User login

Rate of objects ingested by young children increased over last two decades

– from an estimated 9 cases per 10,000 children to 18 cases per 10,000 (R2 = 0.90; P less than .001) – according to an analysis in Pediatrics.

The analysis was conducted by Danielle Orsagh-Yentis, MD, of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., and her colleagues. They estimated that, during the study period, 759,074 children younger than 6 years of age were evaluated in U.S. EDs for suspected or confirmed foreign-body ingestions. These estimates were based on data for 29,893 actual cases taken from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS), which represents about 100 hospitals. Each case in this system is given a sample weight by the Consumer Product Safety Commission using a validated method, and the estimates are based on this weighting.

The analysis showed that children aged 1 year (21%) and boys (53%) were the most likely to ingest foreign bodies. Coins were the most frequently ingested objects, at 62%. Among cases which had the location noted (59%), most ingestions occurred in the home (97%).

The authors noted that, although batteries and magnets represented only 7% and 2% of all cases, respectively, “they can both enact considerable damage when ingested.” For example, despite being only the fourth mostly likely object to be ingested, batteries were the second mostly likely to be implicated among hospitalized patients.

The authors noted that the NEISS captures patients in the ED only; the total number of foreign-body ingestions, then, was likely underestimated. Despite this, the authors felt the long study period and large sample were strengths of their analysis.

Dr. Orsagh-Yentis and her associates disclosed no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Orsagh-Yentis D et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Apr 12. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-1988.

– from an estimated 9 cases per 10,000 children to 18 cases per 10,000 (R2 = 0.90; P less than .001) – according to an analysis in Pediatrics.

The analysis was conducted by Danielle Orsagh-Yentis, MD, of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., and her colleagues. They estimated that, during the study period, 759,074 children younger than 6 years of age were evaluated in U.S. EDs for suspected or confirmed foreign-body ingestions. These estimates were based on data for 29,893 actual cases taken from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS), which represents about 100 hospitals. Each case in this system is given a sample weight by the Consumer Product Safety Commission using a validated method, and the estimates are based on this weighting.

The analysis showed that children aged 1 year (21%) and boys (53%) were the most likely to ingest foreign bodies. Coins were the most frequently ingested objects, at 62%. Among cases which had the location noted (59%), most ingestions occurred in the home (97%).

The authors noted that, although batteries and magnets represented only 7% and 2% of all cases, respectively, “they can both enact considerable damage when ingested.” For example, despite being only the fourth mostly likely object to be ingested, batteries were the second mostly likely to be implicated among hospitalized patients.

The authors noted that the NEISS captures patients in the ED only; the total number of foreign-body ingestions, then, was likely underestimated. Despite this, the authors felt the long study period and large sample were strengths of their analysis.

Dr. Orsagh-Yentis and her associates disclosed no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Orsagh-Yentis D et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Apr 12. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-1988.

– from an estimated 9 cases per 10,000 children to 18 cases per 10,000 (R2 = 0.90; P less than .001) – according to an analysis in Pediatrics.

The analysis was conducted by Danielle Orsagh-Yentis, MD, of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., and her colleagues. They estimated that, during the study period, 759,074 children younger than 6 years of age were evaluated in U.S. EDs for suspected or confirmed foreign-body ingestions. These estimates were based on data for 29,893 actual cases taken from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS), which represents about 100 hospitals. Each case in this system is given a sample weight by the Consumer Product Safety Commission using a validated method, and the estimates are based on this weighting.

The analysis showed that children aged 1 year (21%) and boys (53%) were the most likely to ingest foreign bodies. Coins were the most frequently ingested objects, at 62%. Among cases which had the location noted (59%), most ingestions occurred in the home (97%).

The authors noted that, although batteries and magnets represented only 7% and 2% of all cases, respectively, “they can both enact considerable damage when ingested.” For example, despite being only the fourth mostly likely object to be ingested, batteries were the second mostly likely to be implicated among hospitalized patients.

The authors noted that the NEISS captures patients in the ED only; the total number of foreign-body ingestions, then, was likely underestimated. Despite this, the authors felt the long study period and large sample were strengths of their analysis.

Dr. Orsagh-Yentis and her associates disclosed no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Orsagh-Yentis D et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Apr 12. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-1988.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Policy statement on drowning highlights high-risk groups

Wider availability of low-cost swim lessons could reduce drowning risk in children over 1 year old, but such lessons are only one component of reducing drowning risk and cannot “drown-proof” children, who should still be fully supervised around water, according to a new policy statement from the American Academy of Pediatrics.

These strategies include barriers, supervision, swim lessons, use of life jackets, and training in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). Parents should be advised to restrict unsupervised access to pools and other bodies of water, as well as understand the risks of substance use around water, Sarah A. Denny, MD, and the members of the AAP’s Council on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention, wrote.

The committee made five major recommendations for pediatricians:

• Recognize high-risk groups and leading causes of drowning in their area and customize advice to parents about drowning risk accordingly.

• Pay special attention to needs of children with medical conditions that increase drowning risk, such as seizure disorders, autism spectrum disorder and cardiac arrhythmias, and advise uninterrupted supervision for these children even in baths.

• Inform parents and children of the increased risk of drowning with substance use, especially for teen boys.

• Discuss water skill levels with parents and children to avoid either overestimating a youth’s competency.

• Encourage CPR training in high schools.

Accidental drowning rates have declined from 2.7 per 100,000 children in 1985 to 1.1 per 100,000 children in 2017, yet drowning remains the top cause of injury death among children ages 1-4 years, reported Dr. Denny, of Nationwide Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, and her colleagues (Pediatrics. March 15, 2019). For those ages 5-19 years old, drowning is the third leading cause of accidental death.

Nearly 1,000 children and adolescents under 20 years old die from drowning each year. An estimated 8,700 others went to the emergency department for drowning-related incidents in 2017. Of these children, 25% required admission or additional care.

“Most victims of nonfatal drowning recover fully with no neurologic deficits, but severe long-term neurologic deficits are seen with extended submersion times (over 6 minutes), prolonged resuscitation efforts, and lack of early bystander-initiated cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR),” the committee wrote.

Children at highest drowning risk include toddlers and teen boys of all races/ethnicities as well as black and Native American/Alaska Native children. Black male teens had the highest overall rates, 4 drowning deaths per 100,000 children, for 2013-2017.

Among those aged 4 years and under, drowning risk was primarily related to the lack of barriers to prevent unanticipated, unsupervised access to water, including swimming pools, hot tubs and spas, bathtubs, natural bodies of water, and standing water in homes (buckets, tubs, and toilets), the committee wrote.

Teens are most likely to die in natural water settings, such as ponds, rivers, lakes and sea water. “The increased risk for fatal drowning in adolescents can be attributed to multiple factors, including overestimation of skills, underestimation of dangerous situations, engaging in high-risk and impulsive behaviors, and substance use,” particularly alcohol consumption, according to the statement.

Children with seizure disorders have up to a 10-times greater risk of drowning, and therefore require constant supervision around water. Whenever possible, children with seizure disorders should shower instead of bathe and swim only at locations where there is a lifeguard.

Similarly, supervision is essential for children with autism spectrum disorder, especially those under age 15 and with greater intellectual disability. Wandering is the most commonly reported behavior leading to drowning, accounting for nearly 74% of fatal drowning incidents among children with autism.

The committee also recommended four community advocacy activities:

• Actively work with legislators to develop policy aimed at reducing the risk of drowning, such as pool/water fencing requirements and laws related to boating, life jacket use, EMS systems and overall water safety.

• Use “non-fatal drowning” — not “near drowning” — to describe drowning incidents that do not result in death and inform parents that “dry drowning” and “secondary drowning” are not medically accurate terms.

• Work with community groups to ensure life jackets are accessible for all people at pools and boating sites.

• Encourage, identify and support “high-quality, culturally sensitive, and affordable” swim lesson programs, particularly for children in low-income, disability or other high-risk groups.“Socioeconomic and cultural disparities in water safety knowledge, swimming skills and drowning risk can be addressed through “community-based programs targeting high-risk groups by providing free or low-cost swim lessons, developing special programs that address cultural concerns as well as swim lessons for youth with developmental disabilities, and changing pool policies to meet the needs of specific communities,” the committee wrote.

The statement did not use external funding, and the authors reported no financial conflicts.

SOURCE: Denny SA et al. Pediatrics.

Wider availability of low-cost swim lessons could reduce drowning risk in children over 1 year old, but such lessons are only one component of reducing drowning risk and cannot “drown-proof” children, who should still be fully supervised around water, according to a new policy statement from the American Academy of Pediatrics.

These strategies include barriers, supervision, swim lessons, use of life jackets, and training in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). Parents should be advised to restrict unsupervised access to pools and other bodies of water, as well as understand the risks of substance use around water, Sarah A. Denny, MD, and the members of the AAP’s Council on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention, wrote.

The committee made five major recommendations for pediatricians:

• Recognize high-risk groups and leading causes of drowning in their area and customize advice to parents about drowning risk accordingly.

• Pay special attention to needs of children with medical conditions that increase drowning risk, such as seizure disorders, autism spectrum disorder and cardiac arrhythmias, and advise uninterrupted supervision for these children even in baths.

• Inform parents and children of the increased risk of drowning with substance use, especially for teen boys.

• Discuss water skill levels with parents and children to avoid either overestimating a youth’s competency.

• Encourage CPR training in high schools.

Accidental drowning rates have declined from 2.7 per 100,000 children in 1985 to 1.1 per 100,000 children in 2017, yet drowning remains the top cause of injury death among children ages 1-4 years, reported Dr. Denny, of Nationwide Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, and her colleagues (Pediatrics. March 15, 2019). For those ages 5-19 years old, drowning is the third leading cause of accidental death.

Nearly 1,000 children and adolescents under 20 years old die from drowning each year. An estimated 8,700 others went to the emergency department for drowning-related incidents in 2017. Of these children, 25% required admission or additional care.

“Most victims of nonfatal drowning recover fully with no neurologic deficits, but severe long-term neurologic deficits are seen with extended submersion times (over 6 minutes), prolonged resuscitation efforts, and lack of early bystander-initiated cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR),” the committee wrote.

Children at highest drowning risk include toddlers and teen boys of all races/ethnicities as well as black and Native American/Alaska Native children. Black male teens had the highest overall rates, 4 drowning deaths per 100,000 children, for 2013-2017.

Among those aged 4 years and under, drowning risk was primarily related to the lack of barriers to prevent unanticipated, unsupervised access to water, including swimming pools, hot tubs and spas, bathtubs, natural bodies of water, and standing water in homes (buckets, tubs, and toilets), the committee wrote.

Teens are most likely to die in natural water settings, such as ponds, rivers, lakes and sea water. “The increased risk for fatal drowning in adolescents can be attributed to multiple factors, including overestimation of skills, underestimation of dangerous situations, engaging in high-risk and impulsive behaviors, and substance use,” particularly alcohol consumption, according to the statement.

Children with seizure disorders have up to a 10-times greater risk of drowning, and therefore require constant supervision around water. Whenever possible, children with seizure disorders should shower instead of bathe and swim only at locations where there is a lifeguard.

Similarly, supervision is essential for children with autism spectrum disorder, especially those under age 15 and with greater intellectual disability. Wandering is the most commonly reported behavior leading to drowning, accounting for nearly 74% of fatal drowning incidents among children with autism.

The committee also recommended four community advocacy activities:

• Actively work with legislators to develop policy aimed at reducing the risk of drowning, such as pool/water fencing requirements and laws related to boating, life jacket use, EMS systems and overall water safety.

• Use “non-fatal drowning” — not “near drowning” — to describe drowning incidents that do not result in death and inform parents that “dry drowning” and “secondary drowning” are not medically accurate terms.

• Work with community groups to ensure life jackets are accessible for all people at pools and boating sites.

• Encourage, identify and support “high-quality, culturally sensitive, and affordable” swim lesson programs, particularly for children in low-income, disability or other high-risk groups.“Socioeconomic and cultural disparities in water safety knowledge, swimming skills and drowning risk can be addressed through “community-based programs targeting high-risk groups by providing free or low-cost swim lessons, developing special programs that address cultural concerns as well as swim lessons for youth with developmental disabilities, and changing pool policies to meet the needs of specific communities,” the committee wrote.

The statement did not use external funding, and the authors reported no financial conflicts.

SOURCE: Denny SA et al. Pediatrics.

Wider availability of low-cost swim lessons could reduce drowning risk in children over 1 year old, but such lessons are only one component of reducing drowning risk and cannot “drown-proof” children, who should still be fully supervised around water, according to a new policy statement from the American Academy of Pediatrics.

These strategies include barriers, supervision, swim lessons, use of life jackets, and training in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). Parents should be advised to restrict unsupervised access to pools and other bodies of water, as well as understand the risks of substance use around water, Sarah A. Denny, MD, and the members of the AAP’s Council on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention, wrote.

The committee made five major recommendations for pediatricians:

• Recognize high-risk groups and leading causes of drowning in their area and customize advice to parents about drowning risk accordingly.

• Pay special attention to needs of children with medical conditions that increase drowning risk, such as seizure disorders, autism spectrum disorder and cardiac arrhythmias, and advise uninterrupted supervision for these children even in baths.

• Inform parents and children of the increased risk of drowning with substance use, especially for teen boys.

• Discuss water skill levels with parents and children to avoid either overestimating a youth’s competency.

• Encourage CPR training in high schools.

Accidental drowning rates have declined from 2.7 per 100,000 children in 1985 to 1.1 per 100,000 children in 2017, yet drowning remains the top cause of injury death among children ages 1-4 years, reported Dr. Denny, of Nationwide Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, and her colleagues (Pediatrics. March 15, 2019). For those ages 5-19 years old, drowning is the third leading cause of accidental death.

Nearly 1,000 children and adolescents under 20 years old die from drowning each year. An estimated 8,700 others went to the emergency department for drowning-related incidents in 2017. Of these children, 25% required admission or additional care.

“Most victims of nonfatal drowning recover fully with no neurologic deficits, but severe long-term neurologic deficits are seen with extended submersion times (over 6 minutes), prolonged resuscitation efforts, and lack of early bystander-initiated cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR),” the committee wrote.

Children at highest drowning risk include toddlers and teen boys of all races/ethnicities as well as black and Native American/Alaska Native children. Black male teens had the highest overall rates, 4 drowning deaths per 100,000 children, for 2013-2017.

Among those aged 4 years and under, drowning risk was primarily related to the lack of barriers to prevent unanticipated, unsupervised access to water, including swimming pools, hot tubs and spas, bathtubs, natural bodies of water, and standing water in homes (buckets, tubs, and toilets), the committee wrote.

Teens are most likely to die in natural water settings, such as ponds, rivers, lakes and sea water. “The increased risk for fatal drowning in adolescents can be attributed to multiple factors, including overestimation of skills, underestimation of dangerous situations, engaging in high-risk and impulsive behaviors, and substance use,” particularly alcohol consumption, according to the statement.

Children with seizure disorders have up to a 10-times greater risk of drowning, and therefore require constant supervision around water. Whenever possible, children with seizure disorders should shower instead of bathe and swim only at locations where there is a lifeguard.

Similarly, supervision is essential for children with autism spectrum disorder, especially those under age 15 and with greater intellectual disability. Wandering is the most commonly reported behavior leading to drowning, accounting for nearly 74% of fatal drowning incidents among children with autism.

The committee also recommended four community advocacy activities:

• Actively work with legislators to develop policy aimed at reducing the risk of drowning, such as pool/water fencing requirements and laws related to boating, life jacket use, EMS systems and overall water safety.

• Use “non-fatal drowning” — not “near drowning” — to describe drowning incidents that do not result in death and inform parents that “dry drowning” and “secondary drowning” are not medically accurate terms.

• Work with community groups to ensure life jackets are accessible for all people at pools and boating sites.

• Encourage, identify and support “high-quality, culturally sensitive, and affordable” swim lesson programs, particularly for children in low-income, disability or other high-risk groups.“Socioeconomic and cultural disparities in water safety knowledge, swimming skills and drowning risk can be addressed through “community-based programs targeting high-risk groups by providing free or low-cost swim lessons, developing special programs that address cultural concerns as well as swim lessons for youth with developmental disabilities, and changing pool policies to meet the needs of specific communities,” the committee wrote.

The statement did not use external funding, and the authors reported no financial conflicts.

SOURCE: Denny SA et al. Pediatrics.

FROM PEDIATRICS

House committee passes AMA-endorsed firearm bill

WASHINGTON – A bill requiring universal background checks for firearm purchases passed the House Judiciary committee and is expected to pass the full House of Representatives when it comes up for consideration.

Rep. Mike Thompson (R-Calif.), chairman of the House Gun Violence Prevention Task Force, thanked the American Medical Association for its endorsement and support of the bill a day before its Feb. 13 committee passage during a speech at a national advocacy conference sponsored by the AMA.

“The new legislation, H.R. 8, which you have endorsed, would put in place universal background checks,” Rep. Thompson said. “This means anybody who buys a gun would have to go through a background check to make sure they are not a criminal, to make sure they are not dangerously mentally ill and a danger to themselves or others.”

The committee passed the Bipartisan Background Checks Act of 2019 by a 23-15 vote. It would require a background check on all firearms transfers, including private sales, with limited exemptions for firearms given as gifts between family members and those transferred for hunting, target shooting, and self-defense.

A second bill, the Enhanced Background Checks Act (H.R. 1112), passed 21-14 during the same session. That bill would close a loophole that currently allows a licensed dealer to transfer a firearm after 3 days if the background check system has not yet reported back.

Rep. Thompson credited the newest members of Congress with pushing these bills to the forefront.

“During the last midterm election, there was a sea change in attitude around gun violence prevention,” Rep. Thompson noted. “All 40 members of the Democratic-elected class who took a seat ran on gun violence prevention. So they came to Washington with more of a willingness to deal with this issue.”

H.R. 8 has 231 cosponsors – 226 Democrats and 5 Republicans – meaning it has more than enough support to pass in the full House, should all cosponsors remain on board.

Getting the bill passed in the Republican-controlled Senate will be a challenge and Rep. Thompson encouraged doctors to continue their advocacy on this legislation.

“You guys have been fabulous,” he said. “Without your help, we would not be where we are today. I can tell you that this bill will pass the House within the first 100 days and will go to the Senate. That is when you will have to start working again. ... Once it goes to the Senate, there is going to be a reluctance to take it up. We need to make sure that every U.S. senator hears from every doc and every doc’s family and every doc’s friend and every doc’s assistant and everybody else and their brother that this important so we can turn up the heat and make sure they take up the issue of background checks. It works. It saves lives.”

WASHINGTON – A bill requiring universal background checks for firearm purchases passed the House Judiciary committee and is expected to pass the full House of Representatives when it comes up for consideration.

Rep. Mike Thompson (R-Calif.), chairman of the House Gun Violence Prevention Task Force, thanked the American Medical Association for its endorsement and support of the bill a day before its Feb. 13 committee passage during a speech at a national advocacy conference sponsored by the AMA.

“The new legislation, H.R. 8, which you have endorsed, would put in place universal background checks,” Rep. Thompson said. “This means anybody who buys a gun would have to go through a background check to make sure they are not a criminal, to make sure they are not dangerously mentally ill and a danger to themselves or others.”

The committee passed the Bipartisan Background Checks Act of 2019 by a 23-15 vote. It would require a background check on all firearms transfers, including private sales, with limited exemptions for firearms given as gifts between family members and those transferred for hunting, target shooting, and self-defense.

A second bill, the Enhanced Background Checks Act (H.R. 1112), passed 21-14 during the same session. That bill would close a loophole that currently allows a licensed dealer to transfer a firearm after 3 days if the background check system has not yet reported back.

Rep. Thompson credited the newest members of Congress with pushing these bills to the forefront.

“During the last midterm election, there was a sea change in attitude around gun violence prevention,” Rep. Thompson noted. “All 40 members of the Democratic-elected class who took a seat ran on gun violence prevention. So they came to Washington with more of a willingness to deal with this issue.”

H.R. 8 has 231 cosponsors – 226 Democrats and 5 Republicans – meaning it has more than enough support to pass in the full House, should all cosponsors remain on board.

Getting the bill passed in the Republican-controlled Senate will be a challenge and Rep. Thompson encouraged doctors to continue their advocacy on this legislation.

“You guys have been fabulous,” he said. “Without your help, we would not be where we are today. I can tell you that this bill will pass the House within the first 100 days and will go to the Senate. That is when you will have to start working again. ... Once it goes to the Senate, there is going to be a reluctance to take it up. We need to make sure that every U.S. senator hears from every doc and every doc’s family and every doc’s friend and every doc’s assistant and everybody else and their brother that this important so we can turn up the heat and make sure they take up the issue of background checks. It works. It saves lives.”

WASHINGTON – A bill requiring universal background checks for firearm purchases passed the House Judiciary committee and is expected to pass the full House of Representatives when it comes up for consideration.

Rep. Mike Thompson (R-Calif.), chairman of the House Gun Violence Prevention Task Force, thanked the American Medical Association for its endorsement and support of the bill a day before its Feb. 13 committee passage during a speech at a national advocacy conference sponsored by the AMA.

“The new legislation, H.R. 8, which you have endorsed, would put in place universal background checks,” Rep. Thompson said. “This means anybody who buys a gun would have to go through a background check to make sure they are not a criminal, to make sure they are not dangerously mentally ill and a danger to themselves or others.”

The committee passed the Bipartisan Background Checks Act of 2019 by a 23-15 vote. It would require a background check on all firearms transfers, including private sales, with limited exemptions for firearms given as gifts between family members and those transferred for hunting, target shooting, and self-defense.

A second bill, the Enhanced Background Checks Act (H.R. 1112), passed 21-14 during the same session. That bill would close a loophole that currently allows a licensed dealer to transfer a firearm after 3 days if the background check system has not yet reported back.

Rep. Thompson credited the newest members of Congress with pushing these bills to the forefront.

“During the last midterm election, there was a sea change in attitude around gun violence prevention,” Rep. Thompson noted. “All 40 members of the Democratic-elected class who took a seat ran on gun violence prevention. So they came to Washington with more of a willingness to deal with this issue.”

H.R. 8 has 231 cosponsors – 226 Democrats and 5 Republicans – meaning it has more than enough support to pass in the full House, should all cosponsors remain on board.

Getting the bill passed in the Republican-controlled Senate will be a challenge and Rep. Thompson encouraged doctors to continue their advocacy on this legislation.

“You guys have been fabulous,” he said. “Without your help, we would not be where we are today. I can tell you that this bill will pass the House within the first 100 days and will go to the Senate. That is when you will have to start working again. ... Once it goes to the Senate, there is going to be a reluctance to take it up. We need to make sure that every U.S. senator hears from every doc and every doc’s family and every doc’s friend and every doc’s assistant and everybody else and their brother that this important so we can turn up the heat and make sure they take up the issue of background checks. It works. It saves lives.”

REPORTING FROM AMA NATIONAL ADVOCACY CONFERENCE

Mild aerobic exercise speeds sports concussion recovery

Mild aerobic exercise significantly shortened recovery time from sports-related concussion in adolescent athletes, compared with a stretching program in a randomized trial of 103 participants.

Sports-related concussion (SRC) remains a major public health problem with no effective treatment, wrote John J. Leddy, MD, of the State University of New York at Buffalo, and his colleagues.

Exercise tolerance after SRC has not been well studied. However, given the demonstrated benefits of aerobic exercise training on autonomic nervous system regulation, cerebral blood flow regulation, cardiovascular physiology, and brain neuroplasticity, the researchers hypothesized that exercise at a level that does not exacerbate symptoms might facilitate recovery in concussion patients.

In a study published in JAMA Pediatrics, the researchers randomized 103 adolescent athletes aged 13-18 years to a program of subsymptom aerobic exercise or a placebo stretching program. The participants were enrolled in the study within 10 days of an SRC, and were followed for 30 days or until recovery.

Athletes in the aerobic exercise group recovered in a median of 13 days, compared with 17 days for those in the stretching group (P = .009). Recovery was defined as “symptom resolution to normal,” based on normal physical and neurological examinations, “further confirmed by demonstration of the ability to exercise to exhaustion without exacerbation of symptoms” according to the Buffalo Concussion Treadmill Test, the researchers wrote.

No demographic differences or difference in previous concussions, time from injury until treatment, initial symptom severity score, initial exercise treadmill test, or physical exam were noted between the groups.

The average age of the participants was 15 years, 47% were female. The athletes performed the aerobic exercise or stretching programs approximately 20 minutes per day, and reported their daily symptoms and compliance via a website. The aerobic exercise consisted of walking or jogging on a treadmill or outdoors, or riding a stationary bike while wearing a heart rate monitor to maintain a target heart rate. The target heart rate was calculated as 80% of the heart rate at symptom exacerbation during the Buffalo Concussion Treadmill Test at each participant’s initial visit.

No adverse events related to the exercise intervention were reported, which supports the safety of subsymptom threshhold exercise, in the study population, Dr. Leddy and his associates noted.

The researchers also found lower rates of persistent symptoms at 1 month in the exercise group, compared with the stretching group (two participants vs. seven participants), but this difference was not statistically significant.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the unblinded design and failure to address the mechanism of action for the effects of exercise. In addition, the results are not generalizable to younger children or other demographic groups, including those with concussions from causes other than sports and adults with heart conditions, the researchers noted.

However, “the results of this study should give clinicians confidence that moderate levels of physical activity, including prescribed subsymptom threshold aerobic exercise, after the first 48 hours following SRC can safely and significantly speed recovery,” Dr. Leddy and his associates concluded.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Leddy JJ et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4397.

In 2009 and 2010, the culture of sports concussion care began to shift with the publication of an initial study by Leddy et al. on the use of exercise at subsymptom levels as part of concussion rehabilitation, Sara P. D. Chrisman, MD, MPH, wrote in an accompanying editorial. Previous guidelines had emphasized total avoidance of physical activity, as well as avoidance of screen time and social activity, until patients were asymptomatic; however, “no definition was provided for the term asymptomatic, and no time limits were placed on rest, and as a result, rest often continued for weeks or months,” Dr. Chrisman said. Additional research over the past decade supported the potential value of moderate exercise, and the 2016 meeting of the Concussion in Sport Group resulted in recommendations limiting rest to 24-48 hours, which prompted further studies of exercise intervention.

The current study by Leddy et al. is a clinical trial using exercise “to treat acute concussion with a goal of reducing symptom duration,” she said. Despite the study’s limitations, including the inability to estimate how much exercise was needed to achieve the treatment outcome, “this is a landmark study that may shift the standard of care toward the use of rehabilitative exercise to decrease the duration of concussion symptoms.

“Future studies will need to explore the limits of exercise treatment for concussion,” and should address questions including the timing, intensity, and duration of exercise and whether the strategy is appropriate for other populations, such as those with mental health comorbidities, Dr. Chrisman concluded.

Dr. Chrisman is at the Center for Child Health, Behavior, and Development, Seattle Children’s Research Institute. These comments are from her editorial accompanying the article by Leddy et al. (JAMA Pedatr. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5281). She had no financial conflicts to disclose.

In 2009 and 2010, the culture of sports concussion care began to shift with the publication of an initial study by Leddy et al. on the use of exercise at subsymptom levels as part of concussion rehabilitation, Sara P. D. Chrisman, MD, MPH, wrote in an accompanying editorial. Previous guidelines had emphasized total avoidance of physical activity, as well as avoidance of screen time and social activity, until patients were asymptomatic; however, “no definition was provided for the term asymptomatic, and no time limits were placed on rest, and as a result, rest often continued for weeks or months,” Dr. Chrisman said. Additional research over the past decade supported the potential value of moderate exercise, and the 2016 meeting of the Concussion in Sport Group resulted in recommendations limiting rest to 24-48 hours, which prompted further studies of exercise intervention.

The current study by Leddy et al. is a clinical trial using exercise “to treat acute concussion with a goal of reducing symptom duration,” she said. Despite the study’s limitations, including the inability to estimate how much exercise was needed to achieve the treatment outcome, “this is a landmark study that may shift the standard of care toward the use of rehabilitative exercise to decrease the duration of concussion symptoms.

“Future studies will need to explore the limits of exercise treatment for concussion,” and should address questions including the timing, intensity, and duration of exercise and whether the strategy is appropriate for other populations, such as those with mental health comorbidities, Dr. Chrisman concluded.

Dr. Chrisman is at the Center for Child Health, Behavior, and Development, Seattle Children’s Research Institute. These comments are from her editorial accompanying the article by Leddy et al. (JAMA Pedatr. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5281). She had no financial conflicts to disclose.

In 2009 and 2010, the culture of sports concussion care began to shift with the publication of an initial study by Leddy et al. on the use of exercise at subsymptom levels as part of concussion rehabilitation, Sara P. D. Chrisman, MD, MPH, wrote in an accompanying editorial. Previous guidelines had emphasized total avoidance of physical activity, as well as avoidance of screen time and social activity, until patients were asymptomatic; however, “no definition was provided for the term asymptomatic, and no time limits were placed on rest, and as a result, rest often continued for weeks or months,” Dr. Chrisman said. Additional research over the past decade supported the potential value of moderate exercise, and the 2016 meeting of the Concussion in Sport Group resulted in recommendations limiting rest to 24-48 hours, which prompted further studies of exercise intervention.

The current study by Leddy et al. is a clinical trial using exercise “to treat acute concussion with a goal of reducing symptom duration,” she said. Despite the study’s limitations, including the inability to estimate how much exercise was needed to achieve the treatment outcome, “this is a landmark study that may shift the standard of care toward the use of rehabilitative exercise to decrease the duration of concussion symptoms.

“Future studies will need to explore the limits of exercise treatment for concussion,” and should address questions including the timing, intensity, and duration of exercise and whether the strategy is appropriate for other populations, such as those with mental health comorbidities, Dr. Chrisman concluded.

Dr. Chrisman is at the Center for Child Health, Behavior, and Development, Seattle Children’s Research Institute. These comments are from her editorial accompanying the article by Leddy et al. (JAMA Pedatr. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5281). She had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Mild aerobic exercise significantly shortened recovery time from sports-related concussion in adolescent athletes, compared with a stretching program in a randomized trial of 103 participants.

Sports-related concussion (SRC) remains a major public health problem with no effective treatment, wrote John J. Leddy, MD, of the State University of New York at Buffalo, and his colleagues.

Exercise tolerance after SRC has not been well studied. However, given the demonstrated benefits of aerobic exercise training on autonomic nervous system regulation, cerebral blood flow regulation, cardiovascular physiology, and brain neuroplasticity, the researchers hypothesized that exercise at a level that does not exacerbate symptoms might facilitate recovery in concussion patients.

In a study published in JAMA Pediatrics, the researchers randomized 103 adolescent athletes aged 13-18 years to a program of subsymptom aerobic exercise or a placebo stretching program. The participants were enrolled in the study within 10 days of an SRC, and were followed for 30 days or until recovery.

Athletes in the aerobic exercise group recovered in a median of 13 days, compared with 17 days for those in the stretching group (P = .009). Recovery was defined as “symptom resolution to normal,” based on normal physical and neurological examinations, “further confirmed by demonstration of the ability to exercise to exhaustion without exacerbation of symptoms” according to the Buffalo Concussion Treadmill Test, the researchers wrote.

No demographic differences or difference in previous concussions, time from injury until treatment, initial symptom severity score, initial exercise treadmill test, or physical exam were noted between the groups.

The average age of the participants was 15 years, 47% were female. The athletes performed the aerobic exercise or stretching programs approximately 20 minutes per day, and reported their daily symptoms and compliance via a website. The aerobic exercise consisted of walking or jogging on a treadmill or outdoors, or riding a stationary bike while wearing a heart rate monitor to maintain a target heart rate. The target heart rate was calculated as 80% of the heart rate at symptom exacerbation during the Buffalo Concussion Treadmill Test at each participant’s initial visit.

No adverse events related to the exercise intervention were reported, which supports the safety of subsymptom threshhold exercise, in the study population, Dr. Leddy and his associates noted.

The researchers also found lower rates of persistent symptoms at 1 month in the exercise group, compared with the stretching group (two participants vs. seven participants), but this difference was not statistically significant.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the unblinded design and failure to address the mechanism of action for the effects of exercise. In addition, the results are not generalizable to younger children or other demographic groups, including those with concussions from causes other than sports and adults with heart conditions, the researchers noted.

However, “the results of this study should give clinicians confidence that moderate levels of physical activity, including prescribed subsymptom threshold aerobic exercise, after the first 48 hours following SRC can safely and significantly speed recovery,” Dr. Leddy and his associates concluded.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Leddy JJ et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4397.

Mild aerobic exercise significantly shortened recovery time from sports-related concussion in adolescent athletes, compared with a stretching program in a randomized trial of 103 participants.

Sports-related concussion (SRC) remains a major public health problem with no effective treatment, wrote John J. Leddy, MD, of the State University of New York at Buffalo, and his colleagues.

Exercise tolerance after SRC has not been well studied. However, given the demonstrated benefits of aerobic exercise training on autonomic nervous system regulation, cerebral blood flow regulation, cardiovascular physiology, and brain neuroplasticity, the researchers hypothesized that exercise at a level that does not exacerbate symptoms might facilitate recovery in concussion patients.

In a study published in JAMA Pediatrics, the researchers randomized 103 adolescent athletes aged 13-18 years to a program of subsymptom aerobic exercise or a placebo stretching program. The participants were enrolled in the study within 10 days of an SRC, and were followed for 30 days or until recovery.

Athletes in the aerobic exercise group recovered in a median of 13 days, compared with 17 days for those in the stretching group (P = .009). Recovery was defined as “symptom resolution to normal,” based on normal physical and neurological examinations, “further confirmed by demonstration of the ability to exercise to exhaustion without exacerbation of symptoms” according to the Buffalo Concussion Treadmill Test, the researchers wrote.

No demographic differences or difference in previous concussions, time from injury until treatment, initial symptom severity score, initial exercise treadmill test, or physical exam were noted between the groups.

The average age of the participants was 15 years, 47% were female. The athletes performed the aerobic exercise or stretching programs approximately 20 minutes per day, and reported their daily symptoms and compliance via a website. The aerobic exercise consisted of walking or jogging on a treadmill or outdoors, or riding a stationary bike while wearing a heart rate monitor to maintain a target heart rate. The target heart rate was calculated as 80% of the heart rate at symptom exacerbation during the Buffalo Concussion Treadmill Test at each participant’s initial visit.

No adverse events related to the exercise intervention were reported, which supports the safety of subsymptom threshhold exercise, in the study population, Dr. Leddy and his associates noted.

The researchers also found lower rates of persistent symptoms at 1 month in the exercise group, compared with the stretching group (two participants vs. seven participants), but this difference was not statistically significant.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the unblinded design and failure to address the mechanism of action for the effects of exercise. In addition, the results are not generalizable to younger children or other demographic groups, including those with concussions from causes other than sports and adults with heart conditions, the researchers noted.

However, “the results of this study should give clinicians confidence that moderate levels of physical activity, including prescribed subsymptom threshold aerobic exercise, after the first 48 hours following SRC can safely and significantly speed recovery,” Dr. Leddy and his associates concluded.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Leddy JJ et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4397.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Teen athletes who performed aerobic exercise recovered from sports-related concussions in 13 days, compared with 17 days for those in a placebo-stretching group.

Study details: The data come from a randomized trial of 103 athletes aged 13-18 years.

Disclosures: The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Leddy JJ et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Feb 4. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4397.

The fog may be lifting

One of the common symptoms described by postconcussion patients is that their heads feel a bit foggy. It may not be simply by chance that “foggy” is the best word to describe the atmosphere surrounding the entire field of concussion diagnosis and management.

Back in the Dark Ages, when the diagnosis of concussion was a simpler binary call, the issue of management seldom created much discussion. If the patient lost consciousness or was amnesic, he (it was less frequently she) could return to activity when his headache was gone and he could remember what he was supposed to do when the quarterback called for a “Red 34, Drive Right Smash” play. That may have even been during the second half of the game in which he was injured.

As it became more widely understood that the diagnosis of concussion didn’t require loss of consciousness and that repeated concussions could have serious sequelae, management became a bit fuzzier. No one had thought much about the recuperative process. Into this vacuum came a wide variety of researchers and providers. Not surprisingly, much of their advice was based on unproven assumptions, including the concept of “brain rest.”

It has taken time, but fortunately, folks with patience and wisdom have questioned these assumptions and begun collecting data. The result of these investigations and others has prompted the American Academy of Pediatrics to publish an updated set of guidelines on concussion management that includes the observation that extended school absence may slow the rehabilitation process (Pediatrics. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3074).

It is becoming clear that management of concussion can be rather complex and must be individualized to each patient. In my experience, the postconcussion period can unmask behavioral, cognitive, and emotional problems that were preexisting but had received little or no attention. For example, the trauma of the event may trigger anxiety about further injury or exacerbate depression that had been building for years. The student who “couldn’t do algebra” following a head injury may have had a lifelong learning disability that had gone unnoticed. The student athlete with prolonged postconcussion symptoms may indeed have another more serious problem. Hopefully, the new guidelines from the AAP will be a first step toward a more thoughtful and scientifically driven approach to concussion management.

It would be nice if that approach could filter down to the management of the more common but less dramatic pediatric injuries. There is hope. Choosing Wisely – a patient/parent–targeted initiative by the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation in cooperation with the AAP – points out that, although half of the pediatric head injury patients seen in emergency departments received CT scan, only a third of those studies were indicated. Parents are encouraged to learn more about the risks of CT scans and question the physician when one is recommended.

But, doctors’ habits and old wives’ tales die slowly. I hope that you no longer recommend that parents keep their children awake after a head injury, or wake them every hour to check their pupils. Those counterproductive recommendations make about as much sense as staying out of the swimming pool for an hour after eating a chocolate chip cookie.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

One of the common symptoms described by postconcussion patients is that their heads feel a bit foggy. It may not be simply by chance that “foggy” is the best word to describe the atmosphere surrounding the entire field of concussion diagnosis and management.

Back in the Dark Ages, when the diagnosis of concussion was a simpler binary call, the issue of management seldom created much discussion. If the patient lost consciousness or was amnesic, he (it was less frequently she) could return to activity when his headache was gone and he could remember what he was supposed to do when the quarterback called for a “Red 34, Drive Right Smash” play. That may have even been during the second half of the game in which he was injured.

As it became more widely understood that the diagnosis of concussion didn’t require loss of consciousness and that repeated concussions could have serious sequelae, management became a bit fuzzier. No one had thought much about the recuperative process. Into this vacuum came a wide variety of researchers and providers. Not surprisingly, much of their advice was based on unproven assumptions, including the concept of “brain rest.”

It has taken time, but fortunately, folks with patience and wisdom have questioned these assumptions and begun collecting data. The result of these investigations and others has prompted the American Academy of Pediatrics to publish an updated set of guidelines on concussion management that includes the observation that extended school absence may slow the rehabilitation process (Pediatrics. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3074).

It is becoming clear that management of concussion can be rather complex and must be individualized to each patient. In my experience, the postconcussion period can unmask behavioral, cognitive, and emotional problems that were preexisting but had received little or no attention. For example, the trauma of the event may trigger anxiety about further injury or exacerbate depression that had been building for years. The student who “couldn’t do algebra” following a head injury may have had a lifelong learning disability that had gone unnoticed. The student athlete with prolonged postconcussion symptoms may indeed have another more serious problem. Hopefully, the new guidelines from the AAP will be a first step toward a more thoughtful and scientifically driven approach to concussion management.

It would be nice if that approach could filter down to the management of the more common but less dramatic pediatric injuries. There is hope. Choosing Wisely – a patient/parent–targeted initiative by the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation in cooperation with the AAP – points out that, although half of the pediatric head injury patients seen in emergency departments received CT scan, only a third of those studies were indicated. Parents are encouraged to learn more about the risks of CT scans and question the physician when one is recommended.

But, doctors’ habits and old wives’ tales die slowly. I hope that you no longer recommend that parents keep their children awake after a head injury, or wake them every hour to check their pupils. Those counterproductive recommendations make about as much sense as staying out of the swimming pool for an hour after eating a chocolate chip cookie.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

One of the common symptoms described by postconcussion patients is that their heads feel a bit foggy. It may not be simply by chance that “foggy” is the best word to describe the atmosphere surrounding the entire field of concussion diagnosis and management.

Back in the Dark Ages, when the diagnosis of concussion was a simpler binary call, the issue of management seldom created much discussion. If the patient lost consciousness or was amnesic, he (it was less frequently she) could return to activity when his headache was gone and he could remember what he was supposed to do when the quarterback called for a “Red 34, Drive Right Smash” play. That may have even been during the second half of the game in which he was injured.

As it became more widely understood that the diagnosis of concussion didn’t require loss of consciousness and that repeated concussions could have serious sequelae, management became a bit fuzzier. No one had thought much about the recuperative process. Into this vacuum came a wide variety of researchers and providers. Not surprisingly, much of their advice was based on unproven assumptions, including the concept of “brain rest.”

It has taken time, but fortunately, folks with patience and wisdom have questioned these assumptions and begun collecting data. The result of these investigations and others has prompted the American Academy of Pediatrics to publish an updated set of guidelines on concussion management that includes the observation that extended school absence may slow the rehabilitation process (Pediatrics. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3074).

It is becoming clear that management of concussion can be rather complex and must be individualized to each patient. In my experience, the postconcussion period can unmask behavioral, cognitive, and emotional problems that were preexisting but had received little or no attention. For example, the trauma of the event may trigger anxiety about further injury or exacerbate depression that had been building for years. The student who “couldn’t do algebra” following a head injury may have had a lifelong learning disability that had gone unnoticed. The student athlete with prolonged postconcussion symptoms may indeed have another more serious problem. Hopefully, the new guidelines from the AAP will be a first step toward a more thoughtful and scientifically driven approach to concussion management.

It would be nice if that approach could filter down to the management of the more common but less dramatic pediatric injuries. There is hope. Choosing Wisely – a patient/parent–targeted initiative by the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation in cooperation with the AAP – points out that, although half of the pediatric head injury patients seen in emergency departments received CT scan, only a third of those studies were indicated. Parents are encouraged to learn more about the risks of CT scans and question the physician when one is recommended.

But, doctors’ habits and old wives’ tales die slowly. I hope that you no longer recommend that parents keep their children awake after a head injury, or wake them every hour to check their pupils. Those counterproductive recommendations make about as much sense as staying out of the swimming pool for an hour after eating a chocolate chip cookie.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

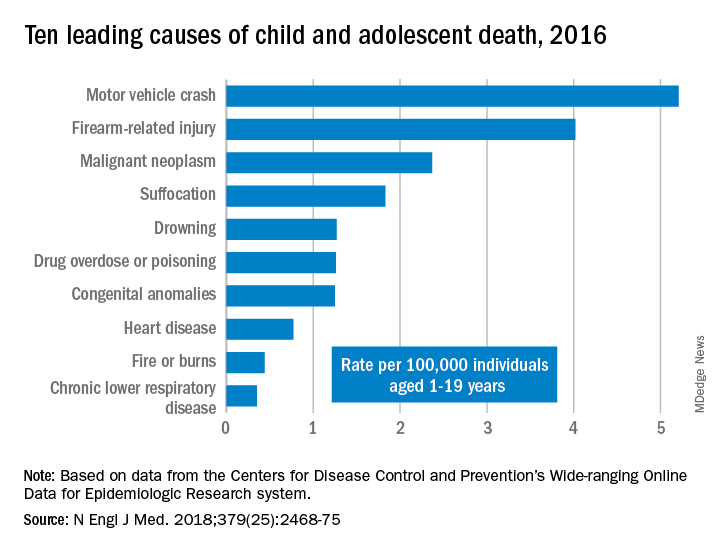

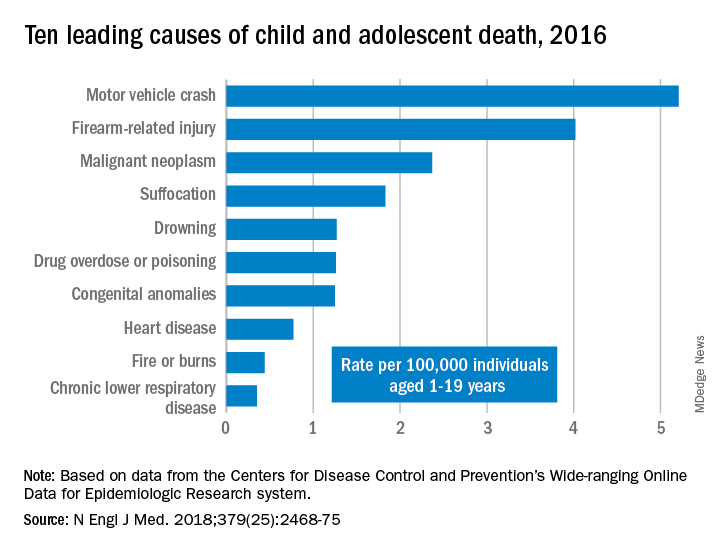

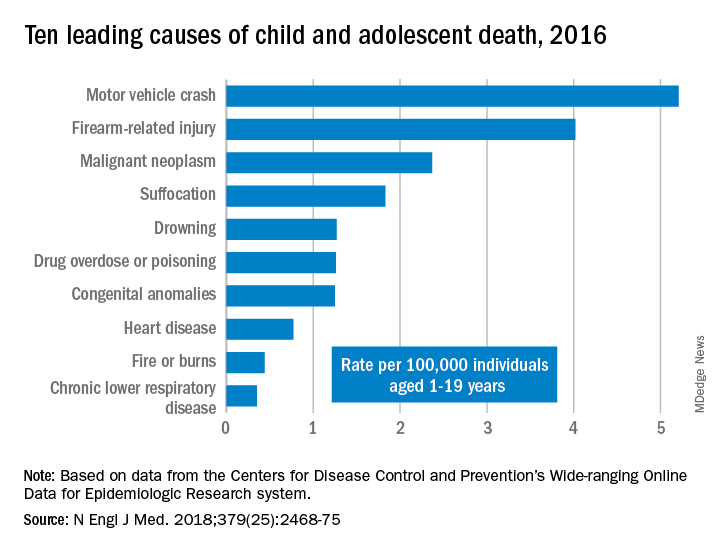

Family handgun ownership linked to young children’s gun deaths

A recent increase in U.S. handgun ownership among white families tracks with a similar trend of recently rising gun deaths among young white children, a new study found. This association held even after adjustments for multiple sociodemographic variables that research previously had linked to higher gun ownership and higher firearm mortality.

“Indeed, firearm ownership, generally, was positively associated with firearm-related mortality among 1- to 5-year-old white children, but this correlation was primarily driven by changes in the proportion of families who owned handguns: firearms more often stored unsecured and loaded,” wrote Kate C. Prickett, PhD, of the Victoria University of Wellington (New Zealand) and her associates in Pediatrics.

“These findings suggest that ease of access and use may be an important consideration when examining firearm-related fatality risk among young children,” they continued. Given the lack of attenuation in the relationship from controlling for sociodemographic variables, they add, “this finding is in line with research documenting that the presence of a firearm in the home matters above and beyond other risk factors associated with child injury.”

Even though U.S. gun ownership and pediatric firearm mortality overall have been dropping over the past several decades, the latter has stagnated recently, and gun deaths among children aged 1-4 years nearly doubled between 2006-2016, the researchers noted.

Given the counterintuitive increase in young children’s gun deaths while overall gun ownership kept dropping, the researchers took a closer look at the relationship between gun deaths among children aged 1-5 years and specific types of firearm ownership among families with children under age 5 years in the home. They relied on household data from the nationally representative General Social Survey and on fatality statistics from the National Vital Statistics System from 1976-2016.

Over those 4 decades, gun ownership in white families with small children decreased from 50% to 45% and in black families with small children from 38% to 6%.

Simultaneously, however, handgun ownership increased from 25% to 32% among white families with young children. In fact, most firearm-owning white families (72%) owned a handgun in 2016 while rifle ownership had declined substantially.

Meanwhile, “firearm-related mortality rate among young white children declined from historic highs in the late 1970s to early 1980s until 2001,” the authors reported. “After 2004, however, the mortality rate began to rise, reaching mid-1980s levels.” Further, gun deaths constituted 2% of young children’s injury deaths in 1976 but nearly 5% in 2016.

When the researchers compared these findings, they found a positive, significant association between white child firearm mortality and the proportion of white families who owned a handgun but not a rifle or shotgun.

The association remained after the researchers adjusted for several covariates already established in the evidence base to have associations with firearm ownership, child injury risk and/or firearm mortality: living in a rural area, living in the South, neither parent having a college degree, and a household income in the bottom quartile nationally. In addition, “the annual national unemployment rate by race was included as an indicator of the broader economic context,” the authors wrote.

Although young black children die from guns nearly three times more frequently than white children, the authors were unable to present detailed findings on associations with gun ownership because of small sample sizes. They noted, however, that handgun ownership actually declined during the study period from 15% to 6% in black families with young children.

The researchers concluded that the recent increase in young children’s gun deaths may be partly driven by an increase in handgun ownership, even as overall gun ownership (primarily rifles and shotguns) has continued dropping.

“For young children, shootings are more likely to be unintentional, making the ease at which firearms can be accessed and used a more important determinant of mortality than perhaps for older children,” the authors wrote. “Moreover, relative to other firearms like hunting rifles, handguns, because they are more likely to be purchased for personal protection, are more likely to be stored loaded with ammunition, unlocked, and in a more easily accessible place, such as a bedroom drawer.”

The research was funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Prickett KC et al. Pediatrics. 2019;143(2):e20181171.

The “unique and important approach” used by Prickett et al. to investigate an association between gun ownership and children’s gun deaths is “novel” because of their focus on firearm types and the youngest children, wrote Shilpa J. Patel, MD; Monika K. Goyal, MD; and Kavita Parikh, MD, all with the Children’s National Health System in Washington, DC, in an editorial published with the study (Pediatrics. 2018 Jan 28. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3611).

The findings are particularly relevant to pediatricians’ conversations with families about safe firearm storage practices. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends all firearms are stored locked and unloaded with ammunition stored separately.

For families who find these guidelines difficult because they keep handguns at the ready for protection, “it is important to note that the risk of unintentional or intentional injury from a household firearm is much greater than the likelihood of providing protection for self-defense,” the editorial’s authors wrote. But they advocate for personalized safe storage strategies and shared decision making based on families’ needs and values.

“This study is a loud and compelling call to action for all pediatricians to start open discussions around firearm ownership with all families and to share data on the significant risks associated with unsafe storage,” they wrote. “It is an even louder call to firearm manufacturers to step up and innovate, test, and design smart handguns that are inoperable by young children to prevent unintentional injury.”

Although having no firearms in the home is the most effective way to reduce children’s risk of gun-related injuries and deaths, developing effective safety controls on guns could also substantially curtail young children’s gun deaths. “We as a society should be advocating for continued research to childproof firearms so that if families choose to have firearms in the home, the safety of their children is not compromised,” they wrote.

Dr. Parikh is a hospitalist, Dr. Goyal is assistant division chief or emergency medicine, and Dr. Patel is an emergency medicine specialist, all with Children’s National Health System in Washington, DC. They reported no funding and no disclosures.

The “unique and important approach” used by Prickett et al. to investigate an association between gun ownership and children’s gun deaths is “novel” because of their focus on firearm types and the youngest children, wrote Shilpa J. Patel, MD; Monika K. Goyal, MD; and Kavita Parikh, MD, all with the Children’s National Health System in Washington, DC, in an editorial published with the study (Pediatrics. 2018 Jan 28. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3611).

The findings are particularly relevant to pediatricians’ conversations with families about safe firearm storage practices. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends all firearms are stored locked and unloaded with ammunition stored separately.

For families who find these guidelines difficult because they keep handguns at the ready for protection, “it is important to note that the risk of unintentional or intentional injury from a household firearm is much greater than the likelihood of providing protection for self-defense,” the editorial’s authors wrote. But they advocate for personalized safe storage strategies and shared decision making based on families’ needs and values.

“This study is a loud and compelling call to action for all pediatricians to start open discussions around firearm ownership with all families and to share data on the significant risks associated with unsafe storage,” they wrote. “It is an even louder call to firearm manufacturers to step up and innovate, test, and design smart handguns that are inoperable by young children to prevent unintentional injury.”

Although having no firearms in the home is the most effective way to reduce children’s risk of gun-related injuries and deaths, developing effective safety controls on guns could also substantially curtail young children’s gun deaths. “We as a society should be advocating for continued research to childproof firearms so that if families choose to have firearms in the home, the safety of their children is not compromised,” they wrote.

Dr. Parikh is a hospitalist, Dr. Goyal is assistant division chief or emergency medicine, and Dr. Patel is an emergency medicine specialist, all with Children’s National Health System in Washington, DC. They reported no funding and no disclosures.

The “unique and important approach” used by Prickett et al. to investigate an association between gun ownership and children’s gun deaths is “novel” because of their focus on firearm types and the youngest children, wrote Shilpa J. Patel, MD; Monika K. Goyal, MD; and Kavita Parikh, MD, all with the Children’s National Health System in Washington, DC, in an editorial published with the study (Pediatrics. 2018 Jan 28. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3611).

The findings are particularly relevant to pediatricians’ conversations with families about safe firearm storage practices. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends all firearms are stored locked and unloaded with ammunition stored separately.

For families who find these guidelines difficult because they keep handguns at the ready for protection, “it is important to note that the risk of unintentional or intentional injury from a household firearm is much greater than the likelihood of providing protection for self-defense,” the editorial’s authors wrote. But they advocate for personalized safe storage strategies and shared decision making based on families’ needs and values.

“This study is a loud and compelling call to action for all pediatricians to start open discussions around firearm ownership with all families and to share data on the significant risks associated with unsafe storage,” they wrote. “It is an even louder call to firearm manufacturers to step up and innovate, test, and design smart handguns that are inoperable by young children to prevent unintentional injury.”

Although having no firearms in the home is the most effective way to reduce children’s risk of gun-related injuries and deaths, developing effective safety controls on guns could also substantially curtail young children’s gun deaths. “We as a society should be advocating for continued research to childproof firearms so that if families choose to have firearms in the home, the safety of their children is not compromised,” they wrote.

Dr. Parikh is a hospitalist, Dr. Goyal is assistant division chief or emergency medicine, and Dr. Patel is an emergency medicine specialist, all with Children’s National Health System in Washington, DC. They reported no funding and no disclosures.

A recent increase in U.S. handgun ownership among white families tracks with a similar trend of recently rising gun deaths among young white children, a new study found. This association held even after adjustments for multiple sociodemographic variables that research previously had linked to higher gun ownership and higher firearm mortality.

“Indeed, firearm ownership, generally, was positively associated with firearm-related mortality among 1- to 5-year-old white children, but this correlation was primarily driven by changes in the proportion of families who owned handguns: firearms more often stored unsecured and loaded,” wrote Kate C. Prickett, PhD, of the Victoria University of Wellington (New Zealand) and her associates in Pediatrics.

“These findings suggest that ease of access and use may be an important consideration when examining firearm-related fatality risk among young children,” they continued. Given the lack of attenuation in the relationship from controlling for sociodemographic variables, they add, “this finding is in line with research documenting that the presence of a firearm in the home matters above and beyond other risk factors associated with child injury.”

Even though U.S. gun ownership and pediatric firearm mortality overall have been dropping over the past several decades, the latter has stagnated recently, and gun deaths among children aged 1-4 years nearly doubled between 2006-2016, the researchers noted.

Given the counterintuitive increase in young children’s gun deaths while overall gun ownership kept dropping, the researchers took a closer look at the relationship between gun deaths among children aged 1-5 years and specific types of firearm ownership among families with children under age 5 years in the home. They relied on household data from the nationally representative General Social Survey and on fatality statistics from the National Vital Statistics System from 1976-2016.

Over those 4 decades, gun ownership in white families with small children decreased from 50% to 45% and in black families with small children from 38% to 6%.

Simultaneously, however, handgun ownership increased from 25% to 32% among white families with young children. In fact, most firearm-owning white families (72%) owned a handgun in 2016 while rifle ownership had declined substantially.

Meanwhile, “firearm-related mortality rate among young white children declined from historic highs in the late 1970s to early 1980s until 2001,” the authors reported. “After 2004, however, the mortality rate began to rise, reaching mid-1980s levels.” Further, gun deaths constituted 2% of young children’s injury deaths in 1976 but nearly 5% in 2016.

When the researchers compared these findings, they found a positive, significant association between white child firearm mortality and the proportion of white families who owned a handgun but not a rifle or shotgun.

The association remained after the researchers adjusted for several covariates already established in the evidence base to have associations with firearm ownership, child injury risk and/or firearm mortality: living in a rural area, living in the South, neither parent having a college degree, and a household income in the bottom quartile nationally. In addition, “the annual national unemployment rate by race was included as an indicator of the broader economic context,” the authors wrote.

Although young black children die from guns nearly three times more frequently than white children, the authors were unable to present detailed findings on associations with gun ownership because of small sample sizes. They noted, however, that handgun ownership actually declined during the study period from 15% to 6% in black families with young children.

The researchers concluded that the recent increase in young children’s gun deaths may be partly driven by an increase in handgun ownership, even as overall gun ownership (primarily rifles and shotguns) has continued dropping.

“For young children, shootings are more likely to be unintentional, making the ease at which firearms can be accessed and used a more important determinant of mortality than perhaps for older children,” the authors wrote. “Moreover, relative to other firearms like hunting rifles, handguns, because they are more likely to be purchased for personal protection, are more likely to be stored loaded with ammunition, unlocked, and in a more easily accessible place, such as a bedroom drawer.”

The research was funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Prickett KC et al. Pediatrics. 2019;143(2):e20181171.

A recent increase in U.S. handgun ownership among white families tracks with a similar trend of recently rising gun deaths among young white children, a new study found. This association held even after adjustments for multiple sociodemographic variables that research previously had linked to higher gun ownership and higher firearm mortality.

“Indeed, firearm ownership, generally, was positively associated with firearm-related mortality among 1- to 5-year-old white children, but this correlation was primarily driven by changes in the proportion of families who owned handguns: firearms more often stored unsecured and loaded,” wrote Kate C. Prickett, PhD, of the Victoria University of Wellington (New Zealand) and her associates in Pediatrics.

“These findings suggest that ease of access and use may be an important consideration when examining firearm-related fatality risk among young children,” they continued. Given the lack of attenuation in the relationship from controlling for sociodemographic variables, they add, “this finding is in line with research documenting that the presence of a firearm in the home matters above and beyond other risk factors associated with child injury.”

Even though U.S. gun ownership and pediatric firearm mortality overall have been dropping over the past several decades, the latter has stagnated recently, and gun deaths among children aged 1-4 years nearly doubled between 2006-2016, the researchers noted.

Given the counterintuitive increase in young children’s gun deaths while overall gun ownership kept dropping, the researchers took a closer look at the relationship between gun deaths among children aged 1-5 years and specific types of firearm ownership among families with children under age 5 years in the home. They relied on household data from the nationally representative General Social Survey and on fatality statistics from the National Vital Statistics System from 1976-2016.

Over those 4 decades, gun ownership in white families with small children decreased from 50% to 45% and in black families with small children from 38% to 6%.

Simultaneously, however, handgun ownership increased from 25% to 32% among white families with young children. In fact, most firearm-owning white families (72%) owned a handgun in 2016 while rifle ownership had declined substantially.

Meanwhile, “firearm-related mortality rate among young white children declined from historic highs in the late 1970s to early 1980s until 2001,” the authors reported. “After 2004, however, the mortality rate began to rise, reaching mid-1980s levels.” Further, gun deaths constituted 2% of young children’s injury deaths in 1976 but nearly 5% in 2016.

When the researchers compared these findings, they found a positive, significant association between white child firearm mortality and the proportion of white families who owned a handgun but not a rifle or shotgun.

The association remained after the researchers adjusted for several covariates already established in the evidence base to have associations with firearm ownership, child injury risk and/or firearm mortality: living in a rural area, living in the South, neither parent having a college degree, and a household income in the bottom quartile nationally. In addition, “the annual national unemployment rate by race was included as an indicator of the broader economic context,” the authors wrote.

Although young black children die from guns nearly three times more frequently than white children, the authors were unable to present detailed findings on associations with gun ownership because of small sample sizes. They noted, however, that handgun ownership actually declined during the study period from 15% to 6% in black families with young children.

The researchers concluded that the recent increase in young children’s gun deaths may be partly driven by an increase in handgun ownership, even as overall gun ownership (primarily rifles and shotguns) has continued dropping.

“For young children, shootings are more likely to be unintentional, making the ease at which firearms can be accessed and used a more important determinant of mortality than perhaps for older children,” the authors wrote. “Moreover, relative to other firearms like hunting rifles, handguns, because they are more likely to be purchased for personal protection, are more likely to be stored loaded with ammunition, unlocked, and in a more easily accessible place, such as a bedroom drawer.”

The research was funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.