User login

For MD-IQ on Family Practice News, but a regular topic for Rheumatology News

Overall physical health strongly predicts arthritis pain

Physical health, previous joint pain, and the presence of diabetes can strongly predict whether a patient with arthritis will experience pain, say researchers presenting their findings at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons in Las Vegas.

Man Hung, Ph.D., of the department of orthopaedic surgery operations at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City and her colleagues created several algorithms for predicting arthritis pain based on data from a sample of 5,721 U.S. adults with arthritis with an average age of 60 years.

They discovered that specific combinations of physical health, mental health, and general health status, as well as diabetes, previous joint pain, and a patient’s education level, predicted pain in people with arthritis.

Physical health status the greatest predictor of pain that limited work, whereas a body mass index greater than 30 kg/m2 was not linked to pain, the researchers found.

One of the algorithms that the researchers developed was able to predict pain at an accuracy rate of 98.6%, they said

The algorithms offer new insights of pain, allowing the development of cost-effective care management programs for those experiencing arthritis, they concluded.

Physical health, previous joint pain, and the presence of diabetes can strongly predict whether a patient with arthritis will experience pain, say researchers presenting their findings at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons in Las Vegas.

Man Hung, Ph.D., of the department of orthopaedic surgery operations at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City and her colleagues created several algorithms for predicting arthritis pain based on data from a sample of 5,721 U.S. adults with arthritis with an average age of 60 years.

They discovered that specific combinations of physical health, mental health, and general health status, as well as diabetes, previous joint pain, and a patient’s education level, predicted pain in people with arthritis.

Physical health status the greatest predictor of pain that limited work, whereas a body mass index greater than 30 kg/m2 was not linked to pain, the researchers found.

One of the algorithms that the researchers developed was able to predict pain at an accuracy rate of 98.6%, they said

The algorithms offer new insights of pain, allowing the development of cost-effective care management programs for those experiencing arthritis, they concluded.

Physical health, previous joint pain, and the presence of diabetes can strongly predict whether a patient with arthritis will experience pain, say researchers presenting their findings at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons in Las Vegas.

Man Hung, Ph.D., of the department of orthopaedic surgery operations at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City and her colleagues created several algorithms for predicting arthritis pain based on data from a sample of 5,721 U.S. adults with arthritis with an average age of 60 years.

They discovered that specific combinations of physical health, mental health, and general health status, as well as diabetes, previous joint pain, and a patient’s education level, predicted pain in people with arthritis.

Physical health status the greatest predictor of pain that limited work, whereas a body mass index greater than 30 kg/m2 was not linked to pain, the researchers found.

One of the algorithms that the researchers developed was able to predict pain at an accuracy rate of 98.6%, they said

The algorithms offer new insights of pain, allowing the development of cost-effective care management programs for those experiencing arthritis, they concluded.

Study: Osteoarthritis develops sooner than thought after ACL injury, repair

People who have had a knee reconstruction following trauma may be susceptible to osteoarthritis sooner than currently thought, according to new MRI findings at 1 year after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.

Almost a third of people studied had some evidence of early osteoarthritis (OA) at that early time point, challenging “existing dogma that degenerative joint disease does not become apparent for years post-ACLR,” reported Dr. Kay Crossley of the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015 Feb. 18 [doi:10.1002/art.39005]).

However, as they did not have access to preoperative images, they could not rule out that some OA features may have been preexisting and not related to knee trauma, they said.

“This is a sample that was taken after the injury and after the reconstruction, so they truly don’t know that what they’re finding is as a result of even the injury, surgery, or the meniscal damage or meniscal resection they had done at the time,” Dr. David J. Hunter, a leading OA expert from Sydney (Australia) University, said when asked to comment on the study’s findings.

“It may well be that these were people that had some underlying structural damage,” he added.

The researchers noted that radiographic knee OA was thought to be as high as 50%-90% a decade after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR). The issue is particularly important because ACL injuries typically occur in younger adults who are then prone to developing knee OA before they reach 40 years, they said.

“Early detection of knee OA after ACLR may permit early intervention such as load management, which is likely to be more effective prior to the development of advanced disease,” they wrote.

Their study included 111 patients aged 18-50 years who had undergone single-bundle hamstring-tendon autograft ACLR 1 year earlier.

MRI scans of their knees were compared with 20 uninjured asymptomatic matched controls. The researchers used the MRI Osteoarthritis Knee Score (MOAKS) to score specific OA features because the more recent Anterior Cruciate Ligament Osteoarthritis Score (ACLOAS) had not been published at the time of their study.

Results showed that 34 (31%) patients had MRI-defined knee OA following an ACLR a year earlier.

MRI-OA features were most frequently found in the patellofemoral compartment, particularly the medial femoral trochlea, a potentially underrecognized site of knee pathology following reconstruction, the researchers said.

Pathology in the patellofemoral joint included not only “early” features of OA, such as bone marrow lesions and partial-thickness cartilage loss, but also frank osteophytes on MRI, they noted.

None of the uninjured control knees had MRI-defined patellofemoral or tibiofemoral OA.

The authors acknowledged that a lack of access to preoperative knee images limited the conclusions they could reach in their study, but they noted that MRI-OA features were rarely seen in the small sample of uninjured matched control knees.

“Combined with the observation that six times as many reconstructed knees had radiographic osteophytes than uninjured contralateral knees, these findings suggest that knee trauma and/or reconstruction was strongly implicated in the development of OA features,” they wrote.

Another limitation that the authors acknowledged was that the MRI definition of OA was relatively new and was likely to be refined as the understanding of OA pathology evolved.

Dr. Hunter, who was the lead investigator involved in developing the MOAKS, agreed that the definition needed more validity and testing.

“This is the third study that uses that definition, and I do think that long-term clinical implications of what MRI definition means is unknown,” he said. “The challenge that we have is that we do kick up a lot of abnormalities, and we don’t truly know what the long-term clinical implications of those abnormalities are at this point.”

“There are a lot of problems with the way this study has been done, but I do think it is really helpful that it highlights how important injury is with regards to predisposing to early OA.”

“It’s something that a lot of people don’t really highlight or pay attention to,” he said.

The study was partly funded by the Queensland Orthopaedic Physiotherapy Network, a University of Melbourne Research Collaboration grant, and University of British Columbia’s Centre for Hip Health and Mobility via the Society for Mobility and Health. One study author is president of Boston Imaging Core Lab, LLC, and is a consultant to Merck Serono, Sanofi-Aventis, Genzyme and TissueGene. No other authors declared conflicts of interest.

People who have had a knee reconstruction following trauma may be susceptible to osteoarthritis sooner than currently thought, according to new MRI findings at 1 year after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.

Almost a third of people studied had some evidence of early osteoarthritis (OA) at that early time point, challenging “existing dogma that degenerative joint disease does not become apparent for years post-ACLR,” reported Dr. Kay Crossley of the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015 Feb. 18 [doi:10.1002/art.39005]).

However, as they did not have access to preoperative images, they could not rule out that some OA features may have been preexisting and not related to knee trauma, they said.

“This is a sample that was taken after the injury and after the reconstruction, so they truly don’t know that what they’re finding is as a result of even the injury, surgery, or the meniscal damage or meniscal resection they had done at the time,” Dr. David J. Hunter, a leading OA expert from Sydney (Australia) University, said when asked to comment on the study’s findings.

“It may well be that these were people that had some underlying structural damage,” he added.

The researchers noted that radiographic knee OA was thought to be as high as 50%-90% a decade after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR). The issue is particularly important because ACL injuries typically occur in younger adults who are then prone to developing knee OA before they reach 40 years, they said.

“Early detection of knee OA after ACLR may permit early intervention such as load management, which is likely to be more effective prior to the development of advanced disease,” they wrote.

Their study included 111 patients aged 18-50 years who had undergone single-bundle hamstring-tendon autograft ACLR 1 year earlier.

MRI scans of their knees were compared with 20 uninjured asymptomatic matched controls. The researchers used the MRI Osteoarthritis Knee Score (MOAKS) to score specific OA features because the more recent Anterior Cruciate Ligament Osteoarthritis Score (ACLOAS) had not been published at the time of their study.

Results showed that 34 (31%) patients had MRI-defined knee OA following an ACLR a year earlier.

MRI-OA features were most frequently found in the patellofemoral compartment, particularly the medial femoral trochlea, a potentially underrecognized site of knee pathology following reconstruction, the researchers said.

Pathology in the patellofemoral joint included not only “early” features of OA, such as bone marrow lesions and partial-thickness cartilage loss, but also frank osteophytes on MRI, they noted.

None of the uninjured control knees had MRI-defined patellofemoral or tibiofemoral OA.

The authors acknowledged that a lack of access to preoperative knee images limited the conclusions they could reach in their study, but they noted that MRI-OA features were rarely seen in the small sample of uninjured matched control knees.

“Combined with the observation that six times as many reconstructed knees had radiographic osteophytes than uninjured contralateral knees, these findings suggest that knee trauma and/or reconstruction was strongly implicated in the development of OA features,” they wrote.

Another limitation that the authors acknowledged was that the MRI definition of OA was relatively new and was likely to be refined as the understanding of OA pathology evolved.

Dr. Hunter, who was the lead investigator involved in developing the MOAKS, agreed that the definition needed more validity and testing.

“This is the third study that uses that definition, and I do think that long-term clinical implications of what MRI definition means is unknown,” he said. “The challenge that we have is that we do kick up a lot of abnormalities, and we don’t truly know what the long-term clinical implications of those abnormalities are at this point.”

“There are a lot of problems with the way this study has been done, but I do think it is really helpful that it highlights how important injury is with regards to predisposing to early OA.”

“It’s something that a lot of people don’t really highlight or pay attention to,” he said.

The study was partly funded by the Queensland Orthopaedic Physiotherapy Network, a University of Melbourne Research Collaboration grant, and University of British Columbia’s Centre for Hip Health and Mobility via the Society for Mobility and Health. One study author is president of Boston Imaging Core Lab, LLC, and is a consultant to Merck Serono, Sanofi-Aventis, Genzyme and TissueGene. No other authors declared conflicts of interest.

People who have had a knee reconstruction following trauma may be susceptible to osteoarthritis sooner than currently thought, according to new MRI findings at 1 year after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.

Almost a third of people studied had some evidence of early osteoarthritis (OA) at that early time point, challenging “existing dogma that degenerative joint disease does not become apparent for years post-ACLR,” reported Dr. Kay Crossley of the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015 Feb. 18 [doi:10.1002/art.39005]).

However, as they did not have access to preoperative images, they could not rule out that some OA features may have been preexisting and not related to knee trauma, they said.

“This is a sample that was taken after the injury and after the reconstruction, so they truly don’t know that what they’re finding is as a result of even the injury, surgery, or the meniscal damage or meniscal resection they had done at the time,” Dr. David J. Hunter, a leading OA expert from Sydney (Australia) University, said when asked to comment on the study’s findings.

“It may well be that these were people that had some underlying structural damage,” he added.

The researchers noted that radiographic knee OA was thought to be as high as 50%-90% a decade after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR). The issue is particularly important because ACL injuries typically occur in younger adults who are then prone to developing knee OA before they reach 40 years, they said.

“Early detection of knee OA after ACLR may permit early intervention such as load management, which is likely to be more effective prior to the development of advanced disease,” they wrote.

Their study included 111 patients aged 18-50 years who had undergone single-bundle hamstring-tendon autograft ACLR 1 year earlier.

MRI scans of their knees were compared with 20 uninjured asymptomatic matched controls. The researchers used the MRI Osteoarthritis Knee Score (MOAKS) to score specific OA features because the more recent Anterior Cruciate Ligament Osteoarthritis Score (ACLOAS) had not been published at the time of their study.

Results showed that 34 (31%) patients had MRI-defined knee OA following an ACLR a year earlier.

MRI-OA features were most frequently found in the patellofemoral compartment, particularly the medial femoral trochlea, a potentially underrecognized site of knee pathology following reconstruction, the researchers said.

Pathology in the patellofemoral joint included not only “early” features of OA, such as bone marrow lesions and partial-thickness cartilage loss, but also frank osteophytes on MRI, they noted.

None of the uninjured control knees had MRI-defined patellofemoral or tibiofemoral OA.

The authors acknowledged that a lack of access to preoperative knee images limited the conclusions they could reach in their study, but they noted that MRI-OA features were rarely seen in the small sample of uninjured matched control knees.

“Combined with the observation that six times as many reconstructed knees had radiographic osteophytes than uninjured contralateral knees, these findings suggest that knee trauma and/or reconstruction was strongly implicated in the development of OA features,” they wrote.

Another limitation that the authors acknowledged was that the MRI definition of OA was relatively new and was likely to be refined as the understanding of OA pathology evolved.

Dr. Hunter, who was the lead investigator involved in developing the MOAKS, agreed that the definition needed more validity and testing.

“This is the third study that uses that definition, and I do think that long-term clinical implications of what MRI definition means is unknown,” he said. “The challenge that we have is that we do kick up a lot of abnormalities, and we don’t truly know what the long-term clinical implications of those abnormalities are at this point.”

“There are a lot of problems with the way this study has been done, but I do think it is really helpful that it highlights how important injury is with regards to predisposing to early OA.”

“It’s something that a lot of people don’t really highlight or pay attention to,” he said.

The study was partly funded by the Queensland Orthopaedic Physiotherapy Network, a University of Melbourne Research Collaboration grant, and University of British Columbia’s Centre for Hip Health and Mobility via the Society for Mobility and Health. One study author is president of Boston Imaging Core Lab, LLC, and is a consultant to Merck Serono, Sanofi-Aventis, Genzyme and TissueGene. No other authors declared conflicts of interest.

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: People who have undergone anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction following trauma may be susceptible to early OA sooner than previously thought, but the study authors did not have access to baseline images to rule out existing pathology.

Major finding: A third of the 111 patients studied had evidence of MRI-defined OA a year after their surgery.

Data source: MRI study of 111 patients who had undergone ACL surgery matched with 20 uninjured asymptomatic controls.

Disclosures: The study was partly funded by the Queensland Orthopaedic Physiotherapy Network, a University of Melbourne Research Collaboration grant, and University of British Columbia’s Centre for Hip Health and Mobility via the Society for Mobility and Health. One study author is president of Boston Imaging Core Lab, LLC, and is a consultant to Merck Serono, Sanofi-Aventis, Genzyme and TissueGene. No other authors declared conflicts of interest.

VIDEO: Homeopathic injectables topped placebo for knee osteoarthritis

MAUI, HAWAII – Two homeopathic injectables, as well as the familiar combination of glucosamine and chondroitin, showed promise in two studies of alternative treatments for osteoarthritis.

In an interview at the 2015 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium, Dr. Martin J. Bergman, of the department of rheumatology at Drexel University in Philadelphia, shared the recent results from the two investigations.

The first pitted intra-articular injections of two homeopathic products, Traumeel and Zeel, against placebo saline injections for knee osteoarthritis; the work was sponsored by the products’ German maker, Biologische Heilmittel Heel.

In the second trial, glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate went head to head against celecoxib (Celebrex), also for knee OA. The work was sponsored by Bioibérica, a Spanish company that makes chondroitin and glucosamine, and the investigators reported financial ties to the company.

Traumeel and Zeel may sound exotic, but they aren’t unknown in the rheumatology world – some U.S. rheumatologists are using them, Dr. Bergman, also chief of rheumatology at Taylor Hospital in Ridley Park, Pa., said.

Dr. Bergman disclosed that he has served as an advisor, speaker, or consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene, and Roche, and holds shares in Bristol-Myers Squibb, Johnson & Johnson, and Pfizer.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

MAUI, HAWAII – Two homeopathic injectables, as well as the familiar combination of glucosamine and chondroitin, showed promise in two studies of alternative treatments for osteoarthritis.

In an interview at the 2015 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium, Dr. Martin J. Bergman, of the department of rheumatology at Drexel University in Philadelphia, shared the recent results from the two investigations.

The first pitted intra-articular injections of two homeopathic products, Traumeel and Zeel, against placebo saline injections for knee osteoarthritis; the work was sponsored by the products’ German maker, Biologische Heilmittel Heel.

In the second trial, glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate went head to head against celecoxib (Celebrex), also for knee OA. The work was sponsored by Bioibérica, a Spanish company that makes chondroitin and glucosamine, and the investigators reported financial ties to the company.

Traumeel and Zeel may sound exotic, but they aren’t unknown in the rheumatology world – some U.S. rheumatologists are using them, Dr. Bergman, also chief of rheumatology at Taylor Hospital in Ridley Park, Pa., said.

Dr. Bergman disclosed that he has served as an advisor, speaker, or consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene, and Roche, and holds shares in Bristol-Myers Squibb, Johnson & Johnson, and Pfizer.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

MAUI, HAWAII – Two homeopathic injectables, as well as the familiar combination of glucosamine and chondroitin, showed promise in two studies of alternative treatments for osteoarthritis.

In an interview at the 2015 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium, Dr. Martin J. Bergman, of the department of rheumatology at Drexel University in Philadelphia, shared the recent results from the two investigations.

The first pitted intra-articular injections of two homeopathic products, Traumeel and Zeel, against placebo saline injections for knee osteoarthritis; the work was sponsored by the products’ German maker, Biologische Heilmittel Heel.

In the second trial, glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate went head to head against celecoxib (Celebrex), also for knee OA. The work was sponsored by Bioibérica, a Spanish company that makes chondroitin and glucosamine, and the investigators reported financial ties to the company.

Traumeel and Zeel may sound exotic, but they aren’t unknown in the rheumatology world – some U.S. rheumatologists are using them, Dr. Bergman, also chief of rheumatology at Taylor Hospital in Ridley Park, Pa., said.

Dr. Bergman disclosed that he has served as an advisor, speaker, or consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene, and Roche, and holds shares in Bristol-Myers Squibb, Johnson & Johnson, and Pfizer.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT RWCS 2015

ACL repair: ‘We have to do better’

SNOWMASS, COLO. – A novel approach to repairing anterior cruciate ligament injuries – and perhaps thereby avoiding a downstream tidal wave of knee osteoarthritis – is creating major buzz in sports medicine circles.

“You’ll probably hear much more about this bioenhanced repair, with the expectation of achieving strength equal to that of ACL reconstruction and perhaps preventing the development of osteoarthritis 15 years down the road,” Dr. M. Timothy Hresko predicted at the Winter Rheumatology Symposium sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology.

He cited research led by his colleague Dr. Martha M. Murray of Boston Children’s Hospital, which has resulted in development of a surgical technique combining a tissue-engineered composite scaffold with a suture repair of the torn ACL in what Dr. Murray has termed a bioenhanced repair.

Her work, to date preclinical, has garnered major awards from both the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine and the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. The Food and Drug Administration recently granted approval for the first clinical safety studies, to begin this year.

There is a major unmet need for better methods of repairing ACL injuries. They’re common, with an estimated 550,000 cases per year. The peak incidence occurs in 15- to 19-year-old female athletes. And the current gold standard therapy consisting of ACL reconstruction using an allograft or hamstring graft has a disturbingly high failure rate, both early and late. The graft failure rate is up to 20% in the first 2 years, climbing to 50% at 10 years.

“We just have to do better,” conceded Dr. Hresko, an orthopedic surgeon at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Boston Children’s Hospital.

“One of the interesting and unfortunate facts,” he continued, “is that roughly 80% of people who have an ACL injury, with or without reconstruction, are still going to have osteoarthritis 14 years after the injury. So, if this is your 15-year-old daughter who plays basketball, she’ll only be 30 and will already have degenerative arthritis of the knee at what should still be a very active period of life.”

The bioenhanced repair now under study uses an extracellular matrix-based scaffold, which is loaded with a few milliliters of the patient’s own platelet-enriched plasma. The scaffold is applied between the torn ligament ends in order to stimulate collagen production and promote ligament healing. The suture repair of the ligament entails much less trauma than does standard reconstructive surgery.

In large-animal studies, the bioenhanced repair resulted in the same yield load, stiffness, and other desirable biomechanical properties at 1 year as with major reconstructive surgery. However, while premature posttraumatic osteoarthritis occurred in 80% of the knees treated with standard ACL reconstruction, there was no evidence of such damage 1 year following bioenhanced repair. Nor have adverse reactions to the scaffold been noted in the porcine model.

Dr. Hresko reported serving as a consultant to Depuy Spine.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – A novel approach to repairing anterior cruciate ligament injuries – and perhaps thereby avoiding a downstream tidal wave of knee osteoarthritis – is creating major buzz in sports medicine circles.

“You’ll probably hear much more about this bioenhanced repair, with the expectation of achieving strength equal to that of ACL reconstruction and perhaps preventing the development of osteoarthritis 15 years down the road,” Dr. M. Timothy Hresko predicted at the Winter Rheumatology Symposium sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology.

He cited research led by his colleague Dr. Martha M. Murray of Boston Children’s Hospital, which has resulted in development of a surgical technique combining a tissue-engineered composite scaffold with a suture repair of the torn ACL in what Dr. Murray has termed a bioenhanced repair.

Her work, to date preclinical, has garnered major awards from both the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine and the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. The Food and Drug Administration recently granted approval for the first clinical safety studies, to begin this year.

There is a major unmet need for better methods of repairing ACL injuries. They’re common, with an estimated 550,000 cases per year. The peak incidence occurs in 15- to 19-year-old female athletes. And the current gold standard therapy consisting of ACL reconstruction using an allograft or hamstring graft has a disturbingly high failure rate, both early and late. The graft failure rate is up to 20% in the first 2 years, climbing to 50% at 10 years.

“We just have to do better,” conceded Dr. Hresko, an orthopedic surgeon at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Boston Children’s Hospital.

“One of the interesting and unfortunate facts,” he continued, “is that roughly 80% of people who have an ACL injury, with or without reconstruction, are still going to have osteoarthritis 14 years after the injury. So, if this is your 15-year-old daughter who plays basketball, she’ll only be 30 and will already have degenerative arthritis of the knee at what should still be a very active period of life.”

The bioenhanced repair now under study uses an extracellular matrix-based scaffold, which is loaded with a few milliliters of the patient’s own platelet-enriched plasma. The scaffold is applied between the torn ligament ends in order to stimulate collagen production and promote ligament healing. The suture repair of the ligament entails much less trauma than does standard reconstructive surgery.

In large-animal studies, the bioenhanced repair resulted in the same yield load, stiffness, and other desirable biomechanical properties at 1 year as with major reconstructive surgery. However, while premature posttraumatic osteoarthritis occurred in 80% of the knees treated with standard ACL reconstruction, there was no evidence of such damage 1 year following bioenhanced repair. Nor have adverse reactions to the scaffold been noted in the porcine model.

Dr. Hresko reported serving as a consultant to Depuy Spine.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – A novel approach to repairing anterior cruciate ligament injuries – and perhaps thereby avoiding a downstream tidal wave of knee osteoarthritis – is creating major buzz in sports medicine circles.

“You’ll probably hear much more about this bioenhanced repair, with the expectation of achieving strength equal to that of ACL reconstruction and perhaps preventing the development of osteoarthritis 15 years down the road,” Dr. M. Timothy Hresko predicted at the Winter Rheumatology Symposium sponsored by the American College of Rheumatology.

He cited research led by his colleague Dr. Martha M. Murray of Boston Children’s Hospital, which has resulted in development of a surgical technique combining a tissue-engineered composite scaffold with a suture repair of the torn ACL in what Dr. Murray has termed a bioenhanced repair.

Her work, to date preclinical, has garnered major awards from both the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine and the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. The Food and Drug Administration recently granted approval for the first clinical safety studies, to begin this year.

There is a major unmet need for better methods of repairing ACL injuries. They’re common, with an estimated 550,000 cases per year. The peak incidence occurs in 15- to 19-year-old female athletes. And the current gold standard therapy consisting of ACL reconstruction using an allograft or hamstring graft has a disturbingly high failure rate, both early and late. The graft failure rate is up to 20% in the first 2 years, climbing to 50% at 10 years.

“We just have to do better,” conceded Dr. Hresko, an orthopedic surgeon at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Boston Children’s Hospital.

“One of the interesting and unfortunate facts,” he continued, “is that roughly 80% of people who have an ACL injury, with or without reconstruction, are still going to have osteoarthritis 14 years after the injury. So, if this is your 15-year-old daughter who plays basketball, she’ll only be 30 and will already have degenerative arthritis of the knee at what should still be a very active period of life.”

The bioenhanced repair now under study uses an extracellular matrix-based scaffold, which is loaded with a few milliliters of the patient’s own platelet-enriched plasma. The scaffold is applied between the torn ligament ends in order to stimulate collagen production and promote ligament healing. The suture repair of the ligament entails much less trauma than does standard reconstructive surgery.

In large-animal studies, the bioenhanced repair resulted in the same yield load, stiffness, and other desirable biomechanical properties at 1 year as with major reconstructive surgery. However, while premature posttraumatic osteoarthritis occurred in 80% of the knees treated with standard ACL reconstruction, there was no evidence of such damage 1 year following bioenhanced repair. Nor have adverse reactions to the scaffold been noted in the porcine model.

Dr. Hresko reported serving as a consultant to Depuy Spine.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE WINTER RHEUMATOLOGY SYMPOSIUM

Intra-articular better than oral therapies for knee OA?

Intra-articular treatments appear to be more effective than oral therapies for knee osteoarthritis, but that may be due to their greater placebo effect, according to a report published online Jan. 5, 2015, in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Until now, the relative effectiveness of various OA treatments has been difficult to discern, in part because few studies have offered direct head-to-head comparisons, and traditional meta-analysis techniques “cannot integrate all of the evidence from several comparators.” So researchers used a network meta-analysis design that enabled multiple comparisons among five oral agents (acetaminophen, diclofenac, ibuprofen, naproxen, and celecoxib), two intra-articular agents (corticosteroids and hyaluronic acid), and two placebos. They included 137 randomized controlled trials involving 33,243 adults with primary knee OA who were treated for at least 3 months between 1980 and 2014, said Dr. Raveendhara R. Bannuru, director of the center for treatment comparison and integrative analysis, at Tufts Medical Center's Institute for Clinical Research and Health Policy Studies, Boston, and his associates.

All the treatments except acetaminophen produced clinically significant improvement in pain. Both of the intra-articular treatments, with effect sizes of up to 0.63, were superior to all of the oral treatments, with effect sizes as low as 0.18. Most striking was the finding that intra-articular hyaluronic acid was the most effective treatment of all, since it is “generally considered by expert panels to be minimally effective.” But this may be because intra-articular delivery itself was found to have a significant placebo effect (effect size of 0.29) – a result that traditional meta-analysis could not have revealed, the investigators said (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015 Jan. 5 [doi:10.7326/M14-1231]).

The study findings raise important questions about whether this is a true placebo response or a physiologic effect from injecting fluid into the knee joint. “Regardless of the mechanism of the apparent benefit attributable to needle placement in the knee, the practical reality is that this procedure contributes to the overall benefit conferred in clinical practice,” Dr. Bannuru and his associates noted.

“This information, along with the safety profiles and relative costs of [the] treatments, should be helpful to clinicians when making care decisions tailored to individual patient needs,” they wrote.

This study was supported by a grant from the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Bannuru’s associates reported ties to the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, the European League Against Rheumatism, Croma, Flexion Therapeutics, and Bioventus.

The brief treatment time of the studies included in this network meta-analysis – as short as 3 months – is an important limitation, and efficacy estimates calculated from such a short time frame may not be accurate.

Moreover, treatment durability is a crucial factor in a chronic disease such as knee OA. Long-term treatment responses cannot be determined from short-term trials, and more than half of OA pain studies, as well as more than 80% of industry-sponsored studies, are less than 6 months in duration.

Dr. Lisa A. Mandl is at the Hospital for Special Surgery, Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York. Elena Losina, Ph.D., is at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston. They made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Bannuru’s report (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015 Jan. 5 [doi:10.7326/M14-2636]).

The brief treatment time of the studies included in this network meta-analysis – as short as 3 months – is an important limitation, and efficacy estimates calculated from such a short time frame may not be accurate.

Moreover, treatment durability is a crucial factor in a chronic disease such as knee OA. Long-term treatment responses cannot be determined from short-term trials, and more than half of OA pain studies, as well as more than 80% of industry-sponsored studies, are less than 6 months in duration.

Dr. Lisa A. Mandl is at the Hospital for Special Surgery, Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York. Elena Losina, Ph.D., is at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston. They made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Bannuru’s report (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015 Jan. 5 [doi:10.7326/M14-2636]).

The brief treatment time of the studies included in this network meta-analysis – as short as 3 months – is an important limitation, and efficacy estimates calculated from such a short time frame may not be accurate.

Moreover, treatment durability is a crucial factor in a chronic disease such as knee OA. Long-term treatment responses cannot be determined from short-term trials, and more than half of OA pain studies, as well as more than 80% of industry-sponsored studies, are less than 6 months in duration.

Dr. Lisa A. Mandl is at the Hospital for Special Surgery, Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York. Elena Losina, Ph.D., is at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston. They made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Bannuru’s report (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015 Jan. 5 [doi:10.7326/M14-2636]).

Intra-articular treatments appear to be more effective than oral therapies for knee osteoarthritis, but that may be due to their greater placebo effect, according to a report published online Jan. 5, 2015, in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Until now, the relative effectiveness of various OA treatments has been difficult to discern, in part because few studies have offered direct head-to-head comparisons, and traditional meta-analysis techniques “cannot integrate all of the evidence from several comparators.” So researchers used a network meta-analysis design that enabled multiple comparisons among five oral agents (acetaminophen, diclofenac, ibuprofen, naproxen, and celecoxib), two intra-articular agents (corticosteroids and hyaluronic acid), and two placebos. They included 137 randomized controlled trials involving 33,243 adults with primary knee OA who were treated for at least 3 months between 1980 and 2014, said Dr. Raveendhara R. Bannuru, director of the center for treatment comparison and integrative analysis, at Tufts Medical Center's Institute for Clinical Research and Health Policy Studies, Boston, and his associates.

All the treatments except acetaminophen produced clinically significant improvement in pain. Both of the intra-articular treatments, with effect sizes of up to 0.63, were superior to all of the oral treatments, with effect sizes as low as 0.18. Most striking was the finding that intra-articular hyaluronic acid was the most effective treatment of all, since it is “generally considered by expert panels to be minimally effective.” But this may be because intra-articular delivery itself was found to have a significant placebo effect (effect size of 0.29) – a result that traditional meta-analysis could not have revealed, the investigators said (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015 Jan. 5 [doi:10.7326/M14-1231]).

The study findings raise important questions about whether this is a true placebo response or a physiologic effect from injecting fluid into the knee joint. “Regardless of the mechanism of the apparent benefit attributable to needle placement in the knee, the practical reality is that this procedure contributes to the overall benefit conferred in clinical practice,” Dr. Bannuru and his associates noted.

“This information, along with the safety profiles and relative costs of [the] treatments, should be helpful to clinicians when making care decisions tailored to individual patient needs,” they wrote.

This study was supported by a grant from the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Bannuru’s associates reported ties to the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, the European League Against Rheumatism, Croma, Flexion Therapeutics, and Bioventus.

Intra-articular treatments appear to be more effective than oral therapies for knee osteoarthritis, but that may be due to their greater placebo effect, according to a report published online Jan. 5, 2015, in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Until now, the relative effectiveness of various OA treatments has been difficult to discern, in part because few studies have offered direct head-to-head comparisons, and traditional meta-analysis techniques “cannot integrate all of the evidence from several comparators.” So researchers used a network meta-analysis design that enabled multiple comparisons among five oral agents (acetaminophen, diclofenac, ibuprofen, naproxen, and celecoxib), two intra-articular agents (corticosteroids and hyaluronic acid), and two placebos. They included 137 randomized controlled trials involving 33,243 adults with primary knee OA who were treated for at least 3 months between 1980 and 2014, said Dr. Raveendhara R. Bannuru, director of the center for treatment comparison and integrative analysis, at Tufts Medical Center's Institute for Clinical Research and Health Policy Studies, Boston, and his associates.

All the treatments except acetaminophen produced clinically significant improvement in pain. Both of the intra-articular treatments, with effect sizes of up to 0.63, were superior to all of the oral treatments, with effect sizes as low as 0.18. Most striking was the finding that intra-articular hyaluronic acid was the most effective treatment of all, since it is “generally considered by expert panels to be minimally effective.” But this may be because intra-articular delivery itself was found to have a significant placebo effect (effect size of 0.29) – a result that traditional meta-analysis could not have revealed, the investigators said (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015 Jan. 5 [doi:10.7326/M14-1231]).

The study findings raise important questions about whether this is a true placebo response or a physiologic effect from injecting fluid into the knee joint. “Regardless of the mechanism of the apparent benefit attributable to needle placement in the knee, the practical reality is that this procedure contributes to the overall benefit conferred in clinical practice,” Dr. Bannuru and his associates noted.

“This information, along with the safety profiles and relative costs of [the] treatments, should be helpful to clinicians when making care decisions tailored to individual patient needs,” they wrote.

This study was supported by a grant from the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Bannuru’s associates reported ties to the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, the European League Against Rheumatism, Croma, Flexion Therapeutics, and Bioventus.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Intra-articular treatments appear more effective than oral therapies for knee OA, but that may be due their greater placebo effect.

Major finding: Both of the intra-articular treatments, with effect sizes of up to 0.63, were superior to all of the oral treatments, with effect sizes as low as 0.18.

Data source: A network meta-analysis of 137 randomized controlled trials involving 33,243 patients, which directly compared different treatments for knee OA.

Disclosures: This study was supported by a grant from the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Bannuru’s associates reported ties to the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, the European League Against Rheumatism, Croma, Flexion Therapeutics, and Bioventus.

VIDEO: No need to stop running for fear of knee osteoarthritis

BOSTON– Current running or a history of running did not raise the odds of knee osteoarthritis in the first population-based study of runners.

Until this cross-sectional analysis of participants in the Osteoarthritis Initiative, most studies examining the risk of knee osteoarthritis from running analyzed elite runners and other high-level runners, making them less generalizable to a larger population, according to Dr. Grace Hsiao-Wei Lo of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

The findings of no higher odds of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis, compared with nonrunners, were largely consistent across age groupings of runners from 12-18 years of age up to 50 years and older, Dr. Lo said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

BOSTON– Current running or a history of running did not raise the odds of knee osteoarthritis in the first population-based study of runners.

Until this cross-sectional analysis of participants in the Osteoarthritis Initiative, most studies examining the risk of knee osteoarthritis from running analyzed elite runners and other high-level runners, making them less generalizable to a larger population, according to Dr. Grace Hsiao-Wei Lo of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

The findings of no higher odds of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis, compared with nonrunners, were largely consistent across age groupings of runners from 12-18 years of age up to 50 years and older, Dr. Lo said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

BOSTON– Current running or a history of running did not raise the odds of knee osteoarthritis in the first population-based study of runners.

Until this cross-sectional analysis of participants in the Osteoarthritis Initiative, most studies examining the risk of knee osteoarthritis from running analyzed elite runners and other high-level runners, making them less generalizable to a larger population, according to Dr. Grace Hsiao-Wei Lo of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

The findings of no higher odds of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis, compared with nonrunners, were largely consistent across age groupings of runners from 12-18 years of age up to 50 years and older, Dr. Lo said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT THE ACR ANNUAL MEETING

Running history doesn’t contribute to knee OA risk

BOSTON– A history of current or past running did not contribute to a higher odds of developing knee osteoarthritis and may even have a slight protective effect, researchers found in a cross-sectional study of participants in the Osteoarthritis Initiative.

“Although this study does not address the question of whether or not running is harmful in people who do have preexisting knee OA [osteoarthritis], among people who do not have knee OA, [the study indicates that] there is no reason to restrict participation in habitual running at any time in life from the perspective that it does not appear to be harmful to the knee joint,” lead author Dr. Grace Hsiao-Wei Lo said at a press briefing at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Physical activities guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend that adults get at least 75 minutes per week of physical activity at a vigorous intensity, which includes running or jogging, noted Dr. Lo of the section of immunology, allergy, and rheumatology at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

The study, which is among the first to examine the potential relationship between running and OA in a population-based study of nonelite or high-level runners, included 2,683 participants (44% male) with a mean age of 64 years and mean body-mass index (BMI) of 28 kg/m2. The investigators found that 29% self-identified as runners as some point in their life up to their inclusion into study, with running history occurring in 49% of those aged older than 50 years, 31% in those aged 35-49 years, 15% in those aged 19-34 years, and 9% in those aged 12-18 years. Patients were identified as runners if they listed it as one of their top three activities during those periods. Runners were slightly younger than the overall population with a mean age of 62 years and were more often male (62%). Nonrunners had a mean age of 65 years and were less often male (36%). BMI did not differ between the two.

Knee pain was significantly less prevalent in runners than in nonrunners (35% vs. 42%, respectively), and runners were 13% less likely to have knee pain (odds ratio, 0.87). The relationship did not change after controlling for age, sex, and BMI.

Radiographic knee OA with a Kellgren-Lawrence grade of 2 or more also was significantly less common among runners than among nonrunners (54% vs. 60%), but the relationship was not significant after controlling for the same variables.

Symptomatic radiographic OA – defined as having at least one knee with both radiographic knee OA and frequent knee pain – occurred in 23% of runners and 30% of nonrunners. The significantly lower likelihood for runners to develop symptomatic knee OA than non-runners (OR, 0.83) was slightly attenuated after controlling for age, sex, and BMI, but remained statistically significant.

“When we did look at each individual age range, the results were very similar. Some of the results were no longer statistically significant, but the results were generally in the same direction,” Dr. Lo noted.

Previous studies that have examined the relationship between running and the development of knee OA have been limited in their generalizability to the general population because of the inclusion of elite runners and those with a high level of running as well as small sample size, Dr. Lo said. Self-selection as runners is an important limitation of this cross-sectional, observational study because “there’s always the possibility that people stopped running because they developed knee symptoms,” she said.

Dr. Lo said that her work on the study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. None of the other authors had disclosures.

BOSTON– A history of current or past running did not contribute to a higher odds of developing knee osteoarthritis and may even have a slight protective effect, researchers found in a cross-sectional study of participants in the Osteoarthritis Initiative.

“Although this study does not address the question of whether or not running is harmful in people who do have preexisting knee OA [osteoarthritis], among people who do not have knee OA, [the study indicates that] there is no reason to restrict participation in habitual running at any time in life from the perspective that it does not appear to be harmful to the knee joint,” lead author Dr. Grace Hsiao-Wei Lo said at a press briefing at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Physical activities guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend that adults get at least 75 minutes per week of physical activity at a vigorous intensity, which includes running or jogging, noted Dr. Lo of the section of immunology, allergy, and rheumatology at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

The study, which is among the first to examine the potential relationship between running and OA in a population-based study of nonelite or high-level runners, included 2,683 participants (44% male) with a mean age of 64 years and mean body-mass index (BMI) of 28 kg/m2. The investigators found that 29% self-identified as runners as some point in their life up to their inclusion into study, with running history occurring in 49% of those aged older than 50 years, 31% in those aged 35-49 years, 15% in those aged 19-34 years, and 9% in those aged 12-18 years. Patients were identified as runners if they listed it as one of their top three activities during those periods. Runners were slightly younger than the overall population with a mean age of 62 years and were more often male (62%). Nonrunners had a mean age of 65 years and were less often male (36%). BMI did not differ between the two.

Knee pain was significantly less prevalent in runners than in nonrunners (35% vs. 42%, respectively), and runners were 13% less likely to have knee pain (odds ratio, 0.87). The relationship did not change after controlling for age, sex, and BMI.

Radiographic knee OA with a Kellgren-Lawrence grade of 2 or more also was significantly less common among runners than among nonrunners (54% vs. 60%), but the relationship was not significant after controlling for the same variables.

Symptomatic radiographic OA – defined as having at least one knee with both radiographic knee OA and frequent knee pain – occurred in 23% of runners and 30% of nonrunners. The significantly lower likelihood for runners to develop symptomatic knee OA than non-runners (OR, 0.83) was slightly attenuated after controlling for age, sex, and BMI, but remained statistically significant.

“When we did look at each individual age range, the results were very similar. Some of the results were no longer statistically significant, but the results were generally in the same direction,” Dr. Lo noted.

Previous studies that have examined the relationship between running and the development of knee OA have been limited in their generalizability to the general population because of the inclusion of elite runners and those with a high level of running as well as small sample size, Dr. Lo said. Self-selection as runners is an important limitation of this cross-sectional, observational study because “there’s always the possibility that people stopped running because they developed knee symptoms,” she said.

Dr. Lo said that her work on the study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. None of the other authors had disclosures.

BOSTON– A history of current or past running did not contribute to a higher odds of developing knee osteoarthritis and may even have a slight protective effect, researchers found in a cross-sectional study of participants in the Osteoarthritis Initiative.

“Although this study does not address the question of whether or not running is harmful in people who do have preexisting knee OA [osteoarthritis], among people who do not have knee OA, [the study indicates that] there is no reason to restrict participation in habitual running at any time in life from the perspective that it does not appear to be harmful to the knee joint,” lead author Dr. Grace Hsiao-Wei Lo said at a press briefing at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Physical activities guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend that adults get at least 75 minutes per week of physical activity at a vigorous intensity, which includes running or jogging, noted Dr. Lo of the section of immunology, allergy, and rheumatology at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

The study, which is among the first to examine the potential relationship between running and OA in a population-based study of nonelite or high-level runners, included 2,683 participants (44% male) with a mean age of 64 years and mean body-mass index (BMI) of 28 kg/m2. The investigators found that 29% self-identified as runners as some point in their life up to their inclusion into study, with running history occurring in 49% of those aged older than 50 years, 31% in those aged 35-49 years, 15% in those aged 19-34 years, and 9% in those aged 12-18 years. Patients were identified as runners if they listed it as one of their top three activities during those periods. Runners were slightly younger than the overall population with a mean age of 62 years and were more often male (62%). Nonrunners had a mean age of 65 years and were less often male (36%). BMI did not differ between the two.

Knee pain was significantly less prevalent in runners than in nonrunners (35% vs. 42%, respectively), and runners were 13% less likely to have knee pain (odds ratio, 0.87). The relationship did not change after controlling for age, sex, and BMI.

Radiographic knee OA with a Kellgren-Lawrence grade of 2 or more also was significantly less common among runners than among nonrunners (54% vs. 60%), but the relationship was not significant after controlling for the same variables.

Symptomatic radiographic OA – defined as having at least one knee with both radiographic knee OA and frequent knee pain – occurred in 23% of runners and 30% of nonrunners. The significantly lower likelihood for runners to develop symptomatic knee OA than non-runners (OR, 0.83) was slightly attenuated after controlling for age, sex, and BMI, but remained statistically significant.

“When we did look at each individual age range, the results were very similar. Some of the results were no longer statistically significant, but the results were generally in the same direction,” Dr. Lo noted.

Previous studies that have examined the relationship between running and the development of knee OA have been limited in their generalizability to the general population because of the inclusion of elite runners and those with a high level of running as well as small sample size, Dr. Lo said. Self-selection as runners is an important limitation of this cross-sectional, observational study because “there’s always the possibility that people stopped running because they developed knee symptoms,” she said.

Dr. Lo said that her work on the study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. None of the other authors had disclosures.

AT THE ACR ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: There’s no need to restrict habitual running in people who don’t already have knee OA.

Major finding: Symptomatic radiographic OA occurred in 23% of runners and 30% of nonrunners

Data source: A cross-sectional study of 2,683 community-dwelling participants in the Osteoarthritis Initiative.

Disclosures: Dr. Lo said that her work on the study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. None of the other authors had disclosures.

OA patients benefit long term from exercise or manual therapy

BOSTON – Improvements in pain, stiffness, and physical function that occur with the addition of exercise therapy or manual therapy to usual care for patients at all stages of osteoarthritis extended out to 2 years in a randomized, controlled trial.

Although evidence already supports the use of exercise therapy or manual therapy for improving the symptoms and physical function of patients with osteoarthritis (OA), the trial is the first to show that either intervention provides benefits over and above that of usual care during the course of 2 years of follow-up.

The investigators, led by Dr. Haxby Abbott of the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand, randomized 206 patients who met American College of Rheumatology criteria for knee or hip OA to usual care alone, exercise therapy plus usual care, manual therapy plus usual care, or both interventions plus usual care.

Those who received one or both of the interventions underwent 10 treatment sessions, including 7 sessions within the first 9 weeks plus 3 booster sessions (2 at 4 months and 1 at 13 months). Between and after those sessions, participants carried out the interventions on their own.

Mean age of the patients was 66 years. The spectrum of OA ranged from mild to severe, with a mean Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) OA index score of 100.8. The patients had been recruited to the trial from primary care and orthopedic services, the investigators reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Exercise therapy consisted of strengthening, range-of-motion, neuromuscular coordination, and aerobics activities; manual therapy consisted of skilled passive movement to joints applied by external force. Physical therapists guided both interventions in one-on-one visits.

The 1-year results, which were published in 2013, showed significant decreases in pain and improvements in physical function in both single-intervention groups, but no significant improvement in the combined therapy group (Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013;21:525-34).

Among the 186 patients who still remained in the study at 2 years of follow-up, scores on the WOMAC – the trial’s primary outcome – improved by 31.7 points in those who received exercise therapy plus usual care, compared with usual care alone, while patients receiving manual therapy in addition to usual care showed a relative improvement of 30.1 points. While the difference in WOMAC improvement for participants receiving combined exercise therapy and manual therapy in addition to usual care did not meet the a priori threshold for clinical significance (28 points), there was a trend toward benefit, with this group improving 26.2 points more than usual care only.

In all three intervention groups, Dr. Abbott noted that those changes represented greater than 20% declines in WOMAC scores from baseline.

In a planned subanalysis that did not include the approximately 20% of patients in each group who had joint replacement surgery, there was still an improvement in scores from baseline to 2 years, whereas those who received usual care alone were 20% worse, he said.

The effect sizes in the exercise group (0.57), manual therapy group (0.55), and combined therapy group (0.55) were substantially better than were the effect sizes of 0.30-0.35 normally attributed to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, Dr. Abbott said. When patients with joint surgery were dropped from the analysis, those effect sizes grew to as high as 0.70 in the manual therapy group.

On the second primary outcome of several physical performance tests (timed up-and-go, 40-meter fast-paced walk, and 30-second sit-to-stand), the participants in the exercise therapy group showed greater mean changes than did patients in the other groups.

The Health Research Council of New Zealand funded the trial. None of the investigators had disclosures.

BOSTON – Improvements in pain, stiffness, and physical function that occur with the addition of exercise therapy or manual therapy to usual care for patients at all stages of osteoarthritis extended out to 2 years in a randomized, controlled trial.

Although evidence already supports the use of exercise therapy or manual therapy for improving the symptoms and physical function of patients with osteoarthritis (OA), the trial is the first to show that either intervention provides benefits over and above that of usual care during the course of 2 years of follow-up.

The investigators, led by Dr. Haxby Abbott of the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand, randomized 206 patients who met American College of Rheumatology criteria for knee or hip OA to usual care alone, exercise therapy plus usual care, manual therapy plus usual care, or both interventions plus usual care.

Those who received one or both of the interventions underwent 10 treatment sessions, including 7 sessions within the first 9 weeks plus 3 booster sessions (2 at 4 months and 1 at 13 months). Between and after those sessions, participants carried out the interventions on their own.

Mean age of the patients was 66 years. The spectrum of OA ranged from mild to severe, with a mean Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) OA index score of 100.8. The patients had been recruited to the trial from primary care and orthopedic services, the investigators reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Exercise therapy consisted of strengthening, range-of-motion, neuromuscular coordination, and aerobics activities; manual therapy consisted of skilled passive movement to joints applied by external force. Physical therapists guided both interventions in one-on-one visits.

The 1-year results, which were published in 2013, showed significant decreases in pain and improvements in physical function in both single-intervention groups, but no significant improvement in the combined therapy group (Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013;21:525-34).

Among the 186 patients who still remained in the study at 2 years of follow-up, scores on the WOMAC – the trial’s primary outcome – improved by 31.7 points in those who received exercise therapy plus usual care, compared with usual care alone, while patients receiving manual therapy in addition to usual care showed a relative improvement of 30.1 points. While the difference in WOMAC improvement for participants receiving combined exercise therapy and manual therapy in addition to usual care did not meet the a priori threshold for clinical significance (28 points), there was a trend toward benefit, with this group improving 26.2 points more than usual care only.

In all three intervention groups, Dr. Abbott noted that those changes represented greater than 20% declines in WOMAC scores from baseline.

In a planned subanalysis that did not include the approximately 20% of patients in each group who had joint replacement surgery, there was still an improvement in scores from baseline to 2 years, whereas those who received usual care alone were 20% worse, he said.

The effect sizes in the exercise group (0.57), manual therapy group (0.55), and combined therapy group (0.55) were substantially better than were the effect sizes of 0.30-0.35 normally attributed to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, Dr. Abbott said. When patients with joint surgery were dropped from the analysis, those effect sizes grew to as high as 0.70 in the manual therapy group.

On the second primary outcome of several physical performance tests (timed up-and-go, 40-meter fast-paced walk, and 30-second sit-to-stand), the participants in the exercise therapy group showed greater mean changes than did patients in the other groups.

The Health Research Council of New Zealand funded the trial. None of the investigators had disclosures.

BOSTON – Improvements in pain, stiffness, and physical function that occur with the addition of exercise therapy or manual therapy to usual care for patients at all stages of osteoarthritis extended out to 2 years in a randomized, controlled trial.

Although evidence already supports the use of exercise therapy or manual therapy for improving the symptoms and physical function of patients with osteoarthritis (OA), the trial is the first to show that either intervention provides benefits over and above that of usual care during the course of 2 years of follow-up.

The investigators, led by Dr. Haxby Abbott of the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand, randomized 206 patients who met American College of Rheumatology criteria for knee or hip OA to usual care alone, exercise therapy plus usual care, manual therapy plus usual care, or both interventions plus usual care.

Those who received one or both of the interventions underwent 10 treatment sessions, including 7 sessions within the first 9 weeks plus 3 booster sessions (2 at 4 months and 1 at 13 months). Between and after those sessions, participants carried out the interventions on their own.

Mean age of the patients was 66 years. The spectrum of OA ranged from mild to severe, with a mean Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) OA index score of 100.8. The patients had been recruited to the trial from primary care and orthopedic services, the investigators reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Exercise therapy consisted of strengthening, range-of-motion, neuromuscular coordination, and aerobics activities; manual therapy consisted of skilled passive movement to joints applied by external force. Physical therapists guided both interventions in one-on-one visits.

The 1-year results, which were published in 2013, showed significant decreases in pain and improvements in physical function in both single-intervention groups, but no significant improvement in the combined therapy group (Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013;21:525-34).

Among the 186 patients who still remained in the study at 2 years of follow-up, scores on the WOMAC – the trial’s primary outcome – improved by 31.7 points in those who received exercise therapy plus usual care, compared with usual care alone, while patients receiving manual therapy in addition to usual care showed a relative improvement of 30.1 points. While the difference in WOMAC improvement for participants receiving combined exercise therapy and manual therapy in addition to usual care did not meet the a priori threshold for clinical significance (28 points), there was a trend toward benefit, with this group improving 26.2 points more than usual care only.

In all three intervention groups, Dr. Abbott noted that those changes represented greater than 20% declines in WOMAC scores from baseline.

In a planned subanalysis that did not include the approximately 20% of patients in each group who had joint replacement surgery, there was still an improvement in scores from baseline to 2 years, whereas those who received usual care alone were 20% worse, he said.

The effect sizes in the exercise group (0.57), manual therapy group (0.55), and combined therapy group (0.55) were substantially better than were the effect sizes of 0.30-0.35 normally attributed to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, Dr. Abbott said. When patients with joint surgery were dropped from the analysis, those effect sizes grew to as high as 0.70 in the manual therapy group.

On the second primary outcome of several physical performance tests (timed up-and-go, 40-meter fast-paced walk, and 30-second sit-to-stand), the participants in the exercise therapy group showed greater mean changes than did patients in the other groups.

The Health Research Council of New Zealand funded the trial. None of the investigators had disclosures.

AT THE ACR ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Prescribing exercise therapy or manual therapy to patients in various stages of OA can provide long-term benefit in addition to usual care.

Major finding: At 2 years, relative to usual care alone, scores on the WOMAC had improved by 31.7 points in those who received exercise therapy plus usual care, 30.1 points in patients on manual therapy in addition to usual care, and 26.2 points in those who received combined exercise therapy and manual therapy in addition to usual care.

Data source: A trial of 206 patients with OA who were randomized to usual care alone, exercise therapy plus usual care, manual therapy plus usual care, or both interventions plus usual care.

Disclosures: The Health Research Council of New Zealand funded the trial. None of the investigators had disclosures.

VIDEO: Exercise, manual therapy for OA add incremental benefits to usual care

BOSTON – Exercise therapy or manual therapy provide benefits for improving osteoarthritis symptoms and physical function that go over and above what is obtained with usual care alone, according to results from a randomized, controlled trial.

The trial is the first to show the additive effect of manual therapy or exercise therapy on top of usual care. The results of the trial, which had 2 years of follow-up, indicate that in the absence of predictive factors, clinicians should prescribe either one of the interventions based on patient preference in addition to the usual care of NSAIDs and other adjunctive treatments such as massage therapy or specialized footwear, lead investigator Dr. Haxby Abbott of the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

BOSTON – Exercise therapy or manual therapy provide benefits for improving osteoarthritis symptoms and physical function that go over and above what is obtained with usual care alone, according to results from a randomized, controlled trial.

The trial is the first to show the additive effect of manual therapy or exercise therapy on top of usual care. The results of the trial, which had 2 years of follow-up, indicate that in the absence of predictive factors, clinicians should prescribe either one of the interventions based on patient preference in addition to the usual care of NSAIDs and other adjunctive treatments such as massage therapy or specialized footwear, lead investigator Dr. Haxby Abbott of the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

BOSTON – Exercise therapy or manual therapy provide benefits for improving osteoarthritis symptoms and physical function that go over and above what is obtained with usual care alone, according to results from a randomized, controlled trial.

The trial is the first to show the additive effect of manual therapy or exercise therapy on top of usual care. The results of the trial, which had 2 years of follow-up, indicate that in the absence of predictive factors, clinicians should prescribe either one of the interventions based on patient preference in addition to the usual care of NSAIDs and other adjunctive treatments such as massage therapy or specialized footwear, lead investigator Dr. Haxby Abbott of the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT THE ACR ANNUAL MEETING

Veterans more likely to have arthritis at any age

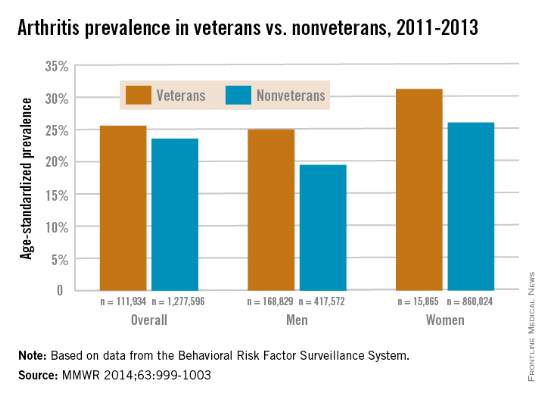

Both male and female veterans were more likely to have arthritis than were nonveterans, according to a study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For male veterans, the age-standardized arthritis rate for 2011-2013 was 25%, while for male nonveterans, the rate was 19.5%. Both female veterans and nonveterans had noticeably higher arthritis incidence than did the respective male group: 31.3% for veterans and 26.1% for nonveterans, the CDC found (MMWR 2014;63:999-1003).

Although arthritis rates were higher overall in middle-aged and older people, arthritis rates were consistently higher in younger veterans aged 18-44 years – 11.6% for males and 17.3% for females – compared with 6.9% in male nonveterans and 9.8% in female nonveterans. This suggests “that arthritis and its effects need to be addressed among male and female veterans of all ages,” the CDC researchers said.

Traumatic and overuse injuries were found to be common among active-duty military personnel in another study, the investigators noted, while pointing out that musculoskeletal injuries are a major risk factor for osteoarthritis, which “represents the largest portion of arthritis cases” among veterans.

The study used data collected by the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

Both male and female veterans were more likely to have arthritis than were nonveterans, according to a study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For male veterans, the age-standardized arthritis rate for 2011-2013 was 25%, while for male nonveterans, the rate was 19.5%. Both female veterans and nonveterans had noticeably higher arthritis incidence than did the respective male group: 31.3% for veterans and 26.1% for nonveterans, the CDC found (MMWR 2014;63:999-1003).

Although arthritis rates were higher overall in middle-aged and older people, arthritis rates were consistently higher in younger veterans aged 18-44 years – 11.6% for males and 17.3% for females – compared with 6.9% in male nonveterans and 9.8% in female nonveterans. This suggests “that arthritis and its effects need to be addressed among male and female veterans of all ages,” the CDC researchers said.

Traumatic and overuse injuries were found to be common among active-duty military personnel in another study, the investigators noted, while pointing out that musculoskeletal injuries are a major risk factor for osteoarthritis, which “represents the largest portion of arthritis cases” among veterans.

The study used data collected by the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

Both male and female veterans were more likely to have arthritis than were nonveterans, according to a study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For male veterans, the age-standardized arthritis rate for 2011-2013 was 25%, while for male nonveterans, the rate was 19.5%. Both female veterans and nonveterans had noticeably higher arthritis incidence than did the respective male group: 31.3% for veterans and 26.1% for nonveterans, the CDC found (MMWR 2014;63:999-1003).

Although arthritis rates were higher overall in middle-aged and older people, arthritis rates were consistently higher in younger veterans aged 18-44 years – 11.6% for males and 17.3% for females – compared with 6.9% in male nonveterans and 9.8% in female nonveterans. This suggests “that arthritis and its effects need to be addressed among male and female veterans of all ages,” the CDC researchers said.