User login

For MD-IQ on Family Practice News, but a regular topic for Rheumatology News

Current use of COX-2 inhibitors linked to increased mortality after ischemic stroke

Current use of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors was associated with an increase in 30-day mortality after ischemic stroke in a population-based cohort study published Nov. 5 in Neurology.

Since the association between COX-2 inhibitors and ischemic stroke mortality was associated only with current use and not former use, the researchers, led by Dr. Morten Schmidt of Aarhus (Denmark) University Hospital, believe that alternative treatment options – such as nonselective NSAIDs, which did not have an impact on overall mortality after ischemic stroke – may be more suitable for treating potential ischemic stroke patients, such as those with atrial fibrillation and a high CHA2DS2-VASc score.

If the association is truly causal, it constitutes a strong argument for increasing the efforts to ensure that patients with a high predicted risk of arterial thromboembolism are not prescribed COX-2 inhibitors when alternative treatment options are available,” Dr. Schmidt and his associates wrote.

In order to determine whether COX-2 inhibitors influenced 30-day mortality at the time of hospitalization for stroke, the researchers examined records of 100,243 people hospitalized for a first-time stroke in Denmark during 2004-2012 and deaths within 1 month after the stroke (Neurology 2014 Nov. 5 [doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000001024]).

The hazard ratio for ischemic stroke was 1.19 (95% confidence interval, 1.02-1.38) for current users of COX-2 inhibitors, while current users of nonselective NSAIDs had an HR of 1.00 (95% CI, 0.87-1.15), compared with nonusers.

The COX-2 inhibitors in the study included diclofenac, etodolac, nabumeton, and meloxicam, as well as coxibs including celecoxib and rofecoxib. The nonselective NSAIDs in the study were ibuprofen, naproxen, ketoprofen, dexibuprofen, piroxicam, tolfenamic acid, and indomethacin.

Though the researchers acknowledged more studies are needed to truly examine the effects of COX-2 inhibitors on stroke mortality, they hypothesized that the increased mortality rate may be caused by COX-2 inhibition interfering with the pathophysiologic response to a stroke, or unwanted effects from the thromboembolic properties of COX-2 inhibitors.

“Our study adds to the increasing body of evidence concerning the vascular risk and prognostic impact associated with use of COX-2 inhibitors,” Dr. Schmidt and his associates wrote.

The study was funded by several Danish research foundations and the Program for Clinical Research Infrastructure, which was established by the Lundbeck Foundation and the Novo Nordisk Foundation. The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

Current use of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors was associated with an increase in 30-day mortality after ischemic stroke in a population-based cohort study published Nov. 5 in Neurology.

Since the association between COX-2 inhibitors and ischemic stroke mortality was associated only with current use and not former use, the researchers, led by Dr. Morten Schmidt of Aarhus (Denmark) University Hospital, believe that alternative treatment options – such as nonselective NSAIDs, which did not have an impact on overall mortality after ischemic stroke – may be more suitable for treating potential ischemic stroke patients, such as those with atrial fibrillation and a high CHA2DS2-VASc score.

If the association is truly causal, it constitutes a strong argument for increasing the efforts to ensure that patients with a high predicted risk of arterial thromboembolism are not prescribed COX-2 inhibitors when alternative treatment options are available,” Dr. Schmidt and his associates wrote.

In order to determine whether COX-2 inhibitors influenced 30-day mortality at the time of hospitalization for stroke, the researchers examined records of 100,243 people hospitalized for a first-time stroke in Denmark during 2004-2012 and deaths within 1 month after the stroke (Neurology 2014 Nov. 5 [doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000001024]).

The hazard ratio for ischemic stroke was 1.19 (95% confidence interval, 1.02-1.38) for current users of COX-2 inhibitors, while current users of nonselective NSAIDs had an HR of 1.00 (95% CI, 0.87-1.15), compared with nonusers.

The COX-2 inhibitors in the study included diclofenac, etodolac, nabumeton, and meloxicam, as well as coxibs including celecoxib and rofecoxib. The nonselective NSAIDs in the study were ibuprofen, naproxen, ketoprofen, dexibuprofen, piroxicam, tolfenamic acid, and indomethacin.

Though the researchers acknowledged more studies are needed to truly examine the effects of COX-2 inhibitors on stroke mortality, they hypothesized that the increased mortality rate may be caused by COX-2 inhibition interfering with the pathophysiologic response to a stroke, or unwanted effects from the thromboembolic properties of COX-2 inhibitors.

“Our study adds to the increasing body of evidence concerning the vascular risk and prognostic impact associated with use of COX-2 inhibitors,” Dr. Schmidt and his associates wrote.

The study was funded by several Danish research foundations and the Program for Clinical Research Infrastructure, which was established by the Lundbeck Foundation and the Novo Nordisk Foundation. The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

Current use of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors was associated with an increase in 30-day mortality after ischemic stroke in a population-based cohort study published Nov. 5 in Neurology.

Since the association between COX-2 inhibitors and ischemic stroke mortality was associated only with current use and not former use, the researchers, led by Dr. Morten Schmidt of Aarhus (Denmark) University Hospital, believe that alternative treatment options – such as nonselective NSAIDs, which did not have an impact on overall mortality after ischemic stroke – may be more suitable for treating potential ischemic stroke patients, such as those with atrial fibrillation and a high CHA2DS2-VASc score.

If the association is truly causal, it constitutes a strong argument for increasing the efforts to ensure that patients with a high predicted risk of arterial thromboembolism are not prescribed COX-2 inhibitors when alternative treatment options are available,” Dr. Schmidt and his associates wrote.

In order to determine whether COX-2 inhibitors influenced 30-day mortality at the time of hospitalization for stroke, the researchers examined records of 100,243 people hospitalized for a first-time stroke in Denmark during 2004-2012 and deaths within 1 month after the stroke (Neurology 2014 Nov. 5 [doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000001024]).

The hazard ratio for ischemic stroke was 1.19 (95% confidence interval, 1.02-1.38) for current users of COX-2 inhibitors, while current users of nonselective NSAIDs had an HR of 1.00 (95% CI, 0.87-1.15), compared with nonusers.

The COX-2 inhibitors in the study included diclofenac, etodolac, nabumeton, and meloxicam, as well as coxibs including celecoxib and rofecoxib. The nonselective NSAIDs in the study were ibuprofen, naproxen, ketoprofen, dexibuprofen, piroxicam, tolfenamic acid, and indomethacin.

Though the researchers acknowledged more studies are needed to truly examine the effects of COX-2 inhibitors on stroke mortality, they hypothesized that the increased mortality rate may be caused by COX-2 inhibition interfering with the pathophysiologic response to a stroke, or unwanted effects from the thromboembolic properties of COX-2 inhibitors.

“Our study adds to the increasing body of evidence concerning the vascular risk and prognostic impact associated with use of COX-2 inhibitors,” Dr. Schmidt and his associates wrote.

The study was funded by several Danish research foundations and the Program for Clinical Research Infrastructure, which was established by the Lundbeck Foundation and the Novo Nordisk Foundation. The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

FROM NEUROLOGY

Key clinical point:Consideration should be given to using treatment options other than COX-2 inhibitors in patients with a high future risk of arterial thromboembolism.

Major finding: Preadmission use of COX-2 inhibitors was associated with increased 30-day mortality after ischemic stroke 1.19 (95% CI, 1.02-1.38), compared with nonusers.

Data source:Population-based cohort study of 100,043 patients from Denmark with first-time stroke.

Disclosures:The study was funded by several Danish research foundations and the Program for Clinical Research Infrastructure, which was established by the Lundbeck Foundation and the Novo Nordisk Foundation. The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

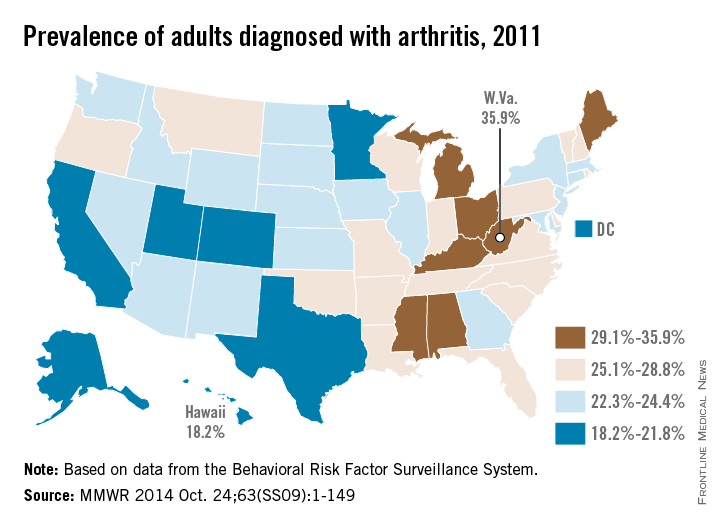

Eastern United States has the highest arthritis rates

The prevalence of arthritis tended to be higher in eastern U.S. states than in western states in 2011, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

All seven states with an arthritis rate below 22% were located west of the Mississippi River, with Hawaii having the lowest rate at 18.2%, followed by Utah (19.8%) and Texas (20.2%). The District of Columbia, which is in the East, had an arthritis rate of 20.9%.

The eight states with an arthritis rate greater than 29% were all east of the Mississippi, with West Virginia having the highest prevalence (35.9%), followed by Kentucky (31.9%) and Michigan (31.0%), according to the report (MMWR 2014;63[SS09]:1-149).

Of 198 reported metropolitan and micropolitan statistical areas (MMSAs), 29 had an arthritis prevalence lower than 20%. Lawrence, Kan., had the lowest rate at 13.5%. Of the 29, only Atlanta; Knoxville, Tenn.; and Raleigh, N.C., are located entirely east of the Mississippi River. Kingsport-Bristol, in Tennessee and Virginia, had the highest arthritis rate at 37%. Of the 16 MMSAs with an arthritis rate greater than 30%, North Platte, Neb., was the only one west of the Mississippi, according to data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

The prevalence of arthritis tended to be higher in eastern U.S. states than in western states in 2011, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

All seven states with an arthritis rate below 22% were located west of the Mississippi River, with Hawaii having the lowest rate at 18.2%, followed by Utah (19.8%) and Texas (20.2%). The District of Columbia, which is in the East, had an arthritis rate of 20.9%.

The eight states with an arthritis rate greater than 29% were all east of the Mississippi, with West Virginia having the highest prevalence (35.9%), followed by Kentucky (31.9%) and Michigan (31.0%), according to the report (MMWR 2014;63[SS09]:1-149).

Of 198 reported metropolitan and micropolitan statistical areas (MMSAs), 29 had an arthritis prevalence lower than 20%. Lawrence, Kan., had the lowest rate at 13.5%. Of the 29, only Atlanta; Knoxville, Tenn.; and Raleigh, N.C., are located entirely east of the Mississippi River. Kingsport-Bristol, in Tennessee and Virginia, had the highest arthritis rate at 37%. Of the 16 MMSAs with an arthritis rate greater than 30%, North Platte, Neb., was the only one west of the Mississippi, according to data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

The prevalence of arthritis tended to be higher in eastern U.S. states than in western states in 2011, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

All seven states with an arthritis rate below 22% were located west of the Mississippi River, with Hawaii having the lowest rate at 18.2%, followed by Utah (19.8%) and Texas (20.2%). The District of Columbia, which is in the East, had an arthritis rate of 20.9%.

The eight states with an arthritis rate greater than 29% were all east of the Mississippi, with West Virginia having the highest prevalence (35.9%), followed by Kentucky (31.9%) and Michigan (31.0%), according to the report (MMWR 2014;63[SS09]:1-149).

Of 198 reported metropolitan and micropolitan statistical areas (MMSAs), 29 had an arthritis prevalence lower than 20%. Lawrence, Kan., had the lowest rate at 13.5%. Of the 29, only Atlanta; Knoxville, Tenn.; and Raleigh, N.C., are located entirely east of the Mississippi River. Kingsport-Bristol, in Tennessee and Virginia, had the highest arthritis rate at 37%. Of the 16 MMSAs with an arthritis rate greater than 30%, North Platte, Neb., was the only one west of the Mississippi, according to data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

FROM MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY WEEKLY REPORT

‘Prehabilitation’ cut postoperative care costs for total hip and knee replacements

Physical therapy before joint replacement surgery cut the predicted use of postoperative care by 29%, saving an estimated $1,215 in health care costs per patient, according to a Medicare claims analysis.

“These data are clinically relevant and can be used in the development of cost-effective and value-based total joint replacement programs,” said Dr. Richard Snow at OhioHealth in Columbus and his associates. The study is the first to evaluate the real-world link between preoperative physical therapy and use of postoperative care, the researchers said.

Numbers of total hip and knee replacements are projected to increase by 1.7 and 6.7 times, respectively, in the United States between 2005 and 2030, Dr. Snow and his coauthors noted. And while average length of hospital stay after these surgeries has dropped by more than 50%, there has been a substantial rise in per-patient costs of skilled nursing facilities, home health agencies, and inpatient rehabilitation, they said (J. Bone Joint Surg. 2014 Oct. 1 [doi:10.2106/JBJS.M.01285]).

The researchers analyzed 4,733 hip and knee replacement cases within a 39-county cluster of Medicare referral hospitals, and looked at the association between preoperative physical therapy (or “prehabilitation”) and use of postoperative care services in the 90 days after hospital discharge. Because of the skewed distribution of payments, the investigators looked only at cases that fell below the 95th percentile (or $41,113) for cost of care, they said.

In all, 79.7% of patients who did not undergo prehabilitation used acute care services after surgery, compared with 54.2% of patients who did (P < .0001). After controlling for comorbidities and demographic variables, prehabilitation was linked to an absolute reduction of 29% from the predicted to the observed rate of post-acute care use, saving an estimated average of $1,215 per patient, they said. Reductions in use of skilled nursing facilities, home health care services, and inpatient rehabilitation were the main drivers of the cost reduction, the researchers reported.

The findings support prior work indicating that prehabilitation can improve the value of care for patients undergoing total joint replacements, said Dr. Snow and his associates. “As the volume of arthroplasties expands within the framework of increasing health care costs, providers are under mounting pressure to identify the most cost-effective method of delivering high-quality, value-based health care,” they said.

Future studies should look at optimal ways to balance preoperative and postoperative care in specific populations of patients, the investigators said.

The research was partially supported by OhioHealth Research Institute. One or more authors reported financial relationships with biomedical entities deemed to possibly influence the research.

Physical therapy before joint replacement surgery cut the predicted use of postoperative care by 29%, saving an estimated $1,215 in health care costs per patient, according to a Medicare claims analysis.

“These data are clinically relevant and can be used in the development of cost-effective and value-based total joint replacement programs,” said Dr. Richard Snow at OhioHealth in Columbus and his associates. The study is the first to evaluate the real-world link between preoperative physical therapy and use of postoperative care, the researchers said.

Numbers of total hip and knee replacements are projected to increase by 1.7 and 6.7 times, respectively, in the United States between 2005 and 2030, Dr. Snow and his coauthors noted. And while average length of hospital stay after these surgeries has dropped by more than 50%, there has been a substantial rise in per-patient costs of skilled nursing facilities, home health agencies, and inpatient rehabilitation, they said (J. Bone Joint Surg. 2014 Oct. 1 [doi:10.2106/JBJS.M.01285]).

The researchers analyzed 4,733 hip and knee replacement cases within a 39-county cluster of Medicare referral hospitals, and looked at the association between preoperative physical therapy (or “prehabilitation”) and use of postoperative care services in the 90 days after hospital discharge. Because of the skewed distribution of payments, the investigators looked only at cases that fell below the 95th percentile (or $41,113) for cost of care, they said.

In all, 79.7% of patients who did not undergo prehabilitation used acute care services after surgery, compared with 54.2% of patients who did (P < .0001). After controlling for comorbidities and demographic variables, prehabilitation was linked to an absolute reduction of 29% from the predicted to the observed rate of post-acute care use, saving an estimated average of $1,215 per patient, they said. Reductions in use of skilled nursing facilities, home health care services, and inpatient rehabilitation were the main drivers of the cost reduction, the researchers reported.

The findings support prior work indicating that prehabilitation can improve the value of care for patients undergoing total joint replacements, said Dr. Snow and his associates. “As the volume of arthroplasties expands within the framework of increasing health care costs, providers are under mounting pressure to identify the most cost-effective method of delivering high-quality, value-based health care,” they said.

Future studies should look at optimal ways to balance preoperative and postoperative care in specific populations of patients, the investigators said.

The research was partially supported by OhioHealth Research Institute. One or more authors reported financial relationships with biomedical entities deemed to possibly influence the research.

Physical therapy before joint replacement surgery cut the predicted use of postoperative care by 29%, saving an estimated $1,215 in health care costs per patient, according to a Medicare claims analysis.

“These data are clinically relevant and can be used in the development of cost-effective and value-based total joint replacement programs,” said Dr. Richard Snow at OhioHealth in Columbus and his associates. The study is the first to evaluate the real-world link between preoperative physical therapy and use of postoperative care, the researchers said.

Numbers of total hip and knee replacements are projected to increase by 1.7 and 6.7 times, respectively, in the United States between 2005 and 2030, Dr. Snow and his coauthors noted. And while average length of hospital stay after these surgeries has dropped by more than 50%, there has been a substantial rise in per-patient costs of skilled nursing facilities, home health agencies, and inpatient rehabilitation, they said (J. Bone Joint Surg. 2014 Oct. 1 [doi:10.2106/JBJS.M.01285]).

The researchers analyzed 4,733 hip and knee replacement cases within a 39-county cluster of Medicare referral hospitals, and looked at the association between preoperative physical therapy (or “prehabilitation”) and use of postoperative care services in the 90 days after hospital discharge. Because of the skewed distribution of payments, the investigators looked only at cases that fell below the 95th percentile (or $41,113) for cost of care, they said.

In all, 79.7% of patients who did not undergo prehabilitation used acute care services after surgery, compared with 54.2% of patients who did (P < .0001). After controlling for comorbidities and demographic variables, prehabilitation was linked to an absolute reduction of 29% from the predicted to the observed rate of post-acute care use, saving an estimated average of $1,215 per patient, they said. Reductions in use of skilled nursing facilities, home health care services, and inpatient rehabilitation were the main drivers of the cost reduction, the researchers reported.

The findings support prior work indicating that prehabilitation can improve the value of care for patients undergoing total joint replacements, said Dr. Snow and his associates. “As the volume of arthroplasties expands within the framework of increasing health care costs, providers are under mounting pressure to identify the most cost-effective method of delivering high-quality, value-based health care,” they said.

Future studies should look at optimal ways to balance preoperative and postoperative care in specific populations of patients, the investigators said.

The research was partially supported by OhioHealth Research Institute. One or more authors reported financial relationships with biomedical entities deemed to possibly influence the research.

FROM JOURNAL OF BONE & JOINT SURGERY

Key clinical point: Physical therapy before total knee or total hip replacement surgeries can improve the value of care.

Major finding: In all, 79.7% of patients who did not undergo presurgical physical therapy used acute care services after surgery, compared with 54.2% of patients who underwent “prehabilitation” (P < .0001).

Data source: Medicare claims analysis of 4,733 total hip or knee replacement surgeries.

Disclosures: The research was partially supported by OhioHealth Research Institute. One or more authors reported financial relationships with biomedical entities deemed to possibly influence the research.

Acupuncture failed to reduce chronic knee pain

Neither traditional nor laser acupuncture is more effective than sham acupuncture at lessening pain or improving function in patients older than 50 years who have moderate to severe chronic knee pain, according to a report published online September 30 in JAMA.

In a randomized, partially blinded clinical trial, 282 participants aged 50 and older were randomly assigned to receive traditional needle acupuncture (70 patients), laser acupuncture (71 patients), sham laser acupuncture (70 patients), or no acupuncture (71 control subjects) in 20-minute sessions delivered once or twice weekly for 12 weeks.

At baseline, all the participants reported having moderate to severe knee pain and morning stiffness lasting less than 30 minutes on most days. They completed detailed questionnaires at baseline, 12 weeks, and 1 year measuring pain on walking or standing, physical function, activity restriction, health-related quality of life, and global change in knee pain and function over time, said Rana S. Hinman, Ph.D., of the Centre for Health, Exercise, and Sports Medicine, University of Melbourne, and her associates.

At 12 weeks and at 1 year, there were no significant differences in any of these outcomes between active acupuncture and sham acupuncture. Both needle and laser acupuncture improved pain at 12 weeks when compared with the control group, but this improvement was “of a clinically unimportant magnitude” and did not persist, the investigators said (JAMA 2014 September 30 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.12660]).

Clinical guidelines vary with regard to acupuncture for knee osteoarthritis. The American College of Rheumatology “conditionally recommends” the treatment in patients who are candidates for arthroplasty, the Osteoarthritis Research Society International is “uncertain” about its efficacy, the European League Against Rheumatism failed to reach consensus on the treatment and doesn’t address it in final recommendations, the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons “cannot recommend” it, and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence’s guidelines recommend against it. “The findings from our trial support these latter recommendations,” Dr. Hinman and her associates said.

Neither traditional nor laser acupuncture is more effective than sham acupuncture at lessening pain or improving function in patients older than 50 years who have moderate to severe chronic knee pain, according to a report published online September 30 in JAMA.

In a randomized, partially blinded clinical trial, 282 participants aged 50 and older were randomly assigned to receive traditional needle acupuncture (70 patients), laser acupuncture (71 patients), sham laser acupuncture (70 patients), or no acupuncture (71 control subjects) in 20-minute sessions delivered once or twice weekly for 12 weeks.

At baseline, all the participants reported having moderate to severe knee pain and morning stiffness lasting less than 30 minutes on most days. They completed detailed questionnaires at baseline, 12 weeks, and 1 year measuring pain on walking or standing, physical function, activity restriction, health-related quality of life, and global change in knee pain and function over time, said Rana S. Hinman, Ph.D., of the Centre for Health, Exercise, and Sports Medicine, University of Melbourne, and her associates.

At 12 weeks and at 1 year, there were no significant differences in any of these outcomes between active acupuncture and sham acupuncture. Both needle and laser acupuncture improved pain at 12 weeks when compared with the control group, but this improvement was “of a clinically unimportant magnitude” and did not persist, the investigators said (JAMA 2014 September 30 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.12660]).

Clinical guidelines vary with regard to acupuncture for knee osteoarthritis. The American College of Rheumatology “conditionally recommends” the treatment in patients who are candidates for arthroplasty, the Osteoarthritis Research Society International is “uncertain” about its efficacy, the European League Against Rheumatism failed to reach consensus on the treatment and doesn’t address it in final recommendations, the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons “cannot recommend” it, and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence’s guidelines recommend against it. “The findings from our trial support these latter recommendations,” Dr. Hinman and her associates said.

Neither traditional nor laser acupuncture is more effective than sham acupuncture at lessening pain or improving function in patients older than 50 years who have moderate to severe chronic knee pain, according to a report published online September 30 in JAMA.

In a randomized, partially blinded clinical trial, 282 participants aged 50 and older were randomly assigned to receive traditional needle acupuncture (70 patients), laser acupuncture (71 patients), sham laser acupuncture (70 patients), or no acupuncture (71 control subjects) in 20-minute sessions delivered once or twice weekly for 12 weeks.

At baseline, all the participants reported having moderate to severe knee pain and morning stiffness lasting less than 30 minutes on most days. They completed detailed questionnaires at baseline, 12 weeks, and 1 year measuring pain on walking or standing, physical function, activity restriction, health-related quality of life, and global change in knee pain and function over time, said Rana S. Hinman, Ph.D., of the Centre for Health, Exercise, and Sports Medicine, University of Melbourne, and her associates.

At 12 weeks and at 1 year, there were no significant differences in any of these outcomes between active acupuncture and sham acupuncture. Both needle and laser acupuncture improved pain at 12 weeks when compared with the control group, but this improvement was “of a clinically unimportant magnitude” and did not persist, the investigators said (JAMA 2014 September 30 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.12660]).

Clinical guidelines vary with regard to acupuncture for knee osteoarthritis. The American College of Rheumatology “conditionally recommends” the treatment in patients who are candidates for arthroplasty, the Osteoarthritis Research Society International is “uncertain” about its efficacy, the European League Against Rheumatism failed to reach consensus on the treatment and doesn’t address it in final recommendations, the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons “cannot recommend” it, and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence’s guidelines recommend against it. “The findings from our trial support these latter recommendations,” Dr. Hinman and her associates said.

Key clinical point: Acupuncture did not decrease chronic knee pain in patients over 50.

Major finding: No pain or function outcomes were significantly different between active and sham acupuncture at 12 weeks or 1 year.

Data source: A randomized, partially blinded Zelen-design clinical trial involving 282 older patients with moderate to severe knee pain who were treated for 12 weeks and followed for 1 year.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the Australian Research Council. Dr. Hinman reported receiving royalties from the sale of the Gel Melbourne OA shoe (Asics), and her associates reported numerous ties to industry sources.

Movement training may lower stress fracture risk

SEATTLE – Correcting jumping and landing techniques may prevent lower-limb stress fractures in active young people, based on the results of a prospective study of 1,772 cadets at the United States Military Academy in West Point, N.Y.

Scores on the Landing Error Scoring System (LESS), which assesses 17 components of jumping and landing, were predictive of lower extremity stress fractures in the study, which was reported at the annual meeting of the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine.

Based on the results, freshman at West Point are now being screened for movement problems that are corrected when necessary. "We’ve seen a pretty impressive reduction – on average 30%-40% – in stress fractures, said lead investigator Kenneth Cameron, Ph.D., director of orthopedic research at Keller Army Community Hospital in West Point.

The reductions have not yet reached statistical significance because the program is fairly new, said Dr. Cameron, who added that the findings might prove useful for preventing post-traumatic osteoarthritis, anterior cruciate ligament tears, and other injuries.

For the study, cadets were instructed to jump off a 30-cm high box, then to leap as high as they could. Subjects were about 19 years old, on average, and had a body mass index of about 24 kg/m2 in men and 23 kg/m2 in women. The investigators videotaped the cadets and graded their movements using the LESS criteria.

Overall, there were 94 first-time fractures in the cohort, giving a cumulative incidence of 5.3%. Stress fractures were three times more likely in women, about one-third of the study population (incidence rate ratio = 2.86; 95% confidence interval, 1.88-4.34; P less than .001).

Controlling for sex and year of entry into the cohort, cadets who consistently landed flat footed or heel to toe were more than twice as likely (IRR = 2.32; 95% CI, 1.35-3.97; P = .002) to have a lower-extremity stress fracture during 4 years of follow-up. Similarly, a higher rate of stress fractures was noted in those who consistently landed asymmetrically (IRR = 2.53; 95% CI, 1.35-4.77; P = .004). Each additional movement error increased the incidence rate of lower-extremity stress fracture by 15% (IRR = 1.15; 95% CI, 1.02-1.31; P = .025).

"Typically, we don’t focus on changing movement patterns" when people have stress fractures, so most "move just as badly if not worse" and are at risk for another injury, he said. "Strength training isn’t enough; there’s a neuromuscular control issue, as well."

In stress fracture, "we see excessive motion in the frontal plane and transverse plane, and not much [side] plane motion. We also see hamstring and quadriceps weakness. Instead of flexing [the hip, knee, and ankle] to absorb force, [subjects] focus on compensatory movements," like internal rotation and abduction.

Hitting the floor with abnormal ankle flexion, stance width, and trunk flexion also increases the stress fracture risk.

The work was funded by the Department of Defense and National Institutes of Health, among others. Dr. Cameron had no relevant disclosures.

SEATTLE – Correcting jumping and landing techniques may prevent lower-limb stress fractures in active young people, based on the results of a prospective study of 1,772 cadets at the United States Military Academy in West Point, N.Y.

Scores on the Landing Error Scoring System (LESS), which assesses 17 components of jumping and landing, were predictive of lower extremity stress fractures in the study, which was reported at the annual meeting of the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine.

Based on the results, freshman at West Point are now being screened for movement problems that are corrected when necessary. "We’ve seen a pretty impressive reduction – on average 30%-40% – in stress fractures, said lead investigator Kenneth Cameron, Ph.D., director of orthopedic research at Keller Army Community Hospital in West Point.

The reductions have not yet reached statistical significance because the program is fairly new, said Dr. Cameron, who added that the findings might prove useful for preventing post-traumatic osteoarthritis, anterior cruciate ligament tears, and other injuries.

For the study, cadets were instructed to jump off a 30-cm high box, then to leap as high as they could. Subjects were about 19 years old, on average, and had a body mass index of about 24 kg/m2 in men and 23 kg/m2 in women. The investigators videotaped the cadets and graded their movements using the LESS criteria.

Overall, there were 94 first-time fractures in the cohort, giving a cumulative incidence of 5.3%. Stress fractures were three times more likely in women, about one-third of the study population (incidence rate ratio = 2.86; 95% confidence interval, 1.88-4.34; P less than .001).

Controlling for sex and year of entry into the cohort, cadets who consistently landed flat footed or heel to toe were more than twice as likely (IRR = 2.32; 95% CI, 1.35-3.97; P = .002) to have a lower-extremity stress fracture during 4 years of follow-up. Similarly, a higher rate of stress fractures was noted in those who consistently landed asymmetrically (IRR = 2.53; 95% CI, 1.35-4.77; P = .004). Each additional movement error increased the incidence rate of lower-extremity stress fracture by 15% (IRR = 1.15; 95% CI, 1.02-1.31; P = .025).

"Typically, we don’t focus on changing movement patterns" when people have stress fractures, so most "move just as badly if not worse" and are at risk for another injury, he said. "Strength training isn’t enough; there’s a neuromuscular control issue, as well."

In stress fracture, "we see excessive motion in the frontal plane and transverse plane, and not much [side] plane motion. We also see hamstring and quadriceps weakness. Instead of flexing [the hip, knee, and ankle] to absorb force, [subjects] focus on compensatory movements," like internal rotation and abduction.

Hitting the floor with abnormal ankle flexion, stance width, and trunk flexion also increases the stress fracture risk.

The work was funded by the Department of Defense and National Institutes of Health, among others. Dr. Cameron had no relevant disclosures.

SEATTLE – Correcting jumping and landing techniques may prevent lower-limb stress fractures in active young people, based on the results of a prospective study of 1,772 cadets at the United States Military Academy in West Point, N.Y.

Scores on the Landing Error Scoring System (LESS), which assesses 17 components of jumping and landing, were predictive of lower extremity stress fractures in the study, which was reported at the annual meeting of the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine.

Based on the results, freshman at West Point are now being screened for movement problems that are corrected when necessary. "We’ve seen a pretty impressive reduction – on average 30%-40% – in stress fractures, said lead investigator Kenneth Cameron, Ph.D., director of orthopedic research at Keller Army Community Hospital in West Point.

The reductions have not yet reached statistical significance because the program is fairly new, said Dr. Cameron, who added that the findings might prove useful for preventing post-traumatic osteoarthritis, anterior cruciate ligament tears, and other injuries.

For the study, cadets were instructed to jump off a 30-cm high box, then to leap as high as they could. Subjects were about 19 years old, on average, and had a body mass index of about 24 kg/m2 in men and 23 kg/m2 in women. The investigators videotaped the cadets and graded their movements using the LESS criteria.

Overall, there were 94 first-time fractures in the cohort, giving a cumulative incidence of 5.3%. Stress fractures were three times more likely in women, about one-third of the study population (incidence rate ratio = 2.86; 95% confidence interval, 1.88-4.34; P less than .001).

Controlling for sex and year of entry into the cohort, cadets who consistently landed flat footed or heel to toe were more than twice as likely (IRR = 2.32; 95% CI, 1.35-3.97; P = .002) to have a lower-extremity stress fracture during 4 years of follow-up. Similarly, a higher rate of stress fractures was noted in those who consistently landed asymmetrically (IRR = 2.53; 95% CI, 1.35-4.77; P = .004). Each additional movement error increased the incidence rate of lower-extremity stress fracture by 15% (IRR = 1.15; 95% CI, 1.02-1.31; P = .025).

"Typically, we don’t focus on changing movement patterns" when people have stress fractures, so most "move just as badly if not worse" and are at risk for another injury, he said. "Strength training isn’t enough; there’s a neuromuscular control issue, as well."

In stress fracture, "we see excessive motion in the frontal plane and transverse plane, and not much [side] plane motion. We also see hamstring and quadriceps weakness. Instead of flexing [the hip, knee, and ankle] to absorb force, [subjects] focus on compensatory movements," like internal rotation and abduction.

Hitting the floor with abnormal ankle flexion, stance width, and trunk flexion also increases the stress fracture risk.

The work was funded by the Department of Defense and National Institutes of Health, among others. Dr. Cameron had no relevant disclosures.

AT THE AOSSM 2014 ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Movement evaluation and training may prevent orthopedic injury.

Major finding: People who land flat-footed or heel-to-toe in jump tests are more than twice as likely to develop lower-extremity stress fractures (IRR = 2.32; 95% CI, 1.35-3.97; P = .002).

Data Source: Prospective cohort study of nearly 1,800 young adults.

Disclosures: The lead investigator has no disclosures. The National Institutes of Health and Department of Defense funded the work.

The Medical Roundtable: Osteoarthritis Coping Guidelines for the Elderly

DR. BLOCK: Throughout the 20th century, we always considered OA to be primarily a degenerative disease of cartilage, but during the past decade or more, 2 things have become apparent: First, from a clinical perspective, OA is not just a structural degenerative process, it is primarily a very painful disease with pain being its most prominent feature. Second, the degenerative process involves not only the cartilage but the entire joint and all the involved structures within it.

A reasonable working definition of OA right now would be a painful degenerative process involving all the joint structures and is not primarily inflammatory but involves progressive deterioration of joint structures including articular cartilage. It’s important to keep in mind that pain itself is critical because as individuals age, everybody has some degenerative processes in their joints, and if we look hard enough, we can find the pathological features of OA in all elderly people. However, not all elderly people actually have the clinical disease.

DR. GALL: In a moment, we’ll talk about the causes of this, but, Dr. Moskowitz, would you tell us what the burden of this disease is here in the United States and worldwide?

DR. MOSKOWITZ: Well, it’s the most common form of arthritis and affects nearly 27 million or more Americans.1 It’s the most common disabling disease of the rheumatologic group, and it’s very disabling among all diseases.

DR. GALL: In the United States, you say that there’s about—

DR. MOSKOWITZ: About 27 million people with OA. And, in a decade, it is anticipated that the number will significantly increase.

DR. GALL: How many of those people are affected to the point that they’re unable to do their normal activities of daily living (ADLs)?

DR. MOSKOWITZ: Well, in terms of disability, about 80% of patients with OA have some degree of movement limitation, 25% cannot perform major ADLs, 11% of adults with knee OA need help with personal care, and 14% require help with routine needs.2

DR. GALL: Dr. Block, you talked about pain as a major manifestation of this disease. Does everybody who has OA present with pain?

DR. BLOCK: Again, it’s a definitional question; there is a distinction between clinically evident OA and asymptomatic structural degeneration of the joint. The population that Dr. Moskowitz was just describing, which comprises 20 to 30 million people, has doctor-diagnosed symptomatic OA, which is a painful disease. A much higher number of people who have structural degenerative disease would be diagnosed by radiography and said to fulfill a radiographic definition of OA, but all of the people who Dr. Moskowitz refer to have pain.

DR. MOSKOWITZ: Pain is what brings a patient to the doctor. I’ll often ask my patients, “How are you doing and what can I do for you?” They have limited motion and can’t get around. They say, “Dr. Moskowitz, I just want to get rid of the pain. I’ll worry about the swelling and getting around later.” And, that’s what really motivates them to get medical attention.

DR. GALL: Often, we will get consultations from primary care physicians for a patient who has OA that’s been picked up by radiography, and the patients will come and really not complain of pain in that area or possibly might have another underlying disease that’s causing the pain that’s not related to the OA. Dr. Block, do you want to say a word about that?

DR. BLOCK: Sure. By the age of 80 years, essentially, 100% of the population will have evidence of radiographic OA in at least one of their large joints. If you start with that number and you’re then referred an elderly patient merely for the radiographic appearance of OA, that doesn’t tell you very much about what’s going on clinically, and so, most of us would not even describe that as a clinical disease.

They may have a degenerative process in their knee, hip, etc, but of that group, say at the age of 80 years where almost 100% of people will have radiographic evidence of OA, only about 15% to 20% have symptomatic disease.3 That’s the culprit that I think we’re talking about clinically—people who not only have degenerative structural disease but also have symptoms that are interfering with their quality of life or their daily activities.

DR. MOSKOWITZ: I think that’s an important point, Dr. Block. For example, we all see patients who come in complaining of hip pain and you examine their knees as well and they have terrible genu varum (bowleg) and you say, “Do your knees bother you?” and they say, “Doctor, my knees are fine.” You think, my goodness, how can you walk? It isn’t necessarily true that if you have a deformity or involvement of a joint that you’re going to have pain, but if you have painful joints, that brings you to the doctor.

DR. GALL: Dr. Block, once again, I would like you to summarize the etiology of OA. Obviously, there has been much research and much information that has come to light in recent years regarding the causes of this disease.

DR. BLOCK: As I said, throughout the 20th century, people interested in the pathophysiology of OA were quite convinced that it was a degenerative process of the articular cartilage. As people age, the articular cartilage starts degenerating, and when there is absence of intact cartilage that ought to be providing essentially frictionless articulation of the bones during motion, there is deterioration, and that’s what we always considered to be OA.

Of course, the missing link in that paradigm is that cartilage itself has no nerve or blood supply and is therefore painless, and yet, people have horrible pain with this disease. So, our understanding over the past 10 or 15 years has really dramatically progressed, and we have begun to appreciate both degenerative and reactive processes in the subchondral bone, the ligaments, and the muscle.

The way we look at the pathophysiology of the onset and progression of the disease today is that there is primarily a degenerative process that stimulates reactive processes throughout the joint and even in the immune and inflammatory pathways. So, the reaction to that degenerative process sometimes causes stimulation of nociceptors and a lot of pain because of either local inflammation or mechanical alterations.

The degeneration itself, as I said, is painless. Often, people can have very degenerative joints, as Dr. Moskowitz just mentioned, and have no pain and therefore no clinical symptoms, so the disease is a combination of the degeneration and the secondary stimulated pain.

DR. GALL: So, is this primarily a biochemical or a cellular disease? Is it a genetic disease?

DR. BLOCK: Yes to all.

DR. MOSKOWITZ: There are a number of factors, Dr. Gall, involved in this condition. First, for example, is aging. We see that the frequency of OA increases logarithmically as we age, and there are pathologic changes with age that appear to lead to OA. For example, pigmented collections in the joint, comprising advanced glycation end products, occur that may predispose a patient to OA. You’re going to find more OA in an aging population.

The second factor is trauma. Professional football and basketball players, for example, who have chronic trauma, meniscal injuries, or cruciate ligament injuries are predisposed to OA. Third—the big risk factor, of course—is being overweight or obese. Patients who are overweight have a much higher frequency of OA, particularly in the knees. Last, there are genetic factors. For example, OA in the hands, which is more often seen in women, is genetically oriented so that if your mother had it or your aunt had it, you’re more likely to get it. Accordingly, there are multifactorial etiological factors that we have to try to address.

DR. GALL: Can you say a word about the different areas of the body that are associated with OA and talk a little bit about the difference between OA of the hands that we see frequently in women in relation to OA of the knee, hips, and spine, which can be devastating for individuals?

DR. MOSKOWITZ: Any joint can have it. It can be in the ankle, for example, if there has been trauma, but we’re looking particularly at the knees, the hips, the hands, and the spine. It’s interesting—certain joints in the hands are predisposed to OA including the distal and proximal interphalangeal joints. It tends not to involve the metacarpophalangeal joints, although it can in severe cases. Of course, the first carpometacarpal joint is frequently involved, and OA in this joint can be very disabling.

I have patients, for example, who are pianists or people who use their hands in their daily occupation. Their problem is often unfortunately minimized, with the doctor saying, “Oh, you’ve got a touch of OA, you can live okay with it.” However, this is hard to do because of pain and decreased function—OA can be a very disabling disease. In a number of women, the joints of the hands can be very inflamed. There’s a form of hand OA called erosive inflammatory OA, which can be especially troublesome because it’s very destructive. It’s almost like a low-grade rheumatoid arthritis where you actually get a lot of joint breakdown and deformity—it can be very disabling. OA of the knees or hips obviously can be a problem because of difficulties with ambulation.

DR. BLOCK: Our medical model trains us that, in general, we should look for an abnormality on a laboratory test to make a diagnosis. We do look for radiographic evidence of OA because, as I have said several times already, almost every elderly patient will have radiographic evidence of OA-like degeneration; however, we primarily use radiography adjunctively to make sure nothing else is going on or to assess the severity of the degeneration.

We make a diagnosis purely clinically. We look for someone who has the appropriate degree of pain in specific joints and does not have evidence of a systemic inflammatory source of that pain or a systemic rheumatic disease and in whom the pain appears to be articular rather than extra-articular. Of course, clinically, we feel for crepitus when we move the joint because of the degenerative processes, and we feel for bony enlargements or osteophytes around the joint to assist in making the diagnosis of OA.

Radiography is helpful in the sense that it can tell us about the severity of the degeneration and help us to make sure that we’re not missing something else such as a malignancy; however, radiography itself is not critical for the clinical diagnosis of OA.

DR. GALL: Dr. Block, how can the clinician who first sees a patient with OA differentiate it from a common type of inflammatory arthritis such as rheumatoid arthritis?

DR. MOSKOWITZ: If I may comment on that; you’re looking at 2 things. First, you are looking for symptoms and signs that you expect to be associated with OA, and then, you are looking for signs and symptoms that are not consistent with OA. As we said earlier, you may get some inflammation in the knee. You may get some swelling, and you can have evidence of increased synovial fluid, but you wouldn’t have the diffuse inflammatory reaction that you would have in rheumatoid arthritis, and there are different joints involved. For example, in rheumatoid arthritis, there may be involvement of the proximal interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joints of the hands, wrists, elbows, or shoulders. You would have involvement of peripheral joints that are different from those that are characteristically involved with OA.

In OA, the patient doesn’t have systemic findings such as fever, weight loss, or generalized prolonged stiffness. The patient often has localized stiffness in the involved joint but not generalized stiffness like that seen in rheumatoid arthritis. In OA, you can have multiple joints involved, such as 2 knees and 1 hip, but involvement doesn’t come on all at once and with the same severity.

DR. BLOCK: I completely agree with everything Dr. Moskowitz said. Additionally, if one is still confused after all of the clinical signs, this is where radiography may be useful because the radiographic appearance of OA is really different from that of the inflammatory arthritides.

In OA, one expects asymmetric narrowing in the joint itself. Additionally, OA results in subchondral sclerosis instead of periarticular osteopenia, which is seen in inflammatory arthritis. Finally, often, in OA, there is osteophyte formation, which is in contrast to the erosions that may be seen in the inflammatory arthritides. This is one area where radiography can really help.

DR. MOSKOWITZ: You have to be careful with respect to diagnosis in older people because if you do a serum rheumatoid factor study, the rheumatoid factor may be positive, but this may be unrelated to the patient’s symptoms. Studies have shown that a positive rheumatoid factor may be nonspecifically related to aging. So, you have to be careful—this finding can be a red herring in the diagnosis.

DR. BLOCK: I agree completely, and because OA is so common, one needs to bear in mind that a patient might have both inflammatory arthritis and underlying OA at the same time.

DR. MOSKOWITZ: Great point. We all see patients who come in to the office with OA of the hands, and then they develop rheumatoid arthritis or lupus engrafted on that previous involvement.

DR. GALL: I’d like to move on now to the management of the disease and, Dr. Moskowitz, would you talk to us about the first approach, which would be prevention? This is an approach that has caught the attention of the Centers for Disease Control and the Arthritis Foundation, and there is a major ongoing campaign at this time about what we can do to prevent this disease. Could you summarize that for us, Dr. Moskowitz?

DR. MOSKOWITZ: Absolutely. It’s generally thought that there’s nothing you can do to prevent OA. Well, we now think that you can slow it down and perhaps prevent it. Number one, we talked about weight. If a patient were to lose just 10 or 12 pounds, that could have a significant impact on the destructive effect of weight on the progression or the development of the disease. Programmed exercise is also very important. People say, “Well, I have arthritis. I can’t exercise,” and this is a problem because if you’re overweight and you have OA of the knees, joint overuse may temporarily lead to more symptoms. But walking at a reasonable pace and duration can be helpful with respect to symptoms and disability—the body puts out pain-relieving endorphins, muscles are strengthened, and joint range-of-motion is improved. Walking on a treadmill at a reasonable pace helps to achieve weight loss.

The patient can walk on a prescribed basis according to his or her capabilities. It’s important not to ask the patient to do something you know they’re not going to be able to do. We wouldn’t ask them to lose 20 pounds in the next 2 months. We have to make the program practical—these things are not easy to do, so we’ve got to be very supportive.

While trying to prevent disease progression, you want to have the patient strengthen their joint-related muscles. You want them to do muscle-building exercises because if you have joint stability, you’re likely going to decrease the osteoarthritic process as well. Losing weight is very important. Exercise is important. Using hot and cold applications for local therapy, which is safer than medication, is helpful.

Importantly, you don’t want to limit the patient’s activities any more than necessary. The way that I’ve always practiced medicine is that you don’t want to take away the patient’s ability to live his or her life as normally as possible. You don’t want to prescribe “don’ts,” like “don’t walk” and “don’t climb steps.” You want the patient to walk and do exercises, but the exercises have to be programmed so that the patient is able to do them.

DR. GALL: This is actually a very common question that primary care physicians are faced with when a patient with this disease comes in and is afraid to exercise and has a difficult time losing weight. But, I think it’s important that we understand that the cartilage gets its nourishment by being compressed and released and it has no blood supply of its own, so a lack of exercise is going to further cartilage degeneration.

DR. MOSKOWITZ: There are other non-weight bearing activities such as aquatic exercises that most people can do. You don’t have to be able to swim. You can do water exercises where you have the buoyancy of the water allowing for passive assistive exercise.

DR. BLOCK: Let me just add one other thing to the exercise discussion. In addition to there being a structural benefit to controlled exercise, every single systematic evaluation that has been performed has demonstrated that there is a really substantial and sustained pain relief component to exercise. People who have OA who are able to exercise regularly get substantial pain relief just from the exercise, and this is really important because the pain is what’s slowing them down in the first place.

The problem, of course, is maintaining an exercise regimen for a long term. Remember, this is a disease of decades, and we are not that good at behavioral modification strategies. Patients often give up on the exercise after a while. But, if you can maintain it, there are structural benefits as well as really substantial pain relief benefits.

DR. MOSKOWITZ: Yes, I agree. The other thing is that it’s hard for the busy physician in the office to start teaching the patient how to exercise, so we need to use arthritis health professionals such as occupational therapists and physical therapists to create exercise programs and teach patients how to exercise more effectively.

DR. BLOCK: Can I add one more thing as long as we’re discussing prevention? One of the major societal risk factors right now is recreational trauma. We have a population of young individuals who are being brought up in various organized sports, and there’s a very substantial risk factor for adolescent and young women who are, for example, playing soccer. They are getting knee and anterior cruciate ligament injuries, and over the upcoming 10 to 15 years, these people are at an enormous risk for developing knee OA. So, we need to develop some strategies to reduce the recreational trauma that results in early OA in this population.

DR. GALL: So, now we realize that weight control and exercise are important. Can we now talk about the medical management of both the pain and the arthritis?

DR. MOSKOWITZ: I know we don’t want to take too much time with this, but before we finish, I wanted to mention that I keep getting asked about tai chi or acupuncture for treatment. There are data suggesting that these programs can be helpful, but they should be adjunctive considerations for patients not responding to more routine therapeutic programs.4

DR. GALL: Yes, I would certainly agree with that. These are adjunctive therapies that may be helpful in select patients, but we need to focus on the more proven aspects of the prevention of the disease. Let’s now divide our talk about treatment into pain management and disease management. Can we start with pain management?

DR. BLOCK: I think that, first of all, it’s really important not to neglect the adjunctive measures that we’ve already discussed, and so, pain management is multifactorial, but one needs to include a physical and occupational therapist because although regular exercise dramatically reduces pain, local measures such as heat or ice are often very useful.

When they don’t get sufficient relief from adjunctive measures, symptomatic patients with OA will need to move to the pharmacologic arena sooner or later. From my practice and from the literature, I would say that there are 2 kinds of pain that need to be treated in OA: Pain that occurs during a painful flare that may last a couple of weeks and chronic ongoing pain that may develop as the disease progresses.

During short painful flares, most of the organizations that have published guidelines over the years have suggested that acetaminophen is a good place to start.5,6 I think that the systematic literature at this point suggests that acetaminophen might be very good for short-term pain relief—meaning, a few weeks at most. It’s probably not very effective for long-term pain relief, and it has a fair amount of potential complications, especially in the elderly. I don’t tend to use a lot of acetaminophen in people who are having chronic pain from OA, but during short-term pain flares, it can be very useful.

One can choose various analgesics including topical nonsteroidal agents, which can be very effective for local and monoarticular pain, for example, pain in superficial joints such as the knees or fingers. However, sooner or later, I believe that if patients don’t have a contraindication, they will end up taking either nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs) or COX-2 inhibitors (coxibs), and that’s probably for a good reason. The nonsteroidals and coxibs have been demonstrated repeatedly to retain pain relief during 2-year studies, and they’re almost unique among the pharmacologic agents in that they retain that pain relief over a couple of years.7,8

Of course, if people are undergoing adequate pharmacologic therapy and they have painful flares in single joints, then intra-articular therapies such as glucocorticoids or hyaluronans are often very effective.

DR. GALL: I’d like to just go back to the NSAIDs for a moment. There is increasing emphasis on the risk of NSAIDs, particularly in the elderly. How do we balance the benefits of NSAID use for chronic therapy versus the risks, and how would you monitor the patient?

DR. MOSKOWITZ: Well, I agree with the premises that Dr. Block mentioned. I think acetaminophen has varying efficacy, but I think it’s worth trying. If I am right, I think it was stated in the past that the acetaminophen dose could go up to 4 g/d.9 The current recommendation is that doses of acetaminophen should not exceed 3 g/d so as not to incur hepatic or renal toxicity. The problem is that acetaminophen is often present in other medicines that patients are taking, and so an excess total intake is not uncommon.10

I think a trial of acetaminophen is worthwhile because even if it doesn’t relieve all the pain, it’s a floor of analgesia that you can add to with nonsteroidals.

With regard to the question about whether nonsteroidals are dangerous in older people, I think that they can be. Most things we use are unfortunately associated with some risk, although pain itself is also a risk factor. Pain increases blood pressure and pulse rate. If you relieve the pain, you’re probably relieving more of the stress on the patient overall as opposed to the risk of the NSAID itself. If you use nonselective NSAIDs, I would suggest adding a proton pump inhibitor, especially if the patient has an increased risk of peptic ulcer disease. If you use a COX-2 selective inhibitor, data suggest there is a decreased gastrointestinal (GI) risk. Overall, I think that NSAIDs can be effective and reasonably safe. I’m more careful about using NSAIDs in individuals older than 75 or 80 years; however, many of these patients are physiologically younger than their numerical age, and they can more safely tolerate these agents.

Intra-articular steroids and intra-articular hyaluronans can be very helpful in the management of knee OA, and they have comfortable safety factors.

DR. GALL: I’ll just make a comment about my own approach to that. When I put a patient on an NSAID, and I do use them frequently, I mark it on a problem list. I’m careful to ask the patients about bleeding and to warn them about the signs of GI bleeding, and I do periodic blood counts to look at hemoglobin and creatinine levels. I also do a urinalysis to rule out silent GI or renal effects of these drugs, but I do use NSAIDs frequently.

Additionally, with the recent attention to the pain component of OA over the past decade, there has been a lot of systematic investigation into various neuroactive pain-directed medications. In fact, duloxetine, which is a neuroactive agent, was approved for use a couple of years ago. There are non–anti-inflammatory, non-purely analgesic medicines that can be very helpful for the treatment of the pain component of OA.

DR. GALL: Thank you. Could we just say a word about opioids and tramadol as adjunctive therapies and what the pluses and minuses of using these drugs are?

DR. MOSKOWITZ: I think there is not only a rationale but a place for these agents in treating OA, but we’ve got to be careful. I’m a little less concerned about using tramadol than using the classic opioids, per se, and I think tramadol can be a reasonable bridge when people are not responding to NSAIDS. A number of years ago, when I was writing a piece for the Arthritis Foundation pamphlet, I stated that there is never a place for opioids in the treatment of OA, and I can’t tell you how many of my colleagues wrote and said, “Dr. Moskowitz, there are times when we feel they need to be available.” I agree, but I think my guidance is that, if you use an opioid, use the lowest dose possible and for the shortest time possible.

I think if someone is in a lot of pain and they’re having a flare, particularly an older individual, it may be safer to use the opioids than to put them on NSAIDs, particularly if they have had past trouble with NSAIDS. I don’t think that we should never use opioids when treating OA. What are your thoughts on that, Dr. Block?

DR. BLOCK: I agree. I think that there is good evidence that the opiates provide really substantial pain relief, so they’re effective in OA. The problem, of course, is that they have very high side effect profiles, and the people that they’re the most dangerous for with regard to falling and injuring oneself are actually the same people who are at high risk with nonsteroidals—the very elderly with congestive heart failure. It really does put us in a bind.

I think that I agree with what you just said, which is that they are effective, and at times, I think that there is clearly a place for opiates in OA, but one needs to be judicious and careful when using them. Tramadol is, I think, much safer. It’s a weak opiate. On the other hand, it also has much less pain-relieving potential, so this is the bind we face.

Well, I think what we haven’t mentioned yet are the surgical approaches, which are critically important.

DR. MOSKOWITZ: Should we discuss glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate?

DR. BLOCK: So, more than half of patients who have symptomatic OA use various complementary medicine approaches. They are widely used because they’re widely believed to be beneficial, and I think that there has been a fair amount of systematic evaluation, specifically of glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate, over the past several years.

When we look at the independently sponsored studies, the evidence suggests that the side effect profile for both agents is very good. As long as they were manufactured in a safe manner, they are very safe and one shouldn’t worry about using them.

On the other hand, the efficacy above placebo is very low, but that doesn’t mean that they’re not effective in individual patients. The thing that’s really important to note here is that whenever there is a placebo-controlled study with pain as an outcome in OA, the placebo response is huge. More than half of the people who get placebo get very substantial clinically significant pain relief, and more importantly, it’s durable. In all of these placebo-controlled studies that go on for 2 years, the placebo group with pain relief had sustainability over 2 years,11,12 and so, if one gets more than a placebo response from glucosamine, and if it’s providing pain relief, I’m happy for them to use it.

The Glucosamine/Chondroitin Arthritis Intervention Trial (GAIT),7 the large National Institutes of Health multicenter study, which was a null study, showed that fundamentally, there was no systematic advantage of a combination glucosamine plus chondroitin sulfate. Even when that came out as a null study and was publicized as such, the market for glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate in the following year didn’t decrease in the United States.13,14

People who are getting a benefit, whether it’s due to an endorphin effect from placebo or the agent, are going to continue using the agent. As long as the agents are safe, I’m comfortable with my patients using them if they really are feeling like they are getting relief.

DR. MOSKOWITZ: Yes, I think that there are conflicting data, but there are a number of studies that seem to show that these agents do help some people. For example, this question about the GAIT study7 not showing an effect, if you’re using glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate in individuals who have high pain to start with—if they had a score of more than 300 mm on the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC)—they appeared to do better, but there wasn’t a predefined endpoint, so the result has to be substantiated in a repeat study. However, I see enough people—like you do, Dr. Block—who seem to respond. They’re safe agents, and I think that they do have merit in patients who are not getting a benefit from other agents.

DR. GALL: Before we move on to surgery and the future of therapy, I just want to discuss intra-articular steroids. What are your thoughts on these?

DR. MOSKOWITZ: I would be lost without them. I remember when they were first used by Dr. Joseph Hollander in Philadelphia, and they failed to help because he used cortisone acetate instead of the hydrocortisone derivative, and cortisone has to be converted to hydrocortisone before it works.15 I use intra-articular corticosteroids a lot. The general recommendation is that you shouldn’t use it more than 4 times a year in the knee. I think maybe if somebody is older—for example, 88 years—and they cannot tolerate other therapy, you might use them that often. Studies have shown that an intra-articular corticosteroid injection every 3 months did not lead to deleterious anatomic effects.16 I think using them 2 or 3 times a year, if indicated, can be symptomatically effective and safe, and I don’t think that will lead to joint breakdown if the patient is careful about doing their exercises and other management.

DR. GALL: Let’s move on to the use of surgery, and without going into all the surgical procedures, when is it appropriate for the clinician and the patient to consider surgical intervention in OA?

DR. BLOCK: It is entirely patient-oriented. You can’t tell by structure or by X-ray. When the patient’s OA is painful and severe enough, when it cannot be controlled with medication and medical regimens, or when it’s interfering with their lifestyle and they can’t live with it, they’ll tell you they need surgery.

DR. MOSKOWITZ: I completely agree. I think you can’t tell them. They’ll let you know. They’ll say, “I just have so much pain and disability. I need something done.”

DR. GALL: I think it’s important also to bring the surgeon in, not as a plumber to fix something, but as a partner in making the decision. Certainly the primary care physician, often the rheumatologist, can also provide guidance and work with the patients and the surgeons in making that decision.

DR. MOSKOWITZ: Yes. Let me just add one thing: I don’t think the patient should be in an extreme state of pain and disability in order to have surgery. If the condition interferes with their ADLs and the pain is really encumbering their daily activities, then it’s not unreasonable to consider surgery. I don’t think they have to be so bad that they’re limping and in terrible distress.

DR. BLOCK: Having said that, we should mention that joint replacement, at least in the knees and the hips, is extraordinarily effective in relieving pain.

DR. GALL: Yes. I would agree and these advances have continued to increase over the years, and these replacements last for a longer period of time, so the amount of satisfaction has increased, and the number of complications in experienced centers has certainly decreased.

Let’s end by talking about the future of OA. There are 2 areas that I’d like to touch on: One is the disease-modifying OA drugs (DMOADs) and the other is cartilage regeneration with stem cells and other techniques. Dr. Moskowitz, maybe you can talk about the DMOADs, and Dr. Block, you can talk about cartilage regeneration.

DR. MOSKOWITZ: Disease retardation or reversal would be the holy grail of OA management: to be able to treat OA with medications—the so-called DMOADS—that not only relieve symptoms but also slow the disease down or actually reverse the disease process. Some of the agents described as possibly having disease-modification potential include glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, intra-articular hyaluronans, diacerein, avocado/soybean unsaponifiables, and doxycycline among others.17 Further studies will help to define the purported role of such agents in disease modification.

DR. BLOCK: I think it’s fair to say that, as of today, there really are no strategies that have been proven to be effective at retarding the progression and pain of OA over long periods of time. I think that is the gold standard that we’re looking for, and there is suggestive evidence from studies performed on each of the agents that Dr. Moskowitz just mentioned and several others.

I think there is a lot of work being done to study various metalloproteinase inhibitors, especially the collagenase 3 (MMP-13) inhibitors, and the aggrecanase inhibitors. I think that if some of these things are demonstrated to be effective in delaying the progression of OA, they could be extremely exciting, but one needs to keep in mind that whatever we use as a DMOAD has to be extremely safe because it’s going to be used for decades in people who are basically asymptomatic. In order to justify that on a public health basis, it has to be extraordinarily safe. It’s a very high bar.

DR. GALL: Okay. Dr. Block, can you now attempt to discuss cartilage regeneration and the use of the stem cell?

DR. BLOCK: Yes. Mesenchymal stem cell technology is extremely exciting, and it has paid off in some areas of bone and other connective tissues. As everybody knows, there is one U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved approach for replacing cartilage that has had some success, but it’s used for isolated chondral defects in young and otherwise healthy people—not for OA.

The problem, of course, is that as we understand OA better and better, it’s more than just cartilage degeneration, and more importantly, the cartilage, which is very important, is a very thin and delicate tissue. If we replace the cartilage alone without normalizing the aberrant biomechanics across the joint—without normalizing the subchondral bone that the cartilage sits on—we have very little chance of getting long-term relief.

Having said that, efforts are being carried out in a variety of laboratories around the world to focus on not only mesenchymal cell-directed cartilage formation but also on actual repair of most tissues of the joint. Once we understand how to grow new cartilage and actually have it integrate with the adjacent tissue, which we still are not able to do, and once we’re able to repair some of the subchondral bone, I think that there is a lot of promise for that strategy in the long run. But, in the short-term, again, it’s a very difficult process that is not yet well understood.

DR. MOSKOWITZ: Well said. I agree. I think that we’re on the brink of being able to repair, particularly, very focal defects—maybe 4- or 5-mm defects. But, to repair the joint, as Dr. Block pointed out, you can’t just repair the cartilage because joint changes such as inflammation, meniscal alterations, varus and valgus deformities, and other changes impacting the joint are going to impair cell-based regeneration. Until we get those impacts controlled, I think it’s going to be some time before we can say to someone, “We’re going to replace your cartilage and normalize your joint.” However, I am optimistic and think that down the line, we may be able to do it.

DR. GALL: Dr. Block also mentioned that the underlying bone has changed too, and so, that needs to be attacked as well in these approaches.

DR. BLOCK: My personal view is that in the short-term future—the next 5 to 10 years—big strides will be made in strategies for better pain relief, and there are a variety of biologics that are in phase II and phase III testing that already look very exciting. Again, my own personal research interest is in trying to normalize the mechanical loads across the joints so that we can protect the joints better and so that the OA won’t progress, and I think those kinds of strategies will be available over the next couple of years.

DR. GALL: I’d like to thank you both for a really enlightening and comprehensive discussion of this common disease. Just to review, we’ve discussed what OA is and defined it, talked about its burden and its diagnosis, and mentioned the various risk factors for OA, particularly in light of what we can do to prevent OA or prevent the progression of the disease. We also had a comprehensive talk about the treatment of OA from both the standpoint of pain and the actual disease, and we touched upon the future of this as well as the research that’s being done in these areas.

I really appreciate your wisdom and discussion, and I think we’re providing the primary care physicians and providers with a really comprehensive look at this disease.

FoxP2 Media LLC is the publisher of The Medical Roundtable.

DR. BLOCK: Throughout the 20th century, we always considered OA to be primarily a degenerative disease of cartilage, but during the past decade or more, 2 things have become apparent: First, from a clinical perspective, OA is not just a structural degenerative process, it is primarily a very painful disease with pain being its most prominent feature. Second, the degenerative process involves not only the cartilage but the entire joint and all the involved structures within it.

A reasonable working definition of OA right now would be a painful degenerative process involving all the joint structures and is not primarily inflammatory but involves progressive deterioration of joint structures including articular cartilage. It’s important to keep in mind that pain itself is critical because as individuals age, everybody has some degenerative processes in their joints, and if we look hard enough, we can find the pathological features of OA in all elderly people. However, not all elderly people actually have the clinical disease.

DR. GALL: In a moment, we’ll talk about the causes of this, but, Dr. Moskowitz, would you tell us what the burden of this disease is here in the United States and worldwide?

DR. MOSKOWITZ: Well, it’s the most common form of arthritis and affects nearly 27 million or more Americans.1 It’s the most common disabling disease of the rheumatologic group, and it’s very disabling among all diseases.

DR. GALL: In the United States, you say that there’s about—

DR. MOSKOWITZ: About 27 million people with OA. And, in a decade, it is anticipated that the number will significantly increase.

DR. GALL: How many of those people are affected to the point that they’re unable to do their normal activities of daily living (ADLs)?