User login

Considerations on the mode of delivery for pregnant women with hepatitis C infection

CASE Pregnant woman with chronic opioid use and HIV, recently diagnosed with HCV

A 34-year-old primigravid woman at 35 weeks' gestation has a history of chronic opioid use. She previously was diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and has been treated with a 3-drug combination antiretroviral regimen. Her most recent HIV viral load was 750 copies/mL. Three weeks ago, she tested positive for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Liver function tests showed mild elevations in transaminase levels. The viral genotype is 1, and the viral load is 2.6 million copies/mL.

How should this patient be delivered? Should she be encouraged to breastfeed her neonate?

The scope of HCV infection

Hepatitis C virus is a positive-sense, enveloped, single-stranded RNA virus that belongs to the Flaviviridae family.1 There are 7 confirmed major genotypes of HCV and 67 confirmed subtypes.2 HCV possesses several important virulence factors. First, the virus's replication is prone to frequent mutations because its RNA polymerase lacks proofreading activity, resulting in significant genetic diversity. The great degree of heterogeneity among HCV leads to high antigenic variability, which is one of the main reasons there is not yet a vaccine for HCV.3 Additionally, HCV's genomic plasticity plays a role in the emergence of drug-resistant variants.4

Virus transmission. Worldwide, approximately 130 to 170 million people are infected with HCV.5 HCV infections are caused primarily by exposure to infected blood, through sharing needles for intravenous drug injection and through receiving a blood transfusion.6 Other routes of transmission include exposure through sexual contact, occupational injury, and perinatal acquisition.

The risk of acquiring HCV varies for each of these transmission mechanisms. Blood transfusion is no longer a common mechanism of transmission in places where blood donations are screened for HCV antibodies and viral RNA. Additionally, unintentional needle-stick injury is the only occupational risk factor associated with HCV infection, and health care workers do not have a greater prevalence of HCV than the general population. Moreover, sexual transmission is not a particularly efficient mechanism for spread of HCV.7 Therefore, unsafe intravenous injections are now the leading cause of HCV infection.6

Consequences of HCV infection. Once infected with HCV, about 25% of people spontaneously clear the virus and approximately 75% progress to chronic HCV infection.5 The consequences of long-term infection with HCV include end-stage liver disease, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Approximately 30% of people infected with HCV will develop cirrhosis and another 2% will develop hepatocellular carcinoma.8 Liver transplant is the only treatment option for patients with decompensated cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma as a result of HCV infection. Currently, HCV infection is the leading indication for liver transplant in the United States.9

Continue to: Risk of perinatal HCV transmission...

Risk of perinatal HCV transmission

Approximately 1% to 8% of pregnant women worldwide are infected with HCV.10 In the United States, 1% to 2.5% of pregnant women are infected.11 Of these, about 6% transmit the infection to their offspring. The risk of HCV vertical transmission increases to about 11% if the mother is co-infected with HIV.12 Vertical transmission is the primary method by which children become infected with HCV.13

Several risk factors increase the likelihood of HCV transmission from mother to child, including HIV co-infection, internal fetal monitoring, and longer duration of membrane rupture.14 The effect that mode of delivery has on vertical transmission rates, however, is still debated, and a Cochrane Review found that there were no randomized controlled trials assessing the effect of mode of delivery on mother-to-infant HCV transmission.15

Serology and genotyping used in diagnosis

The serological enzyme immunoassay is the first test used in screening for HCV infection. Currently, third- and fourth-generation enzyme immunoassays are used in the United States.16 However, even these newer serological assays cannot consistently and precisely distinguish between acute and chronic HCV infections.17 After the initial diagnosis is made with serology, it usually is confirmed by assays that detect the virus's genomic RNA in the patient's serum or plasma.

The patient's HCV genotype should be identified so that the best treatment options can be determined. HCV genotyping can be accomplished using reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) amplification. Three different RT-qPCR assessments usually are performed using different primers and probes specific to different genotypes of HCV. While direct sequencing of the HCV genome also can be performed, this method is usually not used clinically due to its technical complexity.16

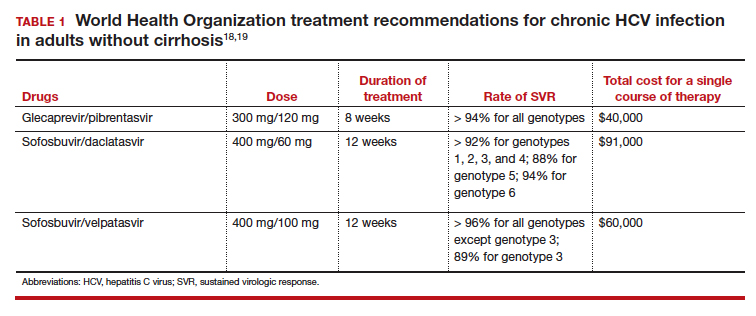

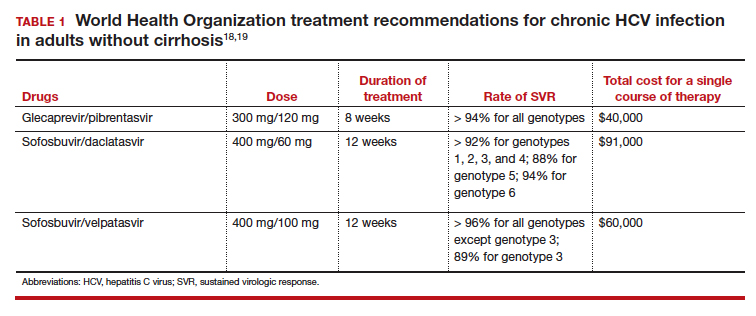

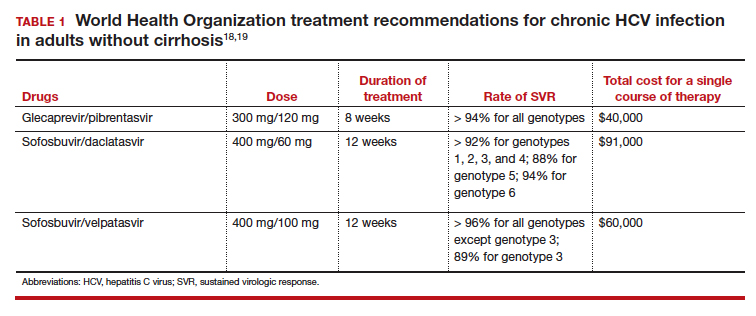

Modern treatments are effective

Introduced in 2011, direct-acting antiviral therapies are now the recommended treatment for HCV infection. These drugs inhibit the virus's replication by targeting different proteins involved in the HCV replication cycle. They are remarkably successful and have achieved sustained virologic response (SVR) rates greater than 90%.11 The World Health Organization recommends several pangenotypic (that is, agents that work against all genotypes) direct-acting antiviral regimens for the treatment of chronic HCV infection in adults without cirrhosis (TABLE 1).18,19

Unfortunately, experience with these drugs in pregnant women is lacking. Many direct-acting antiviral agents have not been tested systematically in pregnant women, and, accordingly, most information about their effects in pregnant women comes from animal models.11

Continue to: Perinatal transmission rates and effect of mode of delivery...

Perinatal transmission rates and effect of mode of delivery

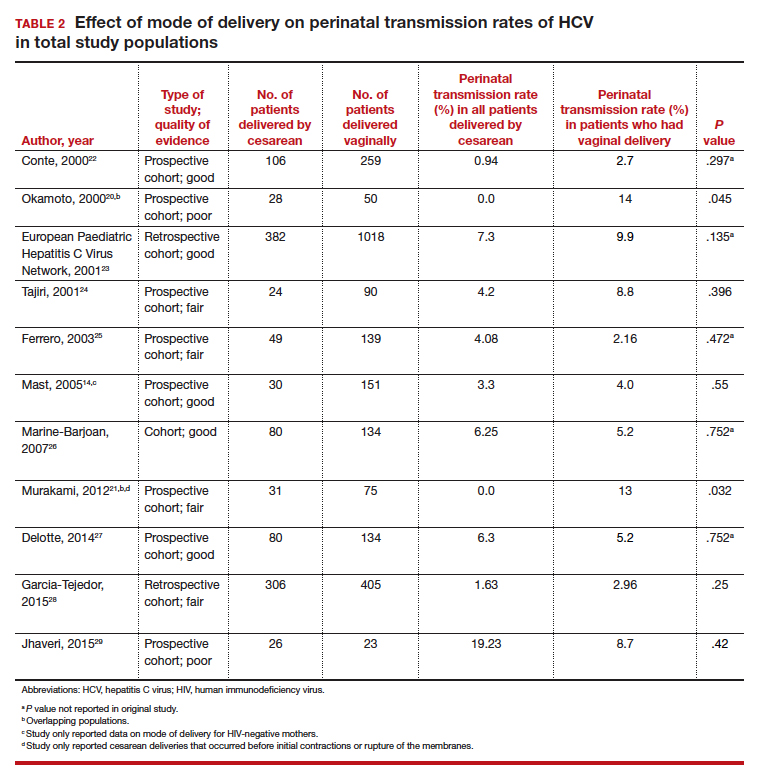

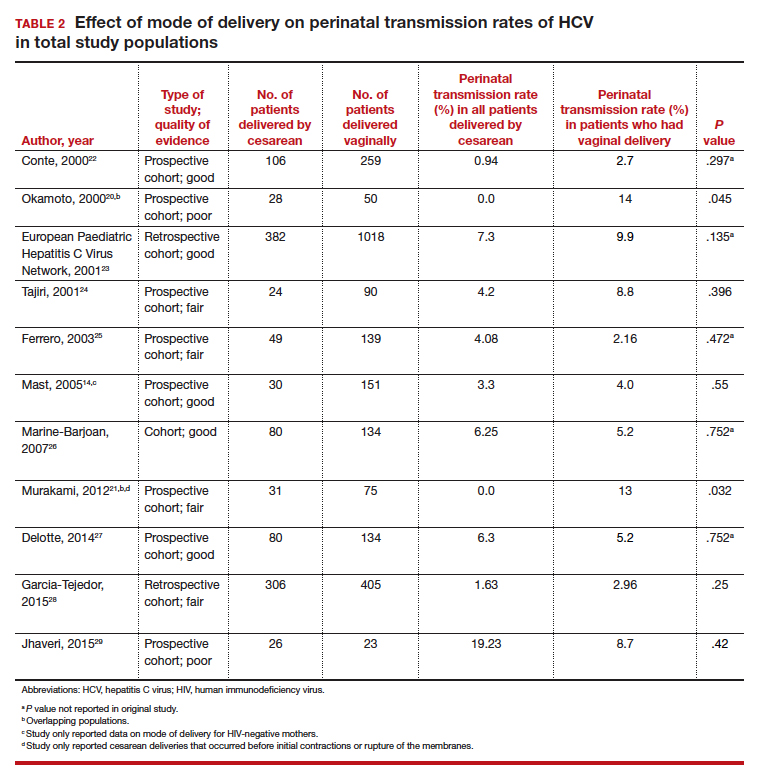

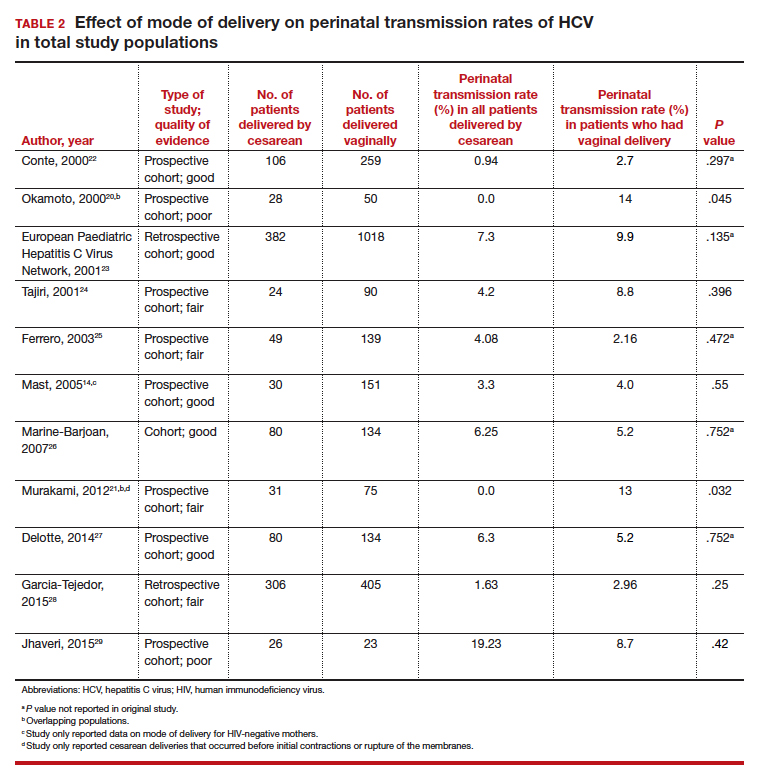

We compiled data from 11 studies that reported the perinatal transmission rate of HCV associated with various modes of delivery. These studies were selected from a MEDLINE literature review from 1999 to 2019. The studies were screened first by title and, subsequently, by abstract. Inclusion was restricted to randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, and case-control studies written in English. Study quality was assessed as good, fair, or poor based on the study design, sample size, and statistical analyses performed. The results from the total population of each study are reported in TABLE 2.14,20-29

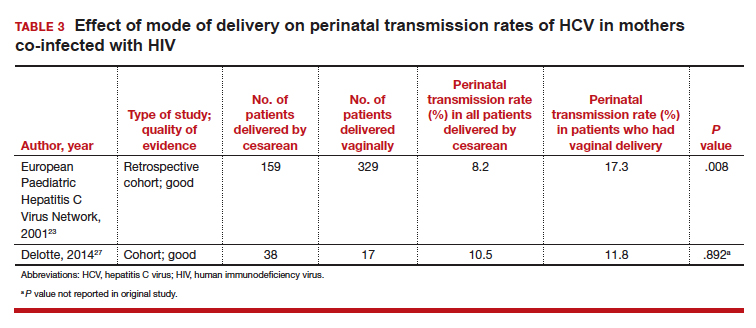

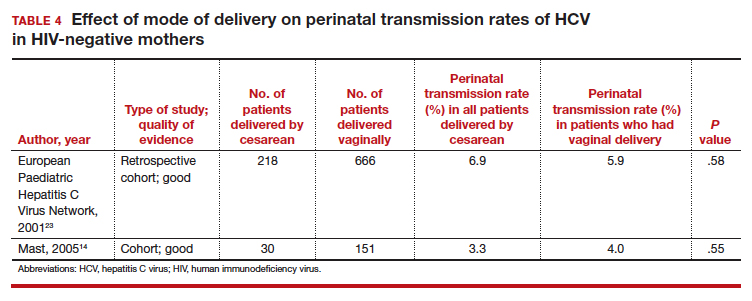

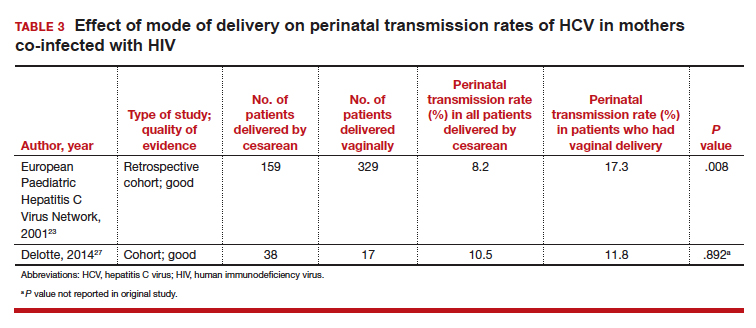

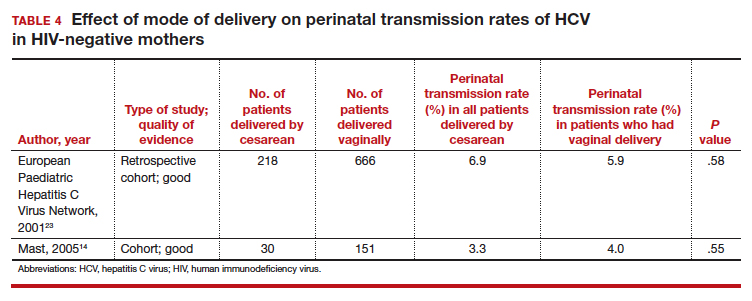

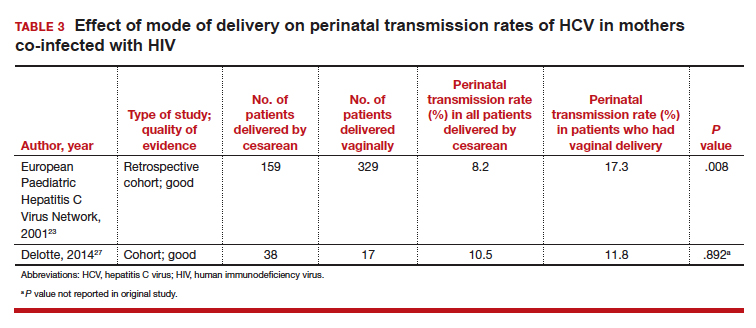

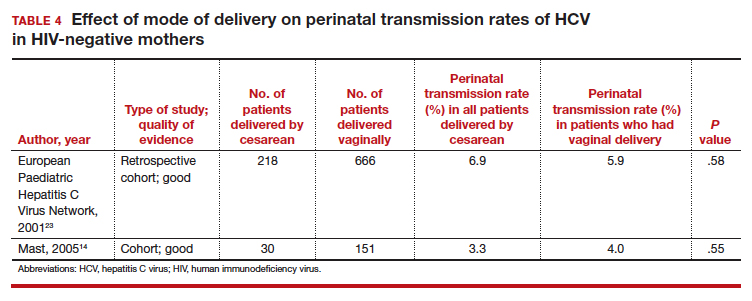

Three studies separated data based on the mother's HIV status. The perinatal transmission rates of HCV for mothers co-infected with HIV are reported in TABLE 3.23,27 The results for HIV-negative mothers are reported in TABLE 4.14,23

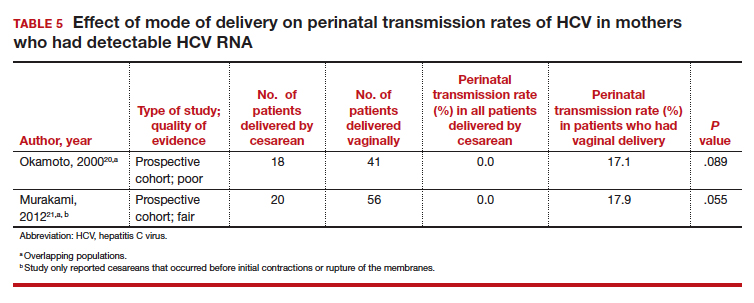

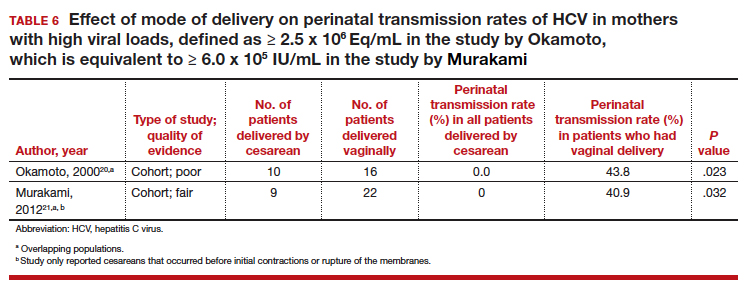

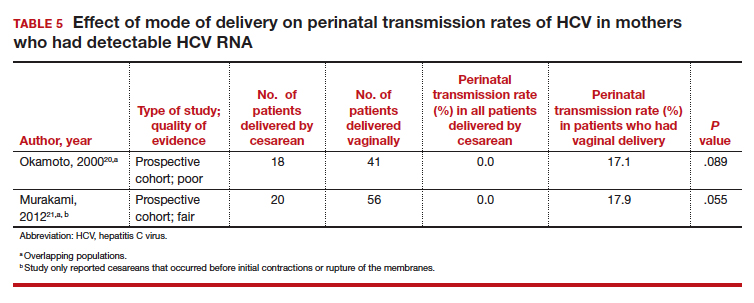

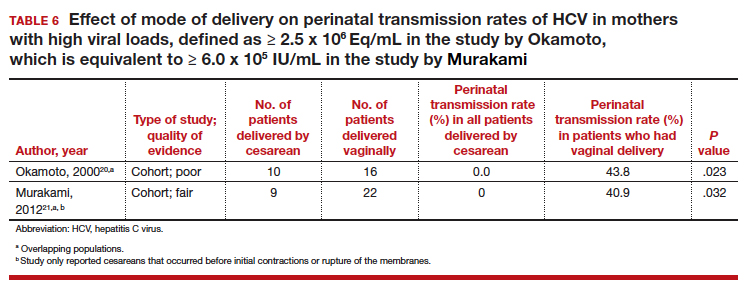

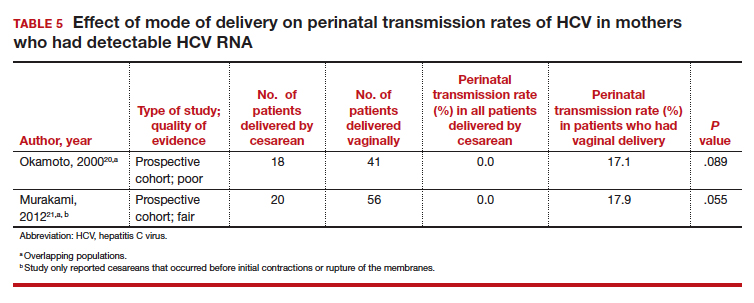

Finally, 2 studies grouped mothers according to their HCV viral load. All of the mothers in these studies were anti-HCV antibody positive, and the perinatal transmission rates for the total study populations were reported previously in TABLE 2. The results for mothers who had detectable HCV RNA are reported in TABLE 5.20,21 High viral load was defined as

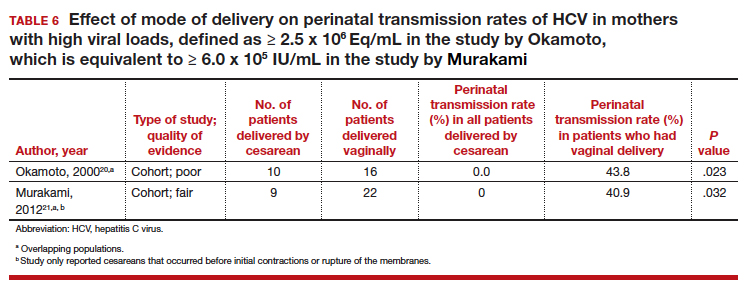

≥ 2.5 x 106 Eq/mL in the study by Okamoto and colleagues, which is equivalent to ≥ 6.0 x 105 IU/mL in the study by Murakami and colleagues due to the different assays that were used.20,21 The perinatal transmission rates for mothers with a high viral load are presented in TABLE 6.20,21

Continue to: For most, CD does not reduce HCV transmission...

For most, CD does not reduce HCV transmission

Nine of the 11 studies found that the mode of delivery did not have a statistically significant impact on the vertical transmission rate of HCV in the total study populations.14,22-29 The remaining 2 studies found that the perinatal transmission rate of HCV was lower with cesarean delivery (CD) than with vaginal delivery.20,21 When considered together, the results of these 11 studies indicate that CD does not provide a significant reduction in the HCV transmission rate in the general population.

Our review confirms the findings of others, including a systematic review by the US Preventive Services Task Force.30 That investigation also failed to demonstrate any measurable increase in risk of HCV transmission as a result of breastfeeding.

Cesarean delivery may benefit 2 groups. Careful assessment of these studies, however, suggests that 2 select groups of patients with HCV may benefit from CD:

- mothers co-infected with HIV, and

- mothers with high viral loads of HCV.

In both of these populations, the vertical transmission rate of HCV was significantly reduced with CD compared with vaginal delivery. Therefore, CD should be strongly considered in mothers with HCV who are co-infected with HIV and/or in mothers who have a high viral load of HCV.

CASE Our recommendation for mode of delivery

The patient in our case scenario has both HIV infection and a very high HCV viral load. We would therefore recommend a planned CD at 38 to 39 weeks' gestation, prior to the onset of labor or membrane rupture. Although HCV infection is not a contraindication to breastfeeding, the mother's HIV infection is a distinct contraindication.

- Dubuisson J, Cosset FL. Virology and cell biology of the hepatitis C virus life cycle: an update. J Hepatol. 2014;61(1 suppl):S3-S13.

- Smith DB, Bukh J, Kuiken C, et al. Expanded classification of hepatitis C virus into 7 genotypes and 67 subtypes: updated criteria and genotype assignment web resource. Hepatology. 2014;59:318-327.

- Rossi LM, Escobar-Gutierrez A, Rahal P. Advanced molecular surveillance of hepatitis C virus. Viruses. 2015;7:1153-1188.

- Dustin LB, Bartolini B, Capobianchi MR, et al. Hepatitis C virus: life cycle in cells, infection and host response, and analysis of molecular markers influencing the outcome of infection and response to therapy. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22:826-832.

- Hajarizadeh B, Grebely J, Dore GJ. Epidemiology and natural history of HCV infection. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:553-562.

- Thomas DL. Global elimination of chronic hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2041-2050.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for prevention and control of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and HCV-related chronic disease. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1998;47(RR19):1-39.

- Gonzalez-Grande R, Jimenez-Perez M, Gonzalez Arjona C, et al. New approaches in the treatment of hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:1421-1432.

- Westbrook RH, Dusheiko G. Natural history of hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2014;61(1 suppl): S58-S68.

- Spera AM, Eldin TK, Tosone G, et al. Antiviral therapy for hepatitis C: has anything changed for pregnant/lactating women? World J Hepatol. 2016;8:557-565.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine; Hughes BL, Page CM, Kuller JA. Hepatitis C in pregnancy: screening, treatment, and management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:B2-B12.

- Benova L, Mohamoud YA, Calvert C, et al. Vertical transmission of hepatitis C virus: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:765-773.

- Ghamar Chehreh ME, Tabatabaei SV, Khazanehdari S, et al. Effect of cesarean section on the risk of perinatal transmission of hepatitis C virus from HCV-RNA+/HIV- mothers: a meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;283:255-260.

- Mast EE, Hwang LY, Seto DS, et al. Risk factors for perinatal transmission of hepatitis C virus (HCV) and the natural history of HCV infection acquired in infancy. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1880-1889.

- McIntyre PG, Tosh K, McGuire W. Caesarean section versus vaginal delivery for preventing mother to infant hepatitis C virus transmission. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4):CD005546.

- Mukherjee R, Burns A, Rodden D, et al. Diagnosis and management of hepatitis C virus infection. J Lab Autom. 2015;20:519-538.

- Araujo AC, Astrakhantseva IV, Fields HA, et al. Distinguishing acute from chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection based on antibody reactivities to specific HCV structural and nonstructural proteins. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:54-57.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for the Care and Treatment of Persons Diagnosed with Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2018.

- CADTH Common Drug Review. Pharmacoeconomic Review Report: Sofosbuvir/Velpatasvir/Voxilaprevir (Vosevi) (Gilead Sciences Canada, Inc): Indication: Hepatitis C infection genotype 1 to 6. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2018.

- Okamoto M, Nagata I, Murakami J, et al. Prospective reevaluation of risk factors in mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis C virus: high virus load, vaginal delivery, and negative anti-NS4 antibody. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:1511-1514.

- Murakami J, Nagata I, Iitsuka T, et al. Risk factors for mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis C virus: maternal high viral load and fetal exposure in the birth canal. Hepatol Res. 2012;42:648-657.

- Conte D, Fraquelli M, Prati D, et al. Prevalence and clinical course of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and rate of HCV vertical transmission in a cohort of 15,250 pregnant women. Hepatology. 2000;31:751-755.

- European Paediatric Hepatitis C Virus Network. Effects of mode of delivery and infant feeding on the risk of mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis C virus. BJOG. 2001;108:371-377.

- Tajiri H, Miyoshi Y, Funada S, et al. Prospective study of mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis C virus. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001;20:10-14.

- Ferrero S, Lungaro P, Bruzzone BM, et al. Prospective study of mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis C virus: a 10-year survey (1990-2000). Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82:229-234.

- Marine-Barjoan E, Berrebi A, Giordanengo V, et al. HCV/HIV co-infection, HCV viral load and mode of delivery: risk factors for mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis C virus? AIDS. 2007;21:1811-1815.

- Delotte J, Barjoan EM, Berrebi A, et al. Obstetric management does not influence vertical transmission of HCV infection: results of the ALHICE group study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;27:664-670.

- Garcia-Tejedor A, Maiques-Montesinos V, Diago-Almela VJ, et al. Risk factors for vertical transmission of hepatitis C virus: a single center experience with 710 HCV-infected mothers. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015;194:173-177.

- Jhaveri R, Hashem M, El-Kamary SS, et al. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) vertical transmission in 12-month-old infants born to HCV-infected women and assessment of maternal risk factors. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2015;2:ofv089.

- Cottrell EB, Chou R, Wasson N, et al. Reducing risk for mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis C virus: a systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:109-113.

CASE Pregnant woman with chronic opioid use and HIV, recently diagnosed with HCV

A 34-year-old primigravid woman at 35 weeks' gestation has a history of chronic opioid use. She previously was diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and has been treated with a 3-drug combination antiretroviral regimen. Her most recent HIV viral load was 750 copies/mL. Three weeks ago, she tested positive for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Liver function tests showed mild elevations in transaminase levels. The viral genotype is 1, and the viral load is 2.6 million copies/mL.

How should this patient be delivered? Should she be encouraged to breastfeed her neonate?

The scope of HCV infection

Hepatitis C virus is a positive-sense, enveloped, single-stranded RNA virus that belongs to the Flaviviridae family.1 There are 7 confirmed major genotypes of HCV and 67 confirmed subtypes.2 HCV possesses several important virulence factors. First, the virus's replication is prone to frequent mutations because its RNA polymerase lacks proofreading activity, resulting in significant genetic diversity. The great degree of heterogeneity among HCV leads to high antigenic variability, which is one of the main reasons there is not yet a vaccine for HCV.3 Additionally, HCV's genomic plasticity plays a role in the emergence of drug-resistant variants.4

Virus transmission. Worldwide, approximately 130 to 170 million people are infected with HCV.5 HCV infections are caused primarily by exposure to infected blood, through sharing needles for intravenous drug injection and through receiving a blood transfusion.6 Other routes of transmission include exposure through sexual contact, occupational injury, and perinatal acquisition.

The risk of acquiring HCV varies for each of these transmission mechanisms. Blood transfusion is no longer a common mechanism of transmission in places where blood donations are screened for HCV antibodies and viral RNA. Additionally, unintentional needle-stick injury is the only occupational risk factor associated with HCV infection, and health care workers do not have a greater prevalence of HCV than the general population. Moreover, sexual transmission is not a particularly efficient mechanism for spread of HCV.7 Therefore, unsafe intravenous injections are now the leading cause of HCV infection.6

Consequences of HCV infection. Once infected with HCV, about 25% of people spontaneously clear the virus and approximately 75% progress to chronic HCV infection.5 The consequences of long-term infection with HCV include end-stage liver disease, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Approximately 30% of people infected with HCV will develop cirrhosis and another 2% will develop hepatocellular carcinoma.8 Liver transplant is the only treatment option for patients with decompensated cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma as a result of HCV infection. Currently, HCV infection is the leading indication for liver transplant in the United States.9

Continue to: Risk of perinatal HCV transmission...

Risk of perinatal HCV transmission

Approximately 1% to 8% of pregnant women worldwide are infected with HCV.10 In the United States, 1% to 2.5% of pregnant women are infected.11 Of these, about 6% transmit the infection to their offspring. The risk of HCV vertical transmission increases to about 11% if the mother is co-infected with HIV.12 Vertical transmission is the primary method by which children become infected with HCV.13

Several risk factors increase the likelihood of HCV transmission from mother to child, including HIV co-infection, internal fetal monitoring, and longer duration of membrane rupture.14 The effect that mode of delivery has on vertical transmission rates, however, is still debated, and a Cochrane Review found that there were no randomized controlled trials assessing the effect of mode of delivery on mother-to-infant HCV transmission.15

Serology and genotyping used in diagnosis

The serological enzyme immunoassay is the first test used in screening for HCV infection. Currently, third- and fourth-generation enzyme immunoassays are used in the United States.16 However, even these newer serological assays cannot consistently and precisely distinguish between acute and chronic HCV infections.17 After the initial diagnosis is made with serology, it usually is confirmed by assays that detect the virus's genomic RNA in the patient's serum or plasma.

The patient's HCV genotype should be identified so that the best treatment options can be determined. HCV genotyping can be accomplished using reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) amplification. Three different RT-qPCR assessments usually are performed using different primers and probes specific to different genotypes of HCV. While direct sequencing of the HCV genome also can be performed, this method is usually not used clinically due to its technical complexity.16

Modern treatments are effective

Introduced in 2011, direct-acting antiviral therapies are now the recommended treatment for HCV infection. These drugs inhibit the virus's replication by targeting different proteins involved in the HCV replication cycle. They are remarkably successful and have achieved sustained virologic response (SVR) rates greater than 90%.11 The World Health Organization recommends several pangenotypic (that is, agents that work against all genotypes) direct-acting antiviral regimens for the treatment of chronic HCV infection in adults without cirrhosis (TABLE 1).18,19

Unfortunately, experience with these drugs in pregnant women is lacking. Many direct-acting antiviral agents have not been tested systematically in pregnant women, and, accordingly, most information about their effects in pregnant women comes from animal models.11

Continue to: Perinatal transmission rates and effect of mode of delivery...

Perinatal transmission rates and effect of mode of delivery

We compiled data from 11 studies that reported the perinatal transmission rate of HCV associated with various modes of delivery. These studies were selected from a MEDLINE literature review from 1999 to 2019. The studies were screened first by title and, subsequently, by abstract. Inclusion was restricted to randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, and case-control studies written in English. Study quality was assessed as good, fair, or poor based on the study design, sample size, and statistical analyses performed. The results from the total population of each study are reported in TABLE 2.14,20-29

Three studies separated data based on the mother's HIV status. The perinatal transmission rates of HCV for mothers co-infected with HIV are reported in TABLE 3.23,27 The results for HIV-negative mothers are reported in TABLE 4.14,23

Finally, 2 studies grouped mothers according to their HCV viral load. All of the mothers in these studies were anti-HCV antibody positive, and the perinatal transmission rates for the total study populations were reported previously in TABLE 2. The results for mothers who had detectable HCV RNA are reported in TABLE 5.20,21 High viral load was defined as

≥ 2.5 x 106 Eq/mL in the study by Okamoto and colleagues, which is equivalent to ≥ 6.0 x 105 IU/mL in the study by Murakami and colleagues due to the different assays that were used.20,21 The perinatal transmission rates for mothers with a high viral load are presented in TABLE 6.20,21

Continue to: For most, CD does not reduce HCV transmission...

For most, CD does not reduce HCV transmission

Nine of the 11 studies found that the mode of delivery did not have a statistically significant impact on the vertical transmission rate of HCV in the total study populations.14,22-29 The remaining 2 studies found that the perinatal transmission rate of HCV was lower with cesarean delivery (CD) than with vaginal delivery.20,21 When considered together, the results of these 11 studies indicate that CD does not provide a significant reduction in the HCV transmission rate in the general population.

Our review confirms the findings of others, including a systematic review by the US Preventive Services Task Force.30 That investigation also failed to demonstrate any measurable increase in risk of HCV transmission as a result of breastfeeding.

Cesarean delivery may benefit 2 groups. Careful assessment of these studies, however, suggests that 2 select groups of patients with HCV may benefit from CD:

- mothers co-infected with HIV, and

- mothers with high viral loads of HCV.

In both of these populations, the vertical transmission rate of HCV was significantly reduced with CD compared with vaginal delivery. Therefore, CD should be strongly considered in mothers with HCV who are co-infected with HIV and/or in mothers who have a high viral load of HCV.

CASE Our recommendation for mode of delivery

The patient in our case scenario has both HIV infection and a very high HCV viral load. We would therefore recommend a planned CD at 38 to 39 weeks' gestation, prior to the onset of labor or membrane rupture. Although HCV infection is not a contraindication to breastfeeding, the mother's HIV infection is a distinct contraindication.

CASE Pregnant woman with chronic opioid use and HIV, recently diagnosed with HCV

A 34-year-old primigravid woman at 35 weeks' gestation has a history of chronic opioid use. She previously was diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and has been treated with a 3-drug combination antiretroviral regimen. Her most recent HIV viral load was 750 copies/mL. Three weeks ago, she tested positive for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Liver function tests showed mild elevations in transaminase levels. The viral genotype is 1, and the viral load is 2.6 million copies/mL.

How should this patient be delivered? Should she be encouraged to breastfeed her neonate?

The scope of HCV infection

Hepatitis C virus is a positive-sense, enveloped, single-stranded RNA virus that belongs to the Flaviviridae family.1 There are 7 confirmed major genotypes of HCV and 67 confirmed subtypes.2 HCV possesses several important virulence factors. First, the virus's replication is prone to frequent mutations because its RNA polymerase lacks proofreading activity, resulting in significant genetic diversity. The great degree of heterogeneity among HCV leads to high antigenic variability, which is one of the main reasons there is not yet a vaccine for HCV.3 Additionally, HCV's genomic plasticity plays a role in the emergence of drug-resistant variants.4

Virus transmission. Worldwide, approximately 130 to 170 million people are infected with HCV.5 HCV infections are caused primarily by exposure to infected blood, through sharing needles for intravenous drug injection and through receiving a blood transfusion.6 Other routes of transmission include exposure through sexual contact, occupational injury, and perinatal acquisition.

The risk of acquiring HCV varies for each of these transmission mechanisms. Blood transfusion is no longer a common mechanism of transmission in places where blood donations are screened for HCV antibodies and viral RNA. Additionally, unintentional needle-stick injury is the only occupational risk factor associated with HCV infection, and health care workers do not have a greater prevalence of HCV than the general population. Moreover, sexual transmission is not a particularly efficient mechanism for spread of HCV.7 Therefore, unsafe intravenous injections are now the leading cause of HCV infection.6

Consequences of HCV infection. Once infected with HCV, about 25% of people spontaneously clear the virus and approximately 75% progress to chronic HCV infection.5 The consequences of long-term infection with HCV include end-stage liver disease, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Approximately 30% of people infected with HCV will develop cirrhosis and another 2% will develop hepatocellular carcinoma.8 Liver transplant is the only treatment option for patients with decompensated cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma as a result of HCV infection. Currently, HCV infection is the leading indication for liver transplant in the United States.9

Continue to: Risk of perinatal HCV transmission...

Risk of perinatal HCV transmission

Approximately 1% to 8% of pregnant women worldwide are infected with HCV.10 In the United States, 1% to 2.5% of pregnant women are infected.11 Of these, about 6% transmit the infection to their offspring. The risk of HCV vertical transmission increases to about 11% if the mother is co-infected with HIV.12 Vertical transmission is the primary method by which children become infected with HCV.13

Several risk factors increase the likelihood of HCV transmission from mother to child, including HIV co-infection, internal fetal monitoring, and longer duration of membrane rupture.14 The effect that mode of delivery has on vertical transmission rates, however, is still debated, and a Cochrane Review found that there were no randomized controlled trials assessing the effect of mode of delivery on mother-to-infant HCV transmission.15

Serology and genotyping used in diagnosis

The serological enzyme immunoassay is the first test used in screening for HCV infection. Currently, third- and fourth-generation enzyme immunoassays are used in the United States.16 However, even these newer serological assays cannot consistently and precisely distinguish between acute and chronic HCV infections.17 After the initial diagnosis is made with serology, it usually is confirmed by assays that detect the virus's genomic RNA in the patient's serum or plasma.

The patient's HCV genotype should be identified so that the best treatment options can be determined. HCV genotyping can be accomplished using reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) amplification. Three different RT-qPCR assessments usually are performed using different primers and probes specific to different genotypes of HCV. While direct sequencing of the HCV genome also can be performed, this method is usually not used clinically due to its technical complexity.16

Modern treatments are effective

Introduced in 2011, direct-acting antiviral therapies are now the recommended treatment for HCV infection. These drugs inhibit the virus's replication by targeting different proteins involved in the HCV replication cycle. They are remarkably successful and have achieved sustained virologic response (SVR) rates greater than 90%.11 The World Health Organization recommends several pangenotypic (that is, agents that work against all genotypes) direct-acting antiviral regimens for the treatment of chronic HCV infection in adults without cirrhosis (TABLE 1).18,19

Unfortunately, experience with these drugs in pregnant women is lacking. Many direct-acting antiviral agents have not been tested systematically in pregnant women, and, accordingly, most information about their effects in pregnant women comes from animal models.11

Continue to: Perinatal transmission rates and effect of mode of delivery...

Perinatal transmission rates and effect of mode of delivery

We compiled data from 11 studies that reported the perinatal transmission rate of HCV associated with various modes of delivery. These studies were selected from a MEDLINE literature review from 1999 to 2019. The studies were screened first by title and, subsequently, by abstract. Inclusion was restricted to randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, and case-control studies written in English. Study quality was assessed as good, fair, or poor based on the study design, sample size, and statistical analyses performed. The results from the total population of each study are reported in TABLE 2.14,20-29

Three studies separated data based on the mother's HIV status. The perinatal transmission rates of HCV for mothers co-infected with HIV are reported in TABLE 3.23,27 The results for HIV-negative mothers are reported in TABLE 4.14,23

Finally, 2 studies grouped mothers according to their HCV viral load. All of the mothers in these studies were anti-HCV antibody positive, and the perinatal transmission rates for the total study populations were reported previously in TABLE 2. The results for mothers who had detectable HCV RNA are reported in TABLE 5.20,21 High viral load was defined as

≥ 2.5 x 106 Eq/mL in the study by Okamoto and colleagues, which is equivalent to ≥ 6.0 x 105 IU/mL in the study by Murakami and colleagues due to the different assays that were used.20,21 The perinatal transmission rates for mothers with a high viral load are presented in TABLE 6.20,21

Continue to: For most, CD does not reduce HCV transmission...

For most, CD does not reduce HCV transmission

Nine of the 11 studies found that the mode of delivery did not have a statistically significant impact on the vertical transmission rate of HCV in the total study populations.14,22-29 The remaining 2 studies found that the perinatal transmission rate of HCV was lower with cesarean delivery (CD) than with vaginal delivery.20,21 When considered together, the results of these 11 studies indicate that CD does not provide a significant reduction in the HCV transmission rate in the general population.

Our review confirms the findings of others, including a systematic review by the US Preventive Services Task Force.30 That investigation also failed to demonstrate any measurable increase in risk of HCV transmission as a result of breastfeeding.

Cesarean delivery may benefit 2 groups. Careful assessment of these studies, however, suggests that 2 select groups of patients with HCV may benefit from CD:

- mothers co-infected with HIV, and

- mothers with high viral loads of HCV.

In both of these populations, the vertical transmission rate of HCV was significantly reduced with CD compared with vaginal delivery. Therefore, CD should be strongly considered in mothers with HCV who are co-infected with HIV and/or in mothers who have a high viral load of HCV.

CASE Our recommendation for mode of delivery

The patient in our case scenario has both HIV infection and a very high HCV viral load. We would therefore recommend a planned CD at 38 to 39 weeks' gestation, prior to the onset of labor or membrane rupture. Although HCV infection is not a contraindication to breastfeeding, the mother's HIV infection is a distinct contraindication.

- Dubuisson J, Cosset FL. Virology and cell biology of the hepatitis C virus life cycle: an update. J Hepatol. 2014;61(1 suppl):S3-S13.

- Smith DB, Bukh J, Kuiken C, et al. Expanded classification of hepatitis C virus into 7 genotypes and 67 subtypes: updated criteria and genotype assignment web resource. Hepatology. 2014;59:318-327.

- Rossi LM, Escobar-Gutierrez A, Rahal P. Advanced molecular surveillance of hepatitis C virus. Viruses. 2015;7:1153-1188.

- Dustin LB, Bartolini B, Capobianchi MR, et al. Hepatitis C virus: life cycle in cells, infection and host response, and analysis of molecular markers influencing the outcome of infection and response to therapy. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22:826-832.

- Hajarizadeh B, Grebely J, Dore GJ. Epidemiology and natural history of HCV infection. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:553-562.

- Thomas DL. Global elimination of chronic hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2041-2050.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for prevention and control of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and HCV-related chronic disease. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1998;47(RR19):1-39.

- Gonzalez-Grande R, Jimenez-Perez M, Gonzalez Arjona C, et al. New approaches in the treatment of hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:1421-1432.

- Westbrook RH, Dusheiko G. Natural history of hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2014;61(1 suppl): S58-S68.

- Spera AM, Eldin TK, Tosone G, et al. Antiviral therapy for hepatitis C: has anything changed for pregnant/lactating women? World J Hepatol. 2016;8:557-565.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine; Hughes BL, Page CM, Kuller JA. Hepatitis C in pregnancy: screening, treatment, and management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:B2-B12.

- Benova L, Mohamoud YA, Calvert C, et al. Vertical transmission of hepatitis C virus: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:765-773.

- Ghamar Chehreh ME, Tabatabaei SV, Khazanehdari S, et al. Effect of cesarean section on the risk of perinatal transmission of hepatitis C virus from HCV-RNA+/HIV- mothers: a meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;283:255-260.

- Mast EE, Hwang LY, Seto DS, et al. Risk factors for perinatal transmission of hepatitis C virus (HCV) and the natural history of HCV infection acquired in infancy. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1880-1889.

- McIntyre PG, Tosh K, McGuire W. Caesarean section versus vaginal delivery for preventing mother to infant hepatitis C virus transmission. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4):CD005546.

- Mukherjee R, Burns A, Rodden D, et al. Diagnosis and management of hepatitis C virus infection. J Lab Autom. 2015;20:519-538.

- Araujo AC, Astrakhantseva IV, Fields HA, et al. Distinguishing acute from chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection based on antibody reactivities to specific HCV structural and nonstructural proteins. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:54-57.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for the Care and Treatment of Persons Diagnosed with Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2018.

- CADTH Common Drug Review. Pharmacoeconomic Review Report: Sofosbuvir/Velpatasvir/Voxilaprevir (Vosevi) (Gilead Sciences Canada, Inc): Indication: Hepatitis C infection genotype 1 to 6. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2018.

- Okamoto M, Nagata I, Murakami J, et al. Prospective reevaluation of risk factors in mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis C virus: high virus load, vaginal delivery, and negative anti-NS4 antibody. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:1511-1514.

- Murakami J, Nagata I, Iitsuka T, et al. Risk factors for mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis C virus: maternal high viral load and fetal exposure in the birth canal. Hepatol Res. 2012;42:648-657.

- Conte D, Fraquelli M, Prati D, et al. Prevalence and clinical course of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and rate of HCV vertical transmission in a cohort of 15,250 pregnant women. Hepatology. 2000;31:751-755.

- European Paediatric Hepatitis C Virus Network. Effects of mode of delivery and infant feeding on the risk of mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis C virus. BJOG. 2001;108:371-377.

- Tajiri H, Miyoshi Y, Funada S, et al. Prospective study of mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis C virus. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001;20:10-14.

- Ferrero S, Lungaro P, Bruzzone BM, et al. Prospective study of mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis C virus: a 10-year survey (1990-2000). Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82:229-234.

- Marine-Barjoan E, Berrebi A, Giordanengo V, et al. HCV/HIV co-infection, HCV viral load and mode of delivery: risk factors for mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis C virus? AIDS. 2007;21:1811-1815.

- Delotte J, Barjoan EM, Berrebi A, et al. Obstetric management does not influence vertical transmission of HCV infection: results of the ALHICE group study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;27:664-670.

- Garcia-Tejedor A, Maiques-Montesinos V, Diago-Almela VJ, et al. Risk factors for vertical transmission of hepatitis C virus: a single center experience with 710 HCV-infected mothers. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015;194:173-177.

- Jhaveri R, Hashem M, El-Kamary SS, et al. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) vertical transmission in 12-month-old infants born to HCV-infected women and assessment of maternal risk factors. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2015;2:ofv089.

- Cottrell EB, Chou R, Wasson N, et al. Reducing risk for mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis C virus: a systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:109-113.

- Dubuisson J, Cosset FL. Virology and cell biology of the hepatitis C virus life cycle: an update. J Hepatol. 2014;61(1 suppl):S3-S13.

- Smith DB, Bukh J, Kuiken C, et al. Expanded classification of hepatitis C virus into 7 genotypes and 67 subtypes: updated criteria and genotype assignment web resource. Hepatology. 2014;59:318-327.

- Rossi LM, Escobar-Gutierrez A, Rahal P. Advanced molecular surveillance of hepatitis C virus. Viruses. 2015;7:1153-1188.

- Dustin LB, Bartolini B, Capobianchi MR, et al. Hepatitis C virus: life cycle in cells, infection and host response, and analysis of molecular markers influencing the outcome of infection and response to therapy. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22:826-832.

- Hajarizadeh B, Grebely J, Dore GJ. Epidemiology and natural history of HCV infection. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:553-562.

- Thomas DL. Global elimination of chronic hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2041-2050.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for prevention and control of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and HCV-related chronic disease. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1998;47(RR19):1-39.

- Gonzalez-Grande R, Jimenez-Perez M, Gonzalez Arjona C, et al. New approaches in the treatment of hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:1421-1432.

- Westbrook RH, Dusheiko G. Natural history of hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2014;61(1 suppl): S58-S68.

- Spera AM, Eldin TK, Tosone G, et al. Antiviral therapy for hepatitis C: has anything changed for pregnant/lactating women? World J Hepatol. 2016;8:557-565.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine; Hughes BL, Page CM, Kuller JA. Hepatitis C in pregnancy: screening, treatment, and management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:B2-B12.

- Benova L, Mohamoud YA, Calvert C, et al. Vertical transmission of hepatitis C virus: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:765-773.

- Ghamar Chehreh ME, Tabatabaei SV, Khazanehdari S, et al. Effect of cesarean section on the risk of perinatal transmission of hepatitis C virus from HCV-RNA+/HIV- mothers: a meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;283:255-260.

- Mast EE, Hwang LY, Seto DS, et al. Risk factors for perinatal transmission of hepatitis C virus (HCV) and the natural history of HCV infection acquired in infancy. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1880-1889.

- McIntyre PG, Tosh K, McGuire W. Caesarean section versus vaginal delivery for preventing mother to infant hepatitis C virus transmission. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4):CD005546.

- Mukherjee R, Burns A, Rodden D, et al. Diagnosis and management of hepatitis C virus infection. J Lab Autom. 2015;20:519-538.

- Araujo AC, Astrakhantseva IV, Fields HA, et al. Distinguishing acute from chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection based on antibody reactivities to specific HCV structural and nonstructural proteins. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:54-57.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for the Care and Treatment of Persons Diagnosed with Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2018.

- CADTH Common Drug Review. Pharmacoeconomic Review Report: Sofosbuvir/Velpatasvir/Voxilaprevir (Vosevi) (Gilead Sciences Canada, Inc): Indication: Hepatitis C infection genotype 1 to 6. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2018.

- Okamoto M, Nagata I, Murakami J, et al. Prospective reevaluation of risk factors in mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis C virus: high virus load, vaginal delivery, and negative anti-NS4 antibody. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:1511-1514.

- Murakami J, Nagata I, Iitsuka T, et al. Risk factors for mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis C virus: maternal high viral load and fetal exposure in the birth canal. Hepatol Res. 2012;42:648-657.

- Conte D, Fraquelli M, Prati D, et al. Prevalence and clinical course of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and rate of HCV vertical transmission in a cohort of 15,250 pregnant women. Hepatology. 2000;31:751-755.

- European Paediatric Hepatitis C Virus Network. Effects of mode of delivery and infant feeding on the risk of mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis C virus. BJOG. 2001;108:371-377.

- Tajiri H, Miyoshi Y, Funada S, et al. Prospective study of mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis C virus. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001;20:10-14.

- Ferrero S, Lungaro P, Bruzzone BM, et al. Prospective study of mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis C virus: a 10-year survey (1990-2000). Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82:229-234.

- Marine-Barjoan E, Berrebi A, Giordanengo V, et al. HCV/HIV co-infection, HCV viral load and mode of delivery: risk factors for mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis C virus? AIDS. 2007;21:1811-1815.

- Delotte J, Barjoan EM, Berrebi A, et al. Obstetric management does not influence vertical transmission of HCV infection: results of the ALHICE group study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;27:664-670.

- Garcia-Tejedor A, Maiques-Montesinos V, Diago-Almela VJ, et al. Risk factors for vertical transmission of hepatitis C virus: a single center experience with 710 HCV-infected mothers. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015;194:173-177.

- Jhaveri R, Hashem M, El-Kamary SS, et al. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) vertical transmission in 12-month-old infants born to HCV-infected women and assessment of maternal risk factors. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2015;2:ofv089.

- Cottrell EB, Chou R, Wasson N, et al. Reducing risk for mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis C virus: a systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:109-113.

Women with obesity need not boost calories during pregnancy

LAS VEGAS – Contrary to current U.S. dietary recommendations for pregnancy, women with obesity should not increase their energy intake during pregnancy to achieve the current recommended level of gestational weight gain, based on findings from an intensive assessment of 54 women with obesity during weeks 13-37 of pregnancy.

To achieve the gestational weight gain of 11-20 pounds (5-9.1 kg) recommended by the Institute of Medicine, women with obesity ‒ those with a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or greater ‒ had an average energy intake during the second and third trimesters of 125 kcal/day less than their energy expenditure, Leanne M. Redman, PhD, said at a meeting presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

However, women in the study who had inadequate gestational weight gain had a daily calorie deficit that was only slightly larger, an average of 262 kcal/day below their energy expenditure. As a consequence, Dr. Redman believes the take-home message from her findings is that pregnant women with obesity should maintain their prepregnancy energy intake, though she also strongly recommended improvements in diet quality.

“Chasing a 100-kcal/day deficit in intake is extremely problematic,” Dr. Redman admitted, so she suggested that women with obesity be advised simply to not increase their calorie intake during pregnancy.

“The message is: Focus on improving diet quality rather than increasing calories,” she said in an interview. Pregnant women with obesity “do not need to increase calorie intake. They need to improve their diet quality,” with increased consumption of fruits and vegetables, said Dr. Redman, a professor and director of the Reproductive Endocrinology and Women’s Health Laboratory at Louisiana State University’s Pennington Biomedical Research Center in Baton Rouge.

The results she reported represent “the first time” researchers have examined energy expenditure and weight-gain trajectories in women with obesity throughout the second and third trimesters. Until now, dietary energy recommendations for women with obesity during pregnancy were based on observations made in women without obesity.

Those observations led the Institute of Medicine to call for a recommended pregnancy weight gain of 11-20 pounds in women with obesity, as well as gains of 25-35 pounds in women with a normal body mass index of 18.5-24.9 kg/m2 (Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines; May 2009). In that 2009 document, the IOM committee said that, in general, pregnant women should add 340 kcal/day to their prepregnancy intake during the second trimester and add 452 kcal/day during the third trimester without regard to their prepregnancy body mass index, a recommendation that clinicians continued to promote in subsequent years (Med Clin North Amer. 2016;100[6]:1199-215), and that was generally affirmed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists in 2013 and reaffirmed in 2018.*

The new evidence collected by Dr. Redman and associates “challenges current practice and argues that women with obesity should not be advised to consume additional energy during pregnancy as currently recommended,” they wrote in an article with their findings published a few days before Dr. Redman gave her talk (J Clin Invest. 2019;129[11]:4682-90).

The MomEE (Determinants of Gestational Weight Gain in Obese Pregnant Women) study enrolled 72 women with obesity during the first trimester of pregnancy and collected complete data through the end of the third trimester from 54 women. The researchers collected data on weight, body fat mass, and energy expenditure at multiple times during the second and third trimesters and calculated energy intake.

Based on body weights at the end of the third trimester, the researchers divided the 54 women into three subgroups: 10 women (19%) with inadequate weight gain by the IOM recommendations, 8 (15%) who had the IOM’s recommended weight gain of 11-20 pounds, and 36 women (67%; total is greater than 100% because of rounding) with excess weight gain, and within each group, they calculated the average level of energy intake relative to energy expenditure.

In addition to the daily calorie deficits associated with women who maintained recommended or inadequate weight, the researchers also found that women with excess weight gain averaged 186 more kcal/day than required to meet their daily energy expenditure.

The analyses showed that the increased energy demand of pregnancy and the fetus is compensated for by mobilization of the maternal fat mass in women with obesity, and that an imbalance between energy intake and expenditure is the main driver of weight gain during pregnancy. The results also highlighted how often pregnant women with obesity fail to follow a diet that results in the recommended weight gain of 11-20 pounds. In the MomEE cohort, two-thirds of enrolled women had excess weight gain.

The finding that women had the recommended weight gain on a diet that cut their daily calorie intake by about 100 kcal/day during the last two trimesters highlighted the nutritional challenge faced by women with obesity who are pregnant. “About three-quarters of women in the study had poor diet quality. There is an opportunity to improve diet with more fruits and vegetables to increase fullness, and [to reduce] energy-dense foods,” Dr. Redman said.

She is planning to collaborate on a study that will test the efficacy and safety of providing pregnant women with extreme obesity (class II-III) with defined meals to provide better control of energy intake and nutritional quality. Dr. Redman said she also hoped that the new findings she reported would be taken into account by the advisory committee assembled by the Department of Health & Human Services and the Department of Agriculture, which are currently preparing a revision of U.S. dietary guidelines for release in 2020.

The National Institutes of Health and the Clinical Research Cores at Pennington Biomedical Research Center funded the study. Dr. Redman had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Redman LM et al. Obesity Week 2019, Abstract T-OR-2079.

*This article was updated 2/7/2020.

The results reported by Dr. Redman from the MomEE study showed that women with obesity need not ingest surplus calories to gain weight during pregnancy. The findings indicate that pregnant women efficiently convert a portion of their accumulated fat mass to fat-free mass in the form of the fetus, uterus, blood volume, and other tissue. A deficit of about approximately 100 kcal/day effectively kept weight gain within the 11- to 20-pound target recommended by the Institute of Medicine in 2009.

But the weight gains recommended for women with obesity may be too high. The desire of the writers of the IOM recommendation to avoid negative perinatal outcomes for infants may instead lead to negative maternal outcomes, such as preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, and need for cesarean birth. Gestational weight gains below what the IOM recommended for women with obesity may be able to serve present-day standards and work better for these pregnant women by reducing their morbidity risk. Future studies should take into careful account overall nutrient values rather than just calorie intake, as well as physical activity.

The MomEE results showed that a striking two-thirds of women with obesity gained an excess of weight during pregnancy, beyond the 2009 recommendations. This finding highlights the need to identify strategies that can prevent excessive weight gain. Furthermore, results from several studies and systematic reviews suggest that the IOM recommendation for weight gain during pregnancy is too high for women with obesity, especially those with class II-III obesity, with a body mass index of 35 kg/m2 or greater. In my opinion, an appropriate weight-gain target to replace the current, blanket recommendation of 11-20 pounds gained for all women with obesity is a target of 5-15 pounds gained for women with class I obesity, less than 10 pounds for class II obesity, and no change in prepregnancy weight for women with class III obesity.

Sarah S. Comstock, PhD, is a nutrition researcher at Michigan State University, East Lansing. She is an inventor named on three patents that involve nutrition. She made these comments in an editorial that accompanied the MomEE report (J Clin Invest. 2019;129[11]:4567-9).

The results reported by Dr. Redman from the MomEE study showed that women with obesity need not ingest surplus calories to gain weight during pregnancy. The findings indicate that pregnant women efficiently convert a portion of their accumulated fat mass to fat-free mass in the form of the fetus, uterus, blood volume, and other tissue. A deficit of about approximately 100 kcal/day effectively kept weight gain within the 11- to 20-pound target recommended by the Institute of Medicine in 2009.

But the weight gains recommended for women with obesity may be too high. The desire of the writers of the IOM recommendation to avoid negative perinatal outcomes for infants may instead lead to negative maternal outcomes, such as preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, and need for cesarean birth. Gestational weight gains below what the IOM recommended for women with obesity may be able to serve present-day standards and work better for these pregnant women by reducing their morbidity risk. Future studies should take into careful account overall nutrient values rather than just calorie intake, as well as physical activity.

The MomEE results showed that a striking two-thirds of women with obesity gained an excess of weight during pregnancy, beyond the 2009 recommendations. This finding highlights the need to identify strategies that can prevent excessive weight gain. Furthermore, results from several studies and systematic reviews suggest that the IOM recommendation for weight gain during pregnancy is too high for women with obesity, especially those with class II-III obesity, with a body mass index of 35 kg/m2 or greater. In my opinion, an appropriate weight-gain target to replace the current, blanket recommendation of 11-20 pounds gained for all women with obesity is a target of 5-15 pounds gained for women with class I obesity, less than 10 pounds for class II obesity, and no change in prepregnancy weight for women with class III obesity.

Sarah S. Comstock, PhD, is a nutrition researcher at Michigan State University, East Lansing. She is an inventor named on three patents that involve nutrition. She made these comments in an editorial that accompanied the MomEE report (J Clin Invest. 2019;129[11]:4567-9).

The results reported by Dr. Redman from the MomEE study showed that women with obesity need not ingest surplus calories to gain weight during pregnancy. The findings indicate that pregnant women efficiently convert a portion of their accumulated fat mass to fat-free mass in the form of the fetus, uterus, blood volume, and other tissue. A deficit of about approximately 100 kcal/day effectively kept weight gain within the 11- to 20-pound target recommended by the Institute of Medicine in 2009.

But the weight gains recommended for women with obesity may be too high. The desire of the writers of the IOM recommendation to avoid negative perinatal outcomes for infants may instead lead to negative maternal outcomes, such as preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, and need for cesarean birth. Gestational weight gains below what the IOM recommended for women with obesity may be able to serve present-day standards and work better for these pregnant women by reducing their morbidity risk. Future studies should take into careful account overall nutrient values rather than just calorie intake, as well as physical activity.

The MomEE results showed that a striking two-thirds of women with obesity gained an excess of weight during pregnancy, beyond the 2009 recommendations. This finding highlights the need to identify strategies that can prevent excessive weight gain. Furthermore, results from several studies and systematic reviews suggest that the IOM recommendation for weight gain during pregnancy is too high for women with obesity, especially those with class II-III obesity, with a body mass index of 35 kg/m2 or greater. In my opinion, an appropriate weight-gain target to replace the current, blanket recommendation of 11-20 pounds gained for all women with obesity is a target of 5-15 pounds gained for women with class I obesity, less than 10 pounds for class II obesity, and no change in prepregnancy weight for women with class III obesity.

Sarah S. Comstock, PhD, is a nutrition researcher at Michigan State University, East Lansing. She is an inventor named on three patents that involve nutrition. She made these comments in an editorial that accompanied the MomEE report (J Clin Invest. 2019;129[11]:4567-9).

LAS VEGAS – Contrary to current U.S. dietary recommendations for pregnancy, women with obesity should not increase their energy intake during pregnancy to achieve the current recommended level of gestational weight gain, based on findings from an intensive assessment of 54 women with obesity during weeks 13-37 of pregnancy.

To achieve the gestational weight gain of 11-20 pounds (5-9.1 kg) recommended by the Institute of Medicine, women with obesity ‒ those with a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or greater ‒ had an average energy intake during the second and third trimesters of 125 kcal/day less than their energy expenditure, Leanne M. Redman, PhD, said at a meeting presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

However, women in the study who had inadequate gestational weight gain had a daily calorie deficit that was only slightly larger, an average of 262 kcal/day below their energy expenditure. As a consequence, Dr. Redman believes the take-home message from her findings is that pregnant women with obesity should maintain their prepregnancy energy intake, though she also strongly recommended improvements in diet quality.

“Chasing a 100-kcal/day deficit in intake is extremely problematic,” Dr. Redman admitted, so she suggested that women with obesity be advised simply to not increase their calorie intake during pregnancy.

“The message is: Focus on improving diet quality rather than increasing calories,” she said in an interview. Pregnant women with obesity “do not need to increase calorie intake. They need to improve their diet quality,” with increased consumption of fruits and vegetables, said Dr. Redman, a professor and director of the Reproductive Endocrinology and Women’s Health Laboratory at Louisiana State University’s Pennington Biomedical Research Center in Baton Rouge.

The results she reported represent “the first time” researchers have examined energy expenditure and weight-gain trajectories in women with obesity throughout the second and third trimesters. Until now, dietary energy recommendations for women with obesity during pregnancy were based on observations made in women without obesity.

Those observations led the Institute of Medicine to call for a recommended pregnancy weight gain of 11-20 pounds in women with obesity, as well as gains of 25-35 pounds in women with a normal body mass index of 18.5-24.9 kg/m2 (Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines; May 2009). In that 2009 document, the IOM committee said that, in general, pregnant women should add 340 kcal/day to their prepregnancy intake during the second trimester and add 452 kcal/day during the third trimester without regard to their prepregnancy body mass index, a recommendation that clinicians continued to promote in subsequent years (Med Clin North Amer. 2016;100[6]:1199-215), and that was generally affirmed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists in 2013 and reaffirmed in 2018.*

The new evidence collected by Dr. Redman and associates “challenges current practice and argues that women with obesity should not be advised to consume additional energy during pregnancy as currently recommended,” they wrote in an article with their findings published a few days before Dr. Redman gave her talk (J Clin Invest. 2019;129[11]:4682-90).

The MomEE (Determinants of Gestational Weight Gain in Obese Pregnant Women) study enrolled 72 women with obesity during the first trimester of pregnancy and collected complete data through the end of the third trimester from 54 women. The researchers collected data on weight, body fat mass, and energy expenditure at multiple times during the second and third trimesters and calculated energy intake.

Based on body weights at the end of the third trimester, the researchers divided the 54 women into three subgroups: 10 women (19%) with inadequate weight gain by the IOM recommendations, 8 (15%) who had the IOM’s recommended weight gain of 11-20 pounds, and 36 women (67%; total is greater than 100% because of rounding) with excess weight gain, and within each group, they calculated the average level of energy intake relative to energy expenditure.

In addition to the daily calorie deficits associated with women who maintained recommended or inadequate weight, the researchers also found that women with excess weight gain averaged 186 more kcal/day than required to meet their daily energy expenditure.

The analyses showed that the increased energy demand of pregnancy and the fetus is compensated for by mobilization of the maternal fat mass in women with obesity, and that an imbalance between energy intake and expenditure is the main driver of weight gain during pregnancy. The results also highlighted how often pregnant women with obesity fail to follow a diet that results in the recommended weight gain of 11-20 pounds. In the MomEE cohort, two-thirds of enrolled women had excess weight gain.

The finding that women had the recommended weight gain on a diet that cut their daily calorie intake by about 100 kcal/day during the last two trimesters highlighted the nutritional challenge faced by women with obesity who are pregnant. “About three-quarters of women in the study had poor diet quality. There is an opportunity to improve diet with more fruits and vegetables to increase fullness, and [to reduce] energy-dense foods,” Dr. Redman said.

She is planning to collaborate on a study that will test the efficacy and safety of providing pregnant women with extreme obesity (class II-III) with defined meals to provide better control of energy intake and nutritional quality. Dr. Redman said she also hoped that the new findings she reported would be taken into account by the advisory committee assembled by the Department of Health & Human Services and the Department of Agriculture, which are currently preparing a revision of U.S. dietary guidelines for release in 2020.

The National Institutes of Health and the Clinical Research Cores at Pennington Biomedical Research Center funded the study. Dr. Redman had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Redman LM et al. Obesity Week 2019, Abstract T-OR-2079.

*This article was updated 2/7/2020.

LAS VEGAS – Contrary to current U.S. dietary recommendations for pregnancy, women with obesity should not increase their energy intake during pregnancy to achieve the current recommended level of gestational weight gain, based on findings from an intensive assessment of 54 women with obesity during weeks 13-37 of pregnancy.

To achieve the gestational weight gain of 11-20 pounds (5-9.1 kg) recommended by the Institute of Medicine, women with obesity ‒ those with a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or greater ‒ had an average energy intake during the second and third trimesters of 125 kcal/day less than their energy expenditure, Leanne M. Redman, PhD, said at a meeting presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

However, women in the study who had inadequate gestational weight gain had a daily calorie deficit that was only slightly larger, an average of 262 kcal/day below their energy expenditure. As a consequence, Dr. Redman believes the take-home message from her findings is that pregnant women with obesity should maintain their prepregnancy energy intake, though she also strongly recommended improvements in diet quality.

“Chasing a 100-kcal/day deficit in intake is extremely problematic,” Dr. Redman admitted, so she suggested that women with obesity be advised simply to not increase their calorie intake during pregnancy.

“The message is: Focus on improving diet quality rather than increasing calories,” she said in an interview. Pregnant women with obesity “do not need to increase calorie intake. They need to improve their diet quality,” with increased consumption of fruits and vegetables, said Dr. Redman, a professor and director of the Reproductive Endocrinology and Women’s Health Laboratory at Louisiana State University’s Pennington Biomedical Research Center in Baton Rouge.

The results she reported represent “the first time” researchers have examined energy expenditure and weight-gain trajectories in women with obesity throughout the second and third trimesters. Until now, dietary energy recommendations for women with obesity during pregnancy were based on observations made in women without obesity.

Those observations led the Institute of Medicine to call for a recommended pregnancy weight gain of 11-20 pounds in women with obesity, as well as gains of 25-35 pounds in women with a normal body mass index of 18.5-24.9 kg/m2 (Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines; May 2009). In that 2009 document, the IOM committee said that, in general, pregnant women should add 340 kcal/day to their prepregnancy intake during the second trimester and add 452 kcal/day during the third trimester without regard to their prepregnancy body mass index, a recommendation that clinicians continued to promote in subsequent years (Med Clin North Amer. 2016;100[6]:1199-215), and that was generally affirmed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists in 2013 and reaffirmed in 2018.*

The new evidence collected by Dr. Redman and associates “challenges current practice and argues that women with obesity should not be advised to consume additional energy during pregnancy as currently recommended,” they wrote in an article with their findings published a few days before Dr. Redman gave her talk (J Clin Invest. 2019;129[11]:4682-90).

The MomEE (Determinants of Gestational Weight Gain in Obese Pregnant Women) study enrolled 72 women with obesity during the first trimester of pregnancy and collected complete data through the end of the third trimester from 54 women. The researchers collected data on weight, body fat mass, and energy expenditure at multiple times during the second and third trimesters and calculated energy intake.

Based on body weights at the end of the third trimester, the researchers divided the 54 women into three subgroups: 10 women (19%) with inadequate weight gain by the IOM recommendations, 8 (15%) who had the IOM’s recommended weight gain of 11-20 pounds, and 36 women (67%; total is greater than 100% because of rounding) with excess weight gain, and within each group, they calculated the average level of energy intake relative to energy expenditure.

In addition to the daily calorie deficits associated with women who maintained recommended or inadequate weight, the researchers also found that women with excess weight gain averaged 186 more kcal/day than required to meet their daily energy expenditure.

The analyses showed that the increased energy demand of pregnancy and the fetus is compensated for by mobilization of the maternal fat mass in women with obesity, and that an imbalance between energy intake and expenditure is the main driver of weight gain during pregnancy. The results also highlighted how often pregnant women with obesity fail to follow a diet that results in the recommended weight gain of 11-20 pounds. In the MomEE cohort, two-thirds of enrolled women had excess weight gain.

The finding that women had the recommended weight gain on a diet that cut their daily calorie intake by about 100 kcal/day during the last two trimesters highlighted the nutritional challenge faced by women with obesity who are pregnant. “About three-quarters of women in the study had poor diet quality. There is an opportunity to improve diet with more fruits and vegetables to increase fullness, and [to reduce] energy-dense foods,” Dr. Redman said.

She is planning to collaborate on a study that will test the efficacy and safety of providing pregnant women with extreme obesity (class II-III) with defined meals to provide better control of energy intake and nutritional quality. Dr. Redman said she also hoped that the new findings she reported would be taken into account by the advisory committee assembled by the Department of Health & Human Services and the Department of Agriculture, which are currently preparing a revision of U.S. dietary guidelines for release in 2020.

The National Institutes of Health and the Clinical Research Cores at Pennington Biomedical Research Center funded the study. Dr. Redman had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Redman LM et al. Obesity Week 2019, Abstract T-OR-2079.

*This article was updated 2/7/2020.

REPORTING FROM OBESITY WEEK 2019

Data build on cardiovascular disease risk after GDM, HDP

WASHINGTON – Cardiovascular risk factors may be elevated “as soon as the first postpartum year” in women who have gestational diabetes or hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, recent findings have affirmed, Deborah B. Ehrenthal, MD, MPH, said at the biennial meeting of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America.

Dr. Ehrenthal was one of several researchers who urged innovative strategies and improved care coordination to boost women’s follow-up after gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) and other adverse pregnancy outcomes and complications. “The metabolic stress of pregnancy can uncover underlying susceptibilities,” she said. “And ”

Evidence that adverse pregnancy outcomes – including GDM and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) – can elevate cardiovascular risk comes most recently from the Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study – Monitoring Mothers to be Heart Health Study (nuMoM2b–HHS study), a prospective observational cohort that followed 4,484 women 2-7 years after their first pregnancy. Women had a follow-up exam, with blood pressure and anthropometric measurements and clinical/biological testing, an average of 3 years post partum.

An analysis published in October 2019 in the Journal of the American Heart Association shows that women with HDP (including preeclampsia and gestational hypertension) had a relative risk of hypertension of 2.5 at follow-up, compared with women without HDP. Women who had preeclampsia specifically were 2.3 times as likely as were women who did not have preeclampsia to have incident hypertension at follow-up, said Dr. Ehrenthal, a coinvestigator of the study.

The analysis focused on incident hypertension as the primary outcome, and adjusted for age, body mass index, and other important cardiovascular disease risk factors, she noted. Researchers utilized the diagnostic threshold for hypertension extant at the time of study design: A systolic blood pressure of 140 mm Hg or greater, or a diastolic BP of 90 mm Hg or greater (J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e013092).

HDP was the most common adverse pregnancy outcome in the nuMoM2b–HHS study (14%). Among all participants, 4% had GDM. Approximately 82% had neither HDP nor GDM. Other adverse pregnancy outcomes included in the analysis were preterm birth, small-for-gestational-age birth, and stillbirth.

Additional preliminary estimates presented by Dr. Ehrenthal show that, based on the new (2017) lower threshold for hypertension – 130 mg Hg systolic or 80 mm Hg diastolic – the disorder afflicted 37% of women who had experienced HDP (relative risk 2.1), and 32% of women who had GDM (RR 1.8). Prediabetes/diabetes (using a fasting blood glucose threshold of 100 mg/dL) at follow-up affected an estimated 21% of women who had HDP (RR 1.4) and 38% of women who had GDM (RR 2.5).

Notably, across the entire study cohort, 20% had hypertension at follow-up, “which is extraordinary” considering the short time frame from pregnancy and the young age of the study population – a mean maternal age of 27 years, said Dr. Ehrenthal, associate professor of population health sciences and obstetrics & gynecology at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Also across the cohort, 15% had prediabetes/diabetes at follow-up. “We need to think about women more generally,” she cautioned. “While we recognize the significant elevated risk of HDP and GDM [for the development of subsequent hypertension and cardiovascular risk], we will miss a lot of women [if we focus only on the history of HDP and GDM.]”

The majority of women found to have hypertension or prediabetes/diabetes at follow-up had experienced neither HDP nor GDM, but a good many of them (47% of those who had hypertension and 47% of those found to have prediabetes/diabetes) had a BMI of 30 or above, Dr. Ehrenthal said at the DPSG-NA meeting.

Nurses Health Study, hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcome follow-up data

The new findings from the nuMoM2b–HHS study add to a robust and growing body of evidence that pregnancy is an important window to future health, and that follow up and screening after GDM and HDP are crucial.

Regarding GDM specifically, “there’s quite a bit of literature by now demonstrating that GDM history is a risk factor for hypertension, even 1-2 years post partum, and that the risk is elevated as well for dyslipidemia and vascular dysfunction,” Deirdre K. Tobias, D.Sc., an epidemiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and assistant professor of nutrition at Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, said at the DPSG meeting.

An analysis of the Nurses Health Study II (NHS II) cohort published in 2017 found a 40% higher relative risk of cardiovascular disease events (largely myocardial infarction) in women who had GDM, compared with women who did not have GDM over a median follow-up of 26 years. This was after adjustments were made for age, time since pregnancy, menopausal status, family history of MI or stroke, hypertension in pregnancy, white race/ethnicity, prepregnancy BMI, and other factors (JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177[12]:1735-42).

The NHS data also have shown, however, that the elevated risk for cardiovascular disease after a GDM pregnancy “can be mitigated by adopting a healthy lifestyle,” said Dr. Tobias, lead author of the 2017 NHS II analysis. Adjustments for postpregnancy weight gain and lifestyle factors attenuated the relative risk of cardiovascular disease events after a GDM pregnancy to a 30% increased risk.

Dr. Tobias and colleagues currently are looking within the NHS cohort for “metabolomic signatures” or signals – various amino acid and lipid metabolites – to identify the progression of GDM to type 2 diabetes. Metabolomics “may help further refine our understanding of the long-term links between GDM and prevention of type 2 diabetes and of cardiovascular disease in mothers,” she said.

The Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) Follow-Up Study, in the meantime, is documenting associations of maternal glucose levels during pregnancy not only with prediabetes or type 2 diabetes 10-14 years later, but also with measures of cardiovascular risk in mothers 10-14 years later.

Just as perinatal outcomes were strongly associated with glucose as a continuous variable in the original HAPO study, “it’s clear there’s a progressive increase in the risk of [later] disorders of glucose metabolism as [fasting blood glucose levels and 1- and-2-hour glucose values] in pregnancy are higher,” said Boyd E. Metzger, MD, the Tom D. Spies emeritus professor of metabolism and nutrition at Northwestern University, Chicago, and principal investigator of the original HAPO study and its follow up.

“Another message is that the more normal you are in pregnancy, the more normal you will be many years later. Good values [during pregnancy] produce good outcomes.”

Currently unpublished data from the HAPO Follow-Up Study are being analyzed, but it appears thus far that GDM is not associated with hypertension (per the old diagnostic threshold) in this cohort after adjustment for maternal age, BMI, smoking, and family history of hypertension. GDM appears to be a significant risk factor for dyslipidemia, however. HDL cholesterol at follow-up was significantly lower for mothers who had GDM compared with those without, whereas LDL cholesterol and triglycerides at follow-up were significantly higher for mothers with GDM, Dr. Metzger said.

Racial/ethnic disparities, postpartum care

Neither long-term study – the NHS II or the HAPO Follow-Up Study – has looked at racial and ethnic differences. The HAPO cohort is racially-ethnically diverse but the NHS II cohort is predominantly white women.

Research suggests that GDM is a heterogeneous condition with some unique phenotypes in subgroups that vary by race and ethnicity. And just as there appear to be racial-ethnic differences in the pathophysiology of GDM, there appear to be racial-ethnic differences in the progression to type 2 diabetes – a known risk factor for cardiovascular disease, said Monique Henderson, PhD, a research scientist at Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC).

On the broadest level, while Asian Americans have the highest prevalence of GDM, African Americans have the highest rates of progressing to type 2 diabetes, Dr. Henderson said. Disparities “may [stem from] metabolic differences in terms of insulin resistance and secretion that are different between pregnancy and the postpartum period, and that might vary [across racial-ethnic subgroups],” she said. Lifestyle differences and variation in postpartum screening rates also may play a role.