User login

FDA clears first mobile rapid test for concussion

, the company has announced.

Eye-Sync is a virtual reality eye-tracking platform that provides objective measurements to aid in the assessment of concussion. It’s the first mobile, rapid test for concussion that has been cleared by the FDA, the company said.

As reported by this news organization, Eye-Sync received breakthrough designation from the FDA for this indication in March 2019.

The FDA initially cleared the Eye-Sync platform for recording, viewing, and analyzing eye movements to help clinicians identify visual tracking impairment.

The Eye-Sync technology uses a series of 60-second eye tracking assessments, neurocognitive batteries, symptom inventories, and standardized patient inventories to identify the type and severity of impairment after concussion.

“The platform generates customizable and interpretive reports that support clinical decision making and offers visual and vestibular therapies to remedy deficits and monitor improvement over time,” the company said.

In support of the application for use in concussion, SyncThink enrolled 1,655 children and adults into a clinical study that collected comprehensive patient and concussion-related data for over 12 months.

The company used these data to develop proprietary algorithms and deep learning models to identify a positive or negative indication of concussion.

The study showed that Eye-Sinc had sensitivity greater than 82% and specificity greater than 93%, “thereby providing clinicians with significant and actionable data when evaluating individuals with concussion,” the company said in a news release.

“The outcome of this study very clearly shows the effectiveness of our technology at detecting concussion and definitively demonstrates the clinical utility of Eye-Sinc,” SyncThink Chief Clinical Officer Scott Anderson said in the release.

“It also shows that the future of concussion diagnosis is no longer purely symptom-based but that of a technology driven multi-modal approach,” Mr. Anderson said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, the company has announced.

Eye-Sync is a virtual reality eye-tracking platform that provides objective measurements to aid in the assessment of concussion. It’s the first mobile, rapid test for concussion that has been cleared by the FDA, the company said.

As reported by this news organization, Eye-Sync received breakthrough designation from the FDA for this indication in March 2019.

The FDA initially cleared the Eye-Sync platform for recording, viewing, and analyzing eye movements to help clinicians identify visual tracking impairment.

The Eye-Sync technology uses a series of 60-second eye tracking assessments, neurocognitive batteries, symptom inventories, and standardized patient inventories to identify the type and severity of impairment after concussion.

“The platform generates customizable and interpretive reports that support clinical decision making and offers visual and vestibular therapies to remedy deficits and monitor improvement over time,” the company said.

In support of the application for use in concussion, SyncThink enrolled 1,655 children and adults into a clinical study that collected comprehensive patient and concussion-related data for over 12 months.

The company used these data to develop proprietary algorithms and deep learning models to identify a positive or negative indication of concussion.

The study showed that Eye-Sinc had sensitivity greater than 82% and specificity greater than 93%, “thereby providing clinicians with significant and actionable data when evaluating individuals with concussion,” the company said in a news release.

“The outcome of this study very clearly shows the effectiveness of our technology at detecting concussion and definitively demonstrates the clinical utility of Eye-Sinc,” SyncThink Chief Clinical Officer Scott Anderson said in the release.

“It also shows that the future of concussion diagnosis is no longer purely symptom-based but that of a technology driven multi-modal approach,” Mr. Anderson said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, the company has announced.

Eye-Sync is a virtual reality eye-tracking platform that provides objective measurements to aid in the assessment of concussion. It’s the first mobile, rapid test for concussion that has been cleared by the FDA, the company said.

As reported by this news organization, Eye-Sync received breakthrough designation from the FDA for this indication in March 2019.

The FDA initially cleared the Eye-Sync platform for recording, viewing, and analyzing eye movements to help clinicians identify visual tracking impairment.

The Eye-Sync technology uses a series of 60-second eye tracking assessments, neurocognitive batteries, symptom inventories, and standardized patient inventories to identify the type and severity of impairment after concussion.

“The platform generates customizable and interpretive reports that support clinical decision making and offers visual and vestibular therapies to remedy deficits and monitor improvement over time,” the company said.

In support of the application for use in concussion, SyncThink enrolled 1,655 children and adults into a clinical study that collected comprehensive patient and concussion-related data for over 12 months.

The company used these data to develop proprietary algorithms and deep learning models to identify a positive or negative indication of concussion.

The study showed that Eye-Sinc had sensitivity greater than 82% and specificity greater than 93%, “thereby providing clinicians with significant and actionable data when evaluating individuals with concussion,” the company said in a news release.

“The outcome of this study very clearly shows the effectiveness of our technology at detecting concussion and definitively demonstrates the clinical utility of Eye-Sinc,” SyncThink Chief Clinical Officer Scott Anderson said in the release.

“It also shows that the future of concussion diagnosis is no longer purely symptom-based but that of a technology driven multi-modal approach,” Mr. Anderson said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Opioid prescriptions decrease in young kids, long dosages increase

The opioid prescription rates have significantly decreased for children, teens, and younger adults between 2006 and 2018, according to new research.

“What’s important about this new study is that it documented that these improvements were also occurring for children and young adults specifically,” said Kao-Ping Chua, MD, PhD, primary care physician and assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, who was not involved in the study. “The reason that’s important is that changes in medical practice for adults aren’t always reflected in pediatrics.”

The study, published in JAMA Pediatrics, found that dispensed opioid prescriptions for this population have decreased by 15% annually since 2013. However, the study also examined specific prescribing variables, such as duration of opioid prescription and high-dosage prescriptions. Researchers found reduced rates of high-dosage and long-duration prescriptions for adolescents and younger adults. However, these types of prescription practices increased in children aged 0-5 years.

“I think [the findings are] promising, suggesting that opiate prescribing practices may be improving,” study author Madeline Renny, MD, pediatric emergency medicine doctor at New York University Langone Health, said in an interview. “But we did find that there were increases in the young children for the practice variables, which we didn’t expect. I think that was kind of one of the findings that we were a bit surprised about and want to explore further.”

Previous studies have linked prescription opioid use in children and teens to an increased risk of future opioid misuse. A 2015 study published in Pediatrics found that using prescribed opioids before the 12th grade is associated with a 33% increase in the risk of future opioid misuse by the age of 23. The study also found that for those with a low predicted risk of future opioid misuse, an opioid prescription increases the risk for misuse after high school threefold.

Furthermore, a 2018 study published in JAMA Network Open found that, between 1999 and 2016, the annual estimated mortality rate for all children and adolescents from prescription and illicit opioid use rose 268.2%.

In the new study, Dr. Renny and colleagues examined data from 2006 to 2018 from IQVIA Longitudinal Prescription Data, which captured 74%-92% of U.S. retail outpatient opioid prescriptions dispensed to people up to the age of 24. Researchers also examined prescribing practice variables, which included opioid dispensing rates, average amount of opioid dispensed per prescription, duration of opioid prescription, high-dosage opioid prescription for individuals, and the rate in which extended-release or long-acting opioids are prescribed.

Researchers found that between 2006 and 2018, the total U.S. annual opioid prescriptions dispensed to patients younger than 25 years was highest in 2007 at 15,689,779 prescriptions, and since 2012 has steadily decreased to 6,705,478 in 2018.

“Our study did show that there were declines, but opioids remain readily dispensed,” Dr. Renny said. “And I think it’s good that rates have gone down, but I think opioids are still commonly dispensed to children and adolescents and young adults and all of our age groups.”

Dr. Chua said that the study was important, but when it came to younger children, it didn’t account for the fact that “the underlying population of patients who were getting opioids changed because it’s not the same group of children.”

“Maybe at the beginning there were more surgical patients who are getting shorter duration, lower dosage opioids,” he added. “Now some of those surgical exceptions kind of went away and who’s left in the population of people who get opioids is a sicker population.”

“Who are the 0 to 5-year-olds who are getting opioids now?” Dr. Chua asked. “Well, some of them are going to be cancer or surgical patients. If you think about it, over time their surgeons may be more judicious and they stop prescribing opioids for some things like circumcision or something like that. So that means that who’s left in the population of children who get opiate prescriptions are the cancer patients. Cancer patients’ opioid dosages are going to be higher because they have chronic pain.”

Dr. Chua said it is important to remember that the number of children who are affected by those high-risk prescriptions are lower because the overall number of opioid prescriptions has gone down. He added that the key piece of missing information is the absolute number of prescriptions that were high risk.

Researchers of the current study suggested that, because of the differences between pediatric and adult pain and indications for opioid prescribing, there should be national guidelines on general opioid prescribing for children and adolescents.

Experts did not disclose relevant financial relationships.

The opioid prescription rates have significantly decreased for children, teens, and younger adults between 2006 and 2018, according to new research.

“What’s important about this new study is that it documented that these improvements were also occurring for children and young adults specifically,” said Kao-Ping Chua, MD, PhD, primary care physician and assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, who was not involved in the study. “The reason that’s important is that changes in medical practice for adults aren’t always reflected in pediatrics.”

The study, published in JAMA Pediatrics, found that dispensed opioid prescriptions for this population have decreased by 15% annually since 2013. However, the study also examined specific prescribing variables, such as duration of opioid prescription and high-dosage prescriptions. Researchers found reduced rates of high-dosage and long-duration prescriptions for adolescents and younger adults. However, these types of prescription practices increased in children aged 0-5 years.

“I think [the findings are] promising, suggesting that opiate prescribing practices may be improving,” study author Madeline Renny, MD, pediatric emergency medicine doctor at New York University Langone Health, said in an interview. “But we did find that there were increases in the young children for the practice variables, which we didn’t expect. I think that was kind of one of the findings that we were a bit surprised about and want to explore further.”

Previous studies have linked prescription opioid use in children and teens to an increased risk of future opioid misuse. A 2015 study published in Pediatrics found that using prescribed opioids before the 12th grade is associated with a 33% increase in the risk of future opioid misuse by the age of 23. The study also found that for those with a low predicted risk of future opioid misuse, an opioid prescription increases the risk for misuse after high school threefold.

Furthermore, a 2018 study published in JAMA Network Open found that, between 1999 and 2016, the annual estimated mortality rate for all children and adolescents from prescription and illicit opioid use rose 268.2%.

In the new study, Dr. Renny and colleagues examined data from 2006 to 2018 from IQVIA Longitudinal Prescription Data, which captured 74%-92% of U.S. retail outpatient opioid prescriptions dispensed to people up to the age of 24. Researchers also examined prescribing practice variables, which included opioid dispensing rates, average amount of opioid dispensed per prescription, duration of opioid prescription, high-dosage opioid prescription for individuals, and the rate in which extended-release or long-acting opioids are prescribed.

Researchers found that between 2006 and 2018, the total U.S. annual opioid prescriptions dispensed to patients younger than 25 years was highest in 2007 at 15,689,779 prescriptions, and since 2012 has steadily decreased to 6,705,478 in 2018.

“Our study did show that there were declines, but opioids remain readily dispensed,” Dr. Renny said. “And I think it’s good that rates have gone down, but I think opioids are still commonly dispensed to children and adolescents and young adults and all of our age groups.”

Dr. Chua said that the study was important, but when it came to younger children, it didn’t account for the fact that “the underlying population of patients who were getting opioids changed because it’s not the same group of children.”

“Maybe at the beginning there were more surgical patients who are getting shorter duration, lower dosage opioids,” he added. “Now some of those surgical exceptions kind of went away and who’s left in the population of people who get opioids is a sicker population.”

“Who are the 0 to 5-year-olds who are getting opioids now?” Dr. Chua asked. “Well, some of them are going to be cancer or surgical patients. If you think about it, over time their surgeons may be more judicious and they stop prescribing opioids for some things like circumcision or something like that. So that means that who’s left in the population of children who get opiate prescriptions are the cancer patients. Cancer patients’ opioid dosages are going to be higher because they have chronic pain.”

Dr. Chua said it is important to remember that the number of children who are affected by those high-risk prescriptions are lower because the overall number of opioid prescriptions has gone down. He added that the key piece of missing information is the absolute number of prescriptions that were high risk.

Researchers of the current study suggested that, because of the differences between pediatric and adult pain and indications for opioid prescribing, there should be national guidelines on general opioid prescribing for children and adolescents.

Experts did not disclose relevant financial relationships.

The opioid prescription rates have significantly decreased for children, teens, and younger adults between 2006 and 2018, according to new research.

“What’s important about this new study is that it documented that these improvements were also occurring for children and young adults specifically,” said Kao-Ping Chua, MD, PhD, primary care physician and assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, who was not involved in the study. “The reason that’s important is that changes in medical practice for adults aren’t always reflected in pediatrics.”

The study, published in JAMA Pediatrics, found that dispensed opioid prescriptions for this population have decreased by 15% annually since 2013. However, the study also examined specific prescribing variables, such as duration of opioid prescription and high-dosage prescriptions. Researchers found reduced rates of high-dosage and long-duration prescriptions for adolescents and younger adults. However, these types of prescription practices increased in children aged 0-5 years.

“I think [the findings are] promising, suggesting that opiate prescribing practices may be improving,” study author Madeline Renny, MD, pediatric emergency medicine doctor at New York University Langone Health, said in an interview. “But we did find that there were increases in the young children for the practice variables, which we didn’t expect. I think that was kind of one of the findings that we were a bit surprised about and want to explore further.”

Previous studies have linked prescription opioid use in children and teens to an increased risk of future opioid misuse. A 2015 study published in Pediatrics found that using prescribed opioids before the 12th grade is associated with a 33% increase in the risk of future opioid misuse by the age of 23. The study also found that for those with a low predicted risk of future opioid misuse, an opioid prescription increases the risk for misuse after high school threefold.

Furthermore, a 2018 study published in JAMA Network Open found that, between 1999 and 2016, the annual estimated mortality rate for all children and adolescents from prescription and illicit opioid use rose 268.2%.

In the new study, Dr. Renny and colleagues examined data from 2006 to 2018 from IQVIA Longitudinal Prescription Data, which captured 74%-92% of U.S. retail outpatient opioid prescriptions dispensed to people up to the age of 24. Researchers also examined prescribing practice variables, which included opioid dispensing rates, average amount of opioid dispensed per prescription, duration of opioid prescription, high-dosage opioid prescription for individuals, and the rate in which extended-release or long-acting opioids are prescribed.

Researchers found that between 2006 and 2018, the total U.S. annual opioid prescriptions dispensed to patients younger than 25 years was highest in 2007 at 15,689,779 prescriptions, and since 2012 has steadily decreased to 6,705,478 in 2018.

“Our study did show that there were declines, but opioids remain readily dispensed,” Dr. Renny said. “And I think it’s good that rates have gone down, but I think opioids are still commonly dispensed to children and adolescents and young adults and all of our age groups.”

Dr. Chua said that the study was important, but when it came to younger children, it didn’t account for the fact that “the underlying population of patients who were getting opioids changed because it’s not the same group of children.”

“Maybe at the beginning there were more surgical patients who are getting shorter duration, lower dosage opioids,” he added. “Now some of those surgical exceptions kind of went away and who’s left in the population of people who get opioids is a sicker population.”

“Who are the 0 to 5-year-olds who are getting opioids now?” Dr. Chua asked. “Well, some of them are going to be cancer or surgical patients. If you think about it, over time their surgeons may be more judicious and they stop prescribing opioids for some things like circumcision or something like that. So that means that who’s left in the population of children who get opiate prescriptions are the cancer patients. Cancer patients’ opioid dosages are going to be higher because they have chronic pain.”

Dr. Chua said it is important to remember that the number of children who are affected by those high-risk prescriptions are lower because the overall number of opioid prescriptions has gone down. He added that the key piece of missing information is the absolute number of prescriptions that were high risk.

Researchers of the current study suggested that, because of the differences between pediatric and adult pain and indications for opioid prescribing, there should be national guidelines on general opioid prescribing for children and adolescents.

Experts did not disclose relevant financial relationships.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Tragic consequences of ignorance for everyone

One of the top stories in the local newspaper recently described an unfortunate incident in which a previously healthy 19-month-old baby was found unresponsive and apneic in a crib at her day-care center. She was successfully resuscitated by the daycare provider but is now blind, has seizures, and no longer walks or talks. According to the day care owner, the child had not settled down during rest time and her talking was preventing the other children from sleeping. This apparently had happened before and the day-care provider had successfully resorted to triple wrapping the child in a blanket and placing her in a crib in a separate room. The day-care provider had checked on the child once and noted she was snoring. When the child failed to wake after the expected interval of time she was found face down with her head partially covered by a pillow.

An investigation of the day-care center is ongoing and no reports or prior violations, warnings, or license suspensions have surfaced at this point. The day-care provider has been charged with aggravated assault and endangering the welfare of a child. The charges could carry a prison sentence of 30 years.

As I reread this very sad story I began wondering how this tragedy is going to unfold in the next months and years. We can assume one young life has already been permanently damaged. Her family will have to deal with the consequences of this event for decades or longer. What about the day-care provider? I hope we can assume that she intended no harm to the child nor had she ignored prior warnings or training about swaddling. Nor does this lapse in judgment fit a previous pattern of behavior. Regardless of what the courts decide she will carry some degree of guilt for the foreseeable future. The day-care center has been closed voluntarily and given that Maine is a small state where word travels fast it is unlikely that it will ever reopen.

Can we imagine any good coming out of this tragedy? It may be that with luck and diligent therapies that the little girl will be able to lead a life she finds rewarding and gives others some pleasure. It is possible that some individuals involved in her life – her parents or therapists – will find the devotion to her care brings new meaning to their lives.

Will the day-care provider find a new career or a cause that can help her restore some of the self worth she may have lost in the wake of the event? Or, will a protracted course through the legal system take its devastating toll on her life and marriage? It is unlikely that she will spend anywhere near 30 years in prison, if any at all. Will the child’s family sue this small family day-care center? It is hard to imagine they will recover anything more than a tiny fraction of the lifetime costs of this child’s care.

It is also unlikely that the message that swaddling children old enough to turn over carries a significant risk will go beyond one or two more stories in the local Maine newspapers. If this child’s father had been a professional football player or her mother had been an actress or U.S. Senator this tragic turn of events could possibly have stirred enough waters to grab national attention, spawn a foundation, or even result in legislation. But, she appears to come from a family with modest means without claims to notoriety. There is no flawed product to ban. She is a victim of ignorance and our failure to educate. As a result, her tragedy and those of thousands of other children will do little more than accumulate as unfortunate statistics.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

One of the top stories in the local newspaper recently described an unfortunate incident in which a previously healthy 19-month-old baby was found unresponsive and apneic in a crib at her day-care center. She was successfully resuscitated by the daycare provider but is now blind, has seizures, and no longer walks or talks. According to the day care owner, the child had not settled down during rest time and her talking was preventing the other children from sleeping. This apparently had happened before and the day-care provider had successfully resorted to triple wrapping the child in a blanket and placing her in a crib in a separate room. The day-care provider had checked on the child once and noted she was snoring. When the child failed to wake after the expected interval of time she was found face down with her head partially covered by a pillow.

An investigation of the day-care center is ongoing and no reports or prior violations, warnings, or license suspensions have surfaced at this point. The day-care provider has been charged with aggravated assault and endangering the welfare of a child. The charges could carry a prison sentence of 30 years.

As I reread this very sad story I began wondering how this tragedy is going to unfold in the next months and years. We can assume one young life has already been permanently damaged. Her family will have to deal with the consequences of this event for decades or longer. What about the day-care provider? I hope we can assume that she intended no harm to the child nor had she ignored prior warnings or training about swaddling. Nor does this lapse in judgment fit a previous pattern of behavior. Regardless of what the courts decide she will carry some degree of guilt for the foreseeable future. The day-care center has been closed voluntarily and given that Maine is a small state where word travels fast it is unlikely that it will ever reopen.

Can we imagine any good coming out of this tragedy? It may be that with luck and diligent therapies that the little girl will be able to lead a life she finds rewarding and gives others some pleasure. It is possible that some individuals involved in her life – her parents or therapists – will find the devotion to her care brings new meaning to their lives.

Will the day-care provider find a new career or a cause that can help her restore some of the self worth she may have lost in the wake of the event? Or, will a protracted course through the legal system take its devastating toll on her life and marriage? It is unlikely that she will spend anywhere near 30 years in prison, if any at all. Will the child’s family sue this small family day-care center? It is hard to imagine they will recover anything more than a tiny fraction of the lifetime costs of this child’s care.

It is also unlikely that the message that swaddling children old enough to turn over carries a significant risk will go beyond one or two more stories in the local Maine newspapers. If this child’s father had been a professional football player or her mother had been an actress or U.S. Senator this tragic turn of events could possibly have stirred enough waters to grab national attention, spawn a foundation, or even result in legislation. But, she appears to come from a family with modest means without claims to notoriety. There is no flawed product to ban. She is a victim of ignorance and our failure to educate. As a result, her tragedy and those of thousands of other children will do little more than accumulate as unfortunate statistics.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

One of the top stories in the local newspaper recently described an unfortunate incident in which a previously healthy 19-month-old baby was found unresponsive and apneic in a crib at her day-care center. She was successfully resuscitated by the daycare provider but is now blind, has seizures, and no longer walks or talks. According to the day care owner, the child had not settled down during rest time and her talking was preventing the other children from sleeping. This apparently had happened before and the day-care provider had successfully resorted to triple wrapping the child in a blanket and placing her in a crib in a separate room. The day-care provider had checked on the child once and noted she was snoring. When the child failed to wake after the expected interval of time she was found face down with her head partially covered by a pillow.

An investigation of the day-care center is ongoing and no reports or prior violations, warnings, or license suspensions have surfaced at this point. The day-care provider has been charged with aggravated assault and endangering the welfare of a child. The charges could carry a prison sentence of 30 years.

As I reread this very sad story I began wondering how this tragedy is going to unfold in the next months and years. We can assume one young life has already been permanently damaged. Her family will have to deal with the consequences of this event for decades or longer. What about the day-care provider? I hope we can assume that she intended no harm to the child nor had she ignored prior warnings or training about swaddling. Nor does this lapse in judgment fit a previous pattern of behavior. Regardless of what the courts decide she will carry some degree of guilt for the foreseeable future. The day-care center has been closed voluntarily and given that Maine is a small state where word travels fast it is unlikely that it will ever reopen.

Can we imagine any good coming out of this tragedy? It may be that with luck and diligent therapies that the little girl will be able to lead a life she finds rewarding and gives others some pleasure. It is possible that some individuals involved in her life – her parents or therapists – will find the devotion to her care brings new meaning to their lives.

Will the day-care provider find a new career or a cause that can help her restore some of the self worth she may have lost in the wake of the event? Or, will a protracted course through the legal system take its devastating toll on her life and marriage? It is unlikely that she will spend anywhere near 30 years in prison, if any at all. Will the child’s family sue this small family day-care center? It is hard to imagine they will recover anything more than a tiny fraction of the lifetime costs of this child’s care.

It is also unlikely that the message that swaddling children old enough to turn over carries a significant risk will go beyond one or two more stories in the local Maine newspapers. If this child’s father had been a professional football player or her mother had been an actress or U.S. Senator this tragic turn of events could possibly have stirred enough waters to grab national attention, spawn a foundation, or even result in legislation. But, she appears to come from a family with modest means without claims to notoriety. There is no flawed product to ban. She is a victim of ignorance and our failure to educate. As a result, her tragedy and those of thousands of other children will do little more than accumulate as unfortunate statistics.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Pediatric minority patients less likely to undergo ED imaging

Significant racial and ethnic differences in diagnostic imaging rates exist among children receiving care in pediatric EDs across the United States, Jennifer R. Marin, MD, of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, and associates reported.

Specifically, visits with non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic patients less frequently included radiography, CT, ultrasonography, and MRI than those of non-Hispanic White patients. The findings persisted across most diagnostic groups, even when stratified according to insurance type, Dr. Marin and colleagues reported in a multicenter cross-sectional study in JAMA Network Open.

The authors collected administrative data from the Pediatric Health Information System on 44 tertiary care children’s hospitals in 17 major metropolitan areas across the United States. They evaluated a total of 13,087,522 ED visits by 6,230,911 patients that occurred between Jan. 1, 2016, and Dec. 31, 2019. Of these, 28.2% included at least one imaging study. Altogether, 33.5% were performed on non-Hispanic White children, compared with just 24.1% of non-Hispanic Black children (adjusted odds ratio, 0.82) and 26.1% of Hispanic children (aOR, 0.87). After adjusting for relevant confounding factors, non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic children were less likely to have any imaging at all during their visits.

“Our findings suggest that a child’s race and ethnicity may be independently associated with the decision to perform imaging during ED visits,” Dr. Marin and associates said, adding that “the differential use of diagnostic imaging by race/ethnicity may reflect underuse of imaging in non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic children, or alternatively, overuse in non-Hispanic White children.”

Overuse vs. underuse: Racial bias or parental anxiety?

Overuse of imaging carries its own risks, but underuse can lead to misdiagnosis, the need for additional care, and possibly worse outcomes in the long run, Dr. Marin and colleagues explained. “Although we were unable to discern underuse from overuse using an administrative database, it is likely that much of the imaging in White children is unnecessary.”

Higher parental anxiety was just one of the explanations the authors offered for excessive imaging in White children. Especially in cases of diagnostic imaging for head trauma, one survey of adult ED patients showed that the peace of mind CT offers with its more definitive diagnosis was worth the additional possible risk of radiation.

Language barriers in non–English-speaking patients may also affect likelihood of testing as part of an ED visit.

Implicit physician racial bias, which can be amplified under the stress of working in an ED, can affect patient interactions, treatment decisions and adherence, and ultimately overall health outcomes, the authors noted. The goal in ensuring parity is to routinely follow clinical guidelines and use objective scoring tools that minimize subjectivity. At the institutional level, internal quality assurance evaluations go a long way toward understanding and limiting bias.

Historically, White patients are more likely than minority patients to have a medical home, which can influence whether ED physicians order imaging studies and whether imaging of White patients may have been triggered by a primary care physician referral, Dr. Marin and associates said.

In an accompanying editorial, Anupam B. Kharbanda, MD, said these findings are “consistent with decades of previous research documenting inequalities in health care delivery ... [and] must be examined in the context of inequities within the social framework of a community.”

Going back to the drawing board

“Physicians, researchers, and health care leaders must partner with the communities they serve to develop and implement interventions to address these substantial inequities in care,” said Dr. Kharbanda, pediatric emergency medicine physician at Children’s Minnesota Hospital, Minneapolis. As previous studies have demonstrated, implicit bias and antiracism training are needed to help physicians develop empathy so they are better equipped to help patients and families in a multicultural environment. Partnering with community-based organizations to ensure that care is more community centered, as has been done successfully within the Kaiser Permanente health system, for example, and employing a more diverse workforce that mirrors the populations cared for will go a long way.

Citing a 1966 speech of the late Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., in which he said: “Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health care is the most shocking and inhumane,” Dr. Kharbanda urged clinicians to not only hear but believe these words and act on them by working in partnerships with the communities they serve.

In a separate interview, Walter Palmer, MD, pediatric emergency medicine fellow at Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, noted: “This study’s findings are disappointing and yet not at all unexpected, as the authors convincingly identify yet another step at which patients of color are treated unequally in the U.S. health care system. It highlights a frightening truth: That we are all at risk of letting invisible implicit biases impact our clinical decision-making process. This is especially true in the busy emergency department environment, where pressure to make swift decisions regarding diagnostic workup and management invites the influence of imperceptible biases. It is now incumbent upon us as health care providers to monitor our personal and departmental patterns of practice for areas in which we can improve racial health equity and become advocates for the children and families who entrust us with their care.”

The authors reported multiple financial disclosures. Dr. Kharbanda and Dr. Palmer had no conflicts of interest and reported no disclosures.

Significant racial and ethnic differences in diagnostic imaging rates exist among children receiving care in pediatric EDs across the United States, Jennifer R. Marin, MD, of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, and associates reported.

Specifically, visits with non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic patients less frequently included radiography, CT, ultrasonography, and MRI than those of non-Hispanic White patients. The findings persisted across most diagnostic groups, even when stratified according to insurance type, Dr. Marin and colleagues reported in a multicenter cross-sectional study in JAMA Network Open.

The authors collected administrative data from the Pediatric Health Information System on 44 tertiary care children’s hospitals in 17 major metropolitan areas across the United States. They evaluated a total of 13,087,522 ED visits by 6,230,911 patients that occurred between Jan. 1, 2016, and Dec. 31, 2019. Of these, 28.2% included at least one imaging study. Altogether, 33.5% were performed on non-Hispanic White children, compared with just 24.1% of non-Hispanic Black children (adjusted odds ratio, 0.82) and 26.1% of Hispanic children (aOR, 0.87). After adjusting for relevant confounding factors, non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic children were less likely to have any imaging at all during their visits.

“Our findings suggest that a child’s race and ethnicity may be independently associated with the decision to perform imaging during ED visits,” Dr. Marin and associates said, adding that “the differential use of diagnostic imaging by race/ethnicity may reflect underuse of imaging in non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic children, or alternatively, overuse in non-Hispanic White children.”

Overuse vs. underuse: Racial bias or parental anxiety?

Overuse of imaging carries its own risks, but underuse can lead to misdiagnosis, the need for additional care, and possibly worse outcomes in the long run, Dr. Marin and colleagues explained. “Although we were unable to discern underuse from overuse using an administrative database, it is likely that much of the imaging in White children is unnecessary.”

Higher parental anxiety was just one of the explanations the authors offered for excessive imaging in White children. Especially in cases of diagnostic imaging for head trauma, one survey of adult ED patients showed that the peace of mind CT offers with its more definitive diagnosis was worth the additional possible risk of radiation.

Language barriers in non–English-speaking patients may also affect likelihood of testing as part of an ED visit.

Implicit physician racial bias, which can be amplified under the stress of working in an ED, can affect patient interactions, treatment decisions and adherence, and ultimately overall health outcomes, the authors noted. The goal in ensuring parity is to routinely follow clinical guidelines and use objective scoring tools that minimize subjectivity. At the institutional level, internal quality assurance evaluations go a long way toward understanding and limiting bias.

Historically, White patients are more likely than minority patients to have a medical home, which can influence whether ED physicians order imaging studies and whether imaging of White patients may have been triggered by a primary care physician referral, Dr. Marin and associates said.

In an accompanying editorial, Anupam B. Kharbanda, MD, said these findings are “consistent with decades of previous research documenting inequalities in health care delivery ... [and] must be examined in the context of inequities within the social framework of a community.”

Going back to the drawing board

“Physicians, researchers, and health care leaders must partner with the communities they serve to develop and implement interventions to address these substantial inequities in care,” said Dr. Kharbanda, pediatric emergency medicine physician at Children’s Minnesota Hospital, Minneapolis. As previous studies have demonstrated, implicit bias and antiracism training are needed to help physicians develop empathy so they are better equipped to help patients and families in a multicultural environment. Partnering with community-based organizations to ensure that care is more community centered, as has been done successfully within the Kaiser Permanente health system, for example, and employing a more diverse workforce that mirrors the populations cared for will go a long way.

Citing a 1966 speech of the late Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., in which he said: “Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health care is the most shocking and inhumane,” Dr. Kharbanda urged clinicians to not only hear but believe these words and act on them by working in partnerships with the communities they serve.

In a separate interview, Walter Palmer, MD, pediatric emergency medicine fellow at Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, noted: “This study’s findings are disappointing and yet not at all unexpected, as the authors convincingly identify yet another step at which patients of color are treated unequally in the U.S. health care system. It highlights a frightening truth: That we are all at risk of letting invisible implicit biases impact our clinical decision-making process. This is especially true in the busy emergency department environment, where pressure to make swift decisions regarding diagnostic workup and management invites the influence of imperceptible biases. It is now incumbent upon us as health care providers to monitor our personal and departmental patterns of practice for areas in which we can improve racial health equity and become advocates for the children and families who entrust us with their care.”

The authors reported multiple financial disclosures. Dr. Kharbanda and Dr. Palmer had no conflicts of interest and reported no disclosures.

Significant racial and ethnic differences in diagnostic imaging rates exist among children receiving care in pediatric EDs across the United States, Jennifer R. Marin, MD, of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, and associates reported.

Specifically, visits with non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic patients less frequently included radiography, CT, ultrasonography, and MRI than those of non-Hispanic White patients. The findings persisted across most diagnostic groups, even when stratified according to insurance type, Dr. Marin and colleagues reported in a multicenter cross-sectional study in JAMA Network Open.

The authors collected administrative data from the Pediatric Health Information System on 44 tertiary care children’s hospitals in 17 major metropolitan areas across the United States. They evaluated a total of 13,087,522 ED visits by 6,230,911 patients that occurred between Jan. 1, 2016, and Dec. 31, 2019. Of these, 28.2% included at least one imaging study. Altogether, 33.5% were performed on non-Hispanic White children, compared with just 24.1% of non-Hispanic Black children (adjusted odds ratio, 0.82) and 26.1% of Hispanic children (aOR, 0.87). After adjusting for relevant confounding factors, non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic children were less likely to have any imaging at all during their visits.

“Our findings suggest that a child’s race and ethnicity may be independently associated with the decision to perform imaging during ED visits,” Dr. Marin and associates said, adding that “the differential use of diagnostic imaging by race/ethnicity may reflect underuse of imaging in non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic children, or alternatively, overuse in non-Hispanic White children.”

Overuse vs. underuse: Racial bias or parental anxiety?

Overuse of imaging carries its own risks, but underuse can lead to misdiagnosis, the need for additional care, and possibly worse outcomes in the long run, Dr. Marin and colleagues explained. “Although we were unable to discern underuse from overuse using an administrative database, it is likely that much of the imaging in White children is unnecessary.”

Higher parental anxiety was just one of the explanations the authors offered for excessive imaging in White children. Especially in cases of diagnostic imaging for head trauma, one survey of adult ED patients showed that the peace of mind CT offers with its more definitive diagnosis was worth the additional possible risk of radiation.

Language barriers in non–English-speaking patients may also affect likelihood of testing as part of an ED visit.

Implicit physician racial bias, which can be amplified under the stress of working in an ED, can affect patient interactions, treatment decisions and adherence, and ultimately overall health outcomes, the authors noted. The goal in ensuring parity is to routinely follow clinical guidelines and use objective scoring tools that minimize subjectivity. At the institutional level, internal quality assurance evaluations go a long way toward understanding and limiting bias.

Historically, White patients are more likely than minority patients to have a medical home, which can influence whether ED physicians order imaging studies and whether imaging of White patients may have been triggered by a primary care physician referral, Dr. Marin and associates said.

In an accompanying editorial, Anupam B. Kharbanda, MD, said these findings are “consistent with decades of previous research documenting inequalities in health care delivery ... [and] must be examined in the context of inequities within the social framework of a community.”

Going back to the drawing board

“Physicians, researchers, and health care leaders must partner with the communities they serve to develop and implement interventions to address these substantial inequities in care,” said Dr. Kharbanda, pediatric emergency medicine physician at Children’s Minnesota Hospital, Minneapolis. As previous studies have demonstrated, implicit bias and antiracism training are needed to help physicians develop empathy so they are better equipped to help patients and families in a multicultural environment. Partnering with community-based organizations to ensure that care is more community centered, as has been done successfully within the Kaiser Permanente health system, for example, and employing a more diverse workforce that mirrors the populations cared for will go a long way.

Citing a 1966 speech of the late Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., in which he said: “Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health care is the most shocking and inhumane,” Dr. Kharbanda urged clinicians to not only hear but believe these words and act on them by working in partnerships with the communities they serve.

In a separate interview, Walter Palmer, MD, pediatric emergency medicine fellow at Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, noted: “This study’s findings are disappointing and yet not at all unexpected, as the authors convincingly identify yet another step at which patients of color are treated unequally in the U.S. health care system. It highlights a frightening truth: That we are all at risk of letting invisible implicit biases impact our clinical decision-making process. This is especially true in the busy emergency department environment, where pressure to make swift decisions regarding diagnostic workup and management invites the influence of imperceptible biases. It is now incumbent upon us as health care providers to monitor our personal and departmental patterns of practice for areas in which we can improve racial health equity and become advocates for the children and families who entrust us with their care.”

The authors reported multiple financial disclosures. Dr. Kharbanda and Dr. Palmer had no conflicts of interest and reported no disclosures.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Child abuse visits to EDs declined in 2020, but not admissions

but the visits in 2020 were significantly more likely to result in hospitalization, based on analysis of a national ED database.

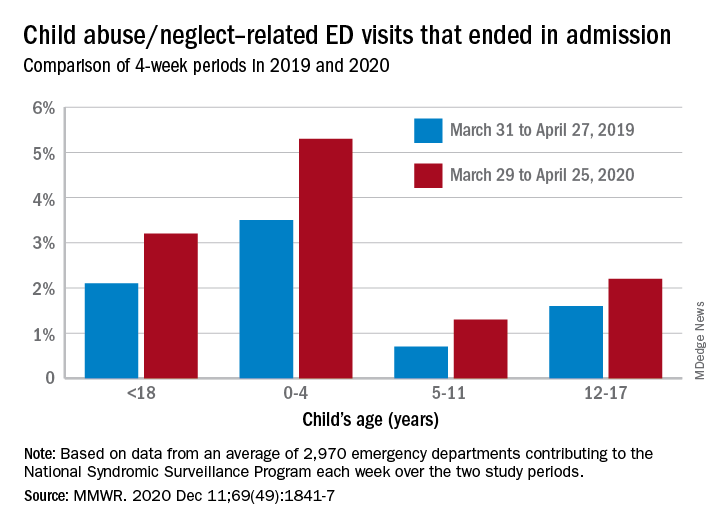

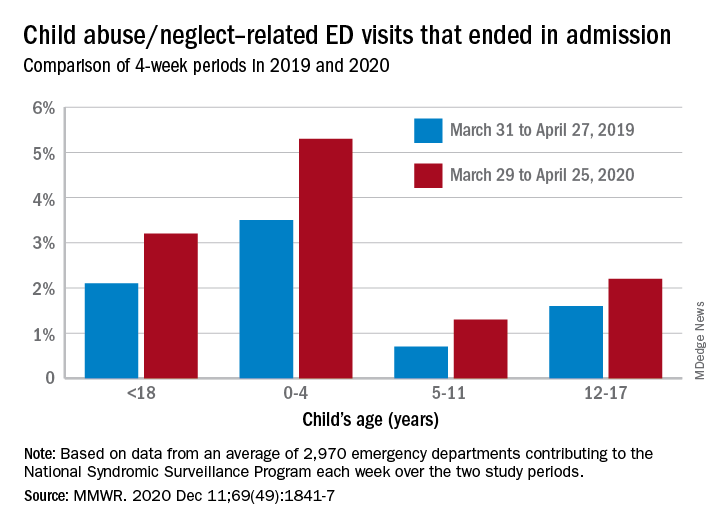

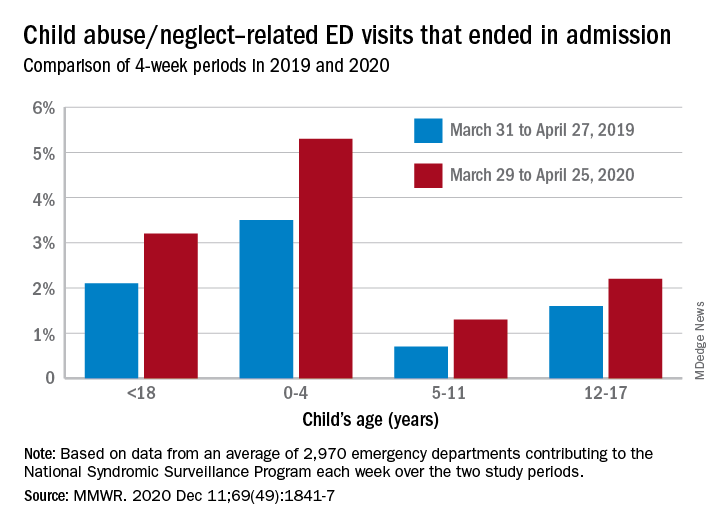

The number of ED visits involving child abuse and neglect was down by 53% during the 4-week period from March 29 to April 25, 2020, compared with the 4 weeks from March 31 to April 27, 2019. The proportion of those ED visits that ended in hospitalizations, however, increased from 2.1% in 2019 to 3.2% in 2020, Elizabeth Swedo, MD, and associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“ED visits related to suspected or confirmed child abuse and neglect decreased beginning the week of March 15, 2020, coinciding with the declaration of a national emergency related to COVID-19 and implementation of community mitigation measures,” they wrote.

An earlier study involving the same database (the National Syndromic Surveillance Program) showed that, over the two same 4-week periods, the volume of all ED visits in 2020 was down 72% for children aged 10 years and younger and 71% for those aged 11-14 years.

In the current study, however, all age subgroups had significant increases in hospital admissions. The proportion of ED visits related to child abuse and neglect that resulted in hospitalization rose from 3.5% in 2019 to 5.3% in 2020 among ages 0-4 years, 0.7% to 1.3% for ages 5-11 years, and 1.6% to 2.2% for adolescents aged 12-17, Dr. Swedo and associates reported.

The absence of a corresponding drop in hospitalizations may be tied to risk factors related to the pandemic, “such as loss of income, increased stress related to parental child care and schooling responsibilities, and increased substance use and mental health conditions among adults,” the investigators added.

The National Syndromic Surveillance Program receives daily data from 3,310 EDs in 47 states, but the number of facilities meeting the investigators’ criteria averaged 2,970 a week for the 8 weeks of the study period.

SOURCE: Swedo E et al. MMWR. 2020 Dec. 11;69(49):1841-7.

but the visits in 2020 were significantly more likely to result in hospitalization, based on analysis of a national ED database.

The number of ED visits involving child abuse and neglect was down by 53% during the 4-week period from March 29 to April 25, 2020, compared with the 4 weeks from March 31 to April 27, 2019. The proportion of those ED visits that ended in hospitalizations, however, increased from 2.1% in 2019 to 3.2% in 2020, Elizabeth Swedo, MD, and associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“ED visits related to suspected or confirmed child abuse and neglect decreased beginning the week of March 15, 2020, coinciding with the declaration of a national emergency related to COVID-19 and implementation of community mitigation measures,” they wrote.

An earlier study involving the same database (the National Syndromic Surveillance Program) showed that, over the two same 4-week periods, the volume of all ED visits in 2020 was down 72% for children aged 10 years and younger and 71% for those aged 11-14 years.

In the current study, however, all age subgroups had significant increases in hospital admissions. The proportion of ED visits related to child abuse and neglect that resulted in hospitalization rose from 3.5% in 2019 to 5.3% in 2020 among ages 0-4 years, 0.7% to 1.3% for ages 5-11 years, and 1.6% to 2.2% for adolescents aged 12-17, Dr. Swedo and associates reported.

The absence of a corresponding drop in hospitalizations may be tied to risk factors related to the pandemic, “such as loss of income, increased stress related to parental child care and schooling responsibilities, and increased substance use and mental health conditions among adults,” the investigators added.

The National Syndromic Surveillance Program receives daily data from 3,310 EDs in 47 states, but the number of facilities meeting the investigators’ criteria averaged 2,970 a week for the 8 weeks of the study period.

SOURCE: Swedo E et al. MMWR. 2020 Dec. 11;69(49):1841-7.

but the visits in 2020 were significantly more likely to result in hospitalization, based on analysis of a national ED database.

The number of ED visits involving child abuse and neglect was down by 53% during the 4-week period from March 29 to April 25, 2020, compared with the 4 weeks from March 31 to April 27, 2019. The proportion of those ED visits that ended in hospitalizations, however, increased from 2.1% in 2019 to 3.2% in 2020, Elizabeth Swedo, MD, and associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“ED visits related to suspected or confirmed child abuse and neglect decreased beginning the week of March 15, 2020, coinciding with the declaration of a national emergency related to COVID-19 and implementation of community mitigation measures,” they wrote.

An earlier study involving the same database (the National Syndromic Surveillance Program) showed that, over the two same 4-week periods, the volume of all ED visits in 2020 was down 72% for children aged 10 years and younger and 71% for those aged 11-14 years.

In the current study, however, all age subgroups had significant increases in hospital admissions. The proportion of ED visits related to child abuse and neglect that resulted in hospitalization rose from 3.5% in 2019 to 5.3% in 2020 among ages 0-4 years, 0.7% to 1.3% for ages 5-11 years, and 1.6% to 2.2% for adolescents aged 12-17, Dr. Swedo and associates reported.

The absence of a corresponding drop in hospitalizations may be tied to risk factors related to the pandemic, “such as loss of income, increased stress related to parental child care and schooling responsibilities, and increased substance use and mental health conditions among adults,” the investigators added.

The National Syndromic Surveillance Program receives daily data from 3,310 EDs in 47 states, but the number of facilities meeting the investigators’ criteria averaged 2,970 a week for the 8 weeks of the study period.

SOURCE: Swedo E et al. MMWR. 2020 Dec. 11;69(49):1841-7.

FROM MMWR

How to help families get through climate-related disasters

Wildfires burned millions of acres in California, Oregon, and Washington this year. Record numbers of tropical storms and hurricanes formed in the Atlantic. “Climate change is here. Disasters are here. They are going to be increasing, which is why we want to talk about this and talk about how pediatricians can help and respond to these events,” Scott Needle, MD, said at the annual meeting American Academy of Pediatrics, held virtually this year.

said Dr. Needle, chief medical officer of Elica Health Centers in Sacramento, California. “We can be a positive influence in terms of getting out proactive messaging and keeping people informed.”

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) 2019 National Household Survey found that about half of households had an emergency plan. A theme across surveys is that, although households take some steps to get ready for disasters, the public generally “is not as prepared for these events as they really need to be,” Dr. Needle said.

The AAP, the Red Cross, and FEMA are among the organizations that offer planning guides, most of which emphasize three simple things: have a kit, have a plan, and be informed, he said.

To prepare for a disaster, parents might refill a child’s medications ahead of time if possible, Dr. Needle suggested. And during the COVID-19 pandemic, families should add masks, sanitizers, and wipes to their go-bags.

Physicians also can help families by asking how they are coping.

Wildfire smoke

“Smoke from wildfires can blanket large, large areas,” Mark Miller, MD, MPH, said during the presentation at the AAP meeting. “This year, we have seen wildfire smoke from the western states reach all the way to the East Coast. So this impacts your patients and your own families sometimes, regardless of wherever you live.”

Children may be more vulnerable to wildfire smoke because they often spend more time outdoors and tend to be more active. In addition, their ongoing development means exposure to air pollutants could have lifelong consequences, said Dr. Miller, who recently reviewed the effects of wildfire smoke on children.

“Children with asthma should have some information about wildfires built into their asthma management plan,” said Dr. Miller, who is affiliated with Western States Pediatric Environmental Health Specialty Unit (PEHSU) and University of California, San Francisco. Pollutants are associated with respiratory visits and admissions, asthma exacerbations, decreased lung function, and neurocognitive effects. They also may be carcinogenic.

A study in monkeys found that smoke exposure during California wildfires in 2008 was associated with immune dysregulation and compromised lung function in adolescence.

Another study of three cohorts of children in southern California found that air pollutant levels were associated with children’s lung function.

Organizations have provided resources on creating cleaner air spaces during wildfires, including guides to build DIY air filter fans. AirNow.gov provides air quality and fire maps that can inform decisions about school closures and outdoor activities. Communities should prioritize establishing schools as clean air shelters, Dr. Miller suggested.

Studies have found that respirators and medical masks may decrease children’s exposure to smoke. Children should not use face coverings, however, if they are younger than 2 years, if they are not able to remove the face covering on their own or tell an adult that they need help, or if they have difficulty breathing with a face covering. Younger children should be observed by an adult.

During the pandemic, families should be aware that some types of masks are sold only for health care use, many foreign respirators are counterfeit, and cloth masks used for COVID-19 are not suitable for reducing wildfire smoke exposure, Dr. Miller said.

Hazards may linger

Long-term mental health issues may be the disaster consequence that pediatricians encounter most often, Dr. Needle said.

Eighteen months after a major wildfire in Canada, more than one-third of middle and high school students in one community had probable posttraumatic stress disorder (that is, intrusive thoughts, avoidance, and increased arousal). In addition, 31% of students had probable depression. Rates were elevated relative to a control group of students in another community that was not affected by the fire.

Findings indicate that a patient’s degree of exposure to a disaster affects the likelihood of adverse outcomes. On the other hand, resiliency may help mitigate adverse effects. “The hope is that if we can find ways to encourage resiliency before or in the aftermath of an event, we may be able to, in a sense, reduce some of these mental health sequelae,” Dr. Needle said.

Posttraumatic reactions in kids are likely after a disaster. “They may not rise to the level of a diagnosable condition, but they are very common in kids,” he said. “It is important to at least be able to counsel parents to recognize some of the common reactions,” such as acting withdrawn or aggressive, somatic complaints, and having trouble sleeping.

The AAP has a policy statement that encourages talking to children about their concerns with honest and age-appropriate responses, he noted.

When returning to an area after a disaster, many hazards may remain, such as floodwaters, ash pits, mold, and carbon monoxide from generators. “Generally speaking, you don’t want to have kids return to these areas until it is safe,” Dr. Needle said.

Exacerbation of existing conditions – perhaps because of lost medications, smoke exposure, or stress – may be another common problem. Other problems after a disaster could include domestic violence (direct or witnessed) and substance abuse.

“We have a responsibility to take care of our own health as well,” Dr. Needle added. “You can’t take care of others if you’re not taking care of yourself. It’s not being selfish. As a matter of fact, it’s being prudent. It’s survival.”

Dr. Needle and Dr. Miller had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Miller’s presentation was supported by the AAP and funded in part by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) provides funding support for the Pediatric Environmental Health Specialty Unit.

Wildfires burned millions of acres in California, Oregon, and Washington this year. Record numbers of tropical storms and hurricanes formed in the Atlantic. “Climate change is here. Disasters are here. They are going to be increasing, which is why we want to talk about this and talk about how pediatricians can help and respond to these events,” Scott Needle, MD, said at the annual meeting American Academy of Pediatrics, held virtually this year.

said Dr. Needle, chief medical officer of Elica Health Centers in Sacramento, California. “We can be a positive influence in terms of getting out proactive messaging and keeping people informed.”

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) 2019 National Household Survey found that about half of households had an emergency plan. A theme across surveys is that, although households take some steps to get ready for disasters, the public generally “is not as prepared for these events as they really need to be,” Dr. Needle said.

The AAP, the Red Cross, and FEMA are among the organizations that offer planning guides, most of which emphasize three simple things: have a kit, have a plan, and be informed, he said.

To prepare for a disaster, parents might refill a child’s medications ahead of time if possible, Dr. Needle suggested. And during the COVID-19 pandemic, families should add masks, sanitizers, and wipes to their go-bags.

Physicians also can help families by asking how they are coping.

Wildfire smoke

“Smoke from wildfires can blanket large, large areas,” Mark Miller, MD, MPH, said during the presentation at the AAP meeting. “This year, we have seen wildfire smoke from the western states reach all the way to the East Coast. So this impacts your patients and your own families sometimes, regardless of wherever you live.”

Children may be more vulnerable to wildfire smoke because they often spend more time outdoors and tend to be more active. In addition, their ongoing development means exposure to air pollutants could have lifelong consequences, said Dr. Miller, who recently reviewed the effects of wildfire smoke on children.

“Children with asthma should have some information about wildfires built into their asthma management plan,” said Dr. Miller, who is affiliated with Western States Pediatric Environmental Health Specialty Unit (PEHSU) and University of California, San Francisco. Pollutants are associated with respiratory visits and admissions, asthma exacerbations, decreased lung function, and neurocognitive effects. They also may be carcinogenic.

A study in monkeys found that smoke exposure during California wildfires in 2008 was associated with immune dysregulation and compromised lung function in adolescence.

Another study of three cohorts of children in southern California found that air pollutant levels were associated with children’s lung function.

Organizations have provided resources on creating cleaner air spaces during wildfires, including guides to build DIY air filter fans. AirNow.gov provides air quality and fire maps that can inform decisions about school closures and outdoor activities. Communities should prioritize establishing schools as clean air shelters, Dr. Miller suggested.

Studies have found that respirators and medical masks may decrease children’s exposure to smoke. Children should not use face coverings, however, if they are younger than 2 years, if they are not able to remove the face covering on their own or tell an adult that they need help, or if they have difficulty breathing with a face covering. Younger children should be observed by an adult.

During the pandemic, families should be aware that some types of masks are sold only for health care use, many foreign respirators are counterfeit, and cloth masks used for COVID-19 are not suitable for reducing wildfire smoke exposure, Dr. Miller said.

Hazards may linger

Long-term mental health issues may be the disaster consequence that pediatricians encounter most often, Dr. Needle said.

Eighteen months after a major wildfire in Canada, more than one-third of middle and high school students in one community had probable posttraumatic stress disorder (that is, intrusive thoughts, avoidance, and increased arousal). In addition, 31% of students had probable depression. Rates were elevated relative to a control group of students in another community that was not affected by the fire.

Findings indicate that a patient’s degree of exposure to a disaster affects the likelihood of adverse outcomes. On the other hand, resiliency may help mitigate adverse effects. “The hope is that if we can find ways to encourage resiliency before or in the aftermath of an event, we may be able to, in a sense, reduce some of these mental health sequelae,” Dr. Needle said.

Posttraumatic reactions in kids are likely after a disaster. “They may not rise to the level of a diagnosable condition, but they are very common in kids,” he said. “It is important to at least be able to counsel parents to recognize some of the common reactions,” such as acting withdrawn or aggressive, somatic complaints, and having trouble sleeping.

The AAP has a policy statement that encourages talking to children about their concerns with honest and age-appropriate responses, he noted.

When returning to an area after a disaster, many hazards may remain, such as floodwaters, ash pits, mold, and carbon monoxide from generators. “Generally speaking, you don’t want to have kids return to these areas until it is safe,” Dr. Needle said.

Exacerbation of existing conditions – perhaps because of lost medications, smoke exposure, or stress – may be another common problem. Other problems after a disaster could include domestic violence (direct or witnessed) and substance abuse.

“We have a responsibility to take care of our own health as well,” Dr. Needle added. “You can’t take care of others if you’re not taking care of yourself. It’s not being selfish. As a matter of fact, it’s being prudent. It’s survival.”

Dr. Needle and Dr. Miller had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Miller’s presentation was supported by the AAP and funded in part by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) provides funding support for the Pediatric Environmental Health Specialty Unit.

Wildfires burned millions of acres in California, Oregon, and Washington this year. Record numbers of tropical storms and hurricanes formed in the Atlantic. “Climate change is here. Disasters are here. They are going to be increasing, which is why we want to talk about this and talk about how pediatricians can help and respond to these events,” Scott Needle, MD, said at the annual meeting American Academy of Pediatrics, held virtually this year.

said Dr. Needle, chief medical officer of Elica Health Centers in Sacramento, California. “We can be a positive influence in terms of getting out proactive messaging and keeping people informed.”

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) 2019 National Household Survey found that about half of households had an emergency plan. A theme across surveys is that, although households take some steps to get ready for disasters, the public generally “is not as prepared for these events as they really need to be,” Dr. Needle said.

The AAP, the Red Cross, and FEMA are among the organizations that offer planning guides, most of which emphasize three simple things: have a kit, have a plan, and be informed, he said.

To prepare for a disaster, parents might refill a child’s medications ahead of time if possible, Dr. Needle suggested. And during the COVID-19 pandemic, families should add masks, sanitizers, and wipes to their go-bags.

Physicians also can help families by asking how they are coping.

Wildfire smoke

“Smoke from wildfires can blanket large, large areas,” Mark Miller, MD, MPH, said during the presentation at the AAP meeting. “This year, we have seen wildfire smoke from the western states reach all the way to the East Coast. So this impacts your patients and your own families sometimes, regardless of wherever you live.”

Children may be more vulnerable to wildfire smoke because they often spend more time outdoors and tend to be more active. In addition, their ongoing development means exposure to air pollutants could have lifelong consequences, said Dr. Miller, who recently reviewed the effects of wildfire smoke on children.

“Children with asthma should have some information about wildfires built into their asthma management plan,” said Dr. Miller, who is affiliated with Western States Pediatric Environmental Health Specialty Unit (PEHSU) and University of California, San Francisco. Pollutants are associated with respiratory visits and admissions, asthma exacerbations, decreased lung function, and neurocognitive effects. They also may be carcinogenic.

A study in monkeys found that smoke exposure during California wildfires in 2008 was associated with immune dysregulation and compromised lung function in adolescence.

Another study of three cohorts of children in southern California found that air pollutant levels were associated with children’s lung function.

Organizations have provided resources on creating cleaner air spaces during wildfires, including guides to build DIY air filter fans. AirNow.gov provides air quality and fire maps that can inform decisions about school closures and outdoor activities. Communities should prioritize establishing schools as clean air shelters, Dr. Miller suggested.

Studies have found that respirators and medical masks may decrease children’s exposure to smoke. Children should not use face coverings, however, if they are younger than 2 years, if they are not able to remove the face covering on their own or tell an adult that they need help, or if they have difficulty breathing with a face covering. Younger children should be observed by an adult.

During the pandemic, families should be aware that some types of masks are sold only for health care use, many foreign respirators are counterfeit, and cloth masks used for COVID-19 are not suitable for reducing wildfire smoke exposure, Dr. Miller said.

Hazards may linger

Long-term mental health issues may be the disaster consequence that pediatricians encounter most often, Dr. Needle said.

Eighteen months after a major wildfire in Canada, more than one-third of middle and high school students in one community had probable posttraumatic stress disorder (that is, intrusive thoughts, avoidance, and increased arousal). In addition, 31% of students had probable depression. Rates were elevated relative to a control group of students in another community that was not affected by the fire.

Findings indicate that a patient’s degree of exposure to a disaster affects the likelihood of adverse outcomes. On the other hand, resiliency may help mitigate adverse effects. “The hope is that if we can find ways to encourage resiliency before or in the aftermath of an event, we may be able to, in a sense, reduce some of these mental health sequelae,” Dr. Needle said.

Posttraumatic reactions in kids are likely after a disaster. “They may not rise to the level of a diagnosable condition, but they are very common in kids,” he said. “It is important to at least be able to counsel parents to recognize some of the common reactions,” such as acting withdrawn or aggressive, somatic complaints, and having trouble sleeping.

The AAP has a policy statement that encourages talking to children about their concerns with honest and age-appropriate responses, he noted.

When returning to an area after a disaster, many hazards may remain, such as floodwaters, ash pits, mold, and carbon monoxide from generators. “Generally speaking, you don’t want to have kids return to these areas until it is safe,” Dr. Needle said.

Exacerbation of existing conditions – perhaps because of lost medications, smoke exposure, or stress – may be another common problem. Other problems after a disaster could include domestic violence (direct or witnessed) and substance abuse.

“We have a responsibility to take care of our own health as well,” Dr. Needle added. “You can’t take care of others if you’re not taking care of yourself. It’s not being selfish. As a matter of fact, it’s being prudent. It’s survival.”

Dr. Needle and Dr. Miller had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Miller’s presentation was supported by the AAP and funded in part by the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) provides funding support for the Pediatric Environmental Health Specialty Unit.

FROM AAP 2020

When should students resume sports after a COVID-19 diagnosis?

Many student athletes who test positive for COVID-19 likely can have an uneventful return to their sports after they have rested for 2 weeks in quarantine, doctors suggest.

There are reasons for caution, however, especially when a patient has symptoms that indicate possible cardiac involvement. In these cases, patients should undergo cardiac testing before a physician clears them to return to play, according to guidance from professional associations. Reports of myocarditis in college athletes who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 but were asymptomatic are among the reasons for concern. Myocarditis may increase the risk of sudden death during exercise.

“The thing that you need to keep in mind is that this is not just a respiratory illness,” David T. Bernhardt, MD, professor of pediatrics, orthopedics, and rehabilitation at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, said in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics, held virtually this year. High school and college athletes have had cardiac, neurologic, hematologic, and renal problems that “can complicate their recovery and their return to sport.”

Still, children who test positive for COVID-19 tend to have mild illness and often are asymptomatic. “It is more than likely going to be safe for the majority of the student athletes who are in the elementary and middle school age to return to sport,” said Dr. Bernhardt. Given that 18-year-old college freshmen have had cardiac complications, there may be reason for more caution with high school students.

Limited data

The AAP has released interim guidance on returning to sports and recommends that primary care physicians clear all patients with COVID-19 before they resume training. Physicians should screen for cardiac symptoms such as chest pain, shortness of breath, fatigue, palpitations, or syncope.

Those with severe illness should be restricted from exercise and participation for 3-6 months. Primary care physicians, preferably in consultation with pediatric cardiologists, should clear athletes who experience severe illness.

“Most of the recommendations come from the fact that we simply do not know what we do not know with COVID-19,” Susannah Briskin, MD, a coauthor of the interim guidance, said in an interview. “We have to be cautious in returning individuals to play and closely monitor them as we learn more about the disease process and its effect on kids.”

Patients with severe illness could include those who were hospitalized and experienced hypotension or arrhythmias, required intubation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support, had kidney or cardiac failure, or developed multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), said Dr. Briskin, a specialist in pediatric sports medicine at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.