User login

Hot flashes and sleep disruption contribute independently to depression in menopause

Hot flashes and sleep disruption contribute independently to the development of depression in menopause, judging from the findings of a recent study.

In that study, 29 premenopausal women, aged 18-45 years, received a single dose of the GnRH agonist leuprolide in order to induce hypoestrogenism and ovarian suppression for the study period. The women in the study had no history of primary sleep disturbances, low estrogen levels, or depression, according to Hadine Joffe, MD, director of the Women’s Hormone and Aging Research Program at Harvard Medical School, in Boston, and her associates.

All the study participants underwent baseline mood evaluation using both the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). Existing sleep disturbances were ruled out at baseline with sleep diaries, questionnaires, and two ambulatory screening polysomnography (PSG) studies.

After 4 weeks of administration of leuprolide, depressive symptoms had developed among most of the women in the study. The mean MADRS score was 4.1, and overall, it was 3.1 points higher than it had been at baseline. One woman had a 15-point increase in her score, suggesting significant depression. The MADRS score increased by at least 5 points in 24% of the women and remained unchanged in 38%, reflecting variability among the women on the impact of leuprolide on depressive symptoms, the investigators reported (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016 Sep 20. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-2348).

Leuprolide universally suppressed estradiol to postmenopausal levels in the women within 2 weeks. Hot flashes developed in 20 (69%) women, with a median of 3.6 hot flashes during the day and 3.8 at night. The median number of objectively measured nighttime hot flashes per night was 3.

Changes to sleep patterns varied widely for each woman; for example, wake time after sleep onset ranged from an additional 140 minutes to 23 fewer minutes for one woman. There was a correlation between the number of subjectively reported nighttime hot flashes with increased sleep fragmentation as measured by PSG. The number of reported nighttime hot flashes was associated with an increase in depressive symptoms that was disproportionate to the number of nighttime hot flashes reported, according to the findings of a univariate analysis. The number of daytime hot flashes had no such effect.

In light of these findings, Dr. Joffe and her associates urged clinicians to screen women who report nighttime hot flashes and sleep interruption for mood disturbance. “Treatment of those with menopause-related depressive symptoms should encompass therapies that improve sleep interruption as well as nocturnal [hot flashes],” they wrote.

The study was sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Joffe has received grant support from Merck and has served as a consultant/adviser for Merck, Mitsubishi Tanabe, NeRRe Therapeutics, and Noven.

Hot flashes and sleep disruption contribute independently to the development of depression in menopause, judging from the findings of a recent study.

In that study, 29 premenopausal women, aged 18-45 years, received a single dose of the GnRH agonist leuprolide in order to induce hypoestrogenism and ovarian suppression for the study period. The women in the study had no history of primary sleep disturbances, low estrogen levels, or depression, according to Hadine Joffe, MD, director of the Women’s Hormone and Aging Research Program at Harvard Medical School, in Boston, and her associates.

All the study participants underwent baseline mood evaluation using both the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). Existing sleep disturbances were ruled out at baseline with sleep diaries, questionnaires, and two ambulatory screening polysomnography (PSG) studies.

After 4 weeks of administration of leuprolide, depressive symptoms had developed among most of the women in the study. The mean MADRS score was 4.1, and overall, it was 3.1 points higher than it had been at baseline. One woman had a 15-point increase in her score, suggesting significant depression. The MADRS score increased by at least 5 points in 24% of the women and remained unchanged in 38%, reflecting variability among the women on the impact of leuprolide on depressive symptoms, the investigators reported (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016 Sep 20. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-2348).

Leuprolide universally suppressed estradiol to postmenopausal levels in the women within 2 weeks. Hot flashes developed in 20 (69%) women, with a median of 3.6 hot flashes during the day and 3.8 at night. The median number of objectively measured nighttime hot flashes per night was 3.

Changes to sleep patterns varied widely for each woman; for example, wake time after sleep onset ranged from an additional 140 minutes to 23 fewer minutes for one woman. There was a correlation between the number of subjectively reported nighttime hot flashes with increased sleep fragmentation as measured by PSG. The number of reported nighttime hot flashes was associated with an increase in depressive symptoms that was disproportionate to the number of nighttime hot flashes reported, according to the findings of a univariate analysis. The number of daytime hot flashes had no such effect.

In light of these findings, Dr. Joffe and her associates urged clinicians to screen women who report nighttime hot flashes and sleep interruption for mood disturbance. “Treatment of those with menopause-related depressive symptoms should encompass therapies that improve sleep interruption as well as nocturnal [hot flashes],” they wrote.

The study was sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Joffe has received grant support from Merck and has served as a consultant/adviser for Merck, Mitsubishi Tanabe, NeRRe Therapeutics, and Noven.

Hot flashes and sleep disruption contribute independently to the development of depression in menopause, judging from the findings of a recent study.

In that study, 29 premenopausal women, aged 18-45 years, received a single dose of the GnRH agonist leuprolide in order to induce hypoestrogenism and ovarian suppression for the study period. The women in the study had no history of primary sleep disturbances, low estrogen levels, or depression, according to Hadine Joffe, MD, director of the Women’s Hormone and Aging Research Program at Harvard Medical School, in Boston, and her associates.

All the study participants underwent baseline mood evaluation using both the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). Existing sleep disturbances were ruled out at baseline with sleep diaries, questionnaires, and two ambulatory screening polysomnography (PSG) studies.

After 4 weeks of administration of leuprolide, depressive symptoms had developed among most of the women in the study. The mean MADRS score was 4.1, and overall, it was 3.1 points higher than it had been at baseline. One woman had a 15-point increase in her score, suggesting significant depression. The MADRS score increased by at least 5 points in 24% of the women and remained unchanged in 38%, reflecting variability among the women on the impact of leuprolide on depressive symptoms, the investigators reported (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016 Sep 20. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-2348).

Leuprolide universally suppressed estradiol to postmenopausal levels in the women within 2 weeks. Hot flashes developed in 20 (69%) women, with a median of 3.6 hot flashes during the day and 3.8 at night. The median number of objectively measured nighttime hot flashes per night was 3.

Changes to sleep patterns varied widely for each woman; for example, wake time after sleep onset ranged from an additional 140 minutes to 23 fewer minutes for one woman. There was a correlation between the number of subjectively reported nighttime hot flashes with increased sleep fragmentation as measured by PSG. The number of reported nighttime hot flashes was associated with an increase in depressive symptoms that was disproportionate to the number of nighttime hot flashes reported, according to the findings of a univariate analysis. The number of daytime hot flashes had no such effect.

In light of these findings, Dr. Joffe and her associates urged clinicians to screen women who report nighttime hot flashes and sleep interruption for mood disturbance. “Treatment of those with menopause-related depressive symptoms should encompass therapies that improve sleep interruption as well as nocturnal [hot flashes],” they wrote.

The study was sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Joffe has received grant support from Merck and has served as a consultant/adviser for Merck, Mitsubishi Tanabe, NeRRe Therapeutics, and Noven.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ENDOCRINOLOGY & METABOLISM

Key clinical point: Hot flashes and sleep disruption contribute independently to the development of depression in menopause.

Major finding: Depression scores increased by 3 points on the MADRS after 4 weeks on GnRH agonist leuprolide. Sleep disruption was also common among the women in the study. Depression developed among many, but not all the women, with univariate analysis showing that hot flashes and sleep disruption contributed independently to their mood changes.

Data source: A prospective study in which 29 young women without depression were subjected to rapid, premature, and reversible menopause with one open-label dose of leuprolide in an experimental model.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Hadine Joffe has received grant support from Merck and has served as a consultant/adviser for Merck, Mitsubishi Tanabe, NeRRe Therapeutics, and Noven.

Letter to the Editor: Menopause and HT

“2016 UPDATE ON MENOPAUSE”

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD (JULY 2016)

Menopause and hormone therapy

As a long-term believer (proven!) of the value of the old comment, “estrogen forever,” I was pleased to see all the positive comments about estrogen in Dr. Kaunitz’s article. I was disappointed, however, in the comments in the box (page 39), “What this evidence means for practice.”

While my prejudice, statistically supported, is old fashioned, omission of the newer and marvelous way to counteract the only bad effects of estrogen (endometrial stimulation leading to endometrial adenocarcinoma) seems to be a major oversight. The new and least (if any) side-effect method means a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) yielding local progesterone counteraction to this major side effect of estrogen therapy.

Arthur A. Fleisher II, MD

Northridge, California

Dr. Kaunitz responds

I thank Dr. Fleisher for his interest in my 2016 Update on Menopause. I agree that off-label use of the LNG-IUD represents an appropriate alternative to systemic progestin when using estrogen to treat menopausal symptoms in women with an intact uterus.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

“2016 UPDATE ON MENOPAUSE”

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD (JULY 2016)

Menopause and hormone therapy

As a long-term believer (proven!) of the value of the old comment, “estrogen forever,” I was pleased to see all the positive comments about estrogen in Dr. Kaunitz’s article. I was disappointed, however, in the comments in the box (page 39), “What this evidence means for practice.”

While my prejudice, statistically supported, is old fashioned, omission of the newer and marvelous way to counteract the only bad effects of estrogen (endometrial stimulation leading to endometrial adenocarcinoma) seems to be a major oversight. The new and least (if any) side-effect method means a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) yielding local progesterone counteraction to this major side effect of estrogen therapy.

Arthur A. Fleisher II, MD

Northridge, California

Dr. Kaunitz responds

I thank Dr. Fleisher for his interest in my 2016 Update on Menopause. I agree that off-label use of the LNG-IUD represents an appropriate alternative to systemic progestin when using estrogen to treat menopausal symptoms in women with an intact uterus.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

“2016 UPDATE ON MENOPAUSE”

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD (JULY 2016)

Menopause and hormone therapy

As a long-term believer (proven!) of the value of the old comment, “estrogen forever,” I was pleased to see all the positive comments about estrogen in Dr. Kaunitz’s article. I was disappointed, however, in the comments in the box (page 39), “What this evidence means for practice.”

While my prejudice, statistically supported, is old fashioned, omission of the newer and marvelous way to counteract the only bad effects of estrogen (endometrial stimulation leading to endometrial adenocarcinoma) seems to be a major oversight. The new and least (if any) side-effect method means a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) yielding local progesterone counteraction to this major side effect of estrogen therapy.

Arthur A. Fleisher II, MD

Northridge, California

Dr. Kaunitz responds

I thank Dr. Fleisher for his interest in my 2016 Update on Menopause. I agree that off-label use of the LNG-IUD represents an appropriate alternative to systemic progestin when using estrogen to treat menopausal symptoms in women with an intact uterus.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Decision rule identifies unprovoked VTE patients who can halt anticoagulation

ROME – Half of all women who experience a first unprovoked venous thromboembolism (VTE) can safely be spared lifelong anticoagulation through application of the newly validated HERDOO2 decision rule, Marc A. Rodger, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“We’ve validated that a simple, memorable decision rule on anticoagulation applied at the clinically relevant time point works. And it is the only clinical decision rule that has now been prospectively validated,” said Dr. Rodger, professor of medicine, chief and chair of the division of hematology, and head of the thrombosis program at the University of Ottawa.

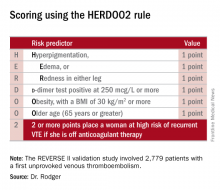

He presented the results of the validation study, known as the REVERSE II study, which included 2,779 patients with a first unprovoked VTE at 44 centers in seven countries. The full name of the decision rule is “Men Continue and HERDOO2,” a name that says it all: the rule posits that all men as well as those women with a HERDOO2 (Hyperpigmentation, Edema, Redness, d-dimer, Obesity, Older age, 2 or more points) score of at least 2 out of a possible 4 points need to stay on anticoagulation indefinitely because their risk of a recurrent VTE off-therapy clearly exceeds that of a bleeding event on-therapy. In contrast, women with a HERDOO2 score of 0 or 1 can safely stop anticoagulation after the standard 3-6 months of acute short-term therapy.

“Sorry, gentlemen, but we could find no low-risk group of men. They were all high risk,” he said. “But 50% of women with unprovoked vein blood clots can be spared the burdens, costs, and risks of lifelong blood thinners.”

Dr. Rodger and coinvestigators began work on developing a multivariate clinical decision rule in 2001. They examined 69 risk predictors, eventually winnowing down to a manageable four potent risk predictors identified by the acronym HERDOO2.

The derivation study was published 8 years ago (CMAJ. 2008;Aug 26;179[5]:417-26). It showed that women with a HERDOO2 score of 2 or more as well as all men had roughly a 14% rate of recurrent VTE in the first year after stopping anticoagulation, while women with a score of 0 or 1 had about a 1.6% risk. The International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis suggests that it’s safe to discontinue anticoagulants if the risk of recurrent thrombosis at 1 year off-therapy is less than 5%, given the significant risk of serious bleeding on-therapy and the fact that a serious bleed event is two to three times more likely than a VTE to be fatal.

Dr. Rodger and coinvestigators recognized that a clinical decision rule needs to be externally validated before it’s ready for prime-time use in clinical practice. Thus, they conducted the REVERSE II study, in which the decision rule was applied after the 2,799 participants had been on anticoagulation for 5-12 months. All had a first proximal deep vein thrombosis and/or a segmental or greater pulmonary embolism. Patients were still on anticoagulation at the time the rule was applied, which is why the cut point for a positive d-dimer test in HERDOO2 is 250 mcg/L, half of the threshold value for a positive test in patients not on anticoagulation.

They identified 631 women as low risk, with a HERDOO2 score of 0 or 1. They and their physicians were instructed to stop anticoagulation at that time. The 2,148 high-risk subjects – that is, all of the men and the high-risk women – were advised to remain on anticoagulation. The primary study endpoint was the rate of recurrent VTE in the 12 months following testing and patient guidance. The lost-to-follow-up rate was 2.2%.

The recurrent VTE rate was 3% in the 591 low-risk women who discontinued anticoagulants and zero in 31 others who elected to stay on medication. In the high-risk group identified by the HERDOO2 rule, the recurrent VTE rate at 12 months was 8.1% in the 323 who opted to discontinue anticoagulants and just 1.6% in 1,802 who continued on therapy as advised, a finding that underscores the effectiveness of selectively applied long-term anticoagulation therapy, he continued.

The recurrent VTE rate among the 291 women with a HERDOO2 score of 0 or 1 who were on exogenous estrogen was 1.4%, while in high-risk women taking estrogen the rate was more than doubled at 3.1%. But in women aged 50-64 identified by the HERDOO2 rule as being low risk, the actual recurrent VTE rate was 5.7%, a finding that raised a red flag for the investigators.

“There may be an evolution of the HERDOO2 decision rule to a lower age cut point. But that’s something that requires further study in postmenopausal women,” according to Dr. Rodger.

The investigators defined a first unprovoked VTE as one occurring in the absence during the previous 90 days of major surgery, a fracture or cast, more than 3 days of immobilization, or malignancy within the last 5 years.

Venous thromboembolism is the second most common cardiovascular disorder and the third most common cause of cardiovascular death. Unprovoked VTEs account for half of all VTEs. Their management has been a controversial subject. Both the American College of Chest Physicians and the European Society of Cardiology recommend continuing anticoagulation indefinitely in patients who aren’t at high bleeding risk.

“But this is a relatively weak 2B recommendation because of the tightly balanced competing risks of recurrent thrombosis off anticoagulation and major bleeding on anticoagulation,” Dr. Rodger said. He added that he considers REVERSE II to be practice changing, and predicted that once the results are published the guidelines will be revised.

Discussant Giancarlo Agnelli, MD, was a tough critic who gave fair warning.

“I am friends with many of the authors of this paper, and in this country we are usually gentle with enemies and nasty with friends,” declared Dr. Agnelli, professor of internal medicine and director of internal and cardiovascular medicine and the stroke unit at the University of Perugia, Italy.

He didn’t find the REVERSE II study or the HERDOO2 rule persuasive. On the plus side, he said, the HERDOO2 rule has now been validated, unlike the proposed DASH and Vienna rules. And it was tested in a diverse multinational patient population. But the fact that the HERDOO2 rule is only applicable in women is a major limitation. And REVERSE II was not a randomized trial, Dr. Agnelli noted.

Moreover, 1 year of follow-up seems insufficient, he continued. He cited a French multicenter trial in which patients with a first unprovoked VTE received 6 months of anticoagulants and were then randomized to another 18 months of anticoagulation or placebo. During that 18 months, the group on anticoagulants had a significantly lower rate of the composite endpoint comprised of recurrent VTE or major bleeding, but once that period was over they experienced catchup. By the time the study ended at 42 months, the two study arms didn’t differ significantly in the composite endpoint (JAMA. 2015 Jul 7;314[1]:31-40).

More broadly, Dr. Agnelli also questioned the need for an anticoagulation discontinuation rule in the contemporary era of new oral anticoagulants (NOACs). He was lead investigator in the AMPLIFY study, a major randomized trial of fixed-dose apixaban (Eliquis) versus conventional therapy with subcutaneous enoxaparin (Lovenox) bridging to warfarin in 5,395 patients with acute VTE. The NOAC was associated with a 69% reduction in the relative risk of bleeding and was noninferior to standard therapy in the risk of recurrent VTE (N Engl J Med. 2013 Aug 29;369[9]:799-808).

“Why should we think about withholding anticoagulation in some patients when we now have such a safe approach?” he asked.

Dr. Rodger reported receiving research grants from the French government as well as from Biomerieux, which funded the REVERSE II study. Dr. Agnelli reported having no financial conflicts.

ROME – Half of all women who experience a first unprovoked venous thromboembolism (VTE) can safely be spared lifelong anticoagulation through application of the newly validated HERDOO2 decision rule, Marc A. Rodger, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“We’ve validated that a simple, memorable decision rule on anticoagulation applied at the clinically relevant time point works. And it is the only clinical decision rule that has now been prospectively validated,” said Dr. Rodger, professor of medicine, chief and chair of the division of hematology, and head of the thrombosis program at the University of Ottawa.

He presented the results of the validation study, known as the REVERSE II study, which included 2,779 patients with a first unprovoked VTE at 44 centers in seven countries. The full name of the decision rule is “Men Continue and HERDOO2,” a name that says it all: the rule posits that all men as well as those women with a HERDOO2 (Hyperpigmentation, Edema, Redness, d-dimer, Obesity, Older age, 2 or more points) score of at least 2 out of a possible 4 points need to stay on anticoagulation indefinitely because their risk of a recurrent VTE off-therapy clearly exceeds that of a bleeding event on-therapy. In contrast, women with a HERDOO2 score of 0 or 1 can safely stop anticoagulation after the standard 3-6 months of acute short-term therapy.

“Sorry, gentlemen, but we could find no low-risk group of men. They were all high risk,” he said. “But 50% of women with unprovoked vein blood clots can be spared the burdens, costs, and risks of lifelong blood thinners.”

Dr. Rodger and coinvestigators began work on developing a multivariate clinical decision rule in 2001. They examined 69 risk predictors, eventually winnowing down to a manageable four potent risk predictors identified by the acronym HERDOO2.

The derivation study was published 8 years ago (CMAJ. 2008;Aug 26;179[5]:417-26). It showed that women with a HERDOO2 score of 2 or more as well as all men had roughly a 14% rate of recurrent VTE in the first year after stopping anticoagulation, while women with a score of 0 or 1 had about a 1.6% risk. The International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis suggests that it’s safe to discontinue anticoagulants if the risk of recurrent thrombosis at 1 year off-therapy is less than 5%, given the significant risk of serious bleeding on-therapy and the fact that a serious bleed event is two to three times more likely than a VTE to be fatal.

Dr. Rodger and coinvestigators recognized that a clinical decision rule needs to be externally validated before it’s ready for prime-time use in clinical practice. Thus, they conducted the REVERSE II study, in which the decision rule was applied after the 2,799 participants had been on anticoagulation for 5-12 months. All had a first proximal deep vein thrombosis and/or a segmental or greater pulmonary embolism. Patients were still on anticoagulation at the time the rule was applied, which is why the cut point for a positive d-dimer test in HERDOO2 is 250 mcg/L, half of the threshold value for a positive test in patients not on anticoagulation.

They identified 631 women as low risk, with a HERDOO2 score of 0 or 1. They and their physicians were instructed to stop anticoagulation at that time. The 2,148 high-risk subjects – that is, all of the men and the high-risk women – were advised to remain on anticoagulation. The primary study endpoint was the rate of recurrent VTE in the 12 months following testing and patient guidance. The lost-to-follow-up rate was 2.2%.

The recurrent VTE rate was 3% in the 591 low-risk women who discontinued anticoagulants and zero in 31 others who elected to stay on medication. In the high-risk group identified by the HERDOO2 rule, the recurrent VTE rate at 12 months was 8.1% in the 323 who opted to discontinue anticoagulants and just 1.6% in 1,802 who continued on therapy as advised, a finding that underscores the effectiveness of selectively applied long-term anticoagulation therapy, he continued.

The recurrent VTE rate among the 291 women with a HERDOO2 score of 0 or 1 who were on exogenous estrogen was 1.4%, while in high-risk women taking estrogen the rate was more than doubled at 3.1%. But in women aged 50-64 identified by the HERDOO2 rule as being low risk, the actual recurrent VTE rate was 5.7%, a finding that raised a red flag for the investigators.

“There may be an evolution of the HERDOO2 decision rule to a lower age cut point. But that’s something that requires further study in postmenopausal women,” according to Dr. Rodger.

The investigators defined a first unprovoked VTE as one occurring in the absence during the previous 90 days of major surgery, a fracture or cast, more than 3 days of immobilization, or malignancy within the last 5 years.

Venous thromboembolism is the second most common cardiovascular disorder and the third most common cause of cardiovascular death. Unprovoked VTEs account for half of all VTEs. Their management has been a controversial subject. Both the American College of Chest Physicians and the European Society of Cardiology recommend continuing anticoagulation indefinitely in patients who aren’t at high bleeding risk.

“But this is a relatively weak 2B recommendation because of the tightly balanced competing risks of recurrent thrombosis off anticoagulation and major bleeding on anticoagulation,” Dr. Rodger said. He added that he considers REVERSE II to be practice changing, and predicted that once the results are published the guidelines will be revised.

Discussant Giancarlo Agnelli, MD, was a tough critic who gave fair warning.

“I am friends with many of the authors of this paper, and in this country we are usually gentle with enemies and nasty with friends,” declared Dr. Agnelli, professor of internal medicine and director of internal and cardiovascular medicine and the stroke unit at the University of Perugia, Italy.

He didn’t find the REVERSE II study or the HERDOO2 rule persuasive. On the plus side, he said, the HERDOO2 rule has now been validated, unlike the proposed DASH and Vienna rules. And it was tested in a diverse multinational patient population. But the fact that the HERDOO2 rule is only applicable in women is a major limitation. And REVERSE II was not a randomized trial, Dr. Agnelli noted.

Moreover, 1 year of follow-up seems insufficient, he continued. He cited a French multicenter trial in which patients with a first unprovoked VTE received 6 months of anticoagulants and were then randomized to another 18 months of anticoagulation or placebo. During that 18 months, the group on anticoagulants had a significantly lower rate of the composite endpoint comprised of recurrent VTE or major bleeding, but once that period was over they experienced catchup. By the time the study ended at 42 months, the two study arms didn’t differ significantly in the composite endpoint (JAMA. 2015 Jul 7;314[1]:31-40).

More broadly, Dr. Agnelli also questioned the need for an anticoagulation discontinuation rule in the contemporary era of new oral anticoagulants (NOACs). He was lead investigator in the AMPLIFY study, a major randomized trial of fixed-dose apixaban (Eliquis) versus conventional therapy with subcutaneous enoxaparin (Lovenox) bridging to warfarin in 5,395 patients with acute VTE. The NOAC was associated with a 69% reduction in the relative risk of bleeding and was noninferior to standard therapy in the risk of recurrent VTE (N Engl J Med. 2013 Aug 29;369[9]:799-808).

“Why should we think about withholding anticoagulation in some patients when we now have such a safe approach?” he asked.

Dr. Rodger reported receiving research grants from the French government as well as from Biomerieux, which funded the REVERSE II study. Dr. Agnelli reported having no financial conflicts.

ROME – Half of all women who experience a first unprovoked venous thromboembolism (VTE) can safely be spared lifelong anticoagulation through application of the newly validated HERDOO2 decision rule, Marc A. Rodger, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“We’ve validated that a simple, memorable decision rule on anticoagulation applied at the clinically relevant time point works. And it is the only clinical decision rule that has now been prospectively validated,” said Dr. Rodger, professor of medicine, chief and chair of the division of hematology, and head of the thrombosis program at the University of Ottawa.

He presented the results of the validation study, known as the REVERSE II study, which included 2,779 patients with a first unprovoked VTE at 44 centers in seven countries. The full name of the decision rule is “Men Continue and HERDOO2,” a name that says it all: the rule posits that all men as well as those women with a HERDOO2 (Hyperpigmentation, Edema, Redness, d-dimer, Obesity, Older age, 2 or more points) score of at least 2 out of a possible 4 points need to stay on anticoagulation indefinitely because their risk of a recurrent VTE off-therapy clearly exceeds that of a bleeding event on-therapy. In contrast, women with a HERDOO2 score of 0 or 1 can safely stop anticoagulation after the standard 3-6 months of acute short-term therapy.

“Sorry, gentlemen, but we could find no low-risk group of men. They were all high risk,” he said. “But 50% of women with unprovoked vein blood clots can be spared the burdens, costs, and risks of lifelong blood thinners.”

Dr. Rodger and coinvestigators began work on developing a multivariate clinical decision rule in 2001. They examined 69 risk predictors, eventually winnowing down to a manageable four potent risk predictors identified by the acronym HERDOO2.

The derivation study was published 8 years ago (CMAJ. 2008;Aug 26;179[5]:417-26). It showed that women with a HERDOO2 score of 2 or more as well as all men had roughly a 14% rate of recurrent VTE in the first year after stopping anticoagulation, while women with a score of 0 or 1 had about a 1.6% risk. The International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis suggests that it’s safe to discontinue anticoagulants if the risk of recurrent thrombosis at 1 year off-therapy is less than 5%, given the significant risk of serious bleeding on-therapy and the fact that a serious bleed event is two to three times more likely than a VTE to be fatal.

Dr. Rodger and coinvestigators recognized that a clinical decision rule needs to be externally validated before it’s ready for prime-time use in clinical practice. Thus, they conducted the REVERSE II study, in which the decision rule was applied after the 2,799 participants had been on anticoagulation for 5-12 months. All had a first proximal deep vein thrombosis and/or a segmental or greater pulmonary embolism. Patients were still on anticoagulation at the time the rule was applied, which is why the cut point for a positive d-dimer test in HERDOO2 is 250 mcg/L, half of the threshold value for a positive test in patients not on anticoagulation.

They identified 631 women as low risk, with a HERDOO2 score of 0 or 1. They and their physicians were instructed to stop anticoagulation at that time. The 2,148 high-risk subjects – that is, all of the men and the high-risk women – were advised to remain on anticoagulation. The primary study endpoint was the rate of recurrent VTE in the 12 months following testing and patient guidance. The lost-to-follow-up rate was 2.2%.

The recurrent VTE rate was 3% in the 591 low-risk women who discontinued anticoagulants and zero in 31 others who elected to stay on medication. In the high-risk group identified by the HERDOO2 rule, the recurrent VTE rate at 12 months was 8.1% in the 323 who opted to discontinue anticoagulants and just 1.6% in 1,802 who continued on therapy as advised, a finding that underscores the effectiveness of selectively applied long-term anticoagulation therapy, he continued.

The recurrent VTE rate among the 291 women with a HERDOO2 score of 0 or 1 who were on exogenous estrogen was 1.4%, while in high-risk women taking estrogen the rate was more than doubled at 3.1%. But in women aged 50-64 identified by the HERDOO2 rule as being low risk, the actual recurrent VTE rate was 5.7%, a finding that raised a red flag for the investigators.

“There may be an evolution of the HERDOO2 decision rule to a lower age cut point. But that’s something that requires further study in postmenopausal women,” according to Dr. Rodger.

The investigators defined a first unprovoked VTE as one occurring in the absence during the previous 90 days of major surgery, a fracture or cast, more than 3 days of immobilization, or malignancy within the last 5 years.

Venous thromboembolism is the second most common cardiovascular disorder and the third most common cause of cardiovascular death. Unprovoked VTEs account for half of all VTEs. Their management has been a controversial subject. Both the American College of Chest Physicians and the European Society of Cardiology recommend continuing anticoagulation indefinitely in patients who aren’t at high bleeding risk.

“But this is a relatively weak 2B recommendation because of the tightly balanced competing risks of recurrent thrombosis off anticoagulation and major bleeding on anticoagulation,” Dr. Rodger said. He added that he considers REVERSE II to be practice changing, and predicted that once the results are published the guidelines will be revised.

Discussant Giancarlo Agnelli, MD, was a tough critic who gave fair warning.

“I am friends with many of the authors of this paper, and in this country we are usually gentle with enemies and nasty with friends,” declared Dr. Agnelli, professor of internal medicine and director of internal and cardiovascular medicine and the stroke unit at the University of Perugia, Italy.

He didn’t find the REVERSE II study or the HERDOO2 rule persuasive. On the plus side, he said, the HERDOO2 rule has now been validated, unlike the proposed DASH and Vienna rules. And it was tested in a diverse multinational patient population. But the fact that the HERDOO2 rule is only applicable in women is a major limitation. And REVERSE II was not a randomized trial, Dr. Agnelli noted.

Moreover, 1 year of follow-up seems insufficient, he continued. He cited a French multicenter trial in which patients with a first unprovoked VTE received 6 months of anticoagulants and were then randomized to another 18 months of anticoagulation or placebo. During that 18 months, the group on anticoagulants had a significantly lower rate of the composite endpoint comprised of recurrent VTE or major bleeding, but once that period was over they experienced catchup. By the time the study ended at 42 months, the two study arms didn’t differ significantly in the composite endpoint (JAMA. 2015 Jul 7;314[1]:31-40).

More broadly, Dr. Agnelli also questioned the need for an anticoagulation discontinuation rule in the contemporary era of new oral anticoagulants (NOACs). He was lead investigator in the AMPLIFY study, a major randomized trial of fixed-dose apixaban (Eliquis) versus conventional therapy with subcutaneous enoxaparin (Lovenox) bridging to warfarin in 5,395 patients with acute VTE. The NOAC was associated with a 69% reduction in the relative risk of bleeding and was noninferior to standard therapy in the risk of recurrent VTE (N Engl J Med. 2013 Aug 29;369[9]:799-808).

“Why should we think about withholding anticoagulation in some patients when we now have such a safe approach?” he asked.

Dr. Rodger reported receiving research grants from the French government as well as from Biomerieux, which funded the REVERSE II study. Dr. Agnelli reported having no financial conflicts.

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2016

Key clinical point: Half of women who have a first unprovoked venous thromboembolism can safely be spared lifelong anticoagulation through application of the newly validated HERDOO2 decision rule.

Major finding: Women with a first unprovoked venous thromboembolism identified as being at low risk of recurrence on the basis of the HERDOO2 decision rule had a 3% recurrence rate in the year after stopping anticoagulation therapy, while those identified as high risk had an 8.1% recurrence rate if they discontinued anticoagulants.

Data source: This was a prospective, multinational, observational study involving 2,779 patients with a first unprovoked venous thromboembolism.

Disclosures: The presenter reported receiving research grants from the French government as well as from Biomerieux, which funded the REVERSE II study.

Does extending aromatase-inhibitor use from 5 to 10 years benefit menopausal women with hormone-positive breast cancer?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Since the current treatment choice for hormone-receptor–positive early breast cancer in postmenopausal women is 5 years of aromatase inhibitor (AI) therapy, or AI therapy following initial tamoxifen treatment, could 10 years of an AI be beneficial to cancer recurrence? Goss and colleagues analyzed this question in the MA.17R trial, a North American Breast Cancer Group trial coordinated by the Canadian Cancer Trials Group. (Results of the prior MA.17 trial were published in 2003.1)

The randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluated the effect of 5 years of extended AI (letrozole 2.5 mg) treatment compared with placebo in menopausal women with hormone-receptor–positive breast cancer who had previously received 5 years of hormonal adjuvant therapy with tamoxifen alone or plus AIs. Of note, this study was funded in part by Novartis, the pharmaceutical manufacturer of letrozole, though the company had no role in either study design or writing of the manuscript. Seven of the 20 authors disclosed some sort of relationship with industry (some with the manufacturer of letrozole), including membership on advisory boards, board of directors, steering committees, or data and safety monitoring committees or receiving lecturer or consulting fees or grant support.

The trial’s primary end point was DFS. Secondary end points included overall survival, the incidence of contralateral breast cancer, quality of life (QOL), and long-term safety.

Details of the studyWomen were eligible to participate in the study if they were disease free after having completed 4.5 to 6 years of therapy with any AI and if their primary tumor was hormone-receptor positive. A total of 1,918 women were included in the trial and were randomly assigned to receive either letrozole treatment (n = 959) or placebo (n = 959).

Clinical evaluation was performed annually and included assessments of new bone fracture and new-onset osteoporosis, blood tests, mammography, and assessment of toxic effects. QOL measures were assessed with a validated health survey and a menopause-specific questionnaire. The Common Toxicity Criteria, version 2.0, was used to assess adverse events.

Impact on disease free, overall survivalThe rate of 5-year DFS was statistically improved in the letrozole group compared with the placebo group, 95% (95% confidence interval [CI], 93–96) versus 91% (95% CI, 89–93), respectively, a 4% improvement in DFS. However, there was no impact on disease-specific mortality and no benefit in overall survival (93% [95% CI, 92–95] with letrozole and 94% [95% CI, 92–95] with placebo), as competing causes of death become increasingly important in this older population. Among women who died during the study follow-up, more than half died of causes not related to breast cancer.

QOL measures. More than 85% of participants completed the QOL assessments at each time point. There was no difference in the various QOL measures between the letrozole and the placebo group.

Adverse effects. Expected adverse effects due to AIs were significantly higher in the letrozole group. For example, new-onset osteoporosis occurred in 109 (11%) of letrozole-treated women and in 54 (6%) of the placebo group (P<.001), and bone fracture occurred in 133 (14%) of the letrozole group and 88 (9%) of the placebo group (P = .001).

Of note, however, fewer toxicities/adverse effects were seen in the AI group in this study than in previously published reports. The authors suggested that these adverse effect data may be lower than expected because the majority of women eligible for this study likely had prior exposure to AIs, and those with significant adverse effects with aromatase inhibitor therapy may have self-selected out of this trial.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICEWhile the study authors selected DFS as the primary outcome, the lack of overall survival, adverse effect profile, and the drug cost (average wholesale price, ~$33,050 for 5 years2) make the choice to routinely continue AIs in menopausal women with hormone-receptor–positive breast cancer less clear, and counseling on both the benefits and limitations of continuing hormonal adjuvant therapy will be important for these women.

Continued follow-up of the study participants over time would be useful to determine if, after 10 to 15 years, the benefit of extending AI therapy for an additional 5 years would provide an overall benefit in longevity, as competing causes of death (bone fracture, cardiovascular risk) actually may increase over time in the extended-treatment group compared with the placebo group.

— Mark D. Pearlman, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Goss PE, Ingle JN, Martino S, et al. A randomized trial of letrozole in postmenopausal women after five years of tamoxifen therapy for early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(19):1793–1802.

- Average Wholesale Price (AWP) Policy. Truven Health Analytics. Red Book. http://sites.truvenhealth.com/redbook /awp/. Accessed July 18, 2016.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Since the current treatment choice for hormone-receptor–positive early breast cancer in postmenopausal women is 5 years of aromatase inhibitor (AI) therapy, or AI therapy following initial tamoxifen treatment, could 10 years of an AI be beneficial to cancer recurrence? Goss and colleagues analyzed this question in the MA.17R trial, a North American Breast Cancer Group trial coordinated by the Canadian Cancer Trials Group. (Results of the prior MA.17 trial were published in 2003.1)

The randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluated the effect of 5 years of extended AI (letrozole 2.5 mg) treatment compared with placebo in menopausal women with hormone-receptor–positive breast cancer who had previously received 5 years of hormonal adjuvant therapy with tamoxifen alone or plus AIs. Of note, this study was funded in part by Novartis, the pharmaceutical manufacturer of letrozole, though the company had no role in either study design or writing of the manuscript. Seven of the 20 authors disclosed some sort of relationship with industry (some with the manufacturer of letrozole), including membership on advisory boards, board of directors, steering committees, or data and safety monitoring committees or receiving lecturer or consulting fees or grant support.

The trial’s primary end point was DFS. Secondary end points included overall survival, the incidence of contralateral breast cancer, quality of life (QOL), and long-term safety.

Details of the studyWomen were eligible to participate in the study if they were disease free after having completed 4.5 to 6 years of therapy with any AI and if their primary tumor was hormone-receptor positive. A total of 1,918 women were included in the trial and were randomly assigned to receive either letrozole treatment (n = 959) or placebo (n = 959).

Clinical evaluation was performed annually and included assessments of new bone fracture and new-onset osteoporosis, blood tests, mammography, and assessment of toxic effects. QOL measures were assessed with a validated health survey and a menopause-specific questionnaire. The Common Toxicity Criteria, version 2.0, was used to assess adverse events.

Impact on disease free, overall survivalThe rate of 5-year DFS was statistically improved in the letrozole group compared with the placebo group, 95% (95% confidence interval [CI], 93–96) versus 91% (95% CI, 89–93), respectively, a 4% improvement in DFS. However, there was no impact on disease-specific mortality and no benefit in overall survival (93% [95% CI, 92–95] with letrozole and 94% [95% CI, 92–95] with placebo), as competing causes of death become increasingly important in this older population. Among women who died during the study follow-up, more than half died of causes not related to breast cancer.

QOL measures. More than 85% of participants completed the QOL assessments at each time point. There was no difference in the various QOL measures between the letrozole and the placebo group.

Adverse effects. Expected adverse effects due to AIs were significantly higher in the letrozole group. For example, new-onset osteoporosis occurred in 109 (11%) of letrozole-treated women and in 54 (6%) of the placebo group (P<.001), and bone fracture occurred in 133 (14%) of the letrozole group and 88 (9%) of the placebo group (P = .001).

Of note, however, fewer toxicities/adverse effects were seen in the AI group in this study than in previously published reports. The authors suggested that these adverse effect data may be lower than expected because the majority of women eligible for this study likely had prior exposure to AIs, and those with significant adverse effects with aromatase inhibitor therapy may have self-selected out of this trial.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICEWhile the study authors selected DFS as the primary outcome, the lack of overall survival, adverse effect profile, and the drug cost (average wholesale price, ~$33,050 for 5 years2) make the choice to routinely continue AIs in menopausal women with hormone-receptor–positive breast cancer less clear, and counseling on both the benefits and limitations of continuing hormonal adjuvant therapy will be important for these women.

Continued follow-up of the study participants over time would be useful to determine if, after 10 to 15 years, the benefit of extending AI therapy for an additional 5 years would provide an overall benefit in longevity, as competing causes of death (bone fracture, cardiovascular risk) actually may increase over time in the extended-treatment group compared with the placebo group.

— Mark D. Pearlman, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Since the current treatment choice for hormone-receptor–positive early breast cancer in postmenopausal women is 5 years of aromatase inhibitor (AI) therapy, or AI therapy following initial tamoxifen treatment, could 10 years of an AI be beneficial to cancer recurrence? Goss and colleagues analyzed this question in the MA.17R trial, a North American Breast Cancer Group trial coordinated by the Canadian Cancer Trials Group. (Results of the prior MA.17 trial were published in 2003.1)

The randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluated the effect of 5 years of extended AI (letrozole 2.5 mg) treatment compared with placebo in menopausal women with hormone-receptor–positive breast cancer who had previously received 5 years of hormonal adjuvant therapy with tamoxifen alone or plus AIs. Of note, this study was funded in part by Novartis, the pharmaceutical manufacturer of letrozole, though the company had no role in either study design or writing of the manuscript. Seven of the 20 authors disclosed some sort of relationship with industry (some with the manufacturer of letrozole), including membership on advisory boards, board of directors, steering committees, or data and safety monitoring committees or receiving lecturer or consulting fees or grant support.

The trial’s primary end point was DFS. Secondary end points included overall survival, the incidence of contralateral breast cancer, quality of life (QOL), and long-term safety.

Details of the studyWomen were eligible to participate in the study if they were disease free after having completed 4.5 to 6 years of therapy with any AI and if their primary tumor was hormone-receptor positive. A total of 1,918 women were included in the trial and were randomly assigned to receive either letrozole treatment (n = 959) or placebo (n = 959).

Clinical evaluation was performed annually and included assessments of new bone fracture and new-onset osteoporosis, blood tests, mammography, and assessment of toxic effects. QOL measures were assessed with a validated health survey and a menopause-specific questionnaire. The Common Toxicity Criteria, version 2.0, was used to assess adverse events.

Impact on disease free, overall survivalThe rate of 5-year DFS was statistically improved in the letrozole group compared with the placebo group, 95% (95% confidence interval [CI], 93–96) versus 91% (95% CI, 89–93), respectively, a 4% improvement in DFS. However, there was no impact on disease-specific mortality and no benefit in overall survival (93% [95% CI, 92–95] with letrozole and 94% [95% CI, 92–95] with placebo), as competing causes of death become increasingly important in this older population. Among women who died during the study follow-up, more than half died of causes not related to breast cancer.

QOL measures. More than 85% of participants completed the QOL assessments at each time point. There was no difference in the various QOL measures between the letrozole and the placebo group.

Adverse effects. Expected adverse effects due to AIs were significantly higher in the letrozole group. For example, new-onset osteoporosis occurred in 109 (11%) of letrozole-treated women and in 54 (6%) of the placebo group (P<.001), and bone fracture occurred in 133 (14%) of the letrozole group and 88 (9%) of the placebo group (P = .001).

Of note, however, fewer toxicities/adverse effects were seen in the AI group in this study than in previously published reports. The authors suggested that these adverse effect data may be lower than expected because the majority of women eligible for this study likely had prior exposure to AIs, and those with significant adverse effects with aromatase inhibitor therapy may have self-selected out of this trial.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICEWhile the study authors selected DFS as the primary outcome, the lack of overall survival, adverse effect profile, and the drug cost (average wholesale price, ~$33,050 for 5 years2) make the choice to routinely continue AIs in menopausal women with hormone-receptor–positive breast cancer less clear, and counseling on both the benefits and limitations of continuing hormonal adjuvant therapy will be important for these women.

Continued follow-up of the study participants over time would be useful to determine if, after 10 to 15 years, the benefit of extending AI therapy for an additional 5 years would provide an overall benefit in longevity, as competing causes of death (bone fracture, cardiovascular risk) actually may increase over time in the extended-treatment group compared with the placebo group.

— Mark D. Pearlman, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Goss PE, Ingle JN, Martino S, et al. A randomized trial of letrozole in postmenopausal women after five years of tamoxifen therapy for early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(19):1793–1802.

- Average Wholesale Price (AWP) Policy. Truven Health Analytics. Red Book. http://sites.truvenhealth.com/redbook /awp/. Accessed July 18, 2016.

- Goss PE, Ingle JN, Martino S, et al. A randomized trial of letrozole in postmenopausal women after five years of tamoxifen therapy for early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(19):1793–1802.

- Average Wholesale Price (AWP) Policy. Truven Health Analytics. Red Book. http://sites.truvenhealth.com/redbook /awp/. Accessed July 18, 2016.

Start time for estrogen conveys no cognitive impact

The cognitive effects of estrogen were no different in women who started taking the hormone within 6 years of menopause, compared with those who began it 10 or more years after menopause, based on data from the double-blind randomized ELITE-Cog trial.

“Some hormone effects on cognition are postulated to vary by age or by timing in relation to the menopause,” wrote Victor W. Henderson, M.D., of Stanford (Calif.) University and his colleagues (Neurology. 2016 Jul 20. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002980).

To test whether the timing of estrogen therapy affected the primary cognitive endpoint of verbal episodic memory, the researchers conducted the ELITE (Early vs. Late Intervention Trial With Estradiol) trial in which they randomized 567 healthy women within 6 years of menopause or 10 or more years post menopause to 1 mg/day of oral 17-beta-estradiol or a placebo. Women with a uterus also received either 45 mg progesterone as a 4% vaginal gel or a matched placebo gel.

The main ELITE trial tested the effect of the timing of estradiol, compared with placebo, on the progression of subclinical atherosclerosis, whereas the ELITE-Cog trial assessed the effects of the timing of estradiol on a composite test of verbal episodic memory.

Overall, composite scores of verbal memory were not significantly different in women randomized to estrogen vs. placebo based on a mean standardized difference of –0.06 (95% confidence interval, –0.22 to 0.09) after an average of 57 months of treatment. The mean standardized difference was similar in the early and late treatment groups. In addition, the mean standardized differences in measures of executive functions (–0.04; 95% CI, –0.21 to 0.14) and global cognition (–0.025; 95% CI, –0.18 to 0.13) were not significantly different between women who started estrogen within 6 years of menopause and those who started estrogen 10 years or more after menopause. Safety profiles were similar between the groups.

“Results of this randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial fail to confirm the timing hypothesis for cognitive outcomes in healthy postmenopausal women,” the researchers wrote.

The results don’t generalize to other subgroups including women of reproductive age, those in transition to menopause, or those with premature menopause caused by surgery or chemotherapy, and the study “was not designed to assess short-term cognitive effects of estradiol or effects on risks of mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer disease,” the researchers noted. However, the findings should be reassuring to healthy, younger postmenopausal women considering estrogen therapy, they said.

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, and the study drugs and placebo were supplied by Teva, Watson, and Abbott Laboratories. Dr. Henderson disclosed research support from the NIH, as well as travel expenses from the NIH, American Academy of Neurology, and International Menopause Society.

The cognitive effects of estrogen were no different in women who started taking the hormone within 6 years of menopause, compared with those who began it 10 or more years after menopause, based on data from the double-blind randomized ELITE-Cog trial.

“Some hormone effects on cognition are postulated to vary by age or by timing in relation to the menopause,” wrote Victor W. Henderson, M.D., of Stanford (Calif.) University and his colleagues (Neurology. 2016 Jul 20. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002980).

To test whether the timing of estrogen therapy affected the primary cognitive endpoint of verbal episodic memory, the researchers conducted the ELITE (Early vs. Late Intervention Trial With Estradiol) trial in which they randomized 567 healthy women within 6 years of menopause or 10 or more years post menopause to 1 mg/day of oral 17-beta-estradiol or a placebo. Women with a uterus also received either 45 mg progesterone as a 4% vaginal gel or a matched placebo gel.

The main ELITE trial tested the effect of the timing of estradiol, compared with placebo, on the progression of subclinical atherosclerosis, whereas the ELITE-Cog trial assessed the effects of the timing of estradiol on a composite test of verbal episodic memory.

Overall, composite scores of verbal memory were not significantly different in women randomized to estrogen vs. placebo based on a mean standardized difference of –0.06 (95% confidence interval, –0.22 to 0.09) after an average of 57 months of treatment. The mean standardized difference was similar in the early and late treatment groups. In addition, the mean standardized differences in measures of executive functions (–0.04; 95% CI, –0.21 to 0.14) and global cognition (–0.025; 95% CI, –0.18 to 0.13) were not significantly different between women who started estrogen within 6 years of menopause and those who started estrogen 10 years or more after menopause. Safety profiles were similar between the groups.

“Results of this randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial fail to confirm the timing hypothesis for cognitive outcomes in healthy postmenopausal women,” the researchers wrote.

The results don’t generalize to other subgroups including women of reproductive age, those in transition to menopause, or those with premature menopause caused by surgery or chemotherapy, and the study “was not designed to assess short-term cognitive effects of estradiol or effects on risks of mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer disease,” the researchers noted. However, the findings should be reassuring to healthy, younger postmenopausal women considering estrogen therapy, they said.

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, and the study drugs and placebo were supplied by Teva, Watson, and Abbott Laboratories. Dr. Henderson disclosed research support from the NIH, as well as travel expenses from the NIH, American Academy of Neurology, and International Menopause Society.

The cognitive effects of estrogen were no different in women who started taking the hormone within 6 years of menopause, compared with those who began it 10 or more years after menopause, based on data from the double-blind randomized ELITE-Cog trial.

“Some hormone effects on cognition are postulated to vary by age or by timing in relation to the menopause,” wrote Victor W. Henderson, M.D., of Stanford (Calif.) University and his colleagues (Neurology. 2016 Jul 20. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002980).

To test whether the timing of estrogen therapy affected the primary cognitive endpoint of verbal episodic memory, the researchers conducted the ELITE (Early vs. Late Intervention Trial With Estradiol) trial in which they randomized 567 healthy women within 6 years of menopause or 10 or more years post menopause to 1 mg/day of oral 17-beta-estradiol or a placebo. Women with a uterus also received either 45 mg progesterone as a 4% vaginal gel or a matched placebo gel.

The main ELITE trial tested the effect of the timing of estradiol, compared with placebo, on the progression of subclinical atherosclerosis, whereas the ELITE-Cog trial assessed the effects of the timing of estradiol on a composite test of verbal episodic memory.

Overall, composite scores of verbal memory were not significantly different in women randomized to estrogen vs. placebo based on a mean standardized difference of –0.06 (95% confidence interval, –0.22 to 0.09) after an average of 57 months of treatment. The mean standardized difference was similar in the early and late treatment groups. In addition, the mean standardized differences in measures of executive functions (–0.04; 95% CI, –0.21 to 0.14) and global cognition (–0.025; 95% CI, –0.18 to 0.13) were not significantly different between women who started estrogen within 6 years of menopause and those who started estrogen 10 years or more after menopause. Safety profiles were similar between the groups.

“Results of this randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial fail to confirm the timing hypothesis for cognitive outcomes in healthy postmenopausal women,” the researchers wrote.

The results don’t generalize to other subgroups including women of reproductive age, those in transition to menopause, or those with premature menopause caused by surgery or chemotherapy, and the study “was not designed to assess short-term cognitive effects of estradiol or effects on risks of mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer disease,” the researchers noted. However, the findings should be reassuring to healthy, younger postmenopausal women considering estrogen therapy, they said.

The study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, and the study drugs and placebo were supplied by Teva, Watson, and Abbott Laboratories. Dr. Henderson disclosed research support from the NIH, as well as travel expenses from the NIH, American Academy of Neurology, and International Menopause Society.

FROM NEUROLOGY

Key clinical point: Estradiol had no significant impact on cognitive function when taken within 6 years of menopause or more than 10 years after menopause.

Major finding: Composite scores of verbal memory were not significantly different in women randomized to estrogen vs. placebo, based on a mean standardized difference of –0.06 (95% confidence interval, –0.22 to 0.09) after an average of 57 months of treatment. The mean standardized difference was similar in the early and late treatment groups.

Data source: A double-blind, randomized ELITE-Cog trial including 567 healthy women within 6 years of menopause or 10 or more years after menopause.

Disclosures: The study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, and the study drugs and placebo were supplied by Teva, Watson, and Abbott Laboratories. Dr. Henderson disclosed research support from the NIH, as well as travel expenses from the NIH, American Academy of Neurology, and International Menopause Society.

2016 Update on menopause

In this Update, I discuss important new study results regarding the cardiovascular safety of hormone therapy (HT) in early menopausal women. In addition, I review survey data that reveal a huge number of US women are using compounded HT preparations, which have unproven efficacy and safety.

Earlier initiation is better: ELITE trial provides strong support for the estrogen timing hypothesis

Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Henderson VW, et al; for the ELITE Research Group. Vascular effects of early versus late postmenopausal treatment with estradiol. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(13):1221-1231.

Keaney JF, Solomon G. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and atherosclerosis--time is of the essence [editorial]. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(13):1279-1280.

A substantial amount of published data, including from the Women's Health Initiative (WHI), supports the timing hypothesis, which proposes that HT slows the progression of atherosclerosis among recently menopausal women but has a neutral or adverse effect among women who are a decade or more past menopause onset.1 To directly test this hypothesis, Hodis and colleagues randomly assigned healthy postmenopausal women (<6 years or ≥10 years past menopause) without cardiovascular disease (CVD) to oral estradiol 1 mg or placebo. Women with a uterus also were randomly assigned to receive either vaginal progesterone gel or placebo gel. The primary outcome was the rate of change in carotid artery intima-media thickness (CIMT), which was assessed at baseline and each 6 months of the study. (An earlier report had noted that baseline CIMT correlated well with CVD risk factors.2) Coronary artery atherosclerosis, a secondary outcome, was assessed at study completion using computed tomography (CT).

Details of the study

Among the 643 participants in the Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol (ELITE), the median years since menopause and the median age at enrollment were 3.5 and 55.4, respectively, in the early postmenopause group and 14.3 and 63.6, respectively, in the late postmenopause group.

Among the younger women, after a median of 5 years of study medications, the estradiol group had less progression of CIMT than the placebo group (P = .008). By contrast, in the older group, rates of CIMT progression were similar in the HT and placebo groups (P = .29). The relationship between estrogen and CIMT progression differed significantly between the younger and older groups (P = .007). Use of progesterone did not change these trends. Coronary artery CT parameters did not differ significantly between the placebo and HT groups in the age group or in the time-since-menopause group.

What this evidence means for practice

In an editorial accompanying the published results of the ELITE trial, Keaney and Solomon concluded that, although estrogen had a favorable effect on atherosclerosis in early menopause, it would be premature to recommend HT for prevention of cardiovascular events. I agree with them, but I also would like to note that the use of HT for the treatment of menopausal symptoms has plummeted since the initial WHI findings in 2002, with infrequent HT use even among symptomatic women in early menopause.3 (And I refer you to the special inset featuring JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH) The takeaway message is that this important new clinical trial provides additional reassurance regarding the cardiovascular safety of HT when initiated by recently menopausal women to treat bothersome vasomotor symptoms. This message represents welcome news for women with bothersome menopausal symptoms considering use of HT.

A word about the vaginal progesterone gel used in the ELITE trial in relation to clinical practice: Given the need for vaginal placement of progesterone gel, potential messiness, and high cost, few clinicians may prescribe this formulation, and few women probably would choose to use it. As an alternative, micronized progesterone 100-mg capsules are less expensive and well accepted by most patients. These capsules are formulated with peanut oil. Because they may cause women to feel drowsy, the capsules should be taken at bedtime. In women with an intact uterus who are taking oral estradiol 1-mg tablets, one appropriate progestogen regimen for endometrial suppression is a 100-mg micronized progesterone capsule each night, continuously.

WHI, ELITE and the timing hypothesis:

New evidence on HT in early menopause is reassuring

Q&A with JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH

In this interview, Dr. JoAnn Manson discusses the reassuring results of recent hormone therapy (HT) trials in early versus later postmenopausal women, examines these outcomes in the context of the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) trial and ELITE trial, and debunks an enduring common misconception about the WHI.

Q You have said for several years that there has been a misconception about the WHI trial. What is that misconception, and what has been its impact on clinicians, women, and the use of HT?

A The WHI HT trial has been largely misunderstood. It was designed to address the balance of benefits and risks of long-term HT for the prevention of chronic disease in postmenopausal women across a broad range of ages (average age 63).1,2 It was not intended to evaluate the clinical role of HT for managing menopausal symptoms in young and early menopausal women.3 Overall, the WHI study findings have been inappropriately extrapolated to women in their 40s and early 50s who report distressing hot flashes, night sweats, and other menopausal symptoms, and they are often used as a reason to deny therapy when in fact many of these women would be appropriate candidates for HT.

There is increasing evidence that younger women in early menopause who are taking HT have a lower risk of adverse outcomes and lower absolute risks of disease than older women.2,3 In younger, early menopausal women with bothersome hot flashes, night sweats, or other menopausal symptoms and who have no contraindications to HT, the benefits of treatment are likely to outweigh the risks, and these patients derive quality-of-life benefits from treatment.

Q How do the results of the recent ELITE (Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol) trial build on cardiovascular safety, in particular, of HT and when HT is optimally initiated?

A The ELITE trial directly tested the "timing hypothesis" and the role of HT in slowing the progression of atherosclerosis in early menopause (defined as within 6 years of menopause onset) compared with the effect in women in later menopause (defined as at least 10 yearspast menopause).4 The investigators used carotid artery intima-media thickness (CIMT) as a surrogate end point. In this trial, 643 women were randomly assigned according to whether they were in early or later menopause to receive either placebo or estradiol 1 mg daily; women with a uterus also received progesterone 45 mg as a 4% vaginal gel or matching placebo gel. The median duration of intervention was 5 years.

The ELITE study results provide support for the "critical window hypothesis" in that the estradiol-treated younger women closer to onset of menopause had slowing of atherosclerosis compared with the placebo group, while the older women more distant from menopause did not have slowing of atherosclerosis with estradiol.

The ELITE trial was not large enough, however, to assess clinical end points--rates of heart attack, stroke, or other cardiovascular events. So it remains unclear whether the findings for the surrogate end point of CIMT would translate into a reduced risk of clinical events in the younger women. Nevertheless, ELITE does provide more reassurance about the use of HT in early menopause and supports the possibility that the overall results of the WHI among women enrolled at an average age of 63 years may not apply directly to younger women in early menopause.

Q What impact on clinical practice do you anticipate as a result of the ELITE trial results?

A The findings provide further support for the timing hypothesis and offer additional reassurance regarding the safety of HT in early menopause for management of menopausal symptoms. However, the trial does not provide conclusive evidence to support recommendations to use HT for the express purpose of preventing cardiovascular disease (CVD), even if HT is started in early menopause. Using a surrogate end point for atherosclerosis (CIMT) is not the same as looking at clinical events. There are many biologic pathways for heart attacks, strokes, and other cardiovascular events. In addition to atherosclerosis, for example, there is thrombosis, clotting, thrombo-occlusion within a blood vessel, and plaque rupture. Again, we do not know whether the CIMT-based results would translate directly into a reduction in clinical heart attacks and stroke.

The main takeaway point from the ELITE trial results is further reassurance for use of HT for management of menopausal symptoms in early menopause, but not for long-term chronic disease prevention at any age.

Q Another recent study, published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, addresses HT and the timing hypothesis but in this instance relating to glucose tolerance.5 What did these study authors find?

A This study by Pereira and colleagues is very interesting and suggests that the window of opportunity for initiating estrogen therapy may apply not only to coronary events but also to glucose tolerance, insulin sensitivity, and diabetes risk.5

The authors investigated the effects of short-term high-dose transdermal estradiol on the insulin-mediated glucose disposal rate (GDR), which is a measure of insulin-stimulated glucose uptake. Participants in this randomized, crossover, placebo-controlled study included 22 women who were in early menopause (6 years or less since final menses) and 24 women who were in later menopause (10 years or longer since final menses). All of the women were naïve to hormone therapy, and baseline GDR did not differ between groups. After 1 week of treatment with transdermal estradiol (a high dose of 150 μg) or placebo, the participants' GDR was measured via a hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp.

The investigators found that in the younger women, estradiol had a favorable effect on insulin sensitivity and GDR, whereas in the older women, there was no evidence of a favorable effect and, in fact, there was a signal for risk and more adverse findings in this group.

Several studies in the WHI also looked at glucose tolerance and at the risk of being diagnosed with diabetes. While the results of the WHI estrogen-alone trial revealed a reduction in diabetes and favorable effects across age groups, in the WHI estrogen-plus-progestin trial we did see a signal that the results for diabetes may have been more favorable in the younger than in the older women, somewhat consistent with the findings of Pereira and colleagues.2,5

Overall this issue requires more research, but the Pereira study provides further support for the possibility that estrogen's metabolic effects may vary by age and time since menopause, and there is evidence that the estrogen receptors may be more functional and more sensitive in early rather than later menopause. These findings are very interesting and consistent with the overall hypothesis about the importance of age and time since menopause in relation to estrogen action. Again, they offer further support for use of HT for managing bothersome menopausal symptoms in early menopause, but they should not be interpreted as endorsing the use of HT to prevent either diabetes or CVD, due to the potential for other risks.

Q Where would you like to see future research conducted regarding the timing hypothesis?

A I would like to see more research on the role of oral versus transdermal estrogen in relation to insulin sensitivity, diabetes risk, and CVD risk, and more research on the role of estrogen dose, different types of progestogens, and the benefits and risks of novel formulations, including selective estrogen receptor modulators and tissue selective estrogen complexes.

Dr. Manson is Professor of Medicine and the Michael and Lee Bell Professor of Women's Health at Harvard Medical School and Chief of the Division of Preventive Medicine at Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts. She is a past President of the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) and a NAMS Certified Menopause Practitioner.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

References

- Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al; Writing Group for the Women's Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(3):321-333.

- Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women's Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013(13);310:1353-1368.

- Manson JE, Kaunitz AM. Menopause management-- getting clinical care back on track. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(19):803-806.

- Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Henderson VW, et al; ELITE Research Group. Vascular effects of early versus late postmenopausal treatment with estradiol. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(13):1221-1231.

- Pereira RI, Casey BA, Swibas TA, Erickson CB, Wolfe P, Van Pelt RE. Timing of estradiol treatment after menopause may determine benefit or harm to insulin action. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(12):4456-4462.

FDA-approved HT is preferable to compounded HT formulations

Pinkerton JV, Santoro N. Compounded bioidentical hormone therapy: identifying use trends and knowledge gaps among US women. Menopause. 2015;22(9):926-936.

Pinkerton JV, Constantine GD. Compounded non-FDA-approved menopausal hormone therapy prescriptions have increased: results of a pharmacy survey. Menopause. 2016;23(4):359-367.

Gass ML, Stuenkel CA, Utian WH, LaCroix A, Liu JH, Shifren JL.; North American Menopause Society (NAMS) Advisory Panel consisting of representatives of NAMS Board of Trustees and other experts in women's health. Use of compounded hormone therapy in the United States: report of The North American Menopause Society Survey. Menopause. 2015;22(12):1276-1284.

Consider how you would manage this clinical scenario: During a well-woman visit, your 54-year-old patient mentions that, after seeing an advertisement on television, she visited a clinic that sells compounded hormones. There, she underwent some testing and received an estrogen-testosterone implant and a progesterone cream that she applies to her skin each night to treat her menopausal symptoms. Now what?