, defined as worry about large medical bills, in 2011 and 2016, Donatus U. Ekwueme, PhD, and his associates reported in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Cancer survivors spend 60% more out of pocket than those with no cancer history: $1,000 a year from 2011 to 2016, compared with $622 for adults without a history of cancer. Spending was lowest among younger people (18-39 years) and increased with age, but the prevalence of both material and psychological hardships was highest in the middle age group (40-49 years) and lowest in the oldest group (50-64 years), they said.

Women had higher out-of-pocket costs than men, although the difference was smaller for those with cancer ($1,023 vs. $976) than for those without ($721 vs. $519). Material and psychological hardships were both more common among women, said Dr. Ekwueme of the CDC’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Atlanta, and his associates.

Mean out-of-pocket spending was much higher for cancer survivors with private health insurance ($1,114) than for survivors with public insurance ($471), but material hardship was much more prevalent among those with public insurance (33.1% vs. 21.9%). Rates of psychological hardship, however, were much closer: 35.9% for those with public insurance and 32.5% for those with private insurance, the investigators said.

“The number of Americans with a history of cancer is projected to increase in the next decade, and the economic burden associated with living with a cancer diagnosis will likely increase as well,” they wrote, and interventions such as “systematic screening for financial hardship at cancer diagnosis and throughout the cancer care trajectory [are needed] to minimize financial hardship for cancer survivors.”

The analysis was based on data for 123,771 adults aged 18-64 years from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Out-of-pocket costs were calculated using data from 2011 to 2016, with all costs adjusted to 2016 dollars, but the hardship calculations involved data from only 2011 and 2016.

SOURCE: Ekwueme DU et al. MMWR 2019 Jun 7;68(22):494-9.

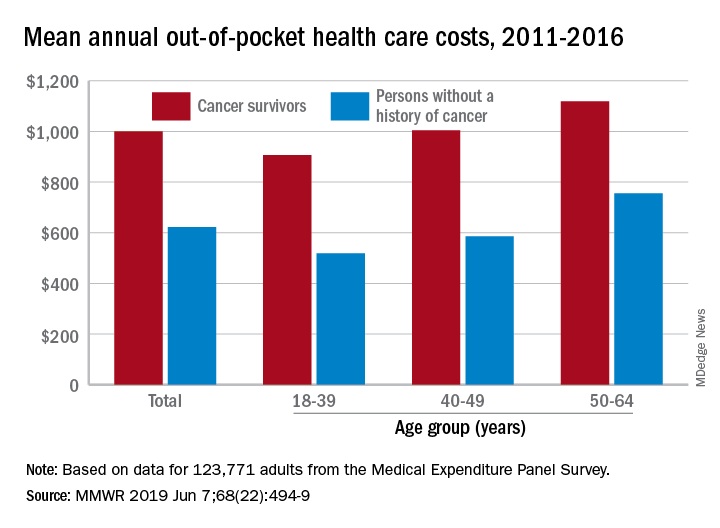

Cancer survivors have significantly higher out-of-pocket medical costs than those with no history of cancer, and a quarter of those survivors have some type of material hardship related to their diagnosis, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Along with those material financial hardships – the need to borrow money, go into debt, or declare bankruptcy – more than 34% of cancer survivors aged 18-64 years experienced psychological financial hardship, defined as worry about large medical bills, in 2011 and 2016, Donatus U. Ekwueme, PhD, and his associates reported in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Cancer survivors spend 60% more out of pocket than those with no cancer history: $1,000 a year from 2011 to 2016, compared with $622 for adults without a history of cancer. Spending was lowest among younger people (18-39 years) and increased with age, but the prevalence of both material and psychological hardships was highest in the middle age group (40-49 years) and lowest in the oldest group (50-64 years), they said.

Women had higher out-of-pocket costs than men, although the difference was smaller for those with cancer ($1,023 vs. $976) than for those without ($721 vs. $519). Material and psychological hardships were both more common among women, said Dr. Ekwueme of the CDC’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Atlanta, and his associates.

Mean out-of-pocket spending was much higher for cancer survivors with private health insurance ($1,114) than for survivors with public insurance ($471), but material hardship was much more prevalent among those with public insurance (33.1% vs. 21.9%). Rates of psychological hardship, however, were much closer: 35.9% for those with public insurance and 32.5% for those with private insurance, the investigators said.

“The number of Americans with a history of cancer is projected to increase in the next decade, and the economic burden associated with living with a cancer diagnosis will likely increase as well,” they wrote, and interventions such as “systematic screening for financial hardship at cancer diagnosis and throughout the cancer care trajectory [are needed] to minimize financial hardship for cancer survivors.”

The analysis was based on data for 123,771 adults aged 18-64 years from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Out-of-pocket costs were calculated using data from 2011 to 2016, with all costs adjusted to 2016 dollars, but the hardship calculations involved data from only 2011 and 2016.

SOURCE: Ekwueme DU et al. MMWR 2019 Jun 7;68(22):494-9.

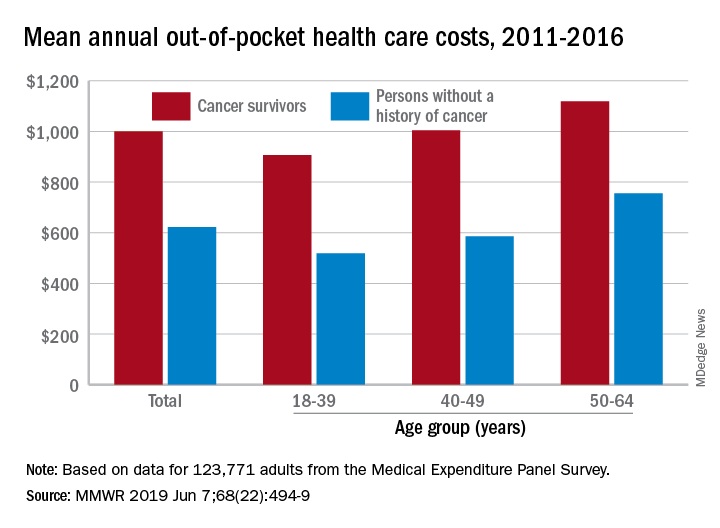

Cancer survivors have significantly higher out-of-pocket medical costs than those with no history of cancer, and a quarter of those survivors have some type of material hardship related to their diagnosis, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Along with those material financial hardships – the need to borrow money, go into debt, or declare bankruptcy – more than 34% of cancer survivors aged 18-64 years experienced psychological financial hardship, defined as worry about large medical bills, in 2011 and 2016, Donatus U. Ekwueme, PhD, and his associates reported in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Cancer survivors spend 60% more out of pocket than those with no cancer history: $1,000 a year from 2011 to 2016, compared with $622 for adults without a history of cancer. Spending was lowest among younger people (18-39 years) and increased with age, but the prevalence of both material and psychological hardships was highest in the middle age group (40-49 years) and lowest in the oldest group (50-64 years), they said.

Women had higher out-of-pocket costs than men, although the difference was smaller for those with cancer ($1,023 vs. $976) than for those without ($721 vs. $519). Material and psychological hardships were both more common among women, said Dr. Ekwueme of the CDC’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Atlanta, and his associates.

Mean out-of-pocket spending was much higher for cancer survivors with private health insurance ($1,114) than for survivors with public insurance ($471), but material hardship was much more prevalent among those with public insurance (33.1% vs. 21.9%). Rates of psychological hardship, however, were much closer: 35.9% for those with public insurance and 32.5% for those with private insurance, the investigators said.

“The number of Americans with a history of cancer is projected to increase in the next decade, and the economic burden associated with living with a cancer diagnosis will likely increase as well,” they wrote, and interventions such as “systematic screening for financial hardship at cancer diagnosis and throughout the cancer care trajectory [are needed] to minimize financial hardship for cancer survivors.”

The analysis was based on data for 123,771 adults aged 18-64 years from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Out-of-pocket costs were calculated using data from 2011 to 2016, with all costs adjusted to 2016 dollars, but the hardship calculations involved data from only 2011 and 2016.

SOURCE: Ekwueme DU et al. MMWR 2019 Jun 7;68(22):494-9.

FROM MMWR

MADIT-CHIC: CRT aids patients with chemotherapy-induced cardiomyopathy

SAN FRANCISCO – Patients with cardiomyopathy secondary to cancer chemotherapy who qualified for cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) by having a wide QRS interval showed a virtually uniform, positive response to this treatment in a multicenter study with 30 patients.

This is the first time this therapy has been prospectively assessed in this patient population.

The results “show for the first time that patients with chemotherapy-induced cardiomyopathy [CHIC] who meet criteria for CRT show significant improvement in left ventricular function and clinical symptoms in the short term” during follow-up of 6 months, Jagmeet P. Singh, MD, said at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society.

Dr. Singh acknowledged that, with 30 patients, the study was small, uncontrolled, had a brief follow-up of 6 months, and was highly selective. It took collaborating investigators at 12 U.S. centers more than 3.5 years to find the 30 participating patients, who had to meet very specific criteria designed to identify true CHIC. Nonetheless, Dr. Singh considered the results convincing enough to shift practice.

Based on the results, “I would certainly feel comfortable using CRT in patients with CHIC,” said Dr. Singh, associate chief of cardiology at Massachusetts General Hospital and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. “If a patient has CHIC with a wide QRS interval and evidence for a conduction defect on their ECG, they are a great candidate for CRT. The results highlight that there is a cohort of patients who develop cardiomyopathy after chemotherapy, and these patients are often written off” and until now have generally received little follow-up for their potential development of cardiomyopathy. Dr. Singh expressed hope that the recent emergence of cardio-oncology as a subspecialty will focus attention on CHIC patients.

The MADIT-CHIC (Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial – Chemotherapy-Induced Cardiomyopathy) study enrolled patients with a history of exposure to a cancer chemotherapy regimen known to cause cardiomyopathy who had no history of heart failure prior to the chemotherapy. All patients had developed clinically apparent heart failure (New York Heart Association functional class II, III, or IV) at least 6 months after completing chemotherapy, had no other apparent cause of the cardiomyopathy as ascertained by a cardio-oncologist, and were on guideline-directed medical therapy. Enrolled patients also had to have a class I or II indication for CRT, with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% or less, a QRS interval of at least 120 milliseconds, sinus rhythm and left bundle branch block, or no left bundle branch block and a QRS of at least 150 milliseconds.

Just over three-quarters of the patients had received an anthracycline drug, and 73% had a history of breast cancer, 20% a history of leukemia or lymphoma, and 7% had a history of sarcoma. The patients averaged 64 years of age, and 87% were women. CRT placement occurred 18-256 months after the end of chemotherapy, with a median of 188 months.

The study’s primary endpoint was the change in left ventricular ejection fraction after 6 months, which increased from an average of 28% at baseline to 39% at follow-up, a statistically significant change. Ejection fraction increased in 29 of the 30 patients, with one patient showing a flat response to CRT. Cardiac function and geometry significantly improved by seven other measures, including left ventricular mass and left atrial volume, and the improved ejection fraction was consistent across several subgroup analyses. Patients’ NYHA functional class improved by at least one level in 41% of patients, and 83% of the patients stopped showing clinical features of heart failure after 6 months on CRT.

MADIT-CHIC received funding from Boston Scientific. Dr. Singh has been a consultant to Abbott, Back Beat, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, EBR, Impulse Dynamics, Medtronic, Microport, St. Jude, and Toray, and he has received research support from Abbott and Boston Scientific.

SOURCE: Singh JP et al. HRS 2019, Abstract S-LBCT02-04.

No guideline currently addresses using cardiac resynchronization therapy to treat chemotherapy-induced cardiomyopathy. The findings from MADIT-CHIC showed a striking benefit from treatment with cardiac resynchronization therapy of a magnitude we would expect to see in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Patients showed improvements in all measures of cardiac performance.

It appears that CHIC can take as long as decades to appear in a patient, but we now need to have a high level of suspicion for this complication. We need to come up with better ways to monitor development of CHIC in patients who have received cancer chemotherapy so that we can give eligible patients this beneficial treatment. We can be optimistic about the potential for benefit from CRT in these patients.

Kenneth A. Ellenbogen, MD , is chief of cardiology and a professor of medicine at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, Va. He has been a consultant to Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and St. Jude; he has received honoraria from Biotronik; and he has received research funding from Boston Scientific and Medtronic. He made these comments as the designated discussant for the MADIT-CHIC report.

No guideline currently addresses using cardiac resynchronization therapy to treat chemotherapy-induced cardiomyopathy. The findings from MADIT-CHIC showed a striking benefit from treatment with cardiac resynchronization therapy of a magnitude we would expect to see in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Patients showed improvements in all measures of cardiac performance.

It appears that CHIC can take as long as decades to appear in a patient, but we now need to have a high level of suspicion for this complication. We need to come up with better ways to monitor development of CHIC in patients who have received cancer chemotherapy so that we can give eligible patients this beneficial treatment. We can be optimistic about the potential for benefit from CRT in these patients.

Kenneth A. Ellenbogen, MD , is chief of cardiology and a professor of medicine at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, Va. He has been a consultant to Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and St. Jude; he has received honoraria from Biotronik; and he has received research funding from Boston Scientific and Medtronic. He made these comments as the designated discussant for the MADIT-CHIC report.

No guideline currently addresses using cardiac resynchronization therapy to treat chemotherapy-induced cardiomyopathy. The findings from MADIT-CHIC showed a striking benefit from treatment with cardiac resynchronization therapy of a magnitude we would expect to see in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Patients showed improvements in all measures of cardiac performance.

It appears that CHIC can take as long as decades to appear in a patient, but we now need to have a high level of suspicion for this complication. We need to come up with better ways to monitor development of CHIC in patients who have received cancer chemotherapy so that we can give eligible patients this beneficial treatment. We can be optimistic about the potential for benefit from CRT in these patients.

Kenneth A. Ellenbogen, MD , is chief of cardiology and a professor of medicine at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, Va. He has been a consultant to Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and St. Jude; he has received honoraria from Biotronik; and he has received research funding from Boston Scientific and Medtronic. He made these comments as the designated discussant for the MADIT-CHIC report.

SAN FRANCISCO – Patients with cardiomyopathy secondary to cancer chemotherapy who qualified for cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) by having a wide QRS interval showed a virtually uniform, positive response to this treatment in a multicenter study with 30 patients.

This is the first time this therapy has been prospectively assessed in this patient population.

The results “show for the first time that patients with chemotherapy-induced cardiomyopathy [CHIC] who meet criteria for CRT show significant improvement in left ventricular function and clinical symptoms in the short term” during follow-up of 6 months, Jagmeet P. Singh, MD, said at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society.

Dr. Singh acknowledged that, with 30 patients, the study was small, uncontrolled, had a brief follow-up of 6 months, and was highly selective. It took collaborating investigators at 12 U.S. centers more than 3.5 years to find the 30 participating patients, who had to meet very specific criteria designed to identify true CHIC. Nonetheless, Dr. Singh considered the results convincing enough to shift practice.

Based on the results, “I would certainly feel comfortable using CRT in patients with CHIC,” said Dr. Singh, associate chief of cardiology at Massachusetts General Hospital and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. “If a patient has CHIC with a wide QRS interval and evidence for a conduction defect on their ECG, they are a great candidate for CRT. The results highlight that there is a cohort of patients who develop cardiomyopathy after chemotherapy, and these patients are often written off” and until now have generally received little follow-up for their potential development of cardiomyopathy. Dr. Singh expressed hope that the recent emergence of cardio-oncology as a subspecialty will focus attention on CHIC patients.

The MADIT-CHIC (Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial – Chemotherapy-Induced Cardiomyopathy) study enrolled patients with a history of exposure to a cancer chemotherapy regimen known to cause cardiomyopathy who had no history of heart failure prior to the chemotherapy. All patients had developed clinically apparent heart failure (New York Heart Association functional class II, III, or IV) at least 6 months after completing chemotherapy, had no other apparent cause of the cardiomyopathy as ascertained by a cardio-oncologist, and were on guideline-directed medical therapy. Enrolled patients also had to have a class I or II indication for CRT, with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% or less, a QRS interval of at least 120 milliseconds, sinus rhythm and left bundle branch block, or no left bundle branch block and a QRS of at least 150 milliseconds.

Just over three-quarters of the patients had received an anthracycline drug, and 73% had a history of breast cancer, 20% a history of leukemia or lymphoma, and 7% had a history of sarcoma. The patients averaged 64 years of age, and 87% were women. CRT placement occurred 18-256 months after the end of chemotherapy, with a median of 188 months.

The study’s primary endpoint was the change in left ventricular ejection fraction after 6 months, which increased from an average of 28% at baseline to 39% at follow-up, a statistically significant change. Ejection fraction increased in 29 of the 30 patients, with one patient showing a flat response to CRT. Cardiac function and geometry significantly improved by seven other measures, including left ventricular mass and left atrial volume, and the improved ejection fraction was consistent across several subgroup analyses. Patients’ NYHA functional class improved by at least one level in 41% of patients, and 83% of the patients stopped showing clinical features of heart failure after 6 months on CRT.

MADIT-CHIC received funding from Boston Scientific. Dr. Singh has been a consultant to Abbott, Back Beat, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, EBR, Impulse Dynamics, Medtronic, Microport, St. Jude, and Toray, and he has received research support from Abbott and Boston Scientific.

SOURCE: Singh JP et al. HRS 2019, Abstract S-LBCT02-04.

SAN FRANCISCO – Patients with cardiomyopathy secondary to cancer chemotherapy who qualified for cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) by having a wide QRS interval showed a virtually uniform, positive response to this treatment in a multicenter study with 30 patients.

This is the first time this therapy has been prospectively assessed in this patient population.

The results “show for the first time that patients with chemotherapy-induced cardiomyopathy [CHIC] who meet criteria for CRT show significant improvement in left ventricular function and clinical symptoms in the short term” during follow-up of 6 months, Jagmeet P. Singh, MD, said at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society.

Dr. Singh acknowledged that, with 30 patients, the study was small, uncontrolled, had a brief follow-up of 6 months, and was highly selective. It took collaborating investigators at 12 U.S. centers more than 3.5 years to find the 30 participating patients, who had to meet very specific criteria designed to identify true CHIC. Nonetheless, Dr. Singh considered the results convincing enough to shift practice.

Based on the results, “I would certainly feel comfortable using CRT in patients with CHIC,” said Dr. Singh, associate chief of cardiology at Massachusetts General Hospital and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. “If a patient has CHIC with a wide QRS interval and evidence for a conduction defect on their ECG, they are a great candidate for CRT. The results highlight that there is a cohort of patients who develop cardiomyopathy after chemotherapy, and these patients are often written off” and until now have generally received little follow-up for their potential development of cardiomyopathy. Dr. Singh expressed hope that the recent emergence of cardio-oncology as a subspecialty will focus attention on CHIC patients.

The MADIT-CHIC (Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial – Chemotherapy-Induced Cardiomyopathy) study enrolled patients with a history of exposure to a cancer chemotherapy regimen known to cause cardiomyopathy who had no history of heart failure prior to the chemotherapy. All patients had developed clinically apparent heart failure (New York Heart Association functional class II, III, or IV) at least 6 months after completing chemotherapy, had no other apparent cause of the cardiomyopathy as ascertained by a cardio-oncologist, and were on guideline-directed medical therapy. Enrolled patients also had to have a class I or II indication for CRT, with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 35% or less, a QRS interval of at least 120 milliseconds, sinus rhythm and left bundle branch block, or no left bundle branch block and a QRS of at least 150 milliseconds.

Just over three-quarters of the patients had received an anthracycline drug, and 73% had a history of breast cancer, 20% a history of leukemia or lymphoma, and 7% had a history of sarcoma. The patients averaged 64 years of age, and 87% were women. CRT placement occurred 18-256 months after the end of chemotherapy, with a median of 188 months.

The study’s primary endpoint was the change in left ventricular ejection fraction after 6 months, which increased from an average of 28% at baseline to 39% at follow-up, a statistically significant change. Ejection fraction increased in 29 of the 30 patients, with one patient showing a flat response to CRT. Cardiac function and geometry significantly improved by seven other measures, including left ventricular mass and left atrial volume, and the improved ejection fraction was consistent across several subgroup analyses. Patients’ NYHA functional class improved by at least one level in 41% of patients, and 83% of the patients stopped showing clinical features of heart failure after 6 months on CRT.

MADIT-CHIC received funding from Boston Scientific. Dr. Singh has been a consultant to Abbott, Back Beat, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, EBR, Impulse Dynamics, Medtronic, Microport, St. Jude, and Toray, and he has received research support from Abbott and Boston Scientific.

SOURCE: Singh JP et al. HRS 2019, Abstract S-LBCT02-04.

REPORTING FROM HEART RHYTHM 2019

ASCO clinical practice guideline update incorporates Oncotype DX

In women with hormone receptor–positive, axillary node–negative breast cancer with Oncotype DX recurrence scores of less than 26, there is minimal to no benefit from chemotherapy, particularly for those greater than age 50 years, according to a clinical practice guideline update by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Furthermore, endocrine therapy alone may be offered for patients greater than age 50 years whose tumors have recurrence scores of less than 26, wrote Fabrice Andre, MD, PhD, of Paris Sud University and associates on the expert panel in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The panel members reviewed recently published findings from the Trial Assigning Individualized Options for Treatment (TAILORx), which evaluated the clinical utility of the Oncotype DX assay in women with early-stage invasive breast cancer.

“This focused update reviews and analyzes new data regarding these recommendations while applying the same criteria of clinical utility as described in the 2016 guideline,” they wrote.

The expert panel provided recommendations on how to integrate the results of the TAILORx study into clinical practice.

“For patients age 50 years or younger with Oncotype DX recurrence scores of 16-25, clinicians may offer chemoendocrine therapy” the panel wrote. “Patients with Oncotype DX recurrence scores of greater than 30 should be considered candidates for chemoendocrine therapy.”

In addition, on the basis of consensus they recommended that chemoendocrine therapy could be offered to patients with recurrence scores of 26-30.

The panel acknowledged that relevant literature on the use of Oncotype DX in this population will be reviewed over the upcoming months to address anticipated practice deviation related to biomarker testing.

More information on the guidelines is available on the ASCO website.

The study was funded by ASCO. The authors reported financial affiliations with AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Roche, and several others.

SOURCE: Andre F et al. J Clin Oncol. 2019 May 31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00945.

In women with hormone receptor–positive, axillary node–negative breast cancer with Oncotype DX recurrence scores of less than 26, there is minimal to no benefit from chemotherapy, particularly for those greater than age 50 years, according to a clinical practice guideline update by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Furthermore, endocrine therapy alone may be offered for patients greater than age 50 years whose tumors have recurrence scores of less than 26, wrote Fabrice Andre, MD, PhD, of Paris Sud University and associates on the expert panel in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The panel members reviewed recently published findings from the Trial Assigning Individualized Options for Treatment (TAILORx), which evaluated the clinical utility of the Oncotype DX assay in women with early-stage invasive breast cancer.

“This focused update reviews and analyzes new data regarding these recommendations while applying the same criteria of clinical utility as described in the 2016 guideline,” they wrote.

The expert panel provided recommendations on how to integrate the results of the TAILORx study into clinical practice.

“For patients age 50 years or younger with Oncotype DX recurrence scores of 16-25, clinicians may offer chemoendocrine therapy” the panel wrote. “Patients with Oncotype DX recurrence scores of greater than 30 should be considered candidates for chemoendocrine therapy.”

In addition, on the basis of consensus they recommended that chemoendocrine therapy could be offered to patients with recurrence scores of 26-30.

The panel acknowledged that relevant literature on the use of Oncotype DX in this population will be reviewed over the upcoming months to address anticipated practice deviation related to biomarker testing.

More information on the guidelines is available on the ASCO website.

The study was funded by ASCO. The authors reported financial affiliations with AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Roche, and several others.

SOURCE: Andre F et al. J Clin Oncol. 2019 May 31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00945.

In women with hormone receptor–positive, axillary node–negative breast cancer with Oncotype DX recurrence scores of less than 26, there is minimal to no benefit from chemotherapy, particularly for those greater than age 50 years, according to a clinical practice guideline update by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Furthermore, endocrine therapy alone may be offered for patients greater than age 50 years whose tumors have recurrence scores of less than 26, wrote Fabrice Andre, MD, PhD, of Paris Sud University and associates on the expert panel in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The panel members reviewed recently published findings from the Trial Assigning Individualized Options for Treatment (TAILORx), which evaluated the clinical utility of the Oncotype DX assay in women with early-stage invasive breast cancer.

“This focused update reviews and analyzes new data regarding these recommendations while applying the same criteria of clinical utility as described in the 2016 guideline,” they wrote.

The expert panel provided recommendations on how to integrate the results of the TAILORx study into clinical practice.

“For patients age 50 years or younger with Oncotype DX recurrence scores of 16-25, clinicians may offer chemoendocrine therapy” the panel wrote. “Patients with Oncotype DX recurrence scores of greater than 30 should be considered candidates for chemoendocrine therapy.”

In addition, on the basis of consensus they recommended that chemoendocrine therapy could be offered to patients with recurrence scores of 26-30.

The panel acknowledged that relevant literature on the use of Oncotype DX in this population will be reviewed over the upcoming months to address anticipated practice deviation related to biomarker testing.

More information on the guidelines is available on the ASCO website.

The study was funded by ASCO. The authors reported financial affiliations with AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Roche, and several others.

SOURCE: Andre F et al. J Clin Oncol. 2019 May 31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00945.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Dear Marisol

I know you don’t remember me. We met when you were just a baby. Now that you’re older, I want to tell you a story about your mom you may not know.

When your mom became pregnant with you, it was a joyous occasion. But strange things started to happen. Your mom noticed that she was bleeding into the toilet bowl. She was told pregnancy would make her gain weight, but the opposite was happening. By her second trimester, her maternity clothes were so baggy she had to exchange them.

She went to see a gastroenterologist and told him about the bleeding. He looked at her pregnant belly, ordered no additional tests, and said he would look into the bleeding if it persisted after her pregnancy.

But that was 5 months away. In the meantime, her symptoms got worse. As you probably know by now, your mom is proactive. She sought a second opinion and then a third. Three different gastroenterologists dismissed your mom. The visits were brief; as soon as each doctor noticed she was pregnant, each deferred dealing with her – even though rectal bleeding and weight loss are in no way explained by pregnancy. Even though a colonoscopy could absolutely be safely performed during pregnancy.

A few months later, she gave birth to you. You were a healthy baby and she and your dad cried. They were so happy to meet you.

The next day, your dad stayed with you while the doctors performed a colonoscopy on your mom. To everyone’s horror, the camera saw a huge colon tumor. While the gastroenterologists had been reassuring her during her pregnancy, the tumor was gnawing through the wall of her colon and invading nearby organs.

She was wheeled on a gurney from the maternity unit to oncology. That’s where I met her.

She asked a lot of good questions, none of which we could answer. Her heart rate was in the 140s, and she developed fevers. Her cancer put her at risk for a serious infection called an abscess, and it took the option of chemotherapy off the table.

We went back and forth on what to do. We got lots of experts involved, and we went through the possibilities. We realized something terrible. There was no cure anymore. There were only trade-offs.

I will never forget the meeting between all of these doctors, your mom, and a Spanish interpreter. We gave your mom a best case scenario: 1 year.

Holding her necklace cross in one hand and your dad’s hand in the other, she repeated something over and over. The interpreter couldn’t hold back tears as she translated in a soft voice: “Please don’t let me die. Please don’t let me die. Please don’t let me die.”

We were all working so hard, doing our best to find a way out for her. Meanwhile, you stayed in the newborn nursery near the maternity ward. Every day your mom would go back and forth between oncology and the nursery to hold you.

Finally, we proceeded with surgery. It was an enormous, delicate, risky operation that took more than 10 hours. There were colorectal surgeons, urologists, and gynecologic oncologists. They scooped out not only the tumor but also your mom’s uterus, her ovaries, her bladder, and part of the abdominal wall. There was just so much cancer.

But your mom made it through the operation. Two days later, she married your dad in her hospital room while a nurse held you. She called it the best day of her life.

But we were still so worried. Everyone in the oncology unit had grown to love your mom, and we knew this was not a permanent fix. She was discharged from the hospital to rehab to get stronger. The plan was to see her in clinic and consider chemotherapy.

I usually keep a list of patients I want to follow even after I’m no longer their doctor. With your mom, I couldn’t put her on any list. It was too personal; I was too invested. I knew what the outcome would be, and I couldn’t bear to see it.

I never forgot your mom though. I decided to become an oncologist, and I thought about her when I met patients, especially young women, who had been dismissed by other doctors. I vowed to be the change as I listened to them and diagnosed them and treated them. I vowed to be a part of the system that would do better.

One day, 3 years after I met your mom, I was rotating in a colon cancer clinic and looked at the schedule. I recognized a name. Was it possible? It had to be someone with the same name. Could it really be your mom?

It was. By this time, she had finished chemotherapy. The goal was to keep the cancer from growing, but it somehow did more than that. Throughout your mom’s entire body, the cancer was gone. Her stoma was reversed, and she had gained back all the weight she lost. You were there too, defying instructions telling you not to touch the medical equipment. You hugged your mom’s leg as she made plans for a routine follow-up in 6 months.

I want you to know this story about your mom because, for the rest of your life, people will tell you what to think and how to feel. They will think it’s their business to tell you when to be worried, they will talk like they know better, and they will try to make you feel small for speaking up. I don’t have a perfect solution for all of this, except to say: Don’t let them.

But I’m not worried about you. If you grow up to be anything like your mom, you will be okay.

Dr. Yurkiewicz is a fellow in hematology and oncology at Stanford (Calif.) University. Follow her on Twitter @ilanayurkiewicz.

I know you don’t remember me. We met when you were just a baby. Now that you’re older, I want to tell you a story about your mom you may not know.

When your mom became pregnant with you, it was a joyous occasion. But strange things started to happen. Your mom noticed that she was bleeding into the toilet bowl. She was told pregnancy would make her gain weight, but the opposite was happening. By her second trimester, her maternity clothes were so baggy she had to exchange them.

She went to see a gastroenterologist and told him about the bleeding. He looked at her pregnant belly, ordered no additional tests, and said he would look into the bleeding if it persisted after her pregnancy.

But that was 5 months away. In the meantime, her symptoms got worse. As you probably know by now, your mom is proactive. She sought a second opinion and then a third. Three different gastroenterologists dismissed your mom. The visits were brief; as soon as each doctor noticed she was pregnant, each deferred dealing with her – even though rectal bleeding and weight loss are in no way explained by pregnancy. Even though a colonoscopy could absolutely be safely performed during pregnancy.

A few months later, she gave birth to you. You were a healthy baby and she and your dad cried. They were so happy to meet you.

The next day, your dad stayed with you while the doctors performed a colonoscopy on your mom. To everyone’s horror, the camera saw a huge colon tumor. While the gastroenterologists had been reassuring her during her pregnancy, the tumor was gnawing through the wall of her colon and invading nearby organs.

She was wheeled on a gurney from the maternity unit to oncology. That’s where I met her.

She asked a lot of good questions, none of which we could answer. Her heart rate was in the 140s, and she developed fevers. Her cancer put her at risk for a serious infection called an abscess, and it took the option of chemotherapy off the table.

We went back and forth on what to do. We got lots of experts involved, and we went through the possibilities. We realized something terrible. There was no cure anymore. There were only trade-offs.

I will never forget the meeting between all of these doctors, your mom, and a Spanish interpreter. We gave your mom a best case scenario: 1 year.

Holding her necklace cross in one hand and your dad’s hand in the other, she repeated something over and over. The interpreter couldn’t hold back tears as she translated in a soft voice: “Please don’t let me die. Please don’t let me die. Please don’t let me die.”

We were all working so hard, doing our best to find a way out for her. Meanwhile, you stayed in the newborn nursery near the maternity ward. Every day your mom would go back and forth between oncology and the nursery to hold you.

Finally, we proceeded with surgery. It was an enormous, delicate, risky operation that took more than 10 hours. There were colorectal surgeons, urologists, and gynecologic oncologists. They scooped out not only the tumor but also your mom’s uterus, her ovaries, her bladder, and part of the abdominal wall. There was just so much cancer.

But your mom made it through the operation. Two days later, she married your dad in her hospital room while a nurse held you. She called it the best day of her life.

But we were still so worried. Everyone in the oncology unit had grown to love your mom, and we knew this was not a permanent fix. She was discharged from the hospital to rehab to get stronger. The plan was to see her in clinic and consider chemotherapy.

I usually keep a list of patients I want to follow even after I’m no longer their doctor. With your mom, I couldn’t put her on any list. It was too personal; I was too invested. I knew what the outcome would be, and I couldn’t bear to see it.

I never forgot your mom though. I decided to become an oncologist, and I thought about her when I met patients, especially young women, who had been dismissed by other doctors. I vowed to be the change as I listened to them and diagnosed them and treated them. I vowed to be a part of the system that would do better.

One day, 3 years after I met your mom, I was rotating in a colon cancer clinic and looked at the schedule. I recognized a name. Was it possible? It had to be someone with the same name. Could it really be your mom?

It was. By this time, she had finished chemotherapy. The goal was to keep the cancer from growing, but it somehow did more than that. Throughout your mom’s entire body, the cancer was gone. Her stoma was reversed, and she had gained back all the weight she lost. You were there too, defying instructions telling you not to touch the medical equipment. You hugged your mom’s leg as she made plans for a routine follow-up in 6 months.

I want you to know this story about your mom because, for the rest of your life, people will tell you what to think and how to feel. They will think it’s their business to tell you when to be worried, they will talk like they know better, and they will try to make you feel small for speaking up. I don’t have a perfect solution for all of this, except to say: Don’t let them.

But I’m not worried about you. If you grow up to be anything like your mom, you will be okay.

Dr. Yurkiewicz is a fellow in hematology and oncology at Stanford (Calif.) University. Follow her on Twitter @ilanayurkiewicz.

I know you don’t remember me. We met when you were just a baby. Now that you’re older, I want to tell you a story about your mom you may not know.

When your mom became pregnant with you, it was a joyous occasion. But strange things started to happen. Your mom noticed that she was bleeding into the toilet bowl. She was told pregnancy would make her gain weight, but the opposite was happening. By her second trimester, her maternity clothes were so baggy she had to exchange them.

She went to see a gastroenterologist and told him about the bleeding. He looked at her pregnant belly, ordered no additional tests, and said he would look into the bleeding if it persisted after her pregnancy.

But that was 5 months away. In the meantime, her symptoms got worse. As you probably know by now, your mom is proactive. She sought a second opinion and then a third. Three different gastroenterologists dismissed your mom. The visits were brief; as soon as each doctor noticed she was pregnant, each deferred dealing with her – even though rectal bleeding and weight loss are in no way explained by pregnancy. Even though a colonoscopy could absolutely be safely performed during pregnancy.

A few months later, she gave birth to you. You were a healthy baby and she and your dad cried. They were so happy to meet you.

The next day, your dad stayed with you while the doctors performed a colonoscopy on your mom. To everyone’s horror, the camera saw a huge colon tumor. While the gastroenterologists had been reassuring her during her pregnancy, the tumor was gnawing through the wall of her colon and invading nearby organs.

She was wheeled on a gurney from the maternity unit to oncology. That’s where I met her.

She asked a lot of good questions, none of which we could answer. Her heart rate was in the 140s, and she developed fevers. Her cancer put her at risk for a serious infection called an abscess, and it took the option of chemotherapy off the table.

We went back and forth on what to do. We got lots of experts involved, and we went through the possibilities. We realized something terrible. There was no cure anymore. There were only trade-offs.

I will never forget the meeting between all of these doctors, your mom, and a Spanish interpreter. We gave your mom a best case scenario: 1 year.

Holding her necklace cross in one hand and your dad’s hand in the other, she repeated something over and over. The interpreter couldn’t hold back tears as she translated in a soft voice: “Please don’t let me die. Please don’t let me die. Please don’t let me die.”

We were all working so hard, doing our best to find a way out for her. Meanwhile, you stayed in the newborn nursery near the maternity ward. Every day your mom would go back and forth between oncology and the nursery to hold you.

Finally, we proceeded with surgery. It was an enormous, delicate, risky operation that took more than 10 hours. There were colorectal surgeons, urologists, and gynecologic oncologists. They scooped out not only the tumor but also your mom’s uterus, her ovaries, her bladder, and part of the abdominal wall. There was just so much cancer.

But your mom made it through the operation. Two days later, she married your dad in her hospital room while a nurse held you. She called it the best day of her life.

But we were still so worried. Everyone in the oncology unit had grown to love your mom, and we knew this was not a permanent fix. She was discharged from the hospital to rehab to get stronger. The plan was to see her in clinic and consider chemotherapy.

I usually keep a list of patients I want to follow even after I’m no longer their doctor. With your mom, I couldn’t put her on any list. It was too personal; I was too invested. I knew what the outcome would be, and I couldn’t bear to see it.

I never forgot your mom though. I decided to become an oncologist, and I thought about her when I met patients, especially young women, who had been dismissed by other doctors. I vowed to be the change as I listened to them and diagnosed them and treated them. I vowed to be a part of the system that would do better.

One day, 3 years after I met your mom, I was rotating in a colon cancer clinic and looked at the schedule. I recognized a name. Was it possible? It had to be someone with the same name. Could it really be your mom?

It was. By this time, she had finished chemotherapy. The goal was to keep the cancer from growing, but it somehow did more than that. Throughout your mom’s entire body, the cancer was gone. Her stoma was reversed, and she had gained back all the weight she lost. You were there too, defying instructions telling you not to touch the medical equipment. You hugged your mom’s leg as she made plans for a routine follow-up in 6 months.

I want you to know this story about your mom because, for the rest of your life, people will tell you what to think and how to feel. They will think it’s their business to tell you when to be worried, they will talk like they know better, and they will try to make you feel small for speaking up. I don’t have a perfect solution for all of this, except to say: Don’t let them.

But I’m not worried about you. If you grow up to be anything like your mom, you will be okay.

Dr. Yurkiewicz is a fellow in hematology and oncology at Stanford (Calif.) University. Follow her on Twitter @ilanayurkiewicz.

Patient-centered care in clinic

Almost 30 years ago a young woman made an appointment to see me. I had just started my internal medicine practice and almost all the patients who saw me were new to me. I assumed she was establishing care with me. Her first words to me were “Hello Dr. Paauw, I would like to interview you to see if you will be a good fit as my doctor.” We talked for the 40-minute appointment time. I asked her about her health, her life, and what she wanted out of both. We shared with each other that we both were parents of young children. When the appointment was over, she said she would really like for me to be her doctor. She told me that the main thing she appreciated about me was that I listened, and that her previous physician never sat down at her appointments and often had his hand on the door handle for much of the visit. Physicians and patients both agree that compassionate care is essential for good patient care, yet about half of patients and 60% of doctors believe it is lacking in our medical system.1

Remember the golden first minutes

I often start by asking the patient to give me an update on how they are doing. This lets me know what is important to them. I do not touch the computer until after this initial check-in.

Use the computer as a bond to strengthen your patient relationship

Many studies have shown patients find the computer gets between the doctor and patient. It is especially problematic if it breaks eye contact with the patient. People are less likely to share scary, sensitive, or embarrassing information if someone is looking at a computer and typing. As you look up tests, radiology reports, or consultant notes, let the patient in on what you are doing. Explain why you are searching in the record, and if it helps make an important point, show your findings to the patient. Offer to print out results, so they have something to carry with them.

Explain what you are looking for and what you find on the physical exam

Being a patient is scary. We all want reassurance that our fears are not true. When you find normal findings on exam, share those with the patient. Hearing “your heart sounds good, your pulses are strong” really helps patients. Explaining what we are doing when we examine is also helpful. Explain why you are feeling for lymph nodes in the neck, why we percuss the abdomen. Patients are often fascinated by getting a window into how we are thinking. I usually have medical students with me, which offers another avenue to explaining the how and why behind the exam. In asking and explaining to students, the patient is also taught why we do what we do.

Make sure that we cover what they are afraid of, not just what their symptom is

Patients come in not just to get symptom relief but to rest their mind from their fears of what it could be. I find it helpful to ask the patient what they think is the cause of the problem, or if they are worried about any specific diagnosis. With certain symptoms this is particularly important (for example, headaches, fatigue, or abdominal pain).

None of these suggestions are easy to do in busy, time-pressured clinic visits. I have found though that when patients feel cared about, listened to and can have their fears addressed they value our advice more, and less time is needed to negotiate the plan, as it has been developed together.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

Reference

Lown BA et al. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011 Sep;30(9):1772-8.

Almost 30 years ago a young woman made an appointment to see me. I had just started my internal medicine practice and almost all the patients who saw me were new to me. I assumed she was establishing care with me. Her first words to me were “Hello Dr. Paauw, I would like to interview you to see if you will be a good fit as my doctor.” We talked for the 40-minute appointment time. I asked her about her health, her life, and what she wanted out of both. We shared with each other that we both were parents of young children. When the appointment was over, she said she would really like for me to be her doctor. She told me that the main thing she appreciated about me was that I listened, and that her previous physician never sat down at her appointments and often had his hand on the door handle for much of the visit. Physicians and patients both agree that compassionate care is essential for good patient care, yet about half of patients and 60% of doctors believe it is lacking in our medical system.1

Remember the golden first minutes

I often start by asking the patient to give me an update on how they are doing. This lets me know what is important to them. I do not touch the computer until after this initial check-in.

Use the computer as a bond to strengthen your patient relationship

Many studies have shown patients find the computer gets between the doctor and patient. It is especially problematic if it breaks eye contact with the patient. People are less likely to share scary, sensitive, or embarrassing information if someone is looking at a computer and typing. As you look up tests, radiology reports, or consultant notes, let the patient in on what you are doing. Explain why you are searching in the record, and if it helps make an important point, show your findings to the patient. Offer to print out results, so they have something to carry with them.

Explain what you are looking for and what you find on the physical exam

Being a patient is scary. We all want reassurance that our fears are not true. When you find normal findings on exam, share those with the patient. Hearing “your heart sounds good, your pulses are strong” really helps patients. Explaining what we are doing when we examine is also helpful. Explain why you are feeling for lymph nodes in the neck, why we percuss the abdomen. Patients are often fascinated by getting a window into how we are thinking. I usually have medical students with me, which offers another avenue to explaining the how and why behind the exam. In asking and explaining to students, the patient is also taught why we do what we do.

Make sure that we cover what they are afraid of, not just what their symptom is

Patients come in not just to get symptom relief but to rest their mind from their fears of what it could be. I find it helpful to ask the patient what they think is the cause of the problem, or if they are worried about any specific diagnosis. With certain symptoms this is particularly important (for example, headaches, fatigue, or abdominal pain).

None of these suggestions are easy to do in busy, time-pressured clinic visits. I have found though that when patients feel cared about, listened to and can have their fears addressed they value our advice more, and less time is needed to negotiate the plan, as it has been developed together.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

Reference

Lown BA et al. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011 Sep;30(9):1772-8.

Almost 30 years ago a young woman made an appointment to see me. I had just started my internal medicine practice and almost all the patients who saw me were new to me. I assumed she was establishing care with me. Her first words to me were “Hello Dr. Paauw, I would like to interview you to see if you will be a good fit as my doctor.” We talked for the 40-minute appointment time. I asked her about her health, her life, and what she wanted out of both. We shared with each other that we both were parents of young children. When the appointment was over, she said she would really like for me to be her doctor. She told me that the main thing she appreciated about me was that I listened, and that her previous physician never sat down at her appointments and often had his hand on the door handle for much of the visit. Physicians and patients both agree that compassionate care is essential for good patient care, yet about half of patients and 60% of doctors believe it is lacking in our medical system.1

Remember the golden first minutes

I often start by asking the patient to give me an update on how they are doing. This lets me know what is important to them. I do not touch the computer until after this initial check-in.

Use the computer as a bond to strengthen your patient relationship

Many studies have shown patients find the computer gets between the doctor and patient. It is especially problematic if it breaks eye contact with the patient. People are less likely to share scary, sensitive, or embarrassing information if someone is looking at a computer and typing. As you look up tests, radiology reports, or consultant notes, let the patient in on what you are doing. Explain why you are searching in the record, and if it helps make an important point, show your findings to the patient. Offer to print out results, so they have something to carry with them.

Explain what you are looking for and what you find on the physical exam

Being a patient is scary. We all want reassurance that our fears are not true. When you find normal findings on exam, share those with the patient. Hearing “your heart sounds good, your pulses are strong” really helps patients. Explaining what we are doing when we examine is also helpful. Explain why you are feeling for lymph nodes in the neck, why we percuss the abdomen. Patients are often fascinated by getting a window into how we are thinking. I usually have medical students with me, which offers another avenue to explaining the how and why behind the exam. In asking and explaining to students, the patient is also taught why we do what we do.

Make sure that we cover what they are afraid of, not just what their symptom is

Patients come in not just to get symptom relief but to rest their mind from their fears of what it could be. I find it helpful to ask the patient what they think is the cause of the problem, or if they are worried about any specific diagnosis. With certain symptoms this is particularly important (for example, headaches, fatigue, or abdominal pain).

None of these suggestions are easy to do in busy, time-pressured clinic visits. I have found though that when patients feel cared about, listened to and can have their fears addressed they value our advice more, and less time is needed to negotiate the plan, as it has been developed together.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

Reference

Lown BA et al. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011 Sep;30(9):1772-8.

FDA approves first drug for steroid-refractory acute GVHD

The Food and Drug Administration has approved Jafaki (ruxolitinib) for treatment of steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) in adult and pediatric patients 12 years and older.

Ruxolitinib will be made available to appropriate patients immediately, according to a statement from Incyte, which markets the drug. The company noted that ruxolitinib is the first FDA-approved treatment for this indication.

The approval is based on data from the open-label, single-arm, multicenter REACH1 trial, which studied ruxolitinib in combination with corticosteroids. The 71 patients in the trial had grade 2-4 acute GVHD after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant; of these patients, 49 were refractory to steroids alone, 12 had received at least two prior therapies for GVHD, and 10 did not otherwise meet the FDA definition of steroid refractory.

The trial’s primary endpoints were day-28 overall response rate and response duration. Among the 49 patients with steroid only–refractory GVHD, the overall response rate was 100% for grade 2 GVHD, 40.7% for grade 3, and 44.4% for grade 4. Median response duration was 16 days. For all 49 of these patients, the overall response rate was 57%, and the complete response rate was 31%.

Among all 71 participants, the most frequently reported adverse reactions were infections (55%) and edema (51%); anemia (71%), thrombocytopenia (75%), and neutropenia (58%) were the most common laboratory abnormalities.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved Jafaki (ruxolitinib) for treatment of steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) in adult and pediatric patients 12 years and older.

Ruxolitinib will be made available to appropriate patients immediately, according to a statement from Incyte, which markets the drug. The company noted that ruxolitinib is the first FDA-approved treatment for this indication.

The approval is based on data from the open-label, single-arm, multicenter REACH1 trial, which studied ruxolitinib in combination with corticosteroids. The 71 patients in the trial had grade 2-4 acute GVHD after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant; of these patients, 49 were refractory to steroids alone, 12 had received at least two prior therapies for GVHD, and 10 did not otherwise meet the FDA definition of steroid refractory.

The trial’s primary endpoints were day-28 overall response rate and response duration. Among the 49 patients with steroid only–refractory GVHD, the overall response rate was 100% for grade 2 GVHD, 40.7% for grade 3, and 44.4% for grade 4. Median response duration was 16 days. For all 49 of these patients, the overall response rate was 57%, and the complete response rate was 31%.

Among all 71 participants, the most frequently reported adverse reactions were infections (55%) and edema (51%); anemia (71%), thrombocytopenia (75%), and neutropenia (58%) were the most common laboratory abnormalities.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved Jafaki (ruxolitinib) for treatment of steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) in adult and pediatric patients 12 years and older.

Ruxolitinib will be made available to appropriate patients immediately, according to a statement from Incyte, which markets the drug. The company noted that ruxolitinib is the first FDA-approved treatment for this indication.

The approval is based on data from the open-label, single-arm, multicenter REACH1 trial, which studied ruxolitinib in combination with corticosteroids. The 71 patients in the trial had grade 2-4 acute GVHD after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant; of these patients, 49 were refractory to steroids alone, 12 had received at least two prior therapies for GVHD, and 10 did not otherwise meet the FDA definition of steroid refractory.

The trial’s primary endpoints were day-28 overall response rate and response duration. Among the 49 patients with steroid only–refractory GVHD, the overall response rate was 100% for grade 2 GVHD, 40.7% for grade 3, and 44.4% for grade 4. Median response duration was 16 days. For all 49 of these patients, the overall response rate was 57%, and the complete response rate was 31%.

Among all 71 participants, the most frequently reported adverse reactions were infections (55%) and edema (51%); anemia (71%), thrombocytopenia (75%), and neutropenia (58%) were the most common laboratory abnormalities.

Literature review shows inconsistent measurement of financial toxicity

The current body of literature lacks validated survey instruments to effectively measure financial distress in cancer patients, according to a systematic review.

“This review systematizes the methods and items that previous studies used for measuring the subjective financial distress of cancer patients,” wrote Julian Witte of Bielefeld (Germany) University and colleagues. Their report is in Annals of Oncology.

In this systematic review, the investigators searched major databases for studies that included data on perceived financial burden experienced by patients with cancer. The team collected and classified all usable validated survey tools, which are necessary to obtain high-quality data for analysis.

“We analyzed all detected instruments, items domains, and questions with regard to their wording, scales, and the domains of financial distress covered,” the researchers wrote.

After applying the search criteria, the investigators identified 40 studies that fit the inclusion criteria. Among those included, 352 unique questions have been used to describe financial distress in cancer patients.

After analysis, the researchers identified six distinct subdomains that characterized patient views and responses to financial distress. In particular, these domains were the use of passive financial resources, support seeking, coping with one’s lifestyle, coping with care, psychosocial responses, and active financial spending.

“We found an inconsistent coverage and use of these domains that makes it difficult to compare and quantify the prevalence of financial distress,” they wrote.

One key limitation of the study was the observational design, which could limit the generalizability of the findings.

“There is a need to join efforts to develop a common understanding of the concept of financial toxicity and related subjective financial distress,” they concluded.

The study was funded by IPSEN Pharma GmbH. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Witte J et al. Ann Oncol. 2019 May 2. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz140.

The current body of literature lacks validated survey instruments to effectively measure financial distress in cancer patients, according to a systematic review.

“This review systematizes the methods and items that previous studies used for measuring the subjective financial distress of cancer patients,” wrote Julian Witte of Bielefeld (Germany) University and colleagues. Their report is in Annals of Oncology.

In this systematic review, the investigators searched major databases for studies that included data on perceived financial burden experienced by patients with cancer. The team collected and classified all usable validated survey tools, which are necessary to obtain high-quality data for analysis.

“We analyzed all detected instruments, items domains, and questions with regard to their wording, scales, and the domains of financial distress covered,” the researchers wrote.

After applying the search criteria, the investigators identified 40 studies that fit the inclusion criteria. Among those included, 352 unique questions have been used to describe financial distress in cancer patients.

After analysis, the researchers identified six distinct subdomains that characterized patient views and responses to financial distress. In particular, these domains were the use of passive financial resources, support seeking, coping with one’s lifestyle, coping with care, psychosocial responses, and active financial spending.

“We found an inconsistent coverage and use of these domains that makes it difficult to compare and quantify the prevalence of financial distress,” they wrote.

One key limitation of the study was the observational design, which could limit the generalizability of the findings.

“There is a need to join efforts to develop a common understanding of the concept of financial toxicity and related subjective financial distress,” they concluded.

The study was funded by IPSEN Pharma GmbH. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Witte J et al. Ann Oncol. 2019 May 2. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz140.

The current body of literature lacks validated survey instruments to effectively measure financial distress in cancer patients, according to a systematic review.

“This review systematizes the methods and items that previous studies used for measuring the subjective financial distress of cancer patients,” wrote Julian Witte of Bielefeld (Germany) University and colleagues. Their report is in Annals of Oncology.

In this systematic review, the investigators searched major databases for studies that included data on perceived financial burden experienced by patients with cancer. The team collected and classified all usable validated survey tools, which are necessary to obtain high-quality data for analysis.

“We analyzed all detected instruments, items domains, and questions with regard to their wording, scales, and the domains of financial distress covered,” the researchers wrote.

After applying the search criteria, the investigators identified 40 studies that fit the inclusion criteria. Among those included, 352 unique questions have been used to describe financial distress in cancer patients.

After analysis, the researchers identified six distinct subdomains that characterized patient views and responses to financial distress. In particular, these domains were the use of passive financial resources, support seeking, coping with one’s lifestyle, coping with care, psychosocial responses, and active financial spending.

“We found an inconsistent coverage and use of these domains that makes it difficult to compare and quantify the prevalence of financial distress,” they wrote.

One key limitation of the study was the observational design, which could limit the generalizability of the findings.

“There is a need to join efforts to develop a common understanding of the concept of financial toxicity and related subjective financial distress,” they concluded.

The study was funded by IPSEN Pharma GmbH. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Witte J et al. Ann Oncol. 2019 May 2. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz140.

FROM ANNALS OF ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Researchers found a lack of validated instruments to effectively measure the financial burden experienced by cancer patients in the current body of literature.

Major finding: After analysis, six distinct subdomains that characterized patient views and responses to financial distress were identified.

Study details: A systematic review that identified 40 studies related to financial distress in cancer patients.

Disclosures: The study was funded by IPSEN Pharma GmbH. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: Witte J et al. Ann Oncol. 2019 May 2. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz140.

Diet linked to lower risk of death from breast cancer

A balanced, low-fat diet was associated with a lower risk of death from breast cancer in a large cohort of postmenopausal women who had no previous history of breast cancer.

Researchers studied nearly 49,000 postmenopausal women and found a 21% lower risk of death from breast cancer among women who followed the balanced, low-fat diet, compared with women who followed their normal diet.

This research is scheduled to be presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Rowan Chlebowski, MD, PhD, of the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor–UCLA Medical Center in Torrance, Calif., discussed the research during a press briefing in advance of the meeting.

About the study

The research is part of the Woman’s Health Initiative (NCT00000611), which is focused on investigating methods for preventing heart disease, breast and colorectal cancer, and osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women.

This trial enrolled 48,835 postmenopausal women, ages 50-79 years, with no history of breast cancer and normal mammograms at enrollment. From 1993 to 1998, the women were randomized to the study diet (n = 19,541) or their normal diet (n = 29,294).

With the normal diet, fat accounted for 32% or more of subjects’ daily calories. With the study diet, the goal was to reduce fat consumption to 20% or less of caloric intake. The study diet also required at least one daily serving of vegetables, fruits, and grains.

Dr. Chlebowski said the study diet is similar to DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension), but is slightly more focused on lowering fat intake.

Diet adherence

Subjects followed the study diet for a median of 8.5 years, and the median cumulative follow-up was 19.6 years.

Dr. Chlebowski noted that most women on the study diet were not able to reduce their daily fat consumption to the 20% goal. They did reduce fat consumption to 24.5% overall, which increased to 29% at the end of the intervention.

In the study-diet group, there was an average weight loss of 3%, significantly different from that of the normal-diet group (P less than .001).

Dr. Chlebowski said the weight loss indicates that subjects did adhere to the study diet, at least in part, as there was no change in physical activity among study participants. Furthermore, the researchers have evidence after 1 year that suggests subjects were incorporating more fruits and vegetables into their diets.

Breast cancer and death

At a median follow-up of 19.6 years, there were 3,374 cases of breast cancer, 1,011 deaths, and 383 deaths attributed to breast cancer.

The risk of death from breast cancer was significantly lower in the study-diet group than in the normal-diet group. The hazard ratio was 0.79 (95% confidence interval, 0.64-0.97; P = .025).

The risk of death (from any cause) after breast cancer was significantly lower in the study diet group as well, with a hazard ratio of 0.85 (95% confidence interval, 0.74-0.96; P = .01).

“Adoption of a low-fat dietary pattern reduces the risk of death from breast cancer in postmenopausal women,” Dr. Chlebowski said. “To our review, this is the only study providing randomized clinical trial evidence that an intervention can reduce a woman’s risk of dying from breast cancer.”

Dr. Chlebowski noted that the researchers have blood samples from all subjects enrolled in this study. The researchers plan to analyze those samples to further explore how the study diet affected the women and determine which components of the diet account for which effects.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. The researchers disclosed relationships with Novartis, Pfizer, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Immunomedics, Metastat, Bayer, and Genentech/Roche.

SOURCE: Chlebowski R. et al. ASCO 2019. Abstract 520.

A balanced, low-fat diet was associated with a lower risk of death from breast cancer in a large cohort of postmenopausal women who had no previous history of breast cancer.

Researchers studied nearly 49,000 postmenopausal women and found a 21% lower risk of death from breast cancer among women who followed the balanced, low-fat diet, compared with women who followed their normal diet.

This research is scheduled to be presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Rowan Chlebowski, MD, PhD, of the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor–UCLA Medical Center in Torrance, Calif., discussed the research during a press briefing in advance of the meeting.

About the study

The research is part of the Woman’s Health Initiative (NCT00000611), which is focused on investigating methods for preventing heart disease, breast and colorectal cancer, and osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women.

This trial enrolled 48,835 postmenopausal women, ages 50-79 years, with no history of breast cancer and normal mammograms at enrollment. From 1993 to 1998, the women were randomized to the study diet (n = 19,541) or their normal diet (n = 29,294).

With the normal diet, fat accounted for 32% or more of subjects’ daily calories. With the study diet, the goal was to reduce fat consumption to 20% or less of caloric intake. The study diet also required at least one daily serving of vegetables, fruits, and grains.

Dr. Chlebowski said the study diet is similar to DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension), but is slightly more focused on lowering fat intake.

Diet adherence

Subjects followed the study diet for a median of 8.5 years, and the median cumulative follow-up was 19.6 years.

Dr. Chlebowski noted that most women on the study diet were not able to reduce their daily fat consumption to the 20% goal. They did reduce fat consumption to 24.5% overall, which increased to 29% at the end of the intervention.

In the study-diet group, there was an average weight loss of 3%, significantly different from that of the normal-diet group (P less than .001).

Dr. Chlebowski said the weight loss indicates that subjects did adhere to the study diet, at least in part, as there was no change in physical activity among study participants. Furthermore, the researchers have evidence after 1 year that suggests subjects were incorporating more fruits and vegetables into their diets.

Breast cancer and death

At a median follow-up of 19.6 years, there were 3,374 cases of breast cancer, 1,011 deaths, and 383 deaths attributed to breast cancer.

The risk of death from breast cancer was significantly lower in the study-diet group than in the normal-diet group. The hazard ratio was 0.79 (95% confidence interval, 0.64-0.97; P = .025).

The risk of death (from any cause) after breast cancer was significantly lower in the study diet group as well, with a hazard ratio of 0.85 (95% confidence interval, 0.74-0.96; P = .01).

“Adoption of a low-fat dietary pattern reduces the risk of death from breast cancer in postmenopausal women,” Dr. Chlebowski said. “To our review, this is the only study providing randomized clinical trial evidence that an intervention can reduce a woman’s risk of dying from breast cancer.”

Dr. Chlebowski noted that the researchers have blood samples from all subjects enrolled in this study. The researchers plan to analyze those samples to further explore how the study diet affected the women and determine which components of the diet account for which effects.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. The researchers disclosed relationships with Novartis, Pfizer, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Immunomedics, Metastat, Bayer, and Genentech/Roche.

SOURCE: Chlebowski R. et al. ASCO 2019. Abstract 520.

A balanced, low-fat diet was associated with a lower risk of death from breast cancer in a large cohort of postmenopausal women who had no previous history of breast cancer.

Researchers studied nearly 49,000 postmenopausal women and found a 21% lower risk of death from breast cancer among women who followed the balanced, low-fat diet, compared with women who followed their normal diet.

This research is scheduled to be presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Rowan Chlebowski, MD, PhD, of the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor–UCLA Medical Center in Torrance, Calif., discussed the research during a press briefing in advance of the meeting.

About the study

The research is part of the Woman’s Health Initiative (NCT00000611), which is focused on investigating methods for preventing heart disease, breast and colorectal cancer, and osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women.

This trial enrolled 48,835 postmenopausal women, ages 50-79 years, with no history of breast cancer and normal mammograms at enrollment. From 1993 to 1998, the women were randomized to the study diet (n = 19,541) or their normal diet (n = 29,294).

With the normal diet, fat accounted for 32% or more of subjects’ daily calories. With the study diet, the goal was to reduce fat consumption to 20% or less of caloric intake. The study diet also required at least one daily serving of vegetables, fruits, and grains.

Dr. Chlebowski said the study diet is similar to DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension), but is slightly more focused on lowering fat intake.

Diet adherence

Subjects followed the study diet for a median of 8.5 years, and the median cumulative follow-up was 19.6 years.