User login

Screen Elderly Cancer Patients for Malnutrition

MANCHESTER, ENGLAND – Elderly cancer patients need to be screened for malnutrition, and individualized, multimodal interventions should be used in those found to require nourishment, according to the chair of a task force on nutrition in geriatric oncology.

"Nutrition is important in [elderly] cancer patients, yet still many oncologists neglect this aspect [of treatment]," the chair, Dr. Federico Bozzetti, told attendees during a special session on nutritional issues at the annual meeting of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology.

Standing in the way is a paucity of randomized clinical trials demonstrating the efficacy of nutritional support in cancer patients, and notably in those who are elderly, acknowledged Dr. Bozzetti, a surgical oncologist from the University of Milan.

Evidence links malnutrition to worse clinical outcomes, increased hospital stays, a longer duration of convalescence, reduced quality of life, increased morbidity, and increased mortality in the general patient population, however (Clin. Nutr. 2008;27:340-9; Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007;62:687-94; Br. J. Nutr. 2004; 92:105-11; Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1997;66:1232), Dr. Bozzetti noted.

"Old people, regardless of whether they are healthy or ill, need to be nourished," he said.

The International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) Task Force on Nutrition has as its initial aim development of a consensus-based report to provide practical guidance on nutritional support. The report is due for publication early next year.

Nutritional support currently falls "somewhere between medicine and supportive care," Dr. Bozzetti suggested, adding that beneficial effects are more likely to be seen in patients who are severely malnourished than in those who are mildly malnourished.

How Can You Screen For Malnutrition?

"Malnutrition is a subacute or chronic state of nutrition," said Dr. Zeno Stanga of University Hospital Bern (Switzerland), citing the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism definition. It is a state "in which a combination of varying degrees of over- or undernutrition and inflammatory activity have led to a change in body composition and diminished function," he added.

Data suggest that up to 56% of geriatric patients are malnourished (Clin. Nutr. 2006;25:563-72), he noted, with around 20%-80% of cancer patients at severe nutritional risk.

"All cancer patients must receive a nutritional screening at presentation," Dr. Stanga proposed. This should be performed in order to plan adequate nutritional therapy, with interventions tailored to the individual’s needs and revised often.

Nutritional status can be influenced by a variety of factors, with food intake, body mass index, pathologic weight loss, and the severity of disease being the four key ones to assess. Measuring a single parameter is not enough, he said, and there are several screening tools that may help to identify if a patient is at risk of malnutrition and requires nutritional support.

Although there is no consensus on which tool is best for nutritional screening, the options include the Malnutritional Universal Screening Tool (MUST), the Nutritional Risk Screening (NRS) 2002, and the Mini Nutritional Assessment Short Form (MNA-SF).

What is important, Dr. Stanga maintained, is that a screening protocol be implemented at institutions using a validated tool, and that patients be given appropriate action plans as a result.

What Type of Nutritional Support?

Adjuvant nutrition can play an important role in the management of cancer patients, said Dr. Paula Ravasco of the University of Lisbon.

"The evidence today argues for the integration of both early and individualized nutritional counseling as adjuvant therapy," said Dr. Ravasco, a member of the SIOG Task Force on Nutrition.

Dr. Ravasco has previously reported the findings of one of the few randomized controlled trials in this area (Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012 Nov. 7 [doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.018838]), showing that individualized nutritional counseling with regular foods is of benefit in patients with colorectal cancer treated with radiotherapy. Patients who underwent nutritional counseling had improved nutritional intake and status, reduced toxicity, and improved quality of life compared with patients who received no counseling.

The evidence-based dietary intervention used at her institution involves counseling and using prescribed therapeutic diets that are modified to fulfill the specific requirement of patients. "We perhaps have to maintain, as far as possible, the usual dietary pattern that the patient usually has," Dr. Ravasco said.

On the topic of tailoring nutritional support, Dr. Bozzetti noted that patients with a functioning gastrointestinal (GI) tract might respond to counseling and the use of oral dietary supplements or stimulants. "These have the potential to be used in a very large number of patients," he said.

Nasogastric or nasojejunal tube feeding might be the best option for short-term nutritional support if the upper GI tract is not working, he suggested. Percutaneous gastrostomy may be needed for long-term support. Parenteral nutrition may be used on its own in those with a nonfunctioning GI tract, or as a practical way to supplement inadequate oral nutrition, Dr. Bozzetti said.

The session on nutritional issues in elderly cancer patients was partially supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Abbott Nutrition. Dr. Bozzetti, Dr. Ravasco, and Dr. Stanga did not make any disclosures about potential conflicts of interest.

MANCHESTER, ENGLAND – Elderly cancer patients need to be screened for malnutrition, and individualized, multimodal interventions should be used in those found to require nourishment, according to the chair of a task force on nutrition in geriatric oncology.

"Nutrition is important in [elderly] cancer patients, yet still many oncologists neglect this aspect [of treatment]," the chair, Dr. Federico Bozzetti, told attendees during a special session on nutritional issues at the annual meeting of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology.

Standing in the way is a paucity of randomized clinical trials demonstrating the efficacy of nutritional support in cancer patients, and notably in those who are elderly, acknowledged Dr. Bozzetti, a surgical oncologist from the University of Milan.

Evidence links malnutrition to worse clinical outcomes, increased hospital stays, a longer duration of convalescence, reduced quality of life, increased morbidity, and increased mortality in the general patient population, however (Clin. Nutr. 2008;27:340-9; Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007;62:687-94; Br. J. Nutr. 2004; 92:105-11; Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1997;66:1232), Dr. Bozzetti noted.

"Old people, regardless of whether they are healthy or ill, need to be nourished," he said.

The International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) Task Force on Nutrition has as its initial aim development of a consensus-based report to provide practical guidance on nutritional support. The report is due for publication early next year.

Nutritional support currently falls "somewhere between medicine and supportive care," Dr. Bozzetti suggested, adding that beneficial effects are more likely to be seen in patients who are severely malnourished than in those who are mildly malnourished.

How Can You Screen For Malnutrition?

"Malnutrition is a subacute or chronic state of nutrition," said Dr. Zeno Stanga of University Hospital Bern (Switzerland), citing the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism definition. It is a state "in which a combination of varying degrees of over- or undernutrition and inflammatory activity have led to a change in body composition and diminished function," he added.

Data suggest that up to 56% of geriatric patients are malnourished (Clin. Nutr. 2006;25:563-72), he noted, with around 20%-80% of cancer patients at severe nutritional risk.

"All cancer patients must receive a nutritional screening at presentation," Dr. Stanga proposed. This should be performed in order to plan adequate nutritional therapy, with interventions tailored to the individual’s needs and revised often.

Nutritional status can be influenced by a variety of factors, with food intake, body mass index, pathologic weight loss, and the severity of disease being the four key ones to assess. Measuring a single parameter is not enough, he said, and there are several screening tools that may help to identify if a patient is at risk of malnutrition and requires nutritional support.

Although there is no consensus on which tool is best for nutritional screening, the options include the Malnutritional Universal Screening Tool (MUST), the Nutritional Risk Screening (NRS) 2002, and the Mini Nutritional Assessment Short Form (MNA-SF).

What is important, Dr. Stanga maintained, is that a screening protocol be implemented at institutions using a validated tool, and that patients be given appropriate action plans as a result.

What Type of Nutritional Support?

Adjuvant nutrition can play an important role in the management of cancer patients, said Dr. Paula Ravasco of the University of Lisbon.

"The evidence today argues for the integration of both early and individualized nutritional counseling as adjuvant therapy," said Dr. Ravasco, a member of the SIOG Task Force on Nutrition.

Dr. Ravasco has previously reported the findings of one of the few randomized controlled trials in this area (Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012 Nov. 7 [doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.018838]), showing that individualized nutritional counseling with regular foods is of benefit in patients with colorectal cancer treated with radiotherapy. Patients who underwent nutritional counseling had improved nutritional intake and status, reduced toxicity, and improved quality of life compared with patients who received no counseling.

The evidence-based dietary intervention used at her institution involves counseling and using prescribed therapeutic diets that are modified to fulfill the specific requirement of patients. "We perhaps have to maintain, as far as possible, the usual dietary pattern that the patient usually has," Dr. Ravasco said.

On the topic of tailoring nutritional support, Dr. Bozzetti noted that patients with a functioning gastrointestinal (GI) tract might respond to counseling and the use of oral dietary supplements or stimulants. "These have the potential to be used in a very large number of patients," he said.

Nasogastric or nasojejunal tube feeding might be the best option for short-term nutritional support if the upper GI tract is not working, he suggested. Percutaneous gastrostomy may be needed for long-term support. Parenteral nutrition may be used on its own in those with a nonfunctioning GI tract, or as a practical way to supplement inadequate oral nutrition, Dr. Bozzetti said.

The session on nutritional issues in elderly cancer patients was partially supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Abbott Nutrition. Dr. Bozzetti, Dr. Ravasco, and Dr. Stanga did not make any disclosures about potential conflicts of interest.

MANCHESTER, ENGLAND – Elderly cancer patients need to be screened for malnutrition, and individualized, multimodal interventions should be used in those found to require nourishment, according to the chair of a task force on nutrition in geriatric oncology.

"Nutrition is important in [elderly] cancer patients, yet still many oncologists neglect this aspect [of treatment]," the chair, Dr. Federico Bozzetti, told attendees during a special session on nutritional issues at the annual meeting of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology.

Standing in the way is a paucity of randomized clinical trials demonstrating the efficacy of nutritional support in cancer patients, and notably in those who are elderly, acknowledged Dr. Bozzetti, a surgical oncologist from the University of Milan.

Evidence links malnutrition to worse clinical outcomes, increased hospital stays, a longer duration of convalescence, reduced quality of life, increased morbidity, and increased mortality in the general patient population, however (Clin. Nutr. 2008;27:340-9; Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007;62:687-94; Br. J. Nutr. 2004; 92:105-11; Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1997;66:1232), Dr. Bozzetti noted.

"Old people, regardless of whether they are healthy or ill, need to be nourished," he said.

The International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) Task Force on Nutrition has as its initial aim development of a consensus-based report to provide practical guidance on nutritional support. The report is due for publication early next year.

Nutritional support currently falls "somewhere between medicine and supportive care," Dr. Bozzetti suggested, adding that beneficial effects are more likely to be seen in patients who are severely malnourished than in those who are mildly malnourished.

How Can You Screen For Malnutrition?

"Malnutrition is a subacute or chronic state of nutrition," said Dr. Zeno Stanga of University Hospital Bern (Switzerland), citing the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism definition. It is a state "in which a combination of varying degrees of over- or undernutrition and inflammatory activity have led to a change in body composition and diminished function," he added.

Data suggest that up to 56% of geriatric patients are malnourished (Clin. Nutr. 2006;25:563-72), he noted, with around 20%-80% of cancer patients at severe nutritional risk.

"All cancer patients must receive a nutritional screening at presentation," Dr. Stanga proposed. This should be performed in order to plan adequate nutritional therapy, with interventions tailored to the individual’s needs and revised often.

Nutritional status can be influenced by a variety of factors, with food intake, body mass index, pathologic weight loss, and the severity of disease being the four key ones to assess. Measuring a single parameter is not enough, he said, and there are several screening tools that may help to identify if a patient is at risk of malnutrition and requires nutritional support.

Although there is no consensus on which tool is best for nutritional screening, the options include the Malnutritional Universal Screening Tool (MUST), the Nutritional Risk Screening (NRS) 2002, and the Mini Nutritional Assessment Short Form (MNA-SF).

What is important, Dr. Stanga maintained, is that a screening protocol be implemented at institutions using a validated tool, and that patients be given appropriate action plans as a result.

What Type of Nutritional Support?

Adjuvant nutrition can play an important role in the management of cancer patients, said Dr. Paula Ravasco of the University of Lisbon.

"The evidence today argues for the integration of both early and individualized nutritional counseling as adjuvant therapy," said Dr. Ravasco, a member of the SIOG Task Force on Nutrition.

Dr. Ravasco has previously reported the findings of one of the few randomized controlled trials in this area (Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012 Nov. 7 [doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.018838]), showing that individualized nutritional counseling with regular foods is of benefit in patients with colorectal cancer treated with radiotherapy. Patients who underwent nutritional counseling had improved nutritional intake and status, reduced toxicity, and improved quality of life compared with patients who received no counseling.

The evidence-based dietary intervention used at her institution involves counseling and using prescribed therapeutic diets that are modified to fulfill the specific requirement of patients. "We perhaps have to maintain, as far as possible, the usual dietary pattern that the patient usually has," Dr. Ravasco said.

On the topic of tailoring nutritional support, Dr. Bozzetti noted that patients with a functioning gastrointestinal (GI) tract might respond to counseling and the use of oral dietary supplements or stimulants. "These have the potential to be used in a very large number of patients," he said.

Nasogastric or nasojejunal tube feeding might be the best option for short-term nutritional support if the upper GI tract is not working, he suggested. Percutaneous gastrostomy may be needed for long-term support. Parenteral nutrition may be used on its own in those with a nonfunctioning GI tract, or as a practical way to supplement inadequate oral nutrition, Dr. Bozzetti said.

The session on nutritional issues in elderly cancer patients was partially supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Abbott Nutrition. Dr. Bozzetti, Dr. Ravasco, and Dr. Stanga did not make any disclosures about potential conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY OF GERIATRIC ONCOLOGY

Geriatric Assessment Predicts Falls, Functioning in Elderly Cancer Patients

MANCHESTER, ENGLAND – Undertaking a few simple baseline assessments in elderly patients may help predict their risk of worsening physical function and falls occurring 2-3 months into cancer therapy, a prospective, multicenter study has shown.

Nearly a fifth (17.2%) of 811 patients in the analysis experienced a worsening in Activities of Daily Living (ADL) during treatment. Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) scores decreased in 38.9%, and 17.5% had at least one fall.

"Parameters from the CGA [Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment] before treatment in older cancer patients can identify at-risk patients for decline in functionality and development of falls," Cindy Kenis, R.N., of the University Hospitals Leuven (Belgium), annual meeting of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG).

This emphasizes the need to "make sure that we foresee the necessary support for older cancer patients based on the results of a geriatric screening and evaluation for the different geriatric problems detected," Ms. Kenis added later in an interview.

A total of 937 patients aged 70 years or older were included in the study. The median age was 76 years, and 63.5% of the study population were female. The most common malignancy was breast cancer (40.4%); other malignancies included colon cancer (20.6%), hematologic malignancies (15.9%), prostate cancer (9%), lung cancer (7.8%), and ovarian cancer (6.3%).

Several geriatric assessment tools were used at baseline, including the G8 and the Flemish Triage Risk Screening Tool (TRST), followed by a Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA).

Follow-up assessments after 2-3 months’ cancer treatment were ADL, IADL, the number of falls, and chemotherapy toxicity. A decline in functionality occurred if there was a worsening of ADL by 2 or more points and IADL by 1 or more points, or if the patient had a fall.

Worsening ADL could be predicted by baseline scores in three measures: IADL, a mininutritional assessment (MNA), and the Flemish TRST (all P less than .05).

Patients classified as "dependent" on IADL at baseline (a score less than 8 for women and less than 5 for men) were almost twice as likely to have worsening ADL at any time point during follow-up as were those not seen as dependent on IADL at baseline (odds ratio, 0.54).

Patients at risk for malnutrition or malnourishment (a score less than 24 on MNA) also had about twice the risk of decline in ADL at the time point of follow-up as did those who had higher MNA scores (OR, 0.51).

Furthermore, patients classified as having a geriatric risk profile (a Flemish TRST score of 1 or higher) also had about twice the risk of ADL decline at follow-up as did those not having a geriatric risk profile (OR, 0.48).

Worsening IADL was predicted by baseline ECOG performance status (PS), Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS)–15 scores, and having chemotherapy (all P less than .05).

Patients with a PS of 0 or 1 at baseline were twice as likely to experience a decline in IADL as were those with worse PS (OR, 2.00). "This sounds somewhat contradictory," Ms. Kenis acknowledged, "but [it] can be explained by the fact that patients who already scored 2 or more on ECOG baseline, couldn’t get much worse," she explained.

Patients with a geriatric risk profile in need of further in-depth CGA (a Flemish TRST score of 1 or greater) had about twice the risk of IADL decline than as did those without such a profile (OR, 0.52).

Patients at risk for depression (a GDS-15 score less than 5) had about a third more risk of a decline in IADL as did those not at risk for depression (OR, 0.58).

Patients who had received any type of chemotherapy were also more likely to experience a decline in IADL (OR, 0.62).

Prior falls, baseline ADL, G8 assessment, living situation, and the disease setting (new diagnosis or cancer progression) were predictive of a future fall (all P less than .05):

• Patients who had already experienced a fall in the year before study inclusion were almost four times more likely to have another fall during follow-up than those who had not had a prior fall the year before (OR, .62).

• Patients classified as dependent on ADL at baseline (Belgian Katz scale score greater than 6) had about three times more risk of new falls. (OR, 0.42).

• Patients in need of further in-depth CGA (G8 score up to 14) had about four times more risk of new falls (OR, 0.38).

• Living alone was also predictive, almost doubling the risk of a fall (OR, 0.63).

• Patients who were included in the study at disease progression were 1.5 times more likely to experience a new fall than were people whose disease had just been diagnosed (OR, 0.58). "This can be explained by the fact that [these] patients were often in a less-good condition than patients [with a] new diagnosis," Ms. Kenis said.

"It is not only the goal to detect problems in a two-step approach (geriatric screening and, if necessary, a full CGA), but [also] to reach the three-step approach (geriatric screening and, if necessary, a full CGA, followed by concrete geriatric advice and interventions)," Ms Kenis said in an interview.

She added: "One of the main goals for the future is to see what the impact is of the implementation of geriatric advice and interventions on functionality and falls in older cancer patients."

The study was supported by Vlaamse Liga tegen Kanker. Ms. Kenis said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

MANCHESTER, ENGLAND – Undertaking a few simple baseline assessments in elderly patients may help predict their risk of worsening physical function and falls occurring 2-3 months into cancer therapy, a prospective, multicenter study has shown.

Nearly a fifth (17.2%) of 811 patients in the analysis experienced a worsening in Activities of Daily Living (ADL) during treatment. Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) scores decreased in 38.9%, and 17.5% had at least one fall.

"Parameters from the CGA [Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment] before treatment in older cancer patients can identify at-risk patients for decline in functionality and development of falls," Cindy Kenis, R.N., of the University Hospitals Leuven (Belgium), annual meeting of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG).

This emphasizes the need to "make sure that we foresee the necessary support for older cancer patients based on the results of a geriatric screening and evaluation for the different geriatric problems detected," Ms. Kenis added later in an interview.

A total of 937 patients aged 70 years or older were included in the study. The median age was 76 years, and 63.5% of the study population were female. The most common malignancy was breast cancer (40.4%); other malignancies included colon cancer (20.6%), hematologic malignancies (15.9%), prostate cancer (9%), lung cancer (7.8%), and ovarian cancer (6.3%).

Several geriatric assessment tools were used at baseline, including the G8 and the Flemish Triage Risk Screening Tool (TRST), followed by a Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA).

Follow-up assessments after 2-3 months’ cancer treatment were ADL, IADL, the number of falls, and chemotherapy toxicity. A decline in functionality occurred if there was a worsening of ADL by 2 or more points and IADL by 1 or more points, or if the patient had a fall.

Worsening ADL could be predicted by baseline scores in three measures: IADL, a mininutritional assessment (MNA), and the Flemish TRST (all P less than .05).

Patients classified as "dependent" on IADL at baseline (a score less than 8 for women and less than 5 for men) were almost twice as likely to have worsening ADL at any time point during follow-up as were those not seen as dependent on IADL at baseline (odds ratio, 0.54).

Patients at risk for malnutrition or malnourishment (a score less than 24 on MNA) also had about twice the risk of decline in ADL at the time point of follow-up as did those who had higher MNA scores (OR, 0.51).

Furthermore, patients classified as having a geriatric risk profile (a Flemish TRST score of 1 or higher) also had about twice the risk of ADL decline at follow-up as did those not having a geriatric risk profile (OR, 0.48).

Worsening IADL was predicted by baseline ECOG performance status (PS), Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS)–15 scores, and having chemotherapy (all P less than .05).

Patients with a PS of 0 or 1 at baseline were twice as likely to experience a decline in IADL as were those with worse PS (OR, 2.00). "This sounds somewhat contradictory," Ms. Kenis acknowledged, "but [it] can be explained by the fact that patients who already scored 2 or more on ECOG baseline, couldn’t get much worse," she explained.

Patients with a geriatric risk profile in need of further in-depth CGA (a Flemish TRST score of 1 or greater) had about twice the risk of IADL decline than as did those without such a profile (OR, 0.52).

Patients at risk for depression (a GDS-15 score less than 5) had about a third more risk of a decline in IADL as did those not at risk for depression (OR, 0.58).

Patients who had received any type of chemotherapy were also more likely to experience a decline in IADL (OR, 0.62).

Prior falls, baseline ADL, G8 assessment, living situation, and the disease setting (new diagnosis or cancer progression) were predictive of a future fall (all P less than .05):

• Patients who had already experienced a fall in the year before study inclusion were almost four times more likely to have another fall during follow-up than those who had not had a prior fall the year before (OR, .62).

• Patients classified as dependent on ADL at baseline (Belgian Katz scale score greater than 6) had about three times more risk of new falls. (OR, 0.42).

• Patients in need of further in-depth CGA (G8 score up to 14) had about four times more risk of new falls (OR, 0.38).

• Living alone was also predictive, almost doubling the risk of a fall (OR, 0.63).

• Patients who were included in the study at disease progression were 1.5 times more likely to experience a new fall than were people whose disease had just been diagnosed (OR, 0.58). "This can be explained by the fact that [these] patients were often in a less-good condition than patients [with a] new diagnosis," Ms. Kenis said.

"It is not only the goal to detect problems in a two-step approach (geriatric screening and, if necessary, a full CGA), but [also] to reach the three-step approach (geriatric screening and, if necessary, a full CGA, followed by concrete geriatric advice and interventions)," Ms Kenis said in an interview.

She added: "One of the main goals for the future is to see what the impact is of the implementation of geriatric advice and interventions on functionality and falls in older cancer patients."

The study was supported by Vlaamse Liga tegen Kanker. Ms. Kenis said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

MANCHESTER, ENGLAND – Undertaking a few simple baseline assessments in elderly patients may help predict their risk of worsening physical function and falls occurring 2-3 months into cancer therapy, a prospective, multicenter study has shown.

Nearly a fifth (17.2%) of 811 patients in the analysis experienced a worsening in Activities of Daily Living (ADL) during treatment. Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) scores decreased in 38.9%, and 17.5% had at least one fall.

"Parameters from the CGA [Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment] before treatment in older cancer patients can identify at-risk patients for decline in functionality and development of falls," Cindy Kenis, R.N., of the University Hospitals Leuven (Belgium), annual meeting of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG).

This emphasizes the need to "make sure that we foresee the necessary support for older cancer patients based on the results of a geriatric screening and evaluation for the different geriatric problems detected," Ms. Kenis added later in an interview.

A total of 937 patients aged 70 years or older were included in the study. The median age was 76 years, and 63.5% of the study population were female. The most common malignancy was breast cancer (40.4%); other malignancies included colon cancer (20.6%), hematologic malignancies (15.9%), prostate cancer (9%), lung cancer (7.8%), and ovarian cancer (6.3%).

Several geriatric assessment tools were used at baseline, including the G8 and the Flemish Triage Risk Screening Tool (TRST), followed by a Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA).

Follow-up assessments after 2-3 months’ cancer treatment were ADL, IADL, the number of falls, and chemotherapy toxicity. A decline in functionality occurred if there was a worsening of ADL by 2 or more points and IADL by 1 or more points, or if the patient had a fall.

Worsening ADL could be predicted by baseline scores in three measures: IADL, a mininutritional assessment (MNA), and the Flemish TRST (all P less than .05).

Patients classified as "dependent" on IADL at baseline (a score less than 8 for women and less than 5 for men) were almost twice as likely to have worsening ADL at any time point during follow-up as were those not seen as dependent on IADL at baseline (odds ratio, 0.54).

Patients at risk for malnutrition or malnourishment (a score less than 24 on MNA) also had about twice the risk of decline in ADL at the time point of follow-up as did those who had higher MNA scores (OR, 0.51).

Furthermore, patients classified as having a geriatric risk profile (a Flemish TRST score of 1 or higher) also had about twice the risk of ADL decline at follow-up as did those not having a geriatric risk profile (OR, 0.48).

Worsening IADL was predicted by baseline ECOG performance status (PS), Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS)–15 scores, and having chemotherapy (all P less than .05).

Patients with a PS of 0 or 1 at baseline were twice as likely to experience a decline in IADL as were those with worse PS (OR, 2.00). "This sounds somewhat contradictory," Ms. Kenis acknowledged, "but [it] can be explained by the fact that patients who already scored 2 or more on ECOG baseline, couldn’t get much worse," she explained.

Patients with a geriatric risk profile in need of further in-depth CGA (a Flemish TRST score of 1 or greater) had about twice the risk of IADL decline than as did those without such a profile (OR, 0.52).

Patients at risk for depression (a GDS-15 score less than 5) had about a third more risk of a decline in IADL as did those not at risk for depression (OR, 0.58).

Patients who had received any type of chemotherapy were also more likely to experience a decline in IADL (OR, 0.62).

Prior falls, baseline ADL, G8 assessment, living situation, and the disease setting (new diagnosis or cancer progression) were predictive of a future fall (all P less than .05):

• Patients who had already experienced a fall in the year before study inclusion were almost four times more likely to have another fall during follow-up than those who had not had a prior fall the year before (OR, .62).

• Patients classified as dependent on ADL at baseline (Belgian Katz scale score greater than 6) had about three times more risk of new falls. (OR, 0.42).

• Patients in need of further in-depth CGA (G8 score up to 14) had about four times more risk of new falls (OR, 0.38).

• Living alone was also predictive, almost doubling the risk of a fall (OR, 0.63).

• Patients who were included in the study at disease progression were 1.5 times more likely to experience a new fall than were people whose disease had just been diagnosed (OR, 0.58). "This can be explained by the fact that [these] patients were often in a less-good condition than patients [with a] new diagnosis," Ms. Kenis said.

"It is not only the goal to detect problems in a two-step approach (geriatric screening and, if necessary, a full CGA), but [also] to reach the three-step approach (geriatric screening and, if necessary, a full CGA, followed by concrete geriatric advice and interventions)," Ms Kenis said in an interview.

She added: "One of the main goals for the future is to see what the impact is of the implementation of geriatric advice and interventions on functionality and falls in older cancer patients."

The study was supported by Vlaamse Liga tegen Kanker. Ms. Kenis said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY OF GERIATRIC ONCOLOGY

Major Finding: ADL worsened in 17.2% of elderly cancer patients, and IADL in 38.9%, and 17.5% experienced at least one fall.

Data Source: Data are from a prospective, multicenter study of 811 elderly patients before and 2-3 months after cancer treatment.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Vlaamse Liga tegen Kanker. Ms. Kenis said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

Highlights from ASCO

We caught up with Debra L Barton, PhD, RN at the eighth annual Chicago Supportive Oncology Conference. and asked her what she believed were the highlights from the 2012 American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting in the area of patient and survivor care research. Dr Barton is involved in research at the Mayo Clinic centering on symptom management in cancer survivors. See the November/December 2012 issue of The Journal of Supportive Oncology for additional ASCO highlights.

We caught up with Debra L Barton, PhD, RN at the eighth annual Chicago Supportive Oncology Conference. and asked her what she believed were the highlights from the 2012 American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting in the area of patient and survivor care research. Dr Barton is involved in research at the Mayo Clinic centering on symptom management in cancer survivors. See the November/December 2012 issue of The Journal of Supportive Oncology for additional ASCO highlights.

We caught up with Debra L Barton, PhD, RN at the eighth annual Chicago Supportive Oncology Conference. and asked her what she believed were the highlights from the 2012 American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting in the area of patient and survivor care research. Dr Barton is involved in research at the Mayo Clinic centering on symptom management in cancer survivors. See the November/December 2012 issue of The Journal of Supportive Oncology for additional ASCO highlights.

Tips to Facing Difficult Patient Conversations

At the eighth annual Chicago Supportive Oncology Conference, we spoke with Dr. Anthony Back about talking to patients about the cost of care and whether the costs are worth it. Dr. Back stressed that it is crucial for cost to be a part of the decision making process, and not a separate stand-alone issue. He added that it is the physician who should take the lead in initiating this discussion.

Dr. Back is a professor in the Department of Medicine, Division of Oncology at the University of Washington's School of Medicine and a medical oncologist with the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance in Seattle, Washington.

At the eighth annual Chicago Supportive Oncology Conference, we spoke with Dr. Anthony Back about talking to patients about the cost of care and whether the costs are worth it. Dr. Back stressed that it is crucial for cost to be a part of the decision making process, and not a separate stand-alone issue. He added that it is the physician who should take the lead in initiating this discussion.

Dr. Back is a professor in the Department of Medicine, Division of Oncology at the University of Washington's School of Medicine and a medical oncologist with the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance in Seattle, Washington.

At the eighth annual Chicago Supportive Oncology Conference, we spoke with Dr. Anthony Back about talking to patients about the cost of care and whether the costs are worth it. Dr. Back stressed that it is crucial for cost to be a part of the decision making process, and not a separate stand-alone issue. He added that it is the physician who should take the lead in initiating this discussion.

Dr. Back is a professor in the Department of Medicine, Division of Oncology at the University of Washington's School of Medicine and a medical oncologist with the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance in Seattle, Washington.

Earlier End-of-Life Talks Deter Aggressive Care of Terminal Cancer Patients

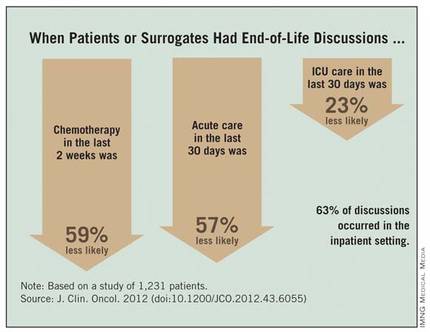

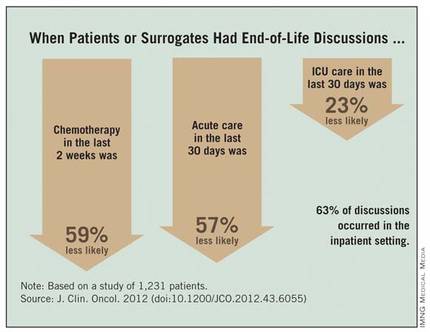

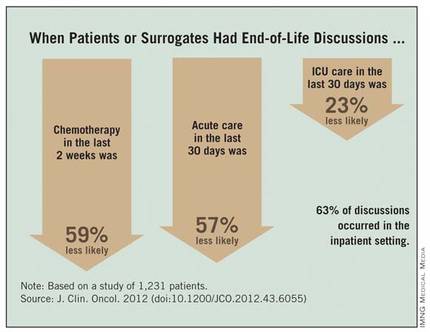

Patients with stage IV lung or colorectal cancer who had end-of-life discussions with caregivers before the last 30 days of life were significantly less likely to receive aggressive care in their final days and more likely to get hospice care and to enter hospice earlier, a study of 1,231 patients found.

Nearly half received some kind of aggressive care in their last 30 days (47%), including chemotherapy in the last 14 days (16%), ICU care in the last 30 days (6%), and/or acute hospital-based care in the last 30 days of life (40%), Dr. Jennifer W. Mack and her associates reported.

Multiple current guidelines recommend starting end-of-life care planning for patients with incurable cancer early in the course of the disease while patients are relatively stable, not when they are acutely deteriorating.

Many physicians in the study postponed the discussion until the final month of life, and many patients didn’t remember or didn’t recognize the end-of-life discussions. Discussions that were documented in charts were not associated with less-aggressive care or greater hospice use, if patients or their surrogates said no end-of-life discussions took place.

Eighty-eight percent of patients in the current study had end-of-life discussions. Twenty-three percent of the discussion were reported by patients or their surrogates in interviews but not documented in records, 17% were documented in medical records but not reported by patients or surrogates, and 48% were both reported and documented.

Among the 794 patients with end-of-life discussions documented in medical records, 39% took place in the last 30 days of life, 63% happened in the inpatient setting, and 40% included an oncologist. Fifty-eight percent of patients entered hospice care, which started in the last 7 days of life for 15% of them, reported Dr. Mack, a pediatric oncologist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The study was published online Nov. 13, 2012 by the Journal of Clinical Oncology (doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.43.6055).

Chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks of life was 59% less likely, acute care in the last 30 days was 57% less likely, and ICU care in the last 30 days was 23% less likely when patients or surrogates reported having end-of-life discussions.

Patients Followed 15 Months After Diagnosis

Patients whose first end-of-life discussion happened while they were hospitalized were more than twice as likely to get any kind of aggressive care at the end of life and three times more likely to get acute care or ICU care in the last 30 days and to have hospice care start within the last week before death.

Having a medical oncologist present at the first end-of-life discussion increased the odds of having chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks of life by 48%, decreased the odds of ICU care in the last 30 days by 56%, increased the likelihood of hospice care by 43%, and doubled the chance of hospice care starting in the last 7 days of life. All of these odds ratios were significant after controlling for other factors.

Data came from a larger cohort of 2,155 patients with stage IV lung or colorectal cancer receiving care in HMOs or Veterans Affairs medical centers in five states. All were followed for 15 months after diagnosis in the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium.

An earlier analysis by the same investigators showed that 87% of the 1,470 patients who died and 41% of the 685 still alive by the end of follow-up had end-of-life care discussions, but oncologists documented end-of-life discussions with only 27% of their patients, suggesting that most discussions were with non-oncologists. Among those who died, documented discussions took place a median of 33 days before death (Ann. Intern. Med. 2012;156:204-10).

"Our previous study on this database found that most physicians do have end-of-life discussions before death, but most occur near the end of life," Dr. Mack said in an interview.

The current study analyzed data for 1,231 of the patients who died but who lived at least 1 month after diagnosis, in order to assess whether the timing of discussions influenced end-of-life care. "Besides the fact that that seems like logical practice, there really wasn’t a clear evidence base that that affects care," she said.

Patients were significantly less likely to say they’d had an end-of-life discussion if they were unmarried, black or non-white Hispanic, or not in an HMO.

Start Talks Closer to Diagnosis

When discussions don’t begin until the last 30 days of life, the end-of-life period usually is already underway, the investigators noted. Physicians should consider moving end-of-life care discussions closer to diagnosis, they suggested, while patients are relatively well and have time to plan for what’s ahead.

"It’s something that any physician can do," but some previous studies report that physicians are reluctant to start end-of-life discussions early because these are emotionally difficult conversations, they worry about taking away hope, and they are concerned about the psychological impact on patients – though there is no clear evidence that it does have psychological consequences for patients, Dr. Mack said.

"It’s a compassionate instinct," she said. "Being in the room with a family when I deliver this kind of news, that emotional impact is right in front of me. I believe there are bigger consequences" from not discussing end-of-life care, such as perpetuating false hopes and asking people to make decisions about what’s ahead without a clear picture of the situation, she added.

The conversation should take place more than once because patient preferences may change over time and patients need time to process the information and their thoughts about it, Dr. Mack said.

Ask Patients What They Hear

Further work is needed on why some documented end-of-life discussions were not reported by patients/surrogates. "Every physician can relate to this, that sometimes we have conversations but they’re not heard or understood by patients," she said. "It reminds me that I need to ask patients what they’re taking away from these conversations and use that to guide me going forward."

That finding echoes two recent large, population-based studies that found many patients with terminal cancer mistakenly think that palliative chemotherapy or radiation will cure their disease.

Some previous studies suggest that patients dying of cancer increasingly are receiving aggressive care at the end of life and that this trend may be modifiable. Cross-sectional studies that assessed one point in time between diagnosis and death have shown that many patients don’t have end-of-life discussions, but these studies probably missed discussions closer to death, Dr. Mack noted.

Other studies have reported an association between having end-of-life discussions and reduced intensity in care. The current study was longitudinal and is one of the first to look at the effects of the timing of these discussions and other factors.

Most patients who realize that they are dying do not want aggressive care, previous studies have shown. Other studies report that less-aggressive end-of-life care is easier on family members and less expensive.

Guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the American College of Physicians and American Society of Internal Medicine recommend beginning end-of-life discussions early for patients with incurable cancer.

When investigators conducted secondary analyses that excluded patients from Veterans Affairs sites or excluded interviews with patient surrogates, the findings were similar to results of the main analysis.

In the current analysis, 82% of patients had lung cancer, and the rest had colorectal cancer.

Future research on this topic could take many paths, Dr. Mack suggested, including implementing routine early discussions and seeing whether that alters the intensity of final care. Much more could be learned about the quality of discussions between physicians and patients. The current study had no data on discussions led by nurses or social workers or that took place among family members without a medical provider present.

"We’re also interested in looking at a longer trajectory of end-of-life decision making" for patients with incurable cancer – from diagnosis to death, she said.

Dr. Mack and her associates reported having no financial disclosures.

This is an important study that documents the fact that early discussions about end-of-life care for patients with stage IV cancer are associated with decreased intensity of care at the end of life, and that the timing of the initiation of these discussions is very important and should happen earlier than it does much of the time.

This is not the first study to show that this communication is associated with decreased intensity of care (JAMA 2008;300:1665-73). However, this is an important study because it is the first to document that early discussions are important (prior to the last 30 days of life).

|

|

Moving end-of-life discussions closer to diagnosis definitely is realistic and the way this should occur. However, it is not an "either-or" situation. Early discussions don’t mean that later discussions aren’t necessary and important. Early discussions set the frame and make it easier to have later discussions if/when patients get worse.

There is a need for physicians to improve communication to make sure patients or their surrogates understand end-of-life discussions. Our challenge now is to find successful ways to teach these communication skills to physicians and help physicians implement these discussions in clinical practice. It is not useful to tell physicians to have these discussions if they haven’t been trained to do it well, and we don’t create systems that make it practical and feasible.

When the Obama administration tried to implement a policy of paying physicians to conduct advance care planning on an annual basis through Medicare, Sarah Palin and others used the "death panel" scare tactics to defeat this important effort. We need to change the public discussion to be more aware of the importance of early and regular discussions about advance care planning.

We also need research to figure out how best to implement "earlier discussions" in clinical practice and to identify the long-term consequences of such a practice.

Dr. J. Randall Curtis is director of the University of Washington Palliative Care Center of Excellence and head of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine at Harborview Medical Center, Seattle. He provided these comments in an interview. Dr. Curtis reported having no financial disclosures.

This is an important study that documents the fact that early discussions about end-of-life care for patients with stage IV cancer are associated with decreased intensity of care at the end of life, and that the timing of the initiation of these discussions is very important and should happen earlier than it does much of the time.

This is not the first study to show that this communication is associated with decreased intensity of care (JAMA 2008;300:1665-73). However, this is an important study because it is the first to document that early discussions are important (prior to the last 30 days of life).

|

|

Moving end-of-life discussions closer to diagnosis definitely is realistic and the way this should occur. However, it is not an "either-or" situation. Early discussions don’t mean that later discussions aren’t necessary and important. Early discussions set the frame and make it easier to have later discussions if/when patients get worse.

There is a need for physicians to improve communication to make sure patients or their surrogates understand end-of-life discussions. Our challenge now is to find successful ways to teach these communication skills to physicians and help physicians implement these discussions in clinical practice. It is not useful to tell physicians to have these discussions if they haven’t been trained to do it well, and we don’t create systems that make it practical and feasible.

When the Obama administration tried to implement a policy of paying physicians to conduct advance care planning on an annual basis through Medicare, Sarah Palin and others used the "death panel" scare tactics to defeat this important effort. We need to change the public discussion to be more aware of the importance of early and regular discussions about advance care planning.

We also need research to figure out how best to implement "earlier discussions" in clinical practice and to identify the long-term consequences of such a practice.

Dr. J. Randall Curtis is director of the University of Washington Palliative Care Center of Excellence and head of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine at Harborview Medical Center, Seattle. He provided these comments in an interview. Dr. Curtis reported having no financial disclosures.

This is an important study that documents the fact that early discussions about end-of-life care for patients with stage IV cancer are associated with decreased intensity of care at the end of life, and that the timing of the initiation of these discussions is very important and should happen earlier than it does much of the time.

This is not the first study to show that this communication is associated with decreased intensity of care (JAMA 2008;300:1665-73). However, this is an important study because it is the first to document that early discussions are important (prior to the last 30 days of life).

|

|

Moving end-of-life discussions closer to diagnosis definitely is realistic and the way this should occur. However, it is not an "either-or" situation. Early discussions don’t mean that later discussions aren’t necessary and important. Early discussions set the frame and make it easier to have later discussions if/when patients get worse.

There is a need for physicians to improve communication to make sure patients or their surrogates understand end-of-life discussions. Our challenge now is to find successful ways to teach these communication skills to physicians and help physicians implement these discussions in clinical practice. It is not useful to tell physicians to have these discussions if they haven’t been trained to do it well, and we don’t create systems that make it practical and feasible.

When the Obama administration tried to implement a policy of paying physicians to conduct advance care planning on an annual basis through Medicare, Sarah Palin and others used the "death panel" scare tactics to defeat this important effort. We need to change the public discussion to be more aware of the importance of early and regular discussions about advance care planning.

We also need research to figure out how best to implement "earlier discussions" in clinical practice and to identify the long-term consequences of such a practice.

Dr. J. Randall Curtis is director of the University of Washington Palliative Care Center of Excellence and head of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine at Harborview Medical Center, Seattle. He provided these comments in an interview. Dr. Curtis reported having no financial disclosures.

Patients with stage IV lung or colorectal cancer who had end-of-life discussions with caregivers before the last 30 days of life were significantly less likely to receive aggressive care in their final days and more likely to get hospice care and to enter hospice earlier, a study of 1,231 patients found.

Nearly half received some kind of aggressive care in their last 30 days (47%), including chemotherapy in the last 14 days (16%), ICU care in the last 30 days (6%), and/or acute hospital-based care in the last 30 days of life (40%), Dr. Jennifer W. Mack and her associates reported.

Multiple current guidelines recommend starting end-of-life care planning for patients with incurable cancer early in the course of the disease while patients are relatively stable, not when they are acutely deteriorating.

Many physicians in the study postponed the discussion until the final month of life, and many patients didn’t remember or didn’t recognize the end-of-life discussions. Discussions that were documented in charts were not associated with less-aggressive care or greater hospice use, if patients or their surrogates said no end-of-life discussions took place.

Eighty-eight percent of patients in the current study had end-of-life discussions. Twenty-three percent of the discussion were reported by patients or their surrogates in interviews but not documented in records, 17% were documented in medical records but not reported by patients or surrogates, and 48% were both reported and documented.

Among the 794 patients with end-of-life discussions documented in medical records, 39% took place in the last 30 days of life, 63% happened in the inpatient setting, and 40% included an oncologist. Fifty-eight percent of patients entered hospice care, which started in the last 7 days of life for 15% of them, reported Dr. Mack, a pediatric oncologist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The study was published online Nov. 13, 2012 by the Journal of Clinical Oncology (doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.43.6055).

Chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks of life was 59% less likely, acute care in the last 30 days was 57% less likely, and ICU care in the last 30 days was 23% less likely when patients or surrogates reported having end-of-life discussions.

Patients Followed 15 Months After Diagnosis

Patients whose first end-of-life discussion happened while they were hospitalized were more than twice as likely to get any kind of aggressive care at the end of life and three times more likely to get acute care or ICU care in the last 30 days and to have hospice care start within the last week before death.

Having a medical oncologist present at the first end-of-life discussion increased the odds of having chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks of life by 48%, decreased the odds of ICU care in the last 30 days by 56%, increased the likelihood of hospice care by 43%, and doubled the chance of hospice care starting in the last 7 days of life. All of these odds ratios were significant after controlling for other factors.

Data came from a larger cohort of 2,155 patients with stage IV lung or colorectal cancer receiving care in HMOs or Veterans Affairs medical centers in five states. All were followed for 15 months after diagnosis in the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium.

An earlier analysis by the same investigators showed that 87% of the 1,470 patients who died and 41% of the 685 still alive by the end of follow-up had end-of-life care discussions, but oncologists documented end-of-life discussions with only 27% of their patients, suggesting that most discussions were with non-oncologists. Among those who died, documented discussions took place a median of 33 days before death (Ann. Intern. Med. 2012;156:204-10).

"Our previous study on this database found that most physicians do have end-of-life discussions before death, but most occur near the end of life," Dr. Mack said in an interview.

The current study analyzed data for 1,231 of the patients who died but who lived at least 1 month after diagnosis, in order to assess whether the timing of discussions influenced end-of-life care. "Besides the fact that that seems like logical practice, there really wasn’t a clear evidence base that that affects care," she said.

Patients were significantly less likely to say they’d had an end-of-life discussion if they were unmarried, black or non-white Hispanic, or not in an HMO.

Start Talks Closer to Diagnosis

When discussions don’t begin until the last 30 days of life, the end-of-life period usually is already underway, the investigators noted. Physicians should consider moving end-of-life care discussions closer to diagnosis, they suggested, while patients are relatively well and have time to plan for what’s ahead.

"It’s something that any physician can do," but some previous studies report that physicians are reluctant to start end-of-life discussions early because these are emotionally difficult conversations, they worry about taking away hope, and they are concerned about the psychological impact on patients – though there is no clear evidence that it does have psychological consequences for patients, Dr. Mack said.

"It’s a compassionate instinct," she said. "Being in the room with a family when I deliver this kind of news, that emotional impact is right in front of me. I believe there are bigger consequences" from not discussing end-of-life care, such as perpetuating false hopes and asking people to make decisions about what’s ahead without a clear picture of the situation, she added.

The conversation should take place more than once because patient preferences may change over time and patients need time to process the information and their thoughts about it, Dr. Mack said.

Ask Patients What They Hear

Further work is needed on why some documented end-of-life discussions were not reported by patients/surrogates. "Every physician can relate to this, that sometimes we have conversations but they’re not heard or understood by patients," she said. "It reminds me that I need to ask patients what they’re taking away from these conversations and use that to guide me going forward."

That finding echoes two recent large, population-based studies that found many patients with terminal cancer mistakenly think that palliative chemotherapy or radiation will cure their disease.

Some previous studies suggest that patients dying of cancer increasingly are receiving aggressive care at the end of life and that this trend may be modifiable. Cross-sectional studies that assessed one point in time between diagnosis and death have shown that many patients don’t have end-of-life discussions, but these studies probably missed discussions closer to death, Dr. Mack noted.

Other studies have reported an association between having end-of-life discussions and reduced intensity in care. The current study was longitudinal and is one of the first to look at the effects of the timing of these discussions and other factors.

Most patients who realize that they are dying do not want aggressive care, previous studies have shown. Other studies report that less-aggressive end-of-life care is easier on family members and less expensive.

Guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the American College of Physicians and American Society of Internal Medicine recommend beginning end-of-life discussions early for patients with incurable cancer.

When investigators conducted secondary analyses that excluded patients from Veterans Affairs sites or excluded interviews with patient surrogates, the findings were similar to results of the main analysis.

In the current analysis, 82% of patients had lung cancer, and the rest had colorectal cancer.

Future research on this topic could take many paths, Dr. Mack suggested, including implementing routine early discussions and seeing whether that alters the intensity of final care. Much more could be learned about the quality of discussions between physicians and patients. The current study had no data on discussions led by nurses or social workers or that took place among family members without a medical provider present.

"We’re also interested in looking at a longer trajectory of end-of-life decision making" for patients with incurable cancer – from diagnosis to death, she said.

Dr. Mack and her associates reported having no financial disclosures.

Patients with stage IV lung or colorectal cancer who had end-of-life discussions with caregivers before the last 30 days of life were significantly less likely to receive aggressive care in their final days and more likely to get hospice care and to enter hospice earlier, a study of 1,231 patients found.

Nearly half received some kind of aggressive care in their last 30 days (47%), including chemotherapy in the last 14 days (16%), ICU care in the last 30 days (6%), and/or acute hospital-based care in the last 30 days of life (40%), Dr. Jennifer W. Mack and her associates reported.

Multiple current guidelines recommend starting end-of-life care planning for patients with incurable cancer early in the course of the disease while patients are relatively stable, not when they are acutely deteriorating.

Many physicians in the study postponed the discussion until the final month of life, and many patients didn’t remember or didn’t recognize the end-of-life discussions. Discussions that were documented in charts were not associated with less-aggressive care or greater hospice use, if patients or their surrogates said no end-of-life discussions took place.

Eighty-eight percent of patients in the current study had end-of-life discussions. Twenty-three percent of the discussion were reported by patients or their surrogates in interviews but not documented in records, 17% were documented in medical records but not reported by patients or surrogates, and 48% were both reported and documented.

Among the 794 patients with end-of-life discussions documented in medical records, 39% took place in the last 30 days of life, 63% happened in the inpatient setting, and 40% included an oncologist. Fifty-eight percent of patients entered hospice care, which started in the last 7 days of life for 15% of them, reported Dr. Mack, a pediatric oncologist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The study was published online Nov. 13, 2012 by the Journal of Clinical Oncology (doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.43.6055).

Chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks of life was 59% less likely, acute care in the last 30 days was 57% less likely, and ICU care in the last 30 days was 23% less likely when patients or surrogates reported having end-of-life discussions.

Patients Followed 15 Months After Diagnosis

Patients whose first end-of-life discussion happened while they were hospitalized were more than twice as likely to get any kind of aggressive care at the end of life and three times more likely to get acute care or ICU care in the last 30 days and to have hospice care start within the last week before death.

Having a medical oncologist present at the first end-of-life discussion increased the odds of having chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks of life by 48%, decreased the odds of ICU care in the last 30 days by 56%, increased the likelihood of hospice care by 43%, and doubled the chance of hospice care starting in the last 7 days of life. All of these odds ratios were significant after controlling for other factors.

Data came from a larger cohort of 2,155 patients with stage IV lung or colorectal cancer receiving care in HMOs or Veterans Affairs medical centers in five states. All were followed for 15 months after diagnosis in the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium.

An earlier analysis by the same investigators showed that 87% of the 1,470 patients who died and 41% of the 685 still alive by the end of follow-up had end-of-life care discussions, but oncologists documented end-of-life discussions with only 27% of their patients, suggesting that most discussions were with non-oncologists. Among those who died, documented discussions took place a median of 33 days before death (Ann. Intern. Med. 2012;156:204-10).

"Our previous study on this database found that most physicians do have end-of-life discussions before death, but most occur near the end of life," Dr. Mack said in an interview.

The current study analyzed data for 1,231 of the patients who died but who lived at least 1 month after diagnosis, in order to assess whether the timing of discussions influenced end-of-life care. "Besides the fact that that seems like logical practice, there really wasn’t a clear evidence base that that affects care," she said.

Patients were significantly less likely to say they’d had an end-of-life discussion if they were unmarried, black or non-white Hispanic, or not in an HMO.

Start Talks Closer to Diagnosis

When discussions don’t begin until the last 30 days of life, the end-of-life period usually is already underway, the investigators noted. Physicians should consider moving end-of-life care discussions closer to diagnosis, they suggested, while patients are relatively well and have time to plan for what’s ahead.

"It’s something that any physician can do," but some previous studies report that physicians are reluctant to start end-of-life discussions early because these are emotionally difficult conversations, they worry about taking away hope, and they are concerned about the psychological impact on patients – though there is no clear evidence that it does have psychological consequences for patients, Dr. Mack said.

"It’s a compassionate instinct," she said. "Being in the room with a family when I deliver this kind of news, that emotional impact is right in front of me. I believe there are bigger consequences" from not discussing end-of-life care, such as perpetuating false hopes and asking people to make decisions about what’s ahead without a clear picture of the situation, she added.

The conversation should take place more than once because patient preferences may change over time and patients need time to process the information and their thoughts about it, Dr. Mack said.

Ask Patients What They Hear

Further work is needed on why some documented end-of-life discussions were not reported by patients/surrogates. "Every physician can relate to this, that sometimes we have conversations but they’re not heard or understood by patients," she said. "It reminds me that I need to ask patients what they’re taking away from these conversations and use that to guide me going forward."

That finding echoes two recent large, population-based studies that found many patients with terminal cancer mistakenly think that palliative chemotherapy or radiation will cure their disease.

Some previous studies suggest that patients dying of cancer increasingly are receiving aggressive care at the end of life and that this trend may be modifiable. Cross-sectional studies that assessed one point in time between diagnosis and death have shown that many patients don’t have end-of-life discussions, but these studies probably missed discussions closer to death, Dr. Mack noted.

Other studies have reported an association between having end-of-life discussions and reduced intensity in care. The current study was longitudinal and is one of the first to look at the effects of the timing of these discussions and other factors.

Most patients who realize that they are dying do not want aggressive care, previous studies have shown. Other studies report that less-aggressive end-of-life care is easier on family members and less expensive.

Guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and the American College of Physicians and American Society of Internal Medicine recommend beginning end-of-life discussions early for patients with incurable cancer.

When investigators conducted secondary analyses that excluded patients from Veterans Affairs sites or excluded interviews with patient surrogates, the findings were similar to results of the main analysis.

In the current analysis, 82% of patients had lung cancer, and the rest had colorectal cancer.

Future research on this topic could take many paths, Dr. Mack suggested, including implementing routine early discussions and seeing whether that alters the intensity of final care. Much more could be learned about the quality of discussions between physicians and patients. The current study had no data on discussions led by nurses or social workers or that took place among family members without a medical provider present.

"We’re also interested in looking at a longer trajectory of end-of-life decision making" for patients with incurable cancer – from diagnosis to death, she said.

Dr. Mack and her associates reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Major Finding: Chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks of life was 59% less likely, acute care in the last 30 days was 57% less likely, and ICU care in the last 30 days was 23% less likely when patients or their surrogates reported having end-of-life discussions.

Data Source: This was a longitudinal study of 1,231 patients with stage IV lung or colorectal cancer at HMOs or Veterans Affairs sites in five states.

Disclosures: Dr. Mack and her associates reported having no financial disclosures.

Experts: Palliative Care Lowers Costs

It is very common for health care professionals to want to shy away from those difficult conversations with patients when caring for them throughout their cancer treatment.

At the eighth annual Chicago Supportive Oncology Conference, Thomas J. Smith, M.D., Director of Palliative Care for Johns Hopkins Medicine and the Hopkins’ Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, offered practical insight on the economics of integrating palliative care.

When it comes to discussing patient preferences for end-of-life and treatment decisions, Dr. Smith said: "People do want this information; it won't make [them] depressed; it won’t take away their hope; it won’t make them die sooner. We can give realistic forecasts for survival. It is always culturally appropriate to ask, 'How much do you know about your illness?' "

Is it possible to provide the best in care while "bending the cost curve" by having open and honest discussions with your patients? Absolutely, said Dr. Smith, because "we are asking [them] what is important to them." (See the commentary, "Talking with Patients about Dying,” by Dr. Smith and Dan L. Longo, M.D.; N Engl J Med 2012;367:1651-2.)

It is very common for health care professionals to want to shy away from those difficult conversations with patients when caring for them throughout their cancer treatment.

At the eighth annual Chicago Supportive Oncology Conference, Thomas J. Smith, M.D., Director of Palliative Care for Johns Hopkins Medicine and the Hopkins’ Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, offered practical insight on the economics of integrating palliative care.

When it comes to discussing patient preferences for end-of-life and treatment decisions, Dr. Smith said: "People do want this information; it won't make [them] depressed; it won’t take away their hope; it won’t make them die sooner. We can give realistic forecasts for survival. It is always culturally appropriate to ask, 'How much do you know about your illness?' "

Is it possible to provide the best in care while "bending the cost curve" by having open and honest discussions with your patients? Absolutely, said Dr. Smith, because "we are asking [them] what is important to them." (See the commentary, "Talking with Patients about Dying,” by Dr. Smith and Dan L. Longo, M.D.; N Engl J Med 2012;367:1651-2.)

It is very common for health care professionals to want to shy away from those difficult conversations with patients when caring for them throughout their cancer treatment.

At the eighth annual Chicago Supportive Oncology Conference, Thomas J. Smith, M.D., Director of Palliative Care for Johns Hopkins Medicine and the Hopkins’ Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, offered practical insight on the economics of integrating palliative care.

When it comes to discussing patient preferences for end-of-life and treatment decisions, Dr. Smith said: "People do want this information; it won't make [them] depressed; it won’t take away their hope; it won’t make them die sooner. We can give realistic forecasts for survival. It is always culturally appropriate to ask, 'How much do you know about your illness?' "

Is it possible to provide the best in care while "bending the cost curve" by having open and honest discussions with your patients? Absolutely, said Dr. Smith, because "we are asking [them] what is important to them." (See the commentary, "Talking with Patients about Dying,” by Dr. Smith and Dan L. Longo, M.D.; N Engl J Med 2012;367:1651-2.)

Twelve Reasons for Considering Buprenorphine as a Frontline Analgesic in the Management of Pain

Mellar P. Davis, MD, FCCP, FAAHPM

ABSTRACT: Buprenorphine is an opioid that has a complex and unique pharmacology which provides some advantages over other potent mu agonists. We review 12 reasons for considering buprenorphine as a frontline analgesic for moderate to severe pain: (1) Buprenorphine is effective in cancer pain; (2) buprenorphine is effective in treating neuropathic pain; (3) buprenorphine treats a broader array of pain phenotypes than do certain potent mu agonists, is associated with less analgesic tolerance, and can be combined with other mu agonists; (4) buprenorphine produces less constipation than do certain other potent mu agonists, and does not adversely affect the sphincter of Oddi; (5) buprenorphine has a ceiling effect on respiratory depression but not analgesia; (6) buprenorphine causes less cognitive impairment than do certain other opioids; (7) buprenorphine is not immunosuppressive like morphine and fentanyl; (8) buprenorphine does not adversely affect the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis or cause hypogonadism; (9) buprenorphine does not significantly prolong the QTc interval, and is associated with less sudden death than is methadone; (10) buprenorphine is a safe and effective analgesic for the elderly; (11) buprenorphine is one of the safest opioids to use in patients in renal failure and those on dialysis; and (12) withdrawal symptoms are milder and drug dependence is less with buprenorphine. In light of evidence for efficacy, safety, versatility, and cost, buprenorphine should be considered as a first-line analgesic.

*For a PDF of the full article and a Commentary by Paul Sloan, MD, click on the links to the left of this introduction.

Mellar P. Davis, MD, FCCP, FAAHPM

ABSTRACT: Buprenorphine is an opioid that has a complex and unique pharmacology which provides some advantages over other potent mu agonists. We review 12 reasons for considering buprenorphine as a frontline analgesic for moderate to severe pain: (1) Buprenorphine is effective in cancer pain; (2) buprenorphine is effective in treating neuropathic pain; (3) buprenorphine treats a broader array of pain phenotypes than do certain potent mu agonists, is associated with less analgesic tolerance, and can be combined with other mu agonists; (4) buprenorphine produces less constipation than do certain other potent mu agonists, and does not adversely affect the sphincter of Oddi; (5) buprenorphine has a ceiling effect on respiratory depression but not analgesia; (6) buprenorphine causes less cognitive impairment than do certain other opioids; (7) buprenorphine is not immunosuppressive like morphine and fentanyl; (8) buprenorphine does not adversely affect the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis or cause hypogonadism; (9) buprenorphine does not significantly prolong the QTc interval, and is associated with less sudden death than is methadone; (10) buprenorphine is a safe and effective analgesic for the elderly; (11) buprenorphine is one of the safest opioids to use in patients in renal failure and those on dialysis; and (12) withdrawal symptoms are milder and drug dependence is less with buprenorphine. In light of evidence for efficacy, safety, versatility, and cost, buprenorphine should be considered as a first-line analgesic.

*For a PDF of the full article and a Commentary by Paul Sloan, MD, click on the links to the left of this introduction.

Mellar P. Davis, MD, FCCP, FAAHPM