User login

‘Fast MRI’ may be option in TBI screening for children

“Fast MRI,” which allows scans to be taken quickly without sedation, is a “reasonable alternative” to screen certain younger children for traumatic brain injury, a new study found.

The fast MRI option has “the potential to eliminate ionizing radiation exposure for thousands of children each year,” the study authors wrote in Pediatrics. “The ability to complete imaging in about 6 minutes, without the need for anesthesia or sedation, suggests that fast MRI is appropriate even in acute settings, where patient throughput is a priority.”

Daniel M. Lindberg, MD, of the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and associates wrote that children make between 600,000 and 1.6 million ED visits in the United States each year for evaluation of possible traumatic brain injury (TBI). While the incidence of clinically significant injury from TBI is low, 20%-70% of these children are exposed to potentially dangerous radiation as they undergo CT.

The new study focuses on fast MRI. Unlike traditional MRI, it doesn’t require children to remain motionless – typically with the help of sedation – to be scanned.

The researchers performed fast MRI in 223 children aged younger than 6 years (median age, 12.6 months; interquartile range, 4.7-32.6) who sought emergency care at a level 1 pediatric trauma center from 2015 to 2018. They had all had CT scans performed.

CT identified TBI in 111 (50%) of the subjects, while fast MRI identified it in 103 (sensitivity, 92.8%; 95% confidence interval, 86.3-96.8). Fast MRI missed six participants with isolated skull fractures and two with subarachnoid hemorrhage; CT missed five participants with subdural hematomas, parenchymal contusions, and subarachnoid hemorrhage.

While the researchers hoped for a higher sensitivity level, they wrote that “we feel that the benefit of avoiding radiation exposure outweighs the concern for missed injury.”

In a commentary, Brett Burstein, MDCM, PhD, MPH, and Christine Saint-Martin, MDCM, MSc, of Montreal Children’s Hospital and McGill University Health Center, also in Montreal, wrote that the study is “well conducted.”

However, they noted that “the reported feasibility reflects a highly selected cohort of stable patients in whom fast MRI is already likely to succeed. Feasibility results in a more generalizable population of head-injured children cannot be extrapolated.”

And, they added, “fast MRI was unavailable for 65 of 299 consenting, eligible patients because of lack of overnight staffing. Although not included among the outcome definitions of imaging time, this would be an important ‘feasibility’ consideration in most centers.”

Dr. Burstein and Dr. Saint-Martin wrote that “centers migrating toward this modality for neuroimaging children with head injuries should still use clinical judgment and highly sensitive, validated clinical decision rules when determining the need for any neuroimaging for head-injured children.”

The study was funded by the Colorado Traumatic Brain Injury Trust Fund (MindSource) and the Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute. The study and commentary authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCES: Lindberg DM et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Sep 18. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0419; Burstein B, Saint-Martin C. Pediatrics. 2019 Sep 18. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2387.

“Fast MRI,” which allows scans to be taken quickly without sedation, is a “reasonable alternative” to screen certain younger children for traumatic brain injury, a new study found.

The fast MRI option has “the potential to eliminate ionizing radiation exposure for thousands of children each year,” the study authors wrote in Pediatrics. “The ability to complete imaging in about 6 minutes, without the need for anesthesia or sedation, suggests that fast MRI is appropriate even in acute settings, where patient throughput is a priority.”

Daniel M. Lindberg, MD, of the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and associates wrote that children make between 600,000 and 1.6 million ED visits in the United States each year for evaluation of possible traumatic brain injury (TBI). While the incidence of clinically significant injury from TBI is low, 20%-70% of these children are exposed to potentially dangerous radiation as they undergo CT.

The new study focuses on fast MRI. Unlike traditional MRI, it doesn’t require children to remain motionless – typically with the help of sedation – to be scanned.

The researchers performed fast MRI in 223 children aged younger than 6 years (median age, 12.6 months; interquartile range, 4.7-32.6) who sought emergency care at a level 1 pediatric trauma center from 2015 to 2018. They had all had CT scans performed.

CT identified TBI in 111 (50%) of the subjects, while fast MRI identified it in 103 (sensitivity, 92.8%; 95% confidence interval, 86.3-96.8). Fast MRI missed six participants with isolated skull fractures and two with subarachnoid hemorrhage; CT missed five participants with subdural hematomas, parenchymal contusions, and subarachnoid hemorrhage.

While the researchers hoped for a higher sensitivity level, they wrote that “we feel that the benefit of avoiding radiation exposure outweighs the concern for missed injury.”

In a commentary, Brett Burstein, MDCM, PhD, MPH, and Christine Saint-Martin, MDCM, MSc, of Montreal Children’s Hospital and McGill University Health Center, also in Montreal, wrote that the study is “well conducted.”

However, they noted that “the reported feasibility reflects a highly selected cohort of stable patients in whom fast MRI is already likely to succeed. Feasibility results in a more generalizable population of head-injured children cannot be extrapolated.”

And, they added, “fast MRI was unavailable for 65 of 299 consenting, eligible patients because of lack of overnight staffing. Although not included among the outcome definitions of imaging time, this would be an important ‘feasibility’ consideration in most centers.”

Dr. Burstein and Dr. Saint-Martin wrote that “centers migrating toward this modality for neuroimaging children with head injuries should still use clinical judgment and highly sensitive, validated clinical decision rules when determining the need for any neuroimaging for head-injured children.”

The study was funded by the Colorado Traumatic Brain Injury Trust Fund (MindSource) and the Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute. The study and commentary authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCES: Lindberg DM et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Sep 18. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0419; Burstein B, Saint-Martin C. Pediatrics. 2019 Sep 18. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2387.

“Fast MRI,” which allows scans to be taken quickly without sedation, is a “reasonable alternative” to screen certain younger children for traumatic brain injury, a new study found.

The fast MRI option has “the potential to eliminate ionizing radiation exposure for thousands of children each year,” the study authors wrote in Pediatrics. “The ability to complete imaging in about 6 minutes, without the need for anesthesia or sedation, suggests that fast MRI is appropriate even in acute settings, where patient throughput is a priority.”

Daniel M. Lindberg, MD, of the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and associates wrote that children make between 600,000 and 1.6 million ED visits in the United States each year for evaluation of possible traumatic brain injury (TBI). While the incidence of clinically significant injury from TBI is low, 20%-70% of these children are exposed to potentially dangerous radiation as they undergo CT.

The new study focuses on fast MRI. Unlike traditional MRI, it doesn’t require children to remain motionless – typically with the help of sedation – to be scanned.

The researchers performed fast MRI in 223 children aged younger than 6 years (median age, 12.6 months; interquartile range, 4.7-32.6) who sought emergency care at a level 1 pediatric trauma center from 2015 to 2018. They had all had CT scans performed.

CT identified TBI in 111 (50%) of the subjects, while fast MRI identified it in 103 (sensitivity, 92.8%; 95% confidence interval, 86.3-96.8). Fast MRI missed six participants with isolated skull fractures and two with subarachnoid hemorrhage; CT missed five participants with subdural hematomas, parenchymal contusions, and subarachnoid hemorrhage.

While the researchers hoped for a higher sensitivity level, they wrote that “we feel that the benefit of avoiding radiation exposure outweighs the concern for missed injury.”

In a commentary, Brett Burstein, MDCM, PhD, MPH, and Christine Saint-Martin, MDCM, MSc, of Montreal Children’s Hospital and McGill University Health Center, also in Montreal, wrote that the study is “well conducted.”

However, they noted that “the reported feasibility reflects a highly selected cohort of stable patients in whom fast MRI is already likely to succeed. Feasibility results in a more generalizable population of head-injured children cannot be extrapolated.”

And, they added, “fast MRI was unavailable for 65 of 299 consenting, eligible patients because of lack of overnight staffing. Although not included among the outcome definitions of imaging time, this would be an important ‘feasibility’ consideration in most centers.”

Dr. Burstein and Dr. Saint-Martin wrote that “centers migrating toward this modality for neuroimaging children with head injuries should still use clinical judgment and highly sensitive, validated clinical decision rules when determining the need for any neuroimaging for head-injured children.”

The study was funded by the Colorado Traumatic Brain Injury Trust Fund (MindSource) and the Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute. The study and commentary authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCES: Lindberg DM et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Sep 18. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0419; Burstein B, Saint-Martin C. Pediatrics. 2019 Sep 18. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2387.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Medical societies urge action to reduce gun violence

“With nearly 40,000 firearm-related deaths in 2017, the United States has reached a 20-year high, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,” the authors noted in the call to action (Ann Intern Med. 2019 Aug 7. doi: 10.7326/M19-2441).

The recommendations “stem largely from the individual positions previously approved by our organizations and ongoing collaborative discussion among leaders,” wrote the authors, who included leaders of the American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Physicians, American College of Surgeons, American Medical Association, and American Psychiatric Association, as well as the American Public Health Association.

“Our organizations support a multifaceted public health approach to prevention of firearm injury and death similar to approaches that have successfully reduced the ill effects of tobacco use, motor vehicle accidents, and unintentional poisoning,” wrote Robert McLean, MD, president of the American College of Physicians, and colleagues. “While we recognize the significant political and philosophical differences about firearm ownership and regulation in the United States, we are committed to reaching out to bridge these differences to improve the health and safety of our patients, their families, and communities, while respecting the U.S. Constitution.”

The organizations specifically call for the following:

- Comprehensive criminal background checks for all firearm purchases and transfers between individuals, with limited exceptions.

- Research into the causes and consequences of firearm-related injury and death and the development and implementation of strategies to reduce these events.

- Extension of federal laws prohibiting access to firearms for domestic abusers to dating partners.

- The passage of child access prevention laws that hold accountable firearm owners who negligently store firearms under circumstances where minors could or do gain access to them.

- Improving access to mental health care for all individuals, while not broadly including all individuals with a mental health or substance use disorder in a category of individuals prohibited from purchasing firearms.

- Enactment of extreme risk protection order (ERPO) laws, which allow a judge to temporarily remove firearms from those who might be at imminent risk for using them to harm themselves or others. ERPO laws should be enacted in a manner consistent with due process.

- Physicians can and must be able to counsel at-risk patients about mitigating firearms-associated risks in the home.

- High-capacity magazines and firearms with features designed to increase their rapid and extended killing capacity should be the subject of special scrutiny and regulation.

For more than 2 decades, the American College of Physicians “has advocated for the urgent need for impactful legislation that would reduce firearms-related injuries and deaths,” ACP officials said in a statement.

“We need to protect our patients, their families, and our communities across the country from needless injuries and deaths; it’s time for the [United States] to put firearms violence prevention at the forefront of the health care conversation,” Dr. McLean said in a statement.“We are committed to working with all stakeholders, and continuing to speak out, to address this public health threat.”

Leaders at the American Academy of Family Physicians concurred.

“We need to come together as a nation on this issue,” AAFP President John Cullen, MD, said in a statement. “Treating firearm injuries as a public health issue is an important first step. We did this for motor vehicle accidents and have seen a significant decrease in injuries. We didn’t try to remove cars, we made them safer ... Both sides of the debate should come together now and work on solutions—including safe storage laws, expanded background checks, research and improved access to mental health services—we can all agree on.”

Additional firearms-related health policy content that has been published in Annals of Internal Medicine is available at: http://annals.org/aim/pages/firearm-related-content.

“With nearly 40,000 firearm-related deaths in 2017, the United States has reached a 20-year high, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,” the authors noted in the call to action (Ann Intern Med. 2019 Aug 7. doi: 10.7326/M19-2441).

The recommendations “stem largely from the individual positions previously approved by our organizations and ongoing collaborative discussion among leaders,” wrote the authors, who included leaders of the American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Physicians, American College of Surgeons, American Medical Association, and American Psychiatric Association, as well as the American Public Health Association.

“Our organizations support a multifaceted public health approach to prevention of firearm injury and death similar to approaches that have successfully reduced the ill effects of tobacco use, motor vehicle accidents, and unintentional poisoning,” wrote Robert McLean, MD, president of the American College of Physicians, and colleagues. “While we recognize the significant political and philosophical differences about firearm ownership and regulation in the United States, we are committed to reaching out to bridge these differences to improve the health and safety of our patients, their families, and communities, while respecting the U.S. Constitution.”

The organizations specifically call for the following:

- Comprehensive criminal background checks for all firearm purchases and transfers between individuals, with limited exceptions.

- Research into the causes and consequences of firearm-related injury and death and the development and implementation of strategies to reduce these events.

- Extension of federal laws prohibiting access to firearms for domestic abusers to dating partners.

- The passage of child access prevention laws that hold accountable firearm owners who negligently store firearms under circumstances where minors could or do gain access to them.

- Improving access to mental health care for all individuals, while not broadly including all individuals with a mental health or substance use disorder in a category of individuals prohibited from purchasing firearms.

- Enactment of extreme risk protection order (ERPO) laws, which allow a judge to temporarily remove firearms from those who might be at imminent risk for using them to harm themselves or others. ERPO laws should be enacted in a manner consistent with due process.

- Physicians can and must be able to counsel at-risk patients about mitigating firearms-associated risks in the home.

- High-capacity magazines and firearms with features designed to increase their rapid and extended killing capacity should be the subject of special scrutiny and regulation.

For more than 2 decades, the American College of Physicians “has advocated for the urgent need for impactful legislation that would reduce firearms-related injuries and deaths,” ACP officials said in a statement.

“We need to protect our patients, their families, and our communities across the country from needless injuries and deaths; it’s time for the [United States] to put firearms violence prevention at the forefront of the health care conversation,” Dr. McLean said in a statement.“We are committed to working with all stakeholders, and continuing to speak out, to address this public health threat.”

Leaders at the American Academy of Family Physicians concurred.

“We need to come together as a nation on this issue,” AAFP President John Cullen, MD, said in a statement. “Treating firearm injuries as a public health issue is an important first step. We did this for motor vehicle accidents and have seen a significant decrease in injuries. We didn’t try to remove cars, we made them safer ... Both sides of the debate should come together now and work on solutions—including safe storage laws, expanded background checks, research and improved access to mental health services—we can all agree on.”

Additional firearms-related health policy content that has been published in Annals of Internal Medicine is available at: http://annals.org/aim/pages/firearm-related-content.

“With nearly 40,000 firearm-related deaths in 2017, the United States has reached a 20-year high, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,” the authors noted in the call to action (Ann Intern Med. 2019 Aug 7. doi: 10.7326/M19-2441).

The recommendations “stem largely from the individual positions previously approved by our organizations and ongoing collaborative discussion among leaders,” wrote the authors, who included leaders of the American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Physicians, American College of Surgeons, American Medical Association, and American Psychiatric Association, as well as the American Public Health Association.

“Our organizations support a multifaceted public health approach to prevention of firearm injury and death similar to approaches that have successfully reduced the ill effects of tobacco use, motor vehicle accidents, and unintentional poisoning,” wrote Robert McLean, MD, president of the American College of Physicians, and colleagues. “While we recognize the significant political and philosophical differences about firearm ownership and regulation in the United States, we are committed to reaching out to bridge these differences to improve the health and safety of our patients, their families, and communities, while respecting the U.S. Constitution.”

The organizations specifically call for the following:

- Comprehensive criminal background checks for all firearm purchases and transfers between individuals, with limited exceptions.

- Research into the causes and consequences of firearm-related injury and death and the development and implementation of strategies to reduce these events.

- Extension of federal laws prohibiting access to firearms for domestic abusers to dating partners.

- The passage of child access prevention laws that hold accountable firearm owners who negligently store firearms under circumstances where minors could or do gain access to them.

- Improving access to mental health care for all individuals, while not broadly including all individuals with a mental health or substance use disorder in a category of individuals prohibited from purchasing firearms.

- Enactment of extreme risk protection order (ERPO) laws, which allow a judge to temporarily remove firearms from those who might be at imminent risk for using them to harm themselves or others. ERPO laws should be enacted in a manner consistent with due process.

- Physicians can and must be able to counsel at-risk patients about mitigating firearms-associated risks in the home.

- High-capacity magazines and firearms with features designed to increase their rapid and extended killing capacity should be the subject of special scrutiny and regulation.

For more than 2 decades, the American College of Physicians “has advocated for the urgent need for impactful legislation that would reduce firearms-related injuries and deaths,” ACP officials said in a statement.

“We need to protect our patients, their families, and our communities across the country from needless injuries and deaths; it’s time for the [United States] to put firearms violence prevention at the forefront of the health care conversation,” Dr. McLean said in a statement.“We are committed to working with all stakeholders, and continuing to speak out, to address this public health threat.”

Leaders at the American Academy of Family Physicians concurred.

“We need to come together as a nation on this issue,” AAFP President John Cullen, MD, said in a statement. “Treating firearm injuries as a public health issue is an important first step. We did this for motor vehicle accidents and have seen a significant decrease in injuries. We didn’t try to remove cars, we made them safer ... Both sides of the debate should come together now and work on solutions—including safe storage laws, expanded background checks, research and improved access to mental health services—we can all agree on.”

Additional firearms-related health policy content that has been published in Annals of Internal Medicine is available at: http://annals.org/aim/pages/firearm-related-content.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

The pool is closed!

At a recent Recreation Commission meeting here in Brunswick, the first agenda item under new business was “Coffin Pond Pool Closing.” As I and my fellow commissioners listened, we were told that for the first time in the last 3 decades the town’s only public swimming area would not be opening. While in the past there have been delayed openings and temporary closings due to water conditions, this year the pool would not open, period. The cause of the pool’s closure was the Parks and Recreation Department’s failure to fill even a skeleton crew of lifeguards.

We learned that the situation here in Brunswick was not unique and most other communities around the state and even around the country were struggling to find lifeguards. The shortage of trained staff has been nationwide for several years, and many beaches and pools particularly in the Northeast and Middle Atlantic states were being forced to close or shorten hours of operation (“During the Pool Season Even Lifeguard Numbers are Taking a Dive,” by Leoneda Inge, July 28, 2015, NPR’s All Thing Considered).

You might think that here on the coast we would have ample places for children to swim, but in Brunswick our shore is rocky and often inaccessible. At the few sandy beaches, the water temperature is too cold for all but the hardy souls until late August. Lower-income families will be particularly affected by the loss of the pool.

When I was growing up, lifeguarding was a plum job that was highly coveted. While it did not pay as well as working construction, the perks of a pleasant atmosphere, the chance to swim every day, and the opportunity to work outside with children prompted me at age 16 to sell my lawn mower and bequeath my lucrative landscaping customers to a couple of preteens. Looking back, my 4 years of lifeguarding were probably a major influence when it came time to choose a specialty.

However, a perfect storm of socioeconomic factors has combined to create a climate in which being a lifeguard has lost its appeal as a summertime job. First, there is record low unemployment nationwide. Young people looking for work have their pick, and while wages still remain low, they can be choosy when it comes to hours and benefits. Lifeguarding does require a skill set and several hoops of certification to be navigated. I don’t recall having to pay much of anything to become certified. But I understand that the process now costs hundreds of dollars of upfront investment with no guarantee of passing the test.

In May, the American Academy of Pediatrics published a policy paper titled “Prevention of Drowning” (Pediatrics. 2019 May 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0850) in which the authors offer the troubling statistics on the toll that water-related accidents take on the children of this country annually. They go on to provide a broad list of actions that parents, communities, and pediatricians can take to prevent drownings. Under the category of Community Interventions and Advocacy Opportunities, recommendation No. 4 is “Pediatricians should work with community partners to provide access to programs that develop water-competency swim skills for all children.”

Obviously, these programs can’t happen without an adequate supply of lifeguards.

Unfortunately, the AAP’s statement fails to acknowledge or directly address the lifeguard shortage that has been going on for several years. While an adequate supply of lifeguards is probably not as important as increasing parental attentiveness and mandating pool fences in the overall scheme of drowning prevention, it is an issue that demands action both by the academy and those of us practicing in communities both large and small.

For my part, I am going to work here in Brunswick to see that we can offer lifeguards pay that is more than competitive and then develop an in-house training program to ensure a continuing supply for the future. If we are committed to encouraging our patients to be active, swimming is one of the best activities we should promote and support.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

At a recent Recreation Commission meeting here in Brunswick, the first agenda item under new business was “Coffin Pond Pool Closing.” As I and my fellow commissioners listened, we were told that for the first time in the last 3 decades the town’s only public swimming area would not be opening. While in the past there have been delayed openings and temporary closings due to water conditions, this year the pool would not open, period. The cause of the pool’s closure was the Parks and Recreation Department’s failure to fill even a skeleton crew of lifeguards.

We learned that the situation here in Brunswick was not unique and most other communities around the state and even around the country were struggling to find lifeguards. The shortage of trained staff has been nationwide for several years, and many beaches and pools particularly in the Northeast and Middle Atlantic states were being forced to close or shorten hours of operation (“During the Pool Season Even Lifeguard Numbers are Taking a Dive,” by Leoneda Inge, July 28, 2015, NPR’s All Thing Considered).

You might think that here on the coast we would have ample places for children to swim, but in Brunswick our shore is rocky and often inaccessible. At the few sandy beaches, the water temperature is too cold for all but the hardy souls until late August. Lower-income families will be particularly affected by the loss of the pool.

When I was growing up, lifeguarding was a plum job that was highly coveted. While it did not pay as well as working construction, the perks of a pleasant atmosphere, the chance to swim every day, and the opportunity to work outside with children prompted me at age 16 to sell my lawn mower and bequeath my lucrative landscaping customers to a couple of preteens. Looking back, my 4 years of lifeguarding were probably a major influence when it came time to choose a specialty.

However, a perfect storm of socioeconomic factors has combined to create a climate in which being a lifeguard has lost its appeal as a summertime job. First, there is record low unemployment nationwide. Young people looking for work have their pick, and while wages still remain low, they can be choosy when it comes to hours and benefits. Lifeguarding does require a skill set and several hoops of certification to be navigated. I don’t recall having to pay much of anything to become certified. But I understand that the process now costs hundreds of dollars of upfront investment with no guarantee of passing the test.

In May, the American Academy of Pediatrics published a policy paper titled “Prevention of Drowning” (Pediatrics. 2019 May 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0850) in which the authors offer the troubling statistics on the toll that water-related accidents take on the children of this country annually. They go on to provide a broad list of actions that parents, communities, and pediatricians can take to prevent drownings. Under the category of Community Interventions and Advocacy Opportunities, recommendation No. 4 is “Pediatricians should work with community partners to provide access to programs that develop water-competency swim skills for all children.”

Obviously, these programs can’t happen without an adequate supply of lifeguards.

Unfortunately, the AAP’s statement fails to acknowledge or directly address the lifeguard shortage that has been going on for several years. While an adequate supply of lifeguards is probably not as important as increasing parental attentiveness and mandating pool fences in the overall scheme of drowning prevention, it is an issue that demands action both by the academy and those of us practicing in communities both large and small.

For my part, I am going to work here in Brunswick to see that we can offer lifeguards pay that is more than competitive and then develop an in-house training program to ensure a continuing supply for the future. If we are committed to encouraging our patients to be active, swimming is one of the best activities we should promote and support.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

At a recent Recreation Commission meeting here in Brunswick, the first agenda item under new business was “Coffin Pond Pool Closing.” As I and my fellow commissioners listened, we were told that for the first time in the last 3 decades the town’s only public swimming area would not be opening. While in the past there have been delayed openings and temporary closings due to water conditions, this year the pool would not open, period. The cause of the pool’s closure was the Parks and Recreation Department’s failure to fill even a skeleton crew of lifeguards.

We learned that the situation here in Brunswick was not unique and most other communities around the state and even around the country were struggling to find lifeguards. The shortage of trained staff has been nationwide for several years, and many beaches and pools particularly in the Northeast and Middle Atlantic states were being forced to close or shorten hours of operation (“During the Pool Season Even Lifeguard Numbers are Taking a Dive,” by Leoneda Inge, July 28, 2015, NPR’s All Thing Considered).

You might think that here on the coast we would have ample places for children to swim, but in Brunswick our shore is rocky and often inaccessible. At the few sandy beaches, the water temperature is too cold for all but the hardy souls until late August. Lower-income families will be particularly affected by the loss of the pool.

When I was growing up, lifeguarding was a plum job that was highly coveted. While it did not pay as well as working construction, the perks of a pleasant atmosphere, the chance to swim every day, and the opportunity to work outside with children prompted me at age 16 to sell my lawn mower and bequeath my lucrative landscaping customers to a couple of preteens. Looking back, my 4 years of lifeguarding were probably a major influence when it came time to choose a specialty.

However, a perfect storm of socioeconomic factors has combined to create a climate in which being a lifeguard has lost its appeal as a summertime job. First, there is record low unemployment nationwide. Young people looking for work have their pick, and while wages still remain low, they can be choosy when it comes to hours and benefits. Lifeguarding does require a skill set and several hoops of certification to be navigated. I don’t recall having to pay much of anything to become certified. But I understand that the process now costs hundreds of dollars of upfront investment with no guarantee of passing the test.

In May, the American Academy of Pediatrics published a policy paper titled “Prevention of Drowning” (Pediatrics. 2019 May 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0850) in which the authors offer the troubling statistics on the toll that water-related accidents take on the children of this country annually. They go on to provide a broad list of actions that parents, communities, and pediatricians can take to prevent drownings. Under the category of Community Interventions and Advocacy Opportunities, recommendation No. 4 is “Pediatricians should work with community partners to provide access to programs that develop water-competency swim skills for all children.”

Obviously, these programs can’t happen without an adequate supply of lifeguards.

Unfortunately, the AAP’s statement fails to acknowledge or directly address the lifeguard shortage that has been going on for several years. While an adequate supply of lifeguards is probably not as important as increasing parental attentiveness and mandating pool fences in the overall scheme of drowning prevention, it is an issue that demands action both by the academy and those of us practicing in communities both large and small.

For my part, I am going to work here in Brunswick to see that we can offer lifeguards pay that is more than competitive and then develop an in-house training program to ensure a continuing supply for the future. If we are committed to encouraging our patients to be active, swimming is one of the best activities we should promote and support.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Y 2 the ED? (Why patients go to the emergency department)

Along with terminal care and inflated drug prices, the excessive number of “inappropriate” ED visits often is cited as a major driver of health care costs in the United States. Why do so many patients choose to go to the ED for complaints that might be better or more economically treated in another setting?

A report by two researchers in the division of emergency medicine at the Boston Children’s Hospital that appeared in the June 2019 Pediatrics suggests that, at least for pediatric patients, “increased insurance coverage neither drove nor counteracted” the recent trends in ED visits. (“Trends in Pediatric Emergency Department Use After the Affordable Care Act,” Pediatrics. 2019 Jun 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3542).

I guess it’s not surprising – and somewhat comforting – to learn that, when parents believe their child has an emergent condition they give little thought to the cost of care. Is the trend of increasing ED use a result of an evolving definition of an “emergency”? Your grandparents, or certainly your great grandparents, might claim that, when they were young most minor injuries were handled at home, or at least in the neighborhood by someone with first aid experience who wasn’t put off by the sight of blood. However, a trend away from self-reliance in everything from food preparation to auto repair, combined with media overexposure to the serious complications of apparently minor illness and injury, has left most parents feeling fearful and helpless in the face of adversity.

We have to accept as a given that many parents are going to interpret their child’s situation as emergent, even though you and I might not. But what are the factors that prompt a concerned parent to take his child to the ED instead of a physician’s office? It may simply be the path of least resistance. The parent’s past experience may include frustrating and time-consuming attempts to navigate a clunky phone system only to be met by a receptionist or triage nurse who seems more committed to deflecting calls and protecting the physician’s schedule than getting the patient seen.

The call may miraculously get through to someone with a caring voice and the patience to listen, but the parent then learns that the office doesn’t do minor wound care or he is told that the physician almost certainly will want to do an x-ray of any injured extremity and that the ED is a better choice. It doesn’t take very many scenarios like this to prompt a parent to make his first and only call to the ED. To some extent, physician behavior has helped mold parents’ definition of an emergency.

We are encouraged to make our offices a “medical home.” However, it appears the medical home model is one that is built around chronic conditions and behavioral problems and gives little attention to the acute complaints. When you came running into the house with a skinned knee, did your mother tell to you go across the street to the neighbor’s house because blood made her squeamish and she didn’t have any bandages?

There are ways to structure an office and a schedule which are more welcoming to patients with minor emergencies, and I know it is a difficult sell to physicians who are handcuffed by their EHRs and already overwhelmed by patients with time-consuming behavioral complaints. However, if your practice is facing competition from pop-up urgent care centers or if you are increasingly troubled that your patients are receiving fragmented care, it may not be too late to make your practice into a true medical home that welcomes minor emergencies.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Along with terminal care and inflated drug prices, the excessive number of “inappropriate” ED visits often is cited as a major driver of health care costs in the United States. Why do so many patients choose to go to the ED for complaints that might be better or more economically treated in another setting?

A report by two researchers in the division of emergency medicine at the Boston Children’s Hospital that appeared in the June 2019 Pediatrics suggests that, at least for pediatric patients, “increased insurance coverage neither drove nor counteracted” the recent trends in ED visits. (“Trends in Pediatric Emergency Department Use After the Affordable Care Act,” Pediatrics. 2019 Jun 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3542).

I guess it’s not surprising – and somewhat comforting – to learn that, when parents believe their child has an emergent condition they give little thought to the cost of care. Is the trend of increasing ED use a result of an evolving definition of an “emergency”? Your grandparents, or certainly your great grandparents, might claim that, when they were young most minor injuries were handled at home, or at least in the neighborhood by someone with first aid experience who wasn’t put off by the sight of blood. However, a trend away from self-reliance in everything from food preparation to auto repair, combined with media overexposure to the serious complications of apparently minor illness and injury, has left most parents feeling fearful and helpless in the face of adversity.

We have to accept as a given that many parents are going to interpret their child’s situation as emergent, even though you and I might not. But what are the factors that prompt a concerned parent to take his child to the ED instead of a physician’s office? It may simply be the path of least resistance. The parent’s past experience may include frustrating and time-consuming attempts to navigate a clunky phone system only to be met by a receptionist or triage nurse who seems more committed to deflecting calls and protecting the physician’s schedule than getting the patient seen.

The call may miraculously get through to someone with a caring voice and the patience to listen, but the parent then learns that the office doesn’t do minor wound care or he is told that the physician almost certainly will want to do an x-ray of any injured extremity and that the ED is a better choice. It doesn’t take very many scenarios like this to prompt a parent to make his first and only call to the ED. To some extent, physician behavior has helped mold parents’ definition of an emergency.

We are encouraged to make our offices a “medical home.” However, it appears the medical home model is one that is built around chronic conditions and behavioral problems and gives little attention to the acute complaints. When you came running into the house with a skinned knee, did your mother tell to you go across the street to the neighbor’s house because blood made her squeamish and she didn’t have any bandages?

There are ways to structure an office and a schedule which are more welcoming to patients with minor emergencies, and I know it is a difficult sell to physicians who are handcuffed by their EHRs and already overwhelmed by patients with time-consuming behavioral complaints. However, if your practice is facing competition from pop-up urgent care centers or if you are increasingly troubled that your patients are receiving fragmented care, it may not be too late to make your practice into a true medical home that welcomes minor emergencies.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Along with terminal care and inflated drug prices, the excessive number of “inappropriate” ED visits often is cited as a major driver of health care costs in the United States. Why do so many patients choose to go to the ED for complaints that might be better or more economically treated in another setting?

A report by two researchers in the division of emergency medicine at the Boston Children’s Hospital that appeared in the June 2019 Pediatrics suggests that, at least for pediatric patients, “increased insurance coverage neither drove nor counteracted” the recent trends in ED visits. (“Trends in Pediatric Emergency Department Use After the Affordable Care Act,” Pediatrics. 2019 Jun 1. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3542).

I guess it’s not surprising – and somewhat comforting – to learn that, when parents believe their child has an emergent condition they give little thought to the cost of care. Is the trend of increasing ED use a result of an evolving definition of an “emergency”? Your grandparents, or certainly your great grandparents, might claim that, when they were young most minor injuries were handled at home, or at least in the neighborhood by someone with first aid experience who wasn’t put off by the sight of blood. However, a trend away from self-reliance in everything from food preparation to auto repair, combined with media overexposure to the serious complications of apparently minor illness and injury, has left most parents feeling fearful and helpless in the face of adversity.

We have to accept as a given that many parents are going to interpret their child’s situation as emergent, even though you and I might not. But what are the factors that prompt a concerned parent to take his child to the ED instead of a physician’s office? It may simply be the path of least resistance. The parent’s past experience may include frustrating and time-consuming attempts to navigate a clunky phone system only to be met by a receptionist or triage nurse who seems more committed to deflecting calls and protecting the physician’s schedule than getting the patient seen.

The call may miraculously get through to someone with a caring voice and the patience to listen, but the parent then learns that the office doesn’t do minor wound care or he is told that the physician almost certainly will want to do an x-ray of any injured extremity and that the ED is a better choice. It doesn’t take very many scenarios like this to prompt a parent to make his first and only call to the ED. To some extent, physician behavior has helped mold parents’ definition of an emergency.

We are encouraged to make our offices a “medical home.” However, it appears the medical home model is one that is built around chronic conditions and behavioral problems and gives little attention to the acute complaints. When you came running into the house with a skinned knee, did your mother tell to you go across the street to the neighbor’s house because blood made her squeamish and she didn’t have any bandages?

There are ways to structure an office and a schedule which are more welcoming to patients with minor emergencies, and I know it is a difficult sell to physicians who are handcuffed by their EHRs and already overwhelmed by patients with time-consuming behavioral complaints. However, if your practice is facing competition from pop-up urgent care centers or if you are increasingly troubled that your patients are receiving fragmented care, it may not be too late to make your practice into a true medical home that welcomes minor emergencies.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

‘Tis the season … for fireworks injuries

according to the Consumer Product Safety Commission.

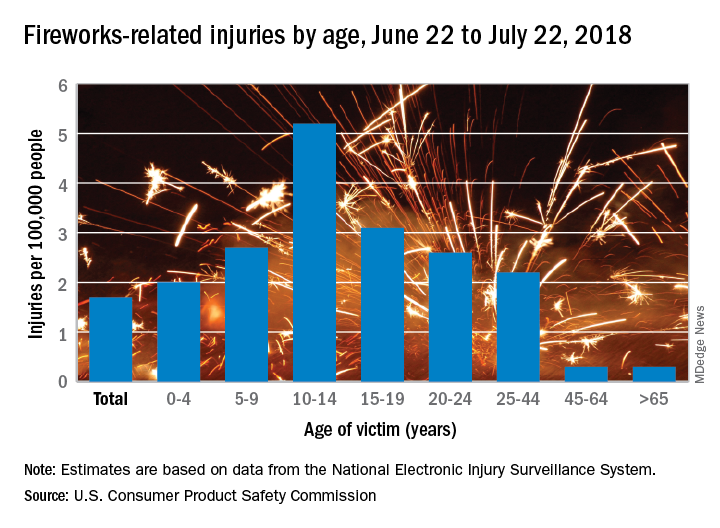

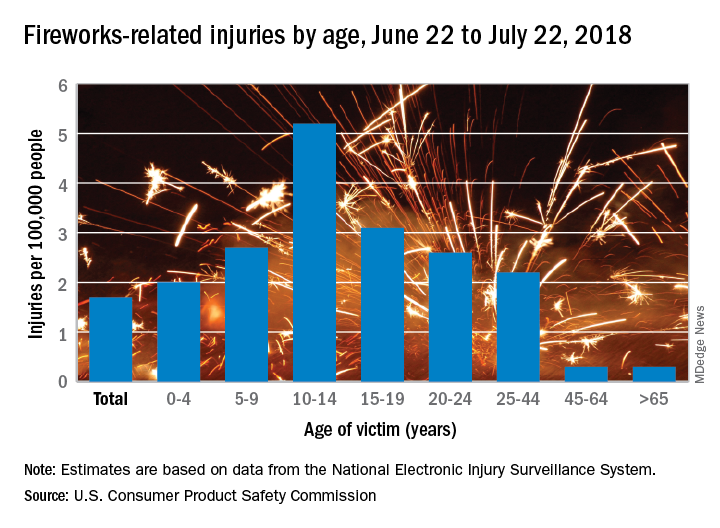

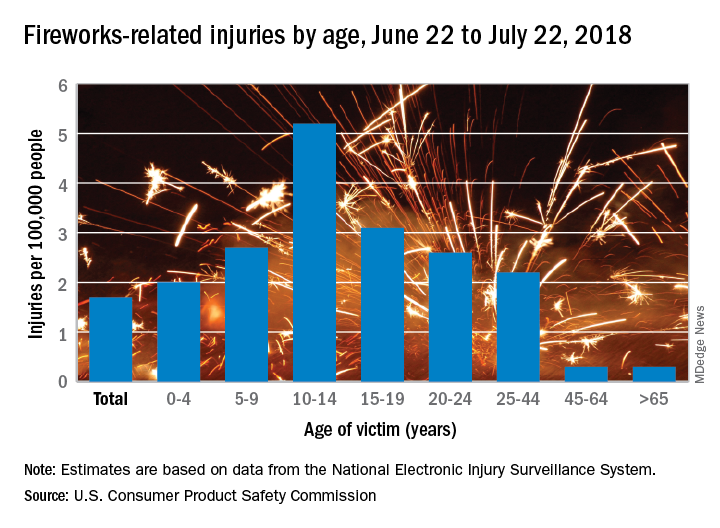

Of the estimated 9,100 fireworks-related injuries treated in emergency departments last year, 5,600 (62%) occurred between June 22 and July 22, 2018. That works out to a rate of 1.7 ED-treated injuries per 100,000 people for that 1 month and a rate of 2.8 per 100,000 for the entire year, the CPSC said in its 2018 Fireworks Annual Report.

Children had higher injury rates than adults in the Fourth of July window, and those aged 10-14 years had the highest rate of all, 5.2 injuries per 100,000 population. They were followed by teens aged 15-19 years (3.1 per 100,000) and children aged 5-9 (2.7 per 100,000), the CPSC investigators said based on data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System.

A deeper dive into the data pool shows that firecrackers caused more injuries – 19% of the total for the month – than any other type of firework device (reloadable shells were second at 12%). Burns were the most common type of injury, making up 44% of the total, and hands and fingers were the body parts most often injured (28% of the total), they reported.

There were five fireworks-related deaths last year – below the average of 7.6 per year since 2003 – but the total for 2018 may go up because reporting for the year is not yet complete. In one of the 2018 cases, an 18-year-old taped a tube to a football helmet and tried to launch a mortar shell while wearing the helmet. The first one worked, but the second shell got stuck and exploded in the tube, the CPSC said.

“CPSC works year-round to help prevent deaths and injuries from fireworks, by verifying fireworks meet safety regulations in our ports, marketplace, and on the road,” acting CPSC Chairman Ann Marie Buerkle said in a written statement. “Beyond CPSC’s efforts, we want to make sure everyone takes simple safety steps to celebrate safely with their family and friends.”

according to the Consumer Product Safety Commission.

Of the estimated 9,100 fireworks-related injuries treated in emergency departments last year, 5,600 (62%) occurred between June 22 and July 22, 2018. That works out to a rate of 1.7 ED-treated injuries per 100,000 people for that 1 month and a rate of 2.8 per 100,000 for the entire year, the CPSC said in its 2018 Fireworks Annual Report.

Children had higher injury rates than adults in the Fourth of July window, and those aged 10-14 years had the highest rate of all, 5.2 injuries per 100,000 population. They were followed by teens aged 15-19 years (3.1 per 100,000) and children aged 5-9 (2.7 per 100,000), the CPSC investigators said based on data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System.

A deeper dive into the data pool shows that firecrackers caused more injuries – 19% of the total for the month – than any other type of firework device (reloadable shells were second at 12%). Burns were the most common type of injury, making up 44% of the total, and hands and fingers were the body parts most often injured (28% of the total), they reported.

There were five fireworks-related deaths last year – below the average of 7.6 per year since 2003 – but the total for 2018 may go up because reporting for the year is not yet complete. In one of the 2018 cases, an 18-year-old taped a tube to a football helmet and tried to launch a mortar shell while wearing the helmet. The first one worked, but the second shell got stuck and exploded in the tube, the CPSC said.

“CPSC works year-round to help prevent deaths and injuries from fireworks, by verifying fireworks meet safety regulations in our ports, marketplace, and on the road,” acting CPSC Chairman Ann Marie Buerkle said in a written statement. “Beyond CPSC’s efforts, we want to make sure everyone takes simple safety steps to celebrate safely with their family and friends.”

according to the Consumer Product Safety Commission.

Of the estimated 9,100 fireworks-related injuries treated in emergency departments last year, 5,600 (62%) occurred between June 22 and July 22, 2018. That works out to a rate of 1.7 ED-treated injuries per 100,000 people for that 1 month and a rate of 2.8 per 100,000 for the entire year, the CPSC said in its 2018 Fireworks Annual Report.

Children had higher injury rates than adults in the Fourth of July window, and those aged 10-14 years had the highest rate of all, 5.2 injuries per 100,000 population. They were followed by teens aged 15-19 years (3.1 per 100,000) and children aged 5-9 (2.7 per 100,000), the CPSC investigators said based on data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System.

A deeper dive into the data pool shows that firecrackers caused more injuries – 19% of the total for the month – than any other type of firework device (reloadable shells were second at 12%). Burns were the most common type of injury, making up 44% of the total, and hands and fingers were the body parts most often injured (28% of the total), they reported.

There were five fireworks-related deaths last year – below the average of 7.6 per year since 2003 – but the total for 2018 may go up because reporting for the year is not yet complete. In one of the 2018 cases, an 18-year-old taped a tube to a football helmet and tried to launch a mortar shell while wearing the helmet. The first one worked, but the second shell got stuck and exploded in the tube, the CPSC said.

“CPSC works year-round to help prevent deaths and injuries from fireworks, by verifying fireworks meet safety regulations in our ports, marketplace, and on the road,” acting CPSC Chairman Ann Marie Buerkle said in a written statement. “Beyond CPSC’s efforts, we want to make sure everyone takes simple safety steps to celebrate safely with their family and friends.”

Key risk factors of pediatric cervical spinal injury identified

Risk factors that have good test accuracy in recognizing pediatric cervical spinal injury (CSI) exist, and they can be incorporated into a clinical prediction rule that has the potential to greatly lower the need for cervical spine imaging during trauma evaluation, Julie C Leonard, MD, MPH, and associates reported in Pediatrics.

Though rare, cervical spine injuries in children lead to significant morbidity and mortality, and the vast majority of these children screened radiographically have no injury at all, which makes the inherent lifetime risk of malignancy from unnecessary radiation exposure troubling to many.

In their 2014-2016 prospective observational study in which 4,091 children aged 0-17 years were evaluated for blunt trauma in one of four U.S. tertiary care children’s hospitals, 2% had CSIs.

The mean age in the cohort was 9 years; the mean age of CSI patients was 11 years. Fully 39% of patients were under 8 years of age and 23 (1%) had CSIs. Among those with CSIs, more were boys, white, and non-Hispanic. Motor vehicle crash and sports-related injuries were reported to be the most common route of injury in all children.

The main goal of the study was to “establish the infrastructure for conducting a larger cohort study,” said Dr. Leonard of Ohio State University Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, and associates. They were successful in confirming the existence of an association between CSI and head injury. Specifically, the greatest independent associations with pediatric CSI were substantial head injury, namely basilar skull fracture; signs of traumatic brain injury, such as altered mental status; respiratory failure and intubation; and head-first impacts.

The authors were careful to point out that risk factors identified in their study differed from other studies focused on adult injury, specifically with regard to neck findings. They speculated that the increased neck and spine tenderness that commonly increase following restrictive supine positioning in a cervical collar on a rigid long board could play a key role. They also speculated that ED clinicians may be more likely to “defer aspects of the neck examination” in cases where children present wearing cervical collars, which limits assessment to self reporting.

As with adult evaluation, in which adult CSI prediction rules for cervical imaging depend upon determining the extent of normal mental status after blunt trauma, successful identification of pediatric candidates will require a similar set of CSI prediction rules. “Future development of a robust pediatric CSI prediction rule should be focused on stratification based on mental status because it may be meaningful in determining which children to triage to CT scan,” the investigators advised.

Future research exploring how these risk factors can be used to build a clear, pediatric CSI prediction rule that is prospective and observational in nature is crucial to improving the timeliness and accuracy of CSI diagnosis, Dr. Leonard and associates said.

In an accompanying editorial, Mark I. Neuman, MD, MPH and Rebekah C. Mannix, MD, MPH, noted that evidence uncovered by Leonard et al. will, no doubt, provide the conceptual foundation for a future multicenter trial that can establish effective criteria needed to consider the use of imaging when evaluating CSI in children.

Previously, the National Emergency X-Ray Utilization Study (NEXUS) was the largest prospective study of CSI that also included children. The Leonard et al. study includes a much higher proportion of children, 39% of whom were younger than 8 years of age. Although the sensitivities of the models used in this latest study are lower than for those used in the NEXUS study, the specificity is much higher at 46%-50%, which has noteworthy implications for classifying children at risk of CSI. “If validated, these findings have the potential to spare imaging in over one-third of children,” said Dr. Neuman and Dr. Mannix, both of the division of emergency medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital, and the department of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“The complex and varying nature of CSI in children, the result of differences in the intrinsic biomechanics of the pediatric cervical spine, mechanism of injury, and variable presentations between younger and older children pose challenges for the development of a universal, simple, and highly sensitive clinical prediction rule,” they concluded.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study, and Dr. Leonard received a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The authors had no relevant disclosures. There was no external funding for the accompanying editorial and Dr. Neuman and Dr. Mannix said they had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Leonard J et al. Pediatrics. 2019;144(1):e20183221; Neuman MI et al. Pediatrics. 2019;144(1):e20184052.

Risk factors that have good test accuracy in recognizing pediatric cervical spinal injury (CSI) exist, and they can be incorporated into a clinical prediction rule that has the potential to greatly lower the need for cervical spine imaging during trauma evaluation, Julie C Leonard, MD, MPH, and associates reported in Pediatrics.

Though rare, cervical spine injuries in children lead to significant morbidity and mortality, and the vast majority of these children screened radiographically have no injury at all, which makes the inherent lifetime risk of malignancy from unnecessary radiation exposure troubling to many.

In their 2014-2016 prospective observational study in which 4,091 children aged 0-17 years were evaluated for blunt trauma in one of four U.S. tertiary care children’s hospitals, 2% had CSIs.

The mean age in the cohort was 9 years; the mean age of CSI patients was 11 years. Fully 39% of patients were under 8 years of age and 23 (1%) had CSIs. Among those with CSIs, more were boys, white, and non-Hispanic. Motor vehicle crash and sports-related injuries were reported to be the most common route of injury in all children.

The main goal of the study was to “establish the infrastructure for conducting a larger cohort study,” said Dr. Leonard of Ohio State University Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, and associates. They were successful in confirming the existence of an association between CSI and head injury. Specifically, the greatest independent associations with pediatric CSI were substantial head injury, namely basilar skull fracture; signs of traumatic brain injury, such as altered mental status; respiratory failure and intubation; and head-first impacts.

The authors were careful to point out that risk factors identified in their study differed from other studies focused on adult injury, specifically with regard to neck findings. They speculated that the increased neck and spine tenderness that commonly increase following restrictive supine positioning in a cervical collar on a rigid long board could play a key role. They also speculated that ED clinicians may be more likely to “defer aspects of the neck examination” in cases where children present wearing cervical collars, which limits assessment to self reporting.

As with adult evaluation, in which adult CSI prediction rules for cervical imaging depend upon determining the extent of normal mental status after blunt trauma, successful identification of pediatric candidates will require a similar set of CSI prediction rules. “Future development of a robust pediatric CSI prediction rule should be focused on stratification based on mental status because it may be meaningful in determining which children to triage to CT scan,” the investigators advised.

Future research exploring how these risk factors can be used to build a clear, pediatric CSI prediction rule that is prospective and observational in nature is crucial to improving the timeliness and accuracy of CSI diagnosis, Dr. Leonard and associates said.

In an accompanying editorial, Mark I. Neuman, MD, MPH and Rebekah C. Mannix, MD, MPH, noted that evidence uncovered by Leonard et al. will, no doubt, provide the conceptual foundation for a future multicenter trial that can establish effective criteria needed to consider the use of imaging when evaluating CSI in children.

Previously, the National Emergency X-Ray Utilization Study (NEXUS) was the largest prospective study of CSI that also included children. The Leonard et al. study includes a much higher proportion of children, 39% of whom were younger than 8 years of age. Although the sensitivities of the models used in this latest study are lower than for those used in the NEXUS study, the specificity is much higher at 46%-50%, which has noteworthy implications for classifying children at risk of CSI. “If validated, these findings have the potential to spare imaging in over one-third of children,” said Dr. Neuman and Dr. Mannix, both of the division of emergency medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital, and the department of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“The complex and varying nature of CSI in children, the result of differences in the intrinsic biomechanics of the pediatric cervical spine, mechanism of injury, and variable presentations between younger and older children pose challenges for the development of a universal, simple, and highly sensitive clinical prediction rule,” they concluded.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study, and Dr. Leonard received a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The authors had no relevant disclosures. There was no external funding for the accompanying editorial and Dr. Neuman and Dr. Mannix said they had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Leonard J et al. Pediatrics. 2019;144(1):e20183221; Neuman MI et al. Pediatrics. 2019;144(1):e20184052.

Risk factors that have good test accuracy in recognizing pediatric cervical spinal injury (CSI) exist, and they can be incorporated into a clinical prediction rule that has the potential to greatly lower the need for cervical spine imaging during trauma evaluation, Julie C Leonard, MD, MPH, and associates reported in Pediatrics.

Though rare, cervical spine injuries in children lead to significant morbidity and mortality, and the vast majority of these children screened radiographically have no injury at all, which makes the inherent lifetime risk of malignancy from unnecessary radiation exposure troubling to many.

In their 2014-2016 prospective observational study in which 4,091 children aged 0-17 years were evaluated for blunt trauma in one of four U.S. tertiary care children’s hospitals, 2% had CSIs.

The mean age in the cohort was 9 years; the mean age of CSI patients was 11 years. Fully 39% of patients were under 8 years of age and 23 (1%) had CSIs. Among those with CSIs, more were boys, white, and non-Hispanic. Motor vehicle crash and sports-related injuries were reported to be the most common route of injury in all children.

The main goal of the study was to “establish the infrastructure for conducting a larger cohort study,” said Dr. Leonard of Ohio State University Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, and associates. They were successful in confirming the existence of an association between CSI and head injury. Specifically, the greatest independent associations with pediatric CSI were substantial head injury, namely basilar skull fracture; signs of traumatic brain injury, such as altered mental status; respiratory failure and intubation; and head-first impacts.

The authors were careful to point out that risk factors identified in their study differed from other studies focused on adult injury, specifically with regard to neck findings. They speculated that the increased neck and spine tenderness that commonly increase following restrictive supine positioning in a cervical collar on a rigid long board could play a key role. They also speculated that ED clinicians may be more likely to “defer aspects of the neck examination” in cases where children present wearing cervical collars, which limits assessment to self reporting.

As with adult evaluation, in which adult CSI prediction rules for cervical imaging depend upon determining the extent of normal mental status after blunt trauma, successful identification of pediatric candidates will require a similar set of CSI prediction rules. “Future development of a robust pediatric CSI prediction rule should be focused on stratification based on mental status because it may be meaningful in determining which children to triage to CT scan,” the investigators advised.

Future research exploring how these risk factors can be used to build a clear, pediatric CSI prediction rule that is prospective and observational in nature is crucial to improving the timeliness and accuracy of CSI diagnosis, Dr. Leonard and associates said.

In an accompanying editorial, Mark I. Neuman, MD, MPH and Rebekah C. Mannix, MD, MPH, noted that evidence uncovered by Leonard et al. will, no doubt, provide the conceptual foundation for a future multicenter trial that can establish effective criteria needed to consider the use of imaging when evaluating CSI in children.

Previously, the National Emergency X-Ray Utilization Study (NEXUS) was the largest prospective study of CSI that also included children. The Leonard et al. study includes a much higher proportion of children, 39% of whom were younger than 8 years of age. Although the sensitivities of the models used in this latest study are lower than for those used in the NEXUS study, the specificity is much higher at 46%-50%, which has noteworthy implications for classifying children at risk of CSI. “If validated, these findings have the potential to spare imaging in over one-third of children,” said Dr. Neuman and Dr. Mannix, both of the division of emergency medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital, and the department of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“The complex and varying nature of CSI in children, the result of differences in the intrinsic biomechanics of the pediatric cervical spine, mechanism of injury, and variable presentations between younger and older children pose challenges for the development of a universal, simple, and highly sensitive clinical prediction rule,” they concluded.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study, and Dr. Leonard received a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The authors had no relevant disclosures. There was no external funding for the accompanying editorial and Dr. Neuman and Dr. Mannix said they had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Leonard J et al. Pediatrics. 2019;144(1):e20183221; Neuman MI et al. Pediatrics. 2019;144(1):e20184052.

FROM PEDIATRICS

FACTS Consortium calls for research on preventing pediatric firearm injuries

The 26 research agenda items from FACTS, which span across the broad topic areas of epidemiology, surveillance, and risk and protective factors; primary, secondary, and cross-cutting protective factors; policy-related issues; and data-enhancement priorities, were published in JAMA Pediatrics.

“Firearms are the second leading cause of death among children and adolescents aged 1 to 18 years in the United States and responsible for more than 2,570 deaths and nearly 12,000 nonfatal injuries requiring emergency department treatment in 2017,” said Rebecca Cunningham, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues who are members of the FACTS Consortium.

“Pediatric firearm injuries result from a range of causes, including the unintentional discharge of a firearm, self-inflicted wounds, or the escalation of interpersonal violence,” they continued. “Nearly 265 million firearms are in civilian hands in the United States, and a 44% increase in pediatric firearm mortality rate has been documented during the past 5 years.”

The FACTS Consortium defined an agenda “to serve as a guide for future research efforts to decrease pediatric death and injury.”

Some of the research agenda items include the following:

- Understanding epidemiologic trends and how demographic factors are associated with fatal and nonfatal outcomes.

- The long-term cost associated with pediatric firearm outcomes.

- The effectiveness of health care–focused primary prevention strategies for children, adolescents, and their families to reduce firearm outcomes.

- Examination of health care–based interventions for children and adolescents who have experienced or witnessed a firearm injury to prevent (or reduce) subsequent firearm outcomes including firearm injury recidivism and mental health, socioemotional, and educational outcomes.

“It is an excellent list, and I think it was very thoughtful to come out with a research agenda for firearm safety for kids,” Marlene Melzer-Lange, MD, chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics subcommittee on violence prevention, said in an interview. “The thing that’s been lacking nationally has been funding for firearm injury prevention, both for children and adults, and to have something focused specifically on children – because children have the biggest chance of living the longest – is really important.”

She described the research agenda as being “comprehensive” and didn’t see anything that stood out as missing from the list, although the big issue that remains is getting funding for the research now that an agenda has been outlined.

And getting that is not going to be easy.

“I think it’s going to take some political will of the people and particularly of our legislators ... to allow the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] to provide funding” said Dr. Melzer-Lange, an attending emergency department physician at Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, adding that AAP has long been asking for such funding. “It’s going [to come down to] the legislators [having] enough guts to actually put the funding in and not be afraid of external groups that might ask them not to do that.”

She remains optimistic and hopeful that the legislators are going to look at it and will eventually say that this is an crisis and will take more action beyond just talking about it.

Dr. Melzer-Lange also emphasized that this is about firearm safety and not firearm control, especially for children and teenagers.

All authors reported receiving grants from National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

SOURCE: Cunningham RM et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1494.

The 26 research agenda items from FACTS, which span across the broad topic areas of epidemiology, surveillance, and risk and protective factors; primary, secondary, and cross-cutting protective factors; policy-related issues; and data-enhancement priorities, were published in JAMA Pediatrics.

“Firearms are the second leading cause of death among children and adolescents aged 1 to 18 years in the United States and responsible for more than 2,570 deaths and nearly 12,000 nonfatal injuries requiring emergency department treatment in 2017,” said Rebecca Cunningham, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues who are members of the FACTS Consortium.

“Pediatric firearm injuries result from a range of causes, including the unintentional discharge of a firearm, self-inflicted wounds, or the escalation of interpersonal violence,” they continued. “Nearly 265 million firearms are in civilian hands in the United States, and a 44% increase in pediatric firearm mortality rate has been documented during the past 5 years.”

The FACTS Consortium defined an agenda “to serve as a guide for future research efforts to decrease pediatric death and injury.”

Some of the research agenda items include the following:

- Understanding epidemiologic trends and how demographic factors are associated with fatal and nonfatal outcomes.

- The long-term cost associated with pediatric firearm outcomes.

- The effectiveness of health care–focused primary prevention strategies for children, adolescents, and their families to reduce firearm outcomes.

- Examination of health care–based interventions for children and adolescents who have experienced or witnessed a firearm injury to prevent (or reduce) subsequent firearm outcomes including firearm injury recidivism and mental health, socioemotional, and educational outcomes.

“It is an excellent list, and I think it was very thoughtful to come out with a research agenda for firearm safety for kids,” Marlene Melzer-Lange, MD, chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics subcommittee on violence prevention, said in an interview. “The thing that’s been lacking nationally has been funding for firearm injury prevention, both for children and adults, and to have something focused specifically on children – because children have the biggest chance of living the longest – is really important.”

She described the research agenda as being “comprehensive” and didn’t see anything that stood out as missing from the list, although the big issue that remains is getting funding for the research now that an agenda has been outlined.

And getting that is not going to be easy.

“I think it’s going to take some political will of the people and particularly of our legislators ... to allow the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] to provide funding” said Dr. Melzer-Lange, an attending emergency department physician at Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, adding that AAP has long been asking for such funding. “It’s going [to come down to] the legislators [having] enough guts to actually put the funding in and not be afraid of external groups that might ask them not to do that.”

She remains optimistic and hopeful that the legislators are going to look at it and will eventually say that this is an crisis and will take more action beyond just talking about it.

Dr. Melzer-Lange also emphasized that this is about firearm safety and not firearm control, especially for children and teenagers.

All authors reported receiving grants from National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

SOURCE: Cunningham RM et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1494.

The 26 research agenda items from FACTS, which span across the broad topic areas of epidemiology, surveillance, and risk and protective factors; primary, secondary, and cross-cutting protective factors; policy-related issues; and data-enhancement priorities, were published in JAMA Pediatrics.

“Firearms are the second leading cause of death among children and adolescents aged 1 to 18 years in the United States and responsible for more than 2,570 deaths and nearly 12,000 nonfatal injuries requiring emergency department treatment in 2017,” said Rebecca Cunningham, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues who are members of the FACTS Consortium.

“Pediatric firearm injuries result from a range of causes, including the unintentional discharge of a firearm, self-inflicted wounds, or the escalation of interpersonal violence,” they continued. “Nearly 265 million firearms are in civilian hands in the United States, and a 44% increase in pediatric firearm mortality rate has been documented during the past 5 years.”

The FACTS Consortium defined an agenda “to serve as a guide for future research efforts to decrease pediatric death and injury.”

Some of the research agenda items include the following:

- Understanding epidemiologic trends and how demographic factors are associated with fatal and nonfatal outcomes.

- The long-term cost associated with pediatric firearm outcomes.

- The effectiveness of health care–focused primary prevention strategies for children, adolescents, and their families to reduce firearm outcomes.

- Examination of health care–based interventions for children and adolescents who have experienced or witnessed a firearm injury to prevent (or reduce) subsequent firearm outcomes including firearm injury recidivism and mental health, socioemotional, and educational outcomes.

“It is an excellent list, and I think it was very thoughtful to come out with a research agenda for firearm safety for kids,” Marlene Melzer-Lange, MD, chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics subcommittee on violence prevention, said in an interview. “The thing that’s been lacking nationally has been funding for firearm injury prevention, both for children and adults, and to have something focused specifically on children – because children have the biggest chance of living the longest – is really important.”

She described the research agenda as being “comprehensive” and didn’t see anything that stood out as missing from the list, although the big issue that remains is getting funding for the research now that an agenda has been outlined.

And getting that is not going to be easy.

“I think it’s going to take some political will of the people and particularly of our legislators ... to allow the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] to provide funding” said Dr. Melzer-Lange, an attending emergency department physician at Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, adding that AAP has long been asking for such funding. “It’s going [to come down to] the legislators [having] enough guts to actually put the funding in and not be afraid of external groups that might ask them not to do that.”

She remains optimistic and hopeful that the legislators are going to look at it and will eventually say that this is an crisis and will take more action beyond just talking about it.

Dr. Melzer-Lange also emphasized that this is about firearm safety and not firearm control, especially for children and teenagers.

All authors reported receiving grants from National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

SOURCE: Cunningham RM et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1494.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

When adolescents visit the ED, 10% leave with an opioid