User login

Cavernous gender gap in Medicare payments to cardiologists

Women cardiologists receive dramatically smaller payments from the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) than their male counterparts, new research suggests.

An analysis of 2016 claims data revealed male cardiologists received on average 45% more reimbursement than women in the inpatient setting, with the median payment 39% higher ($62,897 vs. $45,288).

In the outpatient setting, men received on average 62% more annual CMS payments, with the median payment 75% higher ($91,053 vs. $51,975; P < .001 for both).

The difference remained significant after the exclusion of the top and bottom 2.5% of earning physicians and cardiology subspecialties, like electrophysiology and interventional cardiology, with high procedural volumes and greater gender imbalances.

“This is one study among others which demonstrates a wage gap between men and women in medicine in cardiology,” lead author Inbar Raber, MD, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, said in an interview. “I hope by increasing awareness [and] understanding of possible etiologies, it will enable some sustainable solutions, and those include access to additional support staff and equitable models surrounding parental leave and childcare support.”

The study, published online September 8 in JAMA Cardiology, comes on the heels of a recent cross-sectional analysis that put cardiology at the bottom of 13 internal medicine subspecialties with just 21% female faculty representation and one of only three specialties in which women’s median salaries did not reach 90% of men’s.

The new findings build on a 2017 report that showed Medicare payments to women physicians in 2013 were 55% of those to male physicians across all specialties.

“It can be disheartening, especially as an early career woman cardiologist, seeing these differences, but I think the responsibility on all of us is to take these observations and really try to understand more deeply why they exist,” Nosheen Reza, MD, from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and coauthor of the cross-sectional analysis, told this news organization.

Several factors could be contributing to the disparity, but “it’s not gender discrimination from Medicare,” Dr. Raber said. “The gap in reimbursement is really driven by the types and the volume of charges submitted.”

Indeed, a direct comparison of the three most common inpatient and outpatient billing codes showed no difference in payments between the sexes.

Men, however, submitted 24% more median inpatient charges to CMS than women (1,190 vs. 959), and 94% more outpatient charges (1,685 vs. 870).

Men also submitted slightly more unique billing codes (median inpatient, 10 vs. 9; median outpatient, 11 vs. 8).

Notably, women made up just 13% of the 17,524 cardiologists who received CMS payments in the inpatient setting in 2016 and 13% of the 16,929 cardiologists who did so in the outpatient setting.

Louisiana had the dubious distinction of having the largest gender gap in mean CMS payments, with male cardiologists earning $145,323 (235%) more than women, whereas women cardiologists in Vermont out-earned men by $31,483 (38%).

Overall, male cardiologists had more years in practice than women cardiologists and cared for slightly older Medicare beneficiaries.

Differences in CMS payments persisted, however, after adjustment for years since graduation, physician subspecialty, number of charges, number of unique billing codes, and patient complexity. The resulting β coefficient was -0.06, which translates into women receiving an average of 94% of the CMS payments received by men.

“The first takeaway, if you were really crass and focused on the bottom line, might be: ‘Hey, let me get a few more male cardiologists because they’re going to bring more into the organization.’ But we shouldn’t do that because, unless you link these data with quality outcomes, they’re an interesting observation and hypothesis-generating,” said Sharonne Hayes, MD, coauthor of the 2017 report and professor of cardiovascular medicine at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., where she has served as director of diversity and inclusion for a decade.

She noted that there are multiple examples that the style of medicine women practice, on average, may be more effective, may be more outcomes based, and may save lives, as suggested by a recent analysis of hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries.

“The gap was not much different, like within 1% or so, but when you take that over the literally millions of Medicare patients cared for each year by hospitalists, that’s a substantial number of people,” Dr. Hayes said. “So, I think we need to take a step back, and we have to include these observations on studies like this and better understand the compensation gaps.”

She pointed out that the present study lacks data on full-time-equivalent status but that female physicians are more likely to work part-time, thus reducing the volume of claims.

Women might also care for different patient populations. “I practice in a women’s heart clinic and take care of [spontaneous coronary artery dissection] SCAD patients where the average age of SCAD is 42. So, the vast majority of patients I see on a day-to-day basis aren’t going to be Medicare age,” observed Dr. Hayes.

The differences in charges might also reflect the increased obligations in nonreimbursed work that women can have, Dr. Raber said. These can be things like mentoring, teaching roles, and serving on committees, which is a hypothesis supported by a 2021 study that showed women physicians spend more time on these “citizenship tasks” than men.

Finally, there could be organizational barriers that affect women’s clinical volumes, including less access to support from health care personnel. Added support is especially important, though, amid a 100-year pandemic, the women agreed.

“Within the first year of the pandemic, we saw women leaving the workforce in droves across all sectors, including medicine, including academic medicine. And, as the pandemic goes on without any signs of abatement, those threats continue to exist and continue to be amplified,” Dr. Reza said.

The groundswell of support surrounding the importance of diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives across the board has helped bring attention to the issue, she said. Some institutions, including the National Institutes of Health, are making efforts to extend relief to women with young families, caregivers, or those in academic medicine who, for example, need extensions on grants or bridge funding.

“There’s certainly a lot left to do, but I do think within the last year, there’s been an acceleration of literature that has come out, not only pointing out the disparities, but pointing out that perhaps women physicians do have better outcomes and are better liked by their patients and that losing women in the workforce would be a huge detriment to the field overall,” Dr. Reza said.

Dr. Raber, Dr. Reza, and Dr. Hayes reports no relevant financial relationships. Coauthor conflict of interest disclosures are listed in the paper.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Women cardiologists receive dramatically smaller payments from the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) than their male counterparts, new research suggests.

An analysis of 2016 claims data revealed male cardiologists received on average 45% more reimbursement than women in the inpatient setting, with the median payment 39% higher ($62,897 vs. $45,288).

In the outpatient setting, men received on average 62% more annual CMS payments, with the median payment 75% higher ($91,053 vs. $51,975; P < .001 for both).

The difference remained significant after the exclusion of the top and bottom 2.5% of earning physicians and cardiology subspecialties, like electrophysiology and interventional cardiology, with high procedural volumes and greater gender imbalances.

“This is one study among others which demonstrates a wage gap between men and women in medicine in cardiology,” lead author Inbar Raber, MD, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, said in an interview. “I hope by increasing awareness [and] understanding of possible etiologies, it will enable some sustainable solutions, and those include access to additional support staff and equitable models surrounding parental leave and childcare support.”

The study, published online September 8 in JAMA Cardiology, comes on the heels of a recent cross-sectional analysis that put cardiology at the bottom of 13 internal medicine subspecialties with just 21% female faculty representation and one of only three specialties in which women’s median salaries did not reach 90% of men’s.

The new findings build on a 2017 report that showed Medicare payments to women physicians in 2013 were 55% of those to male physicians across all specialties.

“It can be disheartening, especially as an early career woman cardiologist, seeing these differences, but I think the responsibility on all of us is to take these observations and really try to understand more deeply why they exist,” Nosheen Reza, MD, from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and coauthor of the cross-sectional analysis, told this news organization.

Several factors could be contributing to the disparity, but “it’s not gender discrimination from Medicare,” Dr. Raber said. “The gap in reimbursement is really driven by the types and the volume of charges submitted.”

Indeed, a direct comparison of the three most common inpatient and outpatient billing codes showed no difference in payments between the sexes.

Men, however, submitted 24% more median inpatient charges to CMS than women (1,190 vs. 959), and 94% more outpatient charges (1,685 vs. 870).

Men also submitted slightly more unique billing codes (median inpatient, 10 vs. 9; median outpatient, 11 vs. 8).

Notably, women made up just 13% of the 17,524 cardiologists who received CMS payments in the inpatient setting in 2016 and 13% of the 16,929 cardiologists who did so in the outpatient setting.

Louisiana had the dubious distinction of having the largest gender gap in mean CMS payments, with male cardiologists earning $145,323 (235%) more than women, whereas women cardiologists in Vermont out-earned men by $31,483 (38%).

Overall, male cardiologists had more years in practice than women cardiologists and cared for slightly older Medicare beneficiaries.

Differences in CMS payments persisted, however, after adjustment for years since graduation, physician subspecialty, number of charges, number of unique billing codes, and patient complexity. The resulting β coefficient was -0.06, which translates into women receiving an average of 94% of the CMS payments received by men.

“The first takeaway, if you were really crass and focused on the bottom line, might be: ‘Hey, let me get a few more male cardiologists because they’re going to bring more into the organization.’ But we shouldn’t do that because, unless you link these data with quality outcomes, they’re an interesting observation and hypothesis-generating,” said Sharonne Hayes, MD, coauthor of the 2017 report and professor of cardiovascular medicine at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., where she has served as director of diversity and inclusion for a decade.

She noted that there are multiple examples that the style of medicine women practice, on average, may be more effective, may be more outcomes based, and may save lives, as suggested by a recent analysis of hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries.

“The gap was not much different, like within 1% or so, but when you take that over the literally millions of Medicare patients cared for each year by hospitalists, that’s a substantial number of people,” Dr. Hayes said. “So, I think we need to take a step back, and we have to include these observations on studies like this and better understand the compensation gaps.”

She pointed out that the present study lacks data on full-time-equivalent status but that female physicians are more likely to work part-time, thus reducing the volume of claims.

Women might also care for different patient populations. “I practice in a women’s heart clinic and take care of [spontaneous coronary artery dissection] SCAD patients where the average age of SCAD is 42. So, the vast majority of patients I see on a day-to-day basis aren’t going to be Medicare age,” observed Dr. Hayes.

The differences in charges might also reflect the increased obligations in nonreimbursed work that women can have, Dr. Raber said. These can be things like mentoring, teaching roles, and serving on committees, which is a hypothesis supported by a 2021 study that showed women physicians spend more time on these “citizenship tasks” than men.

Finally, there could be organizational barriers that affect women’s clinical volumes, including less access to support from health care personnel. Added support is especially important, though, amid a 100-year pandemic, the women agreed.

“Within the first year of the pandemic, we saw women leaving the workforce in droves across all sectors, including medicine, including academic medicine. And, as the pandemic goes on without any signs of abatement, those threats continue to exist and continue to be amplified,” Dr. Reza said.

The groundswell of support surrounding the importance of diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives across the board has helped bring attention to the issue, she said. Some institutions, including the National Institutes of Health, are making efforts to extend relief to women with young families, caregivers, or those in academic medicine who, for example, need extensions on grants or bridge funding.

“There’s certainly a lot left to do, but I do think within the last year, there’s been an acceleration of literature that has come out, not only pointing out the disparities, but pointing out that perhaps women physicians do have better outcomes and are better liked by their patients and that losing women in the workforce would be a huge detriment to the field overall,” Dr. Reza said.

Dr. Raber, Dr. Reza, and Dr. Hayes reports no relevant financial relationships. Coauthor conflict of interest disclosures are listed in the paper.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Women cardiologists receive dramatically smaller payments from the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) than their male counterparts, new research suggests.

An analysis of 2016 claims data revealed male cardiologists received on average 45% more reimbursement than women in the inpatient setting, with the median payment 39% higher ($62,897 vs. $45,288).

In the outpatient setting, men received on average 62% more annual CMS payments, with the median payment 75% higher ($91,053 vs. $51,975; P < .001 for both).

The difference remained significant after the exclusion of the top and bottom 2.5% of earning physicians and cardiology subspecialties, like electrophysiology and interventional cardiology, with high procedural volumes and greater gender imbalances.

“This is one study among others which demonstrates a wage gap between men and women in medicine in cardiology,” lead author Inbar Raber, MD, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, said in an interview. “I hope by increasing awareness [and] understanding of possible etiologies, it will enable some sustainable solutions, and those include access to additional support staff and equitable models surrounding parental leave and childcare support.”

The study, published online September 8 in JAMA Cardiology, comes on the heels of a recent cross-sectional analysis that put cardiology at the bottom of 13 internal medicine subspecialties with just 21% female faculty representation and one of only three specialties in which women’s median salaries did not reach 90% of men’s.

The new findings build on a 2017 report that showed Medicare payments to women physicians in 2013 were 55% of those to male physicians across all specialties.

“It can be disheartening, especially as an early career woman cardiologist, seeing these differences, but I think the responsibility on all of us is to take these observations and really try to understand more deeply why they exist,” Nosheen Reza, MD, from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and coauthor of the cross-sectional analysis, told this news organization.

Several factors could be contributing to the disparity, but “it’s not gender discrimination from Medicare,” Dr. Raber said. “The gap in reimbursement is really driven by the types and the volume of charges submitted.”

Indeed, a direct comparison of the three most common inpatient and outpatient billing codes showed no difference in payments between the sexes.

Men, however, submitted 24% more median inpatient charges to CMS than women (1,190 vs. 959), and 94% more outpatient charges (1,685 vs. 870).

Men also submitted slightly more unique billing codes (median inpatient, 10 vs. 9; median outpatient, 11 vs. 8).

Notably, women made up just 13% of the 17,524 cardiologists who received CMS payments in the inpatient setting in 2016 and 13% of the 16,929 cardiologists who did so in the outpatient setting.

Louisiana had the dubious distinction of having the largest gender gap in mean CMS payments, with male cardiologists earning $145,323 (235%) more than women, whereas women cardiologists in Vermont out-earned men by $31,483 (38%).

Overall, male cardiologists had more years in practice than women cardiologists and cared for slightly older Medicare beneficiaries.

Differences in CMS payments persisted, however, after adjustment for years since graduation, physician subspecialty, number of charges, number of unique billing codes, and patient complexity. The resulting β coefficient was -0.06, which translates into women receiving an average of 94% of the CMS payments received by men.

“The first takeaway, if you were really crass and focused on the bottom line, might be: ‘Hey, let me get a few more male cardiologists because they’re going to bring more into the organization.’ But we shouldn’t do that because, unless you link these data with quality outcomes, they’re an interesting observation and hypothesis-generating,” said Sharonne Hayes, MD, coauthor of the 2017 report and professor of cardiovascular medicine at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., where she has served as director of diversity and inclusion for a decade.

She noted that there are multiple examples that the style of medicine women practice, on average, may be more effective, may be more outcomes based, and may save lives, as suggested by a recent analysis of hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries.

“The gap was not much different, like within 1% or so, but when you take that over the literally millions of Medicare patients cared for each year by hospitalists, that’s a substantial number of people,” Dr. Hayes said. “So, I think we need to take a step back, and we have to include these observations on studies like this and better understand the compensation gaps.”

She pointed out that the present study lacks data on full-time-equivalent status but that female physicians are more likely to work part-time, thus reducing the volume of claims.

Women might also care for different patient populations. “I practice in a women’s heart clinic and take care of [spontaneous coronary artery dissection] SCAD patients where the average age of SCAD is 42. So, the vast majority of patients I see on a day-to-day basis aren’t going to be Medicare age,” observed Dr. Hayes.

The differences in charges might also reflect the increased obligations in nonreimbursed work that women can have, Dr. Raber said. These can be things like mentoring, teaching roles, and serving on committees, which is a hypothesis supported by a 2021 study that showed women physicians spend more time on these “citizenship tasks” than men.

Finally, there could be organizational barriers that affect women’s clinical volumes, including less access to support from health care personnel. Added support is especially important, though, amid a 100-year pandemic, the women agreed.

“Within the first year of the pandemic, we saw women leaving the workforce in droves across all sectors, including medicine, including academic medicine. And, as the pandemic goes on without any signs of abatement, those threats continue to exist and continue to be amplified,” Dr. Reza said.

The groundswell of support surrounding the importance of diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives across the board has helped bring attention to the issue, she said. Some institutions, including the National Institutes of Health, are making efforts to extend relief to women with young families, caregivers, or those in academic medicine who, for example, need extensions on grants or bridge funding.

“There’s certainly a lot left to do, but I do think within the last year, there’s been an acceleration of literature that has come out, not only pointing out the disparities, but pointing out that perhaps women physicians do have better outcomes and are better liked by their patients and that losing women in the workforce would be a huge detriment to the field overall,” Dr. Reza said.

Dr. Raber, Dr. Reza, and Dr. Hayes reports no relevant financial relationships. Coauthor conflict of interest disclosures are listed in the paper.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Feds slap UPMC, lead cardiothoracic surgeon with fraud lawsuit

Following a 2-year investigation, the U.S. government has filed suit against the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC), University of Pittsburgh Physicians (UPP), and James Luketich, MD, for billing related to concurrent surgeries performed by the long-time chair of cardiothoracic surgery.

The lawsuit alleges that UPMC “knowingly allowed” Dr. Luketich to “book and perform three surgeries at the same time, to miss the surgical time outs at the outset of those procedures, to go back-and-forth between operating rooms and even hospital facilities while his surgical patients remain under general anesthesia...”

UPMC, the lawsuit claims, also allowed Dr. Luketich to falsely attest that “he was with his patients throughout the entirety of their surgical procedures or during all ‘key and critical’ portions of those procedures and to unlawfully bill Government Health Benefit Programs for those procedures, all in order to increase surgical volume, maximize UPMC and UPP’s revenue, and/or appease Dr. Luketich.”

These practices violate the statutes and regulations governing the defendants, including those that prohibit “teaching physicians” like Dr. Luketich from performing and billing the U.S. for concurrent surgeries, the Department of Justice said in news release.

The Justice Department contends the defendants “knowingly submitted hundreds of materially false claims for payment” to Medicare, Medicaid, and other government programs over the past 6 years.

“The laws prohibiting ‘concurrent surgeries’ are in place for a reason: To protect patients and ensure they receive appropriate and focused medical care,” Stephen R. Kaufman, Acting U.S. Attorney for the Western District of Pennsylvania, said in the release.

According to the lawsuit, “some of Dr. Luketich’s patients were forced to endure additional surgical procedures and/or extended hospital stays as a result of his unlawful conduct. Numerous patients developed painful pressure ulcers. A few were diagnosed with compartment syndrome. And at least two had to undergo amputations.”

The allegations were originally brought forward under the federal False Claims Act’s whistleblower provisions by Jonathan D’Cunha, MD, PhD, who worked closely with Dr. Luketich from 2012 to 2019 and now chairs the department of cardiothoracic surgery at the Mayo Clinic, Phoenix.

The charges cited in the lawsuit include three counts of violating the False Claims Act, one count of unjust enrichment, and one count of payment by mistake.

The 56-page lawsuit includes numerous case examples and cites an October 2015 Boston Globe Spotlight Team report on the safety of running concurrent operations, which reportedly prompted UPMC to reevaluate its policies and identify physicians or departments in potential violation.

Hospital officials met with Dr. Luketich in March 2016 and devised a “plan” to ensure his availability and “compliance with concurrency rules,” it alleges, but also highlights an email that notes “continued problems” with Dr. Luketich’s schedule.

“UPMC has persistently ignored or minimized complaints by employees and staff regarding Dr. Luketich, his hyper-busy schedule, his refusal to delegate surgeries and surgical tasks” and “protected him from meaningful sanction; refused to curtail his surgical practice; and continued to allow Dr. Luketich to skirt the rules and endanger his patients,” according to the lawsuit.

The suit notes that Dr. Luketich is one of UPMC and UPP’s highest sources of revenue and that UPMC advertises him as a “life-saving pioneer” who routinely performs dramatic, last-ditch procedures on patients who are otherwise hopeless.

In response to an interview request from this news organization, a UPMC spokesperson wrote: “As the government itself concedes in its complaint, many of Dr. Luketich’s surgical patients are elderly, frail, and/or very ill. They include the ‘hopeless’ patients ... who suffer from chronic illness or metastatic cancer, and/or have extensive surgical histories and choose UPMC and Dr. Luketich when other physicians and health care providers have turned them down.”

“Dr. Luketich always performs the most critical portions of every operation he undertakes,” the spokesperson said, adding that no law or regulation prohibits overlapping surgeries or billing for those surgeries, “let alone surgeries conducted by teams of surgeons like those led by Dr. Luketich.”

“The government’s claims are, rather, based on a misapplication or misinterpretation of UPMC’s internal policies and [Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services] guidance, neither of which can support a claim for fraudulent billing. UPMC and Dr. Luketich plan to vigorously defend against the government’s claims,” the spokesperson concluded.

The claims asserted against the defendants are allegations only; there has been no determination of liability. The government is seeking three times the amount of actual damages suffered as a result of the alleged false claims and/or fraud; a sum of $23,331 (or the maximum penalty, whichever is greater) for each false claim submitted by UPMC, UPP, and/or Dr. Luketich; and costs and expenses associated with the civil suit.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Following a 2-year investigation, the U.S. government has filed suit against the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC), University of Pittsburgh Physicians (UPP), and James Luketich, MD, for billing related to concurrent surgeries performed by the long-time chair of cardiothoracic surgery.

The lawsuit alleges that UPMC “knowingly allowed” Dr. Luketich to “book and perform three surgeries at the same time, to miss the surgical time outs at the outset of those procedures, to go back-and-forth between operating rooms and even hospital facilities while his surgical patients remain under general anesthesia...”

UPMC, the lawsuit claims, also allowed Dr. Luketich to falsely attest that “he was with his patients throughout the entirety of their surgical procedures or during all ‘key and critical’ portions of those procedures and to unlawfully bill Government Health Benefit Programs for those procedures, all in order to increase surgical volume, maximize UPMC and UPP’s revenue, and/or appease Dr. Luketich.”

These practices violate the statutes and regulations governing the defendants, including those that prohibit “teaching physicians” like Dr. Luketich from performing and billing the U.S. for concurrent surgeries, the Department of Justice said in news release.

The Justice Department contends the defendants “knowingly submitted hundreds of materially false claims for payment” to Medicare, Medicaid, and other government programs over the past 6 years.

“The laws prohibiting ‘concurrent surgeries’ are in place for a reason: To protect patients and ensure they receive appropriate and focused medical care,” Stephen R. Kaufman, Acting U.S. Attorney for the Western District of Pennsylvania, said in the release.

According to the lawsuit, “some of Dr. Luketich’s patients were forced to endure additional surgical procedures and/or extended hospital stays as a result of his unlawful conduct. Numerous patients developed painful pressure ulcers. A few were diagnosed with compartment syndrome. And at least two had to undergo amputations.”

The allegations were originally brought forward under the federal False Claims Act’s whistleblower provisions by Jonathan D’Cunha, MD, PhD, who worked closely with Dr. Luketich from 2012 to 2019 and now chairs the department of cardiothoracic surgery at the Mayo Clinic, Phoenix.

The charges cited in the lawsuit include three counts of violating the False Claims Act, one count of unjust enrichment, and one count of payment by mistake.

The 56-page lawsuit includes numerous case examples and cites an October 2015 Boston Globe Spotlight Team report on the safety of running concurrent operations, which reportedly prompted UPMC to reevaluate its policies and identify physicians or departments in potential violation.

Hospital officials met with Dr. Luketich in March 2016 and devised a “plan” to ensure his availability and “compliance with concurrency rules,” it alleges, but also highlights an email that notes “continued problems” with Dr. Luketich’s schedule.

“UPMC has persistently ignored or minimized complaints by employees and staff regarding Dr. Luketich, his hyper-busy schedule, his refusal to delegate surgeries and surgical tasks” and “protected him from meaningful sanction; refused to curtail his surgical practice; and continued to allow Dr. Luketich to skirt the rules and endanger his patients,” according to the lawsuit.

The suit notes that Dr. Luketich is one of UPMC and UPP’s highest sources of revenue and that UPMC advertises him as a “life-saving pioneer” who routinely performs dramatic, last-ditch procedures on patients who are otherwise hopeless.

In response to an interview request from this news organization, a UPMC spokesperson wrote: “As the government itself concedes in its complaint, many of Dr. Luketich’s surgical patients are elderly, frail, and/or very ill. They include the ‘hopeless’ patients ... who suffer from chronic illness or metastatic cancer, and/or have extensive surgical histories and choose UPMC and Dr. Luketich when other physicians and health care providers have turned them down.”

“Dr. Luketich always performs the most critical portions of every operation he undertakes,” the spokesperson said, adding that no law or regulation prohibits overlapping surgeries or billing for those surgeries, “let alone surgeries conducted by teams of surgeons like those led by Dr. Luketich.”

“The government’s claims are, rather, based on a misapplication or misinterpretation of UPMC’s internal policies and [Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services] guidance, neither of which can support a claim for fraudulent billing. UPMC and Dr. Luketich plan to vigorously defend against the government’s claims,” the spokesperson concluded.

The claims asserted against the defendants are allegations only; there has been no determination of liability. The government is seeking three times the amount of actual damages suffered as a result of the alleged false claims and/or fraud; a sum of $23,331 (or the maximum penalty, whichever is greater) for each false claim submitted by UPMC, UPP, and/or Dr. Luketich; and costs and expenses associated with the civil suit.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Following a 2-year investigation, the U.S. government has filed suit against the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC), University of Pittsburgh Physicians (UPP), and James Luketich, MD, for billing related to concurrent surgeries performed by the long-time chair of cardiothoracic surgery.

The lawsuit alleges that UPMC “knowingly allowed” Dr. Luketich to “book and perform three surgeries at the same time, to miss the surgical time outs at the outset of those procedures, to go back-and-forth between operating rooms and even hospital facilities while his surgical patients remain under general anesthesia...”

UPMC, the lawsuit claims, also allowed Dr. Luketich to falsely attest that “he was with his patients throughout the entirety of their surgical procedures or during all ‘key and critical’ portions of those procedures and to unlawfully bill Government Health Benefit Programs for those procedures, all in order to increase surgical volume, maximize UPMC and UPP’s revenue, and/or appease Dr. Luketich.”

These practices violate the statutes and regulations governing the defendants, including those that prohibit “teaching physicians” like Dr. Luketich from performing and billing the U.S. for concurrent surgeries, the Department of Justice said in news release.

The Justice Department contends the defendants “knowingly submitted hundreds of materially false claims for payment” to Medicare, Medicaid, and other government programs over the past 6 years.

“The laws prohibiting ‘concurrent surgeries’ are in place for a reason: To protect patients and ensure they receive appropriate and focused medical care,” Stephen R. Kaufman, Acting U.S. Attorney for the Western District of Pennsylvania, said in the release.

According to the lawsuit, “some of Dr. Luketich’s patients were forced to endure additional surgical procedures and/or extended hospital stays as a result of his unlawful conduct. Numerous patients developed painful pressure ulcers. A few were diagnosed with compartment syndrome. And at least two had to undergo amputations.”

The allegations were originally brought forward under the federal False Claims Act’s whistleblower provisions by Jonathan D’Cunha, MD, PhD, who worked closely with Dr. Luketich from 2012 to 2019 and now chairs the department of cardiothoracic surgery at the Mayo Clinic, Phoenix.

The charges cited in the lawsuit include three counts of violating the False Claims Act, one count of unjust enrichment, and one count of payment by mistake.

The 56-page lawsuit includes numerous case examples and cites an October 2015 Boston Globe Spotlight Team report on the safety of running concurrent operations, which reportedly prompted UPMC to reevaluate its policies and identify physicians or departments in potential violation.

Hospital officials met with Dr. Luketich in March 2016 and devised a “plan” to ensure his availability and “compliance with concurrency rules,” it alleges, but also highlights an email that notes “continued problems” with Dr. Luketich’s schedule.

“UPMC has persistently ignored or minimized complaints by employees and staff regarding Dr. Luketich, his hyper-busy schedule, his refusal to delegate surgeries and surgical tasks” and “protected him from meaningful sanction; refused to curtail his surgical practice; and continued to allow Dr. Luketich to skirt the rules and endanger his patients,” according to the lawsuit.

The suit notes that Dr. Luketich is one of UPMC and UPP’s highest sources of revenue and that UPMC advertises him as a “life-saving pioneer” who routinely performs dramatic, last-ditch procedures on patients who are otherwise hopeless.

In response to an interview request from this news organization, a UPMC spokesperson wrote: “As the government itself concedes in its complaint, many of Dr. Luketich’s surgical patients are elderly, frail, and/or very ill. They include the ‘hopeless’ patients ... who suffer from chronic illness or metastatic cancer, and/or have extensive surgical histories and choose UPMC and Dr. Luketich when other physicians and health care providers have turned them down.”

“Dr. Luketich always performs the most critical portions of every operation he undertakes,” the spokesperson said, adding that no law or regulation prohibits overlapping surgeries or billing for those surgeries, “let alone surgeries conducted by teams of surgeons like those led by Dr. Luketich.”

“The government’s claims are, rather, based on a misapplication or misinterpretation of UPMC’s internal policies and [Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services] guidance, neither of which can support a claim for fraudulent billing. UPMC and Dr. Luketich plan to vigorously defend against the government’s claims,” the spokesperson concluded.

The claims asserted against the defendants are allegations only; there has been no determination of liability. The government is seeking three times the amount of actual damages suffered as a result of the alleged false claims and/or fraud; a sum of $23,331 (or the maximum penalty, whichever is greater) for each false claim submitted by UPMC, UPP, and/or Dr. Luketich; and costs and expenses associated with the civil suit.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

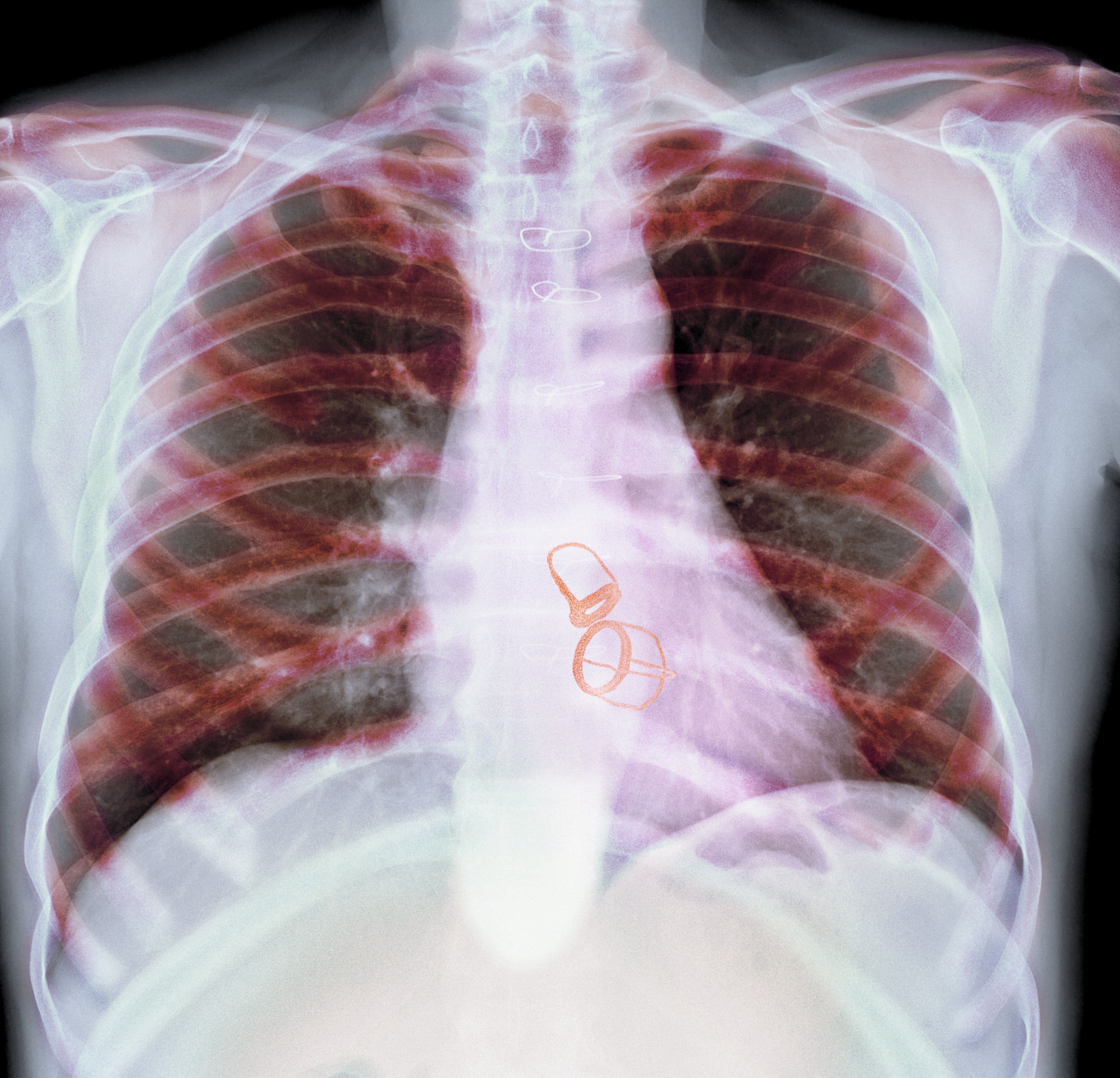

STOP-DAPT 2 ACS: 1 month of DAPT proves inadequate for patients with recent ACS

One month of dual antiplatelet therapy followed by 11 months of clopidogrel monotherapy failed to prove noninferiority to 12 unbroken months of DAPT for net clinical benefit in a multicenter Japanese trial that randomized more than 4,000 patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) after a recent acute coronary syndrome episode.

The outcomes showed that while truncating DAPT duration could, as expected, cut major bleeding episodes roughly in half, it also led to a significant near doubling of myocardial infarction and showed a strong trend toward also increasing a composite tally of several types of ischemic events. These data were reported this week by Hirotoshi Watanabe, MD, PhD, at the virtual annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. All study patients had undergone PCI with cobalt-chromium everolimus-eluting (CCEE) coronary stents (Xience).

These findings from the STOPDAPT-2 ACS trial highlighted the limits of minimizing DAPT after PCI in patients at high ischemic risk, such as after an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) event.

It also was a counterpoint to a somewhat similar study also reported at the congress, MASTER DAPT, which showed that 1 month of DAPT was noninferior to 3 or more months of DAPT for net clinical benefit in a distinctly different population of patients undergoing PCI (and using a different type of coronary stent) – those at high bleeding risk and with only about half the patients having had a recent ACS.

The results of STOPDAPT-2 ACS “do not support use of 1 month of DAPT followed by P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy with clopidogrel compared with standard DAPT,” commented Robert A. Byrne, MBBCh, PhD, designated discussant for the report and professor at the RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences in Dublin.

“Although major bleeding was significantly reduced with this approach, there appeared to be a significant increase in adverse ischemic events, and there was a clear signal in relation to overall mortality, the ultimate arbiter of net clinical benefit,” added Dr. Byrne, who is also director of cardiology at Mater Private Hospital in Dublin.

He suggested that a mechanistic explanation for the signal of harm seem in STOPDAPT-2 ACS was the relatively low potency of clopidogrel (Plavix) as an antiplatelet agent, compared with other P2Y12 inhibitors such as prasugrel (Effient) and ticagrelor (Brilinta), as well as the genetically driven variability in response to clopidogrel that’s also absent with alternative agents.

These between-agent differences are of “particular clinical relevance in the early aftermath of an ACS event,” Dr. Byrne said.

12-month DAPT remains standard for PCI patients with recent ACS

The totality of clinical evidence “continues to support a standard 12-month duration of DAPT – using aspirin and either prasugrel or ticagrelor – as the preferred default approach,” Dr. Byrne concluded.

He acknowledged that an abbreviated duration of DAPT followed by P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy “might be considered as an alternative.” In patients following an ACS event who do not have high risk for bleeding, he said, the minimum duration of DAPT should be at least 3 months and with preferential use of a more potent P2Y12 inhibitor.

Twelve months of DAPT treatment with aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor for patients following PCI “remains the standard of care in guidelines,” noted Marco Roffi, MD, a second discussant at the congress. But several questions remain, he added, such as which P2Y12 inhibitors work best and whether DAPT can be less than 12 months.

“The investigators [for STOPDAPT-2 ACS] pushed these questions to the limit with 1 month of DAPT and clopidogrel monotherapy,” said Dr. Roffi, professor and director of interventional cardiology at University Hospital, Geneva.

“This was a risky bet, and the investigators lost by not proving noninferiority and with excess ischemic events,” he commented.

First came STOPDAPT-2

Dr. Watanabe and colleagues designed STOPDAPT-2 ACS as a follow-up to their prior STOPDAPT-2 trial, which randomly assigned slightly more than 3000 patients at 90 Japanese centers to the identical two treatment options: 1 month of DAPT followed by 11 months of clopidogrel monotherapy or 12 months of DAPT, except the trial enrolled all types of patients undergoing PCI. This meant that a minority, 38%, had a recent ACS event, while the remaining patients had chronic coronary artery disease. As in STOPDAPT-2 ACS, all patients in STOPDAPT-2 had received a CCEE stent.

STOPDAPT-2 also used the same primary endpoint to tally net clinical benefit as STOPDAPT-2 ACS: cardiovascular death, MI, stroke of any type, definite stent thrombosis, or TIMI major or minor bleeding classification.

In STOPDAPT-2, using the mixed population with both recent ACS and chronic coronary disease, the regimen of 1 month of DAPT followed by 11 months of clopidogrel monotherapy was both noninferior to and superior to 12 months of DAPT, reducing the net adverse-event tally by 36% relative to 12-month DAPT and by an absolute reduction of 1.34%, as reported in 2019.

Despite this superiority, the results from STOPDAPT-2 had little impact on global practice, commented Kurt Huber, MD, professor and director of the cardiology ICU at the Medical University of Vienna.

“STOP-DAPT-2 did not give us a clear message with respect to reducing antiplatelet treatment after 1 month. I thought that for ACS patients 1 month might be too short,” Dr. Huber said during a press briefing.

Focusing on post-ACS

To directly address this issue, the investigators launched STOPDAPT-2 ACS, which used the same design as the preceding study but only enrolled patients soon after an ACS event. The trial included for its main analysis 3,008 newly enrolled patients with recent ACS, and 1,161 patients who had a recent ACS event and had been randomly assigned in STOPDAPT-2, creating a total study cohort for the new analysis of 4136 patients treated and followed for the study’s full 12 months.

The patients averaged 67 years old, 79% were men, and 30% had diabetes. About 56% had a recent ST-elevation MI, about 20% a recent non–ST-elevation MI, and the remaining 24% had unstable angina. For their unspecified P2Y12 inhibition, roughly half the patients received clopidogrel and the rest received prasugrel. Adherence to the two assigned treatment regimens was very good, with a very small number of patients not adhering to their assigned protocol.

The composite adverse event incidence over 12 months was 3.2% among those who received 1-month DAPT and 2.83% in those on DAPT for 12 months, a difference that failed to achieve the prespecified definition of noninferiority for 1-month DAPT, reported Dr. Watanabe, an interventional cardiologist at Kyoto University.

The ischemic event composite was 50% lower among those on 12-month DAPT, compared with 1 month of DAPT, a difference that just missed significance. The rate of MI was 91% higher with 1-month DAPT, compared with 12 months, a significant difference.

One-month DAPT also significantly reduced the primary measure of bleeding events – the combination of TIMI major and minor bleeds – by a significant 54%, compared with 12-month DAPT. A second metric of clinically meaningful bleeds, those that meet either the type 3 or 5 definition of the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium, were reduced by a significant 59% by 1-month DAPT, compared with 12 months of DAPT.

The new findings from STOPDAPT-2 ACS contrasted with those from MASTER DAPT, but in an explicable way that related to different patient types, different P2Y12 inhibitors, different treatment durations, and different stents.

“We’ve seen in MASTER DAPT that if you use the right stent and use ticagrelor for monotherapy there may be some ability to shorten DAPT, but we still do not know what would happen in patients with very high ischemic risk,” concluded Dr. Huber.

“A reduction in DAPT duration might work in patients without high bleeding risk, but I would exclude patients with very high ischemic risk,” he added. “I also can’t tell you whether 1 month or 3 months is the right approach, and I think clopidogrel is not the right drug to use for monotherapy after ACS.”

STOPDAPT-2 and STOPDAPT-2 ACS were both sponsored by Abbott Vascular, which markets the CCEE (Xience) stents used in both studies. Dr. Watanabe has received lecture fees from Abbott and from Daiichi-Sankyo. Dr. Byrne has received research funding from Abbott Vascular as well as from Biosensors, Biotronik, and Boston Scientific. Roffi has received research funding from Biotronik, Boston Scientific, GE Healthcare, Medtronic, and Terumo. Dr. Huber has received lecture fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, and The Medicines Company.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

One month of dual antiplatelet therapy followed by 11 months of clopidogrel monotherapy failed to prove noninferiority to 12 unbroken months of DAPT for net clinical benefit in a multicenter Japanese trial that randomized more than 4,000 patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) after a recent acute coronary syndrome episode.

The outcomes showed that while truncating DAPT duration could, as expected, cut major bleeding episodes roughly in half, it also led to a significant near doubling of myocardial infarction and showed a strong trend toward also increasing a composite tally of several types of ischemic events. These data were reported this week by Hirotoshi Watanabe, MD, PhD, at the virtual annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. All study patients had undergone PCI with cobalt-chromium everolimus-eluting (CCEE) coronary stents (Xience).

These findings from the STOPDAPT-2 ACS trial highlighted the limits of minimizing DAPT after PCI in patients at high ischemic risk, such as after an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) event.

It also was a counterpoint to a somewhat similar study also reported at the congress, MASTER DAPT, which showed that 1 month of DAPT was noninferior to 3 or more months of DAPT for net clinical benefit in a distinctly different population of patients undergoing PCI (and using a different type of coronary stent) – those at high bleeding risk and with only about half the patients having had a recent ACS.

The results of STOPDAPT-2 ACS “do not support use of 1 month of DAPT followed by P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy with clopidogrel compared with standard DAPT,” commented Robert A. Byrne, MBBCh, PhD, designated discussant for the report and professor at the RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences in Dublin.

“Although major bleeding was significantly reduced with this approach, there appeared to be a significant increase in adverse ischemic events, and there was a clear signal in relation to overall mortality, the ultimate arbiter of net clinical benefit,” added Dr. Byrne, who is also director of cardiology at Mater Private Hospital in Dublin.

He suggested that a mechanistic explanation for the signal of harm seem in STOPDAPT-2 ACS was the relatively low potency of clopidogrel (Plavix) as an antiplatelet agent, compared with other P2Y12 inhibitors such as prasugrel (Effient) and ticagrelor (Brilinta), as well as the genetically driven variability in response to clopidogrel that’s also absent with alternative agents.

These between-agent differences are of “particular clinical relevance in the early aftermath of an ACS event,” Dr. Byrne said.

12-month DAPT remains standard for PCI patients with recent ACS

The totality of clinical evidence “continues to support a standard 12-month duration of DAPT – using aspirin and either prasugrel or ticagrelor – as the preferred default approach,” Dr. Byrne concluded.

He acknowledged that an abbreviated duration of DAPT followed by P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy “might be considered as an alternative.” In patients following an ACS event who do not have high risk for bleeding, he said, the minimum duration of DAPT should be at least 3 months and with preferential use of a more potent P2Y12 inhibitor.

Twelve months of DAPT treatment with aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor for patients following PCI “remains the standard of care in guidelines,” noted Marco Roffi, MD, a second discussant at the congress. But several questions remain, he added, such as which P2Y12 inhibitors work best and whether DAPT can be less than 12 months.

“The investigators [for STOPDAPT-2 ACS] pushed these questions to the limit with 1 month of DAPT and clopidogrel monotherapy,” said Dr. Roffi, professor and director of interventional cardiology at University Hospital, Geneva.

“This was a risky bet, and the investigators lost by not proving noninferiority and with excess ischemic events,” he commented.

First came STOPDAPT-2

Dr. Watanabe and colleagues designed STOPDAPT-2 ACS as a follow-up to their prior STOPDAPT-2 trial, which randomly assigned slightly more than 3000 patients at 90 Japanese centers to the identical two treatment options: 1 month of DAPT followed by 11 months of clopidogrel monotherapy or 12 months of DAPT, except the trial enrolled all types of patients undergoing PCI. This meant that a minority, 38%, had a recent ACS event, while the remaining patients had chronic coronary artery disease. As in STOPDAPT-2 ACS, all patients in STOPDAPT-2 had received a CCEE stent.

STOPDAPT-2 also used the same primary endpoint to tally net clinical benefit as STOPDAPT-2 ACS: cardiovascular death, MI, stroke of any type, definite stent thrombosis, or TIMI major or minor bleeding classification.

In STOPDAPT-2, using the mixed population with both recent ACS and chronic coronary disease, the regimen of 1 month of DAPT followed by 11 months of clopidogrel monotherapy was both noninferior to and superior to 12 months of DAPT, reducing the net adverse-event tally by 36% relative to 12-month DAPT and by an absolute reduction of 1.34%, as reported in 2019.

Despite this superiority, the results from STOPDAPT-2 had little impact on global practice, commented Kurt Huber, MD, professor and director of the cardiology ICU at the Medical University of Vienna.

“STOP-DAPT-2 did not give us a clear message with respect to reducing antiplatelet treatment after 1 month. I thought that for ACS patients 1 month might be too short,” Dr. Huber said during a press briefing.

Focusing on post-ACS

To directly address this issue, the investigators launched STOPDAPT-2 ACS, which used the same design as the preceding study but only enrolled patients soon after an ACS event. The trial included for its main analysis 3,008 newly enrolled patients with recent ACS, and 1,161 patients who had a recent ACS event and had been randomly assigned in STOPDAPT-2, creating a total study cohort for the new analysis of 4136 patients treated and followed for the study’s full 12 months.

The patients averaged 67 years old, 79% were men, and 30% had diabetes. About 56% had a recent ST-elevation MI, about 20% a recent non–ST-elevation MI, and the remaining 24% had unstable angina. For their unspecified P2Y12 inhibition, roughly half the patients received clopidogrel and the rest received prasugrel. Adherence to the two assigned treatment regimens was very good, with a very small number of patients not adhering to their assigned protocol.

The composite adverse event incidence over 12 months was 3.2% among those who received 1-month DAPT and 2.83% in those on DAPT for 12 months, a difference that failed to achieve the prespecified definition of noninferiority for 1-month DAPT, reported Dr. Watanabe, an interventional cardiologist at Kyoto University.

The ischemic event composite was 50% lower among those on 12-month DAPT, compared with 1 month of DAPT, a difference that just missed significance. The rate of MI was 91% higher with 1-month DAPT, compared with 12 months, a significant difference.

One-month DAPT also significantly reduced the primary measure of bleeding events – the combination of TIMI major and minor bleeds – by a significant 54%, compared with 12-month DAPT. A second metric of clinically meaningful bleeds, those that meet either the type 3 or 5 definition of the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium, were reduced by a significant 59% by 1-month DAPT, compared with 12 months of DAPT.

The new findings from STOPDAPT-2 ACS contrasted with those from MASTER DAPT, but in an explicable way that related to different patient types, different P2Y12 inhibitors, different treatment durations, and different stents.

“We’ve seen in MASTER DAPT that if you use the right stent and use ticagrelor for monotherapy there may be some ability to shorten DAPT, but we still do not know what would happen in patients with very high ischemic risk,” concluded Dr. Huber.

“A reduction in DAPT duration might work in patients without high bleeding risk, but I would exclude patients with very high ischemic risk,” he added. “I also can’t tell you whether 1 month or 3 months is the right approach, and I think clopidogrel is not the right drug to use for monotherapy after ACS.”

STOPDAPT-2 and STOPDAPT-2 ACS were both sponsored by Abbott Vascular, which markets the CCEE (Xience) stents used in both studies. Dr. Watanabe has received lecture fees from Abbott and from Daiichi-Sankyo. Dr. Byrne has received research funding from Abbott Vascular as well as from Biosensors, Biotronik, and Boston Scientific. Roffi has received research funding from Biotronik, Boston Scientific, GE Healthcare, Medtronic, and Terumo. Dr. Huber has received lecture fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, and The Medicines Company.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

One month of dual antiplatelet therapy followed by 11 months of clopidogrel monotherapy failed to prove noninferiority to 12 unbroken months of DAPT for net clinical benefit in a multicenter Japanese trial that randomized more than 4,000 patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) after a recent acute coronary syndrome episode.

The outcomes showed that while truncating DAPT duration could, as expected, cut major bleeding episodes roughly in half, it also led to a significant near doubling of myocardial infarction and showed a strong trend toward also increasing a composite tally of several types of ischemic events. These data were reported this week by Hirotoshi Watanabe, MD, PhD, at the virtual annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. All study patients had undergone PCI with cobalt-chromium everolimus-eluting (CCEE) coronary stents (Xience).

These findings from the STOPDAPT-2 ACS trial highlighted the limits of minimizing DAPT after PCI in patients at high ischemic risk, such as after an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) event.

It also was a counterpoint to a somewhat similar study also reported at the congress, MASTER DAPT, which showed that 1 month of DAPT was noninferior to 3 or more months of DAPT for net clinical benefit in a distinctly different population of patients undergoing PCI (and using a different type of coronary stent) – those at high bleeding risk and with only about half the patients having had a recent ACS.

The results of STOPDAPT-2 ACS “do not support use of 1 month of DAPT followed by P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy with clopidogrel compared with standard DAPT,” commented Robert A. Byrne, MBBCh, PhD, designated discussant for the report and professor at the RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences in Dublin.

“Although major bleeding was significantly reduced with this approach, there appeared to be a significant increase in adverse ischemic events, and there was a clear signal in relation to overall mortality, the ultimate arbiter of net clinical benefit,” added Dr. Byrne, who is also director of cardiology at Mater Private Hospital in Dublin.

He suggested that a mechanistic explanation for the signal of harm seem in STOPDAPT-2 ACS was the relatively low potency of clopidogrel (Plavix) as an antiplatelet agent, compared with other P2Y12 inhibitors such as prasugrel (Effient) and ticagrelor (Brilinta), as well as the genetically driven variability in response to clopidogrel that’s also absent with alternative agents.

These between-agent differences are of “particular clinical relevance in the early aftermath of an ACS event,” Dr. Byrne said.

12-month DAPT remains standard for PCI patients with recent ACS

The totality of clinical evidence “continues to support a standard 12-month duration of DAPT – using aspirin and either prasugrel or ticagrelor – as the preferred default approach,” Dr. Byrne concluded.

He acknowledged that an abbreviated duration of DAPT followed by P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy “might be considered as an alternative.” In patients following an ACS event who do not have high risk for bleeding, he said, the minimum duration of DAPT should be at least 3 months and with preferential use of a more potent P2Y12 inhibitor.

Twelve months of DAPT treatment with aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor for patients following PCI “remains the standard of care in guidelines,” noted Marco Roffi, MD, a second discussant at the congress. But several questions remain, he added, such as which P2Y12 inhibitors work best and whether DAPT can be less than 12 months.

“The investigators [for STOPDAPT-2 ACS] pushed these questions to the limit with 1 month of DAPT and clopidogrel monotherapy,” said Dr. Roffi, professor and director of interventional cardiology at University Hospital, Geneva.

“This was a risky bet, and the investigators lost by not proving noninferiority and with excess ischemic events,” he commented.

First came STOPDAPT-2

Dr. Watanabe and colleagues designed STOPDAPT-2 ACS as a follow-up to their prior STOPDAPT-2 trial, which randomly assigned slightly more than 3000 patients at 90 Japanese centers to the identical two treatment options: 1 month of DAPT followed by 11 months of clopidogrel monotherapy or 12 months of DAPT, except the trial enrolled all types of patients undergoing PCI. This meant that a minority, 38%, had a recent ACS event, while the remaining patients had chronic coronary artery disease. As in STOPDAPT-2 ACS, all patients in STOPDAPT-2 had received a CCEE stent.

STOPDAPT-2 also used the same primary endpoint to tally net clinical benefit as STOPDAPT-2 ACS: cardiovascular death, MI, stroke of any type, definite stent thrombosis, or TIMI major or minor bleeding classification.

In STOPDAPT-2, using the mixed population with both recent ACS and chronic coronary disease, the regimen of 1 month of DAPT followed by 11 months of clopidogrel monotherapy was both noninferior to and superior to 12 months of DAPT, reducing the net adverse-event tally by 36% relative to 12-month DAPT and by an absolute reduction of 1.34%, as reported in 2019.

Despite this superiority, the results from STOPDAPT-2 had little impact on global practice, commented Kurt Huber, MD, professor and director of the cardiology ICU at the Medical University of Vienna.

“STOP-DAPT-2 did not give us a clear message with respect to reducing antiplatelet treatment after 1 month. I thought that for ACS patients 1 month might be too short,” Dr. Huber said during a press briefing.

Focusing on post-ACS

To directly address this issue, the investigators launched STOPDAPT-2 ACS, which used the same design as the preceding study but only enrolled patients soon after an ACS event. The trial included for its main analysis 3,008 newly enrolled patients with recent ACS, and 1,161 patients who had a recent ACS event and had been randomly assigned in STOPDAPT-2, creating a total study cohort for the new analysis of 4136 patients treated and followed for the study’s full 12 months.

The patients averaged 67 years old, 79% were men, and 30% had diabetes. About 56% had a recent ST-elevation MI, about 20% a recent non–ST-elevation MI, and the remaining 24% had unstable angina. For their unspecified P2Y12 inhibition, roughly half the patients received clopidogrel and the rest received prasugrel. Adherence to the two assigned treatment regimens was very good, with a very small number of patients not adhering to their assigned protocol.

The composite adverse event incidence over 12 months was 3.2% among those who received 1-month DAPT and 2.83% in those on DAPT for 12 months, a difference that failed to achieve the prespecified definition of noninferiority for 1-month DAPT, reported Dr. Watanabe, an interventional cardiologist at Kyoto University.

The ischemic event composite was 50% lower among those on 12-month DAPT, compared with 1 month of DAPT, a difference that just missed significance. The rate of MI was 91% higher with 1-month DAPT, compared with 12 months, a significant difference.

One-month DAPT also significantly reduced the primary measure of bleeding events – the combination of TIMI major and minor bleeds – by a significant 54%, compared with 12-month DAPT. A second metric of clinically meaningful bleeds, those that meet either the type 3 or 5 definition of the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium, were reduced by a significant 59% by 1-month DAPT, compared with 12 months of DAPT.

The new findings from STOPDAPT-2 ACS contrasted with those from MASTER DAPT, but in an explicable way that related to different patient types, different P2Y12 inhibitors, different treatment durations, and different stents.

“We’ve seen in MASTER DAPT that if you use the right stent and use ticagrelor for monotherapy there may be some ability to shorten DAPT, but we still do not know what would happen in patients with very high ischemic risk,” concluded Dr. Huber.

“A reduction in DAPT duration might work in patients without high bleeding risk, but I would exclude patients with very high ischemic risk,” he added. “I also can’t tell you whether 1 month or 3 months is the right approach, and I think clopidogrel is not the right drug to use for monotherapy after ACS.”

STOPDAPT-2 and STOPDAPT-2 ACS were both sponsored by Abbott Vascular, which markets the CCEE (Xience) stents used in both studies. Dr. Watanabe has received lecture fees from Abbott and from Daiichi-Sankyo. Dr. Byrne has received research funding from Abbott Vascular as well as from Biosensors, Biotronik, and Boston Scientific. Roffi has received research funding from Biotronik, Boston Scientific, GE Healthcare, Medtronic, and Terumo. Dr. Huber has received lecture fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, and The Medicines Company.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New valvular heart disease guidelines change several repair indications

Antithrombotic recommendations also altered

New European guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease offer more than 45 revised or completely new recommendations relative to the previous version published in 2017, according to members of the writing committee who presented the changes during the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

With their emphasis on early diagnosis and expansion of indications, these 2021 ESC/European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery guidelines are likely to further accelerate the already steep growth in this area of interventional cardiology, according to Alec Vahanian, MD, a professor of cardiology at the University of Paris.

“Valvular heart disease is too often undetected, and these guidelines stress the importance of clinical examination and the best strategies for diagnosis as well as treatment,” he said.

Of the multiple sections and subsections, which follow the same format of the previous guidelines, the greatest number of revisions and new additions involve perioperative antithrombotic therapy, according to the document, which was published in conjunction with the ESC Congress.

Eleven new guidelines for anticoagulants

On the basis of evidence published since the previous guidelines, there are 11 completely new recommendations regarding the use of anticoagulants or antiplatelet therapies. The majority of these have received a grade I indication, which signifies “recommended” or “indicated.” These include indications for stopping or starting anticoagulants and which anticoagulants or antiplatelet drugs to consider in specific patient populations.

The next most common focus of new or revised recommendations involves when to consider surgical aortic valve repair (SAVR) relative to transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) in severe aortic stenosis. Most of these represent revisions from the previous guidelines, but almost all are also grade I recommendations.

“SAVR and TAVI are both excellent options in appropriate patients, but they are not interchangeable,” explained Bernard D. Prendergast, BMedSci, MD, director of the cardiac structural intervention program, Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital, London.

While the previous guidelines generally reserved TAVI for those not suitable for SAVR, the new guidelines are more nuanced.

As a rule, SAVR is generally preferred for younger patients. The reason, according to Dr. Prendergast, is concern that younger patients might outlive the expected lifespan of the prosthetic TAVI device.

No single criterion for selecting SAVR over TAVI

However, there are many exceptions and additional considerations beyond age. When both SAVR and TAVI are otherwise suitable options, but TAVI cannot be performed with a transfemoral access, Dr. Prendergast pointed out that SAVR might be a better choice.

Transfemoral access is the preferred strategy in TAVI, but Dr. Prendergast emphasized that a collaborative “heart team” should help patients select the most appropriate option. In fact, there is a grade IIb recommendation (“usefulness or efficacy is less well established”) to consider other access sites in patients at high surgical risk with contraindications for transfemoral TAVI.

Of new recommendations in the area of severe aortic stenosis, valvular repair may now be considered in asymptomatic patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 55%, according to a grade IIb recommendation. The 2017 guidelines did not address this issue.

Grade I recommendation for bioprostheses

A substantial number of the revisions involve minor clarifications without a change in the grade, but a revision regarding bioprosthetics is substantial. In the 2017 guidelines, there was a grade IIa recommendation (“weight of evidence is in favor”) to consider bioprosthetics in patients with a life expectancy less than the expected durability of the device. The 2021 guidelines have changed this to a grade I indication, adding an indication for bioprostheses in patients contraindicated for or unlikely to achieve good-quality anticoagulation.

On this same topic, there is a new grade IIb recommendation to consider bioprosthesis over alternative devices in patients already on a long-term non–vitamin K oral anticoagulant because of the high risk of thromboembolism.

There are two new recommendations in the realm of severe secondary mitral regurgitation, reported Fabien Praz, MD, an interventional cardiologist at the University of Bern (Switzerland). The first, which is perhaps the most significant, is a grade I recommendation for valve surgery in patients with severe secondary mitral regurgitation who remain symptomatic despite optimized medical therapy.

The second is a grade IIa recommendation for invasive procedures, such as a percutaneous coronary intervention, for patients with symptomatic secondary mitral regurgitation and coexisting coronary artery disease. In both cases, however, Dr. Praz emphasized language in the guidelines that calls for a collaborative heart team to agree on the suitability of these treatments.

Ultimately, none of these recommendations can be divorced from patient expectations and values, according to Friedhelm Beyersdorf, MD, chairman of the department of cardiovascular surgery at the Heart Center of the University of Freiburg (Germany).

Even if treatment is not expected to prolong life, “symptom relief on its own may justify intervention,” said Dr. Beyersdorf. However, he emphasized that “thoroughly informed” patients are an essential part of the process in selecting a treatment strategy most likely to satisfy patient goals.

Dr. Vahanian and Dr. Prendergast reported no conflicts of interest relevant to these guidelines. Dr. Praz reported a financial relationship with Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Beyersdorf reported a financial relationship with Resuscitec.

Antithrombotic recommendations also altered

Antithrombotic recommendations also altered

New European guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease offer more than 45 revised or completely new recommendations relative to the previous version published in 2017, according to members of the writing committee who presented the changes during the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

With their emphasis on early diagnosis and expansion of indications, these 2021 ESC/European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery guidelines are likely to further accelerate the already steep growth in this area of interventional cardiology, according to Alec Vahanian, MD, a professor of cardiology at the University of Paris.

“Valvular heart disease is too often undetected, and these guidelines stress the importance of clinical examination and the best strategies for diagnosis as well as treatment,” he said.

Of the multiple sections and subsections, which follow the same format of the previous guidelines, the greatest number of revisions and new additions involve perioperative antithrombotic therapy, according to the document, which was published in conjunction with the ESC Congress.

Eleven new guidelines for anticoagulants

On the basis of evidence published since the previous guidelines, there are 11 completely new recommendations regarding the use of anticoagulants or antiplatelet therapies. The majority of these have received a grade I indication, which signifies “recommended” or “indicated.” These include indications for stopping or starting anticoagulants and which anticoagulants or antiplatelet drugs to consider in specific patient populations.

The next most common focus of new or revised recommendations involves when to consider surgical aortic valve repair (SAVR) relative to transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) in severe aortic stenosis. Most of these represent revisions from the previous guidelines, but almost all are also grade I recommendations.

“SAVR and TAVI are both excellent options in appropriate patients, but they are not interchangeable,” explained Bernard D. Prendergast, BMedSci, MD, director of the cardiac structural intervention program, Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital, London.

While the previous guidelines generally reserved TAVI for those not suitable for SAVR, the new guidelines are more nuanced.

As a rule, SAVR is generally preferred for younger patients. The reason, according to Dr. Prendergast, is concern that younger patients might outlive the expected lifespan of the prosthetic TAVI device.

No single criterion for selecting SAVR over TAVI

However, there are many exceptions and additional considerations beyond age. When both SAVR and TAVI are otherwise suitable options, but TAVI cannot be performed with a transfemoral access, Dr. Prendergast pointed out that SAVR might be a better choice.

Transfemoral access is the preferred strategy in TAVI, but Dr. Prendergast emphasized that a collaborative “heart team” should help patients select the most appropriate option. In fact, there is a grade IIb recommendation (“usefulness or efficacy is less well established”) to consider other access sites in patients at high surgical risk with contraindications for transfemoral TAVI.

Of new recommendations in the area of severe aortic stenosis, valvular repair may now be considered in asymptomatic patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 55%, according to a grade IIb recommendation. The 2017 guidelines did not address this issue.

Grade I recommendation for bioprostheses

A substantial number of the revisions involve minor clarifications without a change in the grade, but a revision regarding bioprosthetics is substantial. In the 2017 guidelines, there was a grade IIa recommendation (“weight of evidence is in favor”) to consider bioprosthetics in patients with a life expectancy less than the expected durability of the device. The 2021 guidelines have changed this to a grade I indication, adding an indication for bioprostheses in patients contraindicated for or unlikely to achieve good-quality anticoagulation.

On this same topic, there is a new grade IIb recommendation to consider bioprosthesis over alternative devices in patients already on a long-term non–vitamin K oral anticoagulant because of the high risk of thromboembolism.

There are two new recommendations in the realm of severe secondary mitral regurgitation, reported Fabien Praz, MD, an interventional cardiologist at the University of Bern (Switzerland). The first, which is perhaps the most significant, is a grade I recommendation for valve surgery in patients with severe secondary mitral regurgitation who remain symptomatic despite optimized medical therapy.

The second is a grade IIa recommendation for invasive procedures, such as a percutaneous coronary intervention, for patients with symptomatic secondary mitral regurgitation and coexisting coronary artery disease. In both cases, however, Dr. Praz emphasized language in the guidelines that calls for a collaborative heart team to agree on the suitability of these treatments.

Ultimately, none of these recommendations can be divorced from patient expectations and values, according to Friedhelm Beyersdorf, MD, chairman of the department of cardiovascular surgery at the Heart Center of the University of Freiburg (Germany).

Even if treatment is not expected to prolong life, “symptom relief on its own may justify intervention,” said Dr. Beyersdorf. However, he emphasized that “thoroughly informed” patients are an essential part of the process in selecting a treatment strategy most likely to satisfy patient goals.

Dr. Vahanian and Dr. Prendergast reported no conflicts of interest relevant to these guidelines. Dr. Praz reported a financial relationship with Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Beyersdorf reported a financial relationship with Resuscitec.

New European guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease offer more than 45 revised or completely new recommendations relative to the previous version published in 2017, according to members of the writing committee who presented the changes during the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

With their emphasis on early diagnosis and expansion of indications, these 2021 ESC/European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery guidelines are likely to further accelerate the already steep growth in this area of interventional cardiology, according to Alec Vahanian, MD, a professor of cardiology at the University of Paris.

“Valvular heart disease is too often undetected, and these guidelines stress the importance of clinical examination and the best strategies for diagnosis as well as treatment,” he said.

Of the multiple sections and subsections, which follow the same format of the previous guidelines, the greatest number of revisions and new additions involve perioperative antithrombotic therapy, according to the document, which was published in conjunction with the ESC Congress.

Eleven new guidelines for anticoagulants

On the basis of evidence published since the previous guidelines, there are 11 completely new recommendations regarding the use of anticoagulants or antiplatelet therapies. The majority of these have received a grade I indication, which signifies “recommended” or “indicated.” These include indications for stopping or starting anticoagulants and which anticoagulants or antiplatelet drugs to consider in specific patient populations.

The next most common focus of new or revised recommendations involves when to consider surgical aortic valve repair (SAVR) relative to transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) in severe aortic stenosis. Most of these represent revisions from the previous guidelines, but almost all are also grade I recommendations.

“SAVR and TAVI are both excellent options in appropriate patients, but they are not interchangeable,” explained Bernard D. Prendergast, BMedSci, MD, director of the cardiac structural intervention program, Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital, London.

While the previous guidelines generally reserved TAVI for those not suitable for SAVR, the new guidelines are more nuanced.

As a rule, SAVR is generally preferred for younger patients. The reason, according to Dr. Prendergast, is concern that younger patients might outlive the expected lifespan of the prosthetic TAVI device.

No single criterion for selecting SAVR over TAVI