User login

Art education benefits blood cancer patients

New research suggests a bedside visual art intervention (BVAI) can reduce pain and anxiety in inpatients with hematologic malignancies, including those undergoing transplant.

The BVAI involved an educator teaching patients art technique one-on-one for approximately 30 minutes.

After a single session, patients had significant improvements in positive mood and pain scores, as well as decreases in negative mood and anxiety.

Alexandra P. Wolanskyj, MD, of Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, and her colleagues reported these results in the European Journal of Cancer Care.

The study included 21 patients, 19 of them female. Their median age was 53.5 (range, 19-75). Six patients were undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

The patients had multiple myeloma (n=5), acute myeloid leukemia (n=5), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (n=3), Hodgkin lymphoma (n=2), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (n=1), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (n=1), amyloidosis (n=1), Gardner-Diamond syndrome (n=1), myelodysplastic syndrome (n=1), and Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia (n=1).

Nearly half of patients had relapsed disease (47.6%), 23.8% had active and new disease, 19.0% had active disease with primary resistance on chemotherapy, and 9.5% of patients were in remission.

Intervention

The researchers recruited an educator from a community art center to teach art at the patients’ bedsides. Sessions were intended to be about 30 minutes. However, patients could stop at any time or continue beyond 30 minutes.

Patients and their families could make art or just observe. Materials used included watercolors, oil pastels, colored pencils, and clay (all non-toxic and odorless). The materials were left with patients so they could continue to use them after the sessions.

Results

The researchers assessed patients’ pain, anxiety, and mood at baseline and after the patients had a session with the art educator.

After the BVAI, patients had a significant decrease in pain, according to the Visual Analog Scale (VAS). The 14 patients who reported any pain at baseline had a mean reduction in VAS score of 1.5, or a 35.1% reduction in pain (P=0.017).

Patients had a 21.6% reduction in anxiety after the BVAI. Among the 20 patients who completed this assessment, there was a mean 9.2-point decrease in State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) score (P=0.001).

In addition, patients had a significant increase in positive mood and a significant decrease in negative mood after the BVAI. Mood was assessed in 20 patients using the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) scale.

Positive mood increased 14.6% (P=0.003), and negative mood decreased 18.0% (P=0.015) after the BVAI. Patients’ mean PANAS scores increased 4.6 points for positive mood and decreased 3.3 points for negative mood.

All 21 patients completed a questionnaire on the BVAI. All but 1 patient (95%) said the intervention was positive overall, and 85% of patients (n=18) said they would be interested in participating in future art-based interventions.

The researchers said these results suggest experiences provided by artists in the community may be an adjunct to conventional treatments in patients with cancer-related mood symptoms and pain.

New research suggests a bedside visual art intervention (BVAI) can reduce pain and anxiety in inpatients with hematologic malignancies, including those undergoing transplant.

The BVAI involved an educator teaching patients art technique one-on-one for approximately 30 minutes.

After a single session, patients had significant improvements in positive mood and pain scores, as well as decreases in negative mood and anxiety.

Alexandra P. Wolanskyj, MD, of Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, and her colleagues reported these results in the European Journal of Cancer Care.

The study included 21 patients, 19 of them female. Their median age was 53.5 (range, 19-75). Six patients were undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

The patients had multiple myeloma (n=5), acute myeloid leukemia (n=5), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (n=3), Hodgkin lymphoma (n=2), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (n=1), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (n=1), amyloidosis (n=1), Gardner-Diamond syndrome (n=1), myelodysplastic syndrome (n=1), and Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia (n=1).

Nearly half of patients had relapsed disease (47.6%), 23.8% had active and new disease, 19.0% had active disease with primary resistance on chemotherapy, and 9.5% of patients were in remission.

Intervention

The researchers recruited an educator from a community art center to teach art at the patients’ bedsides. Sessions were intended to be about 30 minutes. However, patients could stop at any time or continue beyond 30 minutes.

Patients and their families could make art or just observe. Materials used included watercolors, oil pastels, colored pencils, and clay (all non-toxic and odorless). The materials were left with patients so they could continue to use them after the sessions.

Results

The researchers assessed patients’ pain, anxiety, and mood at baseline and after the patients had a session with the art educator.

After the BVAI, patients had a significant decrease in pain, according to the Visual Analog Scale (VAS). The 14 patients who reported any pain at baseline had a mean reduction in VAS score of 1.5, or a 35.1% reduction in pain (P=0.017).

Patients had a 21.6% reduction in anxiety after the BVAI. Among the 20 patients who completed this assessment, there was a mean 9.2-point decrease in State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) score (P=0.001).

In addition, patients had a significant increase in positive mood and a significant decrease in negative mood after the BVAI. Mood was assessed in 20 patients using the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) scale.

Positive mood increased 14.6% (P=0.003), and negative mood decreased 18.0% (P=0.015) after the BVAI. Patients’ mean PANAS scores increased 4.6 points for positive mood and decreased 3.3 points for negative mood.

All 21 patients completed a questionnaire on the BVAI. All but 1 patient (95%) said the intervention was positive overall, and 85% of patients (n=18) said they would be interested in participating in future art-based interventions.

The researchers said these results suggest experiences provided by artists in the community may be an adjunct to conventional treatments in patients with cancer-related mood symptoms and pain.

New research suggests a bedside visual art intervention (BVAI) can reduce pain and anxiety in inpatients with hematologic malignancies, including those undergoing transplant.

The BVAI involved an educator teaching patients art technique one-on-one for approximately 30 minutes.

After a single session, patients had significant improvements in positive mood and pain scores, as well as decreases in negative mood and anxiety.

Alexandra P. Wolanskyj, MD, of Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, and her colleagues reported these results in the European Journal of Cancer Care.

The study included 21 patients, 19 of them female. Their median age was 53.5 (range, 19-75). Six patients were undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

The patients had multiple myeloma (n=5), acute myeloid leukemia (n=5), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (n=3), Hodgkin lymphoma (n=2), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (n=1), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (n=1), amyloidosis (n=1), Gardner-Diamond syndrome (n=1), myelodysplastic syndrome (n=1), and Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia (n=1).

Nearly half of patients had relapsed disease (47.6%), 23.8% had active and new disease, 19.0% had active disease with primary resistance on chemotherapy, and 9.5% of patients were in remission.

Intervention

The researchers recruited an educator from a community art center to teach art at the patients’ bedsides. Sessions were intended to be about 30 minutes. However, patients could stop at any time or continue beyond 30 minutes.

Patients and their families could make art or just observe. Materials used included watercolors, oil pastels, colored pencils, and clay (all non-toxic and odorless). The materials were left with patients so they could continue to use them after the sessions.

Results

The researchers assessed patients’ pain, anxiety, and mood at baseline and after the patients had a session with the art educator.

After the BVAI, patients had a significant decrease in pain, according to the Visual Analog Scale (VAS). The 14 patients who reported any pain at baseline had a mean reduction in VAS score of 1.5, or a 35.1% reduction in pain (P=0.017).

Patients had a 21.6% reduction in anxiety after the BVAI. Among the 20 patients who completed this assessment, there was a mean 9.2-point decrease in State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) score (P=0.001).

In addition, patients had a significant increase in positive mood and a significant decrease in negative mood after the BVAI. Mood was assessed in 20 patients using the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) scale.

Positive mood increased 14.6% (P=0.003), and negative mood decreased 18.0% (P=0.015) after the BVAI. Patients’ mean PANAS scores increased 4.6 points for positive mood and decreased 3.3 points for negative mood.

All 21 patients completed a questionnaire on the BVAI. All but 1 patient (95%) said the intervention was positive overall, and 85% of patients (n=18) said they would be interested in participating in future art-based interventions.

The researchers said these results suggest experiences provided by artists in the community may be an adjunct to conventional treatments in patients with cancer-related mood symptoms and pain.

Therapy shows early promise in phase 1 MM trial

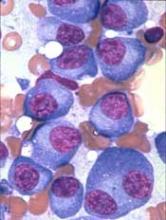

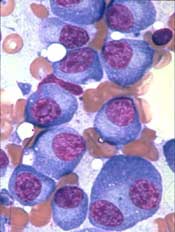

CHICAGO—Early phase 1 results suggest a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy can induce tumor regression in heavily pretreated patients with multiple myeloma (MM).

The therapy, P-BCMA-101, has only been tested in 3 patients in the lowest dose cohort.

However, signs of efficacy have been seen in all 3 patients, including a lasting partial response in 1 patient.

There have been no dose-limiting toxicities, and none of the patients have developed cytokine release syndrome (CRS).

“The results from the first cohort of the phase 1 P-BCMA-101 study have surpassed historical benchmarks of safety and efficacy in multiple myeloma at this dose level and give us confidence to move ahead into additional dose cohorts,” said Eric Ostertag, MD, PhD, chief executive officer of Poseida Therapeutics, Inc.

Dr Ostertag and his colleagues presented these results at the AACR Annual Meeting 2018 (abstract CT130). The trial is sponsored by Poseida Therapeutics, Inc.

The trial is enrolling patients with relapsed/refractory MM who have received a proteasome inhibitor and immunomodulatory agent.

Conditioning consists of standard cyclophosphamide (300 mg/m2) and fludarabine (30 mg/m2) on days -5 to -3. Patients then receive a single dose of P-BCMA-101 on day 0.

The trial has a 3+3 dose-escalation design, with up to 6 dose levels. The first dose level is 0.75 x 106 P-BCMA-101 cells/kg.

The 3 patients who have received this dose had 6 to 9 prior therapies.

Patient 1

The first patient was a 54-year-old female with lambda light chain MM. She had t(11;14), del13q14, and 11q23(x3).

Before she received P-BCMA-101, the patient had an increase in free light chains (FLCs) to 3290 mg/L, which caused renal failure. She was treated with cyclophosphamide/prednisone and plasmapheresis bridging therapy before proceeding to P-BCMA-101.

The patient achieved a partial response 2 weeks after receiving P-BCMA-101, and this has persisted through week 12. She had a maximal reduction in urine M-protein of 92% and a reduction in plasma FLCs of 79%.

The patient did not experience any adverse events (AEs) considered related to P-BCMA-101.

Patient 2

The second patient was a 50-year-old female with oligosecretory kappa light chain MM and plasmacytomas. She had del17p (TP53) and 11q13(x3).

Due to enlarging plasmacytomas, the patient was treated with DT-PACE (dexamethasone plus thalidomide with cisplatin, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and etoposide) before receiving P-BCMA-101.

Her bone plasmacytomas resolved to below background within 4 to 8 weeks of P-BCMA-101 administration, but 1 new non-bone lesion appeared months later.

AEs considered at least possibly related to treatment in this patient included grade 2-4 neutropenia as well as grade 3-4 thrombocytopenia.

Patient 3

The third patient was a 65-year-old female with lambda light chain MM and del13q14.

Her urine M-protein and FLCs briefly dipped and rose after she received bridging therapy with lenalidomide and dexamethasone, but they decreased at 4 weeks after P-BCMA-101 administration, which corresponded with P-BCMA-101 expansion in the peripheral blood.

AEs considered at least possibly related to treatment included easy bruising (grade 1), fatigue (grade 2), febrile neutropenia (grade 3), hypogammaglobinemia (grade 2), neutropenia (grade 2-3), and thrombocytopenia (grade 3-4).

“The lack of cytokine release syndrome in any of the 3 patients, in spite of marked efficacy, is unprecedented at this dose, which we believe is attributable to multiple differentiated aspects of our technology, resulting in a highly purified CAR T product with a high percentage of cells with a T stem cell memory phenotype,” Dr Ostertag said.

In addition to a lack of CRS, there were no dose-limiting toxicities. Therefore, the dose has been escalated to 2 x 106 P-BCMA-101+ CAR T cells/kg for the next patient cohort. The first patient has been treated at this dose level, with no CRS yet reported.

About P-BCMA-101

P-BCMA-101 employs a B-cell maturation antigen-specific Centyrin™ fused to a second-generation CAR scaffold (a CARTyrin) rather than a single-chain variable fragment (scFv).

Centyrins have similar binding affinities as scFvs but are said to be potentially less immunogenic than scFvs, more stable at the cell surface, and resistant to antigen/ligand-independent tonic signaling.

P-BCMA-101 is engineered using PiggyBac™, a transposon-based system requiring only mRNA and plasmid DNA (no virus).

The increased cargo capacity of PiggyBac allows for the incorporation of a safety switch and a selectable gene. The safety switch can be activated to enable depletion in case AEs occur. And the selectable gene allows for enrichment of CAR+ cells.

CHICAGO—Early phase 1 results suggest a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy can induce tumor regression in heavily pretreated patients with multiple myeloma (MM).

The therapy, P-BCMA-101, has only been tested in 3 patients in the lowest dose cohort.

However, signs of efficacy have been seen in all 3 patients, including a lasting partial response in 1 patient.

There have been no dose-limiting toxicities, and none of the patients have developed cytokine release syndrome (CRS).

“The results from the first cohort of the phase 1 P-BCMA-101 study have surpassed historical benchmarks of safety and efficacy in multiple myeloma at this dose level and give us confidence to move ahead into additional dose cohorts,” said Eric Ostertag, MD, PhD, chief executive officer of Poseida Therapeutics, Inc.

Dr Ostertag and his colleagues presented these results at the AACR Annual Meeting 2018 (abstract CT130). The trial is sponsored by Poseida Therapeutics, Inc.

The trial is enrolling patients with relapsed/refractory MM who have received a proteasome inhibitor and immunomodulatory agent.

Conditioning consists of standard cyclophosphamide (300 mg/m2) and fludarabine (30 mg/m2) on days -5 to -3. Patients then receive a single dose of P-BCMA-101 on day 0.

The trial has a 3+3 dose-escalation design, with up to 6 dose levels. The first dose level is 0.75 x 106 P-BCMA-101 cells/kg.

The 3 patients who have received this dose had 6 to 9 prior therapies.

Patient 1

The first patient was a 54-year-old female with lambda light chain MM. She had t(11;14), del13q14, and 11q23(x3).

Before she received P-BCMA-101, the patient had an increase in free light chains (FLCs) to 3290 mg/L, which caused renal failure. She was treated with cyclophosphamide/prednisone and plasmapheresis bridging therapy before proceeding to P-BCMA-101.

The patient achieved a partial response 2 weeks after receiving P-BCMA-101, and this has persisted through week 12. She had a maximal reduction in urine M-protein of 92% and a reduction in plasma FLCs of 79%.

The patient did not experience any adverse events (AEs) considered related to P-BCMA-101.

Patient 2

The second patient was a 50-year-old female with oligosecretory kappa light chain MM and plasmacytomas. She had del17p (TP53) and 11q13(x3).

Due to enlarging plasmacytomas, the patient was treated with DT-PACE (dexamethasone plus thalidomide with cisplatin, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and etoposide) before receiving P-BCMA-101.

Her bone plasmacytomas resolved to below background within 4 to 8 weeks of P-BCMA-101 administration, but 1 new non-bone lesion appeared months later.

AEs considered at least possibly related to treatment in this patient included grade 2-4 neutropenia as well as grade 3-4 thrombocytopenia.

Patient 3

The third patient was a 65-year-old female with lambda light chain MM and del13q14.

Her urine M-protein and FLCs briefly dipped and rose after she received bridging therapy with lenalidomide and dexamethasone, but they decreased at 4 weeks after P-BCMA-101 administration, which corresponded with P-BCMA-101 expansion in the peripheral blood.

AEs considered at least possibly related to treatment included easy bruising (grade 1), fatigue (grade 2), febrile neutropenia (grade 3), hypogammaglobinemia (grade 2), neutropenia (grade 2-3), and thrombocytopenia (grade 3-4).

“The lack of cytokine release syndrome in any of the 3 patients, in spite of marked efficacy, is unprecedented at this dose, which we believe is attributable to multiple differentiated aspects of our technology, resulting in a highly purified CAR T product with a high percentage of cells with a T stem cell memory phenotype,” Dr Ostertag said.

In addition to a lack of CRS, there were no dose-limiting toxicities. Therefore, the dose has been escalated to 2 x 106 P-BCMA-101+ CAR T cells/kg for the next patient cohort. The first patient has been treated at this dose level, with no CRS yet reported.

About P-BCMA-101

P-BCMA-101 employs a B-cell maturation antigen-specific Centyrin™ fused to a second-generation CAR scaffold (a CARTyrin) rather than a single-chain variable fragment (scFv).

Centyrins have similar binding affinities as scFvs but are said to be potentially less immunogenic than scFvs, more stable at the cell surface, and resistant to antigen/ligand-independent tonic signaling.

P-BCMA-101 is engineered using PiggyBac™, a transposon-based system requiring only mRNA and plasmid DNA (no virus).

The increased cargo capacity of PiggyBac allows for the incorporation of a safety switch and a selectable gene. The safety switch can be activated to enable depletion in case AEs occur. And the selectable gene allows for enrichment of CAR+ cells.

CHICAGO—Early phase 1 results suggest a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy can induce tumor regression in heavily pretreated patients with multiple myeloma (MM).

The therapy, P-BCMA-101, has only been tested in 3 patients in the lowest dose cohort.

However, signs of efficacy have been seen in all 3 patients, including a lasting partial response in 1 patient.

There have been no dose-limiting toxicities, and none of the patients have developed cytokine release syndrome (CRS).

“The results from the first cohort of the phase 1 P-BCMA-101 study have surpassed historical benchmarks of safety and efficacy in multiple myeloma at this dose level and give us confidence to move ahead into additional dose cohorts,” said Eric Ostertag, MD, PhD, chief executive officer of Poseida Therapeutics, Inc.

Dr Ostertag and his colleagues presented these results at the AACR Annual Meeting 2018 (abstract CT130). The trial is sponsored by Poseida Therapeutics, Inc.

The trial is enrolling patients with relapsed/refractory MM who have received a proteasome inhibitor and immunomodulatory agent.

Conditioning consists of standard cyclophosphamide (300 mg/m2) and fludarabine (30 mg/m2) on days -5 to -3. Patients then receive a single dose of P-BCMA-101 on day 0.

The trial has a 3+3 dose-escalation design, with up to 6 dose levels. The first dose level is 0.75 x 106 P-BCMA-101 cells/kg.

The 3 patients who have received this dose had 6 to 9 prior therapies.

Patient 1

The first patient was a 54-year-old female with lambda light chain MM. She had t(11;14), del13q14, and 11q23(x3).

Before she received P-BCMA-101, the patient had an increase in free light chains (FLCs) to 3290 mg/L, which caused renal failure. She was treated with cyclophosphamide/prednisone and plasmapheresis bridging therapy before proceeding to P-BCMA-101.

The patient achieved a partial response 2 weeks after receiving P-BCMA-101, and this has persisted through week 12. She had a maximal reduction in urine M-protein of 92% and a reduction in plasma FLCs of 79%.

The patient did not experience any adverse events (AEs) considered related to P-BCMA-101.

Patient 2

The second patient was a 50-year-old female with oligosecretory kappa light chain MM and plasmacytomas. She had del17p (TP53) and 11q13(x3).

Due to enlarging plasmacytomas, the patient was treated with DT-PACE (dexamethasone plus thalidomide with cisplatin, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and etoposide) before receiving P-BCMA-101.

Her bone plasmacytomas resolved to below background within 4 to 8 weeks of P-BCMA-101 administration, but 1 new non-bone lesion appeared months later.

AEs considered at least possibly related to treatment in this patient included grade 2-4 neutropenia as well as grade 3-4 thrombocytopenia.

Patient 3

The third patient was a 65-year-old female with lambda light chain MM and del13q14.

Her urine M-protein and FLCs briefly dipped and rose after she received bridging therapy with lenalidomide and dexamethasone, but they decreased at 4 weeks after P-BCMA-101 administration, which corresponded with P-BCMA-101 expansion in the peripheral blood.

AEs considered at least possibly related to treatment included easy bruising (grade 1), fatigue (grade 2), febrile neutropenia (grade 3), hypogammaglobinemia (grade 2), neutropenia (grade 2-3), and thrombocytopenia (grade 3-4).

“The lack of cytokine release syndrome in any of the 3 patients, in spite of marked efficacy, is unprecedented at this dose, which we believe is attributable to multiple differentiated aspects of our technology, resulting in a highly purified CAR T product with a high percentage of cells with a T stem cell memory phenotype,” Dr Ostertag said.

In addition to a lack of CRS, there were no dose-limiting toxicities. Therefore, the dose has been escalated to 2 x 106 P-BCMA-101+ CAR T cells/kg for the next patient cohort. The first patient has been treated at this dose level, with no CRS yet reported.

About P-BCMA-101

P-BCMA-101 employs a B-cell maturation antigen-specific Centyrin™ fused to a second-generation CAR scaffold (a CARTyrin) rather than a single-chain variable fragment (scFv).

Centyrins have similar binding affinities as scFvs but are said to be potentially less immunogenic than scFvs, more stable at the cell surface, and resistant to antigen/ligand-independent tonic signaling.

P-BCMA-101 is engineered using PiggyBac™, a transposon-based system requiring only mRNA and plasmid DNA (no virus).

The increased cargo capacity of PiggyBac allows for the incorporation of a safety switch and a selectable gene. The safety switch can be activated to enable depletion in case AEs occur. And the selectable gene allows for enrichment of CAR+ cells.

BET inhibitor has lasting effects in AML, MM

CHICAGO—A BET inhibitor can have potent and long-lasting effects against leukemia and multiple myeloma (MM), according to researchers.

The inhibitor, TG-1601 (or CK-103), exhibited cytotoxicity in MM and leukemia cell lines but did not affect the growth of normal cell lines.

TG-1601 also reduced tumor volume in mouse models of MM and acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and drug holidays had little impact on this activity.

Furthermore, researchers observed enduring MYC inhibition in mice treated with TG-1601.

This research was presented at the AACR Annual Meeting 2018 (abstract 5790).

The work was conducted by researchers from TG Therapeutics and Checkpoint Therapeutics—the companies developing TG-1601—as well as Jubilant Biosys.

In vitro activity

Researchers assessed the cytotoxic activity of TG-1601 in leukemia, MM, and normal cell lines by incubating the cells with increasing concentrations of the drug for 72 hours.

The results suggested TG-1601 inhibits MM and leukemia cell growth, as all EC50 values were below 100 nM.

In the leukemia cell lines, EC50 values were 35 nM (Jurkat), 31 nM (HEL92.1.7), 24 nM (CCRF-CEM and MV4-11), and 18 nM (OCI-AML3).

In the MM cell lines, EC50 values were 85 nM (RPMI8226), 32 nM (KMS28PE), 24 nM (KMS28BM), 21 nM (MOLP8), and 15 nM (MM1s).

In the normal cell lines (Beas2B and WT9-12), cell growth wasn’t inhibited more than 50% with TG-1601 at 10 μM.

In vivo activity

For their MM model, researchers used mice inoculated with MM1 cells. The mice received TG-1601 at 10 mg/kg twice a day.

At day 17 after treatment initiation, there was a 70% reduction in tumor volume. During a week-long drug holiday, tumors did not grow back as fast in TG-1601-treated mice as they did in vehicle control mice.

For their AML model, researchers used mice inoculated with MV4-11 cells. The mice received TG-1601 as a single dose of 20 mg/kg/day—continuously or with 2, 3, or 4 days off per week—or at 10 mg/kg twice a day.

At day 15, 100% of mice that received the drug at 10 mg/kg twice a day were tumor-free. Mice that received the single 20 mg/kg dose had a 94% reduction in tumor volume.

The reduction in tumor volume was 91% in mice with the 2-day drug holiday, 78% in those with the 3-day holiday, and 82% in those with the 4-day holiday.

The researchers also found that TG-1601 had synergistic antitumor activity with an anti-PD-1 antibody in a mouse model of melanoma.

Pharmacodynamic activity

In the MV4-11 cell line, TG-1601 induced “rapid” downregulation of MYC and BCL2 and an increase of p21 mRNA, according to the researchers.

The team also assessed MYC expression in mice with MV4-11 tumors. They said MYC levels rapidly decreased in the tumors and were undetectable at 3 hours after a single dose of TG-1601.

The researchers noted that, at 24 hours after dosing, TG-1601 was cleared from the tumor. However, MYC levels remained below 40% their initial level.

The team said this suggests a long-lasting effect of TG-1601 that may be attributed to its enhanced binding affinity.

“These data demonstrate [TG-1601’s] potential to be a novel BET inhibitor that potently inhibits MYC expression,” said James F. Oliviero, president and chief executive officer of Checkpoint Therapeutics.

“We believe the preclinical data presented today provides encouraging evidence to support the development of [TG-1601] as an anticancer agent, alone and in combination with our anti-PD-L1 antibody, and look forward to the advancement of [TG-1601] into a first-in-human phase 1 trial expected to commence later this year.”

CHICAGO—A BET inhibitor can have potent and long-lasting effects against leukemia and multiple myeloma (MM), according to researchers.

The inhibitor, TG-1601 (or CK-103), exhibited cytotoxicity in MM and leukemia cell lines but did not affect the growth of normal cell lines.

TG-1601 also reduced tumor volume in mouse models of MM and acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and drug holidays had little impact on this activity.

Furthermore, researchers observed enduring MYC inhibition in mice treated with TG-1601.

This research was presented at the AACR Annual Meeting 2018 (abstract 5790).

The work was conducted by researchers from TG Therapeutics and Checkpoint Therapeutics—the companies developing TG-1601—as well as Jubilant Biosys.

In vitro activity

Researchers assessed the cytotoxic activity of TG-1601 in leukemia, MM, and normal cell lines by incubating the cells with increasing concentrations of the drug for 72 hours.

The results suggested TG-1601 inhibits MM and leukemia cell growth, as all EC50 values were below 100 nM.

In the leukemia cell lines, EC50 values were 35 nM (Jurkat), 31 nM (HEL92.1.7), 24 nM (CCRF-CEM and MV4-11), and 18 nM (OCI-AML3).

In the MM cell lines, EC50 values were 85 nM (RPMI8226), 32 nM (KMS28PE), 24 nM (KMS28BM), 21 nM (MOLP8), and 15 nM (MM1s).

In the normal cell lines (Beas2B and WT9-12), cell growth wasn’t inhibited more than 50% with TG-1601 at 10 μM.

In vivo activity

For their MM model, researchers used mice inoculated with MM1 cells. The mice received TG-1601 at 10 mg/kg twice a day.

At day 17 after treatment initiation, there was a 70% reduction in tumor volume. During a week-long drug holiday, tumors did not grow back as fast in TG-1601-treated mice as they did in vehicle control mice.

For their AML model, researchers used mice inoculated with MV4-11 cells. The mice received TG-1601 as a single dose of 20 mg/kg/day—continuously or with 2, 3, or 4 days off per week—or at 10 mg/kg twice a day.

At day 15, 100% of mice that received the drug at 10 mg/kg twice a day were tumor-free. Mice that received the single 20 mg/kg dose had a 94% reduction in tumor volume.

The reduction in tumor volume was 91% in mice with the 2-day drug holiday, 78% in those with the 3-day holiday, and 82% in those with the 4-day holiday.

The researchers also found that TG-1601 had synergistic antitumor activity with an anti-PD-1 antibody in a mouse model of melanoma.

Pharmacodynamic activity

In the MV4-11 cell line, TG-1601 induced “rapid” downregulation of MYC and BCL2 and an increase of p21 mRNA, according to the researchers.

The team also assessed MYC expression in mice with MV4-11 tumors. They said MYC levels rapidly decreased in the tumors and were undetectable at 3 hours after a single dose of TG-1601.

The researchers noted that, at 24 hours after dosing, TG-1601 was cleared from the tumor. However, MYC levels remained below 40% their initial level.

The team said this suggests a long-lasting effect of TG-1601 that may be attributed to its enhanced binding affinity.

“These data demonstrate [TG-1601’s] potential to be a novel BET inhibitor that potently inhibits MYC expression,” said James F. Oliviero, president and chief executive officer of Checkpoint Therapeutics.

“We believe the preclinical data presented today provides encouraging evidence to support the development of [TG-1601] as an anticancer agent, alone and in combination with our anti-PD-L1 antibody, and look forward to the advancement of [TG-1601] into a first-in-human phase 1 trial expected to commence later this year.”

CHICAGO—A BET inhibitor can have potent and long-lasting effects against leukemia and multiple myeloma (MM), according to researchers.

The inhibitor, TG-1601 (or CK-103), exhibited cytotoxicity in MM and leukemia cell lines but did not affect the growth of normal cell lines.

TG-1601 also reduced tumor volume in mouse models of MM and acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and drug holidays had little impact on this activity.

Furthermore, researchers observed enduring MYC inhibition in mice treated with TG-1601.

This research was presented at the AACR Annual Meeting 2018 (abstract 5790).

The work was conducted by researchers from TG Therapeutics and Checkpoint Therapeutics—the companies developing TG-1601—as well as Jubilant Biosys.

In vitro activity

Researchers assessed the cytotoxic activity of TG-1601 in leukemia, MM, and normal cell lines by incubating the cells with increasing concentrations of the drug for 72 hours.

The results suggested TG-1601 inhibits MM and leukemia cell growth, as all EC50 values were below 100 nM.

In the leukemia cell lines, EC50 values were 35 nM (Jurkat), 31 nM (HEL92.1.7), 24 nM (CCRF-CEM and MV4-11), and 18 nM (OCI-AML3).

In the MM cell lines, EC50 values were 85 nM (RPMI8226), 32 nM (KMS28PE), 24 nM (KMS28BM), 21 nM (MOLP8), and 15 nM (MM1s).

In the normal cell lines (Beas2B and WT9-12), cell growth wasn’t inhibited more than 50% with TG-1601 at 10 μM.

In vivo activity

For their MM model, researchers used mice inoculated with MM1 cells. The mice received TG-1601 at 10 mg/kg twice a day.

At day 17 after treatment initiation, there was a 70% reduction in tumor volume. During a week-long drug holiday, tumors did not grow back as fast in TG-1601-treated mice as they did in vehicle control mice.

For their AML model, researchers used mice inoculated with MV4-11 cells. The mice received TG-1601 as a single dose of 20 mg/kg/day—continuously or with 2, 3, or 4 days off per week—or at 10 mg/kg twice a day.

At day 15, 100% of mice that received the drug at 10 mg/kg twice a day were tumor-free. Mice that received the single 20 mg/kg dose had a 94% reduction in tumor volume.

The reduction in tumor volume was 91% in mice with the 2-day drug holiday, 78% in those with the 3-day holiday, and 82% in those with the 4-day holiday.

The researchers also found that TG-1601 had synergistic antitumor activity with an anti-PD-1 antibody in a mouse model of melanoma.

Pharmacodynamic activity

In the MV4-11 cell line, TG-1601 induced “rapid” downregulation of MYC and BCL2 and an increase of p21 mRNA, according to the researchers.

The team also assessed MYC expression in mice with MV4-11 tumors. They said MYC levels rapidly decreased in the tumors and were undetectable at 3 hours after a single dose of TG-1601.

The researchers noted that, at 24 hours after dosing, TG-1601 was cleared from the tumor. However, MYC levels remained below 40% their initial level.

The team said this suggests a long-lasting effect of TG-1601 that may be attributed to its enhanced binding affinity.

“These data demonstrate [TG-1601’s] potential to be a novel BET inhibitor that potently inhibits MYC expression,” said James F. Oliviero, president and chief executive officer of Checkpoint Therapeutics.

“We believe the preclinical data presented today provides encouraging evidence to support the development of [TG-1601] as an anticancer agent, alone and in combination with our anti-PD-L1 antibody, and look forward to the advancement of [TG-1601] into a first-in-human phase 1 trial expected to commence later this year.”

Ibrutinib plus carfilzomib active in relapsed multiple myeloma

In patients with multiple myeloma who had already undergone multiple lines of therapy, the combination of ibrutinib and carfilzomib with or without dexamethasone produced a favorable rate of response and progression-free survival.

Ibrutinib and carfilzomib combination therapy was also associated with manageable safety in the phase 1 results of the ongoing study, investigators wrote in the journal Leukemia & Lymphoma.

The reported overall response rate in the study was 67%. Median progression-free survival was 7.2 months, which was “encouraging considering the poor outcomes often observed in this group,” Dr. Chari and colleagues wrote.

Carfilzomib, a selective and irreversible proteasome inhibitor, is indicated for patients with previously treated multiple myeloma. Ibrutinib, an orally administered covalent inhibitor of Bruton tyrosine kinase, already has Food and Drug Administration approval for treatment of several B-cell malignancies. Bruton tyrosine kinase is expressed in more than 85% of myeloma tumor cells, according to the researchers, and its signaling may contribute to development of drug resistance.

In an earlier phase 2 study, ibrutinib plus dexamethasone produced a 28% clinical benefit rate and median progression-free survival of 4.6 months. Preclinical data suggest combining ibrutinib and carfilzomib may have a synergistic effect, according to researchers.

To test that hypothesis, Dr. Chari and colleagues conducted a phase 1 dose-finding study including 43 myeloma patients who had previously received at least two lines of therapy, including bortezomib and an immunomodulatory agent. Among those patients, about three-quarters were refractory to bortezomib and one-quarter had high-risk cytogenetics.

A total of 35 patients in the study received ibrutinib and carfilzomib plus dexamethasone; 8 patients received only ibrutinib and carfilzomib.

Key phase 1 results included the 67% response rate, of which 21% had very good partial response and 2% had stringent complete response. No dose-limiting toxicities were observed.

Both carfilzomib and ibrutinib have known cardiac toxicities, but cardiac adverse events in this study did not reach dose-limiting toxicity criteria and were effectively managed by dose reductions or rechallenge, researchers reported.

Hypertension, anemia, pneumonia, fatigue, diarrhea, and thrombocytopenia were the most common grade 3 events observed. “Ultimately, toxicities and/or treatment discontinuations could be attributed to comorbidities, underlying disease factors, or toxicities due to prior therapies,” the researchers wrote.

Enrollment in phase 2b of the study is ongoing.

Dr. Chari received research funding from Pharmacyclics during the study and grants from other companies outside of the study work.

SOURCE: Chari A et al. Leuk Lymphoma. 2018 Apr 4. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2018.1443337.

In patients with multiple myeloma who had already undergone multiple lines of therapy, the combination of ibrutinib and carfilzomib with or without dexamethasone produced a favorable rate of response and progression-free survival.

Ibrutinib and carfilzomib combination therapy was also associated with manageable safety in the phase 1 results of the ongoing study, investigators wrote in the journal Leukemia & Lymphoma.

The reported overall response rate in the study was 67%. Median progression-free survival was 7.2 months, which was “encouraging considering the poor outcomes often observed in this group,” Dr. Chari and colleagues wrote.

Carfilzomib, a selective and irreversible proteasome inhibitor, is indicated for patients with previously treated multiple myeloma. Ibrutinib, an orally administered covalent inhibitor of Bruton tyrosine kinase, already has Food and Drug Administration approval for treatment of several B-cell malignancies. Bruton tyrosine kinase is expressed in more than 85% of myeloma tumor cells, according to the researchers, and its signaling may contribute to development of drug resistance.

In an earlier phase 2 study, ibrutinib plus dexamethasone produced a 28% clinical benefit rate and median progression-free survival of 4.6 months. Preclinical data suggest combining ibrutinib and carfilzomib may have a synergistic effect, according to researchers.

To test that hypothesis, Dr. Chari and colleagues conducted a phase 1 dose-finding study including 43 myeloma patients who had previously received at least two lines of therapy, including bortezomib and an immunomodulatory agent. Among those patients, about three-quarters were refractory to bortezomib and one-quarter had high-risk cytogenetics.

A total of 35 patients in the study received ibrutinib and carfilzomib plus dexamethasone; 8 patients received only ibrutinib and carfilzomib.

Key phase 1 results included the 67% response rate, of which 21% had very good partial response and 2% had stringent complete response. No dose-limiting toxicities were observed.

Both carfilzomib and ibrutinib have known cardiac toxicities, but cardiac adverse events in this study did not reach dose-limiting toxicity criteria and were effectively managed by dose reductions or rechallenge, researchers reported.

Hypertension, anemia, pneumonia, fatigue, diarrhea, and thrombocytopenia were the most common grade 3 events observed. “Ultimately, toxicities and/or treatment discontinuations could be attributed to comorbidities, underlying disease factors, or toxicities due to prior therapies,” the researchers wrote.

Enrollment in phase 2b of the study is ongoing.

Dr. Chari received research funding from Pharmacyclics during the study and grants from other companies outside of the study work.

SOURCE: Chari A et al. Leuk Lymphoma. 2018 Apr 4. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2018.1443337.

In patients with multiple myeloma who had already undergone multiple lines of therapy, the combination of ibrutinib and carfilzomib with or without dexamethasone produced a favorable rate of response and progression-free survival.

Ibrutinib and carfilzomib combination therapy was also associated with manageable safety in the phase 1 results of the ongoing study, investigators wrote in the journal Leukemia & Lymphoma.

The reported overall response rate in the study was 67%. Median progression-free survival was 7.2 months, which was “encouraging considering the poor outcomes often observed in this group,” Dr. Chari and colleagues wrote.

Carfilzomib, a selective and irreversible proteasome inhibitor, is indicated for patients with previously treated multiple myeloma. Ibrutinib, an orally administered covalent inhibitor of Bruton tyrosine kinase, already has Food and Drug Administration approval for treatment of several B-cell malignancies. Bruton tyrosine kinase is expressed in more than 85% of myeloma tumor cells, according to the researchers, and its signaling may contribute to development of drug resistance.

In an earlier phase 2 study, ibrutinib plus dexamethasone produced a 28% clinical benefit rate and median progression-free survival of 4.6 months. Preclinical data suggest combining ibrutinib and carfilzomib may have a synergistic effect, according to researchers.

To test that hypothesis, Dr. Chari and colleagues conducted a phase 1 dose-finding study including 43 myeloma patients who had previously received at least two lines of therapy, including bortezomib and an immunomodulatory agent. Among those patients, about three-quarters were refractory to bortezomib and one-quarter had high-risk cytogenetics.

A total of 35 patients in the study received ibrutinib and carfilzomib plus dexamethasone; 8 patients received only ibrutinib and carfilzomib.

Key phase 1 results included the 67% response rate, of which 21% had very good partial response and 2% had stringent complete response. No dose-limiting toxicities were observed.

Both carfilzomib and ibrutinib have known cardiac toxicities, but cardiac adverse events in this study did not reach dose-limiting toxicity criteria and were effectively managed by dose reductions or rechallenge, researchers reported.

Hypertension, anemia, pneumonia, fatigue, diarrhea, and thrombocytopenia were the most common grade 3 events observed. “Ultimately, toxicities and/or treatment discontinuations could be attributed to comorbidities, underlying disease factors, or toxicities due to prior therapies,” the researchers wrote.

Enrollment in phase 2b of the study is ongoing.

Dr. Chari received research funding from Pharmacyclics during the study and grants from other companies outside of the study work.

SOURCE: Chari A et al. Leuk Lymphoma. 2018 Apr 4. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2018.1443337.

FROM LEUKEMIA & LYMPHOMA

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The overall response rate was 67%, including a 21% very good partial response and 2% stringent complete response.

Study details: A phase 1 dose-finding study including 43 myeloma patients who had previously received at least two lines of therapy.

Disclosures: Dr. Chari received research funding from Pharmacyclics during the study and grants from other companies outside of the study work.

Source: Chari A et al. Leuk Lymphoma. 2018 Apr 4. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2018.1443337.

Generic melphalan available in US

Fresenius Kabi’s Melphalan Hydrochloride for Injection, a generic version of Alkeran®, is now available in the US.

Melphalan Hydrochloride for Injection is available as a 2-vial kit containing 1 single-dose vial of melphalan hydrochloride equivalent to 50 mg of melphalan and 1 vial of sterile diluent.

Melphalan Hydrochloride for Injection is indicated for the palliative treatment of patients with multiple myeloma for whom oral therapy is not appropriate.

For more details on Melphalan Hydrochloride for Injection, see the full prescribing information.

Fresenius Kabi’s Melphalan Hydrochloride for Injection, a generic version of Alkeran®, is now available in the US.

Melphalan Hydrochloride for Injection is available as a 2-vial kit containing 1 single-dose vial of melphalan hydrochloride equivalent to 50 mg of melphalan and 1 vial of sterile diluent.

Melphalan Hydrochloride for Injection is indicated for the palliative treatment of patients with multiple myeloma for whom oral therapy is not appropriate.

For more details on Melphalan Hydrochloride for Injection, see the full prescribing information.

Fresenius Kabi’s Melphalan Hydrochloride for Injection, a generic version of Alkeran®, is now available in the US.

Melphalan Hydrochloride for Injection is available as a 2-vial kit containing 1 single-dose vial of melphalan hydrochloride equivalent to 50 mg of melphalan and 1 vial of sterile diluent.

Melphalan Hydrochloride for Injection is indicated for the palliative treatment of patients with multiple myeloma for whom oral therapy is not appropriate.

For more details on Melphalan Hydrochloride for Injection, see the full prescribing information.

Group identifies novel genes involved in MM development

Researchers have identified novel genes involved in the development of multiple myeloma (MM), according to a paper published in Leukemia.

The team’s analyses revealed regions of coding and non-coding DNA that appear to drive MM development.

The researchers analyzed whole-exome sequencing data from 804 MM patients and whole-genome sequencing data from 765 MM patients.

This revealed 16 novel genes that were disrupted in coding regions of DNA and 15 novel genes disrupted in non-coding regions.

There were 5 genes disrupted by structural variants in coding regions—CD96, PRDM1, FBXW7, MAP3K14, and CCND2.

There were also 11 genes disrupted by single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and indels in coding regions—BAX, C8orf86, FAM154B, FTL, HIST1H4H, LEMD2, PABPC1, RPN1, RPS3A, SGPP1, and TBC1D29.

Among the novel genes disrupted by mutations in non-coding regions was NBPF1, a promoter disrupted by SNVs. The researchers noted that NBPF1 is directly regulated by NF-κB, and the NF-κB pathway is recurrently affected in MM.

The team also identified 7 cis-regulatory elements (CREs) disrupted by SNVs—CALCB, COBLL1, HOXB3, ST6GAL1, PAX5, ATP13A2, and TPRG1.

The researchers said the SNVs in PAX5 and HOXB3 reduced gene expression, suggesting PAX5 and HOXB3 function as tumor suppressors in MM. On the other hand, the SNVs in ST6GAL1 increased gene expression, which may contribute to the aberrant immunoglobulin-G glycosylation seen in MM.

Finally, there were 7 CREs disrupted by copy number variations—MYC, PLD4, KDM3B, SP110, RAB36, PACS2, and TEX22.

The researchers noted that, with the exception of MYC, these genes reside close to regions of common structural variation, so their relevance in MM is not clear.

The team also said it’s well known that MYC is upregulated in MM through gene amplification or translocation, but this research shows that MYC can be dysregulated by alternative mechanisms.

“We need smarter, kinder treatments for myeloma that are more tailored to each person’s cancer,” said study author Richard Houlston, MD, PhD, of The Institute of Cancer Research in London, UK.

“Exhaustive genetic research like this is helping us to make that possible. Our findings should now open up new avenues for discovering treatments that target the genes driving myeloma.”

Researchers have identified novel genes involved in the development of multiple myeloma (MM), according to a paper published in Leukemia.

The team’s analyses revealed regions of coding and non-coding DNA that appear to drive MM development.

The researchers analyzed whole-exome sequencing data from 804 MM patients and whole-genome sequencing data from 765 MM patients.

This revealed 16 novel genes that were disrupted in coding regions of DNA and 15 novel genes disrupted in non-coding regions.

There were 5 genes disrupted by structural variants in coding regions—CD96, PRDM1, FBXW7, MAP3K14, and CCND2.

There were also 11 genes disrupted by single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and indels in coding regions—BAX, C8orf86, FAM154B, FTL, HIST1H4H, LEMD2, PABPC1, RPN1, RPS3A, SGPP1, and TBC1D29.

Among the novel genes disrupted by mutations in non-coding regions was NBPF1, a promoter disrupted by SNVs. The researchers noted that NBPF1 is directly regulated by NF-κB, and the NF-κB pathway is recurrently affected in MM.

The team also identified 7 cis-regulatory elements (CREs) disrupted by SNVs—CALCB, COBLL1, HOXB3, ST6GAL1, PAX5, ATP13A2, and TPRG1.

The researchers said the SNVs in PAX5 and HOXB3 reduced gene expression, suggesting PAX5 and HOXB3 function as tumor suppressors in MM. On the other hand, the SNVs in ST6GAL1 increased gene expression, which may contribute to the aberrant immunoglobulin-G glycosylation seen in MM.

Finally, there were 7 CREs disrupted by copy number variations—MYC, PLD4, KDM3B, SP110, RAB36, PACS2, and TEX22.

The researchers noted that, with the exception of MYC, these genes reside close to regions of common structural variation, so their relevance in MM is not clear.

The team also said it’s well known that MYC is upregulated in MM through gene amplification or translocation, but this research shows that MYC can be dysregulated by alternative mechanisms.

“We need smarter, kinder treatments for myeloma that are more tailored to each person’s cancer,” said study author Richard Houlston, MD, PhD, of The Institute of Cancer Research in London, UK.

“Exhaustive genetic research like this is helping us to make that possible. Our findings should now open up new avenues for discovering treatments that target the genes driving myeloma.”

Researchers have identified novel genes involved in the development of multiple myeloma (MM), according to a paper published in Leukemia.

The team’s analyses revealed regions of coding and non-coding DNA that appear to drive MM development.

The researchers analyzed whole-exome sequencing data from 804 MM patients and whole-genome sequencing data from 765 MM patients.

This revealed 16 novel genes that were disrupted in coding regions of DNA and 15 novel genes disrupted in non-coding regions.

There were 5 genes disrupted by structural variants in coding regions—CD96, PRDM1, FBXW7, MAP3K14, and CCND2.

There were also 11 genes disrupted by single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and indels in coding regions—BAX, C8orf86, FAM154B, FTL, HIST1H4H, LEMD2, PABPC1, RPN1, RPS3A, SGPP1, and TBC1D29.

Among the novel genes disrupted by mutations in non-coding regions was NBPF1, a promoter disrupted by SNVs. The researchers noted that NBPF1 is directly regulated by NF-κB, and the NF-κB pathway is recurrently affected in MM.

The team also identified 7 cis-regulatory elements (CREs) disrupted by SNVs—CALCB, COBLL1, HOXB3, ST6GAL1, PAX5, ATP13A2, and TPRG1.

The researchers said the SNVs in PAX5 and HOXB3 reduced gene expression, suggesting PAX5 and HOXB3 function as tumor suppressors in MM. On the other hand, the SNVs in ST6GAL1 increased gene expression, which may contribute to the aberrant immunoglobulin-G glycosylation seen in MM.

Finally, there were 7 CREs disrupted by copy number variations—MYC, PLD4, KDM3B, SP110, RAB36, PACS2, and TEX22.

The researchers noted that, with the exception of MYC, these genes reside close to regions of common structural variation, so their relevance in MM is not clear.

The team also said it’s well known that MYC is upregulated in MM through gene amplification or translocation, but this research shows that MYC can be dysregulated by alternative mechanisms.

“We need smarter, kinder treatments for myeloma that are more tailored to each person’s cancer,” said study author Richard Houlston, MD, PhD, of The Institute of Cancer Research in London, UK.

“Exhaustive genetic research like this is helping us to make that possible. Our findings should now open up new avenues for discovering treatments that target the genes driving myeloma.”

Generic antiemetic now available in US

Palonosetron Hydrochloride Injection, a generic alternative to Aloxi®, is now available in the US.

Fresenius Kabi’s Palonosetron Hydrochloride Injection is a 5-HT3 serotonin receptor that is approved for the prevention of nausea and vomiting in certain adults.

Palonosetron Hydrochloride Injection is available in a single-dose vial (0.25 mg per 5 mL).

In the US, Palonosetron Hydrochloride Injection is approved for the prevention of acute and delayed nausea and vomiting associated with initial and repeat courses of moderately emetogenic cancer chemotherapy.

The drug is also approved for the prevention of acute nausea and vomiting associated with initial and repeat courses of highly emetogenic cancer chemotherapy.

And Palonosetron Hydrochloride Injection is approved for the prevention of post-operative nausea and vomiting for up to 24 hours after surgery. Efficacy beyond 24 hours has not been demonstrated.

The full prescribing information for Palonosetron Hydrochloride Injection can be found on the Fresenius Kabi website.

Palonosetron Hydrochloride Injection, a generic alternative to Aloxi®, is now available in the US.

Fresenius Kabi’s Palonosetron Hydrochloride Injection is a 5-HT3 serotonin receptor that is approved for the prevention of nausea and vomiting in certain adults.

Palonosetron Hydrochloride Injection is available in a single-dose vial (0.25 mg per 5 mL).

In the US, Palonosetron Hydrochloride Injection is approved for the prevention of acute and delayed nausea and vomiting associated with initial and repeat courses of moderately emetogenic cancer chemotherapy.

The drug is also approved for the prevention of acute nausea and vomiting associated with initial and repeat courses of highly emetogenic cancer chemotherapy.

And Palonosetron Hydrochloride Injection is approved for the prevention of post-operative nausea and vomiting for up to 24 hours after surgery. Efficacy beyond 24 hours has not been demonstrated.

The full prescribing information for Palonosetron Hydrochloride Injection can be found on the Fresenius Kabi website.

Palonosetron Hydrochloride Injection, a generic alternative to Aloxi®, is now available in the US.

Fresenius Kabi’s Palonosetron Hydrochloride Injection is a 5-HT3 serotonin receptor that is approved for the prevention of nausea and vomiting in certain adults.

Palonosetron Hydrochloride Injection is available in a single-dose vial (0.25 mg per 5 mL).

In the US, Palonosetron Hydrochloride Injection is approved for the prevention of acute and delayed nausea and vomiting associated with initial and repeat courses of moderately emetogenic cancer chemotherapy.

The drug is also approved for the prevention of acute nausea and vomiting associated with initial and repeat courses of highly emetogenic cancer chemotherapy.

And Palonosetron Hydrochloride Injection is approved for the prevention of post-operative nausea and vomiting for up to 24 hours after surgery. Efficacy beyond 24 hours has not been demonstrated.

The full prescribing information for Palonosetron Hydrochloride Injection can be found on the Fresenius Kabi website.

Selinexor receives fast track designation for MM

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to selinexor for the treatment of patients with penta-refractory multiple myeloma (MM).

The patients must have received at least 3 prior lines of therapy that included an alkylating agent, a glucocorticoid, bortezomib, carfilzomib, lenalidomide, pomalidomide, and daratumumab.

In addition, the patients must have disease that is refractory to at least 1 proteasome inhibitor, at least 1 immunomodulatory agent, glucocorticoids, daratumumab, and the patients’ most recent therapy.

“The designation of fast track for selinexor represents important recognition by the FDA of the potential of this anticancer agent to address the significant unmet need in the treatment of patients with penta-refractory myeloma that has continued to progress despite available therapies,” said Sharon Shacham, PhD, founder, president, and chief scientific officer of Karyopharm Therapeutics Inc., the company developing selinexor.

The FDA’s fast track drug development program is designed to expedite clinical development and submission of new drug applications for medicines with the potential to treat serious or life-threatening conditions and address unmet medical needs.

Fast track designation facilitates frequent interactions with the FDA review team, including meetings to discuss all aspects of development to support a drug’s approval, and also provides the opportunity to submit sections of a new drug application on a rolling basis as data become available.

About selinexor

Selinexor (formerly KPT-330) is a first-in-class, oral selective inhibitor of nuclear export compound.

Selinexor functions by binding with and inhibiting the nuclear export protein XPO1 (also called CRM1), leading to the accumulation of tumor suppressor proteins in the cell nucleus. This reinitiates and amplifies their tumor suppressor function and is believed to lead to apoptosis in cancer cells while largely sparing normal cells.

Selinexor is currently being evaluated in several clinical trials across multiple cancer indications.

In the phase 2 STORM trial, researchers are testing selinexor in combination with low-dose dexamethasone for patients with penta-refractory MM. Karyopharm Therapeutics plans to report top-line data from this study at the end of this month.

Trials of selinexor were placed on partial clinical hold in mid-March last year due to a lack of information about serious adverse events. However, the hold was lifted for trials of patients with hematologic malignancies at the end of that same month.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to selinexor for the treatment of patients with penta-refractory multiple myeloma (MM).

The patients must have received at least 3 prior lines of therapy that included an alkylating agent, a glucocorticoid, bortezomib, carfilzomib, lenalidomide, pomalidomide, and daratumumab.

In addition, the patients must have disease that is refractory to at least 1 proteasome inhibitor, at least 1 immunomodulatory agent, glucocorticoids, daratumumab, and the patients’ most recent therapy.

“The designation of fast track for selinexor represents important recognition by the FDA of the potential of this anticancer agent to address the significant unmet need in the treatment of patients with penta-refractory myeloma that has continued to progress despite available therapies,” said Sharon Shacham, PhD, founder, president, and chief scientific officer of Karyopharm Therapeutics Inc., the company developing selinexor.

The FDA’s fast track drug development program is designed to expedite clinical development and submission of new drug applications for medicines with the potential to treat serious or life-threatening conditions and address unmet medical needs.

Fast track designation facilitates frequent interactions with the FDA review team, including meetings to discuss all aspects of development to support a drug’s approval, and also provides the opportunity to submit sections of a new drug application on a rolling basis as data become available.

About selinexor

Selinexor (formerly KPT-330) is a first-in-class, oral selective inhibitor of nuclear export compound.

Selinexor functions by binding with and inhibiting the nuclear export protein XPO1 (also called CRM1), leading to the accumulation of tumor suppressor proteins in the cell nucleus. This reinitiates and amplifies their tumor suppressor function and is believed to lead to apoptosis in cancer cells while largely sparing normal cells.

Selinexor is currently being evaluated in several clinical trials across multiple cancer indications.

In the phase 2 STORM trial, researchers are testing selinexor in combination with low-dose dexamethasone for patients with penta-refractory MM. Karyopharm Therapeutics plans to report top-line data from this study at the end of this month.

Trials of selinexor were placed on partial clinical hold in mid-March last year due to a lack of information about serious adverse events. However, the hold was lifted for trials of patients with hematologic malignancies at the end of that same month.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to selinexor for the treatment of patients with penta-refractory multiple myeloma (MM).

The patients must have received at least 3 prior lines of therapy that included an alkylating agent, a glucocorticoid, bortezomib, carfilzomib, lenalidomide, pomalidomide, and daratumumab.

In addition, the patients must have disease that is refractory to at least 1 proteasome inhibitor, at least 1 immunomodulatory agent, glucocorticoids, daratumumab, and the patients’ most recent therapy.

“The designation of fast track for selinexor represents important recognition by the FDA of the potential of this anticancer agent to address the significant unmet need in the treatment of patients with penta-refractory myeloma that has continued to progress despite available therapies,” said Sharon Shacham, PhD, founder, president, and chief scientific officer of Karyopharm Therapeutics Inc., the company developing selinexor.

The FDA’s fast track drug development program is designed to expedite clinical development and submission of new drug applications for medicines with the potential to treat serious or life-threatening conditions and address unmet medical needs.

Fast track designation facilitates frequent interactions with the FDA review team, including meetings to discuss all aspects of development to support a drug’s approval, and also provides the opportunity to submit sections of a new drug application on a rolling basis as data become available.

About selinexor

Selinexor (formerly KPT-330) is a first-in-class, oral selective inhibitor of nuclear export compound.

Selinexor functions by binding with and inhibiting the nuclear export protein XPO1 (also called CRM1), leading to the accumulation of tumor suppressor proteins in the cell nucleus. This reinitiates and amplifies their tumor suppressor function and is believed to lead to apoptosis in cancer cells while largely sparing normal cells.

Selinexor is currently being evaluated in several clinical trials across multiple cancer indications.

In the phase 2 STORM trial, researchers are testing selinexor in combination with low-dose dexamethasone for patients with penta-refractory MM. Karyopharm Therapeutics plans to report top-line data from this study at the end of this month.

Trials of selinexor were placed on partial clinical hold in mid-March last year due to a lack of information about serious adverse events. However, the hold was lifted for trials of patients with hematologic malignancies at the end of that same month.

Age and race affect access to myeloma treatment

Older patients, African Americans, and individuals of low socioeconomic status may be less likely to receive systemic treatment for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, results of a recent study suggest.

Comorbidities and poor performance indicators also reduced the likelihood of receiving first-line treatment, according to results of the retrospective cohort study published in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia.

The findings highlight the need for a “multifaceted approach” to address outcome disparities in multiple myeloma, according to researcher Bita Fakhri, MD, MPH, of the division of oncology at Washington University, St. Louis, and her coinvestigators.

“Particular attention to aging-related issues is essential to ensure older patients will benefit from the advances achieved in the field, similar to young patients,” the investigators wrote.

Racial and socioeconomic barriers should also be addressed, they added.

The retrospective cohort analysis included data on 3,814 patients with active multiple myeloma in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results–Medicare database from 2007 to 2011. Investigators found that overall, 1,445 patients (38%) had no insurance claims confirming that they had received systemic treatment.

Older age increased the odds of not receiving treatment, with the likelihood increasing by 7% for each year of advancing age (adjusted odds ratio, 1.07; 95% confidence interval, 1.06-1.08). Likewise, African American patients were 26% more likely to have had no treatment (aOR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.03-1.54), and patients who were enrolled in both Medicaid and Medicare – a proxy for lower income – had a 21% increased odds of no treatment (aOR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.02-1.42).

Similarly increased odds of no treatment were reported for patients with comorbidities and poor performance status indicators.

“In a subset of older and frail patients, the risks of treatments approved for [multiple myeloma] might outweigh the benefits or might not be in line with the individual’s goals of care,” the investigators wrote.

The study did not track supportive-care treatments that patients may have received instead of active disease treatment, such as bisphosphonates for skeletal lesions or plasmapheresis for hyperviscosity syndrome.

Lack of treatment was associated with poorer survival in the study. Median overall survival was just 9.6 months for individuals with no record of treatment, compared with 32.3 months for patients who had received treatment.

Dr. Fakhri and coauthors reported having no financial disclosures related to the study, which was supported by the National Cancer Institute.

SOURCE: Fakhri B et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018 Mar;18(3):219-24.

Older patients, African Americans, and individuals of low socioeconomic status may be less likely to receive systemic treatment for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, results of a recent study suggest.

Comorbidities and poor performance indicators also reduced the likelihood of receiving first-line treatment, according to results of the retrospective cohort study published in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia.

The findings highlight the need for a “multifaceted approach” to address outcome disparities in multiple myeloma, according to researcher Bita Fakhri, MD, MPH, of the division of oncology at Washington University, St. Louis, and her coinvestigators.

“Particular attention to aging-related issues is essential to ensure older patients will benefit from the advances achieved in the field, similar to young patients,” the investigators wrote.

Racial and socioeconomic barriers should also be addressed, they added.

The retrospective cohort analysis included data on 3,814 patients with active multiple myeloma in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results–Medicare database from 2007 to 2011. Investigators found that overall, 1,445 patients (38%) had no insurance claims confirming that they had received systemic treatment.

Older age increased the odds of not receiving treatment, with the likelihood increasing by 7% for each year of advancing age (adjusted odds ratio, 1.07; 95% confidence interval, 1.06-1.08). Likewise, African American patients were 26% more likely to have had no treatment (aOR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.03-1.54), and patients who were enrolled in both Medicaid and Medicare – a proxy for lower income – had a 21% increased odds of no treatment (aOR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.02-1.42).

Similarly increased odds of no treatment were reported for patients with comorbidities and poor performance status indicators.

“In a subset of older and frail patients, the risks of treatments approved for [multiple myeloma] might outweigh the benefits or might not be in line with the individual’s goals of care,” the investigators wrote.

The study did not track supportive-care treatments that patients may have received instead of active disease treatment, such as bisphosphonates for skeletal lesions or plasmapheresis for hyperviscosity syndrome.

Lack of treatment was associated with poorer survival in the study. Median overall survival was just 9.6 months for individuals with no record of treatment, compared with 32.3 months for patients who had received treatment.

Dr. Fakhri and coauthors reported having no financial disclosures related to the study, which was supported by the National Cancer Institute.

SOURCE: Fakhri B et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018 Mar;18(3):219-24.

Older patients, African Americans, and individuals of low socioeconomic status may be less likely to receive systemic treatment for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, results of a recent study suggest.

Comorbidities and poor performance indicators also reduced the likelihood of receiving first-line treatment, according to results of the retrospective cohort study published in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia.

The findings highlight the need for a “multifaceted approach” to address outcome disparities in multiple myeloma, according to researcher Bita Fakhri, MD, MPH, of the division of oncology at Washington University, St. Louis, and her coinvestigators.

“Particular attention to aging-related issues is essential to ensure older patients will benefit from the advances achieved in the field, similar to young patients,” the investigators wrote.

Racial and socioeconomic barriers should also be addressed, they added.

The retrospective cohort analysis included data on 3,814 patients with active multiple myeloma in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results–Medicare database from 2007 to 2011. Investigators found that overall, 1,445 patients (38%) had no insurance claims confirming that they had received systemic treatment.

Older age increased the odds of not receiving treatment, with the likelihood increasing by 7% for each year of advancing age (adjusted odds ratio, 1.07; 95% confidence interval, 1.06-1.08). Likewise, African American patients were 26% more likely to have had no treatment (aOR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.03-1.54), and patients who were enrolled in both Medicaid and Medicare – a proxy for lower income – had a 21% increased odds of no treatment (aOR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.02-1.42).

Similarly increased odds of no treatment were reported for patients with comorbidities and poor performance status indicators.

“In a subset of older and frail patients, the risks of treatments approved for [multiple myeloma] might outweigh the benefits or might not be in line with the individual’s goals of care,” the investigators wrote.

The study did not track supportive-care treatments that patients may have received instead of active disease treatment, such as bisphosphonates for skeletal lesions or plasmapheresis for hyperviscosity syndrome.

Lack of treatment was associated with poorer survival in the study. Median overall survival was just 9.6 months for individuals with no record of treatment, compared with 32.3 months for patients who had received treatment.

Dr. Fakhri and coauthors reported having no financial disclosures related to the study, which was supported by the National Cancer Institute.

SOURCE: Fakhri B et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018 Mar;18(3):219-24.

FROM CLINICAL LYMPHOMA, MYELOMA & LEUKEMIA

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Factors significantly associated with no systemic treatment included older age (adjusted odds ratio, 1.07 per year), African American descent (aOR, 1.26), and dual Medicare-Medicaid enrollment (aOR, 1.21).

Study details: A retrospective cohort analysis including data on 3,814 patients with active multiple myeloma in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results–Medicare database from 2007 to 2011.

Disclosures: The research was supported by the National Cancer Institute. The investigators reported having no financial disclosures.

Source: Fakhri B et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. Mar 2018;18(3):219-24.

Screening may reduce prevalence of MM

Targeted screening could potentially reduce the prevalence of multiple myeloma (MM), according to research published in JCO Clinical Cancer Informatics.

Researchers found that screening for monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) might reduce the risk of MM in individuals with a high lifetime risk of MGUS, which includes men, African Americans, and people with a family history of MM.

The researchers said patients who screen positive for MGUS could seek medical care early and try strategies such as aspirin, metformin, or weight reduction to potentially reduce their risk of progression from MGUS to MM.

However, additional studies are needed to confirm the effectiveness of aspirin, metformin, and weight-loss strategies in preventing MGUS progression.

“Screening for MGUS may have significant benefits by lowering the incidence of multiple myeloma, provided that effective and non-toxic interventions can be identified,” said study author Philipp Altrock, PhD, of Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Florida.

Dr Altrock and his colleagues performed a series of computational modeling experiments to determine the best screening strategies in different groups of patients. The goal was to determine when screening should begin, how often it should occur, and in which individuals it could be most effective.

The researchers designed their model to predict the progression of MGUS to MM, the changes in MGUS and MM prevalence, and the annual follow-up mortality due to disease.

The team found evidence to suggest that screening strategies could reduce the risk of progression and the prevalence of MM. This effect was more pronounced in individuals who had a higher risk of MGUS.

Modeling suggested the prevalence of MM could be reduced by 19% in patients who begin screening at age 55 and have follow-up screening every 6 years.

A similar reduction in prevalence could also be achieved by starting screening at age 65 and following up every 2 years.

“Regular screening of MGUS candidates should start as early as possible, with biannual follow-up, and focus on high-risk individuals, especially with a family history of multiple myeloma or in groups with a strong indication of MGUS progression,” Dr Altrock said.

Targeted screening could potentially reduce the prevalence of multiple myeloma (MM), according to research published in JCO Clinical Cancer Informatics.

Researchers found that screening for monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) might reduce the risk of MM in individuals with a high lifetime risk of MGUS, which includes men, African Americans, and people with a family history of MM.

The researchers said patients who screen positive for MGUS could seek medical care early and try strategies such as aspirin, metformin, or weight reduction to potentially reduce their risk of progression from MGUS to MM.

However, additional studies are needed to confirm the effectiveness of aspirin, metformin, and weight-loss strategies in preventing MGUS progression.

“Screening for MGUS may have significant benefits by lowering the incidence of multiple myeloma, provided that effective and non-toxic interventions can be identified,” said study author Philipp Altrock, PhD, of Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Florida.

Dr Altrock and his colleagues performed a series of computational modeling experiments to determine the best screening strategies in different groups of patients. The goal was to determine when screening should begin, how often it should occur, and in which individuals it could be most effective.

The researchers designed their model to predict the progression of MGUS to MM, the changes in MGUS and MM prevalence, and the annual follow-up mortality due to disease.

The team found evidence to suggest that screening strategies could reduce the risk of progression and the prevalence of MM. This effect was more pronounced in individuals who had a higher risk of MGUS.

Modeling suggested the prevalence of MM could be reduced by 19% in patients who begin screening at age 55 and have follow-up screening every 6 years.

A similar reduction in prevalence could also be achieved by starting screening at age 65 and following up every 2 years.

“Regular screening of MGUS candidates should start as early as possible, with biannual follow-up, and focus on high-risk individuals, especially with a family history of multiple myeloma or in groups with a strong indication of MGUS progression,” Dr Altrock said.

Targeted screening could potentially reduce the prevalence of multiple myeloma (MM), according to research published in JCO Clinical Cancer Informatics.

Researchers found that screening for monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) might reduce the risk of MM in individuals with a high lifetime risk of MGUS, which includes men, African Americans, and people with a family history of MM.

The researchers said patients who screen positive for MGUS could seek medical care early and try strategies such as aspirin, metformin, or weight reduction to potentially reduce their risk of progression from MGUS to MM.

However, additional studies are needed to confirm the effectiveness of aspirin, metformin, and weight-loss strategies in preventing MGUS progression.