User login

Menstrual Changes Still Top Indicator of Reproductive Aging

Changes to the menstrual cycle remain the most important clinical indicators of women’s reproductive aging, according to new standardized staging criteria.

The changes identified by the most recent Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop are now defined in 10 stages, whereas the 2001 STRAW criteria had 7. The new criteria, called STRAW-10 and published Feb. 16 in Menopause, offer more detail on the characteristics of flow and cycle length at each stage, along with corresponding endocrine changes. The article was published simultaneously in Climacteric, Fertility and Sterility, and the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

For example, the late reproductive stage is now subdivided into two stages, –3b and –3a, instead of only stage –3 as before (Menopause 2012 Feb. 16 [doi:10.1097/gme0b013c31824d8f40]). In stage –3b, flow remains regular, whereas in stage –3a there are subtle changes in flow and length of cycle.

The postmenopausal stage +1, identified in the earlier STRAW criteria, also has been subdivided into three lettered stages, with the endocrine changes and duration of each stage described.

Unlike the previous STRAW criteria, the menstrual changes identified in STRAW-10 are relevant to any healthy woman, regardless of ethnicity, age, body mass index, or lifestyle, researchers said, noting that although factors such as smoking status and BMI may affect the timing of menopause, the bleeding patterns remain reliable indicators of the reproductive stage.

"Despite the availability of blood tests and sonograms, the menstrual cycle remains the single best way to estimate where a woman is along the reproductive path," commented Dr. Margery Gass, one of the coauthors of the new criteria, the executive director of the North American Menopause Society, and the editor of Menopause.

"According to STRAW-10, most women (and their clinicians) can use the changes in their menstrual pattern to determine how close they are to menopause: late reproductive phase (subtle changes in cycle length and blood flow), early menopause transition (menstrual period 7 or more days early or late), and late menopause transition (the occurrence of more than 60 days between cycles)," Dr. Gass said in an interview.

STRAW-10 incorporates three biomarkers – anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), inhibin B, and antral follicle count – that are not mentioned in the original STRAW criteria, along with follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), which was included in the original criteria.

In developing the new criteria, an international group of 41 researchers, led by epidemiologist Siobán D. Harlow, Ph.D., of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, evaluated data from cohort studies of midlife women with the aim to incorporate the scientific findings of the past decade on ovarian aging and its endocrine and clinical indicators.

Although much has been learned since 2001 with regard to biomarkers, Dr. Harlow and colleagues emphasized that the biomarker criteria outlined in STRAW-10 must still be considered "supportive," in part because more research is needed and in part because of the invasiveness and expense of testing.

Dr. Gass commented that for clinicians, checking hormone levels should not be considered necessary "except in women who have undergone endometrial ablation or hysterectomy, or who have unusual health circumstances."

Women for whom the STRAW-10 criteria are not applicable include those with polycystic ovarian syndrome or hypothalamic amenorrhea. Women with chronic illnesses such as HIV-AIDS, or those who are undergoing certain types of cancer treatments, also are difficult to assess under STRAW-10, as cycles and hormone levels can change in response to medication.

Although the new criteria do not use age in determining reproductive staging, women younger than 40 years who have premature ovarian insufficiency or premature ovarian failure do not fit well under STRAW-10, the researchers noted, as their course of reproductive aging is more variable.

The STRAW-10 meetings received funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Health and Human Services through the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and the Office of Research on Women’s Health, as well as the North American Menopause Society (NAMS), the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM), the International Menopause Society in Cape Town, South Africa, and the Endocrine Society.

Dr. Gass receives support from NAMS. Dr. Harlow disclosed support from the NIA and NAMS and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Coauthor Dr. Janet E. Hall disclosed support from NIA and the Endocrine Society. Dr. Roger Lobo is a past president of the ASRM, and Dr. Robert W. Rebar disclosed salary support from ASRM. Pauline Maki, Ph.D., disclosed support from the NIA and other public sources along with board membership on NAMS, a consultant relationship with Noven Pharmaceuticals, and lecture fees from Pfizer and others. Dr. Tobie J. de Villiers disclosed past support from Adcock Ingram, Servier, Pfizer, Bayer, and Amgen without direct bearing on the STRAW-10 work. The remaining two coauthors said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

The main changes [in STRAW-10] have to do with the late reproductive stage and the early postmenopausal stage, which has been subdivided to give more detail, and in turn help understand the physiologic changes which occur at these times. In particular, the late reproductive stage has been subdivided so the measurement of the anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) and follicle count can be used as a measure of decreased fertility, but the menstrual bleeding is still regular and unchanged. Inhibin B also may be low.

The next stage adds a change in menstrual pattern, usually shorter cycles, and also some variability in FSH levels early in the cycle (days 2-5). Unfortunately, there is no standardization for the AMH assay, so a quantitative measurement is not available.

The bottom line is that these definitions will be helpful mostly for research, but will only give us some guidance to counsel patients about their fertility.

In terms of the late reproductive stages, there now are three subdivisions based on stabilization of key hormones at this time (FSH and estradiol). Perimenopause also is better defined and the addition of symptoms with a description of bleeding patterns will be helpful both to researchers and clinicians. This will lead to more research and understanding of the key physiologic events that lead to reproductive decline and menopausal changes. There also is a description of what happens to reproduction with various dysfunctions, such as chemotherapy and in polycystic ovarian syndrome, which can be helpful both clinically and particularly in research.

Dr. Michelle Warren is professor of medicine and obstetrics and gynecology at Columbia University Medical Center, New York, and medical director of the Center for Menopause, Hormonal Disorders, and Women's Health at Columbia. She commented in an interview regarding the STRAW-10 findings. She disclosed ties with Pfizer and Yoplait, and Ascend Therapeutics.

The main changes [in STRAW-10] have to do with the late reproductive stage and the early postmenopausal stage, which has been subdivided to give more detail, and in turn help understand the physiologic changes which occur at these times. In particular, the late reproductive stage has been subdivided so the measurement of the anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) and follicle count can be used as a measure of decreased fertility, but the menstrual bleeding is still regular and unchanged. Inhibin B also may be low.

The next stage adds a change in menstrual pattern, usually shorter cycles, and also some variability in FSH levels early in the cycle (days 2-5). Unfortunately, there is no standardization for the AMH assay, so a quantitative measurement is not available.

The bottom line is that these definitions will be helpful mostly for research, but will only give us some guidance to counsel patients about their fertility.

In terms of the late reproductive stages, there now are three subdivisions based on stabilization of key hormones at this time (FSH and estradiol). Perimenopause also is better defined and the addition of symptoms with a description of bleeding patterns will be helpful both to researchers and clinicians. This will lead to more research and understanding of the key physiologic events that lead to reproductive decline and menopausal changes. There also is a description of what happens to reproduction with various dysfunctions, such as chemotherapy and in polycystic ovarian syndrome, which can be helpful both clinically and particularly in research.

Dr. Michelle Warren is professor of medicine and obstetrics and gynecology at Columbia University Medical Center, New York, and medical director of the Center for Menopause, Hormonal Disorders, and Women's Health at Columbia. She commented in an interview regarding the STRAW-10 findings. She disclosed ties with Pfizer and Yoplait, and Ascend Therapeutics.

The main changes [in STRAW-10] have to do with the late reproductive stage and the early postmenopausal stage, which has been subdivided to give more detail, and in turn help understand the physiologic changes which occur at these times. In particular, the late reproductive stage has been subdivided so the measurement of the anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) and follicle count can be used as a measure of decreased fertility, but the menstrual bleeding is still regular and unchanged. Inhibin B also may be low.

The next stage adds a change in menstrual pattern, usually shorter cycles, and also some variability in FSH levels early in the cycle (days 2-5). Unfortunately, there is no standardization for the AMH assay, so a quantitative measurement is not available.

The bottom line is that these definitions will be helpful mostly for research, but will only give us some guidance to counsel patients about their fertility.

In terms of the late reproductive stages, there now are three subdivisions based on stabilization of key hormones at this time (FSH and estradiol). Perimenopause also is better defined and the addition of symptoms with a description of bleeding patterns will be helpful both to researchers and clinicians. This will lead to more research and understanding of the key physiologic events that lead to reproductive decline and menopausal changes. There also is a description of what happens to reproduction with various dysfunctions, such as chemotherapy and in polycystic ovarian syndrome, which can be helpful both clinically and particularly in research.

Dr. Michelle Warren is professor of medicine and obstetrics and gynecology at Columbia University Medical Center, New York, and medical director of the Center for Menopause, Hormonal Disorders, and Women's Health at Columbia. She commented in an interview regarding the STRAW-10 findings. She disclosed ties with Pfizer and Yoplait, and Ascend Therapeutics.

Changes to the menstrual cycle remain the most important clinical indicators of women’s reproductive aging, according to new standardized staging criteria.

The changes identified by the most recent Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop are now defined in 10 stages, whereas the 2001 STRAW criteria had 7. The new criteria, called STRAW-10 and published Feb. 16 in Menopause, offer more detail on the characteristics of flow and cycle length at each stage, along with corresponding endocrine changes. The article was published simultaneously in Climacteric, Fertility and Sterility, and the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

For example, the late reproductive stage is now subdivided into two stages, –3b and –3a, instead of only stage –3 as before (Menopause 2012 Feb. 16 [doi:10.1097/gme0b013c31824d8f40]). In stage –3b, flow remains regular, whereas in stage –3a there are subtle changes in flow and length of cycle.

The postmenopausal stage +1, identified in the earlier STRAW criteria, also has been subdivided into three lettered stages, with the endocrine changes and duration of each stage described.

Unlike the previous STRAW criteria, the menstrual changes identified in STRAW-10 are relevant to any healthy woman, regardless of ethnicity, age, body mass index, or lifestyle, researchers said, noting that although factors such as smoking status and BMI may affect the timing of menopause, the bleeding patterns remain reliable indicators of the reproductive stage.

"Despite the availability of blood tests and sonograms, the menstrual cycle remains the single best way to estimate where a woman is along the reproductive path," commented Dr. Margery Gass, one of the coauthors of the new criteria, the executive director of the North American Menopause Society, and the editor of Menopause.

"According to STRAW-10, most women (and their clinicians) can use the changes in their menstrual pattern to determine how close they are to menopause: late reproductive phase (subtle changes in cycle length and blood flow), early menopause transition (menstrual period 7 or more days early or late), and late menopause transition (the occurrence of more than 60 days between cycles)," Dr. Gass said in an interview.

STRAW-10 incorporates three biomarkers – anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), inhibin B, and antral follicle count – that are not mentioned in the original STRAW criteria, along with follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), which was included in the original criteria.

In developing the new criteria, an international group of 41 researchers, led by epidemiologist Siobán D. Harlow, Ph.D., of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, evaluated data from cohort studies of midlife women with the aim to incorporate the scientific findings of the past decade on ovarian aging and its endocrine and clinical indicators.

Although much has been learned since 2001 with regard to biomarkers, Dr. Harlow and colleagues emphasized that the biomarker criteria outlined in STRAW-10 must still be considered "supportive," in part because more research is needed and in part because of the invasiveness and expense of testing.

Dr. Gass commented that for clinicians, checking hormone levels should not be considered necessary "except in women who have undergone endometrial ablation or hysterectomy, or who have unusual health circumstances."

Women for whom the STRAW-10 criteria are not applicable include those with polycystic ovarian syndrome or hypothalamic amenorrhea. Women with chronic illnesses such as HIV-AIDS, or those who are undergoing certain types of cancer treatments, also are difficult to assess under STRAW-10, as cycles and hormone levels can change in response to medication.

Although the new criteria do not use age in determining reproductive staging, women younger than 40 years who have premature ovarian insufficiency or premature ovarian failure do not fit well under STRAW-10, the researchers noted, as their course of reproductive aging is more variable.

The STRAW-10 meetings received funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Health and Human Services through the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and the Office of Research on Women’s Health, as well as the North American Menopause Society (NAMS), the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM), the International Menopause Society in Cape Town, South Africa, and the Endocrine Society.

Dr. Gass receives support from NAMS. Dr. Harlow disclosed support from the NIA and NAMS and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Coauthor Dr. Janet E. Hall disclosed support from NIA and the Endocrine Society. Dr. Roger Lobo is a past president of the ASRM, and Dr. Robert W. Rebar disclosed salary support from ASRM. Pauline Maki, Ph.D., disclosed support from the NIA and other public sources along with board membership on NAMS, a consultant relationship with Noven Pharmaceuticals, and lecture fees from Pfizer and others. Dr. Tobie J. de Villiers disclosed past support from Adcock Ingram, Servier, Pfizer, Bayer, and Amgen without direct bearing on the STRAW-10 work. The remaining two coauthors said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

Changes to the menstrual cycle remain the most important clinical indicators of women’s reproductive aging, according to new standardized staging criteria.

The changes identified by the most recent Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop are now defined in 10 stages, whereas the 2001 STRAW criteria had 7. The new criteria, called STRAW-10 and published Feb. 16 in Menopause, offer more detail on the characteristics of flow and cycle length at each stage, along with corresponding endocrine changes. The article was published simultaneously in Climacteric, Fertility and Sterility, and the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

For example, the late reproductive stage is now subdivided into two stages, –3b and –3a, instead of only stage –3 as before (Menopause 2012 Feb. 16 [doi:10.1097/gme0b013c31824d8f40]). In stage –3b, flow remains regular, whereas in stage –3a there are subtle changes in flow and length of cycle.

The postmenopausal stage +1, identified in the earlier STRAW criteria, also has been subdivided into three lettered stages, with the endocrine changes and duration of each stage described.

Unlike the previous STRAW criteria, the menstrual changes identified in STRAW-10 are relevant to any healthy woman, regardless of ethnicity, age, body mass index, or lifestyle, researchers said, noting that although factors such as smoking status and BMI may affect the timing of menopause, the bleeding patterns remain reliable indicators of the reproductive stage.

"Despite the availability of blood tests and sonograms, the menstrual cycle remains the single best way to estimate where a woman is along the reproductive path," commented Dr. Margery Gass, one of the coauthors of the new criteria, the executive director of the North American Menopause Society, and the editor of Menopause.

"According to STRAW-10, most women (and their clinicians) can use the changes in their menstrual pattern to determine how close they are to menopause: late reproductive phase (subtle changes in cycle length and blood flow), early menopause transition (menstrual period 7 or more days early or late), and late menopause transition (the occurrence of more than 60 days between cycles)," Dr. Gass said in an interview.

STRAW-10 incorporates three biomarkers – anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), inhibin B, and antral follicle count – that are not mentioned in the original STRAW criteria, along with follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), which was included in the original criteria.

In developing the new criteria, an international group of 41 researchers, led by epidemiologist Siobán D. Harlow, Ph.D., of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, evaluated data from cohort studies of midlife women with the aim to incorporate the scientific findings of the past decade on ovarian aging and its endocrine and clinical indicators.

Although much has been learned since 2001 with regard to biomarkers, Dr. Harlow and colleagues emphasized that the biomarker criteria outlined in STRAW-10 must still be considered "supportive," in part because more research is needed and in part because of the invasiveness and expense of testing.

Dr. Gass commented that for clinicians, checking hormone levels should not be considered necessary "except in women who have undergone endometrial ablation or hysterectomy, or who have unusual health circumstances."

Women for whom the STRAW-10 criteria are not applicable include those with polycystic ovarian syndrome or hypothalamic amenorrhea. Women with chronic illnesses such as HIV-AIDS, or those who are undergoing certain types of cancer treatments, also are difficult to assess under STRAW-10, as cycles and hormone levels can change in response to medication.

Although the new criteria do not use age in determining reproductive staging, women younger than 40 years who have premature ovarian insufficiency or premature ovarian failure do not fit well under STRAW-10, the researchers noted, as their course of reproductive aging is more variable.

The STRAW-10 meetings received funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Health and Human Services through the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and the Office of Research on Women’s Health, as well as the North American Menopause Society (NAMS), the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM), the International Menopause Society in Cape Town, South Africa, and the Endocrine Society.

Dr. Gass receives support from NAMS. Dr. Harlow disclosed support from the NIA and NAMS and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Coauthor Dr. Janet E. Hall disclosed support from NIA and the Endocrine Society. Dr. Roger Lobo is a past president of the ASRM, and Dr. Robert W. Rebar disclosed salary support from ASRM. Pauline Maki, Ph.D., disclosed support from the NIA and other public sources along with board membership on NAMS, a consultant relationship with Noven Pharmaceuticals, and lecture fees from Pfizer and others. Dr. Tobie J. de Villiers disclosed past support from Adcock Ingram, Servier, Pfizer, Bayer, and Amgen without direct bearing on the STRAW-10 work. The remaining two coauthors said they had no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM MENOPAUSE

Vulvar pain syndromes: Causes and treatment of vestibulodynia

- Part 1: Making the correct diagnosis

(September 2011) - Part 2: A bounty of treatments—but not all of them are proven

(October 2011)

This three-part series concludes with a look at vestibulodynia—pain that is localized to the vulvar vestibule. Much is known about this disorder, compared with our knowledge base in the recent past, but much remains to be discovered. Among the questions explored by the panelists in this article is whether vestibulodynia and generalized vulvodynia are distinct entities—or different manifestations of the same process.

Other questions addressed here:

- Do oral contraceptives (OCs) contribute to vestibulodynia?

- What about herpes and genital warts? Are they causes of vestibular pain?

- Are some women more vulnerable to vestibulodynia than others?

- Is the disorder curable?

- Does vestibulectomy provide definitive treatment?

Part 1 of this series, which appeared in the September 2011 issue, focused on generalized vulvar pain and its causes, features, and diagnosis. Part 2, in the October issue, took as its subject the treatment of vulvar pain. Both are available in the archive at obgmanagement.com.

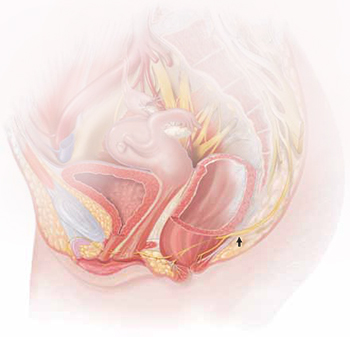

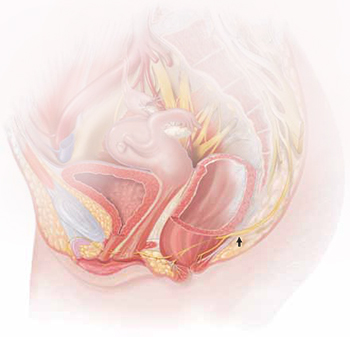

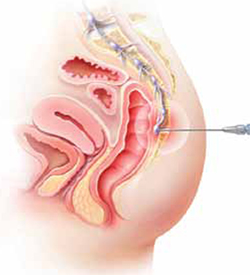

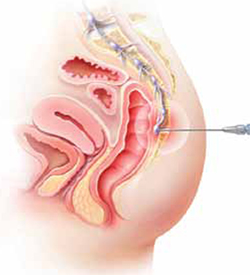

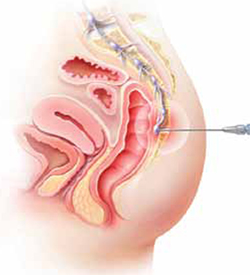

The lower vagina and vulva are richly supplied with peripheral nerves and are, therefore, sensitive to pain, particularly the region of the hymeneal ring. Although the pudendal nerve (arrow) courses through the area, it is an uncommon source of vulvar pain.

What do we know about the causes of vestibulodynia?

Dr. Lonky: What are the causes of provoked vestibulodynia (PVD), also known as vulvar vestibulitis syndrome? And what are the theories behind those causes?

Dr. Haefner: The specific cause is unknown. Most likely, there isn’t a single cause. Theories that have been proposed include abnormalities of embryologic development, infection, inflammation, genetic and immune factors, and nerve pathways.

Patients who have vestibulodynia may also have interstitial cystitis. It has been noted that tissues from the vestibule and bladder have a common embryologic origin and, therefore, are predisposed to similar pathologic responses when challenged.1,2

Candida albicans infection in patients who experience vestibular pain has also been studied. The exact association is difficult to determine because many patients report Candida infections without verified testing for yeast. Bazin and colleagues found a very weak association between infection and pain on the vestibule.3

Inflammation—the “itis” in vestibulitis—has been excluded from the recent International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) terminology because studies found no association between excised tissue and inflammation. Bohm-Starke and colleagues found low expression of the inflammatory markers cyclooxygenase 2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase in the vestibular mucosa of women who had localized vestibular pain, as well as in healthy women in the control group.4

Goetsch was one of the first researchers to explore a genetic association with localized vulvar pain.5 Fifteen percent of patients questioned over a 6-month period were found to have localized vestibular pain. Thirty-two percent had a female relative who had dyspareunia or tampon intolerance, raising the issue of a genetic predisposition. Another genetic connection was found in a study evaluating gene coding for interleukin 1-receptor antagonist.6–8

Krantz examined the nerve characteristics of the vulva and vagina.9 The region of the hymeneal ring was richly supplied with free nerve endings. No corpuscular endings of any form were observed. Only free nerve endings were observed in the fossa navicularis. A sparsity of nerve endings occurred in the vagina, as compared with the region of the fourchette, fossa navicularis, and hymeneal ring. More recent studies have analyzed the nerve factors, thermoreceptors, and nociceptors in women with vulvar pain.10,11

Dr. Edwards: I feel strongly that vestibulodynia and generalized vulvodynia are the same process. For example, tension headaches are supposed to be occipital, but some people experience tension headaches that are periorbital. Both are tension headaches despite the different locations. And almost all patients who experience any subset of vulvodynia have provoked vestibular pain. So the only thing that separates vestibulodynia from other patterns of vulvodynia is the option of vestibulectomy for therapy.

I don’t think that vulvodynia and vestibulodynia are “wastebasket” names for undiagnosable vulvar pain; rather, they are specific disease processes produced by pelvic floor dysfunction that predisposes a woman to neuropathic pain with a trigger or to a systemic pain syndrome that includes an abnormal pelvic floor.

Dr. Gunter: There are probably many causes of PVD, as Dr. Haefner suggested. There may be an ignition hypothesis, whereby some outside inflammatory trigger or trauma produces local neurogenic inflammation. However, given the prevalence of other pain disorders, there is probably also a need to have a lowered threshold for these changes to occur—basically, a vulnerable neurologic platform.

For some women, local neural hyperplasia is probably a factor. It is possible that there are different causes for primary and secondary vestibulodynia.

Vulvodynia and depression often travel together. They are such common comorbidities, in fact, that some physicians theorize that vulvodynia may be a symptom of an underlying mood disorder, such as depression, or that depression may be one manifestation of chronic vulvar pain. Suffice it to say that chronic pain and depression are often associated, and it is frequently difficult to determine whether the relationship is one of cause and effect.

Comprehensive care of the patient who has vulvar pain, therefore, should include a thorough history, looking specifically for depression (including sleep disorders) and eliciting information on any suicidal thoughts or intentions.

Although many patients who have vulvodynia are treated with an antidepressant, the dose that relieves pain may not be high enough to attenuate an accompanying mood disorder. My approach is to team up with a psychiatrist or psychologist who is familiar with vulvar pain syndromes. Together, we monitor the patient and fine-tune the therapeutic response.

—Neal M. Lonky, MD, MPH

Do oral contraceptives contribute to vestibulodynia?

Dr. Lonky: Is PVD more prevalent among OC users?

Dr. Haefner: Controversy surrounds the question of whether vestibulodynia and OC use are linked. Some studies suggest no association12–14 and others suggest a possible effect of OCs on vulvodynia.15–17 A study by Reed and colleagues found no association between taking OCs or hormone therapy at enrollment and incident vulvodynia only in the univariable analysis, but not when controlling for age at enrollment.18 This reflects the finding that younger age was associated with incident disease; younger age and use of OCs are similarly associated.

Dr. Gunter: I am not a believer in a cause-and-effect relationship between OC use and vestibulodynia. I do not find the studies demonstrating an association convincing. Given the supraphysiologic levels of hormones during pregnancy, if high hormone levels played a role, we should also see a greater incidence of vestibulodynia among women who have several pregnancies at an early age.

Dr. Edwards: In my practice, stopping, starting, and changing OCs has made no difference for patients. Topical estrogen supplementation in the occasional OC user who has signs of low estrogen has been useful at times.

Do herpes or genital warts contribute to PVD?

Dr. Lonky: Does a history of vulvar herpes or genital warts have any impact on the incidence of PVD?

Dr. Edwards: No.

Dr. Gunter: I agree that it has no impact.

Dr. Haefner: Herpes is sometimes associated with vulvar pain. The lesions resolve, but pain may continue as post-herpetic neuralgia. As with shingles, a low threshold for starting a patient on gabapentin to control pain after herpes may be beneficial.

Genital warts rarely cause vulvar pain—but the treatment may. Patients sometimes feel pain following topical treatment, as well as pain from surgical wart treatment.

Effect of demographic variables

Dr. Lonky: Does race, skin type, or hair or eye color make a difference in the prevalence, manifestation of symptoms, or treatment of PVD?

Dr. Gunter: I am not aware of any studies that confirm an association between vulvodynia and those factors.

Dr. Edwards: I don’t know whether any of these variables make a difference. My own impression—confirmed by informal study in my office—is that vulvodynia patients weigh less than my general dermatology patients and are better educated. I sometimes get the sense that my vulvodynia patients are more likely to be fair.

Dr. Lonky: What age group is most commonly affected by PVD?

Dr. Edwards: In my experience the most common age group is women 25 to 45 years old, probably because they are the most sexually active group old enough and tough enough to pursue this issue.

Dr. Gunter: I believe it affects all women equally, although women in their reproductive years are more likely to visit a gynecologist and, therefore, probably more likely to be given this diagnosis.

Dr. Lonky: Do you believe that PVD and generalized vulvar dysesthesia are curable—or just treatable?

Dr. Gunter: That depends on many variables. It is far more challenging to cure a patient who has multiple pain syndromes (for example, fibromyalgia, migraines, and irritable bowel syndrome) than the woman who simply has vestibulodynia or generalized vulvar pain. In addition, stress, anxiety, coping skills, and depression all play a role. In my opinion, a woman without comorbidity has a good chance of having her symptoms well-controlled. Some will be cured (that is, able to discontinue medications), and others will need ongoing treatment but will not be bothered by their symptoms.

Dr. Haefner: The response to treatment in many pain patients depends on the amount of time that the pain has been present. Someone who has had pain for 30 years will probably not be cured 3 months after starting treatment. However, someone with a short duration of pain often gets good improvement. One hundred percent improvement is rare, however. Many patients are able to approach the 80% improvement mark.

Dr. Edwards: I would say that these conditions are manageable more than curable, although pure vestibulodynia—which is uncommon—is curable with surgery.

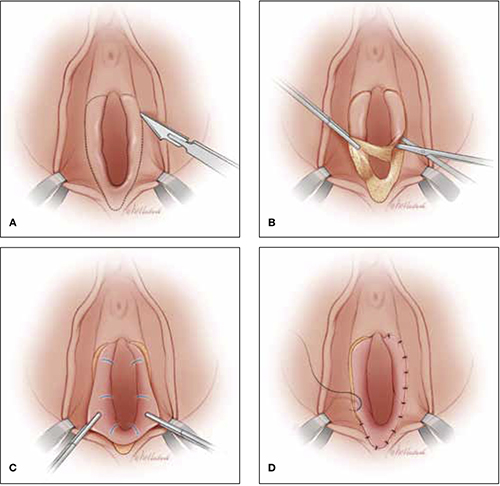

Vestibulectomy technique

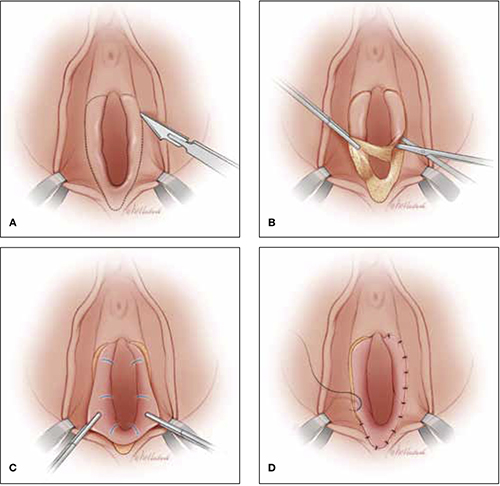

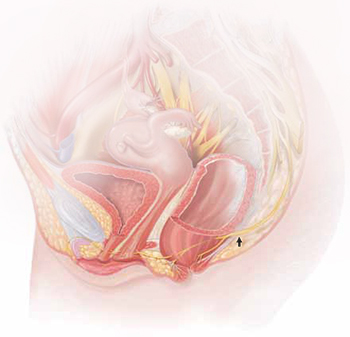

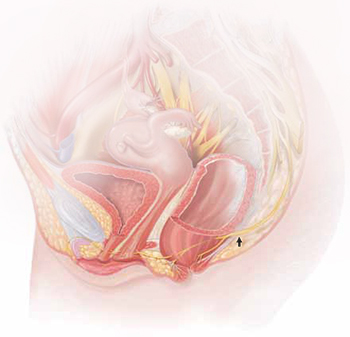

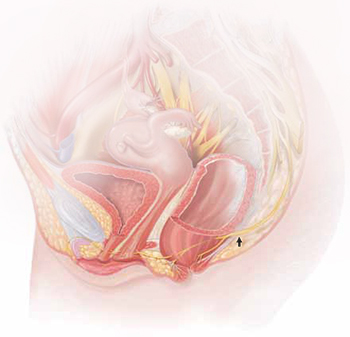

(A) Incision. In many cases, the incision needs to extend up to the opening of the Skene’s ducts on the vestibule before it is carried down laterally along Hart’s line to the perianal skin, with the mucosa undermined above the hymeneal ring. (B) Excision. Remove the tissue superior to the hymeneal ring. (C) Advancement of vaginal mucosa. Further undermine the mucosa and advance it to close the defect. (D) Suturing. Close the defect in two layers using absorbable suture.

Is vestibulectomy definitive treatment?

Dr. Lonky: Does vestibulectomy work as a definitive treatment for PVD?

Dr. Gunter: Vestibulectomy—that is, resection of the vestibule and advancement of vaginal mucosa—is well described for women who have localized vestibulodynia. The complication rate is low, with only 3% of women reporting worsening of symptoms after the procedure.19,20 Success rates range from 17% to 89%, although many studies are retrospective reviews or include nonhomogenous populations, or both.19–21 A prospective study (Level II) indicates a 52% reduction in pain scores for women 6 months after vestibulectomy—and the scores continued to improve at evaluation at 2.5 years.22,23

Prospective studies indicate that vestibulectomy improves pain scores more than cognitive behavioral therapy, biofeedback, oral despiramine, and topical lidocaine.22,23 However, even surgery carries a robust placebo response rate, and vulvar biopsy alone has been associated with an improvement in pain scores in 67% of women.24,25

I offer surgery for vestibulodynia after the patient has failed at least two therapies (two topical treatments or one topical and one oral treatment). I offer injections before proceeding, and almost all patients opt to try them. I do not offer vestibulectomy to patients who have unprovoked pain or pain outside of resection margins.

Dr. Haefner: Surgical excision of the vulvar vestibule has met with success, in some studies, in more than 80% of cases, but it should be reserved for women who have longstanding and localized vestibular pain in whom other management options have failed.

The patient should undergo cotton-swab testing to outline areas of pain before anesthesia is administered in the operating room. Often, the incision will need to extend up to the opening of the Skene’s ducts on the vestibule (FIGURE). The incision is carried down laterally along Hart’s line to the perianal skin, and the mucosa is undermined above the hymeneal ring. The specimen is excised superior to the hymeneal ring. The vaginal tissue is further undermined and brought down to close the defect in two layers using absorbable suture. A review of this technique with illustrations has been published.26

Dr. Lonky: Thank you all again for sharing your considerable expertise, experience, and insight.

Harlow BL, Stewart EG. A population-based assessment of chronic unexplained vulvar pain: have we underestimated the prevalence of vulvodynia? J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2003;58(2):82–88.

In this population-based study, 16% of women reported a history of chronic unexplained vulvar pain, and nearly 7% reported current symptoms.

Khandker M, Brady SS, Vitonis AF, Maclehose RF, Stewart EG, Harlow BL. The influence of depression and anxiety on risk of adult onset vulvodynia [published online ahead of print August 8, 2011].

J Womens Health (Larchmt). doi:10.1089/jwh.2010.2661.

Vulvodynia was four times more likely among women who had antecedent mood or anxiety disorders than in women who didn’t. Vulvodynia was also associated with new or recurrent onset of mood or anxiety disorders.

Masheb RM, Wang E, Lozano C, Kerns RD. Prevalence and correlates of depression in treatment-seeking women with vulvodynia. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;25(8):786–791.

Comorbid major depressive disorders in women who have vulvodynia are related to greater pain severity and worse functioning.

Reed BD, Haefner HK, Punch MR, Roth RS, Gorenflo DW, Gillespie BW. Psychosocial and sexual functioning in women with vulvodynia and chronic pelvic pain. A comparative evaluation. J Reprod Med. 2000;45(8):624–632.

Women who have vulvodynia are psychologically similar to women who don’t. A primary psychological cause of vulvodynia is not supported.

Tribo MJ, Andion O, Ros S, et al. Clinical characteristics and psychopathological profile of patients with vulvodynia: an observational and descriptive study. Dermatology. 2008;216(1):24–30.

Psychiatric treatment may be a useful option to improve symptoms of vulvodynia.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think about this series on Vulvar Pain Syndromes.

1. McCormack WM. Two urogenital sinus syndromes. Interstitial cystitis and focal vulvitis. J Reprod Med. 1990;35(9):873-876.

2. Fitzpatrick CC, DeLancey JP, Elkins TE, McGuire EJ. Vulvar vestibulitis and interstitial cystitis: a disorder of urogenital sinusderived epithelium. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81(5 Pt 2):860-862.

3. Bazin S, Bouchard C, Brisson J, Morin C, Meisels A, Fortier M. Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome: an exploratory case-control study. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83(1):47-50.

4. Bohm-Starke N, Falconer C, Rylander E, Hilliges M. The expression of cyclooxygenase 2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase indicates no active inflammation in vulvar vestibulitis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80(7):638-644.

5. Goetsch MF. Vulvar vestibulitis: prevalence and historic features in a general gynecologic practice population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164(6 Pt 1):1609-1616.

6. Jeremias J, Ledger WJ, Witkin SS. Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist gene polymorphism in women with vulvar vestibulitis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182(2):283-285.

7. Witkin SS, Gerber S, Ledger WJ. Differential characterization of women with vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(3):589-594.

8. Foster DC, Piekarz KH, Murant TI, LaPoint R, Haidaris CG, Phipps RP. Enhanced synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines by vulvar vestibular fibroblasts: implications for vulvar vestibulitis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(4):346. e1-8.

9. Krantz KE. Innervation of the human vulva and vagina: a microscopic study. Obstet Gynecol. 1958;12:382-396.

10. Bohm-Starke N, Hilliges M, Brodda-Jansen G, Rylander E, Torebjork E. Psychophysical evidence of nociceptor sensitization in vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. Pain. 2001;94(2):177-183.

11. Tympanidis P, Terenghi G, Dowd P. Increased innervation of the vulval vestibule in patients with vulvodynia. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148(5):1021-1027.

12. Bachman GA, Rosen R, Pinn VW, et al. Vulvodynia: a state-of-the-art consensus on definitions, diagnosis and management. J Reprod Med. 2006;51(6):447-456.

13. Harlow BL, Vitonis AF, Stewart EG. Influence of oral contraceptive use on the risk of adult-onset vulvodynia. J Reprod Med. 2008;53(2):102-110.

14. Danielsson I, Sjoberg I, Stenlund H, Wikman M. Prevalence and incidence of prolonged and severe dyspareunia in women: results from a population study. Scand J Public Health. 2003;31(2):113-118.

15. Bohm-Starke N, Johannesson U, Hilliges M, Rylander E, Torebjork E. Decreased mechanical pain threshold in the vestibular mucosa of women using oral contraceptives: a contributing factor in vulvar vestibulitis? J Reprod Med. 2004;49(11):888-892.

16. Greenstein A, Ben-Aroya Z, Fass O, et al. Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome and estrogen dose of oral contraceptive pills. J Sexual Med. 2007;4(6):1679-1683.

17. Bouchard C, Brisson J, Fortier M, Morin C, Blanchette C. Use of oral contraceptive pills and vulvar vestibulitis: a case-control study. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(3):254-261.

18. Reed BD, Haefner HK, Sen A, Gorenflo DW. Vulvodynia incidence and remission rates among adult women: a 2-year follow-up study. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 Pt 1):231-237.

19. Goldstein AT, Klingman D, Christopher K, Johnson C, Marinoff SC. Surgical treatment of vulvar vestibulitis syndrome: outcome assessment derived from a postoperative questionnaire. J Sex Med. 2006;3(5):923-931.

20. Eva LJ, Narain S, Orakwue CO, Luesley DM. Is modified vestibulectomy for localized provoked vulvodynia an effective long-term treatment? A follow-up study. J Reprod Med. 2008;53(6):435-440.

21. Haefner HK, Collins ME, Davis GD, et al. The vulvodynia guideline. J Lower Genit Tract Dis. 2005;9(1):40-51.

22. Bergeron S, Binik YM, Khalife S, et al. A randomized comparison of group cognitive-behavioral therapy, surface electromyographic biofeedback, and vestibulectomy in the treatment of dyspareunia resulting from vulvar vestibulitis. Pain. 2001;91(3):297-306.

23. Bergeron S, Khalife S, Glazer HI, Binik Y. Surgical and behavioral treatments for vestibulodynia: two-and-one-half-year follow-up and predictors of outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(1):159-166.

24. Gunter J. Vulvodynia: new thoughts on a devastating condition. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2007;62(12):812-819.

25. Tympanidis P, Terenghi G, Dowd P. Increased innervation of the vulvar vestibule in patients with vulvodynia. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148(5):1021-1027.

26. Haefner HK. Critique of new gynecologic surgical procedures: surgery for vulvar vestibulitis. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2000;43(3):689-700.

- Part 1: Making the correct diagnosis

(September 2011) - Part 2: A bounty of treatments—but not all of them are proven

(October 2011)

This three-part series concludes with a look at vestibulodynia—pain that is localized to the vulvar vestibule. Much is known about this disorder, compared with our knowledge base in the recent past, but much remains to be discovered. Among the questions explored by the panelists in this article is whether vestibulodynia and generalized vulvodynia are distinct entities—or different manifestations of the same process.

Other questions addressed here:

- Do oral contraceptives (OCs) contribute to vestibulodynia?

- What about herpes and genital warts? Are they causes of vestibular pain?

- Are some women more vulnerable to vestibulodynia than others?

- Is the disorder curable?

- Does vestibulectomy provide definitive treatment?

Part 1 of this series, which appeared in the September 2011 issue, focused on generalized vulvar pain and its causes, features, and diagnosis. Part 2, in the October issue, took as its subject the treatment of vulvar pain. Both are available in the archive at obgmanagement.com.

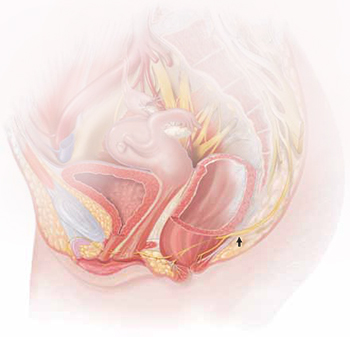

The lower vagina and vulva are richly supplied with peripheral nerves and are, therefore, sensitive to pain, particularly the region of the hymeneal ring. Although the pudendal nerve (arrow) courses through the area, it is an uncommon source of vulvar pain.

What do we know about the causes of vestibulodynia?

Dr. Lonky: What are the causes of provoked vestibulodynia (PVD), also known as vulvar vestibulitis syndrome? And what are the theories behind those causes?

Dr. Haefner: The specific cause is unknown. Most likely, there isn’t a single cause. Theories that have been proposed include abnormalities of embryologic development, infection, inflammation, genetic and immune factors, and nerve pathways.

Patients who have vestibulodynia may also have interstitial cystitis. It has been noted that tissues from the vestibule and bladder have a common embryologic origin and, therefore, are predisposed to similar pathologic responses when challenged.1,2

Candida albicans infection in patients who experience vestibular pain has also been studied. The exact association is difficult to determine because many patients report Candida infections without verified testing for yeast. Bazin and colleagues found a very weak association between infection and pain on the vestibule.3

Inflammation—the “itis” in vestibulitis—has been excluded from the recent International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) terminology because studies found no association between excised tissue and inflammation. Bohm-Starke and colleagues found low expression of the inflammatory markers cyclooxygenase 2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase in the vestibular mucosa of women who had localized vestibular pain, as well as in healthy women in the control group.4

Goetsch was one of the first researchers to explore a genetic association with localized vulvar pain.5 Fifteen percent of patients questioned over a 6-month period were found to have localized vestibular pain. Thirty-two percent had a female relative who had dyspareunia or tampon intolerance, raising the issue of a genetic predisposition. Another genetic connection was found in a study evaluating gene coding for interleukin 1-receptor antagonist.6–8

Krantz examined the nerve characteristics of the vulva and vagina.9 The region of the hymeneal ring was richly supplied with free nerve endings. No corpuscular endings of any form were observed. Only free nerve endings were observed in the fossa navicularis. A sparsity of nerve endings occurred in the vagina, as compared with the region of the fourchette, fossa navicularis, and hymeneal ring. More recent studies have analyzed the nerve factors, thermoreceptors, and nociceptors in women with vulvar pain.10,11

Dr. Edwards: I feel strongly that vestibulodynia and generalized vulvodynia are the same process. For example, tension headaches are supposed to be occipital, but some people experience tension headaches that are periorbital. Both are tension headaches despite the different locations. And almost all patients who experience any subset of vulvodynia have provoked vestibular pain. So the only thing that separates vestibulodynia from other patterns of vulvodynia is the option of vestibulectomy for therapy.

I don’t think that vulvodynia and vestibulodynia are “wastebasket” names for undiagnosable vulvar pain; rather, they are specific disease processes produced by pelvic floor dysfunction that predisposes a woman to neuropathic pain with a trigger or to a systemic pain syndrome that includes an abnormal pelvic floor.

Dr. Gunter: There are probably many causes of PVD, as Dr. Haefner suggested. There may be an ignition hypothesis, whereby some outside inflammatory trigger or trauma produces local neurogenic inflammation. However, given the prevalence of other pain disorders, there is probably also a need to have a lowered threshold for these changes to occur—basically, a vulnerable neurologic platform.

For some women, local neural hyperplasia is probably a factor. It is possible that there are different causes for primary and secondary vestibulodynia.

Vulvodynia and depression often travel together. They are such common comorbidities, in fact, that some physicians theorize that vulvodynia may be a symptom of an underlying mood disorder, such as depression, or that depression may be one manifestation of chronic vulvar pain. Suffice it to say that chronic pain and depression are often associated, and it is frequently difficult to determine whether the relationship is one of cause and effect.

Comprehensive care of the patient who has vulvar pain, therefore, should include a thorough history, looking specifically for depression (including sleep disorders) and eliciting information on any suicidal thoughts or intentions.

Although many patients who have vulvodynia are treated with an antidepressant, the dose that relieves pain may not be high enough to attenuate an accompanying mood disorder. My approach is to team up with a psychiatrist or psychologist who is familiar with vulvar pain syndromes. Together, we monitor the patient and fine-tune the therapeutic response.

—Neal M. Lonky, MD, MPH

Do oral contraceptives contribute to vestibulodynia?

Dr. Lonky: Is PVD more prevalent among OC users?

Dr. Haefner: Controversy surrounds the question of whether vestibulodynia and OC use are linked. Some studies suggest no association12–14 and others suggest a possible effect of OCs on vulvodynia.15–17 A study by Reed and colleagues found no association between taking OCs or hormone therapy at enrollment and incident vulvodynia only in the univariable analysis, but not when controlling for age at enrollment.18 This reflects the finding that younger age was associated with incident disease; younger age and use of OCs are similarly associated.

Dr. Gunter: I am not a believer in a cause-and-effect relationship between OC use and vestibulodynia. I do not find the studies demonstrating an association convincing. Given the supraphysiologic levels of hormones during pregnancy, if high hormone levels played a role, we should also see a greater incidence of vestibulodynia among women who have several pregnancies at an early age.

Dr. Edwards: In my practice, stopping, starting, and changing OCs has made no difference for patients. Topical estrogen supplementation in the occasional OC user who has signs of low estrogen has been useful at times.

Do herpes or genital warts contribute to PVD?

Dr. Lonky: Does a history of vulvar herpes or genital warts have any impact on the incidence of PVD?

Dr. Edwards: No.

Dr. Gunter: I agree that it has no impact.

Dr. Haefner: Herpes is sometimes associated with vulvar pain. The lesions resolve, but pain may continue as post-herpetic neuralgia. As with shingles, a low threshold for starting a patient on gabapentin to control pain after herpes may be beneficial.

Genital warts rarely cause vulvar pain—but the treatment may. Patients sometimes feel pain following topical treatment, as well as pain from surgical wart treatment.

Effect of demographic variables

Dr. Lonky: Does race, skin type, or hair or eye color make a difference in the prevalence, manifestation of symptoms, or treatment of PVD?

Dr. Gunter: I am not aware of any studies that confirm an association between vulvodynia and those factors.

Dr. Edwards: I don’t know whether any of these variables make a difference. My own impression—confirmed by informal study in my office—is that vulvodynia patients weigh less than my general dermatology patients and are better educated. I sometimes get the sense that my vulvodynia patients are more likely to be fair.

Dr. Lonky: What age group is most commonly affected by PVD?

Dr. Edwards: In my experience the most common age group is women 25 to 45 years old, probably because they are the most sexually active group old enough and tough enough to pursue this issue.

Dr. Gunter: I believe it affects all women equally, although women in their reproductive years are more likely to visit a gynecologist and, therefore, probably more likely to be given this diagnosis.

Dr. Lonky: Do you believe that PVD and generalized vulvar dysesthesia are curable—or just treatable?

Dr. Gunter: That depends on many variables. It is far more challenging to cure a patient who has multiple pain syndromes (for example, fibromyalgia, migraines, and irritable bowel syndrome) than the woman who simply has vestibulodynia or generalized vulvar pain. In addition, stress, anxiety, coping skills, and depression all play a role. In my opinion, a woman without comorbidity has a good chance of having her symptoms well-controlled. Some will be cured (that is, able to discontinue medications), and others will need ongoing treatment but will not be bothered by their symptoms.

Dr. Haefner: The response to treatment in many pain patients depends on the amount of time that the pain has been present. Someone who has had pain for 30 years will probably not be cured 3 months after starting treatment. However, someone with a short duration of pain often gets good improvement. One hundred percent improvement is rare, however. Many patients are able to approach the 80% improvement mark.

Dr. Edwards: I would say that these conditions are manageable more than curable, although pure vestibulodynia—which is uncommon—is curable with surgery.

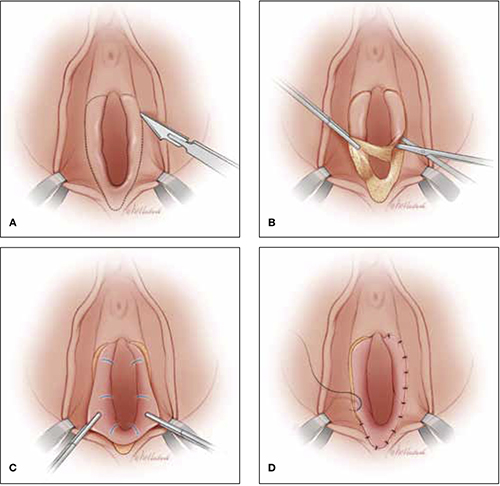

Vestibulectomy technique

(A) Incision. In many cases, the incision needs to extend up to the opening of the Skene’s ducts on the vestibule before it is carried down laterally along Hart’s line to the perianal skin, with the mucosa undermined above the hymeneal ring. (B) Excision. Remove the tissue superior to the hymeneal ring. (C) Advancement of vaginal mucosa. Further undermine the mucosa and advance it to close the defect. (D) Suturing. Close the defect in two layers using absorbable suture.

Is vestibulectomy definitive treatment?

Dr. Lonky: Does vestibulectomy work as a definitive treatment for PVD?

Dr. Gunter: Vestibulectomy—that is, resection of the vestibule and advancement of vaginal mucosa—is well described for women who have localized vestibulodynia. The complication rate is low, with only 3% of women reporting worsening of symptoms after the procedure.19,20 Success rates range from 17% to 89%, although many studies are retrospective reviews or include nonhomogenous populations, or both.19–21 A prospective study (Level II) indicates a 52% reduction in pain scores for women 6 months after vestibulectomy—and the scores continued to improve at evaluation at 2.5 years.22,23

Prospective studies indicate that vestibulectomy improves pain scores more than cognitive behavioral therapy, biofeedback, oral despiramine, and topical lidocaine.22,23 However, even surgery carries a robust placebo response rate, and vulvar biopsy alone has been associated with an improvement in pain scores in 67% of women.24,25

I offer surgery for vestibulodynia after the patient has failed at least two therapies (two topical treatments or one topical and one oral treatment). I offer injections before proceeding, and almost all patients opt to try them. I do not offer vestibulectomy to patients who have unprovoked pain or pain outside of resection margins.

Dr. Haefner: Surgical excision of the vulvar vestibule has met with success, in some studies, in more than 80% of cases, but it should be reserved for women who have longstanding and localized vestibular pain in whom other management options have failed.

The patient should undergo cotton-swab testing to outline areas of pain before anesthesia is administered in the operating room. Often, the incision will need to extend up to the opening of the Skene’s ducts on the vestibule (FIGURE). The incision is carried down laterally along Hart’s line to the perianal skin, and the mucosa is undermined above the hymeneal ring. The specimen is excised superior to the hymeneal ring. The vaginal tissue is further undermined and brought down to close the defect in two layers using absorbable suture. A review of this technique with illustrations has been published.26

Dr. Lonky: Thank you all again for sharing your considerable expertise, experience, and insight.

Harlow BL, Stewart EG. A population-based assessment of chronic unexplained vulvar pain: have we underestimated the prevalence of vulvodynia? J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2003;58(2):82–88.

In this population-based study, 16% of women reported a history of chronic unexplained vulvar pain, and nearly 7% reported current symptoms.

Khandker M, Brady SS, Vitonis AF, Maclehose RF, Stewart EG, Harlow BL. The influence of depression and anxiety on risk of adult onset vulvodynia [published online ahead of print August 8, 2011].

J Womens Health (Larchmt). doi:10.1089/jwh.2010.2661.

Vulvodynia was four times more likely among women who had antecedent mood or anxiety disorders than in women who didn’t. Vulvodynia was also associated with new or recurrent onset of mood or anxiety disorders.

Masheb RM, Wang E, Lozano C, Kerns RD. Prevalence and correlates of depression in treatment-seeking women with vulvodynia. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;25(8):786–791.

Comorbid major depressive disorders in women who have vulvodynia are related to greater pain severity and worse functioning.

Reed BD, Haefner HK, Punch MR, Roth RS, Gorenflo DW, Gillespie BW. Psychosocial and sexual functioning in women with vulvodynia and chronic pelvic pain. A comparative evaluation. J Reprod Med. 2000;45(8):624–632.

Women who have vulvodynia are psychologically similar to women who don’t. A primary psychological cause of vulvodynia is not supported.

Tribo MJ, Andion O, Ros S, et al. Clinical characteristics and psychopathological profile of patients with vulvodynia: an observational and descriptive study. Dermatology. 2008;216(1):24–30.

Psychiatric treatment may be a useful option to improve symptoms of vulvodynia.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think about this series on Vulvar Pain Syndromes.

- Part 1: Making the correct diagnosis

(September 2011) - Part 2: A bounty of treatments—but not all of them are proven

(October 2011)

This three-part series concludes with a look at vestibulodynia—pain that is localized to the vulvar vestibule. Much is known about this disorder, compared with our knowledge base in the recent past, but much remains to be discovered. Among the questions explored by the panelists in this article is whether vestibulodynia and generalized vulvodynia are distinct entities—or different manifestations of the same process.

Other questions addressed here:

- Do oral contraceptives (OCs) contribute to vestibulodynia?

- What about herpes and genital warts? Are they causes of vestibular pain?

- Are some women more vulnerable to vestibulodynia than others?

- Is the disorder curable?

- Does vestibulectomy provide definitive treatment?

Part 1 of this series, which appeared in the September 2011 issue, focused on generalized vulvar pain and its causes, features, and diagnosis. Part 2, in the October issue, took as its subject the treatment of vulvar pain. Both are available in the archive at obgmanagement.com.

The lower vagina and vulva are richly supplied with peripheral nerves and are, therefore, sensitive to pain, particularly the region of the hymeneal ring. Although the pudendal nerve (arrow) courses through the area, it is an uncommon source of vulvar pain.

What do we know about the causes of vestibulodynia?

Dr. Lonky: What are the causes of provoked vestibulodynia (PVD), also known as vulvar vestibulitis syndrome? And what are the theories behind those causes?

Dr. Haefner: The specific cause is unknown. Most likely, there isn’t a single cause. Theories that have been proposed include abnormalities of embryologic development, infection, inflammation, genetic and immune factors, and nerve pathways.

Patients who have vestibulodynia may also have interstitial cystitis. It has been noted that tissues from the vestibule and bladder have a common embryologic origin and, therefore, are predisposed to similar pathologic responses when challenged.1,2

Candida albicans infection in patients who experience vestibular pain has also been studied. The exact association is difficult to determine because many patients report Candida infections without verified testing for yeast. Bazin and colleagues found a very weak association between infection and pain on the vestibule.3

Inflammation—the “itis” in vestibulitis—has been excluded from the recent International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) terminology because studies found no association between excised tissue and inflammation. Bohm-Starke and colleagues found low expression of the inflammatory markers cyclooxygenase 2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase in the vestibular mucosa of women who had localized vestibular pain, as well as in healthy women in the control group.4

Goetsch was one of the first researchers to explore a genetic association with localized vulvar pain.5 Fifteen percent of patients questioned over a 6-month period were found to have localized vestibular pain. Thirty-two percent had a female relative who had dyspareunia or tampon intolerance, raising the issue of a genetic predisposition. Another genetic connection was found in a study evaluating gene coding for interleukin 1-receptor antagonist.6–8

Krantz examined the nerve characteristics of the vulva and vagina.9 The region of the hymeneal ring was richly supplied with free nerve endings. No corpuscular endings of any form were observed. Only free nerve endings were observed in the fossa navicularis. A sparsity of nerve endings occurred in the vagina, as compared with the region of the fourchette, fossa navicularis, and hymeneal ring. More recent studies have analyzed the nerve factors, thermoreceptors, and nociceptors in women with vulvar pain.10,11

Dr. Edwards: I feel strongly that vestibulodynia and generalized vulvodynia are the same process. For example, tension headaches are supposed to be occipital, but some people experience tension headaches that are periorbital. Both are tension headaches despite the different locations. And almost all patients who experience any subset of vulvodynia have provoked vestibular pain. So the only thing that separates vestibulodynia from other patterns of vulvodynia is the option of vestibulectomy for therapy.

I don’t think that vulvodynia and vestibulodynia are “wastebasket” names for undiagnosable vulvar pain; rather, they are specific disease processes produced by pelvic floor dysfunction that predisposes a woman to neuropathic pain with a trigger or to a systemic pain syndrome that includes an abnormal pelvic floor.

Dr. Gunter: There are probably many causes of PVD, as Dr. Haefner suggested. There may be an ignition hypothesis, whereby some outside inflammatory trigger or trauma produces local neurogenic inflammation. However, given the prevalence of other pain disorders, there is probably also a need to have a lowered threshold for these changes to occur—basically, a vulnerable neurologic platform.

For some women, local neural hyperplasia is probably a factor. It is possible that there are different causes for primary and secondary vestibulodynia.

Vulvodynia and depression often travel together. They are such common comorbidities, in fact, that some physicians theorize that vulvodynia may be a symptom of an underlying mood disorder, such as depression, or that depression may be one manifestation of chronic vulvar pain. Suffice it to say that chronic pain and depression are often associated, and it is frequently difficult to determine whether the relationship is one of cause and effect.

Comprehensive care of the patient who has vulvar pain, therefore, should include a thorough history, looking specifically for depression (including sleep disorders) and eliciting information on any suicidal thoughts or intentions.

Although many patients who have vulvodynia are treated with an antidepressant, the dose that relieves pain may not be high enough to attenuate an accompanying mood disorder. My approach is to team up with a psychiatrist or psychologist who is familiar with vulvar pain syndromes. Together, we monitor the patient and fine-tune the therapeutic response.

—Neal M. Lonky, MD, MPH

Do oral contraceptives contribute to vestibulodynia?

Dr. Lonky: Is PVD more prevalent among OC users?

Dr. Haefner: Controversy surrounds the question of whether vestibulodynia and OC use are linked. Some studies suggest no association12–14 and others suggest a possible effect of OCs on vulvodynia.15–17 A study by Reed and colleagues found no association between taking OCs or hormone therapy at enrollment and incident vulvodynia only in the univariable analysis, but not when controlling for age at enrollment.18 This reflects the finding that younger age was associated with incident disease; younger age and use of OCs are similarly associated.

Dr. Gunter: I am not a believer in a cause-and-effect relationship between OC use and vestibulodynia. I do not find the studies demonstrating an association convincing. Given the supraphysiologic levels of hormones during pregnancy, if high hormone levels played a role, we should also see a greater incidence of vestibulodynia among women who have several pregnancies at an early age.

Dr. Edwards: In my practice, stopping, starting, and changing OCs has made no difference for patients. Topical estrogen supplementation in the occasional OC user who has signs of low estrogen has been useful at times.

Do herpes or genital warts contribute to PVD?

Dr. Lonky: Does a history of vulvar herpes or genital warts have any impact on the incidence of PVD?

Dr. Edwards: No.

Dr. Gunter: I agree that it has no impact.

Dr. Haefner: Herpes is sometimes associated with vulvar pain. The lesions resolve, but pain may continue as post-herpetic neuralgia. As with shingles, a low threshold for starting a patient on gabapentin to control pain after herpes may be beneficial.

Genital warts rarely cause vulvar pain—but the treatment may. Patients sometimes feel pain following topical treatment, as well as pain from surgical wart treatment.

Effect of demographic variables

Dr. Lonky: Does race, skin type, or hair or eye color make a difference in the prevalence, manifestation of symptoms, or treatment of PVD?

Dr. Gunter: I am not aware of any studies that confirm an association between vulvodynia and those factors.

Dr. Edwards: I don’t know whether any of these variables make a difference. My own impression—confirmed by informal study in my office—is that vulvodynia patients weigh less than my general dermatology patients and are better educated. I sometimes get the sense that my vulvodynia patients are more likely to be fair.

Dr. Lonky: What age group is most commonly affected by PVD?

Dr. Edwards: In my experience the most common age group is women 25 to 45 years old, probably because they are the most sexually active group old enough and tough enough to pursue this issue.

Dr. Gunter: I believe it affects all women equally, although women in their reproductive years are more likely to visit a gynecologist and, therefore, probably more likely to be given this diagnosis.

Dr. Lonky: Do you believe that PVD and generalized vulvar dysesthesia are curable—or just treatable?

Dr. Gunter: That depends on many variables. It is far more challenging to cure a patient who has multiple pain syndromes (for example, fibromyalgia, migraines, and irritable bowel syndrome) than the woman who simply has vestibulodynia or generalized vulvar pain. In addition, stress, anxiety, coping skills, and depression all play a role. In my opinion, a woman without comorbidity has a good chance of having her symptoms well-controlled. Some will be cured (that is, able to discontinue medications), and others will need ongoing treatment but will not be bothered by their symptoms.

Dr. Haefner: The response to treatment in many pain patients depends on the amount of time that the pain has been present. Someone who has had pain for 30 years will probably not be cured 3 months after starting treatment. However, someone with a short duration of pain often gets good improvement. One hundred percent improvement is rare, however. Many patients are able to approach the 80% improvement mark.

Dr. Edwards: I would say that these conditions are manageable more than curable, although pure vestibulodynia—which is uncommon—is curable with surgery.

Vestibulectomy technique

(A) Incision. In many cases, the incision needs to extend up to the opening of the Skene’s ducts on the vestibule before it is carried down laterally along Hart’s line to the perianal skin, with the mucosa undermined above the hymeneal ring. (B) Excision. Remove the tissue superior to the hymeneal ring. (C) Advancement of vaginal mucosa. Further undermine the mucosa and advance it to close the defect. (D) Suturing. Close the defect in two layers using absorbable suture.

Is vestibulectomy definitive treatment?

Dr. Lonky: Does vestibulectomy work as a definitive treatment for PVD?

Dr. Gunter: Vestibulectomy—that is, resection of the vestibule and advancement of vaginal mucosa—is well described for women who have localized vestibulodynia. The complication rate is low, with only 3% of women reporting worsening of symptoms after the procedure.19,20 Success rates range from 17% to 89%, although many studies are retrospective reviews or include nonhomogenous populations, or both.19–21 A prospective study (Level II) indicates a 52% reduction in pain scores for women 6 months after vestibulectomy—and the scores continued to improve at evaluation at 2.5 years.22,23

Prospective studies indicate that vestibulectomy improves pain scores more than cognitive behavioral therapy, biofeedback, oral despiramine, and topical lidocaine.22,23 However, even surgery carries a robust placebo response rate, and vulvar biopsy alone has been associated with an improvement in pain scores in 67% of women.24,25

I offer surgery for vestibulodynia after the patient has failed at least two therapies (two topical treatments or one topical and one oral treatment). I offer injections before proceeding, and almost all patients opt to try them. I do not offer vestibulectomy to patients who have unprovoked pain or pain outside of resection margins.

Dr. Haefner: Surgical excision of the vulvar vestibule has met with success, in some studies, in more than 80% of cases, but it should be reserved for women who have longstanding and localized vestibular pain in whom other management options have failed.

The patient should undergo cotton-swab testing to outline areas of pain before anesthesia is administered in the operating room. Often, the incision will need to extend up to the opening of the Skene’s ducts on the vestibule (FIGURE). The incision is carried down laterally along Hart’s line to the perianal skin, and the mucosa is undermined above the hymeneal ring. The specimen is excised superior to the hymeneal ring. The vaginal tissue is further undermined and brought down to close the defect in two layers using absorbable suture. A review of this technique with illustrations has been published.26

Dr. Lonky: Thank you all again for sharing your considerable expertise, experience, and insight.

Harlow BL, Stewart EG. A population-based assessment of chronic unexplained vulvar pain: have we underestimated the prevalence of vulvodynia? J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2003;58(2):82–88.

In this population-based study, 16% of women reported a history of chronic unexplained vulvar pain, and nearly 7% reported current symptoms.

Khandker M, Brady SS, Vitonis AF, Maclehose RF, Stewart EG, Harlow BL. The influence of depression and anxiety on risk of adult onset vulvodynia [published online ahead of print August 8, 2011].

J Womens Health (Larchmt). doi:10.1089/jwh.2010.2661.

Vulvodynia was four times more likely among women who had antecedent mood or anxiety disorders than in women who didn’t. Vulvodynia was also associated with new or recurrent onset of mood or anxiety disorders.

Masheb RM, Wang E, Lozano C, Kerns RD. Prevalence and correlates of depression in treatment-seeking women with vulvodynia. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;25(8):786–791.

Comorbid major depressive disorders in women who have vulvodynia are related to greater pain severity and worse functioning.

Reed BD, Haefner HK, Punch MR, Roth RS, Gorenflo DW, Gillespie BW. Psychosocial and sexual functioning in women with vulvodynia and chronic pelvic pain. A comparative evaluation. J Reprod Med. 2000;45(8):624–632.

Women who have vulvodynia are psychologically similar to women who don’t. A primary psychological cause of vulvodynia is not supported.

Tribo MJ, Andion O, Ros S, et al. Clinical characteristics and psychopathological profile of patients with vulvodynia: an observational and descriptive study. Dermatology. 2008;216(1):24–30.

Psychiatric treatment may be a useful option to improve symptoms of vulvodynia.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think about this series on Vulvar Pain Syndromes.

1. McCormack WM. Two urogenital sinus syndromes. Interstitial cystitis and focal vulvitis. J Reprod Med. 1990;35(9):873-876.

2. Fitzpatrick CC, DeLancey JP, Elkins TE, McGuire EJ. Vulvar vestibulitis and interstitial cystitis: a disorder of urogenital sinusderived epithelium. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81(5 Pt 2):860-862.

3. Bazin S, Bouchard C, Brisson J, Morin C, Meisels A, Fortier M. Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome: an exploratory case-control study. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83(1):47-50.

4. Bohm-Starke N, Falconer C, Rylander E, Hilliges M. The expression of cyclooxygenase 2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase indicates no active inflammation in vulvar vestibulitis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80(7):638-644.

5. Goetsch MF. Vulvar vestibulitis: prevalence and historic features in a general gynecologic practice population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164(6 Pt 1):1609-1616.

6. Jeremias J, Ledger WJ, Witkin SS. Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist gene polymorphism in women with vulvar vestibulitis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182(2):283-285.

7. Witkin SS, Gerber S, Ledger WJ. Differential characterization of women with vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(3):589-594.

8. Foster DC, Piekarz KH, Murant TI, LaPoint R, Haidaris CG, Phipps RP. Enhanced synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines by vulvar vestibular fibroblasts: implications for vulvar vestibulitis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(4):346. e1-8.

9. Krantz KE. Innervation of the human vulva and vagina: a microscopic study. Obstet Gynecol. 1958;12:382-396.

10. Bohm-Starke N, Hilliges M, Brodda-Jansen G, Rylander E, Torebjork E. Psychophysical evidence of nociceptor sensitization in vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. Pain. 2001;94(2):177-183.

11. Tympanidis P, Terenghi G, Dowd P. Increased innervation of the vulval vestibule in patients with vulvodynia. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148(5):1021-1027.

12. Bachman GA, Rosen R, Pinn VW, et al. Vulvodynia: a state-of-the-art consensus on definitions, diagnosis and management. J Reprod Med. 2006;51(6):447-456.

13. Harlow BL, Vitonis AF, Stewart EG. Influence of oral contraceptive use on the risk of adult-onset vulvodynia. J Reprod Med. 2008;53(2):102-110.

14. Danielsson I, Sjoberg I, Stenlund H, Wikman M. Prevalence and incidence of prolonged and severe dyspareunia in women: results from a population study. Scand J Public Health. 2003;31(2):113-118.

15. Bohm-Starke N, Johannesson U, Hilliges M, Rylander E, Torebjork E. Decreased mechanical pain threshold in the vestibular mucosa of women using oral contraceptives: a contributing factor in vulvar vestibulitis? J Reprod Med. 2004;49(11):888-892.

16. Greenstein A, Ben-Aroya Z, Fass O, et al. Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome and estrogen dose of oral contraceptive pills. J Sexual Med. 2007;4(6):1679-1683.

17. Bouchard C, Brisson J, Fortier M, Morin C, Blanchette C. Use of oral contraceptive pills and vulvar vestibulitis: a case-control study. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(3):254-261.

18. Reed BD, Haefner HK, Sen A, Gorenflo DW. Vulvodynia incidence and remission rates among adult women: a 2-year follow-up study. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 Pt 1):231-237.

19. Goldstein AT, Klingman D, Christopher K, Johnson C, Marinoff SC. Surgical treatment of vulvar vestibulitis syndrome: outcome assessment derived from a postoperative questionnaire. J Sex Med. 2006;3(5):923-931.

20. Eva LJ, Narain S, Orakwue CO, Luesley DM. Is modified vestibulectomy for localized provoked vulvodynia an effective long-term treatment? A follow-up study. J Reprod Med. 2008;53(6):435-440.

21. Haefner HK, Collins ME, Davis GD, et al. The vulvodynia guideline. J Lower Genit Tract Dis. 2005;9(1):40-51.

22. Bergeron S, Binik YM, Khalife S, et al. A randomized comparison of group cognitive-behavioral therapy, surface electromyographic biofeedback, and vestibulectomy in the treatment of dyspareunia resulting from vulvar vestibulitis. Pain. 2001;91(3):297-306.

23. Bergeron S, Khalife S, Glazer HI, Binik Y. Surgical and behavioral treatments for vestibulodynia: two-and-one-half-year follow-up and predictors of outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(1):159-166.

24. Gunter J. Vulvodynia: new thoughts on a devastating condition. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2007;62(12):812-819.

25. Tympanidis P, Terenghi G, Dowd P. Increased innervation of the vulvar vestibule in patients with vulvodynia. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148(5):1021-1027.

26. Haefner HK. Critique of new gynecologic surgical procedures: surgery for vulvar vestibulitis. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2000;43(3):689-700.

1. McCormack WM. Two urogenital sinus syndromes. Interstitial cystitis and focal vulvitis. J Reprod Med. 1990;35(9):873-876.

2. Fitzpatrick CC, DeLancey JP, Elkins TE, McGuire EJ. Vulvar vestibulitis and interstitial cystitis: a disorder of urogenital sinusderived epithelium. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81(5 Pt 2):860-862.

3. Bazin S, Bouchard C, Brisson J, Morin C, Meisels A, Fortier M. Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome: an exploratory case-control study. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83(1):47-50.

4. Bohm-Starke N, Falconer C, Rylander E, Hilliges M. The expression of cyclooxygenase 2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase indicates no active inflammation in vulvar vestibulitis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80(7):638-644.

5. Goetsch MF. Vulvar vestibulitis: prevalence and historic features in a general gynecologic practice population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164(6 Pt 1):1609-1616.

6. Jeremias J, Ledger WJ, Witkin SS. Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist gene polymorphism in women with vulvar vestibulitis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182(2):283-285.

7. Witkin SS, Gerber S, Ledger WJ. Differential characterization of women with vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(3):589-594.

8. Foster DC, Piekarz KH, Murant TI, LaPoint R, Haidaris CG, Phipps RP. Enhanced synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines by vulvar vestibular fibroblasts: implications for vulvar vestibulitis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(4):346. e1-8.

9. Krantz KE. Innervation of the human vulva and vagina: a microscopic study. Obstet Gynecol. 1958;12:382-396.

10. Bohm-Starke N, Hilliges M, Brodda-Jansen G, Rylander E, Torebjork E. Psychophysical evidence of nociceptor sensitization in vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. Pain. 2001;94(2):177-183.

11. Tympanidis P, Terenghi G, Dowd P. Increased innervation of the vulval vestibule in patients with vulvodynia. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148(5):1021-1027.

12. Bachman GA, Rosen R, Pinn VW, et al. Vulvodynia: a state-of-the-art consensus on definitions, diagnosis and management. J Reprod Med. 2006;51(6):447-456.

13. Harlow BL, Vitonis AF, Stewart EG. Influence of oral contraceptive use on the risk of adult-onset vulvodynia. J Reprod Med. 2008;53(2):102-110.