User login

High-dose vitamin D for bone health may do more harm than good

In fact, rather than a hypothesized increase in volumetric bone mineral density (BMD) with doses well above the recommended dietary allowance, a negative dose-response relationship was observed, Lauren A. Burt, PhD, of the McCaig Institute for Bone and Joint Health at the University of Calgary (Alta.) and colleagues found.

The total volumetric radial BMD was significantly lower in 101 and 97 study participants randomized to receive daily vitamin D3 doses of 10,000 IU or 4,000 IU for 3 years, respectively (–7.5 and –3.9 mg of calcium hydroxyapatite [HA] per cm3), compared with 105 participants randomized to a reference group that received 400 IU (mean percent changes, –3.5%, –2.4%, and –1.2%, respectively). Total volumetric tibial BMD was also significantly lower in the 10,000 IU arm, compared with the reference arm (–4.1 mg HA per cm3; mean percent change –1.7% vs. –0.4%), the investigators reported Aug. 27 in JAMA.

There also were no significant differences seen between the three groups for the coprimary endpoint of bone strength at either the radius or tibia.

Participants in the double-blind trial were community-dwelling healthy men and women aged 55-70 years (mean age, 62.2 years) without osteoporosis and with baseline levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) of 30-125 nmol/L. They were enrolled from a single center between August 2013 and December 2017 and treated with daily oral vitamin D3 drops at the assigned dosage for 3 years and with calcium supplementation if dietary calcium intake was less than 1,200 mg daily.

Mean supplementation adherence was 99% among the 303 participants who completed the trial (out of 311 enrolled), and adherence was similar across the groups.

Baseline 25(OH)D levels in the 400 IU group were 76.3 nmol/L at baseline, 76.7 nmol/L at 3 months, and 77.4 nmol/L at 3 years. The corresponding measures for the 4,000 IU group were 81.3, 115.3, and 132.2 nmol/L, and for the 10,000 IU group, they were 78.4, 188.0, and 144.4, the investigators said, noting that significant group-by-time interactions were noted for volumetric BMD.

Bone strength decreased over time, but group-by-time interactions for that measure were not statistically significant, they said.

A total of 44 serious adverse events occurred in 38 participants (12.2%), and one death from presumed myocardial infarction occurred in the 400 IU group. Of eight prespecified adverse events, only hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria had significant dose-response effects; all episodes of hypercalcemia were mild and had resolved at follow-up, and the two hypercalcemia events, which occurred in one participant in the 10,000 IU group, were also transient. No significant difference in fall rates was seen in the three groups, they noted.

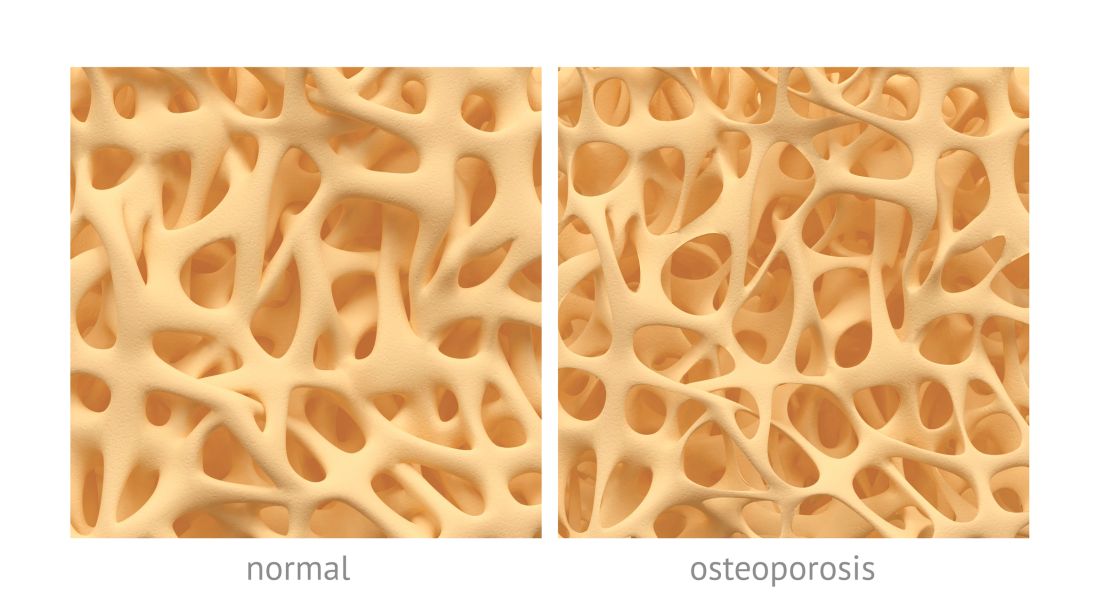

Vitamin D is considered beneficial for preventing and treating osteoporosis, and data support supplementation in individuals with 25(OH)D levels less than 30 nmol/L, but recent meta-analyses did not find a major treatment benefit for osteoporosis or for preventing falls and fractures, the investigators said.

Further, while most supplementation recommendations call for 400-2,000 IU daily, with a tolerable upper intake level of 4,000-10,000 IU, 3% of U.S. adults in 2013-2014 reported intake of at least 4,000 IU per day, but few studies have assessed the effects of doses at or above the upper intake level for 12 months or longer, they noted, adding that this study was “motivated by the prevalence of high-dose vitamin D supplementation among healthy adults.”

“It was hypothesized that a higher dose of vitamin D has a positive effect on high-resolution peripheral quantitative CT measures of volumetric density and strength, perhaps via suppression of parathyroid hormone (PTH)–mediated bone turnover,” they wrote.

However, based on the significantly lower radial BMD seen with both 4,000 and 10,000 IU, compared with 400 IU; the lower tibial BMD with 10,000 IU, compared with 400 IU; and the lack of a difference in bone strength at the radius and tibia, the findings do not support a benefit of high-dose vitamin D supplementation for bone health, they said, noting that additional study is needed to determine whether such doses are harmful.

“Because these results are in the opposite direction of the research hypothesis, this evidence of high-dose vitamin D having a negative effect on bone should be regarded as hypothesis generating, requiring confirmation with further research,” they concluded.

SOURCE: Burt L et al. JAMA. 2019 Aug 27;322(8):736-45.

In fact, rather than a hypothesized increase in volumetric bone mineral density (BMD) with doses well above the recommended dietary allowance, a negative dose-response relationship was observed, Lauren A. Burt, PhD, of the McCaig Institute for Bone and Joint Health at the University of Calgary (Alta.) and colleagues found.

The total volumetric radial BMD was significantly lower in 101 and 97 study participants randomized to receive daily vitamin D3 doses of 10,000 IU or 4,000 IU for 3 years, respectively (–7.5 and –3.9 mg of calcium hydroxyapatite [HA] per cm3), compared with 105 participants randomized to a reference group that received 400 IU (mean percent changes, –3.5%, –2.4%, and –1.2%, respectively). Total volumetric tibial BMD was also significantly lower in the 10,000 IU arm, compared with the reference arm (–4.1 mg HA per cm3; mean percent change –1.7% vs. –0.4%), the investigators reported Aug. 27 in JAMA.

There also were no significant differences seen between the three groups for the coprimary endpoint of bone strength at either the radius or tibia.

Participants in the double-blind trial were community-dwelling healthy men and women aged 55-70 years (mean age, 62.2 years) without osteoporosis and with baseline levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) of 30-125 nmol/L. They were enrolled from a single center between August 2013 and December 2017 and treated with daily oral vitamin D3 drops at the assigned dosage for 3 years and with calcium supplementation if dietary calcium intake was less than 1,200 mg daily.

Mean supplementation adherence was 99% among the 303 participants who completed the trial (out of 311 enrolled), and adherence was similar across the groups.

Baseline 25(OH)D levels in the 400 IU group were 76.3 nmol/L at baseline, 76.7 nmol/L at 3 months, and 77.4 nmol/L at 3 years. The corresponding measures for the 4,000 IU group were 81.3, 115.3, and 132.2 nmol/L, and for the 10,000 IU group, they were 78.4, 188.0, and 144.4, the investigators said, noting that significant group-by-time interactions were noted for volumetric BMD.

Bone strength decreased over time, but group-by-time interactions for that measure were not statistically significant, they said.

A total of 44 serious adverse events occurred in 38 participants (12.2%), and one death from presumed myocardial infarction occurred in the 400 IU group. Of eight prespecified adverse events, only hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria had significant dose-response effects; all episodes of hypercalcemia were mild and had resolved at follow-up, and the two hypercalcemia events, which occurred in one participant in the 10,000 IU group, were also transient. No significant difference in fall rates was seen in the three groups, they noted.

Vitamin D is considered beneficial for preventing and treating osteoporosis, and data support supplementation in individuals with 25(OH)D levels less than 30 nmol/L, but recent meta-analyses did not find a major treatment benefit for osteoporosis or for preventing falls and fractures, the investigators said.

Further, while most supplementation recommendations call for 400-2,000 IU daily, with a tolerable upper intake level of 4,000-10,000 IU, 3% of U.S. adults in 2013-2014 reported intake of at least 4,000 IU per day, but few studies have assessed the effects of doses at or above the upper intake level for 12 months or longer, they noted, adding that this study was “motivated by the prevalence of high-dose vitamin D supplementation among healthy adults.”

“It was hypothesized that a higher dose of vitamin D has a positive effect on high-resolution peripheral quantitative CT measures of volumetric density and strength, perhaps via suppression of parathyroid hormone (PTH)–mediated bone turnover,” they wrote.

However, based on the significantly lower radial BMD seen with both 4,000 and 10,000 IU, compared with 400 IU; the lower tibial BMD with 10,000 IU, compared with 400 IU; and the lack of a difference in bone strength at the radius and tibia, the findings do not support a benefit of high-dose vitamin D supplementation for bone health, they said, noting that additional study is needed to determine whether such doses are harmful.

“Because these results are in the opposite direction of the research hypothesis, this evidence of high-dose vitamin D having a negative effect on bone should be regarded as hypothesis generating, requiring confirmation with further research,” they concluded.

SOURCE: Burt L et al. JAMA. 2019 Aug 27;322(8):736-45.

In fact, rather than a hypothesized increase in volumetric bone mineral density (BMD) with doses well above the recommended dietary allowance, a negative dose-response relationship was observed, Lauren A. Burt, PhD, of the McCaig Institute for Bone and Joint Health at the University of Calgary (Alta.) and colleagues found.

The total volumetric radial BMD was significantly lower in 101 and 97 study participants randomized to receive daily vitamin D3 doses of 10,000 IU or 4,000 IU for 3 years, respectively (–7.5 and –3.9 mg of calcium hydroxyapatite [HA] per cm3), compared with 105 participants randomized to a reference group that received 400 IU (mean percent changes, –3.5%, –2.4%, and –1.2%, respectively). Total volumetric tibial BMD was also significantly lower in the 10,000 IU arm, compared with the reference arm (–4.1 mg HA per cm3; mean percent change –1.7% vs. –0.4%), the investigators reported Aug. 27 in JAMA.

There also were no significant differences seen between the three groups for the coprimary endpoint of bone strength at either the radius or tibia.

Participants in the double-blind trial were community-dwelling healthy men and women aged 55-70 years (mean age, 62.2 years) without osteoporosis and with baseline levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) of 30-125 nmol/L. They were enrolled from a single center between August 2013 and December 2017 and treated with daily oral vitamin D3 drops at the assigned dosage for 3 years and with calcium supplementation if dietary calcium intake was less than 1,200 mg daily.

Mean supplementation adherence was 99% among the 303 participants who completed the trial (out of 311 enrolled), and adherence was similar across the groups.

Baseline 25(OH)D levels in the 400 IU group were 76.3 nmol/L at baseline, 76.7 nmol/L at 3 months, and 77.4 nmol/L at 3 years. The corresponding measures for the 4,000 IU group were 81.3, 115.3, and 132.2 nmol/L, and for the 10,000 IU group, they were 78.4, 188.0, and 144.4, the investigators said, noting that significant group-by-time interactions were noted for volumetric BMD.

Bone strength decreased over time, but group-by-time interactions for that measure were not statistically significant, they said.

A total of 44 serious adverse events occurred in 38 participants (12.2%), and one death from presumed myocardial infarction occurred in the 400 IU group. Of eight prespecified adverse events, only hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria had significant dose-response effects; all episodes of hypercalcemia were mild and had resolved at follow-up, and the two hypercalcemia events, which occurred in one participant in the 10,000 IU group, were also transient. No significant difference in fall rates was seen in the three groups, they noted.

Vitamin D is considered beneficial for preventing and treating osteoporosis, and data support supplementation in individuals with 25(OH)D levels less than 30 nmol/L, but recent meta-analyses did not find a major treatment benefit for osteoporosis or for preventing falls and fractures, the investigators said.

Further, while most supplementation recommendations call for 400-2,000 IU daily, with a tolerable upper intake level of 4,000-10,000 IU, 3% of U.S. adults in 2013-2014 reported intake of at least 4,000 IU per day, but few studies have assessed the effects of doses at or above the upper intake level for 12 months or longer, they noted, adding that this study was “motivated by the prevalence of high-dose vitamin D supplementation among healthy adults.”

“It was hypothesized that a higher dose of vitamin D has a positive effect on high-resolution peripheral quantitative CT measures of volumetric density and strength, perhaps via suppression of parathyroid hormone (PTH)–mediated bone turnover,” they wrote.

However, based on the significantly lower radial BMD seen with both 4,000 and 10,000 IU, compared with 400 IU; the lower tibial BMD with 10,000 IU, compared with 400 IU; and the lack of a difference in bone strength at the radius and tibia, the findings do not support a benefit of high-dose vitamin D supplementation for bone health, they said, noting that additional study is needed to determine whether such doses are harmful.

“Because these results are in the opposite direction of the research hypothesis, this evidence of high-dose vitamin D having a negative effect on bone should be regarded as hypothesis generating, requiring confirmation with further research,” they concluded.

SOURCE: Burt L et al. JAMA. 2019 Aug 27;322(8):736-45.

FROM JAMA

FRAX with BMD may not be accurate for women with diabetes

according to data from 566 women aged 40-90 years.

In a study published in Bone Reports, Lelia L.F. de Abreu, MD, of Deakin University, Geelong, Australia, and colleagues investigated the accuracy of FRAX scores and the role of impaired fasting glucose (IFG) and bone mineral density (BMD) on fracture risk by comparing FRAX scores for 252 normoglycemic women, 247 women with IFG, and 67 women with diabetes.

When BMD was not included, women with diabetes had a higher median FRAX score for major osteoporotic fractures of the hip, clinical spine, forearm, and wrist than women without diabetes or women with IFG (7.1, 4.3, and 5.1, respectively). In the diabetes group, 11 major osteoporotic fractures were observed versus 5 predicted by FRAX. In the normoglycemic group, 28 fractures were observed versus 15 predicted, and in the IFG group 31 fractures were observed versus 16 predicted.

When BMD was included, major osteoporotic fractures and hip fractures also were underestimated in the diabetes group (11 observed vs. 4 observed; 6 observed vs. 1 predicted, respectively), but the difference in observed versus predicted fractures trended toward statistical significance but was not significant (P = .055; P = .52, respectively). FRAX with BMD increased the underestimation of major osteoporotic fractures in the normoglycemic and IFG groups (28 observed vs. 13 predicted; 31 observed vs. 13 predicted).

The study findings were limited by several factors including the inability to determine the impact of specific types of diabetes on fracture risk, lack of data on the duration of diabetes in study participants, the use of self-reports, and a relatively small and homogeneous sample size, the researchers noted.

However, the results support data from previous studies showing an increased fracture risk in diabetes patients regardless of BMD, and suggest that FRAX may be unreliable as a predictor of fractures in the diabetes population, they concluded.

The study was supported in part by the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, National Health and Medical Research Council Australia, and the Geelong Region Medical Research Foundation. Two researchers were supported by university postgraduate rewards and one researcher was supported by a university postdoctoral research fellowship. The remaining coauthors reported no relevant financial conflicts.

SOURCE: de Abreu LLF et al. Bone Reports. 2019 Aug 13. doi: 10.1016/j.bonr.2019.100223.

according to data from 566 women aged 40-90 years.

In a study published in Bone Reports, Lelia L.F. de Abreu, MD, of Deakin University, Geelong, Australia, and colleagues investigated the accuracy of FRAX scores and the role of impaired fasting glucose (IFG) and bone mineral density (BMD) on fracture risk by comparing FRAX scores for 252 normoglycemic women, 247 women with IFG, and 67 women with diabetes.

When BMD was not included, women with diabetes had a higher median FRAX score for major osteoporotic fractures of the hip, clinical spine, forearm, and wrist than women without diabetes or women with IFG (7.1, 4.3, and 5.1, respectively). In the diabetes group, 11 major osteoporotic fractures were observed versus 5 predicted by FRAX. In the normoglycemic group, 28 fractures were observed versus 15 predicted, and in the IFG group 31 fractures were observed versus 16 predicted.

When BMD was included, major osteoporotic fractures and hip fractures also were underestimated in the diabetes group (11 observed vs. 4 observed; 6 observed vs. 1 predicted, respectively), but the difference in observed versus predicted fractures trended toward statistical significance but was not significant (P = .055; P = .52, respectively). FRAX with BMD increased the underestimation of major osteoporotic fractures in the normoglycemic and IFG groups (28 observed vs. 13 predicted; 31 observed vs. 13 predicted).

The study findings were limited by several factors including the inability to determine the impact of specific types of diabetes on fracture risk, lack of data on the duration of diabetes in study participants, the use of self-reports, and a relatively small and homogeneous sample size, the researchers noted.

However, the results support data from previous studies showing an increased fracture risk in diabetes patients regardless of BMD, and suggest that FRAX may be unreliable as a predictor of fractures in the diabetes population, they concluded.

The study was supported in part by the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, National Health and Medical Research Council Australia, and the Geelong Region Medical Research Foundation. Two researchers were supported by university postgraduate rewards and one researcher was supported by a university postdoctoral research fellowship. The remaining coauthors reported no relevant financial conflicts.

SOURCE: de Abreu LLF et al. Bone Reports. 2019 Aug 13. doi: 10.1016/j.bonr.2019.100223.

according to data from 566 women aged 40-90 years.

In a study published in Bone Reports, Lelia L.F. de Abreu, MD, of Deakin University, Geelong, Australia, and colleagues investigated the accuracy of FRAX scores and the role of impaired fasting glucose (IFG) and bone mineral density (BMD) on fracture risk by comparing FRAX scores for 252 normoglycemic women, 247 women with IFG, and 67 women with diabetes.

When BMD was not included, women with diabetes had a higher median FRAX score for major osteoporotic fractures of the hip, clinical spine, forearm, and wrist than women without diabetes or women with IFG (7.1, 4.3, and 5.1, respectively). In the diabetes group, 11 major osteoporotic fractures were observed versus 5 predicted by FRAX. In the normoglycemic group, 28 fractures were observed versus 15 predicted, and in the IFG group 31 fractures were observed versus 16 predicted.

When BMD was included, major osteoporotic fractures and hip fractures also were underestimated in the diabetes group (11 observed vs. 4 observed; 6 observed vs. 1 predicted, respectively), but the difference in observed versus predicted fractures trended toward statistical significance but was not significant (P = .055; P = .52, respectively). FRAX with BMD increased the underestimation of major osteoporotic fractures in the normoglycemic and IFG groups (28 observed vs. 13 predicted; 31 observed vs. 13 predicted).

The study findings were limited by several factors including the inability to determine the impact of specific types of diabetes on fracture risk, lack of data on the duration of diabetes in study participants, the use of self-reports, and a relatively small and homogeneous sample size, the researchers noted.

However, the results support data from previous studies showing an increased fracture risk in diabetes patients regardless of BMD, and suggest that FRAX may be unreliable as a predictor of fractures in the diabetes population, they concluded.

The study was supported in part by the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, National Health and Medical Research Council Australia, and the Geelong Region Medical Research Foundation. Two researchers were supported by university postgraduate rewards and one researcher was supported by a university postdoctoral research fellowship. The remaining coauthors reported no relevant financial conflicts.

SOURCE: de Abreu LLF et al. Bone Reports. 2019 Aug 13. doi: 10.1016/j.bonr.2019.100223.

FROM BONE REPORTS

Self-reported falls can predict osteoporotic fracture risk

A single, simple question about a patient’s experience of falls in the previous year can help predict their risk of fractures, a study suggests.

In Osteoporosis International, researchers reported the outcomes of a cohort study using Manitoba clinical registry data from 24,943 men and women aged 40 years and older within the province who had undergone a fracture-probability assessment, and had data on self-reported falls for the previous year and fracture outcomes.

William D. Leslie, MD, of the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, and coauthors wrote that a frequent criticism of the FRAX fracture risk assessment tool was the fact that it didn’t include falls or fall risk in predicting fractures.

“Recent evidence derived from carefully conducted research cohort studies in men found that falls increase fracture risk independent of FRAX probability,” they wrote. “However, data are inconsistent with a paucity of evidence demonstrating usefulness of self-reported fall data as collected in routine clinical practice.”

0.8% experienced a hip fracture, and 4.9% experienced any incident fracture.

The analysis showed an increased risk of fracture with the increasing number of self-reported falls experienced in the previous year. The risk of major osteoporotic fracture was 49% higher among individuals who reported one fall, 74% in those who reported two falls and 2.6-fold higher for those who reported three or more falls in the previous year, compared with those who did not report any falls.

A similar pattern was seen for any incident fracture and hip fracture, with a 3.4-fold higher risk of hip fracture seen in those who reported three or more falls. The study also showed an increase in mortality risk with increasing number of falls.

“We documented that a simple question regarding self-reported falls in the previous year could be easily collected during routine clinical practice and that this information was strongly predictive of short-term fracture risk independent of multiple clinical risk factors including fracture probability using the FRAX tool with BMD [bone mineral density],” the authors wrote.

The analysis did not find an interaction with age or sex and the number of falls.

John A. Kanis, MD, reported grants from Amgen, Lily, and Radius Health. Three other coauthors reported nothing to declare for the context of this article, but reported research grants, speaking honoraria, consultancies from a variety of pharmaceutical companies and organizations. The remaining five coauthors declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Leslie WD et al. Osteoporos Int. 2019 Aug. 2. doi: 10.1007/s00198-019-05106-3.

Fragility fractures remain a major contributor to morbidity and even mortality of aging populations. Concerted efforts of clinicians, epidemiologists, and researchers have yielded an assortment of diagnostic strategies and prognostic algorithms in efforts to identify individuals at fracture risk. A variety of demographic (age, sex), biological (family history, specific disorders and medications), anatomical (bone mineral density, body mass index), and behavioral (smoking, alcohol consumption) parameters are recognized as predictors of fracture risk, and often are incorporated in predictive algorithms for fracture predisposition. FRAX (Fracture Risk Assessment) is a widely used screening tool that is valid in offering fracture risk quantification across populations (Arch Osteoporos. 2016 Dec;11[1]:25; World Health Organization Assessment of Osteoporosis at the Primary Health Care Level).

Aging and accompanying neurocognitive deterioration, visual impairment, as well as iatrogenic factors are recognized to contribute to predisposition to falls in aging populations. A propensity for falls has long been regarded as a fracture risk (Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2008;6[4]:149-54). However, the evidence to support this logical assumption has been mixed with resulting exclusion of tendency to fall from commonly utilized fracture risk predictive models and tools. A predisposition to and frequency of falls is considered neither a risk modulator nor a mediator in the commonly utilized FRAX-based fracture risk assessments, and it is believed that fracture probability may be underestimated by FRAX in those predisposed to frequent falls (J Clin Densitom. 2011 Jul-Sep;14[3]:194–204).

The landscape of fracture risk assessment and quantification in the aforementioned backdrop has been refreshingly enhanced by a recent contribution by Leslie et al. wherein the authors provide real-life evidence relating self-reported falls to fracture risk. In a robust population sample nearing 25,000 women, increasing number of falls within the past year was associated with an increasing fracture risk, and this relationship persisted after adjusting for covariates that are recognized to predispose to fragility fractures, including age, body mass index, and bone mineral density. Women’s health providers are encouraged to familiarize themselves with the work of Leslie et al.; the authors’ message, that fall history be incorporated into risk quantification measures, is striking in its simplicity and profound in its preventative potential given that fall risk in and of itself may be mitigated in many through targeted interventions.

Lubna Pal, MBBS, MS, is professor and fellowship director of the division of reproductive endocrinology & infertility at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. She also is the director of the Yale reproductive endocrinology & infertility menopause program. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Fragility fractures remain a major contributor to morbidity and even mortality of aging populations. Concerted efforts of clinicians, epidemiologists, and researchers have yielded an assortment of diagnostic strategies and prognostic algorithms in efforts to identify individuals at fracture risk. A variety of demographic (age, sex), biological (family history, specific disorders and medications), anatomical (bone mineral density, body mass index), and behavioral (smoking, alcohol consumption) parameters are recognized as predictors of fracture risk, and often are incorporated in predictive algorithms for fracture predisposition. FRAX (Fracture Risk Assessment) is a widely used screening tool that is valid in offering fracture risk quantification across populations (Arch Osteoporos. 2016 Dec;11[1]:25; World Health Organization Assessment of Osteoporosis at the Primary Health Care Level).

Aging and accompanying neurocognitive deterioration, visual impairment, as well as iatrogenic factors are recognized to contribute to predisposition to falls in aging populations. A propensity for falls has long been regarded as a fracture risk (Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2008;6[4]:149-54). However, the evidence to support this logical assumption has been mixed with resulting exclusion of tendency to fall from commonly utilized fracture risk predictive models and tools. A predisposition to and frequency of falls is considered neither a risk modulator nor a mediator in the commonly utilized FRAX-based fracture risk assessments, and it is believed that fracture probability may be underestimated by FRAX in those predisposed to frequent falls (J Clin Densitom. 2011 Jul-Sep;14[3]:194–204).

The landscape of fracture risk assessment and quantification in the aforementioned backdrop has been refreshingly enhanced by a recent contribution by Leslie et al. wherein the authors provide real-life evidence relating self-reported falls to fracture risk. In a robust population sample nearing 25,000 women, increasing number of falls within the past year was associated with an increasing fracture risk, and this relationship persisted after adjusting for covariates that are recognized to predispose to fragility fractures, including age, body mass index, and bone mineral density. Women’s health providers are encouraged to familiarize themselves with the work of Leslie et al.; the authors’ message, that fall history be incorporated into risk quantification measures, is striking in its simplicity and profound in its preventative potential given that fall risk in and of itself may be mitigated in many through targeted interventions.

Lubna Pal, MBBS, MS, is professor and fellowship director of the division of reproductive endocrinology & infertility at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. She also is the director of the Yale reproductive endocrinology & infertility menopause program. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

Fragility fractures remain a major contributor to morbidity and even mortality of aging populations. Concerted efforts of clinicians, epidemiologists, and researchers have yielded an assortment of diagnostic strategies and prognostic algorithms in efforts to identify individuals at fracture risk. A variety of demographic (age, sex), biological (family history, specific disorders and medications), anatomical (bone mineral density, body mass index), and behavioral (smoking, alcohol consumption) parameters are recognized as predictors of fracture risk, and often are incorporated in predictive algorithms for fracture predisposition. FRAX (Fracture Risk Assessment) is a widely used screening tool that is valid in offering fracture risk quantification across populations (Arch Osteoporos. 2016 Dec;11[1]:25; World Health Organization Assessment of Osteoporosis at the Primary Health Care Level).

Aging and accompanying neurocognitive deterioration, visual impairment, as well as iatrogenic factors are recognized to contribute to predisposition to falls in aging populations. A propensity for falls has long been regarded as a fracture risk (Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2008;6[4]:149-54). However, the evidence to support this logical assumption has been mixed with resulting exclusion of tendency to fall from commonly utilized fracture risk predictive models and tools. A predisposition to and frequency of falls is considered neither a risk modulator nor a mediator in the commonly utilized FRAX-based fracture risk assessments, and it is believed that fracture probability may be underestimated by FRAX in those predisposed to frequent falls (J Clin Densitom. 2011 Jul-Sep;14[3]:194–204).

The landscape of fracture risk assessment and quantification in the aforementioned backdrop has been refreshingly enhanced by a recent contribution by Leslie et al. wherein the authors provide real-life evidence relating self-reported falls to fracture risk. In a robust population sample nearing 25,000 women, increasing number of falls within the past year was associated with an increasing fracture risk, and this relationship persisted after adjusting for covariates that are recognized to predispose to fragility fractures, including age, body mass index, and bone mineral density. Women’s health providers are encouraged to familiarize themselves with the work of Leslie et al.; the authors’ message, that fall history be incorporated into risk quantification measures, is striking in its simplicity and profound in its preventative potential given that fall risk in and of itself may be mitigated in many through targeted interventions.

Lubna Pal, MBBS, MS, is professor and fellowship director of the division of reproductive endocrinology & infertility at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. She also is the director of the Yale reproductive endocrinology & infertility menopause program. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at [email protected].

A single, simple question about a patient’s experience of falls in the previous year can help predict their risk of fractures, a study suggests.

In Osteoporosis International, researchers reported the outcomes of a cohort study using Manitoba clinical registry data from 24,943 men and women aged 40 years and older within the province who had undergone a fracture-probability assessment, and had data on self-reported falls for the previous year and fracture outcomes.

William D. Leslie, MD, of the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, and coauthors wrote that a frequent criticism of the FRAX fracture risk assessment tool was the fact that it didn’t include falls or fall risk in predicting fractures.

“Recent evidence derived from carefully conducted research cohort studies in men found that falls increase fracture risk independent of FRAX probability,” they wrote. “However, data are inconsistent with a paucity of evidence demonstrating usefulness of self-reported fall data as collected in routine clinical practice.”

0.8% experienced a hip fracture, and 4.9% experienced any incident fracture.

The analysis showed an increased risk of fracture with the increasing number of self-reported falls experienced in the previous year. The risk of major osteoporotic fracture was 49% higher among individuals who reported one fall, 74% in those who reported two falls and 2.6-fold higher for those who reported three or more falls in the previous year, compared with those who did not report any falls.

A similar pattern was seen for any incident fracture and hip fracture, with a 3.4-fold higher risk of hip fracture seen in those who reported three or more falls. The study also showed an increase in mortality risk with increasing number of falls.

“We documented that a simple question regarding self-reported falls in the previous year could be easily collected during routine clinical practice and that this information was strongly predictive of short-term fracture risk independent of multiple clinical risk factors including fracture probability using the FRAX tool with BMD [bone mineral density],” the authors wrote.

The analysis did not find an interaction with age or sex and the number of falls.

John A. Kanis, MD, reported grants from Amgen, Lily, and Radius Health. Three other coauthors reported nothing to declare for the context of this article, but reported research grants, speaking honoraria, consultancies from a variety of pharmaceutical companies and organizations. The remaining five coauthors declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Leslie WD et al. Osteoporos Int. 2019 Aug. 2. doi: 10.1007/s00198-019-05106-3.

A single, simple question about a patient’s experience of falls in the previous year can help predict their risk of fractures, a study suggests.

In Osteoporosis International, researchers reported the outcomes of a cohort study using Manitoba clinical registry data from 24,943 men and women aged 40 years and older within the province who had undergone a fracture-probability assessment, and had data on self-reported falls for the previous year and fracture outcomes.

William D. Leslie, MD, of the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, and coauthors wrote that a frequent criticism of the FRAX fracture risk assessment tool was the fact that it didn’t include falls or fall risk in predicting fractures.

“Recent evidence derived from carefully conducted research cohort studies in men found that falls increase fracture risk independent of FRAX probability,” they wrote. “However, data are inconsistent with a paucity of evidence demonstrating usefulness of self-reported fall data as collected in routine clinical practice.”

0.8% experienced a hip fracture, and 4.9% experienced any incident fracture.

The analysis showed an increased risk of fracture with the increasing number of self-reported falls experienced in the previous year. The risk of major osteoporotic fracture was 49% higher among individuals who reported one fall, 74% in those who reported two falls and 2.6-fold higher for those who reported three or more falls in the previous year, compared with those who did not report any falls.

A similar pattern was seen for any incident fracture and hip fracture, with a 3.4-fold higher risk of hip fracture seen in those who reported three or more falls. The study also showed an increase in mortality risk with increasing number of falls.

“We documented that a simple question regarding self-reported falls in the previous year could be easily collected during routine clinical practice and that this information was strongly predictive of short-term fracture risk independent of multiple clinical risk factors including fracture probability using the FRAX tool with BMD [bone mineral density],” the authors wrote.

The analysis did not find an interaction with age or sex and the number of falls.

John A. Kanis, MD, reported grants from Amgen, Lily, and Radius Health. Three other coauthors reported nothing to declare for the context of this article, but reported research grants, speaking honoraria, consultancies from a variety of pharmaceutical companies and organizations. The remaining five coauthors declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Leslie WD et al. Osteoporos Int. 2019 Aug. 2. doi: 10.1007/s00198-019-05106-3.

FROM OSTEOPOROSIS INTERNATIONAL

Analysis finds no mortality reductions with osteoporosis drugs

A paper published in JAMA Internal Medicine analyzed data from 38 randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials of osteoporosis drugs involving a total of 101,642 participants.

“Studies have estimated that less than 30% of the mortality following hip and vertebral fractures may be attributed to the fracture itself and, therefore, potentially avoidable by preventing the fracture,” wrote Steven R. Cummings, MD, of the San Francisco Coordinating Center at the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues. “Some studies have suggested that treatments for osteoporosis may directly reduce overall mortality rates in addition to decreasing fracture risk.”

Despite including a diversity of drugs including bisphosphonates, denosumab (Prolia), selective estrogen receptor modulators, parathyroid hormone analogues, odanacatib, and romosozumab (Evenity), the analysis found no significant association between receiving a drug treatment for osteoporosis and overall mortality.

The researchers did a separate analysis of the 21 clinical trials of bisphosphonate treatments, again finding no impact of the treatment on overall mortality. Similarly, analysis of six zoledronate clinical trials found no statistically significant impact on mortality, although the authors noted that there was some heterogeneity in the results. For example, two large trials found 28% and 35% reductions in mortality, however these effects were not seen in another other zoledronate trials.

An analysis limited to nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates (alendronate, risedronate, ibandronate, and zoledronate) showed a nonsignificant trend toward lower overall mortality, although this became even less statistically significant when trials of zoledronate were excluded.

“More data from placebo-controlled clinical trials of zoledronate therapy and mortality rates are needed to resolve whether treatment with zoledronate is associated with reduced mortality in addition to decreased fracture risk,” the authors wrote.

They added that the 25%-60% mortality reductions seen in previous observational were too large to be attributable solely to reductions in the risk of fracture, but were perhaps the result of unmeasured confounders that could have contributed to lower mortality.

“The apparent reduction in mortality may be an example of the ‘healthy adherer effect,’ which has been documented in studies reporting that participants who adhered to placebo treatment in clinical trials had lower mortality,” they wrote, citing data from the Women’s Health Study that showed 36% lower mortality in those who were at least 80% adherent to placebo.

“This effect is particularly applicable to observational studies of treatments for osteoporosis because only an estimated half of women taking oral drugs for the treatment of osteoporosis continued the regimen for 1 year, and even fewer continued longer,” they added.

They did note one limitation of their analysis was that it did not include a large clinical trial of the antiresorptive drug odanacatib, which was only available in abstract form at the time.

One author reported receiving grants and personal fees from a pharmaceutical company during the conduct of the study, and another reported receiving grants and personal fees outside the submitted work. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Cummings SR et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Aug 19. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2779.

A paper published in JAMA Internal Medicine analyzed data from 38 randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials of osteoporosis drugs involving a total of 101,642 participants.

“Studies have estimated that less than 30% of the mortality following hip and vertebral fractures may be attributed to the fracture itself and, therefore, potentially avoidable by preventing the fracture,” wrote Steven R. Cummings, MD, of the San Francisco Coordinating Center at the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues. “Some studies have suggested that treatments for osteoporosis may directly reduce overall mortality rates in addition to decreasing fracture risk.”

Despite including a diversity of drugs including bisphosphonates, denosumab (Prolia), selective estrogen receptor modulators, parathyroid hormone analogues, odanacatib, and romosozumab (Evenity), the analysis found no significant association between receiving a drug treatment for osteoporosis and overall mortality.

The researchers did a separate analysis of the 21 clinical trials of bisphosphonate treatments, again finding no impact of the treatment on overall mortality. Similarly, analysis of six zoledronate clinical trials found no statistically significant impact on mortality, although the authors noted that there was some heterogeneity in the results. For example, two large trials found 28% and 35% reductions in mortality, however these effects were not seen in another other zoledronate trials.

An analysis limited to nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates (alendronate, risedronate, ibandronate, and zoledronate) showed a nonsignificant trend toward lower overall mortality, although this became even less statistically significant when trials of zoledronate were excluded.

“More data from placebo-controlled clinical trials of zoledronate therapy and mortality rates are needed to resolve whether treatment with zoledronate is associated with reduced mortality in addition to decreased fracture risk,” the authors wrote.

They added that the 25%-60% mortality reductions seen in previous observational were too large to be attributable solely to reductions in the risk of fracture, but were perhaps the result of unmeasured confounders that could have contributed to lower mortality.

“The apparent reduction in mortality may be an example of the ‘healthy adherer effect,’ which has been documented in studies reporting that participants who adhered to placebo treatment in clinical trials had lower mortality,” they wrote, citing data from the Women’s Health Study that showed 36% lower mortality in those who were at least 80% adherent to placebo.

“This effect is particularly applicable to observational studies of treatments for osteoporosis because only an estimated half of women taking oral drugs for the treatment of osteoporosis continued the regimen for 1 year, and even fewer continued longer,” they added.

They did note one limitation of their analysis was that it did not include a large clinical trial of the antiresorptive drug odanacatib, which was only available in abstract form at the time.

One author reported receiving grants and personal fees from a pharmaceutical company during the conduct of the study, and another reported receiving grants and personal fees outside the submitted work. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Cummings SR et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Aug 19. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2779.

A paper published in JAMA Internal Medicine analyzed data from 38 randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials of osteoporosis drugs involving a total of 101,642 participants.

“Studies have estimated that less than 30% of the mortality following hip and vertebral fractures may be attributed to the fracture itself and, therefore, potentially avoidable by preventing the fracture,” wrote Steven R. Cummings, MD, of the San Francisco Coordinating Center at the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues. “Some studies have suggested that treatments for osteoporosis may directly reduce overall mortality rates in addition to decreasing fracture risk.”

Despite including a diversity of drugs including bisphosphonates, denosumab (Prolia), selective estrogen receptor modulators, parathyroid hormone analogues, odanacatib, and romosozumab (Evenity), the analysis found no significant association between receiving a drug treatment for osteoporosis and overall mortality.

The researchers did a separate analysis of the 21 clinical trials of bisphosphonate treatments, again finding no impact of the treatment on overall mortality. Similarly, analysis of six zoledronate clinical trials found no statistically significant impact on mortality, although the authors noted that there was some heterogeneity in the results. For example, two large trials found 28% and 35% reductions in mortality, however these effects were not seen in another other zoledronate trials.

An analysis limited to nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates (alendronate, risedronate, ibandronate, and zoledronate) showed a nonsignificant trend toward lower overall mortality, although this became even less statistically significant when trials of zoledronate were excluded.

“More data from placebo-controlled clinical trials of zoledronate therapy and mortality rates are needed to resolve whether treatment with zoledronate is associated with reduced mortality in addition to decreased fracture risk,” the authors wrote.

They added that the 25%-60% mortality reductions seen in previous observational were too large to be attributable solely to reductions in the risk of fracture, but were perhaps the result of unmeasured confounders that could have contributed to lower mortality.

“The apparent reduction in mortality may be an example of the ‘healthy adherer effect,’ which has been documented in studies reporting that participants who adhered to placebo treatment in clinical trials had lower mortality,” they wrote, citing data from the Women’s Health Study that showed 36% lower mortality in those who were at least 80% adherent to placebo.

“This effect is particularly applicable to observational studies of treatments for osteoporosis because only an estimated half of women taking oral drugs for the treatment of osteoporosis continued the regimen for 1 year, and even fewer continued longer,” they added.

They did note one limitation of their analysis was that it did not include a large clinical trial of the antiresorptive drug odanacatib, which was only available in abstract form at the time.

One author reported receiving grants and personal fees from a pharmaceutical company during the conduct of the study, and another reported receiving grants and personal fees outside the submitted work. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Cummings SR et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Aug 19. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2779.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Lower BMD found in patients with severe hemophilia A

Men with severe hemophilia A showed reduced levels of bone mineral density, compared with controls representative of the general population, according to findings from a case-control study.

In addition, the decrease in bone mineral density (BMD) was correlated with reduced functional ability and body mass index (BMI), and vitamin D insufficiency or deficiency.

“We aimed to investigate the presence of low BMD in adult patients diagnosed with severe hemophilia A and to evaluate the potential risk factors associated with low BMD and musculoskeletal function levels,” wrote Omer Ekinci, MD, of Firat University in Elazig, Turkey, and colleagues in Haemophilia.

The study included 41 men with severe hemophilia A and 40 men without hemophilia who were matched for age. All patients with hemophilia A received regular prophylactic therapy, and one patient had a high titre (greater than 5 Bethesda units) inhibitor against FVIII.

The researchers performed several laboratory tests: BMD was measured using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry; BMI was recorded; and laboratory tests were performed to ascertain levels of vitamin D, calcium, phosphorus, alkaline phosphatase, parathyroid hormone, and hepatitis C and HIV antibodies. The Functional Independence Score in Hemophilia (FISH) was used to measure functional-ability status only in the study group.

After analysis, the researchers found a significant difference between patients in the case and control groups for femoral neck and total hip BMD (P = .017 and P less than .001, respectively), but not for lumbar spine BMD (P = .071).

In patients with hemophilia aged younger than 50 years, 27.8% were found to have “low normal” BMD levels, and 19.4% showed “lower than expected” BMD levels with respect to age.

“Vitamin D insufficiency and deficiency were present in 63.4% of the patients with hemophilia, significantly higher than the control group [37.5%; P less than .001],” the researchers wrote.

There were also statistically significant positive correlations between FISH score and femoral neck BMD (P = .001, r = .530), femoral neck z score (P = .001, r = .514), femoral neck T score (P = .002, r = .524), and lumbar spine BMD (P = .033, r = .334). No correlation was found between dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry measurements and the other variables (age, calcium, phosphorus, and alkaline phosphatase levels), and no results were reported for hepatitis C or HIV because none of the participants tested positive for those measures.

The most frequently reported causes of reduced BMD levels was vitamin D deficiency, low BMI, and low functional movement ability, although none of these was a strong independent risk factor in multivariate analysis, the authors reported.

They acknowledged that the results may not be generalizable to all patients because the study was conducted at a single center in Turkey.

“The results of our study emphasize the importance of early detection of comorbid conditions that decrease bone mass in severe hemophilia A patients,” they concluded.

The study was funded by the Yüzüncü Yıl University Scientific Research Project Committee. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ekinci O et al. Haemophilia. 2019 Aug 8. doi: 10.1111/hae.13836.

Men with severe hemophilia A showed reduced levels of bone mineral density, compared with controls representative of the general population, according to findings from a case-control study.

In addition, the decrease in bone mineral density (BMD) was correlated with reduced functional ability and body mass index (BMI), and vitamin D insufficiency or deficiency.

“We aimed to investigate the presence of low BMD in adult patients diagnosed with severe hemophilia A and to evaluate the potential risk factors associated with low BMD and musculoskeletal function levels,” wrote Omer Ekinci, MD, of Firat University in Elazig, Turkey, and colleagues in Haemophilia.

The study included 41 men with severe hemophilia A and 40 men without hemophilia who were matched for age. All patients with hemophilia A received regular prophylactic therapy, and one patient had a high titre (greater than 5 Bethesda units) inhibitor against FVIII.

The researchers performed several laboratory tests: BMD was measured using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry; BMI was recorded; and laboratory tests were performed to ascertain levels of vitamin D, calcium, phosphorus, alkaline phosphatase, parathyroid hormone, and hepatitis C and HIV antibodies. The Functional Independence Score in Hemophilia (FISH) was used to measure functional-ability status only in the study group.

After analysis, the researchers found a significant difference between patients in the case and control groups for femoral neck and total hip BMD (P = .017 and P less than .001, respectively), but not for lumbar spine BMD (P = .071).

In patients with hemophilia aged younger than 50 years, 27.8% were found to have “low normal” BMD levels, and 19.4% showed “lower than expected” BMD levels with respect to age.

“Vitamin D insufficiency and deficiency were present in 63.4% of the patients with hemophilia, significantly higher than the control group [37.5%; P less than .001],” the researchers wrote.

There were also statistically significant positive correlations between FISH score and femoral neck BMD (P = .001, r = .530), femoral neck z score (P = .001, r = .514), femoral neck T score (P = .002, r = .524), and lumbar spine BMD (P = .033, r = .334). No correlation was found between dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry measurements and the other variables (age, calcium, phosphorus, and alkaline phosphatase levels), and no results were reported for hepatitis C or HIV because none of the participants tested positive for those measures.

The most frequently reported causes of reduced BMD levels was vitamin D deficiency, low BMI, and low functional movement ability, although none of these was a strong independent risk factor in multivariate analysis, the authors reported.

They acknowledged that the results may not be generalizable to all patients because the study was conducted at a single center in Turkey.

“The results of our study emphasize the importance of early detection of comorbid conditions that decrease bone mass in severe hemophilia A patients,” they concluded.

The study was funded by the Yüzüncü Yıl University Scientific Research Project Committee. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ekinci O et al. Haemophilia. 2019 Aug 8. doi: 10.1111/hae.13836.

Men with severe hemophilia A showed reduced levels of bone mineral density, compared with controls representative of the general population, according to findings from a case-control study.

In addition, the decrease in bone mineral density (BMD) was correlated with reduced functional ability and body mass index (BMI), and vitamin D insufficiency or deficiency.

“We aimed to investigate the presence of low BMD in adult patients diagnosed with severe hemophilia A and to evaluate the potential risk factors associated with low BMD and musculoskeletal function levels,” wrote Omer Ekinci, MD, of Firat University in Elazig, Turkey, and colleagues in Haemophilia.

The study included 41 men with severe hemophilia A and 40 men without hemophilia who were matched for age. All patients with hemophilia A received regular prophylactic therapy, and one patient had a high titre (greater than 5 Bethesda units) inhibitor against FVIII.

The researchers performed several laboratory tests: BMD was measured using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry; BMI was recorded; and laboratory tests were performed to ascertain levels of vitamin D, calcium, phosphorus, alkaline phosphatase, parathyroid hormone, and hepatitis C and HIV antibodies. The Functional Independence Score in Hemophilia (FISH) was used to measure functional-ability status only in the study group.

After analysis, the researchers found a significant difference between patients in the case and control groups for femoral neck and total hip BMD (P = .017 and P less than .001, respectively), but not for lumbar spine BMD (P = .071).

In patients with hemophilia aged younger than 50 years, 27.8% were found to have “low normal” BMD levels, and 19.4% showed “lower than expected” BMD levels with respect to age.

“Vitamin D insufficiency and deficiency were present in 63.4% of the patients with hemophilia, significantly higher than the control group [37.5%; P less than .001],” the researchers wrote.

There were also statistically significant positive correlations between FISH score and femoral neck BMD (P = .001, r = .530), femoral neck z score (P = .001, r = .514), femoral neck T score (P = .002, r = .524), and lumbar spine BMD (P = .033, r = .334). No correlation was found between dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry measurements and the other variables (age, calcium, phosphorus, and alkaline phosphatase levels), and no results were reported for hepatitis C or HIV because none of the participants tested positive for those measures.

The most frequently reported causes of reduced BMD levels was vitamin D deficiency, low BMI, and low functional movement ability, although none of these was a strong independent risk factor in multivariate analysis, the authors reported.

They acknowledged that the results may not be generalizable to all patients because the study was conducted at a single center in Turkey.

“The results of our study emphasize the importance of early detection of comorbid conditions that decrease bone mass in severe hemophilia A patients,” they concluded.

The study was funded by the Yüzüncü Yıl University Scientific Research Project Committee. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ekinci O et al. Haemophilia. 2019 Aug 8. doi: 10.1111/hae.13836.

FROM HAEMOPHILIA

Bisphosphonates improve BMD in pediatric rheumatic disease

Prophylactic treatment with bisphosphonates could significantly improve bone mineral density (BMD) in children and adolescents receiving steroids for chronic rheumatic disease, a study has found.

A paper published in EClinicalMedicine reported the outcomes of a multicenter, double-dummy, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involving 217 patients who were receiving steroid therapy for juvenile idiopathic arthritis, juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus, juvenile dermatomyositis, or juvenile vasculitis. The patients were randomized to risedronate, alfacalcidol, or placebo, and all of the participants received 500 mg calcium and 400 IU vitamin D daily.

Lumbar spine and total body (less head) BMD increased in all groups, but the greatest increase was seen in patients treated with risedronate.

After 1 year, lumbar spine and total body (less head) BMD had increased in all groups, compared with baseline, but the greatest increase was seen in patients who had been treated with risedronate.

The lumbar spine areal BMD z score remained the same in the placebo group (−1.15 to −1.13), decreased from −0.96 to −1.00 in the alfacalcidol group, and increased from −0.99 to −0.75 in the risedronate group.

The change in z scores was significantly different between placebo and risedronate groups, and between risedronate and alfacalcidol groups, but not between placebo and alfacalcidol.

“The acquisition of adequate peak bone mass is not only important for the young person in reducing fracture risk but also has significant implications for the development of osteoporosis in later life, if peak bone mass is suboptimal,” wrote Madeleine Rooney, MBBCH, from the Queens University of Belfast, Northern Ireland, and associates.

There were no significant differences between the three groups in fracture rates. However, researchers were also able to compare Genant scores for vertebral fractures in 187 patients with pre- and posttreatment lateral spinal x-rays. That showed that the 54 patients in the placebo arm and 52 patients in the alfacalcidol arm had no change in their baseline Genant score of 0 (normal). However, although all 53 patients in the risedronate group had a Genant score of 0 at baseline, at 1-year follow-up, 2 patients had a Genant score of 1 (mild fracture), and 1 patient had a score of 3 (severe fracture).

In biochemical parameters, researchers saw a drop in parathyroid hormone in the placebo and alfacalcidol groups, but a rise in the risedronate group. However, the authors were not able to see any changes in bone markers that might have indicated which patients responded better to treatment.

Around 90% of participants in each group were also being treated with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. The rates of biologic use were 10.5% in the placebo group, 23.9% in the alfacalcidol group, and 10.1% in the risedronate group.

The researchers also noted a 7% higher rate of serious adverse events in the risedronate group, but emphasized that there were no differences in events related to the treatment.

In an accompanying editorial, Ian R. Reid, MBBCH, of the department of medicine, University of Auckland (New Zealand) noted that the study was an important step toward finding interventions for the prevention of steroid-induced bone loss in children. “The present study indicates that risedronate, and probably other potent bisphosphonates, can provide bone preservation in children and young people receiving therapeutic doses of glucocorticoid drugs, whereas alfacalcidol is without benefit. The targeted use of bisphosphonates in children and young people judged to be at significant fracture risk is appropriate. However, whether preventing loss of bone density will reduce fracture incidence remains to be established.”

The study was funded by Arthritis Research UK. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Rooney M et al. EClinicalMedicine. 2019 Jul 3. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.06.004.

Prophylactic treatment with bisphosphonates could significantly improve bone mineral density (BMD) in children and adolescents receiving steroids for chronic rheumatic disease, a study has found.

A paper published in EClinicalMedicine reported the outcomes of a multicenter, double-dummy, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involving 217 patients who were receiving steroid therapy for juvenile idiopathic arthritis, juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus, juvenile dermatomyositis, or juvenile vasculitis. The patients were randomized to risedronate, alfacalcidol, or placebo, and all of the participants received 500 mg calcium and 400 IU vitamin D daily.

Lumbar spine and total body (less head) BMD increased in all groups, but the greatest increase was seen in patients treated with risedronate.

After 1 year, lumbar spine and total body (less head) BMD had increased in all groups, compared with baseline, but the greatest increase was seen in patients who had been treated with risedronate.

The lumbar spine areal BMD z score remained the same in the placebo group (−1.15 to −1.13), decreased from −0.96 to −1.00 in the alfacalcidol group, and increased from −0.99 to −0.75 in the risedronate group.

The change in z scores was significantly different between placebo and risedronate groups, and between risedronate and alfacalcidol groups, but not between placebo and alfacalcidol.

“The acquisition of adequate peak bone mass is not only important for the young person in reducing fracture risk but also has significant implications for the development of osteoporosis in later life, if peak bone mass is suboptimal,” wrote Madeleine Rooney, MBBCH, from the Queens University of Belfast, Northern Ireland, and associates.

There were no significant differences between the three groups in fracture rates. However, researchers were also able to compare Genant scores for vertebral fractures in 187 patients with pre- and posttreatment lateral spinal x-rays. That showed that the 54 patients in the placebo arm and 52 patients in the alfacalcidol arm had no change in their baseline Genant score of 0 (normal). However, although all 53 patients in the risedronate group had a Genant score of 0 at baseline, at 1-year follow-up, 2 patients had a Genant score of 1 (mild fracture), and 1 patient had a score of 3 (severe fracture).

In biochemical parameters, researchers saw a drop in parathyroid hormone in the placebo and alfacalcidol groups, but a rise in the risedronate group. However, the authors were not able to see any changes in bone markers that might have indicated which patients responded better to treatment.

Around 90% of participants in each group were also being treated with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. The rates of biologic use were 10.5% in the placebo group, 23.9% in the alfacalcidol group, and 10.1% in the risedronate group.

The researchers also noted a 7% higher rate of serious adverse events in the risedronate group, but emphasized that there were no differences in events related to the treatment.

In an accompanying editorial, Ian R. Reid, MBBCH, of the department of medicine, University of Auckland (New Zealand) noted that the study was an important step toward finding interventions for the prevention of steroid-induced bone loss in children. “The present study indicates that risedronate, and probably other potent bisphosphonates, can provide bone preservation in children and young people receiving therapeutic doses of glucocorticoid drugs, whereas alfacalcidol is without benefit. The targeted use of bisphosphonates in children and young people judged to be at significant fracture risk is appropriate. However, whether preventing loss of bone density will reduce fracture incidence remains to be established.”

The study was funded by Arthritis Research UK. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Rooney M et al. EClinicalMedicine. 2019 Jul 3. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.06.004.

Prophylactic treatment with bisphosphonates could significantly improve bone mineral density (BMD) in children and adolescents receiving steroids for chronic rheumatic disease, a study has found.

A paper published in EClinicalMedicine reported the outcomes of a multicenter, double-dummy, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involving 217 patients who were receiving steroid therapy for juvenile idiopathic arthritis, juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus, juvenile dermatomyositis, or juvenile vasculitis. The patients were randomized to risedronate, alfacalcidol, or placebo, and all of the participants received 500 mg calcium and 400 IU vitamin D daily.

Lumbar spine and total body (less head) BMD increased in all groups, but the greatest increase was seen in patients treated with risedronate.

After 1 year, lumbar spine and total body (less head) BMD had increased in all groups, compared with baseline, but the greatest increase was seen in patients who had been treated with risedronate.

The lumbar spine areal BMD z score remained the same in the placebo group (−1.15 to −1.13), decreased from −0.96 to −1.00 in the alfacalcidol group, and increased from −0.99 to −0.75 in the risedronate group.

The change in z scores was significantly different between placebo and risedronate groups, and between risedronate and alfacalcidol groups, but not between placebo and alfacalcidol.

“The acquisition of adequate peak bone mass is not only important for the young person in reducing fracture risk but also has significant implications for the development of osteoporosis in later life, if peak bone mass is suboptimal,” wrote Madeleine Rooney, MBBCH, from the Queens University of Belfast, Northern Ireland, and associates.

There were no significant differences between the three groups in fracture rates. However, researchers were also able to compare Genant scores for vertebral fractures in 187 patients with pre- and posttreatment lateral spinal x-rays. That showed that the 54 patients in the placebo arm and 52 patients in the alfacalcidol arm had no change in their baseline Genant score of 0 (normal). However, although all 53 patients in the risedronate group had a Genant score of 0 at baseline, at 1-year follow-up, 2 patients had a Genant score of 1 (mild fracture), and 1 patient had a score of 3 (severe fracture).

In biochemical parameters, researchers saw a drop in parathyroid hormone in the placebo and alfacalcidol groups, but a rise in the risedronate group. However, the authors were not able to see any changes in bone markers that might have indicated which patients responded better to treatment.

Around 90% of participants in each group were also being treated with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. The rates of biologic use were 10.5% in the placebo group, 23.9% in the alfacalcidol group, and 10.1% in the risedronate group.

The researchers also noted a 7% higher rate of serious adverse events in the risedronate group, but emphasized that there were no differences in events related to the treatment.

In an accompanying editorial, Ian R. Reid, MBBCH, of the department of medicine, University of Auckland (New Zealand) noted that the study was an important step toward finding interventions for the prevention of steroid-induced bone loss in children. “The present study indicates that risedronate, and probably other potent bisphosphonates, can provide bone preservation in children and young people receiving therapeutic doses of glucocorticoid drugs, whereas alfacalcidol is without benefit. The targeted use of bisphosphonates in children and young people judged to be at significant fracture risk is appropriate. However, whether preventing loss of bone density will reduce fracture incidence remains to be established.”

The study was funded by Arthritis Research UK. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Rooney M et al. EClinicalMedicine. 2019 Jul 3. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.06.004.

FROM ECLINICALMEDICINE

Inadequate glycemic control in type 1 diabetes leads to increased fracture risk

A single percentage increase in the level of hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) in patients with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes is significantly associated with an increase in fracture risk, according to findings in a study published in Diabetic Medicine.

To determine the effect of glycemic control on fracture risk, Rasiah Thayakaran, PhD, of the University of Birmingham (England) and colleagues analyzed data from 5,368 patients with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes in the United Kingdom. HbA1c measurements were collected until either fracture or the end of the study, and were then converted from percentages to mmol/mol. Patient age ranged between 1 and 60 years, and the mean age was 22 years.

During 37,830 person‐years of follow‐up, 525 fractures were observed, with an incidence rate of 14 per 1,000 person‐years. The rate among men was 15 per 1,000 person‐years, compared with 12 per 1,000 person‐years among women. There was a significant association between hemoglobin level and risk of fractures (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.007 mmol/mol; 95% confidence interval, 1.002-1.011 mmol/mol), representing an increase of 7% in risk for fracture for each percentage increase in hemoglobin level.

“When assessing an individual with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes and high HbA1c, increased clinical awareness about the fracture risk may be incorporated in decision‐making regarding the clinical management and even in prompting early antiosteoporotic intervention,” Dr. Thayakaran and coauthors wrote.

The researchers acknowledged the study’s limitations, including a possibility of residual confounding because of their use of observational data. In addition, they could not confirm whether the increase in fracture risk should be attributed to bone fragility or to increased risk of falls. Finally, though they noted using a comprehensive list of codes to identify fractures, they could not verify “completeness of recording ... and therefore reported overall fracture incidence should be interpreted with caution.”

The study was not funded. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Thayakaran R et al. Diab Med. 2019 Mar 8. doi: 10.1111/dme.13945.

A single percentage increase in the level of hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) in patients with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes is significantly associated with an increase in fracture risk, according to findings in a study published in Diabetic Medicine.

To determine the effect of glycemic control on fracture risk, Rasiah Thayakaran, PhD, of the University of Birmingham (England) and colleagues analyzed data from 5,368 patients with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes in the United Kingdom. HbA1c measurements were collected until either fracture or the end of the study, and were then converted from percentages to mmol/mol. Patient age ranged between 1 and 60 years, and the mean age was 22 years.

During 37,830 person‐years of follow‐up, 525 fractures were observed, with an incidence rate of 14 per 1,000 person‐years. The rate among men was 15 per 1,000 person‐years, compared with 12 per 1,000 person‐years among women. There was a significant association between hemoglobin level and risk of fractures (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.007 mmol/mol; 95% confidence interval, 1.002-1.011 mmol/mol), representing an increase of 7% in risk for fracture for each percentage increase in hemoglobin level.

“When assessing an individual with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes and high HbA1c, increased clinical awareness about the fracture risk may be incorporated in decision‐making regarding the clinical management and even in prompting early antiosteoporotic intervention,” Dr. Thayakaran and coauthors wrote.

The researchers acknowledged the study’s limitations, including a possibility of residual confounding because of their use of observational data. In addition, they could not confirm whether the increase in fracture risk should be attributed to bone fragility or to increased risk of falls. Finally, though they noted using a comprehensive list of codes to identify fractures, they could not verify “completeness of recording ... and therefore reported overall fracture incidence should be interpreted with caution.”

The study was not funded. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Thayakaran R et al. Diab Med. 2019 Mar 8. doi: 10.1111/dme.13945.

A single percentage increase in the level of hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) in patients with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes is significantly associated with an increase in fracture risk, according to findings in a study published in Diabetic Medicine.

To determine the effect of glycemic control on fracture risk, Rasiah Thayakaran, PhD, of the University of Birmingham (England) and colleagues analyzed data from 5,368 patients with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes in the United Kingdom. HbA1c measurements were collected until either fracture or the end of the study, and were then converted from percentages to mmol/mol. Patient age ranged between 1 and 60 years, and the mean age was 22 years.

During 37,830 person‐years of follow‐up, 525 fractures were observed, with an incidence rate of 14 per 1,000 person‐years. The rate among men was 15 per 1,000 person‐years, compared with 12 per 1,000 person‐years among women. There was a significant association between hemoglobin level and risk of fractures (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.007 mmol/mol; 95% confidence interval, 1.002-1.011 mmol/mol), representing an increase of 7% in risk for fracture for each percentage increase in hemoglobin level.

“When assessing an individual with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes and high HbA1c, increased clinical awareness about the fracture risk may be incorporated in decision‐making regarding the clinical management and even in prompting early antiosteoporotic intervention,” Dr. Thayakaran and coauthors wrote.

The researchers acknowledged the study’s limitations, including a possibility of residual confounding because of their use of observational data. In addition, they could not confirm whether the increase in fracture risk should be attributed to bone fragility or to increased risk of falls. Finally, though they noted using a comprehensive list of codes to identify fractures, they could not verify “completeness of recording ... and therefore reported overall fracture incidence should be interpreted with caution.”

The study was not funded. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Thayakaran R et al. Diab Med. 2019 Mar 8. doi: 10.1111/dme.13945.

FROM DIABETIC MEDICINE

Cathepsin Z identified as a potential biomarker for osteoporosis

The presence of cathepsin Z messenger RNA in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of people with osteopenia, osteoporosis, and women with osteoporosis and older than 50 years could be used as a biomarker to help diagnose osteoporosis, according to a recent study published in Scientific Reports.

Dong L. Barraclough, PhD, of the Institute of Ageing and Chronic Disease at the University of Liverpool, England, and colleagues studied the expression of cathepsin Z messenger RNA (mRNA) in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of 88 participants (71 women, 17 men). The participants were grouped according to their bone mineral density and T score, where a T score of −1.0 or higher was considered nonosteoporotic, a score between −1.0 and −2.5 was classified as osteopenia, and −2.5 or less was classified as osteoporosis.

Overall, there were 48 participants with osteopenia (38 women, 10 men; 55% of total participants; average age, 65 years), 23 participants with osteoporosis (19 women, 4 men; 26%; 69 years), and 17 participants in the nonosteoporotic control group (14 women, 3 men; 19%; 56 years), with 88% of the total number of participants aged 50 years and older (82% women, 18% men).

The researchers found significantly higher differential expression of cathepsin Z mRNA in PBMCs when comparing the nonosteoporotic control group and participants with osteopenia (95% confidence interval, −0.32 to −0.053; P = .0067), the control group with participants with osteoporosis (95% CI, −0.543 to −0.24; P less than .0001), and participants with osteopenia and those with osteoporosis (95% CI, −0.325 to −0.084; P = .0011).