User login

AI could identify fracture risk

A natural language processing algorithm, designed to scour emergency department records for fracture cases, has the potential to improve treatment of osteoporosis and prevent future, more severe fractures.

The approach led to a notable increase in referrals to the osteoporosis refracture prevention service at the Prince of Wales Hospital in Sydney, where the work was done.

The strongest predictor of a future fracture is a recent previous fracture, said Christopher White, MBBS, the hospital’s director of research, who presented results of an analysis at a virtual news conference held by the Endocrine Society. The study was slated for presentation during ENDO 2020, the society’s annual meeting, which was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We have really effective therapies that can reduce the risk of [future] fractures by 50%, and yet 80% of osteoporotic patients leave the hospital untreated after fracture,” said Dr. White.

That, he explained, is because of a fundamental disconnect in fracture care – emergency department physicians tackle the immediate aftermath of a broken bone, but they are not tasked with treating the underlying condition. As a result, many patients who would be candidates for follow-up care are not referred.

The current work grew out of Dr. White’s frustration with not being able to recruit patients for osteoporosis clinical trials. In fact, he got so annoyed trying to recruit and not getting patients referred to him – even though he’d find they were actually in the hospital – that he decided “to start an AI [artificial intelligence] program that would read the radiology report and bypass the referrer,” he said.

To that end, with the help of an industry partner, he developed a software program called XRAIT (X-Ray Artificial Intelligence Tool), which analyzed the reports and, with Dr. White’s iterated guidance, learned to identify fractures.

The system performed a little too well. “You have to be careful what you wish for, because suddenly I went from 70 referrals to 339,” he said.

That influx is a potential downside, however, according to Angela Cheung, MD, PhD, director of the Centre of Excellence in Skeletal Health Assessment and Osteoporosis Program at the University of Toronto’s University Health Network. Natural language processing can help identify patients that a human reviewer would miss, because reviewers tend to focus on cases in which the fracture was the reason for the hospital visit, rather than on incidental findings. But not all incidental findings are clinically important. “A pneumonia patient might have had the fracture 30 years ago, falling off a tree as a college student. It may not pick up the highest-risk group in terms of fractures, because we know that recency of fractures matters,” Dr. Cheung, who was not associated with the research, said in an interview.

“It means the fracture liaison coordinator would need to review [more] numbers in trying to figure out whether the patient should get attention and whether they should be treated as well,” said Dr. Cheung, adding that more studies would need to be done to determine if the approach would be cost effective.

The researchers performed a technical evaluation of 2,445 nonfracture and 433 fracture reports, in which the tool performed with more than 99% sensitivity and specificity.

In a clinical validation, a fracture clinician and XRAIT reviewed 5,089 x-ray and computed tomography reports from ED patients who were older than 50 years. The ED referred 70 cases, leading to identification of 65 fractures. The combination of ED referral and a fracture clinician’s review of 224 cases revealed 98 fracture cases. By contrast, XRAIT nearly instantaneously analyzed 5,089 reports from 3,217 patients, and identified fractures in 349 patients – a nearly fivefold higher number than the manual case finding of 70. Of those 349 patients, results for 10 were false positives, leading to a total find of 339 patients.

In all, 57 cases were found both by XRAIT and the ED referral/fracture clinician, resulting in 282 unique cases identified by XRAIT alone. That translated to a 3.5-fold increase in cases that were identifiable using XRAIT.

In an external validation, the researchers tested the system on 327 reports from a subset of the Dubbo Osteoporosis Epidemiology Study, based in the city of Dubbo in New South Wales, Australia. In that cohort, XRAIT identified 97 positive cases, of which 87 were true fractures (10 false positives). Of 230 cases that it considered not to be fractures, there were 38 false negatives. Those numbers translated to a sensitivity of 69.6% and a specificity of 95.0%.

All of those hits have the potential to overwhelm osteoporosis services. “I now have to adjust to that, and further development will be to link the AI with clinical risk factors and treatment data to assist my fracture coordinators to target the right patients. We’ll increase the number of patients with osteoporosis on treatment, improve productivity and safety, and reduce the burden of care,” said Dr. White.

The study was funded by The Sydney Partnership for Health, Education, Research and Enterprise and the Musculoskeletal Consumer Advisory Group. The researchers reported no financial conflicts of interest, as did Dr. Cheung.

The research will be published in a special supplemental issue of the Journal of the Endocrine Society. In addition to a series of news conferences on March 30-31, the society will host ENDO Online 2020 during June 8-22, which will present programming for clinicians and researchers.

A natural language processing algorithm, designed to scour emergency department records for fracture cases, has the potential to improve treatment of osteoporosis and prevent future, more severe fractures.

The approach led to a notable increase in referrals to the osteoporosis refracture prevention service at the Prince of Wales Hospital in Sydney, where the work was done.

The strongest predictor of a future fracture is a recent previous fracture, said Christopher White, MBBS, the hospital’s director of research, who presented results of an analysis at a virtual news conference held by the Endocrine Society. The study was slated for presentation during ENDO 2020, the society’s annual meeting, which was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We have really effective therapies that can reduce the risk of [future] fractures by 50%, and yet 80% of osteoporotic patients leave the hospital untreated after fracture,” said Dr. White.

That, he explained, is because of a fundamental disconnect in fracture care – emergency department physicians tackle the immediate aftermath of a broken bone, but they are not tasked with treating the underlying condition. As a result, many patients who would be candidates for follow-up care are not referred.

The current work grew out of Dr. White’s frustration with not being able to recruit patients for osteoporosis clinical trials. In fact, he got so annoyed trying to recruit and not getting patients referred to him – even though he’d find they were actually in the hospital – that he decided “to start an AI [artificial intelligence] program that would read the radiology report and bypass the referrer,” he said.

To that end, with the help of an industry partner, he developed a software program called XRAIT (X-Ray Artificial Intelligence Tool), which analyzed the reports and, with Dr. White’s iterated guidance, learned to identify fractures.

The system performed a little too well. “You have to be careful what you wish for, because suddenly I went from 70 referrals to 339,” he said.

That influx is a potential downside, however, according to Angela Cheung, MD, PhD, director of the Centre of Excellence in Skeletal Health Assessment and Osteoporosis Program at the University of Toronto’s University Health Network. Natural language processing can help identify patients that a human reviewer would miss, because reviewers tend to focus on cases in which the fracture was the reason for the hospital visit, rather than on incidental findings. But not all incidental findings are clinically important. “A pneumonia patient might have had the fracture 30 years ago, falling off a tree as a college student. It may not pick up the highest-risk group in terms of fractures, because we know that recency of fractures matters,” Dr. Cheung, who was not associated with the research, said in an interview.

“It means the fracture liaison coordinator would need to review [more] numbers in trying to figure out whether the patient should get attention and whether they should be treated as well,” said Dr. Cheung, adding that more studies would need to be done to determine if the approach would be cost effective.

The researchers performed a technical evaluation of 2,445 nonfracture and 433 fracture reports, in which the tool performed with more than 99% sensitivity and specificity.

In a clinical validation, a fracture clinician and XRAIT reviewed 5,089 x-ray and computed tomography reports from ED patients who were older than 50 years. The ED referred 70 cases, leading to identification of 65 fractures. The combination of ED referral and a fracture clinician’s review of 224 cases revealed 98 fracture cases. By contrast, XRAIT nearly instantaneously analyzed 5,089 reports from 3,217 patients, and identified fractures in 349 patients – a nearly fivefold higher number than the manual case finding of 70. Of those 349 patients, results for 10 were false positives, leading to a total find of 339 patients.

In all, 57 cases were found both by XRAIT and the ED referral/fracture clinician, resulting in 282 unique cases identified by XRAIT alone. That translated to a 3.5-fold increase in cases that were identifiable using XRAIT.

In an external validation, the researchers tested the system on 327 reports from a subset of the Dubbo Osteoporosis Epidemiology Study, based in the city of Dubbo in New South Wales, Australia. In that cohort, XRAIT identified 97 positive cases, of which 87 were true fractures (10 false positives). Of 230 cases that it considered not to be fractures, there were 38 false negatives. Those numbers translated to a sensitivity of 69.6% and a specificity of 95.0%.

All of those hits have the potential to overwhelm osteoporosis services. “I now have to adjust to that, and further development will be to link the AI with clinical risk factors and treatment data to assist my fracture coordinators to target the right patients. We’ll increase the number of patients with osteoporosis on treatment, improve productivity and safety, and reduce the burden of care,” said Dr. White.

The study was funded by The Sydney Partnership for Health, Education, Research and Enterprise and the Musculoskeletal Consumer Advisory Group. The researchers reported no financial conflicts of interest, as did Dr. Cheung.

The research will be published in a special supplemental issue of the Journal of the Endocrine Society. In addition to a series of news conferences on March 30-31, the society will host ENDO Online 2020 during June 8-22, which will present programming for clinicians and researchers.

A natural language processing algorithm, designed to scour emergency department records for fracture cases, has the potential to improve treatment of osteoporosis and prevent future, more severe fractures.

The approach led to a notable increase in referrals to the osteoporosis refracture prevention service at the Prince of Wales Hospital in Sydney, where the work was done.

The strongest predictor of a future fracture is a recent previous fracture, said Christopher White, MBBS, the hospital’s director of research, who presented results of an analysis at a virtual news conference held by the Endocrine Society. The study was slated for presentation during ENDO 2020, the society’s annual meeting, which was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We have really effective therapies that can reduce the risk of [future] fractures by 50%, and yet 80% of osteoporotic patients leave the hospital untreated after fracture,” said Dr. White.

That, he explained, is because of a fundamental disconnect in fracture care – emergency department physicians tackle the immediate aftermath of a broken bone, but they are not tasked with treating the underlying condition. As a result, many patients who would be candidates for follow-up care are not referred.

The current work grew out of Dr. White’s frustration with not being able to recruit patients for osteoporosis clinical trials. In fact, he got so annoyed trying to recruit and not getting patients referred to him – even though he’d find they were actually in the hospital – that he decided “to start an AI [artificial intelligence] program that would read the radiology report and bypass the referrer,” he said.

To that end, with the help of an industry partner, he developed a software program called XRAIT (X-Ray Artificial Intelligence Tool), which analyzed the reports and, with Dr. White’s iterated guidance, learned to identify fractures.

The system performed a little too well. “You have to be careful what you wish for, because suddenly I went from 70 referrals to 339,” he said.

That influx is a potential downside, however, according to Angela Cheung, MD, PhD, director of the Centre of Excellence in Skeletal Health Assessment and Osteoporosis Program at the University of Toronto’s University Health Network. Natural language processing can help identify patients that a human reviewer would miss, because reviewers tend to focus on cases in which the fracture was the reason for the hospital visit, rather than on incidental findings. But not all incidental findings are clinically important. “A pneumonia patient might have had the fracture 30 years ago, falling off a tree as a college student. It may not pick up the highest-risk group in terms of fractures, because we know that recency of fractures matters,” Dr. Cheung, who was not associated with the research, said in an interview.

“It means the fracture liaison coordinator would need to review [more] numbers in trying to figure out whether the patient should get attention and whether they should be treated as well,” said Dr. Cheung, adding that more studies would need to be done to determine if the approach would be cost effective.

The researchers performed a technical evaluation of 2,445 nonfracture and 433 fracture reports, in which the tool performed with more than 99% sensitivity and specificity.

In a clinical validation, a fracture clinician and XRAIT reviewed 5,089 x-ray and computed tomography reports from ED patients who were older than 50 years. The ED referred 70 cases, leading to identification of 65 fractures. The combination of ED referral and a fracture clinician’s review of 224 cases revealed 98 fracture cases. By contrast, XRAIT nearly instantaneously analyzed 5,089 reports from 3,217 patients, and identified fractures in 349 patients – a nearly fivefold higher number than the manual case finding of 70. Of those 349 patients, results for 10 were false positives, leading to a total find of 339 patients.

In all, 57 cases were found both by XRAIT and the ED referral/fracture clinician, resulting in 282 unique cases identified by XRAIT alone. That translated to a 3.5-fold increase in cases that were identifiable using XRAIT.

In an external validation, the researchers tested the system on 327 reports from a subset of the Dubbo Osteoporosis Epidemiology Study, based in the city of Dubbo in New South Wales, Australia. In that cohort, XRAIT identified 97 positive cases, of which 87 were true fractures (10 false positives). Of 230 cases that it considered not to be fractures, there were 38 false negatives. Those numbers translated to a sensitivity of 69.6% and a specificity of 95.0%.

All of those hits have the potential to overwhelm osteoporosis services. “I now have to adjust to that, and further development will be to link the AI with clinical risk factors and treatment data to assist my fracture coordinators to target the right patients. We’ll increase the number of patients with osteoporosis on treatment, improve productivity and safety, and reduce the burden of care,” said Dr. White.

The study was funded by The Sydney Partnership for Health, Education, Research and Enterprise and the Musculoskeletal Consumer Advisory Group. The researchers reported no financial conflicts of interest, as did Dr. Cheung.

The research will be published in a special supplemental issue of the Journal of the Endocrine Society. In addition to a series of news conferences on March 30-31, the society will host ENDO Online 2020 during June 8-22, which will present programming for clinicians and researchers.

FROM ENDO 2020

High and low trauma yield similar future osteoporotic fracture risk

Average measures of bone mineral density were similar for individuals with high-trauma and low-trauma fractures, and both were significantly distinct from those with no fracture history, based on data from a cohort study of adults aged 40 years and older.

In the past, low-trauma fractures have typically been associated with osteoporosis, wrote William D. Leslie, MD, of the University of Manitoba, Canada, and his colleagues. However, features distinguishing between low- and high-trauma fractures are often arbitrary and “empirical data have questioned whether distinguishing low-trauma from high-trauma fractures is clinically useful for purposes of risk assessment and treatment,” they wrote.

In a study published in Osteoporosis International, the researchers reviewed data from 64,626 individuals with no prior fracture, 858 with high-trauma fractures, and 14,758 with low-trauma fractures. Overall, the average BMD Z-scores for individuals with no previous fracture were slightly positive, while those with either a high-trauma or low-trauma fracture were negative. The scores for individuals with high-trauma fractures or major osteoporotic fractures were similar to those with low-trauma fractures, and significantly lower (P less than .001) than among individuals with no prior fractures.

The study population included adults aged 40 years and older with baseline DXA scans between Jan. 1, 1996, and Mar. 31, 2016. Those with high-trauma fractures were younger than those with low-trauma fractures (65 years vs. 67 years), and fewer individuals with high-trauma fractures were women (77% vs. 87%).

Both high-trauma and low-trauma fractures were similarly and significantly associated with increased risk for incident major osteoporotic fractures (adjusted hazard ratios 1.31 and 1.55, respectively).

The study findings were limited by several factors including incomplete data on external injury codes, the retrospective study design, and the lack of analysis of the time since prior fractures, the researchers noted. However, the results were strengthened by the large sample size, long-term follow-up, and large numbers of incident fractures, they wrote.

The results support data from previous studies and support “the inclusion of high-trauma clinical fractures in clinical assessment for underlying osteoporosis and in the evaluation for intervention to reduce future fracture risk,” they wrote.

In an accompanying editorial, Steven R. Cummings, MD, of California Pacific Medical Center Research Institute, San Francisco, and Richard Eastell, MD, of the University of Sheffield, England, wrote that the practice of rating fractures according to degree of trauma should be eliminated.

“The study adds evidence to the case that it is time to abandon the mistaken beliefs that fractures rated as high trauma are not associated with decreased BMD, indicate no higher risk of subsequent fracture, or are less likely to be prevented by treatments for osteoporosis,” they wrote.

Describing some fractures as due to trauma reinforces the mistaken belief that the fractures are simply due to the trauma, not decreased bone strength, they noted.

“Indeed, we recommend that people stop attempting to rate or record degree of trauma because such ratings are at best inaccurate and would promote the continued neglect of those patients who are misclassified as having fractures that do not warrant evaluation and treatment,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Leslie, the study’s first author, reported having no financial conflicts to disclose.

Dr. Cummings disclosed consultancy and grant funding from Amgen and Radius. Dr. Eastell disclosed consultancy funding from IDS, Roche Diagnostics, GSK Nutrition, FNIH, Mereo, Lilly, Sandoz, Nittobo, Abbvie, Samsung, and Haoma Medica and grant funding from Nittobo, IDS, Roche, Amgen, and Alexion.

SOURCE: Leslie WD et al. Osteroporos Int. 2020 Mar 16. doi: 10.1007/s00198-019-05274-2.

Average measures of bone mineral density were similar for individuals with high-trauma and low-trauma fractures, and both were significantly distinct from those with no fracture history, based on data from a cohort study of adults aged 40 years and older.

In the past, low-trauma fractures have typically been associated with osteoporosis, wrote William D. Leslie, MD, of the University of Manitoba, Canada, and his colleagues. However, features distinguishing between low- and high-trauma fractures are often arbitrary and “empirical data have questioned whether distinguishing low-trauma from high-trauma fractures is clinically useful for purposes of risk assessment and treatment,” they wrote.

In a study published in Osteoporosis International, the researchers reviewed data from 64,626 individuals with no prior fracture, 858 with high-trauma fractures, and 14,758 with low-trauma fractures. Overall, the average BMD Z-scores for individuals with no previous fracture were slightly positive, while those with either a high-trauma or low-trauma fracture were negative. The scores for individuals with high-trauma fractures or major osteoporotic fractures were similar to those with low-trauma fractures, and significantly lower (P less than .001) than among individuals with no prior fractures.

The study population included adults aged 40 years and older with baseline DXA scans between Jan. 1, 1996, and Mar. 31, 2016. Those with high-trauma fractures were younger than those with low-trauma fractures (65 years vs. 67 years), and fewer individuals with high-trauma fractures were women (77% vs. 87%).

Both high-trauma and low-trauma fractures were similarly and significantly associated with increased risk for incident major osteoporotic fractures (adjusted hazard ratios 1.31 and 1.55, respectively).

The study findings were limited by several factors including incomplete data on external injury codes, the retrospective study design, and the lack of analysis of the time since prior fractures, the researchers noted. However, the results were strengthened by the large sample size, long-term follow-up, and large numbers of incident fractures, they wrote.

The results support data from previous studies and support “the inclusion of high-trauma clinical fractures in clinical assessment for underlying osteoporosis and in the evaluation for intervention to reduce future fracture risk,” they wrote.

In an accompanying editorial, Steven R. Cummings, MD, of California Pacific Medical Center Research Institute, San Francisco, and Richard Eastell, MD, of the University of Sheffield, England, wrote that the practice of rating fractures according to degree of trauma should be eliminated.

“The study adds evidence to the case that it is time to abandon the mistaken beliefs that fractures rated as high trauma are not associated with decreased BMD, indicate no higher risk of subsequent fracture, or are less likely to be prevented by treatments for osteoporosis,” they wrote.

Describing some fractures as due to trauma reinforces the mistaken belief that the fractures are simply due to the trauma, not decreased bone strength, they noted.

“Indeed, we recommend that people stop attempting to rate or record degree of trauma because such ratings are at best inaccurate and would promote the continued neglect of those patients who are misclassified as having fractures that do not warrant evaluation and treatment,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Leslie, the study’s first author, reported having no financial conflicts to disclose.

Dr. Cummings disclosed consultancy and grant funding from Amgen and Radius. Dr. Eastell disclosed consultancy funding from IDS, Roche Diagnostics, GSK Nutrition, FNIH, Mereo, Lilly, Sandoz, Nittobo, Abbvie, Samsung, and Haoma Medica and grant funding from Nittobo, IDS, Roche, Amgen, and Alexion.

SOURCE: Leslie WD et al. Osteroporos Int. 2020 Mar 16. doi: 10.1007/s00198-019-05274-2.

Average measures of bone mineral density were similar for individuals with high-trauma and low-trauma fractures, and both were significantly distinct from those with no fracture history, based on data from a cohort study of adults aged 40 years and older.

In the past, low-trauma fractures have typically been associated with osteoporosis, wrote William D. Leslie, MD, of the University of Manitoba, Canada, and his colleagues. However, features distinguishing between low- and high-trauma fractures are often arbitrary and “empirical data have questioned whether distinguishing low-trauma from high-trauma fractures is clinically useful for purposes of risk assessment and treatment,” they wrote.

In a study published in Osteoporosis International, the researchers reviewed data from 64,626 individuals with no prior fracture, 858 with high-trauma fractures, and 14,758 with low-trauma fractures. Overall, the average BMD Z-scores for individuals with no previous fracture were slightly positive, while those with either a high-trauma or low-trauma fracture were negative. The scores for individuals with high-trauma fractures or major osteoporotic fractures were similar to those with low-trauma fractures, and significantly lower (P less than .001) than among individuals with no prior fractures.

The study population included adults aged 40 years and older with baseline DXA scans between Jan. 1, 1996, and Mar. 31, 2016. Those with high-trauma fractures were younger than those with low-trauma fractures (65 years vs. 67 years), and fewer individuals with high-trauma fractures were women (77% vs. 87%).

Both high-trauma and low-trauma fractures were similarly and significantly associated with increased risk for incident major osteoporotic fractures (adjusted hazard ratios 1.31 and 1.55, respectively).

The study findings were limited by several factors including incomplete data on external injury codes, the retrospective study design, and the lack of analysis of the time since prior fractures, the researchers noted. However, the results were strengthened by the large sample size, long-term follow-up, and large numbers of incident fractures, they wrote.

The results support data from previous studies and support “the inclusion of high-trauma clinical fractures in clinical assessment for underlying osteoporosis and in the evaluation for intervention to reduce future fracture risk,” they wrote.

In an accompanying editorial, Steven R. Cummings, MD, of California Pacific Medical Center Research Institute, San Francisco, and Richard Eastell, MD, of the University of Sheffield, England, wrote that the practice of rating fractures according to degree of trauma should be eliminated.

“The study adds evidence to the case that it is time to abandon the mistaken beliefs that fractures rated as high trauma are not associated with decreased BMD, indicate no higher risk of subsequent fracture, or are less likely to be prevented by treatments for osteoporosis,” they wrote.

Describing some fractures as due to trauma reinforces the mistaken belief that the fractures are simply due to the trauma, not decreased bone strength, they noted.

“Indeed, we recommend that people stop attempting to rate or record degree of trauma because such ratings are at best inaccurate and would promote the continued neglect of those patients who are misclassified as having fractures that do not warrant evaluation and treatment,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Leslie, the study’s first author, reported having no financial conflicts to disclose.

Dr. Cummings disclosed consultancy and grant funding from Amgen and Radius. Dr. Eastell disclosed consultancy funding from IDS, Roche Diagnostics, GSK Nutrition, FNIH, Mereo, Lilly, Sandoz, Nittobo, Abbvie, Samsung, and Haoma Medica and grant funding from Nittobo, IDS, Roche, Amgen, and Alexion.

SOURCE: Leslie WD et al. Osteroporos Int. 2020 Mar 16. doi: 10.1007/s00198-019-05274-2.

FROM OSTEOPOROSIS INTERNATIONAL

Fracture liaison services confer benefit on recurrent fracture risk

Implementation of fracture liaison services (FLS) at two Swedish hospitals was associated with an 18% reduction of recurrent fracture over a median follow-up of 2.2 years, results from an observational cohort study found.

“Patients receiving fracture care within an FLS have higher rates of [bone mineral density] testing, treatment initiation and better adherence,” first author Kristian F. Axelsson, MD, and colleagues wrote in a study published in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. “However, the evidence regarding FLS and association to reduced risk of recurrent fracture is insufficient, consisting of smaller studies, studies with short follow-up time, and studies with high risk of various biases.”

Dr. Axelsson, of the department of orthopedic surgery at Skaraborg Hospital, Skövde, Sweden, and colleagues used electronic patient records from four hospitals in Western Sweden to identify all patients aged 50 years or older with a major osteoporotic fracture – defined as a fracture of the wrist, upper arm, hip, vertebra, or pelvis – between 2012 and 2017. The study population consisted of 15,449 patients from two hospitals with FLS and 5,634 patients from two hospitals with no FLS. The researchers used multivariable Cox models to compare all patients with a major osteoporotic fracture during the FLS period with all patients with a major osteoporotic fracture prior to the FLS implementation. The FLS hospitals and non-FLS hospitals were analyzed separately using the same methodology.

The mean age of patients was 74 years, 76% were female, and the most common index fracture site was the wrist (42%). In the hospitals with FLS, the researchers observed 1,247 recurrent fractures during a median follow-up time of 2.2 years. In an unadjusted Cox model, the risk of recurrent fracture was 18% lower in the FLS period, compared with the control period (hazard ratio, 0.82; P = .001). This corresponded to a 3-year number needed to screen of 61, and did not change after adjustment for clinical risk factors. In the non-FLS hospitals, no change in recurrent fracture rate was observed.

Osteoporosis medication treatment rates after fracture did not differ between the FLS and non-FLS hospitals, prior to FLS implementation (14.7% vs. 13.3%, respectively; P = .10). However, following FLS implementation, a larger proportion of fracture patients were treated at the FLS hospitals, compared with those at the non-FLS hospitals (28% vs. 12.9%; P less than .001).

“Our study is the largest yet, including both historic controls and controls at nearby hospitals without implementations of fracture liaison services,” one of the study authors, Mattias Lorentzon, MD, said in an interview. “We were able to rule out temporal trends in refracture risk and show that, [in] patients who had an index fracture at a hospital with an FLS, the refracture rate was lower than for patients who had an index fracture before the FLS was started, indicating that FLS reduce the risk of recurrent fracture. No such trends were observed in hospitals without FLS during the same time period.”

Dr. Lorentzon, head of geriatric medicine at Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Mölndal, Sweden, said that FLS implementation “led to a large increase in the use of osteoporosis medication, which we believe is the reason for the reduction in recurrent fracture risk observed. We believe that our results provide solid evidence that FLS implementation can reduce the rate of recurrent fractures, suggesting that all hospitals treating fracture patients should have fracture liaison services.”

In an interview, Stuart L. Silverman, MD, said that the study adds to compelling data on the efficacy and need for patients with clinical fracture to have case management by a FLS. “We recognize that near term risk is substantial in the year following a fracture,” said Dr. Silverman, who is clinical professor of medicine at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and the University of California, Los Angeles, and is not affiliated with the Swedish study. “For example, the risk of a subsequent fracture after hip fracture is 8.3%, which is similar to the risk of subsequent acute myocardial infarction after an initial acute MI. However, only 23% of patients receive osteoporosis medication after a hip fracture. Yet a fracture is to osteoporosis what an acute MI is to cardiovascular disease. We recognize that men and women age 65 years and older who have suffered a hip or vertebral fracture should be evaluated for treatment, as this subpopulation is at high risk for a second fracture and evidence supporting treatment efficacy is robust. We need a multidisciplinary clinical system which includes case management such as a fracture liaison service. We know FLS can reduce hip fracture rate in a closed system such as Kaiser by over 40%. This manuscript addresses the utility of a FLS in terms of reducing risk of future fracture.”

The researchers acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its observational design and the fact that patients prior to the FLS period were fewer and had longer follow-up time, compared with patients during the FLS period.

The study was funded by the Swedish Research Council and by grants from the Sahlgrenska University Hospital. Dr. Axelsson reported that he has received lecture fees from Lilly, Meda/Mylan, and Amgen. Dr. Lorentzon has received lecture fees from Amgen, Lilly, UCB, Radius Health, Meda, GE-Lunar, and Santax Medico/Hologic. The other coauthors reported having no financial disclosures. Dr. Silverman reported that he is a member of the speakers’ bureaus for Amgen and Radius. He is also a consultant for Lilly, Pfizer, and Amgen and has received research grants from Radius and Amgen.

SOURCE: Axelsson K et al. J Bone Min Res. 2020 Feb 25. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3990.

Implementation of fracture liaison services (FLS) at two Swedish hospitals was associated with an 18% reduction of recurrent fracture over a median follow-up of 2.2 years, results from an observational cohort study found.

“Patients receiving fracture care within an FLS have higher rates of [bone mineral density] testing, treatment initiation and better adherence,” first author Kristian F. Axelsson, MD, and colleagues wrote in a study published in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. “However, the evidence regarding FLS and association to reduced risk of recurrent fracture is insufficient, consisting of smaller studies, studies with short follow-up time, and studies with high risk of various biases.”

Dr. Axelsson, of the department of orthopedic surgery at Skaraborg Hospital, Skövde, Sweden, and colleagues used electronic patient records from four hospitals in Western Sweden to identify all patients aged 50 years or older with a major osteoporotic fracture – defined as a fracture of the wrist, upper arm, hip, vertebra, or pelvis – between 2012 and 2017. The study population consisted of 15,449 patients from two hospitals with FLS and 5,634 patients from two hospitals with no FLS. The researchers used multivariable Cox models to compare all patients with a major osteoporotic fracture during the FLS period with all patients with a major osteoporotic fracture prior to the FLS implementation. The FLS hospitals and non-FLS hospitals were analyzed separately using the same methodology.

The mean age of patients was 74 years, 76% were female, and the most common index fracture site was the wrist (42%). In the hospitals with FLS, the researchers observed 1,247 recurrent fractures during a median follow-up time of 2.2 years. In an unadjusted Cox model, the risk of recurrent fracture was 18% lower in the FLS period, compared with the control period (hazard ratio, 0.82; P = .001). This corresponded to a 3-year number needed to screen of 61, and did not change after adjustment for clinical risk factors. In the non-FLS hospitals, no change in recurrent fracture rate was observed.

Osteoporosis medication treatment rates after fracture did not differ between the FLS and non-FLS hospitals, prior to FLS implementation (14.7% vs. 13.3%, respectively; P = .10). However, following FLS implementation, a larger proportion of fracture patients were treated at the FLS hospitals, compared with those at the non-FLS hospitals (28% vs. 12.9%; P less than .001).

“Our study is the largest yet, including both historic controls and controls at nearby hospitals without implementations of fracture liaison services,” one of the study authors, Mattias Lorentzon, MD, said in an interview. “We were able to rule out temporal trends in refracture risk and show that, [in] patients who had an index fracture at a hospital with an FLS, the refracture rate was lower than for patients who had an index fracture before the FLS was started, indicating that FLS reduce the risk of recurrent fracture. No such trends were observed in hospitals without FLS during the same time period.”

Dr. Lorentzon, head of geriatric medicine at Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Mölndal, Sweden, said that FLS implementation “led to a large increase in the use of osteoporosis medication, which we believe is the reason for the reduction in recurrent fracture risk observed. We believe that our results provide solid evidence that FLS implementation can reduce the rate of recurrent fractures, suggesting that all hospitals treating fracture patients should have fracture liaison services.”

In an interview, Stuart L. Silverman, MD, said that the study adds to compelling data on the efficacy and need for patients with clinical fracture to have case management by a FLS. “We recognize that near term risk is substantial in the year following a fracture,” said Dr. Silverman, who is clinical professor of medicine at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and the University of California, Los Angeles, and is not affiliated with the Swedish study. “For example, the risk of a subsequent fracture after hip fracture is 8.3%, which is similar to the risk of subsequent acute myocardial infarction after an initial acute MI. However, only 23% of patients receive osteoporosis medication after a hip fracture. Yet a fracture is to osteoporosis what an acute MI is to cardiovascular disease. We recognize that men and women age 65 years and older who have suffered a hip or vertebral fracture should be evaluated for treatment, as this subpopulation is at high risk for a second fracture and evidence supporting treatment efficacy is robust. We need a multidisciplinary clinical system which includes case management such as a fracture liaison service. We know FLS can reduce hip fracture rate in a closed system such as Kaiser by over 40%. This manuscript addresses the utility of a FLS in terms of reducing risk of future fracture.”

The researchers acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its observational design and the fact that patients prior to the FLS period were fewer and had longer follow-up time, compared with patients during the FLS period.

The study was funded by the Swedish Research Council and by grants from the Sahlgrenska University Hospital. Dr. Axelsson reported that he has received lecture fees from Lilly, Meda/Mylan, and Amgen. Dr. Lorentzon has received lecture fees from Amgen, Lilly, UCB, Radius Health, Meda, GE-Lunar, and Santax Medico/Hologic. The other coauthors reported having no financial disclosures. Dr. Silverman reported that he is a member of the speakers’ bureaus for Amgen and Radius. He is also a consultant for Lilly, Pfizer, and Amgen and has received research grants from Radius and Amgen.

SOURCE: Axelsson K et al. J Bone Min Res. 2020 Feb 25. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3990.

Implementation of fracture liaison services (FLS) at two Swedish hospitals was associated with an 18% reduction of recurrent fracture over a median follow-up of 2.2 years, results from an observational cohort study found.

“Patients receiving fracture care within an FLS have higher rates of [bone mineral density] testing, treatment initiation and better adherence,” first author Kristian F. Axelsson, MD, and colleagues wrote in a study published in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. “However, the evidence regarding FLS and association to reduced risk of recurrent fracture is insufficient, consisting of smaller studies, studies with short follow-up time, and studies with high risk of various biases.”

Dr. Axelsson, of the department of orthopedic surgery at Skaraborg Hospital, Skövde, Sweden, and colleagues used electronic patient records from four hospitals in Western Sweden to identify all patients aged 50 years or older with a major osteoporotic fracture – defined as a fracture of the wrist, upper arm, hip, vertebra, or pelvis – between 2012 and 2017. The study population consisted of 15,449 patients from two hospitals with FLS and 5,634 patients from two hospitals with no FLS. The researchers used multivariable Cox models to compare all patients with a major osteoporotic fracture during the FLS period with all patients with a major osteoporotic fracture prior to the FLS implementation. The FLS hospitals and non-FLS hospitals were analyzed separately using the same methodology.

The mean age of patients was 74 years, 76% were female, and the most common index fracture site was the wrist (42%). In the hospitals with FLS, the researchers observed 1,247 recurrent fractures during a median follow-up time of 2.2 years. In an unadjusted Cox model, the risk of recurrent fracture was 18% lower in the FLS period, compared with the control period (hazard ratio, 0.82; P = .001). This corresponded to a 3-year number needed to screen of 61, and did not change after adjustment for clinical risk factors. In the non-FLS hospitals, no change in recurrent fracture rate was observed.

Osteoporosis medication treatment rates after fracture did not differ between the FLS and non-FLS hospitals, prior to FLS implementation (14.7% vs. 13.3%, respectively; P = .10). However, following FLS implementation, a larger proportion of fracture patients were treated at the FLS hospitals, compared with those at the non-FLS hospitals (28% vs. 12.9%; P less than .001).

“Our study is the largest yet, including both historic controls and controls at nearby hospitals without implementations of fracture liaison services,” one of the study authors, Mattias Lorentzon, MD, said in an interview. “We were able to rule out temporal trends in refracture risk and show that, [in] patients who had an index fracture at a hospital with an FLS, the refracture rate was lower than for patients who had an index fracture before the FLS was started, indicating that FLS reduce the risk of recurrent fracture. No such trends were observed in hospitals without FLS during the same time period.”

Dr. Lorentzon, head of geriatric medicine at Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Mölndal, Sweden, said that FLS implementation “led to a large increase in the use of osteoporosis medication, which we believe is the reason for the reduction in recurrent fracture risk observed. We believe that our results provide solid evidence that FLS implementation can reduce the rate of recurrent fractures, suggesting that all hospitals treating fracture patients should have fracture liaison services.”

In an interview, Stuart L. Silverman, MD, said that the study adds to compelling data on the efficacy and need for patients with clinical fracture to have case management by a FLS. “We recognize that near term risk is substantial in the year following a fracture,” said Dr. Silverman, who is clinical professor of medicine at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and the University of California, Los Angeles, and is not affiliated with the Swedish study. “For example, the risk of a subsequent fracture after hip fracture is 8.3%, which is similar to the risk of subsequent acute myocardial infarction after an initial acute MI. However, only 23% of patients receive osteoporosis medication after a hip fracture. Yet a fracture is to osteoporosis what an acute MI is to cardiovascular disease. We recognize that men and women age 65 years and older who have suffered a hip or vertebral fracture should be evaluated for treatment, as this subpopulation is at high risk for a second fracture and evidence supporting treatment efficacy is robust. We need a multidisciplinary clinical system which includes case management such as a fracture liaison service. We know FLS can reduce hip fracture rate in a closed system such as Kaiser by over 40%. This manuscript addresses the utility of a FLS in terms of reducing risk of future fracture.”

The researchers acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its observational design and the fact that patients prior to the FLS period were fewer and had longer follow-up time, compared with patients during the FLS period.

The study was funded by the Swedish Research Council and by grants from the Sahlgrenska University Hospital. Dr. Axelsson reported that he has received lecture fees from Lilly, Meda/Mylan, and Amgen. Dr. Lorentzon has received lecture fees from Amgen, Lilly, UCB, Radius Health, Meda, GE-Lunar, and Santax Medico/Hologic. The other coauthors reported having no financial disclosures. Dr. Silverman reported that he is a member of the speakers’ bureaus for Amgen and Radius. He is also a consultant for Lilly, Pfizer, and Amgen and has received research grants from Radius and Amgen.

SOURCE: Axelsson K et al. J Bone Min Res. 2020 Feb 25. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3990.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF BONE AND MINERAL RESEARCH

TBI deaths from falls on the rise

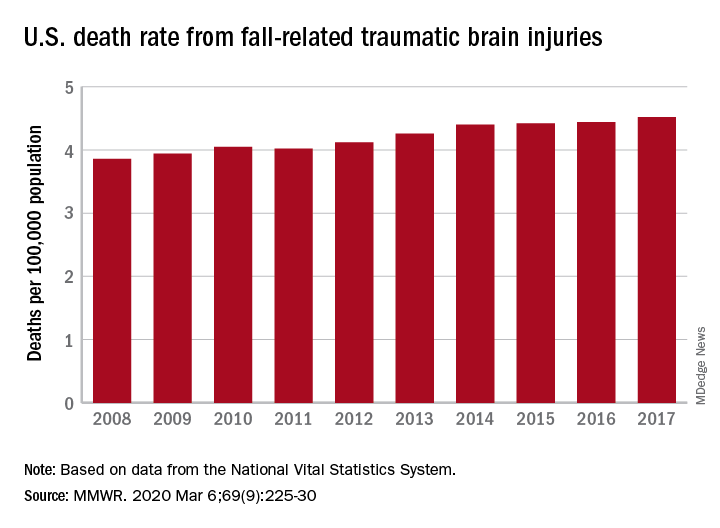

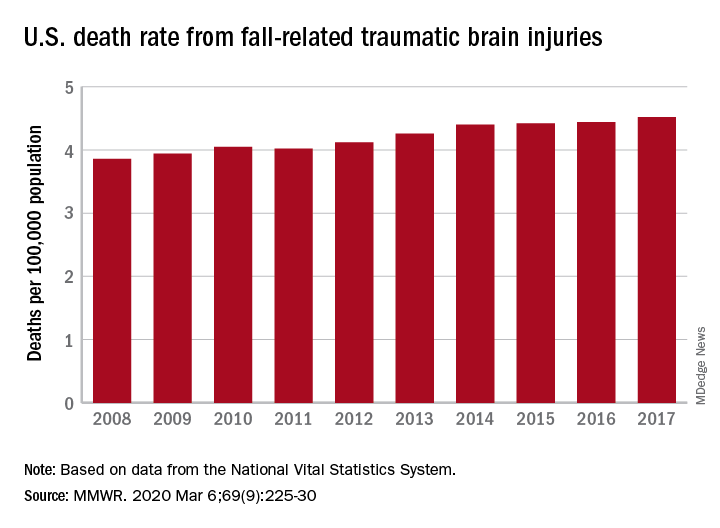

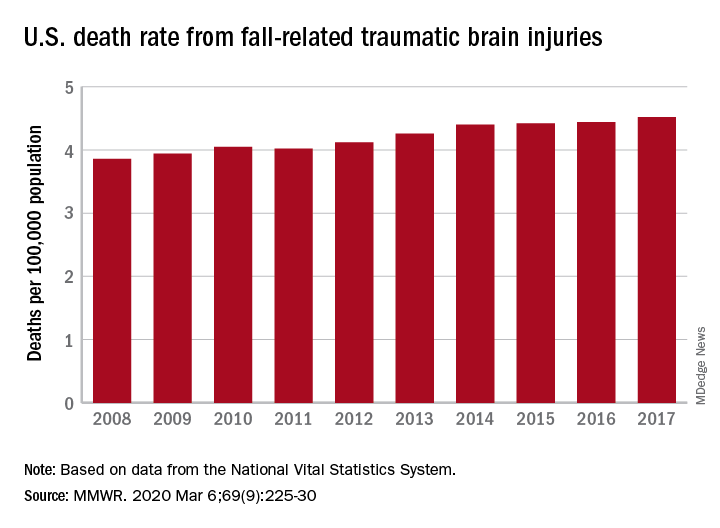

A 17% surge in mortality from fall-related traumatic brain injuries from 2008 to 2017 was driven largely by increases among those aged 75 years and older, according to investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Nationally, the rate of deaths from traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) caused by unintentional falls rose from 3.86 per 100,000 population in 2008 to 4.52 per 100,000 in 2017, as the number of deaths went from 12,311 to 17,408, said Alexis B. Peterson, PhD, and Scott R. Kegler, PhD, of the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control in Atlanta.

“This increase might be explained by longer survival following the onset of common diseases such as stroke, cancer, and heart disease or be attributable to the increasing population of older adults in the United States,” they suggested in the Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report.

The rate of fall-related TBI among Americans aged 75 years and older increased by an average of 2.6% per year from 2008 to 2017, compared with 1.8% in those aged 55-74. Over that same time, death rates dropped for those aged 35-44 (–0.3%), 18-34 (–1.1%), and 0-17 (–4.3%), they said, based on data from the National Vital Statistics System’s multiple cause-of-death database.

The death rate increased fastest in residents of rural areas (2.9% per year), but deaths from fall-related TBI were up at all levels of urbanization. The largest central cities and fringe metro areas were up by 1.4% a year, with larger annual increases seen in medium-size cities (2.1%), small cities (2.2%), and small towns (2.1%), Dr. Peterson and Dr. Kegler said.

Rates of TBI-related mortality in general are higher in rural areas, they noted, and “heterogeneity in the availability and accessibility of resources (e.g., access to high-level trauma centers and rehabilitative services) can result in disparities in postinjury outcomes.”

State-specific rates increased in 45 states, although Alaska was excluded from the analysis because of its small number of cases (less than 20). Increases were significant in 29 states, but none of the changes were significant in the 4 states with lower rates at the end of the study period, the investigators reported.

“In older adults, evidence-based fall prevention strategies can prevent falls and avert costly medical expenditures,” Dr. Peterson and Dr. Kegler said, suggesting that health care providers “consider prescribing exercises that incorporate balance, strength and gait activities, such as tai chi, and reviewing and managing medications linked to falls.”

SOURCE: Peterson AB, Kegler SR. MMWR. 2019 Mar 6;69(9):225-30.

A 17% surge in mortality from fall-related traumatic brain injuries from 2008 to 2017 was driven largely by increases among those aged 75 years and older, according to investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Nationally, the rate of deaths from traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) caused by unintentional falls rose from 3.86 per 100,000 population in 2008 to 4.52 per 100,000 in 2017, as the number of deaths went from 12,311 to 17,408, said Alexis B. Peterson, PhD, and Scott R. Kegler, PhD, of the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control in Atlanta.

“This increase might be explained by longer survival following the onset of common diseases such as stroke, cancer, and heart disease or be attributable to the increasing population of older adults in the United States,” they suggested in the Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report.

The rate of fall-related TBI among Americans aged 75 years and older increased by an average of 2.6% per year from 2008 to 2017, compared with 1.8% in those aged 55-74. Over that same time, death rates dropped for those aged 35-44 (–0.3%), 18-34 (–1.1%), and 0-17 (–4.3%), they said, based on data from the National Vital Statistics System’s multiple cause-of-death database.

The death rate increased fastest in residents of rural areas (2.9% per year), but deaths from fall-related TBI were up at all levels of urbanization. The largest central cities and fringe metro areas were up by 1.4% a year, with larger annual increases seen in medium-size cities (2.1%), small cities (2.2%), and small towns (2.1%), Dr. Peterson and Dr. Kegler said.

Rates of TBI-related mortality in general are higher in rural areas, they noted, and “heterogeneity in the availability and accessibility of resources (e.g., access to high-level trauma centers and rehabilitative services) can result in disparities in postinjury outcomes.”

State-specific rates increased in 45 states, although Alaska was excluded from the analysis because of its small number of cases (less than 20). Increases were significant in 29 states, but none of the changes were significant in the 4 states with lower rates at the end of the study period, the investigators reported.

“In older adults, evidence-based fall prevention strategies can prevent falls and avert costly medical expenditures,” Dr. Peterson and Dr. Kegler said, suggesting that health care providers “consider prescribing exercises that incorporate balance, strength and gait activities, such as tai chi, and reviewing and managing medications linked to falls.”

SOURCE: Peterson AB, Kegler SR. MMWR. 2019 Mar 6;69(9):225-30.

A 17% surge in mortality from fall-related traumatic brain injuries from 2008 to 2017 was driven largely by increases among those aged 75 years and older, according to investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Nationally, the rate of deaths from traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) caused by unintentional falls rose from 3.86 per 100,000 population in 2008 to 4.52 per 100,000 in 2017, as the number of deaths went from 12,311 to 17,408, said Alexis B. Peterson, PhD, and Scott R. Kegler, PhD, of the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control in Atlanta.

“This increase might be explained by longer survival following the onset of common diseases such as stroke, cancer, and heart disease or be attributable to the increasing population of older adults in the United States,” they suggested in the Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report.

The rate of fall-related TBI among Americans aged 75 years and older increased by an average of 2.6% per year from 2008 to 2017, compared with 1.8% in those aged 55-74. Over that same time, death rates dropped for those aged 35-44 (–0.3%), 18-34 (–1.1%), and 0-17 (–4.3%), they said, based on data from the National Vital Statistics System’s multiple cause-of-death database.

The death rate increased fastest in residents of rural areas (2.9% per year), but deaths from fall-related TBI were up at all levels of urbanization. The largest central cities and fringe metro areas were up by 1.4% a year, with larger annual increases seen in medium-size cities (2.1%), small cities (2.2%), and small towns (2.1%), Dr. Peterson and Dr. Kegler said.

Rates of TBI-related mortality in general are higher in rural areas, they noted, and “heterogeneity in the availability and accessibility of resources (e.g., access to high-level trauma centers and rehabilitative services) can result in disparities in postinjury outcomes.”

State-specific rates increased in 45 states, although Alaska was excluded from the analysis because of its small number of cases (less than 20). Increases were significant in 29 states, but none of the changes were significant in the 4 states with lower rates at the end of the study period, the investigators reported.

“In older adults, evidence-based fall prevention strategies can prevent falls and avert costly medical expenditures,” Dr. Peterson and Dr. Kegler said, suggesting that health care providers “consider prescribing exercises that incorporate balance, strength and gait activities, such as tai chi, and reviewing and managing medications linked to falls.”

SOURCE: Peterson AB, Kegler SR. MMWR. 2019 Mar 6;69(9):225-30.

FROM MMWR

RA magnifies fragility fracture risk in ESRD

MAUI, HAWAII – Comorbid rheumatoid arthritis is a force multiplier for fragility fracture risk in patients with end-stage renal disease, Renée Peterkin-McCalman, MD, reported at the 2020 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

“Patients with RA and ESRD are at substantially increased risk of osteoporotic fragility fractures compared to the overall population of ESRD patients. So fracture prevention prior to initiation of dialysis should be a focus of care in patients with RA,” said Dr. Peterkin-McCalman, a rheumatology fellow at the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta.

She presented a retrospective cohort study of 10,706 adults who initiated hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis for ESRD during 2005-2008, including 1,040 who also had RA. All subjects were drawn from the United States Renal Data System. The impetus for the study, Dr. Peterkin-McCalman explained in an interview, was that although prior studies have established that RA and ESRD are independent risk factors for osteoporotic fractures, the interplay between the two was previously unknown.

The risk of incident osteoporotic fractures during the first 3 years after going on renal dialysis was 14.7% in patients with ESRD only, vaulting to 25.6% in those with comorbid RA. Individuals with both RA and ESRD were at an adjusted 1.83-fold increased overall risk for new fragility fractures and at 1.85-fold increased risk for hip fracture, compared to those without RA.

Far and away the strongest risk factor for incident osteoporotic fractures in the group with RA plus ESRD was a history of a fracture sustained within 5 years prior to initiation of dialysis, with an associated 11.5-fold increased fracture risk overall and an 8.2-fold increased risk of hip fracture.

“The reason that’s important is we don’t really have any medications to reduce fracture risk once you get to ESRD. Of course, we have bisphosphonates and Prolia (denosumab) and things like that, but that’s in patients with milder CKD [chronic kidney disease] or no renal disease at all. So the goal is to identify the patients early who are at higher risk so that we can protect those bones before they get to ESRD and we have nothing left to treat them with,” she said.

In addition to a history of prevalent fracture prior to starting ESRD, the other risk factors for fracture in patients with ESRD and comorbid RA Dr. Peterkin-McCalman identified in her study included age greater than 50 years at the start of dialysis and female gender, which was associated with a twofold greater fracture risk than in men. Black patients with ESRD and RA were 64% less likely than whites to experience an incident fragility fracture. And the fracture risk was higher in patients on hemodialysis than with peritoneal dialysis.

Her study was supported by the Medical College of Georgia and a research grant from Dialysis Clinic Inc.

SOURCE: Peterkin-McCalman R et al. RWCS 2020.

MAUI, HAWAII – Comorbid rheumatoid arthritis is a force multiplier for fragility fracture risk in patients with end-stage renal disease, Renée Peterkin-McCalman, MD, reported at the 2020 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

“Patients with RA and ESRD are at substantially increased risk of osteoporotic fragility fractures compared to the overall population of ESRD patients. So fracture prevention prior to initiation of dialysis should be a focus of care in patients with RA,” said Dr. Peterkin-McCalman, a rheumatology fellow at the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta.

She presented a retrospective cohort study of 10,706 adults who initiated hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis for ESRD during 2005-2008, including 1,040 who also had RA. All subjects were drawn from the United States Renal Data System. The impetus for the study, Dr. Peterkin-McCalman explained in an interview, was that although prior studies have established that RA and ESRD are independent risk factors for osteoporotic fractures, the interplay between the two was previously unknown.

The risk of incident osteoporotic fractures during the first 3 years after going on renal dialysis was 14.7% in patients with ESRD only, vaulting to 25.6% in those with comorbid RA. Individuals with both RA and ESRD were at an adjusted 1.83-fold increased overall risk for new fragility fractures and at 1.85-fold increased risk for hip fracture, compared to those without RA.

Far and away the strongest risk factor for incident osteoporotic fractures in the group with RA plus ESRD was a history of a fracture sustained within 5 years prior to initiation of dialysis, with an associated 11.5-fold increased fracture risk overall and an 8.2-fold increased risk of hip fracture.

“The reason that’s important is we don’t really have any medications to reduce fracture risk once you get to ESRD. Of course, we have bisphosphonates and Prolia (denosumab) and things like that, but that’s in patients with milder CKD [chronic kidney disease] or no renal disease at all. So the goal is to identify the patients early who are at higher risk so that we can protect those bones before they get to ESRD and we have nothing left to treat them with,” she said.

In addition to a history of prevalent fracture prior to starting ESRD, the other risk factors for fracture in patients with ESRD and comorbid RA Dr. Peterkin-McCalman identified in her study included age greater than 50 years at the start of dialysis and female gender, which was associated with a twofold greater fracture risk than in men. Black patients with ESRD and RA were 64% less likely than whites to experience an incident fragility fracture. And the fracture risk was higher in patients on hemodialysis than with peritoneal dialysis.

Her study was supported by the Medical College of Georgia and a research grant from Dialysis Clinic Inc.

SOURCE: Peterkin-McCalman R et al. RWCS 2020.

MAUI, HAWAII – Comorbid rheumatoid arthritis is a force multiplier for fragility fracture risk in patients with end-stage renal disease, Renée Peterkin-McCalman, MD, reported at the 2020 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

“Patients with RA and ESRD are at substantially increased risk of osteoporotic fragility fractures compared to the overall population of ESRD patients. So fracture prevention prior to initiation of dialysis should be a focus of care in patients with RA,” said Dr. Peterkin-McCalman, a rheumatology fellow at the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta.

She presented a retrospective cohort study of 10,706 adults who initiated hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis for ESRD during 2005-2008, including 1,040 who also had RA. All subjects were drawn from the United States Renal Data System. The impetus for the study, Dr. Peterkin-McCalman explained in an interview, was that although prior studies have established that RA and ESRD are independent risk factors for osteoporotic fractures, the interplay between the two was previously unknown.

The risk of incident osteoporotic fractures during the first 3 years after going on renal dialysis was 14.7% in patients with ESRD only, vaulting to 25.6% in those with comorbid RA. Individuals with both RA and ESRD were at an adjusted 1.83-fold increased overall risk for new fragility fractures and at 1.85-fold increased risk for hip fracture, compared to those without RA.

Far and away the strongest risk factor for incident osteoporotic fractures in the group with RA plus ESRD was a history of a fracture sustained within 5 years prior to initiation of dialysis, with an associated 11.5-fold increased fracture risk overall and an 8.2-fold increased risk of hip fracture.

“The reason that’s important is we don’t really have any medications to reduce fracture risk once you get to ESRD. Of course, we have bisphosphonates and Prolia (denosumab) and things like that, but that’s in patients with milder CKD [chronic kidney disease] or no renal disease at all. So the goal is to identify the patients early who are at higher risk so that we can protect those bones before they get to ESRD and we have nothing left to treat them with,” she said.

In addition to a history of prevalent fracture prior to starting ESRD, the other risk factors for fracture in patients with ESRD and comorbid RA Dr. Peterkin-McCalman identified in her study included age greater than 50 years at the start of dialysis and female gender, which was associated with a twofold greater fracture risk than in men. Black patients with ESRD and RA were 64% less likely than whites to experience an incident fragility fracture. And the fracture risk was higher in patients on hemodialysis than with peritoneal dialysis.

Her study was supported by the Medical College of Georgia and a research grant from Dialysis Clinic Inc.

SOURCE: Peterkin-McCalman R et al. RWCS 2020.

REPORTING FROM RWCS 2020

Endocrine Society advises on use of romosozumab for osteoporosis

Latest guidelines on the treatment of osteoporosis have been released that include new recommendations for the use of romosozumab (Evenity) in postmenopausal women with severe osteoporosis, but they contain caveats as to which women should – and should not – receive the drug.

The updated clinical practice guideline from the Endocrine Society is in response to the approval of romosozumab by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in April 2019, and more recently, by the European Medicines Agency.

It was published online February 18 in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

In the new guidelines, committee members recommend the use of romosozumab for postmenopausal women with osteoporosis at very high risk of fracture. Candidates would include women with severe osteoporosis (T-score of less than –2.5 and a prior fracture) or women with a history of multiple vertebral fractures.

Women should be treated with romosozumab for up to 1 year, followed by an antiresorptive agent to maintain bone mineral density gains and further reduce fracture risk.

“The recommended dosage is 210 mg monthly by subcutaneous injection for 12 months,” the authors wrote.

However, and very importantly, romosozumab should not be considered for women at high risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) or cerebrovascular disease. A high risk of CVD includes women who have had a previous myocardial infarction (MI) or stroke.

Experts questioned by Medscape Medical News stressed that romosozumab should not be a first-line, or even generally a second-line, option for osteoporosis, but it can be a considered for select patients with severe osteoporosis, taking into account CV risk.

Boxed warning

In the Active-Controlled Fracture Study in Postmenopausal Women With Osteoporosis at High Risk (ARCH), there were more major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in the first year of the trial with romosozumab, and patients had a 31% higher risk of MACE with romosozumab, compared with the bisphosphonate alendronate.

As a result, the drug was initially rejected by a number of regulatory agencies.

In the United States and Canada, it was eventually approved with a boxed warning, which cautions against the use of the drug in patients at risk for myocardial infarction, stroke, and CVD-related death.

“Romosozumab offers promising results for postmenopausal women with severe osteoporosis or who have a history of fractures,” Clifford Rosen, MD, Maine Medical Center Research Institute in Scarborough and chair of the writing committee, said in an Endocrine Society statement. “It does, however, come with a risk of heart disease, so clinicians need to be careful when selecting patients for this therapy.”

Exact risk unknown

Asked by Medscape Medical News to comment, Kenneth Saag, MD, professor of medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham and principle investigator of the ARCH study, said that physicians needed more data from real-world studies to resolve the issue around whether romosozumab heightens the risk of CV events in women with osteoporosis or whether that particular finding from ARCH was an artifact.

“Women who have had a recent cardiovascular event should not receive the drug,” he said, agreeing with the new guidelines.

But it remains unclear, for example, whether women who are at slightly higher risk of having a CV event by virtue of their age alone, are also at risk, he noted.

In the meantime, results from the ARCH study clearly showed that not only was romosozumab more effective than alendronate, “but it is more effective than other bone-building drugs as well,” Dr. Saag observed, and it leads to a significantly greater reduction in vertebral, nonvertebral, and hip fractures, compared with the alendronate, the current standard of care in osteoporosis.

“In patients who have very severe osteoporosis and who have had a recent fracture or who are at risk for imminent future fracture, physicians need to balance the benefit versus the risk in favor of using romosozumab,” Dr. Saag suggested.

“And while I would say most women prefer not to inject themselves, the women I have put on this medicine have all had recent fractures and they are very aware of the pain and the disability of having a broken bone, so it is something they are willing to do,” he added.

Not for all women

Giving his opinion, Bart Clarke, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, underscored the fact that the Fracture Study in Postmenopausal Women With Osteoporosis (FRAME), again conducted in postmenopausal women, showed no increase in CV events in patients treated with romosozumab compared with placebo.

“So there are questions about what this means, because if these events really were a drug effect, then that effect would be even more evident compared with placebo and they did not see any signal of CV events [in FRAME],” said Dr. Clarke, past president of the American Society of Bone and Mineral Research.

Like everything else in medicine, “there is always some risk,” Dr. Clarke observed.

However, what physicians should do is talk to women, ensure they have not had either an MI or stroke in the last year, and if patients have severe osteoporosis and a high risk of fracture, “then we can say, here’s another option,” he suggested.

“Then, if a woman develops chest pain or shortness of breath while on the drug, [she needs] to let us know ,and then we’ll stop the drug and reassess the situation,” he added.

Dr. Clarke also pointed out that if the FDA had received further reports of CV events linked to romosozumab, physicians would know about it by now, but to his knowledge, there has been no change to the drug’s current warning label.

Furthermore, neither he nor any of his colleagues who treat metabolic bone disease at the Mayo Clinic has seen a single CV event in patients prescribed the agent.

“This is not a drug we would use as first-line for most patients, and we don’t even use it as second-line for most patients, but in people who have not responded to other drugs or who have had terrible things happen to them already, hip fracture especially, then we are saying, you can consider this, he concluded.

The guidelines were supported by the Endocrine Society. Dr. Rosen and Dr. Clarke reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Saag reported receiving grants and personal fees from Amgen, personal fees from Radius, and is a consultant for Amgen, Radius, Roche, and Daiichi Sankyo.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Latest guidelines on the treatment of osteoporosis have been released that include new recommendations for the use of romosozumab (Evenity) in postmenopausal women with severe osteoporosis, but they contain caveats as to which women should – and should not – receive the drug.

The updated clinical practice guideline from the Endocrine Society is in response to the approval of romosozumab by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in April 2019, and more recently, by the European Medicines Agency.

It was published online February 18 in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

In the new guidelines, committee members recommend the use of romosozumab for postmenopausal women with osteoporosis at very high risk of fracture. Candidates would include women with severe osteoporosis (T-score of less than –2.5 and a prior fracture) or women with a history of multiple vertebral fractures.

Women should be treated with romosozumab for up to 1 year, followed by an antiresorptive agent to maintain bone mineral density gains and further reduce fracture risk.

“The recommended dosage is 210 mg monthly by subcutaneous injection for 12 months,” the authors wrote.

However, and very importantly, romosozumab should not be considered for women at high risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) or cerebrovascular disease. A high risk of CVD includes women who have had a previous myocardial infarction (MI) or stroke.

Experts questioned by Medscape Medical News stressed that romosozumab should not be a first-line, or even generally a second-line, option for osteoporosis, but it can be a considered for select patients with severe osteoporosis, taking into account CV risk.

Boxed warning

In the Active-Controlled Fracture Study in Postmenopausal Women With Osteoporosis at High Risk (ARCH), there were more major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in the first year of the trial with romosozumab, and patients had a 31% higher risk of MACE with romosozumab, compared with the bisphosphonate alendronate.

As a result, the drug was initially rejected by a number of regulatory agencies.

In the United States and Canada, it was eventually approved with a boxed warning, which cautions against the use of the drug in patients at risk for myocardial infarction, stroke, and CVD-related death.

“Romosozumab offers promising results for postmenopausal women with severe osteoporosis or who have a history of fractures,” Clifford Rosen, MD, Maine Medical Center Research Institute in Scarborough and chair of the writing committee, said in an Endocrine Society statement. “It does, however, come with a risk of heart disease, so clinicians need to be careful when selecting patients for this therapy.”

Exact risk unknown

Asked by Medscape Medical News to comment, Kenneth Saag, MD, professor of medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham and principle investigator of the ARCH study, said that physicians needed more data from real-world studies to resolve the issue around whether romosozumab heightens the risk of CV events in women with osteoporosis or whether that particular finding from ARCH was an artifact.

“Women who have had a recent cardiovascular event should not receive the drug,” he said, agreeing with the new guidelines.

But it remains unclear, for example, whether women who are at slightly higher risk of having a CV event by virtue of their age alone, are also at risk, he noted.

In the meantime, results from the ARCH study clearly showed that not only was romosozumab more effective than alendronate, “but it is more effective than other bone-building drugs as well,” Dr. Saag observed, and it leads to a significantly greater reduction in vertebral, nonvertebral, and hip fractures, compared with the alendronate, the current standard of care in osteoporosis.

“In patients who have very severe osteoporosis and who have had a recent fracture or who are at risk for imminent future fracture, physicians need to balance the benefit versus the risk in favor of using romosozumab,” Dr. Saag suggested.

“And while I would say most women prefer not to inject themselves, the women I have put on this medicine have all had recent fractures and they are very aware of the pain and the disability of having a broken bone, so it is something they are willing to do,” he added.

Not for all women

Giving his opinion, Bart Clarke, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, underscored the fact that the Fracture Study in Postmenopausal Women With Osteoporosis (FRAME), again conducted in postmenopausal women, showed no increase in CV events in patients treated with romosozumab compared with placebo.

“So there are questions about what this means, because if these events really were a drug effect, then that effect would be even more evident compared with placebo and they did not see any signal of CV events [in FRAME],” said Dr. Clarke, past president of the American Society of Bone and Mineral Research.

Like everything else in medicine, “there is always some risk,” Dr. Clarke observed.

However, what physicians should do is talk to women, ensure they have not had either an MI or stroke in the last year, and if patients have severe osteoporosis and a high risk of fracture, “then we can say, here’s another option,” he suggested.

“Then, if a woman develops chest pain or shortness of breath while on the drug, [she needs] to let us know ,and then we’ll stop the drug and reassess the situation,” he added.

Dr. Clarke also pointed out that if the FDA had received further reports of CV events linked to romosozumab, physicians would know about it by now, but to his knowledge, there has been no change to the drug’s current warning label.

Furthermore, neither he nor any of his colleagues who treat metabolic bone disease at the Mayo Clinic has seen a single CV event in patients prescribed the agent.

“This is not a drug we would use as first-line for most patients, and we don’t even use it as second-line for most patients, but in people who have not responded to other drugs or who have had terrible things happen to them already, hip fracture especially, then we are saying, you can consider this, he concluded.

The guidelines were supported by the Endocrine Society. Dr. Rosen and Dr. Clarke reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Saag reported receiving grants and personal fees from Amgen, personal fees from Radius, and is a consultant for Amgen, Radius, Roche, and Daiichi Sankyo.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Latest guidelines on the treatment of osteoporosis have been released that include new recommendations for the use of romosozumab (Evenity) in postmenopausal women with severe osteoporosis, but they contain caveats as to which women should – and should not – receive the drug.

The updated clinical practice guideline from the Endocrine Society is in response to the approval of romosozumab by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in April 2019, and more recently, by the European Medicines Agency.

It was published online February 18 in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

In the new guidelines, committee members recommend the use of romosozumab for postmenopausal women with osteoporosis at very high risk of fracture. Candidates would include women with severe osteoporosis (T-score of less than –2.5 and a prior fracture) or women with a history of multiple vertebral fractures.

Women should be treated with romosozumab for up to 1 year, followed by an antiresorptive agent to maintain bone mineral density gains and further reduce fracture risk.

“The recommended dosage is 210 mg monthly by subcutaneous injection for 12 months,” the authors wrote.

However, and very importantly, romosozumab should not be considered for women at high risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) or cerebrovascular disease. A high risk of CVD includes women who have had a previous myocardial infarction (MI) or stroke.

Experts questioned by Medscape Medical News stressed that romosozumab should not be a first-line, or even generally a second-line, option for osteoporosis, but it can be a considered for select patients with severe osteoporosis, taking into account CV risk.

Boxed warning

In the Active-Controlled Fracture Study in Postmenopausal Women With Osteoporosis at High Risk (ARCH), there were more major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in the first year of the trial with romosozumab, and patients had a 31% higher risk of MACE with romosozumab, compared with the bisphosphonate alendronate.

As a result, the drug was initially rejected by a number of regulatory agencies.

In the United States and Canada, it was eventually approved with a boxed warning, which cautions against the use of the drug in patients at risk for myocardial infarction, stroke, and CVD-related death.