User login

VIDEO: How to improve cancer survivorship planning

BRUSSELS – National Cancer Institute Director Catherine Alfano, Ph.D., summarizes the institute’s work on improving cancer survivor planning, better coordinating survivor care, and gathering new data on long-term outcomes. She made her remarks during the Cancer Survivorship Summit in a video interview.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BRUSSELS – National Cancer Institute Director Catherine Alfano, Ph.D., summarizes the institute’s work on improving cancer survivor planning, better coordinating survivor care, and gathering new data on long-term outcomes. She made her remarks during the Cancer Survivorship Summit in a video interview.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BRUSSELS – National Cancer Institute Director Catherine Alfano, Ph.D., summarizes the institute’s work on improving cancer survivor planning, better coordinating survivor care, and gathering new data on long-term outcomes. She made her remarks during the Cancer Survivorship Summit in a video interview.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CANCER SURVIVORSHIP SUMMIT

Recognize the range of skin reactions to EGFR inhibitors

The most common skin manifestation of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors is a papulopustular eruption that typically develops 8-10 days after the beginning of therapy, mainly on the scalp and in other areas with a high concentration of sebaceous glands, according to a review of the topic.

"Although the eruption typically spontaneously resolves after 12 weeks of EGFR inhibitor therapy, long-term postinflammatory erythema or hyperpigmentation is not unusual and may last for years after therapy has been discontinued," Rachel L. Kyllo and Dr. Milan J. Anadkat wrote in Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery (in press).

As part of a larger review of the cutaneous manifestations of chemotherapeutic agents, Ms. Kyllo and Dr. Anadkat of the division of dermatology at Washington University, St. Louis, noted that EGFR receptor inhibitors have been approved for treating solid tumors including pancreatic cancer, non–small cell lung cancer, colorectal cancer, head and neck squamous cell cancer, and breast cancer. The two main types are small molecule inhibitors, including gefitinib, erlotinib,and lapatinib, and the monoclonal antibodies cetuximab and panitumumab.

Monoclonal antibodies are associated with a higher incidence of papulopustular eruption. Histology "demonstrates a mixed superficial inflammatory infiltrate which leads to follicular rupture and acantholysis," the authors wrote. "These findings are consistent with dysregulation of molecular pathways downstream from EGFR signaling, which are known to be important in keratinocyte migration, maturation, and survival."

Although having an EGFR inhibitor–related papulopustular eruption appears to be associated with an increased median survival time, high-grade rash often leads to treatment modification or dose adjustment. "Prophylactic treatment with systemic tetracycline antibiotics for the first 8 weeks of EGFR inhibitor therapy significantly reduces the severity of the papulopustular eruption, theoretically decreasing the need for dosage adjustment," the authors wrote. "Severe cases should prompt consideration of systemic therapy with corticosteroids, low-dose isotretinoin, or acitretin."

EGFR inhibitor therapy also can affect the hair, most commonly causing a change in hair texture with increased breakability and curliness. This side effect is more likely with long-term exposure and can appear months after treatment begins. "Nonscarring alopecia typically develops 8-12 weeks after initiation of EGFR inhibitor therapy in 5% of patients and resolves spontaneously after discontinuation of the drug," the authors added. "Rarely, scarring alopecia results in permanent hair loss; prophylactic doxycycline to reduce papulopustular eruption severity ... and topical high-dose corticosteroid preparations reduce the likelihood of subsequent scarring."

They went on to note that 12%-16% of patients develop paronychia 8-12 weeks after initiation of EGFR therapy, with local trauma believed to be an aggravating factor. A course of antibiotics is warranted only in cases of culture-proven bacterial superinfection.

Another potential side effect of EGFR therapy, xerosis, occurs in 4%-35% of patients, usually 4-8 weeks after initiation of treatment. It most commonly affects elderly patients, as well as those with preexisting eczema and those who have undergone prior treatment with cytotoxic agents. "Treatments include topical emollients and keratolytics; use of topical retinoids or benzoyl peroxide is not recommended as they may exacerbate skin dryness," the authors wrote. "Use of topical corticosteroids is reserved for cases of frank dermatitis."

Dr. Anadkat disclosed having received honoraria as a consultant and/or speaker from ImClone, Genentech, AstraZeneca, Therakos, Eisai, and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

The most common skin manifestation of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors is a papulopustular eruption that typically develops 8-10 days after the beginning of therapy, mainly on the scalp and in other areas with a high concentration of sebaceous glands, according to a review of the topic.

"Although the eruption typically spontaneously resolves after 12 weeks of EGFR inhibitor therapy, long-term postinflammatory erythema or hyperpigmentation is not unusual and may last for years after therapy has been discontinued," Rachel L. Kyllo and Dr. Milan J. Anadkat wrote in Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery (in press).

As part of a larger review of the cutaneous manifestations of chemotherapeutic agents, Ms. Kyllo and Dr. Anadkat of the division of dermatology at Washington University, St. Louis, noted that EGFR receptor inhibitors have been approved for treating solid tumors including pancreatic cancer, non–small cell lung cancer, colorectal cancer, head and neck squamous cell cancer, and breast cancer. The two main types are small molecule inhibitors, including gefitinib, erlotinib,and lapatinib, and the monoclonal antibodies cetuximab and panitumumab.

Monoclonal antibodies are associated with a higher incidence of papulopustular eruption. Histology "demonstrates a mixed superficial inflammatory infiltrate which leads to follicular rupture and acantholysis," the authors wrote. "These findings are consistent with dysregulation of molecular pathways downstream from EGFR signaling, which are known to be important in keratinocyte migration, maturation, and survival."

Although having an EGFR inhibitor–related papulopustular eruption appears to be associated with an increased median survival time, high-grade rash often leads to treatment modification or dose adjustment. "Prophylactic treatment with systemic tetracycline antibiotics for the first 8 weeks of EGFR inhibitor therapy significantly reduces the severity of the papulopustular eruption, theoretically decreasing the need for dosage adjustment," the authors wrote. "Severe cases should prompt consideration of systemic therapy with corticosteroids, low-dose isotretinoin, or acitretin."

EGFR inhibitor therapy also can affect the hair, most commonly causing a change in hair texture with increased breakability and curliness. This side effect is more likely with long-term exposure and can appear months after treatment begins. "Nonscarring alopecia typically develops 8-12 weeks after initiation of EGFR inhibitor therapy in 5% of patients and resolves spontaneously after discontinuation of the drug," the authors added. "Rarely, scarring alopecia results in permanent hair loss; prophylactic doxycycline to reduce papulopustular eruption severity ... and topical high-dose corticosteroid preparations reduce the likelihood of subsequent scarring."

They went on to note that 12%-16% of patients develop paronychia 8-12 weeks after initiation of EGFR therapy, with local trauma believed to be an aggravating factor. A course of antibiotics is warranted only in cases of culture-proven bacterial superinfection.

Another potential side effect of EGFR therapy, xerosis, occurs in 4%-35% of patients, usually 4-8 weeks after initiation of treatment. It most commonly affects elderly patients, as well as those with preexisting eczema and those who have undergone prior treatment with cytotoxic agents. "Treatments include topical emollients and keratolytics; use of topical retinoids or benzoyl peroxide is not recommended as they may exacerbate skin dryness," the authors wrote. "Use of topical corticosteroids is reserved for cases of frank dermatitis."

Dr. Anadkat disclosed having received honoraria as a consultant and/or speaker from ImClone, Genentech, AstraZeneca, Therakos, Eisai, and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

The most common skin manifestation of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors is a papulopustular eruption that typically develops 8-10 days after the beginning of therapy, mainly on the scalp and in other areas with a high concentration of sebaceous glands, according to a review of the topic.

"Although the eruption typically spontaneously resolves after 12 weeks of EGFR inhibitor therapy, long-term postinflammatory erythema or hyperpigmentation is not unusual and may last for years after therapy has been discontinued," Rachel L. Kyllo and Dr. Milan J. Anadkat wrote in Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery (in press).

As part of a larger review of the cutaneous manifestations of chemotherapeutic agents, Ms. Kyllo and Dr. Anadkat of the division of dermatology at Washington University, St. Louis, noted that EGFR receptor inhibitors have been approved for treating solid tumors including pancreatic cancer, non–small cell lung cancer, colorectal cancer, head and neck squamous cell cancer, and breast cancer. The two main types are small molecule inhibitors, including gefitinib, erlotinib,and lapatinib, and the monoclonal antibodies cetuximab and panitumumab.

Monoclonal antibodies are associated with a higher incidence of papulopustular eruption. Histology "demonstrates a mixed superficial inflammatory infiltrate which leads to follicular rupture and acantholysis," the authors wrote. "These findings are consistent with dysregulation of molecular pathways downstream from EGFR signaling, which are known to be important in keratinocyte migration, maturation, and survival."

Although having an EGFR inhibitor–related papulopustular eruption appears to be associated with an increased median survival time, high-grade rash often leads to treatment modification or dose adjustment. "Prophylactic treatment with systemic tetracycline antibiotics for the first 8 weeks of EGFR inhibitor therapy significantly reduces the severity of the papulopustular eruption, theoretically decreasing the need for dosage adjustment," the authors wrote. "Severe cases should prompt consideration of systemic therapy with corticosteroids, low-dose isotretinoin, or acitretin."

EGFR inhibitor therapy also can affect the hair, most commonly causing a change in hair texture with increased breakability and curliness. This side effect is more likely with long-term exposure and can appear months after treatment begins. "Nonscarring alopecia typically develops 8-12 weeks after initiation of EGFR inhibitor therapy in 5% of patients and resolves spontaneously after discontinuation of the drug," the authors added. "Rarely, scarring alopecia results in permanent hair loss; prophylactic doxycycline to reduce papulopustular eruption severity ... and topical high-dose corticosteroid preparations reduce the likelihood of subsequent scarring."

They went on to note that 12%-16% of patients develop paronychia 8-12 weeks after initiation of EGFR therapy, with local trauma believed to be an aggravating factor. A course of antibiotics is warranted only in cases of culture-proven bacterial superinfection.

Another potential side effect of EGFR therapy, xerosis, occurs in 4%-35% of patients, usually 4-8 weeks after initiation of treatment. It most commonly affects elderly patients, as well as those with preexisting eczema and those who have undergone prior treatment with cytotoxic agents. "Treatments include topical emollients and keratolytics; use of topical retinoids or benzoyl peroxide is not recommended as they may exacerbate skin dryness," the authors wrote. "Use of topical corticosteroids is reserved for cases of frank dermatitis."

Dr. Anadkat disclosed having received honoraria as a consultant and/or speaker from ImClone, Genentech, AstraZeneca, Therakos, Eisai, and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

FROM SEMINARS IN CUTANEOUS MEDICINE AND SURGERY

U.K. ahead of U.S.A. in cancer survivorship planning

BRUSSELS – Cancer survivorship planning in the United Kingdom is ahead of the United States and the rest of Europe with the recent rollout of a model care plan for cancer patients, along with a guide for conversations between cancer-care health care providers and patients at the time they start long-term follow-up surveillance.

A care plan guides patients as they segue from acute cancer treatment to longer-term health maintenance and follow-up. The plan can include a personalized record of treatment received, prognosis, recommended follow-up examinations, symptoms to be alert for, and other critical information when patients transition to life as a cancer survivor.

The U.K.’s National Health System (NHS) first released a hard-copy version of a model care plan for cancer patients along with a guide for conversations with patients at the time they start long-term follow-up surveillance in 2012. Although the hard-copy form is available from the agency’s National Cancer Survivorship Initiative, the NHS continues to test the care plan and simultaneously is finalizing an electronic version planned for release next year, Dr. Jane Maher said at the first EORTC Cancer Survivorship Summit hosted by the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer.

"The paper version is freely available," while testing continues at 160 U.K. sites," said Dr. Maher, chief medical officer at Macmillan Cancer Support, London, and a clinical leader with the NHS.

"The first evaluation is done. Patients really liked it and found it helpful and it was possible to do, so it’s at the point where it can be spread, but key elements are still in evaluation until 2015," she said in an interview.

"We can now say that we have a tool to shape the conversation" between a cancer patient who has finished the initial phase of treatment and her care provider. "We have a framework for patient education, for treatment, and for review of their cancer care." Patients who have gone through this care-planning conversation "felt more controlled and that their care was more coordinated."

Prevailing attitudes about cancer management pose some of the biggest challenges in developing and implementing cancer plans, Dr. Maher said. "Cancer is seen as an acute illness that is managed acutely by specialists," she noted. Timing the discussions introduces another challenge. "Physicians were prepared to discuss treatment-related consequences at the time of treatment, but patients did not want to hear it then because they were in life-and-death mode," she said.

In contrast, when patients felt ready to get this information, at the end of their treatment, "physicians weren’t prepared to discuss it for fear of frightening patients." But having some type of conversation on long-term prospects is very important, more critical than any of the individual tools, she said.

U.S. efforts still in process

This rollout puts U.K. cancer survivorship planning ahead of the United States and the rest of Europe. The U.S. National Cancer Institute (NCI) "has a research call out to test models for having that conversation with patient-centered goals," said Catherine Alfano, Ph.D., deputy director of survivorship research at the NCI in Bethesda, Md.

"How do you sit with a patient and family members and friends and talk about what just happened and what will happen in the future? Right now we don’t have a best model for this, but I think we owe it to survivors to identify best practices and get it to all of them, and make it patient centered, so it’s not just an oncologist who hands a piece of paper to the cancer patient and says this is what you need to do, because that won’t work. We need a conversation to take place where cancer patients are engaged in setting their survivorship care goals," Dr. Alfano said in an interview.

"We’re talking a lot right now about giving cancer survivors a treatment summary so they know what they received, and equally important a survivorship care plan that talks about what the patient needs to look out for, what providers they’ll see, how often, and how will their care be coordinated. This is implemented in very different ways throughout the U.S. right now. There is a mad rush to do it. What we want is for a conversation to take place so that cancer survivors are engaged in setting goals for their survivorship care," Dr. Alfano said.

Late last year, NCI researchers and their collaborators published results from a recent survey of more than 1,100 U.S. oncologists and more than 1,000 U.S. primary-care physicians about their practice regarding survivor care plans for their cancer patients (J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1579-87). These plans were used by about 20% of the surveyed oncologists and 13% of primary care physicians. Higher numbers reported giving patients treatment summaries at the end of their acute care, usual practice for half of the responding oncologists and about a third of the primary-care physicians.

Survivorship needs grow and diversify

Optimizing care for cancer survivors and better involving them in long-term surveillance and care has become increasingly important as the numbers continue to climb. "The number of cancer survivors is larger than ever, and as U.S. boomers become 65 years and older, there will be a tsunami of more cancer survivors, Dr. Alfano predicted.

"This huge tsunami [of cancer patients] is coming over the next decade, and we are completely unprepared. We have done a poor job of understanding the needs of adult cancer survivors," she warned. "There is a scramble underway now to understand what adult cancer survivors need."

For example, cardiovascular adverse effects from several different cancer treatments often occur many years after treatment. "Usually, these patients are not in surveillance anymore," said Dr. Thomas M. Suter of the Swiss Cardiovascular Center in Bern, Switzerland. "No one is looking at these patients. They need to be on medical treatment to improve their prognosis," such as treatment with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, he said in his talk at the meeting.

Another shortcoming of U.S. cancer survivor care is the fragmented care many patients receive and a glaring lack of coordination.

U.S. cancer survivors "wind up seeing multiple providers for late effects like cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, and diabetes, which is on top of their surveillance for a recurrence of their primary cancer or appearance of a second primary cancer," said Dr. Alfano. "We have to create a more coordinated form of care that is truly team based to make it easier for patients and relieve the huge burden on them and their families. I hear from cancer survivors and families all the time that it takes hours each week just to coordinate a cancer patient’s care. We need to ease this burden. We have done a poor job understanding the needs of adult cancer survivors."

An especially pressing need is for information on lifestyle change, said Dr. Alfano. "Cancer survivors are looking for things they can do personally to take control back over their morbidity and mortality."

Cancer patients are often highly motivated to take steps to cut their risk of treatment-related adverse outcomes, recurrence, or development of a second primary cancer. In 2012, the American Cancer Society issued nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors (CA Cancer J. Clin. 2012;62:30-67), noted Dr. Kevin D. Stein, managing director of the behavioral research center of the ACS in a talk at the meeting.

"We’ve done a poor job of getting lifestyle-change information to cancer survivors. We need to include lifestyle change as part of survivorship plans," said Dr. Alfano.

Despite the shortcomings in survivorship planning in the United States and United Kingdom, it outstrips what currently occurs in most of Europe. "We are far behind the United States," said Dr. Elizabeth Charlotte Moser, professor at the Champalimaud Foundation in Lisbon and chair of the EORTC Survivorship Task Force.

In addition to having Europe follow the United Kingdom and United States in expanding survivor planning, she anticipates a contribution from several European-based cancer-treatment trials for which long-term follow-up data are available. For example, six EORTC-sponsored trials in patients with either early-stage breast cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ together enrolled more than 20,000 patients starting in 1986. EORTC researchers are planning to collect long-term outcome data from as many of these patients as can be tracked down, Dr. Moser said.

Dr. Maher, Dr. Alfano, Dr. Stein, and Dr. Moser said they had no disclosures. Dr. Suter said that he has been a speaker on behalf of Roche, RoboPharma, and Novartis.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BRUSSELS – Cancer survivorship planning in the United Kingdom is ahead of the United States and the rest of Europe with the recent rollout of a model care plan for cancer patients, along with a guide for conversations between cancer-care health care providers and patients at the time they start long-term follow-up surveillance.

A care plan guides patients as they segue from acute cancer treatment to longer-term health maintenance and follow-up. The plan can include a personalized record of treatment received, prognosis, recommended follow-up examinations, symptoms to be alert for, and other critical information when patients transition to life as a cancer survivor.

The U.K.’s National Health System (NHS) first released a hard-copy version of a model care plan for cancer patients along with a guide for conversations with patients at the time they start long-term follow-up surveillance in 2012. Although the hard-copy form is available from the agency’s National Cancer Survivorship Initiative, the NHS continues to test the care plan and simultaneously is finalizing an electronic version planned for release next year, Dr. Jane Maher said at the first EORTC Cancer Survivorship Summit hosted by the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer.

"The paper version is freely available," while testing continues at 160 U.K. sites," said Dr. Maher, chief medical officer at Macmillan Cancer Support, London, and a clinical leader with the NHS.

"The first evaluation is done. Patients really liked it and found it helpful and it was possible to do, so it’s at the point where it can be spread, but key elements are still in evaluation until 2015," she said in an interview.

"We can now say that we have a tool to shape the conversation" between a cancer patient who has finished the initial phase of treatment and her care provider. "We have a framework for patient education, for treatment, and for review of their cancer care." Patients who have gone through this care-planning conversation "felt more controlled and that their care was more coordinated."

Prevailing attitudes about cancer management pose some of the biggest challenges in developing and implementing cancer plans, Dr. Maher said. "Cancer is seen as an acute illness that is managed acutely by specialists," she noted. Timing the discussions introduces another challenge. "Physicians were prepared to discuss treatment-related consequences at the time of treatment, but patients did not want to hear it then because they were in life-and-death mode," she said.

In contrast, when patients felt ready to get this information, at the end of their treatment, "physicians weren’t prepared to discuss it for fear of frightening patients." But having some type of conversation on long-term prospects is very important, more critical than any of the individual tools, she said.

U.S. efforts still in process

This rollout puts U.K. cancer survivorship planning ahead of the United States and the rest of Europe. The U.S. National Cancer Institute (NCI) "has a research call out to test models for having that conversation with patient-centered goals," said Catherine Alfano, Ph.D., deputy director of survivorship research at the NCI in Bethesda, Md.

"How do you sit with a patient and family members and friends and talk about what just happened and what will happen in the future? Right now we don’t have a best model for this, but I think we owe it to survivors to identify best practices and get it to all of them, and make it patient centered, so it’s not just an oncologist who hands a piece of paper to the cancer patient and says this is what you need to do, because that won’t work. We need a conversation to take place where cancer patients are engaged in setting their survivorship care goals," Dr. Alfano said in an interview.

"We’re talking a lot right now about giving cancer survivors a treatment summary so they know what they received, and equally important a survivorship care plan that talks about what the patient needs to look out for, what providers they’ll see, how often, and how will their care be coordinated. This is implemented in very different ways throughout the U.S. right now. There is a mad rush to do it. What we want is for a conversation to take place so that cancer survivors are engaged in setting goals for their survivorship care," Dr. Alfano said.

Late last year, NCI researchers and their collaborators published results from a recent survey of more than 1,100 U.S. oncologists and more than 1,000 U.S. primary-care physicians about their practice regarding survivor care plans for their cancer patients (J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1579-87). These plans were used by about 20% of the surveyed oncologists and 13% of primary care physicians. Higher numbers reported giving patients treatment summaries at the end of their acute care, usual practice for half of the responding oncologists and about a third of the primary-care physicians.

Survivorship needs grow and diversify

Optimizing care for cancer survivors and better involving them in long-term surveillance and care has become increasingly important as the numbers continue to climb. "The number of cancer survivors is larger than ever, and as U.S. boomers become 65 years and older, there will be a tsunami of more cancer survivors, Dr. Alfano predicted.

"This huge tsunami [of cancer patients] is coming over the next decade, and we are completely unprepared. We have done a poor job of understanding the needs of adult cancer survivors," she warned. "There is a scramble underway now to understand what adult cancer survivors need."

For example, cardiovascular adverse effects from several different cancer treatments often occur many years after treatment. "Usually, these patients are not in surveillance anymore," said Dr. Thomas M. Suter of the Swiss Cardiovascular Center in Bern, Switzerland. "No one is looking at these patients. They need to be on medical treatment to improve their prognosis," such as treatment with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, he said in his talk at the meeting.

Another shortcoming of U.S. cancer survivor care is the fragmented care many patients receive and a glaring lack of coordination.

U.S. cancer survivors "wind up seeing multiple providers for late effects like cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, and diabetes, which is on top of their surveillance for a recurrence of their primary cancer or appearance of a second primary cancer," said Dr. Alfano. "We have to create a more coordinated form of care that is truly team based to make it easier for patients and relieve the huge burden on them and their families. I hear from cancer survivors and families all the time that it takes hours each week just to coordinate a cancer patient’s care. We need to ease this burden. We have done a poor job understanding the needs of adult cancer survivors."

An especially pressing need is for information on lifestyle change, said Dr. Alfano. "Cancer survivors are looking for things they can do personally to take control back over their morbidity and mortality."

Cancer patients are often highly motivated to take steps to cut their risk of treatment-related adverse outcomes, recurrence, or development of a second primary cancer. In 2012, the American Cancer Society issued nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors (CA Cancer J. Clin. 2012;62:30-67), noted Dr. Kevin D. Stein, managing director of the behavioral research center of the ACS in a talk at the meeting.

"We’ve done a poor job of getting lifestyle-change information to cancer survivors. We need to include lifestyle change as part of survivorship plans," said Dr. Alfano.

Despite the shortcomings in survivorship planning in the United States and United Kingdom, it outstrips what currently occurs in most of Europe. "We are far behind the United States," said Dr. Elizabeth Charlotte Moser, professor at the Champalimaud Foundation in Lisbon and chair of the EORTC Survivorship Task Force.

In addition to having Europe follow the United Kingdom and United States in expanding survivor planning, she anticipates a contribution from several European-based cancer-treatment trials for which long-term follow-up data are available. For example, six EORTC-sponsored trials in patients with either early-stage breast cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ together enrolled more than 20,000 patients starting in 1986. EORTC researchers are planning to collect long-term outcome data from as many of these patients as can be tracked down, Dr. Moser said.

Dr. Maher, Dr. Alfano, Dr. Stein, and Dr. Moser said they had no disclosures. Dr. Suter said that he has been a speaker on behalf of Roche, RoboPharma, and Novartis.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BRUSSELS – Cancer survivorship planning in the United Kingdom is ahead of the United States and the rest of Europe with the recent rollout of a model care plan for cancer patients, along with a guide for conversations between cancer-care health care providers and patients at the time they start long-term follow-up surveillance.

A care plan guides patients as they segue from acute cancer treatment to longer-term health maintenance and follow-up. The plan can include a personalized record of treatment received, prognosis, recommended follow-up examinations, symptoms to be alert for, and other critical information when patients transition to life as a cancer survivor.

The U.K.’s National Health System (NHS) first released a hard-copy version of a model care plan for cancer patients along with a guide for conversations with patients at the time they start long-term follow-up surveillance in 2012. Although the hard-copy form is available from the agency’s National Cancer Survivorship Initiative, the NHS continues to test the care plan and simultaneously is finalizing an electronic version planned for release next year, Dr. Jane Maher said at the first EORTC Cancer Survivorship Summit hosted by the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer.

"The paper version is freely available," while testing continues at 160 U.K. sites," said Dr. Maher, chief medical officer at Macmillan Cancer Support, London, and a clinical leader with the NHS.

"The first evaluation is done. Patients really liked it and found it helpful and it was possible to do, so it’s at the point where it can be spread, but key elements are still in evaluation until 2015," she said in an interview.

"We can now say that we have a tool to shape the conversation" between a cancer patient who has finished the initial phase of treatment and her care provider. "We have a framework for patient education, for treatment, and for review of their cancer care." Patients who have gone through this care-planning conversation "felt more controlled and that their care was more coordinated."

Prevailing attitudes about cancer management pose some of the biggest challenges in developing and implementing cancer plans, Dr. Maher said. "Cancer is seen as an acute illness that is managed acutely by specialists," she noted. Timing the discussions introduces another challenge. "Physicians were prepared to discuss treatment-related consequences at the time of treatment, but patients did not want to hear it then because they were in life-and-death mode," she said.

In contrast, when patients felt ready to get this information, at the end of their treatment, "physicians weren’t prepared to discuss it for fear of frightening patients." But having some type of conversation on long-term prospects is very important, more critical than any of the individual tools, she said.

U.S. efforts still in process

This rollout puts U.K. cancer survivorship planning ahead of the United States and the rest of Europe. The U.S. National Cancer Institute (NCI) "has a research call out to test models for having that conversation with patient-centered goals," said Catherine Alfano, Ph.D., deputy director of survivorship research at the NCI in Bethesda, Md.

"How do you sit with a patient and family members and friends and talk about what just happened and what will happen in the future? Right now we don’t have a best model for this, but I think we owe it to survivors to identify best practices and get it to all of them, and make it patient centered, so it’s not just an oncologist who hands a piece of paper to the cancer patient and says this is what you need to do, because that won’t work. We need a conversation to take place where cancer patients are engaged in setting their survivorship care goals," Dr. Alfano said in an interview.

"We’re talking a lot right now about giving cancer survivors a treatment summary so they know what they received, and equally important a survivorship care plan that talks about what the patient needs to look out for, what providers they’ll see, how often, and how will their care be coordinated. This is implemented in very different ways throughout the U.S. right now. There is a mad rush to do it. What we want is for a conversation to take place so that cancer survivors are engaged in setting goals for their survivorship care," Dr. Alfano said.

Late last year, NCI researchers and their collaborators published results from a recent survey of more than 1,100 U.S. oncologists and more than 1,000 U.S. primary-care physicians about their practice regarding survivor care plans for their cancer patients (J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1579-87). These plans were used by about 20% of the surveyed oncologists and 13% of primary care physicians. Higher numbers reported giving patients treatment summaries at the end of their acute care, usual practice for half of the responding oncologists and about a third of the primary-care physicians.

Survivorship needs grow and diversify

Optimizing care for cancer survivors and better involving them in long-term surveillance and care has become increasingly important as the numbers continue to climb. "The number of cancer survivors is larger than ever, and as U.S. boomers become 65 years and older, there will be a tsunami of more cancer survivors, Dr. Alfano predicted.

"This huge tsunami [of cancer patients] is coming over the next decade, and we are completely unprepared. We have done a poor job of understanding the needs of adult cancer survivors," she warned. "There is a scramble underway now to understand what adult cancer survivors need."

For example, cardiovascular adverse effects from several different cancer treatments often occur many years after treatment. "Usually, these patients are not in surveillance anymore," said Dr. Thomas M. Suter of the Swiss Cardiovascular Center in Bern, Switzerland. "No one is looking at these patients. They need to be on medical treatment to improve their prognosis," such as treatment with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, he said in his talk at the meeting.

Another shortcoming of U.S. cancer survivor care is the fragmented care many patients receive and a glaring lack of coordination.

U.S. cancer survivors "wind up seeing multiple providers for late effects like cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, and diabetes, which is on top of their surveillance for a recurrence of their primary cancer or appearance of a second primary cancer," said Dr. Alfano. "We have to create a more coordinated form of care that is truly team based to make it easier for patients and relieve the huge burden on them and their families. I hear from cancer survivors and families all the time that it takes hours each week just to coordinate a cancer patient’s care. We need to ease this burden. We have done a poor job understanding the needs of adult cancer survivors."

An especially pressing need is for information on lifestyle change, said Dr. Alfano. "Cancer survivors are looking for things they can do personally to take control back over their morbidity and mortality."

Cancer patients are often highly motivated to take steps to cut their risk of treatment-related adverse outcomes, recurrence, or development of a second primary cancer. In 2012, the American Cancer Society issued nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors (CA Cancer J. Clin. 2012;62:30-67), noted Dr. Kevin D. Stein, managing director of the behavioral research center of the ACS in a talk at the meeting.

"We’ve done a poor job of getting lifestyle-change information to cancer survivors. We need to include lifestyle change as part of survivorship plans," said Dr. Alfano.

Despite the shortcomings in survivorship planning in the United States and United Kingdom, it outstrips what currently occurs in most of Europe. "We are far behind the United States," said Dr. Elizabeth Charlotte Moser, professor at the Champalimaud Foundation in Lisbon and chair of the EORTC Survivorship Task Force.

In addition to having Europe follow the United Kingdom and United States in expanding survivor planning, she anticipates a contribution from several European-based cancer-treatment trials for which long-term follow-up data are available. For example, six EORTC-sponsored trials in patients with either early-stage breast cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ together enrolled more than 20,000 patients starting in 1986. EORTC researchers are planning to collect long-term outcome data from as many of these patients as can be tracked down, Dr. Moser said.

Dr. Maher, Dr. Alfano, Dr. Stein, and Dr. Moser said they had no disclosures. Dr. Suter said that he has been a speaker on behalf of Roche, RoboPharma, and Novartis.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE CANCER SURVIVORSHIP SUMMIT

Randomized trial of vitamin B6 for preventing hand-foot syndrome from capecitabine chemotherapy

Background Capecitabine is an oral fluoropyrimidine that is used to treat various malignancies. Hand-foot syndrome (HFS) is a dose-limiting toxicity of capecitabine that can limit the use of this agent in some patients. Some investigators have observed that pyridoxine (vitamin B6) can ameliorate HFS that is caused by capecitabine. We designed a prospective trial to determine if pyridoxine can prevent HFS in patients who receive capecitabine.

Methods In our double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, we randomly assigned eligible patients who were treated with capecitabine to receive either daily pyridoxine 100 mg or placebo along with their capecitabine-containing chemotherapy regimen. Patients were observed during the first 4 cycles of capecitabine treatment. The primary endpoint was the incidence and grade of HFS that occurred in both study arms.

Results Between 2008 and 2011, 77 patients were randomly assigned to receive either pyridoxine (n = 38) or placebo (n = 39). Dosages of capecitabine were equally matched between both arms of the study. HFS occurred after a median of 2 chemotherapy cycles in both groups. HFS developed in 10 of 38 (26%) patients in the pyridoxine group and in 8 of 39 (21%) patients in the placebo group (P = .547). Therefore, the risk of HFS was 5 percentage points higher in pyridoxine group (95% confdence interval [CI] for difference, –13 percentage points to +25 percentage points). Given our study results, a true beneft from pyridoxine can be excluded. No difference in HFS grades was observed.

Limitations Single-institution study.

Conclusion Prophylactic pyridoxine (vitamin B6), given concomitantly with capecitabine-containing chemotherapy, was not effective for the prevention of HFS.

*To read the full article, click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction.

Background Capecitabine is an oral fluoropyrimidine that is used to treat various malignancies. Hand-foot syndrome (HFS) is a dose-limiting toxicity of capecitabine that can limit the use of this agent in some patients. Some investigators have observed that pyridoxine (vitamin B6) can ameliorate HFS that is caused by capecitabine. We designed a prospective trial to determine if pyridoxine can prevent HFS in patients who receive capecitabine.

Methods In our double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, we randomly assigned eligible patients who were treated with capecitabine to receive either daily pyridoxine 100 mg or placebo along with their capecitabine-containing chemotherapy regimen. Patients were observed during the first 4 cycles of capecitabine treatment. The primary endpoint was the incidence and grade of HFS that occurred in both study arms.

Results Between 2008 and 2011, 77 patients were randomly assigned to receive either pyridoxine (n = 38) or placebo (n = 39). Dosages of capecitabine were equally matched between both arms of the study. HFS occurred after a median of 2 chemotherapy cycles in both groups. HFS developed in 10 of 38 (26%) patients in the pyridoxine group and in 8 of 39 (21%) patients in the placebo group (P = .547). Therefore, the risk of HFS was 5 percentage points higher in pyridoxine group (95% confdence interval [CI] for difference, –13 percentage points to +25 percentage points). Given our study results, a true beneft from pyridoxine can be excluded. No difference in HFS grades was observed.

Limitations Single-institution study.

Conclusion Prophylactic pyridoxine (vitamin B6), given concomitantly with capecitabine-containing chemotherapy, was not effective for the prevention of HFS.

*To read the full article, click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction.

Background Capecitabine is an oral fluoropyrimidine that is used to treat various malignancies. Hand-foot syndrome (HFS) is a dose-limiting toxicity of capecitabine that can limit the use of this agent in some patients. Some investigators have observed that pyridoxine (vitamin B6) can ameliorate HFS that is caused by capecitabine. We designed a prospective trial to determine if pyridoxine can prevent HFS in patients who receive capecitabine.

Methods In our double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, we randomly assigned eligible patients who were treated with capecitabine to receive either daily pyridoxine 100 mg or placebo along with their capecitabine-containing chemotherapy regimen. Patients were observed during the first 4 cycles of capecitabine treatment. The primary endpoint was the incidence and grade of HFS that occurred in both study arms.

Results Between 2008 and 2011, 77 patients were randomly assigned to receive either pyridoxine (n = 38) or placebo (n = 39). Dosages of capecitabine were equally matched between both arms of the study. HFS occurred after a median of 2 chemotherapy cycles in both groups. HFS developed in 10 of 38 (26%) patients in the pyridoxine group and in 8 of 39 (21%) patients in the placebo group (P = .547). Therefore, the risk of HFS was 5 percentage points higher in pyridoxine group (95% confdence interval [CI] for difference, –13 percentage points to +25 percentage points). Given our study results, a true beneft from pyridoxine can be excluded. No difference in HFS grades was observed.

Limitations Single-institution study.

Conclusion Prophylactic pyridoxine (vitamin B6), given concomitantly with capecitabine-containing chemotherapy, was not effective for the prevention of HFS.

*To read the full article, click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction.

Bridging the gap: a palliative care consultation service in a hematological malignancy–bone marrow transplant unit

Background There is often a lack of collaboration between hematological malignancy–bone marrow transplantation (HM-BMT) units and palliative care (PC) services. In this paper, we describe a quality improvement project that sought to close this gap at a tertiary care hospital in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, from August 2006 to May 2010.

Design and methods Through a needs assessment, didactic lectures, clinical consultation, and the informal presence of PC clinicians, the team created a palliative care service in HM-BMT unit of the Western Pennsylvania Hospital in Pittsburgh. The following data were collected for each consult: referral reason, daily pain assessments, whether or not a “goals of care” conversation took place, and hospice enrollment. Lastly, satisfaction surveys were administered.

Results During the program, 392 PC consultations were provided to 256 unique patients. Of these 256 patients, the PC clinicians documented the first goals of care conversations in 67% of patients (n = 172). Of the 278 consults referred for pain, 70% (n = 194) involved reports of unacceptable or very unacceptable pain at baseline. Sixty-six percent (n = 129) of these 194 consults involved reports of pain that was acceptable or very acceptable within 48 hours of consultation. In addition, the hospice referral rate grew from a pre-implementation rate of 5% to 41% (n = 67) of 165 patients who died during the period of program implementation. Lastly, hematological oncologists reported high levels of satisfaction with the program.

Limitations The main limitation of this project is that it was a single institution study.

Conclusion The successful integration of a PC team into a hematological malignancy unit suggests great potential for positive interdisciplinary collaboration between these two fields.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Background There is often a lack of collaboration between hematological malignancy–bone marrow transplantation (HM-BMT) units and palliative care (PC) services. In this paper, we describe a quality improvement project that sought to close this gap at a tertiary care hospital in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, from August 2006 to May 2010.

Design and methods Through a needs assessment, didactic lectures, clinical consultation, and the informal presence of PC clinicians, the team created a palliative care service in HM-BMT unit of the Western Pennsylvania Hospital in Pittsburgh. The following data were collected for each consult: referral reason, daily pain assessments, whether or not a “goals of care” conversation took place, and hospice enrollment. Lastly, satisfaction surveys were administered.

Results During the program, 392 PC consultations were provided to 256 unique patients. Of these 256 patients, the PC clinicians documented the first goals of care conversations in 67% of patients (n = 172). Of the 278 consults referred for pain, 70% (n = 194) involved reports of unacceptable or very unacceptable pain at baseline. Sixty-six percent (n = 129) of these 194 consults involved reports of pain that was acceptable or very acceptable within 48 hours of consultation. In addition, the hospice referral rate grew from a pre-implementation rate of 5% to 41% (n = 67) of 165 patients who died during the period of program implementation. Lastly, hematological oncologists reported high levels of satisfaction with the program.

Limitations The main limitation of this project is that it was a single institution study.

Conclusion The successful integration of a PC team into a hematological malignancy unit suggests great potential for positive interdisciplinary collaboration between these two fields.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Background There is often a lack of collaboration between hematological malignancy–bone marrow transplantation (HM-BMT) units and palliative care (PC) services. In this paper, we describe a quality improvement project that sought to close this gap at a tertiary care hospital in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, from August 2006 to May 2010.

Design and methods Through a needs assessment, didactic lectures, clinical consultation, and the informal presence of PC clinicians, the team created a palliative care service in HM-BMT unit of the Western Pennsylvania Hospital in Pittsburgh. The following data were collected for each consult: referral reason, daily pain assessments, whether or not a “goals of care” conversation took place, and hospice enrollment. Lastly, satisfaction surveys were administered.

Results During the program, 392 PC consultations were provided to 256 unique patients. Of these 256 patients, the PC clinicians documented the first goals of care conversations in 67% of patients (n = 172). Of the 278 consults referred for pain, 70% (n = 194) involved reports of unacceptable or very unacceptable pain at baseline. Sixty-six percent (n = 129) of these 194 consults involved reports of pain that was acceptable or very acceptable within 48 hours of consultation. In addition, the hospice referral rate grew from a pre-implementation rate of 5% to 41% (n = 67) of 165 patients who died during the period of program implementation. Lastly, hematological oncologists reported high levels of satisfaction with the program.

Limitations The main limitation of this project is that it was a single institution study.

Conclusion The successful integration of a PC team into a hematological malignancy unit suggests great potential for positive interdisciplinary collaboration between these two fields.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Your voice on our pages

As practicing oncologists, we know the importance of having a professional support system in place, platforms that allow us to dissect and discuss all aspects of our work, from diagnosis to therapy decisions, that rare case presentation, supportive and palliative care, maintenance therapy, and yes, practice management, the impact of health reform, the dreaded EMRs, and much more. Such exchanges, whether they take the form of routine roundtable meetings, conference calls, or tumor boards and whether they are in-person or online, are crucial in shaping how we practice our specialty at both the individual and collective levels.

As practicing oncologists, we know the importance of having a professional support system in place, platforms that allow us to dissect and discuss all aspects of our work, from diagnosis to therapy decisions, that rare case presentation, supportive and palliative care, maintenance therapy, and yes, practice management, the impact of health reform, the dreaded EMRs, and much more. Such exchanges, whether they take the form of routine roundtable meetings, conference calls, or tumor boards and whether they are in-person or online, are crucial in shaping how we practice our specialty at both the individual and collective levels.

As practicing oncologists, we know the importance of having a professional support system in place, platforms that allow us to dissect and discuss all aspects of our work, from diagnosis to therapy decisions, that rare case presentation, supportive and palliative care, maintenance therapy, and yes, practice management, the impact of health reform, the dreaded EMRs, and much more. Such exchanges, whether they take the form of routine roundtable meetings, conference calls, or tumor boards and whether they are in-person or online, are crucial in shaping how we practice our specialty at both the individual and collective levels.

Implementing inpatient, evidence-based, antihistamine-transfusion premedication guidelines at a single academic US hospital

Allergic transfusion reactions (ATRs) are a common complication of blood transfusions. Advances in transfusion medicine have significantly decreased the incidence of ATRs; however, ATRs continue to be burdensome for patients and problematic for providers who regularly order packed red blood cells and platelet transfusions. To further decrease the frequency of ATRs, routine premedication with diphenhydramine is common practice and is part of “transfusion culture” in a majority of institutions. In this article, we review the history, practice, and literature of transfusion premedication, specifically antihistamines given the adverse-effect profile. We discuss the rationale and original academic studies, which have supported the use of premedication for transfusions for decades.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Allergic transfusion reactions (ATRs) are a common complication of blood transfusions. Advances in transfusion medicine have significantly decreased the incidence of ATRs; however, ATRs continue to be burdensome for patients and problematic for providers who regularly order packed red blood cells and platelet transfusions. To further decrease the frequency of ATRs, routine premedication with diphenhydramine is common practice and is part of “transfusion culture” in a majority of institutions. In this article, we review the history, practice, and literature of transfusion premedication, specifically antihistamines given the adverse-effect profile. We discuss the rationale and original academic studies, which have supported the use of premedication for transfusions for decades.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Allergic transfusion reactions (ATRs) are a common complication of blood transfusions. Advances in transfusion medicine have significantly decreased the incidence of ATRs; however, ATRs continue to be burdensome for patients and problematic for providers who regularly order packed red blood cells and platelet transfusions. To further decrease the frequency of ATRs, routine premedication with diphenhydramine is common practice and is part of “transfusion culture” in a majority of institutions. In this article, we review the history, practice, and literature of transfusion premedication, specifically antihistamines given the adverse-effect profile. We discuss the rationale and original academic studies, which have supported the use of premedication for transfusions for decades.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

ICD-10 price tag going up for doctors

Making the switch from the ICD-9 to the ICD-10 diagnosis code set could cost as much as $225,000 for some small practices and up to $8 million in some large practices, according to a study from the American Medical Association.

Physician offices and hospitals must use the ICD-10 code sets beginning Oct. 1, but the preparation for the switch is taking years and involves hours of staff training, the purchase of new hardware and software, and testing with vendors and payers.

A follow-up report prepared for the AMA by Nachimson Advisors found that in certain cases, implementation costs are nearly three times higher than what the firm predicted in 2008.

In their original report, Nachimson Advisors estimated that it would cost more than $83,000 for a typical small practice (3 physicians, 2 administrative staff) to implement ICD-10, rising to $285,000 for a typical medium-size practice (10 physicians, 1 full-time coder, 6 administrative staff), and about $2.7 million for a typical large practice (100 physicians, 10 full-time coders, 64 administrative staff).

Now those costs are estimated to range from $56,000 to $226,000 for small practices and $213,000 to $824,000 for medium-size practices. And for large practices, implementing ICD-10 could cost anywhere from $2 million to $8 million.

About two-thirds of physician practices are expected to have costs in the upper range of those estimates, according to the AMA.

One reason for the increased cost is new requirements related to the adoption of electronic health records (EHRs). Nachimson Advisors also projects a larger potential for payment disruptions, estimating that 2%-6% of claims could be denied after the Oct. 1 implementation date.

"The markedly higher implementation costs for ICD-10 place a crushing burden on physicians, straining vital resources needed to invest in new health care delivery models and well-developed technology that promotes care coordination with real value to patients," Dr. Ardis Dee Hoven, AMA president, said in a statement. "Continuing to compel physicians to adopt this new coding structure threatens to disrupt innovations by diverting resources away from areas that are expected to help lower costs and improve the quality of care."

The AMA is calling on Health & Human Services secretary Kathleen Sebelius to reconsider ICD-10 implementation. But if the agency sticks to its plan, the AMA has requested several changes to mitigate some of the costs.

For example, the AMA recommends that Medicare provide a 2-year implementation period during which the agency would not be allowed to deny payments based on the specificity of the ICD-10 code provided. And the agency would provide feedback on coding to physicians during this time.

The AMA also is asking Medicare to simplify its claims requirements by adopting a policy that when the most specific ICD-10 code is used, no additional information or attachments will be required before paying the claim.

On Twitter @maryellenny

Making the switch from the ICD-9 to the ICD-10 diagnosis code set could cost as much as $225,000 for some small practices and up to $8 million in some large practices, according to a study from the American Medical Association.

Physician offices and hospitals must use the ICD-10 code sets beginning Oct. 1, but the preparation for the switch is taking years and involves hours of staff training, the purchase of new hardware and software, and testing with vendors and payers.

A follow-up report prepared for the AMA by Nachimson Advisors found that in certain cases, implementation costs are nearly three times higher than what the firm predicted in 2008.

In their original report, Nachimson Advisors estimated that it would cost more than $83,000 for a typical small practice (3 physicians, 2 administrative staff) to implement ICD-10, rising to $285,000 for a typical medium-size practice (10 physicians, 1 full-time coder, 6 administrative staff), and about $2.7 million for a typical large practice (100 physicians, 10 full-time coders, 64 administrative staff).

Now those costs are estimated to range from $56,000 to $226,000 for small practices and $213,000 to $824,000 for medium-size practices. And for large practices, implementing ICD-10 could cost anywhere from $2 million to $8 million.

About two-thirds of physician practices are expected to have costs in the upper range of those estimates, according to the AMA.

One reason for the increased cost is new requirements related to the adoption of electronic health records (EHRs). Nachimson Advisors also projects a larger potential for payment disruptions, estimating that 2%-6% of claims could be denied after the Oct. 1 implementation date.

"The markedly higher implementation costs for ICD-10 place a crushing burden on physicians, straining vital resources needed to invest in new health care delivery models and well-developed technology that promotes care coordination with real value to patients," Dr. Ardis Dee Hoven, AMA president, said in a statement. "Continuing to compel physicians to adopt this new coding structure threatens to disrupt innovations by diverting resources away from areas that are expected to help lower costs and improve the quality of care."

The AMA is calling on Health & Human Services secretary Kathleen Sebelius to reconsider ICD-10 implementation. But if the agency sticks to its plan, the AMA has requested several changes to mitigate some of the costs.

For example, the AMA recommends that Medicare provide a 2-year implementation period during which the agency would not be allowed to deny payments based on the specificity of the ICD-10 code provided. And the agency would provide feedback on coding to physicians during this time.

The AMA also is asking Medicare to simplify its claims requirements by adopting a policy that when the most specific ICD-10 code is used, no additional information or attachments will be required before paying the claim.

On Twitter @maryellenny

Making the switch from the ICD-9 to the ICD-10 diagnosis code set could cost as much as $225,000 for some small practices and up to $8 million in some large practices, according to a study from the American Medical Association.

Physician offices and hospitals must use the ICD-10 code sets beginning Oct. 1, but the preparation for the switch is taking years and involves hours of staff training, the purchase of new hardware and software, and testing with vendors and payers.

A follow-up report prepared for the AMA by Nachimson Advisors found that in certain cases, implementation costs are nearly three times higher than what the firm predicted in 2008.

In their original report, Nachimson Advisors estimated that it would cost more than $83,000 for a typical small practice (3 physicians, 2 administrative staff) to implement ICD-10, rising to $285,000 for a typical medium-size practice (10 physicians, 1 full-time coder, 6 administrative staff), and about $2.7 million for a typical large practice (100 physicians, 10 full-time coders, 64 administrative staff).

Now those costs are estimated to range from $56,000 to $226,000 for small practices and $213,000 to $824,000 for medium-size practices. And for large practices, implementing ICD-10 could cost anywhere from $2 million to $8 million.

About two-thirds of physician practices are expected to have costs in the upper range of those estimates, according to the AMA.

One reason for the increased cost is new requirements related to the adoption of electronic health records (EHRs). Nachimson Advisors also projects a larger potential for payment disruptions, estimating that 2%-6% of claims could be denied after the Oct. 1 implementation date.

"The markedly higher implementation costs for ICD-10 place a crushing burden on physicians, straining vital resources needed to invest in new health care delivery models and well-developed technology that promotes care coordination with real value to patients," Dr. Ardis Dee Hoven, AMA president, said in a statement. "Continuing to compel physicians to adopt this new coding structure threatens to disrupt innovations by diverting resources away from areas that are expected to help lower costs and improve the quality of care."

The AMA is calling on Health & Human Services secretary Kathleen Sebelius to reconsider ICD-10 implementation. But if the agency sticks to its plan, the AMA has requested several changes to mitigate some of the costs.

For example, the AMA recommends that Medicare provide a 2-year implementation period during which the agency would not be allowed to deny payments based on the specificity of the ICD-10 code provided. And the agency would provide feedback on coding to physicians during this time.

The AMA also is asking Medicare to simplify its claims requirements by adopting a policy that when the most specific ICD-10 code is used, no additional information or attachments will be required before paying the claim.

On Twitter @maryellenny

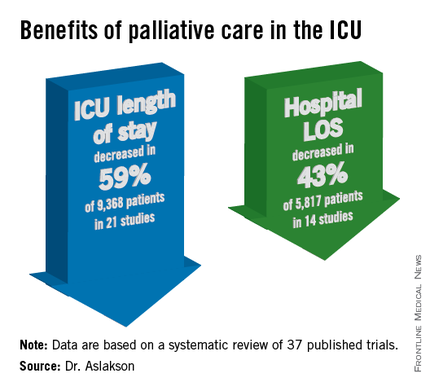

Palliative care shortens ICU, hospital stays, review data show

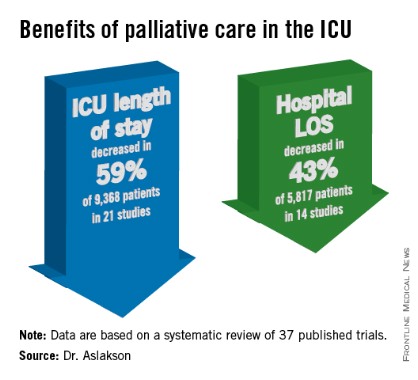

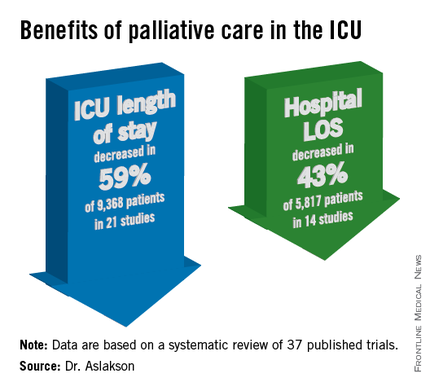

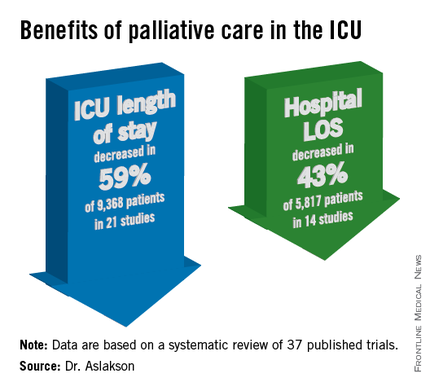

SAN FRANCISCO – Palliative care in the intensive care unit reduces the length of stay in the ICU and the hospital without changing mortality rates or family satisfaction, according to a review of the literature.

Although measurements of family satisfaction overall didn’t change much from palliative care of a loved one in the ICU, some measures of components of satisfaction increased with palliative care, such as improved communication with the physician, better consensus around the goals of care, and decreased anxiety and depression in family members, reported Dr. Rebecca A. Aslakson of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

The findings have been submitted for publication, she said at the Critical Care Congress, sponsored by the Society for Critical Care Medicine.

Dr. Aslakson and her associates were unable to perform a formal meta-analysis of the 37 published trials of palliative care in the ICU because of the heterogeneity of the studies, which looked at more than 40 different outcomes. Instead, their systematic review grouped results under four outcomes that commonly were measured, and assessed those either by the number of studies or by the number of patients studied.

ICU length of stay decreased with palliative care in 13 of 21 studies (62%) that used this outcome and in 59% of 9,368 patients in those studies. Hospital length of stay decreased with palliative care in 8 of 14 studies (57%) and in 43% of 5,817 patients. Family satisfaction did not decrease in any studies or families and increased in only 1 of 14 studies (7%) and in 2% of families of 4,927 patients, Dr. Aslakson reported.

Mortality rates did not change with palliative care in 14 of 16 studies (88%) that assessed mortality and in 57% of 5,969 patients in those studies. Mortality increased in one small study (6%) and decreased in one larger study (6%).

"Talking about big-picture issues and goals of care doesn’t lead to people dying," Dr. Aslakson said. "No harm came in any of these studies." Some separate studies of palliative care outside of ICUs reported that this increases hope, "because people feel that they have more control over their choices and what’s happening to their loved ones," she added.

Integrative vs. consultative model

Dr. Aslakson and her associates also reviewed studies based on whether the interventions used integrative or consultative models of palliative care.

Generally, consultative models bring outsiders into the ICU to help provide palliative care, and integrative models train the ICU team to be the palliative care providers. In reality, the two models may overlap. For this review, the investigators applied mutually exclusive definitions to 36 of the studies. In 18 studies of integrative interventions, members of the ICU team were the only caregivers in face-to-face interactions with the patient and families. In 18 studies of consultative interventions, palliative care providers included others besides the ICU team.

In the studies of integrative palliative care, ICU length of stay decreased with palliative care in four of nine studies (44%) that measured this outcome and in 52% of 6,963 patients in those studies, she reported. Hospital length of stay decreased in two of five studies (40%) and in 24% of 3,812 patients. Family satisfaction changed in none of 15 studies, and mortality decreased in 1 of 5 studies (20%) and in 34% of 3,807 patients.

In the studies of consultative care, ICU length of stay decreased with palliative care in 9 of 12 studies (75%) that measured this outcome and in 79% of 2,405 patients in those studies. Hospital length of stay decreased in six of nine studies (67%) and in 79% of 2,005 patients. Family satisfaction increased in one of four studies (25%) and in 21% of 429 patients. Mortality increased in 1 of 11 studies (9%) and in 5% of 2,162 patients.

One model isn’t necessarily better than the other, Dr. Aslakson said. Integrative palliative care may work best in a closed ICU with perhaps four or five intensivists in a relatively small unit. An integrative approach can be much more difficult in open or semiopen ICUs that have "40 different doctors floating around," she said. "We tried that in my unit, and it didn’t work that well."

Different ICUs need palliative care models that fit them. "Look at your unit, the way it works, and who the providers are, then look at the literature and see what matches that and what might work for your unit," she said.

Outcomes of improved communication

A previous, separate review of the medical literature identified 21 controlled trials of 16 interventions to improve communication in ICUs between families and care providers. Overall, the interventions improved emotional outcomes for families and reduced ICU length of stay and treatment intensity (Chest 2011;139:543-54), she noted.

Yet another prior review of the literature reported that interventions to promote family meetings, use empathetic communication skills, and employ palliative care consultations improved family satisfaction and reduced ICU length of stay and the adverse effects of family bereavement (Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2009;15:569-77).

Dr. Aslakson reported having no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN FRANCISCO – Palliative care in the intensive care unit reduces the length of stay in the ICU and the hospital without changing mortality rates or family satisfaction, according to a review of the literature.

Although measurements of family satisfaction overall didn’t change much from palliative care of a loved one in the ICU, some measures of components of satisfaction increased with palliative care, such as improved communication with the physician, better consensus around the goals of care, and decreased anxiety and depression in family members, reported Dr. Rebecca A. Aslakson of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

The findings have been submitted for publication, she said at the Critical Care Congress, sponsored by the Society for Critical Care Medicine.

Dr. Aslakson and her associates were unable to perform a formal meta-analysis of the 37 published trials of palliative care in the ICU because of the heterogeneity of the studies, which looked at more than 40 different outcomes. Instead, their systematic review grouped results under four outcomes that commonly were measured, and assessed those either by the number of studies or by the number of patients studied.

ICU length of stay decreased with palliative care in 13 of 21 studies (62%) that used this outcome and in 59% of 9,368 patients in those studies. Hospital length of stay decreased with palliative care in 8 of 14 studies (57%) and in 43% of 5,817 patients. Family satisfaction did not decrease in any studies or families and increased in only 1 of 14 studies (7%) and in 2% of families of 4,927 patients, Dr. Aslakson reported.

Mortality rates did not change with palliative care in 14 of 16 studies (88%) that assessed mortality and in 57% of 5,969 patients in those studies. Mortality increased in one small study (6%) and decreased in one larger study (6%).

"Talking about big-picture issues and goals of care doesn’t lead to people dying," Dr. Aslakson said. "No harm came in any of these studies." Some separate studies of palliative care outside of ICUs reported that this increases hope, "because people feel that they have more control over their choices and what’s happening to their loved ones," she added.

Integrative vs. consultative model

Dr. Aslakson and her associates also reviewed studies based on whether the interventions used integrative or consultative models of palliative care.

Generally, consultative models bring outsiders into the ICU to help provide palliative care, and integrative models train the ICU team to be the palliative care providers. In reality, the two models may overlap. For this review, the investigators applied mutually exclusive definitions to 36 of the studies. In 18 studies of integrative interventions, members of the ICU team were the only caregivers in face-to-face interactions with the patient and families. In 18 studies of consultative interventions, palliative care providers included others besides the ICU team.

In the studies of integrative palliative care, ICU length of stay decreased with palliative care in four of nine studies (44%) that measured this outcome and in 52% of 6,963 patients in those studies, she reported. Hospital length of stay decreased in two of five studies (40%) and in 24% of 3,812 patients. Family satisfaction changed in none of 15 studies, and mortality decreased in 1 of 5 studies (20%) and in 34% of 3,807 patients.

In the studies of consultative care, ICU length of stay decreased with palliative care in 9 of 12 studies (75%) that measured this outcome and in 79% of 2,405 patients in those studies. Hospital length of stay decreased in six of nine studies (67%) and in 79% of 2,005 patients. Family satisfaction increased in one of four studies (25%) and in 21% of 429 patients. Mortality increased in 1 of 11 studies (9%) and in 5% of 2,162 patients.

One model isn’t necessarily better than the other, Dr. Aslakson said. Integrative palliative care may work best in a closed ICU with perhaps four or five intensivists in a relatively small unit. An integrative approach can be much more difficult in open or semiopen ICUs that have "40 different doctors floating around," she said. "We tried that in my unit, and it didn’t work that well."

Different ICUs need palliative care models that fit them. "Look at your unit, the way it works, and who the providers are, then look at the literature and see what matches that and what might work for your unit," she said.

Outcomes of improved communication

A previous, separate review of the medical literature identified 21 controlled trials of 16 interventions to improve communication in ICUs between families and care providers. Overall, the interventions improved emotional outcomes for families and reduced ICU length of stay and treatment intensity (Chest 2011;139:543-54), she noted.

Yet another prior review of the literature reported that interventions to promote family meetings, use empathetic communication skills, and employ palliative care consultations improved family satisfaction and reduced ICU length of stay and the adverse effects of family bereavement (Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2009;15:569-77).

Dr. Aslakson reported having no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN FRANCISCO – Palliative care in the intensive care unit reduces the length of stay in the ICU and the hospital without changing mortality rates or family satisfaction, according to a review of the literature.

Although measurements of family satisfaction overall didn’t change much from palliative care of a loved one in the ICU, some measures of components of satisfaction increased with palliative care, such as improved communication with the physician, better consensus around the goals of care, and decreased anxiety and depression in family members, reported Dr. Rebecca A. Aslakson of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

The findings have been submitted for publication, she said at the Critical Care Congress, sponsored by the Society for Critical Care Medicine.

Dr. Aslakson and her associates were unable to perform a formal meta-analysis of the 37 published trials of palliative care in the ICU because of the heterogeneity of the studies, which looked at more than 40 different outcomes. Instead, their systematic review grouped results under four outcomes that commonly were measured, and assessed those either by the number of studies or by the number of patients studied.

ICU length of stay decreased with palliative care in 13 of 21 studies (62%) that used this outcome and in 59% of 9,368 patients in those studies. Hospital length of stay decreased with palliative care in 8 of 14 studies (57%) and in 43% of 5,817 patients. Family satisfaction did not decrease in any studies or families and increased in only 1 of 14 studies (7%) and in 2% of families of 4,927 patients, Dr. Aslakson reported.

Mortality rates did not change with palliative care in 14 of 16 studies (88%) that assessed mortality and in 57% of 5,969 patients in those studies. Mortality increased in one small study (6%) and decreased in one larger study (6%).

"Talking about big-picture issues and goals of care doesn’t lead to people dying," Dr. Aslakson said. "No harm came in any of these studies." Some separate studies of palliative care outside of ICUs reported that this increases hope, "because people feel that they have more control over their choices and what’s happening to their loved ones," she added.

Integrative vs. consultative model

Dr. Aslakson and her associates also reviewed studies based on whether the interventions used integrative or consultative models of palliative care.

Generally, consultative models bring outsiders into the ICU to help provide palliative care, and integrative models train the ICU team to be the palliative care providers. In reality, the two models may overlap. For this review, the investigators applied mutually exclusive definitions to 36 of the studies. In 18 studies of integrative interventions, members of the ICU team were the only caregivers in face-to-face interactions with the patient and families. In 18 studies of consultative interventions, palliative care providers included others besides the ICU team.

In the studies of integrative palliative care, ICU length of stay decreased with palliative care in four of nine studies (44%) that measured this outcome and in 52% of 6,963 patients in those studies, she reported. Hospital length of stay decreased in two of five studies (40%) and in 24% of 3,812 patients. Family satisfaction changed in none of 15 studies, and mortality decreased in 1 of 5 studies (20%) and in 34% of 3,807 patients.