User login

WHI hormone trials offer reassurance on long-term mortality risk

Postmenopausal women treated with conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) for a median of 5.6 years, or with CEE alone for a median of 7.2 years had no increased risk of all-cause, cardiovascular, or cancer mortality over a cumulative follow-up of 18 years, according to the latest report from the Women’s Health Initiative hormone therapy trials.

All-cause mortality among the 27,347 participants in the two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials was 27.1% in the hormone therapy group versus 27.6% in the placebo group (hazard ratio, 0.99), JoAnn E. Manson, MD, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and her colleagues reported.

For those who received CEE plus MPA, the hazard ratio was 1.02, while for CEE alone the hazard ratio was 0.94 (JAMA. 2017 Sep;318[10]:927-38).

Cardiovascular mortality among the pooled cohort was 8.9% with hormone therapy and 9.0% with placebo (HR, 1.00), and total cancer mortality was 8.2% and 8.0%, respectively (HR, 1.03). Mortality from other causes was 10.0% with hormone therapy, compared with 10.7% with placebo (HR, 0.95). The results did not differ significantly between the trials, the investigators noted.

An analysis by age showed that women aged 50-59 years tended to have lower hazard ratios for mortality from cardiovascular disease, cancer, and other causes during the intervention phases of the trials, but only the difference for “other” causes in the CEE-alone trial showed a statistically significant trend with age. This was influenced in part by adverse effects of the treatment in women aged 70-79 years. During cumulative follow-up, trends related to mortality across age groups were not statistically significantly different.

The trials included women aged 50-79 years who were enrolled between 1993 and 1998 and followed through 2014. Given the hormone-therapy-related risks identified in the CEE plus MPA and CEE-alone trials – which were stopped early because of increased risk of breast cancer/overall risks exceeding benefits, and for increased stroke risk, respectively – the absence of an increase in all-cause mortality during the intervention and cumulative follow-up phases of the trials is noteworthy, the investigators wrote.

“Although these findings lend support to practice guidelines endorsing use of hormone therapy for recently menopausal women with moderate to severe symptoms, in the absence of contraindications, the attenuation of age differences with longer follow-up and potential health risks of treatment would not support use of hormone therapy for reducing chronic disease or mortality,” they wrote. “Moreover, it is unclear whether benefits would outweigh risks with longer duration of treatment.”

They added that “in clinical decision making, these considerations must be weighed against the evidence linking untreated vasomotor symptoms in midlife women to impaired health and quality of life, disrupted sleep, reduced work productivity, and increased health care expenditures.”

The Women’s Health Initiative is funded by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Study drugs were donated by Wyeth Ayerst. Dr. Manson reported having no financial disclosures. Several of her coauthors reported receiving grants and research funding from the National Institutes of Health, and receiving personal fees, speaking fees, and honoraria from various pharmaceutical companies.

The findings from the Women’s Health Initiative hormone therapy trials as reported by Dr. Manson and her colleagues expand the understanding of the long-term risks and benefits of hormone therapy, which is an important issue for women around the world, Melissa A. McNeil, MD, wrote in an editorial.

The information will be helpful for counseling women considering whether to start hormone therapy, and “hopefully will alleviate concerns that many patients and physicians have about the initiation of hormone therapy,” she said, explaining that the effect of hormone therapy on cancer mortality, and especially on breast cancer mortality, has generated concern and reluctance to prescribe and take hormone therapy for troubling menopausal symptoms.

“The current report ... provides substantial reassurance for patients and physicians about this issue,” she said. “For women with troubling vasomotor symptoms, premature menopause, or early-onset osteoporosis, hormone therapy appears to be both safe and efficacious.”

While several questions remain, including about optimal duration of therapy, whether there is a difference in mortality by age and menopausal status at hormone therapy initiation, and if earlier initiation would provide additional benefits, the data “fully support the newly released 2017 hormone therapy position statement of the North American Menopause Society and are a welcome addition to current knowledge regarding hormone therapy administration,” she wrote.

Dr. McNeil is with the University of Pittsburgh. She reported having no financial disclosures. Her comments come from an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2017 Sep;318[10]:911-13).

The findings from the Women’s Health Initiative hormone therapy trials as reported by Dr. Manson and her colleagues expand the understanding of the long-term risks and benefits of hormone therapy, which is an important issue for women around the world, Melissa A. McNeil, MD, wrote in an editorial.

The information will be helpful for counseling women considering whether to start hormone therapy, and “hopefully will alleviate concerns that many patients and physicians have about the initiation of hormone therapy,” she said, explaining that the effect of hormone therapy on cancer mortality, and especially on breast cancer mortality, has generated concern and reluctance to prescribe and take hormone therapy for troubling menopausal symptoms.

“The current report ... provides substantial reassurance for patients and physicians about this issue,” she said. “For women with troubling vasomotor symptoms, premature menopause, or early-onset osteoporosis, hormone therapy appears to be both safe and efficacious.”

While several questions remain, including about optimal duration of therapy, whether there is a difference in mortality by age and menopausal status at hormone therapy initiation, and if earlier initiation would provide additional benefits, the data “fully support the newly released 2017 hormone therapy position statement of the North American Menopause Society and are a welcome addition to current knowledge regarding hormone therapy administration,” she wrote.

Dr. McNeil is with the University of Pittsburgh. She reported having no financial disclosures. Her comments come from an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2017 Sep;318[10]:911-13).

The findings from the Women’s Health Initiative hormone therapy trials as reported by Dr. Manson and her colleagues expand the understanding of the long-term risks and benefits of hormone therapy, which is an important issue for women around the world, Melissa A. McNeil, MD, wrote in an editorial.

The information will be helpful for counseling women considering whether to start hormone therapy, and “hopefully will alleviate concerns that many patients and physicians have about the initiation of hormone therapy,” she said, explaining that the effect of hormone therapy on cancer mortality, and especially on breast cancer mortality, has generated concern and reluctance to prescribe and take hormone therapy for troubling menopausal symptoms.

“The current report ... provides substantial reassurance for patients and physicians about this issue,” she said. “For women with troubling vasomotor symptoms, premature menopause, or early-onset osteoporosis, hormone therapy appears to be both safe and efficacious.”

While several questions remain, including about optimal duration of therapy, whether there is a difference in mortality by age and menopausal status at hormone therapy initiation, and if earlier initiation would provide additional benefits, the data “fully support the newly released 2017 hormone therapy position statement of the North American Menopause Society and are a welcome addition to current knowledge regarding hormone therapy administration,” she wrote.

Dr. McNeil is with the University of Pittsburgh. She reported having no financial disclosures. Her comments come from an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2017 Sep;318[10]:911-13).

Postmenopausal women treated with conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) for a median of 5.6 years, or with CEE alone for a median of 7.2 years had no increased risk of all-cause, cardiovascular, or cancer mortality over a cumulative follow-up of 18 years, according to the latest report from the Women’s Health Initiative hormone therapy trials.

All-cause mortality among the 27,347 participants in the two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials was 27.1% in the hormone therapy group versus 27.6% in the placebo group (hazard ratio, 0.99), JoAnn E. Manson, MD, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and her colleagues reported.

For those who received CEE plus MPA, the hazard ratio was 1.02, while for CEE alone the hazard ratio was 0.94 (JAMA. 2017 Sep;318[10]:927-38).

Cardiovascular mortality among the pooled cohort was 8.9% with hormone therapy and 9.0% with placebo (HR, 1.00), and total cancer mortality was 8.2% and 8.0%, respectively (HR, 1.03). Mortality from other causes was 10.0% with hormone therapy, compared with 10.7% with placebo (HR, 0.95). The results did not differ significantly between the trials, the investigators noted.

An analysis by age showed that women aged 50-59 years tended to have lower hazard ratios for mortality from cardiovascular disease, cancer, and other causes during the intervention phases of the trials, but only the difference for “other” causes in the CEE-alone trial showed a statistically significant trend with age. This was influenced in part by adverse effects of the treatment in women aged 70-79 years. During cumulative follow-up, trends related to mortality across age groups were not statistically significantly different.

The trials included women aged 50-79 years who were enrolled between 1993 and 1998 and followed through 2014. Given the hormone-therapy-related risks identified in the CEE plus MPA and CEE-alone trials – which were stopped early because of increased risk of breast cancer/overall risks exceeding benefits, and for increased stroke risk, respectively – the absence of an increase in all-cause mortality during the intervention and cumulative follow-up phases of the trials is noteworthy, the investigators wrote.

“Although these findings lend support to practice guidelines endorsing use of hormone therapy for recently menopausal women with moderate to severe symptoms, in the absence of contraindications, the attenuation of age differences with longer follow-up and potential health risks of treatment would not support use of hormone therapy for reducing chronic disease or mortality,” they wrote. “Moreover, it is unclear whether benefits would outweigh risks with longer duration of treatment.”

They added that “in clinical decision making, these considerations must be weighed against the evidence linking untreated vasomotor symptoms in midlife women to impaired health and quality of life, disrupted sleep, reduced work productivity, and increased health care expenditures.”

The Women’s Health Initiative is funded by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Study drugs were donated by Wyeth Ayerst. Dr. Manson reported having no financial disclosures. Several of her coauthors reported receiving grants and research funding from the National Institutes of Health, and receiving personal fees, speaking fees, and honoraria from various pharmaceutical companies.

Postmenopausal women treated with conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) for a median of 5.6 years, or with CEE alone for a median of 7.2 years had no increased risk of all-cause, cardiovascular, or cancer mortality over a cumulative follow-up of 18 years, according to the latest report from the Women’s Health Initiative hormone therapy trials.

All-cause mortality among the 27,347 participants in the two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials was 27.1% in the hormone therapy group versus 27.6% in the placebo group (hazard ratio, 0.99), JoAnn E. Manson, MD, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and her colleagues reported.

For those who received CEE plus MPA, the hazard ratio was 1.02, while for CEE alone the hazard ratio was 0.94 (JAMA. 2017 Sep;318[10]:927-38).

Cardiovascular mortality among the pooled cohort was 8.9% with hormone therapy and 9.0% with placebo (HR, 1.00), and total cancer mortality was 8.2% and 8.0%, respectively (HR, 1.03). Mortality from other causes was 10.0% with hormone therapy, compared with 10.7% with placebo (HR, 0.95). The results did not differ significantly between the trials, the investigators noted.

An analysis by age showed that women aged 50-59 years tended to have lower hazard ratios for mortality from cardiovascular disease, cancer, and other causes during the intervention phases of the trials, but only the difference for “other” causes in the CEE-alone trial showed a statistically significant trend with age. This was influenced in part by adverse effects of the treatment in women aged 70-79 years. During cumulative follow-up, trends related to mortality across age groups were not statistically significantly different.

The trials included women aged 50-79 years who were enrolled between 1993 and 1998 and followed through 2014. Given the hormone-therapy-related risks identified in the CEE plus MPA and CEE-alone trials – which were stopped early because of increased risk of breast cancer/overall risks exceeding benefits, and for increased stroke risk, respectively – the absence of an increase in all-cause mortality during the intervention and cumulative follow-up phases of the trials is noteworthy, the investigators wrote.

“Although these findings lend support to practice guidelines endorsing use of hormone therapy for recently menopausal women with moderate to severe symptoms, in the absence of contraindications, the attenuation of age differences with longer follow-up and potential health risks of treatment would not support use of hormone therapy for reducing chronic disease or mortality,” they wrote. “Moreover, it is unclear whether benefits would outweigh risks with longer duration of treatment.”

They added that “in clinical decision making, these considerations must be weighed against the evidence linking untreated vasomotor symptoms in midlife women to impaired health and quality of life, disrupted sleep, reduced work productivity, and increased health care expenditures.”

The Women’s Health Initiative is funded by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Study drugs were donated by Wyeth Ayerst. Dr. Manson reported having no financial disclosures. Several of her coauthors reported receiving grants and research funding from the National Institutes of Health, and receiving personal fees, speaking fees, and honoraria from various pharmaceutical companies.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point:

Major finding: All-cause mortality was 27.1% in the hormone therapy group versus 27.6% in the placebo group (hazard ratio, 0.99).

Data source: The randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Women’s Health Initiative hormone therapy trials of 27,347 women.

Disclosures: The Women’s Health Initiative is funded by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Study drugs were donated by Wyeth Ayerst. Dr. Manson reported having no disclosures. Several of her coauthors reported receiving grants and research funding from the National Institutes of Health, and receiving personal fees, speaking fees, and honoraria from various pharmaceutical companies.

Sleep issues vary by menopausal status

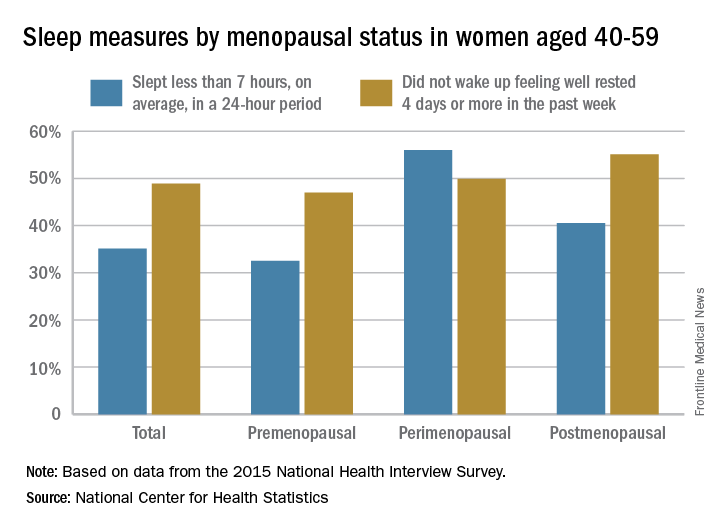

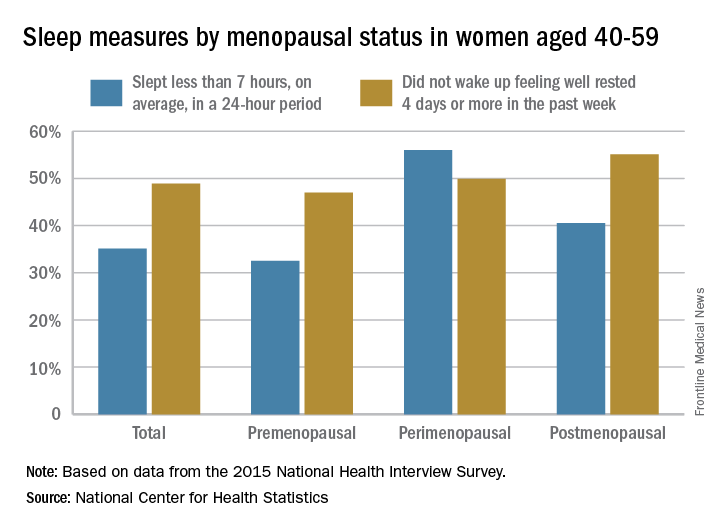

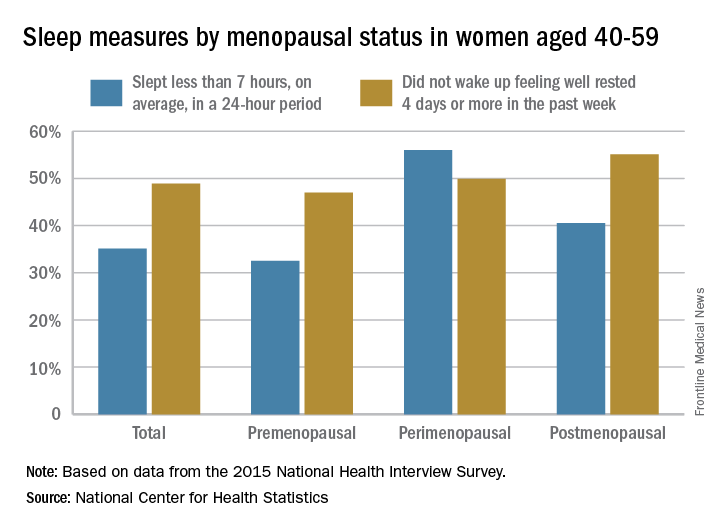

Perimenopausal women aged 40-59 years were less likely than were others in the same age group to average at least 7 hours’ sleep each night in 2015, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

Among the perimenopausal women in that age group, 56% said that they slept less than 7 hours, on average, in a 24-hour period, compared with 40.5% of postmenopausal women and 32.5% of those who were premenopausal. Overall, 35.1% of women aged 40-59 did not average at least 7 hours of sleep per night, the NCHS reported in a data brief released Sept. 7.

For this analysis, about 74% of the women included were premenopausal (still had a menstrual cycle), 4% were perimenopausal (last menstrual cycle was 1 year before or less), and 22% were postmenopausal (no menstrual cycle for more than 1 year or surgical menopause after removal of their ovaries).

Perimenopausal women aged 40-59 years were less likely than were others in the same age group to average at least 7 hours’ sleep each night in 2015, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

Among the perimenopausal women in that age group, 56% said that they slept less than 7 hours, on average, in a 24-hour period, compared with 40.5% of postmenopausal women and 32.5% of those who were premenopausal. Overall, 35.1% of women aged 40-59 did not average at least 7 hours of sleep per night, the NCHS reported in a data brief released Sept. 7.

For this analysis, about 74% of the women included were premenopausal (still had a menstrual cycle), 4% were perimenopausal (last menstrual cycle was 1 year before or less), and 22% were postmenopausal (no menstrual cycle for more than 1 year or surgical menopause after removal of their ovaries).

Perimenopausal women aged 40-59 years were less likely than were others in the same age group to average at least 7 hours’ sleep each night in 2015, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

Among the perimenopausal women in that age group, 56% said that they slept less than 7 hours, on average, in a 24-hour period, compared with 40.5% of postmenopausal women and 32.5% of those who were premenopausal. Overall, 35.1% of women aged 40-59 did not average at least 7 hours of sleep per night, the NCHS reported in a data brief released Sept. 7.

For this analysis, about 74% of the women included were premenopausal (still had a menstrual cycle), 4% were perimenopausal (last menstrual cycle was 1 year before or less), and 22% were postmenopausal (no menstrual cycle for more than 1 year or surgical menopause after removal of their ovaries).

Study finds low risk for jaw osteonecrosis with denosumab for postmenopausal osteoporosis

AT ASBMR

DENVER – Osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) was a rare adverse event in women taking denosumab for postmenopausal osteoporosis, with a 0.7% rate for women who reported an invasive oral procedure or event while taking the drug and a 0.05% rate for women who did not have such procedures, Nelson Watts, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Bone and Mineral Research.

The finding comes from a new analysis of a 7-year extension study of denosumab use in 4,550 women who participated in the 3-year, double-blind, phase 3 FREEDOM trial (NCT00089791) that compared denosumab 60 mg and placebo every 6 months. Those who missed 1 dose or fewer and completed visits through year 3 of the initial study were eligible to continue in the 7-year, open-label extension study. Those who had received placebo in the initial trial were crossed over to denosumab for the extension study.

Extension study participants were instructed to chronicle invasive oral procedures and events that had occurred in the initial trial and completed an oral event questionnaire once every 6 months of the extension trial.

All surveys were completed by 3,591 (79%) of the extension study participants, and 45.1% reported at least one invasive oral procedure or event during that time. The frequency of events was similar for the crossover and long-term denosumab groups; these events included scaling or root planing (29.1% and 28.5%), tooth extraction (25.1% and 24.6%), dental implant (5.8% and 6.0%), natural tooth loss (4.2% and 4.0%), and jaw surgery (0.9% and 0.9%). ONJ occurred at a rate of 5.2 cases per 10,000 patient-years of denosumab use, said Nelson Watts, MD, director of osteoporosis and bone health services at Mercy Health Services in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Of the 12 ONJ cases identified in the study, 11 occurred in women who reported an invasive oral procedure or event. This translated to a 0.7% risk of ONJ in women who reported an invasive oral procedure or event (11 in 1,621) and a 0.05% risk in women who did not (1 in 1,970).

The most common inciting event for ONJ appeared to be dental extractions, often of two or three teeth. The next most common dental issue associated with ONJ seemed to be poorly-fitted dentures.

ONJ resolved with treatment in 10 of 12 cases; one case was ongoing at the end of the study and one had an unknown outcome because the subject had withdrawn from the study. “With effective dental therapy, healing is the most likely outcome,” said Dr. Watts.

In clinical trials, ONJ occurred at a rate between 1 and 10 per 10,000 patient-years. A report in 2003, however, described severe ONJ in 36 cancer patients who received bisphosphonates (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12966493).

The denosumab doses that cancer patients receive can be 10 to 12 times higher than the typical dose given to a postmenopausal woman being treated for osteoporosis.

“I can’t tell you how many phone calls I get from patients who are worried somehow or worried in situations created by their dentists that whatever procedure they’re going to have is going to end horribly,” Dr. Watts said. “In some cases dentists are telling my patients to either stop the drug that I’m giving them or to wait to get the next dose, and there’s absolutely nothing to support that.”

The study was funded by Amgen, the maker of denosumab (Prolia). Dr. Watts has received research support from Shire and has consulted for Abbvie, Amgen, and Radius. He is on the speakers’ bureau for Amgen, Radius, and Shire.

AT ASBMR

DENVER – Osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) was a rare adverse event in women taking denosumab for postmenopausal osteoporosis, with a 0.7% rate for women who reported an invasive oral procedure or event while taking the drug and a 0.05% rate for women who did not have such procedures, Nelson Watts, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Bone and Mineral Research.

The finding comes from a new analysis of a 7-year extension study of denosumab use in 4,550 women who participated in the 3-year, double-blind, phase 3 FREEDOM trial (NCT00089791) that compared denosumab 60 mg and placebo every 6 months. Those who missed 1 dose or fewer and completed visits through year 3 of the initial study were eligible to continue in the 7-year, open-label extension study. Those who had received placebo in the initial trial were crossed over to denosumab for the extension study.

Extension study participants were instructed to chronicle invasive oral procedures and events that had occurred in the initial trial and completed an oral event questionnaire once every 6 months of the extension trial.

All surveys were completed by 3,591 (79%) of the extension study participants, and 45.1% reported at least one invasive oral procedure or event during that time. The frequency of events was similar for the crossover and long-term denosumab groups; these events included scaling or root planing (29.1% and 28.5%), tooth extraction (25.1% and 24.6%), dental implant (5.8% and 6.0%), natural tooth loss (4.2% and 4.0%), and jaw surgery (0.9% and 0.9%). ONJ occurred at a rate of 5.2 cases per 10,000 patient-years of denosumab use, said Nelson Watts, MD, director of osteoporosis and bone health services at Mercy Health Services in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Of the 12 ONJ cases identified in the study, 11 occurred in women who reported an invasive oral procedure or event. This translated to a 0.7% risk of ONJ in women who reported an invasive oral procedure or event (11 in 1,621) and a 0.05% risk in women who did not (1 in 1,970).

The most common inciting event for ONJ appeared to be dental extractions, often of two or three teeth. The next most common dental issue associated with ONJ seemed to be poorly-fitted dentures.

ONJ resolved with treatment in 10 of 12 cases; one case was ongoing at the end of the study and one had an unknown outcome because the subject had withdrawn from the study. “With effective dental therapy, healing is the most likely outcome,” said Dr. Watts.

In clinical trials, ONJ occurred at a rate between 1 and 10 per 10,000 patient-years. A report in 2003, however, described severe ONJ in 36 cancer patients who received bisphosphonates (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12966493).

The denosumab doses that cancer patients receive can be 10 to 12 times higher than the typical dose given to a postmenopausal woman being treated for osteoporosis.

“I can’t tell you how many phone calls I get from patients who are worried somehow or worried in situations created by their dentists that whatever procedure they’re going to have is going to end horribly,” Dr. Watts said. “In some cases dentists are telling my patients to either stop the drug that I’m giving them or to wait to get the next dose, and there’s absolutely nothing to support that.”

The study was funded by Amgen, the maker of denosumab (Prolia). Dr. Watts has received research support from Shire and has consulted for Abbvie, Amgen, and Radius. He is on the speakers’ bureau for Amgen, Radius, and Shire.

AT ASBMR

DENVER – Osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) was a rare adverse event in women taking denosumab for postmenopausal osteoporosis, with a 0.7% rate for women who reported an invasive oral procedure or event while taking the drug and a 0.05% rate for women who did not have such procedures, Nelson Watts, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Bone and Mineral Research.

The finding comes from a new analysis of a 7-year extension study of denosumab use in 4,550 women who participated in the 3-year, double-blind, phase 3 FREEDOM trial (NCT00089791) that compared denosumab 60 mg and placebo every 6 months. Those who missed 1 dose or fewer and completed visits through year 3 of the initial study were eligible to continue in the 7-year, open-label extension study. Those who had received placebo in the initial trial were crossed over to denosumab for the extension study.

Extension study participants were instructed to chronicle invasive oral procedures and events that had occurred in the initial trial and completed an oral event questionnaire once every 6 months of the extension trial.

All surveys were completed by 3,591 (79%) of the extension study participants, and 45.1% reported at least one invasive oral procedure or event during that time. The frequency of events was similar for the crossover and long-term denosumab groups; these events included scaling or root planing (29.1% and 28.5%), tooth extraction (25.1% and 24.6%), dental implant (5.8% and 6.0%), natural tooth loss (4.2% and 4.0%), and jaw surgery (0.9% and 0.9%). ONJ occurred at a rate of 5.2 cases per 10,000 patient-years of denosumab use, said Nelson Watts, MD, director of osteoporosis and bone health services at Mercy Health Services in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Of the 12 ONJ cases identified in the study, 11 occurred in women who reported an invasive oral procedure or event. This translated to a 0.7% risk of ONJ in women who reported an invasive oral procedure or event (11 in 1,621) and a 0.05% risk in women who did not (1 in 1,970).

The most common inciting event for ONJ appeared to be dental extractions, often of two or three teeth. The next most common dental issue associated with ONJ seemed to be poorly-fitted dentures.

ONJ resolved with treatment in 10 of 12 cases; one case was ongoing at the end of the study and one had an unknown outcome because the subject had withdrawn from the study. “With effective dental therapy, healing is the most likely outcome,” said Dr. Watts.

In clinical trials, ONJ occurred at a rate between 1 and 10 per 10,000 patient-years. A report in 2003, however, described severe ONJ in 36 cancer patients who received bisphosphonates (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12966493).

The denosumab doses that cancer patients receive can be 10 to 12 times higher than the typical dose given to a postmenopausal woman being treated for osteoporosis.

“I can’t tell you how many phone calls I get from patients who are worried somehow or worried in situations created by their dentists that whatever procedure they’re going to have is going to end horribly,” Dr. Watts said. “In some cases dentists are telling my patients to either stop the drug that I’m giving them or to wait to get the next dose, and there’s absolutely nothing to support that.”

The study was funded by Amgen, the maker of denosumab (Prolia). Dr. Watts has received research support from Shire and has consulted for Abbvie, Amgen, and Radius. He is on the speakers’ bureau for Amgen, Radius, and Shire.

2017 Update on female sexual dysfunction

Sexual function is a complex, multifaceted process mediated by neurologic functions, hormonal regulation, and ps

As it turns out, quite a lot. Female sexual dysfunction is a common, vastly undertreated sexual health problem that can have wide-reaching effects on a woman’s life. These effects may include impaired body image, self-confidence, and self-worth. Sexual dysfunction also can contribute to relationship dissatisfaction and leave one feeling less connected with her partner.1,2 Studies have shown women with sexual dysfunction have higher health care expenditures3 and that depression and fatigue are common comorbidities, as is frequently seen in other chronic conditions such as diabetes and back pain.4

Understanding the pathogenesis of female sexual dysfunction helps to guide our approach to its management. Indeed, increased understanding of its pathology has helped to usher in new and emerging treatment options, as well as a personalized, biopsychosocial approach to its management.

Related article:

2016 Update on female sexual dysfunction

In this Update, I discuss the interplay of physiologic and psychological factors that affect female sexual function as well as the latest options for its management. I have also assembled a panel of experts to discuss 2 cases representative of sexual dysfunction that you may encounter in your clinical practice and how prescribing decisions are made for their management.

Read about factors that impact sexual function and agents to help manage dysfunction.

Multiple transmitters in the brain can increase or decrease sexual desire and function

Neurotransmitters involved in sexual excitation include brain dopamine, melanocortin, oxytocin, vasopressin, and norepinephrine, whereas brain opioids, serotonin, prolactin, and endocannabinoids function as sexual inhibitors. Inhibitory transmitters are activated normally during sexual refractoriness but also from primary aversion or secondary avoidance disorders.1 Drugs or conditions that reduce brain dopamine levels, increase the action of brain serotonin, or enhance brain opioid pathways have been shown to inhibit sexual desire, while those that increase hypothalamic and mesolimbic dopamine or decrease serotonin release have been shown to stimulate sexual desire.1

Estradiol and progesterone can impact sexual function and desire

In addition to the neurotransmitters, hormones are important modulators of female sexual function. Decreasing levels of circulating estrogen after menopause lead to physiologic, biologic, and clinical changes in the urogenital tissues, such as decreased elastin, thinning of the epithelium, reduced vaginal blood flow, diminished lubrication, and decreased flexibility and elasticity. These changes result in the symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), which affects as many as half of all menopausal women.5,6 In clinical trials, dyspareunia and vaginal dryness are the most bothersome GSM symptoms reported.7

The role of hormonal regulation in sexual dysfunction among premenopausal women is not yet fully understood, but we do know that estradiol has been shown to improve sexual desire, progesterone tends to dampen sexual desire, and that testosterone at physiological levels has been shown in most studies to have a neutral effect on sexual desire in a well-estrogenized patient.8

Related article:

Focus on treating genital atrophy symptoms

Experience and behavior modulate or reinforce sexual dysfunction

The most common psychological factors that trigger or amplify female sexual dysfunction are depression, anxiety, distraction, negative body image, sexual abuse, and emotional neglect.9 Contextual or sociocultural factors, such as relationship discord, life-stage stressors (the empty nest syndrome or anxiety and sleep deprivation from a new baby), as well as cultural or religious values that suppress sexuality, also should be considered.9 Experience-based neuroplasticity (changes in brain pathways that become solidified by negative or positive experiences) may elucidate how a multimodal approach, utilizing medical and psychological treatment, can be beneficial for patients, particularly those with hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD).1

New and emerging approaches to managing female sexual dysfunction

Three agents, one of which has been available for prescription for some time, one that is newly available, and one in the pipeline, are or may soon be in the gynecologist's armamentarium.

Flibanserin

Medications that target excitatory pathways or blunt inhibitory pathways are in development, and one, flibanserin (Addyi), has been US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for the treatment of acquired, generalized HSDD in premenopausal women.1,10 Flibanserin is a nonhormonal, centrally acting, postsynaptic serotonin 1A receptor agonist and a serotonin 2A receptor antagonist that is taken daily at bedtime (100 mg); several weeks are usually needed before any effects are noted.1 It is not approved for postmenopausal women and has a boxed warning about the risks of hypotension and syncope; its use is contraindicated in women who drink alcohol, in those who have hepatic impairment, and with the use of moderate or strong CYP3A4 inhibitors.11

Also keep in mind that flibanserin is only available through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy program, so clinicians who wish to prescribe it must enroll in and complete training to become certified providers.9

Related article:

What you need to know (and do) to prescribe the new drug flibanserin

Prasterone

Prasterone (Intrarosa), a once-daily intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) product, is a prohormone that increases local estrogen and testosterone and has the advantage of improved sexual function, desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, as well as pain at sexual activity.12 It was approved by the FDA in November 2016 to treat moderate to severe dyspareunia and has been available for prescribing since July 2017. Its cost is comparable to topical estrogen products, with a $25 copay program.

Because prasterone is not an estrogen, it does not have the boxed warning that all estrogen products are mandated by the FDA to have. This may make it more acceptable to patients, who often decline to use an estrogen product after seeing the boxed warning on the package. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) does not have prasterone on its list of potentially hazardous drugs for the elderly. However, keep in mind that because its label is for dyspareunia and not specifically for GSM, CMS considers it a drug of choice--in other words, like sildenafil (Viagra), a lifestyle choice and not for treatment of a medical condition. As such, at the present time, Medicare does not cover it.

Bremelanotide

Late-stage trials of bremelanotide, a melanocortin receptor agonist, are underway. Its mechanism of action is somewhat like that of flibanserin in that both drugs increase dopamine and norepinephrine levels. The advantage of bremelanotide is that it is used as needed. It is dosed subcutaneously (1.75 mg) and it can be used as often as a woman would like to use it. The FDA is expected to consider it for approval in about a year. Unpublished data from poster sessions at recent meetings show that, in a phase 3 study of 1,247 premenopausal women with HSDD (who had already been screened for depression and were found to have a physiologic condition), improvements in desire, arousal, lubrication, and orgasm were shown with bremelanotide. About 18% of women stopped using the drug because of adverse effects (nausea, vomiting, flushing, or headache) versus 2% for placebo. Like flibanserin, it is expected to be approved for premenopausal women only.

Read how 3 experts would manage differing GSM symptoms.

What would you prescribe for these patients?

CASE Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) in a 55-year-old woman

A 55-year-old widow is beginning a new relationship. She has not had partnered sexual activity for several years, but she recently has begun a relationship. She describes pain with attempted penetration with her new partner. Her last menstrual period was 3 years ago and she has experienced very minor menopausal symptoms, which are not bothersome. On examination, the vulva and vagina are pale, with thin epithelium and absent rugae. The tissue lacks elasticity. A virginal speculum is needed to visualize the cervix.

How would you go about deciding which of the many options for management of GSM you will recommend for this patient? What do you weigh as you consider DHEA versus estrogen and topical versus oral therapy?

JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD: Vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA), part of GSM, is associated with postmenopausal estrogen deficiency and includes the signs and symptoms seen on this patient's physical exam: vaginal narrowing, pallor, loss of elasticity, as well as pain with intercourse.6 Estrogen therapy is the most effective treatment for vaginal atrophy.13 Since she does not have significant menopausal symptoms, low-dose vaginal estrogen preparations are effective and generally safe treatments for VVA; these include creams, tablets containing estradiol or conjugated equine estrogen (CEE), and a low-dose vaginal estradiol ring--all available at doses that result in minimal systemic absorption.

Choice is usually made based on patient desire and likely adherence. If the patient prefers nonestrogen therapies that improve VVA and have been approved for relief of dyspareunia in postmenopausal women, I would discuss with the patient the oral selective estrogen receptor modulator ospemifene,14 and the new intravaginal DHEA suppositories, prasterone.15 Ospemifene is taken daily as an oral tablet, has a small risk of blood clots, and is my choice for women who do not need systemic hormone therapy and prefer to avoid vaginal therapy.

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD: GSM is prevalent in menopausal women and, if not treated, causes progressive vaginal dryness and sexual discomfort. When the main indication for hormonal management in a menopausal woman is GSM (as opposed to treatment of vasomotor symptoms or prevention of osteoporosis), the treatment of choice is low-dose local vaginal estrogen, ospemifene, or prasterone (DHEA). Prasterone is a vaginally administered nonestrogen steroid that was approved by the FDA to treat dyspareunia associated with GSM. DHEA is an endogenous inactive steroid that is converted locally into androgens and estrogens; one vaginal insert is placed nightly.16,17

This 55-year-old widow has not been sexually active for some time. The facts that attempted penetration was painful and only an ultrathin (virginal) speculum could be used for examination indicate that contraction of the pelvic floor muscles is likely present. Simply starting medical management may not lead to comfortable/successful penetrative sex for this woman. In addition to medical management, she would likely benefit from referral for physical therapy. Using dilators and other strategies, along with the positive impact that medical management will have on the vaginal mucosa, a woman's physical therapist can work with this patient to help the pelvic floor muscles relax and facilitate comfortable penetrative sex.

James A. Simon, MD: With only minor vasomotor symptoms, I would assess the other potential benefits of a systemic therapy. These might include cardiovascular risk reduction (systemic estrogens or estrogens/progesterone in some), breast cancer risk reduction (some data suggesting ospemifene can accomplish this), osteoporosis prevention (systemic estrogens and estrogen/androgens), etc. If there is an option for a treatment to address more than one symptom, in this case GSM, assessing the risks/benefits of each of these therapies should be estimated for this specific patient.

If there are no systemic benefits to be had, then any of the local treatments should be helpful. As there are no head-to-head comparisons available, local estrogen cream, tablets, rings, local DHEA, or systemic ospemifene each should be considered possible treatments. I also feel this patient may benefit from supplementary self-dilation and/or physical therapy.

Related article:

2017 Update on menopause

CASE Dyspareunia and vasomotor symptoms in a 42-year-old breast cancer survivor

A 42-year-old woman with a BRCA1 mutation has undergone prophylactic mastectomies as well as hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. She reports mild to moderate hot flashes and bothersome vaginal dryness and dyspareunia. Examination confirms GSM.

Would you advise systemic hormone therapy for this patient? What would your recommendation be for management of her GSM symptoms?

Dr. Simon: While one's gut reaction would be to avoid systemic estrogen therapy in a patient with a BRCA1 mutation, the scientific information confirming this fear is lacking.18 Such patients may benefit significantly from systemic estrogen therapy (reduced risk of cardiovascular disease and cognitive decline, etc.), and with both breasts and both ovaries removed, estrogen's breast cancer risks, if any in this population, are largely avoided. The patient also may benefit from additional local therapy with either estrogens or DHEA.

Dr. Kaunitz: Due to her high lifetime risk of breast and ovarian cancer, this woman has proceeded with risk-reducing breast and gynecologic surgery. As more BRCA mutation carriers are being identified and undergo risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy (usually with reconstruction) and salpingo-oophorectomy, clinicians and mutation carriers more frequently face decisions regarding use of systemic hormone therapy.

Mutation carriers who have undergone bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy experience a very low baseline future risk for breast cancer; accordingly, concerns regarding this disease should not prevent use of systemic hormone therapy. Furthermore, without hormone replacement, induced menopause in women this age is associated with an elevated risk of osteoporosis, persistent vasomotor symptoms, cardiovascular disease, stroke, mood changes, dementia, Parkinson disease, and overall mortality. Recognizing the safety of estrogen therapy in this setting, this 42-year-old BRCA1 mutation carrier can initiate estrogen therapy. Standard dose estrogen therapy refers to oral estradiol 1.0 mg, conjugated equine estrogen 0.625 mg,or transdermal estradiol 0.05 mg. In younger women like this 42-year-old with surgically induced menopause, higher than standard replacement doses of estrogen are often appropriate.17

Due to concerns the hormone therapy might further increase future risk of breast cancer, some mutation carriers may delay or avoid risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, a potentially lifesaving surgery which reduces not only future risk of ovarian cancer but also future risk for breast cancer.

Among mutation carriers with intact breasts, several studies address risk of breast cancer with use of systemic hormone therapy. Although limited in numbers of participants and years of follow-up, in aggregate, these studies provide reassurance that short-term use of systemic hormone therapy does not increase breast cancer risk in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and intact breasts.19

Dr. Pinkerton: For this woman with early surgical menopause and hysterectomy, estrogen therapy could improve her vasomotor symptoms and decrease her risk of bone loss and GSM.17 In the Women's Health Initiative trial, there were 7 fewer breast cancers per 10,000 women-years in the estrogen-onlyarm.20 Observational studies suggest that hormone therapy, when given to the average age of menopause, decreases the risks of heart disease, Parkinson disease, and dementia.21 Limited observational evidence suggests that hormone therapy use does not further increase risk of breast cancer in women following oophorectomy for BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutation.22

The absolute risks observed with hormone therapy tended to be small, especially in younger, healthy women. Systemic hormone therapy could treat her hot flashes and her GSM symptoms and potentially decrease health risks associated with premature estrogen deficiency. Nonestrogen therapies for hot flashes include low-dose antidepressants, gabapentin, and mind-body options, such as cognitive behavioral therapy and hypnosis, but these would not decrease her health risks or treat her GSM.

If she only requests treatment of her GSM symptoms, she would be a candidate for low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy, given as a cream, tablet, or ring depending on her choice. I would not choose ospemifene as my first choice as she is having hot flashes, and there are no data yet on the drug's health benefits in early menopause. If she prefers nonestrogen vaginal therapy, the new intravaginal DHEA might be a good choice as both estrogen and testosterone are increased locally in the vagina while hormone levels remain in the postmenopausal range. There is no boxed warning on the patient insert, although safety in women with breast cancer or in those with elevated risk of breast cancer has not been tested.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Goldstein I, Kim NN, Clayton AH, et al. Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder: International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) Expert Consensus Panel Review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):114–128.

- Kingsberg SA. Attitudinal survey of women living with low sexual desire. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2014;23(10):817–823.

- Foley K, Foley D, Johnson BH. Healthcare resource utilization and expenditures of women diagnosed with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Med Econ. 2010;13(4):583–590.

- Biddle AK, West SL, D’Aloisio AA, Wheeler SB, Borisov NN, Thorp J. Hypoactive sexual desire disorder in postmenopausal women: quality of life and health burden. Value Health. 2009;12(5):763–772.

- Portman DJ, Gass ML; Vulvovaginal Atrophy Terminology Consensus Conference Panel. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2014;21(10):1063–1068.

- Management of symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy: 2013 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2013;20(9):888–902.

- Ettinger B, Hait H, Reape KZ, Shu H. Measuring symptom relief in studies of vaginal and vulvar atrophy: the most bothersome symptom approach. Menopause. 2008;15(5):885–889.

- Dennerstein L, Randolph J, Taffe J, Dudley E, Burger H. Hormones, mood, sexuality, and the menopausal transition. Fertil Steril. 2002;77(suppl 4):S42–S48.

- Brotto LA, Bitzer J, Laan E, Leiblum S, Luria M. Women’s sexual desire and arousal disorders [published correction appears in J Sex Med. 2010;7(2 pt 1):856]. J Sex Med. 2010;7(1 pt 2):586–614.

- US Food and Drug Administration website. FDA approves first treatment for sexual desire disorder. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm458734.htm. Accessed August 14, 2017.

- Addyi (flibanserin) [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America, LLC; 2016.

- Labrie F, Derogatis L, Archer DF, et al; Members of the VVA Prasterone Research Group. Effect of intravaginal prasterone on sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women with vulvovaginal atrophy. J Sex Med. 2015;12(12):2401–2412.

- Lethaby A, Ayeleke RO, Roberts H. Local oestrogen for vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;8:CD001500.

- Portman DJ, Bachmann GA, Simon JA; Ospemifene Study Group. Ospemifene, a novel selective estrogen receptor modulator for treating dyspareunia associated with postmenopausal vulvar and vaginal atrophy. Menopause. 2013;20(6):623–630.

- Labrie F, Archer DF, Koltun, W, et al; VVA Prasterone Research Group. Efficacy of intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) on moderate to severe dyspareunia and vaginal dryness, symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy, and of the genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Menopause. 2016;23(3):243–256.

- Kaunitz AM. Focus on treating genital atrophy symptoms. OBG Manag. 2017;29(1):14, 16–17.

- The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2017;24(7):728–753.

- Crandall CJ, Hovey KM, Andrews CA, et al. Breast cancer, endometrial cancer, and cardiovascular events in participants who used vaginal estrogen in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Menopause. August 14, 2017. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000956.

- Domchek S, Kaunitz AM. Use of systemic hormone therapy in BRCA mutation carriers. Menopause. 2016;23(9):1026–1027.

- Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, et al; Women’s Health Initiative Steering Committee. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291(14):1701–1712.

- Faubion SS, Kuhle CL, Shuster LT, Rocca WA. Long-term health consequences of premature or early menopause and considerations for management. Climacteric. 2015;18(4):483–491.

- Gabriel CA, Tigges-Cardwell J, Stopfer J, Erlichman J, Nathanson K, Domchek SM. Use of total abdominal hysterectomy and hormone replacement therapy in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers undergoing risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy. Fam Cancer. 2009;8(1):23-28.

Sexual function is a complex, multifaceted process mediated by neurologic functions, hormonal regulation, and ps

As it turns out, quite a lot. Female sexual dysfunction is a common, vastly undertreated sexual health problem that can have wide-reaching effects on a woman’s life. These effects may include impaired body image, self-confidence, and self-worth. Sexual dysfunction also can contribute to relationship dissatisfaction and leave one feeling less connected with her partner.1,2 Studies have shown women with sexual dysfunction have higher health care expenditures3 and that depression and fatigue are common comorbidities, as is frequently seen in other chronic conditions such as diabetes and back pain.4

Understanding the pathogenesis of female sexual dysfunction helps to guide our approach to its management. Indeed, increased understanding of its pathology has helped to usher in new and emerging treatment options, as well as a personalized, biopsychosocial approach to its management.

Related article:

2016 Update on female sexual dysfunction

In this Update, I discuss the interplay of physiologic and psychological factors that affect female sexual function as well as the latest options for its management. I have also assembled a panel of experts to discuss 2 cases representative of sexual dysfunction that you may encounter in your clinical practice and how prescribing decisions are made for their management.

Read about factors that impact sexual function and agents to help manage dysfunction.

Multiple transmitters in the brain can increase or decrease sexual desire and function

Neurotransmitters involved in sexual excitation include brain dopamine, melanocortin, oxytocin, vasopressin, and norepinephrine, whereas brain opioids, serotonin, prolactin, and endocannabinoids function as sexual inhibitors. Inhibitory transmitters are activated normally during sexual refractoriness but also from primary aversion or secondary avoidance disorders.1 Drugs or conditions that reduce brain dopamine levels, increase the action of brain serotonin, or enhance brain opioid pathways have been shown to inhibit sexual desire, while those that increase hypothalamic and mesolimbic dopamine or decrease serotonin release have been shown to stimulate sexual desire.1

Estradiol and progesterone can impact sexual function and desire

In addition to the neurotransmitters, hormones are important modulators of female sexual function. Decreasing levels of circulating estrogen after menopause lead to physiologic, biologic, and clinical changes in the urogenital tissues, such as decreased elastin, thinning of the epithelium, reduced vaginal blood flow, diminished lubrication, and decreased flexibility and elasticity. These changes result in the symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), which affects as many as half of all menopausal women.5,6 In clinical trials, dyspareunia and vaginal dryness are the most bothersome GSM symptoms reported.7

The role of hormonal regulation in sexual dysfunction among premenopausal women is not yet fully understood, but we do know that estradiol has been shown to improve sexual desire, progesterone tends to dampen sexual desire, and that testosterone at physiological levels has been shown in most studies to have a neutral effect on sexual desire in a well-estrogenized patient.8

Related article:

Focus on treating genital atrophy symptoms

Experience and behavior modulate or reinforce sexual dysfunction

The most common psychological factors that trigger or amplify female sexual dysfunction are depression, anxiety, distraction, negative body image, sexual abuse, and emotional neglect.9 Contextual or sociocultural factors, such as relationship discord, life-stage stressors (the empty nest syndrome or anxiety and sleep deprivation from a new baby), as well as cultural or religious values that suppress sexuality, also should be considered.9 Experience-based neuroplasticity (changes in brain pathways that become solidified by negative or positive experiences) may elucidate how a multimodal approach, utilizing medical and psychological treatment, can be beneficial for patients, particularly those with hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD).1

New and emerging approaches to managing female sexual dysfunction

Three agents, one of which has been available for prescription for some time, one that is newly available, and one in the pipeline, are or may soon be in the gynecologist's armamentarium.

Flibanserin

Medications that target excitatory pathways or blunt inhibitory pathways are in development, and one, flibanserin (Addyi), has been US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for the treatment of acquired, generalized HSDD in premenopausal women.1,10 Flibanserin is a nonhormonal, centrally acting, postsynaptic serotonin 1A receptor agonist and a serotonin 2A receptor antagonist that is taken daily at bedtime (100 mg); several weeks are usually needed before any effects are noted.1 It is not approved for postmenopausal women and has a boxed warning about the risks of hypotension and syncope; its use is contraindicated in women who drink alcohol, in those who have hepatic impairment, and with the use of moderate or strong CYP3A4 inhibitors.11

Also keep in mind that flibanserin is only available through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy program, so clinicians who wish to prescribe it must enroll in and complete training to become certified providers.9

Related article:

What you need to know (and do) to prescribe the new drug flibanserin

Prasterone

Prasterone (Intrarosa), a once-daily intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) product, is a prohormone that increases local estrogen and testosterone and has the advantage of improved sexual function, desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, as well as pain at sexual activity.12 It was approved by the FDA in November 2016 to treat moderate to severe dyspareunia and has been available for prescribing since July 2017. Its cost is comparable to topical estrogen products, with a $25 copay program.

Because prasterone is not an estrogen, it does not have the boxed warning that all estrogen products are mandated by the FDA to have. This may make it more acceptable to patients, who often decline to use an estrogen product after seeing the boxed warning on the package. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) does not have prasterone on its list of potentially hazardous drugs for the elderly. However, keep in mind that because its label is for dyspareunia and not specifically for GSM, CMS considers it a drug of choice--in other words, like sildenafil (Viagra), a lifestyle choice and not for treatment of a medical condition. As such, at the present time, Medicare does not cover it.

Bremelanotide

Late-stage trials of bremelanotide, a melanocortin receptor agonist, are underway. Its mechanism of action is somewhat like that of flibanserin in that both drugs increase dopamine and norepinephrine levels. The advantage of bremelanotide is that it is used as needed. It is dosed subcutaneously (1.75 mg) and it can be used as often as a woman would like to use it. The FDA is expected to consider it for approval in about a year. Unpublished data from poster sessions at recent meetings show that, in a phase 3 study of 1,247 premenopausal women with HSDD (who had already been screened for depression and were found to have a physiologic condition), improvements in desire, arousal, lubrication, and orgasm were shown with bremelanotide. About 18% of women stopped using the drug because of adverse effects (nausea, vomiting, flushing, or headache) versus 2% for placebo. Like flibanserin, it is expected to be approved for premenopausal women only.

Read how 3 experts would manage differing GSM symptoms.

What would you prescribe for these patients?

CASE Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) in a 55-year-old woman

A 55-year-old widow is beginning a new relationship. She has not had partnered sexual activity for several years, but she recently has begun a relationship. She describes pain with attempted penetration with her new partner. Her last menstrual period was 3 years ago and she has experienced very minor menopausal symptoms, which are not bothersome. On examination, the vulva and vagina are pale, with thin epithelium and absent rugae. The tissue lacks elasticity. A virginal speculum is needed to visualize the cervix.

How would you go about deciding which of the many options for management of GSM you will recommend for this patient? What do you weigh as you consider DHEA versus estrogen and topical versus oral therapy?

JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD: Vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA), part of GSM, is associated with postmenopausal estrogen deficiency and includes the signs and symptoms seen on this patient's physical exam: vaginal narrowing, pallor, loss of elasticity, as well as pain with intercourse.6 Estrogen therapy is the most effective treatment for vaginal atrophy.13 Since she does not have significant menopausal symptoms, low-dose vaginal estrogen preparations are effective and generally safe treatments for VVA; these include creams, tablets containing estradiol or conjugated equine estrogen (CEE), and a low-dose vaginal estradiol ring--all available at doses that result in minimal systemic absorption.

Choice is usually made based on patient desire and likely adherence. If the patient prefers nonestrogen therapies that improve VVA and have been approved for relief of dyspareunia in postmenopausal women, I would discuss with the patient the oral selective estrogen receptor modulator ospemifene,14 and the new intravaginal DHEA suppositories, prasterone.15 Ospemifene is taken daily as an oral tablet, has a small risk of blood clots, and is my choice for women who do not need systemic hormone therapy and prefer to avoid vaginal therapy.

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD: GSM is prevalent in menopausal women and, if not treated, causes progressive vaginal dryness and sexual discomfort. When the main indication for hormonal management in a menopausal woman is GSM (as opposed to treatment of vasomotor symptoms or prevention of osteoporosis), the treatment of choice is low-dose local vaginal estrogen, ospemifene, or prasterone (DHEA). Prasterone is a vaginally administered nonestrogen steroid that was approved by the FDA to treat dyspareunia associated with GSM. DHEA is an endogenous inactive steroid that is converted locally into androgens and estrogens; one vaginal insert is placed nightly.16,17

This 55-year-old widow has not been sexually active for some time. The facts that attempted penetration was painful and only an ultrathin (virginal) speculum could be used for examination indicate that contraction of the pelvic floor muscles is likely present. Simply starting medical management may not lead to comfortable/successful penetrative sex for this woman. In addition to medical management, she would likely benefit from referral for physical therapy. Using dilators and other strategies, along with the positive impact that medical management will have on the vaginal mucosa, a woman's physical therapist can work with this patient to help the pelvic floor muscles relax and facilitate comfortable penetrative sex.

James A. Simon, MD: With only minor vasomotor symptoms, I would assess the other potential benefits of a systemic therapy. These might include cardiovascular risk reduction (systemic estrogens or estrogens/progesterone in some), breast cancer risk reduction (some data suggesting ospemifene can accomplish this), osteoporosis prevention (systemic estrogens and estrogen/androgens), etc. If there is an option for a treatment to address more than one symptom, in this case GSM, assessing the risks/benefits of each of these therapies should be estimated for this specific patient.

If there are no systemic benefits to be had, then any of the local treatments should be helpful. As there are no head-to-head comparisons available, local estrogen cream, tablets, rings, local DHEA, or systemic ospemifene each should be considered possible treatments. I also feel this patient may benefit from supplementary self-dilation and/or physical therapy.

Related article:

2017 Update on menopause

CASE Dyspareunia and vasomotor symptoms in a 42-year-old breast cancer survivor

A 42-year-old woman with a BRCA1 mutation has undergone prophylactic mastectomies as well as hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. She reports mild to moderate hot flashes and bothersome vaginal dryness and dyspareunia. Examination confirms GSM.

Would you advise systemic hormone therapy for this patient? What would your recommendation be for management of her GSM symptoms?

Dr. Simon: While one's gut reaction would be to avoid systemic estrogen therapy in a patient with a BRCA1 mutation, the scientific information confirming this fear is lacking.18 Such patients may benefit significantly from systemic estrogen therapy (reduced risk of cardiovascular disease and cognitive decline, etc.), and with both breasts and both ovaries removed, estrogen's breast cancer risks, if any in this population, are largely avoided. The patient also may benefit from additional local therapy with either estrogens or DHEA.

Dr. Kaunitz: Due to her high lifetime risk of breast and ovarian cancer, this woman has proceeded with risk-reducing breast and gynecologic surgery. As more BRCA mutation carriers are being identified and undergo risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy (usually with reconstruction) and salpingo-oophorectomy, clinicians and mutation carriers more frequently face decisions regarding use of systemic hormone therapy.

Mutation carriers who have undergone bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy experience a very low baseline future risk for breast cancer; accordingly, concerns regarding this disease should not prevent use of systemic hormone therapy. Furthermore, without hormone replacement, induced menopause in women this age is associated with an elevated risk of osteoporosis, persistent vasomotor symptoms, cardiovascular disease, stroke, mood changes, dementia, Parkinson disease, and overall mortality. Recognizing the safety of estrogen therapy in this setting, this 42-year-old BRCA1 mutation carrier can initiate estrogen therapy. Standard dose estrogen therapy refers to oral estradiol 1.0 mg, conjugated equine estrogen 0.625 mg,or transdermal estradiol 0.05 mg. In younger women like this 42-year-old with surgically induced menopause, higher than standard replacement doses of estrogen are often appropriate.17

Due to concerns the hormone therapy might further increase future risk of breast cancer, some mutation carriers may delay or avoid risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, a potentially lifesaving surgery which reduces not only future risk of ovarian cancer but also future risk for breast cancer.

Among mutation carriers with intact breasts, several studies address risk of breast cancer with use of systemic hormone therapy. Although limited in numbers of participants and years of follow-up, in aggregate, these studies provide reassurance that short-term use of systemic hormone therapy does not increase breast cancer risk in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and intact breasts.19

Dr. Pinkerton: For this woman with early surgical menopause and hysterectomy, estrogen therapy could improve her vasomotor symptoms and decrease her risk of bone loss and GSM.17 In the Women's Health Initiative trial, there were 7 fewer breast cancers per 10,000 women-years in the estrogen-onlyarm.20 Observational studies suggest that hormone therapy, when given to the average age of menopause, decreases the risks of heart disease, Parkinson disease, and dementia.21 Limited observational evidence suggests that hormone therapy use does not further increase risk of breast cancer in women following oophorectomy for BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutation.22

The absolute risks observed with hormone therapy tended to be small, especially in younger, healthy women. Systemic hormone therapy could treat her hot flashes and her GSM symptoms and potentially decrease health risks associated with premature estrogen deficiency. Nonestrogen therapies for hot flashes include low-dose antidepressants, gabapentin, and mind-body options, such as cognitive behavioral therapy and hypnosis, but these would not decrease her health risks or treat her GSM.

If she only requests treatment of her GSM symptoms, she would be a candidate for low-dose vaginal estrogen therapy, given as a cream, tablet, or ring depending on her choice. I would not choose ospemifene as my first choice as she is having hot flashes, and there are no data yet on the drug's health benefits in early menopause. If she prefers nonestrogen vaginal therapy, the new intravaginal DHEA might be a good choice as both estrogen and testosterone are increased locally in the vagina while hormone levels remain in the postmenopausal range. There is no boxed warning on the patient insert, although safety in women with breast cancer or in those with elevated risk of breast cancer has not been tested.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Sexual function is a complex, multifaceted process mediated by neurologic functions, hormonal regulation, and ps

As it turns out, quite a lot. Female sexual dysfunction is a common, vastly undertreated sexual health problem that can have wide-reaching effects on a woman’s life. These effects may include impaired body image, self-confidence, and self-worth. Sexual dysfunction also can contribute to relationship dissatisfaction and leave one feeling less connected with her partner.1,2 Studies have shown women with sexual dysfunction have higher health care expenditures3 and that depression and fatigue are common comorbidities, as is frequently seen in other chronic conditions such as diabetes and back pain.4

Understanding the pathogenesis of female sexual dysfunction helps to guide our approach to its management. Indeed, increased understanding of its pathology has helped to usher in new and emerging treatment options, as well as a personalized, biopsychosocial approach to its management.

Related article:

2016 Update on female sexual dysfunction

In this Update, I discuss the interplay of physiologic and psychological factors that affect female sexual function as well as the latest options for its management. I have also assembled a panel of experts to discuss 2 cases representative of sexual dysfunction that you may encounter in your clinical practice and how prescribing decisions are made for their management.

Read about factors that impact sexual function and agents to help manage dysfunction.

Multiple transmitters in the brain can increase or decrease sexual desire and function

Neurotransmitters involved in sexual excitation include brain dopamine, melanocortin, oxytocin, vasopressin, and norepinephrine, whereas brain opioids, serotonin, prolactin, and endocannabinoids function as sexual inhibitors. Inhibitory transmitters are activated normally during sexual refractoriness but also from primary aversion or secondary avoidance disorders.1 Drugs or conditions that reduce brain dopamine levels, increase the action of brain serotonin, or enhance brain opioid pathways have been shown to inhibit sexual desire, while those that increase hypothalamic and mesolimbic dopamine or decrease serotonin release have been shown to stimulate sexual desire.1

Estradiol and progesterone can impact sexual function and desire

In addition to the neurotransmitters, hormones are important modulators of female sexual function. Decreasing levels of circulating estrogen after menopause lead to physiologic, biologic, and clinical changes in the urogenital tissues, such as decreased elastin, thinning of the epithelium, reduced vaginal blood flow, diminished lubrication, and decreased flexibility and elasticity. These changes result in the symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), which affects as many as half of all menopausal women.5,6 In clinical trials, dyspareunia and vaginal dryness are the most bothersome GSM symptoms reported.7

The role of hormonal regulation in sexual dysfunction among premenopausal women is not yet fully understood, but we do know that estradiol has been shown to improve sexual desire, progesterone tends to dampen sexual desire, and that testosterone at physiological levels has been shown in most studies to have a neutral effect on sexual desire in a well-estrogenized patient.8

Related article:

Focus on treating genital atrophy symptoms

Experience and behavior modulate or reinforce sexual dysfunction

The most common psychological factors that trigger or amplify female sexual dysfunction are depression, anxiety, distraction, negative body image, sexual abuse, and emotional neglect.9 Contextual or sociocultural factors, such as relationship discord, life-stage stressors (the empty nest syndrome or anxiety and sleep deprivation from a new baby), as well as cultural or religious values that suppress sexuality, also should be considered.9 Experience-based neuroplasticity (changes in brain pathways that become solidified by negative or positive experiences) may elucidate how a multimodal approach, utilizing medical and psychological treatment, can be beneficial for patients, particularly those with hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD).1

New and emerging approaches to managing female sexual dysfunction

Three agents, one of which has been available for prescription for some time, one that is newly available, and one in the pipeline, are or may soon be in the gynecologist's armamentarium.

Flibanserin

Medications that target excitatory pathways or blunt inhibitory pathways are in development, and one, flibanserin (Addyi), has been US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for the treatment of acquired, generalized HSDD in premenopausal women.1,10 Flibanserin is a nonhormonal, centrally acting, postsynaptic serotonin 1A receptor agonist and a serotonin 2A receptor antagonist that is taken daily at bedtime (100 mg); several weeks are usually needed before any effects are noted.1 It is not approved for postmenopausal women and has a boxed warning about the risks of hypotension and syncope; its use is contraindicated in women who drink alcohol, in those who have hepatic impairment, and with the use of moderate or strong CYP3A4 inhibitors.11

Also keep in mind that flibanserin is only available through a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy program, so clinicians who wish to prescribe it must enroll in and complete training to become certified providers.9

Related article:

What you need to know (and do) to prescribe the new drug flibanserin

Prasterone

Prasterone (Intrarosa), a once-daily intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) product, is a prohormone that increases local estrogen and testosterone and has the advantage of improved sexual function, desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, as well as pain at sexual activity.12 It was approved by the FDA in November 2016 to treat moderate to severe dyspareunia and has been available for prescribing since July 2017. Its cost is comparable to topical estrogen products, with a $25 copay program.

Because prasterone is not an estrogen, it does not have the boxed warning that all estrogen products are mandated by the FDA to have. This may make it more acceptable to patients, who often decline to use an estrogen product after seeing the boxed warning on the package. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) does not have prasterone on its list of potentially hazardous drugs for the elderly. However, keep in mind that because its label is for dyspareunia and not specifically for GSM, CMS considers it a drug of choice--in other words, like sildenafil (Viagra), a lifestyle choice and not for treatment of a medical condition. As such, at the present time, Medicare does not cover it.

Bremelanotide

Late-stage trials of bremelanotide, a melanocortin receptor agonist, are underway. Its mechanism of action is somewhat like that of flibanserin in that both drugs increase dopamine and norepinephrine levels. The advantage of bremelanotide is that it is used as needed. It is dosed subcutaneously (1.75 mg) and it can be used as often as a woman would like to use it. The FDA is expected to consider it for approval in about a year. Unpublished data from poster sessions at recent meetings show that, in a phase 3 study of 1,247 premenopausal women with HSDD (who had already been screened for depression and were found to have a physiologic condition), improvements in desire, arousal, lubrication, and orgasm were shown with bremelanotide. About 18% of women stopped using the drug because of adverse effects (nausea, vomiting, flushing, or headache) versus 2% for placebo. Like flibanserin, it is expected to be approved for premenopausal women only.

Read how 3 experts would manage differing GSM symptoms.

What would you prescribe for these patients?

CASE Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) in a 55-year-old woman

A 55-year-old widow is beginning a new relationship. She has not had partnered sexual activity for several years, but she recently has begun a relationship. She describes pain with attempted penetration with her new partner. Her last menstrual period was 3 years ago and she has experienced very minor menopausal symptoms, which are not bothersome. On examination, the vulva and vagina are pale, with thin epithelium and absent rugae. The tissue lacks elasticity. A virginal speculum is needed to visualize the cervix.

How would you go about deciding which of the many options for management of GSM you will recommend for this patient? What do you weigh as you consider DHEA versus estrogen and topical versus oral therapy?

JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD: Vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA), part of GSM, is associated with postmenopausal estrogen deficiency and includes the signs and symptoms seen on this patient's physical exam: vaginal narrowing, pallor, loss of elasticity, as well as pain with intercourse.6 Estrogen therapy is the most effective treatment for vaginal atrophy.13 Since she does not have significant menopausal symptoms, low-dose vaginal estrogen preparations are effective and generally safe treatments for VVA; these include creams, tablets containing estradiol or conjugated equine estrogen (CEE), and a low-dose vaginal estradiol ring--all available at doses that result in minimal systemic absorption.

Choice is usually made based on patient desire and likely adherence. If the patient prefers nonestrogen therapies that improve VVA and have been approved for relief of dyspareunia in postmenopausal women, I would discuss with the patient the oral selective estrogen receptor modulator ospemifene,14 and the new intravaginal DHEA suppositories, prasterone.15 Ospemifene is taken daily as an oral tablet, has a small risk of blood clots, and is my choice for women who do not need systemic hormone therapy and prefer to avoid vaginal therapy.

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD: GSM is prevalent in menopausal women and, if not treated, causes progressive vaginal dryness and sexual discomfort. When the main indication for hormonal management in a menopausal woman is GSM (as opposed to treatment of vasomotor symptoms or prevention of osteoporosis), the treatment of choice is low-dose local vaginal estrogen, ospemifene, or prasterone (DHEA). Prasterone is a vaginally administered nonestrogen steroid that was approved by the FDA to treat dyspareunia associated with GSM. DHEA is an endogenous inactive steroid that is converted locally into androgens and estrogens; one vaginal insert is placed nightly.16,17