User login

Is Hospital Discharge the Rube Goldberg Machine of Academic Internal Medicine?

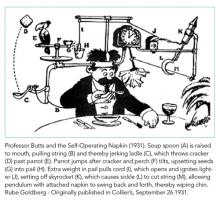

One of the least taught yet most complicated tasks confronting new trainees is the bewildering process of discharging a patient. On an internal medicine service, this process can often resemble a Rube Goldberg machine, in which a “simple” task is accomplished through a series of interconnected, almost comically convoluted, yet separate steps that are triggered one after another and must be executed perfectly in sequence for success. It seems easy at first; just tap out a few sentences in the discharge paperwork, do a quick medication reconciliation, and a click of a button later, voila! The patient magically falls off the list and is on their merry way home. In reality, it only takes one wrench thrown into the Rube Goldberg machine to take down the whole operation. Much to the chagrin of internal medicine interns across the country, residents quickly learn that discharge planning is usually far from straightforward and that a myriad of obstacles (often dynamic and frustratingly unpredictable) can stand in the way of a successful discharge.

While some surgical services can streamline discharge processes to target defined lengths of stay based on a particular diagnosis, general medicine patients tend to have greater numbers of comorbid conditions, complex hospital courses, and wider variation in access to posthospital healthcare. In addition, there is very little formal instruction in transitions of care, and most residents identify direct patient care (learning by doing) as the primary mode of education.1,2 Struggling through the process of finding an appropriate placement, ensuring adequate outpatient follow-up, and untangling a jumbled mess of a medication reconciliation is often the only way that housestaff learn the Sisyphean task of transitioning care out of the hospital. The unpredictability and intensity of patient care adds to the ever growing list of competing demands on the time and attention of residents. Attendings face pressure on all sides to not only provide exemplary patient care and an educational experience but also to optimize hospital throughput by discharging patients as soon as possible (and ideally before noon). No wonder that the discharge process can threaten to unravel at any time, with delays and complications in discharge metamorphosing into increased length of stay (LOS), poorer outcomes, and increased 30-day readmission rates. As on-the-ground providers, what realities do we face when challenging ourselves to discharge patients before noon, and what practical changes in our workflow can we make to reach this goal?

In this month’s Journal of Hospital Medicine, Zoucha et al. examine these questions in real time by identifying barriers preventing both “definite” and “possible” discharges at three representative time points over the course of randomly chosen weekdays. They surveyed both housestaff and attendings at five academic hospitals across the United States, and the majority of patients were cared for on teaching services.3 Reflecting the inherent differences in workflow between teaching and nonteaching services, delays in definite discharges on teaching services were most often hindered by completing rounds and the need to staff the patient with the attending, whereas nonresident services identified other patient-care-related (both urgent and nonurgent) issues to be the culprits. Late-afternoon discharges were delayed on teaching services due to outstanding paperwork and follow-up arrangements, both of which most senior residents are keenly aware of and make their best effort to complete ahead of time. Patients designated as “possible” discharges were awaiting clinical improvement and resolution of disposition issues dependent on social work and safe placement, which reasonably seemed independent of service type. These descriptive findings suggest that nonresident services are more efficient than resident teams, and we are keen to identify novel solutions, such as dedicated discharge coordinators,4 to facilitate the discharge process on resident teams without detracting from the educational value of the rotation.

Zoucha et al. also found that factors beyond our control (having a lower daily census, attending on a nonresident service) were significantly associated with both earlier discharge order entry times and the actual time of patient discharge.3 While it is tempting to foist the entirety of the blame on extrinsic factors such as discharge placement and insurance issues, the reality is there might be some workflow changes that could expedite the discharge process. The authors are correct to emphasize that rounding style, in which discharges are prioritized to be seen first, is a behavior modification worth targeting. The percentage of teams that routinely see discharges first is not well studied, as other factors, such as clinically unstable patients, new admissions from overnight, and even mundane characteristics such as geographic location in the hospital, can also compete for prioritization in rounding order. Given the authors’ findings, we are eager to see further work in this area as prioritization of discharges during rounds could conceivably be studied within the context of a randomized controlled trial. Other innovations in rounding styles such as rounding-in-flow5 (in which all tasks are completed for a single patient before rounding on the next patient) can also significantly reduce the time to discharge order placement.

With help from the Penn Medicine Center for Health Care Innovation, we are actively studying bottlenecks in the discharge process by developing an interactive platform focused on delivering real-time information to all members of the healthcare team. Rapid rounds are held every morning with the attending physician, floor nursing leadership, physical therapy, social worker, and case management to quickly identify pending tasks, anticipated disposition, and a target date of discharge. Efficiency is key, as each team is limited to approximately 5-10 minutes. Previous studies (mostly pre–post studies) have shown that this simple intervention significantly reduced LOS,6,7 increased rates of discharge before noon,8 and was improved by electronic tracking tools.9 Our multidisciplinary rounds are unique in that information is then entered into an intuitive, web-based platform, which allows consolidation and analysis that permits generation of real-time statistics. By standardizing the discharge planning process, we hope to streamline a previously fragmented process and maximize the efficiency of hospital resource utilization.

Ultimately, high-quality care of complex patients on internal medicine services from admission to discharge requires hard work, smart utilization of resources, and a little bit of luck. There may not be a secret ingredient that guarantees perfectly efficient discharges 100% of the time, but this study inspires us to ponder additional approaches to this longstanding problem. The authors are to be congratulated for a rigorous study that illuminates where we as healthcare providers are able to realistically intervene to expedite the discharge process. First, having a lower census cap may not be possible in this era of maximal hospital usage, but this work suggests that thoughtful management of time on rounds may be a way to address the underlying problem. Secondly, the superior efficiency of nonteaching services may merely reflect the increased experience of the providers, and a realistic solution could be to implement a formal curriculum to educate housestaff about the discharge process, which would simultaneously address residency competency standards for transitions of care. Finally, the role of innovative informatics tools will surely open further avenues of investigation, as we continually evolve in response to intensifying standards of modern, efficient healthcare delivery in the 21st century. It may not be possible to eliminate the complexity from this particular Rube Goldberg machine, but taking the steps above may allow us to implement as many fail-safes as we can.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Young E, Stickrath C, McNulty M, et al. Residents’ exposure to educational experiences in facilitating hospital discharges. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(2):184-189. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00503.1. PubMed

2. Greysen SR, Schiliro D, Curry L, et al. “Learning by doing” - Resident perspectives on developing competency in high-quality discharge care. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(9):1188-1194. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2094-5. PubMed

3. Zoucha J, Hull M, Keniston A, et al. Barriers to Early Hospital Discharge: A Cross-Sectional Study at Five Academic Hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(12):816-822. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3074. PubMed

4. Finn KM, Heffner R, Chang Y, et al. Improving the discharge process by embedding a discharge facilitator in a resident team. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(9):494-500. doi: 10.1002/jhm.924. PubMed

5. Calderon AS, Blackmore CC, Williams BL, et al. Transforming ward rounds through rounding-in-flow. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(4):750-755. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-13-00324.1. PubMed

6. Kane M, Rohatgi N, Heidenreich PA, et al. Lean-based redesign of multidisciplinary rounds on general medicine service. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(7):482-485. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2908. PubMed

7. Gonçalves-Bradley D, Lannin N, Clemson L, Cameron ID, Shepperd S. Discharge planning from hospital. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;1-3. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000313.pub5.www.cochranelibrary.com. PubMed

8. Wertheimer B, Jacobs REA, Bailey M, et al. Discharge before noon: an achievable hospital goal. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(4):210-214. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2154. PubMed

9. Meo N, Paul E, Wilson C, Powers J, Magbual M, Miles KM. Introducing an electronic tracking tool into daily multidisciplinary discharge rounds on a medicine service: a quality improvement project to reduce length of stay. BMJ Open Qual. 2018;7(3):e000174. doi: 10.1136/bmjoq-2017-000174. PubMed

One of the least taught yet most complicated tasks confronting new trainees is the bewildering process of discharging a patient. On an internal medicine service, this process can often resemble a Rube Goldberg machine, in which a “simple” task is accomplished through a series of interconnected, almost comically convoluted, yet separate steps that are triggered one after another and must be executed perfectly in sequence for success. It seems easy at first; just tap out a few sentences in the discharge paperwork, do a quick medication reconciliation, and a click of a button later, voila! The patient magically falls off the list and is on their merry way home. In reality, it only takes one wrench thrown into the Rube Goldberg machine to take down the whole operation. Much to the chagrin of internal medicine interns across the country, residents quickly learn that discharge planning is usually far from straightforward and that a myriad of obstacles (often dynamic and frustratingly unpredictable) can stand in the way of a successful discharge.

While some surgical services can streamline discharge processes to target defined lengths of stay based on a particular diagnosis, general medicine patients tend to have greater numbers of comorbid conditions, complex hospital courses, and wider variation in access to posthospital healthcare. In addition, there is very little formal instruction in transitions of care, and most residents identify direct patient care (learning by doing) as the primary mode of education.1,2 Struggling through the process of finding an appropriate placement, ensuring adequate outpatient follow-up, and untangling a jumbled mess of a medication reconciliation is often the only way that housestaff learn the Sisyphean task of transitioning care out of the hospital. The unpredictability and intensity of patient care adds to the ever growing list of competing demands on the time and attention of residents. Attendings face pressure on all sides to not only provide exemplary patient care and an educational experience but also to optimize hospital throughput by discharging patients as soon as possible (and ideally before noon). No wonder that the discharge process can threaten to unravel at any time, with delays and complications in discharge metamorphosing into increased length of stay (LOS), poorer outcomes, and increased 30-day readmission rates. As on-the-ground providers, what realities do we face when challenging ourselves to discharge patients before noon, and what practical changes in our workflow can we make to reach this goal?

In this month’s Journal of Hospital Medicine, Zoucha et al. examine these questions in real time by identifying barriers preventing both “definite” and “possible” discharges at three representative time points over the course of randomly chosen weekdays. They surveyed both housestaff and attendings at five academic hospitals across the United States, and the majority of patients were cared for on teaching services.3 Reflecting the inherent differences in workflow between teaching and nonteaching services, delays in definite discharges on teaching services were most often hindered by completing rounds and the need to staff the patient with the attending, whereas nonresident services identified other patient-care-related (both urgent and nonurgent) issues to be the culprits. Late-afternoon discharges were delayed on teaching services due to outstanding paperwork and follow-up arrangements, both of which most senior residents are keenly aware of and make their best effort to complete ahead of time. Patients designated as “possible” discharges were awaiting clinical improvement and resolution of disposition issues dependent on social work and safe placement, which reasonably seemed independent of service type. These descriptive findings suggest that nonresident services are more efficient than resident teams, and we are keen to identify novel solutions, such as dedicated discharge coordinators,4 to facilitate the discharge process on resident teams without detracting from the educational value of the rotation.

Zoucha et al. also found that factors beyond our control (having a lower daily census, attending on a nonresident service) were significantly associated with both earlier discharge order entry times and the actual time of patient discharge.3 While it is tempting to foist the entirety of the blame on extrinsic factors such as discharge placement and insurance issues, the reality is there might be some workflow changes that could expedite the discharge process. The authors are correct to emphasize that rounding style, in which discharges are prioritized to be seen first, is a behavior modification worth targeting. The percentage of teams that routinely see discharges first is not well studied, as other factors, such as clinically unstable patients, new admissions from overnight, and even mundane characteristics such as geographic location in the hospital, can also compete for prioritization in rounding order. Given the authors’ findings, we are eager to see further work in this area as prioritization of discharges during rounds could conceivably be studied within the context of a randomized controlled trial. Other innovations in rounding styles such as rounding-in-flow5 (in which all tasks are completed for a single patient before rounding on the next patient) can also significantly reduce the time to discharge order placement.

With help from the Penn Medicine Center for Health Care Innovation, we are actively studying bottlenecks in the discharge process by developing an interactive platform focused on delivering real-time information to all members of the healthcare team. Rapid rounds are held every morning with the attending physician, floor nursing leadership, physical therapy, social worker, and case management to quickly identify pending tasks, anticipated disposition, and a target date of discharge. Efficiency is key, as each team is limited to approximately 5-10 minutes. Previous studies (mostly pre–post studies) have shown that this simple intervention significantly reduced LOS,6,7 increased rates of discharge before noon,8 and was improved by electronic tracking tools.9 Our multidisciplinary rounds are unique in that information is then entered into an intuitive, web-based platform, which allows consolidation and analysis that permits generation of real-time statistics. By standardizing the discharge planning process, we hope to streamline a previously fragmented process and maximize the efficiency of hospital resource utilization.

Ultimately, high-quality care of complex patients on internal medicine services from admission to discharge requires hard work, smart utilization of resources, and a little bit of luck. There may not be a secret ingredient that guarantees perfectly efficient discharges 100% of the time, but this study inspires us to ponder additional approaches to this longstanding problem. The authors are to be congratulated for a rigorous study that illuminates where we as healthcare providers are able to realistically intervene to expedite the discharge process. First, having a lower census cap may not be possible in this era of maximal hospital usage, but this work suggests that thoughtful management of time on rounds may be a way to address the underlying problem. Secondly, the superior efficiency of nonteaching services may merely reflect the increased experience of the providers, and a realistic solution could be to implement a formal curriculum to educate housestaff about the discharge process, which would simultaneously address residency competency standards for transitions of care. Finally, the role of innovative informatics tools will surely open further avenues of investigation, as we continually evolve in response to intensifying standards of modern, efficient healthcare delivery in the 21st century. It may not be possible to eliminate the complexity from this particular Rube Goldberg machine, but taking the steps above may allow us to implement as many fail-safes as we can.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

One of the least taught yet most complicated tasks confronting new trainees is the bewildering process of discharging a patient. On an internal medicine service, this process can often resemble a Rube Goldberg machine, in which a “simple” task is accomplished through a series of interconnected, almost comically convoluted, yet separate steps that are triggered one after another and must be executed perfectly in sequence for success. It seems easy at first; just tap out a few sentences in the discharge paperwork, do a quick medication reconciliation, and a click of a button later, voila! The patient magically falls off the list and is on their merry way home. In reality, it only takes one wrench thrown into the Rube Goldberg machine to take down the whole operation. Much to the chagrin of internal medicine interns across the country, residents quickly learn that discharge planning is usually far from straightforward and that a myriad of obstacles (often dynamic and frustratingly unpredictable) can stand in the way of a successful discharge.

While some surgical services can streamline discharge processes to target defined lengths of stay based on a particular diagnosis, general medicine patients tend to have greater numbers of comorbid conditions, complex hospital courses, and wider variation in access to posthospital healthcare. In addition, there is very little formal instruction in transitions of care, and most residents identify direct patient care (learning by doing) as the primary mode of education.1,2 Struggling through the process of finding an appropriate placement, ensuring adequate outpatient follow-up, and untangling a jumbled mess of a medication reconciliation is often the only way that housestaff learn the Sisyphean task of transitioning care out of the hospital. The unpredictability and intensity of patient care adds to the ever growing list of competing demands on the time and attention of residents. Attendings face pressure on all sides to not only provide exemplary patient care and an educational experience but also to optimize hospital throughput by discharging patients as soon as possible (and ideally before noon). No wonder that the discharge process can threaten to unravel at any time, with delays and complications in discharge metamorphosing into increased length of stay (LOS), poorer outcomes, and increased 30-day readmission rates. As on-the-ground providers, what realities do we face when challenging ourselves to discharge patients before noon, and what practical changes in our workflow can we make to reach this goal?

In this month’s Journal of Hospital Medicine, Zoucha et al. examine these questions in real time by identifying barriers preventing both “definite” and “possible” discharges at three representative time points over the course of randomly chosen weekdays. They surveyed both housestaff and attendings at five academic hospitals across the United States, and the majority of patients were cared for on teaching services.3 Reflecting the inherent differences in workflow between teaching and nonteaching services, delays in definite discharges on teaching services were most often hindered by completing rounds and the need to staff the patient with the attending, whereas nonresident services identified other patient-care-related (both urgent and nonurgent) issues to be the culprits. Late-afternoon discharges were delayed on teaching services due to outstanding paperwork and follow-up arrangements, both of which most senior residents are keenly aware of and make their best effort to complete ahead of time. Patients designated as “possible” discharges were awaiting clinical improvement and resolution of disposition issues dependent on social work and safe placement, which reasonably seemed independent of service type. These descriptive findings suggest that nonresident services are more efficient than resident teams, and we are keen to identify novel solutions, such as dedicated discharge coordinators,4 to facilitate the discharge process on resident teams without detracting from the educational value of the rotation.

Zoucha et al. also found that factors beyond our control (having a lower daily census, attending on a nonresident service) were significantly associated with both earlier discharge order entry times and the actual time of patient discharge.3 While it is tempting to foist the entirety of the blame on extrinsic factors such as discharge placement and insurance issues, the reality is there might be some workflow changes that could expedite the discharge process. The authors are correct to emphasize that rounding style, in which discharges are prioritized to be seen first, is a behavior modification worth targeting. The percentage of teams that routinely see discharges first is not well studied, as other factors, such as clinically unstable patients, new admissions from overnight, and even mundane characteristics such as geographic location in the hospital, can also compete for prioritization in rounding order. Given the authors’ findings, we are eager to see further work in this area as prioritization of discharges during rounds could conceivably be studied within the context of a randomized controlled trial. Other innovations in rounding styles such as rounding-in-flow5 (in which all tasks are completed for a single patient before rounding on the next patient) can also significantly reduce the time to discharge order placement.

With help from the Penn Medicine Center for Health Care Innovation, we are actively studying bottlenecks in the discharge process by developing an interactive platform focused on delivering real-time information to all members of the healthcare team. Rapid rounds are held every morning with the attending physician, floor nursing leadership, physical therapy, social worker, and case management to quickly identify pending tasks, anticipated disposition, and a target date of discharge. Efficiency is key, as each team is limited to approximately 5-10 minutes. Previous studies (mostly pre–post studies) have shown that this simple intervention significantly reduced LOS,6,7 increased rates of discharge before noon,8 and was improved by electronic tracking tools.9 Our multidisciplinary rounds are unique in that information is then entered into an intuitive, web-based platform, which allows consolidation and analysis that permits generation of real-time statistics. By standardizing the discharge planning process, we hope to streamline a previously fragmented process and maximize the efficiency of hospital resource utilization.

Ultimately, high-quality care of complex patients on internal medicine services from admission to discharge requires hard work, smart utilization of resources, and a little bit of luck. There may not be a secret ingredient that guarantees perfectly efficient discharges 100% of the time, but this study inspires us to ponder additional approaches to this longstanding problem. The authors are to be congratulated for a rigorous study that illuminates where we as healthcare providers are able to realistically intervene to expedite the discharge process. First, having a lower census cap may not be possible in this era of maximal hospital usage, but this work suggests that thoughtful management of time on rounds may be a way to address the underlying problem. Secondly, the superior efficiency of nonteaching services may merely reflect the increased experience of the providers, and a realistic solution could be to implement a formal curriculum to educate housestaff about the discharge process, which would simultaneously address residency competency standards for transitions of care. Finally, the role of innovative informatics tools will surely open further avenues of investigation, as we continually evolve in response to intensifying standards of modern, efficient healthcare delivery in the 21st century. It may not be possible to eliminate the complexity from this particular Rube Goldberg machine, but taking the steps above may allow us to implement as many fail-safes as we can.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Young E, Stickrath C, McNulty M, et al. Residents’ exposure to educational experiences in facilitating hospital discharges. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(2):184-189. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00503.1. PubMed

2. Greysen SR, Schiliro D, Curry L, et al. “Learning by doing” - Resident perspectives on developing competency in high-quality discharge care. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(9):1188-1194. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2094-5. PubMed

3. Zoucha J, Hull M, Keniston A, et al. Barriers to Early Hospital Discharge: A Cross-Sectional Study at Five Academic Hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(12):816-822. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3074. PubMed

4. Finn KM, Heffner R, Chang Y, et al. Improving the discharge process by embedding a discharge facilitator in a resident team. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(9):494-500. doi: 10.1002/jhm.924. PubMed

5. Calderon AS, Blackmore CC, Williams BL, et al. Transforming ward rounds through rounding-in-flow. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(4):750-755. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-13-00324.1. PubMed

6. Kane M, Rohatgi N, Heidenreich PA, et al. Lean-based redesign of multidisciplinary rounds on general medicine service. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(7):482-485. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2908. PubMed

7. Gonçalves-Bradley D, Lannin N, Clemson L, Cameron ID, Shepperd S. Discharge planning from hospital. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;1-3. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000313.pub5.www.cochranelibrary.com. PubMed

8. Wertheimer B, Jacobs REA, Bailey M, et al. Discharge before noon: an achievable hospital goal. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(4):210-214. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2154. PubMed

9. Meo N, Paul E, Wilson C, Powers J, Magbual M, Miles KM. Introducing an electronic tracking tool into daily multidisciplinary discharge rounds on a medicine service: a quality improvement project to reduce length of stay. BMJ Open Qual. 2018;7(3):e000174. doi: 10.1136/bmjoq-2017-000174. PubMed

1. Young E, Stickrath C, McNulty M, et al. Residents’ exposure to educational experiences in facilitating hospital discharges. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(2):184-189. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00503.1. PubMed

2. Greysen SR, Schiliro D, Curry L, et al. “Learning by doing” - Resident perspectives on developing competency in high-quality discharge care. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(9):1188-1194. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2094-5. PubMed

3. Zoucha J, Hull M, Keniston A, et al. Barriers to Early Hospital Discharge: A Cross-Sectional Study at Five Academic Hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(12):816-822. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3074. PubMed

4. Finn KM, Heffner R, Chang Y, et al. Improving the discharge process by embedding a discharge facilitator in a resident team. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(9):494-500. doi: 10.1002/jhm.924. PubMed

5. Calderon AS, Blackmore CC, Williams BL, et al. Transforming ward rounds through rounding-in-flow. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(4):750-755. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-13-00324.1. PubMed

6. Kane M, Rohatgi N, Heidenreich PA, et al. Lean-based redesign of multidisciplinary rounds on general medicine service. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(7):482-485. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2908. PubMed

7. Gonçalves-Bradley D, Lannin N, Clemson L, Cameron ID, Shepperd S. Discharge planning from hospital. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;1-3. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000313.pub5.www.cochranelibrary.com. PubMed

8. Wertheimer B, Jacobs REA, Bailey M, et al. Discharge before noon: an achievable hospital goal. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(4):210-214. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2154. PubMed

9. Meo N, Paul E, Wilson C, Powers J, Magbual M, Miles KM. Introducing an electronic tracking tool into daily multidisciplinary discharge rounds on a medicine service: a quality improvement project to reduce length of stay. BMJ Open Qual. 2018;7(3):e000174. doi: 10.1136/bmjoq-2017-000174. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

We May Not “Have It All,” But We Can Make It Better through Structural Changes

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, the paper by Gottenborg et al. captures the experiences of female academic hospitalists navigating one of the most significant transitions they will face—becoming new mothers.1 This article gives an accessible voice to impersonal statistics about the barriers women physicians encounter within and across specialties in academia. The challenges and anecdotes shared by the study participants were eminently relatable and captured the all-too-familiar circumstances most of us with children have faced in our careers as physician mothers.

STUDY COMMENTARY AND DISCUSSION

This study uses qualitative research methods to illustrate the hurdles faced by mothers in hospital medicine beyond what is demonstrated by quantitative measures and provides the helpful step of proposing some solutions to the obstacles they have faced. While the sample size was very small, the women interviewed were diverse in their years in practice, geographic distribution, and percent clinical effort, providing evidence that the themes discussed prevail across demographic categories.

The snowball sampling via the Society of Hospital Medicine committees may not have yielded a representative sample of female hospitalists. It seems possible that women who are involved in this type of leadership may be better supported and/or have different work schedules than their peers who are not in leadership positions. We also wish there had been more emphasis on the systemic and structural factors that can improve the quality of life of physician mothers. These policies include paternity leave and other creative ways of acknowledging the useful skills and experience that motherhood brings to bear on clinical practice, such as increased empathy and compassion, as mentioned by one of the study participants.

Even with the aforementioned limitations, this study is important because it combines authentic quotes from practicing academic hospitalists with concrete and tangible suggestions for structural changes. The most striking element is that the majority of the study participants experienced uncertainty and a lack of transparency around parental leave policies. As nearly half of hospitalists are women and 80% are under age 40,2 it seems unimaginable that there would not be explicit policies in place for what is a common and largely anticipated life event. Medicine has made great strides toward gender equality, but we are unlikely to ever reach the goal of true parity without openly addressing the disproportionate effect of childbearing and child rearing on women physicians. Standardized, readily available, and equitable parental leave policies (for both birth parents and nonbirth parents) are the first and most critical step.

The absence of standard leave policies naturally puts physician mothers in the position of having to negotiate or “haggle” with various supervisors, the majority of whom are male division chiefs and department chairs,3 which places all parties in an uncomfortable position, further reinforcing inequities and sowing discord and resentment. Having formal policies around leave protects not only those who utilize parental leave but also the other members of a hospital medicine practice who take on the workload of the person on leave.

Uncertainty around how to address the increased clinical load and for how long, also creates anxiety among other group members and may lead to feelings of bitterness toward clinicians on leave, further contributing to the negative impact of new parenthood on female hospitalists. We can think of no other medical circumstance in which there is as much advance notice of the need for significant time away from work. Yet pregnancy, which is subject to complications and emergencies just like other medical conditions, is treated with so little concern that one may be asked to arrange for their own coverage during such an emergency, as one study subject reported.

We also empathize with the study participants’ reports of feeling that supervisors often mentally discounted their ability to participate in projects on return to work. These pernicious assumptions can compound a cycle of lost productivity, disengagement, and attrition from the workforce.

Female hospitalists returning from leave face additional challenges that place an undue burden on their professional activities, most notably related to breastfeeding. This is particularly relevant in the context of the intensity inherent in practicing hospital medicine, which includes long days of being the primary provider for acutely ill inpatients, as well as long stretches of many consecutive days when it may not be possible to return home before children’s bedtime. Even at our own institution, which has been recognized as a “Healthy Mothers Workplace,” breastfeeding accommodations are not set up to allow for ongoing clinical activities while taking time to express breastmilk, and the clinical schedule does not build in adjustments for this time-consuming and psychologically taxing commitment. Breastfeeding for at least one year is the medical recommendation of the American Academy of Pediatrics in line with a substantial body of evidence.4 One quote from the article poignantly notes, “Pumping every 3-4 hours: stopping what you’re doing, finding an empty room to pump, finding a place to store your milk, then going back to work, three times per shift, for the next 9 months of your life, was hell.” If we cannot enable our own medical providers to follow evidence-based recommendations, how can we possibly expect this of our patients?

CONCLUSIONS

The notion of women “having it all” is an impossible ideal—both work and life outside of work will inevitably require tradeoffs. However, there is an abundance of evidence and recommendations for concrete steps that can be taken to improve the experience of female physicians who have children. These include formal policies for childbearing and child rearing leave (the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends at least six to nine months5), convenient space and protected time for pumping milk during the first year, on-site childcare services and back-up child care, and flexible work schedules.6 It is time to stop treating childbirth among female physicians like an unexpected inconvenience and acknowledge the undeniable demographics of physicians in hospital medicine and the duty of healthcare systems and hospital medicine leaders to effectively plan for the needs of half of their workforce.

Disclosures

Neither of the authors have any financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Gottenborg E, Maw A, Ngov LK, Burden M, Ponomaryova A, Jones CD. You can’t have it all: The experience of academic hospitalists during pregnancy, parental leave, and return to work. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(12):836-839. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3076. PubMed

2. Reid MB, Misky GJ, Harrison RA, Sharpe B, Auerbach A, Glasheen JJ. Mentorship, productivity, and promotion among academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):23-27. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1892-5. PubMed

3. Association of American Medical Colleges. The state of women in academic medicine: The pipeline and pathways to leadership, 2015-2016. https://www.aamc.org/members/gwims/statistics/. Accessed October 1, 2018.

4. American Academy of Pediatrics. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e827-e841. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3552. PubMed

5. National Public Radio. A Pediatrician’s View of Paid Parental Leave. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/10/10/497052014/a-pediatricians-view-of-paid-parental-leave. Accessed September 26, 2018.

6. Mangurian C, Linos E, Sarkar U, Rodriguez C, Jagsi R. What’s holding women in medicine back from leadership? (2018, June 19). Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2018/06/whats-holding-women-in-medicine-back-from-leadership. Accessed October 1, 2018.

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, the paper by Gottenborg et al. captures the experiences of female academic hospitalists navigating one of the most significant transitions they will face—becoming new mothers.1 This article gives an accessible voice to impersonal statistics about the barriers women physicians encounter within and across specialties in academia. The challenges and anecdotes shared by the study participants were eminently relatable and captured the all-too-familiar circumstances most of us with children have faced in our careers as physician mothers.

STUDY COMMENTARY AND DISCUSSION

This study uses qualitative research methods to illustrate the hurdles faced by mothers in hospital medicine beyond what is demonstrated by quantitative measures and provides the helpful step of proposing some solutions to the obstacles they have faced. While the sample size was very small, the women interviewed were diverse in their years in practice, geographic distribution, and percent clinical effort, providing evidence that the themes discussed prevail across demographic categories.

The snowball sampling via the Society of Hospital Medicine committees may not have yielded a representative sample of female hospitalists. It seems possible that women who are involved in this type of leadership may be better supported and/or have different work schedules than their peers who are not in leadership positions. We also wish there had been more emphasis on the systemic and structural factors that can improve the quality of life of physician mothers. These policies include paternity leave and other creative ways of acknowledging the useful skills and experience that motherhood brings to bear on clinical practice, such as increased empathy and compassion, as mentioned by one of the study participants.

Even with the aforementioned limitations, this study is important because it combines authentic quotes from practicing academic hospitalists with concrete and tangible suggestions for structural changes. The most striking element is that the majority of the study participants experienced uncertainty and a lack of transparency around parental leave policies. As nearly half of hospitalists are women and 80% are under age 40,2 it seems unimaginable that there would not be explicit policies in place for what is a common and largely anticipated life event. Medicine has made great strides toward gender equality, but we are unlikely to ever reach the goal of true parity without openly addressing the disproportionate effect of childbearing and child rearing on women physicians. Standardized, readily available, and equitable parental leave policies (for both birth parents and nonbirth parents) are the first and most critical step.

The absence of standard leave policies naturally puts physician mothers in the position of having to negotiate or “haggle” with various supervisors, the majority of whom are male division chiefs and department chairs,3 which places all parties in an uncomfortable position, further reinforcing inequities and sowing discord and resentment. Having formal policies around leave protects not only those who utilize parental leave but also the other members of a hospital medicine practice who take on the workload of the person on leave.

Uncertainty around how to address the increased clinical load and for how long, also creates anxiety among other group members and may lead to feelings of bitterness toward clinicians on leave, further contributing to the negative impact of new parenthood on female hospitalists. We can think of no other medical circumstance in which there is as much advance notice of the need for significant time away from work. Yet pregnancy, which is subject to complications and emergencies just like other medical conditions, is treated with so little concern that one may be asked to arrange for their own coverage during such an emergency, as one study subject reported.

We also empathize with the study participants’ reports of feeling that supervisors often mentally discounted their ability to participate in projects on return to work. These pernicious assumptions can compound a cycle of lost productivity, disengagement, and attrition from the workforce.

Female hospitalists returning from leave face additional challenges that place an undue burden on their professional activities, most notably related to breastfeeding. This is particularly relevant in the context of the intensity inherent in practicing hospital medicine, which includes long days of being the primary provider for acutely ill inpatients, as well as long stretches of many consecutive days when it may not be possible to return home before children’s bedtime. Even at our own institution, which has been recognized as a “Healthy Mothers Workplace,” breastfeeding accommodations are not set up to allow for ongoing clinical activities while taking time to express breastmilk, and the clinical schedule does not build in adjustments for this time-consuming and psychologically taxing commitment. Breastfeeding for at least one year is the medical recommendation of the American Academy of Pediatrics in line with a substantial body of evidence.4 One quote from the article poignantly notes, “Pumping every 3-4 hours: stopping what you’re doing, finding an empty room to pump, finding a place to store your milk, then going back to work, three times per shift, for the next 9 months of your life, was hell.” If we cannot enable our own medical providers to follow evidence-based recommendations, how can we possibly expect this of our patients?

CONCLUSIONS

The notion of women “having it all” is an impossible ideal—both work and life outside of work will inevitably require tradeoffs. However, there is an abundance of evidence and recommendations for concrete steps that can be taken to improve the experience of female physicians who have children. These include formal policies for childbearing and child rearing leave (the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends at least six to nine months5), convenient space and protected time for pumping milk during the first year, on-site childcare services and back-up child care, and flexible work schedules.6 It is time to stop treating childbirth among female physicians like an unexpected inconvenience and acknowledge the undeniable demographics of physicians in hospital medicine and the duty of healthcare systems and hospital medicine leaders to effectively plan for the needs of half of their workforce.

Disclosures

Neither of the authors have any financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, the paper by Gottenborg et al. captures the experiences of female academic hospitalists navigating one of the most significant transitions they will face—becoming new mothers.1 This article gives an accessible voice to impersonal statistics about the barriers women physicians encounter within and across specialties in academia. The challenges and anecdotes shared by the study participants were eminently relatable and captured the all-too-familiar circumstances most of us with children have faced in our careers as physician mothers.

STUDY COMMENTARY AND DISCUSSION

This study uses qualitative research methods to illustrate the hurdles faced by mothers in hospital medicine beyond what is demonstrated by quantitative measures and provides the helpful step of proposing some solutions to the obstacles they have faced. While the sample size was very small, the women interviewed were diverse in their years in practice, geographic distribution, and percent clinical effort, providing evidence that the themes discussed prevail across demographic categories.

The snowball sampling via the Society of Hospital Medicine committees may not have yielded a representative sample of female hospitalists. It seems possible that women who are involved in this type of leadership may be better supported and/or have different work schedules than their peers who are not in leadership positions. We also wish there had been more emphasis on the systemic and structural factors that can improve the quality of life of physician mothers. These policies include paternity leave and other creative ways of acknowledging the useful skills and experience that motherhood brings to bear on clinical practice, such as increased empathy and compassion, as mentioned by one of the study participants.

Even with the aforementioned limitations, this study is important because it combines authentic quotes from practicing academic hospitalists with concrete and tangible suggestions for structural changes. The most striking element is that the majority of the study participants experienced uncertainty and a lack of transparency around parental leave policies. As nearly half of hospitalists are women and 80% are under age 40,2 it seems unimaginable that there would not be explicit policies in place for what is a common and largely anticipated life event. Medicine has made great strides toward gender equality, but we are unlikely to ever reach the goal of true parity without openly addressing the disproportionate effect of childbearing and child rearing on women physicians. Standardized, readily available, and equitable parental leave policies (for both birth parents and nonbirth parents) are the first and most critical step.

The absence of standard leave policies naturally puts physician mothers in the position of having to negotiate or “haggle” with various supervisors, the majority of whom are male division chiefs and department chairs,3 which places all parties in an uncomfortable position, further reinforcing inequities and sowing discord and resentment. Having formal policies around leave protects not only those who utilize parental leave but also the other members of a hospital medicine practice who take on the workload of the person on leave.

Uncertainty around how to address the increased clinical load and for how long, also creates anxiety among other group members and may lead to feelings of bitterness toward clinicians on leave, further contributing to the negative impact of new parenthood on female hospitalists. We can think of no other medical circumstance in which there is as much advance notice of the need for significant time away from work. Yet pregnancy, which is subject to complications and emergencies just like other medical conditions, is treated with so little concern that one may be asked to arrange for their own coverage during such an emergency, as one study subject reported.

We also empathize with the study participants’ reports of feeling that supervisors often mentally discounted their ability to participate in projects on return to work. These pernicious assumptions can compound a cycle of lost productivity, disengagement, and attrition from the workforce.

Female hospitalists returning from leave face additional challenges that place an undue burden on their professional activities, most notably related to breastfeeding. This is particularly relevant in the context of the intensity inherent in practicing hospital medicine, which includes long days of being the primary provider for acutely ill inpatients, as well as long stretches of many consecutive days when it may not be possible to return home before children’s bedtime. Even at our own institution, which has been recognized as a “Healthy Mothers Workplace,” breastfeeding accommodations are not set up to allow for ongoing clinical activities while taking time to express breastmilk, and the clinical schedule does not build in adjustments for this time-consuming and psychologically taxing commitment. Breastfeeding for at least one year is the medical recommendation of the American Academy of Pediatrics in line with a substantial body of evidence.4 One quote from the article poignantly notes, “Pumping every 3-4 hours: stopping what you’re doing, finding an empty room to pump, finding a place to store your milk, then going back to work, three times per shift, for the next 9 months of your life, was hell.” If we cannot enable our own medical providers to follow evidence-based recommendations, how can we possibly expect this of our patients?

CONCLUSIONS

The notion of women “having it all” is an impossible ideal—both work and life outside of work will inevitably require tradeoffs. However, there is an abundance of evidence and recommendations for concrete steps that can be taken to improve the experience of female physicians who have children. These include formal policies for childbearing and child rearing leave (the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends at least six to nine months5), convenient space and protected time for pumping milk during the first year, on-site childcare services and back-up child care, and flexible work schedules.6 It is time to stop treating childbirth among female physicians like an unexpected inconvenience and acknowledge the undeniable demographics of physicians in hospital medicine and the duty of healthcare systems and hospital medicine leaders to effectively plan for the needs of half of their workforce.

Disclosures

Neither of the authors have any financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Gottenborg E, Maw A, Ngov LK, Burden M, Ponomaryova A, Jones CD. You can’t have it all: The experience of academic hospitalists during pregnancy, parental leave, and return to work. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(12):836-839. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3076. PubMed

2. Reid MB, Misky GJ, Harrison RA, Sharpe B, Auerbach A, Glasheen JJ. Mentorship, productivity, and promotion among academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):23-27. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1892-5. PubMed

3. Association of American Medical Colleges. The state of women in academic medicine: The pipeline and pathways to leadership, 2015-2016. https://www.aamc.org/members/gwims/statistics/. Accessed October 1, 2018.

4. American Academy of Pediatrics. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e827-e841. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3552. PubMed

5. National Public Radio. A Pediatrician’s View of Paid Parental Leave. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/10/10/497052014/a-pediatricians-view-of-paid-parental-leave. Accessed September 26, 2018.

6. Mangurian C, Linos E, Sarkar U, Rodriguez C, Jagsi R. What’s holding women in medicine back from leadership? (2018, June 19). Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2018/06/whats-holding-women-in-medicine-back-from-leadership. Accessed October 1, 2018.

1. Gottenborg E, Maw A, Ngov LK, Burden M, Ponomaryova A, Jones CD. You can’t have it all: The experience of academic hospitalists during pregnancy, parental leave, and return to work. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(12):836-839. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3076. PubMed

2. Reid MB, Misky GJ, Harrison RA, Sharpe B, Auerbach A, Glasheen JJ. Mentorship, productivity, and promotion among academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):23-27. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1892-5. PubMed

3. Association of American Medical Colleges. The state of women in academic medicine: The pipeline and pathways to leadership, 2015-2016. https://www.aamc.org/members/gwims/statistics/. Accessed October 1, 2018.

4. American Academy of Pediatrics. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e827-e841. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3552. PubMed

5. National Public Radio. A Pediatrician’s View of Paid Parental Leave. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/10/10/497052014/a-pediatricians-view-of-paid-parental-leave. Accessed September 26, 2018.

6. Mangurian C, Linos E, Sarkar U, Rodriguez C, Jagsi R. What’s holding women in medicine back from leadership? (2018, June 19). Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2018/06/whats-holding-women-in-medicine-back-from-leadership. Accessed October 1, 2018.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

On Decreasing Utilization: Models of Care for Frequently Hospitalized Patients and Their Effect on Outcomes

In this month’s edition of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Goodwin and colleagues report their findings from their systematic review of models of care for frequently hospitalized patients. The authors reviewed the literature for interventions to reduce hospital admissions in frequently hospitalized patients with the goal of assessing the success of the interventions. This report contributes to the literature base of interventions to reduce healthcare utilization, particularly in the area of inpatient hospitalization.1

Goodwin et al. report that only nine studies met their criteria for review after a thorough search of the published literature. Of these nine studies, only four were determined to be high-quality studies. Interestingly, the low-quality studies found positive results in reducing hospital utilization, whereas the high-quality studies found decreases that were mirrored by their control groups. Impressive heterogeneity was found in the range of definitions, interventions, and outcome measures in the studies. These studies highlight the issue of “regression to the mean” for sicker individuals; however, they may not address readmission rates of specific medical systems or procedures that are also cost drivers, even if the patients are not considered critically ill. They also show where research partnerships can assist in increasing the number of members included in the studies for robust analyses.

From the perspective of a health plan, we applaud all efforts to improve patient outcomes and reduce cost. This report states that efforts to reduce chronic hospitalizations have not been unqualified successes. We must reflect upon how reducing utilization and improving outcomes align with our overall goals as a society. Recently, Federal Reserve Chairman Jay Powell summed up our nation’s particular issue, stating, “It is widely understood that the United States is on an unsustainable fiscal path, largely due to the interaction between an aging population and a healthcare system that delivers pretty average healthcare at a cost that is much higher than that of any other advanced economy.”2

A recent Kaiser Family Foundation analysis showed that 1% of patients accounted for 23% of all medical spending in the United States, and 97% of medical spending is attributed to the top 50% of patients.3 Pharmaceutical costs also play a role in this trend. Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Texas (BCBSTX) found that 2.5% of our population accounted for just under 50% of total medical spending. Conversely, when looking at patients with very high costs, only 0.4% had over $100,000 in spending exclusive of pharmacy. When including pharmacy, that number rises to 0.5%. As we consider annual medical and pharmacy trends year over year, we find that pharmacy spending may outpace hospital expenses in the near future.

Our internal data are also consistent with published reports that fewer than half of high-cost patients in one year continue to be high-cost cases the following year. Niall Brennan et al. reported that only 39% of the top 5% of spenders in a given year are also high spenders the following year.4 This finding not only coincides with the author’s statement around regression to the mean for the high admission utilizers, but it may be instructive to those looking to a Pareto method of attacking cost. If more than half of targeted patients will move out of the high cost category on their own, then demonstrating the effectiveness of interventions becomes challenging. Moreover, this regression finding speaks to the need to create effective programs to manage population health on a broad basis, which can address quality to all members and streamline costs for a large group that covers well more than 50% of medical spending.

BCBSTX emphasizes the creation of systems that let providers become responsible and accountable to outcomes and cost. Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) and Intensive Medical Homes (IMHs) have played important roles in this journey, but physicians need to continue to invent and prioritize interventions that may achieve both goals. In particular, hospitalists have an important role to play. As ACOs flourish, hospitalists will need to join under the value-based umbrella and continue to intervene in patient care, policies, and procedures to reduce avoidable hospitalizations.

The development of value-based arrangements offers the healthcare system a unique opportunity to bring much-needed change. In our medical partnerships, direct communication with providers regarding their member experience and sharing of vital information about their patients’ health status have helped improve patient outcomes and decrease cost. Our IMH partnerships show a savings of up to $45,000 per member per year driven by decreases in admissions and ER visits, and in some cases, expensive medications. The hard work in these successes lies within the subtleties of fostering the relationship between payers and providers. Each pillar within the ecosystem plays a key role offering strengths, but the upside toward change comes in how we support each other’s weaknesses. This support is manifested in two ways: collaboration through communication and transparency through data sharing.

The road to change is one less traveled but not unpaved; advances in technology allow us to take experiences and build from them. At its core, technology has enhanced our collaboration and data capabilities. The ability to stay in touch with providers allows for almost real-time addressing of issues, promoting efficiency. The connection we have with providers has evolved from being solely paper contracts to a multichannel, multifunctional system. The ability to take claims experience, insert clinical acumen, and perform data analysis brings actionable solutions to be executed by our providers.

Those in the healthcare system will need to come together to continue to create interventions that improve quality while decreasing costs. The second part may require even more work than the first. The Health Care Cost Institute recently published data showing that inpatient utilization over a five-year period fell 12.9% in the commercially insured.5 However, over that same period, hospital prices for inpatient care rose 24.3%. The fundamental reason for the excess amount of money spent in US healthcare is that the prices are incredibly high.6 Currently, when diligence is exercised in reducing utilization, hospitals simply raise prices as a response to compensate for the lost income. Likewise, although prescription drug utilization only increased 1.8% during that period, the prices increased by 24.9%.

For the United States healthcare system to improve its quality and reduce its cost, we will need inventive partnerships to continue to create new systems to interact with patients in the most efficient and effective way possible. Readmissions and hospital utilization will be a large part of that improvement. Hospitals and hospitalists should ensure that they continue to focus on making healthcare more affordable by improving efficiency and outcomes and by resisting the tendencies of hospitals and pharmaceutical companies to raise prices in reaction to the improved efficiency.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Goodwin A, Henschen BL, O’Dwyer LC, Nichols N, O’Leary KJ. Interventions for Frequently Hospitalized Patients and their Effect on Outcomes: A Systematic Review. J Hosp Med. 2018; 13(12):853-859. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3089. PubMed

2. Marketplace. Fed Chair Jay Powel. https://www.marketplace.org/2018/07/12/economy/powell-transcript. Accessed August 3, 2018.

3. Health System Tracker. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/health-expenditures-vary-across-population/#item-start%2012/01/2017. Accessed August 3, 2018.

4. NEJM Catalyst. Consistently High Turnover in the Group of Top Health Care Spenders. https://catalyst.nejm.org/high-turnover-top-health-care-spenders/. Accessed August 3, 2018.

5. Health Care Cost Institute. 2016 Health Care Cost and Utilization Report. http://www.healthcostinstitute.org/report/2016-health-care-cost-utilization-report/. Accessed August 3, 2018.

6. Anderson GF, Reinhardt UE, Hussey PS, Peterosyan V. It’s the prices, stupid: why the United States is so different from other countries. Health Aff (Millwood). 2003;22(3):89-105. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.3.89. PubMed

In this month’s edition of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Goodwin and colleagues report their findings from their systematic review of models of care for frequently hospitalized patients. The authors reviewed the literature for interventions to reduce hospital admissions in frequently hospitalized patients with the goal of assessing the success of the interventions. This report contributes to the literature base of interventions to reduce healthcare utilization, particularly in the area of inpatient hospitalization.1

Goodwin et al. report that only nine studies met their criteria for review after a thorough search of the published literature. Of these nine studies, only four were determined to be high-quality studies. Interestingly, the low-quality studies found positive results in reducing hospital utilization, whereas the high-quality studies found decreases that were mirrored by their control groups. Impressive heterogeneity was found in the range of definitions, interventions, and outcome measures in the studies. These studies highlight the issue of “regression to the mean” for sicker individuals; however, they may not address readmission rates of specific medical systems or procedures that are also cost drivers, even if the patients are not considered critically ill. They also show where research partnerships can assist in increasing the number of members included in the studies for robust analyses.

From the perspective of a health plan, we applaud all efforts to improve patient outcomes and reduce cost. This report states that efforts to reduce chronic hospitalizations have not been unqualified successes. We must reflect upon how reducing utilization and improving outcomes align with our overall goals as a society. Recently, Federal Reserve Chairman Jay Powell summed up our nation’s particular issue, stating, “It is widely understood that the United States is on an unsustainable fiscal path, largely due to the interaction between an aging population and a healthcare system that delivers pretty average healthcare at a cost that is much higher than that of any other advanced economy.”2

A recent Kaiser Family Foundation analysis showed that 1% of patients accounted for 23% of all medical spending in the United States, and 97% of medical spending is attributed to the top 50% of patients.3 Pharmaceutical costs also play a role in this trend. Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Texas (BCBSTX) found that 2.5% of our population accounted for just under 50% of total medical spending. Conversely, when looking at patients with very high costs, only 0.4% had over $100,000 in spending exclusive of pharmacy. When including pharmacy, that number rises to 0.5%. As we consider annual medical and pharmacy trends year over year, we find that pharmacy spending may outpace hospital expenses in the near future.

Our internal data are also consistent with published reports that fewer than half of high-cost patients in one year continue to be high-cost cases the following year. Niall Brennan et al. reported that only 39% of the top 5% of spenders in a given year are also high spenders the following year.4 This finding not only coincides with the author’s statement around regression to the mean for the high admission utilizers, but it may be instructive to those looking to a Pareto method of attacking cost. If more than half of targeted patients will move out of the high cost category on their own, then demonstrating the effectiveness of interventions becomes challenging. Moreover, this regression finding speaks to the need to create effective programs to manage population health on a broad basis, which can address quality to all members and streamline costs for a large group that covers well more than 50% of medical spending.

BCBSTX emphasizes the creation of systems that let providers become responsible and accountable to outcomes and cost. Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) and Intensive Medical Homes (IMHs) have played important roles in this journey, but physicians need to continue to invent and prioritize interventions that may achieve both goals. In particular, hospitalists have an important role to play. As ACOs flourish, hospitalists will need to join under the value-based umbrella and continue to intervene in patient care, policies, and procedures to reduce avoidable hospitalizations.

The development of value-based arrangements offers the healthcare system a unique opportunity to bring much-needed change. In our medical partnerships, direct communication with providers regarding their member experience and sharing of vital information about their patients’ health status have helped improve patient outcomes and decrease cost. Our IMH partnerships show a savings of up to $45,000 per member per year driven by decreases in admissions and ER visits, and in some cases, expensive medications. The hard work in these successes lies within the subtleties of fostering the relationship between payers and providers. Each pillar within the ecosystem plays a key role offering strengths, but the upside toward change comes in how we support each other’s weaknesses. This support is manifested in two ways: collaboration through communication and transparency through data sharing.

The road to change is one less traveled but not unpaved; advances in technology allow us to take experiences and build from them. At its core, technology has enhanced our collaboration and data capabilities. The ability to stay in touch with providers allows for almost real-time addressing of issues, promoting efficiency. The connection we have with providers has evolved from being solely paper contracts to a multichannel, multifunctional system. The ability to take claims experience, insert clinical acumen, and perform data analysis brings actionable solutions to be executed by our providers.

Those in the healthcare system will need to come together to continue to create interventions that improve quality while decreasing costs. The second part may require even more work than the first. The Health Care Cost Institute recently published data showing that inpatient utilization over a five-year period fell 12.9% in the commercially insured.5 However, over that same period, hospital prices for inpatient care rose 24.3%. The fundamental reason for the excess amount of money spent in US healthcare is that the prices are incredibly high.6 Currently, when diligence is exercised in reducing utilization, hospitals simply raise prices as a response to compensate for the lost income. Likewise, although prescription drug utilization only increased 1.8% during that period, the prices increased by 24.9%.

For the United States healthcare system to improve its quality and reduce its cost, we will need inventive partnerships to continue to create new systems to interact with patients in the most efficient and effective way possible. Readmissions and hospital utilization will be a large part of that improvement. Hospitals and hospitalists should ensure that they continue to focus on making healthcare more affordable by improving efficiency and outcomes and by resisting the tendencies of hospitals and pharmaceutical companies to raise prices in reaction to the improved efficiency.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

In this month’s edition of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Goodwin and colleagues report their findings from their systematic review of models of care for frequently hospitalized patients. The authors reviewed the literature for interventions to reduce hospital admissions in frequently hospitalized patients with the goal of assessing the success of the interventions. This report contributes to the literature base of interventions to reduce healthcare utilization, particularly in the area of inpatient hospitalization.1

Goodwin et al. report that only nine studies met their criteria for review after a thorough search of the published literature. Of these nine studies, only four were determined to be high-quality studies. Interestingly, the low-quality studies found positive results in reducing hospital utilization, whereas the high-quality studies found decreases that were mirrored by their control groups. Impressive heterogeneity was found in the range of definitions, interventions, and outcome measures in the studies. These studies highlight the issue of “regression to the mean” for sicker individuals; however, they may not address readmission rates of specific medical systems or procedures that are also cost drivers, even if the patients are not considered critically ill. They also show where research partnerships can assist in increasing the number of members included in the studies for robust analyses.

From the perspective of a health plan, we applaud all efforts to improve patient outcomes and reduce cost. This report states that efforts to reduce chronic hospitalizations have not been unqualified successes. We must reflect upon how reducing utilization and improving outcomes align with our overall goals as a society. Recently, Federal Reserve Chairman Jay Powell summed up our nation’s particular issue, stating, “It is widely understood that the United States is on an unsustainable fiscal path, largely due to the interaction between an aging population and a healthcare system that delivers pretty average healthcare at a cost that is much higher than that of any other advanced economy.”2

A recent Kaiser Family Foundation analysis showed that 1% of patients accounted for 23% of all medical spending in the United States, and 97% of medical spending is attributed to the top 50% of patients.3 Pharmaceutical costs also play a role in this trend. Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Texas (BCBSTX) found that 2.5% of our population accounted for just under 50% of total medical spending. Conversely, when looking at patients with very high costs, only 0.4% had over $100,000 in spending exclusive of pharmacy. When including pharmacy, that number rises to 0.5%. As we consider annual medical and pharmacy trends year over year, we find that pharmacy spending may outpace hospital expenses in the near future.

Our internal data are also consistent with published reports that fewer than half of high-cost patients in one year continue to be high-cost cases the following year. Niall Brennan et al. reported that only 39% of the top 5% of spenders in a given year are also high spenders the following year.4 This finding not only coincides with the author’s statement around regression to the mean for the high admission utilizers, but it may be instructive to those looking to a Pareto method of attacking cost. If more than half of targeted patients will move out of the high cost category on their own, then demonstrating the effectiveness of interventions becomes challenging. Moreover, this regression finding speaks to the need to create effective programs to manage population health on a broad basis, which can address quality to all members and streamline costs for a large group that covers well more than 50% of medical spending.

BCBSTX emphasizes the creation of systems that let providers become responsible and accountable to outcomes and cost. Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) and Intensive Medical Homes (IMHs) have played important roles in this journey, but physicians need to continue to invent and prioritize interventions that may achieve both goals. In particular, hospitalists have an important role to play. As ACOs flourish, hospitalists will need to join under the value-based umbrella and continue to intervene in patient care, policies, and procedures to reduce avoidable hospitalizations.

The development of value-based arrangements offers the healthcare system a unique opportunity to bring much-needed change. In our medical partnerships, direct communication with providers regarding their member experience and sharing of vital information about their patients’ health status have helped improve patient outcomes and decrease cost. Our IMH partnerships show a savings of up to $45,000 per member per year driven by decreases in admissions and ER visits, and in some cases, expensive medications. The hard work in these successes lies within the subtleties of fostering the relationship between payers and providers. Each pillar within the ecosystem plays a key role offering strengths, but the upside toward change comes in how we support each other’s weaknesses. This support is manifested in two ways: collaboration through communication and transparency through data sharing.

The road to change is one less traveled but not unpaved; advances in technology allow us to take experiences and build from them. At its core, technology has enhanced our collaboration and data capabilities. The ability to stay in touch with providers allows for almost real-time addressing of issues, promoting efficiency. The connection we have with providers has evolved from being solely paper contracts to a multichannel, multifunctional system. The ability to take claims experience, insert clinical acumen, and perform data analysis brings actionable solutions to be executed by our providers.

Those in the healthcare system will need to come together to continue to create interventions that improve quality while decreasing costs. The second part may require even more work than the first. The Health Care Cost Institute recently published data showing that inpatient utilization over a five-year period fell 12.9% in the commercially insured.5 However, over that same period, hospital prices for inpatient care rose 24.3%. The fundamental reason for the excess amount of money spent in US healthcare is that the prices are incredibly high.6 Currently, when diligence is exercised in reducing utilization, hospitals simply raise prices as a response to compensate for the lost income. Likewise, although prescription drug utilization only increased 1.8% during that period, the prices increased by 24.9%.

For the United States healthcare system to improve its quality and reduce its cost, we will need inventive partnerships to continue to create new systems to interact with patients in the most efficient and effective way possible. Readmissions and hospital utilization will be a large part of that improvement. Hospitals and hospitalists should ensure that they continue to focus on making healthcare more affordable by improving efficiency and outcomes and by resisting the tendencies of hospitals and pharmaceutical companies to raise prices in reaction to the improved efficiency.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

1. Goodwin A, Henschen BL, O’Dwyer LC, Nichols N, O’Leary KJ. Interventions for Frequently Hospitalized Patients and their Effect on Outcomes: A Systematic Review. J Hosp Med. 2018; 13(12):853-859. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3089. PubMed

2. Marketplace. Fed Chair Jay Powel. https://www.marketplace.org/2018/07/12/economy/powell-transcript. Accessed August 3, 2018.

3. Health System Tracker. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/health-expenditures-vary-across-population/#item-start%2012/01/2017. Accessed August 3, 2018.

4. NEJM Catalyst. Consistently High Turnover in the Group of Top Health Care Spenders. https://catalyst.nejm.org/high-turnover-top-health-care-spenders/. Accessed August 3, 2018.

5. Health Care Cost Institute. 2016 Health Care Cost and Utilization Report. http://www.healthcostinstitute.org/report/2016-health-care-cost-utilization-report/. Accessed August 3, 2018.

6. Anderson GF, Reinhardt UE, Hussey PS, Peterosyan V. It’s the prices, stupid: why the United States is so different from other countries. Health Aff (Millwood). 2003;22(3):89-105. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.3.89. PubMed

1. Goodwin A, Henschen BL, O’Dwyer LC, Nichols N, O’Leary KJ. Interventions for Frequently Hospitalized Patients and their Effect on Outcomes: A Systematic Review. J Hosp Med. 2018; 13(12):853-859. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3089. PubMed

2. Marketplace. Fed Chair Jay Powel. https://www.marketplace.org/2018/07/12/economy/powell-transcript. Accessed August 3, 2018.

3. Health System Tracker. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/health-expenditures-vary-across-population/#item-start%2012/01/2017. Accessed August 3, 2018.

4. NEJM Catalyst. Consistently High Turnover in the Group of Top Health Care Spenders. https://catalyst.nejm.org/high-turnover-top-health-care-spenders/. Accessed August 3, 2018.

5. Health Care Cost Institute. 2016 Health Care Cost and Utilization Report. http://www.healthcostinstitute.org/report/2016-health-care-cost-utilization-report/. Accessed August 3, 2018.