User login

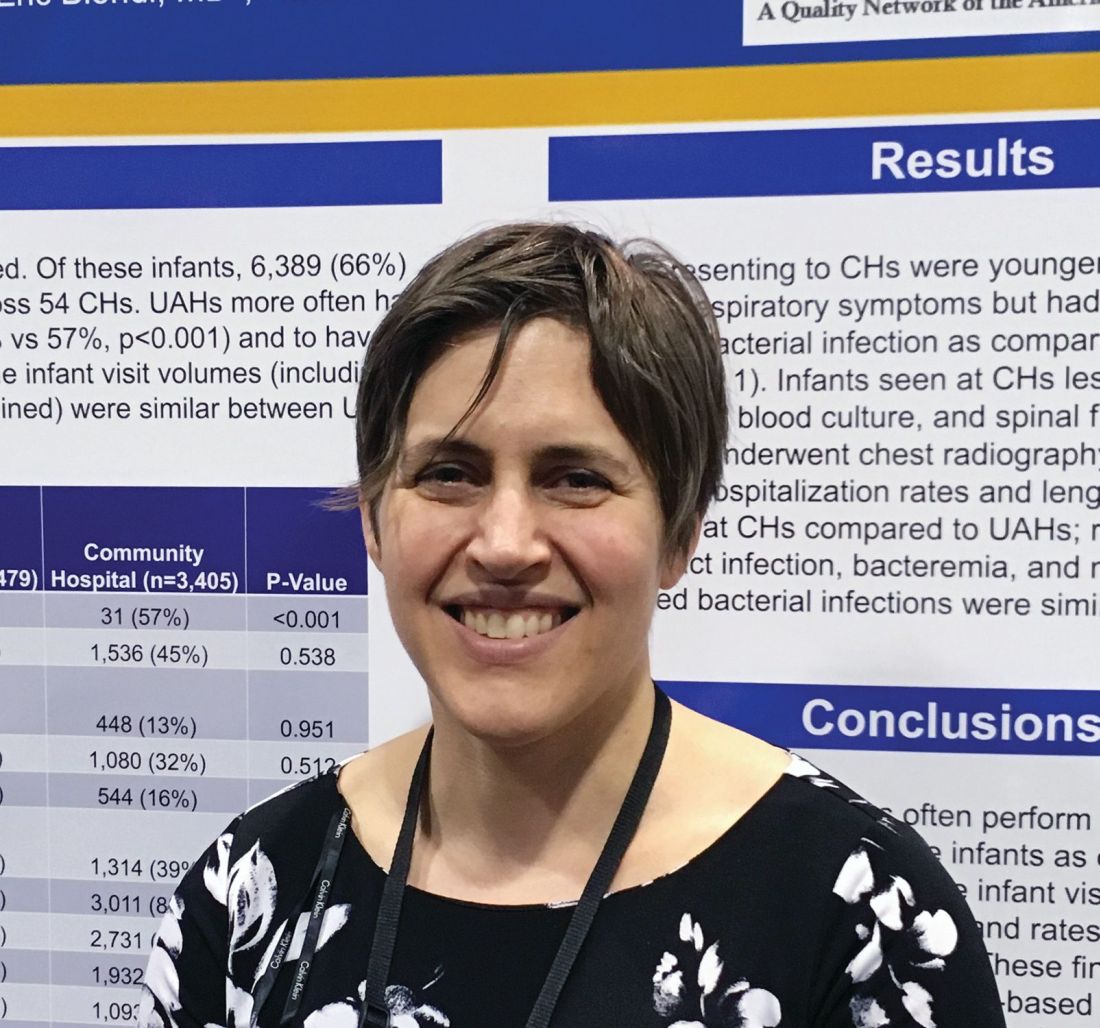

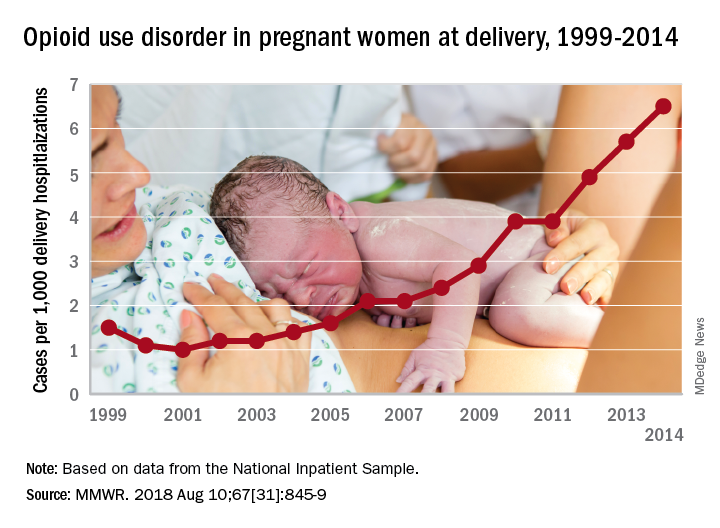

More deliveries now include opioid use disorder

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The national prevalence of opioid use disorder increased by 333% as it went from 1.5 cases per 1,000 delivery hospitalizations in 1999 to 6.5 cases per 1,000 in 2014. At the state level, there were significant increases in all 28 states with data available for at least 3 consecutive years during the study period, Sarah C. Haight, MPH, and her associates at the CDC in Atlanta said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Average annual rate changes for those states ranged from a low of 0.01 per 1,000 delivery hospitalizations per year in California to 5.37 per year in Vermont, with the national rate change coming in at 0.39 per year. Of the 14 states with data available in 1999, Iowa had the lowest rate at 0.1 per 1,000 deliveries and Maryland had the highest at 8.2. In 2014, when data were available for 26 states and the District of Columbia, the highest rate was Vermont’s 48.6 per 1,000 deliveries and the lowest was 0.7 in Washington, D.C., the investigators reported.

Although “increasing trends might represent actual increases in prevalence or improved screening and diagnosis,” Ms. Haight and her associates added that “these estimates also correlate with state opioid prescribing rates in the general population. West Virginia, for example, had a prescribing rate estimated at 138 opioid prescriptions per 100 persons in 2012.”

“These findings illustrate the devastating impact of the opioid epidemic on families across the U.S., including on the very youngest,” said CDC Director Robert R. Redfield, MD. “Untreated opioid use disorder during pregnancy can lead to heartbreaking results. Each case represents a mother, a child, and a family in need of continued treatment and support.”

Data for the analysis came from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s National Inpatient Sample and State Inpatient Databases.

SOURCE: Haight SC et al. MMWR. 2018 Aug 10;67[31]:845-9.

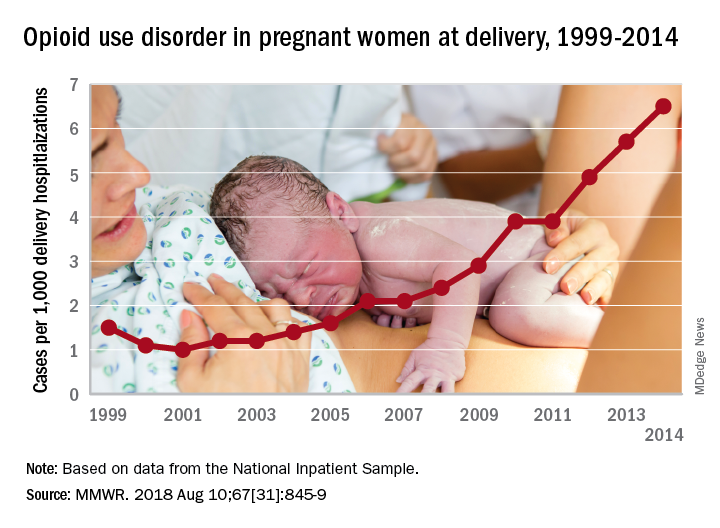

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The national prevalence of opioid use disorder increased by 333% as it went from 1.5 cases per 1,000 delivery hospitalizations in 1999 to 6.5 cases per 1,000 in 2014. At the state level, there were significant increases in all 28 states with data available for at least 3 consecutive years during the study period, Sarah C. Haight, MPH, and her associates at the CDC in Atlanta said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Average annual rate changes for those states ranged from a low of 0.01 per 1,000 delivery hospitalizations per year in California to 5.37 per year in Vermont, with the national rate change coming in at 0.39 per year. Of the 14 states with data available in 1999, Iowa had the lowest rate at 0.1 per 1,000 deliveries and Maryland had the highest at 8.2. In 2014, when data were available for 26 states and the District of Columbia, the highest rate was Vermont’s 48.6 per 1,000 deliveries and the lowest was 0.7 in Washington, D.C., the investigators reported.

Although “increasing trends might represent actual increases in prevalence or improved screening and diagnosis,” Ms. Haight and her associates added that “these estimates also correlate with state opioid prescribing rates in the general population. West Virginia, for example, had a prescribing rate estimated at 138 opioid prescriptions per 100 persons in 2012.”

“These findings illustrate the devastating impact of the opioid epidemic on families across the U.S., including on the very youngest,” said CDC Director Robert R. Redfield, MD. “Untreated opioid use disorder during pregnancy can lead to heartbreaking results. Each case represents a mother, a child, and a family in need of continued treatment and support.”

Data for the analysis came from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s National Inpatient Sample and State Inpatient Databases.

SOURCE: Haight SC et al. MMWR. 2018 Aug 10;67[31]:845-9.

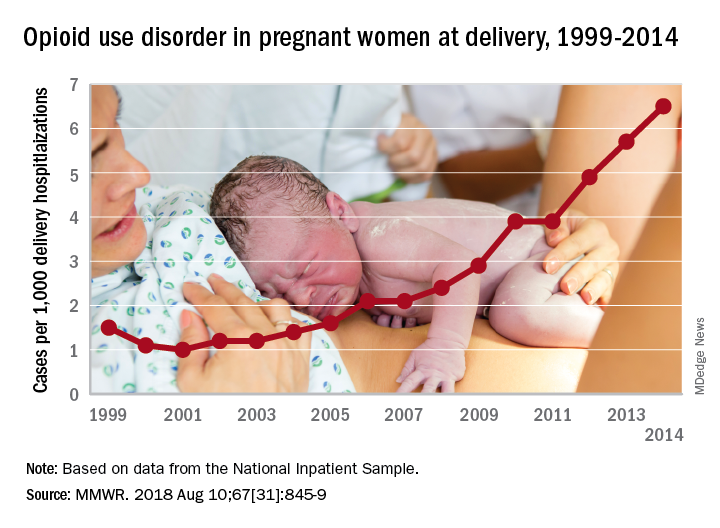

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The national prevalence of opioid use disorder increased by 333% as it went from 1.5 cases per 1,000 delivery hospitalizations in 1999 to 6.5 cases per 1,000 in 2014. At the state level, there were significant increases in all 28 states with data available for at least 3 consecutive years during the study period, Sarah C. Haight, MPH, and her associates at the CDC in Atlanta said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Average annual rate changes for those states ranged from a low of 0.01 per 1,000 delivery hospitalizations per year in California to 5.37 per year in Vermont, with the national rate change coming in at 0.39 per year. Of the 14 states with data available in 1999, Iowa had the lowest rate at 0.1 per 1,000 deliveries and Maryland had the highest at 8.2. In 2014, when data were available for 26 states and the District of Columbia, the highest rate was Vermont’s 48.6 per 1,000 deliveries and the lowest was 0.7 in Washington, D.C., the investigators reported.

Although “increasing trends might represent actual increases in prevalence or improved screening and diagnosis,” Ms. Haight and her associates added that “these estimates also correlate with state opioid prescribing rates in the general population. West Virginia, for example, had a prescribing rate estimated at 138 opioid prescriptions per 100 persons in 2012.”

“These findings illustrate the devastating impact of the opioid epidemic on families across the U.S., including on the very youngest,” said CDC Director Robert R. Redfield, MD. “Untreated opioid use disorder during pregnancy can lead to heartbreaking results. Each case represents a mother, a child, and a family in need of continued treatment and support.”

Data for the analysis came from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s National Inpatient Sample and State Inpatient Databases.

SOURCE: Haight SC et al. MMWR. 2018 Aug 10;67[31]:845-9.

FROM MMWR

Short-course IV antibiotics okay for newborn bacteremic UTI

ATLANTA – A short course of IV antibiotics – 7 days or less – is fine for most infants with uncomplicated bacteremic urinary tract infections, according to a review of 116 children younger than 60 days.

How long to treat bacteremic UTIs in the very young has been debated in pediatrics for a while, with some centers opting for a few days and others for 2 weeks or more. Shorter courses reduce length of stay, costs, and complications, but there hasn’t been much research to see whether they work as well.

The new investigation has suggested they do. “Young infants with bacteremic UTI who received less than or equal to 7 days of IV antibiotic therapy did not have more recurrent UTIs,” compared “to infants who received longer courses. Short course IV therapy with early conversion to oral antibiotics may be considered in this population,” said lead investigator Sanyukta Desai, MD, at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

The team compared outcomes of 58 infants treated for 7 days or less to outcomes of 58 infants treated for more than 7 days at 11 children’s hospitals scattered across the United States.

Urine was collected by catheter, and each child grew the same organism in their blood and urine cultures, confirming the diagnosis of bacteremic UTI. Children with bacterial meningitis, or suspected of having it, were excluded. The subjects had all been admitted through the ED.

There was quite a bit of variation among the 11 hospitals, with the proportion of children treated with short courses ranging from 10% to 81%.

As for the results, two patients in the short-course group (3%) and four in the long-course group (7%) had recurrent UTIs within 30 days. None of them developed meningitis, and none required ICU admission. Propensity-score matching revealed an odds ratio for recurrence that favored shorter treatment, but it wasn’t statistically significant.

The mean length of stay was 5 days in the short-course arm and 11 days in the long-course arm. There were no serious adverse events within 30 days of the index admission in either group.

Among the recurrences, the two children in the short-course arm were initially treated for 3 and 5 days. Both were older than 28 days at their initial presentation, and both had vesicoureteral reflux of at least grade 2, which was not diagnosed in one child until after the recurrence. The other child had been on prophylactic trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole before the recurrence.

The four recurrent cases in the long arm initially received either 10 or 14 days of IV antibiotics. Two children had grade 4 vesicoureteral reflux and had been on prophylactic amoxicillin.

Infants treated with longer antibiotic courses were more likely to be under 28 days old, appear ill at presentation, have had bacteremia for more than 24 hours, and have and grow out pathogens other than Escherichia coli. The two groups were otherwise balanced for sex, prematurity, complex chronic conditions, and known genitourinary anomalies.

With such low event rates, the study wasn’t powered to detect small but potentially meaningful differences in outcomes, and further work is needed to define which children would benefit from longer treatment courses. Even so, “it was reassuring that patients did well in both arms,” said Dr. Desai, a clinical fellow in the division of hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

“At our institution with uncomplicated UTI, we wait to see what the culture grows.” If there’s an oral antibiotic that will work, “we send [infants] home in 3-4 days. We haven’t had any poor outcomes, even when they’re bacteremic,” she said.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators didn’t have any disclosures.

ATLANTA – A short course of IV antibiotics – 7 days or less – is fine for most infants with uncomplicated bacteremic urinary tract infections, according to a review of 116 children younger than 60 days.

How long to treat bacteremic UTIs in the very young has been debated in pediatrics for a while, with some centers opting for a few days and others for 2 weeks or more. Shorter courses reduce length of stay, costs, and complications, but there hasn’t been much research to see whether they work as well.

The new investigation has suggested they do. “Young infants with bacteremic UTI who received less than or equal to 7 days of IV antibiotic therapy did not have more recurrent UTIs,” compared “to infants who received longer courses. Short course IV therapy with early conversion to oral antibiotics may be considered in this population,” said lead investigator Sanyukta Desai, MD, at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

The team compared outcomes of 58 infants treated for 7 days or less to outcomes of 58 infants treated for more than 7 days at 11 children’s hospitals scattered across the United States.

Urine was collected by catheter, and each child grew the same organism in their blood and urine cultures, confirming the diagnosis of bacteremic UTI. Children with bacterial meningitis, or suspected of having it, were excluded. The subjects had all been admitted through the ED.

There was quite a bit of variation among the 11 hospitals, with the proportion of children treated with short courses ranging from 10% to 81%.

As for the results, two patients in the short-course group (3%) and four in the long-course group (7%) had recurrent UTIs within 30 days. None of them developed meningitis, and none required ICU admission. Propensity-score matching revealed an odds ratio for recurrence that favored shorter treatment, but it wasn’t statistically significant.

The mean length of stay was 5 days in the short-course arm and 11 days in the long-course arm. There were no serious adverse events within 30 days of the index admission in either group.

Among the recurrences, the two children in the short-course arm were initially treated for 3 and 5 days. Both were older than 28 days at their initial presentation, and both had vesicoureteral reflux of at least grade 2, which was not diagnosed in one child until after the recurrence. The other child had been on prophylactic trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole before the recurrence.

The four recurrent cases in the long arm initially received either 10 or 14 days of IV antibiotics. Two children had grade 4 vesicoureteral reflux and had been on prophylactic amoxicillin.

Infants treated with longer antibiotic courses were more likely to be under 28 days old, appear ill at presentation, have had bacteremia for more than 24 hours, and have and grow out pathogens other than Escherichia coli. The two groups were otherwise balanced for sex, prematurity, complex chronic conditions, and known genitourinary anomalies.

With such low event rates, the study wasn’t powered to detect small but potentially meaningful differences in outcomes, and further work is needed to define which children would benefit from longer treatment courses. Even so, “it was reassuring that patients did well in both arms,” said Dr. Desai, a clinical fellow in the division of hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

“At our institution with uncomplicated UTI, we wait to see what the culture grows.” If there’s an oral antibiotic that will work, “we send [infants] home in 3-4 days. We haven’t had any poor outcomes, even when they’re bacteremic,” she said.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators didn’t have any disclosures.

ATLANTA – A short course of IV antibiotics – 7 days or less – is fine for most infants with uncomplicated bacteremic urinary tract infections, according to a review of 116 children younger than 60 days.

How long to treat bacteremic UTIs in the very young has been debated in pediatrics for a while, with some centers opting for a few days and others for 2 weeks or more. Shorter courses reduce length of stay, costs, and complications, but there hasn’t been much research to see whether they work as well.

The new investigation has suggested they do. “Young infants with bacteremic UTI who received less than or equal to 7 days of IV antibiotic therapy did not have more recurrent UTIs,” compared “to infants who received longer courses. Short course IV therapy with early conversion to oral antibiotics may be considered in this population,” said lead investigator Sanyukta Desai, MD, at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine meeting.

The team compared outcomes of 58 infants treated for 7 days or less to outcomes of 58 infants treated for more than 7 days at 11 children’s hospitals scattered across the United States.

Urine was collected by catheter, and each child grew the same organism in their blood and urine cultures, confirming the diagnosis of bacteremic UTI. Children with bacterial meningitis, or suspected of having it, were excluded. The subjects had all been admitted through the ED.

There was quite a bit of variation among the 11 hospitals, with the proportion of children treated with short courses ranging from 10% to 81%.

As for the results, two patients in the short-course group (3%) and four in the long-course group (7%) had recurrent UTIs within 30 days. None of them developed meningitis, and none required ICU admission. Propensity-score matching revealed an odds ratio for recurrence that favored shorter treatment, but it wasn’t statistically significant.

The mean length of stay was 5 days in the short-course arm and 11 days in the long-course arm. There were no serious adverse events within 30 days of the index admission in either group.

Among the recurrences, the two children in the short-course arm were initially treated for 3 and 5 days. Both were older than 28 days at their initial presentation, and both had vesicoureteral reflux of at least grade 2, which was not diagnosed in one child until after the recurrence. The other child had been on prophylactic trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole before the recurrence.

The four recurrent cases in the long arm initially received either 10 or 14 days of IV antibiotics. Two children had grade 4 vesicoureteral reflux and had been on prophylactic amoxicillin.

Infants treated with longer antibiotic courses were more likely to be under 28 days old, appear ill at presentation, have had bacteremia for more than 24 hours, and have and grow out pathogens other than Escherichia coli. The two groups were otherwise balanced for sex, prematurity, complex chronic conditions, and known genitourinary anomalies.

With such low event rates, the study wasn’t powered to detect small but potentially meaningful differences in outcomes, and further work is needed to define which children would benefit from longer treatment courses. Even so, “it was reassuring that patients did well in both arms,” said Dr. Desai, a clinical fellow in the division of hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

“At our institution with uncomplicated UTI, we wait to see what the culture grows.” If there’s an oral antibiotic that will work, “we send [infants] home in 3-4 days. We haven’t had any poor outcomes, even when they’re bacteremic,” she said.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators didn’t have any disclosures.

REPORTING FROM PHM 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Two patients in the short-course group (3%) and four in the long-course group (7%) had recurrent UTIs within 30 days.

Study details: Review of 116 infants.

Disclosures: The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators didn’t have any disclosures.

Preterm birth rate ‘is on the rise again’

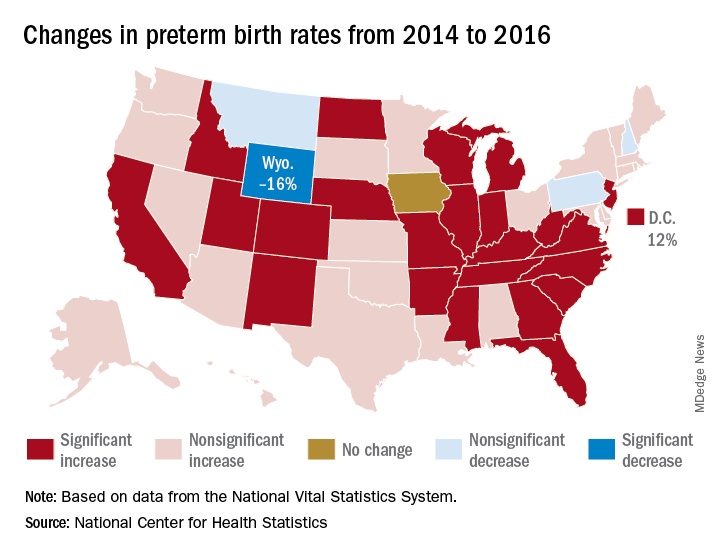

After several years of decline, the incidence of preterm births in the United States “is on the rise again,” according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

That 3% increase was spread pretty evenly: 23 states and the District of Columbia experienced statistically significant increases from 2014 to 2016, and 22 other states also had increases, although these were not statistically significant. One state, Iowa, had no change; three states – Montana, New Hampshire, and Pennsylvania – had nonsignificant declines, and Wyoming was the only state with a statistically significant drop (16%) in preterm birth incidence, they said based on data from the National Vital Statistics System.

The largest increase, 12%, was seen in the District of Columbia, followed by Idaho and North Dakota at 10% and Arkansas, New Mexico, and West Virginia at 9%, the researchers reported.

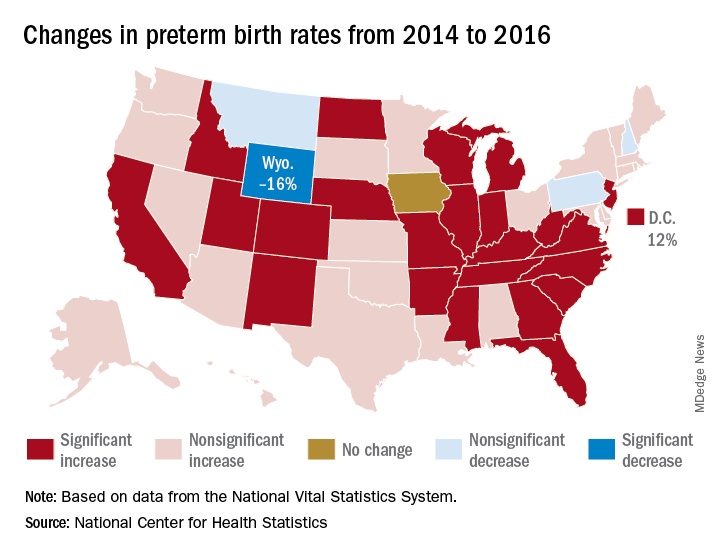

After several years of decline, the incidence of preterm births in the United States “is on the rise again,” according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

That 3% increase was spread pretty evenly: 23 states and the District of Columbia experienced statistically significant increases from 2014 to 2016, and 22 other states also had increases, although these were not statistically significant. One state, Iowa, had no change; three states – Montana, New Hampshire, and Pennsylvania – had nonsignificant declines, and Wyoming was the only state with a statistically significant drop (16%) in preterm birth incidence, they said based on data from the National Vital Statistics System.

The largest increase, 12%, was seen in the District of Columbia, followed by Idaho and North Dakota at 10% and Arkansas, New Mexico, and West Virginia at 9%, the researchers reported.

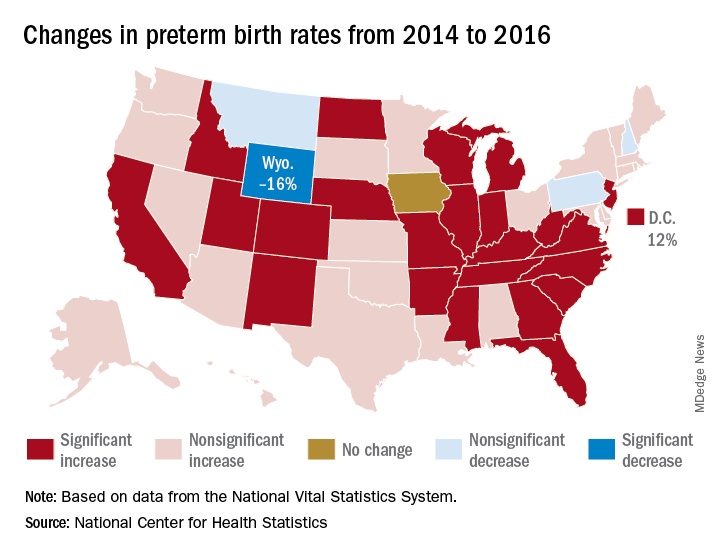

After several years of decline, the incidence of preterm births in the United States “is on the rise again,” according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

That 3% increase was spread pretty evenly: 23 states and the District of Columbia experienced statistically significant increases from 2014 to 2016, and 22 other states also had increases, although these were not statistically significant. One state, Iowa, had no change; three states – Montana, New Hampshire, and Pennsylvania – had nonsignificant declines, and Wyoming was the only state with a statistically significant drop (16%) in preterm birth incidence, they said based on data from the National Vital Statistics System.

The largest increase, 12%, was seen in the District of Columbia, followed by Idaho and North Dakota at 10% and Arkansas, New Mexico, and West Virginia at 9%, the researchers reported.

Spinal muscular atrophy added to newborn screening panel recommendations

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is now among the disorders officially included in the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP), which is used by state public health departments to screen newborns for genetic disorders.

Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services Alex M. Azar II formally added SMA to the panel July 2 on the recommendation of the Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children.

“Adding SMA to the list will help ensure that babies born with SMA are identified, so that they have the opportunity to benefit from early treatment and intervention,” according to a statement from the Muscular Dystrophy Association about the decision. “This testing can also provide families with a genetic diagnosis – information that often is required to determine whether their child is eligible to participate in clinical trials.”

Adding SMA to the RUSP does not mean states must screen newborns for the disorder. Each state’s public health apparatus decides independently whether to accept the recommendation and which disorders on the RUSP to screen for. Most states screen for most disorders on the RUSP. Evidence compiled by the advisory committee suggested wide variation in resources, infrastructure, funding, and time to implementation among states.

An estimated 1 in 11,000 newborns have SMA, a disorder caused by mutations in the survival motor neuron 1 (SMN1) gene. SMA affects motor neurons in the brain stem and spinal cord leading to motor weakness and atrophy. The only treatment for SMA had been palliative care until the Food and Drug Administration approved nusinersen (Spinraza) for the disorder in December 2016, although the drug’s approval has raised some ethical questions.1-3

After reviewing the evidence at their February 8, 2018 meeting, the advisory committee recommended the addition of spinal muscular atrophy screening to the RUSP in a March 8, 2018, letter from committee chair Joseph A. Bocchini Jr., MD, who is a professor and the chairman of the department of pediatrics at Louisiana State University Health in Shreveport.

Secretary Azar accepted the recommendation based on the evidence the committee provided; he also requested a follow-up report within 2 years “describing the status of implementing newborn screening for SMA and clinical outcomes of early treatment, including any potential harms, for infants diagnosed with SMA.”

The advisory committee makes its recommendations to the HHS on which heritable disorders to include in the RUSP after they have assessed a systematic, evidence-based review assigned by the committee to an external independent group. Alex R. Kemper, MD, MPH, a professor of pediatrics at the Ohio State University and division chief of ambulatory pediatrics at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, both in Columbus, led the review group for SMA. Dr. Kemper is also deputy editor of the journal Pediatrics and a member of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

According to Secretary Azar’s summary in his July 2, 2018, letter of acceptance, the evidence review suggested that “early screening and treatment can lead to decreased mortality for individuals with SMA and improved motor milestones.”

Dr. Kemper elaborated in an interview that, “SMA can be detected through newborn screening, and treatment is now available that can not only reduce the risk of death but decrease the development of neurologic impairment. As with adding any condition to newborn screening, public health laboratories will need to develop strategies to incorporate the screening test. The current FDA-approved treatment, nusinersen, is delivered by lumbar puncture into the spinal fluid. In addition, there are exciting advances in gene therapy leading to new treatment approaches.”

Approximately 95% of SMA cases result from the deletion of exon 7 from both alleles of SMN1. (Other rarer cases are caused by mutations in different genes.) Without the SMN protein produced by SMN1, a person gradually loses muscle function.

A similar gene, SMN2, also can produce the SMN protein but in much lower amounts, typically less than 10% of what a person needs. People can, however, have multiple copies of SMN2, which can produce slightly more SMN protein for a slower disease process.

The five types of spinal muscular atrophy are determined according to symptom onset, which directly correlates with disorder severity and prognosis. Just over half (54%) of SMA cases are Type I, in which progressive weakness occurs over the first 6 months of life and results in early death. Only 18% of children with Type I live past age 4 years, and 68% die by age 2 years. Type 0 is rarer but more severe, usually causing fetal loss or early infant death.

Type II represents 18% of SMA cases and causes progressive weakness by age 15 months. Most people with Type II survive to their 30s but then experience respiratory failure and rarely reach their fourth decade. Individuals with Types III and IV typically have a normal lifespan and only begin to see progressive muscle weakness after 1 year old or in adulthood.

Dr. Kemper’s group focused on the three types diagnosed in infancy: types I, II, and III.

Dr. Kemper emphasized in an interview that “it will be critical to make sure that infants diagnosed with SMA through newborn screening receive follow-up shortly afterward to determine whether they would benefit from nusinersen. More information is needed about the long-term outcomes of those infants who begin treatment following newborn screening so we not only know about outcomes in later childhood and adolescence but treatment approaches can be further refined and personalized.”

Nusinersen works by altering the splicing of precursor messenger RNA in SMN2 so that the mRNA strands are longer, which thereby increases how much SMN protein is produced. Concerns about the medication, however, have included its cost – $750,000 in the first year and $375,000 every following year for life – and potential adverse events from repeated administration. Nusinersen is injected into the spinal canal four times in the first year and then once annually, and the painful injections require patient immobilization. Potential adverse events include thrombocytopenia and nephrotoxicity, along with potential complications from repeated lumbar punctures over time.2

Other concerns about the drug include its limited evidence base, lack of long-term data, associated costs with administration (for example, travel costs), the potential for patients taking nusinersen to be excluded from future clinical trials on other treatments, and ensuring parents have enough information on the drug’s limitations and potential risks to provide adequate informed consent.2

Yet evidence to date is favorable in children with early onset. Dr. Bocchini wrote in the letter to Secretary Azar that “limited data suggest that treatment effect is greater when the treatment is initiated before symptoms develop and when the individual has more copies of SMN2.”

Dr. Kemper’s group concluded that screening can detect SMA in newborns and that treatment can modify disease course. “Grey literature suggests those with total disease duration less than or equal to 12 weeks before nusinersen treatment were more likely to have better outcomes than those with longer periods of disease duration.”

“Presymptomatic treatment alters the natural history” of the disorder, the group found, although outcome data past 1 year of age are not yet available. Based on findings from a New York pilot program, they predicted that nationwide newborn screening would avert 33 deaths and 48 cases of children who were dependent on a ventilator among an annual cohort of 4 million births.

At the time of the evidence review, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Missouri, North Carolina, New York, Utah, and Wisconsin initiated pilot programs or whole-population mandated screening for SMA. Of the three states that reported costs, all reported costs at $1 or less per screen.

The research for the evidence review was funded by a Health Resources and Services Administration grant to Duke University, Durham, N.C. No disclosures were provided for evidence review group members.

References

1. Gene Ther. 2017 Sep;24(9):534-8.

2. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Jun 1;178(6):743-44.

3. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Feb 1;172(2):188-92.

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is now among the disorders officially included in the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP), which is used by state public health departments to screen newborns for genetic disorders.

Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services Alex M. Azar II formally added SMA to the panel July 2 on the recommendation of the Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children.

“Adding SMA to the list will help ensure that babies born with SMA are identified, so that they have the opportunity to benefit from early treatment and intervention,” according to a statement from the Muscular Dystrophy Association about the decision. “This testing can also provide families with a genetic diagnosis – information that often is required to determine whether their child is eligible to participate in clinical trials.”

Adding SMA to the RUSP does not mean states must screen newborns for the disorder. Each state’s public health apparatus decides independently whether to accept the recommendation and which disorders on the RUSP to screen for. Most states screen for most disorders on the RUSP. Evidence compiled by the advisory committee suggested wide variation in resources, infrastructure, funding, and time to implementation among states.

An estimated 1 in 11,000 newborns have SMA, a disorder caused by mutations in the survival motor neuron 1 (SMN1) gene. SMA affects motor neurons in the brain stem and spinal cord leading to motor weakness and atrophy. The only treatment for SMA had been palliative care until the Food and Drug Administration approved nusinersen (Spinraza) for the disorder in December 2016, although the drug’s approval has raised some ethical questions.1-3

After reviewing the evidence at their February 8, 2018 meeting, the advisory committee recommended the addition of spinal muscular atrophy screening to the RUSP in a March 8, 2018, letter from committee chair Joseph A. Bocchini Jr., MD, who is a professor and the chairman of the department of pediatrics at Louisiana State University Health in Shreveport.

Secretary Azar accepted the recommendation based on the evidence the committee provided; he also requested a follow-up report within 2 years “describing the status of implementing newborn screening for SMA and clinical outcomes of early treatment, including any potential harms, for infants diagnosed with SMA.”

The advisory committee makes its recommendations to the HHS on which heritable disorders to include in the RUSP after they have assessed a systematic, evidence-based review assigned by the committee to an external independent group. Alex R. Kemper, MD, MPH, a professor of pediatrics at the Ohio State University and division chief of ambulatory pediatrics at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, both in Columbus, led the review group for SMA. Dr. Kemper is also deputy editor of the journal Pediatrics and a member of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

According to Secretary Azar’s summary in his July 2, 2018, letter of acceptance, the evidence review suggested that “early screening and treatment can lead to decreased mortality for individuals with SMA and improved motor milestones.”

Dr. Kemper elaborated in an interview that, “SMA can be detected through newborn screening, and treatment is now available that can not only reduce the risk of death but decrease the development of neurologic impairment. As with adding any condition to newborn screening, public health laboratories will need to develop strategies to incorporate the screening test. The current FDA-approved treatment, nusinersen, is delivered by lumbar puncture into the spinal fluid. In addition, there are exciting advances in gene therapy leading to new treatment approaches.”

Approximately 95% of SMA cases result from the deletion of exon 7 from both alleles of SMN1. (Other rarer cases are caused by mutations in different genes.) Without the SMN protein produced by SMN1, a person gradually loses muscle function.

A similar gene, SMN2, also can produce the SMN protein but in much lower amounts, typically less than 10% of what a person needs. People can, however, have multiple copies of SMN2, which can produce slightly more SMN protein for a slower disease process.

The five types of spinal muscular atrophy are determined according to symptom onset, which directly correlates with disorder severity and prognosis. Just over half (54%) of SMA cases are Type I, in which progressive weakness occurs over the first 6 months of life and results in early death. Only 18% of children with Type I live past age 4 years, and 68% die by age 2 years. Type 0 is rarer but more severe, usually causing fetal loss or early infant death.

Type II represents 18% of SMA cases and causes progressive weakness by age 15 months. Most people with Type II survive to their 30s but then experience respiratory failure and rarely reach their fourth decade. Individuals with Types III and IV typically have a normal lifespan and only begin to see progressive muscle weakness after 1 year old or in adulthood.

Dr. Kemper’s group focused on the three types diagnosed in infancy: types I, II, and III.

Dr. Kemper emphasized in an interview that “it will be critical to make sure that infants diagnosed with SMA through newborn screening receive follow-up shortly afterward to determine whether they would benefit from nusinersen. More information is needed about the long-term outcomes of those infants who begin treatment following newborn screening so we not only know about outcomes in later childhood and adolescence but treatment approaches can be further refined and personalized.”

Nusinersen works by altering the splicing of precursor messenger RNA in SMN2 so that the mRNA strands are longer, which thereby increases how much SMN protein is produced. Concerns about the medication, however, have included its cost – $750,000 in the first year and $375,000 every following year for life – and potential adverse events from repeated administration. Nusinersen is injected into the spinal canal four times in the first year and then once annually, and the painful injections require patient immobilization. Potential adverse events include thrombocytopenia and nephrotoxicity, along with potential complications from repeated lumbar punctures over time.2

Other concerns about the drug include its limited evidence base, lack of long-term data, associated costs with administration (for example, travel costs), the potential for patients taking nusinersen to be excluded from future clinical trials on other treatments, and ensuring parents have enough information on the drug’s limitations and potential risks to provide adequate informed consent.2

Yet evidence to date is favorable in children with early onset. Dr. Bocchini wrote in the letter to Secretary Azar that “limited data suggest that treatment effect is greater when the treatment is initiated before symptoms develop and when the individual has more copies of SMN2.”

Dr. Kemper’s group concluded that screening can detect SMA in newborns and that treatment can modify disease course. “Grey literature suggests those with total disease duration less than or equal to 12 weeks before nusinersen treatment were more likely to have better outcomes than those with longer periods of disease duration.”

“Presymptomatic treatment alters the natural history” of the disorder, the group found, although outcome data past 1 year of age are not yet available. Based on findings from a New York pilot program, they predicted that nationwide newborn screening would avert 33 deaths and 48 cases of children who were dependent on a ventilator among an annual cohort of 4 million births.

At the time of the evidence review, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Missouri, North Carolina, New York, Utah, and Wisconsin initiated pilot programs or whole-population mandated screening for SMA. Of the three states that reported costs, all reported costs at $1 or less per screen.

The research for the evidence review was funded by a Health Resources and Services Administration grant to Duke University, Durham, N.C. No disclosures were provided for evidence review group members.

References

1. Gene Ther. 2017 Sep;24(9):534-8.

2. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Jun 1;178(6):743-44.

3. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Feb 1;172(2):188-92.

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is now among the disorders officially included in the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP), which is used by state public health departments to screen newborns for genetic disorders.

Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services Alex M. Azar II formally added SMA to the panel July 2 on the recommendation of the Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children.

“Adding SMA to the list will help ensure that babies born with SMA are identified, so that they have the opportunity to benefit from early treatment and intervention,” according to a statement from the Muscular Dystrophy Association about the decision. “This testing can also provide families with a genetic diagnosis – information that often is required to determine whether their child is eligible to participate in clinical trials.”

Adding SMA to the RUSP does not mean states must screen newborns for the disorder. Each state’s public health apparatus decides independently whether to accept the recommendation and which disorders on the RUSP to screen for. Most states screen for most disorders on the RUSP. Evidence compiled by the advisory committee suggested wide variation in resources, infrastructure, funding, and time to implementation among states.

An estimated 1 in 11,000 newborns have SMA, a disorder caused by mutations in the survival motor neuron 1 (SMN1) gene. SMA affects motor neurons in the brain stem and spinal cord leading to motor weakness and atrophy. The only treatment for SMA had been palliative care until the Food and Drug Administration approved nusinersen (Spinraza) for the disorder in December 2016, although the drug’s approval has raised some ethical questions.1-3

After reviewing the evidence at their February 8, 2018 meeting, the advisory committee recommended the addition of spinal muscular atrophy screening to the RUSP in a March 8, 2018, letter from committee chair Joseph A. Bocchini Jr., MD, who is a professor and the chairman of the department of pediatrics at Louisiana State University Health in Shreveport.

Secretary Azar accepted the recommendation based on the evidence the committee provided; he also requested a follow-up report within 2 years “describing the status of implementing newborn screening for SMA and clinical outcomes of early treatment, including any potential harms, for infants diagnosed with SMA.”

The advisory committee makes its recommendations to the HHS on which heritable disorders to include in the RUSP after they have assessed a systematic, evidence-based review assigned by the committee to an external independent group. Alex R. Kemper, MD, MPH, a professor of pediatrics at the Ohio State University and division chief of ambulatory pediatrics at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, both in Columbus, led the review group for SMA. Dr. Kemper is also deputy editor of the journal Pediatrics and a member of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

According to Secretary Azar’s summary in his July 2, 2018, letter of acceptance, the evidence review suggested that “early screening and treatment can lead to decreased mortality for individuals with SMA and improved motor milestones.”

Dr. Kemper elaborated in an interview that, “SMA can be detected through newborn screening, and treatment is now available that can not only reduce the risk of death but decrease the development of neurologic impairment. As with adding any condition to newborn screening, public health laboratories will need to develop strategies to incorporate the screening test. The current FDA-approved treatment, nusinersen, is delivered by lumbar puncture into the spinal fluid. In addition, there are exciting advances in gene therapy leading to new treatment approaches.”

Approximately 95% of SMA cases result from the deletion of exon 7 from both alleles of SMN1. (Other rarer cases are caused by mutations in different genes.) Without the SMN protein produced by SMN1, a person gradually loses muscle function.

A similar gene, SMN2, also can produce the SMN protein but in much lower amounts, typically less than 10% of what a person needs. People can, however, have multiple copies of SMN2, which can produce slightly more SMN protein for a slower disease process.

The five types of spinal muscular atrophy are determined according to symptom onset, which directly correlates with disorder severity and prognosis. Just over half (54%) of SMA cases are Type I, in which progressive weakness occurs over the first 6 months of life and results in early death. Only 18% of children with Type I live past age 4 years, and 68% die by age 2 years. Type 0 is rarer but more severe, usually causing fetal loss or early infant death.

Type II represents 18% of SMA cases and causes progressive weakness by age 15 months. Most people with Type II survive to their 30s but then experience respiratory failure and rarely reach their fourth decade. Individuals with Types III and IV typically have a normal lifespan and only begin to see progressive muscle weakness after 1 year old or in adulthood.

Dr. Kemper’s group focused on the three types diagnosed in infancy: types I, II, and III.

Dr. Kemper emphasized in an interview that “it will be critical to make sure that infants diagnosed with SMA through newborn screening receive follow-up shortly afterward to determine whether they would benefit from nusinersen. More information is needed about the long-term outcomes of those infants who begin treatment following newborn screening so we not only know about outcomes in later childhood and adolescence but treatment approaches can be further refined and personalized.”

Nusinersen works by altering the splicing of precursor messenger RNA in SMN2 so that the mRNA strands are longer, which thereby increases how much SMN protein is produced. Concerns about the medication, however, have included its cost – $750,000 in the first year and $375,000 every following year for life – and potential adverse events from repeated administration. Nusinersen is injected into the spinal canal four times in the first year and then once annually, and the painful injections require patient immobilization. Potential adverse events include thrombocytopenia and nephrotoxicity, along with potential complications from repeated lumbar punctures over time.2

Other concerns about the drug include its limited evidence base, lack of long-term data, associated costs with administration (for example, travel costs), the potential for patients taking nusinersen to be excluded from future clinical trials on other treatments, and ensuring parents have enough information on the drug’s limitations and potential risks to provide adequate informed consent.2

Yet evidence to date is favorable in children with early onset. Dr. Bocchini wrote in the letter to Secretary Azar that “limited data suggest that treatment effect is greater when the treatment is initiated before symptoms develop and when the individual has more copies of SMN2.”

Dr. Kemper’s group concluded that screening can detect SMA in newborns and that treatment can modify disease course. “Grey literature suggests those with total disease duration less than or equal to 12 weeks before nusinersen treatment were more likely to have better outcomes than those with longer periods of disease duration.”

“Presymptomatic treatment alters the natural history” of the disorder, the group found, although outcome data past 1 year of age are not yet available. Based on findings from a New York pilot program, they predicted that nationwide newborn screening would avert 33 deaths and 48 cases of children who were dependent on a ventilator among an annual cohort of 4 million births.

At the time of the evidence review, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Missouri, North Carolina, New York, Utah, and Wisconsin initiated pilot programs or whole-population mandated screening for SMA. Of the three states that reported costs, all reported costs at $1 or less per screen.

The research for the evidence review was funded by a Health Resources and Services Administration grant to Duke University, Durham, N.C. No disclosures were provided for evidence review group members.

References

1. Gene Ther. 2017 Sep;24(9):534-8.

2. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Jun 1;178(6):743-44.

3. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Feb 1;172(2):188-92.

More testing of febrile infants at teaching vs. community hospitals, but similar outcomes

TORONTO – according to a study presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

“The community hospitals are doing less procedures on the infants, but with basically the exact same outcomes,” said Beth C. Natt, MD, MPH, director of pediatric hospital medicine at Bridgeport (Conn.) Hospital.

Babies who presented to university-affiliated hospitals were more likely to be hospitalized (70% vs. 67%; P = .001) than were those at community hospitals, but had a similar likelihood of being diagnosed with bacteremia, meningitis, or urinary tract infection. The rates of missed bacterial infection were 0.8% for teaching hospitals and 1% for community hospitals (P = .346).

“There is some thought that in community settings, because we’re not completing the workup in the standard, protocolized way seen at teaching hospitals, we might be doing wrong by the children, but these data show we’re actually doing just fine,” Dr. Natt said in an interview.

She and her colleagues reviewed 9,884 febrile infant evaluations occurring at 132 hospitals participating in the Reducing Excessive Variation in the Infant Sepsis Evaluation (REVISE) quality improvement project. Two-thirds of the infants (n = 6,479) were evaluated across 78 university-affiliated hospitals and 3,405 (or 34%) were seen at 54 community hospitals. Hospital status was self-reported.

The teaching hospitals more often had at least one pediatric emergency medicine provider, compared with community hospitals (90% vs. 57%; P = .001) and were more likely to see babies between 7 and 30 days old (90% vs. 57%; P = .001). They also were more likely to obtain urine cultures (92% vs. 88%; P = 0.001), blood cultures (84% vs. 80%; P = .001), and cerebral spinal fluid cultures (62% vs. 57%; P = .001).

On the other hand, community hospitals were significantly more likely to see children presenting with respiratory symptoms (39% vs. 36% for teaching hospitals; P = .014), and were more likely to order chest x-rays on febrile infants (32% vs. 24% for university-affiliated hospitals; P = .001).

“As a community hospitalist, the results weren’t that surprising to me,” said Dr. Natt. “If anything was surprising it was how often we were doing chest x-rays, but I think that had to do with the fact that we had more children with respiratory symptoms coming to community hospitals.

“The American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for fever were written last in 1993, when I was in high school, so they are very due to be revised,” said Dr. Natt. “I suspect the new guidelines will have us doing fewer spinal taps in children and more watchful waiting.”

TORONTO – according to a study presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

“The community hospitals are doing less procedures on the infants, but with basically the exact same outcomes,” said Beth C. Natt, MD, MPH, director of pediatric hospital medicine at Bridgeport (Conn.) Hospital.

Babies who presented to university-affiliated hospitals were more likely to be hospitalized (70% vs. 67%; P = .001) than were those at community hospitals, but had a similar likelihood of being diagnosed with bacteremia, meningitis, or urinary tract infection. The rates of missed bacterial infection were 0.8% for teaching hospitals and 1% for community hospitals (P = .346).

“There is some thought that in community settings, because we’re not completing the workup in the standard, protocolized way seen at teaching hospitals, we might be doing wrong by the children, but these data show we’re actually doing just fine,” Dr. Natt said in an interview.

She and her colleagues reviewed 9,884 febrile infant evaluations occurring at 132 hospitals participating in the Reducing Excessive Variation in the Infant Sepsis Evaluation (REVISE) quality improvement project. Two-thirds of the infants (n = 6,479) were evaluated across 78 university-affiliated hospitals and 3,405 (or 34%) were seen at 54 community hospitals. Hospital status was self-reported.

The teaching hospitals more often had at least one pediatric emergency medicine provider, compared with community hospitals (90% vs. 57%; P = .001) and were more likely to see babies between 7 and 30 days old (90% vs. 57%; P = .001). They also were more likely to obtain urine cultures (92% vs. 88%; P = 0.001), blood cultures (84% vs. 80%; P = .001), and cerebral spinal fluid cultures (62% vs. 57%; P = .001).

On the other hand, community hospitals were significantly more likely to see children presenting with respiratory symptoms (39% vs. 36% for teaching hospitals; P = .014), and were more likely to order chest x-rays on febrile infants (32% vs. 24% for university-affiliated hospitals; P = .001).

“As a community hospitalist, the results weren’t that surprising to me,” said Dr. Natt. “If anything was surprising it was how often we were doing chest x-rays, but I think that had to do with the fact that we had more children with respiratory symptoms coming to community hospitals.

“The American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for fever were written last in 1993, when I was in high school, so they are very due to be revised,” said Dr. Natt. “I suspect the new guidelines will have us doing fewer spinal taps in children and more watchful waiting.”

TORONTO – according to a study presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

“The community hospitals are doing less procedures on the infants, but with basically the exact same outcomes,” said Beth C. Natt, MD, MPH, director of pediatric hospital medicine at Bridgeport (Conn.) Hospital.

Babies who presented to university-affiliated hospitals were more likely to be hospitalized (70% vs. 67%; P = .001) than were those at community hospitals, but had a similar likelihood of being diagnosed with bacteremia, meningitis, or urinary tract infection. The rates of missed bacterial infection were 0.8% for teaching hospitals and 1% for community hospitals (P = .346).

“There is some thought that in community settings, because we’re not completing the workup in the standard, protocolized way seen at teaching hospitals, we might be doing wrong by the children, but these data show we’re actually doing just fine,” Dr. Natt said in an interview.

She and her colleagues reviewed 9,884 febrile infant evaluations occurring at 132 hospitals participating in the Reducing Excessive Variation in the Infant Sepsis Evaluation (REVISE) quality improvement project. Two-thirds of the infants (n = 6,479) were evaluated across 78 university-affiliated hospitals and 3,405 (or 34%) were seen at 54 community hospitals. Hospital status was self-reported.

The teaching hospitals more often had at least one pediatric emergency medicine provider, compared with community hospitals (90% vs. 57%; P = .001) and were more likely to see babies between 7 and 30 days old (90% vs. 57%; P = .001). They also were more likely to obtain urine cultures (92% vs. 88%; P = 0.001), blood cultures (84% vs. 80%; P = .001), and cerebral spinal fluid cultures (62% vs. 57%; P = .001).

On the other hand, community hospitals were significantly more likely to see children presenting with respiratory symptoms (39% vs. 36% for teaching hospitals; P = .014), and were more likely to order chest x-rays on febrile infants (32% vs. 24% for university-affiliated hospitals; P = .001).

“As a community hospitalist, the results weren’t that surprising to me,” said Dr. Natt. “If anything was surprising it was how often we were doing chest x-rays, but I think that had to do with the fact that we had more children with respiratory symptoms coming to community hospitals.

“The American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for fever were written last in 1993, when I was in high school, so they are very due to be revised,” said Dr. Natt. “I suspect the new guidelines will have us doing fewer spinal taps in children and more watchful waiting.”

AT PAS 18

Key clinical point: University-affiliated hospitals do more invasive testing in febrile infants, but have outcomes similar to those of community hospitals.

Major finding: The rate of missed bacterial infection did not differ between hospital types: 0.8% for teaching hospitals and 1% for community hospitals (P = .346).

Study details: Review of 9,884 febrile infant evaluations occurring at 132 hospitals, 66% of which were university-affiliated hospitals and 34% of which were community hospitals.

Disclosures: The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

Risk of adverse birth outcomes for singleton infants born to ART-treated or subfertile women

Singleton infants born to mothers who are subfertile or treated with assisted reproductive technology (ART) are at higher risk for multiple adverse health outcomes beyond prematurity, a recent retrospective study shows.

Risks of chromosomal abnormalities, infectious diseases, and cardiovascular and respiratory conditions were all increased, compared with infants born to fertile mothers, in analyses of neonatal outcomes stratified by gestational age.

This population-based study is among the first to show differences in adverse birth outcomes beyond preterm birth and, more specifically, by organ system conditions across gestational age categories, according to Sunah S. Hwang, MD, MPH, of the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and her coinvestigators.

“With this approach, we offer more detailed associations between maternal fertility and the receipt of treatment along the continuum of fetal organ development and subsequent infant health conditions,” Dr. Hwang and her coauthors wrote in Pediatrics.

The study, which included singleton infants of at least 23 weeks’ gestational age born during 2004-2010, was based on data from a Massachusetts clinical ART database (MOSART) that was linked with state vital records.

Out of 350,123 infants with birth hospitalization records in the study cohort, 336,705 were born to fertile women, while 8,375 were born to women treated with ART, and 5,403 were born to subfertile women.

After adjustment for key maternal and infant characteristics, infants born to subfertile or ART-treated women were more often preterm as compared with infants to fertile mothers. Adjusted odds ratios were 1.39 (95% confidence interval, 1.26-1.54) and 1.72 (95% CI, 1.60-1.85) for infants of subfertile and ART-treated women, respectively, Dr. Hwang and her coinvestigators reported.

Infants born to subfertile or ART-treated women were also more likely to have adverse respiratory, gastrointestinal, or nutritional outcomes, with adjusted ORs ranging from 1.12 to 1.18, they added in the report.

Looking specifically at outcomes stratified by gestational age, they found an increased risk of congenital malformations, infectious diseases, and cardiovascular or respiratory outcomes, with adjusted ORs from 1.30 to 2.61, in the data published in the journal.

By contrast, there were no differences in risks of neonatal mortality, length of hospitalization, low birth weight, or neurologic and hematologic abnormalities for infants of subfertile and ART-treated women, compared with fertile women, according to Dr. Hwang and her coauthors.

These results confirm results of some previous studies that suggested a higher risk of adverse birth outcomes among infants born as singletons, according to the study authors.

“Although it is clearly accepted that multiple gestation is a significant predictor of preterm birth and low birth weight, recent studies have also revealed that, even among singleton births, mothers with infertility without ART treatment along with those who do undergo ART treatment are at higher risk for preterm delivery,” they wrote.

The study was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Authors said they had no financial relationships relevant to the study.

SOURCE: Hwang SS et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Aug;142(2):e20174069.

Singleton infants born to mothers who are subfertile or treated with assisted reproductive technology (ART) are at higher risk for multiple adverse health outcomes beyond prematurity, a recent retrospective study shows.

Risks of chromosomal abnormalities, infectious diseases, and cardiovascular and respiratory conditions were all increased, compared with infants born to fertile mothers, in analyses of neonatal outcomes stratified by gestational age.

This population-based study is among the first to show differences in adverse birth outcomes beyond preterm birth and, more specifically, by organ system conditions across gestational age categories, according to Sunah S. Hwang, MD, MPH, of the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and her coinvestigators.

“With this approach, we offer more detailed associations between maternal fertility and the receipt of treatment along the continuum of fetal organ development and subsequent infant health conditions,” Dr. Hwang and her coauthors wrote in Pediatrics.

The study, which included singleton infants of at least 23 weeks’ gestational age born during 2004-2010, was based on data from a Massachusetts clinical ART database (MOSART) that was linked with state vital records.

Out of 350,123 infants with birth hospitalization records in the study cohort, 336,705 were born to fertile women, while 8,375 were born to women treated with ART, and 5,403 were born to subfertile women.

After adjustment for key maternal and infant characteristics, infants born to subfertile or ART-treated women were more often preterm as compared with infants to fertile mothers. Adjusted odds ratios were 1.39 (95% confidence interval, 1.26-1.54) and 1.72 (95% CI, 1.60-1.85) for infants of subfertile and ART-treated women, respectively, Dr. Hwang and her coinvestigators reported.

Infants born to subfertile or ART-treated women were also more likely to have adverse respiratory, gastrointestinal, or nutritional outcomes, with adjusted ORs ranging from 1.12 to 1.18, they added in the report.

Looking specifically at outcomes stratified by gestational age, they found an increased risk of congenital malformations, infectious diseases, and cardiovascular or respiratory outcomes, with adjusted ORs from 1.30 to 2.61, in the data published in the journal.

By contrast, there were no differences in risks of neonatal mortality, length of hospitalization, low birth weight, or neurologic and hematologic abnormalities for infants of subfertile and ART-treated women, compared with fertile women, according to Dr. Hwang and her coauthors.

These results confirm results of some previous studies that suggested a higher risk of adverse birth outcomes among infants born as singletons, according to the study authors.

“Although it is clearly accepted that multiple gestation is a significant predictor of preterm birth and low birth weight, recent studies have also revealed that, even among singleton births, mothers with infertility without ART treatment along with those who do undergo ART treatment are at higher risk for preterm delivery,” they wrote.

The study was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Authors said they had no financial relationships relevant to the study.

SOURCE: Hwang SS et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Aug;142(2):e20174069.

Singleton infants born to mothers who are subfertile or treated with assisted reproductive technology (ART) are at higher risk for multiple adverse health outcomes beyond prematurity, a recent retrospective study shows.

Risks of chromosomal abnormalities, infectious diseases, and cardiovascular and respiratory conditions were all increased, compared with infants born to fertile mothers, in analyses of neonatal outcomes stratified by gestational age.

This population-based study is among the first to show differences in adverse birth outcomes beyond preterm birth and, more specifically, by organ system conditions across gestational age categories, according to Sunah S. Hwang, MD, MPH, of the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and her coinvestigators.

“With this approach, we offer more detailed associations between maternal fertility and the receipt of treatment along the continuum of fetal organ development and subsequent infant health conditions,” Dr. Hwang and her coauthors wrote in Pediatrics.

The study, which included singleton infants of at least 23 weeks’ gestational age born during 2004-2010, was based on data from a Massachusetts clinical ART database (MOSART) that was linked with state vital records.

Out of 350,123 infants with birth hospitalization records in the study cohort, 336,705 were born to fertile women, while 8,375 were born to women treated with ART, and 5,403 were born to subfertile women.

After adjustment for key maternal and infant characteristics, infants born to subfertile or ART-treated women were more often preterm as compared with infants to fertile mothers. Adjusted odds ratios were 1.39 (95% confidence interval, 1.26-1.54) and 1.72 (95% CI, 1.60-1.85) for infants of subfertile and ART-treated women, respectively, Dr. Hwang and her coinvestigators reported.

Infants born to subfertile or ART-treated women were also more likely to have adverse respiratory, gastrointestinal, or nutritional outcomes, with adjusted ORs ranging from 1.12 to 1.18, they added in the report.

Looking specifically at outcomes stratified by gestational age, they found an increased risk of congenital malformations, infectious diseases, and cardiovascular or respiratory outcomes, with adjusted ORs from 1.30 to 2.61, in the data published in the journal.

By contrast, there were no differences in risks of neonatal mortality, length of hospitalization, low birth weight, or neurologic and hematologic abnormalities for infants of subfertile and ART-treated women, compared with fertile women, according to Dr. Hwang and her coauthors.

These results confirm results of some previous studies that suggested a higher risk of adverse birth outcomes among infants born as singletons, according to the study authors.

“Although it is clearly accepted that multiple gestation is a significant predictor of preterm birth and low birth weight, recent studies have also revealed that, even among singleton births, mothers with infertility without ART treatment along with those who do undergo ART treatment are at higher risk for preterm delivery,” they wrote.

The study was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Authors said they had no financial relationships relevant to the study.

SOURCE: Hwang SS et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Aug;142(2):e20174069.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Subfertility, whether treated by ART or not, is associated with adverse health outcomes for infants.

Major finding: Infants of subfertile and ART-treated women were more likely to be born preterm (odds ratios, 1.39 and 1.72, respectively) than were the infants of fertile women.

Study details: Population-based study of 350,123 infants from a Massachusetts clinical database.

Disclosures: The study was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. The authors said they had no financial relationships relevant to the study.

Source: Hwang SS et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Aug;142(2):e20174069.

Urge expectant parents to have prenatal pediatrician visit

All parents-to-be, especially first-time parents, should visit a pediatrician during the third trimester of pregnancy to establish a relationship, according to an updated clinical report on the prenatal visit issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics. The report was published online June 25 and in the July issue of Pediatrics.

“It’s a chance to talk about how to keep a baby safe and thriving physically, but also ways to build strong parent-child bonds that promote resilience and help a child stay emotionally healthy,” Michael Yogman, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in a statement. Dr. Yogman was the lead author of the report and chair of the AAP Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health.

A comprehensive prenatal visit gives pediatricians the opportunity to meet four objectives: build a trusting relationship with parents, gather information about family history, provide advice and guidance on infant care and safety, and identify risk factors for psychosocial issues such as perinatal depression, according to the report in Pediatrics.

The prenatal visit allows families and clinicians to learn whether their philosophies align to start a relationship that may last for many years and this visit can include extended family members such as grandparents. In addition, pediatricians can use the prenatal visit as an opportunity to learn more about family history including past pregnancies, failed and successful, as well as pregnancy complications, chronic medical conditions in family members that may affect the home environment, and plans for child care if parents will be working outside the home.

The report also emphasizes “positive parenting” and the role of pediatricians at a prenatal visit in offering support and guidance to help prepare parents for infant care. This guidance may include advice on feeding, sleeping, diapering, and bathing, as well as acknowledging cultural practices.

The authors noted that a prime opporunity to schedule the prenatal visit is when an expectant parent seeking information about insurance, practice hours, and whether the practice is taking new patients.

The AAP advises clinicians to encourage same sex parents, parents expecting via surrogate, and parents who are adopting to schedule a prenatal visit to identify particular concerns they may have.

“This is the only routine child wellness visit recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics that doesn’t actually require a child in the room,” coauthor Arthur Lavin, MD, also of Harvard Medical School, said in a statement.

The prenatal visit “gives parents an opportunity to really focus on any questions and concerns they may have. They can talk with a pediatrician before the fatigue of new parenthood sets in and there’s an adorably distracting little human in their arms who may be crying, spitting up, or in immediate need of feeding or a diaper change,” Dr. Lavin said.

“At its heart and soul,” Dr. Lavin noted, “this visit is about laying a foundation for a trusting, supportive relationship between the family and their pediatrician, who will work together to keep the child healthy for the next 18 or 20 years.”

The report recommends the Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents, Fourth Edition, as a resource for clinicians. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Yogman M et al. Pediatrics. 2018; doi: 10.1542/peds. 2018-1218

All parents-to-be, especially first-time parents, should visit a pediatrician during the third trimester of pregnancy to establish a relationship, according to an updated clinical report on the prenatal visit issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics. The report was published online June 25 and in the July issue of Pediatrics.

“It’s a chance to talk about how to keep a baby safe and thriving physically, but also ways to build strong parent-child bonds that promote resilience and help a child stay emotionally healthy,” Michael Yogman, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in a statement. Dr. Yogman was the lead author of the report and chair of the AAP Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health.

A comprehensive prenatal visit gives pediatricians the opportunity to meet four objectives: build a trusting relationship with parents, gather information about family history, provide advice and guidance on infant care and safety, and identify risk factors for psychosocial issues such as perinatal depression, according to the report in Pediatrics.

The prenatal visit allows families and clinicians to learn whether their philosophies align to start a relationship that may last for many years and this visit can include extended family members such as grandparents. In addition, pediatricians can use the prenatal visit as an opportunity to learn more about family history including past pregnancies, failed and successful, as well as pregnancy complications, chronic medical conditions in family members that may affect the home environment, and plans for child care if parents will be working outside the home.

The report also emphasizes “positive parenting” and the role of pediatricians at a prenatal visit in offering support and guidance to help prepare parents for infant care. This guidance may include advice on feeding, sleeping, diapering, and bathing, as well as acknowledging cultural practices.

The authors noted that a prime opporunity to schedule the prenatal visit is when an expectant parent seeking information about insurance, practice hours, and whether the practice is taking new patients.

The AAP advises clinicians to encourage same sex parents, parents expecting via surrogate, and parents who are adopting to schedule a prenatal visit to identify particular concerns they may have.

“This is the only routine child wellness visit recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics that doesn’t actually require a child in the room,” coauthor Arthur Lavin, MD, also of Harvard Medical School, said in a statement.

The prenatal visit “gives parents an opportunity to really focus on any questions and concerns they may have. They can talk with a pediatrician before the fatigue of new parenthood sets in and there’s an adorably distracting little human in their arms who may be crying, spitting up, or in immediate need of feeding or a diaper change,” Dr. Lavin said.

“At its heart and soul,” Dr. Lavin noted, “this visit is about laying a foundation for a trusting, supportive relationship between the family and their pediatrician, who will work together to keep the child healthy for the next 18 or 20 years.”

The report recommends the Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents, Fourth Edition, as a resource for clinicians. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Yogman M et al. Pediatrics. 2018; doi: 10.1542/peds. 2018-1218

All parents-to-be, especially first-time parents, should visit a pediatrician during the third trimester of pregnancy to establish a relationship, according to an updated clinical report on the prenatal visit issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics. The report was published online June 25 and in the July issue of Pediatrics.

“It’s a chance to talk about how to keep a baby safe and thriving physically, but also ways to build strong parent-child bonds that promote resilience and help a child stay emotionally healthy,” Michael Yogman, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in a statement. Dr. Yogman was the lead author of the report and chair of the AAP Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health.

A comprehensive prenatal visit gives pediatricians the opportunity to meet four objectives: build a trusting relationship with parents, gather information about family history, provide advice and guidance on infant care and safety, and identify risk factors for psychosocial issues such as perinatal depression, according to the report in Pediatrics.

The prenatal visit allows families and clinicians to learn whether their philosophies align to start a relationship that may last for many years and this visit can include extended family members such as grandparents. In addition, pediatricians can use the prenatal visit as an opportunity to learn more about family history including past pregnancies, failed and successful, as well as pregnancy complications, chronic medical conditions in family members that may affect the home environment, and plans for child care if parents will be working outside the home.

The report also emphasizes “positive parenting” and the role of pediatricians at a prenatal visit in offering support and guidance to help prepare parents for infant care. This guidance may include advice on feeding, sleeping, diapering, and bathing, as well as acknowledging cultural practices.

The authors noted that a prime opporunity to schedule the prenatal visit is when an expectant parent seeking information about insurance, practice hours, and whether the practice is taking new patients.

The AAP advises clinicians to encourage same sex parents, parents expecting via surrogate, and parents who are adopting to schedule a prenatal visit to identify particular concerns they may have.

“This is the only routine child wellness visit recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics that doesn’t actually require a child in the room,” coauthor Arthur Lavin, MD, also of Harvard Medical School, said in a statement.

The prenatal visit “gives parents an opportunity to really focus on any questions and concerns they may have. They can talk with a pediatrician before the fatigue of new parenthood sets in and there’s an adorably distracting little human in their arms who may be crying, spitting up, or in immediate need of feeding or a diaper change,” Dr. Lavin said.

“At its heart and soul,” Dr. Lavin noted, “this visit is about laying a foundation for a trusting, supportive relationship between the family and their pediatrician, who will work together to keep the child healthy for the next 18 or 20 years.”

The report recommends the Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents, Fourth Edition, as a resource for clinicians. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Yogman M et al. Pediatrics. 2018; doi: 10.1542/peds. 2018-1218

FROM PEDIATRICS

Research provides more evidence of a maternal diabetes/autism link

ORLANDO – Longer-term data are providing more evidence of a possible link between maternal diabetes and autism spectrum disorder in their children.

Anny Xiang, PhD, and coathors with Kaiser Permanente of Southern California sought to further understand the possible effect of maternal T1D on offspring’s development of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) by expanding the cohort and timeline of their earlier work (JAMA. 2015;313(14):1425-1434).

Across the cohort, 1.3% of children were diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The rate was barely different, at 1.5%, for those whose mothers developed gestational diabetes after 26 weeks. But rates of ASD were higher – 3.1%, 2.5%, 2.1% – among those whose mothers had T1D, T2D, and gestational diabetes that developed at 26 weeks or earlier, respectively. The findings were adjusted for co-founders such as birth year, age at delivery, eduction level and income, Dr. Xiang said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Compared to offspring of mothers without diabetes, ASD was more common in the children of mothers with T1D (adjusted HR=2.36, 95% CI, 1.36-4.12) mothers with type 2 diabetes (AHR= 1.45, 95% CI, 1.24-1.70) and gestational diabetes mellitus that developed by 26 weeks gestation (1.30, 95% CI, 1.12-1.51).

The numbers remained similar after they were adjusted for smoking during pregnancy and prepregnancy BMI, statistics which were available for about 36% of the subjects, according to the findings which were published simultaneously in JAMA (June 23, 2018. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.7614).

Possible explanations for the link between ASD and maternal diabetes include maternal glycemic control, prematurity, and levels of neonatal hypoglycemia, Dr. Xiang said.

The results do not take into account any paternal risks for offspring developing ASD, which also includes diabetes, Dr. Xiang said, noting that two previous studies linked diabetes in fathers to ASD, although to a lesser extent than diabetes in mothers. (Epidemiology. 2010 Nov;21(6):805-8; Pediatrics. 2009 Aug;124(2):687-94)

The study also doesn’t take breastfeeding into account, Dr. Xiang noted. A 2016 study found that women with T2D were less likely to breastfeed (J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29(15):2513-8), and some research has suggested that breastfeeding may be protective against the development of ASD in children (Nutrition 2012;28(7-8):e27-32).

In addition, the study doesn’t track maternal glucose levels over time.

Session co-chair Peter Damm, MD, professor of obstetrics at the University of Copenhagen, said in an interview that he is impressed by the study. He cautioned, however, that it does not prove a connection.“This not a proof, but it seems likely, or like a possibility,” he said.

One possible explanation for a diabetes/ASD connection is the fact that the fetal brain is evolving throughout pregnancy unlike other body organs, which simply grow after developing in the first trimester, he said. As a result, glucose levels may affect the brain’s development in a unique way compared to other organs.

He also noted that the impact may be reduced when pregnancy is further along, potentially explaining why researchers didn’t connect late-developing gestational diabetes to ASD.

There’s still a “low risk” of ASD even in children born to mothers with diabetes, he said. “You shouldn’t scare anyone with this.”