User login

Once-weekly teriparatide still achieves bone mineral density gains

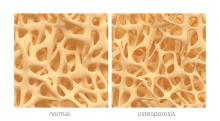

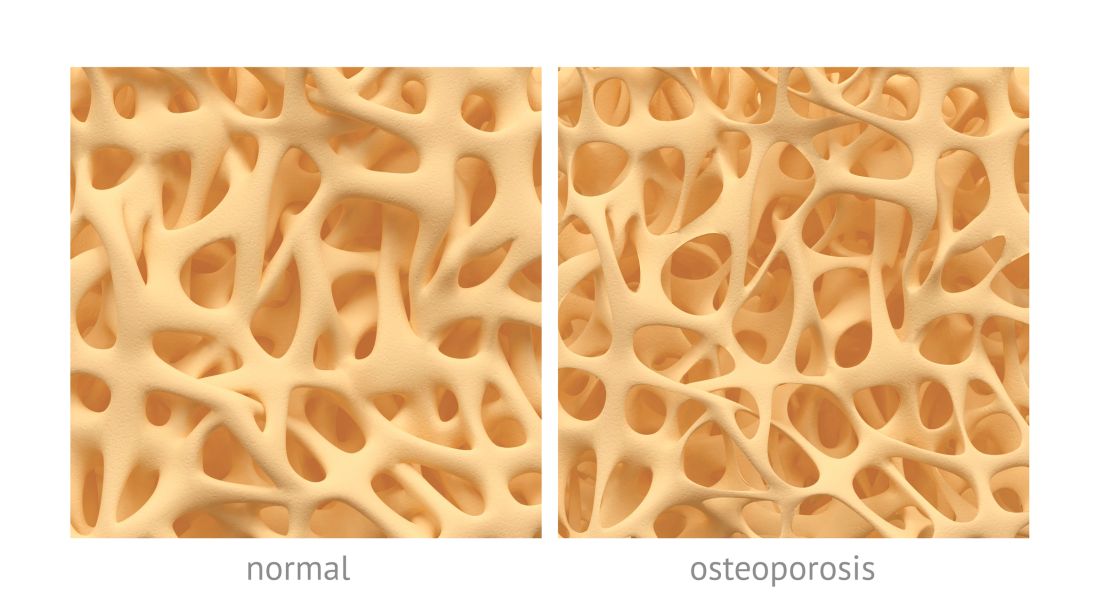

Once-weekly subcutaneous injections of the osteoporosis drug teriparatide still achieve increases in bone mineral density, according to a postmarketing observational study published online in Osteoporosis and Sarcopenia.

Teriparatide is widely used as a daily, self-injection formula for osteoporosis, but in Japan, a once-weekly injectable formulation of 56.5 ug is also being used in individuals with osteoporosis who are at high risk of fracture.

In a study of 3,573 Japanese patients with osteoporosis, investigators found increases of 2.8%, 4.9%, and 6.1% in lumbar spine bone mineral density measured at 24, 48, and 72 weeks respectively. In the femoral neck, bone mineral density increased by 1.6%, 1.4%, and 2.5% at 24, 48, and 72 weeks, and total hip bone mineral density increased by 1%, 1.6%, and 2.5%.

At 24 weeks, the median percent change from baseline in the level of serum bone formation marker procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide increased 23%, and then decreased to a 4.3% median change at 48 weeks and 8.7% at 72 weeks. There were no significant changes in serum bone-type alkaline phosphatase by 48 and 72 weeks, and no changes at all in the bone turnover markers tartrate-resistant acid phosphate-5b and cross-linked N-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen.

Researchers also saw reductions in low back pain scores at all the time points, although the authors noted that the mechanism of this association was not well understood and needed further study.

“The results for efficacy parameters, including fracture incidences, in this surveillance were as expected based on the clinical studies prior to approval, indicating that the medical benefits of teriparatide were demonstrated in actual clinical practice after marketing,” wrote Dr. Emiko Ifuku and colleagues from Asahi Kasei Pharma, which manufactures the drug in Japan.

The study also looked at adherence to the once-weekly therapy, and found that 59.4% of patients were still taking the treatment at 24 weeks, and 39% were taking it at 72 weeks.

Around a quarter of patients experienced adverse reactions, with the most common being nausea (12.3%), vomiting (2.8%), headache (2.7%), and dizziness (2.2%) and most occurring within 24 weeks of starting treatment. Serious adverse reactions were reported in 26 patients (0.7%).

Asahi Kasei Pharma sponsored the study. All of the authors were employees of the company.

SOURCE: Ifuku E et al. Osteoporos Sarcopenia. 2019 Jun 26. doi: 10.1016/j.afos.2019.06.002.

Once-weekly subcutaneous injections of the osteoporosis drug teriparatide still achieve increases in bone mineral density, according to a postmarketing observational study published online in Osteoporosis and Sarcopenia.

Teriparatide is widely used as a daily, self-injection formula for osteoporosis, but in Japan, a once-weekly injectable formulation of 56.5 ug is also being used in individuals with osteoporosis who are at high risk of fracture.

In a study of 3,573 Japanese patients with osteoporosis, investigators found increases of 2.8%, 4.9%, and 6.1% in lumbar spine bone mineral density measured at 24, 48, and 72 weeks respectively. In the femoral neck, bone mineral density increased by 1.6%, 1.4%, and 2.5% at 24, 48, and 72 weeks, and total hip bone mineral density increased by 1%, 1.6%, and 2.5%.

At 24 weeks, the median percent change from baseline in the level of serum bone formation marker procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide increased 23%, and then decreased to a 4.3% median change at 48 weeks and 8.7% at 72 weeks. There were no significant changes in serum bone-type alkaline phosphatase by 48 and 72 weeks, and no changes at all in the bone turnover markers tartrate-resistant acid phosphate-5b and cross-linked N-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen.

Researchers also saw reductions in low back pain scores at all the time points, although the authors noted that the mechanism of this association was not well understood and needed further study.

“The results for efficacy parameters, including fracture incidences, in this surveillance were as expected based on the clinical studies prior to approval, indicating that the medical benefits of teriparatide were demonstrated in actual clinical practice after marketing,” wrote Dr. Emiko Ifuku and colleagues from Asahi Kasei Pharma, which manufactures the drug in Japan.

The study also looked at adherence to the once-weekly therapy, and found that 59.4% of patients were still taking the treatment at 24 weeks, and 39% were taking it at 72 weeks.

Around a quarter of patients experienced adverse reactions, with the most common being nausea (12.3%), vomiting (2.8%), headache (2.7%), and dizziness (2.2%) and most occurring within 24 weeks of starting treatment. Serious adverse reactions were reported in 26 patients (0.7%).

Asahi Kasei Pharma sponsored the study. All of the authors were employees of the company.

SOURCE: Ifuku E et al. Osteoporos Sarcopenia. 2019 Jun 26. doi: 10.1016/j.afos.2019.06.002.

Once-weekly subcutaneous injections of the osteoporosis drug teriparatide still achieve increases in bone mineral density, according to a postmarketing observational study published online in Osteoporosis and Sarcopenia.

Teriparatide is widely used as a daily, self-injection formula for osteoporosis, but in Japan, a once-weekly injectable formulation of 56.5 ug is also being used in individuals with osteoporosis who are at high risk of fracture.

In a study of 3,573 Japanese patients with osteoporosis, investigators found increases of 2.8%, 4.9%, and 6.1% in lumbar spine bone mineral density measured at 24, 48, and 72 weeks respectively. In the femoral neck, bone mineral density increased by 1.6%, 1.4%, and 2.5% at 24, 48, and 72 weeks, and total hip bone mineral density increased by 1%, 1.6%, and 2.5%.

At 24 weeks, the median percent change from baseline in the level of serum bone formation marker procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide increased 23%, and then decreased to a 4.3% median change at 48 weeks and 8.7% at 72 weeks. There were no significant changes in serum bone-type alkaline phosphatase by 48 and 72 weeks, and no changes at all in the bone turnover markers tartrate-resistant acid phosphate-5b and cross-linked N-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen.

Researchers also saw reductions in low back pain scores at all the time points, although the authors noted that the mechanism of this association was not well understood and needed further study.

“The results for efficacy parameters, including fracture incidences, in this surveillance were as expected based on the clinical studies prior to approval, indicating that the medical benefits of teriparatide were demonstrated in actual clinical practice after marketing,” wrote Dr. Emiko Ifuku and colleagues from Asahi Kasei Pharma, which manufactures the drug in Japan.

The study also looked at adherence to the once-weekly therapy, and found that 59.4% of patients were still taking the treatment at 24 weeks, and 39% were taking it at 72 weeks.

Around a quarter of patients experienced adverse reactions, with the most common being nausea (12.3%), vomiting (2.8%), headache (2.7%), and dizziness (2.2%) and most occurring within 24 weeks of starting treatment. Serious adverse reactions were reported in 26 patients (0.7%).

Asahi Kasei Pharma sponsored the study. All of the authors were employees of the company.

SOURCE: Ifuku E et al. Osteoporos Sarcopenia. 2019 Jun 26. doi: 10.1016/j.afos.2019.06.002.

FROM OSTEOPOROSIS AND SARCOPENIA

Osteoporotic fracture risk appears higher in adults with hemophilia

Adults with newly diagnosed hemophilia may be at a higher risk of developing osteoporotic fractures, according to results from a retrospective study.

Sheng-Hui Tuan, MD, of Cishan Hospital in Kaohsiung, Taiwan, and colleagues conducted a population-based nationwide cohort study that included 75 patients with hemophilia and 300 control subjects without hemophilia matched for age and sex. Data was obtained from a national insurance database in Taiwan from January 2000 to December 2013. The findings were published in Haemophilia.

The primary outcome measured was newly diagnosed osteoporotic fractures, defined as wrist, vertebral, and hip fractures among individuals from both groups. Patients with osteoporotic fractures before hemophilia diagnosis were excluded.

In the analysis, the team calculated hazard ratios and incidence rates of new-onset osteoporotic fractures in both cohorts.

After analysis, the researchers found that the risk of developing new-onset osteoporotic fractures was greater in the hemophilia group versus the comparison group (HR, 5.41; 95% confidence interval, 2.42-12.1; P less than .001).

After adjusting for covariates, such as socioeconomic status, age, sex, and other comorbidities, patients with hemophilia had a 337% higher risk of developing osteoporotic fractures post diagnosis versus matched controls (95% CI, 1.88-10.17; P = .001).

“The risk of osteoporotic fractures following haemophilia increased with time and was significantly higher at 5 years after the diagnosis,” the researchers wrote.

The underlying mechanisms driving these associations remain unknown, according to the authors. Possible risk factors include reduced physical activity, HIV and hepatitis C virus infections, and arthropathy.

The researchers acknowledged that a key limitation of the study was the absence of some relevant clinical information within the database. As a result, information bias could have lowered the accuracy of the analysis.

No funding sources were reported. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Tuan S-H et al. Haemophilia. 2019 Jul 7. doi: 10.1111/hae.13814.

Adults with newly diagnosed hemophilia may be at a higher risk of developing osteoporotic fractures, according to results from a retrospective study.

Sheng-Hui Tuan, MD, of Cishan Hospital in Kaohsiung, Taiwan, and colleagues conducted a population-based nationwide cohort study that included 75 patients with hemophilia and 300 control subjects without hemophilia matched for age and sex. Data was obtained from a national insurance database in Taiwan from January 2000 to December 2013. The findings were published in Haemophilia.

The primary outcome measured was newly diagnosed osteoporotic fractures, defined as wrist, vertebral, and hip fractures among individuals from both groups. Patients with osteoporotic fractures before hemophilia diagnosis were excluded.

In the analysis, the team calculated hazard ratios and incidence rates of new-onset osteoporotic fractures in both cohorts.

After analysis, the researchers found that the risk of developing new-onset osteoporotic fractures was greater in the hemophilia group versus the comparison group (HR, 5.41; 95% confidence interval, 2.42-12.1; P less than .001).

After adjusting for covariates, such as socioeconomic status, age, sex, and other comorbidities, patients with hemophilia had a 337% higher risk of developing osteoporotic fractures post diagnosis versus matched controls (95% CI, 1.88-10.17; P = .001).

“The risk of osteoporotic fractures following haemophilia increased with time and was significantly higher at 5 years after the diagnosis,” the researchers wrote.

The underlying mechanisms driving these associations remain unknown, according to the authors. Possible risk factors include reduced physical activity, HIV and hepatitis C virus infections, and arthropathy.

The researchers acknowledged that a key limitation of the study was the absence of some relevant clinical information within the database. As a result, information bias could have lowered the accuracy of the analysis.

No funding sources were reported. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Tuan S-H et al. Haemophilia. 2019 Jul 7. doi: 10.1111/hae.13814.

Adults with newly diagnosed hemophilia may be at a higher risk of developing osteoporotic fractures, according to results from a retrospective study.

Sheng-Hui Tuan, MD, of Cishan Hospital in Kaohsiung, Taiwan, and colleagues conducted a population-based nationwide cohort study that included 75 patients with hemophilia and 300 control subjects without hemophilia matched for age and sex. Data was obtained from a national insurance database in Taiwan from January 2000 to December 2013. The findings were published in Haemophilia.

The primary outcome measured was newly diagnosed osteoporotic fractures, defined as wrist, vertebral, and hip fractures among individuals from both groups. Patients with osteoporotic fractures before hemophilia diagnosis were excluded.

In the analysis, the team calculated hazard ratios and incidence rates of new-onset osteoporotic fractures in both cohorts.

After analysis, the researchers found that the risk of developing new-onset osteoporotic fractures was greater in the hemophilia group versus the comparison group (HR, 5.41; 95% confidence interval, 2.42-12.1; P less than .001).

After adjusting for covariates, such as socioeconomic status, age, sex, and other comorbidities, patients with hemophilia had a 337% higher risk of developing osteoporotic fractures post diagnosis versus matched controls (95% CI, 1.88-10.17; P = .001).

“The risk of osteoporotic fractures following haemophilia increased with time and was significantly higher at 5 years after the diagnosis,” the researchers wrote.

The underlying mechanisms driving these associations remain unknown, according to the authors. Possible risk factors include reduced physical activity, HIV and hepatitis C virus infections, and arthropathy.

The researchers acknowledged that a key limitation of the study was the absence of some relevant clinical information within the database. As a result, information bias could have lowered the accuracy of the analysis.

No funding sources were reported. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Tuan S-H et al. Haemophilia. 2019 Jul 7. doi: 10.1111/hae.13814.

FROM HAEMOPHILIA

Bisphosphonates before denosumab may prevent postdenosumab BMD rebound effect

MADRID – Results from an ongoing study of postmenopausal women who discontinue osteoporosis treatment with denosumab (Prolia) so far support the use of denosumab as a second-line therapy after a bisphosphonate, unless otherwise indicated, in order to reduce the loss of bone mineral density (BMD) after its discontinuation and also to support treatment to reduce bone turnover biomarkers as much as possible after stopping denosumab.

“We saw in our study that, even if you give bisphosphonates after denosumab discontinuation, [patients] could lose bone, and the group that controlled the loss of bone had very high control of bone turnover markers,” study author and presenter Bérengère Rozier Aubry, MD, said in an interview at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

She and her colleagues at the Center of Bone Diseases at Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital are conducting the ReoLaus (Rebound Effect Observatory in Lausanne) Bone Project to determine whether giving a bisphosphonate to postmenopausal women with osteoporosis after they have discontinued denosumab can stop the loss of bone mineral density (BMD) observed in many patients up to 2 years after stopping denosumab. This postdenosumab BMD loss has also been observed to occur with multiple spontaneous vertebral fractures.

Nearly half of patients who start denosumab discontinue it within 1 year, and 64% by 2 years, according to U.S. administrative claims data (Osteoporos Int. 2017 Apr. doi: 10.1007/s00198-016-3886-y), even though it can be taken for up to 10 years. The discontinuation is either because the patient wishes to do so or there’s a medical indication such as stopping aromatase inhibitor treatment, resolution of osteoporosis, or side effects, Dr. Rozier Aubry said in a press conference at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

Upon discontinuing denosumab, there’s a marked rebound effect in which levels of bone turnover markers rise for 2 years, and some or all of the BMD that was gained is lost (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011 Apr. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1502). Multiple spontaneous vertebral fractures also have been reported in 5%-7%, as Dr. Rozier Aubry and colleagues first described in 2016 (Osteoporos Int. 2016 May. doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3380-y) and others have reported subsequently.

Recommendations from the Endocrine Society in March 2019, a 2017 position statement from the European Calcified Tissue Society, and guidelines from other groups advise giving antiresorptive treatment (bisphosphonates, hormone therapy, or selective estrogen-receptor modulators) but do not say which one, in what dose, when, or for how long, Dr. Rozier Aubry noted.

Treatment with zoledronate 6 months after the last denosumab injection achieves partial preservation of BMD, but multiple vertebral fractures have still been reported when raloxifene, ibandronate, or alendronate have been given after stopping denosumab, she said.

In the ReoLaus Bone Project, Dr. Rozier Aubry and associates are following 170 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis at Lausanne University Hospital who are taking denosumab therapy. At the congress, she reported on the first 71 women in the cohort with 1 year of follow-up. They had a mean age of 64 years, had fewer than one prevalent fracture before starting denosumab, and stopped denosumab after a mean of 7.7 injections. Overall, 8% took glucocorticoids, and 22% took aromatase inhibitors.

The investigators collected data on what treatment was used after denosumab, how bone turnover markers changed 1-3 months after the last denosumab injection and then regularly afterward, how bone mineral density changed after 1 year, and any new osteoporotic fractures.

At the time of denosumab discontinuation, 59% received zoledronate, 24% alendronate, 3% other drugs, and 14% nothing. At a mean of about 17 months after the last denosumab injection, the investigators classified 30 patients as BMD losers (losing at least 3.96%), and 41 had stable BMD. The researchers found that BMD losers were younger (61.4 years vs. 65.5 years), were less likely to use zoledronate before starting denosumab (0% vs. 12%), and had greater serum CTX (C-telopeptide cross-linked type 1 collagen) levels at denosumab initiation (644 ng/mL vs. 474 ng/mL) and 12.8 months after stopping denosumab (592 ng/mL vs. 336 ng/mL) than did those with stable BMD. All differences were statistically significant.

“Our results support the use of denosumab in second line after bisphosphonate therapy to restrain the BMD loss at its discontinuation ... and a strategy to maintain the bone turnover marker serum CTX as low as possible after denosumab discontinuation,” she concluded.

“Our proposition is to start with 1 or 2 years of bisphosphonates, and if the osteoporosis is severe, to switch to denosumab treatment for 4, 6 years. … We can use denosumab for 10 years without side effects, and after that we give bisphosphonates to consolidate the treatment,” she said.

Dr. Rozier Aubry and her associates plan to follow patients in their study for 2 years.

Dr. Rozier Aubry disclosed serving on speakers bureaus for Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Amgen, and Novartis.

SOURCE: Rozier Aubry B et al. Ann Rheum Dis. Jun 2019;78(Suppl 2):115; Abstract OP0085. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.4175.

MADRID – Results from an ongoing study of postmenopausal women who discontinue osteoporosis treatment with denosumab (Prolia) so far support the use of denosumab as a second-line therapy after a bisphosphonate, unless otherwise indicated, in order to reduce the loss of bone mineral density (BMD) after its discontinuation and also to support treatment to reduce bone turnover biomarkers as much as possible after stopping denosumab.

“We saw in our study that, even if you give bisphosphonates after denosumab discontinuation, [patients] could lose bone, and the group that controlled the loss of bone had very high control of bone turnover markers,” study author and presenter Bérengère Rozier Aubry, MD, said in an interview at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

She and her colleagues at the Center of Bone Diseases at Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital are conducting the ReoLaus (Rebound Effect Observatory in Lausanne) Bone Project to determine whether giving a bisphosphonate to postmenopausal women with osteoporosis after they have discontinued denosumab can stop the loss of bone mineral density (BMD) observed in many patients up to 2 years after stopping denosumab. This postdenosumab BMD loss has also been observed to occur with multiple spontaneous vertebral fractures.

Nearly half of patients who start denosumab discontinue it within 1 year, and 64% by 2 years, according to U.S. administrative claims data (Osteoporos Int. 2017 Apr. doi: 10.1007/s00198-016-3886-y), even though it can be taken for up to 10 years. The discontinuation is either because the patient wishes to do so or there’s a medical indication such as stopping aromatase inhibitor treatment, resolution of osteoporosis, or side effects, Dr. Rozier Aubry said in a press conference at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

Upon discontinuing denosumab, there’s a marked rebound effect in which levels of bone turnover markers rise for 2 years, and some or all of the BMD that was gained is lost (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011 Apr. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1502). Multiple spontaneous vertebral fractures also have been reported in 5%-7%, as Dr. Rozier Aubry and colleagues first described in 2016 (Osteoporos Int. 2016 May. doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3380-y) and others have reported subsequently.

Recommendations from the Endocrine Society in March 2019, a 2017 position statement from the European Calcified Tissue Society, and guidelines from other groups advise giving antiresorptive treatment (bisphosphonates, hormone therapy, or selective estrogen-receptor modulators) but do not say which one, in what dose, when, or for how long, Dr. Rozier Aubry noted.

Treatment with zoledronate 6 months after the last denosumab injection achieves partial preservation of BMD, but multiple vertebral fractures have still been reported when raloxifene, ibandronate, or alendronate have been given after stopping denosumab, she said.

In the ReoLaus Bone Project, Dr. Rozier Aubry and associates are following 170 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis at Lausanne University Hospital who are taking denosumab therapy. At the congress, she reported on the first 71 women in the cohort with 1 year of follow-up. They had a mean age of 64 years, had fewer than one prevalent fracture before starting denosumab, and stopped denosumab after a mean of 7.7 injections. Overall, 8% took glucocorticoids, and 22% took aromatase inhibitors.

The investigators collected data on what treatment was used after denosumab, how bone turnover markers changed 1-3 months after the last denosumab injection and then regularly afterward, how bone mineral density changed after 1 year, and any new osteoporotic fractures.

At the time of denosumab discontinuation, 59% received zoledronate, 24% alendronate, 3% other drugs, and 14% nothing. At a mean of about 17 months after the last denosumab injection, the investigators classified 30 patients as BMD losers (losing at least 3.96%), and 41 had stable BMD. The researchers found that BMD losers were younger (61.4 years vs. 65.5 years), were less likely to use zoledronate before starting denosumab (0% vs. 12%), and had greater serum CTX (C-telopeptide cross-linked type 1 collagen) levels at denosumab initiation (644 ng/mL vs. 474 ng/mL) and 12.8 months after stopping denosumab (592 ng/mL vs. 336 ng/mL) than did those with stable BMD. All differences were statistically significant.

“Our results support the use of denosumab in second line after bisphosphonate therapy to restrain the BMD loss at its discontinuation ... and a strategy to maintain the bone turnover marker serum CTX as low as possible after denosumab discontinuation,” she concluded.

“Our proposition is to start with 1 or 2 years of bisphosphonates, and if the osteoporosis is severe, to switch to denosumab treatment for 4, 6 years. … We can use denosumab for 10 years without side effects, and after that we give bisphosphonates to consolidate the treatment,” she said.

Dr. Rozier Aubry and her associates plan to follow patients in their study for 2 years.

Dr. Rozier Aubry disclosed serving on speakers bureaus for Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Amgen, and Novartis.

SOURCE: Rozier Aubry B et al. Ann Rheum Dis. Jun 2019;78(Suppl 2):115; Abstract OP0085. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.4175.

MADRID – Results from an ongoing study of postmenopausal women who discontinue osteoporosis treatment with denosumab (Prolia) so far support the use of denosumab as a second-line therapy after a bisphosphonate, unless otherwise indicated, in order to reduce the loss of bone mineral density (BMD) after its discontinuation and also to support treatment to reduce bone turnover biomarkers as much as possible after stopping denosumab.

“We saw in our study that, even if you give bisphosphonates after denosumab discontinuation, [patients] could lose bone, and the group that controlled the loss of bone had very high control of bone turnover markers,” study author and presenter Bérengère Rozier Aubry, MD, said in an interview at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

She and her colleagues at the Center of Bone Diseases at Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital are conducting the ReoLaus (Rebound Effect Observatory in Lausanne) Bone Project to determine whether giving a bisphosphonate to postmenopausal women with osteoporosis after they have discontinued denosumab can stop the loss of bone mineral density (BMD) observed in many patients up to 2 years after stopping denosumab. This postdenosumab BMD loss has also been observed to occur with multiple spontaneous vertebral fractures.

Nearly half of patients who start denosumab discontinue it within 1 year, and 64% by 2 years, according to U.S. administrative claims data (Osteoporos Int. 2017 Apr. doi: 10.1007/s00198-016-3886-y), even though it can be taken for up to 10 years. The discontinuation is either because the patient wishes to do so or there’s a medical indication such as stopping aromatase inhibitor treatment, resolution of osteoporosis, or side effects, Dr. Rozier Aubry said in a press conference at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

Upon discontinuing denosumab, there’s a marked rebound effect in which levels of bone turnover markers rise for 2 years, and some or all of the BMD that was gained is lost (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011 Apr. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1502). Multiple spontaneous vertebral fractures also have been reported in 5%-7%, as Dr. Rozier Aubry and colleagues first described in 2016 (Osteoporos Int. 2016 May. doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3380-y) and others have reported subsequently.

Recommendations from the Endocrine Society in March 2019, a 2017 position statement from the European Calcified Tissue Society, and guidelines from other groups advise giving antiresorptive treatment (bisphosphonates, hormone therapy, or selective estrogen-receptor modulators) but do not say which one, in what dose, when, or for how long, Dr. Rozier Aubry noted.

Treatment with zoledronate 6 months after the last denosumab injection achieves partial preservation of BMD, but multiple vertebral fractures have still been reported when raloxifene, ibandronate, or alendronate have been given after stopping denosumab, she said.

In the ReoLaus Bone Project, Dr. Rozier Aubry and associates are following 170 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis at Lausanne University Hospital who are taking denosumab therapy. At the congress, she reported on the first 71 women in the cohort with 1 year of follow-up. They had a mean age of 64 years, had fewer than one prevalent fracture before starting denosumab, and stopped denosumab after a mean of 7.7 injections. Overall, 8% took glucocorticoids, and 22% took aromatase inhibitors.

The investigators collected data on what treatment was used after denosumab, how bone turnover markers changed 1-3 months after the last denosumab injection and then regularly afterward, how bone mineral density changed after 1 year, and any new osteoporotic fractures.

At the time of denosumab discontinuation, 59% received zoledronate, 24% alendronate, 3% other drugs, and 14% nothing. At a mean of about 17 months after the last denosumab injection, the investigators classified 30 patients as BMD losers (losing at least 3.96%), and 41 had stable BMD. The researchers found that BMD losers were younger (61.4 years vs. 65.5 years), were less likely to use zoledronate before starting denosumab (0% vs. 12%), and had greater serum CTX (C-telopeptide cross-linked type 1 collagen) levels at denosumab initiation (644 ng/mL vs. 474 ng/mL) and 12.8 months after stopping denosumab (592 ng/mL vs. 336 ng/mL) than did those with stable BMD. All differences were statistically significant.

“Our results support the use of denosumab in second line after bisphosphonate therapy to restrain the BMD loss at its discontinuation ... and a strategy to maintain the bone turnover marker serum CTX as low as possible after denosumab discontinuation,” she concluded.

“Our proposition is to start with 1 or 2 years of bisphosphonates, and if the osteoporosis is severe, to switch to denosumab treatment for 4, 6 years. … We can use denosumab for 10 years without side effects, and after that we give bisphosphonates to consolidate the treatment,” she said.

Dr. Rozier Aubry and her associates plan to follow patients in their study for 2 years.

Dr. Rozier Aubry disclosed serving on speakers bureaus for Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Amgen, and Novartis.

SOURCE: Rozier Aubry B et al. Ann Rheum Dis. Jun 2019;78(Suppl 2):115; Abstract OP0085. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-eular.4175.

REPORTING FROM EULAR 2019 CONGRESS

Consider drug treatment in late-life women with osteoporosis

and therefore have more to gain from osteoporosis treatment, regardless of the presence of any comorbidities, according to a new study.

To determine how and when to treat older women for osteoporosis, Kristine E. Ensrud, MD, of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and coauthors studied active surviving participants in the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. The cohort comprised 1,528 women who met criteria for either osteoporosis (n = 761) or without osteoporosis but at high fracture risk (n = 767). Mean age at the time of examination was 84 years and mean femoral neck bone mineral density (BMD) T-score was −2.24.

During an average follow-up period of 4.4 years after initial examination, 125 women (9%) experienced a hip fracture and 287 (19%) died without experiencing that outcome. The 5-year absolute probability of mortality was 25% (95% confidence interval, 21.8%-28.1%) in women with osteoporosis and 19% (95% CI, 16.6%-22.3%) in women without osteoporosis but at high fracture risk. Although both groups saw mortality probability increase with more comorbidities and poorer prognosis, 5-year hip fracture probability was 13% (95% CI, 10.7%-15.5%) among women with osteoporosis and 4% (95% CI, 2.8%-5.6%) among women without osteoporosis but at high fracture risk.

This probability of the women with osteoporosis experiencing a hip fracture, “even after considering their competing mortality risk” suggests that “initiation of drug treatment in late-life women with osteoporosis may still be effective in the prevention of subsequent hip fracture,” the researchers wrote in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Dr. Ensrud and associates acknowledged their study’s limitations, including the cohort being made up of community-dwelling white women and thus the results not being generalizable to men or women of other racial or ethnic groups. But the researchers noted that the mean femoral neck BMD of women in the study “was essentially identical to that of a nationally representative sample of community-dwelling women 80 years and older enrolled in the 2005 to 2008 NHANES [National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey].”

Dr. Cynthia M. Boyd reported receiving royalties from UpToDate and a grant from the National Institutes of Aging Dr. Katie L. Stone reported receiving grant support from Merck, and Dr. Lisa Langsetmo reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and Merck. No other authors reported any relevant financial disclosures. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures was supported by NIH and grants from NIA.

SOURCE: Ensrud KE et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Jun 17. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0682.

Older patients with osteoporosis with multimorbidities are the most at risk for hip fractures, which should place an emphasis on research into their treatment, Sarah D. Berry, MD, MPH; Sandra Shi, MD; and Douglas P. Kiel, MD, MPH, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, wrote in an invited commentary.

The coauthors noted that the study by Ensrud et al. is of “great clinical importance, given the ongoing recognition that clinical guidelines should consider multimorbidity.” Currently, the guidelines for treating osteoporosis do not consider age, comorbidities, or frailty, but this study indicates that older women can see benefits from treatment.

They also acknowledged the value of patient preference, referencing a study where 80% of older women “would prefer death as opposed to a hip fracture leading to institutionalization.” All in all, the work of Ensrud et al. is a reminder of “the dangers in ignoring the problem” and the need for future guidelines in osteoporosis treatment to address osteoporosis treatment for older patients with multimorbidity.

These comments are adapted from an invited commentary accompanying the article by Ensrud et al. (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Jun 17. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0688 ). Dr. Berry reported receiving royalties from UpToDate outside the submitted work. Dr. Kiel reported receiving royalties from UpToDate, along with grants from the Dairy Council and Radius Health, and personal fees from Springer outside the submitted work. Dr. Shi reported no relevant financial disclosures. No funding for this editorial was reported.

Older patients with osteoporosis with multimorbidities are the most at risk for hip fractures, which should place an emphasis on research into their treatment, Sarah D. Berry, MD, MPH; Sandra Shi, MD; and Douglas P. Kiel, MD, MPH, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, wrote in an invited commentary.

The coauthors noted that the study by Ensrud et al. is of “great clinical importance, given the ongoing recognition that clinical guidelines should consider multimorbidity.” Currently, the guidelines for treating osteoporosis do not consider age, comorbidities, or frailty, but this study indicates that older women can see benefits from treatment.

They also acknowledged the value of patient preference, referencing a study where 80% of older women “would prefer death as opposed to a hip fracture leading to institutionalization.” All in all, the work of Ensrud et al. is a reminder of “the dangers in ignoring the problem” and the need for future guidelines in osteoporosis treatment to address osteoporosis treatment for older patients with multimorbidity.

These comments are adapted from an invited commentary accompanying the article by Ensrud et al. (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Jun 17. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0688 ). Dr. Berry reported receiving royalties from UpToDate outside the submitted work. Dr. Kiel reported receiving royalties from UpToDate, along with grants from the Dairy Council and Radius Health, and personal fees from Springer outside the submitted work. Dr. Shi reported no relevant financial disclosures. No funding for this editorial was reported.

Older patients with osteoporosis with multimorbidities are the most at risk for hip fractures, which should place an emphasis on research into their treatment, Sarah D. Berry, MD, MPH; Sandra Shi, MD; and Douglas P. Kiel, MD, MPH, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, wrote in an invited commentary.

The coauthors noted that the study by Ensrud et al. is of “great clinical importance, given the ongoing recognition that clinical guidelines should consider multimorbidity.” Currently, the guidelines for treating osteoporosis do not consider age, comorbidities, or frailty, but this study indicates that older women can see benefits from treatment.

They also acknowledged the value of patient preference, referencing a study where 80% of older women “would prefer death as opposed to a hip fracture leading to institutionalization.” All in all, the work of Ensrud et al. is a reminder of “the dangers in ignoring the problem” and the need for future guidelines in osteoporosis treatment to address osteoporosis treatment for older patients with multimorbidity.

These comments are adapted from an invited commentary accompanying the article by Ensrud et al. (JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Jun 17. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0688 ). Dr. Berry reported receiving royalties from UpToDate outside the submitted work. Dr. Kiel reported receiving royalties from UpToDate, along with grants from the Dairy Council and Radius Health, and personal fees from Springer outside the submitted work. Dr. Shi reported no relevant financial disclosures. No funding for this editorial was reported.

and therefore have more to gain from osteoporosis treatment, regardless of the presence of any comorbidities, according to a new study.

To determine how and when to treat older women for osteoporosis, Kristine E. Ensrud, MD, of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and coauthors studied active surviving participants in the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. The cohort comprised 1,528 women who met criteria for either osteoporosis (n = 761) or without osteoporosis but at high fracture risk (n = 767). Mean age at the time of examination was 84 years and mean femoral neck bone mineral density (BMD) T-score was −2.24.

During an average follow-up period of 4.4 years after initial examination, 125 women (9%) experienced a hip fracture and 287 (19%) died without experiencing that outcome. The 5-year absolute probability of mortality was 25% (95% confidence interval, 21.8%-28.1%) in women with osteoporosis and 19% (95% CI, 16.6%-22.3%) in women without osteoporosis but at high fracture risk. Although both groups saw mortality probability increase with more comorbidities and poorer prognosis, 5-year hip fracture probability was 13% (95% CI, 10.7%-15.5%) among women with osteoporosis and 4% (95% CI, 2.8%-5.6%) among women without osteoporosis but at high fracture risk.

This probability of the women with osteoporosis experiencing a hip fracture, “even after considering their competing mortality risk” suggests that “initiation of drug treatment in late-life women with osteoporosis may still be effective in the prevention of subsequent hip fracture,” the researchers wrote in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Dr. Ensrud and associates acknowledged their study’s limitations, including the cohort being made up of community-dwelling white women and thus the results not being generalizable to men or women of other racial or ethnic groups. But the researchers noted that the mean femoral neck BMD of women in the study “was essentially identical to that of a nationally representative sample of community-dwelling women 80 years and older enrolled in the 2005 to 2008 NHANES [National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey].”

Dr. Cynthia M. Boyd reported receiving royalties from UpToDate and a grant from the National Institutes of Aging Dr. Katie L. Stone reported receiving grant support from Merck, and Dr. Lisa Langsetmo reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and Merck. No other authors reported any relevant financial disclosures. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures was supported by NIH and grants from NIA.

SOURCE: Ensrud KE et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Jun 17. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0682.

and therefore have more to gain from osteoporosis treatment, regardless of the presence of any comorbidities, according to a new study.

To determine how and when to treat older women for osteoporosis, Kristine E. Ensrud, MD, of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and coauthors studied active surviving participants in the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. The cohort comprised 1,528 women who met criteria for either osteoporosis (n = 761) or without osteoporosis but at high fracture risk (n = 767). Mean age at the time of examination was 84 years and mean femoral neck bone mineral density (BMD) T-score was −2.24.

During an average follow-up period of 4.4 years after initial examination, 125 women (9%) experienced a hip fracture and 287 (19%) died without experiencing that outcome. The 5-year absolute probability of mortality was 25% (95% confidence interval, 21.8%-28.1%) in women with osteoporosis and 19% (95% CI, 16.6%-22.3%) in women without osteoporosis but at high fracture risk. Although both groups saw mortality probability increase with more comorbidities and poorer prognosis, 5-year hip fracture probability was 13% (95% CI, 10.7%-15.5%) among women with osteoporosis and 4% (95% CI, 2.8%-5.6%) among women without osteoporosis but at high fracture risk.

This probability of the women with osteoporosis experiencing a hip fracture, “even after considering their competing mortality risk” suggests that “initiation of drug treatment in late-life women with osteoporosis may still be effective in the prevention of subsequent hip fracture,” the researchers wrote in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Dr. Ensrud and associates acknowledged their study’s limitations, including the cohort being made up of community-dwelling white women and thus the results not being generalizable to men or women of other racial or ethnic groups. But the researchers noted that the mean femoral neck BMD of women in the study “was essentially identical to that of a nationally representative sample of community-dwelling women 80 years and older enrolled in the 2005 to 2008 NHANES [National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey].”

Dr. Cynthia M. Boyd reported receiving royalties from UpToDate and a grant from the National Institutes of Aging Dr. Katie L. Stone reported receiving grant support from Merck, and Dr. Lisa Langsetmo reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and Merck. No other authors reported any relevant financial disclosures. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures was supported by NIH and grants from NIA.

SOURCE: Ensrud KE et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Jun 17. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0682.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Medical treatment to prevent osteoporotic hip fracture in women over age 80 likely is worthwhile.

Major finding: Five-year hip fracture probability was 13% among women with osteoporosis and 4% among women without osteoporosis but at high fracture risk.

Study details: A prospective cohort study of 1,528 women 80 years and older who were potential candidates for osteoporosis drug treatment.

Disclosures: Dr. Cynthia M. Boyd reported receiving royalties from UpToDate and a grant from the National Institutes of Aging Dr. Katie L. Stone reported receiving grant support from Merck, and Dr. Lisa Langsetmo reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and Merck. No other authors reported any relevant financial disclosures. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures was supported by NIH and grants from NIA.

Source: Ensrud KE et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Jun 17. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0682.

An app to help women and clinicians manage menopausal symptoms

In North America, women experience menopause (the permanent cessation of menstruation due to loss of ovarian activity) at a median age of 51 years. They may experience symptoms of perimenopause, or the menopause transition, for several years before menstruation ceases. Menopausal symptoms include vasomotor symptoms, such as hot flushes, and vaginal symptoms, such as vaginal dryness and pain during intercourse.1

Women may have questions about treating menopausal symptoms, maintaining their health, and preventing such age-related diseases as osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease. The decision to treat menopausal symptoms is challenging for women as well as their clinicians given that recommendations have changed over the past few years.

A free app with multiple features. The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) has developed a no-cost mobile health application called MenoPro for menopausal symptom management based on the organization’s 2017 recommendations.2 The app has 2 modes: one for clinicians and one for women/patients to support shared decision making.

For clinicians, the app helps identify which patients with menopausal symptoms are candidates for pharmacologic treatment and the options for optimal therapy. The app also can be used to calculate a 10-year cardiovascular disease (heart disease and stroke) risk assessment. In addition, it contains links to a breast cancer risk assessment as well as an osteoporosis/bone fracture risk assessment tool (FRAX model calculator). Finally, MenoPro includes NAMS’s educational materials and information pages on lifestyle modifications to reduce hot flushes, contraindications and cautions to hormone therapy, pros and cons of hormonal versus nonhormonal options, a comparison of oral (pills) and transdermal (patches, gels, sprays) therapies, treatment options for vaginal dryness and pain with sexual activities, and direct links to tables with the various formulations and doses of medications.

The TABLE details the features of the MenoPro app based on a shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (app comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature used, and important special features).3 I hope that the app described here will assist you in caring for women in the menopausal transition.

1. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 141: Management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:202-216.

2. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2018;25:13621387.

3. Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1478-1483.

In North America, women experience menopause (the permanent cessation of menstruation due to loss of ovarian activity) at a median age of 51 years. They may experience symptoms of perimenopause, or the menopause transition, for several years before menstruation ceases. Menopausal symptoms include vasomotor symptoms, such as hot flushes, and vaginal symptoms, such as vaginal dryness and pain during intercourse.1

Women may have questions about treating menopausal symptoms, maintaining their health, and preventing such age-related diseases as osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease. The decision to treat menopausal symptoms is challenging for women as well as their clinicians given that recommendations have changed over the past few years.

A free app with multiple features. The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) has developed a no-cost mobile health application called MenoPro for menopausal symptom management based on the organization’s 2017 recommendations.2 The app has 2 modes: one for clinicians and one for women/patients to support shared decision making.

For clinicians, the app helps identify which patients with menopausal symptoms are candidates for pharmacologic treatment and the options for optimal therapy. The app also can be used to calculate a 10-year cardiovascular disease (heart disease and stroke) risk assessment. In addition, it contains links to a breast cancer risk assessment as well as an osteoporosis/bone fracture risk assessment tool (FRAX model calculator). Finally, MenoPro includes NAMS’s educational materials and information pages on lifestyle modifications to reduce hot flushes, contraindications and cautions to hormone therapy, pros and cons of hormonal versus nonhormonal options, a comparison of oral (pills) and transdermal (patches, gels, sprays) therapies, treatment options for vaginal dryness and pain with sexual activities, and direct links to tables with the various formulations and doses of medications.

The TABLE details the features of the MenoPro app based on a shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (app comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature used, and important special features).3 I hope that the app described here will assist you in caring for women in the menopausal transition.

In North America, women experience menopause (the permanent cessation of menstruation due to loss of ovarian activity) at a median age of 51 years. They may experience symptoms of perimenopause, or the menopause transition, for several years before menstruation ceases. Menopausal symptoms include vasomotor symptoms, such as hot flushes, and vaginal symptoms, such as vaginal dryness and pain during intercourse.1

Women may have questions about treating menopausal symptoms, maintaining their health, and preventing such age-related diseases as osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease. The decision to treat menopausal symptoms is challenging for women as well as their clinicians given that recommendations have changed over the past few years.

A free app with multiple features. The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) has developed a no-cost mobile health application called MenoPro for menopausal symptom management based on the organization’s 2017 recommendations.2 The app has 2 modes: one for clinicians and one for women/patients to support shared decision making.

For clinicians, the app helps identify which patients with menopausal symptoms are candidates for pharmacologic treatment and the options for optimal therapy. The app also can be used to calculate a 10-year cardiovascular disease (heart disease and stroke) risk assessment. In addition, it contains links to a breast cancer risk assessment as well as an osteoporosis/bone fracture risk assessment tool (FRAX model calculator). Finally, MenoPro includes NAMS’s educational materials and information pages on lifestyle modifications to reduce hot flushes, contraindications and cautions to hormone therapy, pros and cons of hormonal versus nonhormonal options, a comparison of oral (pills) and transdermal (patches, gels, sprays) therapies, treatment options for vaginal dryness and pain with sexual activities, and direct links to tables with the various formulations and doses of medications.

The TABLE details the features of the MenoPro app based on a shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (app comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature used, and important special features).3 I hope that the app described here will assist you in caring for women in the menopausal transition.

1. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 141: Management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:202-216.

2. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2018;25:13621387.

3. Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1478-1483.

1. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 141: Management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:202-216.

2. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2018;25:13621387.

3. Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1478-1483.

Younger men and women show similar rates of osteopenia

according to findings from a cross-sectional study.

The high prevalence of osteopenia – once viewed as restricted largely to older women – in the study’s younger, cross-sex population should spur physicians to ask all patients about calcium intake and exercise as well as to screen for osteoporosis in all patients, Martha A. Bass, PhD,`wrote in the Journal of the American Osteopathic Association.

“It is important that early detection of the precursors for osteoporosis become part of the annual physical for people in this age range, as well as in older patients,” noted Dr Bass of the University of Mississippi School of Applied Sciences in Oxford, and coauthors. “Primary care physicians should begin educating patients as early as adolescence or young adulthood so the consequences of osteoporosis can be prevented. The result would be the prevention of future bone fractures and the morbidity and mortality associated with bone fractures, thus leading to improved quality of life.”

The researchers set out to examine the likelihood of low bone mineral density (BMD) and related risk factors in 173 adults aged 35-50 years. All of the participants completed a questionnaire assessing calcium intake, weekly exercise, smoking, and body mass index, and all underwent screening for BMD. The study’s primary outcome was BMD at the femoral neck, trochanter, intertrochanteric crest, total femur, and lumbar spine.

Among the 81 men in the sample, 25 (30%) had a normal body mass index, and the remainder were either overweight (47.5%) or obese (22.5%). One of the women was underweight, 48.9% were normal weight, 28.3% were overweight, and 21.7% were obese.

Most of the sample, regardless of gender, reported consuming fewer than three dairy items per day. Exercise frequency was better, with 68% of men and 56.4% of women saying they exercised at least 20 times per month.

There were no total femur osteoporosis findings in either sex. However, osteopenia at the femoral neck was present in 28.4% of the men and 26.1% of the women. Osteopenia at the lumbar spine occurred in 21% of men and 15.2% of women, with 6.2% of men and 2.2% of women showing osteoporosis at this site.

An adjusted analysis determined that exercise correlated significantly and negatively with femoral neck BMD in men. But in women, there was a significant and positive correlation with BMD at the lumbar spine and at all femoral measurements.

Body mass index also played into the risk picture. Among men, almost all BMD measurements (trochanter, intertrochanteric crest, total femur, and lumbar spine) were positively associated with higher BMI. For women, higher BMI was associated with better BMD at the all the femoral sites, but not at the lumbar spine.

The negative correlation between femoral neck BMD and exercise in men seemed to contradict findings from previous studies. The authors said that could be a result of reporting bias, with men overestimating their amount of exercise, and could suggest that higher BMI confers some protection against bone loss in men.

The study found no significant correlations between dairy intake and BMD at any site in either sex. The finding suggests that both sexes need to improve both vitamin D and calcium intake.

None of the authors reported any financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Bass MA et al. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2019;119(6):357-63.

according to findings from a cross-sectional study.

The high prevalence of osteopenia – once viewed as restricted largely to older women – in the study’s younger, cross-sex population should spur physicians to ask all patients about calcium intake and exercise as well as to screen for osteoporosis in all patients, Martha A. Bass, PhD,`wrote in the Journal of the American Osteopathic Association.

“It is important that early detection of the precursors for osteoporosis become part of the annual physical for people in this age range, as well as in older patients,” noted Dr Bass of the University of Mississippi School of Applied Sciences in Oxford, and coauthors. “Primary care physicians should begin educating patients as early as adolescence or young adulthood so the consequences of osteoporosis can be prevented. The result would be the prevention of future bone fractures and the morbidity and mortality associated with bone fractures, thus leading to improved quality of life.”

The researchers set out to examine the likelihood of low bone mineral density (BMD) and related risk factors in 173 adults aged 35-50 years. All of the participants completed a questionnaire assessing calcium intake, weekly exercise, smoking, and body mass index, and all underwent screening for BMD. The study’s primary outcome was BMD at the femoral neck, trochanter, intertrochanteric crest, total femur, and lumbar spine.

Among the 81 men in the sample, 25 (30%) had a normal body mass index, and the remainder were either overweight (47.5%) or obese (22.5%). One of the women was underweight, 48.9% were normal weight, 28.3% were overweight, and 21.7% were obese.

Most of the sample, regardless of gender, reported consuming fewer than three dairy items per day. Exercise frequency was better, with 68% of men and 56.4% of women saying they exercised at least 20 times per month.

There were no total femur osteoporosis findings in either sex. However, osteopenia at the femoral neck was present in 28.4% of the men and 26.1% of the women. Osteopenia at the lumbar spine occurred in 21% of men and 15.2% of women, with 6.2% of men and 2.2% of women showing osteoporosis at this site.

An adjusted analysis determined that exercise correlated significantly and negatively with femoral neck BMD in men. But in women, there was a significant and positive correlation with BMD at the lumbar spine and at all femoral measurements.

Body mass index also played into the risk picture. Among men, almost all BMD measurements (trochanter, intertrochanteric crest, total femur, and lumbar spine) were positively associated with higher BMI. For women, higher BMI was associated with better BMD at the all the femoral sites, but not at the lumbar spine.

The negative correlation between femoral neck BMD and exercise in men seemed to contradict findings from previous studies. The authors said that could be a result of reporting bias, with men overestimating their amount of exercise, and could suggest that higher BMI confers some protection against bone loss in men.

The study found no significant correlations between dairy intake and BMD at any site in either sex. The finding suggests that both sexes need to improve both vitamin D and calcium intake.

None of the authors reported any financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Bass MA et al. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2019;119(6):357-63.

according to findings from a cross-sectional study.

The high prevalence of osteopenia – once viewed as restricted largely to older women – in the study’s younger, cross-sex population should spur physicians to ask all patients about calcium intake and exercise as well as to screen for osteoporosis in all patients, Martha A. Bass, PhD,`wrote in the Journal of the American Osteopathic Association.

“It is important that early detection of the precursors for osteoporosis become part of the annual physical for people in this age range, as well as in older patients,” noted Dr Bass of the University of Mississippi School of Applied Sciences in Oxford, and coauthors. “Primary care physicians should begin educating patients as early as adolescence or young adulthood so the consequences of osteoporosis can be prevented. The result would be the prevention of future bone fractures and the morbidity and mortality associated with bone fractures, thus leading to improved quality of life.”

The researchers set out to examine the likelihood of low bone mineral density (BMD) and related risk factors in 173 adults aged 35-50 years. All of the participants completed a questionnaire assessing calcium intake, weekly exercise, smoking, and body mass index, and all underwent screening for BMD. The study’s primary outcome was BMD at the femoral neck, trochanter, intertrochanteric crest, total femur, and lumbar spine.

Among the 81 men in the sample, 25 (30%) had a normal body mass index, and the remainder were either overweight (47.5%) or obese (22.5%). One of the women was underweight, 48.9% were normal weight, 28.3% were overweight, and 21.7% were obese.

Most of the sample, regardless of gender, reported consuming fewer than three dairy items per day. Exercise frequency was better, with 68% of men and 56.4% of women saying they exercised at least 20 times per month.

There were no total femur osteoporosis findings in either sex. However, osteopenia at the femoral neck was present in 28.4% of the men and 26.1% of the women. Osteopenia at the lumbar spine occurred in 21% of men and 15.2% of women, with 6.2% of men and 2.2% of women showing osteoporosis at this site.

An adjusted analysis determined that exercise correlated significantly and negatively with femoral neck BMD in men. But in women, there was a significant and positive correlation with BMD at the lumbar spine and at all femoral measurements.

Body mass index also played into the risk picture. Among men, almost all BMD measurements (trochanter, intertrochanteric crest, total femur, and lumbar spine) were positively associated with higher BMI. For women, higher BMI was associated with better BMD at the all the femoral sites, but not at the lumbar spine.

The negative correlation between femoral neck BMD and exercise in men seemed to contradict findings from previous studies. The authors said that could be a result of reporting bias, with men overestimating their amount of exercise, and could suggest that higher BMI confers some protection against bone loss in men.

The study found no significant correlations between dairy intake and BMD at any site in either sex. The finding suggests that both sexes need to improve both vitamin D and calcium intake.

None of the authors reported any financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Bass MA et al. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2019;119(6):357-63.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN OSTEOPATHIC ASSOCIATION

More empathy for women

At the risk of too much personal self-disclosure, I feel the need to write about my having developed more empathy for women. Having been described as a “manly man,” by a woman who feels she knows me, it has always been difficult for me to understand women. Fortunately, an experience I’ve had has given me more insight into women – shallow though it may still be.

About a year ago, I had learned I had prostate carcinoma, which is now in remission – thanks to a proctectomy, radiation, and hormone therapy. The antitestosterone hormones I need to take for 2 years are turning me into an old woman, thus my newfound empathy.

After the surgery, I found myself leaking – something that I probably only experienced as a child and of which I have little memory. I now have some more empathy for the problems women have with leaking each month or in general – it is a constant preoccupation. The leuprolide shots I am taking are giving me hot flashes, causing me to be more emotional about things I really don’t understand, and apparently I am at risk for getting osteoporosis – all things that happen to women that have been mildly on my radar for years but for which I lacked direct and personal experience.

Since having my testosterone turned off by the leuprolide, my joints are more prone to aches and pains from various injuries over the years. Because I understand that “motion is lotion,” I have some control of this problem. However, the hormone therapy has greatly reduced my endurance, so my exercise tolerance is far more limited – I understand fatigue now. When I was telling another woman who feels she knows me about my experience, she told me it was hormones that made it more difficult to lose weight. And, I am gaining weight.

All in all, I believe my experience has given me more empathy for women, but I realize I still have a very long way to go. Nonetheless, I will continue in my quest to understand the opposite sex, as I am told “women hold up half the sky,” and I have always believed that to be true.

Fortunately, women are ascending in psychiatry and, with some serious dedication, the dearth of scientific understanding of women’s issues will be a thing of the past. and fill that void of knowledge that we men psychiatrists have in our testosterone-bathed brains.

Dr. Bell is a staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital’s Medical/Surgical-Psychiatry Inpatient Unit in Chicago, clinical psychiatrist emeritus in the department of psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago, former president/CEO of Community Mental Health Council, and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (birthplace of child psychiatry), also in Chicago.

At the risk of too much personal self-disclosure, I feel the need to write about my having developed more empathy for women. Having been described as a “manly man,” by a woman who feels she knows me, it has always been difficult for me to understand women. Fortunately, an experience I’ve had has given me more insight into women – shallow though it may still be.

About a year ago, I had learned I had prostate carcinoma, which is now in remission – thanks to a proctectomy, radiation, and hormone therapy. The antitestosterone hormones I need to take for 2 years are turning me into an old woman, thus my newfound empathy.

After the surgery, I found myself leaking – something that I probably only experienced as a child and of which I have little memory. I now have some more empathy for the problems women have with leaking each month or in general – it is a constant preoccupation. The leuprolide shots I am taking are giving me hot flashes, causing me to be more emotional about things I really don’t understand, and apparently I am at risk for getting osteoporosis – all things that happen to women that have been mildly on my radar for years but for which I lacked direct and personal experience.

Since having my testosterone turned off by the leuprolide, my joints are more prone to aches and pains from various injuries over the years. Because I understand that “motion is lotion,” I have some control of this problem. However, the hormone therapy has greatly reduced my endurance, so my exercise tolerance is far more limited – I understand fatigue now. When I was telling another woman who feels she knows me about my experience, she told me it was hormones that made it more difficult to lose weight. And, I am gaining weight.

All in all, I believe my experience has given me more empathy for women, but I realize I still have a very long way to go. Nonetheless, I will continue in my quest to understand the opposite sex, as I am told “women hold up half the sky,” and I have always believed that to be true.

Fortunately, women are ascending in psychiatry and, with some serious dedication, the dearth of scientific understanding of women’s issues will be a thing of the past. and fill that void of knowledge that we men psychiatrists have in our testosterone-bathed brains.

Dr. Bell is a staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital’s Medical/Surgical-Psychiatry Inpatient Unit in Chicago, clinical psychiatrist emeritus in the department of psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago, former president/CEO of Community Mental Health Council, and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (birthplace of child psychiatry), also in Chicago.

At the risk of too much personal self-disclosure, I feel the need to write about my having developed more empathy for women. Having been described as a “manly man,” by a woman who feels she knows me, it has always been difficult for me to understand women. Fortunately, an experience I’ve had has given me more insight into women – shallow though it may still be.

About a year ago, I had learned I had prostate carcinoma, which is now in remission – thanks to a proctectomy, radiation, and hormone therapy. The antitestosterone hormones I need to take for 2 years are turning me into an old woman, thus my newfound empathy.

After the surgery, I found myself leaking – something that I probably only experienced as a child and of which I have little memory. I now have some more empathy for the problems women have with leaking each month or in general – it is a constant preoccupation. The leuprolide shots I am taking are giving me hot flashes, causing me to be more emotional about things I really don’t understand, and apparently I am at risk for getting osteoporosis – all things that happen to women that have been mildly on my radar for years but for which I lacked direct and personal experience.

Since having my testosterone turned off by the leuprolide, my joints are more prone to aches and pains from various injuries over the years. Because I understand that “motion is lotion,” I have some control of this problem. However, the hormone therapy has greatly reduced my endurance, so my exercise tolerance is far more limited – I understand fatigue now. When I was telling another woman who feels she knows me about my experience, she told me it was hormones that made it more difficult to lose weight. And, I am gaining weight.

All in all, I believe my experience has given me more empathy for women, but I realize I still have a very long way to go. Nonetheless, I will continue in my quest to understand the opposite sex, as I am told “women hold up half the sky,” and I have always believed that to be true.

Fortunately, women are ascending in psychiatry and, with some serious dedication, the dearth of scientific understanding of women’s issues will be a thing of the past. and fill that void of knowledge that we men psychiatrists have in our testosterone-bathed brains.

Dr. Bell is a staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital’s Medical/Surgical-Psychiatry Inpatient Unit in Chicago, clinical psychiatrist emeritus in the department of psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago, former president/CEO of Community Mental Health Council, and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (birthplace of child psychiatry), also in Chicago.

Emerging data support anabolic-first regimens for severe osteoporosis

LOS ANGELES – In the opinion of Felicia Cosman, MD, the current state of osteoporosis treatment is fraught with clinical challenges.

First, most patients at highest risk for future fractures are not being treated. “In fact, fewer than 25% of patients with new clinical fractures are treated for their underlying disease,” Dr. Cosman, professor of medicine at Columbia University, New York, said at the annual scientific and clinical congress of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE).

“One of the reasons doctors are not treating these patients is that many of them do not have a T-score in the osteoporosis range. There’s a misunderstanding here. A fracture that occurs in people with low bone mass in the setting of minimal trauma – such as a fall from standing height – meets the criteria for the clinical diagnosis of osteoporosis and qualifies a person for being at high risk of more fractures. This is likely because bone weakness or fragility is related not just to quantitative aspects, but also to structural and qualitative aspects that cannot be measured as easily.”

Another problem is that some of the highest-risk patients are those with a vertebral fracture. “However, vertebral fractures are particularly difficult to find and treat because they’re often asymptomatic and we’re not [identifying] these patients,” she said. “Targeted screening [with] spine imaging to find vertebral fractures is probably as important as BMD [bone mineral density] testing.”

To complicate matters, Dr. Cosman said that clinicians and patients “misunderstand the balance between benefits and risks of osteoporosis medications and they don’t consider the risk of not treating the underlying disease. Lastly, there’s little evidence to help guide long-term strategies. Guidelines across medical specialties are incredibly inconsistent. With the exception of guidelines from AACE, the one thing that they’re very consistent about is underrecognizing the value of anabolic therapy for people with severe osteoporosis.”

It is well known that previous bone fracture is the most important risk factor for a future fracture, but the recency of the fracture is also important. In a recent study, researchers followed 377,561 female Medicare beneficiaries with a first fracture for up to 5 years (Osteoporos Int. 2019;30[1]:79-92). They found that at 1 year, the risk of another fracture was 10%. The fracture risk rose to 18% at 2 years, and to 31% at 5 years. “I like to think of this as the osteoporosis emergency,” said Dr. Cosman, co–editor-in-chief of Osteoporosis International. “We need to treat these people right away to prevent more fractures and related disability, morbidity, and mortality.”

According to data from pivotal trials, the anabolic agents teriparatide, abaloparatide, and romosozumab appear to produce more rapid and larger effects against all fractures, compared with even the best antiresorptive agents. “However, comparing across studies can be problematic, because the different populations have varying baseline characteristics and different underlying risk,” Dr. Cosman said. “The protocols and the outcome definitions might be different. It’s better to compare anabolic agents with antiresorptive agents in head-to-head trials, and we now have a few of these.”

Two trials are older studies in which fracture outcomes were not the primary endpoints. One study evaluated a population of patients with glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis and found that over 18 months, teriparatide reduced vertebral fractures by 90%, compared with alendronate (N Engl J Med. 2007;357[20]:2028-39). The other trial focused on a population of patients with acute, painful vertebral fractures. It found that over 1 year, teriparatide reduced vertebral fractures by 50%, compared with risedronate (Osteoporos Int. 2012;23[8]:2141-50). Two more recent studies compared anabolic and antiresorptive therapies on fracture outcomes as primary endpoints in patients with prevalent fractures. The VERO trial compared teriparatide with risedronate (Lancet. 2018;391[10117]:230-40), and ARCH compared romosozumab with alendronate (N Engl J Med. 2017;377[15]:1417-27).

In VERO, 1,360 patients with a prevalent vertebral fracture were randomized to receive teriparatide or risedronate for 2 years. At 12 months, the proportion of patients with a new vertebral fracture was 3.1% and 6% in the teriparatide and risedronate groups, respectively, a pattern that held true at 24 months (6.4% vs. 12%). The study also showed that the number of nonvertebral fractures was significantly lower in teriparatide-treated patients, compared with those on risedronate. In ARCH, 4,093 postmenopausal women at high risk of fracture were randomized to receive romosozumab or alendronate for 1 year and then followed for a median period of 33 months. At 12 months, the proportion of patients with a new vertebral fracture was 4% and 6.3% in the romosozumab and alendronate groups, respectively, a pattern that held true at 24 months (6.2% vs. 11.9%).

“These trials showed that the antifracture effects are faster and larger with anabolic agents, compared with antiresorptive agents,” Dr. Cosman said. “They also showed that antifracture effects are sustained after transition to antiresorptive therapy.” In ARCH, both nonvertebral and hip fracture incidences were lower in the romosozumab group, compared with the alendronate group.

The trials demonstrated that improving total hip BMD is associated with improved bone strength and resistance to fracture, yet treatment sequence matters. “The greatest BMD gains of the hip are seen when anabolic agents are used first-line, followed by a potent antiresorptive agent,” she said.

Dr. Cosman offered a strategy for patients on potent antiresorptive agents who need anabolic medication. In patients on bisphosphonates, especially with an incident hip fracture or very low hip BMD, consider combination therapy with initiation of teriparatide or abaloparatide, along with an antiresorptive agent. “There are very little data addressing patients on denosumab, but I would suggest perhaps adding teriparatide or abaloparatide in this population, and continuing denosumab,” she said. “That could lead to BMD gain. Switching to romosozumab might also be an option. But, if possible, use an anabolic agent first. The role of anabolic medication for osteoporosis is evolving as evidence continues to suggest superior benefit of anabolic-first regimens for high-risk patients.”

Dr. Cosman disclosed that she has received advising, consulting, and speaking fees from Amgen and Radius. She has received consulting fees from Tarsa and research grants and medication from Amgen.

LOS ANGELES – In the opinion of Felicia Cosman, MD, the current state of osteoporosis treatment is fraught with clinical challenges.

First, most patients at highest risk for future fractures are not being treated. “In fact, fewer than 25% of patients with new clinical fractures are treated for their underlying disease,” Dr. Cosman, professor of medicine at Columbia University, New York, said at the annual scientific and clinical congress of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE).

“One of the reasons doctors are not treating these patients is that many of them do not have a T-score in the osteoporosis range. There’s a misunderstanding here. A fracture that occurs in people with low bone mass in the setting of minimal trauma – such as a fall from standing height – meets the criteria for the clinical diagnosis of osteoporosis and qualifies a person for being at high risk of more fractures. This is likely because bone weakness or fragility is related not just to quantitative aspects, but also to structural and qualitative aspects that cannot be measured as easily.”

Another problem is that some of the highest-risk patients are those with a vertebral fracture. “However, vertebral fractures are particularly difficult to find and treat because they’re often asymptomatic and we’re not [identifying] these patients,” she said. “Targeted screening [with] spine imaging to find vertebral fractures is probably as important as BMD [bone mineral density] testing.”