User login

Recurrent leg lesions

Tender erythematous nodules or plaques on the extensor surfaces—usually on the legs and occasionally on the arms—are the hallmarks for erythema nodosum, which was diagnosed in this case. It typically occurs in young women, ages 15 to 30, and the nodules or plaques are often accompanied by prodromal fever and malaise. The lesions often are painful and tender to pressure or palpation; they are thought to be caused by a reaction to a stimulus, leading to inflammation of the septa in the subcutaneous fat. While the trigger is often unknown, in some cases, an underlying infection, particularly Streptococcus or tuberculosis (TB), is identified. Sarcoidosis, malignancy, or an increase in estrogen (exogenous or endogenous) also can provoke the disorder.

Due to the risk of underlying disease or triggers, it is prudent to perform radiography of the chest, as well as obtain a complete blood count, sedimentation rate or C reactive protein, and an antistreptolysin O titer when you suspect erythema nodosum. TB testing is also advised. Biopsy typically is not performed because the diagnosis usually is made clinically. If the diagnosis is in doubt, a biopsy can offer confirmation or lead to a different diagnosis such as vasculitis—especially if the lesions are eroded. Since erythema nodosum is an inflammation of the subcutaneous fat, it is important to sample skin lesions deeper than the usual punch biopsy; an incisional biopsy may be required to get an adequate sample.

Erythema nodosum typically resolves spontaneously over a period of weeks, even if there is underlying disease. Therefore, it may be possible to defer treatment if minimal symptoms are present. Otherwise, first-line treatment for the pain and malaise is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). Oral potassium iodide (360-900 mg/d) is considered second-line treatment and systemic corticosteroids are a third-line option.

For this patient, biopsy was deferred and diagnostic tests were all negative. She had notable pain and a history of good resolution of symptoms with prednisone (5 mg/d), so this drug was prescribed for a 7-day course. She was counseled to avoid taking the NSAIDs and prednisone together due to increased risk of gastritis and ulceration. Recurrent disease can be treated with dapsone (100 mg/d) or hydroxychloroquine (200 mg bid).

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Blake T, Manahan M, Rodins K. Erythema nodosum - a review of an uncommon panniculitis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:22376.

Tender erythematous nodules or plaques on the extensor surfaces—usually on the legs and occasionally on the arms—are the hallmarks for erythema nodosum, which was diagnosed in this case. It typically occurs in young women, ages 15 to 30, and the nodules or plaques are often accompanied by prodromal fever and malaise. The lesions often are painful and tender to pressure or palpation; they are thought to be caused by a reaction to a stimulus, leading to inflammation of the septa in the subcutaneous fat. While the trigger is often unknown, in some cases, an underlying infection, particularly Streptococcus or tuberculosis (TB), is identified. Sarcoidosis, malignancy, or an increase in estrogen (exogenous or endogenous) also can provoke the disorder.

Due to the risk of underlying disease or triggers, it is prudent to perform radiography of the chest, as well as obtain a complete blood count, sedimentation rate or C reactive protein, and an antistreptolysin O titer when you suspect erythema nodosum. TB testing is also advised. Biopsy typically is not performed because the diagnosis usually is made clinically. If the diagnosis is in doubt, a biopsy can offer confirmation or lead to a different diagnosis such as vasculitis—especially if the lesions are eroded. Since erythema nodosum is an inflammation of the subcutaneous fat, it is important to sample skin lesions deeper than the usual punch biopsy; an incisional biopsy may be required to get an adequate sample.

Erythema nodosum typically resolves spontaneously over a period of weeks, even if there is underlying disease. Therefore, it may be possible to defer treatment if minimal symptoms are present. Otherwise, first-line treatment for the pain and malaise is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). Oral potassium iodide (360-900 mg/d) is considered second-line treatment and systemic corticosteroids are a third-line option.

For this patient, biopsy was deferred and diagnostic tests were all negative. She had notable pain and a history of good resolution of symptoms with prednisone (5 mg/d), so this drug was prescribed for a 7-day course. She was counseled to avoid taking the NSAIDs and prednisone together due to increased risk of gastritis and ulceration. Recurrent disease can be treated with dapsone (100 mg/d) or hydroxychloroquine (200 mg bid).

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Tender erythematous nodules or plaques on the extensor surfaces—usually on the legs and occasionally on the arms—are the hallmarks for erythema nodosum, which was diagnosed in this case. It typically occurs in young women, ages 15 to 30, and the nodules or plaques are often accompanied by prodromal fever and malaise. The lesions often are painful and tender to pressure or palpation; they are thought to be caused by a reaction to a stimulus, leading to inflammation of the septa in the subcutaneous fat. While the trigger is often unknown, in some cases, an underlying infection, particularly Streptococcus or tuberculosis (TB), is identified. Sarcoidosis, malignancy, or an increase in estrogen (exogenous or endogenous) also can provoke the disorder.

Due to the risk of underlying disease or triggers, it is prudent to perform radiography of the chest, as well as obtain a complete blood count, sedimentation rate or C reactive protein, and an antistreptolysin O titer when you suspect erythema nodosum. TB testing is also advised. Biopsy typically is not performed because the diagnosis usually is made clinically. If the diagnosis is in doubt, a biopsy can offer confirmation or lead to a different diagnosis such as vasculitis—especially if the lesions are eroded. Since erythema nodosum is an inflammation of the subcutaneous fat, it is important to sample skin lesions deeper than the usual punch biopsy; an incisional biopsy may be required to get an adequate sample.

Erythema nodosum typically resolves spontaneously over a period of weeks, even if there is underlying disease. Therefore, it may be possible to defer treatment if minimal symptoms are present. Otherwise, first-line treatment for the pain and malaise is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). Oral potassium iodide (360-900 mg/d) is considered second-line treatment and systemic corticosteroids are a third-line option.

For this patient, biopsy was deferred and diagnostic tests were all negative. She had notable pain and a history of good resolution of symptoms with prednisone (5 mg/d), so this drug was prescribed for a 7-day course. She was counseled to avoid taking the NSAIDs and prednisone together due to increased risk of gastritis and ulceration. Recurrent disease can be treated with dapsone (100 mg/d) or hydroxychloroquine (200 mg bid).

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Blake T, Manahan M, Rodins K. Erythema nodosum - a review of an uncommon panniculitis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:22376.

Blake T, Manahan M, Rodins K. Erythema nodosum - a review of an uncommon panniculitis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:22376.

FDA orders stronger warnings on benzodiazepines

The Food and Drug Administration wants updated boxed warnings on benzodiazepines to reflect the “serious” risks of abuse, misuse, addiction, physical dependence, and withdrawal reactions associated with these medications.

“The current prescribing information for benzodiazepines does not provide adequate warnings about these serious risks and harms associated with these medicines so they may be prescribed and used inappropriately,” the FDA said in a safety communication.

The FDA also wants revisions to the patient medication guides for benzodiazepines to help educate patients and caregivers about these risks.

“While benzodiazepines are important therapies for many Americans, they are also commonly abused and misused, often together with opioid pain relievers and other medicines, alcohol, and illicit drugs,” FDA Commissioner Stephen M. Hahn, MD, said in a statement.

“We are taking measures and requiring new labeling information to help health care professionals and patients better understand that, while benzodiazepines have many treatment benefits, they also carry with them an increased risk of abuse, misuse, addiction, and dependence,” said Dr. Hahn.

Ninety-two million prescriptions in 2019

Benzodiazepines are widely used to treat anxiety, insomnia, seizures, and other conditions, often for extended periods of time.

According to the FDA, in 2019, an estimated 92 million benzodiazepine prescriptions were dispensed from U.S. outpatient pharmacies, most commonly alprazolam, clonazepam, and lorazepam.

Data from 2018 show that roughly 5.4 million people in the United States 12 years and older abused or misused benzodiazepines in the previous year.

Although the precise risk of benzodiazepine addiction remains unclear, population data “clearly indicate that both primary benzodiazepine use disorders and polysubstance addiction involving benzodiazepines do occur,” the FDA said.

Data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health from 2015-2016 suggest that half million community-dwelling U.S. adults were estimated to have a benzodiazepine use disorder.

Jump in overdose deaths

Overdose deaths involving benzodiazepines jumped from 1,298 in 2010 to 11,537 in 2017 – an increase of more 780%. Most of these deaths involved benzodiazepines taken with prescription opioids.

the FDA said.

The agency urged particular caution when prescribing benzodiazepines with opioids and other central nervous system depressants, which has resulted in serious adverse events including severe respiratory depression and death.

The FDA also says patients and caregivers should be warned about the risks of abuse, misuse, addiction, dependence, and withdrawal with benzodiazepines and the associated signs and symptoms.

Physicians are encouraged to report adverse events involving benzodiazepines or other medicines to the FDA’s MedWatch program.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration wants updated boxed warnings on benzodiazepines to reflect the “serious” risks of abuse, misuse, addiction, physical dependence, and withdrawal reactions associated with these medications.

“The current prescribing information for benzodiazepines does not provide adequate warnings about these serious risks and harms associated with these medicines so they may be prescribed and used inappropriately,” the FDA said in a safety communication.

The FDA also wants revisions to the patient medication guides for benzodiazepines to help educate patients and caregivers about these risks.

“While benzodiazepines are important therapies for many Americans, they are also commonly abused and misused, often together with opioid pain relievers and other medicines, alcohol, and illicit drugs,” FDA Commissioner Stephen M. Hahn, MD, said in a statement.

“We are taking measures and requiring new labeling information to help health care professionals and patients better understand that, while benzodiazepines have many treatment benefits, they also carry with them an increased risk of abuse, misuse, addiction, and dependence,” said Dr. Hahn.

Ninety-two million prescriptions in 2019

Benzodiazepines are widely used to treat anxiety, insomnia, seizures, and other conditions, often for extended periods of time.

According to the FDA, in 2019, an estimated 92 million benzodiazepine prescriptions were dispensed from U.S. outpatient pharmacies, most commonly alprazolam, clonazepam, and lorazepam.

Data from 2018 show that roughly 5.4 million people in the United States 12 years and older abused or misused benzodiazepines in the previous year.

Although the precise risk of benzodiazepine addiction remains unclear, population data “clearly indicate that both primary benzodiazepine use disorders and polysubstance addiction involving benzodiazepines do occur,” the FDA said.

Data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health from 2015-2016 suggest that half million community-dwelling U.S. adults were estimated to have a benzodiazepine use disorder.

Jump in overdose deaths

Overdose deaths involving benzodiazepines jumped from 1,298 in 2010 to 11,537 in 2017 – an increase of more 780%. Most of these deaths involved benzodiazepines taken with prescription opioids.

the FDA said.

The agency urged particular caution when prescribing benzodiazepines with opioids and other central nervous system depressants, which has resulted in serious adverse events including severe respiratory depression and death.

The FDA also says patients and caregivers should be warned about the risks of abuse, misuse, addiction, dependence, and withdrawal with benzodiazepines and the associated signs and symptoms.

Physicians are encouraged to report adverse events involving benzodiazepines or other medicines to the FDA’s MedWatch program.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration wants updated boxed warnings on benzodiazepines to reflect the “serious” risks of abuse, misuse, addiction, physical dependence, and withdrawal reactions associated with these medications.

“The current prescribing information for benzodiazepines does not provide adequate warnings about these serious risks and harms associated with these medicines so they may be prescribed and used inappropriately,” the FDA said in a safety communication.

The FDA also wants revisions to the patient medication guides for benzodiazepines to help educate patients and caregivers about these risks.

“While benzodiazepines are important therapies for many Americans, they are also commonly abused and misused, often together with opioid pain relievers and other medicines, alcohol, and illicit drugs,” FDA Commissioner Stephen M. Hahn, MD, said in a statement.

“We are taking measures and requiring new labeling information to help health care professionals and patients better understand that, while benzodiazepines have many treatment benefits, they also carry with them an increased risk of abuse, misuse, addiction, and dependence,” said Dr. Hahn.

Ninety-two million prescriptions in 2019

Benzodiazepines are widely used to treat anxiety, insomnia, seizures, and other conditions, often for extended periods of time.

According to the FDA, in 2019, an estimated 92 million benzodiazepine prescriptions were dispensed from U.S. outpatient pharmacies, most commonly alprazolam, clonazepam, and lorazepam.

Data from 2018 show that roughly 5.4 million people in the United States 12 years and older abused or misused benzodiazepines in the previous year.

Although the precise risk of benzodiazepine addiction remains unclear, population data “clearly indicate that both primary benzodiazepine use disorders and polysubstance addiction involving benzodiazepines do occur,” the FDA said.

Data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health from 2015-2016 suggest that half million community-dwelling U.S. adults were estimated to have a benzodiazepine use disorder.

Jump in overdose deaths

Overdose deaths involving benzodiazepines jumped from 1,298 in 2010 to 11,537 in 2017 – an increase of more 780%. Most of these deaths involved benzodiazepines taken with prescription opioids.

the FDA said.

The agency urged particular caution when prescribing benzodiazepines with opioids and other central nervous system depressants, which has resulted in serious adverse events including severe respiratory depression and death.

The FDA also says patients and caregivers should be warned about the risks of abuse, misuse, addiction, dependence, and withdrawal with benzodiazepines and the associated signs and symptoms.

Physicians are encouraged to report adverse events involving benzodiazepines or other medicines to the FDA’s MedWatch program.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Health Care Disparities Among Adolescents and Adults With Sickle Cell Disease: A Community-Based Needs Assessment to Inform Intervention Strategies

From the University of California San Francisco (Dr. Treadwell, Dr. Hessler, Yumei Chen, Swapandeep Mushiana, Dr. Potter, and Dr. Vichinsky), the University of California Los Angeles (Dr. Jacob), and the University of California Berkeley (Alex Chen).

Abstract

- Objective: Adolescents and adults with sickle cell disease (SCD) face pervasive disparities in health resources and outcomes. We explored barriers to and facilitators of care to identify opportunities to support implementation of evidence-based interventions aimed at improving care quality for patients with SCD.

- Methods: We engaged a representative sample of adolescents and adults with SCD (n = 58), health care providers (n = 51), and community stakeholders (health care administrators and community-based organization leads (n = 5) in Northern California in a community-based needs assessment. We conducted group interviews separately with participant groups to obtain in-depth perspectives. Adolescents and adults with SCD completed validated measures of pain interference, quality of care, self-efficacy, and barriers to care. Providers and community stakeholders completed surveys about barriers to SCD care.

- Results: We triangulated qualitative and quantitative data and found that participants with SCD (mean age, 31 ± 8.6 years), providers, and community stakeholders emphasized the social and emotional burden of SCD as barriers. Concrete barriers agreed upon included insurance and lack of resources for addressing pain impact. Adolescents and adults with SCD identified provider issues (lack of knowledge, implicit bias), transportation, and limited social support as barriers. Negative encounters with the health care system contributed to 84% of adolescents and adults with SCD reporting they chose to manage severe pain at home. Providers focused on structural barriers: lack of access to care guidelines, comfort level with and knowledge of SCD management, and poor care coordination.

- Conclusion: Strategies for improving access to compassionate, evidence-based quality care, as well as strategies for minimizing the burden of having SCD, are warranted for this medically complex population.

Keywords: barriers to care; quality of care; care access; care coordination.

Sickle cell disease (SCD), an inherited chronic medical condition, affects about 100,000 individuals in the United States, a population that is predominantly African American.1 These individuals experience multiple serious and life-threatening complications, most frequently recurrent vaso-occlusive pain episodes,2 and they require interactions with multidisciplinary specialists from childhood. Because of advances in treatments, the majority are reaching adulthood; however, there is a dearth of adult health care providers with the training and expertise to manage their complex medical needs.3 Other concrete barriers to adequate SCD care include insurance and distance to comprehensive SCD centers.4,5

Social, behavioral, and emotional factors may also contribute to challenges with SCD management. SCD may limit daily functional abilities and lead to diminished overall quality of life.6,7 Some adolescents and adults may require high doses of opioids, which contributes to health care providers’ perceptions that there is a high prevalence of drug addiction in the population.8,9 These providers express negative attitudes towards adults with SCD, and, consequently, delay medication administration when it is acutely needed and provide otherwise suboptimal treatment.8,10,11 Adult care providers may also be uncomfortable with prescribing and managing disease-modifying therapies (blood transfusion, hydroxyurea) that have established efficacy.12-17

As 1 of 8 programs funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s (NHLBI) Sickle Cell Disease Implementation Consortium (SCDIC), we are using implementation science to reduce barriers to care and improve quality of care and health care outcomes in SCD.18,19 Given that adolescents and adults with SCD experience high mortality, severe pain, and progressive decline in their ability to function day to day, and also face lack of access to knowledgeable, compassionate providers in primary and emergency settings, the SCDIC focuses on individuals aged 15 to 45 years.6,8,9,11,12

Our regional SCDIC program, the Sickle Cell Care Coordination Initiative (SCCCI), brings together researchers, clinicians, adolescents, and adults with SCD and their families, dedicated community members, policy makers, and administrators to identify and address barriers to health care within 5 counties in Northern California. One of our first steps was to conduct a community-based needs assessment, designed to inform implementation of evidence-based interventions, accounting for unique contextual factors in our region.

Conceptual Framework for Improving Medical Practice

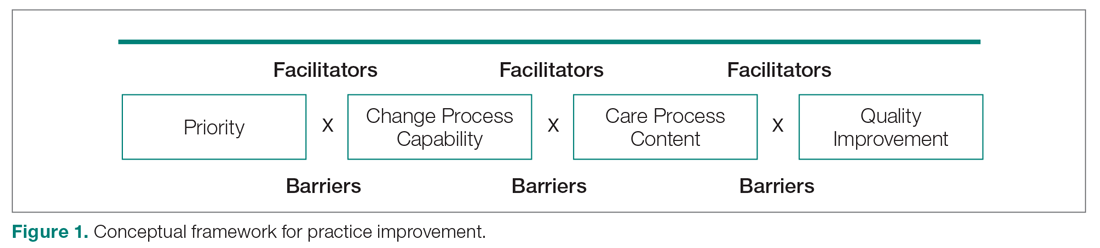

Our needs assessment is guided by Solberg’s Conceptual Framework for Improving Medical Practice (Figure 1).20 Consistent with the overarching principles of the SCDIC, this conceptual framework focuses on the inadequate implementation of evidence-based guidelines, and on the need to first understand multifactorial facilitators and barriers to guideline implementation in order to effect change. The framework identifies 3 main elements that must be present to ensure improvements in quality-of-care processes and patient outcomes: priority, change process capability, and care process content. Priority refers to ample resource allocation for the specific change, as well as freedom from competing priorities for those implementing the change. Change process capability includes strong, effective leadership, adequate infrastructure for managing change (including resources and time), change management skills at all levels, and an established clinical information system. Care process content refers to context and systems-level changes, such as delivery system redesign as needed, support for self-management to lessen the impact of the disease, and decision support.21-23

The purpose of our community-based needs assessment was to evaluate barriers to care and quality of care in SCD, within Solberg’s conceptual model for improving medical practice. The specific aims were to evaluate access and barriers to care (eg, lack of provider expertise and training, health care system barriers such as poor care coordination and provider communication); evaluate quality of care; and assess patient needs related to pain, pain interference, self-efficacy, and self-management for adolescents and adults with SCD. We gathered the perspectives of a representative community of adolescents and adults with SCD, their providers, and community stakeholders in order to examine barriers, quality of life and care, and patient experiences in our region.

Methods

Design

In this cross-sectional study, adolescents and adults with SCD, their providers, and community stakeholders participated in group or individual qualitative interviews and completed surveys between October 2017 and March 2018.

Setting and Sample

Recruitment flyers were posted on a regional SCD-focused website, and clinical providers or a study coordinator introduced information about the needs assessment to potential participants with SCD during clinic visits at the participating centers. Participants with SCD were eligible if they had any diagnosis of SCD, were aged 15 to 48 years, and received health services within 5 Northern California counties (Alameda, Contra Costa, Sacramento, San Francisco, and Solano). They were excluded if they did not have a SCD diagnosis or had not received health services within the catchment area. As the project proceeded, participants were asked to refer other adolescents and adults with SCD for the interviews and surveys (snowball sampling). Our goal was to recruit 50 adolescents and adults with SCD into the study, aiming for 10 representatives from each county.

Providers and community stakeholders were recruited via emails, letters and informational flyers. We engaged our partner, the Sickle Cell Data Collection Program,2 to generate a list of providers and institutions that had seen patients with SCD in primary, emergency, or inpatient settings in the region. We contacted these institutions to describe the SCCCI and invite participation in the needs assessment. We also invited community-based organization leads and health care administrators who worked with SCD to participate. Providers accessed confidential surveys via a secure link on the study website or completed paper versions. Common data collected across providers included demographics and descriptions of practice settings.

Participants were eligible to be part of the study if they were health care providers (physicians and nurses) representing hematology, primary care, family medicine, internal medicine, or emergency medicine; ancillary staff (social work, psychology, child life); or leaders or administrators of clinical or sickle cell community-based organizations in Northern California (recruitment goal of n = 50). Providers were excluded if they practiced in specialties other than those noted or did not practice within the region.

Data Collection Procedures

After providing assent/consent, participating adolescents and adults with SCD took part in individual and group interviews and completed survey questionnaires. All procedures were conducted in a private space in the sickle cell center or community. Adolescents and adults with SCD completed the survey questionnaire on a tablet, with responses recorded directly in a REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) database,24 or on a paper version. Interviews lasted 60 (individual) to 90 (group) minutes, while survey completion time was 20 to 25 minutes. Each participant received a gift card upon completion as an expression of appreciation. All procedures were approved by the institutional review boards of the participating health care facilities.

Group and Individual Interviews

Participants with SCD and providers were invited to participate in a semi-structured qualitative interview prior to being presented with the surveys. Adolescents and adults with SCD were interviewed about barriers to care, quality of care, and pain-related experiences. Providers were asked about barriers to care and treatments. Interview guides were modified for community-based organization leaders and health care administrators who did not provide clinical services. Interview guides can be found in the Appendix. Interviews were conducted by research coordinators trained in qualitative research methods by the first author (MT). As appropriate with semi-structured interviews, the interviewers could word questions spontaneously, change the order of questions for ease of flow of conversation, and inform simultaneous coding of interviews with new themes as those might arise, as long as they touched on all topics within the interview guide.25 The interview guides were written, per qualitative research standards, based on the aims and purpose of the research,26 and were informed by existing literature on access and barriers to care in SCD, quality of care, and the needs of individuals with SCD, including in relation to impact of the disease, self-efficacy, and self-management.

Interviewees participated in either individual or group interviews, but not both. The decision for which type of interview an individual participated in was based on 2 factors: if there were not comparable participants for group interviews (eg, health care administrator and community-based organization lead), these interviews were done individually; and given that we were drawing participants from a 5-county area in Northern California, scheduling was challenging for individuals with SCD with regard to aligning schedules and traveling to a central location where the group interviews were conducted. Provider group interviews were easier to arrange because we could schedule them at the same time as regularly scheduled meetings at the participants’ health care institutions.

Interview Data Gathering and Analysis

Digital recordings of the interviews were cleaned of any participant identifying data and sent for transcription to an outside service. Transcripts were reviewed for completeness and imported into NVivo (www.qsrinternational.com), a qualitative data management program.

A thematic content analysis and deductive and inductive approaches were used to analyze the verbatim transcripts generated from the interviews. The research team was trained in the use of NVivo software to facilitate the coding process. A deductive coding scheme was initially used based on existing concepts in the literature regarding challenges to optimal SCD care, with new codes added as the thematic content analyses progressed. The initial coding, pattern coding, and use of displays to examine the relationships between different categories were conducted simultaneously.27,28 Using the constant comparative method, new concepts from participants with SCD and providers could be incorporated into subsequent interviews with other participants. For this study, the only additional concepts added were in relation to participant recruitment and retention in the SCDIC Registry. Research team members coded transcripts separately and came together weekly, constantly comparing codes and developing the consensus coding scheme. Where differences between coders existed, code meanings were discussed and clarified until consensus was reached.29

Quantitative data were analyzed using SPSS (v. 25, Chicago, IL). Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, frequencies, percentages) were used to summarize demographics (eg, age, gender, and race), economic status, and type of SCD. No systematic differences were detected from cases with missing values. Scale reliabilities (ie, Cronbach α) were evaluated for self-report measures.

Measurement

Adolescents and adults with SCD completed items from the PhenX Toolkit (consensus measures for Phenotypes and eXposures), assessing sociodemographics (age, sex, race, ethnicity, educational attainment, occupation, marital status, annual income, insurance), and clinical characteristics (sickle cell diagnosis and emergency department [ED] and hospital utilization for pain).30

Pain Interference Short Form (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System [PROMIS]). The Pain Interference Form consists of 8 items that assess the degree to which pain interfered with day-to-day activities in the previous 7 days at home, including impacts on social, cognitive, emotional, and physical functioning; household chores and recreational activities; sleep; and enjoyment in life. Reliability and validity of the PROMIS Pain Interference Scale has been demonstrated, with strong negative correlations with Physical Function Scales (r = 0.717, P < 0.01), indicating that higher scores are associated with lower function (β = 0.707, P < 0.001).31 The Cronbach α estimate for the other items on the pain interference scale was 0.99. Validity analysis indicated strong correlations with pain-related domains: BPI Interference Subscale (rho = 0.90), SF-36 Bodily Pain Subscale (rho = –0.84), and 0–10 Numerical Rating of Pain Intensity (rho = 0.48).32

Adult Sickle Cell Quality of Life Measurement Information System (ASCQ-Me) Quality of Care (QOC). ASCQ-Me QOC consists of 27 items that measure the quality of care that adults with SCD have received from health care providers.33 There are 3 composites: provider communication (quality of patient and provider communication), ED care (quality of care in the ED), and access (to routine and emergency care). Internal consistency reliability for all 3 composites is greater than 0.70. Strong correlations of the provider communication composite with overall ratings of routine care (r = 0.65) and overall provider ratings (r = 0.83) provided evidence of construct validity. Similarly, the ED care composite was strongly correlated with overall ratings of QOC in the ED, and the access composite was highly correlated with overall evaluations of ED care (r = 0.70). Access, provider interaction, and ED care composites were reliable (Cronbach α, 0.70–0.83) and correlated with ratings of global care (r = 0.32–0.83), further indicating construct validity.33

Sickle Cell Self-Efficacy Scale (SCSES). The SCSES is a 9-item, self-administered questionnaire measuring perceptions of the ability to manage day-to-day issues resulting from SCD. SCSES items are scored on a 5-point scale ranging from Not sure at all (1) to Very sure (5). Individual item responses are summed to give an overall score, with higher scores indicating greater self-efficacy. The SCSES has acceptable reliability (r = 0.45, P < 0.001) and validity (α = 0.89).34,35

Sickle Cell Disease Barriers Checklist. This checklist consists of 53 items organized into 8 categories: insurance, transportation, accommodations and accessibility, provider knowledge and attitudes, social support, individual barriers such as forgetting or difficulties understanding instructions, emotional barriers (fear, anger), and disease-related barriers. Participants check applicable barriers, with a total score range of 0 to 53 and higher scores indicating more barriers to care. The SCD Barriers Checklist has demonstrated face validity and test-retest reliability (Pearson r = 0.74, P < 0.05).5

ED Provider Checklist. The ED provider survey is a checklist of 14 statements pertaining to issues regarding patient care, with which the provider rates level of agreement. Items representing the attitudes and beliefs of providers towards patients with SCD are rated on a Likert-type scale, with level of agreement indicated as 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The positive attitudes subscale consists of 4 items (Cronbach α= 0.85), and the negative attitudes subscale consists of 6 items (Cronbach α = 0.89). The Red-Flag Behaviors subscale includes 4 items that indicate behavior concerns about drug-seeking, such as requesting specific narcotics and changing behavior when the provider walks in.8,36,37

Sickle cell and primary care providers also completed a survey consisting of sets of items compiled from existing provider surveys; this survey consisted of a list of 16 barriers to using opioids, which the providers rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1, not a barrier; 5, complete barrier).13,16,38 Providers indicated their level of experience with caring for patients with SCD; care provided, such as routine health screenings; and comfort level with providing preventive care, managing comorbidities, and managing acute and chronic pain. Providers were asked what potential facilitators might improve care for patients with SCD, including higher reimbursement, case management services, access to pain management specialists, and access to clinical decision-support tools. Providers responded to specific questions about management with hydroxyurea (eg, criteria for, barriers to, and comfort level with prescribing).39 The surveys are included in the Appendix.

Triangulation

Data from the interviews and surveys were triangulated to enhance understanding of results generated from the different data sources.40 Convergence of findings, different facets of the same phenomenon, or new perspectives were examined.

Results

Qualitative Data

Adolescents and adults with SCD (n = 55) and health care providers and community stakeholders (n = 56) participated in group or individual interviews to help us gain an in-depth understanding of the needs and barriers related to SCD care in our 5-county region. Participants with SCD described their experiences, which included stigma, racism, labeling, and, consequently, stress. They also identified barriers such as lack of transportation, challenges with insurance, and lack of access to providers who were competent with pain management. They reported that having SCD in a health care system that was unable to meet their needs was burdensome.

Barriers to Care and Treatments. Adolescents and adults indicated that SCD and its sequelae posed significant barriers to health care. Feelings of tiredness and pain make it more difficult for them to seek care. The emotional burden of SCD (fear and anger) was a frequently cited barrier, which was fueled by previous negative encounters with the health care system. All adolescents and adults with SCD reported that they knew of stigma in relation to seeking pain management that was pervasive and long-standing, and the majority reported they had directly experienced stigma. They reported that being labeled as “drug-seekers” was typical when in the ED for pain management. Participants articulated unconscious bias or overt racism among providers: “people with sickle cell are Black ... and Black pain is never as valuable as White pain” (25-year-old male). Respondents with SCD described challenges to the credibility of their pain reports in the ED. They reported that ED providers expressed doubts regarding the existence and/or severity of their pain, consequently creating a feeling of disrespect for patients seeking pain relief. The issue of stigma was mentioned by only 2 of 56 providers during their interviews.

Lack of Access to Knowledgeable, Compassionate Providers. Lack of access to knowledgeable care providers was another prevalent theme expressed by adolescents and adults with SCD. Frustration occurred when providers did not have knowledge of SCD and its management, particularly pain assessment. Adolescents and adults with SCD noted the lack of compassion among providers: “I’ve been kicked out of the hospital because they felt like okay, well we gave you enough medication, you should be all right” (29-year-old female). Providers specifically mentioned lack of compassion and knowledge as barriers to SCD care much less often during their interviews compared with the adolescents and adults with SCD.

Health Care System Barriers. Patient participants often expressed concerns about concrete and structural aspects of care. Getting to their appointments was a challenge for half of the interviewees, as they either did not have access to a vehicle or could not afford to travel the needed distance to obtain quality care. Even when hospitals were accessible by public transportation, those with excruciating pain understandably preferred a more comfortable and private way to travel: “I would like to change that, something that will be much easier, convenient for sickle cell patients that do suffer with pain, that they don’t have to travel always to see the doctor” (30-year-old male).

Insurance and other financial barriers also played an important role in influencing decisions to seek health care services. Medical expenses were not covered, or co-pays were too high. The Medicaid managed care system could prevent access to knowledgeable providers who were not within network. Such a lack of access discouraged some adolescents and adults with SCD from seeking acute and preventive care.

Transition From Pediatric to Adult Care. Interviewees with SCD expressed distress about the gap between pediatric and adult care. They described how they had a long-standing relationship with their medical providers, who were familiar with their medical background and history from childhood. Adolescent interviewees reported an understanding of their own pain management as well as adherence to and satisfaction with their individualized pain plans. However, adults noted that satisfaction plummeted with increasing age due to the limited number of experienced adult SCD providers, which was compounded by negative experiences (stigma, racism, drug-seeking label).

One interviewee emphasized the difficulty of finding knowledgeable providers after transition: “When you’re a pediatric sickle cell [patient], you have the doctors there every step of the way, but not with adult sickle cell… I know when I first transitioned I never felt more alone in my life… you look at that ER doctor kind of with the same mindset as you would your hematologist who just hand walked you through everything. And adult care providers were a lot more blunt and cold and they’re like… ‘I don’t know; I’m not really educated in sickle cell.’” A sickle cell provider shared his insight about the problem of transitioning: “I think it’s particularly challenging because we, as a community, don’t really set them up for success. It’s different from other chronic conditions [in that] it’s much harder to find an adult sickle cell provider. There’s not a lot of adult hematologists that will take care of our adult patients, and so I know statistically, there’s like a drop-down in the overall outcomes of our kids after they age out of our pediatric program.”

Self-Management, Supporting Hydroxyurea Use. Interview participants with SCD reported using a variety of methods to manage pain at home and chose to go to the ED only when the pain became intolerable. Patients and providers expressed awareness of different resources for managing pain at home, yet they also indicated that these resources have not been consolidated in an accessible way for patients and families. Some resources cited included heat therapy, acupuncture, meditation, medical marijuana, virtual reality devices, and pain medications other than opioids.

Patients and providers expressed the need for increasing awareness and education about hydroxyurea. Many interview participants with SCD were concerned about side effects, multiple visits with a provider during dose titration, and ongoing laboratory monitoring. They also expressed difficulties with scheduling multiple appointments, depending on access to transportation and limited provider clinic hours. They were aware of strategies for improving adherence with hydroxyurea, including setting phone alarms, educating family members about hydroxyurea, and eliciting family support, but expressed needing help to consistently implement these strategies.

Safe Opioid Prescribing. Adult care providers expressed concerns about safe opioid prescribing for patients with SCD. They were reluctant to prescribe opioid doses needed to adequately control SCD pain. Providers expressed uncertainty and fear or concern about medical/legal liability or about their judgment about what’s safe and not safe for patients with chronic use/very high doses of opioids. “I know we’re in like this opiate epidemic here in this country but I feel like these patients don’t really fit under that umbrella that the problem is coming from so [I am] just trying to learn more about how to take care of them.”

Care Coordination and Provider Communication. Adolescents and adults with SCD reported having positive experiences—good communication, established trust, and compassionate care—with their usual providers. However, they perceived that ED physicians and nurses did not really care about them. Both interviewees with SCD and providers recognized the importance of good communication in all settings as the key to overcoming barriers to receiving quality care. All agreed on the importance of using individual pain plans so that all providers, especially ED providers, can be more at ease with treating adolescents and adults with SCD.

Quantitative Data: Adolescents and Adults With SCD

Fifty-eight adolescents and adults with SCD (aged 15 to 48 years) completed the survey. Three additional individuals who did not complete the interview completed the survey. Reasons for not completing the interview included scheduling challenges (n = 2) or a sickle cell pain episode (n = 1). The average age of participants was 31 years ± 8.6, more than half (57%) were female, and the majority (93%) were African American (Table 1). Most (71%) had never been married. Half (50%) had some college or an associate degree, and 40% were employed and reported an annual household income of less than $30,000. Insurance coverage was predominantly Medi-Cal (Medicaid, 69%). The majority of participants resided in Alameda (34.5%) or Contra Costa (21%) counties. The majority of sickle cell care was received in Alameda County, whether outpatient (52%), inpatient (40%), or ED care (41%). The majority (71%) had a diagnosis of SCD hemoglobin SS.

Pain. More than one-third of individuals with SCD reported 1 or 2 ED visits for pain in the previous 6 months (34%), and more than 3 hospitalizations (36%) related to pain in the previous year (Table 2). The majority (85%) reported having severe pain at home in the previous 6 months that they did not seek health care for, consistent with their reports in the qualitative interviews. More than half (59%) reported 4 or more of these severe pain episodes that led to inability to perform daily activities for 1 week or more. While pain interference on the PROMIS Pain Interference Short Form on average (T-score, 59.6 ± 8.6) was similar to that of the general population (T-score, 50 ± 10), a higher proportion of patients with SCD reported pain interference compared with the general population. The mean self-efficacy (confidence in ability to manage complications of SCD) score on the SCSES of 30.0 ± 7.3 (range, 9–45) was similar to that of other adults with SCD (mean, 32.2 ± 7.0). Twenty-five percent of the present sample had a low self-efficacy score (< 25).

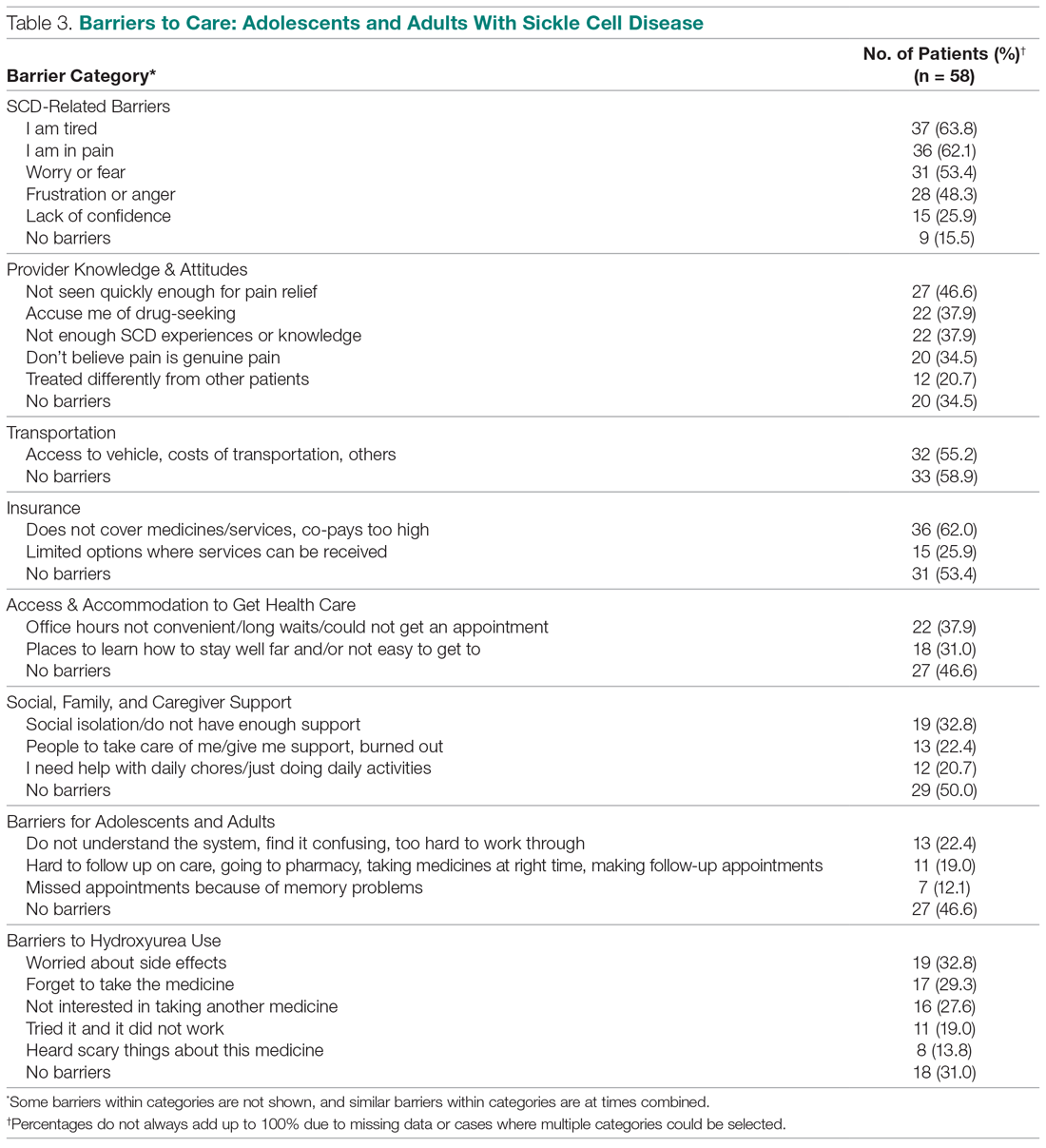

Barriers to Care and Treatments. Consistent with the qualitative data, SCD-related symptoms such as tiredness (64%) and pain (62%) were reported most often as barriers to care (Table 3). Emotions (> 25%) such as worry/fear, frustration/anger, and lack of confidence were other important barriers to care. Provider knowledge and attitudes were cited next most often, with 38% of the sample indicating “Providers accuse me of drug-seeking” and “It is hard for me to find a provider who has enough experiences with or knowledge about SCD.” Participants expressed that they were not believed when in pain and “I am treated differently from other patients.” Almost half of respondents cited “I am not seen quickly enough when I am in pain” as a barrier to their care.

Consistent with the qualitative data, transportation barriers (not having a vehicle, costs of transportation, public transit not easy to get to) were cited by 55% of participants. About half of participants reported that insurance was an important barrier, with high co-pays and medications and other services not covered. In addition, gathering approvals was a long and fragmented process, particularly for consultations among providers (hematology, primary care provider, pain specialist). Furthermore, insurance provided limited choices about location for services.

Participants reported social support system burnout (22%), help needed with daily activities (21%), and social isolation or generally not having enough support (33%) as ongoing barriers. Difficulties were encountered with self-management (eg, taking medications on time or making follow-up appointments, 19%), with 22% of participants finding the health care system confusing or hard to understand. Thirty percent reported “Places for me to go to learn how to stay well are not close by or easy to get to.” ”Worry about side effects” (33%) was a common barrier to hydroxyurea use. Participants described “forgetting to take the medicine,” “tried before but it did not work,” “heard scary things” about hydroxyurea, and “not interested in taking another medicine” as barriers.

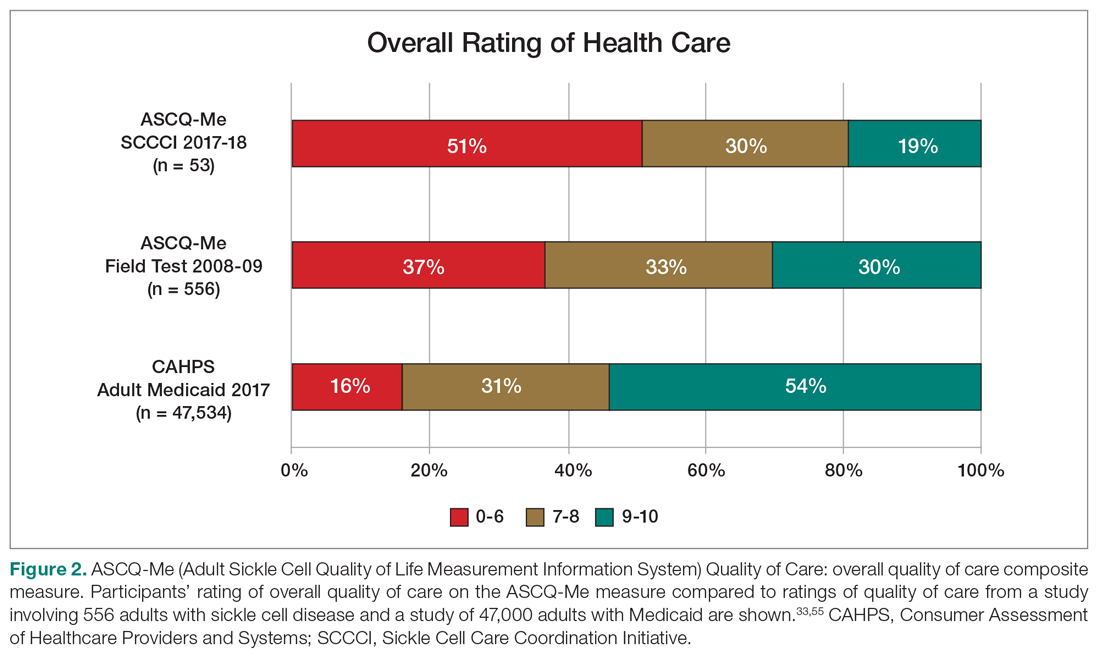

Quality of Care. More than half (51%) of the 53 participants who had accessed health care in the previous year rated their overall health care as poor on the ASCQ-Me QOC measure. This was significantly higher compared to the reports from more than 47,000 adults with Medicaid in 2017 (16%),41 and to the 2008-2009 report from 556 adults with SCD from across the United States (37%, Figure 2).33 The major contributor to these poor ratings for participants in our sample was low satisfaction with ED care.

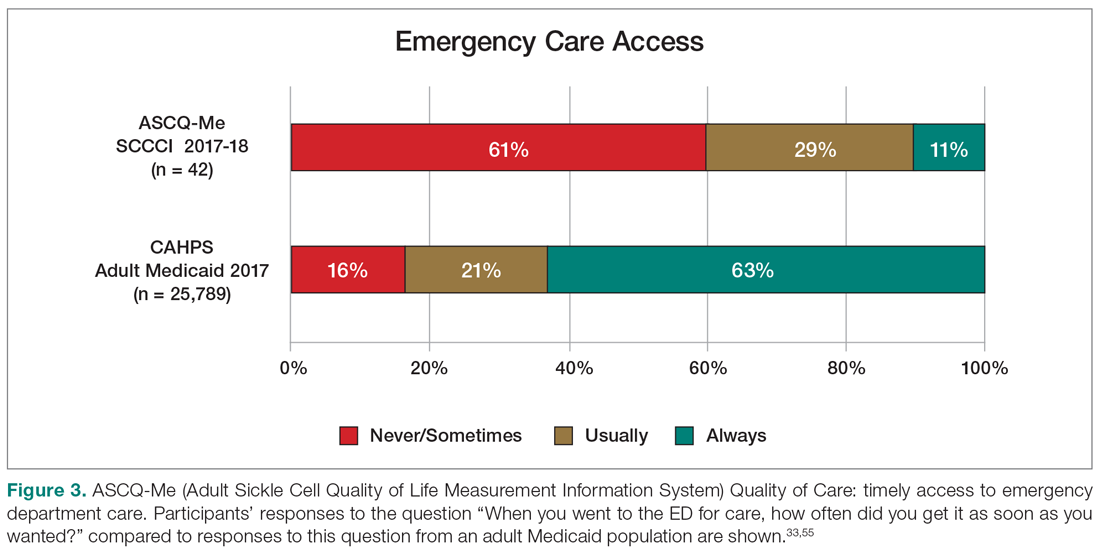

Sixty percent of the 42 participants who had accessed ED care in the past year indicated “never” or “sometimes” to the question “When you went to the ED for care, how often did you get it as soon as you wanted?” compared with only 16% of the 2017 adult Medicaid population responding (n = 25,789) (Figure 3). Forty-seven percent of those with an ED visit indicated that, in the previous 12 months, they had been made to wait “more than 2 hours before receiving treatment for acute pain in the ED.” However, in the previous 12 months, 39% reported that their wait time in the ED had been only “between five minutes and one hour.”

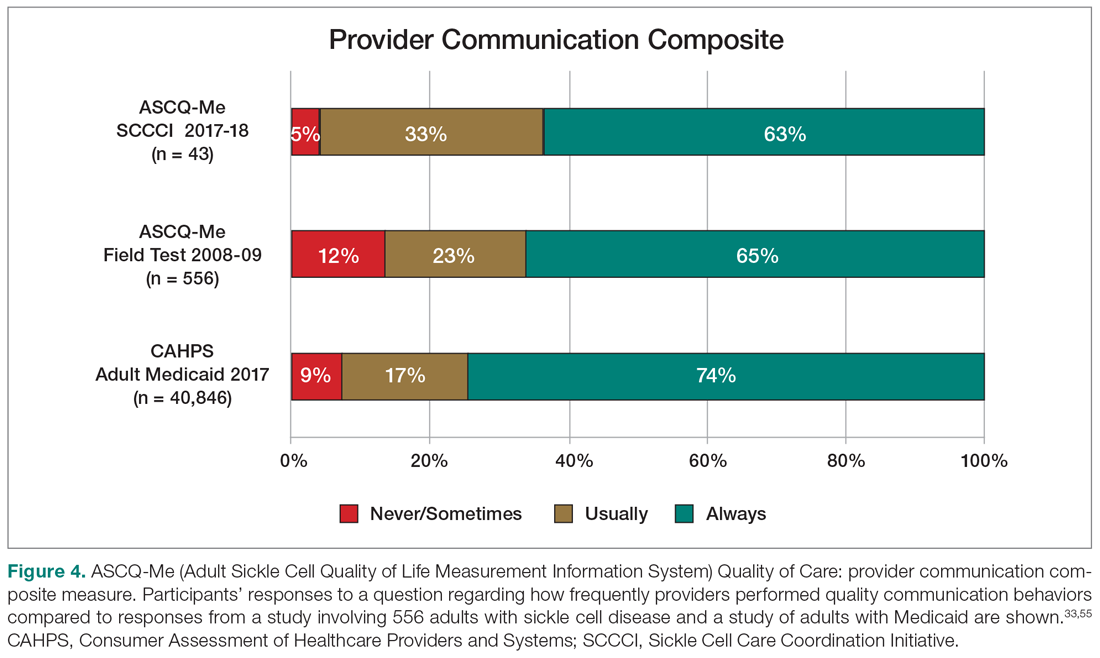

On the ASCQ-Me QOC Access to Care composite measure, 33% of 42 participants responding reported they were seen at a routine appointment as soon as they would have liked. This is significantly lower compared to 56% of the adult Medicaid population responding to the same question. Reports of provider communication (Provider Communication composite) for adolescents and adults with SCD were comparable to reports of adults with SCD from the ASCQ-Me field test,33 but adults with Medicaid reported higher ratings of quality communication behaviors (Figure 4).33,41 Nearly 60% of both groups with SCD reported that providers “always” performed quality communication behaviors—listened carefully, spent enough time, treated them with respect, and explained things well—compared with more than 70% of adults with Medicaid.

Participants from all counties reported the same number of barriers to care on average (3.3 ± 2.1). Adolescents and adults who reported more barriers to care also reported lower satisfaction with care (r = –0.47, P < 0.01) and less confidence in their ability to manage their SCD (self-efficacy, r = – 0.36, P < 0.05). Female participants reported more barriers to care on average compared with male participants (2.6 ± 2.4 vs 1.4 ± 2.0, P = 0.05). Participants with higher self-efficacy reported lower pain ratings (r = –0.47, P < 0.001).

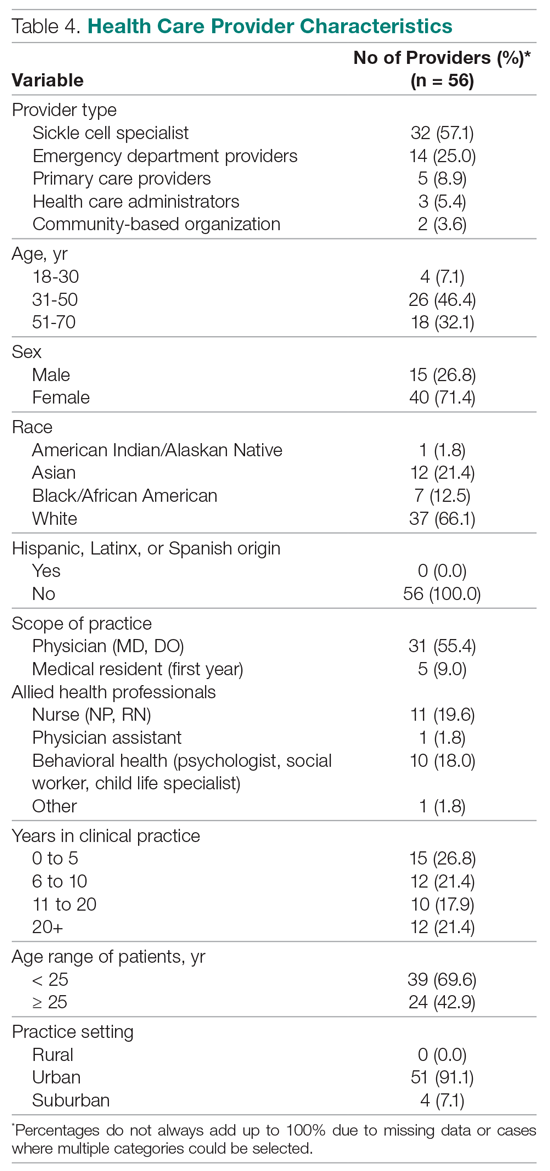

Quantitative Data: Health Care Providers

Providers (n = 56) and community stakeholders (2 leaders of community-based organizations and 3 health care administrators) were interviewed, with 29 also completing the survey. The reason for not completing (n = 22) was not having the time once the interview was complete. A link to the survey was sent to any provider not completing at the time of the interview, with 2 follow-up reminders. The majority of providers were between the ages of 31 and 50 years (46.4%), female (71.4%), and white (66.1%) (Table 4). None were of Hispanic, Latinx, or Spanish origin. Thirty-six were physicians (64.3%), and 16 were allied health professionals (28.6%). Of the 56 providers, 32 indicated they had expertise caring for patients with SCD (57.1%), 14 were ED providers (25%), and 5 were primary care providers. Most of the providers practiced in an urban setting (91.1%).

Barriers to Care: ED Provider Perspectives. Nine of 14 ED providers interviewed completed the survey on their perspectives regarding barriers to care in the ED, difficulty with follow-ups, ED training resources, and pain control for patients with SCD. ED providers (n = 8) indicated that “provider attitudes” were a barrier to care delivery in the ED for patients with SCD. Some providers (n = 7) indicated that “implicit bias,” “opioid epidemic,” “concern about addiction,” and “patient behavior” were barriers. Respondents indicated that “overcrowding” (n = 6) and “lack of care pathway/protocol” (n = 5) were barriers. When asked to express their level of agreement with statements about SCD care in the ED, respondents disagreed/strongly disagreed (n = 5) that they were “able to make a follow-up appointment” with a sickle cell specialist or primary care provider upon discharge from the ED, and others disagreed/strongly disagreed (n = 4) that they were able to make a “referral to a case management program.”

ED training and resources. Providers agreed/strongly agreed (n = 8) that they had the knowledge and training to care for patients with SCD, that they had access to needed medications, and that they had access to knowledgeable nursing staff with expertise in SCD care. All 9 ED providers indicated that they had sufficient physician/provider staffing to provide good pain management to persons with SCD in the ED.

Pain control in the ED. Seven ED providers indicated that their ED used individualized dosing protocols to treat sickle cell pain, and 5 respondents indicated their ED had a protocol for treating sickle cell pain. Surprisingly, only 3 indicated that they were aware of the NHLBI recommendations for the treatment of vaso-occlusive pain.

Barriers to Care: Primary Care Provider Perspectives. Twenty providers completed the SCD provider section of the survey, including 17 multidisciplinary SCD providers from 4 sickle cell special care centers and 3 community primary care providers. Of the 20, 12 were primary care providers for patients with SCD (Table 4).

Patient needs. Six primary care providers indicated that the medical needs of patients with SCD were being met, but none indicated that the behavioral health or mental health needs were being met.

Managing SCD comorbidities. Five primary care providers indicated they were very comfortable providing preventive ambulatory care to patients with SCD. Six indicated they were very comfortable managing acute pain episodes, but none were very comfortable managing comorbidities such as pulmonary hypertension, diabetes, or chronic pain.

Barriers to opioid use. Only 3 of 12 providers reviewing a list of 15 potential barriers to the use of opioids for SCD pain management indicated a perceived lack of efficacy of opioids, development of tolerance and dependence, and concerns about community perceptions as barriers. Two providers selected potential for diversion as a moderate barrier to opioid use.

Barriers to hydroxyurea use. Eight of 12 providers indicated that the common reasons that patients/families refuse hydroxyurea were “worry about side effects”; 7 chose “don’t want to take another medicine,” and 6 chose “worry about carcinogenic potential.” Others (n = 10) indicated that “patient/family adherence with hydroxyurea” and “patient/family adherence with required blood tests” were important barriers to hydroxyurea use. Eight of the 12 providers indicated that they were comfortable with managing hydroxyurea in patients with SCD.

Care redesign. Twenty SCD and primary care providers completed the Care Redesign section of the survey. Respondents (n = 11) indicated that they would see more patients with SCD if they had accessible case management services available without charge or if patient access to transportation to clinic was also available. Ten indicated that they would see more patients with SCD if they had an accessible community health worker (who understands patient’s/family’s social situation) and access to a pain management specialist on call to answer questions and who would manage chronic pain. All (n = 20) were willing to see more patients with SCD in their practices. Most reported that a clinical decision-support tool for SCD treatment (n = 13) and avoidance of complications (n = 12) would be useful.

Discussion

We evaluated access and barriers to care, quality of care, care coordination, and provider communication from the perspectives of adolescents and adults with SCD, their care providers, and community stakeholders, within the Solberg conceptual model for quality improvement. We found that barriers within the care process content domain (context and systems) were most salient for this population of adolescents and adults with SCD, with lack of provider knowledge and poor attitudes toward adolescents and adults with SCD, particularly in the ED, cited consistently by participant groups. Stigmatization and lack of provider compassion that affected the quality of care were particularly problematic. These findings are consistent with previous reports.42,43 Adult health care (particularly ED) provider biases and negative attitudes have been recognized as major barriers to optimal pain management in SCD.8,11,44,45 Interestingly, ED providers in our needs assessment indicated that they felt they had the training and resources to manage patients with SCD. However, only a few actually reported knowing about the NHLBI recommendations for the treatment of vaso-occlusive pain.

Within the care process content domain, we also found that SCD-related complications and associated emotions (fear, worry, anxiety), compounded by lack of access to knowledgeable and compassionate providers, pose a significant burden. Negative encounters with the health care system contributed to a striking 84% of patient participants choosing to manage severe pain at home, with pain seriously interfering with their ability to function on a daily basis. ED providers agreed that provider attitudes and implicit bias pose important barriers to care for adolescents and adults with SCD. Adolescents and adults with SCD wanted, and understood the need, to enhance self-management skills. Both they and their providers agreed that barriers to hydroxyurea uptake included worries about potential side effects, challenges with adherence to repeated laboratory testing, and support with remembering to take the medicine. However, providers uniformly expressed that access to behavioral and mental health services were, if not nonexistent, impossible to access.

Participants with SCD and their providers reported infrastructural challenges (change process capability), as manifested in limitations with accessing acute and preventive care due to transportation- and insurance- related issues. There were health system barriers that were particularly encountered during the transition from pediatric to adult care. These findings are consistent with previous reports that have found fewer interdisciplinary services available in the adult care settings compared with pediatrics.46,47 Furthermore, adult care providers were less willing to accept adults with SCD because of the complexity of their management, for which the providers did not have the necessary expertise.3,48-50 In addition, both adolescents and adults with SCD and primary care providers highlighted the inadequacies of the current system in addressing the chronic pain needs of this population. Linking back to the Solberg conceptual framework, our needs assessment results confirm the important role of establishing SCD care as a priority within a health care system—this requires leadership and vision. The vision and priorities must be implemented by effective health care teams. Multilevel approaches or interventions, when implemented, will lead to the desired outcomes.

Findings from our needs assessment within our 5-county region mirror needs assessment results from the broader consortium.51 The SCDIC has prioritized developing an intervention that addresses the challenges identified within the care process domain by directly enhancing provider access to patient individualized care plans in the electronic health record in the ED. Importantly, ED providers will be asked to view a short video that directly challenges bias and stigma in the ED. Previous studies have indeed found that attitudes can be improved by providers viewing short video segments of adults with SCD discussing their experiences.36,52 This ED protocol will be one of the interventions that we will roll out in Northern California, given the significance of negative ED encounters reported by needs assessment participants. An additional feature of the intervention is a script for adults with SCD that guides them through introducing their individualized pain plan to their ED providers, thereby enhancing their self-efficacy in a situation that has been so overwhelmingly challenging.

We will implement a second SCDIC intervention that utilizes a mobile app to support self-management on the part of the patient, by supporting motivation and adherence with hydroxyurea.53 A companion app supports hydroxyurea guideline adherence on the part of the provider, in keeping with one of our findings that providers are in need of decision-support tools. Elements of the intervention also align with our findings related to the importance of a support system in managing SCD, in that participants will identify a supportive partner who will play a specific role in supporting their adherence with hydroxyurea.

On our local level, we have, by necessity, partnered with leaders and community stakeholders throughout the region to ensure that these interventions to improve SCD care are prioritized. Grant funds provide initial resources for the SCDIC interventions, but our partnering health care administrators and medical directors must ensure that participating ED and hematology providers are free from competing priorities in order to implement the changes. We have partnered with a SCD community-based organization that is designing additional educational presentations for local emergency medicine providers, with the goal to bring to life very personal stories of bias and stigma within the EDs that directly contribute to decisions to avoid ED care despite severe symptoms.

Although we attempted to obtain samples of adolescents and adults with SCD and their providers that were representative across the 5-county region, the larger proportion of respondents were from 1 county. We did not assess concerns of age- and race-matched adults in our catchment area, so we cannot definitively say that our findings are unique to SCD. However, our results are consistent with findings from the national sample of adults with SCD who participated in the ASCQ-Me field test, and with results from the SCDIC needs assessment.33,51 Interviews and surveys are subject to self-report bias and, therefore, may or may not reflect the actual behaviors or thoughts of participants. Confidence is increased in our results given the triangulation of expressed concerns across participant groups and across data collection strategies. The majority of adolescents and adults with SCD (95%) completed both the interview and survey, while 64% of ED providers interviewed completed the survey, compared with 54% of SCD specialists and primary care providers. These response rates are more than acceptable within the realm of survey response rates.54,55

Although we encourage examining issues with care delivery within the conceptual framework for quality improvement presented, we recognize that grant funding allowed us to conduct an in-depth needs assessment that might not be feasible in other settings. Still, we would like readers to understand the importance of gathering data for improvement in a systematic manner across a range of participant groups, to ultimately inform the development of interventions and provide for evaluation of outcomes as a result of the interventions. This is particularly important for a disease, such as SCD, that is both medically and sociopolitically complex.

Conclusion

Our needs assessment brought into focus the multiple factors contributing to the disparities in health care experienced by adolescents and adults with SCD on our local level, and within the context of inequities in health resources and outcomes on the national level. We propose solutions that include specific interventions developed by a consortium of SCD and implementation science experts. We utilize a quality improvement framework to ensure that the elements of the interventions also address the barriers identified by our local providers and patients that are unique to our community. The pervasive challenges in SCD care, coupled with its medical complexities, may seem insurmountable, but our survey and qualitative results provide us with a road map for the way forward.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank the adolescents and adults with sickle cell disease, the providers, and the community stakeholders who completed the interviews and surveys. The authors also acknowledge the SCCCI co-investigators for their contributions to this project, including Michael Bell, MD, Ward Hagar, MD, Christine Hoehner, FNP, Kimberly Major, MSW, Anne Marsh, MD, Lynne Neumayr, MD, and Ted Wun, MD. We also thank Kamilah Bailey, Jameelah Hodge, Jennifer Kim, Michael Rowland, Adria Stauber, Amber Fearon, and Shanda Robertson, and the Sickle Cell Data Collection Program for their contributions.

Corresponding author: Marsha J. Treadwell, PhD, University of California San Francisco Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland, 747 52nd St., Oakland, CA 94609; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

Funding/support: This work was supported by grant # 1U01HL134007 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute to the University of California San Francisco Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland.

1. Hassell KL. Population Estimates of sickle cell disease in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2010; 38:S512-S521.

2. Data & Statistics on Sickle Cell Disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/sicklecell/data.html. Accessed March 25, 2020.

3. Inusa BPD, Stewart CE, Mathurin-Charles S, et al. Paediatric to adult transition care for patients with sickle cell disease: a global perspective. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7:e329-e341.

4. Smith SK, Johnston J, Rutherford C, et al. Identifying social-behavioral health needs of adults with sickle cell disease in the emergency department. J Emerg Nurs. 2017;43:444-450.

5. Treadwell MJ, Barreda F, Kaur K, et al. Emotional distress, barriers to care, and health-related quality of life in sickle cell disease. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2015;22:8-17.

6. Treadwell MJ, Hassell K, Levine R, et al. Adult Sickle Cell Quality-of-Life Measurement Information System (ASCQ-Me): conceptual model based on review of the literature and formative research. Clin J Pain. 2014;30:902-914.

7. Rizio AA, Bhor M, Lin X, et al. The relationship between frequency and severity of vaso-occlusive crises and health-related quality of life and work productivity in adults with sickle cell disease. Qual Life Res. 2020;29:1533-1547.

8. Freiermuth CE, Haywood C, Silva S, et al. Attitudes toward patients with sickle cell disease in a multicenter sample of emergency department providers. Adv Emerg Nurs J. 2014;36:335-347.

9. Jenerette CM, Brewer C. Health-related stigma in young adults with sickle cell disease. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102:1050-1055.

10. Lazio MP, Costello HH, Courtney DM, et al. A comparison of analgesic management for emergency department patients with sickle cell disease and renal colic. Clin J Pain. 2010;26:199-205.

11. Haywood C, Tanabe P, Naik R, et al. The impact of race and disease on sickle cell patient wait times in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:651-656.

12. Haywood C, Beach MC, Lanzkron S, et al. A systematic review of barriers and interventions to improve appropriate use of therapies for sickle cell disease. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101:1022-1033.

13. Mainous AG, Tanner RJ, Harle CA, et al. Attitudes toward management of sickle cell disease and its complications: a national survey of academic family physicians. Anemia. 2015;2015:1-6.

14. Yawn BP, Buchanan GR, Afenyi-Annan AN, et al. Management of sickle cell disease: summary of the 2014 evidence-based report by expert panel members. JAMA. 2014;312:1033.

15. Lunyera J, Jonassaint C, Jonassaint J, et al. Attitudes of primary care physicians toward sickle cell disease care, guidelines, and comanaging hydroxyurea with a specialist. J Prim Care Community Health. 2017;8:37-40.

16. Whiteman LN, Haywood C, Lanzkron S, et al. Primary care providers’ comfort levels in caring for patients with sickle cell disease. South Med J. 2015;108:531-536.

17. Wong TE, Brandow AM, Lim W, Lottenberg R. Update on the use of hydroxyurea therapy in sickle cell disease. Blood. 2014;124:3850-4004.

18. DiMartino LD, Baumann AA, Hsu LL, et al. The sickle cell disease implementation consortium: Translating evidence-based guidelines into practice for sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol. 2018;93:E391-E395.

19. King AA, Baumann AA. Sickle cell disease and implementation science: A partnership to accelerate advances. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64:e26649.

20. Solberg LI. Improving medical practice: a conceptual framework. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:251-256.

21. Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. J Am Med Assoc. 2002;288:5.

22. Bodenheimer T. Interventions to improve chronic illness care: evaluating their effectiveness. Dis Manag. 2003;6:63-71.

23. Tsai AC, Morton SC, Mangione CM, Keeler EB. A meta-analysis of interventions to improve care for chronic illnesses. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11:478-488.

24. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377-381.

25. Kallio H, Pietilä A-M, Johnson M, et al. Systematic methodological review: developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72:2954-2965.

26. Clarke V, Braun V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. First. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2013.

27. Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277-1288.

28. Creswell JW, Hanson WE, Clark Plano VL, et al. Qualitative research designs: selection and implementation. Couns Psychol. 2007;35:236-264.

29. Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J. Qualitative Data Analysis A Methods Sourcebook. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2019.

30. Eckman JR, Hassell KL, Huggins W, et al. Standard measures for sickle cell disease research: the PhenX Toolkit sickle cell disease collections. Blood Adv. 2017; 1: 2703-2711.

31. Kendall R, Wagner B, Brodke D, et al. The relationship of PROMIS pain interference and physical function scales. Pain Med. 2018;19:1720-1724.

32. Amtmann D, Cook KF, Jensen MP, et al. Development of a PROMIS item bank to measure pain interference. Pain. 2010;150:173-182.

33. Evensen CT, Treadwell MJ, Keller S, et al. Quality of care in sickle cell disease: Cross-sectional study and development of a measure for adults reporting on ambulatory and emergency department care. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e4528.

34. Edwards R, Telfair J, Cecil H, et al. Reliability and validity of a self-efficacy instrument specific to sickle cell disease. Behav Res Ther. 2000;38:951-963.

35. Edwards R, Telfair J, Cecil H, et al. Self-efficacy as a predictor of adult adjustment to sickle cell disease: one-year outcomes. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:850-858.

36. Puri Singh A, Haywood C, Beach MC, et al. Improving emergency providers’ attitudes toward sickle cell patients in pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51:628-632.e3.

37. Glassberg JA, Tanabe P, Chow A, et al. Emergency provider analgesic practices and attitudes towards patients with sickle cell disease. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62:293-302.e10.

38. Grahmann PH, Jackson KC 2nd, Lipman AG. Clinician beliefs about opioid use and barriers in chronic nonmalignant pain [published correction appears in J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2004;18:145-6]. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2004;18:7-28.

39. Brandow AM, Panepinto JA. Hydroxyurea use in sickle cell disease: the battle with low prescription rates, poor patient compliance and fears of toxicities. Expert Rev Hematol. 2010;3:255-260.

40. Fielding N. Triangulation and mixed methods designs: data integration with new research technologies. J Mixed Meth Res. 2012;6:124-136.

41. 2017 CAHPS Health Plan Survey Chartbook. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality website. www.ahrq.gov/cahps/cahps-database/comparative-data/2017-health-plan-chartbook/results-enrollee-population.html. Accessed September 8, 2020.

42. Bulgin D, Tanabe P, Jenerette C. Stigma of sickle cell disease: a systematic review. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2018;1-11.

43. Wakefield EO, Zempsky WT, Puhl RM, et al. Conceptualizing pain-related stigma in adolescent chronic pain: a literature review and preliminary focus group findings. PAIN Rep. 2018;3:e679.

44. Nelson SC, Hackman HW. Race matters: Perceptions of race and racism in a sickle cell center. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:451-454.

45. Dyal BW, Abudawood K, Schoppee TM, et al. Reflections of healthcare experiences of african americans with sickle cell disease or cancer: a qualitative study. Cancer Nurs. 2019;10.1097/NCC.0000000000000750.

46. Renedo A. Not being heard: barriers to high quality unplanned hospital care during young people’s transition to adult services - evidence from ‘this sickle cell life’ research. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:876.

47. Ballas S, Vichinsky E. Is the medical home for adult patients with sickle cell disease a reality or an illusion? Hemoglobin. 2015;39:130-133.

48. Hankins JS, Osarogiagbon R, Adams-Graves P, et al. A transition pilot program for adolescents with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Health Care. 2012;26 e45-e49.

49. Smith WR, Sisler IY, Johnson S, et al. Lessons learned from building a pediatric-to-adult sickle cell transition program. South Med J. 2019;112:190-197.

50. Lanzkron S, Sawicki GS, Hassell KL, et al. Transition to adulthood and adult health care for patients with sickle cell disease or cystic fibrosis: Current practices and research priorities. J Clin Transl Sci. 2018;2:334-342.

51. Kanter J, Gibson R, Lawrence RH, et al. Perceptions of US adolescents and adults with sickle cell disease on their quality of care. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e206016.

52. Haywood C, Lanzkron S, Hughes MT, et al. A video-intervention to improve clinician attitudes toward patients with sickle cell disease: the results of a randomized experiment. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:518-523.

53. Hankins JS, Shah N, DiMartino L, et al. Integration of mobile health into sickle cell disease care to increase hydroxyurea utilization: protocol for an efficacy and implementation study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2020;9:e16319.

54. Fan W, Yan Z. Factors affecting response rates of the web survey: A systematic review. Comput Hum Behav. 2010;26:132-139.

55. Millar MM, Dillman DA. Improving response to web and mixed-mode surveys. Public Opin Q. 2011;75:249-269.

From the University of California San Francisco (Dr. Treadwell, Dr. Hessler, Yumei Chen, Swapandeep Mushiana, Dr. Potter, and Dr. Vichinsky), the University of California Los Angeles (Dr. Jacob), and the University of California Berkeley (Alex Chen).

Abstract

- Objective: Adolescents and adults with sickle cell disease (SCD) face pervasive disparities in health resources and outcomes. We explored barriers to and facilitators of care to identify opportunities to support implementation of evidence-based interventions aimed at improving care quality for patients with SCD.

- Methods: We engaged a representative sample of adolescents and adults with SCD (n = 58), health care providers (n = 51), and community stakeholders (health care administrators and community-based organization leads (n = 5) in Northern California in a community-based needs assessment. We conducted group interviews separately with participant groups to obtain in-depth perspectives. Adolescents and adults with SCD completed validated measures of pain interference, quality of care, self-efficacy, and barriers to care. Providers and community stakeholders completed surveys about barriers to SCD care.

- Results: We triangulated qualitative and quantitative data and found that participants with SCD (mean age, 31 ± 8.6 years), providers, and community stakeholders emphasized the social and emotional burden of SCD as barriers. Concrete barriers agreed upon included insurance and lack of resources for addressing pain impact. Adolescents and adults with SCD identified provider issues (lack of knowledge, implicit bias), transportation, and limited social support as barriers. Negative encounters with the health care system contributed to 84% of adolescents and adults with SCD reporting they chose to manage severe pain at home. Providers focused on structural barriers: lack of access to care guidelines, comfort level with and knowledge of SCD management, and poor care coordination.

- Conclusion: Strategies for improving access to compassionate, evidence-based quality care, as well as strategies for minimizing the burden of having SCD, are warranted for this medically complex population.

Keywords: barriers to care; quality of care; care access; care coordination.

Sickle cell disease (SCD), an inherited chronic medical condition, affects about 100,000 individuals in the United States, a population that is predominantly African American.1 These individuals experience multiple serious and life-threatening complications, most frequently recurrent vaso-occlusive pain episodes,2 and they require interactions with multidisciplinary specialists from childhood. Because of advances in treatments, the majority are reaching adulthood; however, there is a dearth of adult health care providers with the training and expertise to manage their complex medical needs.3 Other concrete barriers to adequate SCD care include insurance and distance to comprehensive SCD centers.4,5