User login

Wide spectrum of feeding problems poses challenge for clinicians

SAN FRANCISCO – Clinicians are likely to encounter diverse feeding problems in daily practice that will challenge their diagnostic and treatment acumen, Dr. Irene Chatoor told attendees of the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

These problems run the gamut from the most prevalent but least serious picky eating, to the least prevalent but most serious feeding disorders, she noted. Correspondingly, management will range from simple reassurance of parents to more intensive behavioral and medical interventions.

Assessment

“When you assess a feeding problem, you have to look at both the mother and father, and the child,” she advised. The parents are evaluated for their feeding style, while the child is evaluated for three feeding problems: limited appetite, selective intake, and fear of feeding (Pediatrics. 2015;135[2]:344-53).

Clinicians must be alert for organic red flags, such as dysphagia, aspiration, and vomiting, and for behavioral red flags, such as food fixation, abrupt cessation of feeding after a trigger event, and anticipatory gagging. An overarching red flag is failure to thrive.

Sometimes, a child will have both an organic condition and a behavioral feeding disorder at the same time. “It’s very important that you don’t think one excludes the other,” she cautioned.

Diagnosis

“To delineate milder feeding difficulties from feeding disorders, there must be some form of impairment caused by the feeding problem,” Dr. Chatoor commented. “Why is this important? For two reasons. One is for the insurance companies, because they don’t pay unless there is a disorder. And then there is research: you cannot do research unless you clearly define what you are studying.”

Children are considered to have impairment if they have weight loss or growth faltering, considerable nutritional deficiency, or a marked interference with psychosocial functioning.

“When we diagnose feeding problems, it is best done with a multidisciplinary team,” Dr. Chatoor maintained. “I have learned many years ago that I’m not effective in helping parents deal with the feeding disorder if they are still in the back of their mind worried that the child has something organically wrong and that’s why the child does not want to eat.”

Accordingly, various team members perform a medical examination, a nutritional assessment, an oral motor and sensory evaluation, and a psychiatric or psychological assessment to identify the root cause or causes of the problem.

When it comes to behavioral etiologies, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) now groups all feeding and eating disorders together in one section, reflecting the fact that disorders starting early in life can and often do track into adolescence and adulthood, according to Dr. Chatoor.

The manual also features a new diagnosis, avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID). Key criteria include the presence of an eating or feeding disturbance that cannot be better explained by lack of available food, culturally sanctioned practices, or a concurrent medical condition or another mental disorder.

The child must have a persistent failure to meet appropriate nutritional and/or energy needs, associated with any of four findings: significant weight loss or failure to achieve expected weight gain or growth, significant nutritional deficiencies, dependence on enteral feeding or oral nutritional supplements, and marked interference with psychosocial functioning.

“You need to have at least one but often you have a combination of nutritional and emotional impairment in the same child,” she commented.

ARFID and its treatment

There are three subtypes of ARFID having different features, treatments, and prognosis, although they all share in common food refusal, according to Dr. Chatoor.

The first subtype – apparent lack of interest in eating or food – emerges by 3 years of age, most often during the transition to self-feeding between 9 and 18 months. Affected children refuse to eat an adequate amount of food for at least 1 month, rarely communicate hunger, lack interest in food, and prefer to play or talk. They typically present with growth deficiency.

“If you have a child who refuses to eat, it generates anxiety in the mother. The mother does things she would not normally do with the child who is eating well. She starts to distract, to cajole, to sometimes even force-feed the child,” Dr. Chatoor explained. “And the more she engages in these behaviors, the more resistant the child becomes. So they become trapped in this vicious cycle.”

Treatment is aimed at removing this conflict with three approaches: explaining to parents the infant’s special temperament (notably, high arousal and difficulty turning off excitement); addressing their background, including any eating issues of their own, and difficulty with setting limits; and providing specific feeding guidelines and a time-out procedure.

The guidelines stress regular feeding, withholding of all snacks, keeping the child at the table for 20 to 30 minutes, and not using any distractions or pressure. Also, importantly, the parents should have dinner with their child. “I always tell the parents what is good for the child is good for you. It’s good for your whole family,” she said. “If they have other children, these rules apply to everybody. Young children learn to eat by watching their parents eating.”

With early and consistent use of these interventions, about two-thirds of children outgrow this eating/feeding disturbance by mid-childhood, according to Dr. Chatoor.

Children with the second subtype of ARFID – avoidance based on the sensory characteristics of food – consistently refuse to eat certain foods having specific tastes, textures, temperatures, smells, and/or appearances. Onset occurs during the toddler years, when a new or different food is introduced.

“Not only do they refuse the same foods that were aversive, but they also generalize it. So these children are afraid to try other foods and they may end up limiting food groups – they don’t eat any vegetables and some of them don’t eat any meats,” she explained. “They are a challenge because this always causes a nutritional deficiency and they also have problems socially as they get older.”

Treatment varies by age, with gradual desensitization for infants and parent modeling of eating new foods for toddlers. A multifaceted approach is used for preschoolers, combining modeling, giving foods attractive shapes and names, having the child participate in food preparation, and using focused play therapy, such as feeding dolls who are “brave” and try new foods.

Clinicians can explain to affected school-aged children that they are “supertasters,” having more taste buds and therefore experiencing food more intensely, and that they can help their taste buds not react so strongly by starting to eat small amounts of new foods and gradually increasing over time. Parents can let the child make a list of 10 foods they would like to eat, and award them points for “courage” for every bite of a new food they try.

Prognosis of this type of ARFID varies, according to Dr. Chatoor. “Through gradual exposure, young children can expand the variety of foods they eat,” she elaborated. However, “some children become very rigid and brand sensitive in regard to the food they are willing to eat and begin to experience social problems during mid-childhood and adolescence. Some children grow up eating a limited diet, but finding ways to compensate nutritionally and socially.”

Children with the third subtype of ARFID – concern about aversive consequences of eating – have an acute onset of consistent food refusal at any age, from infancy onward, after experiencing a traumatic event or repeated traumatic insults to the oropharynx or gastrointestinal tract that trigger distress in the child. These children often have comorbidities such as gastroesophageal reflux, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, or anxiety disorder.

“Treatment involves gradual desensitization to feared objects: the highchair, bib, bottle, or spoon,” Dr. Chatoor explained. “It also involves training of the mother in behavioral techniques to feed the child in spite of the child’s fear and distress.”

Any underlying medical condition causing pain or distress should be treated. Additional measures may include, for example, use of a graduated approach, starting with liquids and progressing to purees, if the child fears solid foods, and prescribing anxiolytic medication in cases of severe anxiety.

Dr. Chatoor disclosed that she has lectured internationally at conferences on feeding disorders that were organized by Abbott Nutrition International and that the company provided a research grant for a study on feeding.

SAN FRANCISCO – Clinicians are likely to encounter diverse feeding problems in daily practice that will challenge their diagnostic and treatment acumen, Dr. Irene Chatoor told attendees of the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

These problems run the gamut from the most prevalent but least serious picky eating, to the least prevalent but most serious feeding disorders, she noted. Correspondingly, management will range from simple reassurance of parents to more intensive behavioral and medical interventions.

Assessment

“When you assess a feeding problem, you have to look at both the mother and father, and the child,” she advised. The parents are evaluated for their feeding style, while the child is evaluated for three feeding problems: limited appetite, selective intake, and fear of feeding (Pediatrics. 2015;135[2]:344-53).

Clinicians must be alert for organic red flags, such as dysphagia, aspiration, and vomiting, and for behavioral red flags, such as food fixation, abrupt cessation of feeding after a trigger event, and anticipatory gagging. An overarching red flag is failure to thrive.

Sometimes, a child will have both an organic condition and a behavioral feeding disorder at the same time. “It’s very important that you don’t think one excludes the other,” she cautioned.

Diagnosis

“To delineate milder feeding difficulties from feeding disorders, there must be some form of impairment caused by the feeding problem,” Dr. Chatoor commented. “Why is this important? For two reasons. One is for the insurance companies, because they don’t pay unless there is a disorder. And then there is research: you cannot do research unless you clearly define what you are studying.”

Children are considered to have impairment if they have weight loss or growth faltering, considerable nutritional deficiency, or a marked interference with psychosocial functioning.

“When we diagnose feeding problems, it is best done with a multidisciplinary team,” Dr. Chatoor maintained. “I have learned many years ago that I’m not effective in helping parents deal with the feeding disorder if they are still in the back of their mind worried that the child has something organically wrong and that’s why the child does not want to eat.”

Accordingly, various team members perform a medical examination, a nutritional assessment, an oral motor and sensory evaluation, and a psychiatric or psychological assessment to identify the root cause or causes of the problem.

When it comes to behavioral etiologies, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) now groups all feeding and eating disorders together in one section, reflecting the fact that disorders starting early in life can and often do track into adolescence and adulthood, according to Dr. Chatoor.

The manual also features a new diagnosis, avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID). Key criteria include the presence of an eating or feeding disturbance that cannot be better explained by lack of available food, culturally sanctioned practices, or a concurrent medical condition or another mental disorder.

The child must have a persistent failure to meet appropriate nutritional and/or energy needs, associated with any of four findings: significant weight loss or failure to achieve expected weight gain or growth, significant nutritional deficiencies, dependence on enteral feeding or oral nutritional supplements, and marked interference with psychosocial functioning.

“You need to have at least one but often you have a combination of nutritional and emotional impairment in the same child,” she commented.

ARFID and its treatment

There are three subtypes of ARFID having different features, treatments, and prognosis, although they all share in common food refusal, according to Dr. Chatoor.

The first subtype – apparent lack of interest in eating or food – emerges by 3 years of age, most often during the transition to self-feeding between 9 and 18 months. Affected children refuse to eat an adequate amount of food for at least 1 month, rarely communicate hunger, lack interest in food, and prefer to play or talk. They typically present with growth deficiency.

“If you have a child who refuses to eat, it generates anxiety in the mother. The mother does things she would not normally do with the child who is eating well. She starts to distract, to cajole, to sometimes even force-feed the child,” Dr. Chatoor explained. “And the more she engages in these behaviors, the more resistant the child becomes. So they become trapped in this vicious cycle.”

Treatment is aimed at removing this conflict with three approaches: explaining to parents the infant’s special temperament (notably, high arousal and difficulty turning off excitement); addressing their background, including any eating issues of their own, and difficulty with setting limits; and providing specific feeding guidelines and a time-out procedure.

The guidelines stress regular feeding, withholding of all snacks, keeping the child at the table for 20 to 30 minutes, and not using any distractions or pressure. Also, importantly, the parents should have dinner with their child. “I always tell the parents what is good for the child is good for you. It’s good for your whole family,” she said. “If they have other children, these rules apply to everybody. Young children learn to eat by watching their parents eating.”

With early and consistent use of these interventions, about two-thirds of children outgrow this eating/feeding disturbance by mid-childhood, according to Dr. Chatoor.

Children with the second subtype of ARFID – avoidance based on the sensory characteristics of food – consistently refuse to eat certain foods having specific tastes, textures, temperatures, smells, and/or appearances. Onset occurs during the toddler years, when a new or different food is introduced.

“Not only do they refuse the same foods that were aversive, but they also generalize it. So these children are afraid to try other foods and they may end up limiting food groups – they don’t eat any vegetables and some of them don’t eat any meats,” she explained. “They are a challenge because this always causes a nutritional deficiency and they also have problems socially as they get older.”

Treatment varies by age, with gradual desensitization for infants and parent modeling of eating new foods for toddlers. A multifaceted approach is used for preschoolers, combining modeling, giving foods attractive shapes and names, having the child participate in food preparation, and using focused play therapy, such as feeding dolls who are “brave” and try new foods.

Clinicians can explain to affected school-aged children that they are “supertasters,” having more taste buds and therefore experiencing food more intensely, and that they can help their taste buds not react so strongly by starting to eat small amounts of new foods and gradually increasing over time. Parents can let the child make a list of 10 foods they would like to eat, and award them points for “courage” for every bite of a new food they try.

Prognosis of this type of ARFID varies, according to Dr. Chatoor. “Through gradual exposure, young children can expand the variety of foods they eat,” she elaborated. However, “some children become very rigid and brand sensitive in regard to the food they are willing to eat and begin to experience social problems during mid-childhood and adolescence. Some children grow up eating a limited diet, but finding ways to compensate nutritionally and socially.”

Children with the third subtype of ARFID – concern about aversive consequences of eating – have an acute onset of consistent food refusal at any age, from infancy onward, after experiencing a traumatic event or repeated traumatic insults to the oropharynx or gastrointestinal tract that trigger distress in the child. These children often have comorbidities such as gastroesophageal reflux, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, or anxiety disorder.

“Treatment involves gradual desensitization to feared objects: the highchair, bib, bottle, or spoon,” Dr. Chatoor explained. “It also involves training of the mother in behavioral techniques to feed the child in spite of the child’s fear and distress.”

Any underlying medical condition causing pain or distress should be treated. Additional measures may include, for example, use of a graduated approach, starting with liquids and progressing to purees, if the child fears solid foods, and prescribing anxiolytic medication in cases of severe anxiety.

Dr. Chatoor disclosed that she has lectured internationally at conferences on feeding disorders that were organized by Abbott Nutrition International and that the company provided a research grant for a study on feeding.

SAN FRANCISCO – Clinicians are likely to encounter diverse feeding problems in daily practice that will challenge their diagnostic and treatment acumen, Dr. Irene Chatoor told attendees of the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

These problems run the gamut from the most prevalent but least serious picky eating, to the least prevalent but most serious feeding disorders, she noted. Correspondingly, management will range from simple reassurance of parents to more intensive behavioral and medical interventions.

Assessment

“When you assess a feeding problem, you have to look at both the mother and father, and the child,” she advised. The parents are evaluated for their feeding style, while the child is evaluated for three feeding problems: limited appetite, selective intake, and fear of feeding (Pediatrics. 2015;135[2]:344-53).

Clinicians must be alert for organic red flags, such as dysphagia, aspiration, and vomiting, and for behavioral red flags, such as food fixation, abrupt cessation of feeding after a trigger event, and anticipatory gagging. An overarching red flag is failure to thrive.

Sometimes, a child will have both an organic condition and a behavioral feeding disorder at the same time. “It’s very important that you don’t think one excludes the other,” she cautioned.

Diagnosis

“To delineate milder feeding difficulties from feeding disorders, there must be some form of impairment caused by the feeding problem,” Dr. Chatoor commented. “Why is this important? For two reasons. One is for the insurance companies, because they don’t pay unless there is a disorder. And then there is research: you cannot do research unless you clearly define what you are studying.”

Children are considered to have impairment if they have weight loss or growth faltering, considerable nutritional deficiency, or a marked interference with psychosocial functioning.

“When we diagnose feeding problems, it is best done with a multidisciplinary team,” Dr. Chatoor maintained. “I have learned many years ago that I’m not effective in helping parents deal with the feeding disorder if they are still in the back of their mind worried that the child has something organically wrong and that’s why the child does not want to eat.”

Accordingly, various team members perform a medical examination, a nutritional assessment, an oral motor and sensory evaluation, and a psychiatric or psychological assessment to identify the root cause or causes of the problem.

When it comes to behavioral etiologies, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) now groups all feeding and eating disorders together in one section, reflecting the fact that disorders starting early in life can and often do track into adolescence and adulthood, according to Dr. Chatoor.

The manual also features a new diagnosis, avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID). Key criteria include the presence of an eating or feeding disturbance that cannot be better explained by lack of available food, culturally sanctioned practices, or a concurrent medical condition or another mental disorder.

The child must have a persistent failure to meet appropriate nutritional and/or energy needs, associated with any of four findings: significant weight loss or failure to achieve expected weight gain or growth, significant nutritional deficiencies, dependence on enteral feeding or oral nutritional supplements, and marked interference with psychosocial functioning.

“You need to have at least one but often you have a combination of nutritional and emotional impairment in the same child,” she commented.

ARFID and its treatment

There are three subtypes of ARFID having different features, treatments, and prognosis, although they all share in common food refusal, according to Dr. Chatoor.

The first subtype – apparent lack of interest in eating or food – emerges by 3 years of age, most often during the transition to self-feeding between 9 and 18 months. Affected children refuse to eat an adequate amount of food for at least 1 month, rarely communicate hunger, lack interest in food, and prefer to play or talk. They typically present with growth deficiency.

“If you have a child who refuses to eat, it generates anxiety in the mother. The mother does things she would not normally do with the child who is eating well. She starts to distract, to cajole, to sometimes even force-feed the child,” Dr. Chatoor explained. “And the more she engages in these behaviors, the more resistant the child becomes. So they become trapped in this vicious cycle.”

Treatment is aimed at removing this conflict with three approaches: explaining to parents the infant’s special temperament (notably, high arousal and difficulty turning off excitement); addressing their background, including any eating issues of their own, and difficulty with setting limits; and providing specific feeding guidelines and a time-out procedure.

The guidelines stress regular feeding, withholding of all snacks, keeping the child at the table for 20 to 30 minutes, and not using any distractions or pressure. Also, importantly, the parents should have dinner with their child. “I always tell the parents what is good for the child is good for you. It’s good for your whole family,” she said. “If they have other children, these rules apply to everybody. Young children learn to eat by watching their parents eating.”

With early and consistent use of these interventions, about two-thirds of children outgrow this eating/feeding disturbance by mid-childhood, according to Dr. Chatoor.

Children with the second subtype of ARFID – avoidance based on the sensory characteristics of food – consistently refuse to eat certain foods having specific tastes, textures, temperatures, smells, and/or appearances. Onset occurs during the toddler years, when a new or different food is introduced.

“Not only do they refuse the same foods that were aversive, but they also generalize it. So these children are afraid to try other foods and they may end up limiting food groups – they don’t eat any vegetables and some of them don’t eat any meats,” she explained. “They are a challenge because this always causes a nutritional deficiency and they also have problems socially as they get older.”

Treatment varies by age, with gradual desensitization for infants and parent modeling of eating new foods for toddlers. A multifaceted approach is used for preschoolers, combining modeling, giving foods attractive shapes and names, having the child participate in food preparation, and using focused play therapy, such as feeding dolls who are “brave” and try new foods.

Clinicians can explain to affected school-aged children that they are “supertasters,” having more taste buds and therefore experiencing food more intensely, and that they can help their taste buds not react so strongly by starting to eat small amounts of new foods and gradually increasing over time. Parents can let the child make a list of 10 foods they would like to eat, and award them points for “courage” for every bite of a new food they try.

Prognosis of this type of ARFID varies, according to Dr. Chatoor. “Through gradual exposure, young children can expand the variety of foods they eat,” she elaborated. However, “some children become very rigid and brand sensitive in regard to the food they are willing to eat and begin to experience social problems during mid-childhood and adolescence. Some children grow up eating a limited diet, but finding ways to compensate nutritionally and socially.”

Children with the third subtype of ARFID – concern about aversive consequences of eating – have an acute onset of consistent food refusal at any age, from infancy onward, after experiencing a traumatic event or repeated traumatic insults to the oropharynx or gastrointestinal tract that trigger distress in the child. These children often have comorbidities such as gastroesophageal reflux, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, or anxiety disorder.

“Treatment involves gradual desensitization to feared objects: the highchair, bib, bottle, or spoon,” Dr. Chatoor explained. “It also involves training of the mother in behavioral techniques to feed the child in spite of the child’s fear and distress.”

Any underlying medical condition causing pain or distress should be treated. Additional measures may include, for example, use of a graduated approach, starting with liquids and progressing to purees, if the child fears solid foods, and prescribing anxiolytic medication in cases of severe anxiety.

Dr. Chatoor disclosed that she has lectured internationally at conferences on feeding disorders that were organized by Abbott Nutrition International and that the company provided a research grant for a study on feeding.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAP 16

Roommates

The American Academy of Pediatrics has recently released a new policy for parents on safe sleep practices that in addition to the previous warnings about bed sharing and positioning includes the recommendation that an infant sleep in the same room as her parent for at least the first 6 months (Pediatrics. 2016 Oct;138[5]:e20162938). Apparently what prompted this new set of recommendations is the observation that deaths from sudden unexpected infant deaths (SUIDS) and sudden infant deaths (SIDS) has plateaued since the dramatic decline we witnessed in the 1990s following the Back-to-Sleep campaign.

Although the policy statement refers to “new research” that has become available since the last policy statement was released in 2011, I have had trouble finding convincing evidence in the references I reviewed to support the room sharing recommendation. In some studies, room sharing was the cultural norm, making it difficult to establish a control group. In one of the most frequently cited papers from New Zealand, the authors could not sort out the effects of prone sleeping and sleeping alone, and wonder whether both factors may be affecting risk “through a common mechanism” (Lancet. 1996 Jan 6;347[8993]:7-12).

For some, parents attempting to follow this recommendation may not be without its negative consequences. Sleeping like a baby is not the same as sleeping quietly. Infants often breathe in a pattern that includes long, anxiety-provoking pauses. The implication of this policy recommendation is that parents can prevent crib death by being more vigilant at night. Do we have enough evidence that this is indeed the case?

Most parents are already anxious, and none of them are getting enough sleep. I can envision that trying to follow this recommendation could aggravate both conditions for some parents. Sleep-deprived parents often are not as capable parents as they could be. And they certainly aren’t as happy as they could be. Postpartum depression compounded by sleep deprivation continues to be an underreported and inadequately managed condition that can have negative effects for the health of the child.

For some parents, room sharing is something they gravitate toward naturally, and it can help them deal with the anxiety of new parenthood. They may sleep better with their infant close by. But for others, the better solution to their own sleep deprivation lies in sleep training, a strategy that is very difficult, if not impossible, for parents who are sharing their bedroom with their infant.

As the authors of one of the most frequently quoted papers that supports room sharing have written, “the traditional habit of labeling one sleep arrangement as being superior to another without awareness of the family context is not only wrong but potentially harmful” (Paediatric Resp Review. 2005, Jun;6[2]:134-52).

I think the academy has gone too far or at least moved prematurely with its room sharing recommendation. For some families, room sharing is a better arrangement, for others it is not. It may well be that the plateau in crib deaths is telling us that we have reached the limits of our abilities to effect any further decline with our recommendations about sleep environments. But more research needs to be done.

On a more positive note, the new recommendation may force parents to reevaluate their habit of having a television in their bedroom. Will it be baby or TV in the bedroom? Unfortunately, I fear too many will opt to have both.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

The American Academy of Pediatrics has recently released a new policy for parents on safe sleep practices that in addition to the previous warnings about bed sharing and positioning includes the recommendation that an infant sleep in the same room as her parent for at least the first 6 months (Pediatrics. 2016 Oct;138[5]:e20162938). Apparently what prompted this new set of recommendations is the observation that deaths from sudden unexpected infant deaths (SUIDS) and sudden infant deaths (SIDS) has plateaued since the dramatic decline we witnessed in the 1990s following the Back-to-Sleep campaign.

Although the policy statement refers to “new research” that has become available since the last policy statement was released in 2011, I have had trouble finding convincing evidence in the references I reviewed to support the room sharing recommendation. In some studies, room sharing was the cultural norm, making it difficult to establish a control group. In one of the most frequently cited papers from New Zealand, the authors could not sort out the effects of prone sleeping and sleeping alone, and wonder whether both factors may be affecting risk “through a common mechanism” (Lancet. 1996 Jan 6;347[8993]:7-12).

For some, parents attempting to follow this recommendation may not be without its negative consequences. Sleeping like a baby is not the same as sleeping quietly. Infants often breathe in a pattern that includes long, anxiety-provoking pauses. The implication of this policy recommendation is that parents can prevent crib death by being more vigilant at night. Do we have enough evidence that this is indeed the case?

Most parents are already anxious, and none of them are getting enough sleep. I can envision that trying to follow this recommendation could aggravate both conditions for some parents. Sleep-deprived parents often are not as capable parents as they could be. And they certainly aren’t as happy as they could be. Postpartum depression compounded by sleep deprivation continues to be an underreported and inadequately managed condition that can have negative effects for the health of the child.

For some parents, room sharing is something they gravitate toward naturally, and it can help them deal with the anxiety of new parenthood. They may sleep better with their infant close by. But for others, the better solution to their own sleep deprivation lies in sleep training, a strategy that is very difficult, if not impossible, for parents who are sharing their bedroom with their infant.

As the authors of one of the most frequently quoted papers that supports room sharing have written, “the traditional habit of labeling one sleep arrangement as being superior to another without awareness of the family context is not only wrong but potentially harmful” (Paediatric Resp Review. 2005, Jun;6[2]:134-52).

I think the academy has gone too far or at least moved prematurely with its room sharing recommendation. For some families, room sharing is a better arrangement, for others it is not. It may well be that the plateau in crib deaths is telling us that we have reached the limits of our abilities to effect any further decline with our recommendations about sleep environments. But more research needs to be done.

On a more positive note, the new recommendation may force parents to reevaluate their habit of having a television in their bedroom. Will it be baby or TV in the bedroom? Unfortunately, I fear too many will opt to have both.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

The American Academy of Pediatrics has recently released a new policy for parents on safe sleep practices that in addition to the previous warnings about bed sharing and positioning includes the recommendation that an infant sleep in the same room as her parent for at least the first 6 months (Pediatrics. 2016 Oct;138[5]:e20162938). Apparently what prompted this new set of recommendations is the observation that deaths from sudden unexpected infant deaths (SUIDS) and sudden infant deaths (SIDS) has plateaued since the dramatic decline we witnessed in the 1990s following the Back-to-Sleep campaign.

Although the policy statement refers to “new research” that has become available since the last policy statement was released in 2011, I have had trouble finding convincing evidence in the references I reviewed to support the room sharing recommendation. In some studies, room sharing was the cultural norm, making it difficult to establish a control group. In one of the most frequently cited papers from New Zealand, the authors could not sort out the effects of prone sleeping and sleeping alone, and wonder whether both factors may be affecting risk “through a common mechanism” (Lancet. 1996 Jan 6;347[8993]:7-12).

For some, parents attempting to follow this recommendation may not be without its negative consequences. Sleeping like a baby is not the same as sleeping quietly. Infants often breathe in a pattern that includes long, anxiety-provoking pauses. The implication of this policy recommendation is that parents can prevent crib death by being more vigilant at night. Do we have enough evidence that this is indeed the case?

Most parents are already anxious, and none of them are getting enough sleep. I can envision that trying to follow this recommendation could aggravate both conditions for some parents. Sleep-deprived parents often are not as capable parents as they could be. And they certainly aren’t as happy as they could be. Postpartum depression compounded by sleep deprivation continues to be an underreported and inadequately managed condition that can have negative effects for the health of the child.

For some parents, room sharing is something they gravitate toward naturally, and it can help them deal with the anxiety of new parenthood. They may sleep better with their infant close by. But for others, the better solution to their own sleep deprivation lies in sleep training, a strategy that is very difficult, if not impossible, for parents who are sharing their bedroom with their infant.

As the authors of one of the most frequently quoted papers that supports room sharing have written, “the traditional habit of labeling one sleep arrangement as being superior to another without awareness of the family context is not only wrong but potentially harmful” (Paediatric Resp Review. 2005, Jun;6[2]:134-52).

I think the academy has gone too far or at least moved prematurely with its room sharing recommendation. For some families, room sharing is a better arrangement, for others it is not. It may well be that the plateau in crib deaths is telling us that we have reached the limits of our abilities to effect any further decline with our recommendations about sleep environments. But more research needs to be done.

On a more positive note, the new recommendation may force parents to reevaluate their habit of having a television in their bedroom. Will it be baby or TV in the bedroom? Unfortunately, I fear too many will opt to have both.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

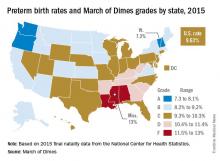

U.S. preterm birth rate rose slightly in 2015

The preterm birth rate in the United States for 2015 increased for the first time in 8 years, according to the March of Dimes.

The national preterm birth rate rose from 9.57% in 2014 to 9.63% last year, earning an overall grade of C on the March of Dimes 2016 Premature Birth Report Card.

The March of Dimes also ranked preterm births in the states by racial/ethnic disparity: Maine had the least disparity, followed by New Hampshire and Utah, while Hawaii had the greatest disparity, just ahead of Pennsylvania and Louisiana. Using an average of the 2012-2014 national preterm birth rates, the March of Dimes calculated that Asian/Pacific Islanders had the lowest preterm birth rate at 8.5%, compared with 9% for whites, 9.1% for Hispanics, 10.4% for American Indian/Alaska Natives, and 13.3% for blacks.

The report card shows “that there is an unfair burden of premature birth among specific racial and ethnic groups as well as geographic areas,” Jennifer L. Howse, PhD, president of the March of Dimes, said in a statement. “Babies in this country have different chances of surviving and thriving simply based on the circumstances of their birth.”

The preterm birth rate in the United States for 2015 increased for the first time in 8 years, according to the March of Dimes.

The national preterm birth rate rose from 9.57% in 2014 to 9.63% last year, earning an overall grade of C on the March of Dimes 2016 Premature Birth Report Card.

The March of Dimes also ranked preterm births in the states by racial/ethnic disparity: Maine had the least disparity, followed by New Hampshire and Utah, while Hawaii had the greatest disparity, just ahead of Pennsylvania and Louisiana. Using an average of the 2012-2014 national preterm birth rates, the March of Dimes calculated that Asian/Pacific Islanders had the lowest preterm birth rate at 8.5%, compared with 9% for whites, 9.1% for Hispanics, 10.4% for American Indian/Alaska Natives, and 13.3% for blacks.

The report card shows “that there is an unfair burden of premature birth among specific racial and ethnic groups as well as geographic areas,” Jennifer L. Howse, PhD, president of the March of Dimes, said in a statement. “Babies in this country have different chances of surviving and thriving simply based on the circumstances of their birth.”

The preterm birth rate in the United States for 2015 increased for the first time in 8 years, according to the March of Dimes.

The national preterm birth rate rose from 9.57% in 2014 to 9.63% last year, earning an overall grade of C on the March of Dimes 2016 Premature Birth Report Card.

The March of Dimes also ranked preterm births in the states by racial/ethnic disparity: Maine had the least disparity, followed by New Hampshire and Utah, while Hawaii had the greatest disparity, just ahead of Pennsylvania and Louisiana. Using an average of the 2012-2014 national preterm birth rates, the March of Dimes calculated that Asian/Pacific Islanders had the lowest preterm birth rate at 8.5%, compared with 9% for whites, 9.1% for Hispanics, 10.4% for American Indian/Alaska Natives, and 13.3% for blacks.

The report card shows “that there is an unfair burden of premature birth among specific racial and ethnic groups as well as geographic areas,” Jennifer L. Howse, PhD, president of the March of Dimes, said in a statement. “Babies in this country have different chances of surviving and thriving simply based on the circumstances of their birth.”

Prenatal triple ART arrests HIV transmission

A triple-drug antiretroviral therapy given to HIV-infected pregnant women significantly reduced transmission of the disease to their newborns, but with greater risk of adverse outcomes for mothers and infants, a study showed.

The findings were based on data from three treatment regimens in approximately 3,500 women and infant sets. The three treatments were zidovudine plus intrapartum single-dose nevirapine with 6-14 days of tenofovir and emtricitabine post partum (zidovudine alone); zidovudine, lamivudine, and lopinavir–ritonavir (zidovudine-based antiretroviral therapy [ART]); or tenofovir, emtricitabine, and lopinavir–ritonavir (tenofovir-based ART). All infants received nevirapine once daily, and infants of mothers coinfected with hepatitis B also received hepatitis B vaccination.

The Promoting Maternal and Infant Survival Everywhere (PROMISE) trial included patients at 14 sites in seven countries (India, Malawi, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe). The current study presented findings from women with a CD4 count of at least 350 cells per cubic millimeter who were randomized at 14 weeks’ gestation to one of the three treatment regimens.

Maternal adverse events (grade 2 or higher) were significantly more common in the zidovudine-based ART group than in the zidovudine-only group (21.1% vs. 17.3%), as was the rate of grade 2 or higher abnormal blood chemical values (5.8% vs. 1.3%).

In addition, rates of abnormal blood chemical values grade 2 or higher were significantly more common in women treated with tenofovir-based ART than with zidovudine alone (2.9% vs. 0.8%).

Low birth weight (less than 2,500 g) was significantly more likely for infants of mothers in the zidovudine-based ART group, compared with the zidovudine-only group (23.0% vs. 12.0%) and in the tenofovir-based ART group, compared with the zidovudine-only group (16.9% vs. 8.9%). Preterm delivery and early infant death rates were significantly more likely in the tenofovir-based ART group than in the zidovudine-based ART group. Overall, the rate of HIV-free survival was highest among infants whose mothers received zidovudine-based ART, the investigators reported.

The findings were limited by several factors, and the safest and most effective regimens have yet to be determined, the researchers said. “Our findings emphasize the need for continued research to assess ART in pregnancy to ensure safer pregnancies for HIV-infected women and healthier outcomes for their uninfected infants,” they wrote.

A study coauthor reported receiving grant support from Gilead Sciences and ViiV Healthcare, and consulting fees from Janssen, paid directly to her institution. None of the other researchers, disclosed any financial conflicts.

A triple-drug antiretroviral therapy given to HIV-infected pregnant women significantly reduced transmission of the disease to their newborns, but with greater risk of adverse outcomes for mothers and infants, a study showed.

The findings were based on data from three treatment regimens in approximately 3,500 women and infant sets. The three treatments were zidovudine plus intrapartum single-dose nevirapine with 6-14 days of tenofovir and emtricitabine post partum (zidovudine alone); zidovudine, lamivudine, and lopinavir–ritonavir (zidovudine-based antiretroviral therapy [ART]); or tenofovir, emtricitabine, and lopinavir–ritonavir (tenofovir-based ART). All infants received nevirapine once daily, and infants of mothers coinfected with hepatitis B also received hepatitis B vaccination.

The Promoting Maternal and Infant Survival Everywhere (PROMISE) trial included patients at 14 sites in seven countries (India, Malawi, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe). The current study presented findings from women with a CD4 count of at least 350 cells per cubic millimeter who were randomized at 14 weeks’ gestation to one of the three treatment regimens.

Maternal adverse events (grade 2 or higher) were significantly more common in the zidovudine-based ART group than in the zidovudine-only group (21.1% vs. 17.3%), as was the rate of grade 2 or higher abnormal blood chemical values (5.8% vs. 1.3%).

In addition, rates of abnormal blood chemical values grade 2 or higher were significantly more common in women treated with tenofovir-based ART than with zidovudine alone (2.9% vs. 0.8%).

Low birth weight (less than 2,500 g) was significantly more likely for infants of mothers in the zidovudine-based ART group, compared with the zidovudine-only group (23.0% vs. 12.0%) and in the tenofovir-based ART group, compared with the zidovudine-only group (16.9% vs. 8.9%). Preterm delivery and early infant death rates were significantly more likely in the tenofovir-based ART group than in the zidovudine-based ART group. Overall, the rate of HIV-free survival was highest among infants whose mothers received zidovudine-based ART, the investigators reported.

The findings were limited by several factors, and the safest and most effective regimens have yet to be determined, the researchers said. “Our findings emphasize the need for continued research to assess ART in pregnancy to ensure safer pregnancies for HIV-infected women and healthier outcomes for their uninfected infants,” they wrote.

A study coauthor reported receiving grant support from Gilead Sciences and ViiV Healthcare, and consulting fees from Janssen, paid directly to her institution. None of the other researchers, disclosed any financial conflicts.

A triple-drug antiretroviral therapy given to HIV-infected pregnant women significantly reduced transmission of the disease to their newborns, but with greater risk of adverse outcomes for mothers and infants, a study showed.

The findings were based on data from three treatment regimens in approximately 3,500 women and infant sets. The three treatments were zidovudine plus intrapartum single-dose nevirapine with 6-14 days of tenofovir and emtricitabine post partum (zidovudine alone); zidovudine, lamivudine, and lopinavir–ritonavir (zidovudine-based antiretroviral therapy [ART]); or tenofovir, emtricitabine, and lopinavir–ritonavir (tenofovir-based ART). All infants received nevirapine once daily, and infants of mothers coinfected with hepatitis B also received hepatitis B vaccination.

The Promoting Maternal and Infant Survival Everywhere (PROMISE) trial included patients at 14 sites in seven countries (India, Malawi, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe). The current study presented findings from women with a CD4 count of at least 350 cells per cubic millimeter who were randomized at 14 weeks’ gestation to one of the three treatment regimens.

Maternal adverse events (grade 2 or higher) were significantly more common in the zidovudine-based ART group than in the zidovudine-only group (21.1% vs. 17.3%), as was the rate of grade 2 or higher abnormal blood chemical values (5.8% vs. 1.3%).

In addition, rates of abnormal blood chemical values grade 2 or higher were significantly more common in women treated with tenofovir-based ART than with zidovudine alone (2.9% vs. 0.8%).

Low birth weight (less than 2,500 g) was significantly more likely for infants of mothers in the zidovudine-based ART group, compared with the zidovudine-only group (23.0% vs. 12.0%) and in the tenofovir-based ART group, compared with the zidovudine-only group (16.9% vs. 8.9%). Preterm delivery and early infant death rates were significantly more likely in the tenofovir-based ART group than in the zidovudine-based ART group. Overall, the rate of HIV-free survival was highest among infants whose mothers received zidovudine-based ART, the investigators reported.

The findings were limited by several factors, and the safest and most effective regimens have yet to be determined, the researchers said. “Our findings emphasize the need for continued research to assess ART in pregnancy to ensure safer pregnancies for HIV-infected women and healthier outcomes for their uninfected infants,” they wrote.

A study coauthor reported receiving grant support from Gilead Sciences and ViiV Healthcare, and consulting fees from Janssen, paid directly to her institution. None of the other researchers, disclosed any financial conflicts.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Prenatal ART significantly lowered rates of early HIV transmission from HIV-infected pregnant women to their newborns, compared with zidovudine alone.

Major finding: The transmission rate for HIV was significantly lower in patients who underwent ART, compared with zidovudine alone (0.5% vs. 1.8%).

Data source: A randomized trial including 3,529 HIV-positive pregnant women at at least 14 weeks’ gestation.

Disclosures: A study coauthor reported receiving grant support from Gilead Sciences and ViiV Healthcare, and consulting fees from Janssen, paid directly to her institution. None of the other researchers disclosed any financial conflicts.

Newborns with CHD have reduced cerebral oxygen delivery

Using a newer form of MRI to investigate oxygen levels in newborns with congenital heart disease, researchers in Canada reported that these patients may have impaired brain growth and development in the first weeks of life because of significantly lower cerebral oxygen delivery levels.

These findings suggest that oxygen delivery may impact brain growth, particularly in newborns with single-ventricle physiology, reported Jessie Mei Lim, BSc, of the University of Toronto, and her colleagues from McGill University, Montreal, and the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto. The findings were published in the October issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2016;152:1095-103). Ms. Lim and her colleagues used cine phase-contrast (PC) MRI to measure cerebral blood flow in newborns with congenital heard disease (CHD). Previous studies used optical measures of tissue oxygenation and MRI arterial spin labeling to suggests that newborns with severe CHD have impaired CBF and cerebral oxygen delivery (CDO2) and CBF.

This single-center study involved 63 newborns from June 2013 to April 2015 at the Hospital for Sick Children. These subjects received an MRI of the head before surgery at an average of age 7.5 days. The scans were done without sedation or contrast while the infants were asleep. The study compared 31 age-matched controls with 32 subjects with various forms of CHD – 12 were managed surgically along a single-ventricle pathway (SVP), 4 had coarctation of the aorta, 13 had transposition of the great arteries (TGA), and 3 had other forms of CHD.

The researchers validated their method by reporting similarities between flows in the basilar and vertebral arteries in 14 controls, “suggesting good consistency and accuracy of our method for measuring CBF,” Ms. Lim and her coauthors noted. A comparison of CBF measured with an unpaired Student t test revealed no significant differences between the CHD group and controls. The average net CBF in CHD patients was 103.5 mL/min vs. 119.7 mL/min in controls.

However, when evaluating CDO2 using a Student t test, the researchers found significantly lower levels in the CHD group – an average of 1,1881 mLO2/min. vs. 2,712 mL O2/min in controls (P less than .0001). And when the researchers indexed CDO2 to brain volume yielding indexed oxygen delivery, the difference between the two groups was still significant: an average of 523.1 mL O2/min-1 .100 g-1 in the CHD group and 685.6 mL O2/min-1.100 g-1 in controls (P = .0006).

Among the CHD group, those with SVP and TGA had significantly lower CDO2 than that of controls. Brain volumes were also lower in those with CHD (mean of 338.5 mL vs. 377.7 mL in controls, P = .002).

The MRI findings were telling in the study population, Ms. Lim and her coauthors said. Five subjects in the CHD group had a combination of diffuse excessive high-signal intensity (DEHSI) and white-matter injury (WMI), 10 had an isolated finding of DEHSI, two had WMI alone and five others had other minor brain abnormalities. But the control group had no abnormal findings on conventional brain MRI.

The researchers acknowledged that, while the impact of reduced cerebral oxygen delivery is unknown, “theoretical reasons for thinking it might adversely impact ongoing brain growth and development during this period of rapid brain growth are considered.”

Cardiovascular surgeons should consider these findings when deciding on when to operate on newborns with CHD, the researchers said. “Further support for the concept that such a mechanism could lead to irreversible deficits in brain growth and development might result in attempts to expedite surgical repair of congenital cardiac lesions, which have conventionally not been addressed in the neonatal period,” they wrote.

Ms. Lim and her coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose.

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is heterogeneous and different types of lesions may cause different hemodynamics, Caitlin K. Rollins, MD, of Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School said in her invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152-960-1).

Ms. Lim and her colleagues in this study confirmed that premise with their finding that newborns with CHD and controls had similar cerebral blood flow, but that those with CHD had reduced oxygen delivery. “These differences were most apparent in the neonates with single-ventricle physiology and transposition of the great arteries,” Dr. Rollins said. The study authors’ finding of an association between reduced oxygen delivery and impaired brain development, along with this group’s previous reports (Circulation 2015;131:1313-23) suggesting preserved cerebral blood flow in the late prenatal period, differ from other studies using traditional methods to show reduced cerebral blood flow in obstructive left-sided lesions, Dr. Rollins said. “Although technical differences may in part account for the discrepancy, the contrasting results also reflect that the relative contributions of abnormal cerebral blood flow and oxygenation differ among forms of CHD,” Dr. Rollins said.

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is heterogeneous and different types of lesions may cause different hemodynamics, Caitlin K. Rollins, MD, of Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School said in her invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152-960-1).

Ms. Lim and her colleagues in this study confirmed that premise with their finding that newborns with CHD and controls had similar cerebral blood flow, but that those with CHD had reduced oxygen delivery. “These differences were most apparent in the neonates with single-ventricle physiology and transposition of the great arteries,” Dr. Rollins said. The study authors’ finding of an association between reduced oxygen delivery and impaired brain development, along with this group’s previous reports (Circulation 2015;131:1313-23) suggesting preserved cerebral blood flow in the late prenatal period, differ from other studies using traditional methods to show reduced cerebral blood flow in obstructive left-sided lesions, Dr. Rollins said. “Although technical differences may in part account for the discrepancy, the contrasting results also reflect that the relative contributions of abnormal cerebral blood flow and oxygenation differ among forms of CHD,” Dr. Rollins said.

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is heterogeneous and different types of lesions may cause different hemodynamics, Caitlin K. Rollins, MD, of Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School said in her invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152-960-1).

Ms. Lim and her colleagues in this study confirmed that premise with their finding that newborns with CHD and controls had similar cerebral blood flow, but that those with CHD had reduced oxygen delivery. “These differences were most apparent in the neonates with single-ventricle physiology and transposition of the great arteries,” Dr. Rollins said. The study authors’ finding of an association between reduced oxygen delivery and impaired brain development, along with this group’s previous reports (Circulation 2015;131:1313-23) suggesting preserved cerebral blood flow in the late prenatal period, differ from other studies using traditional methods to show reduced cerebral blood flow in obstructive left-sided lesions, Dr. Rollins said. “Although technical differences may in part account for the discrepancy, the contrasting results also reflect that the relative contributions of abnormal cerebral blood flow and oxygenation differ among forms of CHD,” Dr. Rollins said.

Using a newer form of MRI to investigate oxygen levels in newborns with congenital heart disease, researchers in Canada reported that these patients may have impaired brain growth and development in the first weeks of life because of significantly lower cerebral oxygen delivery levels.

These findings suggest that oxygen delivery may impact brain growth, particularly in newborns with single-ventricle physiology, reported Jessie Mei Lim, BSc, of the University of Toronto, and her colleagues from McGill University, Montreal, and the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto. The findings were published in the October issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2016;152:1095-103). Ms. Lim and her colleagues used cine phase-contrast (PC) MRI to measure cerebral blood flow in newborns with congenital heard disease (CHD). Previous studies used optical measures of tissue oxygenation and MRI arterial spin labeling to suggests that newborns with severe CHD have impaired CBF and cerebral oxygen delivery (CDO2) and CBF.

This single-center study involved 63 newborns from June 2013 to April 2015 at the Hospital for Sick Children. These subjects received an MRI of the head before surgery at an average of age 7.5 days. The scans were done without sedation or contrast while the infants were asleep. The study compared 31 age-matched controls with 32 subjects with various forms of CHD – 12 were managed surgically along a single-ventricle pathway (SVP), 4 had coarctation of the aorta, 13 had transposition of the great arteries (TGA), and 3 had other forms of CHD.

The researchers validated their method by reporting similarities between flows in the basilar and vertebral arteries in 14 controls, “suggesting good consistency and accuracy of our method for measuring CBF,” Ms. Lim and her coauthors noted. A comparison of CBF measured with an unpaired Student t test revealed no significant differences between the CHD group and controls. The average net CBF in CHD patients was 103.5 mL/min vs. 119.7 mL/min in controls.

However, when evaluating CDO2 using a Student t test, the researchers found significantly lower levels in the CHD group – an average of 1,1881 mLO2/min. vs. 2,712 mL O2/min in controls (P less than .0001). And when the researchers indexed CDO2 to brain volume yielding indexed oxygen delivery, the difference between the two groups was still significant: an average of 523.1 mL O2/min-1 .100 g-1 in the CHD group and 685.6 mL O2/min-1.100 g-1 in controls (P = .0006).

Among the CHD group, those with SVP and TGA had significantly lower CDO2 than that of controls. Brain volumes were also lower in those with CHD (mean of 338.5 mL vs. 377.7 mL in controls, P = .002).

The MRI findings were telling in the study population, Ms. Lim and her coauthors said. Five subjects in the CHD group had a combination of diffuse excessive high-signal intensity (DEHSI) and white-matter injury (WMI), 10 had an isolated finding of DEHSI, two had WMI alone and five others had other minor brain abnormalities. But the control group had no abnormal findings on conventional brain MRI.

The researchers acknowledged that, while the impact of reduced cerebral oxygen delivery is unknown, “theoretical reasons for thinking it might adversely impact ongoing brain growth and development during this period of rapid brain growth are considered.”

Cardiovascular surgeons should consider these findings when deciding on when to operate on newborns with CHD, the researchers said. “Further support for the concept that such a mechanism could lead to irreversible deficits in brain growth and development might result in attempts to expedite surgical repair of congenital cardiac lesions, which have conventionally not been addressed in the neonatal period,” they wrote.

Ms. Lim and her coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose.

Using a newer form of MRI to investigate oxygen levels in newborns with congenital heart disease, researchers in Canada reported that these patients may have impaired brain growth and development in the first weeks of life because of significantly lower cerebral oxygen delivery levels.

These findings suggest that oxygen delivery may impact brain growth, particularly in newborns with single-ventricle physiology, reported Jessie Mei Lim, BSc, of the University of Toronto, and her colleagues from McGill University, Montreal, and the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto. The findings were published in the October issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2016;152:1095-103). Ms. Lim and her colleagues used cine phase-contrast (PC) MRI to measure cerebral blood flow in newborns with congenital heard disease (CHD). Previous studies used optical measures of tissue oxygenation and MRI arterial spin labeling to suggests that newborns with severe CHD have impaired CBF and cerebral oxygen delivery (CDO2) and CBF.

This single-center study involved 63 newborns from June 2013 to April 2015 at the Hospital for Sick Children. These subjects received an MRI of the head before surgery at an average of age 7.5 days. The scans were done without sedation or contrast while the infants were asleep. The study compared 31 age-matched controls with 32 subjects with various forms of CHD – 12 were managed surgically along a single-ventricle pathway (SVP), 4 had coarctation of the aorta, 13 had transposition of the great arteries (TGA), and 3 had other forms of CHD.

The researchers validated their method by reporting similarities between flows in the basilar and vertebral arteries in 14 controls, “suggesting good consistency and accuracy of our method for measuring CBF,” Ms. Lim and her coauthors noted. A comparison of CBF measured with an unpaired Student t test revealed no significant differences between the CHD group and controls. The average net CBF in CHD patients was 103.5 mL/min vs. 119.7 mL/min in controls.

However, when evaluating CDO2 using a Student t test, the researchers found significantly lower levels in the CHD group – an average of 1,1881 mLO2/min. vs. 2,712 mL O2/min in controls (P less than .0001). And when the researchers indexed CDO2 to brain volume yielding indexed oxygen delivery, the difference between the two groups was still significant: an average of 523.1 mL O2/min-1 .100 g-1 in the CHD group and 685.6 mL O2/min-1.100 g-1 in controls (P = .0006).

Among the CHD group, those with SVP and TGA had significantly lower CDO2 than that of controls. Brain volumes were also lower in those with CHD (mean of 338.5 mL vs. 377.7 mL in controls, P = .002).

The MRI findings were telling in the study population, Ms. Lim and her coauthors said. Five subjects in the CHD group had a combination of diffuse excessive high-signal intensity (DEHSI) and white-matter injury (WMI), 10 had an isolated finding of DEHSI, two had WMI alone and five others had other minor brain abnormalities. But the control group had no abnormal findings on conventional brain MRI.

The researchers acknowledged that, while the impact of reduced cerebral oxygen delivery is unknown, “theoretical reasons for thinking it might adversely impact ongoing brain growth and development during this period of rapid brain growth are considered.”

Cardiovascular surgeons should consider these findings when deciding on when to operate on newborns with CHD, the researchers said. “Further support for the concept that such a mechanism could lead to irreversible deficits in brain growth and development might result in attempts to expedite surgical repair of congenital cardiac lesions, which have conventionally not been addressed in the neonatal period,” they wrote.

Ms. Lim and her coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THORACIC AND CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point: Cerebral blood flow is maintained but cerebral oxygen delivery is decreased in preoperative newborns with cyanotic congenital heart disease (CHD).

Major finding: Average cerebral oxygen delivery measured 1,1881 mLO2/min in the CHD group when measured with Student t testing vs. 2,712 mLO2/min in controls (P less than .0001).

Data source: Single-center study of 32 neonates with various forms of CHD 31 age-matched controls.

Disclosures: Ms. Lim and coauthors have no financial relationships to disclose.

Updated AAP safe sleep recs for infants reinforce life-saving messages

SAN FRANCISCO – At sleep time, infants should share their parents’ bedroom on a separate sleep surface without bed sharing, should be placed on their backs on a firm surface, and should have a sleep area free of blankets and soft objects, according to updated guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics aimed at reducing the risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and other sleep-related infant deaths.

Drafted by a multidisciplinary task force, the set of 19 evidence-based recommendations largely reiterate messages that the academy has promoted for years such as “back to sleep for every sleep,” according to task force member Fern R. Hauck, MD, the Spencer P. Bass, MD, Twenty-First Century Professor of Family Medicine at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville. They were unveiled in a press briefing at the academy’s annual meeting and simultaneously published (Pediatrics. 2016;138[5]:e20162938).

Progress, but still a ways to go

Education campaigns that convey these and related messages to new parents and other caregivers have led to a more than halving of the rate of SIDS in recent decades. Yet, 3,500 infants are still lost each year to this syndrome and other sleep-related causes of infant death, such as unintentional suffocation, collectively called sudden unexpected infant death (SUID).

New is a recommendation for skin-to-skin care for at least the first hour of life for healthy newborns, as soon as the mother is alert enough to respond to her infant, according to Dr. Hauck. The aims here are to optimize neurodevelopment and promote temperature regulation.

There is no evidence that swaddling reduces the risk of SIDS, but parents can still use this technique if they wish as long as infants are placed on their back and it is discontinued as soon as they start to show signs of rolling over, she said. Evidence is also lacking for new technologies marketed as protective, for example, crib mattresses designed to reduce re-breathing of carbon dioxide should an infant become prone.

Sleeping in the parents’ room but on a separate surface decreases the risk of SIDS by as much as 50%, according to several studies. Bed sharing is not recommended because of the risk of suffocation, strangulation, and entrapment, the policy states.

The updated recommendations should be followed for every sleep and by every caregiver, until the child reaches 1 year of age, Dr. Hauck stressed. “This includes nap time and bedtime sleep, at home, in day care, or in any other locations where the baby is sleeping.”

“We feel that these messages need to start while the mom’s pregnant because some of the decisions that are made that are not always the best decisions, when the mother is exhausted, can occur spur of the moment,” she added. “As pediatricians, you can set up a prebirth visit to start talking about this, and obstetricians should be doing more as well to bring this up during their prenatal visits.”

Other recommendations include offering a pacifier at nap time and bedtime; avoiding smoke exposure during pregnancy and after birth; and avoiding alcohol and illicit drug use during pregnancy and after birth.

Breastfeeding issues

Although breastfeeding protects against SIDS, it can pose some problems for safe sleep practices, acknowledged Lori B. Feldman-Winter, MD, a liaison from the AAP section on breastfeeding to the task force, as well as head of the division of adolescent medicine and professor of pediatrics at Cooper University Health Care in Camden, N.J.

Bedside sleepers (also called sidecar sleepers) that attach to the parents’ bed may help facilitate the dual aims of breastfeeding and safe sleep, but they have not been formally studied to assess their impact on SIDS risk.

Raising awareness

“As a father and pediatrician, I want parents to know that their baby is safest following the AAP safe sleep recommendations, and spreading this message has become my life’s mission,” said Dr. Samuel P. Hanke, a pediatric cardiologist at the University of Cincinnati, who knows the heartbreak of SIDS firsthand.

“We know practicing safe sleep is hard. We have to be vigilant. We need to start adopting a mentality that safe sleep is not negotiable,” Dr. Hanke asserted. “We cannot emphasize enough that practicing safe sleep for every sleep is as important as buckling your child into a car seat for every drive. And just like car seats, this change won’t occur overnight.”

Federal commitment

Since the 1970s, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) in Bethesda, Md., has been supporting and performing much of the research on which the updated recommendations are based. This research continues to help identify areas where greater efforts are needed, according to acting director Catherine Y. Spong, MD.

NICHD also conducts and collaborates on related education campaigns, such as Safe to Sleep, to disseminate messages such as those in the updated AAP recommendations as widely as possible.

“I encourage all physicians, pediatricians, nurses, and other health care and child care providers to lend their authoritative voices to the Safe to Sleep effort,” Dr. Spong said. “Join us all in sharing safe infant sleep recommendations and in supporting parents and caregivers to make informed decisions that will help keep their baby safe during sleep.”

A closer look at setting

Published in conjunction with the guidelines is a study on risk factors that looked at the role of the setting in which sleep-related infant deaths occur (Pediatrics. 2016 Oct 24:e20161124).

The analysis of nearly 12,000 such deaths found that, relative to counterparts who died in their home, infants who died outside of their home were more likely to be in a stroller or car seat at the time (adjusted odds ratio, 2.6) and in other locations, such as on the floor or a futon (1.9), and to have been placed prone (1.1). They were less likely to have been sharing a bed (0.7).

The groups did not differ in terms of whether the infant was sleeping in an adult bed or on a person, on a couch or chair, or with any objects in their sleep environment.

“Caregivers should be educated on the importance of placing infants to sleep supine in cribs/bassinets to protect against sleep-related deaths, both in and out of the home,” conclude the investigators, one of whom disclosed serving as a paid expert witness in cases of sleep-related infant death.

SAN FRANCISCO – At sleep time, infants should share their parents’ bedroom on a separate sleep surface without bed sharing, should be placed on their backs on a firm surface, and should have a sleep area free of blankets and soft objects, according to updated guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics aimed at reducing the risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and other sleep-related infant deaths.

Drafted by a multidisciplinary task force, the set of 19 evidence-based recommendations largely reiterate messages that the academy has promoted for years such as “back to sleep for every sleep,” according to task force member Fern R. Hauck, MD, the Spencer P. Bass, MD, Twenty-First Century Professor of Family Medicine at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville. They were unveiled in a press briefing at the academy’s annual meeting and simultaneously published (Pediatrics. 2016;138[5]:e20162938).

Progress, but still a ways to go

Education campaigns that convey these and related messages to new parents and other caregivers have led to a more than halving of the rate of SIDS in recent decades. Yet, 3,500 infants are still lost each year to this syndrome and other sleep-related causes of infant death, such as unintentional suffocation, collectively called sudden unexpected infant death (SUID).

New is a recommendation for skin-to-skin care for at least the first hour of life for healthy newborns, as soon as the mother is alert enough to respond to her infant, according to Dr. Hauck. The aims here are to optimize neurodevelopment and promote temperature regulation.

There is no evidence that swaddling reduces the risk of SIDS, but parents can still use this technique if they wish as long as infants are placed on their back and it is discontinued as soon as they start to show signs of rolling over, she said. Evidence is also lacking for new technologies marketed as protective, for example, crib mattresses designed to reduce re-breathing of carbon dioxide should an infant become prone.

Sleeping in the parents’ room but on a separate surface decreases the risk of SIDS by as much as 50%, according to several studies. Bed sharing is not recommended because of the risk of suffocation, strangulation, and entrapment, the policy states.

The updated recommendations should be followed for every sleep and by every caregiver, until the child reaches 1 year of age, Dr. Hauck stressed. “This includes nap time and bedtime sleep, at home, in day care, or in any other locations where the baby is sleeping.”

“We feel that these messages need to start while the mom’s pregnant because some of the decisions that are made that are not always the best decisions, when the mother is exhausted, can occur spur of the moment,” she added. “As pediatricians, you can set up a prebirth visit to start talking about this, and obstetricians should be doing more as well to bring this up during their prenatal visits.”

Other recommendations include offering a pacifier at nap time and bedtime; avoiding smoke exposure during pregnancy and after birth; and avoiding alcohol and illicit drug use during pregnancy and after birth.

Breastfeeding issues

Although breastfeeding protects against SIDS, it can pose some problems for safe sleep practices, acknowledged Lori B. Feldman-Winter, MD, a liaison from the AAP section on breastfeeding to the task force, as well as head of the division of adolescent medicine and professor of pediatrics at Cooper University Health Care in Camden, N.J.

Bedside sleepers (also called sidecar sleepers) that attach to the parents’ bed may help facilitate the dual aims of breastfeeding and safe sleep, but they have not been formally studied to assess their impact on SIDS risk.

Raising awareness

“As a father and pediatrician, I want parents to know that their baby is safest following the AAP safe sleep recommendations, and spreading this message has become my life’s mission,” said Dr. Samuel P. Hanke, a pediatric cardiologist at the University of Cincinnati, who knows the heartbreak of SIDS firsthand.

“We know practicing safe sleep is hard. We have to be vigilant. We need to start adopting a mentality that safe sleep is not negotiable,” Dr. Hanke asserted. “We cannot emphasize enough that practicing safe sleep for every sleep is as important as buckling your child into a car seat for every drive. And just like car seats, this change won’t occur overnight.”

Federal commitment

Since the 1970s, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) in Bethesda, Md., has been supporting and performing much of the research on which the updated recommendations are based. This research continues to help identify areas where greater efforts are needed, according to acting director Catherine Y. Spong, MD.

NICHD also conducts and collaborates on related education campaigns, such as Safe to Sleep, to disseminate messages such as those in the updated AAP recommendations as widely as possible.

“I encourage all physicians, pediatricians, nurses, and other health care and child care providers to lend their authoritative voices to the Safe to Sleep effort,” Dr. Spong said. “Join us all in sharing safe infant sleep recommendations and in supporting parents and caregivers to make informed decisions that will help keep their baby safe during sleep.”

A closer look at setting

Published in conjunction with the guidelines is a study on risk factors that looked at the role of the setting in which sleep-related infant deaths occur (Pediatrics. 2016 Oct 24:e20161124).

The analysis of nearly 12,000 such deaths found that, relative to counterparts who died in their home, infants who died outside of their home were more likely to be in a stroller or car seat at the time (adjusted odds ratio, 2.6) and in other locations, such as on the floor or a futon (1.9), and to have been placed prone (1.1). They were less likely to have been sharing a bed (0.7).